User login

Doug Brunk is a San Diego-based award-winning reporter who began covering health care in 1991. Before joining the company, he wrote for the health sciences division of Columbia University and was an associate editor at Contemporary Long Term Care magazine when it won a Jesse H. Neal Award. His work has been syndicated by the Los Angeles Times and he is the author of two books related to the University of Kentucky Wildcats men's basketball program. Doug has a master’s degree in magazine journalism from the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University. Follow him on Twitter @dougbrunk.

In COVID-19 era: Infusion centers shuffle services

It’s anything but business as usual for clinicians who oversee office-based infusion centers, as they scramble to maintain services for patients considered to be at heightened risk for severe illness should they become infected with COVID-19.

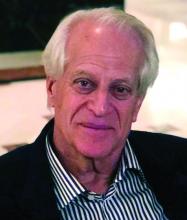

“For many reasons, the guidance for patients right now is that they stay on their medications,” Max I. Hamburger, MD, a managing partner at Rheumatology Associates of Long Island (N.Y.), said in an interview. “Some have decided to stop the drug, and then they call us up to tell us that they’re flaring. The beginning of a flare is tiredness and other things. Now they’re worried: Are they tired because of the disease, or are they tired because they have COVID-19?”

With five offices located in a region considered to be the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, Dr. Hamburger and his colleagues are hypervigilant about screening patients for symptoms of the virus before they visit one of the three practice locations that provide infusion services. This starts with an automated phone system that reminds patients of their appointment time. “Part of that robocall now has some questions like, ‘Do you have any symptoms of COVID-19?’ ‘Are you running a fever?’ ” The infusion nurses are also calling the patients in advance of their appointment to check on their status. “When they get to the office location, we ask them again about their general health and check their temperature,” said Dr. Hamburger. “We’re doing everything we can to talk to them about their own state of health and to question them about what I call extended paranoia: like, ‘Who are you living with?’ ‘Who are you hanging out with?’... We do everything we can to see if there’s anybody who might have had the slightest [contact with someone who has COVID-19]. Because if I lose my infusion nurse, then I’m up the creek.”

The infusion nurse wears scrubs, a face mask, and latex gloves. She and her staff are using hand sanitizer and cleaning infusion equipment with sanitizing wipes as one might do in a surgical setting. “Every surface is wiped down between patients, and the nurse is changing gloves between patients,” said Dr. Hamburger, who was founding president of the New York State Rheumatology Society before retiring from that post in 2017. “Getting masks has been tough. We’re doing the best we can there. We’re not gloving patients but we’re masking patients.”

As noted in guidance from the American College of Rheumatology and other medical organizations, following the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommendation to stay at home during the pandemic has jump-started conversations between physicians and their patients about modifying the time interval between infusions. “If they have been doing well for the last 9 months, we’re having a conversation such as ‘Maybe instead of getting your Orencia every 4 weeks, maybe we’ll push it out to 5 weeks, or maybe we’ll push the Enbrel out to 10 days and the Humira out 3 weeks, et cetera,” Dr. Hamburger said. “One has to be very careful about when you do that, because you don’t want the patient to flare up because it’s hard to get them in, but it is a natural opportunity to look at this. We’re seeing how we can optimize the dose, but I don’t want to send the message that we’re doing this because it changes the patient’s outcome, because there’s zero evidence that it’s a good thing to do in terms of resistance.”

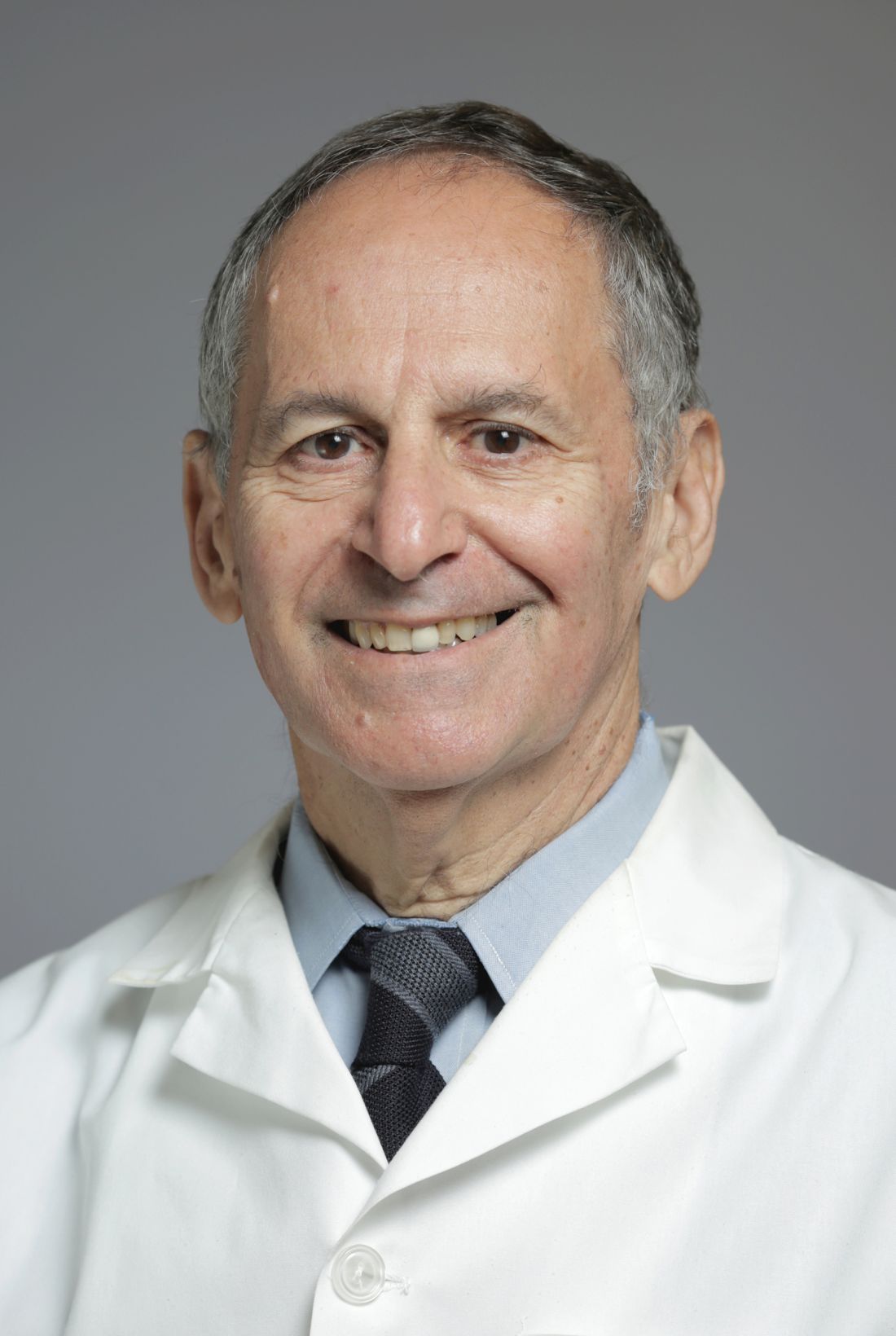

At the infusion centers operated by the Johns Hopkins division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Baltimore, clinicians are not increasing the time interval between infusions for patients at this time. “We’re keeping them as they are, to prevent any flare-ups. Our main goal is to keep patients in remission and out of the hospital,” said Alyssa M. Parian, MD, medical director of the infusion center and associate director of the university’s GI department. “With Remicade specifically, there’s also the risk of developing antibodies if you delay treatment, so we’re basically keeping everyone on track. We’re not recommending a switch from infusions to injectables, and we also are not speeding up infusions, either. Before this pandemic happened, we had already tried to decrease all Remicade infusions from 2 hours to 1 hour for patient satisfaction. The Entyvio is a pretty quick, 30-minute infusion.”

To accommodate patients during this era of physical distancing measures recommended by the CDC, Dr. Parian and her infusion nurse manager Elisheva Weiser converted one of their two outpatient GI centers into an infusion-only suite with 12 individual clinic rooms. As soon as patients exit the second-floor elevator, they encounter a workstation prior to entering the office where they are screened for COVID-19 symptoms and their temperature is taken. “If any symptoms or temperature comes back positive, we’re asking them to postpone their treatment and consider COVID testing,” she said.Instead of one nurse looking after four patients in one room during infusion therapy, now one nurse looks after two patients who are in rooms next to each other. All patients and all staff wear masks while in the center. “We always have physician oversight at our infusion centers,” Dr. Parian said. “We are trying to maintain a ‘COVID-free zone.’ Therefore, no physicians who have served in a hospital ward are allowed in the infusion suite because we don’t want any carriers of COVID-19. Same with the nurses. Additionally, we limit the staff within the suite to only those who are essential and don’t allow anyone to perform telemedicine or urgent clinic visits in this location. Our infusion center staff are on a strict protocol to not come in with any symptoms at all. They are asked to take their temperature before coming in to work.”

