User login

Children are vulnerable to diseases emerging because of climate change

ORLANDO – “Expect the unexpected” when considering the health impacts of climate change on children, Susan Pacheo, MD, advised in her presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“We don’t know what we’re going to see, and we need to be ready,” said Dr. Pacheo of the University of Texas, Houston.

Climate change is categorized by an increase in droughts, fires, storms, floods, mudslides, and extreme temperatures. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the impacts of climate change on human health are multiple, but can include an increased rate of infectious disease, respiratory conditions, injury, cardiovascular-related health issues, malnutrition, and mental health problems.

These problems can especially target children, Dr. Pacheo noted. “Kids are vulnerable. You’ve heard this, you’ve experienced this, you see this every day in your pediatric population.”

Children are more vulnerable because of the increased exposure they have to the environment. They spend more time outdoors, they are closer to the ground, and they are likely to put objects in their mouth. Children also tend to swallow more water when swimming, compared with adults. A 2014 study by de Man et al. found that children exposed to storm sewers and combined sewers swallowed 1.7 mL of water per exposure event and that the risk of infection from pathogens such as noroviruses, enteroviruses, Campylobacter jejuni, Cryptosporidium, and Giardia was 23%-33% per event, compared with 0.016 mL of water per exposure in adults and a mean infection risk of 0.58%-3.90% per event (Water Research. 2014 Jan 1. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.09.022).

In addition, socioeconomic status and built environment as well as a child’s immature lung development and higher respiratory rate can lead to children being impacted by factors such as air pollution. Poverty, access to medical care, and the structure and dynamics of family also can affect children.

“We need to do something because this is a problem of social justice and we, as pediatricians, are advocates of the vulnerable,” Dr. Pacheo said.

Expect to see an increase in the number of vector-borne, airborne, and pollution-related disease, as well as water- and food-borne diseases, as a result of climate change, in addition to other issues such as hand, foot, and mouth disease and antibiotic resistance, she noted. As historically colder parts of the world continue to have milder winters, disease-carrying insects such as ticks and mosquitoes will expand their habitats and transmission of diseases such as Zika virus, malaria, dengue fever, and chikungunya will increase.

Leptospirosis and Naegleria fowleri, the latter which can cause primary amebic meningoencephalitis, are also becoming more common. Food-borne illnesses like vibriosis are being seen in more northern areas of the world like Alaska, and ciguatera fish poisoning is expected to be more prevalent in the southeastern United States and Gulf of Mexico, Dr. Pacheo said.

Air pollution carries a risk of respiratory diseases, pneumonia, and bronchiolitis, with a 2017 systematic review by Nhung et al. finding increased exposure to ambient air pollution markers such as sulfur dioxide, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and carbon monoxide was associated with pneumonia in children (Environ Pollut. 2017 Jul 25. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.07.063). Coccidioidomycosis, or valley fever, is caused by inhaling a fungus in the soil and is associated with dust storms primarily in the southwestern United States. Warmer temperatures also have caused toxic algae blooms that have killed marine life and caused respiratory distress; children should not go near or play in water when algae blooms are growing, she noted.

Recent studies have linked an increase in temperature with incidence of Escherichia coli, with a 2016 study by Philipsborn et al. showing a 1° Celsius increase in mean monthly temperature was associated with an 8% increase in incidence of diarrheagenic E. coli (J Infect Dis. 2016 Feb 29. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw081). The incidence of hand, foot, and mouth disease also is linked to temperature and humidity, with a 2018 study by Cheng et al. showing a 1° Celsius increase in temperature and humidity was significantly associated with hand, foot, and mouth disease (Sci Total Environ. 2018 Jan 12. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.01.006). Rates of influenza are controlled by the changing environment as well, and increasing the number of vaccinations will help lower the number of influenza cases.

“We need to be advocates, we need to educate ourselves like we’re doing now so that we can educate our patients and to create a plan for preparedness,” Dr. Pacheo said.

She reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – “Expect the unexpected” when considering the health impacts of climate change on children, Susan Pacheo, MD, advised in her presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“We don’t know what we’re going to see, and we need to be ready,” said Dr. Pacheo of the University of Texas, Houston.

Climate change is categorized by an increase in droughts, fires, storms, floods, mudslides, and extreme temperatures. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the impacts of climate change on human health are multiple, but can include an increased rate of infectious disease, respiratory conditions, injury, cardiovascular-related health issues, malnutrition, and mental health problems.

These problems can especially target children, Dr. Pacheo noted. “Kids are vulnerable. You’ve heard this, you’ve experienced this, you see this every day in your pediatric population.”

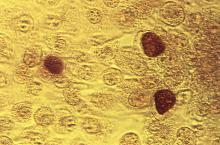

Children are more vulnerable because of the increased exposure they have to the environment. They spend more time outdoors, they are closer to the ground, and they are likely to put objects in their mouth. Children also tend to swallow more water when swimming, compared with adults. A 2014 study by de Man et al. found that children exposed to storm sewers and combined sewers swallowed 1.7 mL of water per exposure event and that the risk of infection from pathogens such as noroviruses, enteroviruses, Campylobacter jejuni, Cryptosporidium, and Giardia was 23%-33% per event, compared with 0.016 mL of water per exposure in adults and a mean infection risk of 0.58%-3.90% per event (Water Research. 2014 Jan 1. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.09.022).

In addition, socioeconomic status and built environment as well as a child’s immature lung development and higher respiratory rate can lead to children being impacted by factors such as air pollution. Poverty, access to medical care, and the structure and dynamics of family also can affect children.

“We need to do something because this is a problem of social justice and we, as pediatricians, are advocates of the vulnerable,” Dr. Pacheo said.

Expect to see an increase in the number of vector-borne, airborne, and pollution-related disease, as well as water- and food-borne diseases, as a result of climate change, in addition to other issues such as hand, foot, and mouth disease and antibiotic resistance, she noted. As historically colder parts of the world continue to have milder winters, disease-carrying insects such as ticks and mosquitoes will expand their habitats and transmission of diseases such as Zika virus, malaria, dengue fever, and chikungunya will increase.

Leptospirosis and Naegleria fowleri, the latter which can cause primary amebic meningoencephalitis, are also becoming more common. Food-borne illnesses like vibriosis are being seen in more northern areas of the world like Alaska, and ciguatera fish poisoning is expected to be more prevalent in the southeastern United States and Gulf of Mexico, Dr. Pacheo said.

Air pollution carries a risk of respiratory diseases, pneumonia, and bronchiolitis, with a 2017 systematic review by Nhung et al. finding increased exposure to ambient air pollution markers such as sulfur dioxide, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and carbon monoxide was associated with pneumonia in children (Environ Pollut. 2017 Jul 25. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.07.063). Coccidioidomycosis, or valley fever, is caused by inhaling a fungus in the soil and is associated with dust storms primarily in the southwestern United States. Warmer temperatures also have caused toxic algae blooms that have killed marine life and caused respiratory distress; children should not go near or play in water when algae blooms are growing, she noted.

Recent studies have linked an increase in temperature with incidence of Escherichia coli, with a 2016 study by Philipsborn et al. showing a 1° Celsius increase in mean monthly temperature was associated with an 8% increase in incidence of diarrheagenic E. coli (J Infect Dis. 2016 Feb 29. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw081). The incidence of hand, foot, and mouth disease also is linked to temperature and humidity, with a 2018 study by Cheng et al. showing a 1° Celsius increase in temperature and humidity was significantly associated with hand, foot, and mouth disease (Sci Total Environ. 2018 Jan 12. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.01.006). Rates of influenza are controlled by the changing environment as well, and increasing the number of vaccinations will help lower the number of influenza cases.

