User login

MIAMI BEACH, Fla.—Muralidharan Reddy, MD, had just finished a five-hour class on the business concepts behind running a hospital and how a hospital CEO thinks—part of the entry-level curriculum at SHM’s Leadership Academy. As he stood up from the round table in a room still buzzing with conversation, he was glad he had signed up—in fact, he had been one of the first to arrive for the 7:30 a.m. session at the Fontainebleau resort.

“It improves my CV, number one,” says Dr. Reddy, a hospitalist at New England Baptist Hospital in Boston. “And it’s not just the CV, but I need the experience to guide me to work as a leader in a hospital group, or even plan on starting a group, or things like that. If I’m going to be a hospitalist, I have to work on trying to get those skills.”

A big plus, he adds, is “you get to learn from experts.”

The four-day academy provides hospitalists an intense learning experience. “Some of these skills, people learn it on the job or you get it through Academy,” Dr. Reddy says. “So I do both.”

Hospitalists who participate in the session repeatedly express concerns that if they don’t hone their understanding of the business aspects of the hospital and refine their skills in interacting with colleagues, they could be left behind in a fast-moving environment.

“I think it’s important,” said Mana Goshtasbi, MD, a hospitalist with Cogent HMG who has worked for two years at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Tampa, Fla. “I think that’s the direction. I think you have to know this stuff because of all the changes.”

Leadership Academy courses come in three levels, which build on one another: Foundations for Effective Leadership, Personal Leadership Excellence, and Strengthening Your Organization. Those who have completed the three levels can apply for certification, which requires completion of a pre-approved leadership project.

Know Your Value, Know Your Customers

In his first-level session, instructor Michael Guthrie, MD, MBA, executive in residence and adjunct professor at the University of Colorado Denver School of Business’ program in health administration, spent most of his presentation on his feet, wending his way among the tables, challenging the physician-students to think differently from the ways they’ve been trained to think about healthcare. That starts with stepping outside of themselves and taking a look at how they are viewed in terms of the hospital they’re working with as hospitalists, says Dr. Guthrie, former CEO of the Good Samaritan Health System in San Jose, Calif., and former COO for the Penrose-St. Francis Healthcare System in Colorado.

“What’s affecting the organization that you operate in, and what does that mean about the kinds of demands that are being made of you and requests that are being made of you?” he asks the attendees. “What does it mean about the value that’s received from the work that you do in that organization?”

A hospitalists’ value is a common theme. “What is it that you offer as hospitalists that has created a group of enthusiasts?” he asks. “What is it that you offer to any customer that’s of value to them that they would give up their hard-earned money in exchange for it? Who are your customers?”

A key “customer” group is primary-care physicians (PCPs) whose patients end up under a hospitalist’s care, he explains. They get value from the hospitalist in a variety of ways.

“That’s a more effective way for them to spend their life [at their own clinic],” he says. “They get to manage their schedule differently, they don’t have to drive. They are all exchange values. … There’s a very definite exchange going on here. If you fail in that exchange, we all know what would happen, right? They’d stop sending you patients.”

A physician chimes in: “If you’re the only hospitalist there, they don’t have a choice.”

Dr. Guthrie, quick to seize upon what he sees as a teaching moment, tells the group to “be careful.”

“In the short term, that’s absolutely true,” he says. “In the long term, there are a lot of other alternatives. And if there aren’t, someone will invent one. You see that’s the thing about our society—if there’s an opportunity with a whole, big, dissatisfied customer segment, somebody will notice and invent the way to satisfy their needs. That’s called capitalism.”

It’s what happened with the late Steve Jobs and the iPod, when he realized customers needed a way to easily access their music collections, Dr. Guthrie points out.

“He understood the dissatisfactions of the market,” he continues. “Before that, they didn’t have any choices.

“Healthcare is the same. But it’s a little more difficult to develop those choices. It’s hard to build a new hospital right in the middle of someplace where there’s only one hospital. So they invent other ways to do it, ways to get their patients taken care of: They travel.”

About 700,000 people flew to Southeast Asia last year for medical procedures, he says, making the point that American patients have options.

“Somewhat difficult, but they do have alternatives,” he says. “Customers will, when pushed hard enough, if dissatisfied enough, leave you, even when you think you have them trapped.”

