User login

Incidental hepatic steatosis

It is important to identify patients at risk of progressive fibrosis.

Calculation of the fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) score (based on age, alanine and aspartate aminotransferase [ALT and AST] levels, and platelet count by the primary care provider, using either an online calculator or the dot phrase “.fib4” in Epic) is a useful first step. If the value is low (with a high negative predictive value for advanced fibrosis), the patient does not need to be referred but can be managed for risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. If the value is high, suggesting advanced fibrosis, the patient requires further evaluation. If the value is indeterminate, options for assessing liver stiffness include vibration-controlled transient elastography (with a controlled attenuation parameter to assess the degree of steatosis) and ultrasound elastography. A low liver stiffness score argues against the need for subspecialty management. An indeterminate score may be followed by magnetic resonance elastography, if available. An alternative to elastography is the enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) blood test, based on serum levels of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP-1), amino-terminal propeptide of type III procollagen (PIIINP), and hyaluronic acid.

Dr. Friedman is the Anton R. Fried, MD, chair of the department of medicine at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Newton, Mass., and assistant chief of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Tufts University, Boston. Dr. Martin is chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases at the University of Miami, where he is the Mandel Chair of Gastroenterology. The authors disclose no conflicts.

Published previously in Gastro Hep Advances (doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2023.03.008).

It is important to identify patients at risk of progressive fibrosis.

Calculation of the fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) score (based on age, alanine and aspartate aminotransferase [ALT and AST] levels, and platelet count by the primary care provider, using either an online calculator or the dot phrase “.fib4” in Epic) is a useful first step. If the value is low (with a high negative predictive value for advanced fibrosis), the patient does not need to be referred but can be managed for risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. If the value is high, suggesting advanced fibrosis, the patient requires further evaluation. If the value is indeterminate, options for assessing liver stiffness include vibration-controlled transient elastography (with a controlled attenuation parameter to assess the degree of steatosis) and ultrasound elastography. A low liver stiffness score argues against the need for subspecialty management. An indeterminate score may be followed by magnetic resonance elastography, if available. An alternative to elastography is the enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) blood test, based on serum levels of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP-1), amino-terminal propeptide of type III procollagen (PIIINP), and hyaluronic acid.

Dr. Friedman is the Anton R. Fried, MD, chair of the department of medicine at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Newton, Mass., and assistant chief of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Tufts University, Boston. Dr. Martin is chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases at the University of Miami, where he is the Mandel Chair of Gastroenterology. The authors disclose no conflicts.

Published previously in Gastro Hep Advances (doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2023.03.008).

It is important to identify patients at risk of progressive fibrosis.

Calculation of the fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) score (based on age, alanine and aspartate aminotransferase [ALT and AST] levels, and platelet count by the primary care provider, using either an online calculator or the dot phrase “.fib4” in Epic) is a useful first step. If the value is low (with a high negative predictive value for advanced fibrosis), the patient does not need to be referred but can be managed for risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. If the value is high, suggesting advanced fibrosis, the patient requires further evaluation. If the value is indeterminate, options for assessing liver stiffness include vibration-controlled transient elastography (with a controlled attenuation parameter to assess the degree of steatosis) and ultrasound elastography. A low liver stiffness score argues against the need for subspecialty management. An indeterminate score may be followed by magnetic resonance elastography, if available. An alternative to elastography is the enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) blood test, based on serum levels of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP-1), amino-terminal propeptide of type III procollagen (PIIINP), and hyaluronic acid.

Dr. Friedman is the Anton R. Fried, MD, chair of the department of medicine at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Newton, Mass., and assistant chief of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Tufts University, Boston. Dr. Martin is chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases at the University of Miami, where he is the Mandel Chair of Gastroenterology. The authors disclose no conflicts.

Published previously in Gastro Hep Advances (doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2023.03.008).

FROM GASTRO HEP ADVANCES

Is there a link between body image concerns and polycystic ovary syndrome?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

At ENDO 2023, I presented our systematic review and meta-analysis related to body image concerns in women and individuals with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). PCOS is the most common endocrine condition affecting women worldwide. It’s as common as 10%-15%.

Previously thought to be a benign condition affecting a small proportion of women of reproductive age, it’s changed now. It affects women of all ages, all ethnicities, and throughout the world. Body image concern is an area where one feels uncomfortable with how they look and how they feel. Someone might wonder, why worry about body image concerns? When people have body image concerns, it leads to low self-esteem.

Low self-esteem can lead to depression and anxiety, eventually making you a not-so-productive member of society. Several studies have also shown that body image concerns can lead to eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia, which can be life threatening. Several studies in the past have shown there is a link between PCOS and body image concerns, but what exactly is the link? We don’t know. How big is the problem? We didn’t know until now.

To answer this, we looked at everything published about PCOS and body image concerns together, be it a randomized study, a cluster study, or any kind of study. We put them all into one place and studied them for evidence. The second objective of our work was that we wanted to share any evidence with the international PCOS guidelines group, who are currently reviewing and revising the guidelines for 2023.

We looked at all the major scientific databases, such as PubMed, PubMed Central, and Medline, for any study that’s been published for polycystic ovary syndrome and body image concerns where they specifically used a validated questionnaire – that’s important, and I’ll come back to that later.

We found 6,221 articles on an initial search. After meticulously looking through all of them, we narrowed it down to 9 articles that were relevant to our work. That’s going from 6,221 articles to 9, which were reviewed by 2 independent researchers. If there was any conflict between them, a third independent researcher resolved the conflict.

We found some studies had used the same questionnaires and some had their own questionnaire. We combined the studies where they used the same questionnaire and we did what we call a meta-analysis. We used their data and combined them to find an additional analysis, which is a combination of the two.

The two most commonly used questionnaires were the Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ) survey and the Body-Esteem Scale for Adolescents and Adults (BESAA). I’m not going into detail, but in simplest terms, the MBSRQ has 69 questions, which breaks down into 5 subscales, and BESAA has 3 subscales, which has 23 questions.

When we combined the results in the MBSRQ questionnaire, women with PCOS fared worse in all the subscales, showing there is a concern about body image in women with PCOS when compared with their colleagues who are healthy and do not have PCOS.

With BESAA, we found a little bit of a mixed picture. There was still a significant difference about weight perception, but how they felt and how they attributed, there was no significant difference. Probably the main reason was that only two studies used it and there was a smaller number of people involved in the study.

Why is this important? We feel that by identifying or diagnosing body image concerns, we will be addressing patient concerns. That is important because we clinicians have our own thoughts of what we need to do to help women with PCOS to prevent long-term risk, but it’s also important to talk to the person sitting in front of you right now. What is their concern?

There’s also been a generational shift where women with PCOS used say, “Oh, I’m worried that I can’t have a kid,” to now say, “I’m worried that I don’t feel well about myself.” We need to address that.

When we shared these findings with the international PCOS guidelines, they said we should probably approach this on an individual case-by-case basis because it will mean that the length of consultation might increase if we spend time with body image concerns.

This is where questionnaires come into play. With a validated questionnaire, a person can complete that before they come into the consultation, thereby minimizing the amount of time spent. If they’re not scoring high on the questionnaire, we don’t need to address that. If they are scoring high, then it can be picked up as a topic to discuss.

As I mentioned, there are a couple of limitations, one being the fewer studies and lower numbers of people in the studies. We need to address this in the future.

Long story short, at the moment, there is evidence to say that body image concerns are quite significantly high in women and individuals with PCOS. This is something we need to address as soon as possible.

We are planning future work to understand how social media comes into play, how society influences body image, and how health care professionals across the world are addressing PCOS and body image concerns. Hopefully, we will be able to share these findings in the near future. Thank you.

Dr. Kempegowda is assistant professor in endocrinology, diabetes, and general medicine at the Institute of Applied Health Research, University of Birmingham, and a consultant in endocrinology, diabetes and acute medicine, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham, England, and disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

At ENDO 2023, I presented our systematic review and meta-analysis related to body image concerns in women and individuals with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). PCOS is the most common endocrine condition affecting women worldwide. It’s as common as 10%-15%.

