User login

Letters to the Editor

Mohamed‐Kalib et al. illustrate 2 important caveats to penicillin skin testing (PST): (1) there is an exceptionally rare potential for resensitization, a phenomenon in which a previously reactive patient is proven tolerant, then develops sensitivity and has a positive PST; (2) consider repeating PST prior to a parenteral ‐lactam prescription in patients who previously reported severe anaphylactic reactions.

Our negative predictive value of 100% does not abate the tentative concern for resensitization.[1] Similar to the likelihood of becoming allergic initially, 0% to 3.2% of PST‐negative patients can become allergic again, more commonly with parenteral therapy and among children.[2, 3, 4]

The author describes a seemingly resensitized patient who reacted in an outpatient setting. Theoretically, anyone could resensitize, regardless of their setting or whether a single dose or full course was given after the PST. Individuals with a proven tolerance by PST and repeated courses are at a very low risk of future immunoglobulin E‐mediated reactions, a risk similar to that of the general population.

Whether previously reactive or not, patients receiving medicinal therapies should always be monitored for allergic reactions. Although PST may not be prudent in the minority of patients who report recent or severe reactions, a repeat PST prior to prescribing parenteral ‐lactam may potentially avoid instances described by Mohamed‐Kalib et al.

- , , , et al. The impact of penicillin skin testing on clinical practice and antimicrobial stewardship. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(6):342–345.

- , , . Lack of penicillin resensitization in patients with a history of penicillin allergy after receiving repeated penicillin courses. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(7):822–826.

- . Elective penicillin skin testing and amoxicillin challenge: effect on outpatient antibiotic use, cost, and clinical outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102(2):281–285.

- , . Drug allergy: an updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105(4):259–273.

Mohamed‐Kalib et al. illustrate 2 important caveats to penicillin skin testing (PST): (1) there is an exceptionally rare potential for resensitization, a phenomenon in which a previously reactive patient is proven tolerant, then develops sensitivity and has a positive PST; (2) consider repeating PST prior to a parenteral ‐lactam prescription in patients who previously reported severe anaphylactic reactions.

Our negative predictive value of 100% does not abate the tentative concern for resensitization.[1] Similar to the likelihood of becoming allergic initially, 0% to 3.2% of PST‐negative patients can become allergic again, more commonly with parenteral therapy and among children.[2, 3, 4]

The author describes a seemingly resensitized patient who reacted in an outpatient setting. Theoretically, anyone could resensitize, regardless of their setting or whether a single dose or full course was given after the PST. Individuals with a proven tolerance by PST and repeated courses are at a very low risk of future immunoglobulin E‐mediated reactions, a risk similar to that of the general population.

Whether previously reactive or not, patients receiving medicinal therapies should always be monitored for allergic reactions. Although PST may not be prudent in the minority of patients who report recent or severe reactions, a repeat PST prior to prescribing parenteral ‐lactam may potentially avoid instances described by Mohamed‐Kalib et al.

Mohamed‐Kalib et al. illustrate 2 important caveats to penicillin skin testing (PST): (1) there is an exceptionally rare potential for resensitization, a phenomenon in which a previously reactive patient is proven tolerant, then develops sensitivity and has a positive PST; (2) consider repeating PST prior to a parenteral ‐lactam prescription in patients who previously reported severe anaphylactic reactions.

Our negative predictive value of 100% does not abate the tentative concern for resensitization.[1] Similar to the likelihood of becoming allergic initially, 0% to 3.2% of PST‐negative patients can become allergic again, more commonly with parenteral therapy and among children.[2, 3, 4]

The author describes a seemingly resensitized patient who reacted in an outpatient setting. Theoretically, anyone could resensitize, regardless of their setting or whether a single dose or full course was given after the PST. Individuals with a proven tolerance by PST and repeated courses are at a very low risk of future immunoglobulin E‐mediated reactions, a risk similar to that of the general population.

Whether previously reactive or not, patients receiving medicinal therapies should always be monitored for allergic reactions. Although PST may not be prudent in the minority of patients who report recent or severe reactions, a repeat PST prior to prescribing parenteral ‐lactam may potentially avoid instances described by Mohamed‐Kalib et al.

- , , , et al. The impact of penicillin skin testing on clinical practice and antimicrobial stewardship. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(6):342–345.

- , , . Lack of penicillin resensitization in patients with a history of penicillin allergy after receiving repeated penicillin courses. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(7):822–826.

- . Elective penicillin skin testing and amoxicillin challenge: effect on outpatient antibiotic use, cost, and clinical outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102(2):281–285.

- , . Drug allergy: an updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105(4):259–273.

- , , , et al. The impact of penicillin skin testing on clinical practice and antimicrobial stewardship. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(6):342–345.

- , , . Lack of penicillin resensitization in patients with a history of penicillin allergy after receiving repeated penicillin courses. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(7):822–826.

- . Elective penicillin skin testing and amoxicillin challenge: effect on outpatient antibiotic use, cost, and clinical outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102(2):281–285.

- , . Drug allergy: an updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105(4):259–273.

Erroneously Reporting Penicillin Allergy

Patient safety is a healthcare provider's top priority. Drug allergies are instated into an electronic medical record (EMR) to avoid potential adverse events in the future. Despite the intention to provide safety, healthcare providers frequently document antimicrobial allergies incorrectly.[1] In turn, this may lead to decreased antibiotic choices, increased healthcare costs, potential adverse reactions, and unnecessary avoidance of optimal, first‐line agents.

Several strategies have been developed to help improve the accuracy of allergy documentation, including pharmacy‐based interventions, but the persistence of corrections, once performed, is unknown.[2] Although most antibiotic allergy errors are identified upon review of prior medication history (eg, penicillin allergy listed in a patient who previously received piperacillintazobactam), no prior studies have evaluated penicillin allergy errors directly after a proven tolerance with a penicillin skin testing (PST) and penicillin confirmatory challenge.[3, 4, 5] We hereby assess factors for erroneous allergy documentation in a cohort of patients with a negative PST.

METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed charts under a protocol approved by the university and medical center institutional review board. Following a PST intervention we have previously described, penicillin was removed from the patients' EMR (Epic, Verona, WI) allergy list from March 2012 through July 2012.[6] We then invested a brief procedure note into the allergy section describing the negative PST and subsequent tolerance of a penicillin agent. During the PST intervention, there was no attempt to convey the result of the PST and corrected allergy information to the outpatient clinicians.

As a follow‐up to our previous study, we reviewed the charts of the 150 subjects who represented the entire population of patients who underwent PST in the March 2012 through July 2012 intervention time period. From August 2012 through July 2013, charts were reviewed to gauge reappearances at Vidant Health, a system of 10 hospitals in eastern North Carolina. Collected data also included demographics, drug allergy or intolerance, penicillin allergy redocumentation, residence, antimicrobial use, and presence of dementia or altered mentation.

Outpatient physician and long‐term care facility (LTCF) allergy records were obtained via EMR records, patient or family inquiry, and referring documents that accompanied the patient upon arrival. In addition to reviewing the LTCF and/or outpatient physician referring documents, the outpatient physician(s) and LTCFs were contacted and asked to review other electronic or paper records that may not have been delivered with the referring documents. Inpatient and outpatient records were reviewed for penicillin allergy, as defined by the drug allergy practice parameters.[7] Fischer exact tests were used to identify significant associated factors.

