User login

Germline testing in advanced cancer can lead to targeted treatment

The study involved 11,974 patients with various tumor types. All the patients underwent germline genetic testing from 2015 to 2019 at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York, using the next-generation sequencing panel MSK-IMPACT.

This testing showed that 17.1% of patients had variants in cancer predisposition genes, and 7.1%-8.6% had variants that could potentially be targeted.

“Of course, these numbers are not static,” commented lead author Zsofia K. Stadler, MD, a medical oncologist at MSKCC. “And with the emergence of novel targeted treatments with new FDA indications, the therapeutic actionability of germline variants is likely to increase over time.

“Our study demonstrates the first comprehensive assessment of the clinical utility of germline alterations for therapeutic actionability in a population of patients with advanced cancer,” she added.

Dr. Stadler presented the study results during a virtual scientific program of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2020.

Testing for somatic mutations is evolving as the standard of care in many cancer types, and somatic genomic testing is rapidly becoming an integral part of the regimen for patients with advanced disease. Some studies suggest that 9%-11% of patients harbor actionable genetic alterations, as determined on the basis of tumor profiling.

“The take-home message from this is that now, more than ever before, germline testing is indicated for the selection of cancer treatment,” said Erin Wysong Hofstatter, MD, from Yale University, New Haven, Conn., in a Highlights of the Day session.

An emerging indication for germline testing is the selection of treatment in the advanced setting, she noted. “And it is important to know your test. Remember that tumor sequencing is not a substitute for comprehensive germline testing.”

Implications in cancer treatment

For their study, Dr. Stadler and colleagues reviewed the medical records of patients with likely pathogenic/pathogenic germline (LP/P) alterations in genes that had known therapeutic targets so as to identify germline-targeted treatment either in a clinical or research setting.

“Since 2015, patients undergoing MSK-IMPACT may also choose to provide additional consent for secondary germline genetic analysis, wherein up to 88 genes known to be associated with cancer predisposition are analyzed,” she said. “Likely pathogenic and pathogenic germline alterations identified are disclosed to the patient and treating physician via the Clinical Genetic Service.”

A total of 2043 (17.1%) patients who harbored LP/P variants in a cancer predisposition gene were identified. Of these, 11% of patients harbored pathogenic alterations in high or moderate penetrance cancer predisposition genes. When the analysis was limited to genes with targeted therapeutic actionability, or what the authors defined as tier 1 and tier 2 genes, 7.1% of patients (n = 849) harbored a targetable pathogenic germline alteration.

BRCA alterations accounted for half (52%) of the findings, and 20% were associated with Lynch syndrome.

The tier 2 genes, which included PALB2, ATM, RAD51C, and RAD51D, accounted for about a quarter of the findings. Dr. Hofstatter noted that, using strict criteria, 7.1% of patients (n = 849) were found to harbor a pathogenic alteration and a targetable gene. Using less stringent criteria, additional tier 3 genes and additional genes associated with DNA homologous recombination repair brought the number up to 8.6% (n = 1,003).

Therapeutic action

For determining therapeutic actionability, the strict criteria were used; 593 patients (4.95%) with recurrent or metastatic disease were identified. For these patients, consideration of a targeted therapy, either as part of standard care or as part of an investigation or research protocol, was important.

Of this group, 44% received therapy targeting the germline alteration. Regarding specific genes, 50% of BRCA1/2 carriers and 58% of Lynch syndrome patients received targeted treatment. With respect to tier 2 genes, 40% of patients with PALB2, 19% with ATM, and 37% with RAD51C or 51D received a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor.

Among patients with a BRCA1/2 mutation who received a PARP inhibitor, 55.1% had breast or ovarian cancer, and 44.8% had other tumor types, including pancreas, prostate, bile duct, gastric cancers. These patients received the drug in a research setting.

For patients with PALB2 alterations who received PARP inhibitors, 53.3% had breast or pancreas cancer, and 46.7% had cancer of the prostate, ovary, or an unknown primary.

Looking ahead

The discussant for the paper, Funda Meric-Bernstam, MD, chair of the Department of Investigational Cancer Therapeutics at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, pointed out that most of the BRCA-positive patients had cancers traditionally associated with the mutation. “There were no patients with PTEN mutations treated, and interestingly, no patients with NF1 were treated,” she said. “But actionability is evolving, as the MEK inhibitor selumitinib was recently approved for NF1.”

Some questions remain unanswered, she noted, such as: “What percentage of patients undergoing tumor-normal testing signed a germline protocol?” and “Does the population introduce a bias – such as younger patients, family history, and so on?”

It is also unknown what percentage of germline alterations were known in comparison with those identified through tumor/normal testing. Also of importance is the fact that in this study, the results of germline testing were delivered in an academic setting, she emphasized. “What if they were delivered elsewhere? What would be the impact of identifying these alterations in an environment with less access to trials?

“But to be fair, it is not easy to seek the germline mutations,” Dr. Meric-Bernstam continued. “These studies were done under institutional review board protocols, and it is important to note that most profiling is done as standard of care without consenting and soliciting patient preference on the return of germline results.”

An infrastructure is needed to return/counsel/offer cascade testing, and “analyses need to be facilitated to ensure that findings can be acted upon in a timely fashion,” she added.

The study was supported by MSKCC internal funding. Dr. Stadler reported relationships (institutional) with Adverum, Alimera Sciences, Allergan, Biomarin, Fortress Biotech, Genentech/Roche, Novartis, Optos, Regeneron, Regenxbio, and Spark Therapeutics. Dr. Meric-Bernstram reported relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study involved 11,974 patients with various tumor types. All the patients underwent germline genetic testing from 2015 to 2019 at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York, using the next-generation sequencing panel MSK-IMPACT.

This testing showed that 17.1% of patients had variants in cancer predisposition genes, and 7.1%-8.6% had variants that could potentially be targeted.

“Of course, these numbers are not static,” commented lead author Zsofia K. Stadler, MD, a medical oncologist at MSKCC. “And with the emergence of novel targeted treatments with new FDA indications, the therapeutic actionability of germline variants is likely to increase over time.

“Our study demonstrates the first comprehensive assessment of the clinical utility of germline alterations for therapeutic actionability in a population of patients with advanced cancer,” she added.

Dr. Stadler presented the study results during a virtual scientific program of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2020.

Testing for somatic mutations is evolving as the standard of care in many cancer types, and somatic genomic testing is rapidly becoming an integral part of the regimen for patients with advanced disease. Some studies suggest that 9%-11% of patients harbor actionable genetic alterations, as determined on the basis of tumor profiling.

“The take-home message from this is that now, more than ever before, germline testing is indicated for the selection of cancer treatment,” said Erin Wysong Hofstatter, MD, from Yale University, New Haven, Conn., in a Highlights of the Day session.

An emerging indication for germline testing is the selection of treatment in the advanced setting, she noted. “And it is important to know your test. Remember that tumor sequencing is not a substitute for comprehensive germline testing.”

Implications in cancer treatment

For their study, Dr. Stadler and colleagues reviewed the medical records of patients with likely pathogenic/pathogenic germline (LP/P) alterations in genes that had known therapeutic targets so as to identify germline-targeted treatment either in a clinical or research setting.

“Since 2015, patients undergoing MSK-IMPACT may also choose to provide additional consent for secondary germline genetic analysis, wherein up to 88 genes known to be associated with cancer predisposition are analyzed,” she said. “Likely pathogenic and pathogenic germline alterations identified are disclosed to the patient and treating physician via the Clinical Genetic Service.”

A total of 2043 (17.1%) patients who harbored LP/P variants in a cancer predisposition gene were identified. Of these, 11% of patients harbored pathogenic alterations in high or moderate penetrance cancer predisposition genes. When the analysis was limited to genes with targeted therapeutic actionability, or what the authors defined as tier 1 and tier 2 genes, 7.1% of patients (n = 849) harbored a targetable pathogenic germline alteration.

BRCA alterations accounted for half (52%) of the findings, and 20% were associated with Lynch syndrome.

