User login

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida who has written about medical topics from nasty infections to ethical dilemmas, runaway tumors to tornado-chasing doctors. He travels the globe gathering conference health news and lives in West Palm Beach.

A Long, Winding Path

Caitlin Foxley, MD, followed a nontraditional path to medicine. While attending Colorado State University in Fort Collins, she took a course in economics to fill her schedule. She enjoyed economics so much, she majored in it.

One year into a graduate program, however, she decided the business world wasn’t for her. She left school and went to work for the American Heart Association to do fundraising and health education, and there she found her calling.

Inspired by the association’s emphasis on disease prevention and the passion displayed by the physician volunteers, she decided medicine could be a good fit for her. She began taking courses part time each semester for a couple of years until she fulfilled all of her prerequisites, then applied to medical school.

Today, Dr. Foxley is medical director of Inpatient Management Inc.’s hospitalist program at Nebraska Medical Center Hospitals, a 680-bed tertiary-care center and Level 1 trauma center in Omaha. “I’d always liked science when I was younger, and it was always a strong point for me,” she says. “But working with the American Heart Association is really what sparked my interest in medicine.”

Question: How did your work with the AHA guide you into medicine?

Answer: I liked the message of prevention of diseases. Even then, in the late 1980s, they were looking at evidence-based medicine. It made sense to me. It seemed like a good way to make a difference. I thought, “This is something I could do and enjoy.”

Q: When did you make the change?

A: I had to do a few undergrad prerequisites, since economics didn’t really prepare me for medical school. I took one class per semester for a couple years while working for the heart association, then applied to medical school.

Q: After medical school, you spent five years in traditional internal-medicine practice. Did you consider going directly into hospital medicine?

A: When I got out of residency (in 2001), there really weren’t many opportunities for hospitalists in Nebraska. It was something I knew I’d like, but it wasn’t available.

Q: You made the switch in 2006. What prompted the move?

A: I was really frustrated doing traditional outpatient medicine. It was becoming increasingly difficult to provide the quality of care I wanted to give my patients. I was seeing people with complex medical problems, and I was having to do it in 15-minute increments.

Somebody I knew from the medical community had formed a hospitalist group, so I started working with him. It’s been a great career move, and it’s something I really love.

Q: What did you enjoy most about the hospital setting?

A: Everything. I like the challenge of seeing patients who are more complicated than those in the office. If I want to spend a half-hour or hour with a patient, I have that opportunity. I like the immediacy of the results, and I like being able to talk to consultants in the hospital to help formulate a diagnosis and a plan. All of that provides for better care.

Q: You assumed your current position in 2008. Did you always envision yourself moving into a leadership role?

A: I never really thought about it, but I’m glad I made the switch. There are days when it’s not all fun and games, but it’s very much been a learning opportunity. I’ve enjoyed it, and it has helped me become a better physician.

Q: How so?

A: I see the big picture. I can see what the administration wants, and I have an inside view to what hospital leadership thinks we can do better. I can share that with the other doctors. It helps us deliver better care knowing what the goals are for the hospital, our group, and the patients.

Q: What is your biggest challenge?

A: Having to be the “bad guy” in an administrative role.

Q: Have you learned any techniques that make that process easier?

A: It’s important, especially when you have to deal with conflict, to be open-minded and listen carefully to all sides of the situation. You have to give everyone a chance to speak their piece.

Q: You recently completed a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Century Ride. What was that experience like?

A: It was like nothing I’d ever done before. I liked getting on my bike and riding a few miles, but I never thought I’d be able to ride 100 miles in one day. It was a life-changing experience, and I raised over $4,000 for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, which felt wonderful.

Q: Did you learn anything that you can apply as a physician?

A: I learned that if you really put your mind to it, you can accomplish a lot. At times, when I’d be going up a difficult hill, I’d think, “This is really hard, but it’s nothing like being the parent of a kid with leukemia.”

Now, as I look at people who are suffering and sick, I remember that. No matter how hard it is for me, I’m not facing what they’re facing. TH

Mark Leiser is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Caitlin Foxley, MD, followed a nontraditional path to medicine. While attending Colorado State University in Fort Collins, she took a course in economics to fill her schedule. She enjoyed economics so much, she majored in it.

One year into a graduate program, however, she decided the business world wasn’t for her. She left school and went to work for the American Heart Association to do fundraising and health education, and there she found her calling.

Inspired by the association’s emphasis on disease prevention and the passion displayed by the physician volunteers, she decided medicine could be a good fit for her. She began taking courses part time each semester for a couple of years until she fulfilled all of her prerequisites, then applied to medical school.

Today, Dr. Foxley is medical director of Inpatient Management Inc.’s hospitalist program at Nebraska Medical Center Hospitals, a 680-bed tertiary-care center and Level 1 trauma center in Omaha. “I’d always liked science when I was younger, and it was always a strong point for me,” she says. “But working with the American Heart Association is really what sparked my interest in medicine.”

Question: How did your work with the AHA guide you into medicine?

Answer: I liked the message of prevention of diseases. Even then, in the late 1980s, they were looking at evidence-based medicine. It made sense to me. It seemed like a good way to make a difference. I thought, “This is something I could do and enjoy.”

Q: When did you make the change?

A: I had to do a few undergrad prerequisites, since economics didn’t really prepare me for medical school. I took one class per semester for a couple years while working for the heart association, then applied to medical school.

Q: After medical school, you spent five years in traditional internal-medicine practice. Did you consider going directly into hospital medicine?

A: When I got out of residency (in 2001), there really weren’t many opportunities for hospitalists in Nebraska. It was something I knew I’d like, but it wasn’t available.

Q: You made the switch in 2006. What prompted the move?

A: I was really frustrated doing traditional outpatient medicine. It was becoming increasingly difficult to provide the quality of care I wanted to give my patients. I was seeing people with complex medical problems, and I was having to do it in 15-minute increments.

Somebody I knew from the medical community had formed a hospitalist group, so I started working with him. It’s been a great career move, and it’s something I really love.

Q: What did you enjoy most about the hospital setting?

A: Everything. I like the challenge of seeing patients who are more complicated than those in the office. If I want to spend a half-hour or hour with a patient, I have that opportunity. I like the immediacy of the results, and I like being able to talk to consultants in the hospital to help formulate a diagnosis and a plan. All of that provides for better care.

Q: You assumed your current position in 2008. Did you always envision yourself moving into a leadership role?

A: I never really thought about it, but I’m glad I made the switch. There are days when it’s not all fun and games, but it’s very much been a learning opportunity. I’ve enjoyed it, and it has helped me become a better physician.

Q: How so?

A: I see the big picture. I can see what the administration wants, and I have an inside view to what hospital leadership thinks we can do better. I can share that with the other doctors. It helps us deliver better care knowing what the goals are for the hospital, our group, and the patients.

Q: What is your biggest challenge?

A: Having to be the “bad guy” in an administrative role.

Q: Have you learned any techniques that make that process easier?

A: It’s important, especially when you have to deal with conflict, to be open-minded and listen carefully to all sides of the situation. You have to give everyone a chance to speak their piece.

Q: You recently completed a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Century Ride. What was that experience like?

A: It was like nothing I’d ever done before. I liked getting on my bike and riding a few miles, but I never thought I’d be able to ride 100 miles in one day. It was a life-changing experience, and I raised over $4,000 for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, which felt wonderful.

Q: Did you learn anything that you can apply as a physician?

