User login

Advances in Hematology and Oncology

- Ordering and Interperting Advanced Solid Tumor Precision Oncology Studies

- Skull Base Regeneration During Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Treatment With Chemoradiation

- Impact of Psychosocial Barriers on Hepatocellular Carinoma Care

- Thrombotic Events in Veterans with Polycythemia Vera

- USPSTF Lung Cancer Screening in a Predominatly Black Veteran Population

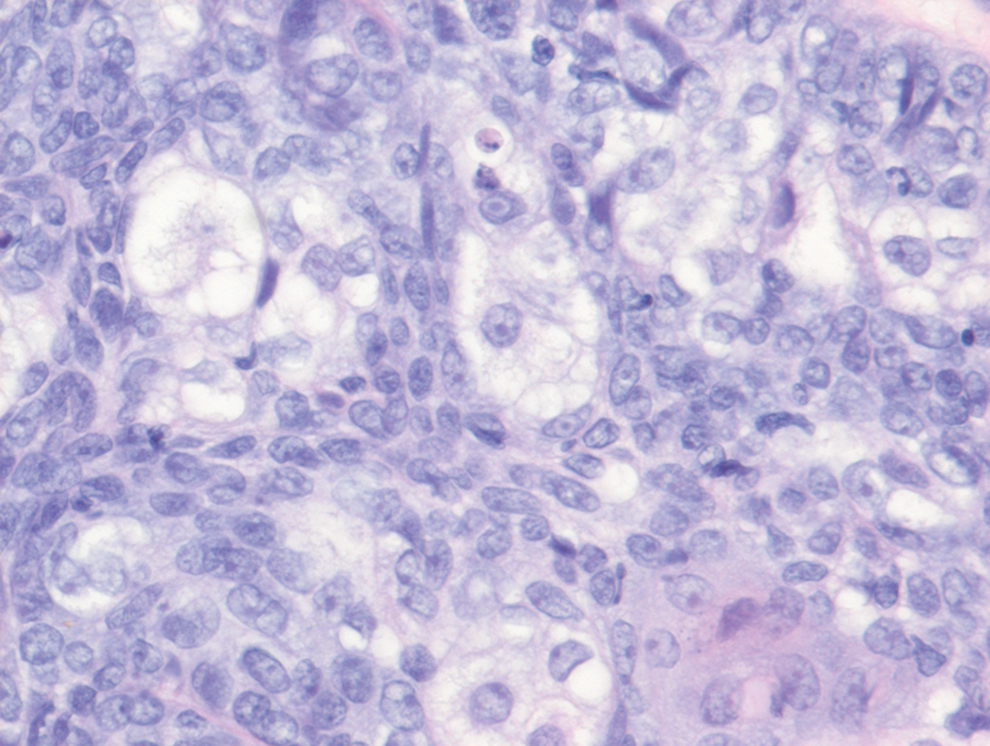

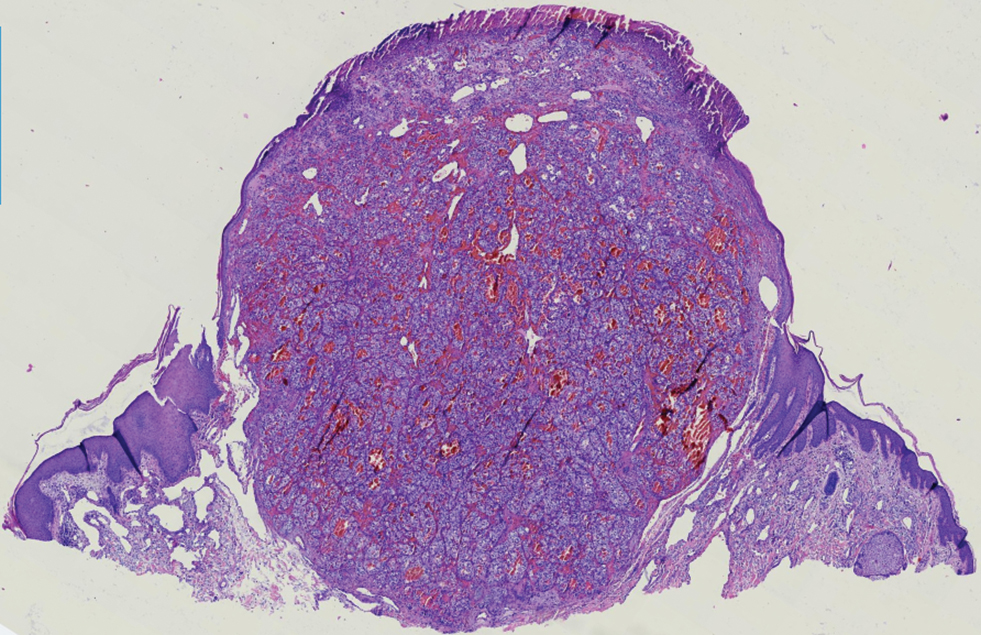

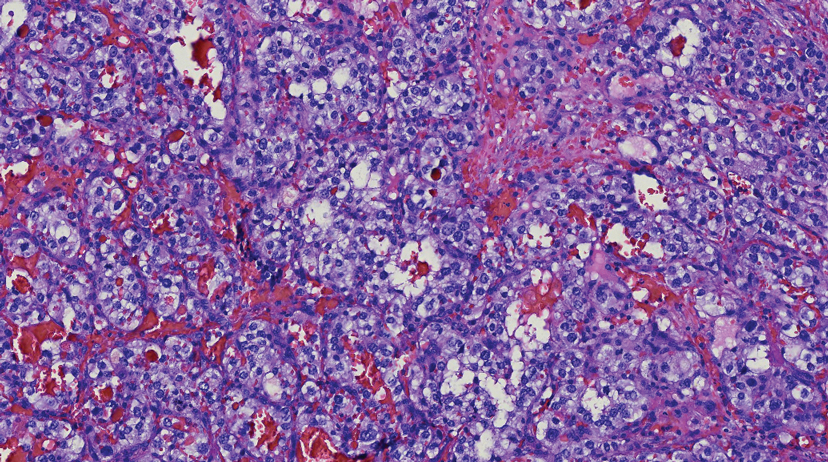

- Leiomyosarcoma of the Penis

- Ordering and Interperting Advanced Solid Tumor Precision Oncology Studies

- Skull Base Regeneration During Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Treatment With Chemoradiation

- Impact of Psychosocial Barriers on Hepatocellular Carinoma Care

- Thrombotic Events in Veterans with Polycythemia Vera

- USPSTF Lung Cancer Screening in a Predominatly Black Veteran Population

- Leiomyosarcoma of the Penis

- Ordering and Interperting Advanced Solid Tumor Precision Oncology Studies

- Skull Base Regeneration During Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Treatment With Chemoradiation

- Impact of Psychosocial Barriers on Hepatocellular Carinoma Care

- Thrombotic Events in Veterans with Polycythemia Vera

- USPSTF Lung Cancer Screening in a Predominatly Black Veteran Population

- Leiomyosarcoma of the Penis

Dupilumab for Allergic Contact Dermatitis: An Overview of Its Use and Impact on Patch Testing

Dupilumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. Through inhibition of the IL-4R α subunit, it prevents activation of the IL-4/IL-13 signaling cascade. This dampens the T H 2 inflammatory response, thereby improving the symptoms associated with atopic dermatitis. 1,2 Recent literature suggests that dupilumab may be useful in the treatment of other chronic dermatologic conditions, including allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) refractory to allergen avoidance and other treatments. Herein, we provide an overview of ACD, the role that dupilumab may play in its management, and its impact on patch testing results.

Pathogenesis of ACD

Allergic contact dermatitis is a cell-mediated type IV hypersensitivity reaction that develops through 2 distinct stages. In the sensitization phase, an allergen penetrates the skin and subsequently is engulfed by a cutaneous antigen-presenting cell. The allergen is then combined with a peptide to form a complex that is presented to naïve T lymphocytes in regional lymph nodes. The result is clonal expansion of a T-cell population that recognizes the allergen. In the elicitation phase, repeat exposure to the allergen leads to the recruitment of primed T cells to the skin, followed by cytokine release, inflammation, and resultant dermatitis.3

Historically, ACD was thought to be primarily driven by the TH1 inflammatory response; however, it is now known that TH2, TH9, TH17, and TH22 also may play a role in its pathogenesis.4,5 Another key finding is that the immune response in ACD appears to be at least partially allergen specific. Molecular profiling has revealed that nickel primarily induces a TH1/TH17 response, while allergens such as fragrance and rubber primarily induce a TH2 response.4

Management of ACD

Allergen avoidance is the mainstay of ACD treatment; however, in some patients, this approach does not always improve symptoms. In addition, eliminating the source of the allergen may not be possible in those with certain occupational, environmental, or medical exposures.

There are no FDA-approved treatments for ACD. When allergen avoidance alone is insufficient, first-line pharmacologic therapy typically includes topical or oral corticosteroids, the choice of which depends on the extent and severity of the dermatitis; however, a steroid-sparing agent often is preferred to avoid the unfavorable effects of long-term steroid use. Other systemic treatments for ACD include methotrexate, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, and azathioprine.6 These agents are used for severe ACD and typically are chosen as a last resort due to their immunosuppressive activity.

Phototherapy is another option, often as an adjunct to other therapies. Narrowband UVB and psoralen plus UVA have both been used. Psoralen plus UVA tends to have more side effects; therefore, narrowband UVB often is preferred.7,8

Use of Dupilumab in ACD

Biologics are unique, as they can target a single step in the immune response to improve a wide variety of symptoms. Research investigating their role as a treatment modality for ACD is still evolving alongside our increasing knowledge of its pathophysiology.9 Of note, studies examining the anti–IL-17 biologic secukinumab revealed it to be ineffective against ACD,10,11 which suggests that targeting specific immune components may not always result in improvement of ACD symptoms, likely because its pathophysiology involves several pathways.

