User login

Family violence after COVID: Understanding coercive relationships

Despite the ability of some couples to pull together and manage through the COVID-19 pandemic, other couples and families failed to thrive. Increasing divorce rates have been noted nationwide with many disagreements being specifically about COVID.1

A review of over 1 million tweets, between April 12 and July 16, 2020, found an increase in calls to hotlines and increased reports of a variety of types of family violence. There were also more inquiries about social services for family violence, an increased presence from social movements, and more domestic violence-related news.2

The literature addressing family violence uses a variety of terms, so here are some definitions.

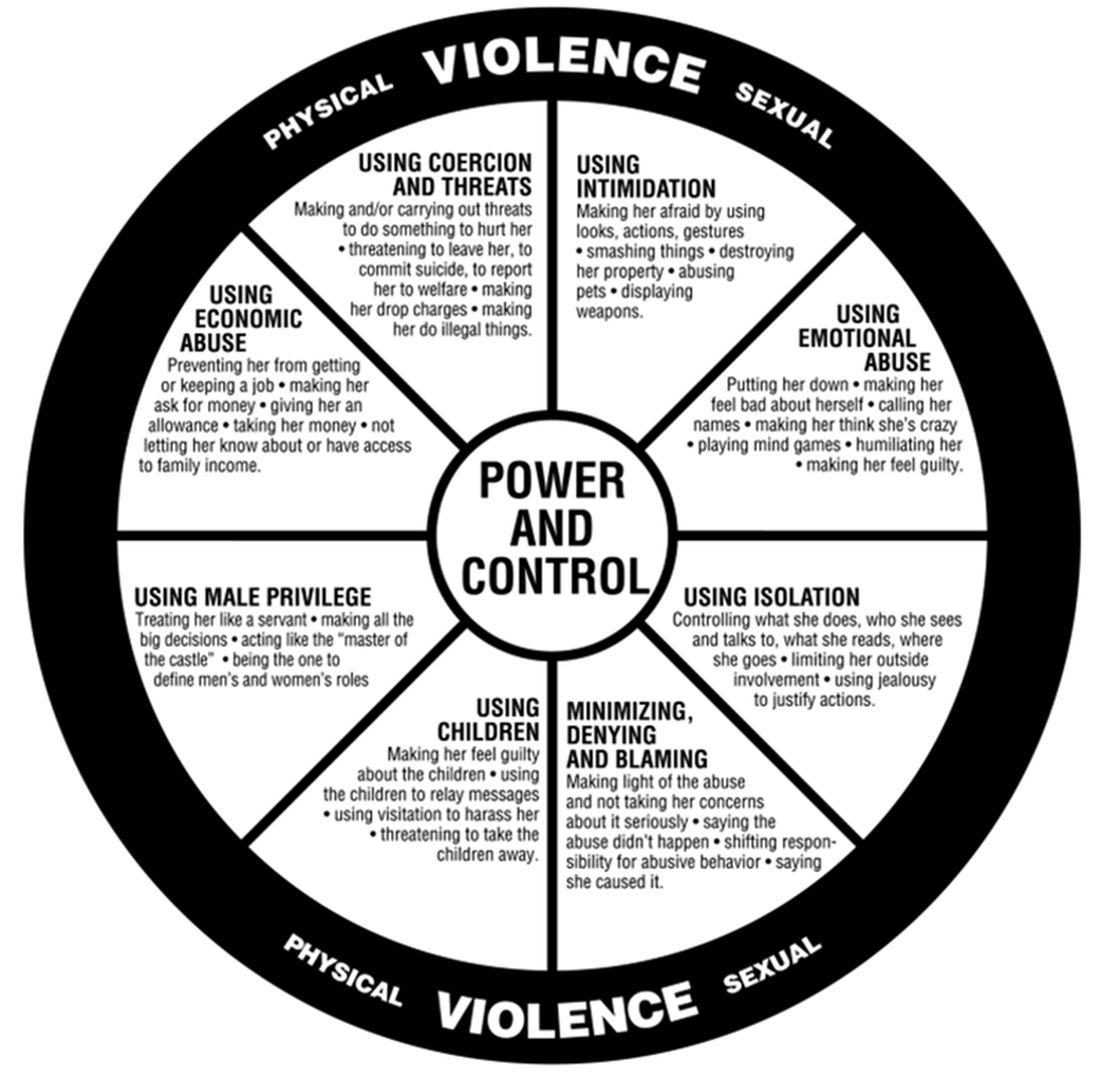

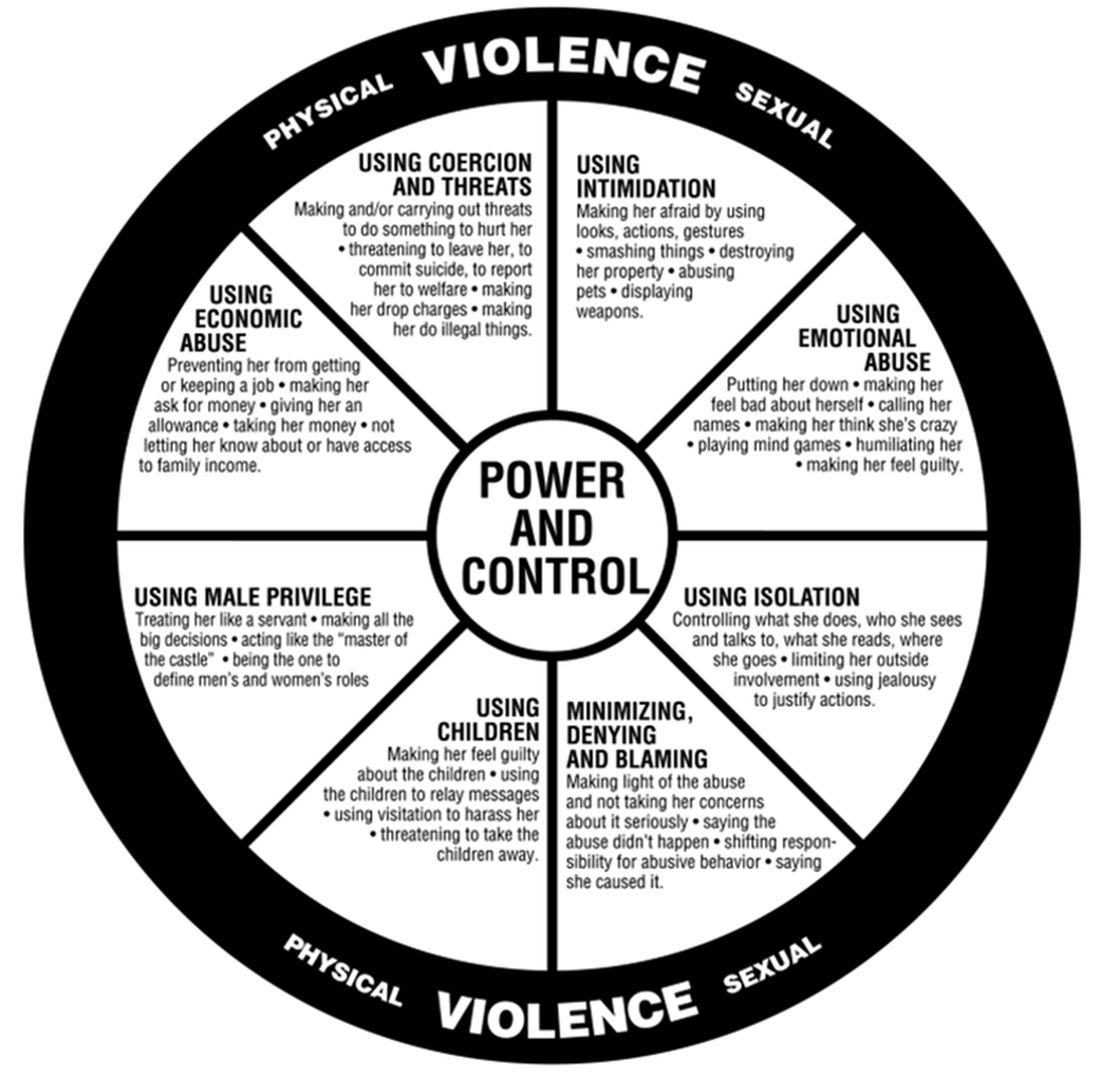

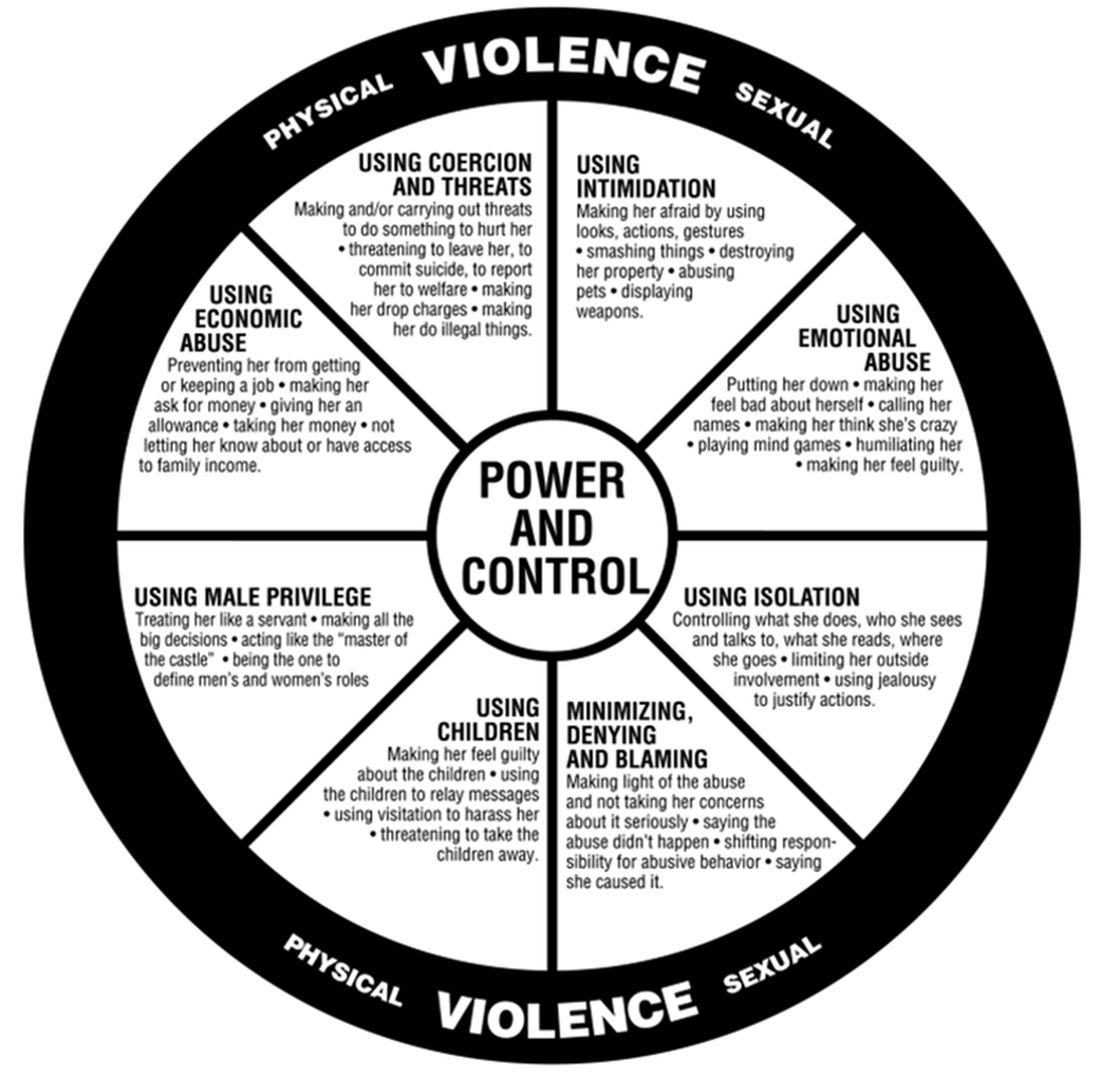

Domestic violence is defined as a pattern of behaviors used to gain or maintain power and control. Broadly speaking, domestic violence includes elder abuse, sibling abuse, child abuse, intimate partner abuse, parent abuse, and can also include people who don’t necessarily live together but who have an intimate relationship. Domestic violence centers use the Power and Control Wheel (see graphic) developed by the Domestic Abuse Intervention Project in Duluth, Minn., to describe how domestic violence occurs.

Intimate partner violence is more specific, referring to violence that happens between people in an ongoing or former intimate or romantic relationship, and is a subcategory of domestic violence.

Coercive control is the use of power for control and compliance. It is a dynamic and systematic process described in the top left corner of the Power and Control Wheel. Overt control occurs with the implication that “if you don’t follow the rules, I’ll kill you.” More subtle control is when obedience is forced through monopolizing resources, dictating preferred choices, microregulating a partner’s behavior, and deprivation of supports needed to exercise independent judgment.

All interpersonal relationships have elements of persuasion and influence; however, the goal of coercive relationships is to maintain power and control. It is a dynamic of the relationship. Coercive control emphasizes the systematic, organized, multifaceted, and patterned nature of this interpersonal dynamic and can be considered to originate in the patriarchal dynamic where men control women.

Most professionals who work in this interdisciplinary area now refer to domestic violence as coercive control. Victimizers target women whom they sense they can control to get their own needs met. They are disinclined to invest in relationships with women who stress their own points of view, who do not readily accept blame when there is a disagreement, and who offer nurturing only when it is reciprocated.

In my office, if I think there are elements of coercion in a relationship, I bring out the Power and Control Wheel and the patient and I go over it. Good education is our responsibility. However, we all have met women who decide to stay in unhealthy relationships.

Assessing people who stay in coercive relationships

Fear

The most important first step is to assess safety. Are they afraid of increased violence if they challenge their partner? Restraining orders or other legal deterrents may not offer solace, as many women are clear that their spouse will come after them, if not tomorrow, then next week, or even next month. They are sure that they will not be safe.

In these cases, I go over safety steps with them so that if they decide to go, they will be prepared. I bring out the “safety box,” which includes the following action steps:

- Memorize important phone numbers of people to call in an emergency.

- If your children are old enough, teach them important phone numbers, including when to dial 911.

- If you can, open your own bank account.

- Stay in touch with friends. Get to know your neighbors. Don’t cut yourself off from people, even if you feel like you want to be alone.

- Rehearse your escape plan until you know it by heart.

- Leave a set of car keys, extra money, a change of clothes and copies of important documents with a trusted friend or relative: your own and your children’s birth certificates, children’s school and medical records, bank books, welfare identification, passport/green card, immigration papers, social security card, lease agreements or mortgage payment books, insurance papers, important addresses, and telephone numbers.

- Keep information about domestic violence in a safe place, where your abuser won’t find it, but where you can get it when you need to review it.

