User login

The importance of diversity and inclusion in medicine

Diversity

There is growing appreciation for diversity and inclusion (DI) as drivers of excellence in medicine. CHEST also promotes excellence in medicine. Therefore, it is intuitive that CHEST promote DI. Diversity encompasses differences in gender, race/ethnicity, vocational training, age, sexual orientation, thought processes, etc.

Academic medicine is rich with examples of how diversity is critical to the health of our nation:

– Diverse student populations have been shown to improve our learners’ satisfaction with their educational experience.

– Diverse teams have been shown to be more capable of solving complex problems than homogenous teams.

– Health care is moving toward a team-based, interprofessional model that values the contributions of a range of providers’ perspectives in improving patient outcomes.

– In biomedical research, investigators ask different research questions based on their own background and experiences. This implies that finding solutions to diseases that affect specific populations will require a diverse pool of biomedical researchers.

– Faculty diversity as a key component of excellence for medical education and research has been documented.

Diversity alone doesn’t drive inclusion. Noted diversity advocate, Verna Myers, stated, “Diversity is being invited to the party. Inclusion is being asked to dance.” In my opinion, diversity is the commencement of work, but inclusion helps complete the task.

Inclusion

An inclusive environment values the unique contributions all members bring. Teams with diversity of thought are more innovative as individual members with different backgrounds and points of view bring an extensive range of ideas and creativity to scientific discovery and decision-making processes. Inclusion leverages the power of our unique differences to accomplish our mutual goals. By valuing everyone’s perspective, we demonstrate excellence.

I recommend an article from the Harvard Business Review (HBR Feb 2017). The authors suggest several ways to promote inclusiveness: (1) ensuring team members speak up and are heard; (2) making it safe to propose novel ideas; (3) empowering team members to make decisions; (4) taking advice and implementing feedback; (5) giving actionable feedback; and ( 6) sharing credit for team success. If the team leader possesses at least three of these traits, 87% of team members say they feel welcome and included in their team; 87% say they feel free to express their views and opinions; and 74% say they feel that their ideas are heard and recognized. If the team leader possessed none of these traits, those percentages dropped to 51%, 46%, and 37%, respectively. I believe this concept is applicable in medicine also.

Sponsors

What can we do to advance diversity and inclusion individually and in our individual institutions? A sponsor is a senior level leader who advocates for key assignments, promotes for and puts his or her reputation on the line for the protégé’s advancement. This invigorates and drives engagement. One key to rising above the playing field for women and people of color is sponsorship. Being a sponsor does not mean one would recommend someone who is not qualified. It means one recommends or supports those who are capable of doing the job but would not otherwise be given the opportunity.

Ask yourself: Have I served as a sponsor? What would prevent me from being a sponsor? Do I believe in this concept?

Cause for Alarm

Numerous publications have recently discussed the crisis of the decline of black men entering medicine. In 1978, there were 1,410 black male applicants to medical school, and in 2014, there were 1,337. Additionally, the number of black male matriculants to medical school over more than 35 years has not surpassed the 1978 numbers. In 1978, there were 542 black male matriculants, and in 2014, there were 515 (J of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2017, 4:317-321). This report is thorough and insightful and illustrates the work that we must do to help improve this situation.

Dr. Marc Nivet, Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Chief Diversity Officer, stated “No other minority group has experienced such declines. The inability to find, engage, and develop candidates for careers in medicine from all members of our society limits our ability to improve health care for all.” I recommend you read the 2015 AAMC publication entitled: Altering the Course: Black Males in Medicine.

Health-care Disparities

Research suggests that the overall health of Americans has improved; however, disparities continue to persist among many populations within the United States. Racial and ethnic minority populations have poorer access to care and worse outcomes than their white counterparts. Approximately 20% of the nation living in rural areas is less likely than those living in urban areas to receive preventive care and more likely to experience language barriers.

Individuals identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender are likely to experience discrimination in health-care settings. These individuals often face insurance-based barriers and are less likely to have a usual source of care than patients who identify as straight.

A 2002 report by the Institute of Medicine entitled: Unequal Treatment: What Healthcare Providers Need to Know about Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare is revealing. Salient information reported is: It is generally accepted that a diverse workforce is a key component in the delivery of quality, competent care throughout the nation. Physicians from racial and ethnic backgrounds typically underrepresented in medicine are significantly more likely to practice primary care than white physicians and are more likely to practice in impoverished and medically underserved areas. Diversity in the physician workforce impacts the quality of care received by patients. Race concordance between patient and physician results in longer visits and increased patient satisfaction, and language concordance is positively associated with adherence to treatment among certain racial or ethnic groups.

Improving the patient experience or quality of care received also requires attention to education and training on cultural competence. By weaving together a diverse and culturally responsive pool of physicians working collaboratively with other health-care professionals, access and quality of care can improve throughout the nation.

CHEST cannot attain more racial diversity in our organization if we don’t have this diversity in medical education and training. This is why CHEST must be actively involved in addressing these issues.

Unconscious Bias

Despite many examples of how diversity enriches the quality of health care and health research, there is still much work to be done to address the human biases that impede our ability to benefit from diversity in medicine. While academic medicine has made progress toward addressing overt discrimination, unconscious bias (implicit bias) represents another threat. Unconscious bias describes the prejudices we don’t know we have. While unconscious biases vary from person to person, we all possess them. The existence of unconscious bias in academic medicine, while uncomfortable and unsettling, is a reality. The AAMC developed an unconscious bias learning lab for the health professions and produced an oft-cited video about addressing unconscious bias in the faculty advancement, promotion, and tenure process. We must consider this and other ways in which we can help promote the acknowledgment of unconscious bias. The CHEST staff have undergone unconscious bias training, and I recommend it for all faculty in academic medicine.

Summary

Diversity and inclusion in medicine is of paramount importance. It leads to better patient care and better trainee education and will decrease health-care disparities. Progress has been made, but there is more work to be done.

CHEST is supportive of these efforts and has worked on this previously and with a renewed push in the past 2 years with the DI Task Force initially and, now, the DI Roundtable, which has representatives from each of the standing committees, including the Board of Regents. This roundtable group will help advance the DI initiatives of the organization. I ask that each person reading this article consider what we as individuals can do in helping make DI in medicine a priority.

Dr. Haynes is Professor of Medicine at The University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, MS. He is also the Executive Vice Chair of the Department of Medicine. At CHEST, he is a member of the training and transitions committee, executive scientific program committee, former chair of the diversity and inclusion task force, and is the current chair of the diversity and inclusion roundtable.

Diversity

There is growing appreciation for diversity and inclusion (DI) as drivers of excellence in medicine. CHEST also promotes excellence in medicine. Therefore, it is intuitive that CHEST promote DI. Diversity encompasses differences in gender, race/ethnicity, vocational training, age, sexual orientation, thought processes, etc.

Academic medicine is rich with examples of how diversity is critical to the health of our nation:

– Diverse student populations have been shown to improve our learners’ satisfaction with their educational experience.

– Diverse teams have been shown to be more capable of solving complex problems than homogenous teams.

– Health care is moving toward a team-based, interprofessional model that values the contributions of a range of providers’ perspectives in improving patient outcomes.

– In biomedical research, investigators ask different research questions based on their own background and experiences. This implies that finding solutions to diseases that affect specific populations will require a diverse pool of biomedical researchers.

– Faculty diversity as a key component of excellence for medical education and research has been documented.

Diversity alone doesn’t drive inclusion. Noted diversity advocate, Verna Myers, stated, “Diversity is being invited to the party. Inclusion is being asked to dance.” In my opinion, diversity is the commencement of work, but inclusion helps complete the task.