A: I learned that if you really put your mind to it, you can accomplish a lot. At times, when I’d be going up a difficult hill, I’d think, “This is really hard, but it’s nothing like being the parent of a kid with leukemia.”

Now, as I look at people who are suffering and sick, I remember that. No matter how hard it is for me, I’m not facing what they’re facing. TH

Mark Leiser is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Caitlin Foxley, MD, followed a nontraditional path to medicine. While attending Colorado State University in Fort Collins, she took a course in economics to fill her schedule. She enjoyed economics so much, she majored in it.

One year into a graduate program, however, she decided the business world wasn’t for her. She left school and went to work for the American Heart Association to do fundraising and health education, and there she found her calling.

Inspired by the association’s emphasis on disease prevention and the passion displayed by the physician volunteers, she decided medicine could be a good fit for her. She began taking courses part time each semester for a couple of years until she fulfilled all of her prerequisites, then applied to medical school.

Today, Dr. Foxley is medical director of Inpatient Management Inc.’s hospitalist program at Nebraska Medical Center Hospitals, a 680-bed tertiary-care center and Level 1 trauma center in Omaha. “I’d always liked science when I was younger, and it was always a strong point for me,” she says. “But working with the American Heart Association is really what sparked my interest in medicine.”

Question: How did your work with the AHA guide you into medicine?

Answer: I liked the message of prevention of diseases. Even then, in the late 1980s, they were looking at evidence-based medicine. It made sense to me. It seemed like a good way to make a difference. I thought, “This is something I could do and enjoy.”

Q: When did you make the change?

A: I had to do a few undergrad prerequisites, since economics didn’t really prepare me for medical school. I took one class per semester for a couple years while working for the heart association, then applied to medical school.

Q: After medical school, you spent five years in traditional internal-medicine practice. Did you consider going directly into hospital medicine?

A: When I got out of residency (in 2001), there really weren’t many opportunities for hospitalists in Nebraska. It was something I knew I’d like, but it wasn’t available.

Q: You made the switch in 2006. What prompted the move?

A: I was really frustrated doing traditional outpatient medicine. It was becoming increasingly difficult to provide the quality of care I wanted to give my patients. I was seeing people with complex medical problems, and I was having to do it in 15-minute increments.

Somebody I knew from the medical community had formed a hospitalist group, so I started working with him. It’s been a great career move, and it’s something I really love.

Q: What did you enjoy most about the hospital setting?

A: Everything. I like the challenge of seeing patients who are more complicated than those in the office. If I want to spend a half-hour or hour with a patient, I have that opportunity. I like the immediacy of the results, and I like being able to talk to consultants in the hospital to help formulate a diagnosis and a plan. All of that provides for better care.

Q: You assumed your current position in 2008. Did you always envision yourself moving into a leadership role?

A: I never really thought about it, but I’m glad I made the switch. There are days when it’s not all fun and games, but it’s very much been a learning opportunity. I’ve enjoyed it, and it has helped me become a better physician.

Q: How so?

A: I see the big picture. I can see what the administration wants, and I have an inside view to what hospital leadership thinks we can do better. I can share that with the other doctors. It helps us deliver better care knowing what the goals are for the hospital, our group, and the patients.

Q: What is your biggest challenge?

A: Having to be the “bad guy” in an administrative role.

Q: Have you learned any techniques that make that process easier?

A: It’s important, especially when you have to deal with conflict, to be open-minded and listen carefully to all sides of the situation. You have to give everyone a chance to speak their piece.

Q: You recently completed a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Century Ride. What was that experience like?

A: It was like nothing I’d ever done before. I liked getting on my bike and riding a few miles, but I never thought I’d be able to ride 100 miles in one day. It was a life-changing experience, and I raised over $4,000 for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, which felt wonderful.

Q: Did you learn anything that you can apply as a physician?

A: I learned that if you really put your mind to it, you can accomplish a lot. At times, when I’d be going up a difficult hill, I’d think, “This is really hard, but it’s nothing like being the parent of a kid with leukemia.”

Now, as I look at people who are suffering and sick, I remember that. No matter how hard it is for me, I’m not facing what they’re facing. TH

Mark Leiser is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

CODE PINK

Something didn’t seem quite right. The person in the hooded sweatshirt standing near the entrance looked suspicious to respiratory therapist Betty Collins as she entered the newborn nursery on the evening of Jan. 12, 2006, during her shift at Ouachita County Medical Center in Camden, Ark. Perhaps this is why she shielded her fingers as she punched in the combination to the lock on the nursery door before entering to check on a baby inside.

Leaving minutes later, her work done, Collins’ suspicions were confirmed when Nikenya Washington, 18, shoved her way into the nursery yelling, “Move out my way, I’ll shoot you b----!”

Collins and the other nurse in the unit bravely wrestled with the would-be abductor. A Code Pink was called.

It is notable that January’s Ouachita Hospital case is unique as the first reported case of physical violence during an in-hospital abduction.

This frightening episode is one example of the phenomenon of infant abduction, and according to Cathy Nahirny of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) it is the first reported case in 2006.

Infant abduction is defined as the act of kidnapping an infant less than six months of age by a non-family member. Code Pink is the almost universally adopted code word signaling that an abduction is taking place. Though infrequent by comparison to other types of kidnapping or exploitation of children, infant abduction—like many pediatric situations—is quite dramatic.

This crime is of particular concern to pediatric hospitalists because about half of these events occur within the hospital setting. It plays on the fears of expectant parents and communities, and a successful abduction can be catastrophic for a hospital’s image and reputation. Preventing infant abduction and maintaining preparedness for Code Pink situations represents an ongoing challenge for the approximately 3,500 hospitals where about 4 million American babies are born each year.

Small Number, Large Impact

According to Daniel Broughton, MD, infant abduction is a small subset of a much larger problem. As the director of the Child Abuse Program at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and co-author of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Clinical Report on the pediatrician’s role in the prevention of missing children, he is an expert on the subject.

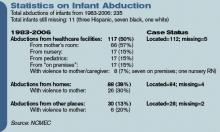

There are an estimated 1-2 million runaways and as many as 200,000 abductions by family members in the United States each year. By contrast, since 1983 when the NCMEC began to collect information on reports of infant abduction, there have been a total of 235 recorded infant kidnappings by non-family members. Nevertheless, “from the standpoint of impact both on families and the hospitals, it is huge,” says Dr. Broughton of infant abduction.

Bob Chicarello, the interim head of security at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, agrees.

“You want to do everything possible to prevent [an infant abduction] because it could really shake an institution to its knees,” he says.

In addition, the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) considers infant abduction such a safety priority that it was made a reportable “Sentinel Event” in 1998. Of the reported 235 reported cases 117 abductions—or 50%—have occurred in the hospital setting. Most children taken from the hospital—57%—are taken from their mother’s room. Roughly 15% each are taken from the newborn nursery, other pediatric wards, or from other parts of the hospital grounds.

Among abductions occurring outside the healthcare setting, 38% of the total occurred from private homes, and the final 13% of the total in other public venues.

A Unique Crime

Infant abduction seems to be distinct from other types of kidnapping in several ways. The first unique characteristic of infant abduction is the profile of the stereotypical perpetrator. Examination of case reports shows that the vast majority of abductors are females of childbearing age. Most live in or near the city where the abduction takes place. Many are overweight, and they may have a history of depression or lying, manipulative behavior.

