User login

Addressing supply-demand mismatch in GI

Impacts of this supply-demand mismatch are felt daily in our GI practices as we strive to expand access in our clinics and endoscopy suites, particularly in rural and urban underserved communities. In gastroenterology, increased demand for care has been driven by a perfect storm of population growth, increased patient awareness of GI health, and rising incidence of digestive diseases.

Between 2019 and 2034, the U.S. population is expected to grow by 10.6%, while the population aged 65 and older expands by over 42%. Recent increases in the CRC screening–eligible population also have contributed to unprecedented demand for GI care. Furthermore, care delivery has become more complex and time-consuming with the evolution of personalized medicine and high prevalence of comorbid conditions. At the same time, we are faced with a dwindling supply of gastroenterology providers. In 2021, there were 15,678 practicing gastroenterologists in the U.S., over half of whom were 55 years or older. This translates to 1 gastroenterologist per 20,830 people captured in the U.S. Census.

Addressing this striking supply-demand mismatch in GI requires a multi-pronged approach that addresses its complex drivers. First and foremost, we must expand the number of GI fellowship training slots to boost our pipeline. There are approximately 1,840 GI fellows currently in training, a third of whom enter the workforce each year. While the number of GI fellowship slots in the GI fellowship match has slowly increased over time (from 525 available slots across 199 programs in 2019 to 657 slots across 230 programs in 2023), this incremental growth is dwarfed by overall need. Continued advocacy for increased funding to support expansion of training slots is necessary to further move the needle – such lobbying recently led to the addition of 1,000 new Medicare-supported graduate medical education positions across specialties over a 5-year period starting in 2020, illustrating that change is possible. At the same time, we must address the factors that are causing gastroenterologists to leave the workforce prematurely through early retirement or part-time work by investing in innovative solutions to address burnout, reduce administrative burdens, enhance the efficiency of care delivery, and maintain financial viability. By investing in our physician workforce and its sustainability, we can ensure that our profession is better prepared to meet the needs of our growing and increasingly complex patient population now and in the future.

We hope you enjoy the November issue of GI & Hepatology News and have a wonderful Thanksgiving.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

Impacts of this supply-demand mismatch are felt daily in our GI practices as we strive to expand access in our clinics and endoscopy suites, particularly in rural and urban underserved communities. In gastroenterology, increased demand for care has been driven by a perfect storm of population growth, increased patient awareness of GI health, and rising incidence of digestive diseases.

Between 2019 and 2034, the U.S. population is expected to grow by 10.6%, while the population aged 65 and older expands by over 42%. Recent increases in the CRC screening–eligible population also have contributed to unprecedented demand for GI care. Furthermore, care delivery has become more complex and time-consuming with the evolution of personalized medicine and high prevalence of comorbid conditions. At the same time, we are faced with a dwindling supply of gastroenterology providers. In 2021, there were 15,678 practicing gastroenterologists in the U.S., over half of whom were 55 years or older. This translates to 1 gastroenterologist per 20,830 people captured in the U.S. Census.

Addressing this striking supply-demand mismatch in GI requires a multi-pronged approach that addresses its complex drivers. First and foremost, we must expand the number of GI fellowship training slots to boost our pipeline. There are approximately 1,840 GI fellows currently in training, a third of whom enter the workforce each year. While the number of GI fellowship slots in the GI fellowship match has slowly increased over time (from 525 available slots across 199 programs in 2019 to 657 slots across 230 programs in 2023), this incremental growth is dwarfed by overall need. Continued advocacy for increased funding to support expansion of training slots is necessary to further move the needle – such lobbying recently led to the addition of 1,000 new Medicare-supported graduate medical education positions across specialties over a 5-year period starting in 2020, illustrating that change is possible. At the same time, we must address the factors that are causing gastroenterologists to leave the workforce prematurely through early retirement or part-time work by investing in innovative solutions to address burnout, reduce administrative burdens, enhance the efficiency of care delivery, and maintain financial viability. By investing in our physician workforce and its sustainability, we can ensure that our profession is better prepared to meet the needs of our growing and increasingly complex patient population now and in the future.

We hope you enjoy the November issue of GI & Hepatology News and have a wonderful Thanksgiving.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

Impacts of this supply-demand mismatch are felt daily in our GI practices as we strive to expand access in our clinics and endoscopy suites, particularly in rural and urban underserved communities. In gastroenterology, increased demand for care has been driven by a perfect storm of population growth, increased patient awareness of GI health, and rising incidence of digestive diseases.

Between 2019 and 2034, the U.S. population is expected to grow by 10.6%, while the population aged 65 and older expands by over 42%. Recent increases in the CRC screening–eligible population also have contributed to unprecedented demand for GI care. Furthermore, care delivery has become more complex and time-consuming with the evolution of personalized medicine and high prevalence of comorbid conditions. At the same time, we are faced with a dwindling supply of gastroenterology providers. In 2021, there were 15,678 practicing gastroenterologists in the U.S., over half of whom were 55 years or older. This translates to 1 gastroenterologist per 20,830 people captured in the U.S. Census.

Addressing this striking supply-demand mismatch in GI requires a multi-pronged approach that addresses its complex drivers. First and foremost, we must expand the number of GI fellowship training slots to boost our pipeline. There are approximately 1,840 GI fellows currently in training, a third of whom enter the workforce each year. While the number of GI fellowship slots in the GI fellowship match has slowly increased over time (from 525 available slots across 199 programs in 2019 to 657 slots across 230 programs in 2023), this incremental growth is dwarfed by overall need. Continued advocacy for increased funding to support expansion of training slots is necessary to further move the needle – such lobbying recently led to the addition of 1,000 new Medicare-supported graduate medical education positions across specialties over a 5-year period starting in 2020, illustrating that change is possible. At the same time, we must address the factors that are causing gastroenterologists to leave the workforce prematurely through early retirement or part-time work by investing in innovative solutions to address burnout, reduce administrative burdens, enhance the efficiency of care delivery, and maintain financial viability. By investing in our physician workforce and its sustainability, we can ensure that our profession is better prepared to meet the needs of our growing and increasingly complex patient population now and in the future.

We hope you enjoy the November issue of GI & Hepatology News and have a wonderful Thanksgiving.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

Selecting therapies in moderate to severe inflammatory bowel disease: Key factors in decision making

Despite new advances in treatment, head to head clinical trials, which are considered the gold standard when comparing therapies, remain limited. Other comparative effectiveness studies and network meta-analyses are the currently available substitutes to guide decision making.1

