User login

Clinical trials unavailable for more than half of all cancer patients

More than half of all cancer patients do not participate in clinical trials because none are available for their cancer type or stage at their institution, according to a meta-analysis of cancer clinical trials that examined the trial decision-making pathway.

“This is the first effort to systematically both define and quantify domains of clinical trial barriers using a meta-analytic approach,” wrote lead author Joseph M. Unger, PhD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle and his coauthors in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

To identify trials that addressed barriers to enrollment, Dr. Unger and his colleagues conducted a literature search using the PubMed, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Ovid Medline databases. The search returned 7,576 unique results, of which they reviewed 38 full articles and eventually decided on 13 studies comprising 8,883 patients. Nine of the studies were focused on academic care settings, and four were focused on community care settings; seven examined patient decision-making patterns in all types of cancers, while the others focused on breast cancer only (n = 2), lung cancer only (n = 2), prostate cancer only (n = 1), and cervix/uterine cancers (n = 1).

Their analysis found that, for 55.6% of patients, no trial was available for their cancer type and stage (95% confidence interval, 43.7%-67.3%). In addition, 21.5% (95% CI, 10.9%-34.6%) were not eligible for an available trial, and 14.8% (95% CI, 9.0%-21.7%) did not enroll; only 8.1% (95% CI, 6.3%-10.0%) enrolled in a trial. Academic sites (15.9%, 95% CI, 13.8%-18.2%) saw much higher rates of participation than community sites (7.0%, 95% CI, 5.1%-9.1%; P less than .001).

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including details on trial availability not being available for all analyzed studies. In addition, several of the studies relied on selected cancer types instead of sampling a representative set of cancers. Finally, these studies may have oversampled research-oriented sites, which would mean “the actual overall trial participation rate may be lower than we estimated.”

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Unger JM et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019 Feb 19. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy221.

More than half of all cancer patients do not participate in clinical trials because none are available for their cancer type or stage at their institution, according to a meta-analysis of cancer clinical trials that examined the trial decision-making pathway.

“This is the first effort to systematically both define and quantify domains of clinical trial barriers using a meta-analytic approach,” wrote lead author Joseph M. Unger, PhD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle and his coauthors in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

To identify trials that addressed barriers to enrollment, Dr. Unger and his colleagues conducted a literature search using the PubMed, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Ovid Medline databases. The search returned 7,576 unique results, of which they reviewed 38 full articles and eventually decided on 13 studies comprising 8,883 patients. Nine of the studies were focused on academic care settings, and four were focused on community care settings; seven examined patient decision-making patterns in all types of cancers, while the others focused on breast cancer only (n = 2), lung cancer only (n = 2), prostate cancer only (n = 1), and cervix/uterine cancers (n = 1).

Their analysis found that, for 55.6% of patients, no trial was available for their cancer type and stage (95% confidence interval, 43.7%-67.3%). In addition, 21.5% (95% CI, 10.9%-34.6%) were not eligible for an available trial, and 14.8% (95% CI, 9.0%-21.7%) did not enroll; only 8.1% (95% CI, 6.3%-10.0%) enrolled in a trial. Academic sites (15.9%, 95% CI, 13.8%-18.2%) saw much higher rates of participation than community sites (7.0%, 95% CI, 5.1%-9.1%; P less than .001).

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including details on trial availability not being available for all analyzed studies. In addition, several of the studies relied on selected cancer types instead of sampling a representative set of cancers. Finally, these studies may have oversampled research-oriented sites, which would mean “the actual overall trial participation rate may be lower than we estimated.”

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Unger JM et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019 Feb 19. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy221.

More than half of all cancer patients do not participate in clinical trials because none are available for their cancer type or stage at their institution, according to a meta-analysis of cancer clinical trials that examined the trial decision-making pathway.

“This is the first effort to systematically both define and quantify domains of clinical trial barriers using a meta-analytic approach,” wrote lead author Joseph M. Unger, PhD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle and his coauthors in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

To identify trials that addressed barriers to enrollment, Dr. Unger and his colleagues conducted a literature search using the PubMed, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Ovid Medline databases. The search returned 7,576 unique results, of which they reviewed 38 full articles and eventually decided on 13 studies comprising 8,883 patients. Nine of the studies were focused on academic care settings, and four were focused on community care settings; seven examined patient decision-making patterns in all types of cancers, while the others focused on breast cancer only (n = 2), lung cancer only (n = 2), prostate cancer only (n = 1), and cervix/uterine cancers (n = 1).

Their analysis found that, for 55.6% of patients, no trial was available for their cancer type and stage (95% confidence interval, 43.7%-67.3%). In addition, 21.5% (95% CI, 10.9%-34.6%) were not eligible for an available trial, and 14.8% (95% CI, 9.0%-21.7%) did not enroll; only 8.1% (95% CI, 6.3%-10.0%) enrolled in a trial. Academic sites (15.9%, 95% CI, 13.8%-18.2%) saw much higher rates of participation than community sites (7.0%, 95% CI, 5.1%-9.1%; P less than .001).

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including details on trial availability not being available for all analyzed studies. In addition, several of the studies relied on selected cancer types instead of sampling a representative set of cancers. Finally, these studies may have oversampled research-oriented sites, which would mean “the actual overall trial participation rate may be lower than we estimated.”

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Unger JM et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019 Feb 19. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy221.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUTE

Bariatric surgery leads to less improvement in black patients

“Per this analysis, there are significant racial disparities in perioperative outcomes, weight loss, and quality of life after bariatric surgery,” wrote lead author Michael H. Wood, MD, of Wayne State University, Detroit, and his coauthors, adding that, “while biological differences may explain some of the disparity in outcomes, environmental, social, and behavioral factors likely play a role.” The study was published online in JAMA Surgery.

This study reviewed data from 14,210 participants in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative (MBSC), a state-wide consortium and clinical registry of bariatric surgery patients. Matching cohorts were established for black (n = 7,105) and white (n = 7,105) patients who underwent a primary bariatric operation (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, or adjustable gastric banding) between June 2006 and January 2017. The only significant differences between cohorts – clarified as “never more than 1 or 2 percentage points” – were in regard to income brackets and procedure type.

At 30-day follow-up, the rate of overall complications was higher in black patients (628, 8.8%) than in white patients (481, 6.8%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.51; P = .02), as was the length of stay (mean, 2.2 days vs. 1.9 days; aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.20-0.40; P less than .001). Black patients also had a higher rate of both ED visits (541 [11.6%] vs. 826 [7.6%]; aOR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.43-1.79; P less than .001) and readmissions (414 [5.8%] vs. 245 [3.5%]; aOR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.47-2.03; P less than .001).

In addition, at 1-year follow-up, black patients had a lower mean weight loss (32.0 kg vs. 38.3 kg; P less than .001) and percentage of total weight loss (26% vs. 29%; P less than .001) compared with white patients. And though black patients were more likely than white patients to report a high quality of life before surgery (2,672 [49.5%] vs. 2,354 [41.4%]; P less than .001), they were less likely to do so 1 year afterward (1,379 [87.2%] vs. 2,133 [90.4%]; P = .002).

The coauthors acknowledged the limitations of their study, including potential unmeasured factors between cohorts such as disease duration or severity. They also noted that a wider time horizon than 30 days post surgery could have altered the results, although “serious adverse events and resource use tend to be highest within the first month after surgery, and we anticipate that this effect would have been negligible.”

The study was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network. Dr. Wood reported no conflicts of interest. Three of his coauthors reported receiving salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network for their work with the MBSC, and one other coauthor reported receiving an honorarium for being the MBSC’s executive committee chair.

The AGA Practice guide on Obesity and Weight management, Education and Resources (POWER) white paper provides physicians with a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to guide and personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management. Learn more at https://www.gastro.org/practice-guidance/practice-updates/obesity-practice-guide.

SOURCE: Wood MH et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0029.

The well-documented disparities between black and white patients after bariatric surgery are brought back to the forefront via to this study from Wood et al., according to Brian Hodgens, MD, and Kenric M. Murayama, MD, of the University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Some of the findings hint at the cultural differences that permeate the time before and after a surgery like this: In particular, they highlighted how black patients were more likely to report good or very good quality of life before surgery but less likely after. This could be related to a “difference in perceptions of obesity by black patients,” where they are more hesitant to pursue the surgery than their white counterparts, Dr. Hodgens and Dr. Murayama wrote.

