User login

William Geers, MD, finished up his residency in 2007, then went to work for a close-knit emergency-medicine group of about 25 doctors in Daytona Beach, Fla.

“Everybody was pretty tight,” he says of his first job.

He had met his wife in residency in Daytona, but after a while, they figured it was time for a change. “We’d been in Daytona for about six years and were ready to go try someplace different,” Dr. Geers says. “Tallahassee seemed like a good match because that’s kind of right in between our families.”

He soon landed a hospitalist job at Capital Regional Medical Center, and he suddenly was a part of EmCare, one of the biggest corporations in the emergency-medicine field and, more recently, in the field of hospital medicine. EmCare provides doctors to about 400 hospitals nationwide.

Dr. Geers said the corporate affiliation didn’t factor into his decision, adding that he took more of a traditional approach when choosing a new job.

“At the time, this program was a little bit smaller, which I liked,” says Dr. Geers, who also looked at the city’s other hospital, Tallahassee Memorial. “I met some of the physicians over here. I liked them.”

But he has noticed perks.

“I think we have some advantages working with EmCare in that we do have a pretty big group that’s backing us,” he explains. “I feel a little more secure with issues like malpractice. If things like that ever come up, I really feel like I have a lot of support with EmCare.”

With the corporate presence on the rise in HM, more and more hospitalists are entering the ranks of large companies. Some are doing so straight out of residency. Some are giving up their private practices and selling them to corporations looking to expand.

Corporations that provide hospitalists to hospitals are getting ever bigger, using sophisticated infrastructure and economies of scale, they say, to make life easier for the people who work for them, allowing the hospitalists to focus on patient care. Their efficiencies are attractive to hospitals looking to simplify.

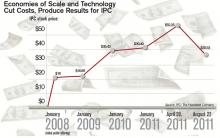

Three years ago, North Hollywood, Calif.-based IPC: The Hospitalist Company became a publicly traded company. Its stock price has more than doubled since then.

In July, Eagle Hospital Physicians acquired North Carolina-based PrimeDoc and its 100 doctors covering seven hospitals. Similar acquisitions by larger corporations have become almost weekly news.

And, probably most significantly, Cogent Healthcare recently completed a merger with Hospitalists Management Group, a union of two of the biggest hospitalist companies in the U.S. The new company, Cogent HMG, now includes a corps of 1,000 doctors, nurses, and physician assistants (PAs), with client hospitals in 28 states.

Cogent had clients that were medium to large in size, generally in more urban areas but scattered geographically. HMG mostly served small- to medium-sized hospitals with densities in certain regions. With the merger came a recognition that the larger a company becomes, the greater the opportunity for efficiency and better services, says Rusty Holman, MD, MHM, chief clinical officer of the new company.

“The real value out of bringing these two companies together is bringing the best of different worlds together, creating new products and services for hospitals that don’t exist today, and to be able to serve a broader customer base,” says Dr. Holman, a former SHM president. “It’s also to leverage some of the infrastructure that has been built over a greater number of programs and hospitals to gain efficiency and scale that way. So that is the primary focus of the integration today.”

Cogent HMG CEO Steve Houff, MD, says the merger will mean investment in clinical support, physician recruiting, and technology, and will benefit patients and hospital partners alike.

“Both Cogent and HMG have a track record for delivering improvements in clinical quality and patient satisfaction at each of the hospitals we serve. The plan is for that to continue on a broader scale,” he wrote in an email to The Hospitalist.

—R. Jeffrey Taylor, president, chief operating officer, IPC: The Hospitalist Company, North Hollywood, Calif.

The Good, the Bad, the Oligopoly

The average size of a hospitalist group in the U.S. is about 10 full-time equivalents, according to recent survey data from SHM and MGMA. With the swelling of the size of HM’s biggest corporate players comes the question of how far the coalescing will go: Will most patient care eventually be provided by only a few groups?

R. Jeffrey Taylor, IPC’s president and chief operating officer, says the mergers and acquisitions will continue, but he doesn’t see a day when there will be just a few titans ruling all.

