User login

Sodium fluorescein emerges as alternative to indigo carmine in cystoscopy

WASHINGTON – Sodium fluorescein is proving to be an excellent agent for helping to verify ureteral efflux during intraoperative cystoscopy, Dr. Jay Goldberg said at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Dr. Goldberg said he first read about the use of the dye as an alternative to indigo carmine, which is no longer available, in a study published in 2015; the study reported good results with a 10% preparation of sodium fluorescein administered at 0.25-1 mL intravenously during intraoperative cystoscopy (Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar;125[3]:548-50).

Since then, he and his colleagues at Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia, have been evaluating the use of 0.1 mL of 10% sodium fluorescein IV during cystoscopies performed at the end of gynecologic surgeries, measuring the time to visualization and the level of satisfaction with the dye.

Thus far, in more than 50 cases, the average time until colored ureteral jets were seen has been 4.3 minutes (a range of 2-6.8 minutes, consistent with the 2015 study). And according to questionnaires completed by each surgeon, the degree of certainty for visualizing the ureteral jets was improved with fluorescein (a rating of 5 on a 5-point scale, compared with 2.9 without the dye).

Compared with both indigo carmine and methylene blue, fluorescein was preferred, Dr. Goldberg reported, with surgeons citing quicker onset, better color contrast, cheaper cost, and fewer side effects.

“Given that it’s at least equivalent and probably better, and that it’s 50 times cheaper [than indigo carmine], even if indigo carmine comes back again, I’m certainly not going to be switching back,” Dr. Goldberg said during a seminar on cystoscopy after hysterectomy.

Intravenous sodium fluorescein is routinely used in ophthalmology in retinal angiography, at a dosage of 5 mL of 10% fluorescein, he said. The most common complications reported in the literature are nausea, vomiting, and flushing or rash (rates of 2.9%, 1.2%, and 0.5%, respectively, according to a 1991 report). None of their patients has experienced any complications, Dr. Goldberg said.

Methylene blue (50 mg IV over a period of 5 minutes) appears to have been a common go-to dye for gynecologic surgeons, along with pyridium (a 200-mg oral dose prior to surgery), ever since production of indigo carmine was discontinued because of a lack of raw material.

“But with methylene blue, it may take longer to see the blue urine efflux from the ureteral orifices,” Dr. Goldberg said. And with pyridium, “by the time cystoscopy is performed, the bladder will have already been stained orange, making it more difficult to see the same colored urine jets.”

“Sodium fluorescein is very quick in onset. I wait [to have it administered] until I am actually ready to insert the cystoscope,” he said.

And at 60 cents per dose, fluorescein is less expensive than methylene blue ($1.50) and significantly less expensive than indigo carmine ($30 a dose), he said.

Dr. Goldberg reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

WASHINGTON – Sodium fluorescein is proving to be an excellent agent for helping to verify ureteral efflux during intraoperative cystoscopy, Dr. Jay Goldberg said at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Dr. Goldberg said he first read about the use of the dye as an alternative to indigo carmine, which is no longer available, in a study published in 2015; the study reported good results with a 10% preparation of sodium fluorescein administered at 0.25-1 mL intravenously during intraoperative cystoscopy (Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar;125[3]:548-50).

Since then, he and his colleagues at Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia, have been evaluating the use of 0.1 mL of 10% sodium fluorescein IV during cystoscopies performed at the end of gynecologic surgeries, measuring the time to visualization and the level of satisfaction with the dye.

Thus far, in more than 50 cases, the average time until colored ureteral jets were seen has been 4.3 minutes (a range of 2-6.8 minutes, consistent with the 2015 study). And according to questionnaires completed by each surgeon, the degree of certainty for visualizing the ureteral jets was improved with fluorescein (a rating of 5 on a 5-point scale, compared with 2.9 without the dye).

Compared with both indigo carmine and methylene blue, fluorescein was preferred, Dr. Goldberg reported, with surgeons citing quicker onset, better color contrast, cheaper cost, and fewer side effects.

“Given that it’s at least equivalent and probably better, and that it’s 50 times cheaper [than indigo carmine], even if indigo carmine comes back again, I’m certainly not going to be switching back,” Dr. Goldberg said during a seminar on cystoscopy after hysterectomy.

Intravenous sodium fluorescein is routinely used in ophthalmology in retinal angiography, at a dosage of 5 mL of 10% fluorescein, he said. The most common complications reported in the literature are nausea, vomiting, and flushing or rash (rates of 2.9%, 1.2%, and 0.5%, respectively, according to a 1991 report). None of their patients has experienced any complications, Dr. Goldberg said.

Methylene blue (50 mg IV over a period of 5 minutes) appears to have been a common go-to dye for gynecologic surgeons, along with pyridium (a 200-mg oral dose prior to surgery), ever since production of indigo carmine was discontinued because of a lack of raw material.

“But with methylene blue, it may take longer to see the blue urine efflux from the ureteral orifices,” Dr. Goldberg said. And with pyridium, “by the time cystoscopy is performed, the bladder will have already been stained orange, making it more difficult to see the same colored urine jets.”

“Sodium fluorescein is very quick in onset. I wait [to have it administered] until I am actually ready to insert the cystoscope,” he said.

And at 60 cents per dose, fluorescein is less expensive than methylene blue ($1.50) and significantly less expensive than indigo carmine ($30 a dose), he said.

Dr. Goldberg reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

WASHINGTON – Sodium fluorescein is proving to be an excellent agent for helping to verify ureteral efflux during intraoperative cystoscopy, Dr. Jay Goldberg said at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Dr. Goldberg said he first read about the use of the dye as an alternative to indigo carmine, which is no longer available, in a study published in 2015; the study reported good results with a 10% preparation of sodium fluorescein administered at 0.25-1 mL intravenously during intraoperative cystoscopy (Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar;125[3]:548-50).

Since then, he and his colleagues at Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia, have been evaluating the use of 0.1 mL of 10% sodium fluorescein IV during cystoscopies performed at the end of gynecologic surgeries, measuring the time to visualization and the level of satisfaction with the dye.

Thus far, in more than 50 cases, the average time until colored ureteral jets were seen has been 4.3 minutes (a range of 2-6.8 minutes, consistent with the 2015 study). And according to questionnaires completed by each surgeon, the degree of certainty for visualizing the ureteral jets was improved with fluorescein (a rating of 5 on a 5-point scale, compared with 2.9 without the dye).

Compared with both indigo carmine and methylene blue, fluorescein was preferred, Dr. Goldberg reported, with surgeons citing quicker onset, better color contrast, cheaper cost, and fewer side effects.

“Given that it’s at least equivalent and probably better, and that it’s 50 times cheaper [than indigo carmine], even if indigo carmine comes back again, I’m certainly not going to be switching back,” Dr. Goldberg said during a seminar on cystoscopy after hysterectomy.

Intravenous sodium fluorescein is routinely used in ophthalmology in retinal angiography, at a dosage of 5 mL of 10% fluorescein, he said. The most common complications reported in the literature are nausea, vomiting, and flushing or rash (rates of 2.9%, 1.2%, and 0.5%, respectively, according to a 1991 report). None of their patients has experienced any complications, Dr. Goldberg said.

Methylene blue (50 mg IV over a period of 5 minutes) appears to have been a common go-to dye for gynecologic surgeons, along with pyridium (a 200-mg oral dose prior to surgery), ever since production of indigo carmine was discontinued because of a lack of raw material.

“But with methylene blue, it may take longer to see the blue urine efflux from the ureteral orifices,” Dr. Goldberg said. And with pyridium, “by the time cystoscopy is performed, the bladder will have already been stained orange, making it more difficult to see the same colored urine jets.”

“Sodium fluorescein is very quick in onset. I wait [to have it administered] until I am actually ready to insert the cystoscope,” he said.

And at 60 cents per dose, fluorescein is less expensive than methylene blue ($1.50) and significantly less expensive than indigo carmine ($30 a dose), he said.