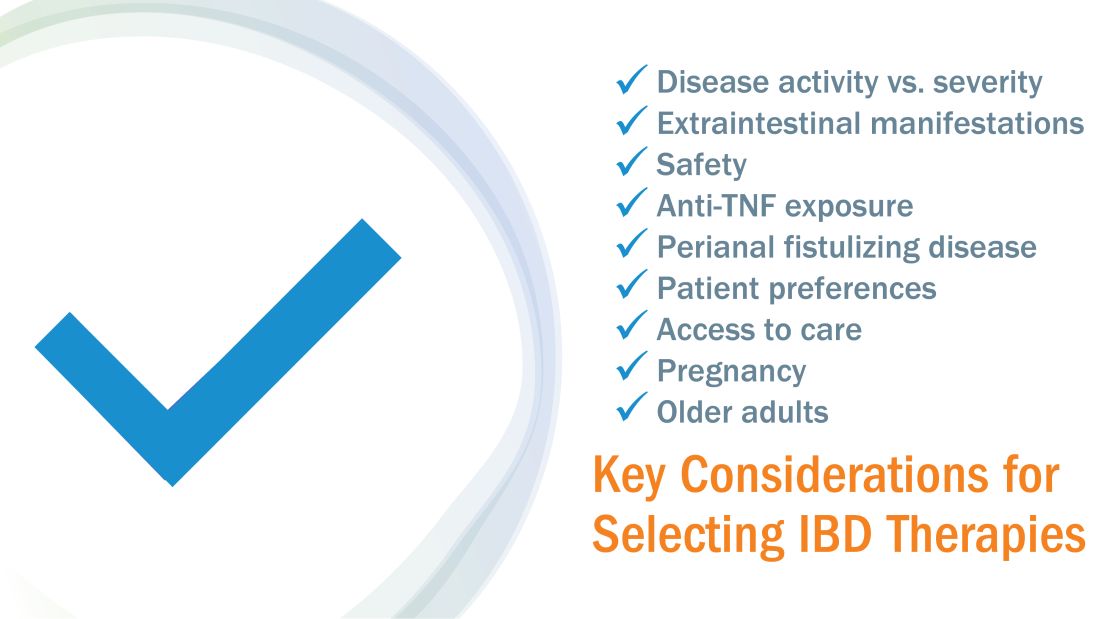

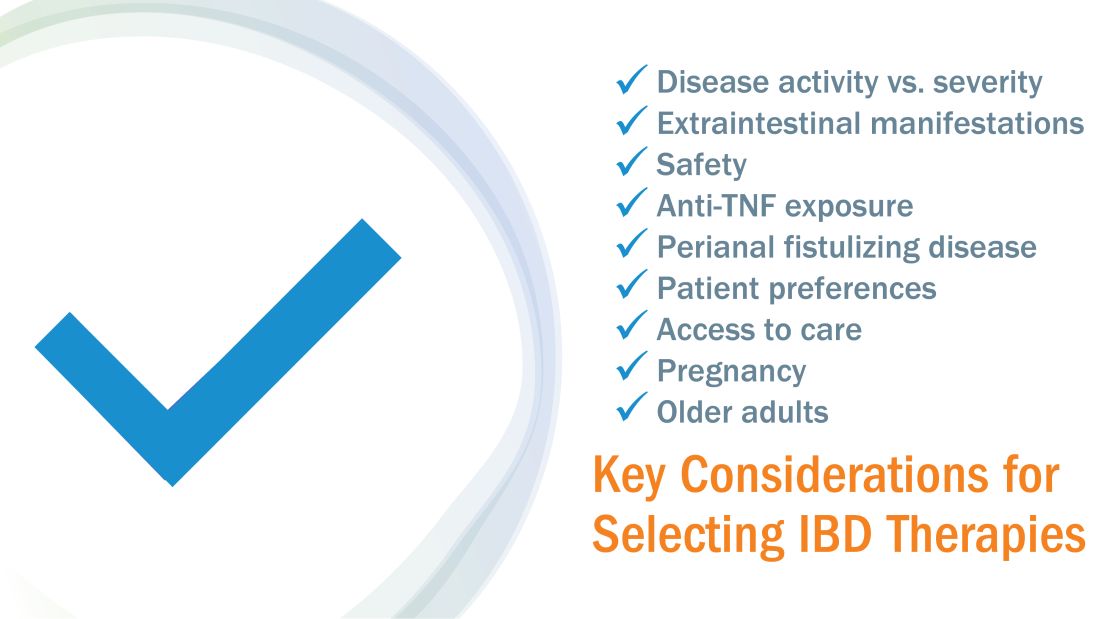

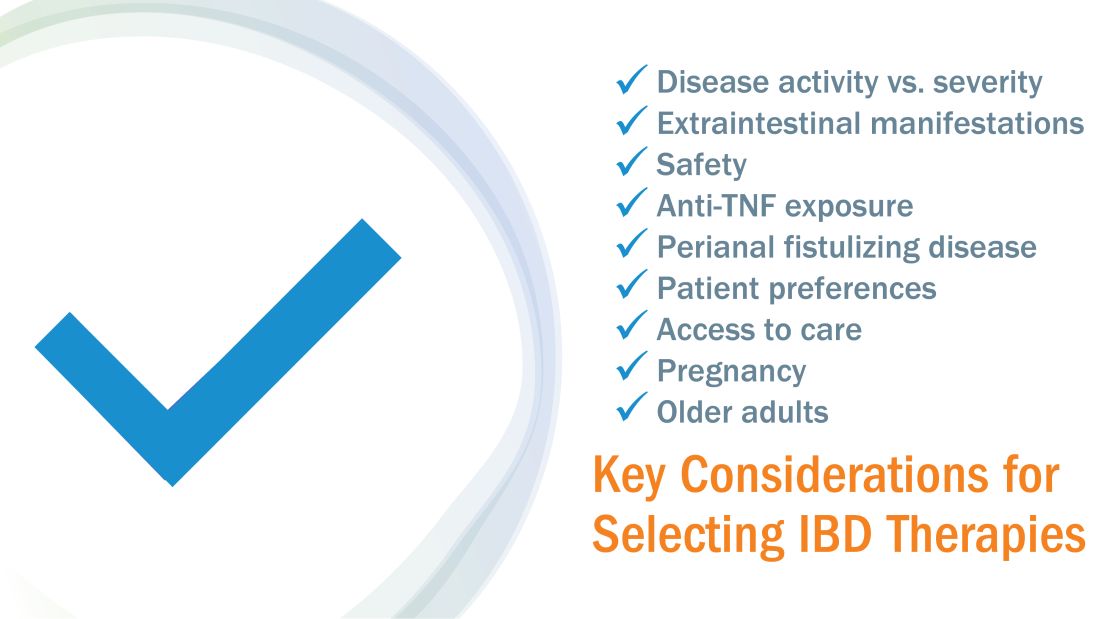

While efficacy is often considered first when choosing a drug, other critical factors play a role in tailoring a treatment plan. This article focuses on key considerations to help guide clinical decision making when treating patients with moderate to severe IBD (Figure 1).

Disease activity versus severity

Both disease activity and disease severity should be considered when evaluating a patient for treatment. Disease activity is a cross-sectional view of one’s signs and symptoms which can vary visit to visit. Standardized indices measure disease activity in both Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).2,3 Disease severity encompasses the overall prognosis of disease over time and includes factors such as the presence or absence of high risk features, prior medication exposure, history of surgery, hospitalizations and the impact on quality of life.4