“We need to be advocates, we need to educate ourselves like we’re doing now so that we can educate our patients and to create a plan for preparedness,” Dr. Pacheo said.

She reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – “Expect the unexpected” when considering the health impacts of climate change on children, Susan Pacheo, MD, advised in her presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“We don’t know what we’re going to see, and we need to be ready,” said Dr. Pacheo of the University of Texas, Houston.

Climate change is categorized by an increase in droughts, fires, storms, floods, mudslides, and extreme temperatures. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the impacts of climate change on human health are multiple, but can include an increased rate of infectious disease, respiratory conditions, injury, cardiovascular-related health issues, malnutrition, and mental health problems.

These problems can especially target children, Dr. Pacheo noted. “Kids are vulnerable. You’ve heard this, you’ve experienced this, you see this every day in your pediatric population.”

Children are more vulnerable because of the increased exposure they have to the environment. They spend more time outdoors, they are closer to the ground, and they are likely to put objects in their mouth. Children also tend to swallow more water when swimming, compared with adults. A 2014 study by de Man et al. found that children exposed to storm sewers and combined sewers swallowed 1.7 mL of water per exposure event and that the risk of infection from pathogens such as noroviruses, enteroviruses, Campylobacter jejuni, Cryptosporidium, and Giardia was 23%-33% per event, compared with 0.016 mL of water per exposure in adults and a mean infection risk of 0.58%-3.90% per event (Water Research. 2014 Jan 1. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.09.022).

In addition, socioeconomic status and built environment as well as a child’s immature lung development and higher respiratory rate can lead to children being impacted by factors such as air pollution. Poverty, access to medical care, and the structure and dynamics of family also can affect children.

“We need to do something because this is a problem of social justice and we, as pediatricians, are advocates of the vulnerable,” Dr. Pacheo said.

Expect to see an increase in the number of vector-borne, airborne, and pollution-related disease, as well as water- and food-borne diseases, as a result of climate change, in addition to other issues such as hand, foot, and mouth disease and antibiotic resistance, she noted. As historically colder parts of the world continue to have milder winters, disease-carrying insects such as ticks and mosquitoes will expand their habitats and transmission of diseases such as Zika virus, malaria, dengue fever, and chikungunya will increase.

Leptospirosis and Naegleria fowleri, the latter which can cause primary amebic meningoencephalitis, are also becoming more common. Food-borne illnesses like vibriosis are being seen in more northern areas of the world like Alaska, and ciguatera fish poisoning is expected to be more prevalent in the southeastern United States and Gulf of Mexico, Dr. Pacheo said.

Air pollution carries a risk of respiratory diseases, pneumonia, and bronchiolitis, with a 2017 systematic review by Nhung et al. finding increased exposure to ambient air pollution markers such as sulfur dioxide, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and carbon monoxide was associated with pneumonia in children (Environ Pollut. 2017 Jul 25. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.07.063). Coccidioidomycosis, or valley fever, is caused by inhaling a fungus in the soil and is associated with dust storms primarily in the southwestern United States. Warmer temperatures also have caused toxic algae blooms that have killed marine life and caused respiratory distress; children should not go near or play in water when algae blooms are growing, she noted.

Recent studies have linked an increase in temperature with incidence of Escherichia coli, with a 2016 study by Philipsborn et al. showing a 1° Celsius increase in mean monthly temperature was associated with an 8% increase in incidence of diarrheagenic E. coli (J Infect Dis. 2016 Feb 29. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw081). The incidence of hand, foot, and mouth disease also is linked to temperature and humidity, with a 2018 study by Cheng et al. showing a 1° Celsius increase in temperature and humidity was significantly associated with hand, foot, and mouth disease (Sci Total Environ. 2018 Jan 12. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.01.006). Rates of influenza are controlled by the changing environment as well, and increasing the number of vaccinations will help lower the number of influenza cases.

“We need to be advocates, we need to educate ourselves like we’re doing now so that we can educate our patients and to create a plan for preparedness,” Dr. Pacheo said.

She reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 2018

You have ‘unique expertise’ to treat opioid use disorder in adolescents

ORLANDO – according to a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“We pediatricians have some unique skills that can really benefit our community of teens,” said Deepa Camenga, MD, of Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

Compared with some other specialists, who may be more reluctant to prescribe buprenorphine, pediatricians are more comfortable and have systems in place to deal with issues surrounding care coordination, adolescent confidentiality, family reassurance, and managing prescriptions for chronic diseases.“We can use those same skills when we’re caring for people with opioid use disorder,” she said.

According to the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual–5), there are 11 criteria for opioid use disorder based on level of physiological dependence, impaired control, social functioning, and risky use. Meeting two or three criteria constitutes mild substance use disorder, while meeting six or more criteria is associated with severe substance use disorder.

Opioid use disorder in adolescents can be characterized by milder symptoms. Adolescents also tend to be in the early stage of this chronic disease when they seek care for opioid use disorder and need to be informed about the seriousness of the disease, Dr. Camenga noted.

“There is a disconnect about the severity of their illness when they present to me,” she said. “This is a disease that we know is chronic, severe – and without treatment – is progressive. We do know it can progress and get worse, and result in death.”

Treatment options for opioid use disorder in adolescents include behavioral interventions such as residential treatment, intensive outpatient (IOP), and partial hospitalization programs and therapy, as well as pharmacologic interventions like clonidine, buprenorphine, and methadone used for detoxification. Buprenorphine/naloxone has been labeled for use by patients 18 years or older; however, three recent randomized controlled trials have studied the effects of the intervention in 16-year-old and 17-year-old patients. In the trials, there were no serious adverse events reported with support of treatment for a minimum of 12 weeks and “many providers are treating up to a year” based on data from observational studies, Dr. Camenga said. Naltrexone also has been indicated for adolescents with opioid use disorder, with feasibility seen in pilot studies.

If you are interested in providing buprenorphine for patients, you need to apply for a Drug Enforcement Administration X-waiver, have access to their state’s prescription-monitoring program, and have a network of behavioral health providers for therapy and counseling, as well as psychiatrists for evaluation and treatment of other psychiatric disorders. Familiarity with naloxone overdose prevention training also is beneficial.

In addition, you must undergo 8 hours of training and apply for a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine in general medication settings. You can receive ongoing support after training on the AAP and Providers Clinical Support System websites.

Adolescent patients who receive buprenorphine for treatment of opioid use disorder typically undergo induction for 2 days where they are observed by a nurse or provider followed by weekly or biweekly medication-monitoring visits. It is “highly recommended” adolescents take urine drug screens during these visits but the results do not need to be observed. Many patients begin treatment when they are in IOP care, but some patients are not identified until they’ve had more severe consequences of opioid use disorder. Parents are involved in care by providing transportation and picking up and helping to administer medication, but there are confidential portions of the visits with the patient only.

“Parents have to be intimately involved and aware, and that’s an ideal situation,” Dr. Camenga said.

Dr. Camenga reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – according to a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“We pediatricians have some unique skills that can really benefit our community of teens,” said Deepa Camenga, MD, of Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

Compared with some other specialists, who may be more reluctant to prescribe buprenorphine, pediatricians are more comfortable and have systems in place to deal with issues surrounding care coordination, adolescent confidentiality, family reassurance, and managing prescriptions for chronic diseases.“We can use those same skills when we’re caring for people with opioid use disorder,” she said.

According to the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual–5), there are 11 criteria for opioid use disorder based on level of physiological dependence, impaired control, social functioning, and risky use. Meeting two or three criteria constitutes mild substance use disorder, while meeting six or more criteria is associated with severe substance use disorder.

