User login

Botulinum Toxin as a Tool to Reduce Hyperhidrosis in Amputees

Botulinum Toxin as a Tool to Reduce Hyperhidrosis in Amputees

Practice Gap

Hyperhidrosis poses a considerable challenge for many amputees who use prosthetic devices, particularly at the interface between the residual limb and the prosthetic socket. The enclosed environment of the socket often leads to excessive sweating, which can compromise suction fit and increase the risk for skin chafing, irritation, and slippage. Persistent moisture also promotes bacterial and fungal growth, raising the likelihood of infections and foul odors within the socket. Research has shown that skin complications are highly prevalent among amputees, affecting up to 73.9% of this population in the United States.1 Commonly reported complications include wounds, abscesses, and blisters, many of which can be triggered or worsened by hyperhidrosis.2 Current treatment options for residual limb sweating include topical antiperspirants, botulinum toxin (BTX) injections, iontophoresis, and liner-liner socks.

While BTX commonly is used to treat hyperhidrosis in areas such as the palms and axillae, it typically is not considered as a first-line therapy for residual limb sweating; however, both BTX type A and type B have shown safety and effectiveness in managing hyperhidrosis in amputees, enhancing prosthetic use, and improving overall quality of life.3 Despite these benefits, BTX remains relatively underutilized for

Tools and Techniques

A 64-year-old man initially presented to our dermatology clinic after undergoing an above-the-knee amputation of the left leg 1 year prior. The amputation had been performed due to chronic prosthetic joint infections with Escherichia coli. He reported persistent sweating of the residual limb, which severely limited his use of a prosthesis and led to frequent falls.

During the initial visit, treatment options for primary hyperhidrosis including topical and injectable therapies were discussed. Due to a fear of needles, the patient chose topical treatment, with the option to pursue BTX injections later if better control was needed. An aluminum chloride hexahydrate prosthetic antiperspirant was prescribed for nightly application on the anterior and posterior

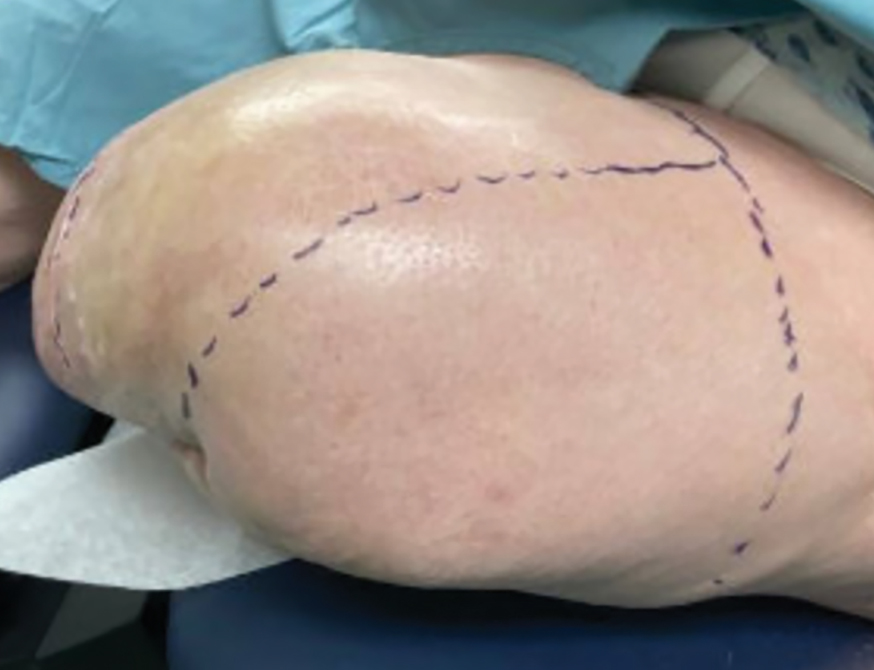

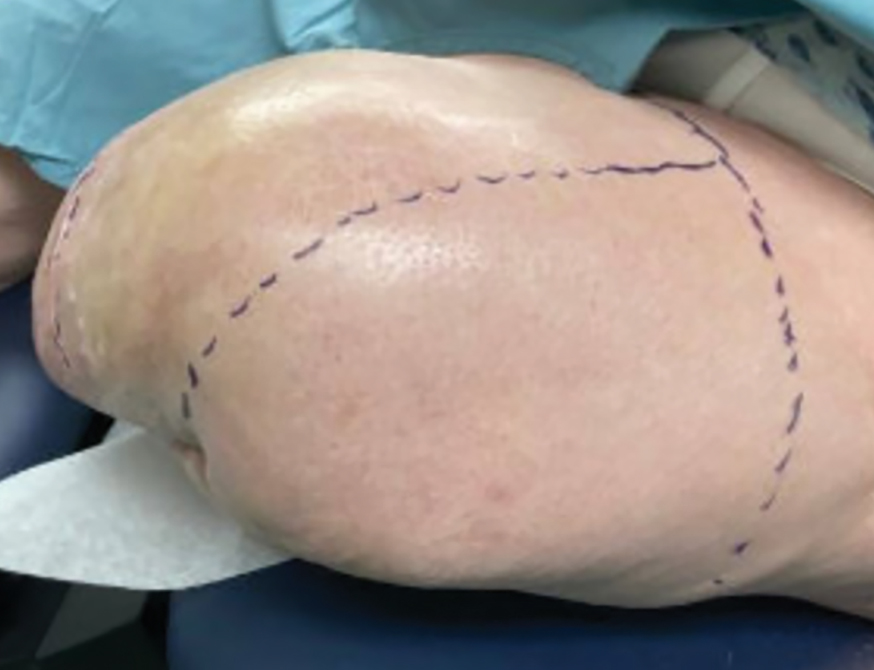

Botulinum toxin injections were administered in a grid-like pattern across the surface area where the residual limb made contact with the prosthetic. Using a surgical marker, the patient assisted the medical team in identifying the areas where sweating occurred most frequently. The area was divided into 4 equal sections, with each section treated per weekly interval sequentially over 4 weeks. The targeted areas included the left anterior (extending from the anterior tensor fasciae latae band to the lateral thigh) and left posterior residual limb (Figure 1 and eFigure 1, respectively).

