User login

What's your diagnosis?

Answer: Colonic Malakoplakia.

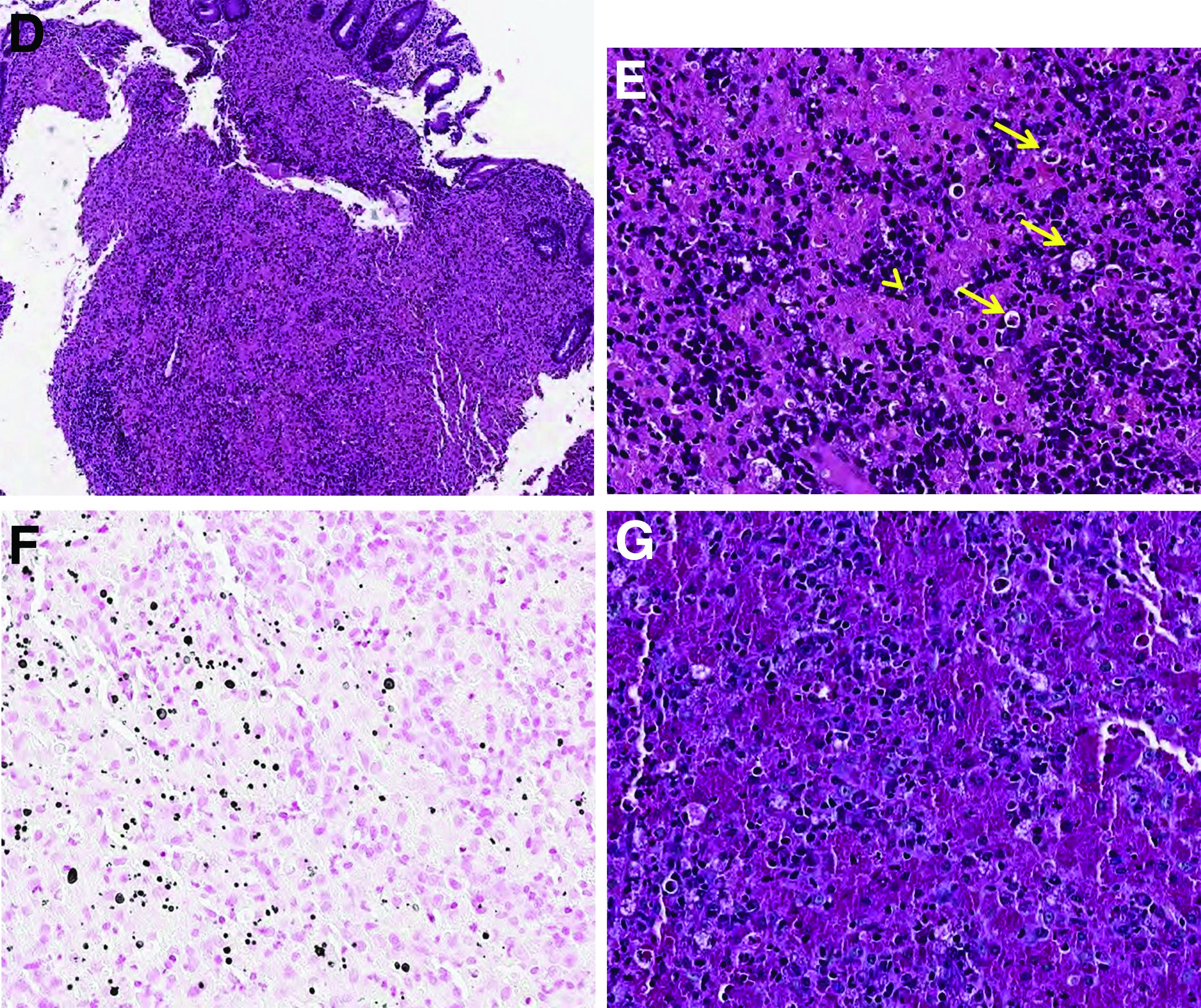

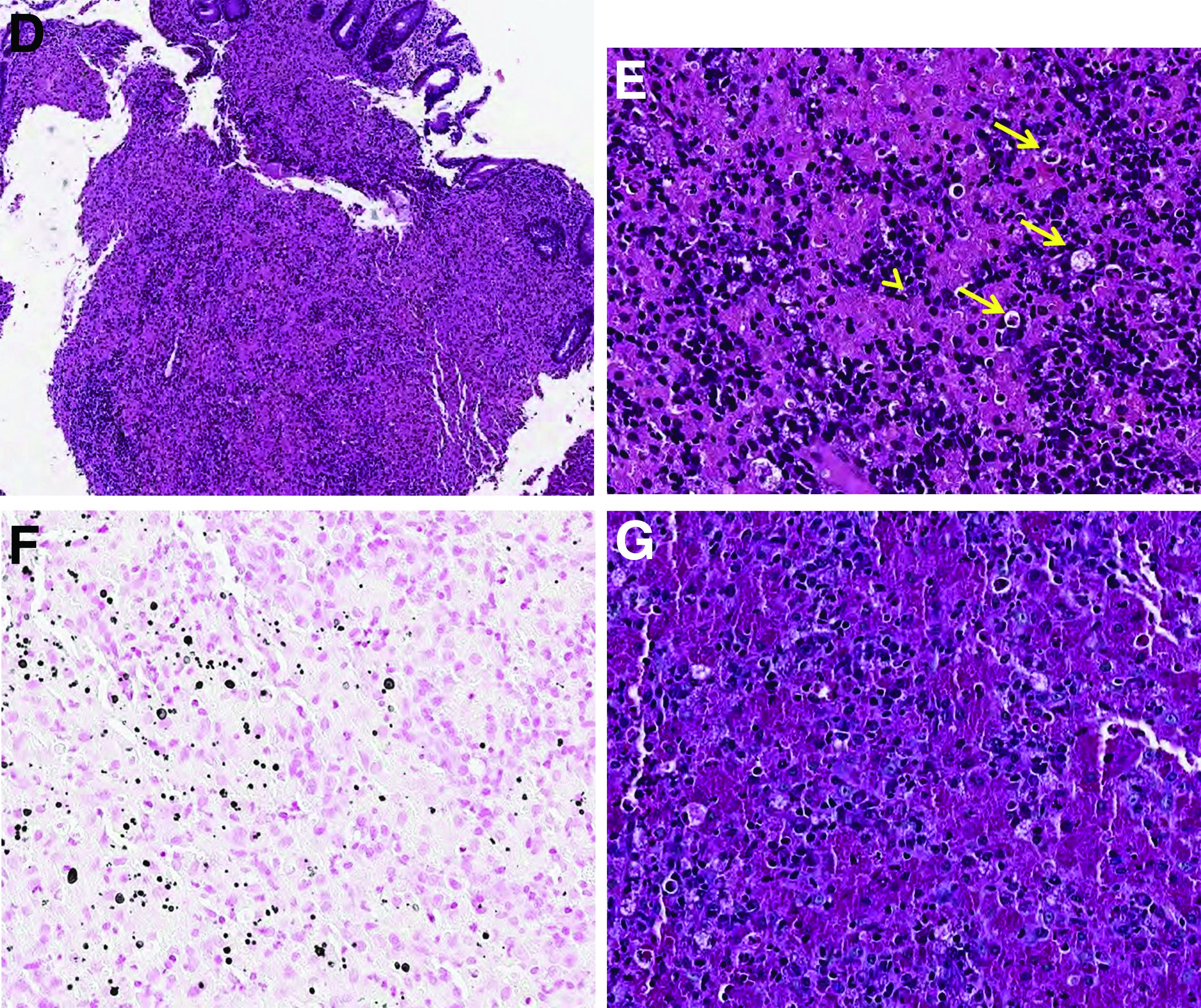

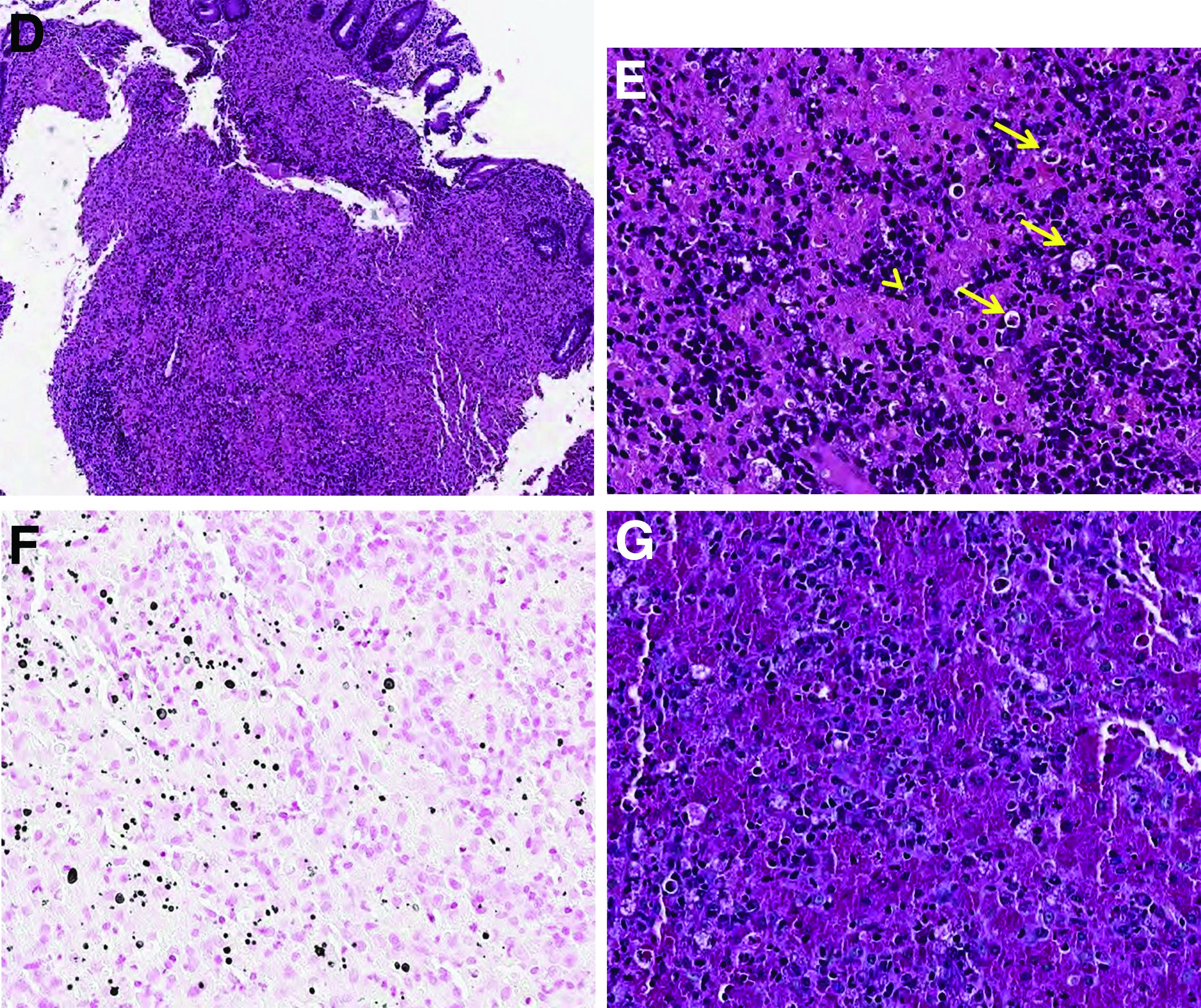

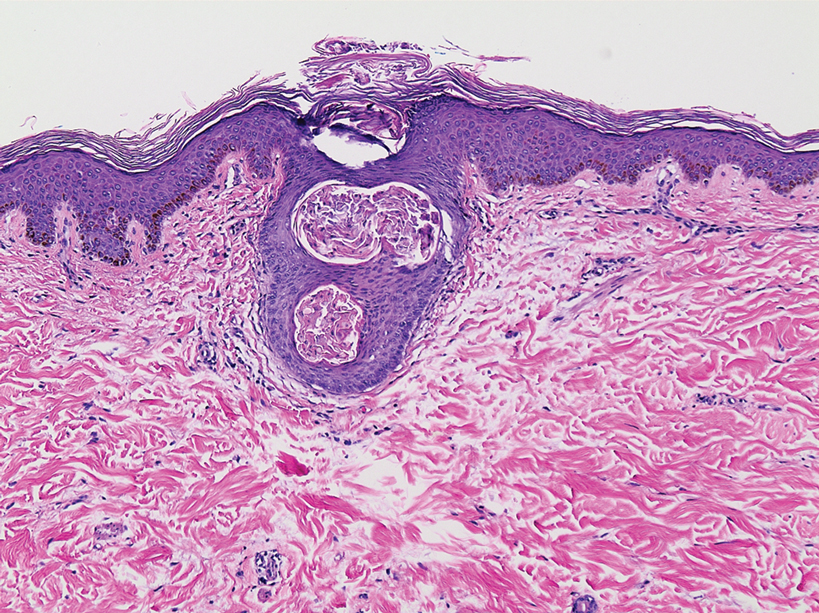

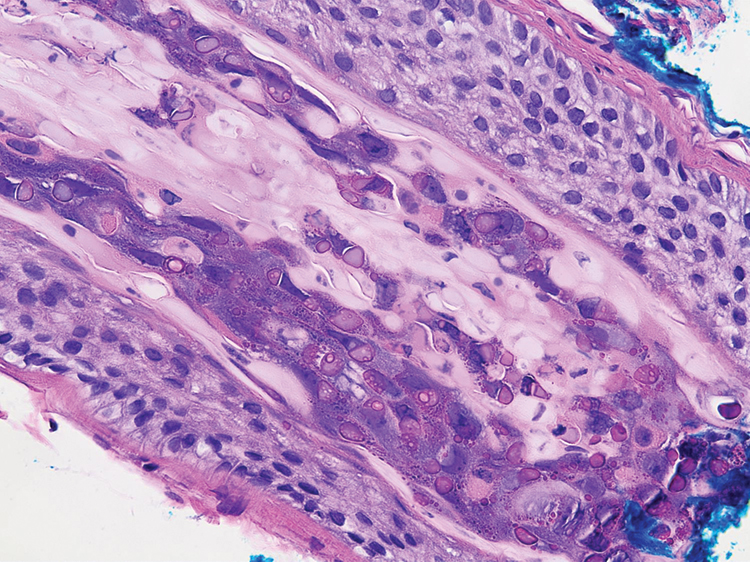

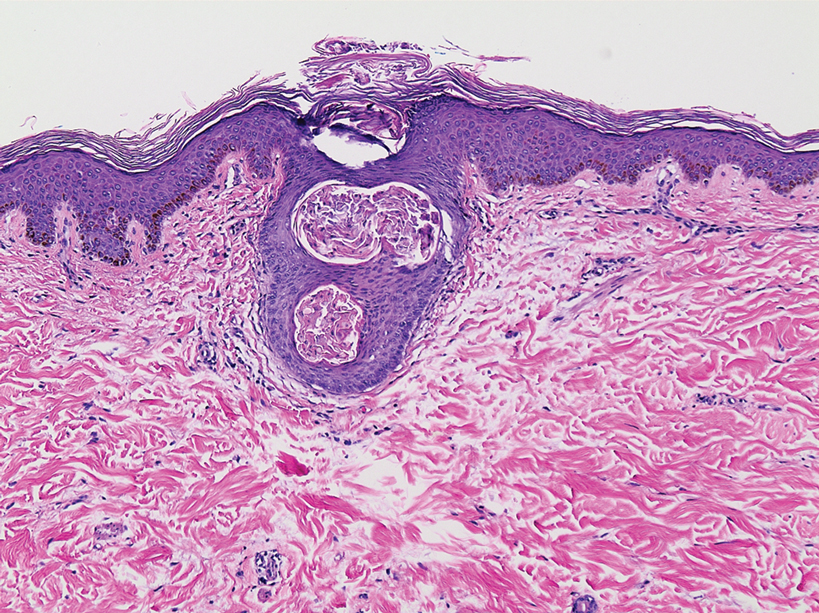

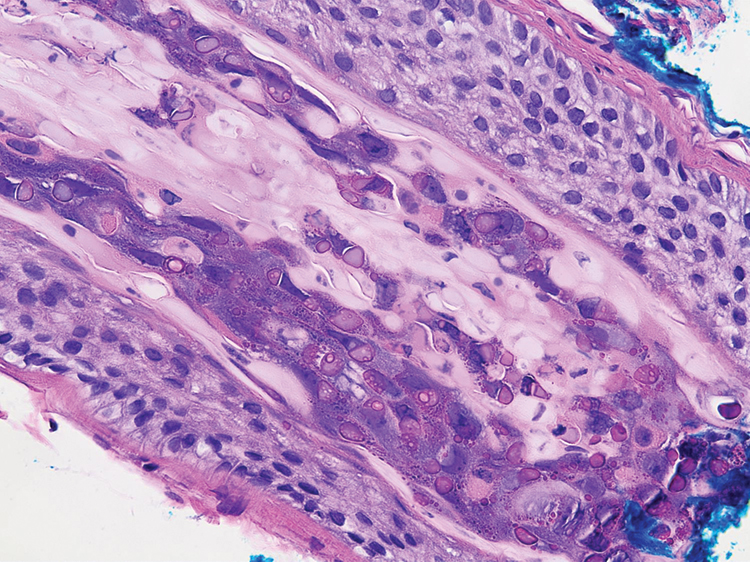

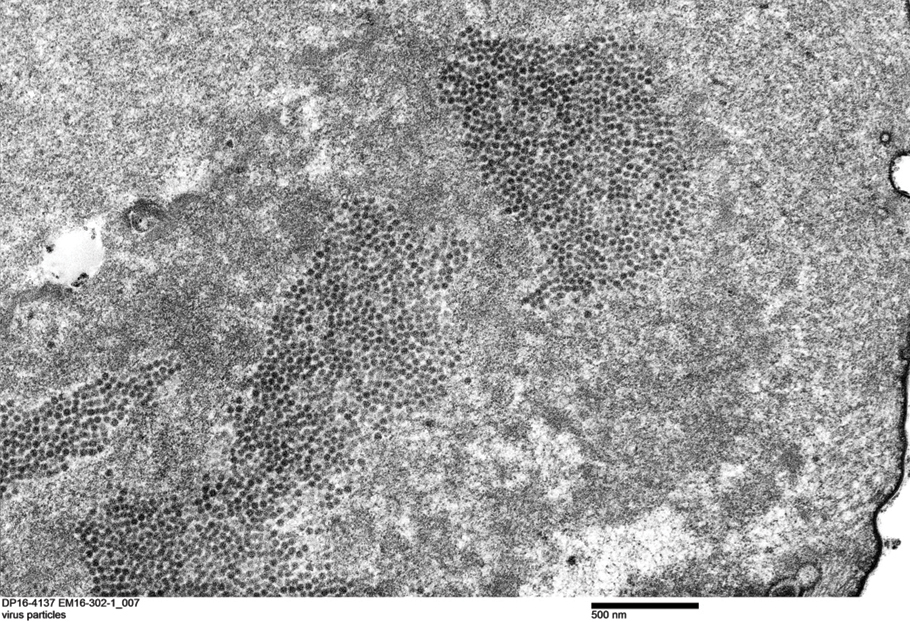

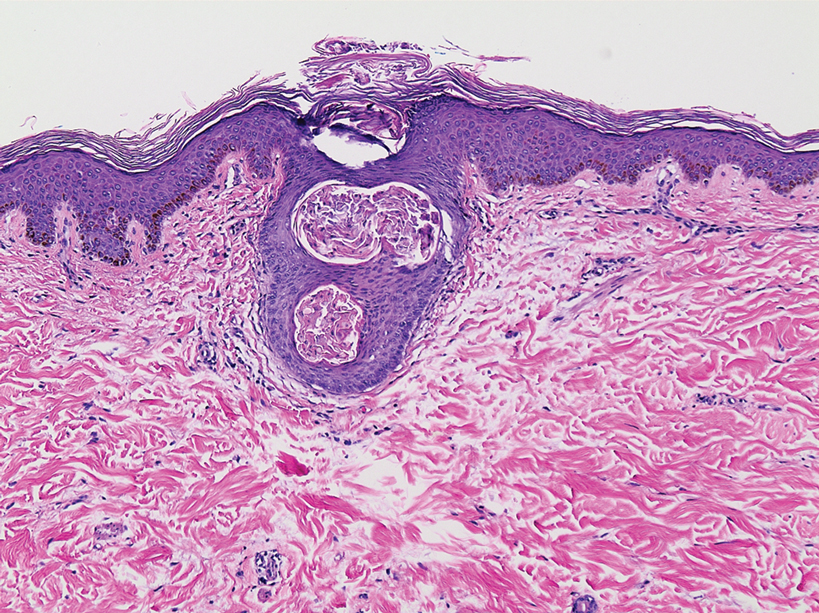

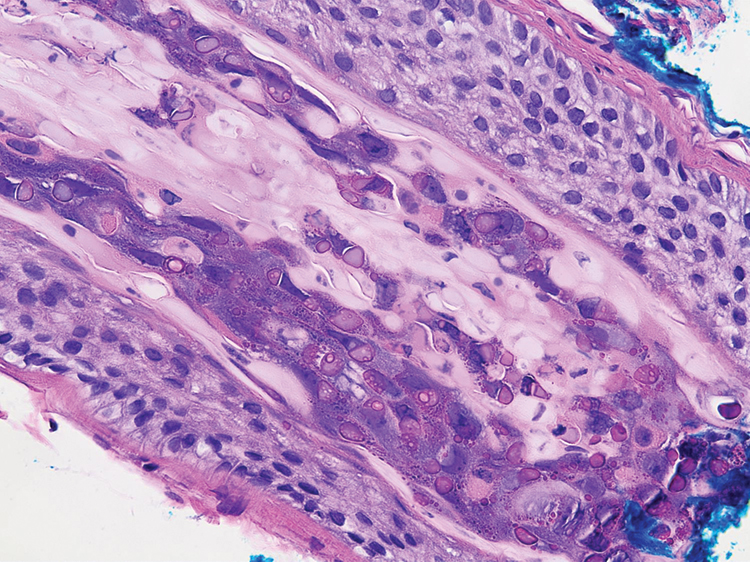

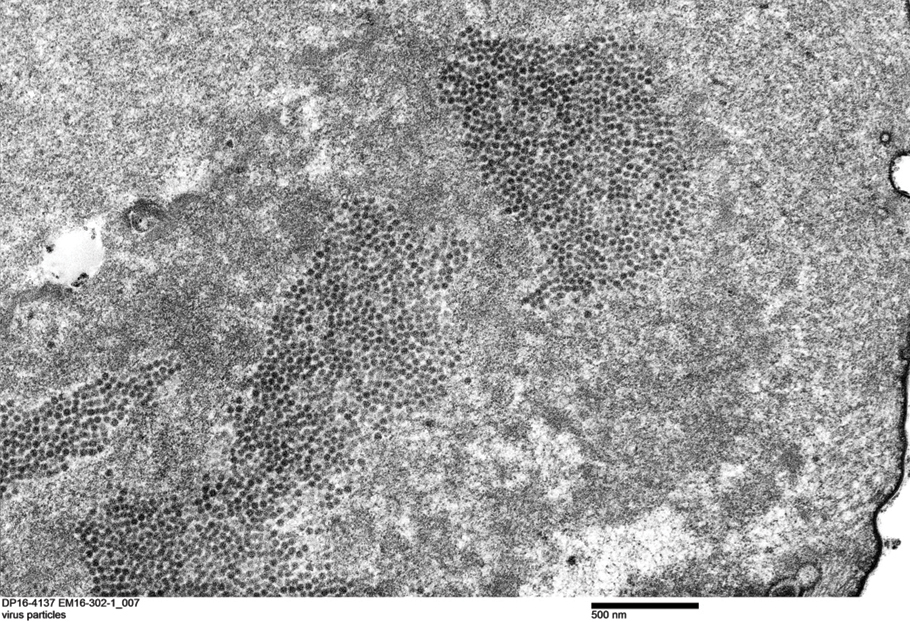

Histopathologic examination of the biopsy specimens revealed nodular mixed inflammatory cells and infiltration of the epithelioid histiocytes in lamina propria (Figure D; stain: hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification 40×). The histiocytes showed foamy and eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure E, arrow) and some of them had a targetoid appearance (Figure E, arrow head; stain: hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification 200×). Von Kossa stains highlighted the targetoid structures in the histiocytes (Figure F, Michaelis-Gutmann bodies). The granular cytoplasm of the histiocytes was positive on periodic acid-Schiff stain (Figure G). Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with colonic malakoplakia.

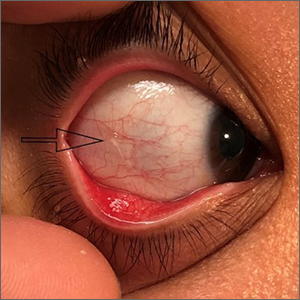

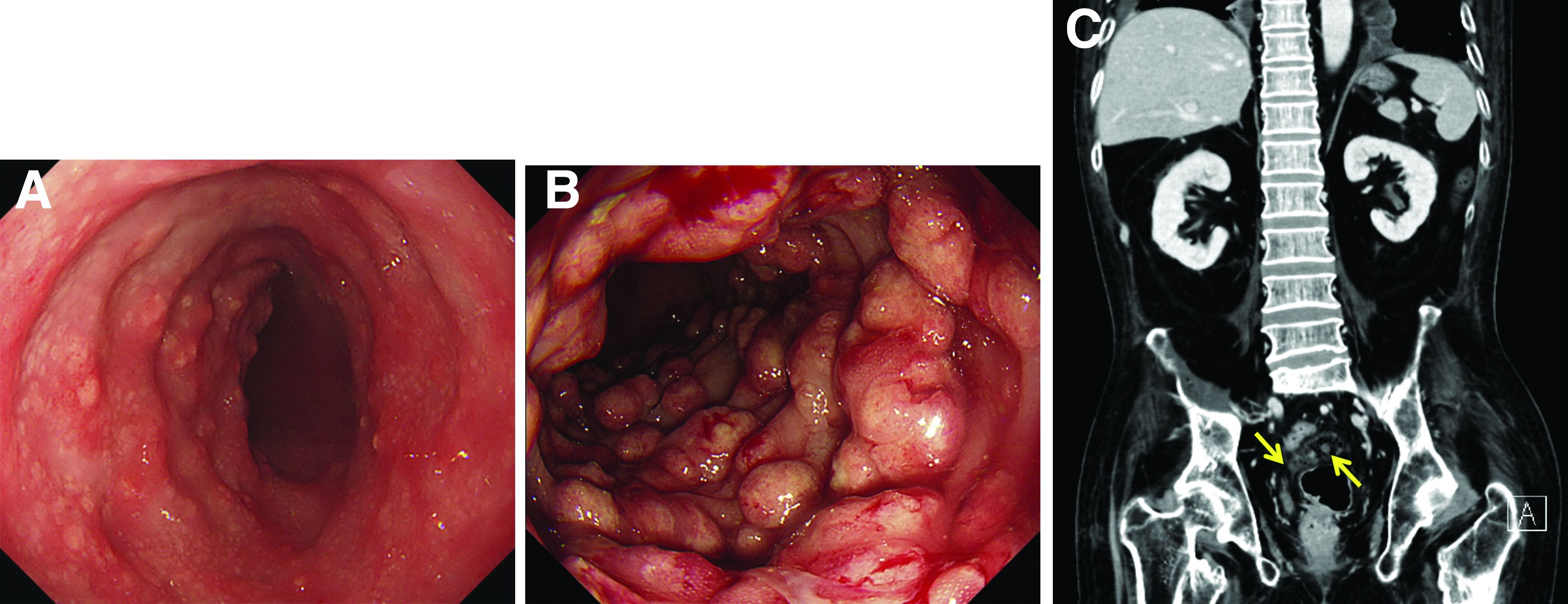

Malakoplakia is an uncommon, chronic, granulomatous inflammatory disease. It most commonly affects the urinary tract and gastrointestinal tract, but may occur at any anatomic site. Malakoplakia of the gastrointestinal tract are seen most frequently in the rectum, sigmoid, and right colon.1 It is diagnosed by the characteristic histologic feature of accumulated histiocytes with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm containing basophilic inclusions, consistent with