User login

Congenital syphilis rates continue skyrocketing alongside other STDs

Rapidly increasing cases of newborn syphilis have reached their highest prevalence in 2 decades, according to a new report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on sexually transmitted disease surveillance in 2017.

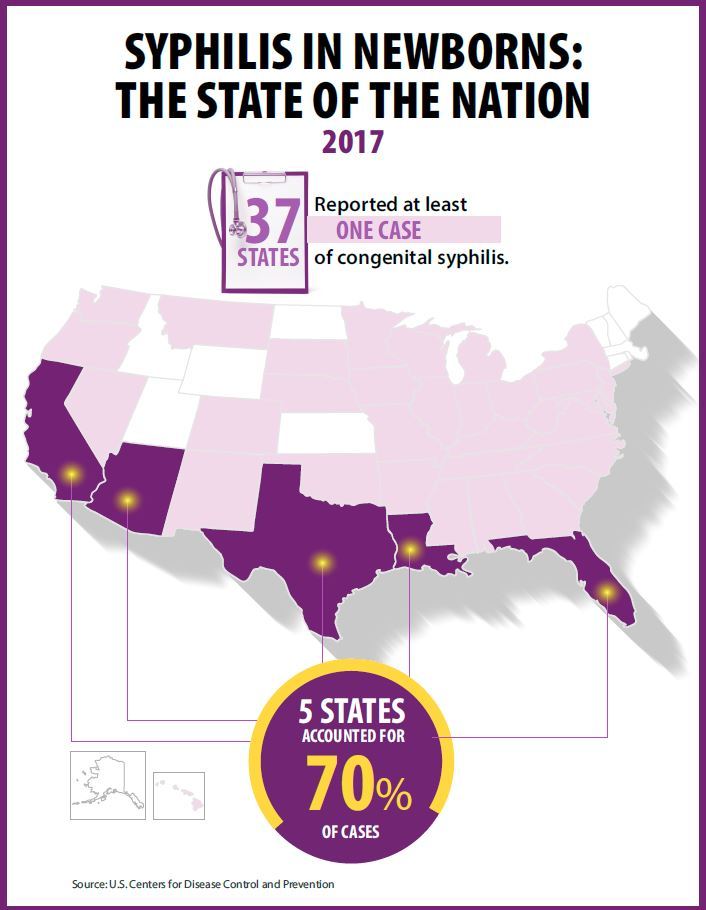

Newborn syphilis incidence has more than doubled, from 362 cases in 2013 to 918 cases in 2017, resulting in 64 syphilitic stillbirths and 13 infant deaths that year, according to data published in Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017.

At least one case was reported in 37 states last year, and the greatest burden of cases occurred in California, Arizona, Texas, Louisiana, and Florida, together accounting for 70% of all 2017 cases.

“The resurgence of syphilis, and particularly congenital syphilis, is not an arbitrary event, but rather a symptom of a deteriorating public health infrastructure and lack of access to health care,” wrote Gail Bolan, MD, director of the Division of STD Prevention at the CDC’s National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD and TB Prevention. “It is exposing hidden, fragile populations in need that are not getting the health care and preventive services they deserve.”

Dr. Bolan recommends modernizing surveillance to capture more of the cases in populations without ready access to diagnosis and treatment and in those choosing not to access care.

“It is imperative that federal, state, and local programs employ strategies that maximize long-term population impact by reducing STD incidence and promoting sexual, reproductive, maternal, and infant health,” she wrote. “Further, it will be important for us to measure and monitor the adverse health consequences of STDs, such as ocular and neurosyphilis, pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, infertility, HIV, congenital syphilis, and neonatal herpes.”

Multiple sources contributed data to the report: state and local STD programs’ notifiable disease reporting, private and federal national surveys, and specific projects that collect STD prevalence data, including the National Job Training Program, the STD Surveillance Network and the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project.

The four nationally notifiable STDs are chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and chancroid.

The rise in newborn syphilis cases, currently at 23.3 cases per 100,000 live births, mirrors the increased U.S. prevalence of both primary and secondary syphilis in 2017, with 9.5 cases per 100,000 people. Syphilis has increased every year since 2000-2001, when prevalence was at a record low.

Chlamydia and gonorrhea rates climb too

The report also noted increases in the prevalence of other STDs. Chlamydia, the most common STD, increased 6.9% as compared to 2016, with 528.8 cases per 100,000 people. This increase occurred in all U.S. regions and independently of sex, race, or ethnicity, though rates were highest in teens and young adults. Nearly two-thirds of chlamydia cases in 2017 occurred in people ages 15-24 years old.

Reported rates were higher in women than in men, likely due to women’s increased likelihood of undergoing screening, the report suggested. Better surveillance may also partly explain the climb in men’s cases.

“Increases in rates among men may reflect an increased number of men, including gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (collectively referred to as MSM) being tested and diagnosed with a chlamydial infection due to increased availability of urine testing and extragenital screening,” according to the report.

The CDC received reports of more than a half million gonorrhea infections in 2017 (555,608 cases), an increase of 18.6% since the previous year, including a 19.3% increase among men and a 17.8% increase among women.

“The magnitude of the increase among men suggests either increased transmission, increased case ascertainment (e.g., through increased extra-genital screening among MSM), or both,” the authors wrote. “The concurrent increase in cases reported among women suggests parallel increases in heterosexual transmission, increased screening among women, or both.”

Overall, gonorrhea cases have skyrocketed 75.2% since their historic low in 2009, compounding the problem of antibiotic resistance that has limited CDC-recommended treatment to just ceftriaxone and azithromycin.

The report was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors did not report having any disclosures.

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017; https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats

Rapidly increasing cases of newborn syphilis have reached their highest prevalence in 2 decades, according to a new report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on sexually transmitted disease surveillance in 2017.

Newborn syphilis incidence has more than doubled, from 362 cases in 2013 to 918 cases in 2017, resulting in 64 syphilitic stillbirths and 13 infant deaths that year, according to data published in Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017.

At least one case was reported in 37 states last year, and the greatest burden of cases occurred in California, Arizona, Texas, Louisiana, and Florida, together accounting for 70% of all 2017 cases.

“The resurgence of syphilis, and particularly congenital syphilis, is not an arbitrary event, but rather a symptom of a deteriorating public health infrastructure and lack of access to health care,” wrote Gail Bolan, MD, director of the Division of STD Prevention at the CDC’s National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD and TB Prevention. “It is exposing hidden, fragile populations in need that are not getting the health care and preventive services they deserve.”

Dr. Bolan recommends modernizing surveillance to capture more of the cases in populations without ready access to diagnosis and treatment and in those choosing not to access care.

“It is imperative that federal, state, and local programs employ strategies that maximize long-term population impact by reducing STD incidence and promoting sexual, reproductive, maternal, and infant health,” she wrote. “Further, it will be important for us to measure and monitor the adverse health consequences of STDs, such as ocular and neurosyphilis, pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, infertility, HIV, congenital syphilis, and neonatal herpes.”

Multiple sources contributed data to the report: state and local STD programs’ notifiable disease reporting, private and federal national surveys, and specific projects that collect STD prevalence data, including the National Job Training Program, the STD Surveillance Network and the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project.

The four nationally notifiable STDs are chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and chancroid.

The rise in newborn syphilis cases, currently at 23.3 cases per 100,000 live births, mirrors the increased U.S. prevalence of both primary and secondary syphilis in 2017, with 9.5 cases per 100,000 people. Syphilis has increased every year since 2000-2001, when prevalence was at a record low.

Chlamydia and gonorrhea rates climb too

The report also noted increases in the prevalence of other STDs. Chlamydia, the most common STD, increased 6.9% as compared to 2016, with 528.8 cases per 100,000 people. This increase occurred in all U.S. regions and independently of sex, race, or ethnicity, though rates were highest in teens and young adults. Nearly two-thirds of chlamydia cases in 2017 occurred in people ages 15-24 years old.