RESULTS

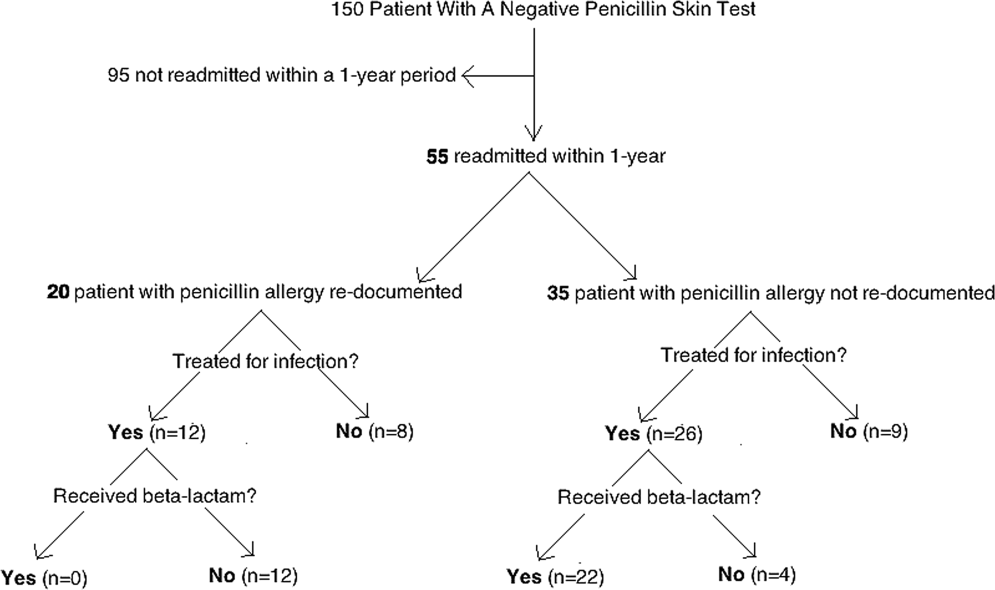

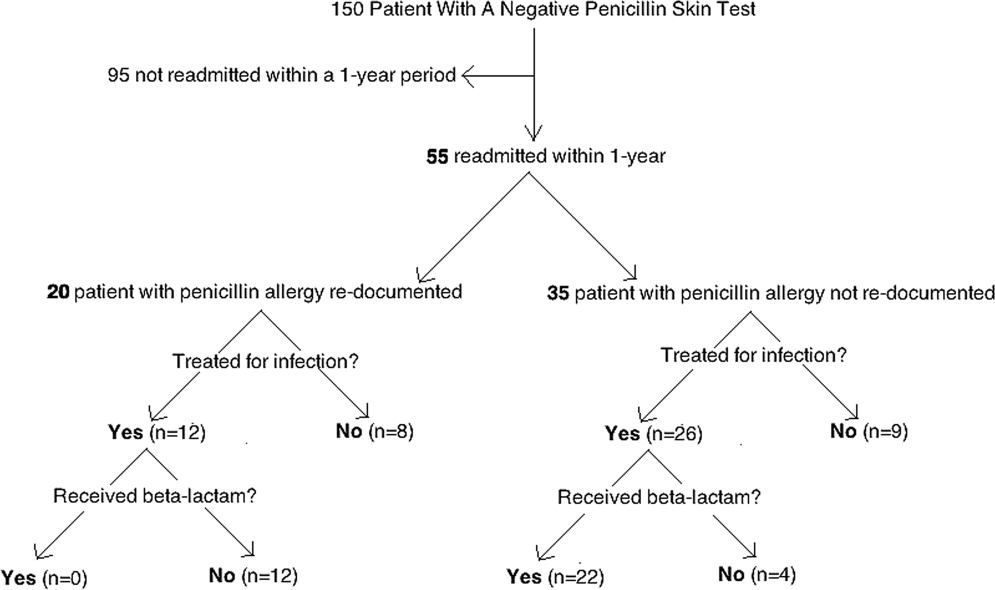

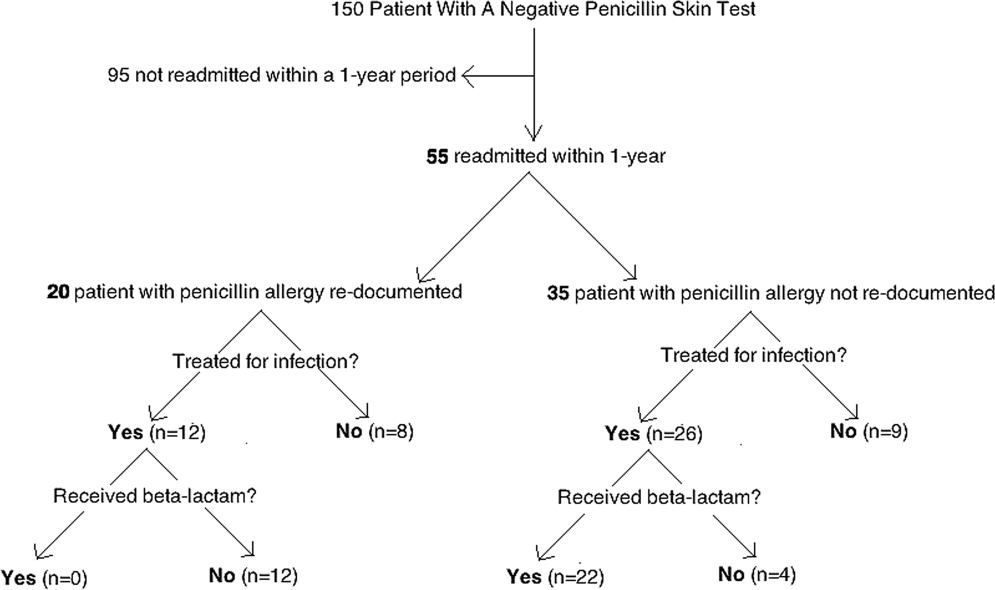

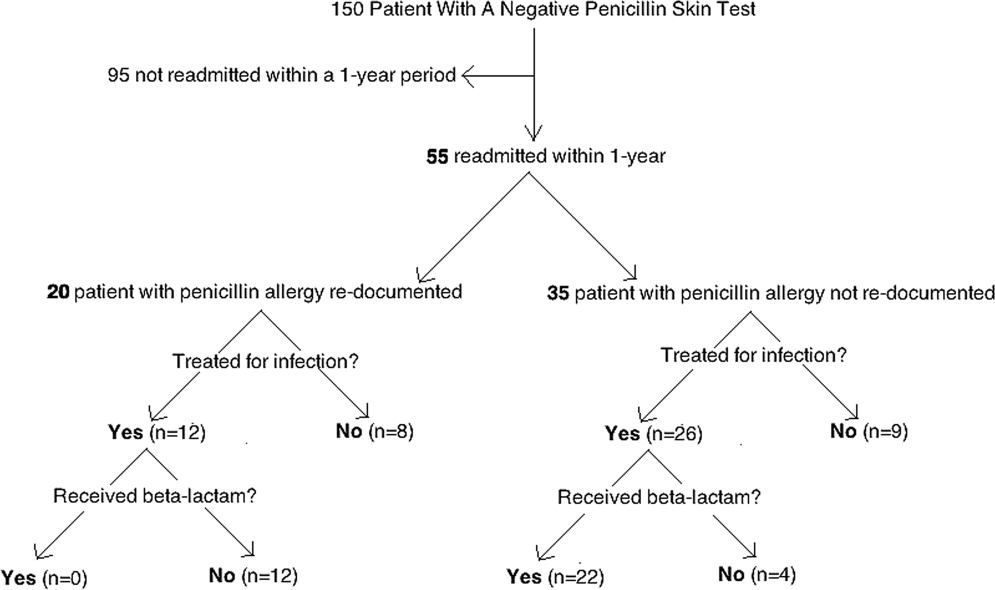

Of the 150 patients with proven penicillin tolerance, 55 (37%) revisited a Vidant Health hospital within a year period, of which 22 (40%) received a ‐lactam agent once again without adverse effects (Table 1). Twenty (36%) of the 55 patients had penicillin allergy redocumented (Figure 1). There was no description of any allergy after the PST in any of the 20 EMR, LTCF records, or outpatient primary care physician records. Factors associated with penicillin allergy redocumentation (vs those not redocumented) included age >65 years (P = 0.011), residence in a LTCF (P = 0.0001), acutely altered mentation (P < 0.0001), and dementia (P < 0.0001). Penicillin allergy was still reported in all 21 (100%) of the LTCF patient records.

| Category | Variables | Penicillin Allergy Not Reinstated, n = 35 | Penicillin Allergy Reinstated, n = 20 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Age, y | 1830 | 5 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 0.011 |

| 3164 | 17 (49%) | 5 (37%) | ||

| >65 | 13 (37%) | 15 (75%) | ||

| Gender | Male | 12 (34%) | 10 (50%) | 0.19 |

| Female | 23 (66%) | 10 (50%) | ||

| Race | White | 20 (57%) | 11 (55%) | 0.36 |

| Black | 14 (40%) | 8 (40%) | ||

| Hispanic | 1 (3%) | 1 (5%) | ||

| Residence | Home | 28 (80%) | 5 (25%) | 0.0001 |

| LTCF | 7 (20%) | 15 (75%) | ||

| Acutely altered mentation | Yes | 8 (23%) | 16 (80%) | <0.0001 |

| No | 27 (77%) | 4 (20%) | ||

| Dementia | Yes | 1 (3%) | 10 (50%) | <0.0001 |

| No | 34 (97%) | 10 (50%) | ||

| Primary service | Residenta | 18 (51%) | 5 (25%) | 0.18 |

| Hospitalist | 8 (23%) | 10 (50%) | ||

| Surgery | 3 (9%) | 3 (15%) | ||

| Emergency medicine | 6 (17%) | 2 (10%) | ||

| Primary language | English | 34 (97%) | 19 (95%) | 0.59 |

| Spanish | 1 (3%) | 1 (5%) | ||

| Hospital diagnosis | Infectious | 19 (54%) | 14 (70%) | 0.20 |

| Noninfectious | 16 (46%) | 6 (30%) | ||

| Antibiotic received | ‐lactamb | 22 (63%) | 0 (0%) | 0.07 |

| Non‐lactamc | 4 (11%) | 12 (60%) | ||

| None | 9 (26%) | 8 (40%) | ||

CONCLUSION

Errors in medication documentation are a major cause of potential harm and death.[8] In the United States, up to 14% of patient harm is due to a preventable medication error, a rate that exceeds death related to breast cancer, vehicular accidents, and AIDS.[9, 10] Inaccurate drug allergy reporting can result in a cascade of consequential medical errors, including medication prescribing (eg, use of less effective, potentially more toxic and/or more expensive agents), and diagnostic errors (eg, repeat PST, unnecessary medication desensitization).

Although EMR systems are designed to improve allergy documentation, they may also increase the risk of inaccurate or out‐of‐date data. Providers may be reluctant to permanently alter the electronic record by removing an allergy from the EMR. Chart lore, the persistence of inaccurate or outdated information, may contribute to error, particularly when the patient is unable to provide information directly. We found, for example, that dementia and acutely altered mentation were associated with allergy reporting errors, likely related to the inability of the patient to give a reliable history. Finally, the EMR does not typically include a function for noting that an allergy does not exist, making it easier to reinstate incorrect allergies. To address this problem, we subsequently began listing a negative PST as an other allergy in the EMR allergy section to improve visibility.

We also found that residence in an LTCF was associated with allergy reporting error, in part perhaps because all LTCF records still included penicillin as an allergy. This finding highlights the need for direct communication of a proven PST tolerance with the primary care physician or LTCF provider, which was not part of our initial intervention. Previous studies have described the benefit of removing incorrectly reported allergies from community pharmacy records as well.[2, 11] Simply recording it into a transfer summary may not suffice, as LTCF providers may not read, or misread, the PST result. Healthcare providers performing PST should attempt to maintain consistent inpatient and outpatient drug allergy reports to avoid drug allergies.

Another possible modality to reduce inaccurate drug allergy documentation is repetitive review of the allergy list. In the Epic EMR system, the allergy list will illustrate when the healthcare provider(s) reviewed the patients' allergies last. At Vidant Health, the allergy list is generally only reviewed during nursing triage in the emergency department. Healthcare providers should avoid chart lore or relying on nursing notes and routinely review allergies directly with the patient. Obtaining allergy information only during routine nursing triage assessment is substandard.[12] This should not substitute acquisition of allergy information from the patient using a structured, direct interview. Supervision and repeated EMR review may help to avoid overlooking an inaccurate history acquisition.[13] This may help not only help to remove drug allergies that were erroneously added to the patient's list, but also to possibly add agents that may have been missed by the triaging team.

Another means by which inaccurate redocumentation of drug allergies can be avoided is avoidance of placing nonallergic drug reactions in the allergy section of the EMR. Antimicrobial agents are often added to the allergy list because of a drug intolerance (eg, gastrointestinal symptoms), and/or pharmacologic effect (eg, electrolyte abnormality). Although these are not true reactions, healthcare providers often avoid rechallenging these agents. These adverse reactions should be placed within the problem list or past medical history section of the EMR, and not within the allergy section. Therefore, healthcare providers should accurately describe the behavior of the allergic reaction(s).[14]

A limitation of our study is our small sample size and single‐site design. This may have limited the ability to analyze the data in a multivariable way and the ability to learn about risk factors across a variety of EMR and workflow settings. Furthermore, we reviewed only the 55 patients who were readmitted, and therefore do not know how accurate records were for the other 95 patients.

In summary, this work highlights the challenges of successful implementation of quality improvement projects in an electronic health record‐based world. Although PST can expand antimicrobial choices and reduce healthcare costs, the benefits may be limited by inadequately removing the allergy from the hospital and outpatient record(s). From the novel data gathered from our study, primary care physicians and LTCFs are now promptly notified of a negative PST to reduce these medical errors, and we believe this process should become a standard of care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Muhammad S. Ashraf for his assistance in preparing this manuscript.

Disclosures: Ramzy H. Rimawi, MD, has a potential conflict of interest with Alk‐Abello (speakers' bureau), the manufacturer of the Pre‐PEN penicillin skin test. Alk‐Abello was not involved in the production of this article. Paul P. Cook, MD has potential conflicts of interest with Gilead (investigator), Pfizer (investigator), Merck (investigator and speakers' bureau) and Forest (speakers' bureau), none of which relate to the use of penicillin or penicillin skin tests. None of the authors have received any source(s) of funding for this article. The corresponding author, Ramzy Rimawi, MD, had full access to all of the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The manuscript is not under review by any other publication.

- , . Accuracy of drug allergy documentation. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1997;54(14):1627–1629.

- , , , et al. Program to remove incorrect allergy documentation in pediatrics medical records. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001;58(18):1722–1727.

- , , . Electronic medication ordering with integrated drug database and clinical decision support system. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2012;180:693–697.

- , , , . Pharmacy‐controlled documentation of drug allergies. Am J Health‐Syst Pharm. 1991;48:260–264.

- , , , et al. Systems analysis of adverse drug events. JAMA. 1995;274:35–43.

- , , , et al. The impact of penicillin skin testing on clinical practice and antimicrobial stewardship. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(6):341–345.

- , , , et al.Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters; American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology;Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Drug allergy: an updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:259–273.

- , , . Prescription quality in an acute medical ward. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(12):1158–1165.

- . Make no mistake! Medical errors can be deadly serious. FDA Consum. 2000;34(5):13–18.

- . Medication errors. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2007;37:343–346.

- , , , et al. A pharmacist‐led information technology intervention for medication errors (PINCER): a multicenter, cluster randomized, controlled trial and cost‐effectiveness analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9823):1301–1309.

- , , , . Getting the data right: information accuracy in pediatric emergency medicine. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(4):296–301.

- , . Antibiotic allergy: inaccurate history taking in a teaching hospital. South Med J. 1994;87(8):805–807.

- , , . Drug allergy documentation—time for a change? Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(4):610–613.

Patient safety is a healthcare provider's top priority. Drug allergies are instated into an electronic medical record (EMR) to avoid potential adverse events in the future. Despite the intention to provide safety, healthcare providers frequently document antimicrobial allergies incorrectly.[1] In turn, this may lead to decreased antibiotic choices, increased healthcare costs, potential adverse reactions, and unnecessary avoidance of optimal, first‐line agents.

Several strategies have been developed to help improve the accuracy of allergy documentation, including pharmacy‐based interventions, but the persistence of corrections, once performed, is unknown.[2] Although most antibiotic allergy errors are identified upon review of prior medication history (eg, penicillin allergy listed in a patient who previously received piperacillintazobactam), no prior studies have evaluated penicillin allergy errors directly after a proven tolerance with a penicillin skin testing (PST) and penicillin confirmatory challenge.[3, 4, 5] We hereby assess factors for erroneous allergy documentation in a cohort of patients with a negative PST.

METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed charts under a protocol approved by the university and medical center institutional review board. Following a PST intervention we have previously described, penicillin was removed from the patients' EMR (Epic, Verona, WI) allergy list from March 2012 through July 2012.[6] We then invested a brief procedure note into the allergy section describing the negative PST and subsequent tolerance of a penicillin agent. During the PST intervention, there was no attempt to convey the result of the PST and corrected allergy information to the outpatient clinicians.

As a follow‐up to our previous study, we reviewed the charts of the 150 subjects who represented the entire population of patients who underwent PST in the March 2012 through July 2012 intervention time period. From August 2012 through July 2013, charts were reviewed to gauge reappearances at Vidant Health, a system of 10 hospitals in eastern North Carolina. Collected data also included demographics, drug allergy or intolerance, penicillin allergy redocumentation, residence, antimicrobial use, and presence of dementia or altered mentation.

Outpatient physician and long‐term care facility (LTCF) allergy records were obtained via EMR records, patient or family inquiry, and referring documents that accompanied the patient upon arrival. In addition to reviewing the LTCF and/or outpatient physician referring documents, the outpatient physician(s) and LTCFs were contacted and asked to review other electronic or paper records that may not have been delivered with the referring documents. Inpatient and outpatient records were reviewed for penicillin allergy, as defined by the drug allergy practice parameters.[7] Fischer exact tests were used to identify significant associated factors.

RESULTS

Of the 150 patients with proven penicillin tolerance, 55 (37%) revisited a Vidant Health hospital within a year period, of which 22 (40%) received a ‐lactam agent once again without adverse effects (Table 1). Twenty (36%) of the 55 patients had penicillin allergy redocumented (Figure 1). There was no description of any allergy after the PST in any of the 20 EMR, LTCF records, or outpatient primary care physician records. Factors associated with penicillin allergy redocumentation (vs those not redocumented) included age >65 years (P = 0.011), residence in a LTCF (P = 0.0001), acutely altered mentation (P < 0.0001), and dementia (P < 0.0001). Penicillin allergy was still reported in all 21 (100%) of the LTCF patient records.

| Category | Variables | Penicillin Allergy Not Reinstated, n = 35 | Penicillin Allergy Reinstated, n = 20 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Age, y | 1830 | 5 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 0.011 |

| 3164 | 17 (49%) | 5 (37%) | ||

| >65 | 13 (37%) | 15 (75%) | ||

| Gender | Male | 12 (34%) | 10 (50%) | 0.19 |

| Female | 23 (66%) | 10 (50%) | ||

| Race | White | 20 (57%) | 11 (55%) | 0.36 |

| Black | 14 (40%) | 8 (40%) | ||

| Hispanic | 1 (3%) | 1 (5%) | ||

| Residence | Home | 28 (80%) | 5 (25%) | 0.0001 |

| LTCF | 7 (20%) | 15 (75%) | ||

| Acutely altered mentation | Yes | 8 (23%) | 16 (80%) | <0.0001 |

| No | 27 (77%) | 4 (20%) | ||

| Dementia | Yes | 1 (3%) | 10 (50%) | <0.0001 |

| No | 34 (97%) | 10 (50%) | ||

| Primary service | Residenta | 18 (51%) | 5 (25%) | 0.18 |

| Hospitalist | 8 (23%) | 10 (50%) | ||

| Surgery | 3 (9%) | 3 (15%) | ||

| Emergency medicine | 6 (17%) | 2 (10%) | ||

| Primary language | English | 34 (97%) | 19 (95%) | 0.59 |

| Spanish | 1 (3%) | 1 (5%) | ||

| Hospital diagnosis | Infectious | 19 (54%) | 14 (70%) | 0.20 |

| Noninfectious | 16 (46%) | 6 (30%) | ||

| Antibiotic received | ‐lactamb | 22 (63%) | 0 (0%) | 0.07 |

| Non‐lactamc | 4 (11%) | 12 (60%) | ||

| None | 9 (26%) | 8 (40%) | ||

CONCLUSION

Errors in medication documentation are a major cause of potential harm and death.[8] In the United States, up to 14% of patient harm is due to a preventable medication error, a rate that exceeds death related to breast cancer, vehicular accidents, and AIDS.[9, 10] Inaccurate drug allergy reporting can result in a cascade of consequential medical errors, including medication prescribing (eg, use of less effective, potentially more toxic and/or more expensive agents), and diagnostic errors (eg, repeat PST, unnecessary medication desensitization).

Although EMR systems are designed to improve allergy documentation, they may also increase the risk of inaccurate or out‐of‐date data. Providers may be reluctant to permanently alter the electronic record by removing an allergy from the EMR. Chart lore, the persistence of inaccurate or outdated information, may contribute to error, particularly when the patient is unable to provide information directly. We found, for example, that dementia and acutely altered mentation were associated with allergy reporting errors, likely related to the inability of the patient to give a reliable history. Finally, the EMR does not typically include a function for noting that an allergy does not exist, making it easier to reinstate incorrect allergies. To address this problem, we subsequently began listing a negative PST as an other allergy in the EMR allergy section to improve visibility.

We also found that residence in an LTCF was associated with allergy reporting error, in part perhaps because all LTCF records still included penicillin as an allergy. This finding highlights the need for direct communication of a proven PST tolerance with the primary care physician or LTCF provider, which was not part of our initial intervention. Previous studies have described the benefit of removing incorrectly reported allergies from community pharmacy records as well.[2, 11] Simply recording it into a transfer summary may not suffice, as LTCF providers may not read, or misread, the PST result. Healthcare providers performing PST should attempt to maintain consistent inpatient and outpatient drug allergy reports to avoid drug allergies.

Another possible modality to reduce inaccurate drug allergy documentation is repetitive review of the allergy list. In the Epic EMR system, the allergy list will illustrate when the healthcare provider(s) reviewed the patients' allergies last. At Vidant Health, the allergy list is generally only reviewed during nursing triage in the emergency department. Healthcare providers should avoid chart lore or relying on nursing notes and routinely review allergies directly with the patient. Obtaining allergy information only during routine nursing triage assessment is substandard.[12] This should not substitute acquisition of allergy information from the patient using a structured, direct interview. Supervision and repeated EMR review may help to avoid overlooking an inaccurate history acquisition.[13] This may help not only help to remove drug allergies that were erroneously added to the patient's list, but also to possibly add agents that may have been missed by the triaging team.

Another means by which inaccurate redocumentation of drug allergies can be avoided is avoidance of placing nonallergic drug reactions in the allergy section of the EMR. Antimicrobial agents are often added to the allergy list because of a drug intolerance (eg, gastrointestinal symptoms), and/or pharmacologic effect (eg, electrolyte abnormality). Although these are not true reactions, healthcare providers often avoid rechallenging these agents. These adverse reactions should be placed within the problem list or past medical history section of the EMR, and not within the allergy section. Therefore, healthcare providers should accurately describe the behavior of the allergic reaction(s).[14]

A limitation of our study is our small sample size and single‐site design. This may have limited the ability to analyze the data in a multivariable way and the ability to learn about risk factors across a variety of EMR and workflow settings. Furthermore, we reviewed only the 55 patients who were readmitted, and therefore do not know how accurate records were for the other 95 patients.

In summary, this work highlights the challenges of successful implementation of quality improvement projects in an electronic health record‐based world. Although PST can expand antimicrobial choices and reduce healthcare costs, the benefits may be limited by inadequately removing the allergy from the hospital and outpatient record(s). From the novel data gathered from our study, primary care physicians and LTCFs are now promptly notified of a negative PST to reduce these medical errors, and we believe this process should become a standard of care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Muhammad S. Ashraf for his assistance in preparing this manuscript.

Disclosures: Ramzy H. Rimawi, MD, has a potential conflict of interest with Alk‐Abello (speakers' bureau), the manufacturer of the Pre‐PEN penicillin skin test. Alk‐Abello was not involved in the production of this article. Paul P. Cook, MD has potential conflicts of interest with Gilead (investigator), Pfizer (investigator), Merck (investigator and speakers' bureau) and Forest (speakers' bureau), none of which relate to the use of penicillin or penicillin skin tests. None of the authors have received any source(s) of funding for this article. The corresponding author, Ramzy Rimawi, MD, had full access to all of the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The manuscript is not under review by any other publication.

Patient safety is a healthcare provider's top priority. Drug allergies are instated into an electronic medical record (EMR) to avoid potential adverse events in the future. Despite the intention to provide safety, healthcare providers frequently document antimicrobial allergies incorrectly.[1] In turn, this may lead to decreased antibiotic choices, increased healthcare costs, potential adverse reactions, and unnecessary avoidance of optimal, first‐line agents.

Several strategies have been developed to help improve the accuracy of allergy documentation, including pharmacy‐based interventions, but the persistence of corrections, once performed, is unknown.[2] Although most antibiotic allergy errors are identified upon review of prior medication history (eg, penicillin allergy listed in a patient who previously received piperacillintazobactam), no prior studies have evaluated penicillin allergy errors directly after a proven tolerance with a penicillin skin testing (PST) and penicillin confirmatory challenge.[3, 4, 5] We hereby assess factors for erroneous allergy documentation in a cohort of patients with a negative PST.

METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed charts under a protocol approved by the university and medical center institutional review board. Following a PST intervention we have previously described, penicillin was removed from the patients' EMR (Epic, Verona, WI) allergy list from March 2012 through July 2012.[6] We then invested a brief procedure note into the allergy section describing the negative PST and subsequent tolerance of a penicillin agent. During the PST intervention, there was no attempt to convey the result of the PST and corrected allergy information to the outpatient clinicians.

As a follow‐up to our previous study, we reviewed the charts of the 150 subjects who represented the entire population of patients who underwent PST in the March 2012 through July 2012 intervention time period. From August 2012 through July 2013, charts were reviewed to gauge reappearances at Vidant Health, a system of 10 hospitals in eastern North Carolina. Collected data also included demographics, drug allergy or intolerance, penicillin allergy redocumentation, residence, antimicrobial use, and presence of dementia or altered mentation.

Outpatient physician and long‐term care facility (LTCF) allergy records were obtained via EMR records, patient or family inquiry, and referring documents that accompanied the patient upon arrival. In addition to reviewing the LTCF and/or outpatient physician referring documents, the outpatient physician(s) and LTCFs were contacted and asked to review other electronic or paper records that may not have been delivered with the referring documents. Inpatient and outpatient records were reviewed for penicillin allergy, as defined by the drug allergy practice parameters.[7] Fischer exact tests were used to identify significant associated factors.