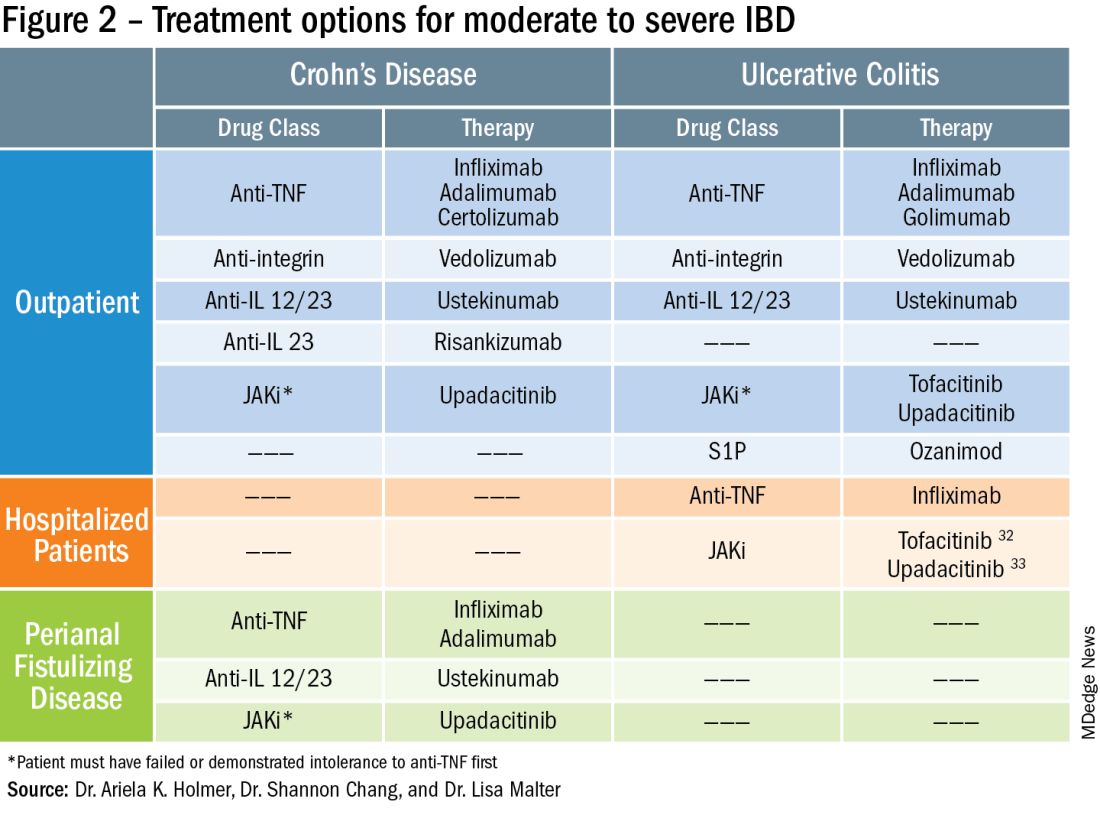

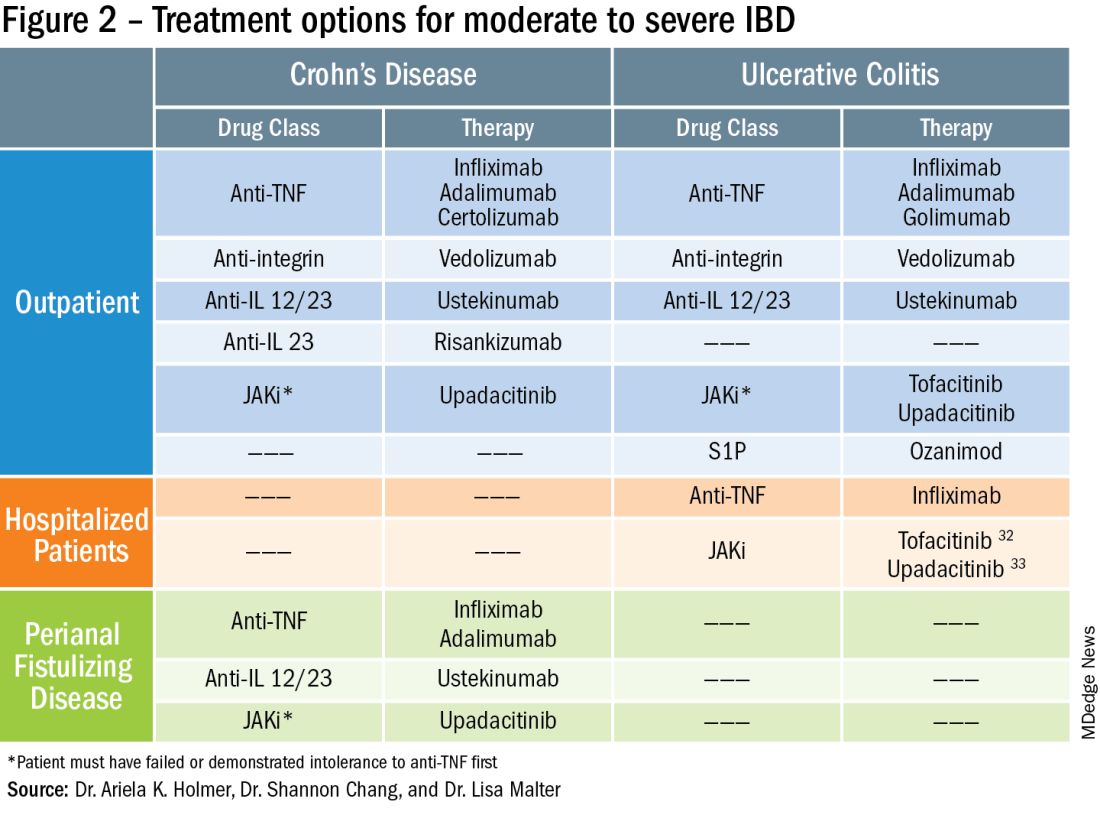

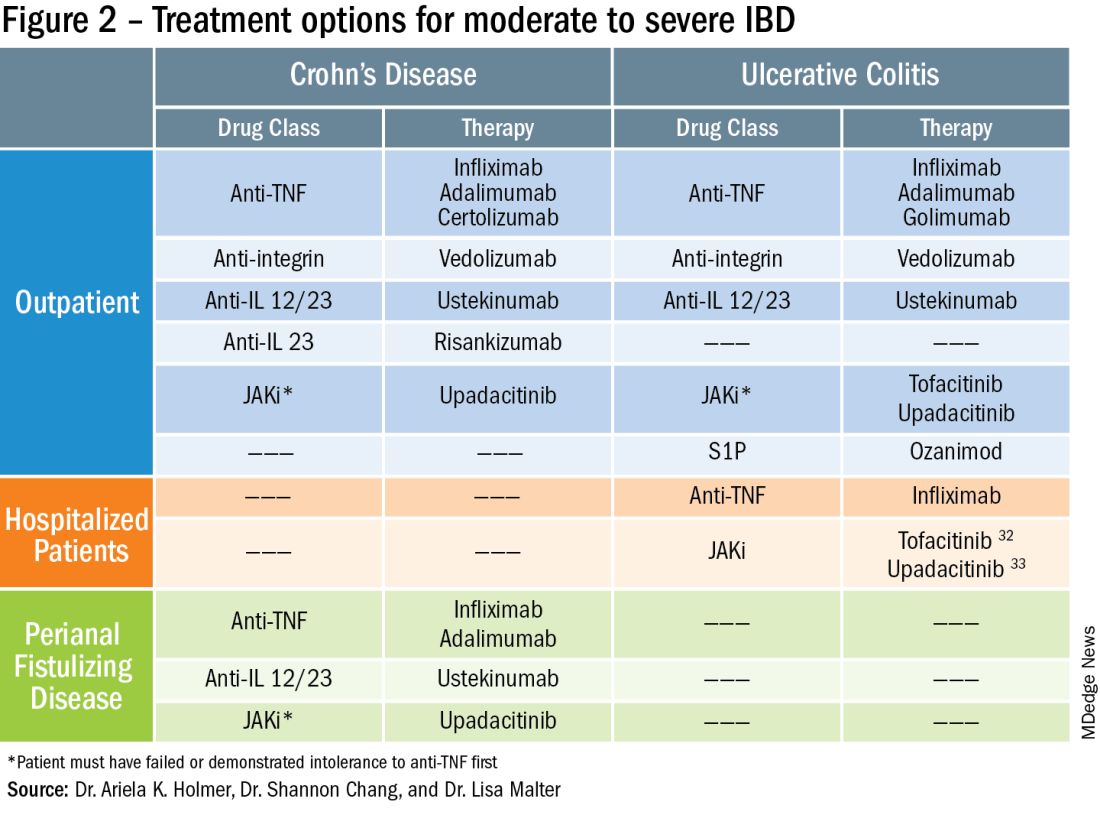

To prevent disease complications, the goals of treatment should be aimed at both reducing active symptoms (disease activity) but also healing mucosal inflammation, preventing disease progression (disease severity) and downstream sequelae including cancer, hospitalization or surgery.5 Determining the best treatment option takes disease activity and severity into account, in addition to the other key factors listed below (Figure 2).

Extraintestinal manifestations

Inflammation of organs outside of the gastrointestinal tract is common and can occur in up to 50% of patients with IBD.6 The most prevalent extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) involve the skin and joints, which will be the primary focus in this article. We will also focus on treatment options with the most evidence supporting their use. Peripheral arthritis is often associated with intestinal inflammation, and treatment of underlying IBD can simultaneously improve joint symptoms. Conversely, axial spondyloarthritis does not commonly parallel intestinal inflammation. Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents including infliximab and adalimumab are effective for the treatment of both peripheral and axial disease.6

Ustekinumab, an interleukin (IL)-12/23 inhibitor, may be effective for peripheral arthritis, however is ineffective for the treatment of axial spondyloarthritis.6 Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors which include tofacitinib and upadacitinib are oral small molecules used to treat peripheral and axial spondyloarthritis and have more recently been approved for moderate to severe IBD.6,7

Erythema nodosum (EN) and pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) are skin manifestations seen in patients with IBD. EN appears as subcutaneous nodules and parallels intestinal inflammation, while PG consists of violaceous, ulcerated plaques, and presents with more significant pain. Anti-TNFs are effective for both EN and PG, with infliximab being the only biologic studied in a randomized control trial of patients with PG.8 In addition, small case reports have described some benefit from ustekinumab and upadacitinib in the treatment of PG.9,10

Safety

The safety of IBD therapies is a key consideration and often the most important factor to patients when choosing a treatment option. It is important to note that untreated disease is associated with significant morbidity, and should be weighed when discussing risks of medications with patients. In general, anti-TNFs and JAK inhibitors may be associated with an increased risk of infection and malignancy, while ustekinumab, vedolizumab, risankizumab and ozanimod offer a more favorable safety profile.11 In large registries and observational studies, infliximab was associated with up to a two times greater risk of serious infection as compared to nonbiologic medications, with the most common infections being pneumonia, sepsis and herpes zoster.12 JAK inhibitors are associated with an increased risk of herpes zoster infection, with a dose dependent effect seen in the maintenance clinical trials with tofacitinib.7

Ozanimod may be associated with atrioventricular conduction delays and bradycardia, however long-term safety data has reported a low incidence of serious cardiac related adverse events.13 Overall, though risks of infection may vary with different therapies, other consistent risk factors associated with greater rates of serious infection include prolonged corticosteroid use, combination therapy with thiopurines, and disease severity. Anti-TNFs have also been associated with a somewhat increased risk of lymphoma, increased when used in combination with thiopurines. Reassuringly, however, in patients with a prior history of cancer, anti-TNFs and non-TNF biologics have not been found to increase the risk of new or recurrent cancer.14

Ultimately, in patients with a prior history of cancer, the choice of biologic or small molecule should be made in collaboration with a patient’s oncologist.

Anti-TNF exposure

Anti-TNFs were the first available biologics for the treatment of IBD. After the approval of vedolizumab in 2014, the first non-TNF biologic, many patients enrolled in clinical trials thereafter had already tried and failed anti-TNFs. In general, exposure to anti-TNFs may reduce the efficacy of a future biologic. In patients treated with vedolizumab, endoscopic and clinical outcomes were negatively impacted by prior anti-TNF exposure.15 However, in VARSITY, a head-to-head clinical trial where 20% of patients with UC were previously exposed to anti-TNFs other than adalimumab, vedolizumab had significantly higher rates of clinical remission and endoscopic improvement compared to adalimumab.16 Clinical remission rates with tofacitinib were not impacted by exposure to anti-TNF treatment, and similar findings were observed with ustekinumab.7,17 Risankizumab, a newly approved selective anti-IL23, also does not appear to be impacted by prior anti-TNF exposure by demonstrating similar rates of clinical remission regardless of biologic exposure status.18 Therefore, in patients with prior history of anti-TNF use, consideration of ustekinumab, risankizumab or JAK inhibitors as second line agents may be more favorable as compared to vedolizumab.

Perianal fistulizing disease

Perianal fistulizing disease can affect up to one-third of patients with CD and significantly impact a patient’s quality of life.19 The most robust data for the treatment of perianal fistulizing disease includes the use of infliximab with up to one-third of patients on maintenance therapy achieving complete resolution of fistula drainage. While no head-to-head trials compare combination therapy with infliximab plus immunomodulators versus infliximab alone for this indication specifically, one observational study demonstrated higher rates of fistula closure with combination therapy as compared to infliximab mono-therapy.19 In a post hoc analysis, higher infliximab concentrations at week 14 were associated with greater fistula response and remission rates.20 In patients with perianal disease, ustekinumab and vedolizumab may also be an effective treatment option by promoting resolution of fistula drainage.21

More recently, emerging data demonstrate that upadacitinib may be an excellent option as a second-line treatment for perianal disease in patients who have failed anti-TNF therapy. Use of upadacitinib was associated with greater rates of complete resolution of fistula drainage and higher rates of external fistula closure (Figure 2).22 Lastly, as an alternative to medical therapy, mesenchymal stem cell therapy has also shown to improve fistula drainage and improve external fistula openings in patients with CD.23 Stem cell therapy is only available through clinical trials at this time.

Patient preferences

Overall, data are lacking for evaluating patient preferences in treatment options for IBD especially with the recent increase in therapeutic options. One survey demonstrated that patient preferences were most impacted by the possibility of improving abdominal pain, with patients accepting additional risk of treatment side effects in order to reduce their abdominal pain.24 An oral route of administration and improving fatigue and bowel urgency were similarly important to patients. Patient preferences can also be highly variable with some valuing avoidance of corticosteroid use while others valuing avoidance of symptoms or risks of medication side effects and surgery. It is important to tailor the discussion on treatment strategies to each individual patient and inquire about the patient’s lifestyle, medical history, and value system, which may impact their treatment preferences utilizing shared decision making.

