User login

Breast cancer screening complexities

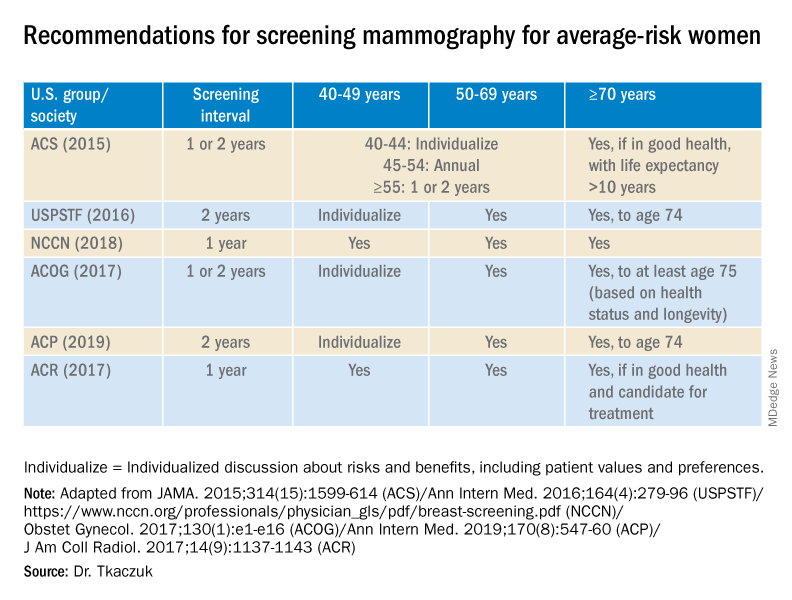

Breast cancer in women remains one of the most common types of cancer in the United States, affecting about one in eight women1 over the course of their lifetime. Despite its pervasiveness, the 5-year survival rate for women with breast cancer remains high, estimated at around 90%2 based on data from 2010-2016, in large part because of early detection and treatment through screening. However, many organizations disagree on when to start and how often to screen women at average risk.

Important to discussions about breast cancer screening is the trend that many women delay childbirth until their 30s and 40s. In 2018 the birth rate increased for women ages 35-44, and the mean age of first birth increased from the prior year across all racial and ethnic groups.3 Therefore, ob.gyns. may need to consider that their patients not only may have increased risk of developing breast cancer based on age alone – women aged 35-44 have four times greater risk of disease than women aged 20-342 – but that the pregnancy itself may further exacerbate risk in older women. A 2019 pooled analysis found that women who were older at first birth had a greater chance of developing breast cancer compared with women with no children.4

In addition, ob.gyns. should consider that their patients may have received a breast cancer diagnosis prior to initiation or completion of their family plans or that their patients are cancer survivors – in 2013-2017, breast cancer was the most common form of cancer in adolescents and young adults.5 Thus, practitioners should be prepared to discuss not only options for fertility preservation but the evidence regarding cancer recurrence after pregnancy.

We have invited Dr. Katherine Tkaczuk, professor of medicine at the University of Maryland School of Medicine* and director of the breast evaluation and treatment program at the Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center, to discuss the vital role of screening in the shared decision-making process of breast cancer prevention.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore,* as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

Correction, 1/8/21: *An earlier version of this article misstated the university affiliations for Dr. Tkaczuk and Dr. Reece.

References

1. U.S. Breast Cancer Statistics. breastcancer.org.

2. “Cancer Stat Facts: Female Breast Cancer,” Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. National Cancer Institute.

3. Martin JA et al. “Births: Final Data for 2018.” National Vital Statistics Reports. 2019 Nov 27;68(13):1-46.

4. Nichols HB et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Jan;170(1):22-30.

5. “Cancer Stat Facts: Cancer Among Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs) (Ages 15-39),” Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. National Cancer Institute.

Breast cancer in women remains one of the most common types of cancer in the United States, affecting about one in eight women1 over the course of their lifetime. Despite its pervasiveness, the 5-year survival rate for women with breast cancer remains high, estimated at around 90%2 based on data from 2010-2016, in large part because of early detection and treatment through screening. However, many organizations disagree on when to start and how often to screen women at average risk.

Important to discussions about breast cancer screening is the trend that many women delay childbirth until their 30s and 40s. In 2018 the birth rate increased for women ages 35-44, and the mean age of first birth increased from the prior year across all racial and ethnic groups.3 Therefore, ob.gyns. may need to consider that their patients not only may have increased risk of developing breast cancer based on age alone – women aged 35-44 have four times greater risk of disease than women aged 20-342 – but that the pregnancy itself may further exacerbate risk in older women. A 2019 pooled analysis found that women who were older at first birth had a greater chance of developing breast cancer compared with women with no children.4

In addition, ob.gyns. should consider that their patients may have received a breast cancer diagnosis prior to initiation or completion of their family plans or that their patients are cancer survivors – in 2013-2017, breast cancer was the most common form of cancer in adolescents and young adults.5 Thus, practitioners should be prepared to discuss not only options for fertility preservation but the evidence regarding cancer recurrence after pregnancy.

We have invited Dr. Katherine Tkaczuk, professor of medicine at the University of Maryland School of Medicine* and director of the breast evaluation and treatment program at the Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center, to discuss the vital role of screening in the shared decision-making process of breast cancer prevention.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore,* as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

Correction, 1/8/21: *An earlier version of this article misstated the university affiliations for Dr. Tkaczuk and Dr. Reece.

References

1. U.S. Breast Cancer Statistics. breastcancer.org.

2. “Cancer Stat Facts: Female Breast Cancer,” Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. National Cancer Institute.

3. Martin JA et al. “Births: Final Data for 2018.” National Vital Statistics Reports. 2019 Nov 27;68(13):1-46.

4. Nichols HB et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Jan;170(1):22-30.

5. “Cancer Stat Facts: Cancer Among Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs) (Ages 15-39),” Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. National Cancer Institute.

Breast cancer in women remains one of the most common types of cancer in the United States, affecting about one in eight women1 over the course of their lifetime. Despite its pervasiveness, the 5-year survival rate for women with breast cancer remains high, estimated at around 90%2 based on data from 2010-2016, in large part because of early detection and treatment through screening. However, many organizations disagree on when to start and how often to screen women at average risk.

Important to discussions about breast cancer screening is the trend that many women delay childbirth until their 30s and 40s. In 2018 the birth rate increased for women ages 35-44, and the mean age of first birth increased from the prior year across all racial and ethnic groups.3 Therefore, ob.gyns. may need to consider that their patients not only may have increased risk of developing breast cancer based on age alone – women aged 35-44 have four times greater risk of disease than women aged 20-342 – but that the pregnancy itself may further exacerbate risk in older women. A 2019 pooled analysis found that women who were older at first birth had a greater chance of developing breast cancer compared with women with no children.4

In addition, ob.gyns. should consider that their patients may have received a breast cancer diagnosis prior to initiation or completion of their family plans or that their patients are cancer survivors – in 2013-2017, breast cancer was the most common form of cancer in adolescents and young adults.5 Thus, practitioners should be prepared to discuss not only options for fertility preservation but the evidence regarding cancer recurrence after pregnancy.

We have invited Dr. Katherine Tkaczuk, professor of medicine at the University of Maryland School of Medicine* and director of the breast evaluation and treatment program at the Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center, to discuss the vital role of screening in the shared decision-making process of breast cancer prevention.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore,* as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

Correction, 1/8/21: *An earlier version of this article misstated the university affiliations for Dr. Tkaczuk and Dr. Reece.

References

1. U.S. Breast Cancer Statistics. breastcancer.org.

2. “Cancer Stat Facts: Female Breast Cancer,” Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. National Cancer Institute.

3. Martin JA et al. “Births: Final Data for 2018.” National Vital Statistics Reports. 2019 Nov 27;68(13):1-46.

4. Nichols HB et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Jan;170(1):22-30.

5. “Cancer Stat Facts: Cancer Among Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs) (Ages 15-39),” Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. National Cancer Institute.