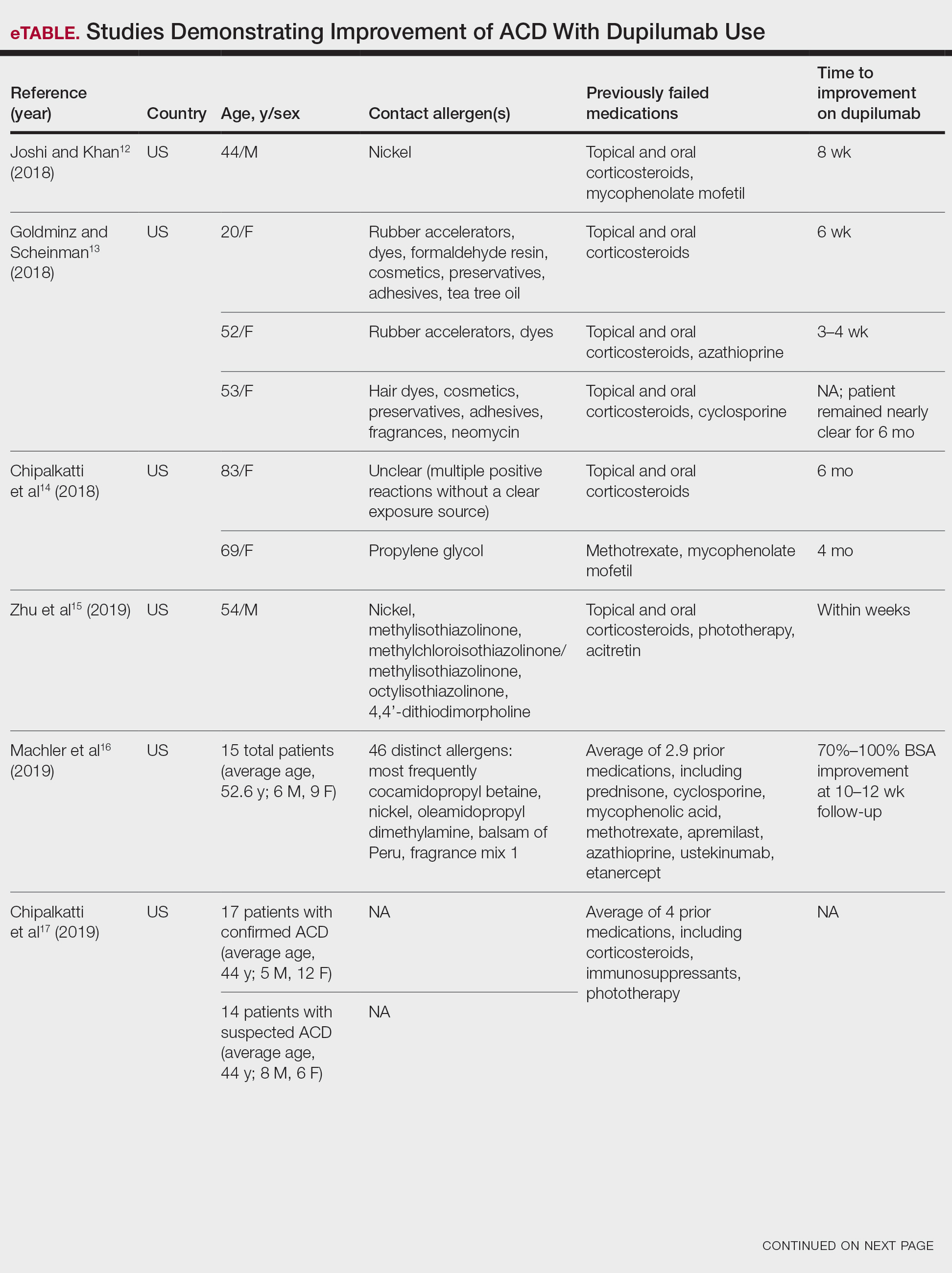

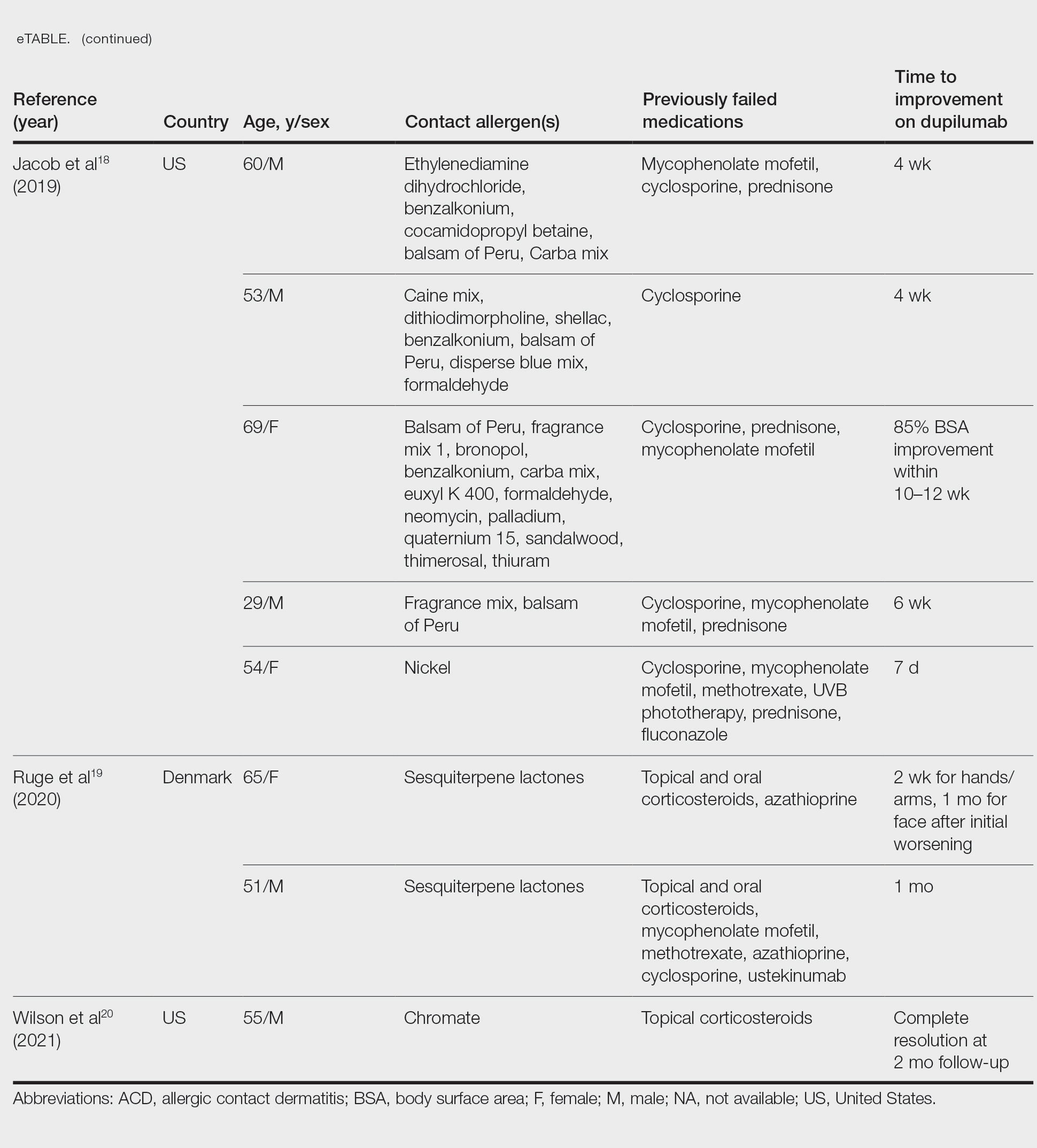

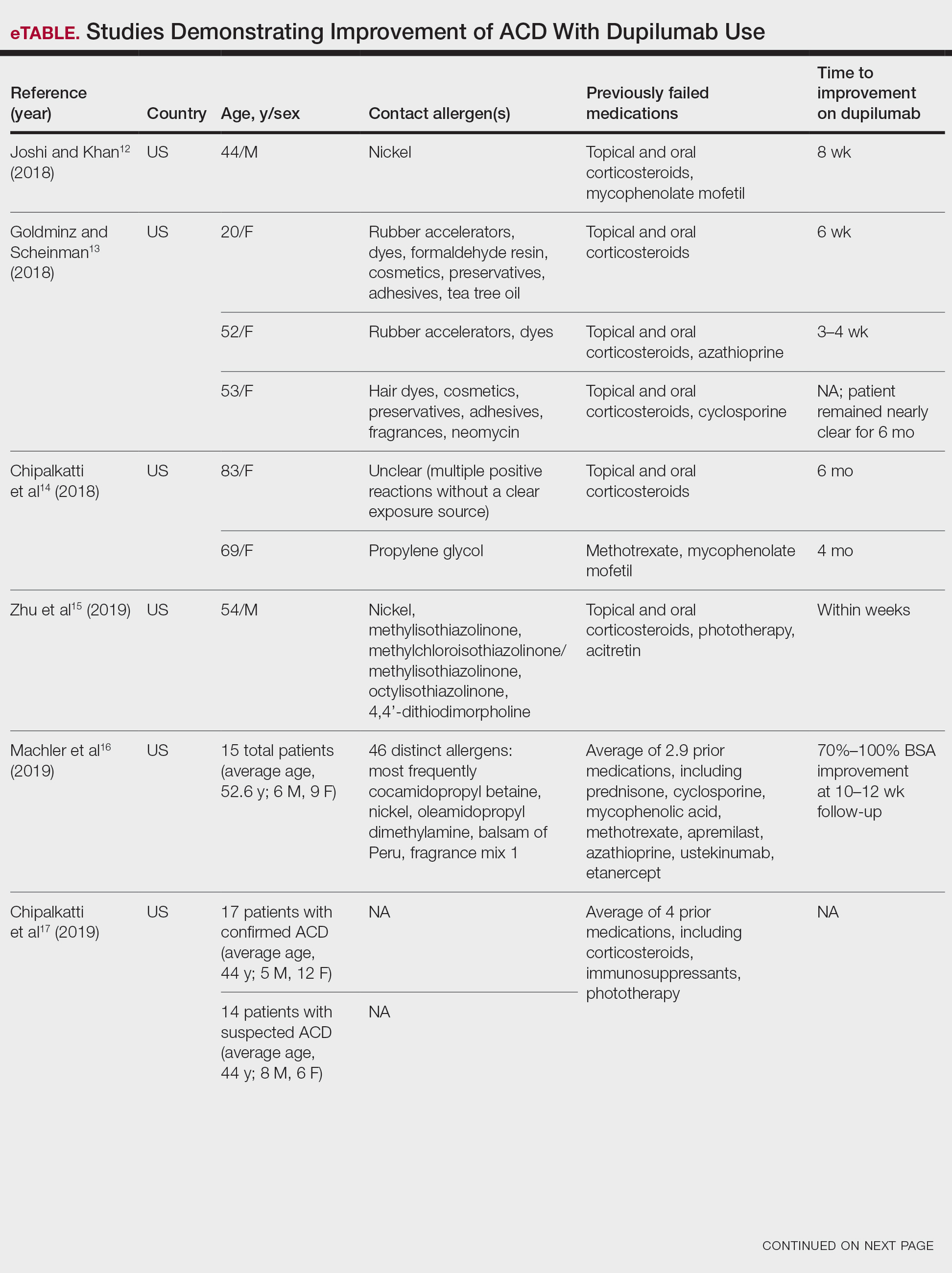

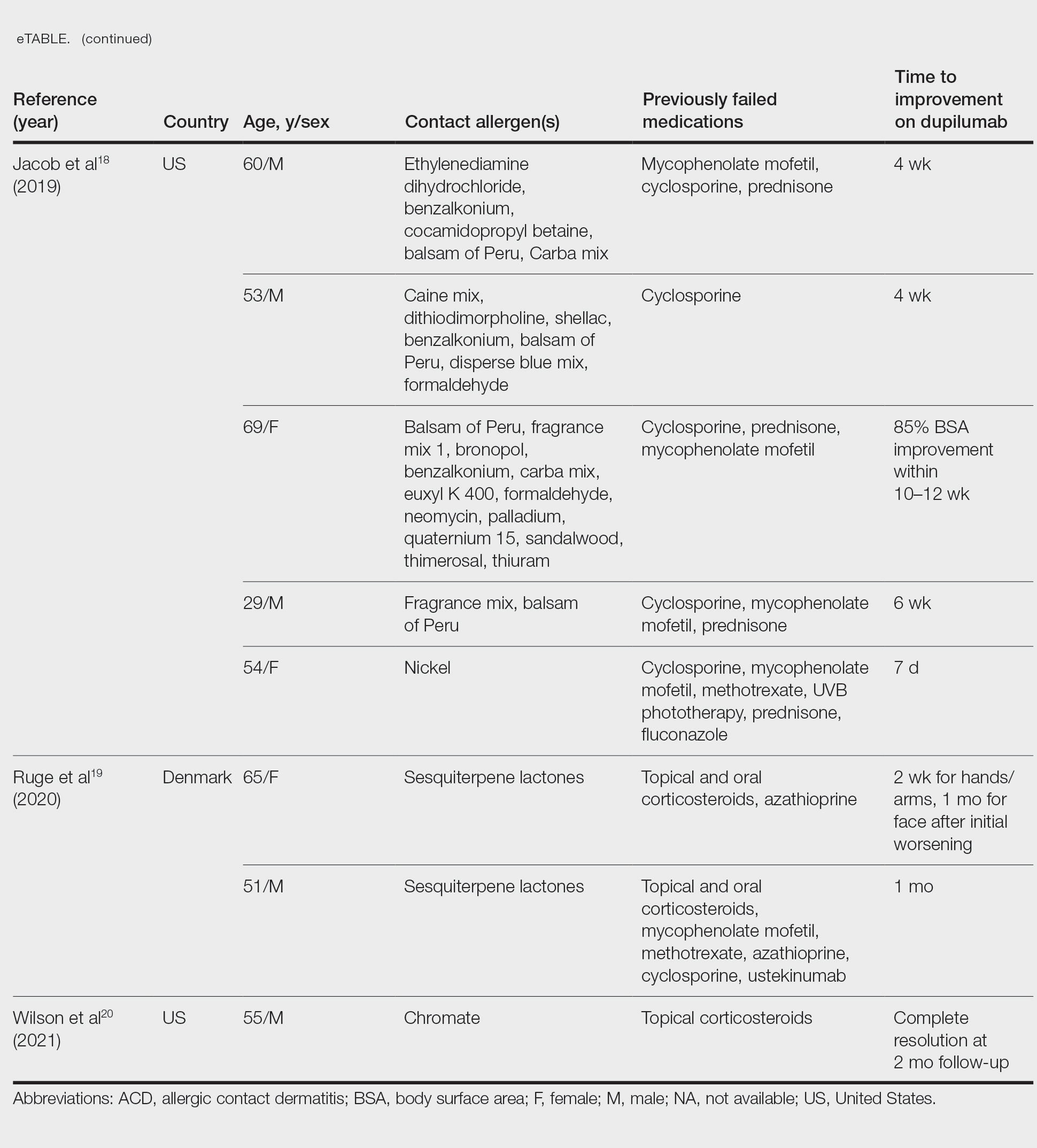

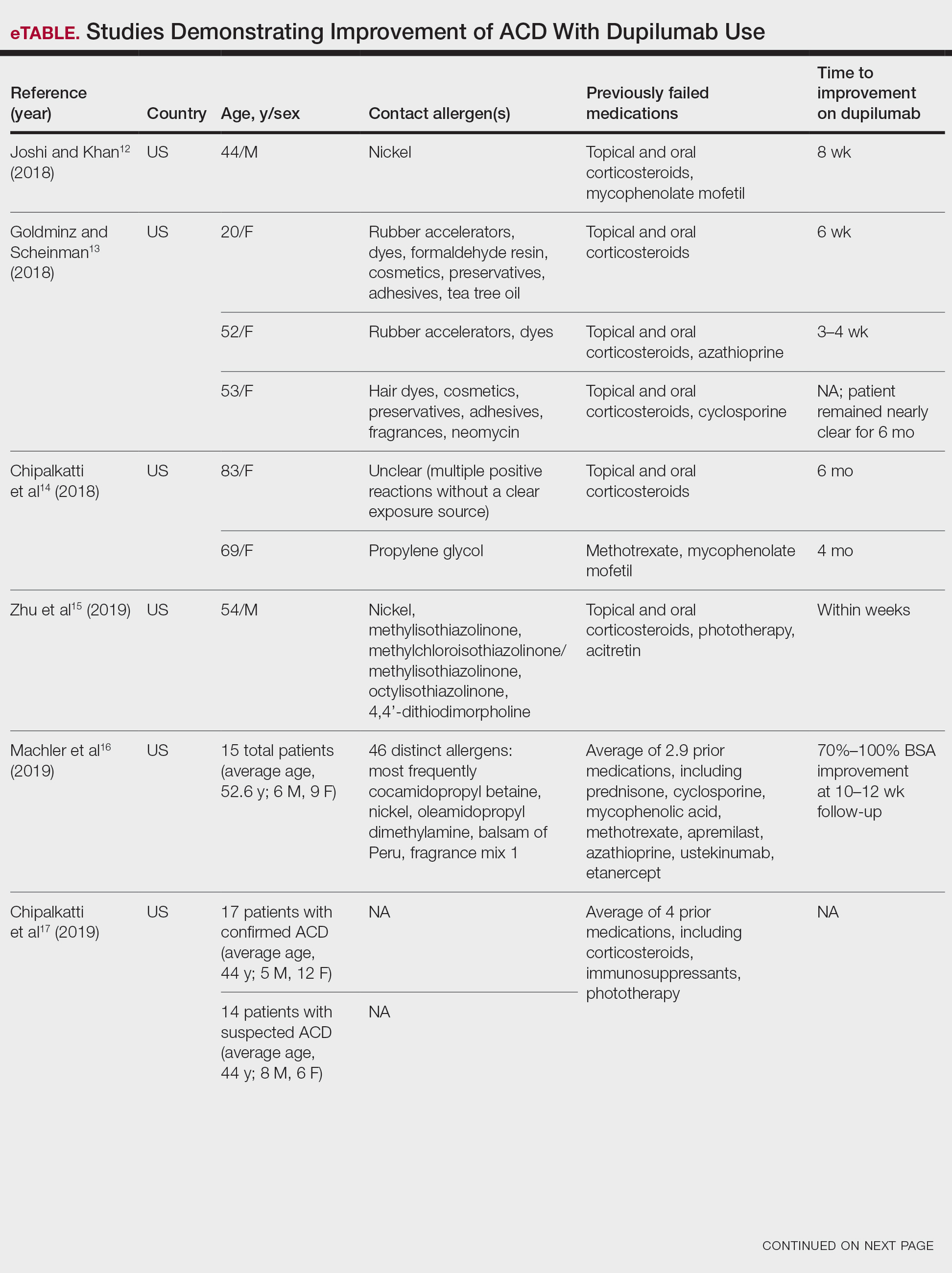

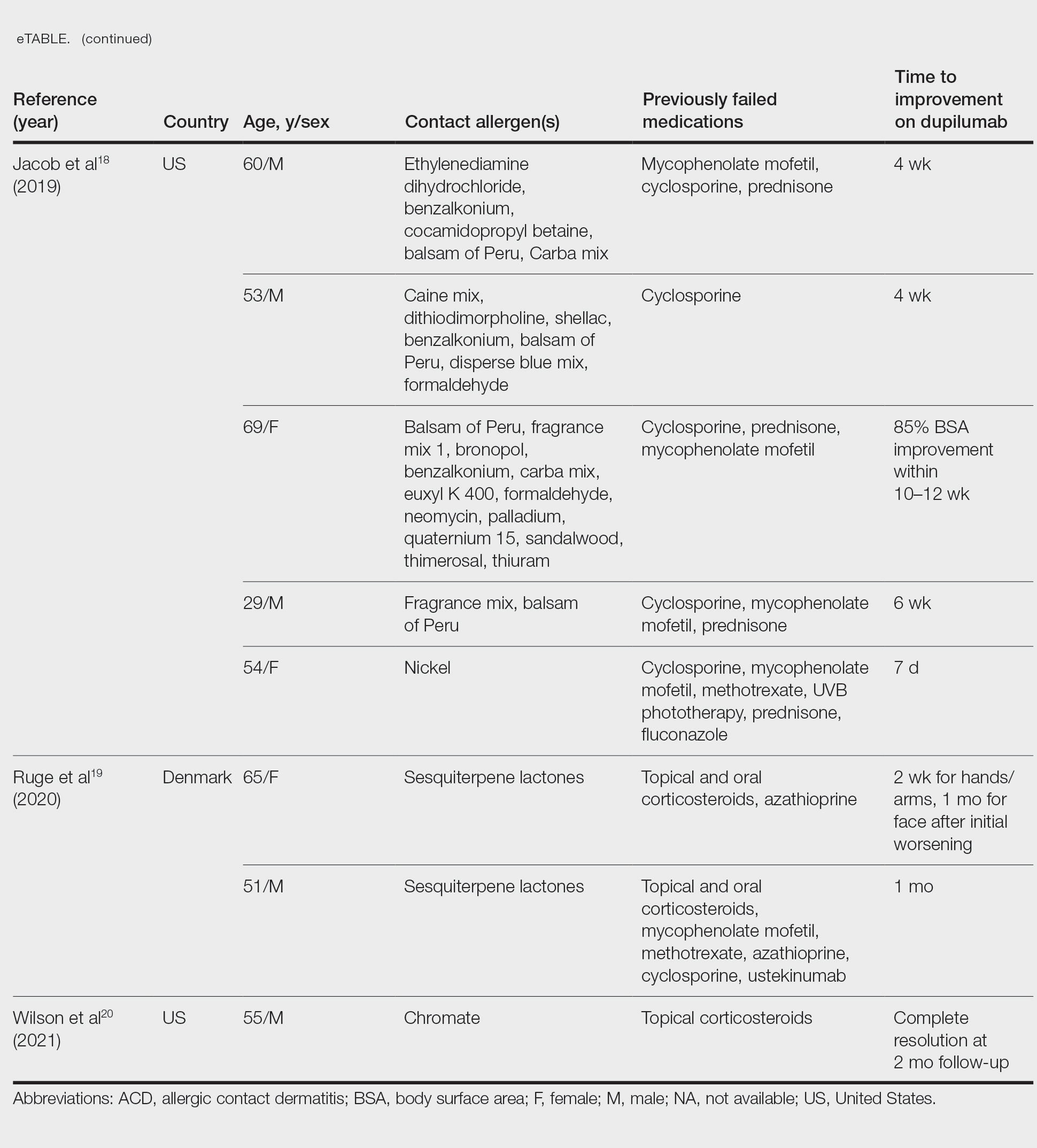

There have been multiple reports demonstrating the effectiveness of dupilumab in the treatment of ACD (eTable).12-20 The findings from these studies show that dupilumab can improve recalcitrant dermatitis caused by a broad range of contact allergens, including nickel. This highlights its ability to improve ACD caused by allergens with a TH1 bias, despite its primarily TH2-dampening effects. Notably, several studies have reported successful use of dupilumab for systemic ACD.12,18 In addition, dupilumab may be able to improve symptoms of ACD in as little as 1 to 4 weeks. Unlike some systemic therapies for ACD, dupilumab also benefits from its lack of notable immunosuppressive effects.9 A phase 4 clinical trial at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts) is recruiting participants, with a primary goal of investigating dupilumab’s impact on ACD in patients who have not improved despite allergen avoidance (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03935971).

There are a few potential disadvantages to dupilumab. Because it is not yet FDA approved for the treatment of ACD, insurance companies may deny coverage, making it likely to be unaffordable for most patients. Furthermore, the side-effect profile has not been fully characterized. In addition to ocular adverse effects, a growing number of studies have reported face and neck erythema after starting dupilumab. Although the cause is unclear, one theory is that the inhibition of IL-4/IL-13 leads to TH1/TH17 polarization, thereby worsening ACD caused by allergens that activate a TH1-predominant response.21 Finally, not all cases of ACD respond to dupilumab.22

Patch Testing While on Dupilumab

Diagnosing ACD is a challenging process. An accurate history and physical examination are critical, and patch testing remains the gold standard when it comes to identifying the source of the contact allergen(s).

There is ongoing debate among contact dermatitis experts regarding the diagnostic accuracy of patch testing for those on immunomodulators or immunosuppressants, as these medications can dampen positive results and increase the risk for false-negative readings.23 Consequently, some have questioned whether patch testing on dupilumab is accurate or feasible.24 Contact dermatitis experts have examined patch testing results before and after initiation of dupilumab to further investigate. Puza and Atwater25 established that patients are able to mount a positive patch test reaction while on dupilumab. Moreover, a retrospective review by Raffi et al26 found that out of 125 before therapy/on therapy patch test pairs, only 13 were lost after administration of dupilumab. Although this would suggest that dupilumab has little impact on patch testing, Jo et al27 found in a systematic review that patch test reactions may remain positive, change to negative, or become newly positive after dupilumab initiation.

This inconsistency in results may relate to the allergen-specific pathogenesis of ACD—one allergen may have a different response to the mechanism of dupilumab than another.28,29 More recently, de Wijs et al30 reported a series of 20 patients in whom more than two-thirds of prior positive patch test reactions were lost after retesting on dupilumab; there were no clear trends according to the immune polarity of the allergens. This finding suggests that patient-specific factors also should be considered, as this too could have an impact on the reliability of patch test findings after starting dupilumab.29

Final Interpretation

Given its overall excellent safety profile, dupilumab may be a feasible off-label option for patients with ACD that does not respond to allergen avoidance or for those who experience adverse effects from traditional therapies; however, it remains difficult to obtain through insurance because it is not yet FDA approved for ACD. Likewise, its impact on the accuracy of patch testing is not yet well defined. Further investigations are needed to elucidate the pathophysiology of ACD and to guide further use of dupilumab in its treatment.

- Harb H, Chatila TA. Mechanisms of dupilumab. Clin Exp Allergy. 2020;50:5-14. doi:10.1111/cea.13491

- Gooderham MJ, Hong HC, Eshtiaghi P, et al. Dupilumab: a review of its use in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(3 suppl 1):S28-S36. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.022

- Murphy PB, Atwater AR, Mueller M. Allergic Contact Dermatitis. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532866/

- Dhingra N, Shemer A, Correa da Rosa J, et al. Molecular profiling of contact dermatitis skin identifies allergen-dependent differences in immune response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:362-372. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.03.009

- Owen JL, Vakharia PP, Silverberg JI. The role and diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:293-302. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0340-7

- Sung CT, McGowan MA, Machler BC, et al. Systemic treatments for allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2019;30:46-53. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000435

- Chan CX, Zug KA. Diagnosis and management of dermatitis, including atopic, contact, and hand eczemas. Med Clin North Am. 2021;105:611-626. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2021.04.003

- Simons JR, Bohnen IJ, van der Valk PG. A left-right comparison of UVB phototherapy and topical photochemotherapy in bilateral chronic hand dermatitis after 6 weeks’ treatment. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1997;22:7-10. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.1997.1640585.x

- Bhatia J, Sarin A, Wollina U, et al. Review of biologics in allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;83:179-181. doi:10.1111/cod.13584

- Todberg T, Zachariae C, Krustrup D, et al. The effect of anti-IL-17 treatment on the reaction to a nickel patch test in patients with allergic contact dermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:E58-E61. doi:10.1111/ijd.14347

- Todberg T, Zachariae C, Krustrup D, et al. The effect of treatment with anti-interleukin-17 in patients with allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:431-432. doi:10.1111/cod.12988

- Joshi SR, Khan DA. Effective use of dupilumab in managing systemic allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2018;29:282-284. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000409

- Goldminz AM, Scheinman PL. A case series of dupilumab-treated allergic contact dermatitis patients. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31:E12701. doi:10.1111/dth.12701

- Chipalkatti N, Lee N, Zancanaro P, et al. Dupilumab as a treatment for allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2018;29:347-348. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000414

- Zhu GA, Chen JK, Chiou A, et al. Repeat patch testing in a patient with allergic contact dermatitis improved on dupilumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:336-338. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.01.023

- Machler BC, Sung CT, Darwin E, et al. Dupilumab use in allergic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:280-281.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.043

- Chipalkatti N, Lee N, Zancanaro P, et al. A retrospective review of dupilumab for atopic dermatitis patients with allergic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1166-1167. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.048

- Jacob SE, Sung CT, Machler BC. Dupilumab for systemic allergy syndrome with dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2019;30:164-167. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000446

- Ruge IF, Skov L, Zachariae C, et al. Dupilumab treatment in two patients with severe allergic contact dermatitis caused by sesquiterpene lactones. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;83:137-139. doi:10.1111/cod.13545

- Wilson B, Balogh E, Rayhan D, et al. Chromate-induced allergic contact dermatitis treated with dupilumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:1340-1342. doi:10.36849/jdd.6246

- Jo CE, Finstad A, Georgakopoulos JR, et al. Facial and neck erythema associated with dupilumab treatment: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1339-1347. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.012

- Koblinski JE, Hamann D. Mixed occupational and iatrogenic allergic contact dermatitis in a hairdresser. Occup Med (Lond). 2020;70:523-526. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqaa152

- Levian B, Chan J, DeLeo VA, et al. Patch testing and immunosuppression: a comprehensive review. Curr Derm Rep. 2021;10:128-139.

- Shah P, Milam EC, Lo Sicco KI, et al. Dupilumab for allergic contact dermatitis and implications for patch testing: irreconcilable differences. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E215-E216. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.036

- Puza CJ, Atwater AR. Positive patch test reaction in a patient taking dupilumab. Dermatitis. 2018;29:89. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000346

- Raffi J, Suresh R, Botto N, et al. The impact of dupilumab on patch testing and the prevalence of comorbid allergic contact dermatitis in recalcitrant atopic dermatitis: a retrospective chart review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:132-138. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.028

- Jo CE, Mufti A, Sachdeva M, et al. Effect of dupilumab on allergic contact dermatitis and patch testing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1772-1776. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.044

- Raffi J, Botto N. Patch testing and allergen-specific inhibition in a patient taking dupilumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:120-121. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4098

- Ludwig CM, Krase JM, Shi VY. T helper 2 inhibitors in allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2021;32:15-18. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000616

- de Wijs LEM, van der Waa JD, Nijsten T, et al. Effects of dupilumab treatment on patch test reactions: a retrospective evaluation. Clin Exp Allergy. 2021;51:959-967. doi:10.1111/cea.13892

Dupilumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. Through inhibition of the IL-4R α subunit, it prevents activation of the IL-4/IL-13 signaling cascade. This dampens the T H 2 inflammatory response, thereby improving the symptoms associated with atopic dermatitis. 1,2 Recent literature suggests that dupilumab may be useful in the treatment of other chronic dermatologic conditions, including allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) refractory to allergen avoidance and other treatments. Herein, we provide an overview of ACD, the role that dupilumab may play in its management, and its impact on patch testing results.