Access to treatment including the role of social determinants of health

The expanded therapeutic armamentarium has the potential to help patients achieve the current goals of care in IBD. However, these medications are not available to all patients due to numerous barriers including step therapy payer policies, prohibitive costs, insurance prior authorizations, and the role of social determinants of health and proximity to IBD expertise.25 While clinicians work with patients to determine the best treatment option, more often than not, the decision lies with the insurance payer. Step therapy is the protocol used by insurance companies that requires patients to try a lower-cost medication and fail to respond before they approve the originally requested treatment. This can lead to treatment delays, progression of disease, and disease complications. The option to incorporate the use of biosimilars, currently available for anti-TNFs, and other biologics in the near future, will reduce cost and potentially increase access.26 Additionally, working with a clinical pharmacist to navigate access and utilize patient assistance programs may help overcome cost related barriers to treatment and prevent delays in care.

Socioeconomic status has been shown to impact IBD disease outcomes, and compliance rates in treatment vary depending on race and ethnicity.27 Certain racial and ethnic groups remain vulnerable and may require additional support to achieve treatment goals. For example, disparities in health literacy in patients with IBD have been demonstrated with older black men at risk.28 Additionally, the patient’s proximity to their health care facility may impact treatment options. Most IBD centers are located in metropolitan areas and numerous “IBD deserts” exist, potentially limiting therapies for patients from more remote/rural settings.29 Access to treatment and the interplay of social determinants of health can have a large role in therapy selection.

Special considerations: Pregnancy and older adults

Certain patient populations warrant special consideration when approaching treatment strategies. Pregnancy in IBD will not be addressed in full depth in this article, however a key takeaway is that planning is critical and providers should emphasize the importance of steroid-free clinical remission for at least 3 months before conception.30 Additionally, biologic use during pregnancy has not been shown to increase adverse fetal outcomes, thus should be continued to minimize disease flare. Newer novel small molecules are generally avoided during pregnancy due to limited available safety data.

Older adults are the largest growing patient population with IBD. Frailty, or a state of decreased reserve, is more commonly observed in older patients and has been shown to increase adverse events including hospitalization and mortaility.31 Ultimately reducing polypharmacy, ensuring adequate nutrition, minimizing corticosteroid exposure and avoiding undertreatment of active IBD are all key in optimizing outcomes in an older patient with IBD.

Conclusion

When discussing treatment options with patients with IBD, it is important to individualize care and share the decision-making process with patients. Goals include improving symptoms and quality of life while working to achieve the goal of healing intestinal inflammation. In summary, this article can serve as a guide to clinicians for key factors in decision making when selecting therapies in moderate to severe IBD.

Dr. Holmer is a gastroenterologist with NYU Langone Health specializing in inflammatory bowel disease. Dr. Chang is director of clinical operations for the NYU Langone Health Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center. Dr. Malter is director of education for the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at NYU Langone Health and director of the inflammatory bowel disease program at Bellevue Hospital Center. Follow Dr. Holmer on X (formerly Twitter) at @HolmerMd and Dr. Chang @shannonchangmd. Dr. Holmer disclosed affiliations with Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, and AvevoRx. Dr. Chang disclosed affiliations with Pfizer and Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr. Malter disclosed receiving educational grants form Abbvie, Janssen, Pfizer and Takeda, and serving on the advisory boards of AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Janssen, Merck, and Takeda.

References

1. Chang S et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023 Aug 24. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002485.

2. Harvey RF et al. The Lancet. 1980;1:514.

3. Lewis JD et al. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2008;14:1660-1666.

4. Siegel CA et al. Gut. 2018;67(2):244-54.

5. Peyrin-Biroulet L et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1324-38

6. Rogler G et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1118-32.

7. Sandborn WJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1723-36.

8. Brooklyn TN et al. Gut. 2006;55:505-9.

9. Fahmy M et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:794-5.

10. Van Eycken L et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;37:89-91.

11. Lasa JS et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:161-70.

12. Lichtenstein GR et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:490-501.

13. Long MD et al. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:S-5-S-6.

14. Holmer AK et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.2023;21:1598-1606.e5.

15. Sands BE et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:618-27.e3.

16. Sands BE et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1215-26.

17. Sands BE et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1201-14.

18. D’Haens G et al. Lancet. 2022;399:2015-30.

19. Bouguen G et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:975-81.e1-4.

20. Papamichael K et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:1007-14.

21. Shehab M et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29:367-75.

22. Colombel JF et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:i620-i623.

23. Garcia-Olmo D et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65:713-20.

24. Louis E et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:231-9.

25. Rubin DT et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:224-32.

26. Gulacsi L et al. Curr Med Chem. 2019;26:259-69.

27. Cai Q et al. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:545.

28. Dos Santos Marques IC et al. Crohns Colitis 360. 2020 Oct;2(4):otaa076.

29. Deepak P et al. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:11-15.

30. Mahadevan U et al. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1508-24.

31. Faye AS et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28:126-32.

32. Berinstein JA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:2112-20.e1.

33. Levine J et al. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:S103-S104.

Despite new advances in treatment, head to head clinical trials, which are considered the gold standard when comparing therapies, remain limited. Other comparative effectiveness studies and network meta-analyses are the currently available substitutes to guide decision making.1

While efficacy is often considered first when choosing a drug, other critical factors play a role in tailoring a treatment plan. This article focuses on key considerations to help guide clinical decision making when treating patients with moderate to severe IBD (Figure 1).

Disease activity versus severity

Both disease activity and disease severity should be considered when evaluating a patient for treatment. Disease activity is a cross-sectional view of one’s signs and symptoms which can vary visit to visit. Standardized indices measure disease activity in both Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).2,3 Disease severity encompasses the overall prognosis of disease over time and includes factors such as the presence or absence of high risk features, prior medication exposure, history of surgery, hospitalizations and the impact on quality of life.4

To prevent disease complications, the goals of treatment should be aimed at both reducing active symptoms (disease activity) but also healing mucosal inflammation, preventing disease progression (disease severity) and downstream sequelae including cancer, hospitalization or surgery.5 Determining the best treatment option takes disease activity and severity into account, in addition to the other key factors listed below (Figure 2).

Extraintestinal manifestations

Inflammation of organs outside of the gastrointestinal tract is common and can occur in up to 50% of patients with IBD.6 The most prevalent extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) involve the skin and joints, which will be the primary focus in this article. We will also focus on treatment options with the most evidence supporting their use. Peripheral arthritis is often associated with intestinal inflammation, and treatment of underlying IBD can simultaneously improve joint symptoms. Conversely, axial spondyloarthritis does not commonly parallel intestinal inflammation. Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents including infliximab and adalimumab are effective for the treatment of both peripheral and axial disease.6

Ustekinumab, an interleukin (IL)-12/23 inhibitor, may be effective for peripheral arthritis, however is ineffective for the treatment of axial spondyloarthritis.6 Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors which include tofacitinib and upadacitinib are oral small molecules used to treat peripheral and axial spondyloarthritis and have more recently been approved for moderate to severe IBD.6,7

Erythema nodosum (EN) and pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) are skin manifestations seen in patients with IBD. EN appears as subcutaneous nodules and parallels intestinal inflammation, while PG consists of violaceous, ulcerated plaques, and presents with more significant pain. Anti-TNFs are effective for both EN and PG, with infliximab being the only biologic studied in a randomized control trial of patients with PG.8 In addition, small case reports have described some benefit from ustekinumab and upadacitinib in the treatment of PG.9,10

Safety

The safety of IBD therapies is a key consideration and often the most important factor to patients when choosing a treatment option. It is important to note that untreated disease is associated with significant morbidity, and should be weighed when discussing risks of medications with patients. In general, anti-TNFs and JAK inhibitors may be associated with an increased risk of infection and malignancy, while ustekinumab, vedolizumab, risankizumab and ozanimod offer a more favorable safety profile.11 In large registries and observational studies, infliximab was associated with up to a two times greater risk of serious infection as compared to nonbiologic medications, with the most common infections being pneumonia, sepsis and herpes zoster.12 JAK inhibitors are associated with an increased risk of herpes zoster infection, with a dose dependent effect seen in the maintenance clinical trials with tofacitinib.7

Ozanimod may be associated with atrioventricular conduction delays and bradycardia, however long-term safety data has reported a low incidence of serious cardiac related adverse events.13 Overall, though risks of infection may vary with different therapies, other consistent risk factors associated with greater rates of serious infection include prolonged corticosteroid use, combination therapy with thiopurines, and disease severity. Anti-TNFs have also been associated with a somewhat increased risk of lymphoma, increased when used in combination with thiopurines. Reassuringly, however, in patients with a prior history of cancer, anti-TNFs and non-TNF biologics have not been found to increase the risk of new or recurrent cancer.14

Ultimately, in patients with a prior history of cancer, the choice of biologic or small molecule should be made in collaboration with a patient’s oncologist.

Anti-TNF exposure

Anti-TNFs were the first available biologics for the treatment of IBD. After the approval of vedolizumab in 2014, the first non-TNF biologic, many patients enrolled in clinical trials thereafter had already tried and failed anti-TNFs. In general, exposure to anti-TNFs may reduce the efficacy of a future biologic. In patients treated with vedolizumab, endoscopic and clinical outcomes were negatively impacted by prior anti-TNF exposure.15 However, in VARSITY, a head-to-head clinical trial where 20% of patients with UC were previously exposed to anti-TNFs other than adalimumab, vedolizumab had significantly higher rates of clinical remission and endoscopic improvement compared to adalimumab.16 Clinical remission rates with tofacitinib were not impacted by exposure to anti-TNF treatment, and similar findings were observed with ustekinumab.7,17 Risankizumab, a newly approved selective anti-IL23, also does not appear to be impacted by prior anti-TNF exposure by demonstrating similar rates of clinical remission regardless of biologic exposure status.18 Therefore, in patients with prior history of anti-TNF use, consideration of ustekinumab, risankizumab or JAK inhibitors as second line agents may be more favorable as compared to vedolizumab.

