User login

Erythematous Plaque on the Groin and Buttocks

The Diagnosis: Pseudomonas Pyoderma

A skin swab confirmed the presence of a ciprofloxacinsusceptible Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain. Our patient received oral ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily for 10 days with remarkable clinical improvement. The remaining skin lesion was successfully treated with more frequent diaper changes and the use of topical corticosteroids and emollients.

The topographical location, cutaneous morphology, clinical context, and sometimes the type of exudate are fundamental for the diagnosis of eruptions in intertriginous areas. Cutaneous Candida infections are common in these locations. They classically present as markedly erythematous plaques that occasionally are erosive, accompanied by satellite papules and pustules.1 Tinea cruris is a dermatophyte infection of the groin, proximal medial thighs, perineum, and buttocks. It usually presents as an erythematous patch that spreads centrifugally with partial central clearing and a slightly elevated, scaly border. Although candidiasis was higher on the differential, it was less likely, as our patient had a concomitant exudate inconsistent with Candida infections. Also, the lack of response to antifungal agents made hypotheses of fungal infections improbable.1

Inverse psoriasis is a variant of psoriasis identified by the development of well-demarcated, nonscaly, shiny plaques on body folds.2 Psoriasis is a chronic disease with several other cutaneous manifestations, such as nail and scalp involvement, as well as erythematous scaly plaques on the extensor surfaces of the limbs. The absence of a history of psoriasis, lack of other cutaneous manifestations, and no response to topical corticosteroids made the diagnosis of inverse psoriasis unlikely in our patient.

Erythrasma is a common superficial cutaneous infection caused by Corynebacterium minutissimum, a grampositive bacillus. It typically presents as an intertriginous eruption characterized by small erythematous to brown patches or thin plaques with fine scaling and sharp borders.3 Erythrasma displays a coral red fluorescence on Wood lamp examination that can be useful in the distinction from other causes of intertrigo.1 Although this examination had not been performed in our patient, the striking exudate made erythrasma less likely, and the culture performed on skin swab material would help to rule out this diagnosis.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a gram-negative strict aerobic bacillus of ubiquitous distribution with a preference for humid environments.4,5 Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections were first reported in the 19th century by physicians who noticed a peculiar odorous condition that caused a blue-green discoloration on bandages. This coloration explains the species name aeruginosa which is derived from the Latin word for copper rust.4 It comes from several water-soluble pigments produced by this microorganism, the most prevalent of which are pyocyanin and pyoverdine. Pyocyanin has a greenish-blue color and is nonfluorescent, while pyoverdine is green-yellowish and fluoresces under Wood light.5 Other pigments, such as pyorubin and pyomelanin, can be produced by some Pseudomonas strains.4

Pseudomonas aeruginosa has become one of the main pathogens involved in hospital-acquired infections,6 especially in immunocompromised patients.6,7 It is a frequent cause of respiratory infections in patients with cystic fibrosis, as it is present in the airways of up to 70% of these patients in adulthood.7 Also, due to a variety of adaptive mechanisms with the development of resistance to a range of antibiotics, P aeruginosa has become a worldwide public health problem and is involved in several life-threatening nosocomial infections.7,8

Cutaneous P aeruginosa infections range from superficial to deep tissue involvement and can affect both immunocompromised and immunocompetent individuals.9 They are classified as primary when they originate directly from the skin or secondary when they occur in the context of bacteremia. Primary infections mostly are mild and often are seen in healthy individuals; they usually occur by inoculation and predominate in moist areas where skin breakdown is frequent. Secondary infections typically affect immunocompromised individuals and portend a poor prognosis.5,9

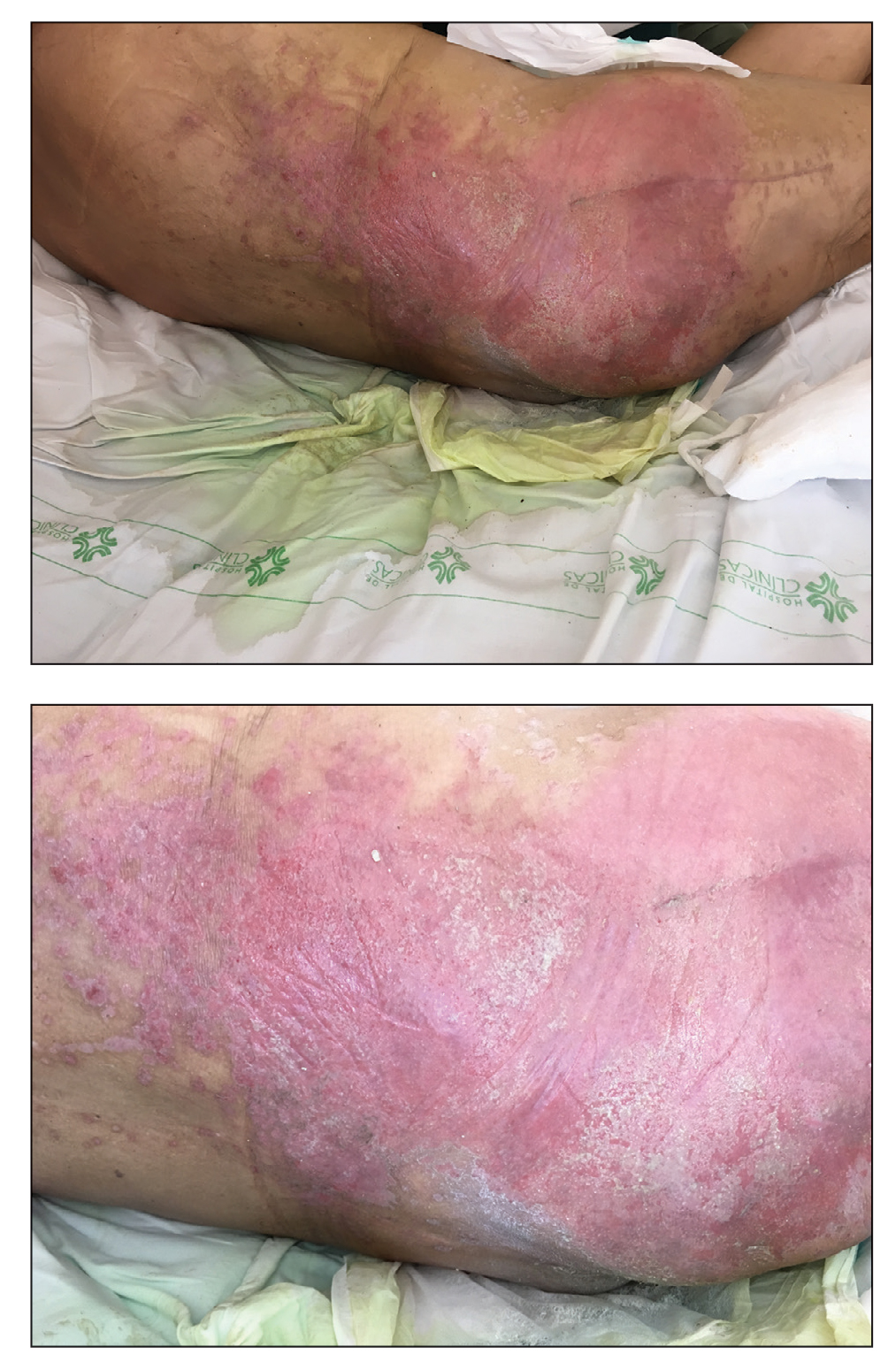

Denominated as Pseudomonas pyoderma, the superficial skin infection by P aeruginosa is described as a condition where the epidermis has a moth-eaten appearance with macerated or eroded borders.10 A blue-greenish exudate and a grape juice odor often are present. This infection usually occurs as a complication of several skin conditions such as tinea pedis, eczema, burns, wounds, and ulcers.5,10

We believe that our patient developed Pseudomonas pyoderma as a complication of diaper dermatitis. His extended hospital stay with the use of different antibiotic regimens for the treatment of several infectious complications may have contributed to the development of infection by P aeruginosa.11 Despite its great clinical relevance, there are few studies in the literature on primary skin infections caused by P aeruginosa, and clinical descriptions with images are rare. Our patient had a nonspecific noneczematous dermatitis, and the projections on the periphery of the lesion resembled the moth-eaten appearance of the classic description of Pseudomonas pyoderma.5,10 The presence of a greenish exudate should promptly raise suspicion for this entity. We believe that the presentation of this case can illustrate this finding and help physicians to recognize this infection.

- Kalra MG, Higgins KE, Kinney BS. Intertrigo and secondary skin infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:569-573.

- Micali G, Verzi AE, Giuffrida G, et al. Inverse psoriasis: from diagnosis to current treatment options. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019; 12:953-959.

- Somerville DA. Erythrasma in normal young adults. J Med Microbiol. 1970;3:57-64.

- D’Agata E. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other Pseudomonas species. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Vol 2. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2015:2518-2531.

- Silvestre JF, Betlloch MI. Cutaneous manifestations due to Pseudomonas infection. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:419-431.

- Young LS, Armstrong D. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. CRC Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1972;3:291-347.

- Moradali MF, Ghods S, Rehm BH. Pseudomonas aeruginosa lifestyle: a paradigm for adaptation, survival, and persistence. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:39.

- Rosenthal VD, Bat-Erdene I, Gupta D, et al. International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) report, data summary of 45 countries for 2012-2017: device-associated module. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48:423-432.

- Wu DC, Chan WW, Metelitsa AI, et al. Pseudomonas skin infection: clinical features, epidemiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:157-169.

- Hall JH, Callaway JL, Tindall JP, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa in dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:312-324.

- Merchant S, Proudfoot EM, Quadri HN, et al. Risk factors for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in Asia-Pacific and consequences of inappropriate initial antimicrobial therapy: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2018;14:33-44.

The Diagnosis: Pseudomonas Pyoderma

A skin swab confirmed the presence of a ciprofloxacinsusceptible Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain. Our patient received oral ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily for 10 days with remarkable clinical improvement. The remaining skin lesion was successfully treated with more frequent diaper changes and the use of topical corticosteroids and emollients.

The topographical location, cutaneous morphology, clinical context, and sometimes the type of exudate are fundamental for the diagnosis of eruptions in intertriginous areas. Cutaneous Candida infections are common in these locations. They classically present as markedly erythematous plaques that occasionally are erosive, accompanied by satellite papules and pustules.1 Tinea cruris is a dermatophyte infection of the groin, proximal medial thighs, perineum, and buttocks. It usually presents as an erythematous patch that spreads centrifugally with partial central clearing and a slightly elevated, scaly border. Although candidiasis was higher on the differential, it was less likely, as our patient had a concomitant exudate inconsistent with Candida infections. Also, the lack of response to antifungal agents made hypotheses of fungal infections improbable.1

Inverse psoriasis is a variant of psoriasis identified by the development of well-demarcated, nonscaly, shiny plaques on body folds.2 Psoriasis is a chronic disease with several other cutaneous manifestations, such as nail and scalp involvement, as well as erythematous scaly plaques on the extensor surfaces of the limbs. The absence of a history of psoriasis, lack of other cutaneous manifestations, and no response to topical corticosteroids made the diagnosis of inverse psoriasis unlikely in our patient.