An oncologist’s view on screening mammography

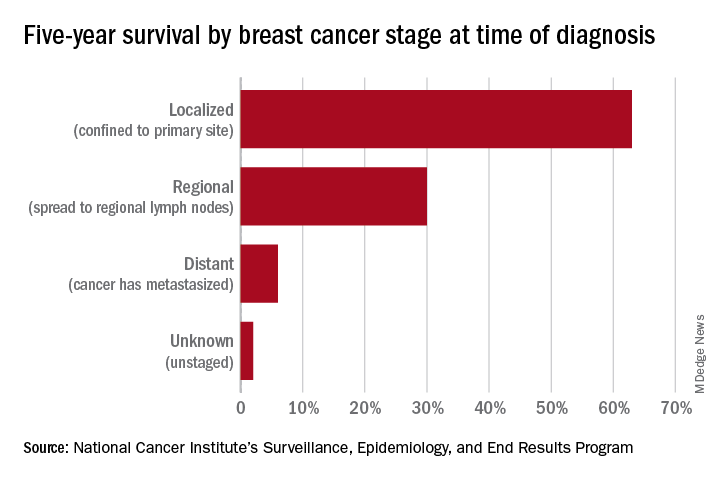

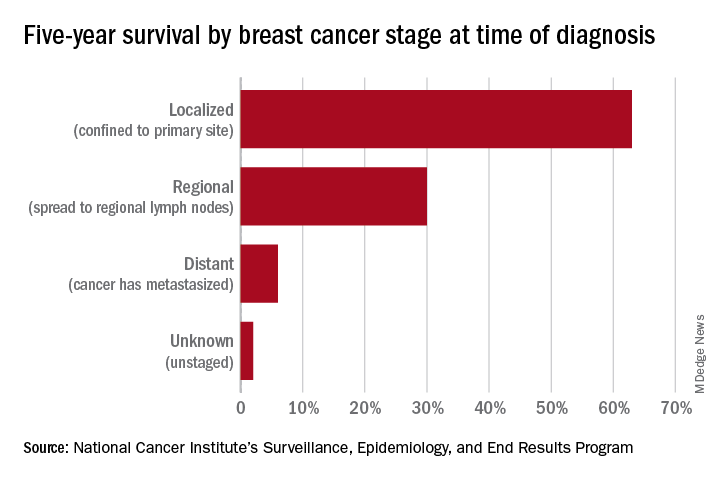

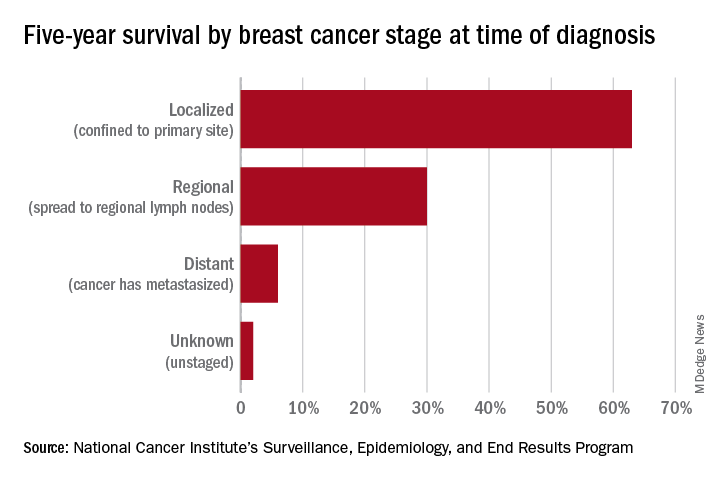

Screening mammography has contributed to the lowering of mortality from breast cancer by facilitating earlier diagnosis and a lower stage at diagnosis. With more effective treatment options for women who are diagnosed with lower-stage breast cancer, the current 5-year survival rate has risen to 90% – significantly higher than the 5-year survival rate of 75% in 1975.1

Women who are at much higher risk for developing breast cancer – mainly because of family history, certain genetic mutations, or a history of radiation therapy to the chest – will benefit the most from earlier and more frequent screening mammography as well as enhanced screening with non-x-ray methods of breast imaging. It is important that ob.gyns. help to identify these women.

However, the majority of women who are screened with mammography are at “average risk,” with a lifetime risk for developing breast cancer of 12.9%, based on 2015-2017 data from the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER).1 The median age at diagnosis of breast cancer in the U.S. is 62 years,1 and advancing age is the most important risk factor for these women.

A 20% relative risk reduction in breast cancer mortality with screening mammography has been demonstrated both in systematic reviews of randomized and observational studies2 and in a meta-analysis of 11 randomized trials comparing screening and no screening.3 Even though the majority of randomized trials were done in the age of film mammography, experts believe that we still see at least a 20% reduction today.

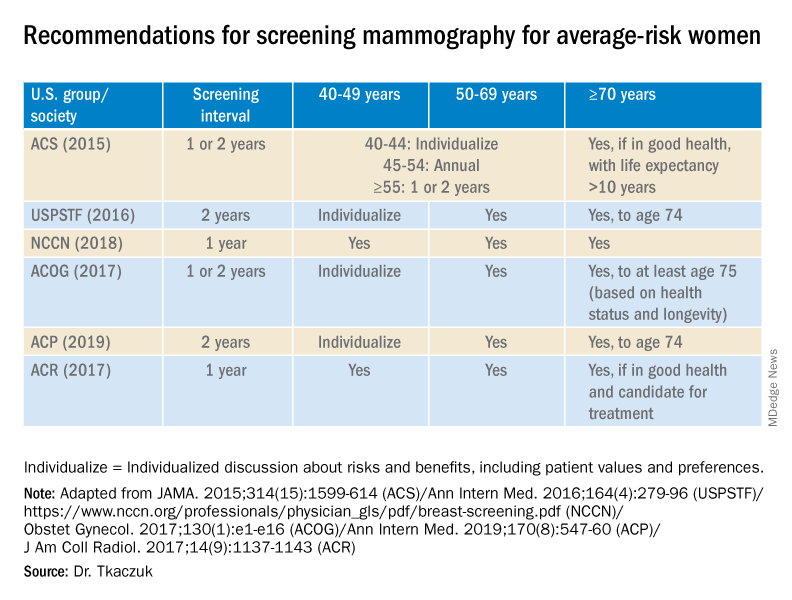

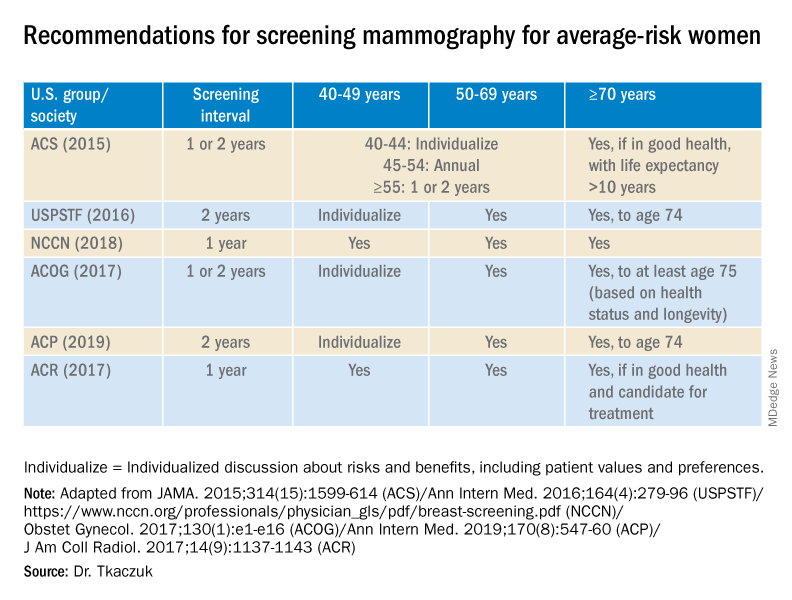

Among average-risk women, those aged 50-74 with a life expectancy of at least 10 years will benefit the most from regular screening. According to the 2016 screening guideline of the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), relative risk reductions in breast cancer mortality from mammography screening, by age group, are 0.88 (confidence interval, 0.73-1.003) for ages 39-49; 0.86 (CI, 0.68-0.97) for ages 50-59; 0.67 (CI, 0.55-0.91) for ages 60-69; and 0.80 (CI, 0.51 to 1.28) for ages 70-74.2

For women aged 40-49 years, most of the guidelines in the United States recommend individualized screening every 1 or 2 years – screening that is guided by shared decision-making that takes into account each woman’s values regarding relative harms and benefits. This is because their risk of developing breast cancer is relatively low while the risk of false-positive results can be higher.

A few exceptions include guidelines by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the American College of Radiology, which recommend annual screening mammography starting at age 40 years for all average-risk women. In our program, we adhere to these latter recommendations and advise annual digital 3-D mammograms starting at age 40 and continuing until age 74, or longer if the woman is otherwise healthy with a life expectancy greater than 10 years.

Screening and overdiagnosis

Overdiagnosis – the diagnosis of cancers that may not actually cause mortality or may not even have become apparent without screening – is a concern for all women undergoing routine screening for breast cancer. There is significant uncertainty about its frequency, however.

Research cited by the USPSTF suggests that as many as one in five women diagnosed with breast cancer over approximately 10 years will be overdiagnosed. Other modeling studies have estimated one in eight overdiagnoses, for women aged 50-75 years specifically. By the more conservative estimate, according to the USPSTF, one breast cancer death will be prevented for every 2-3 cases of unnecessary treatment.2

Ductal carcinoma in situ is confined to the mammary ductal-lobular system and lacks the classic characteristics of cancer. Technically, it should not metastasize. But we do not know with certainty which cases of DCIS will or will not progress to invasive cancer. Therefore these women often are offered surgical approaches mirroring invasive cancer treatments (lumpectomy with radiation or even mastectomy in some cases), while for some, such treatments may be unnecessary.

