User login

Preleukemic Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: A Case Report and Literature Review

Background

CML is usually classified in chronic phase (CP), accelerated phase (AP) and/or Blast phase (BP). Studies have described another provisional entity as Preleukemic phase of CML which precedes CP and is without leukocytosis and blood features of CP phase of CML. Here we will present a case of metastatic prostate cancer, where next-generation sequencing showed BCR-ABL1 but no overt leukocytosis and then later developed clinical CML after 11 months.

Case Presentation

Our patient was 87-yr-old male with history of metastatic prostate cancer, who presented with elevated PSA levels and new bony metastasis. He underwent next-generation-sequencing (foundation one liquid cdx) in April 2022. It did not show reportable alterations related to prostate cancer but BCR-ABL1 (p210) fusion was detected. It also showed ASXL1-S846fs5 and TET2-Q1548 that are also markers of clonal hematopoiesis. In March 2023 (11 months after the finding of BCR-ABL1), he developed asymptomatic leukocytosis, Workup showed BCR-ABL1(210) of 44% in peripheral blood and bone marrow showed 9% blasts. He was started on Imatinib after shared decision-making and considering the toxicity profile and comorbidities. He followed up regularly with improvement in leukocytosis.

Discussion

The diagnosis of CML is first suspected by typical findings in blood and/or bone marrow and then confirmed by presence of Philadelphia chromosome. Along with chronic and accelerated phases, there is another term described in few cases called “preleukemic or smoldering or aleukemic phase.” This is not a wellestablished term but mostly defined as normal leukocyte count with presence of BCR/ABL1 fusion gene/ ph chromosome. Preleukemic phase of CML is mostly underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed. Our case is unique in that BCR/ABL1 fusion was detected incidentally on next-generation sequencing and patient progressed to chronic phase of CML 11 months later. Upon literature review, few case reports and case series documenting aleukemic/preleukemic phase of CML but timing from the appearance of BCR/ABL1 mutation to actual development to leukocytosis is not well documented. Especially in the era of NGS testing, patients with incidental BCR-ABL1 should be evaluated further irrespective of normal WBC. Further studies need to be done to recognize this early and decrease the delay in treatment.

Background

CML is usually classified in chronic phase (CP), accelerated phase (AP) and/or Blast phase (BP). Studies have described another provisional entity as Preleukemic phase of CML which precedes CP and is without leukocytosis and blood features of CP phase of CML. Here we will present a case of metastatic prostate cancer, where next-generation sequencing showed BCR-ABL1 but no overt leukocytosis and then later developed clinical CML after 11 months.

Case Presentation

Our patient was 87-yr-old male with history of metastatic prostate cancer, who presented with elevated PSA levels and new bony metastasis. He underwent next-generation-sequencing (foundation one liquid cdx) in April 2022. It did not show reportable alterations related to prostate cancer but BCR-ABL1 (p210) fusion was detected. It also showed ASXL1-S846fs5 and TET2-Q1548 that are also markers of clonal hematopoiesis. In March 2023 (11 months after the finding of BCR-ABL1), he developed asymptomatic leukocytosis, Workup showed BCR-ABL1(210) of 44% in peripheral blood and bone marrow showed 9% blasts. He was started on Imatinib after shared decision-making and considering the toxicity profile and comorbidities. He followed up regularly with improvement in leukocytosis.

Discussion

The diagnosis of CML is first suspected by typical findings in blood and/or bone marrow and then confirmed by presence of Philadelphia chromosome. Along with chronic and accelerated phases, there is another term described in few cases called “preleukemic or smoldering or aleukemic phase.” This is not a wellestablished term but mostly defined as normal leukocyte count with presence of BCR/ABL1 fusion gene/ ph chromosome. Preleukemic phase of CML is mostly underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed. Our case is unique in that BCR/ABL1 fusion was detected incidentally on next-generation sequencing and patient progressed to chronic phase of CML 11 months later. Upon literature review, few case reports and case series documenting aleukemic/preleukemic phase of CML but timing from the appearance of BCR/ABL1 mutation to actual development to leukocytosis is not well documented. Especially in the era of NGS testing, patients with incidental BCR-ABL1 should be evaluated further irrespective of normal WBC. Further studies need to be done to recognize this early and decrease the delay in treatment.

Background

CML is usually classified in chronic phase (CP), accelerated phase (AP) and/or Blast phase (BP). Studies have described another provisional entity as Preleukemic phase of CML which precedes CP and is without leukocytosis and blood features of CP phase of CML. Here we will present a case of metastatic prostate cancer, where next-generation sequencing showed BCR-ABL1 but no overt leukocytosis and then later developed clinical CML after 11 months.

Case Presentation

Our patient was 87-yr-old male with history of metastatic prostate cancer, who presented with elevated PSA levels and new bony metastasis. He underwent next-generation-sequencing (foundation one liquid cdx) in April 2022. It did not show reportable alterations related to prostate cancer but BCR-ABL1 (p210) fusion was detected. It also showed ASXL1-S846fs5 and TET2-Q1548 that are also markers of clonal hematopoiesis. In March 2023 (11 months after the finding of BCR-ABL1), he developed asymptomatic leukocytosis, Workup showed BCR-ABL1(210) of 44% in peripheral blood and bone marrow showed 9% blasts. He was started on Imatinib after shared decision-making and considering the toxicity profile and comorbidities. He followed up regularly with improvement in leukocytosis.

Discussion

The diagnosis of CML is first suspected by typical findings in blood and/or bone marrow and then confirmed by presence of Philadelphia chromosome. Along with chronic and accelerated phases, there is another term described in few cases called “preleukemic or smoldering or aleukemic phase.” This is not a wellestablished term but mostly defined as normal leukocyte count with presence of BCR/ABL1 fusion gene/ ph chromosome. Preleukemic phase of CML is mostly underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed. Our case is unique in that BCR/ABL1 fusion was detected incidentally on next-generation sequencing and patient progressed to chronic phase of CML 11 months later. Upon literature review, few case reports and case series documenting aleukemic/preleukemic phase of CML but timing from the appearance of BCR/ABL1 mutation to actual development to leukocytosis is not well documented. Especially in the era of NGS testing, patients with incidental BCR-ABL1 should be evaluated further irrespective of normal WBC. Further studies need to be done to recognize this early and decrease the delay in treatment.

Male Patient With a History of Monoclonal B Cell Lymphocytosis Presenting with Breast Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma: A Case Report and Literature Review

Background

Monoclonal B cell lymphocytosis (MBL) is defined as presence of clonal b cell population that is fewer than 5 × 10(9)/L B-cells in peripheral blood and no other signs of a lymphoproliferative disorder. Patients with MBL are usually monitored with periodic history, physical exam and blood counts. Here we presented a case of chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) in breast in a patient with a history of MBL.

Case Presentation

68-year-old male with history of MBL underwent mammogram for breast mass. It showed suspicious 4.4 x 1.6 cm solid and cystic lesion containing a 1.7 x 0.9 x 1.8 cm solid hypervascular mass. Patient underwent left breast mass excision. Histologic sections focus of ADH involving papilloma with uninvolved margins. Lymphoid infiltrates noted had CLL/SLL immunophenotype and that it consists mostly of small B cells positive for CD5, CD20, CD23, CD43, Bcl-2, LEF1. CT CAP and PET/CT were negative for lymphadenopathy. Bone marrow biopsy showed marrow involvement by mature B-cell lymphoproliferative process, immunophenotypically consistent with CLL/SLL. As intra-ductal papilloma completely excised and hemogram was normal tumor board recommended surveillance only for CLL/SLL.

Discussion

MBL can progress to CLL, but it can rarely be presented as an extra-nodal mass in solid organs. We described a case of MBL that progressed to CLL/ SLL in breast mass in a male patient. This is the first reported case in literature where MBL progressed to CLL/ SLL of breast without lymphadenopathy. Upon literature review 8 case reports were found where CLL/SLL were described in breast tissue. 7 of them were in females and 1 one was in male. Two patients had CLL before breast mass but none of them had a history of MBL. 3 described cases in females had CLL/SLL infiltration of breast along with invasive ductal carcinoma. So, a patient with MBL can progress to involve solid organs despite no absolute lymphocytosis and should be considered in differentials of a new mass. Although more common in females, but it can occur in males as well. It’s important to consider the possibility of both CLL/SLL and breast cancer existing simultaneously.

Background

Monoclonal B cell lymphocytosis (MBL) is defined as presence of clonal b cell population that is fewer than 5 × 10(9)/L B-cells in peripheral blood and no other signs of a lymphoproliferative disorder. Patients with MBL are usually monitored with periodic history, physical exam and blood counts. Here we presented a case of chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) in breast in a patient with a history of MBL.