More work is needed, they added, but “this study and others like it can better equip practicing bariatric surgeons to educate themselves and patients on expectations before and after bariatric surgery.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial ( JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 1 0.1001/jamasurg.2019.0067 ). Dr. Murayama reported receiving personal fees from Medtronic outside the submitted work.

The well-documented disparities between black and white patients after bariatric surgery are brought back to the forefront via to this study from Wood et al., according to Brian Hodgens, MD, and Kenric M. Murayama, MD, of the University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Some of the findings hint at the cultural differences that permeate the time before and after a surgery like this: In particular, they highlighted how black patients were more likely to report good or very good quality of life before surgery but less likely after. This could be related to a “difference in perceptions of obesity by black patients,” where they are more hesitant to pursue the surgery than their white counterparts, Dr. Hodgens and Dr. Murayama wrote.

More work is needed, they added, but “this study and others like it can better equip practicing bariatric surgeons to educate themselves and patients on expectations before and after bariatric surgery.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial ( JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 1 0.1001/jamasurg.2019.0067 ). Dr. Murayama reported receiving personal fees from Medtronic outside the submitted work.

The well-documented disparities between black and white patients after bariatric surgery are brought back to the forefront via to this study from Wood et al., according to Brian Hodgens, MD, and Kenric M. Murayama, MD, of the University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Some of the findings hint at the cultural differences that permeate the time before and after a surgery like this: In particular, they highlighted how black patients were more likely to report good or very good quality of life before surgery but less likely after. This could be related to a “difference in perceptions of obesity by black patients,” where they are more hesitant to pursue the surgery than their white counterparts, Dr. Hodgens and Dr. Murayama wrote.

More work is needed, they added, but “this study and others like it can better equip practicing bariatric surgeons to educate themselves and patients on expectations before and after bariatric surgery.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial ( JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 1 0.1001/jamasurg.2019.0067 ). Dr. Murayama reported receiving personal fees from Medtronic outside the submitted work.

“Per this analysis, there are significant racial disparities in perioperative outcomes, weight loss, and quality of life after bariatric surgery,” wrote lead author Michael H. Wood, MD, of Wayne State University, Detroit, and his coauthors, adding that, “while biological differences may explain some of the disparity in outcomes, environmental, social, and behavioral factors likely play a role.” The study was published online in JAMA Surgery.

This study reviewed data from 14,210 participants in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative (MBSC), a state-wide consortium and clinical registry of bariatric surgery patients. Matching cohorts were established for black (n = 7,105) and white (n = 7,105) patients who underwent a primary bariatric operation (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, or adjustable gastric banding) between June 2006 and January 2017. The only significant differences between cohorts – clarified as “never more than 1 or 2 percentage points” – were in regard to income brackets and procedure type.

At 30-day follow-up, the rate of overall complications was higher in black patients (628, 8.8%) than in white patients (481, 6.8%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.51; P = .02), as was the length of stay (mean, 2.2 days vs. 1.9 days; aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.20-0.40; P less than .001). Black patients also had a higher rate of both ED visits (541 [11.6%] vs. 826 [7.6%]; aOR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.43-1.79; P less than .001) and readmissions (414 [5.8%] vs. 245 [3.5%]; aOR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.47-2.03; P less than .001).

In addition, at 1-year follow-up, black patients had a lower mean weight loss (32.0 kg vs. 38.3 kg; P less than .001) and percentage of total weight loss (26% vs. 29%; P less than .001) compared with white patients. And though black patients were more likely than white patients to report a high quality of life before surgery (2,672 [49.5%] vs. 2,354 [41.4%]; P less than .001), they were less likely to do so 1 year afterward (1,379 [87.2%] vs. 2,133 [90.4%]; P = .002).

The coauthors acknowledged the limitations of their study, including potential unmeasured factors between cohorts such as disease duration or severity. They also noted that a wider time horizon than 30 days post surgery could have altered the results, although “serious adverse events and resource use tend to be highest within the first month after surgery, and we anticipate that this effect would have been negligible.”

The study was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network. Dr. Wood reported no conflicts of interest. Three of his coauthors reported receiving salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network for their work with the MBSC, and one other coauthor reported receiving an honorarium for being the MBSC’s executive committee chair.

The AGA Practice guide on Obesity and Weight management, Education and Resources (POWER) white paper provides physicians with a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to guide and personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management. Learn more at https://www.gastro.org/practice-guidance/practice-updates/obesity-practice-guide.

SOURCE: Wood MH et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0029.

“Per this analysis, there are significant racial disparities in perioperative outcomes, weight loss, and quality of life after bariatric surgery,” wrote lead author Michael H. Wood, MD, of Wayne State University, Detroit, and his coauthors, adding that, “while biological differences may explain some of the disparity in outcomes, environmental, social, and behavioral factors likely play a role.” The study was published online in JAMA Surgery.

This study reviewed data from 14,210 participants in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative (MBSC), a state-wide consortium and clinical registry of bariatric surgery patients. Matching cohorts were established for black (n = 7,105) and white (n = 7,105) patients who underwent a primary bariatric operation (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, or adjustable gastric banding) between June 2006 and January 2017. The only significant differences between cohorts – clarified as “never more than 1 or 2 percentage points” – were in regard to income brackets and procedure type.

At 30-day follow-up, the rate of overall complications was higher in black patients (628, 8.8%) than in white patients (481, 6.8%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.51; P = .02), as was the length of stay (mean, 2.2 days vs. 1.9 days; aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.20-0.40; P less than .001). Black patients also had a higher rate of both ED visits (541 [11.6%] vs. 826 [7.6%]; aOR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.43-1.79; P less than .001) and readmissions (414 [5.8%] vs. 245 [3.5%]; aOR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.47-2.03; P less than .001).

In addition, at 1-year follow-up, black patients had a lower mean weight loss (32.0 kg vs. 38.3 kg; P less than .001) and percentage of total weight loss (26% vs. 29%; P less than .001) compared with white patients. And though black patients were more likely than white patients to report a high quality of life before surgery (2,672 [49.5%] vs. 2,354 [41.4%]; P less than .001), they were less likely to do so 1 year afterward (1,379 [87.2%] vs. 2,133 [90.4%]; P = .002).

The coauthors acknowledged the limitations of their study, including potential unmeasured factors between cohorts such as disease duration or severity. They also noted that a wider time horizon than 30 days post surgery could have altered the results, although “serious adverse events and resource use tend to be highest within the first month after surgery, and we anticipate that this effect would have been negligible.”

The study was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network. Dr. Wood reported no conflicts of interest. Three of his coauthors reported receiving salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network for their work with the MBSC, and one other coauthor reported receiving an honorarium for being the MBSC’s executive committee chair.

The AGA Practice guide on Obesity and Weight management, Education and Resources (POWER) white paper provides physicians with a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to guide and personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management. Learn more at https://www.gastro.org/practice-guidance/practice-updates/obesity-practice-guide.

SOURCE: Wood MH et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0029.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point: Black patients who underwent bariatric surgery suffered more overall complications and reported a lower quality of life than white patients.

Major finding: The rate of overall complications was higher in black patients (628, 8.8%) than in white patients (481, 6.8%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.51; P = .02).

Study details: A matched cohort study of 14,210 patients, half black and half white, who underwent a primary bariatric operation in Michigan between June 2006 and January 2017.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network. Dr. Wood reported no conflicts of interest. Three of his coauthors reported receiving salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network for their work with the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative, and one other coauthor reported receiving an honorarium for being the collaborative’s executive committee chair.

Source: Wood MH et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0029.

Bariatric surgery leads to less improvement in black patients

“Per this analysis, there are significant racial disparities in perioperative outcomes, weight loss, and quality of life after bariatric surgery,” wrote lead author Michael H. Wood, MD, of Wayne State University, Detroit, and his coauthors, adding that, “while biological differences may explain some of the disparity in outcomes, environmental, social, and behavioral factors likely play a role.” The study was published online in JAMA Surgery.

