User login

Applications of office hysteroscopy for the infertility patient

What role does diagnostic office hysteroscopy play in an infertility evaluation?

.1

More specifically, hysteroscopy is the gold standard for assessing the uterine cavity. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive and negative predictive values of hysterosalpingography (HSG) in evaluating uterine cavity abnormalities were 44.83%; 86.67%; 56.52%; and 80.25%, respectively.2 Given the poor sensitivity of HSG, a diagnosis of endometrial polyps and/or chronic endometritis is more likely to be missed.

Our crossover trial comparing HSG to office hysteroscopy for tubal patency showed that women were 110 times more likely to have the maximum level of pain with HSG than diagnostic hysteroscopy when using a 2.8-mm flexible hysteroscope.3 Further, infection rates and vasovagal events were far lower with hysteroscopy.1

Finally, compared with HSG, we showed 98%-100% sensitivity and 84% specificity for tubal occlusion with hysteroscopy by air-infused saline. Conversely, HSG typically is associated with 76%-96% sensitivity and 67%-100% specificity.4 Additionally, we can often perform diagnostic hysteroscopies for approximately $35 per procedure for total fixed and disposable equipment costs.

How should physicians perform office hysteroscopy to minimize patient discomfort?

The classic paradigm has been to focus on paracervical blocks, anxiolytics, and a supportive environment (such as mood music). However, those are far more important when your hysteroscope is larger than the natural cervical lumen. If you can use small hysteroscopes (< 3 mm for the nulliparous cervix, < 4 mm for the parous cervix), most women will not require cervical dilation, which further enhances the patient experience.

Using a flexible hysteroscope for suspected pathology, making sure not to overdistend the uterus (particularly in high-risk patients such as those with tubal occlusion and cervical stenosis), and vaginoscopy can all minimize patient discomfort. We have published data showing that by using a 2.8-mm flexible diagnostic hysteroscope in a group of mostly nulliparous women, greater than 50% have no discomfort, and more than 90% will have mild to no discomfort.3

What operative hysteroscopy procedures can be performed safely in a physician’s office, and what equipment is required?

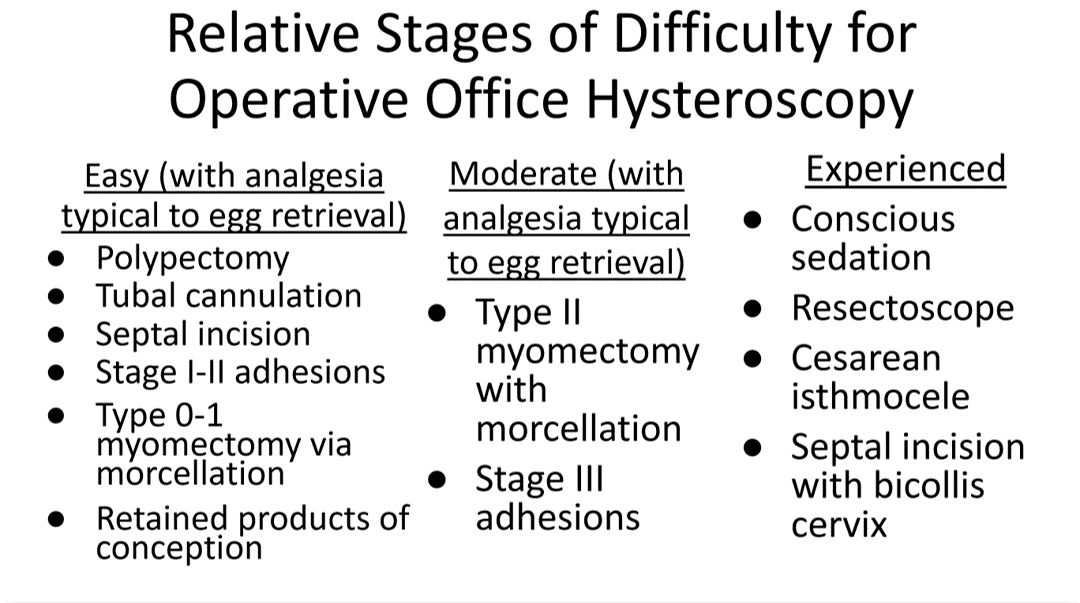

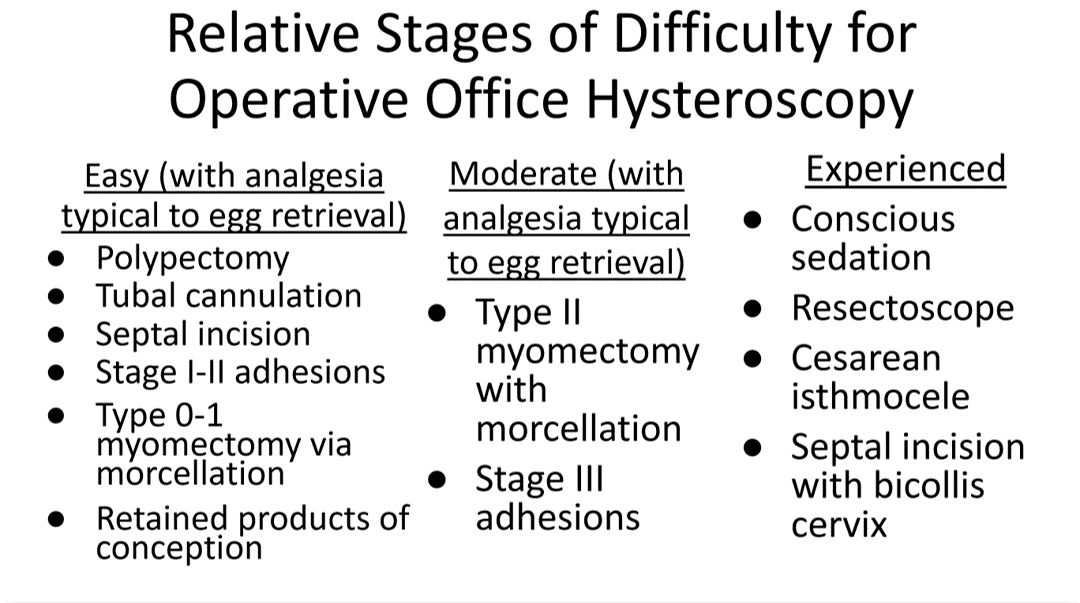

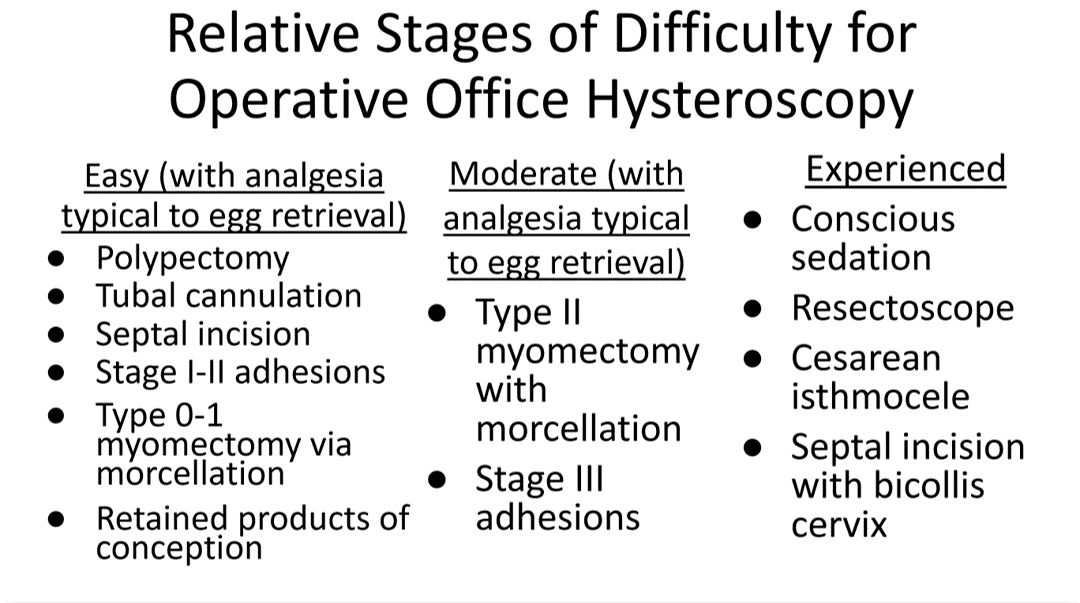

Though highly dependent on experience and resources, reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialists (REIs) arguably have the easiest transition to operative office hysteroscopy by utilizing the analgesia and procedure room that is standard for oocyte retrieval and simply adding hysteroscopic procedures. The accompanying table stratifies general hysteroscopic procedures by difficulty.

If one can use propofol or a similar level of sedation (which is routinely utilized for oocyte aspiration), there are few hysteroscopies that cannot be accomplished in the office. However, the less sedation and analgesia, the more judicious one must be in patient selection. Moreover, there are trade-offs between visualization, comfort, and instrumentation.

The greater the uterine distention and diameter of the hysteroscope, the more patients experience pain. One-third of patients (especially nulliparous) will discontinue a procedure with a 5-mm hysteroscope because of discomfort.5 However, as one drops to 4.5 mm and smaller operative hysteroscopes, instruments often occupy the inflow channel, limiting distention and visualization, which also can affect completion rates and safety.

When is operative hysteroscopy best suited for the OR?

In addition to physician experience and clinical resources, the critical factors guiding our choices for selecting the OR rather than the office, include:

- Loss of landmarks. Though Dr. Parry now does most severe intrauterine adhesion cases in the office with ultrasound guidance, when neither ostia can be visualized there is meaningful risk for perforation. Preoperative estrogen, development of planes with the diagnostic hysteroscope prior, and preparing the patient for a possible multistage procedure are all important.

- Use of energy. There are many excellent hysteroscopic surgeons who use the resectoscope well in the office. However, with possible patient movement and potential perforation with energy leading to a bowel injury, there can be greater risk when using energy relative to other methods (such as forceps, scissors, and mechanical morcellation).

- Deeper fibroids. Fibroids displace rather than invade the myometrium, and one can sonographically visualize the myometrium reapproximate over a fibroid as it herniates more into the uterine cavity. Nevertheless, the closer a fibroid comes to the serosa, the more mindful one should be of risks and balances for hysteroscopic removal.

In a patient with a severely stenotic cervix or tortuous endocervical canal, what preprocedure methods do you find helpful, and do you utilize abdominal ultrasound guidance?

If using a 2.8-mm flexible diagnostic hysteroscope, we find 99.8%-99.9% of cervices can be successfully cannulated in the office, with rare exception, that is, following cryotherapy or chlamydia cervicitis. This is the equivalent of your dilator having a camera on the tip and fully articulating to adjust to the cervical path.

Transvaginal sonography prior to hysteroscopy where one maps the cervical lumen helps anticipate problems (along with being familiar with the patient’s history). For the rare dilation under anesthesia, concurrent sonography with a 2.8-mm flexible hysteroscope and intermittent dilator use has been sufficient for our exceptions without the need for lacrimal dilators, vasopressin, misoprostol, and other adjuncts. Of note, we use a 1080p flexible endoscope, as lower resolution would make this more challenging.

In patients with recurrent implantation failure following IVF, is hysteroscopy superior to 3D saline infusion sonogram?

At an American Society of Reproductive Medicine 2021 session, Ilan Tur-Kaspa, MD, and Dr. Parry debated the topic of 2D ultrasound combined with hysteroscopy vs. 3D saline infusion sonography. Core areas of agreement were that expert hands for any approach are better than nonexpert, and high-resolution technology is better than lower resolution. There was also agreement that extrauterine and myometrial disease, such as intramural fibroids and adenomyosis, are contributory factors.

So, sonography will always have a role. However, existing and forthcoming data show hysteroscopy to improve live birth rates for patients with recurrent implantation failure after IVF. Dr. Parry finds diagnostic hysteroscopy easier for identifying endometritis, sessile and cornual polyps, retained products of conception (which are often isoechogenic with the endometrium) and lateral adhesions.

The reality is that there is variability among physicians and midlevel providers in both sonographic and diagnostic hysteroscopic skill. If one wants to verify findings with another team member, acknowledging that there can be nuances to identifying these pathologies by sonography, it is easier to share and discuss findings through hysteroscopic video than sonographic records.

When is endometrial biopsy indicated during office hysteroscopy?

The patients of an REI are very unlikely to have endometrial cancer (or even hyperplasia) outside of polyps (or arguably hypervascular areas of overgrowth), so the focus is on resecting visualized pathology relative to random biopsy.

However, the threshold for biopsy should be adjusted to the patient population, as well as to individual findings and risk. RVUs are greatly increased (11.1 > 41.57) with biopsy, helping sustainability. Additionally, if one places the hysteroscope on endometrium and applies suction through the inflow channel, one can obtain a sample with small-caliber diagnostic hysteroscopes and without having to use forceps.

What is your threshold for fluid deficit in hysteroscopy?

