User login

Data Trends 2024: Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD)

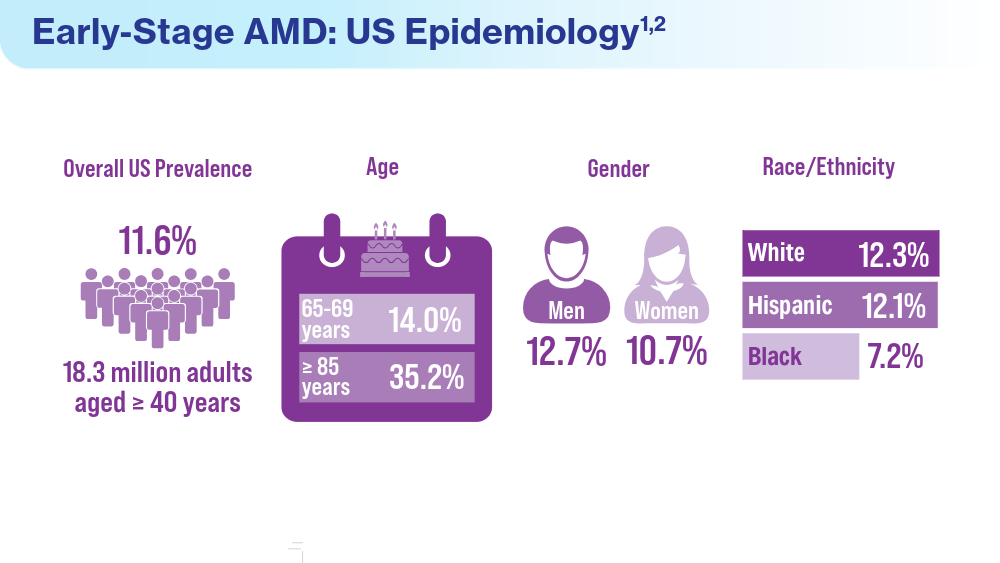

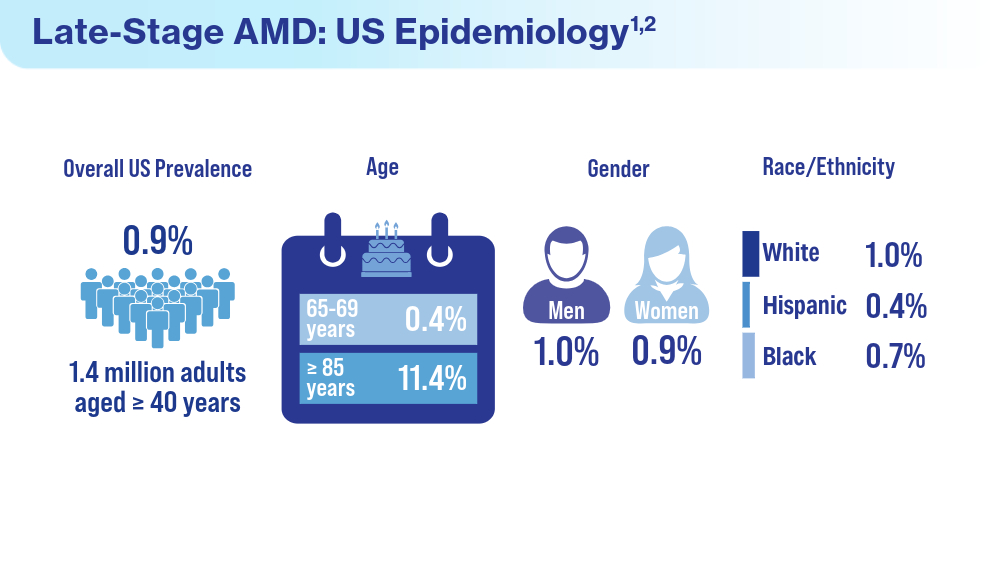

- Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Burke-Conte Z, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the US in 2019. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022;140(12):1202-1208. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2022.4401

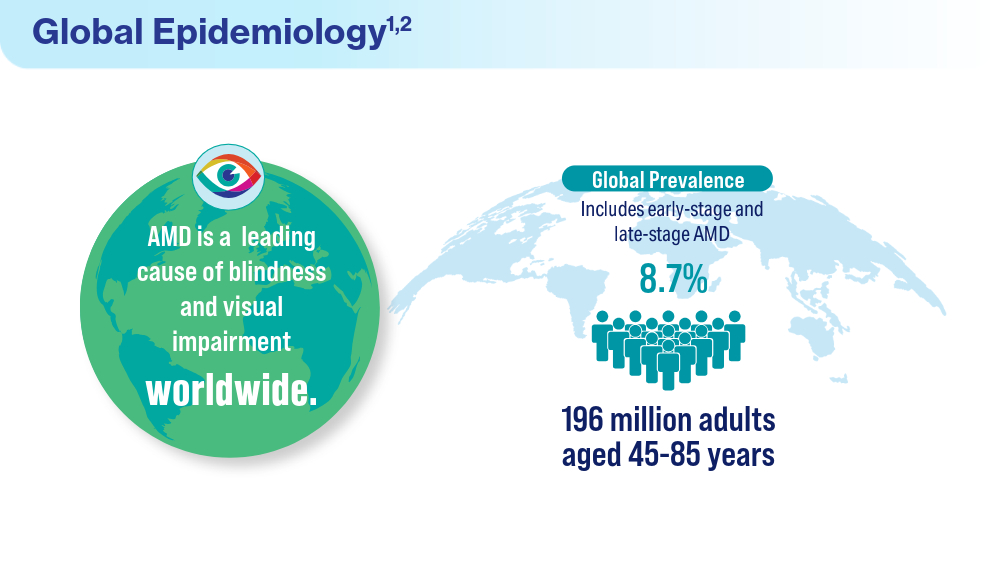

- Fleckenstein M, Schmitz-Valckenberg S, Chakravarthy U. Age-related macular degeneration: a review. JAMA. 2024;331(2):147-157. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.26074

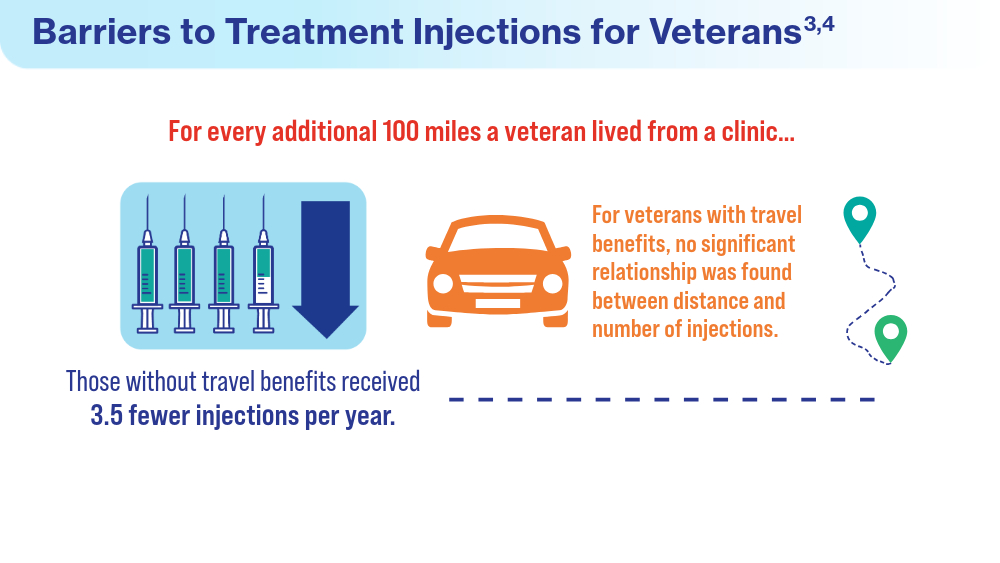

- Meer EA, Targ S, Zhang N, Hoggatt KJ, Mehta KM, Brodie F. Age-related macular degeneration injection frequency: effects of distance traveled and travel support. Retina. 2024;44(2):230-236. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000003947

- Bhisitkul RB, Mendes TS, Rofagha S, et al. Macular atrophy progression and 7-year vision outcomes in subjects from the ANCHOR, MARINA, and HORIZON studies: the SEVEN-UP study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159(5):915-24.e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2015.01.032

- Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Burke-Conte Z, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the US in 2019. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022;140(12):1202-1208. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2022.4401

- Fleckenstein M, Schmitz-Valckenberg S, Chakravarthy U. Age-related macular degeneration: a review. JAMA. 2024;331(2):147-157. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.26074

- Meer EA, Targ S, Zhang N, Hoggatt KJ, Mehta KM, Brodie F. Age-related macular degeneration injection frequency: effects of distance traveled and travel support. Retina. 2024;44(2):230-236. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000003947

- Bhisitkul RB, Mendes TS, Rofagha S, et al. Macular atrophy progression and 7-year vision outcomes in subjects from the ANCHOR, MARINA, and HORIZON studies: the SEVEN-UP study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159(5):915-24.e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2015.01.032

- Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Burke-Conte Z, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the US in 2019. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022;140(12):1202-1208. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2022.4401

- Fleckenstein M, Schmitz-Valckenberg S, Chakravarthy U. Age-related macular degeneration: a review. JAMA. 2024;331(2):147-157. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.26074

- Meer EA, Targ S, Zhang N, Hoggatt KJ, Mehta KM, Brodie F. Age-related macular degeneration injection frequency: effects of distance traveled and travel support. Retina. 2024;44(2):230-236. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000003947

- Bhisitkul RB, Mendes TS, Rofagha S, et al. Macular atrophy progression and 7-year vision outcomes in subjects from the ANCHOR, MARINA, and HORIZON studies: the SEVEN-UP study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159(5):915-24.e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2015.01.032

