User login

BMI, age, and sex affect COVID-19 vaccine antibody response

The capacity to mount humoral immune responses to COVID-19 vaccinations may be reduced among people who are heavier, older, and male, new findings suggest.

The data pertain specifically to the mRNA vaccine, BNT162b2, developed by BioNTech and Pfizer. The study was conducted by Italian researchers and was published Feb. 26 as a preprint.

The study involved 248 health care workers who each received two doses of the vaccine. Of the participants, 99.5% developed a humoral immune response after the second dose. Those responses varied by body mass index (BMI), age, and sex.

“The findings imply that female, lean, and young people have an increased capacity to mount humoral immune responses, compared to male, overweight, and older populations,” Raul Pellini, MD, professor at the IRCCS Regina Elena National Cancer Institute, Rome, and colleagues said.

“To our knowledge, this study is the first to analyze Covid-19 vaccine response in correlation to BMI,” they noted.

“Although further studies are needed, this data may have important implications to the development of vaccination strategies for COVID-19, particularly in obese people,” they wrote. If the data are confirmed by larger studies, “giving obese people an extra dose of the vaccine or a higher dose could be options to be evaluated in this population.”

Results contrast with Pfizer trials of vaccine

The BMI finding seemingly contrasts with final data from the phase 3 clinical trial of the vaccine, which were reported in a supplement to an article published Dec. 31, 2020, in the New England Journal of Medicine. In that study, vaccine efficacy did not differ by obesity status.

Akiko Iwasaki, PhD, professor of immunology at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and an investigator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., noted that, although the current Italian study showed somewhat lower levels of antibodies in people with obesity, compared with people who did not have obesity, the phase 3 trial found no difference in symptomatic infection rates.

“These results indicate that even with a slightly lower level of antibody induced in obese people, that level was sufficient to protect against symptomatic infection,” Dr. Iwasaki said in an interview.

Indeed, Dr. Pellini and colleagues pointed out that responses to vaccines against influenza, hepatitis B, and rabies are also reduced in those with obesity, compared with lean individuals.

However, they said, it was especially important to study the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in people with obesity, because obesity is a major risk factor for morbidity and mortality in COVID-19.

“The constant state of low-grade inflammation, present in overweight people, can weaken some immune responses, including those launched by T cells, which can directly kill infected cells,” the authors noted.

Findings reported in British newspapers

The findings of the Italian study were widely covered in the lay press in the United Kingdom, with headlines such as “Pfizer Vaccine May Be Less Effective in People With Obesity, Says Study” and “Pfizer Vaccine: Overweight People Might Need Bigger Dose, Italian Study Says.” In tabloid newspapers, some headlines were slightly more stigmatizing.

The reports do stress that the Italian research was published as a preprint and has not been peer reviewed, or “is yet to be scrutinized by fellow scientists.”

Most make the point that there were only 26 people with obesity among the 248 persons in the study.

“We always knew that BMI was an enormous predictor of poor immune response to vaccines, so this paper is definitely interesting, although it is based on a rather small preliminary dataset,” Danny Altmann, PhD, a professor of immunology at Imperial College London, told the Guardian.

“It confirms that having a vaccinated population isn’t synonymous with having an immune population, especially in a country with high obesity, and emphasizes the vital need for long-term immune monitoring programs,” he added.

Antibody responses differ by BMI, age, and sex

In the Italian study, the participants – 158 women and 90 men – were assigned to receive a priming BNT162b2 vaccine dose with a booster at day 21. Blood and nasopharyngeal swabs were collected at baseline and 7 days after the second vaccine dose.

After the second dose, 99.5% of participants developed a humoral immune response; one person did not respond. None tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Titers of SARS-CoV-2–binding antibodies were greater in younger than in older participants. There were statistically significant differences between those aged 37 years and younger (453.5 AU/mL) and those aged 47-56 years (239.8 AU/mL; P = .005), those aged 37 years and younger versus those older than 56 years (453.5 vs 182.4 AU/mL; P < .0001), and those aged 37-47 years versus those older than 56 years (330.9 vs. 182.4 AU/mL; P = .01).

Antibody response was significantly greater for women than for men (338.5 vs. 212.6 AU/mL; P = .001).

Humoral responses were greater in persons of normal-weight BMI (18.5-24.9 kg/m2; 325.8 AU/mL) and those of underweight BMI (<18.5 kg/m2; 455.4 AU/mL), compared with persons with preobesity, defined as BMI of 25-29.9 (222.4 AU/mL), and those with obesity (BMI ≥30; 167.0 AU/mL; P < .0001). This association remained after adjustment for age (P = .003).

“Our data stresses the importance of close vaccination monitoring of obese people, considering the growing list of countries with obesity problems,” the researchers noted.

Hypertension was also associated with lower antibody titers (P = .006), but that lost statistical significance after matching for age (P = .22).

“We strongly believe that our results are extremely encouraging and useful for the scientific community,” Dr. Pellini and colleagues concluded.

The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Iwasaki is a cofounder of RIGImmune and is a member of its scientific advisory board.

This article was updated on 3/8/21.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The capacity to mount humoral immune responses to COVID-19 vaccinations may be reduced among people who are heavier, older, and male, new findings suggest.

The data pertain specifically to the mRNA vaccine, BNT162b2, developed by BioNTech and Pfizer. The study was conducted by Italian researchers and was published Feb. 26 as a preprint.

The study involved 248 health care workers who each received two doses of the vaccine. Of the participants, 99.5% developed a humoral immune response after the second dose. Those responses varied by body mass index (BMI), age, and sex.

“The findings imply that female, lean, and young people have an increased capacity to mount humoral immune responses, compared to male, overweight, and older populations,” Raul Pellini, MD, professor at the IRCCS Regina Elena National Cancer Institute, Rome, and colleagues said.

“To our knowledge, this study is the first to analyze Covid-19 vaccine response in correlation to BMI,” they noted.

“Although further studies are needed, this data may have important implications to the development of vaccination strategies for COVID-19, particularly in obese people,” they wrote. If the data are confirmed by larger studies, “giving obese people an extra dose of the vaccine or a higher dose could be options to be evaluated in this population.”

Results contrast with Pfizer trials of vaccine

The BMI finding seemingly contrasts with final data from the phase 3 clinical trial of the vaccine, which were reported in a supplement to an article published Dec. 31, 2020, in the New England Journal of Medicine. In that study, vaccine efficacy did not differ by obesity status.

Akiko Iwasaki, PhD, professor of immunology at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and an investigator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., noted that, although the current Italian study showed somewhat lower levels of antibodies in people with obesity, compared with people who did not have obesity, the phase 3 trial found no difference in symptomatic infection rates.

“These results indicate that even with a slightly lower level of antibody induced in obese people, that level was sufficient to protect against symptomatic infection,” Dr. Iwasaki said in an interview.

Indeed, Dr. Pellini and colleagues pointed out that responses to vaccines against influenza, hepatitis B, and rabies are also reduced in those with obesity, compared with lean individuals.

However, they said, it was especially important to study the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in people with obesity, because obesity is a major risk factor for morbidity and mortality in COVID-19.

“The constant state of low-grade inflammation, present in overweight people, can weaken some immune responses, including those launched by T cells, which can directly kill infected cells,” the authors noted.

Findings reported in British newspapers

The findings of the Italian study were widely covered in the lay press in the United Kingdom, with headlines such as “Pfizer Vaccine May Be Less Effective in People With Obesity, Says Study” and “Pfizer Vaccine: Overweight People Might Need Bigger Dose, Italian Study Says.” In tabloid newspapers, some headlines were slightly more stigmatizing.

The reports do stress that the Italian research was published as a preprint and has not been peer reviewed, or “is yet to be scrutinized by fellow scientists.”

Most make the point that there were only 26 people with obesity among the 248 persons in the study.

“We always knew that BMI was an enormous predictor of poor immune response to vaccines, so this paper is definitely interesting, although it is based on a rather small preliminary dataset,” Danny Altmann, PhD, a professor of immunology at Imperial College London, told the Guardian.