Erythrasma is a common superficial cutaneous infection caused by Corynebacterium minutissimum, a grampositive bacillus. It typically presents as an intertriginous eruption characterized by small erythematous to brown patches or thin plaques with fine scaling and sharp borders.3 Erythrasma displays a coral red fluorescence on Wood lamp examination that can be useful in the distinction from other causes of intertrigo.1 Although this examination had not been performed in our patient, the striking exudate made erythrasma less likely, and the culture performed on skin swab material would help to rule out this diagnosis.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a gram-negative strict aerobic bacillus of ubiquitous distribution with a preference for humid environments.4,5 Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections were first reported in the 19th century by physicians who noticed a peculiar odorous condition that caused a blue-green discoloration on bandages. This coloration explains the species name aeruginosa which is derived from the Latin word for copper rust.4 It comes from several water-soluble pigments produced by this microorganism, the most prevalent of which are pyocyanin and pyoverdine. Pyocyanin has a greenish-blue color and is nonfluorescent, while pyoverdine is green-yellowish and fluoresces under Wood light.5 Other pigments, such as pyorubin and pyomelanin, can be produced by some Pseudomonas strains.4

Pseudomonas aeruginosa has become one of the main pathogens involved in hospital-acquired infections,6 especially in immunocompromised patients.6,7 It is a frequent cause of respiratory infections in patients with cystic fibrosis, as it is present in the airways of up to 70% of these patients in adulthood.7 Also, due to a variety of adaptive mechanisms with the development of resistance to a range of antibiotics, P aeruginosa has become a worldwide public health problem and is involved in several life-threatening nosocomial infections.7,8

Cutaneous P aeruginosa infections range from superficial to deep tissue involvement and can affect both immunocompromised and immunocompetent individuals.9 They are classified as primary when they originate directly from the skin or secondary when they occur in the context of bacteremia. Primary infections mostly are mild and often are seen in healthy individuals; they usually occur by inoculation and predominate in moist areas where skin breakdown is frequent. Secondary infections typically affect immunocompromised individuals and portend a poor prognosis.5,9

Denominated as Pseudomonas pyoderma, the superficial skin infection by P aeruginosa is described as a condition where the epidermis has a moth-eaten appearance with macerated or eroded borders.10 A blue-greenish exudate and a grape juice odor often are present. This infection usually occurs as a complication of several skin conditions such as tinea pedis, eczema, burns, wounds, and ulcers.5,10

We believe that our patient developed Pseudomonas pyoderma as a complication of diaper dermatitis. His extended hospital stay with the use of different antibiotic regimens for the treatment of several infectious complications may have contributed to the development of infection by P aeruginosa.11 Despite its great clinical relevance, there are few studies in the literature on primary skin infections caused by P aeruginosa, and clinical descriptions with images are rare. Our patient had a nonspecific noneczematous dermatitis, and the projections on the periphery of the lesion resembled the moth-eaten appearance of the classic description of Pseudomonas pyoderma.5,10 The presence of a greenish exudate should promptly raise suspicion for this entity. We believe that the presentation of this case can illustrate this finding and help physicians to recognize this infection.

The Diagnosis: Pseudomonas Pyoderma

A skin swab confirmed the presence of a ciprofloxacinsusceptible Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain. Our patient received oral ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily for 10 days with remarkable clinical improvement. The remaining skin lesion was successfully treated with more frequent diaper changes and the use of topical corticosteroids and emollients.

The topographical location, cutaneous morphology, clinical context, and sometimes the type of exudate are fundamental for the diagnosis of eruptions in intertriginous areas. Cutaneous Candida infections are common in these locations. They classically present as markedly erythematous plaques that occasionally are erosive, accompanied by satellite papules and pustules.1 Tinea cruris is a dermatophyte infection of the groin, proximal medial thighs, perineum, and buttocks. It usually presents as an erythematous patch that spreads centrifugally with partial central clearing and a slightly elevated, scaly border. Although candidiasis was higher on the differential, it was less likely, as our patient had a concomitant exudate inconsistent with Candida infections. Also, the lack of response to antifungal agents made hypotheses of fungal infections improbable.1

Inverse psoriasis is a variant of psoriasis identified by the development of well-demarcated, nonscaly, shiny plaques on body folds.2 Psoriasis is a chronic disease with several other cutaneous manifestations, such as nail and scalp involvement, as well as erythematous scaly plaques on the extensor surfaces of the limbs. The absence of a history of psoriasis, lack of other cutaneous manifestations, and no response to topical corticosteroids made the diagnosis of inverse psoriasis unlikely in our patient.

Erythrasma is a common superficial cutaneous infection caused by Corynebacterium minutissimum, a grampositive bacillus. It typically presents as an intertriginous eruption characterized by small erythematous to brown patches or thin plaques with fine scaling and sharp borders.3 Erythrasma displays a coral red fluorescence on Wood lamp examination that can be useful in the distinction from other causes of intertrigo.1 Although this examination had not been performed in our patient, the striking exudate made erythrasma less likely, and the culture performed on skin swab material would help to rule out this diagnosis.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a gram-negative strict aerobic bacillus of ubiquitous distribution with a preference for humid environments.4,5 Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections were first reported in the 19th century by physicians who noticed a peculiar odorous condition that caused a blue-green discoloration on bandages. This coloration explains the species name aeruginosa which is derived from the Latin word for copper rust.4 It comes from several water-soluble pigments produced by this microorganism, the most prevalent of which are pyocyanin and pyoverdine. Pyocyanin has a greenish-blue color and is nonfluorescent, while pyoverdine is green-yellowish and fluoresces under Wood light.5 Other pigments, such as pyorubin and pyomelanin, can be produced by some Pseudomonas strains.4

Pseudomonas aeruginosa has become one of the main pathogens involved in hospital-acquired infections,6 especially in immunocompromised patients.6,7 It is a frequent cause of respiratory infections in patients with cystic fibrosis, as it is present in the airways of up to 70% of these patients in adulthood.7 Also, due to a variety of adaptive mechanisms with the development of resistance to a range of antibiotics, P aeruginosa has become a worldwide public health problem and is involved in several life-threatening nosocomial infections.7,8

Cutaneous P aeruginosa infections range from superficial to deep tissue involvement and can affect both immunocompromised and immunocompetent individuals.9 They are classified as primary when they originate directly from the skin or secondary when they occur in the context of bacteremia. Primary infections mostly are mild and often are seen in healthy individuals; they usually occur by inoculation and predominate in moist areas where skin breakdown is frequent. Secondary infections typically affect immunocompromised individuals and portend a poor prognosis.5,9

Denominated as Pseudomonas pyoderma, the superficial skin infection by P aeruginosa is described as a condition where the epidermis has a moth-eaten appearance with macerated or eroded borders.10 A blue-greenish exudate and a grape juice odor often are present. This infection usually occurs as a complication of several skin conditions such as tinea pedis, eczema, burns, wounds, and ulcers.5,10

We believe that our patient developed Pseudomonas pyoderma as a complication of diaper dermatitis. His extended hospital stay with the use of different antibiotic regimens for the treatment of several infectious complications may have contributed to the development of infection by P aeruginosa.11 Despite its great clinical relevance, there are few studies in the literature on primary skin infections caused by P aeruginosa, and clinical descriptions with images are rare. Our patient had a nonspecific noneczematous dermatitis, and the projections on the periphery of the lesion resembled the moth-eaten appearance of the classic description of Pseudomonas pyoderma.5,10 The presence of a greenish exudate should promptly raise suspicion for this entity. We believe that the presentation of this case can illustrate this finding and help physicians to recognize this infection.

- Kalra MG, Higgins KE, Kinney BS. Intertrigo and secondary skin infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:569-573.

- Micali G, Verzi AE, Giuffrida G, et al. Inverse psoriasis: from diagnosis to current treatment options. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019; 12:953-959.

- Somerville DA. Erythrasma in normal young adults. J Med Microbiol. 1970;3:57-64.

- D’Agata E. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other Pseudomonas species. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Vol 2. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2015:2518-2531.

- Silvestre JF, Betlloch MI. Cutaneous manifestations due to Pseudomonas infection. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:419-431.

- Young LS, Armstrong D. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. CRC Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1972;3:291-347.

- Moradali MF, Ghods S, Rehm BH. Pseudomonas aeruginosa lifestyle: a paradigm for adaptation, survival, and persistence. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:39.

- Rosenthal VD, Bat-Erdene I, Gupta D, et al. International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) report, data summary of 45 countries for 2012-2017: device-associated module. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48:423-432.

- Wu DC, Chan WW, Metelitsa AI, et al. Pseudomonas skin infection: clinical features, epidemiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:157-169.

- Hall JH, Callaway JL, Tindall JP, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa in dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:312-324.

- Merchant S, Proudfoot EM, Quadri HN, et al. Risk factors for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in Asia-Pacific and consequences of inappropriate initial antimicrobial therapy: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2018;14:33-44.

- Kalra MG, Higgins KE, Kinney BS. Intertrigo and secondary skin infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:569-573.

- Micali G, Verzi AE, Giuffrida G, et al. Inverse psoriasis: from diagnosis to current treatment options. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019; 12:953-959.

- Somerville DA. Erythrasma in normal young adults. J Med Microbiol. 1970;3:57-64.

- D’Agata E. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other Pseudomonas species. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Vol 2. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2015:2518-2531.

- Silvestre JF, Betlloch MI. Cutaneous manifestations due to Pseudomonas infection. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:419-431.

- Young LS, Armstrong D. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. CRC Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1972;3:291-347.

- Moradali MF, Ghods S, Rehm BH. Pseudomonas aeruginosa lifestyle: a paradigm for adaptation, survival, and persistence. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:39.

- Rosenthal VD, Bat-Erdene I, Gupta D, et al. International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) report, data summary of 45 countries for 2012-2017: device-associated module. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48:423-432.

- Wu DC, Chan WW, Metelitsa AI, et al. Pseudomonas skin infection: clinical features, epidemiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:157-169.

- Hall JH, Callaway JL, Tindall JP, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa in dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:312-324.

- Merchant S, Proudfoot EM, Quadri HN, et al. Risk factors for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in Asia-Pacific and consequences of inappropriate initial antimicrobial therapy: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2018;14:33-44.

A 68-year-old man presented with an extensive erythematous plaque of 3 weeks’ duration that started in the groin and spread to the buttocks. It was associated with pruritus and a burning sensation. He was admitted to the palliative care unit 1 year prior for the management of terminal lung cancer. Despite the use of topical corticosteroids and antifungals, the lesions gradually worsened with dissemination to the back. Physical examination revealed an erythematous macerated plaque that extended from the buttocks and groin region to the scapular area (top). Its borders had an eroded appearance with projections compatible with radial spread (bottom). A greenish exudate soaked the diaper and sheets. No other cutaneous lesions were noted.

Harlequin Syndrome: Discovery of an Ancient Schwannoma

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old man who was otherwise healthy and a long-distance runner presented with the sudden onset of diminished sweating on the left side of the body of 6 weeks’ duration. While training for a marathon, he reported that he perspired only on the right side of the body during runs of 12 to 15 miles; he observed a lack of sweating on the left side of the face, left side of the trunk, left arm, and left leg. This absence of sweating was accompanied by intense flushing on the right side of the face and trunk.