RESULTS

Of the 150 patients with proven penicillin tolerance, 55 (37%) revisited a Vidant Health hospital within a year period, of which 22 (40%) received a ‐lactam agent once again without adverse effects (Table 1). Twenty (36%) of the 55 patients had penicillin allergy redocumented (Figure 1). There was no description of any allergy after the PST in any of the 20 EMR, LTCF records, or outpatient primary care physician records. Factors associated with penicillin allergy redocumentation (vs those not redocumented) included age >65 years (P = 0.011), residence in a LTCF (P = 0.0001), acutely altered mentation (P < 0.0001), and dementia (P < 0.0001). Penicillin allergy was still reported in all 21 (100%) of the LTCF patient records.

| Category | Variables | Penicillin Allergy Not Reinstated, n = 35 | Penicillin Allergy Reinstated, n = 20 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Age, y | 1830 | 5 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 0.011 |

| 3164 | 17 (49%) | 5 (37%) | ||

| >65 | 13 (37%) | 15 (75%) | ||

| Gender | Male | 12 (34%) | 10 (50%) | 0.19 |

| Female | 23 (66%) | 10 (50%) | ||

| Race | White | 20 (57%) | 11 (55%) | 0.36 |

| Black | 14 (40%) | 8 (40%) | ||

| Hispanic | 1 (3%) | 1 (5%) | ||

| Residence | Home | 28 (80%) | 5 (25%) | 0.0001 |

| LTCF | 7 (20%) | 15 (75%) | ||

| Acutely altered mentation | Yes | 8 (23%) | 16 (80%) | <0.0001 |

| No | 27 (77%) | 4 (20%) | ||

| Dementia | Yes | 1 (3%) | 10 (50%) | <0.0001 |

| No | 34 (97%) | 10 (50%) | ||

| Primary service | Residenta | 18 (51%) | 5 (25%) | 0.18 |

| Hospitalist | 8 (23%) | 10 (50%) | ||

| Surgery | 3 (9%) | 3 (15%) | ||

| Emergency medicine | 6 (17%) | 2 (10%) | ||

| Primary language | English | 34 (97%) | 19 (95%) | 0.59 |

| Spanish | 1 (3%) | 1 (5%) | ||

| Hospital diagnosis | Infectious | 19 (54%) | 14 (70%) | 0.20 |

| Noninfectious | 16 (46%) | 6 (30%) | ||

| Antibiotic received | ‐lactamb | 22 (63%) | 0 (0%) | 0.07 |

| Non‐lactamc | 4 (11%) | 12 (60%) | ||

| None | 9 (26%) | 8 (40%) | ||

CONCLUSION

Errors in medication documentation are a major cause of potential harm and death.[8] In the United States, up to 14% of patient harm is due to a preventable medication error, a rate that exceeds death related to breast cancer, vehicular accidents, and AIDS.[9, 10] Inaccurate drug allergy reporting can result in a cascade of consequential medical errors, including medication prescribing (eg, use of less effective, potentially more toxic and/or more expensive agents), and diagnostic errors (eg, repeat PST, unnecessary medication desensitization).

Although EMR systems are designed to improve allergy documentation, they may also increase the risk of inaccurate or out‐of‐date data. Providers may be reluctant to permanently alter the electronic record by removing an allergy from the EMR. Chart lore, the persistence of inaccurate or outdated information, may contribute to error, particularly when the patient is unable to provide information directly. We found, for example, that dementia and acutely altered mentation were associated with allergy reporting errors, likely related to the inability of the patient to give a reliable history. Finally, the EMR does not typically include a function for noting that an allergy does not exist, making it easier to reinstate incorrect allergies. To address this problem, we subsequently began listing a negative PST as an other allergy in the EMR allergy section to improve visibility.

We also found that residence in an LTCF was associated with allergy reporting error, in part perhaps because all LTCF records still included penicillin as an allergy. This finding highlights the need for direct communication of a proven PST tolerance with the primary care physician or LTCF provider, which was not part of our initial intervention. Previous studies have described the benefit of removing incorrectly reported allergies from community pharmacy records as well.[2, 11] Simply recording it into a transfer summary may not suffice, as LTCF providers may not read, or misread, the PST result. Healthcare providers performing PST should attempt to maintain consistent inpatient and outpatient drug allergy reports to avoid drug allergies.

Another possible modality to reduce inaccurate drug allergy documentation is repetitive review of the allergy list. In the Epic EMR system, the allergy list will illustrate when the healthcare provider(s) reviewed the patients' allergies last. At Vidant Health, the allergy list is generally only reviewed during nursing triage in the emergency department. Healthcare providers should avoid chart lore or relying on nursing notes and routinely review allergies directly with the patient. Obtaining allergy information only during routine nursing triage assessment is substandard.[12] This should not substitute acquisition of allergy information from the patient using a structured, direct interview. Supervision and repeated EMR review may help to avoid overlooking an inaccurate history acquisition.[13] This may help not only help to remove drug allergies that were erroneously added to the patient's list, but also to possibly add agents that may have been missed by the triaging team.

Another means by which inaccurate redocumentation of drug allergies can be avoided is avoidance of placing nonallergic drug reactions in the allergy section of the EMR. Antimicrobial agents are often added to the allergy list because of a drug intolerance (eg, gastrointestinal symptoms), and/or pharmacologic effect (eg, electrolyte abnormality). Although these are not true reactions, healthcare providers often avoid rechallenging these agents. These adverse reactions should be placed within the problem list or past medical history section of the EMR, and not within the allergy section. Therefore, healthcare providers should accurately describe the behavior of the allergic reaction(s).[14]

A limitation of our study is our small sample size and single‐site design. This may have limited the ability to analyze the data in a multivariable way and the ability to learn about risk factors across a variety of EMR and workflow settings. Furthermore, we reviewed only the 55 patients who were readmitted, and therefore do not know how accurate records were for the other 95 patients.

In summary, this work highlights the challenges of successful implementation of quality improvement projects in an electronic health record‐based world. Although PST can expand antimicrobial choices and reduce healthcare costs, the benefits may be limited by inadequately removing the allergy from the hospital and outpatient record(s). From the novel data gathered from our study, primary care physicians and LTCFs are now promptly notified of a negative PST to reduce these medical errors, and we believe this process should become a standard of care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Muhammad S. Ashraf for his assistance in preparing this manuscript.

Disclosures: Ramzy H. Rimawi, MD, has a potential conflict of interest with Alk‐Abello (speakers' bureau), the manufacturer of the Pre‐PEN penicillin skin test. Alk‐Abello was not involved in the production of this article. Paul P. Cook, MD has potential conflicts of interest with Gilead (investigator), Pfizer (investigator), Merck (investigator and speakers' bureau) and Forest (speakers' bureau), none of which relate to the use of penicillin or penicillin skin tests. None of the authors have received any source(s) of funding for this article. The corresponding author, Ramzy Rimawi, MD, had full access to all of the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The manuscript is not under review by any other publication.

- , . Accuracy of drug allergy documentation. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1997;54(14):1627–1629.

- , , , et al. Program to remove incorrect allergy documentation in pediatrics medical records. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001;58(18):1722–1727.

- , , . Electronic medication ordering with integrated drug database and clinical decision support system. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2012;180:693–697.

- , , , . Pharmacy‐controlled documentation of drug allergies. Am J Health‐Syst Pharm. 1991;48:260–264.

- , , , et al. Systems analysis of adverse drug events. JAMA. 1995;274:35–43.

- , , , et al. The impact of penicillin skin testing on clinical practice and antimicrobial stewardship. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(6):341–345.

- , , , et al.Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters; American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology;Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Drug allergy: an updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:259–273.

- , , . Prescription quality in an acute medical ward. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(12):1158–1165.

- . Make no mistake! Medical errors can be deadly serious. FDA Consum. 2000;34(5):13–18.

- . Medication errors. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2007;37:343–346.

- , , , et al. A pharmacist‐led information technology intervention for medication errors (PINCER): a multicenter, cluster randomized, controlled trial and cost‐effectiveness analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9823):1301–1309.

- , , , . Getting the data right: information accuracy in pediatric emergency medicine. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(4):296–301.

- , . Antibiotic allergy: inaccurate history taking in a teaching hospital. South Med J. 1994;87(8):805–807.

- , , . Drug allergy documentation—time for a change? Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(4):610–613.

- , . Accuracy of drug allergy documentation. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1997;54(14):1627–1629.

- , , , et al. Program to remove incorrect allergy documentation in pediatrics medical records. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001;58(18):1722–1727.

- , , . Electronic medication ordering with integrated drug database and clinical decision support system. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2012;180:693–697.

- , , , . Pharmacy‐controlled documentation of drug allergies. Am J Health‐Syst Pharm. 1991;48:260–264.

- , , , et al. Systems analysis of adverse drug events. JAMA. 1995;274:35–43.

- , , , et al. The impact of penicillin skin testing on clinical practice and antimicrobial stewardship. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(6):341–345.

- , , , et al.Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters; American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology;Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Drug allergy: an updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:259–273.

- , , . Prescription quality in an acute medical ward. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(12):1158–1165.

- . Make no mistake! Medical errors can be deadly serious. FDA Consum. 2000;34(5):13–18.

- . Medication errors. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2007;37:343–346.

- , , , et al. A pharmacist‐led information technology intervention for medication errors (PINCER): a multicenter, cluster randomized, controlled trial and cost‐effectiveness analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9823):1301–1309.

- , , , . Getting the data right: information accuracy in pediatric emergency medicine. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(4):296–301.

- , . Antibiotic allergy: inaccurate history taking in a teaching hospital. South Med J. 1994;87(8):805–807.

- , , . Drug allergy documentation—time for a change? Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(4):610–613.

© 2013 Society of Hospital Medicine

Impact of Penicillin Skin Testing

Self‐reported penicillin allergy is common and frequently limits the available antimicrobial agents to choose from. This often results in the use of more expensive, potentially more toxic, and possibly less efficacious agents.[1, 2]

For over 30 years, penicilloyl‐polylysine (PPL) penicillin skin testing (PST) was widely used to diagnose penicillin allergy with a negative predictive value (NPV) of about 97% to 99%.[3] After being off the market for 5 years, PPL PST was reapproved in 2009 as PRE‐PEN.[4] However, many clinicians still fail to utilize PST despite its simplicity and substantial clinical impact. The main purpose of this study was to describe the predictive value of PST and impact on antibiotic selection in a sample of hospitalized patients with a reported history of penicillin allergy.

METHODS

In 2010, PST was introduced as a quality‐improvement measure after approval and support from the chief of professional services and the medical staff executive committee at Vidant Medical Center, an 861‐bed tertiary care and teaching hospital. Our antimicrobial stewardship program is regularly contacted for approval of alternative therapies in penicillin allergic patients. The PST quality‐improvement intervention was implemented to avoid resorting to less appropriate therapies in these situations. Following approval by the University and Medical Center Institutional Review Board, we designed a 4‐month study to assess the impact of this ongoing quality improvement measure from March 2012 to July 2012.

Hospitalized patients of all ages with reported penicillin allergies were obtained from our antimicrobial stewardship database. Their charts were reviewed for demographics, antibiotic use, clinical infection, and allergic description. Deciding whether to alter antibiotic therapy to a ‐lactam regimen was based on microbiologic results, laboratory values, clinical infection, and history of immunoglobulin E (IgE)‐mediated reactions, as defined by the updated drug allergy practice parameters.[5] IgE‐mediated reactions included: (1) immediate urticaria, laryngeal edema, or hypotension; (2) anemia; and (3) fever, arthralgias, lymphadenopathy, and an urticarial rash after 7 to 21 days.[5, 6, 7] We defined anaphylaxis as the development of angioedema or hemodynamic instability within 1 hour of penicillin administration. A true negative reaction was a lack of an IgE‐mediated reaction to all the drug challenges.

Patients in the medical, surgical, labor, and delivery wards; intensive care units; and emergency department underwent testing. The ‐lactam agent used after a negative PST was recorded, and the patients were followed for 24 hours after transitioning their therapy to a ‐lactam regimen. Excluded subjects included those with (1) nonIgE‐mediated reactions, (2) skin conditions that can give false positive results, (3) medications that may interfere with anaphylactic therapy, (4) history of severe exfoliative reactions to ‐lactams, (5) anaphylaxis less than 4 weeks prior, (6) allergies to antibiotics other than penicillin, and (7) uncertain allergy history.

PST Reagents/Procedure

Our benzylpenicilloyl major determinant molecule, commercially produced as PPL, was purchased as a PRE‐PEN from ALK‐Abello, Round Rock, Texas. Penicillin G potassium, purchased from Pfizer, New York, New York, is the only commercially available minor determinant and can improve identification of penicillin allergy by up to 97%.[2] The PST panel also included histamine (positive control) and normal saline (negative control).

Skin Testing Procedure

An infectious diseases fellow (R.H.R. or B.K.) was supervised in preparing for potential anaphylaxis, applying the reagents and interpreting the results based on drug allergy practice parameters.[5] The preliminary epicutaneous prick/puncture test was performed with a lancet in subjects without prior anaphylaxis using full‐strength PPL and penicillin G potassium reagents. If there was no response within 15 minutes, which we defined as a lack of wheal formation 3 mm or greater than that of the negative control, 0.02 to 0.03 mL of each reagent was injected intradermally using a tuberculin syringe and examined for 15 minutes.[5] If there was no response, patients were then challenged with either a single oral dose of penicillin V potassium 250 mg or whichever oral penicillin agent they previously reported an allergy to. If no reaction was appreciated within 2 hours, their therapy was changed to a ‐lactam agent including penicillins, cephalosporins, and carbapenems for the remaining duration of therapy (Figure 1) An estimate of NPV was obtained after 24 hours follow‐up.