Reported rates were higher in women than in men, likely due to women’s increased likelihood of undergoing screening, the report suggested. Better surveillance may also partly explain the climb in men’s cases.

“Increases in rates among men may reflect an increased number of men, including gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (collectively referred to as MSM) being tested and diagnosed with a chlamydial infection due to increased availability of urine testing and extragenital screening,” according to the report.

The CDC received reports of more than a half million gonorrhea infections in 2017 (555,608 cases), an increase of 18.6% since the previous year, including a 19.3% increase among men and a 17.8% increase among women.

“The magnitude of the increase among men suggests either increased transmission, increased case ascertainment (e.g., through increased extra-genital screening among MSM), or both,” the authors wrote. “The concurrent increase in cases reported among women suggests parallel increases in heterosexual transmission, increased screening among women, or both.”

Overall, gonorrhea cases have skyrocketed 75.2% since their historic low in 2009, compounding the problem of antibiotic resistance that has limited CDC-recommended treatment to just ceftriaxone and azithromycin.

The report was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors did not report having any disclosures.

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017; https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats

Rapidly increasing cases of newborn syphilis have reached their highest prevalence in 2 decades, according to a new report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on sexually transmitted disease surveillance in 2017.

Newborn syphilis incidence has more than doubled, from 362 cases in 2013 to 918 cases in 2017, resulting in 64 syphilitic stillbirths and 13 infant deaths that year, according to data published in Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017.

At least one case was reported in 37 states last year, and the greatest burden of cases occurred in California, Arizona, Texas, Louisiana, and Florida, together accounting for 70% of all 2017 cases.

“The resurgence of syphilis, and particularly congenital syphilis, is not an arbitrary event, but rather a symptom of a deteriorating public health infrastructure and lack of access to health care,” wrote Gail Bolan, MD, director of the Division of STD Prevention at the CDC’s National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD and TB Prevention. “It is exposing hidden, fragile populations in need that are not getting the health care and preventive services they deserve.”

Dr. Bolan recommends modernizing surveillance to capture more of the cases in populations without ready access to diagnosis and treatment and in those choosing not to access care.

“It is imperative that federal, state, and local programs employ strategies that maximize long-term population impact by reducing STD incidence and promoting sexual, reproductive, maternal, and infant health,” she wrote. “Further, it will be important for us to measure and monitor the adverse health consequences of STDs, such as ocular and neurosyphilis, pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, infertility, HIV, congenital syphilis, and neonatal herpes.”

Multiple sources contributed data to the report: state and local STD programs’ notifiable disease reporting, private and federal national surveys, and specific projects that collect STD prevalence data, including the National Job Training Program, the STD Surveillance Network and the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project.

The four nationally notifiable STDs are chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and chancroid.

The rise in newborn syphilis cases, currently at 23.3 cases per 100,000 live births, mirrors the increased U.S. prevalence of both primary and secondary syphilis in 2017, with 9.5 cases per 100,000 people. Syphilis has increased every year since 2000-2001, when prevalence was at a record low.

Chlamydia and gonorrhea rates climb too

The report also noted increases in the prevalence of other STDs. Chlamydia, the most common STD, increased 6.9% as compared to 2016, with 528.8 cases per 100,000 people. This increase occurred in all U.S. regions and independently of sex, race, or ethnicity, though rates were highest in teens and young adults. Nearly two-thirds of chlamydia cases in 2017 occurred in people ages 15-24 years old.

Reported rates were higher in women than in men, likely due to women’s increased likelihood of undergoing screening, the report suggested. Better surveillance may also partly explain the climb in men’s cases.

“Increases in rates among men may reflect an increased number of men, including gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (collectively referred to as MSM) being tested and diagnosed with a chlamydial infection due to increased availability of urine testing and extragenital screening,” according to the report.

The CDC received reports of more than a half million gonorrhea infections in 2017 (555,608 cases), an increase of 18.6% since the previous year, including a 19.3% increase among men and a 17.8% increase among women.

“The magnitude of the increase among men suggests either increased transmission, increased case ascertainment (e.g., through increased extra-genital screening among MSM), or both,” the authors wrote. “The concurrent increase in cases reported among women suggests parallel increases in heterosexual transmission, increased screening among women, or both.”

Overall, gonorrhea cases have skyrocketed 75.2% since their historic low in 2009, compounding the problem of antibiotic resistance that has limited CDC-recommended treatment to just ceftriaxone and azithromycin.

The report was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors did not report having any disclosures.

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017; https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats

Key clinical point: Newborn syphilis cases have more than doubled in 5 years along with substantial increases in chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis.

Major finding: 918 cases of newborn syphilis were reported in 37 states in 2017.

Study details: The findings are based on data from public health notifiable disease reports and multiple federal and private surveillance projects.

Disclosures: The report was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors did not report having any disclosures.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017.

Pertussis vaccine at birth shows immune response, tolerability

compared with a group receiving only the hepatitis B vaccine, a randomized clinical trial from Australia has found.

“These results indicate that a birth dose of aP vaccine is immunogenic in newborns and significantly narrows the immunity gap between birth and 14 days after receipt of DTaP at 6 or 8 weeks of age, marking the critical period when infants are most vulnerable to severe pertussis infection,” reported Nicholas Wood, PhD, of the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance of Vaccine Preventable Diseases in New South Wales, Australia, and his colleagues.

“Administration of the acellular pertussis vaccine at birth has the potential to reduce severe morbidity from Bordetella pertussis infection in the first 3 months of life, especially for infants of mothers who have not received a pertussis vaccine during pregnancy,” the researchers concluded in JAMA Pediatrics.

The researchers enrolled 417 infants from Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, and Perth between June 2010 and March 2013 and randomized them to receive either the hepatitis B vaccine alone (n = 205) or the hepatitis B vaccine with a monovalent acellular pertussis vaccine (n = 212) within the first 5 days after birth. The randomization was stratified for mothers’ receipt of the Tdap before pregnancy.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends all newborns receive the hepatitis B vaccine shortly after birth and that pregnant women receive the Tdap vaccine during each pregnancy. There is not currently a monovalent acellular pertussis vaccine licensed in the United States.

The study infants then received the hexavalent DTaP-Hib-hep B-polio vaccine and the 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine at 6 weeks, 4 months, and 6 months.

The primary outcome was detectable levels of IgG antibody to pertussis toxin and pertactin at 10 weeks old.

Of the 206 infants receiving the pertussis vaccine at birth, 93% had detectable antibodies to pertussis toxin and pertactin at 10 weeks, compared with 51% of the 193 infants who received only the hepatitis B shot (P less than .001). Geometric mean concentration for pertussis toxin IgG also was four times higher in infants who received the pertussis vaccine at birth.

Adverse events were similar in the two groups both at birth and at 32 weeks, demonstrating that the pertussis birth dose is safe and tolerable.

“More important, in this study, the prevalence of fever after receipt of the birth dose, which can mistakenly be associated with potential sepsis and result in additional investigations in the neonatal period, was similar in both the group that received the aP vaccine at birth and the control group,” the authors reported.

A remaining question is the potential impact of maternal antibodies on protection from pertussis.

“The presence of maternal pertussis antibodies at birth can negatively affect postprimary responses to pertussis, diphtheria, and diphtheria-related CRM197 conjugate vaccines with a variety of infant immunization schedules and vaccines,” the authors noted. “The clinical significance of reductions in pertussis antibody related to maternal interference will require ongoing clinical evaluation, because there are no accepted serologic correlates of protection.”

The research was funded by a Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) grant, and several authors received NHMRC grants. One author also was supported by a Murdoch Children’s Research Institute Career Development Award. GlaxoSmithKline provided the vaccine and conducted the serologic assays. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wood N et al, JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Sep 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2349.

Pertussis is most likely to cause morbidity or kill neonates between birth and when they are given their first pertussis vaccine at 6-8 weeks of age. This is well known.