Pathogenesis of ACD

Allergic contact dermatitis is a cell-mediated type IV hypersensitivity reaction that develops through 2 distinct stages. In the sensitization phase, an allergen penetrates the skin and subsequently is engulfed by a cutaneous antigen-presenting cell. The allergen is then combined with a peptide to form a complex that is presented to naïve T lymphocytes in regional lymph nodes. The result is clonal expansion of a T-cell population that recognizes the allergen. In the elicitation phase, repeat exposure to the allergen leads to the recruitment of primed T cells to the skin, followed by cytokine release, inflammation, and resultant dermatitis.3

Historically, ACD was thought to be primarily driven by the TH1 inflammatory response; however, it is now known that TH2, TH9, TH17, and TH22 also may play a role in its pathogenesis.4,5 Another key finding is that the immune response in ACD appears to be at least partially allergen specific. Molecular profiling has revealed that nickel primarily induces a TH1/TH17 response, while allergens such as fragrance and rubber primarily induce a TH2 response.4

Management of ACD

Allergen avoidance is the mainstay of ACD treatment; however, in some patients, this approach does not always improve symptoms. In addition, eliminating the source of the allergen may not be possible in those with certain occupational, environmental, or medical exposures.

There are no FDA-approved treatments for ACD. When allergen avoidance alone is insufficient, first-line pharmacologic therapy typically includes topical or oral corticosteroids, the choice of which depends on the extent and severity of the dermatitis; however, a steroid-sparing agent often is preferred to avoid the unfavorable effects of long-term steroid use. Other systemic treatments for ACD include methotrexate, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, and azathioprine.6 These agents are used for severe ACD and typically are chosen as a last resort due to their immunosuppressive activity.

Phototherapy is another option, often as an adjunct to other therapies. Narrowband UVB and psoralen plus UVA have both been used. Psoralen plus UVA tends to have more side effects; therefore, narrowband UVB often is preferred.7,8

Use of Dupilumab in ACD

Biologics are unique, as they can target a single step in the immune response to improve a wide variety of symptoms. Research investigating their role as a treatment modality for ACD is still evolving alongside our increasing knowledge of its pathophysiology.9 Of note, studies examining the anti–IL-17 biologic secukinumab revealed it to be ineffective against ACD,10,11 which suggests that targeting specific immune components may not always result in improvement of ACD symptoms, likely because its pathophysiology involves several pathways.

There have been multiple reports demonstrating the effectiveness of dupilumab in the treatment of ACD (eTable).12-20 The findings from these studies show that dupilumab can improve recalcitrant dermatitis caused by a broad range of contact allergens, including nickel. This highlights its ability to improve ACD caused by allergens with a TH1 bias, despite its primarily TH2-dampening effects. Notably, several studies have reported successful use of dupilumab for systemic ACD.12,18 In addition, dupilumab may be able to improve symptoms of ACD in as little as 1 to 4 weeks. Unlike some systemic therapies for ACD, dupilumab also benefits from its lack of notable immunosuppressive effects.9 A phase 4 clinical trial at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts) is recruiting participants, with a primary goal of investigating dupilumab’s impact on ACD in patients who have not improved despite allergen avoidance (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03935971).

There are a few potential disadvantages to dupilumab. Because it is not yet FDA approved for the treatment of ACD, insurance companies may deny coverage, making it likely to be unaffordable for most patients. Furthermore, the side-effect profile has not been fully characterized. In addition to ocular adverse effects, a growing number of studies have reported face and neck erythema after starting dupilumab. Although the cause is unclear, one theory is that the inhibition of IL-4/IL-13 leads to TH1/TH17 polarization, thereby worsening ACD caused by allergens that activate a TH1-predominant response.21 Finally, not all cases of ACD respond to dupilumab.22

Patch Testing While on Dupilumab

Diagnosing ACD is a challenging process. An accurate history and physical examination are critical, and patch testing remains the gold standard when it comes to identifying the source of the contact allergen(s).

There is ongoing debate among contact dermatitis experts regarding the diagnostic accuracy of patch testing for those on immunomodulators or immunosuppressants, as these medications can dampen positive results and increase the risk for false-negative readings.23 Consequently, some have questioned whether patch testing on dupilumab is accurate or feasible.24 Contact dermatitis experts have examined patch testing results before and after initiation of dupilumab to further investigate. Puza and Atwater25 established that patients are able to mount a positive patch test reaction while on dupilumab. Moreover, a retrospective review by Raffi et al26 found that out of 125 before therapy/on therapy patch test pairs, only 13 were lost after administration of dupilumab. Although this would suggest that dupilumab has little impact on patch testing, Jo et al27 found in a systematic review that patch test reactions may remain positive, change to negative, or become newly positive after dupilumab initiation.

This inconsistency in results may relate to the allergen-specific pathogenesis of ACD—one allergen may have a different response to the mechanism of dupilumab than another.28,29 More recently, de Wijs et al30 reported a series of 20 patients in whom more than two-thirds of prior positive patch test reactions were lost after retesting on dupilumab; there were no clear trends according to the immune polarity of the allergens. This finding suggests that patient-specific factors also should be considered, as this too could have an impact on the reliability of patch test findings after starting dupilumab.29

Final Interpretation

Given its overall excellent safety profile, dupilumab may be a feasible off-label option for patients with ACD that does not respond to allergen avoidance or for those who experience adverse effects from traditional therapies; however, it remains difficult to obtain through insurance because it is not yet FDA approved for ACD. Likewise, its impact on the accuracy of patch testing is not yet well defined. Further investigations are needed to elucidate the pathophysiology of ACD and to guide further use of dupilumab in its treatment.

Dupilumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. Through inhibition of the IL-4R α subunit, it prevents activation of the IL-4/IL-13 signaling cascade. This dampens the T H 2 inflammatory response, thereby improving the symptoms associated with atopic dermatitis. 1,2 Recent literature suggests that dupilumab may be useful in the treatment of other chronic dermatologic conditions, including allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) refractory to allergen avoidance and other treatments. Herein, we provide an overview of ACD, the role that dupilumab may play in its management, and its impact on patch testing results.

Pathogenesis of ACD

Allergic contact dermatitis is a cell-mediated type IV hypersensitivity reaction that develops through 2 distinct stages. In the sensitization phase, an allergen penetrates the skin and subsequently is engulfed by a cutaneous antigen-presenting cell. The allergen is then combined with a peptide to form a complex that is presented to naïve T lymphocytes in regional lymph nodes. The result is clonal expansion of a T-cell population that recognizes the allergen. In the elicitation phase, repeat exposure to the allergen leads to the recruitment of primed T cells to the skin, followed by cytokine release, inflammation, and resultant dermatitis.3

Historically, ACD was thought to be primarily driven by the TH1 inflammatory response; however, it is now known that TH2, TH9, TH17, and TH22 also may play a role in its pathogenesis.4,5 Another key finding is that the immune response in ACD appears to be at least partially allergen specific. Molecular profiling has revealed that nickel primarily induces a TH1/TH17 response, while allergens such as fragrance and rubber primarily induce a TH2 response.4

Management of ACD

Allergen avoidance is the mainstay of ACD treatment; however, in some patients, this approach does not always improve symptoms. In addition, eliminating the source of the allergen may not be possible in those with certain occupational, environmental, or medical exposures.

There are no FDA-approved treatments for ACD. When allergen avoidance alone is insufficient, first-line pharmacologic therapy typically includes topical or oral corticosteroids, the choice of which depends on the extent and severity of the dermatitis; however, a steroid-sparing agent often is preferred to avoid the unfavorable effects of long-term steroid use. Other systemic treatments for ACD include methotrexate, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, and azathioprine.6 These agents are used for severe ACD and typically are chosen as a last resort due to their immunosuppressive activity.

Phototherapy is another option, often as an adjunct to other therapies. Narrowband UVB and psoralen plus UVA have both been used. Psoralen plus UVA tends to have more side effects; therefore, narrowband UVB often is preferred.7,8

Use of Dupilumab in ACD

Biologics are unique, as they can target a single step in the immune response to improve a wide variety of symptoms. Research investigating their role as a treatment modality for ACD is still evolving alongside our increasing knowledge of its pathophysiology.9 Of note, studies examining the anti–IL-17 biologic secukinumab revealed it to be ineffective against ACD,10,11 which suggests that targeting specific immune components may not always result in improvement of ACD symptoms, likely because its pathophysiology involves several pathways.

There have been multiple reports demonstrating the effectiveness of dupilumab in the treatment of ACD (eTable).12-20 The findings from these studies show that dupilumab can improve recalcitrant dermatitis caused by a broad range of contact allergens, including nickel. This highlights its ability to improve ACD caused by allergens with a TH1 bias, despite its primarily TH2-dampening effects. Notably, several studies have reported successful use of dupilumab for systemic ACD.12,18 In addition, dupilumab may be able to improve symptoms of ACD in as little as 1 to 4 weeks. Unlike some systemic therapies for ACD, dupilumab also benefits from its lack of notable immunosuppressive effects.9 A phase 4 clinical trial at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts) is recruiting participants, with a primary goal of investigating dupilumab’s impact on ACD in patients who have not improved despite allergen avoidance (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03935971).

There are a few potential disadvantages to dupilumab. Because it is not yet FDA approved for the treatment of ACD, insurance companies may deny coverage, making it likely to be unaffordable for most patients. Furthermore, the side-effect profile has not been fully characterized. In addition to ocular adverse effects, a growing number of studies have reported face and neck erythema after starting dupilumab. Although the cause is unclear, one theory is that the inhibition of IL-4/IL-13 leads to TH1/TH17 polarization, thereby worsening ACD caused by allergens that activate a TH1-predominant response.21 Finally, not all cases of ACD respond to dupilumab.22

Patch Testing While on Dupilumab

Diagnosing ACD is a challenging process. An accurate history and physical examination are critical, and patch testing remains the gold standard when it comes to identifying the source of the contact allergen(s).

There is ongoing debate among contact dermatitis experts regarding the diagnostic accuracy of patch testing for those on immunomodulators or immunosuppressants, as these medications can dampen positive results and increase the risk for false-negative readings.23 Consequently, some have questioned whether patch testing on dupilumab is accurate or feasible.24 Contact dermatitis experts have examined patch testing results before and after initiation of dupilumab to further investigate. Puza and Atwater25 established that patients are able to mount a positive patch test reaction while on dupilumab. Moreover, a retrospective review by Raffi et al26 found that out of 125 before therapy/on therapy patch test pairs, only 13 were lost after administration of dupilumab. Although this would suggest that dupilumab has little impact on patch testing, Jo et al27 found in a systematic review that patch test reactions may remain positive, change to negative, or become newly positive after dupilumab initiation.

This inconsistency in results may relate to the allergen-specific pathogenesis of ACD—one allergen may have a different response to the mechanism of dupilumab than another.28,29 More recently, de Wijs et al30 reported a series of 20 patients in whom more than two-thirds of prior positive patch test reactions were lost after retesting on dupilumab; there were no clear trends according to the immune polarity of the allergens. This finding suggests that patient-specific factors also should be considered, as this too could have an impact on the reliability of patch test findings after starting dupilumab.29

Final Interpretation

Given its overall excellent safety profile, dupilumab may be a feasible off-label option for patients with ACD that does not respond to allergen avoidance or for those who experience adverse effects from traditional therapies; however, it remains difficult to obtain through insurance because it is not yet FDA approved for ACD. Likewise, its impact on the accuracy of patch testing is not yet well defined. Further investigations are needed to elucidate the pathophysiology of ACD and to guide further use of dupilumab in its treatment.

- Harb H, Chatila TA. Mechanisms of dupilumab. Clin Exp Allergy. 2020;50:5-14. doi:10.1111/cea.13491

- Gooderham MJ, Hong HC, Eshtiaghi P, et al. Dupilumab: a review of its use in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(3 suppl 1):S28-S36. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.022

- Murphy PB, Atwater AR, Mueller M. Allergic Contact Dermatitis. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532866/

- Dhingra N, Shemer A, Correa da Rosa J, et al. Molecular profiling of contact dermatitis skin identifies allergen-dependent differences in immune response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:362-372. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.03.009

- Owen JL, Vakharia PP, Silverberg JI. The role and diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:293-302. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0340-7

- Sung CT, McGowan MA, Machler BC, et al. Systemic treatments for allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2019;30:46-53. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000435

- Chan CX, Zug KA. Diagnosis and management of dermatitis, including atopic, contact, and hand eczemas. Med Clin North Am. 2021;105:611-626. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2021.04.003

- Simons JR, Bohnen IJ, van der Valk PG. A left-right comparison of UVB phototherapy and topical photochemotherapy in bilateral chronic hand dermatitis after 6 weeks’ treatment. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1997;22:7-10. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.1997.1640585.x

- Bhatia J, Sarin A, Wollina U, et al. Review of biologics in allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;83:179-181. doi:10.1111/cod.13584

- Todberg T, Zachariae C, Krustrup D, et al. The effect of anti-IL-17 treatment on the reaction to a nickel patch test in patients with allergic contact dermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:E58-E61. doi:10.1111/ijd.14347

- Todberg T, Zachariae C, Krustrup D, et al. The effect of treatment with anti-interleukin-17 in patients with allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:431-432. doi:10.1111/cod.12988

- Joshi SR, Khan DA. Effective use of dupilumab in managing systemic allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2018;29:282-284. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000409

- Goldminz AM, Scheinman PL. A case series of dupilumab-treated allergic contact dermatitis patients. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31:E12701. doi:10.1111/dth.12701

- Chipalkatti N, Lee N, Zancanaro P, et al. Dupilumab as a treatment for allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2018;29:347-348. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000414

- Zhu GA, Chen JK, Chiou A, et al. Repeat patch testing in a patient with allergic contact dermatitis improved on dupilumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:336-338. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.01.023

- Machler BC, Sung CT, Darwin E, et al. Dupilumab use in allergic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:280-281.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.043

- Chipalkatti N, Lee N, Zancanaro P, et al. A retrospective review of dupilumab for atopic dermatitis patients with allergic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1166-1167. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.048

- Jacob SE, Sung CT, Machler BC. Dupilumab for systemic allergy syndrome with dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2019;30:164-167. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000446

- Ruge IF, Skov L, Zachariae C, et al. Dupilumab treatment in two patients with severe allergic contact dermatitis caused by sesquiterpene lactones. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;83:137-139. doi:10.1111/cod.13545

- Wilson B, Balogh E, Rayhan D, et al. Chromate-induced allergic contact dermatitis treated with dupilumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:1340-1342. doi:10.36849/jdd.6246

- Jo CE, Finstad A, Georgakopoulos JR, et al. Facial and neck erythema associated with dupilumab treatment: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1339-1347. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.012

- Koblinski JE, Hamann D. Mixed occupational and iatrogenic allergic contact dermatitis in a hairdresser. Occup Med (Lond). 2020;70:523-526. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqaa152

- Levian B, Chan J, DeLeo VA, et al. Patch testing and immunosuppression: a comprehensive review. Curr Derm Rep. 2021;10:128-139.

- Shah P, Milam EC, Lo Sicco KI, et al. Dupilumab for allergic contact dermatitis and implications for patch testing: irreconcilable differences. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E215-E216. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.036

- Puza CJ, Atwater AR. Positive patch test reaction in a patient taking dupilumab. Dermatitis. 2018;29:89. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000346

- Raffi J, Suresh R, Botto N, et al. The impact of dupilumab on patch testing and the prevalence of comorbid allergic contact dermatitis in recalcitrant atopic dermatitis: a retrospective chart review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:132-138. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.028

- Jo CE, Mufti A, Sachdeva M, et al. Effect of dupilumab on allergic contact dermatitis and patch testing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1772-1776. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.044

- Raffi J, Botto N. Patch testing and allergen-specific inhibition in a patient taking dupilumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:120-121. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4098

- Ludwig CM, Krase JM, Shi VY. T helper 2 inhibitors in allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2021;32:15-18. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000616

- de Wijs LEM, van der Waa JD, Nijsten T, et al. Effects of dupilumab treatment on patch test reactions: a retrospective evaluation. Clin Exp Allergy. 2021;51:959-967. doi:10.1111/cea.13892

- Harb H, Chatila TA. Mechanisms of dupilumab. Clin Exp Allergy. 2020;50:5-14. doi:10.1111/cea.13491

- Gooderham MJ, Hong HC, Eshtiaghi P, et al. Dupilumab: a review of its use in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(3 suppl 1):S28-S36. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.022

- Murphy PB, Atwater AR, Mueller M. Allergic Contact Dermatitis. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532866/

- Dhingra N, Shemer A, Correa da Rosa J, et al. Molecular profiling of contact dermatitis skin identifies allergen-dependent differences in immune response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:362-372. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.03.009

- Owen JL, Vakharia PP, Silverberg JI. The role and diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:293-302. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0340-7

- Sung CT, McGowan MA, Machler BC, et al. Systemic treatments for allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2019;30:46-53. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000435

- Chan CX, Zug KA. Diagnosis and management of dermatitis, including atopic, contact, and hand eczemas. Med Clin North Am. 2021;105:611-626. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2021.04.003

- Simons JR, Bohnen IJ, van der Valk PG. A left-right comparison of UVB phototherapy and topical photochemotherapy in bilateral chronic hand dermatitis after 6 weeks’ treatment. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1997;22:7-10. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.1997.1640585.x

- Bhatia J, Sarin A, Wollina U, et al. Review of biologics in allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;83:179-181. doi:10.1111/cod.13584

- Todberg T, Zachariae C, Krustrup D, et al. The effect of anti-IL-17 treatment on the reaction to a nickel patch test in patients with allergic contact dermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:E58-E61. doi:10.1111/ijd.14347

- Todberg T, Zachariae C, Krustrup D, et al. The effect of treatment with anti-interleukin-17 in patients with allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:431-432. doi:10.1111/cod.12988

- Joshi SR, Khan DA. Effective use of dupilumab in managing systemic allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2018;29:282-284. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000409

- Goldminz AM, Scheinman PL. A case series of dupilumab-treated allergic contact dermatitis patients. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31:E12701. doi:10.1111/dth.12701

- Chipalkatti N, Lee N, Zancanaro P, et al. Dupilumab as a treatment for allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2018;29:347-348. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000414

- Zhu GA, Chen JK, Chiou A, et al. Repeat patch testing in a patient with allergic contact dermatitis improved on dupilumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:336-338. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.01.023

- Machler BC, Sung CT, Darwin E, et al. Dupilumab use in allergic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:280-281.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.043

- Chipalkatti N, Lee N, Zancanaro P, et al. A retrospective review of dupilumab for atopic dermatitis patients with allergic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1166-1167. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.048

- Jacob SE, Sung CT, Machler BC. Dupilumab for systemic allergy syndrome with dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2019;30:164-167. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000446

- Ruge IF, Skov L, Zachariae C, et al. Dupilumab treatment in two patients with severe allergic contact dermatitis caused by sesquiterpene lactones. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;83:137-139. doi:10.1111/cod.13545

- Wilson B, Balogh E, Rayhan D, et al. Chromate-induced allergic contact dermatitis treated with dupilumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:1340-1342. doi:10.36849/jdd.6246

- Jo CE, Finstad A, Georgakopoulos JR, et al. Facial and neck erythema associated with dupilumab treatment: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1339-1347. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.012

- Koblinski JE, Hamann D. Mixed occupational and iatrogenic allergic contact dermatitis in a hairdresser. Occup Med (Lond). 2020;70:523-526. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqaa152

- Levian B, Chan J, DeLeo VA, et al. Patch testing and immunosuppression: a comprehensive review. Curr Derm Rep. 2021;10:128-139.

- Shah P, Milam EC, Lo Sicco KI, et al. Dupilumab for allergic contact dermatitis and implications for patch testing: irreconcilable differences. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E215-E216. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.036

- Puza CJ, Atwater AR. Positive patch test reaction in a patient taking dupilumab. Dermatitis. 2018;29:89. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000346

- Raffi J, Suresh R, Botto N, et al. The impact of dupilumab on patch testing and the prevalence of comorbid allergic contact dermatitis in recalcitrant atopic dermatitis: a retrospective chart review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:132-138. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.028

- Jo CE, Mufti A, Sachdeva M, et al. Effect of dupilumab on allergic contact dermatitis and patch testing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1772-1776. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.044

- Raffi J, Botto N. Patch testing and allergen-specific inhibition in a patient taking dupilumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:120-121. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4098

- Ludwig CM, Krase JM, Shi VY. T helper 2 inhibitors in allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2021;32:15-18. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000616

- de Wijs LEM, van der Waa JD, Nijsten T, et al. Effects of dupilumab treatment on patch test reactions: a retrospective evaluation. Clin Exp Allergy. 2021;51:959-967. doi:10.1111/cea.13892

Practice Points

- Dupilumab is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.

- Multiple reports have suggested that dupilumab may be effective in the treatment of allergic contact dermatitis, and a phase 4 clinical trial is ongoing.

- The accuracy of patch testing after dupilumab initiation is unclear, as reactions may remain positive, change to negative, or become newly positive after its administration.

