User login

An Atypical Syphilis Presentation

Syphilis is a chronic systemic infection that has been allotted the epithet “the great imitator” for its gross and histologic similarity to numerous other skin pathologies. Well-characterized for centuries, syphilis features diverse clinical manifestations including a number of cutaneous symptoms.1

RELATED AUDIOCAST: The Syphilis Epidemic: Dermatologists on the Frontline of Treatment and Diagnosis

The primary stage of infection is classically defined by an asymptomatic chancre at the inoculation site. The secondary stage results from the systemic dissemination of the infection and typically is characterized by cutaneous eruptions, regional lymphadenopathy, and flulike symptoms. This stage gained its notoriety as the great imitator owing to its ability to present with a variety of papulosquamous eruptions. The secondary stage is followed by an asymptomatic latent period that may last months to years, followed by the tertiary stage, which is characterized by the neurologic, cardiovascular, and/or gummatous manifestations that represent the major sources of morbidity and mortality associated with syphilis. It is during the primary, secondary, and early latent stages that the infection is communicable.1

Case Report

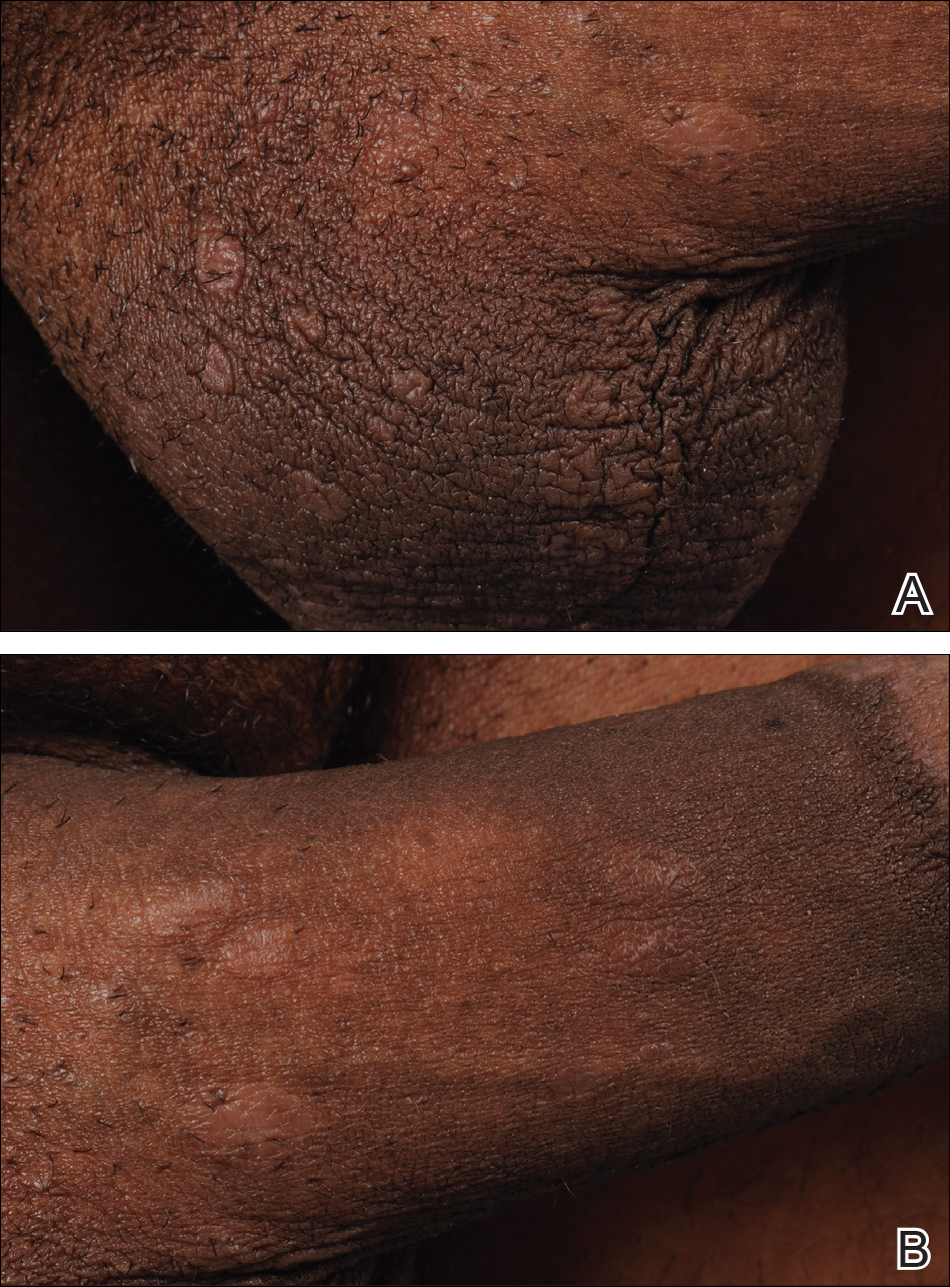

A 40-year-old man presented with multiple intensely pruritic, scattered, erythematous and slightly violaceous, flat-topped papules on the scrotum (Figure 1A) and penile shaft (Figure 1B) of 1 week’s duration. Some of these lesions were annular in appearance. The patient denied any other dermatologic concerns and showed no other skin lesions. A shave biopsy of the right side of the penile shaft was performed, revealing minimal papillary dermis and superficial perivascular dermatitis with substantial perivascular plasmalymphocytic infiltration. The epidermal layer was mildly acanthotic with parakeratosis. A tentative diagnosis of secondary syphilis of unknown latency was made and confirmatory laboratory studies were ordered.