Dr. Goldberg reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

AT ACOG 2016

Key clinical point: Sodium fluorescein is an effective, and possibly superior, alternative to the unavailable indigo carmine.Major finding: In more than 50 cases of intraoperative cystoscopy, the average time from intravenous administration of the dye to visualization of colored ureteral jets has been 4.3 minutes.

Data source: An observational study of more than 50 cystoscopies.

Disclosures: Dr. Goldberg and his colleagues reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

Cystoscopy after hysterectomy: Consider more frequent use

WASHINGTON – Universal cystoscopy at the time of hysterectomy – or at least more frequent use of the procedure – is worth considering since delayed diagnosis of urinary tract injury causes increased morbidity for patients, and in all likelihood increases litigation, Dr. Jay Goldberg and Dr. Cheung Kim suggested at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“We’re often hesitant to do cystoscopy because we don’t want to add time,” said Dr. Kim. “But I always feel that no matter how much time it takes, I’ll be happier in the end if I do it. [And] if you have [experience], a routine, and readily available equipment, it can take as little as 10 minutes.”

Universal cystoscopy to confirm ureteral patency is “fairly straightforward, low risk, and more likely to detect most injuries [than visual inspection alone], particularly ureteral injuries,” Dr. Kim said. On the other hand, it adds to operating time and increases procedure cost, and there is some research suggesting it may be relatively “low yield” and lead to some false positives.

Dr. Kim and Dr. Goldberg both practice at the Einstein Healthcare Network in Philadelphia. Here are some of the findings they shared, and advice they gave, on the use of cystoscopy – universal or selective – after hysterectomy.

Conflicting findings

There is conflicting opinion as to whether universal or selective cystoscopy after hysterectomy is best, and “there’s data on both sides,” said Dr. Goldberg, vice chairman of ob.gyn. and director of the Philadelphia Fibroid Center at Einstein.

A prospective study done at Louisiana State University, New Orleans, to evaluate the impact of a universal approach, for instance, showed an incidence of urinary tract injury of 4.3% (2.9% bladder injury, 1.8% ureteral injury, plus cases of simultaneous injury) in 839 hysterectomies for benign disease. The injury detection rate using intraoperative cystoscopy was 97.4%, and the majority of injuries – 76% – were not suspected prior to cystoscopy being performed (Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Jan;113[1]:6-10).

But researchers in Boston who looked retrospectively at 1,982 hysterectomies performed for any gynecologic indication found a much lower incidence of complications, and reported that cystoscopy did not detect any of the bladder injuries (0.71%) or ureteral injuries (0.25%) incurred in the group. Cystoscopy was performed selectively, however, in 250 of the patients, and was either normal or omitted in the patients who had complications (Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Dec;120[6]:1363-70).

Cystoscopy failed to detect any of the bladder injuries, but “all five of the ureteral injuries occurred in patients who had not undergone cystoscopy,” said Dr. Kim, chairman of ob.gyn. at Einstein Medical Center Montgomery in East Norriton, Pa.

Possible false-positives

Cystoscopy may lead on occasion to an incorrect presumption of a ureteral injury in patients with a pre-existing nonfunctional kidney, Dr. Goldberg noted.

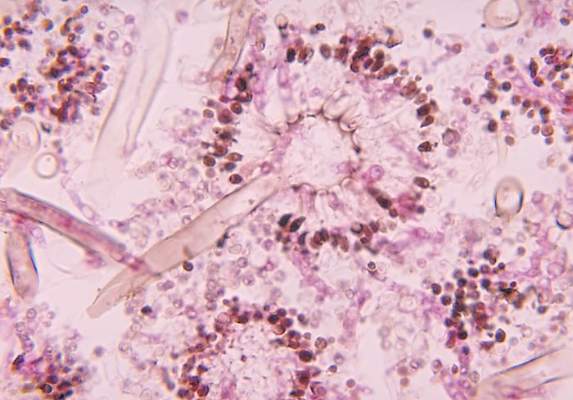

He relayed the case of a 42-year-old patient who underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy without apparent complication. Cystoscopy was then performed with indigo carmine. An efflux of dye was seen from the left ureteral orifice but not from the right orifice.

Urology was consulted and investigated the presumed ureteral injury with additional surgical exploration. An intraoperative intravenous pyelogram (IVP) was eventually performed and was unable to identify the right kidney. A CT then showed an atrophic right kidney with compensatory hypertrophy of the left kidney, probably due to congenital right multicystic dysplastic kidney.

An estimated 0.2% of the population – 1 in 500 – will have a unilateral nonfunctional kidney, the majority of which have not been previously diagnosed. Etiologies include multicystic dysplastic kidney, congenital unilateral renal agenesis, and vascular events. “As we do more and more cystoscopies, this scenario is going to come up every so often,” said Dr. Goldberg, who reported on two such cases last year (Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Sep;126[3]:635-7).

It is also possible, Dr. Kim noted, that a weak urine jet observed on cystoscopy may not necessarily reflect injury. In the LSU study evaluating a universal approach, there was no injury detected on further evaluation in each of the 21 cases of low, subnormal dye efflux from the ureteral orifices. “So it’s not a benign process to undergo cystoscopy in terms of what the ramifications might be,” Dr. Kim said.

Increasing use

Ob.gyn. residents are required by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education to have completed 15 cystoscopies by the time they graduate, and according to recent survey findings, residents are more likely to utilize universal cystoscopy at the time of hysterectomy than currently practicing gynecologic surgeons.

The survey of ob.gyn residents (n = 56) shows universal cystoscopy (defined as greater than 90%) was performed in only a minority of cases during residency: 27% of total laparoscopic hysterectomies (TLH), 14% of laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomies (LAVH), 12% of vaginal hysterectomies (VH), 2% of total abdominal hysterectomies (TAH), and 0% of supracervical hysterectomies (SCH), for instance.

Yet for every hysterectomy type, residents planned to perform universal cystoscopy post-residency more often than they had during their training (49% TLH, 34% LAVH, 34% VH, 15% TAH, 12% SCH), and “residents familiar with the literature on cystoscopy were statistically more likely to plan to perform universal cystoscopy,” said Dr. Goldberg, the senior author of the paper (Womens Health (Lond Engl). 2015 Nov;11[6]:825-31).

Litigation possible

Failure to detect a urinary tract injury at the time of hysterectomy may result in the need for future additional surgeries. Litigation in the Philadelphia market suggests that “if you have an injury that’s missed, there’s a chance that litigation may result,” Dr. Kim said.

Plaintiff’s attorneys have argued that not recognizing ureteral injury during surgery is a deviation from acceptable practice, while defense attorneys have contended that unavoidable complications occur and that no evaluation is required, or supported by the medical literature, when injury is not intraoperatively suspected. Currently, as cystoscopy is performed less than 25% of the time for all types of hysterectomy, the standard of care does not require the procedure intraoperatively if no injury is suspected, Dr. Goldberg said.

Primary prevention of urinary tract injury is most important, both physicians emphasized. The best way to accomplish this is to meticulously identify the anatomy and know the path of the ureter, and to document that the ureter has been identified and viewed as outside of the operative area, they said.

Dr. Kim and Dr. Goldberg reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – Universal cystoscopy at the time of hysterectomy – or at least more frequent use of the procedure – is worth considering since delayed diagnosis of urinary tract injury causes increased morbidity for patients, and in all likelihood increases litigation, Dr. Jay Goldberg and Dr. Cheung Kim suggested at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“We’re often hesitant to do cystoscopy because we don’t want to add time,” said Dr. Kim. “But I always feel that no matter how much time it takes, I’ll be happier in the end if I do it. [And] if you have [experience], a routine, and readily available equipment, it can take as little as 10 minutes.”

Universal cystoscopy to confirm ureteral patency is “fairly straightforward, low risk, and more likely to detect most injuries [than visual inspection alone], particularly ureteral injuries,” Dr. Kim said. On the other hand, it adds to operating time and increases procedure cost, and there is some research suggesting it may be relatively “low yield” and lead to some false positives.

