User login

Making the Final Rule Meaningful: What It Means for You

On Oct. 6, after many months of anticipation, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT published the 2015 Meaningful Use final rule. This long-awaited document, weighing in at almost 800 pages, contains some major changes to the Meaningful Use program beginning this year. By the time you read this, you’ll no doubt have heard about the major aspects of the changes. Regardless, we thought it would be useful to focus our lens on the new rules and consider how they will translate from the legislature into the real world.

What’s new?

Contrary to its name, the electronic health record incentive program has been considered hardly “meaningful” by physicians struggling to meet the objectives. Up to this point, it’s seemingly been more about busywork and aimless button-clicking than meaningful work. The 2015 final rule seeks to finally change that. In the press release accompanying the announcement, Dr. Patrick Conway, CMS Deputy Administrator, offered the following:

“We have a shared goal of electronic health records helping physicians, clinicians, and hospitals to deliver better care, smarter spending, and healthier people. We eliminated unnecessary requirements, simplified and increased flexibility for those that remain, and focused on interoperability, information exchange, and patient engagement.”

Expanding on his comments, we’ll first point out the change in length of the meaningful use reporting period. In 2015, it has been shortened to 90 days, regardless of stage. For most, this will elicit a huge sigh of relief, as providers now have the option to choose any continuous 90-day period within 2015 instead of being forced to report for the full year. This fundamental change adds tremendous flexibility to the program, as it eliminates the do-or-die scenario of full-year reporting and allows providers to retrospectively select an optimal attestation period.

Next is the streamlining of the required measures. From 20 measures, the list has been brought down to 10: 9 core objectives and 1 public health objective. In doing this, the CMS sought to remove the “checkbox processes” that have become a much-maligned hallmark of meaningful use. The agency also made an attempt to remove measures considered redundant, duplicative, or topped-out (such as demographic and vital sign documentation). Finally, the CMS essentially removed the core and menu structure and consolidated all measures, so that all providers are working off the same playbook, regardless of stage.

Third, and perhaps most interestingly, is the focus of the remaining objectives. As Dr. Conway related, the measures that the CMS has chosen to retain aim very clearly at a few key goals, with data-sharing principal among them. In fact, more than half the measures rely on information exchange. CMS has admitted that efforts thus far have not produced the kind of transformational interoperability intended, but that ultimately this is the direction EHRs need to take if they are to fulfill their true promise. Although we tend to agree (and we will be writing in greater detail about this in future columns), we feel it’s important to note that this will continue to be challenging for providers and vendors. Until data standards are universally adopted by EHR vendors, health care providers will be forced to bear the burden of imperfect interoperability.

Fortunately, one area in which the burden on physicians has been lightened is patient participation in meaningful use. The CMS has realized the impracticality of measures that rely completely on patients for success and removed the compliance thresholds for secure electronic messages and electronic portal usage. These tools need to be made available to patients, but providers are no longer held responsible for whether or not a certain percentage of patients choose to use them. In 2015, only one patient needs to “view, download, or transmit” information through a patient portal, and secure email capability only needs to be enabled, even if no one opts to use it.

Finally, the CMS is clear to point out that it sympathizes with those who have been unsuccessful in attaining meaningful use, encouraging them to submit requests for hardship exceptions “through the existing request process.” Unfortunately, this process is fairly narrow in scope and really only applies in cases of vendor delays or significant unforeseen consequences (such as bankruptcy, fire, or natural disasters). Still, there is no penalty in applying for an exception even if it is not granted, so, while CMS plans to grant only a limited number of exceptions, we would echo the encouragement to apply if needed.

What’s next?

The 2015 final rule is yet another step in laying groundwork for Meaningful Use stage III, which will be optional in 2017 and mandatory in 2018. The delay offers providers and vendors additional time to adapt and comply with the new regulations, while hopefully adding simplicity and flexibility to the process. Ultimately, this also better aligns reporting Meaningful Use with other incentive programs, all of which will be eventually consolidated under MIPS, the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (we’ll have more on this in a later column, but we want you to know that it is a new system of value-based reimbursement that will sunset the Meaningful Use payment adjustment at the end of calendar year 2018).

We applaud the efforts taken by CMS and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT to further streamline the Meaningful Use program and agree with their intent. According to the press release, they have attempted to “shift the paradigm so health IT becomes a tool for care improvement, not an end in itself.” We firmly believe in this idea, and are ultimately encouraged by the 2015 final rule.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

On Oct. 6, after many months of anticipation, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT published the 2015 Meaningful Use final rule. This long-awaited document, weighing in at almost 800 pages, contains some major changes to the Meaningful Use program beginning this year. By the time you read this, you’ll no doubt have heard about the major aspects of the changes. Regardless, we thought it would be useful to focus our lens on the new rules and consider how they will translate from the legislature into the real world.

What’s new?

Contrary to its name, the electronic health record incentive program has been considered hardly “meaningful” by physicians struggling to meet the objectives. Up to this point, it’s seemingly been more about busywork and aimless button-clicking than meaningful work. The 2015 final rule seeks to finally change that. In the press release accompanying the announcement, Dr. Patrick Conway, CMS Deputy Administrator, offered the following:

“We have a shared goal of electronic health records helping physicians, clinicians, and hospitals to deliver better care, smarter spending, and healthier people. We eliminated unnecessary requirements, simplified and increased flexibility for those that remain, and focused on interoperability, information exchange, and patient engagement.”

Expanding on his comments, we’ll first point out the change in length of the meaningful use reporting period. In 2015, it has been shortened to 90 days, regardless of stage. For most, this will elicit a huge sigh of relief, as providers now have the option to choose any continuous 90-day period within 2015 instead of being forced to report for the full year. This fundamental change adds tremendous flexibility to the program, as it eliminates the do-or-die scenario of full-year reporting and allows providers to retrospectively select an optimal attestation period.

Next is the streamlining of the required measures. From 20 measures, the list has been brought down to 10: 9 core objectives and 1 public health objective. In doing this, the CMS sought to remove the “checkbox processes” that have become a much-maligned hallmark of meaningful use. The agency also made an attempt to remove measures considered redundant, duplicative, or topped-out (such as demographic and vital sign documentation). Finally, the CMS essentially removed the core and menu structure and consolidated all measures, so that all providers are working off the same playbook, regardless of stage.

Third, and perhaps most interestingly, is the focus of the remaining objectives. As Dr. Conway related, the measures that the CMS has chosen to retain aim very clearly at a few key goals, with data-sharing principal among them. In fact, more than half the measures rely on information exchange. CMS has admitted that efforts thus far have not produced the kind of transformational interoperability intended, but that ultimately this is the direction EHRs need to take if they are to fulfill their true promise. Although we tend to agree (and we will be writing in greater detail about this in future columns), we feel it’s important to note that this will continue to be challenging for providers and vendors. Until data standards are universally adopted by EHR vendors, health care providers will be forced to bear the burden of imperfect interoperability.

Fortunately, one area in which the burden on physicians has been lightened is patient participation in meaningful use. The CMS has realized the impracticality of measures that rely completely on patients for success and removed the compliance thresholds for secure electronic messages and electronic portal usage. These tools need to be made available to patients, but providers are no longer held responsible for whether or not a certain percentage of patients choose to use them. In 2015, only one patient needs to “view, download, or transmit” information through a patient portal, and secure email capability only needs to be enabled, even if no one opts to use it.