This study reviewed data from 14,210 participants in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative (MBSC), a state-wide consortium and clinical registry of bariatric surgery patients. Matching cohorts were established for black (n = 7,105) and white (n = 7,105) patients who underwent a primary bariatric operation (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, or adjustable gastric banding) between June 2006 and January 2017. The only significant differences between cohorts – clarified as “never more than 1 or 2 percentage points” – were in regard to income brackets and procedure type.

At 30-day follow-up, the rate of overall complications was higher in black patients (628, 8.8%) than in white patients (481, 6.8%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.51; P = .02), as was the length of stay (mean, 2.2 days vs. 1.9 days; aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.20-0.40; P less than .001). Black patients also had a higher rate of both ED visits (541 [11.6%] vs. 826 [7.6%]; aOR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.43-1.79; P less than .001) and readmissions (414 [5.8%] vs. 245 [3.5%]; aOR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.47-2.03; P less than .001).

In addition, at 1-year follow-up, black patients had a lower mean weight loss (32.0 kg vs. 38.3 kg; P less than .001) and percentage of total weight loss (26% vs. 29%; P less than .001) compared with white patients. And though black patients were more likely than white patients to report a high quality of life before surgery (2,672 [49.5%] vs. 2,354 [41.4%]; P less than .001), they were less likely to do so 1 year afterward (1,379 [87.2%] vs. 2,133 [90.4%]; P = .002).

The coauthors acknowledged the limitations of their study, including potential unmeasured factors between cohorts such as disease duration or severity. They also noted that a wider time horizon than 30 days post surgery could have altered the results, although “serious adverse events and resource use tend to be highest within the first month after surgery, and we anticipate that this effect would have been negligible.”

The study was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network. Dr. Wood reported no conflicts of interest. Three of his coauthors reported receiving salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network for their work with the MBSC, and one other coauthor reported receiving an honorarium for being the MBSC’s executive committee chair.

SOURCE: Wood MH et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0029.

The well-documented disparities between black and white patients after bariatric surgery are brought back to the forefront via to this study from Wood et al., according to Brian Hodgens, MD, and Kenric M. Murayama, MD, of the University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Some of the findings hint at the cultural differences that permeate the time before and after a surgery like this: In particular, they highlighted how black patients were more likely to report good or very good quality of life before surgery but less likely after. This could be related to a “difference in perceptions of obesity by black patients,” where they are more hesitant to pursue the surgery than their white counterparts, Dr. Hodgens and Dr. Murayama wrote.

More work is needed, they added, but “this study and others like it can better equip practicing bariatric surgeons to educate themselves and patients on expectations before and after bariatric surgery.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial ( JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 1 0.1001/jamasurg.2019.0067 ). Dr. Murayama reported receiving personal fees from Medtronic outside the submitted work.

The well-documented disparities between black and white patients after bariatric surgery are brought back to the forefront via to this study from Wood et al., according to Brian Hodgens, MD, and Kenric M. Murayama, MD, of the University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Some of the findings hint at the cultural differences that permeate the time before and after a surgery like this: In particular, they highlighted how black patients were more likely to report good or very good quality of life before surgery but less likely after. This could be related to a “difference in perceptions of obesity by black patients,” where they are more hesitant to pursue the surgery than their white counterparts, Dr. Hodgens and Dr. Murayama wrote.

More work is needed, they added, but “this study and others like it can better equip practicing bariatric surgeons to educate themselves and patients on expectations before and after bariatric surgery.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial ( JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 1 0.1001/jamasurg.2019.0067 ). Dr. Murayama reported receiving personal fees from Medtronic outside the submitted work.

The well-documented disparities between black and white patients after bariatric surgery are brought back to the forefront via to this study from Wood et al., according to Brian Hodgens, MD, and Kenric M. Murayama, MD, of the University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Some of the findings hint at the cultural differences that permeate the time before and after a surgery like this: In particular, they highlighted how black patients were more likely to report good or very good quality of life before surgery but less likely after. This could be related to a “difference in perceptions of obesity by black patients,” where they are more hesitant to pursue the surgery than their white counterparts, Dr. Hodgens and Dr. Murayama wrote.

More work is needed, they added, but “this study and others like it can better equip practicing bariatric surgeons to educate themselves and patients on expectations before and after bariatric surgery.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial ( JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 1 0.1001/jamasurg.2019.0067 ). Dr. Murayama reported receiving personal fees from Medtronic outside the submitted work.

“Per this analysis, there are significant racial disparities in perioperative outcomes, weight loss, and quality of life after bariatric surgery,” wrote lead author Michael H. Wood, MD, of Wayne State University, Detroit, and his coauthors, adding that, “while biological differences may explain some of the disparity in outcomes, environmental, social, and behavioral factors likely play a role.” The study was published online in JAMA Surgery.

This study reviewed data from 14,210 participants in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative (MBSC), a state-wide consortium and clinical registry of bariatric surgery patients. Matching cohorts were established for black (n = 7,105) and white (n = 7,105) patients who underwent a primary bariatric operation (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, or adjustable gastric banding) between June 2006 and January 2017. The only significant differences between cohorts – clarified as “never more than 1 or 2 percentage points” – were in regard to income brackets and procedure type.

At 30-day follow-up, the rate of overall complications was higher in black patients (628, 8.8%) than in white patients (481, 6.8%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.51; P = .02), as was the length of stay (mean, 2.2 days vs. 1.9 days; aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.20-0.40; P less than .001). Black patients also had a higher rate of both ED visits (541 [11.6%] vs. 826 [7.6%]; aOR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.43-1.79; P less than .001) and readmissions (414 [5.8%] vs. 245 [3.5%]; aOR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.47-2.03; P less than .001).

In addition, at 1-year follow-up, black patients had a lower mean weight loss (32.0 kg vs. 38.3 kg; P less than .001) and percentage of total weight loss (26% vs. 29%; P less than .001) compared with white patients. And though black patients were more likely than white patients to report a high quality of life before surgery (2,672 [49.5%] vs. 2,354 [41.4%]; P less than .001), they were less likely to do so 1 year afterward (1,379 [87.2%] vs. 2,133 [90.4%]; P = .002).

The coauthors acknowledged the limitations of their study, including potential unmeasured factors between cohorts such as disease duration or severity. They also noted that a wider time horizon than 30 days post surgery could have altered the results, although “serious adverse events and resource use tend to be highest within the first month after surgery, and we anticipate that this effect would have been negligible.”

The study was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network. Dr. Wood reported no conflicts of interest. Three of his coauthors reported receiving salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network for their work with the MBSC, and one other coauthor reported receiving an honorarium for being the MBSC’s executive committee chair.

SOURCE: Wood MH et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0029.

“Per this analysis, there are significant racial disparities in perioperative outcomes, weight loss, and quality of life after bariatric surgery,” wrote lead author Michael H. Wood, MD, of Wayne State University, Detroit, and his coauthors, adding that, “while biological differences may explain some of the disparity in outcomes, environmental, social, and behavioral factors likely play a role.” The study was published online in JAMA Surgery.

This study reviewed data from 14,210 participants in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative (MBSC), a state-wide consortium and clinical registry of bariatric surgery patients. Matching cohorts were established for black (n = 7,105) and white (n = 7,105) patients who underwent a primary bariatric operation (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, or adjustable gastric banding) between June 2006 and January 2017. The only significant differences between cohorts – clarified as “never more than 1 or 2 percentage points” – were in regard to income brackets and procedure type.

At 30-day follow-up, the rate of overall complications was higher in black patients (628, 8.8%) than in white patients (481, 6.8%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.51; P = .02), as was the length of stay (mean, 2.2 days vs. 1.9 days; aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.20-0.40; P less than .001). Black patients also had a higher rate of both ED visits (541 [11.6%] vs. 826 [7.6%]; aOR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.43-1.79; P less than .001) and readmissions (414 [5.8%] vs. 245 [3.5%]; aOR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.47-2.03; P less than .001).

