User login

Better blood pressure, glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes on CPAP for apnea

Treatment with continuous positive airway pressure leads to significantly better diabetes and blood pressure control at 5 years among diabetics with obstructive sleep apnea, according to results from a case-control study in 300 patients.

The researchers, led by Julian F. Guest, Ph.D., of Catalyst Health Economics Consultants in Middlesex, England, and King’s College London, examined records from 150 patients with type 2 diabetes and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) from a national health database who had been treated with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for up to 5 consecutive years, of whom 139 remained on CPAP at year 5, and compared these with 150 controls with both OSA and type 2 diabetes who were not on CPAP.

Dr. Guest and his colleagues sought to discern not only clinical differences between the study groups but also differences in cost effectiveness, and found advantages with CPAP for both. CPAP-treated patients had better-controlled diabetes than did the control patients at 5 years, with hemoglobin A1c of 8.2% in the CPAP group, compared with 12.1% among controls, a significant difference (Diabetes Care 2014 [doi:10.2337/dc13-2539]).

CPAP was also seen increasing patients’ health status significantly, by 0.27 quality-adjusted life years/patient over the 5-year period, while diminishing costs incurred. In both CPAP users and control patients, blood pressure declined over the study period, and patients’ blood pressure in the CPAP-treated group was significantly lower than that of control patients by year 5.

One unexplained finding was that more CPAP-treated than control patients had a diagnosis of cardiac arrhythmias; Dr. Guest and his colleagues suggested that this might be because patients on CPAP may have had more severe OSA at baseline, though this information was not available.

The investigators described their findings as compelling but cautioned that analyses of clinical outcomes "were based on clinicians’ entries into their patients’ records and inevitably subject to a certain amount of imprecision and lack of detail." Moreover, they wrote, the information collected in the database used was done so "for clinical care purposes and not for research."

The study was funded by a grant from ResMed, a maker of CPAP devices, with no other conflicts of interest reported.

Treatment with continuous positive airway pressure leads to significantly better diabetes and blood pressure control at 5 years among diabetics with obstructive sleep apnea, according to results from a case-control study in 300 patients.

The researchers, led by Julian F. Guest, Ph.D., of Catalyst Health Economics Consultants in Middlesex, England, and King’s College London, examined records from 150 patients with type 2 diabetes and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) from a national health database who had been treated with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for up to 5 consecutive years, of whom 139 remained on CPAP at year 5, and compared these with 150 controls with both OSA and type 2 diabetes who were not on CPAP.

Dr. Guest and his colleagues sought to discern not only clinical differences between the study groups but also differences in cost effectiveness, and found advantages with CPAP for both. CPAP-treated patients had better-controlled diabetes than did the control patients at 5 years, with hemoglobin A1c of 8.2% in the CPAP group, compared with 12.1% among controls, a significant difference (Diabetes Care 2014 [doi:10.2337/dc13-2539]).

CPAP was also seen increasing patients’ health status significantly, by 0.27 quality-adjusted life years/patient over the 5-year period, while diminishing costs incurred. In both CPAP users and control patients, blood pressure declined over the study period, and patients’ blood pressure in the CPAP-treated group was significantly lower than that of control patients by year 5.

One unexplained finding was that more CPAP-treated than control patients had a diagnosis of cardiac arrhythmias; Dr. Guest and his colleagues suggested that this might be because patients on CPAP may have had more severe OSA at baseline, though this information was not available.

The investigators described their findings as compelling but cautioned that analyses of clinical outcomes "were based on clinicians’ entries into their patients’ records and inevitably subject to a certain amount of imprecision and lack of detail." Moreover, they wrote, the information collected in the database used was done so "for clinical care purposes and not for research."

The study was funded by a grant from ResMed, a maker of CPAP devices, with no other conflicts of interest reported.

Treatment with continuous positive airway pressure leads to significantly better diabetes and blood pressure control at 5 years among diabetics with obstructive sleep apnea, according to results from a case-control study in 300 patients.

The researchers, led by Julian F. Guest, Ph.D., of Catalyst Health Economics Consultants in Middlesex, England, and King’s College London, examined records from 150 patients with type 2 diabetes and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) from a national health database who had been treated with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for up to 5 consecutive years, of whom 139 remained on CPAP at year 5, and compared these with 150 controls with both OSA and type 2 diabetes who were not on CPAP.

Dr. Guest and his colleagues sought to discern not only clinical differences between the study groups but also differences in cost effectiveness, and found advantages with CPAP for both. CPAP-treated patients had better-controlled diabetes than did the control patients at 5 years, with hemoglobin A1c of 8.2% in the CPAP group, compared with 12.1% among controls, a significant difference (Diabetes Care 2014 [doi:10.2337/dc13-2539]).

CPAP was also seen increasing patients’ health status significantly, by 0.27 quality-adjusted life years/patient over the 5-year period, while diminishing costs incurred. In both CPAP users and control patients, blood pressure declined over the study period, and patients’ blood pressure in the CPAP-treated group was significantly lower than that of control patients by year 5.

One unexplained finding was that more CPAP-treated than control patients had a diagnosis of cardiac arrhythmias; Dr. Guest and his colleagues suggested that this might be because patients on CPAP may have had more severe OSA at baseline, though this information was not available.

The investigators described their findings as compelling but cautioned that analyses of clinical outcomes "were based on clinicians’ entries into their patients’ records and inevitably subject to a certain amount of imprecision and lack of detail." Moreover, they wrote, the information collected in the database used was done so "for clinical care purposes and not for research."

The study was funded by a grant from ResMed, a maker of CPAP devices, with no other conflicts of interest reported.

FROM DIABETES CARE

Major finding: OSA patients with T2D patients treated with CPAP had significantly lower HbA1c at 5 years than did those not on CPAP, at 8.2% and 12.1%, respectively.

Data source: A case-control study in 300 patients.

Disclosures: The study was funded by ResMed, a maker of CPAP devices, with no other conflicts of interest reported.

First ASCO survivor care guidelines tackle fatigue, anxiety/depression, neuropathy

The American Society of Clinical Oncology has issued three new practice guidelines related to fatigue; anxiety and depression; and chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in patients with cancer.

For fatigue, the guideline emphasizes regular screening, treatment of treatable contributing factors, and nonpharmacological interventions such as exercise and cognitive behavioral therapy, allowing for the use of psychostimulants in some patients. For depression and anxiety, the guidelines name no favored medications or regimens but stress identification of at-risk patients through regular screening, along with careful referral to treatment. The guidelines recommend duloxetine to treat chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy.

The guidelines represent the first of what ASCO says is a continuing series on survivorship care. The organization cited the growing importance of managing late treatment and cancer-related effects, as cancer survivors are expected to reach 18 million in the United States by 2022, an increase of nearly 4 million from 2012.

ASCO’s anxiety and depression guideline (doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4611) derives largely from a Pan-Canadian practice guideline. For its guideline on fatigue in survivors (doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.4495), ASCO integrated recommendations from existing Pan-Canadian guidelines, along with guidelines published by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. ASCO’s guideline on chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) is original (doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.0914).

The CIPN guideline is based on a review of 48 randomized controlled trials of interventions designed to prevent or alleviate CIPN, which is "relatively distinct from other forms of neuropathic pain in many ways, including pathophysiology and symptomatology," the guideline authors noted, and affects nearly 40% of patients treated with multiple agents.

The new guideline does not recommended any agents for the prevention of CIPN, and rejects a host of agents used in other forms of neuropathic pain – including acetyl-l-carnitine, amifostine, amitriptyline, nimodipine, and vitamin E, among others – for treating established CIPN. Venlafaxine is not recommended either, though "data support its potential utility," the guideline authors acknowledged, saying that further evidence was needed. "The identification of new agents to prevent and/or treat CIPN is essential," they wrote.