Screening younger women (40-49)

Shared decision-making is always important for breast cancer screening, but in our program we routinely recommend annual screening in average-risk women starting at age 40 for several reasons. For one, younger women may present with more aggressive types of breast cancer such as triple-negative breast cancer. These are much less common than hormone-receptor positive breast cancers – they represent 15%-20% of all breast cancers – but they are faster growing and may develop in the interim if women are screened less often (at 2-year intervals).

In addition, finding an invasive breast cancer early is almost always beneficial. Earlier diagnosis (lower stage at diagnosis) is associated with increased breast cancer-specific and overall survival, as well as less-aggressive treatment approaches.

As a medical oncologist who treats women with breast cancer, I see these benefits firsthand. With earlier diagnosis, we are more likely to offer less aggressive surgical approaches such as partial mastectomy (lumpectomy) and sentinel lymph node biopsy as opposed to total mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection, the latter of which is more likely to be associated with lymphedema and which can lead to postmastectomy chest wall pain syndromes.

We also are able to use less aggressive radiation therapy approaches such as partial breast radiation, and less aggressive breast cancer–specific systemic treatments for women with a lower stage of breast cancer at diagnosis. In some cases, adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy may not be needed – and when it is necessary, shorter courses of chemotherapy or targeted chemotherapeutic regimens may be offered. This means lower systemic toxicities, both early and late, such as less cytopenias, risk of infections, mucositis, hair loss, cardiotoxicity, secondary malignancies/leukemia, and peripheral sensory neuropathy.

It is important to note that Black women in the United States have the highest death rate from breast cancer – 27.3 per 100,000 per year, versus 19.6 per 100,000 per year for White women1 – and that younger Black women appear to have a higher risk of developing triple-negative breast cancer, a more aggressive type of breast cancer. The higher breast cancer mortality in Black women is likely multifactorial and may be attributed partly to disparities in health care and partly to tumor biology. The case for annual screening in this population thus seems especially strong.

Screening modalities

Digital 3-D mammography, or digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT), is widely considered to be a more sensitive screening tool than conventional digital mammography alone. The NCCN recommends DBT for women with an average risk of developing breast cancer starting at age 40,4,5 and the USPSTF, while offering no recommendation on DBT as a primary screening method (“insufficient evidence”), says that DBT appears to increase cancer detection rates.2 So, I do routinely recommend it.

DBT may be especially beneficial for women with dense breast tissue (determined mammographically), who are most often premenopausal women – particularly non-Hispanic White women. Dense breast tissue itself can contribute to an increased risk of breast cancer – an approximately 20% higher relative risk in an average-risk woman with heterogeneously dense breast tissue, and an approximately 100% higher relative risk in a woman with extremely dense breasts6 – but unfortunately it affects the sensitivity and specificity of screening mammography.

I do not recommend routine supplemental screening with other methods (breast ultrasonography or MRI) for women at average risk of breast cancer who have dense breasts. MRI with gadolinium contrast is recommended as an adjunct to mammography for women who have a lifetime risk of developing breast cancer of more than 20%-25% (e.g., women with known BRCA1/2 mutations or radiation to breast tissue), and can be done annually at the same time as the screening mammogram is done. Some clinicians and patients prefer to alternate these two tests – one every 6 months.

Screening breast MRI is more sensitive but less specific than mammography; combining the two screening modalities leads to overall increased sensitivity and specificity in high-risk populations.

Risk assessment

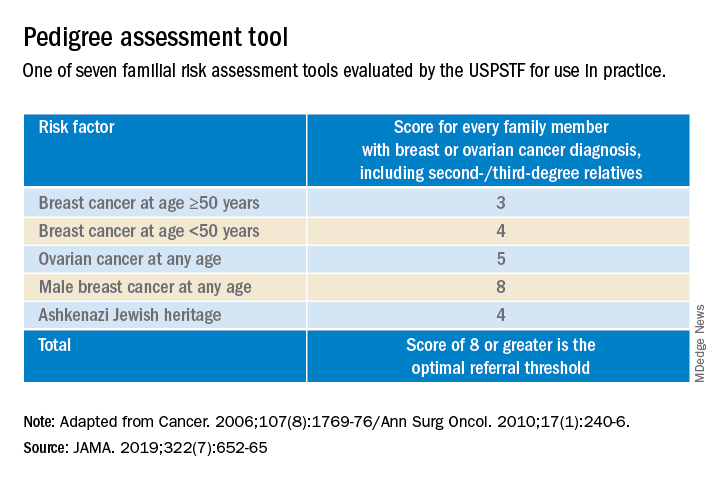

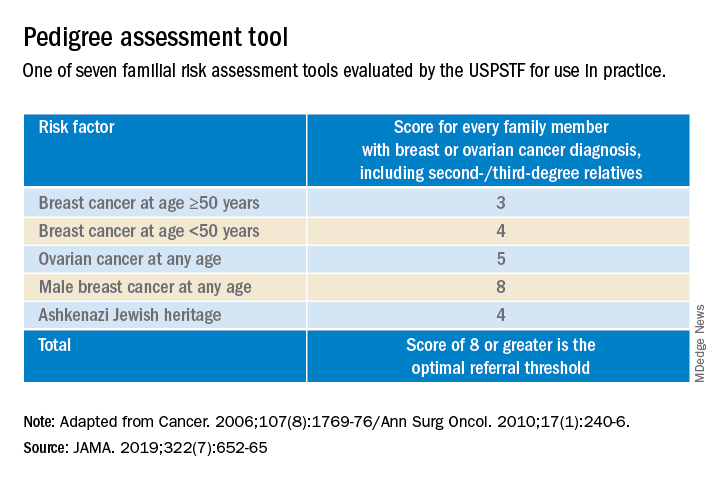

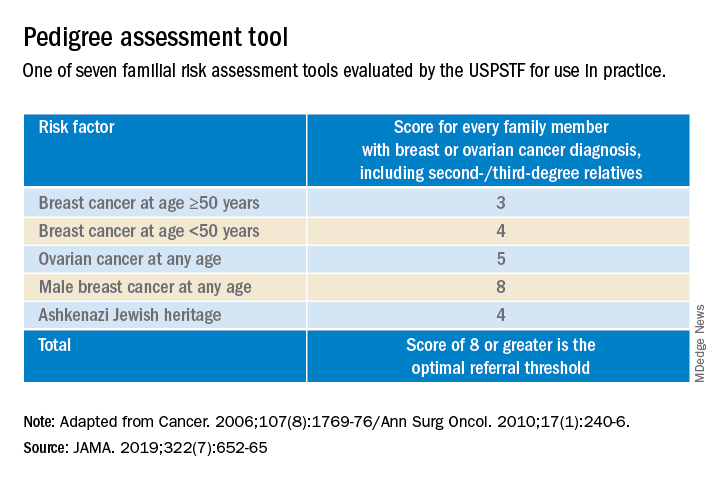

Identifying higher-risk women who need to be sent to a genetic counselor is critically important. The USPSTF recommends that women who have family members with breast, ovarian, tubal or peritoneal cancer, or who have an ancestry associated with BRCA1/2 gene mutations, be assessed with a brief familial risk assessment tool such as the Pedigree Assessment Tool. This and other validated tools have been evaluated by the USPSTF and can be used to guide referrals to genetic counseling for more definitive risk assessment.7

These tools are different from general breast cancer risk assessment models, such as the NCI’s Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool,8 which are designed to calculate the 5-year and lifetime risk of developing invasive breast cancer for an average-risk woman but not to identify BRCA-related cancer risk. (The NCI’s tool is based on the Gail model, which has been widely used over the years.)

The general risk assessment models use a women’s personal medical and reproductive history as well as the history of breast cancer among her first-degree relatives to estimate her risk.

Dr. Tkaczuk reported that she has no disclosures.

References

1. “Cancer Stat Facts: Female Breast Cancer.” Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. National Cancer Institute.