Dr. Kim and Dr. Goldberg both practice at the Einstein Healthcare Network in Philadelphia. Here are some of the findings they shared, and advice they gave, on the use of cystoscopy – universal or selective – after hysterectomy.

Conflicting findings

There is conflicting opinion as to whether universal or selective cystoscopy after hysterectomy is best, and “there’s data on both sides,” said Dr. Goldberg, vice chairman of ob.gyn. and director of the Philadelphia Fibroid Center at Einstein.

A prospective study done at Louisiana State University, New Orleans, to evaluate the impact of a universal approach, for instance, showed an incidence of urinary tract injury of 4.3% (2.9% bladder injury, 1.8% ureteral injury, plus cases of simultaneous injury) in 839 hysterectomies for benign disease. The injury detection rate using intraoperative cystoscopy was 97.4%, and the majority of injuries – 76% – were not suspected prior to cystoscopy being performed (Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Jan;113[1]:6-10).

But researchers in Boston who looked retrospectively at 1,982 hysterectomies performed for any gynecologic indication found a much lower incidence of complications, and reported that cystoscopy did not detect any of the bladder injuries (0.71%) or ureteral injuries (0.25%) incurred in the group. Cystoscopy was performed selectively, however, in 250 of the patients, and was either normal or omitted in the patients who had complications (Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Dec;120[6]:1363-70).

Cystoscopy failed to detect any of the bladder injuries, but “all five of the ureteral injuries occurred in patients who had not undergone cystoscopy,” said Dr. Kim, chairman of ob.gyn. at Einstein Medical Center Montgomery in East Norriton, Pa.

Possible false-positives

Cystoscopy may lead on occasion to an incorrect presumption of a ureteral injury in patients with a pre-existing nonfunctional kidney, Dr. Goldberg noted.

He relayed the case of a 42-year-old patient who underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy without apparent complication. Cystoscopy was then performed with indigo carmine. An efflux of dye was seen from the left ureteral orifice but not from the right orifice.

Urology was consulted and investigated the presumed ureteral injury with additional surgical exploration. An intraoperative intravenous pyelogram (IVP) was eventually performed and was unable to identify the right kidney. A CT then showed an atrophic right kidney with compensatory hypertrophy of the left kidney, probably due to congenital right multicystic dysplastic kidney.

An estimated 0.2% of the population – 1 in 500 – will have a unilateral nonfunctional kidney, the majority of which have not been previously diagnosed. Etiologies include multicystic dysplastic kidney, congenital unilateral renal agenesis, and vascular events. “As we do more and more cystoscopies, this scenario is going to come up every so often,” said Dr. Goldberg, who reported on two such cases last year (Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Sep;126[3]:635-7).

It is also possible, Dr. Kim noted, that a weak urine jet observed on cystoscopy may not necessarily reflect injury. In the LSU study evaluating a universal approach, there was no injury detected on further evaluation in each of the 21 cases of low, subnormal dye efflux from the ureteral orifices. “So it’s not a benign process to undergo cystoscopy in terms of what the ramifications might be,” Dr. Kim said.

Increasing use

Ob.gyn. residents are required by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education to have completed 15 cystoscopies by the time they graduate, and according to recent survey findings, residents are more likely to utilize universal cystoscopy at the time of hysterectomy than currently practicing gynecologic surgeons.

The survey of ob.gyn residents (n = 56) shows universal cystoscopy (defined as greater than 90%) was performed in only a minority of cases during residency: 27% of total laparoscopic hysterectomies (TLH), 14% of laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomies (LAVH), 12% of vaginal hysterectomies (VH), 2% of total abdominal hysterectomies (TAH), and 0% of supracervical hysterectomies (SCH), for instance.

Yet for every hysterectomy type, residents planned to perform universal cystoscopy post-residency more often than they had during their training (49% TLH, 34% LAVH, 34% VH, 15% TAH, 12% SCH), and “residents familiar with the literature on cystoscopy were statistically more likely to plan to perform universal cystoscopy,” said Dr. Goldberg, the senior author of the paper (Womens Health (Lond Engl). 2015 Nov;11[6]:825-31).

Litigation possible

Failure to detect a urinary tract injury at the time of hysterectomy may result in the need for future additional surgeries. Litigation in the Philadelphia market suggests that “if you have an injury that’s missed, there’s a chance that litigation may result,” Dr. Kim said.

Plaintiff’s attorneys have argued that not recognizing ureteral injury during surgery is a deviation from acceptable practice, while defense attorneys have contended that unavoidable complications occur and that no evaluation is required, or supported by the medical literature, when injury is not intraoperatively suspected. Currently, as cystoscopy is performed less than 25% of the time for all types of hysterectomy, the standard of care does not require the procedure intraoperatively if no injury is suspected, Dr. Goldberg said.

Primary prevention of urinary tract injury is most important, both physicians emphasized. The best way to accomplish this is to meticulously identify the anatomy and know the path of the ureter, and to document that the ureter has been identified and viewed as outside of the operative area, they said.

Dr. Kim and Dr. Goldberg reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – Universal cystoscopy at the time of hysterectomy – or at least more frequent use of the procedure – is worth considering since delayed diagnosis of urinary tract injury causes increased morbidity for patients, and in all likelihood increases litigation, Dr. Jay Goldberg and Dr. Cheung Kim suggested at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“We’re often hesitant to do cystoscopy because we don’t want to add time,” said Dr. Kim. “But I always feel that no matter how much time it takes, I’ll be happier in the end if I do it. [And] if you have [experience], a routine, and readily available equipment, it can take as little as 10 minutes.”

Universal cystoscopy to confirm ureteral patency is “fairly straightforward, low risk, and more likely to detect most injuries [than visual inspection alone], particularly ureteral injuries,” Dr. Kim said. On the other hand, it adds to operating time and increases procedure cost, and there is some research suggesting it may be relatively “low yield” and lead to some false positives.

Dr. Kim and Dr. Goldberg both practice at the Einstein Healthcare Network in Philadelphia. Here are some of the findings they shared, and advice they gave, on the use of cystoscopy – universal or selective – after hysterectomy.

Conflicting findings

There is conflicting opinion as to whether universal or selective cystoscopy after hysterectomy is best, and “there’s data on both sides,” said Dr. Goldberg, vice chairman of ob.gyn. and director of the Philadelphia Fibroid Center at Einstein.

A prospective study done at Louisiana State University, New Orleans, to evaluate the impact of a universal approach, for instance, showed an incidence of urinary tract injury of 4.3% (2.9% bladder injury, 1.8% ureteral injury, plus cases of simultaneous injury) in 839 hysterectomies for benign disease. The injury detection rate using intraoperative cystoscopy was 97.4%, and the majority of injuries – 76% – were not suspected prior to cystoscopy being performed (Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Jan;113[1]:6-10).

But researchers in Boston who looked retrospectively at 1,982 hysterectomies performed for any gynecologic indication found a much lower incidence of complications, and reported that cystoscopy did not detect any of the bladder injuries (0.71%) or ureteral injuries (0.25%) incurred in the group. Cystoscopy was performed selectively, however, in 250 of the patients, and was either normal or omitted in the patients who had complications (Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Dec;120[6]:1363-70).

Cystoscopy failed to detect any of the bladder injuries, but “all five of the ureteral injuries occurred in patients who had not undergone cystoscopy,” said Dr. Kim, chairman of ob.gyn. at Einstein Medical Center Montgomery in East Norriton, Pa.

Possible false-positives

Cystoscopy may lead on occasion to an incorrect presumption of a ureteral injury in patients with a pre-existing nonfunctional kidney, Dr. Goldberg noted.

He relayed the case of a 42-year-old patient who underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy without apparent complication. Cystoscopy was then performed with indigo carmine. An efflux of dye was seen from the left ureteral orifice but not from the right orifice.

Urology was consulted and investigated the presumed ureteral injury with additional surgical exploration. An intraoperative intravenous pyelogram (IVP) was eventually performed and was unable to identify the right kidney. A CT then showed an atrophic right kidney with compensatory hypertrophy of the left kidney, probably due to congenital right multicystic dysplastic kidney.