We follow AAGL guidelines, which for operative hysteroscopy are 2,500 mL of isotonic fluids or 1,000 mL of hypotonic fluids in low-risk patients. This should be further reduced to 500 mL of isotonic fluids in the elderly and even 300 mL in those with cardiovascular compromise.6

For patients who request sedation for office hysteroscopy, which option do you recommend – paracervical block alone, nitrous oxide, or the combination?

For diagnostic, greater than 95% of our patients do not require even over-the-counter analgesic medications. For operative, we consider all permissible resources that allow for a safe combination that is appropriate to the pathology and clinical setting, such as paracervical blocks, nitrous oxide, NSAIDs such as ketorolac, anxiolytics, and more.

The goal is to optimize the patient experience. However, the top three criteria that influence successful operative office hysteroscopy for a conscious patient are a parous cervix, judicious patient selection, and pre- and intraoperative verbal analgesia. Informed consent and engagement improve the experience of both the patient and physician.

Dr. Parry is the founder of Positive Steps Fertility in Madison, Miss. Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

References

1. Parry JP et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017 May-Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2017.02.010.

2. Wadhwa L et al. 2017 Apr-Jun. doi: 10.4103/jhrs.JHRS_123_16.

3. Parry JP et al. Fertil Steril. 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.07.1159.

4. Penzias A et al. Fertil Steril. 2021 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.08.038.

5. Campo R et al. Hum Reprod. 2005 Jan;20(1):258-63. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh559.

6. AAGL AAGL practice report: Practice guidelines for the management of hysteroscopic distending media. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013 Mar-Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2012.12.002.

What role does diagnostic office hysteroscopy play in an infertility evaluation?

.1

More specifically, hysteroscopy is the gold standard for assessing the uterine cavity. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive and negative predictive values of hysterosalpingography (HSG) in evaluating uterine cavity abnormalities were 44.83%; 86.67%; 56.52%; and 80.25%, respectively.2 Given the poor sensitivity of HSG, a diagnosis of endometrial polyps and/or chronic endometritis is more likely to be missed.

Our crossover trial comparing HSG to office hysteroscopy for tubal patency showed that women were 110 times more likely to have the maximum level of pain with HSG than diagnostic hysteroscopy when using a 2.8-mm flexible hysteroscope.3 Further, infection rates and vasovagal events were far lower with hysteroscopy.1

Finally, compared with HSG, we showed 98%-100% sensitivity and 84% specificity for tubal occlusion with hysteroscopy by air-infused saline. Conversely, HSG typically is associated with 76%-96% sensitivity and 67%-100% specificity.4 Additionally, we can often perform diagnostic hysteroscopies for approximately $35 per procedure for total fixed and disposable equipment costs.

How should physicians perform office hysteroscopy to minimize patient discomfort?

The classic paradigm has been to focus on paracervical blocks, anxiolytics, and a supportive environment (such as mood music). However, those are far more important when your hysteroscope is larger than the natural cervical lumen. If you can use small hysteroscopes (< 3 mm for the nulliparous cervix, < 4 mm for the parous cervix), most women will not require cervical dilation, which further enhances the patient experience.

Using a flexible hysteroscope for suspected pathology, making sure not to overdistend the uterus (particularly in high-risk patients such as those with tubal occlusion and cervical stenosis), and vaginoscopy can all minimize patient discomfort. We have published data showing that by using a 2.8-mm flexible diagnostic hysteroscope in a group of mostly nulliparous women, greater than 50% have no discomfort, and more than 90% will have mild to no discomfort.3

What operative hysteroscopy procedures can be performed safely in a physician’s office, and what equipment is required?

Though highly dependent on experience and resources, reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialists (REIs) arguably have the easiest transition to operative office hysteroscopy by utilizing the analgesia and procedure room that is standard for oocyte retrieval and simply adding hysteroscopic procedures. The accompanying table stratifies general hysteroscopic procedures by difficulty.

If one can use propofol or a similar level of sedation (which is routinely utilized for oocyte aspiration), there are few hysteroscopies that cannot be accomplished in the office. However, the less sedation and analgesia, the more judicious one must be in patient selection. Moreover, there are trade-offs between visualization, comfort, and instrumentation.

The greater the uterine distention and diameter of the hysteroscope, the more patients experience pain. One-third of patients (especially nulliparous) will discontinue a procedure with a 5-mm hysteroscope because of discomfort.5 However, as one drops to 4.5 mm and smaller operative hysteroscopes, instruments often occupy the inflow channel, limiting distention and visualization, which also can affect completion rates and safety.

When is operative hysteroscopy best suited for the OR?

In addition to physician experience and clinical resources, the critical factors guiding our choices for selecting the OR rather than the office, include:

- Loss of landmarks. Though Dr. Parry now does most severe intrauterine adhesion cases in the office with ultrasound guidance, when neither ostia can be visualized there is meaningful risk for perforation. Preoperative estrogen, development of planes with the diagnostic hysteroscope prior, and preparing the patient for a possible multistage procedure are all important.

- Use of energy. There are many excellent hysteroscopic surgeons who use the resectoscope well in the office. However, with possible patient movement and potential perforation with energy leading to a bowel injury, there can be greater risk when using energy relative to other methods (such as forceps, scissors, and mechanical morcellation).

- Deeper fibroids. Fibroids displace rather than invade the myometrium, and one can sonographically visualize the myometrium reapproximate over a fibroid as it herniates more into the uterine cavity. Nevertheless, the closer a fibroid comes to the serosa, the more mindful one should be of risks and balances for hysteroscopic removal.

In a patient with a severely stenotic cervix or tortuous endocervical canal, what preprocedure methods do you find helpful, and do you utilize abdominal ultrasound guidance?

If using a 2.8-mm flexible diagnostic hysteroscope, we find 99.8%-99.9% of cervices can be successfully cannulated in the office, with rare exception, that is, following cryotherapy or chlamydia cervicitis. This is the equivalent of your dilator having a camera on the tip and fully articulating to adjust to the cervical path.

Transvaginal sonography prior to hysteroscopy where one maps the cervical lumen helps anticipate problems (along with being familiar with the patient’s history). For the rare dilation under anesthesia, concurrent sonography with a 2.8-mm flexible hysteroscope and intermittent dilator use has been sufficient for our exceptions without the need for lacrimal dilators, vasopressin, misoprostol, and other adjuncts. Of note, we use a 1080p flexible endoscope, as lower resolution would make this more challenging.

In patients with recurrent implantation failure following IVF, is hysteroscopy superior to 3D saline infusion sonogram?

At an American Society of Reproductive Medicine 2021 session, Ilan Tur-Kaspa, MD, and Dr. Parry debated the topic of 2D ultrasound combined with hysteroscopy vs. 3D saline infusion sonography. Core areas of agreement were that expert hands for any approach are better than nonexpert, and high-resolution technology is better than lower resolution. There was also agreement that extrauterine and myometrial disease, such as intramural fibroids and adenomyosis, are contributory factors.

So, sonography will always have a role. However, existing and forthcoming data show hysteroscopy to improve live birth rates for patients with recurrent implantation failure after IVF. Dr. Parry finds diagnostic hysteroscopy easier for identifying endometritis, sessile and cornual polyps, retained products of conception (which are often isoechogenic with the endometrium) and lateral adhesions.

The reality is that there is variability among physicians and midlevel providers in both sonographic and diagnostic hysteroscopic skill. If one wants to verify findings with another team member, acknowledging that there can be nuances to identifying these pathologies by sonography, it is easier to share and discuss findings through hysteroscopic video than sonographic records.

When is endometrial biopsy indicated during office hysteroscopy?

The patients of an REI are very unlikely to have endometrial cancer (or even hyperplasia) outside of polyps (or arguably hypervascular areas of overgrowth), so the focus is on resecting visualized pathology relative to random biopsy.

However, the threshold for biopsy should be adjusted to the patient population, as well as to individual findings and risk. RVUs are greatly increased (11.1 > 41.57) with biopsy, helping sustainability. Additionally, if one places the hysteroscope on endometrium and applies suction through the inflow channel, one can obtain a sample with small-caliber diagnostic hysteroscopes and without having to use forceps.

What is your threshold for fluid deficit in hysteroscopy?

We follow AAGL guidelines, which for operative hysteroscopy are 2,500 mL of isotonic fluids or 1,000 mL of hypotonic fluids in low-risk patients. This should be further reduced to 500 mL of isotonic fluids in the elderly and even 300 mL in those with cardiovascular compromise.6

For patients who request sedation for office hysteroscopy, which option do you recommend – paracervical block alone, nitrous oxide, or the combination?

For diagnostic, greater than 95% of our patients do not require even over-the-counter analgesic medications. For operative, we consider all permissible resources that allow for a safe combination that is appropriate to the pathology and clinical setting, such as paracervical blocks, nitrous oxide, NSAIDs such as ketorolac, anxiolytics, and more.

The goal is to optimize the patient experience. However, the top three criteria that influence successful operative office hysteroscopy for a conscious patient are a parous cervix, judicious patient selection, and pre- and intraoperative verbal analgesia. Informed consent and engagement improve the experience of both the patient and physician.

Dr. Parry is the founder of Positive Steps Fertility in Madison, Miss. Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

References

1. Parry JP et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017 May-Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2017.02.010.

2. Wadhwa L et al. 2017 Apr-Jun. doi: 10.4103/jhrs.JHRS_123_16.

3. Parry JP et al. Fertil Steril. 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.07.1159.

4. Penzias A et al. Fertil Steril. 2021 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.08.038.

5. Campo R et al. Hum Reprod. 2005 Jan;20(1):258-63. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh559.

6. AAGL AAGL practice report: Practice guidelines for the management of hysteroscopic distending media. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013 Mar-Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2012.12.002.

What role does diagnostic office hysteroscopy play in an infertility evaluation?

.1

More specifically, hysteroscopy is the gold standard for assessing the uterine cavity. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive and negative predictive values of hysterosalpingography (HSG) in evaluating uterine cavity abnormalities were 44.83%; 86.67%; 56.52%; and 80.25%, respectively.2 Given the poor sensitivity of HSG, a diagnosis of endometrial polyps and/or chronic endometritis is more likely to be missed.

Our crossover trial comparing HSG to office hysteroscopy for tubal patency showed that women were 110 times more likely to have the maximum level of pain with HSG than diagnostic hysteroscopy when using a 2.8-mm flexible hysteroscope.3 Further, infection rates and vasovagal events were far lower with hysteroscopy.1

Finally, compared with HSG, we showed 98%-100% sensitivity and 84% specificity for tubal occlusion with hysteroscopy by air-infused saline. Conversely, HSG typically is associated with 76%-96% sensitivity and 67%-100% specificity.4 Additionally, we can often perform diagnostic hysteroscopies for approximately $35 per procedure for total fixed and disposable equipment costs.

How should physicians perform office hysteroscopy to minimize patient discomfort?

The classic paradigm has been to focus on paracervical blocks, anxiolytics, and a supportive environment (such as mood music). However, those are far more important when your hysteroscope is larger than the natural cervical lumen. If you can use small hysteroscopes (< 3 mm for the nulliparous cervix, < 4 mm for the parous cervix), most women will not require cervical dilation, which further enhances the patient experience.

Using a flexible hysteroscope for suspected pathology, making sure not to overdistend the uterus (particularly in high-risk patients such as those with tubal occlusion and cervical stenosis), and vaginoscopy can all minimize patient discomfort. We have published data showing that by using a 2.8-mm flexible diagnostic hysteroscope in a group of mostly nulliparous women, greater than 50% have no discomfort, and more than 90% will have mild to no discomfort.3

What operative hysteroscopy procedures can be performed safely in a physician’s office, and what equipment is required?

Though highly dependent on experience and resources, reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialists (REIs) arguably have the easiest transition to operative office hysteroscopy by utilizing the analgesia and procedure room that is standard for oocyte retrieval and simply adding hysteroscopic procedures. The accompanying table stratifies general hysteroscopic procedures by difficulty.

If one can use propofol or a similar level of sedation (which is routinely utilized for oocyte aspiration), there are few hysteroscopies that cannot be accomplished in the office. However, the less sedation and analgesia, the more judicious one must be in patient selection. Moreover, there are trade-offs between visualization, comfort, and instrumentation.

The greater the uterine distention and diameter of the hysteroscope, the more patients experience pain. One-third of patients (especially nulliparous) will discontinue a procedure with a 5-mm hysteroscope because of discomfort.5 However, as one drops to 4.5 mm and smaller operative hysteroscopes, instruments often occupy the inflow channel, limiting distention and visualization, which also can affect completion rates and safety.

When is operative hysteroscopy best suited for the OR?

In addition to physician experience and clinical resources, the critical factors guiding our choices for selecting the OR rather than the office, include:

- Loss of landmarks. Though Dr. Parry now does most severe intrauterine adhesion cases in the office with ultrasound guidance, when neither ostia can be visualized there is meaningful risk for perforation. Preoperative estrogen, development of planes with the diagnostic hysteroscope prior, and preparing the patient for a possible multistage procedure are all important.

