User login

Papules on the Face and Body

The Diagnosis: Lichen Spinulosus

Lichen spinulosus, also referred to as keratosis spinulosa, is a disorder of keratinization characterized by grouped 1- to 3-mm papules with a horny spine localized to follicles (Figure).1 These lesions most commonly occur in the first through third decades of life, presenting as 2- to 6-cm patches on the neck, buttocks, thighs, abdomen, or extensor surfaces.1-4 Some patients report mild pruritus.1 The cause is unknown.1-3,5-7 Several proposed but unproven explanations include atopy,2,4 genetic predisposition,1,2 toxins,3,5 infection,5 abnormal immune response,8 and vitamin deficiency.1,6,7

Our patient’s presentation is atypical due to her age and the involvement of her face. Generalized lichen spinulosus in adults likely is rare. A few similar cases have been reported: a 61-year-old woman with Crohn disease and lichen spinulosus affecting the groin, inframammary region, and back8; 2 case reports linked to alcoholism-associated nutritional deficiency6,7; and generalized lichen spinulosus–like eruptions in 2 patients with human immuno-deficiency virus infection.9,10 Our patient’s medical history indicated an extensive smoking history; thiamine deficiency 5 years prior treated with vitamin B complex supplements, which she still takes; and a recent diagnosis of vitamin D deficiency. She had no evidence of immunodeficiency or systemic illness on routine screening.

The disorders of follicular keratinization are lichen spinulosus, keratosis pilaris, keratosis pilaris atrophicans, pityriasis rubra pilaris, lichen planopilaris, erythromelanosis follicularis faciei, and phrynoderma.11 The clinical differential diagnosis of lichen spinulosus includes keratosis pilaris, phrynoderma, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and frictional lichenoid eruption. Lichen spinulosus can be distinguished from keratosis pilaris by 4 factors1,11: (1) keratosis pilaris lesions develop slowly over time as opposed to the rapid onset in lichen spinulosus; (2) keratosis pilaris is preferentially located on the upper arms and legs; (3) keratosis pilaris does not develop in small clusters; (4) keratosis pilaris, unlike lichen spinulosus, often has a thin outline of perifollicular erythema. Histopathologically, lichen spinulosus is similar to keratosis pilaris, showing dilated hair follicles with a keratin plug and perifollicular and perivascular dermal lymphocytic infiltrate.1 A punch biopsy from our patient’s cheek demonstrated focal follicular hyperkeratosis with dermal perivascular inflammation. Periodic acid–Schiff with diastase stain was negative for pathogenic fungal organisms.

Treatment of lichen spinulosus is initiated to address cosmetic concerns. Traditionally, keratolytics and emollients are utilized. Success has been described with salicylic acid gel 6% without occlusion for 8 weeks12 or with occlusion for 2 weeks.13 Tar preparations and mid-potency topical corticosteroids may be used on lesions not located on the face.2,4,15 Topical vitamin A,2 lactic acid,4 and ammonium lactate lotion2 have been therapeutic in some cases. Facial lesions have been successfully treated with tacalcitol14 or tretinoin gel 0.04% in combination with hydroactive adhesive applications.15 In the case of lichen spinulosus accompanying alcoholism, oral vitamin supplementation has been sufficient for resolution.6,7

Our patient was initially prescribed ammonium lactate lotion twice daily and tretinoin cream 0.025% for facial application nightly. She only used the tretinoin briefly due to skin irritation, and she discontinued use of ammonium lactate due to lotion texture. Three months of vitamin A and vitamin B complex supplementation did not lead to any improvement. She believed the papules softened by scrubbing them with a loofah in the shower and then moisturizing. Malignancy workup, including a colonoscopy, mammography, chest radiograph, and basic blood tests, were negative. No remarkable change was noted by the patient at 1-year follow-up.

1. Friedman SJ. Lichen spinulosus. clinicopathologic review of thirty-five cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:261-264.

2. Boyd AS. Lichen spinulosus: case report and overview. Cutis. 1989;43:557-560.

3. Adamson H. Lichen pilaris, seu spinulosis. Br J Dermatol. 1905;17:39-54.

4. Strickling WA, Norton SA. Spiny eruption on the neck. diagnosis: lichen spinulosus (LS). Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1165-1170.

5. Becker S. Lichen spinulosus following intradermal application of diphtheria toxin. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1930;21:839-840.

6. Irgang S. Lichen spinulosus responsive to ascorbic acid (vitamin C). case in an alcoholic adult. Skin. 1964;3:145-146.

7. Kabashima R, Sugita K, Kabashima K, et al. Lichen spinulosus in an alcoholic patient. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:311-312.

8. Kano Y, Orihara M, Yagita A, et al. Lichen spinulosus in a patient with Crohn disease. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:670-671.

9. Cohen SJ, Dicken CH. Generalized lichen spinulosus in an HIV-positive man. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:116-118.

10. Resnick SD, Murrell DF, Woosley J. Acne conglobata and a generalized lichen spinulosus-like eruption in a man seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:1013-1014.

11. McMichael A, Curtis A, Guzman-Sanchez D, et al. Folliculitis and other follicular disorders. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2012:571-586.

12. Tuyp E, McLeod WA, Boyko W. Lichen spinulosus with immunofluorescent studies. Cutis. 1984;33:197-200.

13. Maiocco KJ, Miller OF. Lichen spinulosus: response to therapy. Cutis. 1976;17:294-299.

14. Kim SH, Kang JH, Seo JK, et al. Successful treatment of lichen spinulosus with topical tacalcitol cream. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:546-547.

15. Forman SB, Hudgins EM, Blaylock WK. Lichen spinulosus: excellent response to tretinoin gel and hydroactive adhesive applications. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:122-123.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Spinulosus

Lichen spinulosus, also referred to as keratosis spinulosa, is a disorder of keratinization characterized by grouped 1- to 3-mm papules with a horny spine localized to follicles (Figure).1 These lesions most commonly occur in the first through third decades of life, presenting as 2- to 6-cm patches on the neck, buttocks, thighs, abdomen, or extensor surfaces.1-4 Some patients report mild pruritus.1 The cause is unknown.1-3,5-7 Several proposed but unproven explanations include atopy,2,4 genetic predisposition,1,2 toxins,3,5 infection,5 abnormal immune response,8 and vitamin deficiency.1,6,7

Our patient’s presentation is atypical due to her age and the involvement of her face. Generalized lichen spinulosus in adults likely is rare. A few similar cases have been reported: a 61-year-old woman with Crohn disease and lichen spinulosus affecting the groin, inframammary region, and back8; 2 case reports linked to alcoholism-associated nutritional deficiency6,7; and generalized lichen spinulosus–like eruptions in 2 patients with human immuno-deficiency virus infection.9,10 Our patient’s medical history indicated an extensive smoking history; thiamine deficiency 5 years prior treated with vitamin B complex supplements, which she still takes; and a recent diagnosis of vitamin D deficiency. She had no evidence of immunodeficiency or systemic illness on routine screening.

The disorders of follicular keratinization are lichen spinulosus, keratosis pilaris, keratosis pilaris atrophicans, pityriasis rubra pilaris, lichen planopilaris, erythromelanosis follicularis faciei, and phrynoderma.11 The clinical differential diagnosis of lichen spinulosus includes keratosis pilaris, phrynoderma, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and frictional lichenoid eruption. Lichen spinulosus can be distinguished from keratosis pilaris by 4 factors1,11: (1) keratosis pilaris lesions develop slowly over time as opposed to the rapid onset in lichen spinulosus; (2) keratosis pilaris is preferentially located on the upper arms and legs; (3) keratosis pilaris does not develop in small clusters; (4) keratosis pilaris, unlike lichen spinulosus, often has a thin outline of perifollicular erythema. Histopathologically, lichen spinulosus is similar to keratosis pilaris, showing dilated hair follicles with a keratin plug and perifollicular and perivascular dermal lymphocytic infiltrate.1 A punch biopsy from our patient’s cheek demonstrated focal follicular hyperkeratosis with dermal perivascular inflammation. Periodic acid–Schiff with diastase stain was negative for pathogenic fungal organisms.