She and her colleagues drew from recommendations from the joint GI society message on COVID-19, the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, and the International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease to inform their approach in serving patients during this unprecedented time. “We went as conservative as possible because these are immunosuppressed patients,” she said. One patient on her panel who receives an infusion every 8 weeks tested positive for COVID-19 between infusions, but was not hospitalized. Dr. Parian said that person will be treated only 14 days after all symptoms disappear. “That person will wear a mask and will be infused in a separate room,” she said.

AGA provides up-to-date news, resources and research COVID-19 to help the GI community navigate the coronavirus pandemic. Learn more at https://www.gastro.org/covid-

It’s anything but business as usual for clinicians who oversee office-based infusion centers, as they scramble to maintain services for patients considered to be at heightened risk for severe illness should they become infected with COVID-19.

“For many reasons, the guidance for patients right now is that they stay on their medications,” Max I. Hamburger, MD, a managing partner at Rheumatology Associates of Long Island (N.Y.), said in an interview. “Some have decided to stop the drug, and then they call us up to tell us that they’re flaring. The beginning of a flare is tiredness and other things. Now they’re worried: Are they tired because of the disease, or are they tired because they have COVID-19?”

With five offices located in a region considered to be the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, Dr. Hamburger and his colleagues are hypervigilant about screening patients for symptoms of the virus before they visit one of the three practice locations that provide infusion services. This starts with an automated phone system that reminds patients of their appointment time. “Part of that robocall now has some questions like, ‘Do you have any symptoms of COVID-19?’ ‘Are you running a fever?’ ” The infusion nurses are also calling the patients in advance of their appointment to check on their status. “When they get to the office location, we ask them again about their general health and check their temperature,” said Dr. Hamburger. “We’re doing everything we can to talk to them about their own state of health and to question them about what I call extended paranoia: like, ‘Who are you living with?’ ‘Who are you hanging out with?’... We do everything we can to see if there’s anybody who might have had the slightest [contact with someone who has COVID-19]. Because if I lose my infusion nurse, then I’m up the creek.”

The infusion nurse wears scrubs, a face mask, and latex gloves. She and her staff are using hand sanitizer and cleaning infusion equipment with sanitizing wipes as one might do in a surgical setting. “Every surface is wiped down between patients, and the nurse is changing gloves between patients,” said Dr. Hamburger, who was founding president of the New York State Rheumatology Society before retiring from that post in 2017. “Getting masks has been tough. We’re doing the best we can there. We’re not gloving patients but we’re masking patients.”

As noted in guidance from the American College of Rheumatology and other medical organizations, following the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommendation to stay at home during the pandemic has jump-started conversations between physicians and their patients about modifying the time interval between infusions. “If they have been doing well for the last 9 months, we’re having a conversation such as ‘Maybe instead of getting your Orencia every 4 weeks, maybe we’ll push it out to 5 weeks, or maybe we’ll push the Enbrel out to 10 days and the Humira out 3 weeks, et cetera,” Dr. Hamburger said. “One has to be very careful about when you do that, because you don’t want the patient to flare up because it’s hard to get them in, but it is a natural opportunity to look at this. We’re seeing how we can optimize the dose, but I don’t want to send the message that we’re doing this because it changes the patient’s outcome, because there’s zero evidence that it’s a good thing to do in terms of resistance.”

At the infusion centers operated by the Johns Hopkins division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Baltimore, clinicians are not increasing the time interval between infusions for patients at this time. “We’re keeping them as they are, to prevent any flare-ups. Our main goal is to keep patients in remission and out of the hospital,” said Alyssa M. Parian, MD, medical director of the infusion center and associate director of the university’s GI department. “With Remicade specifically, there’s also the risk of developing antibodies if you delay treatment, so we’re basically keeping everyone on track. We’re not recommending a switch from infusions to injectables, and we also are not speeding up infusions, either. Before this pandemic happened, we had already tried to decrease all Remicade infusions from 2 hours to 1 hour for patient satisfaction. The Entyvio is a pretty quick, 30-minute infusion.”

To accommodate patients during this era of physical distancing measures recommended by the CDC, Dr. Parian and her infusion nurse manager Elisheva Weiser converted one of their two outpatient GI centers into an infusion-only suite with 12 individual clinic rooms. As soon as patients exit the second-floor elevator, they encounter a workstation prior to entering the office where they are screened for COVID-19 symptoms and their temperature is taken. “If any symptoms or temperature comes back positive, we’re asking them to postpone their treatment and consider COVID testing,” she said.Instead of one nurse looking after four patients in one room during infusion therapy, now one nurse looks after two patients who are in rooms next to each other. All patients and all staff wear masks while in the center. “We always have physician oversight at our infusion centers,” Dr. Parian said. “We are trying to maintain a ‘COVID-free zone.’ Therefore, no physicians who have served in a hospital ward are allowed in the infusion suite because we don’t want any carriers of COVID-19. Same with the nurses. Additionally, we limit the staff within the suite to only those who are essential and don’t allow anyone to perform telemedicine or urgent clinic visits in this location. Our infusion center staff are on a strict protocol to not come in with any symptoms at all. They are asked to take their temperature before coming in to work.”

She and her colleagues drew from recommendations from the joint GI society message on COVID-19, the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, and the International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease to inform their approach in serving patients during this unprecedented time. “We went as conservative as possible because these are immunosuppressed patients,” she said. One patient on her panel who receives an infusion every 8 weeks tested positive for COVID-19 between infusions, but was not hospitalized. Dr. Parian said that person will be treated only 14 days after all symptoms disappear. “That person will wear a mask and will be infused in a separate room,” she said.

AGA provides up-to-date news, resources and research COVID-19 to help the GI community navigate the coronavirus pandemic. Learn more at https://www.gastro.org/covid-

It’s anything but business as usual for clinicians who oversee office-based infusion centers, as they scramble to maintain services for patients considered to be at heightened risk for severe illness should they become infected with COVID-19.

“For many reasons, the guidance for patients right now is that they stay on their medications,” Max I. Hamburger, MD, a managing partner at Rheumatology Associates of Long Island (N.Y.), said in an interview. “Some have decided to stop the drug, and then they call us up to tell us that they’re flaring. The beginning of a flare is tiredness and other things. Now they’re worried: Are they tired because of the disease, or are they tired because they have COVID-19?”

With five offices located in a region considered to be the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, Dr. Hamburger and his colleagues are hypervigilant about screening patients for symptoms of the virus before they visit one of the three practice locations that provide infusion services. This starts with an automated phone system that reminds patients of their appointment time. “Part of that robocall now has some questions like, ‘Do you have any symptoms of COVID-19?’ ‘Are you running a fever?’ ” The infusion nurses are also calling the patients in advance of their appointment to check on their status. “When they get to the office location, we ask them again about their general health and check their temperature,” said Dr. Hamburger. “We’re doing everything we can to talk to them about their own state of health and to question them about what I call extended paranoia: like, ‘Who are you living with?’ ‘Who are you hanging out with?’... We do everything we can to see if there’s anybody who might have had the slightest [contact with someone who has COVID-19]. Because if I lose my infusion nurse, then I’m up the creek.”

The infusion nurse wears scrubs, a face mask, and latex gloves. She and her staff are using hand sanitizer and cleaning infusion equipment with sanitizing wipes as one might do in a surgical setting. “Every surface is wiped down between patients, and the nurse is changing gloves between patients,” said Dr. Hamburger, who was founding president of the New York State Rheumatology Society before retiring from that post in 2017. “Getting masks has been tough. We’re doing the best we can there. We’re not gloving patients but we’re masking patients.”

As noted in guidance from the American College of Rheumatology and other medical organizations, following the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommendation to stay at home during the pandemic has jump-started conversations between physicians and their patients about modifying the time interval between infusions. “If they have been doing well for the last 9 months, we’re having a conversation such as ‘Maybe instead of getting your Orencia every 4 weeks, maybe we’ll push it out to 5 weeks, or maybe we’ll push the Enbrel out to 10 days and the Humira out 3 weeks, et cetera,” Dr. Hamburger said. “One has to be very careful about when you do that, because you don’t want the patient to flare up because it’s hard to get them in, but it is a natural opportunity to look at this. We’re seeing how we can optimize the dose, but I don’t want to send the message that we’re doing this because it changes the patient’s outcome, because there’s zero evidence that it’s a good thing to do in terms of resistance.”

At the infusion centers operated by the Johns Hopkins division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Baltimore, clinicians are not increasing the time interval between infusions for patients at this time. “We’re keeping them as they are, to prevent any flare-ups. Our main goal is to keep patients in remission and out of the hospital,” said Alyssa M. Parian, MD, medical director of the infusion center and associate director of the university’s GI department. “With Remicade specifically, there’s also the risk of developing antibodies if you delay treatment, so we’re basically keeping everyone on track. We’re not recommending a switch from infusions to injectables, and we also are not speeding up infusions, either. Before this pandemic happened, we had already tried to decrease all Remicade infusions from 2 hours to 1 hour for patient satisfaction. The Entyvio is a pretty quick, 30-minute infusion.”