Additionally, the motives of these women are notably different than those of other kidnappers who are interested in sexual exploitation, money, or revenge. Instead, these women most often desire to have a child of their own. This may be to replace a child or pregnancy that was lost, or to appease a significant other who they perceive may leave them if they cannot produce a child. Notably, many of the kidnappers, later caught, have been observed to provide adequate care for the infants.

Though the timing of an infant abduction can be impulsive, many kidnappers show evidence of elaborate planning beforehand. Several women have staged fictitious pregnancies on one or more occasions. Some kidnappers have even bought baby items or furnished nurseries in anticipation of having a child. Many offenders visit the hospitals or other facilities they later target on several occasions prior to an attempted abduction. They will try to become familiar with hospital personnel often by asking probing questions about security and procedure. A common ploy is for the kidnappers to impersonate nurses, lab technicians, or other hospital personnel in an attempt to gain access to the children. Some even acquire hospital uniforms or other disguises.

They may pose as family members of other patients in order to befriend the parents of their victims. This was the case of Nikenya Washington, who actually entered the room of the would-be victim’s mother early in the evening on the night of the crime. She stated that she had walked into the wrong room and tried to strike up a conversation before leaving.

Prevention is Key

Preventing infant abduction is key, and this process starts by putting proper procedures and hardware in place at healthcare facilities.

“We use a multilayered approach,” says Chicarello. This includes prior planning, physical barriers, electronic aides, and ongoing training and education of staff and parents alike. At Brigham and Women’s, security starts in the lobby where admittance to the maternity ward is gained only after signing in and using a specific elevator. Hospital personnel wear specific nursery badges, and they obtain access to the ward by key card.

The hospital also uses various forms of technology including closed circuit TV monitors, silent “panic” buttons at the nurse’s stations, and electronic wrist/ankle bracelets for the babies.

Chicarello stresses the importance of both initial training for new personnel as well as ongoing education throughout the hospital. This includes hospital-wide awareness drives and an annual Code Pink Fair. Education for parents is incorporated into a pre-natal curriculum. A big part of ongoing training is the use of monthly unscheduled Code Pink drills.

“We try to vary the scenarios to keep the staff on their toes and to expose any weaknesses,” he says. Such scenarios might include having people pose as lab personnel or pulling the fire alarm to create a diversion. “My favorite was once when we had a pizza delivered to the nurses station.” Fortunately, this didn’t work.

Dr. Broughton echoes the notion that a multifaceted approach is important. In addition to well-defined procedures in the birthing suite, the Mayo Clinic’s plan for preventing infant abduction extends to the larger children’s hospital and even to the clinic. Having a well-defined abduction plan has other positive effects as well, notes Dr. Broughton. Such programs are useful in preventing other types of theft, in aiding infection control efforts, and in locating ambulatory children who might wander or get lost.

The process requires input from several disciplines including nursing, security, and physicians. “I think pediatricians should be completely supportive of programs that provide a safety net,” says Dr. Broughton. “[Physicians] should be the leaders in the hospital setting.” One problem he has seen is that physicians sometimes don’t want to be bothered by little details like wearing a proper ID or leaving doors properly locked. Getting physicians to say, “this is important” is an essential first step.

A Disturbing Trend

Though changes in the landscape of infant abduction are difficult to discern, a few trends are notable. Encouragingly, in-hospital abductions are a smaller fraction of the total incidence, perhaps in response to better deterrence by medical facilities. As evidence of this, there was a recent 20-month period without a single abduction from a hospital setting. More disturbingly, though, the incidence of out-of-hospital abductions and the use of violence in abductions seem on the rise. Among these about 29% have involved violence to the parents or family of the infant including eight cases of homicide.

Obviously, preventing abductions outside the hospital presents its own challenges. Nahirny cautions strongly against the publication of birth information on the local press or on Web sites. “These shouldn’t include any specifically identifying information,” she states, such as full names of parents or a home address.

Second, parents must understand the potential danger of posting signs or balloons outside the home after a birth, as these might alert a potential abductor to the presence of an infant. Finally, parents should be careful with unknown, unexpected, or recently acquainted visitors shortly after coming home from the hospital. There are several cases of abductors posing as home-health nurses, social workers, or other official personnel.

Conclusion

Even though she was able to grab the child and make it out of the room, Nikenya Washington did not make if off the hospital ward before being subdued by a security guard and other hospital personnel. Thankfully, the healthy 8-pound, 1-once baby girl was safely returned to her mother. In fact, hospital personnel in conjunction with local law enforcement and media safely recover most abducted infants thanks to orderly responses. However, the best option for all parties involved is a well-planned strategy of prevention. This includes physical barriers, electronic aides, and education of personnel and parents, as well as constant vigilance.

For those who want to get involved in preventing infant abduction, several resources are available. The NCMEC has quite a bit of information on its Web site (www.missingkids.com). There is also an excellent educational video produced by Mead Johnson Nutritionals called “Safeguard Their Tomorrows” available for viewing.

The most definitive resource for clinicians is a book entitled Guidelines for the Prevention of and Response to Infant Abduction. Currently in its eighth edition by John Rabun of the NCEMC, the book discusses the problem of infant abduction and defines its scope. There are various practical recommendations on the general, proactive, and physical measures to prevent abductions and on how to respond once an incident has occurred. There are also sections on how to advise parents and how to assess level of preparedness.

Dr. Axon is an instructor, Departments of Medicine and Pediatrics, Medical University of South Carolina Medical Center, Charleston.

Bibliography

- Ankrom LG, Lent CJ. Cradle robbers: A study of the infant abductor. The FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. 1995;64(9):112-118.

- Hillen M. Teen held in attempt to abduct newborn. Arkansas Democrat Gazette. 16 January, 2006.

- Rabun J. For Healthcare Professionals: Guidelines for the Prevention of and Response to Infant Abduction. 8th ed. Alexandria, Virginia: National Center for Missing and Exploited Children; 2005.

Pediatric Special Section

In the Literature

By G. Ronald Nicholis, MD, Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, Mo., Gina Weddle, RN, CPNP, Section of Pediatric Hospitalists, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics (Kansas City, Mo.), and J. Christopher Day, MD, Section of Pediatric Hospitalists, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics (Kansas City, Mo.)

Computerized Physician Order Entry—Not a Finished Product

Han YY, Carcillo JA, Venkataraman ST, et al. Unexpected increased mortality after implementation of a commercially sold computerized physician order entry system. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):1506-1512.

Over the past several years attention has been increasingly focused on the inadequacy of patient safety in our practices. In response, hospitals, insurers, and practices have examined many potential changes to current systems in an effort to improve safety.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) and the Leapfrog Group have championed computerized physician order entry (CPOE) as necessary for improving patient safety, citing the inadequacy of paper and pen for the ordering process. Research documenting that CPOE systems used in the hospital setting can decrease adverse drug events has fostered the promise and potential for CPOE to make the hospital a safer place for our patients, particularly when enhanced with decision support. Decision support can allow the physician to be alerted to errors in dose, drug-drug interaction, drug-food interaction, allergies, and the need for dosage corrections based on laboratory values at the time of ordering. Contrary to the research demonstrating improved safety, some studies have shown an increase in unique errors after implementation of CPOE.

The current study from the Departments of Critical Care Medicine and Pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh calls our attention to significant issues with implementation of CPOE that have potential to inhibit the goal of improving patient safety. Citing a study by Upperman, et al. from their own institution, which noted significant improvement in adverse drug events after implementation of CPOE, the authors of the current study state, “Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh implemented … Cerner’s commercial CPOE system in October 2002 in an effort to become one of the first children’s hospitals in the U.S. to attain 100% CPOE status.”