Opioid use disorder in adolescents can be characterized by milder symptoms. Adolescents also tend to be in the early stage of this chronic disease when they seek care for opioid use disorder and need to be informed about the seriousness of the disease, Dr. Camenga noted.

“There is a disconnect about the severity of their illness when they present to me,” she said. “This is a disease that we know is chronic, severe – and without treatment – is progressive. We do know it can progress and get worse, and result in death.”

Treatment options for opioid use disorder in adolescents include behavioral interventions such as residential treatment, intensive outpatient (IOP), and partial hospitalization programs and therapy, as well as pharmacologic interventions like clonidine, buprenorphine, and methadone used for detoxification. Buprenorphine/naloxone has been labeled for use by patients 18 years or older; however, three recent randomized controlled trials have studied the effects of the intervention in 16-year-old and 17-year-old patients. In the trials, there were no serious adverse events reported with support of treatment for a minimum of 12 weeks and “many providers are treating up to a year” based on data from observational studies, Dr. Camenga said. Naltrexone also has been indicated for adolescents with opioid use disorder, with feasibility seen in pilot studies.

If you are interested in providing buprenorphine for patients, you need to apply for a Drug Enforcement Administration X-waiver, have access to their state’s prescription-monitoring program, and have a network of behavioral health providers for therapy and counseling, as well as psychiatrists for evaluation and treatment of other psychiatric disorders. Familiarity with naloxone overdose prevention training also is beneficial.

In addition, you must undergo 8 hours of training and apply for a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine in general medication settings. You can receive ongoing support after training on the AAP and Providers Clinical Support System websites.

Adolescent patients who receive buprenorphine for treatment of opioid use disorder typically undergo induction for 2 days where they are observed by a nurse or provider followed by weekly or biweekly medication-monitoring visits. It is “highly recommended” adolescents take urine drug screens during these visits but the results do not need to be observed. Many patients begin treatment when they are in IOP care, but some patients are not identified until they’ve had more severe consequences of opioid use disorder. Parents are involved in care by providing transportation and picking up and helping to administer medication, but there are confidential portions of the visits with the patient only.

“Parents have to be intimately involved and aware, and that’s an ideal situation,” Dr. Camenga said.

Dr. Camenga reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – according to a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“We pediatricians have some unique skills that can really benefit our community of teens,” said Deepa Camenga, MD, of Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

Compared with some other specialists, who may be more reluctant to prescribe buprenorphine, pediatricians are more comfortable and have systems in place to deal with issues surrounding care coordination, adolescent confidentiality, family reassurance, and managing prescriptions for chronic diseases.“We can use those same skills when we’re caring for people with opioid use disorder,” she said.

According to the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual–5), there are 11 criteria for opioid use disorder based on level of physiological dependence, impaired control, social functioning, and risky use. Meeting two or three criteria constitutes mild substance use disorder, while meeting six or more criteria is associated with severe substance use disorder.

Opioid use disorder in adolescents can be characterized by milder symptoms. Adolescents also tend to be in the early stage of this chronic disease when they seek care for opioid use disorder and need to be informed about the seriousness of the disease, Dr. Camenga noted.

“There is a disconnect about the severity of their illness when they present to me,” she said. “This is a disease that we know is chronic, severe – and without treatment – is progressive. We do know it can progress and get worse, and result in death.”

Treatment options for opioid use disorder in adolescents include behavioral interventions such as residential treatment, intensive outpatient (IOP), and partial hospitalization programs and therapy, as well as pharmacologic interventions like clonidine, buprenorphine, and methadone used for detoxification. Buprenorphine/naloxone has been labeled for use by patients 18 years or older; however, three recent randomized controlled trials have studied the effects of the intervention in 16-year-old and 17-year-old patients. In the trials, there were no serious adverse events reported with support of treatment for a minimum of 12 weeks and “many providers are treating up to a year” based on data from observational studies, Dr. Camenga said. Naltrexone also has been indicated for adolescents with opioid use disorder, with feasibility seen in pilot studies.

If you are interested in providing buprenorphine for patients, you need to apply for a Drug Enforcement Administration X-waiver, have access to their state’s prescription-monitoring program, and have a network of behavioral health providers for therapy and counseling, as well as psychiatrists for evaluation and treatment of other psychiatric disorders. Familiarity with naloxone overdose prevention training also is beneficial.

In addition, you must undergo 8 hours of training and apply for a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine in general medication settings. You can receive ongoing support after training on the AAP and Providers Clinical Support System websites.

Adolescent patients who receive buprenorphine for treatment of opioid use disorder typically undergo induction for 2 days where they are observed by a nurse or provider followed by weekly or biweekly medication-monitoring visits. It is “highly recommended” adolescents take urine drug screens during these visits but the results do not need to be observed. Many patients begin treatment when they are in IOP care, but some patients are not identified until they’ve had more severe consequences of opioid use disorder. Parents are involved in care by providing transportation and picking up and helping to administer medication, but there are confidential portions of the visits with the patient only.

“Parents have to be intimately involved and aware, and that’s an ideal situation,” Dr. Camenga said.

Dr. Camenga reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT AAP 18

Rate of STIs is rising, and many U.S. teens are sexually active

ORLANDO – Consider point-of-care testing and treat potentially infected partners when diagnosing and treating adolescents for STIs, Diane M. Straub, MD, MPH, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

In addition, adolescents are sometimes reluctant to disclose their full sexual history to their health care provider, which can complicate diagnosis and treatment, noted Dr. Straub, professor of pediatrics at the University of South Florida, Tampa. “That sometimes takes a few questions,” but can be achieved by asking the same questions in different ways and emphasizing the clinical importance of testing.

According to the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance survey, 40% of adolescents reported ever having sexual intercourse, with 20% of 9th-grade, 36% of 10th-grade, 47% of 11th-grade, and 57% of 12th-grade students reporting they had sexual intercourse. By gender, 41% of adolescent males and 38% of adolescent females reported ever having sexual intercourse; by race, 39% of white, 41% of Hispanic, and 46% of black participants reported any sexual activity. Overall, 10% of adolescents said they had four or more partners, 3% said they had intercourse before age 13 years, 54% used a condom the last time they had intercourse, and 7% said they were raped.

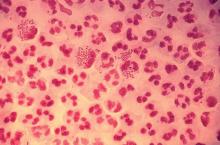

The rate of STIs in the United States is rising. There has been a sharp increase in the number of combined diagnoses of gonorrhea, syphilis, and chlamydia, with an increase from 1.8 million in 2013 to 2.3 million cases in 2017, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. During that same time period, gonorrhea increased 67% from 333,004 to 555,608 cases, syphilis (primary and secondary) rose 76% from 17,375 to 30,644 cases, and chlamydia increased 22% to 1.7 million cases.

According to a 2013 CDC infographic shown by Dr. Straub, young people in the United States aged 15-24 years old represent 27% of the total sexually active population but account for 50% of new STI cases each year. Persons in this population account for 70% of gonorrhea cases, 63% of chlamydia cases, 49% of human papillomavirus (HPV) cases, 45% of genital herpes cases, and 20% of syphilis cases.

All sexually active females aged 25 years or younger should be screened for chlamydia and gonorrhea, as well as “at-risk” young men who have sex with men (YMSM), Dr. Straub said. All adolescent males and females aged over 13 years should be offered HIV screening, and HIV screening should be discussed “at least once.” And depending on how at risk each subpopulation is, health care providers should be have that conversation and offer screening multiple times.

