User login

Patient and physician outreach boost CRC screening rates

Can outreach improve the globally low rates of adherence to colorectal cancer screening? Yes, according to two recent studies in JAMA; the studies found that both patient-focused and physician-focused outreach approaches can result in significantly better patient participation in colorectal cancer (CRC) screening.

The first study (JAMA. 2017;318[9]:806-15) compared a colonoscopy outreach program and a fecal immunochemical test (FIT) outreach program both with each other and with usual care. The results of the pragmatic, single-site, randomized, clinical trial showed that completed screenings were higher for both outreach groups, compared with the usual-care group.

The primary outcome measure of the study was completion of the screening process, wrote Amit Singal, MD, and his coauthors. This was defined as any adherence to colonoscopy completion, the completion of annual testing for patients who had a normal FIT test, or treatment evaluation if CRC was detected during the screening process. Screenings were considered complete even if, for example, a patient in the colonoscopy arm eventually went on to have three consecutive annual FIT tests rather than a colonoscopy.

A total of 5,999 patients eligible for screening were initially randomized to one of the three study arms. Across all study arms, approximately half were lost to follow-up. These patients were excluded from the primary analysis but were included in an additional intention-to-screen analysis. A total of 2,400 patients received a colonoscopy outreach mailing; 2,400 received FIT outreach, including a letter, the home FIT testing kit, and instructions; 1,199 received usual care. Patients in both intervention arms also received up to two phone calls if they didn’t respond to the initial mailing within 2 weeks. Mailings and phone calls were conducted in English or Spanish, according to the patients’ stated language preferences (those whose spoke neither language were excluded from the study).

Of the patients in the colonoscopy outreach group, 922 (38.4%) completed the screening process, compared with 671 (28.0%) in the FIT outreach group and 128 (10.7%) in the usual-care group.

Compared with the group receiving usual care, completion of the screening process was 27.7% higher in the colonoscopy outreach group and 17.3% higher in the FIT outreach group. Screening process completion was 10.4% higher for the colonoscopy outreach group, compared with the FIT outreach group (P less than .001 for all).

Dr. Singal, who is with the department of internal medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and his colleagues also performed several post-hoc secondary analyses. In one, they used a less-stringent definition of screening process completion in which biennial FIT testing was considered satisfactory. When this definition was applied, the colonoscopy outreach group had 0.5% lower screening process completion than the FIT outreach group. The chances of a patient receiving any screening during the study period was highest in the FIT group (65%), with 51.7% of those in the colonoscopy outreach group and 39% of those in the usual-care group receiving any screening.

“FIT has lower barriers to one-time participation but requires annual screening and diagnostic evaluation of abnormal results,” wrote Dr. Singal and his colleagues.

Strengths of the study, said Dr. Singal and his colleagues, included the fact that the study took place at a “safety net” institution with a racially and socioeconomically diverse population. Also, the study design avoided volunteer bias, and offered a pragmatic head-to-head comparison of colonoscopy and FIT.

The second study took place in western France, and targeted outreach to physicians rather than patients (JAMA. 2017;318[9];816-84). When physicians were given a list of their own patients who were not up to date on CRC screening, investigators saw a small, but significant, uptick in patient participation in FIT screening.

One year after the reminders went out, FIT screening had been initiated in 24.8% of patients whose physicians had received the list, compared with 21.7% of patients of physicians who had received a more generic notice and 20.6% of patients whose physicians received no notification, according to first author Cedric Rat, MD, and his colleagues.

The study examined which notification approach was most effective in increasing FIT screening among the physicians’ patient panels: sending general practitioners (GPs) letters that included a list of their own patients who had not undergone CRC screening, or sending them generic letters describing CRC screening adherence rates specific to their region. A usual-care group of practices received no notifications in this three-group randomized cluster design.

Patients in the patient-specific reminders group had an odds ratio of 1.27 for participation in FIT screening (P less than .001) compared to the usual-care group. The odds ratio for the generic-reminders group was 1.09, a nonsignificant difference.

Between-group comparison showed statistical significance for both the 3.1% difference between the patient-specific and generic-reminders groups, and for the 4.2% difference between the patient-specific and usual-care groups (P less than .001 for both). There was no significant difference between the generic- reminders group and the usual-care group.

Dr. Rat, professor of medicine at the Faculty of Medicine, Nantes, France, and his colleagues enrolled GPs in a total of 801 practices that included patients aged 50. Participating GPs cared for 33,044 patients who met study criteria.

Physician characteristics that were associated with higher FIT participation included younger age and an initially smaller number of unscreened patients. Patients with low socioeconomic status and those with a higher chronic disease burden were less likely to participate in FIT screening.

Dr. Rat and his colleagues noted that the busiest practices actually had higher CRC screening rates. The investigators hypothesized that a recent physician pay-for-performance grant for CRC completion might be more appealing for some busy physicians.

This was the largest study of CRC screening participation to date, according to Dr. Rat and his coauthors, and showed the small but detectable efficacy of an inexpensive intervention that, given complete patient records, is relatively easy to effect. Though the effect size was smaller than the 12% difference the investigators had anticipated seeing for the patient-specific reminders group, the study still showed that targeting physicians can be an effective public health intervention to increase CRC screening rates, said Dr. Rat and his colleagues.

None of the investigators in either study reported conflicts of interest.

The AGA Colorectal Cancer Clinical Service Line provides tools to help you become more efficient, understand quality standards and improve the process of care for patients. Learn more at www.gastro.org/crc.

Both studies, though they used different outreach interventions, highlight the same problem: the need to identify and execute effective colorectal cancer (CRC) screening programs. Effective screening has great lifesaving potential; if screening rates were elevated to greater than 80% in the United States, an estimated 200,000 deaths would be prevented within the next 2 decades.

The nature of CRC screening options means that a home fecal sample collection is inexpensive, and will result in an initial higher screening rate; however, complete screening via fecal occult blood testing requires annual repeats of negative tests, and patients with positive fecal occult blood tests still need colonoscopy.

Colonoscopy, although it’s burdensome for patients and perhaps cost prohibitive for those without health insurance, offers a one-time test that, if negative, provides patients with a 10-year window of screening coverage.

Any effective programs to increase CRC screening rates will need to use a systems change approach, with creative interventions that take patient education, and even delivery of preventive health services, out of the context of the already too-full office visit.

Staff supports, such as the follow-up telephone calls used in the patient-targeted intervention, are key to effective interventions, especially for vulnerable populations. Additionally, institutions must ensure that they have adequate physical and staff resources to support the increased screening they are seeking to achieve.

Michael Pignone, MD, MPH is a professor of medicine at the University of Texas at Austin. David Miller Jr., MD is a professor of internal medicine, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C. Dr. Pignone is a medical director for Healthwise; Dr. Miller reported no relevant conflicts of interest. These remarks were drawn from an editorial accompanying the two clinical trials.

Both studies, though they used different outreach interventions, highlight the same problem: the need to identify and execute effective colorectal cancer (CRC) screening programs. Effective screening has great lifesaving potential; if screening rates were elevated to greater than 80% in the United States, an estimated 200,000 deaths would be prevented within the next 2 decades.

The nature of CRC screening options means that a home fecal sample collection is inexpensive, and will result in an initial higher screening rate; however, complete screening via fecal occult blood testing requires annual repeats of negative tests, and patients with positive fecal occult blood tests still need colonoscopy.

Colonoscopy, although it’s burdensome for patients and perhaps cost prohibitive for those without health insurance, offers a one-time test that, if negative, provides patients with a 10-year window of screening coverage.

Any effective programs to increase CRC screening rates will need to use a systems change approach, with creative interventions that take patient education, and even delivery of preventive health services, out of the context of the already too-full office visit.