Statistical Analysis

We designed a study to estimate whether the reapproved PST achieves an NPV of at least 95%.[3] We hypothesized that clinicians will be willing to utilize PST even if it has an NPV of slightly less than 98% compared to the current standard of treating patients without PST.[7] Assuming an equivalence margin of 3%, we estimated a sample size of 146 to achieve at least 82% power to test a hypothesis of NPV 95% using a 1‐sided Z test with a type‐I error rate of 5%.[8] Once the sample size of 146 subjects was reached, we stopped recruiting patients.

Sample characteristics of the subjects who underwent testing were summarized using descriptive statistics. Sample proportions were calculated to summarize categorical variables. Mean and standard deviation were calculated to summarize continuous variables. Cost analysis of antibiotic therapy was estimated from the Vidant Medical Center antibiotic pharmaceutical acquisition costs. Estimated cost of peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) placement and removal as well as laboratory testing costs were obtained from our institution's medical billing department. Marketing costs of pharmacist drug calibration and nursing assessments with dressing changes were obtained from hospital‐affiliated outpatient antibiotic infusion companies.

RESULTS

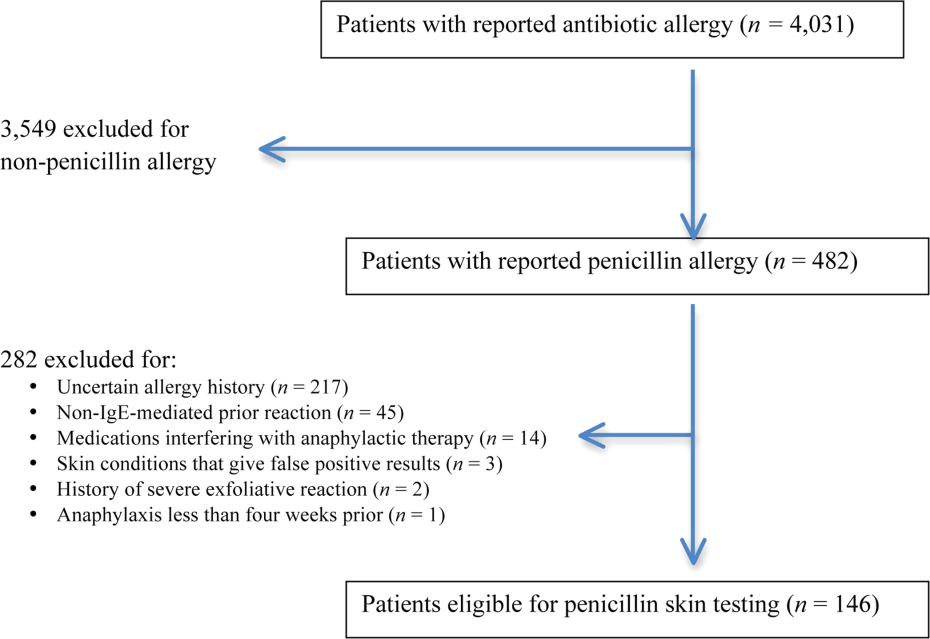

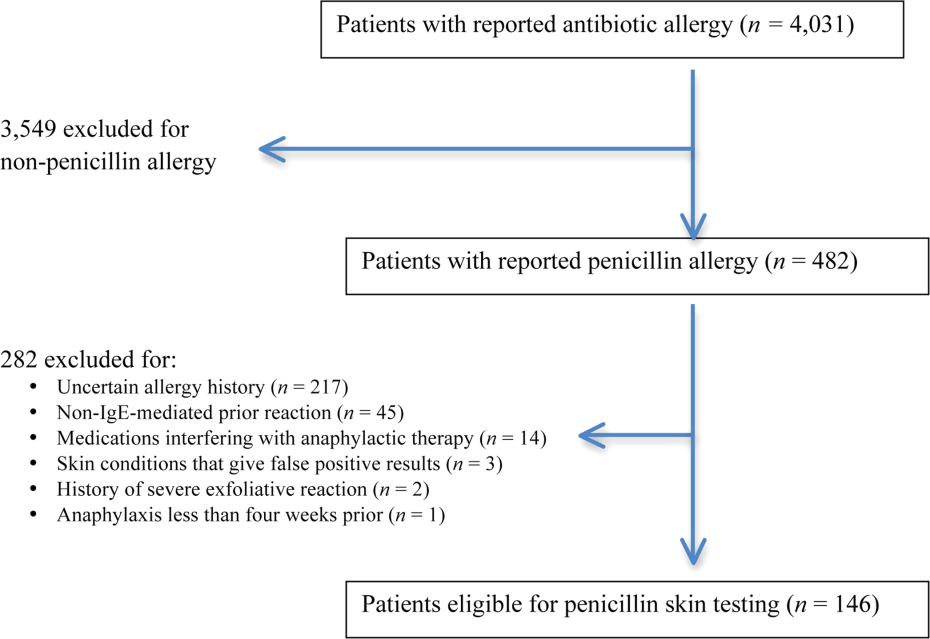

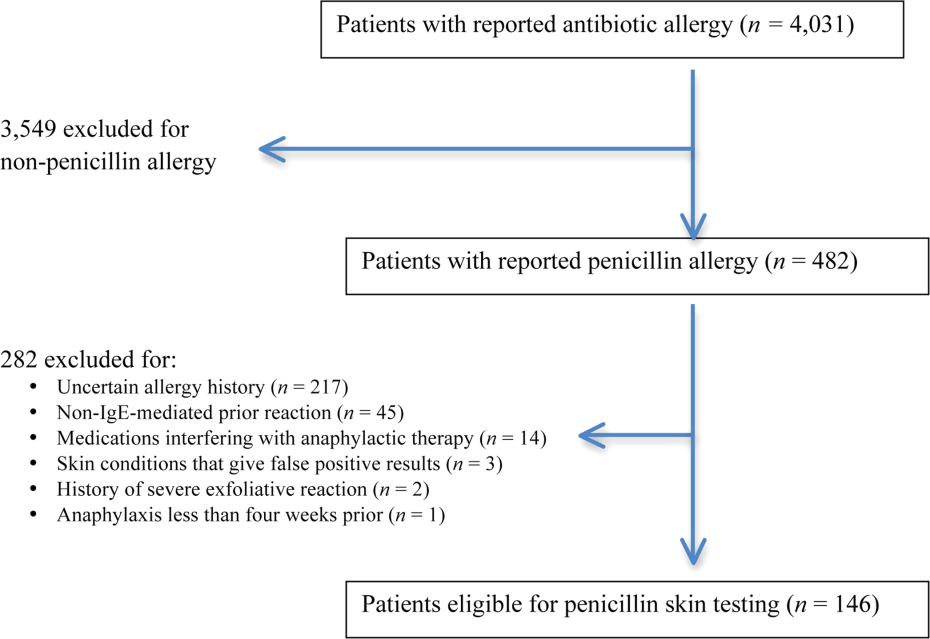

A total of 4031 allergy histories were reviewed during the 5‐month study period to achieve the sample size of 146 patients (Table 1). Of those, 3885 were excluded (Figure 2). Common infections included pneumonias (26%) and urinary tract infections (20%) (Table 2) Only 1 subject had a positive reaction with hives, edema, and itching approximately 6 minutes after the agents were injected intradermally. The remaining 145 (99%) had negative reactions to the PST and oral challenge and were then successfully transitioned to a ‐lactam agent without any reaction at 24 hours, giving an NPV of 100%. Ten subjects were switched from intravenous to oral ‐lactam agents (Figure 1). Avoidance of PICC placement ($1,200) and removal ($65), dressing changes, weekly drug‐level testing, laboratory technician, and pharmaceutical drug calibration costs allowed for a healthcare reduction of $5,233 ($520/patient) based on the 146 patients studied. The total cost of therapy would have been $113,991 if the PST had not been performed. However, the cost of altered therapy following a negative PST was $81,180, a difference of $32,811 ($225/per patient) in a 5‐month period. The total estimated annual difference, including antibiotic alteration and associated drug‐costs, would be $82,000.

| Antibiotic | No. of Patients Reporting An Allergy | % Per Total Charts Reviewed |

|---|---|---|

| Penicillin | 428 | 10.6 |

| Sulfonamide | 271 | 6.7 |

| Quinolone | 108 | 2.7 |

| Cephalosporin | 81 | 2.0 |

| Macrolide | 65 | 1.6 |

| Vancomycin | 39 | 0.9 |

| Tetracycline | 20 | 0.5 |

| Clindamycin | 18 | 0.4 |

| Metronidazole | 9 | 0.2 |

| Linezolid | 2 | 0.05 |

| Categories | No. of Patients (%) |

|---|---|

| |

| Time since last reported penicillin use | |

| 1 month1 year | 6 (4) |

| 25 years | 39 (27) |

| 610 years | 23 (16) |

| >10 years | 78 (53) |

| Reported IgE‐mediated reactions | |

| Bronchospasm | 23 (16) |

| Urticarial rash | 100 (68) |

| Edema | 32 (22) |

| Anaphylaxis | 21 (14) |

| Age on admission, y | |

| 2050 | 28 (19) |

| 5160 | 29 (20) |

| 6170 | 41 (28) |

| 7180 | 24 (16) |

| >80 | 24 (16) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 55 (40) |

| Female | 88 (60) |

| Race | |

| White | 82 (56) |

| Black | 61 (42) |

| Hispanic | 3 (2) |

| Infections being treated | |

| Bacteremia | 7 (4.8) |

| Catheter‐related bloodstream infection | 2 (1.4) |

| Empyema | 1 (0.7) |

| Epidural abscess | 2 (1.4) |

| Infective endocarditis | 4 (2.7) |

| Intra‐abdominal infection | 24 (16.4) |

| Meningitis | 1 (0.7) |

| Neutropenic fever | 1 (0.7) |

| Osteomyelitis | 6 (4.1) |

| Pericardial effusion | 1 (0.7) |

| Prosthetic joint infection | 5 (3.4) |

| Pneumonia | 40 (27.4) |

| Skin and soft‐tissue infection | 20 (13.7) |

| Syphilis | 3 (2.1) |

| Urinary tract infection | 29 (19.7) |

DISCUSSION

PST is the most rapid, sensitive, and cost‐effective modality for evaluating patients with immediate allergic reactions to penicillin. Over 90% of individuals with a true history of penicillin allergy have confirmed sensitivity with a PST, implying most patients who are skin tested negative are truly not allergic.[7, 9, 10, 11, 12] Our study shows that the reapproved PST with the PPL and penicillin G determinants continues to have a high NPV. A patient with a negative PST result is generally at a low risk of developing an immediate‐type hypersensitivity reaction to penicillin.[2, 11] PST frequently allowed for less expensive agents that would have been avoided due to a reported allergy. The estimated annual savings of $82,000 dollars from antibiotic alteration with successful transition to a ‐lactam agent after a negative PST illustrates its value, supports its validity, and makes this study novel.

Many ‐lactamase inhibitors (ie, piperacillin‐tazobactam), fourth generation cephalosporins (ie, cefepime), and carbapenems still remain costly. Despite this, we were still able to achieve a significant reduction in overall cost. In addition to financial benefits, PST allowed for the use of more appropriate agents with less potential adverse effects. Narrow‐spectrum, non‐lactam agents were sometimes altered to a broader‐spectrum ‐lactam agent. We also frequently tailored 2 agents to just 1 broad‐spectrum ‐lactam. This led to more patients being given broad‐spectrum agents after the PST (72 vs 89 patients). However, we were able to avoid using second‐line agents, such as aztreonam, vancomycin, linezolid, daptomycin, and tobramycin, in many patients with infections that are often best treated with penicillin‐based antibiotics (ie, syphilis, group B Streptococcus infections). With increasing incidence and recovery of multidrug‐resistant bacteria, PST may also allow use of potentially more effective antimicrobial agents.