The treated section was cleaned with an alcohol wipe prior to each injection, and 50 units of BTX (diluted to 2.5 units per 0.1 mL in bacteriostatic saline) were injected intradermally into each section (Figure 2 and eFigure 2). The injections were administered in rows, with the needle inserted at evenly spaced intervals approximately 1 inch apart. A total of 100 units were administered per section at each weekly appointment. The patient tolerated the procedure well, and no complications were observed.

Practice Implications

This staged approach to administering BTX ensures even distribution of the injections, optimizes hyperhidrosis control, minimizes the risk for complications, and allows for precise targeting of the affected areas to maximize therapeutic benefit. Following the initial procedure, our patient was scheduled for follow-ups approximately every 3 to 4 months starting from the first set of injections for each area. Over 9 months, the patient successfully completed 3 treatment sessions using this method. The patient reported improved quality of life after starting the BTX injections.

After evaluating the initial treatment outcomes with 100 units per section, the dosage was increased to 200 units per section to reduce the number of visits from 4 every 3 months to cover the entire area to 2 visits every 3 months. This adjustment aimed to optimize results and better manage the patient’s ongoing symptoms. At about 1 to 2 weeks after beginning treatment, the patient noticed decreased sweating and discomfort during his daily activities and reduced friction with his prosthetic leg. No adverse effects were noted with the increased dosage during a clinical visit.

Our case highlights the importance of ensuring equitable access to hyperhidrosis treatment. Dermatologists should prioritize patient-centered care by factoring in financial constraints when recommending therapies. In this patient’s case, offering a range of options including over-the-counter antiperspirants and prescription treatments allowed for a management plan tailored to his individual needs and circumstances.

DaxibotulinumtoxinA, known for its longer duration of action compared to other BTX formulations, presents a promising alternative for treating hyperhidrosis.4 However, a gap in care emerged for our patient when prescription antiperspirant was not covered by his insurance, and daxibotulinumtoxinA, which could have offered a more durable solution, was not yet available at our clinic for hyperhidrosis management. Expanding insurance coverage for effective prescription treatments and improving access to newer treatment options are crucial for enhancing patient outcomes and ensuring more equitable care.

Focusing dermatologic care on amputees presents distinct challenges and opportunities for improving their care and decreasing discomfort. Amputees, particularly those with residual limb hyperhidrosis, often experience additional discomfort and difficulty while using prosthetics, as excessive sweating can interfere with fit and function.5,6 Dermatologists should proactively address these specific needs by tailoring treatment accordingly. Incorporating targeted therapies, such as BTX injections, in addition to education on lifestyle modifications and managing treatment expectations, ensures comprehensive care that enhances both quality of life and functional outcomes. Engaging patients in discussions about all available options, including emerging therapies, is essential for improving care for this underserved population.

- Koc E, Tunca M, Akar A, et al. Skin problems in amputees: a descriptive study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:463–466. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03604.x

- Bui KM, Raugi GJ, Nguyen VQ, et al. Skin problems in individuals with lower-limb loss: literature review and proposed classification system. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46:1085-1090. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2009.04.0052

- Rocha Melo J, Rodrigues MA, Caetano M, et al. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of residual limb hyperhidrosis: a systematic review. Rehabilitacion (Madr). 2023;57:100754. doi:10.1016/j.rh.2022.07.003

- Hansen C, Godfrey B, Wixom J, et al. Incidence, severity, and impact of hyperhidrosis in people with lower-limb amputation. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2015;52:31-40. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2014.04.0108

- Lannan FM, Powell J, Kim GM, et al. Hyperhidrosis of the residual limb: a narrative review of the measurement and treatment of excess perspiration affecting individuals with amputation. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2021;45:477-486. doi:10.1097/PXR.0000000000000040

- Pace S, Kentosh J. Managing residual limb hyperhidrosis in wounded warriors. Cutis. 2016;97:401-403.

Practice Gap

Hyperhidrosis poses a considerable challenge for many amputees who use prosthetic devices, particularly at the interface between the residual limb and the prosthetic socket. The enclosed environment of the socket often leads to excessive sweating, which can compromise suction fit and increase the risk for skin chafing, irritation, and slippage. Persistent moisture also promotes bacterial and fungal growth, raising the likelihood of infections and foul odors within the socket. Research has shown that skin complications are highly prevalent among amputees, affecting up to 73.9% of this population in the United States.1 Commonly reported complications include wounds, abscesses, and blisters, many of which can be triggered or worsened by hyperhidrosis.2 Current treatment options for residual limb sweating include topical antiperspirants, botulinum toxin (BTX) injections, iontophoresis, and liner-liner socks.

While BTX commonly is used to treat hyperhidrosis in areas such as the palms and axillae, it typically is not considered as a first-line therapy for residual limb sweating; however, both BTX type A and type B have shown safety and effectiveness in managing hyperhidrosis in amputees, enhancing prosthetic use, and improving overall quality of life.3 Despite these benefits, BTX remains relatively underutilized for

Tools and Techniques

A 64-year-old man initially presented to our dermatology clinic after undergoing an above-the-knee amputation of the left leg 1 year prior. The amputation had been performed due to chronic prosthetic joint infections with Escherichia coli. He reported persistent sweating of the residual limb, which severely limited his use of a prosthesis and led to frequent falls.