“I do think there will be more consolidation going forward than there is now, but I don’t see a future in which there are, you know, two or three groups that completely dominate the landscape,” he says. “There’s always that concern that that’s going to happen in the hospital industry, or that’s going to happen with payors. And there are always new entrants.”

For all the movement toward bigger companies, “this is still an unconsolidated industry,” and new physician practices will always continue to be formed, he says.

“We’re the largest group, and we’re maybe 3 1/2 percent of all the hospitals in the country. I wouldn’t consider this, today, a terribly consolidated industry,” he adds. “I do think it will move in that direction. I just don’t think it will get all the way there, because of the sort of private, entrepreneurial, independent spirit that’s common among physicians.”

Mike Tarwater, a board member of the American Hospital Association, says private hospitalist providers will only be an alternative to—and not a replacement provider for—large, self-contained systems like the Carolinas Medical Center (CMC), for which he serves as CEO. The health system has a wide spectrum of facilities—from large, urban academic centers like the 874-bed medical center in Charlotte, N.C., to 52-bed Anson Community Hospital in Wadesboro, N.C., population 5,780.

“As a system, we have the wherewithal and the recruiting expertise, and, with 1,700 physician associates across the system, we’ve kind of got critical mass,” Tarwater says. “So we will be an alternative to that in our region.”

Frank Michota, MD, FHM, director of academic affairs in the Department of Hospital Medicine at The Cleveland Clinic, says that the extensive training programs of many of the larger hospitalist groups (e.g. Cogent Academy, IPC’s extensive onboarding process and leadership conferences) could be a very good thing for the field.

“I have always thought that companies like Cogent did a very nice job in orienting their hospitalists to the patient-care goals and the process variables that were being measured,” Dr. Michota says. “I think that by making an even larger group, they have the opportunity to continue to standardize the approach to hospital care so that one hospitalist equals one hospitalist equals one hospitalist. I think that’s a positive.”

The flip side, though, is that anything that might be done wrong would be magnified in such a system.

“I think that there are some dangers in how these large companies will incentivize their hospitalists,” he adds. “If they are consistent from hospitalist to hospitalist, but if there’s a perverse adverse effect from one of their financial incentives, it will be carried out across a lot of hospitals all at the same time. “But I think it’s a little early to tell what the impact of this might be. But, at least for right now, it’s actually a positive thing because it standardizes the hospitalist.”

Tarwater says that even when larger corporations buy smaller practices, familiarity tends to remain.

“Most of what I have seen are existing groups that join through merger or acquisition, and so we already have experience with the doctors, we already have long-standing relationships with the doctors,” he says. “I think any health system or hospital would be reticent to sign up with somebody that they’ve never heard of, that doesn’t have a track record, or that they don’t know already at least some of the players.” Hospitals looking to hire a private company have to exercise caution, particularly if the company is trying to break into a new region where it isn’t known.

“Those hospitals and healthcare systems just have to be really careful who they’re signing contracts with,” he said. “It’s no different than anything else we do. You just have to know who your partners are, and what drives them and where they stand on important issues.”

Executives say patient care is not at risk, even as consolidation continues. “With or without competition, we are relentlessly trying to improve our approach to patient care, our performance, and our hospital partnerships,” Cogent HMG’s Dr. Houff says.

Money Talks

It doesn’t appear that more hospitalist companies are planning to go public—at least for now.

The largest privately held company, Cogent HMG, is not planning an initial public offering anytime soon, Dr. Houff says. The company’s goal is to “continue investing in smart growth to capture more of the hospital medicine market, expand offerings to our existing hospital clients, and provide additional support to our clinical teams on the ground,” he says. “We have a strong capital partner to help us in that effort and are not looking at the public markets at this time.”

Taking on stockholders is a tricky business—one that requires careful planning and a willingness from practice leaders and administrators to relinquish some autonomy to outside interests. And then there are the financial requirements.

“They’ve really got to be able to produce some serious revenue in order for somebody to be willing to put some money into them,” says Mark Hamm, CEO of EmCare Inpatient Services.

