User login

Can a Polygenic Risk Score Turn the Tide on Prostate Cancer Screening?

Incorporating a polygenic risk score into prostate cancer screening could enhance the detection of clinically significant prostate cancer that conventional screening may miss, according to results of the BARCODE 1 clinical trial conducted in the United Kingdom.

The study found that about 72% of participants with high polygenic risk scores were diagnosed with clinically significant prostate cancers, which would not have been detected with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing or MRI.

“With this test, it could be possible to turn the tide on prostate cancer,” study author Ros Eeles, PhD, professor of oncogenetics at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, England, said in a statement following the publication of the analysis in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Prostate cancer remains the second most commonly diagnosed cancer among men. As a screening tool, PSA testing has been criticized for leading to a high rate of false positive results and overdiagnosis — defined as a screen-detected cancer that would take longer to progress to clinical cancer than the patient’s lifetime. Both issues can result in overtreatment.

Given prostate cancer’s high heritability and the proliferation of genome-wide association studies identifying common genetic variants, there has been growing interest in using polygenic risk scores to improve risk stratification and guide screening.

“Building on decades of research into the genetic markers of prostate cancer, our study shows that the theory does work in practice — we can identify men at risk of aggressive cancers who need further tests and spare the men who are at lower risk from unnecessary treatments,” said Eeles.

An Adjunct to Screening?

The BARCODE 1 study, conducted in the United Kingdom, tested the clinical utility of a polygenic risk score as an adjunct to screening.

The researchers recruited men aged 55-69 years from primary care centers in the United Kingdom. Using germline DNA extracted from saliva, they derived polygenic risk scores from 130 genetic variants known to be associated with an increased risk for prostate cancer.

Among a total of 6393 men who had their scores calculated, 745 (12%) had a score in the top 10% of genetic risk (≥ 90th percentile) and were invited to undergo further screening.

Of these, 468 (63%) accepted the invite and underwent multiparametric MRI and transperineal prostate biopsy, irrespective of the PSA level. Overall, 187 (40%) were diagnosed with prostate cancer following biopsy. Of the 187 men with prostate cancer, 55% (n = 103) had disease classified as intermediate or high risk (Gleason score ≥ 7) per National Comprehensive Cancer Network criteria and therefore warranted further treatment.

Researchers then compared screening that incorporated polygenic risk scores with standard screening with PSA levels and MRI.

When participants’ risk was stratified by their polygenic risk score, 103 patients (55%) with prostate cancer could be classified as intermediate or higher risk, thus warranting treatment. Overall, 74 (71.8%) of those cancers would have been missed using the standard diagnostic pathway in the United Kingdom, which requires patients to have a high PSA level (> 3.0 μg/L) as well as a positive MRI result. These 74 patients either had PSA levels ≤ 3.0 μg/L or negative MRIs, which would mean these patients would typically fall below the action threshold for further testing.

Of the 103 participants warranting treatment, 40 of these men would have been classified as unfavorable intermediate, high, or very high risk, which would require radical treatment. Among this group, roughly 43% would have been missed using the UK diagnostic pathway.

However, the investigators estimated a rate of overdiagnosis with the use of polygenic risk scores of 16%-21%, similar to the overdiagnosis estimates in two prior PSA-based screening studies, signaling that the addition of polygenic risk scores does not necessarily reduce the risk for overdiagnosis.

Overall, “this study is the strongest evidence to date on the clinical utility of a polygenic score for prostate cancer screening,” commented Michael Inouye, professor of systems genomics & population health, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, England, in a statement from the UK nonprofit Science Media Centre (SMC).

“I suspect we will look back on this as a landmark study that really made the clinical case for polygenic scores as a new tool that moved health systems from disease management to early detection and prevention,” said Inouye, who was not involved in the study.

However, other experts were more cautious about the findings.

Dusko Ilic, MD, professor of stem cell sciences, King’s College London, London, England, said the results are “promising, especially in identifying significant cancers that would otherwise be missed,” but cautioned that “there is no direct evidence yet that using [polygenic risk scores] improves long-term outcomes such as mortality or quality-adjusted life years.”

“Modeling suggests benefit, but empirical confirmation is needed,” Ilic said in the SMC statement.

The hope is that the recently launched TRANSFORM trial will help answer some of these outstanding questions.

The current study suggests that polygenic risk scores for prostate cancer “would be a useful component of a multimodality screening program that assesses age, family history of prostate cancer, PSA, and MRI results as triage tools before biopsy is recommended,” David Hunter, MPH, ScD, with Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and University of Oxford, Oxford, England, wrote in an editorial accompanying the study.

“To make this integrated program a reality, however, changes to infrastructure would be needed to make running and analyzing a regulated genome array as easy as requesting a PSA level or ordering an MRI. Clearly, we are far from that future,” Hunter cautioned.

“A possible first step that would require less infrastructure could be to order a polygenic risk score only for men with a positive PSA result, then use the polygenic risk score to determine who should undergo an MRI, and then use all the information to determine whether biopsy is recommended,” Hunter said.

In his view, the current study is a “first step on a long road to evaluating new components of any disease screening pathway.”

The research received funding from the European Research Council, the Bob Willis Fund, Cancer Research UK, the Peacock Trust, and the National Institute for Health and Care Research Biomedical Research Centre at The Royal Marsden and The Institute of Cancer Research. Disclosures for authors and editorialists are available with the original article. Inouye and Ilic reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Incorporating a polygenic risk score into prostate cancer screening could enhance the detection of clinically significant prostate cancer that conventional screening may miss, according to results of the BARCODE 1 clinical trial conducted in the United Kingdom.

The study found that about 72% of participants with high polygenic risk scores were diagnosed with clinically significant prostate cancers, which would not have been detected with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing or MRI.

“With this test, it could be possible to turn the tide on prostate cancer,” study author Ros Eeles, PhD, professor of oncogenetics at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, England, said in a statement following the publication of the analysis in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Prostate cancer remains the second most commonly diagnosed cancer among men. As a screening tool, PSA testing has been criticized for leading to a high rate of false positive results and overdiagnosis — defined as a screen-detected cancer that would take longer to progress to clinical cancer than the patient’s lifetime. Both issues can result in overtreatment.

Given prostate cancer’s high heritability and the proliferation of genome-wide association studies identifying common genetic variants, there has been growing interest in using polygenic risk scores to improve risk stratification and guide screening.

“Building on decades of research into the genetic markers of prostate cancer, our study shows that the theory does work in practice — we can identify men at risk of aggressive cancers who need further tests and spare the men who are at lower risk from unnecessary treatments,” said Eeles.

An Adjunct to Screening?

The BARCODE 1 study, conducted in the United Kingdom, tested the clinical utility of a polygenic risk score as an adjunct to screening.

The researchers recruited men aged 55-69 years from primary care centers in the United Kingdom. Using germline DNA extracted from saliva, they derived polygenic risk scores from 130 genetic variants known to be associated with an increased risk for prostate cancer.

Among a total of 6393 men who had their scores calculated, 745 (12%) had a score in the top 10% of genetic risk (≥ 90th percentile) and were invited to undergo further screening.

Of these, 468 (63%) accepted the invite and underwent multiparametric MRI and transperineal prostate biopsy, irrespective of the PSA level. Overall, 187 (40%) were diagnosed with prostate cancer following biopsy. Of the 187 men with prostate cancer, 55% (n = 103) had disease classified as intermediate or high risk (Gleason score ≥ 7) per National Comprehensive Cancer Network criteria and therefore warranted further treatment.

Researchers then compared screening that incorporated polygenic risk scores with standard screening with PSA levels and MRI.

When participants’ risk was stratified by their polygenic risk score, 103 patients (55%) with prostate cancer could be classified as intermediate or higher risk, thus warranting treatment. Overall, 74 (71.8%) of those cancers would have been missed using the standard diagnostic pathway in the United Kingdom, which requires patients to have a high PSA level (> 3.0 μg/L) as well as a positive MRI result. These 74 patients either had PSA levels ≤ 3.0 μg/L or negative MRIs, which would mean these patients would typically fall below the action threshold for further testing.

Of the 103 participants warranting treatment, 40 of these men would have been classified as unfavorable intermediate, high, or very high risk, which would require radical treatment. Among this group, roughly 43% would have been missed using the UK diagnostic pathway.