Perianal fistulizing disease

Perianal fistulizing disease can affect up to one-third of patients with CD and significantly impact a patient’s quality of life.19 The most robust data for the treatment of perianal fistulizing disease includes the use of infliximab with up to one-third of patients on maintenance therapy achieving complete resolution of fistula drainage. While no head-to-head trials compare combination therapy with infliximab plus immunomodulators versus infliximab alone for this indication specifically, one observational study demonstrated higher rates of fistula closure with combination therapy as compared to infliximab mono-therapy.19 In a post hoc analysis, higher infliximab concentrations at week 14 were associated with greater fistula response and remission rates.20 In patients with perianal disease, ustekinumab and vedolizumab may also be an effective treatment option by promoting resolution of fistula drainage.21

More recently, emerging data demonstrate that upadacitinib may be an excellent option as a second-line treatment for perianal disease in patients who have failed anti-TNF therapy. Use of upadacitinib was associated with greater rates of complete resolution of fistula drainage and higher rates of external fistula closure (Figure 2).22 Lastly, as an alternative to medical therapy, mesenchymal stem cell therapy has also shown to improve fistula drainage and improve external fistula openings in patients with CD.23 Stem cell therapy is only available through clinical trials at this time.

Patient preferences

Overall, data are lacking for evaluating patient preferences in treatment options for IBD especially with the recent increase in therapeutic options. One survey demonstrated that patient preferences were most impacted by the possibility of improving abdominal pain, with patients accepting additional risk of treatment side effects in order to reduce their abdominal pain.24 An oral route of administration and improving fatigue and bowel urgency were similarly important to patients. Patient preferences can also be highly variable with some valuing avoidance of corticosteroid use while others valuing avoidance of symptoms or risks of medication side effects and surgery. It is important to tailor the discussion on treatment strategies to each individual patient and inquire about the patient’s lifestyle, medical history, and value system, which may impact their treatment preferences utilizing shared decision making.

Access to treatment including the role of social determinants of health

The expanded therapeutic armamentarium has the potential to help patients achieve the current goals of care in IBD. However, these medications are not available to all patients due to numerous barriers including step therapy payer policies, prohibitive costs, insurance prior authorizations, and the role of social determinants of health and proximity to IBD expertise.25 While clinicians work with patients to determine the best treatment option, more often than not, the decision lies with the insurance payer. Step therapy is the protocol used by insurance companies that requires patients to try a lower-cost medication and fail to respond before they approve the originally requested treatment. This can lead to treatment delays, progression of disease, and disease complications. The option to incorporate the use of biosimilars, currently available for anti-TNFs, and other biologics in the near future, will reduce cost and potentially increase access.26 Additionally, working with a clinical pharmacist to navigate access and utilize patient assistance programs may help overcome cost related barriers to treatment and prevent delays in care.

Socioeconomic status has been shown to impact IBD disease outcomes, and compliance rates in treatment vary depending on race and ethnicity.27 Certain racial and ethnic groups remain vulnerable and may require additional support to achieve treatment goals. For example, disparities in health literacy in patients with IBD have been demonstrated with older black men at risk.28 Additionally, the patient’s proximity to their health care facility may impact treatment options. Most IBD centers are located in metropolitan areas and numerous “IBD deserts” exist, potentially limiting therapies for patients from more remote/rural settings.29 Access to treatment and the interplay of social determinants of health can have a large role in therapy selection.

Special considerations: Pregnancy and older adults

Certain patient populations warrant special consideration when approaching treatment strategies. Pregnancy in IBD will not be addressed in full depth in this article, however a key takeaway is that planning is critical and providers should emphasize the importance of steroid-free clinical remission for at least 3 months before conception.30 Additionally, biologic use during pregnancy has not been shown to increase adverse fetal outcomes, thus should be continued to minimize disease flare. Newer novel small molecules are generally avoided during pregnancy due to limited available safety data.

Older adults are the largest growing patient population with IBD. Frailty, or a state of decreased reserve, is more commonly observed in older patients and has been shown to increase adverse events including hospitalization and mortaility.31 Ultimately reducing polypharmacy, ensuring adequate nutrition, minimizing corticosteroid exposure and avoiding undertreatment of active IBD are all key in optimizing outcomes in an older patient with IBD.

Conclusion

When discussing treatment options with patients with IBD, it is important to individualize care and share the decision-making process with patients. Goals include improving symptoms and quality of life while working to achieve the goal of healing intestinal inflammation. In summary, this article can serve as a guide to clinicians for key factors in decision making when selecting therapies in moderate to severe IBD.

Dr. Holmer is a gastroenterologist with NYU Langone Health specializing in inflammatory bowel disease. Dr. Chang is director of clinical operations for the NYU Langone Health Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center. Dr. Malter is director of education for the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at NYU Langone Health and director of the inflammatory bowel disease program at Bellevue Hospital Center. Follow Dr. Holmer on X (formerly Twitter) at @HolmerMd and Dr. Chang @shannonchangmd. Dr. Holmer disclosed affiliations with Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, and AvevoRx. Dr. Chang disclosed affiliations with Pfizer and Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr. Malter disclosed receiving educational grants form Abbvie, Janssen, Pfizer and Takeda, and serving on the advisory boards of AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Janssen, Merck, and Takeda.

References

1. Chang S et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023 Aug 24. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002485.

2. Harvey RF et al. The Lancet. 1980;1:514.

3. Lewis JD et al. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2008;14:1660-1666.

4. Siegel CA et al. Gut. 2018;67(2):244-54.

5. Peyrin-Biroulet L et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1324-38

6. Rogler G et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1118-32.

7. Sandborn WJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1723-36.

8. Brooklyn TN et al. Gut. 2006;55:505-9.

9. Fahmy M et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:794-5.

10. Van Eycken L et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;37:89-91.

11. Lasa JS et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:161-70.

12. Lichtenstein GR et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:490-501.

13. Long MD et al. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:S-5-S-6.

14. Holmer AK et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.2023;21:1598-1606.e5.

15. Sands BE et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:618-27.e3.

16. Sands BE et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1215-26.

17. Sands BE et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1201-14.

18. D’Haens G et al. Lancet. 2022;399:2015-30.

19. Bouguen G et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:975-81.e1-4.

20. Papamichael K et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:1007-14.

21. Shehab M et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29:367-75.

22. Colombel JF et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:i620-i623.

23. Garcia-Olmo D et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65:713-20.

24. Louis E et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:231-9.

25. Rubin DT et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:224-32.

26. Gulacsi L et al. Curr Med Chem. 2019;26:259-69.

27. Cai Q et al. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:545.

28. Dos Santos Marques IC et al. Crohns Colitis 360. 2020 Oct;2(4):otaa076.

29. Deepak P et al. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:11-15.

30. Mahadevan U et al. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1508-24.

31. Faye AS et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28:126-32.

32. Berinstein JA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:2112-20.e1.

33. Levine J et al. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:S103-S104.

Despite new advances in treatment, head to head clinical trials, which are considered the gold standard when comparing therapies, remain limited. Other comparative effectiveness studies and network meta-analyses are the currently available substitutes to guide decision making.1

While efficacy is often considered first when choosing a drug, other critical factors play a role in tailoring a treatment plan. This article focuses on key considerations to help guide clinical decision making when treating patients with moderate to severe IBD (Figure 1).

Disease activity versus severity

Both disease activity and disease severity should be considered when evaluating a patient for treatment. Disease activity is a cross-sectional view of one’s signs and symptoms which can vary visit to visit. Standardized indices measure disease activity in both Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).2,3 Disease severity encompasses the overall prognosis of disease over time and includes factors such as the presence or absence of high risk features, prior medication exposure, history of surgery, hospitalizations and the impact on quality of life.4

To prevent disease complications, the goals of treatment should be aimed at both reducing active symptoms (disease activity) but also healing mucosal inflammation, preventing disease progression (disease severity) and downstream sequelae including cancer, hospitalization or surgery.5 Determining the best treatment option takes disease activity and severity into account, in addition to the other key factors listed below (Figure 2).

Extraintestinal manifestations

Inflammation of organs outside of the gastrointestinal tract is common and can occur in up to 50% of patients with IBD.6 The most prevalent extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) involve the skin and joints, which will be the primary focus in this article. We will also focus on treatment options with the most evidence supporting their use. Peripheral arthritis is often associated with intestinal inflammation, and treatment of underlying IBD can simultaneously improve joint symptoms. Conversely, axial spondyloarthritis does not commonly parallel intestinal inflammation. Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents including infliximab and adalimumab are effective for the treatment of both peripheral and axial disease.6

Ustekinumab, an interleukin (IL)-12/23 inhibitor, may be effective for peripheral arthritis, however is ineffective for the treatment of axial spondyloarthritis.6 Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors which include tofacitinib and upadacitinib are oral small molecules used to treat peripheral and axial spondyloarthritis and have more recently been approved for moderate to severe IBD.6,7

Erythema nodosum (EN) and pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) are skin manifestations seen in patients with IBD. EN appears as subcutaneous nodules and parallels intestinal inflammation, while PG consists of violaceous, ulcerated plaques, and presents with more significant pain. Anti-TNFs are effective for both EN and PG, with infliximab being the only biologic studied in a randomized control trial of patients with PG.8 In addition, small case reports have described some benefit from ustekinumab and upadacitinib in the treatment of PG.9,10

Safety

The safety of IBD therapies is a key consideration and often the most important factor to patients when choosing a treatment option. It is important to note that untreated disease is associated with significant morbidity, and should be weighed when discussing risks of medications with patients. In general, anti-TNFs and JAK inhibitors may be associated with an increased risk of infection and malignancy, while ustekinumab, vedolizumab, risankizumab and ozanimod offer a more favorable safety profile.11 In large registries and observational studies, infliximab was associated with up to a two times greater risk of serious infection as compared to nonbiologic medications, with the most common infections being pneumonia, sepsis and herpes zoster.12 JAK inhibitors are associated with an increased risk of herpes zoster infection, with a dose dependent effect seen in the maintenance clinical trials with tofacitinib.7

Ozanimod may be associated with atrioventricular conduction delays and bradycardia, however long-term safety data has reported a low incidence of serious cardiac related adverse events.13 Overall, though risks of infection may vary with different therapies, other consistent risk factors associated with greater rates of serious infection include prolonged corticosteroid use, combination therapy with thiopurines, and disease severity. Anti-TNFs have also been associated with a somewhat increased risk of lymphoma, increased when used in combination with thiopurines. Reassuringly, however, in patients with a prior history of cancer, anti-TNFs and non-TNF biologics have not been found to increase the risk of new or recurrent cancer.14

Ultimately, in patients with a prior history of cancer, the choice of biologic or small molecule should be made in collaboration with a patient’s oncologist.

