User login

The future of pediatrics

Things will change. That is a constant. The practice of pediatrics will be different in the future. The pandemic has changed some things; mostly it has accelerated changes, advancements, improvements, and losses that were already occurring. Telemedicine will play a more prominent role in the future. The finances of solo and small-group practice have become more difficult.

As I wrote my prior column on the character traits/virtues of an admirable physician, I also began brainstorming this column on the traits of an admirable profession. Then the American Academy of Pediatrics’ virtual National Conference & Exhibition had many presentations encouraging pediatricians to adopt a conglomeration of activities in their offices. I became skeptical. Which should be selected? To make a wise choice, I review the major goals of medicine, which I have evolved to embrace as the quadruple aims.

First and hopefully always foremost, the health professions are dedicated to the health of their patients and, hopefully, the population at large. This trait dates to the Hippocratic Oath.

Second, physicians have a stewardship over a vast collection of knowledge, skills, resources, and funds. When I started my career, U.S. health care had increased from 6% of the gross domestic product to 9%, nearly twice that of other developed nations, and was expanding rapidly, contributing to widespread economic problems including the national debt. The health economists of the 1980’s made dire predictions that the nation was headed up to 12% of the GDP, which would cause the sky to start falling. Last I checked U.S. health care is approaching 18% of the GDP. The sky seems intact, although the oceans are rising and the hillsides are burning.

Managed care of the 1990s became focused on the consumer experience. Evaluations of physicians and nurses became dependent on consumer surveys. I recall one survey about the care I personally had received as day surgery. It was mostly about scheduling, being greeted on arrival, the waiting room, and other fluff. Only 1 of the over 20 questions had any bearing on whether I thought the diagnosis was correct, the treatment was effective, or my physician was competent. As a cancer patient, my priorities were not aligned with that survey’s concept of quality.

From 2008, I recall the Triple Aim: “Improving the U.S. health care system requires simultaneous pursuit of three aims: improving the experience of care, improving the health of populations, and reducing per capita costs of health care.”

Over the ensuing decade, physician wellness has been added to make a quadruple aim. If the system isn’t professionally rewarding, burnout occurs. Skills and experience are lost. The best and brightest are not attracted to the specialty. Quality goes down. So physicians must factor this into decisions about the future of pediatrics.

There are many social determinants of health that have large impacts on the population health of children, and it does not necessarily follow that I should spend my patient care time on those determinants. As a professional, I have a responsibility to ensure that I am treating important problems that match my extensive (and expensive) training, knowledge, skills, and experience.

I recently read a persuasive argument that caring for ADHD is an important and doable part of modern general pediatrics. I agree, but I agreed with the proponent’s idea 25 years ago when I joined a large group and saw my own ADHD patients. Change can be slow.

Pharmacology options for anxiety have become safer, more effective, and better understood in children. General pediatricians may now be able to provide important, earlier, and accessible intervention for pediatric anxiety and other mental health issues.

Food insecurity is a worsening issue during the pandemic, but not one which I have specialized abilities to address. A brochure listing available local resources could be posted in waiting rooms and exam rooms. Is spending time asking about it during a visit the best use of a pediatrician’s time? That is a choice a professional needs to make. It may depend on your patient panel and community resources. In the past, I was more inclined to focus on medical care and donate the extra income to my church’s food bank. But the world has changed. Perhaps the pediatrician’s office of the 2020s is a department store, with social workers, psychologists, and therapists located under the same roof. It reminds me of the Mayo model. Wealthy people would travel to Rochester for an executive physical. That physical would frequently recommend seeing a couple specialists before leaving town. It is an effective model but also luxurious.

Racism causes major harms, both to physical health and mental health. Is asking about it a wise use of limited time for well-child visits? What resources will you offer?

Climate change, hurricanes, and wildfires are harming children. Is debating the issue with your patient’s parents productive? I am zealous about the topic. I spend considerable time and money promoting the credibility of science within various religious organizations, but I try to avoid bringing politics into my interactions with patients.

As a professional, your choices may be different. Many people are telling you what you should care about. The executive well-child visit would be beneficial, but it would also take 2 hours. Don’t be misled into spending too much effort on issues not in your expertise. Choose wisely.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

Things will change. That is a constant. The practice of pediatrics will be different in the future. The pandemic has changed some things; mostly it has accelerated changes, advancements, improvements, and losses that were already occurring. Telemedicine will play a more prominent role in the future. The finances of solo and small-group practice have become more difficult.

As I wrote my prior column on the character traits/virtues of an admirable physician, I also began brainstorming this column on the traits of an admirable profession. Then the American Academy of Pediatrics’ virtual National Conference & Exhibition had many presentations encouraging pediatricians to adopt a conglomeration of activities in their offices. I became skeptical. Which should be selected? To make a wise choice, I review the major goals of medicine, which I have evolved to embrace as the quadruple aims.

First and hopefully always foremost, the health professions are dedicated to the health of their patients and, hopefully, the population at large. This trait dates to the Hippocratic Oath.

Second, physicians have a stewardship over a vast collection of knowledge, skills, resources, and funds. When I started my career, U.S. health care had increased from 6% of the gross domestic product to 9%, nearly twice that of other developed nations, and was expanding rapidly, contributing to widespread economic problems including the national debt. The health economists of the 1980’s made dire predictions that the nation was headed up to 12% of the GDP, which would cause the sky to start falling. Last I checked U.S. health care is approaching 18% of the GDP. The sky seems intact, although the oceans are rising and the hillsides are burning.

Managed care of the 1990s became focused on the consumer experience. Evaluations of physicians and nurses became dependent on consumer surveys. I recall one survey about the care I personally had received as day surgery. It was mostly about scheduling, being greeted on arrival, the waiting room, and other fluff. Only 1 of the over 20 questions had any bearing on whether I thought the diagnosis was correct, the treatment was effective, or my physician was competent. As a cancer patient, my priorities were not aligned with that survey’s concept of quality.

From 2008, I recall the Triple Aim: “Improving the U.S. health care system requires simultaneous pursuit of three aims: improving the experience of care, improving the health of populations, and reducing per capita costs of health care.”

Over the ensuing decade, physician wellness has been added to make a quadruple aim. If the system isn’t professionally rewarding, burnout occurs. Skills and experience are lost. The best and brightest are not attracted to the specialty. Quality goes down. So physicians must factor this into decisions about the future of pediatrics.

There are many social determinants of health that have large impacts on the population health of children, and it does not necessarily follow that I should spend my patient care time on those determinants. As a professional, I have a responsibility to ensure that I am treating important problems that match my extensive (and expensive) training, knowledge, skills, and experience.

I recently read a persuasive argument that caring for ADHD is an important and doable part of modern general pediatrics. I agree, but I agreed with the proponent’s idea 25 years ago when I joined a large group and saw my own ADHD patients. Change can be slow.

Pharmacology options for anxiety have become safer, more effective, and better understood in children. General pediatricians may now be able to provide important, earlier, and accessible intervention for pediatric anxiety and other mental health issues.

Food insecurity is a worsening issue during the pandemic, but not one which I have specialized abilities to address. A brochure listing available local resources could be posted in waiting rooms and exam rooms. Is spending time asking about it during a visit the best use of a pediatrician’s time? That is a choice a professional needs to make. It may depend on your patient panel and community resources. In the past, I was more inclined to focus on medical care and donate the extra income to my church’s food bank. But the world has changed. Perhaps the pediatrician’s office of the 2020s is a department store, with social workers, psychologists, and therapists located under the same roof. It reminds me of the Mayo model. Wealthy people would travel to Rochester for an executive physical. That physical would frequently recommend seeing a couple specialists before leaving town. It is an effective model but also luxurious.

Racism causes major harms, both to physical health and mental health. Is asking about it a wise use of limited time for well-child visits? What resources will you offer?

Climate change, hurricanes, and wildfires are harming children. Is debating the issue with your patient’s parents productive? I am zealous about the topic. I spend considerable time and money promoting the credibility of science within various religious organizations, but I try to avoid bringing politics into my interactions with patients.

