User login

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida who has written about medical topics from nasty infections to ethical dilemmas, runaway tumors to tornado-chasing doctors. He travels the globe gathering conference health news and lives in West Palm Beach.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Listen to Russell Holman and Ed Weinberg discuss companies' acquisition strategies

What’s Next for Hospital Medicine?

At the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) in Charleston, a familiar scene plays out in the hospitalist program. New hospitalists express an interest in a certain area and the university tries to accommodate them, making time for them to pursue additional training as they juggle the daily demands of treating patients, says Patrick Cawley, MD, MBA, SFHM, associate professor at the university and a former SHM president.

"We try to have a personal growth plan for each hospitalist that aligns with their interest," Dr. Cawley says. "So if we have a hospitalist that’s very, very interested in quality improvement, we’ll seek out opportunities to get that hospitalist experience, and start with smaller projects and then bigger projects."

As the field of HM hits a notable mark in its history—it’s been 15 years since the term "hospitalist" was coined—more advanced training will continue to emerge as a key issue and obstacle in the field, say experts who were asked to take a look into HM’s crystal ball.

They also predict continued growth of the field, with tens of thousands of new hospitalists emerging in the next decade or so. They also say that hospitalists will emerge as leaders in the application and use of new technology, and that there will be more demands placed on hospitalists to show their worth in hard data.

There also promises to be a growing presence of private management firms providing hospitalists to hospitals, which doctors both inside and outside of those firms say could have a beneficial effect on the overall quality of patient care.

-Patrick Cawley, MD, MBA, SFHM, associate professor, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, former SHM president

Father Time

For now, Dr. Cawley says, at MUSC and elsewhere, hospitalist programs are scrambling for time to enhance the skills needed to tend to increased demands.

"You have to carve out time. That’s literally what you have to do," he explains. "That’s expensive to take a doctor away from clinical service for a week, or an even an hour or two a week. I mean, somebody’s got to pay for that."

Training on hospitalist-specific management topics, he says, needs to evolve further. "I think there’s a recognition that this stuff is important and that hospitals and hospitalists need to get better aligned," he says. "This is something that will continue to mature over the next 10 years."

The range of tasks is growing ever broader for the hospitalist, and so the need for enhanced training is greater, says Larry Wellikson, MD, SFHM, CEO of SHM.

"They’re being asked to do bedside patient care, but they’re being asked to do more. They’re asked to be systems engineers, they’re asked to be safety experts, they’re asked to be the information manager, if you will, the IT guys," he says. "These skills they have not been trained to do and they need … either to say, ‘No, I can’t do that because I haven’t been trained,’ or they need to go and look where they can get that expertise.

"That’s what we try to do at SHM, with our Leadership Academy and our Practice Management Academy."

Frank Michota, MD, FHM, director of academic affairs in the Department of Hospital Medicine at The Cleveland Clinic, says that one of the biggest challenges the field needs to tackle over the next several years is to better standardize the education of hospitalists, saying there is "incredible inconsistency from hospitalist to hospitalist in terms of knowledge base, experience and … understanding the scope of practice."

"We continue to have significant variation in hospital practice models and the types of measurements that are available to those hospitalists for practice improvement," he says. "We continue to see significant turnover in the field with kind of a lack of maturity"—and not the kind of experience base that "you would like to see 15 years in."

"There is really no confidence that everyone at the base of that iceberg will ever make it to the tip because it’s still not viewed by many who entered the field as being a long-term career choice," Dr. Michota says. For many, he said, it is "a look-and-see proposition."

All of this, he says, points to the need for a full certification process by an HM board.

"I don’t want to make it sound like it has not been an impressive evolution to this point, but I think if we are going to meet the expectations, we do have to do more than we’re doing now," Dr. Michota says.

Some of the gaps in training might be able to be filled by private hospital management groups, which have training programs for their doctors that are made possible by their scale and whose presence is predicted to grow over the next 15 years.

Robert Bessler, MD, who in 2001 founded Tacoma, Wash.-based Sound Physicians, which has become one of the largest private hospitalist organizations in the country, says private companies are able to conduct training that is impossible for many hospitals to conduct themselves.

"You’re going to get good people who are all of good training and good knowledge, but they’re not all going to have experience," he says, "and so what are the hospitals that are employing 50% of the hospitalists in this country going to do about that? It’s pretty much nothing. They’re going to occasionally send some people to conferences and hope—because they don’t have that infrastructure."

At teaching institutes like those at private firms, the process is sped up, Dr. Bessler adds.

"That’s why we built our hospitalists’ institute at Sound—to turn really good, quality doctors into effective hospitalists in a much more rapid fashion," he says. "Because before we built this, it was just get them involved and hope after a couple of years they’ve really become efficient. Our hospital partners and the patients can’t wait that long."

Robert Reynolds, MD, founder of PrimeDoc, an Asheville, N.C.-based company that provides doctors for 12 hospitalist programs and employs about 100 doctors, says there needs to be more focus on teaching the "realistic side of the business of medicine," as well as on quality outcomes and patient satisfaction. But he also doubts there will be much change in training.

"[From] my cynical side and the voice of experience, I don’t see any change in the near future," he says. "What we’re seeing now is physicians come out of residency with a good clinical base, but really having no idea of how the healthcare system works in a bigger picture, how it works as an industry. So we’re having to spend a lot of time and effort training physicians to start thinking like practicing physicians."

The experts all agree that there will be an increase in hospitalists being provided by private corporations. Dr. Reynolds says that trend will continue in part due to healthcare reform’s emphasis on outcomes for reimbursement and a corporation’s ability to assist with physician training, as well as data and reporting needs.

"More and more hospital compensation and physician compensation is going to be based on actual data, performance data," he says. "And in order to really do a good job of capturing and reporting that kind of data, you need enough size to support an IT system and training systems that will produce and capture the kind of data that will be necessary."

Erin Fisher, MD, MHM, a pediatric hospitalist at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, says a major goal of the future should be to change the reimbursement structure "so that you have something that is reasonable and encourages appropriate testing, treatments, and coordination of our healthcare system in a systematic way, rather than pieces." In such a system, hospitalists might see something to prompt them to intervene in a preventive way.

"The bigger question is, can our healthcare system, in five to 10 years, change itself enough that it uses every episode of care as an opportunity to do preventive care and coordinate care in the best way?" says Dr. Fisher, an SHM board member.

Continued Growth?

There is agreement that the field will continue to expand, with SHM predicting that the number of hospitalists in the U.S. will reach 40,000 in the next several years, up from today’s 30,000 figure.

Dr. Wellikson says that the figure could rise to as many as 70,000 or more if specialty hospitalists—such as surgical hospitalists, neuro-hospitalists, and laborists—are included. Those hospital-based specialties are now only in their infancy.

"Everything you can see shows that people are still flocking into hospital medicine," Dr. Wellikson adds.

Hospitalists numbered in the hundreds just 15 years ago, so growth has been explosive the past decade. Dr. Cawley, however, says the pace of growth might be starting to slow already, shifting to undeveloped or underserved areas. "Hospitalist programs are at almost all the large [hospitals] and really the growth has been at the smaller hospitals in the last several years," he says.

With the projected rise of Medicare beneficiaries due to the aging of the baby-boom generation, use of hospitals is expected to skyrocket, meaning more hospitalists will be needed, Dr. Bessler says. He also cites data from the National Rural Health Association noting that 25% of the U.S. population lives in areas considered rural, but that only 10% of the physicians live in those areas, indicating a potential growth area for hospitalists.

"That would tell me that demand will continue to outpace supply," he says.

Mike Tarwater, a member of the board of the American Hospital Association and CEO of Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte, N.C., agrees with Dr. Bessler. Even with the move toward more outpatient care, Tarwater says, the aging of the population will mean a higher demand for hospitalists.

-Mike Tarwater, board member, American Hospital Association, CEO, Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, N.C.

