User login

Ramucirumab-mediated survival benefit in advanced HCC unperturbed by baseline prognostic covariates

Key clinical point: Patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC) and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels ≥400 ng/mL experience a consistent survival benefit with ramucirumab therapy irrespective of baseline prognostic covariates.

Major finding: Ramucirumab vs. placebo improved overall survival in patients with viral (hazard ratio [HR] 0.76; 95% CI 0.60-0.97) and nonviral (HR 0.56; 95% CI 0.49-0.79) etiologies and in those with above-median AFP levels (≥4,081.5 ng/mL; HR 0.71; 95% CI 0.54-0.95).

Study details: Findings are from a post hoc meta-analysis of the phase 3 REACH and REACH-2 trials involving 542 patients with aHCC and AFP levels ≥400 ng/mL who were randomly assigned to receive ramucirumab (n = 316) or placebo (n = 226).

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company. JM Llovet, A Singal, A Villanueva, R Finn, M Kudo, P Galle, M Ikeda, and A Zhu reported receiving grants, personal/advisory board/consulting fees, or honoraria from various sources, including Eli Lilly. The other authors are employees or shareholders of Eli Lilly.

Source: Llovet JM et al. Prognostic and predictive factors in patients with advanced HCC and elevated alpha-fetoprotein treated with ramucirumab in two randomized phase III trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2022 (Mar 4). Doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-4000

Key clinical point: Patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC) and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels ≥400 ng/mL experience a consistent survival benefit with ramucirumab therapy irrespective of baseline prognostic covariates.

Major finding: Ramucirumab vs. placebo improved overall survival in patients with viral (hazard ratio [HR] 0.76; 95% CI 0.60-0.97) and nonviral (HR 0.56; 95% CI 0.49-0.79) etiologies and in those with above-median AFP levels (≥4,081.5 ng/mL; HR 0.71; 95% CI 0.54-0.95).

Study details: Findings are from a post hoc meta-analysis of the phase 3 REACH and REACH-2 trials involving 542 patients with aHCC and AFP levels ≥400 ng/mL who were randomly assigned to receive ramucirumab (n = 316) or placebo (n = 226).

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company. JM Llovet, A Singal, A Villanueva, R Finn, M Kudo, P Galle, M Ikeda, and A Zhu reported receiving grants, personal/advisory board/consulting fees, or honoraria from various sources, including Eli Lilly. The other authors are employees or shareholders of Eli Lilly.

Source: Llovet JM et al. Prognostic and predictive factors in patients with advanced HCC and elevated alpha-fetoprotein treated with ramucirumab in two randomized phase III trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2022 (Mar 4). Doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-4000

Key clinical point: Patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC) and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels ≥400 ng/mL experience a consistent survival benefit with ramucirumab therapy irrespective of baseline prognostic covariates.

Major finding: Ramucirumab vs. placebo improved overall survival in patients with viral (hazard ratio [HR] 0.76; 95% CI 0.60-0.97) and nonviral (HR 0.56; 95% CI 0.49-0.79) etiologies and in those with above-median AFP levels (≥4,081.5 ng/mL; HR 0.71; 95% CI 0.54-0.95).

Study details: Findings are from a post hoc meta-analysis of the phase 3 REACH and REACH-2 trials involving 542 patients with aHCC and AFP levels ≥400 ng/mL who were randomly assigned to receive ramucirumab (n = 316) or placebo (n = 226).

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company. JM Llovet, A Singal, A Villanueva, R Finn, M Kudo, P Galle, M Ikeda, and A Zhu reported receiving grants, personal/advisory board/consulting fees, or honoraria from various sources, including Eli Lilly. The other authors are employees or shareholders of Eli Lilly.

Source: Llovet JM et al. Prognostic and predictive factors in patients with advanced HCC and elevated alpha-fetoprotein treated with ramucirumab in two randomized phase III trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2022 (Mar 4). Doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-4000

Meta-analysis underscores the need for improved HCC surveillance in NAFLD without cirrhosis

Key clinical point: Compared with patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) due to other causes, a higher proportion of those with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)-related HCC do not have cirrhosis and lack an indication for HCC surveillance, thus calling for surveillance strategies for patients with NAFLD without cirrhosis but at high risk for HCC.

Major finding: The proportion of patients without cirrhosis was higher among those with NAFLD-related HCC vs. HCC due to other causes (38.5% vs. 14.6%; P < .0001). Before cancer diagnosis, only 32.8% of patients with NAFLD-related HCC underwent HCC surveillance relative to 55.7% of those with HCC due to other causes (odds ratio 0.36; P < .0001).

Study details: This was a meta-analysis of 61 studies including 94,636 patients with HCC related to either NAFLD (n = 15,377) or other causes (n = 79,259).

Disclosures: No funding was received for the study. Some authors declared having stock options from, serving as paid/unpaid consultants or advisory board members for, and receiving royalties or research grants from various organizations.

Source: Tan DJH et al. Clinical characteristics, surveillance, treatment allocation, and outcomes of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2022 (Mar 4). Doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00078-X

Key clinical point: Compared with patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) due to other causes, a higher proportion of those with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)-related HCC do not have cirrhosis and lack an indication for HCC surveillance, thus calling for surveillance strategies for patients with NAFLD without cirrhosis but at high risk for HCC.

Major finding: The proportion of patients without cirrhosis was higher among those with NAFLD-related HCC vs. HCC due to other causes (38.5% vs. 14.6%; P < .0001). Before cancer diagnosis, only 32.8% of patients with NAFLD-related HCC underwent HCC surveillance relative to 55.7% of those with HCC due to other causes (odds ratio 0.36; P < .0001).

Study details: This was a meta-analysis of 61 studies including 94,636 patients with HCC related to either NAFLD (n = 15,377) or other causes (n = 79,259).

Disclosures: No funding was received for the study. Some authors declared having stock options from, serving as paid/unpaid consultants or advisory board members for, and receiving royalties or research grants from various organizations.

Source: Tan DJH et al. Clinical characteristics, surveillance, treatment allocation, and outcomes of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2022 (Mar 4). Doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00078-X

Key clinical point: Compared with patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) due to other causes, a higher proportion of those with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)-related HCC do not have cirrhosis and lack an indication for HCC surveillance, thus calling for surveillance strategies for patients with NAFLD without cirrhosis but at high risk for HCC.

Major finding: The proportion of patients without cirrhosis was higher among those with NAFLD-related HCC vs. HCC due to other causes (38.5% vs. 14.6%; P < .0001). Before cancer diagnosis, only 32.8% of patients with NAFLD-related HCC underwent HCC surveillance relative to 55.7% of those with HCC due to other causes (odds ratio 0.36; P < .0001).

Study details: This was a meta-analysis of 61 studies including 94,636 patients with HCC related to either NAFLD (n = 15,377) or other causes (n = 79,259).

Disclosures: No funding was received for the study. Some authors declared having stock options from, serving as paid/unpaid consultants or advisory board members for, and receiving royalties or research grants from various organizations.

Source: Tan DJH et al. Clinical characteristics, surveillance, treatment allocation, and outcomes of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2022 (Mar 4). Doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00078-X

Inpatient Dermatology Consultations for Suspected Skin Cancer: A Retrospective Review

To the Editor:

Dermatologists sometimes are consulted in the inpatient setting to rule out possible skin cancer. This scenario provides an opportunity to facilitate the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous malignancy, often in patients who might not have sought regular outpatient dermatology care. Few studies have described the outcomes of inpatient biopsies to identify skin cancer.1,2

Seeking to better understand the nature of these patient encounters, we reviewed all consultations at a medical center for which the referring physician suspected skin cancer rather than only those lesions that were biopsied by the dermatologist. We also collected data about subsequent treatment to better understand the outcomes of these patient encounters.

We conducted a retrospective review of inpatient dermatology referrals at an academic-affiliated tertiary medical center. We identified all patients who were provided with an inpatient dermatology consultation for suspected skin cancer or what was identified as a “skin lesion” between July 1, 2013, and July 1, 2019. We collected information on each patient’s sex, age at time of consultation, and race, as well as the specialty of the referring provider, lesion location, maximum diameter of the lesion, whether a biopsy was performed, where the biopsy was performed (inpatient or outpatient setting), clinical diagnosis, histopathologic diagnosis, and subsequent treatment.