As a professional, your choices may be different. Many people are telling you what you should care about. The executive well-child visit would be beneficial, but it would also take 2 hours. Don’t be misled into spending too much effort on issues not in your expertise. Choose wisely.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

Things will change. That is a constant. The practice of pediatrics will be different in the future. The pandemic has changed some things; mostly it has accelerated changes, advancements, improvements, and losses that were already occurring. Telemedicine will play a more prominent role in the future. The finances of solo and small-group practice have become more difficult.

As I wrote my prior column on the character traits/virtues of an admirable physician, I also began brainstorming this column on the traits of an admirable profession. Then the American Academy of Pediatrics’ virtual National Conference & Exhibition had many presentations encouraging pediatricians to adopt a conglomeration of activities in their offices. I became skeptical. Which should be selected? To make a wise choice, I review the major goals of medicine, which I have evolved to embrace as the quadruple aims.

First and hopefully always foremost, the health professions are dedicated to the health of their patients and, hopefully, the population at large. This trait dates to the Hippocratic Oath.

Second, physicians have a stewardship over a vast collection of knowledge, skills, resources, and funds. When I started my career, U.S. health care had increased from 6% of the gross domestic product to 9%, nearly twice that of other developed nations, and was expanding rapidly, contributing to widespread economic problems including the national debt. The health economists of the 1980’s made dire predictions that the nation was headed up to 12% of the GDP, which would cause the sky to start falling. Last I checked U.S. health care is approaching 18% of the GDP. The sky seems intact, although the oceans are rising and the hillsides are burning.

Managed care of the 1990s became focused on the consumer experience. Evaluations of physicians and nurses became dependent on consumer surveys. I recall one survey about the care I personally had received as day surgery. It was mostly about scheduling, being greeted on arrival, the waiting room, and other fluff. Only 1 of the over 20 questions had any bearing on whether I thought the diagnosis was correct, the treatment was effective, or my physician was competent. As a cancer patient, my priorities were not aligned with that survey’s concept of quality.

From 2008, I recall the Triple Aim: “Improving the U.S. health care system requires simultaneous pursuit of three aims: improving the experience of care, improving the health of populations, and reducing per capita costs of health care.”

Over the ensuing decade, physician wellness has been added to make a quadruple aim. If the system isn’t professionally rewarding, burnout occurs. Skills and experience are lost. The best and brightest are not attracted to the specialty. Quality goes down. So physicians must factor this into decisions about the future of pediatrics.

There are many social determinants of health that have large impacts on the population health of children, and it does not necessarily follow that I should spend my patient care time on those determinants. As a professional, I have a responsibility to ensure that I am treating important problems that match my extensive (and expensive) training, knowledge, skills, and experience.

I recently read a persuasive argument that caring for ADHD is an important and doable part of modern general pediatrics. I agree, but I agreed with the proponent’s idea 25 years ago when I joined a large group and saw my own ADHD patients. Change can be slow.

Pharmacology options for anxiety have become safer, more effective, and better understood in children. General pediatricians may now be able to provide important, earlier, and accessible intervention for pediatric anxiety and other mental health issues.

Food insecurity is a worsening issue during the pandemic, but not one which I have specialized abilities to address. A brochure listing available local resources could be posted in waiting rooms and exam rooms. Is spending time asking about it during a visit the best use of a pediatrician’s time? That is a choice a professional needs to make. It may depend on your patient panel and community resources. In the past, I was more inclined to focus on medical care and donate the extra income to my church’s food bank. But the world has changed. Perhaps the pediatrician’s office of the 2020s is a department store, with social workers, psychologists, and therapists located under the same roof. It reminds me of the Mayo model. Wealthy people would travel to Rochester for an executive physical. That physical would frequently recommend seeing a couple specialists before leaving town. It is an effective model but also luxurious.

Racism causes major harms, both to physical health and mental health. Is asking about it a wise use of limited time for well-child visits? What resources will you offer?

Climate change, hurricanes, and wildfires are harming children. Is debating the issue with your patient’s parents productive? I am zealous about the topic. I spend considerable time and money promoting the credibility of science within various religious organizations, but I try to avoid bringing politics into my interactions with patients.

As a professional, your choices may be different. Many people are telling you what you should care about. The executive well-child visit would be beneficial, but it would also take 2 hours. Don’t be misled into spending too much effort on issues not in your expertise. Choose wisely.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

Fenway data, the final frontier

Data, as we all know, have taken over the world. ”

Statistical objectivity is in, individuality is out. You may have taught for 30 years and gained a sense for which child has a problem that needs intervention and which one just needs patience and time to develop. You may have managed patients for decades and have a hunch about who needs immediate help and who can be watched. But “senses” and “hunches” can’t be measured and therefore do not exist, or better, don’t count. Numbers count!

Data-obsession reflects what Germans call the Zeitgeist, the spirit of the age. But the Germans will have to come up with a different word for our age, won’t they? Nobody can measure a “spirit.”

Still, you know the spirit’s there, when it knocks you over and stomps on you.

The one sphere of life that has resisted being reduced to numbers is sports. In sports, you don’t need complex analysis to know who’s No. 1 and who’s number everything else. No. 1 crosses the finish line first, wins the most games, knocks out the opponent. The one lying on the mat is No. 2.

Of course, sports always had lots of numbers. Baseball fans have always known about batting averages, runs batted in, earned run averages. But there were always those individual intangibles that goggle the eyes of small boys and keep sportswriters in business: this athlete’s “ferocious drive,” that one’s “will to win,” the way a third “always comes through in the clutch.” Pitchers who couldn’t throw fast anymore were “crafty.” Grizzled, tobacco-chewing scouts could sense which youngster “looked like a ballplayer.”

As if you didn’t already know, you can tell how old I am to talk this way. Bill James and his statistical acolytes put paid to that old kind of thinking a long time ago. Read Moneyball or see the movie. In sports too, it’s now all about the stats.

To generate flagging interest among the young for America’s now-stodgy pastime, Major League Baseball has brought out Statcast 2.0., which adds, according to a recent news story, “Doppler-based tracking of pitch velocity, exit velocity, launch angles, and spin rates, and defensive tracking of players.” Multicamera arrays produce “biomechanical imaging and skeletal models that can help pitchers with delivery issues or batters with swing path quandaries.”

And so we have lots of new data to ponder: exit velocity – how fast a hit ball leaves the bat; launch angle – what angle it leaves at; spin rate – how fast a thrown curveball spins; and defensive tracking – how many feet this shortstop can move left to snag a ground ball, or a right-fielder to catch a fly. And there are new, composite stats, like OPS (on-base plus slugging). I will not try to explain OPS, because it is a mathematical abstraction that I cannot grasp. It signifies a blend of on-base percentage and slugging percentage, which to me is like what you get when you blend a tomato with a broccoli. Or something.

And, stats aside, you do still have to win. Not long ago the Boston Red Sox had a relief pitcher whose spin rate was splendid, but he couldn’t get anybody out.

The real aim of the new broadcast innovations noted above comes at the end of the report:

In an effort to at least reach, if not grow, a younger fan base, MLB from now on will focus on video engagement, gaming, and augmented reality on Snapchat.

You got it: the goal is to reduce baseball to a video game, and its players to gaming characters, perhaps with big contracts and marketing deals. Hey, check out that dude’s OPS!

You can’t measure a Zeitgeist, but you certainly know when it’s sitting on your chest. Your respirations get depressed. Measurably.

Yeah, I sound like every cranky old man in history. But hey – I’m Emeritus! See this column’s title!

In addition, the article has one more detail:

Curiosity about whether a fly ball to deep right field at Fenway Park would be a home run at Yankee Stadium can be satisfied by overlaying the Yankee Stadium footprint on top of Fenway.

Maybe it would satisfy you, buddy, but anything that superimposes Yankee Stadium on top of Fenway Park dissatisfies me by a factor of 6.7!