Finally, the CMS is clear to point out that it sympathizes with those who have been unsuccessful in attaining meaningful use, encouraging them to submit requests for hardship exceptions “through the existing request process.” Unfortunately, this process is fairly narrow in scope and really only applies in cases of vendor delays or significant unforeseen consequences (such as bankruptcy, fire, or natural disasters). Still, there is no penalty in applying for an exception even if it is not granted, so, while CMS plans to grant only a limited number of exceptions, we would echo the encouragement to apply if needed.

What’s next?

The 2015 final rule is yet another step in laying groundwork for Meaningful Use stage III, which will be optional in 2017 and mandatory in 2018. The delay offers providers and vendors additional time to adapt and comply with the new regulations, while hopefully adding simplicity and flexibility to the process. Ultimately, this also better aligns reporting Meaningful Use with other incentive programs, all of which will be eventually consolidated under MIPS, the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (we’ll have more on this in a later column, but we want you to know that it is a new system of value-based reimbursement that will sunset the Meaningful Use payment adjustment at the end of calendar year 2018).

We applaud the efforts taken by CMS and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT to further streamline the Meaningful Use program and agree with their intent. According to the press release, they have attempted to “shift the paradigm so health IT becomes a tool for care improvement, not an end in itself.” We firmly believe in this idea, and are ultimately encouraged by the 2015 final rule.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

On Oct. 6, after many months of anticipation, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT published the 2015 Meaningful Use final rule. This long-awaited document, weighing in at almost 800 pages, contains some major changes to the Meaningful Use program beginning this year. By the time you read this, you’ll no doubt have heard about the major aspects of the changes. Regardless, we thought it would be useful to focus our lens on the new rules and consider how they will translate from the legislature into the real world.

What’s new?

Contrary to its name, the electronic health record incentive program has been considered hardly “meaningful” by physicians struggling to meet the objectives. Up to this point, it’s seemingly been more about busywork and aimless button-clicking than meaningful work. The 2015 final rule seeks to finally change that. In the press release accompanying the announcement, Dr. Patrick Conway, CMS Deputy Administrator, offered the following:

“We have a shared goal of electronic health records helping physicians, clinicians, and hospitals to deliver better care, smarter spending, and healthier people. We eliminated unnecessary requirements, simplified and increased flexibility for those that remain, and focused on interoperability, information exchange, and patient engagement.”

Expanding on his comments, we’ll first point out the change in length of the meaningful use reporting period. In 2015, it has been shortened to 90 days, regardless of stage. For most, this will elicit a huge sigh of relief, as providers now have the option to choose any continuous 90-day period within 2015 instead of being forced to report for the full year. This fundamental change adds tremendous flexibility to the program, as it eliminates the do-or-die scenario of full-year reporting and allows providers to retrospectively select an optimal attestation period.

Next is the streamlining of the required measures. From 20 measures, the list has been brought down to 10: 9 core objectives and 1 public health objective. In doing this, the CMS sought to remove the “checkbox processes” that have become a much-maligned hallmark of meaningful use. The agency also made an attempt to remove measures considered redundant, duplicative, or topped-out (such as demographic and vital sign documentation). Finally, the CMS essentially removed the core and menu structure and consolidated all measures, so that all providers are working off the same playbook, regardless of stage.

Third, and perhaps most interestingly, is the focus of the remaining objectives. As Dr. Conway related, the measures that the CMS has chosen to retain aim very clearly at a few key goals, with data-sharing principal among them. In fact, more than half the measures rely on information exchange. CMS has admitted that efforts thus far have not produced the kind of transformational interoperability intended, but that ultimately this is the direction EHRs need to take if they are to fulfill their true promise. Although we tend to agree (and we will be writing in greater detail about this in future columns), we feel it’s important to note that this will continue to be challenging for providers and vendors. Until data standards are universally adopted by EHR vendors, health care providers will be forced to bear the burden of imperfect interoperability.

Fortunately, one area in which the burden on physicians has been lightened is patient participation in meaningful use. The CMS has realized the impracticality of measures that rely completely on patients for success and removed the compliance thresholds for secure electronic messages and electronic portal usage. These tools need to be made available to patients, but providers are no longer held responsible for whether or not a certain percentage of patients choose to use them. In 2015, only one patient needs to “view, download, or transmit” information through a patient portal, and secure email capability only needs to be enabled, even if no one opts to use it.

Finally, the CMS is clear to point out that it sympathizes with those who have been unsuccessful in attaining meaningful use, encouraging them to submit requests for hardship exceptions “through the existing request process.” Unfortunately, this process is fairly narrow in scope and really only applies in cases of vendor delays or significant unforeseen consequences (such as bankruptcy, fire, or natural disasters). Still, there is no penalty in applying for an exception even if it is not granted, so, while CMS plans to grant only a limited number of exceptions, we would echo the encouragement to apply if needed.

What’s next?

The 2015 final rule is yet another step in laying groundwork for Meaningful Use stage III, which will be optional in 2017 and mandatory in 2018. The delay offers providers and vendors additional time to adapt and comply with the new regulations, while hopefully adding simplicity and flexibility to the process. Ultimately, this also better aligns reporting Meaningful Use with other incentive programs, all of which will be eventually consolidated under MIPS, the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (we’ll have more on this in a later column, but we want you to know that it is a new system of value-based reimbursement that will sunset the Meaningful Use payment adjustment at the end of calendar year 2018).

We applaud the efforts taken by CMS and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT to further streamline the Meaningful Use program and agree with their intent. According to the press release, they have attempted to “shift the paradigm so health IT becomes a tool for care improvement, not an end in itself.” We firmly believe in this idea, and are ultimately encouraged by the 2015 final rule.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

Making the final rule meaningful: What it means for you

On Oct. 6, after many months of anticipation, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT published the 2015 Meaningful Use final rule. This long-awaited document, weighing in at almost 800 pages, contains some major changes to the Meaningful Use program beginning this year. By the time you read this, you’ll no doubt have heard about the major aspects of the changes. Regardless, we thought it would be useful to focus our lens on the new rules and consider how they will translate from the legislature into the real world.

What’s new?

Contrary to its name, the electronic health record incentive program has been considered hardly “meaningful” by physicians struggling to meet the objectives. Up to this point, it’s seemingly been more about busywork and aimless button-clicking than meaningful work. The 2015 final rule seeks to finally change that. In the press release accompanying the announcement, Dr. Patrick Conway, CMS Deputy Administrator, offered the following:

“We have a shared goal of electronic health records helping physicians, clinicians, and hospitals to deliver better care, smarter spending, and healthier people. We eliminated unnecessary requirements, simplified and increased flexibility for those that remain, and focused on interoperability, information exchange, and patient engagement.”

Expanding on his comments, we’ll first point out the change in length of the meaningful use reporting period. In 2015, it has been shortened to 90 days, regardless of stage. For most, this will elicit a huge sigh of relief, as providers now have the option to choose any continuous 90-day period within 2015 instead of being forced to report for the full year. This fundamental change adds tremendous flexibility to the program, as it eliminates the do-or-die scenario of full-year reporting and allows providers to retrospectively select an optimal attestation period.

