User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Omecamtiv mecarbil fails to improve exercise capacity in HFrEF

Treatment with the novel agent omecamtiv mecarbil did not improve exercise capacity in people with chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), in the METEORIC-HF trial.

The double-blind, phase 3 study failed to achieve its primary endpoint of change in peak oxygen uptake (VO2) after 20 weeks of treatment with omecamtiv mecarbil, compared with placebo.

There also was no benefit on secondary measures of total workload, ventilatory efficiency, and daily physical activity, according to results presented earlier this year at ACC 2022 and formally published this month in JAMA.

“These findings do not support the use of omecamtiv mecarbil for treatment of HFrEF for improvement of exercise capacity,” lead author Gregory D. Lewis, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and colleagues conclude in the paper.

Researchers had hoped that the oral selective myosin activator would prove useful in this subset of patients, having previously shown in the GALACTIC-HF trial to provide a significant improvement in heart failure (HF) events and cardiovascular death.

A prespecified subgroup analysis from that trial also found that HF patients with the lowest ejection fraction derived the greatest relative benefit from omecamtiv mecarbil.

“The lack of effect of omecamtiv mecarbil on exercise performance is inconsistent with its known mechanism of action of directly enhancing ventricular performance and reducing the risk of cardiovascular events,” Dr. Lewis and colleagues observe.

The drug’s novel mechanism of action, direct activation of myosin, contrasts with that of currently available inotropic agents, such as dobutamine or milrinone. It is not yet approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration but is scheduled for an advisory committee meeting on Dec. 13, 2022, and has been assigned a Prescription Drug User Fee Act date of Feb. 28, 2023.

METEORIC-HF randomly assigned 276 patients with New York Heart Association class II or III symptoms and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less to omecamtiv mecarbil (n = 185) or placebo (n = 91), given orally twice daily at a dose of 25 mg, 37.5 mg, or 50 mg based on target plasma levels for 20 weeks, on top of guideline-directed medical therapy.

The patients’ median age was 64 years and 15% were women. The median ejection fraction was 28% and median baseline peak VO2 was 14.2 mL/kg per minute in the omecamtiv mecarbil group and 15.0 mL/kg per minute in the control group.

At 20 weeks, the mean change in peak VO2 in the omecamtiv mecarbil group was –0.24 mL/kg per minute and 0.21 mL/kg per minute in the placebo group (95% confidence interval, –1.02-0.13; P = .13).

For the secondary outcomes, the change in workload achieved on stress testing declined in the omecamtiv mecarbil group (–3.8 vs. 1.6). The drug had a neutral effect on minute ventilation relative to carbon dioxide production throughout exercise (0.28 vs. –0.14 VE/VCO2 slope) and average total daily activity units, measured over 2 weeks by accelerometer (–0.2 vs. –0.5).

The authors suggest that “one possible explanation for discordance between clinical events in a long-term follow-up study and exercise capacity improvement is that cardiac performance was not exclusively responsible for limiting exercise capacity in trial participants with HFrEF who were stable and very well treated with both pharmacologic and device HFrEF therapy.”

In an accompanying editorial, Mark H. Drazner, MD, MSc, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, writes that another possible explanation is that participants in METEORIC-HF had less severe heart failure, compared with participants in GALACTIC-HF, and so were less likely to benefit from omecamtiv mecarbil.

METEORIC-HF excluded participants who had a HF hospitalization that required intravenous diuretics in the preceding 3 months, whereas 25% of participants in GALACTIC-HF were inpatients for decompensated HF and 36% had a HF hospitalization within the preceding 3 months.

Another plausible explanation for the differing results is that a therapy that improves long-term clinical outcomes may not improve exercise capacity, Dr. Drazner writes. “The available data are persuasive to suggest this may be the case.”

Some pharmacologic therapies, such as flosequinan, improved exercise capacity in patients with HF yet increased long-term mortality, he noted. Several medications that have a class I recommendation in the 2022 Heart Failure Guideline for the treatment of HFrEF also have not been shown to improve exercise capacity, as measured by peak VO2 or by 6-minute walk distance.

In this context, Dr. Drazner said he doesn’t anticipate the METEORIC-HF findings to derail FDA approval. However, should the drug be approved, clinicians will have increasingly complex decisions to make about which therapies should be prescribed to which patients.

“Some clinicians may contemplate using omecamtiv mecarbil either in the subgroup of patients with very low ejection fractions or more severe disease, believing this strategy will maximize the benefits of this therapy, but those approaches should be pursued with caution given they are predicated on subgroup and post hoc analyses, respectively,” he wrote.

Dr. Drazner concludes that medications known to improve survival in patients with HFrEF are used at “disappointingly low rates and suboptimal doses in the United States. Implementation strategies to improve use of such therapies are needed, and those efforts should be prioritized before adoption of therapies that reduce morbidity but not cardiovascular mortality.”

The study was sponsored by Amgen and Cytokinetics. Dr. Lewis reports financial relationships with the National Institutes of Health, American Heart Association, Amgen, Cytokinetics, Applied Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, SoniVie, Pfizer, Merck, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, American Regent, Cyclerion, MyoKardia, Novo Nordisk, and UpToDate. Dr. Drazner reports being a member of the writing committee of the 2022 Heart Failure guidelines; and that he is supported by the James M. Wooten Chair in Cardiology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, which was a clinical site in METEORIC-HF. However, Dr. Drazner was not a study investigator in the trial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Treatment with the novel agent omecamtiv mecarbil did not improve exercise capacity in people with chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), in the METEORIC-HF trial.

The double-blind, phase 3 study failed to achieve its primary endpoint of change in peak oxygen uptake (VO2) after 20 weeks of treatment with omecamtiv mecarbil, compared with placebo.

There also was no benefit on secondary measures of total workload, ventilatory efficiency, and daily physical activity, according to results presented earlier this year at ACC 2022 and formally published this month in JAMA.

“These findings do not support the use of omecamtiv mecarbil for treatment of HFrEF for improvement of exercise capacity,” lead author Gregory D. Lewis, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and colleagues conclude in the paper.

Researchers had hoped that the oral selective myosin activator would prove useful in this subset of patients, having previously shown in the GALACTIC-HF trial to provide a significant improvement in heart failure (HF) events and cardiovascular death.

A prespecified subgroup analysis from that trial also found that HF patients with the lowest ejection fraction derived the greatest relative benefit from omecamtiv mecarbil.

“The lack of effect of omecamtiv mecarbil on exercise performance is inconsistent with its known mechanism of action of directly enhancing ventricular performance and reducing the risk of cardiovascular events,” Dr. Lewis and colleagues observe.

The drug’s novel mechanism of action, direct activation of myosin, contrasts with that of currently available inotropic agents, such as dobutamine or milrinone. It is not yet approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration but is scheduled for an advisory committee meeting on Dec. 13, 2022, and has been assigned a Prescription Drug User Fee Act date of Feb. 28, 2023.

METEORIC-HF randomly assigned 276 patients with New York Heart Association class II or III symptoms and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less to omecamtiv mecarbil (n = 185) or placebo (n = 91), given orally twice daily at a dose of 25 mg, 37.5 mg, or 50 mg based on target plasma levels for 20 weeks, on top of guideline-directed medical therapy.

The patients’ median age was 64 years and 15% were women. The median ejection fraction was 28% and median baseline peak VO2 was 14.2 mL/kg per minute in the omecamtiv mecarbil group and 15.0 mL/kg per minute in the control group.

At 20 weeks, the mean change in peak VO2 in the omecamtiv mecarbil group was –0.24 mL/kg per minute and 0.21 mL/kg per minute in the placebo group (95% confidence interval, –1.02-0.13; P = .13).

For the secondary outcomes, the change in workload achieved on stress testing declined in the omecamtiv mecarbil group (–3.8 vs. 1.6). The drug had a neutral effect on minute ventilation relative to carbon dioxide production throughout exercise (0.28 vs. –0.14 VE/VCO2 slope) and average total daily activity units, measured over 2 weeks by accelerometer (–0.2 vs. –0.5).

The authors suggest that “one possible explanation for discordance between clinical events in a long-term follow-up study and exercise capacity improvement is that cardiac performance was not exclusively responsible for limiting exercise capacity in trial participants with HFrEF who were stable and very well treated with both pharmacologic and device HFrEF therapy.”

In an accompanying editorial, Mark H. Drazner, MD, MSc, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, writes that another possible explanation is that participants in METEORIC-HF had less severe heart failure, compared with participants in GALACTIC-HF, and so were less likely to benefit from omecamtiv mecarbil.

METEORIC-HF excluded participants who had a HF hospitalization that required intravenous diuretics in the preceding 3 months, whereas 25% of participants in GALACTIC-HF were inpatients for decompensated HF and 36% had a HF hospitalization within the preceding 3 months.