2. Siu AL et al. Ann Intern Med. 2016 Feb 16. doi: 10.7326/M15-2886.

3. Independent UK Panel on Breast Cancer Screening. Lancet. 2012 Nov 17;380(9855):1778-86.

4. NCCN guidelines for Detection, Prevention, & Risk Reduction: Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis. National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

5. NCCN guidelines for Detection, Prevention, & Risk Reduction: Breast Cancer Risk Reduction. National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

6. Ziv E et al. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(12):2090-5.

7. USPSTF. JAMA. 2019;322(7):652-65.

8. The Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool. National Cancer Institute.

Screening mammography has contributed to the lowering of mortality from breast cancer by facilitating earlier diagnosis and a lower stage at diagnosis. With more effective treatment options for women who are diagnosed with lower-stage breast cancer, the current 5-year survival rate has risen to 90% – significantly higher than the 5-year survival rate of 75% in 1975.1

Women who are at much higher risk for developing breast cancer – mainly because of family history, certain genetic mutations, or a history of radiation therapy to the chest – will benefit the most from earlier and more frequent screening mammography as well as enhanced screening with non-x-ray methods of breast imaging. It is important that ob.gyns. help to identify these women.

However, the majority of women who are screened with mammography are at “average risk,” with a lifetime risk for developing breast cancer of 12.9%, based on 2015-2017 data from the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER).1 The median age at diagnosis of breast cancer in the U.S. is 62 years,1 and advancing age is the most important risk factor for these women.

A 20% relative risk reduction in breast cancer mortality with screening mammography has been demonstrated both in systematic reviews of randomized and observational studies2 and in a meta-analysis of 11 randomized trials comparing screening and no screening.3 Even though the majority of randomized trials were done in the age of film mammography, experts believe that we still see at least a 20% reduction today.

Among average-risk women, those aged 50-74 with a life expectancy of at least 10 years will benefit the most from regular screening. According to the 2016 screening guideline of the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), relative risk reductions in breast cancer mortality from mammography screening, by age group, are 0.88 (confidence interval, 0.73-1.003) for ages 39-49; 0.86 (CI, 0.68-0.97) for ages 50-59; 0.67 (CI, 0.55-0.91) for ages 60-69; and 0.80 (CI, 0.51 to 1.28) for ages 70-74.2

For women aged 40-49 years, most of the guidelines in the United States recommend individualized screening every 1 or 2 years – screening that is guided by shared decision-making that takes into account each woman’s values regarding relative harms and benefits. This is because their risk of developing breast cancer is relatively low while the risk of false-positive results can be higher.

A few exceptions include guidelines by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the American College of Radiology, which recommend annual screening mammography starting at age 40 years for all average-risk women. In our program, we adhere to these latter recommendations and advise annual digital 3-D mammograms starting at age 40 and continuing until age 74, or longer if the woman is otherwise healthy with a life expectancy greater than 10 years.

Screening and overdiagnosis

Overdiagnosis – the diagnosis of cancers that may not actually cause mortality or may not even have become apparent without screening – is a concern for all women undergoing routine screening for breast cancer. There is significant uncertainty about its frequency, however.

Research cited by the USPSTF suggests that as many as one in five women diagnosed with breast cancer over approximately 10 years will be overdiagnosed. Other modeling studies have estimated one in eight overdiagnoses, for women aged 50-75 years specifically. By the more conservative estimate, according to the USPSTF, one breast cancer death will be prevented for every 2-3 cases of unnecessary treatment.2

Ductal carcinoma in situ is confined to the mammary ductal-lobular system and lacks the classic characteristics of cancer. Technically, it should not metastasize. But we do not know with certainty which cases of DCIS will or will not progress to invasive cancer. Therefore these women often are offered surgical approaches mirroring invasive cancer treatments (lumpectomy with radiation or even mastectomy in some cases), while for some, such treatments may be unnecessary.

Screening younger women (40-49)

Shared decision-making is always important for breast cancer screening, but in our program we routinely recommend annual screening in average-risk women starting at age 40 for several reasons. For one, younger women may present with more aggressive types of breast cancer such as triple-negative breast cancer. These are much less common than hormone-receptor positive breast cancers – they represent 15%-20% of all breast cancers – but they are faster growing and may develop in the interim if women are screened less often (at 2-year intervals).

In addition, finding an invasive breast cancer early is almost always beneficial. Earlier diagnosis (lower stage at diagnosis) is associated with increased breast cancer-specific and overall survival, as well as less-aggressive treatment approaches.

As a medical oncologist who treats women with breast cancer, I see these benefits firsthand. With earlier diagnosis, we are more likely to offer less aggressive surgical approaches such as partial mastectomy (lumpectomy) and sentinel lymph node biopsy as opposed to total mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection, the latter of which is more likely to be associated with lymphedema and which can lead to postmastectomy chest wall pain syndromes.

We also are able to use less aggressive radiation therapy approaches such as partial breast radiation, and less aggressive breast cancer–specific systemic treatments for women with a lower stage of breast cancer at diagnosis. In some cases, adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy may not be needed – and when it is necessary, shorter courses of chemotherapy or targeted chemotherapeutic regimens may be offered. This means lower systemic toxicities, both early and late, such as less cytopenias, risk of infections, mucositis, hair loss, cardiotoxicity, secondary malignancies/leukemia, and peripheral sensory neuropathy.

It is important to note that Black women in the United States have the highest death rate from breast cancer – 27.3 per 100,000 per year, versus 19.6 per 100,000 per year for White women1 – and that younger Black women appear to have a higher risk of developing triple-negative breast cancer, a more aggressive type of breast cancer. The higher breast cancer mortality in Black women is likely multifactorial and may be attributed partly to disparities in health care and partly to tumor biology. The case for annual screening in this population thus seems especially strong.

Screening modalities

Digital 3-D mammography, or digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT), is widely considered to be a more sensitive screening tool than conventional digital mammography alone. The NCCN recommends DBT for women with an average risk of developing breast cancer starting at age 40,4,5 and the USPSTF, while offering no recommendation on DBT as a primary screening method (“insufficient evidence”), says that DBT appears to increase cancer detection rates.2 So, I do routinely recommend it.

DBT may be especially beneficial for women with dense breast tissue (determined mammographically), who are most often premenopausal women – particularly non-Hispanic White women. Dense breast tissue itself can contribute to an increased risk of breast cancer – an approximately 20% higher relative risk in an average-risk woman with heterogeneously dense breast tissue, and an approximately 100% higher relative risk in a woman with extremely dense breasts6 – but unfortunately it affects the sensitivity and specificity of screening mammography.

I do not recommend routine supplemental screening with other methods (breast ultrasonography or MRI) for women at average risk of breast cancer who have dense breasts. MRI with gadolinium contrast is recommended as an adjunct to mammography for women who have a lifetime risk of developing breast cancer of more than 20%-25% (e.g., women with known BRCA1/2 mutations or radiation to breast tissue), and can be done annually at the same time as the screening mammogram is done. Some clinicians and patients prefer to alternate these two tests – one every 6 months.

Screening breast MRI is more sensitive but less specific than mammography; combining the two screening modalities leads to overall increased sensitivity and specificity in high-risk populations.

Risk assessment

Identifying higher-risk women who need to be sent to a genetic counselor is critically important. The USPSTF recommends that women who have family members with breast, ovarian, tubal or peritoneal cancer, or who have an ancestry associated with BRCA1/2 gene mutations, be assessed with a brief familial risk assessment tool such as the Pedigree Assessment Tool. This and other validated tools have been evaluated by the USPSTF and can be used to guide referrals to genetic counseling for more definitive risk assessment.7

These tools are different from general breast cancer risk assessment models, such as the NCI’s Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool,8 which are designed to calculate the 5-year and lifetime risk of developing invasive breast cancer for an average-risk woman but not to identify BRCA-related cancer risk. (The NCI’s tool is based on the Gail model, which has been widely used over the years.)

The general risk assessment models use a women’s personal medical and reproductive history as well as the history of breast cancer among her first-degree relatives to estimate her risk.

Dr. Tkaczuk reported that she has no disclosures.

References

1. “Cancer Stat Facts: Female Breast Cancer.” Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. National Cancer Institute.

2. Siu AL et al. Ann Intern Med. 2016 Feb 16. doi: 10.7326/M15-2886.

3. Independent UK Panel on Breast Cancer Screening. Lancet. 2012 Nov 17;380(9855):1778-86.

4. NCCN guidelines for Detection, Prevention, & Risk Reduction: Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis. National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

5. NCCN guidelines for Detection, Prevention, & Risk Reduction: Breast Cancer Risk Reduction. National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

6. Ziv E et al. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(12):2090-5.

7. USPSTF. JAMA. 2019;322(7):652-65.

8. The Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool. National Cancer Institute.

Screening mammography has contributed to the lowering of mortality from breast cancer by facilitating earlier diagnosis and a lower stage at diagnosis. With more effective treatment options for women who are diagnosed with lower-stage breast cancer, the current 5-year survival rate has risen to 90% – significantly higher than the 5-year survival rate of 75% in 1975.1

Women who are at much higher risk for developing breast cancer – mainly because of family history, certain genetic mutations, or a history of radiation therapy to the chest – will benefit the most from earlier and more frequent screening mammography as well as enhanced screening with non-x-ray methods of breast imaging. It is important that ob.gyns. help to identify these women.