Previously thought to be a benign condition affecting a small proportion of women of reproductive age, it’s changed now. It affects women of all ages, all ethnicities, and throughout the world. Body image concern is an area where one feels uncomfortable with how they look and how they feel. Someone might wonder, why worry about body image concerns? When people have body image concerns, it leads to low self-esteem.

Low self-esteem can lead to depression and anxiety, eventually making you a not-so-productive member of society. Several studies have also shown that body image concerns can lead to eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia, which can be life threatening. Several studies in the past have shown there is a link between PCOS and body image concerns, but what exactly is the link? We don’t know. How big is the problem? We didn’t know until now.

To answer this, we looked at everything published about PCOS and body image concerns together, be it a randomized study, a cluster study, or any kind of study. We put them all into one place and studied them for evidence. The second objective of our work was that we wanted to share any evidence with the international PCOS guidelines group, who are currently reviewing and revising the guidelines for 2023.

We looked at all the major scientific databases, such as PubMed, PubMed Central, and Medline, for any study that’s been published for polycystic ovary syndrome and body image concerns where they specifically used a validated questionnaire – that’s important, and I’ll come back to that later.

We found 6,221 articles on an initial search. After meticulously looking through all of them, we narrowed it down to 9 articles that were relevant to our work. That’s going from 6,221 articles to 9, which were reviewed by 2 independent researchers. If there was any conflict between them, a third independent researcher resolved the conflict.

We found some studies had used the same questionnaires and some had their own questionnaire. We combined the studies where they used the same questionnaire and we did what we call a meta-analysis. We used their data and combined them to find an additional analysis, which is a combination of the two.

The two most commonly used questionnaires were the Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ) survey and the Body-Esteem Scale for Adolescents and Adults (BESAA). I’m not going into detail, but in simplest terms, the MBSRQ has 69 questions, which breaks down into 5 subscales, and BESAA has 3 subscales, which has 23 questions.

When we combined the results in the MBSRQ questionnaire, women with PCOS fared worse in all the subscales, showing there is a concern about body image in women with PCOS when compared with their colleagues who are healthy and do not have PCOS.

With BESAA, we found a little bit of a mixed picture. There was still a significant difference about weight perception, but how they felt and how they attributed, there was no significant difference. Probably the main reason was that only two studies used it and there was a smaller number of people involved in the study.

Why is this important? We feel that by identifying or diagnosing body image concerns, we will be addressing patient concerns. That is important because we clinicians have our own thoughts of what we need to do to help women with PCOS to prevent long-term risk, but it’s also important to talk to the person sitting in front of you right now. What is their concern?

There’s also been a generational shift where women with PCOS used say, “Oh, I’m worried that I can’t have a kid,” to now say, “I’m worried that I don’t feel well about myself.” We need to address that.

When we shared these findings with the international PCOS guidelines, they said we should probably approach this on an individual case-by-case basis because it will mean that the length of consultation might increase if we spend time with body image concerns.

This is where questionnaires come into play. With a validated questionnaire, a person can complete that before they come into the consultation, thereby minimizing the amount of time spent. If they’re not scoring high on the questionnaire, we don’t need to address that. If they are scoring high, then it can be picked up as a topic to discuss.

As I mentioned, there are a couple of limitations, one being the fewer studies and lower numbers of people in the studies. We need to address this in the future.

Long story short, at the moment, there is evidence to say that body image concerns are quite significantly high in women and individuals with PCOS. This is something we need to address as soon as possible.

We are planning future work to understand how social media comes into play, how society influences body image, and how health care professionals across the world are addressing PCOS and body image concerns. Hopefully, we will be able to share these findings in the near future. Thank you.

Dr. Kempegowda is assistant professor in endocrinology, diabetes, and general medicine at the Institute of Applied Health Research, University of Birmingham, and a consultant in endocrinology, diabetes and acute medicine, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham, England, and disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

At ENDO 2023, I presented our systematic review and meta-analysis related to body image concerns in women and individuals with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). PCOS is the most common endocrine condition affecting women worldwide. It’s as common as 10%-15%.

Previously thought to be a benign condition affecting a small proportion of women of reproductive age, it’s changed now. It affects women of all ages, all ethnicities, and throughout the world. Body image concern is an area where one feels uncomfortable with how they look and how they feel. Someone might wonder, why worry about body image concerns? When people have body image concerns, it leads to low self-esteem.

Low self-esteem can lead to depression and anxiety, eventually making you a not-so-productive member of society. Several studies have also shown that body image concerns can lead to eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia, which can be life threatening. Several studies in the past have shown there is a link between PCOS and body image concerns, but what exactly is the link? We don’t know. How big is the problem? We didn’t know until now.

To answer this, we looked at everything published about PCOS and body image concerns together, be it a randomized study, a cluster study, or any kind of study. We put them all into one place and studied them for evidence. The second objective of our work was that we wanted to share any evidence with the international PCOS guidelines group, who are currently reviewing and revising the guidelines for 2023.

We looked at all the major scientific databases, such as PubMed, PubMed Central, and Medline, for any study that’s been published for polycystic ovary syndrome and body image concerns where they specifically used a validated questionnaire – that’s important, and I’ll come back to that later.

We found 6,221 articles on an initial search. After meticulously looking through all of them, we narrowed it down to 9 articles that were relevant to our work. That’s going from 6,221 articles to 9, which were reviewed by 2 independent researchers. If there was any conflict between them, a third independent researcher resolved the conflict.

We found some studies had used the same questionnaires and some had their own questionnaire. We combined the studies where they used the same questionnaire and we did what we call a meta-analysis. We used their data and combined them to find an additional analysis, which is a combination of the two.

The two most commonly used questionnaires were the Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ) survey and the Body-Esteem Scale for Adolescents and Adults (BESAA). I’m not going into detail, but in simplest terms, the MBSRQ has 69 questions, which breaks down into 5 subscales, and BESAA has 3 subscales, which has 23 questions.

When we combined the results in the MBSRQ questionnaire, women with PCOS fared worse in all the subscales, showing there is a concern about body image in women with PCOS when compared with their colleagues who are healthy and do not have PCOS.

With BESAA, we found a little bit of a mixed picture. There was still a significant difference about weight perception, but how they felt and how they attributed, there was no significant difference. Probably the main reason was that only two studies used it and there was a smaller number of people involved in the study.

Why is this important? We feel that by identifying or diagnosing body image concerns, we will be addressing patient concerns. That is important because we clinicians have our own thoughts of what we need to do to help women with PCOS to prevent long-term risk, but it’s also important to talk to the person sitting in front of you right now. What is their concern?

There’s also been a generational shift where women with PCOS used say, “Oh, I’m worried that I can’t have a kid,” to now say, “I’m worried that I don’t feel well about myself.” We need to address that.

When we shared these findings with the international PCOS guidelines, they said we should probably approach this on an individual case-by-case basis because it will mean that the length of consultation might increase if we spend time with body image concerns.

This is where questionnaires come into play. With a validated questionnaire, a person can complete that before they come into the consultation, thereby minimizing the amount of time spent. If they’re not scoring high on the questionnaire, we don’t need to address that. If they are scoring high, then it can be picked up as a topic to discuss.

As I mentioned, there are a couple of limitations, one being the fewer studies and lower numbers of people in the studies. We need to address this in the future.

Long story short, at the moment, there is evidence to say that body image concerns are quite significantly high in women and individuals with PCOS. This is something we need to address as soon as possible.

We are planning future work to understand how social media comes into play, how society influences body image, and how health care professionals across the world are addressing PCOS and body image concerns. Hopefully, we will be able to share these findings in the near future. Thank you.

Dr. Kempegowda is assistant professor in endocrinology, diabetes, and general medicine at the Institute of Applied Health Research, University of Birmingham, and a consultant in endocrinology, diabetes and acute medicine, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham, England, and disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A teenage girl refuses more cancer treatment; her father disagrees

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan, PhD. I’m director of the division of medical ethics at the New York University Grossman School of Medicine.

Every once in a while at my school, I get referrals about interesting or difficult clinical cases where doctors would like some input or advice that they can consider in managing a patient. Sometimes those requests come from other hospitals to me. I’ve been doing that kind of ethics consulting, both as a member of various ethics committees and sometimes individually, when, for various reasons, doctors don’t want to go to the Ethics Committee as a first stop.