In the current study giving the acellular pertussis (aP) vaccine at birth led to “significantly higher antibody titers to pertussis antigens at 10 weeks of age,” compared with those who did not receive it. Those infants who received the birth dose of aP vaccine also had higher pertussis antibodies at 6 weeks, whether or not their mothers had received Tdap within 5 years prior to delivery.

When this study began in 2009, maternal immunization was not a well accepted concept, but this attitude has changed, in part due to the safe vaccination of pregnant women with the pandemic flu vaccine. Despite this, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2016 data showed that only 49% of pregnant women in the United Stated received Tdap. These rates need to increase.

Administering the aP vaccine with the existing hepatitis B vaccine at birth to infants whose mothers who did not receive Tdap during pregnancy would be a practical solution, if the aP vaccine were universally available.

But the aP vaccine currently is not available in the United States and many other countries as a standalone vaccine, and the administration of DTaP as a birth dose has been linked with “significant immune interference.” The aP vaccine could have a place in countries where it is available, and there is no maternal immunization program. Otherwise, boosting maternal immunization appears to be the primary approach for now.

Kathryn M. Edwards, MD, is the Sarah H. Sell and Cornelius Vanderbilt Chair in Pediatrics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville. She specializes in pediatric infectious diseases. These comments are a summary of her editorial accompanying the article by Wood et al. (Pediatrics. 2018 Sep 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2363). Dr. Edwards said she had no conflicts of interest.

Pertussis is most likely to cause morbidity or kill neonates between birth and when they are given their first pertussis vaccine at 6-8 weeks of age. This is well known.

In the current study giving the acellular pertussis (aP) vaccine at birth led to “significantly higher antibody titers to pertussis antigens at 10 weeks of age,” compared with those who did not receive it. Those infants who received the birth dose of aP vaccine also had higher pertussis antibodies at 6 weeks, whether or not their mothers had received Tdap within 5 years prior to delivery.

When this study began in 2009, maternal immunization was not a well accepted concept, but this attitude has changed, in part due to the safe vaccination of pregnant women with the pandemic flu vaccine. Despite this, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2016 data showed that only 49% of pregnant women in the United Stated received Tdap. These rates need to increase.

Administering the aP vaccine with the existing hepatitis B vaccine at birth to infants whose mothers who did not receive Tdap during pregnancy would be a practical solution, if the aP vaccine were universally available.

But the aP vaccine currently is not available in the United States and many other countries as a standalone vaccine, and the administration of DTaP as a birth dose has been linked with “significant immune interference.” The aP vaccine could have a place in countries where it is available, and there is no maternal immunization program. Otherwise, boosting maternal immunization appears to be the primary approach for now.

Kathryn M. Edwards, MD, is the Sarah H. Sell and Cornelius Vanderbilt Chair in Pediatrics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville. She specializes in pediatric infectious diseases. These comments are a summary of her editorial accompanying the article by Wood et al. (Pediatrics. 2018 Sep 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2363). Dr. Edwards said she had no conflicts of interest.

Pertussis is most likely to cause morbidity or kill neonates between birth and when they are given their first pertussis vaccine at 6-8 weeks of age. This is well known.

In the current study giving the acellular pertussis (aP) vaccine at birth led to “significantly higher antibody titers to pertussis antigens at 10 weeks of age,” compared with those who did not receive it. Those infants who received the birth dose of aP vaccine also had higher pertussis antibodies at 6 weeks, whether or not their mothers had received Tdap within 5 years prior to delivery.

When this study began in 2009, maternal immunization was not a well accepted concept, but this attitude has changed, in part due to the safe vaccination of pregnant women with the pandemic flu vaccine. Despite this, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2016 data showed that only 49% of pregnant women in the United Stated received Tdap. These rates need to increase.

Administering the aP vaccine with the existing hepatitis B vaccine at birth to infants whose mothers who did not receive Tdap during pregnancy would be a practical solution, if the aP vaccine were universally available.

But the aP vaccine currently is not available in the United States and many other countries as a standalone vaccine, and the administration of DTaP as a birth dose has been linked with “significant immune interference.” The aP vaccine could have a place in countries where it is available, and there is no maternal immunization program. Otherwise, boosting maternal immunization appears to be the primary approach for now.

Kathryn M. Edwards, MD, is the Sarah H. Sell and Cornelius Vanderbilt Chair in Pediatrics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville. She specializes in pediatric infectious diseases. These comments are a summary of her editorial accompanying the article by Wood et al. (Pediatrics. 2018 Sep 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2363). Dr. Edwards said she had no conflicts of interest.

compared with a group receiving only the hepatitis B vaccine, a randomized clinical trial from Australia has found.

“These results indicate that a birth dose of aP vaccine is immunogenic in newborns and significantly narrows the immunity gap between birth and 14 days after receipt of DTaP at 6 or 8 weeks of age, marking the critical period when infants are most vulnerable to severe pertussis infection,” reported Nicholas Wood, PhD, of the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance of Vaccine Preventable Diseases in New South Wales, Australia, and his colleagues.

“Administration of the acellular pertussis vaccine at birth has the potential to reduce severe morbidity from Bordetella pertussis infection in the first 3 months of life, especially for infants of mothers who have not received a pertussis vaccine during pregnancy,” the researchers concluded in JAMA Pediatrics.

The researchers enrolled 417 infants from Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, and Perth between June 2010 and March 2013 and randomized them to receive either the hepatitis B vaccine alone (n = 205) or the hepatitis B vaccine with a monovalent acellular pertussis vaccine (n = 212) within the first 5 days after birth. The randomization was stratified for mothers’ receipt of the Tdap before pregnancy.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends all newborns receive the hepatitis B vaccine shortly after birth and that pregnant women receive the Tdap vaccine during each pregnancy. There is not currently a monovalent acellular pertussis vaccine licensed in the United States.

The study infants then received the hexavalent DTaP-Hib-hep B-polio vaccine and the 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine at 6 weeks, 4 months, and 6 months.

The primary outcome was detectable levels of IgG antibody to pertussis toxin and pertactin at 10 weeks old.

Of the 206 infants receiving the pertussis vaccine at birth, 93% had detectable antibodies to pertussis toxin and pertactin at 10 weeks, compared with 51% of the 193 infants who received only the hepatitis B shot (P less than .001). Geometric mean concentration for pertussis toxin IgG also was four times higher in infants who received the pertussis vaccine at birth.

Adverse events were similar in the two groups both at birth and at 32 weeks, demonstrating that the pertussis birth dose is safe and tolerable.

“More important, in this study, the prevalence of fever after receipt of the birth dose, which can mistakenly be associated with potential sepsis and result in additional investigations in the neonatal period, was similar in both the group that received the aP vaccine at birth and the control group,” the authors reported.

A remaining question is the potential impact of maternal antibodies on protection from pertussis.

“The presence of maternal pertussis antibodies at birth can negatively affect postprimary responses to pertussis, diphtheria, and diphtheria-related CRM197 conjugate vaccines with a variety of infant immunization schedules and vaccines,” the authors noted. “The clinical significance of reductions in pertussis antibody related to maternal interference will require ongoing clinical evaluation, because there are no accepted serologic correlates of protection.”

The research was funded by a Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) grant, and several authors received NHMRC grants. One author also was supported by a Murdoch Children’s Research Institute Career Development Award. GlaxoSmithKline provided the vaccine and conducted the serologic assays. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wood N et al, JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Sep 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2349.

compared with a group receiving only the hepatitis B vaccine, a randomized clinical trial from Australia has found.

“These results indicate that a birth dose of aP vaccine is immunogenic in newborns and significantly narrows the immunity gap between birth and 14 days after receipt of DTaP at 6 or 8 weeks of age, marking the critical period when infants are most vulnerable to severe pertussis infection,” reported Nicholas Wood, PhD, of the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance of Vaccine Preventable Diseases in New South Wales, Australia, and his colleagues.