Only duloxetine, also used in patients with diabetic neuropathy, is recommended for CIPN. Duloxetine may work better for oxaliplatin-induced, as opposed to paclitaxel-induced, painful neuropathy, the guideline noted, adding that more studies were necessary to confirm this.

ASCO cited three other options as acceptable to try, despite limited evidence, in patients with CIPN: a tricyclic antidepressant such as nortriptyline; gabapentin or pregabalin; and a compounded topical gel made containing baclofen, amitriptyline HCl, and ketamine. But the guideline authors stopped short of making formal recommendations for any of these, citing unproven benefit.

The fatigue guideline promotes a program of physical activity after cancer treatment, also recommending cognitive behavioral therapy and other psychosocial interventions. Yoga and other mind-body interventions are sanctioned, and the stimulant wakefulness agents modafinil and methylphenidate are given cautious recommendation with the caveat that there is limited evidence for their use in patients who have completed treatment and are disease free.

The anxiety and depression guideline stresses that all patients with cancer and who have completed treatment be evaluated regularly for symptoms of depression and anxiety, using validated measures, throughout the trajectory of care. Clinicians are asked to identify the resources available in their communities to treat these disorders.

Four of the CIPN guideline authors, Robert Dworkin, Bryan Schneider, Ellen M. Lavoie Smith, and Charles L. Loprinzi, disclosed receiving compensation or research funding from biomedical or pharmaceutical firms. Of the fatigue guideline authors, Carmelita P. Escalante, Patricia A. Ganz, Gary Lyman, and Paul Jacobsen disclosed research support. None of the depression and anxiety guideline authors disclosed conflicts of interest.

ASCO has reported three new guidelines related to survivorship care, involving anxiety and depression symptoms in patients with cancer; cancer-associated fatigue; and prevention and/or treatment of chemotherapy-induced neuropathy.

|

|

In the first, dealing with anxiety and depression, ASCO did not start from scratch but instead utilized Pan-Canadian practice guidelines on screening, assessment, and care of psychosocial distress in patients with cancer, recommending that patients be evaluated for depression and anxiety symptoms during and following treatment. ASCO also recommends that practitioners identify resources available in their practices for treating these disorders. Noting that patients do not often comply with follow-up recommendations for treatment of depression and anxiety symptoms, the guidelines additionally suggest that patients be reassessed routinely.

In its guidelines for managing fatigue in adult patients with cancer, ASCO again chose to rely on previously developed Pan-Canadian guidelines that it supplemented with two National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines, one on fatigue and another on cancer survivorship. These ASCO guidelines recommend that providers intermittently assess patients for fatigue, and that the cause of the fatigue be evaluated with an appropriate history and physical examination – including, if appropriate, follow-up with selected screening laboratory evaluations. They also recommend that patients receive counseling. As far as interventions for treating cancer-related fatigue (assuming that other contributing factors such as pain, depression, and sleep disturbances have been treated appropriately), they most strongly recommend physical activity. In terms of pharmacological interventions, these guidelines suggest that there is some evidence, albeit limited, that psychostimulant/wakefulness agents, such as methylphenidate and modafinil, might provide some benefit. They also note that preliminary data support that ginseng and vitamin D show some promising effects, but need to be further evaluated.

The ASCO guidelines regarding chemotherapy-induced neuropathy did not rely on earlier guidelines, as none exist that relate to this issue. The authors extensively reviewed the literature for agents that had been tested as potential ways to prevent chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. Despite a large number of drugs evaluated, none of them, to date, has been proven effective in this regard. The guidelines support duloxetine as the best agent to use in practice, based on a recent positive placebo-controlled clinical trial, and list additional treatment options that, while lacking in strong evidence, are worth considering, including gabapentin/pregabalin; tricyclic antidepressants; and a topical formulation of baclofen, amitriptyline, and ketamine.

These three new ASCO supportive-care guidelines address three prominent symptoms for cancer survivors and, while there are not, at this time, very effective means for preventing or alleviating these symptoms, they do set the stage for what is currently known. Hopefully, future updates of these guidelines will be able to identify more effective means of managing these important symptoms.

Dr. Charles L. Loprinzi is professor of oncology at the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center, Rochester, Minn. He served on the ASCO panel that developed the chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy guideline, and has received research funding from Pfizer and Competitive Technologies.

ASCO has reported three new guidelines related to survivorship care, involving anxiety and depression symptoms in patients with cancer; cancer-associated fatigue; and prevention and/or treatment of chemotherapy-induced neuropathy.

|

|

In the first, dealing with anxiety and depression, ASCO did not start from scratch but instead utilized Pan-Canadian practice guidelines on screening, assessment, and care of psychosocial distress in patients with cancer, recommending that patients be evaluated for depression and anxiety symptoms during and following treatment. ASCO also recommends that practitioners identify resources available in their practices for treating these disorders. Noting that patients do not often comply with follow-up recommendations for treatment of depression and anxiety symptoms, the guidelines additionally suggest that patients be reassessed routinely.

In its guidelines for managing fatigue in adult patients with cancer, ASCO again chose to rely on previously developed Pan-Canadian guidelines that it supplemented with two National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines, one on fatigue and another on cancer survivorship. These ASCO guidelines recommend that providers intermittently assess patients for fatigue, and that the cause of the fatigue be evaluated with an appropriate history and physical examination – including, if appropriate, follow-up with selected screening laboratory evaluations. They also recommend that patients receive counseling. As far as interventions for treating cancer-related fatigue (assuming that other contributing factors such as pain, depression, and sleep disturbances have been treated appropriately), they most strongly recommend physical activity. In terms of pharmacological interventions, these guidelines suggest that there is some evidence, albeit limited, that psychostimulant/wakefulness agents, such as methylphenidate and modafinil, might provide some benefit. They also note that preliminary data support that ginseng and vitamin D show some promising effects, but need to be further evaluated.

The ASCO guidelines regarding chemotherapy-induced neuropathy did not rely on earlier guidelines, as none exist that relate to this issue. The authors extensively reviewed the literature for agents that had been tested as potential ways to prevent chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. Despite a large number of drugs evaluated, none of them, to date, has been proven effective in this regard. The guidelines support duloxetine as the best agent to use in practice, based on a recent positive placebo-controlled clinical trial, and list additional treatment options that, while lacking in strong evidence, are worth considering, including gabapentin/pregabalin; tricyclic antidepressants; and a topical formulation of baclofen, amitriptyline, and ketamine.

These three new ASCO supportive-care guidelines address three prominent symptoms for cancer survivors and, while there are not, at this time, very effective means for preventing or alleviating these symptoms, they do set the stage for what is currently known. Hopefully, future updates of these guidelines will be able to identify more effective means of managing these important symptoms.

Dr. Charles L. Loprinzi is professor of oncology at the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center, Rochester, Minn. He served on the ASCO panel that developed the chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy guideline, and has received research funding from Pfizer and Competitive Technologies.

ASCO has reported three new guidelines related to survivorship care, involving anxiety and depression symptoms in patients with cancer; cancer-associated fatigue; and prevention and/or treatment of chemotherapy-induced neuropathy.

|

|

In the first, dealing with anxiety and depression, ASCO did not start from scratch but instead utilized Pan-Canadian practice guidelines on screening, assessment, and care of psychosocial distress in patients with cancer, recommending that patients be evaluated for depression and anxiety symptoms during and following treatment. ASCO also recommends that practitioners identify resources available in their practices for treating these disorders. Noting that patients do not often comply with follow-up recommendations for treatment of depression and anxiety symptoms, the guidelines additionally suggest that patients be reassessed routinely.