Michaelis-Gutmann bodies. Although the exact etiology and pathogenesis of malakoplakia are unclear, it seems to originate from an acquired defect in the intracellular destruction of phagocytosed bacteria, usually associated with Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and Mycobacterium.2 It can have various causes, such as immunosuppression, malignant neoplasms, systemic diseases, and genetic diseases. Clinical manifestation of colonic malakoplakia is diverse, ranging from asymptomatic to malaise, fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea, hematochezia, and intestinal obstruction. Granulomatous reaction of malakoplakia generates the endoscopic appearance of lesions, which ranges from plaques to nodules and yellow-brown masses. In the early stage, malakoplakia commonly presents as soft yellow to tan mucosal plaques endoscopically, as seen in our case (Figure A). As the disease progresses in the later stage, malakoplakia presents as raised, grey to tan polypoid lesions of various sizes with peripheral hyperemia and a central depressed area, as seen in our case (Figure B).3 Owing to this endoscopic morphology, colonic malakoplakia may be misdiagnosed as atypical lymphoma, familial adenomatous polyposis, and metastatic carcinoma. To date, the natural course of malakoplakia of the colon is unclear, and no guidelines for treatment, treatment methods, duration of treatment, or surveillance are currently available. However, treatment of malakoplakia is essential to reduce immunosuppression and includes antibiotics with intracellular action and choline agonists that replenish the decreased cyclic 3’, 5’-guanosine monophosphate levels. In summary, although malakoplakia of the colon is very rare, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of polypoid colonic lesions, especially in immunocompromised or malnourished patients.