“It confirms that having a vaccinated population isn’t synonymous with having an immune population, especially in a country with high obesity, and emphasizes the vital need for long-term immune monitoring programs,” he added.

Antibody responses differ by BMI, age, and sex

In the Italian study, the participants – 158 women and 90 men – were assigned to receive a priming BNT162b2 vaccine dose with a booster at day 21. Blood and nasopharyngeal swabs were collected at baseline and 7 days after the second vaccine dose.

After the second dose, 99.5% of participants developed a humoral immune response; one person did not respond. None tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Titers of SARS-CoV-2–binding antibodies were greater in younger than in older participants. There were statistically significant differences between those aged 37 years and younger (453.5 AU/mL) and those aged 47-56 years (239.8 AU/mL; P = .005), those aged 37 years and younger versus those older than 56 years (453.5 vs 182.4 AU/mL; P < .0001), and those aged 37-47 years versus those older than 56 years (330.9 vs. 182.4 AU/mL; P = .01).

Antibody response was significantly greater for women than for men (338.5 vs. 212.6 AU/mL; P = .001).

Humoral responses were greater in persons of normal-weight BMI (18.5-24.9 kg/m2; 325.8 AU/mL) and those of underweight BMI (<18.5 kg/m2; 455.4 AU/mL), compared with persons with preobesity, defined as BMI of 25-29.9 (222.4 AU/mL), and those with obesity (BMI ≥30; 167.0 AU/mL; P < .0001). This association remained after adjustment for age (P = .003).

“Our data stresses the importance of close vaccination monitoring of obese people, considering the growing list of countries with obesity problems,” the researchers noted.

Hypertension was also associated with lower antibody titers (P = .006), but that lost statistical significance after matching for age (P = .22).

“We strongly believe that our results are extremely encouraging and useful for the scientific community,” Dr. Pellini and colleagues concluded.

The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Iwasaki is a cofounder of RIGImmune and is a member of its scientific advisory board.

This article was updated on 3/8/21.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The capacity to mount humoral immune responses to COVID-19 vaccinations may be reduced among people who are heavier, older, and male, new findings suggest.

The data pertain specifically to the mRNA vaccine, BNT162b2, developed by BioNTech and Pfizer. The study was conducted by Italian researchers and was published Feb. 26 as a preprint.

The study involved 248 health care workers who each received two doses of the vaccine. Of the participants, 99.5% developed a humoral immune response after the second dose. Those responses varied by body mass index (BMI), age, and sex.

“The findings imply that female, lean, and young people have an increased capacity to mount humoral immune responses, compared to male, overweight, and older populations,” Raul Pellini, MD, professor at the IRCCS Regina Elena National Cancer Institute, Rome, and colleagues said.

“To our knowledge, this study is the first to analyze Covid-19 vaccine response in correlation to BMI,” they noted.

“Although further studies are needed, this data may have important implications to the development of vaccination strategies for COVID-19, particularly in obese people,” they wrote. If the data are confirmed by larger studies, “giving obese people an extra dose of the vaccine or a higher dose could be options to be evaluated in this population.”

Results contrast with Pfizer trials of vaccine

The BMI finding seemingly contrasts with final data from the phase 3 clinical trial of the vaccine, which were reported in a supplement to an article published Dec. 31, 2020, in the New England Journal of Medicine. In that study, vaccine efficacy did not differ by obesity status.

Akiko Iwasaki, PhD, professor of immunology at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and an investigator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., noted that, although the current Italian study showed somewhat lower levels of antibodies in people with obesity, compared with people who did not have obesity, the phase 3 trial found no difference in symptomatic infection rates.

“These results indicate that even with a slightly lower level of antibody induced in obese people, that level was sufficient to protect against symptomatic infection,” Dr. Iwasaki said in an interview.

Indeed, Dr. Pellini and colleagues pointed out that responses to vaccines against influenza, hepatitis B, and rabies are also reduced in those with obesity, compared with lean individuals.

However, they said, it was especially important to study the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in people with obesity, because obesity is a major risk factor for morbidity and mortality in COVID-19.

“The constant state of low-grade inflammation, present in overweight people, can weaken some immune responses, including those launched by T cells, which can directly kill infected cells,” the authors noted.

Findings reported in British newspapers

The findings of the Italian study were widely covered in the lay press in the United Kingdom, with headlines such as “Pfizer Vaccine May Be Less Effective in People With Obesity, Says Study” and “Pfizer Vaccine: Overweight People Might Need Bigger Dose, Italian Study Says.” In tabloid newspapers, some headlines were slightly more stigmatizing.

The reports do stress that the Italian research was published as a preprint and has not been peer reviewed, or “is yet to be scrutinized by fellow scientists.”

Most make the point that there were only 26 people with obesity among the 248 persons in the study.

“We always knew that BMI was an enormous predictor of poor immune response to vaccines, so this paper is definitely interesting, although it is based on a rather small preliminary dataset,” Danny Altmann, PhD, a professor of immunology at Imperial College London, told the Guardian.

“It confirms that having a vaccinated population isn’t synonymous with having an immune population, especially in a country with high obesity, and emphasizes the vital need for long-term immune monitoring programs,” he added.

Antibody responses differ by BMI, age, and sex

In the Italian study, the participants – 158 women and 90 men – were assigned to receive a priming BNT162b2 vaccine dose with a booster at day 21. Blood and nasopharyngeal swabs were collected at baseline and 7 days after the second vaccine dose.

After the second dose, 99.5% of participants developed a humoral immune response; one person did not respond. None tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Titers of SARS-CoV-2–binding antibodies were greater in younger than in older participants. There were statistically significant differences between those aged 37 years and younger (453.5 AU/mL) and those aged 47-56 years (239.8 AU/mL; P = .005), those aged 37 years and younger versus those older than 56 years (453.5 vs 182.4 AU/mL; P < .0001), and those aged 37-47 years versus those older than 56 years (330.9 vs. 182.4 AU/mL; P = .01).

Antibody response was significantly greater for women than for men (338.5 vs. 212.6 AU/mL; P = .001).

Humoral responses were greater in persons of normal-weight BMI (18.5-24.9 kg/m2; 325.8 AU/mL) and those of underweight BMI (<18.5 kg/m2; 455.4 AU/mL), compared with persons with preobesity, defined as BMI of 25-29.9 (222.4 AU/mL), and those with obesity (BMI ≥30; 167.0 AU/mL; P < .0001). This association remained after adjustment for age (P = .003).

“Our data stresses the importance of close vaccination monitoring of obese people, considering the growing list of countries with obesity problems,” the researchers noted.

Hypertension was also associated with lower antibody titers (P = .006), but that lost statistical significance after matching for age (P = .22).

“We strongly believe that our results are extremely encouraging and useful for the scientific community,” Dr. Pellini and colleagues concluded.

The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Iwasaki is a cofounder of RIGImmune and is a member of its scientific advisory board.

This article was updated on 3/8/21.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Opioids prescribed for diabetic neuropathy pain, against advice

Prescriptions for opioids as a first-line treatment for painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) outnumbered those for other medications between 2014 and 2018, despite the fact that the former is not recommended, new research indicates.

“We know that for any kind of chronic pain, opioids are not ideal. They’re not very effective for chronic pain in general, and they’re definitely not safe,” senior author Rozalina G. McCoy, MD, an endocrinologist and primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., told this news organization.

That’s true even for severe DPN pain or painful exacerbations, she added.

“There’s a myth that opioids are the strongest pain meds possible ... For painful neuropathic pain, duloxetine [Cymbalta], pregabalin [Lyrica], and gabapentin [Neurontin] are the most effective pain medications based on multiple studies and extensive experience using them,” she explained. “But I think the public perception is that opioids are the strongest. When a patient comes with severe pain, I think there’s that kind of gut feeling that if the pain is severe, I need to give opioids.”

What’s more, she noted, “evidence is emerging for other harms, not only the potential for dependency and potential overdose, but also the potential for opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Opioids themselves can cause chronic pain. When we think about using opioids for chronic pain, we are really shooting ourselves in the foot. We’re going to harm patients.”