Another plausible explanation for the differing results is that a therapy that improves long-term clinical outcomes may not improve exercise capacity, Dr. Drazner writes. “The available data are persuasive to suggest this may be the case.”

Some pharmacologic therapies, such as flosequinan, improved exercise capacity in patients with HF yet increased long-term mortality, he noted. Several medications that have a class I recommendation in the 2022 Heart Failure Guideline for the treatment of HFrEF also have not been shown to improve exercise capacity, as measured by peak VO2 or by 6-minute walk distance.

In this context, Dr. Drazner said he doesn’t anticipate the METEORIC-HF findings to derail FDA approval. However, should the drug be approved, clinicians will have increasingly complex decisions to make about which therapies should be prescribed to which patients.

“Some clinicians may contemplate using omecamtiv mecarbil either in the subgroup of patients with very low ejection fractions or more severe disease, believing this strategy will maximize the benefits of this therapy, but those approaches should be pursued with caution given they are predicated on subgroup and post hoc analyses, respectively,” he wrote.

Dr. Drazner concludes that medications known to improve survival in patients with HFrEF are used at “disappointingly low rates and suboptimal doses in the United States. Implementation strategies to improve use of such therapies are needed, and those efforts should be prioritized before adoption of therapies that reduce morbidity but not cardiovascular mortality.”

The study was sponsored by Amgen and Cytokinetics. Dr. Lewis reports financial relationships with the National Institutes of Health, American Heart Association, Amgen, Cytokinetics, Applied Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, SoniVie, Pfizer, Merck, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, American Regent, Cyclerion, MyoKardia, Novo Nordisk, and UpToDate. Dr. Drazner reports being a member of the writing committee of the 2022 Heart Failure guidelines; and that he is supported by the James M. Wooten Chair in Cardiology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, which was a clinical site in METEORIC-HF. However, Dr. Drazner was not a study investigator in the trial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Treatment with the novel agent omecamtiv mecarbil did not improve exercise capacity in people with chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), in the METEORIC-HF trial.

The double-blind, phase 3 study failed to achieve its primary endpoint of change in peak oxygen uptake (VO2) after 20 weeks of treatment with omecamtiv mecarbil, compared with placebo.

There also was no benefit on secondary measures of total workload, ventilatory efficiency, and daily physical activity, according to results presented earlier this year at ACC 2022 and formally published this month in JAMA.

“These findings do not support the use of omecamtiv mecarbil for treatment of HFrEF for improvement of exercise capacity,” lead author Gregory D. Lewis, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and colleagues conclude in the paper.

Researchers had hoped that the oral selective myosin activator would prove useful in this subset of patients, having previously shown in the GALACTIC-HF trial to provide a significant improvement in heart failure (HF) events and cardiovascular death.

A prespecified subgroup analysis from that trial also found that HF patients with the lowest ejection fraction derived the greatest relative benefit from omecamtiv mecarbil.

“The lack of effect of omecamtiv mecarbil on exercise performance is inconsistent with its known mechanism of action of directly enhancing ventricular performance and reducing the risk of cardiovascular events,” Dr. Lewis and colleagues observe.

The drug’s novel mechanism of action, direct activation of myosin, contrasts with that of currently available inotropic agents, such as dobutamine or milrinone. It is not yet approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration but is scheduled for an advisory committee meeting on Dec. 13, 2022, and has been assigned a Prescription Drug User Fee Act date of Feb. 28, 2023.

METEORIC-HF randomly assigned 276 patients with New York Heart Association class II or III symptoms and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less to omecamtiv mecarbil (n = 185) or placebo (n = 91), given orally twice daily at a dose of 25 mg, 37.5 mg, or 50 mg based on target plasma levels for 20 weeks, on top of guideline-directed medical therapy.

The patients’ median age was 64 years and 15% were women. The median ejection fraction was 28% and median baseline peak VO2 was 14.2 mL/kg per minute in the omecamtiv mecarbil group and 15.0 mL/kg per minute in the control group.

At 20 weeks, the mean change in peak VO2 in the omecamtiv mecarbil group was –0.24 mL/kg per minute and 0.21 mL/kg per minute in the placebo group (95% confidence interval, –1.02-0.13; P = .13).

For the secondary outcomes, the change in workload achieved on stress testing declined in the omecamtiv mecarbil group (–3.8 vs. 1.6). The drug had a neutral effect on minute ventilation relative to carbon dioxide production throughout exercise (0.28 vs. –0.14 VE/VCO2 slope) and average total daily activity units, measured over 2 weeks by accelerometer (–0.2 vs. –0.5).

The authors suggest that “one possible explanation for discordance between clinical events in a long-term follow-up study and exercise capacity improvement is that cardiac performance was not exclusively responsible for limiting exercise capacity in trial participants with HFrEF who were stable and very well treated with both pharmacologic and device HFrEF therapy.”

In an accompanying editorial, Mark H. Drazner, MD, MSc, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, writes that another possible explanation is that participants in METEORIC-HF had less severe heart failure, compared with participants in GALACTIC-HF, and so were less likely to benefit from omecamtiv mecarbil.

METEORIC-HF excluded participants who had a HF hospitalization that required intravenous diuretics in the preceding 3 months, whereas 25% of participants in GALACTIC-HF were inpatients for decompensated HF and 36% had a HF hospitalization within the preceding 3 months.

Another plausible explanation for the differing results is that a therapy that improves long-term clinical outcomes may not improve exercise capacity, Dr. Drazner writes. “The available data are persuasive to suggest this may be the case.”

Some pharmacologic therapies, such as flosequinan, improved exercise capacity in patients with HF yet increased long-term mortality, he noted. Several medications that have a class I recommendation in the 2022 Heart Failure Guideline for the treatment of HFrEF also have not been shown to improve exercise capacity, as measured by peak VO2 or by 6-minute walk distance.

In this context, Dr. Drazner said he doesn’t anticipate the METEORIC-HF findings to derail FDA approval. However, should the drug be approved, clinicians will have increasingly complex decisions to make about which therapies should be prescribed to which patients.

“Some clinicians may contemplate using omecamtiv mecarbil either in the subgroup of patients with very low ejection fractions or more severe disease, believing this strategy will maximize the benefits of this therapy, but those approaches should be pursued with caution given they are predicated on subgroup and post hoc analyses, respectively,” he wrote.

Dr. Drazner concludes that medications known to improve survival in patients with HFrEF are used at “disappointingly low rates and suboptimal doses in the United States. Implementation strategies to improve use of such therapies are needed, and those efforts should be prioritized before adoption of therapies that reduce morbidity but not cardiovascular mortality.”

The study was sponsored by Amgen and Cytokinetics. Dr. Lewis reports financial relationships with the National Institutes of Health, American Heart Association, Amgen, Cytokinetics, Applied Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, SoniVie, Pfizer, Merck, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, American Regent, Cyclerion, MyoKardia, Novo Nordisk, and UpToDate. Dr. Drazner reports being a member of the writing committee of the 2022 Heart Failure guidelines; and that he is supported by the James M. Wooten Chair in Cardiology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, which was a clinical site in METEORIC-HF. However, Dr. Drazner was not a study investigator in the trial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Onset and awareness of hypertension varies by race, ethnicity