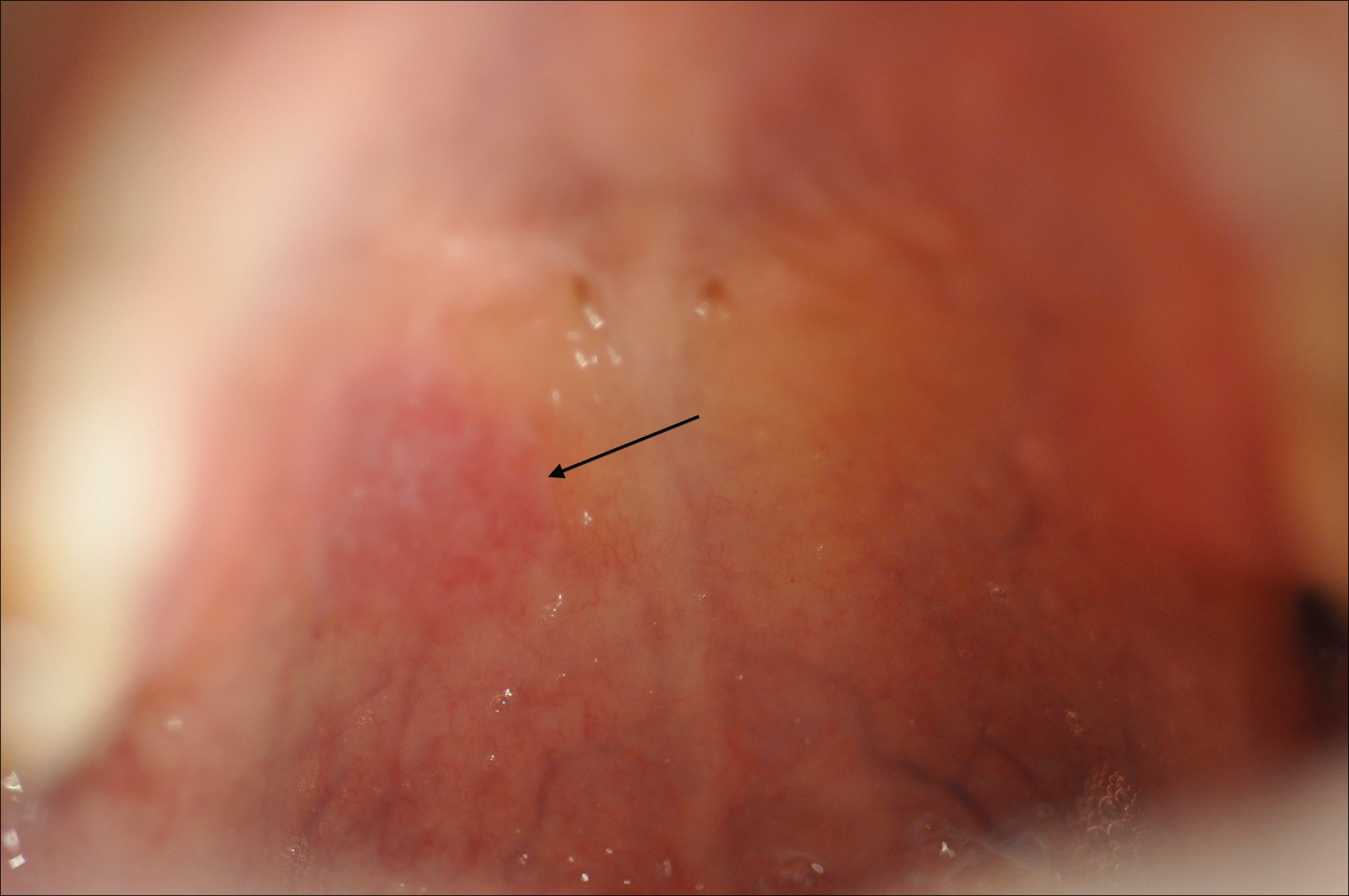

Within weeks, the patient developed a painful 7-mm white patch on the right lower mucosal lip followed several days later by the appearance of a painful lesion on the hard palate (Figure 2 [arrow indicates palatal lesion]) and odynophagia. He presented to the emergency department roughly 3 weeks from the time of index presentation and was started empirically on amoxicillin 500 mg 3 times daily for 10 days for suspicion of strep throat. At a scheduled follow-up with his dermatologist 1 week later, physical examination showed complete resolution of the mucosal lip patch and genital lesions. A round erythematous patch on the right hard palate consistent with a resolving mucosal patch also was noted. A diagnosis of secondary syphilitic infection was made with a rapid plasma reagin (RPR) titer of 1:32 (reference range, <1:1) and positive Treponema antibodies. The patient was treated with a single dose of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million U to prevent the development of tertiary syphilis.

Comment

Incidence

Syphilis has been well characterized since the early 15th century, though its geographic origin remains a topic of controversy.2 Although acquired syphilis infections represented a major source of morbidity and mortality in the early 20th century, the prevalence of syphilis in the United States declined substantially thereafter due to improved public health management.2 Syphilis was relatively rare in the United States by the year 1956, with fewer than 7000 cases of primary and secondary disease reported annually.3 The incidence of primary and secondary syphilis infections in the United States increased gradually until 1990 before declining precipitously and reaching an unprecedented low of 2.2 cases per 100,000 individuals in 2000.4 These shifts ultimately have resulted in decreased clinical familiarity with the disease presentation of syphilis among many health care providers. Since 2000, the incidence of syphilis infection has increased in the United States, with the greatest increases seen in men who have sex with men, intravenous drug users, and human immunodeficiency virus–infected individuals.5-7

RELATED ARTICLE: Syphilis and the Dermatologist

Pathogenesis and Transmission

The causative agent in syphilis infection is the bacterium Treponema pallidum, a member of the family Spirochaetaceae, which is distinguished by its thin, regularly coiled form and distinctive corkscrew motility.8 Syphilis is communicated primarily by sexual contact or in utero exposure during the primary and secondary stages of maternal infection.9 At the time of presentation, our patient denied having any new sexual partners or practices. He reported a monogamous heterosexual relationship within the months preceding presentation, suggesting historical inaccuracy on the part of the patient or probable infidelity in the reported relationship as an alternative means of infection transmission. Untreated individuals may be contagious for longer than 1 year,9 making transmission patterns difficult to track clinically.