Inclusion

An inclusive environment values the unique contributions all members bring. Teams with diversity of thought are more innovative as individual members with different backgrounds and points of view bring an extensive range of ideas and creativity to scientific discovery and decision-making processes. Inclusion leverages the power of our unique differences to accomplish our mutual goals. By valuing everyone’s perspective, we demonstrate excellence.

I recommend an article from the Harvard Business Review (HBR Feb 2017). The authors suggest several ways to promote inclusiveness: (1) ensuring team members speak up and are heard; (2) making it safe to propose novel ideas; (3) empowering team members to make decisions; (4) taking advice and implementing feedback; (5) giving actionable feedback; and ( 6) sharing credit for team success. If the team leader possesses at least three of these traits, 87% of team members say they feel welcome and included in their team; 87% say they feel free to express their views and opinions; and 74% say they feel that their ideas are heard and recognized. If the team leader possessed none of these traits, those percentages dropped to 51%, 46%, and 37%, respectively. I believe this concept is applicable in medicine also.

Sponsors

What can we do to advance diversity and inclusion individually and in our individual institutions? A sponsor is a senior level leader who advocates for key assignments, promotes for and puts his or her reputation on the line for the protégé’s advancement. This invigorates and drives engagement. One key to rising above the playing field for women and people of color is sponsorship. Being a sponsor does not mean one would recommend someone who is not qualified. It means one recommends or supports those who are capable of doing the job but would not otherwise be given the opportunity.

Ask yourself: Have I served as a sponsor? What would prevent me from being a sponsor? Do I believe in this concept?

Cause for Alarm

Numerous publications have recently discussed the crisis of the decline of black men entering medicine. In 1978, there were 1,410 black male applicants to medical school, and in 2014, there were 1,337. Additionally, the number of black male matriculants to medical school over more than 35 years has not surpassed the 1978 numbers. In 1978, there were 542 black male matriculants, and in 2014, there were 515 (J of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2017, 4:317-321). This report is thorough and insightful and illustrates the work that we must do to help improve this situation.

Dr. Marc Nivet, Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Chief Diversity Officer, stated “No other minority group has experienced such declines. The inability to find, engage, and develop candidates for careers in medicine from all members of our society limits our ability to improve health care for all.” I recommend you read the 2015 AAMC publication entitled: Altering the Course: Black Males in Medicine.

Health-care Disparities

Research suggests that the overall health of Americans has improved; however, disparities continue to persist among many populations within the United States. Racial and ethnic minority populations have poorer access to care and worse outcomes than their white counterparts. Approximately 20% of the nation living in rural areas is less likely than those living in urban areas to receive preventive care and more likely to experience language barriers.

Individuals identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender are likely to experience discrimination in health-care settings. These individuals often face insurance-based barriers and are less likely to have a usual source of care than patients who identify as straight.

A 2002 report by the Institute of Medicine entitled: Unequal Treatment: What Healthcare Providers Need to Know about Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare is revealing. Salient information reported is: It is generally accepted that a diverse workforce is a key component in the delivery of quality, competent care throughout the nation. Physicians from racial and ethnic backgrounds typically underrepresented in medicine are significantly more likely to practice primary care than white physicians and are more likely to practice in impoverished and medically underserved areas. Diversity in the physician workforce impacts the quality of care received by patients. Race concordance between patient and physician results in longer visits and increased patient satisfaction, and language concordance is positively associated with adherence to treatment among certain racial or ethnic groups.

Improving the patient experience or quality of care received also requires attention to education and training on cultural competence. By weaving together a diverse and culturally responsive pool of physicians working collaboratively with other health-care professionals, access and quality of care can improve throughout the nation.

CHEST cannot attain more racial diversity in our organization if we don’t have this diversity in medical education and training. This is why CHEST must be actively involved in addressing these issues.

Unconscious Bias

Despite many examples of how diversity enriches the quality of health care and health research, there is still much work to be done to address the human biases that impede our ability to benefit from diversity in medicine. While academic medicine has made progress toward addressing overt discrimination, unconscious bias (implicit bias) represents another threat. Unconscious bias describes the prejudices we don’t know we have. While unconscious biases vary from person to person, we all possess them. The existence of unconscious bias in academic medicine, while uncomfortable and unsettling, is a reality. The AAMC developed an unconscious bias learning lab for the health professions and produced an oft-cited video about addressing unconscious bias in the faculty advancement, promotion, and tenure process. We must consider this and other ways in which we can help promote the acknowledgment of unconscious bias. The CHEST staff have undergone unconscious bias training, and I recommend it for all faculty in academic medicine.

Summary

Diversity and inclusion in medicine is of paramount importance. It leads to better patient care and better trainee education and will decrease health-care disparities. Progress has been made, but there is more work to be done.

CHEST is supportive of these efforts and has worked on this previously and with a renewed push in the past 2 years with the DI Task Force initially and, now, the DI Roundtable, which has representatives from each of the standing committees, including the Board of Regents. This roundtable group will help advance the DI initiatives of the organization. I ask that each person reading this article consider what we as individuals can do in helping make DI in medicine a priority.

Dr. Haynes is Professor of Medicine at The University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, MS. He is also the Executive Vice Chair of the Department of Medicine. At CHEST, he is a member of the training and transitions committee, executive scientific program committee, former chair of the diversity and inclusion task force, and is the current chair of the diversity and inclusion roundtable.

Diversity

There is growing appreciation for diversity and inclusion (DI) as drivers of excellence in medicine. CHEST also promotes excellence in medicine. Therefore, it is intuitive that CHEST promote DI. Diversity encompasses differences in gender, race/ethnicity, vocational training, age, sexual orientation, thought processes, etc.

Academic medicine is rich with examples of how diversity is critical to the health of our nation:

– Diverse student populations have been shown to improve our learners’ satisfaction with their educational experience.

– Diverse teams have been shown to be more capable of solving complex problems than homogenous teams.

– Health care is moving toward a team-based, interprofessional model that values the contributions of a range of providers’ perspectives in improving patient outcomes.

– In biomedical research, investigators ask different research questions based on their own background and experiences. This implies that finding solutions to diseases that affect specific populations will require a diverse pool of biomedical researchers.

– Faculty diversity as a key component of excellence for medical education and research has been documented.

Diversity alone doesn’t drive inclusion. Noted diversity advocate, Verna Myers, stated, “Diversity is being invited to the party. Inclusion is being asked to dance.” In my opinion, diversity is the commencement of work, but inclusion helps complete the task.

Inclusion

An inclusive environment values the unique contributions all members bring. Teams with diversity of thought are more innovative as individual members with different backgrounds and points of view bring an extensive range of ideas and creativity to scientific discovery and decision-making processes. Inclusion leverages the power of our unique differences to accomplish our mutual goals. By valuing everyone’s perspective, we demonstrate excellence.

I recommend an article from the Harvard Business Review (HBR Feb 2017). The authors suggest several ways to promote inclusiveness: (1) ensuring team members speak up and are heard; (2) making it safe to propose novel ideas; (3) empowering team members to make decisions; (4) taking advice and implementing feedback; (5) giving actionable feedback; and ( 6) sharing credit for team success. If the team leader possesses at least three of these traits, 87% of team members say they feel welcome and included in their team; 87% say they feel free to express their views and opinions; and 74% say they feel that their ideas are heard and recognized. If the team leader possessed none of these traits, those percentages dropped to 51%, 46%, and 37%, respectively. I believe this concept is applicable in medicine also.

Sponsors

What can we do to advance diversity and inclusion individually and in our individual institutions? A sponsor is a senior level leader who advocates for key assignments, promotes for and puts his or her reputation on the line for the protégé’s advancement. This invigorates and drives engagement. One key to rising above the playing field for women and people of color is sponsorship. Being a sponsor does not mean one would recommend someone who is not qualified. It means one recommends or supports those who are capable of doing the job but would not otherwise be given the opportunity.