Case Presentation

68-year-old male with history of MBL underwent mammogram for breast mass. It showed suspicious 4.4 x 1.6 cm solid and cystic lesion containing a 1.7 x 0.9 x 1.8 cm solid hypervascular mass. Patient underwent left breast mass excision. Histologic sections focus of ADH involving papilloma with uninvolved margins. Lymphoid infiltrates noted had CLL/SLL immunophenotype and that it consists mostly of small B cells positive for CD5, CD20, CD23, CD43, Bcl-2, LEF1. CT CAP and PET/CT were negative for lymphadenopathy. Bone marrow biopsy showed marrow involvement by mature B-cell lymphoproliferative process, immunophenotypically consistent with CLL/SLL. As intra-ductal papilloma completely excised and hemogram was normal tumor board recommended surveillance only for CLL/SLL.

Discussion

MBL can progress to CLL, but it can rarely be presented as an extra-nodal mass in solid organs. We described a case of MBL that progressed to CLL/ SLL in breast mass in a male patient. This is the first reported case in literature where MBL progressed to CLL/ SLL of breast without lymphadenopathy. Upon literature review 8 case reports were found where CLL/SLL were described in breast tissue. 7 of them were in females and 1 one was in male. Two patients had CLL before breast mass but none of them had a history of MBL. 3 described cases in females had CLL/SLL infiltration of breast along with invasive ductal carcinoma. So, a patient with MBL can progress to involve solid organs despite no absolute lymphocytosis and should be considered in differentials of a new mass. Although more common in females, but it can occur in males as well. It’s important to consider the possibility of both CLL/SLL and breast cancer existing simultaneously.

Background

Monoclonal B cell lymphocytosis (MBL) is defined as presence of clonal b cell population that is fewer than 5 × 10(9)/L B-cells in peripheral blood and no other signs of a lymphoproliferative disorder. Patients with MBL are usually monitored with periodic history, physical exam and blood counts. Here we presented a case of chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) in breast in a patient with a history of MBL.

Case Presentation

68-year-old male with history of MBL underwent mammogram for breast mass. It showed suspicious 4.4 x 1.6 cm solid and cystic lesion containing a 1.7 x 0.9 x 1.8 cm solid hypervascular mass. Patient underwent left breast mass excision. Histologic sections focus of ADH involving papilloma with uninvolved margins. Lymphoid infiltrates noted had CLL/SLL immunophenotype and that it consists mostly of small B cells positive for CD5, CD20, CD23, CD43, Bcl-2, LEF1. CT CAP and PET/CT were negative for lymphadenopathy. Bone marrow biopsy showed marrow involvement by mature B-cell lymphoproliferative process, immunophenotypically consistent with CLL/SLL. As intra-ductal papilloma completely excised and hemogram was normal tumor board recommended surveillance only for CLL/SLL.

Discussion

MBL can progress to CLL, but it can rarely be presented as an extra-nodal mass in solid organs. We described a case of MBL that progressed to CLL/ SLL in breast mass in a male patient. This is the first reported case in literature where MBL progressed to CLL/ SLL of breast without lymphadenopathy. Upon literature review 8 case reports were found where CLL/SLL were described in breast tissue. 7 of them were in females and 1 one was in male. Two patients had CLL before breast mass but none of them had a history of MBL. 3 described cases in females had CLL/SLL infiltration of breast along with invasive ductal carcinoma. So, a patient with MBL can progress to involve solid organs despite no absolute lymphocytosis and should be considered in differentials of a new mass. Although more common in females, but it can occur in males as well. It’s important to consider the possibility of both CLL/SLL and breast cancer existing simultaneously.

UC as a Culprit for Hemolytic Anemia

Introduction

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) can rarely be seen as an extra-intestinal manifestation (EIM) of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), mostly ulcerative colitis (UC). This case report describes the clinical significance of recognizing AIHA in the context of UC.

Case Presentation

A 32-year-old male presented with profound fatigue, pallor, and dyspnea on exertion for one month. He also recalled intermittent bloody diarrhea for two years for which he never sought medical attention. Physical examination was unremarkable except for mid-abdominal tenderness. Labs revealed microcytosis, hemoglobin of 3.8 g/dL, total bilirubin 2.9 mg/ dL, indirect bilirubin of 2.0 mg/dL, LDH 132 U/L alk-p 459 U/L AST 98 U/L ALT 22 U/L. Direct Coombs test was positive suggesting warm AIHA with pan-agglutinin positive on the eluate test. Further testing revealed negative hepatitis and HIV panels and positive fecal calprotectin. CT abdomen and pelvis showed ascites, right pleural effusion and hepatosplenomegaly. Colonoscopy confirmed the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis, with extensive involvement of the colon. Mesalamine was initiated. Hematology was consulted for AIHA, who started the patient on methylprednisone leading to resolution of hemolytic anemia and improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms.

Discussion

IBD typically manifests as colitis, and the incidence of EIM as an initial symptom is observed in less than 10% cases. However, over the course of their lifetime, approximately 25% of patients will experience EIM, underscoring their relevance to clinical outcomes. Anemia is very common in IBD patients, mostly iron deficiency anemia (IDA) or anemia of chronic disease (ACD). However, AIHA can represent a rare but significant EIM of ulcerative colitis (UC), often posing diagnostic challenges. The underlying pathophysiological mechanisms linking UC and AIHA remain incompletely understood, necessitating a multidisciplinary approach to management. Treatment strategies focus on controlling both the hemolysis and the underlying IBD, emphasizing the importance of tailored interventions.

Conclusion

This case underscores the clinical significance of AIHA as an EIM of ulcerative colitis (UC), particularly when presenting as the primary symptom. Timely recognition is paramount to optimizing patient outcomes and preventing disease progression. Further research is warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and therapeutic strategies for AIHA in the context of UC.

Introduction

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) can rarely be seen as an extra-intestinal manifestation (EIM) of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), mostly ulcerative colitis (UC). This case report describes the clinical significance of recognizing AIHA in the context of UC.

Case Presentation

A 32-year-old male presented with profound fatigue, pallor, and dyspnea on exertion for one month. He also recalled intermittent bloody diarrhea for two years for which he never sought medical attention. Physical examination was unremarkable except for mid-abdominal tenderness. Labs revealed microcytosis, hemoglobin of 3.8 g/dL, total bilirubin 2.9 mg/ dL, indirect bilirubin of 2.0 mg/dL, LDH 132 U/L alk-p 459 U/L AST 98 U/L ALT 22 U/L. Direct Coombs test was positive suggesting warm AIHA with pan-agglutinin positive on the eluate test. Further testing revealed negative hepatitis and HIV panels and positive fecal calprotectin. CT abdomen and pelvis showed ascites, right pleural effusion and hepatosplenomegaly. Colonoscopy confirmed the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis, with extensive involvement of the colon. Mesalamine was initiated. Hematology was consulted for AIHA, who started the patient on methylprednisone leading to resolution of hemolytic anemia and improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms.

Discussion

IBD typically manifests as colitis, and the incidence of EIM as an initial symptom is observed in less than 10% cases. However, over the course of their lifetime, approximately 25% of patients will experience EIM, underscoring their relevance to clinical outcomes. Anemia is very common in IBD patients, mostly iron deficiency anemia (IDA) or anemia of chronic disease (ACD). However, AIHA can represent a rare but significant EIM of ulcerative colitis (UC), often posing diagnostic challenges. The underlying pathophysiological mechanisms linking UC and AIHA remain incompletely understood, necessitating a multidisciplinary approach to management. Treatment strategies focus on controlling both the hemolysis and the underlying IBD, emphasizing the importance of tailored interventions.

Conclusion

This case underscores the clinical significance of AIHA as an EIM of ulcerative colitis (UC), particularly when presenting as the primary symptom. Timely recognition is paramount to optimizing patient outcomes and preventing disease progression. Further research is warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and therapeutic strategies for AIHA in the context of UC.

Introduction

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) can rarely be seen as an extra-intestinal manifestation (EIM) of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), mostly ulcerative colitis (UC). This case report describes the clinical significance of recognizing AIHA in the context of UC.