The tier 2 genes, which included PALB2, ATM, RAD51C, and RAD51D, accounted for about a quarter of the findings. Dr. Hofstatter noted that, using strict criteria, 7.1% of patients (n = 849) were found to harbor a pathogenic alteration and a targetable gene. Using less stringent criteria, additional tier 3 genes and additional genes associated with DNA homologous recombination repair brought the number up to 8.6% (n = 1,003).

Therapeutic action

For determining therapeutic actionability, the strict criteria were used; 593 patients (4.95%) with recurrent or metastatic disease were identified. For these patients, consideration of a targeted therapy, either as part of standard care or as part of an investigation or research protocol, was important.

Of this group, 44% received therapy targeting the germline alteration. Regarding specific genes, 50% of BRCA1/2 carriers and 58% of Lynch syndrome patients received targeted treatment. With respect to tier 2 genes, 40% of patients with PALB2, 19% with ATM, and 37% with RAD51C or 51D received a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor.

Among patients with a BRCA1/2 mutation who received a PARP inhibitor, 55.1% had breast or ovarian cancer, and 44.8% had other tumor types, including pancreas, prostate, bile duct, gastric cancers. These patients received the drug in a research setting.

For patients with PALB2 alterations who received PARP inhibitors, 53.3% had breast or pancreas cancer, and 46.7% had cancer of the prostate, ovary, or an unknown primary.

Looking ahead

The discussant for the paper, Funda Meric-Bernstam, MD, chair of the Department of Investigational Cancer Therapeutics at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, pointed out that most of the BRCA-positive patients had cancers traditionally associated with the mutation. “There were no patients with PTEN mutations treated, and interestingly, no patients with NF1 were treated,” she said. “But actionability is evolving, as the MEK inhibitor selumitinib was recently approved for NF1.”

Some questions remain unanswered, she noted, such as: “What percentage of patients undergoing tumor-normal testing signed a germline protocol?” and “Does the population introduce a bias – such as younger patients, family history, and so on?”

It is also unknown what percentage of germline alterations were known in comparison with those identified through tumor/normal testing. Also of importance is the fact that in this study, the results of germline testing were delivered in an academic setting, she emphasized. “What if they were delivered elsewhere? What would be the impact of identifying these alterations in an environment with less access to trials?

“But to be fair, it is not easy to seek the germline mutations,” Dr. Meric-Bernstam continued. “These studies were done under institutional review board protocols, and it is important to note that most profiling is done as standard of care without consenting and soliciting patient preference on the return of germline results.”

An infrastructure is needed to return/counsel/offer cascade testing, and “analyses need to be facilitated to ensure that findings can be acted upon in a timely fashion,” she added.

The study was supported by MSKCC internal funding. Dr. Stadler reported relationships (institutional) with Adverum, Alimera Sciences, Allergan, Biomarin, Fortress Biotech, Genentech/Roche, Novartis, Optos, Regeneron, Regenxbio, and Spark Therapeutics. Dr. Meric-Bernstram reported relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study involved 11,974 patients with various tumor types. All the patients underwent germline genetic testing from 2015 to 2019 at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York, using the next-generation sequencing panel MSK-IMPACT.

This testing showed that 17.1% of patients had variants in cancer predisposition genes, and 7.1%-8.6% had variants that could potentially be targeted.

“Of course, these numbers are not static,” commented lead author Zsofia K. Stadler, MD, a medical oncologist at MSKCC. “And with the emergence of novel targeted treatments with new FDA indications, the therapeutic actionability of germline variants is likely to increase over time.

“Our study demonstrates the first comprehensive assessment of the clinical utility of germline alterations for therapeutic actionability in a population of patients with advanced cancer,” she added.

Dr. Stadler presented the study results during a virtual scientific program of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2020.

Testing for somatic mutations is evolving as the standard of care in many cancer types, and somatic genomic testing is rapidly becoming an integral part of the regimen for patients with advanced disease. Some studies suggest that 9%-11% of patients harbor actionable genetic alterations, as determined on the basis of tumor profiling.

“The take-home message from this is that now, more than ever before, germline testing is indicated for the selection of cancer treatment,” said Erin Wysong Hofstatter, MD, from Yale University, New Haven, Conn., in a Highlights of the Day session.

An emerging indication for germline testing is the selection of treatment in the advanced setting, she noted. “And it is important to know your test. Remember that tumor sequencing is not a substitute for comprehensive germline testing.”

Implications in cancer treatment

For their study, Dr. Stadler and colleagues reviewed the medical records of patients with likely pathogenic/pathogenic germline (LP/P) alterations in genes that had known therapeutic targets so as to identify germline-targeted treatment either in a clinical or research setting.

“Since 2015, patients undergoing MSK-IMPACT may also choose to provide additional consent for secondary germline genetic analysis, wherein up to 88 genes known to be associated with cancer predisposition are analyzed,” she said. “Likely pathogenic and pathogenic germline alterations identified are disclosed to the patient and treating physician via the Clinical Genetic Service.”

A total of 2043 (17.1%) patients who harbored LP/P variants in a cancer predisposition gene were identified. Of these, 11% of patients harbored pathogenic alterations in high or moderate penetrance cancer predisposition genes. When the analysis was limited to genes with targeted therapeutic actionability, or what the authors defined as tier 1 and tier 2 genes, 7.1% of patients (n = 849) harbored a targetable pathogenic germline alteration.

BRCA alterations accounted for half (52%) of the findings, and 20% were associated with Lynch syndrome.

The tier 2 genes, which included PALB2, ATM, RAD51C, and RAD51D, accounted for about a quarter of the findings. Dr. Hofstatter noted that, using strict criteria, 7.1% of patients (n = 849) were found to harbor a pathogenic alteration and a targetable gene. Using less stringent criteria, additional tier 3 genes and additional genes associated with DNA homologous recombination repair brought the number up to 8.6% (n = 1,003).

Therapeutic action

For determining therapeutic actionability, the strict criteria were used; 593 patients (4.95%) with recurrent or metastatic disease were identified. For these patients, consideration of a targeted therapy, either as part of standard care or as part of an investigation or research protocol, was important.

Of this group, 44% received therapy targeting the germline alteration. Regarding specific genes, 50% of BRCA1/2 carriers and 58% of Lynch syndrome patients received targeted treatment. With respect to tier 2 genes, 40% of patients with PALB2, 19% with ATM, and 37% with RAD51C or 51D received a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor.

Among patients with a BRCA1/2 mutation who received a PARP inhibitor, 55.1% had breast or ovarian cancer, and 44.8% had other tumor types, including pancreas, prostate, bile duct, gastric cancers. These patients received the drug in a research setting.

For patients with PALB2 alterations who received PARP inhibitors, 53.3% had breast or pancreas cancer, and 46.7% had cancer of the prostate, ovary, or an unknown primary.

Looking ahead

The discussant for the paper, Funda Meric-Bernstam, MD, chair of the Department of Investigational Cancer Therapeutics at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, pointed out that most of the BRCA-positive patients had cancers traditionally associated with the mutation. “There were no patients with PTEN mutations treated, and interestingly, no patients with NF1 were treated,” she said. “But actionability is evolving, as the MEK inhibitor selumitinib was recently approved for NF1.”

Some questions remain unanswered, she noted, such as: “What percentage of patients undergoing tumor-normal testing signed a germline protocol?” and “Does the population introduce a bias – such as younger patients, family history, and so on?”

It is also unknown what percentage of germline alterations were known in comparison with those identified through tumor/normal testing. Also of importance is the fact that in this study, the results of germline testing were delivered in an academic setting, she emphasized. “What if they were delivered elsewhere? What would be the impact of identifying these alterations in an environment with less access to trials?

“But to be fair, it is not easy to seek the germline mutations,” Dr. Meric-Bernstam continued. “These studies were done under institutional review board protocols, and it is important to note that most profiling is done as standard of care without consenting and soliciting patient preference on the return of germline results.”

An infrastructure is needed to return/counsel/offer cascade testing, and “analyses need to be facilitated to ensure that findings can be acted upon in a timely fashion,” she added.