An estimated 0.2% of the population – 1 in 500 – will have a unilateral nonfunctional kidney, the majority of which have not been previously diagnosed. Etiologies include multicystic dysplastic kidney, congenital unilateral renal agenesis, and vascular events. “As we do more and more cystoscopies, this scenario is going to come up every so often,” said Dr. Goldberg, who reported on two such cases last year (Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Sep;126[3]:635-7).

It is also possible, Dr. Kim noted, that a weak urine jet observed on cystoscopy may not necessarily reflect injury. In the LSU study evaluating a universal approach, there was no injury detected on further evaluation in each of the 21 cases of low, subnormal dye efflux from the ureteral orifices. “So it’s not a benign process to undergo cystoscopy in terms of what the ramifications might be,” Dr. Kim said.

Increasing use

Ob.gyn. residents are required by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education to have completed 15 cystoscopies by the time they graduate, and according to recent survey findings, residents are more likely to utilize universal cystoscopy at the time of hysterectomy than currently practicing gynecologic surgeons.

The survey of ob.gyn residents (n = 56) shows universal cystoscopy (defined as greater than 90%) was performed in only a minority of cases during residency: 27% of total laparoscopic hysterectomies (TLH), 14% of laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomies (LAVH), 12% of vaginal hysterectomies (VH), 2% of total abdominal hysterectomies (TAH), and 0% of supracervical hysterectomies (SCH), for instance.

Yet for every hysterectomy type, residents planned to perform universal cystoscopy post-residency more often than they had during their training (49% TLH, 34% LAVH, 34% VH, 15% TAH, 12% SCH), and “residents familiar with the literature on cystoscopy were statistically more likely to plan to perform universal cystoscopy,” said Dr. Goldberg, the senior author of the paper (Womens Health (Lond Engl). 2015 Nov;11[6]:825-31).

Litigation possible

Failure to detect a urinary tract injury at the time of hysterectomy may result in the need for future additional surgeries. Litigation in the Philadelphia market suggests that “if you have an injury that’s missed, there’s a chance that litigation may result,” Dr. Kim said.

Plaintiff’s attorneys have argued that not recognizing ureteral injury during surgery is a deviation from acceptable practice, while defense attorneys have contended that unavoidable complications occur and that no evaluation is required, or supported by the medical literature, when injury is not intraoperatively suspected. Currently, as cystoscopy is performed less than 25% of the time for all types of hysterectomy, the standard of care does not require the procedure intraoperatively if no injury is suspected, Dr. Goldberg said.

Primary prevention of urinary tract injury is most important, both physicians emphasized. The best way to accomplish this is to meticulously identify the anatomy and know the path of the ureter, and to document that the ureter has been identified and viewed as outside of the operative area, they said.

Dr. Kim and Dr. Goldberg reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ACOG 2016

Care bundle reduces cesarean surgical site infections

WASHINGTON – The rate of cesarean delivery surgical site infections fell significantly at Yale New Haven (Conn.) Hospital after implementation of a multidisciplinary care bundle with protocols covering preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative care.

An analysis of two 3-month sampling periods – one before implementation of the bundle of care and one after – showed a drop in the surgical site infection (SSI) rate among total cesarean sections from 3.4% to 2.2%.

At the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Dr. Ashley Pritchard of the hospital described the care bundle and urged obstetricians to consider the impact of even small reductions in SSIs after a cesarean.

“Infection is the most common complication following cesarean delivery … 2.5%-16% of all cesarean deliveries will result in a surgical site infection, and there is significant underestimation as between 15% to 80% of infections are diagnosed after patients leave the hospital,” she said.

A cesarean delivery SSI task force created by the hospital’s obstetric patient safety program developed the care bundle after reviewing best practices, guidelines, and evidence-based reviews.

Preoperative protocols for planned cesareans focused on patient education and included a preoperative appointment and instructions for showering the night before surgery, not shaving for more than 24 hours prior to scheduled surgery, using 2% chlorhexidine wipes both the night prior to surgery and the day of surgery, and other hygiene processes.

“We know from numerous studies that chlorhexidine is superior to iodine, but we also have found that with these wipes you get a level of antibiosis on the skin surface that decreases surgical site infections at the time of incisions,” Dr. Pritchard said.

For the operative care part of the bundle, staff were reeducated about the scrubbing protocol, proper attire and limits on operating room traffic, and the correct and timely use of antibiotics (for example, a cephalosporin administered within 30 minutes of incision). Staff also watched a video and were quizzed on the proper technique and timing for preoperative skin preparation.

Increased attention was paid to normothermia and included preoperative use of warming blankets and proper temperature in the operating room and post–anesthesia care unit.

“We’ve learned from colorectal and trauma surgery that normothermia and patient warming lead to reduced SSI,” Dr. Pritchard said. “This hasn’t been proven with cesarean delivery, but we know there’s improved maternal and fetal well-being with preoperative warming.”

Postoperatively, the use of supplemental oxygen was discontinued unless clinically indicated “since it’s been shown to have no positive effect on SSI,” she said. Incision dressing application and removal were also standardized, with sterile dressings maintained for at least 24 hours – with a tag labeling the date and time of application – and no more than 48 hours. At discharge, patients were given clear discharge instructions and a postpartum appointment for an incision check.

During the 3-month sampling period prior to implementation of the care bundle, there were 382 cesarean deliveries, and 147 patients presented for a postpartum appointment (either the prescribed visit or a later “issue visit”) within 30 days (38%). Of these patients, 8.6% were diagnosed with an SSI.

In the postimplementation sampling period, which began 6 months after rollout, there were 361 cesarean deliveries at the hospital, and 297 patients (77%) presented for postpartum care. Of these patients, 2.9% were diagnosed with an SSI.

An analysis based on the total number of cesarean deliveries performed at the hospital (planned and unplanned) during the two 3-month periods showed a decline in the cesarean delivery SSI rate from 3.4% to 2.2%. “This is statistically significant. It shows a dramatic decline in the SSI rate in our patient population … a clear impact of the bundle of care,” Dr. Pritchard said.

The Yale team attributes the significant increase in postoperative visit attendance to the preoperative protocol for planned cesareans. “We think it had something to do with our creating better relationships by having [patients] present preoperatively and starting their care prior to incision,” she said.

The preoperative visit also provided an opportunity to identify and treat any active skin infections, upper respiratory infections, or chronic colonizations (without evidence of completion of treatment) before delivery. “If necessary and if possible, [we could] push back their cesarean section date to ensure adequate treatment had been achieved,” Dr. Pritchard said.

All aspects of the care bundle were rolled out simultaneously. Next steps for the New Haven team include further analysis of provider and patient views, a look at the sustainability of the bundle of care and its impact, and a cost analysis. “We reduced our SSIs, but we’ve also added a number of elements to our care spectrum, pre- and postoperatively,” Dr. Pritchard said.

For now, one thing seems clear: “We learned from cardiac and colorectal surgery that there really is strength in the bundle, that the sum of the parts is greater than the individual aspects,” she said.

Dr. Pritchard reported that she and her coinvestigators have no relevant financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – The rate of cesarean delivery surgical site infections fell significantly at Yale New Haven (Conn.) Hospital after implementation of a multidisciplinary care bundle with protocols covering preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative care.

An analysis of two 3-month sampling periods – one before implementation of the bundle of care and one after – showed a drop in the surgical site infection (SSI) rate among total cesarean sections from 3.4% to 2.2%.

At the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Dr. Ashley Pritchard of the hospital described the care bundle and urged obstetricians to consider the impact of even small reductions in SSIs after a cesarean.

“Infection is the most common complication following cesarean delivery … 2.5%-16% of all cesarean deliveries will result in a surgical site infection, and there is significant underestimation as between 15% to 80% of infections are diagnosed after patients leave the hospital,” she said.

A cesarean delivery SSI task force created by the hospital’s obstetric patient safety program developed the care bundle after reviewing best practices, guidelines, and evidence-based reviews.