Case Presentation

A 32-year-old male presented with profound fatigue, pallor, and dyspnea on exertion for one month. He also recalled intermittent bloody diarrhea for two years for which he never sought medical attention. Physical examination was unremarkable except for mid-abdominal tenderness. Labs revealed microcytosis, hemoglobin of 3.8 g/dL, total bilirubin 2.9 mg/ dL, indirect bilirubin of 2.0 mg/dL, LDH 132 U/L alk-p 459 U/L AST 98 U/L ALT 22 U/L. Direct Coombs test was positive suggesting warm AIHA with pan-agglutinin positive on the eluate test. Further testing revealed negative hepatitis and HIV panels and positive fecal calprotectin. CT abdomen and pelvis showed ascites, right pleural effusion and hepatosplenomegaly. Colonoscopy confirmed the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis, with extensive involvement of the colon. Mesalamine was initiated. Hematology was consulted for AIHA, who started the patient on methylprednisone leading to resolution of hemolytic anemia and improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms.

Discussion

IBD typically manifests as colitis, and the incidence of EIM as an initial symptom is observed in less than 10% cases. However, over the course of their lifetime, approximately 25% of patients will experience EIM, underscoring their relevance to clinical outcomes. Anemia is very common in IBD patients, mostly iron deficiency anemia (IDA) or anemia of chronic disease (ACD). However, AIHA can represent a rare but significant EIM of ulcerative colitis (UC), often posing diagnostic challenges. The underlying pathophysiological mechanisms linking UC and AIHA remain incompletely understood, necessitating a multidisciplinary approach to management. Treatment strategies focus on controlling both the hemolysis and the underlying IBD, emphasizing the importance of tailored interventions.

Conclusion

This case underscores the clinical significance of AIHA as an EIM of ulcerative colitis (UC), particularly when presenting as the primary symptom. Timely recognition is paramount to optimizing patient outcomes and preventing disease progression. Further research is warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and therapeutic strategies for AIHA in the context of UC.

Recent Incidence and Survival Trends in Pancreatic Cancer at Young Age (<50 Years)

Background

Pancreatic cancer stands as a prominent contributor to cancer-related mortality in the United States. In this abstract, we reviewed the SEER database to uncover the latest trends in pancreatic cancer among individuals diagnosed under the age of 50.

Methods

Information was obtained from the SEER database November 2023 which covers 22 national cancer registries. Only patients with age < 50 years were included. Age adjusted incidence and 5-year relative survival were compared between different ethnic groups.

Results

We identified 124691 patients with pancreatic cancer diagnosed between 2017-2021, among them 6477 were with age less than 50 years at the time of diagnosis. 3074 were male and 3403 were male. Age adjusted incidence rate was 1.2/100,000 in females and 1.4/100,000 in males. Overall, Average Annual Percent Change (AAPC) of 2.6% (95% CI: 1.9 – 4.3) was noticed between 2017-2021 when compared to previously reported rates. AAPC among different ethnic groups were Hispanics, any race: 5.3% (CI: 4-7.5), Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native: 1.1 (CI: -2.7-5.1), Non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander: 1.9 (CI: 1.1-2.9), Non-Hispanic Black: 1.0 (CI: 0.3-1.7), and Non-Hispanic White: 1.6 (CI: 1.1-2.1). Stage 4 was the most common stage. Overall, the 5-year relative survival from 2014- 2020 was 37.4% (CI: 36.1-38.7). 5-year relative survival among ethnic groups from 2014-2020 were: Hispanics, any race: 40.3% (CI: 37.6-43.0), Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native: 21.4 (CI: 8.5-38.2), Non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander: 40.2 (CI: 35.7-44.7), Non-Hispanic Black: 33.1 (CI: 29.9-36.3), and Non-Hispanic White: 36.6 (CI: 34.8-38.4).

Conclusions

Our analysis reveals a rise in the ageadjusted incidence of pancreatic cancer among younger demographics. Particularly noteworthy is the sharp increase observed over the past five years among Hispanics when compared to other ethnic populations. This rise is observed in both males and females. Further studies need to be done to study the risk factors associated with this increase in trend of pancreatic cancer at young age specifically in Hispanic population.

Background

Pancreatic cancer stands as a prominent contributor to cancer-related mortality in the United States. In this abstract, we reviewed the SEER database to uncover the latest trends in pancreatic cancer among individuals diagnosed under the age of 50.

Methods

Information was obtained from the SEER database November 2023 which covers 22 national cancer registries. Only patients with age < 50 years were included. Age adjusted incidence and 5-year relative survival were compared between different ethnic groups.

Results

We identified 124691 patients with pancreatic cancer diagnosed between 2017-2021, among them 6477 were with age less than 50 years at the time of diagnosis. 3074 were male and 3403 were male. Age adjusted incidence rate was 1.2/100,000 in females and 1.4/100,000 in males. Overall, Average Annual Percent Change (AAPC) of 2.6% (95% CI: 1.9 – 4.3) was noticed between 2017-2021 when compared to previously reported rates. AAPC among different ethnic groups were Hispanics, any race: 5.3% (CI: 4-7.5), Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native: 1.1 (CI: -2.7-5.1), Non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander: 1.9 (CI: 1.1-2.9), Non-Hispanic Black: 1.0 (CI: 0.3-1.7), and Non-Hispanic White: 1.6 (CI: 1.1-2.1). Stage 4 was the most common stage. Overall, the 5-year relative survival from 2014- 2020 was 37.4% (CI: 36.1-38.7). 5-year relative survival among ethnic groups from 2014-2020 were: Hispanics, any race: 40.3% (CI: 37.6-43.0), Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native: 21.4 (CI: 8.5-38.2), Non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander: 40.2 (CI: 35.7-44.7), Non-Hispanic Black: 33.1 (CI: 29.9-36.3), and Non-Hispanic White: 36.6 (CI: 34.8-38.4).

Conclusions

Our analysis reveals a rise in the ageadjusted incidence of pancreatic cancer among younger demographics. Particularly noteworthy is the sharp increase observed over the past five years among Hispanics when compared to other ethnic populations. This rise is observed in both males and females. Further studies need to be done to study the risk factors associated with this increase in trend of pancreatic cancer at young age specifically in Hispanic population.

Background

Pancreatic cancer stands as a prominent contributor to cancer-related mortality in the United States. In this abstract, we reviewed the SEER database to uncover the latest trends in pancreatic cancer among individuals diagnosed under the age of 50.

Methods

Information was obtained from the SEER database November 2023 which covers 22 national cancer registries. Only patients with age < 50 years were included. Age adjusted incidence and 5-year relative survival were compared between different ethnic groups.

Results

We identified 124691 patients with pancreatic cancer diagnosed between 2017-2021, among them 6477 were with age less than 50 years at the time of diagnosis. 3074 were male and 3403 were male. Age adjusted incidence rate was 1.2/100,000 in females and 1.4/100,000 in males. Overall, Average Annual Percent Change (AAPC) of 2.6% (95% CI: 1.9 – 4.3) was noticed between 2017-2021 when compared to previously reported rates. AAPC among different ethnic groups were Hispanics, any race: 5.3% (CI: 4-7.5), Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native: 1.1 (CI: -2.7-5.1), Non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander: 1.9 (CI: 1.1-2.9), Non-Hispanic Black: 1.0 (CI: 0.3-1.7), and Non-Hispanic White: 1.6 (CI: 1.1-2.1). Stage 4 was the most common stage. Overall, the 5-year relative survival from 2014- 2020 was 37.4% (CI: 36.1-38.7). 5-year relative survival among ethnic groups from 2014-2020 were: Hispanics, any race: 40.3% (CI: 37.6-43.0), Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native: 21.4 (CI: 8.5-38.2), Non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander: 40.2 (CI: 35.7-44.7), Non-Hispanic Black: 33.1 (CI: 29.9-36.3), and Non-Hispanic White: 36.6 (CI: 34.8-38.4).

Conclusions

Our analysis reveals a rise in the ageadjusted incidence of pancreatic cancer among younger demographics. Particularly noteworthy is the sharp increase observed over the past five years among Hispanics when compared to other ethnic populations. This rise is observed in both males and females. Further studies need to be done to study the risk factors associated with this increase in trend of pancreatic cancer at young age specifically in Hispanic population.

Laterality in Renal Cancer: Effect on Survival in Veteran Population

Background

Kidney and renal pelvis cancers (KC) represent 4% of new cancer cases in the US. Although it is a common cancer, there is no data to compare the effect of laterality on survival in veteran population. In this abstract, we attempt to bridge this gap and compare the effect of laterality on survival.

Methods

We obtained data from Albany VA (VAMC) for patients diagnosed with KC between 2010-2020. Data were analyzed for age, stage at diagnosis, histopathological type, laterality of tumor, and 6,12 and 60-months survival after the diagnosis and performed a comparison of overall survival of left versus rightsided cancer by calculating odds ratio using logistic regression, significance level was established at p< 0.05.