The institutional review board at Eastern Virginia Medical School (Norfolk, Virginia) approved this study, and all protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

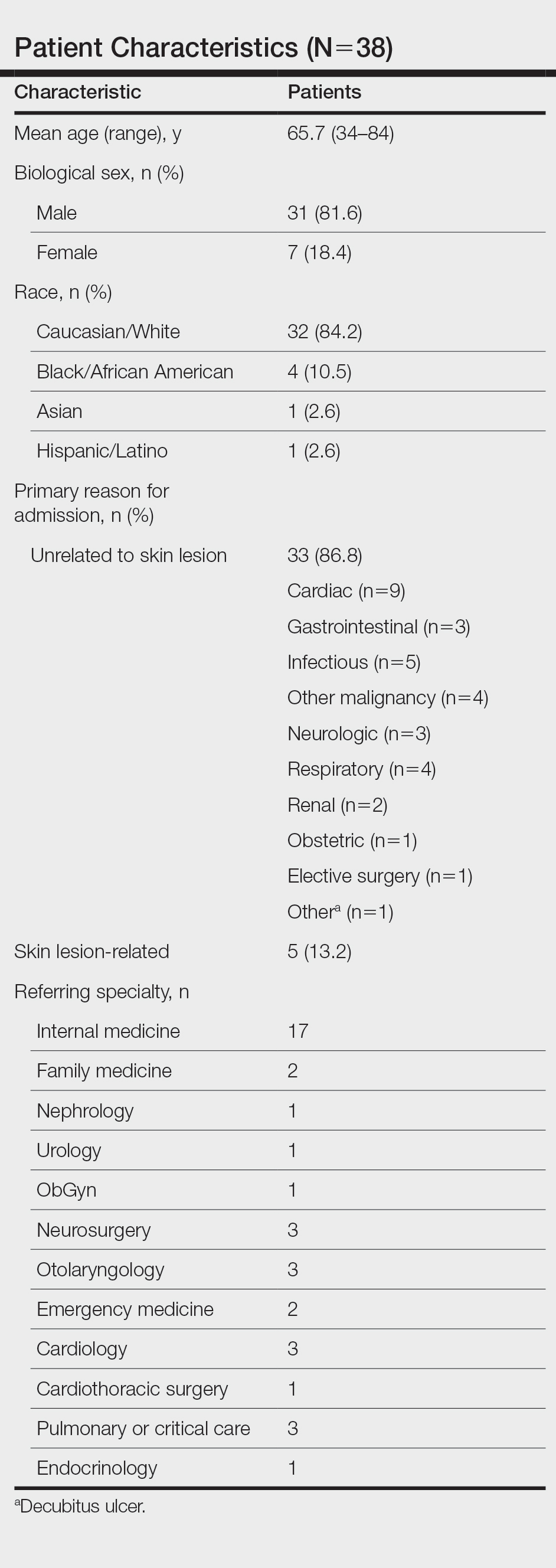

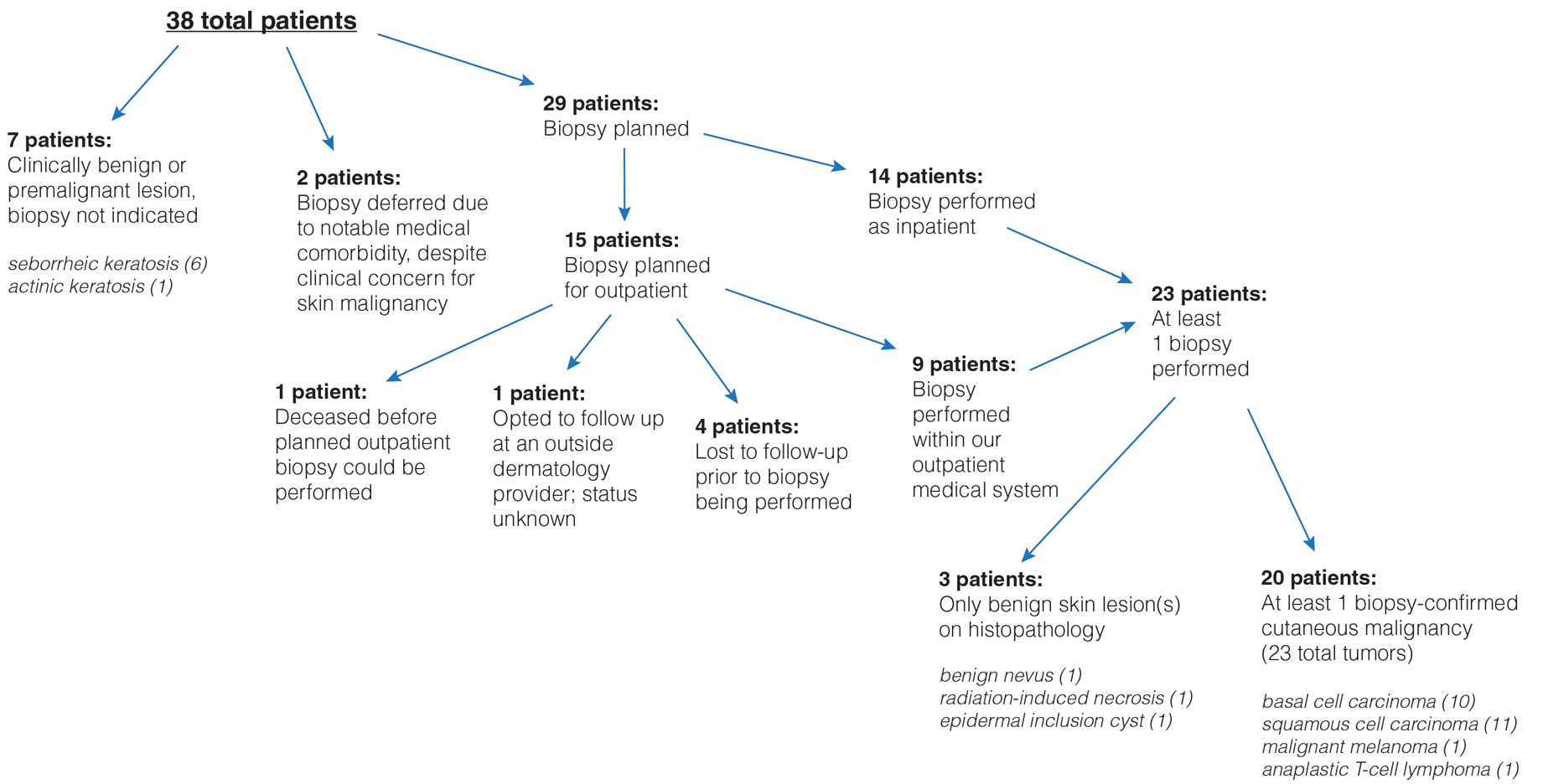

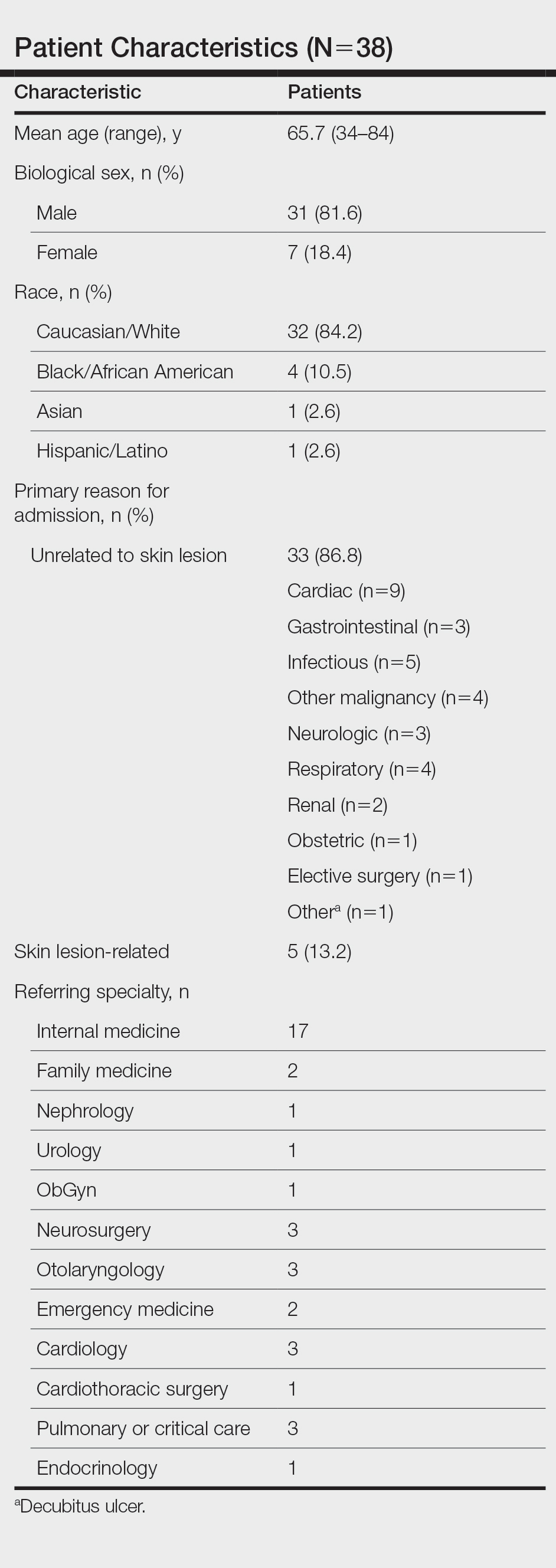

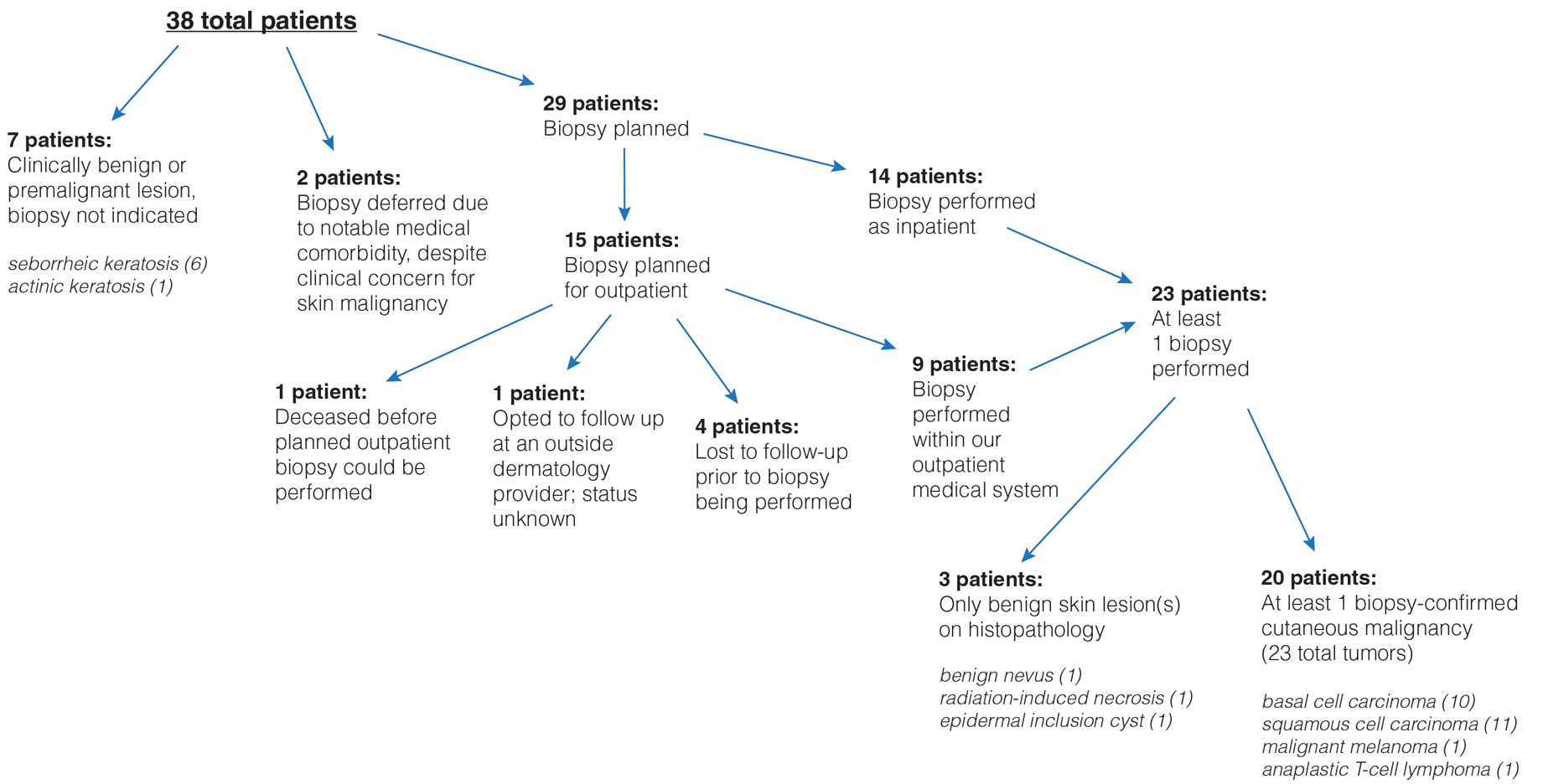

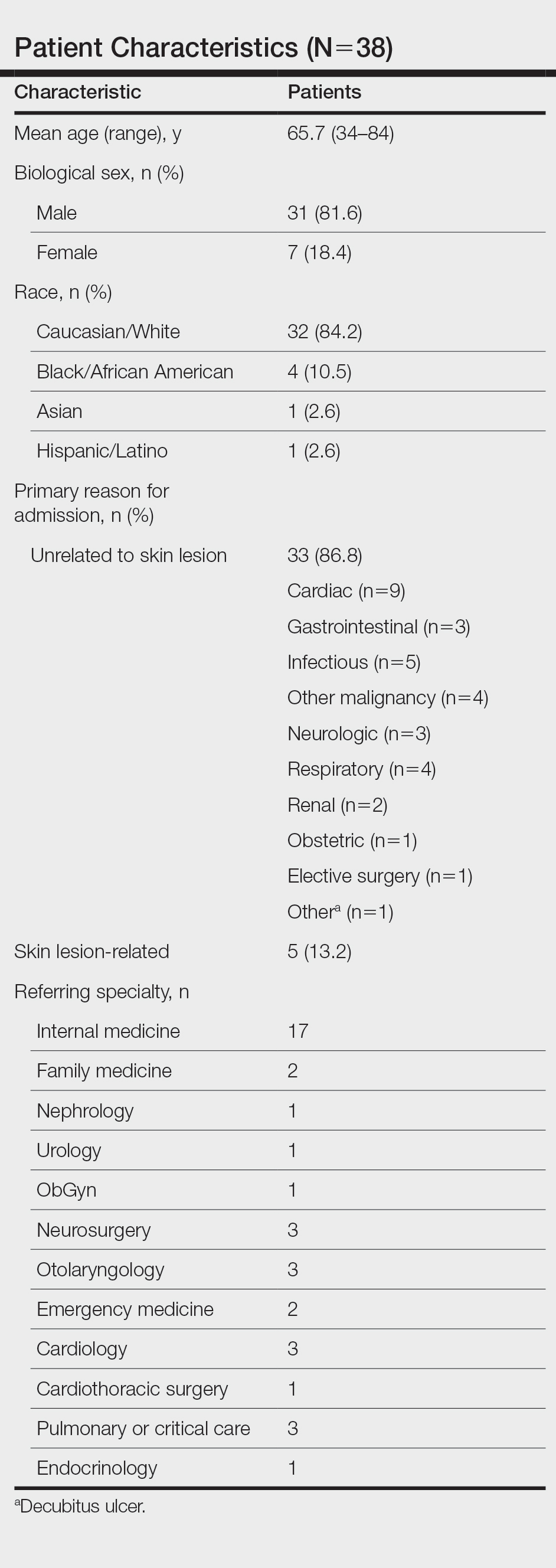

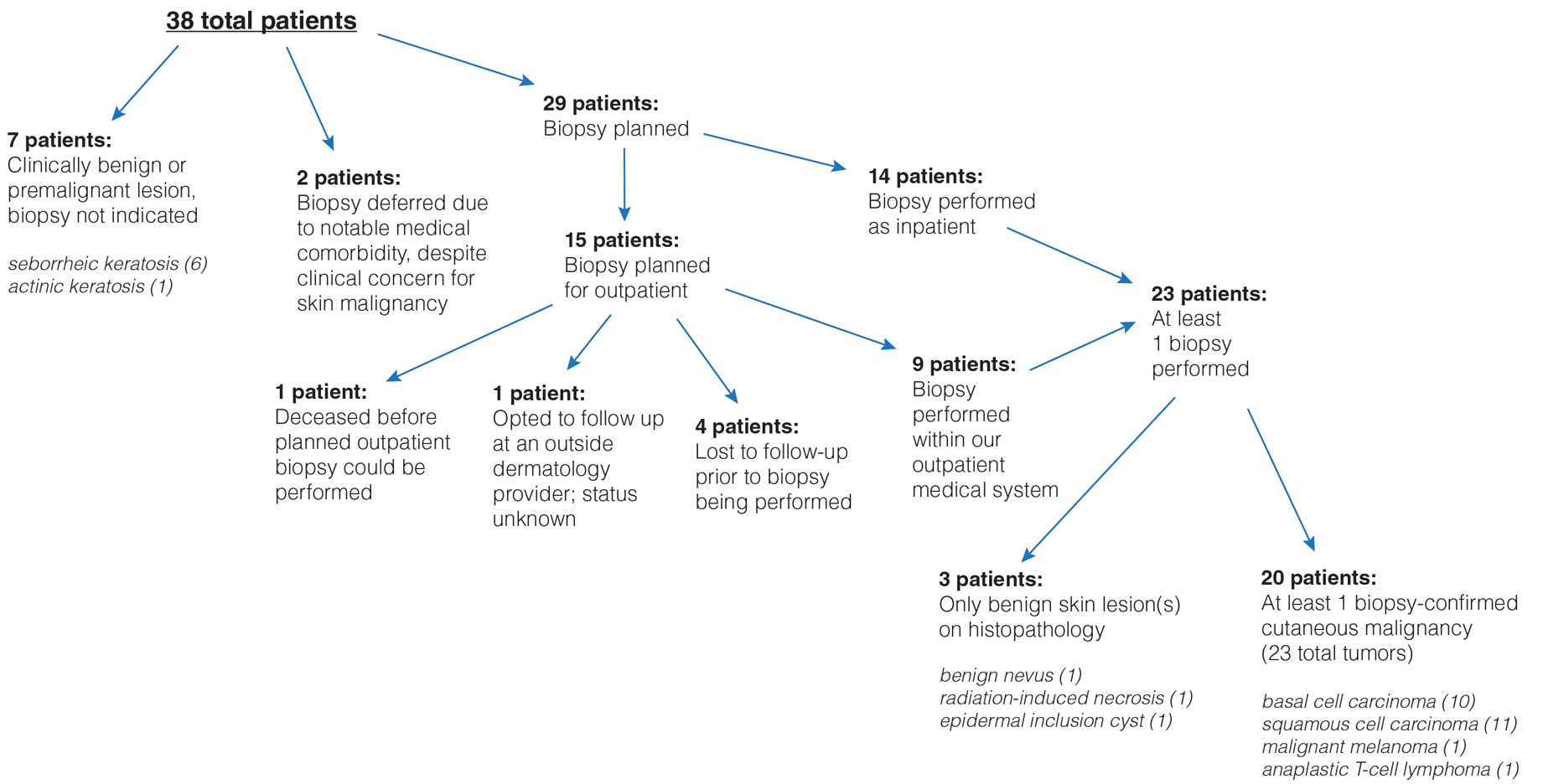

Thirty-eight patients met the inclusion criteria. Their characteristics are listed in the Table. Consultations for possible skin cancer accounted for 4% (38/950) of all inpatient dermatology consultations over the study period. Outcomes of the referrals are shown in the Figure. Consultations were received from 12 different physician specialties.

In the 38 patients, 47 lesions were identified; most (66% [31/47]) were on the head and neck. Twenty of 38 patients were found to have at least 1 biopsy-confirmed cutaneous malignancy (23 total tumors). Of those 23 identified malignancies, 10 were basal cell carcinoma, 11 squamous cell carcinoma, 1 malignant melanoma, and 1 anaplastic T-cell lymphoma. Of note, 17 of 23 (74%) identified cutaneous malignancies were 2.0 cm in diameter at biopsy or larger. Subsequently performed treatments for these patients included wide local excision (n=3), Mohs micrographic surgery (n=5), radiation therapy (n=3), topical fluorouracil (n=1), electrodesiccation and curettage (n=4), and chemotherapy or immunotherapy (n=2). Two patients who were diagnosed with skin cancer died of unrelated causes before treatment was completed.

In 10 of 38 patients, only nonmalignant entities were diagnosed, including seborrheic keratosis (n=6), benign melanocytic nevus (n=1), epidermal inclusion cyst (n=1), actinic keratosis (n=1), and radiation-induced necrosis (n=1). Of the 8 remaining patients, 4 were ultimately lost to