“Administration of the acellular pertussis vaccine at birth has the potential to reduce severe morbidity from Bordetella pertussis infection in the first 3 months of life, especially for infants of mothers who have not received a pertussis vaccine during pregnancy,” the researchers concluded in JAMA Pediatrics.

The researchers enrolled 417 infants from Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, and Perth between June 2010 and March 2013 and randomized them to receive either the hepatitis B vaccine alone (n = 205) or the hepatitis B vaccine with a monovalent acellular pertussis vaccine (n = 212) within the first 5 days after birth. The randomization was stratified for mothers’ receipt of the Tdap before pregnancy.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends all newborns receive the hepatitis B vaccine shortly after birth and that pregnant women receive the Tdap vaccine during each pregnancy. There is not currently a monovalent acellular pertussis vaccine licensed in the United States.

The study infants then received the hexavalent DTaP-Hib-hep B-polio vaccine and the 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine at 6 weeks, 4 months, and 6 months.

The primary outcome was detectable levels of IgG antibody to pertussis toxin and pertactin at 10 weeks old.

Of the 206 infants receiving the pertussis vaccine at birth, 93% had detectable antibodies to pertussis toxin and pertactin at 10 weeks, compared with 51% of the 193 infants who received only the hepatitis B shot (P less than .001). Geometric mean concentration for pertussis toxin IgG also was four times higher in infants who received the pertussis vaccine at birth.

Adverse events were similar in the two groups both at birth and at 32 weeks, demonstrating that the pertussis birth dose is safe and tolerable.

“More important, in this study, the prevalence of fever after receipt of the birth dose, which can mistakenly be associated with potential sepsis and result in additional investigations in the neonatal period, was similar in both the group that received the aP vaccine at birth and the control group,” the authors reported.

A remaining question is the potential impact of maternal antibodies on protection from pertussis.

“The presence of maternal pertussis antibodies at birth can negatively affect postprimary responses to pertussis, diphtheria, and diphtheria-related CRM197 conjugate vaccines with a variety of infant immunization schedules and vaccines,” the authors noted. “The clinical significance of reductions in pertussis antibody related to maternal interference will require ongoing clinical evaluation, because there are no accepted serologic correlates of protection.”

The research was funded by a Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) grant, and several authors received NHMRC grants. One author also was supported by a Murdoch Children’s Research Institute Career Development Award. GlaxoSmithKline provided the vaccine and conducted the serologic assays. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wood N et al, JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Sep 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2349.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: A monovalent acellular pertussis vaccine dose at birth appears safe, tolerable, and effective.

Major finding: 93% of 212 newborns receiving an acellular pertussis vaccine at birth showed antibodies against pertussis toxin and pertactin at 10 weeks, compared with 51% of 205 newborns without the birth dose.

Study details: The findings are based on a randomized controlled trial involving 417 healthy term newborns in four Australian cities from June 2010 to March 2013.

Disclosures: The research was funded by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) grant, and several authors received NHMRC grants. One author also was supported by a Murdoch Children’s Research Institute Career Development Award. GlaxoSmithKline provided the vaccine and conducted the serologic assays. The authors reporting having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wood N et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Sep. 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2349.

Russian Twitter bots and trolls amplify vaccine controversy

Russian trolls and bots significantly intensified the polarization of vaccine messaging on Twitter, fostering discord on the social network, according to researchers who analyzed the content of tweets over a 3-year period.

“Bots and trolls are actively involved in the online public health discourse, skewing discussions about vaccination,” wrote David A. Broniatowski, PhD, of George Washington University, Washington, D.C., and his associates.

in the American Journal of Public Health (Am J Public Health. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304567).

“This is vital knowledge for risk communicators, especially considering that neither members of the public nor algorithmic approaches may be able to easily identify bots, trolls, or cyborgs.”

The researchers conducted two content analyses and one qualitative analysis of tweets from July 2014 to September 2017. Their data set included 1% of all tweets during that time period and a sample of tweets containing vaccine-related keywords.

First they compared rates of vaccine-related tweets between bots and average users, and then they assessed the attitude of these tweets from different account types. Their qualitative case study focused on the use of the hashtag #vaccinateUS which was predominantly used by Russian trolls.

The researchers relied on seven publicly available lists to identify which accounts were bots or trolls and then compared them to randomly selected tweets posted in the same time period.

In their second analysis, the researchers used Botometer, a program created by the Indiana University Network Science Institute (IUNI) and the Center for Complex Networks and Systems Research (CNetS), to categorize tweets as very likely to be human, very likely to be bots, or of uncertain provenance.

Results revealed that Russian trolls, sophisticated bot accounts, and “content polluters” – those that spread malware and unsolicited content – are more likely than average users to tweet about vaccination. Content polluters tweeted more anti-vaccine messages while Russian trolls and sophisticated bots promoted both anti-vaccine and pro-vaccine messages that amplified the polarization (P less than .001).

The higher rate of antivaccine messages from content polluters suggested that antivaccine advocates may have exploited existing bot networks for their messaging.

“These accounts may also use the compelling nature of antivaccine content as clickbait to drive up advertising revenue and expose users to malware,” Dr. Broniatowski and colleagues wrote. “Antivaccine content may increase the risks of infection by both computer and biological viruses.”

The qualitative analysis of the #VaccinateUS hashtag found that 43% were provaccine, 38% were antivaccine and the other 19% were neutral.

“Whereas most non-neutral vaccine-relevant hashtags were clearly identifiable as either provaccine (#vaccineswork, #vaxwithme) or antivaccine (#Vaxxed, #b1less, #CDCWhistleblower), with limited appropriation by the opposing side, #VaccinateUS is unique in that it appears with very polarized messages on both sides,” the researchers reported.

Tweets using the #VaccinateUS hashtags were also more likely to contain grammatical errors, unnatural word choices, and irregular phrasing – but fewer spelling or punctuation errors than average tweets related to vaccines.

“The #VaccinateUS messages are also distinctive in that they contain no links to outside content, rare @mentions of other users, and no images (but occasionally use some emojis),” the researchers found.

Although messages with that hashtag “mirrored” Twitter’s overall vaccine discourse, subtle differences included greater emphasis on “freedom,” “democracy,” and “constitutional rights” than the more common “parental choice” focus of tweets using other vaccine-related hashtags. The conspiracy-theory targets of #VaccinateUS tweets also focused almost entirely on the U.S. government instead of a wide range of conspiracy theories at large, which was more common in other anti-vaccine tweets.

Antivaccine content was densest among accounts, with accounts falling in the middle bot category of uncertainty.

“Although we speculate that this set of accounts contains more sophisticated bots, trolls, and cyborgs, their provenance is ultimately unknown,” the researchers wrote. “Therefore, beyond attempting to prevent bots from spreading messages over social media, public health practitioners should focus on combating the messages themselves while not feeding the trolls.”

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were noted.

SOURCE: Broniatowski DA et al. Am J Public Health. 2018 Aug 23. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304567.

Russian trolls and bots significantly intensified the polarization of vaccine messaging on Twitter, fostering discord on the social network, according to researchers who analyzed the content of tweets over a 3-year period.

“Bots and trolls are actively involved in the online public health discourse, skewing discussions about vaccination,” wrote David A. Broniatowski, PhD, of George Washington University, Washington, D.C., and his associates.

in the American Journal of Public Health (Am J Public Health. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304567).

“This is vital knowledge for risk communicators, especially considering that neither members of the public nor algorithmic approaches may be able to easily identify bots, trolls, or cyborgs.”

The researchers conducted two content analyses and one qualitative analysis of tweets from July 2014 to September 2017. Their data set included 1% of all tweets during that time period and a sample of tweets containing vaccine-related keywords.

First they compared rates of vaccine-related tweets between bots and average users, and then they assessed the attitude of these tweets from different account types. Their qualitative case study focused on the use of the hashtag #vaccinateUS which was predominantly used by Russian trolls.

The researchers relied on seven publicly available lists to identify which accounts were bots or trolls and then compared them to randomly selected tweets posted in the same time period.