The patient did not take any medications. He reported no history of trauma and exhibited no neurologic deficits. A chest radiograph was negative. Thyroid function testing and a comprehensive metabolic panel were normal. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the chest and abdomen revealed a 4.3-cm soft-tissue mass in the left superior mediastinum that was superior to the aortic arch, posterior to the left subclavian artery in proximity to the sympathetic chain, and lateral to the trachea. The patient was diagnosed with Harlequin syndrome (HS).

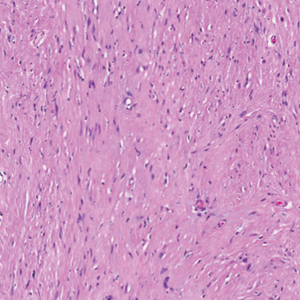

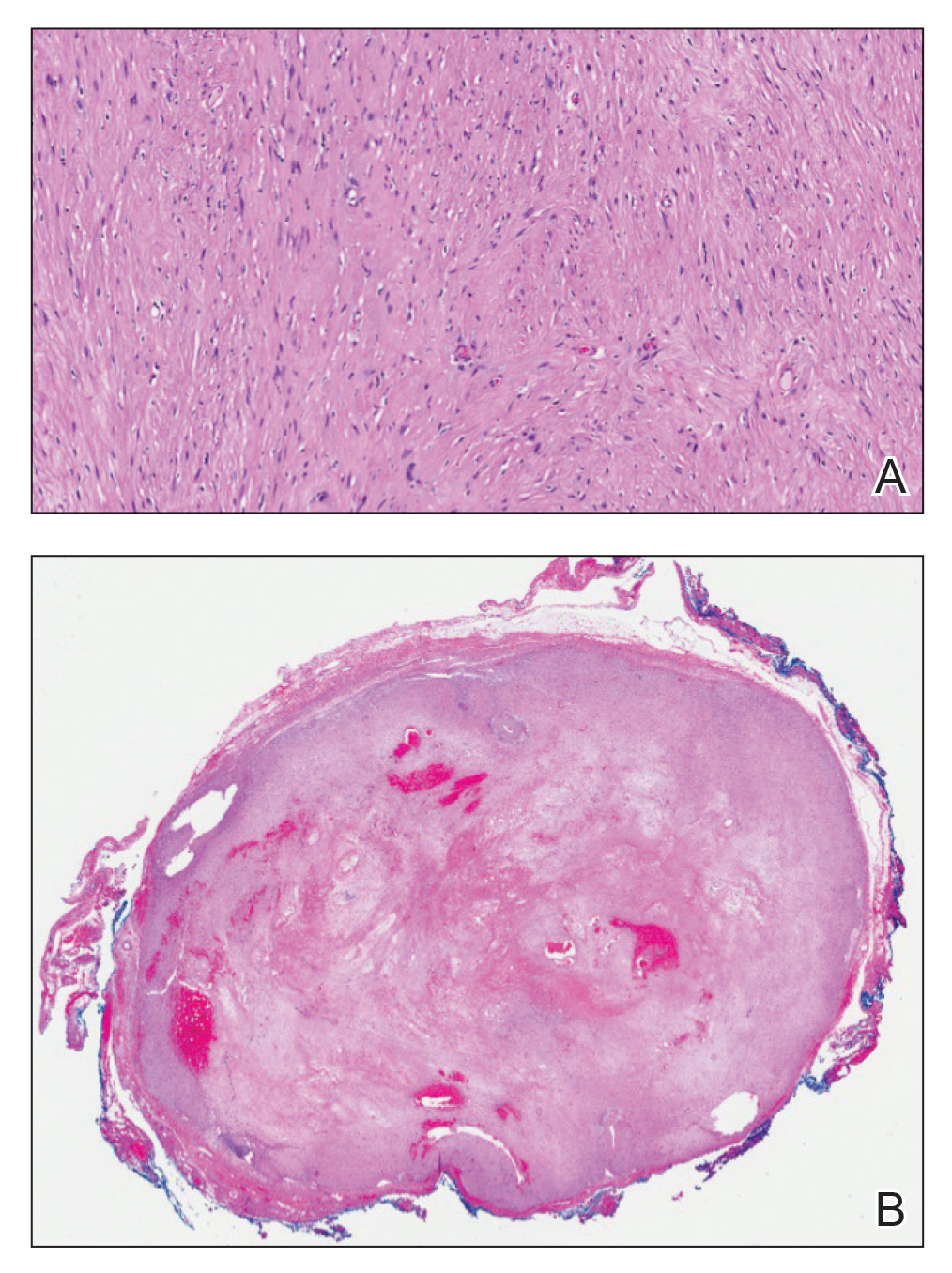

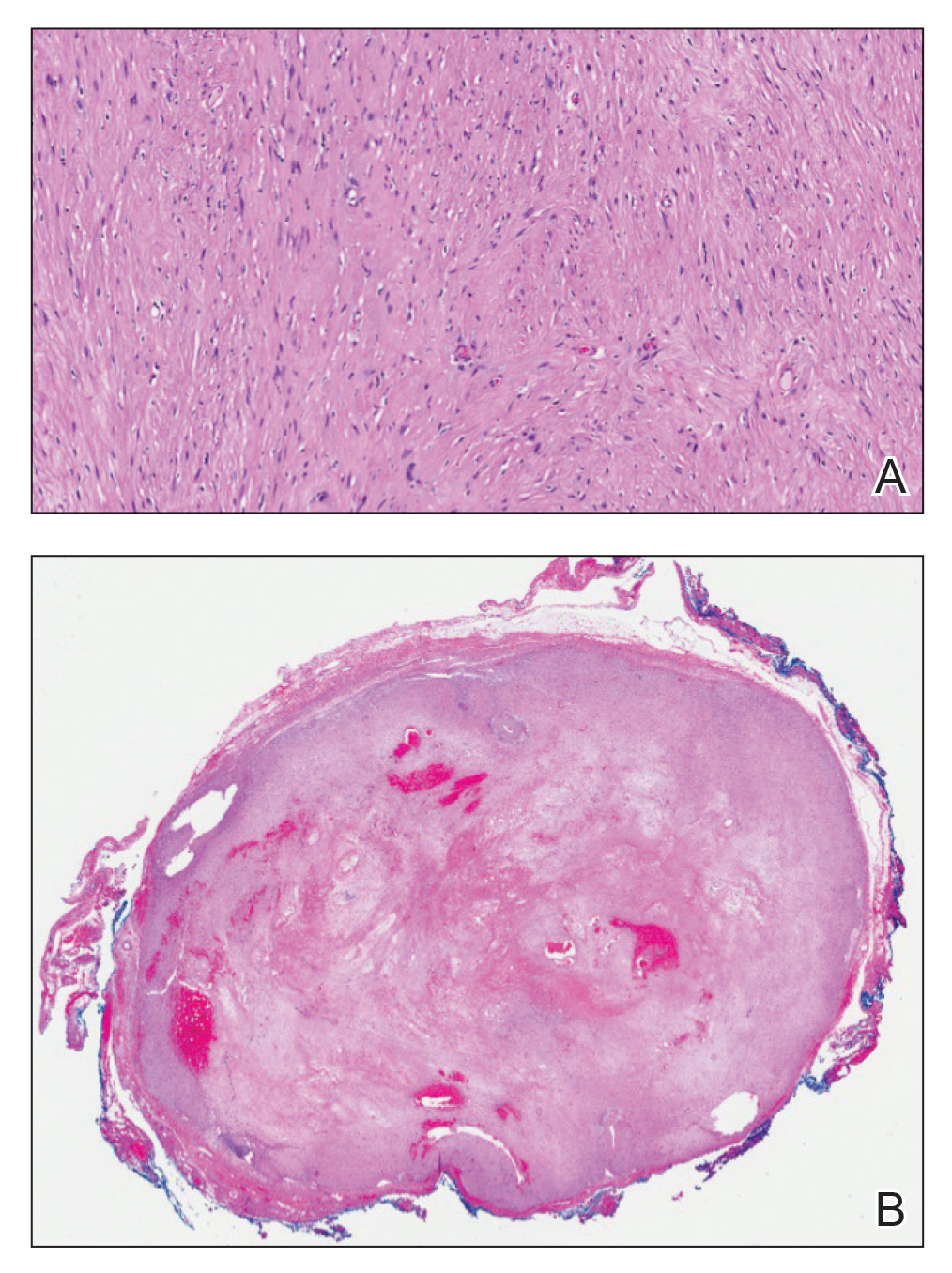

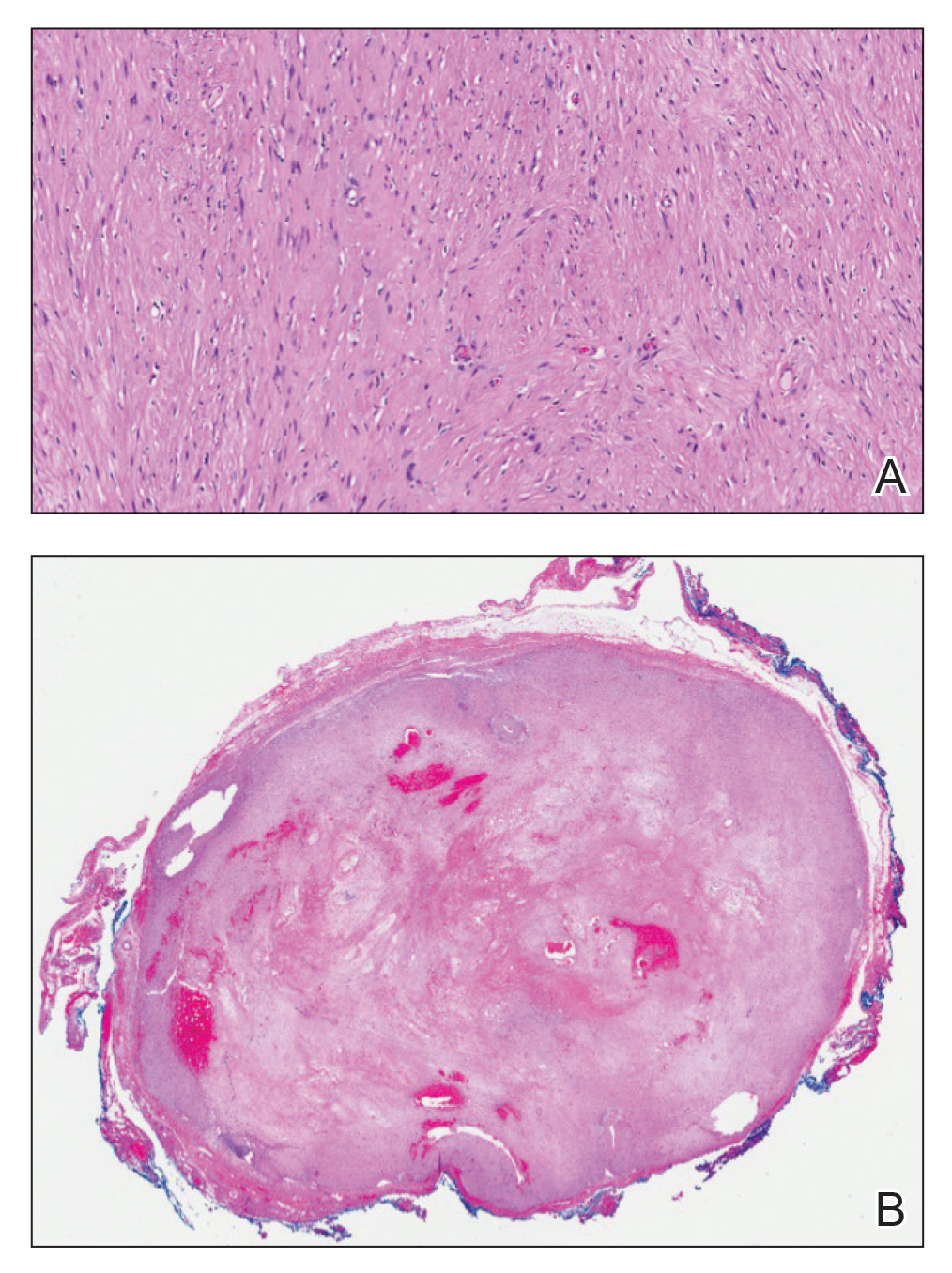

Open thoracotomy was performed to remove the lesion. Analysis of the mass showed cystic areas, areas of hemorrhage (Figure 1A), and alternating zones of compact Antoni A spindle cells admixed with areas of less orderly Antoni B spindle cells within a hypocellular stroma (Figure 1B). Individual cells were characterized by eosinophilic cytoplasm and tapered nuclei. The mass appeared to be completely encapsulated. No mitotic figures were seen on multiple slides. The cells stained diffusely positive for S-100 proteins. At 6-month follow-up, the patient reported that he did not notice any return of normal sweating on the left side. However, the right-sided flushing had resolved.