However, the investigators estimated a rate of overdiagnosis with the use of polygenic risk scores of 16%-21%, similar to the overdiagnosis estimates in two prior PSA-based screening studies, signaling that the addition of polygenic risk scores does not necessarily reduce the risk for overdiagnosis.

Overall, “this study is the strongest evidence to date on the clinical utility of a polygenic score for prostate cancer screening,” commented Michael Inouye, professor of systems genomics & population health, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, England, in a statement from the UK nonprofit Science Media Centre (SMC).

“I suspect we will look back on this as a landmark study that really made the clinical case for polygenic scores as a new tool that moved health systems from disease management to early detection and prevention,” said Inouye, who was not involved in the study.

However, other experts were more cautious about the findings.

Dusko Ilic, MD, professor of stem cell sciences, King’s College London, London, England, said the results are “promising, especially in identifying significant cancers that would otherwise be missed,” but cautioned that “there is no direct evidence yet that using [polygenic risk scores] improves long-term outcomes such as mortality or quality-adjusted life years.”

“Modeling suggests benefit, but empirical confirmation is needed,” Ilic said in the SMC statement.

The hope is that the recently launched TRANSFORM trial will help answer some of these outstanding questions.

The current study suggests that polygenic risk scores for prostate cancer “would be a useful component of a multimodality screening program that assesses age, family history of prostate cancer, PSA, and MRI results as triage tools before biopsy is recommended,” David Hunter, MPH, ScD, with Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and University of Oxford, Oxford, England, wrote in an editorial accompanying the study.

“To make this integrated program a reality, however, changes to infrastructure would be needed to make running and analyzing a regulated genome array as easy as requesting a PSA level or ordering an MRI. Clearly, we are far from that future,” Hunter cautioned.

“A possible first step that would require less infrastructure could be to order a polygenic risk score only for men with a positive PSA result, then use the polygenic risk score to determine who should undergo an MRI, and then use all the information to determine whether biopsy is recommended,” Hunter said.

In his view, the current study is a “first step on a long road to evaluating new components of any disease screening pathway.”

The research received funding from the European Research Council, the Bob Willis Fund, Cancer Research UK, the Peacock Trust, and the National Institute for Health and Care Research Biomedical Research Centre at The Royal Marsden and The Institute of Cancer Research. Disclosures for authors and editorialists are available with the original article. Inouye and Ilic reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Incorporating a polygenic risk score into prostate cancer screening could enhance the detection of clinically significant prostate cancer that conventional screening may miss, according to results of the BARCODE 1 clinical trial conducted in the United Kingdom.

The study found that about 72% of participants with high polygenic risk scores were diagnosed with clinically significant prostate cancers, which would not have been detected with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing or MRI.

“With this test, it could be possible to turn the tide on prostate cancer,” study author Ros Eeles, PhD, professor of oncogenetics at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, England, said in a statement following the publication of the analysis in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Prostate cancer remains the second most commonly diagnosed cancer among men. As a screening tool, PSA testing has been criticized for leading to a high rate of false positive results and overdiagnosis — defined as a screen-detected cancer that would take longer to progress to clinical cancer than the patient’s lifetime. Both issues can result in overtreatment.

Given prostate cancer’s high heritability and the proliferation of genome-wide association studies identifying common genetic variants, there has been growing interest in using polygenic risk scores to improve risk stratification and guide screening.

“Building on decades of research into the genetic markers of prostate cancer, our study shows that the theory does work in practice — we can identify men at risk of aggressive cancers who need further tests and spare the men who are at lower risk from unnecessary treatments,” said Eeles.

An Adjunct to Screening?

The BARCODE 1 study, conducted in the United Kingdom, tested the clinical utility of a polygenic risk score as an adjunct to screening.

The researchers recruited men aged 55-69 years from primary care centers in the United Kingdom. Using germline DNA extracted from saliva, they derived polygenic risk scores from 130 genetic variants known to be associated with an increased risk for prostate cancer.

Among a total of 6393 men who had their scores calculated, 745 (12%) had a score in the top 10% of genetic risk (≥ 90th percentile) and were invited to undergo further screening.

Of these, 468 (63%) accepted the invite and underwent multiparametric MRI and transperineal prostate biopsy, irrespective of the PSA level. Overall, 187 (40%) were diagnosed with prostate cancer following biopsy. Of the 187 men with prostate cancer, 55% (n = 103) had disease classified as intermediate or high risk (Gleason score ≥ 7) per National Comprehensive Cancer Network criteria and therefore warranted further treatment.

Researchers then compared screening that incorporated polygenic risk scores with standard screening with PSA levels and MRI.

When participants’ risk was stratified by their polygenic risk score, 103 patients (55%) with prostate cancer could be classified as intermediate or higher risk, thus warranting treatment. Overall, 74 (71.8%) of those cancers would have been missed using the standard diagnostic pathway in the United Kingdom, which requires patients to have a high PSA level (> 3.0 μg/L) as well as a positive MRI result. These 74 patients either had PSA levels ≤ 3.0 μg/L or negative MRIs, which would mean these patients would typically fall below the action threshold for further testing.

Of the 103 participants warranting treatment, 40 of these men would have been classified as unfavorable intermediate, high, or very high risk, which would require radical treatment. Among this group, roughly 43% would have been missed using the UK diagnostic pathway.

However, the investigators estimated a rate of overdiagnosis with the use of polygenic risk scores of 16%-21%, similar to the overdiagnosis estimates in two prior PSA-based screening studies, signaling that the addition of polygenic risk scores does not necessarily reduce the risk for overdiagnosis.

Overall, “this study is the strongest evidence to date on the clinical utility of a polygenic score for prostate cancer screening,” commented Michael Inouye, professor of systems genomics & population health, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, England, in a statement from the UK nonprofit Science Media Centre (SMC).

“I suspect we will look back on this as a landmark study that really made the clinical case for polygenic scores as a new tool that moved health systems from disease management to early detection and prevention,” said Inouye, who was not involved in the study.

However, other experts were more cautious about the findings.

Dusko Ilic, MD, professor of stem cell sciences, King’s College London, London, England, said the results are “promising, especially in identifying significant cancers that would otherwise be missed,” but cautioned that “there is no direct evidence yet that using [polygenic risk scores] improves long-term outcomes such as mortality or quality-adjusted life years.”

“Modeling suggests benefit, but empirical confirmation is needed,” Ilic said in the SMC statement.

The hope is that the recently launched TRANSFORM trial will help answer some of these outstanding questions.

The current study suggests that polygenic risk scores for prostate cancer “would be a useful component of a multimodality screening program that assesses age, family history of prostate cancer, PSA, and MRI results as triage tools before biopsy is recommended,” David Hunter, MPH, ScD, with Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and University of Oxford, Oxford, England, wrote in an editorial accompanying the study.

“To make this integrated program a reality, however, changes to infrastructure would be needed to make running and analyzing a regulated genome array as easy as requesting a PSA level or ordering an MRI. Clearly, we are far from that future,” Hunter cautioned.

“A possible first step that would require less infrastructure could be to order a polygenic risk score only for men with a positive PSA result, then use the polygenic risk score to determine who should undergo an MRI, and then use all the information to determine whether biopsy is recommended,” Hunter said.

In his view, the current study is a “first step on a long road to evaluating new components of any disease screening pathway.”

The research received funding from the European Research Council, the Bob Willis Fund, Cancer Research UK, the Peacock Trust, and the National Institute for Health and Care Research Biomedical Research Centre at The Royal Marsden and The Institute of Cancer Research. Disclosures for authors and editorialists are available with the original article. Inouye and Ilic reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Simple Score Predicts Advanced Colorectal Neoplasia in Young Adults

While colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence has declined overall due to screening, early-onset CRC is on the rise, particularly in individuals younger than 45 years — an age group not currently recommended for CRC screening.

Studies have shown that the risk for early-onset advanced neoplasia varies based on several factors, including sex, race, family history of CRC, smoking, alcohol consumption, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and diet.

A score that incorporates some of these factors to identify which younger adults are at higher risk for advanced neoplasia, a precursor to CRC, could support earlier, more targeted screening interventions.