follow-up before planned outpatient biopsy could be completed; 1 opted to follow up for biopsy at an unaffiliated outpatient dermatology provider. For 2 patients, the decision was made to forgo biopsy despite clinical suspicion of skin cancer because of overall poor health status, and 1 additional patient died before a planned outpatient biopsy could be performed.

In summary, approximately half of the inpatient dermatology consultations for suspected cutaneous malignancy resulted in a diagnosis of skin cancer. The patients in this population were admitted for a range of diagnoses, most unrelated to their cutaneous malignancy, suggesting that the inpatient setting offers the opportunity for physicians in a variety of specialties to help identify skin cancer that might otherwise be unaddressed and then facilitate management, whether ultimately in an inpatient or outpatient setting.

In many of these cases, it might be most appropriate to arrange subsequent outpatient dermatology follow-up after hospitalization, rather than making an inpatient consultation, as these situations usually are nonurgent and not directly related to hospitalization. However, in cases in which the lesion is directly related to admission, the lesion is advanced, there is concern for metastatic disease, or extenuating circumstances make outpatient follow-up difficult, inpatient dermatology consultation may be reasonable. There sometimes can be compelling reasons to expedite diagnosis and treatment as an inpatient.

In hospitalized, medically complex patients, in whom a new cutaneous malignancy is identified, dermatologists should discuss the situation thoughtfully with the patient, the patient’s family (when appropriate), and other physicians on the treatment team to determine the most appropriate course of action. In some cases, the most appropriate course might be to delay