User login

Time or money?

The authors of a recent study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine estimate that physician burnout is costing this country’s health care system $4.6 billion annually, using a conservative base-case model (Ann Intern Med. 2019;170[11]:784-90). I guess we shouldn’t be surprised at the magnitude of the drain on our economy caused by unhappy physicians. We all know colleagues who are showing signs of burnout. And, you may be feeling yourself that the challenges of work are taking too great a toll on your physical and mental health? Would you be happier if you had more time?

A study reported in Harvard Business Review has looked at recent college graduates to determine if how they prioritize time and money can predict their future happiness (“Are New Graduates Happier Making More Money or Having More Time?” July 25, 2019). The researchers at the Harvard Business School surveyed 1,000 college students in the 2015 and 2016 classes of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. The students were asked to match themselves with descriptions of fictitious individuals to determine whether in general they prioritized time or money. The researchers then assessed the students’ level of happiness by asking them, “How satisfied are you with life overall?”

At a 2-year follow-up, the researchers found that, even taking into account the students’ level of happiness at the beginning of the study, “those who prioritized time were happier.” The authors also found that time-oriented people don’t necessarily work less or even earn more money, prompting their conclusion there is “strong evidence that valuing time puts people on a trajectory toward job satisfaction and well-being.”

Do the results of this study of Canadian college students provide any answers for our epidemic of physician burnout? One could argue that, if we wanted to minimize burnout, medical schools should include an assessment of each applicant’s level of happiness and how she or he prioritizes time and money using methods similar those used in this study? The problem is that some students are so heavily committed to becoming physicians that they would game the system and provide answers that will project the image that they are happy and prioritize time over money, when in reality they are ticking time bombs of discontent.

The bigger problem with interpreting the results of this study is that the subjects were Canadians who have significantly less educational debt than the medical students in this country. And as the authors observe, “people with objective financial constraints ... are more likely to focus on having more money.” Until we solve the problem of the high cost of medical education the system will continue to select for physicians whose decisions are too heavily influenced by their educational debt.

Finally, it is important to consider that time-oriented individuals don’t always work less, rather they make decisions that make it more likely that they will pursue activities they find enjoyable. For example, accepting a higher-paying job that requires an additional 3 hours of commute each day lays the foundation for a life in which a large portion of one’s day is expended in an activity that few of us find enjoyable. Choosing a long commute is a personal decision. Spending nearly 2 hours each day tethered to an EHR system was not something most physicians anticipated when they were choosing a career.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

The authors of a recent study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine estimate that physician burnout is costing this country’s health care system $4.6 billion annually, using a conservative base-case model (Ann Intern Med. 2019;170[11]:784-90). I guess we shouldn’t be surprised at the magnitude of the drain on our economy caused by unhappy physicians. We all know colleagues who are showing signs of burnout. And, you may be feeling yourself that the challenges of work are taking too great a toll on your physical and mental health? Would you be happier if you had more time?

A study reported in Harvard Business Review has looked at recent college graduates to determine if how they prioritize time and money can predict their future happiness (“Are New Graduates Happier Making More Money or Having More Time?” July 25, 2019). The researchers at the Harvard Business School surveyed 1,000 college students in the 2015 and 2016 classes of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. The students were asked to match themselves with descriptions of fictitious individuals to determine whether in general they prioritized time or money. The researchers then assessed the students’ level of happiness by asking them, “How satisfied are you with life overall?”

At a 2-year follow-up, the researchers found that, even taking into account the students’ level of happiness at the beginning of the study, “those who prioritized time were happier.” The authors also found that time-oriented people don’t necessarily work less or even earn more money, prompting their conclusion there is “strong evidence that valuing time puts people on a trajectory toward job satisfaction and well-being.”

Do the results of this study of Canadian college students provide any answers for our epidemic of physician burnout? One could argue that, if we wanted to minimize burnout, medical schools should include an assessment of each applicant’s level of happiness and how she or he prioritizes time and money using methods similar those used in this study? The problem is that some students are so heavily committed to becoming physicians that they would game the system and provide answers that will project the image that they are happy and prioritize time over money, when in reality they are ticking time bombs of discontent.

The bigger problem with interpreting the results of this study is that the subjects were Canadians who have significantly less educational debt than the medical students in this country. And as the authors observe, “people with objective financial constraints ... are more likely to focus on having more money.” Until we solve the problem of the high cost of medical education the system will continue to select for physicians whose decisions are too heavily influenced by their educational debt.

Finally, it is important to consider that time-oriented individuals don’t always work less, rather they make decisions that make it more likely that they will pursue activities they find enjoyable. For example, accepting a higher-paying job that requires an additional 3 hours of commute each day lays the foundation for a life in which a large portion of one’s day is expended in an activity that few of us find enjoyable. Choosing a long commute is a personal decision. Spending nearly 2 hours each day tethered to an EHR system was not something most physicians anticipated when they were choosing a career.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

The authors of a recent study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine estimate that physician burnout is costing this country’s health care system $4.6 billion annually, using a conservative base-case model (Ann Intern Med. 2019;170[11]:784-90). I guess we shouldn’t be surprised at the magnitude of the drain on our economy caused by unhappy physicians. We all know colleagues who are showing signs of burnout. And, you may be feeling yourself that the challenges of work are taking too great a toll on your physical and mental health? Would you be happier if you had more time?

A study reported in Harvard Business Review has looked at recent college graduates to determine if how they prioritize time and money can predict their future happiness (“Are New Graduates Happier Making More Money or Having More Time?” July 25, 2019). The researchers at the Harvard Business School surveyed 1,000 college students in the 2015 and 2016 classes of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. The students were asked to match themselves with descriptions of fictitious individuals to determine whether in general they prioritized time or money. The researchers then assessed the students’ level of happiness by asking them, “How satisfied are you with life overall?”

At a 2-year follow-up, the researchers found that, even taking into account the students’ level of happiness at the beginning of the study, “those who prioritized time were happier.” The authors also found that time-oriented people don’t necessarily work less or even earn more money, prompting their conclusion there is “strong evidence that valuing time puts people on a trajectory toward job satisfaction and well-being.”

Do the results of this study of Canadian college students provide any answers for our epidemic of physician burnout? One could argue that, if we wanted to minimize burnout, medical schools should include an assessment of each applicant’s level of happiness and how she or he prioritizes time and money using methods similar those used in this study? The problem is that some students are so heavily committed to becoming physicians that they would game the system and provide answers that will project the image that they are happy and prioritize time over money, when in reality they are ticking time bombs of discontent.

The bigger problem with interpreting the results of this study is that the subjects were Canadians who have significantly less educational debt than the medical students in this country. And as the authors observe, “people with objective financial constraints ... are more likely to focus on having more money.” Until we solve the problem of the high cost of medical education the system will continue to select for physicians whose decisions are too heavily influenced by their educational debt.