In its guidelines for managing fatigue in adult patients with cancer, ASCO again chose to rely on previously developed Pan-Canadian guidelines that it supplemented with two National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines, one on fatigue and another on cancer survivorship. These ASCO guidelines recommend that providers intermittently assess patients for fatigue, and that the cause of the fatigue be evaluated with an appropriate history and physical examination – including, if appropriate, follow-up with selected screening laboratory evaluations. They also recommend that patients receive counseling. As far as interventions for treating cancer-related fatigue (assuming that other contributing factors such as pain, depression, and sleep disturbances have been treated appropriately), they most strongly recommend physical activity. In terms of pharmacological interventions, these guidelines suggest that there is some evidence, albeit limited, that psychostimulant/wakefulness agents, such as methylphenidate and modafinil, might provide some benefit. They also note that preliminary data support that ginseng and vitamin D show some promising effects, but need to be further evaluated.

The ASCO guidelines regarding chemotherapy-induced neuropathy did not rely on earlier guidelines, as none exist that relate to this issue. The authors extensively reviewed the literature for agents that had been tested as potential ways to prevent chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. Despite a large number of drugs evaluated, none of them, to date, has been proven effective in this regard. The guidelines support duloxetine as the best agent to use in practice, based on a recent positive placebo-controlled clinical trial, and list additional treatment options that, while lacking in strong evidence, are worth considering, including gabapentin/pregabalin; tricyclic antidepressants; and a topical formulation of baclofen, amitriptyline, and ketamine.

These three new ASCO supportive-care guidelines address three prominent symptoms for cancer survivors and, while there are not, at this time, very effective means for preventing or alleviating these symptoms, they do set the stage for what is currently known. Hopefully, future updates of these guidelines will be able to identify more effective means of managing these important symptoms.

Dr. Charles L. Loprinzi is professor of oncology at the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center, Rochester, Minn. He served on the ASCO panel that developed the chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy guideline, and has received research funding from Pfizer and Competitive Technologies.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology has issued three new practice guidelines related to fatigue; anxiety and depression; and chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in patients with cancer.

For fatigue, the guideline emphasizes regular screening, treatment of treatable contributing factors, and nonpharmacological interventions such as exercise and cognitive behavioral therapy, allowing for the use of psychostimulants in some patients. For depression and anxiety, the guidelines name no favored medications or regimens but stress identification of at-risk patients through regular screening, along with careful referral to treatment. The guidelines recommend duloxetine to treat chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy.

The guidelines represent the first of what ASCO says is a continuing series on survivorship care. The organization cited the growing importance of managing late treatment and cancer-related effects, as cancer survivors are expected to reach 18 million in the United States by 2022, an increase of nearly 4 million from 2012.

ASCO’s anxiety and depression guideline (doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4611) derives largely from a Pan-Canadian practice guideline. For its guideline on fatigue in survivors (doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.4495), ASCO integrated recommendations from existing Pan-Canadian guidelines, along with guidelines published by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. ASCO’s guideline on chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) is original (doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.0914).

The CIPN guideline is based on a review of 48 randomized controlled trials of interventions designed to prevent or alleviate CIPN, which is "relatively distinct from other forms of neuropathic pain in many ways, including pathophysiology and symptomatology," the guideline authors noted, and affects nearly 40% of patients treated with multiple agents.

The new guideline does not recommended any agents for the prevention of CIPN, and rejects a host of agents used in other forms of neuropathic pain – including acetyl-l-carnitine, amifostine, amitriptyline, nimodipine, and vitamin E, among others – for treating established CIPN. Venlafaxine is not recommended either, though "data support its potential utility," the guideline authors acknowledged, saying that further evidence was needed. "The identification of new agents to prevent and/or treat CIPN is essential," they wrote.

Only duloxetine, also used in patients with diabetic neuropathy, is recommended for CIPN. Duloxetine may work better for oxaliplatin-induced, as opposed to paclitaxel-induced, painful neuropathy, the guideline noted, adding that more studies were necessary to confirm this.

ASCO cited three other options as acceptable to try, despite limited evidence, in patients with CIPN: a tricyclic antidepressant such as nortriptyline; gabapentin or pregabalin; and a compounded topical gel made containing baclofen, amitriptyline HCl, and ketamine. But the guideline authors stopped short of making formal recommendations for any of these, citing unproven benefit.

The fatigue guideline promotes a program of physical activity after cancer treatment, also recommending cognitive behavioral therapy and other psychosocial interventions. Yoga and other mind-body interventions are sanctioned, and the stimulant wakefulness agents modafinil and methylphenidate are given cautious recommendation with the caveat that there is limited evidence for their use in patients who have completed treatment and are disease free.

The anxiety and depression guideline stresses that all patients with cancer and who have completed treatment be evaluated regularly for symptoms of depression and anxiety, using validated measures, throughout the trajectory of care. Clinicians are asked to identify the resources available in their communities to treat these disorders.

Four of the CIPN guideline authors, Robert Dworkin, Bryan Schneider, Ellen M. Lavoie Smith, and Charles L. Loprinzi, disclosed receiving compensation or research funding from biomedical or pharmaceutical firms. Of the fatigue guideline authors, Carmelita P. Escalante, Patricia A. Ganz, Gary Lyman, and Paul Jacobsen disclosed research support. None of the depression and anxiety guideline authors disclosed conflicts of interest.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology has issued three new practice guidelines related to fatigue; anxiety and depression; and chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in patients with cancer.

For fatigue, the guideline emphasizes regular screening, treatment of treatable contributing factors, and nonpharmacological interventions such as exercise and cognitive behavioral therapy, allowing for the use of psychostimulants in some patients. For depression and anxiety, the guidelines name no favored medications or regimens but stress identification of at-risk patients through regular screening, along with careful referral to treatment. The guidelines recommend duloxetine to treat chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy.

The guidelines represent the first of what ASCO says is a continuing series on survivorship care. The organization cited the growing importance of managing late treatment and cancer-related effects, as cancer survivors are expected to reach 18 million in the United States by 2022, an increase of nearly 4 million from 2012.

ASCO’s anxiety and depression guideline (doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4611) derives largely from a Pan-Canadian practice guideline. For its guideline on fatigue in survivors (doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.4495), ASCO integrated recommendations from existing Pan-Canadian guidelines, along with guidelines published by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. ASCO’s guideline on chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) is original (doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.0914).

The CIPN guideline is based on a review of 48 randomized controlled trials of interventions designed to prevent or alleviate CIPN, which is "relatively distinct from other forms of neuropathic pain in many ways, including pathophysiology and symptomatology," the guideline authors noted, and affects nearly 40% of patients treated with multiple agents.

The new guideline does not recommended any agents for the prevention of CIPN, and rejects a host of agents used in other forms of neuropathic pain – including acetyl-l-carnitine, amifostine, amitriptyline, nimodipine, and vitamin E, among others – for treating established CIPN. Venlafaxine is not recommended either, though "data support its potential utility," the guideline authors acknowledged, saying that further evidence was needed. "The identification of new agents to prevent and/or treat CIPN is essential," they wrote.

Only duloxetine, also used in patients with diabetic neuropathy, is recommended for CIPN. Duloxetine may work better for oxaliplatin-induced, as opposed to paclitaxel-induced, painful neuropathy, the guideline noted, adding that more studies were necessary to confirm this.

ASCO cited three other options as acceptable to try, despite limited evidence, in patients with CIPN: a tricyclic antidepressant such as nortriptyline; gabapentin or pregabalin; and a compounded topical gel made containing baclofen, amitriptyline HCl, and ketamine. But the guideline authors stopped short of making formal recommendations for any of these, citing unproven benefit.

The fatigue guideline promotes a program of physical activity after cancer treatment, also recommending cognitive behavioral therapy and other psychosocial interventions. Yoga and other mind-body interventions are sanctioned, and the stimulant wakefulness agents modafinil and methylphenidate are given cautious recommendation with the caveat that there is limited evidence for their use in patients who have completed treatment and are disease free.