Staff supports, such as the follow-up telephone calls used in the patient-targeted intervention, are key to effective interventions, especially for vulnerable populations. Additionally, institutions must ensure that they have adequate physical and staff resources to support the increased screening they are seeking to achieve.

Michael Pignone, MD, MPH is a professor of medicine at the University of Texas at Austin. David Miller Jr., MD is a professor of internal medicine, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C. Dr. Pignone is a medical director for Healthwise; Dr. Miller reported no relevant conflicts of interest. These remarks were drawn from an editorial accompanying the two clinical trials.

Both studies, though they used different outreach interventions, highlight the same problem: the need to identify and execute effective colorectal cancer (CRC) screening programs. Effective screening has great lifesaving potential; if screening rates were elevated to greater than 80% in the United States, an estimated 200,000 deaths would be prevented within the next 2 decades.

The nature of CRC screening options means that a home fecal sample collection is inexpensive, and will result in an initial higher screening rate; however, complete screening via fecal occult blood testing requires annual repeats of negative tests, and patients with positive fecal occult blood tests still need colonoscopy.

Colonoscopy, although it’s burdensome for patients and perhaps cost prohibitive for those without health insurance, offers a one-time test that, if negative, provides patients with a 10-year window of screening coverage.

Any effective programs to increase CRC screening rates will need to use a systems change approach, with creative interventions that take patient education, and even delivery of preventive health services, out of the context of the already too-full office visit.

Staff supports, such as the follow-up telephone calls used in the patient-targeted intervention, are key to effective interventions, especially for vulnerable populations. Additionally, institutions must ensure that they have adequate physical and staff resources to support the increased screening they are seeking to achieve.

Michael Pignone, MD, MPH is a professor of medicine at the University of Texas at Austin. David Miller Jr., MD is a professor of internal medicine, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C. Dr. Pignone is a medical director for Healthwise; Dr. Miller reported no relevant conflicts of interest. These remarks were drawn from an editorial accompanying the two clinical trials.

Can outreach improve the globally low rates of adherence to colorectal cancer screening? Yes, according to two recent studies in JAMA; the studies found that both patient-focused and physician-focused outreach approaches can result in significantly better patient participation in colorectal cancer (CRC) screening.

The first study (JAMA. 2017;318[9]:806-15) compared a colonoscopy outreach program and a fecal immunochemical test (FIT) outreach program both with each other and with usual care. The results of the pragmatic, single-site, randomized, clinical trial showed that completed screenings were higher for both outreach groups, compared with the usual-care group.

The primary outcome measure of the study was completion of the screening process, wrote Amit Singal, MD, and his coauthors. This was defined as any adherence to colonoscopy completion, the completion of annual testing for patients who had a normal FIT test, or treatment evaluation if CRC was detected during the screening process. Screenings were considered complete even if, for example, a patient in the colonoscopy arm eventually went on to have three consecutive annual FIT tests rather than a colonoscopy.

A total of 5,999 patients eligible for screening were initially randomized to one of the three study arms. Across all study arms, approximately half were lost to follow-up. These patients were excluded from the primary analysis but were included in an additional intention-to-screen analysis. A total of 2,400 patients received a colonoscopy outreach mailing; 2,400 received FIT outreach, including a letter, the home FIT testing kit, and instructions; 1,199 received usual care. Patients in both intervention arms also received up to two phone calls if they didn’t respond to the initial mailing within 2 weeks. Mailings and phone calls were conducted in English or Spanish, according to the patients’ stated language preferences (those whose spoke neither language were excluded from the study).

Of the patients in the colonoscopy outreach group, 922 (38.4%) completed the screening process, compared with 671 (28.0%) in the FIT outreach group and 128 (10.7%) in the usual-care group.

Compared with the group receiving usual care, completion of the screening process was 27.7% higher in the colonoscopy outreach group and 17.3% higher in the FIT outreach group. Screening process completion was 10.4% higher for the colonoscopy outreach group, compared with the FIT outreach group (P less than .001 for all).

Dr. Singal, who is with the department of internal medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and his colleagues also performed several post-hoc secondary analyses. In one, they used a less-stringent definition of screening process completion in which biennial FIT testing was considered satisfactory. When this definition was applied, the colonoscopy outreach group had 0.5% lower screening process completion than the FIT outreach group. The chances of a patient receiving any screening during the study period was highest in the FIT group (65%), with 51.7% of those in the colonoscopy outreach group and 39% of those in the usual-care group receiving any screening.

“FIT has lower barriers to one-time participation but requires annual screening and diagnostic evaluation of abnormal results,” wrote Dr. Singal and his colleagues.

Strengths of the study, said Dr. Singal and his colleagues, included the fact that the study took place at a “safety net” institution with a racially and socioeconomically diverse population. Also, the study design avoided volunteer bias, and offered a pragmatic head-to-head comparison of colonoscopy and FIT.

The second study took place in western France, and targeted outreach to physicians rather than patients (JAMA. 2017;318[9];816-84). When physicians were given a list of their own patients who were not up to date on CRC screening, investigators saw a small, but significant, uptick in patient participation in FIT screening.

One year after the reminders went out, FIT screening had been initiated in 24.8% of patients whose physicians had received the list, compared with 21.7% of patients of physicians who had received a more generic notice and 20.6% of patients whose physicians received no notification, according to first author Cedric Rat, MD, and his colleagues.

The study examined which notification approach was most effective in increasing FIT screening among the physicians’ patient panels: sending general practitioners (GPs) letters that included a list of their own patients who had not undergone CRC screening, or sending them generic letters describing CRC screening adherence rates specific to their region. A usual-care group of practices received no notifications in this three-group randomized cluster design.

Patients in the patient-specific reminders group had an odds ratio of 1.27 for participation in FIT screening (P less than .001) compared to the usual-care group. The odds ratio for the generic-reminders group was 1.09, a nonsignificant difference.

Between-group comparison showed statistical significance for both the 3.1% difference between the patient-specific and generic-reminders groups, and for the 4.2% difference between the patient-specific and usual-care groups (P less than .001 for both). There was no significant difference between the generic- reminders group and the usual-care group.

Dr. Rat, professor of medicine at the Faculty of Medicine, Nantes, France, and his colleagues enrolled GPs in a total of 801 practices that included patients aged 50. Participating GPs cared for 33,044 patients who met study criteria.

Physician characteristics that were associated with higher FIT participation included younger age and an initially smaller number of unscreened patients. Patients with low socioeconomic status and those with a higher chronic disease burden were less likely to participate in FIT screening.

Dr. Rat and his colleagues noted that the busiest practices actually had higher CRC screening rates. The investigators hypothesized that a recent physician pay-for-performance grant for CRC completion might be more appealing for some busy physicians.

This was the largest study of CRC screening participation to date, according to Dr. Rat and his coauthors, and showed the small but detectable efficacy of an inexpensive intervention that, given complete patient records, is relatively easy to effect. Though the effect size was smaller than the 12% difference the investigators had anticipated seeing for the patient-specific reminders group, the study still showed that targeting physicians can be an effective public health intervention to increase CRC screening rates, said Dr. Rat and his colleagues.

None of the investigators in either study reported conflicts of interest.

The AGA Colorectal Cancer Clinical Service Line provides tools to help you become more efficient, understand quality standards and improve the process of care for patients. Learn more at www.gastro.org/crc.

Can outreach improve the globally low rates of adherence to colorectal cancer screening? Yes, according to two recent studies in JAMA; the studies found that both patient-focused and physician-focused outreach approaches can result in significantly better patient participation in colorectal cancer (CRC) screening.

The first study (JAMA. 2017;318[9]:806-15) compared a colonoscopy outreach program and a fecal immunochemical test (FIT) outreach program both with each other and with usual care. The results of the pragmatic, single-site, randomized, clinical trial showed that completed screenings were higher for both outreach groups, compared with the usual-care group.