Finally, it is important to consider that time-oriented individuals don’t always work less, rather they make decisions that make it more likely that they will pursue activities they find enjoyable. For example, accepting a higher-paying job that requires an additional 3 hours of commute each day lays the foundation for a life in which a large portion of one’s day is expended in an activity that few of us find enjoyable. Choosing a long commute is a personal decision. Spending nearly 2 hours each day tethered to an EHR system was not something most physicians anticipated when they were choosing a career.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Before the die is cast

When asked about my decision to choose pediatrics over the other specialty opportunities I was being offered, I have always answered that my choice was primarily based on my desire to work with children. That affinity certainly didn’t stem from my experience with my sister who is 7 years my junior. By her own admission, she was a bratty little thing and a major annoyance during my journey through adolescence. However, during the summers of high school and college I worked as a lifeguard, and one of my duties was to teach swimming classes. The joy and reward of watching children overcome their fear of the water and become competent swimmers left a positive impression, which was in stark contrast to the few classes of adult nonswimmers my coworkers and I taught. Our success rate with adults was pretty close to zero.

If I was going to spend my time and effort becoming a physician, I decided I wanted to be working with patients with the high potential for positive change and ones who had yet to accumulate a several decades long list of bad health habits. I wanted to be practicing in situations well before the die had been cast.

With this background in mind, you can understand why I was drawn to a recent article in the Harvard Gazette titled “Social spending on kids yields the biggest bang for the buck,” by Clea Simon. The article describes a recent study by Opportunity Insights, a Harvard-based institute of policy analysts and social scientists (“A Unified Welfare Analysis of Government Policies” by Nathaniel Hendren, PhD, and Ben Sprung-Keyser). Using computer algorithms capable of mining large pools of data, the researchers looked at 133 government policy changes over the last 50 years and compared the long-term results of those changes by assessing dollars spent against those returned in the form of tax revenue.

The Harvard article quotes Dr. Hendren as saying, This association was most impressive for children who came from lower-income families. This was especially true for programs that aimed at improving child health and increasing educational attainment.

Of course, these observations don’t come as a surprise to those of us who have accepted the challenge of improving the health of children. But it’s always nice to hear some new data that warms our hearts and reinforces our commitment to building healthy communities by focusing our efforts on its youngest members.

However, the paper did provide a finding that disappointed me. This big data analysis revealed that programs aimed at encouraging young people to attend college produced higher future earnings than did those focused on job training. I guess this shouldn’t be much of a surprise, but I believe we have been overemphasizing college track programs when we should be destigmatizing a career path in one of the trades. It may be that job training has been poorly done or at least not flexible enough to meet the changing demands of industry.

The investigators were surprised that their analysis demonstrated that policy changes targeted at children through their middle and high school years and even into college yielded return on investment at least as great if not greater than some successful preschool programs. Dr. Hendren responded to this finding by observing that “it’s never too late.” However, I think his comment deserves the loud and clear caveat, “as long as we are still talking about children.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

When asked about my decision to choose pediatrics over the other specialty opportunities I was being offered, I have always answered that my choice was primarily based on my desire to work with children. That affinity certainly didn’t stem from my experience with my sister who is 7 years my junior. By her own admission, she was a bratty little thing and a major annoyance during my journey through adolescence. However, during the summers of high school and college I worked as a lifeguard, and one of my duties was to teach swimming classes. The joy and reward of watching children overcome their fear of the water and become competent swimmers left a positive impression, which was in stark contrast to the few classes of adult nonswimmers my coworkers and I taught. Our success rate with adults was pretty close to zero.

If I was going to spend my time and effort becoming a physician, I decided I wanted to be working with patients with the high potential for positive change and ones who had yet to accumulate a several decades long list of bad health habits. I wanted to be practicing in situations well before the die had been cast.

With this background in mind, you can understand why I was drawn to a recent article in the Harvard Gazette titled “Social spending on kids yields the biggest bang for the buck,” by Clea Simon. The article describes a recent study by Opportunity Insights, a Harvard-based institute of policy analysts and social scientists (“A Unified Welfare Analysis of Government Policies” by Nathaniel Hendren, PhD, and Ben Sprung-Keyser). Using computer algorithms capable of mining large pools of data, the researchers looked at 133 government policy changes over the last 50 years and compared the long-term results of those changes by assessing dollars spent against those returned in the form of tax revenue.

The Harvard article quotes Dr. Hendren as saying, This association was most impressive for children who came from lower-income families. This was especially true for programs that aimed at improving child health and increasing educational attainment.

Of course, these observations don’t come as a surprise to those of us who have accepted the challenge of improving the health of children. But it’s always nice to hear some new data that warms our hearts and reinforces our commitment to building healthy communities by focusing our efforts on its youngest members.

However, the paper did provide a finding that disappointed me. This big data analysis revealed that programs aimed at encouraging young people to attend college produced higher future earnings than did those focused on job training. I guess this shouldn’t be much of a surprise, but I believe we have been overemphasizing college track programs when we should be destigmatizing a career path in one of the trades. It may be that job training has been poorly done or at least not flexible enough to meet the changing demands of industry.

The investigators were surprised that their analysis demonstrated that policy changes targeted at children through their middle and high school years and even into college yielded return on investment at least as great if not greater than some successful preschool programs. Dr. Hendren responded to this finding by observing that “it’s never too late.” However, I think his comment deserves the loud and clear caveat, “as long as we are still talking about children.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

When asked about my decision to choose pediatrics over the other specialty opportunities I was being offered, I have always answered that my choice was primarily based on my desire to work with children. That affinity certainly didn’t stem from my experience with my sister who is 7 years my junior. By her own admission, she was a bratty little thing and a major annoyance during my journey through adolescence. However, during the summers of high school and college I worked as a lifeguard, and one of my duties was to teach swimming classes. The joy and reward of watching children overcome their fear of the water and become competent swimmers left a positive impression, which was in stark contrast to the few classes of adult nonswimmers my coworkers and I taught. Our success rate with adults was pretty close to zero.

If I was going to spend my time and effort becoming a physician, I decided I wanted to be working with patients with the high potential for positive change and ones who had yet to accumulate a several decades long list of bad health habits. I wanted to be practicing in situations well before the die had been cast.

With this background in mind, you can understand why I was drawn to a recent article in the Harvard Gazette titled “Social spending on kids yields the biggest bang for the buck,” by Clea Simon. The article describes a recent study by Opportunity Insights, a Harvard-based institute of policy analysts and social scientists (“A Unified Welfare Analysis of Government Policies” by Nathaniel Hendren, PhD, and Ben Sprung-Keyser). Using computer algorithms capable of mining large pools of data, the researchers looked at 133 government policy changes over the last 50 years and compared the long-term results of those changes by assessing dollars spent against those returned in the form of tax revenue.

The Harvard article quotes Dr. Hendren as saying, This association was most impressive for children who came from lower-income families. This was especially true for programs that aimed at improving child health and increasing educational attainment.

Of course, these observations don’t come as a surprise to those of us who have accepted the challenge of improving the health of children. But it’s always nice to hear some new data that warms our hearts and reinforces our commitment to building healthy communities by focusing our efforts on its youngest members.