Preoperative protocols for planned cesareans focused on patient education and included a preoperative appointment and instructions for showering the night before surgery, not shaving for more than 24 hours prior to scheduled surgery, using 2% chlorhexidine wipes both the night prior to surgery and the day of surgery, and other hygiene processes.

“We know from numerous studies that chlorhexidine is superior to iodine, but we also have found that with these wipes you get a level of antibiosis on the skin surface that decreases surgical site infections at the time of incisions,” Dr. Pritchard said.

For the operative care part of the bundle, staff were reeducated about the scrubbing protocol, proper attire and limits on operating room traffic, and the correct and timely use of antibiotics (for example, a cephalosporin administered within 30 minutes of incision). Staff also watched a video and were quizzed on the proper technique and timing for preoperative skin preparation.

Increased attention was paid to normothermia and included preoperative use of warming blankets and proper temperature in the operating room and post–anesthesia care unit.

“We’ve learned from colorectal and trauma surgery that normothermia and patient warming lead to reduced SSI,” Dr. Pritchard said. “This hasn’t been proven with cesarean delivery, but we know there’s improved maternal and fetal well-being with preoperative warming.”

Postoperatively, the use of supplemental oxygen was discontinued unless clinically indicated “since it’s been shown to have no positive effect on SSI,” she said. Incision dressing application and removal were also standardized, with sterile dressings maintained for at least 24 hours – with a tag labeling the date and time of application – and no more than 48 hours. At discharge, patients were given clear discharge instructions and a postpartum appointment for an incision check.

During the 3-month sampling period prior to implementation of the care bundle, there were 382 cesarean deliveries, and 147 patients presented for a postpartum appointment (either the prescribed visit or a later “issue visit”) within 30 days (38%). Of these patients, 8.6% were diagnosed with an SSI.

In the postimplementation sampling period, which began 6 months after rollout, there were 361 cesarean deliveries at the hospital, and 297 patients (77%) presented for postpartum care. Of these patients, 2.9% were diagnosed with an SSI.

An analysis based on the total number of cesarean deliveries performed at the hospital (planned and unplanned) during the two 3-month periods showed a decline in the cesarean delivery SSI rate from 3.4% to 2.2%. “This is statistically significant. It shows a dramatic decline in the SSI rate in our patient population … a clear impact of the bundle of care,” Dr. Pritchard said.

The Yale team attributes the significant increase in postoperative visit attendance to the preoperative protocol for planned cesareans. “We think it had something to do with our creating better relationships by having [patients] present preoperatively and starting their care prior to incision,” she said.

The preoperative visit also provided an opportunity to identify and treat any active skin infections, upper respiratory infections, or chronic colonizations (without evidence of completion of treatment) before delivery. “If necessary and if possible, [we could] push back their cesarean section date to ensure adequate treatment had been achieved,” Dr. Pritchard said.

All aspects of the care bundle were rolled out simultaneously. Next steps for the New Haven team include further analysis of provider and patient views, a look at the sustainability of the bundle of care and its impact, and a cost analysis. “We reduced our SSIs, but we’ve also added a number of elements to our care spectrum, pre- and postoperatively,” Dr. Pritchard said.

For now, one thing seems clear: “We learned from cardiac and colorectal surgery that there really is strength in the bundle, that the sum of the parts is greater than the individual aspects,” she said.

Dr. Pritchard reported that she and her coinvestigators have no relevant financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – The rate of cesarean delivery surgical site infections fell significantly at Yale New Haven (Conn.) Hospital after implementation of a multidisciplinary care bundle with protocols covering preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative care.

An analysis of two 3-month sampling periods – one before implementation of the bundle of care and one after – showed a drop in the surgical site infection (SSI) rate among total cesarean sections from 3.4% to 2.2%.

At the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Dr. Ashley Pritchard of the hospital described the care bundle and urged obstetricians to consider the impact of even small reductions in SSIs after a cesarean.

“Infection is the most common complication following cesarean delivery … 2.5%-16% of all cesarean deliveries will result in a surgical site infection, and there is significant underestimation as between 15% to 80% of infections are diagnosed after patients leave the hospital,” she said.

A cesarean delivery SSI task force created by the hospital’s obstetric patient safety program developed the care bundle after reviewing best practices, guidelines, and evidence-based reviews.

Preoperative protocols for planned cesareans focused on patient education and included a preoperative appointment and instructions for showering the night before surgery, not shaving for more than 24 hours prior to scheduled surgery, using 2% chlorhexidine wipes both the night prior to surgery and the day of surgery, and other hygiene processes.

“We know from numerous studies that chlorhexidine is superior to iodine, but we also have found that with these wipes you get a level of antibiosis on the skin surface that decreases surgical site infections at the time of incisions,” Dr. Pritchard said.

For the operative care part of the bundle, staff were reeducated about the scrubbing protocol, proper attire and limits on operating room traffic, and the correct and timely use of antibiotics (for example, a cephalosporin administered within 30 minutes of incision). Staff also watched a video and were quizzed on the proper technique and timing for preoperative skin preparation.

Increased attention was paid to normothermia and included preoperative use of warming blankets and proper temperature in the operating room and post–anesthesia care unit.

“We’ve learned from colorectal and trauma surgery that normothermia and patient warming lead to reduced SSI,” Dr. Pritchard said. “This hasn’t been proven with cesarean delivery, but we know there’s improved maternal and fetal well-being with preoperative warming.”

Postoperatively, the use of supplemental oxygen was discontinued unless clinically indicated “since it’s been shown to have no positive effect on SSI,” she said. Incision dressing application and removal were also standardized, with sterile dressings maintained for at least 24 hours – with a tag labeling the date and time of application – and no more than 48 hours. At discharge, patients were given clear discharge instructions and a postpartum appointment for an incision check.

During the 3-month sampling period prior to implementation of the care bundle, there were 382 cesarean deliveries, and 147 patients presented for a postpartum appointment (either the prescribed visit or a later “issue visit”) within 30 days (38%). Of these patients, 8.6% were diagnosed with an SSI.

In the postimplementation sampling period, which began 6 months after rollout, there were 361 cesarean deliveries at the hospital, and 297 patients (77%) presented for postpartum care. Of these patients, 2.9% were diagnosed with an SSI.

An analysis based on the total number of cesarean deliveries performed at the hospital (planned and unplanned) during the two 3-month periods showed a decline in the cesarean delivery SSI rate from 3.4% to 2.2%. “This is statistically significant. It shows a dramatic decline in the SSI rate in our patient population … a clear impact of the bundle of care,” Dr. Pritchard said.

The Yale team attributes the significant increase in postoperative visit attendance to the preoperative protocol for planned cesareans. “We think it had something to do with our creating better relationships by having [patients] present preoperatively and starting their care prior to incision,” she said.

The preoperative visit also provided an opportunity to identify and treat any active skin infections, upper respiratory infections, or chronic colonizations (without evidence of completion of treatment) before delivery. “If necessary and if possible, [we could] push back their cesarean section date to ensure adequate treatment had been achieved,” Dr. Pritchard said.

All aspects of the care bundle were rolled out simultaneously. Next steps for the New Haven team include further analysis of provider and patient views, a look at the sustainability of the bundle of care and its impact, and a cost analysis. “We reduced our SSIs, but we’ve also added a number of elements to our care spectrum, pre- and postoperatively,” Dr. Pritchard said.

For now, one thing seems clear: “We learned from cardiac and colorectal surgery that there really is strength in the bundle, that the sum of the parts is greater than the individual aspects,” she said.

Dr. Pritchard reported that she and her coinvestigators have no relevant financial disclosures.

AT ACOG 2016

Key clinical point: A multidisciplinary bundle of care was effective in reducing the rate of surgical site infections with cesarean delivery.

Major finding: The rate of cesarean delivery SSIs decreased from 3.4% to 2.2% after implementation of a care bundle.

Data source: An analysis of a quality improvement project at Yale New Haven Hospital.