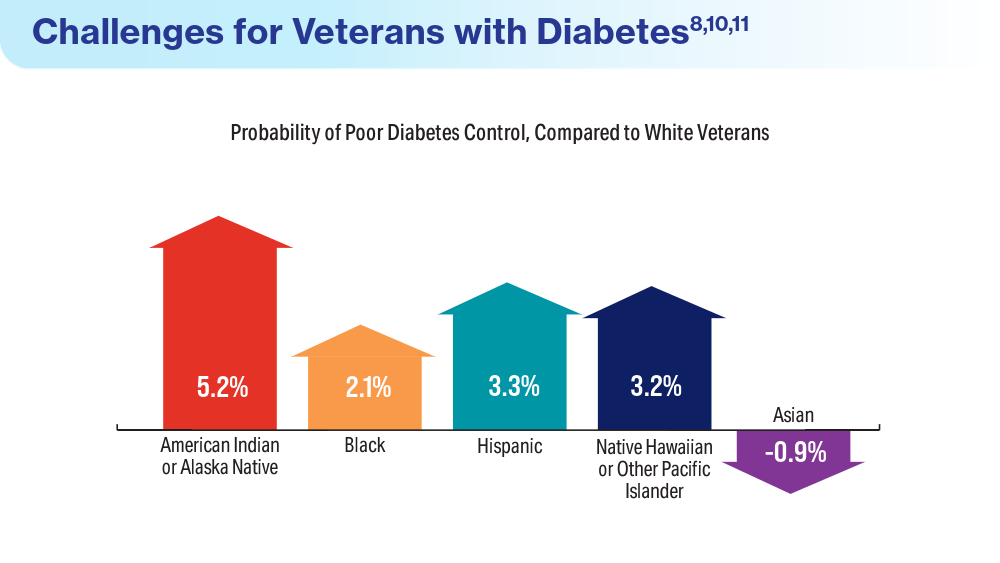

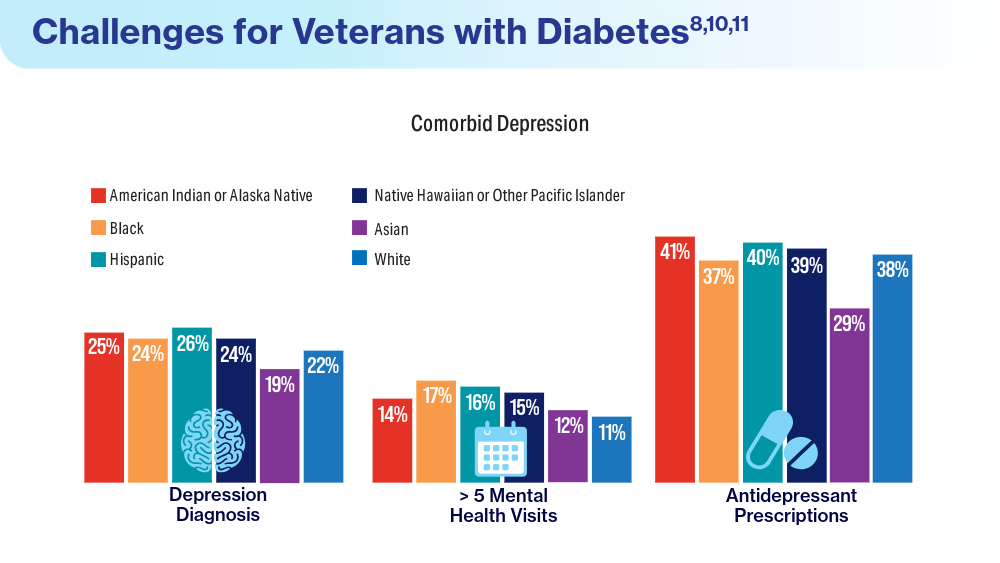

Data Trends 2024: Diabetes

- Martin SS, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al; for the American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. 2024 Heart disease and stroke statistics: a report of US and global data from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024;149(8):e347-e913. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001209

- Utech A. VA supports veterans who have type 2 diabetes. VA News. August 18, 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://news.va.gov/107579/va-supportsveterans-who-have-type-2-diabetes/

- Betancourt JA, Granados PS, Pacheco GJ, Shanmugam R, Kruse CS, Fulton LV. Obesity and morbidity risk in the U.S. veteran. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(3):191. doi:10.3390/healthcare8030191

- Briskin A. Obesity and diabetes: causes, treatments, and stigma. diaTribe. October 4, 2021. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://diatribe.org/obesity-and-diabetescauses-

treatments-and-stigma - Leonard C, Sayre G, Williams S, et al. Understanding the experience of veterans who require lower limb amputation in the Veterans Health Administration. PLOS One. 2022;17(3):e0265620. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0265620

- Armstrong DG. Diabetic foot ulcers: a silent killer of veterans. Stat News. November 11, 2019. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.statnews.com/2019/11/11/diabetic-foot-ulcers-veterans-silent-killer/

- Koleda EW. The veteran diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) epidemic: a U.S. Department of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) services review. TreatNOW. October 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://treatnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/The-VA-Diabetic-Foot-Ulcer-Epidemic-10-14-22.pdf

- CDC identifies diabetes belt. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/46013

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Updated June 7, 2024. Accessed June 19, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/veteran_population.asp

- Avramovic S, Alemi F, Kanchi R, et al. US Veterans Administration diabetes risk (VADR) national cohort: cohort profile. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e039489. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039489

- Breland JY, Tseng CH, Toyama J, Washington DL. Influence of depression on racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes control. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2023;11(6):e003612. doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2023-003612

- Martin SS, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al; for the American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. 2024 Heart disease and stroke statistics: a report of US and global data from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024;149(8):e347-e913. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001209

- Utech A. VA supports veterans who have type 2 diabetes. VA News. August 18, 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://news.va.gov/107579/va-supportsveterans-who-have-type-2-diabetes/

- Betancourt JA, Granados PS, Pacheco GJ, Shanmugam R, Kruse CS, Fulton LV. Obesity and morbidity risk in the U.S. veteran. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(3):191. doi:10.3390/healthcare8030191

- Briskin A. Obesity and diabetes: causes, treatments, and stigma. diaTribe. October 4, 2021. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://diatribe.org/obesity-and-diabetescauses-

treatments-and-stigma - Leonard C, Sayre G, Williams S, et al. Understanding the experience of veterans who require lower limb amputation in the Veterans Health Administration. PLOS One. 2022;17(3):e0265620. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0265620

- Armstrong DG. Diabetic foot ulcers: a silent killer of veterans. Stat News. November 11, 2019. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.statnews.com/2019/11/11/diabetic-foot-ulcers-veterans-silent-killer/

- Koleda EW. The veteran diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) epidemic: a U.S. Department of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) services review. TreatNOW. October 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://treatnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/The-VA-Diabetic-Foot-Ulcer-Epidemic-10-14-22.pdf

- CDC identifies diabetes belt. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/46013

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Updated June 7, 2024. Accessed June 19, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/veteran_population.asp

- Avramovic S, Alemi F, Kanchi R, et al. US Veterans Administration diabetes risk (VADR) national cohort: cohort profile. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e039489. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039489

- Breland JY, Tseng CH, Toyama J, Washington DL. Influence of depression on racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes control. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2023;11(6):e003612. doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2023-003612

- Martin SS, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al; for the American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. 2024 Heart disease and stroke statistics: a report of US and global data from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024;149(8):e347-e913. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001209

- Utech A. VA supports veterans who have type 2 diabetes. VA News. August 18, 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://news.va.gov/107579/va-supportsveterans-who-have-type-2-diabetes/

- Betancourt JA, Granados PS, Pacheco GJ, Shanmugam R, Kruse CS, Fulton LV. Obesity and morbidity risk in the U.S. veteran. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(3):191. doi:10.3390/healthcare8030191

- Briskin A. Obesity and diabetes: causes, treatments, and stigma. diaTribe. October 4, 2021. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://diatribe.org/obesity-and-diabetescauses-

treatments-and-stigma - Leonard C, Sayre G, Williams S, et al. Understanding the experience of veterans who require lower limb amputation in the Veterans Health Administration. PLOS One. 2022;17(3):e0265620. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0265620

- Armstrong DG. Diabetic foot ulcers: a silent killer of veterans. Stat News. November 11, 2019. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.statnews.com/2019/11/11/diabetic-foot-ulcers-veterans-silent-killer/

- Koleda EW. The veteran diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) epidemic: a U.S. Department of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) services review. TreatNOW. October 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://treatnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/The-VA-Diabetic-Foot-Ulcer-Epidemic-10-14-22.pdf

- CDC identifies diabetes belt. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/46013

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Updated June 7, 2024. Accessed June 19, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/veteran_population.asp

- Avramovic S, Alemi F, Kanchi R, et al. US Veterans Administration diabetes risk (VADR) national cohort: cohort profile. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e039489. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039489

- Breland JY, Tseng CH, Toyama J, Washington DL. Influence of depression on racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes control. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2023;11(6):e003612. doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2023-003612