Presentation

The clinical presentation of infection with T pallidum results from dual humoral and cell-mediated inflammatory responses in the host. The primary stage is classically defined by a single chancre, which develops at the inoculation site(s) 9 to 90 days following exposure. The chancre typically begins as a small papule that rapidly develops into a painless ulcer characterized by an indurated border, red base, bordering edema, and a diameter of 2 cm or less. Indolent regional lymphadenopathy often is observed in conjunction with the primary chancre.10 Our case is notable for the absence of a primary syphilitic lesion and lack of adenopathy. The primary chancre of syphilis typically resolves within 3 to 6 weeks of onset regardless of whether the patient is treated,4 thus suggesting the rare possibility that our patient developed a painless primary chancre without realizing it.

The secondary stage of syphilis infection arises weeks to months after resolution of the primary chancre and is triggered by hematogenous and lymphatic dissemination of the bacteria. The symptoms of secondary syphilis are primarily flulike and may include headache, malaise, fatigue, sore throat, arthralgia, and low-grade fever.9 Nontender regional lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly also have been reported.11 Our patient denied any systemic concerns throughout the duration of his illness, with the exception of odynophagia in association with ulceration of the oral mucosa. Abnormal laboratory findings in secondary syphilis are nonspecific and may include an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and/or an increased white blood cell count with absolute lymphocytosis.12 Laboratory studies drawn at the time of presentation showed no such abnormalities in our patient.

The cutaneous signs of secondary syphilis arise concurrently with systemic manifestations and are a common finding, with lesions of the skin or oral mucosa present in up to 80% of patients,13 as in our case. Oral lesions classically involve ulcerations at the tip and sides of the tongue,12 which is distinct from our patient who developed oral lesions of the mucosal lip and hard palate.

Secondary syphilis classically features a copper-colored maculopapular rash with sharply delineated margins typically present on the palmar and plantar surfaces.14 Verrucous lesions appearing as moist exophytic plaques on the genitals, intertriginous areas, and/or perineum also have been described and are referred to as condyloma lata in the setting of secondary syphilis.15 In contrast to these classic findings, our patient demonstrated lichenoid lesions on the genitalia and white mucosal patches on the oral mucosa. Our case also was highly unusual because of the intense pruritus associated with the genital lesions, which starkly contrasts most secondary-stage cutaneous lesions that are classically asymptomatic.14 Additionally, our case was distinctive due to the lack of palmar or plantar involvement, which is considered a characteristic feature of secondary cutaneous syphilis.1 Finally, our case was notable for the presence of multiple annular cutaneous lesions, which indicated a late secondary-stage infection during which involution of the lesions produced endarteritis as deeper vessels became involved. A 20-year retrospective study by Abell et al11 demonstrated that 40% of syphilitic rashes are macular, 40% are maculopapular, 10% are papular (as in our case), and the remaining 10% are not easily grouped within these categories.

Differential Diagnosis

It has been estimated that approximately 8% of cutaneous syphilitic lesions demonstrate morphology and distributions suggestive of other dermatologic conditions, including atopic dermatitis, pityriasis rosea, psoriasis, drug-induced eruptions, erythema multiforme, mycosis fungoides, and far more uncommonly lichenoid lesions,16,17 as in our case.

Histopathology

It has been demonstrated that the gross appearance of the secondary syphilitic lesion depends both on the degree of inflammatory infiltrate and the extent of vascular involvement producing ischemia of the skin.1 Our case presented with small, flat-topped, papular lesions that grossly resembled lichen planus and were ultimately shown to be the product of dense lymphomononuclear infiltration extending perivascularly and throughout the superficial and deep dermis.

Biopsy of a lesion is one means of diagnosis, though the histologic appearance of secondary syphilis can mimic many other diseases. In primary and secondary syphilis, skin biopsy characteristically shows central thinning or ulceration of the epidermal layer with heavy dermal lymphocyte infiltration, lymphovascular proliferation with endarteritis, small-vessel thrombosis, and dermal necrosis. Lichen planus–type dermatitis is histologically characterized by hyperkeratosis, irregular epidermal hyperplasia, and a dermoepidermal junction that may be obscured by a dense lymphomononuclear infiltrate.9 The specimen taken from our patient showed minimal infiltrate in the papillary dermis, suggesting a diagnosis of secondary syphilis with lichenoid features. Despite a gross appearance consistent with lichen planus, the biopsy lacked the hydropic degeneration of the basal layer and keratinocyte necrosis that typically characterize this condition.

Diagnosis

Serologic testing for syphilis infection is comprised of nontreponemal and treponemal studies. Nontreponemal testing, which includes the RPR and VDRL test, detects antibodies to cardiolipin-lecithin antigen, a lipid component of the cell membranes of T pallidum. Because the specificity of these tests is fairly low, they typically are used only for screening and monitoring of disease progression and/or response to treatment. Approximately 25% of cases in the United States of primary syphilis are not detected by nontreponemal testing, whereas a nonreactive test nearly always excludes a diagnosis of secondary or latent-stage syphilitic infection.9 Indeed, nontreponemal studies show the highest antibody titers during the late secondary and early latent stages of infection with declining titers thereafter, even in the absence of antibiotic treatment. In our case, diagnosis was made by biopsy and RPR was used for staging; RPR was reactive at a dilution of 1:32, indicative of secondary or early latent infection.

Treponemal testing, which includes the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test, and multiplex flow immunoassay detects antibodies that are specific to syphilis infection. Treponemal antibodies are detectable earlier in the course of infection than nontreponemal antibodies and remain permanently detectable even following treatment. Because of its high specificity, treponemal testing often is used to confirm diagnosis after positive screening with nontreponemal tests.4 Positive fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption testing and positive multiplex flow immunoassay may be used to confirm the diagnosis of T pallidum infection.

The tertiary stage of syphilis infection can occur years after conclusion of the secondary stage and is comprised of one or more of the following: gummas, aortic dilatation or dissection, and neurosyphilitic manifestations such as tabes dorsalis or general paresis.1 It is of vital importance to identify syphilis infection prior to the onset of the tertiary stage to prevent substantial morbidity and mortality.