Treatment of lichen spinulosus is initiated to address cosmetic concerns. Traditionally, keratolytics and emollients are utilized. Success has been described with salicylic acid gel 6% without occlusion for 8 weeks12 or with occlusion for 2 weeks.13 Tar preparations and mid-potency topical corticosteroids may be used on lesions not located on the face.2,4,15 Topical vitamin A,2 lactic acid,4 and ammonium lactate lotion2 have been therapeutic in some cases. Facial lesions have been successfully treated with tacalcitol14 or tretinoin gel 0.04% in combination with hydroactive adhesive applications.15 In the case of lichen spinulosus accompanying alcoholism, oral vitamin supplementation has been sufficient for resolution.6,7

Our patient was initially prescribed ammonium lactate lotion twice daily and tretinoin cream 0.025% for facial application nightly. She only used the tretinoin briefly due to skin irritation, and she discontinued use of ammonium lactate due to lotion texture. Three months of vitamin A and vitamin B complex supplementation did not lead to any improvement. She believed the papules softened by scrubbing them with a loofah in the shower and then moisturizing. Malignancy workup, including a colonoscopy, mammography, chest radiograph, and basic blood tests, were negative. No remarkable change was noted by the patient at 1-year follow-up.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Spinulosus

Lichen spinulosus, also referred to as keratosis spinulosa, is a disorder of keratinization characterized by grouped 1- to 3-mm papules with a horny spine localized to follicles (Figure).1 These lesions most commonly occur in the first through third decades of life, presenting as 2- to 6-cm patches on the neck, buttocks, thighs, abdomen, or extensor surfaces.1-4 Some patients report mild pruritus.1 The cause is unknown.1-3,5-7 Several proposed but unproven explanations include atopy,2,4 genetic predisposition,1,2 toxins,3,5 infection,5 abnormal immune response,8 and vitamin deficiency.1,6,7

Our patient’s presentation is atypical due to her age and the involvement of her face. Generalized lichen spinulosus in adults likely is rare. A few similar cases have been reported: a 61-year-old woman with Crohn disease and lichen spinulosus affecting the groin, inframammary region, and back8; 2 case reports linked to alcoholism-associated nutritional deficiency6,7; and generalized lichen spinulosus–like eruptions in 2 patients with human immuno-deficiency virus infection.9,10 Our patient’s medical history indicated an extensive smoking history; thiamine deficiency 5 years prior treated with vitamin B complex supplements, which she still takes; and a recent diagnosis of vitamin D deficiency. She had no evidence of immunodeficiency or systemic illness on routine screening.

The disorders of follicular keratinization are lichen spinulosus, keratosis pilaris, keratosis pilaris atrophicans, pityriasis rubra pilaris, lichen planopilaris, erythromelanosis follicularis faciei, and phrynoderma.11 The clinical differential diagnosis of lichen spinulosus includes keratosis pilaris, phrynoderma, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and frictional lichenoid eruption. Lichen spinulosus can be distinguished from keratosis pilaris by 4 factors1,11: (1) keratosis pilaris lesions develop slowly over time as opposed to the rapid onset in lichen spinulosus; (2) keratosis pilaris is preferentially located on the upper arms and legs; (3) keratosis pilaris does not develop in small clusters; (4) keratosis pilaris, unlike lichen spinulosus, often has a thin outline of perifollicular erythema. Histopathologically, lichen spinulosus is similar to keratosis pilaris, showing dilated hair follicles with a keratin plug and perifollicular and perivascular dermal lymphocytic infiltrate.1 A punch biopsy from our patient’s cheek demonstrated focal follicular hyperkeratosis with dermal perivascular inflammation. Periodic acid–Schiff with diastase stain was negative for pathogenic fungal organisms.

Treatment of lichen spinulosus is initiated to address cosmetic concerns. Traditionally, keratolytics and emollients are utilized. Success has been described with salicylic acid gel 6% without occlusion for 8 weeks12 or with occlusion for 2 weeks.13 Tar preparations and mid-potency topical corticosteroids may be used on lesions not located on the face.2,4,15 Topical vitamin A,2 lactic acid,4 and ammonium lactate lotion2 have been therapeutic in some cases. Facial lesions have been successfully treated with tacalcitol14 or tretinoin gel 0.04% in combination with hydroactive adhesive applications.15 In the case of lichen spinulosus accompanying alcoholism, oral vitamin supplementation has been sufficient for resolution.6,7

Our patient was initially prescribed ammonium lactate lotion twice daily and tretinoin cream 0.025% for facial application nightly. She only used the tretinoin briefly due to skin irritation, and she discontinued use of ammonium lactate due to lotion texture. Three months of vitamin A and vitamin B complex supplementation did not lead to any improvement. She believed the papules softened by scrubbing them with a loofah in the shower and then moisturizing. Malignancy workup, including a colonoscopy, mammography, chest radiograph, and basic blood tests, were negative. No remarkable change was noted by the patient at 1-year follow-up.

1. Friedman SJ. Lichen spinulosus. clinicopathologic review of thirty-five cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:261-264.

2. Boyd AS. Lichen spinulosus: case report and overview. Cutis. 1989;43:557-560.

3. Adamson H. Lichen pilaris, seu spinulosis. Br J Dermatol. 1905;17:39-54.

4. Strickling WA, Norton SA. Spiny eruption on the neck. diagnosis: lichen spinulosus (LS). Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1165-1170.

5. Becker S. Lichen spinulosus following intradermal application of diphtheria toxin. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1930;21:839-840.

6. Irgang S. Lichen spinulosus responsive to ascorbic acid (vitamin C). case in an alcoholic adult. Skin. 1964;3:145-146.

7. Kabashima R, Sugita K, Kabashima K, et al. Lichen spinulosus in an alcoholic patient. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:311-312.

8. Kano Y, Orihara M, Yagita A, et al. Lichen spinulosus in a patient with Crohn disease. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:670-671.

9. Cohen SJ, Dicken CH. Generalized lichen spinulosus in an HIV-positive man. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:116-118.

10. Resnick SD, Murrell DF, Woosley J. Acne conglobata and a generalized lichen spinulosus-like eruption in a man seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:1013-1014.

11. McMichael A, Curtis A, Guzman-Sanchez D, et al. Folliculitis and other follicular disorders. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2012:571-586.

12. Tuyp E, McLeod WA, Boyko W. Lichen spinulosus with immunofluorescent studies. Cutis. 1984;33:197-200.

13. Maiocco KJ, Miller OF. Lichen spinulosus: response to therapy. Cutis. 1976;17:294-299.

14. Kim SH, Kang JH, Seo JK, et al. Successful treatment of lichen spinulosus with topical tacalcitol cream. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:546-547.

15. Forman SB, Hudgins EM, Blaylock WK. Lichen spinulosus: excellent response to tretinoin gel and hydroactive adhesive applications. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:122-123.

1. Friedman SJ. Lichen spinulosus. clinicopathologic review of thirty-five cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:261-264.

2. Boyd AS. Lichen spinulosus: case report and overview. Cutis. 1989;43:557-560.

3. Adamson H. Lichen pilaris, seu spinulosis. Br J Dermatol. 1905;17:39-54.

4. Strickling WA, Norton SA. Spiny eruption on the neck. diagnosis: lichen spinulosus (LS). Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1165-1170.

5. Becker S. Lichen spinulosus following intradermal application of diphtheria toxin. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1930;21:839-840.

6. Irgang S. Lichen spinulosus responsive to ascorbic acid (vitamin C). case in an alcoholic adult. Skin. 1964;3:145-146.

7. Kabashima R, Sugita K, Kabashima K, et al. Lichen spinulosus in an alcoholic patient. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:311-312.

8. Kano Y, Orihara M, Yagita A, et al. Lichen spinulosus in a patient with Crohn disease. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:670-671.

9. Cohen SJ, Dicken CH. Generalized lichen spinulosus in an HIV-positive man. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:116-118.

10. Resnick SD, Murrell DF, Woosley J. Acne conglobata and a generalized lichen spinulosus-like eruption in a man seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:1013-1014.

11. McMichael A, Curtis A, Guzman-Sanchez D, et al. Folliculitis and other follicular disorders. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2012:571-586.

12. Tuyp E, McLeod WA, Boyko W. Lichen spinulosus with immunofluorescent studies. Cutis. 1984;33:197-200.

13. Maiocco KJ, Miller OF. Lichen spinulosus: response to therapy. Cutis. 1976;17:294-299.

14. Kim SH, Kang JH, Seo JK, et al. Successful treatment of lichen spinulosus with topical tacalcitol cream. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:546-547.

15. Forman SB, Hudgins EM, Blaylock WK. Lichen spinulosus: excellent response to tretinoin gel and hydroactive adhesive applications. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:122-123.

A 65-year-old woman presented for evaluation of papules on the face and body that had developed over a short period of time approximately 1.5 years prior. The papules were entirely asymptomatic. She had no prior treatment. On physical examination multiple flesh-colored papules with a central keratotic spicule were noted on the face, neck, arms, and legs.

Erythematous Friable Papule Under the Great Toenail

The Diagnosis: Subungual Eccrine Poroma

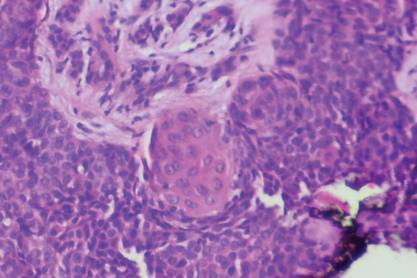

Histologic examination revealed a solitary papule (Figure 1). The epidermis was replaced with a well-defined proliferation of cuboidal and poroid cells. These cells demonstrated a downgrowth into the dermis in broad anastomosing bands that were surrounded by a fibrovascular stroma. Notably, there were few scattered foci of maturation into the ductal lumina of eccrine origin, which confirmed the diagnosis (Figure 2).

|

First described in 1956 by Goldman et al,1 eccrine poromas are benign, slow-growing tumors that account for approximately 10% of sweat gland neoplasms.2 Onset is typically in mid to late adulthood, and there is no ethnic or gender predilection. Classically, eccrine poromas present as soft, sessile, reddish papules or nodules measuring less than 2 cm that protrude from a well-circumscribed depression.