The anxiety and depression guideline stresses that all patients with cancer and who have completed treatment be evaluated regularly for symptoms of depression and anxiety, using validated measures, throughout the trajectory of care. Clinicians are asked to identify the resources available in their communities to treat these disorders.

Four of the CIPN guideline authors, Robert Dworkin, Bryan Schneider, Ellen M. Lavoie Smith, and Charles L. Loprinzi, disclosed receiving compensation or research funding from biomedical or pharmaceutical firms. Of the fatigue guideline authors, Carmelita P. Escalante, Patricia A. Ganz, Gary Lyman, and Paul Jacobsen disclosed research support. None of the depression and anxiety guideline authors disclosed conflicts of interest.

Biomarkers of vulnerability for schizophrenia identified in youth

Adolescents and young adults with early-onset schizophrenia and those at high clinical risk for schizophrenia share certain patterns of abnormality in the white matter of their brains, according to results from a study that compared brain imaging in those groups along with healthy controls and otherwise healthy heavy users of cannabis.

The study, led by Katherine A. Epstein of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, suggests that adolescents with clinical high risk of developing schizophrenia – but not those with heavy cannabis use alone – had abnormalities in the same key brain regions as young people with early-onset schizophrenia (J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2014;53:362-72).

For their study, Ms. Epstein and her colleagues enrolled 162 participants aged 10-23 years: 55 were diagnosed with early-onset schizophrenia; 55 were age, sex, and handedness-matched healthy controls; 31 were nonpsychotic heavy cannabis users recruited from treatment programs; and 21 were deemed at high risk for developing schizophrenia or a psychotic illness.

Using diffusion tensor imaging, Ms. Epstein and her colleagues found that those in the high-risk and early-onset schizophrenia groups had significant white-matter deficiencies, compared with healthy controls, in the left inferior longitudinal fasciculus and the left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus – both areas that affect functioning of ventral visual and language streams and whose disruption can produce deficits that affect higher-order cognitive abilities. These groups also saw white-matter deficiencies in the bilateral cortico-spinal tract, compared with healthy controls.

Heavy cannabis users, by contrast, had deficiencies only in the left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus. The finding that the same areas were altered in both early-onset schizophrenia and clinical high-risk patients was important because the high-risk patients "had lower doses of antipsychotic medication prescribed at time of MRI scan, and less cumulative exposure to antipsychotic medication," Ms. Epstein and her colleagues wrote.

They acknowledged as a limitation of the study that many of the patients were on antipsychotic medications; however, they noted that "the presence of similar abnormalities in [high-risk] participants makes it unlikely that the observed alterations ... are primarily due to antipsychotic medication exposure."

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. Its corresponding author, Dr. Sanjiv Kumra, also of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, disclosed receiving research support from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression and from Otsuka Pharmaceutical. None of the other study authors reported conflicts of interest.

Adolescents and young adults with early-onset schizophrenia and those at high clinical risk for schizophrenia share certain patterns of abnormality in the white matter of their brains, according to results from a study that compared brain imaging in those groups along with healthy controls and otherwise healthy heavy users of cannabis.

The study, led by Katherine A. Epstein of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, suggests that adolescents with clinical high risk of developing schizophrenia – but not those with heavy cannabis use alone – had abnormalities in the same key brain regions as young people with early-onset schizophrenia (J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2014;53:362-72).

For their study, Ms. Epstein and her colleagues enrolled 162 participants aged 10-23 years: 55 were diagnosed with early-onset schizophrenia; 55 were age, sex, and handedness-matched healthy controls; 31 were nonpsychotic heavy cannabis users recruited from treatment programs; and 21 were deemed at high risk for developing schizophrenia or a psychotic illness.

Using diffusion tensor imaging, Ms. Epstein and her colleagues found that those in the high-risk and early-onset schizophrenia groups had significant white-matter deficiencies, compared with healthy controls, in the left inferior longitudinal fasciculus and the left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus – both areas that affect functioning of ventral visual and language streams and whose disruption can produce deficits that affect higher-order cognitive abilities. These groups also saw white-matter deficiencies in the bilateral cortico-spinal tract, compared with healthy controls.

Heavy cannabis users, by contrast, had deficiencies only in the left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus. The finding that the same areas were altered in both early-onset schizophrenia and clinical high-risk patients was important because the high-risk patients "had lower doses of antipsychotic medication prescribed at time of MRI scan, and less cumulative exposure to antipsychotic medication," Ms. Epstein and her colleagues wrote.

They acknowledged as a limitation of the study that many of the patients were on antipsychotic medications; however, they noted that "the presence of similar abnormalities in [high-risk] participants makes it unlikely that the observed alterations ... are primarily due to antipsychotic medication exposure."

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. Its corresponding author, Dr. Sanjiv Kumra, also of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, disclosed receiving research support from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression and from Otsuka Pharmaceutical. None of the other study authors reported conflicts of interest.

Adolescents and young adults with early-onset schizophrenia and those at high clinical risk for schizophrenia share certain patterns of abnormality in the white matter of their brains, according to results from a study that compared brain imaging in those groups along with healthy controls and otherwise healthy heavy users of cannabis.

The study, led by Katherine A. Epstein of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, suggests that adolescents with clinical high risk of developing schizophrenia – but not those with heavy cannabis use alone – had abnormalities in the same key brain regions as young people with early-onset schizophrenia (J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2014;53:362-72).

For their study, Ms. Epstein and her colleagues enrolled 162 participants aged 10-23 years: 55 were diagnosed with early-onset schizophrenia; 55 were age, sex, and handedness-matched healthy controls; 31 were nonpsychotic heavy cannabis users recruited from treatment programs; and 21 were deemed at high risk for developing schizophrenia or a psychotic illness.

Using diffusion tensor imaging, Ms. Epstein and her colleagues found that those in the high-risk and early-onset schizophrenia groups had significant white-matter deficiencies, compared with healthy controls, in the left inferior longitudinal fasciculus and the left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus – both areas that affect functioning of ventral visual and language streams and whose disruption can produce deficits that affect higher-order cognitive abilities. These groups also saw white-matter deficiencies in the bilateral cortico-spinal tract, compared with healthy controls.

Heavy cannabis users, by contrast, had deficiencies only in the left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus. The finding that the same areas were altered in both early-onset schizophrenia and clinical high-risk patients was important because the high-risk patients "had lower doses of antipsychotic medication prescribed at time of MRI scan, and less cumulative exposure to antipsychotic medication," Ms. Epstein and her colleagues wrote.

They acknowledged as a limitation of the study that many of the patients were on antipsychotic medications; however, they noted that "the presence of similar abnormalities in [high-risk] participants makes it unlikely that the observed alterations ... are primarily due to antipsychotic medication exposure."

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. Its corresponding author, Dr. Sanjiv Kumra, also of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, disclosed receiving research support from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression and from Otsuka Pharmaceutical. None of the other study authors reported conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF CHILD & ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRY

Negative symptoms linked to poor functioning in schizophrenia

Negative symptoms undermine social, vocational, and recreational functioning in people with schizophrenia, according to results from a study evaluating a large patient sample.

The study, published recently (Eur. Psychiatry 2014 [doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2014.01.007]), is one of few that have looked at the relationship between primary negative symptoms and functional outcomes while also controlling for potential secondary sources of negative symptoms, such as drug-related akinesia.

Distinguishing between primary and secondary negative symptoms is difficult but important in clinical practice, the study’s authors noted, because underlying pathophysiology and treatment strategies can differ between the two.

The researchers, led by Gagan Fervaha of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and the University of Toronto, hypothesized that a higher burden or severity of primary negative symptoms – including blunted affect, emotional withdrawal, poor rapport, motor retardation, and active social avoidance – would have a significant effect on functional outcomes.

