User login

New Delivery Models Improve Access to Germline Testing for Patients With Advanced Prostate Cancer

Objectives

The VA Oncology Clinical Pathway for Prostate Cancer is the first to include both tumor and germline testing to inform treatment and clinical trial eligibility for advanced disease. Anticipating increased germline testing demand, new germline testing delivery models were created to augment the existing traditional model of referring patients to genetics providers (VA or non-VA) for germline testing. The new models include: a non-traditional model where oncology clinicians perform all pre- and post-test activities and consult genetics when needed, and a hybrid model where oncology clinicians obtain informed consent and place e-consults for germline test ordering, results disclosure, and genetics follow-up, as needed. We sought to assess germline testing by delivery model.

Methods

Data sources included the National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP) dashboard and NPOP-contracted germline testing laboratories. Patient inclusion criteria: living as of 5/2/2021 with VA oncology or urology visits after 5/2/2021. We used multivariate regression to assess associations between patient characteristics and germline testing between 5/3/2021 (pathway launch) and 5/2/2022, accounting for clustering of patients within ordering clinicians.

Results

We identified 16,041 patients from 129 VA facilities with average age 75 years (SD, 8.2; range, 36- 102), 28.7% Black and 60.0% White. Only 5.6% had germline testing ordered by 60 clinicians at 67 facilities with 52.2% of orders by the hybrid model, 32.1% the non-traditional model, and 15.4% the traditional model. Patient characteristics positively associated with germline testing included care at hybrid model (OR, 6.03; 95% CI, 4.62-7.88) or non-traditional model facilities (OR, 5.66; 95% CI, 4.24-7.56) compared to the traditional model, completing tumor molecular testing (OR, 5.80; 95%CI, 4.98-6.75), and Black compared with White race (OR, 1.24; 95%CI, 1.06-1.45). Compared to patients aged < 66 years, patients aged 66-75 years and 76-85 years were less likely to have germline testing (OR, 0.74; 95%CI, 0.60-0.90; and OR, 0.67; 95%CI, 0.53-0.84, respectively).

Conclusions/Implications

Though only a small percentage of patients with advanced prostate cancer had NPOP-supported germline testing since the pathway launch, the new delivery models were instrumental to improving access to germline testing. Ongoing evaluation will help to understand observed demographic differences in germline testing. Implementation and evaluation of strategies that promote adoption of the new germline testing delivery models is needed. 0922FED AVAHO_Abstracts.indd 15 8

Objectives

The VA Oncology Clinical Pathway for Prostate Cancer is the first to include both tumor and germline testing to inform treatment and clinical trial eligibility for advanced disease. Anticipating increased germline testing demand, new germline testing delivery models were created to augment the existing traditional model of referring patients to genetics providers (VA or non-VA) for germline testing. The new models include: a non-traditional model where oncology clinicians perform all pre- and post-test activities and consult genetics when needed, and a hybrid model where oncology clinicians obtain informed consent and place e-consults for germline test ordering, results disclosure, and genetics follow-up, as needed. We sought to assess germline testing by delivery model.

Methods

Data sources included the National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP) dashboard and NPOP-contracted germline testing laboratories. Patient inclusion criteria: living as of 5/2/2021 with VA oncology or urology visits after 5/2/2021. We used multivariate regression to assess associations between patient characteristics and germline testing between 5/3/2021 (pathway launch) and 5/2/2022, accounting for clustering of patients within ordering clinicians.

Results

We identified 16,041 patients from 129 VA facilities with average age 75 years (SD, 8.2; range, 36- 102), 28.7% Black and 60.0% White. Only 5.6% had germline testing ordered by 60 clinicians at 67 facilities with 52.2% of orders by the hybrid model, 32.1% the non-traditional model, and 15.4% the traditional model. Patient characteristics positively associated with germline testing included care at hybrid model (OR, 6.03; 95% CI, 4.62-7.88) or non-traditional model facilities (OR, 5.66; 95% CI, 4.24-7.56) compared to the traditional model, completing tumor molecular testing (OR, 5.80; 95%CI, 4.98-6.75), and Black compared with White race (OR, 1.24; 95%CI, 1.06-1.45). Compared to patients aged < 66 years, patients aged 66-75 years and 76-85 years were less likely to have germline testing (OR, 0.74; 95%CI, 0.60-0.90; and OR, 0.67; 95%CI, 0.53-0.84, respectively).

Conclusions/Implications

Though only a small percentage of patients with advanced prostate cancer had NPOP-supported germline testing since the pathway launch, the new delivery models were instrumental to improving access to germline testing. Ongoing evaluation will help to understand observed demographic differences in germline testing. Implementation and evaluation of strategies that promote adoption of the new germline testing delivery models is needed. 0922FED AVAHO_Abstracts.indd 15 8

Objectives

The VA Oncology Clinical Pathway for Prostate Cancer is the first to include both tumor and germline testing to inform treatment and clinical trial eligibility for advanced disease. Anticipating increased germline testing demand, new germline testing delivery models were created to augment the existing traditional model of referring patients to genetics providers (VA or non-VA) for germline testing. The new models include: a non-traditional model where oncology clinicians perform all pre- and post-test activities and consult genetics when needed, and a hybrid model where oncology clinicians obtain informed consent and place e-consults for germline test ordering, results disclosure, and genetics follow-up, as needed. We sought to assess germline testing by delivery model.

Methods

Data sources included the National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP) dashboard and NPOP-contracted germline testing laboratories. Patient inclusion criteria: living as of 5/2/2021 with VA oncology or urology visits after 5/2/2021. We used multivariate regression to assess associations between patient characteristics and germline testing between 5/3/2021 (pathway launch) and 5/2/2022, accounting for clustering of patients within ordering clinicians.

Results

We identified 16,041 patients from 129 VA facilities with average age 75 years (SD, 8.2; range, 36- 102), 28.7% Black and 60.0% White. Only 5.6% had germline testing ordered by 60 clinicians at 67 facilities with 52.2% of orders by the hybrid model, 32.1% the non-traditional model, and 15.4% the traditional model. Patient characteristics positively associated with germline testing included care at hybrid model (OR, 6.03; 95% CI, 4.62-7.88) or non-traditional model facilities (OR, 5.66; 95% CI, 4.24-7.56) compared to the traditional model, completing tumor molecular testing (OR, 5.80; 95%CI, 4.98-6.75), and Black compared with White race (OR, 1.24; 95%CI, 1.06-1.45). Compared to patients aged < 66 years, patients aged 66-75 years and 76-85 years were less likely to have germline testing (OR, 0.74; 95%CI, 0.60-0.90; and OR, 0.67; 95%CI, 0.53-0.84, respectively).

Conclusions/Implications

Though only a small percentage of patients with advanced prostate cancer had NPOP-supported germline testing since the pathway launch, the new delivery models were instrumental to improving access to germline testing. Ongoing evaluation will help to understand observed demographic differences in germline testing. Implementation and evaluation of strategies that promote adoption of the new germline testing delivery models is needed. 0922FED AVAHO_Abstracts.indd 15 8

MYO1E DNA Methylation in U.S. Military Veterans With Adenocarcinoma of the Lung Is Associated With Increased Mortality Risk

Project Purpose

The aim is to assess the role of MYO1E in survival among veterans with lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD).

Background

Veterans have a higher smoking exposure than civilians; a higher incidence of lung cancer; and a younger age at diagnosis of lung cancer. We recently showed that MYO1E DNA methylation and RNA expression in LUAD are associated with survival among civilians.

Methods

This is a retrospective cohort study involving LUAD among civilians and veterans with biopsy or pathologically proven LUAD from surgical specimens. DNA extraction and isolation from FFPE cancer tissues was performed using methylation-onbeads as previously published, followed by qMSP with bisulfite treatment to quantify DNA methylation. RNA extraction and quantification from lung tissues was obtained as described in previous publications.

Data Analysis

Differences were assessed with Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical. Two-tailed log-rank test was used to estimate overall survival differences and Cox hazard models, to quantify risk of mortality using hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

There were 91 LUAD patients, 27 veterans and 64 civilians. Veterans were older than civilians, aged 70 years vs aged 66 years (P = .003); with higher proportions of males, 93% vs 69% (P = .03); higher proportion of African Americans, 67% vs 39% (P = .03); smoking more, 50 pack-year vs 40 (0.005), and having a higher proportion of grade I, 78% vs 55% (P = .036). Survival was statistically longer for MYO1E high DNA methylation group 48 months vs 33 for low methylation (P = .049). MYO1E RNA expression did not show statistically significant differences (P = .32). Multivariate Cox regression analysis adjusted by age, veteran/civil status, gender, race, packyear, and stage showed that DNA methylation was significantly associated with mortality risk (HR 5.14; 95% CI, 1.12-23.60) (P = .035).

Conclusions/Implications

This study suggests the utility of MYO1E DNA methylation as a prognostic biomarker for veterans with LUAD. Further studies are necessary to understand the role of MYO1E in chemotherapy resistance and microenvironment immune modulation. Given the low expression of MYO1E in blood cells, MYO1E DNA methylation has the potential to be used as circulating tumor marker in liquid biopsies.

Project Purpose

The aim is to assess the role of MYO1E in survival among veterans with lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD).

Background

Veterans have a higher smoking exposure than civilians; a higher incidence of lung cancer; and a younger age at diagnosis of lung cancer. We recently showed that MYO1E DNA methylation and RNA expression in LUAD are associated with survival among civilians.

Methods

This is a retrospective cohort study involving LUAD among civilians and veterans with biopsy or pathologically proven LUAD from surgical specimens. DNA extraction and isolation from FFPE cancer tissues was performed using methylation-onbeads as previously published, followed by qMSP with bisulfite treatment to quantify DNA methylation. RNA extraction and quantification from lung tissues was obtained as described in previous publications.