The study was designed to measure the effect of CPOE implementation on mortality rate for patients transferred into this pediatric tertiary care facility who required “immediate processing … and stabilization orders.” This retrospective study examined an 18-month period of mortality data: Thirteen months before the implementation of CPOE and five months after.

They discovered an unexpected increase in unadjusted mortality rate after the implementation of CPOE from 2.8% to 6.57%, (P<0.001). Mortality odds ratios were calculated, and observed mortality before CPOE implementation was consistently better than after CPOE implementation. Regression analysis with and without Pediatric Risk of Mortality comparisons were performed and CPOE, in addition to other factors, was associated with increased mortality in both analyses. How should this be interpreted?

The authors note several factors having impact on the validity of the study, specifically mentioning that “study design precludes any statements regarding cause and effect,” “[researchers] examined a unique patient population admitted through interfacility transport … (thus) findings may not be generalizable to the hospital experience as a whole,” and “[the] observation period after CPOE implementation was brief.”

Seasonal variability was also a potential confounding factor because CPOE implementation was in October and the observation period post-CPOE extended only five months—to March of the next year. However, a statistical comparison between matched five-month periods supported the association between implementation of CPOE and increased mortality in this population.

In addition, the authors discuss how their institution’s chosen implementation process for CPOE affected the work processes and pattern of care provided to these critically ill patients. Issues such as being unable to enter orders on a patient in preparation of their arrival because they were not yet enrolled in the electronic system hampered the availability of important medications at the time of arrival. Forcing all of the orders to go through their designed CPOE process in an effort to use the error prevention capabilities of the system caused potentially significant delays in the administration of life-saving medications.

The lack of functional order sets further delayed the physician’s ability to efficiently enter orders electronically. These variables may have impacted mortality rates. Further delays were evident due to the fact that a nurse had to activate orders placed by the physician, bypassing some of the efficiency of an electronic system. Similarly, the pharmacy reviewed and processed the order before the medication was available to the nurse for delivery to the patient.

These checks and balances have the potential to prevent errors in medication ordering, but if inefficient, they may not be appropriate for an intensive care setting in every circumstance. Researchers stated the new workflow took the physicians and nurses away from the patient’s bedside, potentially decreasing observation benefits for the patient. The capacity of the system to compute at times seemed “frozen” causing further delays—not necessarily an uncommon occurrence with any electronic system.

The practice of medicine is complex and work processes do not easily translate to the electronic models currently available. It is crucial that hospitalists, other specialists, all ancillary services, as well as administration be involved in the building and implementation of the systems to be used in our individual facilities. The systems and technology for effective CPOE in hospital settings—especially in pediatric settings—have yet to be developed. The implementation of CPOE for improved patient safety requires exploration given the exposed inadequacies of our current methods of practice.

Like any best practice this exploration will be continuous and require evaluation and improvement. While we must involve ourselves with the development and implementation of CPOE, we must not let the inadequacies of new systems negatively affect patient care. The dichotomy may be omnipresent: Use the system to gain protections from errors and bypass the system when its design or function interferes with good patient practice. This will require us to possess the wisdom to determine the correct path to follow in any instance.

Every day in our practice we make efforts to compensate for failures in our methods to prevent errors from affecting our patient’s care. Electronic systems do not excuse us from continued vigilance, communication, and action to protect our patients from medical errors. The authors appropriately state that “accurate evaluation of CPOE will require systems-based troubleshooting with well-funded, well-designed, multicenter studies that can adequately address these questions.”

Unfortunately, because of the proven inadequacies of the current system, CPOE, like other methodologies we use in the advancement of patient care, cannot wait for proof of perfection before being used to enhance the outcomes of our patients. Thus we need to be vigorous in our participation of the development and implementation of CPOE for our individual institutions and alert to the prevention of harm in all we do. Software companies cannot accomplish improvement in our practices without our involvement, and we cannot meet our demands for quality without good software companies.

The Link between Age and Orchiectomy Due to Testicular Torsion

Mansbach J, Forbes P, Peters C. Testicular torsion and risk factors for orchiectomy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(12):1167-1171.

Testicular torsion is a urologic emergency that requires a four- to eight-hour window from presentation of symptoms until intervention in order to increase the potential for a viable testis. Steps to ensure a viable testis include timely presentation, rapid diagnosis, and curative intervention.

Chart review was done from a national database consisting of 984 hospitals in 22 states. The review included 436 patients ranging from one to 25 years. The incidence of torsion was 4.5 cases/100,000 male subjects with a peak at 10-19 years of age. Of the 436 subjects, 34% required orchiectomy. After all factors (race, insurance status, income, region, and hospital location) were evaluated, increased age at presentation was the only statistically significant factor associated orchiectomy. Male subjects were hesitant to seek medical attention for conditions associated with the genitals. Healthcare providers need to provide anticipatory guidance when educating males about testicular disorders. Testicular exam should be incorporated as part of every physical exam, especially if an abdominal complaint exists.

Heliox Aids Peds with Moderate to Severe Asthma

Kim K, Phrampus E, Venkataraman S, et al. Helium/oxygen-driven albuterol nebulization in the treatment of children with moderate to severe asthma exacerbations: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2005;116(5):1127-1133.

Heliox is a 70%/30% helium/oxygen mixture. Heliox mixtures have a lower gas density than oxygen and, therefore, can increase pulmonary gas delivery. This study compared heliox versus oxygen delivery of continuous albuterol nebulization for patients with asthma treated in the emergency department.

Investigators enrolled 30 subjects between ages two and 18 with moderate to severe asthma. Severity of asthma was determined by a pulmonary index (PI) of >8. PI scores are based on respiratory rate, wheezing, accessory muscle use, inspiratory/expiratory ratio, and pulse oximetry. All children were given one 5mg albuterol treatment using traditional oxygen delivery along with oral steroids dosed at 2mg/kg. After the initial treatment and steroids if the PI score was >8 they were randomly assigned to receive continuous albuterol by heliox or traditional oxygen delivery.

The study showed that continuous albuterol delivered by heliox mixture lowered PI scores from baseline to 240 minutes into the study (P<0.001). Results also demonstrated a trend towards improved rate of discharge from the emergency department and hospital, but the study was not powered to adequately evaluate these outcomes Limitations of the study include lack of complete blinding and a small sample size. TH

Something didn’t seem quite right. The person in the hooded sweatshirt standing near the entrance looked suspicious to respiratory therapist Betty Collins as she entered the newborn nursery on the evening of Jan. 12, 2006, during her shift at Ouachita County Medical Center in Camden, Ark. Perhaps this is why she shielded her fingers as she punched in the combination to the lock on the nursery door before entering to check on a baby inside.

Leaving minutes later, her work done, Collins’ suspicions were confirmed when Nikenya Washington, 18, shoved her way into the nursery yelling, “Move out my way, I’ll shoot you b----!”

Collins and the other nurse in the unit bravely wrestled with the would-be abductor. A Code Pink was called.

It is notable that January’s Ouachita Hospital case is unique as the first reported case of physical violence during an in-hospital abduction.

This frightening episode is one example of the phenomenon of infant abduction, and according to Cathy Nahirny of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) it is the first reported case in 2006.

Infant abduction is defined as the act of kidnapping an infant less than six months of age by a non-family member. Code Pink is the almost universally adopted code word signaling that an abduction is taking place. Though infrequent by comparison to other types of kidnapping or exploitation of children, infant abduction—like many pediatric situations—is quite dramatic.