In their second analysis, the researchers used Botometer, a program created by the Indiana University Network Science Institute (IUNI) and the Center for Complex Networks and Systems Research (CNetS), to categorize tweets as very likely to be human, very likely to be bots, or of uncertain provenance.

Results revealed that Russian trolls, sophisticated bot accounts, and “content polluters” – those that spread malware and unsolicited content – are more likely than average users to tweet about vaccination. Content polluters tweeted more anti-vaccine messages while Russian trolls and sophisticated bots promoted both anti-vaccine and pro-vaccine messages that amplified the polarization (P less than .001).

The higher rate of antivaccine messages from content polluters suggested that antivaccine advocates may have exploited existing bot networks for their messaging.

“These accounts may also use the compelling nature of antivaccine content as clickbait to drive up advertising revenue and expose users to malware,” Dr. Broniatowski and colleagues wrote. “Antivaccine content may increase the risks of infection by both computer and biological viruses.”

The qualitative analysis of the #VaccinateUS hashtag found that 43% were provaccine, 38% were antivaccine and the other 19% were neutral.

“Whereas most non-neutral vaccine-relevant hashtags were clearly identifiable as either provaccine (#vaccineswork, #vaxwithme) or antivaccine (#Vaxxed, #b1less, #CDCWhistleblower), with limited appropriation by the opposing side, #VaccinateUS is unique in that it appears with very polarized messages on both sides,” the researchers reported.

Tweets using the #VaccinateUS hashtags were also more likely to contain grammatical errors, unnatural word choices, and irregular phrasing – but fewer spelling or punctuation errors than average tweets related to vaccines.

“The #VaccinateUS messages are also distinctive in that they contain no links to outside content, rare @mentions of other users, and no images (but occasionally use some emojis),” the researchers found.

Although messages with that hashtag “mirrored” Twitter’s overall vaccine discourse, subtle differences included greater emphasis on “freedom,” “democracy,” and “constitutional rights” than the more common “parental choice” focus of tweets using other vaccine-related hashtags. The conspiracy-theory targets of #VaccinateUS tweets also focused almost entirely on the U.S. government instead of a wide range of conspiracy theories at large, which was more common in other anti-vaccine tweets.

Antivaccine content was densest among accounts, with accounts falling in the middle bot category of uncertainty.

“Although we speculate that this set of accounts contains more sophisticated bots, trolls, and cyborgs, their provenance is ultimately unknown,” the researchers wrote. “Therefore, beyond attempting to prevent bots from spreading messages over social media, public health practitioners should focus on combating the messages themselves while not feeding the trolls.”

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were noted.

SOURCE: Broniatowski DA et al. Am J Public Health. 2018 Aug 23. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304567.

Russian trolls and bots significantly intensified the polarization of vaccine messaging on Twitter, fostering discord on the social network, according to researchers who analyzed the content of tweets over a 3-year period.

“Bots and trolls are actively involved in the online public health discourse, skewing discussions about vaccination,” wrote David A. Broniatowski, PhD, of George Washington University, Washington, D.C., and his associates.

in the American Journal of Public Health (Am J Public Health. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304567).

“This is vital knowledge for risk communicators, especially considering that neither members of the public nor algorithmic approaches may be able to easily identify bots, trolls, or cyborgs.”

The researchers conducted two content analyses and one qualitative analysis of tweets from July 2014 to September 2017. Their data set included 1% of all tweets during that time period and a sample of tweets containing vaccine-related keywords.

First they compared rates of vaccine-related tweets between bots and average users, and then they assessed the attitude of these tweets from different account types. Their qualitative case study focused on the use of the hashtag #vaccinateUS which was predominantly used by Russian trolls.

The researchers relied on seven publicly available lists to identify which accounts were bots or trolls and then compared them to randomly selected tweets posted in the same time period.

In their second analysis, the researchers used Botometer, a program created by the Indiana University Network Science Institute (IUNI) and the Center for Complex Networks and Systems Research (CNetS), to categorize tweets as very likely to be human, very likely to be bots, or of uncertain provenance.

Results revealed that Russian trolls, sophisticated bot accounts, and “content polluters” – those that spread malware and unsolicited content – are more likely than average users to tweet about vaccination. Content polluters tweeted more anti-vaccine messages while Russian trolls and sophisticated bots promoted both anti-vaccine and pro-vaccine messages that amplified the polarization (P less than .001).

The higher rate of antivaccine messages from content polluters suggested that antivaccine advocates may have exploited existing bot networks for their messaging.

“These accounts may also use the compelling nature of antivaccine content as clickbait to drive up advertising revenue and expose users to malware,” Dr. Broniatowski and colleagues wrote. “Antivaccine content may increase the risks of infection by both computer and biological viruses.”

The qualitative analysis of the #VaccinateUS hashtag found that 43% were provaccine, 38% were antivaccine and the other 19% were neutral.

“Whereas most non-neutral vaccine-relevant hashtags were clearly identifiable as either provaccine (#vaccineswork, #vaxwithme) or antivaccine (#Vaxxed, #b1less, #CDCWhistleblower), with limited appropriation by the opposing side, #VaccinateUS is unique in that it appears with very polarized messages on both sides,” the researchers reported.

Tweets using the #VaccinateUS hashtags were also more likely to contain grammatical errors, unnatural word choices, and irregular phrasing – but fewer spelling or punctuation errors than average tweets related to vaccines.

“The #VaccinateUS messages are also distinctive in that they contain no links to outside content, rare @mentions of other users, and no images (but occasionally use some emojis),” the researchers found.

Although messages with that hashtag “mirrored” Twitter’s overall vaccine discourse, subtle differences included greater emphasis on “freedom,” “democracy,” and “constitutional rights” than the more common “parental choice” focus of tweets using other vaccine-related hashtags. The conspiracy-theory targets of #VaccinateUS tweets also focused almost entirely on the U.S. government instead of a wide range of conspiracy theories at large, which was more common in other anti-vaccine tweets.

Antivaccine content was densest among accounts, with accounts falling in the middle bot category of uncertainty.

“Although we speculate that this set of accounts contains more sophisticated bots, trolls, and cyborgs, their provenance is ultimately unknown,” the researchers wrote. “Therefore, beyond attempting to prevent bots from spreading messages over social media, public health practitioners should focus on combating the messages themselves while not feeding the trolls.”

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were noted.

SOURCE: Broniatowski DA et al. Am J Public Health. 2018 Aug 23. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304567.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PUBLIC HEALTH

Key clinical point: Twitter bots and trolls are polluting social media vaccine discussions.

Major finding: Russian trolls and bots are more likely to amplify polarization of vaccine Twitter messaging while other trolls and bots are more likely to promote anti-vaccine messages and malware.

Study details: The findings are based on three content analyses of vaccine-related Twitter content samples from July 2014 to September 2017.

Disclosures: The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were noted.

Source: Broniatowski, D et al. Am J Public Health. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304567.

The second victim: More ob.gyn. organizations recognize need for support

When Patrice Weiss, MD, was a resident, a healthy, low-risk patient underwent what should have been an uncomplicated vaginal hysterectomy. But the patient developed a series of postoperative complications leading to multisystem organ failure and a lengthy stay in intensive care.

“None of us could really figure out how this happened. I still can’t figure out how this person who was relatively young developed all these complications,” said Dr. Weiss, now chief medical officer of Carilion Clinic and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine and Research Institute, both in Roanoke, Va. “There are times when you don’t know why something happened or what you could have done differently – and the answer may be nothing – but that dramatic, potentially very complicated outcome can really weigh on people. You still harbor those feelings of a second victim.”

It’s the health care professional who is that “second victim,” a term coined in 2000 by Albert W. Wu, MD, professor of public health at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, to describe an increasingly recognized phenomenon following unexpected adverse patient events, medical errors, or patient injuries (BMJ. 2000 Mar 18;320[7237]:726-7). The patients and their loved ones are the first victims, but a health care professional’s feelings of guilt, shame, inadequacy, and other powerful, complicated emotions can have long-lasting effects on his or her psyche, clinical practice, and career, particularly if he or she does not receive validation, support, and access to resources to work through the experience.