During the initial visit, treatment options for primary hyperhidrosis including topical and injectable therapies were discussed. Due to a fear of needles, the patient chose topical treatment, with the option to pursue BTX injections later if better control was needed. An aluminum chloride hexahydrate prosthetic antiperspirant was prescribed for nightly application on the anterior and posterior

Botulinum toxin injections were administered in a grid-like pattern across the surface area where the residual limb made contact with the prosthetic. Using a surgical marker, the patient assisted the medical team in identifying the areas where sweating occurred most frequently. The area was divided into 4 equal sections, with each section treated per weekly interval sequentially over 4 weeks. The targeted areas included the left anterior (extending from the anterior tensor fasciae latae band to the lateral thigh) and left posterior residual limb (Figure 1 and eFigure 1, respectively).

The treated section was cleaned with an alcohol wipe prior to each injection, and 50 units of BTX (diluted to 2.5 units per 0.1 mL in bacteriostatic saline) were injected intradermally into each section (Figure 2 and eFigure 2). The injections were administered in rows, with the needle inserted at evenly spaced intervals approximately 1 inch apart. A total of 100 units were administered per section at each weekly appointment. The patient tolerated the procedure well, and no complications were observed.

Practice Implications

This staged approach to administering BTX ensures even distribution of the injections, optimizes hyperhidrosis control, minimizes the risk for complications, and allows for precise targeting of the affected areas to maximize therapeutic benefit. Following the initial procedure, our patient was scheduled for follow-ups approximately every 3 to 4 months starting from the first set of injections for each area. Over 9 months, the patient successfully completed 3 treatment sessions using this method. The patient reported improved quality of life after starting the BTX injections.

After evaluating the initial treatment outcomes with 100 units per section, the dosage was increased to 200 units per section to reduce the number of visits from 4 every 3 months to cover the entire area to 2 visits every 3 months. This adjustment aimed to optimize results and better manage the patient’s ongoing symptoms. At about 1 to 2 weeks after beginning treatment, the patient noticed decreased sweating and discomfort during his daily activities and reduced friction with his prosthetic leg. No adverse effects were noted with the increased dosage during a clinical visit.

Our case highlights the importance of ensuring equitable access to hyperhidrosis treatment. Dermatologists should prioritize patient-centered care by factoring in financial constraints when recommending therapies. In this patient’s case, offering a range of options including over-the-counter antiperspirants and prescription treatments allowed for a management plan tailored to his individual needs and circumstances.

DaxibotulinumtoxinA, known for its longer duration of action compared to other BTX formulations, presents a promising alternative for treating hyperhidrosis.4 However, a gap in care emerged for our patient when prescription antiperspirant was not covered by his insurance, and daxibotulinumtoxinA, which could have offered a more durable solution, was not yet available at our clinic for hyperhidrosis management. Expanding insurance coverage for effective prescription treatments and improving access to newer treatment options are crucial for enhancing patient outcomes and ensuring more equitable care.

Focusing dermatologic care on amputees presents distinct challenges and opportunities for improving their care and decreasing discomfort. Amputees, particularly those with residual limb hyperhidrosis, often experience additional discomfort and difficulty while using prosthetics, as excessive sweating can interfere with fit and function.5,6 Dermatologists should proactively address these specific needs by tailoring treatment accordingly. Incorporating targeted therapies, such as BTX injections, in addition to education on lifestyle modifications and managing treatment expectations, ensures comprehensive care that enhances both quality of life and functional outcomes. Engaging patients in discussions about all available options, including emerging therapies, is essential for improving care for this underserved population.

Practice Gap

Hyperhidrosis poses a considerable challenge for many amputees who use prosthetic devices, particularly at the interface between the residual limb and the prosthetic socket. The enclosed environment of the socket often leads to excessive sweating, which can compromise suction fit and increase the risk for skin chafing, irritation, and slippage. Persistent moisture also promotes bacterial and fungal growth, raising the likelihood of infections and foul odors within the socket. Research has shown that skin complications are highly prevalent among amputees, affecting up to 73.9% of this population in the United States.1 Commonly reported complications include wounds, abscesses, and blisters, many of which can be triggered or worsened by hyperhidrosis.2 Current treatment options for residual limb sweating include topical antiperspirants, botulinum toxin (BTX) injections, iontophoresis, and liner-liner socks.

While BTX commonly is used to treat hyperhidrosis in areas such as the palms and axillae, it typically is not considered as a first-line therapy for residual limb sweating; however, both BTX type A and type B have shown safety and effectiveness in managing hyperhidrosis in amputees, enhancing prosthetic use, and improving overall quality of life.3 Despite these benefits, BTX remains relatively underutilized for

Tools and Techniques

A 64-year-old man initially presented to our dermatology clinic after undergoing an above-the-knee amputation of the left leg 1 year prior. The amputation had been performed due to chronic prosthetic joint infections with Escherichia coli. He reported persistent sweating of the residual limb, which severely limited his use of a prosthesis and led to frequent falls.

During the initial visit, treatment options for primary hyperhidrosis including topical and injectable therapies were discussed. Due to a fear of needles, the patient chose topical treatment, with the option to pursue BTX injections later if better control was needed. An aluminum chloride hexahydrate prosthetic antiperspirant was prescribed for nightly application on the anterior and posterior

Botulinum toxin injections were administered in a grid-like pattern across the surface area where the residual limb made contact with the prosthetic. Using a surgical marker, the patient assisted the medical team in identifying the areas where sweating occurred most frequently. The area was divided into 4 equal sections, with each section treated per weekly interval sequentially over 4 weeks. The targeted areas included the left anterior (extending from the anterior tensor fasciae latae band to the lateral thigh) and left posterior residual limb (Figure 1 and eFigure 1, respectively).

The treated section was cleaned with an alcohol wipe prior to each injection, and 50 units of BTX (diluted to 2.5 units per 0.1 mL in bacteriostatic saline) were injected intradermally into each section (Figure 2 and eFigure 2). The injections were administered in rows, with the needle inserted at evenly spaced intervals approximately 1 inch apart. A total of 100 units were administered per section at each weekly appointment. The patient tolerated the procedure well, and no complications were observed.