References

1. Cipolletta L et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995 Mar;41(3):255-8.

2. Berney T et al. Transpl Int. 1999;12(4):293-6.

3. Weinrach DM et al. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004 Oct;128(10):e133-4.

Answer: Colonic Malakoplakia.

Histopathologic examination of the biopsy specimens revealed nodular mixed inflammatory cells and infiltration of the epithelioid histiocytes in lamina propria (Figure D; stain: hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification 40×). The histiocytes showed foamy and eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure E, arrow) and some of them had a targetoid appearance (Figure E, arrow head; stain: hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification 200×). Von Kossa stains highlighted the targetoid structures in the histiocytes (Figure F, Michaelis-Gutmann bodies). The granular cytoplasm of the histiocytes was positive on periodic acid-Schiff stain (Figure G). Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with colonic malakoplakia.

Malakoplakia is an uncommon, chronic, granulomatous inflammatory disease. It most commonly affects the urinary tract and gastrointestinal tract, but may occur at any anatomic site. Malakoplakia of the gastrointestinal tract are seen most frequently in the rectum, sigmoid, and right colon.1 It is diagnosed by the characteristic histologic feature of accumulated histiocytes with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm containing basophilic inclusions, consistent with Michaelis-Gutmann bodies. Although the exact etiology and pathogenesis of malakoplakia are unclear, it seems to originate from an acquired defect in the intracellular destruction of phagocytosed bacteria, usually associated with Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and Mycobacterium.2 It can have various causes, such as immunosuppression, malignant neoplasms, systemic diseases, and genetic diseases. Clinical manifestation of colonic malakoplakia is diverse, ranging from asymptomatic to malaise, fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea, hematochezia, and intestinal obstruction. Granulomatous reaction of malakoplakia generates the endoscopic appearance of lesions, which ranges from plaques to nodules and yellow-brown masses. In the early stage, malakoplakia commonly presents as soft yellow to tan mucosal plaques endoscopically, as seen in our case (Figure A). As the disease progresses in the later stage, malakoplakia presents as raised, grey to tan polypoid lesions of various sizes with peripheral hyperemia and a central depressed area, as seen in our case (Figure B).3 Owing to this endoscopic morphology, colonic malakoplakia may be misdiagnosed as atypical lymphoma, familial adenomatous polyposis, and metastatic carcinoma. To date, the natural course of malakoplakia of the colon is unclear, and no guidelines for treatment, treatment methods, duration of treatment, or surveillance are currently available. However, treatment of malakoplakia is essential to reduce immunosuppression and includes antibiotics with intracellular action and choline agonists that replenish the decreased cyclic 3’, 5’-guanosine monophosphate levels. In summary, although malakoplakia of the colon is very rare, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of polypoid colonic lesions, especially in immunocompromised or malnourished patients.

References

1. Cipolletta L et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995 Mar;41(3):255-8.

2. Berney T et al. Transpl Int. 1999;12(4):293-6.

3. Weinrach DM et al. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004 Oct;128(10):e133-4.

Answer: Colonic Malakoplakia.

Histopathologic examination of the biopsy specimens revealed nodular mixed inflammatory cells and infiltration of the epithelioid histiocytes in lamina propria (Figure D; stain: hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification 40×). The histiocytes showed foamy and eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure E, arrow) and some of them had a targetoid appearance (Figure E, arrow head; stain: hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification 200×). Von Kossa stains highlighted the targetoid structures in the histiocytes (Figure F, Michaelis-Gutmann bodies). The granular cytoplasm of the histiocytes was positive on periodic acid-Schiff stain (Figure G). Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with colonic malakoplakia.

Malakoplakia is an uncommon, chronic, granulomatous inflammatory disease. It most commonly affects the urinary tract and gastrointestinal tract, but may occur at any anatomic site. Malakoplakia of the gastrointestinal tract are seen most frequently in the rectum, sigmoid, and right colon.1 It is diagnosed by the characteristic histologic feature of accumulated histiocytes with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm containing basophilic inclusions, consistent with Michaelis-Gutmann bodies. Although the exact etiology and pathogenesis of malakoplakia are unclear, it seems to originate from an acquired defect in the intracellular destruction of phagocytosed bacteria, usually associated with Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and Mycobacterium.2 It can have various causes, such as immunosuppression, malignant neoplasms, systemic diseases, and genetic diseases. Clinical manifestation of colonic malakoplakia is diverse, ranging from asymptomatic to malaise, fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea, hematochezia, and intestinal obstruction. Granulomatous reaction of malakoplakia generates the endoscopic appearance of lesions, which ranges from plaques to nodules and yellow-brown masses. In the early stage, malakoplakia commonly presents as soft yellow to tan mucosal plaques endoscopically, as seen in our case (Figure A). As the disease progresses in the later stage, malakoplakia presents as raised, grey to tan polypoid lesions of various sizes with peripheral hyperemia and a central depressed area, as seen in our case (Figure B).3 Owing to this endoscopic morphology, colonic malakoplakia may be misdiagnosed as atypical lymphoma, familial adenomatous polyposis, and metastatic carcinoma. To date, the natural course of malakoplakia of the colon is unclear, and no guidelines for treatment, treatment methods, duration of treatment, or surveillance are currently available. However, treatment of malakoplakia is essential to reduce immunosuppression and includes antibiotics with intracellular action and choline agonists that replenish the decreased cyclic 3’, 5’-guanosine monophosphate levels. In summary, although malakoplakia of the colon is very rare, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of polypoid colonic lesions, especially in immunocompromised or malnourished patients.

References

1. Cipolletta L et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995 Mar;41(3):255-8.

2. Berney T et al. Transpl Int. 1999;12(4):293-6.

3. Weinrach DM et al. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004 Oct;128(10):e133-4.

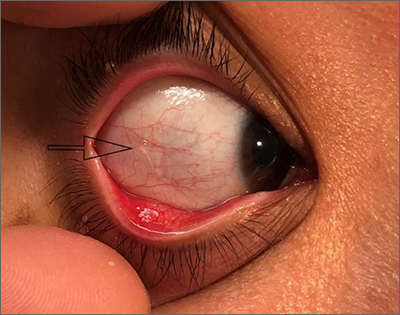

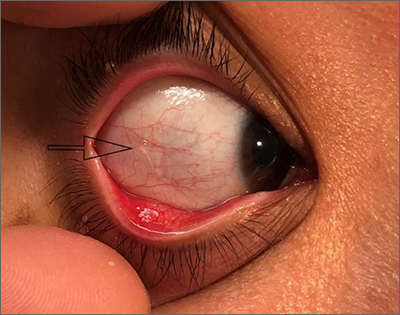

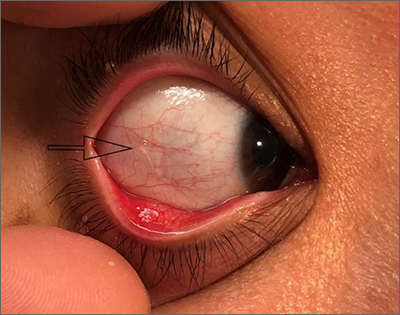

A 60-year-old man with C3 tetraplegia was referred to our department for evaluation of abdominal pain and hematochezia. He was diagnosed with adrenal insufficiency 5 years prior and has been taking low-dose prednisolone (7.5 mg) once a day. One year before presentation, he complained of intermittent loose, mucoid stool and abdominal pain. Sigmoidoscopy revealed multiple small yellowish plaques in the sigmoid colon (Figure A). However, symptoms improved without any treatment, and he was discharged from the rehabilitation department. He was readmitted for respiratory rehabilitation owing to dyspnea. On hospital day 4, he complained of abdominal pain and passing loose stool with foul odor 4-5 times a day. On hospital day 7, the abdominal pain worsened, and hematochezia occurred.

On physical examination, he was hemodynamically stable and afebrile. The abdomen was soft with mild tenderness on palpation in the periumbilical area without peritoneal signs. Laboratory studies were notable with a hemoglobin level of 10.7 g/dL, total protein of 4.09 g/dL, and albumin of 2.21 g/dL. Inflammatory marker (C-reactive protein) was mildly elevated to 1.83 mg/dL. Serology for human immunodeficiency virus was negative. Tumor markers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigenic determinant, and alpha-fetoprotein, were within the normal range. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody was negative, and rheumatic factor was within the normal range. Findings from stool for acid-fast bacillus and Clostridioides difficile toxin were negative; no pathogens were cultured, and no parasites were identified.

Sigmoidoscopy revealed diverse, multiple polypoid lesions (3-10 mm) with erythema, edema, and friability surrounding the entire lumen on the sigmoid colon (Figure B). The number and size of the polypoid lesions increased compared with the endoscopic findings obtained 1 year prior. The lesions easily bled on contact. Multiple biopsies of different sites were taken. An abdominal computed tomography scan showed multiple polyps of <1 cm that were confined to the sigmoid colon (Figure C, arrow).

Based on this information, what is the most likely diagnosis?

Previously published in Gastroenterology (2020 Feb;158[3]:482-4).

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: HCC May 2022

Clinical trials for unresectable HCC (uHCC) have mandated excellent underlying liver function. Patients with Child-Pugh (CP) A cirrhosis do not have cirrhosis as their most life-limiting disease. In clinical practice, there are many patients with uHCC who are functionally well yet have CP-B cirrhosis. D'Alessio and colleagues undertook a retrospective evaluation of 202 patients with either CP-A or CP-B cirrhosis who received atezolizumab and bevacizumab as first-line treatment of uHCC. The majority, 154 patients (76%), had CP-A cirrhosis, whereas 48 (24%) had CP-B, including 21 B7, 21 B8, and 6 B9. The authors found that in the overall population, median overall survival (mOS) was 14.9 months (95% CI 13.6-16.3), with patients with CP-A mOS of 16.8 months (95% CI 14.1-23.9), and CP-B mOS of 6.7 months (95% CI 4.3-15.6; P = .0003). Overall response rates (ORR) were comparable, with an ORR of 26% in CP-A and 21% in CP-B, not influenced by Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage, performance status, etiology (viral vs nonviral), portal vein thrombosis (PVT), or extrahepatic spread (P > .05 for all associations). The investigators concluded that atezolizumab and bevacizumab in patients with CP-B was well tolerated, with no relevant difference in terms of clinically significant treatment-related adverse events compared with patients with CP-A.

Shi and colleagues reported a randomized controlled trial of patients with HCC and microvascular invasion (MVI) who underwent suboptimal resection (distance from tumor edge to the cut surface < 1 mm), followed by either stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) or observation. From August 2015 to December 2016, 76 patients with BCLC stage 0/A liver disease, MVI, and no macroscopic vascular invasion were randomized after partial hepatectomy to either observation or SBRT (35 Gy delivered in a week). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year disease free survival (DFS) rates were 92.1%, 65.8%, and 56.1% in the SBRT group vs 76.3%, 36.8%, and 26.3% in the surgery alone group, respectively (P = .005). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival (OS) rates were 100%, 89.5%, and 75.0% in SBRT group vs 100.0%, 68.4%, and 53.7% in the surgery alone group, respectively (P = .053). The authors concluded that SBRT eradicates residual tumor cells present at the margin and improves surgical outcomes.

Roth and colleagues evaluated the safety and efficacy of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) in older (> 70 years) patients with intermediate HCC. Out of 271 patients evaluated, 88 were older patients. 20.5% of older patients experienced serious adverse events vs 21.3% of younger patients (P = .87). The predictive factors of serious adverse events were CP stage ≥ B7 (P < .0001), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale ≥ 1 (P = .0019), and Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score ≥ 9 (P = .0415). The serious adverse event rate was not increased with age (P = .87). The authors concluded that age should not be an exclusionary factor when considering TACE.

Clinical trials for unresectable HCC (uHCC) have mandated excellent underlying liver function. Patients with Child-Pugh (CP) A cirrhosis do not have cirrhosis as their most life-limiting disease. In clinical practice, there are many patients with uHCC who are functionally well yet have CP-B cirrhosis. D'Alessio and colleagues undertook a retrospective evaluation of 202 patients with either CP-A or CP-B cirrhosis who received atezolizumab and bevacizumab as first-line treatment of uHCC. The majority, 154 patients (76%), had CP-A cirrhosis, whereas 48 (24%) had CP-B, including 21 B7, 21 B8, and 6 B9. The authors found that in the overall population, median overall survival (mOS) was 14.9 months (95% CI 13.6-16.3), with patients with CP-A mOS of 16.8 months (95% CI 14.1-23.9), and CP-B mOS of 6.7 months (95% CI 4.3-15.6; P = .0003). Overall response rates (ORR) were comparable, with an ORR of 26% in CP-A and 21% in CP-B, not influenced by Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage, performance status, etiology (viral vs nonviral), portal vein thrombosis (PVT), or extrahepatic spread (P > .05 for all associations). The investigators concluded that atezolizumab and bevacizumab in patients with CP-B was well tolerated, with no relevant difference in terms of clinically significant treatment-related adverse events compared with patients with CP-A.

Shi and colleagues reported a randomized controlled trial of patients with HCC and microvascular invasion (MVI) who underwent suboptimal resection (distance from tumor edge to the cut surface < 1 mm), followed by either stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) or observation. From August 2015 to December 2016, 76 patients with BCLC stage 0/A liver disease, MVI, and no macroscopic vascular invasion were randomized after partial hepatectomy to either observation or SBRT (35 Gy delivered in a week). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year disease free survival (DFS) rates were 92.1%, 65.8%, and 56.1% in the SBRT group vs 76.3%, 36.8%, and 26.3% in the surgery alone group, respectively (P = .005). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival (OS) rates were 100%, 89.5%, and 75.0% in SBRT group vs 100.0%, 68.4%, and 53.7% in the surgery alone group, respectively (P = .053). The authors concluded that SBRT eradicates residual tumor cells present at the margin and improves surgical outcomes.

Roth and colleagues evaluated the safety and efficacy of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) in older (> 70 years) patients with intermediate HCC. Out of 271 patients evaluated, 88 were older patients. 20.5% of older patients experienced serious adverse events vs 21.3% of younger patients (P = .87). The predictive factors of serious adverse events were CP stage ≥ B7 (P < .0001), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale ≥ 1 (P = .0019), and Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score ≥ 9 (P = .0415). The serious adverse event rate was not increased with age (P = .87). The authors concluded that age should not be an exclusionary factor when considering TACE.

