User login

Loneliness: How psychiatry can help

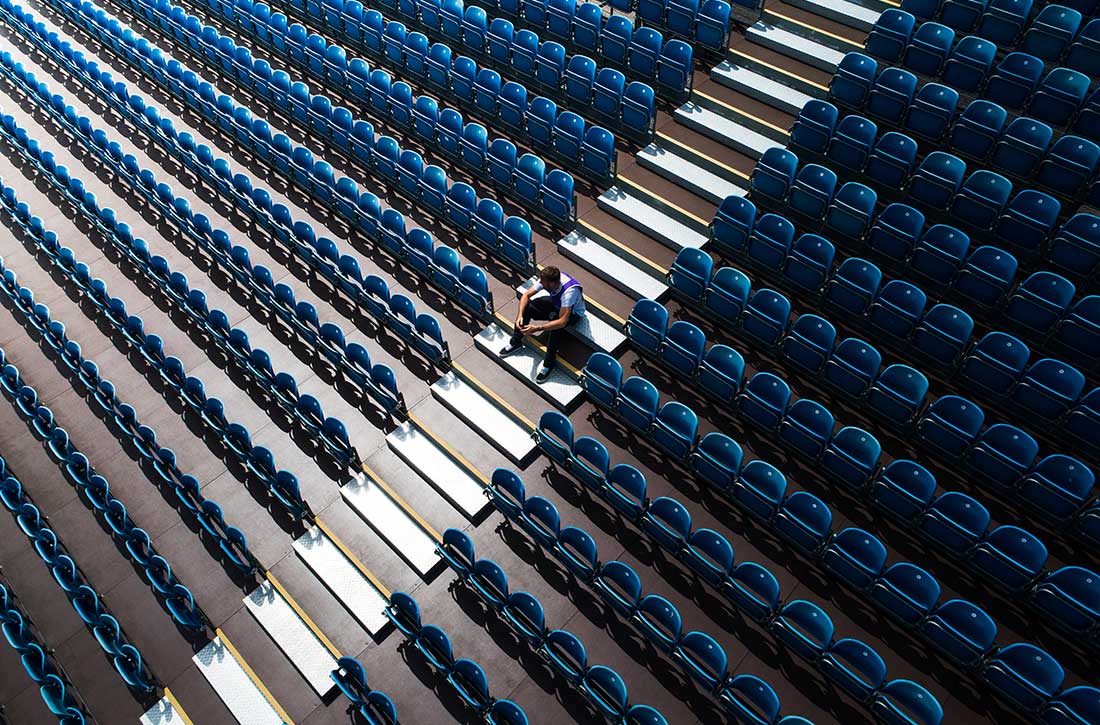

Loneliness is distress that occurs when the quality or quantity of social relationships are less than desired.1 It is a symptom of many psychiatric disorders, and can lead to multiple negative health consequences, including depression, sleep deprivation, executive dysfunction, accelerated cognitive decline, and hypertension. Loneliness can increase the likelihood of immunocompromising conditions, including (but not limited to) stroke, anxiety, and depression, resulting in frequent emergency department visits and costly health expenses.2 Up to 80% of individuals younger than age 18 and 40% of adults older than age 65 report being lonely at least sometimes, with levels of loneliness gradually diminishing during middle age and then increasing in older adults.1 Loneliness is such a common and pervasive problem that in 2017, the government of the United Kingdom created a commission on loneliness and developed a Minister of Loneliness to find solutions to reduce it.3 In this article, I discuss the detrimental impact loneliness can have on our patients, and steps we can take to address it.

What contributes to loneliness?

Most people prefer the company of others, but some psychiatric disorders can cause individuals to become antisocial. For example, patients with schizoid personality disorder avoid social activities and interaction with others. Other patients may want to form bonds with others but their psychiatric disorder hinders this. For example, those with paranoia and social anxiety may avoid interacting with people due to their mistrust of others or their actions. Patients with substance use disorders can drive away those closest to them and lose familial bonds as a result of their behaviors. Patients with depression might not have the energy to pursue relationships and often have faulty cognitive patterns that lead them to believe they are unloved and unwanted.

Situational factors play a significant role in feelings of loneliness. Loss of a job or friends, ending a relationship, death of a loved one, or social isolation as experienced by COVID-19 or other illnesses can lead to loneliness. Social factors such as lack of income or transportation can make it difficult to attend or take part in social activities and events.

Some patients with dementia express feeling lonely, even after a visit from loved ones, because they forget the visit occurred. Nursing home residents often experience loneliness. Children may feel lonely after being subjected to bullying. College students, especially freshmen who are away from home for the first time, report significant levels of loneliness. Members of the LGBTQ+ community are often lonely due to familial rejection, prejudice, and religious beliefs. Anyone can experience loneliness, even married individuals if the marriage is unsatisfying.

What can psychiatry do to help?

Fortunately, psychiatric clinicians can play a large role in helping patients with loneliness.

Assessment. Ask the patient about the status of their present relationships and if they are feeling lonely. If yes, ask additional questions to identify possible causes. Are there conflicts that can be resolved? Is there abuse? What do they believe is the cause of their loneliness, and what might be the solution? How would their life be different if they weren’t lonely?

Treatment. When indicated, pharmacologic interventions might relieve symptoms that interfere with relationships and social interactions. For example, several types of antidepressants can improve mood and reduce anxiety, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may relieve panic symptoms. Benzodiazepines and beta-blockers can reduce symptoms of social anxiety. Antipsychotics can reduce paranoia. Stimulants can aid patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder by improving their ability to interact with others.

Continue to: Psychotherapy and counseling...

Psychotherapy and counseling can specifically target loneliness. Solution-focused therapy, for example, involves solving the problem by deciding which actions the patient needs to take to relieve symptoms of loneliness. Dialectal behavior therapy can help patients with borderline and other personality disorders regulate their emotions and accept their feelings. Cognitive therapy and rational emotive therapy use various techniques to assist patients in changing their negative thought patterns. For example, a therapist might assign a patient to introduce themselves to a stranger or attend an event with others. The assignment is then discussed at the next session. Client-centered, psychodynamic, and behavior therapies also may be appropriate for a patient experiencing loneliness. Positive psychology can aid patients by helping them appreciate and not discount others in their lives. Meditation and mindfulness can motivate individuals to live in the present and enjoy those around them.

Referral and psychosocial support can be offered to direct patients to social services for help in improving their living circumstances. For example, a patient with an alcohol use disorder may benefit from a referral to a self-help organization such as Alcoholics Anonymous, where they can receive additional support and develop friendships. Other resources might offer patients the ability to discuss solutions, such as the benefits of owning a pet, attending a class, or volunteering opportunities, to combat loneliness.

Living a purposeful life is essential to engaging with others and avoiding isolation. Many people have turned to online support rooms, chat rooms, gaming, and social media to maintain relationships and meet others. Excessive computer use can be detrimental, however, if used in a manner that doesn’t involve interaction with others.

Regardless of the specific intervention, psychiatrists and other psychiatric clinicians can play a major role in reducing a patient’s loneliness. Simply by being present, you are showing the patient that at least one person in their life listens and cares.

1. Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40(2):218-227.

2. Pimlott N. The ministry of loneliness. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64(3):166.

3. Leach N. The health consequences of loneliness. Causes and health consequences of being lonely. 2020. Accessed March 24, 2022. https://www.awpnow.com/main/2020/02/04/the-health-consequences-of-loneliness/

Loneliness is distress that occurs when the quality or quantity of social relationships are less than desired.1 It is a symptom of many psychiatric disorders, and can lead to multiple negative health consequences, including depression, sleep deprivation, executive dysfunction, accelerated cognitive decline, and hypertension. Loneliness can increase the likelihood of immunocompromising conditions, including (but not limited to) stroke, anxiety, and depression, resulting in frequent emergency department visits and costly health expenses.2 Up to 80% of individuals younger than age 18 and 40% of adults older than age 65 report being lonely at least sometimes, with levels of loneliness gradually diminishing during middle age and then increasing in older adults.1 Loneliness is such a common and pervasive problem that in 2017, the government of the United Kingdom created a commission on loneliness and developed a Minister of Loneliness to find solutions to reduce it.3 In this article, I discuss the detrimental impact loneliness can have on our patients, and steps we can take to address it.