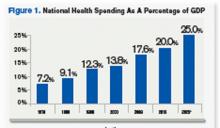

Source: Hartman, M: Martin, A; McDonnell, P et al. (2009). National Helath Spending In 2007: Slower Drug Spending Contributes To Lowest Rate Of Overall Growth Since 1998. Health Affairs, Jan/Feb., p 247. www.healthaffairs.org). See also, Orzag, Peter; Congressional Budget Office (2008). Growth in Health Care Costs, testimony before the Sentae Budget Committee, Jan. 31, p.1. (www.cbo.gov/doc.cfm?index-8948). Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services, January 2011.

Think Tanks

A key part of the session is time set aside for group work, in which Dr. Guthrie gives the class an assignment and attendees tackle it at their tables as a unit. The first task is to identify business drivers at hospitals, what the objectives of the hospital should be in response to those things, and how those objectives affect the work of hospitalists.

Then the groups go to work. A few minutes later, though, Dr. Guthrie speaks up through the chatter.

“Let’s stop for a minute. I want to tell you that most of you are on completely the wrong track,” he says, drawing chuckles. “But this is part of the reason we do it this way. The idea here is to get outside of your head.”

One group lists “profit” as a business driver.

“Profit is not a business driver,” he says. “I know you’re sort of raised to think that way. It isn’t. It’s a measurement. It’s like blood pressure. So it is not a business driver. We use it as a measurement of the success with which we’re synthesizing the business drivers and the environment and meeting the objectives of those drivers, or those trends.”

Business drivers are more along the lines of government mandates and an aging population, which some of the groups had mentioned. “That’s the level of abstraction I want you get to,” he says. “Think out in the marketplace.”

When it comes down to it, Dr. Guthrie explains, the hospitalist plays a role in just about every measurement used to determine excellence at a hospital—from quality to customer loyalty, from retention of patients to productivity.

He also emphasizes the difference between how a doctor has been trained essentially to be an individual expert—patient presents a problem, doctor presents a solution—and how those trained to be managers and leaders operate through other people.

Leaders of the Future

Daniel Duzan, MD, a hospitalist for TeamHealth at Fort Loudoun Medical Center in Lenoir City, Tenn., southwest of Knoxville, says doctors he knows recommended the academy. He says it made sense to him because he’s “migrating toward a leadership role in my own hospital.”

“My goal for coming was to kind of lay some foundation for skills and requirements that it takes to kind of migrate from just being a regular hospitalist to being one that’s got some extra responsibility,” Dr. Duzan says.

He was happy to learn more about “some of the jargon, lingo, that’s getting pushed our direction in terms of business drivers and the objectives” as well as “what would it be like to be the CEO, etc., and kind of putting us in their shoes, hearing things, seeing things and how they think about things, then developing plans.”

Jeet Gujral, MD, a hospitalist at Southside Hospital on Long Island, N.Y., says her motivation to learn about practice management is due in part to the new demands she is feeling because of the business considerations of the hospital. Talking with other hospitalists about their experiences was a big help, she says. In fact, she adds, that was probably even more helpful than the actual content of the session.

“I think what I’m getting more out of it [is that] there are several who are feeling the same heat,” she says. “It’s nice not feeling alone.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer based in Florida.

MIAMI BEACH, Fla.—Muralidharan Reddy, MD, had just finished a five-hour class on the business concepts behind running a hospital and how a hospital CEO thinks—part of the entry-level curriculum at SHM’s Leadership Academy. As he stood up from the round table in a room still buzzing with conversation, he was glad he had signed up—in fact, he had been one of the first to arrive for the 7:30 a.m. session at the Fontainebleau resort.

“It improves my CV, number one,” says Dr. Reddy, a hospitalist at New England Baptist Hospital in Boston. “And it’s not just the CV, but I need the experience to guide me to work as a leader in a hospital group, or even plan on starting a group, or things like that. If I’m going to be a hospitalist, I have to work on trying to get those skills.”

A big plus, he adds, is “you get to learn from experts.”

The four-day academy provides hospitalists an intense learning experience. “Some of these skills, people learn it on the job or you get it through Academy,” Dr. Reddy says. “So I do both.”

Hospitalists who participate in the session repeatedly express concerns that if they don’t hone their understanding of the business aspects of the hospital and refine their skills in interacting with colleagues, they could be left behind in a fast-moving environment.

“I think it’s important,” said Mana Goshtasbi, MD, a hospitalist with Cogent HMG who has worked for two years at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Tampa, Fla. “I think that’s the direction. I think you have to know this stuff because of all the changes.”