Some women may acknowledge that the risk of physical violence is not the determining factor in their decision to stay and have difficulty explaining why they choose to stay. I suggest that we then consider the following frames that have their origin in the study of the impact of trauma.

Shame

From this lens, abusive events are humiliating experiences, now represented as shame experiences. Humiliation and shame hide hostile feelings that the patient is not able to acknowledge.

“In shame, the self is the failure and others may reject or be critical of this exposed, flawed self.”3 Women will therefore remain attached to an abuser to avoid the exposure of their defective self.

Action steps: Empathic engagement and acknowledgment of shame and humiliation are key. For someone to overcome shame, they must face their sense of their defective self and have strategies to manage these feelings. The development of such strategies is the next step.

Trauma repetition and trauma bonding

Women subjected to domestic violence often respond with incapacitating traumatic syndromes. The concept of “trauma repetition” is suggested as a cause of vulnerability to repeated abuse, and “trauma bonding” is the term for the intense and tenacious bond that can form between abusers and victims.4

Trauma bonding implies that a sense of safety and closeness and secure attachment can only be reached through highly abusive engagement; anything else is experienced as “superficial, cold, or irrelevant.”5 Trauma bonding may have its origins in emotional neglect, according to self reports of 116 women.6Action steps: The literature on trauma is growing and many patients will benefit from good curated sources. Having a good list of books and website on hand is important. Discussion and exploration of the impact of trauma will be needed, and can be provided by someone who is available on a consistent and frequent basis. This work may be time consuming and difficult.

Some asides

1. Some psychiatrists proffer the explanation that these women who stay must be masochistic. The misogynistic concept of masochism still haunts the halls of psychiatry. It is usually offered as a way to dismiss these women’s concerns.

2. One of the obstacles to recognizing chronic mistreatment in relationships is that most abusive men simply “do not seem like abusers.” They have many good qualities, including times of kindness, warmth, and humor, especially in the initial period of a relationship. An abuser’s friends may think the world of him. He may have a successful work life and have no problems with drugs or alcohol. He may simply not fit anyone’s image of a cruel or intimidating person. So, when a woman feels her relationship spinning out of control, it may not occur to her that her partner is an abuser. Even if she does consider her partner to be overly controlling, others may question her perception.

3. Neutrality in family courts is systemic sexism/misogyny. When it comes to domestic violence, family courts tend to split the difference. Stephanie Brandt, MD, notes that The assumption that it is violence alone that matters has formed the basis of much clinical and legal confusion.7 As an analyst, she has gone against the grain of a favored neutrality and become active in the courts, noting the secondary victimization that occurs when a woman enters the legal system.

In summary, psychiatrists must reclaim our expertise in systemic dynamics and point out the role of systemic misogyny. Justices and other court officials need to be educated. Ideally, justice should be based on the equality of men and women in a society free of systemic misogyny. Unfortunately our society has not yet reached this position. In the meanwhile, we must think systemically about interpersonal dynamics. This is our lane. This should not be controversial.

Dr. Heru is professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (New York: Routledge, 2013). She has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Contact Dr. Heru at [email protected]. Dr. Heru would like to thank Dr. Stephanie Brandt for discussing this topic with her and supporting this work.

References

1. Ellyatt H. Arguing with your partner over Covid? You’re not alone, with the pandemic straining many relationships. 2022 Jan 21. https://www.cnbc.com/2022/01/21/covid-has-put-pressures-and-strains-on-relationships.html

2. Xue J et al. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Nov 6;22(11):e24361. doi: 10.2196/24361.

3. Dorahy MJ. J Trauma Dissociation. 2017 May-Jun;18(3):383-96. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1295422.