Anti-TNF exposure

Anti-TNFs were the first available biologics for the treatment of IBD. After the approval of vedolizumab in 2014, the first non-TNF biologic, many patients enrolled in clinical trials thereafter had already tried and failed anti-TNFs. In general, exposure to anti-TNFs may reduce the efficacy of a future biologic. In patients treated with vedolizumab, endoscopic and clinical outcomes were negatively impacted by prior anti-TNF exposure.15 However, in VARSITY, a head-to-head clinical trial where 20% of patients with UC were previously exposed to anti-TNFs other than adalimumab, vedolizumab had significantly higher rates of clinical remission and endoscopic improvement compared to adalimumab.16 Clinical remission rates with tofacitinib were not impacted by exposure to anti-TNF treatment, and similar findings were observed with ustekinumab.7,17 Risankizumab, a newly approved selective anti-IL23, also does not appear to be impacted by prior anti-TNF exposure by demonstrating similar rates of clinical remission regardless of biologic exposure status.18 Therefore, in patients with prior history of anti-TNF use, consideration of ustekinumab, risankizumab or JAK inhibitors as second line agents may be more favorable as compared to vedolizumab.

Perianal fistulizing disease

Perianal fistulizing disease can affect up to one-third of patients with CD and significantly impact a patient’s quality of life.19 The most robust data for the treatment of perianal fistulizing disease includes the use of infliximab with up to one-third of patients on maintenance therapy achieving complete resolution of fistula drainage. While no head-to-head trials compare combination therapy with infliximab plus immunomodulators versus infliximab alone for this indication specifically, one observational study demonstrated higher rates of fistula closure with combination therapy as compared to infliximab mono-therapy.19 In a post hoc analysis, higher infliximab concentrations at week 14 were associated with greater fistula response and remission rates.20 In patients with perianal disease, ustekinumab and vedolizumab may also be an effective treatment option by promoting resolution of fistula drainage.21

More recently, emerging data demonstrate that upadacitinib may be an excellent option as a second-line treatment for perianal disease in patients who have failed anti-TNF therapy. Use of upadacitinib was associated with greater rates of complete resolution of fistula drainage and higher rates of external fistula closure (Figure 2).22 Lastly, as an alternative to medical therapy, mesenchymal stem cell therapy has also shown to improve fistula drainage and improve external fistula openings in patients with CD.23 Stem cell therapy is only available through clinical trials at this time.

Patient preferences

Overall, data are lacking for evaluating patient preferences in treatment options for IBD especially with the recent increase in therapeutic options. One survey demonstrated that patient preferences were most impacted by the possibility of improving abdominal pain, with patients accepting additional risk of treatment side effects in order to reduce their abdominal pain.24 An oral route of administration and improving fatigue and bowel urgency were similarly important to patients. Patient preferences can also be highly variable with some valuing avoidance of corticosteroid use while others valuing avoidance of symptoms or risks of medication side effects and surgery. It is important to tailor the discussion on treatment strategies to each individual patient and inquire about the patient’s lifestyle, medical history, and value system, which may impact their treatment preferences utilizing shared decision making.

Access to treatment including the role of social determinants of health

The expanded therapeutic armamentarium has the potential to help patients achieve the current goals of care in IBD. However, these medications are not available to all patients due to numerous barriers including step therapy payer policies, prohibitive costs, insurance prior authorizations, and the role of social determinants of health and proximity to IBD expertise.25 While clinicians work with patients to determine the best treatment option, more often than not, the decision lies with the insurance payer. Step therapy is the protocol used by insurance companies that requires patients to try a lower-cost medication and fail to respond before they approve the originally requested treatment. This can lead to treatment delays, progression of disease, and disease complications. The option to incorporate the use of biosimilars, currently available for anti-TNFs, and other biologics in the near future, will reduce cost and potentially increase access.26 Additionally, working with a clinical pharmacist to navigate access and utilize patient assistance programs may help overcome cost related barriers to treatment and prevent delays in care.

Socioeconomic status has been shown to impact IBD disease outcomes, and compliance rates in treatment vary depending on race and ethnicity.27 Certain racial and ethnic groups remain vulnerable and may require additional support to achieve treatment goals. For example, disparities in health literacy in patients with IBD have been demonstrated with older black men at risk.28 Additionally, the patient’s proximity to their health care facility may impact treatment options. Most IBD centers are located in metropolitan areas and numerous “IBD deserts” exist, potentially limiting therapies for patients from more remote/rural settings.29 Access to treatment and the interplay of social determinants of health can have a large role in therapy selection.

Special considerations: Pregnancy and older adults

Certain patient populations warrant special consideration when approaching treatment strategies. Pregnancy in IBD will not be addressed in full depth in this article, however a key takeaway is that planning is critical and providers should emphasize the importance of steroid-free clinical remission for at least 3 months before conception.30 Additionally, biologic use during pregnancy has not been shown to increase adverse fetal outcomes, thus should be continued to minimize disease flare. Newer novel small molecules are generally avoided during pregnancy due to limited available safety data.

Older adults are the largest growing patient population with IBD. Frailty, or a state of decreased reserve, is more commonly observed in older patients and has been shown to increase adverse events including hospitalization and mortaility.31 Ultimately reducing polypharmacy, ensuring adequate nutrition, minimizing corticosteroid exposure and avoiding undertreatment of active IBD are all key in optimizing outcomes in an older patient with IBD.

Conclusion

When discussing treatment options with patients with IBD, it is important to individualize care and share the decision-making process with patients. Goals include improving symptoms and quality of life while working to achieve the goal of healing intestinal inflammation. In summary, this article can serve as a guide to clinicians for key factors in decision making when selecting therapies in moderate to severe IBD.

Dr. Holmer is a gastroenterologist with NYU Langone Health specializing in inflammatory bowel disease. Dr. Chang is director of clinical operations for the NYU Langone Health Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center. Dr. Malter is director of education for the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at NYU Langone Health and director of the inflammatory bowel disease program at Bellevue Hospital Center. Follow Dr. Holmer on X (formerly Twitter) at @HolmerMd and Dr. Chang @shannonchangmd. Dr. Holmer disclosed affiliations with Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, and AvevoRx. Dr. Chang disclosed affiliations with Pfizer and Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr. Malter disclosed receiving educational grants form Abbvie, Janssen, Pfizer and Takeda, and serving on the advisory boards of AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Janssen, Merck, and Takeda.

References

1. Chang S et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023 Aug 24. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002485.

2. Harvey RF et al. The Lancet. 1980;1:514.

3. Lewis JD et al. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2008;14:1660-1666.

4. Siegel CA et al. Gut. 2018;67(2):244-54.

5. Peyrin-Biroulet L et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1324-38

6. Rogler G et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1118-32.

7. Sandborn WJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1723-36.

8. Brooklyn TN et al. Gut. 2006;55:505-9.

9. Fahmy M et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:794-5.

10. Van Eycken L et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;37:89-91.

11. Lasa JS et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:161-70.

12. Lichtenstein GR et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:490-501.

13. Long MD et al. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:S-5-S-6.

14. Holmer AK et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.2023;21:1598-1606.e5.

15. Sands BE et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:618-27.e3.

16. Sands BE et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1215-26.

17. Sands BE et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1201-14.

18. D’Haens G et al. Lancet. 2022;399:2015-30.

19. Bouguen G et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:975-81.e1-4.

20. Papamichael K et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:1007-14.

21. Shehab M et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29:367-75.

22. Colombel JF et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:i620-i623.

23. Garcia-Olmo D et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65:713-20.

24. Louis E et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:231-9.

25. Rubin DT et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:224-32.

26. Gulacsi L et al. Curr Med Chem. 2019;26:259-69.

27. Cai Q et al. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:545.

28. Dos Santos Marques IC et al. Crohns Colitis 360. 2020 Oct;2(4):otaa076.

29. Deepak P et al. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:11-15.

30. Mahadevan U et al. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1508-24.

31. Faye AS et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28:126-32.

32. Berinstein JA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:2112-20.e1.

33. Levine J et al. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:S103-S104.

Cysteamine and melasma

Most subjects covered in this column are botanical ingredients used for multiple conditions in topical skin care. The focus this month, though, is a natural agent garnering attention primarily for one indication. Present in many mammals and in various cells in the human body (and particularly highly concentrated in human milk), cysteamine is a stable aminothiol that acts as an antioxidant as a result of the degradation of coenzyme A and is known to play a protective function.1 Melasma, an acquired recurrent, chronic hyperpigmentary disorder, continues to be a treatment challenge and is often psychologically troublesome for those affected, approximately 90% of whom are women.2 Individuals with Fitzpatrick skin types IV and V who reside in regions where UV exposure is likely are particularly prominent among those with melasma.2 While triple combination therapy (also known as Kligman’s formula) continues to be the modern gold standard of care for melasma (over the last 30 years),3 cysteamine, a nonmelanocytotoxic molecule, is considered viable for long-term use and safer than the long-time skin-lightening gold standard over several decades, hydroquinone (HQ), which is associated with safety concerns.4 .