Leadership Academy courses come in three levels, which build on one another: Foundations for Effective Leadership, Personal Leadership Excellence, and Strengthening Your Organization. Those who have completed the three levels can apply for certification, which requires completion of a pre-approved leadership project.

Know Your Value, Know Your Customers

In his first-level session, instructor Michael Guthrie, MD, MBA, executive in residence and adjunct professor at the University of Colorado Denver School of Business’ program in health administration, spent most of his presentation on his feet, wending his way among the tables, challenging the physician-students to think differently from the ways they’ve been trained to think about healthcare. That starts with stepping outside of themselves and taking a look at how they are viewed in terms of the hospital they’re working with as hospitalists, says Dr. Guthrie, former CEO of the Good Samaritan Health System in San Jose, Calif., and former COO for the Penrose-St. Francis Healthcare System in Colorado.

“What’s affecting the organization that you operate in, and what does that mean about the kinds of demands that are being made of you and requests that are being made of you?” he asks the attendees. “What does it mean about the value that’s received from the work that you do in that organization?”

A hospitalists’ value is a common theme. “What is it that you offer as hospitalists that has created a group of enthusiasts?” he asks. “What is it that you offer to any customer that’s of value to them that they would give up their hard-earned money in exchange for it? Who are your customers?”

A key “customer” group is primary-care physicians (PCPs) whose patients end up under a hospitalist’s care, he explains. They get value from the hospitalist in a variety of ways.

“That’s a more effective way for them to spend their life [at their own clinic],” he says. “They get to manage their schedule differently, they don’t have to drive. They are all exchange values. … There’s a very definite exchange going on here. If you fail in that exchange, we all know what would happen, right? They’d stop sending you patients.”

A physician chimes in: “If you’re the only hospitalist there, they don’t have a choice.”

Dr. Guthrie, quick to seize upon what he sees as a teaching moment, tells the group to “be careful.”

“In the short term, that’s absolutely true,” he says. “In the long term, there are a lot of other alternatives. And if there aren’t, someone will invent one. You see that’s the thing about our society—if there’s an opportunity with a whole, big, dissatisfied customer segment, somebody will notice and invent the way to satisfy their needs. That’s called capitalism.”

It’s what happened with the late Steve Jobs and the iPod, when he realized customers needed a way to easily access their music collections, Dr. Guthrie points out.

“He understood the dissatisfactions of the market,” he continues. “Before that, they didn’t have any choices.

“Healthcare is the same. But it’s a little more difficult to develop those choices. It’s hard to build a new hospital right in the middle of someplace where there’s only one hospital. So they invent other ways to do it, ways to get their patients taken care of: They travel.”

About 700,000 people flew to Southeast Asia last year for medical procedures, he says, making the point that American patients have options.

“Somewhat difficult, but they do have alternatives,” he says. “Customers will, when pushed hard enough, if dissatisfied enough, leave you, even when you think you have them trapped.”

Source: Hartman, M: Martin, A; McDonnell, P et al. (2009). National Helath Spending In 2007: Slower Drug Spending Contributes To Lowest Rate Of Overall Growth Since 1998. Health Affairs, Jan/Feb., p 247. www.healthaffairs.org). See also, Orzag, Peter; Congressional Budget Office (2008). Growth in Health Care Costs, testimony before the Sentae Budget Committee, Jan. 31, p.1. (www.cbo.gov/doc.cfm?index-8948). Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services, January 2011.

Think Tanks

A key part of the session is time set aside for group work, in which Dr. Guthrie gives the class an assignment and attendees tackle it at their tables as a unit. The first task is to identify business drivers at hospitals, what the objectives of the hospital should be in response to those things, and how those objectives affect the work of hospitalists.

Then the groups go to work. A few minutes later, though, Dr. Guthrie speaks up through the chatter.

“Let’s stop for a minute. I want to tell you that most of you are on completely the wrong track,” he says, drawing chuckles. “But this is part of the reason we do it this way. The idea here is to get outside of your head.”

One group lists “profit” as a business driver.

“Profit is not a business driver,” he says. “I know you’re sort of raised to think that way. It isn’t. It’s a measurement. It’s like blood pressure. So it is not a business driver. We use it as a measurement of the success with which we’re synthesizing the business drivers and the environment and meeting the objectives of those drivers, or those trends.”

Business drivers are more along the lines of government mandates and an aging population, which some of the groups had mentioned. “That’s the level of abstraction I want you get to,” he says. “Think out in the marketplace.”