4. Dutton DG and Painter SL. Victimology. 1981 Jan;6(1):139-55.

5. Sachs A. J Trauma Dissociation. 2017 May-Jun;18(3):319-39. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1295400.

6. Krüger C and Fletcher L. J Trauma Dissociation. 2017 May-Jun;18(3):356-72. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1295420.

7. Brandt S and Rudden M. Int J Appl Psychoanal Studies. 2020 Sept;17(3):215-31. doi: 10.1002/aps.1671.

Despite the ability of some couples to pull together and manage through the COVID-19 pandemic, other couples and families failed to thrive. Increasing divorce rates have been noted nationwide with many disagreements being specifically about COVID.1

A review of over 1 million tweets, between April 12 and July 16, 2020, found an increase in calls to hotlines and increased reports of a variety of types of family violence. There were also more inquiries about social services for family violence, an increased presence from social movements, and more domestic violence-related news.2

The literature addressing family violence uses a variety of terms, so here are some definitions.

Domestic violence is defined as a pattern of behaviors used to gain or maintain power and control. Broadly speaking, domestic violence includes elder abuse, sibling abuse, child abuse, intimate partner abuse, parent abuse, and can also include people who don’t necessarily live together but who have an intimate relationship. Domestic violence centers use the Power and Control Wheel (see graphic) developed by the Domestic Abuse Intervention Project in Duluth, Minn., to describe how domestic violence occurs.

Intimate partner violence is more specific, referring to violence that happens between people in an ongoing or former intimate or romantic relationship, and is a subcategory of domestic violence.

Coercive control is the use of power for control and compliance. It is a dynamic and systematic process described in the top left corner of the Power and Control Wheel. Overt control occurs with the implication that “if you don’t follow the rules, I’ll kill you.” More subtle control is when obedience is forced through monopolizing resources, dictating preferred choices, microregulating a partner’s behavior, and deprivation of supports needed to exercise independent judgment.

All interpersonal relationships have elements of persuasion and influence; however, the goal of coercive relationships is to maintain power and control. It is a dynamic of the relationship. Coercive control emphasizes the systematic, organized, multifaceted, and patterned nature of this interpersonal dynamic and can be considered to originate in the patriarchal dynamic where men control women.

Most professionals who work in this interdisciplinary area now refer to domestic violence as coercive control. Victimizers target women whom they sense they can control to get their own needs met. They are disinclined to invest in relationships with women who stress their own points of view, who do not readily accept blame when there is a disagreement, and who offer nurturing only when it is reciprocated.

In my office, if I think there are elements of coercion in a relationship, I bring out the Power and Control Wheel and the patient and I go over it. Good education is our responsibility. However, we all have met women who decide to stay in unhealthy relationships.

Assessing people who stay in coercive relationships

Fear

The most important first step is to assess safety. Are they afraid of increased violence if they challenge their partner? Restraining orders or other legal deterrents may not offer solace, as many women are clear that their spouse will come after them, if not tomorrow, then next week, or even next month. They are sure that they will not be safe.

In these cases, I go over safety steps with them so that if they decide to go, they will be prepared. I bring out the “safety box,” which includes the following action steps:

- Memorize important phone numbers of people to call in an emergency.

- If your children are old enough, teach them important phone numbers, including when to dial 911.

- If you can, open your own bank account.

- Stay in touch with friends. Get to know your neighbors. Don’t cut yourself off from people, even if you feel like you want to be alone.

- Rehearse your escape plan until you know it by heart.

- Leave a set of car keys, extra money, a change of clothes and copies of important documents with a trusted friend or relative: your own and your children’s birth certificates, children’s school and medical records, bank books, welfare identification, passport/green card, immigration papers, social security card, lease agreements or mortgage payment books, insurance papers, important addresses, and telephone numbers.

- Keep information about domestic violence in a safe place, where your abuser won’t find it, but where you can get it when you need to review it.

Some women may acknowledge that the risk of physical violence is not the determining factor in their decision to stay and have difficulty explaining why they choose to stay. I suggest that we then consider the following frames that have their origin in the study of the impact of trauma.

Shame

From this lens, abusive events are humiliating experiences, now represented as shame experiences. Humiliation and shame hide hostile feelings that the patient is not able to acknowledge.

“In shame, the self is the failure and others may reject or be critical of this exposed, flawed self.”3 Women will therefore remain attached to an abuser to avoid the exposure of their defective self.

Action steps: Empathic engagement and acknowledgment of shame and humiliation are key. For someone to overcome shame, they must face their sense of their defective self and have strategies to manage these feelings. The development of such strategies is the next step.

Trauma repetition and trauma bonding

Women subjected to domestic violence often respond with incapacitating traumatic syndromes. The concept of “trauma repetition” is suggested as a cause of vulnerability to repeated abuse, and “trauma bonding” is the term for the intense and tenacious bond that can form between abusers and victims.4

Trauma bonding implies that a sense of safety and closeness and secure attachment can only be reached through highly abusive engagement; anything else is experienced as “superficial, cold, or irrelevant.”5 Trauma bonding may have its origins in emotional neglect, according to self reports of 116 women.6Action steps: The literature on trauma is growing and many patients will benefit from good curated sources. Having a good list of books and website on hand is important. Discussion and exploration of the impact of trauma will be needed, and can be provided by someone who is available on a consistent and frequent basis. This work may be time consuming and difficult.

Some asides

1. Some psychiatrists proffer the explanation that these women who stay must be masochistic. The misogynistic concept of masochism still haunts the halls of psychiatry. It is usually offered as a way to dismiss these women’s concerns.

2. One of the obstacles to recognizing chronic mistreatment in relationships is that most abusive men simply “do not seem like abusers.” They have many good qualities, including times of kindness, warmth, and humor, especially in the initial period of a relationship. An abuser’s friends may think the world of him. He may have a successful work life and have no problems with drugs or alcohol. He may simply not fit anyone’s image of a cruel or intimidating person. So, when a woman feels her relationship spinning out of control, it may not occur to her that her partner is an abuser. Even if she does consider her partner to be overly controlling, others may question her perception.

3. Neutrality in family courts is systemic sexism/misogyny. When it comes to domestic violence, family courts tend to split the difference. Stephanie Brandt, MD, notes that The assumption that it is violence alone that matters has formed the basis of much clinical and legal confusion.7 As an analyst, she has gone against the grain of a favored neutrality and become active in the courts, noting the secondary victimization that occurs when a woman enters the legal system.

In summary, psychiatrists must reclaim our expertise in systemic dynamics and point out the role of systemic misogyny. Justices and other court officials need to be educated. Ideally, justice should be based on the equality of men and women in a society free of systemic misogyny. Unfortunately our society has not yet reached this position. In the meanwhile, we must think systemically about interpersonal dynamics. This is our lane. This should not be controversial.

Dr. Heru is professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (New York: Routledge, 2013). She has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Contact Dr. Heru at [email protected]. Dr. Heru would like to thank Dr. Stephanie Brandt for discussing this topic with her and supporting this work.

References

1. Ellyatt H. Arguing with your partner over Covid? You’re not alone, with the pandemic straining many relationships. 2022 Jan 21. https://www.cnbc.com/2022/01/21/covid-has-put-pressures-and-strains-on-relationships.html

2. Xue J et al. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Nov 6;22(11):e24361. doi: 10.2196/24361.

3. Dorahy MJ. J Trauma Dissociation. 2017 May-Jun;18(3):383-96. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1295422.

4. Dutton DG and Painter SL. Victimology. 1981 Jan;6(1):139-55.

5. Sachs A. J Trauma Dissociation. 2017 May-Jun;18(3):319-39. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1295400.

6. Krüger C and Fletcher L. J Trauma Dissociation. 2017 May-Jun;18(3):356-72. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1295420.

7. Brandt S and Rudden M. Int J Appl Psychoanal Studies. 2020 Sept;17(3):215-31. doi: 10.1002/aps.1671.

Despite the ability of some couples to pull together and manage through the COVID-19 pandemic, other couples and families failed to thrive. Increasing divorce rates have been noted nationwide with many disagreements being specifically about COVID.1

A review of over 1 million tweets, between April 12 and July 16, 2020, found an increase in calls to hotlines and increased reports of a variety of types of family violence. There were also more inquiries about social services for family violence, an increased presence from social movements, and more domestic violence-related news.2

The literature addressing family violence uses a variety of terms, so here are some definitions.

Domestic violence is defined as a pattern of behaviors used to gain or maintain power and control. Broadly speaking, domestic violence includes elder abuse, sibling abuse, child abuse, intimate partner abuse, parent abuse, and can also include people who don’t necessarily live together but who have an intimate relationship. Domestic violence centers use the Power and Control Wheel (see graphic) developed by the Domestic Abuse Intervention Project in Duluth, Minn., to describe how domestic violence occurs.

Intimate partner violence is more specific, referring to violence that happens between people in an ongoing or former intimate or romantic relationship, and is a subcategory of domestic violence.

Coercive control is the use of power for control and compliance. It is a dynamic and systematic process described in the top left corner of the Power and Control Wheel. Overt control occurs with the implication that “if you don’t follow the rules, I’ll kill you.” More subtle control is when obedience is forced through monopolizing resources, dictating preferred choices, microregulating a partner’s behavior, and deprivation of supports needed to exercise independent judgment.

