User login

Consider here my journey in psychiatry since my adolescence. Growing up in the 1960s and 1970s, I did not watch much television; my father was convinced TV would be “too distracting” for us children. At first, I was angry about his rule, and would occasionally watch programs such as Bonanza at sleep-overs.

The lure of psychoanalysis

Gradually, I became grateful to my father because—in contrast to my classmates, who sat passively for hours watching TV after school—I voraciously read the piles of fiction and nonfiction books that I checked out from the school library every week, expanding my general knowledge and perspectives. One of my favorite genres became psychology and psychiatry, including many of Sigmund Freud’s works.

I was enchanted by psychoanalysis and its explanation of mental illness because, growing up, I had been told that madness is caused by demonic spirits and bad behavior and it is completely untreatable. By the time I was in high school, I had decided to become a psychiatrist, and was practicing what I read by “counseling” my classmates about family conflicts, raging drives, and frustrating relationships with girlfriends.

Rising tide of psychopharmacology

My love for psychiatry never wavered during my undergraduate years. I focused not only on required pre-med courses but enthusiastically took many psychology, sociology, and anthropology electives to expand my understanding of human behavior. In medical school, I enjoyed all rotations, but psychiatry was simply sublime. Often, I offered (to my classmates’ delight) to take their weekend call at the psychiatric hospital so I could see more patients.

After my internship, I married my wife (a behavioral psychologist) and embarked on psychiatry residency training with gusto. I was far better prepared, I realized, than my fellow residents; my faculty supervisors noticed that I answered questions more often than many others during rounds and lectures. (Thanks, Dad, for banning television!) I relished every psychotherapy session and spent hours listening to audiotapes of my patients’ sessions to improve my skills and to discover the psychodynamic nuances of their psychopathology. Being supervised by expert psychoanalysts was the highlight of my week as I honed my psychodynamic psychotherapy skills.

But something interesting happened during my residency: Psychopharmacology and electroconvulsive therapy were helping my severely ill psychotic, manic, and depressed patients much faster than psychotherapy could. Length of stay in the wards typically was 30 days (there was no managed care back then to limit stay to an absurd 5 days), and I saw substantial improvement in many of my patients before discharge.

I was so enthralled by the rising tide of psychopharmacology that I decided in PGY-2 to conduct psychopharmacology research—which, I came to realize, was easier than research on psychotherapy. I secured a mentor from the department of pharmacology. In PGY-3, I presented my data at the Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; in PGY-4, the paper was published in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

By the end of residency, I had applied to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) to pursue a research fellowship in the neuropharmacology of schizophrenia to prepare me for an academic career. I participated in numerous studies on the NIMH research ward, brimming with patients who had refractory schizophrenia (before the advent of clozapine in 1989), and I published many articles with mentors and fellow researchers.

Investigating brain biology

Then another funny thing happened: During my fellowship, one of my mentors shared with me some early studies about postmortem structural changes in the brain of schizophrenia patients. That prompted me to spend hours in the basement of the pathology department examining the brains of dozens of patients with schizophrenia, noting atrophic changes and performing measurements and histopathologic studies.

Consequently, I embarked on neuroimaging research to study the morphological abnormalities of cortical and subcortical regions in living patients. I found myself going beyond neuropsychopharmacology and diving into neuroanatomy books and neuroscience journals. I realized that I was continuously learning and using a new scientific language in my daily work.

After I left NIMH to begin a career of teaching, research, and patient care in a medical school setting, I was engulfed by meteoric advances in neuroscience producing unprecedented insights about the molecular biology of schizophrenia and other severe neuropsychiatric disorders, leading me to pursue new opportunities in neurobiology while continuing my psychopharmacology research.