- Use of energy. There are many excellent hysteroscopic surgeons who use the resectoscope well in the office. However, with possible patient movement and potential perforation with energy leading to a bowel injury, there can be greater risk when using energy relative to other methods (such as forceps, scissors, and mechanical morcellation).

- Deeper fibroids. Fibroids displace rather than invade the myometrium, and one can sonographically visualize the myometrium reapproximate over a fibroid as it herniates more into the uterine cavity. Nevertheless, the closer a fibroid comes to the serosa, the more mindful one should be of risks and balances for hysteroscopic removal.

In a patient with a severely stenotic cervix or tortuous endocervical canal, what preprocedure methods do you find helpful, and do you utilize abdominal ultrasound guidance?

If using a 2.8-mm flexible diagnostic hysteroscope, we find 99.8%-99.9% of cervices can be successfully cannulated in the office, with rare exception, that is, following cryotherapy or chlamydia cervicitis. This is the equivalent of your dilator having a camera on the tip and fully articulating to adjust to the cervical path.

Transvaginal sonography prior to hysteroscopy where one maps the cervical lumen helps anticipate problems (along with being familiar with the patient’s history). For the rare dilation under anesthesia, concurrent sonography with a 2.8-mm flexible hysteroscope and intermittent dilator use has been sufficient for our exceptions without the need for lacrimal dilators, vasopressin, misoprostol, and other adjuncts. Of note, we use a 1080p flexible endoscope, as lower resolution would make this more challenging.

In patients with recurrent implantation failure following IVF, is hysteroscopy superior to 3D saline infusion sonogram?

At an American Society of Reproductive Medicine 2021 session, Ilan Tur-Kaspa, MD, and Dr. Parry debated the topic of 2D ultrasound combined with hysteroscopy vs. 3D saline infusion sonography. Core areas of agreement were that expert hands for any approach are better than nonexpert, and high-resolution technology is better than lower resolution. There was also agreement that extrauterine and myometrial disease, such as intramural fibroids and adenomyosis, are contributory factors.

So, sonography will always have a role. However, existing and forthcoming data show hysteroscopy to improve live birth rates for patients with recurrent implantation failure after IVF. Dr. Parry finds diagnostic hysteroscopy easier for identifying endometritis, sessile and cornual polyps, retained products of conception (which are often isoechogenic with the endometrium) and lateral adhesions.

The reality is that there is variability among physicians and midlevel providers in both sonographic and diagnostic hysteroscopic skill. If one wants to verify findings with another team member, acknowledging that there can be nuances to identifying these pathologies by sonography, it is easier to share and discuss findings through hysteroscopic video than sonographic records.

When is endometrial biopsy indicated during office hysteroscopy?

The patients of an REI are very unlikely to have endometrial cancer (or even hyperplasia) outside of polyps (or arguably hypervascular areas of overgrowth), so the focus is on resecting visualized pathology relative to random biopsy.

However, the threshold for biopsy should be adjusted to the patient population, as well as to individual findings and risk. RVUs are greatly increased (11.1 > 41.57) with biopsy, helping sustainability. Additionally, if one places the hysteroscope on endometrium and applies suction through the inflow channel, one can obtain a sample with small-caliber diagnostic hysteroscopes and without having to use forceps.

What is your threshold for fluid deficit in hysteroscopy?

We follow AAGL guidelines, which for operative hysteroscopy are 2,500 mL of isotonic fluids or 1,000 mL of hypotonic fluids in low-risk patients. This should be further reduced to 500 mL of isotonic fluids in the elderly and even 300 mL in those with cardiovascular compromise.6

For patients who request sedation for office hysteroscopy, which option do you recommend – paracervical block alone, nitrous oxide, or the combination?

For diagnostic, greater than 95% of our patients do not require even over-the-counter analgesic medications. For operative, we consider all permissible resources that allow for a safe combination that is appropriate to the pathology and clinical setting, such as paracervical blocks, nitrous oxide, NSAIDs such as ketorolac, anxiolytics, and more.

The goal is to optimize the patient experience. However, the top three criteria that influence successful operative office hysteroscopy for a conscious patient are a parous cervix, judicious patient selection, and pre- and intraoperative verbal analgesia. Informed consent and engagement improve the experience of both the patient and physician.

Dr. Parry is the founder of Positive Steps Fertility in Madison, Miss. Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

References

1. Parry JP et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017 May-Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2017.02.010.

2. Wadhwa L et al. 2017 Apr-Jun. doi: 10.4103/jhrs.JHRS_123_16.

3. Parry JP et al. Fertil Steril. 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.07.1159.

4. Penzias A et al. Fertil Steril. 2021 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.08.038.

5. Campo R et al. Hum Reprod. 2005 Jan;20(1):258-63. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh559.

6. AAGL AAGL practice report: Practice guidelines for the management of hysteroscopic distending media. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013 Mar-Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2012.12.002.

What's your diagnosis?

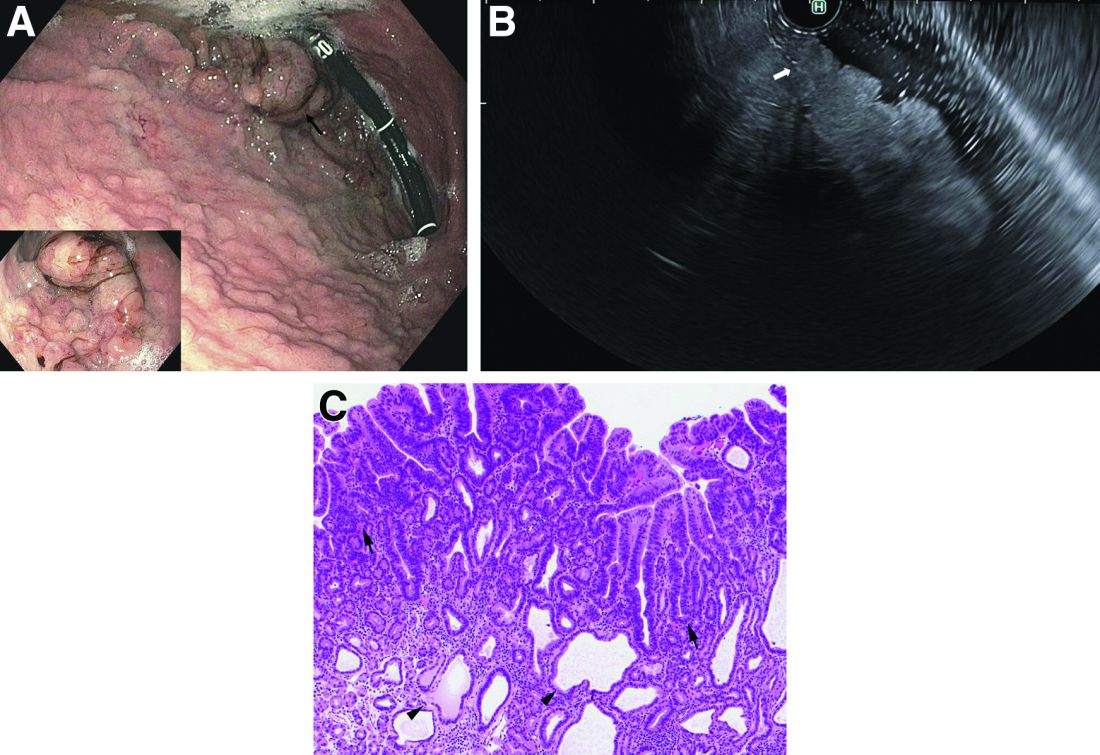

Answer to ‘What’s your diagnosis?’: Gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach syndrome.

Fundic gland polyps (FGPs) are the most common gastric polyps and when occurring in the sporadic setting are typically benign; however, FGPs that occur in gastrointestinal polyposis syndromes such as familial adenomatosis polyposis can progress to adenocarcinoma and require surveillance. Therefore, it is important to distinguish sporadic versus syndromic fundic gland polyposis. Gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach is a recently described condition that significantly increases the risk of developing invasive gastric adenocarcinoma from FGPs. Diagnostic criteria include (1) gastric polyposis restricted to the body and fundus with no small bowel or colonic involvement, (2) >100 gastric polyps or >30 polyps in a first-degree relative, (3) histology consistent with FGP with areas of dysplasia, (4) a family history consistent with an autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance, and (5) exclusion of other syndromes and proton pump inhibitor use.1 Unlike familial adenomatosis polyposis, the polyposis is restricted to the oxyntic mucosa of the gastric body and fundus with sparing of the gastric antrum, small bowel, and colon. The genetic basis of the disease has been attributed to a point mutation in the APC gene promotor IB region leading to a loss of tumor suppressor function.2 Typical histology shows large FGPs with areas of low-grade and high-grade dysplasia, as seen in our patient.

There are few data on the natural history of gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach, but effective surveillance is limited by the degree of polyposis. There are multiple reports of hidden adenocarcinoma on surgically resected specimens, as well as rapid progression to metastatic adenocarcinoma despite adequate diagnosis and surveillance.1,3 Therefore, total gastrectomy should be offered to patients who are surgical candidates. Our patient underwent genetic testing that revealed a point mutation in the APC promotor IB. He declined surgical intervention and opted for surveillance endoscopy every 6 months.

References

1. Worthley D.L. et al. Gut. 2012;61:774-9

2. Li J et al. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98:830-42

3. Rudloff U. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2018;11:447-59

Answer to ‘What’s your diagnosis?’: Gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach syndrome.

Fundic gland polyps (FGPs) are the most common gastric polyps and when occurring in the sporadic setting are typically benign; however, FGPs that occur in gastrointestinal polyposis syndromes such as familial adenomatosis polyposis can progress to adenocarcinoma and require surveillance. Therefore, it is important to distinguish sporadic versus syndromic fundic gland polyposis. Gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach is a recently described condition that significantly increases the risk of developing invasive gastric adenocarcinoma from FGPs. Diagnostic criteria include (1) gastric polyposis restricted to the body and fundus with no small bowel or colonic involvement, (2) >100 gastric polyps or >30 polyps in a first-degree relative, (3) histology consistent with FGP with areas of dysplasia, (4) a family history consistent with an autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance, and (5) exclusion of other syndromes and proton pump inhibitor use.1 Unlike familial adenomatosis polyposis, the polyposis is restricted to the oxyntic mucosa of the gastric body and fundus with sparing of the gastric antrum, small bowel, and colon. The genetic basis of the disease has been attributed to a point mutation in the APC gene promotor IB region leading to a loss of tumor suppressor function.2 Typical histology shows large FGPs with areas of low-grade and high-grade dysplasia, as seen in our patient.

There are few data on the natural history of gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach, but effective surveillance is limited by the degree of polyposis. There are multiple reports of hidden adenocarcinoma on surgically resected specimens, as well as rapid progression to metastatic adenocarcinoma despite adequate diagnosis and surveillance.1,3 Therefore, total gastrectomy should be offered to patients who are surgical candidates. Our patient underwent genetic testing that revealed a point mutation in the APC promotor IB. He declined surgical intervention and opted for surveillance endoscopy every 6 months.

References

1. Worthley D.L. et al. Gut. 2012;61:774-9

2. Li J et al. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98:830-42

3. Rudloff U. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2018;11:447-59

Answer to ‘What’s your diagnosis?’: Gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach syndrome.

Fundic gland polyps (FGPs) are the most common gastric polyps and when occurring in the sporadic setting are typically benign; however, FGPs that occur in gastrointestinal polyposis syndromes such as familial adenomatosis polyposis can progress to adenocarcinoma and require surveillance. Therefore, it is important to distinguish sporadic versus syndromic fundic gland polyposis. Gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach is a recently described condition that significantly increases the risk of developing invasive gastric adenocarcinoma from FGPs. Diagnostic criteria include (1) gastric polyposis restricted to the body and fundus with no small bowel or colonic involvement, (2) >100 gastric polyps or >30 polyps in a first-degree relative, (3) histology consistent with FGP with areas of dysplasia, (4) a family history consistent with an autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance, and (5) exclusion of other syndromes and proton pump inhibitor use.1 Unlike familial adenomatosis polyposis, the polyposis is restricted to the oxyntic mucosa of the gastric body and fundus with sparing of the gastric antrum, small bowel, and colon. The genetic basis of the disease has been attributed to a point mutation in the APC gene promotor IB region leading to a loss of tumor suppressor function.2 Typical histology shows large FGPs with areas of low-grade and high-grade dysplasia, as seen in our patient.

There are few data on the natural history of gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach, but effective surveillance is limited by the degree of polyposis. There are multiple reports of hidden adenocarcinoma on surgically resected specimens, as well as rapid progression to metastatic adenocarcinoma despite adequate diagnosis and surveillance.1,3 Therefore, total gastrectomy should be offered to patients who are surgical candidates. Our patient underwent genetic testing that revealed a point mutation in the APC promotor IB. He declined surgical intervention and opted for surveillance endoscopy every 6 months.