The study was supported by MSKCC internal funding. Dr. Stadler reported relationships (institutional) with Adverum, Alimera Sciences, Allergan, Biomarin, Fortress Biotech, Genentech/Roche, Novartis, Optos, Regeneron, Regenxbio, and Spark Therapeutics. Dr. Meric-Bernstram reported relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ASCO 2020

Oncologists’ income and satisfaction are up

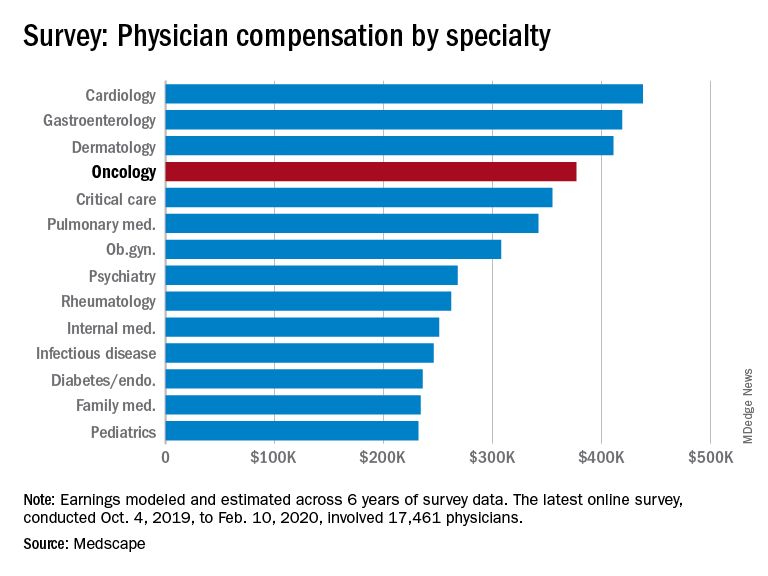

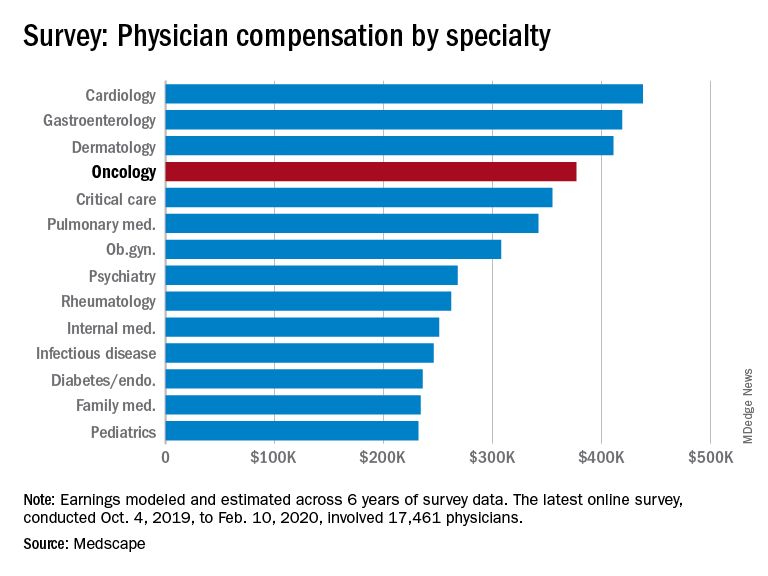

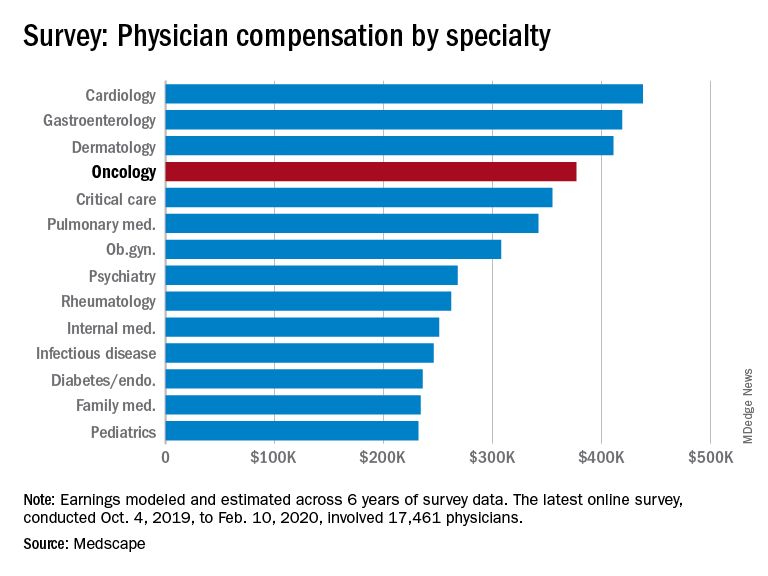

Oncologists continue to rank above the middle range for all specialties in annual compensation for physicians, according to findings from the newly released Medscape Oncologist Compensation Report 2020.

The average earnings for oncologists who participated in the survey was $377,000, which was a 5% increase from the $359,000 reported for 2018.

Just over two-thirds (67%) of oncologists reported that they felt that they were fairly compensated, which is quite a jump from 53% last year.

In addition, oncologists appear to be very satisfied with their profession. Similar to last year’s findings, 84% said they would choose medicine again, and 96% said they would choose the specialty of oncology again.

Earning in top third of all specialties

The average annual earnings reported by oncologists put this specialty in eleventh place among 29 specialties. Orthopedic specialists remain at the head of the list, with estimated earnings of $511,000, followed by plastic surgeons ($479,000), otolaryngologists ($455,000), and cardiologists ($438,000), according to Medscape’s compensation report, which included responses from 17,461 physicians in over 30 specialties.

At the bottom of the estimated earnings list were public health and preventive medicine doctors and pediatricians. For both specialties, the reported annual earnings was $232,000. Family medicine specialists were only marginally higher at $234,000.

Radiologists ($427,000), gastroenterologists ($419,000), and urologists ($417,000) all reported higher earnings than oncologists, whereas neurologists, at $280,000, rheumatologists, at $262,000, and internal medicine physicians, at $251,000, earned less.

The report also found that gender disparities in income persist, with male oncologists earning 17% more than their female colleagues. The gender gap in oncology is somewhat less than that seen for all specialties combined, in which men earned 31% more than women, similar to last year’s figure of 33%.

Male oncologists reported spending 38.8 hours per week seeing patients, compared with 34.9 hours reported by female oncologists. This could be a factor contributing to the gender pay disparity. Overall, the average amount of time seeing patients was 37.9 hours per week.

Frustrations with paperwork and denied claims

Surveyed oncologists cited some of the frustrations they are facing, such as spending nearly 17 hours a week on paperwork and administrative tasks. They reported that 16% of claims are denied or have to be resubmitted. As for the most challenging part of the job, oncologists (22%), similar to physicians overall (26%), found that having so many rules and regulations takes first place, followed by working with electronic health record systems (20%), difficulties getting fair reimbursement (19%), having to work long hours (12%), and dealing with difficult patients (8%). Few oncologists were concerned about lawsuits (4%), and 4% reported that there were no challenges.

Oncologists reported that the most rewarding part of their job was gratitude/relationships with patients (31%), followed by knowing that they are making the world a better place (27%). After that, oncologists agreed with statements about being very good at what they do/finding answers/diagnoses (22%), having pride in being a doctor (9%), and making good money at a job they like (8%).

Other key findings

Other key findings from the Medscape Oncologist Compensation Report 2020 included the following:

- Regarding payment models, 80% take insurance, 41% are in fee-for-service arrangements, and 18% are in accountable care organizations (21%). Only 3% are in direct primary care, and 1% are cash-only practices or have a concierge practice.

- 65% of oncologists state that they will continue taking new and current Medicare/Medicaid patients. None said that they would not take on new Medicare/Medicaid patients, and 35% remain undecided. These numbers differed from physicians overall; 73% of all physicians surveyed said they would continue taking new/current Medicare/Medicaid patients, 6% said that will not take on new Medicare patients, and 4% said they will not take new Medicaid patients. In addition, 3% and 2% said that they would stop treating some or all of their Medicare and Medicaid patients, respectively.

- About half (51%) of oncologists use nurse practitioners, about a third (34%) use physician assistants, and 37% use neither. This was about the same as physicians overall.