Treatment

Our patient’s symptoms abated after empiric treatment with amoxicillin for presumed streptococcal throat infection after he presented to the emergency department with odynophagia, which is not surprising given the moderate-spectrum coverage of this β-lactam antibiotic as well as the near-complete susceptibility of Treponema spirochetes to amoxicillin in primary and secondary syphilis with notably lower efficacy in latent or tertiary disease. It was essential to treat the patient with a single dose of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million U, which has been shown to reliably prevent recurrence of infection or progression to tertiary syphilis.18

Conclusion

We present a rare case of lichenoid secondary syphilis in the absence of lesions on the palmar and plantar surfaces. The patient lacked any other cutaneous or systemic manifestations, except for odynophagia in association with oral mucosal lesions. He denied any new sexual partners and did not recall having a primary chancre. Also strikingly unusual in this case was the intense pruritus associated with the genital eruption, which is unlike the classic lack of symptoms experienced in the great majority of eruptions due to secondary syphilis. A clinical appreciation of the many cutaneous manifestations of syphilis infection remains critical to early identification of the disease prior to progression to the tertiary stage and its devastating sequelae.

- Dourmishev LA, Assen L. Syphilis: uncommon presentations in adults. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:555-564.

- Seña AC, White BL, Sparling PF. Novel Treponema pallidum serologic tests: a paradigm shift in syphilis screening for the 21st century. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:700-708.

- Kilmarx PH, St Louis ME. The evolving epidemiology of syphilis. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(8, pt 1):1053-1054.

- Patton ME, Su JR, Nelson R, et al. Primary and secondary syphilis—United States, 2005-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:402-406.

- Coffin LS, Newberry A, Hagan H, et al. Syphilis in drug users in low and middle income countries. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21:20-27.

- Gao L, Zhang L, Jin Q. Meta-analysis: prevalence of HIV infection and syphilis among MSM in China. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85:354-358.

- Karp G, Schlaeffer F, Jotkowitz A, et al. Syphilis and HIV co-infection. Eur J Int Med. 2009;20:9-13.

- Hol EL, Lukehart SA. Syphilis: using modern approaches to understand an old disease. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4584-4592.

- Schnirring-Judge M, Gustaferro C, Terol C. Vesiculobullous syphilis: a case involving an unusual cutaneous manifestation of secondary syphilis. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50:96-101.

- Brown DL, Frank JE. Diagnosis and management of syphilis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:283-290.

- Abell E, Marks R, Jones W. Secondary syphilis: a clinicopathological review. Br J Dermatol. 1975;93:53-61.

- Fiumara N. The treponematoses. Int Dermatol. 1992;1:953-974.

- Martin DH, Mroczkowski TF. Dermatological manifestations of sexually transmitted diseases other than HIV. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1994;8:533-583.

- Morton RS. The treponematoses. In: Champion RH, Bourton JL, Burns DA, et al. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 6th ed. London, United Kingdom: Blackwell Science; 1998:1237-1275.

- Rosen T, Hwong H. Pedal interdigital condylomata lata: a rare sign of secondary syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28:184-186.

- Jeerapaet P, Ackerman AB. Histologic patterns of secondary syphilis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:373-377.

- Tang MBY, Yosipovitch G, Tan SH. Secondary syphilis presenting as a lichen planus-like rash. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:185-187.

- Onoda Y. Clinical evaluation of amoxicillin in the treatment of syphilis. J Int Med. 1979;7:539-545.

Syphilis is a chronic systemic infection that has been allotted the epithet “the great imitator” for its gross and histologic similarity to numerous other skin pathologies. Well-characterized for centuries, syphilis features diverse clinical manifestations including a number of cutaneous symptoms.1

RELATED AUDIOCAST: The Syphilis Epidemic: Dermatologists on the Frontline of Treatment and Diagnosis

The primary stage of infection is classically defined by an asymptomatic chancre at the inoculation site. The secondary stage results from the systemic dissemination of the infection and typically is characterized by cutaneous eruptions, regional lymphadenopathy, and flulike symptoms. This stage gained its notoriety as the great imitator owing to its ability to present with a variety of papulosquamous eruptions. The secondary stage is followed by an asymptomatic latent period that may last months to years, followed by the tertiary stage, which is characterized by the neurologic, cardiovascular, and/or gummatous manifestations that represent the major sources of morbidity and mortality associated with syphilis. It is during the primary, secondary, and early latent stages that the infection is communicable.1

Case Report

A 40-year-old man presented with multiple intensely pruritic, scattered, erythematous and slightly violaceous, flat-topped papules on the scrotum (Figure 1A) and penile shaft (Figure 1B) of 1 week’s duration. Some of these lesions were annular in appearance. The patient denied any other dermatologic concerns and showed no other skin lesions. A shave biopsy of the right side of the penile shaft was performed, revealing minimal papillary dermis and superficial perivascular dermatitis with substantial perivascular plasmalymphocytic infiltration. The epidermal layer was mildly acanthotic with parakeratosis. A tentative diagnosis of secondary syphilis of unknown latency was made and confirmatory laboratory studies were ordered.

Within weeks, the patient developed a painful 7-mm white patch on the right lower mucosal lip followed several days later by the appearance of a painful lesion on the hard palate (Figure 2 [arrow indicates palatal lesion]) and odynophagia. He presented to the emergency department roughly 3 weeks from the time of index presentation and was started empirically on amoxicillin 500 mg 3 times daily for 10 days for suspicion of strep throat. At a scheduled follow-up with his dermatologist 1 week later, physical examination showed complete resolution of the mucosal lip patch and genital lesions. A round erythematous patch on the right hard palate consistent with a resolving mucosal patch also was noted. A diagnosis of secondary syphilitic infection was made with a rapid plasma reagin (RPR) titer of 1:32 (reference range, <1:1) and positive Treponema antibodies. The patient was treated with a single dose of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million U to prevent the development of tertiary syphilis.