The lure of working for a private hospitalist company promises to continue to be an attractive one. Some are drawn by the leadership possibilities—those who “aspire to be the true alpha doctor,” as IPC’s Taylor puts it. Others are drawn by the stability of a larger company.

There also is flexibility in location, Dr. Holman notes.

“Now, with Cogent HMG, [hospitalists] have even more choices in terms of relocating within the same company,” he says. “So they can keep all of the benefits, keep all of the knowledge and familiarity of the system and philosophy of care that we employ, and just be able to transfer.”

continued below...

Dr. Houff says the majority of newly recruited physicians are coming out of residency but that the company is attracting physicians in the middle of their careers, along with physicians having backgrounds beyond internal medicine.

In Tallahassee at Capital Regional, Dr. Geers says that he feels there is support from the company that can protect his job quality, with “a little bit more room to negotiate with the hospital if the hospital wants us to take on new responsibilities.

“Whereas if we worked directly for the hospital, I don’t think we’d have much say in the matter,” he says.

He also says he is happy with the predictable schedule; he’s responsible for 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. and nothing more.

“If you’re finished rounding and you’ve seen all your patients and tied up all your loose ends, you’re not always there till 7 p.m.,” he points out. “Sometimes you can leave a little early....Once 7 p.m. comes, you’re not going to get paged in the middle of the night.”

Thomas R. Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

William Geers, MD, finished up his residency in 2007, then went to work for a close-knit emergency-medicine group of about 25 doctors in Daytona Beach, Fla.

“Everybody was pretty tight,” he says of his first job.

He had met his wife in residency in Daytona, but after a while, they figured it was time for a change. “We’d been in Daytona for about six years and were ready to go try someplace different,” Dr. Geers says. “Tallahassee seemed like a good match because that’s kind of right in between our families.”

He soon landed a hospitalist job at Capital Regional Medical Center, and he suddenly was a part of EmCare, one of the biggest corporations in the emergency-medicine field and, more recently, in the field of hospital medicine. EmCare provides doctors to about 400 hospitals nationwide.

Dr. Geers said the corporate affiliation didn’t factor into his decision, adding that he took more of a traditional approach when choosing a new job.

“At the time, this program was a little bit smaller, which I liked,” says Dr. Geers, who also looked at the city’s other hospital, Tallahassee Memorial. “I met some of the physicians over here. I liked them.”

But he has noticed perks.

“I think we have some advantages working with EmCare in that we do have a pretty big group that’s backing us,” he explains. “I feel a little more secure with issues like malpractice. If things like that ever come up, I really feel like I have a lot of support with EmCare.”

With the corporate presence on the rise in HM, more and more hospitalists are entering the ranks of large companies. Some are doing so straight out of residency. Some are giving up their private practices and selling them to corporations looking to expand.

Corporations that provide hospitalists to hospitals are getting ever bigger, using sophisticated infrastructure and economies of scale, they say, to make life easier for the people who work for them, allowing the hospitalists to focus on patient care. Their efficiencies are attractive to hospitals looking to simplify.

Three years ago, North Hollywood, Calif.-based IPC: The Hospitalist Company became a publicly traded company. Its stock price has more than doubled since then.

In July, Eagle Hospital Physicians acquired North Carolina-based PrimeDoc and its 100 doctors covering seven hospitals. Similar acquisitions by larger corporations have become almost weekly news.

And, probably most significantly, Cogent Healthcare recently completed a merger with Hospitalists Management Group, a union of two of the biggest hospitalist companies in the U.S. The new company, Cogent HMG, now includes a corps of 1,000 doctors, nurses, and physician assistants (PAs), with client hospitals in 28 states.

Cogent had clients that were medium to large in size, generally in more urban areas but scattered geographically. HMG mostly served small- to medium-sized hospitals with densities in certain regions. With the merger came a recognition that the larger a company becomes, the greater the opportunity for efficiency and better services, says Rusty Holman, MD, MHM, chief clinical officer of the new company.