Dr. Rockoff, who wrote the Dermatology News column “Under My Skin,” is now semiretired, after 40 years of practice in Brookline, Mass. He served on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available online. Write to him at [email protected].

Data, as we all know, have taken over the world. ”

Statistical objectivity is in, individuality is out. You may have taught for 30 years and gained a sense for which child has a problem that needs intervention and which one just needs patience and time to develop. You may have managed patients for decades and have a hunch about who needs immediate help and who can be watched. But “senses” and “hunches” can’t be measured and therefore do not exist, or better, don’t count. Numbers count!

Data-obsession reflects what Germans call the Zeitgeist, the spirit of the age. But the Germans will have to come up with a different word for our age, won’t they? Nobody can measure a “spirit.”

Still, you know the spirit’s there, when it knocks you over and stomps on you.

The one sphere of life that has resisted being reduced to numbers is sports. In sports, you don’t need complex analysis to know who’s No. 1 and who’s number everything else. No. 1 crosses the finish line first, wins the most games, knocks out the opponent. The one lying on the mat is No. 2.

Of course, sports always had lots of numbers. Baseball fans have always known about batting averages, runs batted in, earned run averages. But there were always those individual intangibles that goggle the eyes of small boys and keep sportswriters in business: this athlete’s “ferocious drive,” that one’s “will to win,” the way a third “always comes through in the clutch.” Pitchers who couldn’t throw fast anymore were “crafty.” Grizzled, tobacco-chewing scouts could sense which youngster “looked like a ballplayer.”

As if you didn’t already know, you can tell how old I am to talk this way. Bill James and his statistical acolytes put paid to that old kind of thinking a long time ago. Read Moneyball or see the movie. In sports too, it’s now all about the stats.

To generate flagging interest among the young for America’s now-stodgy pastime, Major League Baseball has brought out Statcast 2.0., which adds, according to a recent news story, “Doppler-based tracking of pitch velocity, exit velocity, launch angles, and spin rates, and defensive tracking of players.” Multicamera arrays produce “biomechanical imaging and skeletal models that can help pitchers with delivery issues or batters with swing path quandaries.”

And so we have lots of new data to ponder: exit velocity – how fast a hit ball leaves the bat; launch angle – what angle it leaves at; spin rate – how fast a thrown curveball spins; and defensive tracking – how many feet this shortstop can move left to snag a ground ball, or a right-fielder to catch a fly. And there are new, composite stats, like OPS (on-base plus slugging). I will not try to explain OPS, because it is a mathematical abstraction that I cannot grasp. It signifies a blend of on-base percentage and slugging percentage, which to me is like what you get when you blend a tomato with a broccoli. Or something.

And, stats aside, you do still have to win. Not long ago the Boston Red Sox had a relief pitcher whose spin rate was splendid, but he couldn’t get anybody out.

The real aim of the new broadcast innovations noted above comes at the end of the report:

In an effort to at least reach, if not grow, a younger fan base, MLB from now on will focus on video engagement, gaming, and augmented reality on Snapchat.

You got it: the goal is to reduce baseball to a video game, and its players to gaming characters, perhaps with big contracts and marketing deals. Hey, check out that dude’s OPS!

You can’t measure a Zeitgeist, but you certainly know when it’s sitting on your chest. Your respirations get depressed. Measurably.

Yeah, I sound like every cranky old man in history. But hey – I’m Emeritus! See this column’s title!

In addition, the article has one more detail:

Curiosity about whether a fly ball to deep right field at Fenway Park would be a home run at Yankee Stadium can be satisfied by overlaying the Yankee Stadium footprint on top of Fenway.

Maybe it would satisfy you, buddy, but anything that superimposes Yankee Stadium on top of Fenway Park dissatisfies me by a factor of 6.7!

Dr. Rockoff, who wrote the Dermatology News column “Under My Skin,” is now semiretired, after 40 years of practice in Brookline, Mass. He served on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available online. Write to him at [email protected].

Data, as we all know, have taken over the world. ”

Statistical objectivity is in, individuality is out. You may have taught for 30 years and gained a sense for which child has a problem that needs intervention and which one just needs patience and time to develop. You may have managed patients for decades and have a hunch about who needs immediate help and who can be watched. But “senses” and “hunches” can’t be measured and therefore do not exist, or better, don’t count. Numbers count!

Data-obsession reflects what Germans call the Zeitgeist, the spirit of the age. But the Germans will have to come up with a different word for our age, won’t they? Nobody can measure a “spirit.”

Still, you know the spirit’s there, when it knocks you over and stomps on you.

The one sphere of life that has resisted being reduced to numbers is sports. In sports, you don’t need complex analysis to know who’s No. 1 and who’s number everything else. No. 1 crosses the finish line first, wins the most games, knocks out the opponent. The one lying on the mat is No. 2.

Of course, sports always had lots of numbers. Baseball fans have always known about batting averages, runs batted in, earned run averages. But there were always those individual intangibles that goggle the eyes of small boys and keep sportswriters in business: this athlete’s “ferocious drive,” that one’s “will to win,” the way a third “always comes through in the clutch.” Pitchers who couldn’t throw fast anymore were “crafty.” Grizzled, tobacco-chewing scouts could sense which youngster “looked like a ballplayer.”

As if you didn’t already know, you can tell how old I am to talk this way. Bill James and his statistical acolytes put paid to that old kind of thinking a long time ago. Read Moneyball or see the movie. In sports too, it’s now all about the stats.

To generate flagging interest among the young for America’s now-stodgy pastime, Major League Baseball has brought out Statcast 2.0., which adds, according to a recent news story, “Doppler-based tracking of pitch velocity, exit velocity, launch angles, and spin rates, and defensive tracking of players.” Multicamera arrays produce “biomechanical imaging and skeletal models that can help pitchers with delivery issues or batters with swing path quandaries.”

And so we have lots of new data to ponder: exit velocity – how fast a hit ball leaves the bat; launch angle – what angle it leaves at; spin rate – how fast a thrown curveball spins; and defensive tracking – how many feet this shortstop can move left to snag a ground ball, or a right-fielder to catch a fly. And there are new, composite stats, like OPS (on-base plus slugging). I will not try to explain OPS, because it is a mathematical abstraction that I cannot grasp. It signifies a blend of on-base percentage and slugging percentage, which to me is like what you get when you blend a tomato with a broccoli. Or something.

And, stats aside, you do still have to win. Not long ago the Boston Red Sox had a relief pitcher whose spin rate was splendid, but he couldn’t get anybody out.

The real aim of the new broadcast innovations noted above comes at the end of the report:

In an effort to at least reach, if not grow, a younger fan base, MLB from now on will focus on video engagement, gaming, and augmented reality on Snapchat.

You got it: the goal is to reduce baseball to a video game, and its players to gaming characters, perhaps with big contracts and marketing deals. Hey, check out that dude’s OPS!

You can’t measure a Zeitgeist, but you certainly know when it’s sitting on your chest. Your respirations get depressed. Measurably.

Yeah, I sound like every cranky old man in history. But hey – I’m Emeritus! See this column’s title!

In addition, the article has one more detail:

Curiosity about whether a fly ball to deep right field at Fenway Park would be a home run at Yankee Stadium can be satisfied by overlaying the Yankee Stadium footprint on top of Fenway.

Maybe it would satisfy you, buddy, but anything that superimposes Yankee Stadium on top of Fenway Park dissatisfies me by a factor of 6.7!

Dr. Rockoff, who wrote the Dermatology News column “Under My Skin,” is now semiretired, after 40 years of practice in Brookline, Mass. He served on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available online. Write to him at [email protected].

Hospitalist Medicare payments are at risk for large cuts in 2021

Now is the time to act

From the beginning, SHM has consciously and consistently taken a unique approach to its advocacy efforts with the federal government. The advocacy priorities of SHM most often concern issues that we feel have an impact on our patients and the broader delivery system, as opposed to a focus on issues that have direct financial benefit to our members.