There was a very interesting case recently involving a young woman I’m going to call Tinslee. She was 17 years old and she suffered, sadly, from recurrent metastatic osteogenic sarcoma. She had bone cancer. It had first been diagnosed at the age of 9. She had received chemotherapy and been under that treatment for a while.

If osteosarcoma is treated before it spreads outside the area where it began, the 5-year survival rate for people like her is about 75%. If the cancer spreads outside of the bones and gets into surrounding tissues, organs, or – worse – into the lymph nodes and starts traveling around, the 5-year survival rate drops to about 60%. The two approaches are chemotherapy and amputation. That’s what we have to offer patients like Tinslee.

Initially, her chemotherapy worked. She went to school and enjoyed sports. She was a real fan of softball and tried to manage the team and be involved. At the time I learned about her, she was planning to go to college. Her love of softball remained, but given the recurrence of the cancer, she had no chance to pursue her athletic interests, not only as a player, but also as a manager or even as a coach for younger players. That was all off the table.

She’d been very compliant up until this time with her chemotherapy. When the recommendation came in that she undergo nonstandard chemotherapy because of the reoccurrence, with experimental drugs using an experimental protocol, she said to her family and the doctors that she didn’t want to do it. She would rather die. She couldn’t take any more chemotherapy and she certainly didn’t want to do it if it was experimental, with the outcomes of this intervention being uncertain.

Her mother said, “Her input matters. I want to listen to her.” Her mom wasn’t as adamant about doing it or not, but she really felt that Tinslee should be heard loudly because she felt she was mature enough or old enough, even though a minor, to really have a position about what it is to undergo chemotherapy.

Time matters in trying to control the spread, and the doctors were pushing for experimental intervention. I should add, by the way, that although it didn’t really drive the decision about whether to do it or not do it, experimental care like this is not covered by most insurance, and it wasn’t covered by their insurance, so they were facing a big bill if the experimental intervention was administered.

There was some money in a grant to cover some of it, but they were going to face some big financial costs. It never came up in my discussions with the doctors about what to do. I’m not sure whether it ever came up with the family’s discussion with the doctors about what to do, or even whether Tinslee was worrying and didn’t want her family to face a financial burden.

I suggested that we bring the family in. We did some counseling. We had a social worker and we brought in a pastor because these people were fairly religious. We talked about all scenarios, including accepting death, knowing that this disease was not likely to go into remission with the experimental effort; maybe it would, but the doctors were not optimistic.

We tried to talk about how much we should listen to what this young woman wanted. We knew there was the possibility of going to court and having a judge decide this, but in my experience, I do not like going to judges and courts because I know what they’re going to say. They almost always say “administer the intervention.” They don’t want to be in a position of saying don’t do something. They’re a little less willing to do that if something is experimental, but generally speaking, if you’re headed to court, it’s because you’ve decided that you want this to happen.

I felt, in all honesty, that this young woman should have some real respect of her position because the treatment was experimental. She is approaching the age of competency and consent, and she’s been through many interventions. She knows what’s involved. I think you really have to listen hard to what she’s saying.

By the way, after this case, I looked and there have been some surveys of residents in pediatrics. A large number of them said that they hadn’t received any training about what to do when mature minors refuse experimental treatments. The study I saw said that 30% had not undergone any training about this, so we certainly want to introduce that into the appropriate areas of medicine and talk about this with residents and fellows.

Long story short, we had the family meeting, we had another meeting with dad and mom and Tinslee, and the dad began to come around and he began to listen hard. Tinslee said what she wanted was to go to her prom. She wanted to get to her sister’s junior high school softball championship game. If you will, setting some smaller goals that seemed to make her very, very happy began to satisfy mom and dad and they could accept her refusal.

Ultimately, an agreement was reached that she would not undergo the experimental intervention. We agreed on a course of palliative care, recommended that as what the doctors follow, and they decided to do so. Sadly, Tinslee died. She died at home. She did make it to her prom.

I think the outcome, while difficult, sad, tragic, and a close call, was correct. Mature minors who have been through a rough life of interventions and know the price to pay – and for those who have recurrent disease and now face only experimental options – if they say no, that’s something we really have to listen to very hard.

Dr. Kaplan is director, division of medical ethics, New York University Langone Medical Center, New York. He reported a conflict of interest with Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan, PhD. I’m director of the division of medical ethics at the New York University Grossman School of Medicine.

Every once in a while at my school, I get referrals about interesting or difficult clinical cases where doctors would like some input or advice that they can consider in managing a patient. Sometimes those requests come from other hospitals to me. I’ve been doing that kind of ethics consulting, both as a member of various ethics committees and sometimes individually, when, for various reasons, doctors don’t want to go to the Ethics Committee as a first stop.

There was a very interesting case recently involving a young woman I’m going to call Tinslee. She was 17 years old and she suffered, sadly, from recurrent metastatic osteogenic sarcoma. She had bone cancer. It had first been diagnosed at the age of 9. She had received chemotherapy and been under that treatment for a while.

If osteosarcoma is treated before it spreads outside the area where it began, the 5-year survival rate for people like her is about 75%. If the cancer spreads outside of the bones and gets into surrounding tissues, organs, or – worse – into the lymph nodes and starts traveling around, the 5-year survival rate drops to about 60%. The two approaches are chemotherapy and amputation. That’s what we have to offer patients like Tinslee.

Initially, her chemotherapy worked. She went to school and enjoyed sports. She was a real fan of softball and tried to manage the team and be involved. At the time I learned about her, she was planning to go to college. Her love of softball remained, but given the recurrence of the cancer, she had no chance to pursue her athletic interests, not only as a player, but also as a manager or even as a coach for younger players. That was all off the table.

She’d been very compliant up until this time with her chemotherapy. When the recommendation came in that she undergo nonstandard chemotherapy because of the reoccurrence, with experimental drugs using an experimental protocol, she said to her family and the doctors that she didn’t want to do it. She would rather die. She couldn’t take any more chemotherapy and she certainly didn’t want to do it if it was experimental, with the outcomes of this intervention being uncertain.

Her mother said, “Her input matters. I want to listen to her.” Her mom wasn’t as adamant about doing it or not, but she really felt that Tinslee should be heard loudly because she felt she was mature enough or old enough, even though a minor, to really have a position about what it is to undergo chemotherapy.

Time matters in trying to control the spread, and the doctors were pushing for experimental intervention. I should add, by the way, that although it didn’t really drive the decision about whether to do it or not do it, experimental care like this is not covered by most insurance, and it wasn’t covered by their insurance, so they were facing a big bill if the experimental intervention was administered.

There was some money in a grant to cover some of it, but they were going to face some big financial costs. It never came up in my discussions with the doctors about what to do. I’m not sure whether it ever came up with the family’s discussion with the doctors about what to do, or even whether Tinslee was worrying and didn’t want her family to face a financial burden.

I suggested that we bring the family in. We did some counseling. We had a social worker and we brought in a pastor because these people were fairly religious. We talked about all scenarios, including accepting death, knowing that this disease was not likely to go into remission with the experimental effort; maybe it would, but the doctors were not optimistic.

We tried to talk about how much we should listen to what this young woman wanted. We knew there was the possibility of going to court and having a judge decide this, but in my experience, I do not like going to judges and courts because I know what they’re going to say. They almost always say “administer the intervention.” They don’t want to be in a position of saying don’t do something. They’re a little less willing to do that if something is experimental, but generally speaking, if you’re headed to court, it’s because you’ve decided that you want this to happen.

I felt, in all honesty, that this young woman should have some real respect of her position because the treatment was experimental. She is approaching the age of competency and consent, and she’s been through many interventions. She knows what’s involved. I think you really have to listen hard to what she’s saying.

By the way, after this case, I looked and there have been some surveys of residents in pediatrics. A large number of them said that they hadn’t received any training about what to do when mature minors refuse experimental treatments. The study I saw said that 30% had not undergone any training about this, so we certainly want to introduce that into the appropriate areas of medicine and talk about this with residents and fellows.

Long story short, we had the family meeting, we had another meeting with dad and mom and Tinslee, and the dad began to come around and he began to listen hard. Tinslee said what she wanted was to go to her prom. She wanted to get to her sister’s junior high school softball championship game. If you will, setting some smaller goals that seemed to make her very, very happy began to satisfy mom and dad and they could accept her refusal.