“The real value out of bringing these two companies together is bringing the best of different worlds together, creating new products and services for hospitals that don’t exist today, and to be able to serve a broader customer base,” says Dr. Holman, a former SHM president. “It’s also to leverage some of the infrastructure that has been built over a greater number of programs and hospitals to gain efficiency and scale that way. So that is the primary focus of the integration today.”

Cogent HMG CEO Steve Houff, MD, says the merger will mean investment in clinical support, physician recruiting, and technology, and will benefit patients and hospital partners alike.

“Both Cogent and HMG have a track record for delivering improvements in clinical quality and patient satisfaction at each of the hospitals we serve. The plan is for that to continue on a broader scale,” he wrote in an email to The Hospitalist.

—R. Jeffrey Taylor, president, chief operating officer, IPC: The Hospitalist Company, North Hollywood, Calif.

The Good, the Bad, the Oligopoly

The average size of a hospitalist group in the U.S. is about 10 full-time equivalents, according to recent survey data from SHM and MGMA. With the swelling of the size of HM’s biggest corporate players comes the question of how far the coalescing will go: Will most patient care eventually be provided by only a few groups?

R. Jeffrey Taylor, IPC’s president and chief operating officer, says the mergers and acquisitions will continue, but he doesn’t see a day when there will be just a few titans ruling all.

“I do think there will be more consolidation going forward than there is now, but I don’t see a future in which there are, you know, two or three groups that completely dominate the landscape,” he says. “There’s always that concern that that’s going to happen in the hospital industry, or that’s going to happen with payors. And there are always new entrants.”

For all the movement toward bigger companies, “this is still an unconsolidated industry,” and new physician practices will always continue to be formed, he says.

“We’re the largest group, and we’re maybe 3 1/2 percent of all the hospitals in the country. I wouldn’t consider this, today, a terribly consolidated industry,” he adds. “I do think it will move in that direction. I just don’t think it will get all the way there, because of the sort of private, entrepreneurial, independent spirit that’s common among physicians.”

Mike Tarwater, a board member of the American Hospital Association, says private hospitalist providers will only be an alternative to—and not a replacement provider for—large, self-contained systems like the Carolinas Medical Center (CMC), for which he serves as CEO. The health system has a wide spectrum of facilities—from large, urban academic centers like the 874-bed medical center in Charlotte, N.C., to 52-bed Anson Community Hospital in Wadesboro, N.C., population 5,780.

“As a system, we have the wherewithal and the recruiting expertise, and, with 1,700 physician associates across the system, we’ve kind of got critical mass,” Tarwater says. “So we will be an alternative to that in our region.”

Frank Michota, MD, FHM, director of academic affairs in the Department of Hospital Medicine at The Cleveland Clinic, says that the extensive training programs of many of the larger hospitalist groups (e.g. Cogent Academy, IPC’s extensive onboarding process and leadership conferences) could be a very good thing for the field.

“I have always thought that companies like Cogent did a very nice job in orienting their hospitalists to the patient-care goals and the process variables that were being measured,” Dr. Michota says. “I think that by making an even larger group, they have the opportunity to continue to standardize the approach to hospital care so that one hospitalist equals one hospitalist equals one hospitalist. I think that’s a positive.”

The flip side, though, is that anything that might be done wrong would be magnified in such a system.

“I think that there are some dangers in how these large companies will incentivize their hospitalists,” he adds. “If they are consistent from hospitalist to hospitalist, but if there’s a perverse adverse effect from one of their financial incentives, it will be carried out across a lot of hospitals all at the same time. “But I think it’s a little early to tell what the impact of this might be. But, at least for right now, it’s actually a positive thing because it standardizes the hospitalist.”

Tarwater says that even when larger corporations buy smaller practices, familiarity tends to remain.

“Most of what I have seen are existing groups that join through merger or acquisition, and so we already have experience with the doctors, we already have long-standing relationships with the doctors,” he says. “I think any health system or hospital would be reticent to sign up with somebody that they’ve never heard of, that doesn’t have a track record, or that they don’t know already at least some of the players.” Hospitals looking to hire a private company have to exercise caution, particularly if the company is trying to break into a new region where it isn’t known.