All interpersonal relationships have elements of persuasion and influence; however, the goal of coercive relationships is to maintain power and control. It is a dynamic of the relationship. Coercive control emphasizes the systematic, organized, multifaceted, and patterned nature of this interpersonal dynamic and can be considered to originate in the patriarchal dynamic where men control women.

Most professionals who work in this interdisciplinary area now refer to domestic violence as coercive control. Victimizers target women whom they sense they can control to get their own needs met. They are disinclined to invest in relationships with women who stress their own points of view, who do not readily accept blame when there is a disagreement, and who offer nurturing only when it is reciprocated.

In my office, if I think there are elements of coercion in a relationship, I bring out the Power and Control Wheel and the patient and I go over it. Good education is our responsibility. However, we all have met women who decide to stay in unhealthy relationships.

Assessing people who stay in coercive relationships

Fear

The most important first step is to assess safety. Are they afraid of increased violence if they challenge their partner? Restraining orders or other legal deterrents may not offer solace, as many women are clear that their spouse will come after them, if not tomorrow, then next week, or even next month. They are sure that they will not be safe.

In these cases, I go over safety steps with them so that if they decide to go, they will be prepared. I bring out the “safety box,” which includes the following action steps:

- Memorize important phone numbers of people to call in an emergency.

- If your children are old enough, teach them important phone numbers, including when to dial 911.

- If you can, open your own bank account.

- Stay in touch with friends. Get to know your neighbors. Don’t cut yourself off from people, even if you feel like you want to be alone.

- Rehearse your escape plan until you know it by heart.

- Leave a set of car keys, extra money, a change of clothes and copies of important documents with a trusted friend or relative: your own and your children’s birth certificates, children’s school and medical records, bank books, welfare identification, passport/green card, immigration papers, social security card, lease agreements or mortgage payment books, insurance papers, important addresses, and telephone numbers.

- Keep information about domestic violence in a safe place, where your abuser won’t find it, but where you can get it when you need to review it.

Some women may acknowledge that the risk of physical violence is not the determining factor in their decision to stay and have difficulty explaining why they choose to stay. I suggest that we then consider the following frames that have their origin in the study of the impact of trauma.

Shame

From this lens, abusive events are humiliating experiences, now represented as shame experiences. Humiliation and shame hide hostile feelings that the patient is not able to acknowledge.

“In shame, the self is the failure and others may reject or be critical of this exposed, flawed self.”3 Women will therefore remain attached to an abuser to avoid the exposure of their defective self.

Action steps: Empathic engagement and acknowledgment of shame and humiliation are key. For someone to overcome shame, they must face their sense of their defective self and have strategies to manage these feelings. The development of such strategies is the next step.

Trauma repetition and trauma bonding

Women subjected to domestic violence often respond with incapacitating traumatic syndromes. The concept of “trauma repetition” is suggested as a cause of vulnerability to repeated abuse, and “trauma bonding” is the term for the intense and tenacious bond that can form between abusers and victims.4

Trauma bonding implies that a sense of safety and closeness and secure attachment can only be reached through highly abusive engagement; anything else is experienced as “superficial, cold, or irrelevant.”5 Trauma bonding may have its origins in emotional neglect, according to self reports of 116 women.6Action steps: The literature on trauma is growing and many patients will benefit from good curated sources. Having a good list of books and website on hand is important. Discussion and exploration of the impact of trauma will be needed, and can be provided by someone who is available on a consistent and frequent basis. This work may be time consuming and difficult.

Some asides

1. Some psychiatrists proffer the explanation that these women who stay must be masochistic. The misogynistic concept of masochism still haunts the halls of psychiatry. It is usually offered as a way to dismiss these women’s concerns.

2. One of the obstacles to recognizing chronic mistreatment in relationships is that most abusive men simply “do not seem like abusers.” They have many good qualities, including times of kindness, warmth, and humor, especially in the initial period of a relationship. An abuser’s friends may think the world of him. He may have a successful work life and have no problems with drugs or alcohol. He may simply not fit anyone’s image of a cruel or intimidating person. So, when a woman feels her relationship spinning out of control, it may not occur to her that her partner is an abuser. Even if she does consider her partner to be overly controlling, others may question her perception.

3. Neutrality in family courts is systemic sexism/misogyny. When it comes to domestic violence, family courts tend to split the difference. Stephanie Brandt, MD, notes that The assumption that it is violence alone that matters has formed the basis of much clinical and legal confusion.7 As an analyst, she has gone against the grain of a favored neutrality and become active in the courts, noting the secondary victimization that occurs when a woman enters the legal system.

In summary, psychiatrists must reclaim our expertise in systemic dynamics and point out the role of systemic misogyny. Justices and other court officials need to be educated. Ideally, justice should be based on the equality of men and women in a society free of systemic misogyny. Unfortunately our society has not yet reached this position. In the meanwhile, we must think systemically about interpersonal dynamics. This is our lane. This should not be controversial.

Dr. Heru is professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (New York: Routledge, 2013). She has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Contact Dr. Heru at [email protected]. Dr. Heru would like to thank Dr. Stephanie Brandt for discussing this topic with her and supporting this work.

References

1. Ellyatt H. Arguing with your partner over Covid? You’re not alone, with the pandemic straining many relationships. 2022 Jan 21. https://www.cnbc.com/2022/01/21/covid-has-put-pressures-and-strains-on-relationships.html

2. Xue J et al. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Nov 6;22(11):e24361. doi: 10.2196/24361.

3. Dorahy MJ. J Trauma Dissociation. 2017 May-Jun;18(3):383-96. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1295422.

4. Dutton DG and Painter SL. Victimology. 1981 Jan;6(1):139-55.

5. Sachs A. J Trauma Dissociation. 2017 May-Jun;18(3):319-39. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1295400.

6. Krüger C and Fletcher L. J Trauma Dissociation. 2017 May-Jun;18(3):356-72. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1295420.

7. Brandt S and Rudden M. Int J Appl Psychoanal Studies. 2020 Sept;17(3):215-31. doi: 10.1002/aps.1671.

TikTok offers to ‘balance your hormones’ are pure hokum

With more than 306 million views, #hormonebalance and #hormonebalancing are among the latest hacks to take over the social media platform TikTok, on which users post short videos. Influencers offer advice such as eating raw carrots for “happy hormones,” eating protein followed by fat for breakfast to regulate blood glucose, or taking vitamin B2 supplements for thyroid health.

Have you ever wondered if you were asleep during the lecture on “hormone balancing” in medical school? No, you weren’t. It was never a class for good reason, and you didn’t fail to read any such breakthrough studies in The New England Journal of Medicine either.

There are over 50 different hormones produced by humans and animals, regulating sleep, growth, metabolism and reproduction, among many other biological processes, so there is certainly no one-size-fits-all solution to ensure these are all working in perfect harmony.

When someone mentions “hormone balancing,” my mind wanders to the last time I took my car to have my tires rotated and balanced. If only it were as simple to balance hormones in real life. The best we can hope for is to get a specific hormone within the ideal physiologic range for that person’s age.

The term “hormone” can mean many things to different people. When a woman comes in with a hormone question, for example, it is often related to estrogen, followed by thyroid hormones. A wealth of misinformation exists in popular literature regarding these hormones alone.

Estrogen can be replaced, but not everyone needs it replaced. It depends on variables including age, underlying medical conditions, the time of day a test was drawn, and concomitant medications. Having low levels of a given hormone does not necessarily call for replacement either.

Insulin is another example of a hormone that can never completely be replaced in people with diabetes in a way that exactly mimics the normal physiologic release.

There are many lesser-known hormones that are measurable and replaceable but are also more difficult to reset to original manufacturer specifications.

A Google search for “hormone balancing” often sends you to “naturopaths” or “integrative medicine” practitioners, who often propose similar solutions to the TikTok influencers. Users are told that their hormones are out of whack and that restoring this “balance” can be achieved by purchasing whatever “natural products” or concoction they are selling.

These TikTok videos and online “experts” are the home-brewed versions of the strip-mall hormone specialists. TikTok videos claiming to help “balance hormones” typically don’t name a specific hormone either, or the end organs that each would have an impact on. Rather, they lump all hormones into a monolithic entity, implying that there is a single solution for all health problems. And personal testimonials extolling the benefits of a TikTok intervention don’t constitute proof of efficacy no matter how many “likes” they get. These influencers assume that viewers can “sense” their hormones are out of tune and no lab tests can convince them otherwise.

In these inflationary times, the cost of seeking medical care from conventional channels is increasingly prohibitive. It’s easy to understand the appeal of getting free advice from TikTok or some other Internet site. At best, following the advice will not have much impact; at worst, it could be harmful.

Don’t try this at home

There are some things that should never be tried at home, and do-it-yourself hormone replacement or remediation both fall under this umbrella.

Generally, the body does a good job of balancing its own hormones. Most patients don’t need to be worried if they’re in good health. If they’re in doubt, they should seek advice from a doctor, ideally an endocrinologist, but an ob.gyn. or general practitioner are also good options.

One of the first questions to ask a patient is “Which hormone are you worried about?” or “What health issue is it specifically that is bothering you?” Narrowing the focus to a single thing, if possible, will lead to a more efficient evaluation.

Often, patients arrive with multiple concerns written on little pieces of paper. These ubiquitous pieces of paper are the red flag for the flood of questions to follow.