Ultimately, an agreement was reached that she would not undergo the experimental intervention. We agreed on a course of palliative care, recommended that as what the doctors follow, and they decided to do so. Sadly, Tinslee died. She died at home. She did make it to her prom.

I think the outcome, while difficult, sad, tragic, and a close call, was correct. Mature minors who have been through a rough life of interventions and know the price to pay – and for those who have recurrent disease and now face only experimental options – if they say no, that’s something we really have to listen to very hard.

Dr. Kaplan is director, division of medical ethics, New York University Langone Medical Center, New York. He reported a conflict of interest with Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan, PhD. I’m director of the division of medical ethics at the New York University Grossman School of Medicine.

Every once in a while at my school, I get referrals about interesting or difficult clinical cases where doctors would like some input or advice that they can consider in managing a patient. Sometimes those requests come from other hospitals to me. I’ve been doing that kind of ethics consulting, both as a member of various ethics committees and sometimes individually, when, for various reasons, doctors don’t want to go to the Ethics Committee as a first stop.

There was a very interesting case recently involving a young woman I’m going to call Tinslee. She was 17 years old and she suffered, sadly, from recurrent metastatic osteogenic sarcoma. She had bone cancer. It had first been diagnosed at the age of 9. She had received chemotherapy and been under that treatment for a while.

If osteosarcoma is treated before it spreads outside the area where it began, the 5-year survival rate for people like her is about 75%. If the cancer spreads outside of the bones and gets into surrounding tissues, organs, or – worse – into the lymph nodes and starts traveling around, the 5-year survival rate drops to about 60%. The two approaches are chemotherapy and amputation. That’s what we have to offer patients like Tinslee.

Initially, her chemotherapy worked. She went to school and enjoyed sports. She was a real fan of softball and tried to manage the team and be involved. At the time I learned about her, she was planning to go to college. Her love of softball remained, but given the recurrence of the cancer, she had no chance to pursue her athletic interests, not only as a player, but also as a manager or even as a coach for younger players. That was all off the table.

She’d been very compliant up until this time with her chemotherapy. When the recommendation came in that she undergo nonstandard chemotherapy because of the reoccurrence, with experimental drugs using an experimental protocol, she said to her family and the doctors that she didn’t want to do it. She would rather die. She couldn’t take any more chemotherapy and she certainly didn’t want to do it if it was experimental, with the outcomes of this intervention being uncertain.

Her mother said, “Her input matters. I want to listen to her.” Her mom wasn’t as adamant about doing it or not, but she really felt that Tinslee should be heard loudly because she felt she was mature enough or old enough, even though a minor, to really have a position about what it is to undergo chemotherapy.

Time matters in trying to control the spread, and the doctors were pushing for experimental intervention. I should add, by the way, that although it didn’t really drive the decision about whether to do it or not do it, experimental care like this is not covered by most insurance, and it wasn’t covered by their insurance, so they were facing a big bill if the experimental intervention was administered.

There was some money in a grant to cover some of it, but they were going to face some big financial costs. It never came up in my discussions with the doctors about what to do. I’m not sure whether it ever came up with the family’s discussion with the doctors about what to do, or even whether Tinslee was worrying and didn’t want her family to face a financial burden.

I suggested that we bring the family in. We did some counseling. We had a social worker and we brought in a pastor because these people were fairly religious. We talked about all scenarios, including accepting death, knowing that this disease was not likely to go into remission with the experimental effort; maybe it would, but the doctors were not optimistic.

We tried to talk about how much we should listen to what this young woman wanted. We knew there was the possibility of going to court and having a judge decide this, but in my experience, I do not like going to judges and courts because I know what they’re going to say. They almost always say “administer the intervention.” They don’t want to be in a position of saying don’t do something. They’re a little less willing to do that if something is experimental, but generally speaking, if you’re headed to court, it’s because you’ve decided that you want this to happen.

I felt, in all honesty, that this young woman should have some real respect of her position because the treatment was experimental. She is approaching the age of competency and consent, and she’s been through many interventions. She knows what’s involved. I think you really have to listen hard to what she’s saying.

By the way, after this case, I looked and there have been some surveys of residents in pediatrics. A large number of them said that they hadn’t received any training about what to do when mature minors refuse experimental treatments. The study I saw said that 30% had not undergone any training about this, so we certainly want to introduce that into the appropriate areas of medicine and talk about this with residents and fellows.

Long story short, we had the family meeting, we had another meeting with dad and mom and Tinslee, and the dad began to come around and he began to listen hard. Tinslee said what she wanted was to go to her prom. She wanted to get to her sister’s junior high school softball championship game. If you will, setting some smaller goals that seemed to make her very, very happy began to satisfy mom and dad and they could accept her refusal.

Ultimately, an agreement was reached that she would not undergo the experimental intervention. We agreed on a course of palliative care, recommended that as what the doctors follow, and they decided to do so. Sadly, Tinslee died. She died at home. She did make it to her prom.

I think the outcome, while difficult, sad, tragic, and a close call, was correct. Mature minors who have been through a rough life of interventions and know the price to pay – and for those who have recurrent disease and now face only experimental options – if they say no, that’s something we really have to listen to very hard.

Dr. Kaplan is director, division of medical ethics, New York University Langone Medical Center, New York. He reported a conflict of interest with Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

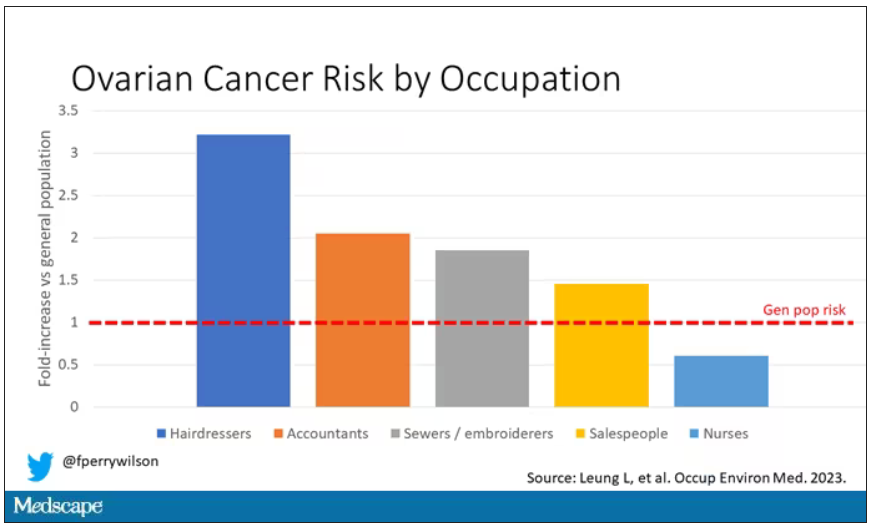

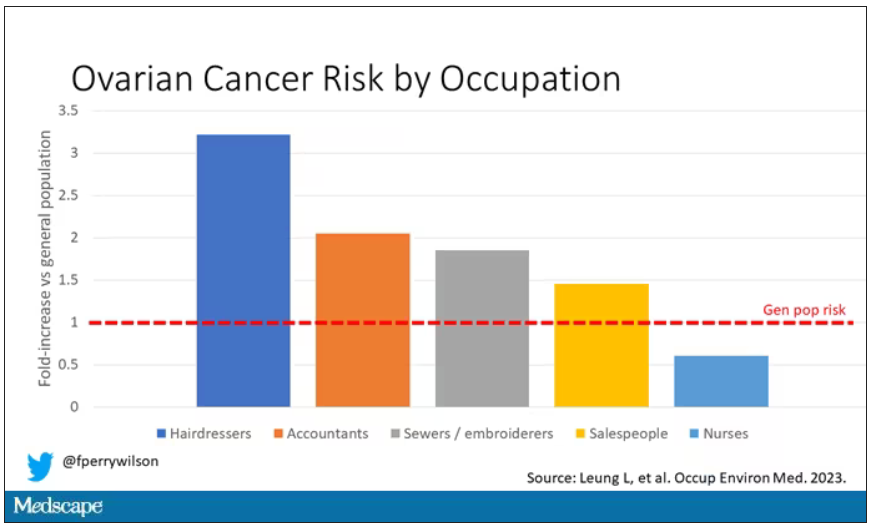

The surprising occupations with higher-than-expected ovarian cancer rates

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study.

