User login

A Review of Patient Adherence to Topical Therapies for Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that typically begins in early childhood (Figure). It is one of the most commonly diagnosed dermatologic conditions, affecting up to 25% of children and 2% to 3% of adults in the United States.1,2 The mainstays of treatment for AD are topical emollients and topical medications, of which corticosteroids are most commonly prescribed.3 Although treatments for AD generally are straightforward and efficacious when used correctly, poor adherence to treatment often prevents patients from achieving disease control.4 Patient adherence to therapy is a familiar challenge in dermatology, especially for diseases like AD that require long-term treatment with topical medications.4,5 In some instances, poor adherence may be misconstrued as poor response to treatment, which may lead to escalation to more powerful and potentially dangerous systemic medications.6 Ensuring good adherence to treatment leads to better outcomes and disease control, averts unnecessary treatment, prevents disease complications, improves quality of life, and decreases treatment cost.4,5 This article provides a review of the literature on patient adherence to topical therapies for AD as well as a discussion of methods to improve patient adherence to treatment in the clinical setting.

Methods

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE from January 2005 to May 2015 was conducted to identify studies that focused on treatment adherence in AD using the search terms atopic dermatitis and medication adherence and atopic dermatitis and patient compliance After excluding duplicate results and those that were not in the English language, a final list of clinical trials that investigated patient adherence/compliance to topical medications for the treatment of AD was extracted for evaluation.

Results

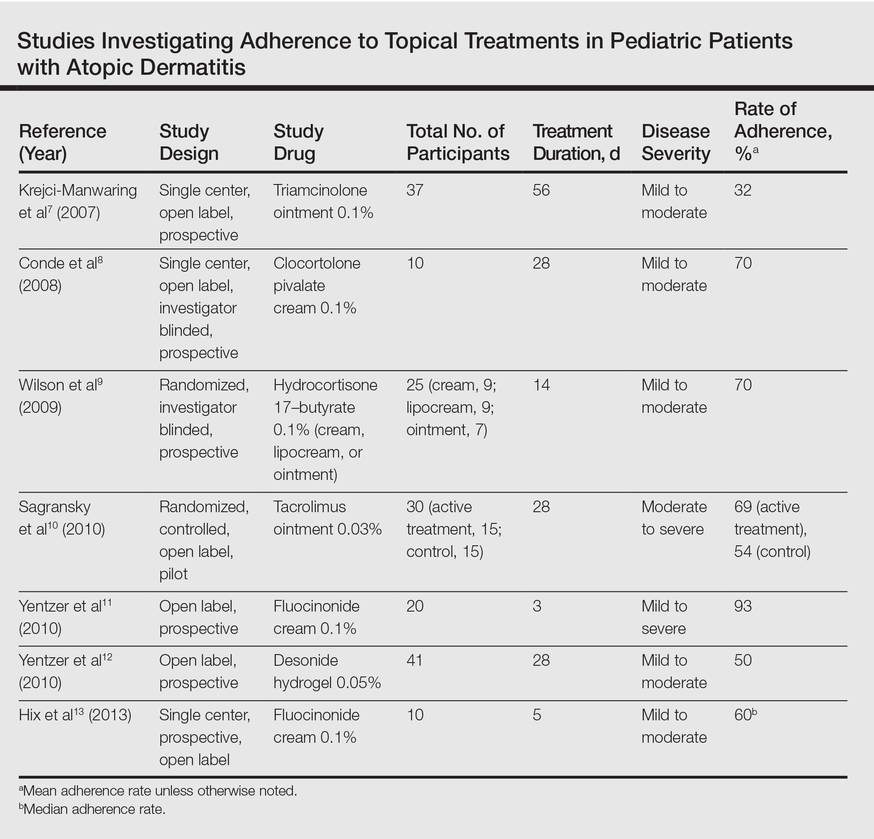

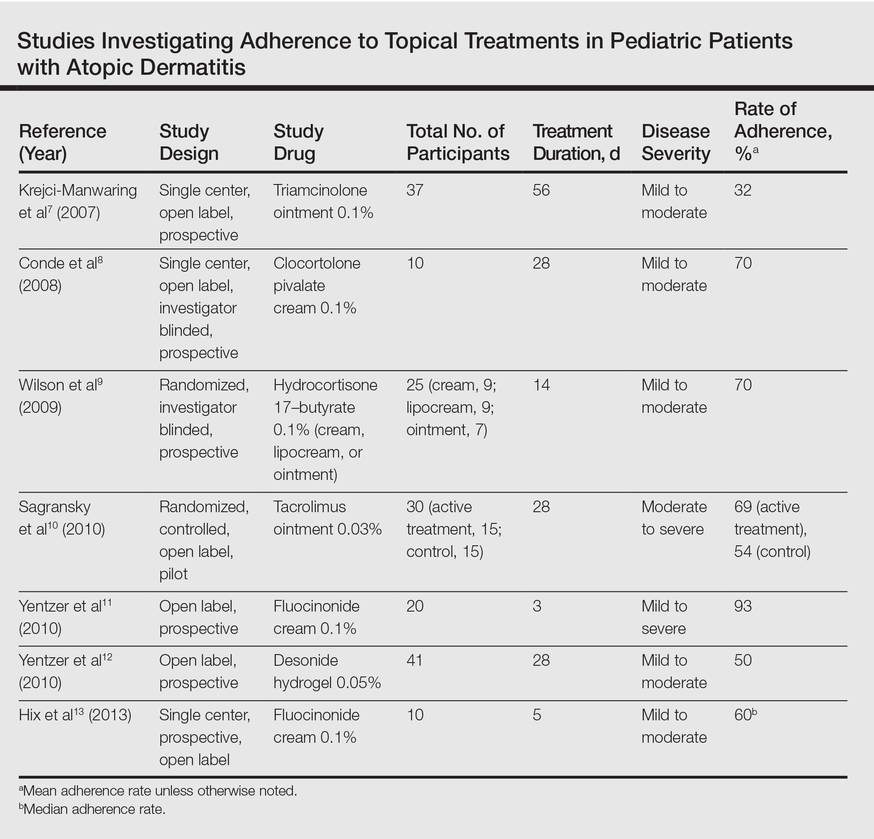

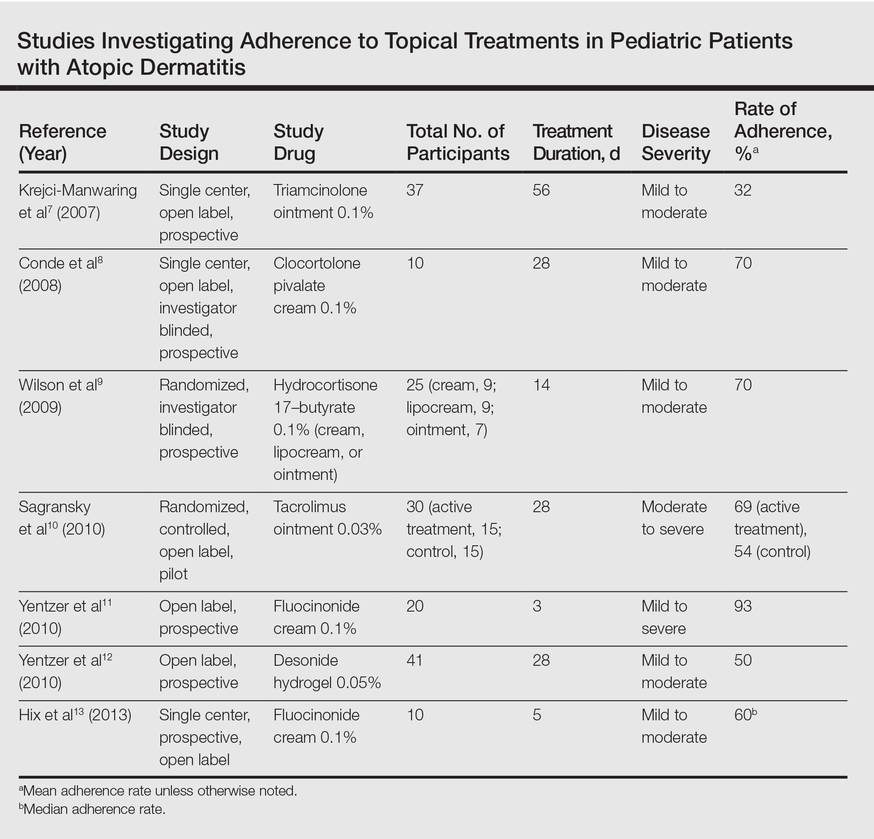

Our review of the literature yielded 7 quantitative studies that evaluated adherence to topical medications in AD using electronic monitoring and/or self-reporting (Table).7-13 Participant demographics, disease severity, drug and vehicle used, duration of treatment, and number of follow-up visits varied. All studies used medication event monitoring system caps on medication jars to objectively track patient adherence by recording the date and time when the cap was removed. To assess disease response, the studies used such measures as the Investigator Global Assessment scale, Eczema Area and Severity Index score, or other visual analog scales.

In all of the studies, treatment proved effective and disease severity declined from baseline regardless of the rate of adherence, with benefit continuing after treatment had ended.7-13 Some results suggested that better adherence increased treatment efficacy and reduced disease severity.8,9 However, one 10-day trial found no difference in severity and efficacy among participants who applied the medication at least once daily, missed applications some days, or applied the medication more than twice daily.13

Study participants typically overestimated their adherence to treatment compared to actual adherence rates, with most reporting near 100% adherence.7-9,11,12 Average measured adherence rates ranged from 32% to 93% (Table). Adherence rates typically were highest at the beginning of the study and decreased as the study continued.7-13 The study with the best average adherence rate of 93% had the shortest treatment period of 3 days,11 and the study with the lowest average adherence rate of 32% had the longest treatment period of 8 weeks.7 The study with the lowest adherence rate was the only study wherein participants were blinded to their enrollment in the study, which would most closely mimic adherence rates in clinical practice.7 The participants in the other studies were not aware that their adherence was being monitored, but their behavior may have been influenced since they were aware of their enrollment in the study.