In addition, at 1-year follow-up, black patients had a lower mean weight loss (32.0 kg vs. 38.3 kg; P less than .001) and percentage of total weight loss (26% vs. 29%; P less than .001) compared with white patients. And though black patients were more likely than white patients to report a high quality of life before surgery (2,672 [49.5%] vs. 2,354 [41.4%]; P less than .001), they were less likely to do so 1 year afterward (1,379 [87.2%] vs. 2,133 [90.4%]; P = .002).

The coauthors acknowledged the limitations of their study, including potential unmeasured factors between cohorts such as disease duration or severity. They also noted that a wider time horizon than 30 days post surgery could have altered the results, although “serious adverse events and resource use tend to be highest within the first month after surgery, and we anticipate that this effect would have been negligible.”

The study was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network. Dr. Wood reported no conflicts of interest. Three of his coauthors reported receiving salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network for their work with the MBSC, and one other coauthor reported receiving an honorarium for being the MBSC’s executive committee chair.

SOURCE: Wood MH et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0029.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

More sleep can help youth manage type 1 diabetes

, according to a study of sleep duration and quality in young diabetes patients.

“This study adds to the growing body of literature that supports the cascading effects of sleep on multiple aspects of diabetes-related outcomes,” wrote lead author Sara S. Frye, PhD, of the University of Arizona, Tucson, and her coauthors, adding that the results “highlight the importance of assessing sleep in this population that appears to be at high risk for insufficient sleep duration.” The study was published in Sleep Medicine.

Dr. Frye and her colleagues recruited 111 children between the ages of 10 and 16 with type 1 diabetes mellitus to participate in their Glucose Regulation and Neurobehavioral Effects of Sleep (GRANES) study. The participants wore wrist actigraphs for an average of 5.5 nights to objectively measure sleep, including duration, quality, timing, and consistency. They completed self-reported sleep diaries each morning of the study. Glycemic control and diabetes management were assessed via hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels and self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) frequency, which were obtained via medical records. The participants and their parents also completed the Diabetes Management Scale.

Based on actigraphy data, the average total sleep time was 7.45 hours (standard deviation, 0.74), below the recommended duration of 9 hours for youths in this age group. All but one participant was recorded as sleeping less than the recommended amount. Average HbA1c of 9.11% (SD, 1.95) indicated poor diabetic control, and the average SMBG frequency was 4.90 (SD, 2.71) with a range of 1-14 checks per day. Per mediation analysis, for every additional hour of sleep, HbA1c was reduced by 0.33% and SMBG frequency went up by 0.88. In addition, SMBG frequency was related to HbA1c, supporting previous findings that “self-management behaviors play a critical role in maintaining diabetes control.”

The coauthors acknowledged the limitations of their study, including actigraphy data being logged over a 1-week period instead of the recommended 2 weeks. They also relied on medical records to determine HbA1c and SMBG rather than collecting that information along with the actigraphy data. However, they did note that HbA1c measures glucose levels over a 3-month period, which would have covered their participation in the study.

The study was supported by American Diabetes Association and cosponsored by the Order of the Amaranth Diabetes Foundation. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Frye SS et al. Sleep Med. 2019 Feb 16. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.01.043.

, according to a study of sleep duration and quality in young diabetes patients.

“This study adds to the growing body of literature that supports the cascading effects of sleep on multiple aspects of diabetes-related outcomes,” wrote lead author Sara S. Frye, PhD, of the University of Arizona, Tucson, and her coauthors, adding that the results “highlight the importance of assessing sleep in this population that appears to be at high risk for insufficient sleep duration.” The study was published in Sleep Medicine.

Dr. Frye and her colleagues recruited 111 children between the ages of 10 and 16 with type 1 diabetes mellitus to participate in their Glucose Regulation and Neurobehavioral Effects of Sleep (GRANES) study. The participants wore wrist actigraphs for an average of 5.5 nights to objectively measure sleep, including duration, quality, timing, and consistency. They completed self-reported sleep diaries each morning of the study. Glycemic control and diabetes management were assessed via hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels and self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) frequency, which were obtained via medical records. The participants and their parents also completed the Diabetes Management Scale.

Based on actigraphy data, the average total sleep time was 7.45 hours (standard deviation, 0.74), below the recommended duration of 9 hours for youths in this age group. All but one participant was recorded as sleeping less than the recommended amount. Average HbA1c of 9.11% (SD, 1.95) indicated poor diabetic control, and the average SMBG frequency was 4.90 (SD, 2.71) with a range of 1-14 checks per day. Per mediation analysis, for every additional hour of sleep, HbA1c was reduced by 0.33% and SMBG frequency went up by 0.88. In addition, SMBG frequency was related to HbA1c, supporting previous findings that “self-management behaviors play a critical role in maintaining diabetes control.”

The coauthors acknowledged the limitations of their study, including actigraphy data being logged over a 1-week period instead of the recommended 2 weeks. They also relied on medical records to determine HbA1c and SMBG rather than collecting that information along with the actigraphy data. However, they did note that HbA1c measures glucose levels over a 3-month period, which would have covered their participation in the study.

The study was supported by American Diabetes Association and cosponsored by the Order of the Amaranth Diabetes Foundation. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Frye SS et al. Sleep Med. 2019 Feb 16. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.01.043.

, according to a study of sleep duration and quality in young diabetes patients.

“This study adds to the growing body of literature that supports the cascading effects of sleep on multiple aspects of diabetes-related outcomes,” wrote lead author Sara S. Frye, PhD, of the University of Arizona, Tucson, and her coauthors, adding that the results “highlight the importance of assessing sleep in this population that appears to be at high risk for insufficient sleep duration.” The study was published in Sleep Medicine.

Dr. Frye and her colleagues recruited 111 children between the ages of 10 and 16 with type 1 diabetes mellitus to participate in their Glucose Regulation and Neurobehavioral Effects of Sleep (GRANES) study. The participants wore wrist actigraphs for an average of 5.5 nights to objectively measure sleep, including duration, quality, timing, and consistency. They completed self-reported sleep diaries each morning of the study. Glycemic control and diabetes management were assessed via hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels and self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) frequency, which were obtained via medical records. The participants and their parents also completed the Diabetes Management Scale.

Based on actigraphy data, the average total sleep time was 7.45 hours (standard deviation, 0.74), below the recommended duration of 9 hours for youths in this age group. All but one participant was recorded as sleeping less than the recommended amount. Average HbA1c of 9.11% (SD, 1.95) indicated poor diabetic control, and the average SMBG frequency was 4.90 (SD, 2.71) with a range of 1-14 checks per day. Per mediation analysis, for every additional hour of sleep, HbA1c was reduced by 0.33% and SMBG frequency went up by 0.88. In addition, SMBG frequency was related to HbA1c, supporting previous findings that “self-management behaviors play a critical role in maintaining diabetes control.”

The coauthors acknowledged the limitations of their study, including actigraphy data being logged over a 1-week period instead of the recommended 2 weeks. They also relied on medical records to determine HbA1c and SMBG rather than collecting that information along with the actigraphy data. However, they did note that HbA1c measures glucose levels over a 3-month period, which would have covered their participation in the study.

The study was supported by American Diabetes Association and cosponsored by the Order of the Amaranth Diabetes Foundation. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Frye SS et al. Sleep Med. 2019 Feb 16. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.01.043.

FROM SLEEP MEDICINE

Groups of physicians produce more accurate diagnoses than individuals

Groups of physicians and trainees diagnose clinical cases with more accuracy than individuals, according to a study of solo and aggregate diagnoses collected through an online medical teaching platform.

“These findings suggest that using the concept of collective intelligence to pool many physicians’ diagnoses could be a scalable approach to improve diagnostic accuracy,” wrote lead author Michael L. Barnett, MD, of Harvard University in Boston and his coauthors, adding that “groups of all sizes outperformed individual subspecialists on cases in their own subspecialty.” The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

This cross-sectional study examined 1,572 cases solved within the Human Diagnosis Project (Human Dx) system, an online platform for authoring and diagnosing teaching cases. The system presents real-life cases from clinical practices and asks respondents to generate ranked differential diagnoses. Cases are tagged for specialties based on both intended diagnoses and the top diagnoses chosen by respondents. All cases used in this study were authored between May 7, 2014, and October 5, 2016, and had 10 or more respondents.