Practice Implications

This staged approach to administering BTX ensures even distribution of the injections, optimizes hyperhidrosis control, minimizes the risk for complications, and allows for precise targeting of the affected areas to maximize therapeutic benefit. Following the initial procedure, our patient was scheduled for follow-ups approximately every 3 to 4 months starting from the first set of injections for each area. Over 9 months, the patient successfully completed 3 treatment sessions using this method. The patient reported improved quality of life after starting the BTX injections.

After evaluating the initial treatment outcomes with 100 units per section, the dosage was increased to 200 units per section to reduce the number of visits from 4 every 3 months to cover the entire area to 2 visits every 3 months. This adjustment aimed to optimize results and better manage the patient’s ongoing symptoms. At about 1 to 2 weeks after beginning treatment, the patient noticed decreased sweating and discomfort during his daily activities and reduced friction with his prosthetic leg. No adverse effects were noted with the increased dosage during a clinical visit.

Our case highlights the importance of ensuring equitable access to hyperhidrosis treatment. Dermatologists should prioritize patient-centered care by factoring in financial constraints when recommending therapies. In this patient’s case, offering a range of options including over-the-counter antiperspirants and prescription treatments allowed for a management plan tailored to his individual needs and circumstances.

DaxibotulinumtoxinA, known for its longer duration of action compared to other BTX formulations, presents a promising alternative for treating hyperhidrosis.4 However, a gap in care emerged for our patient when prescription antiperspirant was not covered by his insurance, and daxibotulinumtoxinA, which could have offered a more durable solution, was not yet available at our clinic for hyperhidrosis management. Expanding insurance coverage for effective prescription treatments and improving access to newer treatment options are crucial for enhancing patient outcomes and ensuring more equitable care.

Focusing dermatologic care on amputees presents distinct challenges and opportunities for improving their care and decreasing discomfort. Amputees, particularly those with residual limb hyperhidrosis, often experience additional discomfort and difficulty while using prosthetics, as excessive sweating can interfere with fit and function.5,6 Dermatologists should proactively address these specific needs by tailoring treatment accordingly. Incorporating targeted therapies, such as BTX injections, in addition to education on lifestyle modifications and managing treatment expectations, ensures comprehensive care that enhances both quality of life and functional outcomes. Engaging patients in discussions about all available options, including emerging therapies, is essential for improving care for this underserved population.

- Koc E, Tunca M, Akar A, et al. Skin problems in amputees: a descriptive study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:463–466. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03604.x

- Bui KM, Raugi GJ, Nguyen VQ, et al. Skin problems in individuals with lower-limb loss: literature review and proposed classification system. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46:1085-1090. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2009.04.0052

- Rocha Melo J, Rodrigues MA, Caetano M, et al. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of residual limb hyperhidrosis: a systematic review. Rehabilitacion (Madr). 2023;57:100754. doi:10.1016/j.rh.2022.07.003

- Hansen C, Godfrey B, Wixom J, et al. Incidence, severity, and impact of hyperhidrosis in people with lower-limb amputation. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2015;52:31-40. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2014.04.0108

- Lannan FM, Powell J, Kim GM, et al. Hyperhidrosis of the residual limb: a narrative review of the measurement and treatment of excess perspiration affecting individuals with amputation. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2021;45:477-486. doi:10.1097/PXR.0000000000000040

- Pace S, Kentosh J. Managing residual limb hyperhidrosis in wounded warriors. Cutis. 2016;97:401-403.

- Koc E, Tunca M, Akar A, et al. Skin problems in amputees: a descriptive study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:463–466. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03604.x

- Bui KM, Raugi GJ, Nguyen VQ, et al. Skin problems in individuals with lower-limb loss: literature review and proposed classification system. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46:1085-1090. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2009.04.0052

- Rocha Melo J, Rodrigues MA, Caetano M, et al. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of residual limb hyperhidrosis: a systematic review. Rehabilitacion (Madr). 2023;57:100754. doi:10.1016/j.rh.2022.07.003

- Hansen C, Godfrey B, Wixom J, et al. Incidence, severity, and impact of hyperhidrosis in people with lower-limb amputation. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2015;52:31-40. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2014.04.0108

- Lannan FM, Powell J, Kim GM, et al. Hyperhidrosis of the residual limb: a narrative review of the measurement and treatment of excess perspiration affecting individuals with amputation. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2021;45:477-486. doi:10.1097/PXR.0000000000000040

- Pace S, Kentosh J. Managing residual limb hyperhidrosis in wounded warriors. Cutis. 2016;97:401-403.

Botulinum Toxin as a Tool to Reduce Hyperhidrosis in Amputees

Botulinum Toxin as a Tool to Reduce Hyperhidrosis in Amputees

Nasal Tanning Sprays: Illuminating the Risks of a Popular TikTok Trend

Nasal tanning spray is a recent phenomenon that has been gaining popularity among consumers on TikTok and other social media platforms. The active ingredient in the tanning spray is melanotan II—a synthetic analog of α‒melanocyte-stimulating hormone,1,2 a naturally occurring hormone responsible for skin pigmentation. α‒Melanocyte-stimulating hormone is a derivative of the precursor proopiomelanocortin, an agonist on the melanocortin-1 receptor that promotes formation of eumelanin.1,3 Eumelanin then provides pigmentation to the skin.3 Apart from its use for tanning, melanotan II has been reported to increase sexual function and aid in weight loss.1

Melanotan II is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration; however, injectable formulations can be obtained illegally on the Internet as well as at some tanning salons and beauty parlors.4 Although injectable forms of melanotan II have been used for years to artificially increase skin pigmentation, the newly hyped nasal tanning sprays are drawing the attention of consumers. The synthetic chemical spray is inhaled into the nasal mucosae, where it is readily absorbed into the bloodstream to act on melanocortin receptors throughout the body, thus enhancing skin pigmentation.2 Because melanotan II is not approved, there is no guarantee that the product purchased from those sources is pure; therefore, consumers risk inhaling or injecting contaminated chemicals.5

In a 2017 study, Kirk and Greenfield6 cited self-image as a common concern among participants who expressed a preference for appearing tanned.6 Societal influence and standards to which young adults, particularly young women, often are accustomed drive some to take steps to achieve tanned skin, which they view as more attractive and healthier than untanned skin.7,8

Social media consumption is a significant risk factor for developing or exacerbating body dissatisfaction among impressionable teenagers and young adults, who may be less risk averse and therefore choose to embrace trends such as nasal tanning sprays to enhance their appearance, without considering possible consequences. Most young adults, and even teens, are aware of the risks associated with tanning beds, which may propel them to seek out what they perceive as a less-risky tanning alternative such as a tanner delivered via a nasal route, but it is unlikely that this group is fully informed about the possible dangers of nasal tanning sprays.