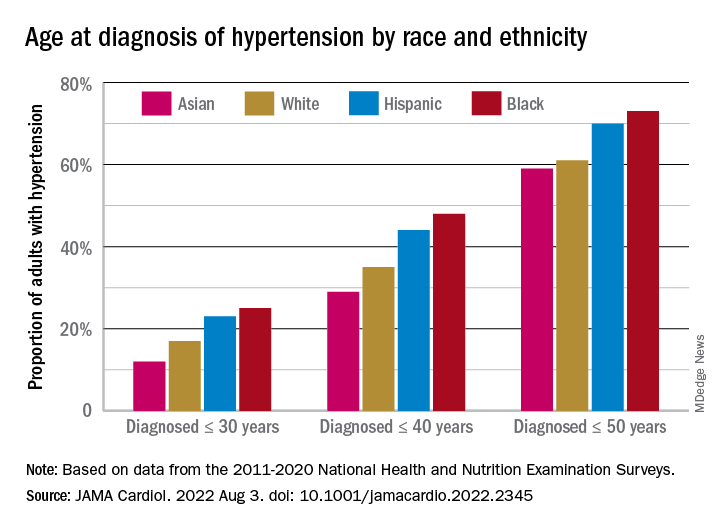

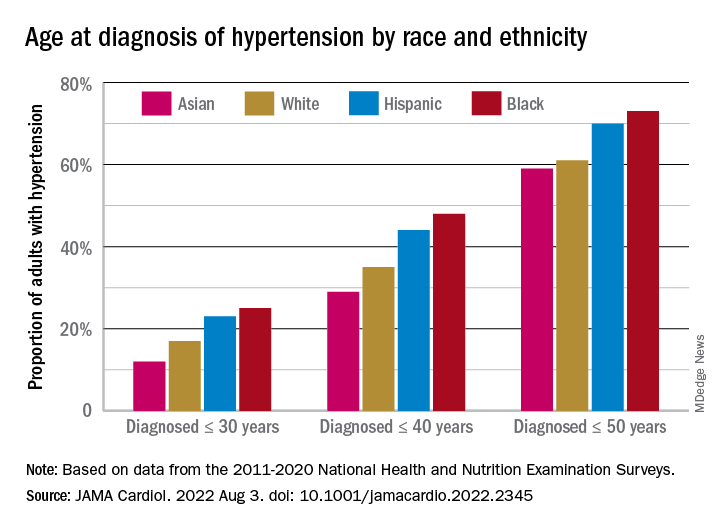

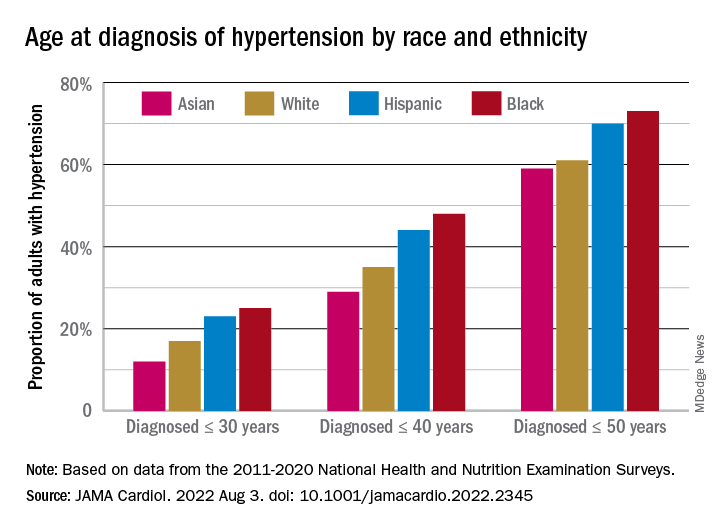

Black and Hispanic adults are diagnosed with hypertension at a significantly younger age than are white adults, and they also are more likely than Whites to be unaware of undiagnosed high blood pressure, based on national survey data collected from 2011 to 2020.

“Earlier hypertension onset in Black and Hispanic adults may contribute to racial and ethnic CVD disparities,” Xiaoning Huang, PhD, and associates wrote in JAMA Cardiology, also noting that “lower hypertension awareness among racial and ethnic minoritized groups suggests potential for underestimating differences in age at onset.”

Overall mean age at diagnosis was 46 years for the overall study sample of 9,627 participants in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys over the 10 years covered in the analysis. Black adults, with a median age of 42 years, and Hispanic adults (median, 43 years) were significantly younger at diagnosis than White adults, who had a median age of 47 years, the investigators reported.

“Earlier age at hypertension onset may mean greater cumulative exposure to high blood pressure across the life course, which is associated with increased risk of [cardiovascular disease] and may contribute to racial disparities in hypertension-related outcomes,” said Dr. Huang and associates at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The increased cumulative exposure can be seen when age at diagnosis is stratified “across the life course.” Black/Hispanic adults were significantly more likely than White/Asian adults to be diagnosed at or before 30 years of age, and that difference continued to at least age 50 years, the investigators said.

Many adults unaware of their hypertension

There was a somewhat different trend among those in the study population who reported BP at or above 140/90 mm Hg but did not report a hypertension diagnosis. Black, Hispanic, and Asian adults all were significantly more likely than White adults to be unaware of their hypertension, the survey data showed.

Overall, 18% of those who did not report a hypertension diagnosis had a BP of 140/90 mm Hg or higher and 38% had a BP of 130/80 mm Hg or more. Broken down by race and ethnicity, 16% and 36% of Whites reporting no hypertension had BPs of 140/90 and 130/80 mm Hg, respectively; those proportions were 21% and 42% for Hispanics, 24% and 44% for Asians, and 28% and 51% for Blacks, with all of the differences between Whites and the others significant, the research team reported.

One investigator is an associate editor for JAMA Cardiology and reported receiving grants from the American Heart Association and the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study. None of the other investigators reported any conflicts.

Black and Hispanic adults are diagnosed with hypertension at a significantly younger age than are white adults, and they also are more likely than Whites to be unaware of undiagnosed high blood pressure, based on national survey data collected from 2011 to 2020.

“Earlier hypertension onset in Black and Hispanic adults may contribute to racial and ethnic CVD disparities,” Xiaoning Huang, PhD, and associates wrote in JAMA Cardiology, also noting that “lower hypertension awareness among racial and ethnic minoritized groups suggests potential for underestimating differences in age at onset.”

Overall mean age at diagnosis was 46 years for the overall study sample of 9,627 participants in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys over the 10 years covered in the analysis. Black adults, with a median age of 42 years, and Hispanic adults (median, 43 years) were significantly younger at diagnosis than White adults, who had a median age of 47 years, the investigators reported.

“Earlier age at hypertension onset may mean greater cumulative exposure to high blood pressure across the life course, which is associated with increased risk of [cardiovascular disease] and may contribute to racial disparities in hypertension-related outcomes,” said Dr. Huang and associates at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The increased cumulative exposure can be seen when age at diagnosis is stratified “across the life course.” Black/Hispanic adults were significantly more likely than White/Asian adults to be diagnosed at or before 30 years of age, and that difference continued to at least age 50 years, the investigators said.

Many adults unaware of their hypertension

There was a somewhat different trend among those in the study population who reported BP at or above 140/90 mm Hg but did not report a hypertension diagnosis. Black, Hispanic, and Asian adults all were significantly more likely than White adults to be unaware of their hypertension, the survey data showed.

Overall, 18% of those who did not report a hypertension diagnosis had a BP of 140/90 mm Hg or higher and 38% had a BP of 130/80 mm Hg or more. Broken down by race and ethnicity, 16% and 36% of Whites reporting no hypertension had BPs of 140/90 and 130/80 mm Hg, respectively; those proportions were 21% and 42% for Hispanics, 24% and 44% for Asians, and 28% and 51% for Blacks, with all of the differences between Whites and the others significant, the research team reported.

One investigator is an associate editor for JAMA Cardiology and reported receiving grants from the American Heart Association and the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study. None of the other investigators reported any conflicts.

Black and Hispanic adults are diagnosed with hypertension at a significantly younger age than are white adults, and they also are more likely than Whites to be unaware of undiagnosed high blood pressure, based on national survey data collected from 2011 to 2020.

“Earlier hypertension onset in Black and Hispanic adults may contribute to racial and ethnic CVD disparities,” Xiaoning Huang, PhD, and associates wrote in JAMA Cardiology, also noting that “lower hypertension awareness among racial and ethnic minoritized groups suggests potential for underestimating differences in age at onset.”

Overall mean age at diagnosis was 46 years for the overall study sample of 9,627 participants in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys over the 10 years covered in the analysis. Black adults, with a median age of 42 years, and Hispanic adults (median, 43 years) were significantly younger at diagnosis than White adults, who had a median age of 47 years, the investigators reported.

“Earlier age at hypertension onset may mean greater cumulative exposure to high blood pressure across the life course, which is associated with increased risk of [cardiovascular disease] and may contribute to racial disparities in hypertension-related outcomes,” said Dr. Huang and associates at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The increased cumulative exposure can be seen when age at diagnosis is stratified “across the life course.” Black/Hispanic adults were significantly more likely than White/Asian adults to be diagnosed at or before 30 years of age, and that difference continued to at least age 50 years, the investigators said.

Many adults unaware of their hypertension

There was a somewhat different trend among those in the study population who reported BP at or above 140/90 mm Hg but did not report a hypertension diagnosis. Black, Hispanic, and Asian adults all were significantly more likely than White adults to be unaware of their hypertension, the survey data showed.

Overall, 18% of those who did not report a hypertension diagnosis had a BP of 140/90 mm Hg or higher and 38% had a BP of 130/80 mm Hg or more. Broken down by race and ethnicity, 16% and 36% of Whites reporting no hypertension had BPs of 140/90 and 130/80 mm Hg, respectively; those proportions were 21% and 42% for Hispanics, 24% and 44% for Asians, and 28% and 51% for Blacks, with all of the differences between Whites and the others significant, the research team reported.

One investigator is an associate editor for JAMA Cardiology and reported receiving grants from the American Heart Association and the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study. None of the other investigators reported any conflicts.

FROM JAMA CARDIOLOGY

One in eight COVID patients likely to develop long COVID: Large study

a large study published in The Lancet indicates.

The researchers determined that percentage by comparing long-term symptoms in people infected by SARS-CoV-2 with similar symptoms in uninfected people over the same time period.

Among the group of infected study participants in the Netherlands, 21.4% had at least one new or severely increased symptom 3-5 months after infection compared with before infection. When that group of 21.4% was compared with 8.7% of uninfected people in the same study, the researchers were able to calculate a prevalence 12.7% with long COVID.