This strategy has served SHM well. It has earned respect among policymakers and we have seen significant success for a young and relatively small medical society. The issues where we spend the bulk of our time and effort include advocating for issues like alternative payment models (APMs), which reward care quality as opposed to volume, as well as issues related to data integrity that APMs require. We have advocated strongly for changes to dysfunctional observation status rules, for workforce adequacy and sustainability, and for recognition of the importance of hospital medicine’s contribution to the redesign of our nations delivery system. And SHM will continue to advocate for many other issues identified as being important to hospital medicine and our patients.

This year, for the first time in the two decades that I have served on the SHM Public Policy Committee, Medicare has proposed changes that would create unprecedented financial hardship for hospital medicine groups. Each year, as a part of its advocacy agenda, SHM reviews and comments on proposed changes to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS). Among other things, the PFS adjusts payment rates to physicians for specific services. Changes under the PFS are required to be budget neutral. In effect, budget neutrality means that whenever certain services receive an increased payment rate, CMS is required to offset these changes by making cuts to other services. This year, in an effort to correct the long-standing underfunding of primary care services, CMS has increased payment for many Evaluation and Management (E&M) codes associated with outpatient primary care services. However, due to budget neutrality requirements, many inpatient E&M care services will be receiving significant cuts.

The goal of increasing payment rates for primary care services is laudable, as many of these cognitive services have been long underfunded. However, the proposed payment increases will only apply to outpatient E&M codes and not their corresponding inpatient codes. While our outpatient Internal Medicine and Family Practice colleagues will benefit from these changes, inpatient providers, including hospitalists, stand to lose a significant amount revenue. SHM and the hospitalists we represent estimate that the proposed budget neutrality adjustment will lead to an approximate 8 percent decrease in Medicare Fee for Services (FFS) revenue. Hospitalists are among the specialties that will be most impacted from these proposed changes. If put into effect, these proposals will leave hospital medicine behind.

These changes have been proposed at a time when hospitalists, along with their colleagues in critical care and emergency medicine, have been caring for patients on the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic at great risk to themselves at their families. While hospitalists are working tirelessly to provide lifesaving care to COVID-positive patients throughout the country, hospitalist groups have struggled financially as a result of the pandemic. Inpatient volumes, and therefore care reimbursement, has dropped significantly. Many hospitalists have already reported pay reductions of 20% or more. Others have seen their shifts reduced, resulting in understaffing, which may compromise the quality of care. For many groups, a Medicare reimbursement cut of this magnitude add fuel to an already strained revenue stream and will not be financially sustainable.

SHM is, of course, fighting back. We are not asking CMS to completely abandon the increases in reimbursement for primary care outpatient codes, and we support properly valuing outpatient care services. However, we are asking CMS to find a solution that does not come at the expense of hospital medicine and the other specialties that care for acutely ill hospitalized patients, including patients with COVID-19. If a better solution requires holding off on the proposal for another year, CMS should do so. Furthermore, SHM is asking Congress to abandon the statutory requirement for budget neutrality in these extraordinary times as CMS and Congress work to find towards a solution that properly values both inpatient and outpatient care services.

To send a message to your representatives urging them to stop these payment cuts, please visit SHM’s Legislative Action Center at www.votervoice.net/SHM/campaigns/77226/respond. You can read our full comments on the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Proposed Rule at www.hospitalmedicine.org/policy--advocacy/letters/2021-physician-fee-schedule-proposed-rule/.

Now is the time to act

Now is the time to act

From the beginning, SHM has consciously and consistently taken a unique approach to its advocacy efforts with the federal government. The advocacy priorities of SHM most often concern issues that we feel have an impact on our patients and the broader delivery system, as opposed to a focus on issues that have direct financial benefit to our members.

This strategy has served SHM well. It has earned respect among policymakers and we have seen significant success for a young and relatively small medical society. The issues where we spend the bulk of our time and effort include advocating for issues like alternative payment models (APMs), which reward care quality as opposed to volume, as well as issues related to data integrity that APMs require. We have advocated strongly for changes to dysfunctional observation status rules, for workforce adequacy and sustainability, and for recognition of the importance of hospital medicine’s contribution to the redesign of our nations delivery system. And SHM will continue to advocate for many other issues identified as being important to hospital medicine and our patients.

This year, for the first time in the two decades that I have served on the SHM Public Policy Committee, Medicare has proposed changes that would create unprecedented financial hardship for hospital medicine groups. Each year, as a part of its advocacy agenda, SHM reviews and comments on proposed changes to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS). Among other things, the PFS adjusts payment rates to physicians for specific services. Changes under the PFS are required to be budget neutral. In effect, budget neutrality means that whenever certain services receive an increased payment rate, CMS is required to offset these changes by making cuts to other services. This year, in an effort to correct the long-standing underfunding of primary care services, CMS has increased payment for many Evaluation and Management (E&M) codes associated with outpatient primary care services. However, due to budget neutrality requirements, many inpatient E&M care services will be receiving significant cuts.

The goal of increasing payment rates for primary care services is laudable, as many of these cognitive services have been long underfunded. However, the proposed payment increases will only apply to outpatient E&M codes and not their corresponding inpatient codes. While our outpatient Internal Medicine and Family Practice colleagues will benefit from these changes, inpatient providers, including hospitalists, stand to lose a significant amount revenue. SHM and the hospitalists we represent estimate that the proposed budget neutrality adjustment will lead to an approximate 8 percent decrease in Medicare Fee for Services (FFS) revenue. Hospitalists are among the specialties that will be most impacted from these proposed changes. If put into effect, these proposals will leave hospital medicine behind.

These changes have been proposed at a time when hospitalists, along with their colleagues in critical care and emergency medicine, have been caring for patients on the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic at great risk to themselves at their families. While hospitalists are working tirelessly to provide lifesaving care to COVID-positive patients throughout the country, hospitalist groups have struggled financially as a result of the pandemic. Inpatient volumes, and therefore care reimbursement, has dropped significantly. Many hospitalists have already reported pay reductions of 20% or more. Others have seen their shifts reduced, resulting in understaffing, which may compromise the quality of care. For many groups, a Medicare reimbursement cut of this magnitude add fuel to an already strained revenue stream and will not be financially sustainable.

SHM is, of course, fighting back. We are not asking CMS to completely abandon the increases in reimbursement for primary care outpatient codes, and we support properly valuing outpatient care services. However, we are asking CMS to find a solution that does not come at the expense of hospital medicine and the other specialties that care for acutely ill hospitalized patients, including patients with COVID-19. If a better solution requires holding off on the proposal for another year, CMS should do so. Furthermore, SHM is asking Congress to abandon the statutory requirement for budget neutrality in these extraordinary times as CMS and Congress work to find towards a solution that properly values both inpatient and outpatient care services.

To send a message to your representatives urging them to stop these payment cuts, please visit SHM’s Legislative Action Center at www.votervoice.net/SHM/campaigns/77226/respond. You can read our full comments on the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Proposed Rule at www.hospitalmedicine.org/policy--advocacy/letters/2021-physician-fee-schedule-proposed-rule/.

From the beginning, SHM has consciously and consistently taken a unique approach to its advocacy efforts with the federal government. The advocacy priorities of SHM most often concern issues that we feel have an impact on our patients and the broader delivery system, as opposed to a focus on issues that have direct financial benefit to our members.

This strategy has served SHM well. It has earned respect among policymakers and we have seen significant success for a young and relatively small medical society. The issues where we spend the bulk of our time and effort include advocating for issues like alternative payment models (APMs), which reward care quality as opposed to volume, as well as issues related to data integrity that APMs require. We have advocated strongly for changes to dysfunctional observation status rules, for workforce adequacy and sustainability, and for recognition of the importance of hospital medicine’s contribution to the redesign of our nations delivery system. And SHM will continue to advocate for many other issues identified as being important to hospital medicine and our patients.