References

1. Worthley D.L. et al. Gut. 2012;61:774-9

2. Li J et al. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98:830-42

3. Rudloff U. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2018;11:447-59

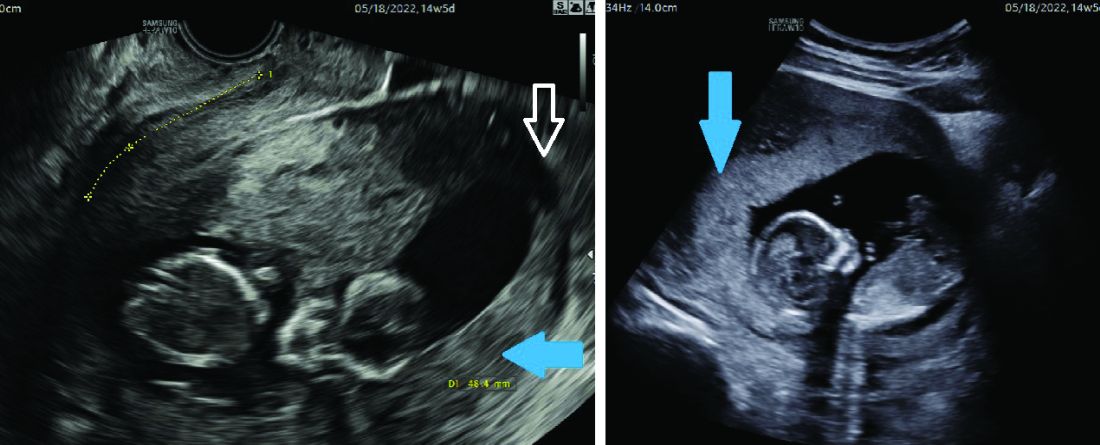

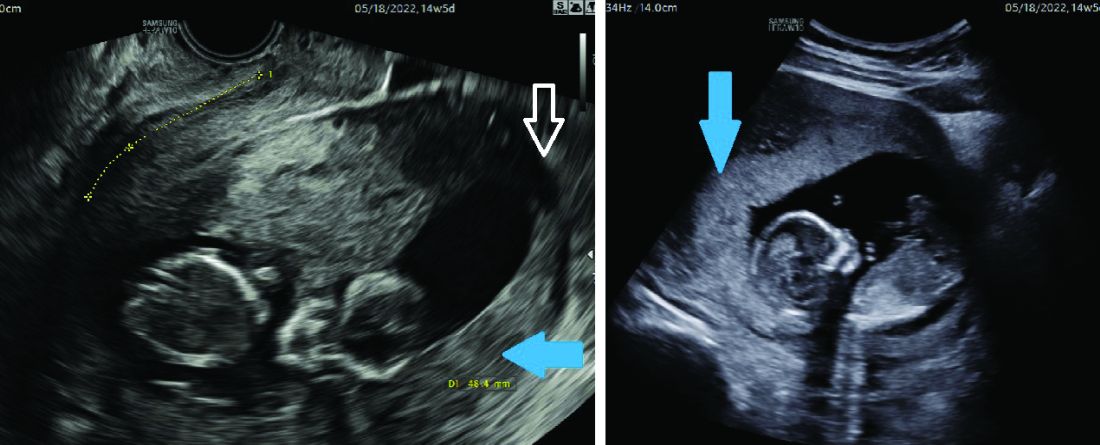

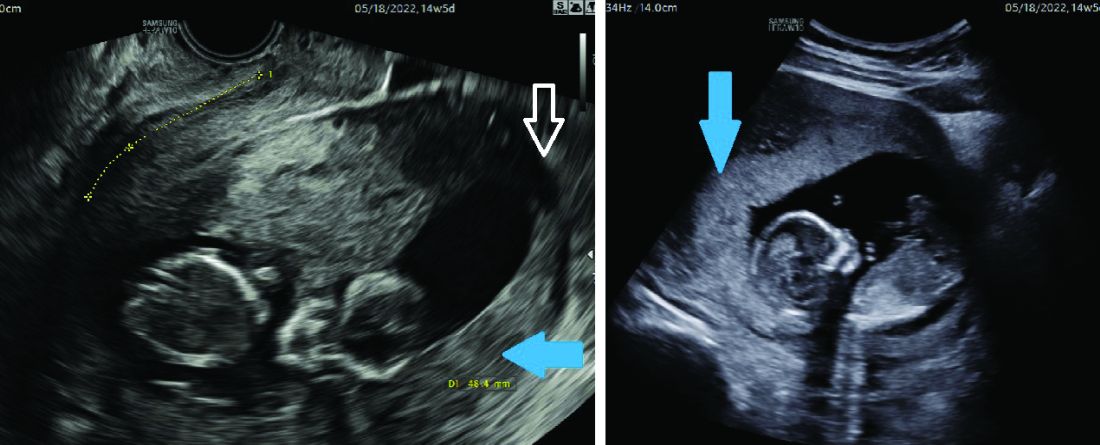

A 72-year-old man with compensated cirrhosis owing to autoimmune hepatitis presented for evaluation of an indeterminate gastric lesion found during an otherwise normal endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography performed for incidental ductal dilation seen on cross-sectional imaging. He did not endorse any abdominal pain, dyspepsia, or weight loss and was not on a proton pump inhibitor. Family history was notable for a daughter diagnosed with metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma at the age of 44 years.

Upper endoscopy showed innumerable sessile polyps of variable size carpeting the gastric body and fundus (Figure A) with a large, mound-like mass lesion in the fundus (Figure A, arrow and inset). Echoendoscopy revealed a hypoechoic, noncircumferential mass restricted to the mucosal surface with well-defined borders (Figure B, arrow). A technically challenging, piecemeal endoscopic mucosal resection was performed. The patient also underwent a colonoscopy that was unremarkable. Pathology of the gastric lesion was consistent with a fundic gland polyp (Figure C, arrowheads) containing low-grade and high-grade dysplasia (Figure C, arrows).

What is the most likely diagnosis?

AI & U: 2

In my most recent column (AI & U), I suggested that artificial intelligence (AI) in its most recent newsworthy iteration, the chatbot, offers some potentially useful opportunities. For example, in the short term the ability of a machine to search for the diagnostic possibilities and treatment options in a matter of seconds sounds very appealing. The skills needed to ask the chatbot the best questions and then interpret the machine’s responses would still require a medical school education. Good news for those of you worried about job security.

However, let’s look further down the road for how AI and other technological advances might change the look and feel of primary care. It is reasonable to expect that a chatbot could engage the patient in a spoken (or written) dialog in the patient’s preferred language and targeted to his/her educational level. You already deal with this kind of interaction in a primitive form when you call the customer service department of even a small company. That is if you were lucky enough to find the number buried in the company’s website.

The “system” could then perform a targeted exam using a variety of sensors. Electronic stethoscopes and tympanographic sensors already exist. While currently most sonograms are performed by trained technicians, one can envision the technology being dumbed down to a point that the patient could operate most of the sensors himself or herself, provided the patient could reach the body part in question. The camera on a basic cell phone can take an image of a skin lesion that can already be compared with a standard set of normals and abnormals. While currently a questionable lesion triggers the provider to perform a biopsy, it is possible that sensors could become so sensitive and the algorithms so clever that the biopsy would be unnecessary. The pandemic has already shown us that patients can obtain sample swabs and accurately perform simple tests in their home.

Once the “system” has made the diagnosis, it would then converse with the patient about the various treatment options and arrange follow up. One would hope that, if the “system’s” diagnosis included a fatal outcome, it would trigger a face-to-face interaction with a counselor and a team of social workers to break the bad news and provide some kind of emotional support.

Those of you who are doubting Dorothys and Thomases may be asking what about scenarios in which the patient’s chief complaint is difficulty breathing or sudden onset of weakness? Remember, I am talking about the usual 8 a.m–6 p.m. primary care office. Any patient with a possibly life-threatening complaint would be triaged by the chatbot and would be seen at some point by a real human. However, it is likely that individual’s training would not require the breadth of the typical medical school education and instead would be targeted at the most common high-risk scenarios. This higher-acuity specialist would, of course, be assisted by a chatbot.

Patients with complaints primarily associated with mental illness would be seen by humans specializing in that area. Although I suspect there are folks somewhere brainstorming on how chatbots could potentially be effective counselors.

Clearly, the future I am suggesting leaves the patient with fewer interactions with a human, and certainly very rarely with a human who has navigated what we think of today as a traditional medical school education.

Would they do it without complaint? Would they have a choice? Do you like it when you are interrogated by the prerecorded voice on the phone tree of some company’s customer service? Do you have a choice? If that interrogation was refined to the point where it saved you time and resulted in the correct answer 99% of the time would you still complain?

If patients found that most of their primary care complaints could be handled more quickly by an AI system with minimal physician intervention and that system offered a success rate of over 90% when measured by the accuracy of the diagnosis and management plan, would they complain? They may have no other choice than to complain if primary care continues to lose favor among recent medical school graduates.

And what would the patients complain about? They already complain about the current system in which they feel that the face-to-face encounters with their physician are becoming less frequent. I often hear complaints that “the doctor just looked at the computer, and he didn’t really examine me.” By which I think they sometimes mean “touched” me.

I suspect we will discover what most of us already suspect and that is there is something special about the eye-to-eye contact and tactile interaction between the physician and the patient. The osteopathic tradition clearly makes this a priority when it utilizes manipulative medicine. It may be that if primary care medicine follows the AI-paved road I have imagined it won’t be able to match the success rate of the current system. Without that human element, with or without the hands-on aspect or even if the diagnosis is correct and the management is spot on, it just won’t work as well.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

In my most recent column (AI & U), I suggested that artificial intelligence (AI) in its most recent newsworthy iteration, the chatbot, offers some potentially useful opportunities. For example, in the short term the ability of a machine to search for the diagnostic possibilities and treatment options in a matter of seconds sounds very appealing. The skills needed to ask the chatbot the best questions and then interpret the machine’s responses would still require a medical school education. Good news for those of you worried about job security.

However, let’s look further down the road for how AI and other technological advances might change the look and feel of primary care. It is reasonable to expect that a chatbot could engage the patient in a spoken (or written) dialog in the patient’s preferred language and targeted to his/her educational level. You already deal with this kind of interaction in a primitive form when you call the customer service department of even a small company. That is if you were lucky enough to find the number buried in the company’s website.

The “system” could then perform a targeted exam using a variety of sensors. Electronic stethoscopes and tympanographic sensors already exist. While currently most sonograms are performed by trained technicians, one can envision the technology being dumbed down to a point that the patient could operate most of the sensors himself or herself, provided the patient could reach the body part in question. The camera on a basic cell phone can take an image of a skin lesion that can already be compared with a standard set of normals and abnormals. While currently a questionable lesion triggers the provider to perform a biopsy, it is possible that sensors could become so sensitive and the algorithms so clever that the biopsy would be unnecessary. The pandemic has already shown us that patients can obtain sample swabs and accurately perform simple tests in their home.

Once the “system” has made the diagnosis, it would then converse with the patient about the various treatment options and arrange follow up. One would hope that, if the “system’s” diagnosis included a fatal outcome, it would trigger a face-to-face interaction with a counselor and a team of social workers to break the bad news and provide some kind of emotional support.

Those of you who are doubting Dorothys and Thomases may be asking what about scenarios in which the patient’s chief complaint is difficulty breathing or sudden onset of weakness? Remember, I am talking about the usual 8 a.m–6 p.m. primary care office. Any patient with a possibly life-threatening complaint would be triaged by the chatbot and would be seen at some point by a real human. However, it is likely that individual’s training would not require the breadth of the typical medical school education and instead would be targeted at the most common high-risk scenarios. This higher-acuity specialist would, of course, be assisted by a chatbot.

Patients with complaints primarily associated with mental illness would be seen by humans specializing in that area. Although I suspect there are folks somewhere brainstorming on how chatbots could potentially be effective counselors.

Clearly, the future I am suggesting leaves the patient with fewer interactions with a human, and certainly very rarely with a human who has navigated what we think of today as a traditional medical school education.

Would they do it without complaint? Would they have a choice? Do you like it when you are interrogated by the prerecorded voice on the phone tree of some company’s customer service? Do you have a choice? If that interrogation was refined to the point where it saved you time and resulted in the correct answer 99% of the time would you still complain?

If patients found that most of their primary care complaints could be handled more quickly by an AI system with minimal physician intervention and that system offered a success rate of over 90% when measured by the accuracy of the diagnosis and management plan, would they complain? They may have no other choice than to complain if primary care continues to lose favor among recent medical school graduates.

And what would the patients complain about? They already complain about the current system in which they feel that the face-to-face encounters with their physician are becoming less frequent. I often hear complaints that “the doctor just looked at the computer, and he didn’t really examine me.” By which I think they sometimes mean “touched” me.