The simple clinical score can be easily calculated by primary care providers in the office, Carole Macaron, MD, lead author of the study and a gastroenterologist at Cleveland Clinic, told GI & Hepatology News. “Patients with a high-risk score would be referred for colorectal cancer screening.”

The study was published in Digestive Diseases and Sciences.

To develop and validate their risk score, Macaron and colleagues did a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of 9446 individuals aged 18-44 years (mean age, 36.8 years; 61% women) who underwent colonoscopy at their center.

Advanced neoplasia was defined as a tubular adenoma ≥ 10 mm or any adenoma with villous features or high-grade dysplasia, sessile serrated polyp ≥ 10 mm, sessile serrated polyp with dysplasia, traditional serrated adenoma, or invasive adenocarcinoma.

The 346 (3.7%) individuals found to have advanced neoplasia served as the case group, and the remainder with normal colonoscopy or non-advanced neoplasia served as controls.

A multivariate logistic regression model identified three independent risk factors significantly associated with advanced neoplasia: Higher body mass index (BMI; P = .0157), former and current tobacco use (P = .0009 and P = .0015, respectively), and having a first-degree relative with CRC < 60 years (P < .0001) or other family history of CRC (P = .0117).

The researchers used these risk factors to develop a risk prediction score to estimate the likelihood of detecting advanced neoplasia, which ranged from a risk of 1.8% for patients with a score of 1 to 22.2% for those with a score of 12. Individuals with a score of ≥ 9 had a 14% or higher risk for advanced neoplasia.

Based on the risk model, the likelihood of detecting advanced neoplasia in an asymptomatic 32-year-old overweight individual, with a history of previous tobacco use and a first-degree relative younger than age 60 with CRC would be 20.3%, Macaron and colleagues noted.

The model demonstrated “moderate” discriminatory power in the validation set (C-statistic: 0.645), indicating that it can effectively differentiate between individuals at a higher and lower risk for advanced neoplasia.

Additionally, the authors are exploring ways to improve the discriminatory power of the score, possibly by including additional risk factors.

Given the score is calculated using easily obtainable risk factors for individuals younger than 45 who are at risk for early-onset colorectal neoplasia, it could help guide individualized screening decisions for those in whom screening is not currently offered, Macaron said. It could also serve as a tool for risk communication and shared decision-making.

Integration into electronic health records or online calculators may enhance its accessibility and clinical utility.

The authors noted that this retrospective study was conducted at a single center caring mainly for White non-Hispanic adults, limiting generalizability to the general population and to other races and ethnicities.

Validation in Real-World Setting Needed

“There are no currently accepted advanced colorectal neoplasia risk scores that are used in general practice,” said Steven H. Itzkowitz, MD, AGAF, professor of medicine, oncological sciences, and medical education, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. “If these lesions can be predicted, it would enable these young individuals to undergo screening colonoscopy, which could detect and remove these lesions, thereby preventing CRC.”

Many of the known risk factors (family history, high BMI, or smoking) for CRC development at any age are incorporated within this tool, so it should be feasible to collect these data,” said Itzkowitz, who was not involved with the study.

But he cautioned that accurate and adequate family histories are not always performed. Clinicians also may not have considered combining these factors into an actionable risk score.

“If this score can be externally validated in a real-world setting, it could be a useful addition in our efforts to lower CRC rates among young individuals,” Itzkowitz said.

The study did not receive any funding. Macaron and Itzkowitz reported no competing interests.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence has declined overall due to screening, early-onset CRC is on the rise, particularly in individuals younger than 45 years — an age group not currently recommended for CRC screening.

Studies have shown that the risk for early-onset advanced neoplasia varies based on several factors, including sex, race, family history of CRC, smoking, alcohol consumption, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and diet.

A score that incorporates some of these factors to identify which younger adults are at higher risk for advanced neoplasia, a precursor to CRC, could support earlier, more targeted screening interventions.

The simple clinical score can be easily calculated by primary care providers in the office, Carole Macaron, MD, lead author of the study and a gastroenterologist at Cleveland Clinic, told GI & Hepatology News. “Patients with a high-risk score would be referred for colorectal cancer screening.”

The study was published in Digestive Diseases and Sciences.

To develop and validate their risk score, Macaron and colleagues did a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of 9446 individuals aged 18-44 years (mean age, 36.8 years; 61% women) who underwent colonoscopy at their center.

Advanced neoplasia was defined as a tubular adenoma ≥ 10 mm or any adenoma with villous features or high-grade dysplasia, sessile serrated polyp ≥ 10 mm, sessile serrated polyp with dysplasia, traditional serrated adenoma, or invasive adenocarcinoma.

The 346 (3.7%) individuals found to have advanced neoplasia served as the case group, and the remainder with normal colonoscopy or non-advanced neoplasia served as controls.

A multivariate logistic regression model identified three independent risk factors significantly associated with advanced neoplasia: Higher body mass index (BMI; P = .0157), former and current tobacco use (P = .0009 and P = .0015, respectively), and having a first-degree relative with CRC < 60 years (P < .0001) or other family history of CRC (P = .0117).

The researchers used these risk factors to develop a risk prediction score to estimate the likelihood of detecting advanced neoplasia, which ranged from a risk of 1.8% for patients with a score of 1 to 22.2% for those with a score of 12. Individuals with a score of ≥ 9 had a 14% or higher risk for advanced neoplasia.

Based on the risk model, the likelihood of detecting advanced neoplasia in an asymptomatic 32-year-old overweight individual, with a history of previous tobacco use and a first-degree relative younger than age 60 with CRC would be 20.3%, Macaron and colleagues noted.

The model demonstrated “moderate” discriminatory power in the validation set (C-statistic: 0.645), indicating that it can effectively differentiate between individuals at a higher and lower risk for advanced neoplasia.

Additionally, the authors are exploring ways to improve the discriminatory power of the score, possibly by including additional risk factors.

Given the score is calculated using easily obtainable risk factors for individuals younger than 45 who are at risk for early-onset colorectal neoplasia, it could help guide individualized screening decisions for those in whom screening is not currently offered, Macaron said. It could also serve as a tool for risk communication and shared decision-making.

Integration into electronic health records or online calculators may enhance its accessibility and clinical utility.

The authors noted that this retrospective study was conducted at a single center caring mainly for White non-Hispanic adults, limiting generalizability to the general population and to other races and ethnicities.

Validation in Real-World Setting Needed

“There are no currently accepted advanced colorectal neoplasia risk scores that are used in general practice,” said Steven H. Itzkowitz, MD, AGAF, professor of medicine, oncological sciences, and medical education, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. “If these lesions can be predicted, it would enable these young individuals to undergo screening colonoscopy, which could detect and remove these lesions, thereby preventing CRC.”

Many of the known risk factors (family history, high BMI, or smoking) for CRC development at any age are incorporated within this tool, so it should be feasible to collect these data,” said Itzkowitz, who was not involved with the study.

But he cautioned that accurate and adequate family histories are not always performed. Clinicians also may not have considered combining these factors into an actionable risk score.

“If this score can be externally validated in a real-world setting, it could be a useful addition in our efforts to lower CRC rates among young individuals,” Itzkowitz said.

The study did not receive any funding. Macaron and Itzkowitz reported no competing interests.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence has declined overall due to screening, early-onset CRC is on the rise, particularly in individuals younger than 45 years — an age group not currently recommended for CRC screening.

Studies have shown that the risk for early-onset advanced neoplasia varies based on several factors, including sex, race, family history of CRC, smoking, alcohol consumption, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and diet.

A score that incorporates some of these factors to identify which younger adults are at higher risk for advanced neoplasia, a precursor to CRC, could support earlier, more targeted screening interventions.

The simple clinical score can be easily calculated by primary care providers in the office, Carole Macaron, MD, lead author of the study and a gastroenterologist at Cleveland Clinic, told GI & Hepatology News. “Patients with a high-risk score would be referred for colorectal cancer screening.”

The study was published in Digestive Diseases and Sciences.

To develop and validate their risk score, Macaron and colleagues did a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of 9446 individuals aged 18-44 years (mean age, 36.8 years; 61% women) who underwent colonoscopy at their center.

Advanced neoplasia was defined as a tubular adenoma ≥ 10 mm or any adenoma with villous features or high-grade dysplasia, sessile serrated polyp ≥ 10 mm, sessile serrated polyp with dysplasia, traditional serrated adenoma, or invasive adenocarcinoma.