Many variables affect treatment adherence in patients with AD. Average adherence rates were significantly higher (P=.03) in participants with greater disease severity.7 There is conflicting evidence regarding the role of medication vehicle in treatment adherence. While Wilson et al9 did not find any difference in adherence based on medication vehicle, Yentzer et al12 found vehicle characteristics and medication side effects were among patients’ top-ranked concerns about using topical medications. Sagransky et al10 compared treatment adherence between 2 groups of AD patients: one control group received a standard-of-care 4-week follow-up, and an active group received an additional 1-week follow-up. The mean adherence rate of the treatment group was 69% compared with 54% in the control group.10

Comment

Poor adherence to treatment is a pervasive problem in patients with AD. Our review of the literature confirmed that patients generally are not accurate historians of their medication usage, often reporting near-perfect treatment adherence even when actual adherence is poor. Rates of adherence from clinical trials are likely higher than those seen in clinical practice due in part to study incentives and differences between how patients in a study are treated compared to those in a physician’s clinic; for example, research study participants often have additional follow-up visits compared to those being treated in the clinical population and by virtue of being enrolled in a study are aware that their behavior is being monitored, which can increase treatment adherence.7

The dogma suggesting that tachyphylaxis can occur with long-term use of topical corticosteroids is not supported by clinical trials.14 Furthermore, in our review of the literature patient adherence was highest in the shortest study11 and lowest in the longest study.7 Given that AD patients cannot benefit from a treatment if they do not use it, the supposed decrease in efficacy of topical corticosteroids over time may be because patients fail to use them consistently.

Our review of the literature was limited by the small body of research that exists on treatment adherence in AD patients, especially relating to topical medications, and did not reveal any studies evaluating systemic medications in AD. Of the studies we examined, sample sizes were small and treatment and follow-up periods were short. Our review only covered adherence to prescribed topical medications in AD, chiefly corticosteroids; thus, we did not evaluate adherence to other therapies (eg, emollients) in this patient population.

The existing research also is limited by the relative paucity of data showing a correlation between improved adherence to topical treatment and improved disease outcomes, which may be due to the methodological limitations of the study designs that have been used; for instance, studies may use objective monitors to describe daily adherence to treatment, but disease severity typically is measured over longer periods of time, usually every few weeks or months. Short-term data may not be an accurate demonstration of how participants’ actual treatment adherence impacts disease outcome, as the data does not account for more complex adherence factors; for example, participants who achieve good disease control using topical corticosteroids for an 8-week study period may actually demonstrate poor treatment adherence overall, as topical corticosteroids have good short-term efficacy and the patient may have stopped using the product after the first few weeks of the treatment period. In contrast, poorly adherent patients may never use the medication well enough to achieve improvement and may continue low-level use throughout the study period. Therefore, studies that measure disease severity at more regular intervals are required to show the true effect of treatment adherence on disease outcomes.

Since AD mainly affects children, family issues can pose special challenges to attaining good treatment adherence.15,16 The physician–patient (or parent) relationship and the family’s perception of the patient’s disease severity are strong predictors of adherence to topical treatment.16 Potential barriers to adherence in the pediatric population are caregivers with negative beliefs about treatment, the time-consuming nature of applying topical therapies, or a child who is uncooperative.15,17 In the treatment of infants, critical factors are caregiver availability and beliefs and fears about medications and their side effects, while in the teenage population, the desire to “fit in” and oppositional behavior can lead to poor adherence to treatment.17 Regardless of age, other barriers to treatment adherence are forgetfulness, belief that the drug is not working, and the messiness of treatment.17

Educational tools (eg, action plans, instructions about how to apply topical medications correctly) may be underutilized in patients with AD. If consistently implemented, these tools could have a positive impact on adherence to medication in patients with AD. For example, written action plans pioneered in the asthma community have shown to improve quality of life and reduce disease severity and may offer the same benefits for AD patients due to the similarities of the diseases.18 Since AD patients and their caregivers often are not well versed in how to apply topical medications correctly, efforts to educate patients could potentially increase adherence to treatment. In one study, AD patients began to use medications more effectively after applying a fluorescent cream to reveal affected areas they had missed, and clinicians were able to provide additional instruction based on the findings.19

Adherence to topical treatments among AD patients is a multifactorial issue. Regimens often are complex and inconvenient due to the need for multiple medications, the topical nature of the products, and the need for frequent application. To optimize prescription treatments, patients also must be diligent with preventive measures such as application of topical emollients and use of bathing techniques (eg, bleach baths). A way to overcome treatment complexity and increase adherence may be to provide a written action plan and involve the patient and caregiver in the plan’s development. If a drug formulation is not aesthetically acceptable to the patient (eg, the greasiness of an ointment), allowing the patient to choose the medication vehicle may increase satisfaction and use.12 Fear of steroid side effects also is common among patients and caregivers and could be overcome with education about the product.20

Conclusion

Treatment adherence can have a dramatic effect on diseases outcomes and can be particularly challenging in AD due to the use of topical medications with complex treatment regimens. Additionally, a large majority of patients with AD are children, from infants to teenagers, adding another layer of treatment challenges. Further research is needed to more definitively develop effective methods for enhancing treatment adherence in this patient population. Although enormous amounts of money are being spent to develop improved treatments for AD, we may be able to achieve far more benefit at a much lower cost by figuring out how to get patients to adhere to the treatments that are already available.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:338-351.

- Landis ET, Davis SA, Taheri A, et al. Top dermatologic diagnoses by age. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22368.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-132.

- Lee IA, Maibach HI. Pharmionics in dermatology: a review of topical medication adherence. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:231-236.

- Tan X, Feldman SR, Chang J, et al. Topical drug delivery systems in dermatology: a review of patient adherence issues. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2012;9:1263-1271.

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349.

- Krejci-Manwaring J, Tusa MG, Carroll C, et al. Stealth monitoring of adherence to topical medication: adherence is very poor in children with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:211-216.

- Conde JF, Kaur M, Fleischer AB Jr, et al. Adherence to clocortolone pivalate cream 0.1% in a pediatric population with atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2008;81:435-441.

- Wilson R, Camacho F, Clark AR, et al. Adherence to topical hydrocortisone 17-butyrate 0.1% in different vehicles in adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:166-168.

- Sagransky MJ, Yentzer BA, Williams LL, et al. A randomized controlled pilot study of the effects of an extra office visit on adherence and outcomes in atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1428-1430.

- Yentzer BA, Ade RA, Fountain JM, et al. Improvement in treatment adherence with a 3-day course of fluocinonide cream 0.1% for atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2010;86:208-213.

- Yentzer BA, Camacho FT, Young T, et al. Good adherence and early efficacy using desonide hydrogel for atopic dermatitis: results from a program addressing patient compliance. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:324-329.

- Hix E, Gustafson CJ, O’Neill JL, et al. Adherence to a five day treatment course of topical fluocinonide 0.1% cream in atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20029.

- Taheri A, Cantrell J, Feldman SR. Tachyphylaxis to topical glucocorticoids; what is the evidence? Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18954.

- Santer M, Burgess H, Yardley L, et al. Managing childhood eczema: qualitative study exploring carers’ experiences of barriers and facilitators to treatment adherence. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69:2493-2501.

- Ohya Y, Williams H, Steptoe A, et al. Psychosocial factors and adherence to treatment advice in childhood atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:852-857.

- Ou HT, Feldman SR, Balkrishnan R. Understanding and improving treatment adherence in pediatric patients. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2010;29:137-140.

- Chisolm SS, Taylor SL, Balkrishnan R, et al. Written action plans: potential for improving outcomes in children with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:677-683.

- Ulff E, Maroti M, Serup J. Fluorescent cream used as an educational intervention to improve the effectiveness of self-application by patients with atopic dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2013;24:268-271.

- Aubert-Wastiaux H, Moret L, Le Rhun A, et al. Topical corticosteroid phobia in atopic dermatitis: a study of its nature, origins and frequency. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:808-814.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that typically begins in early childhood (Figure). It is one of the most commonly diagnosed dermatologic conditions, affecting up to 25% of children and 2% to 3% of adults in the United States.1,2 The mainstays of treatment for AD are topical emollients and topical medications, of which corticosteroids are most commonly prescribed.3 Although treatments for AD generally are straightforward and efficacious when used correctly, poor adherence to treatment often prevents patients from achieving disease control.4 Patient adherence to therapy is a familiar challenge in dermatology, especially for diseases like AD that require long-term treatment with topical medications.4,5 In some instances, poor adherence may be misconstrued as poor response to treatment, which may lead to escalation to more powerful and potentially dangerous systemic medications.6 Ensuring good adherence to treatment leads to better outcomes and disease control, averts unnecessary treatment, prevents disease complications, improves quality of life, and decreases treatment cost.4,5 This article provides a review of the literature on patient adherence to topical therapies for AD as well as a discussion of methods to improve patient adherence to treatment in the clinical setting.

Methods

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE from January 2005 to May 2015 was conducted to identify studies that focused on treatment adherence in AD using the search terms atopic dermatitis and medication adherence and atopic dermatitis and patient compliance After excluding duplicate results and those that were not in the English language, a final list of clinical trials that investigated patient adherence/compliance to topical medications for the treatment of AD was extracted for evaluation.

Results

Our review of the literature yielded 7 quantitative studies that evaluated adherence to topical medications in AD using electronic monitoring and/or self-reporting (Table).7-13 Participant demographics, disease severity, drug and vehicle used, duration of treatment, and number of follow-up visits varied. All studies used medication event monitoring system caps on medication jars to objectively track patient adherence by recording the date and time when the cap was removed. To assess disease response, the studies used such measures as the Investigator Global Assessment scale, Eczema Area and Severity Index score, or other visual analog scales.