Women who have sex with women (WSW) are a diverse population and should be treated based on their individual sexual identities, behaviors, and practices. “Most self-identified WSWs report having sex with men, so therefore adolescent WSWs and females with both male and female sex partners might be at increased risk for STIs, such as syphillis, chlamydia, and HPV as well as HIV, so you may want to adjust your screening accordingly,” she said.

Pregnant women, if at risk, should be screened for HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B, gonorrhea, and chlamydia.

YMSM should have annual screenings for syphilis and HIV, screenings for chlamydia and gonorrhea by infection site; also consider herpes simplex virus serology and anal cytology in these patients, Dr. Straub said. They also should be screened for hepatitis B surface antigen, vaccinated for hepatitis A, hepatitis B and, if using drugs, screened* for hepatitis C virus.

Dr. Straub recommended licensed health care professionals who may treat minor patients review their state’s laws on minors and their legal ability to consent to treatment of STIs without the involvement of their parent or guardian, including disclosure of positive results and in the case of HIV care.

In places where index insured are allowed to find out about any services a beneficiary receives on their insurance, “this is a little problematic, because in some states, this is in direct conflict with the explanation of benefits requirement,” she said. “There are certain ways to get around that, but it’s really important for you to know what the statutes are where you’re practicing and where the breaches of confidentiality [are].”

Expedited partner therapy, or treating one or multiple partners of patients with an STI, is recommended for certain patients and infections, such as male partners of female patients with chlamydia and gonorrhea. While this is recommended less for YMSM because of a higher rate of concurrent infection, “if you have a young person who has partners who are unlikely to have access to care and get treated, it’s recommended you give that treatment to your index patient and to then treat their partners,” Dr. Straub said.

A recent and frequently updated resource on STI treatment can be found at the CDC website.

Dr. Straub reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

*This article was updated 1/11/19.

ORLANDO – Consider point-of-care testing and treat potentially infected partners when diagnosing and treating adolescents for STIs, Diane M. Straub, MD, MPH, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

In addition, adolescents are sometimes reluctant to disclose their full sexual history to their health care provider, which can complicate diagnosis and treatment, noted Dr. Straub, professor of pediatrics at the University of South Florida, Tampa. “That sometimes takes a few questions,” but can be achieved by asking the same questions in different ways and emphasizing the clinical importance of testing.

According to the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance survey, 40% of adolescents reported ever having sexual intercourse, with 20% of 9th-grade, 36% of 10th-grade, 47% of 11th-grade, and 57% of 12th-grade students reporting they had sexual intercourse. By gender, 41% of adolescent males and 38% of adolescent females reported ever having sexual intercourse; by race, 39% of white, 41% of Hispanic, and 46% of black participants reported any sexual activity. Overall, 10% of adolescents said they had four or more partners, 3% said they had intercourse before age 13 years, 54% used a condom the last time they had intercourse, and 7% said they were raped.

The rate of STIs in the United States is rising. There has been a sharp increase in the number of combined diagnoses of gonorrhea, syphilis, and chlamydia, with an increase from 1.8 million in 2013 to 2.3 million cases in 2017, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. During that same time period, gonorrhea increased 67% from 333,004 to 555,608 cases, syphilis (primary and secondary) rose 76% from 17,375 to 30,644 cases, and chlamydia increased 22% to 1.7 million cases.

According to a 2013 CDC infographic shown by Dr. Straub, young people in the United States aged 15-24 years old represent 27% of the total sexually active population but account for 50% of new STI cases each year. Persons in this population account for 70% of gonorrhea cases, 63% of chlamydia cases, 49% of human papillomavirus (HPV) cases, 45% of genital herpes cases, and 20% of syphilis cases.

All sexually active females aged 25 years or younger should be screened for chlamydia and gonorrhea, as well as “at-risk” young men who have sex with men (YMSM), Dr. Straub said. All adolescent males and females aged over 13 years should be offered HIV screening, and HIV screening should be discussed “at least once.” And depending on how at risk each subpopulation is, health care providers should be have that conversation and offer screening multiple times.

Women who have sex with women (WSW) are a diverse population and should be treated based on their individual sexual identities, behaviors, and practices. “Most self-identified WSWs report having sex with men, so therefore adolescent WSWs and females with both male and female sex partners might be at increased risk for STIs, such as syphillis, chlamydia, and HPV as well as HIV, so you may want to adjust your screening accordingly,” she said.

Pregnant women, if at risk, should be screened for HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B, gonorrhea, and chlamydia.

YMSM should have annual screenings for syphilis and HIV, screenings for chlamydia and gonorrhea by infection site; also consider herpes simplex virus serology and anal cytology in these patients, Dr. Straub said. They also should be screened for hepatitis B surface antigen, vaccinated for hepatitis A, hepatitis B and, if using drugs, screened* for hepatitis C virus.

Dr. Straub recommended licensed health care professionals who may treat minor patients review their state’s laws on minors and their legal ability to consent to treatment of STIs without the involvement of their parent or guardian, including disclosure of positive results and in the case of HIV care.

In places where index insured are allowed to find out about any services a beneficiary receives on their insurance, “this is a little problematic, because in some states, this is in direct conflict with the explanation of benefits requirement,” she said. “There are certain ways to get around that, but it’s really important for you to know what the statutes are where you’re practicing and where the breaches of confidentiality [are].”

Expedited partner therapy, or treating one or multiple partners of patients with an STI, is recommended for certain patients and infections, such as male partners of female patients with chlamydia and gonorrhea. While this is recommended less for YMSM because of a higher rate of concurrent infection, “if you have a young person who has partners who are unlikely to have access to care and get treated, it’s recommended you give that treatment to your index patient and to then treat their partners,” Dr. Straub said.

A recent and frequently updated resource on STI treatment can be found at the CDC website.

Dr. Straub reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

*This article was updated 1/11/19.

ORLANDO – Consider point-of-care testing and treat potentially infected partners when diagnosing and treating adolescents for STIs, Diane M. Straub, MD, MPH, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

In addition, adolescents are sometimes reluctant to disclose their full sexual history to their health care provider, which can complicate diagnosis and treatment, noted Dr. Straub, professor of pediatrics at the University of South Florida, Tampa. “That sometimes takes a few questions,” but can be achieved by asking the same questions in different ways and emphasizing the clinical importance of testing.

According to the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance survey, 40% of adolescents reported ever having sexual intercourse, with 20% of 9th-grade, 36% of 10th-grade, 47% of 11th-grade, and 57% of 12th-grade students reporting they had sexual intercourse. By gender, 41% of adolescent males and 38% of adolescent females reported ever having sexual intercourse; by race, 39% of white, 41% of Hispanic, and 46% of black participants reported any sexual activity. Overall, 10% of adolescents said they had four or more partners, 3% said they had intercourse before age 13 years, 54% used a condom the last time they had intercourse, and 7% said they were raped.

The rate of STIs in the United States is rising. There has been a sharp increase in the number of combined diagnoses of gonorrhea, syphilis, and chlamydia, with an increase from 1.8 million in 2013 to 2.3 million cases in 2017, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. During that same time period, gonorrhea increased 67% from 333,004 to 555,608 cases, syphilis (primary and secondary) rose 76% from 17,375 to 30,644 cases, and chlamydia increased 22% to 1.7 million cases.

According to a 2013 CDC infographic shown by Dr. Straub, young people in the United States aged 15-24 years old represent 27% of the total sexually active population but account for 50% of new STI cases each year. Persons in this population account for 70% of gonorrhea cases, 63% of chlamydia cases, 49% of human papillomavirus (HPV) cases, 45% of genital herpes cases, and 20% of syphilis cases.