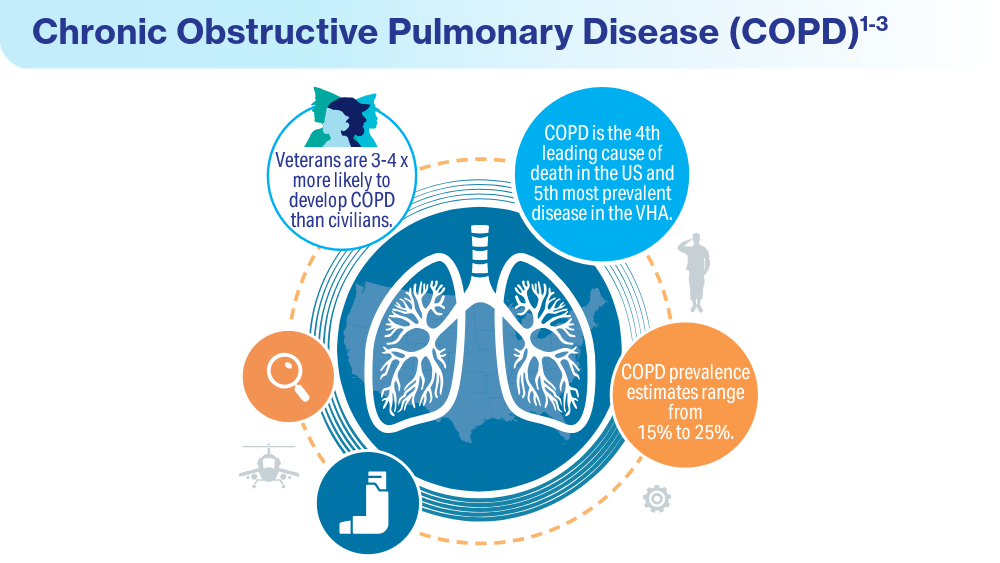

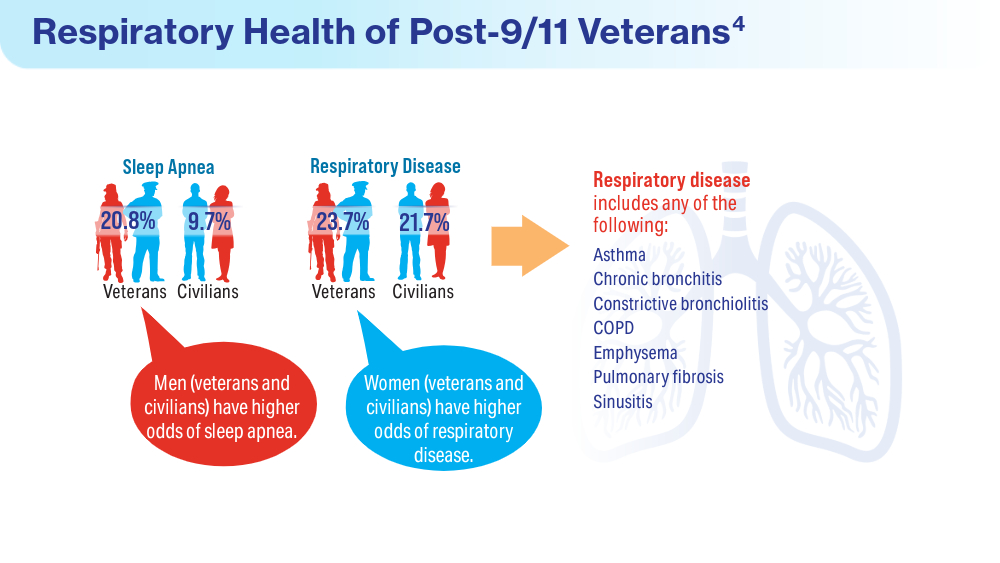

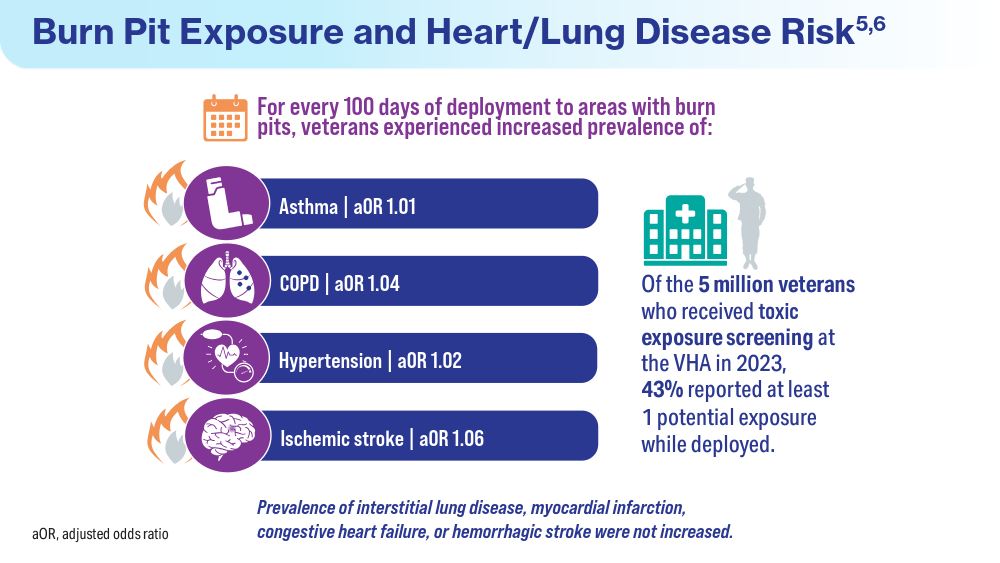

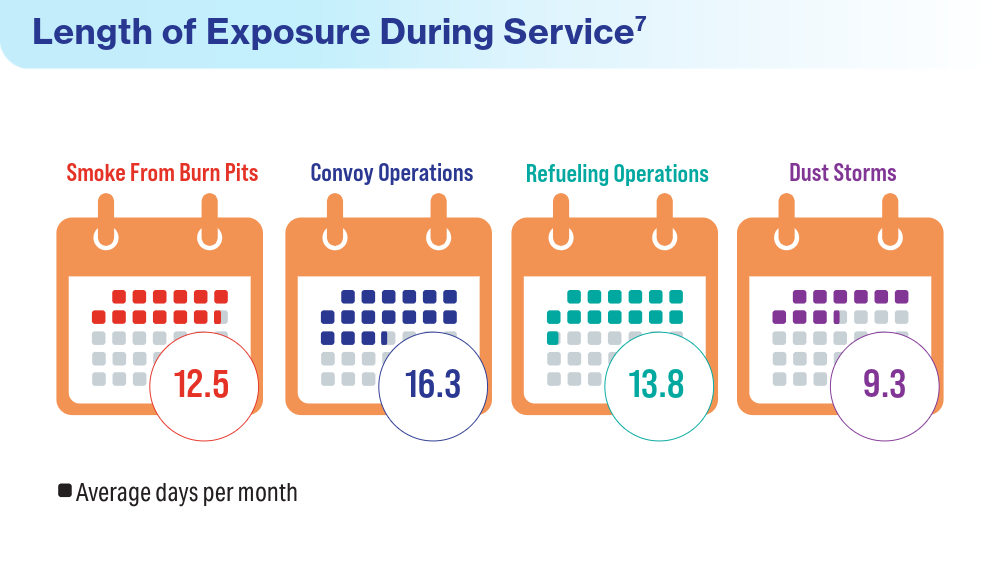

Data Trends 2024: Respiratory Health

- McVeigh C, Reid J, Carvalho P. Healthcare professionals’ views of palliative care for American war veterans with non-malignant respiratory disease living in a rural area: a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18(1):22. doi:10.1186/s12904-019-0408-7

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Study finds uptick in lung disease in recent veterans. May 23, 2016. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/currents/0516-3.cfm

- Sanders JW, Putnam SD, Frankart C, et al. Impact of illness and non-combat injury during Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73(4):713-719.

- Trupin L, Schmajuk G, Ying D, Yelin E, Blanc PD. Military service and COPD risk. Chest. 2022;162(4):792-795. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2022.04.016

- Bastian LA. Pain-related anxiety intervention for smokers with chronic pain: a comparative effectiveness trial of smoking cessation counseling for veterans. Veteran’s Health Systems Research, IIR 15-092-HSR Study. Published January 2022. Accessed April 2024. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/research/abstracts.cfm?Project_ID=2141704797

- Rivera AC, Powell TM, Boyko EJ, et al; for the Millennium Cohort Study Team. New-onset asthma and combat deployment: findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(10):2136-2144. doi:10.1093/aje/kwy112

- Savitz DA, Woskie SR, Bello A, et al. Deployment to Military Bases With Open Burn Pits and Respiratory and Cardiovascular Disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(4):e247629. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.7629

- McVeigh C, Reid J, Carvalho P. Healthcare professionals’ views of palliative care for American war veterans with non-malignant respiratory disease living in a rural area: a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18(1):22. doi:10.1186/s12904-019-0408-7

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Study finds uptick in lung disease in recent veterans. May 23, 2016. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/currents/0516-3.cfm

- Sanders JW, Putnam SD, Frankart C, et al. Impact of illness and non-combat injury during Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73(4):713-719.

- Trupin L, Schmajuk G, Ying D, Yelin E, Blanc PD. Military service and COPD risk. Chest. 2022;162(4):792-795. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2022.04.016

- Bastian LA. Pain-related anxiety intervention for smokers with chronic pain: a comparative effectiveness trial of smoking cessation counseling for veterans. Veteran’s Health Systems Research, IIR 15-092-HSR Study. Published January 2022. Accessed April 2024. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/research/abstracts.cfm?Project_ID=2141704797

- Rivera AC, Powell TM, Boyko EJ, et al; for the Millennium Cohort Study Team. New-onset asthma and combat deployment: findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(10):2136-2144. doi:10.1093/aje/kwy112

- Savitz DA, Woskie SR, Bello A, et al. Deployment to Military Bases With Open Burn Pits and Respiratory and Cardiovascular Disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(4):e247629. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.7629

- McVeigh C, Reid J, Carvalho P. Healthcare professionals’ views of palliative care for American war veterans with non-malignant respiratory disease living in a rural area: a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18(1):22. doi:10.1186/s12904-019-0408-7

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Study finds uptick in lung disease in recent veterans. May 23, 2016. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/currents/0516-3.cfm

- Sanders JW, Putnam SD, Frankart C, et al. Impact of illness and non-combat injury during Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73(4):713-719.

