User login

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida who has written about medical topics from nasty infections to ethical dilemmas, runaway tumors to tornado-chasing doctors. He travels the globe gathering conference health news and lives in West Palm Beach.

FDA Investigates Major Bleeding Events in Dabigatran Patients

A little more than a year after the new anticoagulant dabigatran (Pradaxa) was approved for stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) patients, the FDA is evaluating post-marketing reports of serious bleeds in patients taking the drug.

The FDA is trying to determine if patients on Pradaxa are experiencing severe bleeding more than expected based on results of the clinical trial that led to Pradaxa’s approval, according to FDA spokeswoman Sandy Walsh.

“At this time, FDA continues to believe that Pradaxa provides an important health benefit when used as directed and recommends that healthcare professionals who prescribe Pradaxa follow the recommendations in the approved drug label,” Walsh tells The Hospitalist.

—Robert Pendleton, MD, director of the hospitalist program, University of Utah Healthcare; medical director, University Healthcare Thrombosis Service

Patients should not stop taking dabigatran without first talking to their doctors, the FDA announcement cautions. While “serious, even fatal events have been reported,” according to the FDA’s announcement, Walsh says the FDA isn’t prepared to say how many reports of serious bleeding events have been received because they’re still being reviewed.

“We often put out ‘early’ communications when we learn of drug safety issues,” she says. “We want to be transparent and make [the] public [aware of] what we do know, but our analysis is not final. At this point, the FDA is still evaluating this issue.”

Bleeding that leads to serious or fatal outcomes is a well-recognized complication of all anticoagulant therapies.

Dabigatran, a direct thrombin inhibitor, was approved in October 2010, becoming the first new oral anticoagulant approved in 50 years. It was the first approved among several new anti-coagulants that are poised to enter the market and are expected to challenge warfarin (Coumadin), the longtime standard of care.

The new drugs—including rivaroxaban (Xarelto), a Factor Xa-inhibitor that was approved in 2011—have been eagerly anticipated because they don’t require frequent blood draws for monitoring, as warfarin does. Hospitalists are especially interested in the new anticoagulant therapies because they treat numerous patients at an increased risk of clotting.

In the RE-LY trial, the 18,000-patient clinical trial comparing dabigatran and warfarin, major bleeding events occurred at similar rates with the two drugs.

Dabigatran manufacturer Boehringer Ingelheim is working with the FDA to evaluate the major bleeding reports, but spokeswoman Anna Moses says the drug has been performing according to expectations.

“Global data collected to date on major bleeding are consistent with our expectations based on the RE-LY trial and are in alignment with the U.S. Prescribing Information, which clearly state the benefits and risks associated with Pradaxa,” Moses says. “Overall, the positive-benefit-risk ratio of Pradaxa in NVAF remains unchanged.” (Visit the manufacturer website for prescribing information [PDF].)

Robert Pendleton, MD, director of the hospitalist program at the University of Utah Healthcare and Medical Director of the University Healthcare Thrombosis Service, expressed no surprise at the FDA’s statement.

“Although the data with new anticoagulants like Pradaxa is very favorable in a clinical trial setting, there’s great risk of enhanced demonstration of harm in the real-world setting if it’s not used optimally,” Dr. Pendleton says. “There will be more liberal sort of prescribing in a less-pure patient population.

So if people are not particularly cognizant of a patient’s renal function, their body weight, prior history of bleeding, etc., then you’re sort of applying new drugs in patients who are even more prone to bleed.”

Dr. Pendleton notes that in subgroup analyses, the slight benefits of the new drugs have come in patients with poor warfarin control, so if patients with good warfarin control are switched, outcomes could generally be expected not to be better, and could be worse.

“It won’t cause me to take people who I have prescribed Pradaxa and switch them back to warfarin,” he says, “but part of that is [that] here, in our healthcare system, we’re pretty cautious in who gets put on one of the new agents. And so those that do are patients who are most like those in the clinical trial.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in Florida.

A little more than a year after the new anticoagulant dabigatran (Pradaxa) was approved for stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) patients, the FDA is evaluating post-marketing reports of serious bleeds in patients taking the drug.

The FDA is trying to determine if patients on Pradaxa are experiencing severe bleeding more than expected based on results of the clinical trial that led to Pradaxa’s approval, according to FDA spokeswoman Sandy Walsh.

“At this time, FDA continues to believe that Pradaxa provides an important health benefit when used as directed and recommends that healthcare professionals who prescribe Pradaxa follow the recommendations in the approved drug label,” Walsh tells The Hospitalist.

—Robert Pendleton, MD, director of the hospitalist program, University of Utah Healthcare; medical director, University Healthcare Thrombosis Service

Patients should not stop taking dabigatran without first talking to their doctors, the FDA announcement cautions. While “serious, even fatal events have been reported,” according to the FDA’s announcement, Walsh says the FDA isn’t prepared to say how many reports of serious bleeding events have been received because they’re still being reviewed.

“We often put out ‘early’ communications when we learn of drug safety issues,” she says. “We want to be transparent and make [the] public [aware of] what we do know, but our analysis is not final. At this point, the FDA is still evaluating this issue.”

Bleeding that leads to serious or fatal outcomes is a well-recognized complication of all anticoagulant therapies.

Dabigatran, a direct thrombin inhibitor, was approved in October 2010, becoming the first new oral anticoagulant approved in 50 years. It was the first approved among several new anti-coagulants that are poised to enter the market and are expected to challenge warfarin (Coumadin), the longtime standard of care.

The new drugs—including rivaroxaban (Xarelto), a Factor Xa-inhibitor that was approved in 2011—have been eagerly anticipated because they don’t require frequent blood draws for monitoring, as warfarin does. Hospitalists are especially interested in the new anticoagulant therapies because they treat numerous patients at an increased risk of clotting.

In the RE-LY trial, the 18,000-patient clinical trial comparing dabigatran and warfarin, major bleeding events occurred at similar rates with the two drugs.

Dabigatran manufacturer Boehringer Ingelheim is working with the FDA to evaluate the major bleeding reports, but spokeswoman Anna Moses says the drug has been performing according to expectations.

“Global data collected to date on major bleeding are consistent with our expectations based on the RE-LY trial and are in alignment with the U.S. Prescribing Information, which clearly state the benefits and risks associated with Pradaxa,” Moses says. “Overall, the positive-benefit-risk ratio of Pradaxa in NVAF remains unchanged.” (Visit the manufacturer website for prescribing information [PDF].)

Robert Pendleton, MD, director of the hospitalist program at the University of Utah Healthcare and Medical Director of the University Healthcare Thrombosis Service, expressed no surprise at the FDA’s statement.

“Although the data with new anticoagulants like Pradaxa is very favorable in a clinical trial setting, there’s great risk of enhanced demonstration of harm in the real-world setting if it’s not used optimally,” Dr. Pendleton says. “There will be more liberal sort of prescribing in a less-pure patient population.

So if people are not particularly cognizant of a patient’s renal function, their body weight, prior history of bleeding, etc., then you’re sort of applying new drugs in patients who are even more prone to bleed.”

Dr. Pendleton notes that in subgroup analyses, the slight benefits of the new drugs have come in patients with poor warfarin control, so if patients with good warfarin control are switched, outcomes could generally be expected not to be better, and could be worse.

“It won’t cause me to take people who I have prescribed Pradaxa and switch them back to warfarin,” he says, “but part of that is [that] here, in our healthcare system, we’re pretty cautious in who gets put on one of the new agents. And so those that do are patients who are most like those in the clinical trial.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in Florida.

A little more than a year after the new anticoagulant dabigatran (Pradaxa) was approved for stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) patients, the FDA is evaluating post-marketing reports of serious bleeds in patients taking the drug.

The FDA is trying to determine if patients on Pradaxa are experiencing severe bleeding more than expected based on results of the clinical trial that led to Pradaxa’s approval, according to FDA spokeswoman Sandy Walsh.