The primary outcome measure of the study was completion of the screening process, wrote Amit Singal, MD, and his coauthors. This was defined as any adherence to colonoscopy completion, the completion of annual testing for patients who had a normal FIT test, or treatment evaluation if CRC was detected during the screening process. Screenings were considered complete even if, for example, a patient in the colonoscopy arm eventually went on to have three consecutive annual FIT tests rather than a colonoscopy.

A total of 5,999 patients eligible for screening were initially randomized to one of the three study arms. Across all study arms, approximately half were lost to follow-up. These patients were excluded from the primary analysis but were included in an additional intention-to-screen analysis. A total of 2,400 patients received a colonoscopy outreach mailing; 2,400 received FIT outreach, including a letter, the home FIT testing kit, and instructions; 1,199 received usual care. Patients in both intervention arms also received up to two phone calls if they didn’t respond to the initial mailing within 2 weeks. Mailings and phone calls were conducted in English or Spanish, according to the patients’ stated language preferences (those whose spoke neither language were excluded from the study).

Of the patients in the colonoscopy outreach group, 922 (38.4%) completed the screening process, compared with 671 (28.0%) in the FIT outreach group and 128 (10.7%) in the usual-care group.

Compared with the group receiving usual care, completion of the screening process was 27.7% higher in the colonoscopy outreach group and 17.3% higher in the FIT outreach group. Screening process completion was 10.4% higher for the colonoscopy outreach group, compared with the FIT outreach group (P less than .001 for all).

Dr. Singal, who is with the department of internal medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and his colleagues also performed several post-hoc secondary analyses. In one, they used a less-stringent definition of screening process completion in which biennial FIT testing was considered satisfactory. When this definition was applied, the colonoscopy outreach group had 0.5% lower screening process completion than the FIT outreach group. The chances of a patient receiving any screening during the study period was highest in the FIT group (65%), with 51.7% of those in the colonoscopy outreach group and 39% of those in the usual-care group receiving any screening.

“FIT has lower barriers to one-time participation but requires annual screening and diagnostic evaluation of abnormal results,” wrote Dr. Singal and his colleagues.

Strengths of the study, said Dr. Singal and his colleagues, included the fact that the study took place at a “safety net” institution with a racially and socioeconomically diverse population. Also, the study design avoided volunteer bias, and offered a pragmatic head-to-head comparison of colonoscopy and FIT.

The second study took place in western France, and targeted outreach to physicians rather than patients (JAMA. 2017;318[9];816-84). When physicians were given a list of their own patients who were not up to date on CRC screening, investigators saw a small, but significant, uptick in patient participation in FIT screening.

One year after the reminders went out, FIT screening had been initiated in 24.8% of patients whose physicians had received the list, compared with 21.7% of patients of physicians who had received a more generic notice and 20.6% of patients whose physicians received no notification, according to first author Cedric Rat, MD, and his colleagues.

The study examined which notification approach was most effective in increasing FIT screening among the physicians’ patient panels: sending general practitioners (GPs) letters that included a list of their own patients who had not undergone CRC screening, or sending them generic letters describing CRC screening adherence rates specific to their region. A usual-care group of practices received no notifications in this three-group randomized cluster design.

Patients in the patient-specific reminders group had an odds ratio of 1.27 for participation in FIT screening (P less than .001) compared to the usual-care group. The odds ratio for the generic-reminders group was 1.09, a nonsignificant difference.

Between-group comparison showed statistical significance for both the 3.1% difference between the patient-specific and generic-reminders groups, and for the 4.2% difference between the patient-specific and usual-care groups (P less than .001 for both). There was no significant difference between the generic- reminders group and the usual-care group.

Dr. Rat, professor of medicine at the Faculty of Medicine, Nantes, France, and his colleagues enrolled GPs in a total of 801 practices that included patients aged 50. Participating GPs cared for 33,044 patients who met study criteria.

Physician characteristics that were associated with higher FIT participation included younger age and an initially smaller number of unscreened patients. Patients with low socioeconomic status and those with a higher chronic disease burden were less likely to participate in FIT screening.

Dr. Rat and his colleagues noted that the busiest practices actually had higher CRC screening rates. The investigators hypothesized that a recent physician pay-for-performance grant for CRC completion might be more appealing for some busy physicians.

This was the largest study of CRC screening participation to date, according to Dr. Rat and his coauthors, and showed the small but detectable efficacy of an inexpensive intervention that, given complete patient records, is relatively easy to effect. Though the effect size was smaller than the 12% difference the investigators had anticipated seeing for the patient-specific reminders group, the study still showed that targeting physicians can be an effective public health intervention to increase CRC screening rates, said Dr. Rat and his colleagues.

None of the investigators in either study reported conflicts of interest.

The AGA Colorectal Cancer Clinical Service Line provides tools to help you become more efficient, understand quality standards and improve the process of care for patients. Learn more at www.gastro.org/crc.

How to have a rational approach to the FUO work-up

CHICAGO – When a child’s worried parents bring him back to be rechecked on his 8th day of fever, what’s next? If the initial work-up is unrevealing, when is it time to consider hospitalization? And which children can safely be managed as outpatients?

These tough scenarios are part of why “most pediatricians really don’t enjoy fever of unknown origin (FUO),” said Brian Williams, MD, speaking at a pediatric infectious disease update at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “It can be really time consuming and frustrating to tease all of this out.”

Dr. Williams comes into the picture when, for the pediatrician, “something about that history, that physical exam, and that lab work has them concerned that the child needs to be hospitalized for closer monitoring and a more extensive work-up.”

“There’s lots of variability for inclusion criteria in the studies for pediatrics,” said Dr. Williams, but most characterize FUO as a fever of at least 100.4° F for 8 days or longer with no clear diagnosis.

he said. “I think it’s one of those diagnoses where a thorough history and exam can oftentimes give you some clues that can help lead to your diagnosis.”

“It’s a diagnosis that always gets my full attention because sometimes you can find some pretty significant infections – an osteomyelitis or a severe pelvic abscess,” he said. “And there’s always the concern of some of these more serious underlying diseases, like rheumatologic diseases; there’s plenty of case reports of [inflammatory bowel disease] presenting with FUO.” Of course, he said, even more dire diagnoses like Hodgkin’s lymphoma and leukemia have to remain in the differential as well.

Although the broad diagnostic differential includes noninfectious causes, they are rarer by far than infections. When the etiology of FUO has been studied in the United States, said Dr. Williams, “infections pretty consistently dominate as the most common cause of FUO … as general pediatricians, it’s our job to really do a good evaluation for infection before we start going after some of these less common diagnoses – the rheumatologic and cancer diagnoses.”

A systematic approach is important, he said. “A really good fever history can, a lot of times, provide important and valuable information.” Take the time to get granular detail: Find out how often the fever is being checked and by whom, what symptoms accompany the fever, and how the fever is being measured.

And don’t forget to ask if there are fever-free days, he said. In an otherwise well-appearing child, a few days’ respite from fever can increase the likelihood that you’re really seeing back-to-back viral illnesses rather than a protracted unexplained fever.

A thorough head-to-toe review of symptoms and history is critical, too. Dr. Williams related the story of a well-appearing 9-year-old boy who’d had many days of high fever with accompanying elevated inflammatory markers. His exam was unremarkable, and the only untoward symptom he could recall was a few days’ worth of left upper quadrant tenderness when running in gym class. The child, said Dr. Williams, turned out to have nephronia. “Sometimes, really subtle clues from the history can guide you.”

Ask about exposures, including travel, animals, foods, insects, and sick contacts. “Obviously, children can get into just about anything,” said Dr. Williams. A detailed family and social history also may turn up clues.