This year, for the first time in the two decades that I have served on the SHM Public Policy Committee, Medicare has proposed changes that would create unprecedented financial hardship for hospital medicine groups. Each year, as a part of its advocacy agenda, SHM reviews and comments on proposed changes to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS). Among other things, the PFS adjusts payment rates to physicians for specific services. Changes under the PFS are required to be budget neutral. In effect, budget neutrality means that whenever certain services receive an increased payment rate, CMS is required to offset these changes by making cuts to other services. This year, in an effort to correct the long-standing underfunding of primary care services, CMS has increased payment for many Evaluation and Management (E&M) codes associated with outpatient primary care services. However, due to budget neutrality requirements, many inpatient E&M care services will be receiving significant cuts.

The goal of increasing payment rates for primary care services is laudable, as many of these cognitive services have been long underfunded. However, the proposed payment increases will only apply to outpatient E&M codes and not their corresponding inpatient codes. While our outpatient Internal Medicine and Family Practice colleagues will benefit from these changes, inpatient providers, including hospitalists, stand to lose a significant amount revenue. SHM and the hospitalists we represent estimate that the proposed budget neutrality adjustment will lead to an approximate 8 percent decrease in Medicare Fee for Services (FFS) revenue. Hospitalists are among the specialties that will be most impacted from these proposed changes. If put into effect, these proposals will leave hospital medicine behind.

These changes have been proposed at a time when hospitalists, along with their colleagues in critical care and emergency medicine, have been caring for patients on the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic at great risk to themselves at their families. While hospitalists are working tirelessly to provide lifesaving care to COVID-positive patients throughout the country, hospitalist groups have struggled financially as a result of the pandemic. Inpatient volumes, and therefore care reimbursement, has dropped significantly. Many hospitalists have already reported pay reductions of 20% or more. Others have seen their shifts reduced, resulting in understaffing, which may compromise the quality of care. For many groups, a Medicare reimbursement cut of this magnitude add fuel to an already strained revenue stream and will not be financially sustainable.

SHM is, of course, fighting back. We are not asking CMS to completely abandon the increases in reimbursement for primary care outpatient codes, and we support properly valuing outpatient care services. However, we are asking CMS to find a solution that does not come at the expense of hospital medicine and the other specialties that care for acutely ill hospitalized patients, including patients with COVID-19. If a better solution requires holding off on the proposal for another year, CMS should do so. Furthermore, SHM is asking Congress to abandon the statutory requirement for budget neutrality in these extraordinary times as CMS and Congress work to find towards a solution that properly values both inpatient and outpatient care services.

To send a message to your representatives urging them to stop these payment cuts, please visit SHM’s Legislative Action Center at www.votervoice.net/SHM/campaigns/77226/respond. You can read our full comments on the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Proposed Rule at www.hospitalmedicine.org/policy--advocacy/letters/2021-physician-fee-schedule-proposed-rule/.

Case of the inappropriate endoscopy referral

A 53-year-old woman was referred for surveillance colonoscopy. She is a current smoker with a history of chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, atrial fibrillation, and two diminutive hyperplastic polyps found on average-risk screening colonoscopy 3 years previously. Her prep at the time was excellent and she was advised to return in 10 years for follow-up. She has taken the day off work, arranged for a driver, is prepped, and is on your schedule for a colonoscopy for a “history of polyps.” Is this an appropriate referral and how should you handle it?

Most of us have had questionable referrals on our endoscopy schedules. While judgments can vary among providers about when a patient should undergo a procedure or what intervention is most needed, some direct-access referrals for endoscopy are considered inappropriate by most standards. In examining referrals for colonoscopy, studies have shown that as many as 23% of screening colonoscopies among Medicare beneficiaries and 14.2% of Veterans Affairs patients in a large colorectal cancer screening study are inappropriate.1,2 A prospective multicenter study found 29% of colonoscopies to be inappropriate, and surveillance studies were confirmed as the most frequent source of inappropriate procedures.3,4 Endoscopies are performed so frequently, effectively, and safely that they can be readily scheduled by gastroenterologists and nongastroenterologists alike. Open access has facilitated and expedited needed procedures, providing benefit to patient and provider and freeing clinic visit time for more complex consults. But while endoscopy is very safe, it is not without risk or cost. What should be the response when a patient in the endoscopy unit appears to be inappropriately referred?

The first step is to determine what is inappropriate. There are several situations when a procedure might be considered inappropriate, particularly when we try to apply ethical principles.

1. The performance of the procedure is contrary to society guidelines. The American Gastroenterological Association, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and American College of Gastroenterology publish clinical guidelines. These documents are drafted after rigorous research and literature review, and the strength of the recommendations is confirmed by incorporation of GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) methodology. Such guidelines allow gastroenterologists across the country to practice confidently in a manner consistent with the current available data and the standards of care for the GI community. A patient who is referred for a procedure for an indication that does not adhere to – or contradicts – guidelines, may be at risk for substandard care and possibly at risk for harm. It is the physician’s ethical responsibility to provide the most “good” and the least harm for patients, consistent with the ethical principle of beneficence.

Guidelines, however, are not mandates, and an argument may be made that in order to provide the best care, alternatives may be offered to a patient. Some circumstances require clinical judgments based on unique patient characteristics and the need for individualized care. As a rule, however, the goal of guidelines is to assist doctors in providing the best care.

2. The procedure is not the correct test for the clinical question. While endoscopy can address many clinical queries, endoscopy is not always the right procedure for a specific medical question. A patient referred for an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to rule out gastroparesis is being subjected to the wrong test to answer the clinical question. Some information may be obtained from an EGD (e.g., retained food may suggest dysmotility or the patient could have gastric outlet obstruction) but this is not the recommended initial management step. Is it reasonable to proceed with a test that cannot answer the question asked? Continuing with the endoscopy would not enhance beneficence and might be a futile service for the patient. Is this doing the best for the patient?

3. The risks of the procedure outweigh the benefits. Some procedures may be consistent with guidelines and able to answer the questions asked, but may present more risk than benefit. Should an elderly patient with multiple significant comorbidities and a likely limited life span undergo a follow-up colonoscopy even at an appropriate interval? The principle of nonmaleficence is the clear standard here.

4. The intent for doing the procedure has questionable merit. Some patients may request an EGD at the time of the screening colonoscopy just to “check,” regardless of symptoms or risk category. A patient has a right to make her/his own decisions but patient autonomy should not be an excuse for a nonindicated procedure.

In the case of the 53-year-old woman referred for surveillance colonoscopy, the physician needs to consider whether performing the test is inappropriate for any of the above reasons. First and foremost, is it doing the most good for the patient?

On the one hand, performing an inappropriately referred procedure contradicts guidelines and may present undue risk of complication from anesthesia or endoscopy. Would the physician be ethically compromised in this situation, or even legally liable should a complication arise during a procedure done for a questionable indication?

On the other hand, canceling such a procedure creates multiple dilemmas. The autonomy and the convenience of the patient need to be respected. The patient who has followed all the instructions, is prepped, has taken off work, arranged for transportation, and wants to have the procedure done may have difficulty accepting a cancellation. Colonoscopy is a safe test. Is it the right thing to cancel her procedure because of an imprudent referral? Would this undermine the patient’s confidence in her referring provider? Physicians may face other pressures to proceed, such as practice or institutional restraints that discourage same-day cancellations. Maintenance of robust financial practices, stable referral sources, and excellent patient satisfaction measures are critical to running an efficient endoscopy unit and maximizing patient service and care.

Is there a sensible way to address the dilemma? One approach is simply to move ahead with the procedure if the physician feels that the benefits outweigh the medical and ethical risks. Besides patient convenience, other “benefits” could be relevant: clinical value from an unexpected finding, affirmation of the patient’s invested time and effort, and avoidance of the apparent undermining of the authority of a referring colleague. Finally, maintaining productive and efficient practices or institutions ultimately allows for better patient care. The physician can explain the enhanced risks, present the alternatives, and – perhaps in less time than the ethical deliberations might take – complete the procedure and have the patient resting comfortably in the recovery unit.