The rate of transformation is mind-boggling

Looking back at the span of time from childhood through the exciting journey of my psychiatry career, I realize how massive a transformation I have witnessed and experienced. The specialty has shifted its clinical and scientific paradigms through several conceptual models—from demonic possession to psychoanalysis to psychopharmacology and, last, to molecular neurobiology. Four times in my life, the lexicon of psychiatry has undergone a complete makeover. This is a light-speed pace of scientific progress over a few decades—truly breathtaking! It’s like rewriting a dictionary over and over, with no 2 successive editions resembling each other whatsoever.

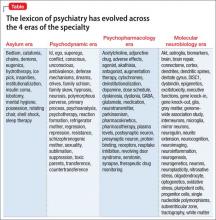

The Table shows 4 sets of examples of psychiatric terminology, each representing 1 of the 4 paradigmatic models that my generation of psychiatrists has had to adopt and use in clinical care and research. I cannot think of any other medical specialty that has come close to evolving and transforming its language and conceptual models of etiology and treatment at such a rapid pace.

When I embraced psychiatry in adolescence as my future career, I never imagined, in my wildest dreams, that I would experience such successive scientific earthquakes in my beloved medical specialty. Perhaps that’s what kept me stimulated and eager to come to work every day; I use all the models and treatment tools I have learned in understanding and helping my patients with evolving psychotherapeutic and biopharmaceutical tools; I also teach my students and residents about the multifaceted wonders of the human mind and the magnificent complexities of the brain in health and disease.

Psychiatry has been, and will continue to be, a Pandora’s box of medicine, full of stunning scientific twists and surprises and a transformative lexicon to match.

Consider here my journey in psychiatry since my adolescence. Growing up in the 1960s and 1970s, I did not watch much television; my father was convinced TV would be “too distracting” for us children. At first, I was angry about his rule, and would occasionally watch programs such as Bonanza at sleep-overs.

The lure of psychoanalysis

Gradually, I became grateful to my father because—in contrast to my classmates, who sat passively for hours watching TV after school—I voraciously read the piles of fiction and nonfiction books that I checked out from the school library every week, expanding my general knowledge and perspectives. One of my favorite genres became psychology and psychiatry, including many of Sigmund Freud’s works.

I was enchanted by psychoanalysis and its explanation of mental illness because, growing up, I had been told that madness is caused by demonic spirits and bad behavior and it is completely untreatable. By the time I was in high school, I had decided to become a psychiatrist, and was practicing what I read by “counseling” my classmates about family conflicts, raging drives, and frustrating relationships with girlfriends.

Rising tide of psychopharmacology

My love for psychiatry never wavered during my undergraduate years. I focused not only on required pre-med courses but enthusiastically took many psychology, sociology, and anthropology electives to expand my understanding of human behavior. In medical school, I enjoyed all rotations, but psychiatry was simply sublime. Often, I offered (to my classmates’ delight) to take their weekend call at the psychiatric hospital so I could see more patients.

After my internship, I married my wife (a behavioral psychologist) and embarked on psychiatry residency training with gusto. I was far better prepared, I realized, than my fellow residents; my faculty supervisors noticed that I answered questions more often than many others during rounds and lectures. (Thanks, Dad, for banning television!) I relished every psychotherapy session and spent hours listening to audiotapes of my patients’ sessions to improve my skills and to discover the psychodynamic nuances of their psychopathology. Being supervised by expert psychoanalysts was the highlight of my week as I honed my psychodynamic psychotherapy skills.

But something interesting happened during my residency: Psychopharmacology and electroconvulsive therapy were helping my severely ill psychotic, manic, and depressed patients much faster than psychotherapy could. Length of stay in the wards typically was 30 days (there was no managed care back then to limit stay to an absurd 5 days), and I saw substantial improvement in many of my patients before discharge.

I was so enthralled by the rising tide of psychopharmacology that I decided in PGY-2 to conduct psychopharmacology research—which, I came to realize, was easier than research on psychotherapy. I secured a mentor from the department of pharmacology. In PGY-3, I presented my data at the Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; in PGY-4, the paper was published in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

By the end of residency, I had applied to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) to pursue a research fellowship in the neuropharmacology of schizophrenia to prepare me for an academic career. I participated in numerous studies on the NIMH research ward, brimming with patients who had refractory schizophrenia (before the advent of clozapine in 1989), and I published many articles with mentors and fellow researchers.