All sexually active females aged 25 years or younger should be screened for chlamydia and gonorrhea, as well as “at-risk” young men who have sex with men (YMSM), Dr. Straub said. All adolescent males and females aged over 13 years should be offered HIV screening, and HIV screening should be discussed “at least once.” And depending on how at risk each subpopulation is, health care providers should be have that conversation and offer screening multiple times.

Women who have sex with women (WSW) are a diverse population and should be treated based on their individual sexual identities, behaviors, and practices. “Most self-identified WSWs report having sex with men, so therefore adolescent WSWs and females with both male and female sex partners might be at increased risk for STIs, such as syphillis, chlamydia, and HPV as well as HIV, so you may want to adjust your screening accordingly,” she said.

Pregnant women, if at risk, should be screened for HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B, gonorrhea, and chlamydia.

YMSM should have annual screenings for syphilis and HIV, screenings for chlamydia and gonorrhea by infection site; also consider herpes simplex virus serology and anal cytology in these patients, Dr. Straub said. They also should be screened for hepatitis B surface antigen, vaccinated for hepatitis A, hepatitis B and, if using drugs, screened* for hepatitis C virus.

Dr. Straub recommended licensed health care professionals who may treat minor patients review their state’s laws on minors and their legal ability to consent to treatment of STIs without the involvement of their parent or guardian, including disclosure of positive results and in the case of HIV care.

In places where index insured are allowed to find out about any services a beneficiary receives on their insurance, “this is a little problematic, because in some states, this is in direct conflict with the explanation of benefits requirement,” she said. “There are certain ways to get around that, but it’s really important for you to know what the statutes are where you’re practicing and where the breaches of confidentiality [are].”

Expedited partner therapy, or treating one or multiple partners of patients with an STI, is recommended for certain patients and infections, such as male partners of female patients with chlamydia and gonorrhea. While this is recommended less for YMSM because of a higher rate of concurrent infection, “if you have a young person who has partners who are unlikely to have access to care and get treated, it’s recommended you give that treatment to your index patient and to then treat their partners,” Dr. Straub said.

A recent and frequently updated resource on STI treatment can be found at the CDC website.

Dr. Straub reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

*This article was updated 1/11/19.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 18

Discussing immunization with vaccine-hesitant parents requires caring, individualized approach

ORLANDO – Putting parents at ease, making vaccination the default option during discussions, appealing to their identity as a good parent, and focusing on positive word choice during discussions are the techniques two pediatricians have recommended using to get vaccine-hesitant parents to immunize their children.

“Your goal is to get parents to immunize their kids,” Katrina Saba, MD, of the Permanente Medical Group in Oakland, Calif., said during an interactive group panel at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “Our goal is not to win a debate. You don’t have to correct every mistaken idea.”

“And really importantly, as we know, belief trumps science,” she added. “Their belief is so much stronger than our proof, and their belief will not be changed by evidence.”

Many parents who are vaccine- hesitant also belong to a social network that forms or reinforces their beliefs, and attacking those beliefs is the same as attacking their identity, Dr. Saba noted. “When you attack someone’s identity, you are immediately seen as not like them, and if you’re not like them, you’ve lost your strength in persuading them.”

Dr. Saba; Kenneth Hempstead, MD; and other pediatricians and educators in the Permanente Medical Group developed a framework for pediatricians and educators to talk with their patients about immunization at their center after California passed a law in 2013 that required health care professionals to discuss vaccines with patients and sign off that they had that discussion.

“We felt that, if we were going to be by law required to have that discussion, maybe we needed some new tools to have [the discussion] more effectively,” Dr. Saba said. “Because clearly, [what we were doing ] wasn’t working or there wouldn’t have been a need for that law.”

Dr. Hempstead explained the concerns of three major categories of vaccine-hesitant parents: those patients who are unsure of whether they should vaccinate, parents who wish to delay vaccination, and parents who refuse vaccination of their children.

Each parent requires a different approach for discussing the importance of vaccination based on their level of vaccine hesitancy, he said. For parents who are unsure, they may require general information about the safety and importance of vaccines.

Parents who delay immunization may have less trust in vaccines, have done research in their own social networks, and may present alternatives to a standard immunization schedule or want to omit certain vaccines from their child’s immunization schedule, he noted. Using the analogy of a car seat is one approach to identify the importance of vaccination to these parents: “Waiting to give the shots is like putting your baby in the car seat after you’ve already arrived at the store – the protection isn’t there for the most important part of the journey!”

In cases where parents refuse vaccination, you should not expect to change a parent’s mind in a single visit, but instead focus on building the patient-provider bond. However, presenting information the parent may have already seen, such as vaccination data from the Food and Drug Administration or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, may alienate parents who identify with groups that share vaccine-hesitant viewpoints and erode your ability to persuade a parent’s intent to vaccinate.

A study by Nyhan et al. randomized parents to receive one of four pieces of interventions about the MMR vaccine: information from the CDC explaining the lack of evidence linking autism and the vaccine, information about the dangers of the diseases prevented by the vaccine, images of children who have had diseases prevented by the vaccine, and a “dramatic narrative” from a CDC fact sheet about a child who nearly died of measles. The researchers found no informational intervention helped in persuading to vaccinate in parents who had the “least favorable” attitudes toward the vaccine. And in the case of the dramatic narrative, there was an increased misperception about the MMR vaccine (Pediatrics. 2014;133[4]:e835-e842).

Dr. Hempstead and Dr. Saba outlined four rhetorical devices to include in conversations with patients about vaccination: cognitive ease, natural assumption, appeal to identity, and using advantageous terms.

Cognitive ease

Cognitive ease means creating an environment in which the patient is relaxed, comfortable, and more likely to be agreeable. Recognize when the tone shifts, and strive to maintain this calm and comfortable environment throughout the discussion. “If your blood pressure is coming up, that means theirs is, too,” Dr. Hempstead said.

Natural assumption

How you are offering the vaccination also matters, he added. Rather than asking whether a patient wants to vaccinate (“Have you thought about your flu vaccine this year?”), instead frame the discussion with vaccination as the default option (“Is your child due for a flu vaccination this year? Yes, he is. Let’s get that taken care of today”). Equating inaction with vaccination prevents the risk fallacy phenomenon from occurring in which, when given multiple options, people give equal weight to each option and may choose not to vaccinate, Dr. Hempstead noted.

Dr. Saba cited research that backed this approach. In a study by Opel et al., using a “presumptive” approach instead of a “participatory” approach when discussing a provider’s recommendation to vaccinate helped: The presumptive conversations had an odds ratio of 17.5, compared with the participatory approach. In cases in which parents resisted the provider’s recommendations, 50% of providers persisted with their original recommendations, and 47% of parents who initially resisted the recommendations agreed to vaccinate (Pediatrics. 2013;132[6]:1037-46).

Appeal to identity

Another strategy to use is appealing to the patient’s identity as a good parent and link the concept of vaccination with the good parent identity. Forging a new common identity with the parents through common beliefs – such as recognizing that networks to which parents belong are an important part of his or her identify – and reemphasizing the mutual desire to protect the child is another strategy.

Using advantageous terms

Positive terms, such as “protection,” “health,” “safety,” and “what’s best,” are much better words to use in conversation with parents and have more staying power than negative terms, like “autism” and “side effects,” Dr. Hempstead said.

“Stay with positive messaging,” he said. “Immediately coming back to the positive impact of this vaccine, why we care so much, why we’re doing this vaccine, is absolutely critical.”

Dr. Hempstead and Dr. Saba reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Putting parents at ease, making vaccination the default option during discussions, appealing to their identity as a good parent, and focusing on positive word choice during discussions are the techniques two pediatricians have recommended using to get vaccine-hesitant parents to immunize their children.