- A larger percentage of oncologists (38%) expect to participate in MIPS (merit-based incentive payment system), and only 8% expect to participate in APMs (alternative payment models). This was similar to the findings for physicians overall, with more than one-third (37%) expecting to participate in MIPS and 9% planning to take part in APMs.

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic

The Medscape compensation reports also gives a glimpse of the impact the COVID-19 pandemic is having on physician compensation.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, practices have reported a 55% decrease in revenue and a 60% drop in patient volume. Physician practices and hospitals have laid off or furloughed personnel and have cut pay, and 9% of practices have closed their doors, at least for the time being.

A total of 43,000 health care workers were laid off in March, the report notes.

The findings tie in with those reported elsewhere. For example, a survey conducted by the Medical Group Management Association, which was reported by Medscape Medical News, found that 97% of physician practices have experienced negative financial effects directly or indirectly related to COVID-19.

Specialties were hard hit, especially those that rely on elective procedures, such as dermatology and cardiology. Oncology care has also been disrupted. For example, a survey conducted by the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network found that half of the cancer patients and survivors who responded reported changes, delays, or disruptions to the care they were receiving.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Oncologists continue to rank above the middle range for all specialties in annual compensation for physicians, according to findings from the newly released Medscape Oncologist Compensation Report 2020.

The average earnings for oncologists who participated in the survey was $377,000, which was a 5% increase from the $359,000 reported for 2018.

Just over two-thirds (67%) of oncologists reported that they felt that they were fairly compensated, which is quite a jump from 53% last year.

In addition, oncologists appear to be very satisfied with their profession. Similar to last year’s findings, 84% said they would choose medicine again, and 96% said they would choose the specialty of oncology again.

Earning in top third of all specialties

The average annual earnings reported by oncologists put this specialty in eleventh place among 29 specialties. Orthopedic specialists remain at the head of the list, with estimated earnings of $511,000, followed by plastic surgeons ($479,000), otolaryngologists ($455,000), and cardiologists ($438,000), according to Medscape’s compensation report, which included responses from 17,461 physicians in over 30 specialties.

At the bottom of the estimated earnings list were public health and preventive medicine doctors and pediatricians. For both specialties, the reported annual earnings was $232,000. Family medicine specialists were only marginally higher at $234,000.

Radiologists ($427,000), gastroenterologists ($419,000), and urologists ($417,000) all reported higher earnings than oncologists, whereas neurologists, at $280,000, rheumatologists, at $262,000, and internal medicine physicians, at $251,000, earned less.

The report also found that gender disparities in income persist, with male oncologists earning 17% more than their female colleagues. The gender gap in oncology is somewhat less than that seen for all specialties combined, in which men earned 31% more than women, similar to last year’s figure of 33%.

Male oncologists reported spending 38.8 hours per week seeing patients, compared with 34.9 hours reported by female oncologists. This could be a factor contributing to the gender pay disparity. Overall, the average amount of time seeing patients was 37.9 hours per week.

Frustrations with paperwork and denied claims

Surveyed oncologists cited some of the frustrations they are facing, such as spending nearly 17 hours a week on paperwork and administrative tasks. They reported that 16% of claims are denied or have to be resubmitted. As for the most challenging part of the job, oncologists (22%), similar to physicians overall (26%), found that having so many rules and regulations takes first place, followed by working with electronic health record systems (20%), difficulties getting fair reimbursement (19%), having to work long hours (12%), and dealing with difficult patients (8%). Few oncologists were concerned about lawsuits (4%), and 4% reported that there were no challenges.

Oncologists reported that the most rewarding part of their job was gratitude/relationships with patients (31%), followed by knowing that they are making the world a better place (27%). After that, oncologists agreed with statements about being very good at what they do/finding answers/diagnoses (22%), having pride in being a doctor (9%), and making good money at a job they like (8%).

Other key findings

Other key findings from the Medscape Oncologist Compensation Report 2020 included the following:

- Regarding payment models, 80% take insurance, 41% are in fee-for-service arrangements, and 18% are in accountable care organizations (21%). Only 3% are in direct primary care, and 1% are cash-only practices or have a concierge practice.

- 65% of oncologists state that they will continue taking new and current Medicare/Medicaid patients. None said that they would not take on new Medicare/Medicaid patients, and 35% remain undecided. These numbers differed from physicians overall; 73% of all physicians surveyed said they would continue taking new/current Medicare/Medicaid patients, 6% said that will not take on new Medicare patients, and 4% said they will not take new Medicaid patients. In addition, 3% and 2% said that they would stop treating some or all of their Medicare and Medicaid patients, respectively.

- About half (51%) of oncologists use nurse practitioners, about a third (34%) use physician assistants, and 37% use neither. This was about the same as physicians overall.

- A larger percentage of oncologists (38%) expect to participate in MIPS (merit-based incentive payment system), and only 8% expect to participate in APMs (alternative payment models). This was similar to the findings for physicians overall, with more than one-third (37%) expecting to participate in MIPS and 9% planning to take part in APMs.

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic

The Medscape compensation reports also gives a glimpse of the impact the COVID-19 pandemic is having on physician compensation.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, practices have reported a 55% decrease in revenue and a 60% drop in patient volume. Physician practices and hospitals have laid off or furloughed personnel and have cut pay, and 9% of practices have closed their doors, at least for the time being.

A total of 43,000 health care workers were laid off in March, the report notes.

The findings tie in with those reported elsewhere. For example, a survey conducted by the Medical Group Management Association, which was reported by Medscape Medical News, found that 97% of physician practices have experienced negative financial effects directly or indirectly related to COVID-19.

Specialties were hard hit, especially those that rely on elective procedures, such as dermatology and cardiology. Oncology care has also been disrupted. For example, a survey conducted by the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network found that half of the cancer patients and survivors who responded reported changes, delays, or disruptions to the care they were receiving.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Oncologists continue to rank above the middle range for all specialties in annual compensation for physicians, according to findings from the newly released Medscape Oncologist Compensation Report 2020.

The average earnings for oncologists who participated in the survey was $377,000, which was a 5% increase from the $359,000 reported for 2018.

Just over two-thirds (67%) of oncologists reported that they felt that they were fairly compensated, which is quite a jump from 53% last year.

In addition, oncologists appear to be very satisfied with their profession. Similar to last year’s findings, 84% said they would choose medicine again, and 96% said they would choose the specialty of oncology again.

Earning in top third of all specialties

The average annual earnings reported by oncologists put this specialty in eleventh place among 29 specialties. Orthopedic specialists remain at the head of the list, with estimated earnings of $511,000, followed by plastic surgeons ($479,000), otolaryngologists ($455,000), and cardiologists ($438,000), according to Medscape’s compensation report, which included responses from 17,461 physicians in over 30 specialties.

At the bottom of the estimated earnings list were public health and preventive medicine doctors and pediatricians. For both specialties, the reported annual earnings was $232,000. Family medicine specialists were only marginally higher at $234,000.

Radiologists ($427,000), gastroenterologists ($419,000), and urologists ($417,000) all reported higher earnings than oncologists, whereas neurologists, at $280,000, rheumatologists, at $262,000, and internal medicine physicians, at $251,000, earned less.

The report also found that gender disparities in income persist, with male oncologists earning 17% more than their female colleagues. The gender gap in oncology is somewhat less than that seen for all specialties combined, in which men earned 31% more than women, similar to last year’s figure of 33%.

Male oncologists reported spending 38.8 hours per week seeing patients, compared with 34.9 hours reported by female oncologists. This could be a factor contributing to the gender pay disparity. Overall, the average amount of time seeing patients was 37.9 hours per week.

Frustrations with paperwork and denied claims

Surveyed oncologists cited some of the frustrations they are facing, such as spending nearly 17 hours a week on paperwork and administrative tasks. They reported that 16% of claims are denied or have to be resubmitted. As for the most challenging part of the job, oncologists (22%), similar to physicians overall (26%), found that having so many rules and regulations takes first place, followed by working with electronic health record systems (20%), difficulties getting fair reimbursement (19%), having to work long hours (12%), and dealing with difficult patients (8%). Few oncologists were concerned about lawsuits (4%), and 4% reported that there were no challenges.