Data Analysis

Differences were assessed with Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical. Two-tailed log-rank test was used to estimate overall survival differences and Cox hazard models, to quantify risk of mortality using hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

There were 91 LUAD patients, 27 veterans and 64 civilians. Veterans were older than civilians, aged 70 years vs aged 66 years (P = .003); with higher proportions of males, 93% vs 69% (P = .03); higher proportion of African Americans, 67% vs 39% (P = .03); smoking more, 50 pack-year vs 40 (0.005), and having a higher proportion of grade I, 78% vs 55% (P = .036). Survival was statistically longer for MYO1E high DNA methylation group 48 months vs 33 for low methylation (P = .049). MYO1E RNA expression did not show statistically significant differences (P = .32). Multivariate Cox regression analysis adjusted by age, veteran/civil status, gender, race, packyear, and stage showed that DNA methylation was significantly associated with mortality risk (HR 5.14; 95% CI, 1.12-23.60) (P = .035).

Conclusions/Implications

This study suggests the utility of MYO1E DNA methylation as a prognostic biomarker for veterans with LUAD. Further studies are necessary to understand the role of MYO1E in chemotherapy resistance and microenvironment immune modulation. Given the low expression of MYO1E in blood cells, MYO1E DNA methylation has the potential to be used as circulating tumor marker in liquid biopsies.

Project Purpose

The aim is to assess the role of MYO1E in survival among veterans with lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD).

Background

Veterans have a higher smoking exposure than civilians; a higher incidence of lung cancer; and a younger age at diagnosis of lung cancer. We recently showed that MYO1E DNA methylation and RNA expression in LUAD are associated with survival among civilians.

Methods

This is a retrospective cohort study involving LUAD among civilians and veterans with biopsy or pathologically proven LUAD from surgical specimens. DNA extraction and isolation from FFPE cancer tissues was performed using methylation-onbeads as previously published, followed by qMSP with bisulfite treatment to quantify DNA methylation. RNA extraction and quantification from lung tissues was obtained as described in previous publications.

Data Analysis

Differences were assessed with Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical. Two-tailed log-rank test was used to estimate overall survival differences and Cox hazard models, to quantify risk of mortality using hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

There were 91 LUAD patients, 27 veterans and 64 civilians. Veterans were older than civilians, aged 70 years vs aged 66 years (P = .003); with higher proportions of males, 93% vs 69% (P = .03); higher proportion of African Americans, 67% vs 39% (P = .03); smoking more, 50 pack-year vs 40 (0.005), and having a higher proportion of grade I, 78% vs 55% (P = .036). Survival was statistically longer for MYO1E high DNA methylation group 48 months vs 33 for low methylation (P = .049). MYO1E RNA expression did not show statistically significant differences (P = .32). Multivariate Cox regression analysis adjusted by age, veteran/civil status, gender, race, packyear, and stage showed that DNA methylation was significantly associated with mortality risk (HR 5.14; 95% CI, 1.12-23.60) (P = .035).

Conclusions/Implications

This study suggests the utility of MYO1E DNA methylation as a prognostic biomarker for veterans with LUAD. Further studies are necessary to understand the role of MYO1E in chemotherapy resistance and microenvironment immune modulation. Given the low expression of MYO1E in blood cells, MYO1E DNA methylation has the potential to be used as circulating tumor marker in liquid biopsies.

Molecular Profiling of Lung Malignancies in Veterans: What We Have Learned About the Impact of Agent Orange Exposure

Background

There are no studies in oncologic literature that report biomarker alterations in Vietnam War veterans with lung cancers. Our study elucidates genetic mutations in veterans with lung cancer exposed to Agent Orange (AO) and compares them to non-Agent Orange exposed (NAO) veterans.

Methods

We collected data of veterans with lung cancers from VA Central California Health Care System who had NGS testing via Foundation One CDx from January 2007 to January 2022. We collected data of AO versus NAO veterans including age, race, gender, smoking and exposure history, histologic subtypes, treatment modalities, PDL-1, and molecular mutations. Median PFS and OS were calculated between AO and NAO in all veterans and adenocarcinoma group after first-line therapy in months by Kaplan-Meier R log-rank test.

Results

There were total of 58 lung cancer veterans, 27 AO and 31 NAO. 33 (56.9%) veterans had adenocarcinoma (20 AO vs 13 NAO). Veterans were White (81%), male (93%) and all had tobacco exposure. The median age at diagnosis was 72 years in both groups. 65.5% had stage III-IV disease. Veterans with AO adenocarcinoma had more early stage I-II disease (50%) as compared to NAO (16%). The AO group had more PDL1 expression (TPS > 1%). 15/31 (48.4%) NAO received immunotherapy vs 7/27 (25.9%) AO. 104 molecular mutations were identified. Veterans with AO had more ROS1, MET, and NRAS while NAO had more EGFR, KRAS, and NF1 mutations. In adenocarcinoma group, AO had more MET and less KRAS while NAO has more KRAS, TP53, and EGFR. The median PFS and OS for all veterans with AO vs NAO were 8 mo vs 6 mo and 12 mo vs 10 mo, respectively (non-significant [NS]). In adenocarcinoma group the median PFS and OS for AO vs NAO veterans were 8 mo vs 4 mo and 11.75 mo vs 6 mo, respectively (NS).

Conclusions

Our study is the first to report molecular biomarkers in AO and NAO veterans with lung cancers. We found different markers between the groups. The median PFS and OS of AO and adenocarcinoma AO veterans were longer due to early stage diagnoses while NAO vetera

Background

There are no studies in oncologic literature that report biomarker alterations in Vietnam War veterans with lung cancers. Our study elucidates genetic mutations in veterans with lung cancer exposed to Agent Orange (AO) and compares them to non-Agent Orange exposed (NAO) veterans.

Methods

We collected data of veterans with lung cancers from VA Central California Health Care System who had NGS testing via Foundation One CDx from January 2007 to January 2022. We collected data of AO versus NAO veterans including age, race, gender, smoking and exposure history, histologic subtypes, treatment modalities, PDL-1, and molecular mutations. Median PFS and OS were calculated between AO and NAO in all veterans and adenocarcinoma group after first-line therapy in months by Kaplan-Meier R log-rank test.

Results

There were total of 58 lung cancer veterans, 27 AO and 31 NAO. 33 (56.9%) veterans had adenocarcinoma (20 AO vs 13 NAO). Veterans were White (81%), male (93%) and all had tobacco exposure. The median age at diagnosis was 72 years in both groups. 65.5% had stage III-IV disease. Veterans with AO adenocarcinoma had more early stage I-II disease (50%) as compared to NAO (16%). The AO group had more PDL1 expression (TPS > 1%). 15/31 (48.4%) NAO received immunotherapy vs 7/27 (25.9%) AO. 104 molecular mutations were identified. Veterans with AO had more ROS1, MET, and NRAS while NAO had more EGFR, KRAS, and NF1 mutations. In adenocarcinoma group, AO had more MET and less KRAS while NAO has more KRAS, TP53, and EGFR. The median PFS and OS for all veterans with AO vs NAO were 8 mo vs 6 mo and 12 mo vs 10 mo, respectively (non-significant [NS]). In adenocarcinoma group the median PFS and OS for AO vs NAO veterans were 8 mo vs 4 mo and 11.75 mo vs 6 mo, respectively (NS).

Conclusions

Our study is the first to report molecular biomarkers in AO and NAO veterans with lung cancers. We found different markers between the groups. The median PFS and OS of AO and adenocarcinoma AO veterans were longer due to early stage diagnoses while NAO vetera

Background

There are no studies in oncologic literature that report biomarker alterations in Vietnam War veterans with lung cancers. Our study elucidates genetic mutations in veterans with lung cancer exposed to Agent Orange (AO) and compares them to non-Agent Orange exposed (NAO) veterans.

Methods

We collected data of veterans with lung cancers from VA Central California Health Care System who had NGS testing via Foundation One CDx from January 2007 to January 2022. We collected data of AO versus NAO veterans including age, race, gender, smoking and exposure history, histologic subtypes, treatment modalities, PDL-1, and molecular mutations. Median PFS and OS were calculated between AO and NAO in all veterans and adenocarcinoma group after first-line therapy in months by Kaplan-Meier R log-rank test.

Results

There were total of 58 lung cancer veterans, 27 AO and 31 NAO. 33 (56.9%) veterans had adenocarcinoma (20 AO vs 13 NAO). Veterans were White (81%), male (93%) and all had tobacco exposure. The median age at diagnosis was 72 years in both groups. 65.5% had stage III-IV disease. Veterans with AO adenocarcinoma had more early stage I-II disease (50%) as compared to NAO (16%). The AO group had more PDL1 expression (TPS > 1%). 15/31 (48.4%) NAO received immunotherapy vs 7/27 (25.9%) AO. 104 molecular mutations were identified. Veterans with AO had more ROS1, MET, and NRAS while NAO had more EGFR, KRAS, and NF1 mutations. In adenocarcinoma group, AO had more MET and less KRAS while NAO has more KRAS, TP53, and EGFR. The median PFS and OS for all veterans with AO vs NAO were 8 mo vs 6 mo and 12 mo vs 10 mo, respectively (non-significant [NS]). In adenocarcinoma group the median PFS and OS for AO vs NAO veterans were 8 mo vs 4 mo and 11.75 mo vs 6 mo, respectively (NS).

Conclusions

Our study is the first to report molecular biomarkers in AO and NAO veterans with lung cancers. We found different markers between the groups. The median PFS and OS of AO and adenocarcinoma AO veterans were longer due to early stage diagnoses while NAO vetera

Utilization of Next Generation Sequencing in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer

Introduction

Metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) is one of the most common and lethal cancers. Nextgeneration sequencing (NGS) has been recommended as a tool to help guide treatment by identifying actionable genetic mutations. However, data regarding realworld usage of NGS in a Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system is lacking. We conducted a retrospective observational study of the patterns of NGS usage in patients with mCRC at the South Texas Veterans Affairs Healthcare System (STVAHCS).

Methods

We identified patients with a diagnosis of mCRC evaluated and treated at STVAHCS between January 1, 2018 and June 1, 2022. We assessed the prevalence of utilizing NGS on solid tumor samples performed by Foundation One and identified the presence of different molecular aberrations detected by NGS.