Although eccrine poromas can develop on hair-bearing regions, they most commonly arise on acral skin. In acral locations, bleeding, discharge, rapid growth, and localized pain can occur. These symptoms are even more common in this lesion’s malignant counterpart, eccrine porocarcinoma.3

Solar damage, radiation exposure, trauma, and human papillomavirus have been indicated in the pathogenesis of eccrine poroma; however, the exact etiology has yet to be defined.2,4 The differential diagnosis includes nevus, pyogenic granu-loma, acrochordon, basal cell carcinoma, and verruca vulgaris.5

Histologically, eccrine poromas consist of a combination of 5 distinct features: poroid cells, cuticular cells, intracytoplasmic or intercellular vacuolization en route to duct formation, massive necrosis or necrosis en masse, and nuclear monomorphism of the poroid and cuticular cells.6 However, all 5 histologic features do not have to be present for the diagnosis. Classically, there is a sharp demarcation of the lesion from the surrounding epidermis.7

Treatment of choice is complete excision to prevent recurrence and risk for malignant transformation in long-standing lesions. One study of eccrine porocarcinomas found that 18% (11/62) arose from a benign preexistent poroma.8 These malignant lesions are found more commonly on the extremities and tend to show a slight female predominance.9

Although there have been 2 reported cases of subungual eccrine porocarcinomas9,10 and 1 case of periungual eccrine porocarcinoma,11 according to an Ovid search using the terms porocarcinoma and nail, the benign subungual eccrine poroma is more rare.

1. Goldman P, Pinkus H, Rogin JR. Eccrine poroma; tumors exhibiting features of the epidermal sweat duct unit. AMA Arch Derm. 1956;74:511-521.

2. Orlandi C, Arcangeli F, Patrizi A, et al. Eccrine poroma in a child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:279-280.

3. Casper DJ, Glass LF, Shenefelt PD. An unusually large eccrine poroma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2011;88:227-229.

4. Kang MC, Kim SA, Lee KS, et al. A case of an unusual eccrine poroma on the left forearm area. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:250-253.

5. Moore TO, Orman HL, Orman SK, et al. Poromas of the head and neck. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:48-52.

6. Chen CC, Chang YT, Liu HN. Clinical and histological characteristics of poroid neoplasms: a study of 25 cases in Taiwan. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:722-727.

7. Smith EV, Madan V, Joshi A, et al. A pigmented lesion on the foot. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:84-86.

8. Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720.

9. Moussallem CD, Abi Hatem NE, El-Khoury ZN.Malignant porocarcinoma of the nail fold: a tricky diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:10.

10. Requena L, Sánchez M, Aguilar A, et al. Periungual porocarcinoma. Dermatologica. 1990;180:177-180.

11. van Gorp J, van der Putte SC. Periungual eccrine porocarcinoma. Dermatology. 1993;187:67-70.

The Diagnosis: Subungual Eccrine Poroma

Histologic examination revealed a solitary papule (Figure 1). The epidermis was replaced with a well-defined proliferation of cuboidal and poroid cells. These cells demonstrated a downgrowth into the dermis in broad anastomosing bands that were surrounded by a fibrovascular stroma. Notably, there were few scattered foci of maturation into the ductal lumina of eccrine origin, which confirmed the diagnosis (Figure 2).

|

First described in 1956 by Goldman et al,1 eccrine poromas are benign, slow-growing tumors that account for approximately 10% of sweat gland neoplasms.2 Onset is typically in mid to late adulthood, and there is no ethnic or gender predilection. Classically, eccrine poromas present as soft, sessile, reddish papules or nodules measuring less than 2 cm that protrude from a well-circumscribed depression.

Although eccrine poromas can develop on hair-bearing regions, they most commonly arise on acral skin. In acral locations, bleeding, discharge, rapid growth, and localized pain can occur. These symptoms are even more common in this lesion’s malignant counterpart, eccrine porocarcinoma.3

Solar damage, radiation exposure, trauma, and human papillomavirus have been indicated in the pathogenesis of eccrine poroma; however, the exact etiology has yet to be defined.2,4 The differential diagnosis includes nevus, pyogenic granu-loma, acrochordon, basal cell carcinoma, and verruca vulgaris.5

Histologically, eccrine poromas consist of a combination of 5 distinct features: poroid cells, cuticular cells, intracytoplasmic or intercellular vacuolization en route to duct formation, massive necrosis or necrosis en masse, and nuclear monomorphism of the poroid and cuticular cells.6 However, all 5 histologic features do not have to be present for the diagnosis. Classically, there is a sharp demarcation of the lesion from the surrounding epidermis.7

Treatment of choice is complete excision to prevent recurrence and risk for malignant transformation in long-standing lesions. One study of eccrine porocarcinomas found that 18% (11/62) arose from a benign preexistent poroma.8 These malignant lesions are found more commonly on the extremities and tend to show a slight female predominance.9

Although there have been 2 reported cases of subungual eccrine porocarcinomas9,10 and 1 case of periungual eccrine porocarcinoma,11 according to an Ovid search using the terms porocarcinoma and nail, the benign subungual eccrine poroma is more rare.

The Diagnosis: Subungual Eccrine Poroma

Histologic examination revealed a solitary papule (Figure 1). The epidermis was replaced with a well-defined proliferation of cuboidal and poroid cells. These cells demonstrated a downgrowth into the dermis in broad anastomosing bands that were surrounded by a fibrovascular stroma. Notably, there were few scattered foci of maturation into the ductal lumina of eccrine origin, which confirmed the diagnosis (Figure 2).

|

First described in 1956 by Goldman et al,1 eccrine poromas are benign, slow-growing tumors that account for approximately 10% of sweat gland neoplasms.2 Onset is typically in mid to late adulthood, and there is no ethnic or gender predilection. Classically, eccrine poromas present as soft, sessile, reddish papules or nodules measuring less than 2 cm that protrude from a well-circumscribed depression.

Although eccrine poromas can develop on hair-bearing regions, they most commonly arise on acral skin. In acral locations, bleeding, discharge, rapid growth, and localized pain can occur. These symptoms are even more common in this lesion’s malignant counterpart, eccrine porocarcinoma.3

Solar damage, radiation exposure, trauma, and human papillomavirus have been indicated in the pathogenesis of eccrine poroma; however, the exact etiology has yet to be defined.2,4 The differential diagnosis includes nevus, pyogenic granu-loma, acrochordon, basal cell carcinoma, and verruca vulgaris.5

Histologically, eccrine poromas consist of a combination of 5 distinct features: poroid cells, cuticular cells, intracytoplasmic or intercellular vacuolization en route to duct formation, massive necrosis or necrosis en masse, and nuclear monomorphism of the poroid and cuticular cells.6 However, all 5 histologic features do not have to be present for the diagnosis. Classically, there is a sharp demarcation of the lesion from the surrounding epidermis.7

Treatment of choice is complete excision to prevent recurrence and risk for malignant transformation in long-standing lesions. One study of eccrine porocarcinomas found that 18% (11/62) arose from a benign preexistent poroma.8 These malignant lesions are found more commonly on the extremities and tend to show a slight female predominance.9

Although there have been 2 reported cases of subungual eccrine porocarcinomas9,10 and 1 case of periungual eccrine porocarcinoma,11 according to an Ovid search using the terms porocarcinoma and nail, the benign subungual eccrine poroma is more rare.

1. Goldman P, Pinkus H, Rogin JR. Eccrine poroma; tumors exhibiting features of the epidermal sweat duct unit. AMA Arch Derm. 1956;74:511-521.

2. Orlandi C, Arcangeli F, Patrizi A, et al. Eccrine poroma in a child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:279-280.

3. Casper DJ, Glass LF, Shenefelt PD. An unusually large eccrine poroma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2011;88:227-229.

4. Kang MC, Kim SA, Lee KS, et al. A case of an unusual eccrine poroma on the left forearm area. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:250-253.

5. Moore TO, Orman HL, Orman SK, et al. Poromas of the head and neck. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:48-52.

6. Chen CC, Chang YT, Liu HN. Clinical and histological characteristics of poroid neoplasms: a study of 25 cases in Taiwan. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:722-727.

7. Smith EV, Madan V, Joshi A, et al. A pigmented lesion on the foot. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:84-86.

8. Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720.

9. Moussallem CD, Abi Hatem NE, El-Khoury ZN.Malignant porocarcinoma of the nail fold: a tricky diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:10.

10. Requena L, Sánchez M, Aguilar A, et al. Periungual porocarcinoma. Dermatologica. 1990;180:177-180.

11. van Gorp J, van der Putte SC. Periungual eccrine porocarcinoma. Dermatology. 1993;187:67-70.

1. Goldman P, Pinkus H, Rogin JR. Eccrine poroma; tumors exhibiting features of the epidermal sweat duct unit. AMA Arch Derm. 1956;74:511-521.

2. Orlandi C, Arcangeli F, Patrizi A, et al. Eccrine poroma in a child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:279-280.

3. Casper DJ, Glass LF, Shenefelt PD. An unusually large eccrine poroma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2011;88:227-229.

4. Kang MC, Kim SA, Lee KS, et al. A case of an unusual eccrine poroma on the left forearm area. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:250-253.