An infection-focused musculoskeletal exam, to include the spine, is a must, as is a top-to-bottom search for lymphadenopathy as part of a complete physical exam.

At this point in the pediatrics office, said Dr. Williams, you’ve come to a decision point: “Does this work-up need to be initiated in the inpatient setting, or is this something that can be started in the outpatient setting?”

“There’s a lot of data to support that, initially, a lot of these patients can be worked up in the outpatient setting with close follow-up,” he said. The outpatient FUO work-up begins with some basic screening labs. In addition to a complete blood count, chemistries, and a urinalysis, labs should include blood and urine cultures, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein levels.

“I’ll actually rely pretty heavily on my ESR and CRP,” said Dr. Williams. “If I have an otherwise well-appearing child with a normal CRP and an unremarkable exam, I think it’s a pretty tough argument to keep that child hospitalized and do a more invasive work-up.”

The advent of the viral polymerase chain reaction panel has helped streamline the FUO work-up as well. In the setting of a well-appearing child with an unremarkable initial work-up, “a positive adenovirus can provide a lot of reassurance to the families.”

Dr. Williams usually also gets a chest radiograph at this point, knowing that pneumonia is in the differential for FUO. He said he’s seen mediastinal masses, as well as picked up dense right upper lobe infiltrates that were missed on exam.

If the answer is still unclear at this point, exam and laboratory findings from the first-tier inquiry can help guide the next steps.

Some less common infectious etiologies can be considered now, said Dr. Williams. These can include Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and cat scratch fever; the latter, he’s found, is the third-most-common cause of FUO in some case series. For the real mystery cases, next-generation sequencing is an option: A blood sample is used to search for DNA fragments from a huge variety of microorganisms. “It’s a little overwhelming,” and very expensive, he said.

If an oncologic process is suspected, second-tier labs can include lactate dehydrogenase, uric acid, ferritin levels, and a peripheral smear. A rheumatologic work-up can be started, with antinuclear antibody and complement levels. At this point, though, a general pediatrician would be considering consults, he said.

Empiric antibiotics can be a tempting diagnostic strategy in some cases. “Is a trial of antibiotics warranted? Usually we advise against it,” but a case can be made for a time-limited trial in certain circumstances, said Dr. Williams.

Dr. Williams is a consultant for Zavante Therapeutics, which markets fosfomycin.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

CHICAGO – When a child’s worried parents bring him back to be rechecked on his 8th day of fever, what’s next? If the initial work-up is unrevealing, when is it time to consider hospitalization? And which children can safely be managed as outpatients?

These tough scenarios are part of why “most pediatricians really don’t enjoy fever of unknown origin (FUO),” said Brian Williams, MD, speaking at a pediatric infectious disease update at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “It can be really time consuming and frustrating to tease all of this out.”

Dr. Williams comes into the picture when, for the pediatrician, “something about that history, that physical exam, and that lab work has them concerned that the child needs to be hospitalized for closer monitoring and a more extensive work-up.”

“There’s lots of variability for inclusion criteria in the studies for pediatrics,” said Dr. Williams, but most characterize FUO as a fever of at least 100.4° F for 8 days or longer with no clear diagnosis.

he said. “I think it’s one of those diagnoses where a thorough history and exam can oftentimes give you some clues that can help lead to your diagnosis.”

“It’s a diagnosis that always gets my full attention because sometimes you can find some pretty significant infections – an osteomyelitis or a severe pelvic abscess,” he said. “And there’s always the concern of some of these more serious underlying diseases, like rheumatologic diseases; there’s plenty of case reports of [inflammatory bowel disease] presenting with FUO.” Of course, he said, even more dire diagnoses like Hodgkin’s lymphoma and leukemia have to remain in the differential as well.

Although the broad diagnostic differential includes noninfectious causes, they are rarer by far than infections. When the etiology of FUO has been studied in the United States, said Dr. Williams, “infections pretty consistently dominate as the most common cause of FUO … as general pediatricians, it’s our job to really do a good evaluation for infection before we start going after some of these less common diagnoses – the rheumatologic and cancer diagnoses.”

A systematic approach is important, he said. “A really good fever history can, a lot of times, provide important and valuable information.” Take the time to get granular detail: Find out how often the fever is being checked and by whom, what symptoms accompany the fever, and how the fever is being measured.

And don’t forget to ask if there are fever-free days, he said. In an otherwise well-appearing child, a few days’ respite from fever can increase the likelihood that you’re really seeing back-to-back viral illnesses rather than a protracted unexplained fever.

A thorough head-to-toe review of symptoms and history is critical, too. Dr. Williams related the story of a well-appearing 9-year-old boy who’d had many days of high fever with accompanying elevated inflammatory markers. His exam was unremarkable, and the only untoward symptom he could recall was a few days’ worth of left upper quadrant tenderness when running in gym class. The child, said Dr. Williams, turned out to have nephronia. “Sometimes, really subtle clues from the history can guide you.”

Ask about exposures, including travel, animals, foods, insects, and sick contacts. “Obviously, children can get into just about anything,” said Dr. Williams. A detailed family and social history also may turn up clues.

An infection-focused musculoskeletal exam, to include the spine, is a must, as is a top-to-bottom search for lymphadenopathy as part of a complete physical exam.

At this point in the pediatrics office, said Dr. Williams, you’ve come to a decision point: “Does this work-up need to be initiated in the inpatient setting, or is this something that can be started in the outpatient setting?”

“There’s a lot of data to support that, initially, a lot of these patients can be worked up in the outpatient setting with close follow-up,” he said. The outpatient FUO work-up begins with some basic screening labs. In addition to a complete blood count, chemistries, and a urinalysis, labs should include blood and urine cultures, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein levels.

“I’ll actually rely pretty heavily on my ESR and CRP,” said Dr. Williams. “If I have an otherwise well-appearing child with a normal CRP and an unremarkable exam, I think it’s a pretty tough argument to keep that child hospitalized and do a more invasive work-up.”

The advent of the viral polymerase chain reaction panel has helped streamline the FUO work-up as well. In the setting of a well-appearing child with an unremarkable initial work-up, “a positive adenovirus can provide a lot of reassurance to the families.”

Dr. Williams usually also gets a chest radiograph at this point, knowing that pneumonia is in the differential for FUO. He said he’s seen mediastinal masses, as well as picked up dense right upper lobe infiltrates that were missed on exam.

If the answer is still unclear at this point, exam and laboratory findings from the first-tier inquiry can help guide the next steps.

Some less common infectious etiologies can be considered now, said Dr. Williams. These can include Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and cat scratch fever; the latter, he’s found, is the third-most-common cause of FUO in some case series. For the real mystery cases, next-generation sequencing is an option: A blood sample is used to search for DNA fragments from a huge variety of microorganisms. “It’s a little overwhelming,” and very expensive, he said.

If an oncologic process is suspected, second-tier labs can include lactate dehydrogenase, uric acid, ferritin levels, and a peripheral smear. A rheumatologic work-up can be started, with antinuclear antibody and complement levels. At this point, though, a general pediatrician would be considering consults, he said.

Empiric antibiotics can be a tempting diagnostic strategy in some cases. “Is a trial of antibiotics warranted? Usually we advise against it,” but a case can be made for a time-limited trial in certain circumstances, said Dr. Williams.

Dr. Williams is a consultant for Zavante Therapeutics, which markets fosfomycin.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

CHICAGO – When a child’s worried parents bring him back to be rechecked on his 8th day of fever, what’s next? If the initial work-up is unrevealing, when is it time to consider hospitalization? And which children can safely be managed as outpatients?

These tough scenarios are part of why “most pediatricians really don’t enjoy fever of unknown origin (FUO),” said Brian Williams, MD, speaking at a pediatric infectious disease update at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “It can be really time consuming and frustrating to tease all of this out.”