biopsy or treatment until the outpatient setting or to even defer further action completely when the prognosis is very limited. Consulting dermatologists must be mindful of patients’ overall medical situation in planning care for a cutaneous malignancy in these inpatient situations.

This study also highlights the surprising number of large-diameter, high-risk tumors identified in these scenarios. Limitations of this study include a relatively small sample size from a single facility that might not be representative of other practice settings and locations. Future multicenter studies could further explore the impact of inpatient dermatologic consultation on the diagnosis and management of skin cancer.

- Bauer J, Maroon M. Dermatology inpatient consultations: a retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:518-519. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.06.030

- Tsai S, Scott JF, Keller JJ, et al. Cutaneous malignancies identified in an inpatient dermatology consultation service. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:E116-E118. doi:10.1111/bjd.15401

To the Editor:

Dermatologists sometimes are consulted in the inpatient setting to rule out possible skin cancer. This scenario provides an opportunity to facilitate the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous malignancy, often in patients who might not have sought regular outpatient dermatology care. Few studies have described the outcomes of inpatient biopsies to identify skin cancer.1,2

Seeking to better understand the nature of these patient encounters, we reviewed all consultations at a medical center for which the referring physician suspected skin cancer rather than only those lesions that were biopsied by the dermatologist. We also collected data about subsequent treatment to better understand the outcomes of these patient encounters.

