User login

Psychoneurogastroenterology: The abdominal brain, the microbiome, and psychiatry

This nervous system is located inside the wall of the GI tract, extending from the esophagus to the rectum. Technically, it is known as the enteric nervous system, or ENS, but it has been given other labels, too: “second brain,”2 “abdominal brain,” “other brain,” and “back-up brain.” Its neurologic disorders include abdominal epilepsy, abdominal migraine, and autism with intestinal symptoms, such as chronic enterocolitis.3

Impressive brain-like features

The ENS includes 100 million neurons (same as the spinal cord) with glia-like support cells. It contains >30 neurotransmitters, including several closely linked to psychopathology (serotonin, dopamine, γ-aminobutyric acid, and acetylcholine). The ENS is not part of the autonomic nervous system. It communicates with the brain via the vagus nerve.

A vast system of gut bacteria

The ENS maintains close links with, and is influenced by, the microbiome, an extensive universe of commensal (that is, symbiotic) bacteria in the gut that play a vital role in immune health, brain function, and signaling systems within the CNS. The role of the microbiome in neuropsychiatric disorders has become a sizzling area of research.

The numbers of the microbiome are astonishing, including approximately 1,000 species of bacteria; 100 trillion total bacterial organisms (outnumbering cells of the body by 100-fold); 4 million bacterial genes (compared with 26,000 genes in the host human genome); and a density as high as 1 trillion bacteria in a cubic milliliter—higher than any known microbial system.4

Significant GI−brain connections

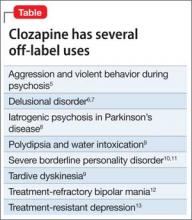

It is of great relevance to psychiatry that 90% of the body’s serotonin and 50% of dopamine are found in the GI brain. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors often are associated with GI symptoms, such as nausea and diarrhea; antipsychotics, which are dopamine antagonists, are known for antiemetic effects. Clozapine’s potent anticholinergic effects can cause serious ileus.

Things get more interesting when one considers the association of GI disorders and psychiatric symptoms:

Irritable bowel syndrome is associated with panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, dysthymia, and major depression.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)— such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (prevalence ranging from 6% in Canada to 14% in the United States to 46% in Mexico5)—is commonly associated with mood and anxiety disorders and personality changes. The psychiatric manifestations of IBD are so common that the authors of a recent article in World Journal of Gastroenterology urged gastroenterologists to collaborate with psychiatrists when managing IBD.6

Celiac disease has been repeatedly associated with several neuropsychiatric disorders, including ataxia, epilepsy, peripheral neuropathy, headache, anxiety, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, and schizophrenia.

New, exciting challenges for medical science

There potentially are important implications for possible exploitation of the ENS and the microbiome in the diagnosis and treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. For example, consider these speculative challenges:

• Can intestinal biopsy reveal neurotransmitter pathology in schizophrenia?

• Can early dopamine deficiency predict Parkinson’s disease, enabling early intervention?

• Can β-amyloid deposits, the degenerative neurologic stigmata of Alzheimer’s disease, be detected in abdominal neurons years before onset of symptoms to allow early intervention?

• Can the ENS become a therapeutic pathway by targeting the various neurotransmitters found there or by engaging the enormous human microbiome to manipulate its beneficial properties?

• Can foods or probiotic supplements be prescribed as microbiomal adjuncts to improve the mood and anxiety spectrum?

One recommendation I came across is that ingesting 10 to 100 million beneficial bacteria, such as Lactobacillus plantarum and Bifidobacterium infantis, might be helpful. Such prescriptions obviously are speculative but also are reasonably testable hypotheses of ways to exploit the “other brain” and the microbiome.

We must summon the guts to seize this opportunity

An independent second brain and a remarkable microbiome appear to be significant evolutionary adaptations and advantages for humans. For too long, neuropsychiatric researchers have ignored the ENS and the microbiome; now, they must focus on how to exploit these entities to yield innovative diagnostic and therapeutic advances. Integrating the ENS and the microbiome and enmeshing them into neuropsychiatric research and clinical applications hold great promise.

The field of psychoneurogastroenterology is in its infancy, but its growth and relevance will be momentous for neuropsychiatry. A major intellectual peristalsis is underway.

1. Robinson B. The abdominal and pelvic brain. Hammond, IN: Frank S. Betz; 1907.

2. Gershon M. The second brain: a groundbreaking new understanding of nervous disorders of the stomach and intestine. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers; 1998.

3. McMillin DL, Richards DG, Mein EA, et al. The abdominal brain and enteric nervous system. J Altern Complement Med. 1999;5(6):575-586.

4. Hill JM, Bhattacharjee S, Pogue AI, et al. The gastrointestinal tract microbiome and potential link to Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurol. 2014;5:43.

5. Olden KW, Lydiard RB. Gastrointestinal disorders. In: Rundell JR, Wise MG. Textbook of consultation-liaison psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

6. Filipovic BR, Filipovic BF. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(13):3552-3563.

This nervous system is located inside the wall of the GI tract, extending from the esophagus to the rectum. Technically, it is known as the enteric nervous system, or ENS, but it has been given other labels, too: “second brain,”2 “abdominal brain,” “other brain,” and “back-up brain.” Its neurologic disorders include abdominal epilepsy, abdominal migraine, and autism with intestinal symptoms, such as chronic enterocolitis.3

Impressive brain-like features

The ENS includes 100 million neurons (same as the spinal cord) with glia-like support cells. It contains >30 neurotransmitters, including several closely linked to psychopathology (serotonin, dopamine, γ-aminobutyric acid, and acetylcholine). The ENS is not part of the autonomic nervous system. It communicates with the brain via the vagus nerve.

A vast system of gut bacteria

The ENS maintains close links with, and is influenced by, the microbiome, an extensive universe of commensal (that is, symbiotic) bacteria in the gut that play a vital role in immune health, brain function, and signaling systems within the CNS. The role of the microbiome in neuropsychiatric disorders has become a sizzling area of research.

The numbers of the microbiome are astonishing, including approximately 1,000 species of bacteria; 100 trillion total bacterial organisms (outnumbering cells of the body by 100-fold); 4 million bacterial genes (compared with 26,000 genes in the host human genome); and a density as high as 1 trillion bacteria in a cubic milliliter—higher than any known microbial system.4

Significant GI−brain connections

It is of great relevance to psychiatry that 90% of the body’s serotonin and 50% of dopamine are found in the GI brain. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors often are associated with GI symptoms, such as nausea and diarrhea; antipsychotics, which are dopamine antagonists, are known for antiemetic effects. Clozapine’s potent anticholinergic effects can cause serious ileus.

Things get more interesting when one considers the association of GI disorders and psychiatric symptoms:

Irritable bowel syndrome is associated with panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, dysthymia, and major depression.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)— such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (prevalence ranging from 6% in Canada to 14% in the United States to 46% in Mexico5)—is commonly associated with mood and anxiety disorders and personality changes. The psychiatric manifestations of IBD are so common that the authors of a recent article in World Journal of Gastroenterology urged gastroenterologists to collaborate with psychiatrists when managing IBD.6

Celiac disease has been repeatedly associated with several neuropsychiatric disorders, including ataxia, epilepsy, peripheral neuropathy, headache, anxiety, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, and schizophrenia.

New, exciting challenges for medical science

There potentially are important implications for possible exploitation of the ENS and the microbiome in the diagnosis and treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. For example, consider these speculative challenges:

• Can intestinal biopsy reveal neurotransmitter pathology in schizophrenia?

• Can early dopamine deficiency predict Parkinson’s disease, enabling early intervention?

• Can β-amyloid deposits, the degenerative neurologic stigmata of Alzheimer’s disease, be detected in abdominal neurons years before onset of symptoms to allow early intervention?

• Can the ENS become a therapeutic pathway by targeting the various neurotransmitters found there or by engaging the enormous human microbiome to manipulate its beneficial properties?

• Can foods or probiotic supplements be prescribed as microbiomal adjuncts to improve the mood and anxiety spectrum?