Of the 2,069 attending physicians and fellows, residents, and medical students (users) who solved cases within the Human Dx system, 1,452 (70.2%) were trained in internal medicine, 1,228 (59.4%) were residents or fellows, 431 (20.8%) were attending physicians, and 410 (19.8%) were medical students. To create a collective differential, Dr. Barnett and his colleagues aggregated the responses of up to nine participants via a weighted combination of each clinician’s top three diagnoses, which they dubbed “collective intelligence.”

The diagnostic accuracy for groups of nine was 85.6% (95% confidence interval, 83.9%-87.4%), compared with individual users at 62.5% (95% CI, 60.1%-64.9%), a difference of 23% (95% CI, 14.9%-31.2%; P less than .001). Groups of five saw a 17.8% difference in accuracy versus an individual (95% CI, 14.0%-21.6%; P less than .001), compared with 12.5% for groups of two (95% CI, 9.3%-15.8%; P less than .001). Taken together, these seem to underline an association between larger groups and increased accuracy.

Individual specialists solved cases in their particular areas with a diagnostic accuracy of 66.3% (95% CI, 59.1%-73.5%), compared with nonmatched specialty accuracy of 63.9% (95% CI, 56.6%-71.2%). Groups, however, outperformed specialists across the board: 77.7% accuracy for a group of 2 (95% CI, 70.1%-84.6%; P less than .001) and 85.5% accuracy for a group of 9 (95% CI, 75.1%-95.9%; P less than .001).

The coauthors shared the limitations of their study, including the possibility that the users who contributed these cases to Human Dx may not be representative of the medical community as a whole. They also noted that, while their 431 attending physicians constituted the “largest number ... to date in a study of collective intelligence,” trainees still made up almost 80% of users. In addition, they acknowledged that Human Dx was not designed to generate collective diagnoses nor assess collective intelligence; another platform created with that ability in mind may have returned different results. Finally, they were unable to assess how exactly greater accuracy would have been linked to changes in treatment, calling it “an important question for future work.”

The authors disclosed several conflicts of interest. One doctor reported receiving personal fees from Greylock McKinnon Associates; another reported receiving personal fees from the Human Diagnosis Project and serving as their nonprofit director during the study. A third doctor reported consulting for a company that makes patient-safety monitoring systems and receiving compensation from a not-for-profit incubator, along with having equity in three medical data and software companies.

SOURCE: Barnett ML et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0096.

Although this study from Barnett et al. is not the silver bullet for misdiagnosis, better understanding why physicians make mistakes is a necessary and valuable undertaking, according to Stephan D. Fihn, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle.

In the past, the “correct” diagnostic approach included making a list of potential diagnoses and systematically ruling them out one by one, a process conveyed via clinicopathologic conferences in teaching hospitals. These, Dr. Fihn recalled, lasted until medical educators recognized them as “more ... theatrical events than meaningful teaching exercises” and understood that master clinicians did not actually think in the manner this approach modeled. Since then, the maturation of cognitive psychology and “a growing literature” have made diagnostic error seem like a common, sometimes unavoidable element of being human.

What can be done? Computers have always been a possibility, but “none have achieved the breadth of content and accuracy necessary to be adopted to any great extent,” Dr. Fihn wrote. Another option is crowdsourcing, as described in this study from Barnett and colleagues. Their approach has its pitfalls: A 62.5% level of diagnostic accuracy from individuals is not very high, which suggests either difficult cases or a preponderance of inexperienced clinicians who may benefit from collective intelligence even more. Regardless, he stated, “clinicians need to be cognizant of their own inherent limitations and acknowledge fallibility”; being humble and willing to seek advice “remain important, albeit imperfect, antidotes to misdiagnosis.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1071 ). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Although this study from Barnett et al. is not the silver bullet for misdiagnosis, better understanding why physicians make mistakes is a necessary and valuable undertaking, according to Stephan D. Fihn, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle.

In the past, the “correct” diagnostic approach included making a list of potential diagnoses and systematically ruling them out one by one, a process conveyed via clinicopathologic conferences in teaching hospitals. These, Dr. Fihn recalled, lasted until medical educators recognized them as “more ... theatrical events than meaningful teaching exercises” and understood that master clinicians did not actually think in the manner this approach modeled. Since then, the maturation of cognitive psychology and “a growing literature” have made diagnostic error seem like a common, sometimes unavoidable element of being human.

What can be done? Computers have always been a possibility, but “none have achieved the breadth of content and accuracy necessary to be adopted to any great extent,” Dr. Fihn wrote. Another option is crowdsourcing, as described in this study from Barnett and colleagues. Their approach has its pitfalls: A 62.5% level of diagnostic accuracy from individuals is not very high, which suggests either difficult cases or a preponderance of inexperienced clinicians who may benefit from collective intelligence even more. Regardless, he stated, “clinicians need to be cognizant of their own inherent limitations and acknowledge fallibility”; being humble and willing to seek advice “remain important, albeit imperfect, antidotes to misdiagnosis.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1071 ). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Although this study from Barnett et al. is not the silver bullet for misdiagnosis, better understanding why physicians make mistakes is a necessary and valuable undertaking, according to Stephan D. Fihn, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle.

In the past, the “correct” diagnostic approach included making a list of potential diagnoses and systematically ruling them out one by one, a process conveyed via clinicopathologic conferences in teaching hospitals. These, Dr. Fihn recalled, lasted until medical educators recognized them as “more ... theatrical events than meaningful teaching exercises” and understood that master clinicians did not actually think in the manner this approach modeled. Since then, the maturation of cognitive psychology and “a growing literature” have made diagnostic error seem like a common, sometimes unavoidable element of being human.

What can be done? Computers have always been a possibility, but “none have achieved the breadth of content and accuracy necessary to be adopted to any great extent,” Dr. Fihn wrote. Another option is crowdsourcing, as described in this study from Barnett and colleagues. Their approach has its pitfalls: A 62.5% level of diagnostic accuracy from individuals is not very high, which suggests either difficult cases or a preponderance of inexperienced clinicians who may benefit from collective intelligence even more. Regardless, he stated, “clinicians need to be cognizant of their own inherent limitations and acknowledge fallibility”; being humble and willing to seek advice “remain important, albeit imperfect, antidotes to misdiagnosis.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1071 ). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Groups of physicians and trainees diagnose clinical cases with more accuracy than individuals, according to a study of solo and aggregate diagnoses collected through an online medical teaching platform.

“These findings suggest that using the concept of collective intelligence to pool many physicians’ diagnoses could be a scalable approach to improve diagnostic accuracy,” wrote lead author Michael L. Barnett, MD, of Harvard University in Boston and his coauthors, adding that “groups of all sizes outperformed individual subspecialists on cases in their own subspecialty.” The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

This cross-sectional study examined 1,572 cases solved within the Human Diagnosis Project (Human Dx) system, an online platform for authoring and diagnosing teaching cases. The system presents real-life cases from clinical practices and asks respondents to generate ranked differential diagnoses. Cases are tagged for specialties based on both intended diagnoses and the top diagnoses chosen by respondents. All cases used in this study were authored between May 7, 2014, and October 5, 2016, and had 10 or more respondents.

Of the 2,069 attending physicians and fellows, residents, and medical students (users) who solved cases within the Human Dx system, 1,452 (70.2%) were trained in internal medicine, 1,228 (59.4%) were residents or fellows, 431 (20.8%) were attending physicians, and 410 (19.8%) were medical students. To create a collective differential, Dr. Barnett and his colleagues aggregated the responses of up to nine participants via a weighted combination of each clinician’s top three diagnoses, which they dubbed “collective intelligence.”

The diagnostic accuracy for groups of nine was 85.6% (95% confidence interval, 83.9%-87.4%), compared with individual users at 62.5% (95% CI, 60.1%-64.9%), a difference of 23% (95% CI, 14.9%-31.2%; P less than .001). Groups of five saw a 17.8% difference in accuracy versus an individual (95% CI, 14.0%-21.6%; P less than .001), compared with 12.5% for groups of two (95% CI, 9.3%-15.8%; P less than .001). Taken together, these seem to underline an association between larger groups and increased accuracy.