Results

65 patients were identified. Median age was 68 years. 63 (96.9%) were males and 2 (3.1%) were females. 29 (44.6%) were Hispanic, 25 (38.5%) were White, 10 (15.4%) were African American and 1 (1.5%) was Pacific Islander. NGS was performed in 34 (52.3%) patients. The most common reasons for not performing NGS were unknown/not documented (54.8%), early mortality (29%), lack of adequate tissue (12.9%) and patient refusal of treatment (3.2%). The most common molecular aberrations identified in patients who had NGS were TP53 (73.5%), APC (64.7%), KRAS (47.1%), ATM (20.6%), SMAD4 (14.7%) and BRAF (14.7%). All patients who had NGS were found to have at least one identifiable mutation.

Conclusions

Approximately 50% of patients with mCRC did not have NGS performed on their tissue sample. This rate is similar to other real-world studies in non-VA settings. Documented reasons for lack of NGS testing included inadequate tissue and early patient mortality. Other potential reasons could be lack of efficient VA clinical testing protocols, use of simple molecular testing rather than comprehensive NGS testing and limited knowledge of availability of NGS among providers. Measures that can be taken to increase utilization of NGS include incorporating NGS testing early in the disease course, incorporating testing into VA clinical pathways, improving physician education, increasing the size of solid tissue samples and ordering liquid biopsies where solid tissue is deficient.

Introduction

Metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) is one of the most common and lethal cancers. Nextgeneration sequencing (NGS) has been recommended as a tool to help guide treatment by identifying actionable genetic mutations. However, data regarding realworld usage of NGS in a Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system is lacking. We conducted a retrospective observational study of the patterns of NGS usage in patients with mCRC at the South Texas Veterans Affairs Healthcare System (STVAHCS).

Methods

We identified patients with a diagnosis of mCRC evaluated and treated at STVAHCS between January 1, 2018 and June 1, 2022. We assessed the prevalence of utilizing NGS on solid tumor samples performed by Foundation One and identified the presence of different molecular aberrations detected by NGS.

Results

65 patients were identified. Median age was 68 years. 63 (96.9%) were males and 2 (3.1%) were females. 29 (44.6%) were Hispanic, 25 (38.5%) were White, 10 (15.4%) were African American and 1 (1.5%) was Pacific Islander. NGS was performed in 34 (52.3%) patients. The most common reasons for not performing NGS were unknown/not documented (54.8%), early mortality (29%), lack of adequate tissue (12.9%) and patient refusal of treatment (3.2%). The most common molecular aberrations identified in patients who had NGS were TP53 (73.5%), APC (64.7%), KRAS (47.1%), ATM (20.6%), SMAD4 (14.7%) and BRAF (14.7%). All patients who had NGS were found to have at least one identifiable mutation.

Conclusions

Approximately 50% of patients with mCRC did not have NGS performed on their tissue sample. This rate is similar to other real-world studies in non-VA settings. Documented reasons for lack of NGS testing included inadequate tissue and early patient mortality. Other potential reasons could be lack of efficient VA clinical testing protocols, use of simple molecular testing rather than comprehensive NGS testing and limited knowledge of availability of NGS among providers. Measures that can be taken to increase utilization of NGS include incorporating NGS testing early in the disease course, incorporating testing into VA clinical pathways, improving physician education, increasing the size of solid tissue samples and ordering liquid biopsies where solid tissue is deficient.

Introduction

Metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) is one of the most common and lethal cancers. Nextgeneration sequencing (NGS) has been recommended as a tool to help guide treatment by identifying actionable genetic mutations. However, data regarding realworld usage of NGS in a Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system is lacking. We conducted a retrospective observational study of the patterns of NGS usage in patients with mCRC at the South Texas Veterans Affairs Healthcare System (STVAHCS).

Methods

We identified patients with a diagnosis of mCRC evaluated and treated at STVAHCS between January 1, 2018 and June 1, 2022. We assessed the prevalence of utilizing NGS on solid tumor samples performed by Foundation One and identified the presence of different molecular aberrations detected by NGS.

Results

65 patients were identified. Median age was 68 years. 63 (96.9%) were males and 2 (3.1%) were females. 29 (44.6%) were Hispanic, 25 (38.5%) were White, 10 (15.4%) were African American and 1 (1.5%) was Pacific Islander. NGS was performed in 34 (52.3%) patients. The most common reasons for not performing NGS were unknown/not documented (54.8%), early mortality (29%), lack of adequate tissue (12.9%) and patient refusal of treatment (3.2%). The most common molecular aberrations identified in patients who had NGS were TP53 (73.5%), APC (64.7%), KRAS (47.1%), ATM (20.6%), SMAD4 (14.7%) and BRAF (14.7%). All patients who had NGS were found to have at least one identifiable mutation.

Conclusions

Approximately 50% of patients with mCRC did not have NGS performed on their tissue sample. This rate is similar to other real-world studies in non-VA settings. Documented reasons for lack of NGS testing included inadequate tissue and early patient mortality. Other potential reasons could be lack of efficient VA clinical testing protocols, use of simple molecular testing rather than comprehensive NGS testing and limited knowledge of availability of NGS among providers. Measures that can be taken to increase utilization of NGS include incorporating NGS testing early in the disease course, incorporating testing into VA clinical pathways, improving physician education, increasing the size of solid tissue samples and ordering liquid biopsies where solid tissue is deficient.

Leg rash

Punch biopsies for standard pathology and direct immunofluorescence were performed and ruled out vesiculobullous disease. Further conversation with the patient revealed that this was a phototoxic drug eruption that resulted from a medication mix-up. The patient had intended to treat an eczema flare with a topical steroid but had inadvertently applied 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), which he had left over from a previous bout of actinic keratosis. While selective to precancerous cells with rapid DNA replication, 5-FU can trigger a significant photodermatitis when applied to heavily sun-exposed skin.

Phototoxic skin reactions can be an adverse result of multiple systemic and topical therapies. Common systemic examples include amiodarone, chlorpromazine, doxycycline, hydrochlorothiazide, isotretinoin, nalidixic acid, naproxen, piroxicam, tetracycline, thioridazine, vemurafenib, and voriconazole.1 Topical examples include retinoids, levulinic acid, and 5-FU. Treatment requires that the patient stop the offending medication and use photoprotection. The patient followed this protocol and his erosions resolved over the course of a few weeks.

This case demonstrates that topical therapies, like systemic medications, can have chemical names that are confusing to patients. Further complicating matters can be the practice of folding metal tubes of cream over their life of use, thus obscuring the label.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Blakely KM, Drucker AM, Rosen CF. Drug-induced photosensitivity-an update: culprit drugs, prevention, and management. Drug Saf. 2019;42:827-847. doi: 10.1007/s40264-019-00806-5

Punch biopsies for standard pathology and direct immunofluorescence were performed and ruled out vesiculobullous disease. Further conversation with the patient revealed that this was a phototoxic drug eruption that resulted from a medication mix-up. The patient had intended to treat an eczema flare with a topical steroid but had inadvertently applied 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), which he had left over from a previous bout of actinic keratosis. While selective to precancerous cells with rapid DNA replication, 5-FU can trigger a significant photodermatitis when applied to heavily sun-exposed skin.

Phototoxic skin reactions can be an adverse result of multiple systemic and topical therapies. Common systemic examples include amiodarone, chlorpromazine, doxycycline, hydrochlorothiazide, isotretinoin, nalidixic acid, naproxen, piroxicam, tetracycline, thioridazine, vemurafenib, and voriconazole.1 Topical examples include retinoids, levulinic acid, and 5-FU. Treatment requires that the patient stop the offending medication and use photoprotection. The patient followed this protocol and his erosions resolved over the course of a few weeks.

This case demonstrates that topical therapies, like systemic medications, can have chemical names that are confusing to patients. Further complicating matters can be the practice of folding metal tubes of cream over their life of use, thus obscuring the label.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Punch biopsies for standard pathology and direct immunofluorescence were performed and ruled out vesiculobullous disease. Further conversation with the patient revealed that this was a phototoxic drug eruption that resulted from a medication mix-up. The patient had intended to treat an eczema flare with a topical steroid but had inadvertently applied 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), which he had left over from a previous bout of actinic keratosis. While selective to precancerous cells with rapid DNA replication, 5-FU can trigger a significant photodermatitis when applied to heavily sun-exposed skin.

Phototoxic skin reactions can be an adverse result of multiple systemic and topical therapies. Common systemic examples include amiodarone, chlorpromazine, doxycycline, hydrochlorothiazide, isotretinoin, nalidixic acid, naproxen, piroxicam, tetracycline, thioridazine, vemurafenib, and voriconazole.1 Topical examples include retinoids, levulinic acid, and 5-FU. Treatment requires that the patient stop the offending medication and use photoprotection. The patient followed this protocol and his erosions resolved over the course of a few weeks.

This case demonstrates that topical therapies, like systemic medications, can have chemical names that are confusing to patients. Further complicating matters can be the practice of folding metal tubes of cream over their life of use, thus obscuring the label.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Blakely KM, Drucker AM, Rosen CF. Drug-induced photosensitivity-an update: culprit drugs, prevention, and management. Drug Saf. 2019;42:827-847. doi: 10.1007/s40264-019-00806-5

1. Blakely KM, Drucker AM, Rosen CF. Drug-induced photosensitivity-an update: culprit drugs, prevention, and management. Drug Saf. 2019;42:827-847. doi: 10.1007/s40264-019-00806-5

Dermatologists and the Aging Eye: Visual Performance in Physicians

The years start coming and they don’t stop coming.

Smash Mouth, “All Star”

Dermatologists, similar to everyone else, are subject to the inevitable: aging. More than 80% of the US population develops presbyopia, an age-related reduction in visual acuity, in their lifetime. The most common cause of refractive error in adults, presbyopia can contribute to reduced professional productivity, and individuals with uncorrected presbyopia face an estimated 8-fold increase in difficulty performing demanding near-vision tasks.1

As specialists who rely heavily on visual assessment, dermatologists likely are aware of presbyopia, seeking care as appropriate; however, visual correction is not one size fits all, and identifying effective job-specific adjustments may require considerable trial and error. To this end, if visual correction may be needed by a large majority of dermatologists at some point, why do we not have specialized recommendations to guide the corrective process according to the individual’s defect and type of practice within the specialty? Do we need resources for dermatologists concerning ophthalmologic wellness and key warning signs of visual acuity deficits and other ocular complications?