Comment

Incidence

Syphilis has been well characterized since the early 15th century, though its geographic origin remains a topic of controversy.2 Although acquired syphilis infections represented a major source of morbidity and mortality in the early 20th century, the prevalence of syphilis in the United States declined substantially thereafter due to improved public health management.2 Syphilis was relatively rare in the United States by the year 1956, with fewer than 7000 cases of primary and secondary disease reported annually.3 The incidence of primary and secondary syphilis infections in the United States increased gradually until 1990 before declining precipitously and reaching an unprecedented low of 2.2 cases per 100,000 individuals in 2000.4 These shifts ultimately have resulted in decreased clinical familiarity with the disease presentation of syphilis among many health care providers. Since 2000, the incidence of syphilis infection has increased in the United States, with the greatest increases seen in men who have sex with men, intravenous drug users, and human immunodeficiency virus–infected individuals.5-7

RELATED ARTICLE: Syphilis and the Dermatologist

Pathogenesis and Transmission

The causative agent in syphilis infection is the bacterium Treponema pallidum, a member of the family Spirochaetaceae, which is distinguished by its thin, regularly coiled form and distinctive corkscrew motility.8 Syphilis is communicated primarily by sexual contact or in utero exposure during the primary and secondary stages of maternal infection.9 At the time of presentation, our patient denied having any new sexual partners or practices. He reported a monogamous heterosexual relationship within the months preceding presentation, suggesting historical inaccuracy on the part of the patient or probable infidelity in the reported relationship as an alternative means of infection transmission. Untreated individuals may be contagious for longer than 1 year,9 making transmission patterns difficult to track clinically.

Presentation

The clinical presentation of infection with T pallidum results from dual humoral and cell-mediated inflammatory responses in the host. The primary stage is classically defined by a single chancre, which develops at the inoculation site(s) 9 to 90 days following exposure. The chancre typically begins as a small papule that rapidly develops into a painless ulcer characterized by an indurated border, red base, bordering edema, and a diameter of 2 cm or less. Indolent regional lymphadenopathy often is observed in conjunction with the primary chancre.10 Our case is notable for the absence of a primary syphilitic lesion and lack of adenopathy. The primary chancre of syphilis typically resolves within 3 to 6 weeks of onset regardless of whether the patient is treated,4 thus suggesting the rare possibility that our patient developed a painless primary chancre without realizing it.

The secondary stage of syphilis infection arises weeks to months after resolution of the primary chancre and is triggered by hematogenous and lymphatic dissemination of the bacteria. The symptoms of secondary syphilis are primarily flulike and may include headache, malaise, fatigue, sore throat, arthralgia, and low-grade fever.9 Nontender regional lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly also have been reported.11 Our patient denied any systemic concerns throughout the duration of his illness, with the exception of odynophagia in association with ulceration of the oral mucosa. Abnormal laboratory findings in secondary syphilis are nonspecific and may include an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and/or an increased white blood cell count with absolute lymphocytosis.12 Laboratory studies drawn at the time of presentation showed no such abnormalities in our patient.

The cutaneous signs of secondary syphilis arise concurrently with systemic manifestations and are a common finding, with lesions of the skin or oral mucosa present in up to 80% of patients,13 as in our case. Oral lesions classically involve ulcerations at the tip and sides of the tongue,12 which is distinct from our patient who developed oral lesions of the mucosal lip and hard palate.

Secondary syphilis classically features a copper-colored maculopapular rash with sharply delineated margins typically present on the palmar and plantar surfaces.14 Verrucous lesions appearing as moist exophytic plaques on the genitals, intertriginous areas, and/or perineum also have been described and are referred to as condyloma lata in the setting of secondary syphilis.15 In contrast to these classic findings, our patient demonstrated lichenoid lesions on the genitalia and white mucosal patches on the oral mucosa. Our case also was highly unusual because of the intense pruritus associated with the genital lesions, which starkly contrasts most secondary-stage cutaneous lesions that are classically asymptomatic.14 Additionally, our case was distinctive due to the lack of palmar or plantar involvement, which is considered a characteristic feature of secondary cutaneous syphilis.1 Finally, our case was notable for the presence of multiple annular cutaneous lesions, which indicated a late secondary-stage infection during which involution of the lesions produced endarteritis as deeper vessels became involved. A 20-year retrospective study by Abell et al11 demonstrated that 40% of syphilitic rashes are macular, 40% are maculopapular, 10% are papular (as in our case), and the remaining 10% are not easily grouped within these categories.

Differential Diagnosis

It has been estimated that approximately 8% of cutaneous syphilitic lesions demonstrate morphology and distributions suggestive of other dermatologic conditions, including atopic dermatitis, pityriasis rosea, psoriasis, drug-induced eruptions, erythema multiforme, mycosis fungoides, and far more uncommonly lichenoid lesions,16,17 as in our case.

Histopathology

It has been demonstrated that the gross appearance of the secondary syphilitic lesion depends both on the degree of inflammatory infiltrate and the extent of vascular involvement producing ischemia of the skin.1 Our case presented with small, flat-topped, papular lesions that grossly resembled lichen planus and were ultimately shown to be the product of dense lymphomononuclear infiltration extending perivascularly and throughout the superficial and deep dermis.

Biopsy of a lesion is one means of diagnosis, though the histologic appearance of secondary syphilis can mimic many other diseases. In primary and secondary syphilis, skin biopsy characteristically shows central thinning or ulceration of the epidermal layer with heavy dermal lymphocyte infiltration, lymphovascular proliferation with endarteritis, small-vessel thrombosis, and dermal necrosis. Lichen planus–type dermatitis is histologically characterized by hyperkeratosis, irregular epidermal hyperplasia, and a dermoepidermal junction that may be obscured by a dense lymphomononuclear infiltrate.9 The specimen taken from our patient showed minimal infiltrate in the papillary dermis, suggesting a diagnosis of secondary syphilis with lichenoid features. Despite a gross appearance consistent with lichen planus, the biopsy lacked the hydropic degeneration of the basal layer and keratinocyte necrosis that typically characterize this condition.

Diagnosis

Serologic testing for syphilis infection is comprised of nontreponemal and treponemal studies. Nontreponemal testing, which includes the RPR and VDRL test, detects antibodies to cardiolipin-lecithin antigen, a lipid component of the cell membranes of T pallidum. Because the specificity of these tests is fairly low, they typically are used only for screening and monitoring of disease progression and/or response to treatment. Approximately 25% of cases in the United States of primary syphilis are not detected by nontreponemal testing, whereas a nonreactive test nearly always excludes a diagnosis of secondary or latent-stage syphilitic infection.9 Indeed, nontreponemal studies show the highest antibody titers during the late secondary and early latent stages of infection with declining titers thereafter, even in the absence of antibiotic treatment. In our case, diagnosis was made by biopsy and RPR was used for staging; RPR was reactive at a dilution of 1:32, indicative of secondary or early latent infection.