“Your goal is to get parents to immunize their kids,” Katrina Saba, MD, of the Permanente Medical Group in Oakland, Calif., said during an interactive group panel at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “Our goal is not to win a debate. You don’t have to correct every mistaken idea.”

“And really importantly, as we know, belief trumps science,” she added. “Their belief is so much stronger than our proof, and their belief will not be changed by evidence.”

Many parents who are vaccine- hesitant also belong to a social network that forms or reinforces their beliefs, and attacking those beliefs is the same as attacking their identity, Dr. Saba noted. “When you attack someone’s identity, you are immediately seen as not like them, and if you’re not like them, you’ve lost your strength in persuading them.”

Dr. Saba; Kenneth Hempstead, MD; and other pediatricians and educators in the Permanente Medical Group developed a framework for pediatricians and educators to talk with their patients about immunization at their center after California passed a law in 2013 that required health care professionals to discuss vaccines with patients and sign off that they had that discussion.

“We felt that, if we were going to be by law required to have that discussion, maybe we needed some new tools to have [the discussion] more effectively,” Dr. Saba said. “Because clearly, [what we were doing ] wasn’t working or there wouldn’t have been a need for that law.”

Dr. Hempstead explained the concerns of three major categories of vaccine-hesitant parents: those patients who are unsure of whether they should vaccinate, parents who wish to delay vaccination, and parents who refuse vaccination of their children.

Each parent requires a different approach for discussing the importance of vaccination based on their level of vaccine hesitancy, he said. For parents who are unsure, they may require general information about the safety and importance of vaccines.

Parents who delay immunization may have less trust in vaccines, have done research in their own social networks, and may present alternatives to a standard immunization schedule or want to omit certain vaccines from their child’s immunization schedule, he noted. Using the analogy of a car seat is one approach to identify the importance of vaccination to these parents: “Waiting to give the shots is like putting your baby in the car seat after you’ve already arrived at the store – the protection isn’t there for the most important part of the journey!”

In cases where parents refuse vaccination, you should not expect to change a parent’s mind in a single visit, but instead focus on building the patient-provider bond. However, presenting information the parent may have already seen, such as vaccination data from the Food and Drug Administration or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, may alienate parents who identify with groups that share vaccine-hesitant viewpoints and erode your ability to persuade a parent’s intent to vaccinate.

A study by Nyhan et al. randomized parents to receive one of four pieces of interventions about the MMR vaccine: information from the CDC explaining the lack of evidence linking autism and the vaccine, information about the dangers of the diseases prevented by the vaccine, images of children who have had diseases prevented by the vaccine, and a “dramatic narrative” from a CDC fact sheet about a child who nearly died of measles. The researchers found no informational intervention helped in persuading to vaccinate in parents who had the “least favorable” attitudes toward the vaccine. And in the case of the dramatic narrative, there was an increased misperception about the MMR vaccine (Pediatrics. 2014;133[4]:e835-e842).

Dr. Hempstead and Dr. Saba outlined four rhetorical devices to include in conversations with patients about vaccination: cognitive ease, natural assumption, appeal to identity, and using advantageous terms.

Cognitive ease

Cognitive ease means creating an environment in which the patient is relaxed, comfortable, and more likely to be agreeable. Recognize when the tone shifts, and strive to maintain this calm and comfortable environment throughout the discussion. “If your blood pressure is coming up, that means theirs is, too,” Dr. Hempstead said.

Natural assumption

How you are offering the vaccination also matters, he added. Rather than asking whether a patient wants to vaccinate (“Have you thought about your flu vaccine this year?”), instead frame the discussion with vaccination as the default option (“Is your child due for a flu vaccination this year? Yes, he is. Let’s get that taken care of today”). Equating inaction with vaccination prevents the risk fallacy phenomenon from occurring in which, when given multiple options, people give equal weight to each option and may choose not to vaccinate, Dr. Hempstead noted.

Dr. Saba cited research that backed this approach. In a study by Opel et al., using a “presumptive” approach instead of a “participatory” approach when discussing a provider’s recommendation to vaccinate helped: The presumptive conversations had an odds ratio of 17.5, compared with the participatory approach. In cases in which parents resisted the provider’s recommendations, 50% of providers persisted with their original recommendations, and 47% of parents who initially resisted the recommendations agreed to vaccinate (Pediatrics. 2013;132[6]:1037-46).

Appeal to identity

Another strategy to use is appealing to the patient’s identity as a good parent and link the concept of vaccination with the good parent identity. Forging a new common identity with the parents through common beliefs – such as recognizing that networks to which parents belong are an important part of his or her identify – and reemphasizing the mutual desire to protect the child is another strategy.

Using advantageous terms

Positive terms, such as “protection,” “health,” “safety,” and “what’s best,” are much better words to use in conversation with parents and have more staying power than negative terms, like “autism” and “side effects,” Dr. Hempstead said.

“Stay with positive messaging,” he said. “Immediately coming back to the positive impact of this vaccine, why we care so much, why we’re doing this vaccine, is absolutely critical.”

Dr. Hempstead and Dr. Saba reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Putting parents at ease, making vaccination the default option during discussions, appealing to their identity as a good parent, and focusing on positive word choice during discussions are the techniques two pediatricians have recommended using to get vaccine-hesitant parents to immunize their children.

“Your goal is to get parents to immunize their kids,” Katrina Saba, MD, of the Permanente Medical Group in Oakland, Calif., said during an interactive group panel at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “Our goal is not to win a debate. You don’t have to correct every mistaken idea.”

“And really importantly, as we know, belief trumps science,” she added. “Their belief is so much stronger than our proof, and their belief will not be changed by evidence.”

Many parents who are vaccine- hesitant also belong to a social network that forms or reinforces their beliefs, and attacking those beliefs is the same as attacking their identity, Dr. Saba noted. “When you attack someone’s identity, you are immediately seen as not like them, and if you’re not like them, you’ve lost your strength in persuading them.”

Dr. Saba; Kenneth Hempstead, MD; and other pediatricians and educators in the Permanente Medical Group developed a framework for pediatricians and educators to talk with their patients about immunization at their center after California passed a law in 2013 that required health care professionals to discuss vaccines with patients and sign off that they had that discussion.

“We felt that, if we were going to be by law required to have that discussion, maybe we needed some new tools to have [the discussion] more effectively,” Dr. Saba said. “Because clearly, [what we were doing ] wasn’t working or there wouldn’t have been a need for that law.”

Dr. Hempstead explained the concerns of three major categories of vaccine-hesitant parents: those patients who are unsure of whether they should vaccinate, parents who wish to delay vaccination, and parents who refuse vaccination of their children.

Each parent requires a different approach for discussing the importance of vaccination based on their level of vaccine hesitancy, he said. For parents who are unsure, they may require general information about the safety and importance of vaccines.

Parents who delay immunization may have less trust in vaccines, have done research in their own social networks, and may present alternatives to a standard immunization schedule or want to omit certain vaccines from their child’s immunization schedule, he noted. Using the analogy of a car seat is one approach to identify the importance of vaccination to these parents: “Waiting to give the shots is like putting your baby in the car seat after you’ve already arrived at the store – the protection isn’t there for the most important part of the journey!”

In cases where parents refuse vaccination, you should not expect to change a parent’s mind in a single visit, but instead focus on building the patient-provider bond. However, presenting information the parent may have already seen, such as vaccination data from the Food and Drug Administration or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, may alienate parents who identify with groups that share vaccine-hesitant viewpoints and erode your ability to persuade a parent’s intent to vaccinate.