What contributes to loneliness?

Most people prefer the company of others, but some psychiatric disorders can cause individuals to become antisocial. For example, patients with schizoid personality disorder avoid social activities and interaction with others. Other patients may want to form bonds with others but their psychiatric disorder hinders this. For example, those with paranoia and social anxiety may avoid interacting with people due to their mistrust of others or their actions. Patients with substance use disorders can drive away those closest to them and lose familial bonds as a result of their behaviors. Patients with depression might not have the energy to pursue relationships and often have faulty cognitive patterns that lead them to believe they are unloved and unwanted.

Situational factors play a significant role in feelings of loneliness. Loss of a job or friends, ending a relationship, death of a loved one, or social isolation as experienced by COVID-19 or other illnesses can lead to loneliness. Social factors such as lack of income or transportation can make it difficult to attend or take part in social activities and events.

Some patients with dementia express feeling lonely, even after a visit from loved ones, because they forget the visit occurred. Nursing home residents often experience loneliness. Children may feel lonely after being subjected to bullying. College students, especially freshmen who are away from home for the first time, report significant levels of loneliness. Members of the LGBTQ+ community are often lonely due to familial rejection, prejudice, and religious beliefs. Anyone can experience loneliness, even married individuals if the marriage is unsatisfying.

What can psychiatry do to help?

Fortunately, psychiatric clinicians can play a large role in helping patients with loneliness.

Assessment. Ask the patient about the status of their present relationships and if they are feeling lonely. If yes, ask additional questions to identify possible causes. Are there conflicts that can be resolved? Is there abuse? What do they believe is the cause of their loneliness, and what might be the solution? How would their life be different if they weren’t lonely?

Treatment. When indicated, pharmacologic interventions might relieve symptoms that interfere with relationships and social interactions. For example, several types of antidepressants can improve mood and reduce anxiety, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may relieve panic symptoms. Benzodiazepines and beta-blockers can reduce symptoms of social anxiety. Antipsychotics can reduce paranoia. Stimulants can aid patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder by improving their ability to interact with others.

Continue to: Psychotherapy and counseling...

Psychotherapy and counseling can specifically target loneliness. Solution-focused therapy, for example, involves solving the problem by deciding which actions the patient needs to take to relieve symptoms of loneliness. Dialectal behavior therapy can help patients with borderline and other personality disorders regulate their emotions and accept their feelings. Cognitive therapy and rational emotive therapy use various techniques to assist patients in changing their negative thought patterns. For example, a therapist might assign a patient to introduce themselves to a stranger or attend an event with others. The assignment is then discussed at the next session. Client-centered, psychodynamic, and behavior therapies also may be appropriate for a patient experiencing loneliness. Positive psychology can aid patients by helping them appreciate and not discount others in their lives. Meditation and mindfulness can motivate individuals to live in the present and enjoy those around them.

Referral and psychosocial support can be offered to direct patients to social services for help in improving their living circumstances. For example, a patient with an alcohol use disorder may benefit from a referral to a self-help organization such as Alcoholics Anonymous, where they can receive additional support and develop friendships. Other resources might offer patients the ability to discuss solutions, such as the benefits of owning a pet, attending a class, or volunteering opportunities, to combat loneliness.

Living a purposeful life is essential to engaging with others and avoiding isolation. Many people have turned to online support rooms, chat rooms, gaming, and social media to maintain relationships and meet others. Excessive computer use can be detrimental, however, if used in a manner that doesn’t involve interaction with others.

Regardless of the specific intervention, psychiatrists and other psychiatric clinicians can play a major role in reducing a patient’s loneliness. Simply by being present, you are showing the patient that at least one person in their life listens and cares.

Loneliness is distress that occurs when the quality or quantity of social relationships are less than desired.1 It is a symptom of many psychiatric disorders, and can lead to multiple negative health consequences, including depression, sleep deprivation, executive dysfunction, accelerated cognitive decline, and hypertension. Loneliness can increase the likelihood of immunocompromising conditions, including (but not limited to) stroke, anxiety, and depression, resulting in frequent emergency department visits and costly health expenses.2 Up to 80% of individuals younger than age 18 and 40% of adults older than age 65 report being lonely at least sometimes, with levels of loneliness gradually diminishing during middle age and then increasing in older adults.1 Loneliness is such a common and pervasive problem that in 2017, the government of the United Kingdom created a commission on loneliness and developed a Minister of Loneliness to find solutions to reduce it.3 In this article, I discuss the detrimental impact loneliness can have on our patients, and steps we can take to address it.

What contributes to loneliness?

Most people prefer the company of others, but some psychiatric disorders can cause individuals to become antisocial. For example, patients with schizoid personality disorder avoid social activities and interaction with others. Other patients may want to form bonds with others but their psychiatric disorder hinders this. For example, those with paranoia and social anxiety may avoid interacting with people due to their mistrust of others or their actions. Patients with substance use disorders can drive away those closest to them and lose familial bonds as a result of their behaviors. Patients with depression might not have the energy to pursue relationships and often have faulty cognitive patterns that lead them to believe they are unloved and unwanted.

Situational factors play a significant role in feelings of loneliness. Loss of a job or friends, ending a relationship, death of a loved one, or social isolation as experienced by COVID-19 or other illnesses can lead to loneliness. Social factors such as lack of income or transportation can make it difficult to attend or take part in social activities and events.

Some patients with dementia express feeling lonely, even after a visit from loved ones, because they forget the visit occurred. Nursing home residents often experience loneliness. Children may feel lonely after being subjected to bullying. College students, especially freshmen who are away from home for the first time, report significant levels of loneliness. Members of the LGBTQ+ community are often lonely due to familial rejection, prejudice, and religious beliefs. Anyone can experience loneliness, even married individuals if the marriage is unsatisfying.

What can psychiatry do to help?

Fortunately, psychiatric clinicians can play a large role in helping patients with loneliness.

Assessment. Ask the patient about the status of their present relationships and if they are feeling lonely. If yes, ask additional questions to identify possible causes. Are there conflicts that can be resolved? Is there abuse? What do they believe is the cause of their loneliness, and what might be the solution? How would their life be different if they weren’t lonely?

Treatment. When indicated, pharmacologic interventions might relieve symptoms that interfere with relationships and social interactions. For example, several types of antidepressants can improve mood and reduce anxiety, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may relieve panic symptoms. Benzodiazepines and beta-blockers can reduce symptoms of social anxiety. Antipsychotics can reduce paranoia. Stimulants can aid patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder by improving their ability to interact with others.

Continue to: Psychotherapy and counseling...

Psychotherapy and counseling can specifically target loneliness. Solution-focused therapy, for example, involves solving the problem by deciding which actions the patient needs to take to relieve symptoms of loneliness. Dialectal behavior therapy can help patients with borderline and other personality disorders regulate their emotions and accept their feelings. Cognitive therapy and rational emotive therapy use various techniques to assist patients in changing their negative thought patterns. For example, a therapist might assign a patient to introduce themselves to a stranger or attend an event with others. The assignment is then discussed at the next session. Client-centered, psychodynamic, and behavior therapies also may be appropriate for a patient experiencing loneliness. Positive psychology can aid patients by helping them appreciate and not discount others in their lives. Meditation and mindfulness can motivate individuals to live in the present and enjoy those around them.

Referral and psychosocial support can be offered to direct patients to social services for help in improving their living circumstances. For example, a patient with an alcohol use disorder may benefit from a referral to a self-help organization such as Alcoholics Anonymous, where they can receive additional support and develop friendships. Other resources might offer patients the ability to discuss solutions, such as the benefits of owning a pet, attending a class, or volunteering opportunities, to combat loneliness.