We conducted a retrospective review of inpatient dermatology referrals at an academic-affiliated tertiary medical center. We identified all patients who were provided with an inpatient dermatology consultation for suspected skin cancer or what was identified as a “skin lesion” between July 1, 2013, and July 1, 2019. We collected information on each patient’s sex, age at time of consultation, and race, as well as the specialty of the referring provider, lesion location, maximum diameter of the lesion, whether a biopsy was performed, where the biopsy was performed (inpatient or outpatient setting), clinical diagnosis, histopathologic diagnosis, and subsequent treatment.

The institutional review board at Eastern Virginia Medical School (Norfolk, Virginia) approved this study, and all protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Thirty-eight patients met the inclusion criteria. Their characteristics are listed in the Table. Consultations for possible skin cancer accounted for 4% (38/950) of all inpatient dermatology consultations over the study period. Outcomes of the referrals are shown in the Figure. Consultations were received from 12 different physician specialties.

In the 38 patients, 47 lesions were identified; most (66% [31/47]) were on the head and neck. Twenty of 38 patients were found to have at least 1 biopsy-confirmed cutaneous malignancy (23 total tumors). Of those 23 identified malignancies, 10 were basal cell carcinoma, 11 squamous cell carcinoma, 1 malignant melanoma, and 1 anaplastic T-cell lymphoma. Of note, 17 of 23 (74%) identified cutaneous malignancies were 2.0 cm in diameter at biopsy or larger. Subsequently performed treatments for these patients included wide local excision (n=3), Mohs micrographic surgery (n=5), radiation therapy (n=3), topical fluorouracil (n=1), electrodesiccation and curettage (n=4), and chemotherapy or immunotherapy (n=2). Two patients who were diagnosed with skin cancer died of unrelated causes before treatment was completed.

In 10 of 38 patients, only nonmalignant entities were diagnosed, including seborrheic keratosis (n=6), benign melanocytic nevus (n=1), epidermal inclusion cyst (n=1), actinic keratosis (n=1), and radiation-induced necrosis (n=1). Of the 8 remaining patients, 4 were ultimately lost to follow-up before planned outpatient biopsy could be completed; 1 opted to follow up for biopsy at an unaffiliated outpatient dermatology provider. For 2 patients, the decision was made to forgo biopsy despite clinical suspicion of skin cancer because of overall poor health status, and 1 additional patient died before a planned outpatient biopsy could be performed.

In summary, approximately half of the inpatient dermatology consultations for suspected cutaneous malignancy resulted in a diagnosis of skin cancer. The patients in this population were admitted for a range of diagnoses, most unrelated to their cutaneous malignancy, suggesting that the inpatient setting offers the opportunity for physicians in a variety of specialties to help identify skin cancer that might otherwise be unaddressed and then facilitate management, whether ultimately in an inpatient or outpatient setting.

In many of these cases, it might be most appropriate to arrange subsequent outpatient dermatology follow-up after hospitalization, rather than making an inpatient consultation, as these situations usually are nonurgent and not directly related to hospitalization. However, in cases in which the lesion is directly related to admission, the lesion is advanced, there is concern for metastatic disease, or extenuating circumstances make outpatient follow-up difficult, inpatient dermatology consultation may be reasonable. There sometimes can be compelling reasons to expedite diagnosis and treatment as an inpatient.

In hospitalized, medically complex patients, in whom a new cutaneous malignancy is identified, dermatologists should discuss the situation thoughtfully with the patient, the patient’s family (when appropriate), and other physicians on the treatment team to determine the most appropriate course of action. In some cases, the most appropriate course might be to delay biopsy or treatment until the outpatient setting or to even defer further action completely when the prognosis is very limited. Consulting dermatologists must be mindful of patients’ overall medical situation in planning care for a cutaneous malignancy in these inpatient situations.

This study also highlights the surprising number of large-diameter, high-risk tumors identified in these scenarios. Limitations of this study include a relatively small sample size from a single facility that might not be representative of other practice settings and locations. Future multicenter studies could further explore the impact of inpatient dermatologic consultation on the diagnosis and management of skin cancer.

To the Editor:

Dermatologists sometimes are consulted in the inpatient setting to rule out possible skin cancer. This scenario provides an opportunity to facilitate the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous malignancy, often in patients who might not have sought regular outpatient dermatology care. Few studies have described the outcomes of inpatient biopsies to identify skin cancer.1,2

Seeking to better understand the nature of these patient encounters, we reviewed all consultations at a medical center for which the referring physician suspected skin cancer rather than only those lesions that were biopsied by the dermatologist. We also collected data about subsequent treatment to better understand the outcomes of these patient encounters.

We conducted a retrospective review of inpatient dermatology referrals at an academic-affiliated tertiary medical center. We identified all patients who were provided with an inpatient dermatology consultation for suspected skin cancer or what was identified as a “skin lesion” between July 1, 2013, and July 1, 2019. We collected information on each patient’s sex, age at time of consultation, and race, as well as the specialty of the referring provider, lesion location, maximum diameter of the lesion, whether a biopsy was performed, where the biopsy was performed (inpatient or outpatient setting), clinical diagnosis, histopathologic diagnosis, and subsequent treatment.

The institutional review board at Eastern Virginia Medical School (Norfolk, Virginia) approved this study, and all protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Thirty-eight patients met the inclusion criteria. Their characteristics are listed in the Table. Consultations for possible skin cancer accounted for 4% (38/950) of all inpatient dermatology consultations over the study period. Outcomes of the referrals are shown in the Figure. Consultations were received from 12 different physician specialties.

In the 38 patients, 47 lesions were identified; most (66% [31/47]) were on the head and neck. Twenty of 38 patients were found to have at least 1 biopsy-confirmed cutaneous malignancy (23 total tumors). Of those 23 identified malignancies, 10 were basal cell carcinoma, 11 squamous cell carcinoma, 1 malignant melanoma, and 1 anaplastic T-cell lymphoma. Of note, 17 of 23 (74%) identified cutaneous malignancies were 2.0 cm in diameter at biopsy or larger. Subsequently performed treatments for these patients included wide local excision (n=3), Mohs micrographic surgery (n=5), radiation therapy (n=3), topical fluorouracil (n=1), electrodesiccation and curettage (n=4), and chemotherapy or immunotherapy (n=2). Two patients who were diagnosed with skin cancer died of unrelated causes before treatment was completed.

In 10 of 38 patients, only nonmalignant entities were diagnosed, including seborrheic keratosis (n=6), benign melanocytic nevus (n=1), epidermal inclusion cyst (n=1), actinic keratosis (n=1), and radiation-induced necrosis (n=1). Of the 8 remaining patients, 4 were ultimately lost to follow-up before planned outpatient biopsy could be completed; 1 opted to follow up for biopsy at an unaffiliated outpatient dermatology provider. For 2 patients, the decision was made to forgo biopsy despite clinical suspicion of skin cancer because of overall poor health status, and 1 additional patient died before a planned outpatient biopsy could be performed.

In summary, approximately half of the inpatient dermatology consultations for suspected cutaneous malignancy resulted in a diagnosis of skin cancer. The patients in this population were admitted for a range of diagnoses, most unrelated to their cutaneous malignancy, suggesting that the inpatient setting offers the opportunity for physicians in a variety of specialties to help identify skin cancer that might otherwise be unaddressed and then facilitate management, whether ultimately in an inpatient or outpatient setting.

In many of these cases, it might be most appropriate to arrange subsequent outpatient dermatology follow-up after hospitalization, rather than making an inpatient consultation, as these situations usually are nonurgent and not directly related to hospitalization. However, in cases in which the lesion is directly related to admission, the lesion is advanced, there is concern for metastatic disease, or extenuating circumstances make outpatient follow-up difficult, inpatient dermatology consultation may be reasonable. There sometimes can be compelling reasons to expedite diagnosis and treatment as an inpatient.