Next is the streamlining of the required measures. From 20 measures, the list has been brought down to 10: 9 core objectives and 1 public health objective. In doing this, the CMS sought to remove the “checkbox processes” that have become a much-maligned hallmark of meaningful use. The agency also made an attempt to remove measures considered redundant, duplicative, or topped-out (such as demographic and vital sign documentation). Finally, the CMS essentially removed the core and menu structure and consolidated all measures, so that all providers are working off the same playbook, regardless of stage.

Third, and perhaps most interestingly, is the focus of the remaining objectives. As Dr. Conway related, the measures that the CMS has chosen to retain aim very clearly at a few key goals, with data-sharing principal among them. In fact, more than half the measures rely on information exchange. CMS has admitted that efforts thus far have not produced the kind of transformational interoperability intended, but that ultimately this is the direction EHRs need to take if they are to fulfill their true promise. Although we tend to agree (and we will be writing in greater detail about this in future columns), we feel it’s important to note that this will continue to be challenging for providers and vendors. Until data standards are universally adopted by EHR vendors, health care providers will be forced to bear the burden of imperfect interoperability.

Fortunately, one area in which the burden on physicians has been lightened is patient participation in meaningful use. The CMS has realized the impracticality of measures that rely completely on patients for success and removed the compliance thresholds for secure electronic messages and electronic portal usage. These tools need to be made available to patients, but providers are no longer held responsible for whether or not a certain percentage of patients choose to use them. In 2015, only one patient needs to “view, download, or transmit” information through a patient portal, and secure email capability only needs to be enabled, even if no one opts to use it.

Finally, the CMS is clear to point out that it sympathizes with those who have been unsuccessful in attaining meaningful use, encouraging them to submit requests for hardship exceptions “through the existing request process.” Unfortunately, this process is fairly narrow in scope and really only applies in cases of vendor delays or significant unforeseen consequences (such as bankruptcy, fire, or natural disasters). Still, there is no penalty in applying for an exception even if it is not granted, so, while CMS plans to grant only a limited number of exceptions, we would echo the encouragement to apply if needed.

What’s next?

The 2015 final rule is yet another step in laying groundwork for Meaningful Use stage III, which will be optional in 2017 and mandatory in 2018. The delay offers providers and vendors additional time to adapt and comply with the new regulations, while hopefully adding simplicity and flexibility to the process. Ultimately, this also better aligns reporting Meaningful Use with other incentive programs, all of which will be eventually consolidated under MIPS, the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (we’ll have more on this in a later column, but we want you to know that it is a new system of value-based reimbursement that will sunset the Meaningful Use payment adjustment at the end of calendar year 2018).

We applaud the efforts taken by CMS and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT to further streamline the Meaningful Use program and agree with their intent. According to the press release, they have attempted to “shift the paradigm so health IT becomes a tool for care improvement, not an end in itself.” We firmly believe in this idea, and are ultimately encouraged by the 2015 final rule.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

On Oct. 6, after many months of anticipation, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT published the 2015 Meaningful Use final rule. This long-awaited document, weighing in at almost 800 pages, contains some major changes to the Meaningful Use program beginning this year. By the time you read this, you’ll no doubt have heard about the major aspects of the changes. Regardless, we thought it would be useful to focus our lens on the new rules and consider how they will translate from the legislature into the real world.

What’s new?

Contrary to its name, the electronic health record incentive program has been considered hardly “meaningful” by physicians struggling to meet the objectives. Up to this point, it’s seemingly been more about busywork and aimless button-clicking than meaningful work. The 2015 final rule seeks to finally change that. In the press release accompanying the announcement, Dr. Patrick Conway, CMS Deputy Administrator, offered the following:

“We have a shared goal of electronic health records helping physicians, clinicians, and hospitals to deliver better care, smarter spending, and healthier people. We eliminated unnecessary requirements, simplified and increased flexibility for those that remain, and focused on interoperability, information exchange, and patient engagement.”

Expanding on his comments, we’ll first point out the change in length of the meaningful use reporting period. In 2015, it has been shortened to 90 days, regardless of stage. For most, this will elicit a huge sigh of relief, as providers now have the option to choose any continuous 90-day period within 2015 instead of being forced to report for the full year. This fundamental change adds tremendous flexibility to the program, as it eliminates the do-or-die scenario of full-year reporting and allows providers to retrospectively select an optimal attestation period.

Next is the streamlining of the required measures. From 20 measures, the list has been brought down to 10: 9 core objectives and 1 public health objective. In doing this, the CMS sought to remove the “checkbox processes” that have become a much-maligned hallmark of meaningful use. The agency also made an attempt to remove measures considered redundant, duplicative, or topped-out (such as demographic and vital sign documentation). Finally, the CMS essentially removed the core and menu structure and consolidated all measures, so that all providers are working off the same playbook, regardless of stage.

Third, and perhaps most interestingly, is the focus of the remaining objectives. As Dr. Conway related, the measures that the CMS has chosen to retain aim very clearly at a few key goals, with data-sharing principal among them. In fact, more than half the measures rely on information exchange. CMS has admitted that efforts thus far have not produced the kind of transformational interoperability intended, but that ultimately this is the direction EHRs need to take if they are to fulfill their true promise. Although we tend to agree (and we will be writing in greater detail about this in future columns), we feel it’s important to note that this will continue to be challenging for providers and vendors. Until data standards are universally adopted by EHR vendors, health care providers will be forced to bear the burden of imperfect interoperability.

Fortunately, one area in which the burden on physicians has been lightened is patient participation in meaningful use. The CMS has realized the impracticality of measures that rely completely on patients for success and removed the compliance thresholds for secure electronic messages and electronic portal usage. These tools need to be made available to patients, but providers are no longer held responsible for whether or not a certain percentage of patients choose to use them. In 2015, only one patient needs to “view, download, or transmit” information through a patient portal, and secure email capability only needs to be enabled, even if no one opts to use it.

Finally, the CMS is clear to point out that it sympathizes with those who have been unsuccessful in attaining meaningful use, encouraging them to submit requests for hardship exceptions “through the existing request process.” Unfortunately, this process is fairly narrow in scope and really only applies in cases of vendor delays or significant unforeseen consequences (such as bankruptcy, fire, or natural disasters). Still, there is no penalty in applying for an exception even if it is not granted, so, while CMS plans to grant only a limited number of exceptions, we would echo the encouragement to apply if needed.

What’s next?

The 2015 final rule is yet another step in laying groundwork for Meaningful Use stage III, which will be optional in 2017 and mandatory in 2018. The delay offers providers and vendors additional time to adapt and comply with the new regulations, while hopefully adding simplicity and flexibility to the process. Ultimately, this also better aligns reporting Meaningful Use with other incentive programs, all of which will be eventually consolidated under MIPS, the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (we’ll have more on this in a later column, but we want you to know that it is a new system of value-based reimbursement that will sunset the Meaningful Use payment adjustment at the end of calendar year 2018).