I suspect we will discover what most of us already suspect and that is there is something special about the eye-to-eye contact and tactile interaction between the physician and the patient. The osteopathic tradition clearly makes this a priority when it utilizes manipulative medicine. It may be that if primary care medicine follows the AI-paved road I have imagined it won’t be able to match the success rate of the current system. Without that human element, with or without the hands-on aspect or even if the diagnosis is correct and the management is spot on, it just won’t work as well.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

In my most recent column (AI & U), I suggested that artificial intelligence (AI) in its most recent newsworthy iteration, the chatbot, offers some potentially useful opportunities. For example, in the short term the ability of a machine to search for the diagnostic possibilities and treatment options in a matter of seconds sounds very appealing. The skills needed to ask the chatbot the best questions and then interpret the machine’s responses would still require a medical school education. Good news for those of you worried about job security.

However, let’s look further down the road for how AI and other technological advances might change the look and feel of primary care. It is reasonable to expect that a chatbot could engage the patient in a spoken (or written) dialog in the patient’s preferred language and targeted to his/her educational level. You already deal with this kind of interaction in a primitive form when you call the customer service department of even a small company. That is if you were lucky enough to find the number buried in the company’s website.

The “system” could then perform a targeted exam using a variety of sensors. Electronic stethoscopes and tympanographic sensors already exist. While currently most sonograms are performed by trained technicians, one can envision the technology being dumbed down to a point that the patient could operate most of the sensors himself or herself, provided the patient could reach the body part in question. The camera on a basic cell phone can take an image of a skin lesion that can already be compared with a standard set of normals and abnormals. While currently a questionable lesion triggers the provider to perform a biopsy, it is possible that sensors could become so sensitive and the algorithms so clever that the biopsy would be unnecessary. The pandemic has already shown us that patients can obtain sample swabs and accurately perform simple tests in their home.

Once the “system” has made the diagnosis, it would then converse with the patient about the various treatment options and arrange follow up. One would hope that, if the “system’s” diagnosis included a fatal outcome, it would trigger a face-to-face interaction with a counselor and a team of social workers to break the bad news and provide some kind of emotional support.

Those of you who are doubting Dorothys and Thomases may be asking what about scenarios in which the patient’s chief complaint is difficulty breathing or sudden onset of weakness? Remember, I am talking about the usual 8 a.m–6 p.m. primary care office. Any patient with a possibly life-threatening complaint would be triaged by the chatbot and would be seen at some point by a real human. However, it is likely that individual’s training would not require the breadth of the typical medical school education and instead would be targeted at the most common high-risk scenarios. This higher-acuity specialist would, of course, be assisted by a chatbot.

Patients with complaints primarily associated with mental illness would be seen by humans specializing in that area. Although I suspect there are folks somewhere brainstorming on how chatbots could potentially be effective counselors.

Clearly, the future I am suggesting leaves the patient with fewer interactions with a human, and certainly very rarely with a human who has navigated what we think of today as a traditional medical school education.

Would they do it without complaint? Would they have a choice? Do you like it when you are interrogated by the prerecorded voice on the phone tree of some company’s customer service? Do you have a choice? If that interrogation was refined to the point where it saved you time and resulted in the correct answer 99% of the time would you still complain?

If patients found that most of their primary care complaints could be handled more quickly by an AI system with minimal physician intervention and that system offered a success rate of over 90% when measured by the accuracy of the diagnosis and management plan, would they complain? They may have no other choice than to complain if primary care continues to lose favor among recent medical school graduates.

And what would the patients complain about? They already complain about the current system in which they feel that the face-to-face encounters with their physician are becoming less frequent. I often hear complaints that “the doctor just looked at the computer, and he didn’t really examine me.” By which I think they sometimes mean “touched” me.

I suspect we will discover what most of us already suspect and that is there is something special about the eye-to-eye contact and tactile interaction between the physician and the patient. The osteopathic tradition clearly makes this a priority when it utilizes manipulative medicine. It may be that if primary care medicine follows the AI-paved road I have imagined it won’t be able to match the success rate of the current system. Without that human element, with or without the hands-on aspect or even if the diagnosis is correct and the management is spot on, it just won’t work as well.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

The power of mentorship

In a 2018 JAMA Viewpoint, Dr. Vineet Chopra, a former colleague of mine at the University of Michigan (now chair of medicine at the University of Colorado) and colleagues wrote about four archetypes of mentorship: mentor, coach, sponsor, and connector. along the way.

For me, DDW serves as an annual reminder of the power of mentorship in building and sustaining careers. Each May, trainees and early career faculty present their projects in oral or poster sessions, cheered on by their research mentors. Senior thought leaders offer career advice and guidance to more junior colleagues through structured sessions or informal conversations and facilitate introductions to new collaborators. Department chairs, division chiefs, and senior practice leaders take time to reconnect with their early mentors who believed in their potential and provided them with opportunities to take their careers to new heights. And, we see the incredible payoff of programs like AGA’s FORWARD and Future Leaders Programs in serving as springboards for career advancement and creating powerful role models and mentors for the future.

This year’s AGA presidential leadership transition served as a particularly poignant example of the power of mentorship as incoming AGA President Dr. Barbara Jung succeeded one of her early mentors, outgoing AGA President Dr. John Carethers, in this prestigious role. I hope you’ll join me in reflecting on the tremendous impact that mentors, coaches, sponsors, and connectors have had on your career, and continue to pay it forward to the next generation.

In this month’s issue, we feature several stories from DDW 2023, including summaries of the AGA presidential address and a study evaluating the impact of state Medicaid expansion on uptake of CRC screening in safety-net practices. From AGA’s flagship journals, we highlight a propensity-matched cohort study assessing the impact of pancreatic cancer surveillance of high-risk patients on important clinical outcomes and a new AGA CPU on management of extraesophageal GERD. In this month’s AGA Policy and Advocacy column, Dr. Amit Patel and Dr. Rotonya Carr review the results of a recent membership survey on policy priorities and outline the many ways you can get involved in advocacy efforts. Finally, our Member Spotlight column celebrates gastroenterologist and humanitarian Kadirawel Iswara, MD, recipient of this year’s AGA Distinguished Clinician Award in Private Practice, who is a cherished mentor to many prominent members of our field.

Megan A. Adams, M.D., J.D., MSc

Editor-in-Chief

In a 2018 JAMA Viewpoint, Dr. Vineet Chopra, a former colleague of mine at the University of Michigan (now chair of medicine at the University of Colorado) and colleagues wrote about four archetypes of mentorship: mentor, coach, sponsor, and connector. along the way.

For me, DDW serves as an annual reminder of the power of mentorship in building and sustaining careers. Each May, trainees and early career faculty present their projects in oral or poster sessions, cheered on by their research mentors. Senior thought leaders offer career advice and guidance to more junior colleagues through structured sessions or informal conversations and facilitate introductions to new collaborators. Department chairs, division chiefs, and senior practice leaders take time to reconnect with their early mentors who believed in their potential and provided them with opportunities to take their careers to new heights. And, we see the incredible payoff of programs like AGA’s FORWARD and Future Leaders Programs in serving as springboards for career advancement and creating powerful role models and mentors for the future.

This year’s AGA presidential leadership transition served as a particularly poignant example of the power of mentorship as incoming AGA President Dr. Barbara Jung succeeded one of her early mentors, outgoing AGA President Dr. John Carethers, in this prestigious role. I hope you’ll join me in reflecting on the tremendous impact that mentors, coaches, sponsors, and connectors have had on your career, and continue to pay it forward to the next generation.

In this month’s issue, we feature several stories from DDW 2023, including summaries of the AGA presidential address and a study evaluating the impact of state Medicaid expansion on uptake of CRC screening in safety-net practices. From AGA’s flagship journals, we highlight a propensity-matched cohort study assessing the impact of pancreatic cancer surveillance of high-risk patients on important clinical outcomes and a new AGA CPU on management of extraesophageal GERD. In this month’s AGA Policy and Advocacy column, Dr. Amit Patel and Dr. Rotonya Carr review the results of a recent membership survey on policy priorities and outline the many ways you can get involved in advocacy efforts. Finally, our Member Spotlight column celebrates gastroenterologist and humanitarian Kadirawel Iswara, MD, recipient of this year’s AGA Distinguished Clinician Award in Private Practice, who is a cherished mentor to many prominent members of our field.

Megan A. Adams, M.D., J.D., MSc

Editor-in-Chief

In a 2018 JAMA Viewpoint, Dr. Vineet Chopra, a former colleague of mine at the University of Michigan (now chair of medicine at the University of Colorado) and colleagues wrote about four archetypes of mentorship: mentor, coach, sponsor, and connector. along the way.

For me, DDW serves as an annual reminder of the power of mentorship in building and sustaining careers. Each May, trainees and early career faculty present their projects in oral or poster sessions, cheered on by their research mentors. Senior thought leaders offer career advice and guidance to more junior colleagues through structured sessions or informal conversations and facilitate introductions to new collaborators. Department chairs, division chiefs, and senior practice leaders take time to reconnect with their early mentors who believed in their potential and provided them with opportunities to take their careers to new heights. And, we see the incredible payoff of programs like AGA’s FORWARD and Future Leaders Programs in serving as springboards for career advancement and creating powerful role models and mentors for the future.

This year’s AGA presidential leadership transition served as a particularly poignant example of the power of mentorship as incoming AGA President Dr. Barbara Jung succeeded one of her early mentors, outgoing AGA President Dr. John Carethers, in this prestigious role. I hope you’ll join me in reflecting on the tremendous impact that mentors, coaches, sponsors, and connectors have had on your career, and continue to pay it forward to the next generation.

In this month’s issue, we feature several stories from DDW 2023, including summaries of the AGA presidential address and a study evaluating the impact of state Medicaid expansion on uptake of CRC screening in safety-net practices. From AGA’s flagship journals, we highlight a propensity-matched cohort study assessing the impact of pancreatic cancer surveillance of high-risk patients on important clinical outcomes and a new AGA CPU on management of extraesophageal GERD. In this month’s AGA Policy and Advocacy column, Dr. Amit Patel and Dr. Rotonya Carr review the results of a recent membership survey on policy priorities and outline the many ways you can get involved in advocacy efforts. Finally, our Member Spotlight column celebrates gastroenterologist and humanitarian Kadirawel Iswara, MD, recipient of this year’s AGA Distinguished Clinician Award in Private Practice, who is a cherished mentor to many prominent members of our field.

Megan A. Adams, M.D., J.D., MSc

Editor-in-Chief

Circadian curiosities

Summer is here. Well, technically not for 3 weeks, but in Phoenix summer as a weather condition generally runs from March to November.

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (yes, the one you learned in neuroanatomy) is pretty tiny, but still remarkable. Nothing brings that into focus like the changing of the seasons.

No matter where you live on Earth, you still have to deal with day and night, even if each is 6 months long. We all have to live with shifting schedules and lengths of night and day and weekdays and weekends.

But what fascinates me is how the internal clock reprograms itself, and then doesn’t change.

Case in point: Except for when I’ve had to catch a flight, I haven’t set an alarm in almost 10 years. Somewhere early in my career (back when I did a lot of hospital work) I began getting up between 4-5 a.m. to start rounds before going to the office.

Today the habit continues. It’s been 14 years since I last did weekday hospital call but I still automatically wake up, ready to go, between 4 a.m. and 5 a.m., Monday through Friday. Without me having to do anything this shuts off on vacations, holidays, and weekends, but is up and running as soon as I have to go back to the office.

It’s fascinating (at least to me) in that the suprachiasmatic nucleus didn’t evolve many millions of years ago so I could get to work without an alarm clock. Early animals needed to respond to changing conditions of night, day, and shifting seasons. Light and dark are universal for almost everything that walks, flies, and swims, so given enough time a way of internally keeping track of them developed. Bears use it to hibernate. Birds to migrate with the seasons.

Of course, it’s not all good. In some people it’s likely behind the bizarre predictability of their cluster headaches.

In the modern era we’ve also found ways to confuse it, with the invention of time zones and air travel. Anyone who’s made the leap across several time zones has had to adjust. It’s certainly not a major issue, but does take some getting used to.

But still, it’s pretty fascinating stuff. A reminder that,

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Summer is here. Well, technically not for 3 weeks, but in Phoenix summer as a weather condition generally runs from March to November.

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (yes, the one you learned in neuroanatomy) is pretty tiny, but still remarkable. Nothing brings that into focus like the changing of the seasons.

No matter where you live on Earth, you still have to deal with day and night, even if each is 6 months long. We all have to live with shifting schedules and lengths of night and day and weekdays and weekends.

But what fascinates me is how the internal clock reprograms itself, and then doesn’t change.

Case in point: Except for when I’ve had to catch a flight, I haven’t set an alarm in almost 10 years. Somewhere early in my career (back when I did a lot of hospital work) I began getting up between 4-5 a.m. to start rounds before going to the office.

Today the habit continues. It’s been 14 years since I last did weekday hospital call but I still automatically wake up, ready to go, between 4 a.m. and 5 a.m., Monday through Friday. Without me having to do anything this shuts off on vacations, holidays, and weekends, but is up and running as soon as I have to go back to the office.

It’s fascinating (at least to me) in that the suprachiasmatic nucleus didn’t evolve many millions of years ago so I could get to work without an alarm clock. Early animals needed to respond to changing conditions of night, day, and shifting seasons. Light and dark are universal for almost everything that walks, flies, and swims, so given enough time a way of internally keeping track of them developed. Bears use it to hibernate. Birds to migrate with the seasons.