Individual specialists solved cases in their particular areas with a diagnostic accuracy of 66.3% (95% CI, 59.1%-73.5%), compared with nonmatched specialty accuracy of 63.9% (95% CI, 56.6%-71.2%). Groups, however, outperformed specialists across the board: 77.7% accuracy for a group of 2 (95% CI, 70.1%-84.6%; P less than .001) and 85.5% accuracy for a group of 9 (95% CI, 75.1%-95.9%; P less than .001).

The coauthors shared the limitations of their study, including the possibility that the users who contributed these cases to Human Dx may not be representative of the medical community as a whole. They also noted that, while their 431 attending physicians constituted the “largest number ... to date in a study of collective intelligence,” trainees still made up almost 80% of users. In addition, they acknowledged that Human Dx was not designed to generate collective diagnoses nor assess collective intelligence; another platform created with that ability in mind may have returned different results. Finally, they were unable to assess how exactly greater accuracy would have been linked to changes in treatment, calling it “an important question for future work.”

The authors disclosed several conflicts of interest. One doctor reported receiving personal fees from Greylock McKinnon Associates; another reported receiving personal fees from the Human Diagnosis Project and serving as their nonprofit director during the study. A third doctor reported consulting for a company that makes patient-safety monitoring systems and receiving compensation from a not-for-profit incubator, along with having equity in three medical data and software companies.

SOURCE: Barnett ML et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0096.

Groups of physicians and trainees diagnose clinical cases with more accuracy than individuals, according to a study of solo and aggregate diagnoses collected through an online medical teaching platform.

“These findings suggest that using the concept of collective intelligence to pool many physicians’ diagnoses could be a scalable approach to improve diagnostic accuracy,” wrote lead author Michael L. Barnett, MD, of Harvard University in Boston and his coauthors, adding that “groups of all sizes outperformed individual subspecialists on cases in their own subspecialty.” The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

This cross-sectional study examined 1,572 cases solved within the Human Diagnosis Project (Human Dx) system, an online platform for authoring and diagnosing teaching cases. The system presents real-life cases from clinical practices and asks respondents to generate ranked differential diagnoses. Cases are tagged for specialties based on both intended diagnoses and the top diagnoses chosen by respondents. All cases used in this study were authored between May 7, 2014, and October 5, 2016, and had 10 or more respondents.

Of the 2,069 attending physicians and fellows, residents, and medical students (users) who solved cases within the Human Dx system, 1,452 (70.2%) were trained in internal medicine, 1,228 (59.4%) were residents or fellows, 431 (20.8%) were attending physicians, and 410 (19.8%) were medical students. To create a collective differential, Dr. Barnett and his colleagues aggregated the responses of up to nine participants via a weighted combination of each clinician’s top three diagnoses, which they dubbed “collective intelligence.”

The diagnostic accuracy for groups of nine was 85.6% (95% confidence interval, 83.9%-87.4%), compared with individual users at 62.5% (95% CI, 60.1%-64.9%), a difference of 23% (95% CI, 14.9%-31.2%; P less than .001). Groups of five saw a 17.8% difference in accuracy versus an individual (95% CI, 14.0%-21.6%; P less than .001), compared with 12.5% for groups of two (95% CI, 9.3%-15.8%; P less than .001). Taken together, these seem to underline an association between larger groups and increased accuracy.

Individual specialists solved cases in their particular areas with a diagnostic accuracy of 66.3% (95% CI, 59.1%-73.5%), compared with nonmatched specialty accuracy of 63.9% (95% CI, 56.6%-71.2%). Groups, however, outperformed specialists across the board: 77.7% accuracy for a group of 2 (95% CI, 70.1%-84.6%; P less than .001) and 85.5% accuracy for a group of 9 (95% CI, 75.1%-95.9%; P less than .001).

The coauthors shared the limitations of their study, including the possibility that the users who contributed these cases to Human Dx may not be representative of the medical community as a whole. They also noted that, while their 431 attending physicians constituted the “largest number ... to date in a study of collective intelligence,” trainees still made up almost 80% of users. In addition, they acknowledged that Human Dx was not designed to generate collective diagnoses nor assess collective intelligence; another platform created with that ability in mind may have returned different results. Finally, they were unable to assess how exactly greater accuracy would have been linked to changes in treatment, calling it “an important question for future work.”

The authors disclosed several conflicts of interest. One doctor reported receiving personal fees from Greylock McKinnon Associates; another reported receiving personal fees from the Human Diagnosis Project and serving as their nonprofit director during the study. A third doctor reported consulting for a company that makes patient-safety monitoring systems and receiving compensation from a not-for-profit incubator, along with having equity in three medical data and software companies.

SOURCE: Barnett ML et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0096.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Supplements and food-related therapy do not prevent depression in overweight adults

Multinutrient supplements and food-related therapy, together or separately, do not reduce major depressive disorder (MDD) episodes, according to a clinical trial of overweight adults with subsyndromal depressive symptoms.

“These findings do not support the use of these interventions for prevention of major depressive disorder in this population,” wrote lead author Mariska Bot, PhD, of Amsterdam University Medical Center, and her coauthors. The study was published in JAMA.

For this randomized clinical trial, Dr. Bot and her colleagues recruited 1,025 overweight adults from four European countries. All had at least mild depressive symptoms – determined through Patient Health Questionnaire–9 scores of 5 or higher – but no MDD episode in the last 6 months. The patients were allocated into four groups: placebo without therapy (n = 257), placebo with therapy (n = 256), supplements without therapy (n = 256), and supplements with therapy (n = 256). The supplements included 1,412 mg of omega-3 fatty acids, 30 mcg of selenium, 400 mcg of folic acid, and 20 mcg of vitamin D3 plus 100 mg of calcium. The therapy sessions were focused on food-related behavioral activation and emphasized a Mediterranean-style diet.

Only 779 (76%) of the patients completed the trial. Of the 105 participants who developed an MDD episode during 12-month follow-up, 25 (9.7%) were receiving placebo alone, 26 (10.2%) were receiving placebo with therapy, 32 (12.5%) were receiving supplements alone, and 22 (8.6%) were receiving supplements with therapy. Three of the four groups had 24 patients hospitalized, and the supplements-only group saw 26 patients hospitalized.

“This study showed that multinutrient supplements containing omega-3 [polyunsaturated fatty acids], vitamin D, folic acid, and selenium neither reduced depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms nor improved health utility measures,” Dr. Bot and her coauthors wrote. “In fact, they appeared to result in slightly poorer depressive and anxiety symptoms scores compared with placebo.”

, roughly a quarter of patients lost to follow-up, and the likelihood that patients in the placebo group might have realized that they were not taking a multivitamin. In addition, participants were not selected based on deficiencies in the nutrients provided, making it possible that “deficient individuals will be more likely to benefit from supplementation.”

The study was funded by the European Union FP7 MooDFOOD Project Multi-country Collaborative Project on the Role of Diet, Food-related Behavior, and Obesity in the Prevention of Depression. Dr. Bot reported no disclosures. Her coauthors reported receiving funding from numerous pharmaceutical companies, the European Union, and Guilford Press.

SOURCE: Bot M et al. JAMA. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0556.

Though links between mental and physical health disorders have been established, this study from Bot et al. reinforces the murkiness of a nascent field like nutritional psychiatry, according to Michael Berk, MD, PhD, and Felice N. Jacka, PhD, of Deakin University in Victoria, Australia.

“Prevention of major depressive disorder is difficult to study,” they wrote, which makes a trial like this so important. However, its findings also emphasize the ambiguous nature of oft-touted remedies, specifically the “liberal and mostly non–evidence-based use of nutrient supplement combinations for psychiatric disorders.”

This study raises as many questions as it answers. Only 71% of those in the food-related behavioral activation therapy group attended more than 8 of the 21 offered sessions, and there is no way to prove how many followed the dietary restrictions. Those who did attend at least of 8 the sessions “showed a significant reduction in risk of depression,” however, which supports other trials that have associated dietary adherence and symptom improvement.