5. Moore TO, Orman HL, Orman SK, et al. Poromas of the head and neck. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:48-52.

6. Chen CC, Chang YT, Liu HN. Clinical and histological characteristics of poroid neoplasms: a study of 25 cases in Taiwan. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:722-727.

7. Smith EV, Madan V, Joshi A, et al. A pigmented lesion on the foot. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:84-86.

8. Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720.

9. Moussallem CD, Abi Hatem NE, El-Khoury ZN.Malignant porocarcinoma of the nail fold: a tricky diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:10.

10. Requena L, Sánchez M, Aguilar A, et al. Periungual porocarcinoma. Dermatologica. 1990;180:177-180.

11. van Gorp J, van der Putte SC. Periungual eccrine porocarcinoma. Dermatology. 1993;187:67-70.

A 20-year-old woman presented with a subungual growth of 1 year’s duration that would intermittently bleed. Despite treatment with silver nitrate in 2 sequential treatments, the lesion continued to increase in size. Physical examination revealed a 6×7-mm erythematous, friable, well-defined papule under the medial aspect of the distal great toenail. Complete surgical excision of the lesion was performed.

Dreadlocks

The Diagnosis: “Pseudonits”

Dreadlocks are matted hairs formed into thick ropelike strands (Figure 1). As a chosen hairstyle dreadlocks are worn by individuals of many different ethnic groups but are most commonly associated with members of the Rastafarian movement, or Rastas. Various techniques are used to form dreadlocks including backcombing (also known as teasing) in which the hair is combed toward the scalp to facilitate tangles and knotting or the neglect method in which the hair is not combed, brushed, or cut, becoming tangled and twisted as it grows long. Manicuring and perming techniques may be used to create the starting point for dreadlocks.

Telogen hairs are the hairs shed as part of normal hair cycling. The average person is estimated to lose 50 telogen hairs per day.1 With dreadlocks, the hairs are entangled distally, so when telogen hairs are released from scalp follicles, the shed hairs remain part of the locks. These “club” hairs have a bulbous white tip situated at the proximal end of the hair shaft (Figure 2) and should not be mistaken for the eggs of Pediculus humanus var capitis, hence the designation pseudonits.2 Hair casts, keratinous material surrounding the hair shafts when there is infundibular or perifollicular hyperkeratosis, also may resemble nits.3 Hair cast pseudonits can be distinguished from true nits by one’s ability to slide the hair casts freely along the hair shaft, whereas lice ova are cemented to the hair shaft and fixed in place.

Figure 2. “Club” hairs with a bulbous white tip situated at the

proximal end of the hair shaft (“pseudonits”).

1. Sperling LC. An Atlas of Hair Pathology with Clinical Correlations. New York, NY: The Parthenon Publishing Group; 2003.

2. Salih S, Bowling JC. Pseudonits in dreadlocked hair: A louse-y case of nits. Dermatology. 2006;213:245.

3. Lam M, Crutchfield CE 3rd, Lewis EJ. Hair casts: a case of pseudonits. Cutis. 1997;60:251-252.

The Diagnosis: “Pseudonits”

Dreadlocks are matted hairs formed into thick ropelike strands (Figure 1). As a chosen hairstyle dreadlocks are worn by individuals of many different ethnic groups but are most commonly associated with members of the Rastafarian movement, or Rastas. Various techniques are used to form dreadlocks including backcombing (also known as teasing) in which the hair is combed toward the scalp to facilitate tangles and knotting or the neglect method in which the hair is not combed, brushed, or cut, becoming tangled and twisted as it grows long. Manicuring and perming techniques may be used to create the starting point for dreadlocks.

Telogen hairs are the hairs shed as part of normal hair cycling. The average person is estimated to lose 50 telogen hairs per day.1 With dreadlocks, the hairs are entangled distally, so when telogen hairs are released from scalp follicles, the shed hairs remain part of the locks. These “club” hairs have a bulbous white tip situated at the proximal end of the hair shaft (Figure 2) and should not be mistaken for the eggs of Pediculus humanus var capitis, hence the designation pseudonits.2 Hair casts, keratinous material surrounding the hair shafts when there is infundibular or perifollicular hyperkeratosis, also may resemble nits.3 Hair cast pseudonits can be distinguished from true nits by one’s ability to slide the hair casts freely along the hair shaft, whereas lice ova are cemented to the hair shaft and fixed in place.

Figure 2. “Club” hairs with a bulbous white tip situated at the

proximal end of the hair shaft (“pseudonits”).

The Diagnosis: “Pseudonits”

Dreadlocks are matted hairs formed into thick ropelike strands (Figure 1). As a chosen hairstyle dreadlocks are worn by individuals of many different ethnic groups but are most commonly associated with members of the Rastafarian movement, or Rastas. Various techniques are used to form dreadlocks including backcombing (also known as teasing) in which the hair is combed toward the scalp to facilitate tangles and knotting or the neglect method in which the hair is not combed, brushed, or cut, becoming tangled and twisted as it grows long. Manicuring and perming techniques may be used to create the starting point for dreadlocks.

Telogen hairs are the hairs shed as part of normal hair cycling. The average person is estimated to lose 50 telogen hairs per day.1 With dreadlocks, the hairs are entangled distally, so when telogen hairs are released from scalp follicles, the shed hairs remain part of the locks. These “club” hairs have a bulbous white tip situated at the proximal end of the hair shaft (Figure 2) and should not be mistaken for the eggs of Pediculus humanus var capitis, hence the designation pseudonits.2 Hair casts, keratinous material surrounding the hair shafts when there is infundibular or perifollicular hyperkeratosis, also may resemble nits.3 Hair cast pseudonits can be distinguished from true nits by one’s ability to slide the hair casts freely along the hair shaft, whereas lice ova are cemented to the hair shaft and fixed in place.

Figure 2. “Club” hairs with a bulbous white tip situated at the

proximal end of the hair shaft (“pseudonits”).

1. Sperling LC. An Atlas of Hair Pathology with Clinical Correlations. New York, NY: The Parthenon Publishing Group; 2003.

2. Salih S, Bowling JC. Pseudonits in dreadlocked hair: A louse-y case of nits. Dermatology. 2006;213:245.

3. Lam M, Crutchfield CE 3rd, Lewis EJ. Hair casts: a case of pseudonits. Cutis. 1997;60:251-252.

1. Sperling LC. An Atlas of Hair Pathology with Clinical Correlations. New York, NY: The Parthenon Publishing Group; 2003.

2. Salih S, Bowling JC. Pseudonits in dreadlocked hair: A louse-y case of nits. Dermatology. 2006;213:245.

3. Lam M, Crutchfield CE 3rd, Lewis EJ. Hair casts: a case of pseudonits. Cutis. 1997;60:251-252.

A 17-year-old adolescent girl presented to our dermatology office with dreadlocks that were unrelated to the reason for her visit. She had mild scalp pruritus. Close inspection of the hair and scalp was performed.

Seizure Prompts Man to Fall

ANSWER

The radiograph shows a fracture dislocation of the ankle. The distal tibia is dislocated medially relative to the talus, as evidenced by the widened joint space. There is also an oblique fracture of the distal fibula.

Since the patient was experiencing neurovascular compromise, the dislocation was promptly reduced in the emergency department. Subsequently, he was taken to the operating room for open reduction and internal fixation of his fibula fracture.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows a fracture dislocation of the ankle. The distal tibia is dislocated medially relative to the talus, as evidenced by the widened joint space. There is also an oblique fracture of the distal fibula.

Since the patient was experiencing neurovascular compromise, the dislocation was promptly reduced in the emergency department. Subsequently, he was taken to the operating room for open reduction and internal fixation of his fibula fracture.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows a fracture dislocation of the ankle. The distal tibia is dislocated medially relative to the talus, as evidenced by the widened joint space. There is also an oblique fracture of the distal fibula.

Since the patient was experiencing neurovascular compromise, the dislocation was promptly reduced in the emergency department. Subsequently, he was taken to the operating room for open reduction and internal fixation of his fibula fracture.

A 70-year-old man is brought to your facility by EMS following a new-onset, witnessed seizure. He reportedly fell down some steps. On arrival, he has returned to baseline but is complaining of left-sided weakness and right ankle pain. Medical history is significant for mild hypertension. Vital signs are stable. The patient exhibits slight confusion. He reports some mild weakness on his left side, especially in his lower extremity. There also appears to be moderate soft-tissue swelling of his right ankle, with a slight deformity noted. Dorsalis pedal pulse appears to be slightly diminished in that foot as well. You send the patient for noncontrast CT of the head, as well as a radiograph of the right ankle (the latter of which is shown). What is your impression?