One recommendation I came across is that ingesting 10 to 100 million beneficial bacteria, such as Lactobacillus plantarum and Bifidobacterium infantis, might be helpful. Such prescriptions obviously are speculative but also are reasonably testable hypotheses of ways to exploit the “other brain” and the microbiome.

We must summon the guts to seize this opportunity

An independent second brain and a remarkable microbiome appear to be significant evolutionary adaptations and advantages for humans. For too long, neuropsychiatric researchers have ignored the ENS and the microbiome; now, they must focus on how to exploit these entities to yield innovative diagnostic and therapeutic advances. Integrating the ENS and the microbiome and enmeshing them into neuropsychiatric research and clinical applications hold great promise.

The field of psychoneurogastroenterology is in its infancy, but its growth and relevance will be momentous for neuropsychiatry. A major intellectual peristalsis is underway.

This nervous system is located inside the wall of the GI tract, extending from the esophagus to the rectum. Technically, it is known as the enteric nervous system, or ENS, but it has been given other labels, too: “second brain,”2 “abdominal brain,” “other brain,” and “back-up brain.” Its neurologic disorders include abdominal epilepsy, abdominal migraine, and autism with intestinal symptoms, such as chronic enterocolitis.3

Impressive brain-like features

The ENS includes 100 million neurons (same as the spinal cord) with glia-like support cells. It contains >30 neurotransmitters, including several closely linked to psychopathology (serotonin, dopamine, γ-aminobutyric acid, and acetylcholine). The ENS is not part of the autonomic nervous system. It communicates with the brain via the vagus nerve.

A vast system of gut bacteria

The ENS maintains close links with, and is influenced by, the microbiome, an extensive universe of commensal (that is, symbiotic) bacteria in the gut that play a vital role in immune health, brain function, and signaling systems within the CNS. The role of the microbiome in neuropsychiatric disorders has become a sizzling area of research.

The numbers of the microbiome are astonishing, including approximately 1,000 species of bacteria; 100 trillion total bacterial organisms (outnumbering cells of the body by 100-fold); 4 million bacterial genes (compared with 26,000 genes in the host human genome); and a density as high as 1 trillion bacteria in a cubic milliliter—higher than any known microbial system.4

Significant GI−brain connections

It is of great relevance to psychiatry that 90% of the body’s serotonin and 50% of dopamine are found in the GI brain. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors often are associated with GI symptoms, such as nausea and diarrhea; antipsychotics, which are dopamine antagonists, are known for antiemetic effects. Clozapine’s potent anticholinergic effects can cause serious ileus.

Things get more interesting when one considers the association of GI disorders and psychiatric symptoms:

Irritable bowel syndrome is associated with panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, dysthymia, and major depression.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)— such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (prevalence ranging from 6% in Canada to 14% in the United States to 46% in Mexico5)—is commonly associated with mood and anxiety disorders and personality changes. The psychiatric manifestations of IBD are so common that the authors of a recent article in World Journal of Gastroenterology urged gastroenterologists to collaborate with psychiatrists when managing IBD.6

Celiac disease has been repeatedly associated with several neuropsychiatric disorders, including ataxia, epilepsy, peripheral neuropathy, headache, anxiety, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, and schizophrenia.

New, exciting challenges for medical science

There potentially are important implications for possible exploitation of the ENS and the microbiome in the diagnosis and treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. For example, consider these speculative challenges:

• Can intestinal biopsy reveal neurotransmitter pathology in schizophrenia?

• Can early dopamine deficiency predict Parkinson’s disease, enabling early intervention?

• Can β-amyloid deposits, the degenerative neurologic stigmata of Alzheimer’s disease, be detected in abdominal neurons years before onset of symptoms to allow early intervention?

• Can the ENS become a therapeutic pathway by targeting the various neurotransmitters found there or by engaging the enormous human microbiome to manipulate its beneficial properties?

• Can foods or probiotic supplements be prescribed as microbiomal adjuncts to improve the mood and anxiety spectrum?

One recommendation I came across is that ingesting 10 to 100 million beneficial bacteria, such as Lactobacillus plantarum and Bifidobacterium infantis, might be helpful. Such prescriptions obviously are speculative but also are reasonably testable hypotheses of ways to exploit the “other brain” and the microbiome.

We must summon the guts to seize this opportunity

An independent second brain and a remarkable microbiome appear to be significant evolutionary adaptations and advantages for humans. For too long, neuropsychiatric researchers have ignored the ENS and the microbiome; now, they must focus on how to exploit these entities to yield innovative diagnostic and therapeutic advances. Integrating the ENS and the microbiome and enmeshing them into neuropsychiatric research and clinical applications hold great promise.

The field of psychoneurogastroenterology is in its infancy, but its growth and relevance will be momentous for neuropsychiatry. A major intellectual peristalsis is underway.

1. Robinson B. The abdominal and pelvic brain. Hammond, IN: Frank S. Betz; 1907.

2. Gershon M. The second brain: a groundbreaking new understanding of nervous disorders of the stomach and intestine. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers; 1998.

3. McMillin DL, Richards DG, Mein EA, et al. The abdominal brain and enteric nervous system. J Altern Complement Med. 1999;5(6):575-586.

4. Hill JM, Bhattacharjee S, Pogue AI, et al. The gastrointestinal tract microbiome and potential link to Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurol. 2014;5:43.

5. Olden KW, Lydiard RB. Gastrointestinal disorders. In: Rundell JR, Wise MG. Textbook of consultation-liaison psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

6. Filipovic BR, Filipovic BF. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(13):3552-3563.

1. Robinson B. The abdominal and pelvic brain. Hammond, IN: Frank S. Betz; 1907.

2. Gershon M. The second brain: a groundbreaking new understanding of nervous disorders of the stomach and intestine. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers; 1998.

3. McMillin DL, Richards DG, Mein EA, et al. The abdominal brain and enteric nervous system. J Altern Complement Med. 1999;5(6):575-586.

4. Hill JM, Bhattacharjee S, Pogue AI, et al. The gastrointestinal tract microbiome and potential link to Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurol. 2014;5:43.

5. Olden KW, Lydiard RB. Gastrointestinal disorders. In: Rundell JR, Wise MG. Textbook of consultation-liaison psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

6. Filipovic BR, Filipovic BF. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(13):3552-3563.

Unmet needs and hassles of psychiatric practice

Recently, my umbrage at these practices soared to a new height when a colleague told me that he had to fight for, and then wait to receive, permission from an insurance employee to increase, by a notch, the maintenance dosage of a long-acting antipsychotic for his patient.

Can anyone justify why an absentee person who has never met the patient should, sight-unseen, second-guess our clinical judgment that a patient’s symptoms are still not well-controlled and require upward adjustment of the dosage? Why are insurance companies allowed to micromanage clinical decision-making? Such outrageous intrusiveness is a signal that insurance companies have “jumped the shark” in their effort to push business interests ahead of the needs of their subscribers.

Whose interests are being put first?

I recall instances when I refused to buckle to pressure from a patient’s third-party payer to switch from 1 antidepressant to another, a move that would save the insurer money but put my patient at risk of relapse. I informed the insurance company representative that my attorney was going to file a lawsuit on behalf of my depressed patient if he were to relapse or attempt suicide because he had been switched from an antidepressant that was working to another that might not.

Fighting back paid off: In each case, I was told the payer would “make an exception” for that patient.

Frustrations of this kind have become commonplace in psychiatric practice. They tend to detract from the stimulating and gratifying aspects of the care we provide, and reinforce the perception that insurance companies’ primary goal is to fatten profits, not facilitate patients’ return to health.

Here are other reasons for chronic frustration in psychiatric practice. They reflect serious, unmet needs that we hope will be resolved soon.

Improved diagnostic schema. We need a valid—and more than simply reliable—evidence-based diagnostic system that is rooted in scientifically established pathophysiology. The basic clinical elements of DSM-5 should be gradually amalgamated with rapidly emerging genetics and biological endophenotypes. The continuum of and boundary between “normal” and “pathologic” human behavior should be further clarified.