To accommodate patients during this era of physical distancing measures recommended by the CDC, Dr. Parian and her infusion nurse manager Elisheva Weiser converted one of their two outpatient GI centers into an infusion-only suite with 12 individual clinic rooms. As soon as patients exit the second-floor elevator, they encounter a workstation prior to entering the office where they are screened for COVID-19 symptoms and their temperature is taken. “If any symptoms or temperature comes back positive, we’re asking them to postpone their treatment and consider COVID testing,” she said.Instead of one nurse looking after four patients in one room during infusion therapy, now one nurse looks after two patients who are in rooms next to each other. All patients and all staff wear masks while in the center. “We always have physician oversight at our infusion centers,” Dr. Parian said. “We are trying to maintain a ‘COVID-free zone.’ Therefore, no physicians who have served in a hospital ward are allowed in the infusion suite because we don’t want any carriers of COVID-19. Same with the nurses. Additionally, we limit the staff within the suite to only those who are essential and don’t allow anyone to perform telemedicine or urgent clinic visits in this location. Our infusion center staff are on a strict protocol to not come in with any symptoms at all. They are asked to take their temperature before coming in to work.”

She and her colleagues drew from recommendations from the joint GI society message on COVID-19, the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, and the International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease to inform their approach in serving patients during this unprecedented time. “We went as conservative as possible because these are immunosuppressed patients,” she said. One patient on her panel who receives an infusion every 8 weeks tested positive for COVID-19 between infusions, but was not hospitalized. Dr. Parian said that person will be treated only 14 days after all symptoms disappear. “That person will wear a mask and will be infused in a separate room,” she said.

AGA provides up-to-date news, resources and research COVID-19 to help the GI community navigate the coronavirus pandemic. Learn more at https://www.gastro.org/covid-

Primary care physicians reshuffle their work, lives in a pandemic

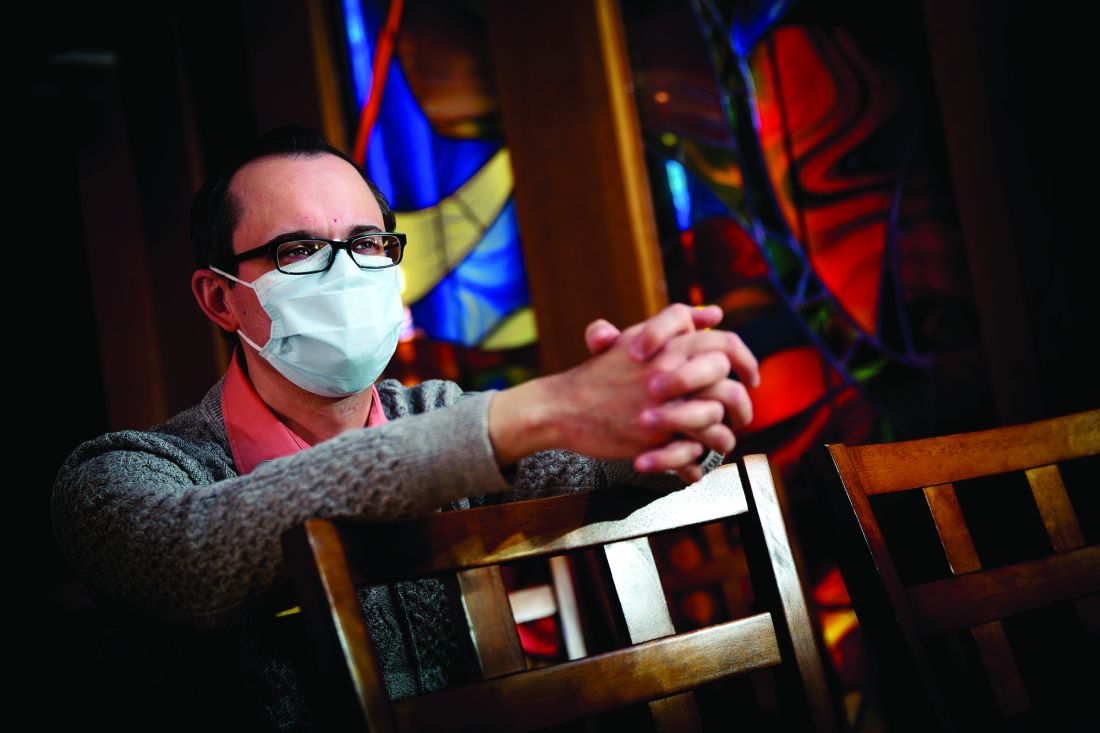

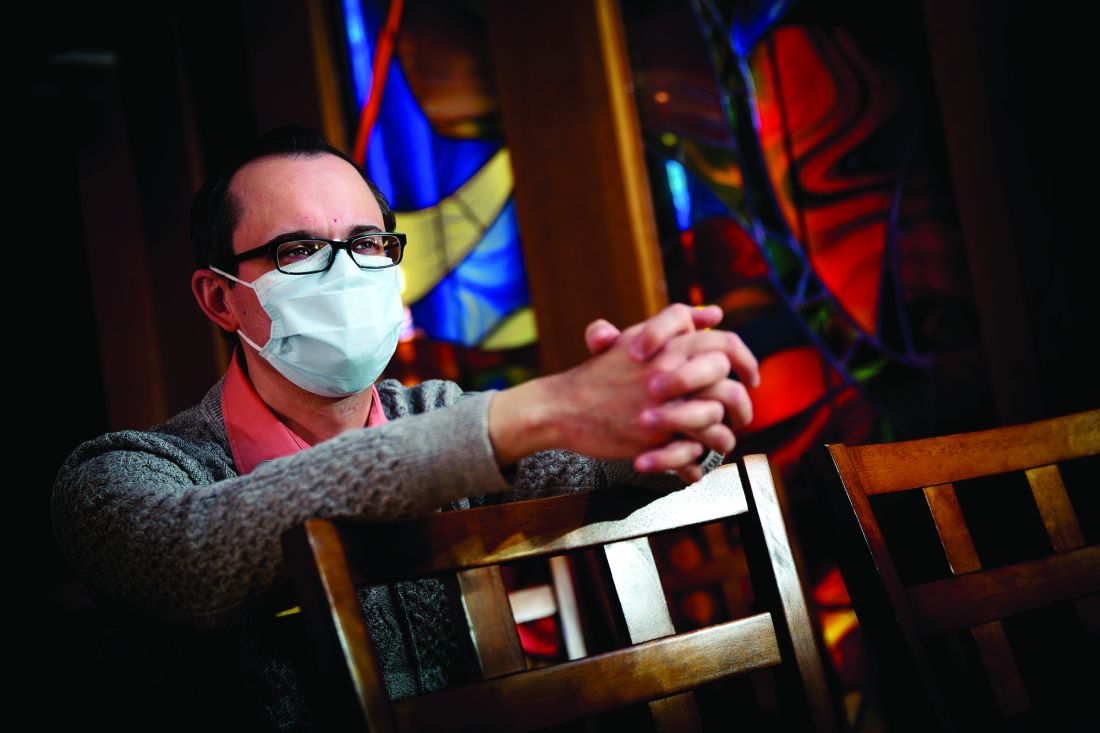

During his shift at a COVID-19 drive-through triage screening area set up outside the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock, Robert Hopkins Jr., MD, noticed a woman bowled over in the front seat of her car.

A nurse practitioner had just informed her that she had met the criteria for undergoing testing for the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

“She was very upset and was crying nearly inconsolably,” said Dr. Hopkins, who directs the division of general internal medicine at the University of Arkansas Medical Sciences College of Medicine. “I went over and visited with her for a few minutes. She was scared to death that we [had] told her she was going to die. In her mind, if she had COVID-19 that meant a death sentence, and if we were testing her that meant she was likely to not survive.”

Dr. Hopkins tried his best to put testing in perspective for the woman. “At least she came to a level of comfort and realized that we were doing this for her, that this was not a death sentence, that this was not her fault,” he said. “She was worried about infecting her kids and her grandkids and ending up in the hospital and being a burden. Being able to spend that few minutes with her and help to bring down her level of anxiety – I think that’s where we need to put our efforts as physicians right now, helping people understand, ‘Yes, this is serious. Yes, we need to continue to social distance. Yes, we need to be cautious. But, we will get through this if we all work together to do so.’ ”

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Hopkins spent part of his time seeing patients in the university’s main hospital, but most of it in an outpatient clinic where he and about 20 other primary care physicians care for patients and precept medical residents. Now, medical residents have been deployed to other services, primarily in the hospital, and he and his physician colleagues are conducting 80%-90% of patient visits by video conferencing or by telephone. It’s a whole new world.

“We’ve gone from a relatively traditional inpatient/outpatient practice where we’re seeing patients face to face to doing some face-to-face visits, but an awful lot of what we do now is in the technology domain,” said Dr. Hopkins, who also assisted with health care relief efforts during hurricanes Rita and Katrina.