Harlequin syndrome (also called the Harlequin sign) is a rare disorder of the sympathetic nervous system and should not be confused with lethal harlequin-type ichthyosis, an autosomal-recessive congenital disorder in which the affected newborn’s skin is hard and thickened over most of the body.1 Harlequin syndrome usually is characterized by unilateral flushing and sweating that can affect the face, trunk, and extremities.2 Physical stimuli, such as exercising (as in our patient), high body temperature, and the consumption of spicy or pungent food, or an emotional response can unmask or exacerbate symptoms of HS. The syndrome also can present with cluster headache.3 Harlequin syndrome is more common in females (66% of cases).4 Originally, the side of the face marked by increased sweating and flushing was perceived to be the pathologic side; now it is recognized that the anhidrotic side is affected by the causative pathology. The side of the face characterized by flushing might gradually darken as it compensates for lack of thermal regulation on the other side.2,5

Usually, HS is an idiopathic condition associated with localized failure of upper thoracic sympathetic chain ganglia.5 A theory is that HS is part of a spectrum of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy.6 Typically, the syndrome is asymptomatic at rest, but testing can reveal an underlying sympathetic lesion.7 Structural lesions have been reported as a cause of the syndrome,6 similar to our patient.

Disrupted thermoregulatory vasodilation in HS is caused by an ipsilateral lesion of the sympathetic vasodilator neurons that innervate the face. Hemifacial anhidrosis also occurs because sudomotor neurons travel within the same pathways as vasodilator neurons.4

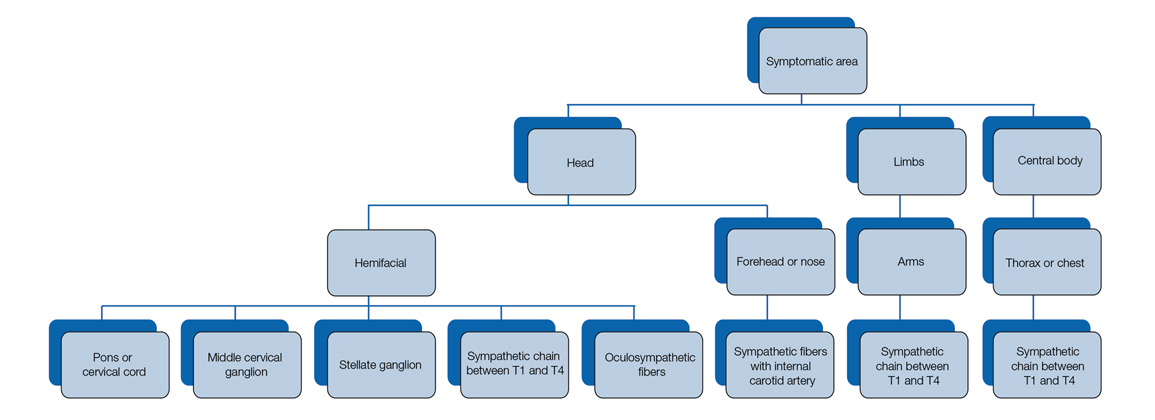

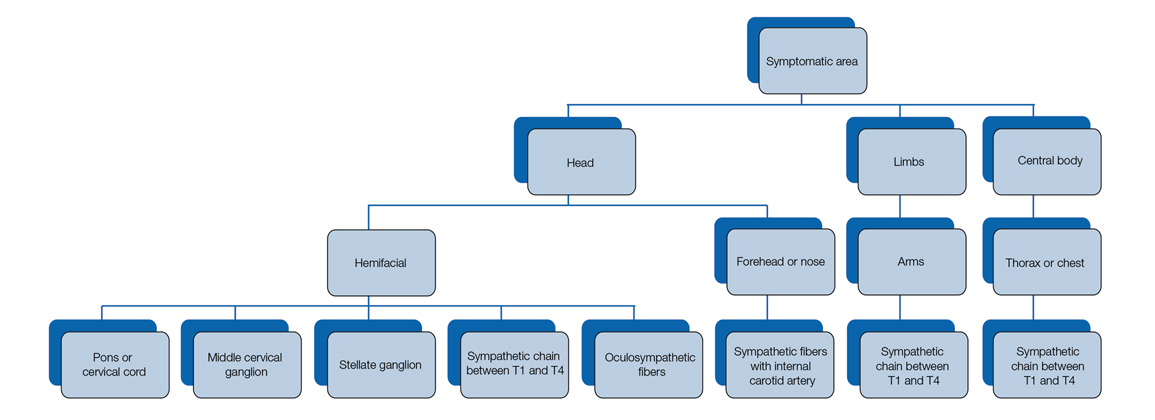

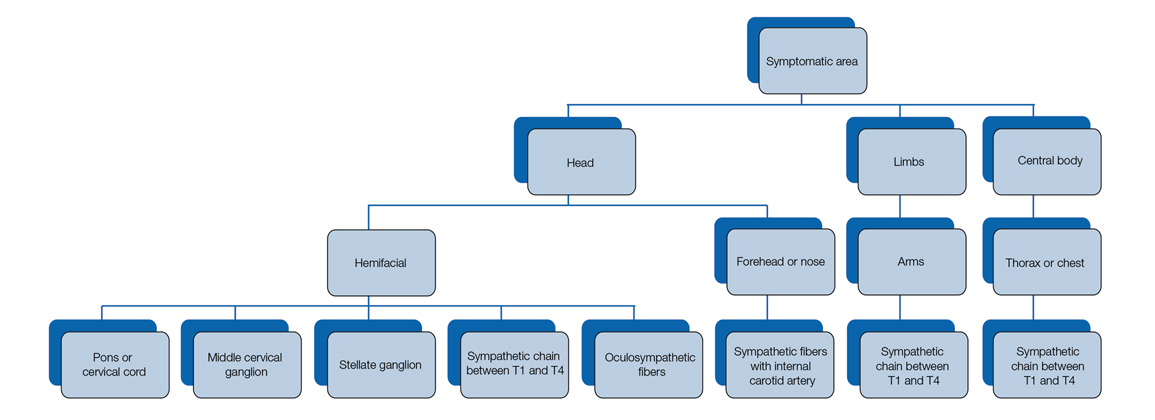

Our patient had a posterior mediastinal ancient schwannoma to the left of the subclavian artery, lateral to the trachea, with ipsilateral anhidrosis of the forehead, cheek, chin, and torso. In the medical literature, the forehead, cheek, and chin are described as being affected in HS when the lesion is located under the bifurcation of the carotid artery.3,5 Most of the sudomotor and vasomotor fibers that innervate the face leave the spinal cord through ventral roots T2-T34 (symptomatic areas are described in Figure 2), which correlates with the hypothesis that HS results from a deficit originating in the third thoracic nerve that is caused by a peripheral lesion affecting sympathetic outflow through the third thoracic root.2 The location of our patient’s lesion supports this claim.

Harlequin syndrome can present simultaneously with ipsilateral Horner, Adie, and Ross syndromes.8 There are varying clinical presentations of Horner syndrome. Some patients with HS show autonomic ocular signs, such as miosis and ptosis, exhibiting Horner syndrome as an additional feature.5 Adie syndrome is characterized by tonic pupils with hyporeflexia and is unilateral in most cases. Ross syndrome is similar to Adie syndrome—including tonic pupils with hyporeflexia—in addition to a finding of segmental anhidrosis; it is bilateral in most cases.4

In some cases, Horner syndrome and HS originate from unilateral pharmaceutical sympathetic denervation (ie, as a consequence of paravertebral spread of local anesthetic to ipsilateral stellate ganglion).9 Facial nonflushing areas in HS typically are identical with anhidrotic areas10; Horner syndrome often is ipsilateral to the affected sympathetic region.11

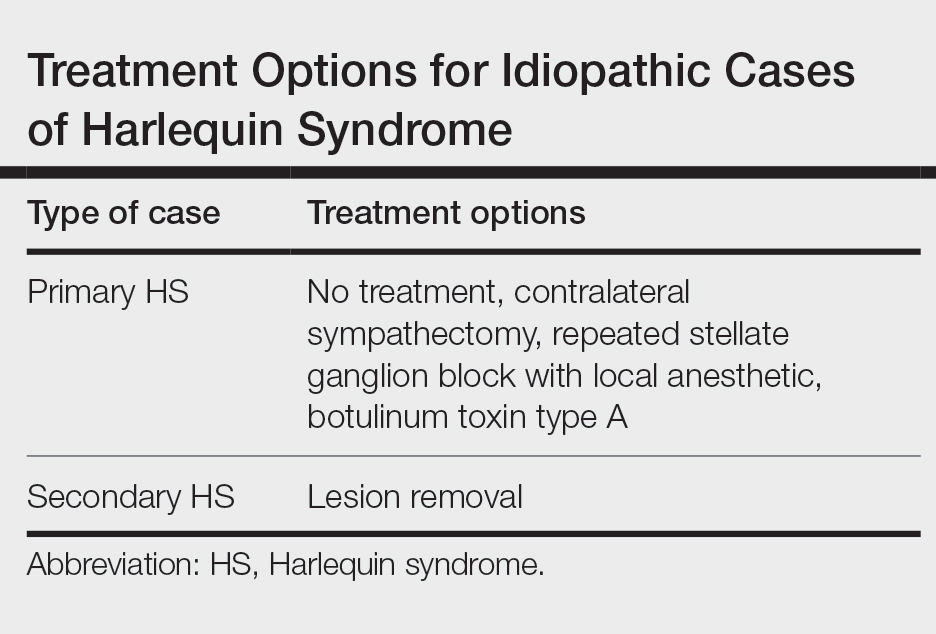

Our patient exhibited secondary HS from a tumor effect; however, an underlying tumor or infarct is absent in many cases. In primary (idiopathic) cases of HS, treatment is not recommended because the syndrome is benign.10,11