The 346 (3.7%) individuals found to have advanced neoplasia served as the case group, and the remainder with normal colonoscopy or non-advanced neoplasia served as controls.

A multivariate logistic regression model identified three independent risk factors significantly associated with advanced neoplasia: Higher body mass index (BMI; P = .0157), former and current tobacco use (P = .0009 and P = .0015, respectively), and having a first-degree relative with CRC < 60 years (P < .0001) or other family history of CRC (P = .0117).

The researchers used these risk factors to develop a risk prediction score to estimate the likelihood of detecting advanced neoplasia, which ranged from a risk of 1.8% for patients with a score of 1 to 22.2% for those with a score of 12. Individuals with a score of ≥ 9 had a 14% or higher risk for advanced neoplasia.

Based on the risk model, the likelihood of detecting advanced neoplasia in an asymptomatic 32-year-old overweight individual, with a history of previous tobacco use and a first-degree relative younger than age 60 with CRC would be 20.3%, Macaron and colleagues noted.

The model demonstrated “moderate” discriminatory power in the validation set (C-statistic: 0.645), indicating that it can effectively differentiate between individuals at a higher and lower risk for advanced neoplasia.

Additionally, the authors are exploring ways to improve the discriminatory power of the score, possibly by including additional risk factors.

Given the score is calculated using easily obtainable risk factors for individuals younger than 45 who are at risk for early-onset colorectal neoplasia, it could help guide individualized screening decisions for those in whom screening is not currently offered, Macaron said. It could also serve as a tool for risk communication and shared decision-making.

Integration into electronic health records or online calculators may enhance its accessibility and clinical utility.

The authors noted that this retrospective study was conducted at a single center caring mainly for White non-Hispanic adults, limiting generalizability to the general population and to other races and ethnicities.

Validation in Real-World Setting Needed

“There are no currently accepted advanced colorectal neoplasia risk scores that are used in general practice,” said Steven H. Itzkowitz, MD, AGAF, professor of medicine, oncological sciences, and medical education, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. “If these lesions can be predicted, it would enable these young individuals to undergo screening colonoscopy, which could detect and remove these lesions, thereby preventing CRC.”

Many of the known risk factors (family history, high BMI, or smoking) for CRC development at any age are incorporated within this tool, so it should be feasible to collect these data,” said Itzkowitz, who was not involved with the study.

But he cautioned that accurate and adequate family histories are not always performed. Clinicians also may not have considered combining these factors into an actionable risk score.

“If this score can be externally validated in a real-world setting, it could be a useful addition in our efforts to lower CRC rates among young individuals,” Itzkowitz said.

The study did not receive any funding. Macaron and Itzkowitz reported no competing interests.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

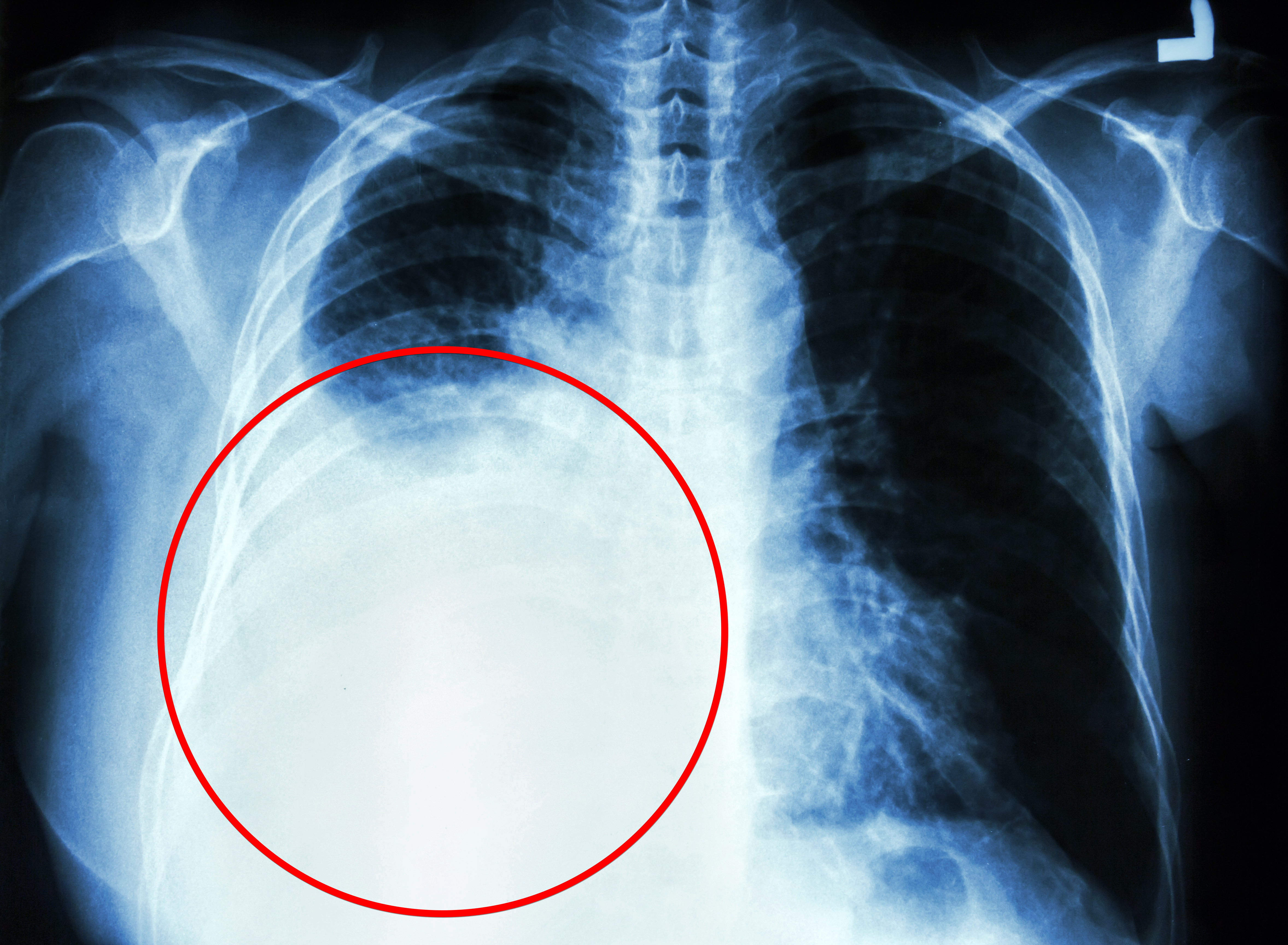

A ‘Fool’s Errand’? Picking a Winner for Treating Early-Stage NSCLC

For years, the default definitive treatment for patients with early-stage I non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has been surgical resection, typically minimally invasive lobectomy with systematic lymph node dissection.

Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the European Society for Medical Oncology all list surgery (in particular, lobectomy) as the primary local therapy for fit, operable patients with stage I NSCLC.

More recently, however, stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), also called stereotactic ablative radiotherapy, has emerged as a definitive treatment option for stage I NSCLC, especially for older, less fit patients who are unsuitable or deemed high-risk for surgery.

“We see patients in our practice who cannot undergo surgery or who may not have adequate lung function to be able to tolerate surgery, and for these patients who are medically inoperable or surgically unresectable, radiation therapy may be a reasonable option,” Charu Aggarwal, MD, MPH, professor and lung cancer specialist, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

Given some encouraging data suggesting that SBRT could provide similar survival outcomes and be an alternative to surgery for operable disease, SBRT is also increasingly being considered in these early-stage patients. However, other evidence indicates that SBRT may be associated with higher rates of regional and distant recurrences and worse long-term survival, particularly in operable patients.

What may ultimately matter most is carefully selecting operable patients who undergo SBRT.

Aggarwal has encountered certain patients who are fit for surgery but would rather have radiation therapy. “This is an individual decision, and these patients are usually discussed at tumor board and in multidisciplinary discussions to really make sure that they’re making the right decision for themselves,” she explained.

The Pros and Cons of SBRT

SBRT is a nonsurgical approach in which precision high-dose radiation is delivered in just a few fractions — typically, 3, 5, or 8, depending on institutional protocols and tumor characteristics.