These matters are difficult to address, made more so by the lack of data examining correctable visual impairment (CVI) in dermatology. The basis for discussion is clear; however, visual skills are highly relevant to the practice of dermatology, and age-related visual changes often are inevitable. This article will provide an overview of CVI in related disciplines and the importance of understanding CVI and corrective options in dermatology.

CVI Across Medical Disciplines

Other predominantly visual medical specialties such as pathology, radiology, and surgery have initiated research evaluating the impact of CVI on their respective practices, although consistent data still are limited. Much of the work surrounding CVI in medicine can be identified in surgery and its subspecialties. A 2020 study by Tuna et al2 found that uncorrected myopia with greater than 1.75 diopter, hyperopia regardless of grade, and presbyopia with greater than 1.25 diopter correlated with reduced surgical performance when using the Da Vinci robotic system. A 2002 report by Wanzel et al3 was among the first of many studies to demonstrate the importance of visuospatial ability in surgical success. In radiology, Krupinski et al4 demonstrated reduced accuracy in detecting pulmonary nodules that correlated with increased myopia and decreased accommodation secondary to visual strain.

Most reports examining CVI across medical disciplines are primarily conversational or observational, with some utilizing surveys to assess the prevalence of CVI and the opinions of physicians in the field. For example, in a survey of 93 pathologists in Turkey, 93.5% (87/93) reported at least 1 type of refractive error. Eyeglasses were the most common form of correction (64.5% [60/93]); of those, 33.3% (31/93) reported using eyeglasses during microscopy.5

The importance of visual ability in other highly visual specialties suggests that parallels can be drawn to similar practices in dermatology. Detection of cutaneous lesions might be affected by changes in vision, similar to detection of pulmonary lesions in radiology. Likewise, dermatologic surgeons might experience a similar reduction in surgical performance due to impaired visual acuity or visuospatial ability.

The Importance of Visual Performancein Dermatology

With presbyopia often becoming clinically apparent at approximately 40 years of age,1,6 CVI has the potential to be present for much of a dermatologist’s career. Responsibility falls on the individual practitioner to recognize their visual deficit and seek appropriate optometric or ophthalmologic care. It should be emphasized that there are many effective avenues to correct refractive error, most of which can functionally restore an individual’s vision; however, each option prioritizes different visual attributes (eg, contrast, depth perception, clarity) that have varying degrees of importance in particular areas of dermatologic practice. For example, in addition to visual acuity, dermatologic surgeons might require optimized depth perception, whereas dermatologists performing detailed visual inspection or dermoscopy might instead require optimized contrast sensitivity and acuity. At present, the literature is silent on guiding dermatologists in selecting corrective approaches that enhance the visual characteristics most important for their practice. Lack of research and direction surrounding which visual correction techniques are best suited for individual tasks risks inaccurate and nonspecific conversations with our eye care providers. Focused educated dialogues about visual needs would streamline the process of finding appropriate correction, thereby reducing unnecessary trial and error. As each dermatologic subspecialty might require a unique subset of visual skills, the conceivable benefit of dermatology-specific visual correction resources is evident.

Additionally (although beyond the scope of this commentary), guidance on how a dermatologist should increase their awareness and approach to more serious ophthalmologic conditions—including retinal tear or detachment, age-related macular degeneration, and glaucoma—also would serve as a valuable resource. Overall, prompt identification of visual changes and educated discussions surrounding their correction would allow for optimization based on the required skill set and would improve overall outcomes.

Final Thoughts

Age-related visual changes are a highly prevalent and normal process that carry the potential to impact clinical practice. Fortunately, there are multiple corrective mechanisms that can functionally restore an individual’s eyesight. However, there are no resources to guide dermatologists in seeking specialty-specific correction centered on their daily tasks, which places the responsibility for such correction on the individual. This is a circumstance in which the task at hand is clear, yet we continue to individually reinvent the wheel. We should consider this an opportunity to work together with our optometry and ophthalmology colleagues to create centralized resources that assist dermatologists in navigating age-related visual changes.

Acknowledgments—The authors thank Delaney Stratton, DNP, FNP-BC (Tucson, Arizona); J. Daniel Twelker, OD, PhD (Tucson, Arizona); and Julia Freeman, MD (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), for their contributions to the manuscript, as well as Susan M. Swetter, MD (Palo Alto, California) for reviewing and providing feedback.

- Berdahl J, Bala C, Dhariwal M, et al. Patient and economic burden of presbyopia: a systematic literature review. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:3439-3450. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S269597

- Tuna MB, Kilavuzoglu AE, Mourmouris P, et al. Impact of refractive errors on Da Vinci SI robotic system. JSLS. 2020;24:e2020.00031. doi:10.4293/JSLS.2020.00031

- Wanzel KR, Hamstra SJ, Anastakis DJ, et al. Effect of visual-spatial ability on learning of spatially-complex surgical skills. Lancet. 2002;359:230-231. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07441-X

- Krupinski EA, Berbaum KS, Caldwell RT, et al. Do long radiology workdays affect nodule detection in dynamic CT interpretation? J Am Coll Radiol. 2012;9:191-198. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2011.11.013

- Akman O, Kösemehmetog˘lu K. Ocular diseases among pathologists and pathologists’ perceptions on ocular diseases: a survey study. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2015;31:194-199. doi:10.5146/tjpath.2015.01326

- Vitale S, Ellwein L, Cotch MF, et al. Prevalence of refractive error in the United States, 1999-2004. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1111-1119. doi:10.1001/archopht.126.8.1111

The years start coming and they don’t stop coming.

Smash Mouth, “All Star”

Dermatologists, similar to everyone else, are subject to the inevitable: aging. More than 80% of the US population develops presbyopia, an age-related reduction in visual acuity, in their lifetime. The most common cause of refractive error in adults, presbyopia can contribute to reduced professional productivity, and individuals with uncorrected presbyopia face an estimated 8-fold increase in difficulty performing demanding near-vision tasks.1

As specialists who rely heavily on visual assessment, dermatologists likely are aware of presbyopia, seeking care as appropriate; however, visual correction is not one size fits all, and identifying effective job-specific adjustments may require considerable trial and error. To this end, if visual correction may be needed by a large majority of dermatologists at some point, why do we not have specialized recommendations to guide the corrective process according to the individual’s defect and type of practice within the specialty? Do we need resources for dermatologists concerning ophthalmologic wellness and key warning signs of visual acuity deficits and other ocular complications?

These matters are difficult to address, made more so by the lack of data examining correctable visual impairment (CVI) in dermatology. The basis for discussion is clear; however, visual skills are highly relevant to the practice of dermatology, and age-related visual changes often are inevitable. This article will provide an overview of CVI in related disciplines and the importance of understanding CVI and corrective options in dermatology.

CVI Across Medical Disciplines

Other predominantly visual medical specialties such as pathology, radiology, and surgery have initiated research evaluating the impact of CVI on their respective practices, although consistent data still are limited. Much of the work surrounding CVI in medicine can be identified in surgery and its subspecialties. A 2020 study by Tuna et al2 found that uncorrected myopia with greater than 1.75 diopter, hyperopia regardless of grade, and presbyopia with greater than 1.25 diopter correlated with reduced surgical performance when using the Da Vinci robotic system. A 2002 report by Wanzel et al3 was among the first of many studies to demonstrate the importance of visuospatial ability in surgical success. In radiology, Krupinski et al4 demonstrated reduced accuracy in detecting pulmonary nodules that correlated with increased myopia and decreased accommodation secondary to visual strain.

Most reports examining CVI across medical disciplines are primarily conversational or observational, with some utilizing surveys to assess the prevalence of CVI and the opinions of physicians in the field. For example, in a survey of 93 pathologists in Turkey, 93.5% (87/93) reported at least 1 type of refractive error. Eyeglasses were the most common form of correction (64.5% [60/93]); of those, 33.3% (31/93) reported using eyeglasses during microscopy.5

The importance of visual ability in other highly visual specialties suggests that parallels can be drawn to similar practices in dermatology. Detection of cutaneous lesions might be affected by changes in vision, similar to detection of pulmonary lesions in radiology. Likewise, dermatologic surgeons might experience a similar reduction in surgical performance due to impaired visual acuity or visuospatial ability.

The Importance of Visual Performancein Dermatology

With presbyopia often becoming clinically apparent at approximately 40 years of age,1,6 CVI has the potential to be present for much of a dermatologist’s career. Responsibility falls on the individual practitioner to recognize their visual deficit and seek appropriate optometric or ophthalmologic care. It should be emphasized that there are many effective avenues to correct refractive error, most of which can functionally restore an individual’s vision; however, each option prioritizes different visual attributes (eg, contrast, depth perception, clarity) that have varying degrees of importance in particular areas of dermatologic practice. For example, in addition to visual acuity, dermatologic surgeons might require optimized depth perception, whereas dermatologists performing detailed visual inspection or dermoscopy might instead require optimized contrast sensitivity and acuity. At present, the literature is silent on guiding dermatologists in selecting corrective approaches that enhance the visual characteristics most important for their practice. Lack of research and direction surrounding which visual correction techniques are best suited for individual tasks risks inaccurate and nonspecific conversations with our eye care providers. Focused educated dialogues about visual needs would streamline the process of finding appropriate correction, thereby reducing unnecessary trial and error. As each dermatologic subspecialty might require a unique subset of visual skills, the conceivable benefit of dermatology-specific visual correction resources is evident.

Additionally (although beyond the scope of this commentary), guidance on how a dermatologist should increase their awareness and approach to more serious ophthalmologic conditions—including retinal tear or detachment, age-related macular degeneration, and glaucoma—also would serve as a valuable resource. Overall, prompt identification of visual changes and educated discussions surrounding their correction would allow for optimization based on the required skill set and would improve overall outcomes.