Biomarkers. Our field eagerly awaits development of biomarkers (laboratory tests) to bolster psychiatric practice in several ways, including:

• confirming the clinical diagnosis

• identifying biological subtypes

• monitoring response

• guiding selection of drugs

• predicting side effects

• measuring severity of disease.

Elusive parity. We’ve been patient, but we’re tired and angry at empty promises of full parity for psychiatric care. We’ve also had it with the stigmatizing and discriminatory “carve-out” status that allows insurance companies to treat reimbursement for psychiatric services more restrictively than for other medical and surgical specialties. Policy makers must end the egregious discrimination that gives half a loaf to some brain disorders (psychiatric) and a full loaf to other brain disorders (neurologic).

Better medications. We need a stronger commitment from the pharmaceutical industry, on which we rely entirely for development of psychoactive drugs, to wage a relentless war on serious mental illness. The private sector should accelerate translation of groundbreaking neuroscientific discoveries—thanks to research funded by the public sector, such as the National Institutes of Health—into innovative new mechanisms of action. Patients who suffer from psychiatric brain disorders for which there are no approved treatments await that commitment and bold action.

Collaborative care. Psychiatry needs a more consistent, more productive bidirectional relationship with primary care. A stronger bond will improve the care of patients on both sides and would, I believe, increase the satisfaction of clinical practice for both specialists. Because structure can facilitate function, co-locating providers can help achieve this vision.

Legal entanglement. Psychiatry must be unshackled from an oppressive set of laws that tie our hands when we treat patients with brain pathology who are incapable of understanding their illness and their need to be treated. Those laws were imposed long before scientific advances showed that prolonged and untreated episodes of psychosis, mania, depression, and anxiety are associated with neurotoxic processes (neuroinflammation, oxidative and nitrosative stress). Medical urgency and patient protection must trump legalisms, just as unconscious stroke and myocardial infarction patients are treated immediately without filing multiple forms or waiting for a court order.

Another legal beef: We psychiatrists are exasperated with the expanding criminalization of our patients— hapless victims of brain diseases that impair their reality testing and behavior. Should a person who suffers a first epileptic seizure or a stroke while driving and kills the driver of an oncoming car be incarcerated with hardened murderers and rapists and treated for epilepsy in a prison instead of a neurology ward? Our patients belong in a secure hospital, a medical asylum, where they are given compassionate medical care, not the degrading treatment afforded to a felon.

More resources. There is a dire need for psychiatric hospital beds in many parts of the country, because many wards were closed and renovated into more profitable, procedure-oriented specialties. There also is a severe shortage of psychiatrists in our country, as I discussed in my editorial, “Signs, symptoms, and treatment of psychiatrynemia,” (December 2014). The 25% of the population who suffer a mental disorder are clearly underserved at this time.

Furthermore, because today’s research is tomorrow’s new treatment, funding for psychiatric research must increase substantially to find cures and to thus reduce huge direct and indirect costs of mental illness and addictions.

Public enlightenment. A well-informed populace would be a major boon to our sophisticated medical specialty, which remains shrouded by primitive beliefs and archaic attitudes. For many people who desperately need mental health care, negative perceptions of psychiatric disorders and their treatment are a major impediment to seeking help. Psychiatrists can catalyze the process of enlightenment by dedicating time to elevating public understanding of the biology and the medical basis of mental illness.

All this notwithstanding, our work is gratifying

Despite the hassles and unmet needs I’ve enumerated, psychiatry continues to be one of the most exciting fields in medicine. We provide more therapeutic face-time and verbal interactions with our patients than any other medical specialty. Imagine, then, how much more enjoyable psychiatric practice would be if these pesky obstacles were eliminated and the unmet needs of patients and practitioners were addressed.

Recently, my umbrage at these practices soared to a new height when a colleague told me that he had to fight for, and then wait to receive, permission from an insurance employee to increase, by a notch, the maintenance dosage of a long-acting antipsychotic for his patient.

Can anyone justify why an absentee person who has never met the patient should, sight-unseen, second-guess our clinical judgment that a patient’s symptoms are still not well-controlled and require upward adjustment of the dosage? Why are insurance companies allowed to micromanage clinical decision-making? Such outrageous intrusiveness is a signal that insurance companies have “jumped the shark” in their effort to push business interests ahead of the needs of their subscribers.

Whose interests are being put first?

I recall instances when I refused to buckle to pressure from a patient’s third-party payer to switch from 1 antidepressant to another, a move that would save the insurer money but put my patient at risk of relapse. I informed the insurance company representative that my attorney was going to file a lawsuit on behalf of my depressed patient if he were to relapse or attempt suicide because he had been switched from an antidepressant that was working to another that might not.

Fighting back paid off: In each case, I was told the payer would “make an exception” for that patient.

Frustrations of this kind have become commonplace in psychiatric practice. They tend to detract from the stimulating and gratifying aspects of the care we provide, and reinforce the perception that insurance companies’ primary goal is to fatten profits, not facilitate patients’ return to health.

Here are other reasons for chronic frustration in psychiatric practice. They reflect serious, unmet needs that we hope will be resolved soon.

Improved diagnostic schema. We need a valid—and more than simply reliable—evidence-based diagnostic system that is rooted in scientifically established pathophysiology. The basic clinical elements of DSM-5 should be gradually amalgamated with rapidly emerging genetics and biological endophenotypes. The continuum of and boundary between “normal” and “pathologic” human behavior should be further clarified.

Biomarkers. Our field eagerly awaits development of biomarkers (laboratory tests) to bolster psychiatric practice in several ways, including:

• confirming the clinical diagnosis

• identifying biological subtypes

• monitoring response

• guiding selection of drugs

• predicting side effects

• measuring severity of disease.

Elusive parity. We’ve been patient, but we’re tired and angry at empty promises of full parity for psychiatric care. We’ve also had it with the stigmatizing and discriminatory “carve-out” status that allows insurance companies to treat reimbursement for psychiatric services more restrictively than for other medical and surgical specialties. Policy makers must end the egregious discrimination that gives half a loaf to some brain disorders (psychiatric) and a full loaf to other brain disorders (neurologic).

Better medications. We need a stronger commitment from the pharmaceutical industry, on which we rely entirely for development of psychoactive drugs, to wage a relentless war on serious mental illness. The private sector should accelerate translation of groundbreaking neuroscientific discoveries—thanks to research funded by the public sector, such as the National Institutes of Health—into innovative new mechanisms of action. Patients who suffer from psychiatric brain disorders for which there are no approved treatments await that commitment and bold action.

Collaborative care. Psychiatry needs a more consistent, more productive bidirectional relationship with primary care. A stronger bond will improve the care of patients on both sides and would, I believe, increase the satisfaction of clinical practice for both specialists. Because structure can facilitate function, co-locating providers can help achieve this vision.

Legal entanglement. Psychiatry must be unshackled from an oppressive set of laws that tie our hands when we treat patients with brain pathology who are incapable of understanding their illness and their need to be treated. Those laws were imposed long before scientific advances showed that prolonged and untreated episodes of psychosis, mania, depression, and anxiety are associated with neurotoxic processes (neuroinflammation, oxidative and nitrosative stress). Medical urgency and patient protection must trump legalisms, just as unconscious stroke and myocardial infarction patients are treated immediately without filing multiple forms or waiting for a court order.

Another legal beef: We psychiatrists are exasperated with the expanding criminalization of our patients— hapless victims of brain diseases that impair their reality testing and behavior. Should a person who suffers a first epileptic seizure or a stroke while driving and kills the driver of an oncoming car be incarcerated with hardened murderers and rapists and treated for epilepsy in a prison instead of a neurology ward? Our patients belong in a secure hospital, a medical asylum, where they are given compassionate medical care, not the degrading treatment afforded to a felon.