SBRT is performed on an outpatient basis, usually over 1-2 weeks, with most patients able to resume usual activities with minimal to no delay. Surgery, on the other hand, requires a hospital stay and takes most people about 2-6 weeks to return to regular activities. SBRT also avoids anesthesia and surgical incisions, both of which come with risks.

The data on SBRT in early-stage NSCLC are mixed. While some studies indicate that SBRT comes with promising survival outcomes, other research has reported worse survival and recurrence rates.

One potential reason for higher recurrence rates with SBRT is the lack of pathologic nodal staging, which only happens after surgery, as well as lower rates of nodal evaluation with endobronchial ultrasound or mediastinoscopy before surgery or SBRT. Without nodal assessments, clinicians may miss a more aggressive histology or more advanced nodal stage, which would go undertreated if patients received SBRT.

Latest Data in Large Cohort

A recent study published in Lung Cancer indicated that, when carefully selected, operable patients with early NSCLC have comparable survival with lobectomy or SBRT.

In the study, Dutch researchers took an in-depth look at survival and recurrence patterns in a retrospective cohort study of 2183 patients with clinical stage I NSCLC treated with minimally invasive lobectomy or SBRT. The study includes one of the largest cohorts to date, with robust data collection on baseline characteristics, comorbidities, tumor size, performance status, and follow-up.

Patients receiving SBRT were typically older (median age, 74 vs 67 years), had higher comorbidity burdens (Charlson index ≥ 5 in 57% of SBRT patients vs 23% of surgical patients), worse performance status, and lower lung function. To adjust for these differences, the researchers used propensity score weighting so the SBRT group’s baseline characteristics were comparable with those in the surgery group.

The surgery cohort had more invasive nodal evaluation: 21% underwent endobronchial ultrasound or mediastinoscopy vs only 12% in the SBRT group. The vast majority in both groups had PET-CT staging, reflecting modern imaging-based workups.

While 5-year local recurrence rates between the two groups were similar (13.1% for SBRT vs 12.1% for surgery), the 5-year regional recurrence rate was significantly higher after SBRT than lobectomy (18.1% vs 14.2%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.74), as was the distant metastasis rate (26.2% vs 20.2%; HR, 0.72).

Mortality at 30 days was higher after surgery than SBRT (1.0% vs 0.2%). And in the unadjusted analysis, 5-year overall survival was significantly better with lobectomy than SBRT (70.2% vs 40.3%).

However, when the analysis only included patients with similar baseline characteristics, overall survival was no longer significantly different in the two groups (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.65-1.20). Lung cancer–specific mortality was also not significantly different between the two treatments (HR, 1.08), but the study was underpowered to detect significant differences in this outcome on the basis of a relatively low number of deaths from NSCLC.

Still, even after comparing similar patients, recurrence-free survival was notably better with surgery (HR, 0.70), due to fewer regional recurrences and distant metastases. Overall, 13% of the surgical cohort had nodal upstaging at pathology, meaning that even in clinically “node-negative” stage I disease, a subset of patients had unsuspected nodal involvement.

Patients receiving SBRT did not have pathologic nodal staging, raising the possibility of occult micrometastases. The authors noted that the proportion of SBRT patients with occult lymph node metastases is likely at least equal to that in the surgery group, but these metastases would go undetected without pathologic assessment.

Missing potential occult micrometastases in the SBRT group likely contributed to higher regional recurrence rates over time. By improving nodal staging, more patients with occult lymph node metastases who would be undertreated with SBRT may be identified before treatment, the authors said.

What Do Experts Say?

So, is SBRT an option for patients with stage I NSCLC?

Opinions vary.

“If you got one shot for a cure, then you want to do the surgery because that’s what results in a cure,” said Raja Flores, MD, chairman of Thoracic Surgery, Mount Sinai Health System, New York City.

Flores noted that the survival rate with surgery is high in this population. “There’s really nothing out there that can compare,” he said.

In his view, surgery “remains the gold standard.” However, “radiation could be considered in nonsurgical candidates,” he said.

The most recent NCCN guidelines align with Flores’ take. The guidelines say that SBRT is indicated for stage IA-IIA (N0) NSCLC in patients who are deemed “medically inoperable, high surgical risk as determined by thoracic surgeon, and those who decline surgery after thoracic surgical consultation.”

Clifford G. Robinson, MD, agreed. “In the United States, we largely treat patients with SBRT who are medically inoperable or high-risk operable and a much smaller proportion who decline surgery,” said Robinson, professor of radiation oncology and chief of SBRT at Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis. “Many patients who are deemed operable are not offered SBRT.”

Still, for Robinson, determining which patients are best suited for surgery or SBRT remains unclear.

“Retrospective comparisons are fraught with problems because of confounding,” Robinson told this news organization. “That is, the healthier patients get surgery, and the less healthy ones get SBRT. No manner of fancy statistical manipulation can remove that fact.”

In fact, a recent meta-analysis found that the most significant variable predicting whether surgery or SBRT was superior in retrospective studies was whether the author was a surgeon or radiation oncologist.

Robinson noted that multiple randomized trials have attempted to randomize patients with medically operable early-stage NSCLC to surgery or SBRT and failed to accrue, largely due to patients’ “understandable unwillingness to be randomized between operative vs nonoperative interventions when most already prefer one or the other approach.”

Flores highlighted another point of caution about interpreting trial results: Not all early-stage NSCLC behaves similarly. “Some are slow-growing ‘turtles,’ and others are aggressive ‘rabbits’ — and the turtles are usually the ones that have been included in these radiotherapy trials, and that’s the danger,” he said.

While medical operability is the primary factor for deciding the treatment modality for early-stage NSCLC, there are other more subtle factors that can play into the decision.

These include prior surgery or radiotherapy to the chest, prior cancers, and social issues, such as the patient being a primary caregiver for another person and job insecurity, that might make recovery from surgery more challenging. And in rare instances, a patient may be medically fit to undergo surgery, but the cancer is technically challenging to resect due to anatomic issues or prior surgery to the chest, Robinson added.

A Winner?

Results from two ongoing, highly anticipated randomized trials expected in the next several years will hopefully provide additional insights and clarify ongoing uncertainties about the optimal treatment strategies for operable patients with stage I NSCLC.

STABLE-MATES is comparing outcomes after sublobar resection and SBRT in high-risk operable stage I NSCLC, and VALOR is evaluating outcomes after anatomic pulmonary resections and SBRT in patients with stage I NSCLC who have a long life expectancy and are fit enough to tolerate surgery.

But Robinson said his group believes that trying to decide on a winner is a “fool’s errand” and is instead running a pragmatic study across multiple academic and community centers around the United States and Canada where patients choose therapy based on their personal preferences and guidance from their physicians. The researchers will carefully track baseline comorbidity and frailty and assess serial quality-of-life changes over time.

“The goal is to create a calculator that a given patient might use in the future to determine what patients like them would have received, complete with expected outcomes and side effects,” Robinson said.

Robinson cautioned, however, that it “seems unlikely, given the existing literature, that one of the treatments will be truly ‘superior’ to the other one and lead to the ‘losing’ treatment fading away since both are excellent options with pros and cons.”

Aggarwal, Robinson, and Flores had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For years, the default definitive treatment for patients with early-stage I non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has been surgical resection, typically minimally invasive lobectomy with systematic lymph node dissection.

Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the European Society for Medical Oncology all list surgery (in particular, lobectomy) as the primary local therapy for fit, operable patients with stage I NSCLC.

More recently, however, stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), also called stereotactic ablative radiotherapy, has emerged as a definitive treatment option for stage I NSCLC, especially for older, less fit patients who are unsuitable or deemed high-risk for surgery.

“We see patients in our practice who cannot undergo surgery or who may not have adequate lung function to be able to tolerate surgery, and for these patients who are medically inoperable or surgically unresectable, radiation therapy may be a reasonable option,” Charu Aggarwal, MD, MPH, professor and lung cancer specialist, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

Given some encouraging data suggesting that SBRT could provide similar survival outcomes and be an alternative to surgery for operable disease, SBRT is also increasingly being considered in these early-stage patients. However, other evidence indicates that SBRT may be associated with higher rates of regional and distant recurrences and worse long-term survival, particularly in operable patients.