"I think that the primary-care physicians—either because of their love for it or their belief that it’s the better way to go with the treatment of their patients—are going to be really stretched to keep that ambulatory practice going and to get to round on patients in the hospitals," he says. "I think there’s going to be a continued growth of the trend that we’ve seen over the last 15 years."

That growth also will mean a greater emphasis on technology use, whether it’s technology used for quick diagnostics like portable ultrasound or more widely used and refined electronic health records (EHR)—or, as Tarwater describes, "probably things we don’t imagine today."

"Our doctors, more than any other doctors, are tech-savvy; they’re early adopters," Dr. Wellikson says.

Hospitalists likely will emerge as leaders in the adoption of new technology, several experts predict.

Without a doubt, I think that hospitalists are going to be a driving force in the adaptation of the electronic [health] record to the clinical care within their hospitals," Dr. Michota says.

As the needs of HM grow, and the field grows more complex, there will inevitably be more divisions and departments of hospital medicine in places where it is now only a section, Dr. Cawley says.

"When you’re a division or a department, you have more autonomy over your own future, so I see this happening," he says. "I think more and more will carve themselves out of general internal medicine, and a lot of that will come because of a demand for more independence and greater autonomy." TH

Thomas R. Collins is a medical writer based in Florida.

At the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) in Charleston, a familiar scene plays out in the hospitalist program. New hospitalists express an interest in a certain area and the university tries to accommodate them, making time for them to pursue additional training as they juggle the daily demands of treating patients, says Patrick Cawley, MD, MBA, SFHM, associate professor at the university and a former SHM president.

"We try to have a personal growth plan for each hospitalist that aligns with their interest," Dr. Cawley says. "So if we have a hospitalist that’s very, very interested in quality improvement, we’ll seek out opportunities to get that hospitalist experience, and start with smaller projects and then bigger projects."

As the field of HM hits a notable mark in its history—it’s been 15 years since the term "hospitalist" was coined—more advanced training will continue to emerge as a key issue and obstacle in the field, say experts who were asked to take a look into HM’s crystal ball.

They also predict continued growth of the field, with tens of thousands of new hospitalists emerging in the next decade or so. They also say that hospitalists will emerge as leaders in the application and use of new technology, and that there will be more demands placed on hospitalists to show their worth in hard data.

There also promises to be a growing presence of private management firms providing hospitalists to hospitals, which doctors both inside and outside of those firms say could have a beneficial effect on the overall quality of patient care.

-Patrick Cawley, MD, MBA, SFHM, associate professor, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, former SHM president

Father Time

For now, Dr. Cawley says, at MUSC and elsewhere, hospitalist programs are scrambling for time to enhance the skills needed to tend to increased demands.

"You have to carve out time. That’s literally what you have to do," he explains. "That’s expensive to take a doctor away from clinical service for a week, or an even an hour or two a week. I mean, somebody’s got to pay for that."

Training on hospitalist-specific management topics, he says, needs to evolve further. "I think there’s a recognition that this stuff is important and that hospitals and hospitalists need to get better aligned," he says. "This is something that will continue to mature over the next 10 years."

The range of tasks is growing ever broader for the hospitalist, and so the need for enhanced training is greater, says Larry Wellikson, MD, SFHM, CEO of SHM.

"They’re being asked to do bedside patient care, but they’re being asked to do more. They’re asked to be systems engineers, they’re asked to be safety experts, they’re asked to be the information manager, if you will, the IT guys," he says. "These skills they have not been trained to do and they need … either to say, ‘No, I can’t do that because I haven’t been trained,’ or they need to go and look where they can get that expertise.

"That’s what we try to do at SHM, with our Leadership Academy and our Practice Management Academy."

Frank Michota, MD, FHM, director of academic affairs in the Department of Hospital Medicine at The Cleveland Clinic, says that one of the biggest challenges the field needs to tackle over the next several years is to better standardize the education of hospitalists, saying there is "incredible inconsistency from hospitalist to hospitalist in terms of knowledge base, experience and … understanding the scope of practice."

"We continue to have significant variation in hospital practice models and the types of measurements that are available to those hospitalists for practice improvement," he says. "We continue to see significant turnover in the field with kind of a lack of maturity"—and not the kind of experience base that "you would like to see 15 years in."

"There is really no confidence that everyone at the base of that iceberg will ever make it to the tip because it’s still not viewed by many who entered the field as being a long-term career choice," Dr. Michota says. For many, he said, it is "a look-and-see proposition."

All of this, he says, points to the need for a full certification process by an HM board.

"I don’t want to make it sound like it has not been an impressive evolution to this point, but I think if we are going to meet the expectations, we do have to do more than we’re doing now," Dr. Michota says.

Some of the gaps in training might be able to be filled by private hospital management groups, which have training programs for their doctors that are made possible by their scale and whose presence is predicted to grow over the next 15 years.

Robert Bessler, MD, who in 2001 founded Tacoma, Wash.-based Sound Physicians, which has become one of the largest private hospitalist organizations in the country, says private companies are able to conduct training that is impossible for many hospitals to conduct themselves.

"You’re going to get good people who are all of good training and good knowledge, but they’re not all going to have experience," he says, "and so what are the hospitals that are employing 50% of the hospitalists in this country going to do about that? It’s pretty much nothing. They’re going to occasionally send some people to conferences and hope—because they don’t have that infrastructure."

At teaching institutes like those at private firms, the process is sped up, Dr. Bessler adds.

"That’s why we built our hospitalists’ institute at Sound—to turn really good, quality doctors into effective hospitalists in a much more rapid fashion," he says. "Because before we built this, it was just get them involved and hope after a couple of years they’ve really become efficient. Our hospital partners and the patients can’t wait that long."

Robert Reynolds, MD, founder of PrimeDoc, an Asheville, N.C.-based company that provides doctors for 12 hospitalist programs and employs about 100 doctors, says there needs to be more focus on teaching the "realistic side of the business of medicine," as well as on quality outcomes and patient satisfaction. But he also doubts there will be much change in training.

"[From] my cynical side and the voice of experience, I don’t see any change in the near future," he says. "What we’re seeing now is physicians come out of residency with a good clinical base, but really having no idea of how the healthcare system works in a bigger picture, how it works as an industry. So we’re having to spend a lot of time and effort training physicians to start thinking like practicing physicians."

The experts all agree that there will be an increase in hospitalists being provided by private corporations. Dr. Reynolds says that trend will continue in part due to healthcare reform’s emphasis on outcomes for reimbursement and a corporation’s ability to assist with physician training, as well as data and reporting needs.

"More and more hospital compensation and physician compensation is going to be based on actual data, performance data," he says. "And in order to really do a good job of capturing and reporting that kind of data, you need enough size to support an IT system and training systems that will produce and capture the kind of data that will be necessary."

Erin Fisher, MD, MHM, a pediatric hospitalist at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, says a major goal of the future should be to change the reimbursement structure "so that you have something that is reasonable and encourages appropriate testing, treatments, and coordination of our healthcare system in a systematic way, rather than pieces." In such a system, hospitalists might see something to prompt them to intervene in a preventive way.

"The bigger question is, can our healthcare system, in five to 10 years, change itself enough that it uses every episode of care as an opportunity to do preventive care and coordinate care in the best way?" says Dr. Fisher, an SHM board member.

Continued Growth?

There is agreement that the field will continue to expand, with SHM predicting that the number of hospitalists in the U.S. will reach 40,000 in the next several years, up from today’s 30,000 figure.

Dr. Wellikson says that the figure could rise to as many as 70,000 or more if specialty hospitalists—such as surgical hospitalists, neuro-hospitalists, and laborists—are included. Those hospital-based specialties are now only in their infancy.

"Everything you can see shows that people are still flocking into hospital medicine," Dr. Wellikson adds.