This crime is of particular concern to pediatric hospitalists because about half of these events occur within the hospital setting. It plays on the fears of expectant parents and communities, and a successful abduction can be catastrophic for a hospital’s image and reputation. Preventing infant abduction and maintaining preparedness for Code Pink situations represents an ongoing challenge for the approximately 3,500 hospitals where about 4 million American babies are born each year.

Small Number, Large Impact

According to Daniel Broughton, MD, infant abduction is a small subset of a much larger problem. As the director of the Child Abuse Program at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and co-author of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Clinical Report on the pediatrician’s role in the prevention of missing children, he is an expert on the subject.

There are an estimated 1-2 million runaways and as many as 200,000 abductions by family members in the United States each year. By contrast, since 1983 when the NCMEC began to collect information on reports of infant abduction, there have been a total of 235 recorded infant kidnappings by non-family members. Nevertheless, “from the standpoint of impact both on families and the hospitals, it is huge,” says Dr. Broughton of infant abduction.

Bob Chicarello, the interim head of security at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, agrees.

“You want to do everything possible to prevent [an infant abduction] because it could really shake an institution to its knees,” he says.

In addition, the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) considers infant abduction such a safety priority that it was made a reportable “Sentinel Event” in 1998. Of the reported 235 reported cases 117 abductions—or 50%—have occurred in the hospital setting. Most children taken from the hospital—57%—are taken from their mother’s room. Roughly 15% each are taken from the newborn nursery, other pediatric wards, or from other parts of the hospital grounds.

Among abductions occurring outside the healthcare setting, 38% of the total occurred from private homes, and the final 13% of the total in other public venues.

A Unique Crime

Infant abduction seems to be distinct from other types of kidnapping in several ways. The first unique characteristic of infant abduction is the profile of the stereotypical perpetrator. Examination of case reports shows that the vast majority of abductors are females of childbearing age. Most live in or near the city where the abduction takes place. Many are overweight, and they may have a history of depression or lying, manipulative behavior.

Additionally, the motives of these women are notably different than those of other kidnappers who are interested in sexual exploitation, money, or revenge. Instead, these women most often desire to have a child of their own. This may be to replace a child or pregnancy that was lost, or to appease a significant other who they perceive may leave them if they cannot produce a child. Notably, many of the kidnappers, later caught, have been observed to provide adequate care for the infants.

Though the timing of an infant abduction can be impulsive, many kidnappers show evidence of elaborate planning beforehand. Several women have staged fictitious pregnancies on one or more occasions. Some kidnappers have even bought baby items or furnished nurseries in anticipation of having a child. Many offenders visit the hospitals or other facilities they later target on several occasions prior to an attempted abduction. They will try to become familiar with hospital personnel often by asking probing questions about security and procedure. A common ploy is for the kidnappers to impersonate nurses, lab technicians, or other hospital personnel in an attempt to gain access to the children. Some even acquire hospital uniforms or other disguises.

They may pose as family members of other patients in order to befriend the parents of their victims. This was the case of Nikenya Washington, who actually entered the room of the would-be victim’s mother early in the evening on the night of the crime. She stated that she had walked into the wrong room and tried to strike up a conversation before leaving.

Prevention is Key

Preventing infant abduction is key, and this process starts by putting proper procedures and hardware in place at healthcare facilities.

“We use a multilayered approach,” says Chicarello. This includes prior planning, physical barriers, electronic aides, and ongoing training and education of staff and parents alike. At Brigham and Women’s, security starts in the lobby where admittance to the maternity ward is gained only after signing in and using a specific elevator. Hospital personnel wear specific nursery badges, and they obtain access to the ward by key card.

The hospital also uses various forms of technology including closed circuit TV monitors, silent “panic” buttons at the nurse’s stations, and electronic wrist/ankle bracelets for the babies.

Chicarello stresses the importance of both initial training for new personnel as well as ongoing education throughout the hospital. This includes hospital-wide awareness drives and an annual Code Pink Fair. Education for parents is incorporated into a pre-natal curriculum. A big part of ongoing training is the use of monthly unscheduled Code Pink drills.

“We try to vary the scenarios to keep the staff on their toes and to expose any weaknesses,” he says. Such scenarios might include having people pose as lab personnel or pulling the fire alarm to create a diversion. “My favorite was once when we had a pizza delivered to the nurses station.” Fortunately, this didn’t work.

Dr. Broughton echoes the notion that a multifaceted approach is important. In addition to well-defined procedures in the birthing suite, the Mayo Clinic’s plan for preventing infant abduction extends to the larger children’s hospital and even to the clinic. Having a well-defined abduction plan has other positive effects as well, notes Dr. Broughton. Such programs are useful in preventing other types of theft, in aiding infection control efforts, and in locating ambulatory children who might wander or get lost.

The process requires input from several disciplines including nursing, security, and physicians. “I think pediatricians should be completely supportive of programs that provide a safety net,” says Dr. Broughton. “[Physicians] should be the leaders in the hospital setting.” One problem he has seen is that physicians sometimes don’t want to be bothered by little details like wearing a proper ID or leaving doors properly locked. Getting physicians to say, “this is important” is an essential first step.

A Disturbing Trend

Though changes in the landscape of infant abduction are difficult to discern, a few trends are notable. Encouragingly, in-hospital abductions are a smaller fraction of the total incidence, perhaps in response to better deterrence by medical facilities. As evidence of this, there was a recent 20-month period without a single abduction from a hospital setting. More disturbingly, though, the incidence of out-of-hospital abductions and the use of violence in abductions seem on the rise. Among these about 29% have involved violence to the parents or family of the infant including eight cases of homicide.

Obviously, preventing abductions outside the hospital presents its own challenges. Nahirny cautions strongly against the publication of birth information on the local press or on Web sites. “These shouldn’t include any specifically identifying information,” she states, such as full names of parents or a home address.

Second, parents must understand the potential danger of posting signs or balloons outside the home after a birth, as these might alert a potential abductor to the presence of an infant. Finally, parents should be careful with unknown, unexpected, or recently acquainted visitors shortly after coming home from the hospital. There are several cases of abductors posing as home-health nurses, social workers, or other official personnel.

Conclusion

Even though she was able to grab the child and make it out of the room, Nikenya Washington did not make if off the hospital ward before being subdued by a security guard and other hospital personnel. Thankfully, the healthy 8-pound, 1-once baby girl was safely returned to her mother. In fact, hospital personnel in conjunction with local law enforcement and media safely recover most abducted infants thanks to orderly responses. However, the best option for all parties involved is a well-planned strategy of prevention. This includes physical barriers, electronic aides, and education of personnel and parents, as well as constant vigilance.

For those who want to get involved in preventing infant abduction, several resources are available. The NCMEC has quite a bit of information on its Web site (www.missingkids.com). There is also an excellent educational video produced by Mead Johnson Nutritionals called “Safeguard Their Tomorrows” available for viewing.

The most definitive resource for clinicians is a book entitled Guidelines for the Prevention of and Response to Infant Abduction. Currently in its eighth edition by John Rabun of the NCEMC, the book discusses the problem of infant abduction and defines its scope. There are various practical recommendations on the general, proactive, and physical measures to prevent abductions and on how to respond once an incident has occurred. There are also sections on how to advise parents and how to assess level of preparedness.

Dr. Axon is an instructor, Departments of Medicine and Pediatrics, Medical University of South Carolina Medical Center, Charleston.