Final Thoughts

Age-related visual changes are a highly prevalent and normal process that carry the potential to impact clinical practice. Fortunately, there are multiple corrective mechanisms that can functionally restore an individual’s eyesight. However, there are no resources to guide dermatologists in seeking specialty-specific correction centered on their daily tasks, which places the responsibility for such correction on the individual. This is a circumstance in which the task at hand is clear, yet we continue to individually reinvent the wheel. We should consider this an opportunity to work together with our optometry and ophthalmology colleagues to create centralized resources that assist dermatologists in navigating age-related visual changes.

Acknowledgments—The authors thank Delaney Stratton, DNP, FNP-BC (Tucson, Arizona); J. Daniel Twelker, OD, PhD (Tucson, Arizona); and Julia Freeman, MD (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), for their contributions to the manuscript, as well as Susan M. Swetter, MD (Palo Alto, California) for reviewing and providing feedback.

The years start coming and they don’t stop coming.

Smash Mouth, “All Star”

Dermatologists, similar to everyone else, are subject to the inevitable: aging. More than 80% of the US population develops presbyopia, an age-related reduction in visual acuity, in their lifetime. The most common cause of refractive error in adults, presbyopia can contribute to reduced professional productivity, and individuals with uncorrected presbyopia face an estimated 8-fold increase in difficulty performing demanding near-vision tasks.1

As specialists who rely heavily on visual assessment, dermatologists likely are aware of presbyopia, seeking care as appropriate; however, visual correction is not one size fits all, and identifying effective job-specific adjustments may require considerable trial and error. To this end, if visual correction may be needed by a large majority of dermatologists at some point, why do we not have specialized recommendations to guide the corrective process according to the individual’s defect and type of practice within the specialty? Do we need resources for dermatologists concerning ophthalmologic wellness and key warning signs of visual acuity deficits and other ocular complications?

These matters are difficult to address, made more so by the lack of data examining correctable visual impairment (CVI) in dermatology. The basis for discussion is clear; however, visual skills are highly relevant to the practice of dermatology, and age-related visual changes often are inevitable. This article will provide an overview of CVI in related disciplines and the importance of understanding CVI and corrective options in dermatology.

CVI Across Medical Disciplines

Other predominantly visual medical specialties such as pathology, radiology, and surgery have initiated research evaluating the impact of CVI on their respective practices, although consistent data still are limited. Much of the work surrounding CVI in medicine can be identified in surgery and its subspecialties. A 2020 study by Tuna et al2 found that uncorrected myopia with greater than 1.75 diopter, hyperopia regardless of grade, and presbyopia with greater than 1.25 diopter correlated with reduced surgical performance when using the Da Vinci robotic system. A 2002 report by Wanzel et al3 was among the first of many studies to demonstrate the importance of visuospatial ability in surgical success. In radiology, Krupinski et al4 demonstrated reduced accuracy in detecting pulmonary nodules that correlated with increased myopia and decreased accommodation secondary to visual strain.

Most reports examining CVI across medical disciplines are primarily conversational or observational, with some utilizing surveys to assess the prevalence of CVI and the opinions of physicians in the field. For example, in a survey of 93 pathologists in Turkey, 93.5% (87/93) reported at least 1 type of refractive error. Eyeglasses were the most common form of correction (64.5% [60/93]); of those, 33.3% (31/93) reported using eyeglasses during microscopy.5

The importance of visual ability in other highly visual specialties suggests that parallels can be drawn to similar practices in dermatology. Detection of cutaneous lesions might be affected by changes in vision, similar to detection of pulmonary lesions in radiology. Likewise, dermatologic surgeons might experience a similar reduction in surgical performance due to impaired visual acuity or visuospatial ability.

The Importance of Visual Performancein Dermatology

With presbyopia often becoming clinically apparent at approximately 40 years of age,1,6 CVI has the potential to be present for much of a dermatologist’s career. Responsibility falls on the individual practitioner to recognize their visual deficit and seek appropriate optometric or ophthalmologic care. It should be emphasized that there are many effective avenues to correct refractive error, most of which can functionally restore an individual’s vision; however, each option prioritizes different visual attributes (eg, contrast, depth perception, clarity) that have varying degrees of importance in particular areas of dermatologic practice. For example, in addition to visual acuity, dermatologic surgeons might require optimized depth perception, whereas dermatologists performing detailed visual inspection or dermoscopy might instead require optimized contrast sensitivity and acuity. At present, the literature is silent on guiding dermatologists in selecting corrective approaches that enhance the visual characteristics most important for their practice. Lack of research and direction surrounding which visual correction techniques are best suited for individual tasks risks inaccurate and nonspecific conversations with our eye care providers. Focused educated dialogues about visual needs would streamline the process of finding appropriate correction, thereby reducing unnecessary trial and error. As each dermatologic subspecialty might require a unique subset of visual skills, the conceivable benefit of dermatology-specific visual correction resources is evident.

Additionally (although beyond the scope of this commentary), guidance on how a dermatologist should increase their awareness and approach to more serious ophthalmologic conditions—including retinal tear or detachment, age-related macular degeneration, and glaucoma—also would serve as a valuable resource. Overall, prompt identification of visual changes and educated discussions surrounding their correction would allow for optimization based on the required skill set and would improve overall outcomes.

Final Thoughts

Age-related visual changes are a highly prevalent and normal process that carry the potential to impact clinical practice. Fortunately, there are multiple corrective mechanisms that can functionally restore an individual’s eyesight. However, there are no resources to guide dermatologists in seeking specialty-specific correction centered on their daily tasks, which places the responsibility for such correction on the individual. This is a circumstance in which the task at hand is clear, yet we continue to individually reinvent the wheel. We should consider this an opportunity to work together with our optometry and ophthalmology colleagues to create centralized resources that assist dermatologists in navigating age-related visual changes.

Acknowledgments—The authors thank Delaney Stratton, DNP, FNP-BC (Tucson, Arizona); J. Daniel Twelker, OD, PhD (Tucson, Arizona); and Julia Freeman, MD (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), for their contributions to the manuscript, as well as Susan M. Swetter, MD (Palo Alto, California) for reviewing and providing feedback.

- Berdahl J, Bala C, Dhariwal M, et al. Patient and economic burden of presbyopia: a systematic literature review. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:3439-3450. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S269597

- Tuna MB, Kilavuzoglu AE, Mourmouris P, et al. Impact of refractive errors on Da Vinci SI robotic system. JSLS. 2020;24:e2020.00031. doi:10.4293/JSLS.2020.00031

- Wanzel KR, Hamstra SJ, Anastakis DJ, et al. Effect of visual-spatial ability on learning of spatially-complex surgical skills. Lancet. 2002;359:230-231. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07441-X

- Krupinski EA, Berbaum KS, Caldwell RT, et al. Do long radiology workdays affect nodule detection in dynamic CT interpretation? J Am Coll Radiol. 2012;9:191-198. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2011.11.013

- Akman O, Kösemehmetog˘lu K. Ocular diseases among pathologists and pathologists’ perceptions on ocular diseases: a survey study. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2015;31:194-199. doi:10.5146/tjpath.2015.01326

- Vitale S, Ellwein L, Cotch MF, et al. Prevalence of refractive error in the United States, 1999-2004. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1111-1119. doi:10.1001/archopht.126.8.1111

- Berdahl J, Bala C, Dhariwal M, et al. Patient and economic burden of presbyopia: a systematic literature review. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:3439-3450. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S269597

- Tuna MB, Kilavuzoglu AE, Mourmouris P, et al. Impact of refractive errors on Da Vinci SI robotic system. JSLS. 2020;24:e2020.00031. doi:10.4293/JSLS.2020.00031

- Wanzel KR, Hamstra SJ, Anastakis DJ, et al. Effect of visual-spatial ability on learning of spatially-complex surgical skills. Lancet. 2002;359:230-231. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07441-X

- Krupinski EA, Berbaum KS, Caldwell RT, et al. Do long radiology workdays affect nodule detection in dynamic CT interpretation? J Am Coll Radiol. 2012;9:191-198. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2011.11.013

- Akman O, Kösemehmetog˘lu K. Ocular diseases among pathologists and pathologists’ perceptions on ocular diseases: a survey study. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2015;31:194-199. doi:10.5146/tjpath.2015.01326

- Vitale S, Ellwein L, Cotch MF, et al. Prevalence of refractive error in the United States, 1999-2004. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1111-1119. doi:10.1001/archopht.126.8.1111

Practice Points

- With presbyopia becoming clinically apparent starting at 40 years of age, dermatologists should be vigilant for correctable visual impairment.

- Although many corrective options exist, more research is needed to understand whether dermatologic subspecialties are better suited to specific options.

- As a specialty, we should consider standardized visual correction guidance.

Transverse Leukonychia and Beau Lines Following COVID-19 Vaccination

To the Editor:

Nail abnormalities associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection that have been reported in the medical literature include nail psoriasis,1 Beau lines,2 onychomadesis,3 heterogeneous red-white discoloration of the nail bed,4 transverse orange nail lesions,3 and the red half‐moon nail sign.3,5 It has been hypothesized that these nail findings may be an indication of microvascular injury to the distal subungual arcade of the digit or may be indicative of a procoagulant state.5,6 Currently, there is limited knowledge of the effect of COVID-19 vaccines on nail changes. We report a patient who presented with transverse leukonychia (Mees lines) and Beau lines shortly after each dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccine was administered (with a total of 2 doses administered on presentation).