Disclosures: Dr. Pritchard reported that she and her coinvestigators have no relevant financial disclosures.

Cervical length screening adopted in most academic programs

WASHINGTON – Universal cervical length screening to prevent preterm birth has been implemented by more two-thirds of institutions with maternal-fetal medicine fellowship programs, but less than half of these programs screen with transvaginal ultrasound, a national survey has found.

The survey of 78 accredited programs also revealed geographic variations in the use of routine screening and the ultrasound approach employed, Dr. Adeeb Khalifeh reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

All 78 programs responded to the survey. Fifty-three programs (68%) indicated they had implemented a universal screening program, defined as cervical length screening of women with singleton gestations who had not had a prior spontaneous preterm delivery. Of these, 28 use transabdominal ultrasound (TAU) and 25 use transvaginal ultrasound (TVU) for screening.

While the survey shows that a majority of academic institutions now perform universal cervical length screening, it also reveals that “almost one-third do not,” despite strong evidence of an inverse relationship between cervical length and risk of spontaneous preterm birth, said Dr. Khalifeh, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia who conducted the survey in 2015 with other physicians there.

Both ACOG and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine recommend transvaginal measurements of cervical length for physicians who decide to implement universal cervical length screening.

ACOG’s 2012 Practice Bulletin on Prediction and Prevention of Preterm Birth, which does not mandate universal screening but supports its consideration, notes that, “if second trimester transabdominal scanning of the lower uterine segment suggests that the cervix may be short or have some other abnormality, it is recommended that a subsequent transvaginal ultrasound examination be performed to better visualize the cervix and establish its length” (Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Oct;120:964-73).

Cervical length assessment performed with TAU is unreliable, and it is less cost effective then assessment using TVU, Dr. Khalifeh said.

Vaginal progesterone as a treatment for short cervix in patients with singleton gestations was assessed and proven to be valuable in studies using TVU, not TAU, he noted.

Institutions in the Midwest had the highest rate of universal screening (94%) and the highest use of TVU (58% of programs with routine screening), while programs in the South had the lowest rate of university screening (58%) and the lowest use of TVU (12.5%).

In the Northeast, universal screening was reported by 60% of institutions, and the use of TVU by 40%. Among institutions in the West, 69% reported performing universal screening, with 40% of these programs using TVU.

Obstetrical volume did not impact the implementation of, or approach to, universal cervical length screening; there were no significant differences between institutions with a higher obstetrical volume (more than 3,000 deliveries annually) and a lower volume.

It’s “hard to extrapolate the practice of academic centers [to the community at large], so the findings might not be representative of what’s happening nationwide,” Dr. Khalifeh said.

He reported that he and his coinvestigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – Universal cervical length screening to prevent preterm birth has been implemented by more two-thirds of institutions with maternal-fetal medicine fellowship programs, but less than half of these programs screen with transvaginal ultrasound, a national survey has found.

The survey of 78 accredited programs also revealed geographic variations in the use of routine screening and the ultrasound approach employed, Dr. Adeeb Khalifeh reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

All 78 programs responded to the survey. Fifty-three programs (68%) indicated they had implemented a universal screening program, defined as cervical length screening of women with singleton gestations who had not had a prior spontaneous preterm delivery. Of these, 28 use transabdominal ultrasound (TAU) and 25 use transvaginal ultrasound (TVU) for screening.

While the survey shows that a majority of academic institutions now perform universal cervical length screening, it also reveals that “almost one-third do not,” despite strong evidence of an inverse relationship between cervical length and risk of spontaneous preterm birth, said Dr. Khalifeh, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia who conducted the survey in 2015 with other physicians there.

Both ACOG and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine recommend transvaginal measurements of cervical length for physicians who decide to implement universal cervical length screening.

ACOG’s 2012 Practice Bulletin on Prediction and Prevention of Preterm Birth, which does not mandate universal screening but supports its consideration, notes that, “if second trimester transabdominal scanning of the lower uterine segment suggests that the cervix may be short or have some other abnormality, it is recommended that a subsequent transvaginal ultrasound examination be performed to better visualize the cervix and establish its length” (Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Oct;120:964-73).

Cervical length assessment performed with TAU is unreliable, and it is less cost effective then assessment using TVU, Dr. Khalifeh said.

Vaginal progesterone as a treatment for short cervix in patients with singleton gestations was assessed and proven to be valuable in studies using TVU, not TAU, he noted.

Institutions in the Midwest had the highest rate of universal screening (94%) and the highest use of TVU (58% of programs with routine screening), while programs in the South had the lowest rate of university screening (58%) and the lowest use of TVU (12.5%).

In the Northeast, universal screening was reported by 60% of institutions, and the use of TVU by 40%. Among institutions in the West, 69% reported performing universal screening, with 40% of these programs using TVU.

Obstetrical volume did not impact the implementation of, or approach to, universal cervical length screening; there were no significant differences between institutions with a higher obstetrical volume (more than 3,000 deliveries annually) and a lower volume.

It’s “hard to extrapolate the practice of academic centers [to the community at large], so the findings might not be representative of what’s happening nationwide,” Dr. Khalifeh said.

He reported that he and his coinvestigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – Universal cervical length screening to prevent preterm birth has been implemented by more two-thirds of institutions with maternal-fetal medicine fellowship programs, but less than half of these programs screen with transvaginal ultrasound, a national survey has found.

The survey of 78 accredited programs also revealed geographic variations in the use of routine screening and the ultrasound approach employed, Dr. Adeeb Khalifeh reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

All 78 programs responded to the survey. Fifty-three programs (68%) indicated they had implemented a universal screening program, defined as cervical length screening of women with singleton gestations who had not had a prior spontaneous preterm delivery. Of these, 28 use transabdominal ultrasound (TAU) and 25 use transvaginal ultrasound (TVU) for screening.

While the survey shows that a majority of academic institutions now perform universal cervical length screening, it also reveals that “almost one-third do not,” despite strong evidence of an inverse relationship between cervical length and risk of spontaneous preterm birth, said Dr. Khalifeh, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia who conducted the survey in 2015 with other physicians there.

Both ACOG and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine recommend transvaginal measurements of cervical length for physicians who decide to implement universal cervical length screening.

ACOG’s 2012 Practice Bulletin on Prediction and Prevention of Preterm Birth, which does not mandate universal screening but supports its consideration, notes that, “if second trimester transabdominal scanning of the lower uterine segment suggests that the cervix may be short or have some other abnormality, it is recommended that a subsequent transvaginal ultrasound examination be performed to better visualize the cervix and establish its length” (Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Oct;120:964-73).

Cervical length assessment performed with TAU is unreliable, and it is less cost effective then assessment using TVU, Dr. Khalifeh said.

Vaginal progesterone as a treatment for short cervix in patients with singleton gestations was assessed and proven to be valuable in studies using TVU, not TAU, he noted.

Institutions in the Midwest had the highest rate of universal screening (94%) and the highest use of TVU (58% of programs with routine screening), while programs in the South had the lowest rate of university screening (58%) and the lowest use of TVU (12.5%).

In the Northeast, universal screening was reported by 60% of institutions, and the use of TVU by 40%. Among institutions in the West, 69% reported performing universal screening, with 40% of these programs using TVU.

Obstetrical volume did not impact the implementation of, or approach to, universal cervical length screening; there were no significant differences between institutions with a higher obstetrical volume (more than 3,000 deliveries annually) and a lower volume.

It’s “hard to extrapolate the practice of academic centers [to the community at large], so the findings might not be representative of what’s happening nationwide,” Dr. Khalifeh said.

He reported that he and his coinvestigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT ACOG 2016

Key clinical point: Universal cervical length screening is performed at a majority of academic institutions.

Major finding: More than two-thirds of institutions have adopted universal cervical length screening, but just under half use transvaginal ultrasound.

Data source: A national survey of 78 institutions with accredited maternal-fetal medicine fellowship programs.

Disclosures: Dr. Khalifeh and his coinvestigators reported having relevant financial disclosures.