What may ultimately matter most is carefully selecting operable patients who undergo SBRT.

Aggarwal has encountered certain patients who are fit for surgery but would rather have radiation therapy. “This is an individual decision, and these patients are usually discussed at tumor board and in multidisciplinary discussions to really make sure that they’re making the right decision for themselves,” she explained.

The Pros and Cons of SBRT

SBRT is a nonsurgical approach in which precision high-dose radiation is delivered in just a few fractions — typically, 3, 5, or 8, depending on institutional protocols and tumor characteristics.

SBRT is performed on an outpatient basis, usually over 1-2 weeks, with most patients able to resume usual activities with minimal to no delay. Surgery, on the other hand, requires a hospital stay and takes most people about 2-6 weeks to return to regular activities. SBRT also avoids anesthesia and surgical incisions, both of which come with risks.

The data on SBRT in early-stage NSCLC are mixed. While some studies indicate that SBRT comes with promising survival outcomes, other research has reported worse survival and recurrence rates.

One potential reason for higher recurrence rates with SBRT is the lack of pathologic nodal staging, which only happens after surgery, as well as lower rates of nodal evaluation with endobronchial ultrasound or mediastinoscopy before surgery or SBRT. Without nodal assessments, clinicians may miss a more aggressive histology or more advanced nodal stage, which would go undertreated if patients received SBRT.

Latest Data in Large Cohort

A recent study published in Lung Cancer indicated that, when carefully selected, operable patients with early NSCLC have comparable survival with lobectomy or SBRT.

In the study, Dutch researchers took an in-depth look at survival and recurrence patterns in a retrospective cohort study of 2183 patients with clinical stage I NSCLC treated with minimally invasive lobectomy or SBRT. The study includes one of the largest cohorts to date, with robust data collection on baseline characteristics, comorbidities, tumor size, performance status, and follow-up.

Patients receiving SBRT were typically older (median age, 74 vs 67 years), had higher comorbidity burdens (Charlson index ≥ 5 in 57% of SBRT patients vs 23% of surgical patients), worse performance status, and lower lung function. To adjust for these differences, the researchers used propensity score weighting so the SBRT group’s baseline characteristics were comparable with those in the surgery group.

The surgery cohort had more invasive nodal evaluation: 21% underwent endobronchial ultrasound or mediastinoscopy vs only 12% in the SBRT group. The vast majority in both groups had PET-CT staging, reflecting modern imaging-based workups.

While 5-year local recurrence rates between the two groups were similar (13.1% for SBRT vs 12.1% for surgery), the 5-year regional recurrence rate was significantly higher after SBRT than lobectomy (18.1% vs 14.2%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.74), as was the distant metastasis rate (26.2% vs 20.2%; HR, 0.72).

Mortality at 30 days was higher after surgery than SBRT (1.0% vs 0.2%). And in the unadjusted analysis, 5-year overall survival was significantly better with lobectomy than SBRT (70.2% vs 40.3%).

However, when the analysis only included patients with similar baseline characteristics, overall survival was no longer significantly different in the two groups (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.65-1.20). Lung cancer–specific mortality was also not significantly different between the two treatments (HR, 1.08), but the study was underpowered to detect significant differences in this outcome on the basis of a relatively low number of deaths from NSCLC.

Still, even after comparing similar patients, recurrence-free survival was notably better with surgery (HR, 0.70), due to fewer regional recurrences and distant metastases. Overall, 13% of the surgical cohort had nodal upstaging at pathology, meaning that even in clinically “node-negative” stage I disease, a subset of patients had unsuspected nodal involvement.

Patients receiving SBRT did not have pathologic nodal staging, raising the possibility of occult micrometastases. The authors noted that the proportion of SBRT patients with occult lymph node metastases is likely at least equal to that in the surgery group, but these metastases would go undetected without pathologic assessment.

Missing potential occult micrometastases in the SBRT group likely contributed to higher regional recurrence rates over time. By improving nodal staging, more patients with occult lymph node metastases who would be undertreated with SBRT may be identified before treatment, the authors said.

What Do Experts Say?

So, is SBRT an option for patients with stage I NSCLC?

Opinions vary.

“If you got one shot for a cure, then you want to do the surgery because that’s what results in a cure,” said Raja Flores, MD, chairman of Thoracic Surgery, Mount Sinai Health System, New York City.

Flores noted that the survival rate with surgery is high in this population. “There’s really nothing out there that can compare,” he said.

In his view, surgery “remains the gold standard.” However, “radiation could be considered in nonsurgical candidates,” he said.

The most recent NCCN guidelines align with Flores’ take. The guidelines say that SBRT is indicated for stage IA-IIA (N0) NSCLC in patients who are deemed “medically inoperable, high surgical risk as determined by thoracic surgeon, and those who decline surgery after thoracic surgical consultation.”

Clifford G. Robinson, MD, agreed. “In the United States, we largely treat patients with SBRT who are medically inoperable or high-risk operable and a much smaller proportion who decline surgery,” said Robinson, professor of radiation oncology and chief of SBRT at Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis. “Many patients who are deemed operable are not offered SBRT.”

Still, for Robinson, determining which patients are best suited for surgery or SBRT remains unclear.

“Retrospective comparisons are fraught with problems because of confounding,” Robinson told this news organization. “That is, the healthier patients get surgery, and the less healthy ones get SBRT. No manner of fancy statistical manipulation can remove that fact.”

In fact, a recent meta-analysis found that the most significant variable predicting whether surgery or SBRT was superior in retrospective studies was whether the author was a surgeon or radiation oncologist.

Robinson noted that multiple randomized trials have attempted to randomize patients with medically operable early-stage NSCLC to surgery or SBRT and failed to accrue, largely due to patients’ “understandable unwillingness to be randomized between operative vs nonoperative interventions when most already prefer one or the other approach.”

Flores highlighted another point of caution about interpreting trial results: Not all early-stage NSCLC behaves similarly. “Some are slow-growing ‘turtles,’ and others are aggressive ‘rabbits’ — and the turtles are usually the ones that have been included in these radiotherapy trials, and that’s the danger,” he said.

While medical operability is the primary factor for deciding the treatment modality for early-stage NSCLC, there are other more subtle factors that can play into the decision.

These include prior surgery or radiotherapy to the chest, prior cancers, and social issues, such as the patient being a primary caregiver for another person and job insecurity, that might make recovery from surgery more challenging. And in rare instances, a patient may be medically fit to undergo surgery, but the cancer is technically challenging to resect due to anatomic issues or prior surgery to the chest, Robinson added.

A Winner?

Results from two ongoing, highly anticipated randomized trials expected in the next several years will hopefully provide additional insights and clarify ongoing uncertainties about the optimal treatment strategies for operable patients with stage I NSCLC.

STABLE-MATES is comparing outcomes after sublobar resection and SBRT in high-risk operable stage I NSCLC, and VALOR is evaluating outcomes after anatomic pulmonary resections and SBRT in patients with stage I NSCLC who have a long life expectancy and are fit enough to tolerate surgery.

But Robinson said his group believes that trying to decide on a winner is a “fool’s errand” and is instead running a pragmatic study across multiple academic and community centers around the United States and Canada where patients choose therapy based on their personal preferences and guidance from their physicians. The researchers will carefully track baseline comorbidity and frailty and assess serial quality-of-life changes over time.

“The goal is to create a calculator that a given patient might use in the future to determine what patients like them would have received, complete with expected outcomes and side effects,” Robinson said.

Robinson cautioned, however, that it “seems unlikely, given the existing literature, that one of the treatments will be truly ‘superior’ to the other one and lead to the ‘losing’ treatment fading away since both are excellent options with pros and cons.”

Aggarwal, Robinson, and Flores had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For years, the default definitive treatment for patients with early-stage I non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has been surgical resection, typically minimally invasive lobectomy with systematic lymph node dissection.

Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the European Society for Medical Oncology all list surgery (in particular, lobectomy) as the primary local therapy for fit, operable patients with stage I NSCLC.

More recently, however, stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), also called stereotactic ablative radiotherapy, has emerged as a definitive treatment option for stage I NSCLC, especially for older, less fit patients who are unsuitable or deemed high-risk for surgery.