In hospitalized, medically complex patients, in whom a new cutaneous malignancy is identified, dermatologists should discuss the situation thoughtfully with the patient, the patient’s family (when appropriate), and other physicians on the treatment team to determine the most appropriate course of action. In some cases, the most appropriate course might be to delay biopsy or treatment until the outpatient setting or to even defer further action completely when the prognosis is very limited. Consulting dermatologists must be mindful of patients’ overall medical situation in planning care for a cutaneous malignancy in these inpatient situations.

This study also highlights the surprising number of large-diameter, high-risk tumors identified in these scenarios. Limitations of this study include a relatively small sample size from a single facility that might not be representative of other practice settings and locations. Future multicenter studies could further explore the impact of inpatient dermatologic consultation on the diagnosis and management of skin cancer.

- Bauer J, Maroon M. Dermatology inpatient consultations: a retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:518-519. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.06.030

- Tsai S, Scott JF, Keller JJ, et al. Cutaneous malignancies identified in an inpatient dermatology consultation service. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:E116-E118. doi:10.1111/bjd.15401

- Bauer J, Maroon M. Dermatology inpatient consultations: a retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:518-519. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.06.030

- Tsai S, Scott JF, Keller JJ, et al. Cutaneous malignancies identified in an inpatient dermatology consultation service. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:E116-E118. doi:10.1111/bjd.15401

Practice Points

- Dermatologists who perform inpatient consultations should be prepared to be consulted for cutaneous malignancies.

- Relatively large skin tumors may be identified, often incidentally, in the inpatient population.

- Careful consideration should be involved when deciding how to diagnose and manage cutaneous malignancies identified in the inpatient setting, taking the overall medical and social context into account.

LEN-TACE sequential therapy tops LEN monotherapy in unresectable HCC responsive to initial LEN treatment

Key clinical point: Lenvatinib (LEN)-transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (LEN-TACE) sequential therapy may be more clinically beneficial than LEN monotherapy in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) responsive to initial LEN treatment without exerting any additional adverse effects.

Major finding: The LEN-TACE vs. LEN monotherapy group showed a significantly higher median overall survival (31.2 months vs. 13.9 months; P = .002) and progression-free survival (12.2 months vs. 7.1 months; P = .037). The LEN-TACE group had an acceptable safety profile, with only liver dysfunction being significantly higher (P = .04).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective, multicenter cohort study on patients with intermediate- or advanced-stage unresectable HCC who responded to initial LEN treatment. Among these, 63 patients receiving LEN-TACE sequential therapy were propensity-score matched to those receiving LEN monotherapy.

Disclosures: The authors declared no source of funding or conflict of interests.

Source: Kuroda H et al. Objective response by mRECIST to initial lenvatinib therapy is an independent factor contributing to deep response in hepatocellular carcinoma treated with lenvatinib-transcatheter arterial chemoembolization sequential therapy. Liver Cancer. 2022 (Feb 15). Doi: 10.1159/000522424

Key clinical point: Lenvatinib (LEN)-transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (LEN-TACE) sequential therapy may be more clinically beneficial than LEN monotherapy in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) responsive to initial LEN treatment without exerting any additional adverse effects.

Major finding: The LEN-TACE vs. LEN monotherapy group showed a significantly higher median overall survival (31.2 months vs. 13.9 months; P = .002) and progression-free survival (12.2 months vs. 7.1 months; P = .037). The LEN-TACE group had an acceptable safety profile, with only liver dysfunction being significantly higher (P = .04).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective, multicenter cohort study on patients with intermediate- or advanced-stage unresectable HCC who responded to initial LEN treatment. Among these, 63 patients receiving LEN-TACE sequential therapy were propensity-score matched to those receiving LEN monotherapy.

Disclosures: The authors declared no source of funding or conflict of interests.

Source: Kuroda H et al. Objective response by mRECIST to initial lenvatinib therapy is an independent factor contributing to deep response in hepatocellular carcinoma treated with lenvatinib-transcatheter arterial chemoembolization sequential therapy. Liver Cancer. 2022 (Feb 15). Doi: 10.1159/000522424

Key clinical point: Lenvatinib (LEN)-transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (LEN-TACE) sequential therapy may be more clinically beneficial than LEN monotherapy in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) responsive to initial LEN treatment without exerting any additional adverse effects.

Major finding: The LEN-TACE vs. LEN monotherapy group showed a significantly higher median overall survival (31.2 months vs. 13.9 months; P = .002) and progression-free survival (12.2 months vs. 7.1 months; P = .037). The LEN-TACE group had an acceptable safety profile, with only liver dysfunction being significantly higher (P = .04).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective, multicenter cohort study on patients with intermediate- or advanced-stage unresectable HCC who responded to initial LEN treatment. Among these, 63 patients receiving LEN-TACE sequential therapy were propensity-score matched to those receiving LEN monotherapy.

Disclosures: The authors declared no source of funding or conflict of interests.

Source: Kuroda H et al. Objective response by mRECIST to initial lenvatinib therapy is an independent factor contributing to deep response in hepatocellular carcinoma treated with lenvatinib-transcatheter arterial chemoembolization sequential therapy. Liver Cancer. 2022 (Feb 15). Doi: 10.1159/000522424

Final phase 2 results testify to the clinical advantage of TACE plus sorafenib in unresectable HCC

Key clinical point: Although treatment with transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) plus sorafenib does not significantly increase overall survival (OS) in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) relative to TACE alone, it does offer a clinically meaningful OS prolongation.

Major finding: Patients receiving TACE plus sorafenib vs. TACE monotherapy showed a median OS of 36.2 months vs. 30.8 months (hazard ratio 0.861; P = .40). Despite being nonsignificant, the benefit (ΔOS 5.4 months) was clinically meaningful.

Study details: The data represent the final results of the multicenter, prospective phase 2 TACTICS trial including 156 patients aged >20 years with unresectable HCC having a life expectancy of ≥12 weeks who were randomly assigned to TACE plus sorafenib (n = 80) or TACE alone (n = 76).

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Bayer Yakuhin Ltd., Japan. Some authors reported serving as speakers/advisory consultants for and receiving grants, personal fees, and consulting/advisory fees from various sources including Bayer. M Kudo is the Editor-in-Chief of Liver Cancer, and some others are its editorial board members.

Source: Kudo M et al. Final results of TACTICS: A randomized, prospective trial comparing transarterial chemoembolization plus sorafenib to transarterial chemoembolization alone in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2022 (Feb 10). Doi: 10.1159/000522547

Key clinical point: Although treatment with transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) plus sorafenib does not significantly increase overall survival (OS) in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) relative to TACE alone, it does offer a clinically meaningful OS prolongation.

Major finding: Patients receiving TACE plus sorafenib vs. TACE monotherapy showed a median OS of 36.2 months vs. 30.8 months (hazard ratio 0.861; P = .40). Despite being nonsignificant, the benefit (ΔOS 5.4 months) was clinically meaningful.

Study details: The data represent the final results of the multicenter, prospective phase 2 TACTICS trial including 156 patients aged >20 years with unresectable HCC having a life expectancy of ≥12 weeks who were randomly assigned to TACE plus sorafenib (n = 80) or TACE alone (n = 76).

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Bayer Yakuhin Ltd., Japan. Some authors reported serving as speakers/advisory consultants for and receiving grants, personal fees, and consulting/advisory fees from various sources including Bayer. M Kudo is the Editor-in-Chief of Liver Cancer, and some others are its editorial board members.

Source: Kudo M et al. Final results of TACTICS: A randomized, prospective trial comparing transarterial chemoembolization plus sorafenib to transarterial chemoembolization alone in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2022 (Feb 10). Doi: 10.1159/000522547

Key clinical point: Although treatment with transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) plus sorafenib does not significantly increase overall survival (OS) in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) relative to TACE alone, it does offer a clinically meaningful OS prolongation.

Major finding: Patients receiving TACE plus sorafenib vs. TACE monotherapy showed a median OS of 36.2 months vs. 30.8 months (hazard ratio 0.861; P = .40). Despite being nonsignificant, the benefit (ΔOS 5.4 months) was clinically meaningful.