However, the paper did provide a finding that disappointed me. This big data analysis revealed that programs aimed at encouraging young people to attend college produced higher future earnings than did those focused on job training. I guess this shouldn’t be much of a surprise, but I believe we have been overemphasizing college track programs when we should be destigmatizing a career path in one of the trades. It may be that job training has been poorly done or at least not flexible enough to meet the changing demands of industry.

The investigators were surprised that their analysis demonstrated that policy changes targeted at children through their middle and high school years and even into college yielded return on investment at least as great if not greater than some successful preschool programs. Dr. Hendren responded to this finding by observing that “it’s never too late.” However, I think his comment deserves the loud and clear caveat, “as long as we are still talking about children.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

How are your otoscopy skills?

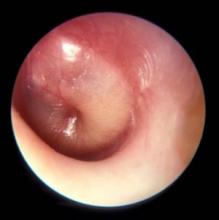

If the name Michael E. Pichichero, MD, is unfamiliar, you haven’t been reading some of the best articles on this website . Dr. Pichichero, an infectious disease specialist at the Research Institute at the Rochester General Hospital in New York, reports in his most recent ID Consult column on new research presented at the June 2019 meeting of the International Society for Otitis Media, including topics such as transtympanic antibiotic delivery, biofilms, probiotics, and biomarkers.

Dr. Pichichero described work he and his colleagues have been doing on the impact of overdiagnosis of acute otitis media (AOM). They found when “validated otoscopists” evaluated children, half as many reached the diagnostic threshold of being labeled “otitis prone” as when community-based pediatricians performed the exams.

Looking around at the colleagues with whom you share patients, do you find that some of them diagnose AOM much more frequently than does the coverage group average? How often do you see a child a day or two after he has been diagnosed with AOM by a colleague and find that the child’s tympanic membranes are transparent and mobile? Do you or your practice group keep track of each provider’s diagnostic tendencies? If these data exists, is there a mechanism for addressing apparent outliers? I suspect that the answer to those last two questions is a firm “No.”

I don’t have the stomach this morning to open those two cans of worms. But certainly Dr. Pichichero’s findings suggest that these are issues that need to be addressed. How the process should proceed in a nonthreatening way is a story for another day. But I’m not sure that involving your community ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist as a resource is the best answer. The scenarios in which pediatricians and ENTs perform otoscopies couldn’t be more different. In the pediatrician’s office, the child is generally sick, feverish, and possibly in pain. In the ENT’s office, the acute process has probably passed and the assessment may lean more heavily on history. The child is more likely to accept the exam without resistance, and the findings are not those of AOM but of a chronic process. The fact that Dr. Pichichero has been able to find and train “validated otoscopists” suggests that improving the quality of otoscopy among the physicians in communities like yours and mine is achievable.

How are your otoscopy skills? Do feel comfortable that you can do a good exam and accurately diagnose AOM? When did you acquire that comfort level? Probably not in medical school. More likely as a house officer when you were guided by a more senior house officer who may nor not been a master otoscopist. How would you rate your training? Or were you self-taught? Do you insufflate? Are you a skilled cerumen extractor? Or do you give up after one attempt? Be honest. How is your equipment? Are the bulbs and batteries fresh? Do you find yourself frustrated by an otoscope that is tethered to the wall charger by a cord that ensnarls you, the parent, and the patient? Have you complained to the practice administrators that your otoscopes are inadequate?

These are not minor issues. It is clear that overdiagnosis of AOM happens. It may occur even more often than Dr. Pichichero suggests, but I doubt it is less. Overdiagnosis can result in overtreatment with antibiotics, and the cascade of consequences both for the patient, the community, and the environment. Overdiagnosis can be the first step on the path to unnecessary surgery. It is incumbent on all of us to make sure that our otoscopy skills and those of our colleagues are sharp, that our equipment is well maintained and that we remain abreast of the latest developments in the diagnosis and treatment of AOM.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

If the name Michael E. Pichichero, MD, is unfamiliar, you haven’t been reading some of the best articles on this website . Dr. Pichichero, an infectious disease specialist at the Research Institute at the Rochester General Hospital in New York, reports in his most recent ID Consult column on new research presented at the June 2019 meeting of the International Society for Otitis Media, including topics such as transtympanic antibiotic delivery, biofilms, probiotics, and biomarkers.

Dr. Pichichero described work he and his colleagues have been doing on the impact of overdiagnosis of acute otitis media (AOM). They found when “validated otoscopists” evaluated children, half as many reached the diagnostic threshold of being labeled “otitis prone” as when community-based pediatricians performed the exams.

Looking around at the colleagues with whom you share patients, do you find that some of them diagnose AOM much more frequently than does the coverage group average? How often do you see a child a day or two after he has been diagnosed with AOM by a colleague and find that the child’s tympanic membranes are transparent and mobile? Do you or your practice group keep track of each provider’s diagnostic tendencies? If these data exists, is there a mechanism for addressing apparent outliers? I suspect that the answer to those last two questions is a firm “No.”

I don’t have the stomach this morning to open those two cans of worms. But certainly Dr. Pichichero’s findings suggest that these are issues that need to be addressed. How the process should proceed in a nonthreatening way is a story for another day. But I’m not sure that involving your community ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist as a resource is the best answer. The scenarios in which pediatricians and ENTs perform otoscopies couldn’t be more different. In the pediatrician’s office, the child is generally sick, feverish, and possibly in pain. In the ENT’s office, the acute process has probably passed and the assessment may lean more heavily on history. The child is more likely to accept the exam without resistance, and the findings are not those of AOM but of a chronic process. The fact that Dr. Pichichero has been able to find and train “validated otoscopists” suggests that improving the quality of otoscopy among the physicians in communities like yours and mine is achievable.

How are your otoscopy skills? Do feel comfortable that you can do a good exam and accurately diagnose AOM? When did you acquire that comfort level? Probably not in medical school. More likely as a house officer when you were guided by a more senior house officer who may nor not been a master otoscopist. How would you rate your training? Or were you self-taught? Do you insufflate? Are you a skilled cerumen extractor? Or do you give up after one attempt? Be honest. How is your equipment? Are the bulbs and batteries fresh? Do you find yourself frustrated by an otoscope that is tethered to the wall charger by a cord that ensnarls you, the parent, and the patient? Have you complained to the practice administrators that your otoscopes are inadequate?

These are not minor issues. It is clear that overdiagnosis of AOM happens. It may occur even more often than Dr. Pichichero suggests, but I doubt it is less. Overdiagnosis can result in overtreatment with antibiotics, and the cascade of consequences both for the patient, the community, and the environment. Overdiagnosis can be the first step on the path to unnecessary surgery. It is incumbent on all of us to make sure that our otoscopy skills and those of our colleagues are sharp, that our equipment is well maintained and that we remain abreast of the latest developments in the diagnosis and treatment of AOM.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

If the name Michael E. Pichichero, MD, is unfamiliar, you haven’t been reading some of the best articles on this website . Dr. Pichichero, an infectious disease specialist at the Research Institute at the Rochester General Hospital in New York, reports in his most recent ID Consult column on new research presented at the June 2019 meeting of the International Society for Otitis Media, including topics such as transtympanic antibiotic delivery, biofilms, probiotics, and biomarkers.