“We see patients in our practice who cannot undergo surgery or who may not have adequate lung function to be able to tolerate surgery, and for these patients who are medically inoperable or surgically unresectable, radiation therapy may be a reasonable option,” Charu Aggarwal, MD, MPH, professor and lung cancer specialist, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

Given some encouraging data suggesting that SBRT could provide similar survival outcomes and be an alternative to surgery for operable disease, SBRT is also increasingly being considered in these early-stage patients. However, other evidence indicates that SBRT may be associated with higher rates of regional and distant recurrences and worse long-term survival, particularly in operable patients.

What may ultimately matter most is carefully selecting operable patients who undergo SBRT.

Aggarwal has encountered certain patients who are fit for surgery but would rather have radiation therapy. “This is an individual decision, and these patients are usually discussed at tumor board and in multidisciplinary discussions to really make sure that they’re making the right decision for themselves,” she explained.

The Pros and Cons of SBRT

SBRT is a nonsurgical approach in which precision high-dose radiation is delivered in just a few fractions — typically, 3, 5, or 8, depending on institutional protocols and tumor characteristics.

SBRT is performed on an outpatient basis, usually over 1-2 weeks, with most patients able to resume usual activities with minimal to no delay. Surgery, on the other hand, requires a hospital stay and takes most people about 2-6 weeks to return to regular activities. SBRT also avoids anesthesia and surgical incisions, both of which come with risks.

The data on SBRT in early-stage NSCLC are mixed. While some studies indicate that SBRT comes with promising survival outcomes, other research has reported worse survival and recurrence rates.

One potential reason for higher recurrence rates with SBRT is the lack of pathologic nodal staging, which only happens after surgery, as well as lower rates of nodal evaluation with endobronchial ultrasound or mediastinoscopy before surgery or SBRT. Without nodal assessments, clinicians may miss a more aggressive histology or more advanced nodal stage, which would go undertreated if patients received SBRT.

Latest Data in Large Cohort

A recent study published in Lung Cancer indicated that, when carefully selected, operable patients with early NSCLC have comparable survival with lobectomy or SBRT.

In the study, Dutch researchers took an in-depth look at survival and recurrence patterns in a retrospective cohort study of 2183 patients with clinical stage I NSCLC treated with minimally invasive lobectomy or SBRT. The study includes one of the largest cohorts to date, with robust data collection on baseline characteristics, comorbidities, tumor size, performance status, and follow-up.

Patients receiving SBRT were typically older (median age, 74 vs 67 years), had higher comorbidity burdens (Charlson index ≥ 5 in 57% of SBRT patients vs 23% of surgical patients), worse performance status, and lower lung function. To adjust for these differences, the researchers used propensity score weighting so the SBRT group’s baseline characteristics were comparable with those in the surgery group.

The surgery cohort had more invasive nodal evaluation: 21% underwent endobronchial ultrasound or mediastinoscopy vs only 12% in the SBRT group. The vast majority in both groups had PET-CT staging, reflecting modern imaging-based workups.

While 5-year local recurrence rates between the two groups were similar (13.1% for SBRT vs 12.1% for surgery), the 5-year regional recurrence rate was significantly higher after SBRT than lobectomy (18.1% vs 14.2%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.74), as was the distant metastasis rate (26.2% vs 20.2%; HR, 0.72).

Mortality at 30 days was higher after surgery than SBRT (1.0% vs 0.2%). And in the unadjusted analysis, 5-year overall survival was significantly better with lobectomy than SBRT (70.2% vs 40.3%).

However, when the analysis only included patients with similar baseline characteristics, overall survival was no longer significantly different in the two groups (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.65-1.20). Lung cancer–specific mortality was also not significantly different between the two treatments (HR, 1.08), but the study was underpowered to detect significant differences in this outcome on the basis of a relatively low number of deaths from NSCLC.

Still, even after comparing similar patients, recurrence-free survival was notably better with surgery (HR, 0.70), due to fewer regional recurrences and distant metastases. Overall, 13% of the surgical cohort had nodal upstaging at pathology, meaning that even in clinically “node-negative” stage I disease, a subset of patients had unsuspected nodal involvement.

Patients receiving SBRT did not have pathologic nodal staging, raising the possibility of occult micrometastases. The authors noted that the proportion of SBRT patients with occult lymph node metastases is likely at least equal to that in the surgery group, but these metastases would go undetected without pathologic assessment.

Missing potential occult micrometastases in the SBRT group likely contributed to higher regional recurrence rates over time. By improving nodal staging, more patients with occult lymph node metastases who would be undertreated with SBRT may be identified before treatment, the authors said.

What Do Experts Say?

So, is SBRT an option for patients with stage I NSCLC?

Opinions vary.

“If you got one shot for a cure, then you want to do the surgery because that’s what results in a cure,” said Raja Flores, MD, chairman of Thoracic Surgery, Mount Sinai Health System, New York City.

Flores noted that the survival rate with surgery is high in this population. “There’s really nothing out there that can compare,” he said.

In his view, surgery “remains the gold standard.” However, “radiation could be considered in nonsurgical candidates,” he said.

The most recent NCCN guidelines align with Flores’ take. The guidelines say that SBRT is indicated for stage IA-IIA (N0) NSCLC in patients who are deemed “medically inoperable, high surgical risk as determined by thoracic surgeon, and those who decline surgery after thoracic surgical consultation.”

Clifford G. Robinson, MD, agreed. “In the United States, we largely treat patients with SBRT who are medically inoperable or high-risk operable and a much smaller proportion who decline surgery,” said Robinson, professor of radiation oncology and chief of SBRT at Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis. “Many patients who are deemed operable are not offered SBRT.”

Still, for Robinson, determining which patients are best suited for surgery or SBRT remains unclear.

“Retrospective comparisons are fraught with problems because of confounding,” Robinson told this news organization. “That is, the healthier patients get surgery, and the less healthy ones get SBRT. No manner of fancy statistical manipulation can remove that fact.”

In fact, a recent meta-analysis found that the most significant variable predicting whether surgery or SBRT was superior in retrospective studies was whether the author was a surgeon or radiation oncologist.

Robinson noted that multiple randomized trials have attempted to randomize patients with medically operable early-stage NSCLC to surgery or SBRT and failed to accrue, largely due to patients’ “understandable unwillingness to be randomized between operative vs nonoperative interventions when most already prefer one or the other approach.”

Flores highlighted another point of caution about interpreting trial results: Not all early-stage NSCLC behaves similarly. “Some are slow-growing ‘turtles,’ and others are aggressive ‘rabbits’ — and the turtles are usually the ones that have been included in these radiotherapy trials, and that’s the danger,” he said.

While medical operability is the primary factor for deciding the treatment modality for early-stage NSCLC, there are other more subtle factors that can play into the decision.

These include prior surgery or radiotherapy to the chest, prior cancers, and social issues, such as the patient being a primary caregiver for another person and job insecurity, that might make recovery from surgery more challenging. And in rare instances, a patient may be medically fit to undergo surgery, but the cancer is technically challenging to resect due to anatomic issues or prior surgery to the chest, Robinson added.

A Winner?

Results from two ongoing, highly anticipated randomized trials expected in the next several years will hopefully provide additional insights and clarify ongoing uncertainties about the optimal treatment strategies for operable patients with stage I NSCLC.

STABLE-MATES is comparing outcomes after sublobar resection and SBRT in high-risk operable stage I NSCLC, and VALOR is evaluating outcomes after anatomic pulmonary resections and SBRT in patients with stage I NSCLC who have a long life expectancy and are fit enough to tolerate surgery.

But Robinson said his group believes that trying to decide on a winner is a “fool’s errand” and is instead running a pragmatic study across multiple academic and community centers around the United States and Canada where patients choose therapy based on their personal preferences and guidance from their physicians. The researchers will carefully track baseline comorbidity and frailty and assess serial quality-of-life changes over time.

“The goal is to create a calculator that a given patient might use in the future to determine what patients like them would have received, complete with expected outcomes and side effects,” Robinson said.

Robinson cautioned, however, that it “seems unlikely, given the existing literature, that one of the treatments will be truly ‘superior’ to the other one and lead to the ‘losing’ treatment fading away since both are excellent options with pros and cons.”