Living a purposeful life is essential to engaging with others and avoiding isolation. Many people have turned to online support rooms, chat rooms, gaming, and social media to maintain relationships and meet others. Excessive computer use can be detrimental, however, if used in a manner that doesn’t involve interaction with others.

Regardless of the specific intervention, psychiatrists and other psychiatric clinicians can play a major role in reducing a patient’s loneliness. Simply by being present, you are showing the patient that at least one person in their life listens and cares.

1. Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40(2):218-227.

2. Pimlott N. The ministry of loneliness. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64(3):166.

3. Leach N. The health consequences of loneliness. Causes and health consequences of being lonely. 2020. Accessed March 24, 2022. https://www.awpnow.com/main/2020/02/04/the-health-consequences-of-loneliness/

1. Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40(2):218-227.

2. Pimlott N. The ministry of loneliness. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64(3):166.

3. Leach N. The health consequences of loneliness. Causes and health consequences of being lonely. 2020. Accessed March 24, 2022. https://www.awpnow.com/main/2020/02/04/the-health-consequences-of-loneliness/

A new era and a new paradox for mental health

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in Current Psychiatry. All submissions to Readers’ Forum undergo peer review and are subject to editing for length and style. For more information, contact [email protected].

As we see the end of the COVID-19 era through a collective windshield, there is hope and optimism at the exit ramps ahead of us. This unforeseen era has brought not only unprecedented change to the practice of medicine, but also a resurgent focus on the impact of medical care. The rapid adoption of telemedicine, the medical heroism lauded in the press during the early days of the pandemic, and the subsequent psychosocial impact of quarantines and lockdowns have brought increased attention to our citizens’ mental health, and not just during a crisis, but in a more holistic sense.

In fact, with the most recent annual Presidential State of the Union Address, mental health has finally received an invitation to the national agenda. This is an admirable achievement, a nod from Uncle Sam that says, “Here’s your seat at the table.” Now that we have earned this seat, have we improved our understanding of mental illness, treatment options, and our access to them? Or have we lost sight of our real challenges? Shouldn’t achieving national prominence have resulted in newfound treatments and strategies to increase access and understanding?

Instead, we are still touting the same (although perhaps nuanced) monoamine hypothesis underlying most of our conditions, as we have for decades. Vast areas of the country are out of reach of a local psychiatrist. Our treatments, largely centered on medications, though hopeful and promising at times, would fall short of the hurdle to become mainstay treatments in other medical specialties. Of course, the counterpoints are obvious: there are novel treatments (eg, ketamine, transcranial magnetic stimulation) and new understandings of glutamate and gamma aminobutyric acid systems in mood regulation and addiction. We also can use telemedicine to improve access to psychiatric care in underserved areas. But the overarching truth remains: an understanding of psychiatric illnesses, specifically the pathophysiology underlying those conditions, remains elusive or partially understood. Until we have a pathophysiology to treat, we can only continue to describe phenomenology and treat symptomatology.

Since we are treating symptoms, we must rely on verbal descriptions of psychiatric conditions. Descriptions and discussions of mental illness have pervaded the airwaves and media. It is not uncommon or unusual to hear people talk about depression, anxiety, insomnia, addiction, or even psychosis in a very normal, unjarring way. These words, which represent severe medical conditions, have now become part of the national nosology and colloquial description of individuals’ day-to-day lives. Have we stripped the severity and seriousness of our conditions from their descriptors in order to increase awareness and make mental health care a more “normal” part of health care?

We see it in clinics, the media, our schools, and our workplaces. Children and teens are talking about social anxiety because they feel a bit nervous on stage as their part in a school play begins. Teens are asking for extra time on a difficult test in a challenging class that is supposed to be strenuous. Employees are asking for mental health leave when a demanding new boss arrives on the scene.

Has our own campaign to increase awareness and destigmatize mental illness caused it to become diluted? Have we raised awareness by diluting its severity and seriousness, by making our nosology equivalent to everyday stressors? Was this a marketing strategy, a failure of our own nosology, or an inadvertent fallout of a decades-long campaign to raise mental health awareness?

Continue to: Until we have clear...

Until we have clear, delineated pathophysiology to treat, we will remain wed to our descriptive nosology. This nosology is flawed, at times ambiguous and overlapping, and now has become diluted to be more palatable to a national and consumer audience.

So yes, let’s grab a chair at the national table, but let’s make sure we’re not just chairwarmers. It’s time we redouble our focus on unraveling the pathophysiology of psychiatric illnesses, and to focus on a new scientific nosology, as opposed to our current, almost colloquial and now diluted descriptors that may raise awareness but do little to advance a real understanding of mental illness. A more holistic understanding of the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders may provide us with a more scientific nosology. Ultimately, we can hope for more effective, and perhaps even curative treatments. That, my colleagues, is what will give us not just a seat at the table, but maybe even a table of our own.

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in Current Psychiatry. All submissions to Readers’ Forum undergo peer review and are subject to editing for length and style. For more information, contact [email protected].

As we see the end of the COVID-19 era through a collective windshield, there is hope and optimism at the exit ramps ahead of us. This unforeseen era has brought not only unprecedented change to the practice of medicine, but also a resurgent focus on the impact of medical care. The rapid adoption of telemedicine, the medical heroism lauded in the press during the early days of the pandemic, and the subsequent psychosocial impact of quarantines and lockdowns have brought increased attention to our citizens’ mental health, and not just during a crisis, but in a more holistic sense.

In fact, with the most recent annual Presidential State of the Union Address, mental health has finally received an invitation to the national agenda. This is an admirable achievement, a nod from Uncle Sam that says, “Here’s your seat at the table.” Now that we have earned this seat, have we improved our understanding of mental illness, treatment options, and our access to them? Or have we lost sight of our real challenges? Shouldn’t achieving national prominence have resulted in newfound treatments and strategies to increase access and understanding?

Instead, we are still touting the same (although perhaps nuanced) monoamine hypothesis underlying most of our conditions, as we have for decades. Vast areas of the country are out of reach of a local psychiatrist. Our treatments, largely centered on medications, though hopeful and promising at times, would fall short of the hurdle to become mainstay treatments in other medical specialties. Of course, the counterpoints are obvious: there are novel treatments (eg, ketamine, transcranial magnetic stimulation) and new understandings of glutamate and gamma aminobutyric acid systems in mood regulation and addiction. We also can use telemedicine to improve access to psychiatric care in underserved areas. But the overarching truth remains: an understanding of psychiatric illnesses, specifically the pathophysiology underlying those conditions, remains elusive or partially understood. Until we have a pathophysiology to treat, we can only continue to describe phenomenology and treat symptomatology.

Since we are treating symptoms, we must rely on verbal descriptions of psychiatric conditions. Descriptions and discussions of mental illness have pervaded the airwaves and media. It is not uncommon or unusual to hear people talk about depression, anxiety, insomnia, addiction, or even psychosis in a very normal, unjarring way. These words, which represent severe medical conditions, have now become part of the national nosology and colloquial description of individuals’ day-to-day lives. Have we stripped the severity and seriousness of our conditions from their descriptors in order to increase awareness and make mental health care a more “normal” part of health care?

We see it in clinics, the media, our schools, and our workplaces. Children and teens are talking about social anxiety because they feel a bit nervous on stage as their part in a school play begins. Teens are asking for extra time on a difficult test in a challenging class that is supposed to be strenuous. Employees are asking for mental health leave when a demanding new boss arrives on the scene.

Has our own campaign to increase awareness and destigmatize mental illness caused it to become diluted? Have we raised awareness by diluting its severity and seriousness, by making our nosology equivalent to everyday stressors? Was this a marketing strategy, a failure of our own nosology, or an inadvertent fallout of a decades-long campaign to raise mental health awareness?