We applaud the efforts taken by CMS and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT to further streamline the Meaningful Use program and agree with their intent. According to the press release, they have attempted to “shift the paradigm so health IT becomes a tool for care improvement, not an end in itself.” We firmly believe in this idea, and are ultimately encouraged by the 2015 final rule.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

On Oct. 6, after many months of anticipation, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT published the 2015 Meaningful Use final rule. This long-awaited document, weighing in at almost 800 pages, contains some major changes to the Meaningful Use program beginning this year. By the time you read this, you’ll no doubt have heard about the major aspects of the changes. Regardless, we thought it would be useful to focus our lens on the new rules and consider how they will translate from the legislature into the real world.

What’s new?

Contrary to its name, the electronic health record incentive program has been considered hardly “meaningful” by physicians struggling to meet the objectives. Up to this point, it’s seemingly been more about busywork and aimless button-clicking than meaningful work. The 2015 final rule seeks to finally change that. In the press release accompanying the announcement, Dr. Patrick Conway, CMS Deputy Administrator, offered the following:

“We have a shared goal of electronic health records helping physicians, clinicians, and hospitals to deliver better care, smarter spending, and healthier people. We eliminated unnecessary requirements, simplified and increased flexibility for those that remain, and focused on interoperability, information exchange, and patient engagement.”

Expanding on his comments, we’ll first point out the change in length of the meaningful use reporting period. In 2015, it has been shortened to 90 days, regardless of stage. For most, this will elicit a huge sigh of relief, as providers now have the option to choose any continuous 90-day period within 2015 instead of being forced to report for the full year. This fundamental change adds tremendous flexibility to the program, as it eliminates the do-or-die scenario of full-year reporting and allows providers to retrospectively select an optimal attestation period.

Next is the streamlining of the required measures. From 20 measures, the list has been brought down to 10: 9 core objectives and 1 public health objective. In doing this, the CMS sought to remove the “checkbox processes” that have become a much-maligned hallmark of meaningful use. The agency also made an attempt to remove measures considered redundant, duplicative, or topped-out (such as demographic and vital sign documentation). Finally, the CMS essentially removed the core and menu structure and consolidated all measures, so that all providers are working off the same playbook, regardless of stage.

Third, and perhaps most interestingly, is the focus of the remaining objectives. As Dr. Conway related, the measures that the CMS has chosen to retain aim very clearly at a few key goals, with data-sharing principal among them. In fact, more than half the measures rely on information exchange. CMS has admitted that efforts thus far have not produced the kind of transformational interoperability intended, but that ultimately this is the direction EHRs need to take if they are to fulfill their true promise. Although we tend to agree (and we will be writing in greater detail about this in future columns), we feel it’s important to note that this will continue to be challenging for providers and vendors. Until data standards are universally adopted by EHR vendors, health care providers will be forced to bear the burden of imperfect interoperability.

Fortunately, one area in which the burden on physicians has been lightened is patient participation in meaningful use. The CMS has realized the impracticality of measures that rely completely on patients for success and removed the compliance thresholds for secure electronic messages and electronic portal usage. These tools need to be made available to patients, but providers are no longer held responsible for whether or not a certain percentage of patients choose to use them. In 2015, only one patient needs to “view, download, or transmit” information through a patient portal, and secure email capability only needs to be enabled, even if no one opts to use it.

Finally, the CMS is clear to point out that it sympathizes with those who have been unsuccessful in attaining meaningful use, encouraging them to submit requests for hardship exceptions “through the existing request process.” Unfortunately, this process is fairly narrow in scope and really only applies in cases of vendor delays or significant unforeseen consequences (such as bankruptcy, fire, or natural disasters). Still, there is no penalty in applying for an exception even if it is not granted, so, while CMS plans to grant only a limited number of exceptions, we would echo the encouragement to apply if needed.

What’s next?

The 2015 final rule is yet another step in laying groundwork for Meaningful Use stage III, which will be optional in 2017 and mandatory in 2018. The delay offers providers and vendors additional time to adapt and comply with the new regulations, while hopefully adding simplicity and flexibility to the process. Ultimately, this also better aligns reporting Meaningful Use with other incentive programs, all of which will be eventually consolidated under MIPS, the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (we’ll have more on this in a later column, but we want you to know that it is a new system of value-based reimbursement that will sunset the Meaningful Use payment adjustment at the end of calendar year 2018).

We applaud the efforts taken by CMS and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT to further streamline the Meaningful Use program and agree with their intent. According to the press release, they have attempted to “shift the paradigm so health IT becomes a tool for care improvement, not an end in itself.” We firmly believe in this idea, and are ultimately encouraged by the 2015 final rule.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

Clinical Guidelines: Pressure ulcers – prevention and treatment

Pressure ulcers affect approximately 3 million adults in the United States and cause significant morbidity, with treatment costs of approximately $11 billion per year. The prevalence varies between 0.4% and 38% in acute care settings and 2%-24% in long-term care settings. Because of the high prevalence and cost associated with pressure ulcers, there has been a push toward prevention and appropriate treatment.

Pressure ulcers are defined as damage to a localized area of skin resulting from pressure or pressure and shear. They are most common in patients who are limited in their mobility. Other risk factors include advanced age, black or Hispanic ethnicity, cognitive and physical impairments, and low body weight. Any comorbid condition that decreases skin integrity or healing may also be considered a risk factor, including fecal or urinary incontinence, diabetes, prolonged edema, a low albumin level, or malnutrition.

The American College of Physicians’s guidelines grade its recommendations by the strength and basis of the supporting data. A strong recommendation is one for which the benefits clearly outweigh the risks and burdens; a weak recommendation is defined as one in which the benefits do not outweigh the risks and burdens. There are three levels of evidence quality: low, moderate, and high.

The first recommendation for the prevention of pressure ulcers is to perform a risk assessment on all patients in order to identify who is at risk. There was no specific recommendation as to which, if any, risk assessment tool should be used. This was a weak recommendation supported by low-quality evidence. There are various scales available for assessing a patient’s risk of pressure ulcer development, including the Braden, Cubbin, Jackson, Norton, and Waterlow scales. There are pitfalls with each tool, and they have all been found to have a low sensitivity and specificity. There has not been any evidence to show that the use of a risk assessment scale is superior to clinical judgment in assessing a patient’s risk for developing pressure ulcers. Although there have been a few studies that directly compared the various risk assessment tools, none of the tools emerged as superior.

The second recommendation for the prevention of pressure ulcers is to use advanced static mattresses or mattress overlays in patients who are at increased risk for developing pressure ulcers. This was a strong recommendation supported by moderate-quality evidence. There are few studies that exist on interventions for pressure ulcer prevention, and the different types of interventions are often each used in only one study. This made comparing the strategies for prevention difficult.

The third recommendation for the prevention of pressure ulcers is not to use alternating air mattresses or air overlays in patients at increased risk for developing pressure ulcers. This weak recommendation is supported by moderate-quality evidence. Most of the studies compared found no significant difference between these and static mattresses; however, air-alternating mattresses were less tolerable to patients and cost more.

It should be noted that the analysis of commonly used methods for the prevention of pressure ulcers – heel support boots, wheelchair cushions, nutritional supplementation, dressings, and repositioning – found no statistically significant difference in the prevention of pressure ulcers. Therefore, they are not part of the recommendations from the ACP. Multicomponent team-based interventions do appear to show a benefit.