Investigating brain biology

Then another funny thing happened: During my fellowship, one of my mentors shared with me some early studies about postmortem structural changes in the brain of schizophrenia patients. That prompted me to spend hours in the basement of the pathology department examining the brains of dozens of patients with schizophrenia, noting atrophic changes and performing measurements and histopathologic studies.

Consequently, I embarked on neuroimaging research to study the morphological abnormalities of cortical and subcortical regions in living patients. I found myself going beyond neuropsychopharmacology and diving into neuroanatomy books and neuroscience journals. I realized that I was continuously learning and using a new scientific language in my daily work.

After I left NIMH to begin a career of teaching, research, and patient care in a medical school setting, I was engulfed by meteoric advances in neuroscience producing unprecedented insights about the molecular biology of schizophrenia and other severe neuropsychiatric disorders, leading me to pursue new opportunities in neurobiology while continuing my psychopharmacology research.

The rate of transformation is mind-boggling

Looking back at the span of time from childhood through the exciting journey of my psychiatry career, I realize how massive a transformation I have witnessed and experienced. The specialty has shifted its clinical and scientific paradigms through several conceptual models—from demonic possession to psychoanalysis to psychopharmacology and, last, to molecular neurobiology. Four times in my life, the lexicon of psychiatry has undergone a complete makeover. This is a light-speed pace of scientific progress over a few decades—truly breathtaking! It’s like rewriting a dictionary over and over, with no 2 successive editions resembling each other whatsoever.

The Table shows 4 sets of examples of psychiatric terminology, each representing 1 of the 4 paradigmatic models that my generation of psychiatrists has had to adopt and use in clinical care and research. I cannot think of any other medical specialty that has come close to evolving and transforming its language and conceptual models of etiology and treatment at such a rapid pace.

When I embraced psychiatry in adolescence as my future career, I never imagined, in my wildest dreams, that I would experience such successive scientific earthquakes in my beloved medical specialty. Perhaps that’s what kept me stimulated and eager to come to work every day; I use all the models and treatment tools I have learned in understanding and helping my patients with evolving psychotherapeutic and biopharmaceutical tools; I also teach my students and residents about the multifaceted wonders of the human mind and the magnificent complexities of the brain in health and disease.

Psychiatry has been, and will continue to be, a Pandora’s box of medicine, full of stunning scientific twists and surprises and a transformative lexicon to match.

Consider here my journey in psychiatry since my adolescence. Growing up in the 1960s and 1970s, I did not watch much television; my father was convinced TV would be “too distracting” for us children. At first, I was angry about his rule, and would occasionally watch programs such as Bonanza at sleep-overs.

The lure of psychoanalysis

Gradually, I became grateful to my father because—in contrast to my classmates, who sat passively for hours watching TV after school—I voraciously read the piles of fiction and nonfiction books that I checked out from the school library every week, expanding my general knowledge and perspectives. One of my favorite genres became psychology and psychiatry, including many of Sigmund Freud’s works.

I was enchanted by psychoanalysis and its explanation of mental illness because, growing up, I had been told that madness is caused by demonic spirits and bad behavior and it is completely untreatable. By the time I was in high school, I had decided to become a psychiatrist, and was practicing what I read by “counseling” my classmates about family conflicts, raging drives, and frustrating relationships with girlfriends.

Rising tide of psychopharmacology

My love for psychiatry never wavered during my undergraduate years. I focused not only on required pre-med courses but enthusiastically took many psychology, sociology, and anthropology electives to expand my understanding of human behavior. In medical school, I enjoyed all rotations, but psychiatry was simply sublime. Often, I offered (to my classmates’ delight) to take their weekend call at the psychiatric hospital so I could see more patients.