Hospitalists numbered in the hundreds just 15 years ago, so growth has been explosive the past decade. Dr. Cawley, however, says the pace of growth might be starting to slow already, shifting to undeveloped or underserved areas. "Hospitalist programs are at almost all the large [hospitals] and really the growth has been at the smaller hospitals in the last several years," he says.

With the projected rise of Medicare beneficiaries due to the aging of the baby-boom generation, use of hospitals is expected to skyrocket, meaning more hospitalists will be needed, Dr. Bessler says. He also cites data from the National Rural Health Association noting that 25% of the U.S. population lives in areas considered rural, but that only 10% of the physicians live in those areas, indicating a potential growth area for hospitalists.

"That would tell me that demand will continue to outpace supply," he says.

Mike Tarwater, a member of the board of the American Hospital Association and CEO of Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte, N.C., agrees with Dr. Bessler. Even with the move toward more outpatient care, Tarwater says, the aging of the population will mean a higher demand for hospitalists.

-Mike Tarwater, board member, American Hospital Association, CEO, Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, N.C.

"I think that the primary-care physicians—either because of their love for it or their belief that it’s the better way to go with the treatment of their patients—are going to be really stretched to keep that ambulatory practice going and to get to round on patients in the hospitals," he says. "I think there’s going to be a continued growth of the trend that we’ve seen over the last 15 years."

That growth also will mean a greater emphasis on technology use, whether it’s technology used for quick diagnostics like portable ultrasound or more widely used and refined electronic health records (EHR)—or, as Tarwater describes, "probably things we don’t imagine today."

"Our doctors, more than any other doctors, are tech-savvy; they’re early adopters," Dr. Wellikson says.

Hospitalists likely will emerge as leaders in the adoption of new technology, several experts predict.

Without a doubt, I think that hospitalists are going to be a driving force in the adaptation of the electronic [health] record to the clinical care within their hospitals," Dr. Michota says.

As the needs of HM grow, and the field grows more complex, there will inevitably be more divisions and departments of hospital medicine in places where it is now only a section, Dr. Cawley says.

"When you’re a division or a department, you have more autonomy over your own future, so I see this happening," he says. "I think more and more will carve themselves out of general internal medicine, and a lot of that will come because of a demand for more independence and greater autonomy." TH

Thomas R. Collins is a medical writer based in Florida.

At the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) in Charleston, a familiar scene plays out in the hospitalist program. New hospitalists express an interest in a certain area and the university tries to accommodate them, making time for them to pursue additional training as they juggle the daily demands of treating patients, says Patrick Cawley, MD, MBA, SFHM, associate professor at the university and a former SHM president.

"We try to have a personal growth plan for each hospitalist that aligns with their interest," Dr. Cawley says. "So if we have a hospitalist that’s very, very interested in quality improvement, we’ll seek out opportunities to get that hospitalist experience, and start with smaller projects and then bigger projects."

As the field of HM hits a notable mark in its history—it’s been 15 years since the term "hospitalist" was coined—more advanced training will continue to emerge as a key issue and obstacle in the field, say experts who were asked to take a look into HM’s crystal ball.

They also predict continued growth of the field, with tens of thousands of new hospitalists emerging in the next decade or so. They also say that hospitalists will emerge as leaders in the application and use of new technology, and that there will be more demands placed on hospitalists to show their worth in hard data.

There also promises to be a growing presence of private management firms providing hospitalists to hospitals, which doctors both inside and outside of those firms say could have a beneficial effect on the overall quality of patient care.

-Patrick Cawley, MD, MBA, SFHM, associate professor, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, former SHM president

Father Time

For now, Dr. Cawley says, at MUSC and elsewhere, hospitalist programs are scrambling for time to enhance the skills needed to tend to increased demands.

"You have to carve out time. That’s literally what you have to do," he explains. "That’s expensive to take a doctor away from clinical service for a week, or an even an hour or two a week. I mean, somebody’s got to pay for that."

Training on hospitalist-specific management topics, he says, needs to evolve further. "I think there’s a recognition that this stuff is important and that hospitals and hospitalists need to get better aligned," he says. "This is something that will continue to mature over the next 10 years."

The range of tasks is growing ever broader for the hospitalist, and so the need for enhanced training is greater, says Larry Wellikson, MD, SFHM, CEO of SHM.

"They’re being asked to do bedside patient care, but they’re being asked to do more. They’re asked to be systems engineers, they’re asked to be safety experts, they’re asked to be the information manager, if you will, the IT guys," he says. "These skills they have not been trained to do and they need … either to say, ‘No, I can’t do that because I haven’t been trained,’ or they need to go and look where they can get that expertise.

"That’s what we try to do at SHM, with our Leadership Academy and our Practice Management Academy."

Frank Michota, MD, FHM, director of academic affairs in the Department of Hospital Medicine at The Cleveland Clinic, says that one of the biggest challenges the field needs to tackle over the next several years is to better standardize the education of hospitalists, saying there is "incredible inconsistency from hospitalist to hospitalist in terms of knowledge base, experience and … understanding the scope of practice."

"We continue to have significant variation in hospital practice models and the types of measurements that are available to those hospitalists for practice improvement," he says. "We continue to see significant turnover in the field with kind of a lack of maturity"—and not the kind of experience base that "you would like to see 15 years in."

"There is really no confidence that everyone at the base of that iceberg will ever make it to the tip because it’s still not viewed by many who entered the field as being a long-term career choice," Dr. Michota says. For many, he said, it is "a look-and-see proposition."

All of this, he says, points to the need for a full certification process by an HM board.

"I don’t want to make it sound like it has not been an impressive evolution to this point, but I think if we are going to meet the expectations, we do have to do more than we’re doing now," Dr. Michota says.

Some of the gaps in training might be able to be filled by private hospital management groups, which have training programs for their doctors that are made possible by their scale and whose presence is predicted to grow over the next 15 years.

Robert Bessler, MD, who in 2001 founded Tacoma, Wash.-based Sound Physicians, which has become one of the largest private hospitalist organizations in the country, says private companies are able to conduct training that is impossible for many hospitals to conduct themselves.

"You’re going to get good people who are all of good training and good knowledge, but they’re not all going to have experience," he says, "and so what are the hospitals that are employing 50% of the hospitalists in this country going to do about that? It’s pretty much nothing. They’re going to occasionally send some people to conferences and hope—because they don’t have that infrastructure."

At teaching institutes like those at private firms, the process is sped up, Dr. Bessler adds.

"That’s why we built our hospitalists’ institute at Sound—to turn really good, quality doctors into effective hospitalists in a much more rapid fashion," he says. "Because before we built this, it was just get them involved and hope after a couple of years they’ve really become efficient. Our hospital partners and the patients can’t wait that long."

Robert Reynolds, MD, founder of PrimeDoc, an Asheville, N.C.-based company that provides doctors for 12 hospitalist programs and employs about 100 doctors, says there needs to be more focus on teaching the "realistic side of the business of medicine," as well as on quality outcomes and patient satisfaction. But he also doubts there will be much change in training.

"[From] my cynical side and the voice of experience, I don’t see any change in the near future," he says. "What we’re seeing now is physicians come out of residency with a good clinical base, but really having no idea of how the healthcare system works in a bigger picture, how it works as an industry. So we’re having to spend a lot of time and effort training physicians to start thinking like practicing physicians."

The experts all agree that there will be an increase in hospitalists being provided by private corporations. Dr. Reynolds says that trend will continue in part due to healthcare reform’s emphasis on outcomes for reimbursement and a corporation’s ability to assist with physician training, as well as data and reporting needs.

"More and more hospital compensation and physician compensation is going to be based on actual data, performance data," he says. "And in order to really do a good job of capturing and reporting that kind of data, you need enough size to support an IT system and training systems that will produce and capture the kind of data that will be necessary."