Bibliography

- Ankrom LG, Lent CJ. Cradle robbers: A study of the infant abductor. The FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. 1995;64(9):112-118.

- Hillen M. Teen held in attempt to abduct newborn. Arkansas Democrat Gazette. 16 January, 2006.

- Rabun J. For Healthcare Professionals: Guidelines for the Prevention of and Response to Infant Abduction. 8th ed. Alexandria, Virginia: National Center for Missing and Exploited Children; 2005.

Pediatric Special Section

In the Literature

By G. Ronald Nicholis, MD, Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, Mo., Gina Weddle, RN, CPNP, Section of Pediatric Hospitalists, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics (Kansas City, Mo.), and J. Christopher Day, MD, Section of Pediatric Hospitalists, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics (Kansas City, Mo.)

Computerized Physician Order Entry—Not a Finished Product

Han YY, Carcillo JA, Venkataraman ST, et al. Unexpected increased mortality after implementation of a commercially sold computerized physician order entry system. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):1506-1512.

Over the past several years attention has been increasingly focused on the inadequacy of patient safety in our practices. In response, hospitals, insurers, and practices have examined many potential changes to current systems in an effort to improve safety.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) and the Leapfrog Group have championed computerized physician order entry (CPOE) as necessary for improving patient safety, citing the inadequacy of paper and pen for the ordering process. Research documenting that CPOE systems used in the hospital setting can decrease adverse drug events has fostered the promise and potential for CPOE to make the hospital a safer place for our patients, particularly when enhanced with decision support. Decision support can allow the physician to be alerted to errors in dose, drug-drug interaction, drug-food interaction, allergies, and the need for dosage corrections based on laboratory values at the time of ordering. Contrary to the research demonstrating improved safety, some studies have shown an increase in unique errors after implementation of CPOE.

The current study from the Departments of Critical Care Medicine and Pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh calls our attention to significant issues with implementation of CPOE that have potential to inhibit the goal of improving patient safety. Citing a study by Upperman, et al. from their own institution, which noted significant improvement in adverse drug events after implementation of CPOE, the authors of the current study state, “Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh implemented … Cerner’s commercial CPOE system in October 2002 in an effort to become one of the first children’s hospitals in the U.S. to attain 100% CPOE status.”

The study was designed to measure the effect of CPOE implementation on mortality rate for patients transferred into this pediatric tertiary care facility who required “immediate processing … and stabilization orders.” This retrospective study examined an 18-month period of mortality data: Thirteen months before the implementation of CPOE and five months after.

They discovered an unexpected increase in unadjusted mortality rate after the implementation of CPOE from 2.8% to 6.57%, (P<0.001). Mortality odds ratios were calculated, and observed mortality before CPOE implementation was consistently better than after CPOE implementation. Regression analysis with and without Pediatric Risk of Mortality comparisons were performed and CPOE, in addition to other factors, was associated with increased mortality in both analyses. How should this be interpreted?

The authors note several factors having impact on the validity of the study, specifically mentioning that “study design precludes any statements regarding cause and effect,” “[researchers] examined a unique patient population admitted through interfacility transport … (thus) findings may not be generalizable to the hospital experience as a whole,” and “[the] observation period after CPOE implementation was brief.”

Seasonal variability was also a potential confounding factor because CPOE implementation was in October and the observation period post-CPOE extended only five months—to March of the next year. However, a statistical comparison between matched five-month periods supported the association between implementation of CPOE and increased mortality in this population.

In addition, the authors discuss how their institution’s chosen implementation process for CPOE affected the work processes and pattern of care provided to these critically ill patients. Issues such as being unable to enter orders on a patient in preparation of their arrival because they were not yet enrolled in the electronic system hampered the availability of important medications at the time of arrival. Forcing all of the orders to go through their designed CPOE process in an effort to use the error prevention capabilities of the system caused potentially significant delays in the administration of life-saving medications.

The lack of functional order sets further delayed the physician’s ability to efficiently enter orders electronically. These variables may have impacted mortality rates. Further delays were evident due to the fact that a nurse had to activate orders placed by the physician, bypassing some of the efficiency of an electronic system. Similarly, the pharmacy reviewed and processed the order before the medication was available to the nurse for delivery to the patient.

These checks and balances have the potential to prevent errors in medication ordering, but if inefficient, they may not be appropriate for an intensive care setting in every circumstance. Researchers stated the new workflow took the physicians and nurses away from the patient’s bedside, potentially decreasing observation benefits for the patient. The capacity of the system to compute at times seemed “frozen” causing further delays—not necessarily an uncommon occurrence with any electronic system.

The practice of medicine is complex and work processes do not easily translate to the electronic models currently available. It is crucial that hospitalists, other specialists, all ancillary services, as well as administration be involved in the building and implementation of the systems to be used in our individual facilities. The systems and technology for effective CPOE in hospital settings—especially in pediatric settings—have yet to be developed. The implementation of CPOE for improved patient safety requires exploration given the exposed inadequacies of our current methods of practice.

Like any best practice this exploration will be continuous and require evaluation and improvement. While we must involve ourselves with the development and implementation of CPOE, we must not let the inadequacies of new systems negatively affect patient care. The dichotomy may be omnipresent: Use the system to gain protections from errors and bypass the system when its design or function interferes with good patient practice. This will require us to possess the wisdom to determine the correct path to follow in any instance.

Every day in our practice we make efforts to compensate for failures in our methods to prevent errors from affecting our patient’s care. Electronic systems do not excuse us from continued vigilance, communication, and action to protect our patients from medical errors. The authors appropriately state that “accurate evaluation of CPOE will require systems-based troubleshooting with well-funded, well-designed, multicenter studies that can adequately address these questions.”

Unfortunately, because of the proven inadequacies of the current system, CPOE, like other methodologies we use in the advancement of patient care, cannot wait for proof of perfection before being used to enhance the outcomes of our patients. Thus we need to be vigorous in our participation of the development and implementation of CPOE for our individual institutions and alert to the prevention of harm in all we do. Software companies cannot accomplish improvement in our practices without our involvement, and we cannot meet our demands for quality without good software companies.

The Link between Age and Orchiectomy Due to Testicular Torsion

Mansbach J, Forbes P, Peters C. Testicular torsion and risk factors for orchiectomy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(12):1167-1171.

Testicular torsion is a urologic emergency that requires a four- to eight-hour window from presentation of symptoms until intervention in order to increase the potential for a viable testis. Steps to ensure a viable testis include timely presentation, rapid diagnosis, and curative intervention.

Chart review was done from a national database consisting of 984 hospitals in 22 states. The review included 436 patients ranging from one to 25 years. The incidence of torsion was 4.5 cases/100,000 male subjects with a peak at 10-19 years of age. Of the 436 subjects, 34% required orchiectomy. After all factors (race, insurance status, income, region, and hospital location) were evaluated, increased age at presentation was the only statistically significant factor associated orchiectomy. Male subjects were hesitant to seek medical attention for conditions associated with the genitals. Healthcare providers need to provide anticipatory guidance when educating males about testicular disorders. Testicular exam should be incorporated as part of every physical exam, especially if an abdominal complaint exists.

Heliox Aids Peds with Moderate to Severe Asthma

Kim K, Phrampus E, Venkataraman S, et al. Helium/oxygen-driven albuterol nebulization in the treatment of children with moderate to severe asthma exacerbations: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2005;116(5):1127-1133.