“Those hospitals and healthcare systems just have to be really careful who they’re signing contracts with,” he said. “It’s no different than anything else we do. You just have to know who your partners are, and what drives them and where they stand on important issues.”

Executives say patient care is not at risk, even as consolidation continues. “With or without competition, we are relentlessly trying to improve our approach to patient care, our performance, and our hospital partnerships,” Cogent HMG’s Dr. Houff says.

Money Talks

It doesn’t appear that more hospitalist companies are planning to go public—at least for now.

The largest privately held company, Cogent HMG, is not planning an initial public offering anytime soon, Dr. Houff says. The company’s goal is to “continue investing in smart growth to capture more of the hospital medicine market, expand offerings to our existing hospital clients, and provide additional support to our clinical teams on the ground,” he says. “We have a strong capital partner to help us in that effort and are not looking at the public markets at this time.”

Taking on stockholders is a tricky business—one that requires careful planning and a willingness from practice leaders and administrators to relinquish some autonomy to outside interests. And then there are the financial requirements.

“They’ve really got to be able to produce some serious revenue in order for somebody to be willing to put some money into them,” says Mark Hamm, CEO of EmCare Inpatient Services.

The lure of working for a private hospitalist company promises to continue to be an attractive one. Some are drawn by the leadership possibilities—those who “aspire to be the true alpha doctor,” as IPC’s Taylor puts it. Others are drawn by the stability of a larger company.

There also is flexibility in location, Dr. Holman notes.

“Now, with Cogent HMG, [hospitalists] have even more choices in terms of relocating within the same company,” he says. “So they can keep all of the benefits, keep all of the knowledge and familiarity of the system and philosophy of care that we employ, and just be able to transfer.”

continued below...

Dr. Houff says the majority of newly recruited physicians are coming out of residency but that the company is attracting physicians in the middle of their careers, along with physicians having backgrounds beyond internal medicine.

In Tallahassee at Capital Regional, Dr. Geers says that he feels there is support from the company that can protect his job quality, with “a little bit more room to negotiate with the hospital if the hospital wants us to take on new responsibilities.

“Whereas if we worked directly for the hospital, I don’t think we’d have much say in the matter,” he says.

He also says he is happy with the predictable schedule; he’s responsible for 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. and nothing more.

“If you’re finished rounding and you’ve seen all your patients and tied up all your loose ends, you’re not always there till 7 p.m.,” he points out. “Sometimes you can leave a little early....Once 7 p.m. comes, you’re not going to get paged in the middle of the night.”

Thomas R. Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

William Geers, MD, finished up his residency in 2007, then went to work for a close-knit emergency-medicine group of about 25 doctors in Daytona Beach, Fla.

“Everybody was pretty tight,” he says of his first job.

He had met his wife in residency in Daytona, but after a while, they figured it was time for a change. “We’d been in Daytona for about six years and were ready to go try someplace different,” Dr. Geers says. “Tallahassee seemed like a good match because that’s kind of right in between our families.”

He soon landed a hospitalist job at Capital Regional Medical Center, and he suddenly was a part of EmCare, one of the biggest corporations in the emergency-medicine field and, more recently, in the field of hospital medicine. EmCare provides doctors to about 400 hospitals nationwide.

Dr. Geers said the corporate affiliation didn’t factor into his decision, adding that he took more of a traditional approach when choosing a new job.

“At the time, this program was a little bit smaller, which I liked,” says Dr. Geers, who also looked at the city’s other hospital, Tallahassee Memorial. “I met some of the physicians over here. I liked them.”

But he has noticed perks.

“I think we have some advantages working with EmCare in that we do have a pretty big group that’s backing us,” he explains. “I feel a little more secure with issues like malpractice. If things like that ever come up, I really feel like I have a lot of support with EmCare.”