If symptoms of HS cause notable social embarrassment, contralateral sympathectomy can be considered.5,12 Repeated stellate ganglion block with a local anesthetic could be a less invasive treatment option.13 When considered on a case-by-case-basis, botulinum toxin type A has been effective as a treatment of compensatory hyperhidrosis on the unaffected side.14

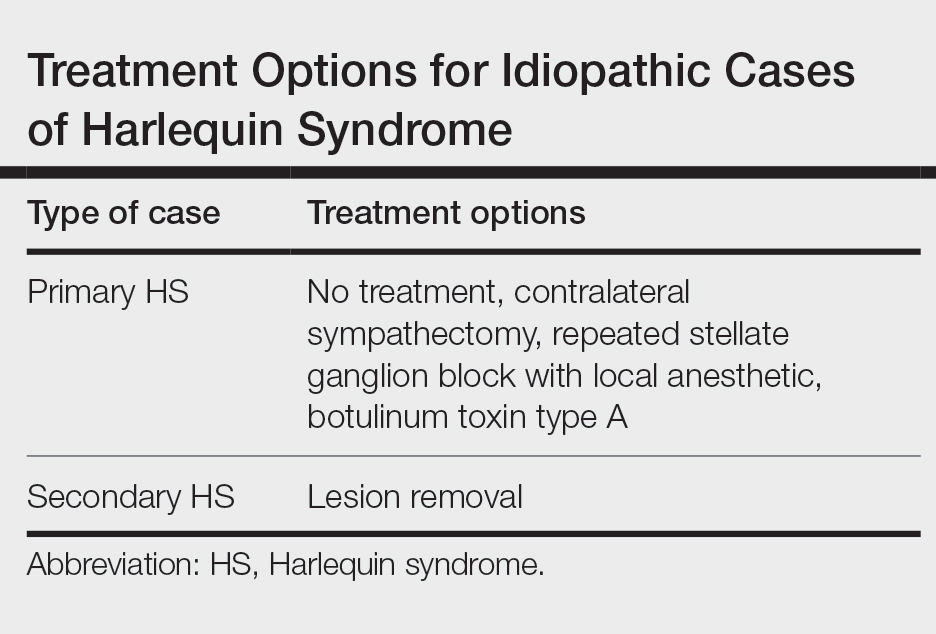

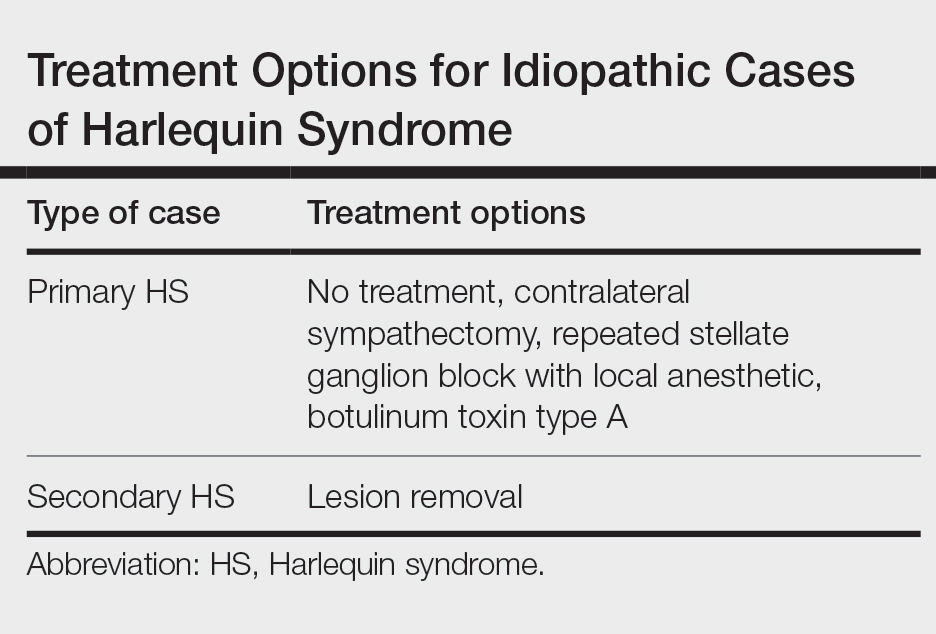

In cases of secondary HS, surgical removal of the lesion may alleviate symptoms, though thoracotomy in our patient to remove the schwannoma did not alleviate anhidrosis. The Table lists treatment options for primary and secondary HS.4,5,11

- Harlequin ichthyosis. MedlinePlus. National Library of Medicine [Internet]. Updated January 7, 2022. Accessed April 5, 2022. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/harlequin-ichthyosis

- Lance JW, Drummond PD, Gandevia SC, et al. Harlequin syndrome: the sudden onset of unilateral flushing and sweating. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 1988;51:635-642. doi:10.1136/jnnp.51.5.635

- Lehman K, Kumar N, Vu Q, et al. Harlequin syndrome in cluster headache. Headache. 2016;56:1053-1054. doi:10.1111/head.12852

- Willaert WIM, Scheltinga MRM, Steenhuisen SF, et al. Harlequin syndrome: two new cases and a management proposal. Acta Neurol Belg. 2009;109:214-220.

- Duddy ME, Baker MR. Images in clinical medicine. Harlequin’s darker side. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:E22. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm067851

- Karam C. Harlequin syndrome in a patient with putative autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy. Auton Neurosci. 2016;194:58-59. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2015.12.004

- Wasner G, Maag R, Ludwig J, et al. Harlequin syndrome—one face of many etiologies. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2005;1:54-59. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0040

- Guilloton L, Demarquay G, Quesnel L, et al. Dysautonomic syndrome of the face with Harlequin sign and syndrome: three new cases and a review of the literature. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2013;169:884-891. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2013.01.628

- Burlacu CL, Buggy DJ. Coexisting Harlequin and Horner syndromes after high thoracic paravertebral anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:822-824. doi:10.1093/bja/aei258

- Morrison DA, Bibby K, Woodruff G. The “Harlequin” sign and congenital Horner’s syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 1997;62:626-628. doi:10.1136/jnnp.62.6.626

- Bremner F, Smith S. Pupillographic findings in 39 consecutive cases of Harlequin syndrome. J Neuroophthalmol. 2008;28:171-177. doi:10.1097/WNO.0b013e318183c885

- Kaur S, Aggarwal P, Jindal N, et al. Harlequin syndrome: a mask of rare dysautonomic syndromes. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21:13030/qt3q39d7mz.

- Reddy H, Fatah S, Gulve A, et al. Novel management of Harlequin syndrome with stellate ganglion block. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:954-956. doi:10.1111/bjd.12561

- ManhRKJV, Spitz M, Vasconcellos LF. Botulinum toxin for treatment of Harlequin syndrome. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;23:112-113. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.11.030

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old man who was otherwise healthy and a long-distance runner presented with the sudden onset of diminished sweating on the left side of the body of 6 weeks’ duration. While training for a marathon, he reported that he perspired only on the right side of the body during runs of 12 to 15 miles; he observed a lack of sweating on the left side of the face, left side of the trunk, left arm, and left leg. This absence of sweating was accompanied by intense flushing on the right side of the face and trunk.

The patient did not take any medications. He reported no history of trauma and exhibited no neurologic deficits. A chest radiograph was negative. Thyroid function testing and a comprehensive metabolic panel were normal. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the chest and abdomen revealed a 4.3-cm soft-tissue mass in the left superior mediastinum that was superior to the aortic arch, posterior to the left subclavian artery in proximity to the sympathetic chain, and lateral to the trachea. The patient was diagnosed with Harlequin syndrome (HS).

Open thoracotomy was performed to remove the lesion. Analysis of the mass showed cystic areas, areas of hemorrhage (Figure 1A), and alternating zones of compact Antoni A spindle cells admixed with areas of less orderly Antoni B spindle cells within a hypocellular stroma (Figure 1B). Individual cells were characterized by eosinophilic cytoplasm and tapered nuclei. The mass appeared to be completely encapsulated. No mitotic figures were seen on multiple slides. The cells stained diffusely positive for S-100 proteins. At 6-month follow-up, the patient reported that he did not notice any return of normal sweating on the left side. However, the right-sided flushing had resolved.

Harlequin syndrome (also called the Harlequin sign) is a rare disorder of the sympathetic nervous system and should not be confused with lethal harlequin-type ichthyosis, an autosomal-recessive congenital disorder in which the affected newborn’s skin is hard and thickened over most of the body.1 Harlequin syndrome usually is characterized by unilateral flushing and sweating that can affect the face, trunk, and extremities.2 Physical stimuli, such as exercising (as in our patient), high body temperature, and the consumption of spicy or pungent food, or an emotional response can unmask or exacerbate symptoms of HS. The syndrome also can present with cluster headache.3 Harlequin syndrome is more common in females (66% of cases).4 Originally, the side of the face marked by increased sweating and flushing was perceived to be the pathologic side; now it is recognized that the anhidrotic side is affected by the causative pathology. The side of the face characterized by flushing might gradually darken as it compensates for lack of thermal regulation on the other side.2,5

Usually, HS is an idiopathic condition associated with localized failure of upper thoracic sympathetic chain ganglia.5 A theory is that HS is part of a spectrum of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy.6 Typically, the syndrome is asymptomatic at rest, but testing can reveal an underlying sympathetic lesion.7 Structural lesions have been reported as a cause of the syndrome,6 similar to our patient.

Disrupted thermoregulatory vasodilation in HS is caused by an ipsilateral lesion of the sympathetic vasodilator neurons that innervate the face. Hemifacial anhidrosis also occurs because sudomotor neurons travel within the same pathways as vasodilator neurons.4

Our patient had a posterior mediastinal ancient schwannoma to the left of the subclavian artery, lateral to the trachea, with ipsilateral anhidrosis of the forehead, cheek, chin, and torso. In the medical literature, the forehead, cheek, and chin are described as being affected in HS when the lesion is located under the bifurcation of the carotid artery.3,5 Most of the sudomotor and vasomotor fibers that innervate the face leave the spinal cord through ventral roots T2-T34 (symptomatic areas are described in Figure 2), which correlates with the hypothesis that HS results from a deficit originating in the third thoracic nerve that is caused by a peripheral lesion affecting sympathetic outflow through the third thoracic root.2 The location of our patient’s lesion supports this claim.