Dr. Pichichero described work he and his colleagues have been doing on the impact of overdiagnosis of acute otitis media (AOM). They found when “validated otoscopists” evaluated children, half as many reached the diagnostic threshold of being labeled “otitis prone” as when community-based pediatricians performed the exams.

Looking around at the colleagues with whom you share patients, do you find that some of them diagnose AOM much more frequently than does the coverage group average? How often do you see a child a day or two after he has been diagnosed with AOM by a colleague and find that the child’s tympanic membranes are transparent and mobile? Do you or your practice group keep track of each provider’s diagnostic tendencies? If these data exists, is there a mechanism for addressing apparent outliers? I suspect that the answer to those last two questions is a firm “No.”

I don’t have the stomach this morning to open those two cans of worms. But certainly Dr. Pichichero’s findings suggest that these are issues that need to be addressed. How the process should proceed in a nonthreatening way is a story for another day. But I’m not sure that involving your community ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist as a resource is the best answer. The scenarios in which pediatricians and ENTs perform otoscopies couldn’t be more different. In the pediatrician’s office, the child is generally sick, feverish, and possibly in pain. In the ENT’s office, the acute process has probably passed and the assessment may lean more heavily on history. The child is more likely to accept the exam without resistance, and the findings are not those of AOM but of a chronic process. The fact that Dr. Pichichero has been able to find and train “validated otoscopists” suggests that improving the quality of otoscopy among the physicians in communities like yours and mine is achievable.

How are your otoscopy skills? Do feel comfortable that you can do a good exam and accurately diagnose AOM? When did you acquire that comfort level? Probably not in medical school. More likely as a house officer when you were guided by a more senior house officer who may nor not been a master otoscopist. How would you rate your training? Or were you self-taught? Do you insufflate? Are you a skilled cerumen extractor? Or do you give up after one attempt? Be honest. How is your equipment? Are the bulbs and batteries fresh? Do you find yourself frustrated by an otoscope that is tethered to the wall charger by a cord that ensnarls you, the parent, and the patient? Have you complained to the practice administrators that your otoscopes are inadequate?

These are not minor issues. It is clear that overdiagnosis of AOM happens. It may occur even more often than Dr. Pichichero suggests, but I doubt it is less. Overdiagnosis can result in overtreatment with antibiotics, and the cascade of consequences both for the patient, the community, and the environment. Overdiagnosis can be the first step on the path to unnecessary surgery. It is incumbent on all of us to make sure that our otoscopy skills and those of our colleagues are sharp, that our equipment is well maintained and that we remain abreast of the latest developments in the diagnosis and treatment of AOM.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Living small

I’m sitting on the porch looking out at our little harbor, listening to the murmurings of the family of renters who have just moved into the cottage next door. We are on the cusp of the tourist season that draws millions of visitors – more than 36 million in 2017 – to a state that has less than a million and a half year-round residents during the other 9 months. Why do the “people from away” come?

The water is too cold for swimming most of the summer in Maine. But we have forested mountains, rocky shores, and we’re small. When I chat with the visitors sharing our stony little beach, they often ask if I live here and tell me how lucky I am because they envy the quiet, the friendly people, the lack of traffic, and the sense of community that they feel here in Vacationland.

My being here in Maine wasn’t a stroke of luck. It was a conscious decision that my wife and I made when I finished my training. The lucky part was meeting my wife who was born here. Through her I learned what Maine was about. I had grown up in a small town of 5,000 (although it was the suburb of a city of millions) and went to a small college in rural New Hampshire with an enrollment of a little more than 3,000. I turned down residencies in pediatric radiology and dermatology because I knew that to have a sustainable patient base we would have needed to live in a major metropolitan center.

I was accustomed to the benefits of living small. In the 1970s, the local economy in mid-coast Maine was shaky, the biggest employer had not yet secured the large military contracts it needed to thrive. But we decided it was a risk worth taking, and we have never regretted for a second living and practicing in a town of less than 20,000.

With this history as a backdrop, you can understand why I am a bit puzzled and disappointed by the results of a 2019 survey final-year medical residents recently published by the medical search and consulting firm Merritt Hawkins. Although the sample size is small (391 respondents out of 20,000 email surveys), the responses probably are a reasonable reflection of the opinions of the entire population of final-year residents. More than 80% of the respondents said that they would most like to practice in a community with a population of more than 100,000, and 65% would prefer a population base of more than 250,000. This would automatically rule out Maine, where our largest city has less than 80,000 people.

I can easily understand why physicians finishing their residency would avoid practice opportunities in remote, thinly populated regions in which they might find themselves as the only, or one of only two physicians serving a medically needy, economically depressed population spread out over a wide geographic area. That kind of challenge has some appeal for the saintly few, or the dreamy-eyed idealists. But in my experience, those work environments require so much energy that most physicians last only a few years because being on call is so taxing.

However, I know of several right here in Maine. What is driving young physicians to seek larger communities? It may be that because teaching hospitals are usually in more densely populated communities, many residents lack sufficient exposure to role models who are practicing in smaller settings. Compounding this dearth of role models is the unfortunate and often inaccurate image in which local doctors are cast as bumbling and clueless. I was fortunate because where I did my first 2 years of training, the local pediatricians played an active role and were very visible role models of how one can enjoy practice in a smaller community.

I guess I can’t ignore the obvious that a larger population base may be able guarantee an income that could sound appealing to the more than 50% of residents who will complete their training with a sizable debt.

However, I fear that too many residents nearing the end of their training believe that the “quality of life” that they claim to be seeking can’t be found in a small community practice. They would do well to speak to a few of us who have enjoyed and prospered by living small.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

I’m sitting on the porch looking out at our little harbor, listening to the murmurings of the family of renters who have just moved into the cottage next door. We are on the cusp of the tourist season that draws millions of visitors – more than 36 million in 2017 – to a state that has less than a million and a half year-round residents during the other 9 months. Why do the “people from away” come?

The water is too cold for swimming most of the summer in Maine. But we have forested mountains, rocky shores, and we’re small. When I chat with the visitors sharing our stony little beach, they often ask if I live here and tell me how lucky I am because they envy the quiet, the friendly people, the lack of traffic, and the sense of community that they feel here in Vacationland.

My being here in Maine wasn’t a stroke of luck. It was a conscious decision that my wife and I made when I finished my training. The lucky part was meeting my wife who was born here. Through her I learned what Maine was about. I had grown up in a small town of 5,000 (although it was the suburb of a city of millions) and went to a small college in rural New Hampshire with an enrollment of a little more than 3,000. I turned down residencies in pediatric radiology and dermatology because I knew that to have a sustainable patient base we would have needed to live in a major metropolitan center.