Ask yourself: Have I served as a sponsor? What would prevent me from being a sponsor? Do I believe in this concept?

Cause for Alarm

Numerous publications have recently discussed the crisis of the decline of black men entering medicine. In 1978, there were 1,410 black male applicants to medical school, and in 2014, there were 1,337. Additionally, the number of black male matriculants to medical school over more than 35 years has not surpassed the 1978 numbers. In 1978, there were 542 black male matriculants, and in 2014, there were 515 (J of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2017, 4:317-321). This report is thorough and insightful and illustrates the work that we must do to help improve this situation.

Dr. Marc Nivet, Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Chief Diversity Officer, stated “No other minority group has experienced such declines. The inability to find, engage, and develop candidates for careers in medicine from all members of our society limits our ability to improve health care for all.” I recommend you read the 2015 AAMC publication entitled: Altering the Course: Black Males in Medicine.

Health-care Disparities

Research suggests that the overall health of Americans has improved; however, disparities continue to persist among many populations within the United States. Racial and ethnic minority populations have poorer access to care and worse outcomes than their white counterparts. Approximately 20% of the nation living in rural areas is less likely than those living in urban areas to receive preventive care and more likely to experience language barriers.

Individuals identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender are likely to experience discrimination in health-care settings. These individuals often face insurance-based barriers and are less likely to have a usual source of care than patients who identify as straight.

A 2002 report by the Institute of Medicine entitled: Unequal Treatment: What Healthcare Providers Need to Know about Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare is revealing. Salient information reported is: It is generally accepted that a diverse workforce is a key component in the delivery of quality, competent care throughout the nation. Physicians from racial and ethnic backgrounds typically underrepresented in medicine are significantly more likely to practice primary care than white physicians and are more likely to practice in impoverished and medically underserved areas. Diversity in the physician workforce impacts the quality of care received by patients. Race concordance between patient and physician results in longer visits and increased patient satisfaction, and language concordance is positively associated with adherence to treatment among certain racial or ethnic groups.

Improving the patient experience or quality of care received also requires attention to education and training on cultural competence. By weaving together a diverse and culturally responsive pool of physicians working collaboratively with other health-care professionals, access and quality of care can improve throughout the nation.

CHEST cannot attain more racial diversity in our organization if we don’t have this diversity in medical education and training. This is why CHEST must be actively involved in addressing these issues.

Unconscious Bias

Despite many examples of how diversity enriches the quality of health care and health research, there is still much work to be done to address the human biases that impede our ability to benefit from diversity in medicine. While academic medicine has made progress toward addressing overt discrimination, unconscious bias (implicit bias) represents another threat. Unconscious bias describes the prejudices we don’t know we have. While unconscious biases vary from person to person, we all possess them. The existence of unconscious bias in academic medicine, while uncomfortable and unsettling, is a reality. The AAMC developed an unconscious bias learning lab for the health professions and produced an oft-cited video about addressing unconscious bias in the faculty advancement, promotion, and tenure process. We must consider this and other ways in which we can help promote the acknowledgment of unconscious bias. The CHEST staff have undergone unconscious bias training, and I recommend it for all faculty in academic medicine.

Summary

Diversity and inclusion in medicine is of paramount importance. It leads to better patient care and better trainee education and will decrease health-care disparities. Progress has been made, but there is more work to be done.

CHEST is supportive of these efforts and has worked on this previously and with a renewed push in the past 2 years with the DI Task Force initially and, now, the DI Roundtable, which has representatives from each of the standing committees, including the Board of Regents. This roundtable group will help advance the DI initiatives of the organization. I ask that each person reading this article consider what we as individuals can do in helping make DI in medicine a priority.

Dr. Haynes is Professor of Medicine at The University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, MS. He is also the Executive Vice Chair of the Department of Medicine. At CHEST, he is a member of the training and transitions committee, executive scientific program committee, former chair of the diversity and inclusion task force, and is the current chair of the diversity and inclusion roundtable.

Could group CBT help survivors of Florence?

Rising waters forced hundreds of people, mainly in the Carolinas, to call for emergency rescues, and some people were forced to abandon their cars because of flooding. One man reportedly died by electrocution while trying to hook up a generator. Another man died after going out to check the status of hunting dogs, according to media reports. And in one of the most heart-wrenching tragedies, a mother and her infant were killed when a tree fell on their home.

Watching the TV reports and listening to the news of Hurricane Florence’s devastating impact on so many millions of people has been shocking. The death toll from this catastrophic weather event as of this writing stands at 39. Besides the current and future physical problems and illnesses left in Florence’s wake, the extent of property damage and loss must be overwhelming for the survivors.

I worry about the extent of the emotional toll left behind by Florence, just as Hurricane Maria did last year in Puerto Rico. The storm and its subsequent damage to the individual psyche – including the loss of identity and the fracturing of social structures and networks – almost certainly will lead to posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and utter despair for many survivors.

While monitoring Florence’s impact, I thought about Hurricane Sandy, which upended me personally when it hit New York in 2012. As I’ve written previously, Sandy’s impact left me without power, running water, or toilet facilities. Almost 3 days of this uncertainty shook me from my comfort zone and truly affected my emotions. Before day 3, I left my home and drove (yes, I could still use my car; the roads were clear and my garage was not flooded) to my older son’s home – where I had a great support system and was able to continue to live a relatively normal life while watching the storm’s developments on TV. To this day, many areas of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut that were hit by Sandy have not fully recovered.

Back to the human tragedy still unfolding for the survivors of Florence: I believe – and the data suggest – that early intervention and treatment of PTSD leads to better outcomes and should be addressed sooner than later. There is no specific medicinal “magic bullet” for PTSD, although some medications may help as well as treat a depressive component of the disorder and other medications may assist in improving sleep and disruptive sleep patterns. It’s been shown, time and again, that cognitive-behavioral therapy, various types of prolonged exposure therapy, and eye movement desensitization therapies work best. The most updated federal guidelines from the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense, coauthored by Lori L. Davis, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, reinforce those treatments.

I also believe that, in situations in which masses of people are affected or potentially affected by PTSD, another first line of care that should be added is supportive, educational, interactive group therapy. In other words, it is possible that a cognitive-behavioral group therapy (CBGT) approach would reach many more people, make psychiatric intervention acceptable, and help the survivors of Florence. A recent study by researchers at the University of Massachusetts Boston that examined the role of “decentering” as part of CBGT for patients with specific anxiety disorders, for example, social anxiety disorder, might provide some hints. Decentering involves learning to observe thoughts and feelings as objective events in the mind rather than identifying with them personally. Aaron T. Beck, MD, and others hypothesized decentering as a mechanism of change in CBT.

In the UMass study, researchers recruited 81 people with a principal diagnosis of social anxiety disorder based on the Anxiety Disorders Interview Scheduled for DSM-IV. Other inclusion criteria for the study included stability on medications for 3 months or 1 month on benzodiazepines (Behav Ther. 2018 Sep;49[5]:809-12). Sixty-three of participants had 12 sessions of CBGT. The researchers found that people who received the CBGT experienced an increase in decentering. An increase in decentering, in turn, predicted improvement on most outcome measures.

Just as primary care physicians and surgeons know how to address serious physical health issues related natural and man-made disasters, psychiatrists must quickly know how to address the mental health aspects of care. Group therapy has the greatest potential to help more people and perhaps treat – and even prevent not only PTSD but many anxiety disorders as well.

Dr. London, a psychiatrist who practices in New York, developed and ran a short-term psychotherapy program for 20 years at NYU Langone Medical Center and has been writing columns for 35 years. His new book about helping people feel better fast is expected to be published in fall 2018. He has no disclosures.