Oncologists reported that the most rewarding part of their job was gratitude/relationships with patients (31%), followed by knowing that they are making the world a better place (27%). After that, oncologists agreed with statements about being very good at what they do/finding answers/diagnoses (22%), having pride in being a doctor (9%), and making good money at a job they like (8%).

Other key findings

Other key findings from the Medscape Oncologist Compensation Report 2020 included the following:

- Regarding payment models, 80% take insurance, 41% are in fee-for-service arrangements, and 18% are in accountable care organizations (21%). Only 3% are in direct primary care, and 1% are cash-only practices or have a concierge practice.

- 65% of oncologists state that they will continue taking new and current Medicare/Medicaid patients. None said that they would not take on new Medicare/Medicaid patients, and 35% remain undecided. These numbers differed from physicians overall; 73% of all physicians surveyed said they would continue taking new/current Medicare/Medicaid patients, 6% said that will not take on new Medicare patients, and 4% said they will not take new Medicaid patients. In addition, 3% and 2% said that they would stop treating some or all of their Medicare and Medicaid patients, respectively.

- About half (51%) of oncologists use nurse practitioners, about a third (34%) use physician assistants, and 37% use neither. This was about the same as physicians overall.

- A larger percentage of oncologists (38%) expect to participate in MIPS (merit-based incentive payment system), and only 8% expect to participate in APMs (alternative payment models). This was similar to the findings for physicians overall, with more than one-third (37%) expecting to participate in MIPS and 9% planning to take part in APMs.

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic

The Medscape compensation reports also gives a glimpse of the impact the COVID-19 pandemic is having on physician compensation.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, practices have reported a 55% decrease in revenue and a 60% drop in patient volume. Physician practices and hospitals have laid off or furloughed personnel and have cut pay, and 9% of practices have closed their doors, at least for the time being.

A total of 43,000 health care workers were laid off in March, the report notes.

The findings tie in with those reported elsewhere. For example, a survey conducted by the Medical Group Management Association, which was reported by Medscape Medical News, found that 97% of physician practices have experienced negative financial effects directly or indirectly related to COVID-19.

Specialties were hard hit, especially those that rely on elective procedures, such as dermatology and cardiology. Oncology care has also been disrupted. For example, a survey conducted by the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network found that half of the cancer patients and survivors who responded reported changes, delays, or disruptions to the care they were receiving.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Tumor molecular profiling may help identify ‘exceptional responders’

Virtually all oncologists, at one time or another, have treated a patient who defied the odds and achieved an unexpectedly long-lasting response. These “exceptional responders” are patients who experience a unique response to therapies that have largely failed to be effective for others with similar cancers.

Genetic and molecular mechanisms may partly account for these responses and may offer clues about why the treatment works for only a few and not for others. To delve more deeply into that area of research, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) began the Exceptional Responders Initiative (ERI) with the goal of identifying potential biological processes that may be responsible, at least in part, for these unusual responses.

NCI researchers have now successfully completed a pilot study that analyzed tumor specimens from more than 100 cases, and the study has affirmed the feasibility of this approach.

Of these cases, six were identified as involving potentially clinically actionable germline mutations.

The findings were published online ahead of print in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

“Clearly, the analysis and validation of these results will prove critical to determining the success of this approach,” write James M. Ford, MD, and Beverly S. Mitchell, MD, both of Stanford University School of Medicine, California, in an accompanying editorial. “Ultimately, prospective studies of tumors from exceptional responders, particularly to novel, genomically-targeted agents, may provide a powerful approach to cancer treatment discoveries.”

A special case

Molecular profiling technology, including next-generation sequencing, has significantly changed the landscape of the development of cancer therapies, and clinical trials in early drug development are increasingly selecting patients on the basis of molecular alterations.

The ERI grew out of several meetings held by the NCI in 2013 and 2014. It was built on the ability to profile archived tumor material, explained study author S. Percy Ivy, PhD, associate chief of the Investigational Drug Branch in the Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis of the NCI. “This made it possible to collect cases from participating clinicians from all over the country.

“Published cases included patients treated with a targeted therapy but not treated with knowledge of their tumor’s genomics, who then later turned out to have genomic changes that made their tumor exquisitely sensitive to inhibition of a driving pathway,” she said. “There have been published cases as well as cases in the experience of practicing oncologists that seem to do much better than expected.

“We wondered if we could find molecular reasons why tumors respond not only to targeted therapies but also to standard chemotherapy,” said Percy. “If so, we could refine our choice of therapy to patients who are most likely to respond to it.”’

On its website, the NCI writes that there was a particular case that triggered the interest in going ahead with this initiative. Mutations in the TSC1 and NF2 genes, which result in a loss of gene function, were detected in a patient with metastatic bladder cancer. In a clinical trial, the patient was treated with everolimus (Afinitor, Novartis), an inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTORC1), and achieved a complete response with a duration of more than 2 years.

In a separate analysis, researchers sequenced tumors from 96 other individuals with high-grade bladder cancer and identified five TSC1 gene mutations. Tumors were sequenced from 13 patients with bladder cancer who had received everolimus. Results showed that 3 of 4 patients with TSC1 gene mutations experienced some degree of tumor shrinkage after treatment; 8 of 9 patients who did not have the mutation experienced disease progression.

The NCI notes that in “subsequent workshops and discussions, it became obvious that all clinicians have seen a few exceptional responders.”

Testing for feasibility

The aim of the current study was to assess the feasibility and potential usefulness of sequencing DNA and RNA from clinical tumor specimens from patients who had experienced unusually profound or durable responses to systemic therapy.

Its main feasibility goal was to identify at least 100 cases involving exceptional responders whose cases could be analyzed in less than 3 years.

An exceptional patient was defined as one who had experienced a complete response to one or more drugs in which complete responses were seen in fewer than 10% of patients who received similar treatment; or a partial response lasting at least 6 months in which such a response is seen in fewer than 10% of patients who receive similar treatment; or a complete or partial response of a duration that is three times the median response duration represented in the literature for the treatment.

Studying exceptional responders presents many challenges, the first being to define what an exceptional response is and what it is not, explained Ivy. “This definition relies on the existence of data that a particular therapy will produce particular responses in groups of patients with similar tumors, as defined by organ of origin,” she said.

Other challenges include obtaining tumor tissue and all the relevant clinical data, such as the number of prior treatments and the patient’s response, as well as any known molecular characteristics (eg, HER2/NEU amplification, estrogen-receptor expression, germline mutations). “We also do not have data on other exposures, such as smoking or chemical exposure,” she said. “In addition, when patients are not on clinical trial, the data are not uniformly obtained ― such as that scans may not be performed at particular intervals.”

Importantly, the molecular tools used to analyze tumors were not available in the past, so many trials did not collect tumor tissue for subsequent research. “Even now, we are learning that there are characteristics beyond DNA and RNA that are potentially important to the ability of a tumor to respond, such as the immune system or epigenetic changes,” she said.

From August 2014 to July 2017, a total of 520 cases were proposed by clinicians as possibly involving exceptional responders, and 222 cases met the criteria.

Analyzable tissue was available for 117 patients. Most of the responders (n = 80, 68.4%) had been treated with combination chemotherapy regimens; 34 patients (29.0%) had received one or more antiangiogenesis agents. In addition, six patients had an exceptional response following treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors. The final analysis included 109 cases.

One exceptional responder was a woman with metastatic squamous lung cancer that was treated with paclitaxel and carboplatin. The patient achieved a 41-month complete response (expected rate, <10%). Another patient with esophageal adenocarcinoma who was treated with docetaxel and cisplatin experienced a partial response that lasted 128 months (reported median response duration, 24 months). After the patient’s tumor recurred, he experienced for the second time a response to concurrent chemoradiation with the same drug regimen.

Overall, potentially clinically relevant germline mutations were identified in six tumors. Pathogenic BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations were found in two breast cancer patients, one patient with non–small cell lung cancer, and one patient with rectal cancer. A breast cancer patient had a pathogenic BRCA1 germline mutation, and another had a likely germline mutation in CHEK2. A patient with poorly differentiated lung cancer and a history of breast cancer had a PALB2 mutation.