The American Diabetes Association DPN guidelines essentially say as much, advising opioids only as a tertiary option for refractory pain, she observed.

The new findings, from a retrospective study of Mayo Clinic electronic health data, were published online in JAMA Network Open by Jungwei Fan, PhD, also of Mayo Clinic, and colleagues.

Are fewer patients with DPN receiving any treatment now?

The data also reveal that, while opioid prescribing dropped over the study period, there wasn’t a comparable rise in prescriptions of recommended pain medications, suggesting that recent efforts to minimize opioid prescribing may have resulted in less overall treatment of significant pain. (The study had to be stopped in 2018 when Mayo switched to a new electronic health record system, Dr. McCoy explained.)

“The proportion of opioids among new prescriptions has been decreasing. I’m hopeful that the rates are even lower now than they were 2 years ago. What was concerning to me was the proportion of people receiving treatment overall had gone down,” Dr. McCoy noted.

“So, while it’s great that opioids aren’t being used, it’s doubtful that people with DPN are any less symptomatic. So I worry that there’s a proportion of patients who have pain who aren’t getting the treatment they need just because we don’t want to give them opioids. There are other options,” Dr. McCoy said, including nonpharmacologic approaches.

Opioids dominated in new-onset DPN prescribing during 2014-2018

The study involved 3,495 adults with newly diagnosed DPN from all three Mayo Clinic locations in Rochester, Minn.; Phoenix, Ariz.; and Jacksonville, Fla. during the period 2014-2018. Of those, 40.2% (1,406) were prescribed a new pain medication after diagnosis. However, that proportion dropped from 45.6% in 2014 to 35.2% in 2018.

The odds of initiating any treatment were significantly greater among patients with depression (odds ratio, 1.61), arthritis (OR, 1.21), and back pain (OR, 1.34), but decreased over time among all patients.

Among those receiving drug treatment, opioids were prescribed to 43.8%, whereas guideline-recommended medications (gabapentin, pregabalin, and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors including duloxetine) were prescribed to 42.9%.

Another 20.6% received medications deemed “acceptable” for treating neuropathic pain, including topical analgesics, tricyclic antidepressants, and other anticonvulsants.

Males were significantly more likely than females to receive opioids (OR, 1.26), while individuals diagnosed with comorbid fibromyalgia were less likely (OR, 0.67). Those with comorbid arthritis were less likely to receive recommended DPN medications (OR, 0.76).

Use of opioids was 29% less likely in 2018, compared with 2014, although this difference did not achieve significance. Similarly, use of recommended medications was 25% more likely in 2018, compared with 2014, also not a significant difference.

Dr. McCoy offers clinical pearls for treating pain in DPN

Clinically, Dr. McCoy said that she individualizes treatment for painful DPN.

“I tend to use duloxetine if the patient also has a mood disorder including depression or anxiety, because it can also help with that. Gabapentin can also be helpful for radiculopathy or for chronic low-back pain. It can even help with degenerative joint disease like arthritis of the knees. So, you maximize benefit if you use one drug to treat multiple things.”

All three recommended medications are generic now, although pregabalin still tends to be more expensive, she noted. Gabapentin can cause drowsiness, which makes it ideal for a patient with insomnia but much less so for a long-haul truck driver. Duloxetine doesn’t cause sleepiness. Pregabalin can, but less so than gabapentin.

“I think that’s why it’s so important to talk to your patient and ask how the neuropathy is affecting them. What other comorbidities do they have? What is their life like? I think you have to figure out what drug works for each individual person.”

Importantly, she advised, if one of the three doesn’t work, stop it and try another. “It doesn’t mean that none of these meds work. All three should be tried to see if they give relief.”

Nonpharmacologic measures such as cognitive behavioral therapy, acupuncture, or physical therapy may help some patients as well.

Supplements such as vitamin B12 – which can also help with metformin-induced B12 deficiency – or alpha-lipoic acid may also be worth a try as long as the patient is made aware of potential risks, she noted.

Dr. McCoy hopes to repeat this study using national data. “I don’t think this is isolated to Mayo ... I think it affects all practices,” she said.

Since the study, “we [Mayo Clinic] have implemented practice changes to limit use of opioids for chronic pain ... so I hope it’s getting better. It’s important to be aware of our patterns in prescribing.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. McCoy reported receiving grants from the AARP Quality Measure Innovation program through a collaboration with OptumLabs and the Mayo Clinic’s Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Prescriptions for opioids as a first-line treatment for painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) outnumbered those for other medications between 2014 and 2018, despite the fact that the former is not recommended, new research indicates.

“We know that for any kind of chronic pain, opioids are not ideal. They’re not very effective for chronic pain in general, and they’re definitely not safe,” senior author Rozalina G. McCoy, MD, an endocrinologist and primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., told this news organization.

That’s true even for severe DPN pain or painful exacerbations, she added.

“There’s a myth that opioids are the strongest pain meds possible ... For painful neuropathic pain, duloxetine [Cymbalta], pregabalin [Lyrica], and gabapentin [Neurontin] are the most effective pain medications based on multiple studies and extensive experience using them,” she explained. “But I think the public perception is that opioids are the strongest. When a patient comes with severe pain, I think there’s that kind of gut feeling that if the pain is severe, I need to give opioids.”

What’s more, she noted, “evidence is emerging for other harms, not only the potential for dependency and potential overdose, but also the potential for opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Opioids themselves can cause chronic pain. When we think about using opioids for chronic pain, we are really shooting ourselves in the foot. We’re going to harm patients.”

The American Diabetes Association DPN guidelines essentially say as much, advising opioids only as a tertiary option for refractory pain, she observed.

The new findings, from a retrospective study of Mayo Clinic electronic health data, were published online in JAMA Network Open by Jungwei Fan, PhD, also of Mayo Clinic, and colleagues.

Are fewer patients with DPN receiving any treatment now?

The data also reveal that, while opioid prescribing dropped over the study period, there wasn’t a comparable rise in prescriptions of recommended pain medications, suggesting that recent efforts to minimize opioid prescribing may have resulted in less overall treatment of significant pain. (The study had to be stopped in 2018 when Mayo switched to a new electronic health record system, Dr. McCoy explained.)

“The proportion of opioids among new prescriptions has been decreasing. I’m hopeful that the rates are even lower now than they were 2 years ago. What was concerning to me was the proportion of people receiving treatment overall had gone down,” Dr. McCoy noted.

“So, while it’s great that opioids aren’t being used, it’s doubtful that people with DPN are any less symptomatic. So I worry that there’s a proportion of patients who have pain who aren’t getting the treatment they need just because we don’t want to give them opioids. There are other options,” Dr. McCoy said, including nonpharmacologic approaches.

Opioids dominated in new-onset DPN prescribing during 2014-2018

The study involved 3,495 adults with newly diagnosed DPN from all three Mayo Clinic locations in Rochester, Minn.; Phoenix, Ariz.; and Jacksonville, Fla. during the period 2014-2018. Of those, 40.2% (1,406) were prescribed a new pain medication after diagnosis. However, that proportion dropped from 45.6% in 2014 to 35.2% in 2018.

The odds of initiating any treatment were significantly greater among patients with depression (odds ratio, 1.61), arthritis (OR, 1.21), and back pain (OR, 1.34), but decreased over time among all patients.

Among those receiving drug treatment, opioids were prescribed to 43.8%, whereas guideline-recommended medications (gabapentin, pregabalin, and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors including duloxetine) were prescribed to 42.9%.

Another 20.6% received medications deemed “acceptable” for treating neuropathic pain, including topical analgesics, tricyclic antidepressants, and other anticonvulsants.

Males were significantly more likely than females to receive opioids (OR, 1.26), while individuals diagnosed with comorbid fibromyalgia were less likely (OR, 0.67). Those with comorbid arthritis were less likely to receive recommended DPN medications (OR, 0.76).

Use of opioids was 29% less likely in 2018, compared with 2014, although this difference did not achieve significance. Similarly, use of recommended medications was 25% more likely in 2018, compared with 2014, also not a significant difference.

Dr. McCoy offers clinical pearls for treating pain in DPN

Clinically, Dr. McCoy said that she individualizes treatment for painful DPN.