“Second victims ... become victimized in the sense that the provider is traumatized by the event,” Susan D. Scott, PhD, of the University of Missouri Health System, Columbia, and her colleagues wrote in a 2009 paper about the phenomenon (Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18[5]:325-30). “Frequently, these individuals feel personally responsible for the patient outcome. Many feel as though they have failed the patient, second-guessing their clinical skills and knowledge base,” they said.

It’s that latter part that can fester and potentially poison a health care professional’s ability to function, according to Charlie Jaynes, MD, senior director of medical operations for Ob Hospitalist Group in Greenville, S.C.

“ and therefore can have a direct effect on patient care and lead to poor outcomes,” Dr. Jaynes said. “It’s a very dangerous phenomenon because it can degrade the quality of medical care provided.”

Most physicians are trained to internalize and compartmentalize these experiences, to “suck it up and get on with it,” he said, but it’s now become clear that such a strategy can have disastrous professional and personal consequences.

“In the worst case scenario, people burn out, drop out or commit suicide, their marriage ends up in shambles, or they turn to drugs and alcohol,” Dr. Jaynes said. “What Dr. Wu did was open the box to allow some empathy and compassion to be introduced to the situation.”

Dangers of unaddressed second victim impact

Estimates vary widely on the prevalence of second victim phenomenon among physicians and nurses who have been involved in a medical error or unexpected serious outcome. Across the medical field, estimates range from 10% in a study among otolaryngologists (Laryngoscope. 2006 Jul;116[7]:1114-20) to up to 30% and 50% more broadly, although some fields may be more susceptible than others (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36[5]:233-40; BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21[4]:267-70).

“In the world of obstetrics, we spend 99.9% of our time in a happy field of medicine filled with joy and new life,” Dr. Weiss said. “Whether consciously or unconsciously, those become the expectations of the patients and the providers, so when there is an outcome that is less than optimal, that’s when you’re even more affected because of what your expectations are going into it.”

Dr. Scott and her colleagues noted that the stages of being a second victim are similar to the Kübler-Ross stages:

- Stage 1: Chaos and event repair.

- Stage 2: Intrusive thoughts, “what if.”

- Stage 3: Restoring personal identity.

- Stage 4: Enduring the inquisition.

- Stage 5: Obtaining emotional first aid.

- Stage 6: Moving on or dropping out; surviving and/or thriving.”

“This can go on for years. Someone can spend years just surviving and not thriving,” Dr. Weiss said. “It can really happen along a continuum.”

Although studies have not looked specifically at second victims and patient care, research has shown that second victims have a higher risk of burnout, and that physicians with high burnout tend to order more tests, spend less time with patients, and have greater risk of making medical errors, Dr. Weiss said.

A study looking at the emotional impact of medical errors on physicians found that 61% had greater anxiety about making future medical errors, 44% had a loss of confidence, 42% had trouble sleeping, and 42% were less satisfied in their job (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33[8]:467-76).

“You have the risk of the provider leaving medicine altogether or significantly changing their practice patterns, or giving up obstetric care because of the emotional toll it takes on providers,” she said. “We already know that one of the crises facing medicine right now is burnout, so you have the risk of additional or worsening burnout.”

Recognizing the need for formal support programs

Research does clearly show a need for programs formally addressing these experiences. A 2007 survey found that only 10% of 3,171 of internal medicine doctors, pediatricians, family physicians, and surgeons felt their health care organizations provided adequate support in managing stress following a medical error, yet about 8 in 10 wanted support (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33[8]:467-76).

Organizations are responding. One of the first second-victim programs is the “forYOU” program implemented at the University of Missouri Health Care’s Office of Clinical Effectiveness in 2007. The free, 24-7 program provides a “safe zone” for expressing emotions and reactions confidentially.

Ob Hospitalist Group just launched the CARE (Clinician Assistance, Recovery & Encouragement) Program, the first national peer-support program for second victims. The first 25 volunteers who underwent training in September will serve the organization’s more than 700 health care professionals across 32 states.

Instead of psychological counseling or intervention, the program emphasizes active listening, nonjudgment, and compassion during confidential calls; peers don’t take notes or record the conversations.

“We will be quiet and listen and speak at the appropriate times to be compassionate and not make judgments,” Dr. Jaynes said. “I think its critical to realize that in order to do that you have to be one of us. If you haven’t been there yourself when a baby dies in utero or you have a mother almost die by hemorrhage or a complication of surgery ... it creates emotional turmoil. Everybody who’s worth their salt questions, ‘What did I do wrong?’ and we’re really harsh on ourselves. If I can say I realize it’s a horrible place to be because I’ve been there myself, I can be a useful peer.”

At Dr. Weiss’s institution, Carilion Clinic spent 5 years developing and implementing the TRUST second-victim program, emphasizing Treatment, Respect, Understanding/compassion, Supportive care, and Transparency. Dr. Weiss said the first step in developing such a program is talking about the problem.

“You need hospital leadership addressing the phenomenon of the second victim, recognizing it is real, that it’s not a sign of weakness for providers to have any of these signs,” she said. “It has to be done at an organizational level. There has to be a place where providers can talk freely about the emotional impact of the outcome, not just the clinical outcomes.”

Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore published findings in September 2017 about its program RISE (Resilience In Stressful Events) (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017 Sep;43[9]:471-83 that was featured by the Joint Commission as a program that employs some of the tools the commission describes in its toolkit for health care organizations to develop second-victim support programs (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012 May;38[5]:235-40, 193).

It’s important that health care professionals are not expected or required to seek counseling or similar interventions, Dr. Weiss said, but they know of available resources.

“People need to be able to talk about it when they’re ready. It doesn’t necessarily matter how your peers judge your actions because these are feelings that come from within,” Dr. Weiss said, although colleagues can validate a second victim’s experience or feelings by sharing their own.

“It’s helpful when someone in a leadership role can acknowledge that this is real and say to a provider, ‘I’ve been there, and this is what helped me,’ or ‘I’ve been there, and there was no resource and I went without help for years,’ ” she said.

In fact, it’s her own past experiences that have made Dr. Weiss so passionate about raising awareness about second victims.

“I’ve been involved in cases of unanticipated outcomes and personally witnessed medical errors, and I’ve seen how very close colleagues can be affected,” she said. “This is a topic that really, really hits home for me.”

Signs and symptoms: How to recognize a possible second victim

Anyone can become a second victim, regardless of their training, experience, or years of practice, Dr. Weiss said. A health care professional may practice for years and witness many unanticipated poor outcomes before one suddenly drums up feelings they don’t expect.

“It’s almost inevitable that providers are going to have unanticipated outcomes or unexpected outcomes,” Dr. Weiss said. “The challenge with the second victim is no one can ever predict how someone is going to respond to an outcome, including ourselves. This may be the first time they have a response to something they never saw coming.”

Two aspects correlated with a higher risk of second victim are the severity of the morbidity or mortality of the patient and the degree of personal responsibility the health care professional feels. The signs and symptoms of being a second victim can be indistinguishable from those of depression, anxiety, or posttraumatic stress syndrome, but the biggest indicator is a change in a person’s normal behavior, Dr. Weiss said.

“The person who is never late to work is late to work. The person who is always mild-mannered is on edge,” she said. “A lot of it is subtle personality or behavior changes, or you begin to notice practice pattern differences, such as ordering a bunch of labs.”

Perhaps the providers are snapping at people when they’ve never snapped before, or they express more cynicism or sarcasm, she added. “A change in their sleeping or eating patterns or in their personal hygiene are all things that one could look for.”