Dr. Williams comes into the picture when, for the pediatrician, “something about that history, that physical exam, and that lab work has them concerned that the child needs to be hospitalized for closer monitoring and a more extensive work-up.”

“There’s lots of variability for inclusion criteria in the studies for pediatrics,” said Dr. Williams, but most characterize FUO as a fever of at least 100.4° F for 8 days or longer with no clear diagnosis.

he said. “I think it’s one of those diagnoses where a thorough history and exam can oftentimes give you some clues that can help lead to your diagnosis.”

“It’s a diagnosis that always gets my full attention because sometimes you can find some pretty significant infections – an osteomyelitis or a severe pelvic abscess,” he said. “And there’s always the concern of some of these more serious underlying diseases, like rheumatologic diseases; there’s plenty of case reports of [inflammatory bowel disease] presenting with FUO.” Of course, he said, even more dire diagnoses like Hodgkin’s lymphoma and leukemia have to remain in the differential as well.

Although the broad diagnostic differential includes noninfectious causes, they are rarer by far than infections. When the etiology of FUO has been studied in the United States, said Dr. Williams, “infections pretty consistently dominate as the most common cause of FUO … as general pediatricians, it’s our job to really do a good evaluation for infection before we start going after some of these less common diagnoses – the rheumatologic and cancer diagnoses.”

A systematic approach is important, he said. “A really good fever history can, a lot of times, provide important and valuable information.” Take the time to get granular detail: Find out how often the fever is being checked and by whom, what symptoms accompany the fever, and how the fever is being measured.

And don’t forget to ask if there are fever-free days, he said. In an otherwise well-appearing child, a few days’ respite from fever can increase the likelihood that you’re really seeing back-to-back viral illnesses rather than a protracted unexplained fever.

A thorough head-to-toe review of symptoms and history is critical, too. Dr. Williams related the story of a well-appearing 9-year-old boy who’d had many days of high fever with accompanying elevated inflammatory markers. His exam was unremarkable, and the only untoward symptom he could recall was a few days’ worth of left upper quadrant tenderness when running in gym class. The child, said Dr. Williams, turned out to have nephronia. “Sometimes, really subtle clues from the history can guide you.”

Ask about exposures, including travel, animals, foods, insects, and sick contacts. “Obviously, children can get into just about anything,” said Dr. Williams. A detailed family and social history also may turn up clues.

An infection-focused musculoskeletal exam, to include the spine, is a must, as is a top-to-bottom search for lymphadenopathy as part of a complete physical exam.

At this point in the pediatrics office, said Dr. Williams, you’ve come to a decision point: “Does this work-up need to be initiated in the inpatient setting, or is this something that can be started in the outpatient setting?”

“There’s a lot of data to support that, initially, a lot of these patients can be worked up in the outpatient setting with close follow-up,” he said. The outpatient FUO work-up begins with some basic screening labs. In addition to a complete blood count, chemistries, and a urinalysis, labs should include blood and urine cultures, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein levels.

“I’ll actually rely pretty heavily on my ESR and CRP,” said Dr. Williams. “If I have an otherwise well-appearing child with a normal CRP and an unremarkable exam, I think it’s a pretty tough argument to keep that child hospitalized and do a more invasive work-up.”

The advent of the viral polymerase chain reaction panel has helped streamline the FUO work-up as well. In the setting of a well-appearing child with an unremarkable initial work-up, “a positive adenovirus can provide a lot of reassurance to the families.”

Dr. Williams usually also gets a chest radiograph at this point, knowing that pneumonia is in the differential for FUO. He said he’s seen mediastinal masses, as well as picked up dense right upper lobe infiltrates that were missed on exam.

If the answer is still unclear at this point, exam and laboratory findings from the first-tier inquiry can help guide the next steps.

Some less common infectious etiologies can be considered now, said Dr. Williams. These can include Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and cat scratch fever; the latter, he’s found, is the third-most-common cause of FUO in some case series. For the real mystery cases, next-generation sequencing is an option: A blood sample is used to search for DNA fragments from a huge variety of microorganisms. “It’s a little overwhelming,” and very expensive, he said.

If an oncologic process is suspected, second-tier labs can include lactate dehydrogenase, uric acid, ferritin levels, and a peripheral smear. A rheumatologic work-up can be started, with antinuclear antibody and complement levels. At this point, though, a general pediatrician would be considering consults, he said.

Empiric antibiotics can be a tempting diagnostic strategy in some cases. “Is a trial of antibiotics warranted? Usually we advise against it,” but a case can be made for a time-limited trial in certain circumstances, said Dr. Williams.

Dr. Williams is a consultant for Zavante Therapeutics, which markets fosfomycin.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 2017

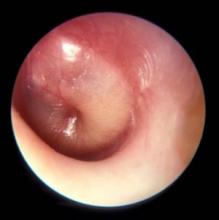

Thinking may be shifting about first-line AOM treatment

CHICAGO – Treating even uncomplicated acute otitis media (AOM) in 2017 may not be as simple as writing an amoxicillin prescription. Changes in pathogens may mean a shift in prescribing practices, Ellen Wald, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Dr. Wald, speaking to an audience that filled the lecture hall and an overflow room, said that there has long been good reason to turn to amoxicillin for AOM. “The reason that pediatricians and others like to reserve the use of amoxicillin as first-line therapy for children with AOM is that it is generally effective, it’s safe, it’s narrow in spectrum, and it’s relatively inexpensive. Those are all very desirable characteristics.”

However, the high-dose amoxicillin strategy is predicated on S. pneumoniae being the most likely cause of bacterial AOM. Since the seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7), and then its successor PCV13, became part of the standard series of childhood immunizations, said Dr. Wald, the microbiology of AOM has shifted.

In 1990, S. pneumoniae was estimated to cause 35%-45% of AOM cases, with Haemophilus influenzae responsible for 25%-30% of cases. Moraxella catarrhalis was thought to cause 12%-15% of cases, with Streptococcus pyogenes–related AOM falling into the single digits.

In 2017, the balance has shifted, with S. pneumoniae only responsible for about a quarter of cases of AOM, and H. influenzae causing about half. The prevalence of M. catarrhalis and S. pyogenes cases hasn’t changed. This, said Dr. Wald, should prompt a shift in thinking about antibiotic strategy for AOM.

“The real problem with amoxicillin is that it’s not active against beta-lactamase–producing H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis. So my recommendation would be, rather than using amoxicillin, to use amoxicillin potassium clavulanate.”

Dr. Wald said she can’t currently recommend using azithromycin to treat AOM. “Azithromycin and the other macrolides have almost no activity against H. influenzae,” she said. “So given the current situation with the high prevalence of H. influenzae, azithromycin really should be avoided in the management of AOM.”

For children with non–type 1 penicillin hypersensitivity or mild type 1 hypersensitivity, a second- or third-generation cephalosporin, such as cefuroxime, cefpodoxime, or cefdinir, can be considered, she said.

“For life-threatening type 1 hypersensitivity reactions, we like to choose a drug of an entirely different class. For that reason, levofloxacin might be something you’d consider,” in those cases, said Dr. Wald, making clear that this is not a Food and Drug Administration–approved indication. Levofloxacin does have the antimicrobial spectrum to cover AOM pathogens, she said.

When parenteral therapy is indicated, as when a child isn’t tolerating oral medications or when nonadherence is likely, a single dose of ceftriaxone IM or IV, dosed at 50 mg/kg, remains a good option. “It’s a suitable agent because all middle ear pathogens are susceptible to ceftriaxone,” said Dr. Wald.

When oral antibiotics are used, how long should they be given? Some experts, she said, recommend a 5-day course for older children who have had infrequent previous episodes of AOM. In this age group, the shorter course can still yield an excellent response, she said.