Diet is not a sole treatment for depression. However, the authors acknowledged that it is likely a piece of the complex puzzle that nutritional psychiatry wishes to solve. “These recent findings,” they wrote, “highlight that an integrated care package incorporating first-line psychological and pharmacological treatments, along with evidence-based lifestyle interventions addressing ... diet quality, may have a more robust effect on this burdensome disorder.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0273 ). Both coauthors reported conflicts of interest, including receiving grants, consulting fees, and research support from numerous boards, pharmaceutical companies, and foundations.

Though links between mental and physical health disorders have been established, this study from Bot et al. reinforces the murkiness of a nascent field like nutritional psychiatry, according to Michael Berk, MD, PhD, and Felice N. Jacka, PhD, of Deakin University in Victoria, Australia.

“Prevention of major depressive disorder is difficult to study,” they wrote, which makes a trial like this so important. However, its findings also emphasize the ambiguous nature of oft-touted remedies, specifically the “liberal and mostly non–evidence-based use of nutrient supplement combinations for psychiatric disorders.”

This study raises as many questions as it answers. Only 71% of those in the food-related behavioral activation therapy group attended more than 8 of the 21 offered sessions, and there is no way to prove how many followed the dietary restrictions. Those who did attend at least of 8 the sessions “showed a significant reduction in risk of depression,” however, which supports other trials that have associated dietary adherence and symptom improvement.

Diet is not a sole treatment for depression. However, the authors acknowledged that it is likely a piece of the complex puzzle that nutritional psychiatry wishes to solve. “These recent findings,” they wrote, “highlight that an integrated care package incorporating first-line psychological and pharmacological treatments, along with evidence-based lifestyle interventions addressing ... diet quality, may have a more robust effect on this burdensome disorder.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0273 ). Both coauthors reported conflicts of interest, including receiving grants, consulting fees, and research support from numerous boards, pharmaceutical companies, and foundations.

Though links between mental and physical health disorders have been established, this study from Bot et al. reinforces the murkiness of a nascent field like nutritional psychiatry, according to Michael Berk, MD, PhD, and Felice N. Jacka, PhD, of Deakin University in Victoria, Australia.

“Prevention of major depressive disorder is difficult to study,” they wrote, which makes a trial like this so important. However, its findings also emphasize the ambiguous nature of oft-touted remedies, specifically the “liberal and mostly non–evidence-based use of nutrient supplement combinations for psychiatric disorders.”

This study raises as many questions as it answers. Only 71% of those in the food-related behavioral activation therapy group attended more than 8 of the 21 offered sessions, and there is no way to prove how many followed the dietary restrictions. Those who did attend at least of 8 the sessions “showed a significant reduction in risk of depression,” however, which supports other trials that have associated dietary adherence and symptom improvement.

Diet is not a sole treatment for depression. However, the authors acknowledged that it is likely a piece of the complex puzzle that nutritional psychiatry wishes to solve. “These recent findings,” they wrote, “highlight that an integrated care package incorporating first-line psychological and pharmacological treatments, along with evidence-based lifestyle interventions addressing ... diet quality, may have a more robust effect on this burdensome disorder.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0273 ). Both coauthors reported conflicts of interest, including receiving grants, consulting fees, and research support from numerous boards, pharmaceutical companies, and foundations.

Multinutrient supplements and food-related therapy, together or separately, do not reduce major depressive disorder (MDD) episodes, according to a clinical trial of overweight adults with subsyndromal depressive symptoms.

“These findings do not support the use of these interventions for prevention of major depressive disorder in this population,” wrote lead author Mariska Bot, PhD, of Amsterdam University Medical Center, and her coauthors. The study was published in JAMA.

For this randomized clinical trial, Dr. Bot and her colleagues recruited 1,025 overweight adults from four European countries. All had at least mild depressive symptoms – determined through Patient Health Questionnaire–9 scores of 5 or higher – but no MDD episode in the last 6 months. The patients were allocated into four groups: placebo without therapy (n = 257), placebo with therapy (n = 256), supplements without therapy (n = 256), and supplements with therapy (n = 256). The supplements included 1,412 mg of omega-3 fatty acids, 30 mcg of selenium, 400 mcg of folic acid, and 20 mcg of vitamin D3 plus 100 mg of calcium. The therapy sessions were focused on food-related behavioral activation and emphasized a Mediterranean-style diet.

Only 779 (76%) of the patients completed the trial. Of the 105 participants who developed an MDD episode during 12-month follow-up, 25 (9.7%) were receiving placebo alone, 26 (10.2%) were receiving placebo with therapy, 32 (12.5%) were receiving supplements alone, and 22 (8.6%) were receiving supplements with therapy. Three of the four groups had 24 patients hospitalized, and the supplements-only group saw 26 patients hospitalized.

“This study showed that multinutrient supplements containing omega-3 [polyunsaturated fatty acids], vitamin D, folic acid, and selenium neither reduced depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms nor improved health utility measures,” Dr. Bot and her coauthors wrote. “In fact, they appeared to result in slightly poorer depressive and anxiety symptoms scores compared with placebo.”

, roughly a quarter of patients lost to follow-up, and the likelihood that patients in the placebo group might have realized that they were not taking a multivitamin. In addition, participants were not selected based on deficiencies in the nutrients provided, making it possible that “deficient individuals will be more likely to benefit from supplementation.”

The study was funded by the European Union FP7 MooDFOOD Project Multi-country Collaborative Project on the Role of Diet, Food-related Behavior, and Obesity in the Prevention of Depression. Dr. Bot reported no disclosures. Her coauthors reported receiving funding from numerous pharmaceutical companies, the European Union, and Guilford Press.

SOURCE: Bot M et al. JAMA. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0556.

Multinutrient supplements and food-related therapy, together or separately, do not reduce major depressive disorder (MDD) episodes, according to a clinical trial of overweight adults with subsyndromal depressive symptoms.

“These findings do not support the use of these interventions for prevention of major depressive disorder in this population,” wrote lead author Mariska Bot, PhD, of Amsterdam University Medical Center, and her coauthors. The study was published in JAMA.

For this randomized clinical trial, Dr. Bot and her colleagues recruited 1,025 overweight adults from four European countries. All had at least mild depressive symptoms – determined through Patient Health Questionnaire–9 scores of 5 or higher – but no MDD episode in the last 6 months. The patients were allocated into four groups: placebo without therapy (n = 257), placebo with therapy (n = 256), supplements without therapy (n = 256), and supplements with therapy (n = 256). The supplements included 1,412 mg of omega-3 fatty acids, 30 mcg of selenium, 400 mcg of folic acid, and 20 mcg of vitamin D3 plus 100 mg of calcium. The therapy sessions were focused on food-related behavioral activation and emphasized a Mediterranean-style diet.

Only 779 (76%) of the patients completed the trial. Of the 105 participants who developed an MDD episode during 12-month follow-up, 25 (9.7%) were receiving placebo alone, 26 (10.2%) were receiving placebo with therapy, 32 (12.5%) were receiving supplements alone, and 22 (8.6%) were receiving supplements with therapy. Three of the four groups had 24 patients hospitalized, and the supplements-only group saw 26 patients hospitalized.

“This study showed that multinutrient supplements containing omega-3 [polyunsaturated fatty acids], vitamin D, folic acid, and selenium neither reduced depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms nor improved health utility measures,” Dr. Bot and her coauthors wrote. “In fact, they appeared to result in slightly poorer depressive and anxiety symptoms scores compared with placebo.”

, roughly a quarter of patients lost to follow-up, and the likelihood that patients in the placebo group might have realized that they were not taking a multivitamin. In addition, participants were not selected based on deficiencies in the nutrients provided, making it possible that “deficient individuals will be more likely to benefit from supplementation.”

The study was funded by the European Union FP7 MooDFOOD Project Multi-country Collaborative Project on the Role of Diet, Food-related Behavior, and Obesity in the Prevention of Depression. Dr. Bot reported no disclosures. Her coauthors reported receiving funding from numerous pharmaceutical companies, the European Union, and Guilford Press.

SOURCE: Bot M et al. JAMA. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0556.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: A combination of multinutrient supplements and food-related behavioral activation therapy did not reduce episodes of major depressive disorder in overweight adults.

Major finding: Of the 105 participants who developed an MDD episode, 25 (9.7%) were receiving placebo alone, 26 (10.2%) were receiving placebo with therapy, 32 (12.5%) were receiving supplements alone, and 22 (8.6%) were receiving supplements with therapy.