I was accustomed to the benefits of living small. In the 1970s, the local economy in mid-coast Maine was shaky, the biggest employer had not yet secured the large military contracts it needed to thrive. But we decided it was a risk worth taking, and we have never regretted for a second living and practicing in a town of less than 20,000.

With this history as a backdrop, you can understand why I am a bit puzzled and disappointed by the results of a 2019 survey final-year medical residents recently published by the medical search and consulting firm Merritt Hawkins. Although the sample size is small (391 respondents out of 20,000 email surveys), the responses probably are a reasonable reflection of the opinions of the entire population of final-year residents. More than 80% of the respondents said that they would most like to practice in a community with a population of more than 100,000, and 65% would prefer a population base of more than 250,000. This would automatically rule out Maine, where our largest city has less than 80,000 people.

I can easily understand why physicians finishing their residency would avoid practice opportunities in remote, thinly populated regions in which they might find themselves as the only, or one of only two physicians serving a medically needy, economically depressed population spread out over a wide geographic area. That kind of challenge has some appeal for the saintly few, or the dreamy-eyed idealists. But in my experience, those work environments require so much energy that most physicians last only a few years because being on call is so taxing.

However, I know of several right here in Maine. What is driving young physicians to seek larger communities? It may be that because teaching hospitals are usually in more densely populated communities, many residents lack sufficient exposure to role models who are practicing in smaller settings. Compounding this dearth of role models is the unfortunate and often inaccurate image in which local doctors are cast as bumbling and clueless. I was fortunate because where I did my first 2 years of training, the local pediatricians played an active role and were very visible role models of how one can enjoy practice in a smaller community.

I guess I can’t ignore the obvious that a larger population base may be able guarantee an income that could sound appealing to the more than 50% of residents who will complete their training with a sizable debt.

However, I fear that too many residents nearing the end of their training believe that the “quality of life” that they claim to be seeking can’t be found in a small community practice. They would do well to speak to a few of us who have enjoyed and prospered by living small.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

I’m sitting on the porch looking out at our little harbor, listening to the murmurings of the family of renters who have just moved into the cottage next door. We are on the cusp of the tourist season that draws millions of visitors – more than 36 million in 2017 – to a state that has less than a million and a half year-round residents during the other 9 months. Why do the “people from away” come?

The water is too cold for swimming most of the summer in Maine. But we have forested mountains, rocky shores, and we’re small. When I chat with the visitors sharing our stony little beach, they often ask if I live here and tell me how lucky I am because they envy the quiet, the friendly people, the lack of traffic, and the sense of community that they feel here in Vacationland.

My being here in Maine wasn’t a stroke of luck. It was a conscious decision that my wife and I made when I finished my training. The lucky part was meeting my wife who was born here. Through her I learned what Maine was about. I had grown up in a small town of 5,000 (although it was the suburb of a city of millions) and went to a small college in rural New Hampshire with an enrollment of a little more than 3,000. I turned down residencies in pediatric radiology and dermatology because I knew that to have a sustainable patient base we would have needed to live in a major metropolitan center.

I was accustomed to the benefits of living small. In the 1970s, the local economy in mid-coast Maine was shaky, the biggest employer had not yet secured the large military contracts it needed to thrive. But we decided it was a risk worth taking, and we have never regretted for a second living and practicing in a town of less than 20,000.

With this history as a backdrop, you can understand why I am a bit puzzled and disappointed by the results of a 2019 survey final-year medical residents recently published by the medical search and consulting firm Merritt Hawkins. Although the sample size is small (391 respondents out of 20,000 email surveys), the responses probably are a reasonable reflection of the opinions of the entire population of final-year residents. More than 80% of the respondents said that they would most like to practice in a community with a population of more than 100,000, and 65% would prefer a population base of more than 250,000. This would automatically rule out Maine, where our largest city has less than 80,000 people.

I can easily understand why physicians finishing their residency would avoid practice opportunities in remote, thinly populated regions in which they might find themselves as the only, or one of only two physicians serving a medically needy, economically depressed population spread out over a wide geographic area. That kind of challenge has some appeal for the saintly few, or the dreamy-eyed idealists. But in my experience, those work environments require so much energy that most physicians last only a few years because being on call is so taxing.

However, I know of several right here in Maine. What is driving young physicians to seek larger communities? It may be that because teaching hospitals are usually in more densely populated communities, many residents lack sufficient exposure to role models who are practicing in smaller settings. Compounding this dearth of role models is the unfortunate and often inaccurate image in which local doctors are cast as bumbling and clueless. I was fortunate because where I did my first 2 years of training, the local pediatricians played an active role and were very visible role models of how one can enjoy practice in a smaller community.

I guess I can’t ignore the obvious that a larger population base may be able guarantee an income that could sound appealing to the more than 50% of residents who will complete their training with a sizable debt.

However, I fear that too many residents nearing the end of their training believe that the “quality of life” that they claim to be seeking can’t be found in a small community practice. They would do well to speak to a few of us who have enjoyed and prospered by living small.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

The pool is closed!

At a recent Recreation Commission meeting here in Brunswick, the first agenda item under new business was “Coffin Pond Pool Closing.” As I and my fellow commissioners listened, we were told that for the first time in the last 3 decades the town’s only public swimming area would not be opening. While in the past there have been delayed openings and temporary closings due to water conditions, this year the pool would not open, period. The cause of the pool’s closure was the Parks and Recreation Department’s failure to fill even a skeleton crew of lifeguards.

We learned that the situation here in Brunswick was not unique and most other communities around the state and even around the country were struggling to find lifeguards. The shortage of trained staff has been nationwide for several years, and many beaches and pools particularly in the Northeast and Middle Atlantic states were being forced to close or shorten hours of operation (“During the Pool Season Even Lifeguard Numbers are Taking a Dive,” by Leoneda Inge, July 28, 2015, NPR’s All Thing Considered).

You might think that here on the coast we would have ample places for children to swim, but in Brunswick our shore is rocky and often inaccessible. At the few sandy beaches, the water temperature is too cold for all but the hardy souls until late August. Lower-income families will be particularly affected by the loss of the pool.

When I was growing up, lifeguarding was a plum job that was highly coveted. While it did not pay as well as working construction, the perks of a pleasant atmosphere, the chance to swim every day, and the opportunity to work outside with children prompted me at age 16 to sell my lawn mower and bequeath my lucrative landscaping customers to a couple of preteens. Looking back, my 4 years of lifeguarding were probably a major influence when it came time to choose a specialty.

However, a perfect storm of socioeconomic factors has combined to create a climate in which being a lifeguard has lost its appeal as a summertime job. First, there is record low unemployment nationwide. Young people looking for work have their pick, and while wages still remain low, they can be choosy when it comes to hours and benefits. Lifeguarding does require a skill set and several hoops of certification to be navigated. I don’t recall having to pay much of anything to become certified. But I understand that the process now costs hundreds of dollars of upfront investment with no guarantee of passing the test.