In all of the studies, treatment proved effective and disease severity declined from baseline regardless of the rate of adherence, with benefit continuing after treatment had ended.7-13 Some results suggested that better adherence increased treatment efficacy and reduced disease severity.8,9 However, one 10-day trial found no difference in severity and efficacy among participants who applied the medication at least once daily, missed applications some days, or applied the medication more than twice daily.13

Study participants typically overestimated their adherence to treatment compared to actual adherence rates, with most reporting near 100% adherence.7-9,11,12 Average measured adherence rates ranged from 32% to 93% (Table). Adherence rates typically were highest at the beginning of the study and decreased as the study continued.7-13 The study with the best average adherence rate of 93% had the shortest treatment period of 3 days,11 and the study with the lowest average adherence rate of 32% had the longest treatment period of 8 weeks.7 The study with the lowest adherence rate was the only study wherein participants were blinded to their enrollment in the study, which would most closely mimic adherence rates in clinical practice.7 The participants in the other studies were not aware that their adherence was being monitored, but their behavior may have been influenced since they were aware of their enrollment in the study.

Many variables affect treatment adherence in patients with AD. Average adherence rates were significantly higher (P=.03) in participants with greater disease severity.7 There is conflicting evidence regarding the role of medication vehicle in treatment adherence. While Wilson et al9 did not find any difference in adherence based on medication vehicle, Yentzer et al12 found vehicle characteristics and medication side effects were among patients’ top-ranked concerns about using topical medications. Sagransky et al10 compared treatment adherence between 2 groups of AD patients: one control group received a standard-of-care 4-week follow-up, and an active group received an additional 1-week follow-up. The mean adherence rate of the treatment group was 69% compared with 54% in the control group.10

Comment

Poor adherence to treatment is a pervasive problem in patients with AD. Our review of the literature confirmed that patients generally are not accurate historians of their medication usage, often reporting near-perfect treatment adherence even when actual adherence is poor. Rates of adherence from clinical trials are likely higher than those seen in clinical practice due in part to study incentives and differences between how patients in a study are treated compared to those in a physician’s clinic; for example, research study participants often have additional follow-up visits compared to those being treated in the clinical population and by virtue of being enrolled in a study are aware that their behavior is being monitored, which can increase treatment adherence.7

The dogma suggesting that tachyphylaxis can occur with long-term use of topical corticosteroids is not supported by clinical trials.14 Furthermore, in our review of the literature patient adherence was highest in the shortest study11 and lowest in the longest study.7 Given that AD patients cannot benefit from a treatment if they do not use it, the supposed decrease in efficacy of topical corticosteroids over time may be because patients fail to use them consistently.

Our review of the literature was limited by the small body of research that exists on treatment adherence in AD patients, especially relating to topical medications, and did not reveal any studies evaluating systemic medications in AD. Of the studies we examined, sample sizes were small and treatment and follow-up periods were short. Our review only covered adherence to prescribed topical medications in AD, chiefly corticosteroids; thus, we did not evaluate adherence to other therapies (eg, emollients) in this patient population.

The existing research also is limited by the relative paucity of data showing a correlation between improved adherence to topical treatment and improved disease outcomes, which may be due to the methodological limitations of the study designs that have been used; for instance, studies may use objective monitors to describe daily adherence to treatment, but disease severity typically is measured over longer periods of time, usually every few weeks or months. Short-term data may not be an accurate demonstration of how participants’ actual treatment adherence impacts disease outcome, as the data does not account for more complex adherence factors; for example, participants who achieve good disease control using topical corticosteroids for an 8-week study period may actually demonstrate poor treatment adherence overall, as topical corticosteroids have good short-term efficacy and the patient may have stopped using the product after the first few weeks of the treatment period. In contrast, poorly adherent patients may never use the medication well enough to achieve improvement and may continue low-level use throughout the study period. Therefore, studies that measure disease severity at more regular intervals are required to show the true effect of treatment adherence on disease outcomes.

Since AD mainly affects children, family issues can pose special challenges to attaining good treatment adherence.15,16 The physician–patient (or parent) relationship and the family’s perception of the patient’s disease severity are strong predictors of adherence to topical treatment.16 Potential barriers to adherence in the pediatric population are caregivers with negative beliefs about treatment, the time-consuming nature of applying topical therapies, or a child who is uncooperative.15,17 In the treatment of infants, critical factors are caregiver availability and beliefs and fears about medications and their side effects, while in the teenage population, the desire to “fit in” and oppositional behavior can lead to poor adherence to treatment.17 Regardless of age, other barriers to treatment adherence are forgetfulness, belief that the drug is not working, and the messiness of treatment.17

Educational tools (eg, action plans, instructions about how to apply topical medications correctly) may be underutilized in patients with AD. If consistently implemented, these tools could have a positive impact on adherence to medication in patients with AD. For example, written action plans pioneered in the asthma community have shown to improve quality of life and reduce disease severity and may offer the same benefits for AD patients due to the similarities of the diseases.18 Since AD patients and their caregivers often are not well versed in how to apply topical medications correctly, efforts to educate patients could potentially increase adherence to treatment. In one study, AD patients began to use medications more effectively after applying a fluorescent cream to reveal affected areas they had missed, and clinicians were able to provide additional instruction based on the findings.19

Adherence to topical treatments among AD patients is a multifactorial issue. Regimens often are complex and inconvenient due to the need for multiple medications, the topical nature of the products, and the need for frequent application. To optimize prescription treatments, patients also must be diligent with preventive measures such as application of topical emollients and use of bathing techniques (eg, bleach baths). A way to overcome treatment complexity and increase adherence may be to provide a written action plan and involve the patient and caregiver in the plan’s development. If a drug formulation is not aesthetically acceptable to the patient (eg, the greasiness of an ointment), allowing the patient to choose the medication vehicle may increase satisfaction and use.12 Fear of steroid side effects also is common among patients and caregivers and could be overcome with education about the product.20

Conclusion

Treatment adherence can have a dramatic effect on diseases outcomes and can be particularly challenging in AD due to the use of topical medications with complex treatment regimens. Additionally, a large majority of patients with AD are children, from infants to teenagers, adding another layer of treatment challenges. Further research is needed to more definitively develop effective methods for enhancing treatment adherence in this patient population. Although enormous amounts of money are being spent to develop improved treatments for AD, we may be able to achieve far more benefit at a much lower cost by figuring out how to get patients to adhere to the treatments that are already available.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that typically begins in early childhood (Figure). It is one of the most commonly diagnosed dermatologic conditions, affecting up to 25% of children and 2% to 3% of adults in the United States.1,2 The mainstays of treatment for AD are topical emollients and topical medications, of which corticosteroids are most commonly prescribed.3 Although treatments for AD generally are straightforward and efficacious when used correctly, poor adherence to treatment often prevents patients from achieving disease control.4 Patient adherence to therapy is a familiar challenge in dermatology, especially for diseases like AD that require long-term treatment with topical medications.4,5 In some instances, poor adherence may be misconstrued as poor response to treatment, which may lead to escalation to more powerful and potentially dangerous systemic medications.6 Ensuring good adherence to treatment leads to better outcomes and disease control, averts unnecessary treatment, prevents disease complications, improves quality of life, and decreases treatment cost.4,5 This article provides a review of the literature on patient adherence to topical therapies for AD as well as a discussion of methods to improve patient adherence to treatment in the clinical setting.

Methods

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE from January 2005 to May 2015 was conducted to identify studies that focused on treatment adherence in AD using the search terms atopic dermatitis and medication adherence and atopic dermatitis and patient compliance After excluding duplicate results and those that were not in the English language, a final list of clinical trials that investigated patient adherence/compliance to topical medications for the treatment of AD was extracted for evaluation.

Results

Our review of the literature yielded 7 quantitative studies that evaluated adherence to topical medications in AD using electronic monitoring and/or self-reporting (Table).7-13 Participant demographics, disease severity, drug and vehicle used, duration of treatment, and number of follow-up visits varied. All studies used medication event monitoring system caps on medication jars to objectively track patient adherence by recording the date and time when the cap was removed. To assess disease response, the studies used such measures as the Investigator Global Assessment scale, Eczema Area and Severity Index score, or other visual analog scales.

In all of the studies, treatment proved effective and disease severity declined from baseline regardless of the rate of adherence, with benefit continuing after treatment had ended.7-13 Some results suggested that better adherence increased treatment efficacy and reduced disease severity.8,9 However, one 10-day trial found no difference in severity and efficacy among participants who applied the medication at least once daily, missed applications some days, or applied the medication more than twice daily.13

Study participants typically overestimated their adherence to treatment compared to actual adherence rates, with most reporting near 100% adherence.7-9,11,12 Average measured adherence rates ranged from 32% to 93% (Table). Adherence rates typically were highest at the beginning of the study and decreased as the study continued.7-13 The study with the best average adherence rate of 93% had the shortest treatment period of 3 days,11 and the study with the lowest average adherence rate of 32% had the longest treatment period of 8 weeks.7 The study with the lowest adherence rate was the only study wherein participants were blinded to their enrollment in the study, which would most closely mimic adherence rates in clinical practice.7 The participants in the other studies were not aware that their adherence was being monitored, but their behavior may have been influenced since they were aware of their enrollment in the study.

Many variables affect treatment adherence in patients with AD. Average adherence rates were significantly higher (P=.03) in participants with greater disease severity.7 There is conflicting evidence regarding the role of medication vehicle in treatment adherence. While Wilson et al9 did not find any difference in adherence based on medication vehicle, Yentzer et al12 found vehicle characteristics and medication side effects were among patients’ top-ranked concerns about using topical medications. Sagransky et al10 compared treatment adherence between 2 groups of AD patients: one control group received a standard-of-care 4-week follow-up, and an active group received an additional 1-week follow-up. The mean adherence rate of the treatment group was 69% compared with 54% in the control group.10

Comment

Poor adherence to treatment is a pervasive problem in patients with AD. Our review of the literature confirmed that patients generally are not accurate historians of their medication usage, often reporting near-perfect treatment adherence even when actual adherence is poor. Rates of adherence from clinical trials are likely higher than those seen in clinical practice due in part to study incentives and differences between how patients in a study are treated compared to those in a physician’s clinic; for example, research study participants often have additional follow-up visits compared to those being treated in the clinical population and by virtue of being enrolled in a study are aware that their behavior is being monitored, which can increase treatment adherence.7

The dogma suggesting that tachyphylaxis can occur with long-term use of topical corticosteroids is not supported by clinical trials.14 Furthermore, in our review of the literature patient adherence was highest in the shortest study11 and lowest in the longest study.7 Given that AD patients cannot benefit from a treatment if they do not use it, the supposed decrease in efficacy of topical corticosteroids over time may be because patients fail to use them consistently.