“A group of six of us has been redeployed to assist with the surge unit for the inpatient facility, so our outpatient duties are being taken on by some of our partners.”

He also pitches in at the drive-through COVID-19 screening clinic, which was set up on March 27 and operates between 8 a.m. and 8 p.m., 7 days a week. “We’re able to measure people’s temperature, take a quick screening history, decide whether their risk is such that we need to do a COVID-19 PCR [polymerase chain reaction] test,” he said. “Then we make a determination of whether they need to go home on quarantine awaiting those results, or if they don’t have anything that needs to be evaluated, or whether they need to be triaged to an urgent care setting or to the emergency department.”

To minimize his risk of acquiring COVID-19, he follows personal hygiene practices recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He also places his work shoes in a shoebox, which he keeps in his car. “I put them on when I get to the parking deck at work, do my work, and then I put them in the shoebox, slip on another pair of shoes and drive home so I’m not tracking in things I potentially had on me,” said Dr. Hopkins, who is married and a father to two college-aged sons and a daughter in fourth grade. “When I get home I immediately shower, and then I exercise or have dinner with my family.”

Despite the longer-than-usual work hours and upheaval to the traditional medical practice model brought on by the pandemic, Dr. Hopkins, a self-described “glass half full person,” said that he does his best to keep watch over his patients and colleagues. “I’m trying to keep an eye out on my team members – physicians, nurses, medical assistants, and folks at the front desk – trying to make sure that people are getting rest, trying to make sure that people are not overcommitting,” he said. “Because if we’re not all working together and working for the long term, we’re going to be in trouble. This is not going to be a sprint; this is going to be a marathon for us to get through.”

To keep mentally centered, he engages in at least 40 minutes of exercise each day on his bicycle or on the elliptical machine at home. Dr. Hopkins hopes that the current efforts to redeploy resources, expand clinician skill sets, and forge relationships with colleagues in other disciplines will carry over into the delivery of health care when COVID-19 is a distant memory. “I hope that some of those relationships are going to continue and result in better care for all of our patients,” he said.

"We are in dire need of hugs"

Typically, Dr. Dakkak, a family physician at Boston University, practices a mix of clinic-based family medicine and obstetrics, and works in inpatient medicine 6 weeks a year. Currently, she is leading a COVID-19 team full time at Boston Medical Center, a 300-bed safety-net hospital located on the campus of Boston University Medical Center.

COVID-19 has also shaken up her life at home.

When Dr. Dakkak volunteered to take on her new role, the first thing that came to her mind was how making the switch would affect the well-being of her 8-year-old son and 10-year-old daughter.

“I thought, ‘How do I get my children somewhere where I don’t have to worry about them?’ ” Dr. Dakkak said.

She floated the idea with her husband of flying their children out to stay with her recently retired parents, who live outside of Sacramento, Calif., until the pandemic eases up. “I was thinking to myself, ‘Am I overreacting? Is the pandemic not going to be that bad?’ because the rest of the country seemed to be in some amount of denial,” she said. “So, I called my dad, who’s a retired pediatric anesthesiologist. He’s from Egypt so he’s done crisis medicine in his time. He encouraged me to send the kids.”

On the same day that Dr. Dakkak began her first 12-hour COVID-19 shift at the hospital, her husband and children boarded a plane to California, where the kids remain in the care of her parents. Her husband returned after staying there for 2 weeks. “Every day when I’m working, I validate my decision,” she said. “When I first started, I worked 5 nights in a row, had 2 days off, and then worked 6 nights in a row. I was busy so I didn’t think about [being away from my kids], but at the same time I was grateful that I didn’t have to come home and worry about homeschooling the kids or infecting them.”

She checks in with them as she can via cell phone or FaceTime. “My son has been very honest,” Dr. Dakkak said. “He says, ‘FaceTime makes me miss you more, and I don’t like it,’ which I understand. I’ll call my mom, and if they want to talk to me, they’ll talk to me. If they don’t want to talk to me, I’m okay. This is about them being healthy and safe. I sent them a care package a few days ago with cards and some workbooks. I’m optimistic that in June I can at least see them if not bring them home.”

Dr. Dakkak describes leading a COVID-19 team as a grueling experience that challenges her medical know-how nearly every day, with seemingly ever-changing algorithms. “Our knowledge of this disease is five steps behind, and changing at lightning speed,” said Dr. Dakkak, who completed a fellowship in surgical and high-risk obstetrics. “It’s hard to balance continuing to teach evidence-based medicine for everything else in medicine [with continuing] to practice minimal and ever-changing evidence-based COVID medicine. We just don’t know enough [about the virus] yet. This is nothing like we were taught in medical school. Everyone has elevated d-dimers with COVID-19, and we don’t get CT pulmonary angiograms [CTPAs] on all of them; we wouldn’t physically be able to. Some patients have d-dimers in the thousands, and only some are stable to get CTPAs. We are also finding pulmonary embolisms. Now we’re basing our algorithm on anticoagulation due to d-dimers because sometimes you can’t always do a CTPA even if you want to. On the other hand, we have people who are coming into the hospital too late. We’ve had a few who have come in after having days of stroke symptoms. I worry about our patients at home who hesitate to come in when they really should.”

Sometimes she feels sad for the medical residents on her team because their instinct is to go in and check on each patient, “but I don’t want them to get exposed,” she said. “So, we check in by phone, or if they need a physical check-in, we minimize the check-ins; only one of us goes in. I’m more willing to put myself in the room than to put them in the room. I also feel for them because they came into medicine for the humanity of medicine – not the charting or the ordering of medicine. I also worry about the acuity and sadness they’re seeing. This is a rough introduction to medicine for them.”

When interviewed for this story in late April, Dr. Dakkak had kept track of her intubated COVID-19 patients. “Most of my patients get to go home without having been intubated, but those aren’t the ones I worry about,” she said. “I have two patients I have been watching. One of them has just been extubated and I’m still worried about him, but I’m hoping he’s going to be fine. The other one is the first pregnant woman we intubated. She is now extubated, doing really well, and went home. Her fetus is doing well, never had any issues while she was intubated. Those cases make me happy. They were both under the age of 35. It is nice to follow those intubations and find that the majority are doing okay.”

The first patient she had cared for who died was a young man “who was always in good spirits,” she recalled. “We called his brother right before intubating him. After intubation, his oxygen saturation didn’t jump up, which made me worry a bit.” About a week later, the young man died. “I kept thinking, ‘We intubated him when he was still comfortable talking. Should I have put it off and had him call more people to say goodbye? Should I have known that he wasn’t going to wake up?’ ” said Dr. Dakkak, who is also women’s health director at Manet Community Health Centers. “A lot of us have worked on our end-of-life discussions in the past month, just being able to tell somebody, ‘This might be your last time to call family. Call family and talk to whoever you want.’ Guilt isn’t the right word, but it’s unsettling if I’m the last person a patient talks to. I feel that, if that’s the case, then I didn’t do a good enough job trying to get them to their family or friends. If I am worried about a patient’s clinical status declining, I tell families now, when I call them, ‘I hope I’m wrong; I hope they don’t need to be intubated, but I think this is the time to talk.’ ”

To keep herself grounded during off hours, Dr. Dakkak spends time resting, checking in with her family, journaling “to get a lot of feelings out,” gardening, hiking, and joining Zoom chats with friends. Once recentered, she draws from a sense of obligation to others as she prepares for her next shift caring for COVID-19 patients.

“I have a lot of love for the world that I get to expend by doing this hard work,” she said. “I love humanity and I love humanity in times of crisis. The interactions I have with patients and their families are still central to why I do this work. I love my medical teams, and I would never want to let them down. It is nice to feel the sense of teamwork across the hospital. The nurses that I sit with and experience this with are amazing. I keep saying that the only thing I want to do when this pandemic is over is hug everyone. I think we are in dire need of hugs.”

Finding light in the darkness

Internist Katie Jobbins, DO, also has worked in a professional role that was created because of COVID-19.

Shortly before Dr. Jobbins was deployed to Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Ma., for 2 weeks in April of 2020 to help clinicians with an anticipated surge of COVID-19 cases, she encountered a patient who walked into Baystate’s High Street Health Center.

“I think I have COVID-19,” the patient proclaimed to her, at the outpatient clinic that serves mostly inner-city, Medicaid patients.

Prior to becoming an ambulatory internist, Dr. Jobbins was a surgical resident. “So I went into that mode of ‘I need to do this, this, and this,’ ” she said. “I went through a checklist in my head to make sure I was prepared to take care of the patient.”

She applied that same systems approach during her redeployment assignment in the tertiary care hospital, which typically involved 10-hour shifts overseeing internal medicine residents in a medical telemetry unit. “We would take care of people under investigation for COVID-19, but we were not assigned to the actual COVID unit,” said Dr. Jobbins, who is also associate program director for the internal medicine residency program at the University of Massachusetts Medical School–Baystate Springfield. “They tried to redeploy other people to those units who had special training, and we were trying to back fill into where those people that got moved to the COVID units or the ICU units were actually working. We were taking more of the medical side of the floors.”