Continue to: Until we have clear...

Until we have clear, delineated pathophysiology to treat, we will remain wed to our descriptive nosology. This nosology is flawed, at times ambiguous and overlapping, and now has become diluted to be more palatable to a national and consumer audience.

So yes, let’s grab a chair at the national table, but let’s make sure we’re not just chairwarmers. It’s time we redouble our focus on unraveling the pathophysiology of psychiatric illnesses, and to focus on a new scientific nosology, as opposed to our current, almost colloquial and now diluted descriptors that may raise awareness but do little to advance a real understanding of mental illness. A more holistic understanding of the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders may provide us with a more scientific nosology. Ultimately, we can hope for more effective, and perhaps even curative treatments. That, my colleagues, is what will give us not just a seat at the table, but maybe even a table of our own.

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in Current Psychiatry. All submissions to Readers’ Forum undergo peer review and are subject to editing for length and style. For more information, contact [email protected].

As we see the end of the COVID-19 era through a collective windshield, there is hope and optimism at the exit ramps ahead of us. This unforeseen era has brought not only unprecedented change to the practice of medicine, but also a resurgent focus on the impact of medical care. The rapid adoption of telemedicine, the medical heroism lauded in the press during the early days of the pandemic, and the subsequent psychosocial impact of quarantines and lockdowns have brought increased attention to our citizens’ mental health, and not just during a crisis, but in a more holistic sense.

In fact, with the most recent annual Presidential State of the Union Address, mental health has finally received an invitation to the national agenda. This is an admirable achievement, a nod from Uncle Sam that says, “Here’s your seat at the table.” Now that we have earned this seat, have we improved our understanding of mental illness, treatment options, and our access to them? Or have we lost sight of our real challenges? Shouldn’t achieving national prominence have resulted in newfound treatments and strategies to increase access and understanding?

Instead, we are still touting the same (although perhaps nuanced) monoamine hypothesis underlying most of our conditions, as we have for decades. Vast areas of the country are out of reach of a local psychiatrist. Our treatments, largely centered on medications, though hopeful and promising at times, would fall short of the hurdle to become mainstay treatments in other medical specialties. Of course, the counterpoints are obvious: there are novel treatments (eg, ketamine, transcranial magnetic stimulation) and new understandings of glutamate and gamma aminobutyric acid systems in mood regulation and addiction. We also can use telemedicine to improve access to psychiatric care in underserved areas. But the overarching truth remains: an understanding of psychiatric illnesses, specifically the pathophysiology underlying those conditions, remains elusive or partially understood. Until we have a pathophysiology to treat, we can only continue to describe phenomenology and treat symptomatology.

Since we are treating symptoms, we must rely on verbal descriptions of psychiatric conditions. Descriptions and discussions of mental illness have pervaded the airwaves and media. It is not uncommon or unusual to hear people talk about depression, anxiety, insomnia, addiction, or even psychosis in a very normal, unjarring way. These words, which represent severe medical conditions, have now become part of the national nosology and colloquial description of individuals’ day-to-day lives. Have we stripped the severity and seriousness of our conditions from their descriptors in order to increase awareness and make mental health care a more “normal” part of health care?

We see it in clinics, the media, our schools, and our workplaces. Children and teens are talking about social anxiety because they feel a bit nervous on stage as their part in a school play begins. Teens are asking for extra time on a difficult test in a challenging class that is supposed to be strenuous. Employees are asking for mental health leave when a demanding new boss arrives on the scene.

Has our own campaign to increase awareness and destigmatize mental illness caused it to become diluted? Have we raised awareness by diluting its severity and seriousness, by making our nosology equivalent to everyday stressors? Was this a marketing strategy, a failure of our own nosology, or an inadvertent fallout of a decades-long campaign to raise mental health awareness?

Continue to: Until we have clear...

Until we have clear, delineated pathophysiology to treat, we will remain wed to our descriptive nosology. This nosology is flawed, at times ambiguous and overlapping, and now has become diluted to be more palatable to a national and consumer audience.

So yes, let’s grab a chair at the national table, but let’s make sure we’re not just chairwarmers. It’s time we redouble our focus on unraveling the pathophysiology of psychiatric illnesses, and to focus on a new scientific nosology, as opposed to our current, almost colloquial and now diluted descriptors that may raise awareness but do little to advance a real understanding of mental illness. A more holistic understanding of the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders may provide us with a more scientific nosology. Ultimately, we can hope for more effective, and perhaps even curative treatments. That, my colleagues, is what will give us not just a seat at the table, but maybe even a table of our own.

Borderline personality disorder: Remember empathy and compassion

Oh, great!” a senior resident sardonically remarked with a smirk as they read up on the next patient in the clinic. “A borderline patient. Get ready for a rough one ... Ugh.”

Before ever stepping foot into the patient’s room, this resident had prematurely established and demonstrated an unfortunate dynamic for any student or trainee within earshot. This is an all-too-familiar occurrence when caring for individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD), or any other patients deemed to be “difficult.” The patient, however, likely walked into the room with a traumatic past that they continue to suffer from, in addition to any other issues for which they were seeking care.

Consider what these patients have experienced

A typical profile of these resilient patients with BPD: They were born emotionally sensitive. They grew up in homes with caretakers who knowingly or unknowingly invalidated their complaints about having their feelings hurt, about being abused emotionally, sexually, or otherwise, or about their worries concerning their interactions with peers at school. These caretakers may have been frightening and unpredictable, randomly showing affection or arbitrarily punishing for any perceived misstep, which led these patients to develop (for their own safety’s sake) a hypersensitivity to the affect of others. Their wariness and distrust of their social surroundings may have led to a skeptical view of kindness from others. Over time, without any guidance from prior demonstrations of healthy coping skills or interpersonal outlets from their caregivers, the emotional pressure builds. This pressure finally erupts in the form of impulsivity, self-harm, desperation, and defensiveness—in other words, survival. This is often followed by these patients’ first experience with receiving some degree of appropriate response to their complaints—their first experience with feeling seen and heard by their caretakers. They learn that their needs are met only when they cry out in desperation.1-3

These patients typically bring these maladaptive coping skills with them into adulthood, which often leads to a series of intense, unhealthy, and short-lived interpersonal and professional connections. They desire healthy, lasting connections with others, but through no fault of their own are unable to appropriately manage the normal stressors therein.1 Often, these patients do not know of their eventual BPD diagnosis, or even reject it due to its ever-negative valence. For other patients, receiving a personality disorder diagnosis is incredibly validating because they are no longer alone regarding this type of suffering, and a doctor—a caretaker—is finally making sense of this tumultuous world.

The countertransference of frustration, anxiety, doubt, and annoyance we may feel when caring for patients with BPD pales in comparison to living in their shoes and carrying the weight of what they have had to endure before presenting to our care. As these resilient patients wait in the exam room for the chance to be heard, let this be a reminder to greet them with the patience, understanding, empathy, and compassion that physicians are known to embody.

Suggestions for working with ‘difficult’ patients

The following tips may be helpful for building rapport with patients with BPD or other “difficult” patients:

- validate their complaints, and the difficulties they cause

- be genuine and honest when discussing their complaints

- acknowledge your own mistakes and misunderstandings in their care

- don’t be defensive—accept criticism with an open mind

- practice listening with intent, and reflective listening

- set ground rules and stick to them (eg, time limits, prescribing expectations, patient-physician relationship boundaries)

- educate and support the patient and their loved ones.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:947.

2. Porter C, Palmier-Claus J, Branitsky A, et al. Childhood adversity and borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2020;141(1):6-20.

3. Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Emotional hyper-reactivity in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2010;7(9):16-20.

Oh, great!” a senior resident sardonically remarked with a smirk as they read up on the next patient in the clinic. “A borderline patient. Get ready for a rough one ... Ugh.”