Ordering the appropriate tests for the conditions they are concerned about can help put their minds at ease. If there are any specific deficiencies, or excesses in any hormones, then appropriate solutions can be discussed.

TikTok hormone-balancing solutions are simply the 21st-century version of the snake oil sold on late-night cable TV in the 1990s.

Needless to say, you should gently encourage your patients to stay away from these non–FDA-approved products, without making them feel stupid. Off-label use of hormones when these are not indicated is also to be avoided, unless a medical practitioner feels it is warranted.

Dr. de la Rosa is an endocrinologist in Englewood, Fla. He disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With more than 306 million views, #hormonebalance and #hormonebalancing are among the latest hacks to take over the social media platform TikTok, on which users post short videos. Influencers offer advice such as eating raw carrots for “happy hormones,” eating protein followed by fat for breakfast to regulate blood glucose, or taking vitamin B2 supplements for thyroid health.

Have you ever wondered if you were asleep during the lecture on “hormone balancing” in medical school? No, you weren’t. It was never a class for good reason, and you didn’t fail to read any such breakthrough studies in The New England Journal of Medicine either.

There are over 50 different hormones produced by humans and animals, regulating sleep, growth, metabolism and reproduction, among many other biological processes, so there is certainly no one-size-fits-all solution to ensure these are all working in perfect harmony.

When someone mentions “hormone balancing,” my mind wanders to the last time I took my car to have my tires rotated and balanced. If only it were as simple to balance hormones in real life. The best we can hope for is to get a specific hormone within the ideal physiologic range for that person’s age.

The term “hormone” can mean many things to different people. When a woman comes in with a hormone question, for example, it is often related to estrogen, followed by thyroid hormones. A wealth of misinformation exists in popular literature regarding these hormones alone.

Estrogen can be replaced, but not everyone needs it replaced. It depends on variables including age, underlying medical conditions, the time of day a test was drawn, and concomitant medications. Having low levels of a given hormone does not necessarily call for replacement either.

Insulin is another example of a hormone that can never completely be replaced in people with diabetes in a way that exactly mimics the normal physiologic release.

There are many lesser-known hormones that are measurable and replaceable but are also more difficult to reset to original manufacturer specifications.

A Google search for “hormone balancing” often sends you to “naturopaths” or “integrative medicine” practitioners, who often propose similar solutions to the TikTok influencers. Users are told that their hormones are out of whack and that restoring this “balance” can be achieved by purchasing whatever “natural products” or concoction they are selling.

These TikTok videos and online “experts” are the home-brewed versions of the strip-mall hormone specialists. TikTok videos claiming to help “balance hormones” typically don’t name a specific hormone either, or the end organs that each would have an impact on. Rather, they lump all hormones into a monolithic entity, implying that there is a single solution for all health problems. And personal testimonials extolling the benefits of a TikTok intervention don’t constitute proof of efficacy no matter how many “likes” they get. These influencers assume that viewers can “sense” their hormones are out of tune and no lab tests can convince them otherwise.

In these inflationary times, the cost of seeking medical care from conventional channels is increasingly prohibitive. It’s easy to understand the appeal of getting free advice from TikTok or some other Internet site. At best, following the advice will not have much impact; at worst, it could be harmful.

Don’t try this at home

There are some things that should never be tried at home, and do-it-yourself hormone replacement or remediation both fall under this umbrella.

Generally, the body does a good job of balancing its own hormones. Most patients don’t need to be worried if they’re in good health. If they’re in doubt, they should seek advice from a doctor, ideally an endocrinologist, but an ob.gyn. or general practitioner are also good options.

One of the first questions to ask a patient is “Which hormone are you worried about?” or “What health issue is it specifically that is bothering you?” Narrowing the focus to a single thing, if possible, will lead to a more efficient evaluation.

Often, patients arrive with multiple concerns written on little pieces of paper. These ubiquitous pieces of paper are the red flag for the flood of questions to follow.

Ordering the appropriate tests for the conditions they are concerned about can help put their minds at ease. If there are any specific deficiencies, or excesses in any hormones, then appropriate solutions can be discussed.

TikTok hormone-balancing solutions are simply the 21st-century version of the snake oil sold on late-night cable TV in the 1990s.

Needless to say, you should gently encourage your patients to stay away from these non–FDA-approved products, without making them feel stupid. Off-label use of hormones when these are not indicated is also to be avoided, unless a medical practitioner feels it is warranted.

Dr. de la Rosa is an endocrinologist in Englewood, Fla. He disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With more than 306 million views, #hormonebalance and #hormonebalancing are among the latest hacks to take over the social media platform TikTok, on which users post short videos. Influencers offer advice such as eating raw carrots for “happy hormones,” eating protein followed by fat for breakfast to regulate blood glucose, or taking vitamin B2 supplements for thyroid health.

Have you ever wondered if you were asleep during the lecture on “hormone balancing” in medical school? No, you weren’t. It was never a class for good reason, and you didn’t fail to read any such breakthrough studies in The New England Journal of Medicine either.

There are over 50 different hormones produced by humans and animals, regulating sleep, growth, metabolism and reproduction, among many other biological processes, so there is certainly no one-size-fits-all solution to ensure these are all working in perfect harmony.

When someone mentions “hormone balancing,” my mind wanders to the last time I took my car to have my tires rotated and balanced. If only it were as simple to balance hormones in real life. The best we can hope for is to get a specific hormone within the ideal physiologic range for that person’s age.

The term “hormone” can mean many things to different people. When a woman comes in with a hormone question, for example, it is often related to estrogen, followed by thyroid hormones. A wealth of misinformation exists in popular literature regarding these hormones alone.

Estrogen can be replaced, but not everyone needs it replaced. It depends on variables including age, underlying medical conditions, the time of day a test was drawn, and concomitant medications. Having low levels of a given hormone does not necessarily call for replacement either.

Insulin is another example of a hormone that can never completely be replaced in people with diabetes in a way that exactly mimics the normal physiologic release.

There are many lesser-known hormones that are measurable and replaceable but are also more difficult to reset to original manufacturer specifications.

A Google search for “hormone balancing” often sends you to “naturopaths” or “integrative medicine” practitioners, who often propose similar solutions to the TikTok influencers. Users are told that their hormones are out of whack and that restoring this “balance” can be achieved by purchasing whatever “natural products” or concoction they are selling.

These TikTok videos and online “experts” are the home-brewed versions of the strip-mall hormone specialists. TikTok videos claiming to help “balance hormones” typically don’t name a specific hormone either, or the end organs that each would have an impact on. Rather, they lump all hormones into a monolithic entity, implying that there is a single solution for all health problems. And personal testimonials extolling the benefits of a TikTok intervention don’t constitute proof of efficacy no matter how many “likes” they get. These influencers assume that viewers can “sense” their hormones are out of tune and no lab tests can convince them otherwise.

In these inflationary times, the cost of seeking medical care from conventional channels is increasingly prohibitive. It’s easy to understand the appeal of getting free advice from TikTok or some other Internet site. At best, following the advice will not have much impact; at worst, it could be harmful.

Don’t try this at home

There are some things that should never be tried at home, and do-it-yourself hormone replacement or remediation both fall under this umbrella.

Generally, the body does a good job of balancing its own hormones. Most patients don’t need to be worried if they’re in good health. If they’re in doubt, they should seek advice from a doctor, ideally an endocrinologist, but an ob.gyn. or general practitioner are also good options.

One of the first questions to ask a patient is “Which hormone are you worried about?” or “What health issue is it specifically that is bothering you?” Narrowing the focus to a single thing, if possible, will lead to a more efficient evaluation.

Often, patients arrive with multiple concerns written on little pieces of paper. These ubiquitous pieces of paper are the red flag for the flood of questions to follow.

Ordering the appropriate tests for the conditions they are concerned about can help put their minds at ease. If there are any specific deficiencies, or excesses in any hormones, then appropriate solutions can be discussed.

TikTok hormone-balancing solutions are simply the 21st-century version of the snake oil sold on late-night cable TV in the 1990s.

Needless to say, you should gently encourage your patients to stay away from these non–FDA-approved products, without making them feel stupid. Off-label use of hormones when these are not indicated is also to be avoided, unless a medical practitioner feels it is warranted.

Dr. de la Rosa is an endocrinologist in Englewood, Fla. He disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Picking up the premotor symptoms of Parkinson’s

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. We had a great discussion on Parkinson’s Disease for Primary Care with Dr. Albert Hung. Paul, this was something that really made me nervous. I didn’t have a lot of comfort with it. But he taught us a lot of tips about how to recognize Parkinson’s.