However, the majority of women who are screened with mammography are at “average risk,” with a lifetime risk for developing breast cancer of 12.9%, based on 2015-2017 data from the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER).1 The median age at diagnosis of breast cancer in the U.S. is 62 years,1 and advancing age is the most important risk factor for these women.

A 20% relative risk reduction in breast cancer mortality with screening mammography has been demonstrated both in systematic reviews of randomized and observational studies2 and in a meta-analysis of 11 randomized trials comparing screening and no screening.3 Even though the majority of randomized trials were done in the age of film mammography, experts believe that we still see at least a 20% reduction today.

Among average-risk women, those aged 50-74 with a life expectancy of at least 10 years will benefit the most from regular screening. According to the 2016 screening guideline of the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), relative risk reductions in breast cancer mortality from mammography screening, by age group, are 0.88 (confidence interval, 0.73-1.003) for ages 39-49; 0.86 (CI, 0.68-0.97) for ages 50-59; 0.67 (CI, 0.55-0.91) for ages 60-69; and 0.80 (CI, 0.51 to 1.28) for ages 70-74.2

For women aged 40-49 years, most of the guidelines in the United States recommend individualized screening every 1 or 2 years – screening that is guided by shared decision-making that takes into account each woman’s values regarding relative harms and benefits. This is because their risk of developing breast cancer is relatively low while the risk of false-positive results can be higher.

A few exceptions include guidelines by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the American College of Radiology, which recommend annual screening mammography starting at age 40 years for all average-risk women. In our program, we adhere to these latter recommendations and advise annual digital 3-D mammograms starting at age 40 and continuing until age 74, or longer if the woman is otherwise healthy with a life expectancy greater than 10 years.

Screening and overdiagnosis

Overdiagnosis – the diagnosis of cancers that may not actually cause mortality or may not even have become apparent without screening – is a concern for all women undergoing routine screening for breast cancer. There is significant uncertainty about its frequency, however.

Research cited by the USPSTF suggests that as many as one in five women diagnosed with breast cancer over approximately 10 years will be overdiagnosed. Other modeling studies have estimated one in eight overdiagnoses, for women aged 50-75 years specifically. By the more conservative estimate, according to the USPSTF, one breast cancer death will be prevented for every 2-3 cases of unnecessary treatment.2

Ductal carcinoma in situ is confined to the mammary ductal-lobular system and lacks the classic characteristics of cancer. Technically, it should not metastasize. But we do not know with certainty which cases of DCIS will or will not progress to invasive cancer. Therefore these women often are offered surgical approaches mirroring invasive cancer treatments (lumpectomy with radiation or even mastectomy in some cases), while for some, such treatments may be unnecessary.

Screening younger women (40-49)

Shared decision-making is always important for breast cancer screening, but in our program we routinely recommend annual screening in average-risk women starting at age 40 for several reasons. For one, younger women may present with more aggressive types of breast cancer such as triple-negative breast cancer. These are much less common than hormone-receptor positive breast cancers – they represent 15%-20% of all breast cancers – but they are faster growing and may develop in the interim if women are screened less often (at 2-year intervals).

In addition, finding an invasive breast cancer early is almost always beneficial. Earlier diagnosis (lower stage at diagnosis) is associated with increased breast cancer-specific and overall survival, as well as less-aggressive treatment approaches.

As a medical oncologist who treats women with breast cancer, I see these benefits firsthand. With earlier diagnosis, we are more likely to offer less aggressive surgical approaches such as partial mastectomy (lumpectomy) and sentinel lymph node biopsy as opposed to total mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection, the latter of which is more likely to be associated with lymphedema and which can lead to postmastectomy chest wall pain syndromes.

We also are able to use less aggressive radiation therapy approaches such as partial breast radiation, and less aggressive breast cancer–specific systemic treatments for women with a lower stage of breast cancer at diagnosis. In some cases, adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy may not be needed – and when it is necessary, shorter courses of chemotherapy or targeted chemotherapeutic regimens may be offered. This means lower systemic toxicities, both early and late, such as less cytopenias, risk of infections, mucositis, hair loss, cardiotoxicity, secondary malignancies/leukemia, and peripheral sensory neuropathy.

It is important to note that Black women in the United States have the highest death rate from breast cancer – 27.3 per 100,000 per year, versus 19.6 per 100,000 per year for White women1 – and that younger Black women appear to have a higher risk of developing triple-negative breast cancer, a more aggressive type of breast cancer. The higher breast cancer mortality in Black women is likely multifactorial and may be attributed partly to disparities in health care and partly to tumor biology. The case for annual screening in this population thus seems especially strong.

Screening modalities

Digital 3-D mammography, or digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT), is widely considered to be a more sensitive screening tool than conventional digital mammography alone. The NCCN recommends DBT for women with an average risk of developing breast cancer starting at age 40,4,5 and the USPSTF, while offering no recommendation on DBT as a primary screening method (“insufficient evidence”), says that DBT appears to increase cancer detection rates.2 So, I do routinely recommend it.

DBT may be especially beneficial for women with dense breast tissue (determined mammographically), who are most often premenopausal women – particularly non-Hispanic White women. Dense breast tissue itself can contribute to an increased risk of breast cancer – an approximately 20% higher relative risk in an average-risk woman with heterogeneously dense breast tissue, and an approximately 100% higher relative risk in a woman with extremely dense breasts6 – but unfortunately it affects the sensitivity and specificity of screening mammography.

I do not recommend routine supplemental screening with other methods (breast ultrasonography or MRI) for women at average risk of breast cancer who have dense breasts. MRI with gadolinium contrast is recommended as an adjunct to mammography for women who have a lifetime risk of developing breast cancer of more than 20%-25% (e.g., women with known BRCA1/2 mutations or radiation to breast tissue), and can be done annually at the same time as the screening mammogram is done. Some clinicians and patients prefer to alternate these two tests – one every 6 months.

Screening breast MRI is more sensitive but less specific than mammography; combining the two screening modalities leads to overall increased sensitivity and specificity in high-risk populations.

Risk assessment

Identifying higher-risk women who need to be sent to a genetic counselor is critically important. The USPSTF recommends that women who have family members with breast, ovarian, tubal or peritoneal cancer, or who have an ancestry associated with BRCA1/2 gene mutations, be assessed with a brief familial risk assessment tool such as the Pedigree Assessment Tool. This and other validated tools have been evaluated by the USPSTF and can be used to guide referrals to genetic counseling for more definitive risk assessment.7

These tools are different from general breast cancer risk assessment models, such as the NCI’s Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool,8 which are designed to calculate the 5-year and lifetime risk of developing invasive breast cancer for an average-risk woman but not to identify BRCA-related cancer risk. (The NCI’s tool is based on the Gail model, which has been widely used over the years.)

The general risk assessment models use a women’s personal medical and reproductive history as well as the history of breast cancer among her first-degree relatives to estimate her risk.

Dr. Tkaczuk reported that she has no disclosures.

References

1. “Cancer Stat Facts: Female Breast Cancer.” Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. National Cancer Institute.

2. Siu AL et al. Ann Intern Med. 2016 Feb 16. doi: 10.7326/M15-2886.

3. Independent UK Panel on Breast Cancer Screening. Lancet. 2012 Nov 17;380(9855):1778-86.

4. NCCN guidelines for Detection, Prevention, & Risk Reduction: Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis. National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

5. NCCN guidelines for Detection, Prevention, & Risk Reduction: Breast Cancer Risk Reduction. National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

6. Ziv E et al. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(12):2090-5.

7. USPSTF. JAMA. 2019;322(7):652-65.

8. The Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool. National Cancer Institute.

The scope of under- and overtreatment in older adults with cancer

Because of physiological changes with aging and differences in cancer biology, caring for older adults (OAs) with cancer requires careful assessment and planning.

Clark Dumontier, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and colleagues sought to define the meaning of the terms “undertreatment” and “overtreatment” for OAs with cancer in a scoping literature review published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Though OAs are typically defined as adults aged 65 years and older, in this review, the authors defined OAs as patients aged 60 years and older.

The authors theorized that a scoping review of papers about this patient population could provide clues about limitations in the oncology literature and guidance about patient management and future research. Despite comprising the majority of cancer patients, OAs are underrepresented in clinical trials.

About scoping reviews

Scoping reviews are used to identify existing evidence in a field, clarify concepts or definitions in the literature, survey how research on a topic is conducted, and identify knowledge gaps. In addition, scoping reviews summarize available evidence without answering a discrete research question.