Mr. Fervaha and his colleagues examined 1,427 records from patients enrolled in the CATIE (Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness) Schizophrenia Trial, a large randomized, controlled trial comparing various antipsychotic medications. All patients in the trial were evaluated before randomization and treatment initiation using validated scores: the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS); the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS); the Simpson-Angus Scale (SAS), which measures extrapyramidal side effects; and the Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale.

Negative symptoms at baseline, Mr. Fervaha and his colleagues found, were significantly correlated with poorer scores in interpersonal relations (r = –0.42; P less than .001), instrumental role functioning (r = –0.24; P less than .001) and use of common objects and activities (r = –0.30; P less than .001). Greater negative symptom burden was associated with worse functioning.

Primary negative symptoms were significantly and inversely related to functioning even after potential sources of secondary negative symptoms – such as psychosis, depression, anxiety, and extrapyramidal symptoms – were controlled for, the researchers found. After further controlling for sociodemographic and clinical variables such as age, sex, substance abuse, and obesity, primary negative symptoms "still held a significant and inverse relationship with each facet of functioning evaluated," they wrote.

"Negative symptoms were found to be a significant contributor to the functional impairment seen in patients with schizophrenia," the authors concluded. "While many studies have noted this relationship, the present study extends these findings and confirms that primary idiopathic negative symptoms serve as an impediment to functional recovery."

Treatments aimed at primary negative symptoms should promote functional recovery, they said, and investigations into the underlying pathobiology of negative symptoms "should take into account the potential for these symptoms to co-vary with other clinical factors."

The researchers noted that the limitations of their study included the fact that subjects were entering into a treatment trial, meaning that the findings might not be generalizable to patients stabilized on their medications. Also, the list of factors included to control for secondary sources of negative symptoms was not exhaustive, "and it is thus possible that some of the variance ascribed to primary negative symptoms is in fact due to nonidiopathic influences (e.g., environmental deprivation)," they said.

The study was funded by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Mr. Fervaha’s three coauthors disclosed financial relationships with Medicure, Neurocrine Biosciences, and several other companies.

Negative symptoms undermine social, vocational, and recreational functioning in people with schizophrenia, according to results from a study evaluating a large patient sample.

The study, published recently (Eur. Psychiatry 2014 [doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2014.01.007]), is one of few that have looked at the relationship between primary negative symptoms and functional outcomes while also controlling for potential secondary sources of negative symptoms, such as drug-related akinesia.

Distinguishing between primary and secondary negative symptoms is difficult but important in clinical practice, the study’s authors noted, because underlying pathophysiology and treatment strategies can differ between the two.

The researchers, led by Gagan Fervaha of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and the University of Toronto, hypothesized that a higher burden or severity of primary negative symptoms – including blunted affect, emotional withdrawal, poor rapport, motor retardation, and active social avoidance – would have a significant effect on functional outcomes.

Mr. Fervaha and his colleagues examined 1,427 records from patients enrolled in the CATIE (Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness) Schizophrenia Trial, a large randomized, controlled trial comparing various antipsychotic medications. All patients in the trial were evaluated before randomization and treatment initiation using validated scores: the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS); the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS); the Simpson-Angus Scale (SAS), which measures extrapyramidal side effects; and the Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale.

Negative symptoms at baseline, Mr. Fervaha and his colleagues found, were significantly correlated with poorer scores in interpersonal relations (r = –0.42; P less than .001), instrumental role functioning (r = –0.24; P less than .001) and use of common objects and activities (r = –0.30; P less than .001). Greater negative symptom burden was associated with worse functioning.

Primary negative symptoms were significantly and inversely related to functioning even after potential sources of secondary negative symptoms – such as psychosis, depression, anxiety, and extrapyramidal symptoms – were controlled for, the researchers found. After further controlling for sociodemographic and clinical variables such as age, sex, substance abuse, and obesity, primary negative symptoms "still held a significant and inverse relationship with each facet of functioning evaluated," they wrote.

"Negative symptoms were found to be a significant contributor to the functional impairment seen in patients with schizophrenia," the authors concluded. "While many studies have noted this relationship, the present study extends these findings and confirms that primary idiopathic negative symptoms serve as an impediment to functional recovery."

Treatments aimed at primary negative symptoms should promote functional recovery, they said, and investigations into the underlying pathobiology of negative symptoms "should take into account the potential for these symptoms to co-vary with other clinical factors."

The researchers noted that the limitations of their study included the fact that subjects were entering into a treatment trial, meaning that the findings might not be generalizable to patients stabilized on their medications. Also, the list of factors included to control for secondary sources of negative symptoms was not exhaustive, "and it is thus possible that some of the variance ascribed to primary negative symptoms is in fact due to nonidiopathic influences (e.g., environmental deprivation)," they said.

The study was funded by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Mr. Fervaha’s three coauthors disclosed financial relationships with Medicure, Neurocrine Biosciences, and several other companies.

Negative symptoms undermine social, vocational, and recreational functioning in people with schizophrenia, according to results from a study evaluating a large patient sample.

The study, published recently (Eur. Psychiatry 2014 [doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2014.01.007]), is one of few that have looked at the relationship between primary negative symptoms and functional outcomes while also controlling for potential secondary sources of negative symptoms, such as drug-related akinesia.

Distinguishing between primary and secondary negative symptoms is difficult but important in clinical practice, the study’s authors noted, because underlying pathophysiology and treatment strategies can differ between the two.

The researchers, led by Gagan Fervaha of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and the University of Toronto, hypothesized that a higher burden or severity of primary negative symptoms – including blunted affect, emotional withdrawal, poor rapport, motor retardation, and active social avoidance – would have a significant effect on functional outcomes.

Mr. Fervaha and his colleagues examined 1,427 records from patients enrolled in the CATIE (Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness) Schizophrenia Trial, a large randomized, controlled trial comparing various antipsychotic medications. All patients in the trial were evaluated before randomization and treatment initiation using validated scores: the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS); the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS); the Simpson-Angus Scale (SAS), which measures extrapyramidal side effects; and the Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale.

Negative symptoms at baseline, Mr. Fervaha and his colleagues found, were significantly correlated with poorer scores in interpersonal relations (r = –0.42; P less than .001), instrumental role functioning (r = –0.24; P less than .001) and use of common objects and activities (r = –0.30; P less than .001). Greater negative symptom burden was associated with worse functioning.

Primary negative symptoms were significantly and inversely related to functioning even after potential sources of secondary negative symptoms – such as psychosis, depression, anxiety, and extrapyramidal symptoms – were controlled for, the researchers found. After further controlling for sociodemographic and clinical variables such as age, sex, substance abuse, and obesity, primary negative symptoms "still held a significant and inverse relationship with each facet of functioning evaluated," they wrote.

"Negative symptoms were found to be a significant contributor to the functional impairment seen in patients with schizophrenia," the authors concluded. "While many studies have noted this relationship, the present study extends these findings and confirms that primary idiopathic negative symptoms serve as an impediment to functional recovery."

Treatments aimed at primary negative symptoms should promote functional recovery, they said, and investigations into the underlying pathobiology of negative symptoms "should take into account the potential for these symptoms to co-vary with other clinical factors."

The researchers noted that the limitations of their study included the fact that subjects were entering into a treatment trial, meaning that the findings might not be generalizable to patients stabilized on their medications. Also, the list of factors included to control for secondary sources of negative symptoms was not exhaustive, "and it is thus possible that some of the variance ascribed to primary negative symptoms is in fact due to nonidiopathic influences (e.g., environmental deprivation)," they said.

The study was funded by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Mr. Fervaha’s three coauthors disclosed financial relationships with Medicure, Neurocrine Biosciences, and several other companies.