Of course, it’s not all good. In some people it’s likely behind the bizarre predictability of their cluster headaches.

In the modern era we’ve also found ways to confuse it, with the invention of time zones and air travel. Anyone who’s made the leap across several time zones has had to adjust. It’s certainly not a major issue, but does take some getting used to.

But still, it’s pretty fascinating stuff. A reminder that,

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Summer is here. Well, technically not for 3 weeks, but in Phoenix summer as a weather condition generally runs from March to November.

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (yes, the one you learned in neuroanatomy) is pretty tiny, but still remarkable. Nothing brings that into focus like the changing of the seasons.

No matter where you live on Earth, you still have to deal with day and night, even if each is 6 months long. We all have to live with shifting schedules and lengths of night and day and weekdays and weekends.

But what fascinates me is how the internal clock reprograms itself, and then doesn’t change.

Case in point: Except for when I’ve had to catch a flight, I haven’t set an alarm in almost 10 years. Somewhere early in my career (back when I did a lot of hospital work) I began getting up between 4-5 a.m. to start rounds before going to the office.

Today the habit continues. It’s been 14 years since I last did weekday hospital call but I still automatically wake up, ready to go, between 4 a.m. and 5 a.m., Monday through Friday. Without me having to do anything this shuts off on vacations, holidays, and weekends, but is up and running as soon as I have to go back to the office.

It’s fascinating (at least to me) in that the suprachiasmatic nucleus didn’t evolve many millions of years ago so I could get to work without an alarm clock. Early animals needed to respond to changing conditions of night, day, and shifting seasons. Light and dark are universal for almost everything that walks, flies, and swims, so given enough time a way of internally keeping track of them developed. Bears use it to hibernate. Birds to migrate with the seasons.

Of course, it’s not all good. In some people it’s likely behind the bizarre predictability of their cluster headaches.

In the modern era we’ve also found ways to confuse it, with the invention of time zones and air travel. Anyone who’s made the leap across several time zones has had to adjust. It’s certainly not a major issue, but does take some getting used to.

But still, it’s pretty fascinating stuff. A reminder that,

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

COVID boosters effective, but not for long

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study.

I am here today to talk about the effectiveness of COVID vaccine boosters in the midst of 2023. The reason I want to talk about this isn’t necessarily to dig into exactly how effective vaccines are. This is an area that’s been trod upon multiple times. But it does give me an opportunity to talk about a neat study design called the “test-negative case-control” design, which has some unique properties when you’re trying to evaluate the effect of something outside of the context of a randomized trial.

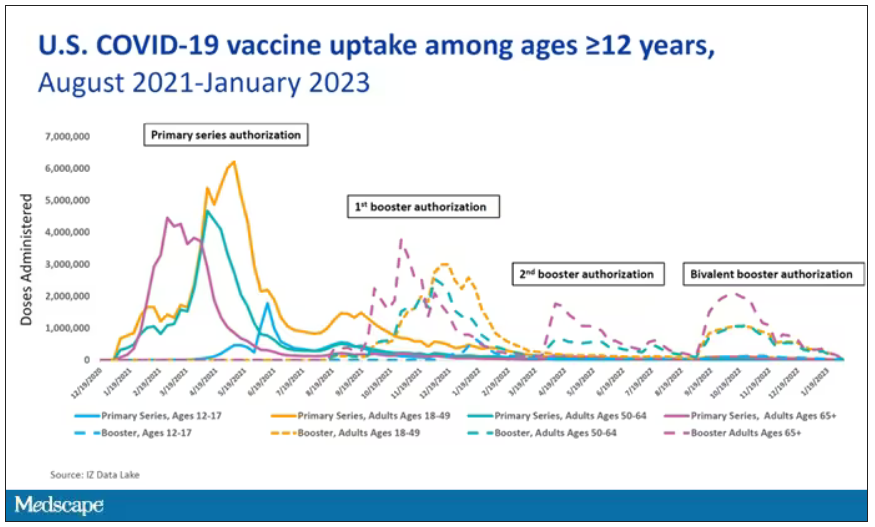

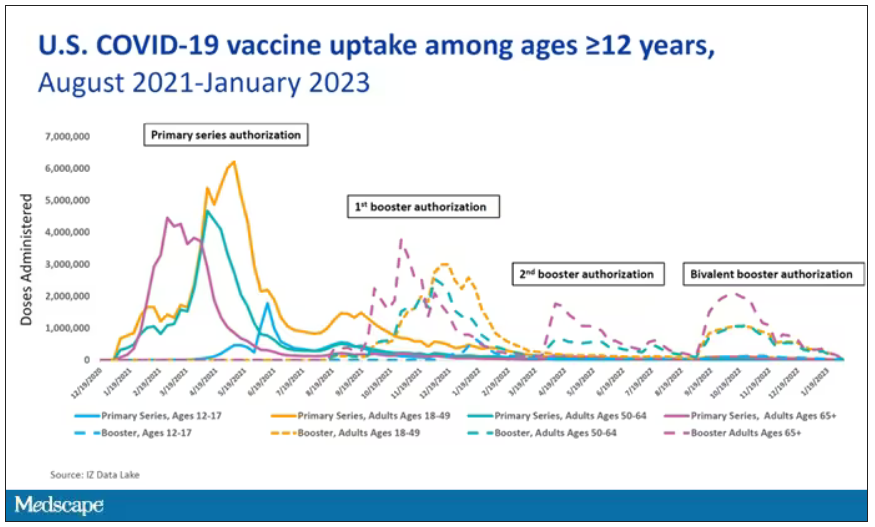

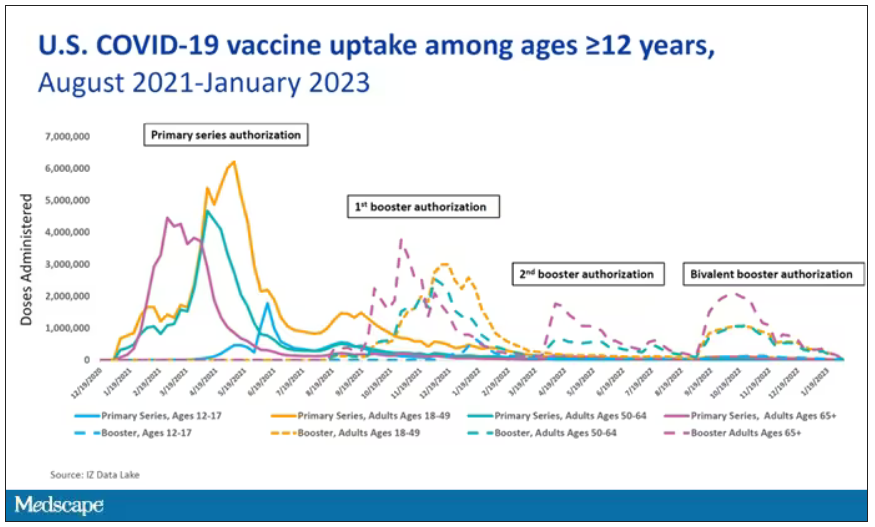

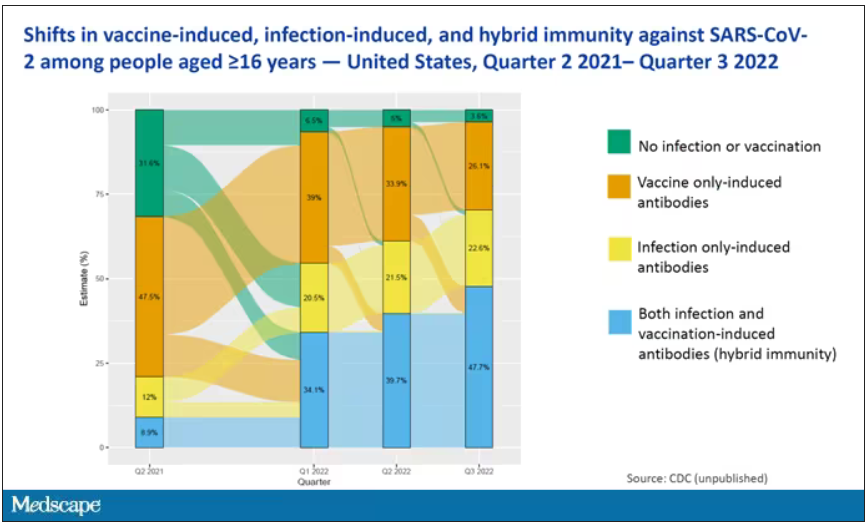

So, just a little bit of background to remind everyone where we are. These are the number of doses of COVID vaccines administered over time throughout the pandemic.

You can see that it’s stratified by age. The orange lines are adults ages 18-49, for example. You can see a big wave of vaccination when the vaccine first came out at the start of 2021. Then subsequently, you can see smaller waves after the first and second booster authorizations, and maybe a bit of a pickup, particularly among older adults, when the bivalent boosters were authorized. But still very little overall pickup of the bivalent booster, compared with the monovalent vaccines, which might suggest vaccine fatigue going on this far into the pandemic. But it’s important to try to understand exactly how effective those new boosters are, at least at this point in time.

I’m talking about Early Estimates of Bivalent mRNA Booster Dose Vaccine Effectiveness in Preventing Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection Attributable to Omicron BA.5– and XBB/XBB.1.5–Related Sublineages Among Immunocompetent Adults – Increasing Community Access to Testing Program, United States, December 2022–January 2023, which came out in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report very recently, which uses this test-negative case-control design to evaluate the ability of bivalent mRNA vaccines to prevent hospitalization.

The question is: Does receipt of a bivalent COVID vaccine booster prevent hospitalizations, ICU stay, or death? That may not be the question that is of interest to everyone. I know people are interested in symptoms, missed work, and transmission, but this paper was looking at hospitalization, ICU stay, and death.

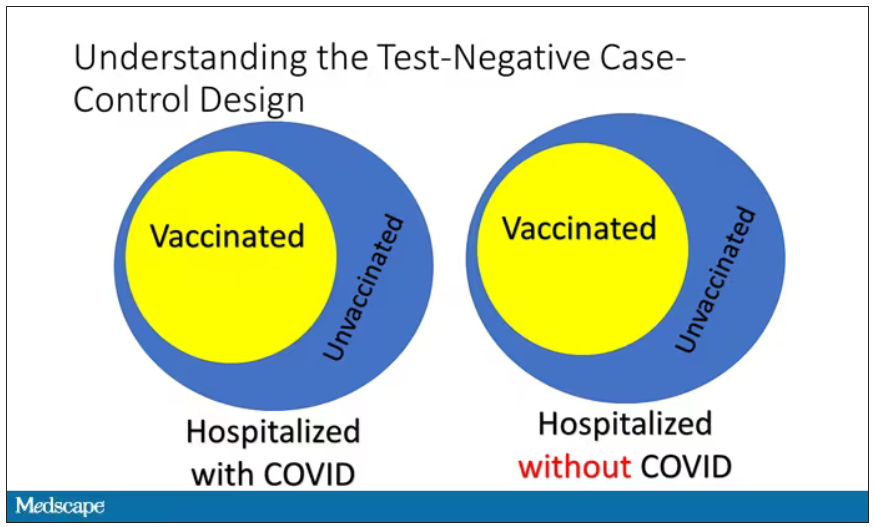

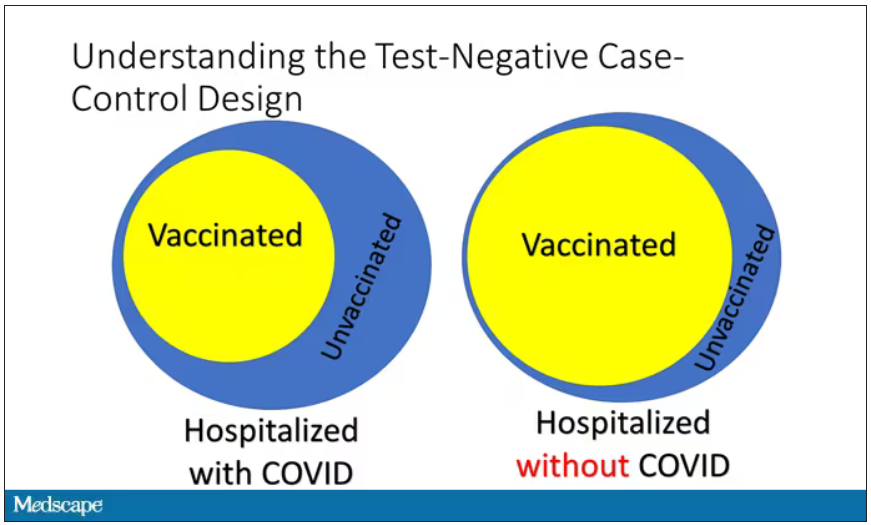

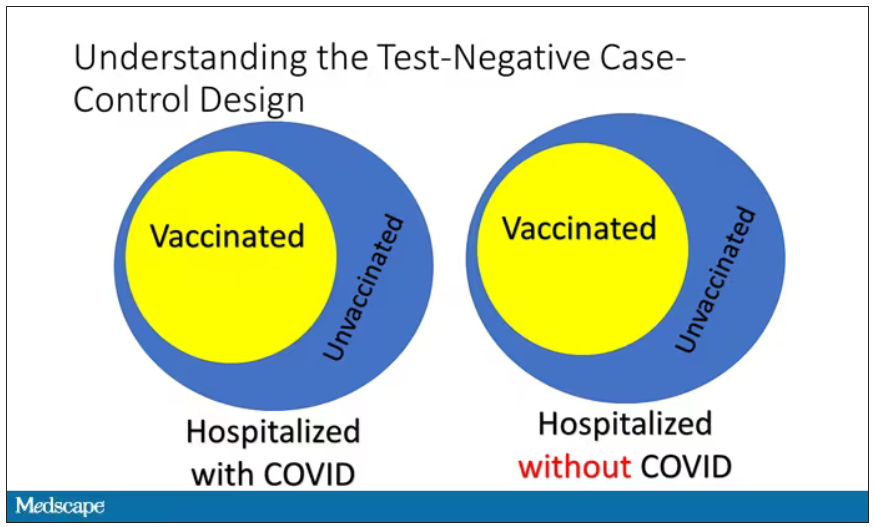

What’s kind of tricky here is that the data they’re using are in people who are hospitalized with various diseases. You might look at that on the surface and say: “Well, you can’t – that’s impossible.” But you can, actually, with this cool test-negative case-control design.