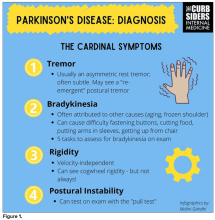

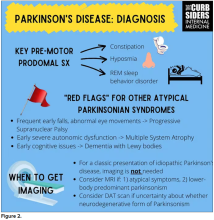

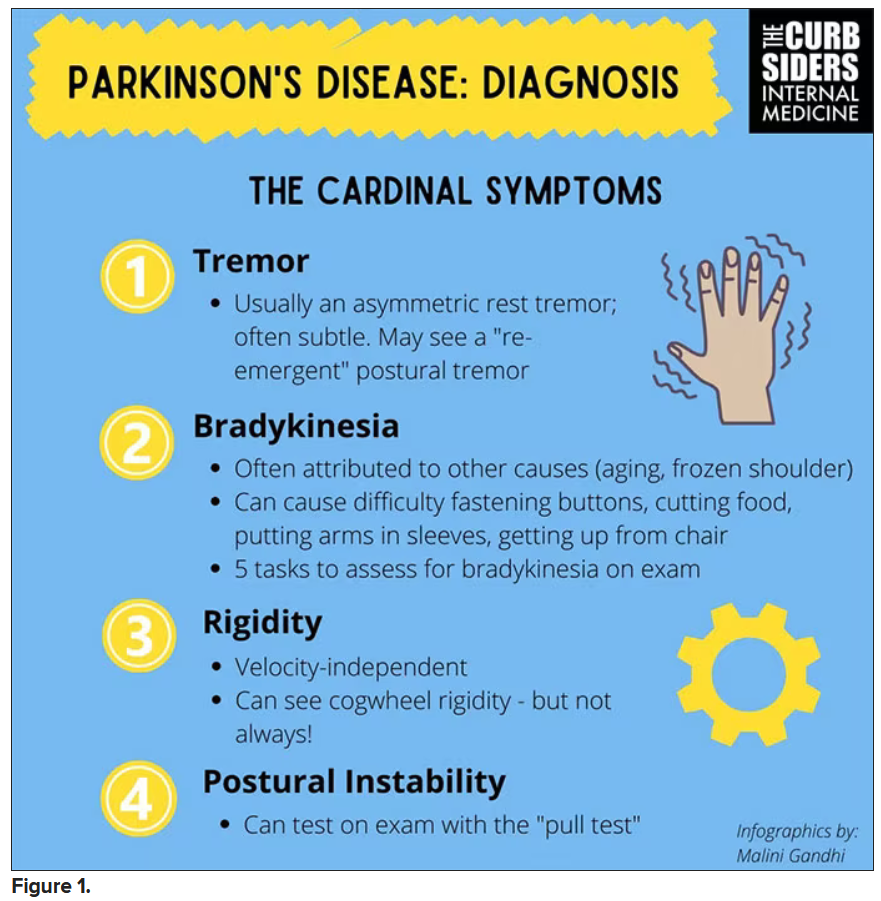

I hadn’t been as aware of the premotor symptoms: constipation, hyposmia (loss of sense of smell), and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. If patients have those early on and they aren’t explained by other things (especially the REM sleep behavior disorder), you should really key in because those patients are at risk of developing Parkinson’s years down the line. Those symptoms could present first, which just kind of blew my mind.

What tips do you have about how to recognize Parkinson’s? Do you want to talk about the physical exam?

Paul N. Williams, MD: You know I love the physical exam stuff, so I’m happy to talk about that.

You were deeply upset that cogwheel rigidity was not pathognomonic for Parkinson’s, but you made the point – and our guest agreed – that asymmetry tends to be the key here. And I really appreciated the point about reemergent tremor. This is this idea of a resting tremor. If someone has more parkinsonian features, you might see an intention tremor with essential tremor. If they reach out, it might seem steady at first, but if they hold long enough, then the tremor may kind of reemerge. I thought that was a neat distinction.

And this idea of cogwheel rigidity is a combination of some of the cardinal features of Parkinson’s – it’s a little bit of tremor and a little bit of rigidity too. There’s a baseline increase in tone, and then the tremor is superimposed on top of that. When you’re feeling cogwheeling, that’s actually what you’re feeling on examination. Parkinson’s, with all of its physical exam findings has always fascinated me.

Dr. Watto: He also told us about some red flags.

With classic idiopathic parkinsonism, there’s asymmetric involvement of the tremor. So red flags include a symmetric tremor, which might be something other than idiopathic parkinsonism. He also mentioned that one of the reasons you may want to get imaging (which is not always necessary if someone has a classic presentation), is if you see lower body–predominant symptoms of parkinsonism. These patients have rigidity or slowness of movement in their legs, but their upper bodies are not affected. They don’t have masked facies or the tremor in their hands. You might get an MRI in that case because that could be presentation of vascular dementia or vascular disease in the brain or even normal pressure hydrocephalus, which is a treatable condition. That would be one reason to get imaging.

What if the patient was exposed to a drug like a dopamine antagonist? They will get better in a couple of days, right?

Dr. Williams: This was a really fascinating point because we typically think if a patient’s symptoms are related to a drug exposure – in this case, drug-induced parkinsonism – we can just stop the medication and the symptoms will disappear in a couple of days as the drug leaves the system. But as it turns out, it might take much longer. A mistake that Dr Hung often sees is that the clinician stops the possibly offending agent, but when they don’t see an immediate relief of symptoms, they assume the drug wasn’t causing them. You really have to give the patient a fair shot off the medication to experience recovery because those symptoms can last weeks or even months after the drug is discontinued.

Dr. Watto: Dr Hung looks at the patient’s problem list and asks whether is there any reason this patient might have been exposed to one of these medications?

We’re not going to get too much into specific Parkinson’s treatment, but I was glad to hear that exercise actually improves mobility and may even have some neuroprotective effects. He mentioned ongoing trials looking at that. We always love an excuse to tell patients that they should be moving around more and being physically active.

Dr. Williams: That was one of the more shocking things I learned, that exercise might actually be good for you. That will deeply inform my practice. Many of the treatments that we use for Parkinson’s only address symptoms. They don’t address progression or fix anything, but exercise can help with that.

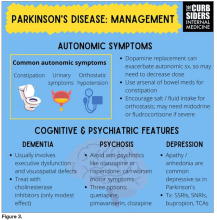

Dr. Watto: Paul, the last question I wanted to ask you is about our role in primary care. Patients with Parkinson’s have autonomic symptoms. They have neurocognitive symptoms. What is our role in that as primary care physicians?

Dr. Williams: Myriad symptoms can accompany Parkinson’s, and we have experience with most of them. We should all feel fairly comfortable dealing with constipation, which can be a very bothersome symptom. And we can use our full arsenal for symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and even apathy – the anhedonia, which apparently can be the predominant feature. We do have the tools to address these problems.

This might be a situation where we might reach for bupropion or a tricyclic antidepressant, which might not be your initial choice for a patient with a possibly annoying mood disorder. But for someone with Parkinson’s disease, this actually may be very helpful. We know how to manage a lot of the symptoms that come along with Parkinson’s that are not just the motor symptoms, and we should take ownership of those things.

Dr. Watto: You can hear the rest of this podcast here. This has been another episode of The Curbsiders bringing you a little knowledge food for your brain hole. Until next time, I’ve been Dr Matthew Frank Watto.

Dr. Williams: And I’m Dr Paul Nelson Williams.

Dr. Watto is a clinical assistant professor, department of medicine, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Williams is Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, at Temple University, Philadelphia. Neither Dr. Watto nor Dr. Williams reported any relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. We had a great discussion on Parkinson’s Disease for Primary Care with Dr. Albert Hung. Paul, this was something that really made me nervous. I didn’t have a lot of comfort with it. But he taught us a lot of tips about how to recognize Parkinson’s.

I hadn’t been as aware of the premotor symptoms: constipation, hyposmia (loss of sense of smell), and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. If patients have those early on and they aren’t explained by other things (especially the REM sleep behavior disorder), you should really key in because those patients are at risk of developing Parkinson’s years down the line. Those symptoms could present first, which just kind of blew my mind.

What tips do you have about how to recognize Parkinson’s? Do you want to talk about the physical exam?

Paul N. Williams, MD: You know I love the physical exam stuff, so I’m happy to talk about that.

You were deeply upset that cogwheel rigidity was not pathognomonic for Parkinson’s, but you made the point – and our guest agreed – that asymmetry tends to be the key here. And I really appreciated the point about reemergent tremor. This is this idea of a resting tremor. If someone has more parkinsonian features, you might see an intention tremor with essential tremor. If they reach out, it might seem steady at first, but if they hold long enough, then the tremor may kind of reemerge. I thought that was a neat distinction.

And this idea of cogwheel rigidity is a combination of some of the cardinal features of Parkinson’s – it’s a little bit of tremor and a little bit of rigidity too. There’s a baseline increase in tone, and then the tremor is superimposed on top of that. When you’re feeling cogwheeling, that’s actually what you’re feeling on examination. Parkinson’s, with all of its physical exam findings has always fascinated me.

Dr. Watto: He also told us about some red flags.

With classic idiopathic parkinsonism, there’s asymmetric involvement of the tremor. So red flags include a symmetric tremor, which might be something other than idiopathic parkinsonism. He also mentioned that one of the reasons you may want to get imaging (which is not always necessary if someone has a classic presentation), is if you see lower body–predominant symptoms of parkinsonism. These patients have rigidity or slowness of movement in their legs, but their upper bodies are not affected. They don’t have masked facies or the tremor in their hands. You might get an MRI in that case because that could be presentation of vascular dementia or vascular disease in the brain or even normal pressure hydrocephalus, which is a treatable condition. That would be one reason to get imaging.

What if the patient was exposed to a drug like a dopamine antagonist? They will get better in a couple of days, right?

Dr. Williams: This was a really fascinating point because we typically think if a patient’s symptoms are related to a drug exposure – in this case, drug-induced parkinsonism – we can just stop the medication and the symptoms will disappear in a couple of days as the drug leaves the system. But as it turns out, it might take much longer. A mistake that Dr Hung often sees is that the clinician stops the possibly offending agent, but when they don’t see an immediate relief of symptoms, they assume the drug wasn’t causing them. You really have to give the patient a fair shot off the medication to experience recovery because those symptoms can last weeks or even months after the drug is discontinued.