Before ever stepping foot into the patient’s room, this resident had prematurely established and demonstrated an unfortunate dynamic for any student or trainee within earshot. This is an all-too-familiar occurrence when caring for individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD), or any other patients deemed to be “difficult.” The patient, however, likely walked into the room with a traumatic past that they continue to suffer from, in addition to any other issues for which they were seeking care.

Consider what these patients have experienced

A typical profile of these resilient patients with BPD: They were born emotionally sensitive. They grew up in homes with caretakers who knowingly or unknowingly invalidated their complaints about having their feelings hurt, about being abused emotionally, sexually, or otherwise, or about their worries concerning their interactions with peers at school. These caretakers may have been frightening and unpredictable, randomly showing affection or arbitrarily punishing for any perceived misstep, which led these patients to develop (for their own safety’s sake) a hypersensitivity to the affect of others. Their wariness and distrust of their social surroundings may have led to a skeptical view of kindness from others. Over time, without any guidance from prior demonstrations of healthy coping skills or interpersonal outlets from their caregivers, the emotional pressure builds. This pressure finally erupts in the form of impulsivity, self-harm, desperation, and defensiveness—in other words, survival. This is often followed by these patients’ first experience with receiving some degree of appropriate response to their complaints—their first experience with feeling seen and heard by their caretakers. They learn that their needs are met only when they cry out in desperation.1-3

These patients typically bring these maladaptive coping skills with them into adulthood, which often leads to a series of intense, unhealthy, and short-lived interpersonal and professional connections. They desire healthy, lasting connections with others, but through no fault of their own are unable to appropriately manage the normal stressors therein.1 Often, these patients do not know of their eventual BPD diagnosis, or even reject it due to its ever-negative valence. For other patients, receiving a personality disorder diagnosis is incredibly validating because they are no longer alone regarding this type of suffering, and a doctor—a caretaker—is finally making sense of this tumultuous world.

The countertransference of frustration, anxiety, doubt, and annoyance we may feel when caring for patients with BPD pales in comparison to living in their shoes and carrying the weight of what they have had to endure before presenting to our care. As these resilient patients wait in the exam room for the chance to be heard, let this be a reminder to greet them with the patience, understanding, empathy, and compassion that physicians are known to embody.

Suggestions for working with ‘difficult’ patients

The following tips may be helpful for building rapport with patients with BPD or other “difficult” patients:

- validate their complaints, and the difficulties they cause

- be genuine and honest when discussing their complaints

- acknowledge your own mistakes and misunderstandings in their care

- don’t be defensive—accept criticism with an open mind

- practice listening with intent, and reflective listening

- set ground rules and stick to them (eg, time limits, prescribing expectations, patient-physician relationship boundaries)

- educate and support the patient and their loved ones.

Oh, great!” a senior resident sardonically remarked with a smirk as they read up on the next patient in the clinic. “A borderline patient. Get ready for a rough one ... Ugh.”

Before ever stepping foot into the patient’s room, this resident had prematurely established and demonstrated an unfortunate dynamic for any student or trainee within earshot. This is an all-too-familiar occurrence when caring for individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD), or any other patients deemed to be “difficult.” The patient, however, likely walked into the room with a traumatic past that they continue to suffer from, in addition to any other issues for which they were seeking care.

Consider what these patients have experienced

A typical profile of these resilient patients with BPD: They were born emotionally sensitive. They grew up in homes with caretakers who knowingly or unknowingly invalidated their complaints about having their feelings hurt, about being abused emotionally, sexually, or otherwise, or about their worries concerning their interactions with peers at school. These caretakers may have been frightening and unpredictable, randomly showing affection or arbitrarily punishing for any perceived misstep, which led these patients to develop (for their own safety’s sake) a hypersensitivity to the affect of others. Their wariness and distrust of their social surroundings may have led to a skeptical view of kindness from others. Over time, without any guidance from prior demonstrations of healthy coping skills or interpersonal outlets from their caregivers, the emotional pressure builds. This pressure finally erupts in the form of impulsivity, self-harm, desperation, and defensiveness—in other words, survival. This is often followed by these patients’ first experience with receiving some degree of appropriate response to their complaints—their first experience with feeling seen and heard by their caretakers. They learn that their needs are met only when they cry out in desperation.1-3

These patients typically bring these maladaptive coping skills with them into adulthood, which often leads to a series of intense, unhealthy, and short-lived interpersonal and professional connections. They desire healthy, lasting connections with others, but through no fault of their own are unable to appropriately manage the normal stressors therein.1 Often, these patients do not know of their eventual BPD diagnosis, or even reject it due to its ever-negative valence. For other patients, receiving a personality disorder diagnosis is incredibly validating because they are no longer alone regarding this type of suffering, and a doctor—a caretaker—is finally making sense of this tumultuous world.

The countertransference of frustration, anxiety, doubt, and annoyance we may feel when caring for patients with BPD pales in comparison to living in their shoes and carrying the weight of what they have had to endure before presenting to our care. As these resilient patients wait in the exam room for the chance to be heard, let this be a reminder to greet them with the patience, understanding, empathy, and compassion that physicians are known to embody.

Suggestions for working with ‘difficult’ patients

The following tips may be helpful for building rapport with patients with BPD or other “difficult” patients:

- validate their complaints, and the difficulties they cause

- be genuine and honest when discussing their complaints

- acknowledge your own mistakes and misunderstandings in their care

- don’t be defensive—accept criticism with an open mind

- practice listening with intent, and reflective listening

- set ground rules and stick to them (eg, time limits, prescribing expectations, patient-physician relationship boundaries)

- educate and support the patient and their loved ones.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:947.

2. Porter C, Palmier-Claus J, Branitsky A, et al. Childhood adversity and borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2020;141(1):6-20.

3. Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Emotional hyper-reactivity in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2010;7(9):16-20.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:947.

2. Porter C, Palmier-Claus J, Branitsky A, et al. Childhood adversity and borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2020;141(1):6-20.

3. Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Emotional hyper-reactivity in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2010;7(9):16-20.

Hepatitis C: Essential Treatment Considerations

Until recently, chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment had poor efficacy and was provided only by specialists such as hepatologists and gastroenterologists. However, the introduction of safe, effective direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) has revolutionized HCV treatment.

One pivotal transformation has been the expansion of treatment to nonspecialist physicians. Nevertheless, various factors must be considered when initiating treatment for HCV.

Dr Elizabeth Verna, director of hepatology research at Columbia University in New York City, examines the essential treatment considerations for chronic HCV in treatment-naive patients.

First, she outlines recommended first-line therapies and the simplified HCV treatment algorithm recently issued by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. She then discusses patient-specific factors, such as cirrhosis, co-infections, age, and pregnancy, that can create treatment challenges and change the algorithm.

In closing, she talks about changes in HCV screening recommendations and how diagnosis and treatment of this infectious disease largely rest in the hands of general practitioners who are the first line of defense in controlling HCV spread.

--

Associate Professor of Medicine, Director of Hepatology Research, Associate Physician, Department of Medicine, Columbia University, New York, NY

Elizabeth Verna, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: Salix

Until recently, chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment had poor efficacy and was provided only by specialists such as hepatologists and gastroenterologists. However, the introduction of safe, effective direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) has revolutionized HCV treatment.

One pivotal transformation has been the expansion of treatment to nonspecialist physicians. Nevertheless, various factors must be considered when initiating treatment for HCV.

Dr Elizabeth Verna, director of hepatology research at Columbia University in New York City, examines the essential treatment considerations for chronic HCV in treatment-naive patients.

First, she outlines recommended first-line therapies and the simplified HCV treatment algorithm recently issued by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. She then discusses patient-specific factors, such as cirrhosis, co-infections, age, and pregnancy, that can create treatment challenges and change the algorithm.

In closing, she talks about changes in HCV screening recommendations and how diagnosis and treatment of this infectious disease largely rest in the hands of general practitioners who are the first line of defense in controlling HCV spread.