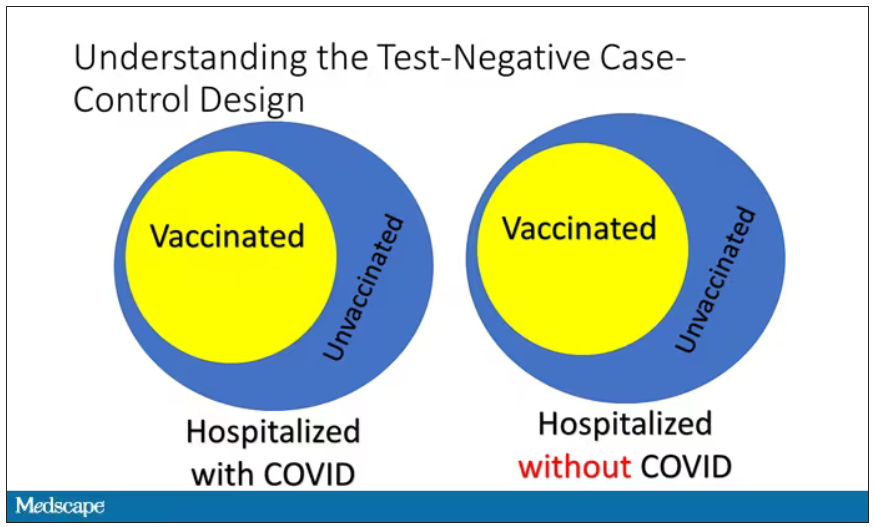

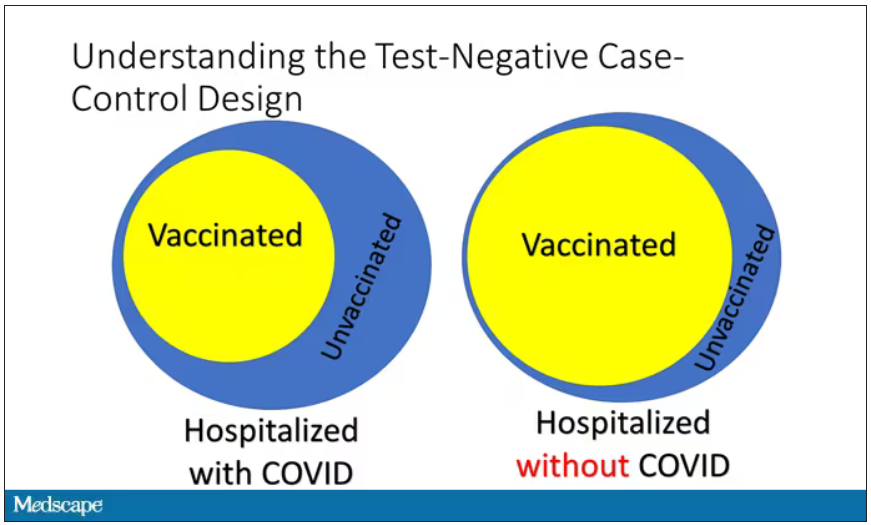

Here’s basically how it works. You take a population of people who are hospitalized and confirmed to have COVID. Some of them will be vaccinated and some of them will be unvaccinated. And the proportion of vaccinated and unvaccinated people doesn’t tell you very much because it depends on how that compares with the rates in the general population, for instance. Let me clarify this. If 100% of the population were vaccinated, then 100% of the people hospitalized with COVID would be vaccinated. That doesn’t mean vaccines are bad. Put another way, if 90% of the population were vaccinated and 60% of people hospitalized with COVID were vaccinated, that would actually show that the vaccines were working to some extent, all else being equal. So it’s not just the raw percentages that tell you anything. Some people are vaccinated, some people aren’t. You need to understand what the baseline rate is.

The test-negative case-control design looks at people who are hospitalized without COVID. Now who those people are (who the controls are, in this case) is something you really need to think about. In the case of this CDC study, they used people who were hospitalized with COVID-like illnesses – flu-like illnesses, respiratory illnesses, pneumonia, influenza, etc. This is a pretty good idea because it standardizes a little bit for people who have access to healthcare. They can get to a hospital and they’re the type of person who would go to a hospital when they’re feeling sick. That’s a better control than the general population overall, which is something I like about this design.

Some of those people who don’t have COVID (they’re in the hospital for flu or whatever) will have been vaccinated for COVID, and some will not have been vaccinated for COVID. And of course, we don’t expect COVID vaccines necessarily to protect against the flu or pneumonia, but that gives us a way to standardize.

If you look at these Venn diagrams, I’ve got vaccinated/unvaccinated being exactly the same proportion, which would suggest that you’re just as likely to be hospitalized with COVID if you’re vaccinated as you are to be hospitalized with some other respiratory illness, which suggests that the vaccine isn’t particularly effective.

However, if you saw something like this, looking at all those patients with flu and other non-COVID illnesses, a lot more of them had been vaccinated for COVID. What that tells you is that we’re seeing fewer vaccinated people hospitalized with COVID than we would expect because we have this standardization from other respiratory infections. We expect this many vaccinated people because that’s how many vaccinated people there are who show up with flu. But in the COVID population, there are fewer, and that would suggest that the vaccines are effective. So that is the test-negative case-control design. You can do the same thing with ICU stays and death.

There are some assumptions here which you might already be thinking about. The most important one is that vaccination status is not associated with the risk for the disease. I always think of older people in this context. During the pandemic, at least in the United States, older people were much more likely to be vaccinated but were also much more likely to contract COVID and be hospitalized with COVID. The test-negative design actually accounts for this in some sense, because older people are also more likely to be hospitalized for things like flu and pneumonia. So there’s some control there.

But to the extent that older people are uniquely susceptible to COVID compared with other respiratory illnesses, that would bias your results to make the vaccines look worse. So the standard approach here is to adjust for these things. I think the CDC adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and a few other things to settle down and see how effective the vaccines were.

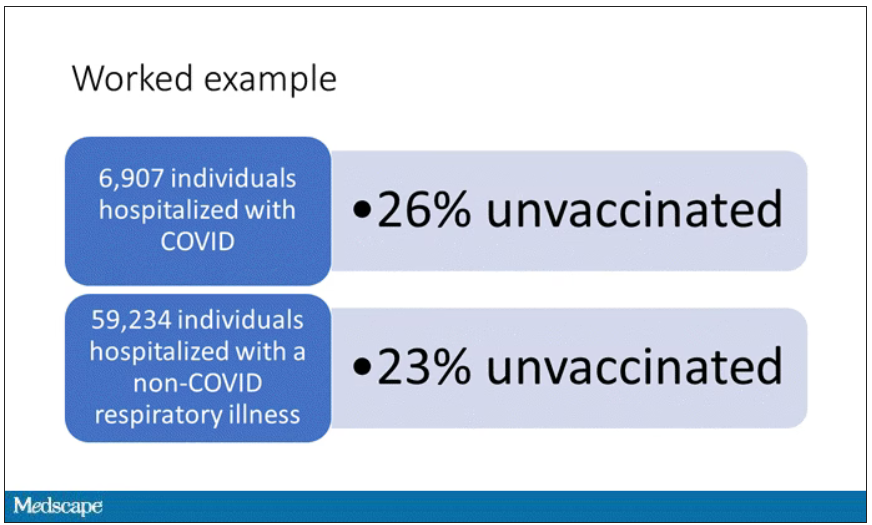

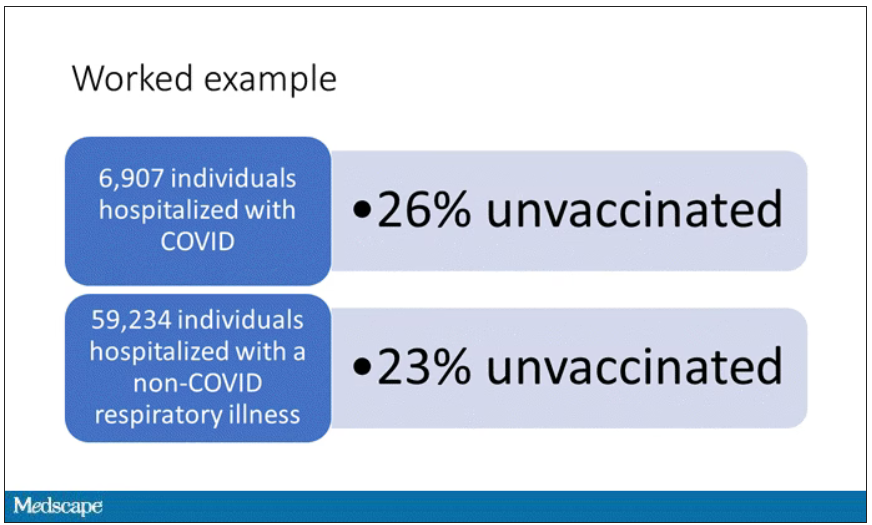

Let’s get to a worked example.

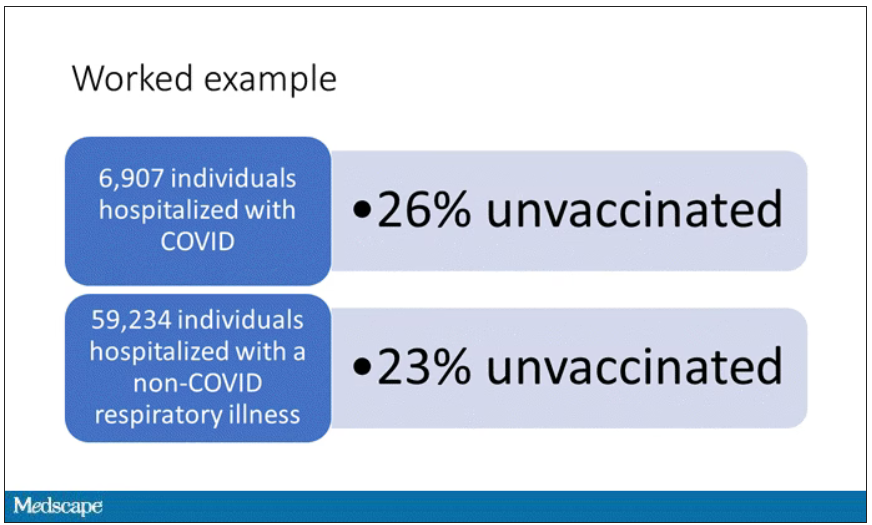

This is the actual data from the CDC paper. They had 6,907 individuals who were hospitalized with COVID, and 26% of them were unvaccinated. What’s the baseline rate that we would expect to be unvaccinated? A total of 59,234 individuals were hospitalized with a non-COVID respiratory illness, and 23% of them were unvaccinated. So you can see that there were more unvaccinated people than you would think in the COVID group. In other words, fewer vaccinated people, which suggests that the vaccine works to some degree because it’s keeping some people out of the hospital.

Now, 26% versus 23% is not a very impressive difference. But it gets more interesting when you break it down by the type of vaccine and how long ago the individual was vaccinated.