Heliox is a 70%/30% helium/oxygen mixture. Heliox mixtures have a lower gas density than oxygen and, therefore, can increase pulmonary gas delivery. This study compared heliox versus oxygen delivery of continuous albuterol nebulization for patients with asthma treated in the emergency department.

Investigators enrolled 30 subjects between ages two and 18 with moderate to severe asthma. Severity of asthma was determined by a pulmonary index (PI) of >8. PI scores are based on respiratory rate, wheezing, accessory muscle use, inspiratory/expiratory ratio, and pulse oximetry. All children were given one 5mg albuterol treatment using traditional oxygen delivery along with oral steroids dosed at 2mg/kg. After the initial treatment and steroids if the PI score was >8 they were randomly assigned to receive continuous albuterol by heliox or traditional oxygen delivery.

The study showed that continuous albuterol delivered by heliox mixture lowered PI scores from baseline to 240 minutes into the study (P<0.001). Results also demonstrated a trend towards improved rate of discharge from the emergency department and hospital, but the study was not powered to adequately evaluate these outcomes Limitations of the study include lack of complete blinding and a small sample size. TH

Something didn’t seem quite right. The person in the hooded sweatshirt standing near the entrance looked suspicious to respiratory therapist Betty Collins as she entered the newborn nursery on the evening of Jan. 12, 2006, during her shift at Ouachita County Medical Center in Camden, Ark. Perhaps this is why she shielded her fingers as she punched in the combination to the lock on the nursery door before entering to check on a baby inside.

Leaving minutes later, her work done, Collins’ suspicions were confirmed when Nikenya Washington, 18, shoved her way into the nursery yelling, “Move out my way, I’ll shoot you b----!”

Collins and the other nurse in the unit bravely wrestled with the would-be abductor. A Code Pink was called.

It is notable that January’s Ouachita Hospital case is unique as the first reported case of physical violence during an in-hospital abduction.

This frightening episode is one example of the phenomenon of infant abduction, and according to Cathy Nahirny of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) it is the first reported case in 2006.

Infant abduction is defined as the act of kidnapping an infant less than six months of age by a non-family member. Code Pink is the almost universally adopted code word signaling that an abduction is taking place. Though infrequent by comparison to other types of kidnapping or exploitation of children, infant abduction—like many pediatric situations—is quite dramatic.

This crime is of particular concern to pediatric hospitalists because about half of these events occur within the hospital setting. It plays on the fears of expectant parents and communities, and a successful abduction can be catastrophic for a hospital’s image and reputation. Preventing infant abduction and maintaining preparedness for Code Pink situations represents an ongoing challenge for the approximately 3,500 hospitals where about 4 million American babies are born each year.

Small Number, Large Impact

According to Daniel Broughton, MD, infant abduction is a small subset of a much larger problem. As the director of the Child Abuse Program at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and co-author of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Clinical Report on the pediatrician’s role in the prevention of missing children, he is an expert on the subject.

There are an estimated 1-2 million runaways and as many as 200,000 abductions by family members in the United States each year. By contrast, since 1983 when the NCMEC began to collect information on reports of infant abduction, there have been a total of 235 recorded infant kidnappings by non-family members. Nevertheless, “from the standpoint of impact both on families and the hospitals, it is huge,” says Dr. Broughton of infant abduction.

Bob Chicarello, the interim head of security at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, agrees.

“You want to do everything possible to prevent [an infant abduction] because it could really shake an institution to its knees,” he says.

In addition, the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) considers infant abduction such a safety priority that it was made a reportable “Sentinel Event” in 1998. Of the reported 235 reported cases 117 abductions—or 50%—have occurred in the hospital setting. Most children taken from the hospital—57%—are taken from their mother’s room. Roughly 15% each are taken from the newborn nursery, other pediatric wards, or from other parts of the hospital grounds.

Among abductions occurring outside the healthcare setting, 38% of the total occurred from private homes, and the final 13% of the total in other public venues.

A Unique Crime

Infant abduction seems to be distinct from other types of kidnapping in several ways. The first unique characteristic of infant abduction is the profile of the stereotypical perpetrator. Examination of case reports shows that the vast majority of abductors are females of childbearing age. Most live in or near the city where the abduction takes place. Many are overweight, and they may have a history of depression or lying, manipulative behavior.

Additionally, the motives of these women are notably different than those of other kidnappers who are interested in sexual exploitation, money, or revenge. Instead, these women most often desire to have a child of their own. This may be to replace a child or pregnancy that was lost, or to appease a significant other who they perceive may leave them if they cannot produce a child. Notably, many of the kidnappers, later caught, have been observed to provide adequate care for the infants.

Though the timing of an infant abduction can be impulsive, many kidnappers show evidence of elaborate planning beforehand. Several women have staged fictitious pregnancies on one or more occasions. Some kidnappers have even bought baby items or furnished nurseries in anticipation of having a child. Many offenders visit the hospitals or other facilities they later target on several occasions prior to an attempted abduction. They will try to become familiar with hospital personnel often by asking probing questions about security and procedure. A common ploy is for the kidnappers to impersonate nurses, lab technicians, or other hospital personnel in an attempt to gain access to the children. Some even acquire hospital uniforms or other disguises.

They may pose as family members of other patients in order to befriend the parents of their victims. This was the case of Nikenya Washington, who actually entered the room of the would-be victim’s mother early in the evening on the night of the crime. She stated that she had walked into the wrong room and tried to strike up a conversation before leaving.

Prevention is Key

Preventing infant abduction is key, and this process starts by putting proper procedures and hardware in place at healthcare facilities.

“We use a multilayered approach,” says Chicarello. This includes prior planning, physical barriers, electronic aides, and ongoing training and education of staff and parents alike. At Brigham and Women’s, security starts in the lobby where admittance to the maternity ward is gained only after signing in and using a specific elevator. Hospital personnel wear specific nursery badges, and they obtain access to the ward by key card.

The hospital also uses various forms of technology including closed circuit TV monitors, silent “panic” buttons at the nurse’s stations, and electronic wrist/ankle bracelets for the babies.

Chicarello stresses the importance of both initial training for new personnel as well as ongoing education throughout the hospital. This includes hospital-wide awareness drives and an annual Code Pink Fair. Education for parents is incorporated into a pre-natal curriculum. A big part of ongoing training is the use of monthly unscheduled Code Pink drills.

“We try to vary the scenarios to keep the staff on their toes and to expose any weaknesses,” he says. Such scenarios might include having people pose as lab personnel or pulling the fire alarm to create a diversion. “My favorite was once when we had a pizza delivered to the nurses station.” Fortunately, this didn’t work.

Dr. Broughton echoes the notion that a multifaceted approach is important. In addition to well-defined procedures in the birthing suite, the Mayo Clinic’s plan for preventing infant abduction extends to the larger children’s hospital and even to the clinic. Having a well-defined abduction plan has other positive effects as well, notes Dr. Broughton. Such programs are useful in preventing other types of theft, in aiding infection control efforts, and in locating ambulatory children who might wander or get lost.

The process requires input from several disciplines including nursing, security, and physicians. “I think pediatricians should be completely supportive of programs that provide a safety net,” says Dr. Broughton. “[Physicians] should be the leaders in the hospital setting.” One problem he has seen is that physicians sometimes don’t want to be bothered by little details like wearing a proper ID or leaving doors properly locked. Getting physicians to say, “this is important” is an essential first step.