Our review of the literature was limited by the small body of research that exists on treatment adherence in AD patients, especially relating to topical medications, and did not reveal any studies evaluating systemic medications in AD. Of the studies we examined, sample sizes were small and treatment and follow-up periods were short. Our review only covered adherence to prescribed topical medications in AD, chiefly corticosteroids; thus, we did not evaluate adherence to other therapies (eg, emollients) in this patient population.

The existing research also is limited by the relative paucity of data showing a correlation between improved adherence to topical treatment and improved disease outcomes, which may be due to the methodological limitations of the study designs that have been used; for instance, studies may use objective monitors to describe daily adherence to treatment, but disease severity typically is measured over longer periods of time, usually every few weeks or months. Short-term data may not be an accurate demonstration of how participants’ actual treatment adherence impacts disease outcome, as the data does not account for more complex adherence factors; for example, participants who achieve good disease control using topical corticosteroids for an 8-week study period may actually demonstrate poor treatment adherence overall, as topical corticosteroids have good short-term efficacy and the patient may have stopped using the product after the first few weeks of the treatment period. In contrast, poorly adherent patients may never use the medication well enough to achieve improvement and may continue low-level use throughout the study period. Therefore, studies that measure disease severity at more regular intervals are required to show the true effect of treatment adherence on disease outcomes.

Since AD mainly affects children, family issues can pose special challenges to attaining good treatment adherence.15,16 The physician–patient (or parent) relationship and the family’s perception of the patient’s disease severity are strong predictors of adherence to topical treatment.16 Potential barriers to adherence in the pediatric population are caregivers with negative beliefs about treatment, the time-consuming nature of applying topical therapies, or a child who is uncooperative.15,17 In the treatment of infants, critical factors are caregiver availability and beliefs and fears about medications and their side effects, while in the teenage population, the desire to “fit in” and oppositional behavior can lead to poor adherence to treatment.17 Regardless of age, other barriers to treatment adherence are forgetfulness, belief that the drug is not working, and the messiness of treatment.17

Educational tools (eg, action plans, instructions about how to apply topical medications correctly) may be underutilized in patients with AD. If consistently implemented, these tools could have a positive impact on adherence to medication in patients with AD. For example, written action plans pioneered in the asthma community have shown to improve quality of life and reduce disease severity and may offer the same benefits for AD patients due to the similarities of the diseases.18 Since AD patients and their caregivers often are not well versed in how to apply topical medications correctly, efforts to educate patients could potentially increase adherence to treatment. In one study, AD patients began to use medications more effectively after applying a fluorescent cream to reveal affected areas they had missed, and clinicians were able to provide additional instruction based on the findings.19

Adherence to topical treatments among AD patients is a multifactorial issue. Regimens often are complex and inconvenient due to the need for multiple medications, the topical nature of the products, and the need for frequent application. To optimize prescription treatments, patients also must be diligent with preventive measures such as application of topical emollients and use of bathing techniques (eg, bleach baths). A way to overcome treatment complexity and increase adherence may be to provide a written action plan and involve the patient and caregiver in the plan’s development. If a drug formulation is not aesthetically acceptable to the patient (eg, the greasiness of an ointment), allowing the patient to choose the medication vehicle may increase satisfaction and use.12 Fear of steroid side effects also is common among patients and caregivers and could be overcome with education about the product.20

Conclusion

Treatment adherence can have a dramatic effect on diseases outcomes and can be particularly challenging in AD due to the use of topical medications with complex treatment regimens. Additionally, a large majority of patients with AD are children, from infants to teenagers, adding another layer of treatment challenges. Further research is needed to more definitively develop effective methods for enhancing treatment adherence in this patient population. Although enormous amounts of money are being spent to develop improved treatments for AD, we may be able to achieve far more benefit at a much lower cost by figuring out how to get patients to adhere to the treatments that are already available.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:338-351.

- Landis ET, Davis SA, Taheri A, et al. Top dermatologic diagnoses by age. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22368.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-132.

- Lee IA, Maibach HI. Pharmionics in dermatology: a review of topical medication adherence. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:231-236.

- Tan X, Feldman SR, Chang J, et al. Topical drug delivery systems in dermatology: a review of patient adherence issues. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2012;9:1263-1271.

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349.

- Krejci-Manwaring J, Tusa MG, Carroll C, et al. Stealth monitoring of adherence to topical medication: adherence is very poor in children with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:211-216.

- Conde JF, Kaur M, Fleischer AB Jr, et al. Adherence to clocortolone pivalate cream 0.1% in a pediatric population with atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2008;81:435-441.

- Wilson R, Camacho F, Clark AR, et al. Adherence to topical hydrocortisone 17-butyrate 0.1% in different vehicles in adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:166-168.

- Sagransky MJ, Yentzer BA, Williams LL, et al. A randomized controlled pilot study of the effects of an extra office visit on adherence and outcomes in atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1428-1430.

- Yentzer BA, Ade RA, Fountain JM, et al. Improvement in treatment adherence with a 3-day course of fluocinonide cream 0.1% for atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2010;86:208-213.

- Yentzer BA, Camacho FT, Young T, et al. Good adherence and early efficacy using desonide hydrogel for atopic dermatitis: results from a program addressing patient compliance. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:324-329.

- Hix E, Gustafson CJ, O’Neill JL, et al. Adherence to a five day treatment course of topical fluocinonide 0.1% cream in atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20029.

- Taheri A, Cantrell J, Feldman SR. Tachyphylaxis to topical glucocorticoids; what is the evidence? Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18954.

- Santer M, Burgess H, Yardley L, et al. Managing childhood eczema: qualitative study exploring carers’ experiences of barriers and facilitators to treatment adherence. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69:2493-2501.

- Ohya Y, Williams H, Steptoe A, et al. Psychosocial factors and adherence to treatment advice in childhood atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:852-857.

- Ou HT, Feldman SR, Balkrishnan R. Understanding and improving treatment adherence in pediatric patients. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2010;29:137-140.

- Chisolm SS, Taylor SL, Balkrishnan R, et al. Written action plans: potential for improving outcomes in children with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:677-683.

- Ulff E, Maroti M, Serup J. Fluorescent cream used as an educational intervention to improve the effectiveness of self-application by patients with atopic dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2013;24:268-271.

- Aubert-Wastiaux H, Moret L, Le Rhun A, et al. Topical corticosteroid phobia in atopic dermatitis: a study of its nature, origins and frequency. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:808-814.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:338-351.

- Landis ET, Davis SA, Taheri A, et al. Top dermatologic diagnoses by age. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22368.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-132.

- Lee IA, Maibach HI. Pharmionics in dermatology: a review of topical medication adherence. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:231-236.

- Tan X, Feldman SR, Chang J, et al. Topical drug delivery systems in dermatology: a review of patient adherence issues. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2012;9:1263-1271.

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349.

- Krejci-Manwaring J, Tusa MG, Carroll C, et al. Stealth monitoring of adherence to topical medication: adherence is very poor in children with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:211-216.

- Conde JF, Kaur M, Fleischer AB Jr, et al. Adherence to clocortolone pivalate cream 0.1% in a pediatric population with atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2008;81:435-441.

- Wilson R, Camacho F, Clark AR, et al. Adherence to topical hydrocortisone 17-butyrate 0.1% in different vehicles in adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:166-168.

- Sagransky MJ, Yentzer BA, Williams LL, et al. A randomized controlled pilot study of the effects of an extra office visit on adherence and outcomes in atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1428-1430.

- Yentzer BA, Ade RA, Fountain JM, et al. Improvement in treatment adherence with a 3-day course of fluocinonide cream 0.1% for atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2010;86:208-213.

- Yentzer BA, Camacho FT, Young T, et al. Good adherence and early efficacy using desonide hydrogel for atopic dermatitis: results from a program addressing patient compliance. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:324-329.

- Hix E, Gustafson CJ, O’Neill JL, et al. Adherence to a five day treatment course of topical fluocinonide 0.1% cream in atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20029.

- Taheri A, Cantrell J, Feldman SR. Tachyphylaxis to topical glucocorticoids; what is the evidence? Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18954.

- Santer M, Burgess H, Yardley L, et al. Managing childhood eczema: qualitative study exploring carers’ experiences of barriers and facilitators to treatment adherence. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69:2493-2501.

- Ohya Y, Williams H, Steptoe A, et al. Psychosocial factors and adherence to treatment advice in childhood atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:852-857.

- Ou HT, Feldman SR, Balkrishnan R. Understanding and improving treatment adherence in pediatric patients. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2010;29:137-140.

- Chisolm SS, Taylor SL, Balkrishnan R, et al. Written action plans: potential for improving outcomes in children with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:677-683.

- Ulff E, Maroti M, Serup J. Fluorescent cream used as an educational intervention to improve the effectiveness of self-application by patients with atopic dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2013;24:268-271.

- Aubert-Wastiaux H, Moret L, Le Rhun A, et al. Topical corticosteroid phobia in atopic dermatitis: a study of its nature, origins and frequency. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:808-814.

Practice Points

- When used correctly, topical treatments for atopic dermatitis (AD) generally are straightforward and efficacious, but poor adherence to treatment can prevent patients from achieving disease control.

- Patients tend to overestimate their adherence to topical treatment regimens for AD compared to actual adherence rates.

- Improved treatment adherence in this patient population may be achieved by allowing patients to choose their preferred topical vehicle and providing patient education about how to apply medications effectively; for pediatric patients, AD action plans also may be useful.

Maintaining Adherence to Psoriasis Treatments

Adherence to psoriasis therapies, especially topical therapy, is remarkably poor. Dr. Steven Feldman discusses the patient-physician relationship and ways that physicians can help patients so they're not fearful of taking their medications. He discusses follow-up with patients and special considerations for patients with scalp psoriasis.