“I tend to use duloxetine if the patient also has a mood disorder including depression or anxiety, because it can also help with that. Gabapentin can also be helpful for radiculopathy or for chronic low-back pain. It can even help with degenerative joint disease like arthritis of the knees. So, you maximize benefit if you use one drug to treat multiple things.”

All three recommended medications are generic now, although pregabalin still tends to be more expensive, she noted. Gabapentin can cause drowsiness, which makes it ideal for a patient with insomnia but much less so for a long-haul truck driver. Duloxetine doesn’t cause sleepiness. Pregabalin can, but less so than gabapentin.

“I think that’s why it’s so important to talk to your patient and ask how the neuropathy is affecting them. What other comorbidities do they have? What is their life like? I think you have to figure out what drug works for each individual person.”

Importantly, she advised, if one of the three doesn’t work, stop it and try another. “It doesn’t mean that none of these meds work. All three should be tried to see if they give relief.”

Nonpharmacologic measures such as cognitive behavioral therapy, acupuncture, or physical therapy may help some patients as well.

Supplements such as vitamin B12 – which can also help with metformin-induced B12 deficiency – or alpha-lipoic acid may also be worth a try as long as the patient is made aware of potential risks, she noted.

Dr. McCoy hopes to repeat this study using national data. “I don’t think this is isolated to Mayo ... I think it affects all practices,” she said.

Since the study, “we [Mayo Clinic] have implemented practice changes to limit use of opioids for chronic pain ... so I hope it’s getting better. It’s important to be aware of our patterns in prescribing.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. McCoy reported receiving grants from the AARP Quality Measure Innovation program through a collaboration with OptumLabs and the Mayo Clinic’s Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Prescriptions for opioids as a first-line treatment for painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) outnumbered those for other medications between 2014 and 2018, despite the fact that the former is not recommended, new research indicates.

“We know that for any kind of chronic pain, opioids are not ideal. They’re not very effective for chronic pain in general, and they’re definitely not safe,” senior author Rozalina G. McCoy, MD, an endocrinologist and primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., told this news organization.

That’s true even for severe DPN pain or painful exacerbations, she added.

“There’s a myth that opioids are the strongest pain meds possible ... For painful neuropathic pain, duloxetine [Cymbalta], pregabalin [Lyrica], and gabapentin [Neurontin] are the most effective pain medications based on multiple studies and extensive experience using them,” she explained. “But I think the public perception is that opioids are the strongest. When a patient comes with severe pain, I think there’s that kind of gut feeling that if the pain is severe, I need to give opioids.”

What’s more, she noted, “evidence is emerging for other harms, not only the potential for dependency and potential overdose, but also the potential for opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Opioids themselves can cause chronic pain. When we think about using opioids for chronic pain, we are really shooting ourselves in the foot. We’re going to harm patients.”

The American Diabetes Association DPN guidelines essentially say as much, advising opioids only as a tertiary option for refractory pain, she observed.

The new findings, from a retrospective study of Mayo Clinic electronic health data, were published online in JAMA Network Open by Jungwei Fan, PhD, also of Mayo Clinic, and colleagues.

Are fewer patients with DPN receiving any treatment now?

The data also reveal that, while opioid prescribing dropped over the study period, there wasn’t a comparable rise in prescriptions of recommended pain medications, suggesting that recent efforts to minimize opioid prescribing may have resulted in less overall treatment of significant pain. (The study had to be stopped in 2018 when Mayo switched to a new electronic health record system, Dr. McCoy explained.)

“The proportion of opioids among new prescriptions has been decreasing. I’m hopeful that the rates are even lower now than they were 2 years ago. What was concerning to me was the proportion of people receiving treatment overall had gone down,” Dr. McCoy noted.

“So, while it’s great that opioids aren’t being used, it’s doubtful that people with DPN are any less symptomatic. So I worry that there’s a proportion of patients who have pain who aren’t getting the treatment they need just because we don’t want to give them opioids. There are other options,” Dr. McCoy said, including nonpharmacologic approaches.

Opioids dominated in new-onset DPN prescribing during 2014-2018

The study involved 3,495 adults with newly diagnosed DPN from all three Mayo Clinic locations in Rochester, Minn.; Phoenix, Ariz.; and Jacksonville, Fla. during the period 2014-2018. Of those, 40.2% (1,406) were prescribed a new pain medication after diagnosis. However, that proportion dropped from 45.6% in 2014 to 35.2% in 2018.

The odds of initiating any treatment were significantly greater among patients with depression (odds ratio, 1.61), arthritis (OR, 1.21), and back pain (OR, 1.34), but decreased over time among all patients.

Among those receiving drug treatment, opioids were prescribed to 43.8%, whereas guideline-recommended medications (gabapentin, pregabalin, and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors including duloxetine) were prescribed to 42.9%.

Another 20.6% received medications deemed “acceptable” for treating neuropathic pain, including topical analgesics, tricyclic antidepressants, and other anticonvulsants.

Males were significantly more likely than females to receive opioids (OR, 1.26), while individuals diagnosed with comorbid fibromyalgia were less likely (OR, 0.67). Those with comorbid arthritis were less likely to receive recommended DPN medications (OR, 0.76).

Use of opioids was 29% less likely in 2018, compared with 2014, although this difference did not achieve significance. Similarly, use of recommended medications was 25% more likely in 2018, compared with 2014, also not a significant difference.

Dr. McCoy offers clinical pearls for treating pain in DPN

Clinically, Dr. McCoy said that she individualizes treatment for painful DPN.

“I tend to use duloxetine if the patient also has a mood disorder including depression or anxiety, because it can also help with that. Gabapentin can also be helpful for radiculopathy or for chronic low-back pain. It can even help with degenerative joint disease like arthritis of the knees. So, you maximize benefit if you use one drug to treat multiple things.”

All three recommended medications are generic now, although pregabalin still tends to be more expensive, she noted. Gabapentin can cause drowsiness, which makes it ideal for a patient with insomnia but much less so for a long-haul truck driver. Duloxetine doesn’t cause sleepiness. Pregabalin can, but less so than gabapentin.

“I think that’s why it’s so important to talk to your patient and ask how the neuropathy is affecting them. What other comorbidities do they have? What is their life like? I think you have to figure out what drug works for each individual person.”

Importantly, she advised, if one of the three doesn’t work, stop it and try another. “It doesn’t mean that none of these meds work. All three should be tried to see if they give relief.”

Nonpharmacologic measures such as cognitive behavioral therapy, acupuncture, or physical therapy may help some patients as well.

Supplements such as vitamin B12 – which can also help with metformin-induced B12 deficiency – or alpha-lipoic acid may also be worth a try as long as the patient is made aware of potential risks, she noted.

Dr. McCoy hopes to repeat this study using national data. “I don’t think this is isolated to Mayo ... I think it affects all practices,” she said.

Since the study, “we [Mayo Clinic] have implemented practice changes to limit use of opioids for chronic pain ... so I hope it’s getting better. It’s important to be aware of our patterns in prescribing.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. McCoy reported receiving grants from the AARP Quality Measure Innovation program through a collaboration with OptumLabs and the Mayo Clinic’s Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Super Bowl ad for diabetes device prompts debate

A commercial for the continuous glucose monitor (CGM) Dexcom G6 shown during the Super Bowl has provoked strong reactions in the diabetes community, both positive and negative.

The 30-second ad, which aired between the first two quarters of the American football game yesterday, features singer-songwriter-actor Nick Jonas, who has type 1 diabetes. During the ad, Mr. Jonas asks – with so much technology available today, including drones that deliver packages and self-driving cars – why are people with diabetes still pricking their fingers to test their blood sugar?

Mr. Jonas goes on to demonstrate the Dexcom G6 smartphone glucose app as it displays three different glucose levels including two trending upward, explaining: “It shows your glucose right in your phone, and where it’s heading, without fingersticks. Finally, technology that makes it easier to manage our diabetes.”