A possible limitation is that our prevalence of a true penicillin allergy was 1%, whereas Bousquet et al. illustrate a higher prevalence of about 20%.[7] Although our prevalence may not be generalizable, Bousquet's study only assessed patients with allergies 5 years prior.

The introduction of PST into clinical practice will allow trained healthcare providers to prescribe cheaper, more appropriate, less toxic antimicrobial agents. The overall benefit of reintroducing penicillin agents when needed in the future is far more cost‐effective than what is described here. PST should become a standard of care when prescribing antibiotics to patients with a history of penicillin allergy. Medical providers should be aware of its utility, acquire training, and incorporate it into their practice.

Acknowledgment

Disclosures: Paul P. Cook, MD, has potential conflicts of interest with Gilead (investigator), Pfizer (investigator), Merck (investigator and speakers' bureau), and Forest (speakers' bureau). Neither he nor any of the other authors has received any sources of funding for this article. For the remaining authors, no conflicts were declared. The corresponding author, Ramzy Rimawi, MD, had full access to all of the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

- , , . Elective penicillin skin testing in a pediatric outpatient setting. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(6):807–812.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs Web site. Benzypenicilloyl polylisine (PRE‐PEN) national drug monograph. May 2012. Available at: http://www.pbm.va.gov/DrugMonograph.aspx. Accessed September 1, 2012.

- , . Diagnosis and management of penicillin allergy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(3):405–410.

- PRE‐PEN penicillin skin test antigen. Available at: http://www.alk‐abello.com/us/products/pre‐pen/Pages/PREPEN.aspx. Accessed September 1, 2012.

- , , , et al.; Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters; American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Drug allergy: an updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:259–273.

- . Immunochemical mechanisms in penicillin allergy. Fed Proc. 1965;24:51–54.

- , , , et al. Oral challenges are needed in the diagnosis of beta‐lactam hypersensitivity. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38(1):185–190.

- , , . Sample Size Calculations in Clinical Research. New York, NY: Chapman 2003.

- , , , et al. Retrospective case series analysis of penicillin allergy testing in a UK specialist regional allergy clinic. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:1014–1018.

- . Prevalence of skin test reactivity in patients with convincing, vague and unnacceptible histories of penicillin allergy. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2005;26(1):59–64.

- , . Frequency of systemic reactions to penicillin skin tests. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:363–365.

- , , , et al. The incidence of antimicrobial allergies in hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160;2819–2822.

Self‐reported penicillin allergy is common and frequently limits the available antimicrobial agents to choose from. This often results in the use of more expensive, potentially more toxic, and possibly less efficacious agents.[1, 2]

For over 30 years, penicilloyl‐polylysine (PPL) penicillin skin testing (PST) was widely used to diagnose penicillin allergy with a negative predictive value (NPV) of about 97% to 99%.[3] After being off the market for 5 years, PPL PST was reapproved in 2009 as PRE‐PEN.[4] However, many clinicians still fail to utilize PST despite its simplicity and substantial clinical impact. The main purpose of this study was to describe the predictive value of PST and impact on antibiotic selection in a sample of hospitalized patients with a reported history of penicillin allergy.

METHODS

In 2010, PST was introduced as a quality‐improvement measure after approval and support from the chief of professional services and the medical staff executive committee at Vidant Medical Center, an 861‐bed tertiary care and teaching hospital. Our antimicrobial stewardship program is regularly contacted for approval of alternative therapies in penicillin allergic patients. The PST quality‐improvement intervention was implemented to avoid resorting to less appropriate therapies in these situations. Following approval by the University and Medical Center Institutional Review Board, we designed a 4‐month study to assess the impact of this ongoing quality improvement measure from March 2012 to July 2012.

Hospitalized patients of all ages with reported penicillin allergies were obtained from our antimicrobial stewardship database. Their charts were reviewed for demographics, antibiotic use, clinical infection, and allergic description. Deciding whether to alter antibiotic therapy to a ‐lactam regimen was based on microbiologic results, laboratory values, clinical infection, and history of immunoglobulin E (IgE)‐mediated reactions, as defined by the updated drug allergy practice parameters.[5] IgE‐mediated reactions included: (1) immediate urticaria, laryngeal edema, or hypotension; (2) anemia; and (3) fever, arthralgias, lymphadenopathy, and an urticarial rash after 7 to 21 days.[5, 6, 7] We defined anaphylaxis as the development of angioedema or hemodynamic instability within 1 hour of penicillin administration. A true negative reaction was a lack of an IgE‐mediated reaction to all the drug challenges.

Patients in the medical, surgical, labor, and delivery wards; intensive care units; and emergency department underwent testing. The ‐lactam agent used after a negative PST was recorded, and the patients were followed for 24 hours after transitioning their therapy to a ‐lactam regimen. Excluded subjects included those with (1) nonIgE‐mediated reactions, (2) skin conditions that can give false positive results, (3) medications that may interfere with anaphylactic therapy, (4) history of severe exfoliative reactions to ‐lactams, (5) anaphylaxis less than 4 weeks prior, (6) allergies to antibiotics other than penicillin, and (7) uncertain allergy history.

PST Reagents/Procedure

Our benzylpenicilloyl major determinant molecule, commercially produced as PPL, was purchased as a PRE‐PEN from ALK‐Abello, Round Rock, Texas. Penicillin G potassium, purchased from Pfizer, New York, New York, is the only commercially available minor determinant and can improve identification of penicillin allergy by up to 97%.[2] The PST panel also included histamine (positive control) and normal saline (negative control).

Skin Testing Procedure

An infectious diseases fellow (R.H.R. or B.K.) was supervised in preparing for potential anaphylaxis, applying the reagents and interpreting the results based on drug allergy practice parameters.[5] The preliminary epicutaneous prick/puncture test was performed with a lancet in subjects without prior anaphylaxis using full‐strength PPL and penicillin G potassium reagents. If there was no response within 15 minutes, which we defined as a lack of wheal formation 3 mm or greater than that of the negative control, 0.02 to 0.03 mL of each reagent was injected intradermally using a tuberculin syringe and examined for 15 minutes.[5] If there was no response, patients were then challenged with either a single oral dose of penicillin V potassium 250 mg or whichever oral penicillin agent they previously reported an allergy to. If no reaction was appreciated within 2 hours, their therapy was changed to a ‐lactam agent including penicillins, cephalosporins, and carbapenems for the remaining duration of therapy (Figure 1) An estimate of NPV was obtained after 24 hours follow‐up.

Statistical Analysis

We designed a study to estimate whether the reapproved PST achieves an NPV of at least 95%.[3] We hypothesized that clinicians will be willing to utilize PST even if it has an NPV of slightly less than 98% compared to the current standard of treating patients without PST.[7] Assuming an equivalence margin of 3%, we estimated a sample size of 146 to achieve at least 82% power to test a hypothesis of NPV 95% using a 1‐sided Z test with a type‐I error rate of 5%.[8] Once the sample size of 146 subjects was reached, we stopped recruiting patients.

Sample characteristics of the subjects who underwent testing were summarized using descriptive statistics. Sample proportions were calculated to summarize categorical variables. Mean and standard deviation were calculated to summarize continuous variables. Cost analysis of antibiotic therapy was estimated from the Vidant Medical Center antibiotic pharmaceutical acquisition costs. Estimated cost of peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) placement and removal as well as laboratory testing costs were obtained from our institution's medical billing department. Marketing costs of pharmacist drug calibration and nursing assessments with dressing changes were obtained from hospital‐affiliated outpatient antibiotic infusion companies.