“This finding shows that post–COVID-19 condition is an urgent problem with a mounting human toll,” the study authors wrote.

The research design was novel, two editorialists said in an accompanying commentary.

Christopher Brightling, PhD, and Rachael Evans, MBChB, PhD, of the Institute for Lung Health, University of Leicester (England), noted: “This is a major advance on prior long COVID prevalence estimates as it includes a matched uninfected group and accounts for symptoms before COVID-19 infection.”

Symptoms that persist

The Lancet study found that 3-5 months after COVID (compared with before COVID) and compared with the non-COVID comparison group, the symptoms that persist were chest pain, breathing difficulties, pain when breathing, muscle pain, loss of taste and/or smell, tingling extremities, lump in throat, feeling hot and cold alternately, heavy limbs, and tiredness.

The authors noted that symptoms such as brain fog were found to be relevant to long COVID after the data collection period for this paper and were not included in this research.

Researcher Aranka V. Ballering, MSc, PhD candidate, said in an interview that the researchers found fever is a symptom that is clearly present during the acute phase of the disease and it peaks the day of the COVID-19 diagnosis, but also wears off.

Loss of taste and smell, however, rapidly increases in severity when COVID-19 is diagnosed, but also persists and is still present 3-5 months after COVID.

Ms. Ballering, with the department of psychiatry at the University of Groningen (the Netherlands), said she was surprised by the sex difference made evident in their research: “Women showed more severe persistent symptoms than men.”

Closer to a clearer definition

The authors said their findings also pinpoint symptoms that bring us closer to a better definition of long COVID, which has many different definitions globally.

“These symptoms have the highest discriminative ability to distinguish between post–COVID-19 condition and non–COVID-19–related symptoms,” they wrote.

Researchers collected data by asking participants in the northern Netherlands, who were part of the population-based Lifelines COVID-19 study, to regularly complete digital questionnaires on 23 symptoms commonly associated with long COVID. The questionnaire was sent out 24 times to the same people between March 2020 and August 2021. At that time, people had the Alpha or earlier variants.

Participants were considered COVID-19 positive if they had either a positive test or a doctor’s diagnosis of COVID-19.

Of 76,422 study participants, the 5.5% (4,231) who had COVID were matched to 8,462 controls. Researchers accounted for sex, age, and time of completing questionnaires.

Effect of hospitalization, vaccination unclear

Ms. Ballering said it’s unclear from this data whether vaccination or whether a person was hospitalized would change the prevalence of persistent symptoms.

Because of the period when the data were collected, “the vast majority of our study population was not fully vaccinated,” she said.

However, she pointed to recent research that shows that immunization against COVID is only partially effective against persistent somatic symptoms after COVID.

Also, only 5% of men and 2.5% of women in the study were hospitalized as a result of COVID-19, so the findings can’t easily be generalized to hospitalized patients.

The Lifelines study was an add-on study to the multidisciplinary, prospective, population-based, observational Dutch Lifelines cohort study examining 167,729 people in the Netherlands. Almost all were White, a limitation of the study, and 58% were female. Average age was 54.

The editorialists also noted additional limitations of the study were that this research “did not fully consider the impact on mental health” and was conducted in one region in the Netherlands.

Janko Nikolich-Žugich, MD, PhD, director of the Aegis Consortium for Pandemic-Free Future and head of the immunobiology department at University of Arizona, Tucson, said in an interview that he agreed with the editorialists that a primary benefit of this study is that it corrected for symptoms people had before COVID, something other studies have not been able to do.

However, he cautioned about generalizing the results for the United States and other countries because of the lack of diversity in the study population with regard to education level, socioeconomic factors, and race. He pointed out that access issues are also different in the Netherlands, which has universal health care.

He said brain fog as a symptom of long COVID is of high interest and will be important to include in future studies that are able to extend the study period.

The work was funded by ZonMw; the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sport; Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs; University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen; and the provinces of Drenthe, Friesland, and Groningen. The study authors and Dr. Nikolich-Žugich have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Brightling has received consultancy and or grants paid to his institution from GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Chiesi, Genentech, Roche, Sanofi, Regeneron, Mologic, and 4DPharma for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease research. Dr. Evans has received consultancy fees from AstraZeneca on the topic of long COVID and from GlaxoSmithKline on digital health, and speaker’s fees from Boehringer Ingelheim on long COVID.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a large study published in The Lancet indicates.

The researchers determined that percentage by comparing long-term symptoms in people infected by SARS-CoV-2 with similar symptoms in uninfected people over the same time period.

Among the group of infected study participants in the Netherlands, 21.4% had at least one new or severely increased symptom 3-5 months after infection compared with before infection. When that group of 21.4% was compared with 8.7% of uninfected people in the same study, the researchers were able to calculate a prevalence 12.7% with long COVID.

“This finding shows that post–COVID-19 condition is an urgent problem with a mounting human toll,” the study authors wrote.

The research design was novel, two editorialists said in an accompanying commentary.

Christopher Brightling, PhD, and Rachael Evans, MBChB, PhD, of the Institute for Lung Health, University of Leicester (England), noted: “This is a major advance on prior long COVID prevalence estimates as it includes a matched uninfected group and accounts for symptoms before COVID-19 infection.”

Symptoms that persist

The Lancet study found that 3-5 months after COVID (compared with before COVID) and compared with the non-COVID comparison group, the symptoms that persist were chest pain, breathing difficulties, pain when breathing, muscle pain, loss of taste and/or smell, tingling extremities, lump in throat, feeling hot and cold alternately, heavy limbs, and tiredness.

The authors noted that symptoms such as brain fog were found to be relevant to long COVID after the data collection period for this paper and were not included in this research.

Researcher Aranka V. Ballering, MSc, PhD candidate, said in an interview that the researchers found fever is a symptom that is clearly present during the acute phase of the disease and it peaks the day of the COVID-19 diagnosis, but also wears off.

Loss of taste and smell, however, rapidly increases in severity when COVID-19 is diagnosed, but also persists and is still present 3-5 months after COVID.

Ms. Ballering, with the department of psychiatry at the University of Groningen (the Netherlands), said she was surprised by the sex difference made evident in their research: “Women showed more severe persistent symptoms than men.”

Closer to a clearer definition

The authors said their findings also pinpoint symptoms that bring us closer to a better definition of long COVID, which has many different definitions globally.

“These symptoms have the highest discriminative ability to distinguish between post–COVID-19 condition and non–COVID-19–related symptoms,” they wrote.

Researchers collected data by asking participants in the northern Netherlands, who were part of the population-based Lifelines COVID-19 study, to regularly complete digital questionnaires on 23 symptoms commonly associated with long COVID. The questionnaire was sent out 24 times to the same people between March 2020 and August 2021. At that time, people had the Alpha or earlier variants.

Participants were considered COVID-19 positive if they had either a positive test or a doctor’s diagnosis of COVID-19.

Of 76,422 study participants, the 5.5% (4,231) who had COVID were matched to 8,462 controls. Researchers accounted for sex, age, and time of completing questionnaires.

Effect of hospitalization, vaccination unclear

Ms. Ballering said it’s unclear from this data whether vaccination or whether a person was hospitalized would change the prevalence of persistent symptoms.

Because of the period when the data were collected, “the vast majority of our study population was not fully vaccinated,” she said.

However, she pointed to recent research that shows that immunization against COVID is only partially effective against persistent somatic symptoms after COVID.

Also, only 5% of men and 2.5% of women in the study were hospitalized as a result of COVID-19, so the findings can’t easily be generalized to hospitalized patients.

The Lifelines study was an add-on study to the multidisciplinary, prospective, population-based, observational Dutch Lifelines cohort study examining 167,729 people in the Netherlands. Almost all were White, a limitation of the study, and 58% were female. Average age was 54.

The editorialists also noted additional limitations of the study were that this research “did not fully consider the impact on mental health” and was conducted in one region in the Netherlands.

Janko Nikolich-Žugich, MD, PhD, director of the Aegis Consortium for Pandemic-Free Future and head of the immunobiology department at University of Arizona, Tucson, said in an interview that he agreed with the editorialists that a primary benefit of this study is that it corrected for symptoms people had before COVID, something other studies have not been able to do.

However, he cautioned about generalizing the results for the United States and other countries because of the lack of diversity in the study population with regard to education level, socioeconomic factors, and race. He pointed out that access issues are also different in the Netherlands, which has universal health care.

He said brain fog as a symptom of long COVID is of high interest and will be important to include in future studies that are able to extend the study period.