- Trupin L, Schmajuk G, Ying D, Yelin E, Blanc PD. Military service and COPD risk. Chest. 2022;162(4):792-795. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2022.04.016

- Bastian LA. Pain-related anxiety intervention for smokers with chronic pain: a comparative effectiveness trial of smoking cessation counseling for veterans. Veteran’s Health Systems Research, IIR 15-092-HSR Study. Published January 2022. Accessed April 2024. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/research/abstracts.cfm?Project_ID=2141704797

- Rivera AC, Powell TM, Boyko EJ, et al; for the Millennium Cohort Study Team. New-onset asthma and combat deployment: findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(10):2136-2144. doi:10.1093/aje/kwy112

- Savitz DA, Woskie SR, Bello A, et al. Deployment to Military Bases With Open Burn Pits and Respiratory and Cardiovascular Disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(4):e247629. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.7629

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2024

Federal Health Care Data Trends is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner, showcasing the latest research in health care for veterans and active-duty military members via compelling infographics. Click below to view highlights from the issue:

Federal Health Care Data Trends is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner, showcasing the latest research in health care for veterans and active-duty military members via compelling infographics. Click below to view highlights from the issue:

Federal Health Care Data Trends is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner, showcasing the latest research in health care for veterans and active-duty military members via compelling infographics. Click below to view highlights from the issue:

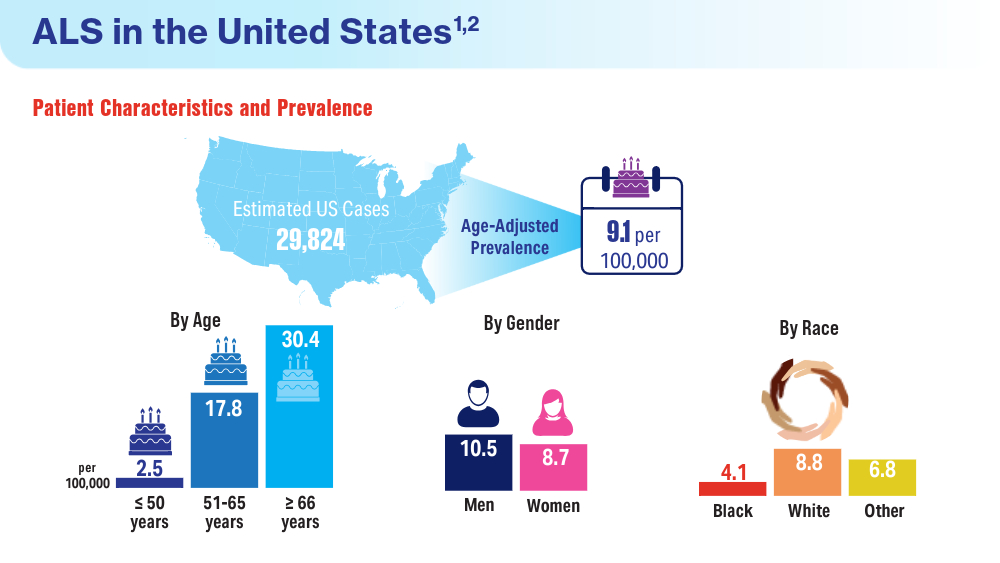

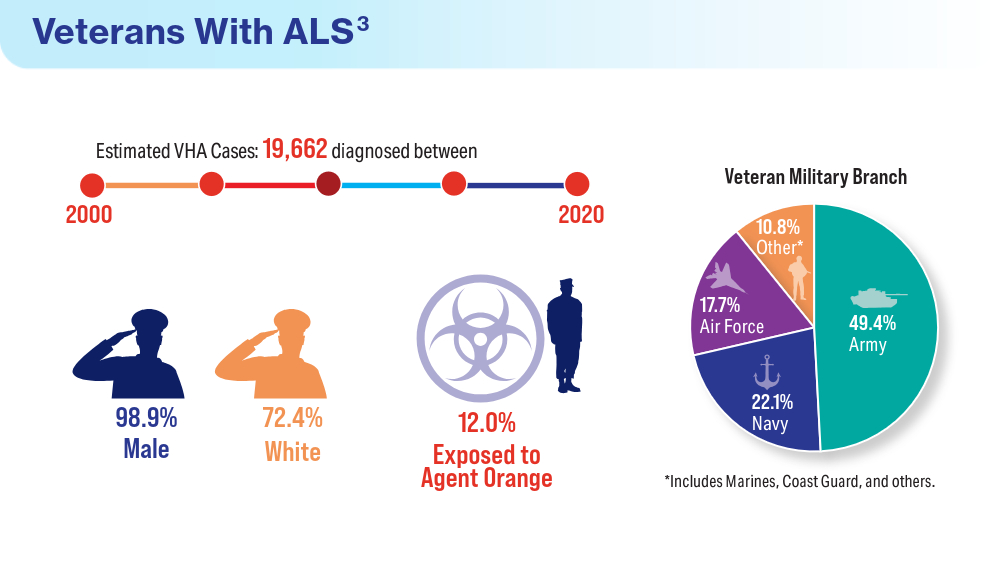

Data Trends 2024: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)

- Mehta P, Raymond J, Zhang Y, et al. Prevalence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in the United States, 2018. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. Published online August 21, 2023. doi:10.1080/21678421.2023.2245858

- What is amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated May 13, 2022. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/als/WhatisAmyotrophiclateralsclerosis.html

- Reimer RJ, Goncalves A, Soper B, et al. An electronic health record cohort of veterans with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. Published online August 9, 2023. doi:10.1080/21678421.2023.2239300

- Kudritzki V, Howard IM. Telehealth-based exercise in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1238916. doi:10.3389/fneur.2023.1238916

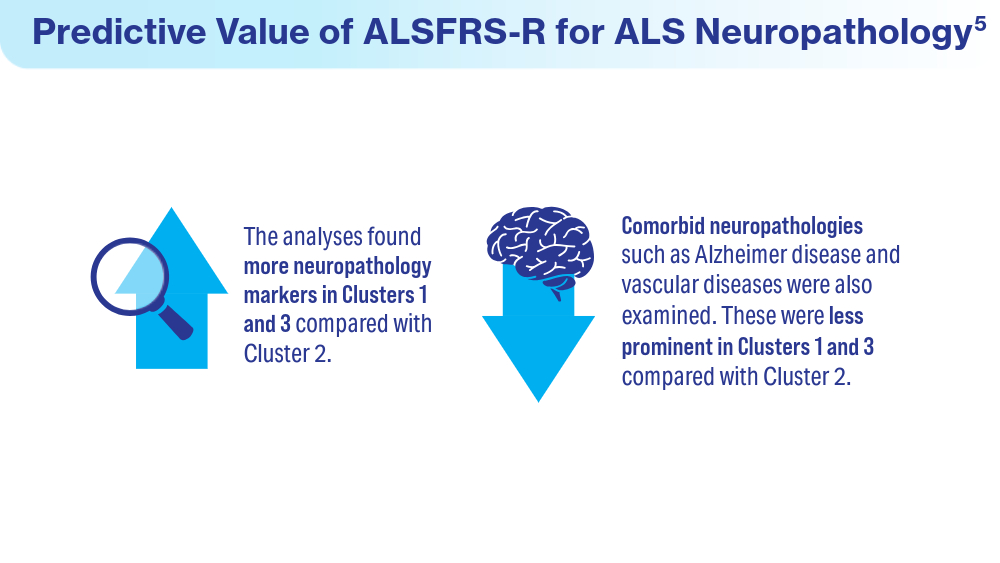

- Colvin LE, Foster ZW, Stein TD, et al. Utility of the ALSFRS-R for predicting ALS and comorbid disease neuropathology: the Veterans Affairs Biorepository Brain Bank. Muscle Nerve. 2022;66(2):167-174. doi:10.1002/mus.27635

- Rabadi MH, Russell KC, Xu C. Predictors of mortality in veterans with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: respiratory status and speech disorder at presentation. Med Sci Monit. 2024;30:e943288. doi:10.12659/MSM.943288

- Mehta P, Raymond J, Zhang Y, et al. Prevalence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in the United States, 2018. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. Published online August 21, 2023. doi:10.1080/21678421.2023.2245858

- What is amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated May 13, 2022. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/als/WhatisAmyotrophiclateralsclerosis.html

- Reimer RJ, Goncalves A, Soper B, et al. An electronic health record cohort of veterans with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. Published online August 9, 2023. doi:10.1080/21678421.2023.2239300

- Kudritzki V, Howard IM. Telehealth-based exercise in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1238916. doi:10.3389/fneur.2023.1238916

- Colvin LE, Foster ZW, Stein TD, et al. Utility of the ALSFRS-R for predicting ALS and comorbid disease neuropathology: the Veterans Affairs Biorepository Brain Bank. Muscle Nerve. 2022;66(2):167-174. doi:10.1002/mus.27635

- Rabadi MH, Russell KC, Xu C. Predictors of mortality in veterans with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: respiratory status and speech disorder at presentation. Med Sci Monit. 2024;30:e943288. doi:10.12659/MSM.943288

- Mehta P, Raymond J, Zhang Y, et al. Prevalence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in the United States, 2018. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. Published online August 21, 2023. doi:10.1080/21678421.2023.2245858

- What is amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated May 13, 2022. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/als/WhatisAmyotrophiclateralsclerosis.html

- Reimer RJ, Goncalves A, Soper B, et al. An electronic health record cohort of veterans with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. Published online August 9, 2023. doi:10.1080/21678421.2023.2239300

- Kudritzki V, Howard IM. Telehealth-based exercise in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1238916. doi:10.3389/fneur.2023.1238916

- Colvin LE, Foster ZW, Stein TD, et al. Utility of the ALSFRS-R for predicting ALS and comorbid disease neuropathology: the Veterans Affairs Biorepository Brain Bank. Muscle Nerve. 2022;66(2):167-174. doi:10.1002/mus.27635

- Rabadi MH, Russell KC, Xu C. Predictors of mortality in veterans with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: respiratory status and speech disorder at presentation. Med Sci Monit. 2024;30:e943288. doi:10.12659/MSM.943288

Data Trends 2024: Arthritis

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Overview of VA research on arthritis. Accessed March 25, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/topics/arthritis.cfm

- Fallon EA, Boring MA, Foster AL, Stowe EW, Lites TD, Allen KD. Arthritis prevalence among veterans — United States, 2017–2021. MMWR Recomm Reports. 2023;72(45):1209-1216. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7245a1

- Huffman KF, Ambrose KR, Nelson AE, Allen KD, Golightly YM, Callahan LF. The critical role of physical activity and weight management in knee and hip osteoarthritis: a narrative review. J Rheumatol. 2023;51(3):224-233. doi:10.3899/ jrheum.2023-0819

- Lo GH. Successfully treating patients with osteoarthritis: how encouragement of physical activity can generate the best outcomes. A physician’s perspective. J Rheumatol. 2023:jrheum.2023-0899. doi:10.3899/jrheum.2023-0899

- Overton C, Nelson AE, Neogi T. Osteoarthritis treatment guidelines from six professional societies: similarities and differences. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2022;48(3):637-657. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2022.03.009

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Overview of VA research on arthritis. Accessed March 25, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/topics/arthritis.cfm

- Fallon EA, Boring MA, Foster AL, Stowe EW, Lites TD, Allen KD. Arthritis prevalence among veterans — United States, 2017–2021. MMWR Recomm Reports. 2023;72(45):1209-1216. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7245a1