Rising waters forced hundreds of people, mainly in the Carolinas, to call for emergency rescues, and some people were forced to abandon their cars because of flooding. One man reportedly died by electrocution while trying to hook up a generator. Another man died after going out to check the status of hunting dogs, according to media reports. And in one of the most heart-wrenching tragedies, a mother and her infant were killed when a tree fell on their home.

Watching the TV reports and listening to the news of Hurricane Florence’s devastating impact on so many millions of people has been shocking. The death toll from this catastrophic weather event as of this writing stands at 39. Besides the current and future physical problems and illnesses left in Florence’s wake, the extent of property damage and loss must be overwhelming for the survivors.

I worry about the extent of the emotional toll left behind by Florence, just as Hurricane Maria did last year in Puerto Rico. The storm and its subsequent damage to the individual psyche – including the loss of identity and the fracturing of social structures and networks – almost certainly will lead to posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and utter despair for many survivors.

While monitoring Florence’s impact, I thought about Hurricane Sandy, which upended me personally when it hit New York in 2012. As I’ve written previously, Sandy’s impact left me without power, running water, or toilet facilities. Almost 3 days of this uncertainty shook me from my comfort zone and truly affected my emotions. Before day 3, I left my home and drove (yes, I could still use my car; the roads were clear and my garage was not flooded) to my older son’s home – where I had a great support system and was able to continue to live a relatively normal life while watching the storm’s developments on TV. To this day, many areas of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut that were hit by Sandy have not fully recovered.

Back to the human tragedy still unfolding for the survivors of Florence: I believe – and the data suggest – that early intervention and treatment of PTSD leads to better outcomes and should be addressed sooner than later. There is no specific medicinal “magic bullet” for PTSD, although some medications may help as well as treat a depressive component of the disorder and other medications may assist in improving sleep and disruptive sleep patterns. It’s been shown, time and again, that cognitive-behavioral therapy, various types of prolonged exposure therapy, and eye movement desensitization therapies work best. The most updated federal guidelines from the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense, coauthored by Lori L. Davis, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, reinforce those treatments.

I also believe that, in situations in which masses of people are affected or potentially affected by PTSD, another first line of care that should be added is supportive, educational, interactive group therapy. In other words, it is possible that a cognitive-behavioral group therapy (CBGT) approach would reach many more people, make psychiatric intervention acceptable, and help the survivors of Florence. A recent study by researchers at the University of Massachusetts Boston that examined the role of “decentering” as part of CBGT for patients with specific anxiety disorders, for example, social anxiety disorder, might provide some hints. Decentering involves learning to observe thoughts and feelings as objective events in the mind rather than identifying with them personally. Aaron T. Beck, MD, and others hypothesized decentering as a mechanism of change in CBT.

In the UMass study, researchers recruited 81 people with a principal diagnosis of social anxiety disorder based on the Anxiety Disorders Interview Scheduled for DSM-IV. Other inclusion criteria for the study included stability on medications for 3 months or 1 month on benzodiazepines (Behav Ther. 2018 Sep;49[5]:809-12). Sixty-three of participants had 12 sessions of CBGT. The researchers found that people who received the CBGT experienced an increase in decentering. An increase in decentering, in turn, predicted improvement on most outcome measures.

Just as primary care physicians and surgeons know how to address serious physical health issues related natural and man-made disasters, psychiatrists must quickly know how to address the mental health aspects of care. Group therapy has the greatest potential to help more people and perhaps treat – and even prevent not only PTSD but many anxiety disorders as well.

Dr. London, a psychiatrist who practices in New York, developed and ran a short-term psychotherapy program for 20 years at NYU Langone Medical Center and has been writing columns for 35 years. His new book about helping people feel better fast is expected to be published in fall 2018. He has no disclosures.

Rising waters forced hundreds of people, mainly in the Carolinas, to call for emergency rescues, and some people were forced to abandon their cars because of flooding. One man reportedly died by electrocution while trying to hook up a generator. Another man died after going out to check the status of hunting dogs, according to media reports. And in one of the most heart-wrenching tragedies, a mother and her infant were killed when a tree fell on their home.

Watching the TV reports and listening to the news of Hurricane Florence’s devastating impact on so many millions of people has been shocking. The death toll from this catastrophic weather event as of this writing stands at 39. Besides the current and future physical problems and illnesses left in Florence’s wake, the extent of property damage and loss must be overwhelming for the survivors.

I worry about the extent of the emotional toll left behind by Florence, just as Hurricane Maria did last year in Puerto Rico. The storm and its subsequent damage to the individual psyche – including the loss of identity and the fracturing of social structures and networks – almost certainly will lead to posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and utter despair for many survivors.

While monitoring Florence’s impact, I thought about Hurricane Sandy, which upended me personally when it hit New York in 2012. As I’ve written previously, Sandy’s impact left me without power, running water, or toilet facilities. Almost 3 days of this uncertainty shook me from my comfort zone and truly affected my emotions. Before day 3, I left my home and drove (yes, I could still use my car; the roads were clear and my garage was not flooded) to my older son’s home – where I had a great support system and was able to continue to live a relatively normal life while watching the storm’s developments on TV. To this day, many areas of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut that were hit by Sandy have not fully recovered.

Back to the human tragedy still unfolding for the survivors of Florence: I believe – and the data suggest – that early intervention and treatment of PTSD leads to better outcomes and should be addressed sooner than later. There is no specific medicinal “magic bullet” for PTSD, although some medications may help as well as treat a depressive component of the disorder and other medications may assist in improving sleep and disruptive sleep patterns. It’s been shown, time and again, that cognitive-behavioral therapy, various types of prolonged exposure therapy, and eye movement desensitization therapies work best. The most updated federal guidelines from the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense, coauthored by Lori L. Davis, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, reinforce those treatments.

I also believe that, in situations in which masses of people are affected or potentially affected by PTSD, another first line of care that should be added is supportive, educational, interactive group therapy. In other words, it is possible that a cognitive-behavioral group therapy (CBGT) approach would reach many more people, make psychiatric intervention acceptable, and help the survivors of Florence. A recent study by researchers at the University of Massachusetts Boston that examined the role of “decentering” as part of CBGT for patients with specific anxiety disorders, for example, social anxiety disorder, might provide some hints. Decentering involves learning to observe thoughts and feelings as objective events in the mind rather than identifying with them personally. Aaron T. Beck, MD, and others hypothesized decentering as a mechanism of change in CBT.

In the UMass study, researchers recruited 81 people with a principal diagnosis of social anxiety disorder based on the Anxiety Disorders Interview Scheduled for DSM-IV. Other inclusion criteria for the study included stability on medications for 3 months or 1 month on benzodiazepines (Behav Ther. 2018 Sep;49[5]:809-12). Sixty-three of participants had 12 sessions of CBGT. The researchers found that people who received the CBGT experienced an increase in decentering. An increase in decentering, in turn, predicted improvement on most outcome measures.

Just as primary care physicians and surgeons know how to address serious physical health issues related natural and man-made disasters, psychiatrists must quickly know how to address the mental health aspects of care. Group therapy has the greatest potential to help more people and perhaps treat – and even prevent not only PTSD but many anxiety disorders as well.

Dr. London, a psychiatrist who practices in New York, developed and ran a short-term psychotherapy program for 20 years at NYU Langone Medical Center and has been writing columns for 35 years. His new book about helping people feel better fast is expected to be published in fall 2018. He has no disclosures.

Chasing the millennial market

I’m not sure why I read the “Letter from the President” in the American Academy of Pediatrics’ AAP News every month. I guess it is out of curiosity about how far the guild to which I belong is drifting from where I think it should be going.