With the corporate presence on the rise in HM, more and more hospitalists are entering the ranks of large companies. Some are doing so straight out of residency. Some are giving up their private practices and selling them to corporations looking to expand.

Corporations that provide hospitalists to hospitals are getting ever bigger, using sophisticated infrastructure and economies of scale, they say, to make life easier for the people who work for them, allowing the hospitalists to focus on patient care. Their efficiencies are attractive to hospitals looking to simplify.

Three years ago, North Hollywood, Calif.-based IPC: The Hospitalist Company became a publicly traded company. Its stock price has more than doubled since then.

In July, Eagle Hospital Physicians acquired North Carolina-based PrimeDoc and its 100 doctors covering seven hospitals. Similar acquisitions by larger corporations have become almost weekly news.

And, probably most significantly, Cogent Healthcare recently completed a merger with Hospitalists Management Group, a union of two of the biggest hospitalist companies in the U.S. The new company, Cogent HMG, now includes a corps of 1,000 doctors, nurses, and physician assistants (PAs), with client hospitals in 28 states.

Cogent had clients that were medium to large in size, generally in more urban areas but scattered geographically. HMG mostly served small- to medium-sized hospitals with densities in certain regions. With the merger came a recognition that the larger a company becomes, the greater the opportunity for efficiency and better services, says Rusty Holman, MD, MHM, chief clinical officer of the new company.

“The real value out of bringing these two companies together is bringing the best of different worlds together, creating new products and services for hospitals that don’t exist today, and to be able to serve a broader customer base,” says Dr. Holman, a former SHM president. “It’s also to leverage some of the infrastructure that has been built over a greater number of programs and hospitals to gain efficiency and scale that way. So that is the primary focus of the integration today.”

Cogent HMG CEO Steve Houff, MD, says the merger will mean investment in clinical support, physician recruiting, and technology, and will benefit patients and hospital partners alike.

“Both Cogent and HMG have a track record for delivering improvements in clinical quality and patient satisfaction at each of the hospitals we serve. The plan is for that to continue on a broader scale,” he wrote in an email to The Hospitalist.

—R. Jeffrey Taylor, president, chief operating officer, IPC: The Hospitalist Company, North Hollywood, Calif.

The Good, the Bad, the Oligopoly

The average size of a hospitalist group in the U.S. is about 10 full-time equivalents, according to recent survey data from SHM and MGMA. With the swelling of the size of HM’s biggest corporate players comes the question of how far the coalescing will go: Will most patient care eventually be provided by only a few groups?

R. Jeffrey Taylor, IPC’s president and chief operating officer, says the mergers and acquisitions will continue, but he doesn’t see a day when there will be just a few titans ruling all.

“I do think there will be more consolidation going forward than there is now, but I don’t see a future in which there are, you know, two or three groups that completely dominate the landscape,” he says. “There’s always that concern that that’s going to happen in the hospital industry, or that’s going to happen with payors. And there are always new entrants.”

For all the movement toward bigger companies, “this is still an unconsolidated industry,” and new physician practices will always continue to be formed, he says.

“We’re the largest group, and we’re maybe 3 1/2 percent of all the hospitals in the country. I wouldn’t consider this, today, a terribly consolidated industry,” he adds. “I do think it will move in that direction. I just don’t think it will get all the way there, because of the sort of private, entrepreneurial, independent spirit that’s common among physicians.”

Mike Tarwater, a board member of the American Hospital Association, says private hospitalist providers will only be an alternative to—and not a replacement provider for—large, self-contained systems like the Carolinas Medical Center (CMC), for which he serves as CEO. The health system has a wide spectrum of facilities—from large, urban academic centers like the 874-bed medical center in Charlotte, N.C., to 52-bed Anson Community Hospital in Wadesboro, N.C., population 5,780.

“As a system, we have the wherewithal and the recruiting expertise, and, with 1,700 physician associates across the system, we’ve kind of got critical mass,” Tarwater says. “So we will be an alternative to that in our region.”