Future steps

Molecular mechanisms are important, but other factors could also play a role in eliciting a response. One is the presence of comorbidities, which was not assessed in the study. Ivy noted that comorbidities could be very important to responses, along with medications that the patient is using for different types of ailments. In addition, the use of complementary and alternative medicines may also have an impact.

“As the field matures, we hope that others will collect these and other characteristics, so that all the data could be used to develop hypotheses about molecular and other factors that can better predict response or resistance,” she said.

The results from this pilot study demonstrated feasibility. Ivy noted that “additional collaboration in similar studies would be welcome, as would methods to use data from various sources to improve our ability to correlate patient characteristics, tumor characteristics and response.

“We envision a larger national and international effort to collect more exceptional responder cases, including more from patients treated with targeted therapies,” she added. “The NCI has been meeting with an interest group that focuses on ER cases in the UK, France, Italy, Canada, and Australia, and this collaborative effort is maturing, albeit slowly.”

The project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the NCI and NIH. Ivy has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors report relationships with industry. The editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Virtually all oncologists, at one time or another, have treated a patient who defied the odds and achieved an unexpectedly long-lasting response. These “exceptional responders” are patients who experience a unique response to therapies that have largely failed to be effective for others with similar cancers.

Genetic and molecular mechanisms may partly account for these responses and may offer clues about why the treatment works for only a few and not for others. To delve more deeply into that area of research, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) began the Exceptional Responders Initiative (ERI) with the goal of identifying potential biological processes that may be responsible, at least in part, for these unusual responses.

NCI researchers have now successfully completed a pilot study that analyzed tumor specimens from more than 100 cases, and the study has affirmed the feasibility of this approach.

Of these cases, six were identified as involving potentially clinically actionable germline mutations.

The findings were published online ahead of print in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

“Clearly, the analysis and validation of these results will prove critical to determining the success of this approach,” write James M. Ford, MD, and Beverly S. Mitchell, MD, both of Stanford University School of Medicine, California, in an accompanying editorial. “Ultimately, prospective studies of tumors from exceptional responders, particularly to novel, genomically-targeted agents, may provide a powerful approach to cancer treatment discoveries.”

A special case

Molecular profiling technology, including next-generation sequencing, has significantly changed the landscape of the development of cancer therapies, and clinical trials in early drug development are increasingly selecting patients on the basis of molecular alterations.

The ERI grew out of several meetings held by the NCI in 2013 and 2014. It was built on the ability to profile archived tumor material, explained study author S. Percy Ivy, PhD, associate chief of the Investigational Drug Branch in the Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis of the NCI. “This made it possible to collect cases from participating clinicians from all over the country.

“Published cases included patients treated with a targeted therapy but not treated with knowledge of their tumor’s genomics, who then later turned out to have genomic changes that made their tumor exquisitely sensitive to inhibition of a driving pathway,” she said. “There have been published cases as well as cases in the experience of practicing oncologists that seem to do much better than expected.

“We wondered if we could find molecular reasons why tumors respond not only to targeted therapies but also to standard chemotherapy,” said Percy. “If so, we could refine our choice of therapy to patients who are most likely to respond to it.”’

On its website, the NCI writes that there was a particular case that triggered the interest in going ahead with this initiative. Mutations in the TSC1 and NF2 genes, which result in a loss of gene function, were detected in a patient with metastatic bladder cancer. In a clinical trial, the patient was treated with everolimus (Afinitor, Novartis), an inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTORC1), and achieved a complete response with a duration of more than 2 years.

In a separate analysis, researchers sequenced tumors from 96 other individuals with high-grade bladder cancer and identified five TSC1 gene mutations. Tumors were sequenced from 13 patients with bladder cancer who had received everolimus. Results showed that 3 of 4 patients with TSC1 gene mutations experienced some degree of tumor shrinkage after treatment; 8 of 9 patients who did not have the mutation experienced disease progression.

The NCI notes that in “subsequent workshops and discussions, it became obvious that all clinicians have seen a few exceptional responders.”

Testing for feasibility

The aim of the current study was to assess the feasibility and potential usefulness of sequencing DNA and RNA from clinical tumor specimens from patients who had experienced unusually profound or durable responses to systemic therapy.

Its main feasibility goal was to identify at least 100 cases involving exceptional responders whose cases could be analyzed in less than 3 years.

An exceptional patient was defined as one who had experienced a complete response to one or more drugs in which complete responses were seen in fewer than 10% of patients who received similar treatment; or a partial response lasting at least 6 months in which such a response is seen in fewer than 10% of patients who receive similar treatment; or a complete or partial response of a duration that is three times the median response duration represented in the literature for the treatment.

Studying exceptional responders presents many challenges, the first being to define what an exceptional response is and what it is not, explained Ivy. “This definition relies on the existence of data that a particular therapy will produce particular responses in groups of patients with similar tumors, as defined by organ of origin,” she said.

Other challenges include obtaining tumor tissue and all the relevant clinical data, such as the number of prior treatments and the patient’s response, as well as any known molecular characteristics (eg, HER2/NEU amplification, estrogen-receptor expression, germline mutations). “We also do not have data on other exposures, such as smoking or chemical exposure,” she said. “In addition, when patients are not on clinical trial, the data are not uniformly obtained ― such as that scans may not be performed at particular intervals.”

Importantly, the molecular tools used to analyze tumors were not available in the past, so many trials did not collect tumor tissue for subsequent research. “Even now, we are learning that there are characteristics beyond DNA and RNA that are potentially important to the ability of a tumor to respond, such as the immune system or epigenetic changes,” she said.

From August 2014 to July 2017, a total of 520 cases were proposed by clinicians as possibly involving exceptional responders, and 222 cases met the criteria.

Analyzable tissue was available for 117 patients. Most of the responders (n = 80, 68.4%) had been treated with combination chemotherapy regimens; 34 patients (29.0%) had received one or more antiangiogenesis agents. In addition, six patients had an exceptional response following treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors. The final analysis included 109 cases.

One exceptional responder was a woman with metastatic squamous lung cancer that was treated with paclitaxel and carboplatin. The patient achieved a 41-month complete response (expected rate, <10%). Another patient with esophageal adenocarcinoma who was treated with docetaxel and cisplatin experienced a partial response that lasted 128 months (reported median response duration, 24 months). After the patient’s tumor recurred, he experienced for the second time a response to concurrent chemoradiation with the same drug regimen.

Overall, potentially clinically relevant germline mutations were identified in six tumors. Pathogenic BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations were found in two breast cancer patients, one patient with non–small cell lung cancer, and one patient with rectal cancer. A breast cancer patient had a pathogenic BRCA1 germline mutation, and another had a likely germline mutation in CHEK2. A patient with poorly differentiated lung cancer and a history of breast cancer had a PALB2 mutation.

Future steps

Molecular mechanisms are important, but other factors could also play a role in eliciting a response. One is the presence of comorbidities, which was not assessed in the study. Ivy noted that comorbidities could be very important to responses, along with medications that the patient is using for different types of ailments. In addition, the use of complementary and alternative medicines may also have an impact.

“As the field matures, we hope that others will collect these and other characteristics, so that all the data could be used to develop hypotheses about molecular and other factors that can better predict response or resistance,” she said.

The results from this pilot study demonstrated feasibility. Ivy noted that “additional collaboration in similar studies would be welcome, as would methods to use data from various sources to improve our ability to correlate patient characteristics, tumor characteristics and response.

“We envision a larger national and international effort to collect more exceptional responder cases, including more from patients treated with targeted therapies,” she added. “The NCI has been meeting with an interest group that focuses on ER cases in the UK, France, Italy, Canada, and Australia, and this collaborative effort is maturing, albeit slowly.”

The project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the NCI and NIH. Ivy has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors report relationships with industry. The editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Virtually all oncologists, at one time or another, have treated a patient who defied the odds and achieved an unexpectedly long-lasting response. These “exceptional responders” are patients who experience a unique response to therapies that have largely failed to be effective for others with similar cancers.