An alternative approach is to cancel the procedure if the physician feels that the indication is not legitimate, or that the risks to the patient and the physician are significant. Explaining the cancellation can be difficult but may be the right decision if ethical principles of beneficence are upheld. It is understood that procedures consume health care resources and can present an undue expense to society if done for improper reasons. Unnecessary procedures clutter schedules for patients who truly need an endoscopy.

Neither approach is completely satisfying, although moving forward with a likely very safe procedure is often the easiest step and probably what many physicians do in this setting.

Is there a better way to approach this problem? Preventing the ethical dilemma is the ideal scenario, although not always feasible. Here are some suggestions to consider.

Reviewing referrals prior to the procedure day allows endoscopists to contact and cancel patients if needed, before the prep and travel begin. This addresses the convenience aspects but not the issue regarding the underlying indication.

The most important step toward avoiding inappropriate referrals is better education for referring providers. Even gastroenterologists, let alone primary care physicians, may struggle to stay current on changing clinical GI guidelines. Colorectal cancer screening, for example, is an area that gives gastroenterologists an opportunity to communicate with and educate colleagues about appropriate management. Keeping our referral base up to date about guidelines and prep and safety recommendations will likely reduce the number of inappropriate colonoscopy referrals and provide many of the benefits described above.

Providing the best care for patients by adhering to medical ethical principles is the goal of our work as physicians. Implementing this goal may demand tough decisions.

Dr. Fisher is professor of clinical medicine and director of small-bowel imaging, division of gastroenterology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

References

1. Sheffield KM et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2013 Apr 8;173(7):542-50.

2. Powell AA et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2015 Jun;30(6):732-41.

3. Petruzziello L et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46(7):590-4.

4. Kapila N et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(10):2798-805.

A 53-year-old woman was referred for surveillance colonoscopy. She is a current smoker with a history of chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, atrial fibrillation, and two diminutive hyperplastic polyps found on average-risk screening colonoscopy 3 years previously. Her prep at the time was excellent and she was advised to return in 10 years for follow-up. She has taken the day off work, arranged for a driver, is prepped, and is on your schedule for a colonoscopy for a “history of polyps.” Is this an appropriate referral and how should you handle it?

Most of us have had questionable referrals on our endoscopy schedules. While judgments can vary among providers about when a patient should undergo a procedure or what intervention is most needed, some direct-access referrals for endoscopy are considered inappropriate by most standards. In examining referrals for colonoscopy, studies have shown that as many as 23% of screening colonoscopies among Medicare beneficiaries and 14.2% of Veterans Affairs patients in a large colorectal cancer screening study are inappropriate.1,2 A prospective multicenter study found 29% of colonoscopies to be inappropriate, and surveillance studies were confirmed as the most frequent source of inappropriate procedures.3,4 Endoscopies are performed so frequently, effectively, and safely that they can be readily scheduled by gastroenterologists and nongastroenterologists alike. Open access has facilitated and expedited needed procedures, providing benefit to patient and provider and freeing clinic visit time for more complex consults. But while endoscopy is very safe, it is not without risk or cost. What should be the response when a patient in the endoscopy unit appears to be inappropriately referred?

The first step is to determine what is inappropriate. There are several situations when a procedure might be considered inappropriate, particularly when we try to apply ethical principles.

1. The performance of the procedure is contrary to society guidelines. The American Gastroenterological Association, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and American College of Gastroenterology publish clinical guidelines. These documents are drafted after rigorous research and literature review, and the strength of the recommendations is confirmed by incorporation of GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) methodology. Such guidelines allow gastroenterologists across the country to practice confidently in a manner consistent with the current available data and the standards of care for the GI community. A patient who is referred for a procedure for an indication that does not adhere to – or contradicts – guidelines, may be at risk for substandard care and possibly at risk for harm. It is the physician’s ethical responsibility to provide the most “good” and the least harm for patients, consistent with the ethical principle of beneficence.

Guidelines, however, are not mandates, and an argument may be made that in order to provide the best care, alternatives may be offered to a patient. Some circumstances require clinical judgments based on unique patient characteristics and the need for individualized care. As a rule, however, the goal of guidelines is to assist doctors in providing the best care.

2. The procedure is not the correct test for the clinical question. While endoscopy can address many clinical queries, endoscopy is not always the right procedure for a specific medical question. A patient referred for an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to rule out gastroparesis is being subjected to the wrong test to answer the clinical question. Some information may be obtained from an EGD (e.g., retained food may suggest dysmotility or the patient could have gastric outlet obstruction) but this is not the recommended initial management step. Is it reasonable to proceed with a test that cannot answer the question asked? Continuing with the endoscopy would not enhance beneficence and might be a futile service for the patient. Is this doing the best for the patient?

3. The risks of the procedure outweigh the benefits. Some procedures may be consistent with guidelines and able to answer the questions asked, but may present more risk than benefit. Should an elderly patient with multiple significant comorbidities and a likely limited life span undergo a follow-up colonoscopy even at an appropriate interval? The principle of nonmaleficence is the clear standard here.

4. The intent for doing the procedure has questionable merit. Some patients may request an EGD at the time of the screening colonoscopy just to “check,” regardless of symptoms or risk category. A patient has a right to make her/his own decisions but patient autonomy should not be an excuse for a nonindicated procedure.

In the case of the 53-year-old woman referred for surveillance colonoscopy, the physician needs to consider whether performing the test is inappropriate for any of the above reasons. First and foremost, is it doing the most good for the patient?

On the one hand, performing an inappropriately referred procedure contradicts guidelines and may present undue risk of complication from anesthesia or endoscopy. Would the physician be ethically compromised in this situation, or even legally liable should a complication arise during a procedure done for a questionable indication?

On the other hand, canceling such a procedure creates multiple dilemmas. The autonomy and the convenience of the patient need to be respected. The patient who has followed all the instructions, is prepped, has taken off work, arranged for transportation, and wants to have the procedure done may have difficulty accepting a cancellation. Colonoscopy is a safe test. Is it the right thing to cancel her procedure because of an imprudent referral? Would this undermine the patient’s confidence in her referring provider? Physicians may face other pressures to proceed, such as practice or institutional restraints that discourage same-day cancellations. Maintenance of robust financial practices, stable referral sources, and excellent patient satisfaction measures are critical to running an efficient endoscopy unit and maximizing patient service and care.

Is there a sensible way to address the dilemma? One approach is simply to move ahead with the procedure if the physician feels that the benefits outweigh the medical and ethical risks. Besides patient convenience, other “benefits” could be relevant: clinical value from an unexpected finding, affirmation of the patient’s invested time and effort, and avoidance of the apparent undermining of the authority of a referring colleague. Finally, maintaining productive and efficient practices or institutions ultimately allows for better patient care. The physician can explain the enhanced risks, present the alternatives, and – perhaps in less time than the ethical deliberations might take – complete the procedure and have the patient resting comfortably in the recovery unit.

An alternative approach is to cancel the procedure if the physician feels that the indication is not legitimate, or that the risks to the patient and the physician are significant. Explaining the cancellation can be difficult but may be the right decision if ethical principles of beneficence are upheld. It is understood that procedures consume health care resources and can present an undue expense to society if done for improper reasons. Unnecessary procedures clutter schedules for patients who truly need an endoscopy.

Neither approach is completely satisfying, although moving forward with a likely very safe procedure is often the easiest step and probably what many physicians do in this setting.

Is there a better way to approach this problem? Preventing the ethical dilemma is the ideal scenario, although not always feasible. Here are some suggestions to consider.

Reviewing referrals prior to the procedure day allows endoscopists to contact and cancel patients if needed, before the prep and travel begin. This addresses the convenience aspects but not the issue regarding the underlying indication.