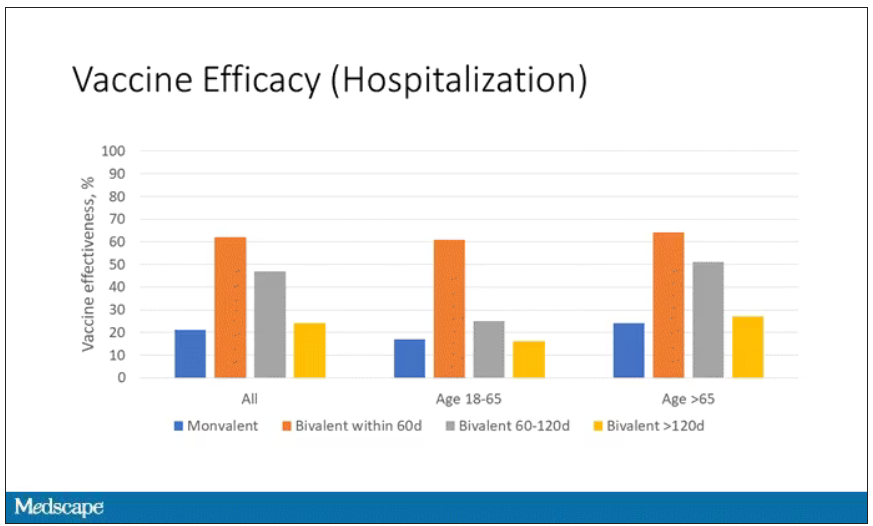

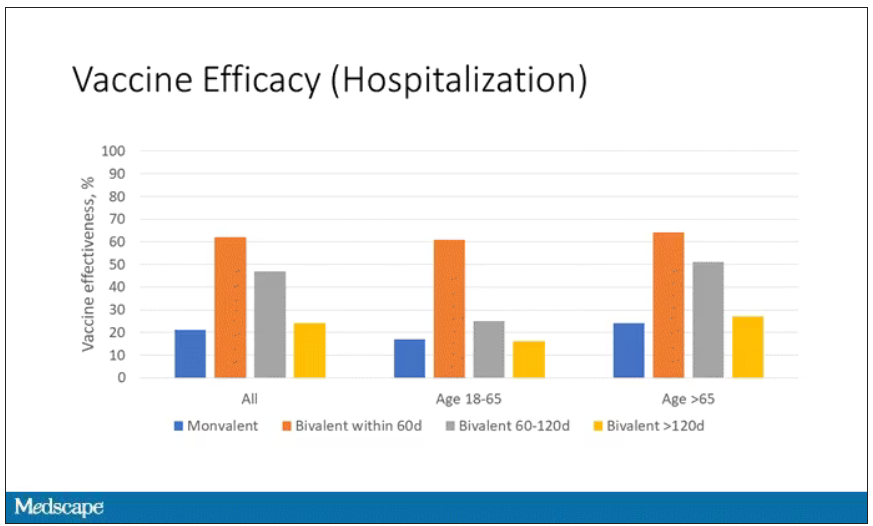

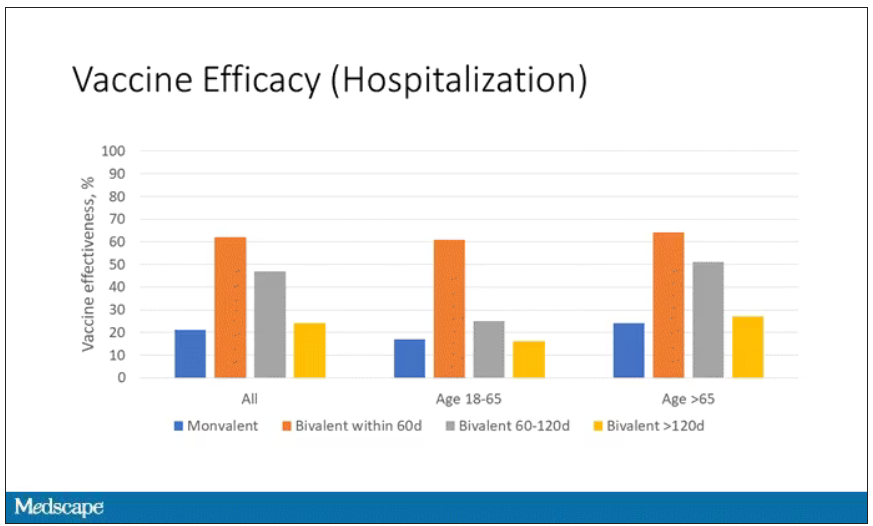

Let’s walk through the “all” group on this figure. What you can see is the calculated vaccine effectiveness. If you look at just the monovalent vaccine here, we see a 20% vaccine effectiveness. This means that you’re preventing 20% of hospitalizations basically due to COVID by people getting vaccinated. That’s okay but it’s certainly not anything to write home about. But we see much better vaccine effectiveness with the bivalent vaccine if it had been received within 60 days.

This compares people who received the bivalent vaccine within 60 days in the COVID group and the non-COVID group. The concern that the vaccine was given very recently affects both groups equally so it shouldn’t result in bias there. You see a step-off in vaccine effectiveness from 60 days, 60-120 days, and greater than 120 days. This is 4 months, and you’ve gone from 60% to 20%. When you break that down by age, you can see a similar pattern in the 18-to-65 group and potentially some more protection the greater than 65 age group.

Why is vaccine efficacy going down? The study doesn’t tell us, but we can hypothesize that this might be an immunologic effect – the antibodies or the protective T cells are waning over time. This could also reflect changes in the virus in the environment as the virus seeks to evade certain immune responses. But overall, this suggests that waiting a year between booster doses may leave you exposed for quite some time, although the take-home here is that bivalent vaccines in general are probably a good idea for the proportion of people who haven’t gotten them.

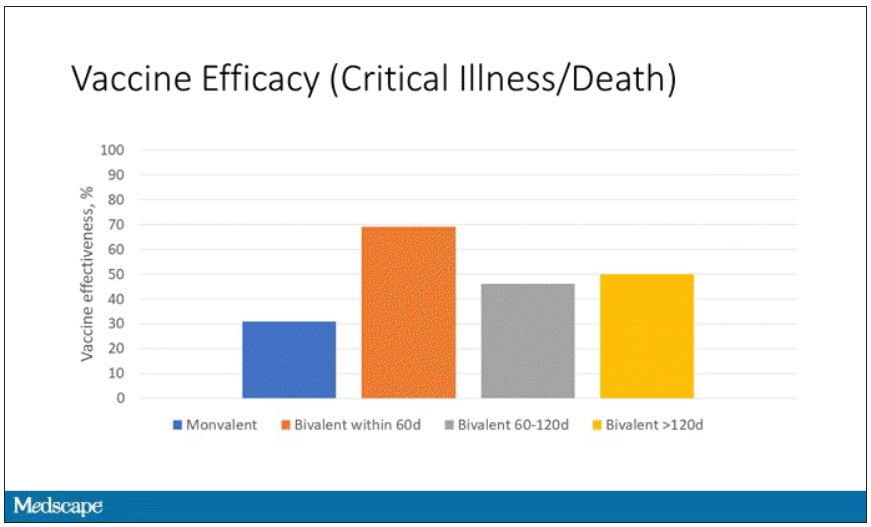

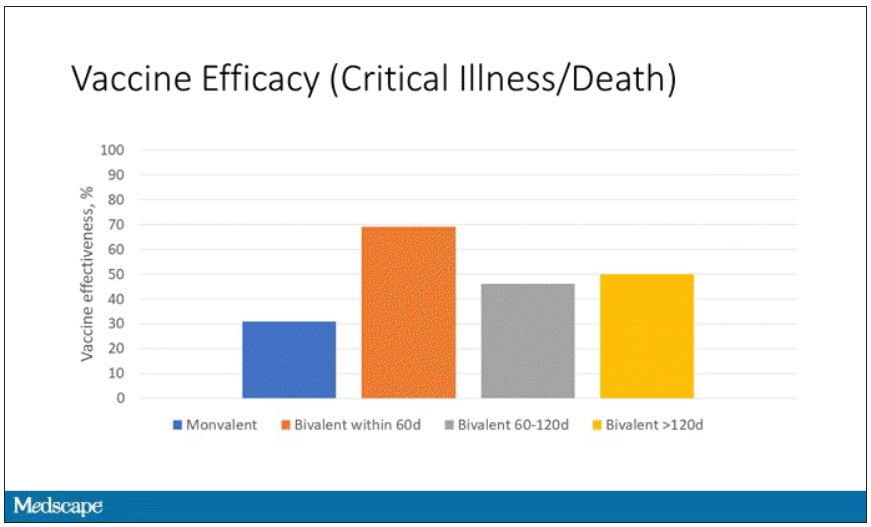

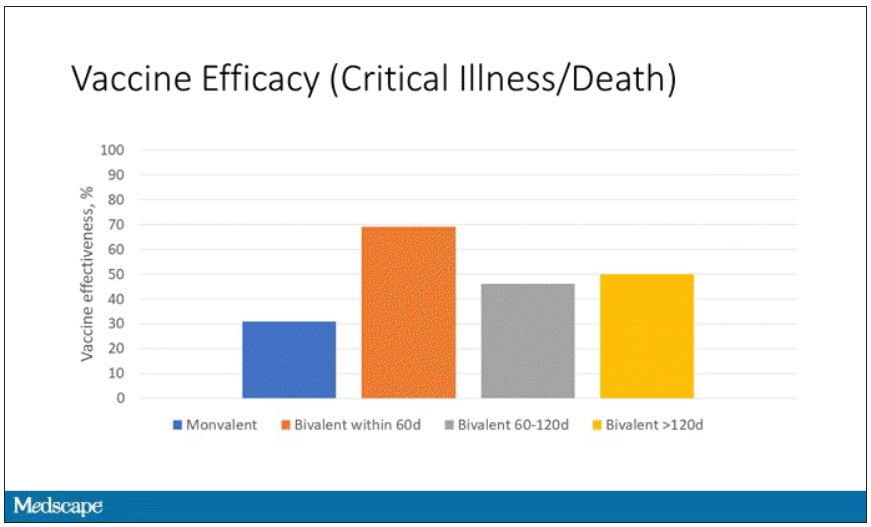

When we look at critical illness and death, the numbers look a little bit better.

You can see that bivalent is better than monovalent – certainly pretty good if you’ve received it within 60 days. It does tend to wane a little bit, but not nearly as much. You’ve still got about 50% vaccine efficacy beyond 120 days when we’re looking at critical illness, which is stays in the ICU and death.

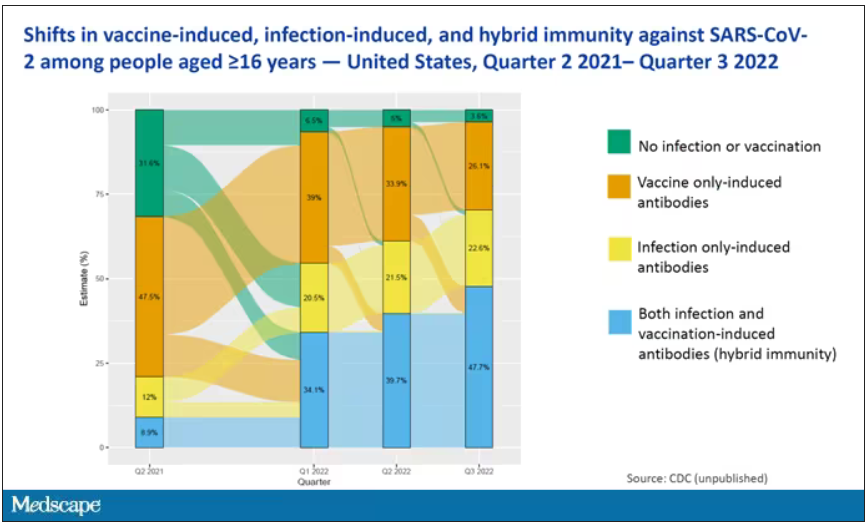

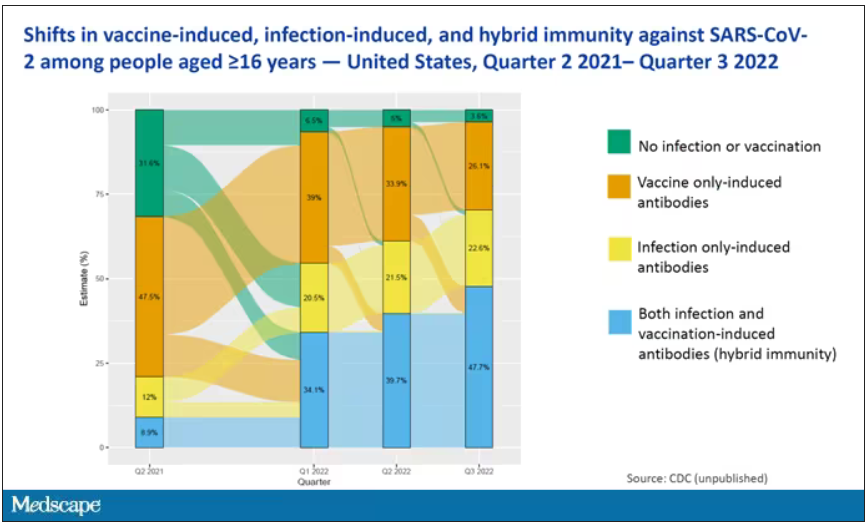

The overriding thing to think about when we think about vaccine policy is that the way you get immunized against COVID is either by vaccine or by getting infected with COVID, or both.