Aggarwal, Robinson, and Flores had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA OKs Guselkumab for Crohn’s Disease

The approval marks the fourth indication for guselkumab, which was approved for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in 2017, active psoriatic arthritis in 2020, and moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis in 2024.

Guselkumab is the first and only interleukin-23 (IL-23) inhibitor that offers both subcutaneous (SC) and intravenous (IV) induction options for CD, the company said in a news release.

“Despite the progress in the management of Crohn’s disease, many patients experience debilitating symptoms and are in need of new treatment options,” Remo Panaccione, MD, director of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Unit at the University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, said in the release.

“The approval of Tremfya offers an IL-23 inhibitor that has shown robust rates of endoscopic remission with both subcutaneous and intravenous induction regimens. Importantly, the fully subcutaneous regimen offers choice and flexibility for patients and providers not available before,” said Panaccione.

The FDA nod in CD was based on positive results from three phase 3 trials evaluating guselkumab in more than 1300 patients with moderately to severely active CD who failed or were intolerant to corticosteroids, immunomodulators, or biologics.

The GRAVITI trial showed that guselkumab as SC induction and maintenance therapy was superior to placebo in clinical remission as well as endoscopic response and remission and deep remission.

Results from GALAXI 2 and GALAXI 3 showed that guselkumab was superior to ustekinumab (Stelara) on all pooled endoscopic endpoints.

Guselkumab is the only IL-23 inhibitor to demonstrate “clinical remission and endoscopic response, both at 1 year, with a fully subcutaneous induction regimen,” the company said.

The recommended SC induction dose of guselkumab is 400 mg (given as two consecutive injections of 200 mg each, dispensed in one induction pack) at weeks 0, 4 and 8. The drug is also available in a 200 mg prefilled syringe. For the IV induction option, 200 mg IV infusions are administered at weeks 0, 4, and 8.

The recommended maintenance dosage is 100 mg administered by SC injection at week 16, and every 8 weeks thereafter, or 200 mg administered by SC injection at week 12, and every 4 weeks thereafter.

Use of the lowest effective recommended dosage to maintain therapeutic response is recommended.

Full prescribing information and medication guide are available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The approval marks the fourth indication for guselkumab, which was approved for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in 2017, active psoriatic arthritis in 2020, and moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis in 2024.

Guselkumab is the first and only interleukin-23 (IL-23) inhibitor that offers both subcutaneous (SC) and intravenous (IV) induction options for CD, the company said in a news release.

“Despite the progress in the management of Crohn’s disease, many patients experience debilitating symptoms and are in need of new treatment options,” Remo Panaccione, MD, director of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Unit at the University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, said in the release.

“The approval of Tremfya offers an IL-23 inhibitor that has shown robust rates of endoscopic remission with both subcutaneous and intravenous induction regimens. Importantly, the fully subcutaneous regimen offers choice and flexibility for patients and providers not available before,” said Panaccione.

The FDA nod in CD was based on positive results from three phase 3 trials evaluating guselkumab in more than 1300 patients with moderately to severely active CD who failed or were intolerant to corticosteroids, immunomodulators, or biologics.

The GRAVITI trial showed that guselkumab as SC induction and maintenance therapy was superior to placebo in clinical remission as well as endoscopic response and remission and deep remission.

Results from GALAXI 2 and GALAXI 3 showed that guselkumab was superior to ustekinumab (Stelara) on all pooled endoscopic endpoints.

Guselkumab is the only IL-23 inhibitor to demonstrate “clinical remission and endoscopic response, both at 1 year, with a fully subcutaneous induction regimen,” the company said.

The recommended SC induction dose of guselkumab is 400 mg (given as two consecutive injections of 200 mg each, dispensed in one induction pack) at weeks 0, 4 and 8. The drug is also available in a 200 mg prefilled syringe. For the IV induction option, 200 mg IV infusions are administered at weeks 0, 4, and 8.

The recommended maintenance dosage is 100 mg administered by SC injection at week 16, and every 8 weeks thereafter, or 200 mg administered by SC injection at week 12, and every 4 weeks thereafter.

Use of the lowest effective recommended dosage to maintain therapeutic response is recommended.

Full prescribing information and medication guide are available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The approval marks the fourth indication for guselkumab, which was approved for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in 2017, active psoriatic arthritis in 2020, and moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis in 2024.

Guselkumab is the first and only interleukin-23 (IL-23) inhibitor that offers both subcutaneous (SC) and intravenous (IV) induction options for CD, the company said in a news release.

“Despite the progress in the management of Crohn’s disease, many patients experience debilitating symptoms and are in need of new treatment options,” Remo Panaccione, MD, director of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Unit at the University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, said in the release.

“The approval of Tremfya offers an IL-23 inhibitor that has shown robust rates of endoscopic remission with both subcutaneous and intravenous induction regimens. Importantly, the fully subcutaneous regimen offers choice and flexibility for patients and providers not available before,” said Panaccione.

The FDA nod in CD was based on positive results from three phase 3 trials evaluating guselkumab in more than 1300 patients with moderately to severely active CD who failed or were intolerant to corticosteroids, immunomodulators, or biologics.

The GRAVITI trial showed that guselkumab as SC induction and maintenance therapy was superior to placebo in clinical remission as well as endoscopic response and remission and deep remission.

Results from GALAXI 2 and GALAXI 3 showed that guselkumab was superior to ustekinumab (Stelara) on all pooled endoscopic endpoints.

Guselkumab is the only IL-23 inhibitor to demonstrate “clinical remission and endoscopic response, both at 1 year, with a fully subcutaneous induction regimen,” the company said.

The recommended SC induction dose of guselkumab is 400 mg (given as two consecutive injections of 200 mg each, dispensed in one induction pack) at weeks 0, 4 and 8. The drug is also available in a 200 mg prefilled syringe. For the IV induction option, 200 mg IV infusions are administered at weeks 0, 4, and 8.

The recommended maintenance dosage is 100 mg administered by SC injection at week 16, and every 8 weeks thereafter, or 200 mg administered by SC injection at week 12, and every 4 weeks thereafter.

Use of the lowest effective recommended dosage to maintain therapeutic response is recommended.

Full prescribing information and medication guide are available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

WATS-3D Biopsy Increases Detection of Barrett’s Esophagus in GERD

, new research showed.

Compared with forceps biopsies (FB) alone, the addition of WATS-3D led to confirmation of BE in an additional one fifth of patients, roughly doubled dysplasia diagnoses, and influenced clinical management in the majority of patients.

“The big take-home point here is that the use of WATS-3D brushing along with conventional biopsies increases the likelihood that intestinal metaplasia will be identified,” first author Nicholas Shaheen, MD, MPH, AGAF, with the Center for Esophageal Diseases and Swallowing, University of North Carolina School of Medicine at Chapel Hill, North Carolina, told GI & Hepatology News.

“Almost 20% of patients who harbor BE were only identified by WATS-3D and might have otherwise gone undiagnosed had only forceps biopsies been performed,” Shaheen said.

The study was published in The American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Beyond Traditional Biopsies

BE develops as a complication of chronic GERD and is the chief precursor to esophageal adenocarcinoma. Early detection of BE and dysplasia is crucial to enable timely intervention.

The current gold standard for BE screening involves upper endoscopy with FB following the Seattle protocol, which consists of four-quadrant biopsies from every 1-2 cm of areas of columnar-lined epithelium (CLE) to confirm the presence of intestinal metaplasia. However, this protocol is prone to sampling errors and high false-negative rates, leading to repeat endoscopy, the study team pointed out.

WATS-3D (CDx Diagnostics) is a complementary technique designed to improve diagnostic yield by using brush biopsy to sample more tissue than routine biopsies.

WATS-3D has been shown to increase detection of dysplasia in patients with BE undergoing surveillance for BE, but less is known about the value of WATS-3D for BE screening in a community-based cohort of patients with GERD.

To investigate, Shaheen and colleagues studied 23,933 consecutive patients enrolled in a prospective observational registry assessing the utility of WATS-3D in the screening of symptomatic GERD patients for BE.

Patients had both WATS-3D and FB in the same endoscopic session. No patient had a history of BE, intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia in esophageal mucosa, or esophageal surgery, endoscopic ablation or endoscopic mucosal resection prior to enrollment.