The work was funded by ZonMw; the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sport; Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs; University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen; and the provinces of Drenthe, Friesland, and Groningen. The study authors and Dr. Nikolich-Žugich have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Brightling has received consultancy and or grants paid to his institution from GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Chiesi, Genentech, Roche, Sanofi, Regeneron, Mologic, and 4DPharma for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease research. Dr. Evans has received consultancy fees from AstraZeneca on the topic of long COVID and from GlaxoSmithKline on digital health, and speaker’s fees from Boehringer Ingelheim on long COVID.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a large study published in The Lancet indicates.

The researchers determined that percentage by comparing long-term symptoms in people infected by SARS-CoV-2 with similar symptoms in uninfected people over the same time period.

Among the group of infected study participants in the Netherlands, 21.4% had at least one new or severely increased symptom 3-5 months after infection compared with before infection. When that group of 21.4% was compared with 8.7% of uninfected people in the same study, the researchers were able to calculate a prevalence 12.7% with long COVID.

“This finding shows that post–COVID-19 condition is an urgent problem with a mounting human toll,” the study authors wrote.

The research design was novel, two editorialists said in an accompanying commentary.

Christopher Brightling, PhD, and Rachael Evans, MBChB, PhD, of the Institute for Lung Health, University of Leicester (England), noted: “This is a major advance on prior long COVID prevalence estimates as it includes a matched uninfected group and accounts for symptoms before COVID-19 infection.”

Symptoms that persist

The Lancet study found that 3-5 months after COVID (compared with before COVID) and compared with the non-COVID comparison group, the symptoms that persist were chest pain, breathing difficulties, pain when breathing, muscle pain, loss of taste and/or smell, tingling extremities, lump in throat, feeling hot and cold alternately, heavy limbs, and tiredness.

The authors noted that symptoms such as brain fog were found to be relevant to long COVID after the data collection period for this paper and were not included in this research.

Researcher Aranka V. Ballering, MSc, PhD candidate, said in an interview that the researchers found fever is a symptom that is clearly present during the acute phase of the disease and it peaks the day of the COVID-19 diagnosis, but also wears off.

Loss of taste and smell, however, rapidly increases in severity when COVID-19 is diagnosed, but also persists and is still present 3-5 months after COVID.

Ms. Ballering, with the department of psychiatry at the University of Groningen (the Netherlands), said she was surprised by the sex difference made evident in their research: “Women showed more severe persistent symptoms than men.”

Closer to a clearer definition

The authors said their findings also pinpoint symptoms that bring us closer to a better definition of long COVID, which has many different definitions globally.

“These symptoms have the highest discriminative ability to distinguish between post–COVID-19 condition and non–COVID-19–related symptoms,” they wrote.

Researchers collected data by asking participants in the northern Netherlands, who were part of the population-based Lifelines COVID-19 study, to regularly complete digital questionnaires on 23 symptoms commonly associated with long COVID. The questionnaire was sent out 24 times to the same people between March 2020 and August 2021. At that time, people had the Alpha or earlier variants.

Participants were considered COVID-19 positive if they had either a positive test or a doctor’s diagnosis of COVID-19.

Of 76,422 study participants, the 5.5% (4,231) who had COVID were matched to 8,462 controls. Researchers accounted for sex, age, and time of completing questionnaires.

Effect of hospitalization, vaccination unclear

Ms. Ballering said it’s unclear from this data whether vaccination or whether a person was hospitalized would change the prevalence of persistent symptoms.

Because of the period when the data were collected, “the vast majority of our study population was not fully vaccinated,” she said.

However, she pointed to recent research that shows that immunization against COVID is only partially effective against persistent somatic symptoms after COVID.

Also, only 5% of men and 2.5% of women in the study were hospitalized as a result of COVID-19, so the findings can’t easily be generalized to hospitalized patients.

The Lifelines study was an add-on study to the multidisciplinary, prospective, population-based, observational Dutch Lifelines cohort study examining 167,729 people in the Netherlands. Almost all were White, a limitation of the study, and 58% were female. Average age was 54.

The editorialists also noted additional limitations of the study were that this research “did not fully consider the impact on mental health” and was conducted in one region in the Netherlands.

Janko Nikolich-Žugich, MD, PhD, director of the Aegis Consortium for Pandemic-Free Future and head of the immunobiology department at University of Arizona, Tucson, said in an interview that he agreed with the editorialists that a primary benefit of this study is that it corrected for symptoms people had before COVID, something other studies have not been able to do.

However, he cautioned about generalizing the results for the United States and other countries because of the lack of diversity in the study population with regard to education level, socioeconomic factors, and race. He pointed out that access issues are also different in the Netherlands, which has universal health care.

He said brain fog as a symptom of long COVID is of high interest and will be important to include in future studies that are able to extend the study period.

The work was funded by ZonMw; the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sport; Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs; University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen; and the provinces of Drenthe, Friesland, and Groningen. The study authors and Dr. Nikolich-Žugich have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Brightling has received consultancy and or grants paid to his institution from GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Chiesi, Genentech, Roche, Sanofi, Regeneron, Mologic, and 4DPharma for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease research. Dr. Evans has received consultancy fees from AstraZeneca on the topic of long COVID and from GlaxoSmithKline on digital health, and speaker’s fees from Boehringer Ingelheim on long COVID.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE LANCET

Long COVID doubles risk of some serious outcomes in children, teens

Researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that

Heart inflammation; a blood clot in the lung; or a blood clot in the lower leg, thigh, or pelvis were the most common bad outcomes in a new study. Even though the risk was higher for these and some other serious events, the overall numbers were small.

“Many of these conditions were rare or uncommon among children in this analysis, but even a small increase in these conditions is notable,” a CDC new release stated.

The investigators said their findings stress the importance of COVID-19 vaccination in Americans under the age of 18.

The study was published online in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Less is known about long COVID in children

Lyudmyla Kompaniyets, PhD, and colleagues noted that most research on long COVID to date has been done in adults, so little information is available about the risks to Americans ages 17 and younger.

To learn more, they compared post–COVID-19 symptoms and conditions between 781,419 children and teenagers with confirmed COVID-19 to another 2,344,257 without COVID-19. They looked at medical claims and laboratory data for these children and teenagers from March 1, 2020, through Jan. 31, 2022, to see who got any of 15 specific outcomes linked to long COVID-19.

Long COVID was defined as a condition where symptoms that last for or begin at least 4 weeks after a COVID-19 diagnosis.

Compared to children with no history of a COVID-19 diagnosis, the long COVID-19 group was 101% more likely to have an acute pulmonary embolism, 99% more likely to have myocarditis or cardiomyopathy, 87% more likely to have a venous thromboembolic event, 32% more likely to have acute and unspecified renal failure, and 23% more likely to have type 1 diabetes.

“This report points to the fact that the risks of COVID infection itself, both in terms of the acute effects, MIS-C [multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children], as well as the long-term effects, are real, are concerning, and are potentially very serious,” said Stuart Berger, MD, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery.

“The message that we should take away from this is that we should be very keen on all the methods of prevention for COVID, especially the vaccine,” said Dr. Berger, chief of cardiology in the department of pediatrics at Northwestern University in Chicago.

A ‘wake-up call’

The study findings are “sobering” and are “a reminder of the seriousness of COVID infection,” says Gregory Poland, MD, an infectious disease expert at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“When you look in particular at the more serious complications from COVID in this young age group, those are life-altering complications that will have consequences and ramifications throughout their lives,” he said.

“I would take this as a serious wake-up call to parents [at a time when] the immunization rates in younger children are so pitifully low,” Dr. Poland said.

Still early days

The study is suggestive but not definitive, said Peter Katona, MD, professor of medicine and infectious diseases expert at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health.

It’s still too early to draw conclusions about long COVID, including in children, because many questions remain, he said: Should long COVID be defined as symptoms at 1 month or 3 months after infection? How do you define brain fog?

Dr. Katona and colleagues are studying long COVID intervention among students at UCLA to answer some of these questions, including the incidence and effect of early intervention.

The study had “at least seven limitations,” the researchers noted. Among them was the use of medical claims data that noted long COVID outcomes but not how severe they were; some people in the no COVID group might have had the illness but not been diagnosed; and the researchers did not adjust for vaccination status.

Dr. Poland noted that the study was done during surges in COVID variants including Delta and Omicron. In other words, any long COVID effects linked to more recent variants such as BA.5 or BA.2.75 are unknown.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that

Heart inflammation; a blood clot in the lung; or a blood clot in the lower leg, thigh, or pelvis were the most common bad outcomes in a new study. Even though the risk was higher for these and some other serious events, the overall numbers were small.

“Many of these conditions were rare or uncommon among children in this analysis, but even a small increase in these conditions is notable,” a CDC new release stated.

The investigators said their findings stress the importance of COVID-19 vaccination in Americans under the age of 18.

The study was published online in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Less is known about long COVID in children

Lyudmyla Kompaniyets, PhD, and colleagues noted that most research on long COVID to date has been done in adults, so little information is available about the risks to Americans ages 17 and younger.