Results

We reviewed 130 patients diagnosed with KC at VAMC. 62 had right-sided, 62 had left-sided, and 6 had bilateral cancer. Clear cell (40.8%) was predominant type. Other less common histopathological types include Papillary RCC, mixed, papillary urothelial and transitional types. 58 patients had stage 1 (28 right versus 30 left), 8 had stage 2 (5 versus 3), 29 had stage 3 (13 versus 16), 16 with stage 4 (12 versus 4), and 14 had stage 0 (papillary-urothelial). 59.2% patients underwent surgical treatment after diagnosis (R=35, L=39). At 6-months, 60 patients (96.8%) with left-sided and 53 (85.5%) with right-sided cancer survived. The odds of surviving 6-months were 12% higher (95% CI: 1.014, 1.236; p=0.03) in left versus right-sided cancer. For 1-year survival, the results were similar. 111 patients completed a 5-year follow-up and there was no evidence to support a difference in survival between cohorts at 5-years: OR (95% CI: 0.88, 1.47; p=0.32).

Conclusions

In this study, we discovered that leftsided cancer showed better survival at 6-months and 1-year compared to right-sided cancer, but 5-year survival rates appeared similar irrespective of laterality of cancer. Both subgroups had similar distribution for baseline characteristics with majority of patients being males, older than 60 years, with stage 1 disease. Further studies in larger populations with wider distribution of baseline characteristics are needed to establish clear role of laterality as a prognostic factor.

Background

Kidney and renal pelvis cancers (KC) represent 4% of new cancer cases in the US. Although it is a common cancer, there is no data to compare the effect of laterality on survival in veteran population. In this abstract, we attempt to bridge this gap and compare the effect of laterality on survival.

Methods

We obtained data from Albany VA (VAMC) for patients diagnosed with KC between 2010-2020. Data were analyzed for age, stage at diagnosis, histopathological type, laterality of tumor, and 6,12 and 60-months survival after the diagnosis and performed a comparison of overall survival of left versus rightsided cancer by calculating odds ratio using logistic regression, significance level was established at p< 0.05.

Results

We reviewed 130 patients diagnosed with KC at VAMC. 62 had right-sided, 62 had left-sided, and 6 had bilateral cancer. Clear cell (40.8%) was predominant type. Other less common histopathological types include Papillary RCC, mixed, papillary urothelial and transitional types. 58 patients had stage 1 (28 right versus 30 left), 8 had stage 2 (5 versus 3), 29 had stage 3 (13 versus 16), 16 with stage 4 (12 versus 4), and 14 had stage 0 (papillary-urothelial). 59.2% patients underwent surgical treatment after diagnosis (R=35, L=39). At 6-months, 60 patients (96.8%) with left-sided and 53 (85.5%) with right-sided cancer survived. The odds of surviving 6-months were 12% higher (95% CI: 1.014, 1.236; p=0.03) in left versus right-sided cancer. For 1-year survival, the results were similar. 111 patients completed a 5-year follow-up and there was no evidence to support a difference in survival between cohorts at 5-years: OR (95% CI: 0.88, 1.47; p=0.32).

Conclusions

In this study, we discovered that leftsided cancer showed better survival at 6-months and 1-year compared to right-sided cancer, but 5-year survival rates appeared similar irrespective of laterality of cancer. Both subgroups had similar distribution for baseline characteristics with majority of patients being males, older than 60 years, with stage 1 disease. Further studies in larger populations with wider distribution of baseline characteristics are needed to establish clear role of laterality as a prognostic factor.

Background

Kidney and renal pelvis cancers (KC) represent 4% of new cancer cases in the US. Although it is a common cancer, there is no data to compare the effect of laterality on survival in veteran population. In this abstract, we attempt to bridge this gap and compare the effect of laterality on survival.

Methods

We obtained data from Albany VA (VAMC) for patients diagnosed with KC between 2010-2020. Data were analyzed for age, stage at diagnosis, histopathological type, laterality of tumor, and 6,12 and 60-months survival after the diagnosis and performed a comparison of overall survival of left versus rightsided cancer by calculating odds ratio using logistic regression, significance level was established at p< 0.05.

Results

We reviewed 130 patients diagnosed with KC at VAMC. 62 had right-sided, 62 had left-sided, and 6 had bilateral cancer. Clear cell (40.8%) was predominant type. Other less common histopathological types include Papillary RCC, mixed, papillary urothelial and transitional types. 58 patients had stage 1 (28 right versus 30 left), 8 had stage 2 (5 versus 3), 29 had stage 3 (13 versus 16), 16 with stage 4 (12 versus 4), and 14 had stage 0 (papillary-urothelial). 59.2% patients underwent surgical treatment after diagnosis (R=35, L=39). At 6-months, 60 patients (96.8%) with left-sided and 53 (85.5%) with right-sided cancer survived. The odds of surviving 6-months were 12% higher (95% CI: 1.014, 1.236; p=0.03) in left versus right-sided cancer. For 1-year survival, the results were similar. 111 patients completed a 5-year follow-up and there was no evidence to support a difference in survival between cohorts at 5-years: OR (95% CI: 0.88, 1.47; p=0.32).

Conclusions

In this study, we discovered that leftsided cancer showed better survival at 6-months and 1-year compared to right-sided cancer, but 5-year survival rates appeared similar irrespective of laterality of cancer. Both subgroups had similar distribution for baseline characteristics with majority of patients being males, older than 60 years, with stage 1 disease. Further studies in larger populations with wider distribution of baseline characteristics are needed to establish clear role of laterality as a prognostic factor.

Identifying Barriers in Germline Genetic Testing Referrals for Breast Cancer: A Single-Center Experience

Background

Purpose: to review the number of genetic testing referrals for breast cancer at the Stratton VA Medical Center and identify barriers that hinder testing, aiming to improve risk reduction strategies and therapeutic options for patients. National guidelines recommend genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility genes in specific patient populations, such as those under 50, those with a high-risk family history, high-risk pathology, male breast cancer, or Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry. Despite efforts to adhere to these guidelines, several barriers persist that limit testing rates among eligible patients.

Methods

The medical oncology team selected breast cancer as the focus for reviewing adherence to germline genetic testing referrals in the Stratton VA Medical Center. With assistance from cancer registrars, a list of genetics referrals for breast cancer from January to December 2023 was compiled. Descriptive analysis was conducted to assess referral rates, evaluation visit completion rates, genetic testing outcomes, and reasons for non-completion of genetic testing.

Results

During the study period, 32 patients were referred for germline genetic testing for breast cancer. Of these, 26 (81%) completed the evaluation visit, and 11 (34%) underwent genetic testing. Of these, 7 patients had noteworthy results, and 2 patients (6%) were found to carry pathogenic variants: BRCA2 and CDH1. Reasons for non-completion included perceived irrelevance without biological children, need for additional time to consider testing, fear of exacerbating self-harm thoughts, and fear of losing service connection. Additionally, 2 patients did not meet the guidelines for testing per genetic counselor.

Conclusions

This project marks the initial step in identifying barriers to germline genetic testing for breast cancer based on an extensive review of patients diagnosed and treated at a single VA site. Despite the removal of the service connection clause from the consent form, some veterans still declined testing due to fear of losing their service connection. The findings emphasize the importance of educating providers on counseling techniques and education of veterans to enhance risk reduction strategies and patient care. Further research is essential to quantify the real-world outcomes and longterm impacts of improving genetic counseling rates on patient management and outcomes.

Background

Purpose: to review the number of genetic testing referrals for breast cancer at the Stratton VA Medical Center and identify barriers that hinder testing, aiming to improve risk reduction strategies and therapeutic options for patients. National guidelines recommend genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility genes in specific patient populations, such as those under 50, those with a high-risk family history, high-risk pathology, male breast cancer, or Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry. Despite efforts to adhere to these guidelines, several barriers persist that limit testing rates among eligible patients.

Methods

The medical oncology team selected breast cancer as the focus for reviewing adherence to germline genetic testing referrals in the Stratton VA Medical Center. With assistance from cancer registrars, a list of genetics referrals for breast cancer from January to December 2023 was compiled. Descriptive analysis was conducted to assess referral rates, evaluation visit completion rates, genetic testing outcomes, and reasons for non-completion of genetic testing.

Results

During the study period, 32 patients were referred for germline genetic testing for breast cancer. Of these, 26 (81%) completed the evaluation visit, and 11 (34%) underwent genetic testing. Of these, 7 patients had noteworthy results, and 2 patients (6%) were found to carry pathogenic variants: BRCA2 and CDH1. Reasons for non-completion included perceived irrelevance without biological children, need for additional time to consider testing, fear of exacerbating self-harm thoughts, and fear of losing service connection. Additionally, 2 patients did not meet the guidelines for testing per genetic counselor.