A study by Nyhan et al. randomized parents to receive one of four pieces of interventions about the MMR vaccine: information from the CDC explaining the lack of evidence linking autism and the vaccine, information about the dangers of the diseases prevented by the vaccine, images of children who have had diseases prevented by the vaccine, and a “dramatic narrative” from a CDC fact sheet about a child who nearly died of measles. The researchers found no informational intervention helped in persuading to vaccinate in parents who had the “least favorable” attitudes toward the vaccine. And in the case of the dramatic narrative, there was an increased misperception about the MMR vaccine (Pediatrics. 2014;133[4]:e835-e842).

Dr. Hempstead and Dr. Saba outlined four rhetorical devices to include in conversations with patients about vaccination: cognitive ease, natural assumption, appeal to identity, and using advantageous terms.

Cognitive ease

Cognitive ease means creating an environment in which the patient is relaxed, comfortable, and more likely to be agreeable. Recognize when the tone shifts, and strive to maintain this calm and comfortable environment throughout the discussion. “If your blood pressure is coming up, that means theirs is, too,” Dr. Hempstead said.

Natural assumption

How you are offering the vaccination also matters, he added. Rather than asking whether a patient wants to vaccinate (“Have you thought about your flu vaccine this year?”), instead frame the discussion with vaccination as the default option (“Is your child due for a flu vaccination this year? Yes, he is. Let’s get that taken care of today”). Equating inaction with vaccination prevents the risk fallacy phenomenon from occurring in which, when given multiple options, people give equal weight to each option and may choose not to vaccinate, Dr. Hempstead noted.

Dr. Saba cited research that backed this approach. In a study by Opel et al., using a “presumptive” approach instead of a “participatory” approach when discussing a provider’s recommendation to vaccinate helped: The presumptive conversations had an odds ratio of 17.5, compared with the participatory approach. In cases in which parents resisted the provider’s recommendations, 50% of providers persisted with their original recommendations, and 47% of parents who initially resisted the recommendations agreed to vaccinate (Pediatrics. 2013;132[6]:1037-46).

Appeal to identity

Another strategy to use is appealing to the patient’s identity as a good parent and link the concept of vaccination with the good parent identity. Forging a new common identity with the parents through common beliefs – such as recognizing that networks to which parents belong are an important part of his or her identify – and reemphasizing the mutual desire to protect the child is another strategy.

Using advantageous terms

Positive terms, such as “protection,” “health,” “safety,” and “what’s best,” are much better words to use in conversation with parents and have more staying power than negative terms, like “autism” and “side effects,” Dr. Hempstead said.

“Stay with positive messaging,” he said. “Immediately coming back to the positive impact of this vaccine, why we care so much, why we’re doing this vaccine, is absolutely critical.”

Dr. Hempstead and Dr. Saba reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 18

Many teens don’t know e-cigarettes contain nicotine

ORLANDO – Flavoring and lack of Food and Drug Administration regulation of e-cigarettes has led to more children and adolescents using these devices, according to American Academy of Pediatrics President Colleen A. Kraft, MD.

In an interview, Dr. Kraft said the FDA should regulate these products and limit their purchase to adults who are at least 21 years old. E-cigarettes were initially intended as an aid for adults to reduce their cigarette use, but the addition of flavoring has attracted children and adolescents to the devices, Dr. Kraft noted.

“When you have these devices that have flavors like gummy bear and cotton candy and bubblegum, you are marketing to children, and we are calling out the FDA because they could actually stop this today,” she said. In fact, Dr. Kraft added, many children and adolescents don’t even realize that e-cigarettes contain nicotine.

Dr. Kraft reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Flavoring and lack of Food and Drug Administration regulation of e-cigarettes has led to more children and adolescents using these devices, according to American Academy of Pediatrics President Colleen A. Kraft, MD.

In an interview, Dr. Kraft said the FDA should regulate these products and limit their purchase to adults who are at least 21 years old. E-cigarettes were initially intended as an aid for adults to reduce their cigarette use, but the addition of flavoring has attracted children and adolescents to the devices, Dr. Kraft noted.

“When you have these devices that have flavors like gummy bear and cotton candy and bubblegum, you are marketing to children, and we are calling out the FDA because they could actually stop this today,” she said. In fact, Dr. Kraft added, many children and adolescents don’t even realize that e-cigarettes contain nicotine.

Dr. Kraft reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Flavoring and lack of Food and Drug Administration regulation of e-cigarettes has led to more children and adolescents using these devices, according to American Academy of Pediatrics President Colleen A. Kraft, MD.

In an interview, Dr. Kraft said the FDA should regulate these products and limit their purchase to adults who are at least 21 years old. E-cigarettes were initially intended as an aid for adults to reduce their cigarette use, but the addition of flavoring has attracted children and adolescents to the devices, Dr. Kraft noted.

“When you have these devices that have flavors like gummy bear and cotton candy and bubblegum, you are marketing to children, and we are calling out the FDA because they could actually stop this today,” she said. In fact, Dr. Kraft added, many children and adolescents don’t even realize that e-cigarettes contain nicotine.

Dr. Kraft reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM AAP 2018

Communicate with Millennials using their preferred methods

ORLANDO – Pediatricians can learn from how Millennials use services and purchase products from popular companies, such as Amazon Alexa, Warby Parker, Instagram, and Snapchat, and use that information to connect with Millennial parents and children in their practice, Kristopher Jones, JD, MS, said.

In a video interview, Mr. Jones explained how Amazon Alexa uses structured data as recommendations when users make queries of the service; for example, a Millennial might make a choice to book an appointment with a pediatrician based on the results Amazon Alexa displays, such as an office’s available hours. An office that is not optimized to appear in those results would be missed by those potential patients.

Warby Parker has a digital-first strategy focused on convenience, ease of use, and an emphasis on mission; one opportunity for pediatricians in this area is to be more overt about which causes they are supporting, Mr. Jones said. In the case of Instagram and Snapchat, pediatricians should consider creating a presence on these platforms and focusing on less text-heavy content to appeal to Millennials.

“It’s a really, really important opportunity to be able to meet the Millennials where they want to be met, and that means developing strategies to leveraging pictures and videos and other forms of Millennial content to communicate with them,” he said.

Mr. Jones reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Pediatricians can learn from how Millennials use services and purchase products from popular companies, such as Amazon Alexa, Warby Parker, Instagram, and Snapchat, and use that information to connect with Millennial parents and children in their practice, Kristopher Jones, JD, MS, said.

In a video interview, Mr. Jones explained how Amazon Alexa uses structured data as recommendations when users make queries of the service; for example, a Millennial might make a choice to book an appointment with a pediatrician based on the results Amazon Alexa displays, such as an office’s available hours. An office that is not optimized to appear in those results would be missed by those potential patients.

Warby Parker has a digital-first strategy focused on convenience, ease of use, and an emphasis on mission; one opportunity for pediatricians in this area is to be more overt about which causes they are supporting, Mr. Jones said. In the case of Instagram and Snapchat, pediatricians should consider creating a presence on these platforms and focusing on less text-heavy content to appeal to Millennials.

“It’s a really, really important opportunity to be able to meet the Millennials where they want to be met, and that means developing strategies to leveraging pictures and videos and other forms of Millennial content to communicate with them,” he said.

Mr. Jones reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Pediatricians can learn from how Millennials use services and purchase products from popular companies, such as Amazon Alexa, Warby Parker, Instagram, and Snapchat, and use that information to connect with Millennial parents and children in their practice, Kristopher Jones, JD, MS, said.

In a video interview, Mr. Jones explained how Amazon Alexa uses structured data as recommendations when users make queries of the service; for example, a Millennial might make a choice to book an appointment with a pediatrician based on the results Amazon Alexa displays, such as an office’s available hours. An office that is not optimized to appear in those results would be missed by those potential patients.