More resources. There is a dire need for psychiatric hospital beds in many parts of the country, because many wards were closed and renovated into more profitable, procedure-oriented specialties. There also is a severe shortage of psychiatrists in our country, as I discussed in my editorial, “Signs, symptoms, and treatment of psychiatrynemia,” (December 2014). The 25% of the population who suffer a mental disorder are clearly underserved at this time.

Furthermore, because today’s research is tomorrow’s new treatment, funding for psychiatric research must increase substantially to find cures and to thus reduce huge direct and indirect costs of mental illness and addictions.

Public enlightenment. A well-informed populace would be a major boon to our sophisticated medical specialty, which remains shrouded by primitive beliefs and archaic attitudes. For many people who desperately need mental health care, negative perceptions of psychiatric disorders and their treatment are a major impediment to seeking help. Psychiatrists can catalyze the process of enlightenment by dedicating time to elevating public understanding of the biology and the medical basis of mental illness.

All this notwithstanding, our work is gratifying

Despite the hassles and unmet needs I’ve enumerated, psychiatry continues to be one of the most exciting fields in medicine. We provide more therapeutic face-time and verbal interactions with our patients than any other medical specialty. Imagine, then, how much more enjoyable psychiatric practice would be if these pesky obstacles were eliminated and the unmet needs of patients and practitioners were addressed.

Recently, my umbrage at these practices soared to a new height when a colleague told me that he had to fight for, and then wait to receive, permission from an insurance employee to increase, by a notch, the maintenance dosage of a long-acting antipsychotic for his patient.

Can anyone justify why an absentee person who has never met the patient should, sight-unseen, second-guess our clinical judgment that a patient’s symptoms are still not well-controlled and require upward adjustment of the dosage? Why are insurance companies allowed to micromanage clinical decision-making? Such outrageous intrusiveness is a signal that insurance companies have “jumped the shark” in their effort to push business interests ahead of the needs of their subscribers.

Whose interests are being put first?

I recall instances when I refused to buckle to pressure from a patient’s third-party payer to switch from 1 antidepressant to another, a move that would save the insurer money but put my patient at risk of relapse. I informed the insurance company representative that my attorney was going to file a lawsuit on behalf of my depressed patient if he were to relapse or attempt suicide because he had been switched from an antidepressant that was working to another that might not.

Fighting back paid off: In each case, I was told the payer would “make an exception” for that patient.

Frustrations of this kind have become commonplace in psychiatric practice. They tend to detract from the stimulating and gratifying aspects of the care we provide, and reinforce the perception that insurance companies’ primary goal is to fatten profits, not facilitate patients’ return to health.

Here are other reasons for chronic frustration in psychiatric practice. They reflect serious, unmet needs that we hope will be resolved soon.

Improved diagnostic schema. We need a valid—and more than simply reliable—evidence-based diagnostic system that is rooted in scientifically established pathophysiology. The basic clinical elements of DSM-5 should be gradually amalgamated with rapidly emerging genetics and biological endophenotypes. The continuum of and boundary between “normal” and “pathologic” human behavior should be further clarified.

Biomarkers. Our field eagerly awaits development of biomarkers (laboratory tests) to bolster psychiatric practice in several ways, including:

• confirming the clinical diagnosis

• identifying biological subtypes

• monitoring response

• guiding selection of drugs

• predicting side effects

• measuring severity of disease.

Elusive parity. We’ve been patient, but we’re tired and angry at empty promises of full parity for psychiatric care. We’ve also had it with the stigmatizing and discriminatory “carve-out” status that allows insurance companies to treat reimbursement for psychiatric services more restrictively than for other medical and surgical specialties. Policy makers must end the egregious discrimination that gives half a loaf to some brain disorders (psychiatric) and a full loaf to other brain disorders (neurologic).

Better medications. We need a stronger commitment from the pharmaceutical industry, on which we rely entirely for development of psychoactive drugs, to wage a relentless war on serious mental illness. The private sector should accelerate translation of groundbreaking neuroscientific discoveries—thanks to research funded by the public sector, such as the National Institutes of Health—into innovative new mechanisms of action. Patients who suffer from psychiatric brain disorders for which there are no approved treatments await that commitment and bold action.

Collaborative care. Psychiatry needs a more consistent, more productive bidirectional relationship with primary care. A stronger bond will improve the care of patients on both sides and would, I believe, increase the satisfaction of clinical practice for both specialists. Because structure can facilitate function, co-locating providers can help achieve this vision.

Legal entanglement. Psychiatry must be unshackled from an oppressive set of laws that tie our hands when we treat patients with brain pathology who are incapable of understanding their illness and their need to be treated. Those laws were imposed long before scientific advances showed that prolonged and untreated episodes of psychosis, mania, depression, and anxiety are associated with neurotoxic processes (neuroinflammation, oxidative and nitrosative stress). Medical urgency and patient protection must trump legalisms, just as unconscious stroke and myocardial infarction patients are treated immediately without filing multiple forms or waiting for a court order.

Another legal beef: We psychiatrists are exasperated with the expanding criminalization of our patients— hapless victims of brain diseases that impair their reality testing and behavior. Should a person who suffers a first epileptic seizure or a stroke while driving and kills the driver of an oncoming car be incarcerated with hardened murderers and rapists and treated for epilepsy in a prison instead of a neurology ward? Our patients belong in a secure hospital, a medical asylum, where they are given compassionate medical care, not the degrading treatment afforded to a felon.

More resources. There is a dire need for psychiatric hospital beds in many parts of the country, because many wards were closed and renovated into more profitable, procedure-oriented specialties. There also is a severe shortage of psychiatrists in our country, as I discussed in my editorial, “Signs, symptoms, and treatment of psychiatrynemia,” (December 2014). The 25% of the population who suffer a mental disorder are clearly underserved at this time.

Furthermore, because today’s research is tomorrow’s new treatment, funding for psychiatric research must increase substantially to find cures and to thus reduce huge direct and indirect costs of mental illness and addictions.

Public enlightenment. A well-informed populace would be a major boon to our sophisticated medical specialty, which remains shrouded by primitive beliefs and archaic attitudes. For many people who desperately need mental health care, negative perceptions of psychiatric disorders and their treatment are a major impediment to seeking help. Psychiatrists can catalyze the process of enlightenment by dedicating time to elevating public understanding of the biology and the medical basis of mental illness.

All this notwithstanding, our work is gratifying

Despite the hassles and unmet needs I’ve enumerated, psychiatry continues to be one of the most exciting fields in medicine. We provide more therapeutic face-time and verbal interactions with our patients than any other medical specialty. Imagine, then, how much more enjoyable psychiatric practice would be if these pesky obstacles were eliminated and the unmet needs of patients and practitioners were addressed.

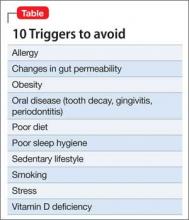

10 Triggers of inflammation to be avoided, to reduce the risk of depression

Neuroinflammation is well-established as an underlying mechanism in depression, as well as in other neuropsychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, multiple sclerosis, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, and sleep disorders.1 There is a dearth of prevention strategies for neuropsychiatric disorders but, given emerging scientific knowledge about immune dysregulation and the associated rise in inflammatory markers during the course of depression,2,3 it is logical to postulate that avoiding triggers of neuroinflammation might be a useful tactic to prevent depression or, perhaps, to minimize its severity.

Challenge your patients to avoid triggers of depression

What is known about what instigates the rise of inflammatory markers in the body and the brain? Actually, quite a substantial body of knowledge exists on the subject.4 Consider the 10 risk factors for depression that I enumerate here (Table), and advise patients to avoid them.

Sedentary lifestyle. Physical inactivity during childhood is associated with depression in adulthood. This is worrisome because video games seem ever more popular among children these days—more popular and prevalent than playing outdoors. Use this knowledge about the preventive benefit of exercise for long-range prevention in young patients.

Adults with a sedentary lifestyle usually have increased adiposity, which increases the risk of depression. Regular exercise has been shown to down-regulate systemic inflammation.