However, a 2016 study that tried a shortened course of amoxicillin/clavulanate for children 6-23 months of age found that clinical failure occurred in 34% of the patients who received 5 days of antibiotics, compared with 16% of those who got the full 10-day course. “The recommendation is pretty clear that, for children under 2 years of age, a 10-day course of therapy is best,” said Dr. Wald.

Dr. Wald reported that she had no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

CHICAGO – Treating even uncomplicated acute otitis media (AOM) in 2017 may not be as simple as writing an amoxicillin prescription. Changes in pathogens may mean a shift in prescribing practices, Ellen Wald, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Dr. Wald, speaking to an audience that filled the lecture hall and an overflow room, said that there has long been good reason to turn to amoxicillin for AOM. “The reason that pediatricians and others like to reserve the use of amoxicillin as first-line therapy for children with AOM is that it is generally effective, it’s safe, it’s narrow in spectrum, and it’s relatively inexpensive. Those are all very desirable characteristics.”

However, the high-dose amoxicillin strategy is predicated on S. pneumoniae being the most likely cause of bacterial AOM. Since the seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7), and then its successor PCV13, became part of the standard series of childhood immunizations, said Dr. Wald, the microbiology of AOM has shifted.

In 1990, S. pneumoniae was estimated to cause 35%-45% of AOM cases, with Haemophilus influenzae responsible for 25%-30% of cases. Moraxella catarrhalis was thought to cause 12%-15% of cases, with Streptococcus pyogenes–related AOM falling into the single digits.

In 2017, the balance has shifted, with S. pneumoniae only responsible for about a quarter of cases of AOM, and H. influenzae causing about half. The prevalence of M. catarrhalis and S. pyogenes cases hasn’t changed. This, said Dr. Wald, should prompt a shift in thinking about antibiotic strategy for AOM.

“The real problem with amoxicillin is that it’s not active against beta-lactamase–producing H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis. So my recommendation would be, rather than using amoxicillin, to use amoxicillin potassium clavulanate.”

Dr. Wald said she can’t currently recommend using azithromycin to treat AOM. “Azithromycin and the other macrolides have almost no activity against H. influenzae,” she said. “So given the current situation with the high prevalence of H. influenzae, azithromycin really should be avoided in the management of AOM.”

For children with non–type 1 penicillin hypersensitivity or mild type 1 hypersensitivity, a second- or third-generation cephalosporin, such as cefuroxime, cefpodoxime, or cefdinir, can be considered, she said.

“For life-threatening type 1 hypersensitivity reactions, we like to choose a drug of an entirely different class. For that reason, levofloxacin might be something you’d consider,” in those cases, said Dr. Wald, making clear that this is not a Food and Drug Administration–approved indication. Levofloxacin does have the antimicrobial spectrum to cover AOM pathogens, she said.

When parenteral therapy is indicated, as when a child isn’t tolerating oral medications or when nonadherence is likely, a single dose of ceftriaxone IM or IV, dosed at 50 mg/kg, remains a good option. “It’s a suitable agent because all middle ear pathogens are susceptible to ceftriaxone,” said Dr. Wald.

When oral antibiotics are used, how long should they be given? Some experts, she said, recommend a 5-day course for older children who have had infrequent previous episodes of AOM. In this age group, the shorter course can still yield an excellent response, she said.

However, a 2016 study that tried a shortened course of amoxicillin/clavulanate for children 6-23 months of age found that clinical failure occurred in 34% of the patients who received 5 days of antibiotics, compared with 16% of those who got the full 10-day course. “The recommendation is pretty clear that, for children under 2 years of age, a 10-day course of therapy is best,” said Dr. Wald.

Dr. Wald reported that she had no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

CHICAGO – Treating even uncomplicated acute otitis media (AOM) in 2017 may not be as simple as writing an amoxicillin prescription. Changes in pathogens may mean a shift in prescribing practices, Ellen Wald, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Dr. Wald, speaking to an audience that filled the lecture hall and an overflow room, said that there has long been good reason to turn to amoxicillin for AOM. “The reason that pediatricians and others like to reserve the use of amoxicillin as first-line therapy for children with AOM is that it is generally effective, it’s safe, it’s narrow in spectrum, and it’s relatively inexpensive. Those are all very desirable characteristics.”

However, the high-dose amoxicillin strategy is predicated on S. pneumoniae being the most likely cause of bacterial AOM. Since the seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7), and then its successor PCV13, became part of the standard series of childhood immunizations, said Dr. Wald, the microbiology of AOM has shifted.

In 1990, S. pneumoniae was estimated to cause 35%-45% of AOM cases, with Haemophilus influenzae responsible for 25%-30% of cases. Moraxella catarrhalis was thought to cause 12%-15% of cases, with Streptococcus pyogenes–related AOM falling into the single digits.

In 2017, the balance has shifted, with S. pneumoniae only responsible for about a quarter of cases of AOM, and H. influenzae causing about half. The prevalence of M. catarrhalis and S. pyogenes cases hasn’t changed. This, said Dr. Wald, should prompt a shift in thinking about antibiotic strategy for AOM.

“The real problem with amoxicillin is that it’s not active against beta-lactamase–producing H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis. So my recommendation would be, rather than using amoxicillin, to use amoxicillin potassium clavulanate.”

Dr. Wald said she can’t currently recommend using azithromycin to treat AOM. “Azithromycin and the other macrolides have almost no activity against H. influenzae,” she said. “So given the current situation with the high prevalence of H. influenzae, azithromycin really should be avoided in the management of AOM.”

For children with non–type 1 penicillin hypersensitivity or mild type 1 hypersensitivity, a second- or third-generation cephalosporin, such as cefuroxime, cefpodoxime, or cefdinir, can be considered, she said.

“For life-threatening type 1 hypersensitivity reactions, we like to choose a drug of an entirely different class. For that reason, levofloxacin might be something you’d consider,” in those cases, said Dr. Wald, making clear that this is not a Food and Drug Administration–approved indication. Levofloxacin does have the antimicrobial spectrum to cover AOM pathogens, she said.

When parenteral therapy is indicated, as when a child isn’t tolerating oral medications or when nonadherence is likely, a single dose of ceftriaxone IM or IV, dosed at 50 mg/kg, remains a good option. “It’s a suitable agent because all middle ear pathogens are susceptible to ceftriaxone,” said Dr. Wald.

When oral antibiotics are used, how long should they be given? Some experts, she said, recommend a 5-day course for older children who have had infrequent previous episodes of AOM. In this age group, the shorter course can still yield an excellent response, she said.

However, a 2016 study that tried a shortened course of amoxicillin/clavulanate for children 6-23 months of age found that clinical failure occurred in 34% of the patients who received 5 days of antibiotics, compared with 16% of those who got the full 10-day course. “The recommendation is pretty clear that, for children under 2 years of age, a 10-day course of therapy is best,” said Dr. Wald.

Dr. Wald reported that she had no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 2017

VA shares its best practices to achieve HCV ‘cascade of cure’

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) cares for more patients with hepatitis C virus than any other care provider in the country, and has achieved a rapid and sharp reduction in hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection among veterans over the past 3 years.

The VA has treated more than 92,000 HCV-infected individuals since the advent of oral direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy in 2014. The number of veterans with HCV who were eligible for treatment was 168,000 in 2014 and 51,000 in July 2017, according to an article in Annals of Internal Medicine (2017 Sep 26. doi: 10.7326/M17-1073).

Given that success in HCV treatment, with a cure rate that exceeds 90% for those prescribed DAAs, the VA is well positioned to share best practices with other organizations, according to Pamela S. Belperio, PharmD, and her coauthors. The best practices harmonize with the recently outlined national strategy to eliminate hepatitis B and C from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

“The leveraging of health systems data transforms numbers into knowledge” that is used both by individual providers and the VA as a whole, wrote Dr. Belperio, national public health pharmacist in the VA’s public health division, and her coauthors.