Basically, all cancers are caused by a mix of genetic and environmental factors, with some cancers driven more strongly by one or the other. When it comes to ovarian cancer, which kills more than 13,000 women per year in the United States, genetic factors like the BRCA gene mutations are well described.

Other risk factors, like early menarche and nulliparity, are difficult to modify. The only slam-dunk environmental toxin to be linked to ovarian cancer is asbestos. Still, the vast majority of women who develop ovarian cancer do not have a known high-risk gene or asbestos exposure, so other triggers may be out there. How do we find them? The answer may just be good old-fashioned epidemiology.

That’s just what researchers, led by Anita Koushik at the University of Montreal, did in a new study appearing in the journal Occupational and Environmental Medicine.

They identified 497 women in Montreal who had recently been diagnosed with ovarian cancer. They then matched those women to 897 women without ovarian cancer, based on age and address. (This approach would not work well in the United States, as diagnosis of ovarian cancer might depend on access to medical care, which is not universal here. In Canada, however, it’s safer to assume that anyone who could have gotten ovarian cancer in Montreal would have been detected.)

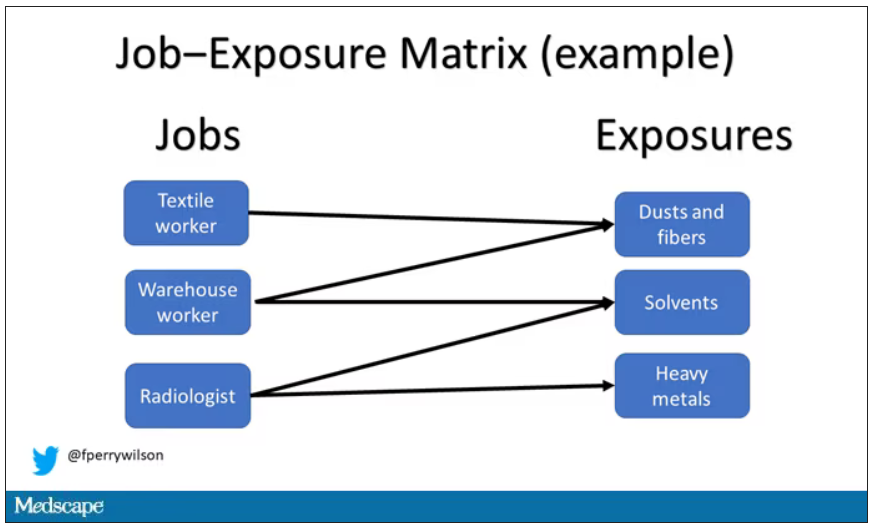

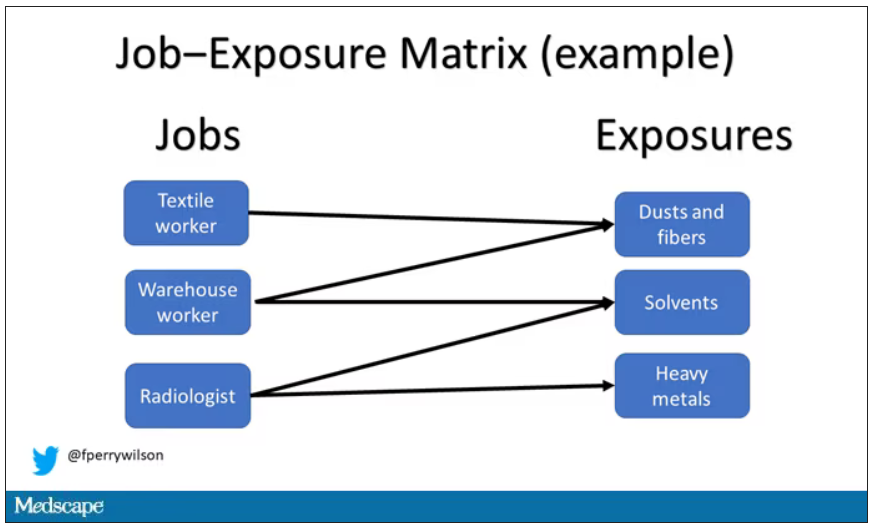

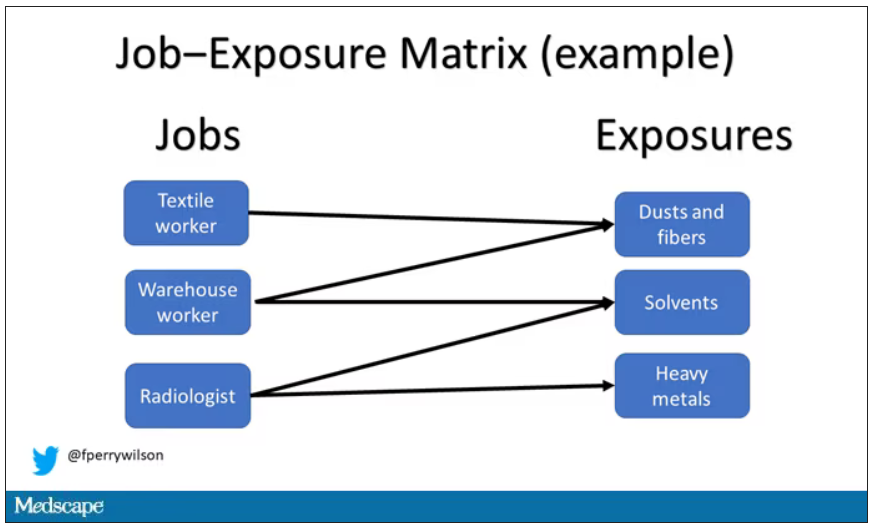

Cases and controls identified, the researchers took a detailed occupational history for each participant: every job they ever worked, and when, and for how long. Each occupation was mapped to a standardized set of industries and, interestingly, to a set of environmental exposures ranging from cosmetic talc to cooking fumes to cotton dust, in what is known as a job-exposure matrix. Of course, they also collected data on other ovarian cancer risk factors.

After that, it’s a simple matter of looking at the rate of ovarian cancer by occupation and occupation-associated exposures, accounting for differences in things like pregnancy rates.

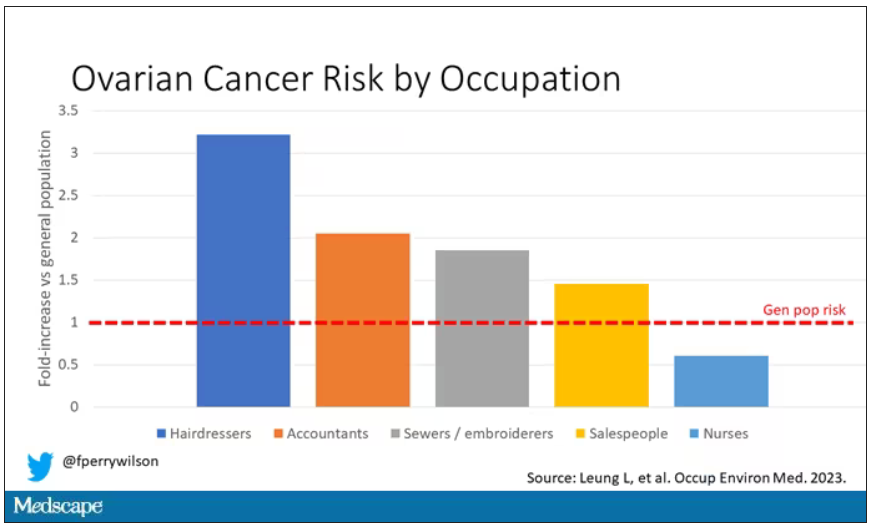

A brief aside here. I was at dinner with my wife the other night and telling her about this study, and I asked, “What do you think the occupation with the highest rate of ovarian cancer is?” And without missing a beat, she said: “Hairdressers.” Which blew my mind because of how random that was, but she was also – as usual – 100% correct.

Hairdressers, at least those who had been in the industry for more than 10 years, had a threefold higher risk for ovarian cancer than matched controls who had never been hairdressers.