“At this time, FDA continues to believe that Pradaxa provides an important health benefit when used as directed and recommends that healthcare professionals who prescribe Pradaxa follow the recommendations in the approved drug label,” Walsh tells The Hospitalist.

—Robert Pendleton, MD, director of the hospitalist program, University of Utah Healthcare; medical director, University Healthcare Thrombosis Service

Patients should not stop taking dabigatran without first talking to their doctors, the FDA announcement cautions. While “serious, even fatal events have been reported,” according to the FDA’s announcement, Walsh says the FDA isn’t prepared to say how many reports of serious bleeding events have been received because they’re still being reviewed.

“We often put out ‘early’ communications when we learn of drug safety issues,” she says. “We want to be transparent and make [the] public [aware of] what we do know, but our analysis is not final. At this point, the FDA is still evaluating this issue.”

Bleeding that leads to serious or fatal outcomes is a well-recognized complication of all anticoagulant therapies.

Dabigatran, a direct thrombin inhibitor, was approved in October 2010, becoming the first new oral anticoagulant approved in 50 years. It was the first approved among several new anti-coagulants that are poised to enter the market and are expected to challenge warfarin (Coumadin), the longtime standard of care.

The new drugs—including rivaroxaban (Xarelto), a Factor Xa-inhibitor that was approved in 2011—have been eagerly anticipated because they don’t require frequent blood draws for monitoring, as warfarin does. Hospitalists are especially interested in the new anticoagulant therapies because they treat numerous patients at an increased risk of clotting.

In the RE-LY trial, the 18,000-patient clinical trial comparing dabigatran and warfarin, major bleeding events occurred at similar rates with the two drugs.

Dabigatran manufacturer Boehringer Ingelheim is working with the FDA to evaluate the major bleeding reports, but spokeswoman Anna Moses says the drug has been performing according to expectations.

“Global data collected to date on major bleeding are consistent with our expectations based on the RE-LY trial and are in alignment with the U.S. Prescribing Information, which clearly state the benefits and risks associated with Pradaxa,” Moses says. “Overall, the positive-benefit-risk ratio of Pradaxa in NVAF remains unchanged.” (Visit the manufacturer website for prescribing information [PDF].)

Robert Pendleton, MD, director of the hospitalist program at the University of Utah Healthcare and Medical Director of the University Healthcare Thrombosis Service, expressed no surprise at the FDA’s statement.

“Although the data with new anticoagulants like Pradaxa is very favorable in a clinical trial setting, there’s great risk of enhanced demonstration of harm in the real-world setting if it’s not used optimally,” Dr. Pendleton says. “There will be more liberal sort of prescribing in a less-pure patient population.

So if people are not particularly cognizant of a patient’s renal function, their body weight, prior history of bleeding, etc., then you’re sort of applying new drugs in patients who are even more prone to bleed.”

Dr. Pendleton notes that in subgroup analyses, the slight benefits of the new drugs have come in patients with poor warfarin control, so if patients with good warfarin control are switched, outcomes could generally be expected not to be better, and could be worse.

“It won’t cause me to take people who I have prescribed Pradaxa and switch them back to warfarin,” he says, “but part of that is [that] here, in our healthcare system, we’re pretty cautious in who gets put on one of the new agents. And so those that do are patients who are most like those in the clinical trial.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in Florida.

Are hospitalists taking C. diff seriously enough? Maybe, maybe not

Clostridium difficile has been on the radar of infectious disease (ID) experts for the better part of a decade now. But how mindful are hospitalists of the problem, and how seriously are they taking it?

“I think we’re getting there,” says Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM, a hospitalist and medical director of quality at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. But she adds, “Because the bugs are invisible, you feel a little bit disconnected from your direct role in all this.”

Stuart Cohen, MD, an ID expert at the University of California Davis and a fellow with the Infectious Diseases Society of America, says not everyone is as concerned about C. diff as they should be.

—Stuart Cohen, MD, infectious disease expert, University of California Davis, fellow, Infectious Diseases Society of America

“I think most people still see C. diff as just basically being a nuisance, and so they don’t really take it quite so seriously. Until somebody sees a patient have to get a colectomy or die from C. diff, I don’t think that there’s necessarily an appreciation to the severity of the illness,” he says. “You don’t really get this sense that it’s anything other than, ‘Well, we’ll just give them some vancomycin or we’ll just give them some metronidazole and we’ll take care of it.’”

Ketino Kobaidze, MD, a hospitalist at Emory University Hospital Midtown in Atlanta, says she thinks hospitalists should be more involved in antibiotic stewardship efforts and in research efforts to combat C. diff.

“I’m sure everybody knows and everybody takes it into consideration,” she says. But she also says not all hospitalists view C. diff as an acute problem that warrants urgent treatment “or we might be in trouble,” she says. “I’m not sure about that.”

Dr. Scheurer says the solution to treating C. diff properly is keeping a mindset on the safety of your patients. “Then it can motivate you and your group,” she says. “Every single number affects a person. It’s not just a rate. Zero is the goal.”

Tom Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

Clostridium difficile has been on the radar of infectious disease (ID) experts for the better part of a decade now. But how mindful are hospitalists of the problem, and how seriously are they taking it?

“I think we’re getting there,” says Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM, a hospitalist and medical director of quality at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. But she adds, “Because the bugs are invisible, you feel a little bit disconnected from your direct role in all this.”

Stuart Cohen, MD, an ID expert at the University of California Davis and a fellow with the Infectious Diseases Society of America, says not everyone is as concerned about C. diff as they should be.

—Stuart Cohen, MD, infectious disease expert, University of California Davis, fellow, Infectious Diseases Society of America

“I think most people still see C. diff as just basically being a nuisance, and so they don’t really take it quite so seriously. Until somebody sees a patient have to get a colectomy or die from C. diff, I don’t think that there’s necessarily an appreciation to the severity of the illness,” he says. “You don’t really get this sense that it’s anything other than, ‘Well, we’ll just give them some vancomycin or we’ll just give them some metronidazole and we’ll take care of it.’”

Ketino Kobaidze, MD, a hospitalist at Emory University Hospital Midtown in Atlanta, says she thinks hospitalists should be more involved in antibiotic stewardship efforts and in research efforts to combat C. diff.

“I’m sure everybody knows and everybody takes it into consideration,” she says. But she also says not all hospitalists view C. diff as an acute problem that warrants urgent treatment “or we might be in trouble,” she says. “I’m not sure about that.”

Dr. Scheurer says the solution to treating C. diff properly is keeping a mindset on the safety of your patients. “Then it can motivate you and your group,” she says. “Every single number affects a person. It’s not just a rate. Zero is the goal.”

Tom Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

Clostridium difficile has been on the radar of infectious disease (ID) experts for the better part of a decade now. But how mindful are hospitalists of the problem, and how seriously are they taking it?

“I think we’re getting there,” says Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM, a hospitalist and medical director of quality at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. But she adds, “Because the bugs are invisible, you feel a little bit disconnected from your direct role in all this.”

Stuart Cohen, MD, an ID expert at the University of California Davis and a fellow with the Infectious Diseases Society of America, says not everyone is as concerned about C. diff as they should be.

—Stuart Cohen, MD, infectious disease expert, University of California Davis, fellow, Infectious Diseases Society of America

“I think most people still see C. diff as just basically being a nuisance, and so they don’t really take it quite so seriously. Until somebody sees a patient have to get a colectomy or die from C. diff, I don’t think that there’s necessarily an appreciation to the severity of the illness,” he says. “You don’t really get this sense that it’s anything other than, ‘Well, we’ll just give them some vancomycin or we’ll just give them some metronidazole and we’ll take care of it.’”

Ketino Kobaidze, MD, a hospitalist at Emory University Hospital Midtown in Atlanta, says she thinks hospitalists should be more involved in antibiotic stewardship efforts and in research efforts to combat C. diff.

“I’m sure everybody knows and everybody takes it into consideration,” she says. But she also says not all hospitalists view C. diff as an acute problem that warrants urgent treatment “or we might be in trouble,” she says. “I’m not sure about that.”