The psoriasis audiocast series is created in collaboration with Cutis® and the National Psoriasis Foundation®.

Adherence to psoriasis therapies, especially topical therapy, is remarkably poor. Dr. Steven Feldman discusses the patient-physician relationship and ways that physicians can help patients so they're not fearful of taking their medications. He discusses follow-up with patients and special considerations for patients with scalp psoriasis.

The psoriasis audiocast series is created in collaboration with Cutis® and the National Psoriasis Foundation®.

Adherence to psoriasis therapies, especially topical therapy, is remarkably poor. Dr. Steven Feldman discusses the patient-physician relationship and ways that physicians can help patients so they're not fearful of taking their medications. He discusses follow-up with patients and special considerations for patients with scalp psoriasis.

The psoriasis audiocast series is created in collaboration with Cutis® and the National Psoriasis Foundation®.

Most Common Dermatologic Conditions Encountered by Dermatologists and Nondermatologists

Skin diseases are highly prevalent in the United States, affecting an estimated 1 in 3 Americans at any given time.1,2 In 2009 the direct medical costs associated with skin-related diseases, including health services and prescriptions, was approximately $22 billion; the annual total economic burden was estimated to be closer to $96 billion when factoring in the cost of lost productivity and pay for symptom relief.3,4 Effective and efficient management of skin disease is essential to minimizing cost and morbidity. Nondermatologists traditionally have diagnosed the majority of skin diseases.5,6 In particular, primary care physicians commonly manage dermatologic conditions and often are the first health care providers to encounter patients presenting with skin problems. A predicted shortage of dermatologists will likely contribute to an increase in this trend.7,8 Therefore, it is important to adequately prepare nondermatologists to evaluate and treat the skin conditions that they are most likely to encounter in their scope of practice.

Residents, particularly in primary care specialties, often have opportunities to spend 2 to 4 weeks with a dermatologist to learn about skin diseases; however, the skin conditions most often encountered by dermatologists may differ from those most often encountered by physicians in other specialties. For instance, one study demonstrated a disparity between the most common skin problems seen by dermatologists and internists.9 These dissimilarities should be recognized and addressed in curriculum content. The purpose of this study was to identify and compare the 20 most common dermatologic conditions reported by dermatologists versus those reported by nondermatologists (ie, internists, pediatricians, family physicians, emergency medicine physicians, general surgeons, otolaryngologists) from 2001 to 2010. Data also were analyzed to determine the top 20 conditions referred to dermatologists by nondermatologists as a potential indicator for areas of further improvement within medical education. With this knowledge, we hope educational curricula and self-study can be modified to reflect the current epidemiology of cutaneous diseases, thereby improving patient care.

Methods

Data from 2001 to 2010 were extracted from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), which is an ongoing survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics. The NAMCS collects descriptive data regarding ambulatory visits to nonfederal office-based physicians in the United States. Participating physicians are instructed to record information about patient visits for a 1-week period, including patient demographics, insurance status, reason for visit, diagnoses, procedures, therapeutics, and referrals made at that time. Data collected for the NAMCS are entered into a multistage probability sample to produce national estimates. Within dermatology, an average of 118 dermatologists are sampled each year, and over the last 10 years, participation rates have ranged from 47% to 77%.

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes were identified to determine the diagnoses that could be classified as dermatologic conditions. Select infectious and neoplastic disorders of the skin and mucous membrane conditions were included as well as the codes for skin diseases. Nondermatologic diagnoses and V codes were not included in the study. Data for all providers were studied to identify outpatient visits associated with the primary diagnosis of a dermatologic condition. Minor diagnoses that were considered to be subsets of major diagnoses were combined to allow better analysis of the data. For example, all tinea infections (ie, dermatophytosis of various sites, dermatomycosis unspecified) were combined into 1 diagnosis referred to as tinea because the recognition and treatment of this disease does not vary tremendously by anatomic location. Visits to dermatologists that listed nonspecific diagnoses and codes (eg, other postsurgical status [V45.89], neoplasm of uncertain behavior site unspecified [238.9]) were assumed to be for dermatologic problems.

Sampling weights were applied to obtain estimates for the number of each diagnosis made nationally. All data analyses were performed using SAS software and linear regression models were generated using SAS PROC SURVEYREG.

Data were analyzed to determine the dermatologic conditions most commonly encountered by dermatologists and nondermatologists in emergency medicine, family medicine, general surgery, internal medicine, otolaryngology, and pediatrics; these specialties include physicians who are known to commonly diagnose and treat skin diseases.10 Data also were analyzed to determine the most common conditions referred to dermatologists for treatment by nondermatologists from the selected specialties. Permission to conduct this study was obtained from the Wake Forest University institutional review board (Winston-Salem, North Carolina).

Results

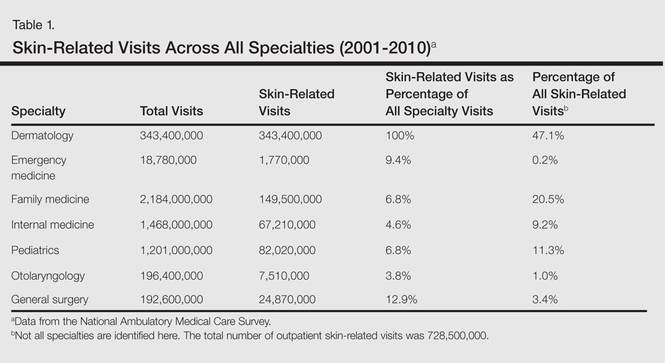

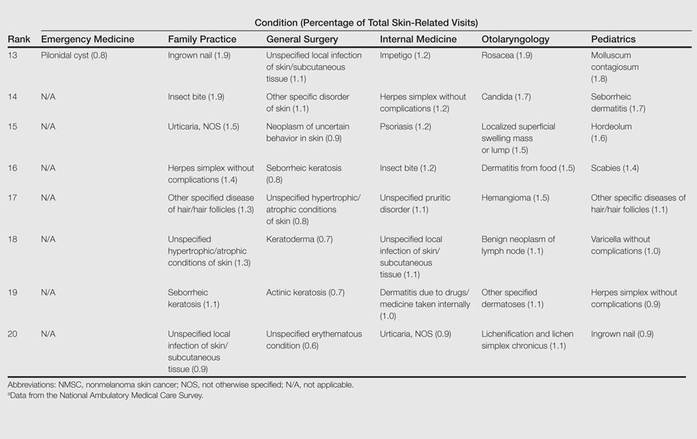

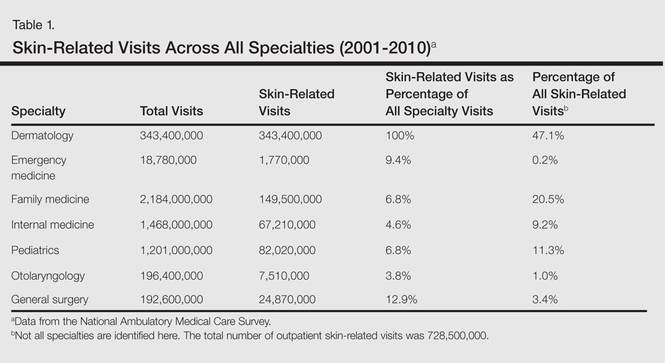

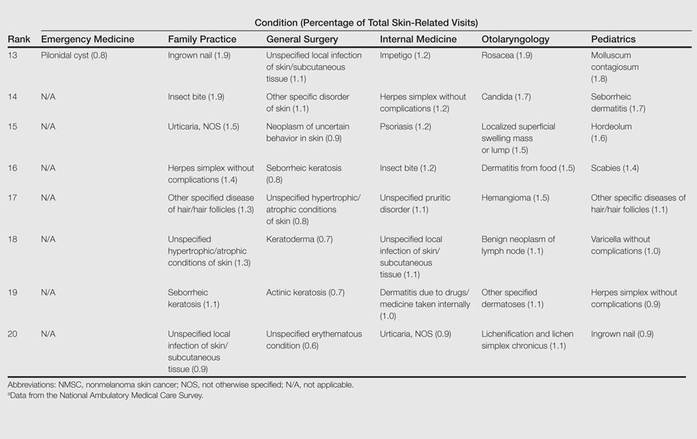

From 2001 to 2010, more than 700 million outpatient visits for skin-related problems were identified, with 676.3 million visits to dermatologists, emergency medicine physicians, family practitioners, general surgeons, internists, otolaryngologists, and pediatricians. More than half (52.9%) of all skin-related visits were addressed by nondermatologists during this time. Among nondermatologists, family practitioners encountered the greatest number of skin diseases (20.5%), followed by pediatricians (11.3%), internists (9.2%), general surgeons (3.4%), otolaryngologists (1.0%), and emergency medicine physicians (0.2%)(Table 1).