Clinical trials for unresectable HCC (uHCC) have mandated excellent underlying liver function. Patients with Child-Pugh (CP) A cirrhosis do not have cirrhosis as their most life-limiting disease. In clinical practice, there are many patients with uHCC who are functionally well yet have CP-B cirrhosis. D'Alessio and colleagues undertook a retrospective evaluation of 202 patients with either CP-A or CP-B cirrhosis who received atezolizumab and bevacizumab as first-line treatment of uHCC. The majority, 154 patients (76%), had CP-A cirrhosis, whereas 48 (24%) had CP-B, including 21 B7, 21 B8, and 6 B9. The authors found that in the overall population, median overall survival (mOS) was 14.9 months (95% CI 13.6-16.3), with patients with CP-A mOS of 16.8 months (95% CI 14.1-23.9), and CP-B mOS of 6.7 months (95% CI 4.3-15.6; P = .0003). Overall response rates (ORR) were comparable, with an ORR of 26% in CP-A and 21% in CP-B, not influenced by Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage, performance status, etiology (viral vs nonviral), portal vein thrombosis (PVT), or extrahepatic spread (P > .05 for all associations). The investigators concluded that atezolizumab and bevacizumab in patients with CP-B was well tolerated, with no relevant difference in terms of clinically significant treatment-related adverse events compared with patients with CP-A.

Shi and colleagues reported a randomized controlled trial of patients with HCC and microvascular invasion (MVI) who underwent suboptimal resection (distance from tumor edge to the cut surface < 1 mm), followed by either stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) or observation. From August 2015 to December 2016, 76 patients with BCLC stage 0/A liver disease, MVI, and no macroscopic vascular invasion were randomized after partial hepatectomy to either observation or SBRT (35 Gy delivered in a week). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year disease free survival (DFS) rates were 92.1%, 65.8%, and 56.1% in the SBRT group vs 76.3%, 36.8%, and 26.3% in the surgery alone group, respectively (P = .005). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival (OS) rates were 100%, 89.5%, and 75.0% in SBRT group vs 100.0%, 68.4%, and 53.7% in the surgery alone group, respectively (P = .053). The authors concluded that SBRT eradicates residual tumor cells present at the margin and improves surgical outcomes.

Roth and colleagues evaluated the safety and efficacy of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) in older (> 70 years) patients with intermediate HCC. Out of 271 patients evaluated, 88 were older patients. 20.5% of older patients experienced serious adverse events vs 21.3% of younger patients (P = .87). The predictive factors of serious adverse events were CP stage ≥ B7 (P < .0001), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale ≥ 1 (P = .0019), and Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score ≥ 9 (P = .0415). The serious adverse event rate was not increased with age (P = .87). The authors concluded that age should not be an exclusionary factor when considering TACE.

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: HCC May 2022

Clinical trials for unresectable HCC (uHCC) have mandated excellent underlying liver function. Patients with Child-Pugh (CP) A cirrhosis do not have cirrhosis as their most life-limiting disease. In clinical practice, there are many patients with uHCC who are functionally well yet have CP-B cirrhosis. D'Alessio and colleagues undertook a retrospective evaluation of 202 patients with either CP-A or CP-B cirrhosis who received atezolizumab and bevacizumab as first-line treatment of uHCC. The majority, 154 patients (76%), had CP-A cirrhosis, whereas 48 (24%) had CP-B, including 21 B7, 21 B8, and 6 B9. The authors found that in the overall population, median overall survival (mOS) was 14.9 months (95% CI 13.6-16.3), with patients with CP-A mOS of 16.8 months (95% CI 14.1-23.9), and CP-B mOS of 6.7 months (95% CI 4.3-15.6; P = .0003). Overall response rates (ORR) were comparable, with an ORR of 26% in CP-A and 21% in CP-B, not influenced by Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage, performance status, etiology (viral vs nonviral), portal vein thrombosis (PVT), or extrahepatic spread (P > .05 for all associations). The investigators concluded that atezolizumab and bevacizumab in patients with CP-B was well tolerated, with no relevant difference in terms of clinically significant treatment-related adverse events compared with patients with CP-A.

Shi and colleagues reported a randomized controlled trial of patients with HCC and microvascular invasion (MVI) who underwent suboptimal resection (distance from tumor edge to the cut surface < 1 mm), followed by either stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) or observation. From August 2015 to December 2016, 76 patients with BCLC stage 0/A liver disease, MVI, and no macroscopic vascular invasion were randomized after partial hepatectomy to either observation or SBRT (35 Gy delivered in a week). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year disease free survival (DFS) rates were 92.1%, 65.8%, and 56.1% in the SBRT group vs 76.3%, 36.8%, and 26.3% in the surgery alone group, respectively (P = .005). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival (OS) rates were 100%, 89.5%, and 75.0% in SBRT group vs 100.0%, 68.4%, and 53.7% in the surgery alone group, respectively (P = .053). The authors concluded that SBRT eradicates residual tumor cells present at the margin and improves surgical outcomes.

Roth and colleagues evaluated the safety and efficacy of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) in older (> 70 years) patients with intermediate HCC. Out of 271 patients evaluated, 88 were older patients. 20.5% of older patients experienced serious adverse events vs 21.3% of younger patients (P = .87). The predictive factors of serious adverse events were CP stage ≥ B7 (P < .0001), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale ≥ 1 (P = .0019), and Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score ≥ 9 (P = .0415). The serious adverse event rate was not increased with age (P = .87). The authors concluded that age should not be an exclusionary factor when considering TACE.

Clinical trials for unresectable HCC (uHCC) have mandated excellent underlying liver function. Patients with Child-Pugh (CP) A cirrhosis do not have cirrhosis as their most life-limiting disease. In clinical practice, there are many patients with uHCC who are functionally well yet have CP-B cirrhosis. D'Alessio and colleagues undertook a retrospective evaluation of 202 patients with either CP-A or CP-B cirrhosis who received atezolizumab and bevacizumab as first-line treatment of uHCC. The majority, 154 patients (76%), had CP-A cirrhosis, whereas 48 (24%) had CP-B, including 21 B7, 21 B8, and 6 B9. The authors found that in the overall population, median overall survival (mOS) was 14.9 months (95% CI 13.6-16.3), with patients with CP-A mOS of 16.8 months (95% CI 14.1-23.9), and CP-B mOS of 6.7 months (95% CI 4.3-15.6; P = .0003). Overall response rates (ORR) were comparable, with an ORR of 26% in CP-A and 21% in CP-B, not influenced by Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage, performance status, etiology (viral vs nonviral), portal vein thrombosis (PVT), or extrahepatic spread (P > .05 for all associations). The investigators concluded that atezolizumab and bevacizumab in patients with CP-B was well tolerated, with no relevant difference in terms of clinically significant treatment-related adverse events compared with patients with CP-A.

Shi and colleagues reported a randomized controlled trial of patients with HCC and microvascular invasion (MVI) who underwent suboptimal resection (distance from tumor edge to the cut surface < 1 mm), followed by either stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) or observation. From August 2015 to December 2016, 76 patients with BCLC stage 0/A liver disease, MVI, and no macroscopic vascular invasion were randomized after partial hepatectomy to either observation or SBRT (35 Gy delivered in a week). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year disease free survival (DFS) rates were 92.1%, 65.8%, and 56.1% in the SBRT group vs 76.3%, 36.8%, and 26.3% in the surgery alone group, respectively (P = .005). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival (OS) rates were 100%, 89.5%, and 75.0% in SBRT group vs 100.0%, 68.4%, and 53.7% in the surgery alone group, respectively (P = .053). The authors concluded that SBRT eradicates residual tumor cells present at the margin and improves surgical outcomes.

Roth and colleagues evaluated the safety and efficacy of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) in older (> 70 years) patients with intermediate HCC. Out of 271 patients evaluated, 88 were older patients. 20.5% of older patients experienced serious adverse events vs 21.3% of younger patients (P = .87). The predictive factors of serious adverse events were CP stage ≥ B7 (P < .0001), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale ≥ 1 (P = .0019), and Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score ≥ 9 (P = .0415). The serious adverse event rate was not increased with age (P = .87). The authors concluded that age should not be an exclusionary factor when considering TACE.

Clinical trials for unresectable HCC (uHCC) have mandated excellent underlying liver function. Patients with Child-Pugh (CP) A cirrhosis do not have cirrhosis as their most life-limiting disease. In clinical practice, there are many patients with uHCC who are functionally well yet have CP-B cirrhosis. D'Alessio and colleagues undertook a retrospective evaluation of 202 patients with either CP-A or CP-B cirrhosis who received atezolizumab and bevacizumab as first-line treatment of uHCC. The majority, 154 patients (76%), had CP-A cirrhosis, whereas 48 (24%) had CP-B, including 21 B7, 21 B8, and 6 B9. The authors found that in the overall population, median overall survival (mOS) was 14.9 months (95% CI 13.6-16.3), with patients with CP-A mOS of 16.8 months (95% CI 14.1-23.9), and CP-B mOS of 6.7 months (95% CI 4.3-15.6; P = .0003). Overall response rates (ORR) were comparable, with an ORR of 26% in CP-A and 21% in CP-B, not influenced by Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage, performance status, etiology (viral vs nonviral), portal vein thrombosis (PVT), or extrahepatic spread (P > .05 for all associations). The investigators concluded that atezolizumab and bevacizumab in patients with CP-B was well tolerated, with no relevant difference in terms of clinically significant treatment-related adverse events compared with patients with CP-A.

Shi and colleagues reported a randomized controlled trial of patients with HCC and microvascular invasion (MVI) who underwent suboptimal resection (distance from tumor edge to the cut surface < 1 mm), followed by either stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) or observation. From August 2015 to December 2016, 76 patients with BCLC stage 0/A liver disease, MVI, and no macroscopic vascular invasion were randomized after partial hepatectomy to either observation or SBRT (35 Gy delivered in a week). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year disease free survival (DFS) rates were 92.1%, 65.8%, and 56.1% in the SBRT group vs 76.3%, 36.8%, and 26.3% in the surgery alone group, respectively (P = .005). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival (OS) rates were 100%, 89.5%, and 75.0% in SBRT group vs 100.0%, 68.4%, and 53.7% in the surgery alone group, respectively (P = .053). The authors concluded that SBRT eradicates residual tumor cells present at the margin and improves surgical outcomes.

Roth and colleagues evaluated the safety and efficacy of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) in older (> 70 years) patients with intermediate HCC. Out of 271 patients evaluated, 88 were older patients. 20.5% of older patients experienced serious adverse events vs 21.3% of younger patients (P = .87). The predictive factors of serious adverse events were CP stage ≥ B7 (P < .0001), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale ≥ 1 (P = .0019), and Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score ≥ 9 (P = .0415). The serious adverse event rate was not increased with age (P = .87). The authors concluded that age should not be an exclusionary factor when considering TACE.

Management of Early Stage Triple-negative Breast Cancer

Based on the work you do at the Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute, what is your standard approach to managing early stage cancer patients?

Dr. Roesch: The approach to managing patients with early stage breast cancer very much depends on the subtype of breast cancer. Clinical stage at presentation and patient factors are considered here. For example, patients with small hormone receptor-positive tumors will often have surgery first, while patients with triple-negative or HER2-positive tumors will often receive preoperative or neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

In situations where there is a need or a desire for downstaging or shrinking of the primary tumor or lymph nodes in the axilla, we will also discuss neoadjuvant systemic therapy. For hormone receptor-positive tumors, endocrine or anti-estrogen therapy will be incorporated into their treatment regimen at some point in the future.

The role of chemotherapy for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer depends on a variety of factors, including pathologic staging, which we obtain at the time of surgery. Exceptions may include very small tumors or patients who have medical comorbidities that affect their candidacy for chemotherapy where the risk may outweigh the benefit.

Are there specific steps you take in managing and treating early stage triple-negative breast cancer?

Dr. Roesch: Most patients with early stage triple-negative breast cancer receive neoadjuvant or preoperative chemotherapy. As I mentioned above, this has the benefits of downstaging the primary tumor itself and the lymph nodes in the axilla as well as providing prognostic information. This approach can also help guide adjuvant therapy recommendations. Additionally, we often discuss the role of genetic counseling for these patients.

Are there targeted therapies you rely upon?

Dr. Roesch: This has been an evolving field with dramatic advances in the past couple of years. One is immunotherapy. There was a phase III study called the KEYONTE-522 trial, which demonstrated improvements in pathologic response rate and event-free survival with a regimen of neoadjuvant pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy followed by the pembrolizumab given in the adjuvant setting, compared to chemotherapy approach alone (1).

For patients who meet criteria for this study, which is essentially stage II/III triple-negative breast cancer, we have adopted this regimen in the neoadjuvant setting. Additionally, we consider adjuvant capecitabine for patients who have received neoadjuvant chemotherapy with an anthracycline, taxane or both and who have residual disease at the time of surgery. This is based on the CREATE-X trial, which showed a survival benefit for patients with triple-negative breast cancer in this situation (2).

Lastly, the PARP inhibitor, olaparib, was recently approved by the FDA in the adjuvant setting for BRCA mutation carriers diagnosed with HER-2-negative high-risk early breast cancer who have received neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy. This treatment also demonstrated survival benefit and is an exciting new option for these patients (3).

A critical question in my mind that has arisen out of these new developments is sequencing of these therapies. For example, if I have a patient who received the KEYNOTE-522 regimen with the immunotherapy agent, pembrolizumab, and has residual disease after surgery, how do we administer the capecitabine with the pembrolizumab? And what about radiation? What if a patient is a BRCA mutation carrier? These are all very relevant questions, which we are encountering every day, and the approach we take is often individualized.

This sounds very exciting. Can you talk about the research on managing early triple-negative breast cancer and what the future might hold?

Dr. Roesch: This is a very exciting time for both us as oncologists and our patients as there is a very rapid pace of new therapies being explored in the context of clinical trials. First, I'd like to mention the adjuvant vaccine trial we have at Cleveland Clinic for patients diagnosed with early stage triple-negative breast cancer at high risk of recurrence. This trial is investigating an alpha lactalbumin vaccine, which has been selected as a vaccine target because it is a breast-specific differentiation protein expressed at high levels in many human breast cancers, particularly in triple-negative breast cancer. The current trial's main objective is to determine the maximum tolerated dose of the vaccine, and other endpoints include looking at biomarkers of immune responses (4).

The I-SPY2 trial is another very exciting study we have open at Cleveland Clinic. This is a multicenter phase II trial using response adaptive randomization within molecular subtypes, which is defined by the receptor status and MammaPrint risk, which is a genomic assay, to evaluate novel agents as neoadjuvant therapy for women with high-risk breast cancer. Patients undergo serial MRIs and biopsies with information on the likelihood of them achieving a pathologic complete response (pCR) provided back in real time, which will then allow for therapy escalation or de-escalation. The goal here is individualized precision therapy based on the specific intrinsic subtype of the tumor itself and response with the ultimate goal being to achieve a pCR (5).