Dr. Scheurer says the solution to treating C. diff properly is keeping a mindset on the safety of your patients. “Then it can motivate you and your group,” she says. “Every single number affects a person. It’s not just a rate. Zero is the goal.”

Tom Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Listen to CDC expert Carolyn Gould and Emory hospitalist Ketino Kobaidze discuss C. diff prevention

Click here to listen to Dr. Gould

Click here to listen to Dr. Kobaidze

Click here to listen to Dr. Gould

Click here to listen to Dr. Kobaidze

Click here to listen to Dr. Gould

Click here to listen to Dr. Kobaidze

Gut Reaction

At 480-bed Emory University Hospital Midtown in Atlanta, the physicians and staff seemingly are doing all the right things to foil one of hospital’s archenemies: Clostridium difficile. The bacteria, better known as C. diff, is responsible for a sharp rise in hospital-acquired infections over the past decade, rivaling even MRSA.

In 2010, Emory Midtown launched a campaign to boost awareness of the importance of hand washing before and after treating patients infected with C. diff and those likely to be infected. They also began using the polymerase-chain-reaction-based assay to detect the bacteria, a test with much higher sensitivity that helps to more efficiently identify those infected so control measures can be more prompt and targeted. They use a hypochlorite mixture to clean the rooms of those infected, which is considered a must. And a committee monitors the use of antibiotics to prevent overuse—often the scapegoat for the rise of the hard-to-kill bacteria.

Still, at Emory, the rate of C. diff is about the same as the national average, says hospitalist Ketino Kobaidze, MD, assistant professor at the Emory University School of Medicine and a member of the antimicrobial stewardship and infectious disease control committees at Midtown. While Dr. Kobaidze says her institution is doing a good job of trying to keep C. diff under control, she thinks hospitalists can do more.

“My feeling is that we are not as involved as we’re supposed to be,” she says. “I think we need to be a little bit more proactive, be involved in committees and research activities across the hospital.”

—Kevin Kavanagh, MD, founder, Health Watch USA

You Are Not Alone

The experience at Emory Midtown is far from unusual—healthcare facilities, and hospitalists, across the country have seen healthcare-related C. diff cases more than double since 2001 to between 400,000 and 500,000 a year, says Carolyn Gould, MD, a medical epidemiologist in the division of healthcare quality promotion at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta.

Hospitalists, whether they realize it or not, are intimately involved in how well the C. diff outbreak is controlled. Infectious-disease (ID) specialists say hospitalists are perfectly situated to make an impact in efforts to help curb the outbreak.

“Hospitalists are critical to this effort,” Dr. Gould says. “They’re in the hospital day in and day out, and they’re constantly interacting with the patients, staff, and administration. They’re often the first on the scene to see a patient who might have suddenly developed diarrhea; they’re the first to react. I think they’re in a prime position to play a leadership role to prevent C. diff infections.”

They’re also situated well to work with infection-control experts on antimicrobial stewardship programs, she says.

“I look at hospitalists just like I would have looked at internists managing their own patients 15 years ago,” says Stuart Cohen, MD, an ID expert with the University of California at Davis and a fellow with the Infectious Diseases Society of America who was lead author of the latest published IDSA guidelines on C. diff treatment. “And so they’re the first-line people.”

continued below...

A Tough Bug

Believed to be aided largely by the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics that knock out the colon’s natural flora, C. diff in the hospital—as well as nursing homes and acute-care facilities—has raged for much of the past decade. Its rise is tied to the emergence of a new hypervirulent strain known as BI/NAP1/027, or NAP1 for short. The strain is highly resistant to fluoroquinolones, such as ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin, which are used often in healthcare settings.

“A fluoroquinolone will wipe out a lot of your normal flora in your gut,” Dr. Gould says. “But it won’t wipe out C. diff, in particular this hypervirulent strain. And so this strain can flourish in the presence of fluoroquinolones.” The strain produces up to 15 to 20 times more toxins than other C. diff strains, according to some data, she adds.

Vancomycin (Vanconin) and metronidazole (Flagyl) are the most common antibiotics used to treat patients infected with C. diff. Mortality rates are higher among the elderly, largely because of their weaker immune system, Dr. Gould says. Studies have generally shown mortality rates of 10% or a bit lower.1

More recent studies have shown that the number of hospital-related C. diff cases might have begun to level off in 2008 and 2009. Dr. Gould says she thinks the leveling off is for real, but there is debate over what the immediate future holds.

“There’s a lot of work and initiatives, especially state-based initiatives, that are being done in hospitals. And there’s reason to believe they’re effective,” she says, adding it’s harder to get a good picture of the problem in long-term care facilities and in the community.

Dr. Cohen with the IDSA says it’s too soon to say whether the problem is hitting a plateau. “CDC data are always a couple of years behind,” he says. “Until you see another data point, you can’t tell whether that’s just a transient flattening and whether it’s going to keep going up or not.”

Kevin Kavanagh, MD, founder of the patient advocacy group Health Watch USA and a retired otolaryngologist in Kentucky who has taken a keen interest in the C. diff problem, says he doesn’t think the end of the tunnel is within view yet.

“I think C. diff is going to get worse before it gets better,” Dr. Kavanagh says. “And that’s not necessarily because the healthcare profession isn’t doing due diligence. This is a tough organism.—it can be tough to treat and can be very tough to kill.”

The Best Defense?

Because C. diff lives within protective spores, sound hand hygiene practices and room-cleaning practices are essential for keeping infections to a minimum. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers, effective against other organisms including MRSA, do not kill C. diff. The bacteria must be mechanically removed through hand washing.

And even hand washing might not be totally effective at getting rid of the spores, which means it’s important for healthcare workers to gown and glove in high-risk rooms.

Sodium hypochlorite solutions, or bleach mixtures, have to be used to clean rooms occupied by patients with C. diff, and the prevailing thought is to clean the rooms of patients suspected of having C. diff, even if those cases might not be confirmed.

Equally important to cleaning and hand washing is systemwide emphasis on antibiotic stewardship. A 2011 study at the State University of New York Buffalo found that the risk of a C. diff infection rose with the number of antibiotics taken.2

—Carolyn Gould, MD, medical epidemiologist, division of healthcare quality promotion, Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta

While a broad-spectrum antibiotic might be necessary at first, once the results of cultures are received, the treatment should be finely tailored to kill only the problem bacteria so that the body’s natural defenses aren’t broken down, Dr. Gould explains.

“If someone is very sick and you’re not sure what is going on, it’s very reasonable to treat them empirically with broad-spectrum antibiotics,” she says. “The important thing is that you send the appropriate cultures before so that you know what you’re treating and you can optimize those antibiotics with daily assessments.”

It’s clear why an overreliance on broad-spectrum drugs prevails in U.S. health settings, Dr. Cohen acknowledges. Recent literature suggests treating critically ill patients with wide-ranging antimicrobials as the mortality rate can be twice as high with narrower options. “I think people have gotten very quick to give broad-spectrum therapy,” he says.

continued below...

National Response, Localized Attention

Dr. Kavanagh of Health Watch USA says that more information about C. diff is needed, particularly publicly available numbers of infections at hospitals. Some states require those figures to be reported, but most don’t. And there is no current federal mandate on reporting of C. diff cases, although acute-care hospitals will be required to report C. diff infection rates starting in 2013.

“We really have scant data,” he says. “There is not a lot of reporting if you look at the nation on a whole. And I think that underscores one of the reasons why you need to have data for action. You need to have reporting of these organisms to the National Healthcare Safety Network so that the CDC can monitor and can make plans and can do effective interventions.

“You want to know where the areas of highest infection are,” he adds. “You want to know what interventions work and don’t work. If you don’t have a national coordinated reporting system, it really makes it difficult to address the problem. C. diff is going to be much harder to control than MRSA or other bacteria because it changes into a hard-to-kill dormant spore stage and then re-occurs at some point.”