Harlequin syndrome can present simultaneously with ipsilateral Horner, Adie, and Ross syndromes.8 There are varying clinical presentations of Horner syndrome. Some patients with HS show autonomic ocular signs, such as miosis and ptosis, exhibiting Horner syndrome as an additional feature.5 Adie syndrome is characterized by tonic pupils with hyporeflexia and is unilateral in most cases. Ross syndrome is similar to Adie syndrome—including tonic pupils with hyporeflexia—in addition to a finding of segmental anhidrosis; it is bilateral in most cases.4

In some cases, Horner syndrome and HS originate from unilateral pharmaceutical sympathetic denervation (ie, as a consequence of paravertebral spread of local anesthetic to ipsilateral stellate ganglion).9 Facial nonflushing areas in HS typically are identical with anhidrotic areas10; Horner syndrome often is ipsilateral to the affected sympathetic region.11

Our patient exhibited secondary HS from a tumor effect; however, an underlying tumor or infarct is absent in many cases. In primary (idiopathic) cases of HS, treatment is not recommended because the syndrome is benign.10,11

If symptoms of HS cause notable social embarrassment, contralateral sympathectomy can be considered.5,12 Repeated stellate ganglion block with a local anesthetic could be a less invasive treatment option.13 When considered on a case-by-case-basis, botulinum toxin type A has been effective as a treatment of compensatory hyperhidrosis on the unaffected side.14

In cases of secondary HS, surgical removal of the lesion may alleviate symptoms, though thoracotomy in our patient to remove the schwannoma did not alleviate anhidrosis. The Table lists treatment options for primary and secondary HS.4,5,11

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old man who was otherwise healthy and a long-distance runner presented with the sudden onset of diminished sweating on the left side of the body of 6 weeks’ duration. While training for a marathon, he reported that he perspired only on the right side of the body during runs of 12 to 15 miles; he observed a lack of sweating on the left side of the face, left side of the trunk, left arm, and left leg. This absence of sweating was accompanied by intense flushing on the right side of the face and trunk.

The patient did not take any medications. He reported no history of trauma and exhibited no neurologic deficits. A chest radiograph was negative. Thyroid function testing and a comprehensive metabolic panel were normal. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the chest and abdomen revealed a 4.3-cm soft-tissue mass in the left superior mediastinum that was superior to the aortic arch, posterior to the left subclavian artery in proximity to the sympathetic chain, and lateral to the trachea. The patient was diagnosed with Harlequin syndrome (HS).

Open thoracotomy was performed to remove the lesion. Analysis of the mass showed cystic areas, areas of hemorrhage (Figure 1A), and alternating zones of compact Antoni A spindle cells admixed with areas of less orderly Antoni B spindle cells within a hypocellular stroma (Figure 1B). Individual cells were characterized by eosinophilic cytoplasm and tapered nuclei. The mass appeared to be completely encapsulated. No mitotic figures were seen on multiple slides. The cells stained diffusely positive for S-100 proteins. At 6-month follow-up, the patient reported that he did not notice any return of normal sweating on the left side. However, the right-sided flushing had resolved.

Harlequin syndrome (also called the Harlequin sign) is a rare disorder of the sympathetic nervous system and should not be confused with lethal harlequin-type ichthyosis, an autosomal-recessive congenital disorder in which the affected newborn’s skin is hard and thickened over most of the body.1 Harlequin syndrome usually is characterized by unilateral flushing and sweating that can affect the face, trunk, and extremities.2 Physical stimuli, such as exercising (as in our patient), high body temperature, and the consumption of spicy or pungent food, or an emotional response can unmask or exacerbate symptoms of HS. The syndrome also can present with cluster headache.3 Harlequin syndrome is more common in females (66% of cases).4 Originally, the side of the face marked by increased sweating and flushing was perceived to be the pathologic side; now it is recognized that the anhidrotic side is affected by the causative pathology. The side of the face characterized by flushing might gradually darken as it compensates for lack of thermal regulation on the other side.2,5

Usually, HS is an idiopathic condition associated with localized failure of upper thoracic sympathetic chain ganglia.5 A theory is that HS is part of a spectrum of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy.6 Typically, the syndrome is asymptomatic at rest, but testing can reveal an underlying sympathetic lesion.7 Structural lesions have been reported as a cause of the syndrome,6 similar to our patient.

Disrupted thermoregulatory vasodilation in HS is caused by an ipsilateral lesion of the sympathetic vasodilator neurons that innervate the face. Hemifacial anhidrosis also occurs because sudomotor neurons travel within the same pathways as vasodilator neurons.4

Our patient had a posterior mediastinal ancient schwannoma to the left of the subclavian artery, lateral to the trachea, with ipsilateral anhidrosis of the forehead, cheek, chin, and torso. In the medical literature, the forehead, cheek, and chin are described as being affected in HS when the lesion is located under the bifurcation of the carotid artery.3,5 Most of the sudomotor and vasomotor fibers that innervate the face leave the spinal cord through ventral roots T2-T34 (symptomatic areas are described in Figure 2), which correlates with the hypothesis that HS results from a deficit originating in the third thoracic nerve that is caused by a peripheral lesion affecting sympathetic outflow through the third thoracic root.2 The location of our patient’s lesion supports this claim.

Harlequin syndrome can present simultaneously with ipsilateral Horner, Adie, and Ross syndromes.8 There are varying clinical presentations of Horner syndrome. Some patients with HS show autonomic ocular signs, such as miosis and ptosis, exhibiting Horner syndrome as an additional feature.5 Adie syndrome is characterized by tonic pupils with hyporeflexia and is unilateral in most cases. Ross syndrome is similar to Adie syndrome—including tonic pupils with hyporeflexia—in addition to a finding of segmental anhidrosis; it is bilateral in most cases.4

In some cases, Horner syndrome and HS originate from unilateral pharmaceutical sympathetic denervation (ie, as a consequence of paravertebral spread of local anesthetic to ipsilateral stellate ganglion).9 Facial nonflushing areas in HS typically are identical with anhidrotic areas10; Horner syndrome often is ipsilateral to the affected sympathetic region.11

Our patient exhibited secondary HS from a tumor effect; however, an underlying tumor or infarct is absent in many cases. In primary (idiopathic) cases of HS, treatment is not recommended because the syndrome is benign.10,11

If symptoms of HS cause notable social embarrassment, contralateral sympathectomy can be considered.5,12 Repeated stellate ganglion block with a local anesthetic could be a less invasive treatment option.13 When considered on a case-by-case-basis, botulinum toxin type A has been effective as a treatment of compensatory hyperhidrosis on the unaffected side.14

In cases of secondary HS, surgical removal of the lesion may alleviate symptoms, though thoracotomy in our patient to remove the schwannoma did not alleviate anhidrosis. The Table lists treatment options for primary and secondary HS.4,5,11

- Harlequin ichthyosis. MedlinePlus. National Library of Medicine [Internet]. Updated January 7, 2022. Accessed April 5, 2022. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/harlequin-ichthyosis

- Lance JW, Drummond PD, Gandevia SC, et al. Harlequin syndrome: the sudden onset of unilateral flushing and sweating. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 1988;51:635-642. doi:10.1136/jnnp.51.5.635

- Lehman K, Kumar N, Vu Q, et al. Harlequin syndrome in cluster headache. Headache. 2016;56:1053-1054. doi:10.1111/head.12852

- Willaert WIM, Scheltinga MRM, Steenhuisen SF, et al. Harlequin syndrome: two new cases and a management proposal. Acta Neurol Belg. 2009;109:214-220.

- Duddy ME, Baker MR. Images in clinical medicine. Harlequin’s darker side. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:E22. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm067851

- Karam C. Harlequin syndrome in a patient with putative autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy. Auton Neurosci. 2016;194:58-59. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2015.12.004

- Wasner G, Maag R, Ludwig J, et al. Harlequin syndrome—one face of many etiologies. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2005;1:54-59. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0040

- Guilloton L, Demarquay G, Quesnel L, et al. Dysautonomic syndrome of the face with Harlequin sign and syndrome: three new cases and a review of the literature. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2013;169:884-891. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2013.01.628

- Burlacu CL, Buggy DJ. Coexisting Harlequin and Horner syndromes after high thoracic paravertebral anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:822-824. doi:10.1093/bja/aei258

- Morrison DA, Bibby K, Woodruff G. The “Harlequin” sign and congenital Horner’s syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 1997;62:626-628. doi:10.1136/jnnp.62.6.626

- Bremner F, Smith S. Pupillographic findings in 39 consecutive cases of Harlequin syndrome. J Neuroophthalmol. 2008;28:171-177. doi:10.1097/WNO.0b013e318183c885

- Kaur S, Aggarwal P, Jindal N, et al. Harlequin syndrome: a mask of rare dysautonomic syndromes. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21:13030/qt3q39d7mz.

- Reddy H, Fatah S, Gulve A, et al. Novel management of Harlequin syndrome with stellate ganglion block. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:954-956. doi:10.1111/bjd.12561

- ManhRKJV, Spitz M, Vasconcellos LF. Botulinum toxin for treatment of Harlequin syndrome. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;23:112-113. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.11.030

- Harlequin ichthyosis. MedlinePlus. National Library of Medicine [Internet]. Updated January 7, 2022. Accessed April 5, 2022. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/harlequin-ichthyosis

- Lance JW, Drummond PD, Gandevia SC, et al. Harlequin syndrome: the sudden onset of unilateral flushing and sweating. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 1988;51:635-642. doi:10.1136/jnnp.51.5.635

- Lehman K, Kumar N, Vu Q, et al. Harlequin syndrome in cluster headache. Headache. 2016;56:1053-1054. doi:10.1111/head.12852

- Willaert WIM, Scheltinga MRM, Steenhuisen SF, et al. Harlequin syndrome: two new cases and a management proposal. Acta Neurol Belg. 2009;109:214-220.

- Duddy ME, Baker MR. Images in clinical medicine. Harlequin’s darker side. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:E22. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm067851

- Karam C. Harlequin syndrome in a patient with putative autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy. Auton Neurosci. 2016;194:58-59. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2015.12.004

- Wasner G, Maag R, Ludwig J, et al. Harlequin syndrome—one face of many etiologies. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2005;1:54-59. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0040

- Guilloton L, Demarquay G, Quesnel L, et al. Dysautonomic syndrome of the face with Harlequin sign and syndrome: three new cases and a review of the literature. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2013;169:884-891. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2013.01.628

- Burlacu CL, Buggy DJ. Coexisting Harlequin and Horner syndromes after high thoracic paravertebral anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:822-824. doi:10.1093/bja/aei258

- Morrison DA, Bibby K, Woodruff G. The “Harlequin” sign and congenital Horner’s syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 1997;62:626-628. doi:10.1136/jnnp.62.6.626

- Bremner F, Smith S. Pupillographic findings in 39 consecutive cases of Harlequin syndrome. J Neuroophthalmol. 2008;28:171-177. doi:10.1097/WNO.0b013e318183c885

- Kaur S, Aggarwal P, Jindal N, et al. Harlequin syndrome: a mask of rare dysautonomic syndromes. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21:13030/qt3q39d7mz.

- Reddy H, Fatah S, Gulve A, et al. Novel management of Harlequin syndrome with stellate ganglion block. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:954-956. doi:10.1111/bjd.12561

- ManhRKJV, Spitz M, Vasconcellos LF. Botulinum toxin for treatment of Harlequin syndrome. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;23:112-113. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.11.030

Practice Points

- Harlequin syndrome is a rare disorder of the sympathetic nervous system that is characterized by unilateral flushing and sweating that can affect the face, trunk, and extremities.

- Secondary causes can be from schwannomas in the cervical chain ganglion.

Post-LT HCC recurrence unaffected by donor sex

Key clinical point: Donor sex did not affect post-liver transplantation (LT) recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and need not be considered during donor selection or organ allocation.

Major finding: After propensity score matching, the female donor (F-D) and male donor (M-D) groups showed comparable 5-year overall recurrence rates (15% vs. 14%; P = .63) and graft recurrence rates (5% vs. 5%; P = .94). Donor sex was not identified as a significant risk factor for HCC recurrence by either univariate or multivariate analysis.