Postpartum readmissions rise in 8-year multistate analysis

WASHINGTON – The postpartum readmission rate increased over a recent 8-year period from 1.72% to 2.16%, with readmitted patients more likely to be publicly insured and more likely to have multiple comorbidities, a multistate analysis shows.

The rise in readmissions from 2004 to 2011 “isn’t solely explained by the increasing cesarean rate,” and appears to be significantly influenced “by increasing maternal comorbidities,” said Dr. Mark A. Clapp, who reported preliminary findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Dr. Clapp and his coinvestigators analyzed postpartum readmissions occurring in the first 6 weeks after delivery in women in California, Florida, and New York – 3 states whose combined 1 million deliveries a year represent approximately a quarter of all deliveries in the United States. Of approximately 8 million deliveries identified over the study period, 6 million were eligible for analysis.

Medical and surgical readmission rates are used in various specialties as indicators of quality and linked to reimbursement, but “very little is known about readmissions in obstetrics,” he said.

The researchers identified deliveries and postpartum readmissions in state inpatient databases and compared maternal, pregnancy, and delivery characteristics of women who were readmitted with those who weren’t readmitted. This included both “primary” indications for readmissions and “associated diagnoses” listed for these patients.

The most common primary indication for readmission, they found, was wound infection or breakdown (15.5%), followed by hypertensive disease (9.3%), and psychiatric illness (7.7%). The most common associated diagnosis among readmitted patients was psychiatric disease, followed by hypertensive disease.

Women who were readmitted “were more likely to have comorbidities across the board,” said Dr. Clapp, a resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. The readmitted women had higher rates of all “associated diagnoses” listed in the state databases, from asthma and diabetes to obesity and thyroid disease, but the most significant differences were in the rates of hypertensive disease, psychiatric disease, and substance abuse.

Regarding mode of delivery, 37.2% of those who were readmitted had undergone a cesarean delivery versus 32.9% of those not readmitted. Patients who were readmitted also were more likely to have had a multiple gestation, preterm labor, or a placental abnormality.

The majority of readmitted patients in the retrospective cohort study were publicly insured: 54% versus 42%. Readmitted patients also were more likely to be older, with a mean age of 36 years, compared with 28 years in the non-readmitted group. They also were more likely to be black (19% of readmitted patients versus 14% of non-readmitted). Over 50% of readmissions occurred in the first week.

The impact of cesarean delivery on readmission risk needs further investigation, Dr. Clapp said, noting that cesarean delivery was an inconsistent predictor of readmission. In Florida, for instance, patients who had cesarean deliveries in 2011 were actually less likely to be readmitted than those who delivered vaginally.

Psychiatric comorbidities also need to be better understood, as does the “influence of increasing maternal comorbidities, which I suspect is driving the increase in readmissions, rather than the mode of delivery,” Dr. Clapp said.

“Hopefully, we can build a body of evidence to either support or refute the use of readmissions as a measure of quality in our field,” he said.

Dr. Clapp and his coauthors reported no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded by an ACOG health policy grant.

WASHINGTON – The postpartum readmission rate increased over a recent 8-year period from 1.72% to 2.16%, with readmitted patients more likely to be publicly insured and more likely to have multiple comorbidities, a multistate analysis shows.

The rise in readmissions from 2004 to 2011 “isn’t solely explained by the increasing cesarean rate,” and appears to be significantly influenced “by increasing maternal comorbidities,” said Dr. Mark A. Clapp, who reported preliminary findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Dr. Clapp and his coinvestigators analyzed postpartum readmissions occurring in the first 6 weeks after delivery in women in California, Florida, and New York – 3 states whose combined 1 million deliveries a year represent approximately a quarter of all deliveries in the United States. Of approximately 8 million deliveries identified over the study period, 6 million were eligible for analysis.

Medical and surgical readmission rates are used in various specialties as indicators of quality and linked to reimbursement, but “very little is known about readmissions in obstetrics,” he said.

The researchers identified deliveries and postpartum readmissions in state inpatient databases and compared maternal, pregnancy, and delivery characteristics of women who were readmitted with those who weren’t readmitted. This included both “primary” indications for readmissions and “associated diagnoses” listed for these patients.

The most common primary indication for readmission, they found, was wound infection or breakdown (15.5%), followed by hypertensive disease (9.3%), and psychiatric illness (7.7%). The most common associated diagnosis among readmitted patients was psychiatric disease, followed by hypertensive disease.

Women who were readmitted “were more likely to have comorbidities across the board,” said Dr. Clapp, a resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. The readmitted women had higher rates of all “associated diagnoses” listed in the state databases, from asthma and diabetes to obesity and thyroid disease, but the most significant differences were in the rates of hypertensive disease, psychiatric disease, and substance abuse.

Regarding mode of delivery, 37.2% of those who were readmitted had undergone a cesarean delivery versus 32.9% of those not readmitted. Patients who were readmitted also were more likely to have had a multiple gestation, preterm labor, or a placental abnormality.

The majority of readmitted patients in the retrospective cohort study were publicly insured: 54% versus 42%. Readmitted patients also were more likely to be older, with a mean age of 36 years, compared with 28 years in the non-readmitted group. They also were more likely to be black (19% of readmitted patients versus 14% of non-readmitted). Over 50% of readmissions occurred in the first week.

The impact of cesarean delivery on readmission risk needs further investigation, Dr. Clapp said, noting that cesarean delivery was an inconsistent predictor of readmission. In Florida, for instance, patients who had cesarean deliveries in 2011 were actually less likely to be readmitted than those who delivered vaginally.

Psychiatric comorbidities also need to be better understood, as does the “influence of increasing maternal comorbidities, which I suspect is driving the increase in readmissions, rather than the mode of delivery,” Dr. Clapp said.

“Hopefully, we can build a body of evidence to either support or refute the use of readmissions as a measure of quality in our field,” he said.

Dr. Clapp and his coauthors reported no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded by an ACOG health policy grant.

WASHINGTON – The postpartum readmission rate increased over a recent 8-year period from 1.72% to 2.16%, with readmitted patients more likely to be publicly insured and more likely to have multiple comorbidities, a multistate analysis shows.

The rise in readmissions from 2004 to 2011 “isn’t solely explained by the increasing cesarean rate,” and appears to be significantly influenced “by increasing maternal comorbidities,” said Dr. Mark A. Clapp, who reported preliminary findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Dr. Clapp and his coinvestigators analyzed postpartum readmissions occurring in the first 6 weeks after delivery in women in California, Florida, and New York – 3 states whose combined 1 million deliveries a year represent approximately a quarter of all deliveries in the United States. Of approximately 8 million deliveries identified over the study period, 6 million were eligible for analysis.

Medical and surgical readmission rates are used in various specialties as indicators of quality and linked to reimbursement, but “very little is known about readmissions in obstetrics,” he said.

The researchers identified deliveries and postpartum readmissions in state inpatient databases and compared maternal, pregnancy, and delivery characteristics of women who were readmitted with those who weren’t readmitted. This included both “primary” indications for readmissions and “associated diagnoses” listed for these patients.

The most common primary indication for readmission, they found, was wound infection or breakdown (15.5%), followed by hypertensive disease (9.3%), and psychiatric illness (7.7%). The most common associated diagnosis among readmitted patients was psychiatric disease, followed by hypertensive disease.

Women who were readmitted “were more likely to have comorbidities across the board,” said Dr. Clapp, a resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. The readmitted women had higher rates of all “associated diagnoses” listed in the state databases, from asthma and diabetes to obesity and thyroid disease, but the most significant differences were in the rates of hypertensive disease, psychiatric disease, and substance abuse.

Regarding mode of delivery, 37.2% of those who were readmitted had undergone a cesarean delivery versus 32.9% of those not readmitted. Patients who were readmitted also were more likely to have had a multiple gestation, preterm labor, or a placental abnormality.