In her August 2018 letter, Colleen A. Kraft, MD, lays out the challenges pediatricians will be facing in the next several decades as the “era of health care consumerism” engulfs us, a change that she suggests will mean “redefining the patient/provider relationship.” As an example, she observes that millennial parents who want “personalized care when and where they want it” have become our “new target market.” Dr. Kraft goes on to suggest that telemedicine may provide a way to reconcile the millennials’ two seemingly incompatible demands. However, she notes that only “15% of pediatricians report using telehealth technologies to provide patient care.” Dr. Kraft recommends that to survive the rising waters of health consumerism more of us should consider climbing onto the telemedicine ship.

There is no question that millennials are aging into the childbearing and child-rearing phases of their lives. They have become the major consumers of pediatric services. Is Dr. Kraft correct that we must change how we practice pediatrics to accommodate the I-want-it-now-delivered-to-my-inbox mentality of the millennials? If we fail to adjust, will we be committing financial suicide?

She makes a valid point. If your practice isn’t providing evening and weekend hours, if your patients’ calls aren’t being answered in a timely manner, and if your receptionists are more about deflecting calls than helping patients get their questions answered, you are running the risk of choking off your income stream to an unsustainable trickle.

But how far should we chase that “target market” made up of people who believe that they can receive personalized care without putting a wrinkle in their device-driven lives? It may be that they have never experienced the benefits of real personalized service from the same person encounter after encounter. I’m convinced that if you provide quality care that is reasonably available, enough patients will stick with you to make your practice sustainable. You will lose some impatient patients to walk-in-quick-care operations, but if you are giving good personalized care, many will return to the quality you are offering. But if you aren’t willing to consider improving your availability, even being the most personable provider in town isn’t going to keep you afloat.

Now to the claim that telemedicine may hold the answer to surviving consumerism. I think we must move cautiously. The fact that only 15% of us aren’t climbing on board doesn’t mean we are all Luddites. It is very likely that many of us are still feeling the sting of investing large amounts of money and time to computerize our health records and seeing little benefit. Telemedicine means lots of things to lots of people. It won’t hurt to keep an open mind and listen as technology evolves. But if you had it to do all over again, wouldn’t you have taken more time and given more thought into signing on for your electronic medical records system?

Finally, let’s remember millennials will be followed by another generation. Although some “experts” suggest that the post-millennials will be just more of the same, I’m not so sure. Millennials and their expectations have become fodder for comedians, even from within their own cohort. The post-millennials may surprise us and provide a refreshing breath of retro and a market that is much easier to reconcile with the realities of good patient care.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

I’m not sure why I read the “Letter from the President” in the American Academy of Pediatrics’ AAP News every month. I guess it is out of curiosity about how far the guild to which I belong is drifting from where I think it should be going.

In her August 2018 letter, Colleen A. Kraft, MD, lays out the challenges pediatricians will be facing in the next several decades as the “era of health care consumerism” engulfs us, a change that she suggests will mean “redefining the patient/provider relationship.” As an example, she observes that millennial parents who want “personalized care when and where they want it” have become our “new target market.” Dr. Kraft goes on to suggest that telemedicine may provide a way to reconcile the millennials’ two seemingly incompatible demands. However, she notes that only “15% of pediatricians report using telehealth technologies to provide patient care.” Dr. Kraft recommends that to survive the rising waters of health consumerism more of us should consider climbing onto the telemedicine ship.

There is no question that millennials are aging into the childbearing and child-rearing phases of their lives. They have become the major consumers of pediatric services. Is Dr. Kraft correct that we must change how we practice pediatrics to accommodate the I-want-it-now-delivered-to-my-inbox mentality of the millennials? If we fail to adjust, will we be committing financial suicide?

She makes a valid point. If your practice isn’t providing evening and weekend hours, if your patients’ calls aren’t being answered in a timely manner, and if your receptionists are more about deflecting calls than helping patients get their questions answered, you are running the risk of choking off your income stream to an unsustainable trickle.

But how far should we chase that “target market” made up of people who believe that they can receive personalized care without putting a wrinkle in their device-driven lives? It may be that they have never experienced the benefits of real personalized service from the same person encounter after encounter. I’m convinced that if you provide quality care that is reasonably available, enough patients will stick with you to make your practice sustainable. You will lose some impatient patients to walk-in-quick-care operations, but if you are giving good personalized care, many will return to the quality you are offering. But if you aren’t willing to consider improving your availability, even being the most personable provider in town isn’t going to keep you afloat.

Now to the claim that telemedicine may hold the answer to surviving consumerism. I think we must move cautiously. The fact that only 15% of us aren’t climbing on board doesn’t mean we are all Luddites. It is very likely that many of us are still feeling the sting of investing large amounts of money and time to computerize our health records and seeing little benefit. Telemedicine means lots of things to lots of people. It won’t hurt to keep an open mind and listen as technology evolves. But if you had it to do all over again, wouldn’t you have taken more time and given more thought into signing on for your electronic medical records system?

Finally, let’s remember millennials will be followed by another generation. Although some “experts” suggest that the post-millennials will be just more of the same, I’m not so sure. Millennials and their expectations have become fodder for comedians, even from within their own cohort. The post-millennials may surprise us and provide a refreshing breath of retro and a market that is much easier to reconcile with the realities of good patient care.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

I’m not sure why I read the “Letter from the President” in the American Academy of Pediatrics’ AAP News every month. I guess it is out of curiosity about how far the guild to which I belong is drifting from where I think it should be going.

In her August 2018 letter, Colleen A. Kraft, MD, lays out the challenges pediatricians will be facing in the next several decades as the “era of health care consumerism” engulfs us, a change that she suggests will mean “redefining the patient/provider relationship.” As an example, she observes that millennial parents who want “personalized care when and where they want it” have become our “new target market.” Dr. Kraft goes on to suggest that telemedicine may provide a way to reconcile the millennials’ two seemingly incompatible demands. However, she notes that only “15% of pediatricians report using telehealth technologies to provide patient care.” Dr. Kraft recommends that to survive the rising waters of health consumerism more of us should consider climbing onto the telemedicine ship.

There is no question that millennials are aging into the childbearing and child-rearing phases of their lives. They have become the major consumers of pediatric services. Is Dr. Kraft correct that we must change how we practice pediatrics to accommodate the I-want-it-now-delivered-to-my-inbox mentality of the millennials? If we fail to adjust, will we be committing financial suicide?

She makes a valid point. If your practice isn’t providing evening and weekend hours, if your patients’ calls aren’t being answered in a timely manner, and if your receptionists are more about deflecting calls than helping patients get their questions answered, you are running the risk of choking off your income stream to an unsustainable trickle.

But how far should we chase that “target market” made up of people who believe that they can receive personalized care without putting a wrinkle in their device-driven lives? It may be that they have never experienced the benefits of real personalized service from the same person encounter after encounter. I’m convinced that if you provide quality care that is reasonably available, enough patients will stick with you to make your practice sustainable. You will lose some impatient patients to walk-in-quick-care operations, but if you are giving good personalized care, many will return to the quality you are offering. But if you aren’t willing to consider improving your availability, even being the most personable provider in town isn’t going to keep you afloat.

Now to the claim that telemedicine may hold the answer to surviving consumerism. I think we must move cautiously. The fact that only 15% of us aren’t climbing on board doesn’t mean we are all Luddites. It is very likely that many of us are still feeling the sting of investing large amounts of money and time to computerize our health records and seeing little benefit. Telemedicine means lots of things to lots of people. It won’t hurt to keep an open mind and listen as technology evolves. But if you had it to do all over again, wouldn’t you have taken more time and given more thought into signing on for your electronic medical records system?