Again, this is a very exciting time for us as medical providers and our patients because new therapies are being developed and studied in clinical trials every day.

- Schmid P, Cortes J, Dent R, et al; KEYNOTE-522 Investigators. Event-free Survival with Pembrolizumab in Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(6):556-567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2112651.

- Masuda N, Lee SJ, Ohtani S, et al. Adjuvant Capecitabine for Breast Cancer after Preoperative Chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(22):2147-2159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1612645.

- Tutt ANJ, Garber JE, Kaufman B, et al; OlympiA Clinical Trial Steering Committee and Investigators. Adjuvant Olaparib for Patients with BRCA1- or BRCA2-Mutated Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(25):2394-2405. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2105215.

- Adjuvant Therapy with an Alpha-lactalbumin Vaccine in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04674306.

- I-SPY TRIAL: Neoadjuvant and Personalized Adaptive Novel Agents to Treat Breast Cancer (I-SPY). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01042379.

Based on the work you do at the Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute, what is your standard approach to managing early stage cancer patients?

Dr. Roesch: The approach to managing patients with early stage breast cancer very much depends on the subtype of breast cancer. Clinical stage at presentation and patient factors are considered here. For example, patients with small hormone receptor-positive tumors will often have surgery first, while patients with triple-negative or HER2-positive tumors will often receive preoperative or neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

In situations where there is a need or a desire for downstaging or shrinking of the primary tumor or lymph nodes in the axilla, we will also discuss neoadjuvant systemic therapy. For hormone receptor-positive tumors, endocrine or anti-estrogen therapy will be incorporated into their treatment regimen at some point in the future.

The role of chemotherapy for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer depends on a variety of factors, including pathologic staging, which we obtain at the time of surgery. Exceptions may include very small tumors or patients who have medical comorbidities that affect their candidacy for chemotherapy where the risk may outweigh the benefit.

Are there specific steps you take in managing and treating early stage triple-negative breast cancer?

Dr. Roesch: Most patients with early stage triple-negative breast cancer receive neoadjuvant or preoperative chemotherapy. As I mentioned above, this has the benefits of downstaging the primary tumor itself and the lymph nodes in the axilla as well as providing prognostic information. This approach can also help guide adjuvant therapy recommendations. Additionally, we often discuss the role of genetic counseling for these patients.

Are there targeted therapies you rely upon?

Dr. Roesch: This has been an evolving field with dramatic advances in the past couple of years. One is immunotherapy. There was a phase III study called the KEYONTE-522 trial, which demonstrated improvements in pathologic response rate and event-free survival with a regimen of neoadjuvant pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy followed by the pembrolizumab given in the adjuvant setting, compared to chemotherapy approach alone (1).

For patients who meet criteria for this study, which is essentially stage II/III triple-negative breast cancer, we have adopted this regimen in the neoadjuvant setting. Additionally, we consider adjuvant capecitabine for patients who have received neoadjuvant chemotherapy with an anthracycline, taxane or both and who have residual disease at the time of surgery. This is based on the CREATE-X trial, which showed a survival benefit for patients with triple-negative breast cancer in this situation (2).

Lastly, the PARP inhibitor, olaparib, was recently approved by the FDA in the adjuvant setting for BRCA mutation carriers diagnosed with HER-2-negative high-risk early breast cancer who have received neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy. This treatment also demonstrated survival benefit and is an exciting new option for these patients (3).

A critical question in my mind that has arisen out of these new developments is sequencing of these therapies. For example, if I have a patient who received the KEYNOTE-522 regimen with the immunotherapy agent, pembrolizumab, and has residual disease after surgery, how do we administer the capecitabine with the pembrolizumab? And what about radiation? What if a patient is a BRCA mutation carrier? These are all very relevant questions, which we are encountering every day, and the approach we take is often individualized.

This sounds very exciting. Can you talk about the research on managing early triple-negative breast cancer and what the future might hold?

Dr. Roesch: This is a very exciting time for both us as oncologists and our patients as there is a very rapid pace of new therapies being explored in the context of clinical trials. First, I'd like to mention the adjuvant vaccine trial we have at Cleveland Clinic for patients diagnosed with early stage triple-negative breast cancer at high risk of recurrence. This trial is investigating an alpha lactalbumin vaccine, which has been selected as a vaccine target because it is a breast-specific differentiation protein expressed at high levels in many human breast cancers, particularly in triple-negative breast cancer. The current trial's main objective is to determine the maximum tolerated dose of the vaccine, and other endpoints include looking at biomarkers of immune responses (4).

The I-SPY2 trial is another very exciting study we have open at Cleveland Clinic. This is a multicenter phase II trial using response adaptive randomization within molecular subtypes, which is defined by the receptor status and MammaPrint risk, which is a genomic assay, to evaluate novel agents as neoadjuvant therapy for women with high-risk breast cancer. Patients undergo serial MRIs and biopsies with information on the likelihood of them achieving a pathologic complete response (pCR) provided back in real time, which will then allow for therapy escalation or de-escalation. The goal here is individualized precision therapy based on the specific intrinsic subtype of the tumor itself and response with the ultimate goal being to achieve a pCR (5).

Again, this is a very exciting time for us as medical providers and our patients because new therapies are being developed and studied in clinical trials every day.

Based on the work you do at the Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute, what is your standard approach to managing early stage cancer patients?

Dr. Roesch: The approach to managing patients with early stage breast cancer very much depends on the subtype of breast cancer. Clinical stage at presentation and patient factors are considered here. For example, patients with small hormone receptor-positive tumors will often have surgery first, while patients with triple-negative or HER2-positive tumors will often receive preoperative or neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

In situations where there is a need or a desire for downstaging or shrinking of the primary tumor or lymph nodes in the axilla, we will also discuss neoadjuvant systemic therapy. For hormone receptor-positive tumors, endocrine or anti-estrogen therapy will be incorporated into their treatment regimen at some point in the future.

The role of chemotherapy for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer depends on a variety of factors, including pathologic staging, which we obtain at the time of surgery. Exceptions may include very small tumors or patients who have medical comorbidities that affect their candidacy for chemotherapy where the risk may outweigh the benefit.

Are there specific steps you take in managing and treating early stage triple-negative breast cancer?

Dr. Roesch: Most patients with early stage triple-negative breast cancer receive neoadjuvant or preoperative chemotherapy. As I mentioned above, this has the benefits of downstaging the primary tumor itself and the lymph nodes in the axilla as well as providing prognostic information. This approach can also help guide adjuvant therapy recommendations. Additionally, we often discuss the role of genetic counseling for these patients.

Are there targeted therapies you rely upon?

Dr. Roesch: This has been an evolving field with dramatic advances in the past couple of years. One is immunotherapy. There was a phase III study called the KEYONTE-522 trial, which demonstrated improvements in pathologic response rate and event-free survival with a regimen of neoadjuvant pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy followed by the pembrolizumab given in the adjuvant setting, compared to chemotherapy approach alone (1).

For patients who meet criteria for this study, which is essentially stage II/III triple-negative breast cancer, we have adopted this regimen in the neoadjuvant setting. Additionally, we consider adjuvant capecitabine for patients who have received neoadjuvant chemotherapy with an anthracycline, taxane or both and who have residual disease at the time of surgery. This is based on the CREATE-X trial, which showed a survival benefit for patients with triple-negative breast cancer in this situation (2).

Lastly, the PARP inhibitor, olaparib, was recently approved by the FDA in the adjuvant setting for BRCA mutation carriers diagnosed with HER-2-negative high-risk early breast cancer who have received neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy. This treatment also demonstrated survival benefit and is an exciting new option for these patients (3).

A critical question in my mind that has arisen out of these new developments is sequencing of these therapies. For example, if I have a patient who received the KEYNOTE-522 regimen with the immunotherapy agent, pembrolizumab, and has residual disease after surgery, how do we administer the capecitabine with the pembrolizumab? And what about radiation? What if a patient is a BRCA mutation carrier? These are all very relevant questions, which we are encountering every day, and the approach we take is often individualized.

This sounds very exciting. Can you talk about the research on managing early triple-negative breast cancer and what the future might hold?

Dr. Roesch: This is a very exciting time for both us as oncologists and our patients as there is a very rapid pace of new therapies being explored in the context of clinical trials. First, I'd like to mention the adjuvant vaccine trial we have at Cleveland Clinic for patients diagnosed with early stage triple-negative breast cancer at high risk of recurrence. This trial is investigating an alpha lactalbumin vaccine, which has been selected as a vaccine target because it is a breast-specific differentiation protein expressed at high levels in many human breast cancers, particularly in triple-negative breast cancer. The current trial's main objective is to determine the maximum tolerated dose of the vaccine, and other endpoints include looking at biomarkers of immune responses (4).

The I-SPY2 trial is another very exciting study we have open at Cleveland Clinic. This is a multicenter phase II trial using response adaptive randomization within molecular subtypes, which is defined by the receptor status and MammaPrint risk, which is a genomic assay, to evaluate novel agents as neoadjuvant therapy for women with high-risk breast cancer. Patients undergo serial MRIs and biopsies with information on the likelihood of them achieving a pathologic complete response (pCR) provided back in real time, which will then allow for therapy escalation or de-escalation. The goal here is individualized precision therapy based on the specific intrinsic subtype of the tumor itself and response with the ultimate goal being to achieve a pCR (5).

Again, this is a very exciting time for us as medical providers and our patients because new therapies are being developed and studied in clinical trials every day.

- Schmid P, Cortes J, Dent R, et al; KEYNOTE-522 Investigators. Event-free Survival with Pembrolizumab in Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(6):556-567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2112651.

- Masuda N, Lee SJ, Ohtani S, et al. Adjuvant Capecitabine for Breast Cancer after Preoperative Chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(22):2147-2159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1612645.

- Tutt ANJ, Garber JE, Kaufman B, et al; OlympiA Clinical Trial Steering Committee and Investigators. Adjuvant Olaparib for Patients with BRCA1- or BRCA2-Mutated Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(25):2394-2405. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2105215.

- Adjuvant Therapy with an Alpha-lactalbumin Vaccine in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04674306.

- I-SPY TRIAL: Neoadjuvant and Personalized Adaptive Novel Agents to Treat Breast Cancer (I-SPY). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01042379.

- Schmid P, Cortes J, Dent R, et al; KEYNOTE-522 Investigators. Event-free Survival with Pembrolizumab in Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(6):556-567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2112651.

- Masuda N, Lee SJ, Ohtani S, et al. Adjuvant Capecitabine for Breast Cancer after Preoperative Chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(22):2147-2159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1612645.

- Tutt ANJ, Garber JE, Kaufman B, et al; OlympiA Clinical Trial Steering Committee and Investigators. Adjuvant Olaparib for Patients with BRCA1- or BRCA2-Mutated Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(25):2394-2405. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2105215.

- Adjuvant Therapy with an Alpha-lactalbumin Vaccine in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04674306.

- I-SPY TRIAL: Neoadjuvant and Personalized Adaptive Novel Agents to Treat Breast Cancer (I-SPY). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01042379.

Treating High-Risk, Early-Stage HR+/HER2- Breast Cancer

Many patients with early-stage HR+/HER2- breast cancer are at high risk for disease recurrence within just a few years of first-line treatment. In this ReCAP, Michelle Melisko, MD, of the University of San Francisco Medical Center, discusses strategies for reducing recurrence rates in these patients.

Dr Melisko begins by identifying the traditional criteria for selecting treatment, including age, comorbidities, tumor size, and nodal status, along with proper utilization of genomic assays. She notes that the RxPONDER and TAILORx trials have demonstrated benefits of chemotherapy plus endocrine therapy in premenopausal patients on the basis of Oncotype DX recurrence scores between 0 and 25.

Next, Dr Melisko discusses how the 2021 FDA approval of abemaciclib plus endocrine therapy in the adjuvant setting mandates that patients have a Ki-67 score of 20%. This is a more restrictive patient population than those who saw benefit in the monarchE clinical trial and presents a challenge for physicians selecting therapy for their patients.

Dr Melisko concludes by sharing 3-year data from the OlympiA trial supporting the use of olaparib in patients with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, as well as findings from the SOFT/TEXT trials that demonstrated the benefit of ovarian suppression in younger patients.

--

Michelle E. Melisko, MD, Associate Clinical Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Hematology-Oncology, University of San Francisco Medical Center; UCSF Bakar Precision Cancer Medicine, San Francisco, California

Michelle E. Melisko, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Many patients with early-stage HR+/HER2- breast cancer are at high risk for disease recurrence within just a few years of first-line treatment. In this ReCAP, Michelle Melisko, MD, of the University of San Francisco Medical Center, discusses strategies for reducing recurrence rates in these patients.

Dr Melisko begins by identifying the traditional criteria for selecting treatment, including age, comorbidities, tumor size, and nodal status, along with proper utilization of genomic assays. She notes that the RxPONDER and TAILORx trials have demonstrated benefits of chemotherapy plus endocrine therapy in premenopausal patients on the basis of Oncotype DX recurrence scores between 0 and 25.

Next, Dr Melisko discusses how the 2021 FDA approval of abemaciclib plus endocrine therapy in the adjuvant setting mandates that patients have a Ki-67 score of 20%. This is a more restrictive patient population than those who saw benefit in the monarchE clinical trial and presents a challenge for physicians selecting therapy for their patients.

Dr Melisko concludes by sharing 3-year data from the OlympiA trial supporting the use of olaparib in patients with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, as well as findings from the SOFT/TEXT trials that demonstrated the benefit of ovarian suppression in younger patients.

--

Michelle E. Melisko, MD, Associate Clinical Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Hematology-Oncology, University of San Francisco Medical Center; UCSF Bakar Precision Cancer Medicine, San Francisco, California

Michelle E. Melisko, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Many patients with early-stage HR+/HER2- breast cancer are at high risk for disease recurrence within just a few years of first-line treatment. In this ReCAP, Michelle Melisko, MD, of the University of San Francisco Medical Center, discusses strategies for reducing recurrence rates in these patients.

Dr Melisko begins by identifying the traditional criteria for selecting treatment, including age, comorbidities, tumor size, and nodal status, along with proper utilization of genomic assays. She notes that the RxPONDER and TAILORx trials have demonstrated benefits of chemotherapy plus endocrine therapy in premenopausal patients on the basis of Oncotype DX recurrence scores between 0 and 25.

Next, Dr Melisko discusses how the 2021 FDA approval of abemaciclib plus endocrine therapy in the adjuvant setting mandates that patients have a Ki-67 score of 20%. This is a more restrictive patient population than those who saw benefit in the monarchE clinical trial and presents a challenge for physicians selecting therapy for their patients.

Dr Melisko concludes by sharing 3-year data from the OlympiA trial supporting the use of olaparib in patients with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, as well as findings from the SOFT/TEXT trials that demonstrated the benefit of ovarian suppression in younger patients.