Warby Parker has a digital-first strategy focused on convenience, ease of use, and an emphasis on mission; one opportunity for pediatricians in this area is to be more overt about which causes they are supporting, Mr. Jones said. In the case of Instagram and Snapchat, pediatricians should consider creating a presence on these platforms and focusing on less text-heavy content to appeal to Millennials.

“It’s a really, really important opportunity to be able to meet the Millennials where they want to be met, and that means developing strategies to leveraging pictures and videos and other forms of Millennial content to communicate with them,” he said.

Mr. Jones reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM AAP 2018

AAP strengthens stance against corporal punishment

ORLANDO – The American Academy of Pediatrics has issued a new policy statement taking a stronger stance against corporal punishment, including spanking, 20 years after releasing its last position statement on effective discipline.

The 1998 policy statement discouraged the use of corporal punishment and encouraged parents to seek other ways to discipline their children, while the latest statement goes further, citing the latest research showing corporal punishment’s harmful effects on children and encouraging pediatricians to counsel parents about the harms of corporal punishment and offer alternative forms of discipline. The 2018 policy statement will be published in the December issue of Pediatrics.

Support for corporal punishment, such as spanking, is declining. According to the Child Trends data bank, 76% of men and 66% of women supported spanking in some cases, compared with 84% of men and 82% of women in 1986. In its latest statement, the AAP noted that 6% of pediatricians (92% in primary care) supported spanking in a 2016 survey of 787 pediatricians.

In a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Ryan D. Brown, MD, of the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, noted that studies have shown children who are spanked are more likely to exhibit mental health problems, antisocial behavior, aggression, negative relationships with a parent, low self-esteem, externalizing behavior such as acting out, substance abuse, low moral internalization, and are more likely to be victims of physical abuse. He cited a study showing that children who were spanked one time per month had a 14%-19% reduction in the decision making area of their brains (Neuroimage. 2009 Aug;47 Suppl 2:T66-T71) and another study showing that children spanked aged between 2 and 9 years had 2.8-5.0 fewer IQ points than children who were not spanked (J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2009 Jul 22;18[5]:459-83).

Science has shown that there are more effective ways of disciplining children, and pediatricians are the experts who can explain the difference between discipline and punishment. Parents can use discipline as a teaching opportunity while corporal punishment inflicts physical pain on children with the intent to modify behavior. However, this does not train children to learn. “We want to teach our children to grow,” Dr. Brown said.

He pointed out the AAP’s policy on ipecac syrup and erythromycin/sulfafurazole for otitis media as examples of recommendations changing when more scientific data becomes available.

“[W]hen we get parents that say, ‘You know what? I was spanked as a kid and I turned out okay,’ I said, ‘You know, I rode in a car without a seat belt, but science has shown seat belts are effective,’ ” Dr. Brown said.

Instead of spanking and other forms of corporal punishment, parents should practice positive parenting, such as telling a child when they are being “good,” so children understand what good behavior looks like to build up self-esteem. Parents also should play with their children daily and provide simple, easy-to-understand commands. “Interact with the kids so they can see what is good behavior,” he said.

Disciplining children should be swift, age appropriate relative to mental rather than chronological age, and the discipline should “fit the crime,” Dr. Brown said. Parents also should not discipline a child in accidental situations, such as dropping a glass when helping clean up the dinner table, he added.

“The only time I kind of say that [discipline] should be delayed is in kids [who] understand the delay,” such as teenagers, Dr. Brown added.

Pediatricians can implement the new guidelines in their practices by providing resources to parents about alternative forms of discipline, such as the AAP sites HealthyChildren.org and Connected Kids, training office staff in diffusing stressful situations between a caregiver and a child, and making their office a “no hit zone” for caregivers and children.

Dr. Brown reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – The American Academy of Pediatrics has issued a new policy statement taking a stronger stance against corporal punishment, including spanking, 20 years after releasing its last position statement on effective discipline.

The 1998 policy statement discouraged the use of corporal punishment and encouraged parents to seek other ways to discipline their children, while the latest statement goes further, citing the latest research showing corporal punishment’s harmful effects on children and encouraging pediatricians to counsel parents about the harms of corporal punishment and offer alternative forms of discipline. The 2018 policy statement will be published in the December issue of Pediatrics.

Support for corporal punishment, such as spanking, is declining. According to the Child Trends data bank, 76% of men and 66% of women supported spanking in some cases, compared with 84% of men and 82% of women in 1986. In its latest statement, the AAP noted that 6% of pediatricians (92% in primary care) supported spanking in a 2016 survey of 787 pediatricians.

In a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Ryan D. Brown, MD, of the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, noted that studies have shown children who are spanked are more likely to exhibit mental health problems, antisocial behavior, aggression, negative relationships with a parent, low self-esteem, externalizing behavior such as acting out, substance abuse, low moral internalization, and are more likely to be victims of physical abuse. He cited a study showing that children who were spanked one time per month had a 14%-19% reduction in the decision making area of their brains (Neuroimage. 2009 Aug;47 Suppl 2:T66-T71) and another study showing that children spanked aged between 2 and 9 years had 2.8-5.0 fewer IQ points than children who were not spanked (J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2009 Jul 22;18[5]:459-83).

Science has shown that there are more effective ways of disciplining children, and pediatricians are the experts who can explain the difference between discipline and punishment. Parents can use discipline as a teaching opportunity while corporal punishment inflicts physical pain on children with the intent to modify behavior. However, this does not train children to learn. “We want to teach our children to grow,” Dr. Brown said.

He pointed out the AAP’s policy on ipecac syrup and erythromycin/sulfafurazole for otitis media as examples of recommendations changing when more scientific data becomes available.

“[W]hen we get parents that say, ‘You know what? I was spanked as a kid and I turned out okay,’ I said, ‘You know, I rode in a car without a seat belt, but science has shown seat belts are effective,’ ” Dr. Brown said.

Instead of spanking and other forms of corporal punishment, parents should practice positive parenting, such as telling a child when they are being “good,” so children understand what good behavior looks like to build up self-esteem. Parents also should play with their children daily and provide simple, easy-to-understand commands. “Interact with the kids so they can see what is good behavior,” he said.

Disciplining children should be swift, age appropriate relative to mental rather than chronological age, and the discipline should “fit the crime,” Dr. Brown said. Parents also should not discipline a child in accidental situations, such as dropping a glass when helping clean up the dinner table, he added.

“The only time I kind of say that [discipline] should be delayed is in kids [who] understand the delay,” such as teenagers, Dr. Brown added.

Pediatricians can implement the new guidelines in their practices by providing resources to parents about alternative forms of discipline, such as the AAP sites HealthyChildren.org and Connected Kids, training office staff in diffusing stressful situations between a caregiver and a child, and making their office a “no hit zone” for caregivers and children.

Dr. Brown reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – The American Academy of Pediatrics has issued a new policy statement taking a stronger stance against corporal punishment, including spanking, 20 years after releasing its last position statement on effective discipline.

The 1998 policy statement discouraged the use of corporal punishment and encouraged parents to seek other ways to discipline their children, while the latest statement goes further, citing the latest research showing corporal punishment’s harmful effects on children and encouraging pediatricians to counsel parents about the harms of corporal punishment and offer alternative forms of discipline. The 2018 policy statement will be published in the December issue of Pediatrics.

Support for corporal punishment, such as spanking, is declining. According to the Child Trends data bank, 76% of men and 66% of women supported spanking in some cases, compared with 84% of men and 82% of women in 1986. In its latest statement, the AAP noted that 6% of pediatricians (92% in primary care) supported spanking in a 2016 survey of 787 pediatricians.