Finally, let’s remember millennials will be followed by another generation. Although some “experts” suggest that the post-millennials will be just more of the same, I’m not so sure. Millennials and their expectations have become fodder for comedians, even from within their own cohort. The post-millennials may surprise us and provide a refreshing breath of retro and a market that is much easier to reconcile with the realities of good patient care.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

The devil is in the headlines

“Breast Milk From Bottle May Not Be As Beneficial As Feeding Directly From The Breast, Researchers Say.” This was the headline on the AAP Daily Briefing that was sent to American Academy of Pediatrics members on Sept 25, 2018.

I suspect that this finding doesn’t surprise you. I can imagine a dozen factors that could make bottled breast milk less advantageous for a baby than milk received directly from the mother’s breast. Antibodies might adhere to the glass surface. A few degrees above or below body temperature could interfere with gastric emptying. Or a temptation to focus on the level in the bottle and inadvertently overfeed could inflate the baby’s body mass index at 3 months, as was found in the study published online in the September 2018 issue of Pediatrics (“Infant Feeding and Weight Gain: Separating Breast Milk From Breastfeeding and Formula From Food”).

I agree that the title of the actual paper is rather dry; it’s a scientific research paper. But the distillation chosen by the folks at AAP Daily Briefing seems ill advised. They were not alone. CCN-Health chose “Breastfeeding better for babies’ weight gain than pumping, new study says” (Michael Nedelman, Sept. 24, 2018). HealthDay News headlined its story with “Milk straight from breast best for baby’s weight” (Sept. 24, 2018).

The articles themselves were well balanced and accurately described this research based on more than 2,500 Canadian mother-infant dyads. But not everyone – including mothers who are struggling with or considering breastfeeding – reads beyond the headlines. How many realize that “better for babies’ weight gain” means a slower weight gain? For the mother who has found that, for a variety of reasons, pumping is the only way she can provide her baby the benefits of breast milk, what these headlines suggest is another blow to her already fragile sense of self-worth.

This research article is excellent and should be read by all of us who counsel young families. It suggests that one of the contributors to our epidemic of childhood obesity may be that bottle-feeding discourages the infant’s own self-regulation skills. It should prompt us to ask every parent who is bottle-feeding his or her baby – regardless of what is in the bottle – exactly how they decide how much to put in the bottle and how long a feeding takes. Even if we are comfortable with the infant’s weight gain, we should caution parents to be more aware of the baby’s cues that he or she has had enough. Not every baby provides cues that are obvious, and parents may need our coaching in deciding how much to feed. This research paper also suggests that as long as breastfeeding was continued, introduction of solids as early as 5 months was not associated with an unhealthy BMI trajectory.

Unfortunately, the reporting of this research article is another example of the hazards of the explosive growth of the Internet. There really is no reason to keep the results of well-crafted research from the lay public, particularly if they are explained in common sense language. However, this places a burden of responsibility on the editors of websites to consider the damage that can be done by a poorly chosen headline.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

“Breast Milk From Bottle May Not Be As Beneficial As Feeding Directly From The Breast, Researchers Say.” This was the headline on the AAP Daily Briefing that was sent to American Academy of Pediatrics members on Sept 25, 2018.

I suspect that this finding doesn’t surprise you. I can imagine a dozen factors that could make bottled breast milk less advantageous for a baby than milk received directly from the mother’s breast. Antibodies might adhere to the glass surface. A few degrees above or below body temperature could interfere with gastric emptying. Or a temptation to focus on the level in the bottle and inadvertently overfeed could inflate the baby’s body mass index at 3 months, as was found in the study published online in the September 2018 issue of Pediatrics (“Infant Feeding and Weight Gain: Separating Breast Milk From Breastfeeding and Formula From Food”).

I agree that the title of the actual paper is rather dry; it’s a scientific research paper. But the distillation chosen by the folks at AAP Daily Briefing seems ill advised. They were not alone. CCN-Health chose “Breastfeeding better for babies’ weight gain than pumping, new study says” (Michael Nedelman, Sept. 24, 2018). HealthDay News headlined its story with “Milk straight from breast best for baby’s weight” (Sept. 24, 2018).

The articles themselves were well balanced and accurately described this research based on more than 2,500 Canadian mother-infant dyads. But not everyone – including mothers who are struggling with or considering breastfeeding – reads beyond the headlines. How many realize that “better for babies’ weight gain” means a slower weight gain? For the mother who has found that, for a variety of reasons, pumping is the only way she can provide her baby the benefits of breast milk, what these headlines suggest is another blow to her already fragile sense of self-worth.

This research article is excellent and should be read by all of us who counsel young families. It suggests that one of the contributors to our epidemic of childhood obesity may be that bottle-feeding discourages the infant’s own self-regulation skills. It should prompt us to ask every parent who is bottle-feeding his or her baby – regardless of what is in the bottle – exactly how they decide how much to put in the bottle and how long a feeding takes. Even if we are comfortable with the infant’s weight gain, we should caution parents to be more aware of the baby’s cues that he or she has had enough. Not every baby provides cues that are obvious, and parents may need our coaching in deciding how much to feed. This research paper also suggests that as long as breastfeeding was continued, introduction of solids as early as 5 months was not associated with an unhealthy BMI trajectory.

Unfortunately, the reporting of this research article is another example of the hazards of the explosive growth of the Internet. There really is no reason to keep the results of well-crafted research from the lay public, particularly if they are explained in common sense language. However, this places a burden of responsibility on the editors of websites to consider the damage that can be done by a poorly chosen headline.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

“Breast Milk From Bottle May Not Be As Beneficial As Feeding Directly From The Breast, Researchers Say.” This was the headline on the AAP Daily Briefing that was sent to American Academy of Pediatrics members on Sept 25, 2018.

I suspect that this finding doesn’t surprise you. I can imagine a dozen factors that could make bottled breast milk less advantageous for a baby than milk received directly from the mother’s breast. Antibodies might adhere to the glass surface. A few degrees above or below body temperature could interfere with gastric emptying. Or a temptation to focus on the level in the bottle and inadvertently overfeed could inflate the baby’s body mass index at 3 months, as was found in the study published online in the September 2018 issue of Pediatrics (“Infant Feeding and Weight Gain: Separating Breast Milk From Breastfeeding and Formula From Food”).

I agree that the title of the actual paper is rather dry; it’s a scientific research paper. But the distillation chosen by the folks at AAP Daily Briefing seems ill advised. They were not alone. CCN-Health chose “Breastfeeding better for babies’ weight gain than pumping, new study says” (Michael Nedelman, Sept. 24, 2018). HealthDay News headlined its story with “Milk straight from breast best for baby’s weight” (Sept. 24, 2018).

The articles themselves were well balanced and accurately described this research based on more than 2,500 Canadian mother-infant dyads. But not everyone – including mothers who are struggling with or considering breastfeeding – reads beyond the headlines. How many realize that “better for babies’ weight gain” means a slower weight gain? For the mother who has found that, for a variety of reasons, pumping is the only way she can provide her baby the benefits of breast milk, what these headlines suggest is another blow to her already fragile sense of self-worth.

This research article is excellent and should be read by all of us who counsel young families. It suggests that one of the contributors to our epidemic of childhood obesity may be that bottle-feeding discourages the infant’s own self-regulation skills. It should prompt us to ask every parent who is bottle-feeding his or her baby – regardless of what is in the bottle – exactly how they decide how much to put in the bottle and how long a feeding takes. Even if we are comfortable with the infant’s weight gain, we should caution parents to be more aware of the baby’s cues that he or she has had enough. Not every baby provides cues that are obvious, and parents may need our coaching in deciding how much to feed. This research paper also suggests that as long as breastfeeding was continued, introduction of solids as early as 5 months was not associated with an unhealthy BMI trajectory.