--

Associate Professor of Medicine, Director of Hepatology Research, Associate Physician, Department of Medicine, Columbia University, New York, NY

Elizabeth Verna, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: Salix

Until recently, chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment had poor efficacy and was provided only by specialists such as hepatologists and gastroenterologists. However, the introduction of safe, effective direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) has revolutionized HCV treatment.

One pivotal transformation has been the expansion of treatment to nonspecialist physicians. Nevertheless, various factors must be considered when initiating treatment for HCV.

Dr Elizabeth Verna, director of hepatology research at Columbia University in New York City, examines the essential treatment considerations for chronic HCV in treatment-naive patients.

First, she outlines recommended first-line therapies and the simplified HCV treatment algorithm recently issued by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. She then discusses patient-specific factors, such as cirrhosis, co-infections, age, and pregnancy, that can create treatment challenges and change the algorithm.

In closing, she talks about changes in HCV screening recommendations and how diagnosis and treatment of this infectious disease largely rest in the hands of general practitioners who are the first line of defense in controlling HCV spread.

--

Associate Professor of Medicine, Director of Hepatology Research, Associate Physician, Department of Medicine, Columbia University, New York, NY

Elizabeth Verna, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: Salix

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: Gastric Cancer, May 2022

In early-stage disease, perioperative chemotherapy plays a critical role. The triple-chemotherapy FLOT regimen is now the standard treatment in patients who are able to tolerate it. However, it is associated with significant toxicities, and modifications frequently are needed. In clinical practice, FOLFOX chemotherapy can be used in patients who are not candidates for FLOT. A phase 2 OGSG 1601 study enrolled 37 patients with clinical stage T3/T4a N1-3 M0 gastric cancer who received perioperative doublet chemotherapy with capecitabine and oxaliplatin. At the 3-year follow-up, this study continues to demonstrate good activity of this doublet chemotherapy, with an overall survival rate of 83.8% at 3 years and relapse-free rate of 73%. These results support the use of this doublet in patients who cannot tolerate a more intense chemotherapy regimen. The interpretation of this study is limited by its small size and nonrandomized design. Given what we know about the activity of this regimen in advanced disease, however, these results add to the body of evidence that supports the use of this doublet in select patients.

There have been efforts to augment the activity of perioperative chemotherapy using antiangiogenic agents. In the advanced setting, studies with antiangiogenic agents have had mixed results. Ramucirumab in combination with paclitaxel is FDA-approved in the second-line setting, but a subsequent study in the first line-setting showed no improvement from the addition of ramucirumab.4,7 In the preoperative setting, the role of ramucirumab in combination with chemotherapy was evaluated in a phase 2 study. Although a hint of activity was seen, there was increased toxicity, especially in Siewert type I tumors.8 The phase 2 study by Tang and colleagues enrolled 32 patients with resectable gastric and gastroesophageal juncture adenocarcinoma who received neoadjuvant oxaliplatin, capecitabine, and apatinib. Apatinib is a small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor with highly selective affinity to vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2. The treatment had manageable toxicity, with hypertension being the most common adverse event, as expected. Early signs of potential clinical efficacy were seen (pathologic complete response and pathologic response were achieved in 6.3% and 34.4% of the patients, respectively), but the true contribution from the addition of apatinib can be established only in a prospective randomized study. For now, chemotherapy alone remains the standard perioperative treatment, although ongoing studies are evaluating the addition of immune checkpoint inhibitors in this setting (NCT03221426, NCT04592913). These types of agents are probably more likely than antiangiogenic agents to become part of standard treatment in the perioperative setting.

Additional References

- Janjigian YY, Shitara K, Moehler M, et al. First-line nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric, gastro-oesophageal junction, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (CheckMate 649): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398:27-40. Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00797-2 Source

- Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko VM, Tjulandin S, et al. Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: A report of the V325 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4991-4997. Doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8429 Source

- Al-Batran S-E, Homann N, Pauligk C, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel versus fluorouracil or capecitabine plus cisplatin and epirubicin for locally advanced, resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4): A randomised, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393:1948-1957. Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32557-1 Source0

- Wilke H, Van Cutsem E, Cheul Oh S, et al. RAINBOW: A global, phase 3, randomized, double-blind study of ramucirumab plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel in the treatment of metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma following disease progression on first-line platinum- and fluoropyrimidine-containing combination therapy: Results of a multiple Cox regression analysis adjusting for prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15, suppl):1076. Doi: 10.1200/jco.2014.32.15_suppl.4076 Source

- Elimova E, Janjigian YY, Mulcahy M, et al. It is time to stop using epirubicin to treat any patient with gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:475-477. Doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.7276 Source

- Park H, Jin RU, Wang-Gillam A, et al. FOLFIRINOX for the treatment of advanced gastroesophageal cancers: A phase 2 nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1231-1240. Doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2020 Source

- Fuchs CS, Shitara K, Di Bartolomeo M, et al. RAINFALL: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study of cisplatin (Cis) plus capecitabine (Cape) or 5FU with or without ramucirumab (RAM) as first-line therapy in patients with metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction (G-GEJ) adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(4, suppl):5. Doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.4_suppl.5 Source

- Al-Batran S-E, Hofheinz RD, Schmalenberg H, et al. Perioperative ramucirumab in combination with FLOT versus FLOT alone for resectable esophagogastric adenocarcinoma (RAMSES/FLOT7): Results of the phase II-portion—A multicenter, randomized phase II/III trial of the German AIO and Italian GOIM. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(15, suppl):4501. Doi: 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.4501 Source

In early-stage disease, perioperative chemotherapy plays a critical role. The triple-chemotherapy FLOT regimen is now the standard treatment in patients who are able to tolerate it. However, it is associated with significant toxicities, and modifications frequently are needed. In clinical practice, FOLFOX chemotherapy can be used in patients who are not candidates for FLOT. A phase 2 OGSG 1601 study enrolled 37 patients with clinical stage T3/T4a N1-3 M0 gastric cancer who received perioperative doublet chemotherapy with capecitabine and oxaliplatin. At the 3-year follow-up, this study continues to demonstrate good activity of this doublet chemotherapy, with an overall survival rate of 83.8% at 3 years and relapse-free rate of 73%. These results support the use of this doublet in patients who cannot tolerate a more intense chemotherapy regimen. The interpretation of this study is limited by its small size and nonrandomized design. Given what we know about the activity of this regimen in advanced disease, however, these results add to the body of evidence that supports the use of this doublet in select patients.

There have been efforts to augment the activity of perioperative chemotherapy using antiangiogenic agents. In the advanced setting, studies with antiangiogenic agents have had mixed results. Ramucirumab in combination with paclitaxel is FDA-approved in the second-line setting, but a subsequent study in the first line-setting showed no improvement from the addition of ramucirumab.4,7 In the preoperative setting, the role of ramucirumab in combination with chemotherapy was evaluated in a phase 2 study. Although a hint of activity was seen, there was increased toxicity, especially in Siewert type I tumors.8 The phase 2 study by Tang and colleagues enrolled 32 patients with resectable gastric and gastroesophageal juncture adenocarcinoma who received neoadjuvant oxaliplatin, capecitabine, and apatinib. Apatinib is a small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor with highly selective affinity to vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2. The treatment had manageable toxicity, with hypertension being the most common adverse event, as expected. Early signs of potential clinical efficacy were seen (pathologic complete response and pathologic response were achieved in 6.3% and 34.4% of the patients, respectively), but the true contribution from the addition of apatinib can be established only in a prospective randomized study. For now, chemotherapy alone remains the standard perioperative treatment, although ongoing studies are evaluating the addition of immune checkpoint inhibitors in this setting (NCT03221426, NCT04592913). These types of agents are probably more likely than antiangiogenic agents to become part of standard treatment in the perioperative setting.