Industry standards for scoping reviews have been established by the Johanna Briggs Institute and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses extension for scoping reviews. According to these standards, scoping reviews should:

- Establish eligibility criteria with a rationale for each criterion clearly explained

- Search multiple databases in multiple languages

- Include “gray literature,” defined as studies that are unpublished or difficult to locate

- Have several independent reviewers screen titles and abstracts

- Ask multiple independent reviewers to review full text articles

- Present results with charts or diagrams that align with the review’s objective

- Graphically depict the decision process for including/excluding sources

- Identify implications for further research.

In their review, Dr. DuMontier and colleagues fulfilled many of the aforementioned criteria. The team searched three English-language databases for titles and abstracts that included the terms undertreatment and/or overtreatment, and were related to OAs with cancer, inclusive of all types of articles, cancer types, and treatments.

Definitions of undertreatment and overtreatment were extracted, and categories underlying these definitions were derived. Within a random subset of articles, two coauthors independently determined final categories of definitions and independently assigned those categories.

Findings and implications

To define OA, Dr. DuMontier and colleagues used a cutoff of 60 years or older. Articles mentioning undertreatment (n = 236), overtreatment (n = 71), or both (n = 51) met criteria for inclusion (n = 256), but only 14 articles (5.5%) explicitly provided formal definitions.

For most of the reviewed articles, the authors judged definitions from the surrounding context. In a random subset of 50 articles, there was a high level of agreement (87.1%; κ = 0.81) between two coauthors in independently assigning categories of definitions.

Undertreatment was applied to therapy that was less than recommended (148 articles; 62.7%) or less than recommended with worse outcomes (88 articles; 37.3%).

Overtreatment most commonly denoted intensive treatment of an OA in whom harms outweighed the benefits of treatment (38 articles; 53.5%) or intensive treatment of a cancer not expected to affect the OA during the patient’s remaining life (33 articles; 46.5%).

Overall, the authors found that undertreatment and overtreatment of OAs with cancer are imprecisely defined concepts. Formal geriatric assessment was recommended in just over half of articles, and only 26.2% recommended formal assessments of age-related vulnerabilities for management. The authors proposed definitions that accounted for both oncologic factors and geriatric domains.

Care of individual patients and clinical research

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for OAs with cancer recommend initial consideration of overall life expectancy. If a patient is a candidate for cancer treatment on that basis, the next recommended assessment is that of the patient’s capacity to understand the relevant information, appreciate the underlying values and overall medical situation, reason through decisions, and communicate a choice that is consistent with the patient’s articulated goals.

In the pretreatment evaluation of OAs in whom there are no concerns about tolerance to antineoplastic therapy, NCCN guidelines suggest geriatric screening with standardized tools and, if abnormal, comprehensive geriatric screening. The guidelines recommend considering alternative treatment options if nonmodifiable abnormalities are identified.

Referral to a geriatric clinical specialist, use of the Cancer and Aging Research Group’s Chemo Toxicity Calculator, and calculation of Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients score are specifically suggested if high-risk procedures (such as chemotherapy, radiation, or complex surgery, which most oncologists would consider to be “another day in the office”) are contemplated.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines for geriatric oncology are similarly detailed and endorse similar evaluations and management.

Employing disease-centric and geriatric domains

Dr. DuMontier and colleagues noted that, for OAs with comorbidity or psychosocial challenges, surrogate survival endpoints are unrelated to quality of life (QOL) outcomes. Nonetheless, QOL is valued by OAs at least as much as survival improvement.

Through no fault of their own, the authors’ conclusion that undertreatment and overtreatment are imperfectly defined concepts has a certain neutrality to it. However, the terms undertreatment and overtreatment are commonly used to signify that inappropriate treatment decisions were made. Therefore, the terms are inherently negative and pejorative.

As with most emotionally charged issues in oncology, it is ideal for professionals in our field to take charge when deficiencies exist. ASCO, NCCN, and the authors of this scoping review have provided a conceptual basis for doing so.

An integrated oncologist-geriatrician approach was shown to be effective in the randomized INTEGERATE trial, showing improved QOL, reduced hospital admissions, and reduced early treatment discontinuation from adverse events (ASCO 2020, Abstract 12011).

Therefore, those clinicians who have not formally, systematically, and routinely supplemented the traditional disease-centric endpoints with patient-centered criteria need to do so.

Similarly, a retrospective study published in JAMA Network Open demonstrated that geriatric and surgical comanagement of OAs with cancer was associated with significantly lower 90-day postoperative mortality and receipt of more supportive care services (physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech and swallow rehabilitation, and nutrition services), in comparison with management from the surgical service only.

These clinical and administrative changes will not only enhance patient management but also facilitate the clinical trials required to clarify optimal treatment intensity. As that occurs, we will be able to apply as much precision to the care of OAs with cancer as we do in other areas of cancer treatment.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Dumontier C et al. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Aug 1;38(22):2558-2569.

Because of physiological changes with aging and differences in cancer biology, caring for older adults (OAs) with cancer requires careful assessment and planning.

Clark Dumontier, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and colleagues sought to define the meaning of the terms “undertreatment” and “overtreatment” for OAs with cancer in a scoping literature review published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Though OAs are typically defined as adults aged 65 years and older, in this review, the authors defined OAs as patients aged 60 years and older.

The authors theorized that a scoping review of papers about this patient population could provide clues about limitations in the oncology literature and guidance about patient management and future research. Despite comprising the majority of cancer patients, OAs are underrepresented in clinical trials.

About scoping reviews

Scoping reviews are used to identify existing evidence in a field, clarify concepts or definitions in the literature, survey how research on a topic is conducted, and identify knowledge gaps. In addition, scoping reviews summarize available evidence without answering a discrete research question.

Industry standards for scoping reviews have been established by the Johanna Briggs Institute and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses extension for scoping reviews. According to these standards, scoping reviews should:

- Establish eligibility criteria with a rationale for each criterion clearly explained

- Search multiple databases in multiple languages

- Include “gray literature,” defined as studies that are unpublished or difficult to locate

- Have several independent reviewers screen titles and abstracts

- Ask multiple independent reviewers to review full text articles

- Present results with charts or diagrams that align with the review’s objective

- Graphically depict the decision process for including/excluding sources

- Identify implications for further research.

In their review, Dr. DuMontier and colleagues fulfilled many of the aforementioned criteria. The team searched three English-language databases for titles and abstracts that included the terms undertreatment and/or overtreatment, and were related to OAs with cancer, inclusive of all types of articles, cancer types, and treatments.

Definitions of undertreatment and overtreatment were extracted, and categories underlying these definitions were derived. Within a random subset of articles, two coauthors independently determined final categories of definitions and independently assigned those categories.

Findings and implications

To define OA, Dr. DuMontier and colleagues used a cutoff of 60 years or older. Articles mentioning undertreatment (n = 236), overtreatment (n = 71), or both (n = 51) met criteria for inclusion (n = 256), but only 14 articles (5.5%) explicitly provided formal definitions.

For most of the reviewed articles, the authors judged definitions from the surrounding context. In a random subset of 50 articles, there was a high level of agreement (87.1%; κ = 0.81) between two coauthors in independently assigning categories of definitions.

Undertreatment was applied to therapy that was less than recommended (148 articles; 62.7%) or less than recommended with worse outcomes (88 articles; 37.3%).

Overtreatment most commonly denoted intensive treatment of an OA in whom harms outweighed the benefits of treatment (38 articles; 53.5%) or intensive treatment of a cancer not expected to affect the OA during the patient’s remaining life (33 articles; 46.5%).

Overall, the authors found that undertreatment and overtreatment of OAs with cancer are imprecisely defined concepts. Formal geriatric assessment was recommended in just over half of articles, and only 26.2% recommended formal assessments of age-related vulnerabilities for management. The authors proposed definitions that accounted for both oncologic factors and geriatric domains.

Care of individual patients and clinical research

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for OAs with cancer recommend initial consideration of overall life expectancy. If a patient is a candidate for cancer treatment on that basis, the next recommended assessment is that of the patient’s capacity to understand the relevant information, appreciate the underlying values and overall medical situation, reason through decisions, and communicate a choice that is consistent with the patient’s articulated goals.

In the pretreatment evaluation of OAs in whom there are no concerns about tolerance to antineoplastic therapy, NCCN guidelines suggest geriatric screening with standardized tools and, if abnormal, comprehensive geriatric screening. The guidelines recommend considering alternative treatment options if nonmodifiable abnormalities are identified.

Referral to a geriatric clinical specialist, use of the Cancer and Aging Research Group’s Chemo Toxicity Calculator, and calculation of Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients score are specifically suggested if high-risk procedures (such as chemotherapy, radiation, or complex surgery, which most oncologists would consider to be “another day in the office”) are contemplated.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines for geriatric oncology are similarly detailed and endorse similar evaluations and management.

Employing disease-centric and geriatric domains

Dr. DuMontier and colleagues noted that, for OAs with comorbidity or psychosocial challenges, surrogate survival endpoints are unrelated to quality of life (QOL) outcomes. Nonetheless, QOL is valued by OAs at least as much as survival improvement.