The most important step toward avoiding inappropriate referrals is better education for referring providers. Even gastroenterologists, let alone primary care physicians, may struggle to stay current on changing clinical GI guidelines. Colorectal cancer screening, for example, is an area that gives gastroenterologists an opportunity to communicate with and educate colleagues about appropriate management. Keeping our referral base up to date about guidelines and prep and safety recommendations will likely reduce the number of inappropriate colonoscopy referrals and provide many of the benefits described above.

Providing the best care for patients by adhering to medical ethical principles is the goal of our work as physicians. Implementing this goal may demand tough decisions.

Dr. Fisher is professor of clinical medicine and director of small-bowel imaging, division of gastroenterology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

References

1. Sheffield KM et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2013 Apr 8;173(7):542-50.

2. Powell AA et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2015 Jun;30(6):732-41.

3. Petruzziello L et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46(7):590-4.

4. Kapila N et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(10):2798-805.

A 53-year-old woman was referred for surveillance colonoscopy. She is a current smoker with a history of chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, atrial fibrillation, and two diminutive hyperplastic polyps found on average-risk screening colonoscopy 3 years previously. Her prep at the time was excellent and she was advised to return in 10 years for follow-up. She has taken the day off work, arranged for a driver, is prepped, and is on your schedule for a colonoscopy for a “history of polyps.” Is this an appropriate referral and how should you handle it?

Most of us have had questionable referrals on our endoscopy schedules. While judgments can vary among providers about when a patient should undergo a procedure or what intervention is most needed, some direct-access referrals for endoscopy are considered inappropriate by most standards. In examining referrals for colonoscopy, studies have shown that as many as 23% of screening colonoscopies among Medicare beneficiaries and 14.2% of Veterans Affairs patients in a large colorectal cancer screening study are inappropriate.1,2 A prospective multicenter study found 29% of colonoscopies to be inappropriate, and surveillance studies were confirmed as the most frequent source of inappropriate procedures.3,4 Endoscopies are performed so frequently, effectively, and safely that they can be readily scheduled by gastroenterologists and nongastroenterologists alike. Open access has facilitated and expedited needed procedures, providing benefit to patient and provider and freeing clinic visit time for more complex consults. But while endoscopy is very safe, it is not without risk or cost. What should be the response when a patient in the endoscopy unit appears to be inappropriately referred?

The first step is to determine what is inappropriate. There are several situations when a procedure might be considered inappropriate, particularly when we try to apply ethical principles.

1. The performance of the procedure is contrary to society guidelines. The American Gastroenterological Association, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and American College of Gastroenterology publish clinical guidelines. These documents are drafted after rigorous research and literature review, and the strength of the recommendations is confirmed by incorporation of GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) methodology. Such guidelines allow gastroenterologists across the country to practice confidently in a manner consistent with the current available data and the standards of care for the GI community. A patient who is referred for a procedure for an indication that does not adhere to – or contradicts – guidelines, may be at risk for substandard care and possibly at risk for harm. It is the physician’s ethical responsibility to provide the most “good” and the least harm for patients, consistent with the ethical principle of beneficence.

Guidelines, however, are not mandates, and an argument may be made that in order to provide the best care, alternatives may be offered to a patient. Some circumstances require clinical judgments based on unique patient characteristics and the need for individualized care. As a rule, however, the goal of guidelines is to assist doctors in providing the best care.

2. The procedure is not the correct test for the clinical question. While endoscopy can address many clinical queries, endoscopy is not always the right procedure for a specific medical question. A patient referred for an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to rule out gastroparesis is being subjected to the wrong test to answer the clinical question. Some information may be obtained from an EGD (e.g., retained food may suggest dysmotility or the patient could have gastric outlet obstruction) but this is not the recommended initial management step. Is it reasonable to proceed with a test that cannot answer the question asked? Continuing with the endoscopy would not enhance beneficence and might be a futile service for the patient. Is this doing the best for the patient?

3. The risks of the procedure outweigh the benefits. Some procedures may be consistent with guidelines and able to answer the questions asked, but may present more risk than benefit. Should an elderly patient with multiple significant comorbidities and a likely limited life span undergo a follow-up colonoscopy even at an appropriate interval? The principle of nonmaleficence is the clear standard here.

4. The intent for doing the procedure has questionable merit. Some patients may request an EGD at the time of the screening colonoscopy just to “check,” regardless of symptoms or risk category. A patient has a right to make her/his own decisions but patient autonomy should not be an excuse for a nonindicated procedure.

In the case of the 53-year-old woman referred for surveillance colonoscopy, the physician needs to consider whether performing the test is inappropriate for any of the above reasons. First and foremost, is it doing the most good for the patient?

On the one hand, performing an inappropriately referred procedure contradicts guidelines and may present undue risk of complication from anesthesia or endoscopy. Would the physician be ethically compromised in this situation, or even legally liable should a complication arise during a procedure done for a questionable indication?

On the other hand, canceling such a procedure creates multiple dilemmas. The autonomy and the convenience of the patient need to be respected. The patient who has followed all the instructions, is prepped, has taken off work, arranged for transportation, and wants to have the procedure done may have difficulty accepting a cancellation. Colonoscopy is a safe test. Is it the right thing to cancel her procedure because of an imprudent referral? Would this undermine the patient’s confidence in her referring provider? Physicians may face other pressures to proceed, such as practice or institutional restraints that discourage same-day cancellations. Maintenance of robust financial practices, stable referral sources, and excellent patient satisfaction measures are critical to running an efficient endoscopy unit and maximizing patient service and care.

Is there a sensible way to address the dilemma? One approach is simply to move ahead with the procedure if the physician feels that the benefits outweigh the medical and ethical risks. Besides patient convenience, other “benefits” could be relevant: clinical value from an unexpected finding, affirmation of the patient’s invested time and effort, and avoidance of the apparent undermining of the authority of a referring colleague. Finally, maintaining productive and efficient practices or institutions ultimately allows for better patient care. The physician can explain the enhanced risks, present the alternatives, and – perhaps in less time than the ethical deliberations might take – complete the procedure and have the patient resting comfortably in the recovery unit.

An alternative approach is to cancel the procedure if the physician feels that the indication is not legitimate, or that the risks to the patient and the physician are significant. Explaining the cancellation can be difficult but may be the right decision if ethical principles of beneficence are upheld. It is understood that procedures consume health care resources and can present an undue expense to society if done for improper reasons. Unnecessary procedures clutter schedules for patients who truly need an endoscopy.

Neither approach is completely satisfying, although moving forward with a likely very safe procedure is often the easiest step and probably what many physicians do in this setting.

Is there a better way to approach this problem? Preventing the ethical dilemma is the ideal scenario, although not always feasible. Here are some suggestions to consider.

Reviewing referrals prior to the procedure day allows endoscopists to contact and cancel patients if needed, before the prep and travel begin. This addresses the convenience aspects but not the issue regarding the underlying indication.

The most important step toward avoiding inappropriate referrals is better education for referring providers. Even gastroenterologists, let alone primary care physicians, may struggle to stay current on changing clinical GI guidelines. Colorectal cancer screening, for example, is an area that gives gastroenterologists an opportunity to communicate with and educate colleagues about appropriate management. Keeping our referral base up to date about guidelines and prep and safety recommendations will likely reduce the number of inappropriate colonoscopy referrals and provide many of the benefits described above.

Providing the best care for patients by adhering to medical ethical principles is the goal of our work as physicians. Implementing this goal may demand tough decisions.