--

Michelle E. Melisko, MD, Associate Clinical Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Hematology-Oncology, University of San Francisco Medical Center; UCSF Bakar Precision Cancer Medicine, San Francisco, California

Michelle E. Melisko, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Neurotransmitter-based diagnosis and treatment: A hypothesis (Part 1)

It is unfortunate that, in some clinical areas, medical conditions are still treated by name and not based on the underlying pathological process. It would be odd in 2022 to treat “dropsy” instead of heart or kidney disease (2 very different causes of edema). Similarly, if the FDA had been approving drugs 150 years ago, we would have medications on label for “dementia praecox,” not schizophrenia or Alzheimer disease. With the help of DSM-5, psychiatry still resides in the descriptive symptomatic world of disorders.

In the United States, thanks to Freud, psychiatric symptoms became separated from medical symptoms, which made it more difficult to associate psychiatric manifestations with the underlying pathophysiology. Though the physical manifestations that parallel emotional symptoms—such as the dry mouth of anxiety, the tremor and leg weakness of fear, the constipation and blurry vision of depression, the breathing difficulty of anger, the abdominal pain of stress, the blushing of shyness, the palpitations of flashbacks, and endless others—are well known, the present classification of psychiatric disorders is blind to it. Neurochemical causes of gastrointestinal spasm or muscle tension are better researched than underlying central neurochemistry, though the same neurotransmitters drive them.

Can the biochemistry of psychiatric symptoms be judged on the basis of peripheral symptoms? Can the mental manifestations be connected to biological causation, and vice versa? Would psychiatrists be better off selecting treatments by recognizing involved neurotransmitters instead of addressing descriptive “depression, anxiety, and psychosis”? Each of these clinical syndromes may be caused by entirely different underlying neuronal mechanisms. Such mechanisms could be suggested if medical symptoms (which are measurable and objective) would become part of the psychiatric diagnosis. Is treating the “cough” sufficient, or would recognition that tuberculosis caused the cough guide better treatment? Is it time to abandon descriptive conditions and replace them with a specific “mechanism-based” viewpoint?

Ample research has shown that serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine, endorphins, glutamate, and gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) are the neurotransmitters most responsible in the process of both psychiatric disorders and chronic pain. These neurotransmitters are involved in much more than emotions (including the feeling of pain). An abundance of medical symptom clusters point toward which neurotransmitter dysfunction may be leading in specific cases of distinct types of depression, psychosis, anxiety, or “chronic pain.” Even presently, there are medications available (both for FDA-approved indications and off-label) that can be used to regulate these neurotransmitters, allowing practitioners to target the possible biological underlining of psychiatric or pain pathology. Hopefully, in the not-so-distant future, there will be specific medications for serotonin, dopamine, and noradrenergic depression as well as for GABAergic anxiety, endorphin psychosis, noradrenergic insomnia, and similar conditions.

Numerous neurotransmitters may be connected to both depression and pain in all their forms. These include (but are not limited to) prostaglandins, bradykinins, substance P, potassium, magnesium, calcium, histamine, adenosine triphosphate, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), nitric oxide (NO), cholecystokinin 7 (CCK7), neurotrophic growth factor (NGF), neurotensin, acetylcholine (Ach), oxytocin, cannabinoids, and others. These have not been researched sufficiently to identify their clinical presentation of excessive or insufficient availability at the sites of neurotransmission. It is difficult to draw conclusions about what kind of clinical symptoms they may cause (outside of pain), and therefore, they are not addressed in this article.

Both high and low levels of certain neurotransmitters may be associated with psychiatric conditions and chronic pain. Too much is as bad as too little.1 This applies to both quantity of neurotransmitters as well as quality of the corresponding receptor activity. An astute clinician may judge which neurotransmitter is dysfunctional based on the patient’s presentation. Reading indirect signs of bodily functions is a basic clinical skill that should not be forgotten, even in the time of advanced technology.

A different way of viewing psychiatric disorders

In this article, we present 4 hypothetical clinical cases to emphasize a possible way of analyzing symptoms to identify underlying pathology and guide more effective treatment. In no way do these descriptions reflect the entire set of symptoms caused by neurotransmitters; we created them based on what is presently known or suspected, and extensive research is required to confirm or disprove what we describe here.

Continue to: There are no well-recognized...

There are no well-recognized, well-established, reliable, or validated syndromes described in our work. Our goal is to suggest an alternative way of looking at psychiatric disorders by viewing syndromal presentation through the lens of specific neurotransmitters. The collection of symptoms associated with various neurotransmitters as presented in this hypothesis is not complete. We have assembled what is described in the literature as a suggestion for specific future research. We simplified these clinical presentations by omitting scenarios in which a specific neurotransmitter increases in one area but not another. For example, all the symptoms of dopamine excess we describe would not have to occur concurrently in the same patient, but they may develop in certain patients depending on which dopaminergic pathway is exhibiting excess activity. Such distinctions may be established only by exhaustive research not yet conducted.

Our proposal may seem radical, but it truly is not. For example, if we know that dopamine excess may cause seizures, psychosis, and blood pressure elevation, why not consider dopamine excess as an underlying cause in a patient with depression who exhibits these symptoms simultaneously? And why not call it “dopamine excess syndrome”? We already have “serotonin syndrome” for a patient experiencing a serotonin storm. However, using the same logic, it should be called “serotonin excess syndrome.” And if we know of “serotonin excess syndrome,” why not consider “serotonin deficiency syndrome”?