Erin Fisher, MD, MHM, a pediatric hospitalist at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, says a major goal of the future should be to change the reimbursement structure "so that you have something that is reasonable and encourages appropriate testing, treatments, and coordination of our healthcare system in a systematic way, rather than pieces." In such a system, hospitalists might see something to prompt them to intervene in a preventive way.

"The bigger question is, can our healthcare system, in five to 10 years, change itself enough that it uses every episode of care as an opportunity to do preventive care and coordinate care in the best way?" says Dr. Fisher, an SHM board member.

Continued Growth?

There is agreement that the field will continue to expand, with SHM predicting that the number of hospitalists in the U.S. will reach 40,000 in the next several years, up from today’s 30,000 figure.

Dr. Wellikson says that the figure could rise to as many as 70,000 or more if specialty hospitalists—such as surgical hospitalists, neuro-hospitalists, and laborists—are included. Those hospital-based specialties are now only in their infancy.

"Everything you can see shows that people are still flocking into hospital medicine," Dr. Wellikson adds.

Hospitalists numbered in the hundreds just 15 years ago, so growth has been explosive the past decade. Dr. Cawley, however, says the pace of growth might be starting to slow already, shifting to undeveloped or underserved areas. "Hospitalist programs are at almost all the large [hospitals] and really the growth has been at the smaller hospitals in the last several years," he says.

With the projected rise of Medicare beneficiaries due to the aging of the baby-boom generation, use of hospitals is expected to skyrocket, meaning more hospitalists will be needed, Dr. Bessler says. He also cites data from the National Rural Health Association noting that 25% of the U.S. population lives in areas considered rural, but that only 10% of the physicians live in those areas, indicating a potential growth area for hospitalists.

"That would tell me that demand will continue to outpace supply," he says.

Mike Tarwater, a member of the board of the American Hospital Association and CEO of Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte, N.C., agrees with Dr. Bessler. Even with the move toward more outpatient care, Tarwater says, the aging of the population will mean a higher demand for hospitalists.

-Mike Tarwater, board member, American Hospital Association, CEO, Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, N.C.

"I think that the primary-care physicians—either because of their love for it or their belief that it’s the better way to go with the treatment of their patients—are going to be really stretched to keep that ambulatory practice going and to get to round on patients in the hospitals," he says. "I think there’s going to be a continued growth of the trend that we’ve seen over the last 15 years."

That growth also will mean a greater emphasis on technology use, whether it’s technology used for quick diagnostics like portable ultrasound or more widely used and refined electronic health records (EHR)—or, as Tarwater describes, "probably things we don’t imagine today."

"Our doctors, more than any other doctors, are tech-savvy; they’re early adopters," Dr. Wellikson says.

Hospitalists likely will emerge as leaders in the adoption of new technology, several experts predict.

Without a doubt, I think that hospitalists are going to be a driving force in the adaptation of the electronic [health] record to the clinical care within their hospitals," Dr. Michota says.

As the needs of HM grow, and the field grows more complex, there will inevitably be more divisions and departments of hospital medicine in places where it is now only a section, Dr. Cawley says.

"When you’re a division or a department, you have more autonomy over your own future, so I see this happening," he says. "I think more and more will carve themselves out of general internal medicine, and a lot of that will come because of a demand for more independence and greater autonomy." TH

Thomas R. Collins is a medical writer based in Florida.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Listen to Pat Cawley and Frank Michota discuss what's next for HM

Click here to listen to Dr. Cawley

Click here to listen to Dr. Michota

Click here to listen to Dr. Cawley

Click here to listen to Dr. Michota

Click here to listen to Dr. Cawley

Click here to listen to Dr. Michota

FDA Approves Another Anticoagulant

Earlier this month, the FDA approved Xarelto (rivaroxaban) to cut the risk of blood clots, DVT, and pulmonary embolism after knee and hip replacement surgery. According to one hospitalist, the drug approval represents another way to prevent blood clots on an outpatient basis.

The drug is a pill that is taken once a day. Those having knee replacements should take the medication for 12 days, and those having hip replacements should take it for 35 days, according to FDA guidelines.

"I think that it has the potential of being a game-changer," says Robert Pendleton, MD, codirector of the hospitalist program and medical director of the University Healthcare Thrombosis Service at the University of Utah Medical Center in Salt Lake City. "It definitely could turn out to be a blockbuster drug."

In a statement, Paul Chang, MD, vice president of medical affairs in internal medicine at Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc., said, "Shorter hospital stays following hip and knee replacement surgeries have made the prevention of venous blood clots an outpatient issue, and Xarelto provides a safe and effective oral treatment option that can be easily transitioned from use in hospital to home."

The approval is the latest challenge to warfarin. It comes on the heels of the approval of Pradaxa (dabigatran) for stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients. (Updated July 21). Xarelto, however, is the only new oral anticoagulant approved for its indication.

Dr. Pendleton says the advantage of Xarelto is that it only has to be taken once a day. He said the full potential lies in the "high likelihood of subsequent indications" for the drug.

Still, this is a new drug and care has to be taken, he says.

"If it's not used appropriately in the proper patient with proper attention to renal function and drug-drug interaction," he adds, "a very promising drug could have difficulty."

Earlier this month, the FDA approved Xarelto (rivaroxaban) to cut the risk of blood clots, DVT, and pulmonary embolism after knee and hip replacement surgery. According to one hospitalist, the drug approval represents another way to prevent blood clots on an outpatient basis.

The drug is a pill that is taken once a day. Those having knee replacements should take the medication for 12 days, and those having hip replacements should take it for 35 days, according to FDA guidelines.

"I think that it has the potential of being a game-changer," says Robert Pendleton, MD, codirector of the hospitalist program and medical director of the University Healthcare Thrombosis Service at the University of Utah Medical Center in Salt Lake City. "It definitely could turn out to be a blockbuster drug."

In a statement, Paul Chang, MD, vice president of medical affairs in internal medicine at Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc., said, "Shorter hospital stays following hip and knee replacement surgeries have made the prevention of venous blood clots an outpatient issue, and Xarelto provides a safe and effective oral treatment option that can be easily transitioned from use in hospital to home."

The approval is the latest challenge to warfarin. It comes on the heels of the approval of Pradaxa (dabigatran) for stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients. (Updated July 21). Xarelto, however, is the only new oral anticoagulant approved for its indication.

Dr. Pendleton says the advantage of Xarelto is that it only has to be taken once a day. He said the full potential lies in the "high likelihood of subsequent indications" for the drug.

Still, this is a new drug and care has to be taken, he says.

"If it's not used appropriately in the proper patient with proper attention to renal function and drug-drug interaction," he adds, "a very promising drug could have difficulty."

Earlier this month, the FDA approved Xarelto (rivaroxaban) to cut the risk of blood clots, DVT, and pulmonary embolism after knee and hip replacement surgery. According to one hospitalist, the drug approval represents another way to prevent blood clots on an outpatient basis.

The drug is a pill that is taken once a day. Those having knee replacements should take the medication for 12 days, and those having hip replacements should take it for 35 days, according to FDA guidelines.

"I think that it has the potential of being a game-changer," says Robert Pendleton, MD, codirector of the hospitalist program and medical director of the University Healthcare Thrombosis Service at the University of Utah Medical Center in Salt Lake City. "It definitely could turn out to be a blockbuster drug."

In a statement, Paul Chang, MD, vice president of medical affairs in internal medicine at Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc., said, "Shorter hospital stays following hip and knee replacement surgeries have made the prevention of venous blood clots an outpatient issue, and Xarelto provides a safe and effective oral treatment option that can be easily transitioned from use in hospital to home."

The approval is the latest challenge to warfarin. It comes on the heels of the approval of Pradaxa (dabigatran) for stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients. (Updated July 21). Xarelto, however, is the only new oral anticoagulant approved for its indication.