Conclusions

This project marks the initial step in identifying barriers to germline genetic testing for breast cancer based on an extensive review of patients diagnosed and treated at a single VA site. Despite the removal of the service connection clause from the consent form, some veterans still declined testing due to fear of losing their service connection. The findings emphasize the importance of educating providers on counseling techniques and education of veterans to enhance risk reduction strategies and patient care. Further research is essential to quantify the real-world outcomes and longterm impacts of improving genetic counseling rates on patient management and outcomes.

Background

Purpose: to review the number of genetic testing referrals for breast cancer at the Stratton VA Medical Center and identify barriers that hinder testing, aiming to improve risk reduction strategies and therapeutic options for patients. National guidelines recommend genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility genes in specific patient populations, such as those under 50, those with a high-risk family history, high-risk pathology, male breast cancer, or Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry. Despite efforts to adhere to these guidelines, several barriers persist that limit testing rates among eligible patients.

Methods

The medical oncology team selected breast cancer as the focus for reviewing adherence to germline genetic testing referrals in the Stratton VA Medical Center. With assistance from cancer registrars, a list of genetics referrals for breast cancer from January to December 2023 was compiled. Descriptive analysis was conducted to assess referral rates, evaluation visit completion rates, genetic testing outcomes, and reasons for non-completion of genetic testing.

Results

During the study period, 32 patients were referred for germline genetic testing for breast cancer. Of these, 26 (81%) completed the evaluation visit, and 11 (34%) underwent genetic testing. Of these, 7 patients had noteworthy results, and 2 patients (6%) were found to carry pathogenic variants: BRCA2 and CDH1. Reasons for non-completion included perceived irrelevance without biological children, need for additional time to consider testing, fear of exacerbating self-harm thoughts, and fear of losing service connection. Additionally, 2 patients did not meet the guidelines for testing per genetic counselor.

Conclusions

This project marks the initial step in identifying barriers to germline genetic testing for breast cancer based on an extensive review of patients diagnosed and treated at a single VA site. Despite the removal of the service connection clause from the consent form, some veterans still declined testing due to fear of losing their service connection. The findings emphasize the importance of educating providers on counseling techniques and education of veterans to enhance risk reduction strategies and patient care. Further research is essential to quantify the real-world outcomes and longterm impacts of improving genetic counseling rates on patient management and outcomes.

Asynchronous Bilateral Breast Cancer in a Male Patient

Background

Bilateral male breast cancer remains a rare occurrence with limited representation in published literature. Here we present a case of an 82-yearold male with asynchronous bilateral breast cancer.

Case Presentation

Our patient is an 82-year-old male past smoker initially diagnosed with left T1aN0M0 invasive lobular carcinoma in 2010 that was ER, PR positive and HER2 negative. He underwent a left mastectomy with sentinel node biopsy and was given tamoxifen therapy for 10 years. In 2020, the patient was also diagnosed with lung squamous cell carcinoma and was treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy. In September 2023, he started noticing discharge from his right nipple. A PET CT scan revealed hyper-metabolic activity in the bilateral upper lung lobes and slightly increased activity in the right breast. A biopsy of the left upper lobe showed atypical cells. He also underwent a right breast mastectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy which showed grade 1-2 ductal carcinoma in situ and negative sentinel lymph nodes. The tumor board recommended no further treatment after his mastectomy and genetic testing which is currently pending.

Discussion

Male breast cancer comprises just 1% of breast cancer cases, with asynchronous bilateral occurrences being exceedingly rare. A review of PubMed literature yielded only 2 documented case reports. Male breast cancer usually diagnosed around ages 60 to 70 years. The predominant histopathological diagnosis is invasive ductal adenocarcinoma that more frequently expresses ER/PR over HER2. It often manifests as a painless lump, frequently diagnosed at an advanced stage, possibly due to factors such as lower screening rates in males and less breast parenchyma. Local treatment options include surgery and radiotherapy. Neoadjuvant tamoxifen therapy is appropriate for ER and PR expressing cancers and chemotherapy can be used for non-hormone expressing or metastatic tumors. Given its rarity, management and diagnostic strategies for male breast cancer are often adapted from research on female breast cancer

Conclusions

Our case is of a relatively uncommon incident of asynchronous bilateral male breast cancer, emphasizing the need for expanded research efforts in male breast cancer. An enhanced understanding could lead to improved diagnosis and management strategies, potentially enhancing survival outcomes.

Background

Bilateral male breast cancer remains a rare occurrence with limited representation in published literature. Here we present a case of an 82-yearold male with asynchronous bilateral breast cancer.

Case Presentation

Our patient is an 82-year-old male past smoker initially diagnosed with left T1aN0M0 invasive lobular carcinoma in 2010 that was ER, PR positive and HER2 negative. He underwent a left mastectomy with sentinel node biopsy and was given tamoxifen therapy for 10 years. In 2020, the patient was also diagnosed with lung squamous cell carcinoma and was treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy. In September 2023, he started noticing discharge from his right nipple. A PET CT scan revealed hyper-metabolic activity in the bilateral upper lung lobes and slightly increased activity in the right breast. A biopsy of the left upper lobe showed atypical cells. He also underwent a right breast mastectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy which showed grade 1-2 ductal carcinoma in situ and negative sentinel lymph nodes. The tumor board recommended no further treatment after his mastectomy and genetic testing which is currently pending.

Discussion

Male breast cancer comprises just 1% of breast cancer cases, with asynchronous bilateral occurrences being exceedingly rare. A review of PubMed literature yielded only 2 documented case reports. Male breast cancer usually diagnosed around ages 60 to 70 years. The predominant histopathological diagnosis is invasive ductal adenocarcinoma that more frequently expresses ER/PR over HER2. It often manifests as a painless lump, frequently diagnosed at an advanced stage, possibly due to factors such as lower screening rates in males and less breast parenchyma. Local treatment options include surgery and radiotherapy. Neoadjuvant tamoxifen therapy is appropriate for ER and PR expressing cancers and chemotherapy can be used for non-hormone expressing or metastatic tumors. Given its rarity, management and diagnostic strategies for male breast cancer are often adapted from research on female breast cancer

Conclusions

Our case is of a relatively uncommon incident of asynchronous bilateral male breast cancer, emphasizing the need for expanded research efforts in male breast cancer. An enhanced understanding could lead to improved diagnosis and management strategies, potentially enhancing survival outcomes.

Background

Bilateral male breast cancer remains a rare occurrence with limited representation in published literature. Here we present a case of an 82-yearold male with asynchronous bilateral breast cancer.

Case Presentation

Our patient is an 82-year-old male past smoker initially diagnosed with left T1aN0M0 invasive lobular carcinoma in 2010 that was ER, PR positive and HER2 negative. He underwent a left mastectomy with sentinel node biopsy and was given tamoxifen therapy for 10 years. In 2020, the patient was also diagnosed with lung squamous cell carcinoma and was treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy. In September 2023, he started noticing discharge from his right nipple. A PET CT scan revealed hyper-metabolic activity in the bilateral upper lung lobes and slightly increased activity in the right breast. A biopsy of the left upper lobe showed atypical cells. He also underwent a right breast mastectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy which showed grade 1-2 ductal carcinoma in situ and negative sentinel lymph nodes. The tumor board recommended no further treatment after his mastectomy and genetic testing which is currently pending.

Discussion

Male breast cancer comprises just 1% of breast cancer cases, with asynchronous bilateral occurrences being exceedingly rare. A review of PubMed literature yielded only 2 documented case reports. Male breast cancer usually diagnosed around ages 60 to 70 years. The predominant histopathological diagnosis is invasive ductal adenocarcinoma that more frequently expresses ER/PR over HER2. It often manifests as a painless lump, frequently diagnosed at an advanced stage, possibly due to factors such as lower screening rates in males and less breast parenchyma. Local treatment options include surgery and radiotherapy. Neoadjuvant tamoxifen therapy is appropriate for ER and PR expressing cancers and chemotherapy can be used for non-hormone expressing or metastatic tumors. Given its rarity, management and diagnostic strategies for male breast cancer are often adapted from research on female breast cancer

Conclusions

Our case is of a relatively uncommon incident of asynchronous bilateral male breast cancer, emphasizing the need for expanded research efforts in male breast cancer. An enhanced understanding could lead to improved diagnosis and management strategies, potentially enhancing survival outcomes.

Metastatic Prostate Cancer Presenting as Pleural and Pericardial Metastases: A Case Report and Literature Review

Background

Metastatic prostate cancer typically manifests with metastases to the lungs, bones, and adrenal glands. Here, we report a unique case where the initial presentation involved pleural nodules, subsequently leading to the discovery of pleural and pericardial metastases.