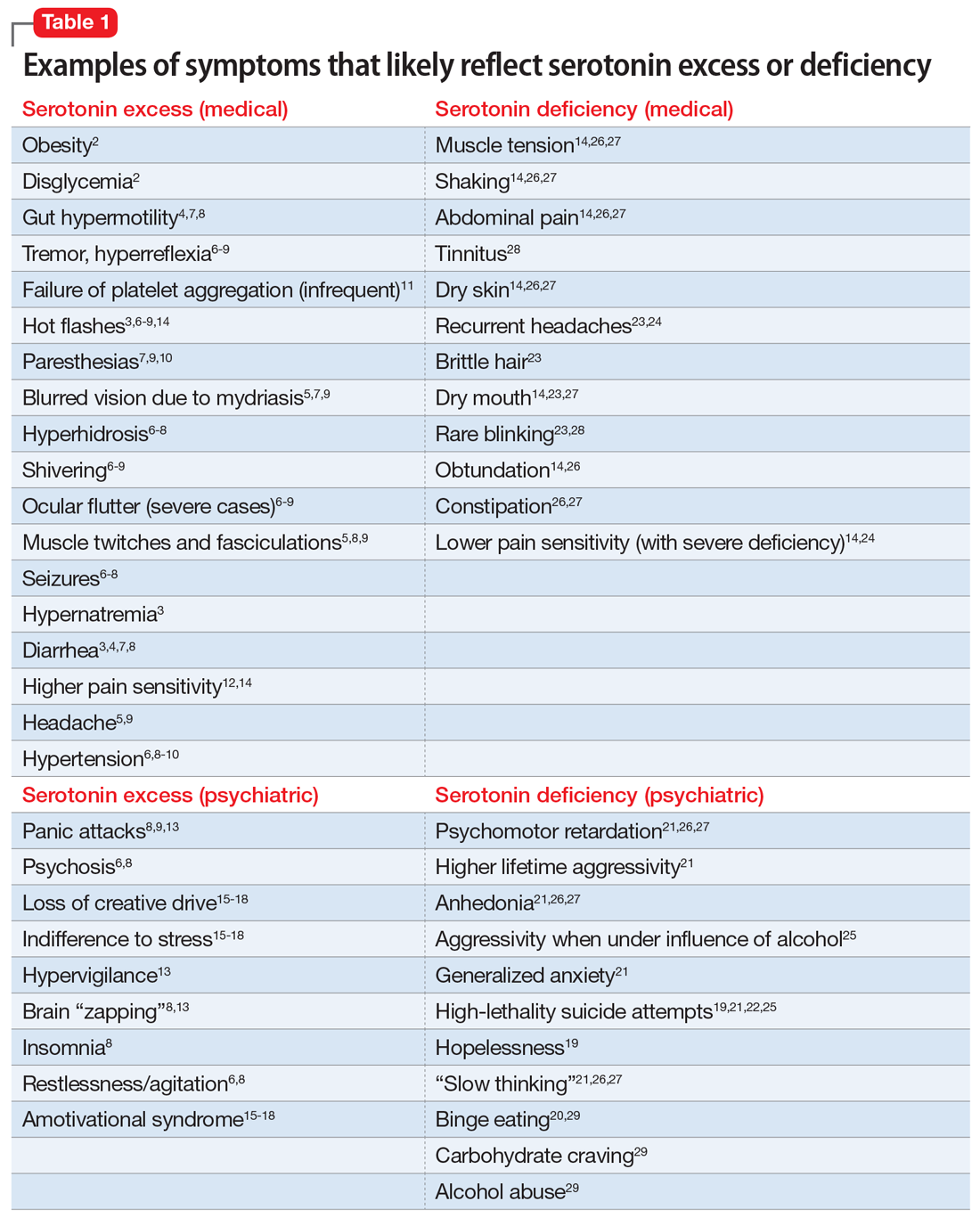

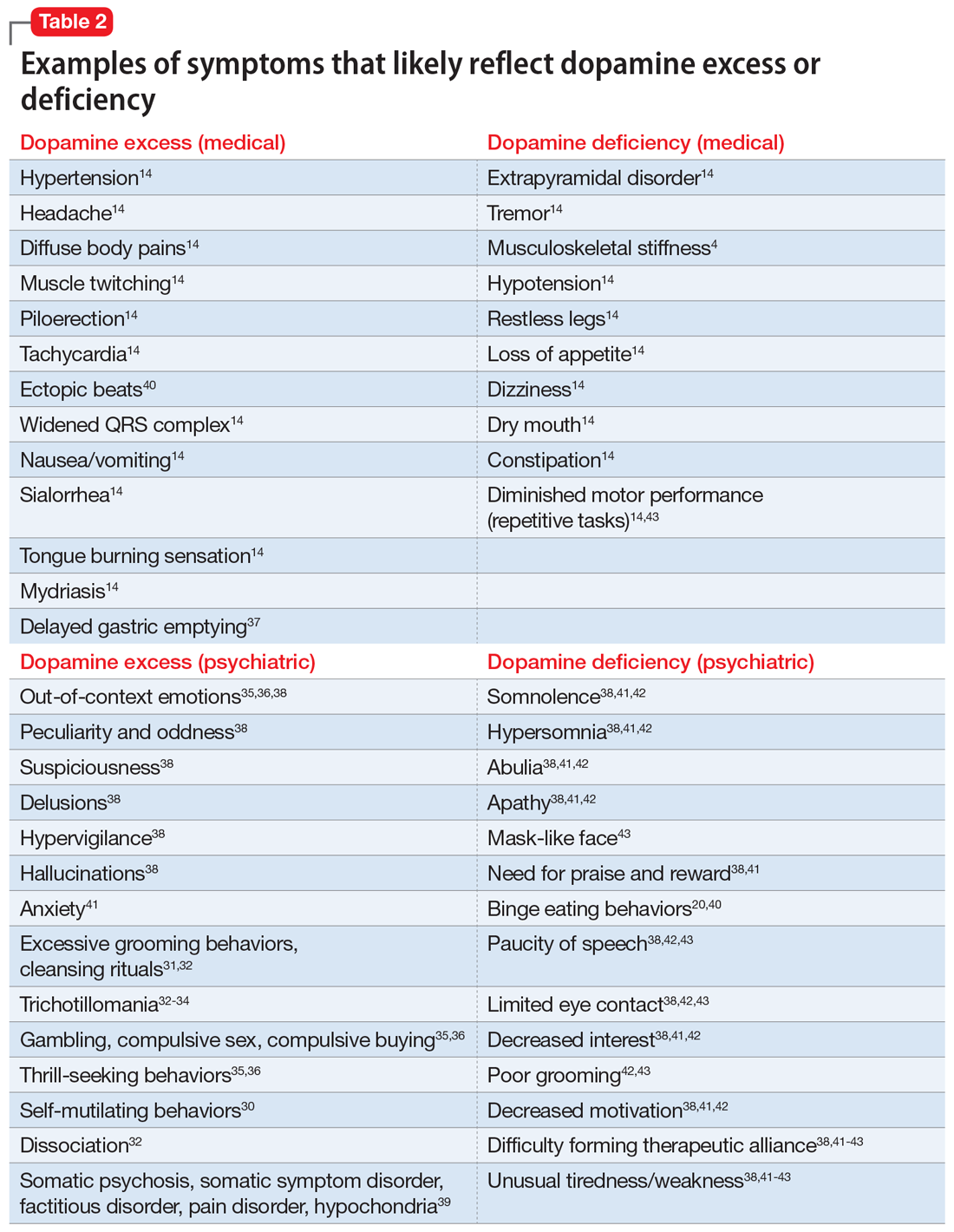

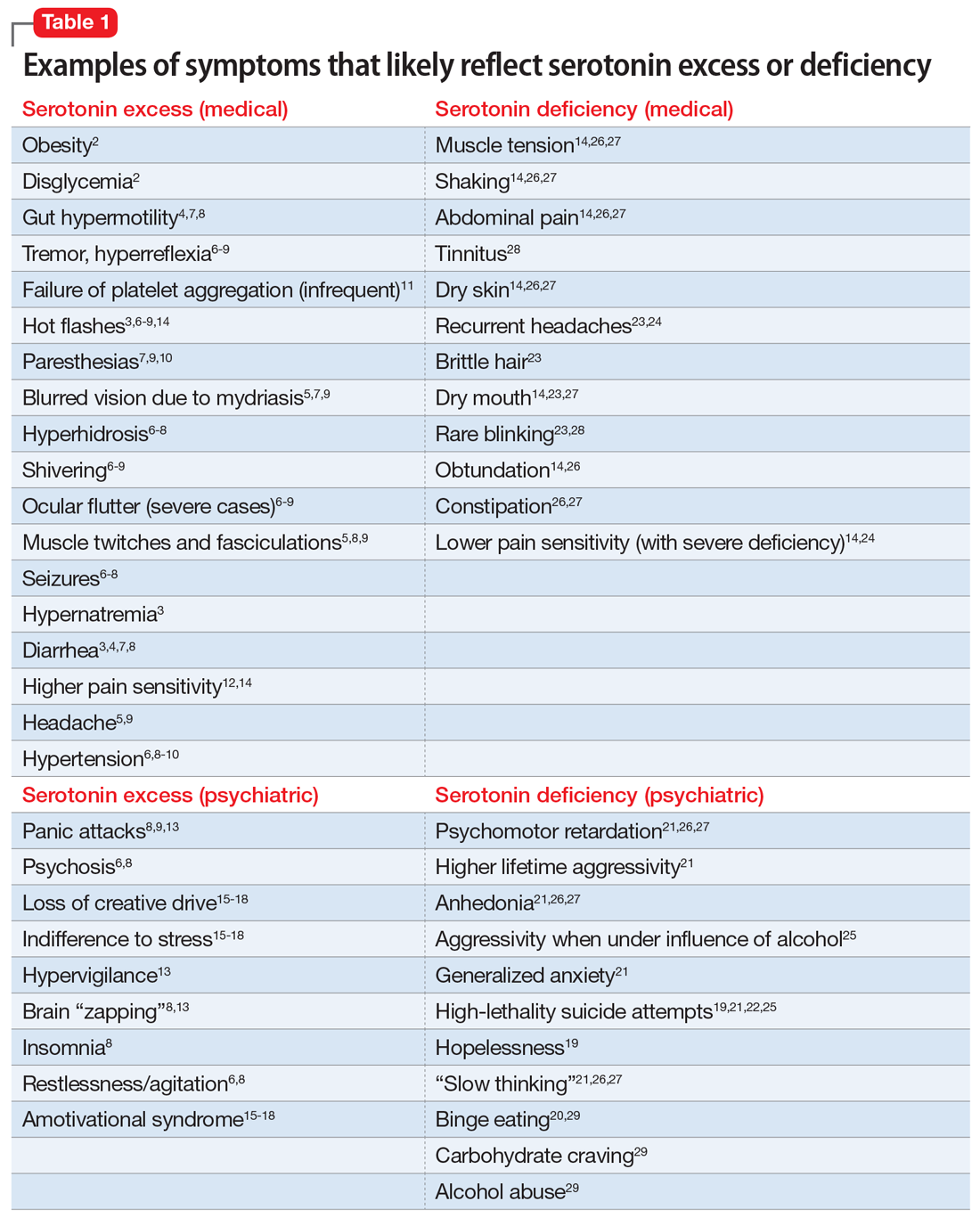

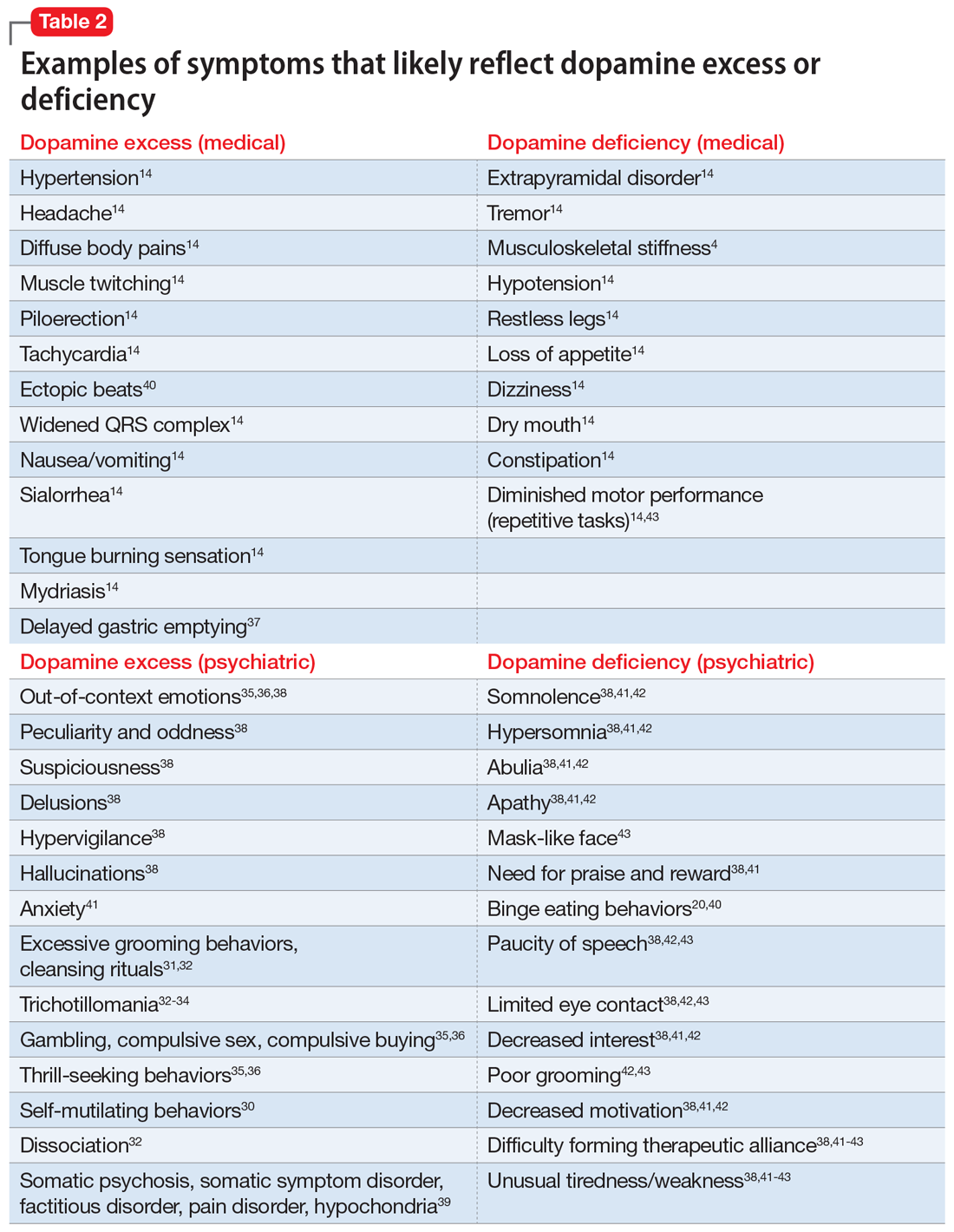

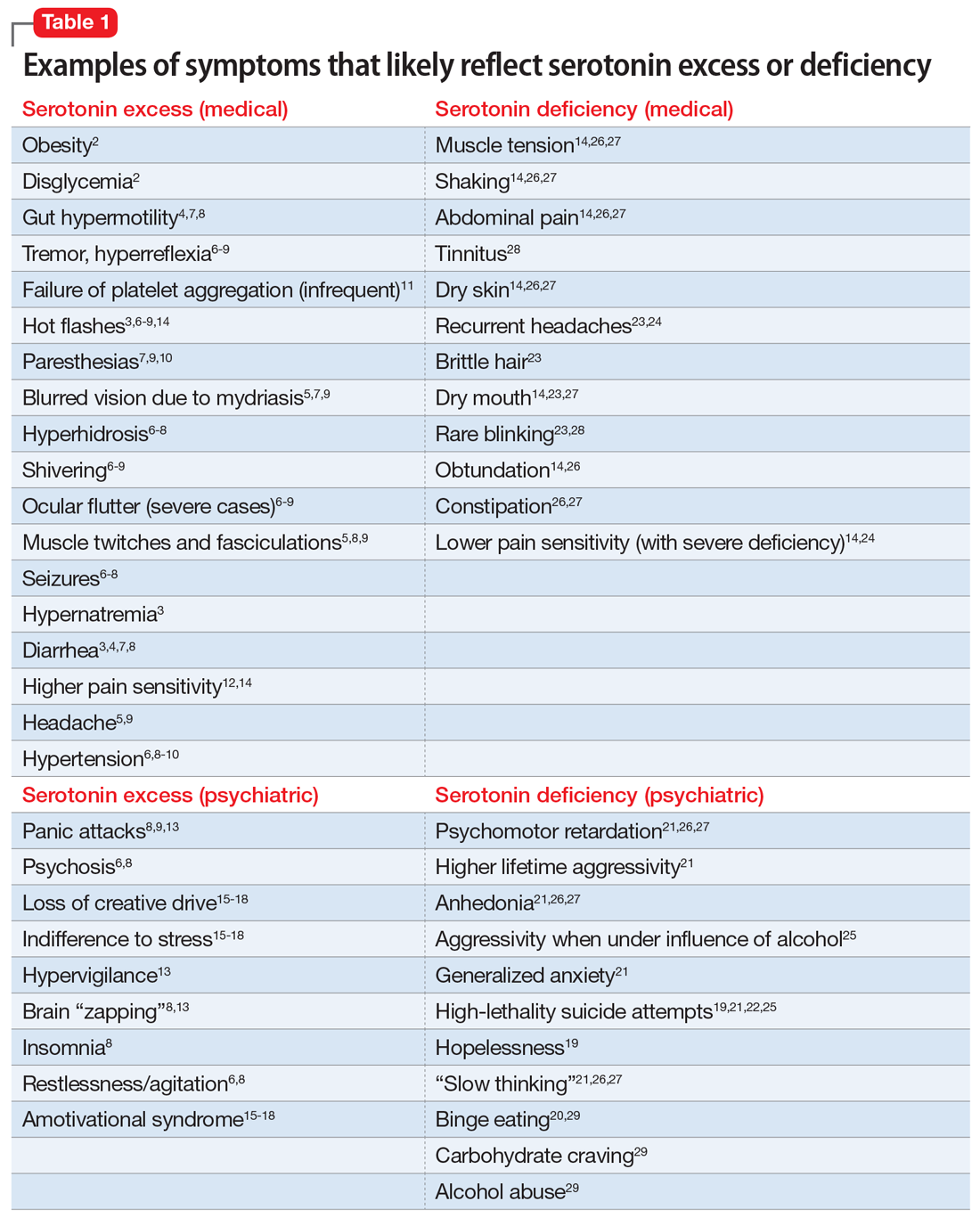

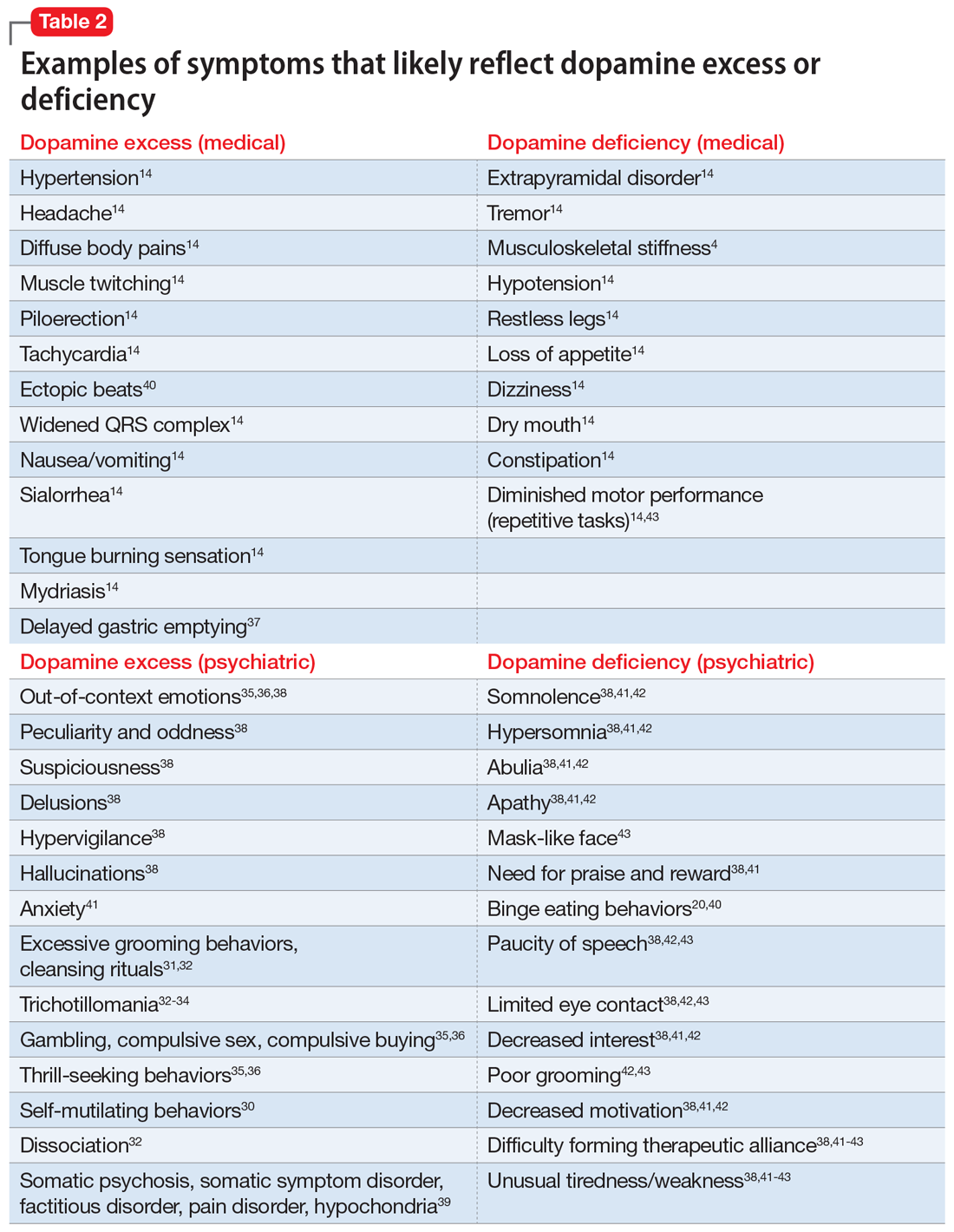

In Part 1 of this article, we discuss serotonin and dopamine. Table 1 outlines medical and psychiatric symptoms that likely reflect serotonin excess2-18 and deficiency,14,19-29 and Table 2 lists symptoms that likely reflect dopamine excess14,30-41 and deficiency.4,14,20,38,40-43 In Part 2 we will touch on endorphins and norepinephrine, and in Part 3 we will conclude by looking at GABA and glutamate.