- Huffman KF, Ambrose KR, Nelson AE, Allen KD, Golightly YM, Callahan LF. The critical role of physical activity and weight management in knee and hip osteoarthritis: a narrative review. J Rheumatol. 2023;51(3):224-233. doi:10.3899/ jrheum.2023-0819

- Lo GH. Successfully treating patients with osteoarthritis: how encouragement of physical activity can generate the best outcomes. A physician’s perspective. J Rheumatol. 2023:jrheum.2023-0899. doi:10.3899/jrheum.2023-0899

- Overton C, Nelson AE, Neogi T. Osteoarthritis treatment guidelines from six professional societies: similarities and differences. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2022;48(3):637-657. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2022.03.009

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Overview of VA research on arthritis. Accessed March 25, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/topics/arthritis.cfm

- Fallon EA, Boring MA, Foster AL, Stowe EW, Lites TD, Allen KD. Arthritis prevalence among veterans — United States, 2017–2021. MMWR Recomm Reports. 2023;72(45):1209-1216. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7245a1

- Huffman KF, Ambrose KR, Nelson AE, Allen KD, Golightly YM, Callahan LF. The critical role of physical activity and weight management in knee and hip osteoarthritis: a narrative review. J Rheumatol. 2023;51(3):224-233. doi:10.3899/ jrheum.2023-0819

- Lo GH. Successfully treating patients with osteoarthritis: how encouragement of physical activity can generate the best outcomes. A physician’s perspective. J Rheumatol. 2023:jrheum.2023-0899. doi:10.3899/jrheum.2023-0899

- Overton C, Nelson AE, Neogi T. Osteoarthritis treatment guidelines from six professional societies: similarities and differences. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2022;48(3):637-657. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2022.03.009

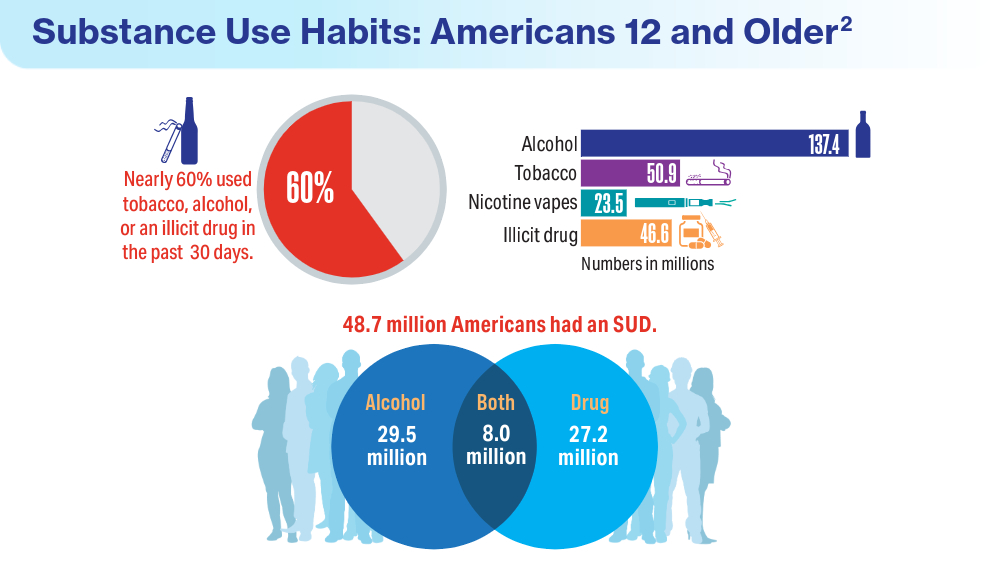

Data Trends 2024: Substance Use Disorder

- Teeters JB, Lancaster CL, Brown DG, Back SE. Substance use disorders in military veterans: prevalence and treatment challenges. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2017;8:69-77. doi:10.2147/sar.s116720

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: a companion infographic. SAMHSA publication no. PEP23-07-01-007. November 13, 2023. Accessed March 25, 2024. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt42730/2022-nsduh-infographic-report.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Among the Veteran Population Aged 18 or Older. Accessed March 25, 2024. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt44472/2022-nsduh-pop-slides-veterans.pdf

- Cypel YS, DePhilippis D, Davey VJ. Substance use in U.S. Vietnam War era veterans and nonveterans: results from the Vietnam Era Health Retrospective Observational Study. Subst Use Misuse. 2023;58(7):858-870. doi:10.1080/10826084.2023.2188427

- Otufowora A, Liu Y, Okusanya A, Ogidan A, Okusanya A, Cottler LB. The effect of veteran status and chronic pain on past 30-day sedative use among community-dwelling adult males. J Am Board Fam Med. 2024;37(1):118-128. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2023.230226R2

- Teeters JB, Lancaster CL, Brown DG, Back SE. Substance use disorders in military veterans: prevalence and treatment challenges. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2017;8:69-77. doi:10.2147/sar.s116720

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: a companion infographic. SAMHSA publication no. PEP23-07-01-007. November 13, 2023. Accessed March 25, 2024. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt42730/2022-nsduh-infographic-report.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Among the Veteran Population Aged 18 or Older. Accessed March 25, 2024. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt44472/2022-nsduh-pop-slides-veterans.pdf

- Cypel YS, DePhilippis D, Davey VJ. Substance use in U.S. Vietnam War era veterans and nonveterans: results from the Vietnam Era Health Retrospective Observational Study. Subst Use Misuse. 2023;58(7):858-870. doi:10.1080/10826084.2023.2188427

- Otufowora A, Liu Y, Okusanya A, Ogidan A, Okusanya A, Cottler LB. The effect of veteran status and chronic pain on past 30-day sedative use among community-dwelling adult males. J Am Board Fam Med. 2024;37(1):118-128. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2023.230226R2

- Teeters JB, Lancaster CL, Brown DG, Back SE. Substance use disorders in military veterans: prevalence and treatment challenges. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2017;8:69-77. doi:10.2147/sar.s116720

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: a companion infographic. SAMHSA publication no. PEP23-07-01-007. November 13, 2023. Accessed March 25, 2024. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt42730/2022-nsduh-infographic-report.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Among the Veteran Population Aged 18 or Older. Accessed March 25, 2024. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt44472/2022-nsduh-pop-slides-veterans.pdf

- Cypel YS, DePhilippis D, Davey VJ. Substance use in U.S. Vietnam War era veterans and nonveterans: results from the Vietnam Era Health Retrospective Observational Study. Subst Use Misuse. 2023;58(7):858-870. doi:10.1080/10826084.2023.2188427

- Otufowora A, Liu Y, Okusanya A, Ogidan A, Okusanya A, Cottler LB. The effect of veteran status and chronic pain on past 30-day sedative use among community-dwelling adult males. J Am Board Fam Med. 2024;37(1):118-128. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2023.230226R2

Data Trends 2024: Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA research on traumatic brain injury. Updated July 2020. Accessed April 19, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/pubs/docs/va_factsheets/tbi.pdf

- Miles SR, Sayer NA, Belanger HG, et al. Comparing outcomes of the Veterans Health Administration's traumatic brain injury and mental health screening programs: types and frequency of specialty services used. J Neurotrauma. 2023;40(1-2):102-111. doi:10.1089/neu.2022.0176

- Pogoda TK, Adams RS, Carlson KF, Dismuke-Greer CE, Amuan M, Pugh MJ. Risk of adverse outcomes among veterans who screen positive for traumatic brain injury in the Veterans Health Administration but do not complete a comprehensive evaluation: a LIMBIC-CENC study. J Head Trauma Rehabil. Published online June 19, 2023. doi:10.1097/HTR.0000000000000881

- Kinney AR, Yan XD, Schneider AL, et al. Unmet need for outpatient occupational therapy services among veterans with mild traumatic brain injury in the Veterans Health Administration: the role of facility characteristics. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2023;104(11):1802-1811. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2023.03.030

- Clark JMR, Ozturk ED, Chanfreau-Coffinier C, Merritt VC; VA Million Veteran Program. Evaluation of clinical outcomes and employment status in veterans with dual diagnosis of traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury. Qual Life Res. 2024;33(1):229-239. doi:10.1007/s11136-023-03518-7

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA research on traumatic brain injury. Updated July 2020. Accessed April 19, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/pubs/docs/va_factsheets/tbi.pdf

- Miles SR, Sayer NA, Belanger HG, et al. Comparing outcomes of the Veterans Health Administration's traumatic brain injury and mental health screening programs: types and frequency of specialty services used. J Neurotrauma. 2023;40(1-2):102-111. doi:10.1089/neu.2022.0176

- Pogoda TK, Adams RS, Carlson KF, Dismuke-Greer CE, Amuan M, Pugh MJ. Risk of adverse outcomes among veterans who screen positive for traumatic brain injury in the Veterans Health Administration but do not complete a comprehensive evaluation: a LIMBIC-CENC study. J Head Trauma Rehabil. Published online June 19, 2023. doi:10.1097/HTR.0000000000000881

- Kinney AR, Yan XD, Schneider AL, et al. Unmet need for outpatient occupational therapy services among veterans with mild traumatic brain injury in the Veterans Health Administration: the role of facility characteristics. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2023;104(11):1802-1811. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2023.03.030

- Clark JMR, Ozturk ED, Chanfreau-Coffinier C, Merritt VC; VA Million Veteran Program. Evaluation of clinical outcomes and employment status in veterans with dual diagnosis of traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury. Qual Life Res. 2024;33(1):229-239. doi:10.1007/s11136-023-03518-7

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA research on traumatic brain injury. Updated July 2020. Accessed April 19, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/pubs/docs/va_factsheets/tbi.pdf

- Miles SR, Sayer NA, Belanger HG, et al. Comparing outcomes of the Veterans Health Administration's traumatic brain injury and mental health screening programs: types and frequency of specialty services used. J Neurotrauma. 2023;40(1-2):102-111. doi:10.1089/neu.2022.0176

- Pogoda TK, Adams RS, Carlson KF, Dismuke-Greer CE, Amuan M, Pugh MJ. Risk of adverse outcomes among veterans who screen positive for traumatic brain injury in the Veterans Health Administration but do not complete a comprehensive evaluation: a LIMBIC-CENC study. J Head Trauma Rehabil. Published online June 19, 2023. doi:10.1097/HTR.0000000000000881