Even so, one patient on the unit was suspected of having COVID-19, so Dr. Jobbins suited up with personal protective equipment and conducted a thorough exam with residents waiting outside the patient’s room, a safe distance away. “I explained everything I found on the exam to the residents, trying to give them some educational benefit, even though they couldn’t physically examine the patient because we’re trying to protect them since they’re in training,” she said. “It was anxiety provoking, on some level, knowing that there’s a potential risk of exposure [to the virus], but knowing that Baystate Health has gone to extraordinary measures to make sure we have the correct PPE and support us is reassuring. I knew I had the right equipment and the right tools to take care of the patient, which calmed my nerves and made me feel like I could do the job. That’s the most important thing as a physician during this time: knowing that you have people supporting you who have your back at all times.”

Like Dr. Dakkak, Dr. Jobbins had to make some adjustments to her interaction with her family.

Before she began the deployment, Dr. Jobbins engaged in a frank discussion with her husband and her two young boys about the risks she faced working in a hospital caring for patients with COVID-19. “My husband and I made sure our wills were up to date, and we talked about what we would do if either of us got the virus,” she said. To minimize the potential risk of transmitting the virus to her loved ones during the two-week deployment, she considered living away from her family in a nearby home owned by her father, but decided against that and to “take it day by day.” Following her hospital shifts, Dr. Jobbins changed into a fresh set of clothes before leaving the hospital. Once she arrived home, she showered to reduce the risk of possibly becoming a vector to her family.

She had to tell her kids: “You can’t kiss me right now.”

“As much as it’s hard for them to understand, we had a conversation [in which I explained] ‘This is a virus. It will go away eventually, but it’s a virus we’re fighting.’ It’s interesting to watch a 3-year-old try to process that and take his play samurai sword or Marvel toys and decide he’s going to run around the neighborhood and try to kill the virus.”

At the High Street Health Center, Dr. Jobbins and her colleagues have transitioned to conducting most patient encounters via telephone or video appointments. “We have tried to maintain as much continuity for our patients to address their chronic medical needs through these visits, such as hypertension management and diabetes care,” she said. “We have begun a rigorous screening process to triage and treat patients suspicious for COVID-19 through telehealth in hopes of keeping them safe and in their own homes. We also continue to see patients for nonrespiratory urgent care needs in person once they have screened negative for COVID-19.”

“In terms of the inpatient setting, we’ve noticed that a lot of people are choosing not to go to the hospital now, unless they’re extremely ill,” Dr. Jobbins noted. “We’re going to need to find a balance with when do people truly need to go to the hospital and when do they not? What can we manage as an outpatient versus having someone go to the emergency department? That’s really the role of the primary care physician. We need to help people understand, ‘You don’t need to go to the ED for everything, but here are the things you really need to go for.’ ”

“It will be interesting to see what health care looks like in 6 months or a year. I’m excited to see where we land,” Dr. Jobbins added.

Hopes for the Future of Telemedicine

When the practice of medicine enters a post–COVID-19 era, Dr. Jobbins hopes that telemedicine will be incorporated more into the delivery of patient care. “I’ve found that many of my patients who often are no-shows to the inpatient version of their visits have had a higher success rate of follow-through when we do the telephone visits,” she said. “It’s been very successful. I hope that the insurance companies and [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid] will continue to reimburse this as they see this is a benefit to our patients.

Dr. Hopkins is also hopeful that physicians will be able to successfully see patients via telemedicine in the postpandemic world.

“For the ups and downs we’ve had with telemedicine, I’d love for us to be able to enhance the positives and incorporate that into our practice going forward. If we can reach our patients and help treat them where they are, rather than them having to come to us, that may be a plus,” he said.

In the meantime, Dr. Jobbins presses on as the curve of COVID-19 cases flattens in Western Massachusetts and remains grateful that she chose to practice medicine.

“The commitment I have to being an educator in addition to being a physician is part of why I keep doing this,” Dr. Jobbins said. “I find this to be one of the most fulfilling jobs and careers you could ever have: being there for people when they need you the most. That’s really what a physician’s job is: being there for people when a family member has passed away or when they just need to talk because they’re having anxiety. At the end of the day, if we can impart that to those we work with and bring in a positive attitude, it’s infectious and it makes people see this is a reason we keep doing what we’re doing.”

She’s also been heartened by the kindness of strangers during this pandemic, from those who made and donated face shields when they were in short supply, to those who delivered food to the hospital as a gesture of thanks.

“I had a patient who made homemade masks and sent them to my office,” she said. “There’s obviously good and bad during this time, but I get hope from seeing all of the good things that are coming out of this, the whole idea of finding the light in the darkness.”

During his shift at a COVID-19 drive-through triage screening area set up outside the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock, Robert Hopkins Jr., MD, noticed a woman bowled over in the front seat of her car.

A nurse practitioner had just informed her that she had met the criteria for undergoing testing for the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

“She was very upset and was crying nearly inconsolably,” said Dr. Hopkins, who directs the division of general internal medicine at the University of Arkansas Medical Sciences College of Medicine. “I went over and visited with her for a few minutes. She was scared to death that we [had] told her she was going to die. In her mind, if she had COVID-19 that meant a death sentence, and if we were testing her that meant she was likely to not survive.”

Dr. Hopkins tried his best to put testing in perspective for the woman. “At least she came to a level of comfort and realized that we were doing this for her, that this was not a death sentence, that this was not her fault,” he said. “She was worried about infecting her kids and her grandkids and ending up in the hospital and being a burden. Being able to spend that few minutes with her and help to bring down her level of anxiety – I think that’s where we need to put our efforts as physicians right now, helping people understand, ‘Yes, this is serious. Yes, we need to continue to social distance. Yes, we need to be cautious. But, we will get through this if we all work together to do so.’ ”

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Hopkins spent part of his time seeing patients in the university’s main hospital, but most of it in an outpatient clinic where he and about 20 other primary care physicians care for patients and precept medical residents. Now, medical residents have been deployed to other services, primarily in the hospital, and he and his physician colleagues are conducting 80%-90% of patient visits by video conferencing or by telephone. It’s a whole new world.

“We’ve gone from a relatively traditional inpatient/outpatient practice where we’re seeing patients face to face to doing some face-to-face visits, but an awful lot of what we do now is in the technology domain,” said Dr. Hopkins, who also assisted with health care relief efforts during hurricanes Rita and Katrina.

“A group of six of us has been redeployed to assist with the surge unit for the inpatient facility, so our outpatient duties are being taken on by some of our partners.”

He also pitches in at the drive-through COVID-19 screening clinic, which was set up on March 27 and operates between 8 a.m. and 8 p.m., 7 days a week. “We’re able to measure people’s temperature, take a quick screening history, decide whether their risk is such that we need to do a COVID-19 PCR [polymerase chain reaction] test,” he said. “Then we make a determination of whether they need to go home on quarantine awaiting those results, or if they don’t have anything that needs to be evaluated, or whether they need to be triaged to an urgent care setting or to the emergency department.”

To minimize his risk of acquiring COVID-19, he follows personal hygiene practices recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He also places his work shoes in a shoebox, which he keeps in his car. “I put them on when I get to the parking deck at work, do my work, and then I put them in the shoebox, slip on another pair of shoes and drive home so I’m not tracking in things I potentially had on me,” said Dr. Hopkins, who is married and a father to two college-aged sons and a daughter in fourth grade. “When I get home I immediately shower, and then I exercise or have dinner with my family.”

Despite the longer-than-usual work hours and upheaval to the traditional medical practice model brought on by the pandemic, Dr. Hopkins, a self-described “glass half full person,” said that he does his best to keep watch over his patients and colleagues. “I’m trying to keep an eye out on my team members – physicians, nurses, medical assistants, and folks at the front desk – trying to make sure that people are getting rest, trying to make sure that people are not overcommitting,” he said. “Because if we’re not all working together and working for the long term, we’re going to be in trouble. This is not going to be a sprint; this is going to be a marathon for us to get through.”

To keep mentally centered, he engages in at least 40 minutes of exercise each day on his bicycle or on the elliptical machine at home. Dr. Hopkins hopes that the current efforts to redeploy resources, expand clinician skill sets, and forge relationships with colleagues in other disciplines will carry over into the delivery of health care when COVID-19 is a distant memory. “I hope that some of those relationships are going to continue and result in better care for all of our patients,” he said.

"We are in dire need of hugs"

Typically, Dr. Dakkak, a family physician at Boston University, practices a mix of clinic-based family medicine and obstetrics, and works in inpatient medicine 6 weeks a year. Currently, she is leading a COVID-19 team full time at Boston Medical Center, a 300-bed safety-net hospital located on the campus of Boston University Medical Center.

COVID-19 has also shaken up her life at home.