In May, the American Academy of Pediatrics published a policy paper titled “Prevention of Drowning” (Pediatrics. 2019 May 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0850) in which the authors offer the troubling statistics on the toll that water-related accidents take on the children of this country annually. They go on to provide a broad list of actions that parents, communities, and pediatricians can take to prevent drownings. Under the category of Community Interventions and Advocacy Opportunities, recommendation No. 4 is “Pediatricians should work with community partners to provide access to programs that develop water-competency swim skills for all children.”

Obviously, these programs can’t happen without an adequate supply of lifeguards.

Unfortunately, the AAP’s statement fails to acknowledge or directly address the lifeguard shortage that has been going on for several years. While an adequate supply of lifeguards is probably not as important as increasing parental attentiveness and mandating pool fences in the overall scheme of drowning prevention, it is an issue that demands action both by the academy and those of us practicing in communities both large and small.

For my part, I am going to work here in Brunswick to see that we can offer lifeguards pay that is more than competitive and then develop an in-house training program to ensure a continuing supply for the future. If we are committed to encouraging our patients to be active, swimming is one of the best activities we should promote and support.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

At a recent Recreation Commission meeting here in Brunswick, the first agenda item under new business was “Coffin Pond Pool Closing.” As I and my fellow commissioners listened, we were told that for the first time in the last 3 decades the town’s only public swimming area would not be opening. While in the past there have been delayed openings and temporary closings due to water conditions, this year the pool would not open, period. The cause of the pool’s closure was the Parks and Recreation Department’s failure to fill even a skeleton crew of lifeguards.

We learned that the situation here in Brunswick was not unique and most other communities around the state and even around the country were struggling to find lifeguards. The shortage of trained staff has been nationwide for several years, and many beaches and pools particularly in the Northeast and Middle Atlantic states were being forced to close or shorten hours of operation (“During the Pool Season Even Lifeguard Numbers are Taking a Dive,” by Leoneda Inge, July 28, 2015, NPR’s All Thing Considered).

You might think that here on the coast we would have ample places for children to swim, but in Brunswick our shore is rocky and often inaccessible. At the few sandy beaches, the water temperature is too cold for all but the hardy souls until late August. Lower-income families will be particularly affected by the loss of the pool.

When I was growing up, lifeguarding was a plum job that was highly coveted. While it did not pay as well as working construction, the perks of a pleasant atmosphere, the chance to swim every day, and the opportunity to work outside with children prompted me at age 16 to sell my lawn mower and bequeath my lucrative landscaping customers to a couple of preteens. Looking back, my 4 years of lifeguarding were probably a major influence when it came time to choose a specialty.

However, a perfect storm of socioeconomic factors has combined to create a climate in which being a lifeguard has lost its appeal as a summertime job. First, there is record low unemployment nationwide. Young people looking for work have their pick, and while wages still remain low, they can be choosy when it comes to hours and benefits. Lifeguarding does require a skill set and several hoops of certification to be navigated. I don’t recall having to pay much of anything to become certified. But I understand that the process now costs hundreds of dollars of upfront investment with no guarantee of passing the test.

In May, the American Academy of Pediatrics published a policy paper titled “Prevention of Drowning” (Pediatrics. 2019 May 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0850) in which the authors offer the troubling statistics on the toll that water-related accidents take on the children of this country annually. They go on to provide a broad list of actions that parents, communities, and pediatricians can take to prevent drownings. Under the category of Community Interventions and Advocacy Opportunities, recommendation No. 4 is “Pediatricians should work with community partners to provide access to programs that develop water-competency swim skills for all children.”

Obviously, these programs can’t happen without an adequate supply of lifeguards.

Unfortunately, the AAP’s statement fails to acknowledge or directly address the lifeguard shortage that has been going on for several years. While an adequate supply of lifeguards is probably not as important as increasing parental attentiveness and mandating pool fences in the overall scheme of drowning prevention, it is an issue that demands action both by the academy and those of us practicing in communities both large and small.

For my part, I am going to work here in Brunswick to see that we can offer lifeguards pay that is more than competitive and then develop an in-house training program to ensure a continuing supply for the future. If we are committed to encouraging our patients to be active, swimming is one of the best activities we should promote and support.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

At a recent Recreation Commission meeting here in Brunswick, the first agenda item under new business was “Coffin Pond Pool Closing.” As I and my fellow commissioners listened, we were told that for the first time in the last 3 decades the town’s only public swimming area would not be opening. While in the past there have been delayed openings and temporary closings due to water conditions, this year the pool would not open, period. The cause of the pool’s closure was the Parks and Recreation Department’s failure to fill even a skeleton crew of lifeguards.

We learned that the situation here in Brunswick was not unique and most other communities around the state and even around the country were struggling to find lifeguards. The shortage of trained staff has been nationwide for several years, and many beaches and pools particularly in the Northeast and Middle Atlantic states were being forced to close or shorten hours of operation (“During the Pool Season Even Lifeguard Numbers are Taking a Dive,” by Leoneda Inge, July 28, 2015, NPR’s All Thing Considered).

You might think that here on the coast we would have ample places for children to swim, but in Brunswick our shore is rocky and often inaccessible. At the few sandy beaches, the water temperature is too cold for all but the hardy souls until late August. Lower-income families will be particularly affected by the loss of the pool.

When I was growing up, lifeguarding was a plum job that was highly coveted. While it did not pay as well as working construction, the perks of a pleasant atmosphere, the chance to swim every day, and the opportunity to work outside with children prompted me at age 16 to sell my lawn mower and bequeath my lucrative landscaping customers to a couple of preteens. Looking back, my 4 years of lifeguarding were probably a major influence when it came time to choose a specialty.

However, a perfect storm of socioeconomic factors has combined to create a climate in which being a lifeguard has lost its appeal as a summertime job. First, there is record low unemployment nationwide. Young people looking for work have their pick, and while wages still remain low, they can be choosy when it comes to hours and benefits. Lifeguarding does require a skill set and several hoops of certification to be navigated. I don’t recall having to pay much of anything to become certified. But I understand that the process now costs hundreds of dollars of upfront investment with no guarantee of passing the test.

In May, the American Academy of Pediatrics published a policy paper titled “Prevention of Drowning” (Pediatrics. 2019 May 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0850) in which the authors offer the troubling statistics on the toll that water-related accidents take on the children of this country annually. They go on to provide a broad list of actions that parents, communities, and pediatricians can take to prevent drownings. Under the category of Community Interventions and Advocacy Opportunities, recommendation No. 4 is “Pediatricians should work with community partners to provide access to programs that develop water-competency swim skills for all children.”

Obviously, these programs can’t happen without an adequate supply of lifeguards.

Unfortunately, the AAP’s statement fails to acknowledge or directly address the lifeguard shortage that has been going on for several years. While an adequate supply of lifeguards is probably not as important as increasing parental attentiveness and mandating pool fences in the overall scheme of drowning prevention, it is an issue that demands action both by the academy and those of us practicing in communities both large and small.