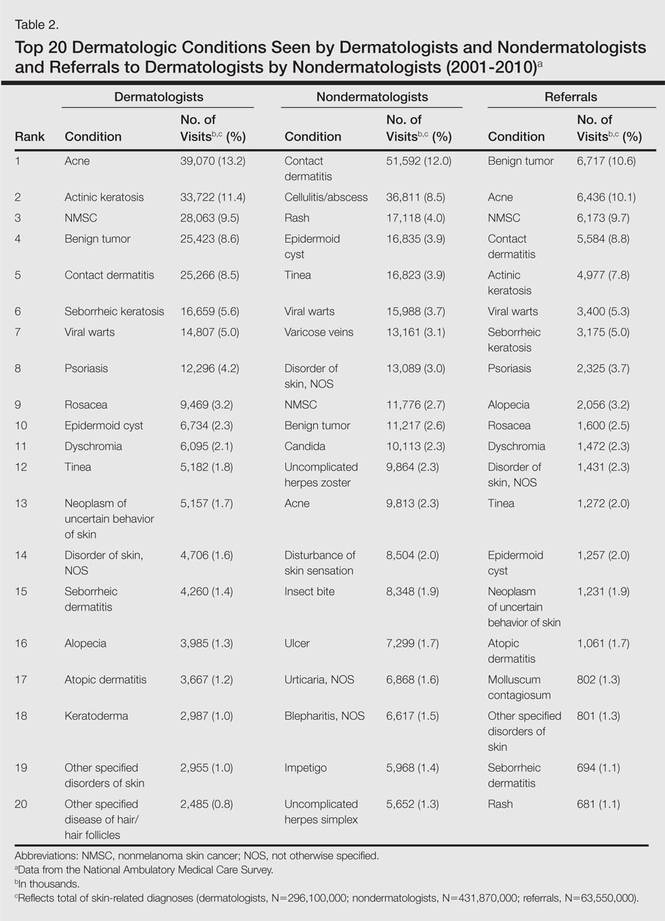

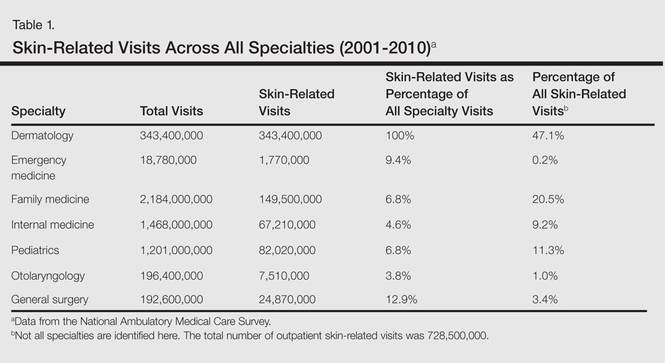

Benign tumors and acne were the most common cutaneous conditions referred to dermatologists by nondermatologists (10.6% and 10.1% of all dermatology referrals, respectively), followed by nonmelanoma skin cancers (9.7%), contact dermatitis (8.8%), and actinic keratosis (7.8%)(Table 2). The top 20 conditions referred to dermatologists accounted for 83.7% of all outpatient referrals to dermatologists.

Among the diseases most frequently reported by nondermatologists, contact dermatitis was the most common (12.0%), with twice the number of visits to nondermatologists for contact dermatitis than to dermatologists (51.6 million vs 25.3 million). In terms of disease categories, infectious skin diseases (ie, bacterial [cellulitis/abscess], viral [warts, herpesvirus], fungal [tinea] and yeast [candida] etiologies) were the most common dermatologic conditions reported by nondermatologists (Table 2).

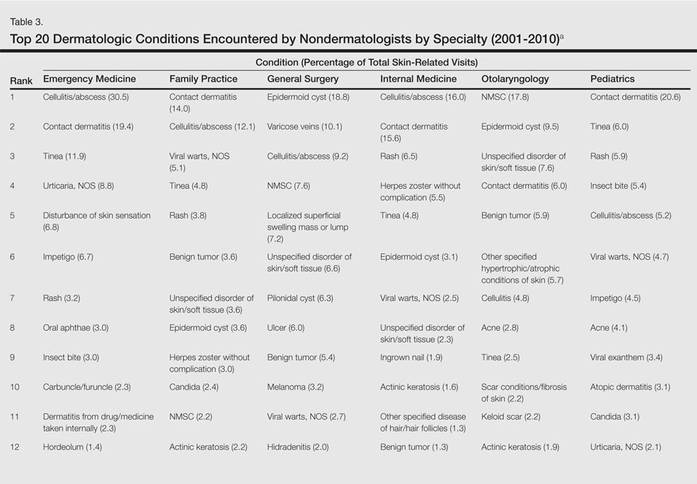

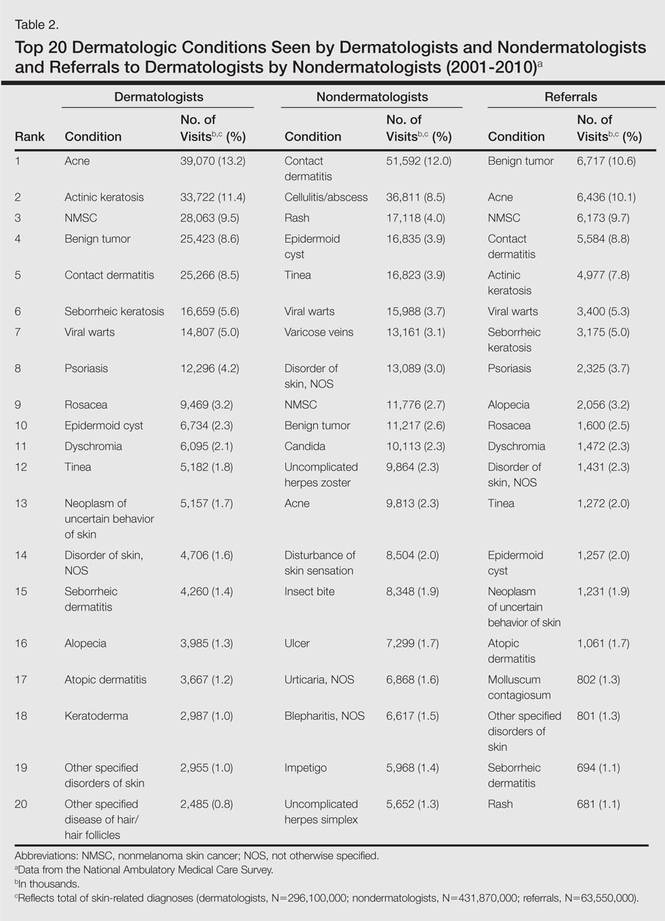

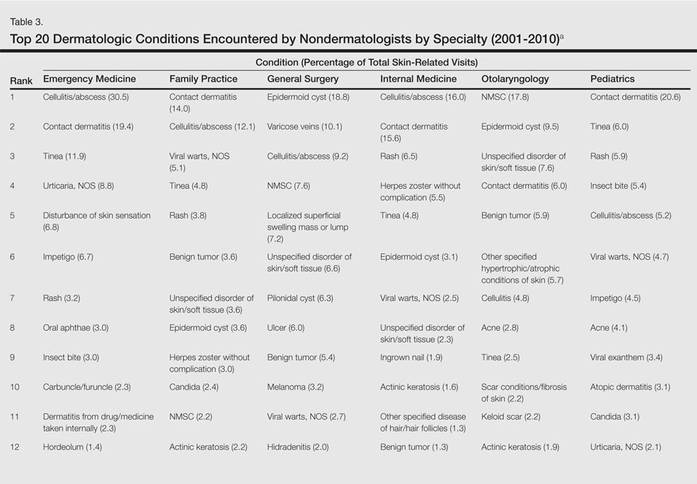

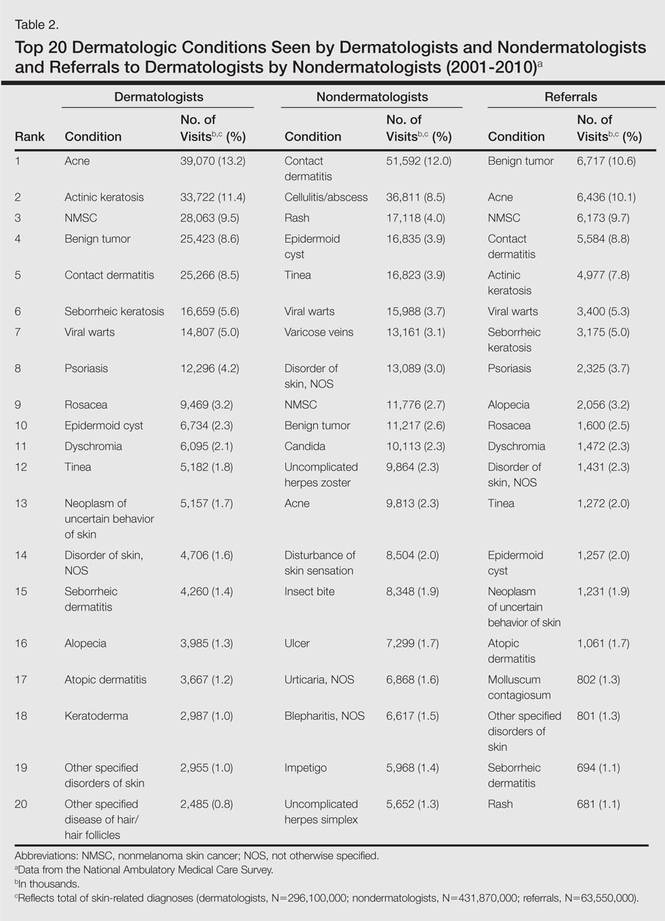

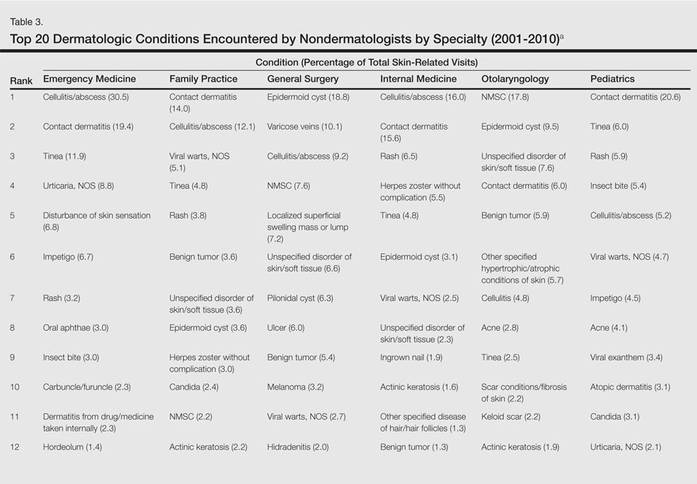

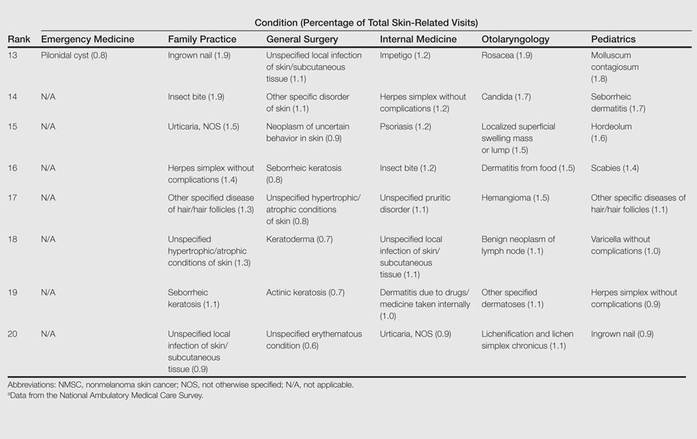

The top 20 dermatologic conditions reported by dermatologists accounted for 85.4% of all diagnoses made by dermatologists. Diseases that were among the top 20 conditions encountered by dermatologists but were not among the top 20 for nondermatologists included actinic keratosis, seborrheic keratosis, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, alopecia, rosacea, dyschromia, seborrheic dermatitis, follicular disease, and neoplasm of uncertain behavior of skin. Additionally, 5 of the top 20 conditions encountered by dermatologists also were among the top 20 for only 1 individual nondermatologic specialty; these included atopic dermatitis (pediatrics), seborrheic dermatitis (pediatrics), psoriasis (internal medicine), rosacea (otolaryngology), and keratoderma (general surgery). Seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, and rosacea also were among the top 20 conditions most commonly referred to dermatologists for treatment by nondermatologists. Table 3 shows the top 20 dermatologic conditions encountered by nondermatologists by comparison.