When Dr. Dakkak volunteered to take on her new role, the first thing that came to her mind was how making the switch would affect the well-being of her 8-year-old son and 10-year-old daughter.

“I thought, ‘How do I get my children somewhere where I don’t have to worry about them?’ ” Dr. Dakkak said.

She floated the idea with her husband of flying their children out to stay with her recently retired parents, who live outside of Sacramento, Calif., until the pandemic eases up. “I was thinking to myself, ‘Am I overreacting? Is the pandemic not going to be that bad?’ because the rest of the country seemed to be in some amount of denial,” she said. “So, I called my dad, who’s a retired pediatric anesthesiologist. He’s from Egypt so he’s done crisis medicine in his time. He encouraged me to send the kids.”

On the same day that Dr. Dakkak began her first 12-hour COVID-19 shift at the hospital, her husband and children boarded a plane to California, where the kids remain in the care of her parents. Her husband returned after staying there for 2 weeks. “Every day when I’m working, I validate my decision,” she said. “When I first started, I worked 5 nights in a row, had 2 days off, and then worked 6 nights in a row. I was busy so I didn’t think about [being away from my kids], but at the same time I was grateful that I didn’t have to come home and worry about homeschooling the kids or infecting them.”

She checks in with them as she can via cell phone or FaceTime. “My son has been very honest,” Dr. Dakkak said. “He says, ‘FaceTime makes me miss you more, and I don’t like it,’ which I understand. I’ll call my mom, and if they want to talk to me, they’ll talk to me. If they don’t want to talk to me, I’m okay. This is about them being healthy and safe. I sent them a care package a few days ago with cards and some workbooks. I’m optimistic that in June I can at least see them if not bring them home.”

Dr. Dakkak describes leading a COVID-19 team as a grueling experience that challenges her medical know-how nearly every day, with seemingly ever-changing algorithms. “Our knowledge of this disease is five steps behind, and changing at lightning speed,” said Dr. Dakkak, who completed a fellowship in surgical and high-risk obstetrics. “It’s hard to balance continuing to teach evidence-based medicine for everything else in medicine [with continuing] to practice minimal and ever-changing evidence-based COVID medicine. We just don’t know enough [about the virus] yet. This is nothing like we were taught in medical school. Everyone has elevated d-dimers with COVID-19, and we don’t get CT pulmonary angiograms [CTPAs] on all of them; we wouldn’t physically be able to. Some patients have d-dimers in the thousands, and only some are stable to get CTPAs. We are also finding pulmonary embolisms. Now we’re basing our algorithm on anticoagulation due to d-dimers because sometimes you can’t always do a CTPA even if you want to. On the other hand, we have people who are coming into the hospital too late. We’ve had a few who have come in after having days of stroke symptoms. I worry about our patients at home who hesitate to come in when they really should.”

Sometimes she feels sad for the medical residents on her team because their instinct is to go in and check on each patient, “but I don’t want them to get exposed,” she said. “So, we check in by phone, or if they need a physical check-in, we minimize the check-ins; only one of us goes in. I’m more willing to put myself in the room than to put them in the room. I also feel for them because they came into medicine for the humanity of medicine – not the charting or the ordering of medicine. I also worry about the acuity and sadness they’re seeing. This is a rough introduction to medicine for them.”

When interviewed for this story in late April, Dr. Dakkak had kept track of her intubated COVID-19 patients. “Most of my patients get to go home without having been intubated, but those aren’t the ones I worry about,” she said. “I have two patients I have been watching. One of them has just been extubated and I’m still worried about him, but I’m hoping he’s going to be fine. The other one is the first pregnant woman we intubated. She is now extubated, doing really well, and went home. Her fetus is doing well, never had any issues while she was intubated. Those cases make me happy. They were both under the age of 35. It is nice to follow those intubations and find that the majority are doing okay.”

The first patient she had cared for who died was a young man “who was always in good spirits,” she recalled. “We called his brother right before intubating him. After intubation, his oxygen saturation didn’t jump up, which made me worry a bit.” About a week later, the young man died. “I kept thinking, ‘We intubated him when he was still comfortable talking. Should I have put it off and had him call more people to say goodbye? Should I have known that he wasn’t going to wake up?’ ” said Dr. Dakkak, who is also women’s health director at Manet Community Health Centers. “A lot of us have worked on our end-of-life discussions in the past month, just being able to tell somebody, ‘This might be your last time to call family. Call family and talk to whoever you want.’ Guilt isn’t the right word, but it’s unsettling if I’m the last person a patient talks to. I feel that, if that’s the case, then I didn’t do a good enough job trying to get them to their family or friends. If I am worried about a patient’s clinical status declining, I tell families now, when I call them, ‘I hope I’m wrong; I hope they don’t need to be intubated, but I think this is the time to talk.’ ”

To keep herself grounded during off hours, Dr. Dakkak spends time resting, checking in with her family, journaling “to get a lot of feelings out,” gardening, hiking, and joining Zoom chats with friends. Once recentered, she draws from a sense of obligation to others as she prepares for her next shift caring for COVID-19 patients.

“I have a lot of love for the world that I get to expend by doing this hard work,” she said. “I love humanity and I love humanity in times of crisis. The interactions I have with patients and their families are still central to why I do this work. I love my medical teams, and I would never want to let them down. It is nice to feel the sense of teamwork across the hospital. The nurses that I sit with and experience this with are amazing. I keep saying that the only thing I want to do when this pandemic is over is hug everyone. I think we are in dire need of hugs.”

Finding light in the darkness

Internist Katie Jobbins, DO, also has worked in a professional role that was created because of COVID-19.

Shortly before Dr. Jobbins was deployed to Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Ma., for 2 weeks in April of 2020 to help clinicians with an anticipated surge of COVID-19 cases, she encountered a patient who walked into Baystate’s High Street Health Center.

“I think I have COVID-19,” the patient proclaimed to her, at the outpatient clinic that serves mostly inner-city, Medicaid patients.

Prior to becoming an ambulatory internist, Dr. Jobbins was a surgical resident. “So I went into that mode of ‘I need to do this, this, and this,’ ” she said. “I went through a checklist in my head to make sure I was prepared to take care of the patient.”

She applied that same systems approach during her redeployment assignment in the tertiary care hospital, which typically involved 10-hour shifts overseeing internal medicine residents in a medical telemetry unit. “We would take care of people under investigation for COVID-19, but we were not assigned to the actual COVID unit,” said Dr. Jobbins, who is also associate program director for the internal medicine residency program at the University of Massachusetts Medical School–Baystate Springfield. “They tried to redeploy other people to those units who had special training, and we were trying to back fill into where those people that got moved to the COVID units or the ICU units were actually working. We were taking more of the medical side of the floors.”

Even so, one patient on the unit was suspected of having COVID-19, so Dr. Jobbins suited up with personal protective equipment and conducted a thorough exam with residents waiting outside the patient’s room, a safe distance away. “I explained everything I found on the exam to the residents, trying to give them some educational benefit, even though they couldn’t physically examine the patient because we’re trying to protect them since they’re in training,” she said. “It was anxiety provoking, on some level, knowing that there’s a potential risk of exposure [to the virus], but knowing that Baystate Health has gone to extraordinary measures to make sure we have the correct PPE and support us is reassuring. I knew I had the right equipment and the right tools to take care of the patient, which calmed my nerves and made me feel like I could do the job. That’s the most important thing as a physician during this time: knowing that you have people supporting you who have your back at all times.”

Like Dr. Dakkak, Dr. Jobbins had to make some adjustments to her interaction with her family.

Before she began the deployment, Dr. Jobbins engaged in a frank discussion with her husband and her two young boys about the risks she faced working in a hospital caring for patients with COVID-19. “My husband and I made sure our wills were up to date, and we talked about what we would do if either of us got the virus,” she said. To minimize the potential risk of transmitting the virus to her loved ones during the two-week deployment, she considered living away from her family in a nearby home owned by her father, but decided against that and to “take it day by day.” Following her hospital shifts, Dr. Jobbins changed into a fresh set of clothes before leaving the hospital. Once she arrived home, she showered to reduce the risk of possibly becoming a vector to her family.

She had to tell her kids: “You can’t kiss me right now.”

“As much as it’s hard for them to understand, we had a conversation [in which I explained] ‘This is a virus. It will go away eventually, but it’s a virus we’re fighting.’ It’s interesting to watch a 3-year-old try to process that and take his play samurai sword or Marvel toys and decide he’s going to run around the neighborhood and try to kill the virus.”

At the High Street Health Center, Dr. Jobbins and her colleagues have transitioned to conducting most patient encounters via telephone or video appointments. “We have tried to maintain as much continuity for our patients to address their chronic medical needs through these visits, such as hypertension management and diabetes care,” she said. “We have begun a rigorous screening process to triage and treat patients suspicious for COVID-19 through telehealth in hopes of keeping them safe and in their own homes. We also continue to see patients for nonrespiratory urgent care needs in person once they have screened negative for COVID-19.”