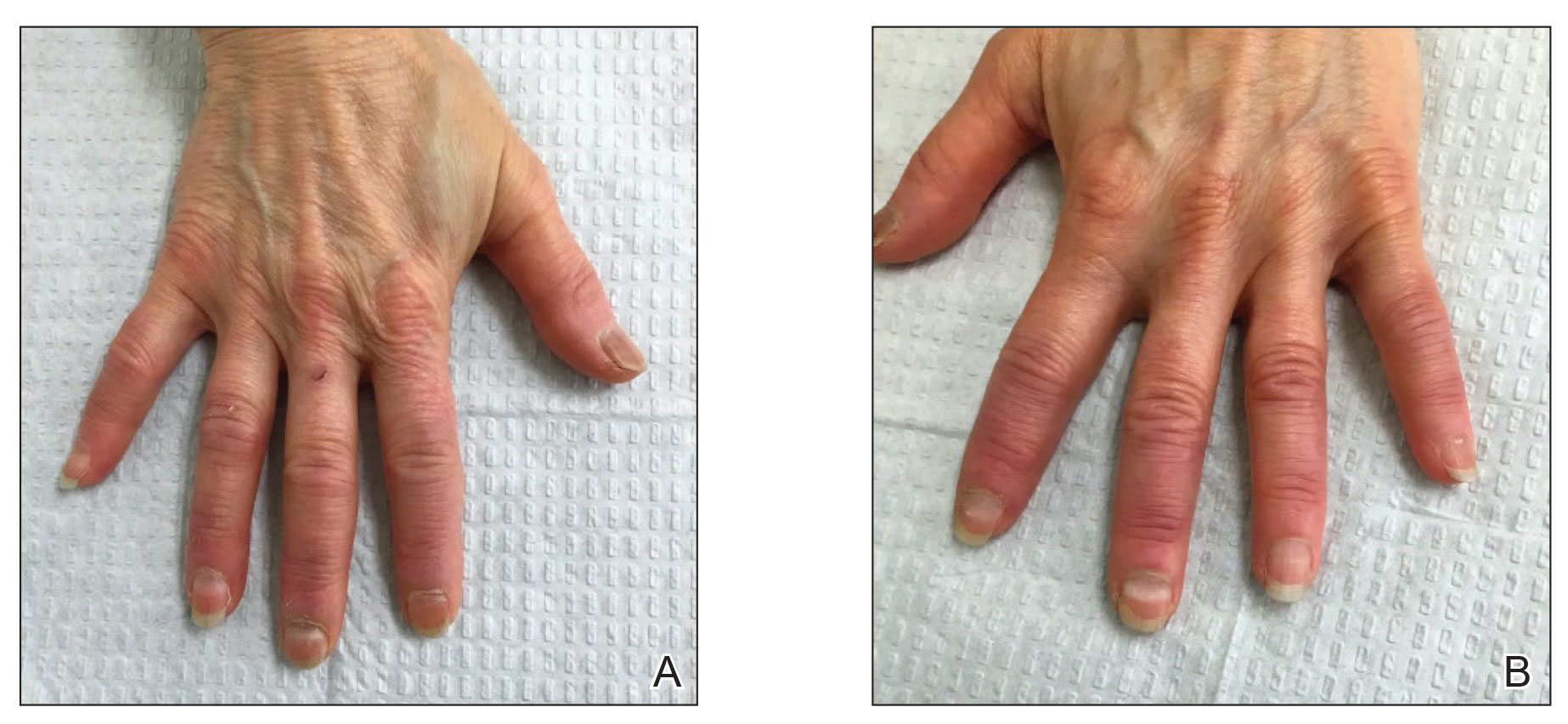

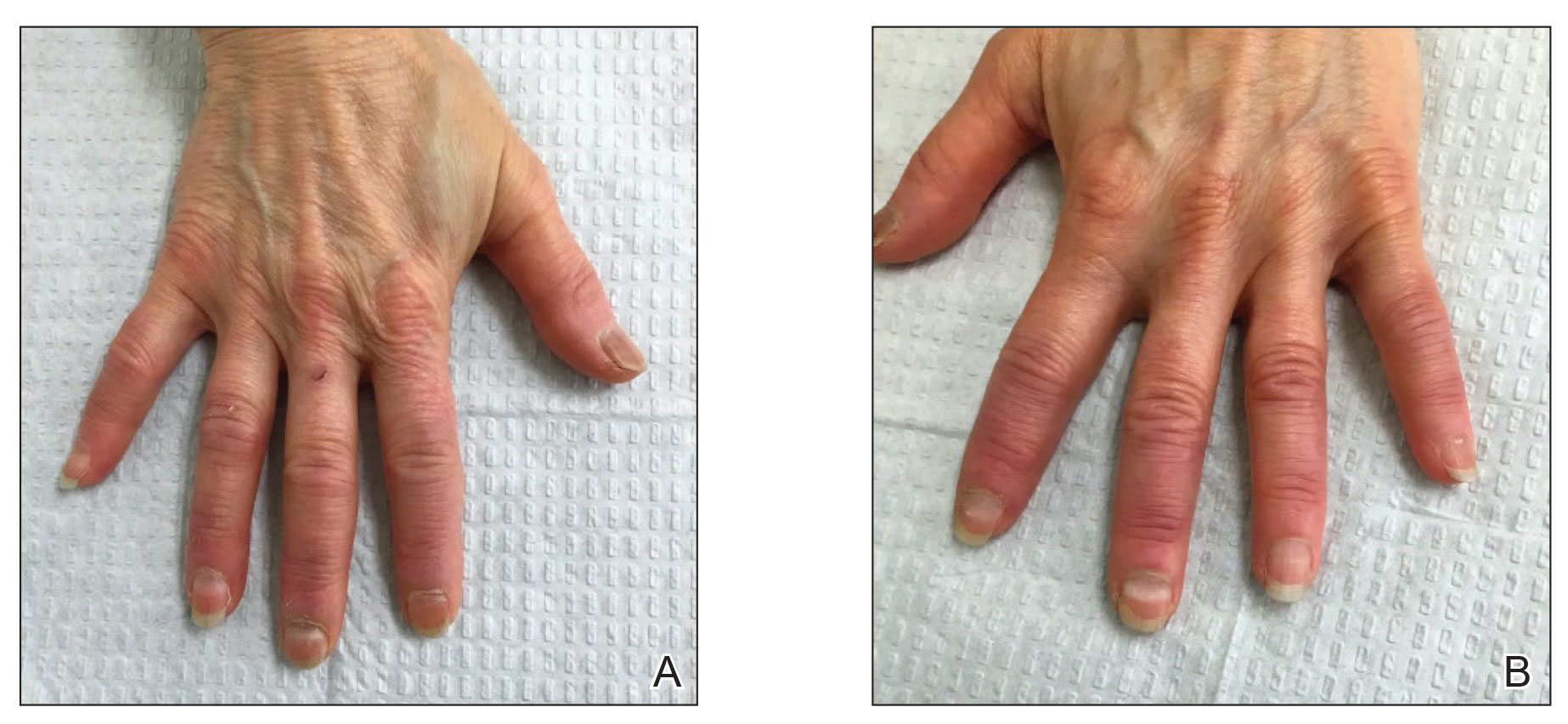

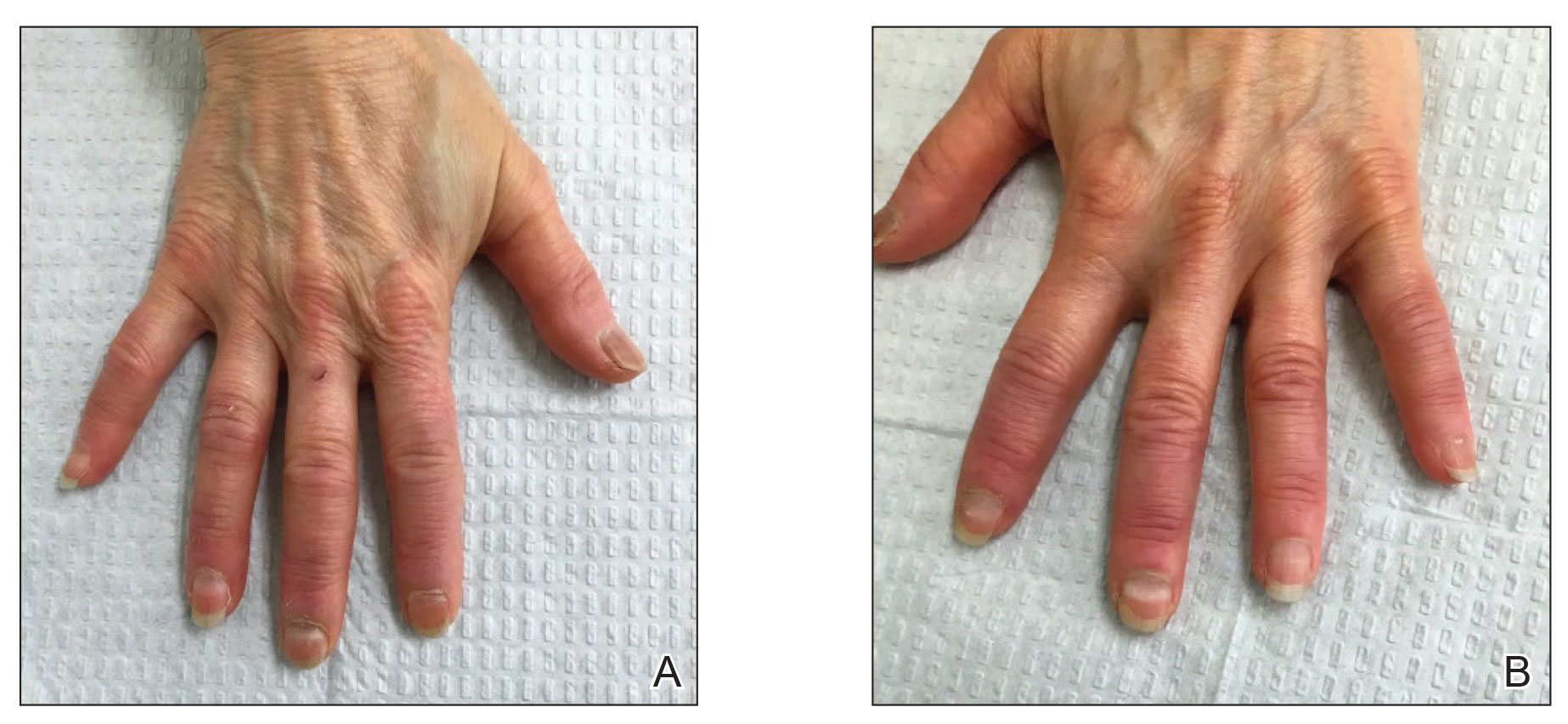

A 64-year-old woman with a history of rheumatoid arthritis presented with peeling of the fingernails and proximal white discoloration of several fingernails of 2 months’ duration. The patient first noticed whitening of the nails 3 weeks after she recevied the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. Five days after receiving the second, she presented to the dermatology clinic and exhibited transverse leukonychia in most fingernails (Figure 1).