After my internship, I married my wife (a behavioral psychologist) and embarked on psychiatry residency training with gusto. I was far better prepared, I realized, than my fellow residents; my faculty supervisors noticed that I answered questions more often than many others during rounds and lectures. (Thanks, Dad, for banning television!) I relished every psychotherapy session and spent hours listening to audiotapes of my patients’ sessions to improve my skills and to discover the psychodynamic nuances of their psychopathology. Being supervised by expert psychoanalysts was the highlight of my week as I honed my psychodynamic psychotherapy skills.

But something interesting happened during my residency: Psychopharmacology and electroconvulsive therapy were helping my severely ill psychotic, manic, and depressed patients much faster than psychotherapy could. Length of stay in the wards typically was 30 days (there was no managed care back then to limit stay to an absurd 5 days), and I saw substantial improvement in many of my patients before discharge.

I was so enthralled by the rising tide of psychopharmacology that I decided in PGY-2 to conduct psychopharmacology research—which, I came to realize, was easier than research on psychotherapy. I secured a mentor from the department of pharmacology. In PGY-3, I presented my data at the Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; in PGY-4, the paper was published in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

By the end of residency, I had applied to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) to pursue a research fellowship in the neuropharmacology of schizophrenia to prepare me for an academic career. I participated in numerous studies on the NIMH research ward, brimming with patients who had refractory schizophrenia (before the advent of clozapine in 1989), and I published many articles with mentors and fellow researchers.

Investigating brain biology

Then another funny thing happened: During my fellowship, one of my mentors shared with me some early studies about postmortem structural changes in the brain of schizophrenia patients. That prompted me to spend hours in the basement of the pathology department examining the brains of dozens of patients with schizophrenia, noting atrophic changes and performing measurements and histopathologic studies.

Consequently, I embarked on neuroimaging research to study the morphological abnormalities of cortical and subcortical regions in living patients. I found myself going beyond neuropsychopharmacology and diving into neuroanatomy books and neuroscience journals. I realized that I was continuously learning and using a new scientific language in my daily work.

After I left NIMH to begin a career of teaching, research, and patient care in a medical school setting, I was engulfed by meteoric advances in neuroscience producing unprecedented insights about the molecular biology of schizophrenia and other severe neuropsychiatric disorders, leading me to pursue new opportunities in neurobiology while continuing my psychopharmacology research.

The rate of transformation is mind-boggling

Looking back at the span of time from childhood through the exciting journey of my psychiatry career, I realize how massive a transformation I have witnessed and experienced. The specialty has shifted its clinical and scientific paradigms through several conceptual models—from demonic possession to psychoanalysis to psychopharmacology and, last, to molecular neurobiology. Four times in my life, the lexicon of psychiatry has undergone a complete makeover. This is a light-speed pace of scientific progress over a few decades—truly breathtaking! It’s like rewriting a dictionary over and over, with no 2 successive editions resembling each other whatsoever.

The Table shows 4 sets of examples of psychiatric terminology, each representing 1 of the 4 paradigmatic models that my generation of psychiatrists has had to adopt and use in clinical care and research. I cannot think of any other medical specialty that has come close to evolving and transforming its language and conceptual models of etiology and treatment at such a rapid pace.

When I embraced psychiatry in adolescence as my future career, I never imagined, in my wildest dreams, that I would experience such successive scientific earthquakes in my beloved medical specialty. Perhaps that’s what kept me stimulated and eager to come to work every day; I use all the models and treatment tools I have learned in understanding and helping my patients with evolving psychotherapeutic and biopharmaceutical tools; I also teach my students and residents about the multifaceted wonders of the human mind and the magnificent complexities of the brain in health and disease.

Psychiatry has been, and will continue to be, a Pandora’s box of medicine, full of stunning scientific twists and surprises and a transformative lexicon to match.