Serotonin excess (Table 12-18)

On a recent office visit, Ms. H reports that most of the time she does not feel much of anything, but she still experiences panic attacks8,9,13,15 and is easily agitated.6,8 Her mother died recently, and Ms. H is concerned that she did not grieve.15-18 She failed her last semester in college and was indifferent to her failure.18 She sleeps poorly,8 is failing her creative classes, and wonders why she has lost her artistic inclination.16-18 Ms. H has difficulty with amotivation, planning, social interactions, and speech.16,17 All of those symptoms worsened after she was prescribed fluoxetine approximately 1 year ago for her “blues.” Ms. H is obese and continues to gain weight,2 though she frequently has diarrhea,3,4,7,8 loud peristalsis, and abdominal cramps.4,7,8 She sweats easily6-8 and her heart frequently races.8,9 Additionally, Ms. H’s primary care physician told her that she has “borderline diabetes.”2 She is prone to frequent bruising11 and is easy to shake, even when she is experiencing minimal anxiety.6-9 Ms. H had consulted with a neurologist because of unusual electrical “zapping” in her brain and muscle twitches.5,8,9,13 She had experienced a seizure as a child, but this was possibly related to hypernatremia,2 and she has not taken any anticonvulsant medication for several years.8 She exhibits hyperactive deep tendon reflexes and tremors5,7,9 and blinks frequently.6,9 She experiences hot flashes,3,6-8,14 does not tolerate heat, and prefers cooler weather.8,9 Her pains and aches,12,14 to which she has been prone all of her life, have recently become much worse, and she was diagnosed with fibromyalgia in part because she frequently feels stiff all over.10 She complains of strange tingling and prickling sensations in her hands and feet, especially when anxious.7,9,10 Her headaches also worsened and may be precipitated by bright light, as her pupils are usually dilated.5,7,9 Her hypertension is fairly controlled with medication.6,8-10 Ms. H says she experienced a psychotic episode when she was in her mid-teens,6,8 but reassures you that “she is not that bad now,” although she remains hypervigilant.13 Also while in her teens, Ms. H was treated with paroxetine and experienced restlessness, agitation, delirium, tachycardia, fluctuating blood pressure, diaphoresis, diarrhea, and neuromuscular excitation, which prompted discontinuation of the antidepressant.5-7,9,10

Impression. Ms. H exhibits symptoms associated with serotonin hyperactivity. Discontinuing and avoiding selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) would be prudent; prescribing an anticonvulsant would be reasonable. Using a GABAergic medication to suppress serotonin (eg, baclofen) is likely to help. Avoiding dopaminergic medications is a must. Antidepressive antipsychotics would be logical to use. The use of serotonin-suppressing medications may be considered. One may argue for the use of beta-blockers in such a patient.

Continue to: Serotonin deficiency

Serotonin deficiency (Table 114,19-29)

Mr. A is chronically depressed, hopeless,19 and easily angered.21 He does not believe anyone can help him.19 You are concerned for his safety because he had attempted to end his life by shooting himself in the chest.19,21,22,25 Even when he’s not particularly depressed, Mr. A does not enjoy much of anything.21,26,27 He becomes particularly agitated when he drinks alcohol,25 which unfortunately is common for him.29 He engages in binge eating to feel better; he knows this is not healthy but he cannot control his behavior.20,29 Mr. A is poorly compliant with his medications, even with a blood thinner, which he was prescribed due to an episode of deep vein thrombosis. He complains of chronic daily headaches and episodic migraines.23,24 He rarely blinks,23,28 his skin is dry and cool, his hair is brittle,23 his mouth is dry,14,23,27 and he constantly licks his chapped lips.14,26,27 Mr. A frequently has general body pain26,31 but is dismissive of his body aches and completely stops reporting pain when his depression gets particularly severe. When depressed, he is slow in movement and thinking.14,21,26,27 He is more concerned with anxiety than depression.21 Mr. A is plagued by constipation, abdominal pain, muscle tension, and episodes of shaking.14,26,27 He also frequently complains about chronic tinnitus.28

Impression. Mr. A shows symptoms associated with serotonin hypoactivity. SSRIs and any other antidepressants with serotonin activity would be an obvious choice for treatment. A mood-stabilizing antipsychotic with serotonin activity would be welcome in treatment. Thyroid hormone supplementation may be of value, especially if thyroid stimulating hormone level is high. Light therapy, a diet with food that contains tryptophan, psychotherapy, and exercise are desirable. Avoiding benzodiazepines would be a good idea.

Dopamine excess (Table 214,30-41)

Ms. L presents with complaints of “fibromyalgia” and “daily headaches,”14 and also dissociation (finding herself in places when she does not know how she got there) and “out-of-body experiences.”32 She is odd, and states that people do not understand her and that she is “different.”38 Her friend, who is present at the appointment, elaborates on Ms. L’s bizarreness and oddness in behavior, out-of-context emotions, suspiciousness, paranoia, and possible hallucinations.35,36,38 Ms. L discloses frequent diffuse body pains, headaches, nausea, excessive salivation, and tongue burning, as well as muscle twitching.14 Sex worsens her headaches and body pain. She reports seizures that are not registered on EEG. In the office, she is suspicious, exhibits odd posturing, tends to misinterpret your words, and makes you feel uncomfortable. Anxiety38 and multiple obsessive-compulsive symptoms, especially excessive cleaning and grooming, complicate Ms. L’s life.31,32,34 On examination, she is hypertensive, and she has scars caused by self-cutting and skin picking on her arms.30-32 An electrocardiogram shows an elevated heart rate, widened QRS complex, and ectopic heartbeats.14 Ms. L has experienced trichotillomania since adolescence32-34 and her fingernails are bitten to the skin.34 She has difficulty with impulse control, and thrill-seeking is a prominent part of her life, mainly via gambling, compulsive sex, and compulsive buying.35,36 She also says she experiences indigestion and delayed gastric emptying.37

Impression. Ms. L exhibits multiple symptoms associated with dopamine excess. Dopamine antagonists should be considered and may help not only with her psychiatric symptoms but also with her pain symptoms. Bupropion (as a dopamine agonist), caffeine, and stimulants should be avoided.

Excessive dopamine is, in extreme cases, associated with somatic psychosis, somatic symptom disorder, factitious disorder, pain disorder, and hypochondria.39 It may come with odd and bizarre/peculiar symptoms out of proportion with objectively identified pathology. These symptoms are common in chronic pain and headache patients, and need to be addressed by appropriate use of dopamine antagonizing medications.39

Continue to: Dopamine deficiency

Dopamine deficiency (Table 24,14,20,38,40-43)

Mr. W experiences widespread pain, including chronic back pain, headaches, and abdominal pain. He also has substantial anhedonia, lack of interest, procrastination, and hypersomnia.41,42 He is apathetic and has difficulty getting up in the morning.41,42 Unusual tiredness and weakness drive him to overuse caffeine; he states that 5 Mountain Dews and 4 cups of regular coffee a day make his headaches bearable.38,41-43 Sex also improves his headaches. Since childhood, he has taken stimulants for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. He reports that occasional use of cocaine helps ease his pain and depression. Mr. W’s wife is concerned with her husband’s low sexual drive and alcohol consumption, and discloses that he has periodic trouble with gambling. Mr. W was forced into psychotherapy but never was able to work productively with his therapist.38,41-43 He loves eating and cannot control his weight.40 This contrasts with episodic anorexia he experienced when he was younger.20 His face is usually emotionless.43 Mr. W is prone to constipation.14 His restless leg syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder are so bad that his wife refuses to share a bed with him.14 He is clumsy and has a problem with repetitive motor tasks.43 A paucity of speech, limited eye contact, poor grooming, and difficulty forming therapeutic alliances have long been part of Mr. W’s history.38,42,43 On physical examination, he has a dry mouth; he is stiff, tremulous, and hypotensive.14

Impression. Mr. W shows multiple symptoms associated with dopamine deficiency. Bupropion may be reasonable to consider. Dopamine augmentation via the use of stimulants is warranted in such patients, especially if stimulants had not been tried before (lisdexamfetamine would be a good choice to minimize addictive potential). For a patient with dopamine deficiency, levodopa may improve more than just restless legs. Amantadine may improve dopaminergic signaling through the accelerated dopamine release and decrease in presynaptic uptake, so this medication may be carefully tried.44 Pain treatment would not be successful for Mr. W without simultaneous treatment for his substance use.

Bottom Line

Both high and low levels of serotonin and dopamine may be associated with certain psychiatric and medical symptoms and disorders. An astute clinician may judge which neurotransmitter is dysfunctional based on the patient’s presentation, and tailor treatment accordingly.

Related Resources

- Abell SR, El-Mallakh RS. Serotonin-mediated anxiety: How to recognize and treat it. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):37-40. doi:10.12788/cp.0168

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Gocovri

Baclofen • Ozobax

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Paroxetine • Paxil

1. Stahl SM. Dazzled by the dominions of dopamine: clinical roles of D3, D2, and D1 receptors. CNS Spectr. 2017;22(4):305-311.

2. Young RL, Lumsden AL, Martin AM, et al. Augmented capacity for peripheral serotonin release in human obesity. Int J Obes (Lond). 2018;42(11):1880-1889.

3. Ahlman H. Serotonin and carcinoid tumors. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1985;7(Suppl 7):S79-S85.

4. Terry N, Margolis KG. Serotonergic mechanisms regulating the GI tract: experimental evidence and therapeutic relevance. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2017;239:319-342.

5. Prakash S, Belani P, Trivedi A. Headache as a presenting feature in patients with serotonin syndrome: a case series. Cephalalgia. 2014;34(2):148-153.

6. van Ewijk CE, Jacobs GE, Girbes ARJ. Unsuspected serotonin toxicity in the ICU. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6(1):85.

7. Pedavally S, Fugate JE, Rabinstein AA. Serotonin syndrome in the intensive care unit: clinical presentations and precipitating medications. Neurocrit Care. 2014;21(1):108-113.

8. Nguyen H, Pan A, Smollin C, et al. An 11-year retrospective review of cyproheptadine use in serotonin syndrome cases reported to the California Poison Control System. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2019;44(2):327-334.

9. Ansari H, Kouti L. Drug interaction and serotonin toxicity with opioid use: another reason to avoid opioids in headache and migraine treatment. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016;20(8):50.

10. Ott M, Mannchen JK, Jamshidi F, et al. Management of severe arterial hypertension associated with serotonin syndrome: a case report analysis based on systematic review techniques. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2019;9:2045125318818814. doi:10.1177/2045125318818814

11. Cerrito F, Lazzaro MP, Gaudio E, et al. 5HT2-receptors and serotonin release: their role in human platelet aggregation. Life Sci. 1993;53(3):209-215.

12. Ohayon MM. Pain sensitivity, depression, and sleep deprivation: links with serotoninergic dysfunction. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43(16):1243-1245.

13. Maron E, Shlik J. Serotonin function in panic disorder: important, but why? Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(1):1-11.

14. Hall JE, Guyton AC. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 12th ed. Spanish version. Elsevier; 2011:120,199,201-204,730-740.

15. Garland EJ, Baerg EA. Amotivational syndrome associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2001;11(2):181-186.

16. George MS, Trimble MR. A fluvoxamine-induced frontal lobe syndrome in a patient with comorbid Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome and obsessive compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1992;53(10):379-380.

17. Hoehn-Saric R, Harris GJ, Pearlson GD, et al. A fluoxetine-induced frontal lobe syndrome in an obsessive compulsive patient. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52(3):131-133.

18. Hoehn-Saric R, Lipsey JR, McLeod DR. Apathy and indifference in patients on fluvoxamine and fluoxetine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1990;10(5):343-345.

19. Samuelsson M, Jokinen J, Nordström AL, et al. CSF 5-HIAA, suicide intent and hopelessness in the prediction of early suicide in male high-risk suicide attempters. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(1):44-47.

20. Brewerton TD. Clinical Handbook of Eating Disorders: An Integrated Approach. CRC Press; 2004:257-281.

21. Mann JJ, Oquendo M, Underwood MD, et al. The neurobiology of suicide risk: a review for the clinician. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60 Suppl 2:7-116.

22. Mann JJ, Malone KM. Cerebrospinal fluid amines and higher-lethality suicide attempts in depressed inpatients. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41(2):162-171.

23. Joseph R, Welch KM, D’Andrea G. Serotonergic hypofunction in migraine: a synthesis of evidence based on platelet dense body dysfunction. Cephalalgia. 1989;9(4):293-299.

24. Pakalnis A, Splaingard M, Splaingard D, et al. Serotonin effects on sleep and emotional disorders in adolescent migraine. Headache. 2009;49(10):1486-1492.

25. Virkkunen M, Goldman D, Nielsen DA, et al. Low brain serotonin turnover rate (low CSF 5-HIAA) and impulsive violence. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1995;20(4):271-275.

26. Liu Y, Zhao J, Fan X, et al. Dysfunction in serotonergic and noradrenergic systems and somatic symptoms in psychiatric disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:286.

27. Ginsburg GS, Riddle MA, Davies M. Somatic symptoms in children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(10):1179-1187.

28. O’Malley PG, Jackson JL, Santoro J, et al. Antidepressant therapy for unexplained symptoms and symptom syndromes. J Fam Pract. 1999;48(12):980-990.

29. Fortuna JL. Sweet preference, sugar addiction and the familial history of alcohol dependence: shared neural pathways and genes. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2010;42(2):147-151.

30. Stanley B, Sher L, Wilson S, et al. Non-suicidal self-injurious behavior, endogenous opioids and monoamine neurotransmitters. J Affect Disord. 2010;124(1-2):134-140.

31. Graybiel AM, Saka E. A genetic basis for obsessive grooming. Neuron. 2002;33(1):1-2.

32. Tse W, Hälbig TD. Skin picking in Parkinson’s disease: a behavioral side-effect of dopaminergic treatment? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;64(2):214.

33. Ayaydın H. Probable emergence of symptoms of trichotillomania by atomoxetine: a case report. Psychiatry and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2019;29(2)220-222.

34. Paholpak P, Mendez MF. Trichotillomania as a manifestation of dementia. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2016;2016:9782702. doi:10.1155/2016/9782702

35. Clark CA, Dagher A. The role of dopamine in risk taking: a specific look at Parkinson’s disease and gambling. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:196.

36. Norbury A, Husain M. Sensation-seeking: dopaminergic modulation and risk for psychopathology. Behav Brain Res. 2015;288:79-93.

37. Chen TS, Chang FY. Elevated serum dopamine increases while coffee consumption decreases the occurrence of reddish streaks in the intact stomach. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(12):1810-1814.

38. Wong-Riley MT. Neuroscience Secrets. 1st edition. Spanish version. Hanley & Belfus; 1999:420-429.

39. Arbuck DM. Antipsychotics, dopamine, and pain. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):25-29,31.

40. Bello NT, Hajnal A. Dopamine and binge eating behaviors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;97(1):25-33.

41. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al; Expert Consensus Panel on Adherence Problems in Serious and Persistent Mental Illness. The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70 Suppl 4:1-46.

42. Milev P, Ho BC, Arndt S, et al. Predictive values of neurocognition and negative symptoms on functional outcome in schizophrenia: a longitudinal first-episode study with 7-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(3):495-506.

43. Gepshtein S, Li X, Snider J, et al. Dopamine function and the efficiency of human movement. J Cogn Neurosci. 2014;26(3):645-657.

44. Scarff JR. The ABCDs of treating tardive dyskinesia. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(4):21,55.

It is unfortunate that, in some clinical areas, medical conditions are still treated by name and not based on the underlying pathological process. It would be odd in 2022 to treat “dropsy” instead of heart or kidney disease (2 very different causes of edema). Similarly, if the FDA had been approving drugs 150 years ago, we would have medications on label for “dementia praecox,” not schizophrenia or Alzheimer disease. With the help of DSM-5, psychiatry still resides in the descriptive symptomatic world of disorders.