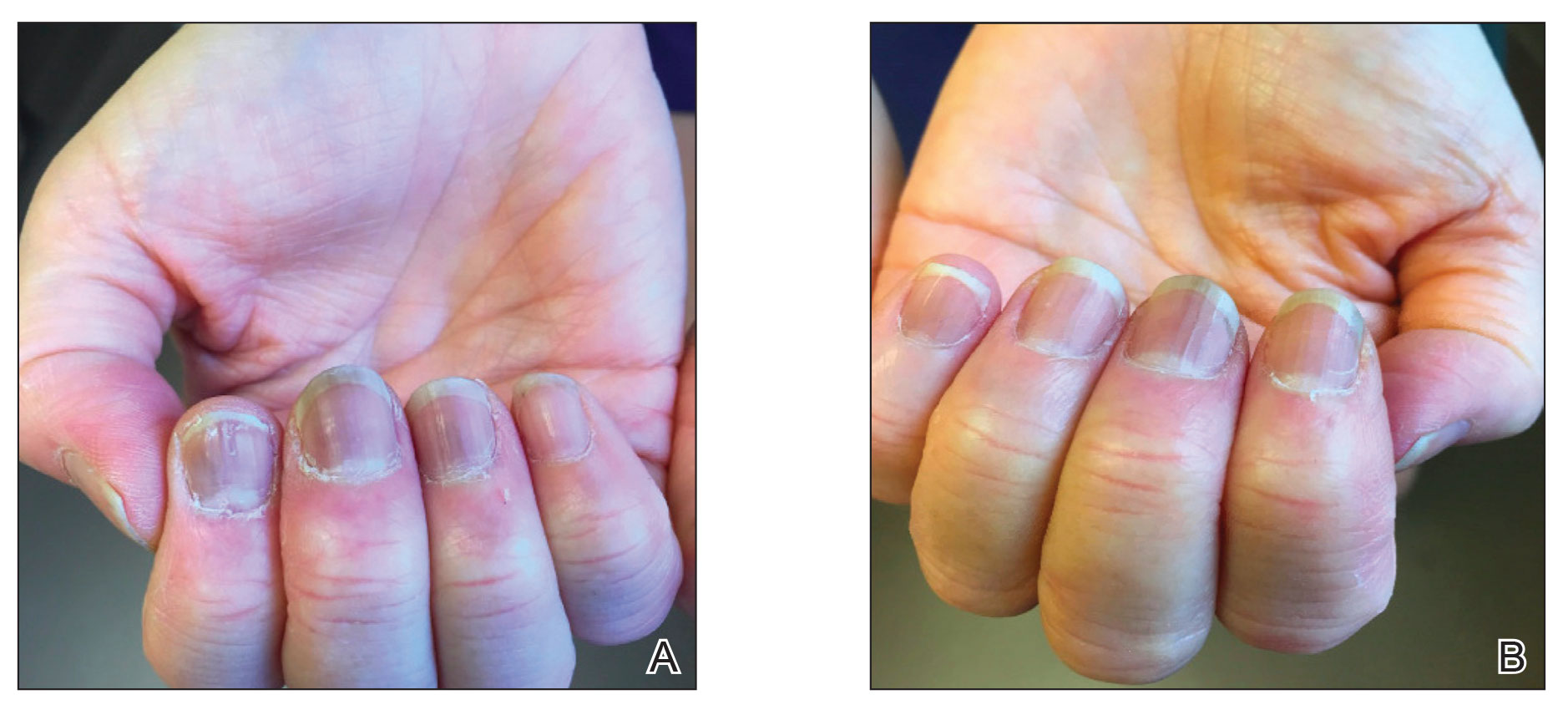

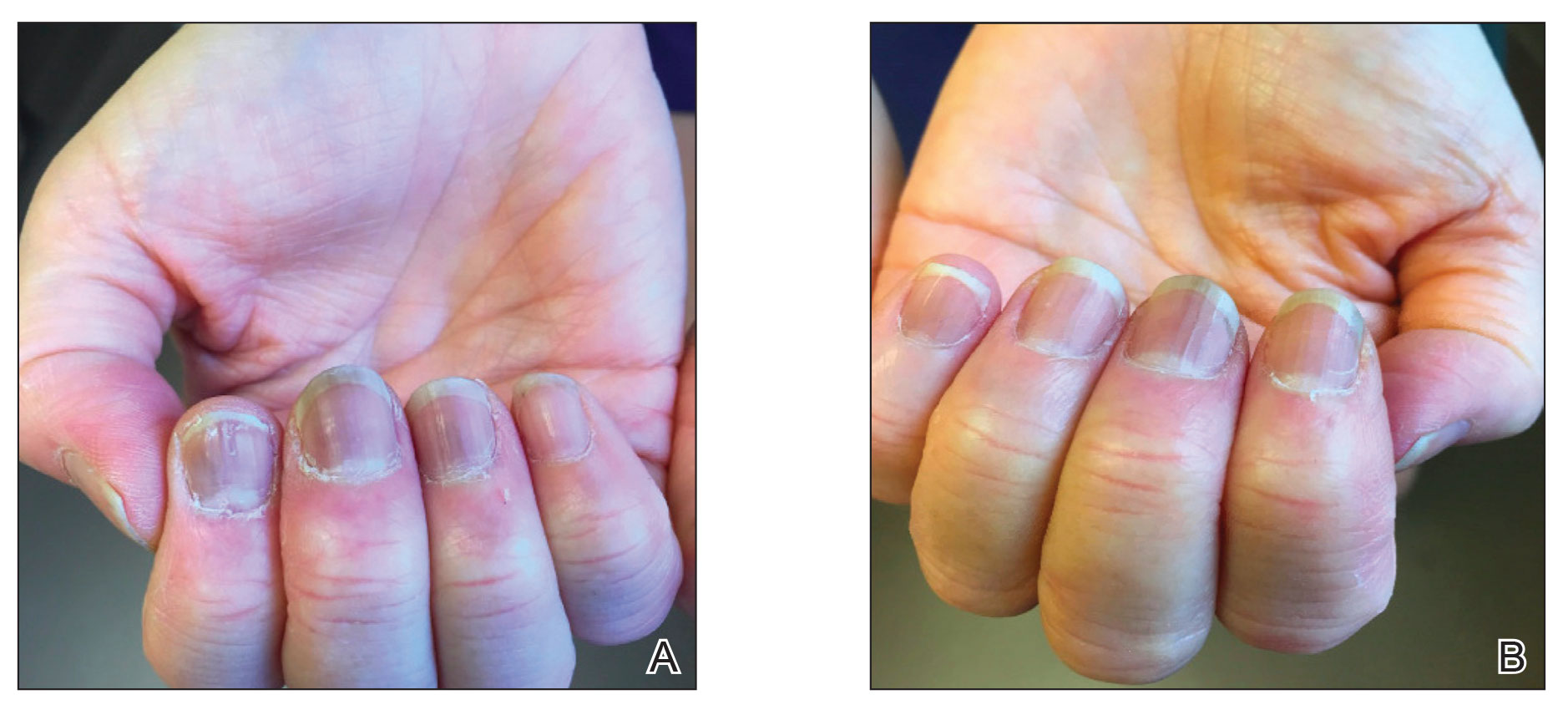

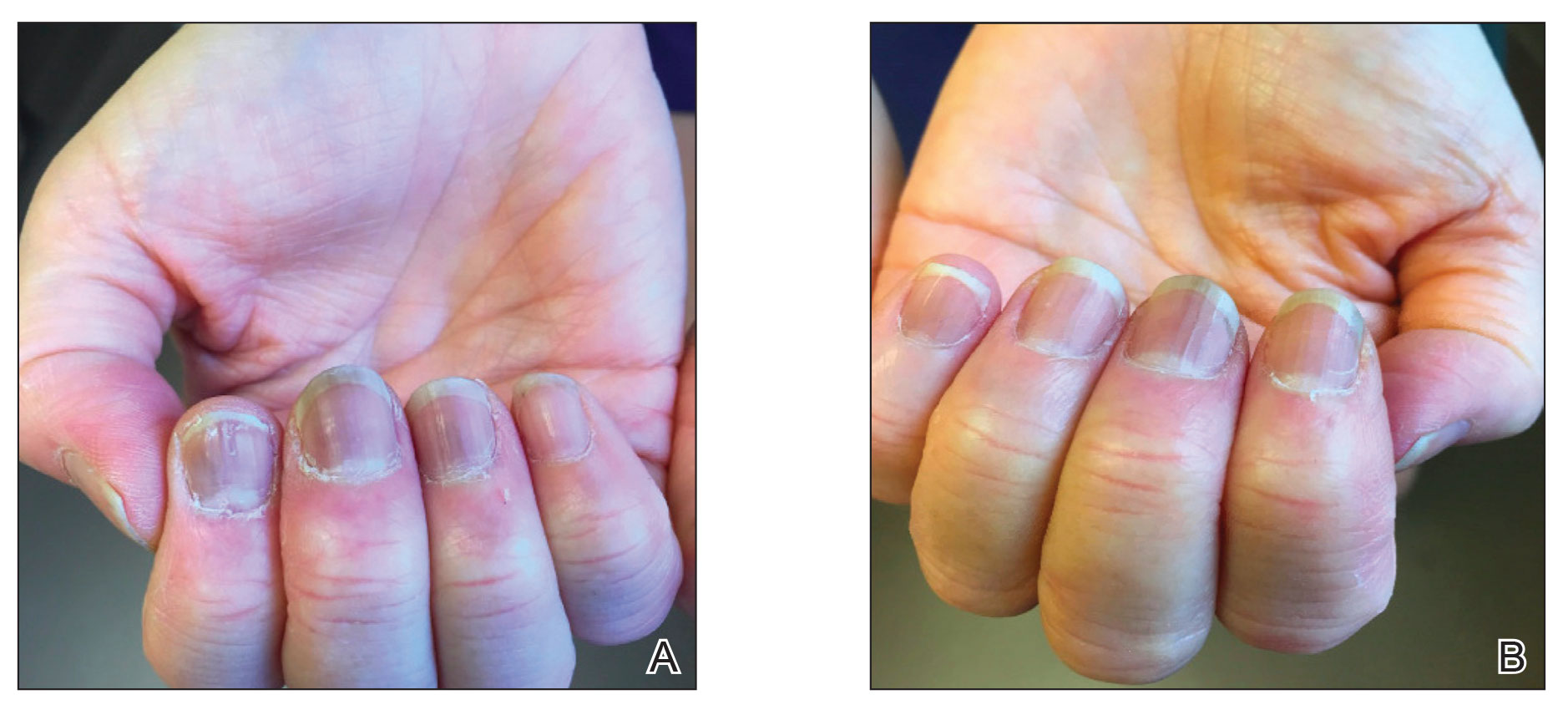

Six weeks following the second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, the patient returned to the dermatology clinic with Beau lines on the second and third fingernails on the right hand (Figure 2A). Subtle erythema of the proximal nail folds and distal fingers was observed in both hands. The patient also exhibited mild onychorrhexis of the left thumbnail and mottled red-brown discoloration of the third finger on the left hand (Figure 2B). Splinter hemorrhages and melanonychia of several fingernails also were observed. Our patient denied any known history of infection with SARS-CoV-2, which was confirmed by a negative COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction test result. She also denied fevers, chills, nausea, and vomiting, she and reported feeling generally well in the context of these postvaccination nail changes.