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has proposed adding C. diff infections to the list of hospital-acquired conditions that will not be reimbursable. It is widely hoped that such a measure will go a long way toward stamping out the problem.

Dr. Kobaidze of Emory notes that C. diff is a dynamic problem, always adapting and posing new challenges. And hospitalists should be more involved in answering these questions through research. One recent question, she points out, is whether proton pump inhibitor use is related to the rise of C. diff.

Ultimately, though, controlling C. diff in hospitals might come down to what is done day to day inside the hospital. And hospitalists can play a big role.

Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM, a hospitalist and medical director of quality at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, says that a full-time pharmacist on the hospital’s antimicrobial stewardship committee is always reviewing antibiotic prescriptions and is prepared to flag cases in which a broad-spectrum is used when one with a more narrow scope might be more appropriate.

The hospital has done its best, as part of its “renovation cycle,” to standardize the layouts of rooms “so that the second you open the door you know exactly where the alcohol gel is and where the soap and the sink is going to be.” The idea is to make compliance as “mindless” as possible. Such efforts can be hampered by structural limitations though, she says.

HM group leaders, she suggests, can play an important part simply by being good role models—gowning and gloving without complaint before entering high-risk rooms and reinforcing the message that such efforts have real effects on patient safety.

But she also acknowledges that “it always sounds easy....There has to be some level of redundancy built into the hospital system. This is more of a system thing than the individual hospitalist.”

One level of redundancy at MUSC that has been particularly effective, she says, are “secret shoppers” who keep an eye out for medical teams that might not be washing their hands as they go in and out of high-risk rooms. Each unit is responsible for their hand hygiene numbers—which include both self-reported figures and those obtained by the secret onlookers—and those numbers are made available to the hospital.

Those units with the best numbers are sometimes given a reward, such as a pizza party, but it’s colleagues’ knowledge of the numbers that matters most, she says.

“That, in and of itself, is a powerful motivator,” Dr. Scheurer says. “We bring it to all of our quality operations meetings, all the administrators, the CEO, the CMO. It’s very motivating for every unit. They don’t want to be the trailing unit.”

Tom Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Miami.

References

- Orenstein R, Aronhalt KC, McManus JE Jr., Fedraw LA. A targeted strategy to wipe out Clostridium difficile. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(11):1137-1139.

- Stevens V, Dumyati G, Fine LS, Fisher SG, van Wijngaarden E. Cumulative antibiotic exposures over time and the risk of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(1):42-48.

At 480-bed Emory University Hospital Midtown in Atlanta, the physicians and staff seemingly are doing all the right things to foil one of hospital’s archenemies: Clostridium difficile. The bacteria, better known as C. diff, is responsible for a sharp rise in hospital-acquired infections over the past decade, rivaling even MRSA.

In 2010, Emory Midtown launched a campaign to boost awareness of the importance of hand washing before and after treating patients infected with C. diff and those likely to be infected. They also began using the polymerase-chain-reaction-based assay to detect the bacteria, a test with much higher sensitivity that helps to more efficiently identify those infected so control measures can be more prompt and targeted. They use a hypochlorite mixture to clean the rooms of those infected, which is considered a must. And a committee monitors the use of antibiotics to prevent overuse—often the scapegoat for the rise of the hard-to-kill bacteria.

Still, at Emory, the rate of C. diff is about the same as the national average, says hospitalist Ketino Kobaidze, MD, assistant professor at the Emory University School of Medicine and a member of the antimicrobial stewardship and infectious disease control committees at Midtown. While Dr. Kobaidze says her institution is doing a good job of trying to keep C. diff under control, she thinks hospitalists can do more.

“My feeling is that we are not as involved as we’re supposed to be,” she says. “I think we need to be a little bit more proactive, be involved in committees and research activities across the hospital.”

—Kevin Kavanagh, MD, founder, Health Watch USA

You Are Not Alone

The experience at Emory Midtown is far from unusual—healthcare facilities, and hospitalists, across the country have seen healthcare-related C. diff cases more than double since 2001 to between 400,000 and 500,000 a year, says Carolyn Gould, MD, a medical epidemiologist in the division of healthcare quality promotion at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta.

Hospitalists, whether they realize it or not, are intimately involved in how well the C. diff outbreak is controlled. Infectious-disease (ID) specialists say hospitalists are perfectly situated to make an impact in efforts to help curb the outbreak.

“Hospitalists are critical to this effort,” Dr. Gould says. “They’re in the hospital day in and day out, and they’re constantly interacting with the patients, staff, and administration. They’re often the first on the scene to see a patient who might have suddenly developed diarrhea; they’re the first to react. I think they’re in a prime position to play a leadership role to prevent C. diff infections.”

They’re also situated well to work with infection-control experts on antimicrobial stewardship programs, she says.

“I look at hospitalists just like I would have looked at internists managing their own patients 15 years ago,” says Stuart Cohen, MD, an ID expert with the University of California at Davis and a fellow with the Infectious Diseases Society of America who was lead author of the latest published IDSA guidelines on C. diff treatment. “And so they’re the first-line people.”

continued below...

A Tough Bug

Believed to be aided largely by the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics that knock out the colon’s natural flora, C. diff in the hospital—as well as nursing homes and acute-care facilities—has raged for much of the past decade. Its rise is tied to the emergence of a new hypervirulent strain known as BI/NAP1/027, or NAP1 for short. The strain is highly resistant to fluoroquinolones, such as ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin, which are used often in healthcare settings.

“A fluoroquinolone will wipe out a lot of your normal flora in your gut,” Dr. Gould says. “But it won’t wipe out C. diff, in particular this hypervirulent strain. And so this strain can flourish in the presence of fluoroquinolones.” The strain produces up to 15 to 20 times more toxins than other C. diff strains, according to some data, she adds.

Vancomycin (Vanconin) and metronidazole (Flagyl) are the most common antibiotics used to treat patients infected with C. diff. Mortality rates are higher among the elderly, largely because of their weaker immune system, Dr. Gould says. Studies have generally shown mortality rates of 10% or a bit lower.1

More recent studies have shown that the number of hospital-related C. diff cases might have begun to level off in 2008 and 2009. Dr. Gould says she thinks the leveling off is for real, but there is debate over what the immediate future holds.

“There’s a lot of work and initiatives, especially state-based initiatives, that are being done in hospitals. And there’s reason to believe they’re effective,” she says, adding it’s harder to get a good picture of the problem in long-term care facilities and in the community.

Dr. Cohen with the IDSA says it’s too soon to say whether the problem is hitting a plateau. “CDC data are always a couple of years behind,” he says. “Until you see another data point, you can’t tell whether that’s just a transient flattening and whether it’s going to keep going up or not.”

Kevin Kavanagh, MD, founder of the patient advocacy group Health Watch USA and a retired otolaryngologist in Kentucky who has taken a keen interest in the C. diff problem, says he doesn’t think the end of the tunnel is within view yet.

“I think C. diff is going to get worse before it gets better,” Dr. Kavanagh says. “And that’s not necessarily because the healthcare profession isn’t doing due diligence. This is a tough organism.—it can be tough to treat and can be very tough to kill.”

The Best Defense?

Because C. diff lives within protective spores, sound hand hygiene practices and room-cleaning practices are essential for keeping infections to a minimum. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers, effective against other organisms including MRSA, do not kill C. diff. The bacteria must be mechanically removed through hand washing.

And even hand washing might not be totally effective at getting rid of the spores, which means it’s important for healthcare workers to gown and glove in high-risk rooms.

Sodium hypochlorite solutions, or bleach mixtures, have to be used to clean rooms occupied by patients with C. diff, and the prevailing thought is to clean the rooms of patients suspected of having C. diff, even if those cases might not be confirmed.