Treponemal testing, which includes the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test, and multiplex flow immunoassay detects antibodies that are specific to syphilis infection. Treponemal antibodies are detectable earlier in the course of infection than nontreponemal antibodies and remain permanently detectable even following treatment. Because of its high specificity, treponemal testing often is used to confirm diagnosis after positive screening with nontreponemal tests.4 Positive fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption testing and positive multiplex flow immunoassay may be used to confirm the diagnosis of T pallidum infection.

The tertiary stage of syphilis infection can occur years after conclusion of the secondary stage and is comprised of one or more of the following: gummas, aortic dilatation or dissection, and neurosyphilitic manifestations such as tabes dorsalis or general paresis.1 It is of vital importance to identify syphilis infection prior to the onset of the tertiary stage to prevent substantial morbidity and mortality.

Treatment

Our patient’s symptoms abated after empiric treatment with amoxicillin for presumed streptococcal throat infection after he presented to the emergency department with odynophagia, which is not surprising given the moderate-spectrum coverage of this β-lactam antibiotic as well as the near-complete susceptibility of Treponema spirochetes to amoxicillin in primary and secondary syphilis with notably lower efficacy in latent or tertiary disease. It was essential to treat the patient with a single dose of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million U, which has been shown to reliably prevent recurrence of infection or progression to tertiary syphilis.18

Conclusion

We present a rare case of lichenoid secondary syphilis in the absence of lesions on the palmar and plantar surfaces. The patient lacked any other cutaneous or systemic manifestations, except for odynophagia in association with oral mucosal lesions. He denied any new sexual partners and did not recall having a primary chancre. Also strikingly unusual in this case was the intense pruritus associated with the genital eruption, which is unlike the classic lack of symptoms experienced in the great majority of eruptions due to secondary syphilis. A clinical appreciation of the many cutaneous manifestations of syphilis infection remains critical to early identification of the disease prior to progression to the tertiary stage and its devastating sequelae.

Syphilis is a chronic systemic infection that has been allotted the epithet “the great imitator” for its gross and histologic similarity to numerous other skin pathologies. Well-characterized for centuries, syphilis features diverse clinical manifestations including a number of cutaneous symptoms.1

RELATED AUDIOCAST: The Syphilis Epidemic: Dermatologists on the Frontline of Treatment and Diagnosis

The primary stage of infection is classically defined by an asymptomatic chancre at the inoculation site. The secondary stage results from the systemic dissemination of the infection and typically is characterized by cutaneous eruptions, regional lymphadenopathy, and flulike symptoms. This stage gained its notoriety as the great imitator owing to its ability to present with a variety of papulosquamous eruptions. The secondary stage is followed by an asymptomatic latent period that may last months to years, followed by the tertiary stage, which is characterized by the neurologic, cardiovascular, and/or gummatous manifestations that represent the major sources of morbidity and mortality associated with syphilis. It is during the primary, secondary, and early latent stages that the infection is communicable.1

Case Report

A 40-year-old man presented with multiple intensely pruritic, scattered, erythematous and slightly violaceous, flat-topped papules on the scrotum (Figure 1A) and penile shaft (Figure 1B) of 1 week’s duration. Some of these lesions were annular in appearance. The patient denied any other dermatologic concerns and showed no other skin lesions. A shave biopsy of the right side of the penile shaft was performed, revealing minimal papillary dermis and superficial perivascular dermatitis with substantial perivascular plasmalymphocytic infiltration. The epidermal layer was mildly acanthotic with parakeratosis. A tentative diagnosis of secondary syphilis of unknown latency was made and confirmatory laboratory studies were ordered.

Within weeks, the patient developed a painful 7-mm white patch on the right lower mucosal lip followed several days later by the appearance of a painful lesion on the hard palate (Figure 2 [arrow indicates palatal lesion]) and odynophagia. He presented to the emergency department roughly 3 weeks from the time of index presentation and was started empirically on amoxicillin 500 mg 3 times daily for 10 days for suspicion of strep throat. At a scheduled follow-up with his dermatologist 1 week later, physical examination showed complete resolution of the mucosal lip patch and genital lesions. A round erythematous patch on the right hard palate consistent with a resolving mucosal patch also was noted. A diagnosis of secondary syphilitic infection was made with a rapid plasma reagin (RPR) titer of 1:32 (reference range, <1:1) and positive Treponema antibodies. The patient was treated with a single dose of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million U to prevent the development of tertiary syphilis.

Comment

Incidence

Syphilis has been well characterized since the early 15th century, though its geographic origin remains a topic of controversy.2 Although acquired syphilis infections represented a major source of morbidity and mortality in the early 20th century, the prevalence of syphilis in the United States declined substantially thereafter due to improved public health management.2 Syphilis was relatively rare in the United States by the year 1956, with fewer than 7000 cases of primary and secondary disease reported annually.3 The incidence of primary and secondary syphilis infections in the United States increased gradually until 1990 before declining precipitously and reaching an unprecedented low of 2.2 cases per 100,000 individuals in 2000.4 These shifts ultimately have resulted in decreased clinical familiarity with the disease presentation of syphilis among many health care providers. Since 2000, the incidence of syphilis infection has increased in the United States, with the greatest increases seen in men who have sex with men, intravenous drug users, and human immunodeficiency virus–infected individuals.5-7

RELATED ARTICLE: Syphilis and the Dermatologist

Pathogenesis and Transmission

The causative agent in syphilis infection is the bacterium Treponema pallidum, a member of the family Spirochaetaceae, which is distinguished by its thin, regularly coiled form and distinctive corkscrew motility.8 Syphilis is communicated primarily by sexual contact or in utero exposure during the primary and secondary stages of maternal infection.9 At the time of presentation, our patient denied having any new sexual partners or practices. He reported a monogamous heterosexual relationship within the months preceding presentation, suggesting historical inaccuracy on the part of the patient or probable infidelity in the reported relationship as an alternative means of infection transmission. Untreated individuals may be contagious for longer than 1 year,9 making transmission patterns difficult to track clinically.