To learn more, they compared post–COVID-19 symptoms and conditions between 781,419 children and teenagers with confirmed COVID-19 to another 2,344,257 without COVID-19. They looked at medical claims and laboratory data for these children and teenagers from March 1, 2020, through Jan. 31, 2022, to see who got any of 15 specific outcomes linked to long COVID-19.

Long COVID was defined as a condition where symptoms that last for or begin at least 4 weeks after a COVID-19 diagnosis.

Compared to children with no history of a COVID-19 diagnosis, the long COVID-19 group was 101% more likely to have an acute pulmonary embolism, 99% more likely to have myocarditis or cardiomyopathy, 87% more likely to have a venous thromboembolic event, 32% more likely to have acute and unspecified renal failure, and 23% more likely to have type 1 diabetes.

“This report points to the fact that the risks of COVID infection itself, both in terms of the acute effects, MIS-C [multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children], as well as the long-term effects, are real, are concerning, and are potentially very serious,” said Stuart Berger, MD, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery.

“The message that we should take away from this is that we should be very keen on all the methods of prevention for COVID, especially the vaccine,” said Dr. Berger, chief of cardiology in the department of pediatrics at Northwestern University in Chicago.

A ‘wake-up call’

The study findings are “sobering” and are “a reminder of the seriousness of COVID infection,” says Gregory Poland, MD, an infectious disease expert at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“When you look in particular at the more serious complications from COVID in this young age group, those are life-altering complications that will have consequences and ramifications throughout their lives,” he said.

“I would take this as a serious wake-up call to parents [at a time when] the immunization rates in younger children are so pitifully low,” Dr. Poland said.

Still early days

The study is suggestive but not definitive, said Peter Katona, MD, professor of medicine and infectious diseases expert at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health.

It’s still too early to draw conclusions about long COVID, including in children, because many questions remain, he said: Should long COVID be defined as symptoms at 1 month or 3 months after infection? How do you define brain fog?

Dr. Katona and colleagues are studying long COVID intervention among students at UCLA to answer some of these questions, including the incidence and effect of early intervention.

The study had “at least seven limitations,” the researchers noted. Among them was the use of medical claims data that noted long COVID outcomes but not how severe they were; some people in the no COVID group might have had the illness but not been diagnosed; and the researchers did not adjust for vaccination status.

Dr. Poland noted that the study was done during surges in COVID variants including Delta and Omicron. In other words, any long COVID effects linked to more recent variants such as BA.5 or BA.2.75 are unknown.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that

Heart inflammation; a blood clot in the lung; or a blood clot in the lower leg, thigh, or pelvis were the most common bad outcomes in a new study. Even though the risk was higher for these and some other serious events, the overall numbers were small.

“Many of these conditions were rare or uncommon among children in this analysis, but even a small increase in these conditions is notable,” a CDC new release stated.

The investigators said their findings stress the importance of COVID-19 vaccination in Americans under the age of 18.

The study was published online in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Less is known about long COVID in children

Lyudmyla Kompaniyets, PhD, and colleagues noted that most research on long COVID to date has been done in adults, so little information is available about the risks to Americans ages 17 and younger.

To learn more, they compared post–COVID-19 symptoms and conditions between 781,419 children and teenagers with confirmed COVID-19 to another 2,344,257 without COVID-19. They looked at medical claims and laboratory data for these children and teenagers from March 1, 2020, through Jan. 31, 2022, to see who got any of 15 specific outcomes linked to long COVID-19.

Long COVID was defined as a condition where symptoms that last for or begin at least 4 weeks after a COVID-19 diagnosis.

Compared to children with no history of a COVID-19 diagnosis, the long COVID-19 group was 101% more likely to have an acute pulmonary embolism, 99% more likely to have myocarditis or cardiomyopathy, 87% more likely to have a venous thromboembolic event, 32% more likely to have acute and unspecified renal failure, and 23% more likely to have type 1 diabetes.

“This report points to the fact that the risks of COVID infection itself, both in terms of the acute effects, MIS-C [multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children], as well as the long-term effects, are real, are concerning, and are potentially very serious,” said Stuart Berger, MD, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery.

“The message that we should take away from this is that we should be very keen on all the methods of prevention for COVID, especially the vaccine,” said Dr. Berger, chief of cardiology in the department of pediatrics at Northwestern University in Chicago.

A ‘wake-up call’

The study findings are “sobering” and are “a reminder of the seriousness of COVID infection,” says Gregory Poland, MD, an infectious disease expert at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“When you look in particular at the more serious complications from COVID in this young age group, those are life-altering complications that will have consequences and ramifications throughout their lives,” he said.

“I would take this as a serious wake-up call to parents [at a time when] the immunization rates in younger children are so pitifully low,” Dr. Poland said.

Still early days

The study is suggestive but not definitive, said Peter Katona, MD, professor of medicine and infectious diseases expert at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health.

It’s still too early to draw conclusions about long COVID, including in children, because many questions remain, he said: Should long COVID be defined as symptoms at 1 month or 3 months after infection? How do you define brain fog?

Dr. Katona and colleagues are studying long COVID intervention among students at UCLA to answer some of these questions, including the incidence and effect of early intervention.

The study had “at least seven limitations,” the researchers noted. Among them was the use of medical claims data that noted long COVID outcomes but not how severe they were; some people in the no COVID group might have had the illness but not been diagnosed; and the researchers did not adjust for vaccination status.

Dr. Poland noted that the study was done during surges in COVID variants including Delta and Omicron. In other words, any long COVID effects linked to more recent variants such as BA.5 or BA.2.75 are unknown.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM THE MMWR

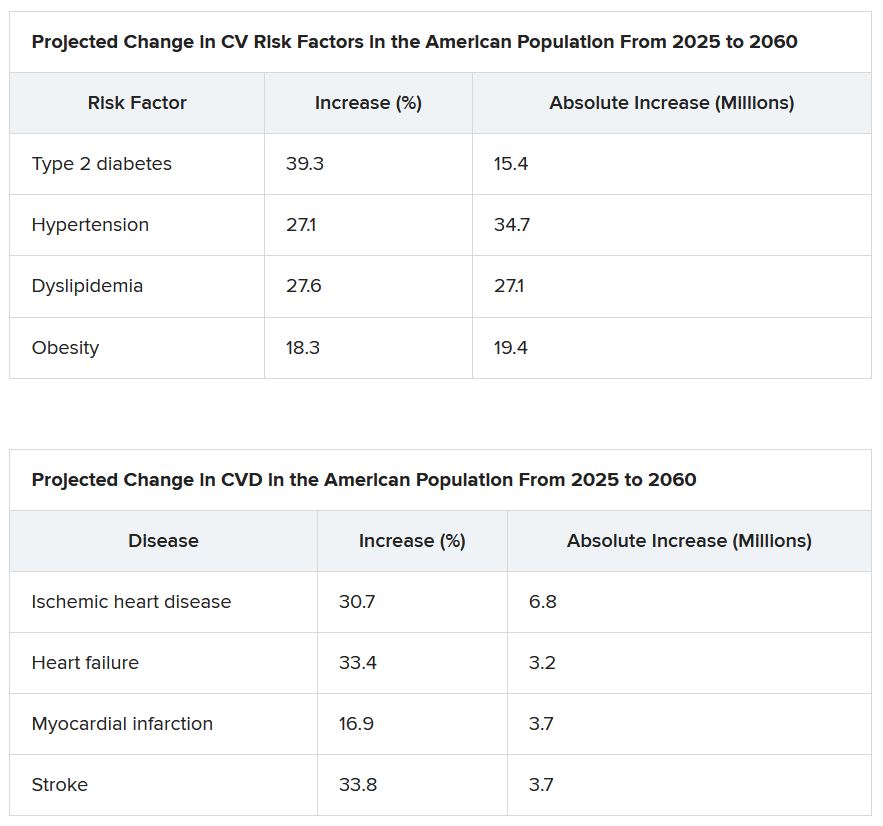

‘Staggering’ CVD rise projected in U.S., especially in minorities

A new analysis projects steep increases by 2060 in the prevalence of cardiovascular (CV) risk factors and disease that will disproportionately affect non-White populations who have limited access to health care.

The study by Reza Mohebi, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, and colleagues was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“Even though several assumptions underlie these projections, the importance of this work cannot be overestimated,” Andreas P. Kalogeropoulos, MD, MPH, PhD, and Javed Butler, MD, MPH, MBA, wrote in an accompanying editorial. “The absolute numbers are staggering.”