Identifying veterans who were infected with HCV is simplified by means of electronic point-of-care reminders that prompt providers to conduct HCV risk assessment and testing. Veterans eligible for testing also receive automated letters that serve as a laboratory order form for HCV testing at a VA laboratory.

Adding HCV birth cohort screening as a performance measure and recommending reflex confirmatory HCV RNA testing for positive antibody tests were additional initiatives that contributed to the 3%-4% annual increase in veterans receiving HCV testing, “substantially higher than in other health care systems,” wrote Dr. Belperio and her colleagues.

To respect regional variations in practice within the VA system, multidisciplinary innovation teams meet in each region to identify opportunities for improving and streamlining HCV testing and treatment, using lean process improvement techniques. Regions also share innovations with each other.

The VA used a multipronged approach to raise awareness about HCV testing and treatment among VA health care providers and veterans. Provider reach has been expanded by extensive use of telemedicine, including real-time video calls between providers and patients or other providers at remote locations. Those telemedicine initiatives allow pharmacists and mental health providers to lend their expertise to physicians and other providers, who are themselves directly caring for HCV-infected individuals.

Patients at more than half of VA facilities receive care from physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and clinical pharmacy specialists, “who have been recognized as delivering the same quality of care and providing more timely access to HCV treatment,” wrote Dr. Belperio and her collaborators. Expanding the use of advanced practice providers allows more targeted use of specialists, and “is an important practice that can be adapted into other health care systems,” they noted.

Non–evidence-based criteria for HCV treatment eligibility remain a major barrier for HCV-infected individuals nationwide, despite VA studies showing “cure rates among veterans with alcohol, substance use, and mental health disorders that are similar to cure rates in those without these conditions,” said Dr. Belperio and her colleagues.

Within the VA, involving alcohol and substance use specialists, mental health providers, case managers, and social workers in the patient’s care team is an approach that can increase adherence and up the chance for a cure among the most vulnerable veterans.

The VA has been able to negotiate reduced pricing for the expensive DAAs, and has continued to receive additional appropriations to fund DAAs and other HCV-related resources. “Financing for HCV treatment and infrastructure resources, coupled with reduced drug prices, has been paramount to the VA’s success in curing HCV infection,” said Dr. Belperio and her colleagues.

However, they added, individual private insurers may not reap the benefits of achieving sweeping HCV cures within their particular patient panel, because patients frequently switch insurers. Still, “consistent leveraging of drug prices and removal of restrictions to HCV treatment among all insurers would help assuage this gap,” they wrote.

Dr. Belperio described the VA’s vision of a “hepatitis C cascade of cure” that occurs when individuals with chronic HCV are identified, linked to care, treated with DAAs, and achieve sustained viral response. The comprehensive strategies employed by the VA have meant that, from 2014 to 2016, the percentage of HCV-infected individuals who have been linked to care and treatment increased from 27% to 59%. Of those treated, SVR rates have risen from 51% to 84% during the same period, said Dr. Belperio and her coauthors.

It will not be easy to extend that success into the nongovernment sector, the article’s authors acknowledged. Still, “the VA recognizes the resources necessary to realize this goal and the innovations that could make it possible, and is poised to extend best practices to other health care organizations and providers delivering HCV care.”

None of the study authors reported conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) cares for more patients with hepatitis C virus than any other care provider in the country, and has achieved a rapid and sharp reduction in hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection among veterans over the past 3 years.

The VA has treated more than 92,000 HCV-infected individuals since the advent of oral direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy in 2014. The number of veterans with HCV who were eligible for treatment was 168,000 in 2014 and 51,000 in July 2017, according to an article in Annals of Internal Medicine (2017 Sep 26. doi: 10.7326/M17-1073).

Given that success in HCV treatment, with a cure rate that exceeds 90% for those prescribed DAAs, the VA is well positioned to share best practices with other organizations, according to Pamela S. Belperio, PharmD, and her coauthors. The best practices harmonize with the recently outlined national strategy to eliminate hepatitis B and C from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

“The leveraging of health systems data transforms numbers into knowledge” that is used both by individual providers and the VA as a whole, wrote Dr. Belperio, national public health pharmacist in the VA’s public health division, and her coauthors.

Identifying veterans who were infected with HCV is simplified by means of electronic point-of-care reminders that prompt providers to conduct HCV risk assessment and testing. Veterans eligible for testing also receive automated letters that serve as a laboratory order form for HCV testing at a VA laboratory.

Adding HCV birth cohort screening as a performance measure and recommending reflex confirmatory HCV RNA testing for positive antibody tests were additional initiatives that contributed to the 3%-4% annual increase in veterans receiving HCV testing, “substantially higher than in other health care systems,” wrote Dr. Belperio and her colleagues.

To respect regional variations in practice within the VA system, multidisciplinary innovation teams meet in each region to identify opportunities for improving and streamlining HCV testing and treatment, using lean process improvement techniques. Regions also share innovations with each other.

The VA used a multipronged approach to raise awareness about HCV testing and treatment among VA health care providers and veterans. Provider reach has been expanded by extensive use of telemedicine, including real-time video calls between providers and patients or other providers at remote locations. Those telemedicine initiatives allow pharmacists and mental health providers to lend their expertise to physicians and other providers, who are themselves directly caring for HCV-infected individuals.

Patients at more than half of VA facilities receive care from physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and clinical pharmacy specialists, “who have been recognized as delivering the same quality of care and providing more timely access to HCV treatment,” wrote Dr. Belperio and her collaborators. Expanding the use of advanced practice providers allows more targeted use of specialists, and “is an important practice that can be adapted into other health care systems,” they noted.

Non–evidence-based criteria for HCV treatment eligibility remain a major barrier for HCV-infected individuals nationwide, despite VA studies showing “cure rates among veterans with alcohol, substance use, and mental health disorders that are similar to cure rates in those without these conditions,” said Dr. Belperio and her colleagues.

Within the VA, involving alcohol and substance use specialists, mental health providers, case managers, and social workers in the patient’s care team is an approach that can increase adherence and up the chance for a cure among the most vulnerable veterans.

The VA has been able to negotiate reduced pricing for the expensive DAAs, and has continued to receive additional appropriations to fund DAAs and other HCV-related resources. “Financing for HCV treatment and infrastructure resources, coupled with reduced drug prices, has been paramount to the VA’s success in curing HCV infection,” said Dr. Belperio and her colleagues.

However, they added, individual private insurers may not reap the benefits of achieving sweeping HCV cures within their particular patient panel, because patients frequently switch insurers. Still, “consistent leveraging of drug prices and removal of restrictions to HCV treatment among all insurers would help assuage this gap,” they wrote.

Dr. Belperio described the VA’s vision of a “hepatitis C cascade of cure” that occurs when individuals with chronic HCV are identified, linked to care, treated with DAAs, and achieve sustained viral response. The comprehensive strategies employed by the VA have meant that, from 2014 to 2016, the percentage of HCV-infected individuals who have been linked to care and treatment increased from 27% to 59%. Of those treated, SVR rates have risen from 51% to 84% during the same period, said Dr. Belperio and her coauthors.

It will not be easy to extend that success into the nongovernment sector, the article’s authors acknowledged. Still, “the VA recognizes the resources necessary to realize this goal and the innovations that could make it possible, and is poised to extend best practices to other health care organizations and providers delivering HCV care.”

None of the study authors reported conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) cares for more patients with hepatitis C virus than any other care provider in the country, and has achieved a rapid and sharp reduction in hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection among veterans over the past 3 years.