Of course, my wife is a cancer surgeon, so she has a bit of a leg up on me here. Many of you may also know that there is actually a decent body of literature showing higher rates of various cancers among hairdressers, presumably due to the variety of chemicals they are exposed to on a continuous basis.

The No. 2 highest-risk profession on the list? Accountants, with about a twofold higher risk. That one is more of a puzzler. It could be a false positive; after all, there were multiple occupations checked and random error might give a few hits that are meaningless. But there are certainly some occupational factors unique to accountants that might bear further investigation – maybe exposure to volatile organic compounds from office printers, or just a particularly sedentary office environment.

In terms of specific exposures, there were high risks seen with mononuclear aromatic hydrocarbons, bleaches, ethanol, and fluorocarbons, among others, but we have to be a bit more careful here. These exposures were not directly measured. Rather, based on the job category a woman described, the exposures were imputed based on the job-exposure matrix. As such, the correlations between the job and the particular exposure are really quite high, making it essentially impossible to tease out whether it is, for example, being a hairdresser, or being exposed to fluorocarbons as a hairdresser, or being exposed to something else as a hairdresser, that is the problem.

This is how these types of studies work; they tend to raise more questions than they answer. But in a world where a cancer diagnosis can seem to come completely out of the blue, they provide the starting point that someday may lead to a more definitive culprit agent or group of agents. Until then, it might be wise for hairdressers to make sure their workplace is well ventilated.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study.

Basically, all cancers are caused by a mix of genetic and environmental factors, with some cancers driven more strongly by one or the other. When it comes to ovarian cancer, which kills more than 13,000 women per year in the United States, genetic factors like the BRCA gene mutations are well described.

Other risk factors, like early menarche and nulliparity, are difficult to modify. The only slam-dunk environmental toxin to be linked to ovarian cancer is asbestos. Still, the vast majority of women who develop ovarian cancer do not have a known high-risk gene or asbestos exposure, so other triggers may be out there. How do we find them? The answer may just be good old-fashioned epidemiology.

That’s just what researchers, led by Anita Koushik at the University of Montreal, did in a new study appearing in the journal Occupational and Environmental Medicine.

They identified 497 women in Montreal who had recently been diagnosed with ovarian cancer. They then matched those women to 897 women without ovarian cancer, based on age and address. (This approach would not work well in the United States, as diagnosis of ovarian cancer might depend on access to medical care, which is not universal here. In Canada, however, it’s safer to assume that anyone who could have gotten ovarian cancer in Montreal would have been detected.)

Cases and controls identified, the researchers took a detailed occupational history for each participant: every job they ever worked, and when, and for how long. Each occupation was mapped to a standardized set of industries and, interestingly, to a set of environmental exposures ranging from cosmetic talc to cooking fumes to cotton dust, in what is known as a job-exposure matrix. Of course, they also collected data on other ovarian cancer risk factors.

After that, it’s a simple matter of looking at the rate of ovarian cancer by occupation and occupation-associated exposures, accounting for differences in things like pregnancy rates.

A brief aside here. I was at dinner with my wife the other night and telling her about this study, and I asked, “What do you think the occupation with the highest rate of ovarian cancer is?” And without missing a beat, she said: “Hairdressers.” Which blew my mind because of how random that was, but she was also – as usual – 100% correct.

Hairdressers, at least those who had been in the industry for more than 10 years, had a threefold higher risk for ovarian cancer than matched controls who had never been hairdressers.

Of course, my wife is a cancer surgeon, so she has a bit of a leg up on me here. Many of you may also know that there is actually a decent body of literature showing higher rates of various cancers among hairdressers, presumably due to the variety of chemicals they are exposed to on a continuous basis.

The No. 2 highest-risk profession on the list? Accountants, with about a twofold higher risk. That one is more of a puzzler. It could be a false positive; after all, there were multiple occupations checked and random error might give a few hits that are meaningless. But there are certainly some occupational factors unique to accountants that might bear further investigation – maybe exposure to volatile organic compounds from office printers, or just a particularly sedentary office environment.

In terms of specific exposures, there were high risks seen with mononuclear aromatic hydrocarbons, bleaches, ethanol, and fluorocarbons, among others, but we have to be a bit more careful here. These exposures were not directly measured. Rather, based on the job category a woman described, the exposures were imputed based on the job-exposure matrix. As such, the correlations between the job and the particular exposure are really quite high, making it essentially impossible to tease out whether it is, for example, being a hairdresser, or being exposed to fluorocarbons as a hairdresser, or being exposed to something else as a hairdresser, that is the problem.

This is how these types of studies work; they tend to raise more questions than they answer. But in a world where a cancer diagnosis can seem to come completely out of the blue, they provide the starting point that someday may lead to a more definitive culprit agent or group of agents. Until then, it might be wise for hairdressers to make sure their workplace is well ventilated.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study.

Basically, all cancers are caused by a mix of genetic and environmental factors, with some cancers driven more strongly by one or the other. When it comes to ovarian cancer, which kills more than 13,000 women per year in the United States, genetic factors like the BRCA gene mutations are well described.

Other risk factors, like early menarche and nulliparity, are difficult to modify. The only slam-dunk environmental toxin to be linked to ovarian cancer is asbestos. Still, the vast majority of women who develop ovarian cancer do not have a known high-risk gene or asbestos exposure, so other triggers may be out there. How do we find them? The answer may just be good old-fashioned epidemiology.

That’s just what researchers, led by Anita Koushik at the University of Montreal, did in a new study appearing in the journal Occupational and Environmental Medicine.

They identified 497 women in Montreal who had recently been diagnosed with ovarian cancer. They then matched those women to 897 women without ovarian cancer, based on age and address. (This approach would not work well in the United States, as diagnosis of ovarian cancer might depend on access to medical care, which is not universal here. In Canada, however, it’s safer to assume that anyone who could have gotten ovarian cancer in Montreal would have been detected.)

Cases and controls identified, the researchers took a detailed occupational history for each participant: every job they ever worked, and when, and for how long. Each occupation was mapped to a standardized set of industries and, interestingly, to a set of environmental exposures ranging from cosmetic talc to cooking fumes to cotton dust, in what is known as a job-exposure matrix. Of course, they also collected data on other ovarian cancer risk factors.

After that, it’s a simple matter of looking at the rate of ovarian cancer by occupation and occupation-associated exposures, accounting for differences in things like pregnancy rates.

A brief aside here. I was at dinner with my wife the other night and telling her about this study, and I asked, “What do you think the occupation with the highest rate of ovarian cancer is?” And without missing a beat, she said: “Hairdressers.” Which blew my mind because of how random that was, but she was also – as usual – 100% correct.

Hairdressers, at least those who had been in the industry for more than 10 years, had a threefold higher risk for ovarian cancer than matched controls who had never been hairdressers.

Of course, my wife is a cancer surgeon, so she has a bit of a leg up on me here. Many of you may also know that there is actually a decent body of literature showing higher rates of various cancers among hairdressers, presumably due to the variety of chemicals they are exposed to on a continuous basis.

The No. 2 highest-risk profession on the list? Accountants, with about a twofold higher risk. That one is more of a puzzler. It could be a false positive; after all, there were multiple occupations checked and random error might give a few hits that are meaningless. But there are certainly some occupational factors unique to accountants that might bear further investigation – maybe exposure to volatile organic compounds from office printers, or just a particularly sedentary office environment.

In terms of specific exposures, there were high risks seen with mononuclear aromatic hydrocarbons, bleaches, ethanol, and fluorocarbons, among others, but we have to be a bit more careful here. These exposures were not directly measured. Rather, based on the job category a woman described, the exposures were imputed based on the job-exposure matrix. As such, the correlations between the job and the particular exposure are really quite high, making it essentially impossible to tease out whether it is, for example, being a hairdresser, or being exposed to fluorocarbons as a hairdresser, or being exposed to something else as a hairdresser, that is the problem.