Skin Cancer Education in the Medical School Curriculum

To the Editor:

Skin cancer represents a notable health care burden of rising incidence.1-3 Nondermatologist health care providers play a key role in skin cancer screening through the use of skin cancer examination (SCE)1,4; however, several factors including poor diagnostic accuracy, low confidence, and lack of training have contributed to limited use of the SCE by these providers.4,5 Therefore, it is important to identify and implement changes in the medical school curriculum that can facilitate improved use of SCE in clinical practice. We sought to examine factors in the medical school curriculum that influence skin cancer education.

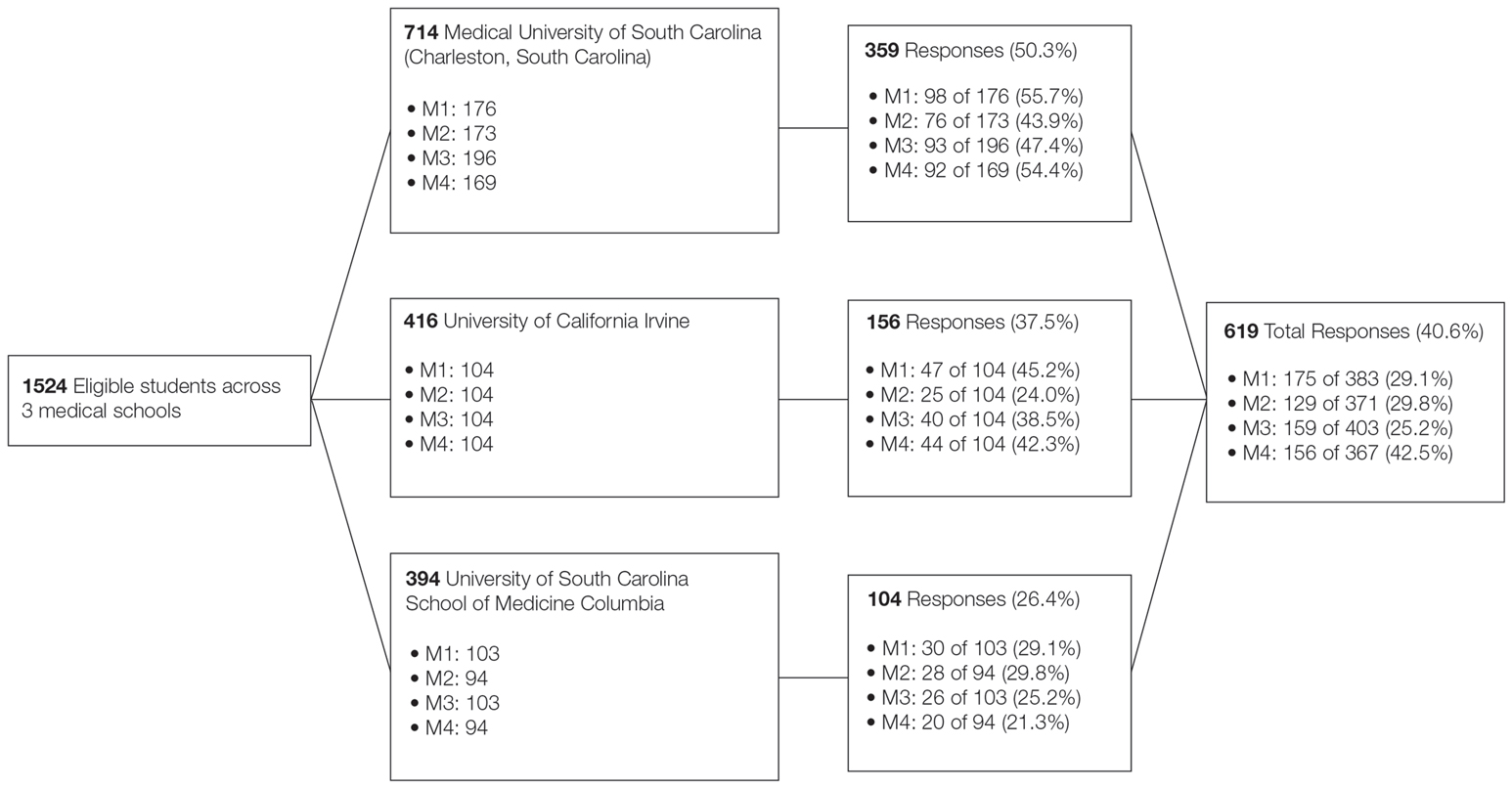

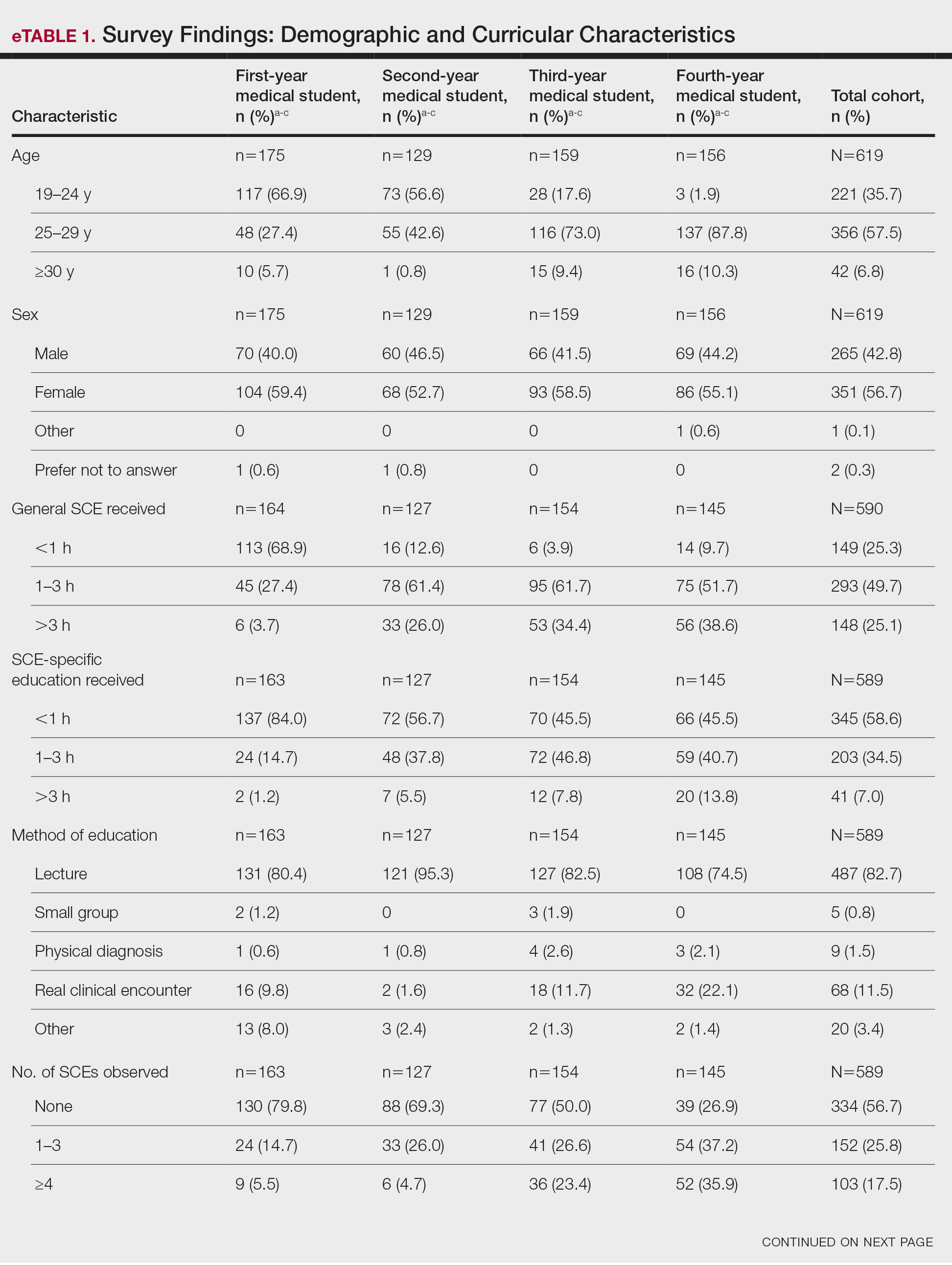

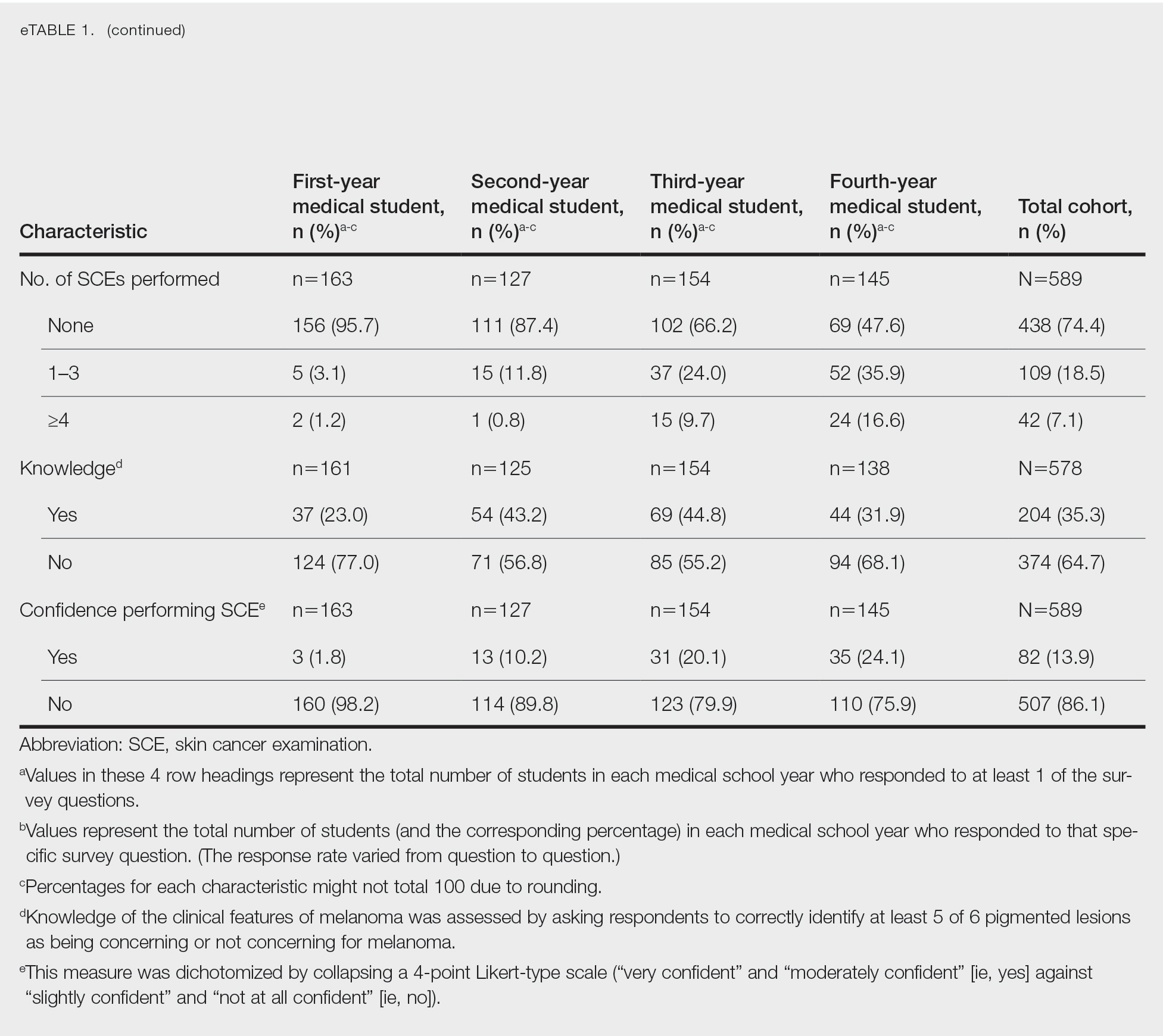

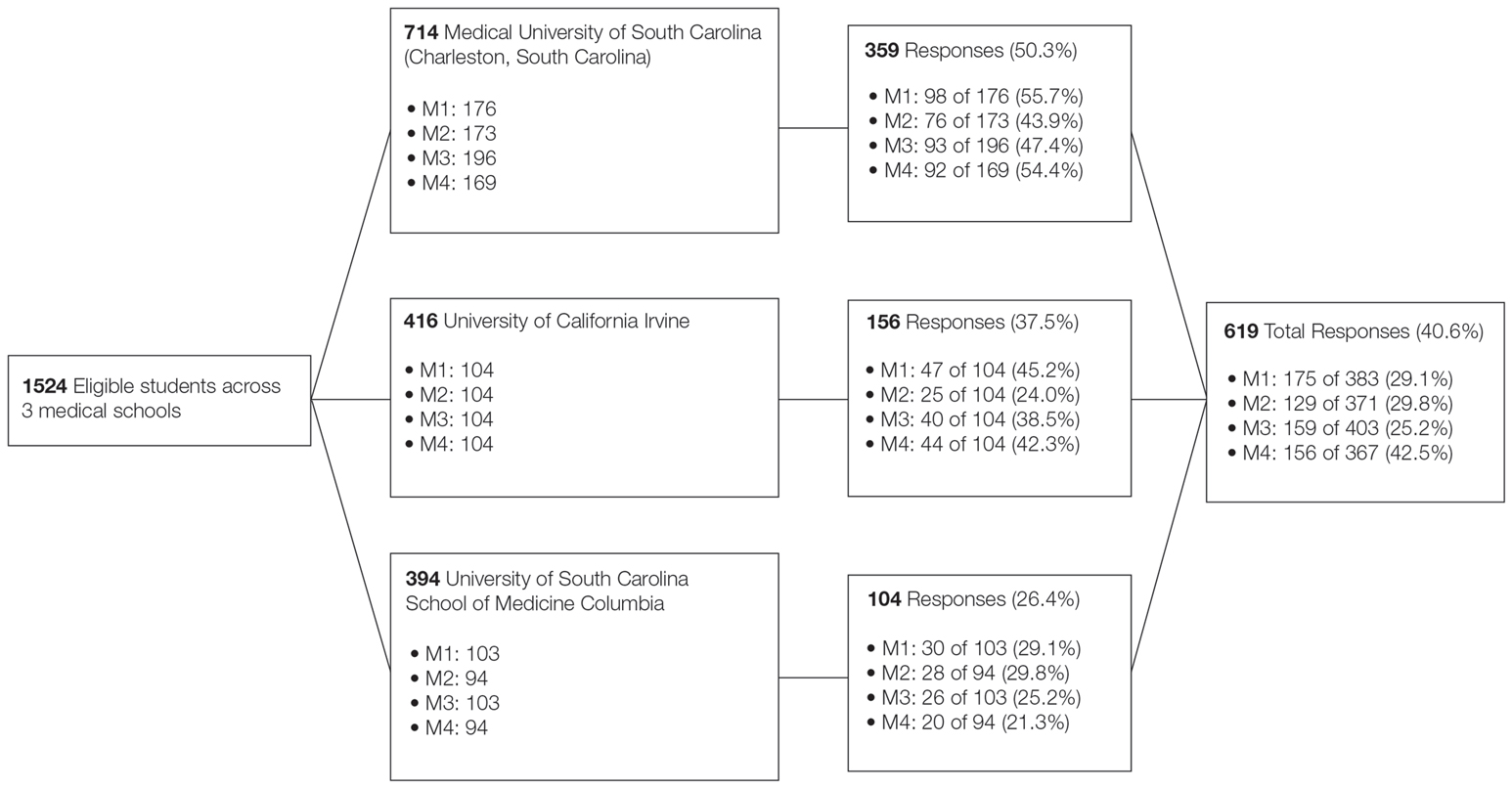

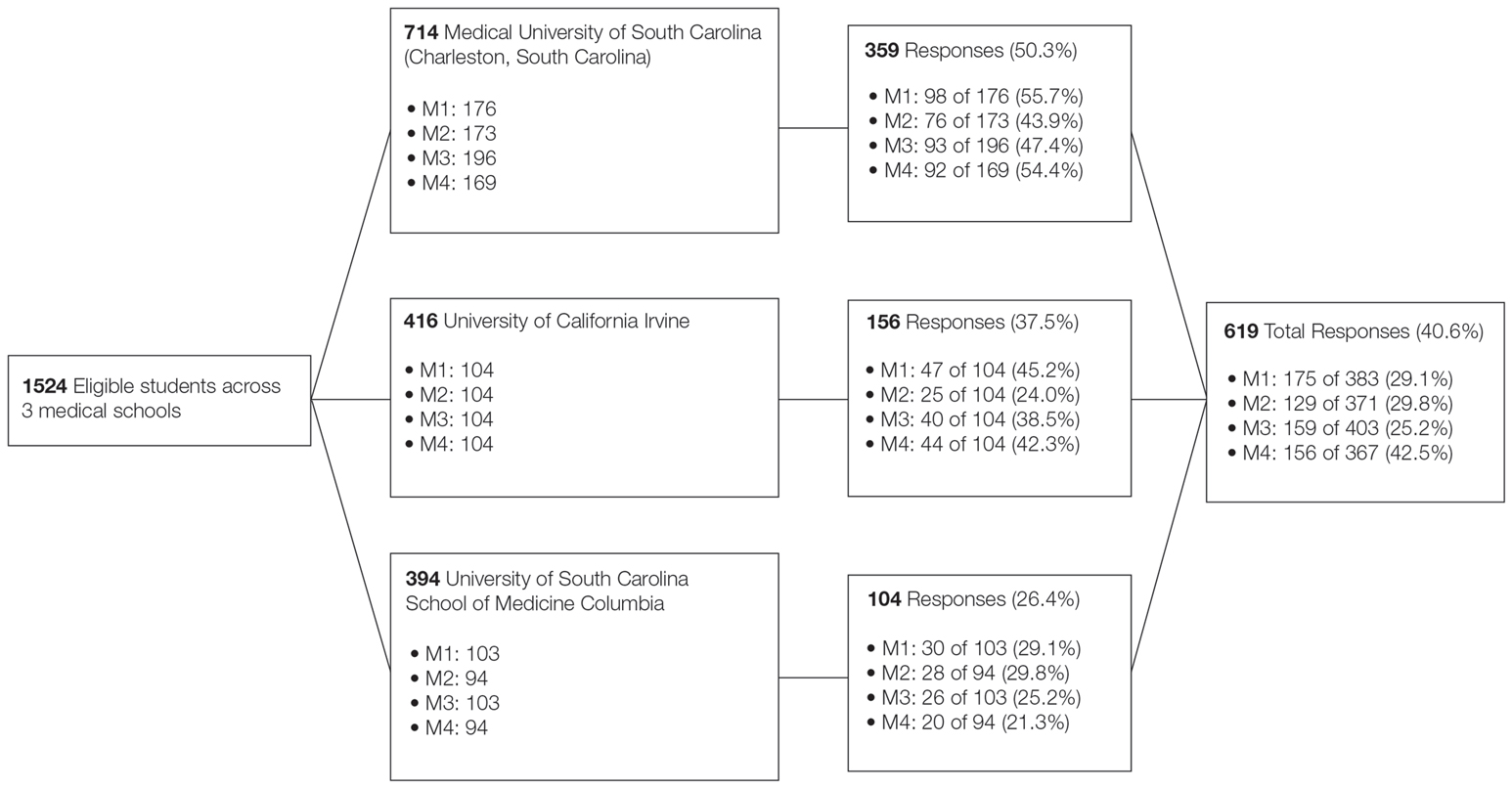

A voluntary electronic survey was distributed through class email and social media to all medical student classes at 4 medical schools (Figure). Responses were collected between March 2 and April 20, 2020. Survey items assessed demographics and curricular factors that influence skin cancer education.

Knowledge of the clinical features of melanoma was assessed by asking participants to correctly identify at least 5 of 6 pigmented lesions as concerning or not concerning for melanoma. Confidence in performing the SCE—the primary outcome—was measured by dichotomizing a 4-point Likert-type scale (“very confident” and “moderately confident” against “slightly confident” and “not at all confident”).

Logistic regression was used to examine curricular factors associated with confidence; descriptive statistics were used for remaining analyses. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 statistical software. Prior to analysis, responses from the University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville were excluded because the response rate was less than 20%.