According to Dr. Jaynes, emotional signs may include irritability, fear, anger, grief, remorse, frustration, desperation, numbness, guilt, loneliness, shock and feeling disconnected, feeling hopeless or out of control. Physical symptoms include headaches, muscle tension, chest pain, extreme fatigue, sleeping problems, appetite changes or gastrointestinal symptoms, dizziness, frequent illnesses, being easily startled, or increased heart rate, blood pressure, or breathing rate. Other possible signs include flashbacks, nightmares, social avoidance, difficulties concentrating, poor memory, avoiding patient care areas, fearing repercussions to their reputations, and decreased job satisfaction. Second victims also may experience a loss in confidence or spiritual connection, or loss of interest in work, usual activities, and connections with others.

Dr. Weiss and Dr. Jaynes said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

When Patrice Weiss, MD, was a resident, a healthy, low-risk patient underwent what should have been an uncomplicated vaginal hysterectomy. But the patient developed a series of postoperative complications leading to multisystem organ failure and a lengthy stay in intensive care.

“None of us could really figure out how this happened. I still can’t figure out how this person who was relatively young developed all these complications,” said Dr. Weiss, now chief medical officer of Carilion Clinic and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine and Research Institute, both in Roanoke, Va. “There are times when you don’t know why something happened or what you could have done differently – and the answer may be nothing – but that dramatic, potentially very complicated outcome can really weigh on people. You still harbor those feelings of a second victim.”

It’s the health care professional who is that “second victim,” a term coined in 2000 by Albert W. Wu, MD, professor of public health at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, to describe an increasingly recognized phenomenon following unexpected adverse patient events, medical errors, or patient injuries (BMJ. 2000 Mar 18;320[7237]:726-7). The patients and their loved ones are the first victims, but a health care professional’s feelings of guilt, shame, inadequacy, and other powerful, complicated emotions can have long-lasting effects on his or her psyche, clinical practice, and career, particularly if he or she does not receive validation, support, and access to resources to work through the experience.

“Second victims ... become victimized in the sense that the provider is traumatized by the event,” Susan D. Scott, PhD, of the University of Missouri Health System, Columbia, and her colleagues wrote in a 2009 paper about the phenomenon (Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18[5]:325-30). “Frequently, these individuals feel personally responsible for the patient outcome. Many feel as though they have failed the patient, second-guessing their clinical skills and knowledge base,” they said.

It’s that latter part that can fester and potentially poison a health care professional’s ability to function, according to Charlie Jaynes, MD, senior director of medical operations for Ob Hospitalist Group in Greenville, S.C.

“ and therefore can have a direct effect on patient care and lead to poor outcomes,” Dr. Jaynes said. “It’s a very dangerous phenomenon because it can degrade the quality of medical care provided.”

Most physicians are trained to internalize and compartmentalize these experiences, to “suck it up and get on with it,” he said, but it’s now become clear that such a strategy can have disastrous professional and personal consequences.

“In the worst case scenario, people burn out, drop out or commit suicide, their marriage ends up in shambles, or they turn to drugs and alcohol,” Dr. Jaynes said. “What Dr. Wu did was open the box to allow some empathy and compassion to be introduced to the situation.”

Dangers of unaddressed second victim impact

Estimates vary widely on the prevalence of second victim phenomenon among physicians and nurses who have been involved in a medical error or unexpected serious outcome. Across the medical field, estimates range from 10% in a study among otolaryngologists (Laryngoscope. 2006 Jul;116[7]:1114-20) to up to 30% and 50% more broadly, although some fields may be more susceptible than others (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36[5]:233-40; BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21[4]:267-70).

“In the world of obstetrics, we spend 99.9% of our time in a happy field of medicine filled with joy and new life,” Dr. Weiss said. “Whether consciously or unconsciously, those become the expectations of the patients and the providers, so when there is an outcome that is less than optimal, that’s when you’re even more affected because of what your expectations are going into it.”

Dr. Scott and her colleagues noted that the stages of being a second victim are similar to the Kübler-Ross stages:

- Stage 1: Chaos and event repair.

- Stage 2: Intrusive thoughts, “what if.”

- Stage 3: Restoring personal identity.

- Stage 4: Enduring the inquisition.

- Stage 5: Obtaining emotional first aid.

- Stage 6: Moving on or dropping out; surviving and/or thriving.”

“This can go on for years. Someone can spend years just surviving and not thriving,” Dr. Weiss said. “It can really happen along a continuum.”

Although studies have not looked specifically at second victims and patient care, research has shown that second victims have a higher risk of burnout, and that physicians with high burnout tend to order more tests, spend less time with patients, and have greater risk of making medical errors, Dr. Weiss said.

A study looking at the emotional impact of medical errors on physicians found that 61% had greater anxiety about making future medical errors, 44% had a loss of confidence, 42% had trouble sleeping, and 42% were less satisfied in their job (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33[8]:467-76).

“You have the risk of the provider leaving medicine altogether or significantly changing their practice patterns, or giving up obstetric care because of the emotional toll it takes on providers,” she said. “We already know that one of the crises facing medicine right now is burnout, so you have the risk of additional or worsening burnout.”

Recognizing the need for formal support programs

Research does clearly show a need for programs formally addressing these experiences. A 2007 survey found that only 10% of 3,171 of internal medicine doctors, pediatricians, family physicians, and surgeons felt their health care organizations provided adequate support in managing stress following a medical error, yet about 8 in 10 wanted support (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33[8]:467-76).

Organizations are responding. One of the first second-victim programs is the “forYOU” program implemented at the University of Missouri Health Care’s Office of Clinical Effectiveness in 2007. The free, 24-7 program provides a “safe zone” for expressing emotions and reactions confidentially.

Ob Hospitalist Group just launched the CARE (Clinician Assistance, Recovery & Encouragement) Program, the first national peer-support program for second victims. The first 25 volunteers who underwent training in September will serve the organization’s more than 700 health care professionals across 32 states.

Instead of psychological counseling or intervention, the program emphasizes active listening, nonjudgment, and compassion during confidential calls; peers don’t take notes or record the conversations.

“We will be quiet and listen and speak at the appropriate times to be compassionate and not make judgments,” Dr. Jaynes said. “I think its critical to realize that in order to do that you have to be one of us. If you haven’t been there yourself when a baby dies in utero or you have a mother almost die by hemorrhage or a complication of surgery ... it creates emotional turmoil. Everybody who’s worth their salt questions, ‘What did I do wrong?’ and we’re really harsh on ourselves. If I can say I realize it’s a horrible place to be because I’ve been there myself, I can be a useful peer.”

At Dr. Weiss’s institution, Carilion Clinic spent 5 years developing and implementing the TRUST second-victim program, emphasizing Treatment, Respect, Understanding/compassion, Supportive care, and Transparency. Dr. Weiss said the first step in developing such a program is talking about the problem.

“You need hospital leadership addressing the phenomenon of the second victim, recognizing it is real, that it’s not a sign of weakness for providers to have any of these signs,” she said. “It has to be done at an organizational level. There has to be a place where providers can talk freely about the emotional impact of the outcome, not just the clinical outcomes.”

Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore published findings in September 2017 about its program RISE (Resilience In Stressful Events) (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017 Sep;43[9]:471-83 that was featured by the Joint Commission as a program that employs some of the tools the commission describes in its toolkit for health care organizations to develop second-victim support programs (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012 May;38[5]:235-40, 193).

It’s important that health care professionals are not expected or required to seek counseling or similar interventions, Dr. Weiss said, but they know of available resources.

“People need to be able to talk about it when they’re ready. It doesn’t necessarily matter how your peers judge your actions because these are feelings that come from within,” Dr. Weiss said, although colleagues can validate a second victim’s experience or feelings by sharing their own.

“It’s helpful when someone in a leadership role can acknowledge that this is real and say to a provider, ‘I’ve been there, and this is what helped me,’ or ‘I’ve been there, and there was no resource and I went without help for years,’ ” she said.

In fact, it’s her own past experiences that have made Dr. Weiss so passionate about raising awareness about second victims.