Case Presentation

Our patient, a 73-year-old male with a history of active tobacco use disorder, COPD, and right shoulder melanoma (2004), initially presented to his primary care physician for a routine visit. Following a Low Dose Chest CT scan (LDCT), numerous new pleural nodules were identified. Physical examination revealed small nevi and skin tags, but no malignant characteristics. Initial concerns centered on the potential recurrence of malignant melanoma with pleural metastases or an inflammatory condition. Subsequent PET scan results raised significant suspicion of malignancy. PSA was 2.41. Pleuroscopy biopsies revealed invasive nonsmall cell carcinoma, positive for NKX31 and MOC31, but negative for S100, PSA, and synaptophysin. This pattern strongly suggests metastatic prostate cancer despite the absence of PSA staining. (Stage IV B: cTxcN1cM1c). A subsequent PSMA PET highlighted extensive metastatic involvement in the pericardium, posterior and mediastinal pleura, mediastinum, and ribs. Treatment commenced with Degarelix followed by the standard regimen of Docetaxel, Abiraterone, and prednisone. Genetic counseling and palliative care services were additionally recommended.

Discussion

Prostate cancer typically spreads to bones, lungs, liver, and adrenal glands. Rarely, it appears in sites like pericardium and pleura. Pleural metastases are usually found postmortem; clinical diagnosis is rare. Pericardial metastases are exceptionally uncommon, with few documented cases. The precise mechanism of metastatic dissemination remains uncertain, with theories suggesting spread through the vertebral-venous plexus or via the vena cava to distant organs. Treatment approaches vary based on symptomatic effusions, ranging from pericardiocentesis, thoracocentesis to chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and hormone therapy. Studies have shown systemic docetaxel to be effective in managing pleural and pericardial symptoms. Despite their rarity, healthcare providers should consider these possibilities when encountering pleural thickening or pericardial abnormalities on imaging studies.

Conclusions

Pleural and pericardial metastases represent uncommon occurrences in prostate cancer. Continued research efforts can facilitate early detection of metastatic disease, enabling more effective and precisely targeted management strategies when symptoms manifest.

Background

Metastatic prostate cancer typically manifests with metastases to the lungs, bones, and adrenal glands. Here, we report a unique case where the initial presentation involved pleural nodules, subsequently leading to the discovery of pleural and pericardial metastases.

Case Presentation

Our patient, a 73-year-old male with a history of active tobacco use disorder, COPD, and right shoulder melanoma (2004), initially presented to his primary care physician for a routine visit. Following a Low Dose Chest CT scan (LDCT), numerous new pleural nodules were identified. Physical examination revealed small nevi and skin tags, but no malignant characteristics. Initial concerns centered on the potential recurrence of malignant melanoma with pleural metastases or an inflammatory condition. Subsequent PET scan results raised significant suspicion of malignancy. PSA was 2.41. Pleuroscopy biopsies revealed invasive nonsmall cell carcinoma, positive for NKX31 and MOC31, but negative for S100, PSA, and synaptophysin. This pattern strongly suggests metastatic prostate cancer despite the absence of PSA staining. (Stage IV B: cTxcN1cM1c). A subsequent PSMA PET highlighted extensive metastatic involvement in the pericardium, posterior and mediastinal pleura, mediastinum, and ribs. Treatment commenced with Degarelix followed by the standard regimen of Docetaxel, Abiraterone, and prednisone. Genetic counseling and palliative care services were additionally recommended.

Discussion

Prostate cancer typically spreads to bones, lungs, liver, and adrenal glands. Rarely, it appears in sites like pericardium and pleura. Pleural metastases are usually found postmortem; clinical diagnosis is rare. Pericardial metastases are exceptionally uncommon, with few documented cases. The precise mechanism of metastatic dissemination remains uncertain, with theories suggesting spread through the vertebral-venous plexus or via the vena cava to distant organs. Treatment approaches vary based on symptomatic effusions, ranging from pericardiocentesis, thoracocentesis to chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and hormone therapy. Studies have shown systemic docetaxel to be effective in managing pleural and pericardial symptoms. Despite their rarity, healthcare providers should consider these possibilities when encountering pleural thickening or pericardial abnormalities on imaging studies.

Conclusions

Pleural and pericardial metastases represent uncommon occurrences in prostate cancer. Continued research efforts can facilitate early detection of metastatic disease, enabling more effective and precisely targeted management strategies when symptoms manifest.

Background

Metastatic prostate cancer typically manifests with metastases to the lungs, bones, and adrenal glands. Here, we report a unique case where the initial presentation involved pleural nodules, subsequently leading to the discovery of pleural and pericardial metastases.

Case Presentation

Our patient, a 73-year-old male with a history of active tobacco use disorder, COPD, and right shoulder melanoma (2004), initially presented to his primary care physician for a routine visit. Following a Low Dose Chest CT scan (LDCT), numerous new pleural nodules were identified. Physical examination revealed small nevi and skin tags, but no malignant characteristics. Initial concerns centered on the potential recurrence of malignant melanoma with pleural metastases or an inflammatory condition. Subsequent PET scan results raised significant suspicion of malignancy. PSA was 2.41. Pleuroscopy biopsies revealed invasive nonsmall cell carcinoma, positive for NKX31 and MOC31, but negative for S100, PSA, and synaptophysin. This pattern strongly suggests metastatic prostate cancer despite the absence of PSA staining. (Stage IV B: cTxcN1cM1c). A subsequent PSMA PET highlighted extensive metastatic involvement in the pericardium, posterior and mediastinal pleura, mediastinum, and ribs. Treatment commenced with Degarelix followed by the standard regimen of Docetaxel, Abiraterone, and prednisone. Genetic counseling and palliative care services were additionally recommended.

Discussion

Prostate cancer typically spreads to bones, lungs, liver, and adrenal glands. Rarely, it appears in sites like pericardium and pleura. Pleural metastases are usually found postmortem; clinical diagnosis is rare. Pericardial metastases are exceptionally uncommon, with few documented cases. The precise mechanism of metastatic dissemination remains uncertain, with theories suggesting spread through the vertebral-venous plexus or via the vena cava to distant organs. Treatment approaches vary based on symptomatic effusions, ranging from pericardiocentesis, thoracocentesis to chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and hormone therapy. Studies have shown systemic docetaxel to be effective in managing pleural and pericardial symptoms. Despite their rarity, healthcare providers should consider these possibilities when encountering pleural thickening or pericardial abnormalities on imaging studies.

Conclusions

Pleural and pericardial metastases represent uncommon occurrences in prostate cancer. Continued research efforts can facilitate early detection of metastatic disease, enabling more effective and precisely targeted management strategies when symptoms manifest.

Beyond Borders: Tonsillar Squamous Cell Carcinoma with Intriguing Liver Metastasis

Background

Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) arises in the middle pharynx, including the tonsils, base of the tongue, and surrounding tissues. While OPSCC commonly metastasizes to regional lymph nodes, distant metastases to sites like the liver are rare, occurring in about 1-4% of cases with advanced disease.

Case Presentation

A 66-year-old male presented to the emergency department with recurrent right-sided facial swelling and a two-week history of sore throat. CT imaging revealed a large right tonsillar mass extending to the base of the tongue. Further evaluation with PET scan showed hypermetabolic activity in the right tonsil, multiple hypermetabolic lymph nodes in the right neck (stations 1B, 2, 3, 4, 5), right supraclavicular fossa, and small retropharyngeal nodes. Additionally, PET scan detected a hypermetabolic lesion in the liver and focal activity at T10 suggestive of bone metastasis. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) confirmed squamous cell carcinoma. Biopsy of the liver lesion revealed metastatic squamous cell carcinoma with basaloid differentiation, positive for p40 and p63 stains. Clinical staging was T2b cN2 cM1. The patient’s case was discussed in tumor boards, leading to a treatment plan of palliative radiotherapy with radiosensitizer (weekly carboplatin/paclitaxel) due to recent myocardial infarction, precluding cisplatin or 5FU use. Post-radiotherapy, Pembrolizumab was planned based on 60% PD-L1 expression. The patient opted to forego additional systemic chemotherapy and currently receives Keytruda every three weeks.

Discussion

Liver metastases from head and neck SCC are rare, highlighting the complexity of treatment decisions in such cases. Effective management requires a multidisciplinary approach to optimize therapeutic outcomes while considering patient-specific factors and comorbidities.

Conclusions

This case underscores the challenges and poor prognosis associated with tonsillar SCC with liver metastases. It underscores the need for personalized treatment strategies tailored to the unique characteristics of each patient’s disease.