When it comes down to it, Dr. Guthrie explains, the hospitalist plays a role in just about every measurement used to determine excellence at a hospital—from quality to customer loyalty, from retention of patients to productivity.

He also emphasizes the difference between how a doctor has been trained essentially to be an individual expert—patient presents a problem, doctor presents a solution—and how those trained to be managers and leaders operate through other people.

Leaders of the Future

Daniel Duzan, MD, a hospitalist for TeamHealth at Fort Loudoun Medical Center in Lenoir City, Tenn., southwest of Knoxville, says doctors he knows recommended the academy. He says it made sense to him because he’s “migrating toward a leadership role in my own hospital.”

“My goal for coming was to kind of lay some foundation for skills and requirements that it takes to kind of migrate from just being a regular hospitalist to being one that’s got some extra responsibility,” Dr. Duzan says.

He was happy to learn more about “some of the jargon, lingo, that’s getting pushed our direction in terms of business drivers and the objectives” as well as “what would it be like to be the CEO, etc., and kind of putting us in their shoes, hearing things, seeing things and how they think about things, then developing plans.”

Jeet Gujral, MD, a hospitalist at Southside Hospital on Long Island, N.Y., says her motivation to learn about practice management is due in part to the new demands she is feeling because of the business considerations of the hospital. Talking with other hospitalists about their experiences was a big help, she says. In fact, she adds, that was probably even more helpful than the actual content of the session.

“I think what I’m getting more out of it [is that] there are several who are feeling the same heat,” she says. “It’s nice not feeling alone.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer based in Florida.

MIAMI BEACH, Fla.—Muralidharan Reddy, MD, had just finished a five-hour class on the business concepts behind running a hospital and how a hospital CEO thinks—part of the entry-level curriculum at SHM’s Leadership Academy. As he stood up from the round table in a room still buzzing with conversation, he was glad he had signed up—in fact, he had been one of the first to arrive for the 7:30 a.m. session at the Fontainebleau resort.

“It improves my CV, number one,” says Dr. Reddy, a hospitalist at New England Baptist Hospital in Boston. “And it’s not just the CV, but I need the experience to guide me to work as a leader in a hospital group, or even plan on starting a group, or things like that. If I’m going to be a hospitalist, I have to work on trying to get those skills.”

A big plus, he adds, is “you get to learn from experts.”

The four-day academy provides hospitalists an intense learning experience. “Some of these skills, people learn it on the job or you get it through Academy,” Dr. Reddy says. “So I do both.”

Hospitalists who participate in the session repeatedly express concerns that if they don’t hone their understanding of the business aspects of the hospital and refine their skills in interacting with colleagues, they could be left behind in a fast-moving environment.

“I think it’s important,” said Mana Goshtasbi, MD, a hospitalist with Cogent HMG who has worked for two years at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Tampa, Fla. “I think that’s the direction. I think you have to know this stuff because of all the changes.”

Leadership Academy courses come in three levels, which build on one another: Foundations for Effective Leadership, Personal Leadership Excellence, and Strengthening Your Organization. Those who have completed the three levels can apply for certification, which requires completion of a pre-approved leadership project.

Know Your Value, Know Your Customers

In his first-level session, instructor Michael Guthrie, MD, MBA, executive in residence and adjunct professor at the University of Colorado Denver School of Business’ program in health administration, spent most of his presentation on his feet, wending his way among the tables, challenging the physician-students to think differently from the ways they’ve been trained to think about healthcare. That starts with stepping outside of themselves and taking a look at how they are viewed in terms of the hospital they’re working with as hospitalists, says Dr. Guthrie, former CEO of the Good Samaritan Health System in San Jose, Calif., and former COO for the Penrose-St. Francis Healthcare System in Colorado.

“What’s affecting the organization that you operate in, and what does that mean about the kinds of demands that are being made of you and requests that are being made of you?” he asks the attendees. “What does it mean about the value that’s received from the work that you do in that organization?”

A hospitalists’ value is a common theme. “What is it that you offer as hospitalists that has created a group of enthusiasts?” he asks. “What is it that you offer to any customer that’s of value to them that they would give up their hard-earned money in exchange for it? Who are your customers?”

A key “customer” group is primary-care physicians (PCPs) whose patients end up under a hospitalist’s care, he explains. They get value from the hospitalist in a variety of ways.

“That’s a more effective way for them to spend their life [at their own clinic],” he says. “They get to manage their schedule differently, they don’t have to drive. They are all exchange values. … There’s a very definite exchange going on here. If you fail in that exchange, we all know what would happen, right? They’d stop sending you patients.”