- Kinney AR, Yan XD, Schneider AL, et al. Unmet need for outpatient occupational therapy services among veterans with mild traumatic brain injury in the Veterans Health Administration: the role of facility characteristics. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2023;104(11):1802-1811. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2023.03.030

- Clark JMR, Ozturk ED, Chanfreau-Coffinier C, Merritt VC; VA Million Veteran Program. Evaluation of clinical outcomes and employment status in veterans with dual diagnosis of traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury. Qual Life Res. 2024;33(1):229-239. doi:10.1007/s11136-023-03518-7

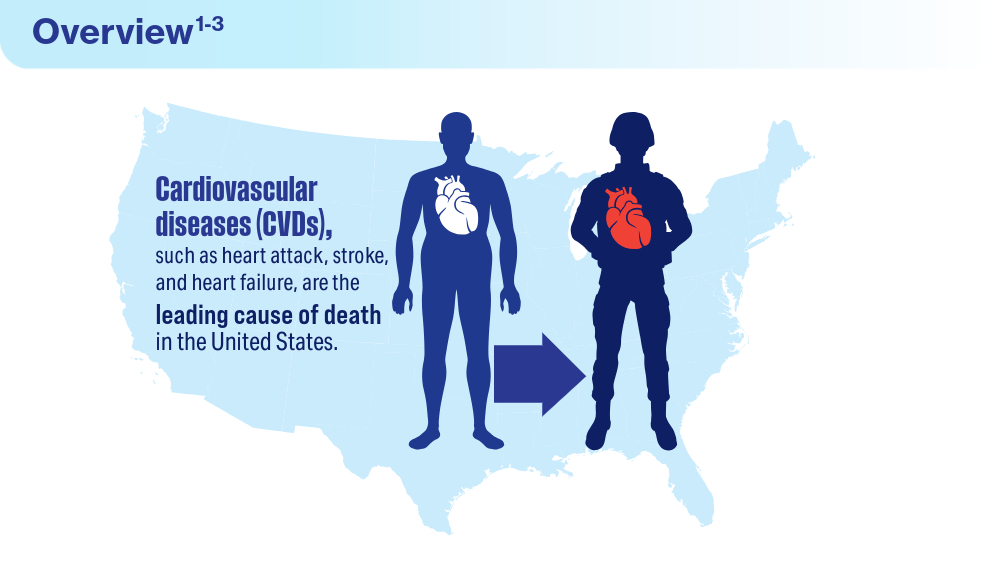

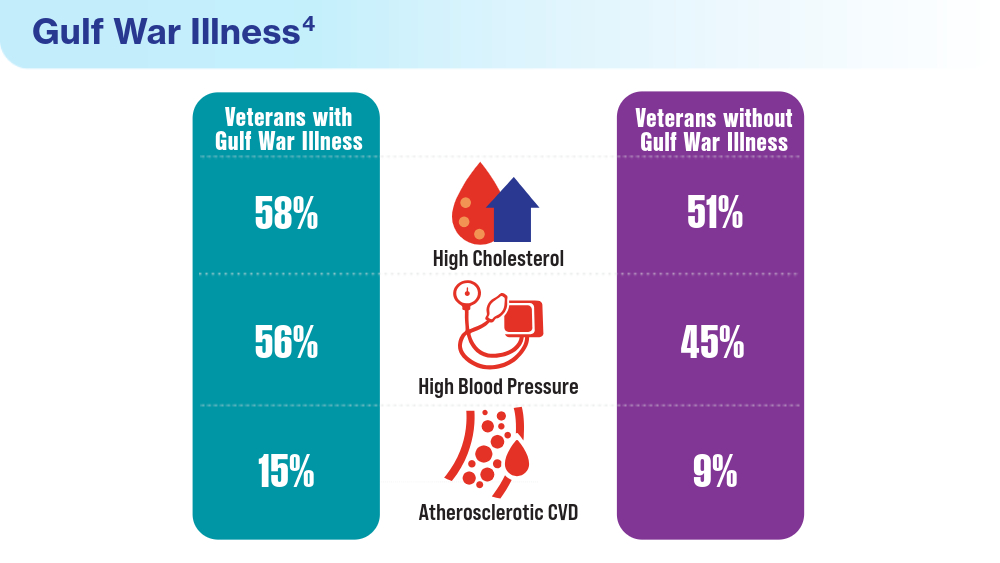

Data Trends 2024: Cardiology

- Boersma P, Cohen RA, Zelaya CE, Moy E. Multiple chronic conditions among veterans and nonveterans: United States, 2015–2018. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2021;(153):1-13. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr153-508.pdf

- Army troops have worse heart health than civilian population, study says. American Heart Association News. June 5, 2019. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.heart.org/en/news/2019/06/05/army-troops-have-worse-heart-health-than-civilian-population-study-says

- Haira RS, Kataruka A, Akeroyd JM, et al. Association of Body Mass Index with Risk Factor Optimization and Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy in US Veterans with Cardiovascular Disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12:e004817 doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.004817

- Merschel M. Gulf War illness may increase risk for heart disease or stroke. American Heart Association News. September 29, 2023. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.heart.org/en/news/2023/09/29/gulf-war-illness-may-increase-risk-for-heart-disease-or-stroke

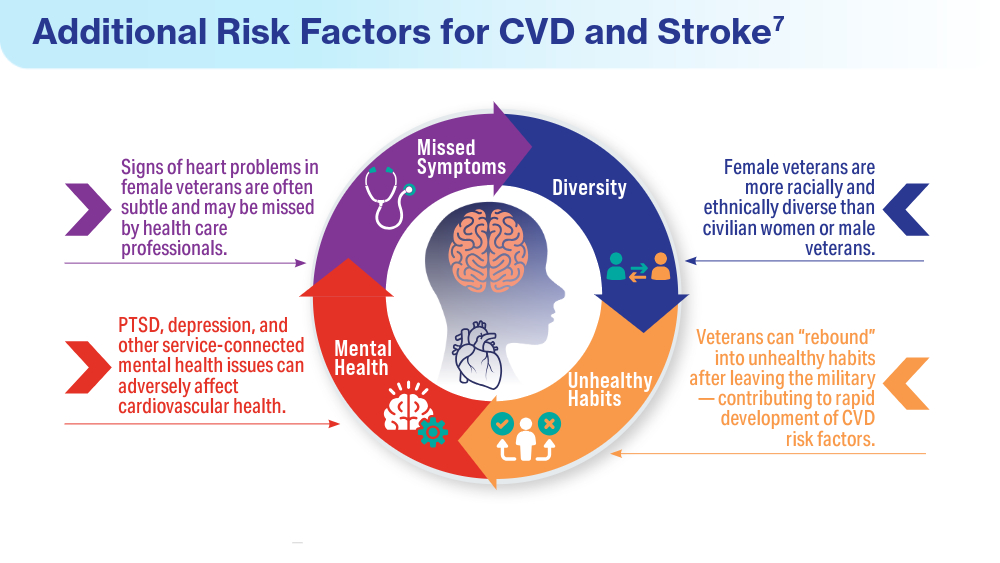

- Women veterans and heart health. American Heart Association: Go Red for Women. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://www.goredforwomen.org/en/about-heart-disease-in-women/facts/women-veterans-and-heart-health

- Heart disease and stroke statistics - 2023 Update. American Heart Association Professional Heart Daily. January 25, 2023. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://professional.heart.org/en/science-news/heart-disease-and-stroke-statistics-2023-update

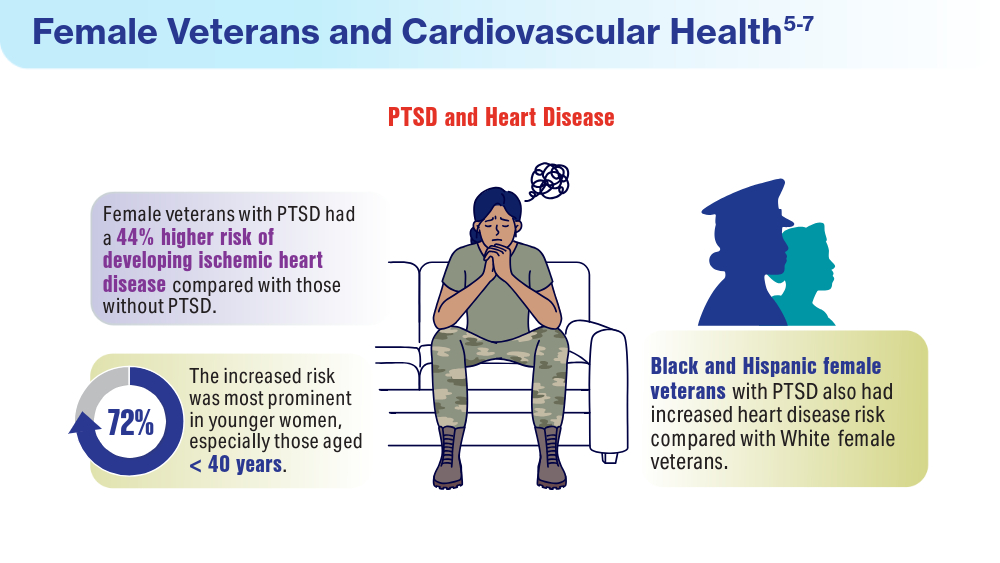

- Ebrahimi R. Sumner J, Lynch K, et al. Women veterans with PTSD have higher rate of heart disease. American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2020, Presentation 314 - P12702. American Heart Association News. November 9, 2020. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://newsroom.heart.org/news/women-veterans-with-ptsd-have-higher-rate-of-heart-disease