The first recommendation for the treatment of pressure ulcers is that protein and amino acid supplementation be used to decrease wound size. This was a weak recommendation based on low-quality evidence. There was no recommendation as to what dose of protein supplementation to use, and it should be noted it is unclear whether this is applicable to the entire population or reserved for patients with nutritional deficiencies. There was no evidence to suggest other supplementation with vitamin C should be recommended.

The second recommendation for the treatment of pressure ulcers is that hydrocolloid or foam dressings be used to decrease wound size. This was a weak recommendation based on low-quality evidence. There was insufficient evidence to comment on complete wound healing with hydrocolloid or foam dressings, and the relationship between the reduction of wound size and complete healing has not been well defined. The analysis evaluated other dressing types – dextranomer paste, topical collagen, and radiant heat dressings – and did not recommend their use.

The third recommendation for the treatment of pressure ulcers from the ACP is the use of electrical stimulation as an adjunctive therapy to help accelerate wound healing. This was a weak recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence. It should be noted that this treatment modality was associated with an increase in adverse events, especially skin irritation, in the elderly population.

Other strategies evaluated for the treatment of pressure ulcers include the use of oxandrolone (an androgen used to promote weight gain), which was found to show no improvement versus placebo in wound healing and to have associated adverse events. Additional therapies evaluated included electromagnetic therapy, therapeutic ultrasound, negative pressure wound therapy, light therapy, and laser therapy, which all showed no improvement in the reduction of wound size, or complete healing, when compared with sham therapies.

Bottom line

For the prevention of pressure ulcers, assess each patient for risk using clinical judgment or a risk assessment tool of your choice. When possible, choose static mattresses or mattress overlays rather than the more costly, and more bothersome, alternating air mattresses. For the treatment of pressure ulcers, use protein or amino acid supplementation to aid in wound healing, use hydrocolloid or foam dressings to help decrease wound size, and consider electrical stimulation as a treatment option in younger patients.

References

Risk Assessment and Prevention of Pressure Ulcers: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162[5]:359-69.

Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162[5]:370-9.

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia. Dr. Carcia is chief resident in the family medicine program at Abington.

Pressure ulcers affect approximately 3 million adults in the United States and cause significant morbidity, with treatment costs of approximately $11 billion per year. The prevalence varies between 0.4% and 38% in acute care settings and 2%-24% in long-term care settings. Because of the high prevalence and cost associated with pressure ulcers, there has been a push toward prevention and appropriate treatment.

Pressure ulcers are defined as damage to a localized area of skin resulting from pressure or pressure and shear. They are most common in patients who are limited in their mobility. Other risk factors include advanced age, black or Hispanic ethnicity, cognitive and physical impairments, and low body weight. Any comorbid condition that decreases skin integrity or healing may also be considered a risk factor, including fecal or urinary incontinence, diabetes, prolonged edema, a low albumin level, or malnutrition.

The American College of Physicians’s guidelines grade its recommendations by the strength and basis of the supporting data. A strong recommendation is one for which the benefits clearly outweigh the risks and burdens; a weak recommendation is defined as one in which the benefits do not outweigh the risks and burdens. There are three levels of evidence quality: low, moderate, and high.

The first recommendation for the prevention of pressure ulcers is to perform a risk assessment on all patients in order to identify who is at risk. There was no specific recommendation as to which, if any, risk assessment tool should be used. This was a weak recommendation supported by low-quality evidence. There are various scales available for assessing a patient’s risk of pressure ulcer development, including the Braden, Cubbin, Jackson, Norton, and Waterlow scales. There are pitfalls with each tool, and they have all been found to have a low sensitivity and specificity. There has not been any evidence to show that the use of a risk assessment scale is superior to clinical judgment in assessing a patient’s risk for developing pressure ulcers. Although there have been a few studies that directly compared the various risk assessment tools, none of the tools emerged as superior.

The second recommendation for the prevention of pressure ulcers is to use advanced static mattresses or mattress overlays in patients who are at increased risk for developing pressure ulcers. This was a strong recommendation supported by moderate-quality evidence. There are few studies that exist on interventions for pressure ulcer prevention, and the different types of interventions are often each used in only one study. This made comparing the strategies for prevention difficult.

The third recommendation for the prevention of pressure ulcers is not to use alternating air mattresses or air overlays in patients at increased risk for developing pressure ulcers. This weak recommendation is supported by moderate-quality evidence. Most of the studies compared found no significant difference between these and static mattresses; however, air-alternating mattresses were less tolerable to patients and cost more.

It should be noted that the analysis of commonly used methods for the prevention of pressure ulcers – heel support boots, wheelchair cushions, nutritional supplementation, dressings, and repositioning – found no statistically significant difference in the prevention of pressure ulcers. Therefore, they are not part of the recommendations from the ACP. Multicomponent team-based interventions do appear to show a benefit.

The first recommendation for the treatment of pressure ulcers is that protein and amino acid supplementation be used to decrease wound size. This was a weak recommendation based on low-quality evidence. There was no recommendation as to what dose of protein supplementation to use, and it should be noted it is unclear whether this is applicable to the entire population or reserved for patients with nutritional deficiencies. There was no evidence to suggest other supplementation with vitamin C should be recommended.

The second recommendation for the treatment of pressure ulcers is that hydrocolloid or foam dressings be used to decrease wound size. This was a weak recommendation based on low-quality evidence. There was insufficient evidence to comment on complete wound healing with hydrocolloid or foam dressings, and the relationship between the reduction of wound size and complete healing has not been well defined. The analysis evaluated other dressing types – dextranomer paste, topical collagen, and radiant heat dressings – and did not recommend their use.

The third recommendation for the treatment of pressure ulcers from the ACP is the use of electrical stimulation as an adjunctive therapy to help accelerate wound healing. This was a weak recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence. It should be noted that this treatment modality was associated with an increase in adverse events, especially skin irritation, in the elderly population.

Other strategies evaluated for the treatment of pressure ulcers include the use of oxandrolone (an androgen used to promote weight gain), which was found to show no improvement versus placebo in wound healing and to have associated adverse events. Additional therapies evaluated included electromagnetic therapy, therapeutic ultrasound, negative pressure wound therapy, light therapy, and laser therapy, which all showed no improvement in the reduction of wound size, or complete healing, when compared with sham therapies.

Bottom line

For the prevention of pressure ulcers, assess each patient for risk using clinical judgment or a risk assessment tool of your choice. When possible, choose static mattresses or mattress overlays rather than the more costly, and more bothersome, alternating air mattresses. For the treatment of pressure ulcers, use protein or amino acid supplementation to aid in wound healing, use hydrocolloid or foam dressings to help decrease wound size, and consider electrical stimulation as a treatment option in younger patients.

References

Risk Assessment and Prevention of Pressure Ulcers: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162[5]:359-69.

Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162[5]:370-9.

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia. Dr. Carcia is chief resident in the family medicine program at Abington.

Pressure ulcers affect approximately 3 million adults in the United States and cause significant morbidity, with treatment costs of approximately $11 billion per year. The prevalence varies between 0.4% and 38% in acute care settings and 2%-24% in long-term care settings. Because of the high prevalence and cost associated with pressure ulcers, there has been a push toward prevention and appropriate treatment.