Smoking. Hundreds of toxic and inflammatory components in tobacco smoke (tars, metals, free radicals) can induce inflammation across the body and brain tissue, which explains not only depression but serious pulmonary and cerebrovascular diseases seen in smokers. People with depression are more likely to smoke than the general population, possibly because nicotine has a mild mood-elevating effect. Yet smoking might make depression worse by exacerbating inflammation, thus negating any mood-elevating effect of nicotine.

Poor diet. It is well known that the Western diet (processed meats, refined sugars, saturated fats) can increase the body’s level of inflammatory markers. The Mediterranean diet, on the other hand, which comprises fruits, vegetables, fish, legumes, and foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids (fish, nuts, leafy green vegetables), is anti-inflammatory. Furthermore, lycopene-containing foods (tomatoes, papaya, red cabbage, watermelon, carrots, asparagus) are rich in antioxidants and thus reduce inflammation.

The possible epigenetic effects of diet are an interesting phenomenon. Offspring of rats who were fed a diet rich in saturated fats have elevated levels of inflammatory markers, even when they had been fed a normal diet, suggesting a transgenerational effect. What parents eat before they conceive might doom their child’s health— regardless of what they feed them.

Tooth decay, gingivitis, periodontitis. Oral inflammation afflicts a large percentage of the population. These conditions can lead to systemic inflammation with elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukins, which are conducive to depression.

Poor sleep hygiene. Sleep disorders, such as insomnia and insufficient sleep (which is epidemic in the United States), are risk factors for mood disorders. Sleep deprivation disrupts immune function and triggers the cascade of elevated cytokines, CRP, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. Just as depression is associated with impaired neurogenesis, so is chronic lack of sleep, suggesting a convergence of neurobiologic mechanisms.

Vitamin D deficiency. A link between vitamin D deficiency, now common in the United States, and depression and immune function has been recognized. Vitamin D has anti-inflammatory effects and can reduce oxidative stress, which culminates in inflammation. Vitamin D supplementation has been shown to alleviate neuro-immune disorders, such as multiple sclerosis.

Obesity. Obese people are >50% more likely to develop depression than non-obese people. Technically, obesity is a pro-inflammatory state, and inflammatory biomarkers, such as cytokines, are abundant in fat cells, especially abdominal (visceral or peri-omental) adiposity. When an obese person loses weight, levels of inflammatory markers (interleukin-6, TNF-α, leptin) decrease. We know that abdominal obesity is associated with neuroinflammation and early dementia.

Allergy involves inflammation triggered by the cascade of events consequent to the body’s fight against antigens, and the well-known hyper-sensitivity reaction, causing edema, coughing, sneezing, and itching. It is well-established that the incidence of atopy and allergy is high among people with depression.

Changes in gut permeability. Intestinal inflammatory diseases, such as ulcerative colitis, are recognized as pathways to depression. The mechanism is believed to be the immune response to lipopolysaccharides by commensal bacteria that live by the trillions in the gut. The result? Abnormal gut permeability, bacterial translocation, and depressed mood, possibly because serotonin is more abundant in the gut than in the CNS.

Stress. Arguably, the most common pathway to depression is stressful events of daily life. Stress-induced systemic inflammation hastens cardiovascular disease and leads to neuro-inflammation and neuropsychiatric disorders as well.

Especially malignant is the severe stress of childhood trauma (physical and sexual abuse, parental discord and death), which stimulates pro-inflammatory cytokines and detrimental neurobiological sensitization that lead to psychopathology, including depression and psychosis in adulthood. Childhood trauma has been reported to shorten life by 7 to 15 years.

Posttraumatic stress disorder is the best known clinical model of stress-induced depression and anxiety. The disorder is associated with a significant increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines and loss of brain tissue.

2-fold challenge: Reduce severity of disease, reduce risk before disease

We psychiatrists almost always see patients after they’ve developed depression and other psychiatric disorders in which neuroinflammation is already present. In addition to pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy (both reduce inflammation), educating patients about adopting a healthy lifestyle—not smoking, exercising, eating wisely, avoiding weight gain, getting enough sleep, maintaining good oral hygiene, and managing stress—might reduce psychiatric relapse and prolong their life.

We also should be challenged by the fact that the pathways to inflammation, including the 10 I’ve described here, are common among the population at large. Let’s increase our efforts to preemptively reduce the risk of brain disorders by encouraging parents and their children to adopt a healthy lifestyle and maintain wellness—and thus avoid falling victim to depression.

1. Baune BT. Inflammation and neurodegenerative disorders: is there still hope for therapeutic intervention? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2015;28(2):148-154.

2. Leonard B, Maes M. Mechanistic explanations how cell-mediated immune activation, inflammation and oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways and their sequels and concomitants play a role in the pathophysiology of unipolar depression. Neurosc Biobehav Rev. 2012;36(2):764-785.

3. Bakunina N, Pariante CM, Zunszain PA. Immune mechanisms linked to depression via oxidative stress and neuroprogression [published online January 10, 2015]. Immunology. 2015. doi: 10.1111/imm.12443.

4. Berk M, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, et al. So depression is an inflammatory disease, but where does the inflammation come from? BMC Med. 2013;11:200.

Neuroinflammation is well-established as an underlying mechanism in depression, as well as in other neuropsychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, multiple sclerosis, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, and sleep disorders.1 There is a dearth of prevention strategies for neuropsychiatric disorders but, given emerging scientific knowledge about immune dysregulation and the associated rise in inflammatory markers during the course of depression,2,3 it is logical to postulate that avoiding triggers of neuroinflammation might be a useful tactic to prevent depression or, perhaps, to minimize its severity.

Challenge your patients to avoid triggers of depression

What is known about what instigates the rise of inflammatory markers in the body and the brain? Actually, quite a substantial body of knowledge exists on the subject.4 Consider the 10 risk factors for depression that I enumerate here (Table), and advise patients to avoid them.

Sedentary lifestyle. Physical inactivity during childhood is associated with depression in adulthood. This is worrisome because video games seem ever more popular among children these days—more popular and prevalent than playing outdoors. Use this knowledge about the preventive benefit of exercise for long-range prevention in young patients.

Adults with a sedentary lifestyle usually have increased adiposity, which increases the risk of depression. Regular exercise has been shown to down-regulate systemic inflammation.

Smoking. Hundreds of toxic and inflammatory components in tobacco smoke (tars, metals, free radicals) can induce inflammation across the body and brain tissue, which explains not only depression but serious pulmonary and cerebrovascular diseases seen in smokers. People with depression are more likely to smoke than the general population, possibly because nicotine has a mild mood-elevating effect. Yet smoking might make depression worse by exacerbating inflammation, thus negating any mood-elevating effect of nicotine.

Poor diet. It is well known that the Western diet (processed meats, refined sugars, saturated fats) can increase the body’s level of inflammatory markers. The Mediterranean diet, on the other hand, which comprises fruits, vegetables, fish, legumes, and foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids (fish, nuts, leafy green vegetables), is anti-inflammatory. Furthermore, lycopene-containing foods (tomatoes, papaya, red cabbage, watermelon, carrots, asparagus) are rich in antioxidants and thus reduce inflammation.

The possible epigenetic effects of diet are an interesting phenomenon. Offspring of rats who were fed a diet rich in saturated fats have elevated levels of inflammatory markers, even when they had been fed a normal diet, suggesting a transgenerational effect. What parents eat before they conceive might doom their child’s health— regardless of what they feed them.

Tooth decay, gingivitis, periodontitis. Oral inflammation afflicts a large percentage of the population. These conditions can lead to systemic inflammation with elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukins, which are conducive to depression.

Poor sleep hygiene. Sleep disorders, such as insomnia and insufficient sleep (which is epidemic in the United States), are risk factors for mood disorders. Sleep deprivation disrupts immune function and triggers the cascade of elevated cytokines, CRP, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. Just as depression is associated with impaired neurogenesis, so is chronic lack of sleep, suggesting a convergence of neurobiologic mechanisms.