Dr. Pendleton says the advantage of Xarelto is that it only has to be taken once a day. He said the full potential lies in the "high likelihood of subsequent indications" for the drug.

Still, this is a new drug and care has to be taken, he says.

"If it's not used appropriately in the proper patient with proper attention to renal function and drug-drug interaction," he adds, "a very promising drug could have difficulty."

First Responder

Every May, Mayo Clinic hospitalist Jason Persoff, MD, SFHM, sheds his doctor’s gear, grabs his camera and camcorder, and heads to the Midwest in search of ferocious weather for two weeks. This year, the Jacksonville, Fla.-based physician put his doctor’s gear back on sooner than he expected.

After 20 years of chasing storms, he found himself in what might have been considered a situation that was inevitable: helping people injured in a tornado. When a monstrous twister barreled through Joplin, Mo., last month, Dr. Persoff was less than a mile from its path. He and his “chase partner,” Robert Balogh, MD, an Oklahoma-based internist and former hospitalist, were able to rush in and assist in the aftermath.

One hospital serving the area, St. John’s Regional Medical Center, was destroyed, its roof ripped off by 200 mph winds.

Dr. Persoff checked in at the emergency room of the other one, Freeman Health System, and offered his help. He spent 10 hours there—first treating trauma patients.

“The initial trauma that came in was pretty fast and furious,” he says. “If somebody could be saved, and it wasn’t going to require an effort that would jeopardize resources, they did everything they could to save people.”

There were amputations, impalements, eviscerations. Some patients were covered in glass, he recalls. When the patients from St. John’s began to arrive at Freeman, Dr. Persoff treated them, doing admission orders on 24 patients.

Dr. Persoff plans to continue storm-chasing next year. But he says he’ll never forget the trauma nurse who was working as he arrived at Freeman and was still working as he left the hospital.

“That was one of the times where I was like, ‘Wow, this is really humbling,’ ” he says.

Check out photos and journal entries of Dr. Persoff’s storm-chasing adventures at http://stormdoctor.com/.

Every May, Mayo Clinic hospitalist Jason Persoff, MD, SFHM, sheds his doctor’s gear, grabs his camera and camcorder, and heads to the Midwest in search of ferocious weather for two weeks. This year, the Jacksonville, Fla.-based physician put his doctor’s gear back on sooner than he expected.

After 20 years of chasing storms, he found himself in what might have been considered a situation that was inevitable: helping people injured in a tornado. When a monstrous twister barreled through Joplin, Mo., last month, Dr. Persoff was less than a mile from its path. He and his “chase partner,” Robert Balogh, MD, an Oklahoma-based internist and former hospitalist, were able to rush in and assist in the aftermath.

One hospital serving the area, St. John’s Regional Medical Center, was destroyed, its roof ripped off by 200 mph winds.

Dr. Persoff checked in at the emergency room of the other one, Freeman Health System, and offered his help. He spent 10 hours there—first treating trauma patients.

“The initial trauma that came in was pretty fast and furious,” he says. “If somebody could be saved, and it wasn’t going to require an effort that would jeopardize resources, they did everything they could to save people.”

There were amputations, impalements, eviscerations. Some patients were covered in glass, he recalls. When the patients from St. John’s began to arrive at Freeman, Dr. Persoff treated them, doing admission orders on 24 patients.

Dr. Persoff plans to continue storm-chasing next year. But he says he’ll never forget the trauma nurse who was working as he arrived at Freeman and was still working as he left the hospital.

“That was one of the times where I was like, ‘Wow, this is really humbling,’ ” he says.

Check out photos and journal entries of Dr. Persoff’s storm-chasing adventures at http://stormdoctor.com/.

Every May, Mayo Clinic hospitalist Jason Persoff, MD, SFHM, sheds his doctor’s gear, grabs his camera and camcorder, and heads to the Midwest in search of ferocious weather for two weeks. This year, the Jacksonville, Fla.-based physician put his doctor’s gear back on sooner than he expected.

After 20 years of chasing storms, he found himself in what might have been considered a situation that was inevitable: helping people injured in a tornado. When a monstrous twister barreled through Joplin, Mo., last month, Dr. Persoff was less than a mile from its path. He and his “chase partner,” Robert Balogh, MD, an Oklahoma-based internist and former hospitalist, were able to rush in and assist in the aftermath.

One hospital serving the area, St. John’s Regional Medical Center, was destroyed, its roof ripped off by 200 mph winds.

Dr. Persoff checked in at the emergency room of the other one, Freeman Health System, and offered his help. He spent 10 hours there—first treating trauma patients.

“The initial trauma that came in was pretty fast and furious,” he says. “If somebody could be saved, and it wasn’t going to require an effort that would jeopardize resources, they did everything they could to save people.”

There were amputations, impalements, eviscerations. Some patients were covered in glass, he recalls. When the patients from St. John’s began to arrive at Freeman, Dr. Persoff treated them, doing admission orders on 24 patients.

Dr. Persoff plans to continue storm-chasing next year. But he says he’ll never forget the trauma nurse who was working as he arrived at Freeman and was still working as he left the hospital.

“That was one of the times where I was like, ‘Wow, this is really humbling,’ ” he says.

Check out photos and journal entries of Dr. Persoff’s storm-chasing adventures at http://stormdoctor.com/.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Listen to experts discuss drug shortages

Click here to listen to Dr. Verma

Click here to listen to ISMP President David Cohen

Click here to listen to Dr. Verma

Click here to listen to ISMP President David Cohen

Click here to listen to Dr. Verma

Click here to listen to ISMP President David Cohen

Fast and Furious

Every May, Mayo Clinic hospitalist Jason Persoff, MD, SFHM, sheds his doctor’s gear, grabs his camera and camcorder, and heads to the Midwest in search of ferocious weather for two weeks. “My wife jokingly calls it my ‘midlife crisis prevention program,’ ” says Dr. Persoff, who works in Jacksonville, Fla.

This year, he put his doctor’s gear back on sooner than he expected.

After 20 years of chasing storms, Dr. Persoff found himself in what might have been considered an inevitable situation: helping people injured in a tornado. When a monstrous twister with winds of more than 200 mph barreled through Joplin, Mo., on May 22, Dr. Persoff was less than a mile from its path. He and a “chase partner,” Robert Balogh, MD, an Oklahoma-based internist and former hospitalist, were able to rush to the scene and assist in the aftermath.

In the moments after the fast-forming storm, Dr. Persoff hoped that the damage wouldn’t be so devastating, despite the first ominous signs he saw along the highway.

“We were dealing with a raining sky of debris,” he says. “There was Styrofoam insulation falling from the sky, papers, there was a Barbie doll in the middle of the road, but I have no idea where that came from. There were trees and twigs and leaves, so I knew that the destruction to Joplin had been significant. But I hoped that it would be very limited.”

As he traveled along another road, he saw two dozen flipped-over semi-trucks.

“There was no decision,” Dr. Balogh says. “We knew right then that the chase was over for us.”

One hospital serving the area, St. John’s Regional Medical Center, was destroyed, its roof ripped off, he learned. At press time, the tornado had killed more than 150 and caused an estimated $3 billion in damage.

Dr. Persoff checked in at the ED of another hospital, Freeman Health System, and offered his help. He spent 10 hours there, first treating trauma patients.

“We were immediately put to work because there were just so many people coming in,” he says. “The initial trauma that came in was pretty fast and furious. If somebody could be saved, and it wasn’t going to require an effort that would jeopardize resources, they did everything they could to save people. They put in chest tubes, ventilated them, [performed] other procedures.

"If somebody was dying and that was pretty obvious, it required us to rethink how we were going to approach things. And I made a diligent effort to help the dying with low doses of pain medication to help them through.”

There were amputations, impalements, eviscerations.

“We had patients who were covered in glass, and by covered I don’t mean they just had glass in their skin—they were covered with it,” he says. “When you’d examine them, there was a risk of your glove getting torn doing an exam.”