Study details: This study evaluated 1118 patients with HCC who underwent LT receiving a liver graft from the F-D (n = 446) or M-D (n = 672) groups.

Disclosures: The authors did not declare any funding source or conflicts of interest.

Source: Taura K et al. No impact of donor sex on the recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2022 (Mar 13). Doi: 10.1002/jhbp.1134

Key clinical point: Donor sex did not affect post-liver transplantation (LT) recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and need not be considered during donor selection or organ allocation.

Major finding: After propensity score matching, the female donor (F-D) and male donor (M-D) groups showed comparable 5-year overall recurrence rates (15% vs. 14%; P = .63) and graft recurrence rates (5% vs. 5%; P = .94). Donor sex was not identified as a significant risk factor for HCC recurrence by either univariate or multivariate analysis.

Study details: This study evaluated 1118 patients with HCC who underwent LT receiving a liver graft from the F-D (n = 446) or M-D (n = 672) groups.

Disclosures: The authors did not declare any funding source or conflicts of interest.

Source: Taura K et al. No impact of donor sex on the recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2022 (Mar 13). Doi: 10.1002/jhbp.1134

Key clinical point: Donor sex did not affect post-liver transplantation (LT) recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and need not be considered during donor selection or organ allocation.

Major finding: After propensity score matching, the female donor (F-D) and male donor (M-D) groups showed comparable 5-year overall recurrence rates (15% vs. 14%; P = .63) and graft recurrence rates (5% vs. 5%; P = .94). Donor sex was not identified as a significant risk factor for HCC recurrence by either univariate or multivariate analysis.

Study details: This study evaluated 1118 patients with HCC who underwent LT receiving a liver graft from the F-D (n = 446) or M-D (n = 672) groups.

Disclosures: The authors did not declare any funding source or conflicts of interest.

Source: Taura K et al. No impact of donor sex on the recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2022 (Mar 13). Doi: 10.1002/jhbp.1134

TACE vs. LR: Better prognosis in HCC with bile duct tumor thrombus?

Key clinical point: When technically feasible, surgical liver resection (LR) should be recommended to patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with bile duct tumor thrombus (BDTT) over transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) because it provides better prognosis.

Major finding: After propensity score matching, patients who underwent LR vs. TACE showed a significantly longer median overall survival (20.0 vs. 11.0 months; P < .001) and disease-free survival (7.0 vs. 2.0 months; P = .007).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective study including 145 patients with HCC with BDTT who underwent LR (n = 105) or TACE (n = 40).

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Liu Z-H et al. Prognostic comparison between liver resection and transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma patients with bile duct tumor thrombus: A propensity-score matching analysis. Front Oncol. 2022;12:835559 (Mar 15). Doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.835559

Key clinical point: When technically feasible, surgical liver resection (LR) should be recommended to patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with bile duct tumor thrombus (BDTT) over transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) because it provides better prognosis.

Major finding: After propensity score matching, patients who underwent LR vs. TACE showed a significantly longer median overall survival (20.0 vs. 11.0 months; P < .001) and disease-free survival (7.0 vs. 2.0 months; P = .007).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective study including 145 patients with HCC with BDTT who underwent LR (n = 105) or TACE (n = 40).

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Liu Z-H et al. Prognostic comparison between liver resection and transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma patients with bile duct tumor thrombus: A propensity-score matching analysis. Front Oncol. 2022;12:835559 (Mar 15). Doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.835559

Key clinical point: When technically feasible, surgical liver resection (LR) should be recommended to patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with bile duct tumor thrombus (BDTT) over transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) because it provides better prognosis.

Major finding: After propensity score matching, patients who underwent LR vs. TACE showed a significantly longer median overall survival (20.0 vs. 11.0 months; P < .001) and disease-free survival (7.0 vs. 2.0 months; P = .007).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective study including 145 patients with HCC with BDTT who underwent LR (n = 105) or TACE (n = 40).

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Liu Z-H et al. Prognostic comparison between liver resection and transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma patients with bile duct tumor thrombus: A propensity-score matching analysis. Front Oncol. 2022;12:835559 (Mar 15). Doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.835559

TACE is safe and effective in elderly patients with intermediate HCC

Key clinical point: Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) demonstrated a comparable safety profile between elderly and younger patients with intermediate hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), with its efficacy remaining uncompromised with advancing age.

Major finding: The occurrence rate of at least one serious adverse event was similar between elderly and younger patients (20.5% vs. 21.3%; P = .87). The objective tumor response rate did not decline in the elderly patients (89.5%) compared with that in younger patients (78.7%).

Study details: The data come from a retrospective study including 271 patients aged >18 years with intermediate HCC who underwent the first session of TACE, of which 88 were elderly patients (≥70 years old).

Disclosures: The study received no financial support. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Roth GS et al. Safety and efficacy of transarterial chemoembolization in elderly patients with intermediate hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers. 2022;14(7):1634 (Mar 23). Doi: 10.3390/cancers14071634

Key clinical point: Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) demonstrated a comparable safety profile between elderly and younger patients with intermediate hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), with its efficacy remaining uncompromised with advancing age.

Major finding: The occurrence rate of at least one serious adverse event was similar between elderly and younger patients (20.5% vs. 21.3%; P = .87). The objective tumor response rate did not decline in the elderly patients (89.5%) compared with that in younger patients (78.7%).

Study details: The data come from a retrospective study including 271 patients aged >18 years with intermediate HCC who underwent the first session of TACE, of which 88 were elderly patients (≥70 years old).

Disclosures: The study received no financial support. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Roth GS et al. Safety and efficacy of transarterial chemoembolization in elderly patients with intermediate hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers. 2022;14(7):1634 (Mar 23). Doi: 10.3390/cancers14071634

Key clinical point: Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) demonstrated a comparable safety profile between elderly and younger patients with intermediate hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), with its efficacy remaining uncompromised with advancing age.

Major finding: The occurrence rate of at least one serious adverse event was similar between elderly and younger patients (20.5% vs. 21.3%; P = .87). The objective tumor response rate did not decline in the elderly patients (89.5%) compared with that in younger patients (78.7%).

Study details: The data come from a retrospective study including 271 patients aged >18 years with intermediate HCC who underwent the first session of TACE, of which 88 were elderly patients (≥70 years old).

Disclosures: The study received no financial support. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Roth GS et al. Safety and efficacy of transarterial chemoembolization in elderly patients with intermediate hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers. 2022;14(7):1634 (Mar 23). Doi: 10.3390/cancers14071634

Tenofovir vs. entecavir: Better therapeutic in HBV-related HCC after radiofrequency ablation

Key clinical point: In patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who had undergone radiofrequency ablation (RFA), tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) performed better at protecting liver function and reducing HBV DNA loads than entecavir (ETV), without significant difference in recurrence or overall survival.

Major finding: Patients receiving TDF vs. ETV showed significantly faster serum HBV DNA reduction (2.75 vs. 9.13 months; P = .015) and a higher stabilization/improvement rate of the albumin-bilirubin grade (64% vs. 41%; P < .001), but similar 5-year recurrence (40.3% vs. 40.8%; P = .35) and overall survival (93.5% vs. 96.9%; P = .12) rates.

Study details: This single-center retrospective cohort study propensity score-matched patients receiving ETV (n = 130) with those receiving TDF (n = 77) for chronic HBV infection after undergoing RFA as a curative treatment for HCC.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center physician scientist funding. No conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Hu Z et al. Tenofovir vs. entecavir on outcomes of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma after radiofrequency ablation. Viruses. 2022;14(4):656 (Mar 22). Doi: 10.3390/v14040656

Key clinical point: In patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who had undergone radiofrequency ablation (RFA), tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) performed better at protecting liver function and reducing HBV DNA loads than entecavir (ETV), without significant difference in recurrence or overall survival.

Major finding: Patients receiving TDF vs. ETV showed significantly faster serum HBV DNA reduction (2.75 vs. 9.13 months; P = .015) and a higher stabilization/improvement rate of the albumin-bilirubin grade (64% vs. 41%; P < .001), but similar 5-year recurrence (40.3% vs. 40.8%; P = .35) and overall survival (93.5% vs. 96.9%; P = .12) rates.

Study details: This single-center retrospective cohort study propensity score-matched patients receiving ETV (n = 130) with those receiving TDF (n = 77) for chronic HBV infection after undergoing RFA as a curative treatment for HCC.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center physician scientist funding. No conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Hu Z et al. Tenofovir vs. entecavir on outcomes of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma after radiofrequency ablation. Viruses. 2022;14(4):656 (Mar 22). Doi: 10.3390/v14040656

Key clinical point: In patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who had undergone radiofrequency ablation (RFA), tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) performed better at protecting liver function and reducing HBV DNA loads than entecavir (ETV), without significant difference in recurrence or overall survival.

Major finding: Patients receiving TDF vs. ETV showed significantly faster serum HBV DNA reduction (2.75 vs. 9.13 months; P = .015) and a higher stabilization/improvement rate of the albumin-bilirubin grade (64% vs. 41%; P < .001), but similar 5-year recurrence (40.3% vs. 40.8%; P = .35) and overall survival (93.5% vs. 96.9%; P = .12) rates.

Study details: This single-center retrospective cohort study propensity score-matched patients receiving ETV (n = 130) with those receiving TDF (n = 77) for chronic HBV infection after undergoing RFA as a curative treatment for HCC.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center physician scientist funding. No conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Hu Z et al. Tenofovir vs. entecavir on outcomes of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma after radiofrequency ablation. Viruses. 2022;14(4):656 (Mar 22). Doi: 10.3390/v14040656

Unresectable HCC: Suboptimal response to lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab beyond the first-line setting

Key clinical point: Although lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab exhibits similar tolerability between systemic therapy-naive and -experienced patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC), the progression-free survival (PFS), objective response rate (ORR), and disease control rate (DCR) may be compromised in patients with prior systemic therapy.

Major finding: After a 9.3-month median follow-up, therapy-naive vs. -experienced patients showed numerically greater median PFS (9.2 vs. 4.9 months; P = .092), ORR (34.1% vs. 18.5%; P = .157), and DCR (84.1% vs. 70.4%; P = .169), but similar incidence rates of treatment-emergent adverse events (96.4% vs. 97.7%).

Study details: Findings are from a prospective study that enrolled 71 patients with uHCC who were systemic therapy-naive (n = 44) or -experienced (n =2 7) and received lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab.

Disclosures: The study received financial support from Taipei Veteran General Hospital, Taiwan. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wu C-J et al. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab for systemic therapy-naïve and -experienced unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2022 (Mar 28). Doi: 10.1007/s00262-022-03185-6

Key clinical point: Although lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab exhibits similar tolerability between systemic therapy-naive and -experienced patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC), the progression-free survival (PFS), objective response rate (ORR), and disease control rate (DCR) may be compromised in patients with prior systemic therapy.

Major finding: After a 9.3-month median follow-up, therapy-naive vs. -experienced patients showed numerically greater median PFS (9.2 vs. 4.9 months; P = .092), ORR (34.1% vs. 18.5%; P = .157), and DCR (84.1% vs. 70.4%; P = .169), but similar incidence rates of treatment-emergent adverse events (96.4% vs. 97.7%).