Additional References

- Janjigian YY, Shitara K, Moehler M, et al. First-line nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric, gastro-oesophageal junction, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (CheckMate 649): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398:27-40. Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00797-2 Source

- Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko VM, Tjulandin S, et al. Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: A report of the V325 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4991-4997. Doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8429 Source

- Al-Batran S-E, Homann N, Pauligk C, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel versus fluorouracil or capecitabine plus cisplatin and epirubicin for locally advanced, resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4): A randomised, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393:1948-1957. Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32557-1 Source0

- Wilke H, Van Cutsem E, Cheul Oh S, et al. RAINBOW: A global, phase 3, randomized, double-blind study of ramucirumab plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel in the treatment of metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma following disease progression on first-line platinum- and fluoropyrimidine-containing combination therapy: Results of a multiple Cox regression analysis adjusting for prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15, suppl):1076. Doi: 10.1200/jco.2014.32.15_suppl.4076 Source

- Elimova E, Janjigian YY, Mulcahy M, et al. It is time to stop using epirubicin to treat any patient with gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:475-477. Doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.7276 Source

- Park H, Jin RU, Wang-Gillam A, et al. FOLFIRINOX for the treatment of advanced gastroesophageal cancers: A phase 2 nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1231-1240. Doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2020 Source

- Fuchs CS, Shitara K, Di Bartolomeo M, et al. RAINFALL: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study of cisplatin (Cis) plus capecitabine (Cape) or 5FU with or without ramucirumab (RAM) as first-line therapy in patients with metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction (G-GEJ) adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(4, suppl):5. Doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.4_suppl.5 Source

- Al-Batran S-E, Hofheinz RD, Schmalenberg H, et al. Perioperative ramucirumab in combination with FLOT versus FLOT alone for resectable esophagogastric adenocarcinoma (RAMSES/FLOT7): Results of the phase II-portion—A multicenter, randomized phase II/III trial of the German AIO and Italian GOIM. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(15, suppl):4501. Doi: 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.4501 Source

In early-stage disease, perioperative chemotherapy plays a critical role. The triple-chemotherapy FLOT regimen is now the standard treatment in patients who are able to tolerate it. However, it is associated with significant toxicities, and modifications frequently are needed. In clinical practice, FOLFOX chemotherapy can be used in patients who are not candidates for FLOT. A phase 2 OGSG 1601 study enrolled 37 patients with clinical stage T3/T4a N1-3 M0 gastric cancer who received perioperative doublet chemotherapy with capecitabine and oxaliplatin. At the 3-year follow-up, this study continues to demonstrate good activity of this doublet chemotherapy, with an overall survival rate of 83.8% at 3 years and relapse-free rate of 73%. These results support the use of this doublet in patients who cannot tolerate a more intense chemotherapy regimen. The interpretation of this study is limited by its small size and nonrandomized design. Given what we know about the activity of this regimen in advanced disease, however, these results add to the body of evidence that supports the use of this doublet in select patients.

There have been efforts to augment the activity of perioperative chemotherapy using antiangiogenic agents. In the advanced setting, studies with antiangiogenic agents have had mixed results. Ramucirumab in combination with paclitaxel is FDA-approved in the second-line setting, but a subsequent study in the first line-setting showed no improvement from the addition of ramucirumab.4,7 In the preoperative setting, the role of ramucirumab in combination with chemotherapy was evaluated in a phase 2 study. Although a hint of activity was seen, there was increased toxicity, especially in Siewert type I tumors.8 The phase 2 study by Tang and colleagues enrolled 32 patients with resectable gastric and gastroesophageal juncture adenocarcinoma who received neoadjuvant oxaliplatin, capecitabine, and apatinib. Apatinib is a small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor with highly selective affinity to vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2. The treatment had manageable toxicity, with hypertension being the most common adverse event, as expected. Early signs of potential clinical efficacy were seen (pathologic complete response and pathologic response were achieved in 6.3% and 34.4% of the patients, respectively), but the true contribution from the addition of apatinib can be established only in a prospective randomized study. For now, chemotherapy alone remains the standard perioperative treatment, although ongoing studies are evaluating the addition of immune checkpoint inhibitors in this setting (NCT03221426, NCT04592913). These types of agents are probably more likely than antiangiogenic agents to become part of standard treatment in the perioperative setting.

Additional References

- Janjigian YY, Shitara K, Moehler M, et al. First-line nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric, gastro-oesophageal junction, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (CheckMate 649): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398:27-40. Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00797-2 Source

- Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko VM, Tjulandin S, et al. Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: A report of the V325 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4991-4997. Doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8429 Source

- Al-Batran S-E, Homann N, Pauligk C, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel versus fluorouracil or capecitabine plus cisplatin and epirubicin for locally advanced, resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4): A randomised, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393:1948-1957. Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32557-1 Source0

- Wilke H, Van Cutsem E, Cheul Oh S, et al. RAINBOW: A global, phase 3, randomized, double-blind study of ramucirumab plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel in the treatment of metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma following disease progression on first-line platinum- and fluoropyrimidine-containing combination therapy: Results of a multiple Cox regression analysis adjusting for prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15, suppl):1076. Doi: 10.1200/jco.2014.32.15_suppl.4076 Source

- Elimova E, Janjigian YY, Mulcahy M, et al. It is time to stop using epirubicin to treat any patient with gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:475-477. Doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.7276 Source

- Park H, Jin RU, Wang-Gillam A, et al. FOLFIRINOX for the treatment of advanced gastroesophageal cancers: A phase 2 nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1231-1240. Doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2020 Source

- Fuchs CS, Shitara K, Di Bartolomeo M, et al. RAINFALL: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study of cisplatin (Cis) plus capecitabine (Cape) or 5FU with or without ramucirumab (RAM) as first-line therapy in patients with metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction (G-GEJ) adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(4, suppl):5. Doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.4_suppl.5 Source

- Al-Batran S-E, Hofheinz RD, Schmalenberg H, et al. Perioperative ramucirumab in combination with FLOT versus FLOT alone for resectable esophagogastric adenocarcinoma (RAMSES/FLOT7): Results of the phase II-portion—A multicenter, randomized phase II/III trial of the German AIO and Italian GOIM. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(15, suppl):4501. Doi: 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.4501 Source

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: PsA May 2022

Although most patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) have concomitant psoriasis, many with PsA who are enrolled in clinic trials as well as in rheumatology clinic do not have severe psoriasis. Therefore, an unanswered question is how much psoriasis symptoms contribute to impaired quality of life (QOL) in PsA patients. This question was addressed in a recent study by Taylor and colleagues. This post hoc analysis of two phase 3 studies, OPAL Broaden and OPAL Beyond, included 816 patients with active PsA and an inadequate response to previous therapies who received tofacitinib, adalimumab, or placebo. The analyses demonstrated that Itch Severity Item (ISI) scores of 7-10, Physician's Global Assessment of Psoriasis (PGA-PsO) scores of 4, and Patient's Global Joint and Skin Assessment-Visual Analog Scale (PGJS-VAS) scores of 90-100 mm corresponded with Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores categorized as having a very large effect on a patient's life. An improvement of ≥ 3 points in ISI, ≥ 2 points in PGA-PsO, and ≥ 40 mm in PGJS-VAS translated to a clinically meaningful improvement in DLQI scores; improvements from baseline of ≥4/≥3/≥40-mm in the above scores, respectively, were also associated with clinically meaningful improvements across SF-36v2 (Short-Form Health Survey) domains. Thus, dermatologic symptoms are substantially associated with QOL in patients with active PsA, and improvements in skin measures could translate to clinically meaningful improvements in their QOL.