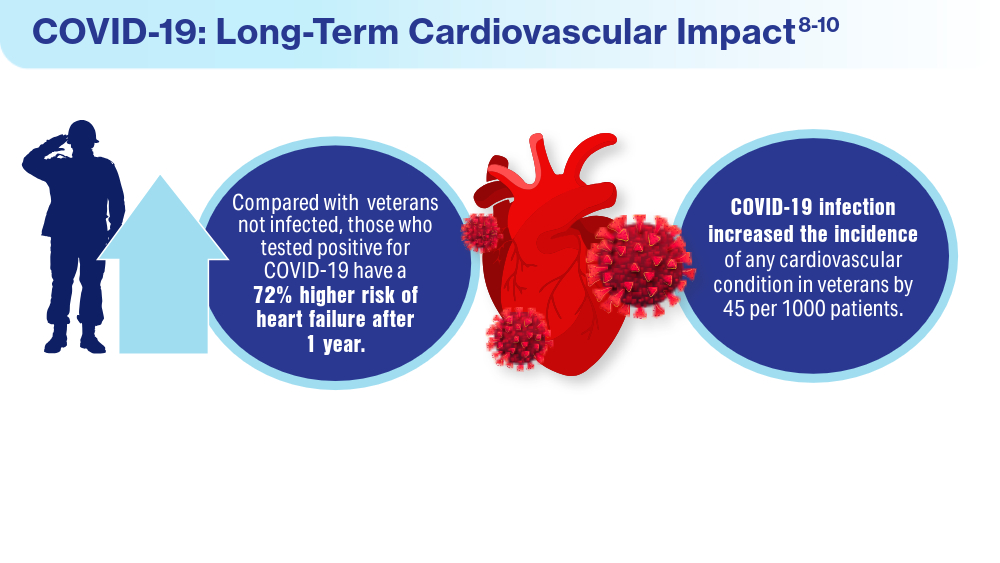

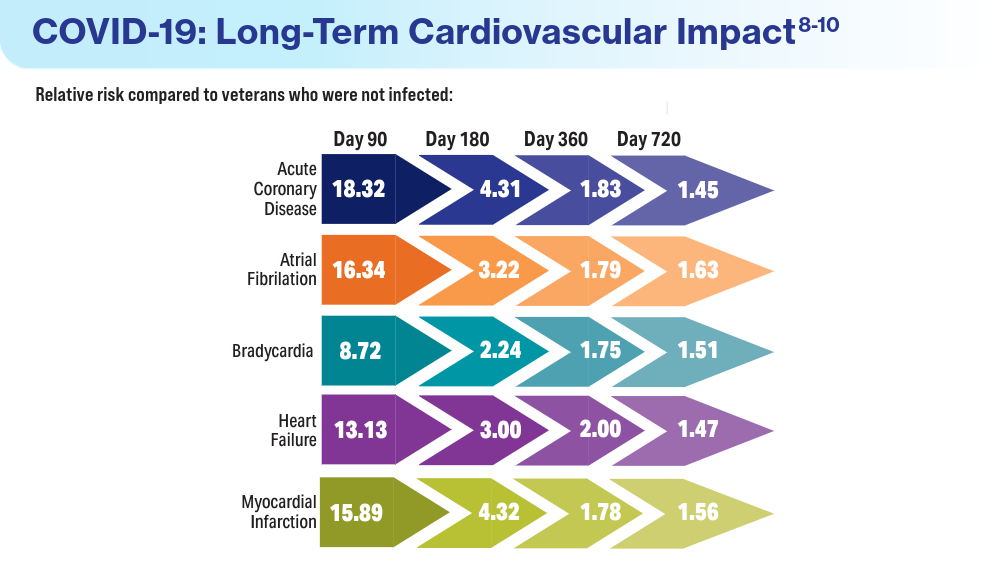

- Wadman M. COVID-19 takes serious toll on heart health—a full year after recovery. Science. Updated February 13, 2022. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://www.science.org/content/article/covid-19-takes-serious-toll-heart-health-full-year-after-recovery

- Bowe B, Xie Y, Al-Aly Z. Postacute sequale of COVID-19 at 2 years. Nature Medicine. 2023;29:2347-2357. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02521-2

- Offord C. COVID-19 boosts risks of health problems 2 years later, giant study of veterans says. Science. August 21, 2023. Accessed March 13, 2024. https://www.science.org/content/article/covid-19-boosts-risks-health-problems-2-years-later-giant-study-veterans-says

- Boersma P, Cohen RA, Zelaya CE, Moy E. Multiple chronic conditions among veterans and nonveterans: United States, 2015–2018. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2021;(153):1-13. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr153-508.pdf

- Army troops have worse heart health than civilian population, study says. American Heart Association News. June 5, 2019. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.heart.org/en/news/2019/06/05/army-troops-have-worse-heart-health-than-civilian-population-study-says

- Haira RS, Kataruka A, Akeroyd JM, et al. Association of Body Mass Index with Risk Factor Optimization and Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy in US Veterans with Cardiovascular Disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12:e004817 doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.004817

- Merschel M. Gulf War illness may increase risk for heart disease or stroke. American Heart Association News. September 29, 2023. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.heart.org/en/news/2023/09/29/gulf-war-illness-may-increase-risk-for-heart-disease-or-stroke

- Women veterans and heart health. American Heart Association: Go Red for Women. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://www.goredforwomen.org/en/about-heart-disease-in-women/facts/women-veterans-and-heart-health

- Heart disease and stroke statistics - 2023 Update. American Heart Association Professional Heart Daily. January 25, 2023. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://professional.heart.org/en/science-news/heart-disease-and-stroke-statistics-2023-update

- Ebrahimi R. Sumner J, Lynch K, et al. Women veterans with PTSD have higher rate of heart disease. American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2020, Presentation 314 - P12702. American Heart Association News. November 9, 2020. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://newsroom.heart.org/news/women-veterans-with-ptsd-have-higher-rate-of-heart-disease

- Wadman M. COVID-19 takes serious toll on heart health—a full year after recovery. Science. Updated February 13, 2022. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://www.science.org/content/article/covid-19-takes-serious-toll-heart-health-full-year-after-recovery

- Bowe B, Xie Y, Al-Aly Z. Postacute sequale of COVID-19 at 2 years. Nature Medicine. 2023;29:2347-2357. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02521-2

- Offord C. COVID-19 boosts risks of health problems 2 years later, giant study of veterans says. Science. August 21, 2023. Accessed March 13, 2024. https://www.science.org/content/article/covid-19-boosts-risks-health-problems-2-years-later-giant-study-veterans-says

- Boersma P, Cohen RA, Zelaya CE, Moy E. Multiple chronic conditions among veterans and nonveterans: United States, 2015–2018. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2021;(153):1-13. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr153-508.pdf

- Army troops have worse heart health than civilian population, study says. American Heart Association News. June 5, 2019. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.heart.org/en/news/2019/06/05/army-troops-have-worse-heart-health-than-civilian-population-study-says

- Haira RS, Kataruka A, Akeroyd JM, et al. Association of Body Mass Index with Risk Factor Optimization and Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy in US Veterans with Cardiovascular Disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12:e004817 doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.004817

- Merschel M. Gulf War illness may increase risk for heart disease or stroke. American Heart Association News. September 29, 2023. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.heart.org/en/news/2023/09/29/gulf-war-illness-may-increase-risk-for-heart-disease-or-stroke

- Women veterans and heart health. American Heart Association: Go Red for Women. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://www.goredforwomen.org/en/about-heart-disease-in-women/facts/women-veterans-and-heart-health

- Heart disease and stroke statistics - 2023 Update. American Heart Association Professional Heart Daily. January 25, 2023. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://professional.heart.org/en/science-news/heart-disease-and-stroke-statistics-2023-update

- Ebrahimi R. Sumner J, Lynch K, et al. Women veterans with PTSD have higher rate of heart disease. American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2020, Presentation 314 - P12702. American Heart Association News. November 9, 2020. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://newsroom.heart.org/news/women-veterans-with-ptsd-have-higher-rate-of-heart-disease

- Wadman M. COVID-19 takes serious toll on heart health—a full year after recovery. Science. Updated February 13, 2022. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://www.science.org/content/article/covid-19-takes-serious-toll-heart-health-full-year-after-recovery

- Bowe B, Xie Y, Al-Aly Z. Postacute sequale of COVID-19 at 2 years. Nature Medicine. 2023;29:2347-2357. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02521-2

- Offord C. COVID-19 boosts risks of health problems 2 years later, giant study of veterans says. Science. August 21, 2023. Accessed March 13, 2024. https://www.science.org/content/article/covid-19-boosts-risks-health-problems-2-years-later-giant-study-veterans-says

Scarring Head Wound

The Diagnosis: Brunsting-Perry Cicatricial Pemphigoid

Physical examination and histopathology are paramount in diagnosing Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid (BPCP). In our patient, histopathology showed subepidermal blistering with a mixed superficial dermal inflammatory cell infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence was positive for linear IgG and C3 antibodies along the basement membrane. The scarring erosions on the scalp combined with the autoantibody findings on direct immunofluorescence were consistent with BPCP. He was started on dapsone 100 mg daily and demonstrated complete resolution of symptoms after 10 months, with the exception of persistent scarring hair loss (Figure).

Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid is a rare dermatologic condition. It was first defined in 1957 when Brunsting and Perry1 examined 7 patients with cicatricial pemphigoid that predominantly affected the head and neck region, with occasional mucous membrane involvement but no mucosal scarring. Characteristically, BPCP manifests as scarring herpetiform plaques with varied blisters, erosions, crusts, and scarring.1 It primarily affects middle-aged men.2

Historically, BPCP has been considered a variant of cicatricial pemphigoid (now known as mucous membrane pemphigoid), bullous pemphigoid, or epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.3 The antigen target has not been established clearly; however, autoantibodies against laminin 332, collagen VII, and BP180 and BP230 have been proposed.2,4,5 Jacoby et al6 described BPCP on a spectrum with bullous pemphigoid and cicatricial pemphigoid, with primarily circulating autoantibodies on one end and tissue-fixed autoantibodies on the other.

The differential for BPCP also includes anti-p200 pemphigoid and anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid. Anti-p200 pemphigoid also is known as bullous pemphigoid with antibodies against the 200-kDa protein.7 It may clinically manifest similar to bullous pemphigoid and other subepidermal autoimmune blistering diseases; thus, immunopathologic differentiation can be helpful. Anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid (also known as anti–laminin gamma-1 pemphigoid) is characterized by autoantibodies targeting the laminin 332 protein in the basement membrane zone, resulting in blistering and erosions.8 Similar to BPCP and epidermolysis bullosa aquisita, anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid may affect cephalic regions and mucous membrane surfaces, resulting in scarring and cicatricial changes. Anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid also has been associated with internal malignancy.8 The use of the salt-split skin technique can be utilized to differentiate these entities based on their autoantibody-binding patterns in relation to the lamina densa.