Unfortunately, the reporting of this research article is another example of the hazards of the explosive growth of the Internet. There really is no reason to keep the results of well-crafted research from the lay public, particularly if they are explained in common sense language. However, this places a burden of responsibility on the editors of websites to consider the damage that can be done by a poorly chosen headline.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

We need to reassess our primitive understanding of the venous system

If one includes the entire spectrum of venous disease, it is a more common pathology than peripheral arterial disease. The financial impact of venous disease is substantial. Why, then, has it taken so long to generate enthusiasm for venous disease of the femorocaval and subclaviocaval segments? For years, the endovascular management of venous disease used technology and techniques borrowed from the arterial space; although results were encouraging, it is clear that they varied widely and continue to do so. Management of these vascular beds is very reminiscent of the barrage of devices we have thrown at the superficial femoral artery.

In peripheral arterial disease, there have been much education and research focused on understanding atherosclerosis and its interaction with arterial devices. However, the paucity of investigation and enlightenment in the venous domain is evident when a literature search is performed. Certainly there are data from Comerota et al. showing an increased amount of collagen in the walls of chronically diseased veins. While this is a reasonable start, it is not sufficient data on which to build an entire treatment paradigm. Just like peripheral arterial disease, venous pathology presents in a continuum. Without an in-depth appreciation of the variability of those presentations, it is difficult to envision targeted therapies.

Although vendors have recently engaged in the development of venous-specific devices, it is in great part grounded in expert opinion rather than in hard data. The Medicare Evidence Development & Coverage Advisory Committee has made it known that we need more evidence on the efficacy of all venous procedures. Peter Gloviczki, MD, a vascular surgeon at Mayo Clinic, in Rochester, Minn., put it succinctly in an issue of Venous News: “We need to focus on venous research and never forget that whoever owns research owns the disease. We must continue innovation and collaboration, with other venous specialties and with industry.” Truth be told, there doesn’t seem to be much fascination with comprehension of the disease, but there appears to be an enormous drive from a variety of specialties to do procedures.

In July 2015, Gerard O’Sullivan, MD, wrote of a multidisciplinary group in Europe established to develop some standardization in venous stenting guidelines. He describes a “need for consistent guidelines for preoperative imaging, follow-up, anticoagulation duration and type, stent diameter, length into the inferior vena cava and lower end in relation to the internal iliac vein/external iliac vein.” I concur, that this would be utopic. I have not come across such guidelines to date.

Current basic science research focuses on pathologic considerations of venous thrombosis, including the consequences related to mechanical behavior of the venous wall in those conditions. In our group’s opinion, these considerations are elemental in determining the next steps in the research paradigm. What determines the remodeling of a vein, with or without intervention? How does a stent influence remodeling? Not surprisingly there are numerous questions that remain unanswered.

Translational investigation has provided insight into innovative ways to use computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. The ability to stage venous disease noninvasively could have a profound impact on how and why we manage the pathology. Additionally, knowing what the pathology looks like and potentially behaves like has the potential to promote more appropriate therapies. Intravascular ultrasound is well described by users and essential to the management of venous disease as it allows us to visualize and appreciate the pathology being treated in real time.

IVUS, though, is primarily used in the context of delivering a therapeutic tool as well as being invasive. Until recently, we have not been able to bring the power of cross-sectional imaging into the operative space. Our group has published on the use of multimodal imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance venography and fluoroscopic image fusion, which can potentially guide future interventions and optimize therapeutic decision-making.

Ultimately, we believe that diseased veins behave differently than arteries do. Therefore, managing veins with tools meant for another space is likely not ideal. Many venous interventions use arterial devices that are not optimized for venous pathologies and underline the fact that we need to continue to develop tools specifically designed for the venous space. The ATTRACT (Acute Venous Thrombosis: Thrombus Removal With Adjunctive Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis) trial has been extremely impactful in the treatment paradigm of venous thrombosis. Although the results remain heavily debated and, on some level, contested, it is a critical trial and should – in many ways – serve as an example of the good research being executed in venous disease.

A quote many have attributed to Albert Einstein says: “The one who follows the crowd will usually go no further than the crowd. Those who walk alone are likely to find themselves in places no one has ever been before.” We have an opportunity to be more enlightened with respect to central venous therapies; let’s not act like lemmings and follow one another off the cliff.

Dr. Bismuth is an associate professor of surgery and associate program director, Houston Methodist Hospital. He reported that he had no relevant disclosures.

References

Comerota AJ et al. 2015 May. Thromb Res. 135(5):882-7.

Vedantham S et al. 2017 Dec 7. N Engl J Med. 377(23):2240-52.

O’Sullivan G 2015 Jul. Endovascular Today.14;7:60-2.

Gloviczki P 2017 Apr. Venous News.1:8.

If one includes the entire spectrum of venous disease, it is a more common pathology than peripheral arterial disease. The financial impact of venous disease is substantial. Why, then, has it taken so long to generate enthusiasm for venous disease of the femorocaval and subclaviocaval segments? For years, the endovascular management of venous disease used technology and techniques borrowed from the arterial space; although results were encouraging, it is clear that they varied widely and continue to do so. Management of these vascular beds is very reminiscent of the barrage of devices we have thrown at the superficial femoral artery.