Comment

According to NAMCS data from 2001 to 2010, visits to nondermatologists accounted for more than half of total outpatient visits for cutaneous diseases in the United States, whereas visits to dermatologists accounted for 47.1%. These findings are consistent with historical data indicating that 30% to 40% of skin-related visits are to dermatologists, and the majority of patients with skin disease are diagnosed by nondermatologists.5,6

Past data indicate that most visits to dermatologists were for evaluation of acne, infections, psoriasis, and neoplasms, whereas most visits to nondermatologists were for evaluation of epidermoid cysts, impetigo, plant dermatitis, cellulitis, and diaper rash.9 Over the last 10 years, acne has been more commonly encountered by nondermatologists, especially pediatricians. Additionally, infectious etiologies have been seen in larger volume by nondermatologists.9 Together, infectious cutaneous conditions make up nearly one-fourth of dermatologic encounters by emergency medicine physicians, internists, and family practitioners but are not within the top 20 diagnoses referred to dermatologists, which suggests that uncomplicated cases of cellulitis, herpes zoster, and other skin-related infections are largely managed by nondermatologists.5,6 Contact dermatitis, often caused by specific allergens such as detergents, solvents, and topical products, was one of the most common reported dermatologic encounters among dermatologists and nondermatologists and also was the fourth most common condition referred to dermatologists by nondermatologists for treatment; however, there may be an element of overuse of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision code, as any presumed contact dermatitis of unspecified cause can be reported under 692.9 defined as contact dermatitis and other eczema, unspecified cause. The high rate of referrals to dermatologists by nondermatologists may be for patch testing and further management. Additionally, there are no specific codes for allergic or irritant dermatitis, thus these diseases may be lumped together.

Although nearly half of all dermatologic encounters were seen by nondermatologists, dermatologists see a much larger proportion of patients with skin disease than nondermatologists and nondermatologists often have limited exposure to the field of dermatology during residency training. Studies have demonstrated differences in the abilities of dermatologists and nondermatologists to correctly diagnose common cutaneous diseases, which unsurprisingly revealed greater diagnostic accuracy demonstrated by dermatologists.11-16 The increase in acne and skin-related infections reported by nondermatologists is consistent with possible efforts to increase formal training in frequently encountered skin diseases. In one study evaluating the impact of a formal 3-week dermatology curriculum on an internal medicine department, internists demonstrated 100% accuracy in the diagnosis of acne and herpes zoster in contrast to 29% for tinea and 12% for lichen planus.5,6

The current Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education guidelines place little emphasis on exposure to dermatology training during residency for internists and pediatricians, as this training is not a required component of these programs.17 Two core problems with current training regarding the evaluation and management of cutaneous disease are minimal exposure to dermatologic conditions in medical school and residency and lack of consensus on the core topics that should be taught to nondermatologists.18 Exposure to dermatologic conditions through rotations in medical school has been shown to increase residents’ self-reported confidence in diagnosing and treating alopecia, cutaneous drug eruptions, warts, acne, rosacea, nonmelanoma skin cancers, sun damage, psoriasis, seborrhea, atopic dermatitis, and contact dermatitis; however, the majority of primary care residents surveyed still felt that this exposure in medical school was inadequate.19

In creating a core curriculum for dermatology training for nondermatologists, it is important to consider the dermatologic conditions that are most frequently encountered by these specialties. Our study revealed that the most commonly encountered dermatologic conditions differ among dermatologists and nondermatologists, with a fair degree of variation even among individual specialties. Failure to recognize these discrepancies has likely contributed to the challenges faced by nondermatologists in the diagnosis and management of dermatologic disease. In this study, contact dermatitis, epidermoid cysts, and skin infections were the most common dermatologic conditions encountered by nondermatologists and also were among the top skin diseases referred to dermatologists by nondermatologists. This finding suggests that nondermatologists are able to identify these conditions but have a tendency to refer approximately 10% of these patients to dermatology for further management. Clinical evaluation and medical management of these cutaneous diseases may be an important area of focus for medical school curricula, as the treatment of these diseases is within the capabilities of the nondermatologist. For example, initial management of dermatitis requires determination of the type of dermatitis (ie, essential, contact, atopic, seborrheic, stasis) and selection of an appropriate topical steroid, with referral to a dermatologist needed for questionable or refractory cases. Although a curriculum cannot be built solely on a list of the top 20 diagnoses provided here, these data may serve as a preliminary platform for medical school dermatology curriculum design. The curriculum also should include serious skin diseases, such as melanoma and severe drug eruptions. Although these conditions are less commonly encountered by nondermatologists, missed diagnosis and/or improper management can be life threatening.

The use of NAMCS data presents a few limitations. For instance, these data only represent outpatient management of skin disease. There is the potential for misdiagnosis and coding errors by the reporting physicians. The volume of data (ie, billions of office visits) prevents verification of diagnostic accuracy. The coding system requires physicians to give a diagnosis but does not provide any means by which to determine the physician’s confidence in that diagnosis. There is no code for “uncertain” or “diagnosis not determined.” Additionally, an “unspecified” diagnosis may reflect uncertainty or may simply imply that no other code accurately described the condition. Despite these limitations, the NAMCS database is a large, nationally representative survey of actual patient visits and represents some of the best data available for a study such as ours.

Conclusion

This study provides an important analysis of the most common outpatient dermatologic conditions encountered by dermatologists and nondermatologists of various specialties and offers a foundation from which to construct curricula for dermatology training tailored to individual specialties based on their needs. In the future, identification of the most common inpatient dermatologic conditions managed by each specialty also may benefit curriculum design.

- Thorpe KE, Florence CS, Joski P. Which medical conditions account for the rise in health care spending? Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;(suppl web exclusives):W4-437-445.

- Johnson ML. Defining the burden of skin disease in the United States—a historical perspective. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:108-110.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medical expenditure panel survey. US Department of Health & Human Services Web site. http://meps.ahrq.gov. Accessed November 17, 2014.

- Bickers DR, Lim HW, Margolis D, et al. The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:490-500.

- Johnson ML. On teaching dermatology to nondermatologists. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:850-852.

- Ramsay DL, Weary PE. Primary care in dermatology: whose role should it be? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:1005-1008.

- Kimball AB, Resneck JS Jr. The US dermatology workforce: a specialty remains in shortage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:741-745.

- Resneck JS Jr, Kimball AB. Who else is providing care in dermatology practices? trends in the use of nonphysician clinicians. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:211-216.

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr, McConnell RC. Most common dermatologic problems identified by internists, 1990-1994. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:726-730.

- Ahn CS, Davis SA, Debade TS, et al. Noncosmetic skin-related procedures performed in the United States: an analysis of national ambulatory medical care survey data from 1995 to 2010. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1912-1921.

- Antic M, Conen D, Itin PH. Teaching effects of dermatological consultations on nondermatologists in the field of internal medicine. a study of 1290 inpatients. Dermatology. 2004;208:32-37.

- Federman DG, Concato J, Kirsner RS. Comparison of dermatologic diagnoses by primary care practitioners and dermatologists. a review of the literature. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:170-172.

- Fleischer AB Jr, Herbert CR, Feldman SR, et al. Diagnosis of skin disease by nondermatologists. Am J Manag Care. 2000;6:1149-1156.

- Kirsner RS, Federman DG. Lack of correlation between internists’ ability in dermatology and their patterns of treating patients with skin disease. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1043-1046.

- McCarthy GM, Lamb GC, Russell TJ, et al. Primary care-based dermatology practice: internists need more training. J Gen Intern Med. 1991;6:52-56.

- Sellheyer K, Bergfeld WF. A retrospective biopsy study of the clinical diagnostic accuracy of common skin diseases by different specialties compared with dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:823-830.

- Medical specialties. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Web site. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/368ProgramandInstitutionalGuidelines/MedicalAccreditation.aspx. Accessed November 17, 2014.

- McCleskey PE, Gilson RT, DeVillez RL. Medical student core curriculum in dermatology survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:30-35.

- Hansra NK, O’Sullivan P, Chen CL, et al. Medical school dermatology curriculum: are we adequately preparing primary care physicians? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:23-29.

Skin diseases are highly prevalent in the United States, affecting an estimated 1 in 3 Americans at any given time.1,2 In 2009 the direct medical costs associated with skin-related diseases, including health services and prescriptions, was approximately $22 billion; the annual total economic burden was estimated to be closer to $96 billion when factoring in the cost of lost productivity and pay for symptom relief.3,4 Effective and efficient management of skin disease is essential to minimizing cost and morbidity. Nondermatologists traditionally have diagnosed the majority of skin diseases.5,6 In particular, primary care physicians commonly manage dermatologic conditions and often are the first health care providers to encounter patients presenting with skin problems. A predicted shortage of dermatologists will likely contribute to an increase in this trend.7,8 Therefore, it is important to adequately prepare nondermatologists to evaluate and treat the skin conditions that they are most likely to encounter in their scope of practice.