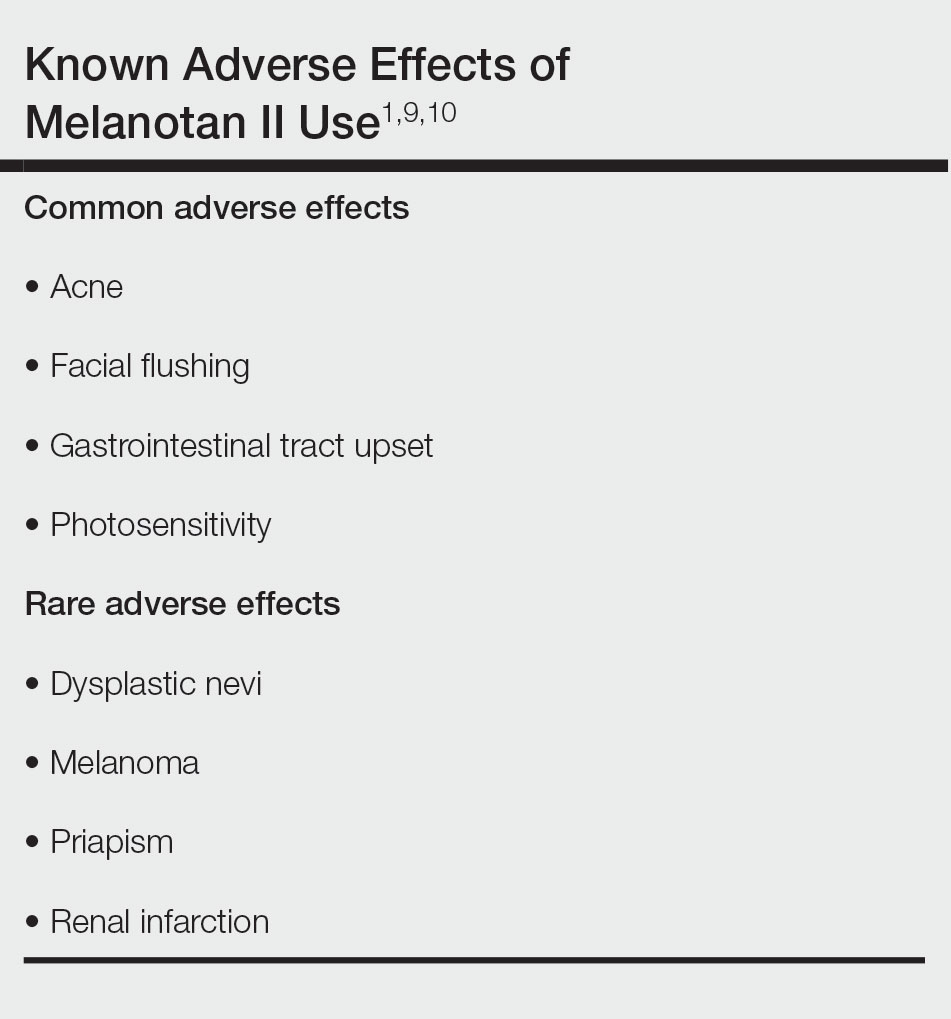

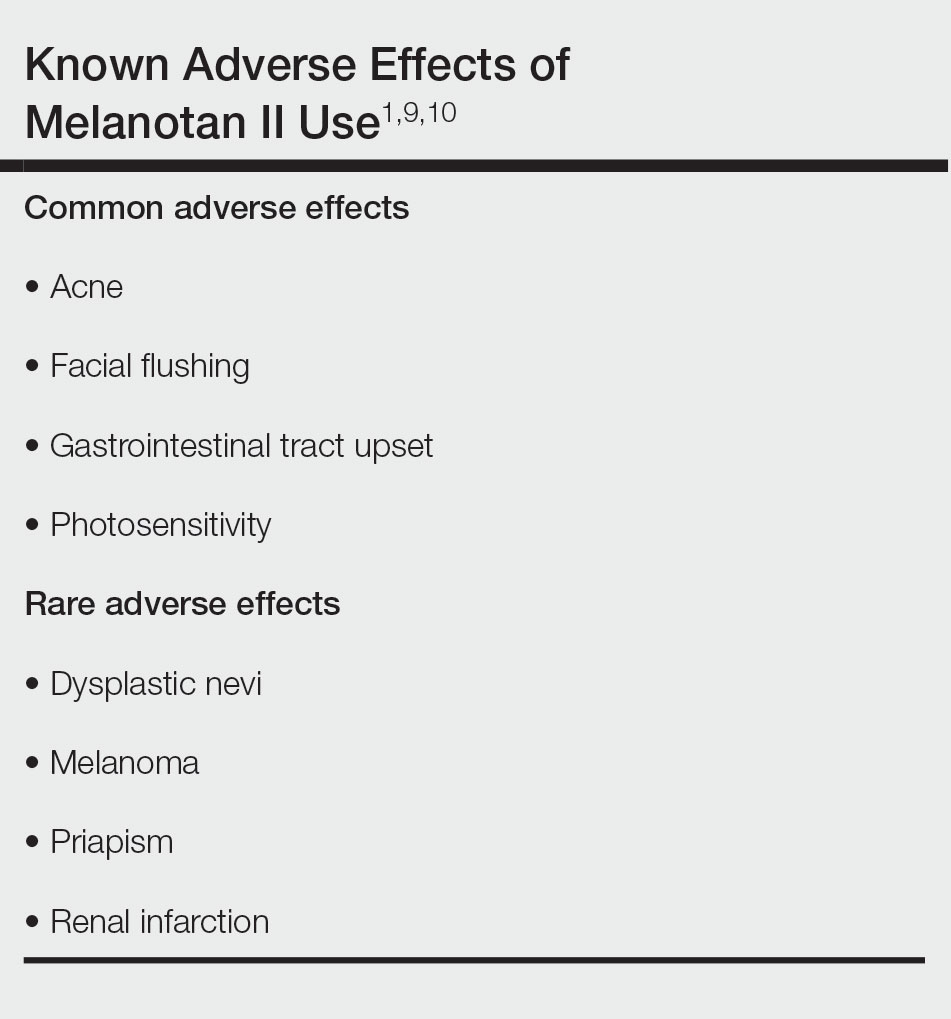

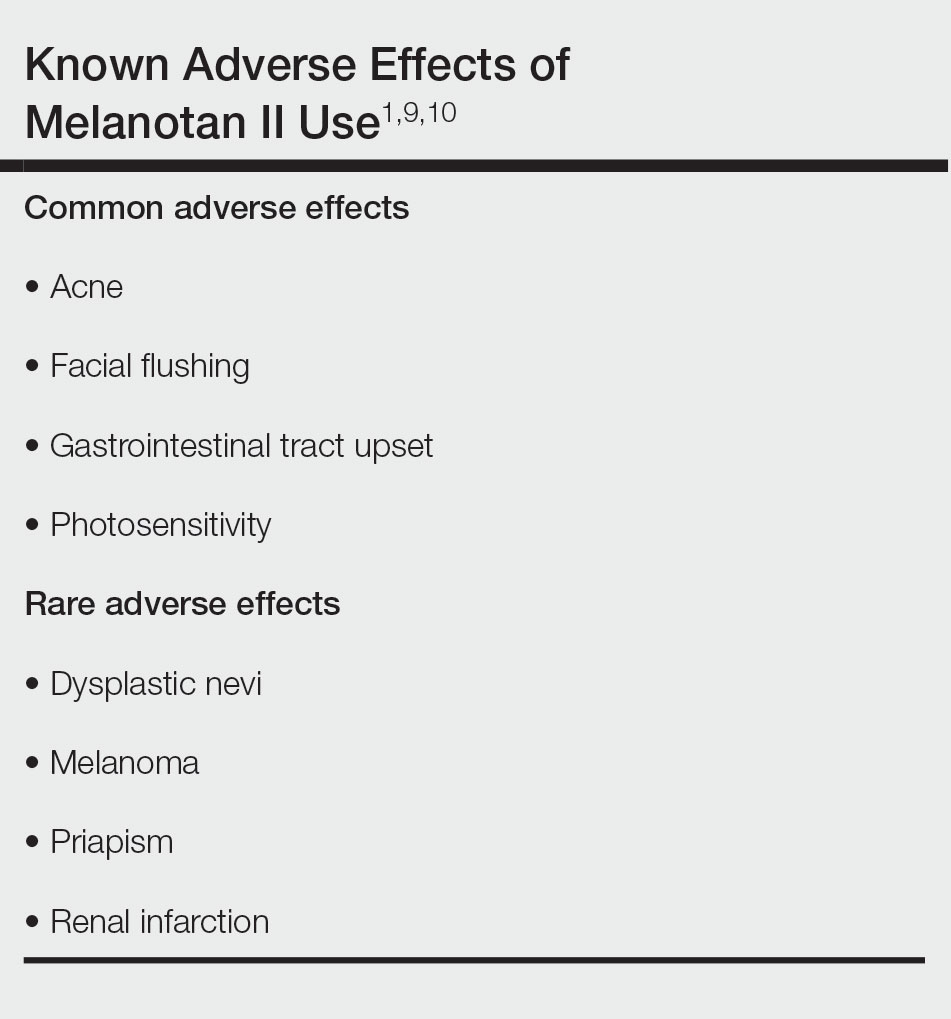

It is crucial for dermatologists and other clinicians to provide awareness and education about the potential harm of nasal tanning sprays. Along with the general risks of using an unregulated substance, common adverse effects include acne, facial flushing, gastrointestinal tract upset, and sensitivity to sunlight (Table).1,9,10 Several case reports have linked melanotan II to cutaneous changes, including dysplastic nevi and even melanoma.1 Less common complications, such as renal infarction and priapism, also have been observed with melanotan II use.9,10

Even with the known risks involving tanning beds and skin cancer, an analysis by Kream et al11 in 2020 showed that 90% (441/488) of tanning-related videos on TikTok promoted a positive view of tanning. Of these TikTok videos involving pro-tanning trends, 3% (12/441) were specifically about melanotan II nasal spray, injection, or both, which has only become more popular since this study was published.11

Dermatologists should be aware of the impact that tanning trends, such as nasal tanning spray, can have on all patients and initiate discussions regarding the risks of using these products with patients as appropriate. Alternatives to nasal tanning sprays such as spray-on tans and self-tanning lotions are safer ways for patients to achieve a tanned look without the health risks associated with melanotan II.