Dr. Fisher is professor of clinical medicine and director of small-bowel imaging, division of gastroenterology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

References

1. Sheffield KM et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2013 Apr 8;173(7):542-50.

2. Powell AA et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2015 Jun;30(6):732-41.

3. Petruzziello L et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46(7):590-4.

4. Kapila N et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(10):2798-805.

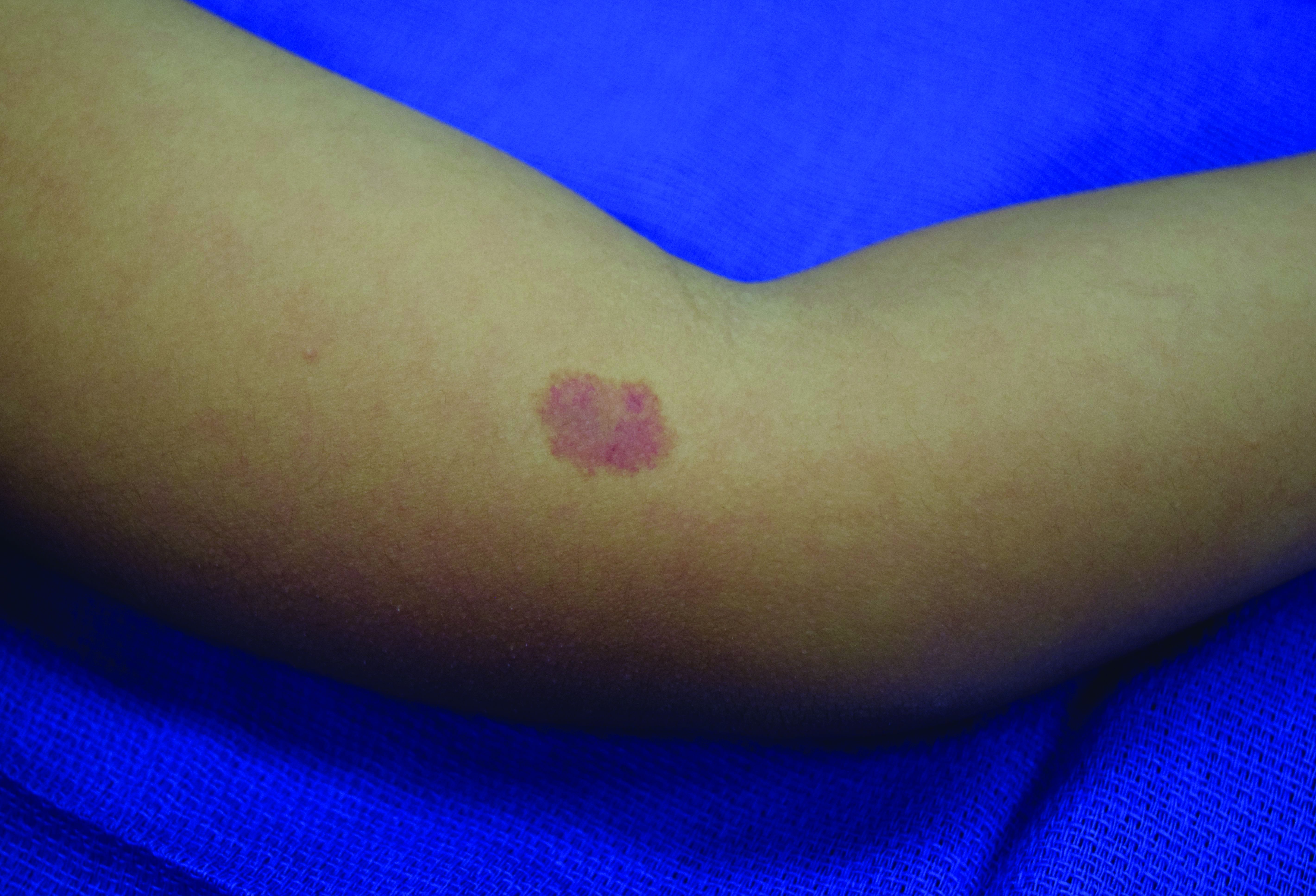

A 4-year-old presented to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of asymptomatic "brown spots."

Capillary malformation-arteriovenous malformation syndrome

with or without arteriovenous malformations, as well as arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs). CM-AVM is an autosomal dominant disorder.1 CM-AVM type 1 is caused by mutations in the RASA1 gene, and CM-AVM type 2 is caused by mutations in the EPHB4 gene.2 Approximately 70% of patients with RASA1-associated CM-AVM syndrome and 80% of patients with EPHB4-associated CM-AVM syndrome have an affected parent, while the remainder have de novo variants.1

In patients with CM-AVM syndrome, CMs are often present at birth and more are typically acquired over time. CMs are characteristically 1-3 cm in diameter, round or oval, dull red or red-brown macules and patches with a blanched halo.3 Some CMs may be warm to touch indicating a possible underlying AVM or AVF.4 This can be confirmed by Doppler ultrasound, which would demonstrate increased arterial flow.4 CMs are most commonly located on the face and limbs and may present in isolation, but approximately one-third of patients have associated AVMs and AVFs.1,5 These high-flow vascular malformations may be present in skin, muscle, bone, brain, and/or spine and may be asymptomatic or lead to serious sequelae, including bleeding, congestive heart failure, and neurologic complications, such as migraine headaches, seizures, or even stroke.5 Symptoms from intracranial and spinal high-flow lesions usually present in early childhood and affect approximately 7% of patients.3

The diagnosis of CM-AVM should be suspected in an individual with numerous characteristic CMs and may be supported by the presence of AVMs and AVFs, family history of CM-AVM, and/or identification of RASA1 or EPHB4 mutation by molecular genetic testing.1,3 Although there are no consensus protocols for imaging CM-AVM patients, MRI of the brain and spine is recommended at diagnosis to identify underlying high-flow lesions.1 This may allow for early treatment before the development of symptoms.1 Any lesions identified on screening imaging may require regular surveillance, which is best determined by discussion with the radiologist.1 Although there are no reports of patients with negative results on screening imaging who later develop AVMs or AVFs, there should be a low threshold for repeat imaging in patients who develop new symptoms or physical exam findings.3,4

It has previously been suggested that the CMs in CM-AVM may actually represent early or small AVMs and pulsed-dye laser (PDL) treatment was not recommended because of concern for potential progression of lesions.4 However, a recent study demonstrated good response to PDL in patients with CM-AVM with no evidence of worsening or recurrence of lesions with long-term follow-up.6 Treatment of CMs that cause cosmetic concerns may be considered following discussion of risks and benefits with a dermatologist. Management of AVMs and AVFs requires a multidisciplinary team that, depending on location and symptoms of these features, may require the expertise of specialists such as neurosurgery, surgery, orthopedics, cardiology, and/or interventional radiology.1

Given the suspicion for CM-AVM in our patient, further workup was completed. A skin biopsy was consistent with CM. Genetic testing with the Vascular Malformations Panel, Sequencing and Deletion/Duplication revealed a pathogenic variant in the RASA1 gene and a variant of unknown clinical significance in the TEK gene. Parental genetic testing for the RASA1 mutation was negative, supporting a de novo mutation in the patient. CNS imaging showed a small developmental venous malformation in the brain that neurosurgery did not think was clinically significant. At the most recent follow-up at age 8 years, our patient had developed a few new small CMs but was otherwise well.

Dr. Leszczynska is trained in pediatrics and is the current dermatology research fellow at the University of Texas at Austin. Ms. Croce is a dermatology-trained pediatric nurse practitioner and PhD student at the University of Texas at Austin School of Nursing. Dr. Diaz is chief of pediatric dermatology at Dell Children’s Medical Center, Austin, assistant professor of pediatrics and medicine (dermatology), and dermatology residency associate program director at University of Texas at Austin . The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. Donna Bilu Martin, MD, is the editor of this column.

References

1. Bayrak-Toydemir P, Stevenson D. Capillary Malformation-Arteriovenous Malformation Syndrome. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., eds. GeneReviews®. Seattle: University of Washington, Seattle; February 22, 2011.

2.Yu J et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017 Sep;34(5):e227-30.

3. Orme CM et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013 Jul-Aug;30(4):409-15.

4. Weitz NA et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015 Jan-Feb;32(1):76-84.

5. Revencu N et al. Hum Mutat. 2013 Dec;34(12):1632-41.

6. Iznardo H et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020 Mar;37(2):342-44.

Capillary malformation-arteriovenous malformation syndrome