This is how these types of studies work; they tend to raise more questions than they answer. But in a world where a cancer diagnosis can seem to come completely out of the blue, they provide the starting point that someday may lead to a more definitive culprit agent or group of agents. Until then, it might be wise for hairdressers to make sure their workplace is well ventilated.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Body size is not a choice’ and deserves legal protections

Legislators in New York City recently approved a bill specifically prohibiting weight- and height-based discrimination, on par with existing protections for gender, race, sexual orientation, and other personal identities. Other U.S. cities, as well as New York state, are considering similar moves.

Weight-based discrimination in the United States has increased by an estimated 66% over the past decade, putting it on par with the prevalence of racial discrimination. More than 40% of adult Americans and 18% of children report experiencing weight discrimination in employment, school, and/or health care settings – as well as within interpersonal relationships – demonstrating a clear need to have legal protections in place.

For obesity advocates in Canada, the news from New York triggered a moment of reflection to consider how our own advocacy efforts have fared over the years, or not. Just like in the United States, body size and obesity (and appearance in general) are not specifically protected grounds under human rights legislation in Canada (for example, the Canadian Human Rights Act), unlike race, gender, sexual orientation, and religion.

Case law is uneven across the Canadian provinces when it comes to determining whether obesity is even a disease and/or a disability. And despite broad support for anti–weight discrimination policies in Canada (Front Public Health. 2023 Apr 17;11:1060794; Milbank Q. 2015 Dec;93[4]:691-731), years of advocacy at the national and provincial levels have not led to any legislative changes (Ramos Salas Obes Rev. 2017 Nov;18[11]:1323-35; Can J Diabetes. 2015 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2015.01.009). A 2017 private members bill seeking to add protection for body size to Manitoba’s human rights code was defeated, with many members of the legislature citing enforcement difficulties as the reason for voting down the proposition.

Some obesity advocates have argued that people living with obesity can be protected under the grounds of disability in the Canadian Human Rights Act. To be protected, however, individuals must demonstrate that there is actual or perceived disability relating to their weight or size; yet, many people living with obesity and those who have a higher weight don’t perceive themselves as having a disability.

In our view, the disparate viewpoints on the worthiness of considering body size a human rights issue could be resolved, at least partially, by wider understanding and adoption of the relatively new clinical definition of obesity. This definition holds that obesity is not about size; an obesity diagnosis can be made only when objective clinical investigations identify that excess or abnormal adiposity (fat tissue) impairs health.

While obesity advocates use the clinical definition of obesity, weight and body size proponents disagree that obesity is a chronic disease, and in fact believe that treating it as such can be stigmatizing. In a sense, this can sometimes be true, as not all people with larger bodies have obesity per the new definition but risk being identified as “unhealthy” in the clinical world. Bias, it turns out, can be a two-way street.

Regardless of the advocacy strategy used, it’s clear that specific anti–weight discrimination laws are needed in Canada. One in four Canadian adults report experiencing discrimination in their day-to-day life, with race, gender, age, and weight being the most commonly reported forms. To refuse to protect them against some, but not all, forms of discrimination is itself unjust, and is surely rooted in the age-old misinformed concept that excess weight is the result of laziness, poor food choices, and lack of physical activity, among other moral failings.

Including body size in human rights codes may provide a mechanism to seek legal remedy from discriminatory acts, but it will do little to address rampant weight bias, in the same way that race-based legal protections don’t eradicate racism. And it’s not just the legal community that fails to understand that weight is, by and large, a product of our environment and our genes. Weight bias and stigma are well documented in media, workplaces, the home, and in health care systems.

The solution, in our minds, is meaningful education across all these domains, reinforcing that weight is not a behavior, just as health is not a size. If we truly understand and embrace these concepts, then as a society we may someday recognize that body size is not a choice, just like race, sexual orientation, gender identity, and other individual characteristics. And if it’s not a choice, if it’s not a behavior, then it deserves the same protections.

At the same time, people with obesity deserve to seek evidence-based treatment, just as those at higher weights who experience no weight or adiposity-related health issues deserve not to be identified as having a disease simply because of their size.

If we all follow the science, we might yet turn a common understanding into more equitable outcomes for all.

Dr. Ramos Salas and Mr. Hussey are research consultants for Replica Communications, Hamilton, Ont. She disclosed ties with the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, European Association for the Study of Obesity, Novo Nordisk, Obesity Canada, The Obesity Society, World Obesity, and the World Health Organization. Mr. Hussey disclosed ties with the European Association for the Study of Obesity, Novo Nordisk, Obesity Canada, and the World Health Organization (Nutrition and Food Safety).

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Legislators in New York City recently approved a bill specifically prohibiting weight- and height-based discrimination, on par with existing protections for gender, race, sexual orientation, and other personal identities. Other U.S. cities, as well as New York state, are considering similar moves.

Weight-based discrimination in the United States has increased by an estimated 66% over the past decade, putting it on par with the prevalence of racial discrimination. More than 40% of adult Americans and 18% of children report experiencing weight discrimination in employment, school, and/or health care settings – as well as within interpersonal relationships – demonstrating a clear need to have legal protections in place.

For obesity advocates in Canada, the news from New York triggered a moment of reflection to consider how our own advocacy efforts have fared over the years, or not. Just like in the United States, body size and obesity (and appearance in general) are not specifically protected grounds under human rights legislation in Canada (for example, the Canadian Human Rights Act), unlike race, gender, sexual orientation, and religion.

Case law is uneven across the Canadian provinces when it comes to determining whether obesity is even a disease and/or a disability. And despite broad support for anti–weight discrimination policies in Canada (Front Public Health. 2023 Apr 17;11:1060794; Milbank Q. 2015 Dec;93[4]:691-731), years of advocacy at the national and provincial levels have not led to any legislative changes (Ramos Salas Obes Rev. 2017 Nov;18[11]:1323-35; Can J Diabetes. 2015 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2015.01.009). A 2017 private members bill seeking to add protection for body size to Manitoba’s human rights code was defeated, with many members of the legislature citing enforcement difficulties as the reason for voting down the proposition.

Some obesity advocates have argued that people living with obesity can be protected under the grounds of disability in the Canadian Human Rights Act. To be protected, however, individuals must demonstrate that there is actual or perceived disability relating to their weight or size; yet, many people living with obesity and those who have a higher weight don’t perceive themselves as having a disability.

In our view, the disparate viewpoints on the worthiness of considering body size a human rights issue could be resolved, at least partially, by wider understanding and adoption of the relatively new clinical definition of obesity. This definition holds that obesity is not about size; an obesity diagnosis can be made only when objective clinical investigations identify that excess or abnormal adiposity (fat tissue) impairs health.

While obesity advocates use the clinical definition of obesity, weight and body size proponents disagree that obesity is a chronic disease, and in fact believe that treating it as such can be stigmatizing. In a sense, this can sometimes be true, as not all people with larger bodies have obesity per the new definition but risk being identified as “unhealthy” in the clinical world. Bias, it turns out, can be a two-way street.

Regardless of the advocacy strategy used, it’s clear that specific anti–weight discrimination laws are needed in Canada. One in four Canadian adults report experiencing discrimination in their day-to-day life, with race, gender, age, and weight being the most commonly reported forms. To refuse to protect them against some, but not all, forms of discrimination is itself unjust, and is surely rooted in the age-old misinformed concept that excess weight is the result of laziness, poor food choices, and lack of physical activity, among other moral failings.

Including body size in human rights codes may provide a mechanism to seek legal remedy from discriminatory acts, but it will do little to address rampant weight bias, in the same way that race-based legal protections don’t eradicate racism. And it’s not just the legal community that fails to understand that weight is, by and large, a product of our environment and our genes. Weight bias and stigma are well documented in media, workplaces, the home, and in health care systems.

The solution, in our minds, is meaningful education across all these domains, reinforcing that weight is not a behavior, just as health is not a size. If we truly understand and embrace these concepts, then as a society we may someday recognize that body size is not a choice, just like race, sexual orientation, gender identity, and other individual characteristics. And if it’s not a choice, if it’s not a behavior, then it deserves the same protections.

At the same time, people with obesity deserve to seek evidence-based treatment, just as those at higher weights who experience no weight or adiposity-related health issues deserve not to be identified as having a disease simply because of their size.

If we all follow the science, we might yet turn a common understanding into more equitable outcomes for all.