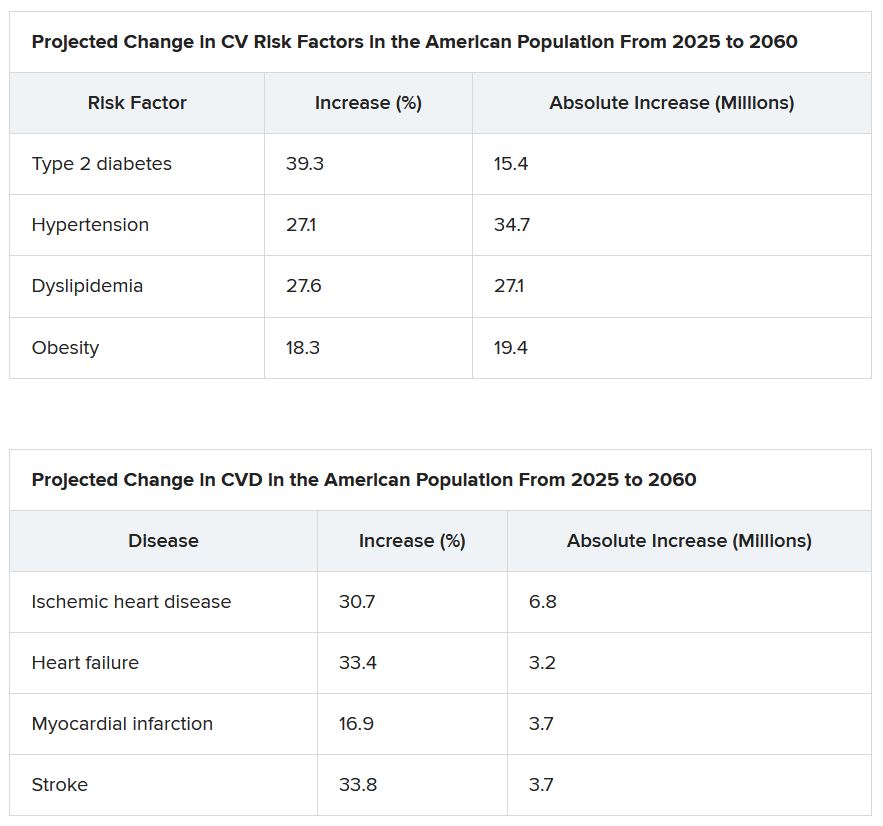

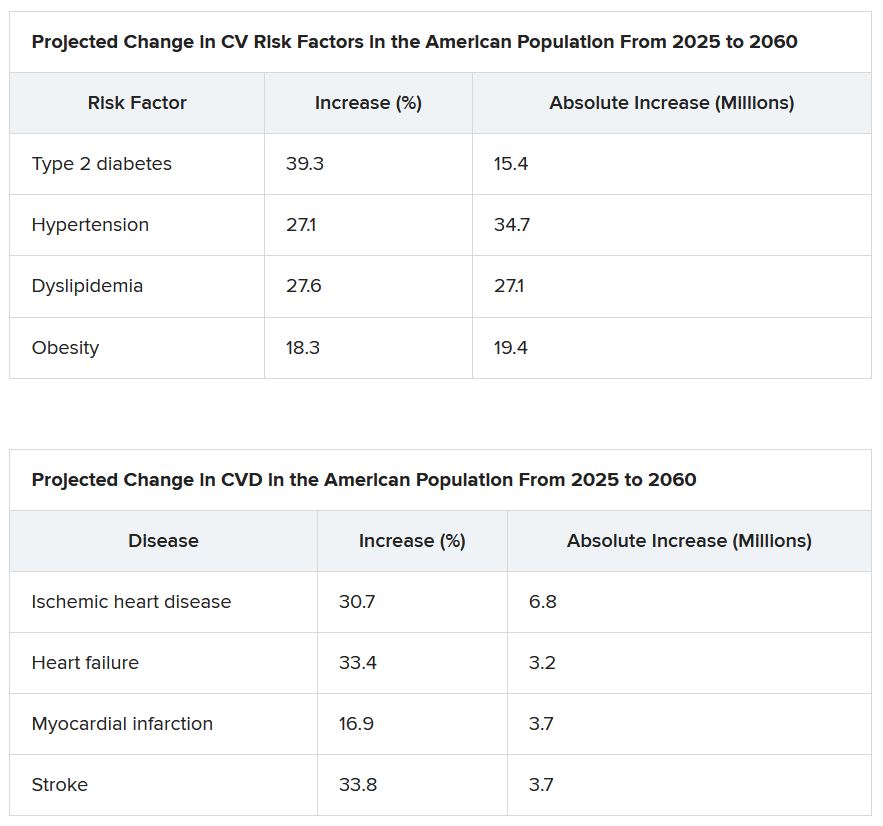

From 2025 to 2060, the number of people with any one of four CV risk factors – type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity – is projected to increase by 15.4 million, to 34.7 million.

And the number of people with of any one of four CV disease types – ischemic heart disease, heart failure, MI, and stroke – is projected to increase by 3.2 million, to 6.8 million.

Although the model predicts that the prevalence of CV risk factors will gradually decrease among White Americans, the highest prevalence of CV risk factors will be among the White population because of its overall size.

Conversely, the projected prevalence of CV risk factors is expected to increase in Black, Hispanic, Asian, and other race/ethnicity populations.

In parallel, the prevalence of CV disease is projected to decrease in the White population and increase among all other race/ethnicities, particularly in the Black and Hispanic populations.

“Our results project a worrisome increase with a particularly ominous increase in risk factors and disease in our most vulnerable patients, including Blacks and Hispanics,” senior author James L. Januzzi Jr., MD, summarized in a video issued by the society.

“The steep rise in CV risk factors and disease reflects the generally higher prevalence in populations projected to increase in the United States, owing to immigration and growth, including Black or Hispanic individuals,” Dr. Januzzi, also from Massachusetts General and Harvard, said in an interview.

“The disproportionate size of the risk is expected in a sense, as minority populations are disproportionately disadvantaged with respect to their health care,” he said. “But whether it is expected or not, the increase in projected prevalence is, nonetheless, concerning and a call to action.”

This study identifies “areas of opportunity for change in the U.S. health care system,” he continued. “Business as usual will result in us encountering a huge number of individuals with CV risk factors and diseases.”

The results from the current analysis assume there will be no modification in health care policies or changes in access to care for at-risk populations, Dr. Mohebi and colleagues noted.

To “stem the rising tide of CV disease in at-risk individuals,” would require strategies such as “emphasis on education regarding CV risk factors, improving access to quality healthcare, and facilitating lower-cost access to effective therapies for treatment of CV risk factors,” according to the researchers.

“Such advances need to be applied in a more equitable way throughout the United States, however,” they cautioned.

Census plus NHANES data

The researchers used 2020 U.S. census data and projected growth and 2013-2018 U.S. National Health and Nutrition Survey data to estimate the number of people with CV risk factors and CV disease from 2025 to 2060.

The estimates are based on a growing population and a fixed frequency.

The projected changes in CV risk factors and disease over time were similar in men and women.

The researchers acknowledge that study limitations include the assumption that the prevalence patterns for CV risk factors and disease will be stable.

“To the extent the frequency of risk factors and disease are not likely to remain static, that assumption may reduce the accuracy of the projections,” Dr. Januzzi said. “However, we would point out that the goals of our analysis were to set general trends, and not to seek to project exact figures.”

Also, they did not take into account the effect of COVID-19. CV diseases were also based on self-report and CV risk factors could have been underestimated in minority populations that do not access health care.

Changing demographic landscape

It is “striking” that the numbers of non-White individuals with CV risk factors is projected to surpass the number of White individuals over time, and the number of non-White individuals with CV disease will be almost as many as White individuals by the year 2060, the editorialists noted.

“From a policy perspective, this means that unless appropriate, targeted action is taken, disparities in the burden of cardiovascular disease are only going to be exacerbated over time,” wrote Dr. Kalogeropoulos, from Stony Brook (N.Y.) University, and Dr. Butler, from Baylor College of Medicine, Dallas.

“On the positive side,” they continued, “the absolute increase in the percent prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and conditions is projected to lie within a manageable range,” assuming that specific prevention policies are implemented.

“This is an opportunity for professional societies, including the cardiovascular care community, to re-evaluate priorities and strategies, for both training and practice, to best match the growing demands of a changing demographic landscape in the United States,” Dr. Kalogeropoulos and Dr. Butler concluded.

Dr. Mohebi is supported by the Barry Fellowship. Dr. Januzzi is supported by the Hutter Family Professorship; is a Trustee of the American College of Cardiology; is a board member of Imbria Pharmaceuticals; has received grant support from Abbott Diagnostics, Applied Therapeutics, Innolife, and Novartis; has received consulting income from Abbott Diagnostics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Novartis, and Roche Diagnostics; and participates in clinical endpoint committees/data safety monitoring boards for AbbVie, Siemens, Takeda, and Vifor. Dr. Kalogeropoulos has received research funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the American Heart Association; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Butler has been a consultant for numerous pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new analysis projects steep increases by 2060 in the prevalence of cardiovascular (CV) risk factors and disease that will disproportionately affect non-White populations who have limited access to health care.