For my part, I am going to work here in Brunswick to see that we can offer lifeguards pay that is more than competitive and then develop an in-house training program to ensure a continuing supply for the future. If we are committed to encouraging our patients to be active, swimming is one of the best activities we should promote and support.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Mothers, migraine, colic ... and sleep

In a recent article on this website, Jake Remaly reports on a study suggesting that maternal migraine is associated with infant colic. In a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society, Amy Gelfand, MD, a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco, reported the results of a national survey of more than 1,400 parents (827 mothers, 592 fathers) collected via social media. She and her colleagues found that mothers with migraine were more likely to have an infant with colic, with an odds ratio of 1.7 that increased to 2.5 for mothers with more frequent migraine. Fathers with migraine were no more likely to have an infant with colic.

In a video clip included in the article, Dr. Gelfand discusses the possibilities that she and her group considered as they attempted to explain the study’s findings. Are there such things as “migraine genes?” If so, the failure to discover a paternal association might suggest that these would be mitochondrial genes. The researchers wondered if a substance in breast milk was acting as trigger, but they found that the association between colic and migraine was unrelated to whether the baby was fed by breast or bottle.

In full disclosure, I was not one of the investigators. Neither my wife nor I have migraine, and although our children cried as infants, they wouldn’t have qualified as having colic. However, I spent more than 40 years immersed in more than 300,000 patient encounters and can claim membership in the International Brother/Sisterhood of Anecdotal Observers. And, as such will offer up my explanation for Dr. Gelfand’s findings.

It is clear to me that most, if not all, children with migraine have their headaches when they are sleep deprived. While my sample size is smaller, I believe the same association also is true for many of the adults I know who have migraine. At least in children, restorative sleep ends the migraine much as it does for an epileptic seizure.

Traditionally, colic has been thought to be somehow related to a gastrointestinal phenomenon by many extended family members and some physicians. However, in my experience, it is usually a symptom of sleep deprivation compounded by the failure of those around the children to realize the obvious and take appropriate action. Of course, some babies are reacting to sore tummies, but my guess is that most are having headaches. We may never know. Dr. Gelfand also shares my observation that colicky crying is more likely to occur “at the end of the day,” a time when we are tired and are less tolerant of overstimulation.

However, the presentation varies depending on the age of the patients. Remember, infants can’t talk. It already has been shown that adults with migraine often were more likely to have been colicky infants. (Dr. Gelfand mentions this as well.) These unfortunate individuals probably have inherited a vulnerability to sleep deprivation that manifests itself as a headache. I hope to live long enough to be around when someone discovers the wrinkle in the genome that creates this vulnerability.

So, why did the researchers fail to find an association between fathers and colic? The answer is simple. We fathers are beginning to take on a larger role in parenting of infants and like to complain about how difficult it is. However, it is mothers who still have the lioness’ share of the work. They lose the most sleep and are starting off parenthood with 9 months of less than optimal sleep followed by who knows how many hours of energy-sapping labor. It’s surprising they all don’t have migraines.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

In a recent article on this website, Jake Remaly reports on a study suggesting that maternal migraine is associated with infant colic. In a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society, Amy Gelfand, MD, a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco, reported the results of a national survey of more than 1,400 parents (827 mothers, 592 fathers) collected via social media. She and her colleagues found that mothers with migraine were more likely to have an infant with colic, with an odds ratio of 1.7 that increased to 2.5 for mothers with more frequent migraine. Fathers with migraine were no more likely to have an infant with colic.

In a video clip included in the article, Dr. Gelfand discusses the possibilities that she and her group considered as they attempted to explain the study’s findings. Are there such things as “migraine genes?” If so, the failure to discover a paternal association might suggest that these would be mitochondrial genes. The researchers wondered if a substance in breast milk was acting as trigger, but they found that the association between colic and migraine was unrelated to whether the baby was fed by breast or bottle.

In full disclosure, I was not one of the investigators. Neither my wife nor I have migraine, and although our children cried as infants, they wouldn’t have qualified as having colic. However, I spent more than 40 years immersed in more than 300,000 patient encounters and can claim membership in the International Brother/Sisterhood of Anecdotal Observers. And, as such will offer up my explanation for Dr. Gelfand’s findings.

It is clear to me that most, if not all, children with migraine have their headaches when they are sleep deprived. While my sample size is smaller, I believe the same association also is true for many of the adults I know who have migraine. At least in children, restorative sleep ends the migraine much as it does for an epileptic seizure.

Traditionally, colic has been thought to be somehow related to a gastrointestinal phenomenon by many extended family members and some physicians. However, in my experience, it is usually a symptom of sleep deprivation compounded by the failure of those around the children to realize the obvious and take appropriate action. Of course, some babies are reacting to sore tummies, but my guess is that most are having headaches. We may never know. Dr. Gelfand also shares my observation that colicky crying is more likely to occur “at the end of the day,” a time when we are tired and are less tolerant of overstimulation.

However, the presentation varies depending on the age of the patients. Remember, infants can’t talk. It already has been shown that adults with migraine often were more likely to have been colicky infants. (Dr. Gelfand mentions this as well.) These unfortunate individuals probably have inherited a vulnerability to sleep deprivation that manifests itself as a headache. I hope to live long enough to be around when someone discovers the wrinkle in the genome that creates this vulnerability.

So, why did the researchers fail to find an association between fathers and colic? The answer is simple. We fathers are beginning to take on a larger role in parenting of infants and like to complain about how difficult it is. However, it is mothers who still have the lioness’ share of the work. They lose the most sleep and are starting off parenthood with 9 months of less than optimal sleep followed by who knows how many hours of energy-sapping labor. It’s surprising they all don’t have migraines.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

In a recent article on this website, Jake Remaly reports on a study suggesting that maternal migraine is associated with infant colic. In a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society, Amy Gelfand, MD, a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco, reported the results of a national survey of more than 1,400 parents (827 mothers, 592 fathers) collected via social media. She and her colleagues found that mothers with migraine were more likely to have an infant with colic, with an odds ratio of 1.7 that increased to 2.5 for mothers with more frequent migraine. Fathers with migraine were no more likely to have an infant with colic.

In a video clip included in the article, Dr. Gelfand discusses the possibilities that she and her group considered as they attempted to explain the study’s findings. Are there such things as “migraine genes?” If so, the failure to discover a paternal association might suggest that these would be mitochondrial genes. The researchers wondered if a substance in breast milk was acting as trigger, but they found that the association between colic and migraine was unrelated to whether the baby was fed by breast or bottle.

In full disclosure, I was not one of the investigators. Neither my wife nor I have migraine, and although our children cried as infants, they wouldn’t have qualified as having colic. However, I spent more than 40 years immersed in more than 300,000 patient encounters and can claim membership in the International Brother/Sisterhood of Anecdotal Observers. And, as such will offer up my explanation for Dr. Gelfand’s findings.