FROM EUROPEAN PSYCHIATRY

Major finding: Negative symptoms at baseline were significantly correlated with poorer scores in interpersonal relations (r = –0.42; P less than .001), instrumental role functioning (r = –0.24; P less than .001), and use of common objects and activities (r = –0.30; P less than .001).

Data source: The findings are based on an analysis of the medical records of 1,427 patients with schizophrenia enrolled in a large randomized, controlled trial comparing various antipsychotic medications.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Mr. Fervaha’s three coauthors disclosed financial relationships with Medicure, Neurocrine Biosciences, and several other companies.

Risk of two types of polymer stents seen as comparable

Biodegradable biolimus-eluting stents are as safe and effective as durable everolimus-eluting stents at 2 years’ follow-up, with no significant differences seen in rates of target lesion revascularization, mortality, or myocardial infarction.

The findings come from NEXT (NOBORI Biolimus-Eluting vs. XIENCE/PROMUS Everolimus-Eluting Stent Trial), a 3-year randomized trial led by Dr. Masahiro Natsuaki of Saiseikai Fukuoka (Japan) General Hospital. They were presented March 31 at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology and published simultaneously in JAMA (doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3584).

NEXT aims to determine the noninferiority of the biodegradable polymer biolimus-eluting stent (BP-BES) to the durable polymer everolimus-eluting stent (DP-EES) as measured by target lesion revascularization and whether BP-DES carries a risk for excess mortality or MI compared with DP-EES, as shorter studies and meta-analyses have suggested.

Dr. Natsuaki and colleagues randomized 3,235 patients from nearly 100 treatment centers to BP-BES (n = 1,617) or DP-EES (n = 1,618), with 98% of all patients completing follow-up.

Mortality and MI were comparable for both stents (7.8% for BP-BES vs. 7.7% for DP-EES; noninferiority, P = .003), and the need for target lesion revascularization was also comparable for both stents (6.2% vs. 6%; noninferiority, P less than .001).

Dr. Natsuaki and colleagues noted that "2 years is not long enough to confirm the long-term safety of BP-BES, and the study was underpowered for the interim analysis. Follow-up at 3 years will be important."

NEXT is the first randomized trial to report outcomes longer than 1 year, Dr. Natsuaki said, which could be why these results differ from those of previous studies. In addition, previous meta-analyses pooled "several different biodegradable drug-eluting stents as a class, different risk profiles of enrolled patients across trials, and the wide variation in the ages of the trials, with changes in clinical practices such as duration of dual antiplatelet therapy." In NEXT, dual antiplatelet therapy continued in 69% of BP-BES patients and 70% of DP-EES patients at 2 years.

The researchers said that patients with MI were underrepresented in their sample and that "event rates were less than expected."

NEXT was sponsored by Terumo Japan, the maker of the biodegradable stents used in the study. Two investigators disclosed that they serve as advisers for Terumo Japan and Abbott Vascular Japan, maker of the durable polymer stents used.

Biodegradable biolimus-eluting stents are as safe and effective as durable everolimus-eluting stents at 2 years’ follow-up, with no significant differences seen in rates of target lesion revascularization, mortality, or myocardial infarction.

The findings come from NEXT (NOBORI Biolimus-Eluting vs. XIENCE/PROMUS Everolimus-Eluting Stent Trial), a 3-year randomized trial led by Dr. Masahiro Natsuaki of Saiseikai Fukuoka (Japan) General Hospital. They were presented March 31 at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology and published simultaneously in JAMA (doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3584).

NEXT aims to determine the noninferiority of the biodegradable polymer biolimus-eluting stent (BP-BES) to the durable polymer everolimus-eluting stent (DP-EES) as measured by target lesion revascularization and whether BP-DES carries a risk for excess mortality or MI compared with DP-EES, as shorter studies and meta-analyses have suggested.

Dr. Natsuaki and colleagues randomized 3,235 patients from nearly 100 treatment centers to BP-BES (n = 1,617) or DP-EES (n = 1,618), with 98% of all patients completing follow-up.

Mortality and MI were comparable for both stents (7.8% for BP-BES vs. 7.7% for DP-EES; noninferiority, P = .003), and the need for target lesion revascularization was also comparable for both stents (6.2% vs. 6%; noninferiority, P less than .001).

Dr. Natsuaki and colleagues noted that "2 years is not long enough to confirm the long-term safety of BP-BES, and the study was underpowered for the interim analysis. Follow-up at 3 years will be important."

NEXT is the first randomized trial to report outcomes longer than 1 year, Dr. Natsuaki said, which could be why these results differ from those of previous studies. In addition, previous meta-analyses pooled "several different biodegradable drug-eluting stents as a class, different risk profiles of enrolled patients across trials, and the wide variation in the ages of the trials, with changes in clinical practices such as duration of dual antiplatelet therapy." In NEXT, dual antiplatelet therapy continued in 69% of BP-BES patients and 70% of DP-EES patients at 2 years.

The researchers said that patients with MI were underrepresented in their sample and that "event rates were less than expected."

NEXT was sponsored by Terumo Japan, the maker of the biodegradable stents used in the study. Two investigators disclosed that they serve as advisers for Terumo Japan and Abbott Vascular Japan, maker of the durable polymer stents used.

Biodegradable biolimus-eluting stents are as safe and effective as durable everolimus-eluting stents at 2 years’ follow-up, with no significant differences seen in rates of target lesion revascularization, mortality, or myocardial infarction.

The findings come from NEXT (NOBORI Biolimus-Eluting vs. XIENCE/PROMUS Everolimus-Eluting Stent Trial), a 3-year randomized trial led by Dr. Masahiro Natsuaki of Saiseikai Fukuoka (Japan) General Hospital. They were presented March 31 at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology and published simultaneously in JAMA (doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3584).

NEXT aims to determine the noninferiority of the biodegradable polymer biolimus-eluting stent (BP-BES) to the durable polymer everolimus-eluting stent (DP-EES) as measured by target lesion revascularization and whether BP-DES carries a risk for excess mortality or MI compared with DP-EES, as shorter studies and meta-analyses have suggested.

Dr. Natsuaki and colleagues randomized 3,235 patients from nearly 100 treatment centers to BP-BES (n = 1,617) or DP-EES (n = 1,618), with 98% of all patients completing follow-up.

Mortality and MI were comparable for both stents (7.8% for BP-BES vs. 7.7% for DP-EES; noninferiority, P = .003), and the need for target lesion revascularization was also comparable for both stents (6.2% vs. 6%; noninferiority, P less than .001).

Dr. Natsuaki and colleagues noted that "2 years is not long enough to confirm the long-term safety of BP-BES, and the study was underpowered for the interim analysis. Follow-up at 3 years will be important."

NEXT is the first randomized trial to report outcomes longer than 1 year, Dr. Natsuaki said, which could be why these results differ from those of previous studies. In addition, previous meta-analyses pooled "several different biodegradable drug-eluting stents as a class, different risk profiles of enrolled patients across trials, and the wide variation in the ages of the trials, with changes in clinical practices such as duration of dual antiplatelet therapy." In NEXT, dual antiplatelet therapy continued in 69% of BP-BES patients and 70% of DP-EES patients at 2 years.

The researchers said that patients with MI were underrepresented in their sample and that "event rates were less than expected."

NEXT was sponsored by Terumo Japan, the maker of the biodegradable stents used in the study. Two investigators disclosed that they serve as advisers for Terumo Japan and Abbott Vascular Japan, maker of the durable polymer stents used.

FROM ACC 14

Major finding: Mortality and myocardial infarction were comparable for BP-BES (7.8%) vs. DP-EES (7.7%); noninferiority, P = .003), as was the need for target lesion revascularization (6.2% vs. 6%; noninferiority, P less than .001).