Through no fault of their own, the authors’ conclusion that undertreatment and overtreatment are imperfectly defined concepts has a certain neutrality to it. However, the terms undertreatment and overtreatment are commonly used to signify that inappropriate treatment decisions were made. Therefore, the terms are inherently negative and pejorative.

As with most emotionally charged issues in oncology, it is ideal for professionals in our field to take charge when deficiencies exist. ASCO, NCCN, and the authors of this scoping review have provided a conceptual basis for doing so.

An integrated oncologist-geriatrician approach was shown to be effective in the randomized INTEGERATE trial, showing improved QOL, reduced hospital admissions, and reduced early treatment discontinuation from adverse events (ASCO 2020, Abstract 12011).

Therefore, those clinicians who have not formally, systematically, and routinely supplemented the traditional disease-centric endpoints with patient-centered criteria need to do so.

Similarly, a retrospective study published in JAMA Network Open demonstrated that geriatric and surgical comanagement of OAs with cancer was associated with significantly lower 90-day postoperative mortality and receipt of more supportive care services (physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech and swallow rehabilitation, and nutrition services), in comparison with management from the surgical service only.

These clinical and administrative changes will not only enhance patient management but also facilitate the clinical trials required to clarify optimal treatment intensity. As that occurs, we will be able to apply as much precision to the care of OAs with cancer as we do in other areas of cancer treatment.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Dumontier C et al. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Aug 1;38(22):2558-2569.

Because of physiological changes with aging and differences in cancer biology, caring for older adults (OAs) with cancer requires careful assessment and planning.

Clark Dumontier, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and colleagues sought to define the meaning of the terms “undertreatment” and “overtreatment” for OAs with cancer in a scoping literature review published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Though OAs are typically defined as adults aged 65 years and older, in this review, the authors defined OAs as patients aged 60 years and older.

The authors theorized that a scoping review of papers about this patient population could provide clues about limitations in the oncology literature and guidance about patient management and future research. Despite comprising the majority of cancer patients, OAs are underrepresented in clinical trials.

About scoping reviews

Scoping reviews are used to identify existing evidence in a field, clarify concepts or definitions in the literature, survey how research on a topic is conducted, and identify knowledge gaps. In addition, scoping reviews summarize available evidence without answering a discrete research question.

Industry standards for scoping reviews have been established by the Johanna Briggs Institute and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses extension for scoping reviews. According to these standards, scoping reviews should:

- Establish eligibility criteria with a rationale for each criterion clearly explained

- Search multiple databases in multiple languages

- Include “gray literature,” defined as studies that are unpublished or difficult to locate

- Have several independent reviewers screen titles and abstracts

- Ask multiple independent reviewers to review full text articles

- Present results with charts or diagrams that align with the review’s objective

- Graphically depict the decision process for including/excluding sources

- Identify implications for further research.

In their review, Dr. DuMontier and colleagues fulfilled many of the aforementioned criteria. The team searched three English-language databases for titles and abstracts that included the terms undertreatment and/or overtreatment, and were related to OAs with cancer, inclusive of all types of articles, cancer types, and treatments.

Definitions of undertreatment and overtreatment were extracted, and categories underlying these definitions were derived. Within a random subset of articles, two coauthors independently determined final categories of definitions and independently assigned those categories.

Findings and implications

To define OA, Dr. DuMontier and colleagues used a cutoff of 60 years or older. Articles mentioning undertreatment (n = 236), overtreatment (n = 71), or both (n = 51) met criteria for inclusion (n = 256), but only 14 articles (5.5%) explicitly provided formal definitions.

For most of the reviewed articles, the authors judged definitions from the surrounding context. In a random subset of 50 articles, there was a high level of agreement (87.1%; κ = 0.81) between two coauthors in independently assigning categories of definitions.

Undertreatment was applied to therapy that was less than recommended (148 articles; 62.7%) or less than recommended with worse outcomes (88 articles; 37.3%).

Overtreatment most commonly denoted intensive treatment of an OA in whom harms outweighed the benefits of treatment (38 articles; 53.5%) or intensive treatment of a cancer not expected to affect the OA during the patient’s remaining life (33 articles; 46.5%).

Overall, the authors found that undertreatment and overtreatment of OAs with cancer are imprecisely defined concepts. Formal geriatric assessment was recommended in just over half of articles, and only 26.2% recommended formal assessments of age-related vulnerabilities for management. The authors proposed definitions that accounted for both oncologic factors and geriatric domains.

Care of individual patients and clinical research

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for OAs with cancer recommend initial consideration of overall life expectancy. If a patient is a candidate for cancer treatment on that basis, the next recommended assessment is that of the patient’s capacity to understand the relevant information, appreciate the underlying values and overall medical situation, reason through decisions, and communicate a choice that is consistent with the patient’s articulated goals.

In the pretreatment evaluation of OAs in whom there are no concerns about tolerance to antineoplastic therapy, NCCN guidelines suggest geriatric screening with standardized tools and, if abnormal, comprehensive geriatric screening. The guidelines recommend considering alternative treatment options if nonmodifiable abnormalities are identified.

Referral to a geriatric clinical specialist, use of the Cancer and Aging Research Group’s Chemo Toxicity Calculator, and calculation of Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients score are specifically suggested if high-risk procedures (such as chemotherapy, radiation, or complex surgery, which most oncologists would consider to be “another day in the office”) are contemplated.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines for geriatric oncology are similarly detailed and endorse similar evaluations and management.

Employing disease-centric and geriatric domains

Dr. DuMontier and colleagues noted that, for OAs with comorbidity or psychosocial challenges, surrogate survival endpoints are unrelated to quality of life (QOL) outcomes. Nonetheless, QOL is valued by OAs at least as much as survival improvement.

Through no fault of their own, the authors’ conclusion that undertreatment and overtreatment are imperfectly defined concepts has a certain neutrality to it. However, the terms undertreatment and overtreatment are commonly used to signify that inappropriate treatment decisions were made. Therefore, the terms are inherently negative and pejorative.

As with most emotionally charged issues in oncology, it is ideal for professionals in our field to take charge when deficiencies exist. ASCO, NCCN, and the authors of this scoping review have provided a conceptual basis for doing so.

An integrated oncologist-geriatrician approach was shown to be effective in the randomized INTEGERATE trial, showing improved QOL, reduced hospital admissions, and reduced early treatment discontinuation from adverse events (ASCO 2020, Abstract 12011).

Therefore, those clinicians who have not formally, systematically, and routinely supplemented the traditional disease-centric endpoints with patient-centered criteria need to do so.

Similarly, a retrospective study published in JAMA Network Open demonstrated that geriatric and surgical comanagement of OAs with cancer was associated with significantly lower 90-day postoperative mortality and receipt of more supportive care services (physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech and swallow rehabilitation, and nutrition services), in comparison with management from the surgical service only.

These clinical and administrative changes will not only enhance patient management but also facilitate the clinical trials required to clarify optimal treatment intensity. As that occurs, we will be able to apply as much precision to the care of OAs with cancer as we do in other areas of cancer treatment.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Dumontier C et al. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Aug 1;38(22):2558-2569.

Cancer disparities: One of the most pressing public health issues

“The burden of cancer is not shouldered equally by all segments of the U.S. population,” the AACR adds. “The adverse differences in cancer burden that exist among certain population groups are one of the most pressing public health challenges that we face in the United States.”

AACR president Antoni Ribas, MD, PhD, gave some examples of these disparities at a September 16 Congressional briefing that focused on the inaugural AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2020.

He noted that:

- Black men have more than double the rate of death from prostate cancer compared with men of other racial and ethnic groups.

- Hispanic children are 24% more likely to develop leukemia than non-Hispanic children.

- Non-Hispanic Black children and adolescents with cancer are more than 50% more likely to die from the cancer than non-Hispanic white children and adolescents with cancer.

- Women of low socioeconomic status with early stage ovarian cancer are 50% less likely to receive recommended care than are women of high socioeconomic status.

- In addition to racial and ethnic minority groups, other populations that bear a disproportionate burden when it comes to cancer include individuals lacking adequate health insurance coverage, immigrants, those with disabilities, residents in rural areas, and members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender communities.

“It is absolutely unacceptable that advances in cancer care and treatment are not benefiting everyone equally,” Ribas commented.

Making progress against cancer

Progress being made against cancer was highlighted in another publication, the annual AACR Cancer Progress Report 2020.

U.S. cancer deaths declined by 29% between 1991 and 2017, translating to nearly 3 million cancer deaths avoided, the report notes. In addition, 5-year survival rates for all cancers combined increased from 49% in the mid-1970s to 70% for patients diagnosed from 2010-2016.