It is clear to me that most, if not all, children with migraine have their headaches when they are sleep deprived. While my sample size is smaller, I believe the same association also is true for many of the adults I know who have migraine. At least in children, restorative sleep ends the migraine much as it does for an epileptic seizure.

Traditionally, colic has been thought to be somehow related to a gastrointestinal phenomenon by many extended family members and some physicians. However, in my experience, it is usually a symptom of sleep deprivation compounded by the failure of those around the children to realize the obvious and take appropriate action. Of course, some babies are reacting to sore tummies, but my guess is that most are having headaches. We may never know. Dr. Gelfand also shares my observation that colicky crying is more likely to occur “at the end of the day,” a time when we are tired and are less tolerant of overstimulation.

However, the presentation varies depending on the age of the patients. Remember, infants can’t talk. It already has been shown that adults with migraine often were more likely to have been colicky infants. (Dr. Gelfand mentions this as well.) These unfortunate individuals probably have inherited a vulnerability to sleep deprivation that manifests itself as a headache. I hope to live long enough to be around when someone discovers the wrinkle in the genome that creates this vulnerability.

So, why did the researchers fail to find an association between fathers and colic? The answer is simple. We fathers are beginning to take on a larger role in parenting of infants and like to complain about how difficult it is. However, it is mothers who still have the lioness’ share of the work. They lose the most sleep and are starting off parenthood with 9 months of less than optimal sleep followed by who knows how many hours of energy-sapping labor. It’s surprising they all don’t have migraines.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Y 2 the ED? (Why patients go to the emergency department)

Along with terminal care and inflated drug prices, the excessive number of “inappropriate” ED visits often is cited as a major driver of health care costs in the United States. Why do so many patients choose to go to the ED for complaints that might be better or more economically treated in another setting?

A report by two researchers in the division of emergency medicine at the Boston Children’s Hospital that appeared in the June 2019 Pediatrics suggests that, at least for pediatric patients, “increased insurance coverage neither drove nor counteracted” the recent trends in ED visits. (“Trends in Pediatric Emergency Department Use After the Affordable Care Act,” Pediatrics. 2019 Jun 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3542).

I guess it’s not surprising – and somewhat comforting – to learn that, when parents believe their child has an emergent condition they give little thought to the cost of care. Is the trend of increasing ED use a result of an evolving definition of an “emergency”? Your grandparents, or certainly your great grandparents, might claim that, when they were young most minor injuries were handled at home, or at least in the neighborhood by someone with first aid experience who wasn’t put off by the sight of blood. However, a trend away from self-reliance in everything from food preparation to auto repair, combined with media overexposure to the serious complications of apparently minor illness and injury, has left most parents feeling fearful and helpless in the face of adversity.

We have to accept as a given that many parents are going to interpret their child’s situation as emergent, even though you and I might not. But what are the factors that prompt a concerned parent to take his child to the ED instead of a physician’s office? It may simply be the path of least resistance. The parent’s past experience may include frustrating and time-consuming attempts to navigate a clunky phone system only to be met by a receptionist or triage nurse who seems more committed to deflecting calls and protecting the physician’s schedule than getting the patient seen.

The call may miraculously get through to someone with a caring voice and the patience to listen, but the parent then learns that the office doesn’t do minor wound care or he is told that the physician almost certainly will want to do an x-ray of any injured extremity and that the ED is a better choice. It doesn’t take very many scenarios like this to prompt a parent to make his first and only call to the ED. To some extent, physician behavior has helped mold parents’ definition of an emergency.

We are encouraged to make our offices a “medical home.” However, it appears the medical home model is one that is built around chronic conditions and behavioral problems and gives little attention to the acute complaints. When you came running into the house with a skinned knee, did your mother tell to you go across the street to the neighbor’s house because blood made her squeamish and she didn’t have any bandages?

There are ways to structure an office and a schedule which are more welcoming to patients with minor emergencies, and I know it is a difficult sell to physicians who are handcuffed by their EHRs and already overwhelmed by patients with time-consuming behavioral complaints. However, if your practice is facing competition from pop-up urgent care centers or if you are increasingly troubled that your patients are receiving fragmented care, it may not be too late to make your practice into a true medical home that welcomes minor emergencies.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Along with terminal care and inflated drug prices, the excessive number of “inappropriate” ED visits often is cited as a major driver of health care costs in the United States. Why do so many patients choose to go to the ED for complaints that might be better or more economically treated in another setting?

A report by two researchers in the division of emergency medicine at the Boston Children’s Hospital that appeared in the June 2019 Pediatrics suggests that, at least for pediatric patients, “increased insurance coverage neither drove nor counteracted” the recent trends in ED visits. (“Trends in Pediatric Emergency Department Use After the Affordable Care Act,” Pediatrics. 2019 Jun 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3542).

I guess it’s not surprising – and somewhat comforting – to learn that, when parents believe their child has an emergent condition they give little thought to the cost of care. Is the trend of increasing ED use a result of an evolving definition of an “emergency”? Your grandparents, or certainly your great grandparents, might claim that, when they were young most minor injuries were handled at home, or at least in the neighborhood by someone with first aid experience who wasn’t put off by the sight of blood. However, a trend away from self-reliance in everything from food preparation to auto repair, combined with media overexposure to the serious complications of apparently minor illness and injury, has left most parents feeling fearful and helpless in the face of adversity.

We have to accept as a given that many parents are going to interpret their child’s situation as emergent, even though you and I might not. But what are the factors that prompt a concerned parent to take his child to the ED instead of a physician’s office? It may simply be the path of least resistance. The parent’s past experience may include frustrating and time-consuming attempts to navigate a clunky phone system only to be met by a receptionist or triage nurse who seems more committed to deflecting calls and protecting the physician’s schedule than getting the patient seen.

The call may miraculously get through to someone with a caring voice and the patience to listen, but the parent then learns that the office doesn’t do minor wound care or he is told that the physician almost certainly will want to do an x-ray of any injured extremity and that the ED is a better choice. It doesn’t take very many scenarios like this to prompt a parent to make his first and only call to the ED. To some extent, physician behavior has helped mold parents’ definition of an emergency.

We are encouraged to make our offices a “medical home.” However, it appears the medical home model is one that is built around chronic conditions and behavioral problems and gives little attention to the acute complaints. When you came running into the house with a skinned knee, did your mother tell to you go across the street to the neighbor’s house because blood made her squeamish and she didn’t have any bandages?

There are ways to structure an office and a schedule which are more welcoming to patients with minor emergencies, and I know it is a difficult sell to physicians who are handcuffed by their EHRs and already overwhelmed by patients with time-consuming behavioral complaints. However, if your practice is facing competition from pop-up urgent care centers or if you are increasingly troubled that your patients are receiving fragmented care, it may not be too late to make your practice into a true medical home that welcomes minor emergencies.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Along with terminal care and inflated drug prices, the excessive number of “inappropriate” ED visits often is cited as a major driver of health care costs in the United States. Why do so many patients choose to go to the ED for complaints that might be better or more economically treated in another setting?