Presentation

The clinical presentation of infection with T pallidum results from dual humoral and cell-mediated inflammatory responses in the host. The primary stage is classically defined by a single chancre, which develops at the inoculation site(s) 9 to 90 days following exposure. The chancre typically begins as a small papule that rapidly develops into a painless ulcer characterized by an indurated border, red base, bordering edema, and a diameter of 2 cm or less. Indolent regional lymphadenopathy often is observed in conjunction with the primary chancre.10 Our case is notable for the absence of a primary syphilitic lesion and lack of adenopathy. The primary chancre of syphilis typically resolves within 3 to 6 weeks of onset regardless of whether the patient is treated,4 thus suggesting the rare possibility that our patient developed a painless primary chancre without realizing it.

The secondary stage of syphilis infection arises weeks to months after resolution of the primary chancre and is triggered by hematogenous and lymphatic dissemination of the bacteria. The symptoms of secondary syphilis are primarily flulike and may include headache, malaise, fatigue, sore throat, arthralgia, and low-grade fever.9 Nontender regional lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly also have been reported.11 Our patient denied any systemic concerns throughout the duration of his illness, with the exception of odynophagia in association with ulceration of the oral mucosa. Abnormal laboratory findings in secondary syphilis are nonspecific and may include an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and/or an increased white blood cell count with absolute lymphocytosis.12 Laboratory studies drawn at the time of presentation showed no such abnormalities in our patient.

The cutaneous signs of secondary syphilis arise concurrently with systemic manifestations and are a common finding, with lesions of the skin or oral mucosa present in up to 80% of patients,13 as in our case. Oral lesions classically involve ulcerations at the tip and sides of the tongue,12 which is distinct from our patient who developed oral lesions of the mucosal lip and hard palate.

Secondary syphilis classically features a copper-colored maculopapular rash with sharply delineated margins typically present on the palmar and plantar surfaces.14 Verrucous lesions appearing as moist exophytic plaques on the genitals, intertriginous areas, and/or perineum also have been described and are referred to as condyloma lata in the setting of secondary syphilis.15 In contrast to these classic findings, our patient demonstrated lichenoid lesions on the genitalia and white mucosal patches on the oral mucosa. Our case also was highly unusual because of the intense pruritus associated with the genital lesions, which starkly contrasts most secondary-stage cutaneous lesions that are classically asymptomatic.14 Additionally, our case was distinctive due to the lack of palmar or plantar involvement, which is considered a characteristic feature of secondary cutaneous syphilis.1 Finally, our case was notable for the presence of multiple annular cutaneous lesions, which indicated a late secondary-stage infection during which involution of the lesions produced endarteritis as deeper vessels became involved. A 20-year retrospective study by Abell et al11 demonstrated that 40% of syphilitic rashes are macular, 40% are maculopapular, 10% are papular (as in our case), and the remaining 10% are not easily grouped within these categories.

Differential Diagnosis

It has been estimated that approximately 8% of cutaneous syphilitic lesions demonstrate morphology and distributions suggestive of other dermatologic conditions, including atopic dermatitis, pityriasis rosea, psoriasis, drug-induced eruptions, erythema multiforme, mycosis fungoides, and far more uncommonly lichenoid lesions,16,17 as in our case.

Histopathology

It has been demonstrated that the gross appearance of the secondary syphilitic lesion depends both on the degree of inflammatory infiltrate and the extent of vascular involvement producing ischemia of the skin.1 Our case presented with small, flat-topped, papular lesions that grossly resembled lichen planus and were ultimately shown to be the product of dense lymphomononuclear infiltration extending perivascularly and throughout the superficial and deep dermis.

Biopsy of a lesion is one means of diagnosis, though the histologic appearance of secondary syphilis can mimic many other diseases. In primary and secondary syphilis, skin biopsy characteristically shows central thinning or ulceration of the epidermal layer with heavy dermal lymphocyte infiltration, lymphovascular proliferation with endarteritis, small-vessel thrombosis, and dermal necrosis. Lichen planus–type dermatitis is histologically characterized by hyperkeratosis, irregular epidermal hyperplasia, and a dermoepidermal junction that may be obscured by a dense lymphomononuclear infiltrate.9 The specimen taken from our patient showed minimal infiltrate in the papillary dermis, suggesting a diagnosis of secondary syphilis with lichenoid features. Despite a gross appearance consistent with lichen planus, the biopsy lacked the hydropic degeneration of the basal layer and keratinocyte necrosis that typically characterize this condition.

Diagnosis

Serologic testing for syphilis infection is comprised of nontreponemal and treponemal studies. Nontreponemal testing, which includes the RPR and VDRL test, detects antibodies to cardiolipin-lecithin antigen, a lipid component of the cell membranes of T pallidum. Because the specificity of these tests is fairly low, they typically are used only for screening and monitoring of disease progression and/or response to treatment. Approximately 25% of cases in the United States of primary syphilis are not detected by nontreponemal testing, whereas a nonreactive test nearly always excludes a diagnosis of secondary or latent-stage syphilitic infection.9 Indeed, nontreponemal studies show the highest antibody titers during the late secondary and early latent stages of infection with declining titers thereafter, even in the absence of antibiotic treatment. In our case, diagnosis was made by biopsy and RPR was used for staging; RPR was reactive at a dilution of 1:32, indicative of secondary or early latent infection.

Treponemal testing, which includes the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test, and multiplex flow immunoassay detects antibodies that are specific to syphilis infection. Treponemal antibodies are detectable earlier in the course of infection than nontreponemal antibodies and remain permanently detectable even following treatment. Because of its high specificity, treponemal testing often is used to confirm diagnosis after positive screening with nontreponemal tests.4 Positive fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption testing and positive multiplex flow immunoassay may be used to confirm the diagnosis of T pallidum infection.

The tertiary stage of syphilis infection can occur years after conclusion of the secondary stage and is comprised of one or more of the following: gummas, aortic dilatation or dissection, and neurosyphilitic manifestations such as tabes dorsalis or general paresis.1 It is of vital importance to identify syphilis infection prior to the onset of the tertiary stage to prevent substantial morbidity and mortality.