Equally important to cleaning and hand washing is systemwide emphasis on antibiotic stewardship. A 2011 study at the State University of New York Buffalo found that the risk of a C. diff infection rose with the number of antibiotics taken.2

—Carolyn Gould, MD, medical epidemiologist, division of healthcare quality promotion, Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta

While a broad-spectrum antibiotic might be necessary at first, once the results of cultures are received, the treatment should be finely tailored to kill only the problem bacteria so that the body’s natural defenses aren’t broken down, Dr. Gould explains.

“If someone is very sick and you’re not sure what is going on, it’s very reasonable to treat them empirically with broad-spectrum antibiotics,” she says. “The important thing is that you send the appropriate cultures before so that you know what you’re treating and you can optimize those antibiotics with daily assessments.”

It’s clear why an overreliance on broad-spectrum drugs prevails in U.S. health settings, Dr. Cohen acknowledges. Recent literature suggests treating critically ill patients with wide-ranging antimicrobials as the mortality rate can be twice as high with narrower options. “I think people have gotten very quick to give broad-spectrum therapy,” he says.

continued below...

National Response, Localized Attention

Dr. Kavanagh of Health Watch USA says that more information about C. diff is needed, particularly publicly available numbers of infections at hospitals. Some states require those figures to be reported, but most don’t. And there is no current federal mandate on reporting of C. diff cases, although acute-care hospitals will be required to report C. diff infection rates starting in 2013.

“We really have scant data,” he says. “There is not a lot of reporting if you look at the nation on a whole. And I think that underscores one of the reasons why you need to have data for action. You need to have reporting of these organisms to the National Healthcare Safety Network so that the CDC can monitor and can make plans and can do effective interventions.

“You want to know where the areas of highest infection are,” he adds. “You want to know what interventions work and don’t work. If you don’t have a national coordinated reporting system, it really makes it difficult to address the problem. C. diff is going to be much harder to control than MRSA or other bacteria because it changes into a hard-to-kill dormant spore stage and then re-occurs at some point.”

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has proposed adding C. diff infections to the list of hospital-acquired conditions that will not be reimbursable. It is widely hoped that such a measure will go a long way toward stamping out the problem.

Dr. Kobaidze of Emory notes that C. diff is a dynamic problem, always adapting and posing new challenges. And hospitalists should be more involved in answering these questions through research. One recent question, she points out, is whether proton pump inhibitor use is related to the rise of C. diff.

Ultimately, though, controlling C. diff in hospitals might come down to what is done day to day inside the hospital. And hospitalists can play a big role.

Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM, a hospitalist and medical director of quality at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, says that a full-time pharmacist on the hospital’s antimicrobial stewardship committee is always reviewing antibiotic prescriptions and is prepared to flag cases in which a broad-spectrum is used when one with a more narrow scope might be more appropriate.

The hospital has done its best, as part of its “renovation cycle,” to standardize the layouts of rooms “so that the second you open the door you know exactly where the alcohol gel is and where the soap and the sink is going to be.” The idea is to make compliance as “mindless” as possible. Such efforts can be hampered by structural limitations though, she says.

HM group leaders, she suggests, can play an important part simply by being good role models—gowning and gloving without complaint before entering high-risk rooms and reinforcing the message that such efforts have real effects on patient safety.

But she also acknowledges that “it always sounds easy....There has to be some level of redundancy built into the hospital system. This is more of a system thing than the individual hospitalist.”

One level of redundancy at MUSC that has been particularly effective, she says, are “secret shoppers” who keep an eye out for medical teams that might not be washing their hands as they go in and out of high-risk rooms. Each unit is responsible for their hand hygiene numbers—which include both self-reported figures and those obtained by the secret onlookers—and those numbers are made available to the hospital.

Those units with the best numbers are sometimes given a reward, such as a pizza party, but it’s colleagues’ knowledge of the numbers that matters most, she says.

“That, in and of itself, is a powerful motivator,” Dr. Scheurer says. “We bring it to all of our quality operations meetings, all the administrators, the CEO, the CMO. It’s very motivating for every unit. They don’t want to be the trailing unit.”

Tom Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Miami.

References

- Orenstein R, Aronhalt KC, McManus JE Jr., Fedraw LA. A targeted strategy to wipe out Clostridium difficile. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(11):1137-1139.

- Stevens V, Dumyati G, Fine LS, Fisher SG, van Wijngaarden E. Cumulative antibiotic exposures over time and the risk of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(1):42-48.

At 480-bed Emory University Hospital Midtown in Atlanta, the physicians and staff seemingly are doing all the right things to foil one of hospital’s archenemies: Clostridium difficile. The bacteria, better known as C. diff, is responsible for a sharp rise in hospital-acquired infections over the past decade, rivaling even MRSA.

In 2010, Emory Midtown launched a campaign to boost awareness of the importance of hand washing before and after treating patients infected with C. diff and those likely to be infected. They also began using the polymerase-chain-reaction-based assay to detect the bacteria, a test with much higher sensitivity that helps to more efficiently identify those infected so control measures can be more prompt and targeted. They use a hypochlorite mixture to clean the rooms of those infected, which is considered a must. And a committee monitors the use of antibiotics to prevent overuse—often the scapegoat for the rise of the hard-to-kill bacteria.

Still, at Emory, the rate of C. diff is about the same as the national average, says hospitalist Ketino Kobaidze, MD, assistant professor at the Emory University School of Medicine and a member of the antimicrobial stewardship and infectious disease control committees at Midtown. While Dr. Kobaidze says her institution is doing a good job of trying to keep C. diff under control, she thinks hospitalists can do more.

“My feeling is that we are not as involved as we’re supposed to be,” she says. “I think we need to be a little bit more proactive, be involved in committees and research activities across the hospital.”

—Kevin Kavanagh, MD, founder, Health Watch USA

You Are Not Alone

The experience at Emory Midtown is far from unusual—healthcare facilities, and hospitalists, across the country have seen healthcare-related C. diff cases more than double since 2001 to between 400,000 and 500,000 a year, says Carolyn Gould, MD, a medical epidemiologist in the division of healthcare quality promotion at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta.

Hospitalists, whether they realize it or not, are intimately involved in how well the C. diff outbreak is controlled. Infectious-disease (ID) specialists say hospitalists are perfectly situated to make an impact in efforts to help curb the outbreak.

“Hospitalists are critical to this effort,” Dr. Gould says. “They’re in the hospital day in and day out, and they’re constantly interacting with the patients, staff, and administration. They’re often the first on the scene to see a patient who might have suddenly developed diarrhea; they’re the first to react. I think they’re in a prime position to play a leadership role to prevent C. diff infections.”

They’re also situated well to work with infection-control experts on antimicrobial stewardship programs, she says.

“I look at hospitalists just like I would have looked at internists managing their own patients 15 years ago,” says Stuart Cohen, MD, an ID expert with the University of California at Davis and a fellow with the Infectious Diseases Society of America who was lead author of the latest published IDSA guidelines on C. diff treatment. “And so they’re the first-line people.”

continued below...

A Tough Bug

Believed to be aided largely by the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics that knock out the colon’s natural flora, C. diff in the hospital—as well as nursing homes and acute-care facilities—has raged for much of the past decade. Its rise is tied to the emergence of a new hypervirulent strain known as BI/NAP1/027, or NAP1 for short. The strain is highly resistant to fluoroquinolones, such as ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin, which are used often in healthcare settings.

“A fluoroquinolone will wipe out a lot of your normal flora in your gut,” Dr. Gould says. “But it won’t wipe out C. diff, in particular this hypervirulent strain. And so this strain can flourish in the presence of fluoroquinolones.” The strain produces up to 15 to 20 times more toxins than other C. diff strains, according to some data, she adds.

Vancomycin (Vanconin) and metronidazole (Flagyl) are the most common antibiotics used to treat patients infected with C. diff. Mortality rates are higher among the elderly, largely because of their weaker immune system, Dr. Gould says. Studies have generally shown mortality rates of 10% or a bit lower.1

More recent studies have shown that the number of hospital-related C. diff cases might have begun to level off in 2008 and 2009. Dr. Gould says she thinks the leveling off is for real, but there is debate over what the immediate future holds.