Genetic and molecular mechanisms may partly account for these responses and may offer clues about why the treatment works for only a few and not for others. To delve more deeply into that area of research, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) began the Exceptional Responders Initiative (ERI) with the goal of identifying potential biological processes that may be responsible, at least in part, for these unusual responses.

NCI researchers have now successfully completed a pilot study that analyzed tumor specimens from more than 100 cases, and the study has affirmed the feasibility of this approach.

Of these cases, six were identified as involving potentially clinically actionable germline mutations.

The findings were published online ahead of print in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

“Clearly, the analysis and validation of these results will prove critical to determining the success of this approach,” write James M. Ford, MD, and Beverly S. Mitchell, MD, both of Stanford University School of Medicine, California, in an accompanying editorial. “Ultimately, prospective studies of tumors from exceptional responders, particularly to novel, genomically-targeted agents, may provide a powerful approach to cancer treatment discoveries.”

A special case

Molecular profiling technology, including next-generation sequencing, has significantly changed the landscape of the development of cancer therapies, and clinical trials in early drug development are increasingly selecting patients on the basis of molecular alterations.

The ERI grew out of several meetings held by the NCI in 2013 and 2014. It was built on the ability to profile archived tumor material, explained study author S. Percy Ivy, PhD, associate chief of the Investigational Drug Branch in the Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis of the NCI. “This made it possible to collect cases from participating clinicians from all over the country.

“Published cases included patients treated with a targeted therapy but not treated with knowledge of their tumor’s genomics, who then later turned out to have genomic changes that made their tumor exquisitely sensitive to inhibition of a driving pathway,” she said. “There have been published cases as well as cases in the experience of practicing oncologists that seem to do much better than expected.

“We wondered if we could find molecular reasons why tumors respond not only to targeted therapies but also to standard chemotherapy,” said Percy. “If so, we could refine our choice of therapy to patients who are most likely to respond to it.”’

On its website, the NCI writes that there was a particular case that triggered the interest in going ahead with this initiative. Mutations in the TSC1 and NF2 genes, which result in a loss of gene function, were detected in a patient with metastatic bladder cancer. In a clinical trial, the patient was treated with everolimus (Afinitor, Novartis), an inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTORC1), and achieved a complete response with a duration of more than 2 years.

In a separate analysis, researchers sequenced tumors from 96 other individuals with high-grade bladder cancer and identified five TSC1 gene mutations. Tumors were sequenced from 13 patients with bladder cancer who had received everolimus. Results showed that 3 of 4 patients with TSC1 gene mutations experienced some degree of tumor shrinkage after treatment; 8 of 9 patients who did not have the mutation experienced disease progression.

The NCI notes that in “subsequent workshops and discussions, it became obvious that all clinicians have seen a few exceptional responders.”

Testing for feasibility

The aim of the current study was to assess the feasibility and potential usefulness of sequencing DNA and RNA from clinical tumor specimens from patients who had experienced unusually profound or durable responses to systemic therapy.

Its main feasibility goal was to identify at least 100 cases involving exceptional responders whose cases could be analyzed in less than 3 years.

An exceptional patient was defined as one who had experienced a complete response to one or more drugs in which complete responses were seen in fewer than 10% of patients who received similar treatment; or a partial response lasting at least 6 months in which such a response is seen in fewer than 10% of patients who receive similar treatment; or a complete or partial response of a duration that is three times the median response duration represented in the literature for the treatment.

Studying exceptional responders presents many challenges, the first being to define what an exceptional response is and what it is not, explained Ivy. “This definition relies on the existence of data that a particular therapy will produce particular responses in groups of patients with similar tumors, as defined by organ of origin,” she said.

Other challenges include obtaining tumor tissue and all the relevant clinical data, such as the number of prior treatments and the patient’s response, as well as any known molecular characteristics (eg, HER2/NEU amplification, estrogen-receptor expression, germline mutations). “We also do not have data on other exposures, such as smoking or chemical exposure,” she said. “In addition, when patients are not on clinical trial, the data are not uniformly obtained ― such as that scans may not be performed at particular intervals.”

Importantly, the molecular tools used to analyze tumors were not available in the past, so many trials did not collect tumor tissue for subsequent research. “Even now, we are learning that there are characteristics beyond DNA and RNA that are potentially important to the ability of a tumor to respond, such as the immune system or epigenetic changes,” she said.

From August 2014 to July 2017, a total of 520 cases were proposed by clinicians as possibly involving exceptional responders, and 222 cases met the criteria.

Analyzable tissue was available for 117 patients. Most of the responders (n = 80, 68.4%) had been treated with combination chemotherapy regimens; 34 patients (29.0%) had received one or more antiangiogenesis agents. In addition, six patients had an exceptional response following treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors. The final analysis included 109 cases.

One exceptional responder was a woman with metastatic squamous lung cancer that was treated with paclitaxel and carboplatin. The patient achieved a 41-month complete response (expected rate, <10%). Another patient with esophageal adenocarcinoma who was treated with docetaxel and cisplatin experienced a partial response that lasted 128 months (reported median response duration, 24 months). After the patient’s tumor recurred, he experienced for the second time a response to concurrent chemoradiation with the same drug regimen.

Overall, potentially clinically relevant germline mutations were identified in six tumors. Pathogenic BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations were found in two breast cancer patients, one patient with non–small cell lung cancer, and one patient with rectal cancer. A breast cancer patient had a pathogenic BRCA1 germline mutation, and another had a likely germline mutation in CHEK2. A patient with poorly differentiated lung cancer and a history of breast cancer had a PALB2 mutation.

Future steps

Molecular mechanisms are important, but other factors could also play a role in eliciting a response. One is the presence of comorbidities, which was not assessed in the study. Ivy noted that comorbidities could be very important to responses, along with medications that the patient is using for different types of ailments. In addition, the use of complementary and alternative medicines may also have an impact.

“As the field matures, we hope that others will collect these and other characteristics, so that all the data could be used to develop hypotheses about molecular and other factors that can better predict response or resistance,” she said.

The results from this pilot study demonstrated feasibility. Ivy noted that “additional collaboration in similar studies would be welcome, as would methods to use data from various sources to improve our ability to correlate patient characteristics, tumor characteristics and response.

“We envision a larger national and international effort to collect more exceptional responder cases, including more from patients treated with targeted therapies,” she added. “The NCI has been meeting with an interest group that focuses on ER cases in the UK, France, Italy, Canada, and Australia, and this collaborative effort is maturing, albeit slowly.”

The project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the NCI and NIH. Ivy has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors report relationships with industry. The editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

First PARP inhibitor approved for metastatic prostate cancer

A completely new approach to the treatment of prostate cancer is now available to clinicians through the approval of the first PARP inhibitor for use in certain patients with this disease.

Rucaparib (Rubraca, Clovis Oncology) is the first PARP inhibitor approved for use in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) that harbors deleterious BRCA mutations (germline and/or somatic). The drug is indicated for use in patients who have already been treated with androgen receptor–directed therapy and a taxane-based chemotherapy.

The drug is already marketed for use in ovarian cancer.

The new prostate cancer indication was granted an accelerated approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on the basis of response rates and effect on levels of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) from the TRITON2 clinical trial. A confirmatory phase 3 trial, TRITON3, is currently underway.

“Standard treatment options for men with mCRPC have been limited to androgen receptor–targeting therapies, taxane chemotherapy, radium-223, and sipuleucel-T,” said Wassim Abida, MD, a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, in a statement.

“Rucaparib is the first in a class of drugs to become newly available to patients with mCRPC who harbor a deleterious BRCA mutation,” said Abida, who is also the principal investigator of the TRITON2 study. “Given the level and duration of responses observed with rucaparib in men with mCRPC and these mutations, it represents an important and timely new treatment option for this patient population.”

Other indications, another PARP inhibitor

Rucaparib is already approved for the treatment of women with advanced BRCA mutation–positive ovarian cancer who have received two or more prior chemotherapies. It is also approved as maintenance treatment for patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer who demonstrate a complete or partial response to platinum-based chemotherapy, regardless of BRCA status.