A Disturbing Trend

Though changes in the landscape of infant abduction are difficult to discern, a few trends are notable. Encouragingly, in-hospital abductions are a smaller fraction of the total incidence, perhaps in response to better deterrence by medical facilities. As evidence of this, there was a recent 20-month period without a single abduction from a hospital setting. More disturbingly, though, the incidence of out-of-hospital abductions and the use of violence in abductions seem on the rise. Among these about 29% have involved violence to the parents or family of the infant including eight cases of homicide.

Obviously, preventing abductions outside the hospital presents its own challenges. Nahirny cautions strongly against the publication of birth information on the local press or on Web sites. “These shouldn’t include any specifically identifying information,” she states, such as full names of parents or a home address.

Second, parents must understand the potential danger of posting signs or balloons outside the home after a birth, as these might alert a potential abductor to the presence of an infant. Finally, parents should be careful with unknown, unexpected, or recently acquainted visitors shortly after coming home from the hospital. There are several cases of abductors posing as home-health nurses, social workers, or other official personnel.

Conclusion

Even though she was able to grab the child and make it out of the room, Nikenya Washington did not make if off the hospital ward before being subdued by a security guard and other hospital personnel. Thankfully, the healthy 8-pound, 1-once baby girl was safely returned to her mother. In fact, hospital personnel in conjunction with local law enforcement and media safely recover most abducted infants thanks to orderly responses. However, the best option for all parties involved is a well-planned strategy of prevention. This includes physical barriers, electronic aides, and education of personnel and parents, as well as constant vigilance.

For those who want to get involved in preventing infant abduction, several resources are available. The NCMEC has quite a bit of information on its Web site (www.missingkids.com). There is also an excellent educational video produced by Mead Johnson Nutritionals called “Safeguard Their Tomorrows” available for viewing.

The most definitive resource for clinicians is a book entitled Guidelines for the Prevention of and Response to Infant Abduction. Currently in its eighth edition by John Rabun of the NCEMC, the book discusses the problem of infant abduction and defines its scope. There are various practical recommendations on the general, proactive, and physical measures to prevent abductions and on how to respond once an incident has occurred. There are also sections on how to advise parents and how to assess level of preparedness.

Dr. Axon is an instructor, Departments of Medicine and Pediatrics, Medical University of South Carolina Medical Center, Charleston.

Bibliography

- Ankrom LG, Lent CJ. Cradle robbers: A study of the infant abductor. The FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. 1995;64(9):112-118.

- Hillen M. Teen held in attempt to abduct newborn. Arkansas Democrat Gazette. 16 January, 2006.

- Rabun J. For Healthcare Professionals: Guidelines for the Prevention of and Response to Infant Abduction. 8th ed. Alexandria, Virginia: National Center for Missing and Exploited Children; 2005.

Pediatric Special Section

In the Literature

By G. Ronald Nicholis, MD, Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, Mo., Gina Weddle, RN, CPNP, Section of Pediatric Hospitalists, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics (Kansas City, Mo.), and J. Christopher Day, MD, Section of Pediatric Hospitalists, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics (Kansas City, Mo.)

Computerized Physician Order Entry—Not a Finished Product

Han YY, Carcillo JA, Venkataraman ST, et al. Unexpected increased mortality after implementation of a commercially sold computerized physician order entry system. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):1506-1512.

Over the past several years attention has been increasingly focused on the inadequacy of patient safety in our practices. In response, hospitals, insurers, and practices have examined many potential changes to current systems in an effort to improve safety.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) and the Leapfrog Group have championed computerized physician order entry (CPOE) as necessary for improving patient safety, citing the inadequacy of paper and pen for the ordering process. Research documenting that CPOE systems used in the hospital setting can decrease adverse drug events has fostered the promise and potential for CPOE to make the hospital a safer place for our patients, particularly when enhanced with decision support. Decision support can allow the physician to be alerted to errors in dose, drug-drug interaction, drug-food interaction, allergies, and the need for dosage corrections based on laboratory values at the time of ordering. Contrary to the research demonstrating improved safety, some studies have shown an increase in unique errors after implementation of CPOE.

The current study from the Departments of Critical Care Medicine and Pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh calls our attention to significant issues with implementation of CPOE that have potential to inhibit the goal of improving patient safety. Citing a study by Upperman, et al. from their own institution, which noted significant improvement in adverse drug events after implementation of CPOE, the authors of the current study state, “Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh implemented … Cerner’s commercial CPOE system in October 2002 in an effort to become one of the first children’s hospitals in the U.S. to attain 100% CPOE status.”

The study was designed to measure the effect of CPOE implementation on mortality rate for patients transferred into this pediatric tertiary care facility who required “immediate processing … and stabilization orders.” This retrospective study examined an 18-month period of mortality data: Thirteen months before the implementation of CPOE and five months after.

They discovered an unexpected increase in unadjusted mortality rate after the implementation of CPOE from 2.8% to 6.57%, (P<0.001). Mortality odds ratios were calculated, and observed mortality before CPOE implementation was consistently better than after CPOE implementation. Regression analysis with and without Pediatric Risk of Mortality comparisons were performed and CPOE, in addition to other factors, was associated with increased mortality in both analyses. How should this be interpreted?

The authors note several factors having impact on the validity of the study, specifically mentioning that “study design precludes any statements regarding cause and effect,” “[researchers] examined a unique patient population admitted through interfacility transport … (thus) findings may not be generalizable to the hospital experience as a whole,” and “[the] observation period after CPOE implementation was brief.”

Seasonal variability was also a potential confounding factor because CPOE implementation was in October and the observation period post-CPOE extended only five months—to March of the next year. However, a statistical comparison between matched five-month periods supported the association between implementation of CPOE and increased mortality in this population.

In addition, the authors discuss how their institution’s chosen implementation process for CPOE affected the work processes and pattern of care provided to these critically ill patients. Issues such as being unable to enter orders on a patient in preparation of their arrival because they were not yet enrolled in the electronic system hampered the availability of important medications at the time of arrival. Forcing all of the orders to go through their designed CPOE process in an effort to use the error prevention capabilities of the system caused potentially significant delays in the administration of life-saving medications.

The lack of functional order sets further delayed the physician’s ability to efficiently enter orders electronically. These variables may have impacted mortality rates. Further delays were evident due to the fact that a nurse had to activate orders placed by the physician, bypassing some of the efficiency of an electronic system. Similarly, the pharmacy reviewed and processed the order before the medication was available to the nurse for delivery to the patient.

These checks and balances have the potential to prevent errors in medication ordering, but if inefficient, they may not be appropriate for an intensive care setting in every circumstance. Researchers stated the new workflow took the physicians and nurses away from the patient’s bedside, potentially decreasing observation benefits for the patient. The capacity of the system to compute at times seemed “frozen” causing further delays—not necessarily an uncommon occurrence with any electronic system.

The practice of medicine is complex and work processes do not easily translate to the electronic models currently available. It is crucial that hospitalists, other specialists, all ancillary services, as well as administration be involved in the building and implementation of the systems to be used in our individual facilities. The systems and technology for effective CPOE in hospital settings—especially in pediatric settings—have yet to be developed. The implementation of CPOE for improved patient safety requires exploration given the exposed inadequacies of our current methods of practice.

Like any best practice this exploration will be continuous and require evaluation and improvement. While we must involve ourselves with the development and implementation of CPOE, we must not let the inadequacies of new systems negatively affect patient care. The dichotomy may be omnipresent: Use the system to gain protections from errors and bypass the system when its design or function interferes with good patient practice. This will require us to possess the wisdom to determine the correct path to follow in any instance.