Diabetes type or insulin treatment are not mentioned in the ad, despite the fact that most insurance plans typically only cover CGMs for people with type 1 diabetes and sometimes for those with type 2 diabetes who take multiple daily insulin doses (given the risk for hypoglycemia).

Ad prompts mixed reaction on social media

Reactions rolled in on Twitter after the ad debuted Feb. 2, and then again after it aired during the game.

Some people who have type 1 diabetes themselves or have children with the disease who use the product were thrilled.

“Thanks to @NickJonas for his advocacy on T1. My 11-year old has been on the Dexcom for 3 weeks. For a newly diagnosed kid, it removes a lot of anxiety (and for his parents, too!) Plus, he is thrilled his meter has a Super Bowl commercial!” tweeted @KatisJewell.

Another positive tweet, from @rturnerroy, read: “@nickjonas Thank you for bringing representation to #type1diabetes. And hey #Dexcom, you’re the best.”

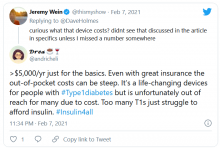

But many others were critical, both of Jonas and Dexcom. @hb_herrick tweeted: “Diabetes awareness is fantastic. Dexcom being able to afford Nick Jonas for a #SuperBowl commercial is not. This is a health care product. Make it more affordable for those who need it.”

Another Twitter user, @universeofdust, tweeted: “Feeling ambivalent about the #Dexcom ad tbh. I love the awareness & representation. But also not a big fan of dexcom spending $5.5 mill+ to make the CGM seem like this ~cool & trendy~ thing when many type 1s can’t afford their insulin, let alone a CGM.”

And @andricheli wrote: “Only people lucky enough to have excellent insurance and be able to afford the out-of-pocket costs have access. Many others do not.”

And in another tweet the same user said, “The #Dexcom is an amazing device. It’s literally lifesaving and life extending. But it’s also very expensive and not available to everyone. Maybe instead of spending $5 mil on a Super Bowl ad, @dexcom should spend that on getting Dex into the handle of people who need it.”

Others, including @1hitwonderdate, criticized Mr. Jonas directly, asking him: “As someone who has struggled with diabetes and is trying to support themselves along with millions of others, why not use this platform to help those who can’t afford their supplies or are rationing them?!”

Dexcom and Jonas’ organization respond

This news organization reached out to both Dexcom and to Beyond Type 1, a nonprofit organization cofounded by Mr. Jonas, for comment. Both emailed responses.

Regarding the intended audience for the ad, Dexcom acknowledged that it hoped to reach a much wider group than just people with type 1 diabetes or even just insulin users.

“We believe our CGM technology has the ability to empower any person with diabetes and significantly improve their treatment and quality of life, whether they are using insulin or not,” the company said, adding that the ad was also aimed at “loved ones, caregivers, and even health care professionals who need to know about this technology.”

According to Dexcom, the G6 is covered by 99% of commercial insurance in the United States, in addition to Medicare, and by Medicaid in more than 40 states. Over 70% of Dexcom patients with pharmacy coverage in the United States pay under $60 per month for CGM, and a third pay $0 out-of-pocket.

“That said, we know there’s more to be done to improve access, and we are working with several partners to broaden access to Dexcom CGM, especially for people with type 2 diabetes not on mealtime insulin,” the company noted.

Beyond Type 1 responded to the criticisms about Mr. Jonas personally, noting that the celebrity is, in fact, heavily involved in advocacy.

“Nick was involved in the launch of GetInsulin.org this past October,” they said. “GetInsulin.org is a tool created by Beyond Type 1 to connect people with diabetes in the United States to the insulin access and affordability options that match their unique circumstances. ... Beyond Type 1 will continue driving awareness of short-term solutions related to insulin access and affordability while fighting for systemic change.”

The organization “is also advocating for systemic payment policies that will make devices less expensive and avoid the same pitfalls (and rising prices) as the drug pricing system in the U.S.”

Mr. Jonas himself appears aware of the concerns.

Is 2021’s most expensive Super Bowl ad justified?

Meanwhile, in a piece in Esquire, Dave Holmes, who has type 1 diabetes, weighs up the pros and cons of the ad.

He writes: “While Jonas makes it look fun and easy to use a Dexcom G6 – a program to just get with like you would a drone or LED eyelashes – the process of acquiring one is complicated and often very expensive, even for people with good insurance. Which makes the year’s most expensive ad buy, for a product that only a small percentage of the U.S. population needs, confusing to me and others.”

Mr. Holmes also spoke with Craig Stubing, founder of the Beta Cell Foundation, a nonprofit that aims to educate and empower those with type 1 diabetes.

“Spending all this money on an ad, when people’s lives are at stake. I don’t know if offensive is the right word, but it seems out of touch with the reality that their patients are facing,” Mr. Stubing told Mr. Holmes.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A commercial for the continuous glucose monitor (CGM) Dexcom G6 shown during the Super Bowl has provoked strong reactions in the diabetes community, both positive and negative.

The 30-second ad, which aired between the first two quarters of the American football game yesterday, features singer-songwriter-actor Nick Jonas, who has type 1 diabetes. During the ad, Mr. Jonas asks – with so much technology available today, including drones that deliver packages and self-driving cars – why are people with diabetes still pricking their fingers to test their blood sugar?

Mr. Jonas goes on to demonstrate the Dexcom G6 smartphone glucose app as it displays three different glucose levels including two trending upward, explaining: “It shows your glucose right in your phone, and where it’s heading, without fingersticks. Finally, technology that makes it easier to manage our diabetes.”

Diabetes type or insulin treatment are not mentioned in the ad, despite the fact that most insurance plans typically only cover CGMs for people with type 1 diabetes and sometimes for those with type 2 diabetes who take multiple daily insulin doses (given the risk for hypoglycemia).

Ad prompts mixed reaction on social media

Reactions rolled in on Twitter after the ad debuted Feb. 2, and then again after it aired during the game.

Some people who have type 1 diabetes themselves or have children with the disease who use the product were thrilled.

“Thanks to @NickJonas for his advocacy on T1. My 11-year old has been on the Dexcom for 3 weeks. For a newly diagnosed kid, it removes a lot of anxiety (and for his parents, too!) Plus, he is thrilled his meter has a Super Bowl commercial!” tweeted @KatisJewell.

Another positive tweet, from @rturnerroy, read: “@nickjonas Thank you for bringing representation to #type1diabetes. And hey #Dexcom, you’re the best.”

But many others were critical, both of Jonas and Dexcom. @hb_herrick tweeted: “Diabetes awareness is fantastic. Dexcom being able to afford Nick Jonas for a #SuperBowl commercial is not. This is a health care product. Make it more affordable for those who need it.”

Another Twitter user, @universeofdust, tweeted: “Feeling ambivalent about the #Dexcom ad tbh. I love the awareness & representation. But also not a big fan of dexcom spending $5.5 mill+ to make the CGM seem like this ~cool & trendy~ thing when many type 1s can’t afford their insulin, let alone a CGM.”

And @andricheli wrote: “Only people lucky enough to have excellent insurance and be able to afford the out-of-pocket costs have access. Many others do not.”

And in another tweet the same user said, “The #Dexcom is an amazing device. It’s literally lifesaving and life extending. But it’s also very expensive and not available to everyone. Maybe instead of spending $5 mil on a Super Bowl ad, @dexcom should spend that on getting Dex into the handle of people who need it.”

Others, including @1hitwonderdate, criticized Mr. Jonas directly, asking him: “As someone who has struggled with diabetes and is trying to support themselves along with millions of others, why not use this platform to help those who can’t afford their supplies or are rationing them?!”

Dexcom and Jonas’ organization respond

This news organization reached out to both Dexcom and to Beyond Type 1, a nonprofit organization cofounded by Mr. Jonas, for comment. Both emailed responses.

Regarding the intended audience for the ad, Dexcom acknowledged that it hoped to reach a much wider group than just people with type 1 diabetes or even just insulin users.

“We believe our CGM technology has the ability to empower any person with diabetes and significantly improve their treatment and quality of life, whether they are using insulin or not,” the company said, adding that the ad was also aimed at “loved ones, caregivers, and even health care professionals who need to know about this technology.”