Vitamin D deficiency. A link between vitamin D deficiency, now common in the United States, and depression and immune function has been recognized. Vitamin D has anti-inflammatory effects and can reduce oxidative stress, which culminates in inflammation. Vitamin D supplementation has been shown to alleviate neuro-immune disorders, such as multiple sclerosis.

Obesity. Obese people are >50% more likely to develop depression than non-obese people. Technically, obesity is a pro-inflammatory state, and inflammatory biomarkers, such as cytokines, are abundant in fat cells, especially abdominal (visceral or peri-omental) adiposity. When an obese person loses weight, levels of inflammatory markers (interleukin-6, TNF-α, leptin) decrease. We know that abdominal obesity is associated with neuroinflammation and early dementia.

Allergy involves inflammation triggered by the cascade of events consequent to the body’s fight against antigens, and the well-known hyper-sensitivity reaction, causing edema, coughing, sneezing, and itching. It is well-established that the incidence of atopy and allergy is high among people with depression.

Changes in gut permeability. Intestinal inflammatory diseases, such as ulcerative colitis, are recognized as pathways to depression. The mechanism is believed to be the immune response to lipopolysaccharides by commensal bacteria that live by the trillions in the gut. The result? Abnormal gut permeability, bacterial translocation, and depressed mood, possibly because serotonin is more abundant in the gut than in the CNS.

Stress. Arguably, the most common pathway to depression is stressful events of daily life. Stress-induced systemic inflammation hastens cardiovascular disease and leads to neuro-inflammation and neuropsychiatric disorders as well.

Especially malignant is the severe stress of childhood trauma (physical and sexual abuse, parental discord and death), which stimulates pro-inflammatory cytokines and detrimental neurobiological sensitization that lead to psychopathology, including depression and psychosis in adulthood. Childhood trauma has been reported to shorten life by 7 to 15 years.

Posttraumatic stress disorder is the best known clinical model of stress-induced depression and anxiety. The disorder is associated with a significant increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines and loss of brain tissue.

2-fold challenge: Reduce severity of disease, reduce risk before disease

We psychiatrists almost always see patients after they’ve developed depression and other psychiatric disorders in which neuroinflammation is already present. In addition to pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy (both reduce inflammation), educating patients about adopting a healthy lifestyle—not smoking, exercising, eating wisely, avoiding weight gain, getting enough sleep, maintaining good oral hygiene, and managing stress—might reduce psychiatric relapse and prolong their life.

We also should be challenged by the fact that the pathways to inflammation, including the 10 I’ve described here, are common among the population at large. Let’s increase our efforts to preemptively reduce the risk of brain disorders by encouraging parents and their children to adopt a healthy lifestyle and maintain wellness—and thus avoid falling victim to depression.

Neuroinflammation is well-established as an underlying mechanism in depression, as well as in other neuropsychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, multiple sclerosis, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, and sleep disorders.1 There is a dearth of prevention strategies for neuropsychiatric disorders but, given emerging scientific knowledge about immune dysregulation and the associated rise in inflammatory markers during the course of depression,2,3 it is logical to postulate that avoiding triggers of neuroinflammation might be a useful tactic to prevent depression or, perhaps, to minimize its severity.

Challenge your patients to avoid triggers of depression

What is known about what instigates the rise of inflammatory markers in the body and the brain? Actually, quite a substantial body of knowledge exists on the subject.4 Consider the 10 risk factors for depression that I enumerate here (Table), and advise patients to avoid them.

Sedentary lifestyle. Physical inactivity during childhood is associated with depression in adulthood. This is worrisome because video games seem ever more popular among children these days—more popular and prevalent than playing outdoors. Use this knowledge about the preventive benefit of exercise for long-range prevention in young patients.

Adults with a sedentary lifestyle usually have increased adiposity, which increases the risk of depression. Regular exercise has been shown to down-regulate systemic inflammation.

Smoking. Hundreds of toxic and inflammatory components in tobacco smoke (tars, metals, free radicals) can induce inflammation across the body and brain tissue, which explains not only depression but serious pulmonary and cerebrovascular diseases seen in smokers. People with depression are more likely to smoke than the general population, possibly because nicotine has a mild mood-elevating effect. Yet smoking might make depression worse by exacerbating inflammation, thus negating any mood-elevating effect of nicotine.

Poor diet. It is well known that the Western diet (processed meats, refined sugars, saturated fats) can increase the body’s level of inflammatory markers. The Mediterranean diet, on the other hand, which comprises fruits, vegetables, fish, legumes, and foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids (fish, nuts, leafy green vegetables), is anti-inflammatory. Furthermore, lycopene-containing foods (tomatoes, papaya, red cabbage, watermelon, carrots, asparagus) are rich in antioxidants and thus reduce inflammation.

The possible epigenetic effects of diet are an interesting phenomenon. Offspring of rats who were fed a diet rich in saturated fats have elevated levels of inflammatory markers, even when they had been fed a normal diet, suggesting a transgenerational effect. What parents eat before they conceive might doom their child’s health— regardless of what they feed them.

Tooth decay, gingivitis, periodontitis. Oral inflammation afflicts a large percentage of the population. These conditions can lead to systemic inflammation with elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukins, which are conducive to depression.

Poor sleep hygiene. Sleep disorders, such as insomnia and insufficient sleep (which is epidemic in the United States), are risk factors for mood disorders. Sleep deprivation disrupts immune function and triggers the cascade of elevated cytokines, CRP, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. Just as depression is associated with impaired neurogenesis, so is chronic lack of sleep, suggesting a convergence of neurobiologic mechanisms.

Vitamin D deficiency. A link between vitamin D deficiency, now common in the United States, and depression and immune function has been recognized. Vitamin D has anti-inflammatory effects and can reduce oxidative stress, which culminates in inflammation. Vitamin D supplementation has been shown to alleviate neuro-immune disorders, such as multiple sclerosis.

Obesity. Obese people are >50% more likely to develop depression than non-obese people. Technically, obesity is a pro-inflammatory state, and inflammatory biomarkers, such as cytokines, are abundant in fat cells, especially abdominal (visceral or peri-omental) adiposity. When an obese person loses weight, levels of inflammatory markers (interleukin-6, TNF-α, leptin) decrease. We know that abdominal obesity is associated with neuroinflammation and early dementia.

Allergy involves inflammation triggered by the cascade of events consequent to the body’s fight against antigens, and the well-known hyper-sensitivity reaction, causing edema, coughing, sneezing, and itching. It is well-established that the incidence of atopy and allergy is high among people with depression.

Changes in gut permeability. Intestinal inflammatory diseases, such as ulcerative colitis, are recognized as pathways to depression. The mechanism is believed to be the immune response to lipopolysaccharides by commensal bacteria that live by the trillions in the gut. The result? Abnormal gut permeability, bacterial translocation, and depressed mood, possibly because serotonin is more abundant in the gut than in the CNS.

Stress. Arguably, the most common pathway to depression is stressful events of daily life. Stress-induced systemic inflammation hastens cardiovascular disease and leads to neuro-inflammation and neuropsychiatric disorders as well.

Especially malignant is the severe stress of childhood trauma (physical and sexual abuse, parental discord and death), which stimulates pro-inflammatory cytokines and detrimental neurobiological sensitization that lead to psychopathology, including depression and psychosis in adulthood. Childhood trauma has been reported to shorten life by 7 to 15 years.

Posttraumatic stress disorder is the best known clinical model of stress-induced depression and anxiety. The disorder is associated with a significant increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines and loss of brain tissue.

2-fold challenge: Reduce severity of disease, reduce risk before disease

We psychiatrists almost always see patients after they’ve developed depression and other psychiatric disorders in which neuroinflammation is already present. In addition to pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy (both reduce inflammation), educating patients about adopting a healthy lifestyle—not smoking, exercising, eating wisely, avoiding weight gain, getting enough sleep, maintaining good oral hygiene, and managing stress—might reduce psychiatric relapse and prolong their life.