Dr. Balogh describes the patient influx as an “absolutely overwhelming” onslaught, with ambulances, cars, and pickup trucks that had rescued strangers on the roadside arriving seemingly nonstop.

It was so frantic, he says, that he was worried “if I even take time to talk to one patient .. I’ve missed the next 15.”

When the patients from St. John’s began to arrive at Freeman, Dr. Persoff treated them, too. He wrote admission orders on 24 patients.

“The patients weren’t able to provide history,” he says. “Some of the medical records fell as far as, I think, Kansas City (160 miles to the north), from the air,” he explains. “So we had no medical records. We had patients who were demented or delirious. We had patients who’d undergone routine procedures, several patients who were postoperative.”

Leaving the hospital, he said, was gut-wrenching.

“I felt like a loser. I felt like I was handing patient-care responsibilities to a completely overtaxed system because I was tired,” he says. “When I started not making good decisions, I knew that I wasn’t helping anybody and it was time for me to step aside. But that was a very hard decision to make.”

Dr. Persoff says he’ll never forget the triage nurse on duty. She was there when he arrived, about 6:30 p.m., and was perfectly orchestrating the trauma care, even though there was no way for any of the hospital staff to know what had become of their own families and homes. And she was still there when he left at 4 a.m., so efficient and fresh it was as if she’d “just come in from having showered.”

“I don’t know what she knew or where her house was or where her family was,” he says. “I just knew that she was there working like there was no tomorrow and doing it in a way that I couldn’t. That was one of the times where I was like, ‘Wow, this is really humbling.’ ”

Dr. Persoff, who writes about his hobby at Stormdoctor.blogspot.com, continued his storm chasing; he even helped provide assistance two days later, after storms near Oklahoma City exacted a human toll that was not nearly as severe. But first, he says, he had to do some soul-searching. After all, he had hoped for a tornado to form in the Joplin area.

“My chase partners and I were talking about how can the rational person want to continue storm-chasing after having seen what we’d seen. And it took me a while to sort of figure out where my own conscience was on this,” he says. “I felt very guilty for having even wanted [a tornado] earlier in the day. Then I also felt like, had the storm not formed where it did, I wouldn’t have been there, my partner Dr. Balogh wouldn’t have been there, and we would not have been able to assist in that disaster.

“So in many ways it was karma. It happened. We were there at a time when Joplin needed some help.”

After the storm, Dr. Persoff received words of thanks from the town.

Jane Culver, a floor nurse with whom he worked, told him via email: “People often say to me, ‘Doctors are just in it for the money, they really don’t really care about me.’ Well, I say they don’t know the Dr. Jason Persoffs of the world. You are a true humanitarian, and the people of Joplin are lucky you were in our midst at our hour of need.”

Stephanie Conrad, whose grandmother Clara had her broken hip cared for by Dr. Persoff, called him “the angel doctor.”

“Thank you so much for using your knowledge, skills, and expertise during this crisis,” Conrad wrote in an email. “It is physicians like you that make a difference in the lives of others. You were truly a blessing that night.”

Tom Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

Every May, Mayo Clinic hospitalist Jason Persoff, MD, SFHM, sheds his doctor’s gear, grabs his camera and camcorder, and heads to the Midwest in search of ferocious weather for two weeks. “My wife jokingly calls it my ‘midlife crisis prevention program,’ ” says Dr. Persoff, who works in Jacksonville, Fla.

This year, he put his doctor’s gear back on sooner than he expected.

After 20 years of chasing storms, Dr. Persoff found himself in what might have been considered an inevitable situation: helping people injured in a tornado. When a monstrous twister with winds of more than 200 mph barreled through Joplin, Mo., on May 22, Dr. Persoff was less than a mile from its path. He and a “chase partner,” Robert Balogh, MD, an Oklahoma-based internist and former hospitalist, were able to rush to the scene and assist in the aftermath.

In the moments after the fast-forming storm, Dr. Persoff hoped that the damage wouldn’t be so devastating, despite the first ominous signs he saw along the highway.

“We were dealing with a raining sky of debris,” he says. “There was Styrofoam insulation falling from the sky, papers, there was a Barbie doll in the middle of the road, but I have no idea where that came from. There were trees and twigs and leaves, so I knew that the destruction to Joplin had been significant. But I hoped that it would be very limited.”

As he traveled along another road, he saw two dozen flipped-over semi-trucks.

“There was no decision,” Dr. Balogh says. “We knew right then that the chase was over for us.”

One hospital serving the area, St. John’s Regional Medical Center, was destroyed, its roof ripped off, he learned. At press time, the tornado had killed more than 150 and caused an estimated $3 billion in damage.

Dr. Persoff checked in at the ED of another hospital, Freeman Health System, and offered his help. He spent 10 hours there, first treating trauma patients.

“We were immediately put to work because there were just so many people coming in,” he says. “The initial trauma that came in was pretty fast and furious. If somebody could be saved, and it wasn’t going to require an effort that would jeopardize resources, they did everything they could to save people. They put in chest tubes, ventilated them, [performed] other procedures.

"If somebody was dying and that was pretty obvious, it required us to rethink how we were going to approach things. And I made a diligent effort to help the dying with low doses of pain medication to help them through.”

There were amputations, impalements, eviscerations.

“We had patients who were covered in glass, and by covered I don’t mean they just had glass in their skin—they were covered with it,” he says. “When you’d examine them, there was a risk of your glove getting torn doing an exam.”

Dr. Balogh describes the patient influx as an “absolutely overwhelming” onslaught, with ambulances, cars, and pickup trucks that had rescued strangers on the roadside arriving seemingly nonstop.

It was so frantic, he says, that he was worried “if I even take time to talk to one patient .. I’ve missed the next 15.”

When the patients from St. John’s began to arrive at Freeman, Dr. Persoff treated them, too. He wrote admission orders on 24 patients.

“The patients weren’t able to provide history,” he says. “Some of the medical records fell as far as, I think, Kansas City (160 miles to the north), from the air,” he explains. “So we had no medical records. We had patients who were demented or delirious. We had patients who’d undergone routine procedures, several patients who were postoperative.”

Leaving the hospital, he said, was gut-wrenching.

“I felt like a loser. I felt like I was handing patient-care responsibilities to a completely overtaxed system because I was tired,” he says. “When I started not making good decisions, I knew that I wasn’t helping anybody and it was time for me to step aside. But that was a very hard decision to make.”

Dr. Persoff says he’ll never forget the triage nurse on duty. She was there when he arrived, about 6:30 p.m., and was perfectly orchestrating the trauma care, even though there was no way for any of the hospital staff to know what had become of their own families and homes. And she was still there when he left at 4 a.m., so efficient and fresh it was as if she’d “just come in from having showered.”

“I don’t know what she knew or where her house was or where her family was,” he says. “I just knew that she was there working like there was no tomorrow and doing it in a way that I couldn’t. That was one of the times where I was like, ‘Wow, this is really humbling.’ ”

Dr. Persoff, who writes about his hobby at Stormdoctor.blogspot.com, continued his storm chasing; he even helped provide assistance two days later, after storms near Oklahoma City exacted a human toll that was not nearly as severe. But first, he says, he had to do some soul-searching. After all, he had hoped for a tornado to form in the Joplin area.

“My chase partners and I were talking about how can the rational person want to continue storm-chasing after having seen what we’d seen. And it took me a while to sort of figure out where my own conscience was on this,” he says. “I felt very guilty for having even wanted [a tornado] earlier in the day. Then I also felt like, had the storm not formed where it did, I wouldn’t have been there, my partner Dr. Balogh wouldn’t have been there, and we would not have been able to assist in that disaster.

“So in many ways it was karma. It happened. We were there at a time when Joplin needed some help.”

After the storm, Dr. Persoff received words of thanks from the town.