The VA has treated more than 92,000 HCV-infected individuals since the advent of oral direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy in 2014. The number of veterans with HCV who were eligible for treatment was 168,000 in 2014 and 51,000 in July 2017, according to an article in Annals of Internal Medicine (2017 Sep 26. doi: 10.7326/M17-1073).

Given that success in HCV treatment, with a cure rate that exceeds 90% for those prescribed DAAs, the VA is well positioned to share best practices with other organizations, according to Pamela S. Belperio, PharmD, and her coauthors. The best practices harmonize with the recently outlined national strategy to eliminate hepatitis B and C from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

“The leveraging of health systems data transforms numbers into knowledge” that is used both by individual providers and the VA as a whole, wrote Dr. Belperio, national public health pharmacist in the VA’s public health division, and her coauthors.

Identifying veterans who were infected with HCV is simplified by means of electronic point-of-care reminders that prompt providers to conduct HCV risk assessment and testing. Veterans eligible for testing also receive automated letters that serve as a laboratory order form for HCV testing at a VA laboratory.

Adding HCV birth cohort screening as a performance measure and recommending reflex confirmatory HCV RNA testing for positive antibody tests were additional initiatives that contributed to the 3%-4% annual increase in veterans receiving HCV testing, “substantially higher than in other health care systems,” wrote Dr. Belperio and her colleagues.

To respect regional variations in practice within the VA system, multidisciplinary innovation teams meet in each region to identify opportunities for improving and streamlining HCV testing and treatment, using lean process improvement techniques. Regions also share innovations with each other.

The VA used a multipronged approach to raise awareness about HCV testing and treatment among VA health care providers and veterans. Provider reach has been expanded by extensive use of telemedicine, including real-time video calls between providers and patients or other providers at remote locations. Those telemedicine initiatives allow pharmacists and mental health providers to lend their expertise to physicians and other providers, who are themselves directly caring for HCV-infected individuals.

Patients at more than half of VA facilities receive care from physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and clinical pharmacy specialists, “who have been recognized as delivering the same quality of care and providing more timely access to HCV treatment,” wrote Dr. Belperio and her collaborators. Expanding the use of advanced practice providers allows more targeted use of specialists, and “is an important practice that can be adapted into other health care systems,” they noted.

Non–evidence-based criteria for HCV treatment eligibility remain a major barrier for HCV-infected individuals nationwide, despite VA studies showing “cure rates among veterans with alcohol, substance use, and mental health disorders that are similar to cure rates in those without these conditions,” said Dr. Belperio and her colleagues.

Within the VA, involving alcohol and substance use specialists, mental health providers, case managers, and social workers in the patient’s care team is an approach that can increase adherence and up the chance for a cure among the most vulnerable veterans.

The VA has been able to negotiate reduced pricing for the expensive DAAs, and has continued to receive additional appropriations to fund DAAs and other HCV-related resources. “Financing for HCV treatment and infrastructure resources, coupled with reduced drug prices, has been paramount to the VA’s success in curing HCV infection,” said Dr. Belperio and her colleagues.

However, they added, individual private insurers may not reap the benefits of achieving sweeping HCV cures within their particular patient panel, because patients frequently switch insurers. Still, “consistent leveraging of drug prices and removal of restrictions to HCV treatment among all insurers would help assuage this gap,” they wrote.

Dr. Belperio described the VA’s vision of a “hepatitis C cascade of cure” that occurs when individuals with chronic HCV are identified, linked to care, treated with DAAs, and achieve sustained viral response. The comprehensive strategies employed by the VA have meant that, from 2014 to 2016, the percentage of HCV-infected individuals who have been linked to care and treatment increased from 27% to 59%. Of those treated, SVR rates have risen from 51% to 84% during the same period, said Dr. Belperio and her coauthors.

It will not be easy to extend that success into the nongovernment sector, the article’s authors acknowledged. Still, “the VA recognizes the resources necessary to realize this goal and the innovations that could make it possible, and is poised to extend best practices to other health care organizations and providers delivering HCV care.”

None of the study authors reported conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

No benefit seen for routine low-dose oxygen after stroke

Routine use of low-dose oxygen supplementation in the first days after stroke doesn’t improve overall survival or reduce disability, according to a large new study.

The poststroke death and disability odds ratio was 0.97 for those receiving one of two continuous low-dose oxygen protocols, compared with the control group (95% confidence interval, 0.89-1.05; P = .47).

Participants, who were not hypoxic at enrollment, were randomized 1:1:1 to receive continuous oxygen supplementation for the first 72 hours after stroke, to receive supplementation only at night, or to receive oxygen when indicated by usual care protocols. The average participant age was 72 years and 55% were men in all study arms, and all stroke severity levels were included in the study.

Patients in the two intervention arms received 2 L of oxygen by nasal cannula when their baseline oxygen saturation was greater than 93%, and 3 L when oxygen saturation at baseline was 93% or less. Participation in the study did not preclude more intensive respiratory support when clinically indicated.

Nocturnal supplementation was included as a study arm for two reasons: Poststroke hypoxia is more common at night, and night-only supplementation would avoid any interference with early rehabilitation caused by cumbersome oxygen apparatus and tubing.

Not only was no benefit seen for patients in the pooled intervention arm cohorts, but no benefit was seen for night-time versus continuous oxygen as well. The odds ratio for a better outcome was 1.03 when comparing those receiving continuous oxygen to those who only received nocturnal supplementation (95% CI, 0.93-1.13; P = .61).

First author Christine Roffe, MD, and her collaborators in the Stroke Oxygen Study Collaborative Group also performed subgroup analyses and did not see benefit of oxygen supplementation for older or younger patients, or for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, or more severe strokes.

“Supplemental oxygen could improve outcomes by preventing hypoxia and secondary brain damage but could also have adverse effects,” according to Dr. Roffe, consultant at Keele (England) University and her collaborators.

A much smaller SOS pilot study, they said, had shown improved early neurologic recovery for patients who received supplemental oxygen after stroke, but the pilot also “suggested that oxygen might adversely affect outcome in patients with mild strokes, possibly through formation of toxic free radicals,” wrote the investigators.

These were effects not seen in the larger SO2S study, which was designed to have statistical power to detect even small differences and to do detailed subgroup analysis. For patients like those included in the study, “These findings do not support low-dose oxygen in this setting,” wrote Dr. Roffe and her collaborators.

Dr. Roffe reported receiving compensation from Air Liquide. The study was funded by the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health Research.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

Routine use of low-dose oxygen supplementation in the first days after stroke doesn’t improve overall survival or reduce disability, according to a large new study.

The poststroke death and disability odds ratio was 0.97 for those receiving one of two continuous low-dose oxygen protocols, compared with the control group (95% confidence interval, 0.89-1.05; P = .47).

Participants, who were not hypoxic at enrollment, were randomized 1:1:1 to receive continuous oxygen supplementation for the first 72 hours after stroke, to receive supplementation only at night, or to receive oxygen when indicated by usual care protocols. The average participant age was 72 years and 55% were men in all study arms, and all stroke severity levels were included in the study.

Patients in the two intervention arms received 2 L of oxygen by nasal cannula when their baseline oxygen saturation was greater than 93%, and 3 L when oxygen saturation at baseline was 93% or less. Participation in the study did not preclude more intensive respiratory support when clinically indicated.

Nocturnal supplementation was included as a study arm for two reasons: Poststroke hypoxia is more common at night, and night-only supplementation would avoid any interference with early rehabilitation caused by cumbersome oxygen apparatus and tubing.

Not only was no benefit seen for patients in the pooled intervention arm cohorts, but no benefit was seen for night-time versus continuous oxygen as well. The odds ratio for a better outcome was 1.03 when comparing those receiving continuous oxygen to those who only received nocturnal supplementation (95% CI, 0.93-1.13; P = .61).