Treatment

Our patient’s symptoms abated after empiric treatment with amoxicillin for presumed streptococcal throat infection after he presented to the emergency department with odynophagia, which is not surprising given the moderate-spectrum coverage of this β-lactam antibiotic as well as the near-complete susceptibility of Treponema spirochetes to amoxicillin in primary and secondary syphilis with notably lower efficacy in latent or tertiary disease. It was essential to treat the patient with a single dose of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million U, which has been shown to reliably prevent recurrence of infection or progression to tertiary syphilis.18

Conclusion

We present a rare case of lichenoid secondary syphilis in the absence of lesions on the palmar and plantar surfaces. The patient lacked any other cutaneous or systemic manifestations, except for odynophagia in association with oral mucosal lesions. He denied any new sexual partners and did not recall having a primary chancre. Also strikingly unusual in this case was the intense pruritus associated with the genital eruption, which is unlike the classic lack of symptoms experienced in the great majority of eruptions due to secondary syphilis. A clinical appreciation of the many cutaneous manifestations of syphilis infection remains critical to early identification of the disease prior to progression to the tertiary stage and its devastating sequelae.

- Dourmishev LA, Assen L. Syphilis: uncommon presentations in adults. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:555-564.

- Seña AC, White BL, Sparling PF. Novel Treponema pallidum serologic tests: a paradigm shift in syphilis screening for the 21st century. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:700-708.

- Kilmarx PH, St Louis ME. The evolving epidemiology of syphilis. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(8, pt 1):1053-1054.

- Patton ME, Su JR, Nelson R, et al. Primary and secondary syphilis—United States, 2005-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:402-406.

- Coffin LS, Newberry A, Hagan H, et al. Syphilis in drug users in low and middle income countries. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21:20-27.

- Gao L, Zhang L, Jin Q. Meta-analysis: prevalence of HIV infection and syphilis among MSM in China. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85:354-358.

- Karp G, Schlaeffer F, Jotkowitz A, et al. Syphilis and HIV co-infection. Eur J Int Med. 2009;20:9-13.

- Hol EL, Lukehart SA. Syphilis: using modern approaches to understand an old disease. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4584-4592.

- Schnirring-Judge M, Gustaferro C, Terol C. Vesiculobullous syphilis: a case involving an unusual cutaneous manifestation of secondary syphilis. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50:96-101.

- Brown DL, Frank JE. Diagnosis and management of syphilis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:283-290.

- Abell E, Marks R, Jones W. Secondary syphilis: a clinicopathological review. Br J Dermatol. 1975;93:53-61.

- Fiumara N. The treponematoses. Int Dermatol. 1992;1:953-974.

- Martin DH, Mroczkowski TF. Dermatological manifestations of sexually transmitted diseases other than HIV. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1994;8:533-583.

- Morton RS. The treponematoses. In: Champion RH, Bourton JL, Burns DA, et al. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 6th ed. London, United Kingdom: Blackwell Science; 1998:1237-1275.

- Rosen T, Hwong H. Pedal interdigital condylomata lata: a rare sign of secondary syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28:184-186.

- Jeerapaet P, Ackerman AB. Histologic patterns of secondary syphilis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:373-377.

- Tang MBY, Yosipovitch G, Tan SH. Secondary syphilis presenting as a lichen planus-like rash. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:185-187.

- Onoda Y. Clinical evaluation of amoxicillin in the treatment of syphilis. J Int Med. 1979;7:539-545.

- Dourmishev LA, Assen L. Syphilis: uncommon presentations in adults. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:555-564.

- Seña AC, White BL, Sparling PF. Novel Treponema pallidum serologic tests: a paradigm shift in syphilis screening for the 21st century. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:700-708.

- Kilmarx PH, St Louis ME. The evolving epidemiology of syphilis. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(8, pt 1):1053-1054.

- Patton ME, Su JR, Nelson R, et al. Primary and secondary syphilis—United States, 2005-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:402-406.

- Coffin LS, Newberry A, Hagan H, et al. Syphilis in drug users in low and middle income countries. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21:20-27.

- Gao L, Zhang L, Jin Q. Meta-analysis: prevalence of HIV infection and syphilis among MSM in China. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85:354-358.

- Karp G, Schlaeffer F, Jotkowitz A, et al. Syphilis and HIV co-infection. Eur J Int Med. 2009;20:9-13.

- Hol EL, Lukehart SA. Syphilis: using modern approaches to understand an old disease. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4584-4592.

- Schnirring-Judge M, Gustaferro C, Terol C. Vesiculobullous syphilis: a case involving an unusual cutaneous manifestation of secondary syphilis. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50:96-101.

- Brown DL, Frank JE. Diagnosis and management of syphilis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:283-290.

- Abell E, Marks R, Jones W. Secondary syphilis: a clinicopathological review. Br J Dermatol. 1975;93:53-61.

- Fiumara N. The treponematoses. Int Dermatol. 1992;1:953-974.

- Martin DH, Mroczkowski TF. Dermatological manifestations of sexually transmitted diseases other than HIV. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1994;8:533-583.

- Morton RS. The treponematoses. In: Champion RH, Bourton JL, Burns DA, et al. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 6th ed. London, United Kingdom: Blackwell Science; 1998:1237-1275.

- Rosen T, Hwong H. Pedal interdigital condylomata lata: a rare sign of secondary syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28:184-186.

- Jeerapaet P, Ackerman AB. Histologic patterns of secondary syphilis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:373-377.

- Tang MBY, Yosipovitch G, Tan SH. Secondary syphilis presenting as a lichen planus-like rash. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:185-187.

- Onoda Y. Clinical evaluation of amoxicillin in the treatment of syphilis. J Int Med. 1979;7:539-545.

Practice Points

- Syphilis retains its reputation as “the great imitator” due to its wide variability in clinical presentation and propensity for misdiagnosis.

- Lichenoid syphilis is a well-described cutaneous presentation of secondary syphilis, though the characteristics of these lesions remain highly variable and require a high degree of clinical suspicion.

- Treponema pallidum is partially susceptible to most β-lactam antibiotics in primary and early secondary stages of infection; thus, use of these medications can obscure symptoms without adequately treating the infection.