Pressure ulcers are defined as damage to a localized area of skin resulting from pressure or pressure and shear. They are most common in patients who are limited in their mobility. Other risk factors include advanced age, black or Hispanic ethnicity, cognitive and physical impairments, and low body weight. Any comorbid condition that decreases skin integrity or healing may also be considered a risk factor, including fecal or urinary incontinence, diabetes, prolonged edema, a low albumin level, or malnutrition.

The American College of Physicians’s guidelines grade its recommendations by the strength and basis of the supporting data. A strong recommendation is one for which the benefits clearly outweigh the risks and burdens; a weak recommendation is defined as one in which the benefits do not outweigh the risks and burdens. There are three levels of evidence quality: low, moderate, and high.

The first recommendation for the prevention of pressure ulcers is to perform a risk assessment on all patients in order to identify who is at risk. There was no specific recommendation as to which, if any, risk assessment tool should be used. This was a weak recommendation supported by low-quality evidence. There are various scales available for assessing a patient’s risk of pressure ulcer development, including the Braden, Cubbin, Jackson, Norton, and Waterlow scales. There are pitfalls with each tool, and they have all been found to have a low sensitivity and specificity. There has not been any evidence to show that the use of a risk assessment scale is superior to clinical judgment in assessing a patient’s risk for developing pressure ulcers. Although there have been a few studies that directly compared the various risk assessment tools, none of the tools emerged as superior.

The second recommendation for the prevention of pressure ulcers is to use advanced static mattresses or mattress overlays in patients who are at increased risk for developing pressure ulcers. This was a strong recommendation supported by moderate-quality evidence. There are few studies that exist on interventions for pressure ulcer prevention, and the different types of interventions are often each used in only one study. This made comparing the strategies for prevention difficult.

The third recommendation for the prevention of pressure ulcers is not to use alternating air mattresses or air overlays in patients at increased risk for developing pressure ulcers. This weak recommendation is supported by moderate-quality evidence. Most of the studies compared found no significant difference between these and static mattresses; however, air-alternating mattresses were less tolerable to patients and cost more.

It should be noted that the analysis of commonly used methods for the prevention of pressure ulcers – heel support boots, wheelchair cushions, nutritional supplementation, dressings, and repositioning – found no statistically significant difference in the prevention of pressure ulcers. Therefore, they are not part of the recommendations from the ACP. Multicomponent team-based interventions do appear to show a benefit.

The first recommendation for the treatment of pressure ulcers is that protein and amino acid supplementation be used to decrease wound size. This was a weak recommendation based on low-quality evidence. There was no recommendation as to what dose of protein supplementation to use, and it should be noted it is unclear whether this is applicable to the entire population or reserved for patients with nutritional deficiencies. There was no evidence to suggest other supplementation with vitamin C should be recommended.

The second recommendation for the treatment of pressure ulcers is that hydrocolloid or foam dressings be used to decrease wound size. This was a weak recommendation based on low-quality evidence. There was insufficient evidence to comment on complete wound healing with hydrocolloid or foam dressings, and the relationship between the reduction of wound size and complete healing has not been well defined. The analysis evaluated other dressing types – dextranomer paste, topical collagen, and radiant heat dressings – and did not recommend their use.

The third recommendation for the treatment of pressure ulcers from the ACP is the use of electrical stimulation as an adjunctive therapy to help accelerate wound healing. This was a weak recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence. It should be noted that this treatment modality was associated with an increase in adverse events, especially skin irritation, in the elderly population.

Other strategies evaluated for the treatment of pressure ulcers include the use of oxandrolone (an androgen used to promote weight gain), which was found to show no improvement versus placebo in wound healing and to have associated adverse events. Additional therapies evaluated included electromagnetic therapy, therapeutic ultrasound, negative pressure wound therapy, light therapy, and laser therapy, which all showed no improvement in the reduction of wound size, or complete healing, when compared with sham therapies.

Bottom line

For the prevention of pressure ulcers, assess each patient for risk using clinical judgment or a risk assessment tool of your choice. When possible, choose static mattresses or mattress overlays rather than the more costly, and more bothersome, alternating air mattresses. For the treatment of pressure ulcers, use protein or amino acid supplementation to aid in wound healing, use hydrocolloid or foam dressings to help decrease wound size, and consider electrical stimulation as a treatment option in younger patients.

References

Risk Assessment and Prevention of Pressure Ulcers: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162[5]:359-69.

Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162[5]:370-9.

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia. Dr. Carcia is chief resident in the family medicine program at Abington.

Updates on Antidepressant Use

MINDFULNESS-BASED COGNITIVE THERAPY AND ANTIDEPRESSANTS

Kuyken W, Hayes R, Barrett B, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy compared with maintenance antidepressant treatment in the prevention of depressive relapse or recurrence (PREVENT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9988):63-73. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62222-4.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy—a group-based psychosocial intervention designed to enhance self-management of prodromal symptoms associated with depressive relapse—with support to taper or discontinue antidepressant treatment (MBCT-TS) is neither superior nor inferior to maintenance antidepressant treatment for preventing a depressive relapse, according to the PREVENT trial.

Researchers randomly assigned 424 patients to MBCT-TS or maintenance therapy and found no difference in time to relapse or recurrence of depression between the two groups. Rates of adverse effects were similar in both groups.

The study authors note that both treatments were associated with positive outcomes regarding relapse or recurrence, residual depressive symptoms, and quality of life.

COMMENTARY

Patients with recurrent depression have a 50% to 80% lifetime rate of relapse, making a prevention strategy an important part of their care. Current recommendations suggest long-term continuation of antidepressant treatment decreases recurrence by 50% to 60%.1 However, antidepressant medication only works for as long as you take it, and many people do not want to be on antidepressants long term. A previous study compared MBCT-TS, continuation of antidepressant medication, and placebo; the respective relapse rates of 28%, 27%, and 71% indicate that both MBCT-TS and antidepressant medication substantially decrease the rate of depression relapse.2 This study provides further evidence that MBCT-TS is an excellent alternative to antidepressant medication for decreasing depression relapse.

1. Geddes JR, Carney SM, Davies C, et al. Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet. 2003;361:653-661.

2. Segal ZV, Bieling P, Young T, et al. Antidepressant monotherapy vs sequential pharmacotherapy and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, or placebo, for relapse prophylaxis in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psych. 2010;67:1256-1264. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.168.

Continue for treating preconception depression: To stop SSRIs or not >>

TREATING PRECONCEPTION DEPRESSION: TO STOP SSRIs OR NOT

Andersen JT, Andersen NL, Horwitz H, et al. Exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in early pregnancy and the risk of miscarriage. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):655-661. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000447.

Miscarriage rates in women taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in early pregnancy were higher than in those not taking SSRIs but similar to those who discontinued SSRI treatment prior to pregnancy, a Danish cohort study revealed.

Out of 1.3 million pregnancies between 1997 and 2010, researchers identified 22,884 women who were exposed to an SSRI during the first 35 days of pregnancy and found miscarriage rates of 13% in those exposed to the antidepressants, compared to 11% for those not exposed. Investigators also identified 14,016 women who discontinued SSRI treatment three to 12 months prior to conception and found a miscarriage rate of 14%.