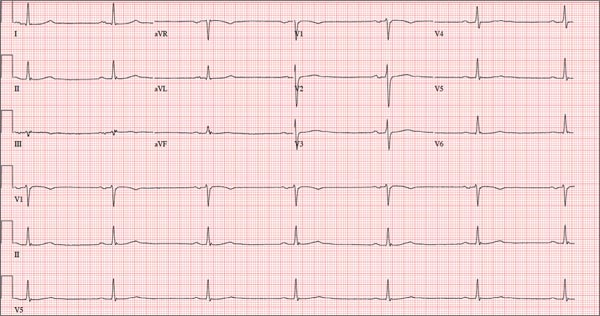

Marathon Runner Has History of A-fib

ANSWER

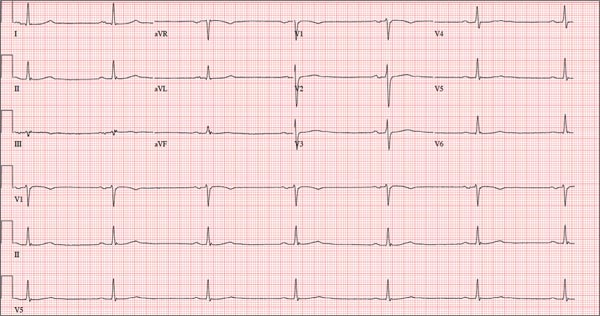

This ECG shows marked sinus bradycardia with a first-degree atrioventricular block and nonspecific T-wave abnormality. The QT interval of 524 ms is consistent with prolonged QT interval but is normal when corrected for rate.

These findings were consistent with previous ECGs. Since the patient’s bradycardia is asymptomatic, no intervention (ie, placement of a permanent pacemaker) is indicated.

ANSWER

This ECG shows marked sinus bradycardia with a first-degree atrioventricular block and nonspecific T-wave abnormality. The QT interval of 524 ms is consistent with prolonged QT interval but is normal when corrected for rate.

These findings were consistent with previous ECGs. Since the patient’s bradycardia is asymptomatic, no intervention (ie, placement of a permanent pacemaker) is indicated.

ANSWER

This ECG shows marked sinus bradycardia with a first-degree atrioventricular block and nonspecific T-wave abnormality. The QT interval of 524 ms is consistent with prolonged QT interval but is normal when corrected for rate.

These findings were consistent with previous ECGs. Since the patient’s bradycardia is asymptomatic, no intervention (ie, placement of a permanent pacemaker) is indicated.

A 52-year-old man has a cardiac diagnosis of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (A-fib). An echocardiogram demonstrates no valvular heart disease and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 62%. There are no symptoms to suggest left ventricular dysfunction or volume overload. He denies exertional angina or dyspnea and says he has had no palpitations or recurrences of A-fib since you saw him six months ago. The patient is very active: In the past year, he has completed two half marathons and one full marathon. In addition to his running schedule, he also swims 30 min/d and trains on an elliptical machine for 1 h/d. His only complaint today is that he recently lost the toenails off each big toe, which he attributes to his running, adding that this isn’t the first time it’s happened. Medical history is remarkable for two episodes of A-fib that manifested with palpitations and a rapid heart rate, which caused dyspnea. The last episode was approximately eight months ago. Both were treated with cardioversion in the emergency department of your institution. He was not started on an anticoagulant or antiarrhythmic medication after either occurrence. The patient currently takes no medications except the occasional ibuprofen for muscle soreness related to training. He has no known drug allergies and does not use naturopathic medications or illicit drugs. He has never smoked, and he only drinks wine socially, usually on weekends. The patient works as a certified public accountant for a large corporation. He is married with two teenage children. A 12-point review of systems is remarkable only for an inguinal rash and the aforementioned missing toenails. On physical exam, the vital signs include a blood pressure of 107/60 mm Hg; pulse, 46 beats/min; respiratory rate, 12 breaths/min-1; and temperature, 97.8°F. His height is 74 in and his weight, 172 lb. The patient is in no distress. The neck veins are flat, the lungs are clear, and the cardiac exam reveals no murmurs or gallops. The abdominal exam is unremarkable. There is no edema in the peripheral extremities, and pulses are strong bilaterally. Both feet reveal multiple callouses, and the two great toes have missing nails but healthy nail beds. The neurologic exam is intact. As part of his clinic visit, a 12-lead ECG is obtained. It reveals a ventricular rate of 38 beats/min; PR interval, 222 ms; QRS duration, 112 ms; QT/QTc interval, 524/416 ms; P axis, 20°; R axis, 26°; and T axis, 33°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Child With “Distressing” Problem

ANSWER

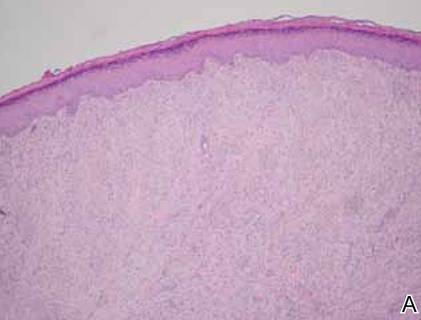

The correct answer is nevus sebaceous (choice “a”). This benign hamartomatous lesion is derived from local tissue and grows at the same rate.

It differs considerably from the other items in the differential, including aplasia cutis congenita (choice “b”). In this condition, a focal area of epidermis simply fails to develop, leaving a permanent hairless scar that contrasts sharply with the raised, mammillated plaque of nevus sebaceous.

Epidermal nevus (choice “c”) is usually a collection of tan to brown superficial nevoid papules that can be linear, agminated, or plaque-like. These lesions lack the color and mammillated surface of those seen in nevus sebaceous.

Neonatal lupus (choice “d”) can present at birth with hairless, cicatricial inflamed lesions. However, these tend to resolve quickly, often leaving focal scarring alopecia but no plaque formation.

DISCUSSION

Nevus sebaceous (NS), first described by Jadassohn in 1895, has long been recognized as an unusual but by no means rare congenital lesion. Occurring equally in both sexes and comprising sebaceous glands in a nevoid morphologic context, NS is considered a variant of sebaceous nevi and verrucous epidermal nevi in some circles. All three are derived from overgrowth of local, normal tissues that typically grow at the same rate as surrounding structures.

The vast majority of NS lesions are found in the scalp, although they can also develop on the ear or neck and, rarely, elsewhere on the body. This patient’s plaque—with its uniform surface; tiny, smooth, shiny papules; and (perhaps most important) total lack of hair—is typical. Other classic features are congenital onset and permanent nature, which distinguish them from the rest of the differential.

Focal malignant transformation of NS lesions has been reported—in fact, this author has seen two such cases in 30 years. Both were small basal cell carcinomas, although cases of melanoma and other malignancies have been reported.

Such changes are rare enough that most experts consider prophylactic removal to be unwarranted. Watching the lesions for change over the years is certainly reasonable, as is protecting them from sun exposure.

Surgical removal—usually performed by a plastic surgeon—is occasionally necessary for cosmetic reasons. This is particularly so when NS covers a portion of the face, or when the cosmetic implications of having a hairless plaque in the scalp are sufficiently distressing.

This patient and her parents were educated about the nature of the diagnosis and apprised of their options.

Editor's note: For a similar presentation with a very different diagnosis, see the March 2015 DermaDiagnosis case (http://bit.ly/1ye69Ym).

ANSWER

The correct answer is nevus sebaceous (choice “a”). This benign hamartomatous lesion is derived from local tissue and grows at the same rate.

It differs considerably from the other items in the differential, including aplasia cutis congenita (choice “b”). In this condition, a focal area of epidermis simply fails to develop, leaving a permanent hairless scar that contrasts sharply with the raised, mammillated plaque of nevus sebaceous.

Epidermal nevus (choice “c”) is usually a collection of tan to brown superficial nevoid papules that can be linear, agminated, or plaque-like. These lesions lack the color and mammillated surface of those seen in nevus sebaceous.

Neonatal lupus (choice “d”) can present at birth with hairless, cicatricial inflamed lesions. However, these tend to resolve quickly, often leaving focal scarring alopecia but no plaque formation.

DISCUSSION

Nevus sebaceous (NS), first described by Jadassohn in 1895, has long been recognized as an unusual but by no means rare congenital lesion. Occurring equally in both sexes and comprising sebaceous glands in a nevoid morphologic context, NS is considered a variant of sebaceous nevi and verrucous epidermal nevi in some circles. All three are derived from overgrowth of local, normal tissues that typically grow at the same rate as surrounding structures.

The vast majority of NS lesions are found in the scalp, although they can also develop on the ear or neck and, rarely, elsewhere on the body. This patient’s plaque—with its uniform surface; tiny, smooth, shiny papules; and (perhaps most important) total lack of hair—is typical. Other classic features are congenital onset and permanent nature, which distinguish them from the rest of the differential.

Focal malignant transformation of NS lesions has been reported—in fact, this author has seen two such cases in 30 years. Both were small basal cell carcinomas, although cases of melanoma and other malignancies have been reported.

Such changes are rare enough that most experts consider prophylactic removal to be unwarranted. Watching the lesions for change over the years is certainly reasonable, as is protecting them from sun exposure.

Surgical removal—usually performed by a plastic surgeon—is occasionally necessary for cosmetic reasons. This is particularly so when NS covers a portion of the face, or when the cosmetic implications of having a hairless plaque in the scalp are sufficiently distressing.

This patient and her parents were educated about the nature of the diagnosis and apprised of their options.

Editor's note: For a similar presentation with a very different diagnosis, see the March 2015 DermaDiagnosis case (http://bit.ly/1ye69Ym).