Study details: A 2 x 2 factorial randomized clinical trial of 1,025 overweight adults from four European countries with elevated depressive symptoms and no major depressive disorder episode in the past 6 months.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the European Union FP7 MooDFOOD Project Multi-country Collaborative Project on the Role of Diet, Food-related Behavior, and Obesity in the Prevention of Depression. Dr. Bot reported no disclosures. Her coauthors reported receiving funding from numerous pharmaceutical companies, the European Union, and Guilford Press.

Source: Bot M et al. JAMA. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0556.

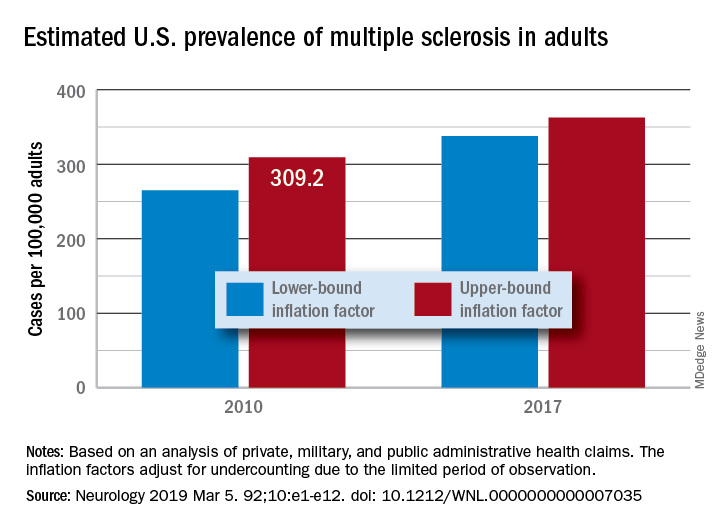

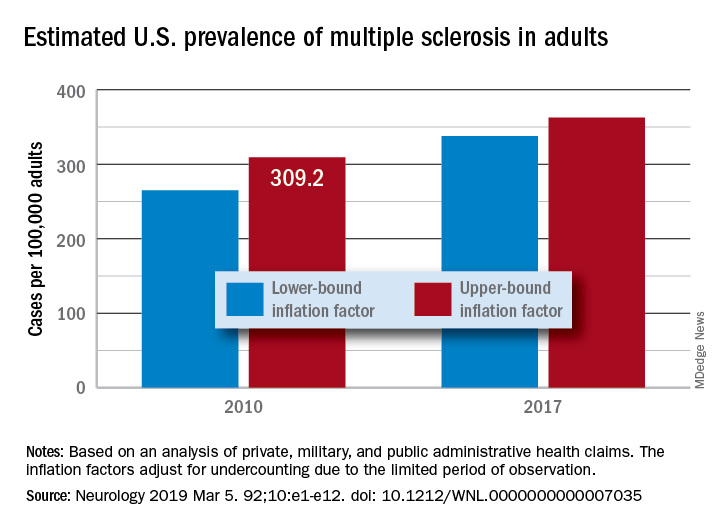

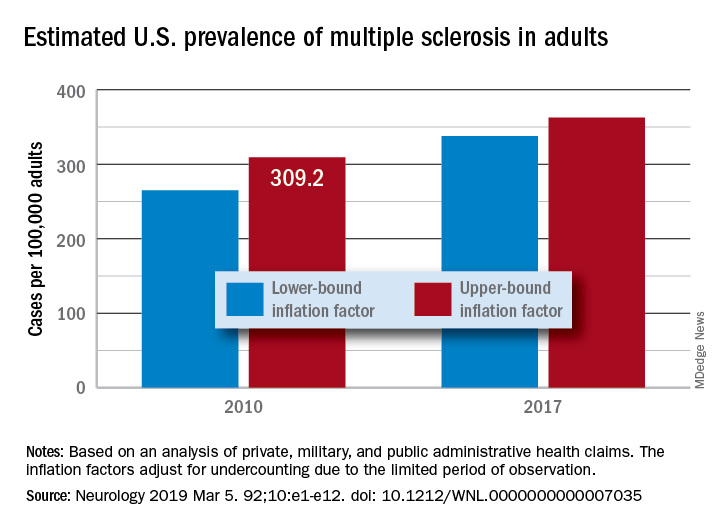

MS prevalence estimates reach highest point to date

“Our findings suggest that there has been a steady rise in the prevalence of MS over the past 5 decades, that the prevalence of MS remains higher for women than men, and that a north-south geographic gradient still persists,” wrote lead author Mitchell T. Wallin, MD, of Georgetown University, Washington, and his coauthors. The study was published in Neurology.

To determine adult cases of MS, Dr. Wallin and colleagues applied a validated algorithm to private, military, and public AHC datasets. Data from the 2010 U.S. Census were also used to standardize age and sex. In total, 125 million people over 18 years of age were captured in the study, nearly 45% of the U.S. population.

After adjustment, the 2010 prevalence for MS cumulated over 10 years was 309.2 per 100,000 adults (95% confidence interval, 308.1-310.1). This represented a total of 727,344 people with MS. The female to male ratio was 2.8, with a prevalence of 450.1 per 100,000 (95% CI, 448.1-451.6) for women versus a prevalence of 159.7 (95% CI, 158.7-160.6) for men. The age group with the highest estimated prevalence was 55-64 years old, and the prevalence in northern regions of the United States was statistically significantly higher than in southern regions.

The limitations of this study included not including children, the Indian Health Service, the U.S. prison system, or undocumented U.S. residents in the prevalence estimates. However, the authors did note that “these segments of the population are relatively small or, in the case of children, would contribute few cases.” In addition, they were unable to acquire more than 3 years of data for all insurance pools because of high costs.

The study was funded by a grant from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. The authors reported numerous disclosures, including receiving consulting fees, researching funding, and grant support from various government agencies, foundations, and pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Wallin MT et al. Neurology. 2019 Feb 15. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007035.

“Our findings suggest that there has been a steady rise in the prevalence of MS over the past 5 decades, that the prevalence of MS remains higher for women than men, and that a north-south geographic gradient still persists,” wrote lead author Mitchell T. Wallin, MD, of Georgetown University, Washington, and his coauthors. The study was published in Neurology.

To determine adult cases of MS, Dr. Wallin and colleagues applied a validated algorithm to private, military, and public AHC datasets. Data from the 2010 U.S. Census were also used to standardize age and sex. In total, 125 million people over 18 years of age were captured in the study, nearly 45% of the U.S. population.

After adjustment, the 2010 prevalence for MS cumulated over 10 years was 309.2 per 100,000 adults (95% confidence interval, 308.1-310.1). This represented a total of 727,344 people with MS. The female to male ratio was 2.8, with a prevalence of 450.1 per 100,000 (95% CI, 448.1-451.6) for women versus a prevalence of 159.7 (95% CI, 158.7-160.6) for men. The age group with the highest estimated prevalence was 55-64 years old, and the prevalence in northern regions of the United States was statistically significantly higher than in southern regions.

The limitations of this study included not including children, the Indian Health Service, the U.S. prison system, or undocumented U.S. residents in the prevalence estimates. However, the authors did note that “these segments of the population are relatively small or, in the case of children, would contribute few cases.” In addition, they were unable to acquire more than 3 years of data for all insurance pools because of high costs.

The study was funded by a grant from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. The authors reported numerous disclosures, including receiving consulting fees, researching funding, and grant support from various government agencies, foundations, and pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Wallin MT et al. Neurology. 2019 Feb 15. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007035.

“Our findings suggest that there has been a steady rise in the prevalence of MS over the past 5 decades, that the prevalence of MS remains higher for women than men, and that a north-south geographic gradient still persists,” wrote lead author Mitchell T. Wallin, MD, of Georgetown University, Washington, and his coauthors. The study was published in Neurology.

To determine adult cases of MS, Dr. Wallin and colleagues applied a validated algorithm to private, military, and public AHC datasets. Data from the 2010 U.S. Census were also used to standardize age and sex. In total, 125 million people over 18 years of age were captured in the study, nearly 45% of the U.S. population.