“In terms of the inpatient setting, we’ve noticed that a lot of people are choosing not to go to the hospital now, unless they’re extremely ill,” Dr. Jobbins noted. “We’re going to need to find a balance with when do people truly need to go to the hospital and when do they not? What can we manage as an outpatient versus having someone go to the emergency department? That’s really the role of the primary care physician. We need to help people understand, ‘You don’t need to go to the ED for everything, but here are the things you really need to go for.’ ”

“It will be interesting to see what health care looks like in 6 months or a year. I’m excited to see where we land,” Dr. Jobbins added.

Hopes for the Future of Telemedicine

When the practice of medicine enters a post–COVID-19 era, Dr. Jobbins hopes that telemedicine will be incorporated more into the delivery of patient care. “I’ve found that many of my patients who often are no-shows to the inpatient version of their visits have had a higher success rate of follow-through when we do the telephone visits,” she said. “It’s been very successful. I hope that the insurance companies and [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid] will continue to reimburse this as they see this is a benefit to our patients.

Dr. Hopkins is also hopeful that physicians will be able to successfully see patients via telemedicine in the postpandemic world.

“For the ups and downs we’ve had with telemedicine, I’d love for us to be able to enhance the positives and incorporate that into our practice going forward. If we can reach our patients and help treat them where they are, rather than them having to come to us, that may be a plus,” he said.

In the meantime, Dr. Jobbins presses on as the curve of COVID-19 cases flattens in Western Massachusetts and remains grateful that she chose to practice medicine.

“The commitment I have to being an educator in addition to being a physician is part of why I keep doing this,” Dr. Jobbins said. “I find this to be one of the most fulfilling jobs and careers you could ever have: being there for people when they need you the most. That’s really what a physician’s job is: being there for people when a family member has passed away or when they just need to talk because they’re having anxiety. At the end of the day, if we can impart that to those we work with and bring in a positive attitude, it’s infectious and it makes people see this is a reason we keep doing what we’re doing.”

She’s also been heartened by the kindness of strangers during this pandemic, from those who made and donated face shields when they were in short supply, to those who delivered food to the hospital as a gesture of thanks.

“I had a patient who made homemade masks and sent them to my office,” she said. “There’s obviously good and bad during this time, but I get hope from seeing all of the good things that are coming out of this, the whole idea of finding the light in the darkness.”

During his shift at a COVID-19 drive-through triage screening area set up outside the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock, Robert Hopkins Jr., MD, noticed a woman bowled over in the front seat of her car.

A nurse practitioner had just informed her that she had met the criteria for undergoing testing for the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

“She was very upset and was crying nearly inconsolably,” said Dr. Hopkins, who directs the division of general internal medicine at the University of Arkansas Medical Sciences College of Medicine. “I went over and visited with her for a few minutes. She was scared to death that we [had] told her she was going to die. In her mind, if she had COVID-19 that meant a death sentence, and if we were testing her that meant she was likely to not survive.”

Dr. Hopkins tried his best to put testing in perspective for the woman. “At least she came to a level of comfort and realized that we were doing this for her, that this was not a death sentence, that this was not her fault,” he said. “She was worried about infecting her kids and her grandkids and ending up in the hospital and being a burden. Being able to spend that few minutes with her and help to bring down her level of anxiety – I think that’s where we need to put our efforts as physicians right now, helping people understand, ‘Yes, this is serious. Yes, we need to continue to social distance. Yes, we need to be cautious. But, we will get through this if we all work together to do so.’ ”

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Hopkins spent part of his time seeing patients in the university’s main hospital, but most of it in an outpatient clinic where he and about 20 other primary care physicians care for patients and precept medical residents. Now, medical residents have been deployed to other services, primarily in the hospital, and he and his physician colleagues are conducting 80%-90% of patient visits by video conferencing or by telephone. It’s a whole new world.

“We’ve gone from a relatively traditional inpatient/outpatient practice where we’re seeing patients face to face to doing some face-to-face visits, but an awful lot of what we do now is in the technology domain,” said Dr. Hopkins, who also assisted with health care relief efforts during hurricanes Rita and Katrina.

“A group of six of us has been redeployed to assist with the surge unit for the inpatient facility, so our outpatient duties are being taken on by some of our partners.”

He also pitches in at the drive-through COVID-19 screening clinic, which was set up on March 27 and operates between 8 a.m. and 8 p.m., 7 days a week. “We’re able to measure people’s temperature, take a quick screening history, decide whether their risk is such that we need to do a COVID-19 PCR [polymerase chain reaction] test,” he said. “Then we make a determination of whether they need to go home on quarantine awaiting those results, or if they don’t have anything that needs to be evaluated, or whether they need to be triaged to an urgent care setting or to the emergency department.”

To minimize his risk of acquiring COVID-19, he follows personal hygiene practices recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He also places his work shoes in a shoebox, which he keeps in his car. “I put them on when I get to the parking deck at work, do my work, and then I put them in the shoebox, slip on another pair of shoes and drive home so I’m not tracking in things I potentially had on me,” said Dr. Hopkins, who is married and a father to two college-aged sons and a daughter in fourth grade. “When I get home I immediately shower, and then I exercise or have dinner with my family.”

Despite the longer-than-usual work hours and upheaval to the traditional medical practice model brought on by the pandemic, Dr. Hopkins, a self-described “glass half full person,” said that he does his best to keep watch over his patients and colleagues. “I’m trying to keep an eye out on my team members – physicians, nurses, medical assistants, and folks at the front desk – trying to make sure that people are getting rest, trying to make sure that people are not overcommitting,” he said. “Because if we’re not all working together and working for the long term, we’re going to be in trouble. This is not going to be a sprint; this is going to be a marathon for us to get through.”

To keep mentally centered, he engages in at least 40 minutes of exercise each day on his bicycle or on the elliptical machine at home. Dr. Hopkins hopes that the current efforts to redeploy resources, expand clinician skill sets, and forge relationships with colleagues in other disciplines will carry over into the delivery of health care when COVID-19 is a distant memory. “I hope that some of those relationships are going to continue and result in better care for all of our patients,” he said.

"We are in dire need of hugs"

Typically, Dr. Dakkak, a family physician at Boston University, practices a mix of clinic-based family medicine and obstetrics, and works in inpatient medicine 6 weeks a year. Currently, she is leading a COVID-19 team full time at Boston Medical Center, a 300-bed safety-net hospital located on the campus of Boston University Medical Center.

COVID-19 has also shaken up her life at home.

When Dr. Dakkak volunteered to take on her new role, the first thing that came to her mind was how making the switch would affect the well-being of her 8-year-old son and 10-year-old daughter.

“I thought, ‘How do I get my children somewhere where I don’t have to worry about them?’ ” Dr. Dakkak said.

She floated the idea with her husband of flying their children out to stay with her recently retired parents, who live outside of Sacramento, Calif., until the pandemic eases up. “I was thinking to myself, ‘Am I overreacting? Is the pandemic not going to be that bad?’ because the rest of the country seemed to be in some amount of denial,” she said. “So, I called my dad, who’s a retired pediatric anesthesiologist. He’s from Egypt so he’s done crisis medicine in his time. He encouraged me to send the kids.”

On the same day that Dr. Dakkak began her first 12-hour COVID-19 shift at the hospital, her husband and children boarded a plane to California, where the kids remain in the care of her parents. Her husband returned after staying there for 2 weeks. “Every day when I’m working, I validate my decision,” she said. “When I first started, I worked 5 nights in a row, had 2 days off, and then worked 6 nights in a row. I was busy so I didn’t think about [being away from my kids], but at the same time I was grateful that I didn’t have to come home and worry about homeschooling the kids or infecting them.”

She checks in with them as she can via cell phone or FaceTime. “My son has been very honest,” Dr. Dakkak said. “He says, ‘FaceTime makes me miss you more, and I don’t like it,’ which I understand. I’ll call my mom, and if they want to talk to me, they’ll talk to me. If they don’t want to talk to me, I’m okay. This is about them being healthy and safe. I sent them a care package a few days ago with cards and some workbooks. I’m optimistic that in June I can at least see them if not bring them home.”

Dr. Dakkak describes leading a COVID-19 team as a grueling experience that challenges her medical know-how nearly every day, with seemingly ever-changing algorithms. “Our knowledge of this disease is five steps behind, and changing at lightning speed,” said Dr. Dakkak, who completed a fellowship in surgical and high-risk obstetrics. “It’s hard to balance continuing to teach evidence-based medicine for everything else in medicine [with continuing] to practice minimal and ever-changing evidence-based COVID medicine. We just don’t know enough [about the virus] yet. This is nothing like we were taught in medical school. Everyone has elevated d-dimers with COVID-19, and we don’t get CT pulmonary angiograms [CTPAs] on all of them; we wouldn’t physically be able to. Some patients have d-dimers in the thousands, and only some are stable to get CTPAs. We are also finding pulmonary embolisms. Now we’re basing our algorithm on anticoagulation due to d-dimers because sometimes you can’t always do a CTPA even if you want to. On the other hand, we have people who are coming into the hospital too late. We’ve had a few who have come in after having days of stroke symptoms. I worry about our patients at home who hesitate to come in when they really should.”