“There’s a lot of work and initiatives, especially state-based initiatives, that are being done in hospitals. And there’s reason to believe they’re effective,” she says, adding it’s harder to get a good picture of the problem in long-term care facilities and in the community.

Dr. Cohen with the IDSA says it’s too soon to say whether the problem is hitting a plateau. “CDC data are always a couple of years behind,” he says. “Until you see another data point, you can’t tell whether that’s just a transient flattening and whether it’s going to keep going up or not.”

Kevin Kavanagh, MD, founder of the patient advocacy group Health Watch USA and a retired otolaryngologist in Kentucky who has taken a keen interest in the C. diff problem, says he doesn’t think the end of the tunnel is within view yet.

“I think C. diff is going to get worse before it gets better,” Dr. Kavanagh says. “And that’s not necessarily because the healthcare profession isn’t doing due diligence. This is a tough organism.—it can be tough to treat and can be very tough to kill.”

The Best Defense?

Because C. diff lives within protective spores, sound hand hygiene practices and room-cleaning practices are essential for keeping infections to a minimum. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers, effective against other organisms including MRSA, do not kill C. diff. The bacteria must be mechanically removed through hand washing.

And even hand washing might not be totally effective at getting rid of the spores, which means it’s important for healthcare workers to gown and glove in high-risk rooms.

Sodium hypochlorite solutions, or bleach mixtures, have to be used to clean rooms occupied by patients with C. diff, and the prevailing thought is to clean the rooms of patients suspected of having C. diff, even if those cases might not be confirmed.

Equally important to cleaning and hand washing is systemwide emphasis on antibiotic stewardship. A 2011 study at the State University of New York Buffalo found that the risk of a C. diff infection rose with the number of antibiotics taken.2

—Carolyn Gould, MD, medical epidemiologist, division of healthcare quality promotion, Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta

While a broad-spectrum antibiotic might be necessary at first, once the results of cultures are received, the treatment should be finely tailored to kill only the problem bacteria so that the body’s natural defenses aren’t broken down, Dr. Gould explains.

“If someone is very sick and you’re not sure what is going on, it’s very reasonable to treat them empirically with broad-spectrum antibiotics,” she says. “The important thing is that you send the appropriate cultures before so that you know what you’re treating and you can optimize those antibiotics with daily assessments.”

It’s clear why an overreliance on broad-spectrum drugs prevails in U.S. health settings, Dr. Cohen acknowledges. Recent literature suggests treating critically ill patients with wide-ranging antimicrobials as the mortality rate can be twice as high with narrower options. “I think people have gotten very quick to give broad-spectrum therapy,” he says.

continued below...

National Response, Localized Attention

Dr. Kavanagh of Health Watch USA says that more information about C. diff is needed, particularly publicly available numbers of infections at hospitals. Some states require those figures to be reported, but most don’t. And there is no current federal mandate on reporting of C. diff cases, although acute-care hospitals will be required to report C. diff infection rates starting in 2013.

“We really have scant data,” he says. “There is not a lot of reporting if you look at the nation on a whole. And I think that underscores one of the reasons why you need to have data for action. You need to have reporting of these organisms to the National Healthcare Safety Network so that the CDC can monitor and can make plans and can do effective interventions.

“You want to know where the areas of highest infection are,” he adds. “You want to know what interventions work and don’t work. If you don’t have a national coordinated reporting system, it really makes it difficult to address the problem. C. diff is going to be much harder to control than MRSA or other bacteria because it changes into a hard-to-kill dormant spore stage and then re-occurs at some point.”

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has proposed adding C. diff infections to the list of hospital-acquired conditions that will not be reimbursable. It is widely hoped that such a measure will go a long way toward stamping out the problem.

Dr. Kobaidze of Emory notes that C. diff is a dynamic problem, always adapting and posing new challenges. And hospitalists should be more involved in answering these questions through research. One recent question, she points out, is whether proton pump inhibitor use is related to the rise of C. diff.

Ultimately, though, controlling C. diff in hospitals might come down to what is done day to day inside the hospital. And hospitalists can play a big role.

Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM, a hospitalist and medical director of quality at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, says that a full-time pharmacist on the hospital’s antimicrobial stewardship committee is always reviewing antibiotic prescriptions and is prepared to flag cases in which a broad-spectrum is used when one with a more narrow scope might be more appropriate.

The hospital has done its best, as part of its “renovation cycle,” to standardize the layouts of rooms “so that the second you open the door you know exactly where the alcohol gel is and where the soap and the sink is going to be.” The idea is to make compliance as “mindless” as possible. Such efforts can be hampered by structural limitations though, she says.

HM group leaders, she suggests, can play an important part simply by being good role models—gowning and gloving without complaint before entering high-risk rooms and reinforcing the message that such efforts have real effects on patient safety.

But she also acknowledges that “it always sounds easy....There has to be some level of redundancy built into the hospital system. This is more of a system thing than the individual hospitalist.”

One level of redundancy at MUSC that has been particularly effective, she says, are “secret shoppers” who keep an eye out for medical teams that might not be washing their hands as they go in and out of high-risk rooms. Each unit is responsible for their hand hygiene numbers—which include both self-reported figures and those obtained by the secret onlookers—and those numbers are made available to the hospital.

Those units with the best numbers are sometimes given a reward, such as a pizza party, but it’s colleagues’ knowledge of the numbers that matters most, she says.

“That, in and of itself, is a powerful motivator,” Dr. Scheurer says. “We bring it to all of our quality operations meetings, all the administrators, the CEO, the CMO. It’s very motivating for every unit. They don’t want to be the trailing unit.”

Tom Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Miami.

References

- Orenstein R, Aronhalt KC, McManus JE Jr., Fedraw LA. A targeted strategy to wipe out Clostridium difficile. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(11):1137-1139.

- Stevens V, Dumyati G, Fine LS, Fisher SG, van Wijngaarden E. Cumulative antibiotic exposures over time and the risk of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(1):42-48.

Business Drivers

MIAMI BEACH, Fla.—Muralidharan Reddy, MD, had just finished a five-hour class on the business concepts behind running a hospital and how a hospital CEO thinks—part of the entry-level curriculum at SHM’s Leadership Academy. As he stood up from the round table in a room still buzzing with conversation, he was glad he had signed up—in fact, he had been one of the first to arrive for the 7:30 a.m. session at the Fontainebleau resort.

“It improves my CV, number one,” says Dr. Reddy, a hospitalist at New England Baptist Hospital in Boston. “And it’s not just the CV, but I need the experience to guide me to work as a leader in a hospital group, or even plan on starting a group, or things like that. If I’m going to be a hospitalist, I have to work on trying to get those skills.”

A big plus, he adds, is “you get to learn from experts.”

The four-day academy provides hospitalists an intense learning experience. “Some of these skills, people learn it on the job or you get it through Academy,” Dr. Reddy says. “So I do both.”

Hospitalists who participate in the session repeatedly express concerns that if they don’t hone their understanding of the business aspects of the hospital and refine their skills in interacting with colleagues, they could be left behind in a fast-moving environment.

“I think it’s important,” said Mana Goshtasbi, MD, a hospitalist with Cogent HMG who has worked for two years at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Tampa, Fla. “I think that’s the direction. I think you have to know this stuff because of all the changes.”

Leadership Academy courses come in three levels, which build on one another: Foundations for Effective Leadership, Personal Leadership Excellence, and Strengthening Your Organization. Those who have completed the three levels can apply for certification, which requires completion of a pre-approved leadership project.

Know Your Value, Know Your Customers

In his first-level session, instructor Michael Guthrie, MD, MBA, executive in residence and adjunct professor at the University of Colorado Denver School of Business’ program in health administration, spent most of his presentation on his feet, wending his way among the tables, challenging the physician-students to think differently from the ways they’ve been trained to think about healthcare. That starts with stepping outside of themselves and taking a look at how they are viewed in terms of the hospital they’re working with as hospitalists, says Dr. Guthrie, former CEO of the Good Samaritan Health System in San Jose, Calif., and former COO for the Penrose-St. Francis Healthcare System in Colorado.