Another PARP inhibitor, olaparib (Lynparza, AstraZeneca), is awaiting approval for use in prostate cancer in men with BRCA mutations. That pending approval is based on results from the phase 3 PROfound trial, which was hailed as a “landmark trial” when it was presented last year. The results showed a significant improved in disease-free progression. The company recently announced that there was also a significant improvement in overall survival.

Olaparib is already approved for the maintenance treatment of platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer regardless of BRCA status and as first-line maintenance treatment in BRCA-mutated advanced ovarian cancer following response to platinum-based chemotherapy. It is also approved for germline BRCA-mutated HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer previously treated with chemotherapy and for the maintenance treatment of germline BRCA-mutated advanced pancreatic cancer following first-line platinum-based chemotherapy.

Details of the TRITON2 study

The accelerated approval for use of rucaparib in BRCA prostate cancer was based on efficacy data from the multicenter, single-arm TRITON2 clinical trial. The cohort included 62 patients with a BRCA (germline and/or somatic) mutation and measurable disease; 115 patients with a BRCA (germline and/or somatic) mutation and measurable or nonmeasurable disease; and 209 patients with homologous recombination deficiency (HRD)–positive mCRPC.

The major efficacy outcomes were objective response rate (ORR) and duration of response. Confirmed PSA response rate was also a prespecified endpoint. Data were assessed by independent radiologic review.

For the patients with measurable disease and a BRCA mutation, the ORR was 44%. The ORR was similar for patients with a germline BRCA mutation.

Median duration of response was not evaluable at data cutoff but ranged from 1.7 to 24+ months. Of the 27 patients with a confirmed objective response, 15 (56%) patients showed a response that lasted 6 months or longer.

In an analysis of 115 patients with a deleterious BRCA mutation (germline and/or somatic) and measurable or nonmeasurable disease, the confirmed PSA response rate was 55%.

The safety evaluation was based on an analysis of the 209 patients with HRD-positive mCRPC and included 115 with deleterious BRCA mutations. The most common adverse events (≥20%; grade 1-4) in the patients with BRCA mutations were fatigue/asthenia (62%), nausea (52%), anemia (43%), AST/ALT elevation (33%), decreased appetite (28%), rash (27%), constipation (27%), thrombocytopenia (25%), vomiting (22%), and diarrhea (20%).

Rucaparib has been associated with hematologic toxicity, including myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML). However, MDS/AML was not observed in the TRITON2 study, regardless of HRD mutation.

Confirmation with TRITON3

A phase 3, randomized, open-label study, TRITON3, is currently underway and is expected to serve as the confirmatory study for the accelerated approval in mCRPC. TRITON3 is comparing rucaparib with physician’s choice of therapy in patients with mCRPC who have specific gene alterations, including BRCA and ATM alterations, and who have experienced disease progression after androgen receptor–directed therapy but have not yet received chemotherapy. The primary endpoint for TRITON3 is radiographic progression-free survival.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A completely new approach to the treatment of prostate cancer is now available to clinicians through the approval of the first PARP inhibitor for use in certain patients with this disease.

Rucaparib (Rubraca, Clovis Oncology) is the first PARP inhibitor approved for use in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) that harbors deleterious BRCA mutations (germline and/or somatic). The drug is indicated for use in patients who have already been treated with androgen receptor–directed therapy and a taxane-based chemotherapy.

The drug is already marketed for use in ovarian cancer.

The new prostate cancer indication was granted an accelerated approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on the basis of response rates and effect on levels of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) from the TRITON2 clinical trial. A confirmatory phase 3 trial, TRITON3, is currently underway.

“Standard treatment options for men with mCRPC have been limited to androgen receptor–targeting therapies, taxane chemotherapy, radium-223, and sipuleucel-T,” said Wassim Abida, MD, a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, in a statement.

“Rucaparib is the first in a class of drugs to become newly available to patients with mCRPC who harbor a deleterious BRCA mutation,” said Abida, who is also the principal investigator of the TRITON2 study. “Given the level and duration of responses observed with rucaparib in men with mCRPC and these mutations, it represents an important and timely new treatment option for this patient population.”

Other indications, another PARP inhibitor

Rucaparib is already approved for the treatment of women with advanced BRCA mutation–positive ovarian cancer who have received two or more prior chemotherapies. It is also approved as maintenance treatment for patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer who demonstrate a complete or partial response to platinum-based chemotherapy, regardless of BRCA status.

Another PARP inhibitor, olaparib (Lynparza, AstraZeneca), is awaiting approval for use in prostate cancer in men with BRCA mutations. That pending approval is based on results from the phase 3 PROfound trial, which was hailed as a “landmark trial” when it was presented last year. The results showed a significant improved in disease-free progression. The company recently announced that there was also a significant improvement in overall survival.

Olaparib is already approved for the maintenance treatment of platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer regardless of BRCA status and as first-line maintenance treatment in BRCA-mutated advanced ovarian cancer following response to platinum-based chemotherapy. It is also approved for germline BRCA-mutated HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer previously treated with chemotherapy and for the maintenance treatment of germline BRCA-mutated advanced pancreatic cancer following first-line platinum-based chemotherapy.

Details of the TRITON2 study

The accelerated approval for use of rucaparib in BRCA prostate cancer was based on efficacy data from the multicenter, single-arm TRITON2 clinical trial. The cohort included 62 patients with a BRCA (germline and/or somatic) mutation and measurable disease; 115 patients with a BRCA (germline and/or somatic) mutation and measurable or nonmeasurable disease; and 209 patients with homologous recombination deficiency (HRD)–positive mCRPC.

The major efficacy outcomes were objective response rate (ORR) and duration of response. Confirmed PSA response rate was also a prespecified endpoint. Data were assessed by independent radiologic review.

For the patients with measurable disease and a BRCA mutation, the ORR was 44%. The ORR was similar for patients with a germline BRCA mutation.

Median duration of response was not evaluable at data cutoff but ranged from 1.7 to 24+ months. Of the 27 patients with a confirmed objective response, 15 (56%) patients showed a response that lasted 6 months or longer.

In an analysis of 115 patients with a deleterious BRCA mutation (germline and/or somatic) and measurable or nonmeasurable disease, the confirmed PSA response rate was 55%.

The safety evaluation was based on an analysis of the 209 patients with HRD-positive mCRPC and included 115 with deleterious BRCA mutations. The most common adverse events (≥20%; grade 1-4) in the patients with BRCA mutations were fatigue/asthenia (62%), nausea (52%), anemia (43%), AST/ALT elevation (33%), decreased appetite (28%), rash (27%), constipation (27%), thrombocytopenia (25%), vomiting (22%), and diarrhea (20%).

Rucaparib has been associated with hematologic toxicity, including myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML). However, MDS/AML was not observed in the TRITON2 study, regardless of HRD mutation.

Confirmation with TRITON3

A phase 3, randomized, open-label study, TRITON3, is currently underway and is expected to serve as the confirmatory study for the accelerated approval in mCRPC. TRITON3 is comparing rucaparib with physician’s choice of therapy in patients with mCRPC who have specific gene alterations, including BRCA and ATM alterations, and who have experienced disease progression after androgen receptor–directed therapy but have not yet received chemotherapy. The primary endpoint for TRITON3 is radiographic progression-free survival.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A completely new approach to the treatment of prostate cancer is now available to clinicians through the approval of the first PARP inhibitor for use in certain patients with this disease.

Rucaparib (Rubraca, Clovis Oncology) is the first PARP inhibitor approved for use in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) that harbors deleterious BRCA mutations (germline and/or somatic). The drug is indicated for use in patients who have already been treated with androgen receptor–directed therapy and a taxane-based chemotherapy.

The drug is already marketed for use in ovarian cancer.

The new prostate cancer indication was granted an accelerated approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on the basis of response rates and effect on levels of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) from the TRITON2 clinical trial. A confirmatory phase 3 trial, TRITON3, is currently underway.

“Standard treatment options for men with mCRPC have been limited to androgen receptor–targeting therapies, taxane chemotherapy, radium-223, and sipuleucel-T,” said Wassim Abida, MD, a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, in a statement.