RESULTS

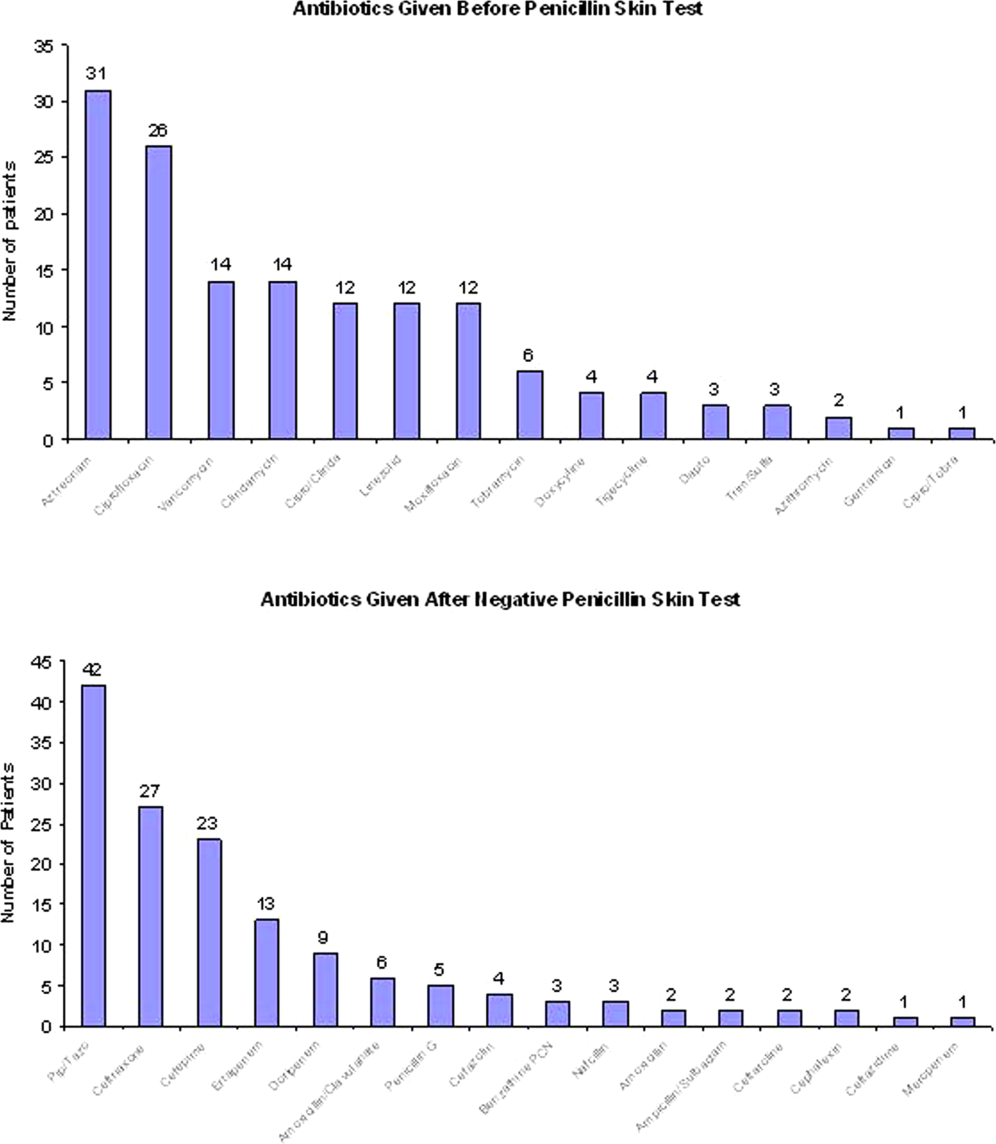

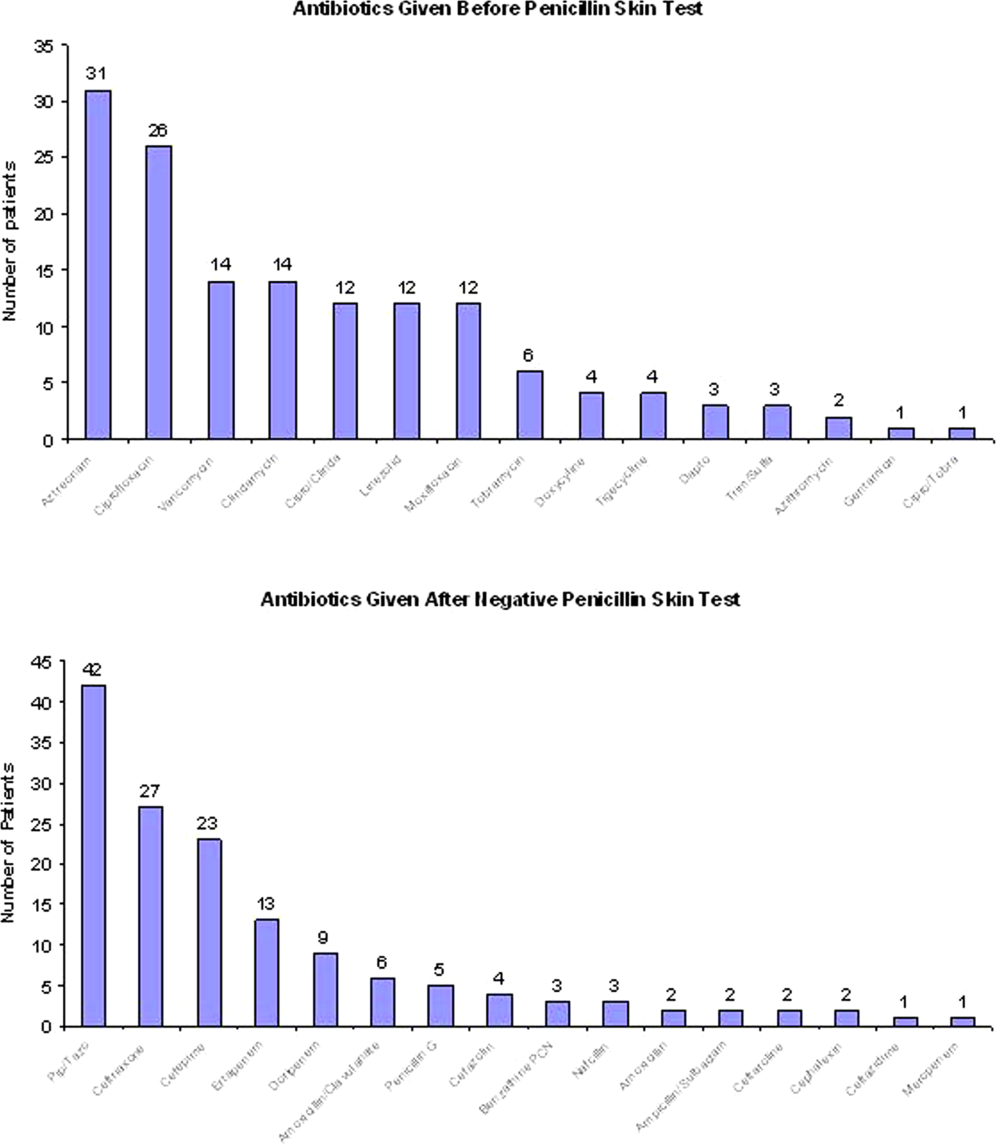

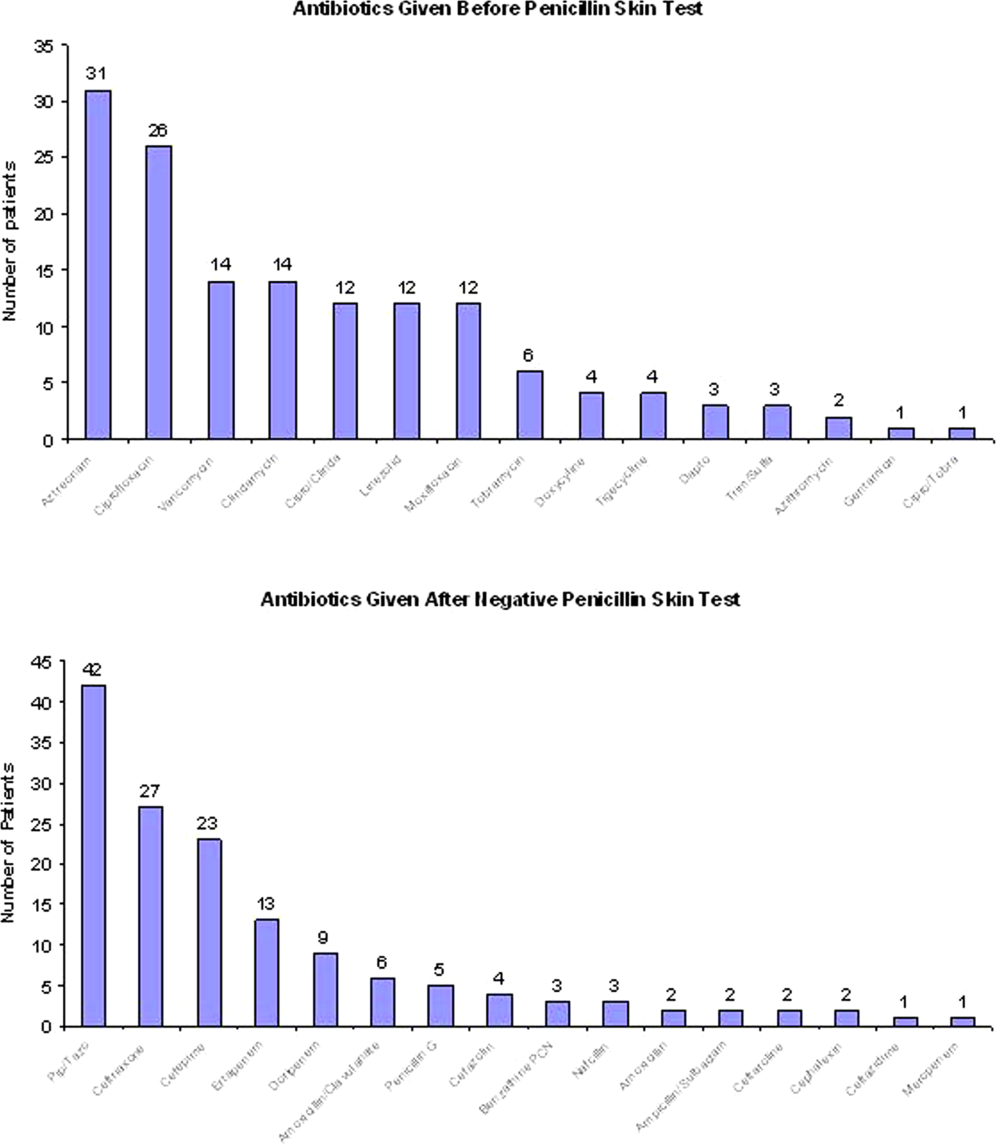

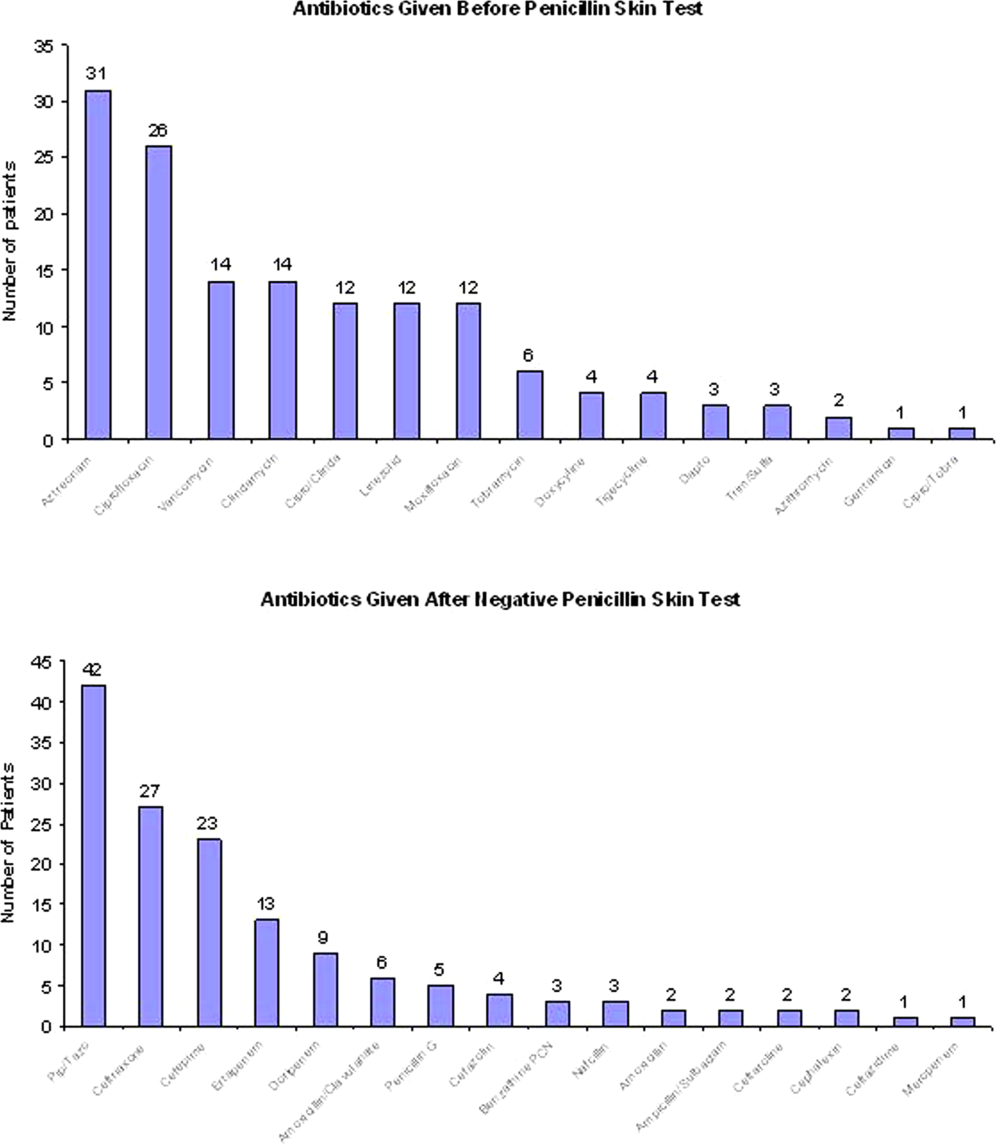

A total of 4031 allergy histories were reviewed during the 5‐month study period to achieve the sample size of 146 patients (Table 1). Of those, 3885 were excluded (Figure 2). Common infections included pneumonias (26%) and urinary tract infections (20%) (Table 2) Only 1 subject had a positive reaction with hives, edema, and itching approximately 6 minutes after the agents were injected intradermally. The remaining 145 (99%) had negative reactions to the PST and oral challenge and were then successfully transitioned to a ‐lactam agent without any reaction at 24 hours, giving an NPV of 100%. Ten subjects were switched from intravenous to oral ‐lactam agents (Figure 1). Avoidance of PICC placement ($1,200) and removal ($65), dressing changes, weekly drug‐level testing, laboratory technician, and pharmaceutical drug calibration costs allowed for a healthcare reduction of $5,233 ($520/patient) based on the 146 patients studied. The total cost of therapy would have been $113,991 if the PST had not been performed. However, the cost of altered therapy following a negative PST was $81,180, a difference of $32,811 ($225/per patient) in a 5‐month period. The total estimated annual difference, including antibiotic alteration and associated drug‐costs, would be $82,000.