Recent history and the 2015 study

Prior to 2015, the quick oxidation and malodorous nature of cysteamine rendered it unsuitable for use as a topical agent. However, stabilization efforts resulted in a product that first began to show efficacy that year.5

Mansouri et al. conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to assess the efficacy of topical cysteamine 5% to treat epidermal melasma in 2015. Over 4 months, 50 volunteers (25 in each group) applied either cysteamine cream or placebo on lesions once nightly. The mean differences at baseline between pigmented and normal skin were 75.2 ± 37 in the cysteamine group and 68.9 ± 31 in the placebo group. Statistically significant differences between the groups were identified at the 2- and 4-month points. At 2 months, the mean differences were 39.7 ± 16.6 in the cysteamine group and 63.8 ± 28.6 in the placebo group; at 4 months, the respective differences were 26.2 ± 16 and 60.7 ± 27.3. Melasma area severity index (MASI) scores were significantly lower in the cysteamine group compared with the placebo group at the end of the study, and investigator global assessment scores and patient questionnaire results revealed substantial comparative efficacy of cysteamine cream.6 Topical cysteamine has also demonstrated notable efficacy in treating senile lentigines, which typically do not respond to topical depigmenting products.5

Farshi et al. used Dermacatch as a novel measurement tool to ascertain the efficacy of cysteamine cream for treating epidermal melasma in a 2018 report of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with 40 patients. During the 4-month trial, cysteamine cream or placebo was applied nightly before sleep. Investigators measured treatment efficacy through Dermacatch, and Mexameter skin colorimetry, MASI scores, investigator global assessments, and patient questionnaires at baseline, 2 months, and 4 months. Through all measurement methods, cysteamine was found to reduce melanin content of melasma lesions, with Dermacatch performing reliably and comparably to Mexameter.7 Since then, cysteamine has been compared to several first-line melasma therapies.

Reviews

A 2019 systematic review by Austin et al. of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on topical treatments for melasma identified 35 original RCTs evaluating a wide range of approximately 20 agents. They identified cysteamine, triple combination therapy, and tranexamic acid as the products netting the most robust recommendations. The researchers characterized cysteamine as conferring strong efficacy and reported anticancer activity while triple combination therapy poses the potential risk of ochronosis and tranexamic acid may present the risk for thrombosis. They concluded that more research is necessary, though, to establish the proper concentration and optimal formulation of cysteamine as a frontline therapy.8

More reviews have since been published to further clarify where cysteamine stands among the optimal treatments for melasma. In a May 2022 systematic PubMed review of topical agents used to treat melasma, González-Molina et al. identified 80 papers meeting inclusion criteria (double or single blinded, prospective, controlled or RCTs, reviews of literature, and meta-analysis studies), with tranexamic acid and cysteamine among the novel well-tolerated agents. Cysteamine was not associated with any severe adverse effects and is recommended as an adjuvant and maintenance therapy.3

A September 2022 review by Niazi et al. found that while the signaling mechanisms through which cysteamine suppresses melasma are not well understood, the topical application of cysteamine cream is seen as safe and effective alone or in combination with other products to treat melasma.2

A systematic review and meta-analysis reported by Gomes dos Santos-Neto et al. at the end of 2022 considered the efficacy of depigmenting formulations containing 5% cysteamine for treating melasma. The meta-analysis covered six studies, with 120 melasma patients treated. The conclusion was that 5% cysteamine was effective with adverse effects unlikely.9

Cysteamine vs. hydroquinone

In 2020, Lima et al. reported the results of a quasi-randomized, multicenter, evaluator-blinded comparative study of topical 0.56% cysteamine and 4% HQ in 40 women with facial melasma. (Note that this study originally claimed a 5% cysteamine concentration, but a letter to the editor of the International Journal of Dermatology in 2020 disputed this and proved it was 0.56%) For 120 days, volunteers applied either 0.56% cysteamine or 4% HQ nightly. Tinted sunscreen (SPF 50; PPD 19) use was required for all participants. There were no differences in colorimetric evaluations between the groups, both of which showed progressive depigmenting, or in photographic assessments. The HQ group demonstrated greater mean decreases in modified melasma area severity index (mMASI) scores (41% for HQ and 24% for cysteamine at 60 days; 53% for HQ and 38% for cysteamine at 120 days). The investigators observed that while cysteamine was safe, well tolerated, and effective, it was outperformed by HQ in terms of mMASI and melasma quality of life (MELASQoL) scores.10

Early the next year, results of a randomized, double-blind, single-center study in 20 women, conducted by Nguyen et al. comparing the efficacy of cysteamine cream with HQ for melasma treatment were published. Participants were given either treatment over 16 weeks. Ultimately, five volunteers in the cysteamine group and nine in the HQ group completed the study. There was no statistically significant difference in mMASI scores between the groups. In this notably small study, HQ was tolerated better. The researchers concluded that their findings supported the argument of comparable efficacy between cysteamine and HQ, with further studies needed to establish whether cysteamine would be an appropriate alternative to HQ.11 Notably, HQ was banned by the Food and Drug Administration in 2020 in over-the-counter products.

Cysteamine vs. Kligman’s formula

Early in 2021, Karrabi et al. published the results of a randomized, double-blind clinical trial of 50 subjects with epidermal melasma to compare cysteamine 5% with Modified Kligman’s formula. Over 4 months, participants applied once daily either cysteamine cream 5% (15 minutes exposure) or the Modified Kligman’s formula (4% hydroquinone, 0.05% retinoic acid and 0.1% betamethasone) for whole night exposure. At 2 and 4 months, a statistically significant difference in mMASI score was noted, with the percentage decline in mMASI score nearly 9% higher in the cysteamine group. The investigators concluded that cysteamine 5% demonstrated greater efficacy than the Modified Kligman’s formula and was also better tolerated.12

Cysteamine vs. tranexamic acid

Later that year, Karrabi et al. published the results of a single-blind, randomized clinical trial assessing the efficacy of tranexamic acid mesotherapy compared with cysteamine 5% cream in 54 melasma patients. For 4 consecutive months, the cysteamine 5% cream group applied the cream on lesions 30 minutes before going to sleep. Every 4 weeks until 2 months, a physician performed tranexamic acid mesotherapy (0.05 mL; 4 mg/mL) on individuals in the tranexamic acid group. The researchers concluded, after measurements using both a Dermacatch device and the mMASI, that neither treatment was significantly better than the other but fewer complications were observed in the cysteamine group.13

Safety

In 2022, Sepaskhah et al. assessed the effects of a cysteamine 5% cream and compared it with HQ 4%/ascorbic acid 3% cream for epidermal melasma in a single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Sixty-five of 80 patients completed the study. The difference in mMASI scores after 4 months was not significant between the groups nor was the improvement in quality of life, but the melanin index was significantly lower in the HQ/ascorbic acid group compared with the less substantial reduction for the cysteamine group. Nevertheless, the researchers concluded that cysteamine is a safe and suitable substitute for HQ/ascorbic acid.4

Conclusion

In the last decade, cysteamine has been established as a potent depigmenting agent. Its suitability and desirability as a top consideration for melasma treatment also appears to be compelling. More RCTs comparing cysteamine and other topline therapies are warranted, but current evidence shows that cysteamine is an effective and safe therapy for melasma.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur in Miami. She founded the division of cosmetic dermatology at the University of Miami in 1997. The third edition of her bestselling textbook, “Cosmetic Dermatology,” was published in 2022. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Johnson & Johnson, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a SaaS company used to generate skin care routines in office and as an ecommerce solution. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Konar MC et al. J Trop Pediatr. 2020 Apr 1;66(2):129-35.

2. Niazi S et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Sep;21(9):3867-75.

3. González-Molina V et al. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022 May;15(5):19-28.

4. Sepaskhah M et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Jul;21(7):2871-8.

5. Desai S et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021 Dec 1;20(12):1276-9.

6. Mansouri P et al. Br J Dermatol. 2015 Jul;173(1):209-17.

7. Farshi S et al. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018 Mar;29(2):182-9.

8. Austin E et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019 Nov 1;18(11):S1545961619P1156X.

9. Gomes dos Santos-Neto A et al. Dermatol Ther. 2022 Dec;35(12):e15961.

10. Lima PB et al. Int J Dermatol. 2020 Dec;59(12):1531-6.

11. Nguyen J et al. Australas J Dermatol. 2021 Feb;62(1):e41-e46.

12. Karrabi M et al. Skin Res Technol. 2021 Jan;27(1):24-31.

13. Karrabi M et al. Arch Dermatol Res. 2021 Sep;313(7):539-47.

Most subjects covered in this column are botanical ingredients used for multiple conditions in topical skin care. The focus this month, though, is a natural agent garnering attention primarily for one indication. Present in many mammals and in various cells in the human body (and particularly highly concentrated in human milk), cysteamine is a stable aminothiol that acts as an antioxidant as a result of the degradation of coenzyme A and is known to play a protective function.1 Melasma, an acquired recurrent, chronic hyperpigmentary disorder, continues to be a treatment challenge and is often psychologically troublesome for those affected, approximately 90% of whom are women.2 Individuals with Fitzpatrick skin types IV and V who reside in regions where UV exposure is likely are particularly prominent among those with melasma.2 While triple combination therapy (also known as Kligman’s formula) continues to be the modern gold standard of care for melasma (over the last 30 years),3 cysteamine, a nonmelanocytotoxic molecule, is considered viable for long-term use and safer than the long-time skin-lightening gold standard over several decades, hydroquinone (HQ), which is associated with safety concerns.4 .