Dr. Watto: Dr Hung looks at the patient’s problem list and asks whether is there any reason this patient might have been exposed to one of these medications?

We’re not going to get too much into specific Parkinson’s treatment, but I was glad to hear that exercise actually improves mobility and may even have some neuroprotective effects. He mentioned ongoing trials looking at that. We always love an excuse to tell patients that they should be moving around more and being physically active.

Dr. Williams: That was one of the more shocking things I learned, that exercise might actually be good for you. That will deeply inform my practice. Many of the treatments that we use for Parkinson’s only address symptoms. They don’t address progression or fix anything, but exercise can help with that.

Dr. Watto: Paul, the last question I wanted to ask you is about our role in primary care. Patients with Parkinson’s have autonomic symptoms. They have neurocognitive symptoms. What is our role in that as primary care physicians?

Dr. Williams: Myriad symptoms can accompany Parkinson’s, and we have experience with most of them. We should all feel fairly comfortable dealing with constipation, which can be a very bothersome symptom. And we can use our full arsenal for symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and even apathy – the anhedonia, which apparently can be the predominant feature. We do have the tools to address these problems.

This might be a situation where we might reach for bupropion or a tricyclic antidepressant, which might not be your initial choice for a patient with a possibly annoying mood disorder. But for someone with Parkinson’s disease, this actually may be very helpful. We know how to manage a lot of the symptoms that come along with Parkinson’s that are not just the motor symptoms, and we should take ownership of those things.

Dr. Watto: You can hear the rest of this podcast here. This has been another episode of The Curbsiders bringing you a little knowledge food for your brain hole. Until next time, I’ve been Dr Matthew Frank Watto.

Dr. Williams: And I’m Dr Paul Nelson Williams.

Dr. Watto is a clinical assistant professor, department of medicine, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Williams is Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, at Temple University, Philadelphia. Neither Dr. Watto nor Dr. Williams reported any relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. We had a great discussion on Parkinson’s Disease for Primary Care with Dr. Albert Hung. Paul, this was something that really made me nervous. I didn’t have a lot of comfort with it. But he taught us a lot of tips about how to recognize Parkinson’s.

I hadn’t been as aware of the premotor symptoms: constipation, hyposmia (loss of sense of smell), and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. If patients have those early on and they aren’t explained by other things (especially the REM sleep behavior disorder), you should really key in because those patients are at risk of developing Parkinson’s years down the line. Those symptoms could present first, which just kind of blew my mind.

What tips do you have about how to recognize Parkinson’s? Do you want to talk about the physical exam?

Paul N. Williams, MD: You know I love the physical exam stuff, so I’m happy to talk about that.

You were deeply upset that cogwheel rigidity was not pathognomonic for Parkinson’s, but you made the point – and our guest agreed – that asymmetry tends to be the key here. And I really appreciated the point about reemergent tremor. This is this idea of a resting tremor. If someone has more parkinsonian features, you might see an intention tremor with essential tremor. If they reach out, it might seem steady at first, but if they hold long enough, then the tremor may kind of reemerge. I thought that was a neat distinction.

And this idea of cogwheel rigidity is a combination of some of the cardinal features of Parkinson’s – it’s a little bit of tremor and a little bit of rigidity too. There’s a baseline increase in tone, and then the tremor is superimposed on top of that. When you’re feeling cogwheeling, that’s actually what you’re feeling on examination. Parkinson’s, with all of its physical exam findings has always fascinated me.

Dr. Watto: He also told us about some red flags.

With classic idiopathic parkinsonism, there’s asymmetric involvement of the tremor. So red flags include a symmetric tremor, which might be something other than idiopathic parkinsonism. He also mentioned that one of the reasons you may want to get imaging (which is not always necessary if someone has a classic presentation), is if you see lower body–predominant symptoms of parkinsonism. These patients have rigidity or slowness of movement in their legs, but their upper bodies are not affected. They don’t have masked facies or the tremor in their hands. You might get an MRI in that case because that could be presentation of vascular dementia or vascular disease in the brain or even normal pressure hydrocephalus, which is a treatable condition. That would be one reason to get imaging.

What if the patient was exposed to a drug like a dopamine antagonist? They will get better in a couple of days, right?

Dr. Williams: This was a really fascinating point because we typically think if a patient’s symptoms are related to a drug exposure – in this case, drug-induced parkinsonism – we can just stop the medication and the symptoms will disappear in a couple of days as the drug leaves the system. But as it turns out, it might take much longer. A mistake that Dr Hung often sees is that the clinician stops the possibly offending agent, but when they don’t see an immediate relief of symptoms, they assume the drug wasn’t causing them. You really have to give the patient a fair shot off the medication to experience recovery because those symptoms can last weeks or even months after the drug is discontinued.

Dr. Watto: Dr Hung looks at the patient’s problem list and asks whether is there any reason this patient might have been exposed to one of these medications?

We’re not going to get too much into specific Parkinson’s treatment, but I was glad to hear that exercise actually improves mobility and may even have some neuroprotective effects. He mentioned ongoing trials looking at that. We always love an excuse to tell patients that they should be moving around more and being physically active.

Dr. Williams: That was one of the more shocking things I learned, that exercise might actually be good for you. That will deeply inform my practice. Many of the treatments that we use for Parkinson’s only address symptoms. They don’t address progression or fix anything, but exercise can help with that.

Dr. Watto: Paul, the last question I wanted to ask you is about our role in primary care. Patients with Parkinson’s have autonomic symptoms. They have neurocognitive symptoms. What is our role in that as primary care physicians?

Dr. Williams: Myriad symptoms can accompany Parkinson’s, and we have experience with most of them. We should all feel fairly comfortable dealing with constipation, which can be a very bothersome symptom. And we can use our full arsenal for symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and even apathy – the anhedonia, which apparently can be the predominant feature. We do have the tools to address these problems.

This might be a situation where we might reach for bupropion or a tricyclic antidepressant, which might not be your initial choice for a patient with a possibly annoying mood disorder. But for someone with Parkinson’s disease, this actually may be very helpful. We know how to manage a lot of the symptoms that come along with Parkinson’s that are not just the motor symptoms, and we should take ownership of those things.

Dr. Watto: You can hear the rest of this podcast here. This has been another episode of The Curbsiders bringing you a little knowledge food for your brain hole. Until next time, I’ve been Dr Matthew Frank Watto.

Dr. Williams: And I’m Dr Paul Nelson Williams.

Dr. Watto is a clinical assistant professor, department of medicine, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Williams is Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, at Temple University, Philadelphia. Neither Dr. Watto nor Dr. Williams reported any relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Parkinson’s disease: What’s trauma got to do with it?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Kathrin LaFaver, MD: Hello. I’m happy to talk today to Dr. Indu Subramanian, clinical professor at University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the Parkinson’s Disease Research, Education and Clinical Center in Los Angeles. I am a neurologist in Saratoga Springs, New York, and we will be talking today about Indu’s new paper on childhood trauma and Parkinson’s disease. Welcome and thanks for taking the time.

Indu Subramanian, MD: Thank you so much for letting us highlight this important topic.

Dr. LaFaver: There are many papers published every month on Parkinson’s disease, but this topic stands out because it’s not a thing that has been commonly looked at. What gave you the idea to study this?

Neurology behind other specialties

Dr. Subramanian: Kathrin, you and I have been looking at things that can inform us about our patients – the person who’s standing in front of us when they come in and we’re giving them this diagnosis. I think that so much of what we’ve done [in the past] is a cookie cutter approach to giving everybody the standard treatment. [We’ve been assuming that] It doesn’t matter if they’re a man or woman. It doesn’t matter if they’re a veteran. It doesn’t matter if they may be from a minoritized population.

We’ve also been interested in approaches that are outside the box, right? We have this integrative medicine and lifestyle medicine background. I’ve been going to those meetings and really been struck by the mounting evidence on the importance of things like early adverse childhood events (ACEs), what zip code you live in, what your pollution index is, and how these things can affect people through their life and their health.

I think that it is high time neurologists pay attention to this. There’s been mounting evidence throughout many disease states, various types of cancers, and mental health. Cardiology is much more advanced, but we haven’t had much data in neurology. In fact, when we went to write this paper, there were just one or two papers that were looking at multiple sclerosis or general neurologic issues, but really nothing in Parkinson’s disease.

We know that Parkinson’s disease is not only a motor disease that affects mental health, but that it also affects nonmotor issues. Childhood adversity may affect how people progress or how quickly they may get a disease, and we were interested in how it may manifest in a disease like Parkinson’s disease.

That was the framework going to meetings. As we wrote this paper and were in various editing stages, there was a beautiful paper that came out by Nadine Burke Harris and team that really was a call to action for neurologists and caring about trauma.

Dr. LaFaver: I couldn’t agree more. It’s really an underrecognized issue. With my own background, being very interested in functional movement disorders, psychosomatic disorders, and so on, it becomes much more evident how common a trauma background is, not only for people we were traditionally asking about.

Why don’t you summarize your findings for us?