According to Dexcom, the G6 is covered by 99% of commercial insurance in the United States, in addition to Medicare, and by Medicaid in more than 40 states. Over 70% of Dexcom patients with pharmacy coverage in the United States pay under $60 per month for CGM, and a third pay $0 out-of-pocket.

“That said, we know there’s more to be done to improve access, and we are working with several partners to broaden access to Dexcom CGM, especially for people with type 2 diabetes not on mealtime insulin,” the company noted.

Beyond Type 1 responded to the criticisms about Mr. Jonas personally, noting that the celebrity is, in fact, heavily involved in advocacy.

“Nick was involved in the launch of GetInsulin.org this past October,” they said. “GetInsulin.org is a tool created by Beyond Type 1 to connect people with diabetes in the United States to the insulin access and affordability options that match their unique circumstances. ... Beyond Type 1 will continue driving awareness of short-term solutions related to insulin access and affordability while fighting for systemic change.”

The organization “is also advocating for systemic payment policies that will make devices less expensive and avoid the same pitfalls (and rising prices) as the drug pricing system in the U.S.”

Mr. Jonas himself appears aware of the concerns.

Is 2021’s most expensive Super Bowl ad justified?

Meanwhile, in a piece in Esquire, Dave Holmes, who has type 1 diabetes, weighs up the pros and cons of the ad.

He writes: “While Jonas makes it look fun and easy to use a Dexcom G6 – a program to just get with like you would a drone or LED eyelashes – the process of acquiring one is complicated and often very expensive, even for people with good insurance. Which makes the year’s most expensive ad buy, for a product that only a small percentage of the U.S. population needs, confusing to me and others.”

Mr. Holmes also spoke with Craig Stubing, founder of the Beta Cell Foundation, a nonprofit that aims to educate and empower those with type 1 diabetes.

“Spending all this money on an ad, when people’s lives are at stake. I don’t know if offensive is the right word, but it seems out of touch with the reality that their patients are facing,” Mr. Stubing told Mr. Holmes.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A commercial for the continuous glucose monitor (CGM) Dexcom G6 shown during the Super Bowl has provoked strong reactions in the diabetes community, both positive and negative.

The 30-second ad, which aired between the first two quarters of the American football game yesterday, features singer-songwriter-actor Nick Jonas, who has type 1 diabetes. During the ad, Mr. Jonas asks – with so much technology available today, including drones that deliver packages and self-driving cars – why are people with diabetes still pricking their fingers to test their blood sugar?

Mr. Jonas goes on to demonstrate the Dexcom G6 smartphone glucose app as it displays three different glucose levels including two trending upward, explaining: “It shows your glucose right in your phone, and where it’s heading, without fingersticks. Finally, technology that makes it easier to manage our diabetes.”

Diabetes type or insulin treatment are not mentioned in the ad, despite the fact that most insurance plans typically only cover CGMs for people with type 1 diabetes and sometimes for those with type 2 diabetes who take multiple daily insulin doses (given the risk for hypoglycemia).

Ad prompts mixed reaction on social media

Reactions rolled in on Twitter after the ad debuted Feb. 2, and then again after it aired during the game.

Some people who have type 1 diabetes themselves or have children with the disease who use the product were thrilled.

“Thanks to @NickJonas for his advocacy on T1. My 11-year old has been on the Dexcom for 3 weeks. For a newly diagnosed kid, it removes a lot of anxiety (and for his parents, too!) Plus, he is thrilled his meter has a Super Bowl commercial!” tweeted @KatisJewell.

Another positive tweet, from @rturnerroy, read: “@nickjonas Thank you for bringing representation to #type1diabetes. And hey #Dexcom, you’re the best.”

But many others were critical, both of Jonas and Dexcom. @hb_herrick tweeted: “Diabetes awareness is fantastic. Dexcom being able to afford Nick Jonas for a #SuperBowl commercial is not. This is a health care product. Make it more affordable for those who need it.”

Another Twitter user, @universeofdust, tweeted: “Feeling ambivalent about the #Dexcom ad tbh. I love the awareness & representation. But also not a big fan of dexcom spending $5.5 mill+ to make the CGM seem like this ~cool & trendy~ thing when many type 1s can’t afford their insulin, let alone a CGM.”

And @andricheli wrote: “Only people lucky enough to have excellent insurance and be able to afford the out-of-pocket costs have access. Many others do not.”

And in another tweet the same user said, “The #Dexcom is an amazing device. It’s literally lifesaving and life extending. But it’s also very expensive and not available to everyone. Maybe instead of spending $5 mil on a Super Bowl ad, @dexcom should spend that on getting Dex into the handle of people who need it.”

Others, including @1hitwonderdate, criticized Mr. Jonas directly, asking him: “As someone who has struggled with diabetes and is trying to support themselves along with millions of others, why not use this platform to help those who can’t afford their supplies or are rationing them?!”

Dexcom and Jonas’ organization respond

This news organization reached out to both Dexcom and to Beyond Type 1, a nonprofit organization cofounded by Mr. Jonas, for comment. Both emailed responses.

Regarding the intended audience for the ad, Dexcom acknowledged that it hoped to reach a much wider group than just people with type 1 diabetes or even just insulin users.

“We believe our CGM technology has the ability to empower any person with diabetes and significantly improve their treatment and quality of life, whether they are using insulin or not,” the company said, adding that the ad was also aimed at “loved ones, caregivers, and even health care professionals who need to know about this technology.”

According to Dexcom, the G6 is covered by 99% of commercial insurance in the United States, in addition to Medicare, and by Medicaid in more than 40 states. Over 70% of Dexcom patients with pharmacy coverage in the United States pay under $60 per month for CGM, and a third pay $0 out-of-pocket.

“That said, we know there’s more to be done to improve access, and we are working with several partners to broaden access to Dexcom CGM, especially for people with type 2 diabetes not on mealtime insulin,” the company noted.

Beyond Type 1 responded to the criticisms about Mr. Jonas personally, noting that the celebrity is, in fact, heavily involved in advocacy.

“Nick was involved in the launch of GetInsulin.org this past October,” they said. “GetInsulin.org is a tool created by Beyond Type 1 to connect people with diabetes in the United States to the insulin access and affordability options that match their unique circumstances. ... Beyond Type 1 will continue driving awareness of short-term solutions related to insulin access and affordability while fighting for systemic change.”

The organization “is also advocating for systemic payment policies that will make devices less expensive and avoid the same pitfalls (and rising prices) as the drug pricing system in the U.S.”

Mr. Jonas himself appears aware of the concerns.

Is 2021’s most expensive Super Bowl ad justified?

Meanwhile, in a piece in Esquire, Dave Holmes, who has type 1 diabetes, weighs up the pros and cons of the ad.

He writes: “While Jonas makes it look fun and easy to use a Dexcom G6 – a program to just get with like you would a drone or LED eyelashes – the process of acquiring one is complicated and often very expensive, even for people with good insurance. Which makes the year’s most expensive ad buy, for a product that only a small percentage of the U.S. population needs, confusing to me and others.”

Mr. Holmes also spoke with Craig Stubing, founder of the Beta Cell Foundation, a nonprofit that aims to educate and empower those with type 1 diabetes.

“Spending all this money on an ad, when people’s lives are at stake. I don’t know if offensive is the right word, but it seems out of touch with the reality that their patients are facing,” Mr. Stubing told Mr. Holmes.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Protecting patients with diabetes from impact of COVID-19

Experts discuss how to best protect people with diabetes from serious COVID-19 outcomes in a newly published article that summarizes in-depth discussions on the topic from a conference held online last year.

Lead author and Diabetes Technology Society founder and director David C. Klonoff, MD, said in an interview: “To my knowledge this is the largest article or learning that has been written anywhere ever about the co-occurrence of COVID-19 and diabetes and how COVID-19 affects diabetes ... There are a lot of different dimensions.”

The 37-page report covers all sessions from the Virtual International COVID-19 and Diabetes Summit, held Aug. 26-27, 2020, which had 800 attendees from six continents, on topics including pathophysiology and COVID-19 risk factors, the impact of social determinants of health on diabetes and COVID-19, and psychological aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic for people with diabetes.