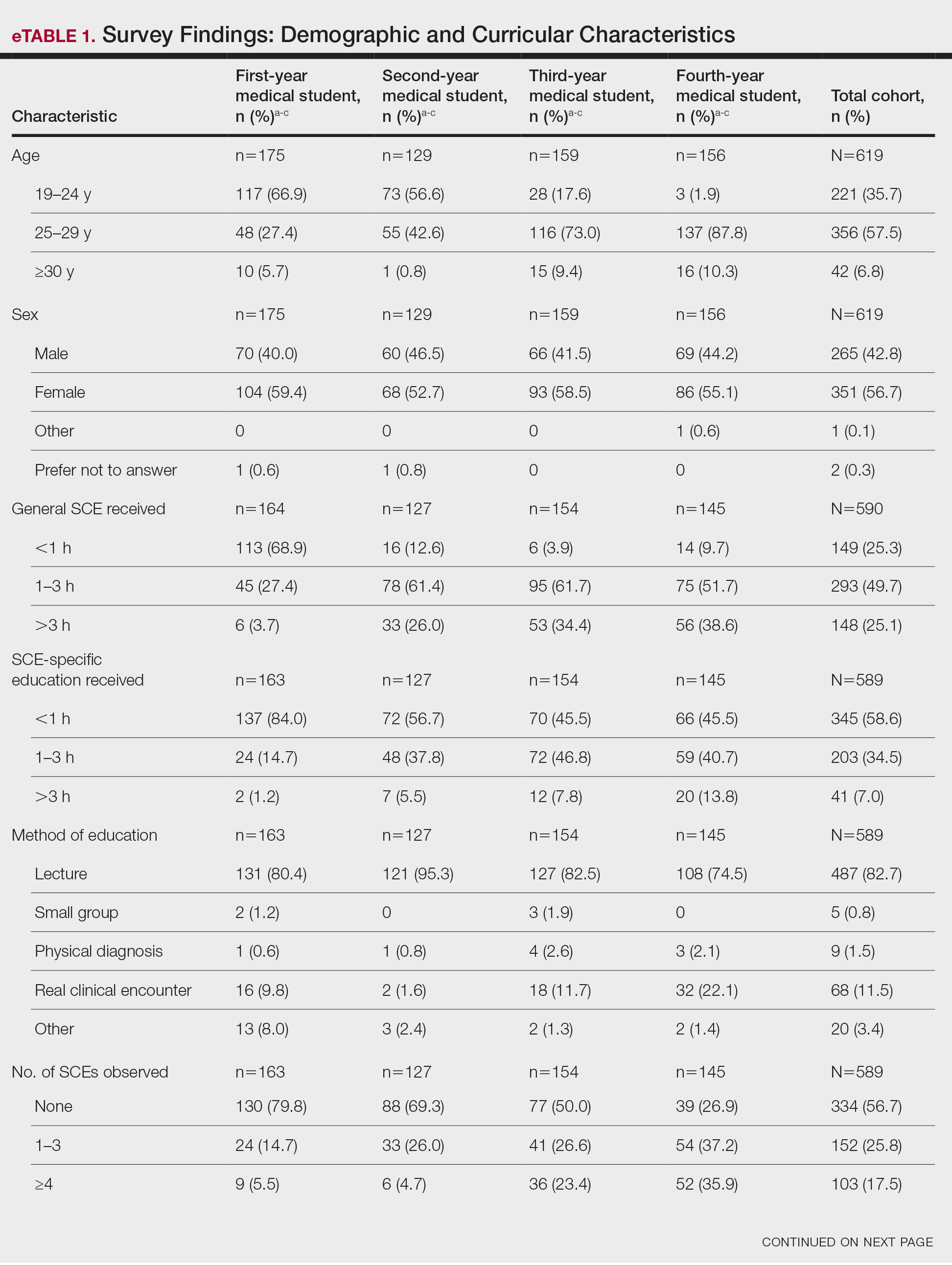

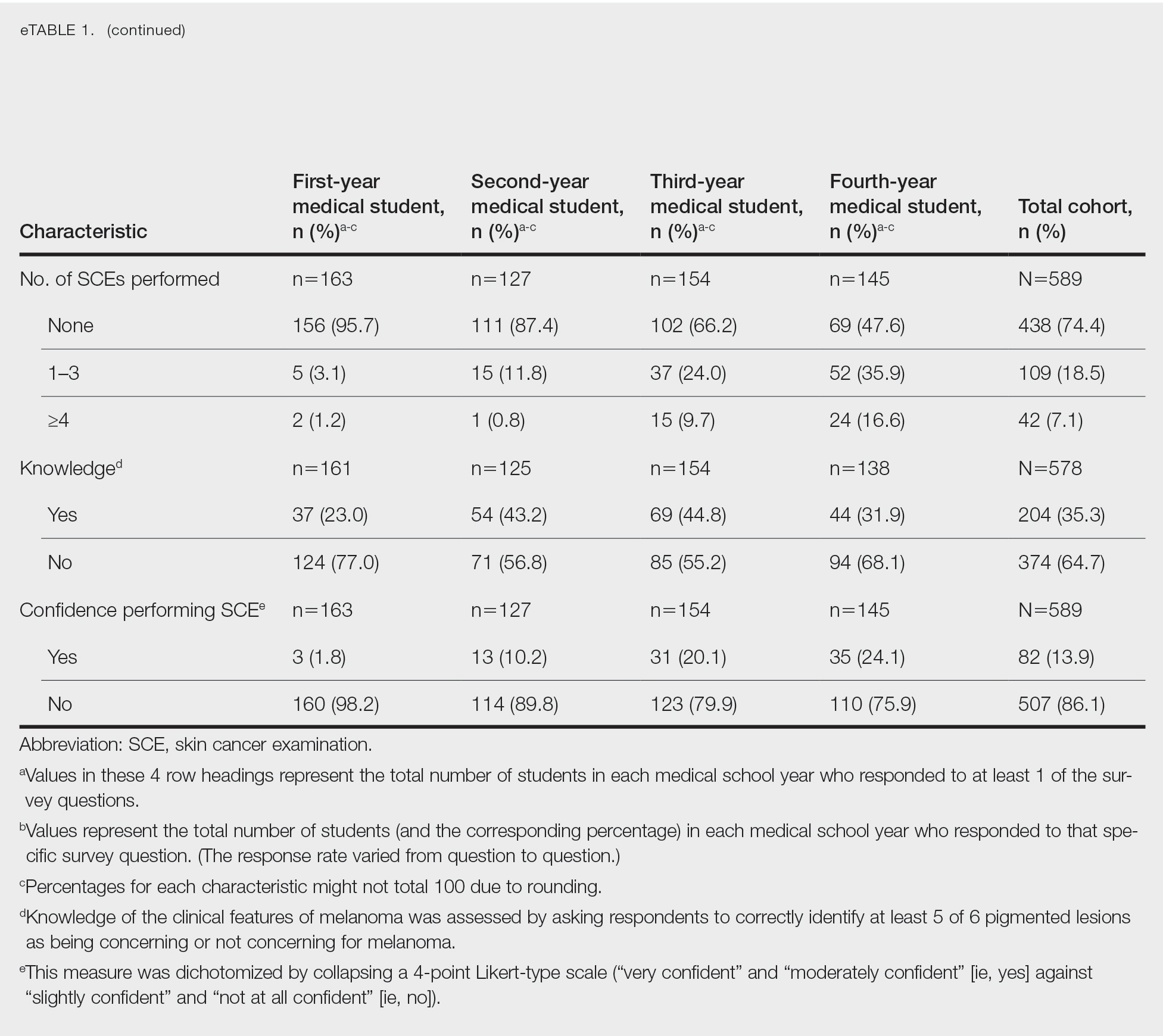

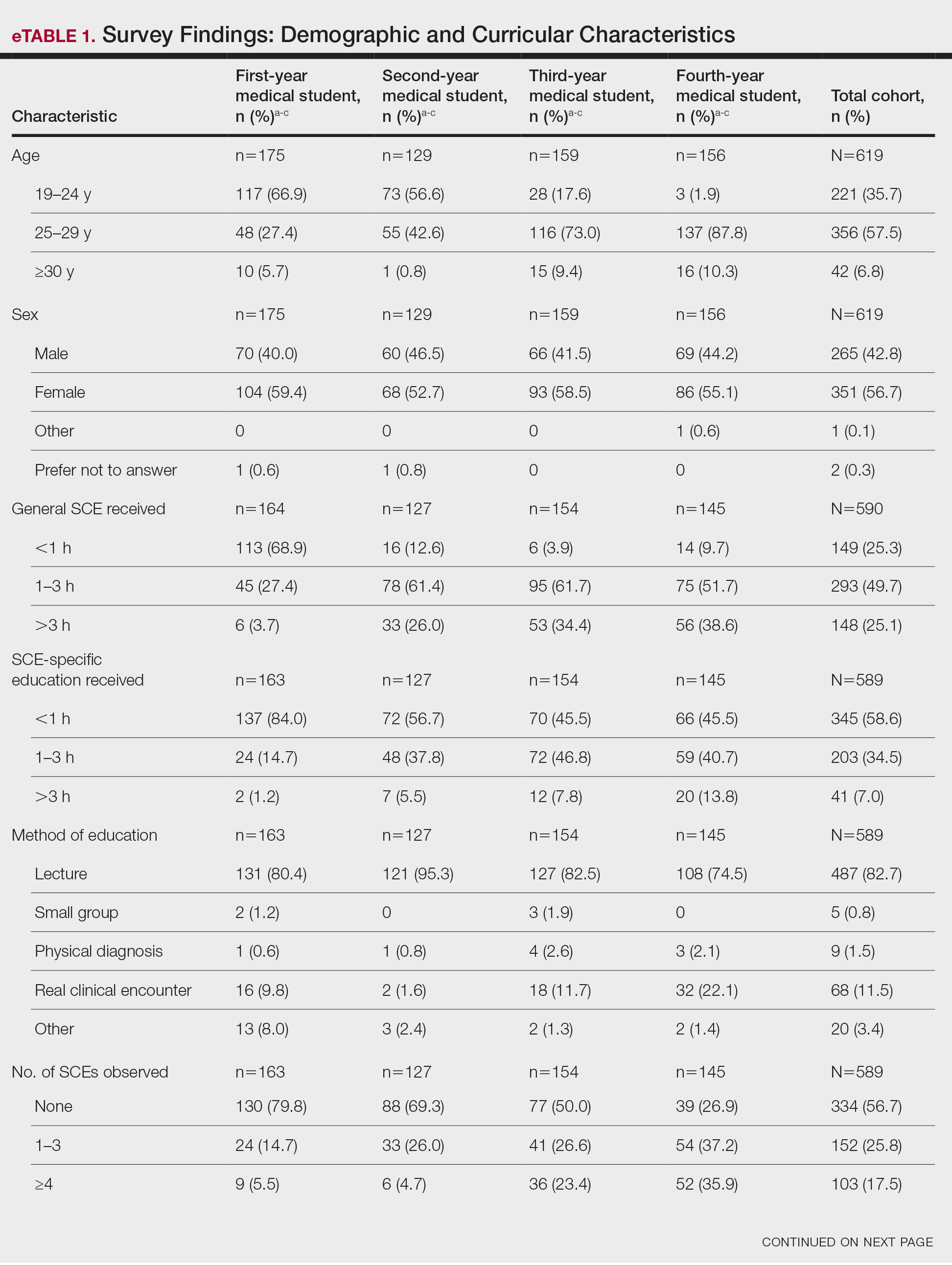

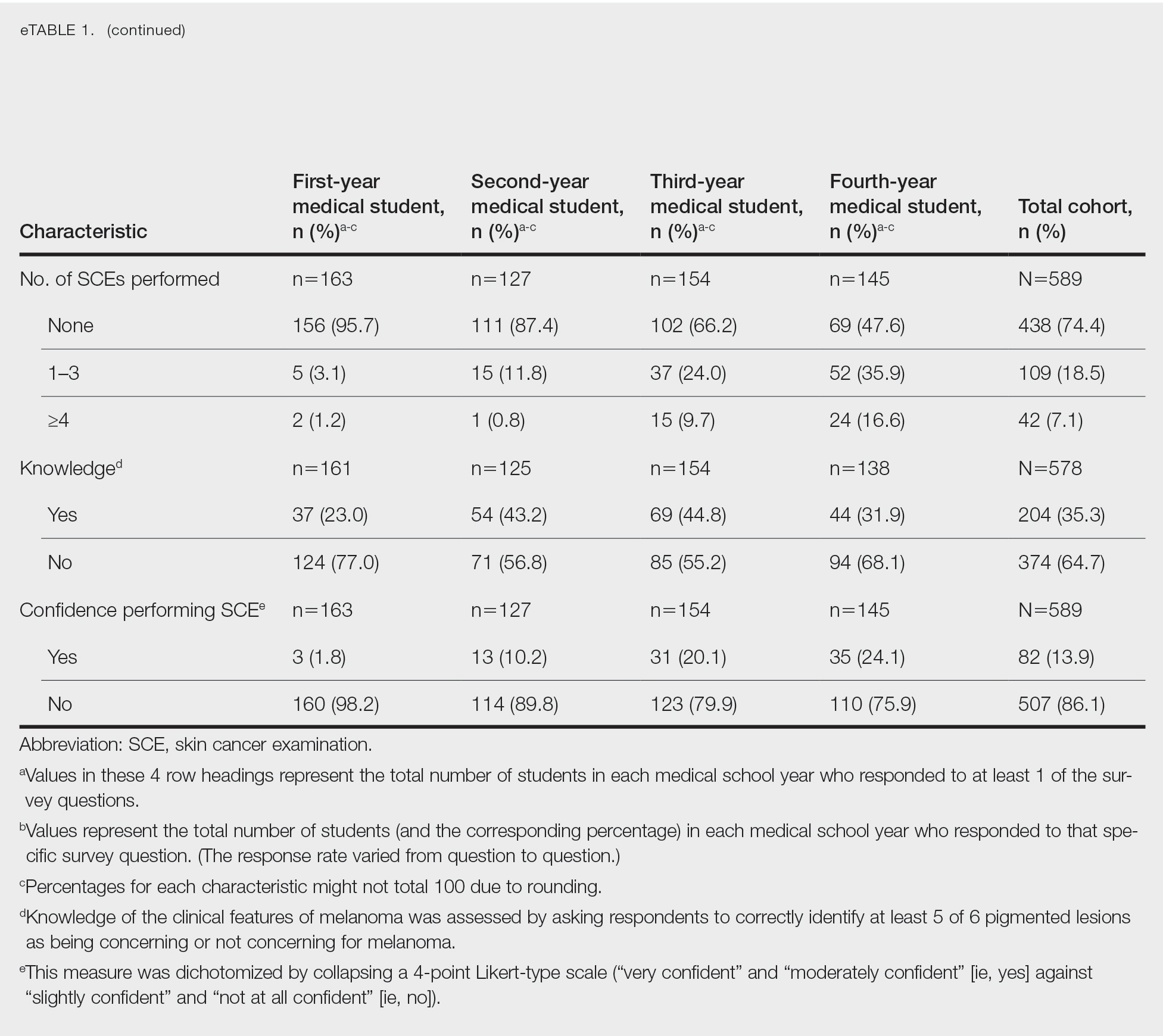

The survey was distributed to 1524 students; 619 (40.6%) answered at least 1 question, with a variable response rate to each item (eTable 1). Most respondents were female (351 [56.7%]); 438 (70.8%) were White.

Most respondents said that they received 3 hours or less of general skin cancer (74.9%) or SCE-specific (93.0%) education by the end of their fourth year of medical training. Lecture was the most common method of instruction. Education was provided most often by dermatologists (48.6%), followed by general practice physicians (21.2%). Numerous (26.9%) fourth-year respondents reported that they had never observed SCE; even more (47.6%) had never performed SCE. Almost half of second- and third-year students (43.2% and 44.8%, respectively) considered themselves knowledgeable about the clinical features of melanoma, but only 31.9% of fourth-year students considered themselves knowledgeable.