There is also increasing scrutiny on sex differences in PsA. Eder and colleagues conducted a post hoc analysis of two phase 3 trials that included 679 patients with active PsA who were either biologic-naive (SPIRIT-P1) or showed an inadequate response to one or two tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) (SPIRIT-P2) and were randomly assigned to receive ixekizumab, an IL-17A inhibitor (IL-17Ai), or placebo. They demonstrated that at baseline female vs male patients had significantly higher Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index scores (P ≤ .003), with a significantly higher proportion of male vs female patients in the ixekizumab every-4-weeks treatment arm (53.8% vs 38.3%) and ixekizumab every-2-weeks treatment arm(41.2% vs 28.1%) achieving ≥50% and ≥70% improvement in the American College of Rheumatology response criteria, respectively (both P < .05). Thus, female patients with PsA exhibited significantly higher disease activity at baseline and a poorer response to ixekizumab.

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors have been shown to improve inflammatory and other types of pain in rheumatoid arthritis. To further evaluate the effect of inhibition of JAK1 on pain, McInnes and colleagues aimed to evaluate the effect of upadacitinib on pain outcomes in patients with active PsA or ankylosing spondylitis across three randomized trials (SELECT-PsA-1 and -2 for PsA; SELECT-AXIS 1 for ankylosing spondylitis). A significantly higher proportion of patients receiving 15 mg upadacitinib vs placebo achieved ≥30%, ≥50%, and ≥70% reductions in pain as early as 2 weeks (P < .05), with improvements sustained up to week 56. Further research on whether improvement in pain is at least partially independent of improvement in musculoskeletal inflammation is required.

Persistence of drug treatment is an important outcome and is a surrogate measure of safety and effectiveness. Vegas and colleagues assessed the long-term persistence of different biologic classes in a nationwide cohort study that included 16,892 adults with psoriasis and 6531 adults with PsA who initiated first-line treatment with a TNFi, IL-12/23 inhibitors (IL-12/23i), or an IL-17i. Treatment persistence was higher with IL-17i than with TNFi (weighted hazard ratio [HR] 0.70; P < .001) or IL-12/23i (weighted HR 0.69; P < .001); however, IL-12/23i and TNFi showed similar persistence (P = .70). Thus, IL-17i may be associated with higher treatment persistence in PsA compared with TNFi.

Although most patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) have concomitant psoriasis, many with PsA who are enrolled in clinic trials as well as in rheumatology clinic do not have severe psoriasis. Therefore, an unanswered question is how much psoriasis symptoms contribute to impaired quality of life (QOL) in PsA patients. This question was addressed in a recent study by Taylor and colleagues. This post hoc analysis of two phase 3 studies, OPAL Broaden and OPAL Beyond, included 816 patients with active PsA and an inadequate response to previous therapies who received tofacitinib, adalimumab, or placebo. The analyses demonstrated that Itch Severity Item (ISI) scores of 7-10, Physician's Global Assessment of Psoriasis (PGA-PsO) scores of 4, and Patient's Global Joint and Skin Assessment-Visual Analog Scale (PGJS-VAS) scores of 90-100 mm corresponded with Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores categorized as having a very large effect on a patient's life. An improvement of ≥ 3 points in ISI, ≥ 2 points in PGA-PsO, and ≥ 40 mm in PGJS-VAS translated to a clinically meaningful improvement in DLQI scores; improvements from baseline of ≥4/≥3/≥40-mm in the above scores, respectively, were also associated with clinically meaningful improvements across SF-36v2 (Short-Form Health Survey) domains. Thus, dermatologic symptoms are substantially associated with QOL in patients with active PsA, and improvements in skin measures could translate to clinically meaningful improvements in their QOL.

There is also increasing scrutiny on sex differences in PsA. Eder and colleagues conducted a post hoc analysis of two phase 3 trials that included 679 patients with active PsA who were either biologic-naive (SPIRIT-P1) or showed an inadequate response to one or two tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) (SPIRIT-P2) and were randomly assigned to receive ixekizumab, an IL-17A inhibitor (IL-17Ai), or placebo. They demonstrated that at baseline female vs male patients had significantly higher Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index scores (P ≤ .003), with a significantly higher proportion of male vs female patients in the ixekizumab every-4-weeks treatment arm (53.8% vs 38.3%) and ixekizumab every-2-weeks treatment arm(41.2% vs 28.1%) achieving ≥50% and ≥70% improvement in the American College of Rheumatology response criteria, respectively (both P < .05). Thus, female patients with PsA exhibited significantly higher disease activity at baseline and a poorer response to ixekizumab.

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors have been shown to improve inflammatory and other types of pain in rheumatoid arthritis. To further evaluate the effect of inhibition of JAK1 on pain, McInnes and colleagues aimed to evaluate the effect of upadacitinib on pain outcomes in patients with active PsA or ankylosing spondylitis across three randomized trials (SELECT-PsA-1 and -2 for PsA; SELECT-AXIS 1 for ankylosing spondylitis). A significantly higher proportion of patients receiving 15 mg upadacitinib vs placebo achieved ≥30%, ≥50%, and ≥70% reductions in pain as early as 2 weeks (P < .05), with improvements sustained up to week 56. Further research on whether improvement in pain is at least partially independent of improvement in musculoskeletal inflammation is required.

Persistence of drug treatment is an important outcome and is a surrogate measure of safety and effectiveness. Vegas and colleagues assessed the long-term persistence of different biologic classes in a nationwide cohort study that included 16,892 adults with psoriasis and 6531 adults with PsA who initiated first-line treatment with a TNFi, IL-12/23 inhibitors (IL-12/23i), or an IL-17i. Treatment persistence was higher with IL-17i than with TNFi (weighted hazard ratio [HR] 0.70; P < .001) or IL-12/23i (weighted HR 0.69; P < .001); however, IL-12/23i and TNFi showed similar persistence (P = .70). Thus, IL-17i may be associated with higher treatment persistence in PsA compared with TNFi.

Although most patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) have concomitant psoriasis, many with PsA who are enrolled in clinic trials as well as in rheumatology clinic do not have severe psoriasis. Therefore, an unanswered question is how much psoriasis symptoms contribute to impaired quality of life (QOL) in PsA patients. This question was addressed in a recent study by Taylor and colleagues. This post hoc analysis of two phase 3 studies, OPAL Broaden and OPAL Beyond, included 816 patients with active PsA and an inadequate response to previous therapies who received tofacitinib, adalimumab, or placebo. The analyses demonstrated that Itch Severity Item (ISI) scores of 7-10, Physician's Global Assessment of Psoriasis (PGA-PsO) scores of 4, and Patient's Global Joint and Skin Assessment-Visual Analog Scale (PGJS-VAS) scores of 90-100 mm corresponded with Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores categorized as having a very large effect on a patient's life. An improvement of ≥ 3 points in ISI, ≥ 2 points in PGA-PsO, and ≥ 40 mm in PGJS-VAS translated to a clinically meaningful improvement in DLQI scores; improvements from baseline of ≥4/≥3/≥40-mm in the above scores, respectively, were also associated with clinically meaningful improvements across SF-36v2 (Short-Form Health Survey) domains. Thus, dermatologic symptoms are substantially associated with QOL in patients with active PsA, and improvements in skin measures could translate to clinically meaningful improvements in their QOL.

There is also increasing scrutiny on sex differences in PsA. Eder and colleagues conducted a post hoc analysis of two phase 3 trials that included 679 patients with active PsA who were either biologic-naive (SPIRIT-P1) or showed an inadequate response to one or two tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) (SPIRIT-P2) and were randomly assigned to receive ixekizumab, an IL-17A inhibitor (IL-17Ai), or placebo. They demonstrated that at baseline female vs male patients had significantly higher Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index scores (P ≤ .003), with a significantly higher proportion of male vs female patients in the ixekizumab every-4-weeks treatment arm (53.8% vs 38.3%) and ixekizumab every-2-weeks treatment arm(41.2% vs 28.1%) achieving ≥50% and ≥70% improvement in the American College of Rheumatology response criteria, respectively (both P < .05). Thus, female patients with PsA exhibited significantly higher disease activity at baseline and a poorer response to ixekizumab.