Study details: The data represent the final results of the multicenter, prospective phase 2 TACTICS trial including 156 patients aged >20 years with unresectable HCC having a life expectancy of ≥12 weeks who were randomly assigned to TACE plus sorafenib (n = 80) or TACE alone (n = 76).

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Bayer Yakuhin Ltd., Japan. Some authors reported serving as speakers/advisory consultants for and receiving grants, personal fees, and consulting/advisory fees from various sources including Bayer. M Kudo is the Editor-in-Chief of Liver Cancer, and some others are its editorial board members.

Source: Kudo M et al. Final results of TACTICS: A randomized, prospective trial comparing transarterial chemoembolization plus sorafenib to transarterial chemoembolization alone in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2022 (Feb 10). Doi: 10.1159/000522547

Overall survival after curative resection for HBV-related HCC is better with tenofovir vs. entecavir

Key clinical point: Patients receiving tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) vs. entecavir (ETV) after curative liver resection for hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) showed significantly better overall survival and protection of liver function but no significant difference in the cumulative incidences of HCC recurrence.

Major finding: Although patients receiving TDF vs. ETV showed no significant difference in recurrence-free survival after propensity-score matching (hazard ratio [HR] 0.91; P = .45), they had significantly better overall survival (HR 0.37; P = .002) and liver function (P = .001).

Study details: This retrospective, single-center study reviewed data on 1,173 adult patients with HBV-related HCC who had undergone liver resection and were initially treated with either TDF or ETV for chronic HBV infection.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center physician-scientist funding and National Science and Technology Major Project of China. The authors reported having no conflict of interests.

Source: Wang XH et al. Tenofovir vs. entecavir on prognosis of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. J Gastroenterol. 2022;57:185-198 (Feb 13). Doi: 10.1007/s00535-022-01855-x

Key clinical point: Patients receiving tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) vs. entecavir (ETV) after curative liver resection for hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) showed significantly better overall survival and protection of liver function but no significant difference in the cumulative incidences of HCC recurrence.

Major finding: Although patients receiving TDF vs. ETV showed no significant difference in recurrence-free survival after propensity-score matching (hazard ratio [HR] 0.91; P = .45), they had significantly better overall survival (HR 0.37; P = .002) and liver function (P = .001).

Study details: This retrospective, single-center study reviewed data on 1,173 adult patients with HBV-related HCC who had undergone liver resection and were initially treated with either TDF or ETV for chronic HBV infection.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center physician-scientist funding and National Science and Technology Major Project of China. The authors reported having no conflict of interests.

Source: Wang XH et al. Tenofovir vs. entecavir on prognosis of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. J Gastroenterol. 2022;57:185-198 (Feb 13). Doi: 10.1007/s00535-022-01855-x

Key clinical point: Patients receiving tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) vs. entecavir (ETV) after curative liver resection for hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) showed significantly better overall survival and protection of liver function but no significant difference in the cumulative incidences of HCC recurrence.

Major finding: Although patients receiving TDF vs. ETV showed no significant difference in recurrence-free survival after propensity-score matching (hazard ratio [HR] 0.91; P = .45), they had significantly better overall survival (HR 0.37; P = .002) and liver function (P = .001).

Study details: This retrospective, single-center study reviewed data on 1,173 adult patients with HBV-related HCC who had undergone liver resection and were initially treated with either TDF or ETV for chronic HBV infection.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center physician-scientist funding and National Science and Technology Major Project of China. The authors reported having no conflict of interests.

Source: Wang XH et al. Tenofovir vs. entecavir on prognosis of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. J Gastroenterol. 2022;57:185-198 (Feb 13). Doi: 10.1007/s00535-022-01855-x

HCC risk differs among various liver cirrhosis etiologies

Key clinical point: The risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) varies with underlying etiologies, with active hepatitis C virus (HCV) cirrhosis posing the highest and alcoholic or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) cirrhosis posing the lowest risk of developing HCC.

Major finding: Patients with active HCV (3.36%) showed the highest annual HCC incidence rate, followed by those with cured HCV (1.71%), alcoholic liver disease (1.32%), and NAFLD cirrhosis (1.24%). Patients with active HCV vs. NAFLD were at a 2.1-fold higher risk for HCC (adjusted hazard ratio 2.16; 95% CI, 1.16-4.04).

Study details: This multicenter, prospective cohort study analyzed data from two multiethnic cohorts enrolling a total of 2,733 patients with cirrhosis.

Disclosures: The study received financial support from the National Cancer Institute; Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas grant; and Center for Gastrointestinal Development, Infection, and Injury. No conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Kanwal F et al. Risk factors for hepatocellular cancer in contemporary cohorts of patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2022 (Mar 1). Doi: 10.1002/hep.32434

Key clinical point: The risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) varies with underlying etiologies, with active hepatitis C virus (HCV) cirrhosis posing the highest and alcoholic or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) cirrhosis posing the lowest risk of developing HCC.

Major finding: Patients with active HCV (3.36%) showed the highest annual HCC incidence rate, followed by those with cured HCV (1.71%), alcoholic liver disease (1.32%), and NAFLD cirrhosis (1.24%). Patients with active HCV vs. NAFLD were at a 2.1-fold higher risk for HCC (adjusted hazard ratio 2.16; 95% CI, 1.16-4.04).

Study details: This multicenter, prospective cohort study analyzed data from two multiethnic cohorts enrolling a total of 2,733 patients with cirrhosis.

Disclosures: The study received financial support from the National Cancer Institute; Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas grant; and Center for Gastrointestinal Development, Infection, and Injury. No conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Kanwal F et al. Risk factors for hepatocellular cancer in contemporary cohorts of patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2022 (Mar 1). Doi: 10.1002/hep.32434

Key clinical point: The risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) varies with underlying etiologies, with active hepatitis C virus (HCV) cirrhosis posing the highest and alcoholic or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) cirrhosis posing the lowest risk of developing HCC.

Major finding: Patients with active HCV (3.36%) showed the highest annual HCC incidence rate, followed by those with cured HCV (1.71%), alcoholic liver disease (1.32%), and NAFLD cirrhosis (1.24%). Patients with active HCV vs. NAFLD were at a 2.1-fold higher risk for HCC (adjusted hazard ratio 2.16; 95% CI, 1.16-4.04).

Study details: This multicenter, prospective cohort study analyzed data from two multiethnic cohorts enrolling a total of 2,733 patients with cirrhosis.

Disclosures: The study received financial support from the National Cancer Institute; Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas grant; and Center for Gastrointestinal Development, Infection, and Injury. No conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Kanwal F et al. Risk factors for hepatocellular cancer in contemporary cohorts of patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2022 (Mar 1). Doi: 10.1002/hep.32434

Active HCV infection worsens the prognosis of very early-stage HCC after ablation therapy

Key clinical point: Active hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection negatively affects overall and recurrence-free survival in patients with very early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) after curative radiofrequency ablation (RFA).

Major finding: Active HCV infection was a significant risk factor for shorter overall survival (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 2.17; P = .003) and early recurrence of HCC (aHR 1.47; P = .022). Patients with vs. without active HCV infection had a shorter median overall (66 months vs. 145 months) and recurrence-free (20 months vs. 31 months) survival (both P < .001).

Study details: Findings are from a single-center retrospective study including 302 patients with very early-stage HCC (Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage 0) who underwent RFA and had follow-up of >6 months, of which 195 had HCV infection, including 132 active infection cases.

Disclosures: M Kurosaki and N Izumi declared funding support from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development and Japanese Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Labor, respectively, and along with K Tsuchiya, receiving lecture fees from several sources.

Source: Takaura K et al. The impact of background liver disease on the long-term prognosis of very-early-stage HCC after ablation therapy. PLoS One. 2022;17(2):e0264075 (Feb 23). Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264075

Key clinical point: Active hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection negatively affects overall and recurrence-free survival in patients with very early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) after curative radiofrequency ablation (RFA).

Major finding: Active HCV infection was a significant risk factor for shorter overall survival (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 2.17; P = .003) and early recurrence of HCC (aHR 1.47; P = .022). Patients with vs. without active HCV infection had a shorter median overall (66 months vs. 145 months) and recurrence-free (20 months vs. 31 months) survival (both P < .001).