Jane Culver, a floor nurse with whom he worked, told him via email: “People often say to me, ‘Doctors are just in it for the money, they really don’t really care about me.’ Well, I say they don’t know the Dr. Jason Persoffs of the world. You are a true humanitarian, and the people of Joplin are lucky you were in our midst at our hour of need.”

Stephanie Conrad, whose grandmother Clara had her broken hip cared for by Dr. Persoff, called him “the angel doctor.”

“Thank you so much for using your knowledge, skills, and expertise during this crisis,” Conrad wrote in an email. “It is physicians like you that make a difference in the lives of others. You were truly a blessing that night.”

Tom Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

Every May, Mayo Clinic hospitalist Jason Persoff, MD, SFHM, sheds his doctor’s gear, grabs his camera and camcorder, and heads to the Midwest in search of ferocious weather for two weeks. “My wife jokingly calls it my ‘midlife crisis prevention program,’ ” says Dr. Persoff, who works in Jacksonville, Fla.

This year, he put his doctor’s gear back on sooner than he expected.

After 20 years of chasing storms, Dr. Persoff found himself in what might have been considered an inevitable situation: helping people injured in a tornado. When a monstrous twister with winds of more than 200 mph barreled through Joplin, Mo., on May 22, Dr. Persoff was less than a mile from its path. He and a “chase partner,” Robert Balogh, MD, an Oklahoma-based internist and former hospitalist, were able to rush to the scene and assist in the aftermath.

In the moments after the fast-forming storm, Dr. Persoff hoped that the damage wouldn’t be so devastating, despite the first ominous signs he saw along the highway.

“We were dealing with a raining sky of debris,” he says. “There was Styrofoam insulation falling from the sky, papers, there was a Barbie doll in the middle of the road, but I have no idea where that came from. There were trees and twigs and leaves, so I knew that the destruction to Joplin had been significant. But I hoped that it would be very limited.”

As he traveled along another road, he saw two dozen flipped-over semi-trucks.

“There was no decision,” Dr. Balogh says. “We knew right then that the chase was over for us.”

One hospital serving the area, St. John’s Regional Medical Center, was destroyed, its roof ripped off, he learned. At press time, the tornado had killed more than 150 and caused an estimated $3 billion in damage.

Dr. Persoff checked in at the ED of another hospital, Freeman Health System, and offered his help. He spent 10 hours there, first treating trauma patients.

“We were immediately put to work because there were just so many people coming in,” he says. “The initial trauma that came in was pretty fast and furious. If somebody could be saved, and it wasn’t going to require an effort that would jeopardize resources, they did everything they could to save people. They put in chest tubes, ventilated them, [performed] other procedures.

"If somebody was dying and that was pretty obvious, it required us to rethink how we were going to approach things. And I made a diligent effort to help the dying with low doses of pain medication to help them through.”

There were amputations, impalements, eviscerations.

“We had patients who were covered in glass, and by covered I don’t mean they just had glass in their skin—they were covered with it,” he says. “When you’d examine them, there was a risk of your glove getting torn doing an exam.”

Dr. Balogh describes the patient influx as an “absolutely overwhelming” onslaught, with ambulances, cars, and pickup trucks that had rescued strangers on the roadside arriving seemingly nonstop.

It was so frantic, he says, that he was worried “if I even take time to talk to one patient .. I’ve missed the next 15.”

When the patients from St. John’s began to arrive at Freeman, Dr. Persoff treated them, too. He wrote admission orders on 24 patients.

“The patients weren’t able to provide history,” he says. “Some of the medical records fell as far as, I think, Kansas City (160 miles to the north), from the air,” he explains. “So we had no medical records. We had patients who were demented or delirious. We had patients who’d undergone routine procedures, several patients who were postoperative.”

Leaving the hospital, he said, was gut-wrenching.

“I felt like a loser. I felt like I was handing patient-care responsibilities to a completely overtaxed system because I was tired,” he says. “When I started not making good decisions, I knew that I wasn’t helping anybody and it was time for me to step aside. But that was a very hard decision to make.”

Dr. Persoff says he’ll never forget the triage nurse on duty. She was there when he arrived, about 6:30 p.m., and was perfectly orchestrating the trauma care, even though there was no way for any of the hospital staff to know what had become of their own families and homes. And she was still there when he left at 4 a.m., so efficient and fresh it was as if she’d “just come in from having showered.”

“I don’t know what she knew or where her house was or where her family was,” he says. “I just knew that she was there working like there was no tomorrow and doing it in a way that I couldn’t. That was one of the times where I was like, ‘Wow, this is really humbling.’ ”

Dr. Persoff, who writes about his hobby at Stormdoctor.blogspot.com, continued his storm chasing; he even helped provide assistance two days later, after storms near Oklahoma City exacted a human toll that was not nearly as severe. But first, he says, he had to do some soul-searching. After all, he had hoped for a tornado to form in the Joplin area.

“My chase partners and I were talking about how can the rational person want to continue storm-chasing after having seen what we’d seen. And it took me a while to sort of figure out where my own conscience was on this,” he says. “I felt very guilty for having even wanted [a tornado] earlier in the day. Then I also felt like, had the storm not formed where it did, I wouldn’t have been there, my partner Dr. Balogh wouldn’t have been there, and we would not have been able to assist in that disaster.

“So in many ways it was karma. It happened. We were there at a time when Joplin needed some help.”

After the storm, Dr. Persoff received words of thanks from the town.

Jane Culver, a floor nurse with whom he worked, told him via email: “People often say to me, ‘Doctors are just in it for the money, they really don’t really care about me.’ Well, I say they don’t know the Dr. Jason Persoffs of the world. You are a true humanitarian, and the people of Joplin are lucky you were in our midst at our hour of need.”

Stephanie Conrad, whose grandmother Clara had her broken hip cared for by Dr. Persoff, called him “the angel doctor.”

“Thank you so much for using your knowledge, skills, and expertise during this crisis,” Conrad wrote in an email. “It is physicians like you that make a difference in the lives of others. You were truly a blessing that night.”

Tom Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

Cause For Concern

When a drug is in short supply at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, a message goes out to the physicians on the hospital’s intranet system. When the shortage gets close to being critically short in supply, a message will be embedded into the physician order-entry system recommending that the physicians use an alternate drug—if there is an alternate.

It’s an alert system that has been put to frequent use lately, says Joseph Li, MD, SFHM, director of the hospital medicine program at Beth Israel Deaconess, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and president of SHM.

The rate of drug shortages has been rising steadily in recent years due to quality questions at manufacturers, consolidation in the drug-manufacturing industry, and other factors, according to data from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and other sources.

“It does seem like there’s more today than previous years,” says Dr. Li, who was a pharmacist before he trained in internal medicine.

Some of the recent shortages at Beth Israel Deaconess have involved the diuretic furosemide, the antiemetic Compazine, and the anticoagulant heparin. “More often than not, there’s a reasonable alternative that can be chosen,” he says. “Not necessarily exactly the same drug, but usually in the same therapeutic class.”

While actual cases of patient harm due to drug shortages appear to be relatively uncommon, having drugs in short supply can lead to a safety problem hovering over a medical center and its hospitalists. In addition to the potential of simply not having an alternate to give to a patient, hospitalists and their pharmacists sometimes have to adjust to a new dosage that comes with a replacement medication.

Plus, having to manage the problem when a drug shortage hits can be a headache, with time and resources spent trying to obtain updates from drug manufacturers and find other drugs that can be used in the meantime, experts say.

With hospitalists now treating so many patients, many of them complex and on multiple medications, it is an important issue for hospitalists to stay aware of and to be prepared for, Dr. Li says. More than 90% of all medical patients at Beth Israel Deaconess are now cared for by hospitalists, he says, and it’s a similar situation for many acute-care hospitals around the country.