- Habbema L, Halk AB, Neumann M, et al. Risks of unregulated use of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone analogues: a review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:975-980. doi:10.1111/ijd.13585

- Why you should never use nasal tanning spray. Cleveland Clinic Health Essentials [Internet]. November 1, 2022. Accessed December 18, 2023. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/nasal-tanning-spray

- Hjuler KF, Lorentzen HF. Melanoma associated with the use of melanotan-II. Dermatology. 2014;228:34-36. doi:10.1159/000356389

- Evans-Brown M, Dawson RT, Chandler M, et al. Use of melanotan I and II in the general population. BMJ. 2009;338:b566. doi:10.116/bmj.b566

- Callaghan DJ III. A glimpse into the underground market of melanotan. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:1-5. doi:10.5070/D3245040036

- Kirk L, Greenfield S. Knowledge and attitudes of UK university students in relation to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) exposure and their sun-related behaviours: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014388. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014388

- Hay JL, Geller AC, Schoenhammer M, et al. Tanning and beauty: mother and teenage daughters in discussion. J Health Psychol. 2016;21:1261-1270. doi:10.1177/1359105314551621

- Gillen MM, Markey CN. The role of body image and depression in tanning behaviors and attitudes. Behav Med. 2017;38:74-82.

- Peters B, Hadimeri H, Wahlberg R, et al. Melanotan II: a possible cause of renal infarction: review of the literature and case report. CEN Case Rep. 2020;9:159-161. doi:10.1007/s13730-020-00447-z

- Mallory CW, Lopategui DM, Cordon BH. Melanotan tanning injection: a rare cause of priapism. Sex Med. 2021;9:100298. doi:10.1016/j.esxm.2020.100298

- Kream E, Watchmaker JD, Dover JS. TikTok sheds light on tanning: tanning is still popular and emerging trends pose new risks. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:1018-1021. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003549

Nasal tanning spray is a recent phenomenon that has been gaining popularity among consumers on TikTok and other social media platforms. The active ingredient in the tanning spray is melanotan II—a synthetic analog of α‒melanocyte-stimulating hormone,1,2 a naturally occurring hormone responsible for skin pigmentation. α‒Melanocyte-stimulating hormone is a derivative of the precursor proopiomelanocortin, an agonist on the melanocortin-1 receptor that promotes formation of eumelanin.1,3 Eumelanin then provides pigmentation to the skin.3 Apart from its use for tanning, melanotan II has been reported to increase sexual function and aid in weight loss.1

Melanotan II is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration; however, injectable formulations can be obtained illegally on the Internet as well as at some tanning salons and beauty parlors.4 Although injectable forms of melanotan II have been used for years to artificially increase skin pigmentation, the newly hyped nasal tanning sprays are drawing the attention of consumers. The synthetic chemical spray is inhaled into the nasal mucosae, where it is readily absorbed into the bloodstream to act on melanocortin receptors throughout the body, thus enhancing skin pigmentation.2 Because melanotan II is not approved, there is no guarantee that the product purchased from those sources is pure; therefore, consumers risk inhaling or injecting contaminated chemicals.5

In a 2017 study, Kirk and Greenfield6 cited self-image as a common concern among participants who expressed a preference for appearing tanned.6 Societal influence and standards to which young adults, particularly young women, often are accustomed drive some to take steps to achieve tanned skin, which they view as more attractive and healthier than untanned skin.7,8

Social media consumption is a significant risk factor for developing or exacerbating body dissatisfaction among impressionable teenagers and young adults, who may be less risk averse and therefore choose to embrace trends such as nasal tanning sprays to enhance their appearance, without considering possible consequences. Most young adults, and even teens, are aware of the risks associated with tanning beds, which may propel them to seek out what they perceive as a less-risky tanning alternative such as a tanner delivered via a nasal route, but it is unlikely that this group is fully informed about the possible dangers of nasal tanning sprays.

It is crucial for dermatologists and other clinicians to provide awareness and education about the potential harm of nasal tanning sprays. Along with the general risks of using an unregulated substance, common adverse effects include acne, facial flushing, gastrointestinal tract upset, and sensitivity to sunlight (Table).1,9,10 Several case reports have linked melanotan II to cutaneous changes, including dysplastic nevi and even melanoma.1 Less common complications, such as renal infarction and priapism, also have been observed with melanotan II use.9,10

Even with the known risks involving tanning beds and skin cancer, an analysis by Kream et al11 in 2020 showed that 90% (441/488) of tanning-related videos on TikTok promoted a positive view of tanning. Of these TikTok videos involving pro-tanning trends, 3% (12/441) were specifically about melanotan II nasal spray, injection, or both, which has only become more popular since this study was published.11

Dermatologists should be aware of the impact that tanning trends, such as nasal tanning spray, can have on all patients and initiate discussions regarding the risks of using these products with patients as appropriate. Alternatives to nasal tanning sprays such as spray-on tans and self-tanning lotions are safer ways for patients to achieve a tanned look without the health risks associated with melanotan II.

Nasal tanning spray is a recent phenomenon that has been gaining popularity among consumers on TikTok and other social media platforms. The active ingredient in the tanning spray is melanotan II—a synthetic analog of α‒melanocyte-stimulating hormone,1,2 a naturally occurring hormone responsible for skin pigmentation. α‒Melanocyte-stimulating hormone is a derivative of the precursor proopiomelanocortin, an agonist on the melanocortin-1 receptor that promotes formation of eumelanin.1,3 Eumelanin then provides pigmentation to the skin.3 Apart from its use for tanning, melanotan II has been reported to increase sexual function and aid in weight loss.1

Melanotan II is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration; however, injectable formulations can be obtained illegally on the Internet as well as at some tanning salons and beauty parlors.4 Although injectable forms of melanotan II have been used for years to artificially increase skin pigmentation, the newly hyped nasal tanning sprays are drawing the attention of consumers. The synthetic chemical spray is inhaled into the nasal mucosae, where it is readily absorbed into the bloodstream to act on melanocortin receptors throughout the body, thus enhancing skin pigmentation.2 Because melanotan II is not approved, there is no guarantee that the product purchased from those sources is pure; therefore, consumers risk inhaling or injecting contaminated chemicals.5

In a 2017 study, Kirk and Greenfield6 cited self-image as a common concern among participants who expressed a preference for appearing tanned.6 Societal influence and standards to which young adults, particularly young women, often are accustomed drive some to take steps to achieve tanned skin, which they view as more attractive and healthier than untanned skin.7,8

Social media consumption is a significant risk factor for developing or exacerbating body dissatisfaction among impressionable teenagers and young adults, who may be less risk averse and therefore choose to embrace trends such as nasal tanning sprays to enhance their appearance, without considering possible consequences. Most young adults, and even teens, are aware of the risks associated with tanning beds, which may propel them to seek out what they perceive as a less-risky tanning alternative such as a tanner delivered via a nasal route, but it is unlikely that this group is fully informed about the possible dangers of nasal tanning sprays.