The freely available report was published online Jan. 21 in the Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology by Jennifer Y. Zhang of the Diabetes Technology Society, Burlingame, Calif., and colleagues.

Other topics include medications and vaccines, outpatient diabetes management during the COVID-19 pandemic and the growth of telehealth, inpatient management of diabetes in patients with or without COVID-19, ethical considerations, children, pregnancy, economics of care for COVID-19, government policy, regulation of tests and treatments, patient surveillance/privacy, and research gaps and opportunities.

“A comprehensive report like this is so important because it covers such a wide range of topics that are all relevant when it comes to protecting patients with diabetes during a pandemic. Our report aims to bring together all these different aspects of policy during the pandemic, patient physiology, and patient psychology, so I hope it will be widely read and widely appreciated,” Ms. Zhang said in an interview.

Two important clinical trends arising as a result of the pandemic – the advent of telehealth in diabetes management and the use of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) in hospital – are expected to continue even after COVID-19 abates, said Dr. Klonoff, medical director of the Diabetes Research Institute at Mills-Peninsula Medical Center, San Mateo, Calif.

Telehealth in diabetes here to stay, in U.S. at least

Dr. Klonoff noted that with diabetes telehealth, or “telediabetes” as it’s been dubbed, by using downloaded device data patients don’t have to travel, pay for parking, or take as much time off work. “There are advantages ... patients really like it,” he said.

And for health care providers, an advantage of remote visits is that the clinician can look at the patient while reviewing the patient’s data. “With telehealth for diabetes, the patient’s face and the software data are right next to each other on the same screen. Even as I’m typing I’m looking at the patient ... I consider that a huge advantage,” Dr. Klonoff said.

Rule changes early in the pandemic made the shift to telehealth in the United States possible, he said.

“Fortunately, Medicare and other payers are covering telehealth. It used to be there was no coverage, so that was a damper. Now that it’s covered I don’t think that’s going to go back. Everybody likes it,” he said.

CGM in hospitals helps detect hypoglycemia on wards

Regarding the increase of inpatient CGM (continuous glucose monitoring) prompted by the need to minimize patient exposure of nursing staff during the pandemic and the relaxing of Food and Drug Administration rules about its use, Dr. Klonoff said this phenomenon has led to two other positive developments.

“For FDA, it’s actually an opportunity to see some data collected. To do a clinical trial [prior to] March 2020 you had to go through a lot of processes to do a study. Once it becomes part of clinical care, then you can collect a lot of data,” he noted.

Moreover, Dr. Klonoff said there’s an important new area where hospital use of CGM is emerging: detection of hypoglycemia on wards.

“When a patient is in the ICU, if they become hypoglycemic or hyperglycemic it will likely be detected. But on the wards, they simply don’t get the same attention. Just about every doctor has had a case where somebody drifted into hypoglycemia that wasn’t recognized and maybe even died,” he explained.

If, however, “patients treated with insulin could all have CGMs that would be so useful. It would send out an alarm. A lot of times people don’t eat when you think they will. Suddenly the insulin dose is inappropriate and the nurse didn’t realize. Or, if IV nutrition stops and the insulin is given [it can be harmful].”

Another example, he said, is a common scenario when insulin is used in patients who are treated with steroids. “They need insulin, but then the steroid is decreased and the insulin dose isn’t decreased fast enough. All those situations can be helped with CGM.”

Overall, he concluded, COVID-19 has provided many lessons, which are “expanding our horizons.”

Ms. Zhang has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Klonoff has reported being a consultant for Dexcom, EOFlow, Fractyl, Lifecare, Novo Nordisk, Roche Diagnostics, Samsung, and Thirdwayv.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Experts discuss how to best protect people with diabetes from serious COVID-19 outcomes in a newly published article that summarizes in-depth discussions on the topic from a conference held online last year.

Lead author and Diabetes Technology Society founder and director David C. Klonoff, MD, said in an interview: “To my knowledge this is the largest article or learning that has been written anywhere ever about the co-occurrence of COVID-19 and diabetes and how COVID-19 affects diabetes ... There are a lot of different dimensions.”

The 37-page report covers all sessions from the Virtual International COVID-19 and Diabetes Summit, held Aug. 26-27, 2020, which had 800 attendees from six continents, on topics including pathophysiology and COVID-19 risk factors, the impact of social determinants of health on diabetes and COVID-19, and psychological aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic for people with diabetes.

The freely available report was published online Jan. 21 in the Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology by Jennifer Y. Zhang of the Diabetes Technology Society, Burlingame, Calif., and colleagues.

Other topics include medications and vaccines, outpatient diabetes management during the COVID-19 pandemic and the growth of telehealth, inpatient management of diabetes in patients with or without COVID-19, ethical considerations, children, pregnancy, economics of care for COVID-19, government policy, regulation of tests and treatments, patient surveillance/privacy, and research gaps and opportunities.

“A comprehensive report like this is so important because it covers such a wide range of topics that are all relevant when it comes to protecting patients with diabetes during a pandemic. Our report aims to bring together all these different aspects of policy during the pandemic, patient physiology, and patient psychology, so I hope it will be widely read and widely appreciated,” Ms. Zhang said in an interview.

Two important clinical trends arising as a result of the pandemic – the advent of telehealth in diabetes management and the use of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) in hospital – are expected to continue even after COVID-19 abates, said Dr. Klonoff, medical director of the Diabetes Research Institute at Mills-Peninsula Medical Center, San Mateo, Calif.

Telehealth in diabetes here to stay, in U.S. at least

Dr. Klonoff noted that with diabetes telehealth, or “telediabetes” as it’s been dubbed, by using downloaded device data patients don’t have to travel, pay for parking, or take as much time off work. “There are advantages ... patients really like it,” he said.

And for health care providers, an advantage of remote visits is that the clinician can look at the patient while reviewing the patient’s data. “With telehealth for diabetes, the patient’s face and the software data are right next to each other on the same screen. Even as I’m typing I’m looking at the patient ... I consider that a huge advantage,” Dr. Klonoff said.

Rule changes early in the pandemic made the shift to telehealth in the United States possible, he said.

“Fortunately, Medicare and other payers are covering telehealth. It used to be there was no coverage, so that was a damper. Now that it’s covered I don’t think that’s going to go back. Everybody likes it,” he said.

CGM in hospitals helps detect hypoglycemia on wards

Regarding the increase of inpatient CGM (continuous glucose monitoring) prompted by the need to minimize patient exposure of nursing staff during the pandemic and the relaxing of Food and Drug Administration rules about its use, Dr. Klonoff said this phenomenon has led to two other positive developments.

“For FDA, it’s actually an opportunity to see some data collected. To do a clinical trial [prior to] March 2020 you had to go through a lot of processes to do a study. Once it becomes part of clinical care, then you can collect a lot of data,” he noted.

Moreover, Dr. Klonoff said there’s an important new area where hospital use of CGM is emerging: detection of hypoglycemia on wards.

“When a patient is in the ICU, if they become hypoglycemic or hyperglycemic it will likely be detected. But on the wards, they simply don’t get the same attention. Just about every doctor has had a case where somebody drifted into hypoglycemia that wasn’t recognized and maybe even died,” he explained.

If, however, “patients treated with insulin could all have CGMs that would be so useful. It would send out an alarm. A lot of times people don’t eat when you think they will. Suddenly the insulin dose is inappropriate and the nurse didn’t realize. Or, if IV nutrition stops and the insulin is given [it can be harmful].”

Another example, he said, is a common scenario when insulin is used in patients who are treated with steroids. “They need insulin, but then the steroid is decreased and the insulin dose isn’t decreased fast enough. All those situations can be helped with CGM.”

Overall, he concluded, COVID-19 has provided many lessons, which are “expanding our horizons.”

Ms. Zhang has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Klonoff has reported being a consultant for Dexcom, EOFlow, Fractyl, Lifecare, Novo Nordisk, Roche Diagnostics, Samsung, and Thirdwayv.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Experts discuss how to best protect people with diabetes from serious COVID-19 outcomes in a newly published article that summarizes in-depth discussions on the topic from a conference held online last year.