We also should be challenged by the fact that the pathways to inflammation, including the 10 I’ve described here, are common among the population at large. Let’s increase our efforts to preemptively reduce the risk of brain disorders by encouraging parents and their children to adopt a healthy lifestyle and maintain wellness—and thus avoid falling victim to depression.

1. Baune BT. Inflammation and neurodegenerative disorders: is there still hope for therapeutic intervention? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2015;28(2):148-154.

2. Leonard B, Maes M. Mechanistic explanations how cell-mediated immune activation, inflammation and oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways and their sequels and concomitants play a role in the pathophysiology of unipolar depression. Neurosc Biobehav Rev. 2012;36(2):764-785.

3. Bakunina N, Pariante CM, Zunszain PA. Immune mechanisms linked to depression via oxidative stress and neuroprogression [published online January 10, 2015]. Immunology. 2015. doi: 10.1111/imm.12443.

4. Berk M, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, et al. So depression is an inflammatory disease, but where does the inflammation come from? BMC Med. 2013;11:200.

1. Baune BT. Inflammation and neurodegenerative disorders: is there still hope for therapeutic intervention? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2015;28(2):148-154.

2. Leonard B, Maes M. Mechanistic explanations how cell-mediated immune activation, inflammation and oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways and their sequels and concomitants play a role in the pathophysiology of unipolar depression. Neurosc Biobehav Rev. 2012;36(2):764-785.

3. Bakunina N, Pariante CM, Zunszain PA. Immune mechanisms linked to depression via oxidative stress and neuroprogression [published online January 10, 2015]. Immunology. 2015. doi: 10.1111/imm.12443.

4. Berk M, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, et al. So depression is an inflammatory disease, but where does the inflammation come from? BMC Med. 2013;11:200.

10 Recent paradigm shifts in the neurobiology and treatment of depression

Nowhere is that change in landscape more apparent than in major depression, the No. 1 disabling condition in all of medicine, according to the World Health Organization. The past decade has generated at least 10 paradigm shifts in the neurobiology and pharmacotherapeutics of depression.

Clinging to simplistic tradition

Most contemporary clinicians continue to practice the traditional model of depression, which is based on the assumption that depression is caused by a deficiency of monoamines: serotonin (5-HT) and norepinephrine (NE). The entire antidepressant armamentarium approved for use by the FDA was designed according to the amine deficiency hypothesis. Depressed patients uniformly receive reuptake inhibitors of 5-HT and NE, but few achieve full remission, as the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study showed.1

As scientific paradigm shifts infiltrate clinical practice, however, the tired notion of “chemical imbalance” will yield to more complex and evidence-based models.

Usually, it would be remarkable to witness a single paradigm shift in the understanding of a brain disorder. Imagine the disruptive impact of multiple scientific shifts within the past decade! Consider the following departures from the old dogma about the simplistic old explanation of depression.

1. From neurotransmitters to neuroplasticity

For half a century, our field tenaciously held to the monoamine theory, which posits that depression is caused by a deficiency of 5-HT or NE, or both. All antidepressants in use today were developed to increase brain monoamines by inhibiting their reuptake at the synaptic cleft. Now, research points to other causes:

• impaired neuroplasticity

• a decrement of neurogenesis

• synaptic deficits

• decreased neurotrophins (such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor)

• dendritic pathology.2,3

2. From ‘chemical imbalance’ to neuroinflammation

The simplistic notion that depression is a chemical imbalance, so to speak, in the brain is giving way to rapidly emerging evidence that depression is associated with neuroinflammation.4

Pro-inflammatory cytokines are elevated in the plasma of depressed patients, and subside when the acute episode is treated. Current antidepressants actually have anti-inflammatory effects that have gone unrecognized.5 A meta-analysis of the use of anti-inflammatory agents (such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and aspirin) in depression shows promising efficacy.6 Some inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein, already have been reported to predict response to some antidepressants, but not to others.7

3. From 5-HT and NE pathways to glutamate NMDA receptors

Recent landmark studies8 have, taken together, demonstrated that a single IV dose of the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist ketamine (a psychotogenic drug of abuse FDA-approved only as an anesthetic) can produce clinical improvement of severe depression and even full remission for several days. Such studies demonstrate that the old dogma of 5-HT and NE deficiency might not be a valid overarching hypothesis of the depression syndrome.

Long-term maintenance studies of ketamine to document its safety and continued efficacy need to be conducted. The mechanism of action of ketamine is believed to be a rapid trigger for enhancing neuroplasticity.

4. From oral to parenteral administration

Several studies have been published showing the efficacy of IV or intranasal administration of new agents for depression. Ketamine studies, for example, were conducted using an IV infusion of a 150-mg dose over 1 hour. Other IV studies used the anticholinergic scopolamine.9

Intranasal ketamine also has been shown to be clinically efficacious.10 Inhalable nitrous oxide (laughing gas, an NMDA antagonist) recently was reported to improve depression as well.11

It is possible that parenteral administration of antidepressant agents may exert a different neurobiological effect and provide a more rapid response than oral medication.

5. From delayed efficacy (weeks) to immediate onset (1 or 2 hours)

The widely entrenched notion that depression takes several weeks to improve with an antidepressant has collapsed with emerging evidence that symptoms of the disorder (even suicidal ideation) can be reversed within 1 or 2 hours.12 IV ketamine isn’t the only example; IV scopolamine,9 inhalable nitrous oxide,11 and overnight sleep deprivation13 also exert a rapid therapeutic effect. This is a major rethinking of how quickly the curtain of severe depression can be lifted, and is great news for patients and their family.

6. From psychological symptoms to cortical or subcortical changes

Depression traditionally has been recognized as a clinical syndrome of sadness, self-deprecation, cognitive dulling, and vegetative symptoms. In recent studies, however, researchers report that low hippocampus volume14 in healthy young girls predicts future depression. Patients with unremitting depression have been reported to have an abnormally shaped hippocampus.15

In addition, gray-matter volume in the subgenual anterior cingulate (Brodmann area 24) is hypoplastic in depressed persons,16 making that area a target for deep-brain stimulation (DBS). Brain morphological changes such as a hypoplastic hippocampus might become useful biomarkers for identifying persons at risk of severe depression, and might become a useful adjunctive biomarker for making a clinical diagnosis.

7. From healing the mind to repairing the brain

It is well-established that depression is associated with loss of dendritic spines and arborizations, loss of synapses, and diminishment of glial cells, especially in the hippocampus17 and anterior cingulate.18 Treating depression, whether pharmaceutical or somatic, involves reversing these changes by increasing neurotrophic factors, enhancing neurogenesis and gliogenesis, and restoring synaptic and dendritic health and cell survival in the hippocampus and frontal cortex.19,20 Treating depression involves brain repair, which is reflected, ultimately, in healing the mind.

8. From pharmacotherapy to neuromodulation

Although drugs remain the predominant treatment modality for depression, there is palpable escalation in the use of neuromodulation methods.

The oldest of these neuromodulatory techniques is electroconvulsive therapy, an excellent treatment for severe depression (and one that enhances hippocampal neurogenesis). In addition, several novel neuromodulation methods have been approved (transcranial magnetic stimulation and vagus nerve stimulation) or are in development (transcranial direct-current stimulation, cranial electrotherapy stimulation, and DBS).21 These somatic approaches to treating the brain directly to alleviate depression target regions involved in depression and reduce the needless risks associated with exposing other organ systems to a drug.

9. From monotherapy to combination therapy

The use of combination therapy for depression has escalated with FDA approval of adjunctive use of atypical antipsychotics in unipolar and bipolar depression. In addition, the landmark STAR*D study1 demonstrated the value of augmentation therapy with a second antidepressant when 1 agent fails. Other controlled studies have shown that combining 2 antidepressants is superior to administering 1.22

Just as other serious medical disorders—such as cancer and hypertension—are treated with 2 or 3 medications, severe depression might require a similar strategy. The field gradually is adopting that approach.