| Antibiotic | No. of Patients Reporting An Allergy | % Per Total Charts Reviewed |

|---|---|---|

| Penicillin | 428 | 10.6 |

| Sulfonamide | 271 | 6.7 |

| Quinolone | 108 | 2.7 |

| Cephalosporin | 81 | 2.0 |

| Macrolide | 65 | 1.6 |

| Vancomycin | 39 | 0.9 |

| Tetracycline | 20 | 0.5 |

| Clindamycin | 18 | 0.4 |

| Metronidazole | 9 | 0.2 |

| Linezolid | 2 | 0.05 |

| Categories | No. of Patients (%) |

|---|---|

| |

| Time since last reported penicillin use | |

| 1 month1 year | 6 (4) |

| 25 years | 39 (27) |

| 610 years | 23 (16) |

| >10 years | 78 (53) |

| Reported IgE‐mediated reactions | |

| Bronchospasm | 23 (16) |

| Urticarial rash | 100 (68) |

| Edema | 32 (22) |

| Anaphylaxis | 21 (14) |

| Age on admission, y | |

| 2050 | 28 (19) |

| 5160 | 29 (20) |

| 6170 | 41 (28) |

| 7180 | 24 (16) |

| >80 | 24 (16) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 55 (40) |

| Female | 88 (60) |

| Race | |

| White | 82 (56) |

| Black | 61 (42) |

| Hispanic | 3 (2) |

| Infections being treated | |

| Bacteremia | 7 (4.8) |

| Catheter‐related bloodstream infection | 2 (1.4) |

| Empyema | 1 (0.7) |

| Epidural abscess | 2 (1.4) |

| Infective endocarditis | 4 (2.7) |

| Intra‐abdominal infection | 24 (16.4) |

| Meningitis | 1 (0.7) |

| Neutropenic fever | 1 (0.7) |

| Osteomyelitis | 6 (4.1) |

| Pericardial effusion | 1 (0.7) |

| Prosthetic joint infection | 5 (3.4) |

| Pneumonia | 40 (27.4) |

| Skin and soft‐tissue infection | 20 (13.7) |

| Syphilis | 3 (2.1) |

| Urinary tract infection | 29 (19.7) |

DISCUSSION

PST is the most rapid, sensitive, and cost‐effective modality for evaluating patients with immediate allergic reactions to penicillin. Over 90% of individuals with a true history of penicillin allergy have confirmed sensitivity with a PST, implying most patients who are skin tested negative are truly not allergic.[7, 9, 10, 11, 12] Our study shows that the reapproved PST with the PPL and penicillin G determinants continues to have a high NPV. A patient with a negative PST result is generally at a low risk of developing an immediate‐type hypersensitivity reaction to penicillin.[2, 11] PST frequently allowed for less expensive agents that would have been avoided due to a reported allergy. The estimated annual savings of $82,000 dollars from antibiotic alteration with successful transition to a ‐lactam agent after a negative PST illustrates its value, supports its validity, and makes this study novel.

Many ‐lactamase inhibitors (ie, piperacillin‐tazobactam), fourth generation cephalosporins (ie, cefepime), and carbapenems still remain costly. Despite this, we were still able to achieve a significant reduction in overall cost. In addition to financial benefits, PST allowed for the use of more appropriate agents with less potential adverse effects. Narrow‐spectrum, non‐lactam agents were sometimes altered to a broader‐spectrum ‐lactam agent. We also frequently tailored 2 agents to just 1 broad‐spectrum ‐lactam. This led to more patients being given broad‐spectrum agents after the PST (72 vs 89 patients). However, we were able to avoid using second‐line agents, such as aztreonam, vancomycin, linezolid, daptomycin, and tobramycin, in many patients with infections that are often best treated with penicillin‐based antibiotics (ie, syphilis, group B Streptococcus infections). With increasing incidence and recovery of multidrug‐resistant bacteria, PST may also allow use of potentially more effective antimicrobial agents.

A possible limitation is that our prevalence of a true penicillin allergy was 1%, whereas Bousquet et al. illustrate a higher prevalence of about 20%.[7] Although our prevalence may not be generalizable, Bousquet's study only assessed patients with allergies 5 years prior.

The introduction of PST into clinical practice will allow trained healthcare providers to prescribe cheaper, more appropriate, less toxic antimicrobial agents. The overall benefit of reintroducing penicillin agents when needed in the future is far more cost‐effective than what is described here. PST should become a standard of care when prescribing antibiotics to patients with a history of penicillin allergy. Medical providers should be aware of its utility, acquire training, and incorporate it into their practice.

Acknowledgment

Disclosures: Paul P. Cook, MD, has potential conflicts of interest with Gilead (investigator), Pfizer (investigator), Merck (investigator and speakers' bureau), and Forest (speakers' bureau). Neither he nor any of the other authors has received any sources of funding for this article. For the remaining authors, no conflicts were declared. The corresponding author, Ramzy Rimawi, MD, had full access to all of the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Self‐reported penicillin allergy is common and frequently limits the available antimicrobial agents to choose from. This often results in the use of more expensive, potentially more toxic, and possibly less efficacious agents.[1, 2]

For over 30 years, penicilloyl‐polylysine (PPL) penicillin skin testing (PST) was widely used to diagnose penicillin allergy with a negative predictive value (NPV) of about 97% to 99%.[3] After being off the market for 5 years, PPL PST was reapproved in 2009 as PRE‐PEN.[4] However, many clinicians still fail to utilize PST despite its simplicity and substantial clinical impact. The main purpose of this study was to describe the predictive value of PST and impact on antibiotic selection in a sample of hospitalized patients with a reported history of penicillin allergy.

METHODS

In 2010, PST was introduced as a quality‐improvement measure after approval and support from the chief of professional services and the medical staff executive committee at Vidant Medical Center, an 861‐bed tertiary care and teaching hospital. Our antimicrobial stewardship program is regularly contacted for approval of alternative therapies in penicillin allergic patients. The PST quality‐improvement intervention was implemented to avoid resorting to less appropriate therapies in these situations. Following approval by the University and Medical Center Institutional Review Board, we designed a 4‐month study to assess the impact of this ongoing quality improvement measure from March 2012 to July 2012.

Hospitalized patients of all ages with reported penicillin allergies were obtained from our antimicrobial stewardship database. Their charts were reviewed for demographics, antibiotic use, clinical infection, and allergic description. Deciding whether to alter antibiotic therapy to a ‐lactam regimen was based on microbiologic results, laboratory values, clinical infection, and history of immunoglobulin E (IgE)‐mediated reactions, as defined by the updated drug allergy practice parameters.[5] IgE‐mediated reactions included: (1) immediate urticaria, laryngeal edema, or hypotension; (2) anemia; and (3) fever, arthralgias, lymphadenopathy, and an urticarial rash after 7 to 21 days.[5, 6, 7] We defined anaphylaxis as the development of angioedema or hemodynamic instability within 1 hour of penicillin administration. A true negative reaction was a lack of an IgE‐mediated reaction to all the drug challenges.

Patients in the medical, surgical, labor, and delivery wards; intensive care units; and emergency department underwent testing. The ‐lactam agent used after a negative PST was recorded, and the patients were followed for 24 hours after transitioning their therapy to a ‐lactam regimen. Excluded subjects included those with (1) nonIgE‐mediated reactions, (2) skin conditions that can give false positive results, (3) medications that may interfere with anaphylactic therapy, (4) history of severe exfoliative reactions to ‐lactams, (5) anaphylaxis less than 4 weeks prior, (6) allergies to antibiotics other than penicillin, and (7) uncertain allergy history.

PST Reagents/Procedure

Our benzylpenicilloyl major determinant molecule, commercially produced as PPL, was purchased as a PRE‐PEN from ALK‐Abello, Round Rock, Texas. Penicillin G potassium, purchased from Pfizer, New York, New York, is the only commercially available minor determinant and can improve identification of penicillin allergy by up to 97%.[2] The PST panel also included histamine (positive control) and normal saline (negative control).

Skin Testing Procedure

An infectious diseases fellow (R.H.R. or B.K.) was supervised in preparing for potential anaphylaxis, applying the reagents and interpreting the results based on drug allergy practice parameters.[5] The preliminary epicutaneous prick/puncture test was performed with a lancet in subjects without prior anaphylaxis using full‐strength PPL and penicillin G potassium reagents. If there was no response within 15 minutes, which we defined as a lack of wheal formation 3 mm or greater than that of the negative control, 0.02 to 0.03 mL of each reagent was injected intradermally using a tuberculin syringe and examined for 15 minutes.[5] If there was no response, patients were then challenged with either a single oral dose of penicillin V potassium 250 mg or whichever oral penicillin agent they previously reported an allergy to. If no reaction was appreciated within 2 hours, their therapy was changed to a ‐lactam agent including penicillins, cephalosporins, and carbapenems for the remaining duration of therapy (Figure 1) An estimate of NPV was obtained after 24 hours follow‐up.

Statistical Analysis

We designed a study to estimate whether the reapproved PST achieves an NPV of at least 95%.[3] We hypothesized that clinicians will be willing to utilize PST even if it has an NPV of slightly less than 98% compared to the current standard of treating patients without PST.[7] Assuming an equivalence margin of 3%, we estimated a sample size of 146 to achieve at least 82% power to test a hypothesis of NPV 95% using a 1‐sided Z test with a type‐I error rate of 5%.[8] Once the sample size of 146 subjects was reached, we stopped recruiting patients.

Sample characteristics of the subjects who underwent testing were summarized using descriptive statistics. Sample proportions were calculated to summarize categorical variables. Mean and standard deviation were calculated to summarize continuous variables. Cost analysis of antibiotic therapy was estimated from the Vidant Medical Center antibiotic pharmaceutical acquisition costs. Estimated cost of peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) placement and removal as well as laboratory testing costs were obtained from our institution's medical billing department. Marketing costs of pharmacist drug calibration and nursing assessments with dressing changes were obtained from hospital‐affiliated outpatient antibiotic infusion companies.

RESULTS

A total of 4031 allergy histories were reviewed during the 5‐month study period to achieve the sample size of 146 patients (Table 1). Of those, 3885 were excluded (Figure 2). Common infections included pneumonias (26%) and urinary tract infections (20%) (Table 2) Only 1 subject had a positive reaction with hives, edema, and itching approximately 6 minutes after the agents were injected intradermally. The remaining 145 (99%) had negative reactions to the PST and oral challenge and were then successfully transitioned to a ‐lactam agent without any reaction at 24 hours, giving an NPV of 100%. Ten subjects were switched from intravenous to oral ‐lactam agents (Figure 1). Avoidance of PICC placement ($1,200) and removal ($65), dressing changes, weekly drug‐level testing, laboratory technician, and pharmaceutical drug calibration costs allowed for a healthcare reduction of $5,233 ($520/patient) based on the 146 patients studied. The total cost of therapy would have been $113,991 if the PST had not been performed. However, the cost of altered therapy following a negative PST was $81,180, a difference of $32,811 ($225/per patient) in a 5‐month period. The total estimated annual difference, including antibiotic alteration and associated drug‐costs, would be $82,000.

| Antibiotic | No. of Patients Reporting An Allergy | % Per Total Charts Reviewed |

|---|---|---|

| Penicillin | 428 | 10.6 |

| Sulfonamide | 271 | 6.7 |

| Quinolone | 108 | 2.7 |

| Cephalosporin | 81 | 2.0 |

| Macrolide | 65 | 1.6 |

| Vancomycin | 39 | 0.9 |

| Tetracycline | 20 | 0.5 |

| Clindamycin | 18 | 0.4 |

| Metronidazole | 9 | 0.2 |

| Linezolid | 2 | 0.05 |

| Categories | No. of Patients (%) |

|---|---|

| |

| Time since last reported penicillin use | |

| 1 month1 year | 6 (4) |

| 25 years | 39 (27) |

| 610 years | 23 (16) |

| >10 years | 78 (53) |

| Reported IgE‐mediated reactions | |

| Bronchospasm | 23 (16) |

| Urticarial rash | 100 (68) |

| Edema | 32 (22) |

| Anaphylaxis | 21 (14) |

| Age on admission, y | |

| 2050 | 28 (19) |

| 5160 | 29 (20) |

| 6170 | 41 (28) |

| 7180 | 24 (16) |

| >80 | 24 (16) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 55 (40) |

| Female | 88 (60) |

| Race | |

| White | 82 (56) |

| Black | 61 (42) |

| Hispanic | 3 (2) |

| Infections being treated | |

| Bacteremia | 7 (4.8) |

| Catheter‐related bloodstream infection | 2 (1.4) |

| Empyema | 1 (0.7) |

| Epidural abscess | 2 (1.4) |