Residents, particularly in primary care specialties, often have opportunities to spend 2 to 4 weeks with a dermatologist to learn about skin diseases; however, the skin conditions most often encountered by dermatologists may differ from those most often encountered by physicians in other specialties. For instance, one study demonstrated a disparity between the most common skin problems seen by dermatologists and internists.9 These dissimilarities should be recognized and addressed in curriculum content. The purpose of this study was to identify and compare the 20 most common dermatologic conditions reported by dermatologists versus those reported by nondermatologists (ie, internists, pediatricians, family physicians, emergency medicine physicians, general surgeons, otolaryngologists) from 2001 to 2010. Data also were analyzed to determine the top 20 conditions referred to dermatologists by nondermatologists as a potential indicator for areas of further improvement within medical education. With this knowledge, we hope educational curricula and self-study can be modified to reflect the current epidemiology of cutaneous diseases, thereby improving patient care.

Methods

Data from 2001 to 2010 were extracted from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), which is an ongoing survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics. The NAMCS collects descriptive data regarding ambulatory visits to nonfederal office-based physicians in the United States. Participating physicians are instructed to record information about patient visits for a 1-week period, including patient demographics, insurance status, reason for visit, diagnoses, procedures, therapeutics, and referrals made at that time. Data collected for the NAMCS are entered into a multistage probability sample to produce national estimates. Within dermatology, an average of 118 dermatologists are sampled each year, and over the last 10 years, participation rates have ranged from 47% to 77%.

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes were identified to determine the diagnoses that could be classified as dermatologic conditions. Select infectious and neoplastic disorders of the skin and mucous membrane conditions were included as well as the codes for skin diseases. Nondermatologic diagnoses and V codes were not included in the study. Data for all providers were studied to identify outpatient visits associated with the primary diagnosis of a dermatologic condition. Minor diagnoses that were considered to be subsets of major diagnoses were combined to allow better analysis of the data. For example, all tinea infections (ie, dermatophytosis of various sites, dermatomycosis unspecified) were combined into 1 diagnosis referred to as tinea because the recognition and treatment of this disease does not vary tremendously by anatomic location. Visits to dermatologists that listed nonspecific diagnoses and codes (eg, other postsurgical status [V45.89], neoplasm of uncertain behavior site unspecified [238.9]) were assumed to be for dermatologic problems.

Sampling weights were applied to obtain estimates for the number of each diagnosis made nationally. All data analyses were performed using SAS software and linear regression models were generated using SAS PROC SURVEYREG.

Data were analyzed to determine the dermatologic conditions most commonly encountered by dermatologists and nondermatologists in emergency medicine, family medicine, general surgery, internal medicine, otolaryngology, and pediatrics; these specialties include physicians who are known to commonly diagnose and treat skin diseases.10 Data also were analyzed to determine the most common conditions referred to dermatologists for treatment by nondermatologists from the selected specialties. Permission to conduct this study was obtained from the Wake Forest University institutional review board (Winston-Salem, North Carolina).

Results

From 2001 to 2010, more than 700 million outpatient visits for skin-related problems were identified, with 676.3 million visits to dermatologists, emergency medicine physicians, family practitioners, general surgeons, internists, otolaryngologists, and pediatricians. More than half (52.9%) of all skin-related visits were addressed by nondermatologists during this time. Among nondermatologists, family practitioners encountered the greatest number of skin diseases (20.5%), followed by pediatricians (11.3%), internists (9.2%), general surgeons (3.4%), otolaryngologists (1.0%), and emergency medicine physicians (0.2%)(Table 1).

Benign tumors and acne were the most common cutaneous conditions referred to dermatologists by nondermatologists (10.6% and 10.1% of all dermatology referrals, respectively), followed by nonmelanoma skin cancers (9.7%), contact dermatitis (8.8%), and actinic keratosis (7.8%)(Table 2). The top 20 conditions referred to dermatologists accounted for 83.7% of all outpatient referrals to dermatologists.

Among the diseases most frequently reported by nondermatologists, contact dermatitis was the most common (12.0%), with twice the number of visits to nondermatologists for contact dermatitis than to dermatologists (51.6 million vs 25.3 million). In terms of disease categories, infectious skin diseases (ie, bacterial [cellulitis/abscess], viral [warts, herpesvirus], fungal [tinea] and yeast [candida] etiologies) were the most common dermatologic conditions reported by nondermatologists (Table 2).

The top 20 dermatologic conditions reported by dermatologists accounted for 85.4% of all diagnoses made by dermatologists. Diseases that were among the top 20 conditions encountered by dermatologists but were not among the top 20 for nondermatologists included actinic keratosis, seborrheic keratosis, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, alopecia, rosacea, dyschromia, seborrheic dermatitis, follicular disease, and neoplasm of uncertain behavior of skin. Additionally, 5 of the top 20 conditions encountered by dermatologists also were among the top 20 for only 1 individual nondermatologic specialty; these included atopic dermatitis (pediatrics), seborrheic dermatitis (pediatrics), psoriasis (internal medicine), rosacea (otolaryngology), and keratoderma (general surgery). Seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, and rosacea also were among the top 20 conditions most commonly referred to dermatologists for treatment by nondermatologists. Table 3 shows the top 20 dermatologic conditions encountered by nondermatologists by comparison.

Comment

According to NAMCS data from 2001 to 2010, visits to nondermatologists accounted for more than half of total outpatient visits for cutaneous diseases in the United States, whereas visits to dermatologists accounted for 47.1%. These findings are consistent with historical data indicating that 30% to 40% of skin-related visits are to dermatologists, and the majority of patients with skin disease are diagnosed by nondermatologists.5,6

Past data indicate that most visits to dermatologists were for evaluation of acne, infections, psoriasis, and neoplasms, whereas most visits to nondermatologists were for evaluation of epidermoid cysts, impetigo, plant dermatitis, cellulitis, and diaper rash.9 Over the last 10 years, acne has been more commonly encountered by nondermatologists, especially pediatricians. Additionally, infectious etiologies have been seen in larger volume by nondermatologists.9 Together, infectious cutaneous conditions make up nearly one-fourth of dermatologic encounters by emergency medicine physicians, internists, and family practitioners but are not within the top 20 diagnoses referred to dermatologists, which suggests that uncomplicated cases of cellulitis, herpes zoster, and other skin-related infections are largely managed by nondermatologists.5,6 Contact dermatitis, often caused by specific allergens such as detergents, solvents, and topical products, was one of the most common reported dermatologic encounters among dermatologists and nondermatologists and also was the fourth most common condition referred to dermatologists by nondermatologists for treatment; however, there may be an element of overuse of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision code, as any presumed contact dermatitis of unspecified cause can be reported under 692.9 defined as contact dermatitis and other eczema, unspecified cause. The high rate of referrals to dermatologists by nondermatologists may be for patch testing and further management. Additionally, there are no specific codes for allergic or irritant dermatitis, thus these diseases may be lumped together.

Although nearly half of all dermatologic encounters were seen by nondermatologists, dermatologists see a much larger proportion of patients with skin disease than nondermatologists and nondermatologists often have limited exposure to the field of dermatology during residency training. Studies have demonstrated differences in the abilities of dermatologists and nondermatologists to correctly diagnose common cutaneous diseases, which unsurprisingly revealed greater diagnostic accuracy demonstrated by dermatologists.11-16 The increase in acne and skin-related infections reported by nondermatologists is consistent with possible efforts to increase formal training in frequently encountered skin diseases. In one study evaluating the impact of a formal 3-week dermatology curriculum on an internal medicine department, internists demonstrated 100% accuracy in the diagnosis of acne and herpes zoster in contrast to 29% for tinea and 12% for lichen planus.5,6

The current Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education guidelines place little emphasis on exposure to dermatology training during residency for internists and pediatricians, as this training is not a required component of these programs.17 Two core problems with current training regarding the evaluation and management of cutaneous disease are minimal exposure to dermatologic conditions in medical school and residency and lack of consensus on the core topics that should be taught to nondermatologists.18 Exposure to dermatologic conditions through rotations in medical school has been shown to increase residents’ self-reported confidence in diagnosing and treating alopecia, cutaneous drug eruptions, warts, acne, rosacea, nonmelanoma skin cancers, sun damage, psoriasis, seborrhea, atopic dermatitis, and contact dermatitis; however, the majority of primary care residents surveyed still felt that this exposure in medical school was inadequate.19

In creating a core curriculum for dermatology training for nondermatologists, it is important to consider the dermatologic conditions that are most frequently encountered by these specialties. Our study revealed that the most commonly encountered dermatologic conditions differ among dermatologists and nondermatologists, with a fair degree of variation even among individual specialties. Failure to recognize these discrepancies has likely contributed to the challenges faced by nondermatologists in the diagnosis and management of dermatologic disease. In this study, contact dermatitis, epidermoid cysts, and skin infections were the most common dermatologic conditions encountered by nondermatologists and also were among the top skin diseases referred to dermatologists by nondermatologists. This finding suggests that nondermatologists are able to identify these conditions but have a tendency to refer approximately 10% of these patients to dermatology for further management. Clinical evaluation and medical management of these cutaneous diseases may be an important area of focus for medical school curricula, as the treatment of these diseases is within the capabilities of the nondermatologist. For example, initial management of dermatitis requires determination of the type of dermatitis (ie, essential, contact, atopic, seborrheic, stasis) and selection of an appropriate topical steroid, with referral to a dermatologist needed for questionable or refractory cases. Although a curriculum cannot be built solely on a list of the top 20 diagnoses provided here, these data may serve as a preliminary platform for medical school dermatology curriculum design. The curriculum also should include serious skin diseases, such as melanoma and severe drug eruptions. Although these conditions are less commonly encountered by nondermatologists, missed diagnosis and/or improper management can be life threatening.