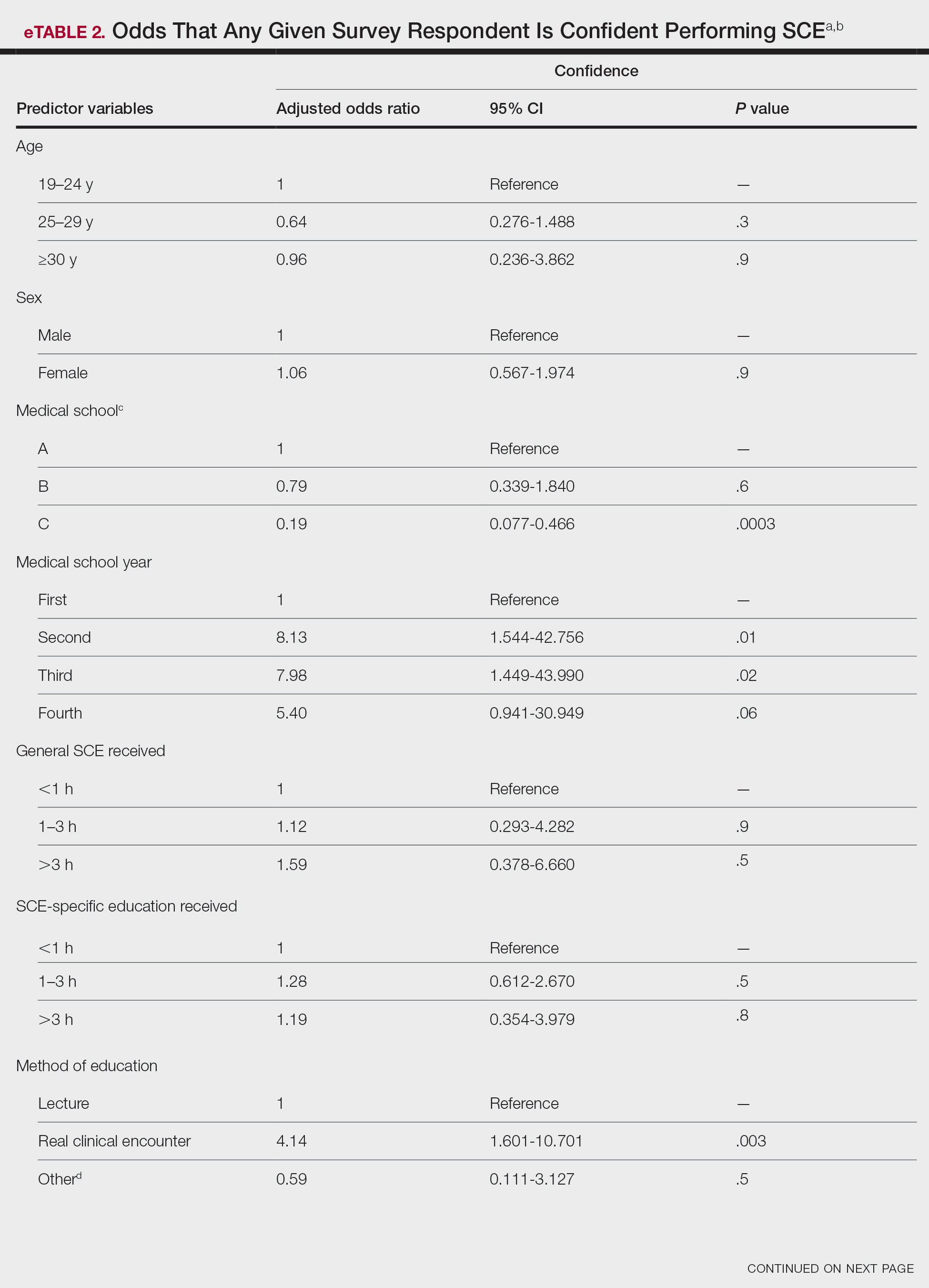

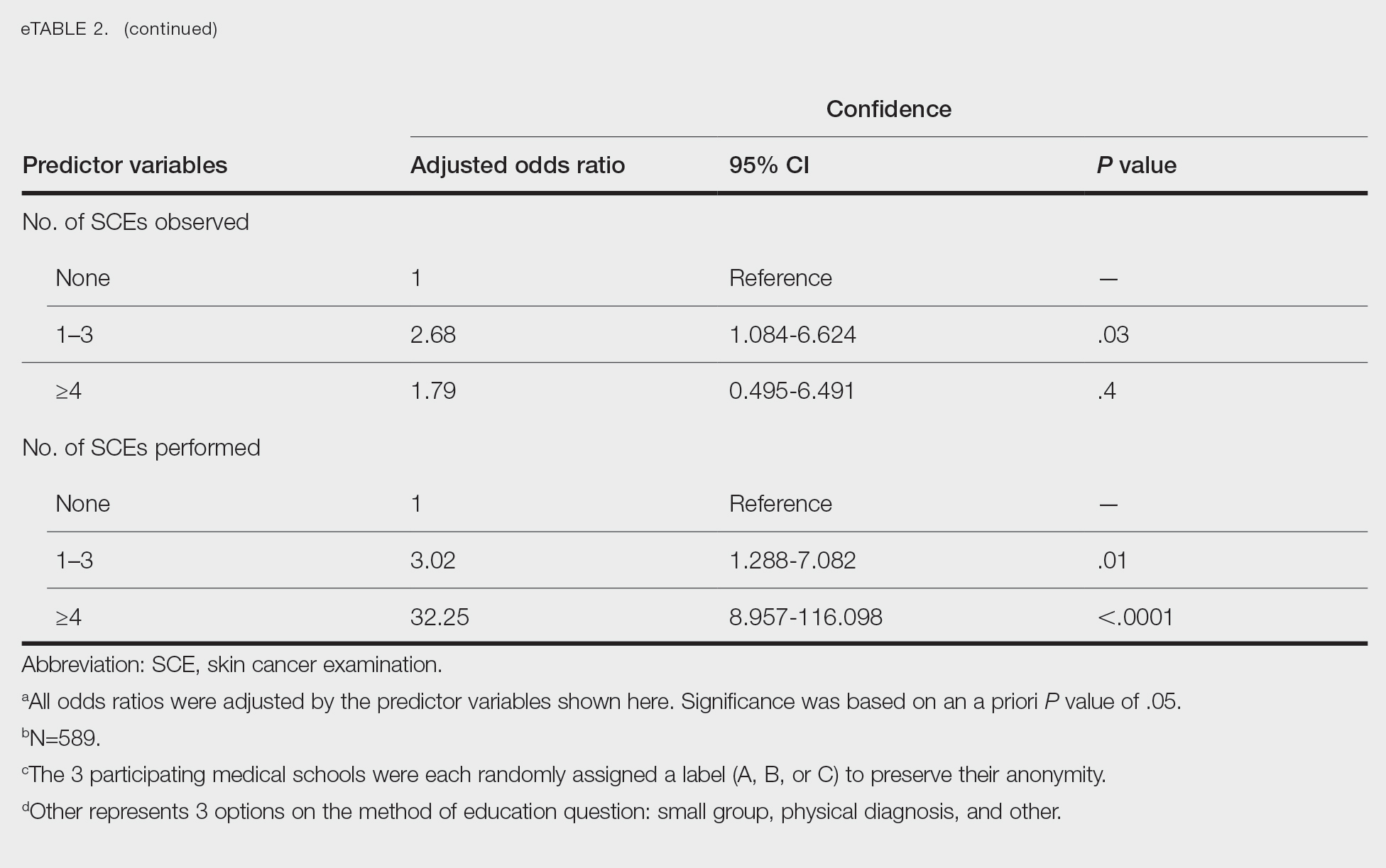

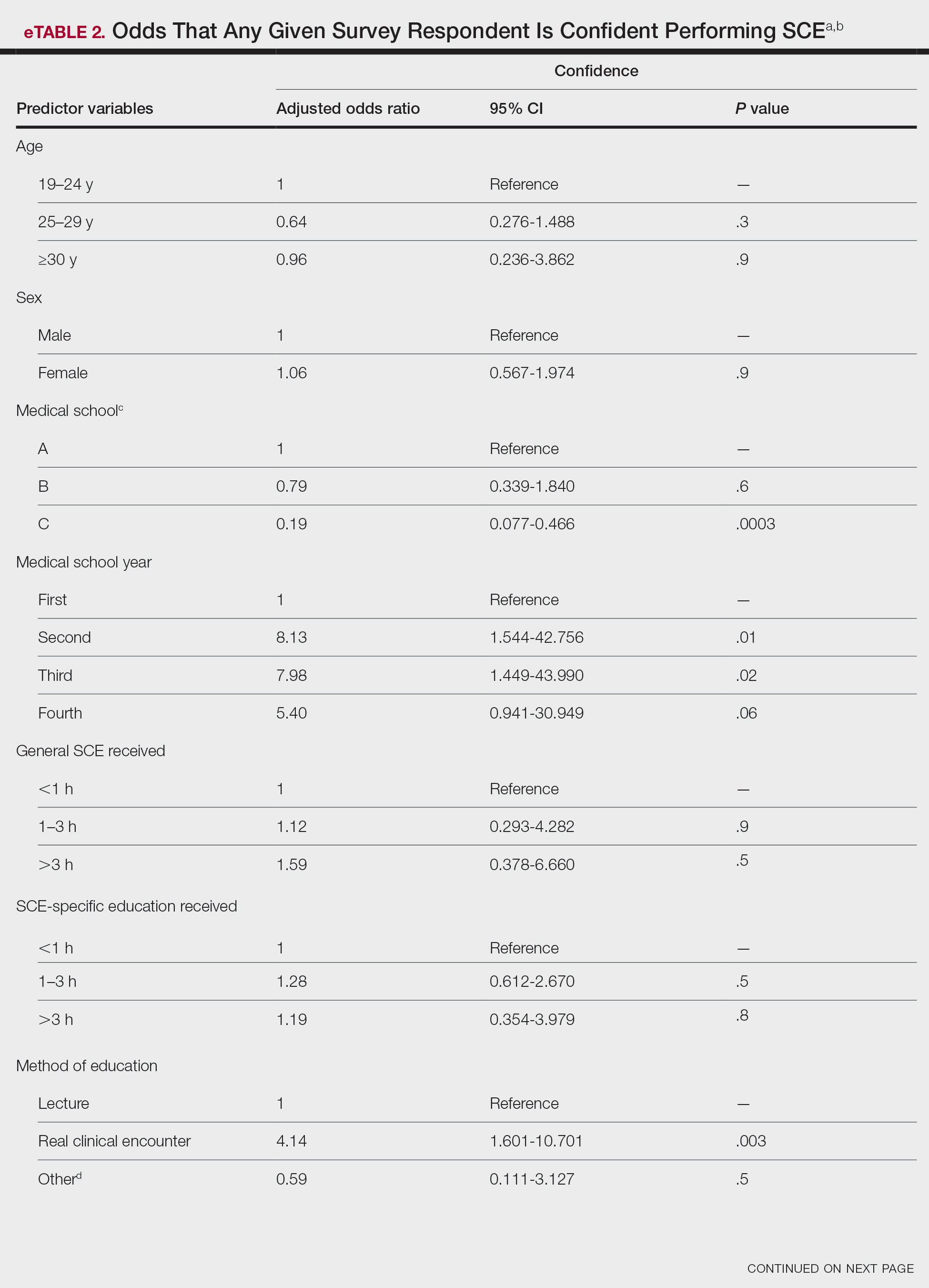

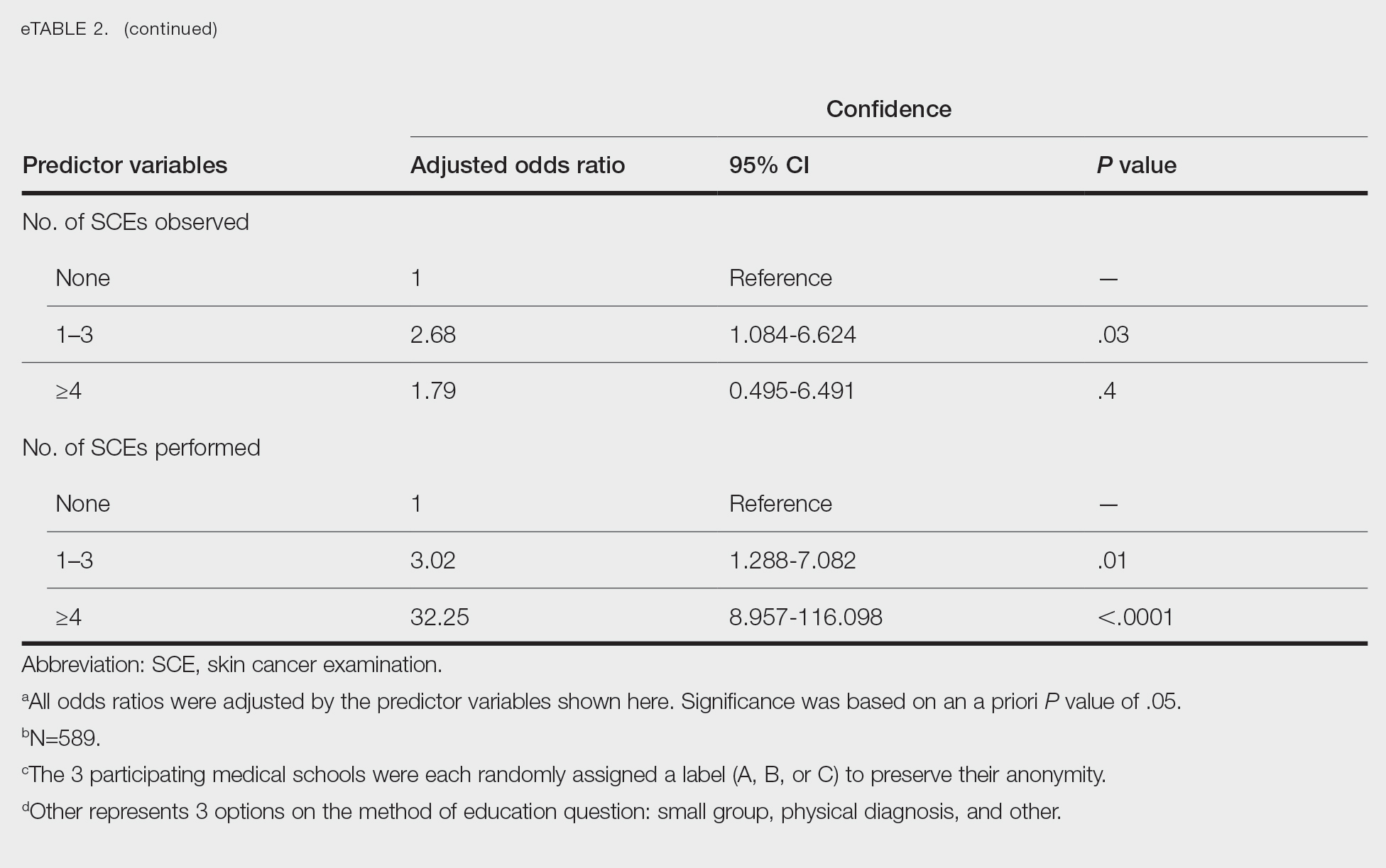

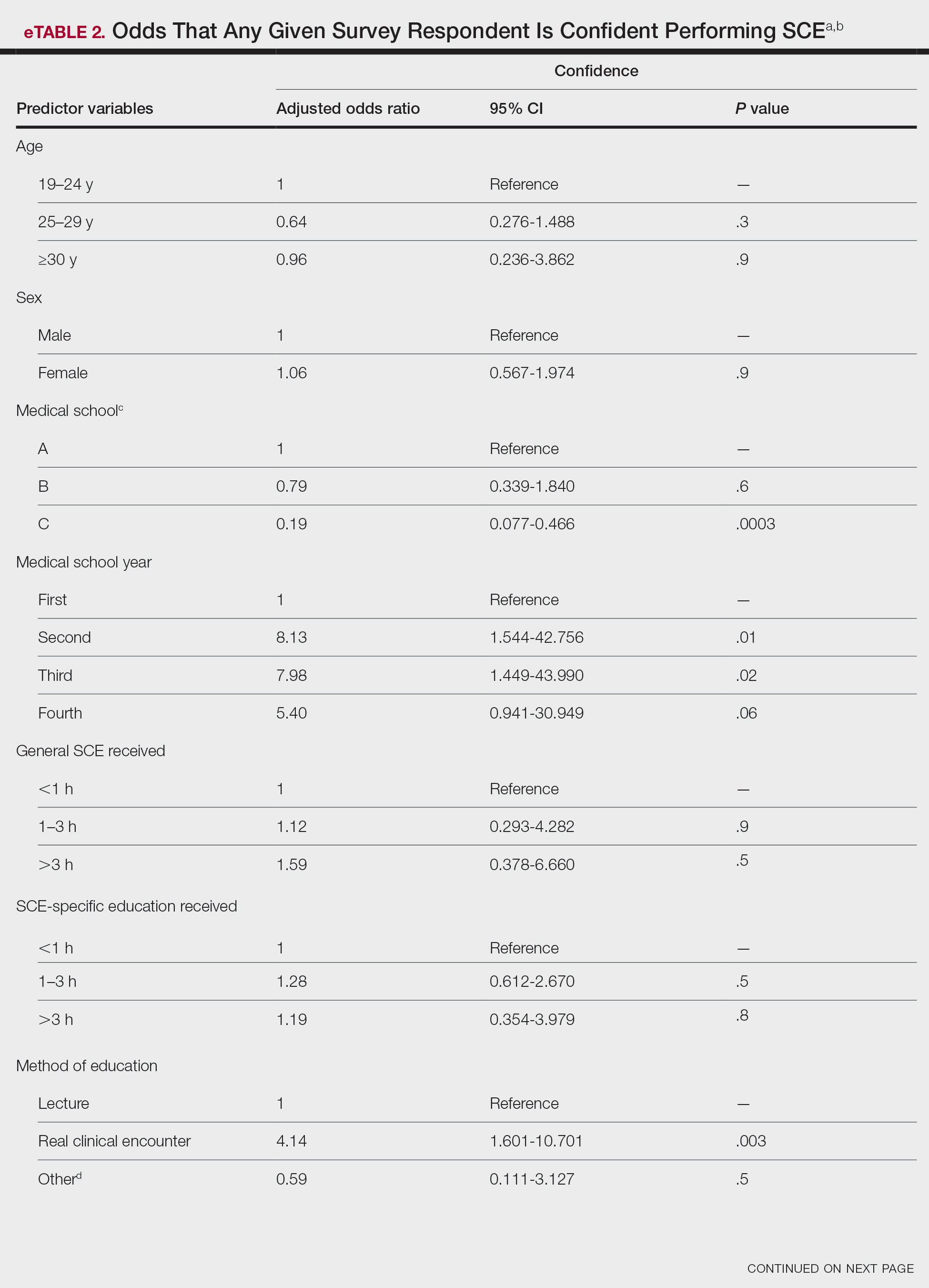

Only 24.1% of fourth-year students reported confidence performing SCE (eTable 1). Students who received most of their instruction through real clinical encounters were 4.14 times more likely to be confident performing SCE than students who had been given lecture-based learning. Students who performed 1 to 3 SCE or 4 or more SCE were 3.02 and 32.25 times, respectively, more likely to be confident than students who had never performed SCE (eTable 2).

Consistent with a recent study,6 our results reflect the discrepancy between the burden and education of skin cancer. This is especially demonstrated by our cohort’s low confidence in performing SCE, a metric associated with both intention to perform and actual performance of SCE in practice.4,5 We also observed a downward trend in knowledge among students who were about to enter residency, potentially indicating the need for longitudinal training.

Given curricular time constraints, it is essential that medical schools implement changes in learning that will have the greatest impact. Although our results strongly support the efficacy of hands-on clinical training, exposure to dermatology in the second half of medical school training is limited nationwide.6 Concentrated efforts to increase clinical exposure might help prepare future physicians in all specialties to combat the burden of this disease.

Limitations of our study include the potential for selection and recall biases. Although our survey spanned multiple institutions in different regions of the United States, results might not be universally representative.

Acknowledgments—We thank Dirk Elston, MD, and Amy Wahlquist, MS (both from Charleston, South Carolina), who helped facilitate the survey on which our research is based. We also acknowledge the assistance of Philip Carmon, MD (Columbia, South Carolina); Julie Flugel (Columbia, South Carolina); Algimantas Simpson, MD (Columbia, South Carolina); Nathan Jasperse, MD (Irvine, California); Jeremy Teruel, MD (Charleston, South Carolina); Alan Snyder, MD, MSCR (Charleston, South Carolina); John Bosland (Charleston, South Carolina); and Daniel Spangler (Greenville, South Carolina).

- Guy GP Jr, Machlin SR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Prevalence and costs of skin cancer treatment in the U.S., 2002–2006 and 2007-2011. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48:183-187. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.036

- Paulson KG, Gupta D, Kim TS, et al. Age-specific incidence of melanoma in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:57-64. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3353

- Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS Jr, et al. Contribution of health care factors to the burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1151-1160.e21. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.03.006

- Garg A, Wang J, Reddy SB, et al; Integrated Skin Exam Consortium. Curricular factors associated with medical students’ practice of the skin cancer examination: an educational enhancement initiative by the Integrated Skin Exam Consortium. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:850-855. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.8723

- Oliveria SA, Heneghan MK, Cushman LF, et al. Skin cancer screening by dermatologists, family practitioners, and internists: barriers and facilitating factors. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:39-44. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.414

- Cahn BA, Harper HE, Halverstam CP, et al. Current status of dermatologic education in US medical schools. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:468-470. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0006

To the Editor:

Skin cancer represents a notable health care burden of rising incidence.1-3 Nondermatologist health care providers play a key role in skin cancer screening through the use of skin cancer examination (SCE)1,4; however, several factors including poor diagnostic accuracy, low confidence, and lack of training have contributed to limited use of the SCE by these providers.4,5 Therefore, it is important to identify and implement changes in the medical school curriculum that can facilitate improved use of SCE in clinical practice. We sought to examine factors in the medical school curriculum that influence skin cancer education.

A voluntary electronic survey was distributed through class email and social media to all medical student classes at 4 medical schools (Figure). Responses were collected between March 2 and April 20, 2020. Survey items assessed demographics and curricular factors that influence skin cancer education.

Knowledge of the clinical features of melanoma was assessed by asking participants to correctly identify at least 5 of 6 pigmented lesions as concerning or not concerning for melanoma. Confidence in performing the SCE—the primary outcome—was measured by dichotomizing a 4-point Likert-type scale (“very confident” and “moderately confident” against “slightly confident” and “not at all confident”).

Logistic regression was used to examine curricular factors associated with confidence; descriptive statistics were used for remaining analyses. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 statistical software. Prior to analysis, responses from the University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville were excluded because the response rate was less than 20%.

The survey was distributed to 1524 students; 619 (40.6%) answered at least 1 question, with a variable response rate to each item (eTable 1). Most respondents were female (351 [56.7%]); 438 (70.8%) were White.

Most respondents said that they received 3 hours or less of general skin cancer (74.9%) or SCE-specific (93.0%) education by the end of their fourth year of medical training. Lecture was the most common method of instruction. Education was provided most often by dermatologists (48.6%), followed by general practice physicians (21.2%). Numerous (26.9%) fourth-year respondents reported that they had never observed SCE; even more (47.6%) had never performed SCE. Almost half of second- and third-year students (43.2% and 44.8%, respectively) considered themselves knowledgeable about the clinical features of melanoma, but only 31.9% of fourth-year students considered themselves knowledgeable.

Only 24.1% of fourth-year students reported confidence performing SCE (eTable 1). Students who received most of their instruction through real clinical encounters were 4.14 times more likely to be confident performing SCE than students who had been given lecture-based learning. Students who performed 1 to 3 SCE or 4 or more SCE were 3.02 and 32.25 times, respectively, more likely to be confident than students who had never performed SCE (eTable 2).

Consistent with a recent study,6 our results reflect the discrepancy between the burden and education of skin cancer. This is especially demonstrated by our cohort’s low confidence in performing SCE, a metric associated with both intention to perform and actual performance of SCE in practice.4,5 We also observed a downward trend in knowledge among students who were about to enter residency, potentially indicating the need for longitudinal training.

Given curricular time constraints, it is essential that medical schools implement changes in learning that will have the greatest impact. Although our results strongly support the efficacy of hands-on clinical training, exposure to dermatology in the second half of medical school training is limited nationwide.6 Concentrated efforts to increase clinical exposure might help prepare future physicians in all specialties to combat the burden of this disease.

Limitations of our study include the potential for selection and recall biases. Although our survey spanned multiple institutions in different regions of the United States, results might not be universally representative.

Acknowledgments—We thank Dirk Elston, MD, and Amy Wahlquist, MS (both from Charleston, South Carolina), who helped facilitate the survey on which our research is based. We also acknowledge the assistance of Philip Carmon, MD (Columbia, South Carolina); Julie Flugel (Columbia, South Carolina); Algimantas Simpson, MD (Columbia, South Carolina); Nathan Jasperse, MD (Irvine, California); Jeremy Teruel, MD (Charleston, South Carolina); Alan Snyder, MD, MSCR (Charleston, South Carolina); John Bosland (Charleston, South Carolina); and Daniel Spangler (Greenville, South Carolina).

To the Editor:

Skin cancer represents a notable health care burden of rising incidence.1-3 Nondermatologist health care providers play a key role in skin cancer screening through the use of skin cancer examination (SCE)1,4; however, several factors including poor diagnostic accuracy, low confidence, and lack of training have contributed to limited use of the SCE by these providers.4,5 Therefore, it is important to identify and implement changes in the medical school curriculum that can facilitate improved use of SCE in clinical practice. We sought to examine factors in the medical school curriculum that influence skin cancer education.