If a drug is in short supply, balancing availability with patient needs can be especially tricky for a hospitalist caring for patients with a multitude of demands, Dr. Li says. “There is an effort to make sure that our most vulnerable population of patients receive these treatments before the general population of patients have access to it,” he adds.

However, the very existence of hospitalists makes it easier to navigate a shortage compared to the days when hundreds of providers would be caring for a pool of patients.

“If you’re trying to notify a group of providers about shortages and have an impact on their prescribing habits, I think it’s easier today,” he says.

Troubled Waters

The FDA says it confirmed a record 178 cases of drug shortages in 2010 (www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/drugshortages/default.htm). That was up from 55 shortages five years ago. And according to the University of Utah Drug Information Service, the problem is actually more pervasive than that, reporting 120 shortages in the U.S. in 2001, with a reported 211 in 2010. And through March of this year, there were 80 reported cases of shortages, on pace for another record year.

“In the past couple of years, it’s just been exponential,” says Diane Ginsburg, president of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists and clinical professor and assistant dean for student affairs at the University of Texas’ College of Pharmacy in Austin.

According to the FDA, 77% of the shortages in 2010 involved sterile injectable drugs.

“There are fewer and fewer firms making these older sterile injectables, and they are often discontinued for newer, more profitable agents,” FDA spokeswoman Yolanda Fultz-Morris said in an email. “When one firm has a delay or a manufacturing problem, it is extremely difficult for the remaining firms to quickly increase production.”

The biggest cause for the shortages in those drugs has been product quality issues, namely microbial contamination and newly identified impurities, according to the FDA. From January to October of 2010, 42% of drug shortages were due to quality problems.

Eighteen percent were due to product discontinuation by the manufacturer and another 18% were due to delays and capacity problems. Nine percent were due to difficulties getting raw materials, and 4% of the sterile injectable shortages were due to increased demand because there was a shortage of another injectable medication. In other words, one shortage led directly to another.

Kevin Schweers, a spokesman for the National Community Pharmacists Association, says generic drugs, especially Schedule II substances, have been in short supply. But there can be problems even when one generic is available to replace another generic.

An example, he says, is when a “new generic substituted in place of the old one is made by a different manufacturer and may come in a different color or shape. That can leave patients”—including those just released from hospitals—“wondering and asking the pharmacist why their medication is different or if a mistake was made.”

Patient Safety and Communication Errors

Lalit Verma, MD, director of the hospital medicine program at Durham Regional Medical Center in North Carolina and assistant professor of medicine at the Duke University School of Medicine, is unaware of any situations in which a shortage put patients in jeopardy at his hospital. He says the pharmacy at Durham Regional, which has seen recent shortages in morphine and heparin, among other drugs, keeps doctors up to date and has adjusted doses appropriately when replacements are used.

“It’s probably been more than I’ve experienced in my 10 years as a hospitalist,” Dr. Verma says. “We have a very good pharmacy program that updates us regularly on drug shortages and offers alternatives.”

Dr. Li also says no patient’s safety has been jeopardized by a shortage.

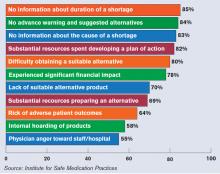

Others say patient safety has been affected, according to 1,800 healthcare practitioners who participated in a survey last year conducted by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), a nonprofit group. Twenty percent of the respondents said drug-shortage-related errors were made, while 32% said they had “near misses” related to drug shortages. Nineteen percent said there had been adverse patient outcomes as a result of drug shortages.

The study noted two instances in which patients died when they were switched to dilaudid because morphine was in short supply; both patients were given morphine doses instead of adjusted doses for dilaudid.

“It’s about six- or sevenfold more potent than morphine,” says Michael Cohen, ISMP president. “And so when that drug is prescribed in a morphine dose, that would be a massive overdose for some patients.”

He adds that hospitals have tried to stay on top of the drug shortage problem, but that “it’s very difficult.”

“A lot of this happens last-minute,” Cohen says. “Physicians aren’t given a chance to even realize that a certain drug isn’t available, so it causes an interruption in the whole flow of things in the hospital.” Some hospitals have had to hire staffers who handle just the inevitable daily drug shortages, he adds.

A law has been proposed in the U.S. Senate that would require drug manufacturers to notify the FDA when circumstances arise that might reasonably lead to a drug shortage (see “Senate Bill Would Require Advance Notice of Potential Shortages,” p. 41).

Cohen says another concern is that some hospitals, faced with shortages in electrolytes, such as potassium phosphate and sodium acetate, have been turning to less-regulated sterile compounding pharmacies for the products.

Dr. Verma, of Durham Regional, says perhaps the biggest challenge is staying on top of changing doses. “I think there was a learning curve for physicians in using dilaudid [rather than morphine] because the dosing is quite different, so that can cause challenges for patient care when you’re switching in and out of drug classes,” he says. “It’s not a perfect science. It doesn’t cripple us, but it does make it more challenging to fine-tune patient care.”

Ginsburg, of the ASHP, urges hospitalists to stay in close contact with the pharmacists at their hospitals and to be diligent about reporting shortages to the ASHP.

“Please work closely with the pharmacists, because we’re the ones that can really help,” she says. “We’re in it together with them, in terms of trying to provide care for their patients.” TH

Thomas R. Collins a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

When a drug is in short supply at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, a message goes out to the physicians on the hospital’s intranet system. When the shortage gets close to being critically short in supply, a message will be embedded into the physician order-entry system recommending that the physicians use an alternate drug—if there is an alternate.

It’s an alert system that has been put to frequent use lately, says Joseph Li, MD, SFHM, director of the hospital medicine program at Beth Israel Deaconess, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and president of SHM.

The rate of drug shortages has been rising steadily in recent years due to quality questions at manufacturers, consolidation in the drug-manufacturing industry, and other factors, according to data from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and other sources.

“It does seem like there’s more today than previous years,” says Dr. Li, who was a pharmacist before he trained in internal medicine.

Some of the recent shortages at Beth Israel Deaconess have involved the diuretic furosemide, the antiemetic Compazine, and the anticoagulant heparin. “More often than not, there’s a reasonable alternative that can be chosen,” he says. “Not necessarily exactly the same drug, but usually in the same therapeutic class.”

While actual cases of patient harm due to drug shortages appear to be relatively uncommon, having drugs in short supply can lead to a safety problem hovering over a medical center and its hospitalists. In addition to the potential of simply not having an alternate to give to a patient, hospitalists and their pharmacists sometimes have to adjust to a new dosage that comes with a replacement medication.

Plus, having to manage the problem when a drug shortage hits can be a headache, with time and resources spent trying to obtain updates from drug manufacturers and find other drugs that can be used in the meantime, experts say.

With hospitalists now treating so many patients, many of them complex and on multiple medications, it is an important issue for hospitalists to stay aware of and to be prepared for, Dr. Li says. More than 90% of all medical patients at Beth Israel Deaconess are now cared for by hospitalists, he says, and it’s a similar situation for many acute-care hospitals around the country.

If a drug is in short supply, balancing availability with patient needs can be especially tricky for a hospitalist caring for patients with a multitude of demands, Dr. Li says. “There is an effort to make sure that our most vulnerable population of patients receive these treatments before the general population of patients have access to it,” he adds.

However, the very existence of hospitalists makes it easier to navigate a shortage compared to the days when hundreds of providers would be caring for a pool of patients.

“If you’re trying to notify a group of providers about shortages and have an impact on their prescribing habits, I think it’s easier today,” he says.

Troubled Waters

The FDA says it confirmed a record 178 cases of drug shortages in 2010 (www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/drugshortages/default.htm). That was up from 55 shortages five years ago. And according to the University of Utah Drug Information Service, the problem is actually more pervasive than that, reporting 120 shortages in the U.S. in 2001, with a reported 211 in 2010. And through March of this year, there were 80 reported cases of shortages, on pace for another record year.