The study by Reza Mohebi, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, and colleagues was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“Even though several assumptions underlie these projections, the importance of this work cannot be overestimated,” Andreas P. Kalogeropoulos, MD, MPH, PhD, and Javed Butler, MD, MPH, MBA, wrote in an accompanying editorial. “The absolute numbers are staggering.”

From 2025 to 2060, the number of people with any one of four CV risk factors – type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity – is projected to increase by 15.4 million, to 34.7 million.

And the number of people with of any one of four CV disease types – ischemic heart disease, heart failure, MI, and stroke – is projected to increase by 3.2 million, to 6.8 million.

Although the model predicts that the prevalence of CV risk factors will gradually decrease among White Americans, the highest prevalence of CV risk factors will be among the White population because of its overall size.

Conversely, the projected prevalence of CV risk factors is expected to increase in Black, Hispanic, Asian, and other race/ethnicity populations.

In parallel, the prevalence of CV disease is projected to decrease in the White population and increase among all other race/ethnicities, particularly in the Black and Hispanic populations.

“Our results project a worrisome increase with a particularly ominous increase in risk factors and disease in our most vulnerable patients, including Blacks and Hispanics,” senior author James L. Januzzi Jr., MD, summarized in a video issued by the society.

“The steep rise in CV risk factors and disease reflects the generally higher prevalence in populations projected to increase in the United States, owing to immigration and growth, including Black or Hispanic individuals,” Dr. Januzzi, also from Massachusetts General and Harvard, said in an interview.

“The disproportionate size of the risk is expected in a sense, as minority populations are disproportionately disadvantaged with respect to their health care,” he said. “But whether it is expected or not, the increase in projected prevalence is, nonetheless, concerning and a call to action.”

This study identifies “areas of opportunity for change in the U.S. health care system,” he continued. “Business as usual will result in us encountering a huge number of individuals with CV risk factors and diseases.”

The results from the current analysis assume there will be no modification in health care policies or changes in access to care for at-risk populations, Dr. Mohebi and colleagues noted.

To “stem the rising tide of CV disease in at-risk individuals,” would require strategies such as “emphasis on education regarding CV risk factors, improving access to quality healthcare, and facilitating lower-cost access to effective therapies for treatment of CV risk factors,” according to the researchers.

“Such advances need to be applied in a more equitable way throughout the United States, however,” they cautioned.

Census plus NHANES data

The researchers used 2020 U.S. census data and projected growth and 2013-2018 U.S. National Health and Nutrition Survey data to estimate the number of people with CV risk factors and CV disease from 2025 to 2060.

The estimates are based on a growing population and a fixed frequency.

The projected changes in CV risk factors and disease over time were similar in men and women.

The researchers acknowledge that study limitations include the assumption that the prevalence patterns for CV risk factors and disease will be stable.

“To the extent the frequency of risk factors and disease are not likely to remain static, that assumption may reduce the accuracy of the projections,” Dr. Januzzi said. “However, we would point out that the goals of our analysis were to set general trends, and not to seek to project exact figures.”

Also, they did not take into account the effect of COVID-19. CV diseases were also based on self-report and CV risk factors could have been underestimated in minority populations that do not access health care.

Changing demographic landscape

It is “striking” that the numbers of non-White individuals with CV risk factors is projected to surpass the number of White individuals over time, and the number of non-White individuals with CV disease will be almost as many as White individuals by the year 2060, the editorialists noted.

“From a policy perspective, this means that unless appropriate, targeted action is taken, disparities in the burden of cardiovascular disease are only going to be exacerbated over time,” wrote Dr. Kalogeropoulos, from Stony Brook (N.Y.) University, and Dr. Butler, from Baylor College of Medicine, Dallas.

“On the positive side,” they continued, “the absolute increase in the percent prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and conditions is projected to lie within a manageable range,” assuming that specific prevention policies are implemented.

“This is an opportunity for professional societies, including the cardiovascular care community, to re-evaluate priorities and strategies, for both training and practice, to best match the growing demands of a changing demographic landscape in the United States,” Dr. Kalogeropoulos and Dr. Butler concluded.

Dr. Mohebi is supported by the Barry Fellowship. Dr. Januzzi is supported by the Hutter Family Professorship; is a Trustee of the American College of Cardiology; is a board member of Imbria Pharmaceuticals; has received grant support from Abbott Diagnostics, Applied Therapeutics, Innolife, and Novartis; has received consulting income from Abbott Diagnostics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Novartis, and Roche Diagnostics; and participates in clinical endpoint committees/data safety monitoring boards for AbbVie, Siemens, Takeda, and Vifor. Dr. Kalogeropoulos has received research funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the American Heart Association; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Butler has been a consultant for numerous pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new analysis projects steep increases by 2060 in the prevalence of cardiovascular (CV) risk factors and disease that will disproportionately affect non-White populations who have limited access to health care.

The study by Reza Mohebi, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, and colleagues was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“Even though several assumptions underlie these projections, the importance of this work cannot be overestimated,” Andreas P. Kalogeropoulos, MD, MPH, PhD, and Javed Butler, MD, MPH, MBA, wrote in an accompanying editorial. “The absolute numbers are staggering.”

From 2025 to 2060, the number of people with any one of four CV risk factors – type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity – is projected to increase by 15.4 million, to 34.7 million.

And the number of people with of any one of four CV disease types – ischemic heart disease, heart failure, MI, and stroke – is projected to increase by 3.2 million, to 6.8 million.

Although the model predicts that the prevalence of CV risk factors will gradually decrease among White Americans, the highest prevalence of CV risk factors will be among the White population because of its overall size.

Conversely, the projected prevalence of CV risk factors is expected to increase in Black, Hispanic, Asian, and other race/ethnicity populations.

In parallel, the prevalence of CV disease is projected to decrease in the White population and increase among all other race/ethnicities, particularly in the Black and Hispanic populations.

“Our results project a worrisome increase with a particularly ominous increase in risk factors and disease in our most vulnerable patients, including Blacks and Hispanics,” senior author James L. Januzzi Jr., MD, summarized in a video issued by the society.

“The steep rise in CV risk factors and disease reflects the generally higher prevalence in populations projected to increase in the United States, owing to immigration and growth, including Black or Hispanic individuals,” Dr. Januzzi, also from Massachusetts General and Harvard, said in an interview.

“The disproportionate size of the risk is expected in a sense, as minority populations are disproportionately disadvantaged with respect to their health care,” he said. “But whether it is expected or not, the increase in projected prevalence is, nonetheless, concerning and a call to action.”

This study identifies “areas of opportunity for change in the U.S. health care system,” he continued. “Business as usual will result in us encountering a huge number of individuals with CV risk factors and diseases.”

The results from the current analysis assume there will be no modification in health care policies or changes in access to care for at-risk populations, Dr. Mohebi and colleagues noted.

To “stem the rising tide of CV disease in at-risk individuals,” would require strategies such as “emphasis on education regarding CV risk factors, improving access to quality healthcare, and facilitating lower-cost access to effective therapies for treatment of CV risk factors,” according to the researchers.

“Such advances need to be applied in a more equitable way throughout the United States, however,” they cautioned.

Census plus NHANES data

The researchers used 2020 U.S. census data and projected growth and 2013-2018 U.S. National Health and Nutrition Survey data to estimate the number of people with CV risk factors and CV disease from 2025 to 2060.

The estimates are based on a growing population and a fixed frequency.

The projected changes in CV risk factors and disease over time were similar in men and women.

The researchers acknowledge that study limitations include the assumption that the prevalence patterns for CV risk factors and disease will be stable.

“To the extent the frequency of risk factors and disease are not likely to remain static, that assumption may reduce the accuracy of the projections,” Dr. Januzzi said. “However, we would point out that the goals of our analysis were to set general trends, and not to seek to project exact figures.”

Also, they did not take into account the effect of COVID-19. CV diseases were also based on self-report and CV risk factors could have been underestimated in minority populations that do not access health care.

Changing demographic landscape

It is “striking” that the numbers of non-White individuals with CV risk factors is projected to surpass the number of White individuals over time, and the number of non-White individuals with CV disease will be almost as many as White individuals by the year 2060, the editorialists noted.

“From a policy perspective, this means that unless appropriate, targeted action is taken, disparities in the burden of cardiovascular disease are only going to be exacerbated over time,” wrote Dr. Kalogeropoulos, from Stony Brook (N.Y.) University, and Dr. Butler, from Baylor College of Medicine, Dallas.

“On the positive side,” they continued, “the absolute increase in the percent prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and conditions is projected to lie within a manageable range,” assuming that specific prevention policies are implemented.

“This is an opportunity for professional societies, including the cardiovascular care community, to re-evaluate priorities and strategies, for both training and practice, to best match the growing demands of a changing demographic landscape in the United States,” Dr. Kalogeropoulos and Dr. Butler concluded.