ANSWER

The correct answer is nevus sebaceous (choice “a”). This benign hamartomatous lesion is derived from local tissue and grows at the same rate.

It differs considerably from the other items in the differential, including aplasia cutis congenita (choice “b”). In this condition, a focal area of epidermis simply fails to develop, leaving a permanent hairless scar that contrasts sharply with the raised, mammillated plaque of nevus sebaceous.

Epidermal nevus (choice “c”) is usually a collection of tan to brown superficial nevoid papules that can be linear, agminated, or plaque-like. These lesions lack the color and mammillated surface of those seen in nevus sebaceous.

Neonatal lupus (choice “d”) can present at birth with hairless, cicatricial inflamed lesions. However, these tend to resolve quickly, often leaving focal scarring alopecia but no plaque formation.

DISCUSSION

Nevus sebaceous (NS), first described by Jadassohn in 1895, has long been recognized as an unusual but by no means rare congenital lesion. Occurring equally in both sexes and comprising sebaceous glands in a nevoid morphologic context, NS is considered a variant of sebaceous nevi and verrucous epidermal nevi in some circles. All three are derived from overgrowth of local, normal tissues that typically grow at the same rate as surrounding structures.

The vast majority of NS lesions are found in the scalp, although they can also develop on the ear or neck and, rarely, elsewhere on the body. This patient’s plaque—with its uniform surface; tiny, smooth, shiny papules; and (perhaps most important) total lack of hair—is typical. Other classic features are congenital onset and permanent nature, which distinguish them from the rest of the differential.

Focal malignant transformation of NS lesions has been reported—in fact, this author has seen two such cases in 30 years. Both were small basal cell carcinomas, although cases of melanoma and other malignancies have been reported.

Such changes are rare enough that most experts consider prophylactic removal to be unwarranted. Watching the lesions for change over the years is certainly reasonable, as is protecting them from sun exposure.

Surgical removal—usually performed by a plastic surgeon—is occasionally necessary for cosmetic reasons. This is particularly so when NS covers a portion of the face, or when the cosmetic implications of having a hairless plaque in the scalp are sufficiently distressing.

This patient and her parents were educated about the nature of the diagnosis and apprised of their options.

Editor's note: For a similar presentation with a very different diagnosis, see the March 2015 DermaDiagnosis case (http://bit.ly/1ye69Ym).

A “bald spot” is the chief complaint of a 12-year-old girl brought for evaluation by her mother. The lesion in her left parietal scalp has been there since birth, slowly growing but producing no symptoms. Although the child’s primary care provider has reassured the family that the “birthmark” is benign, they remain concerned. Furthermore, the patient has become increasingly distressed by the hairlessness. The child is otherwise healthy. There is no history of excessive sun exposure. The lesion is a roughly oval, uniformly pink, hairless 3.6-cm plaque with a faintly mammillated surface and well-defined margins. It is only visible when the surrounding hair is parted sufficiently to reveal it. Examination of the rest of the patient’s skin is unremarkable.

Nodule on the Second Toe in an Infant

The Diagnosis: Infantile Digital Fibromatosis

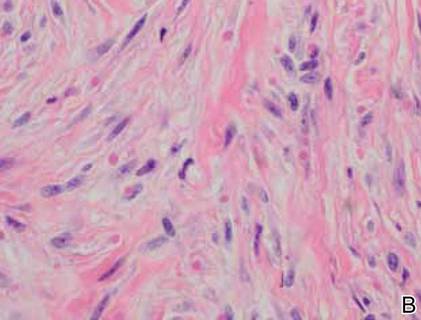

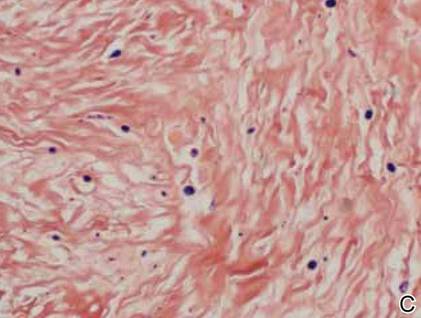

On examination, the patient appeared well developed, well nourished, and had a 1×0.5-cm, flesh-colored, firm, nontender nodule on the dorsolateral aspect of the left second toe. After excision by a pediatric surgeon, the specimen was submitted for histopathologic examination. Dense bands of collagen with spindled myofibroblasts containing characteristic eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusion bodies staining with phosphotungstic acid hematoxylin confirmed the diagnosis of infantile digital fibromatosis (Figure). Postoperatively the patient did well with normal healing and no complications. After 4 months, a recurrence was noted and the parents were considering reexcision.

|

Infantile digital fibromatosis is a rare, benign, often spontaneously regressing, fibrous tissue tumor of infancy and childhood.1 The prevalence of this tumor is unknown. It can be present at birth or more commonly appears in the first year of life. The lesions present as 1- to 2-cm, firm, flesh-colored nodules that initially grow slowly but have the potential for rapid growth in subsequent months. They occur preferentially on the extensor aspects of the digits, typically sparing the thumb and great toe.1 The clinical differential diagnosis includes keloids or hypertrophic scars, granuloma annulare, sarcoidosis, acral fibrokeratomas, periungual fibromas, supernumerary digits, pachydermodactyly, juvenile aponeurotic fibroma, and terminal osseous dysplasia and pigmentary defects.2

The histology of infantile digital fibromatosis is distinctive. Spindled myofibroblasts that contain round or ovoid, eosinophilic, cytoplasmic inclusion bodies composed of an accumulation of actin and vimentin filaments are characteristic.1 Inclusions are typically juxtanuclear and may indent the adjacent nucleus. The inclusion bodies stain red with Masson trichrome stain and purple with phosphotungstic acid hematoxylin stain.1 The histopathologic differential diagnosis includes scar, angiofibroma, dermatofibroma, neurofibroma, and angiofibromatous verruca vulgaris.

Although many treatments exist for infantile digital fibromatosis, optimal therapy is not standardized. Most lesions spontaneously regress, but func-tional disability with deforming contractures can occur if untreated. Topical therapy with imiquimod cream 5% and diflucortolone valerate cream have been reported to produce no effect on tumor size.3 Intralesional 5-fluorouracil was successful in treating a patient after 5 monthly injections.4 Intralesional triamcinolone 10 mg/cc injections were shown to be a well-tolerated and successful treatment in a case series of 7 patients.5 The most utilized intervention appears to be standard surgery, with a few patients treated with Mohs micrographic surgery.6,7

Treatment with surgical excision often results in recurrence, with studies showing a 50% to 75% recurrence rate.8,9 Our case is not atypical and illustrates this phenomenon. Other reported complications of surgical management include hypertrophic scarring and reduced distal interphalangeal joint mobility.5 Unless infantile digital fibromatosis causes mobility dysfunction or related disabilities, observation with regular follow-up should be considered, as lesions can spontaneously regress.

1. Heymann WR. Infantile digital fibromatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:122-123.

2. Niamba P, Léauté-Labrèze C, Boralevi F, et al. Further documentation of spontaneous regression of infantile digital fibromatosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:280-284.

3. Failla V, Wauters O, Nikkels-Tassoudji N, et al. Congenital infantile digital fibromatosis: a case report and review of the literature. Rare Tumors. 2009;1:e47.

4. Oh CK, Son HS, Kwon YW, et al. Intralesional fluorouracil injection in infantile digital fibromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:549-550

5. Holmes WJ, Mishra A, McArthur P. Intra-lesional steroid for the management of symptomatic infantile digital fibromatosis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:632-637.

6. Campbell LB, Petrick MG. Mohs micrographic surgery for a problematic infantile digital fibroma. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:385-387.

7. Albertini JG, Welsch MJ, Conger LA, et al. Infantile digital fibroma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:959-961.

8. Kang SK, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. A case of congenital infantile digital fibromatosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:462-463.

9. Rimareix F, Bardot J, Andrac L, et al. Infantile digital fibroma—report on eleven cases. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1997;7:345-348.

The Diagnosis: Infantile Digital Fibromatosis

On examination, the patient appeared well developed, well nourished, and had a 1×0.5-cm, flesh-colored, firm, nontender nodule on the dorsolateral aspect of the left second toe. After excision by a pediatric surgeon, the specimen was submitted for histopathologic examination. Dense bands of collagen with spindled myofibroblasts containing characteristic eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusion bodies staining with phosphotungstic acid hematoxylin confirmed the diagnosis of infantile digital fibromatosis (Figure). Postoperatively the patient did well with normal healing and no complications. After 4 months, a recurrence was noted and the parents were considering reexcision.

|

Infantile digital fibromatosis is a rare, benign, often spontaneously regressing, fibrous tissue tumor of infancy and childhood.1 The prevalence of this tumor is unknown. It can be present at birth or more commonly appears in the first year of life. The lesions present as 1- to 2-cm, firm, flesh-colored nodules that initially grow slowly but have the potential for rapid growth in subsequent months. They occur preferentially on the extensor aspects of the digits, typically sparing the thumb and great toe.1 The clinical differential diagnosis includes keloids or hypertrophic scars, granuloma annulare, sarcoidosis, acral fibrokeratomas, periungual fibromas, supernumerary digits, pachydermodactyly, juvenile aponeurotic fibroma, and terminal osseous dysplasia and pigmentary defects.2

The histology of infantile digital fibromatosis is distinctive. Spindled myofibroblasts that contain round or ovoid, eosinophilic, cytoplasmic inclusion bodies composed of an accumulation of actin and vimentin filaments are characteristic.1 Inclusions are typically juxtanuclear and may indent the adjacent nucleus. The inclusion bodies stain red with Masson trichrome stain and purple with phosphotungstic acid hematoxylin stain.1 The histopathologic differential diagnosis includes scar, angiofibroma, dermatofibroma, neurofibroma, and angiofibromatous verruca vulgaris.