The adjusted hazard ratio for miscarriage while taking SSRIs in early pregnancy was 1.27, and for miscarriage after discontinuing SSRIs prior to pregnancy, 1.24. When the data were stratified according to specific SSRIs, rates were lowest among those taking fluoxetine during pregnancy (1.10) and highest among those taking sertraline (1.45). Miscarriage rates among women who stopped SSRIs prior to pregnancy were lowest for fluoxetine (1.2) and highest for escitalopram (1.33).

“Because the risk for miscarriage is elevated in both groups compared with an unexposed population, there is likely no benefit in discontinuing SSRI use before pregnancy to decrease one’s chances of miscarriage,” the study authors conclude.

COMMENTARY

The effects of depression on a woman’s experience during pregnancy are large, as are the effects of depression on pregnancy outcomes. Depression during pregnancy is associated with increased rates of prematurity, low birth weight, and preeclampsia.1 Depression during pregnancy is also an important risk factor for postpartum depression, which affects babies as well as mothers and is associated with maternal suicide.

At the same time, use of SSRIs in pregnancy has been inconsistently associated with miscarriage, cardiac defects, premature birth, and primary pulmonary hypertension in the newborn.2 This study is reassuring in that SSRIs are unlikely to be a significant contributor to miscarriage. But it is important to realize that this article only addresses miscarriage rates, not other potential effects of SSRIs on the fetus. The decision about the use of SSRIs in pregnancy remains a difficult one, balancing risk and benefit. When determining that balance, bear in mind that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown in other studies to be equally effective to medication in treating depression and may also be considered in our range of options for treatment of depression in pregnancy.3,4

The decision about whether to use or continue an SSRI and whether to use or supplement with CBT instead is an important one and always requires detailed discussion with the mother-to-be.

1. Grigoriadis S, VonderPorten EH, Mamisashvili L, et al. The impact of maternal depression during pregnancy on perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psych. 2013;74:e321-341.

2. Meltzer-Brody S. Treating perinatal depression: risks and stigma. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):653-654. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000498.

3. Keller MB, McCullough JP, Klein DN, et al. A comparison of nefazodone, the cognitive behavioral-analysis system of psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2001;345(3):232]. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(20): 1462-1470.

4. Cuijpers P, Hollon SD, van Straten A, et al. Does cognitive behaviour therapy have an enduring effect that is superior to keeping patients on continuation pharmacotherapy? A meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2013;3(4). pii: e002542. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002542.

Continue for suicide, self-harm rates, and antidepressants >>

SUICIDE, SELF-HARM RATES, AND ANTIDEPRESSANTS

Coupland C, Hill T, Morriss R, et al. Antidepressant use and risk of suicide and attempted suicide or self harm in people aged 20 to 64: cohort study using a primary care database. BMJ. 2015;350:h517. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h517.

In patients with clinical depression, rates of suicide and self-harm are similar among those treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants but significantly higher among those treated with other antidepressants, according to a review of 238,963 patients who were diagnosed with depression.

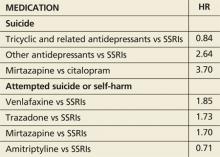

During an average five years’ follow-up, researchers noted 198 cases of suicide and 5,243 cases of attempted suicide or self-harm. The following hazard ratios (HR) were associated with antidepressant use:

Absolute risk for suicide over one year ranged from 0.02% for amitriptyline to 0.19% for mirtazapine.

COMMENTARY

This large study suggests suicide rates may be greater with non-SSRI antidepressants than with SSRIs. The data are far from solid, though, because of the small number of events and the potential for systematic differences in how these antidepressants are prescribed. For instance, if dual norepinephrine and serotonin agents are prescribed more often to individuals with more severe depression, then the increased suicide risk with use of combined norepinephrine/serotonin agents (eg, venlafaxine) could relate to the severity of the depression treated, not to an effect of the medication. Of importance is that the rate of suicide was increased in the first 28 days after starting an antidepressant and in the 28 days after stopping the antidepressant, times when we should have increased vigilance for suicidal ideation.

MINDFULNESS-BASED COGNITIVE THERAPY AND ANTIDEPRESSANTS

Kuyken W, Hayes R, Barrett B, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy compared with maintenance antidepressant treatment in the prevention of depressive relapse or recurrence (PREVENT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9988):63-73. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62222-4.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy—a group-based psychosocial intervention designed to enhance self-management of prodromal symptoms associated with depressive relapse—with support to taper or discontinue antidepressant treatment (MBCT-TS) is neither superior nor inferior to maintenance antidepressant treatment for preventing a depressive relapse, according to the PREVENT trial.

Researchers randomly assigned 424 patients to MBCT-TS or maintenance therapy and found no difference in time to relapse or recurrence of depression between the two groups. Rates of adverse effects were similar in both groups.

The study authors note that both treatments were associated with positive outcomes regarding relapse or recurrence, residual depressive symptoms, and quality of life.

COMMENTARY

Patients with recurrent depression have a 50% to 80% lifetime rate of relapse, making a prevention strategy an important part of their care. Current recommendations suggest long-term continuation of antidepressant treatment decreases recurrence by 50% to 60%.1 However, antidepressant medication only works for as long as you take it, and many people do not want to be on antidepressants long term. A previous study compared MBCT-TS, continuation of antidepressant medication, and placebo; the respective relapse rates of 28%, 27%, and 71% indicate that both MBCT-TS and antidepressant medication substantially decrease the rate of depression relapse.2 This study provides further evidence that MBCT-TS is an excellent alternative to antidepressant medication for decreasing depression relapse.

1. Geddes JR, Carney SM, Davies C, et al. Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet. 2003;361:653-661.

2. Segal ZV, Bieling P, Young T, et al. Antidepressant monotherapy vs sequential pharmacotherapy and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, or placebo, for relapse prophylaxis in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psych. 2010;67:1256-1264. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.168.

Continue for treating preconception depression: To stop SSRIs or not >>

TREATING PRECONCEPTION DEPRESSION: TO STOP SSRIs OR NOT

Andersen JT, Andersen NL, Horwitz H, et al. Exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in early pregnancy and the risk of miscarriage. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):655-661. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000447.

Miscarriage rates in women taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in early pregnancy were higher than in those not taking SSRIs but similar to those who discontinued SSRI treatment prior to pregnancy, a Danish cohort study revealed.

Out of 1.3 million pregnancies between 1997 and 2010, researchers identified 22,884 women who were exposed to an SSRI during the first 35 days of pregnancy and found miscarriage rates of 13% in those exposed to the antidepressants, compared to 11% for those not exposed. Investigators also identified 14,016 women who discontinued SSRI treatment three to 12 months prior to conception and found a miscarriage rate of 14%.

The adjusted hazard ratio for miscarriage while taking SSRIs in early pregnancy was 1.27, and for miscarriage after discontinuing SSRIs prior to pregnancy, 1.24. When the data were stratified according to specific SSRIs, rates were lowest among those taking fluoxetine during pregnancy (1.10) and highest among those taking sertraline (1.45). Miscarriage rates among women who stopped SSRIs prior to pregnancy were lowest for fluoxetine (1.2) and highest for escitalopram (1.33).