Study details: Findings are from a prospective study that enrolled 71 patients with uHCC who were systemic therapy-naive (n = 44) or -experienced (n =2 7) and received lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab.

Disclosures: The study received financial support from Taipei Veteran General Hospital, Taiwan. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wu C-J et al. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab for systemic therapy-naïve and -experienced unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2022 (Mar 28). Doi: 10.1007/s00262-022-03185-6

Key clinical point: Although lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab exhibits similar tolerability between systemic therapy-naive and -experienced patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC), the progression-free survival (PFS), objective response rate (ORR), and disease control rate (DCR) may be compromised in patients with prior systemic therapy.

Major finding: After a 9.3-month median follow-up, therapy-naive vs. -experienced patients showed numerically greater median PFS (9.2 vs. 4.9 months; P = .092), ORR (34.1% vs. 18.5%; P = .157), and DCR (84.1% vs. 70.4%; P = .169), but similar incidence rates of treatment-emergent adverse events (96.4% vs. 97.7%).

Study details: Findings are from a prospective study that enrolled 71 patients with uHCC who were systemic therapy-naive (n = 44) or -experienced (n =2 7) and received lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab.

Disclosures: The study received financial support from Taipei Veteran General Hospital, Taiwan. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wu C-J et al. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab for systemic therapy-naïve and -experienced unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2022 (Mar 28). Doi: 10.1007/s00262-022-03185-6

Preliminary results call for evaluating AtezoBev in unresectable HCC beyond the CP-A criteria

Key clinical point: Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab (AtezoBev) is an effective therapeutic option for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC) in routine clinical practice and is safe even in patients with Child-Pugh (CP)-B grade liver function.

Major finding: After a 9-month median follow-up, median overall survival was 14.9 months (95% CI 13.6-16.3 months) and median progression-free survival was 6.8 months (95% CI 5.2-8.5 months). Tolerability was similar across CP classes, with comparable bevacizumab-related (CP-A, 48%; CP-B, 46%) and atezolizumab-related (CP-A, 53%; CP-B, 40%) adverse event rates of any grade.

Study details: This was a multicenter retrospective study that included 202 adult patients with uHCC and CP-A (76%) or CP-B (24%) cirrhosis who received AtezoBev as the first-line systemic treatment.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institute of Health Research Imperial Biomedical Research Centre, among others. Some authors declared serving as consultants or advisors for or receiving advisory board honoraria, lecture/speaker fees, research grants, or travel/accommodation expenses from various sources.

Source: D'Alessio A et al. Preliminary evidence of safety and tolerability of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and Child-Pugh A and B cirrhosis: A real-world study. Hepatology. 2022 (Mar 21). Doi: 10.1002/hep.32468

Key clinical point: Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab (AtezoBev) is an effective therapeutic option for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC) in routine clinical practice and is safe even in patients with Child-Pugh (CP)-B grade liver function.

Major finding: After a 9-month median follow-up, median overall survival was 14.9 months (95% CI 13.6-16.3 months) and median progression-free survival was 6.8 months (95% CI 5.2-8.5 months). Tolerability was similar across CP classes, with comparable bevacizumab-related (CP-A, 48%; CP-B, 46%) and atezolizumab-related (CP-A, 53%; CP-B, 40%) adverse event rates of any grade.

Study details: This was a multicenter retrospective study that included 202 adult patients with uHCC and CP-A (76%) or CP-B (24%) cirrhosis who received AtezoBev as the first-line systemic treatment.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institute of Health Research Imperial Biomedical Research Centre, among others. Some authors declared serving as consultants or advisors for or receiving advisory board honoraria, lecture/speaker fees, research grants, or travel/accommodation expenses from various sources.

Source: D'Alessio A et al. Preliminary evidence of safety and tolerability of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and Child-Pugh A and B cirrhosis: A real-world study. Hepatology. 2022 (Mar 21). Doi: 10.1002/hep.32468

Key clinical point: Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab (AtezoBev) is an effective therapeutic option for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC) in routine clinical practice and is safe even in patients with Child-Pugh (CP)-B grade liver function.

Major finding: After a 9-month median follow-up, median overall survival was 14.9 months (95% CI 13.6-16.3 months) and median progression-free survival was 6.8 months (95% CI 5.2-8.5 months). Tolerability was similar across CP classes, with comparable bevacizumab-related (CP-A, 48%; CP-B, 46%) and atezolizumab-related (CP-A, 53%; CP-B, 40%) adverse event rates of any grade.

Study details: This was a multicenter retrospective study that included 202 adult patients with uHCC and CP-A (76%) or CP-B (24%) cirrhosis who received AtezoBev as the first-line systemic treatment.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institute of Health Research Imperial Biomedical Research Centre, among others. Some authors declared serving as consultants or advisors for or receiving advisory board honoraria, lecture/speaker fees, research grants, or travel/accommodation expenses from various sources.

Source: D'Alessio A et al. Preliminary evidence of safety and tolerability of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and Child-Pugh A and B cirrhosis: A real-world study. Hepatology. 2022 (Mar 21). Doi: 10.1002/hep.32468

Adjuvant SBRT after marginal resection: A safe therapeutic option for MVI-positive HCC

Key clinical point: Postoperative adjuvant stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) on suboptimal resection margin safely and effectively improves disease-free survival (DFS) and prevents local recurrence in microvascular invasion (MVI)-positive hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: SBRT vs. surgery alone led to significantly higher 1-year (92.1% vs. 76.3%) and 5-year (56.1% vs. 26.3%) DFS rates (P = .005) and similar local recurrence (P = .236) rates. No grade ≥3 adverse events were noted.

Study details: This randomized controlled trial included 76 adult patients with MVI-positive HCC who underwent marginal resection and were randomly assigned to receive postoperative adjuvant SBRT or surgery alone.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Clinical Science and Technology Innovation Project of Shenkang Hospital Development Center, Shanghai Jiading District Fund, and Shanghai Municipal Health Commission Program, China. No conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Shi C et al. Adjuvant stereotactic body radiotherapy after marginal resection for hepatocellular carcinoma with microvascular invasion: A randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer. 2022;166:176-184 (Mar 16). Doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.02.012

Key clinical point: Postoperative adjuvant stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) on suboptimal resection margin safely and effectively improves disease-free survival (DFS) and prevents local recurrence in microvascular invasion (MVI)-positive hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: SBRT vs. surgery alone led to significantly higher 1-year (92.1% vs. 76.3%) and 5-year (56.1% vs. 26.3%) DFS rates (P = .005) and similar local recurrence (P = .236) rates. No grade ≥3 adverse events were noted.

Study details: This randomized controlled trial included 76 adult patients with MVI-positive HCC who underwent marginal resection and were randomly assigned to receive postoperative adjuvant SBRT or surgery alone.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Clinical Science and Technology Innovation Project of Shenkang Hospital Development Center, Shanghai Jiading District Fund, and Shanghai Municipal Health Commission Program, China. No conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Shi C et al. Adjuvant stereotactic body radiotherapy after marginal resection for hepatocellular carcinoma with microvascular invasion: A randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer. 2022;166:176-184 (Mar 16). Doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.02.012

Key clinical point: Postoperative adjuvant stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) on suboptimal resection margin safely and effectively improves disease-free survival (DFS) and prevents local recurrence in microvascular invasion (MVI)-positive hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: SBRT vs. surgery alone led to significantly higher 1-year (92.1% vs. 76.3%) and 5-year (56.1% vs. 26.3%) DFS rates (P = .005) and similar local recurrence (P = .236) rates. No grade ≥3 adverse events were noted.

Study details: This randomized controlled trial included 76 adult patients with MVI-positive HCC who underwent marginal resection and were randomly assigned to receive postoperative adjuvant SBRT or surgery alone.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Clinical Science and Technology Innovation Project of Shenkang Hospital Development Center, Shanghai Jiading District Fund, and Shanghai Municipal Health Commission Program, China. No conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Shi C et al. Adjuvant stereotactic body radiotherapy after marginal resection for hepatocellular carcinoma with microvascular invasion: A randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer. 2022;166:176-184 (Mar 16). Doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.02.012

Surveillance for HCC occurrence in NAFLD: Why concentrate our efforts?

Key clinical point: Compared with other liver disease etiologies, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) was associated with lower hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) surveillance receipt and early-stage detection, thus calling for interventions for increased surveillance implementation and improved prognosis of patients with NAFLD-related HCC.

Major finding: NAFLD vs. hepatitis C virus etiology was associated with a lower likelihood of consistent or inconsistent HCC surveillance receipt (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.37; 95% CI 0.32-0.44) and detection of early-stage HCC (aOR 0.49; 95% CI 0.40-0.60) and worse overall survival (adjusted hazard ratio 1.20; 95% CI 1.09-1.32).

Study details: This was a population-based cohort study of US Medicare beneficiaries including 5098 patients aged ≥68 years with HCC, which was attributable to NAFLD in most patients (35.6%).

Disclosures: The study was funded by the American College of Gastroenterology, US Department of Defense, and US National Institute of Health. Some authors reported being consultants, advisory board members, or shareholders of and receiving research grants from various organizations.

Source: Karim MA et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease–associated hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 (Mar 17). Doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.010

Key clinical point: Compared with other liver disease etiologies, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) was associated with lower hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) surveillance receipt and early-stage detection, thus calling for interventions for increased surveillance implementation and improved prognosis of patients with NAFLD-related HCC.

Major finding: NAFLD vs. hepatitis C virus etiology was associated with a lower likelihood of consistent or inconsistent HCC surveillance receipt (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.37; 95% CI 0.32-0.44) and detection of early-stage HCC (aOR 0.49; 95% CI 0.40-0.60) and worse overall survival (adjusted hazard ratio 1.20; 95% CI 1.09-1.32).

Study details: This was a population-based cohort study of US Medicare beneficiaries including 5098 patients aged ≥68 years with HCC, which was attributable to NAFLD in most patients (35.6%).

Disclosures: The study was funded by the American College of Gastroenterology, US Department of Defense, and US National Institute of Health. Some authors reported being consultants, advisory board members, or shareholders of and receiving research grants from various organizations.

Source: Karim MA et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease–associated hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 (Mar 17). Doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.010

Key clinical point: Compared with other liver disease etiologies, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) was associated with lower hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) surveillance receipt and early-stage detection, thus calling for interventions for increased surveillance implementation and improved prognosis of patients with NAFLD-related HCC.

Major finding: NAFLD vs. hepatitis C virus etiology was associated with a lower likelihood of consistent or inconsistent HCC surveillance receipt (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.37; 95% CI 0.32-0.44) and detection of early-stage HCC (aOR 0.49; 95% CI 0.40-0.60) and worse overall survival (adjusted hazard ratio 1.20; 95% CI 1.09-1.32).

Study details: This was a population-based cohort study of US Medicare beneficiaries including 5098 patients aged ≥68 years with HCC, which was attributable to NAFLD in most patients (35.6%).

Disclosures: The study was funded by the American College of Gastroenterology, US Department of Defense, and US National Institute of Health. Some authors reported being consultants, advisory board members, or shareholders of and receiving research grants from various organizations.

Source: Karim MA et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease–associated hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 (Mar 17). Doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.010