Data source: The NOBORI Biolimus-Eluting vs. XIENCE/PROMUS Everolimus-Eluting Stent Trial, a randomized trial of 3,235 patients.

Disclosures: NEXT was sponsored by Terumo Japan, the maker of BP-BES. Two investigators disclosed that they serve as advisers for Terumo Japan and Abbott Vascular Japan, maker of DP-EES.

Rise in infections resistant to extended-spectrum beta-lactams

Antibiotic-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections among U.S. children more than doubled from nearly 1.5% to 3% over a 12-year period.

While such infections remain uncommon in the pediatric population, the trend, as in adults, is a rising one, based on research published in the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (2014 March 19 [doi: 10.1093/jpids/piu010]). The findings also indicate that third-generation cephalosporin–resistant (G3CR) and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing infections have increased across pediatric patient settings, geographical regions, and age groups.

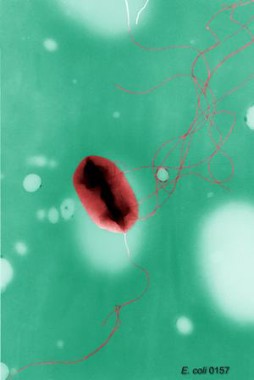

Looking at 368,398 pediatric isolates of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus mirabilis collected from about 300 clinics nationwide between 1999 and 2011, researchers led by Dr. Latania K. Logan of Rush University in Chicago found that the prevalence of G3CR infections had increased from 1.39% in the 1999-2001 period to 3% in 2010-2011. The prevalence of ESBL infections rose from 0.28% to 0.92% across the same study periods.

The children ranged from 1 to 17 years old, with about 38% of isolates taken from 1-5 year olds. These younger subjects represented 47.1% of G3CR and 50.5% of ESBL-producing isolates.

The vast majority of isolates were E. coli; most were taken from urine, most were taken in outpatient settings, and most were from girls – about 15% of the isolates examined in the study came from boys. However, among those positive for G3CR and ESBL types, the proportion that affected boys was 32.4% and 39.2%, respectively.

More than half of all ESBL isolates came from outpatient settings. The high prevalence outside hospital settings, Dr. Logan and her colleagues wrote, suggested that these could be CTX-M-type ESBL, a community-acquired type that "results in multidrug-resistant infections in people with no significant history of health care exposure."

"Additional studies in children to assess risk factors for acquisition, prevalence in ambulatory and long-term health care facilities, and the molecular epidemiology of ESBL-producing bacteria are warranted," the researchers wrote.

Dr. Logan and her colleagues acknowledged several limitations to their study, including its limited data on patient characteristics and prior medical histories, and its inability to capture isolates from infants younger than 1 year. And only a small proportion – 0.22% – of isolates in the study came from children in long-term care facilities, which are known reservoirs of antibiotic-resistant bacteria for adults.

However, a linked case-control study also led by Dr. Logan and published concurrently with the larger study (J. Ped. Infect. Dis. 2014 March 19 [doi: 10.1093/jpids/piu011]) did uncover several relevant risk factors related to ESBL infections in children, including in children younger than 1 year.

For that study, Dr. Logan and her colleagues examined 30 subjects aged 0-17 years with ESBL–producing Enterobacteriaceae infections recruited at two Chicago hospitals over a 4-year period, comparing these to uninfected controls. The researchers also recruited 30 children with non-ESBL–producing bacterial infections and compared those to uninfected controls.

The median age of ESBL cases in the study was 1.06 years. Prevalence of ESBL infection was 1.7% during the study period and was not seen as changing significantly over time. Of the ESBL infections, 30% occurred in outpatient settings, 63% were isolated from urine, and 60% were E. coli. The majority of ESBL infections (77%) were resistant to three or more classes of antibiotics.

ESBL cases were more likely to have gastrointestinal (P = .001; odds ratio, 5.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.9-17.0) or neurological (P = .001; OR, 3.3; CI, 1.1-3.7) comorbidities compared with controls, and non-ESBL cases were also more likely to have gastrointestinal comorbidities compared with controls (P = .014; OR, 3.6; CI, 1.2-10.1). Of the 16 children with neurological comorbidities and EBSL infection, half had a history of cerebrovascular disease or diffuse encephalopathy, and 75% of infections were associated with a foreign body such as a catheter or ventilatory device.

Dr. Logan and her colleagues did not see worse outcomes in children with ESBL infections, as mortality and length of hospital stay after infection did not differ significantly between cases and controls. Nor was ESBL infection found to be significantly associated with recent antibiotic exposure. However, the authors acknowledged that this could have been due to the study’s small sample size.

Dr. Logan and her coauthors received funding for their research from Rush University, the Children’s Foundation, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and Princeton University. None of the authors declared conflicts of interest.

Antibiotic-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections among U.S. children more than doubled from nearly 1.5% to 3% over a 12-year period.

While such infections remain uncommon in the pediatric population, the trend, as in adults, is a rising one, based on research published in the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (2014 March 19 [doi: 10.1093/jpids/piu010]). The findings also indicate that third-generation cephalosporin–resistant (G3CR) and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing infections have increased across pediatric patient settings, geographical regions, and age groups.

Looking at 368,398 pediatric isolates of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus mirabilis collected from about 300 clinics nationwide between 1999 and 2011, researchers led by Dr. Latania K. Logan of Rush University in Chicago found that the prevalence of G3CR infections had increased from 1.39% in the 1999-2001 period to 3% in 2010-2011. The prevalence of ESBL infections rose from 0.28% to 0.92% across the same study periods.

The children ranged from 1 to 17 years old, with about 38% of isolates taken from 1-5 year olds. These younger subjects represented 47.1% of G3CR and 50.5% of ESBL-producing isolates.

The vast majority of isolates were E. coli; most were taken from urine, most were taken in outpatient settings, and most were from girls – about 15% of the isolates examined in the study came from boys. However, among those positive for G3CR and ESBL types, the proportion that affected boys was 32.4% and 39.2%, respectively.

More than half of all ESBL isolates came from outpatient settings. The high prevalence outside hospital settings, Dr. Logan and her colleagues wrote, suggested that these could be CTX-M-type ESBL, a community-acquired type that "results in multidrug-resistant infections in people with no significant history of health care exposure."

"Additional studies in children to assess risk factors for acquisition, prevalence in ambulatory and long-term health care facilities, and the molecular epidemiology of ESBL-producing bacteria are warranted," the researchers wrote.

Dr. Logan and her colleagues acknowledged several limitations to their study, including its limited data on patient characteristics and prior medical histories, and its inability to capture isolates from infants younger than 1 year. And only a small proportion – 0.22% – of isolates in the study came from children in long-term care facilities, which are known reservoirs of antibiotic-resistant bacteria for adults.

However, a linked case-control study also led by Dr. Logan and published concurrently with the larger study (J. Ped. Infect. Dis. 2014 March 19 [doi: 10.1093/jpids/piu011]) did uncover several relevant risk factors related to ESBL infections in children, including in children younger than 1 year.

For that study, Dr. Logan and her colleagues examined 30 subjects aged 0-17 years with ESBL–producing Enterobacteriaceae infections recruited at two Chicago hospitals over a 4-year period, comparing these to uninfected controls. The researchers also recruited 30 children with non-ESBL–producing bacterial infections and compared those to uninfected controls.

The median age of ESBL cases in the study was 1.06 years. Prevalence of ESBL infection was 1.7% during the study period and was not seen as changing significantly over time. Of the ESBL infections, 30% occurred in outpatient settings, 63% were isolated from urine, and 60% were E. coli. The majority of ESBL infections (77%) were resistant to three or more classes of antibiotics.