Although many treatments exist for infantile digital fibromatosis, optimal therapy is not standardized. Most lesions spontaneously regress, but func-tional disability with deforming contractures can occur if untreated. Topical therapy with imiquimod cream 5% and diflucortolone valerate cream have been reported to produce no effect on tumor size.3 Intralesional 5-fluorouracil was successful in treating a patient after 5 monthly injections.4 Intralesional triamcinolone 10 mg/cc injections were shown to be a well-tolerated and successful treatment in a case series of 7 patients.5 The most utilized intervention appears to be standard surgery, with a few patients treated with Mohs micrographic surgery.6,7

Treatment with surgical excision often results in recurrence, with studies showing a 50% to 75% recurrence rate.8,9 Our case is not atypical and illustrates this phenomenon. Other reported complications of surgical management include hypertrophic scarring and reduced distal interphalangeal joint mobility.5 Unless infantile digital fibromatosis causes mobility dysfunction or related disabilities, observation with regular follow-up should be considered, as lesions can spontaneously regress.

The Diagnosis: Infantile Digital Fibromatosis

On examination, the patient appeared well developed, well nourished, and had a 1×0.5-cm, flesh-colored, firm, nontender nodule on the dorsolateral aspect of the left second toe. After excision by a pediatric surgeon, the specimen was submitted for histopathologic examination. Dense bands of collagen with spindled myofibroblasts containing characteristic eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusion bodies staining with phosphotungstic acid hematoxylin confirmed the diagnosis of infantile digital fibromatosis (Figure). Postoperatively the patient did well with normal healing and no complications. After 4 months, a recurrence was noted and the parents were considering reexcision.

|

Infantile digital fibromatosis is a rare, benign, often spontaneously regressing, fibrous tissue tumor of infancy and childhood.1 The prevalence of this tumor is unknown. It can be present at birth or more commonly appears in the first year of life. The lesions present as 1- to 2-cm, firm, flesh-colored nodules that initially grow slowly but have the potential for rapid growth in subsequent months. They occur preferentially on the extensor aspects of the digits, typically sparing the thumb and great toe.1 The clinical differential diagnosis includes keloids or hypertrophic scars, granuloma annulare, sarcoidosis, acral fibrokeratomas, periungual fibromas, supernumerary digits, pachydermodactyly, juvenile aponeurotic fibroma, and terminal osseous dysplasia and pigmentary defects.2

The histology of infantile digital fibromatosis is distinctive. Spindled myofibroblasts that contain round or ovoid, eosinophilic, cytoplasmic inclusion bodies composed of an accumulation of actin and vimentin filaments are characteristic.1 Inclusions are typically juxtanuclear and may indent the adjacent nucleus. The inclusion bodies stain red with Masson trichrome stain and purple with phosphotungstic acid hematoxylin stain.1 The histopathologic differential diagnosis includes scar, angiofibroma, dermatofibroma, neurofibroma, and angiofibromatous verruca vulgaris.

Although many treatments exist for infantile digital fibromatosis, optimal therapy is not standardized. Most lesions spontaneously regress, but func-tional disability with deforming contractures can occur if untreated. Topical therapy with imiquimod cream 5% and diflucortolone valerate cream have been reported to produce no effect on tumor size.3 Intralesional 5-fluorouracil was successful in treating a patient after 5 monthly injections.4 Intralesional triamcinolone 10 mg/cc injections were shown to be a well-tolerated and successful treatment in a case series of 7 patients.5 The most utilized intervention appears to be standard surgery, with a few patients treated with Mohs micrographic surgery.6,7

Treatment with surgical excision often results in recurrence, with studies showing a 50% to 75% recurrence rate.8,9 Our case is not atypical and illustrates this phenomenon. Other reported complications of surgical management include hypertrophic scarring and reduced distal interphalangeal joint mobility.5 Unless infantile digital fibromatosis causes mobility dysfunction or related disabilities, observation with regular follow-up should be considered, as lesions can spontaneously regress.

1. Heymann WR. Infantile digital fibromatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:122-123.

2. Niamba P, Léauté-Labrèze C, Boralevi F, et al. Further documentation of spontaneous regression of infantile digital fibromatosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:280-284.

3. Failla V, Wauters O, Nikkels-Tassoudji N, et al. Congenital infantile digital fibromatosis: a case report and review of the literature. Rare Tumors. 2009;1:e47.

4. Oh CK, Son HS, Kwon YW, et al. Intralesional fluorouracil injection in infantile digital fibromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:549-550

5. Holmes WJ, Mishra A, McArthur P. Intra-lesional steroid for the management of symptomatic infantile digital fibromatosis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:632-637.

6. Campbell LB, Petrick MG. Mohs micrographic surgery for a problematic infantile digital fibroma. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:385-387.

7. Albertini JG, Welsch MJ, Conger LA, et al. Infantile digital fibroma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:959-961.

8. Kang SK, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. A case of congenital infantile digital fibromatosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:462-463.

9. Rimareix F, Bardot J, Andrac L, et al. Infantile digital fibroma—report on eleven cases. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1997;7:345-348.

1. Heymann WR. Infantile digital fibromatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:122-123.

2. Niamba P, Léauté-Labrèze C, Boralevi F, et al. Further documentation of spontaneous regression of infantile digital fibromatosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:280-284.

3. Failla V, Wauters O, Nikkels-Tassoudji N, et al. Congenital infantile digital fibromatosis: a case report and review of the literature. Rare Tumors. 2009;1:e47.

4. Oh CK, Son HS, Kwon YW, et al. Intralesional fluorouracil injection in infantile digital fibromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:549-550

5. Holmes WJ, Mishra A, McArthur P. Intra-lesional steroid for the management of symptomatic infantile digital fibromatosis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:632-637.

6. Campbell LB, Petrick MG. Mohs micrographic surgery for a problematic infantile digital fibroma. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:385-387.

7. Albertini JG, Welsch MJ, Conger LA, et al. Infantile digital fibroma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:959-961.

8. Kang SK, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. A case of congenital infantile digital fibromatosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:462-463.

9. Rimareix F, Bardot J, Andrac L, et al. Infantile digital fibroma—report on eleven cases. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1997;7:345-348.

A 6-month-old male infant presented with a 1×0.5-cm, flesh-colored nodule on the dorsolateral aspect of the left second toe. The persistent, slowly enlarging, painless lesion was first noticed at 3 months of age and did not cause functional impairment. There was no preceding trauma and the patient’s medical history was otherwise noncontributory.

Fibrous Forehead Plaque

The Diagnosis: Tuberous Sclerosis Complex

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous syndrome characterized by multiple hamartomas distributed in multiple organs of the body, most commonly the skin, brain, eyes, heart, kidneys, liver, and lungs. In 1908, Vogt1 elucidated the classic diagnostic triad of seizures, mental retardation, and facial angiofibromas (formerly termed adenoma sebaceum). However, the full triad is evident in only 29% of cases; 6% of TSC patients have none of these 3 findings.2 The disease is caused by alterations in 2 TSC genes, TSC1 and TSC2, on chromosomes 9 and 16, respectively. Both are tumor suppressor genes and mutations in either can be responsible for all the complications seen in the disease.3 The gene products of the 2 genes, hamartin and tuberin, appear to act together in the regulation of cell growth by inhibiting a substance known as the mechanistic target of rapamycin.4,5 Up to two-thirds of cases may occur from spontaneous mutations.2,6 The disease is extremely variable in its manifestations, particularly the skin manifestations. This discussion will review the many cutaneous manifestations of TSC, most of them documented in our patient, and their frequency of occurrence.