Treatment options for mild BPCP include potent topical or intralesional steroids and dapsone, while more severe cases may require systemic therapy with rituximab, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or cyclophosphamide.4

This case highlights the importance of histopathologic examination of skin lesions with an unusual history or clinical presentation. Dermatologists should consider BPCP when presented with erosions, ulcerations, or blisters of the head and neck in middle-aged male patients.

- Brunsting LA, Perry HO. Benign pemphigoid? a report of seven cases with chronic, scarring, herpetiform plaques about the head and neck. AMA Arch Derm. 1957;75:489-501. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1957.01550160015002

- Jedlickova H, Neidermeier A, Zgažarová S, et al. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid of the scalp with antibodies against laminin 332. Dermatology. 2011;222:193-195. doi:10.1159/000322842

- Eichhoff G. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid as differential diagnosis of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Cureus. 2019;11:E5400. doi:10.7759/cureus.5400

- Asfour L, Chong H, Mee J, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid variant) localized to the face and diagnosed with antigen identification using skin deficient in type VII collagen. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:e90-e96. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0000000000000829

- Zhou S, Zou Y, Pan M. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid transitioning from previous bullous pemphigoid. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:192-194. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.018

- Jacoby WD Jr, Bartholome CW, Ramchand SC, et al. Cicatricial pemphigoid (Brunsting-Perry type). case report and immunofluorescence findings. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:779-781. doi:10.1001/archderm.1978.01640170079018

- Kridin K, Ahmed AR. Anti-p200 pemphigoid: a systematic review. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2466. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02466

- Shi L, Li X, Qian H. Anti-laminin 332-type mucous membrane pemphigoid. Biomolecules. 2022;12:1461. doi:10.3390/biom12101461

The Diagnosis: Brunsting-Perry Cicatricial Pemphigoid

Physical examination and histopathology are paramount in diagnosing Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid (BPCP). In our patient, histopathology showed subepidermal blistering with a mixed superficial dermal inflammatory cell infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence was positive for linear IgG and C3 antibodies along the basement membrane. The scarring erosions on the scalp combined with the autoantibody findings on direct immunofluorescence were consistent with BPCP. He was started on dapsone 100 mg daily and demonstrated complete resolution of symptoms after 10 months, with the exception of persistent scarring hair loss (Figure).

Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid is a rare dermatologic condition. It was first defined in 1957 when Brunsting and Perry1 examined 7 patients with cicatricial pemphigoid that predominantly affected the head and neck region, with occasional mucous membrane involvement but no mucosal scarring. Characteristically, BPCP manifests as scarring herpetiform plaques with varied blisters, erosions, crusts, and scarring.1 It primarily affects middle-aged men.2

Historically, BPCP has been considered a variant of cicatricial pemphigoid (now known as mucous membrane pemphigoid), bullous pemphigoid, or epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.3 The antigen target has not been established clearly; however, autoantibodies against laminin 332, collagen VII, and BP180 and BP230 have been proposed.2,4,5 Jacoby et al6 described BPCP on a spectrum with bullous pemphigoid and cicatricial pemphigoid, with primarily circulating autoantibodies on one end and tissue-fixed autoantibodies on the other.

The differential for BPCP also includes anti-p200 pemphigoid and anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid. Anti-p200 pemphigoid also is known as bullous pemphigoid with antibodies against the 200-kDa protein.7 It may clinically manifest similar to bullous pemphigoid and other subepidermal autoimmune blistering diseases; thus, immunopathologic differentiation can be helpful. Anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid (also known as anti–laminin gamma-1 pemphigoid) is characterized by autoantibodies targeting the laminin 332 protein in the basement membrane zone, resulting in blistering and erosions.8 Similar to BPCP and epidermolysis bullosa aquisita, anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid may affect cephalic regions and mucous membrane surfaces, resulting in scarring and cicatricial changes. Anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid also has been associated with internal malignancy.8 The use of the salt-split skin technique can be utilized to differentiate these entities based on their autoantibody-binding patterns in relation to the lamina densa.

Treatment options for mild BPCP include potent topical or intralesional steroids and dapsone, while more severe cases may require systemic therapy with rituximab, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or cyclophosphamide.4

This case highlights the importance of histopathologic examination of skin lesions with an unusual history or clinical presentation. Dermatologists should consider BPCP when presented with erosions, ulcerations, or blisters of the head and neck in middle-aged male patients.

The Diagnosis: Brunsting-Perry Cicatricial Pemphigoid

Physical examination and histopathology are paramount in diagnosing Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid (BPCP). In our patient, histopathology showed subepidermal blistering with a mixed superficial dermal inflammatory cell infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence was positive for linear IgG and C3 antibodies along the basement membrane. The scarring erosions on the scalp combined with the autoantibody findings on direct immunofluorescence were consistent with BPCP. He was started on dapsone 100 mg daily and demonstrated complete resolution of symptoms after 10 months, with the exception of persistent scarring hair loss (Figure).

Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid is a rare dermatologic condition. It was first defined in 1957 when Brunsting and Perry1 examined 7 patients with cicatricial pemphigoid that predominantly affected the head and neck region, with occasional mucous membrane involvement but no mucosal scarring. Characteristically, BPCP manifests as scarring herpetiform plaques with varied blisters, erosions, crusts, and scarring.1 It primarily affects middle-aged men.2

Historically, BPCP has been considered a variant of cicatricial pemphigoid (now known as mucous membrane pemphigoid), bullous pemphigoid, or epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.3 The antigen target has not been established clearly; however, autoantibodies against laminin 332, collagen VII, and BP180 and BP230 have been proposed.2,4,5 Jacoby et al6 described BPCP on a spectrum with bullous pemphigoid and cicatricial pemphigoid, with primarily circulating autoantibodies on one end and tissue-fixed autoantibodies on the other.

The differential for BPCP also includes anti-p200 pemphigoid and anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid. Anti-p200 pemphigoid also is known as bullous pemphigoid with antibodies against the 200-kDa protein.7 It may clinically manifest similar to bullous pemphigoid and other subepidermal autoimmune blistering diseases; thus, immunopathologic differentiation can be helpful. Anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid (also known as anti–laminin gamma-1 pemphigoid) is characterized by autoantibodies targeting the laminin 332 protein in the basement membrane zone, resulting in blistering and erosions.8 Similar to BPCP and epidermolysis bullosa aquisita, anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid may affect cephalic regions and mucous membrane surfaces, resulting in scarring and cicatricial changes. Anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid also has been associated with internal malignancy.8 The use of the salt-split skin technique can be utilized to differentiate these entities based on their autoantibody-binding patterns in relation to the lamina densa.

Treatment options for mild BPCP include potent topical or intralesional steroids and dapsone, while more severe cases may require systemic therapy with rituximab, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or cyclophosphamide.4

This case highlights the importance of histopathologic examination of skin lesions with an unusual history or clinical presentation. Dermatologists should consider BPCP when presented with erosions, ulcerations, or blisters of the head and neck in middle-aged male patients.

- Brunsting LA, Perry HO. Benign pemphigoid? a report of seven cases with chronic, scarring, herpetiform plaques about the head and neck. AMA Arch Derm. 1957;75:489-501. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1957.01550160015002

- Jedlickova H, Neidermeier A, Zgažarová S, et al. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid of the scalp with antibodies against laminin 332. Dermatology. 2011;222:193-195. doi:10.1159/000322842

- Eichhoff G. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid as differential diagnosis of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Cureus. 2019;11:E5400. doi:10.7759/cureus.5400

- Asfour L, Chong H, Mee J, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid variant) localized to the face and diagnosed with antigen identification using skin deficient in type VII collagen. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:e90-e96. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0000000000000829

- Zhou S, Zou Y, Pan M. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid transitioning from previous bullous pemphigoid. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:192-194. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.018

- Jacoby WD Jr, Bartholome CW, Ramchand SC, et al. Cicatricial pemphigoid (Brunsting-Perry type). case report and immunofluorescence findings. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:779-781. doi:10.1001/archderm.1978.01640170079018

- Kridin K, Ahmed AR. Anti-p200 pemphigoid: a systematic review. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2466. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02466

- Shi L, Li X, Qian H. Anti-laminin 332-type mucous membrane pemphigoid. Biomolecules. 2022;12:1461. doi:10.3390/biom12101461

- Brunsting LA, Perry HO. Benign pemphigoid? a report of seven cases with chronic, scarring, herpetiform plaques about the head and neck. AMA Arch Derm. 1957;75:489-501. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1957.01550160015002

- Jedlickova H, Neidermeier A, Zgažarová S, et al. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid of the scalp with antibodies against laminin 332. Dermatology. 2011;222:193-195. doi:10.1159/000322842

- Eichhoff G. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid as differential diagnosis of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Cureus. 2019;11:E5400. doi:10.7759/cureus.5400

- Asfour L, Chong H, Mee J, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid variant) localized to the face and diagnosed with antigen identification using skin deficient in type VII collagen. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:e90-e96. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0000000000000829

- Zhou S, Zou Y, Pan M. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid transitioning from previous bullous pemphigoid. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:192-194. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.018

- Jacoby WD Jr, Bartholome CW, Ramchand SC, et al. Cicatricial pemphigoid (Brunsting-Perry type). case report and immunofluorescence findings. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:779-781. doi:10.1001/archderm.1978.01640170079018

- Kridin K, Ahmed AR. Anti-p200 pemphigoid: a systematic review. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2466. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02466

- Shi L, Li X, Qian H. Anti-laminin 332-type mucous membrane pemphigoid. Biomolecules. 2022;12:1461. doi:10.3390/biom12101461

A 60-year-old man presented to a dermatology clinic with a wound on the scalp that had persisted for 11 months. The lesion started as a small erosion that eventually progressed to involve the entire parietal scalp. He had a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and Graves disease. Physical examination demonstrated a large scar over the vertex scalp with central erosion, overlying crust, peripheral scalp atrophy, hypopigmentation at the periphery, and exaggerated superficial vasculature. Some oral erosions also were observed. A review of systems was negative for any constitutional symptoms. A month prior, the patient had been started on dapsone 50 mg with a prednisone taper by an outside dermatologist and noticed some improvement.