Sometimes she feels sad for the medical residents on her team because their instinct is to go in and check on each patient, “but I don’t want them to get exposed,” she said. “So, we check in by phone, or if they need a physical check-in, we minimize the check-ins; only one of us goes in. I’m more willing to put myself in the room than to put them in the room. I also feel for them because they came into medicine for the humanity of medicine – not the charting or the ordering of medicine. I also worry about the acuity and sadness they’re seeing. This is a rough introduction to medicine for them.”

When interviewed for this story in late April, Dr. Dakkak had kept track of her intubated COVID-19 patients. “Most of my patients get to go home without having been intubated, but those aren’t the ones I worry about,” she said. “I have two patients I have been watching. One of them has just been extubated and I’m still worried about him, but I’m hoping he’s going to be fine. The other one is the first pregnant woman we intubated. She is now extubated, doing really well, and went home. Her fetus is doing well, never had any issues while she was intubated. Those cases make me happy. They were both under the age of 35. It is nice to follow those intubations and find that the majority are doing okay.”

The first patient she had cared for who died was a young man “who was always in good spirits,” she recalled. “We called his brother right before intubating him. After intubation, his oxygen saturation didn’t jump up, which made me worry a bit.” About a week later, the young man died. “I kept thinking, ‘We intubated him when he was still comfortable talking. Should I have put it off and had him call more people to say goodbye? Should I have known that he wasn’t going to wake up?’ ” said Dr. Dakkak, who is also women’s health director at Manet Community Health Centers. “A lot of us have worked on our end-of-life discussions in the past month, just being able to tell somebody, ‘This might be your last time to call family. Call family and talk to whoever you want.’ Guilt isn’t the right word, but it’s unsettling if I’m the last person a patient talks to. I feel that, if that’s the case, then I didn’t do a good enough job trying to get them to their family or friends. If I am worried about a patient’s clinical status declining, I tell families now, when I call them, ‘I hope I’m wrong; I hope they don’t need to be intubated, but I think this is the time to talk.’ ”

To keep herself grounded during off hours, Dr. Dakkak spends time resting, checking in with her family, journaling “to get a lot of feelings out,” gardening, hiking, and joining Zoom chats with friends. Once recentered, she draws from a sense of obligation to others as she prepares for her next shift caring for COVID-19 patients.

“I have a lot of love for the world that I get to expend by doing this hard work,” she said. “I love humanity and I love humanity in times of crisis. The interactions I have with patients and their families are still central to why I do this work. I love my medical teams, and I would never want to let them down. It is nice to feel the sense of teamwork across the hospital. The nurses that I sit with and experience this with are amazing. I keep saying that the only thing I want to do when this pandemic is over is hug everyone. I think we are in dire need of hugs.”

Finding light in the darkness

Internist Katie Jobbins, DO, also has worked in a professional role that was created because of COVID-19.

Shortly before Dr. Jobbins was deployed to Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Ma., for 2 weeks in April of 2020 to help clinicians with an anticipated surge of COVID-19 cases, she encountered a patient who walked into Baystate’s High Street Health Center.

“I think I have COVID-19,” the patient proclaimed to her, at the outpatient clinic that serves mostly inner-city, Medicaid patients.

Prior to becoming an ambulatory internist, Dr. Jobbins was a surgical resident. “So I went into that mode of ‘I need to do this, this, and this,’ ” she said. “I went through a checklist in my head to make sure I was prepared to take care of the patient.”

She applied that same systems approach during her redeployment assignment in the tertiary care hospital, which typically involved 10-hour shifts overseeing internal medicine residents in a medical telemetry unit. “We would take care of people under investigation for COVID-19, but we were not assigned to the actual COVID unit,” said Dr. Jobbins, who is also associate program director for the internal medicine residency program at the University of Massachusetts Medical School–Baystate Springfield. “They tried to redeploy other people to those units who had special training, and we were trying to back fill into where those people that got moved to the COVID units or the ICU units were actually working. We were taking more of the medical side of the floors.”

Even so, one patient on the unit was suspected of having COVID-19, so Dr. Jobbins suited up with personal protective equipment and conducted a thorough exam with residents waiting outside the patient’s room, a safe distance away. “I explained everything I found on the exam to the residents, trying to give them some educational benefit, even though they couldn’t physically examine the patient because we’re trying to protect them since they’re in training,” she said. “It was anxiety provoking, on some level, knowing that there’s a potential risk of exposure [to the virus], but knowing that Baystate Health has gone to extraordinary measures to make sure we have the correct PPE and support us is reassuring. I knew I had the right equipment and the right tools to take care of the patient, which calmed my nerves and made me feel like I could do the job. That’s the most important thing as a physician during this time: knowing that you have people supporting you who have your back at all times.”

Like Dr. Dakkak, Dr. Jobbins had to make some adjustments to her interaction with her family.

Before she began the deployment, Dr. Jobbins engaged in a frank discussion with her husband and her two young boys about the risks she faced working in a hospital caring for patients with COVID-19. “My husband and I made sure our wills were up to date, and we talked about what we would do if either of us got the virus,” she said. To minimize the potential risk of transmitting the virus to her loved ones during the two-week deployment, she considered living away from her family in a nearby home owned by her father, but decided against that and to “take it day by day.” Following her hospital shifts, Dr. Jobbins changed into a fresh set of clothes before leaving the hospital. Once she arrived home, she showered to reduce the risk of possibly becoming a vector to her family.

She had to tell her kids: “You can’t kiss me right now.”

“As much as it’s hard for them to understand, we had a conversation [in which I explained] ‘This is a virus. It will go away eventually, but it’s a virus we’re fighting.’ It’s interesting to watch a 3-year-old try to process that and take his play samurai sword or Marvel toys and decide he’s going to run around the neighborhood and try to kill the virus.”

At the High Street Health Center, Dr. Jobbins and her colleagues have transitioned to conducting most patient encounters via telephone or video appointments. “We have tried to maintain as much continuity for our patients to address their chronic medical needs through these visits, such as hypertension management and diabetes care,” she said. “We have begun a rigorous screening process to triage and treat patients suspicious for COVID-19 through telehealth in hopes of keeping them safe and in their own homes. We also continue to see patients for nonrespiratory urgent care needs in person once they have screened negative for COVID-19.”

“In terms of the inpatient setting, we’ve noticed that a lot of people are choosing not to go to the hospital now, unless they’re extremely ill,” Dr. Jobbins noted. “We’re going to need to find a balance with when do people truly need to go to the hospital and when do they not? What can we manage as an outpatient versus having someone go to the emergency department? That’s really the role of the primary care physician. We need to help people understand, ‘You don’t need to go to the ED for everything, but here are the things you really need to go for.’ ”

“It will be interesting to see what health care looks like in 6 months or a year. I’m excited to see where we land,” Dr. Jobbins added.

Hopes for the Future of Telemedicine

When the practice of medicine enters a post–COVID-19 era, Dr. Jobbins hopes that telemedicine will be incorporated more into the delivery of patient care. “I’ve found that many of my patients who often are no-shows to the inpatient version of their visits have had a higher success rate of follow-through when we do the telephone visits,” she said. “It’s been very successful. I hope that the insurance companies and [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid] will continue to reimburse this as they see this is a benefit to our patients.

Dr. Hopkins is also hopeful that physicians will be able to successfully see patients via telemedicine in the postpandemic world.

“For the ups and downs we’ve had with telemedicine, I’d love for us to be able to enhance the positives and incorporate that into our practice going forward. If we can reach our patients and help treat them where they are, rather than them having to come to us, that may be a plus,” he said.

In the meantime, Dr. Jobbins presses on as the curve of COVID-19 cases flattens in Western Massachusetts and remains grateful that she chose to practice medicine.

“The commitment I have to being an educator in addition to being a physician is part of why I keep doing this,” Dr. Jobbins said. “I find this to be one of the most fulfilling jobs and careers you could ever have: being there for people when they need you the most. That’s really what a physician’s job is: being there for people when a family member has passed away or when they just need to talk because they’re having anxiety. At the end of the day, if we can impart that to those we work with and bring in a positive attitude, it’s infectious and it makes people see this is a reason we keep doing what we’re doing.”

She’s also been heartened by the kindness of strangers during this pandemic, from those who made and donated face shields when they were in short supply, to those who delivered food to the hospital as a gesture of thanks.

“I had a patient who made homemade masks and sent them to my office,” she said. “There’s obviously good and bad during this time, but I get hope from seeing all of the good things that are coming out of this, the whole idea of finding the light in the darkness.”

Use of cannabinoids in dermatology here to stay

In the clinical opinion of .

“There’s no question in my mind about that. Don’t play catch-up; be at the forefront, because at a minimum your patients are going to ask you about this,” he said in a video presentation during a virtual meeting held by the George Washington University department of dermatology.