A voluntary electronic survey was distributed through class email and social media to all medical student classes at 4 medical schools (Figure). Responses were collected between March 2 and April 20, 2020. Survey items assessed demographics and curricular factors that influence skin cancer education.

Knowledge of the clinical features of melanoma was assessed by asking participants to correctly identify at least 5 of 6 pigmented lesions as concerning or not concerning for melanoma. Confidence in performing the SCE—the primary outcome—was measured by dichotomizing a 4-point Likert-type scale (“very confident” and “moderately confident” against “slightly confident” and “not at all confident”).

Logistic regression was used to examine curricular factors associated with confidence; descriptive statistics were used for remaining analyses. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 statistical software. Prior to analysis, responses from the University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville were excluded because the response rate was less than 20%.

The survey was distributed to 1524 students; 619 (40.6%) answered at least 1 question, with a variable response rate to each item (eTable 1). Most respondents were female (351 [56.7%]); 438 (70.8%) were White.

Most respondents said that they received 3 hours or less of general skin cancer (74.9%) or SCE-specific (93.0%) education by the end of their fourth year of medical training. Lecture was the most common method of instruction. Education was provided most often by dermatologists (48.6%), followed by general practice physicians (21.2%). Numerous (26.9%) fourth-year respondents reported that they had never observed SCE; even more (47.6%) had never performed SCE. Almost half of second- and third-year students (43.2% and 44.8%, respectively) considered themselves knowledgeable about the clinical features of melanoma, but only 31.9% of fourth-year students considered themselves knowledgeable.

Only 24.1% of fourth-year students reported confidence performing SCE (eTable 1). Students who received most of their instruction through real clinical encounters were 4.14 times more likely to be confident performing SCE than students who had been given lecture-based learning. Students who performed 1 to 3 SCE or 4 or more SCE were 3.02 and 32.25 times, respectively, more likely to be confident than students who had never performed SCE (eTable 2).

Consistent with a recent study,6 our results reflect the discrepancy between the burden and education of skin cancer. This is especially demonstrated by our cohort’s low confidence in performing SCE, a metric associated with both intention to perform and actual performance of SCE in practice.4,5 We also observed a downward trend in knowledge among students who were about to enter residency, potentially indicating the need for longitudinal training.

Given curricular time constraints, it is essential that medical schools implement changes in learning that will have the greatest impact. Although our results strongly support the efficacy of hands-on clinical training, exposure to dermatology in the second half of medical school training is limited nationwide.6 Concentrated efforts to increase clinical exposure might help prepare future physicians in all specialties to combat the burden of this disease.

Limitations of our study include the potential for selection and recall biases. Although our survey spanned multiple institutions in different regions of the United States, results might not be universally representative.

Acknowledgments—We thank Dirk Elston, MD, and Amy Wahlquist, MS (both from Charleston, South Carolina), who helped facilitate the survey on which our research is based. We also acknowledge the assistance of Philip Carmon, MD (Columbia, South Carolina); Julie Flugel (Columbia, South Carolina); Algimantas Simpson, MD (Columbia, South Carolina); Nathan Jasperse, MD (Irvine, California); Jeremy Teruel, MD (Charleston, South Carolina); Alan Snyder, MD, MSCR (Charleston, South Carolina); John Bosland (Charleston, South Carolina); and Daniel Spangler (Greenville, South Carolina).

- Guy GP Jr, Machlin SR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Prevalence and costs of skin cancer treatment in the U.S., 2002–2006 and 2007-2011. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48:183-187. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.036

- Paulson KG, Gupta D, Kim TS, et al. Age-specific incidence of melanoma in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:57-64. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3353

- Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS Jr, et al. Contribution of health care factors to the burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1151-1160.e21. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.03.006

- Garg A, Wang J, Reddy SB, et al; Integrated Skin Exam Consortium. Curricular factors associated with medical students’ practice of the skin cancer examination: an educational enhancement initiative by the Integrated Skin Exam Consortium. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:850-855. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.8723

- Oliveria SA, Heneghan MK, Cushman LF, et al. Skin cancer screening by dermatologists, family practitioners, and internists: barriers and facilitating factors. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:39-44. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.414

- Cahn BA, Harper HE, Halverstam CP, et al. Current status of dermatologic education in US medical schools. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:468-470. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0006

- Guy GP Jr, Machlin SR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Prevalence and costs of skin cancer treatment in the U.S., 2002–2006 and 2007-2011. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48:183-187. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.036

- Paulson KG, Gupta D, Kim TS, et al. Age-specific incidence of melanoma in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:57-64. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3353

- Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS Jr, et al. Contribution of health care factors to the burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1151-1160.e21. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.03.006

- Garg A, Wang J, Reddy SB, et al; Integrated Skin Exam Consortium. Curricular factors associated with medical students’ practice of the skin cancer examination: an educational enhancement initiative by the Integrated Skin Exam Consortium. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:850-855. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.8723

- Oliveria SA, Heneghan MK, Cushman LF, et al. Skin cancer screening by dermatologists, family practitioners, and internists: barriers and facilitating factors. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:39-44. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.414

- Cahn BA, Harper HE, Halverstam CP, et al. Current status of dermatologic education in US medical schools. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:468-470. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0006

Practice Points

- Nondermatologist practitioners play a notable role in mitigating the health care burden of skin cancer by screening with the skin cancer examination.

- Exposure to the skin cancer examination should occur during medical school prior to graduates’ entering diverse specialties.

- Most medical students received relatively few hours of skin cancer education, and many never performed or even observed a skin cancer examination prior to graduating medical school.

- Increasing hands-on training and clinical exposure during medical school is imperative to adequately prepare future physicians.

Aquatic Antagonists: Marine Rashes (Seabather’s Eruption and Diver’s Dermatitis)

Background and Clinical Presentation

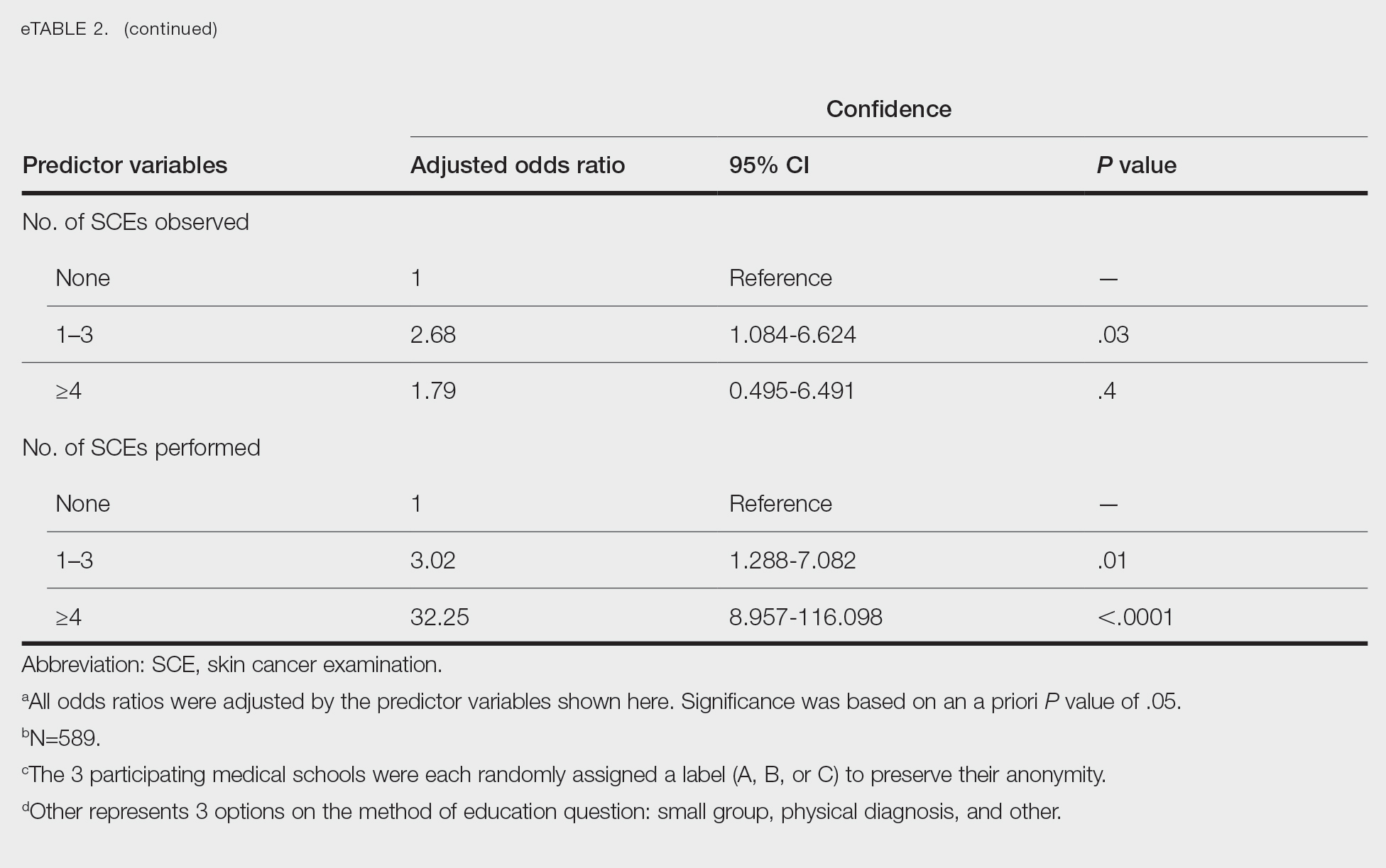

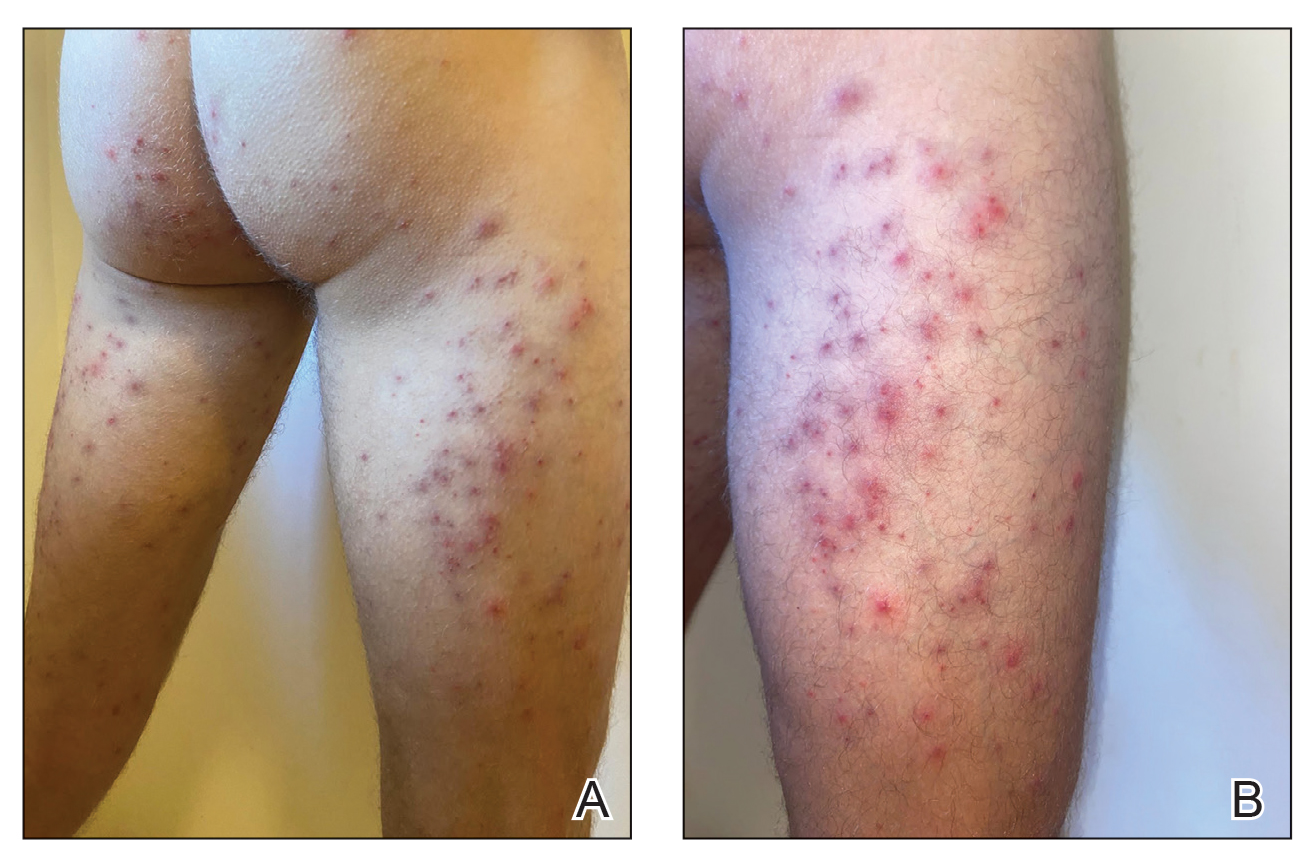

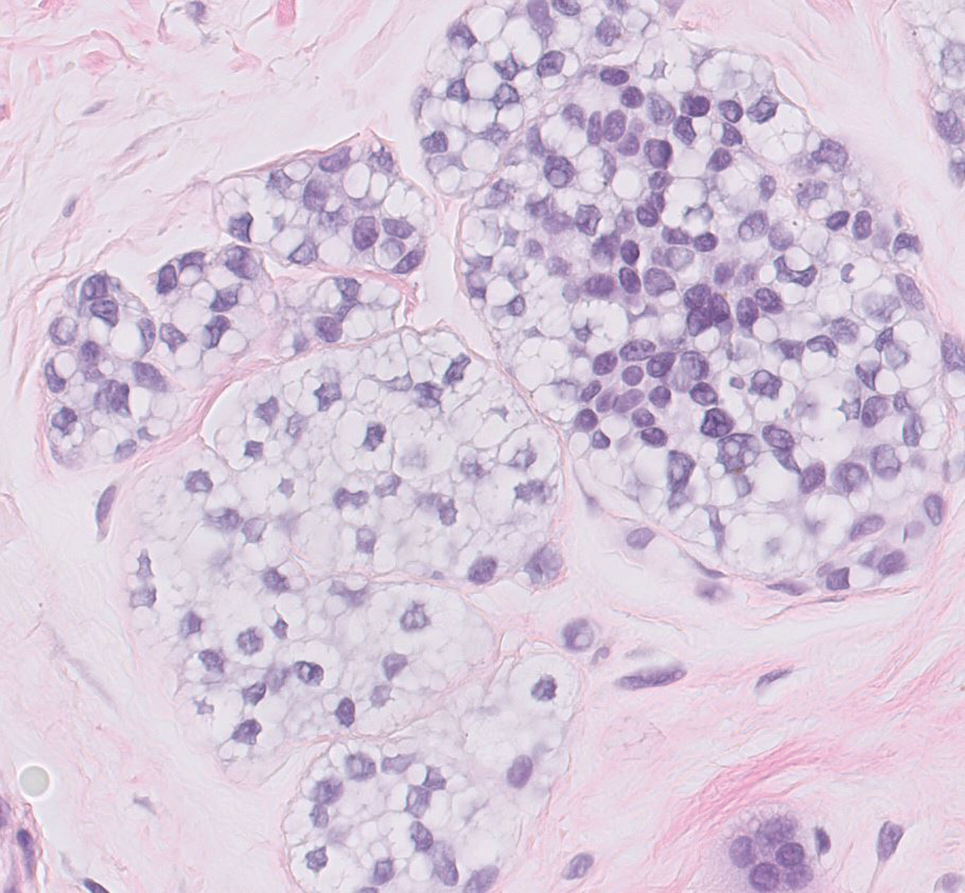

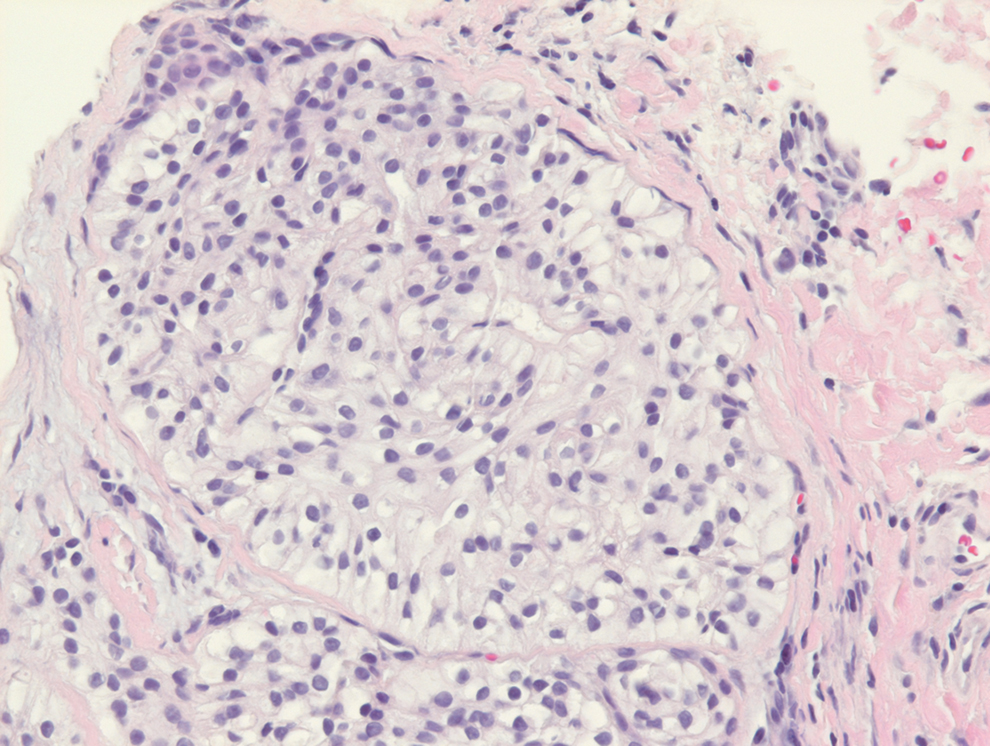

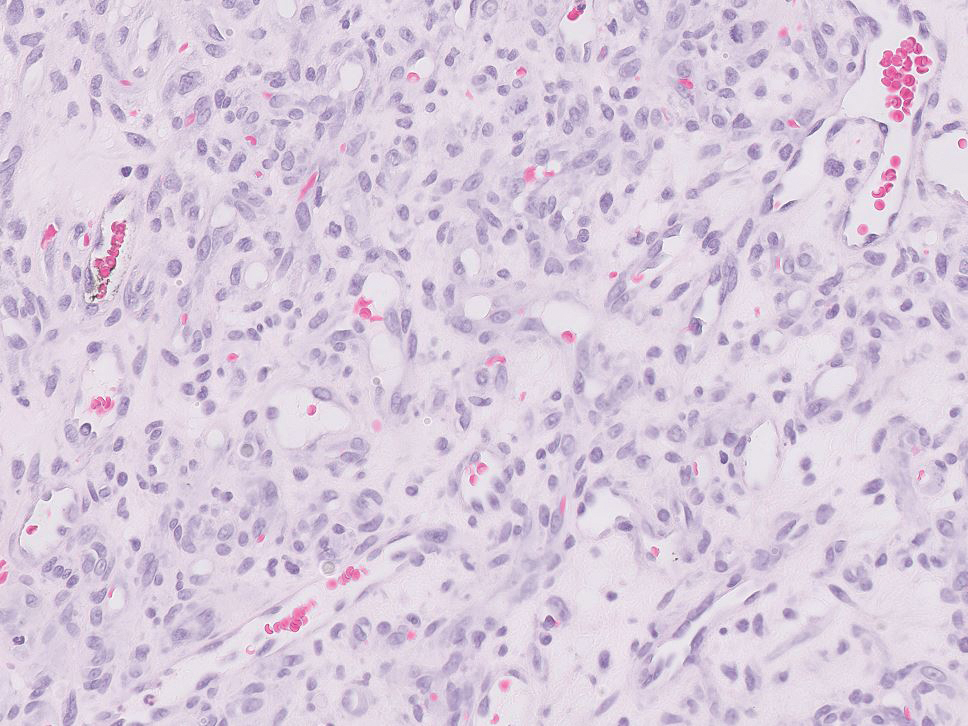

Seabather’s Eruption—Seabather’s eruption is a type I and IV hypersensitivity reaction caused by nematocysts of larval-stage thimble jellyfish (Linuche unguiculata), sea anemones (eg, Edwardsiella lineata), and larval cnidarians.1Linuche unguiculata commonly is found along the southeast coast of the United States and in the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico, and the coasts of Florida; less commonly, it has been reported along the coasts of Brazil and Papua New Guinea. Edwardsiella lineata more commonly is seen along the East Coast of the United States.2 Seabather’s eruption presents as numerous scattered, pruritic, red macules and papules (measuring 1 mm to 1.5 cm in size) distributed in areas covered by skin folds, wet clothing, or hair following exposure to marine water (Figure 1). This maculopapular rash generally appears shortly after exiting the water and can last up to several weeks in some cases.3 The cause for this delayed presentation is that the marine organisms become entrapped between the skin of the human contact and another object (eg, swimwear) but do not release their preformed antivenom until they are exposed to air after removal from the water, at which point the organisms die and cell lysis results in injection of the venom.