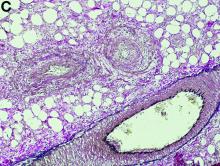

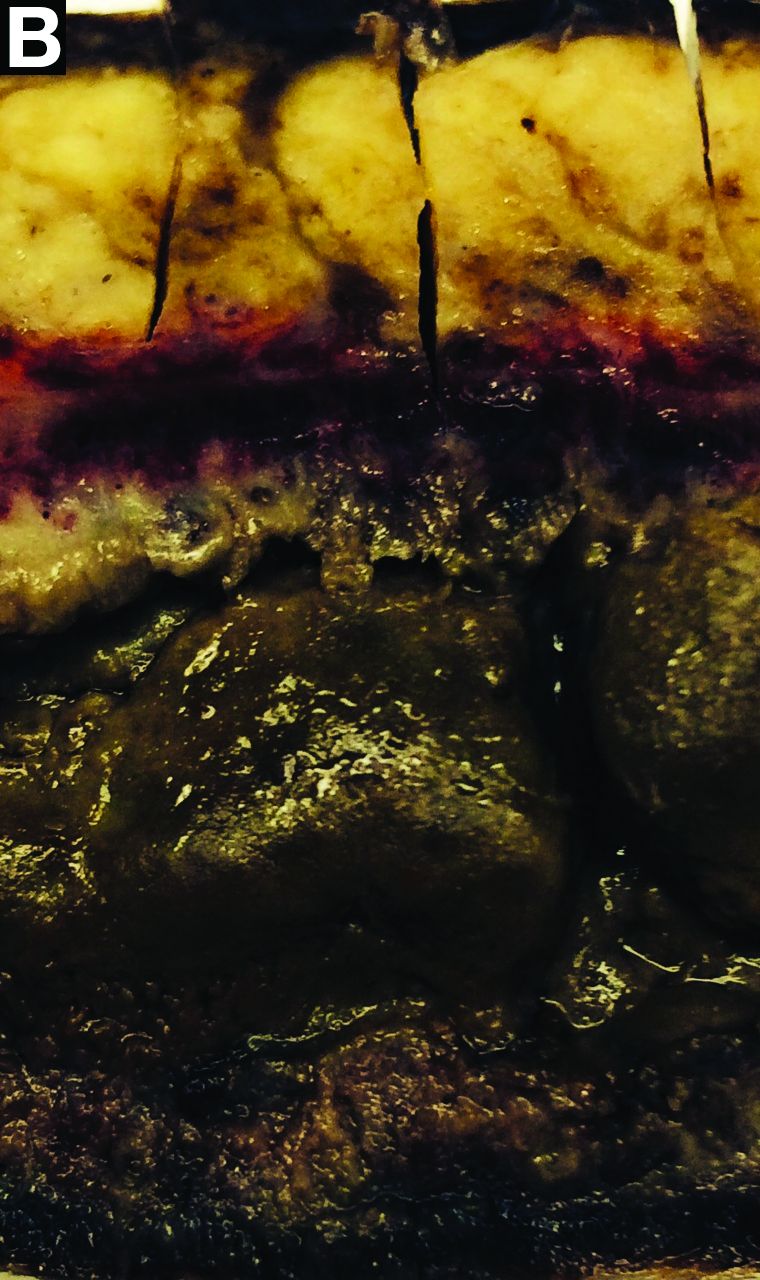

In peripheral arterial disease, there have been much education and research focused on understanding atherosclerosis and its interaction with arterial devices. However, the paucity of investigation and enlightenment in the venous domain is evident when a literature search is performed. Certainly there are data from Comerota et al. showing an increased amount of collagen in the walls of chronically diseased veins. While this is a reasonable start, it is not sufficient data on which to build an entire treatment paradigm. Just like peripheral arterial disease, venous pathology presents in a continuum. Without an in-depth appreciation of the variability of those presentations, it is difficult to envision targeted therapies.

Although vendors have recently engaged in the development of venous-specific devices, it is in great part grounded in expert opinion rather than in hard data. The Medicare Evidence Development & Coverage Advisory Committee has made it known that we need more evidence on the efficacy of all venous procedures. Peter Gloviczki, MD, a vascular surgeon at Mayo Clinic, in Rochester, Minn., put it succinctly in an issue of Venous News: “We need to focus on venous research and never forget that whoever owns research owns the disease. We must continue innovation and collaboration, with other venous specialties and with industry.” Truth be told, there doesn’t seem to be much fascination with comprehension of the disease, but there appears to be an enormous drive from a variety of specialties to do procedures.

In July 2015, Gerard O’Sullivan, MD, wrote of a multidisciplinary group in Europe established to develop some standardization in venous stenting guidelines. He describes a “need for consistent guidelines for preoperative imaging, follow-up, anticoagulation duration and type, stent diameter, length into the inferior vena cava and lower end in relation to the internal iliac vein/external iliac vein.” I concur, that this would be utopic. I have not come across such guidelines to date.

Current basic science research focuses on pathologic considerations of venous thrombosis, including the consequences related to mechanical behavior of the venous wall in those conditions. In our group’s opinion, these considerations are elemental in determining the next steps in the research paradigm. What determines the remodeling of a vein, with or without intervention? How does a stent influence remodeling? Not surprisingly there are numerous questions that remain unanswered.

Translational investigation has provided insight into innovative ways to use computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. The ability to stage venous disease noninvasively could have a profound impact on how and why we manage the pathology. Additionally, knowing what the pathology looks like and potentially behaves like has the potential to promote more appropriate therapies. Intravascular ultrasound is well described by users and essential to the management of venous disease as it allows us to visualize and appreciate the pathology being treated in real time.

IVUS, though, is primarily used in the context of delivering a therapeutic tool as well as being invasive. Until recently, we have not been able to bring the power of cross-sectional imaging into the operative space. Our group has published on the use of multimodal imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance venography and fluoroscopic image fusion, which can potentially guide future interventions and optimize therapeutic decision-making.

Ultimately, we believe that diseased veins behave differently than arteries do. Therefore, managing veins with tools meant for another space is likely not ideal. Many venous interventions use arterial devices that are not optimized for venous pathologies and underline the fact that we need to continue to develop tools specifically designed for the venous space. The ATTRACT (Acute Venous Thrombosis: Thrombus Removal With Adjunctive Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis) trial has been extremely impactful in the treatment paradigm of venous thrombosis. Although the results remain heavily debated and, on some level, contested, it is a critical trial and should – in many ways – serve as an example of the good research being executed in venous disease.

A quote many have attributed to Albert Einstein says: “The one who follows the crowd will usually go no further than the crowd. Those who walk alone are likely to find themselves in places no one has ever been before.” We have an opportunity to be more enlightened with respect to central venous therapies; let’s not act like lemmings and follow one another off the cliff.

Dr. Bismuth is an associate professor of surgery and associate program director, Houston Methodist Hospital. He reported that he had no relevant disclosures.

References

Comerota AJ et al. 2015 May. Thromb Res. 135(5):882-7.

Vedantham S et al. 2017 Dec 7. N Engl J Med. 377(23):2240-52.

O’Sullivan G 2015 Jul. Endovascular Today.14;7:60-2.

Gloviczki P 2017 Apr. Venous News.1:8.

If one includes the entire spectrum of venous disease, it is a more common pathology than peripheral arterial disease. The financial impact of venous disease is substantial. Why, then, has it taken so long to generate enthusiasm for venous disease of the femorocaval and subclaviocaval segments? For years, the endovascular management of venous disease used technology and techniques borrowed from the arterial space; although results were encouraging, it is clear that they varied widely and continue to do so. Management of these vascular beds is very reminiscent of the barrage of devices we have thrown at the superficial femoral artery.

In peripheral arterial disease, there have been much education and research focused on understanding atherosclerosis and its interaction with arterial devices. However, the paucity of investigation and enlightenment in the venous domain is evident when a literature search is performed. Certainly there are data from Comerota et al. showing an increased amount of collagen in the walls of chronically diseased veins. While this is a reasonable start, it is not sufficient data on which to build an entire treatment paradigm. Just like peripheral arterial disease, venous pathology presents in a continuum. Without an in-depth appreciation of the variability of those presentations, it is difficult to envision targeted therapies.

Although vendors have recently engaged in the development of venous-specific devices, it is in great part grounded in expert opinion rather than in hard data. The Medicare Evidence Development & Coverage Advisory Committee has made it known that we need more evidence on the efficacy of all venous procedures. Peter Gloviczki, MD, a vascular surgeon at Mayo Clinic, in Rochester, Minn., put it succinctly in an issue of Venous News: “We need to focus on venous research and never forget that whoever owns research owns the disease. We must continue innovation and collaboration, with other venous specialties and with industry.” Truth be told, there doesn’t seem to be much fascination with comprehension of the disease, but there appears to be an enormous drive from a variety of specialties to do procedures.

In July 2015, Gerard O’Sullivan, MD, wrote of a multidisciplinary group in Europe established to develop some standardization in venous stenting guidelines. He describes a “need for consistent guidelines for preoperative imaging, follow-up, anticoagulation duration and type, stent diameter, length into the inferior vena cava and lower end in relation to the internal iliac vein/external iliac vein.” I concur, that this would be utopic. I have not come across such guidelines to date.

Current basic science research focuses on pathologic considerations of venous thrombosis, including the consequences related to mechanical behavior of the venous wall in those conditions. In our group’s opinion, these considerations are elemental in determining the next steps in the research paradigm. What determines the remodeling of a vein, with or without intervention? How does a stent influence remodeling? Not surprisingly there are numerous questions that remain unanswered.

Translational investigation has provided insight into innovative ways to use computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. The ability to stage venous disease noninvasively could have a profound impact on how and why we manage the pathology. Additionally, knowing what the pathology looks like and potentially behaves like has the potential to promote more appropriate therapies. Intravascular ultrasound is well described by users and essential to the management of venous disease as it allows us to visualize and appreciate the pathology being treated in real time.

IVUS, though, is primarily used in the context of delivering a therapeutic tool as well as being invasive. Until recently, we have not been able to bring the power of cross-sectional imaging into the operative space. Our group has published on the use of multimodal imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance venography and fluoroscopic image fusion, which can potentially guide future interventions and optimize therapeutic decision-making.