Early recognition of TSC is vital because prompt implementation of the recommended diagnostic evaluation (eg, neuroimaging studies, electroencephalogram, electrocardiography, renal ultrasonography, chest computed tomography) may prevent serious clinical consequences.7 Neurologic manifestations are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with TSC.2,8,9 Brain hamartomas in the form of cortical tubers, subependymal nodules, and subependymal giant cell astrocytomas often are responsible for intractable seizures, most commonly as infantile spasms. Approximately 90% to 96% of TSC patients have seizures.6 Renal manifestations are strongly associated with TSC. Angiomyolipoma is the most common renal lesion found in TSC patients.4,9,10 Up to 80% of patients have renal angiomyolipomas. Their incidence increases with age.4,11,12 Tuberous sclerosis complex is known as a cause of epilepsy and mental retardation, but renal disease is a major cause of morbidity.13 Cardiovascular manifestations often are the earliest diagnostic findings in patients with TSC. Rhabdomyoma is the most common primary cardiac tumor in infants and children.11,13,14 The most common ocular findings in TSC are retinal hamartomas, appearing in 40% to 50% of patients.15

Cutaneous features frequently occur and are the most clinically apparent findings of TSC; if overlooked, diagnosis could be delayed, which ultimately increases mortality. The diagnosis of TSC continues to be based primarily on clinical grounds because most patients older than 5 years demonstrate multiple skin lesions.6 In 1992, specific diagnostic clinical criteria were created for TSC, which stratified the clinical features of TSC into 3 tiers—primary, secondary, and tertiary—based on their specificity.16 In subsequent years, some of the classic clinical signs once regarded as pathognomonic for TSC, such as single ungual fibroma or multiple renal angiomyolipomas, were questioned. New modifications to the original diagnostic criteria were necessary given the advances in both TSC clinical information and molecular genetics. In the summer of 1998, a consensus conference held in Annapolis, Maryland, was assembled by the Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance for the purpose of reevaluating and updating the clinical diagnostic criteria.7 The revised criteria were simplified into 2 main categories—major and minor features—based on the diagnostic importance and degree of specificity for TSC of each clinical and radiographic feature (Table 1). There are a number of considerations that merit close attention when applying these clinical criteria. Despite the large number of clinical features delineated, the diagnosis of TSC may be challenging early in life, particularly in patients younger than 2 years. The value of the clinical criteria for early diagnosis and prompt management of TSC is limited by the fact that many stigmata become apparent only in late childhood or adulthood. The lack of pathognomonic signs of TSC can add to the challenge of diagnosing subtle or atypical cases.6

A careful skin examination of individuals at risk for TSC is the best and the easiest method of establishing the diagnosis in most cases. According to Gomez,17 96% of patients with TSC have one or more main skin lesions of the disease, including facial angiofibromas, ungual fibromas, shagreen patches, or hypomelanotic macules. However, the diagnosis is more difficult in small children because many skin lesions become obvious with age; in fact, the full dermatological spectrum may never develop.17

Facial angiofibromas, also known as sebaceous adenomas, are the most visible and unsightly cutaneous manifestations of TSC, often resulting in stigmatization for both the affected individuals and their family members. These facial lesions often do not appear until late childhood or adulthood. In this case, the initial diagnosis often is made by the dermatologist who appreciates the significance of the white macules in a neonate. However, these hypomelanotic macules cannot be detected by the unaided eye, thus a physician would be wise to examine an infant with infantile spasms or mental retardation with a Wood lamp, which accentuates the lesions.2

Hypomelanotic macules were the overwhelmingly most common early findings in TSC. Infants with seizures or other possible stigmata of TSC should be carefully evaluated for these hypomelanotic macules as well as for other associated findings. Hypomelanotic macules can appear anywhere on the body, except the hands, feet, and genitalia; they are most commonly found on the lower extremities. Wood lamp examination reveals an accentuation of the hypopigmentation, which is a decrease in but not an absence of pigmentation. Lance ovate hypomelanotic macules are pathognomonic for TSC, thus the presence of 3 or more macules in an infant seriously suggests the diagnosis of TSC and echocardiography should be performed. The combination of white macules and seizures also increases the likelihood of TSC.18

Angiofibromas typically are found in the butterfly region of the face. Nico et al19 reported 2 patients with the complete syndrome of TSC who had multiple papules on the genital area in addition to classic facial lesions. Thus, it is important to examine the genital region of TSC patients and not misdiagnose these lesions as genital warts.

Jóźwiak et al18 screened 106 children with TSC and listed the prevalence of the most common cutaneous lesions. The results are presented in Table 2.

In a study by Webb et al,2 131 patients with TSC were examined and 126 (96%) exhibited skin signs. Although there was considerable variation in the age of expression of all the skin lesions, there was a trend toward the earlier expression of hypomelanotic macules and forehead fibrous plaques compared with facial angiofibromas and ungual fibromas. Shagreen patches usually were present by puberty. Ungual fibromas appeared for the first time as late as the fifth decade of life and were the only clinical feature in 3 patients. Ungual fibromas were present in 36% (47/131). Ten patients (8%) presented because of the skin manifestations and 21% (28/131) received treatment of symptomatic skin lesions. Two patients had large hamartomas at unusual sites, the occiput and forearm.2

Our 30-year-old patient presented to our clinic accompanied by her grandmother who served as legal guardian and historian for the patient. The patient experienced her first seizure at 15 months of age. She was evaluated by the neurology department at that time and was diagnosed with epilepsy. In the months following, she developed strabismus of the eyes and was examined by the ophthalmology department. Retinal hamartomas were discovered and she was diagnosed with TSC. Her seizure disorder was managed by a neurologist with the use of topiramate. In her 20s, she had renal and cardiac workups, which were negative, and she continued to be free of any genitourinary or cardiac concerns. One year prior to presentation she underwent a brain computed tomography scan after a bicycle accident and was informed that she had “scarlike” lesions within the cerebral cortex. There was no known history of TSC in other family members. On physical examination, she was noted to be delayed in mental development and intelligence. She stated her first notable skin lesions appeared at 10 years of age and were skin tags of the upper back and neck and over the face. Soon after, the cheeks and nose developed numerous shiny brownish pink papules (Figure 1). Over the course of the next 20 years she developed other skin findings noted on our present skin examination. The superior aspect of the mid forehead revealed a 4×2-cm, raised, flesh-colored, firm tumorous plaque. The neck and upper back had multiple 2- to 5-mm, soft, pedunculated, polypoid, brownish pink papules. Her mid back revealed ill-defined, slightly elevated, rosy plaques and macules with a roughened speckled appearance (Figure 2). Several of the toenails and fingernails showed firm, fleshy, spiculelike papules around and under the nail bed (Figure 3). The lower anterior tibia revealed several oval-shaped, flat, well-demarcated, hypopigmented macules (Figure 4). Lesions on the face and mid back were biopsied and histopathology confirmed angiofibroma and shagreen patch, or connective tissue nevus, respectively. Our patient did not undergo treatment of any of these skin lesions, particularly the facial angiofibromas. Cosmetic treatment options such as laser or surgical removal were presented to her, but she declined.

|

|

A brief review of the literature for treatment options of facial angiofibromas and the fibrous forehead plaque indicated that current treatments include but are not limited to cryotherapy, electrocautery, electrosurgery, shave excision, chemical peels, argon laser, CO2 laser, and radiofrequency equipment.20 For the best outcome, these treatments have to be repeated throughout childhood and teenage years. Rapamycin, also known as sirolimus, and its analogs are new therapeutic options for TSC. Rapamycin is an inhibitor of the mechanistic target of rapamycin and can normalize this unregulated pathway in a TSC patient. Various preclinical models have shown that rapamycin treatment reduces TSC-related tumors, including brain, skin, and kidney tumors.21 A pilot study by Foster et al22 revealed improvement in the facial angiofibromas of 4 children treated with 2 topical preparations of rapamycin. The study revealed that younger patients with smaller angiofibromas had the best response with near-complete clearance. Rapamycin topical preparations were more cost effective than pulsed dye laser under general anesthesia.22

|

|

Tuberous sclerosis complex is not the only syndrome that can present with facial angiofibromas or numerous skin tag–type lesions such as those in our patient. It is important to also consider Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 in the differential diagnosis of multiple facial angiofibromas, particularly with adult onset.23

Our case was presented to review the cutaneous manifestations of TSC and their presentation frequency, with the intent to enable the dermatologist to make a more accurate and earlier diagnosis of TSC. In doing so, morbidity of TSC patients could be decreased and quality of life increased.

1. Vogt H. Zur Diagnostik der tuberosen sklerose. Z Erforsch Behandl Jugeudl Schwachsinns. 1908;2:1-6.

2. Webb DW, Clarke A, Fryer A, et al. The cutaneous features of tuberous sclerosis: a population study. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:1-5.

3. van Slegtenhorst M, de Hoogt R, Hermans C, et al. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis gene TSC1 on chromosome 9q34. Science. 1997;277:805-808.

4. O’Callaghan F. Tuberous sclerosis complex: from basic science to clinical phenotypes. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:985.

5. Kwiatkowski DJ. Tuberous sclerosis: from tubers to mTOR. Ann Hum Genet. 2003;67:87-96.

6. Schwartz RA. Tuberous sclerosis complex: advances in diagnosis, genetics, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:189-202.

7. Roach ES, Gomez MR, Northrup H. Tuberous sclerosis complex consensus conference: revised clinical diagnostic criteria. J Child Neurol. 1998;13:624-628.

8. Tworetzky W, McElhinney DB, Margossian R, et al. Association between cardiac tumors and tuberous sclerosis in the fetus and neonate. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:487-489.

9. Casper KA, Donnelly LF, Chen B, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: renal imaging findings. Radiology. 2002;225:451-456.

10. El-Hashemite N, Zhang H, Henske EP, et al. Mutation in TSC2 and activation of mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway in renal angiomyolipoma. Lancet. 2003;361:1348-1349.

11. Jóźwiak S, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK, et al. Usefulness of diagnostic criteria of tuberous sclerosis complex in pediatric patients. J Child Neurol. 2000;15:652-659.