Between August 2019 and July 31 of this year, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved 20 new anticancer drugs for various cancer types and 15 new indications for previously approved cancer drugs, marking the highest number of approvals in one 12-month period since AACR started producing these reports 10 years ago.

A continuing reduction in the cigarette smoking rate among US adults, which is now below 14%, is contributing greatly to declines in lung cancer rates, which have largely driven the improvements in cancer survival, the AACR noted.

This report also notes that progress has been made toward reducing cancer disparities. Overall disparities in cancer death rates among racial and ethnic groups are less pronounced now than they have been in the past two decades. For example, the overall cancer death rate for African American patients was 33% higher than for White patients in 1990 but just 14% higher in 2016.

However, both reports agree that more must be done to reduce cancer disparities even further.

They highlight initiatives that are underway, including:

- The draft guidance issued by the FDA to promote diversification of clinical trial populations.

- The National Institutes of Health’s (NIH’s) Continuing Umbrella of Research Experiences (CURE) program supporting underrepresented students and scientists along their academic and research career pathway.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) program, a grant-making program focused on encouraging preventive behaviors in underserved communities.

- The NIH’s All of Us program, which is gathering information from the genomes of 1 million healthy individuals with a focus on recruitment from historically underrepresented populations.

Ribas also announced that AACR has established a task force to focus on racial inequalities in cancer research.

Eliminating disparities would save money, argued John D. Carpten, PhD, from the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, who chaired the steering committee that developed the AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report.

Carpten noted research showing that eliminating disparities for racial and ethnic minorities between 2003 and 2006 would have reduced health care costs by more than $1 trillion in the United States. This underscores the potentially far-reaching impact of efforts to eliminate disparities, he said.

“Without a doubt, socioeconomics and inequities in access to quality care represent major factors influencing cancer health disparities, and these disparities will persist until we address these issues” he said.

Both progress reports culminate in a call to action, largely focused on the need for “unwavering, bipartisan support from Congress, in the form of robust and sustained annual increases in funding for the NIH, NCI [National Cancer Institute], and FDA,” which is vital for accelerating the pace of progress.

The challenge is now compounded by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic: Both progress reports note that racial and ethnic minorities, including African Americans, are not only affected disproportionately by cancer, but also by COVID-19, further highlighting the “stark inequities in health care.”

Ribas further called for action from national leadership and the scientific community.

“During this unprecedented time in our nation’s history, there is also a need for our nation’s leaders to take on a much bigger role in confronting and combating the structural and systemic racism that contributes to health disparities,” he said. The “pervasive racism and social injustices” that have contributed to disparities in both COVID-19 and cancer underscore the need for “the scientific community to step up and partner with Congress to assess and address this issue within the research community.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“The burden of cancer is not shouldered equally by all segments of the U.S. population,” the AACR adds. “The adverse differences in cancer burden that exist among certain population groups are one of the most pressing public health challenges that we face in the United States.”

AACR president Antoni Ribas, MD, PhD, gave some examples of these disparities at a September 16 Congressional briefing that focused on the inaugural AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2020.

He noted that:

- Black men have more than double the rate of death from prostate cancer compared with men of other racial and ethnic groups.

- Hispanic children are 24% more likely to develop leukemia than non-Hispanic children.

- Non-Hispanic Black children and adolescents with cancer are more than 50% more likely to die from the cancer than non-Hispanic white children and adolescents with cancer.

- Women of low socioeconomic status with early stage ovarian cancer are 50% less likely to receive recommended care than are women of high socioeconomic status.

- In addition to racial and ethnic minority groups, other populations that bear a disproportionate burden when it comes to cancer include individuals lacking adequate health insurance coverage, immigrants, those with disabilities, residents in rural areas, and members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender communities.

“It is absolutely unacceptable that advances in cancer care and treatment are not benefiting everyone equally,” Ribas commented.

Making progress against cancer

Progress being made against cancer was highlighted in another publication, the annual AACR Cancer Progress Report 2020.

U.S. cancer deaths declined by 29% between 1991 and 2017, translating to nearly 3 million cancer deaths avoided, the report notes. In addition, 5-year survival rates for all cancers combined increased from 49% in the mid-1970s to 70% for patients diagnosed from 2010-2016.

Between August 2019 and July 31 of this year, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved 20 new anticancer drugs for various cancer types and 15 new indications for previously approved cancer drugs, marking the highest number of approvals in one 12-month period since AACR started producing these reports 10 years ago.

A continuing reduction in the cigarette smoking rate among US adults, which is now below 14%, is contributing greatly to declines in lung cancer rates, which have largely driven the improvements in cancer survival, the AACR noted.

This report also notes that progress has been made toward reducing cancer disparities. Overall disparities in cancer death rates among racial and ethnic groups are less pronounced now than they have been in the past two decades. For example, the overall cancer death rate for African American patients was 33% higher than for White patients in 1990 but just 14% higher in 2016.

However, both reports agree that more must be done to reduce cancer disparities even further.

They highlight initiatives that are underway, including:

- The draft guidance issued by the FDA to promote diversification of clinical trial populations.

- The National Institutes of Health’s (NIH’s) Continuing Umbrella of Research Experiences (CURE) program supporting underrepresented students and scientists along their academic and research career pathway.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) program, a grant-making program focused on encouraging preventive behaviors in underserved communities.

- The NIH’s All of Us program, which is gathering information from the genomes of 1 million healthy individuals with a focus on recruitment from historically underrepresented populations.

Ribas also announced that AACR has established a task force to focus on racial inequalities in cancer research.

Eliminating disparities would save money, argued John D. Carpten, PhD, from the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, who chaired the steering committee that developed the AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report.

Carpten noted research showing that eliminating disparities for racial and ethnic minorities between 2003 and 2006 would have reduced health care costs by more than $1 trillion in the United States. This underscores the potentially far-reaching impact of efforts to eliminate disparities, he said.

“Without a doubt, socioeconomics and inequities in access to quality care represent major factors influencing cancer health disparities, and these disparities will persist until we address these issues” he said.

Both progress reports culminate in a call to action, largely focused on the need for “unwavering, bipartisan support from Congress, in the form of robust and sustained annual increases in funding for the NIH, NCI [National Cancer Institute], and FDA,” which is vital for accelerating the pace of progress.

The challenge is now compounded by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic: Both progress reports note that racial and ethnic minorities, including African Americans, are not only affected disproportionately by cancer, but also by COVID-19, further highlighting the “stark inequities in health care.”

Ribas further called for action from national leadership and the scientific community.

“During this unprecedented time in our nation’s history, there is also a need for our nation’s leaders to take on a much bigger role in confronting and combating the structural and systemic racism that contributes to health disparities,” he said. The “pervasive racism and social injustices” that have contributed to disparities in both COVID-19 and cancer underscore the need for “the scientific community to step up and partner with Congress to assess and address this issue within the research community.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“The burden of cancer is not shouldered equally by all segments of the U.S. population,” the AACR adds. “The adverse differences in cancer burden that exist among certain population groups are one of the most pressing public health challenges that we face in the United States.”

AACR president Antoni Ribas, MD, PhD, gave some examples of these disparities at a September 16 Congressional briefing that focused on the inaugural AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2020.

He noted that:

- Black men have more than double the rate of death from prostate cancer compared with men of other racial and ethnic groups.

- Hispanic children are 24% more likely to develop leukemia than non-Hispanic children.

- Non-Hispanic Black children and adolescents with cancer are more than 50% more likely to die from the cancer than non-Hispanic white children and adolescents with cancer.

- Women of low socioeconomic status with early stage ovarian cancer are 50% less likely to receive recommended care than are women of high socioeconomic status.

- In addition to racial and ethnic minority groups, other populations that bear a disproportionate burden when it comes to cancer include individuals lacking adequate health insurance coverage, immigrants, those with disabilities, residents in rural areas, and members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender communities.

“It is absolutely unacceptable that advances in cancer care and treatment are not benefiting everyone equally,” Ribas commented.

Making progress against cancer

Progress being made against cancer was highlighted in another publication, the annual AACR Cancer Progress Report 2020.

U.S. cancer deaths declined by 29% between 1991 and 2017, translating to nearly 3 million cancer deaths avoided, the report notes. In addition, 5-year survival rates for all cancers combined increased from 49% in the mid-1970s to 70% for patients diagnosed from 2010-2016.

Between August 2019 and July 31 of this year, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved 20 new anticancer drugs for various cancer types and 15 new indications for previously approved cancer drugs, marking the highest number of approvals in one 12-month period since AACR started producing these reports 10 years ago.

A continuing reduction in the cigarette smoking rate among US adults, which is now below 14%, is contributing greatly to declines in lung cancer rates, which have largely driven the improvements in cancer survival, the AACR noted.