Background

Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) arises in the middle pharynx, including the tonsils, base of the tongue, and surrounding tissues. While OPSCC commonly metastasizes to regional lymph nodes, distant metastases to sites like the liver are rare, occurring in about 1-4% of cases with advanced disease.

Case Presentation

A 66-year-old male presented to the emergency department with recurrent right-sided facial swelling and a two-week history of sore throat. CT imaging revealed a large right tonsillar mass extending to the base of the tongue. Further evaluation with PET scan showed hypermetabolic activity in the right tonsil, multiple hypermetabolic lymph nodes in the right neck (stations 1B, 2, 3, 4, 5), right supraclavicular fossa, and small retropharyngeal nodes. Additionally, PET scan detected a hypermetabolic lesion in the liver and focal activity at T10 suggestive of bone metastasis. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) confirmed squamous cell carcinoma. Biopsy of the liver lesion revealed metastatic squamous cell carcinoma with basaloid differentiation, positive for p40 and p63 stains. Clinical staging was T2b cN2 cM1. The patient’s case was discussed in tumor boards, leading to a treatment plan of palliative radiotherapy with radiosensitizer (weekly carboplatin/paclitaxel) due to recent myocardial infarction, precluding cisplatin or 5FU use. Post-radiotherapy, Pembrolizumab was planned based on 60% PD-L1 expression. The patient opted to forego additional systemic chemotherapy and currently receives Keytruda every three weeks.

Discussion

Liver metastases from head and neck SCC are rare, highlighting the complexity of treatment decisions in such cases. Effective management requires a multidisciplinary approach to optimize therapeutic outcomes while considering patient-specific factors and comorbidities.

Conclusions

This case underscores the challenges and poor prognosis associated with tonsillar SCC with liver metastases. It underscores the need for personalized treatment strategies tailored to the unique characteristics of each patient’s disease.

Background

Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) arises in the middle pharynx, including the tonsils, base of the tongue, and surrounding tissues. While OPSCC commonly metastasizes to regional lymph nodes, distant metastases to sites like the liver are rare, occurring in about 1-4% of cases with advanced disease.

Case Presentation

A 66-year-old male presented to the emergency department with recurrent right-sided facial swelling and a two-week history of sore throat. CT imaging revealed a large right tonsillar mass extending to the base of the tongue. Further evaluation with PET scan showed hypermetabolic activity in the right tonsil, multiple hypermetabolic lymph nodes in the right neck (stations 1B, 2, 3, 4, 5), right supraclavicular fossa, and small retropharyngeal nodes. Additionally, PET scan detected a hypermetabolic lesion in the liver and focal activity at T10 suggestive of bone metastasis. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) confirmed squamous cell carcinoma. Biopsy of the liver lesion revealed metastatic squamous cell carcinoma with basaloid differentiation, positive for p40 and p63 stains. Clinical staging was T2b cN2 cM1. The patient’s case was discussed in tumor boards, leading to a treatment plan of palliative radiotherapy with radiosensitizer (weekly carboplatin/paclitaxel) due to recent myocardial infarction, precluding cisplatin or 5FU use. Post-radiotherapy, Pembrolizumab was planned based on 60% PD-L1 expression. The patient opted to forego additional systemic chemotherapy and currently receives Keytruda every three weeks.

Discussion

Liver metastases from head and neck SCC are rare, highlighting the complexity of treatment decisions in such cases. Effective management requires a multidisciplinary approach to optimize therapeutic outcomes while considering patient-specific factors and comorbidities.

Conclusions

This case underscores the challenges and poor prognosis associated with tonsillar SCC with liver metastases. It underscores the need for personalized treatment strategies tailored to the unique characteristics of each patient’s disease.

Leiomyosarcoma of the Penis: A Case Report and Re-Appraisal

Penile cancer is rare with a worldwide incidence of 0.8 cases per 100,000 men.1 The most common type is squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) followed by soft tissue sarcoma (STS) and Kaposi sarcoma.2 Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is the second most common STS subtype at this location.3 Approximately 50 cases of penile LMS have been reported in the English literature, most as isolated case reports while Fetsch and colleagues reported 14 cases from a single institute.4 We present a case of penile LMS with a review of 31 cases. We also describe presentation, treatment options, and recurrence pattern of this rare malignancy.

Case Presentation

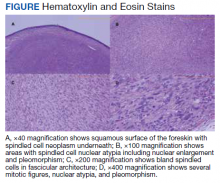

A patient aged 70 years presented to the urology clinic with 1-year history of a slowly enlarging penile mass associated with phimosis. He reported no pain, dysuria, or hesitancy. On examination a 2 × 2-cm smooth, mobile, nonulcerating mass was seen on the tip of his left glans without inguinal lymphadenopathy. He underwent circumcision and excision biopsy that revealed an encapsulated tan-white mass measuring 3 × 2.2 × 1.5 cm under the surface of the foreskin. Histology showed a spindle cell tumor with areas of increased cellularity, prominent atypia, and pleomorphism, focal necrosis, and scattered mitoses, including atypical forms. The tumor stained positive for smooth muscle actin and desmin. Ki-67 staining showed foci with a very high proliferation index (Figure). Resection margins were negative. Final Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre Le Cancer score was grade 2 (differentiation, 1; mitotic, 3; necrosis, 1). Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis did not show evidence of metastasis. The tumor was classified as superficial, stage IIA (pT1cN0cM0). Local excision with negative margins was deemed adequate treatment.

Discussion

Penile LMS is rare and arises from smooth muscles, which in the penis can be from dartos fascia, erector pili in the skin covering the shaft, or from tunica media of the superficial vessels and cavernosa.5 It commonly presents as a nodule or ulcer that might be accompanied by paraphimosis, phimosis, erectile dysfunction, and lower urinary tract symptoms depending on the extent of local tissue involvement. In our review of 31 cases, the age at presentation ranged from 38 to 85 years, with 1 case report of LMS in a 6-year-old. The highest incidence was in the 6th decade. Tumor behavior can be indolent or aggressive. Most patients in our review had asymptomatic, slow-growing lesions for 6 to 24 months before presentation—including our patient—while others had an aggressive tumor with symptoms for a few weeks followed by rapid metastatic spread.6,7

Histology and Staging

Diagnosis requires biopsy followed by histologic examination and immunohistochemistry of the lesion. Typically, LMS shows fascicles of spindle cells with varying degrees of nuclear atypia, pleomorphisms, and necrotic regions. Mitotic rate is variable and usually > 5 per high power field. Cells stain positive for smooth muscle actin, desmin, and h-caldesmon.8 TNM (tumor, nodes, metastasis) stage is determined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer guidelines for STS.

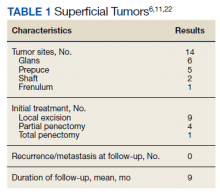

Pratt and colleagues were the first to categorize penile LMS as superficial or deep.9 The former includes all lesions superficial to tunica albuginea while the latter run deep to this layer. Anatomical distinction is an important factor in tumor behavior, treatment selection, and prognosis. In our review, we found 14 cases of superficial and 17 cases of deep LMS.

Treatment

There are no established guidelines on optimum treatment of penile LMS. However, we can extrapolate principles from current guidelines on penile cancer, cutaneous leiomyosarcoma, and limb sarcomas. At present, the first-line treatment for superficial penile LMS is wide local excision to achieve negative margins. Circumcision alone might be sufficient for tumors of the distal prepuce, as in our case.10 Radical resection generally is not required for these early-stage tumors. In our review, no patient in this category developed recurrence or metastasis regardless of initial surgery type (Table 1).6,11,12

For deep lesions, partial—if functional penile stump and negative margins can be achieved—or total penectomy is required.10 In our review, more conservative approaches to deep tumors were associated with local recurrences.7,13,14 Lymphatic spread is rare for LMS. Additionally, involvement of local lymph nodes usually coincides with distant spread. Inguinal lymph node dissection is not indicated if initial negative surgical margins are achieved.

For STS at other sites in the body, radiation therapy is recommended postoperatively for high-grade lesions, which can be extrapolated to penile LMS as well. The benefit of preoperative radiation therapy is less certain. In limb sarcomas, radiation is associated with better local control for large-sized tumors and is used for patients with initial unresectable tumors.15 Similar recommendation could be extended to penile LMS with local spread to inguinal lymph nodes, scrotum, or abdominal wall. In our review, postoperative radiation therapy was used in 3 patients with deep tumors.16-18 Of these, short-term relapse occurred in 1 patient.