“Because the risk for miscarriage is elevated in both groups compared with an unexposed population, there is likely no benefit in discontinuing SSRI use before pregnancy to decrease one’s chances of miscarriage,” the study authors conclude.

COMMENTARY

The effects of depression on a woman’s experience during pregnancy are large, as are the effects of depression on pregnancy outcomes. Depression during pregnancy is associated with increased rates of prematurity, low birth weight, and preeclampsia.1 Depression during pregnancy is also an important risk factor for postpartum depression, which affects babies as well as mothers and is associated with maternal suicide.

At the same time, use of SSRIs in pregnancy has been inconsistently associated with miscarriage, cardiac defects, premature birth, and primary pulmonary hypertension in the newborn.2 This study is reassuring in that SSRIs are unlikely to be a significant contributor to miscarriage. But it is important to realize that this article only addresses miscarriage rates, not other potential effects of SSRIs on the fetus. The decision about the use of SSRIs in pregnancy remains a difficult one, balancing risk and benefit. When determining that balance, bear in mind that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown in other studies to be equally effective to medication in treating depression and may also be considered in our range of options for treatment of depression in pregnancy.3,4

The decision about whether to use or continue an SSRI and whether to use or supplement with CBT instead is an important one and always requires detailed discussion with the mother-to-be.

1. Grigoriadis S, VonderPorten EH, Mamisashvili L, et al. The impact of maternal depression during pregnancy on perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psych. 2013;74:e321-341.

2. Meltzer-Brody S. Treating perinatal depression: risks and stigma. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):653-654. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000498.

3. Keller MB, McCullough JP, Klein DN, et al. A comparison of nefazodone, the cognitive behavioral-analysis system of psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2001;345(3):232]. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(20): 1462-1470.

4. Cuijpers P, Hollon SD, van Straten A, et al. Does cognitive behaviour therapy have an enduring effect that is superior to keeping patients on continuation pharmacotherapy? A meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2013;3(4). pii: e002542. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002542.

Continue for suicide, self-harm rates, and antidepressants >>

SUICIDE, SELF-HARM RATES, AND ANTIDEPRESSANTS

Coupland C, Hill T, Morriss R, et al. Antidepressant use and risk of suicide and attempted suicide or self harm in people aged 20 to 64: cohort study using a primary care database. BMJ. 2015;350:h517. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h517.

In patients with clinical depression, rates of suicide and self-harm are similar among those treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants but significantly higher among those treated with other antidepressants, according to a review of 238,963 patients who were diagnosed with depression.

During an average five years’ follow-up, researchers noted 198 cases of suicide and 5,243 cases of attempted suicide or self-harm. The following hazard ratios (HR) were associated with antidepressant use:

Absolute risk for suicide over one year ranged from 0.02% for amitriptyline to 0.19% for mirtazapine.

COMMENTARY

This large study suggests suicide rates may be greater with non-SSRI antidepressants than with SSRIs. The data are far from solid, though, because of the small number of events and the potential for systematic differences in how these antidepressants are prescribed. For instance, if dual norepinephrine and serotonin agents are prescribed more often to individuals with more severe depression, then the increased suicide risk with use of combined norepinephrine/serotonin agents (eg, venlafaxine) could relate to the severity of the depression treated, not to an effect of the medication. Of importance is that the rate of suicide was increased in the first 28 days after starting an antidepressant and in the 28 days after stopping the antidepressant, times when we should have increased vigilance for suicidal ideation.

MINDFULNESS-BASED COGNITIVE THERAPY AND ANTIDEPRESSANTS

Kuyken W, Hayes R, Barrett B, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy compared with maintenance antidepressant treatment in the prevention of depressive relapse or recurrence (PREVENT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9988):63-73. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62222-4.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy—a group-based psychosocial intervention designed to enhance self-management of prodromal symptoms associated with depressive relapse—with support to taper or discontinue antidepressant treatment (MBCT-TS) is neither superior nor inferior to maintenance antidepressant treatment for preventing a depressive relapse, according to the PREVENT trial.

Researchers randomly assigned 424 patients to MBCT-TS or maintenance therapy and found no difference in time to relapse or recurrence of depression between the two groups. Rates of adverse effects were similar in both groups.

The study authors note that both treatments were associated with positive outcomes regarding relapse or recurrence, residual depressive symptoms, and quality of life.

COMMENTARY

Patients with recurrent depression have a 50% to 80% lifetime rate of relapse, making a prevention strategy an important part of their care. Current recommendations suggest long-term continuation of antidepressant treatment decreases recurrence by 50% to 60%.1 However, antidepressant medication only works for as long as you take it, and many people do not want to be on antidepressants long term. A previous study compared MBCT-TS, continuation of antidepressant medication, and placebo; the respective relapse rates of 28%, 27%, and 71% indicate that both MBCT-TS and antidepressant medication substantially decrease the rate of depression relapse.2 This study provides further evidence that MBCT-TS is an excellent alternative to antidepressant medication for decreasing depression relapse.

1. Geddes JR, Carney SM, Davies C, et al. Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet. 2003;361:653-661.

2. Segal ZV, Bieling P, Young T, et al. Antidepressant monotherapy vs sequential pharmacotherapy and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, or placebo, for relapse prophylaxis in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psych. 2010;67:1256-1264. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.168.

Continue for treating preconception depression: To stop SSRIs or not >>

TREATING PRECONCEPTION DEPRESSION: TO STOP SSRIs OR NOT

Andersen JT, Andersen NL, Horwitz H, et al. Exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in early pregnancy and the risk of miscarriage. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):655-661. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000447.

Miscarriage rates in women taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in early pregnancy were higher than in those not taking SSRIs but similar to those who discontinued SSRI treatment prior to pregnancy, a Danish cohort study revealed.

Out of 1.3 million pregnancies between 1997 and 2010, researchers identified 22,884 women who were exposed to an SSRI during the first 35 days of pregnancy and found miscarriage rates of 13% in those exposed to the antidepressants, compared to 11% for those not exposed. Investigators also identified 14,016 women who discontinued SSRI treatment three to 12 months prior to conception and found a miscarriage rate of 14%.

The adjusted hazard ratio for miscarriage while taking SSRIs in early pregnancy was 1.27, and for miscarriage after discontinuing SSRIs prior to pregnancy, 1.24. When the data were stratified according to specific SSRIs, rates were lowest among those taking fluoxetine during pregnancy (1.10) and highest among those taking sertraline (1.45). Miscarriage rates among women who stopped SSRIs prior to pregnancy were lowest for fluoxetine (1.2) and highest for escitalopram (1.33).

“Because the risk for miscarriage is elevated in both groups compared with an unexposed population, there is likely no benefit in discontinuing SSRI use before pregnancy to decrease one’s chances of miscarriage,” the study authors conclude.

COMMENTARY

The effects of depression on a woman’s experience during pregnancy are large, as are the effects of depression on pregnancy outcomes. Depression during pregnancy is associated with increased rates of prematurity, low birth weight, and preeclampsia.1 Depression during pregnancy is also an important risk factor for postpartum depression, which affects babies as well as mothers and is associated with maternal suicide.