Adverse childhood events

Dr. Subramanian: This is a web-based survey, so obviously, these are patient self-reports of their disease. We have a large cohort of people that we’ve been following over 7 years. I’m looking at modifiable variables and what really impacts Parkinson’s disease. Some of our previous papers have looked at diet, exercise, and loneliness. This is the same cohort.

We ended up putting the ACEs questionnaire, which is 10 questions looking at whether you were exposed to certain things in your household below the age of 18. This is a relatively standard questionnaire that’s administered one time, and you get a score out of 10. This is something that has been pushed, at least in the state of California, as something that we should be checking more in all people coming in.

We introduced the survey, and we didn’t force everyone to take it. Unfortunately, there was 20% or so of our patients who chose not to answer these questions. One has to ask, who are those people that didn’t answer the questions? Are they the ones that may have had trauma and these questions were triggering? It was a gap. We didn’t add extra questions to explore why people didn’t answer those questions.

We have to also put this in context. We have a patient population that’s largely quite affluent, who are able to access web-based surveys through their computer, and largely Caucasian; there are not many minoritized populations in our cohort. We want to do better with that. We actually were able to gather a decent number of women. We represent women quite well in our survey. I think that’s because of this online approach and some of the things that we’re studying.

In our survey, we broke it down into people who had no ACEs, one to three ACEs, or four or more ACEs. This is a standard way to break down ACEs so that we’re able to categorize what to do with these patient populations.

What we saw – and it’s preliminary evidence – is that people who had higher ACE scores seemed to have more symptom severity when we controlled for things like years since diagnosis, age, and gender. They also seem to have a worse quality of life. There was some indication that there were more nonmotor issues in those populations, as you might expect, such as anxiety, depression, and things that presumably ACEs can affect separately.

There are some confounders, but I think we really want to use this as the first piece of evidence to hopefully pave the way for caring about trauma in Parkinson’s disease moving forward.

Dr. LaFaver: Thank you so much for that summary. You already mentioned the main methodology you used.

What is the next step for you? How do you see these findings informing our clinical care? Do you have suggestions for all of the neurologists listening in this regard?

PD not yet considered ACE-related

Dr. Subramanian: Dr. Burke Harris was the former surgeon general in California. She’s a woman of color and a brilliant speaker, and she had worked in inner cities, I think in San Francisco, with pediatric populations, seeing these effects of adversity in that time frame.

You see this population at risk, and then you’re following this cohort, which we knew from the Kaiser cohort determines earlier morbidity and mortality across a number of disease states. We’re seeing things like more heart attacks, more diabetes, and all kinds of things in these populations. This is not new news; we just have not been focusing on this.

In her paper, this call to action, they had talked about some ACE-related conditions that currently do not include Parkinson’s disease. There are three ACE-related neurologic conditions that people should be aware of. One is in the headache/pain universe. Another is in the stroke universe, and that’s understandable, given cardiovascular risk factors . Then the third is in this dementia risk category. I think Parkinson’s disease, as we know, can be associated with dementia. A large percentage of our patients get dementia, but we don’t have Parkinson’s disease called out in this framework.

What people are talking about is if you have no ACEs or are in this middle category of one to three ACEs and you don’t have an ACE-related diagnosis – which Parkinson’s disease is not currently – we just give some basic counseling about the importance of lifestyle. I think we would love to see that anyway. They’re talking about things like exercise, diet, sleep, social connection, getting out in nature, things like that, so just general counseling on the importance of that.

Then if you’re in this higher-risk category, and so with these ACE-related neurologic conditions, including dementia, headache, and stroke, if you had this middle range of one to three ACEs, they’re getting additional resources. Some of them may be referred for social work help or mental health support and things like that.

I’d really love to see that happening in Parkinson’s disease, because I think we have so many needs in our population. I’m always hoping to advocate for more mental health needs that are scarce and resources in the social support realm because I believe that social connection and social support is a huge buffer for this trauma.

ACEs are just one type of trauma. I take care of veterans in the Veterans [Affairs Department]. We have some information now coming out about posttraumatic stress disorder, predisposing to certain things in Parkinson’s disease, possibly head injury, and things like that. I think we have populations at risk that we can hopefully screen at intake, and I’m really pushing for that.

Maybe it’s not the neurologist that does this intake. It might be someone else on the team that can spend some time doing these questionnaires and understand if your patient has a high ACE score. Unless you ask, many patients don’t necessarily come forward to talk about this. I really am pushing for trying to screen and trying to advocate for more research in this area so that we can classify Parkinson’s disease as an ACE-related condition and thus give more resources from the mental health world, and also the social support world, to our patients.

Dr. LaFaver: Thank you. There are many important points, and I think it’s a very important thing to recognize that it may not be only trauma in childhood but also throughout life, as you said, and might really influence nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease in particular, including anxiety and pain, which are often difficult to treat.

I think there’s much more to do in research, advocacy, and education. We’re going to educate patients about this, and also educate other neurologists and providers. I think you mentioned that trauma-informed care is getting its spotlight in primary care and other specialties. I think we have catching up to do in neurology, and I think this is a really important work toward that goal.

Thank you so much for your work and for taking the time to share your thoughts. I hope to talk to you again soon.

Dr. Subramanian: Thank you so much, Kathrin.

Dr. LaFaver has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Subramanian disclosed ties with Acorda Therapeutics.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Kathrin LaFaver, MD: Hello. I’m happy to talk today to Dr. Indu Subramanian, clinical professor at University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the Parkinson’s Disease Research, Education and Clinical Center in Los Angeles. I am a neurologist in Saratoga Springs, New York, and we will be talking today about Indu’s new paper on childhood trauma and Parkinson’s disease. Welcome and thanks for taking the time.

Indu Subramanian, MD: Thank you so much for letting us highlight this important topic.

Dr. LaFaver: There are many papers published every month on Parkinson’s disease, but this topic stands out because it’s not a thing that has been commonly looked at. What gave you the idea to study this?

Neurology behind other specialties

Dr. Subramanian: Kathrin, you and I have been looking at things that can inform us about our patients – the person who’s standing in front of us when they come in and we’re giving them this diagnosis. I think that so much of what we’ve done [in the past] is a cookie cutter approach to giving everybody the standard treatment. [We’ve been assuming that] It doesn’t matter if they’re a man or woman. It doesn’t matter if they’re a veteran. It doesn’t matter if they may be from a minoritized population.

We’ve also been interested in approaches that are outside the box, right? We have this integrative medicine and lifestyle medicine background. I’ve been going to those meetings and really been struck by the mounting evidence on the importance of things like early adverse childhood events (ACEs), what zip code you live in, what your pollution index is, and how these things can affect people through their life and their health.

I think that it is high time neurologists pay attention to this. There’s been mounting evidence throughout many disease states, various types of cancers, and mental health. Cardiology is much more advanced, but we haven’t had much data in neurology. In fact, when we went to write this paper, there were just one or two papers that were looking at multiple sclerosis or general neurologic issues, but really nothing in Parkinson’s disease.

We know that Parkinson’s disease is not only a motor disease that affects mental health, but that it also affects nonmotor issues. Childhood adversity may affect how people progress or how quickly they may get a disease, and we were interested in how it may manifest in a disease like Parkinson’s disease.

That was the framework going to meetings. As we wrote this paper and were in various editing stages, there was a beautiful paper that came out by Nadine Burke Harris and team that really was a call to action for neurologists and caring about trauma.

Dr. LaFaver: I couldn’t agree more. It’s really an underrecognized issue. With my own background, being very interested in functional movement disorders, psychosomatic disorders, and so on, it becomes much more evident how common a trauma background is, not only for people we were traditionally asking about.

Why don’t you summarize your findings for us?

Adverse childhood events

Dr. Subramanian: This is a web-based survey, so obviously, these are patient self-reports of their disease. We have a large cohort of people that we’ve been following over 7 years. I’m looking at modifiable variables and what really impacts Parkinson’s disease. Some of our previous papers have looked at diet, exercise, and loneliness. This is the same cohort.

We ended up putting the ACEs questionnaire, which is 10 questions looking at whether you were exposed to certain things in your household below the age of 18. This is a relatively standard questionnaire that’s administered one time, and you get a score out of 10. This is something that has been pushed, at least in the state of California, as something that we should be checking more in all people coming in.

We introduced the survey, and we didn’t force everyone to take it. Unfortunately, there was 20% or so of our patients who chose not to answer these questions. One has to ask, who are those people that didn’t answer the questions? Are they the ones that may have had trauma and these questions were triggering? It was a gap. We didn’t add extra questions to explore why people didn’t answer those questions.

We have to also put this in context. We have a patient population that’s largely quite affluent, who are able to access web-based surveys through their computer, and largely Caucasian; there are not many minoritized populations in our cohort. We want to do better with that. We actually were able to gather a decent number of women. We represent women quite well in our survey. I think that’s because of this online approach and some of the things that we’re studying.

In our survey, we broke it down into people who had no ACEs, one to three ACEs, or four or more ACEs. This is a standard way to break down ACEs so that we’re able to categorize what to do with these patient populations.

What we saw – and it’s preliminary evidence – is that people who had higher ACE scores seemed to have more symptom severity when we controlled for things like years since diagnosis, age, and gender. They also seem to have a worse quality of life. There was some indication that there were more nonmotor issues in those populations, as you might expect, such as anxiety, depression, and things that presumably ACEs can affect separately.