“What’s affecting the organization that you operate in, and what does that mean about the kinds of demands that are being made of you and requests that are being made of you?” he asks the attendees. “What does it mean about the value that’s received from the work that you do in that organization?”

A hospitalists’ value is a common theme. “What is it that you offer as hospitalists that has created a group of enthusiasts?” he asks. “What is it that you offer to any customer that’s of value to them that they would give up their hard-earned money in exchange for it? Who are your customers?”

A key “customer” group is primary-care physicians (PCPs) whose patients end up under a hospitalist’s care, he explains. They get value from the hospitalist in a variety of ways.

“That’s a more effective way for them to spend their life [at their own clinic],” he says. “They get to manage their schedule differently, they don’t have to drive. They are all exchange values. … There’s a very definite exchange going on here. If you fail in that exchange, we all know what would happen, right? They’d stop sending you patients.”

A physician chimes in: “If you’re the only hospitalist there, they don’t have a choice.”

Dr. Guthrie, quick to seize upon what he sees as a teaching moment, tells the group to “be careful.”

“In the short term, that’s absolutely true,” he says. “In the long term, there are a lot of other alternatives. And if there aren’t, someone will invent one. You see that’s the thing about our society—if there’s an opportunity with a whole, big, dissatisfied customer segment, somebody will notice and invent the way to satisfy their needs. That’s called capitalism.”

It’s what happened with the late Steve Jobs and the iPod, when he realized customers needed a way to easily access their music collections, Dr. Guthrie points out.

“He understood the dissatisfactions of the market,” he continues. “Before that, they didn’t have any choices.

“Healthcare is the same. But it’s a little more difficult to develop those choices. It’s hard to build a new hospital right in the middle of someplace where there’s only one hospital. So they invent other ways to do it, ways to get their patients taken care of: They travel.”

About 700,000 people flew to Southeast Asia last year for medical procedures, he says, making the point that American patients have options.

“Somewhat difficult, but they do have alternatives,” he says. “Customers will, when pushed hard enough, if dissatisfied enough, leave you, even when you think you have them trapped.”

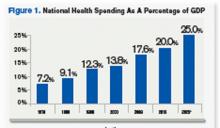

Source: Hartman, M: Martin, A; McDonnell, P et al. (2009). National Helath Spending In 2007: Slower Drug Spending Contributes To Lowest Rate Of Overall Growth Since 1998. Health Affairs, Jan/Feb., p 247. www.healthaffairs.org). See also, Orzag, Peter; Congressional Budget Office (2008). Growth in Health Care Costs, testimony before the Sentae Budget Committee, Jan. 31, p.1. (www.cbo.gov/doc.cfm?index-8948). Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services, January 2011.

Think Tanks

A key part of the session is time set aside for group work, in which Dr. Guthrie gives the class an assignment and attendees tackle it at their tables as a unit. The first task is to identify business drivers at hospitals, what the objectives of the hospital should be in response to those things, and how those objectives affect the work of hospitalists.

Then the groups go to work. A few minutes later, though, Dr. Guthrie speaks up through the chatter.

“Let’s stop for a minute. I want to tell you that most of you are on completely the wrong track,” he says, drawing chuckles. “But this is part of the reason we do it this way. The idea here is to get outside of your head.”

One group lists “profit” as a business driver.

“Profit is not a business driver,” he says. “I know you’re sort of raised to think that way. It isn’t. It’s a measurement. It’s like blood pressure. So it is not a business driver. We use it as a measurement of the success with which we’re synthesizing the business drivers and the environment and meeting the objectives of those drivers, or those trends.”

Business drivers are more along the lines of government mandates and an aging population, which some of the groups had mentioned. “That’s the level of abstraction I want you get to,” he says. “Think out in the marketplace.”

When it comes down to it, Dr. Guthrie explains, the hospitalist plays a role in just about every measurement used to determine excellence at a hospital—from quality to customer loyalty, from retention of patients to productivity.

He also emphasizes the difference between how a doctor has been trained essentially to be an individual expert—patient presents a problem, doctor presents a solution—and how those trained to be managers and leaders operate through other people.

Leaders of the Future

Daniel Duzan, MD, a hospitalist for TeamHealth at Fort Loudoun Medical Center in Lenoir City, Tenn., southwest of Knoxville, says doctors he knows recommended the academy. He says it made sense to him because he’s “migrating toward a leadership role in my own hospital.”

“My goal for coming was to kind of lay some foundation for skills and requirements that it takes to kind of migrate from just being a regular hospitalist to being one that’s got some extra responsibility,” Dr. Duzan says.

He was happy to learn more about “some of the jargon, lingo, that’s getting pushed our direction in terms of business drivers and the objectives” as well as “what would it be like to be the CEO, etc., and kind of putting us in their shoes, hearing things, seeing things and how they think about things, then developing plans.”

Jeet Gujral, MD, a hospitalist at Southside Hospital on Long Island, N.Y., says her motivation to learn about practice management is due in part to the new demands she is feeling because of the business considerations of the hospital. Talking with other hospitalists about their experiences was a big help, she says. In fact, she adds, that was probably even more helpful than the actual content of the session.

“I think what I’m getting more out of it [is that] there are several who are feeling the same heat,” she says. “It’s nice not feeling alone.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer based in Florida.

MIAMI BEACH, Fla.—Muralidharan Reddy, MD, had just finished a five-hour class on the business concepts behind running a hospital and how a hospital CEO thinks—part of the entry-level curriculum at SHM’s Leadership Academy. As he stood up from the round table in a room still buzzing with conversation, he was glad he had signed up—in fact, he had been one of the first to arrive for the 7:30 a.m. session at the Fontainebleau resort.

“It improves my CV, number one,” says Dr. Reddy, a hospitalist at New England Baptist Hospital in Boston. “And it’s not just the CV, but I need the experience to guide me to work as a leader in a hospital group, or even plan on starting a group, or things like that. If I’m going to be a hospitalist, I have to work on trying to get those skills.”

A big plus, he adds, is “you get to learn from experts.”

The four-day academy provides hospitalists an intense learning experience. “Some of these skills, people learn it on the job or you get it through Academy,” Dr. Reddy says. “So I do both.”

Hospitalists who participate in the session repeatedly express concerns that if they don’t hone their understanding of the business aspects of the hospital and refine their skills in interacting with colleagues, they could be left behind in a fast-moving environment.

“I think it’s important,” said Mana Goshtasbi, MD, a hospitalist with Cogent HMG who has worked for two years at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Tampa, Fla. “I think that’s the direction. I think you have to know this stuff because of all the changes.”

Leadership Academy courses come in three levels, which build on one another: Foundations for Effective Leadership, Personal Leadership Excellence, and Strengthening Your Organization. Those who have completed the three levels can apply for certification, which requires completion of a pre-approved leadership project.

Know Your Value, Know Your Customers

In his first-level session, instructor Michael Guthrie, MD, MBA, executive in residence and adjunct professor at the University of Colorado Denver School of Business’ program in health administration, spent most of his presentation on his feet, wending his way among the tables, challenging the physician-students to think differently from the ways they’ve been trained to think about healthcare. That starts with stepping outside of themselves and taking a look at how they are viewed in terms of the hospital they’re working with as hospitalists, says Dr. Guthrie, former CEO of the Good Samaritan Health System in San Jose, Calif., and former COO for the Penrose-St. Francis Healthcare System in Colorado.

“What’s affecting the organization that you operate in, and what does that mean about the kinds of demands that are being made of you and requests that are being made of you?” he asks the attendees. “What does it mean about the value that’s received from the work that you do in that organization?”

A hospitalists’ value is a common theme. “What is it that you offer as hospitalists that has created a group of enthusiasts?” he asks. “What is it that you offer to any customer that’s of value to them that they would give up their hard-earned money in exchange for it? Who are your customers?”