Study details: Findings are from a single-center retrospective study including 302 patients with very early-stage HCC (Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage 0) who underwent RFA and had follow-up of >6 months, of which 195 had HCV infection, including 132 active infection cases.

Disclosures: M Kurosaki and N Izumi declared funding support from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development and Japanese Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Labor, respectively, and along with K Tsuchiya, receiving lecture fees from several sources.

Source: Takaura K et al. The impact of background liver disease on the long-term prognosis of very-early-stage HCC after ablation therapy. PLoS One. 2022;17(2):e0264075 (Feb 23). Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264075

Key clinical point: Active hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection negatively affects overall and recurrence-free survival in patients with very early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) after curative radiofrequency ablation (RFA).

Major finding: Active HCV infection was a significant risk factor for shorter overall survival (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 2.17; P = .003) and early recurrence of HCC (aHR 1.47; P = .022). Patients with vs. without active HCV infection had a shorter median overall (66 months vs. 145 months) and recurrence-free (20 months vs. 31 months) survival (both P < .001).

Study details: Findings are from a single-center retrospective study including 302 patients with very early-stage HCC (Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage 0) who underwent RFA and had follow-up of >6 months, of which 195 had HCV infection, including 132 active infection cases.

Disclosures: M Kurosaki and N Izumi declared funding support from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development and Japanese Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Labor, respectively, and along with K Tsuchiya, receiving lecture fees from several sources.

Source: Takaura K et al. The impact of background liver disease on the long-term prognosis of very-early-stage HCC after ablation therapy. PLoS One. 2022;17(2):e0264075 (Feb 23). Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264075

Risk factors for recurrence after hepatic resection for early-stage HCC

Key clinical point: Independent risk factors for postoperative recurrence among patients undergoing curative hepatic resection for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) include preoperative alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level >400 µg/L, tumor size >5 cm, satellite nodules, multiple tumors, and microvascular invasion.

Major finding: Cirrhosis (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.49; P < .001), preoperative AFP level >400 µg/L (aHR 1.28; P = .004), tumor size >5 cm (aHR 1.74; P < .001), satellite nodules (aHR 1.35; P = .040), multiple tumors (aHR 1.63; P = .015), microvascular invasion (aHR 1.51; P < .001), and intraoperative blood transfusion (aHR 1.50; P = .013) were identified as independent risk factors associated with postoperative recurrence.

Study details: The data come from a large-scale, multicenter retrospective study including 1,424 adult patients who underwent curative hepatic resection for early-stage HCC (Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage 0/A).

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors reported no conflict of interests.

Source: Yao L-Q et al. Clinical features of recurrence after hepatic resection for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma and long-term survival outcomes of patients with recurrence: A multi-institutional analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022 Feb 22. Doi: 10.1245/s10434-022-11454-y

Key clinical point: Independent risk factors for postoperative recurrence among patients undergoing curative hepatic resection for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) include preoperative alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level >400 µg/L, tumor size >5 cm, satellite nodules, multiple tumors, and microvascular invasion.

Major finding: Cirrhosis (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.49; P < .001), preoperative AFP level >400 µg/L (aHR 1.28; P = .004), tumor size >5 cm (aHR 1.74; P < .001), satellite nodules (aHR 1.35; P = .040), multiple tumors (aHR 1.63; P = .015), microvascular invasion (aHR 1.51; P < .001), and intraoperative blood transfusion (aHR 1.50; P = .013) were identified as independent risk factors associated with postoperative recurrence.

Study details: The data come from a large-scale, multicenter retrospective study including 1,424 adult patients who underwent curative hepatic resection for early-stage HCC (Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage 0/A).

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors reported no conflict of interests.

Source: Yao L-Q et al. Clinical features of recurrence after hepatic resection for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma and long-term survival outcomes of patients with recurrence: A multi-institutional analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022 Feb 22. Doi: 10.1245/s10434-022-11454-y

Key clinical point: Independent risk factors for postoperative recurrence among patients undergoing curative hepatic resection for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) include preoperative alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level >400 µg/L, tumor size >5 cm, satellite nodules, multiple tumors, and microvascular invasion.

Major finding: Cirrhosis (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.49; P < .001), preoperative AFP level >400 µg/L (aHR 1.28; P = .004), tumor size >5 cm (aHR 1.74; P < .001), satellite nodules (aHR 1.35; P = .040), multiple tumors (aHR 1.63; P = .015), microvascular invasion (aHR 1.51; P < .001), and intraoperative blood transfusion (aHR 1.50; P = .013) were identified as independent risk factors associated with postoperative recurrence.

Study details: The data come from a large-scale, multicenter retrospective study including 1,424 adult patients who underwent curative hepatic resection for early-stage HCC (Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage 0/A).

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors reported no conflict of interests.

Source: Yao L-Q et al. Clinical features of recurrence after hepatic resection for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma and long-term survival outcomes of patients with recurrence: A multi-institutional analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022 Feb 22. Doi: 10.1245/s10434-022-11454-y

Inadequate ultrasound quality negatively influences HCC surveillance test performance

Key clinical point: Hampered ultrasound visualization in patients with cirrhosis receiving hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) surveillance is associated with worse test performance, negatively affecting both sensitivity and specificity of surveillance.

Major finding: Patients with cirrhosis and HCC having severely impaired ultrasound visualization before HCC diagnosis showed increased odds of false-negative results (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 7.94; 95% CI 1.23-51.16), whereas those with only cirrhosis having moderately impaired visualization showed increased odds of false-positive results (aOR 1.60; 95% CI 1.13-2.27).

Study details: This was a retrospective cohort study involving 2,238 patients with cirrhosis, with (n = 186) or without (n = 2,052) HCC, who underwent at least one abdominal ultrasound examination.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the United States National Institute of Health. A Singal and D Fetzer declared serving as consultants or advisory board members of or having research agreements with various organizations.

Source: Chong N et al. Association between ultrasound quality and test performance for HCC surveillance in patients with cirrhosis: a retrospective cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55(6):683-690 (Feb 15). Doi: 10.1111/apt.16779

Key clinical point: Hampered ultrasound visualization in patients with cirrhosis receiving hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) surveillance is associated with worse test performance, negatively affecting both sensitivity and specificity of surveillance.

Major finding: Patients with cirrhosis and HCC having severely impaired ultrasound visualization before HCC diagnosis showed increased odds of false-negative results (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 7.94; 95% CI 1.23-51.16), whereas those with only cirrhosis having moderately impaired visualization showed increased odds of false-positive results (aOR 1.60; 95% CI 1.13-2.27).

Study details: This was a retrospective cohort study involving 2,238 patients with cirrhosis, with (n = 186) or without (n = 2,052) HCC, who underwent at least one abdominal ultrasound examination.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the United States National Institute of Health. A Singal and D Fetzer declared serving as consultants or advisory board members of or having research agreements with various organizations.

Source: Chong N et al. Association between ultrasound quality and test performance for HCC surveillance in patients with cirrhosis: a retrospective cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55(6):683-690 (Feb 15). Doi: 10.1111/apt.16779

Key clinical point: Hampered ultrasound visualization in patients with cirrhosis receiving hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) surveillance is associated with worse test performance, negatively affecting both sensitivity and specificity of surveillance.

Major finding: Patients with cirrhosis and HCC having severely impaired ultrasound visualization before HCC diagnosis showed increased odds of false-negative results (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 7.94; 95% CI 1.23-51.16), whereas those with only cirrhosis having moderately impaired visualization showed increased odds of false-positive results (aOR 1.60; 95% CI 1.13-2.27).

Study details: This was a retrospective cohort study involving 2,238 patients with cirrhosis, with (n = 186) or without (n = 2,052) HCC, who underwent at least one abdominal ultrasound examination.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the United States National Institute of Health. A Singal and D Fetzer declared serving as consultants or advisory board members of or having research agreements with various organizations.

Source: Chong N et al. Association between ultrasound quality and test performance for HCC surveillance in patients with cirrhosis: a retrospective cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55(6):683-690 (Feb 15). Doi: 10.1111/apt.16779