Recent history and the 2015 study

Prior to 2015, the quick oxidation and malodorous nature of cysteamine rendered it unsuitable for use as a topical agent. However, stabilization efforts resulted in a product that first began to show efficacy that year.5

Mansouri et al. conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to assess the efficacy of topical cysteamine 5% to treat epidermal melasma in 2015. Over 4 months, 50 volunteers (25 in each group) applied either cysteamine cream or placebo on lesions once nightly. The mean differences at baseline between pigmented and normal skin were 75.2 ± 37 in the cysteamine group and 68.9 ± 31 in the placebo group. Statistically significant differences between the groups were identified at the 2- and 4-month points. At 2 months, the mean differences were 39.7 ± 16.6 in the cysteamine group and 63.8 ± 28.6 in the placebo group; at 4 months, the respective differences were 26.2 ± 16 and 60.7 ± 27.3. Melasma area severity index (MASI) scores were significantly lower in the cysteamine group compared with the placebo group at the end of the study, and investigator global assessment scores and patient questionnaire results revealed substantial comparative efficacy of cysteamine cream.6 Topical cysteamine has also demonstrated notable efficacy in treating senile lentigines, which typically do not respond to topical depigmenting products.5

Farshi et al. used Dermacatch as a novel measurement tool to ascertain the efficacy of cysteamine cream for treating epidermal melasma in a 2018 report of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with 40 patients. During the 4-month trial, cysteamine cream or placebo was applied nightly before sleep. Investigators measured treatment efficacy through Dermacatch, and Mexameter skin colorimetry, MASI scores, investigator global assessments, and patient questionnaires at baseline, 2 months, and 4 months. Through all measurement methods, cysteamine was found to reduce melanin content of melasma lesions, with Dermacatch performing reliably and comparably to Mexameter.7 Since then, cysteamine has been compared to several first-line melasma therapies.

Reviews

A 2019 systematic review by Austin et al. of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on topical treatments for melasma identified 35 original RCTs evaluating a wide range of approximately 20 agents. They identified cysteamine, triple combination therapy, and tranexamic acid as the products netting the most robust recommendations. The researchers characterized cysteamine as conferring strong efficacy and reported anticancer activity while triple combination therapy poses the potential risk of ochronosis and tranexamic acid may present the risk for thrombosis. They concluded that more research is necessary, though, to establish the proper concentration and optimal formulation of cysteamine as a frontline therapy.8

More reviews have since been published to further clarify where cysteamine stands among the optimal treatments for melasma. In a May 2022 systematic PubMed review of topical agents used to treat melasma, González-Molina et al. identified 80 papers meeting inclusion criteria (double or single blinded, prospective, controlled or RCTs, reviews of literature, and meta-analysis studies), with tranexamic acid and cysteamine among the novel well-tolerated agents. Cysteamine was not associated with any severe adverse effects and is recommended as an adjuvant and maintenance therapy.3

A September 2022 review by Niazi et al. found that while the signaling mechanisms through which cysteamine suppresses melasma are not well understood, the topical application of cysteamine cream is seen as safe and effective alone or in combination with other products to treat melasma.2

A systematic review and meta-analysis reported by Gomes dos Santos-Neto et al. at the end of 2022 considered the efficacy of depigmenting formulations containing 5% cysteamine for treating melasma. The meta-analysis covered six studies, with 120 melasma patients treated. The conclusion was that 5% cysteamine was effective with adverse effects unlikely.9

Cysteamine vs. hydroquinone

In 2020, Lima et al. reported the results of a quasi-randomized, multicenter, evaluator-blinded comparative study of topical 0.56% cysteamine and 4% HQ in 40 women with facial melasma. (Note that this study originally claimed a 5% cysteamine concentration, but a letter to the editor of the International Journal of Dermatology in 2020 disputed this and proved it was 0.56%) For 120 days, volunteers applied either 0.56% cysteamine or 4% HQ nightly. Tinted sunscreen (SPF 50; PPD 19) use was required for all participants. There were no differences in colorimetric evaluations between the groups, both of which showed progressive depigmenting, or in photographic assessments. The HQ group demonstrated greater mean decreases in modified melasma area severity index (mMASI) scores (41% for HQ and 24% for cysteamine at 60 days; 53% for HQ and 38% for cysteamine at 120 days). The investigators observed that while cysteamine was safe, well tolerated, and effective, it was outperformed by HQ in terms of mMASI and melasma quality of life (MELASQoL) scores.10

Early the next year, results of a randomized, double-blind, single-center study in 20 women, conducted by Nguyen et al. comparing the efficacy of cysteamine cream with HQ for melasma treatment were published. Participants were given either treatment over 16 weeks. Ultimately, five volunteers in the cysteamine group and nine in the HQ group completed the study. There was no statistically significant difference in mMASI scores between the groups. In this notably small study, HQ was tolerated better. The researchers concluded that their findings supported the argument of comparable efficacy between cysteamine and HQ, with further studies needed to establish whether cysteamine would be an appropriate alternative to HQ.11 Notably, HQ was banned by the Food and Drug Administration in 2020 in over-the-counter products.

Cysteamine vs. Kligman’s formula

Early in 2021, Karrabi et al. published the results of a randomized, double-blind clinical trial of 50 subjects with epidermal melasma to compare cysteamine 5% with Modified Kligman’s formula. Over 4 months, participants applied once daily either cysteamine cream 5% (15 minutes exposure) or the Modified Kligman’s formula (4% hydroquinone, 0.05% retinoic acid and 0.1% betamethasone) for whole night exposure. At 2 and 4 months, a statistically significant difference in mMASI score was noted, with the percentage decline in mMASI score nearly 9% higher in the cysteamine group. The investigators concluded that cysteamine 5% demonstrated greater efficacy than the Modified Kligman’s formula and was also better tolerated.12

Cysteamine vs. tranexamic acid

Later that year, Karrabi et al. published the results of a single-blind, randomized clinical trial assessing the efficacy of tranexamic acid mesotherapy compared with cysteamine 5% cream in 54 melasma patients. For 4 consecutive months, the cysteamine 5% cream group applied the cream on lesions 30 minutes before going to sleep. Every 4 weeks until 2 months, a physician performed tranexamic acid mesotherapy (0.05 mL; 4 mg/mL) on individuals in the tranexamic acid group. The researchers concluded, after measurements using both a Dermacatch device and the mMASI, that neither treatment was significantly better than the other but fewer complications were observed in the cysteamine group.13

Safety

In 2022, Sepaskhah et al. assessed the effects of a cysteamine 5% cream and compared it with HQ 4%/ascorbic acid 3% cream for epidermal melasma in a single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Sixty-five of 80 patients completed the study. The difference in mMASI scores after 4 months was not significant between the groups nor was the improvement in quality of life, but the melanin index was significantly lower in the HQ/ascorbic acid group compared with the less substantial reduction for the cysteamine group. Nevertheless, the researchers concluded that cysteamine is a safe and suitable substitute for HQ/ascorbic acid.4

Conclusion

In the last decade, cysteamine has been established as a potent depigmenting agent. Its suitability and desirability as a top consideration for melasma treatment also appears to be compelling. More RCTs comparing cysteamine and other topline therapies are warranted, but current evidence shows that cysteamine is an effective and safe therapy for melasma.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur in Miami. She founded the division of cosmetic dermatology at the University of Miami in 1997. The third edition of her bestselling textbook, “Cosmetic Dermatology,” was published in 2022. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Johnson & Johnson, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a SaaS company used to generate skin care routines in office and as an ecommerce solution. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Konar MC et al. J Trop Pediatr. 2020 Apr 1;66(2):129-35.

2. Niazi S et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Sep;21(9):3867-75.

3. González-Molina V et al. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022 May;15(5):19-28.

4. Sepaskhah M et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Jul;21(7):2871-8.

5. Desai S et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021 Dec 1;20(12):1276-9.

6. Mansouri P et al. Br J Dermatol. 2015 Jul;173(1):209-17.

7. Farshi S et al. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018 Mar;29(2):182-9.

8. Austin E et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019 Nov 1;18(11):S1545961619P1156X.

9. Gomes dos Santos-Neto A et al. Dermatol Ther. 2022 Dec;35(12):e15961.

10. Lima PB et al. Int J Dermatol. 2020 Dec;59(12):1531-6.

11. Nguyen J et al. Australas J Dermatol. 2021 Feb;62(1):e41-e46.

12. Karrabi M et al. Skin Res Technol. 2021 Jan;27(1):24-31.

13. Karrabi M et al. Arch Dermatol Res. 2021 Sep;313(7):539-47.

Most subjects covered in this column are botanical ingredients used for multiple conditions in topical skin care. The focus this month, though, is a natural agent garnering attention primarily for one indication. Present in many mammals and in various cells in the human body (and particularly highly concentrated in human milk), cysteamine is a stable aminothiol that acts as an antioxidant as a result of the degradation of coenzyme A and is known to play a protective function.1 Melasma, an acquired recurrent, chronic hyperpigmentary disorder, continues to be a treatment challenge and is often psychologically troublesome for those affected, approximately 90% of whom are women.2 Individuals with Fitzpatrick skin types IV and V who reside in regions where UV exposure is likely are particularly prominent among those with melasma.2 While triple combination therapy (also known as Kligman’s formula) continues to be the modern gold standard of care for melasma (over the last 30 years),3 cysteamine, a nonmelanocytotoxic molecule, is considered viable for long-term use and safer than the long-time skin-lightening gold standard over several decades, hydroquinone (HQ), which is associated with safety concerns.4 .

Recent history and the 2015 study

Prior to 2015, the quick oxidation and malodorous nature of cysteamine rendered it unsuitable for use as a topical agent. However, stabilization efforts resulted in a product that first began to show efficacy that year.5