Dr. Ramos Salas and Mr. Hussey are research consultants for Replica Communications, Hamilton, Ont. She disclosed ties with the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, European Association for the Study of Obesity, Novo Nordisk, Obesity Canada, The Obesity Society, World Obesity, and the World Health Organization. Mr. Hussey disclosed ties with the European Association for the Study of Obesity, Novo Nordisk, Obesity Canada, and the World Health Organization (Nutrition and Food Safety).

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Legislators in New York City recently approved a bill specifically prohibiting weight- and height-based discrimination, on par with existing protections for gender, race, sexual orientation, and other personal identities. Other U.S. cities, as well as New York state, are considering similar moves.

Weight-based discrimination in the United States has increased by an estimated 66% over the past decade, putting it on par with the prevalence of racial discrimination. More than 40% of adult Americans and 18% of children report experiencing weight discrimination in employment, school, and/or health care settings – as well as within interpersonal relationships – demonstrating a clear need to have legal protections in place.

For obesity advocates in Canada, the news from New York triggered a moment of reflection to consider how our own advocacy efforts have fared over the years, or not. Just like in the United States, body size and obesity (and appearance in general) are not specifically protected grounds under human rights legislation in Canada (for example, the Canadian Human Rights Act), unlike race, gender, sexual orientation, and religion.

Case law is uneven across the Canadian provinces when it comes to determining whether obesity is even a disease and/or a disability. And despite broad support for anti–weight discrimination policies in Canada (Front Public Health. 2023 Apr 17;11:1060794; Milbank Q. 2015 Dec;93[4]:691-731), years of advocacy at the national and provincial levels have not led to any legislative changes (Ramos Salas Obes Rev. 2017 Nov;18[11]:1323-35; Can J Diabetes. 2015 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2015.01.009). A 2017 private members bill seeking to add protection for body size to Manitoba’s human rights code was defeated, with many members of the legislature citing enforcement difficulties as the reason for voting down the proposition.

Some obesity advocates have argued that people living with obesity can be protected under the grounds of disability in the Canadian Human Rights Act. To be protected, however, individuals must demonstrate that there is actual or perceived disability relating to their weight or size; yet, many people living with obesity and those who have a higher weight don’t perceive themselves as having a disability.

In our view, the disparate viewpoints on the worthiness of considering body size a human rights issue could be resolved, at least partially, by wider understanding and adoption of the relatively new clinical definition of obesity. This definition holds that obesity is not about size; an obesity diagnosis can be made only when objective clinical investigations identify that excess or abnormal adiposity (fat tissue) impairs health.

While obesity advocates use the clinical definition of obesity, weight and body size proponents disagree that obesity is a chronic disease, and in fact believe that treating it as such can be stigmatizing. In a sense, this can sometimes be true, as not all people with larger bodies have obesity per the new definition but risk being identified as “unhealthy” in the clinical world. Bias, it turns out, can be a two-way street.

Regardless of the advocacy strategy used, it’s clear that specific anti–weight discrimination laws are needed in Canada. One in four Canadian adults report experiencing discrimination in their day-to-day life, with race, gender, age, and weight being the most commonly reported forms. To refuse to protect them against some, but not all, forms of discrimination is itself unjust, and is surely rooted in the age-old misinformed concept that excess weight is the result of laziness, poor food choices, and lack of physical activity, among other moral failings.

Including body size in human rights codes may provide a mechanism to seek legal remedy from discriminatory acts, but it will do little to address rampant weight bias, in the same way that race-based legal protections don’t eradicate racism. And it’s not just the legal community that fails to understand that weight is, by and large, a product of our environment and our genes. Weight bias and stigma are well documented in media, workplaces, the home, and in health care systems.

The solution, in our minds, is meaningful education across all these domains, reinforcing that weight is not a behavior, just as health is not a size. If we truly understand and embrace these concepts, then as a society we may someday recognize that body size is not a choice, just like race, sexual orientation, gender identity, and other individual characteristics. And if it’s not a choice, if it’s not a behavior, then it deserves the same protections.

At the same time, people with obesity deserve to seek evidence-based treatment, just as those at higher weights who experience no weight or adiposity-related health issues deserve not to be identified as having a disease simply because of their size.

If we all follow the science, we might yet turn a common understanding into more equitable outcomes for all.

Dr. Ramos Salas and Mr. Hussey are research consultants for Replica Communications, Hamilton, Ont. She disclosed ties with the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, European Association for the Study of Obesity, Novo Nordisk, Obesity Canada, The Obesity Society, World Obesity, and the World Health Organization. Mr. Hussey disclosed ties with the European Association for the Study of Obesity, Novo Nordisk, Obesity Canada, and the World Health Organization (Nutrition and Food Safety).

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Affirmative action 2.0

The recent decisions by the United States Supreme Court (SCOTUS) declaring the current admission policies at Harvard and the University of North Carolina illegal have sent shock waves through the university and graduate school communities. In the minds of many observers, these decisions have effectively eliminated affirmative action as a tool for leveling the playing field for ethnic minorities.

However, there are some commentators who feel that affirmative action has never been as effective as others have believed. They point out that the number of students admitted to the most selective schools is very small compared with the entire nation’s collection of colleges and universities. Regardless of where you come down on the effectiveness of past affirmative action policies, the SCOTUS decision is a done deal. It’s time to move on and begin anew our search for inclusion-promoting strategies that will pass the Court’s litmus test of legality.

I count myself among those who are optimistic that there are enough of us committed individuals that a new and better version of affirmative action is just over the horizon. Some of my supporting evidence can be found in a New York Times article by Stephanie Saul describing the admissions policy at the University of California Davis Medical School. The keystone of the university’s policy is a “socioeconomic disadvantage scale” that takes into account the applicant’s life circumstances, such as parental education and family income. This ranking – on a scale of 0 to 99 – is tossed into the standard mix of grades, test scores, essays, interviews, and recommendations. It shouldn’t surprise that UC Davis is now one of the most diverse medical schools in the United States despite the fact that California voted to ban affirmative action in 1996.

The socioeconomic disadvantage scale may, in the long run, be more effective than the current affirmative action strategies that have been race based. It certainly makes more sense to me. For example, in 2020 the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) made a significant philosophical change by broadening and deepening its focus on the social sciences. To some extent, this refocusing may have reflected the American Association of Medical Colleges’ search for more well-rounded students and, by extension, more physicians sensitive to the plight of their disadvantaged patients. By weighting the questions more toward subjects such as how bias can influence patient care, it was hoped that the newly minted physicians would view and treat patients not just as victims of illness but as multifaceted individuals who reside in an environment that may be influencing their health.

While I agree with the goal of creating physicians with a broader and more holistic view, the notion that adding questions from social science disciplines is going to achieve this goal never made much sense to me. Answering questions posed by social scientists teaching in a selective academic setting doesn’t necessarily guarantee that the applicant has a full understanding of the real-world consequences of poverty and bias.

On the other hand, an applicant’s responses to a questionnaire about the socioeconomic conditions in which she or he grew up is far more likely to unearth candidates with a deep, broad, and very personal understanding of the challenges that disadvantaged patients face. It’s another one of those been-there-know-how-it-feels kind of things. Reading a book about how to ride a bicycle cannot quite capture the challenge of balancing yourself on two thin wheels.

The pathway to becoming a practicing physician takes a minimum of 6 or 7 years. Much of that education comes in the form of watching and listening to physicians who, in turn, modeled their behavior after the cohort that preceded them in a very old system, and so on. There is no guarantee that even the most sensitively selected students will remain immune to incorporating into their practice style some of the systemic bias that will inevitably surround them. But a socioeconomic disadvantage scale is certainly worth a try.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

The recent decisions by the United States Supreme Court (SCOTUS) declaring the current admission policies at Harvard and the University of North Carolina illegal have sent shock waves through the university and graduate school communities. In the minds of many observers, these decisions have effectively eliminated affirmative action as a tool for leveling the playing field for ethnic minorities.

However, there are some commentators who feel that affirmative action has never been as effective as others have believed. They point out that the number of students admitted to the most selective schools is very small compared with the entire nation’s collection of colleges and universities. Regardless of where you come down on the effectiveness of past affirmative action policies, the SCOTUS decision is a done deal. It’s time to move on and begin anew our search for inclusion-promoting strategies that will pass the Court’s litmus test of legality.