The majority of readmitted patients in the retrospective cohort study were publicly insured: 54% versus 42%. Readmitted patients also were more likely to be older, with a mean age of 36 years, compared with 28 years in the non-readmitted group. They also were more likely to be black (19% of readmitted patients versus 14% of non-readmitted). Over 50% of readmissions occurred in the first week.

The impact of cesarean delivery on readmission risk needs further investigation, Dr. Clapp said, noting that cesarean delivery was an inconsistent predictor of readmission. In Florida, for instance, patients who had cesarean deliveries in 2011 were actually less likely to be readmitted than those who delivered vaginally.

Psychiatric comorbidities also need to be better understood, as does the “influence of increasing maternal comorbidities, which I suspect is driving the increase in readmissions, rather than the mode of delivery,” Dr. Clapp said.

“Hopefully, we can build a body of evidence to either support or refute the use of readmissions as a measure of quality in our field,” he said.

Dr. Clapp and his coauthors reported no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded by an ACOG health policy grant.

AT ACOG 2016

Key clinical point: Postpartum readmission rates rise, and reasons are not limited to increasing cesarean deliveries.

Major finding: Postpartum admission rates rose in the 2004-2011 period from 1.72% to 2.16%.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of data in three state inpatient databases.

Disclosures: The study was funded by a health policy grant awarded by ACOG. Dr. Clapp and his coauthors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Women reach for the top in ob.gyn.

Dr. Gloria E. Sarto was one of just six women in her medical school graduating class of 76 in 1958 – a time when many medical schools, she recalled, had quota systems for women and minorities. Later, she became the first female ob.gyn. resident at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

“When I was interviewing for a residency position, the department chair told me ‘I’m going to treat you like one of the boys,’” the 86-year-old professor emeritus said. “And I said, ‘If you do that, it will be just fine.’”

Yet she still had to lobby sometimes for equal treatment – convincing the department chief in one instance that sleeping on a delivery table during hospital duty because there weren’t any rooms for women was not being treated “like one of the boys.” And she was often bothered by her observation that, in general, “the women [residents] weren’t noticed... they weren’t being recognized.”

Dr. Sarto has since chaired two ob.gyn. departments and was the first woman president of the American Gynecological and Obstetrical Society. Today, however, as she continues mentoring junior faculty and works to ensure the smooth succession of programs she founded, she sees a much different field – one in which women not only command more respect but where they make up a majority of ob.gyns.

Impact on women’s health

In 2014, 62% of all ob.gyns. were women (Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jan;127[1]:148-52). The majority has been years in the making; more women than men have been entering the specialty since 1993. And if current trends continue, the percentage of women active in the specialty will only increase further. In 2010, women comprised more than 80% of all ob.gyn. residents/fellows, more than any other specialty, according to data from the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Such numerical strength is significant, but for Dr. Sarto and other leaders in the specialty who spoke about their experiences as female ob.gyns., it’s the impact that women physicians have had on women’s health that’s most important.

Dr. Sarto helped to start Lamaze classes in a hospital basement amidst widespread opposition from the male-dominated leadership and staff who felt that women didn’t need such help with labor. She also takes pride in her collaboration with Dr. Florence Haseltine, Phyllis Greenberger, and several other women to address biases in biomedical research. Their work with Congress led to a federal audit of National Institutes of Health policies and practices.

“We knew that when that report came out [in 1990], it would hit every newspaper in the country,” Dr. Sarto said. It just about did, and soon after that, the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health was established to ensure that women were included in clinical trials and that gaps in knowledge of women’s health were addressed.

Dr. Barbara Levy, who left a private practice and two medical directorships in 2012 to become Vice President for Health Policy at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, recalls feeling early in her career that women’s health needed to be approached much more holistically.

“What I was seeing and experiencing didn’t match the textbooks,” she said. “The connection, for instance, between chronic pelvic pain and women who’d been victims of sexual abuse – there wasn’t anything in the literature. I’d see women with the same kinds of physical characteristics on their exams... and patients were willing to share with me things that they wouldn’t have been willing to share with my colleagues.”

Dr. Levy graduated from Princeton University in 1974 with the second class of admitted women, and after a year off, went west for medical school. She graduated in 1979 from the University of California, San Diego, with nine other women in a class of 110.

Her desire to care for the “whole patient” had her leaning toward family medicine until a beloved mentor, Dr. Donna Brooks, “reminded me that there were so few women to take care of women... and that as an ob.gyn. I could follow women through pregnancy, delivery, surgeries, hormone issues, and so many [other facets of their health].”

Dr. Levy, who served as president of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists in 1995, recalls a world “that was very tolerant of sexual harassment” and remembers the energy she needed to expend to be taken seriously and to correct unconscious bias.

When she applied for fellowship in the American College of Surgeons in the late 1980s, the committee members who conducted an interview “told me right away that I couldn’t expect to be a fellow if I hadn’t done my duty [serving on hospital committees],” Dr. Levy said.

“I told them I had volunteered for more than three committees every single year I’d been on staff, and had never been asked to serve,” she said. “They had no idea. Their assumption was that I had children at home and I wasn’t taking the time.”

Entering leadership

When it comes to leadership, a look at academic medicine suggests that women ob.gyns. have made significant strides. In 2013, compared with other major specialties, obstetrics and gynecology had the highest proportion of department leaders who were women. Yet the picture is mixed. According to an analysis published earlier in 2016, women in ob.gyn. and nine other major specialties “were not represented in the proportions in which they entered their fields” (Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Mar;127[3]:442-7).

Women comprised 57% of all faculty in departments of ob.gyn. in 2013. And, according to the analysis, they comprised 62% of ob.gyn. residency program directors, 30% of division directors, and 24% of department chairs.

The high numbers of women serving as residency program directors raises concern because such positions “do not result in advancement in the same way,” said Dr. Levy, adding that women have excelled in such positions and may desire them, but should be mentored early on about what tracks have the potential for upper-level leadership roles.

Dr. Maureen Phipps, who in 2013 was appointed as chair of ob.gyn. and assistant dean in the Warren Albert Medical School of Brown University in Providence, said she carries with her the fact that women are not yet proportionally represented at the upper levels. “I know that my being in this position and in other positions I’ve held is important for women to see,” she said.

Dr. Phipps graduated from the University of Vermont’s College of Medicine in 1994 as a part of a class in which men and women were fairly evenly represented. In addition to her role as department chair and assistant dean, she is also now chief of ob.gyn. at Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island, where she did her residency, and executive chief of ob.gyn for the Care New England Health System.

“I’ve had amazing male leaders and mentors in my career – the people who’ve gone to bat for me have been men,” said Dr. Phipps. Yet, “it’s important to have women in leadership... It’s known that we think differently and approach things differently. Having balance and a variety of different lenses will allow us to [further] grow the field.”

Gender pay gap

Both in academic medicine and in practice, a gender pay gap still reportedly affects women physicians across the board. Various reports and analyses have shown women earning disproportionately less than their male colleagues in similar positions.

Notably, a 2011 analysis in Health Affairs found a nearly $17,000 gap between the starting salaries for men and women physicians. This differential accounted for variables such as patient care hours, practice type, and location. It is possible, the study authors reported, that practices “may now be offering greater flexibility and family-friendly attributes that are more appealing but that come at the price of commensurately lower pay” (Health Aff. 2011:30;193-201).

The American Medical Women’s Association, which promotes advocacy on a gender pay gap, said in a statement about the study, however, that “gender discrimination still exists within the echelons of medicine, and gender stereotyping frequently leads to the devaluation of women physicians.”

From her perspective, Dr. Levy said it’s “complicated” to tease apart and understand all the factors that may be involved.

The challenges of balancing work and family/caregiving and are “still really tough” for women ob.gyns., she said, especially those who want to practice obstetrics. Dr. Levy said she gave up obstetrics when it became apparent that she and her husband would need to hire an additional child care provider.

While the hospitalist-laborist model has been a valuable addition to obstetrics, Dr. Phipps said, “it’s our challenge to continue to think creatively about how we can keep clinicians engaged when they’re in the earlier parts of their careers and challenged by family responsibilities and other commitments.”