A key “customer” group is primary-care physicians (PCPs) whose patients end up under a hospitalist’s care, he explains. They get value from the hospitalist in a variety of ways.

“That’s a more effective way for them to spend their life [at their own clinic],” he says. “They get to manage their schedule differently, they don’t have to drive. They are all exchange values. … There’s a very definite exchange going on here. If you fail in that exchange, we all know what would happen, right? They’d stop sending you patients.”

A physician chimes in: “If you’re the only hospitalist there, they don’t have a choice.”

Dr. Guthrie, quick to seize upon what he sees as a teaching moment, tells the group to “be careful.”

“In the short term, that’s absolutely true,” he says. “In the long term, there are a lot of other alternatives. And if there aren’t, someone will invent one. You see that’s the thing about our society—if there’s an opportunity with a whole, big, dissatisfied customer segment, somebody will notice and invent the way to satisfy their needs. That’s called capitalism.”

It’s what happened with the late Steve Jobs and the iPod, when he realized customers needed a way to easily access their music collections, Dr. Guthrie points out.

“He understood the dissatisfactions of the market,” he continues. “Before that, they didn’t have any choices.

“Healthcare is the same. But it’s a little more difficult to develop those choices. It’s hard to build a new hospital right in the middle of someplace where there’s only one hospital. So they invent other ways to do it, ways to get their patients taken care of: They travel.”

About 700,000 people flew to Southeast Asia last year for medical procedures, he says, making the point that American patients have options.

“Somewhat difficult, but they do have alternatives,” he says. “Customers will, when pushed hard enough, if dissatisfied enough, leave you, even when you think you have them trapped.”

Source: Hartman, M: Martin, A; McDonnell, P et al. (2009). National Helath Spending In 2007: Slower Drug Spending Contributes To Lowest Rate Of Overall Growth Since 1998. Health Affairs, Jan/Feb., p 247. www.healthaffairs.org). See also, Orzag, Peter; Congressional Budget Office (2008). Growth in Health Care Costs, testimony before the Sentae Budget Committee, Jan. 31, p.1. (www.cbo.gov/doc.cfm?index-8948). Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services, January 2011.

Think Tanks

A key part of the session is time set aside for group work, in which Dr. Guthrie gives the class an assignment and attendees tackle it at their tables as a unit. The first task is to identify business drivers at hospitals, what the objectives of the hospital should be in response to those things, and how those objectives affect the work of hospitalists.

Then the groups go to work. A few minutes later, though, Dr. Guthrie speaks up through the chatter.

“Let’s stop for a minute. I want to tell you that most of you are on completely the wrong track,” he says, drawing chuckles. “But this is part of the reason we do it this way. The idea here is to get outside of your head.”

One group lists “profit” as a business driver.

“Profit is not a business driver,” he says. “I know you’re sort of raised to think that way. It isn’t. It’s a measurement. It’s like blood pressure. So it is not a business driver. We use it as a measurement of the success with which we’re synthesizing the business drivers and the environment and meeting the objectives of those drivers, or those trends.”

Business drivers are more along the lines of government mandates and an aging population, which some of the groups had mentioned. “That’s the level of abstraction I want you get to,” he says. “Think out in the marketplace.”

When it comes down to it, Dr. Guthrie explains, the hospitalist plays a role in just about every measurement used to determine excellence at a hospital—from quality to customer loyalty, from retention of patients to productivity.

He also emphasizes the difference between how a doctor has been trained essentially to be an individual expert—patient presents a problem, doctor presents a solution—and how those trained to be managers and leaders operate through other people.

Leaders of the Future

Daniel Duzan, MD, a hospitalist for TeamHealth at Fort Loudoun Medical Center in Lenoir City, Tenn., southwest of Knoxville, says doctors he knows recommended the academy. He says it made sense to him because he’s “migrating toward a leadership role in my own hospital.”

“My goal for coming was to kind of lay some foundation for skills and requirements that it takes to kind of migrate from just being a regular hospitalist to being one that’s got some extra responsibility,” Dr. Duzan says.

He was happy to learn more about “some of the jargon, lingo, that’s getting pushed our direction in terms of business drivers and the objectives” as well as “what would it be like to be the CEO, etc., and kind of putting us in their shoes, hearing things, seeing things and how they think about things, then developing plans.”

Jeet Gujral, MD, a hospitalist at Southside Hospital on Long Island, N.Y., says her motivation to learn about practice management is due in part to the new demands she is feeling because of the business considerations of the hospital. Talking with other hospitalists about their experiences was a big help, she says. In fact, she adds, that was probably even more helpful than the actual content of the session.

“I think what I’m getting more out of it [is that] there are several who are feeling the same heat,” she says. “It’s nice not feeling alone.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer based in Florida.

MIAMI BEACH, Fla.—Muralidharan Reddy, MD, had just finished a five-hour class on the business concepts behind running a hospital and how a hospital CEO thinks—part of the entry-level curriculum at SHM’s Leadership Academy. As he stood up from the round table in a room still buzzing with conversation, he was glad he had signed up—in fact, he had been one of the first to arrive for the 7:30 a.m. session at the Fontainebleau resort.

“It improves my CV, number one,” says Dr. Reddy, a hospitalist at New England Baptist Hospital in Boston. “And it’s not just the CV, but I need the experience to guide me to work as a leader in a hospital group, or even plan on starting a group, or things like that. If I’m going to be a hospitalist, I have to work on trying to get those skills.”

A big plus, he adds, is “you get to learn from experts.”

The four-day academy provides hospitalists an intense learning experience. “Some of these skills, people learn it on the job or you get it through Academy,” Dr. Reddy says. “So I do both.”

Hospitalists who participate in the session repeatedly express concerns that if they don’t hone their understanding of the business aspects of the hospital and refine their skills in interacting with colleagues, they could be left behind in a fast-moving environment.

“I think it’s important,” said Mana Goshtasbi, MD, a hospitalist with Cogent HMG who has worked for two years at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Tampa, Fla. “I think that’s the direction. I think you have to know this stuff because of all the changes.”

Leadership Academy courses come in three levels, which build on one another: Foundations for Effective Leadership, Personal Leadership Excellence, and Strengthening Your Organization. Those who have completed the three levels can apply for certification, which requires completion of a pre-approved leadership project.

Know Your Value, Know Your Customers

In his first-level session, instructor Michael Guthrie, MD, MBA, executive in residence and adjunct professor at the University of Colorado Denver School of Business’ program in health administration, spent most of his presentation on his feet, wending his way among the tables, challenging the physician-students to think differently from the ways they’ve been trained to think about healthcare. That starts with stepping outside of themselves and taking a look at how they are viewed in terms of the hospital they’re working with as hospitalists, says Dr. Guthrie, former CEO of the Good Samaritan Health System in San Jose, Calif., and former COO for the Penrose-St. Francis Healthcare System in Colorado.

“What’s affecting the organization that you operate in, and what does that mean about the kinds of demands that are being made of you and requests that are being made of you?” he asks the attendees. “What does it mean about the value that’s received from the work that you do in that organization?”

A hospitalists’ value is a common theme. “What is it that you offer as hospitalists that has created a group of enthusiasts?” he asks. “What is it that you offer to any customer that’s of value to them that they would give up their hard-earned money in exchange for it? Who are your customers?”

A key “customer” group is primary-care physicians (PCPs) whose patients end up under a hospitalist’s care, he explains. They get value from the hospitalist in a variety of ways.

“That’s a more effective way for them to spend their life [at their own clinic],” he says. “They get to manage their schedule differently, they don’t have to drive. They are all exchange values. … There’s a very definite exchange going on here. If you fail in that exchange, we all know what would happen, right? They’d stop sending you patients.”

A physician chimes in: “If you’re the only hospitalist there, they don’t have a choice.”

Dr. Guthrie, quick to seize upon what he sees as a teaching moment, tells the group to “be careful.”