ESBL cases were more likely to have gastrointestinal (P = .001; odds ratio, 5.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.9-17.0) or neurological (P = .001; OR, 3.3; CI, 1.1-3.7) comorbidities compared with controls, and non-ESBL cases were also more likely to have gastrointestinal comorbidities compared with controls (P = .014; OR, 3.6; CI, 1.2-10.1). Of the 16 children with neurological comorbidities and EBSL infection, half had a history of cerebrovascular disease or diffuse encephalopathy, and 75% of infections were associated with a foreign body such as a catheter or ventilatory device.

Dr. Logan and her colleagues did not see worse outcomes in children with ESBL infections, as mortality and length of hospital stay after infection did not differ significantly between cases and controls. Nor was ESBL infection found to be significantly associated with recent antibiotic exposure. However, the authors acknowledged that this could have been due to the study’s small sample size.

Dr. Logan and her coauthors received funding for their research from Rush University, the Children’s Foundation, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and Princeton University. None of the authors declared conflicts of interest.

Antibiotic-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections among U.S. children more than doubled from nearly 1.5% to 3% over a 12-year period.

While such infections remain uncommon in the pediatric population, the trend, as in adults, is a rising one, based on research published in the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (2014 March 19 [doi: 10.1093/jpids/piu010]). The findings also indicate that third-generation cephalosporin–resistant (G3CR) and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing infections have increased across pediatric patient settings, geographical regions, and age groups.

Looking at 368,398 pediatric isolates of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus mirabilis collected from about 300 clinics nationwide between 1999 and 2011, researchers led by Dr. Latania K. Logan of Rush University in Chicago found that the prevalence of G3CR infections had increased from 1.39% in the 1999-2001 period to 3% in 2010-2011. The prevalence of ESBL infections rose from 0.28% to 0.92% across the same study periods.

The children ranged from 1 to 17 years old, with about 38% of isolates taken from 1-5 year olds. These younger subjects represented 47.1% of G3CR and 50.5% of ESBL-producing isolates.

The vast majority of isolates were E. coli; most were taken from urine, most were taken in outpatient settings, and most were from girls – about 15% of the isolates examined in the study came from boys. However, among those positive for G3CR and ESBL types, the proportion that affected boys was 32.4% and 39.2%, respectively.

More than half of all ESBL isolates came from outpatient settings. The high prevalence outside hospital settings, Dr. Logan and her colleagues wrote, suggested that these could be CTX-M-type ESBL, a community-acquired type that "results in multidrug-resistant infections in people with no significant history of health care exposure."

"Additional studies in children to assess risk factors for acquisition, prevalence in ambulatory and long-term health care facilities, and the molecular epidemiology of ESBL-producing bacteria are warranted," the researchers wrote.

Dr. Logan and her colleagues acknowledged several limitations to their study, including its limited data on patient characteristics and prior medical histories, and its inability to capture isolates from infants younger than 1 year. And only a small proportion – 0.22% – of isolates in the study came from children in long-term care facilities, which are known reservoirs of antibiotic-resistant bacteria for adults.

However, a linked case-control study also led by Dr. Logan and published concurrently with the larger study (J. Ped. Infect. Dis. 2014 March 19 [doi: 10.1093/jpids/piu011]) did uncover several relevant risk factors related to ESBL infections in children, including in children younger than 1 year.

For that study, Dr. Logan and her colleagues examined 30 subjects aged 0-17 years with ESBL–producing Enterobacteriaceae infections recruited at two Chicago hospitals over a 4-year period, comparing these to uninfected controls. The researchers also recruited 30 children with non-ESBL–producing bacterial infections and compared those to uninfected controls.

The median age of ESBL cases in the study was 1.06 years. Prevalence of ESBL infection was 1.7% during the study period and was not seen as changing significantly over time. Of the ESBL infections, 30% occurred in outpatient settings, 63% were isolated from urine, and 60% were E. coli. The majority of ESBL infections (77%) were resistant to three or more classes of antibiotics.

ESBL cases were more likely to have gastrointestinal (P = .001; odds ratio, 5.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.9-17.0) or neurological (P = .001; OR, 3.3; CI, 1.1-3.7) comorbidities compared with controls, and non-ESBL cases were also more likely to have gastrointestinal comorbidities compared with controls (P = .014; OR, 3.6; CI, 1.2-10.1). Of the 16 children with neurological comorbidities and EBSL infection, half had a history of cerebrovascular disease or diffuse encephalopathy, and 75% of infections were associated with a foreign body such as a catheter or ventilatory device.

Dr. Logan and her colleagues did not see worse outcomes in children with ESBL infections, as mortality and length of hospital stay after infection did not differ significantly between cases and controls. Nor was ESBL infection found to be significantly associated with recent antibiotic exposure. However, the authors acknowledged that this could have been due to the study’s small sample size.

Dr. Logan and her coauthors received funding for their research from Rush University, the Children’s Foundation, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and Princeton University. None of the authors declared conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES SOCIETY

Key clinical point: Efforts should focus on identifying host factors and exposures leading to the rise of Enterobacteriaceae infections resistant to extended-spectrum beta-lactams.

Major finding: The prevalence of infections resistant to third-generation cephalosporins increased from 1.39% in 1999-2001 to 3% in 2010-2011. The prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase infections rose from 0.28% to 0.92% across the same study periods.

Data source: Nearly 370,000 pediatric bacterial isolates taken from about 300 clinics across a wide geographical range.

Disclosures: Dr. Logan and her coauthors received funding for their research from Rush University, the Children’s Foundation, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and Princeton University. None of the authors declared conflicts of interest.

Smoking bans see 10% declines in preterm births, asthma flares in children

A systematic review and meta-analysis from North America and Europe has found that the introduction of antismoking legislation covering workplaces and public spaces is associated with significant reductions of about 10% in both preterm births and pediatric hospital visits for asthma.

The findings, published online March 27 in the Lancet, also suggest that significant health benefits and associated public-health cost savings from smoking bans may be reaped beginning in the first year after antismoking legislation takes hold (doi:10.1016/S0140-6736[14]60082-9).

For their research, Jasper V. Been, Ph.D., of Maastricht University, the Netherlands, and his colleagues, evaluated 11 studies (5 from North America and 6 from European countries) published during 2008 and 2013. The included studies captured 247,168 million asthma exacerbations and about 2.5 million births. In these study areas, which fell within either local or national bans on smoking in the workplace, public places, and/or restaurants and bars, bans were followed by significant drops in preterm births (–10.4%) and childhood emergency department visits and hospital attendances (–10.1%).

Low birth weight was not seen as significantly changed in Dr. Been and his colleagues’ study (–1.7%; P = .31), but the researchers did see about a 5% decline in children born very small for their gestational age.

For several of the included studies, the drops were immediate. Significant drops in preterm births of 3% or more were seen in the first year following the implementation of some bans, with additional gradual declines occurring in subsequent years. With hospital visits for pediatric asthma, some studies saw drops as high as 20% per year after bans.

In an editorial comment accompanying the study, Dr. Sara Kalkhoran and Stanton A. Glantz, Ph.D., of the University of California, San Francisco, wrote that the findings add to a growing body of evidence that "smoke-free laws bring rapid health benefits and improved lives, whilst, at the same time, reducing medical costs by avoiding emergency department visits and admissions to hospitals."

Dr. Been and his colleagues’ study was funded by the Thrasher Fund, Lung Foundation Netherlands, the International Pediatric Research Fund, Commonwealth Fund, and Maastricht University. None of the study authors or editorial writers declared conflicts of interest.

A systematic review and meta-analysis from North America and Europe has found that the introduction of antismoking legislation covering workplaces and public spaces is associated with significant reductions of about 10% in both preterm births and pediatric hospital visits for asthma.

The findings, published online March 27 in the Lancet, also suggest that significant health benefits and associated public-health cost savings from smoking bans may be reaped beginning in the first year after antismoking legislation takes hold (doi:10.1016/S0140-6736[14]60082-9).