A physician chimes in: “If you’re the only hospitalist there, they don’t have a choice.”

Dr. Guthrie, quick to seize upon what he sees as a teaching moment, tells the group to “be careful.”

“In the short term, that’s absolutely true,” he says. “In the long term, there are a lot of other alternatives. And if there aren’t, someone will invent one. You see that’s the thing about our society—if there’s an opportunity with a whole, big, dissatisfied customer segment, somebody will notice and invent the way to satisfy their needs. That’s called capitalism.”

It’s what happened with the late Steve Jobs and the iPod, when he realized customers needed a way to easily access their music collections, Dr. Guthrie points out.

“He understood the dissatisfactions of the market,” he continues. “Before that, they didn’t have any choices.

“Healthcare is the same. But it’s a little more difficult to develop those choices. It’s hard to build a new hospital right in the middle of someplace where there’s only one hospital. So they invent other ways to do it, ways to get their patients taken care of: They travel.”

About 700,000 people flew to Southeast Asia last year for medical procedures, he says, making the point that American patients have options.

“Somewhat difficult, but they do have alternatives,” he says. “Customers will, when pushed hard enough, if dissatisfied enough, leave you, even when you think you have them trapped.”

Source: Hartman, M: Martin, A; McDonnell, P et al. (2009). National Helath Spending In 2007: Slower Drug Spending Contributes To Lowest Rate Of Overall Growth Since 1998. Health Affairs, Jan/Feb., p 247. www.healthaffairs.org). See also, Orzag, Peter; Congressional Budget Office (2008). Growth in Health Care Costs, testimony before the Sentae Budget Committee, Jan. 31, p.1. (www.cbo.gov/doc.cfm?index-8948). Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services, January 2011.

Think Tanks

A key part of the session is time set aside for group work, in which Dr. Guthrie gives the class an assignment and attendees tackle it at their tables as a unit. The first task is to identify business drivers at hospitals, what the objectives of the hospital should be in response to those things, and how those objectives affect the work of hospitalists.

Then the groups go to work. A few minutes later, though, Dr. Guthrie speaks up through the chatter.

“Let’s stop for a minute. I want to tell you that most of you are on completely the wrong track,” he says, drawing chuckles. “But this is part of the reason we do it this way. The idea here is to get outside of your head.”

One group lists “profit” as a business driver.

“Profit is not a business driver,” he says. “I know you’re sort of raised to think that way. It isn’t. It’s a measurement. It’s like blood pressure. So it is not a business driver. We use it as a measurement of the success with which we’re synthesizing the business drivers and the environment and meeting the objectives of those drivers, or those trends.”

Business drivers are more along the lines of government mandates and an aging population, which some of the groups had mentioned. “That’s the level of abstraction I want you get to,” he says. “Think out in the marketplace.”

When it comes down to it, Dr. Guthrie explains, the hospitalist plays a role in just about every measurement used to determine excellence at a hospital—from quality to customer loyalty, from retention of patients to productivity.

He also emphasizes the difference between how a doctor has been trained essentially to be an individual expert—patient presents a problem, doctor presents a solution—and how those trained to be managers and leaders operate through other people.

Leaders of the Future

Daniel Duzan, MD, a hospitalist for TeamHealth at Fort Loudoun Medical Center in Lenoir City, Tenn., southwest of Knoxville, says doctors he knows recommended the academy. He says it made sense to him because he’s “migrating toward a leadership role in my own hospital.”

“My goal for coming was to kind of lay some foundation for skills and requirements that it takes to kind of migrate from just being a regular hospitalist to being one that’s got some extra responsibility,” Dr. Duzan says.

He was happy to learn more about “some of the jargon, lingo, that’s getting pushed our direction in terms of business drivers and the objectives” as well as “what would it be like to be the CEO, etc., and kind of putting us in their shoes, hearing things, seeing things and how they think about things, then developing plans.”

Jeet Gujral, MD, a hospitalist at Southside Hospital on Long Island, N.Y., says her motivation to learn about practice management is due in part to the new demands she is feeling because of the business considerations of the hospital. Talking with other hospitalists about their experiences was a big help, she says. In fact, she adds, that was probably even more helpful than the actual content of the session.

“I think what I’m getting more out of it [is that] there are several who are feeling the same heat,” she says. “It’s nice not feeling alone.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer based in Florida.