Frank Michota, MD, FHM, director of academic affairs in the Department of Hospital Medicine at The Cleveland Clinic, says that the extensive training programs of many of the larger hospitalist groups (e.g. Cogent Academy, IPC’s extensive onboarding process and leadership conferences) could be a very good thing for the field.

“I have always thought that companies like Cogent did a very nice job in orienting their hospitalists to the patient-care goals and the process variables that were being measured,” Dr. Michota says. “I think that by making an even larger group, they have the opportunity to continue to standardize the approach to hospital care so that one hospitalist equals one hospitalist equals one hospitalist. I think that’s a positive.”

The flip side, though, is that anything that might be done wrong would be magnified in such a system.

“I think that there are some dangers in how these large companies will incentivize their hospitalists,” he adds. “If they are consistent from hospitalist to hospitalist, but if there’s a perverse adverse effect from one of their financial incentives, it will be carried out across a lot of hospitals all at the same time. “But I think it’s a little early to tell what the impact of this might be. But, at least for right now, it’s actually a positive thing because it standardizes the hospitalist.”

Tarwater says that even when larger corporations buy smaller practices, familiarity tends to remain.

“Most of what I have seen are existing groups that join through merger or acquisition, and so we already have experience with the doctors, we already have long-standing relationships with the doctors,” he says. “I think any health system or hospital would be reticent to sign up with somebody that they’ve never heard of, that doesn’t have a track record, or that they don’t know already at least some of the players.” Hospitals looking to hire a private company have to exercise caution, particularly if the company is trying to break into a new region where it isn’t known.

“Those hospitals and healthcare systems just have to be really careful who they’re signing contracts with,” he said. “It’s no different than anything else we do. You just have to know who your partners are, and what drives them and where they stand on important issues.”

Executives say patient care is not at risk, even as consolidation continues. “With or without competition, we are relentlessly trying to improve our approach to patient care, our performance, and our hospital partnerships,” Cogent HMG’s Dr. Houff says.

Money Talks

It doesn’t appear that more hospitalist companies are planning to go public—at least for now.

The largest privately held company, Cogent HMG, is not planning an initial public offering anytime soon, Dr. Houff says. The company’s goal is to “continue investing in smart growth to capture more of the hospital medicine market, expand offerings to our existing hospital clients, and provide additional support to our clinical teams on the ground,” he says. “We have a strong capital partner to help us in that effort and are not looking at the public markets at this time.”

Taking on stockholders is a tricky business—one that requires careful planning and a willingness from practice leaders and administrators to relinquish some autonomy to outside interests. And then there are the financial requirements.

“They’ve really got to be able to produce some serious revenue in order for somebody to be willing to put some money into them,” says Mark Hamm, CEO of EmCare Inpatient Services.

The lure of working for a private hospitalist company promises to continue to be an attractive one. Some are drawn by the leadership possibilities—those who “aspire to be the true alpha doctor,” as IPC’s Taylor puts it. Others are drawn by the stability of a larger company.

There also is flexibility in location, Dr. Holman notes.

“Now, with Cogent HMG, [hospitalists] have even more choices in terms of relocating within the same company,” he says. “So they can keep all of the benefits, keep all of the knowledge and familiarity of the system and philosophy of care that we employ, and just be able to transfer.”

continued below...

Dr. Houff says the majority of newly recruited physicians are coming out of residency but that the company is attracting physicians in the middle of their careers, along with physicians having backgrounds beyond internal medicine.

In Tallahassee at Capital Regional, Dr. Geers says that he feels there is support from the company that can protect his job quality, with “a little bit more room to negotiate with the hospital if the hospital wants us to take on new responsibilities.

“Whereas if we worked directly for the hospital, I don’t think we’d have much say in the matter,” he says.

He also says he is happy with the predictable schedule; he’s responsible for 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. and nothing more.

“If you’re finished rounding and you’ve seen all your patients and tied up all your loose ends, you’re not always there till 7 p.m.,” he points out. “Sometimes you can leave a little early....Once 7 p.m. comes, you’re not going to get paged in the middle of the night.”

Thomas R. Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.