“I’ve been involved in cases of unanticipated outcomes and personally witnessed medical errors, and I’ve seen how very close colleagues can be affected,” she said. “This is a topic that really, really hits home for me.”

Signs and symptoms: How to recognize a possible second victim

Anyone can become a second victim, regardless of their training, experience, or years of practice, Dr. Weiss said. A health care professional may practice for years and witness many unanticipated poor outcomes before one suddenly drums up feelings they don’t expect.

“It’s almost inevitable that providers are going to have unanticipated outcomes or unexpected outcomes,” Dr. Weiss said. “The challenge with the second victim is no one can ever predict how someone is going to respond to an outcome, including ourselves. This may be the first time they have a response to something they never saw coming.”

Two aspects correlated with a higher risk of second victim are the severity of the morbidity or mortality of the patient and the degree of personal responsibility the health care professional feels. The signs and symptoms of being a second victim can be indistinguishable from those of depression, anxiety, or posttraumatic stress syndrome, but the biggest indicator is a change in a person’s normal behavior, Dr. Weiss said.

“The person who is never late to work is late to work. The person who is always mild-mannered is on edge,” she said. “A lot of it is subtle personality or behavior changes, or you begin to notice practice pattern differences, such as ordering a bunch of labs.”

Perhaps the providers are snapping at people when they’ve never snapped before, or they express more cynicism or sarcasm, she added. “A change in their sleeping or eating patterns or in their personal hygiene are all things that one could look for.”

According to Dr. Jaynes, emotional signs may include irritability, fear, anger, grief, remorse, frustration, desperation, numbness, guilt, loneliness, shock and feeling disconnected, feeling hopeless or out of control. Physical symptoms include headaches, muscle tension, chest pain, extreme fatigue, sleeping problems, appetite changes or gastrointestinal symptoms, dizziness, frequent illnesses, being easily startled, or increased heart rate, blood pressure, or breathing rate. Other possible signs include flashbacks, nightmares, social avoidance, difficulties concentrating, poor memory, avoiding patient care areas, fearing repercussions to their reputations, and decreased job satisfaction. Second victims also may experience a loss in confidence or spiritual connection, or loss of interest in work, usual activities, and connections with others.

Dr. Weiss and Dr. Jaynes said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

When Patrice Weiss, MD, was a resident, a healthy, low-risk patient underwent what should have been an uncomplicated vaginal hysterectomy. But the patient developed a series of postoperative complications leading to multisystem organ failure and a lengthy stay in intensive care.

“None of us could really figure out how this happened. I still can’t figure out how this person who was relatively young developed all these complications,” said Dr. Weiss, now chief medical officer of Carilion Clinic and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine and Research Institute, both in Roanoke, Va. “There are times when you don’t know why something happened or what you could have done differently – and the answer may be nothing – but that dramatic, potentially very complicated outcome can really weigh on people. You still harbor those feelings of a second victim.”

It’s the health care professional who is that “second victim,” a term coined in 2000 by Albert W. Wu, MD, professor of public health at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, to describe an increasingly recognized phenomenon following unexpected adverse patient events, medical errors, or patient injuries (BMJ. 2000 Mar 18;320[7237]:726-7). The patients and their loved ones are the first victims, but a health care professional’s feelings of guilt, shame, inadequacy, and other powerful, complicated emotions can have long-lasting effects on his or her psyche, clinical practice, and career, particularly if he or she does not receive validation, support, and access to resources to work through the experience.

“Second victims ... become victimized in the sense that the provider is traumatized by the event,” Susan D. Scott, PhD, of the University of Missouri Health System, Columbia, and her colleagues wrote in a 2009 paper about the phenomenon (Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18[5]:325-30). “Frequently, these individuals feel personally responsible for the patient outcome. Many feel as though they have failed the patient, second-guessing their clinical skills and knowledge base,” they said.

It’s that latter part that can fester and potentially poison a health care professional’s ability to function, according to Charlie Jaynes, MD, senior director of medical operations for Ob Hospitalist Group in Greenville, S.C.

“ and therefore can have a direct effect on patient care and lead to poor outcomes,” Dr. Jaynes said. “It’s a very dangerous phenomenon because it can degrade the quality of medical care provided.”

Most physicians are trained to internalize and compartmentalize these experiences, to “suck it up and get on with it,” he said, but it’s now become clear that such a strategy can have disastrous professional and personal consequences.

“In the worst case scenario, people burn out, drop out or commit suicide, their marriage ends up in shambles, or they turn to drugs and alcohol,” Dr. Jaynes said. “What Dr. Wu did was open the box to allow some empathy and compassion to be introduced to the situation.”

Dangers of unaddressed second victim impact

Estimates vary widely on the prevalence of second victim phenomenon among physicians and nurses who have been involved in a medical error or unexpected serious outcome. Across the medical field, estimates range from 10% in a study among otolaryngologists (Laryngoscope. 2006 Jul;116[7]:1114-20) to up to 30% and 50% more broadly, although some fields may be more susceptible than others (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36[5]:233-40; BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21[4]:267-70).

“In the world of obstetrics, we spend 99.9% of our time in a happy field of medicine filled with joy and new life,” Dr. Weiss said. “Whether consciously or unconsciously, those become the expectations of the patients and the providers, so when there is an outcome that is less than optimal, that’s when you’re even more affected because of what your expectations are going into it.”

Dr. Scott and her colleagues noted that the stages of being a second victim are similar to the Kübler-Ross stages:

- Stage 1: Chaos and event repair.

- Stage 2: Intrusive thoughts, “what if.”

- Stage 3: Restoring personal identity.

- Stage 4: Enduring the inquisition.

- Stage 5: Obtaining emotional first aid.

- Stage 6: Moving on or dropping out; surviving and/or thriving.”

“This can go on for years. Someone can spend years just surviving and not thriving,” Dr. Weiss said. “It can really happen along a continuum.”

Although studies have not looked specifically at second victims and patient care, research has shown that second victims have a higher risk of burnout, and that physicians with high burnout tend to order more tests, spend less time with patients, and have greater risk of making medical errors, Dr. Weiss said.

A study looking at the emotional impact of medical errors on physicians found that 61% had greater anxiety about making future medical errors, 44% had a loss of confidence, 42% had trouble sleeping, and 42% were less satisfied in their job (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33[8]:467-76).

“You have the risk of the provider leaving medicine altogether or significantly changing their practice patterns, or giving up obstetric care because of the emotional toll it takes on providers,” she said. “We already know that one of the crises facing medicine right now is burnout, so you have the risk of additional or worsening burnout.”

Recognizing the need for formal support programs

Research does clearly show a need for programs formally addressing these experiences. A 2007 survey found that only 10% of 3,171 of internal medicine doctors, pediatricians, family physicians, and surgeons felt their health care organizations provided adequate support in managing stress following a medical error, yet about 8 in 10 wanted support (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33[8]:467-76).

Organizations are responding. One of the first second-victim programs is the “forYOU” program implemented at the University of Missouri Health Care’s Office of Clinical Effectiveness in 2007. The free, 24-7 program provides a “safe zone” for expressing emotions and reactions confidentially.

Ob Hospitalist Group just launched the CARE (Clinician Assistance, Recovery & Encouragement) Program, the first national peer-support program for second victims. The first 25 volunteers who underwent training in September will serve the organization’s more than 700 health care professionals across 32 states.

Instead of psychological counseling or intervention, the program emphasizes active listening, nonjudgment, and compassion during confidential calls; peers don’t take notes or record the conversations.

“We will be quiet and listen and speak at the appropriate times to be compassionate and not make judgments,” Dr. Jaynes said. “I think its critical to realize that in order to do that you have to be one of us. If you haven’t been there yourself when a baby dies in utero or you have a mother almost die by hemorrhage or a complication of surgery ... it creates emotional turmoil. Everybody who’s worth their salt questions, ‘What did I do wrong?’ and we’re really harsh on ourselves. If I can say I realize it’s a horrible place to be because I’ve been there myself, I can be a useful peer.”