Diver’s Dermatitis—Diver’s dermatitis (also referred to as “swimmer’s itch”) is a type I and IV hypersensitivity reaction caused by schistosome cercariae released by aquatic snails.4 There are several different cercarial species known to be capable of causing diver dermatitis, but the most commonly implicated genera are Trichobilharzia and Gigantobilharzia. These parasites most commonly are found in freshwater lakes but also occur in oceans, particularly in brackish areas adjacent to freshwater access. Factors associated with increased concentrations of these parasites include shallow, slow-moving water and prolonged onshore wind causing accumulation near the shoreline. It also is thought that the snail host will shed greater concentrations of the parasitic worm in the morning hours and after prolonged exposure to sunlight.4 These flatworm trematodes have a 2-host life cycle. The snails function as intermediate hosts for the parasites before they enter their final host, which are birds. Humans only function as incidental and nonviable hosts for these worms. The parasites gain access to the human body by burrowing into exposed skin. Because the parasite is unable to survive on human hosts, it dies shortly after penetrating the skin, which leads to an intense inflammatory response causing symptoms of pruritus within hours of exposure (Figure 2). The initial eruption progresses over a few days into a diffuse, maculopapular, pruritic rash, similar to that seen in seabather’s eruption. This rash then regresses completely in 1 to 3 weeks. Subsequent exposure to the same parasite is associated with increased severity of future rashes, likely due to antibody-mediated sensitization.4

Diagnosis—Marine-derived dermatoses from various sources can present very similarly; thus, it is difficult to discern the specific etiology behind the clinical presentation. No commonly utilized imaging modalities can differentiate between seabather’s eruption and diver’s dermatitis, but eliciting a thorough patient history often can aid in differentiation of the cause of the eruption. For example, lesions located only on nonexposed areas of the skin increases the likelihood of seabather’s eruption due to nematocysts being trapped between clothing and the skin. In contrast, diver’s dermatitis generally appears on areas of the skin that were directly exposed to water and uncovered by clothing.5 Patient reports of a lack of symptoms until shortly after exiting the water further support a diagnosis of seabather’s eruption, as this delayed presentation of symptoms is caused by lysis of the culprit organisms following removal from the marine environment. The cell lysis is responsible for the widespread injection of preformed venom via the numerous nematocysts trapped between clothing and the patient’s body.1

Treatment

For both conditions, the symptoms are treated with hydrocortisone or other topical steroid solutions in conjunction with oral hydroxyzine. Alternative treatments include calamine lotion with 1% menthol and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Taking baths with oatmeal, Epsom salts, or baking soda also may alleviate some of the pruritic symptoms.2

Prevention

The ability to diagnose the precise cause of these similar marine rashes can bring peace of mind to both patients and physicians regardless of their similar management strategies. Severe contact dermatitis of unknown etiology can be disconcerting for patients. Additionally, documenting the causes of marine rashes in particular geographic locations can be beneficial for establishing which organisms are most likely to affect visitors to those areas. This type of data collection can be utilized to develop preventative recommendations, such as deciding when to avoid the water. Education of the public can be done with the use of informational posters located near popular swimming areas and online public service announcements. Informing the general public about the dangers of entering the ocean, especially during certain times of the year when nematocyst-equipped sea creatures are in abundance, could serve to prevent numerous cases of seabather’s eruption. Likewise, advising against immersion in shallow, slow-moving water during the morning hours or after prolonged sun exposure in trematode-endemic areas could prevent numerous cases of diver’s dermatitis. Basic information on what to expect if afflicted by a marine rash also may reduce the number of emergency department visits for these conditions, thus providing economic benefit for patients and for hospitals since patients would better know how to acutely treat these rashes and lessen the patient load at hospital emergency departments. If individuals can assure themselves of the self-limited nature of these types of dermatoses, they may be less inclined to seek medical consultation.

Final Thoughts

As the climate continues to change, the incidence of marine rashes such as seabather’s eruption and diver’s dermatitis is expected to increase due to warmer surface temperatures causing more frequent and earlier blooms of L unguiculata and E lineata. Cases of diver’s dermatitis also could increase due to a longer season of more frequent human exposure from an increase in warmer temperatures. The projected uptick in incidences of these marine rashes makes understanding these pathologies even more pertinent for physicians.6 Increasing our understanding of the different types of marine rashes and their causes will help guide future recommendations for the general public when visiting the ocean.

Future research may wish to investigate unique ways in which to prevent contact between these organisms and humans. Past research on mice indicated that topical application of DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide) prior to trematode exposure prevented penetration of the skin by parasitic worms.7 Future studies are needed to examine the effectiveness of this preventative technique on humans. For now, dermatologists may counsel our ocean-going patients on preventative behaviors as well as provide reassurance and symptomatic relief when they present to our clinics with marine rashes.

- Parrish DO. Seabather’s eruption or diver’s dermatitis? JAMA. 1993;270:2300-2301. doi:10.1001/jama.1993.03510190054021

- Tomchik RS, Russell MT, Szmant AM, et al. Clinical perspectives on seabather’s eruption, also known as ‘sea lice’. JAMA. 1993;269:1669-1672. doi:10.1001/jama.1993.03500130083037

- Bonamonte D, Filoni A, Verni P, et al. Dermatitis caused by algae and Bryozoans. In: Bonamonte D, Angelini G, eds. Aquatic Dermatology: Biotic, Chemical, and Physical Agents. Springer; 2016:127-137.

- Tracz ES, Al-Jubury A, Buchmann K, et al. Outbreak of swimmer’s itch in Denmark. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:1116-1120. doi:10.2340/00015555-3309

- Freudenthal AR, Joseph PR. Seabather’s eruption. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:542-544. doi:10.1056/NEJM199308193290805

- Kaffenberger BH, Shetlar D, Norton SA, et al. The effect of climate change on skin disease in North America. JAAD. 2016;76:140-147. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.014

- Salafsky B, Ramaswamy K, He YX, et al. Development and evaluation of LIPODEET, a new long-acting formulation of N, N-diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET) for the prevention of schistosomiasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:743-750. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.743

Background and Clinical Presentation

Seabather’s Eruption—Seabather’s eruption is a type I and IV hypersensitivity reaction caused by nematocysts of larval-stage thimble jellyfish (Linuche unguiculata), sea anemones (eg, Edwardsiella lineata), and larval cnidarians.1Linuche unguiculata commonly is found along the southeast coast of the United States and in the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico, and the coasts of Florida; less commonly, it has been reported along the coasts of Brazil and Papua New Guinea. Edwardsiella lineata more commonly is seen along the East Coast of the United States.2 Seabather’s eruption presents as numerous scattered, pruritic, red macules and papules (measuring 1 mm to 1.5 cm in size) distributed in areas covered by skin folds, wet clothing, or hair following exposure to marine water (Figure 1). This maculopapular rash generally appears shortly after exiting the water and can last up to several weeks in some cases.3 The cause for this delayed presentation is that the marine organisms become entrapped between the skin of the human contact and another object (eg, swimwear) but do not release their preformed antivenom until they are exposed to air after removal from the water, at which point the organisms die and cell lysis results in injection of the venom.

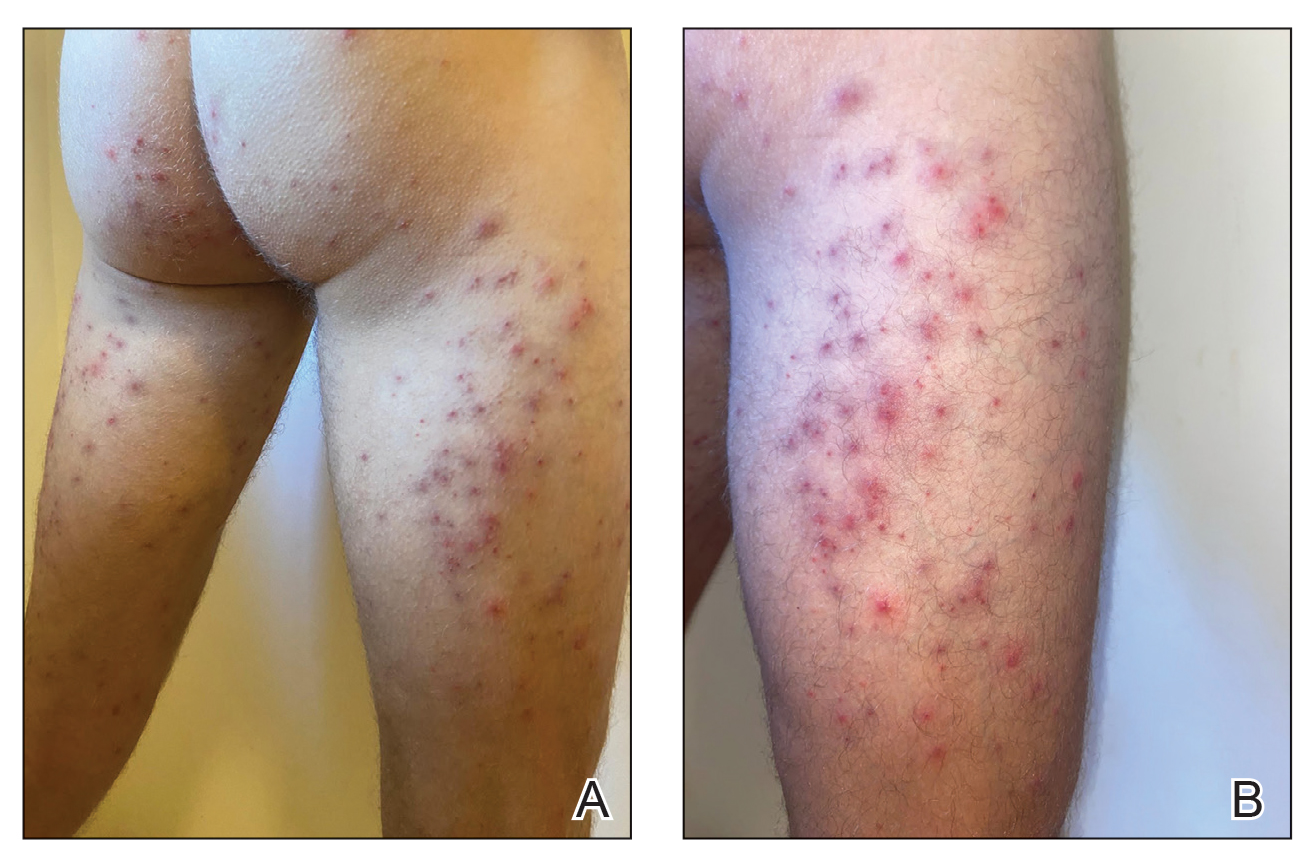

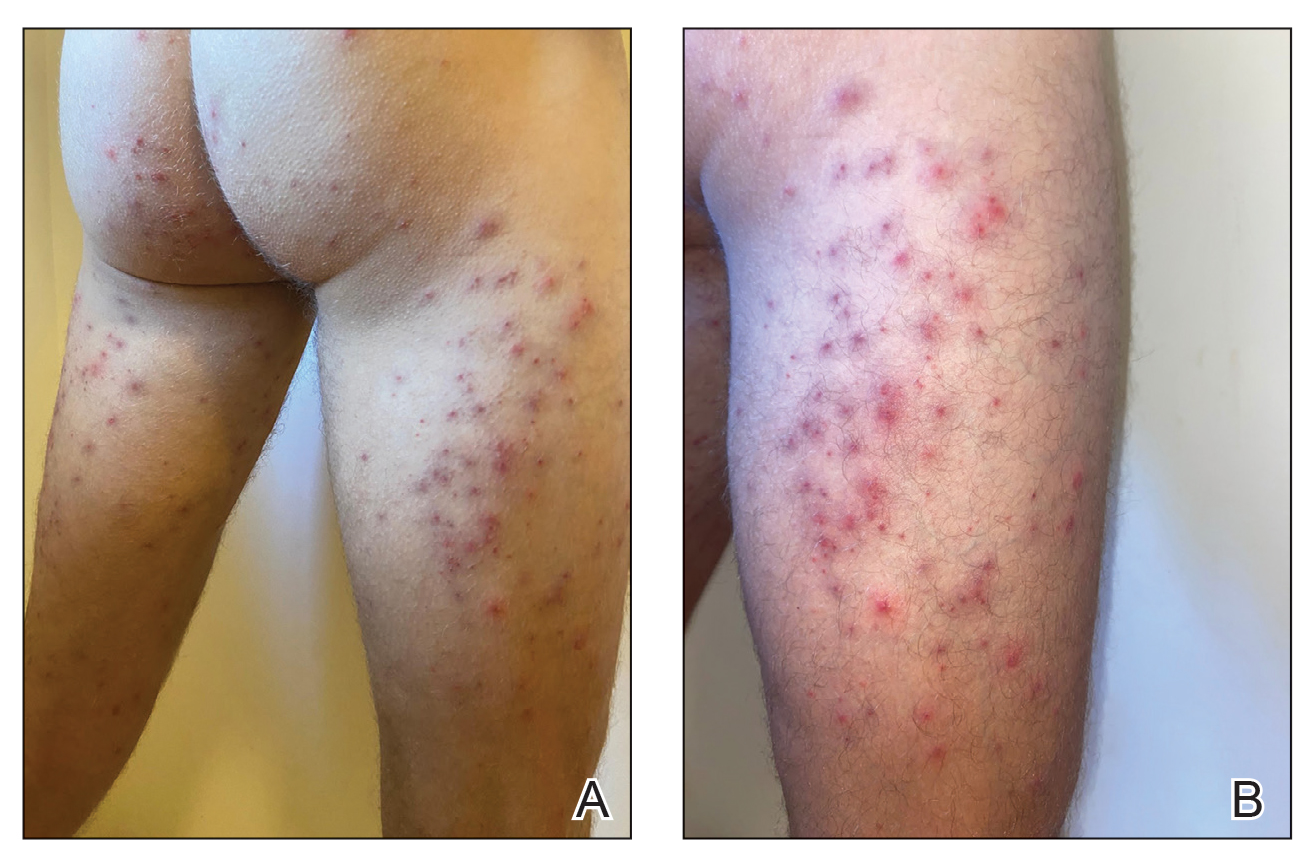

Diver’s Dermatitis—Diver’s dermatitis (also referred to as “swimmer’s itch”) is a type I and IV hypersensitivity reaction caused by schistosome cercariae released by aquatic snails.4 There are several different cercarial species known to be capable of causing diver dermatitis, but the most commonly implicated genera are Trichobilharzia and Gigantobilharzia. These parasites most commonly are found in freshwater lakes but also occur in oceans, particularly in brackish areas adjacent to freshwater access. Factors associated with increased concentrations of these parasites include shallow, slow-moving water and prolonged onshore wind causing accumulation near the shoreline. It also is thought that the snail host will shed greater concentrations of the parasitic worm in the morning hours and after prolonged exposure to sunlight.4 These flatworm trematodes have a 2-host life cycle. The snails function as intermediate hosts for the parasites before they enter their final host, which are birds. Humans only function as incidental and nonviable hosts for these worms. The parasites gain access to the human body by burrowing into exposed skin. Because the parasite is unable to survive on human hosts, it dies shortly after penetrating the skin, which leads to an intense inflammatory response causing symptoms of pruritus within hours of exposure (Figure 2). The initial eruption progresses over a few days into a diffuse, maculopapular, pruritic rash, similar to that seen in seabather’s eruption. This rash then regresses completely in 1 to 3 weeks. Subsequent exposure to the same parasite is associated with increased severity of future rashes, likely due to antibody-mediated sensitization.4

Diagnosis—Marine-derived dermatoses from various sources can present very similarly; thus, it is difficult to discern the specific etiology behind the clinical presentation. No commonly utilized imaging modalities can differentiate between seabather’s eruption and diver’s dermatitis, but eliciting a thorough patient history often can aid in differentiation of the cause of the eruption. For example, lesions located only on nonexposed areas of the skin increases the likelihood of seabather’s eruption due to nematocysts being trapped between clothing and the skin. In contrast, diver’s dermatitis generally appears on areas of the skin that were directly exposed to water and uncovered by clothing.5 Patient reports of a lack of symptoms until shortly after exiting the water further support a diagnosis of seabather’s eruption, as this delayed presentation of symptoms is caused by lysis of the culprit organisms following removal from the marine environment. The cell lysis is responsible for the widespread injection of preformed venom via the numerous nematocysts trapped between clothing and the patient’s body.1

Treatment

For both conditions, the symptoms are treated with hydrocortisone or other topical steroid solutions in conjunction with oral hydroxyzine. Alternative treatments include calamine lotion with 1% menthol and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Taking baths with oatmeal, Epsom salts, or baking soda also may alleviate some of the pruritic symptoms.2

Prevention

The ability to diagnose the precise cause of these similar marine rashes can bring peace of mind to both patients and physicians regardless of their similar management strategies. Severe contact dermatitis of unknown etiology can be disconcerting for patients. Additionally, documenting the causes of marine rashes in particular geographic locations can be beneficial for establishing which organisms are most likely to affect visitors to those areas. This type of data collection can be utilized to develop preventative recommendations, such as deciding when to avoid the water. Education of the public can be done with the use of informational posters located near popular swimming areas and online public service announcements. Informing the general public about the dangers of entering the ocean, especially during certain times of the year when nematocyst-equipped sea creatures are in abundance, could serve to prevent numerous cases of seabather’s eruption. Likewise, advising against immersion in shallow, slow-moving water during the morning hours or after prolonged sun exposure in trematode-endemic areas could prevent numerous cases of diver’s dermatitis. Basic information on what to expect if afflicted by a marine rash also may reduce the number of emergency department visits for these conditions, thus providing economic benefit for patients and for hospitals since patients would better know how to acutely treat these rashes and lessen the patient load at hospital emergency departments. If individuals can assure themselves of the self-limited nature of these types of dermatoses, they may be less inclined to seek medical consultation.

Final Thoughts

As the climate continues to change, the incidence of marine rashes such as seabather’s eruption and diver’s dermatitis is expected to increase due to warmer surface temperatures causing more frequent and earlier blooms of L unguiculata and E lineata. Cases of diver’s dermatitis also could increase due to a longer season of more frequent human exposure from an increase in warmer temperatures. The projected uptick in incidences of these marine rashes makes understanding these pathologies even more pertinent for physicians.6 Increasing our understanding of the different types of marine rashes and their causes will help guide future recommendations for the general public when visiting the ocean.

Future research may wish to investigate unique ways in which to prevent contact between these organisms and humans. Past research on mice indicated that topical application of DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide) prior to trematode exposure prevented penetration of the skin by parasitic worms.7 Future studies are needed to examine the effectiveness of this preventative technique on humans. For now, dermatologists may counsel our ocean-going patients on preventative behaviors as well as provide reassurance and symptomatic relief when they present to our clinics with marine rashes.

Background and Clinical Presentation

Seabather’s Eruption—Seabather’s eruption is a type I and IV hypersensitivity reaction caused by nematocysts of larval-stage thimble jellyfish (Linuche unguiculata), sea anemones (eg, Edwardsiella lineata), and larval cnidarians.1Linuche unguiculata commonly is found along the southeast coast of the United States and in the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico, and the coasts of Florida; less commonly, it has been reported along the coasts of Brazil and Papua New Guinea. Edwardsiella lineata more commonly is seen along the East Coast of the United States.2 Seabather’s eruption presents as numerous scattered, pruritic, red macules and papules (measuring 1 mm to 1.5 cm in size) distributed in areas covered by skin folds, wet clothing, or hair following exposure to marine water (Figure 1). This maculopapular rash generally appears shortly after exiting the water and can last up to several weeks in some cases.3 The cause for this delayed presentation is that the marine organisms become entrapped between the skin of the human contact and another object (eg, swimwear) but do not release their preformed antivenom until they are exposed to air after removal from the water, at which point the organisms die and cell lysis results in injection of the venom.