It is crucial for dermatologists and other clinicians to provide awareness and education about the potential harm of nasal tanning sprays. Along with the general risks of using an unregulated substance, common adverse effects include acne, facial flushing, gastrointestinal tract upset, and sensitivity to sunlight (Table).1,9,10 Several case reports have linked melanotan II to cutaneous changes, including dysplastic nevi and even melanoma.1 Less common complications, such as renal infarction and priapism, also have been observed with melanotan II use.9,10

Even with the known risks involving tanning beds and skin cancer, an analysis by Kream et al11 in 2020 showed that 90% (441/488) of tanning-related videos on TikTok promoted a positive view of tanning. Of these TikTok videos involving pro-tanning trends, 3% (12/441) were specifically about melanotan II nasal spray, injection, or both, which has only become more popular since this study was published.11

Dermatologists should be aware of the impact that tanning trends, such as nasal tanning spray, can have on all patients and initiate discussions regarding the risks of using these products with patients as appropriate. Alternatives to nasal tanning sprays such as spray-on tans and self-tanning lotions are safer ways for patients to achieve a tanned look without the health risks associated with melanotan II.

- Habbema L, Halk AB, Neumann M, et al. Risks of unregulated use of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone analogues: a review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:975-980. doi:10.1111/ijd.13585

- Why you should never use nasal tanning spray. Cleveland Clinic Health Essentials [Internet]. November 1, 2022. Accessed December 18, 2023. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/nasal-tanning-spray

- Hjuler KF, Lorentzen HF. Melanoma associated with the use of melanotan-II. Dermatology. 2014;228:34-36. doi:10.1159/000356389

- Evans-Brown M, Dawson RT, Chandler M, et al. Use of melanotan I and II in the general population. BMJ. 2009;338:b566. doi:10.116/bmj.b566

- Callaghan DJ III. A glimpse into the underground market of melanotan. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:1-5. doi:10.5070/D3245040036

- Kirk L, Greenfield S. Knowledge and attitudes of UK university students in relation to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) exposure and their sun-related behaviours: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014388. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014388

- Hay JL, Geller AC, Schoenhammer M, et al. Tanning and beauty: mother and teenage daughters in discussion. J Health Psychol. 2016;21:1261-1270. doi:10.1177/1359105314551621

- Gillen MM, Markey CN. The role of body image and depression in tanning behaviors and attitudes. Behav Med. 2017;38:74-82.

- Peters B, Hadimeri H, Wahlberg R, et al. Melanotan II: a possible cause of renal infarction: review of the literature and case report. CEN Case Rep. 2020;9:159-161. doi:10.1007/s13730-020-00447-z

- Mallory CW, Lopategui DM, Cordon BH. Melanotan tanning injection: a rare cause of priapism. Sex Med. 2021;9:100298. doi:10.1016/j.esxm.2020.100298

- Kream E, Watchmaker JD, Dover JS. TikTok sheds light on tanning: tanning is still popular and emerging trends pose new risks. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:1018-1021. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003549

- Habbema L, Halk AB, Neumann M, et al. Risks of unregulated use of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone analogues: a review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:975-980. doi:10.1111/ijd.13585

- Why you should never use nasal tanning spray. Cleveland Clinic Health Essentials [Internet]. November 1, 2022. Accessed December 18, 2023. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/nasal-tanning-spray

- Hjuler KF, Lorentzen HF. Melanoma associated with the use of melanotan-II. Dermatology. 2014;228:34-36. doi:10.1159/000356389

- Evans-Brown M, Dawson RT, Chandler M, et al. Use of melanotan I and II in the general population. BMJ. 2009;338:b566. doi:10.116/bmj.b566

- Callaghan DJ III. A glimpse into the underground market of melanotan. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:1-5. doi:10.5070/D3245040036

- Kirk L, Greenfield S. Knowledge and attitudes of UK university students in relation to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) exposure and their sun-related behaviours: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014388. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014388

- Hay JL, Geller AC, Schoenhammer M, et al. Tanning and beauty: mother and teenage daughters in discussion. J Health Psychol. 2016;21:1261-1270. doi:10.1177/1359105314551621

- Gillen MM, Markey CN. The role of body image and depression in tanning behaviors and attitudes. Behav Med. 2017;38:74-82.

- Peters B, Hadimeri H, Wahlberg R, et al. Melanotan II: a possible cause of renal infarction: review of the literature and case report. CEN Case Rep. 2020;9:159-161. doi:10.1007/s13730-020-00447-z

- Mallory CW, Lopategui DM, Cordon BH. Melanotan tanning injection: a rare cause of priapism. Sex Med. 2021;9:100298. doi:10.1016/j.esxm.2020.100298

- Kream E, Watchmaker JD, Dover JS. TikTok sheds light on tanning: tanning is still popular and emerging trends pose new risks. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:1018-1021. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003549

PRACTICE POINTS

- Although tanning beds are arguably the most common and dangerous method used by patients to tan their skin, dermatologists should be aware of the other means by which patients may artificially increase skin pigmentation and the risks imposed by undertaking such practices.

- We challenge dermatologists to note the influence of social media on tanning trends and consider creating a platform on these mediums to combat misinformation and promote sun safety and skin health.

- We encourage dermatologists to diligently stay informed about the popular societal trends related to the skin such as the use of nasal tanning products (eg, melanotan I and II) and be proactive in discussing their risks with patients as deemed appropriate.