Lead author and Diabetes Technology Society founder and director David C. Klonoff, MD, said in an interview: “To my knowledge this is the largest article or learning that has been written anywhere ever about the co-occurrence of COVID-19 and diabetes and how COVID-19 affects diabetes ... There are a lot of different dimensions.”

The 37-page report covers all sessions from the Virtual International COVID-19 and Diabetes Summit, held Aug. 26-27, 2020, which had 800 attendees from six continents, on topics including pathophysiology and COVID-19 risk factors, the impact of social determinants of health on diabetes and COVID-19, and psychological aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic for people with diabetes.

The freely available report was published online Jan. 21 in the Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology by Jennifer Y. Zhang of the Diabetes Technology Society, Burlingame, Calif., and colleagues.

Other topics include medications and vaccines, outpatient diabetes management during the COVID-19 pandemic and the growth of telehealth, inpatient management of diabetes in patients with or without COVID-19, ethical considerations, children, pregnancy, economics of care for COVID-19, government policy, regulation of tests and treatments, patient surveillance/privacy, and research gaps and opportunities.

“A comprehensive report like this is so important because it covers such a wide range of topics that are all relevant when it comes to protecting patients with diabetes during a pandemic. Our report aims to bring together all these different aspects of policy during the pandemic, patient physiology, and patient psychology, so I hope it will be widely read and widely appreciated,” Ms. Zhang said in an interview.

Two important clinical trends arising as a result of the pandemic – the advent of telehealth in diabetes management and the use of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) in hospital – are expected to continue even after COVID-19 abates, said Dr. Klonoff, medical director of the Diabetes Research Institute at Mills-Peninsula Medical Center, San Mateo, Calif.

Telehealth in diabetes here to stay, in U.S. at least

Dr. Klonoff noted that with diabetes telehealth, or “telediabetes” as it’s been dubbed, by using downloaded device data patients don’t have to travel, pay for parking, or take as much time off work. “There are advantages ... patients really like it,” he said.

And for health care providers, an advantage of remote visits is that the clinician can look at the patient while reviewing the patient’s data. “With telehealth for diabetes, the patient’s face and the software data are right next to each other on the same screen. Even as I’m typing I’m looking at the patient ... I consider that a huge advantage,” Dr. Klonoff said.

Rule changes early in the pandemic made the shift to telehealth in the United States possible, he said.

“Fortunately, Medicare and other payers are covering telehealth. It used to be there was no coverage, so that was a damper. Now that it’s covered I don’t think that’s going to go back. Everybody likes it,” he said.

CGM in hospitals helps detect hypoglycemia on wards

Regarding the increase of inpatient CGM (continuous glucose monitoring) prompted by the need to minimize patient exposure of nursing staff during the pandemic and the relaxing of Food and Drug Administration rules about its use, Dr. Klonoff said this phenomenon has led to two other positive developments.

“For FDA, it’s actually an opportunity to see some data collected. To do a clinical trial [prior to] March 2020 you had to go through a lot of processes to do a study. Once it becomes part of clinical care, then you can collect a lot of data,” he noted.

Moreover, Dr. Klonoff said there’s an important new area where hospital use of CGM is emerging: detection of hypoglycemia on wards.

“When a patient is in the ICU, if they become hypoglycemic or hyperglycemic it will likely be detected. But on the wards, they simply don’t get the same attention. Just about every doctor has had a case where somebody drifted into hypoglycemia that wasn’t recognized and maybe even died,” he explained.

If, however, “patients treated with insulin could all have CGMs that would be so useful. It would send out an alarm. A lot of times people don’t eat when you think they will. Suddenly the insulin dose is inappropriate and the nurse didn’t realize. Or, if IV nutrition stops and the insulin is given [it can be harmful].”

Another example, he said, is a common scenario when insulin is used in patients who are treated with steroids. “They need insulin, but then the steroid is decreased and the insulin dose isn’t decreased fast enough. All those situations can be helped with CGM.”

Overall, he concluded, COVID-19 has provided many lessons, which are “expanding our horizons.”

Ms. Zhang has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Klonoff has reported being a consultant for Dexcom, EOFlow, Fractyl, Lifecare, Novo Nordisk, Roche Diagnostics, Samsung, and Thirdwayv.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Further warning on SGLT2 inhibitor use and DKA risk in COVID-19

a new case series suggests.

Five patients with type 2 diabetes who were taking SGLT2 inhibitors presented in DKA despite having glucose levels below 300 mg/dL. The report was published online last month in AACE Clinical Case Reports by Rebecca J. Vitale, MD, and colleagues at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“A cluster of euglycemic DKA cases at our hospital during the first wave of the pandemic suggests that patients with diabetes taking SGLT2 inhibitors may be at enhanced risk for euDKA when they contract COVID-19,” senior author Naomi D.L. Fisher, MD, said in an interview.

Dr. Fisher, an endocrinologist, added: “This complication is preventable with the simple measure of holding the drug. We are hopeful that widespread patient and physician education will prevent future cases of euDKA as COVID-19 infections continue to surge.”

These cases underscore recommendations published early in the COVID-19 pandemic by an international panel, she noted.

“Patients who are acutely ill with nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, or diarrhea, or who are experiencing loss of appetite with reduced food and fluid intake, should be advised to hold their SGLT2 inhibitor. This medication should not be resumed until patients are feeling better and eating and drinking normally.”

On the other hand, “If patients with asymptomatic or mild COVID-19 infection are otherwise well, and are eating and drinking normally, there is no evidence that SGLT2 inhibitors need to be stopped. These patients should monitor [themselves] closely for worsening symptoms, especially resulting in poor hydration and nutrition, which would be reason to discontinue their medication.”

Pay special attention to the elderly, those with complications

However, special consideration should be given to elderly patients and those with medical conditions known to increase the likelihood of severe infection, like heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Dr. Fisher added.

The SGLT2 inhibitor class of drugs causes significant urinary glucose excretion, and they are also diuretics. A decrease in available glucose and volume depletion are probably both important contributors to euDKA, she explained.

With COVID-19 infection the euDKA risk is compounded by several mechanisms. Most cases of euDKA are associated with an underlying state of starvation that can be triggered by vomiting, diarrhea, loss of appetite, and poor oral intake.

In addition – although not yet known for certain – SARS-CoV-2 may also be toxic to pancreatic beta cells and thus reduce insulin secretion. The maladaptive inflammatory response seen with COVID-19 may also contribute, she said.

The patients in the current case series were three men and two women seen between March and May 2020. They ranged in age from 52 to 79 years.

None had a prior history of DKA or any known diabetes complications. In all of them, antihyperglycemic medications, including SGLT2 inhibitors, were stopped on hospital admission. The patients were initially treated with intravenous insulin, and then subcutaneous insulin after the DKA diagnosis.

Three of the patients were discharged to rehabilitation facilities on hospital days 28-47 and one (age 53 years) was discharged home on day 11. The other patient also had hypertension and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a new case series suggests.

Five patients with type 2 diabetes who were taking SGLT2 inhibitors presented in DKA despite having glucose levels below 300 mg/dL. The report was published online last month in AACE Clinical Case Reports by Rebecca J. Vitale, MD, and colleagues at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“A cluster of euglycemic DKA cases at our hospital during the first wave of the pandemic suggests that patients with diabetes taking SGLT2 inhibitors may be at enhanced risk for euDKA when they contract COVID-19,” senior author Naomi D.L. Fisher, MD, said in an interview.

Dr. Fisher, an endocrinologist, added: “This complication is preventable with the simple measure of holding the drug. We are hopeful that widespread patient and physician education will prevent future cases of euDKA as COVID-19 infections continue to surge.”

These cases underscore recommendations published early in the COVID-19 pandemic by an international panel, she noted.

“Patients who are acutely ill with nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, or diarrhea, or who are experiencing loss of appetite with reduced food and fluid intake, should be advised to hold their SGLT2 inhibitor. This medication should not be resumed until patients are feeling better and eating and drinking normally.”