10. From cortical folds to wrinkles on the face

Last, a new (and unexpected) paradigm shift recently emerged, which is genuinely intriguing—even baffling. Using placebo-controlled designs, several researchers have reported significant, persistent improvement of depressive symptoms after injection of onabotulinumtoxinA in the corrugator muscles of the glabellar region of the face, where the omega sign often appears in a depressed person.23,24

The longest of the studies25 was 6 months; investigators reported that improvement continued even after the effect of the botulinum toxin on the omega sign wore off. The proposed mechanism of action is the facial feedback hypothesis, which suggests that, biologically, facial expression has an impact on one’s emotional state.

Big payoffs coming from research in neuroscience

These 10 paradigm shifts in a single psychiatric syndrome are emblematic of exciting clinical and research advances in our field. Like all syndromes, depression is associated with multiple genetic and environmental causes; it isn’t surprising that myriad treatment approaches are emerging.

The days of clinging to monolithic, serendipity-generated models surely are over. Evidence-based psychiatric brain research is shattering aging dogmas that have, for decades, stifled innovation in psychiatric therapeutics that is now moving in novel directions.

Take note, however, that the only paradigm shift that matters to depressed patients is the one that transcends mere control of their symptoms and restores their wellness, functional capacity, and quality of life. With the explosive momentum of neuroscience discovery, psychiatry is, at last, poised to deliver—in splendid, even seismic, fashion.

1. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Eng J Med. 2006;354(12):1243-1252.

2. Serafini G, Hayley S, Pompili M, et al. Hippocampal neurogenesis, neurotrophic factors and depression: possible therapeutic targets [published online November 30, 2014]? CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. doi: 10.2174/1871527313666141130223723.

3. Duman RS, Aghajanian GK. Synaptic dysfunction in depression: potential therapeutic targets. Science. 2012;338(6103):68-72.

4. Iwata M, Ota KT, Duman RS. The inflammasome: pathways linking psychological stress, depression, and systemic illnesses. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;31:105-114.

5. Sacre S, Medghalichi M, Gregory B, et al. Fluoxetine and citalopram exhibit potent anti-inflammatory activity in human and murine models of rheumatoid arthritis and inhibit toll-like receptors. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(3):683-693.

6. Köhler O, Benros ME, Nordentoft M, et al. Effect of anti-inflammatory treatment on depression, depressive symptoms, and adverse effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(12): 1381-1391.

7. Uher R, Tansey KE, Dew T, et al. An inflammatory biomarker as a differential predictor of outcome of depression treatment with escitalopram and nortiptyline. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(14):1278-1286.

8. Abdallah CG, Sanacora G, Duman RS, et al. Ketamine and rapid-acting antidepressants: a window into a new neurobiology for mood disorder therapeutics [published online October 17, 2014]. Annual Rev Med. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-053013-062946.

9. Furey ML, Khanna A, Hoffman EM, et al. Scopolamine produces larger antidepressant and antianxiety effects in women than in men. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(12):2479-2488.

10. Lapidus KA, Levitch CF, Perez AM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of intranasal ketamine in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2014; 76(12):970-976.

11. Nagele P, Duma A, Kopec M, et al. Nitrous oxide for treatment-resistant major depression: a proof-of-concept trial [published December 14, 2014]. Biol Psychiatry. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.11.016.

12. Köhler O, Benros ME, Nordentoft M, et al. Effect of anti-inflammatory treatment on depression, depressive symptoms, and adverse effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(12): 1381-1391.

13. Bunney BG, Bunney WE. Mechanisms of rapid antidepressant effects of sleep deprivation therapy: clock genes and circadian rhythms. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(12):1164-1171.

14. Chen MC, Hamilton JP, Gotlib IH. Decreased hippocampal volume in healthy girls at risk for depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):270-276.

15. Tae WS, Kim SS, Lee KU, et al. Hippocampal shape deformation in female patients with unremitting major depressive disorder. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32(4):671-676.

16. Hamani C, Mayberg H, Synder B, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the subcallosal cingulate gyrus for depression: anatomical location of active contacts in clinical responders and a suggested guideline for targeting. J Neurosurg. 2009;111(6):1209-1215.

17. Sheline YI, Gado MH, Kraemer HC. Untreated depression and hippocampal volume loss. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(8):1516-1518.

18. Redlich R, Almeoda JJ, Grotegerd D, et al. Brain morphometric biomarkers distinguishing unipolar and bipolar depression. A voxel-based morphometry-pattern classification approach. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(11):1222-1230.

19. Mendez-David I, Hen R, Gardier AM, et al. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis: an actor in the antidepressant-like action. Ann Pharm Fr. 2013;71(3):143-149.

20. Serafini G. Neuroplasticity and major depression, the role of modern antidepressant drugs. World J Psychiatry. 2012;2(3):49-57.

21. Rosa MA, Lisanby SH. Somatic treatments for mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):102-116.

22. Blier P, Ward HE, Tremblay P, et al. Combination of antidepressant medications from treatment initiation for major depressive disorder: a double-blind randomized study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):281-288.

23. Wollmer MA, de Boer C, Kalak N, et al. Facing depression with botulinum toxin: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(5):574-581.

24. Finzi E, Rosenthal NE. Treatment of depression with onabotulinumtoxinA: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;52:1-6.

25. Magid M, Reichenberg JS, Poth PE, et al. Treatment of major depressive disorder using botulinum toxin A: a 24-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(8):837-844.

Nowhere is that change in landscape more apparent than in major depression, the No. 1 disabling condition in all of medicine, according to the World Health Organization. The past decade has generated at least 10 paradigm shifts in the neurobiology and pharmacotherapeutics of depression.

Clinging to simplistic tradition

Most contemporary clinicians continue to practice the traditional model of depression, which is based on the assumption that depression is caused by a deficiency of monoamines: serotonin (5-HT) and norepinephrine (NE). The entire antidepressant armamentarium approved for use by the FDA was designed according to the amine deficiency hypothesis. Depressed patients uniformly receive reuptake inhibitors of 5-HT and NE, but few achieve full remission, as the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study showed.1

As scientific paradigm shifts infiltrate clinical practice, however, the tired notion of “chemical imbalance” will yield to more complex and evidence-based models.

Usually, it would be remarkable to witness a single paradigm shift in the understanding of a brain disorder. Imagine the disruptive impact of multiple scientific shifts within the past decade! Consider the following departures from the old dogma about the simplistic old explanation of depression.

1. From neurotransmitters to neuroplasticity

For half a century, our field tenaciously held to the monoamine theory, which posits that depression is caused by a deficiency of 5-HT or NE, or both. All antidepressants in use today were developed to increase brain monoamines by inhibiting their reuptake at the synaptic cleft. Now, research points to other causes:

• impaired neuroplasticity

• a decrement of neurogenesis

• synaptic deficits

• decreased neurotrophins (such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor)

• dendritic pathology.2,3

2. From ‘chemical imbalance’ to neuroinflammation

The simplistic notion that depression is a chemical imbalance, so to speak, in the brain is giving way to rapidly emerging evidence that depression is associated with neuroinflammation.4

Pro-inflammatory cytokines are elevated in the plasma of depressed patients, and subside when the acute episode is treated. Current antidepressants actually have anti-inflammatory effects that have gone unrecognized.5 A meta-analysis of the use of anti-inflammatory agents (such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and aspirin) in depression shows promising efficacy.6 Some inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein, already have been reported to predict response to some antidepressants, but not to others.7

3. From 5-HT and NE pathways to glutamate NMDA receptors

Recent landmark studies8 have, taken together, demonstrated that a single IV dose of the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist ketamine (a psychotogenic drug of abuse FDA-approved only as an anesthetic) can produce clinical improvement of severe depression and even full remission for several days. Such studies demonstrate that the old dogma of 5-HT and NE deficiency might not be a valid overarching hypothesis of the depression syndrome.

Long-term maintenance studies of ketamine to document its safety and continued efficacy need to be conducted. The mechanism of action of ketamine is believed to be a rapid trigger for enhancing neuroplasticity.

4. From oral to parenteral administration