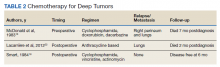

Chemotherapy for LMS remains controversial. The tumor generally is resistant to chemotherapy and systemic therapy, if employed, is for palliative purpose. The most promising results for adjuvant chemotherapy for resectable STS is seen in limb and uterine sarcomas with high-grade, metastatic, or relapsed tumors but improvement in overall survival has been marginal.19,20Single and multidrug regimens based on doxorubicin, ifosfamide, and gemcitabine have been studied with results showing no efficacy or a slight benefit.8,21 Immunotherapy and targeted therapy for penile STS have not been studied. In our review, postoperative chemotherapy was used for 2 patients with deep tumors and 1 patient with a superficial tumor while preoperative chemotherapy was used for 1 patient.16,18,22 Short-term relapse was seen in 2 of 4 of these patients (Table 2).

Metastatic Disease

LMS tends to metastasize hematogenously and lymphatic spread is uncommon. In our review, 7 patients developed metastasis. These patients had deep tumors at presentation with tumor size > 3 cm. Five of 7 patients had involvement of corpora cavernosa at presentation. The lung was the most common site of metastasis, followed by local extension to lower abdominal wall and scrotum. Of the 7 patients, 3 were treated with initial limited excision or partial penectomy and then experienced local recurrence or distant metastasis.7,13,14,23 This supports the use of radical surgery in large, deep tumors. In an additional 4 cases, metastasis occurred despite initial treatment with total penectomy and use of adjuvant chemoradiation therapy.

In most cases penile LMS is a de novo tumor, however, on occasion it could be accompanied by another epithelial malignancy. Similarly, penile LMS might be a site of recurrence for a primary LMS at another site, as seen in 3 of the reviewed cases. In the first, a patient presented with a nodule on the glans suspicious for SCC, second with synchronous SCC and LMS, and a third case where a patient presented with penile LMS 9 years after being treated for similar tumor in the epididymis.17,24,25

Prognosis

Penile LMS prognosis is difficult to ascertain because reported cases are rare. In our review, the longest documented disease-free survival was 3.5 years for a patient with superficial LMS treated with local excision.26 In cases of distant metastasis, average survival was 4.6 months, while the longest survival since initial presentation and last documented local recurrence was 16 years.14 Five-year survival has not been reported.

Conclusions

LMS of the penis is a rare and potentially aggressive malignancy. It can be classified as superficial or deep based on tumor relation to the tunica albuginea. Deep tumors, those > 3 cm, high-grade lesions, and tumors with involvement of corpora cavernosa, tend to spread locally, metastasize to distant areas, and require more radical surgery with or without postoperative radiation therapy. In comparison, superficial lesions can be treated with local excision only. Both superficial and deep tumors require close follow-up.

1. Montes Cardona CE, García-Perdomo HA. Incidence of penile cancer worldwide: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2017;41:e117. Published 2017 Nov 30. doi:10.26633/RPSP.2017.117

2. Volker HU, Zettl A, Haralambieva E, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the larynx as a local relapse of squamous cell carcinoma—report of an unusual case. Head Neck. 2010;32(5):679-683. doi:10.1002/hed.21127

3. Wollina U, Steinbach F, Verma S, et al. Penile tumours: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(10):1267-1276. doi:10.1111/jdv.12491

4. Fetsch JF, Davis CJ Jr, Miettinen M, Sesterhenn IA. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis: a clinicopathologic study of 14 cases with review of the literature and discussion of the differential diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(1):115-125. doi:10.1097/00000478-200401000-00014

5. Sundersingh S, Majhi U, Narayanaswamy K, Balasubramanian S. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the penis. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52(3):447-448. doi:10.4103/0377-4929.55028

6. Mendis D, Bott SR, Davies JH. Subcutaneous leiomyosarcoma of the frenulum. Scientific World J. 2005;5:571-575. doi:10.1100/tsw.2005.76

7. Elem B, Nieslanik J. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. Br J Urol. 1979;51(1):46. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410x.1979.tb04244.x

8. Serrano C, George S. Leiomyosarcoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013;27(5):957-974. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2013.07.002

9. Pratt RM, Ross RT. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. A report of a case. Br J Surg. 1969;56(11):870-872. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800561122

10. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Penile cancer. NCCN evidence blocks. Version 2.2022 Updated January 26, 2022. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/penile_blocks.pdf

11. Ashley DJ, Edwards EC. Sarcoma of the penis; leiomyosarcoma of the penis: report of a case with a review of the literature on sarcoma of the penis. Br J Surg. 1957;45(190):170-179. doi:10.1002/bjs.18004519011

12. Pow-Sang MR, Orihuela E. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. J Urol. 1994;151(6):1643-1645. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35328-413. Isa SS, Almaraz R, Magovern J. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. Case report and review of the literature. Cancer. 1984;54(5):939-942. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19840901)54:5<939::aid-cncr2820540533>3.0.co;2-y

14. Hutcheson JB, Wittaker WW, Fronstin MH. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis: case report and review of literature. J Urol. 1969;101(6):874-875. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)62446-7

15. Grimer R, Judson I, Peake D, et al. Guidelines for the management of soft tissue sarcomas. Sarcoma. 2010;2010:506182. doi:10.1155/2010/506182

16. McDonald MW, O’Connell JR, Manning JT, Benjamin RS. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. J Urol. 1983;130(4):788-789. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)51464-0

17. Planz B, Brunner K, Kalem T, Schlick RW, Kind M. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the epididymis and late recurrence on the penis. J Urol. 1998;159(2):508. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(01)63966-1

18. Smart RH. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. J Urol. 1984;132(2):356-357. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49624-8

19. Patrikidou A, Domont J, Cioffi A, Le Cesne A. Treating soft tissue sarcomas with adjuvant chemotherapy. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2011;12(1):21-31. doi:10.1007/s11864-011-0145-5

20. Italiano A, Delva F, Mathoulin-Pelissier S, et al. Effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on survival in FNCLCC grade 3 soft tissue sarcomas: a multivariate analysis of the French Sarcoma Group Database. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(12):2436-2441. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdq238

21. Pervaiz N, Colterjohn N, Farrokhyar F, Tozer R, Figueredo A, Ghert M. A systematic meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of adjuvant chemotherapy for localized resectable soft-tissue sarcoma. Cancer. 2008;113(3):573-581. doi:10.1002/cncr.23592

22. Lacarrière E, Galliot I, Gobet F, Sibert L. Leiomyosarcoma of the corpus cavernosum mimicking a Peyronie’s plaque. Urology. 2012;79(4):e53-e54. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2011.07.1410

23. Hamal PB. Leiomyosarcoma of penis—case report and review of the literature. Br J Urol. 1975;47(3):319-324. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410x.1975.tb03974.x

24. Greenwood N, Fox H, Edwards EC. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. Cancer. 1972;29(2):481-483. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(197202)29:2<481::aid -cncr2820290237>3.0.co;2-q

25. Koizumi H, Nagano K, Kosaka S. A case of penile tumor: combination of leiomyosarcoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Hinyokika Kiyo. 1987;33(9):1489-1491.

26. Romero Gonzalez EJ, Marenco Jimenez JL, Mayorga Pineda MP, Martínez Morán A, Castiñeiras Fernández J. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis, an exceptional entity. Urol Case Rep. 2015;3(3):63-64. doi:10.1016/j.eucr.2014.12.007

Penile cancer is rare with a worldwide incidence of 0.8 cases per 100,000 men.1 The most common type is squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) followed by soft tissue sarcoma (STS) and Kaposi sarcoma.2 Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is the second most common STS subtype at this location.3 Approximately 50 cases of penile LMS have been reported in the English literature, most as isolated case reports while Fetsch and colleagues reported 14 cases from a single institute.4 We present a case of penile LMS with a review of 31 cases. We also describe presentation, treatment options, and recurrence pattern of this rare malignancy.

Case Presentation

A patient aged 70 years presented to the urology clinic with 1-year history of a slowly enlarging penile mass associated with phimosis. He reported no pain, dysuria, or hesitancy. On examination a 2 × 2-cm smooth, mobile, nonulcerating mass was seen on the tip of his left glans without inguinal lymphadenopathy. He underwent circumcision and excision biopsy that revealed an encapsulated tan-white mass measuring 3 × 2.2 × 1.5 cm under the surface of the foreskin. Histology showed a spindle cell tumor with areas of increased cellularity, prominent atypia, and pleomorphism, focal necrosis, and scattered mitoses, including atypical forms. The tumor stained positive for smooth muscle actin and desmin. Ki-67 staining showed foci with a very high proliferation index (Figure). Resection margins were negative. Final Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre Le Cancer score was grade 2 (differentiation, 1; mitotic, 3; necrosis, 1). Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis did not show evidence of metastasis. The tumor was classified as superficial, stage IIA (pT1cN0cM0). Local excision with negative margins was deemed adequate treatment.

Discussion