She reported no trauma or worsening of rheumatoid arthritis before or after COVID-19 vaccination. She was seronegative for rheumatoid arthritis and was being treated with hydroxychloroquine for the last year and methotrexate for the last 2 years. After each dose of the vaccine, methotrexate was withheld for 1 week and then resumed.

Subsequent follow-up examinations revealed the migration and resolution of transverse leukonychia and Beau lines. There also was interval improvement of the splinter hemorrhages. At 17 weeks following the second vaccine dose, all transverse leukonychia and Beau lines had resolved (Figure 3). The patient’s melanonychia remained unchanged.

Laboratory evaluations drawn 1 month following the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, including comprehensive metabolic panel; erythrocyte sedimentation rate; C-reactive protein; and vitamin B12, ferritin, and iron levels were within reference range. The complete blood cell count only showed a mildly decreased white blood cell count (3.55×103/µL [reference range, 4.16–9.95×103/µL]) and mildly elevated mean corpuscular volume (101.9 fL [reference range, 79.3–98.6 fL), both near the patient’s baseline values prior to vaccination.

Documented cutaneous manifestations of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection have included perniolike lesions (known as COVID toes) and vesicular, urticarial, petechial, livedoid, or retiform purpura eruptions. Less frequently, nail findings in patients infected with COVID-19 have been reported, including Beau lines,2 onychomadesis,3 transverse leukonychia,3,7 and the red half‐moon nail sign.3,5 Single or multiple nails may be affected. Although the pathogenesis of nail manifestations related to COVID-19 remains unclear, complement-mediated microvascular injury and thrombosis as well as the procoagulant state, which have been associated with COVID-19, may offer possible explanations.5,6 The presence of microvascular abnormalities was observed in a nail fold video capillaroscopy study of the nails of 82 patients with COVID-19, revealing pericapillary edema, capillary ectasia, sludge flow, meandering capillaries and microvascular derangement, and low capillary density.8

Our patient exhibited transverse leukonychia of the fingernails, which is thought to result from abnormal keratinization of the nail plate due to systemic disorders that induce a temporary dysfunction of nail growth.9 Fernandez-Nieto et al7 reported transverse leukonychia in a patient with COVID-19 that was hypothesized to be due to a transitory nail matrix injury.

Beau lines and onychomadesis, which represent nail matrix arrest, commonly are seen with systemic drug treatments such as chemotherapy and in infectious diseases that precipitate systemic illness, such as hand, foot, and mouth disease. Although histologic examination was not performed in our patient due to cosmetic concerns, we believe that inflammation induced by the vaccine response also can trigger nail abnormalities such as transverse leukonychia and Beau lines. Both SARS-CoV-2 infections and the COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccines can induce systemic inflammation largely due a TH1-dominant response, and they also can trigger other inflammatory conditions. Reports of lichen planus and psoriasis triggered by vaccination—the hepatitis B vaccine,10 influenza vaccine,11 and even COVID-19 vaccines1,12—have been reported. Beau lines have been observed to spontaneously resolve in a self-limiting manner in asymptomatic patients with COVID-19.

Interestingly, our patient only showed 2 nails with Beau lines. We hypothesize that the immune response triggered by vaccination was more subdued than that caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Additionally, our patient was already being treated with immunosuppressants, which may have been associated with a reduced immune response despite being withheld right before vaccination. One may debate whether the nail abnormalities observed in our patient constituted an isolated finding from COVID-19 vaccination or were caused by reactivation of rheumatoid arthritis. We favor the former, as the rheumatoid arthritis remained stable before and after COVID-19 vaccination. Laboratory evaluations and physical examination revealed no evidence of flares, and our patient was otherwise healthy. Although the splinter hemorrhages also improved, it is difficult to comment as to whether they were caused by the vaccine or had existed prior to vaccination. However, we believe the melanonychia observed in the nails was unrelated to the vaccine and was likely a chronic manifestation due to long-term hydroxychloroquine and/or methotrexate use.

Given accelerated global vaccination efforts to control the COVID-19 pandemic, more cases of adverse nail manifestations associated with COVID-19 vaccines are expected. Dermatologists should be aware of and use the reported nail findings to educate patients and reassure them that ungual abnormalities are potential adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccines, but they should not discourage vaccination because they usually are temporary and self-resolving.

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Case of de novo nail psoriasis triggered by the second dose of Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccine. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;17:18-20.

- Deng J, Ngo T, Zhu TH, et al. Telogen effluvium, Beau lines, and acral peeling associated with COVID-19 infection. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;13:138-140.

- Hadeler E, Morrison BW, Tosti A. A review of nail findings associated with COVID-19 infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:E699-E709.

- Demir B, Yuksel EI, Cicek D, et al. Heterogeneous red-white discoloration of the nail bed and distal onycholysis in a patient with COVID-19. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:E551-E553.

- Neri I, Guglielmo A, Virdi A, et al. The red half-moon nail sign: a novel manifestation of coronavirus infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E663-E665.

- Magro C, Mulvey JJ, Berlin D, et al. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res. 2020;220:1-13.

- Fernandez-Nieto D, Jimenez-Cauhe J, Ortega-Quijano D, et al. Transverse leukonychia (Mees’ lines) nail alterations in a COVID-19 patient. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13863.

- Natalello G, De Luca G, Gigante L, et al. Nailfold capillaroscopy findings in patients with coronavirus disease 2019: broadening the spectrum of COVID-19 microvascular involvement [published online September 17, 2020]. Microvasc Res. doi:10.1016/j.mvr.2020.104071

- Piccolo V, Corneli P, Zalaudek I, et al. Mees’ lines because of chemotherapy for Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:E38.

- Miteva L. Bullous lichen planus with nail involvement induced by hepatitis B vaccine in a child. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:142-144.

- Gunes AT, Fetil E, Akarsu S, et al. Possible triggering effect of influenza vaccination on psoriasis [published online August 25, 2015]. J Immunol Res. doi:10.1155/2015/258430

- Hiltun I, Sarriugarte J, Martínez-de-Espronceda I, et al. Lichen planus arising after COVID-19 vaccination. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:e414-e415.

To the Editor:

Nail abnormalities associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection that have been reported in the medical literature include nail psoriasis,1 Beau lines,2 onychomadesis,3 heterogeneous red-white discoloration of the nail bed,4 transverse orange nail lesions,3 and the red half‐moon nail sign.3,5 It has been hypothesized that these nail findings may be an indication of microvascular injury to the distal subungual arcade of the digit or may be indicative of a procoagulant state.5,6 Currently, there is limited knowledge of the effect of COVID-19 vaccines on nail changes. We report a patient who presented with transverse leukonychia (Mees lines) and Beau lines shortly after each dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccine was administered (with a total of 2 doses administered on presentation).

A 64-year-old woman with a history of rheumatoid arthritis presented with peeling of the fingernails and proximal white discoloration of several fingernails of 2 months’ duration. The patient first noticed whitening of the nails 3 weeks after she recevied the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. Five days after receiving the second, she presented to the dermatology clinic and exhibited transverse leukonychia in most fingernails (Figure 1).

Six weeks following the second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, the patient returned to the dermatology clinic with Beau lines on the second and third fingernails on the right hand (Figure 2A). Subtle erythema of the proximal nail folds and distal fingers was observed in both hands. The patient also exhibited mild onychorrhexis of the left thumbnail and mottled red-brown discoloration of the third finger on the left hand (Figure 2B). Splinter hemorrhages and melanonychia of several fingernails also were observed. Our patient denied any known history of infection with SARS-CoV-2, which was confirmed by a negative COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction test result. She also denied fevers, chills, nausea, and vomiting, she and reported feeling generally well in the context of these postvaccination nail changes.

She reported no trauma or worsening of rheumatoid arthritis before or after COVID-19 vaccination. She was seronegative for rheumatoid arthritis and was being treated with hydroxychloroquine for the last year and methotrexate for the last 2 years. After each dose of the vaccine, methotrexate was withheld for 1 week and then resumed.

Subsequent follow-up examinations revealed the migration and resolution of transverse leukonychia and Beau lines. There also was interval improvement of the splinter hemorrhages. At 17 weeks following the second vaccine dose, all transverse leukonychia and Beau lines had resolved (Figure 3). The patient’s melanonychia remained unchanged.

Laboratory evaluations drawn 1 month following the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, including comprehensive metabolic panel; erythrocyte sedimentation rate; C-reactive protein; and vitamin B12, ferritin, and iron levels were within reference range. The complete blood cell count only showed a mildly decreased white blood cell count (3.55×103/µL [reference range, 4.16–9.95×103/µL]) and mildly elevated mean corpuscular volume (101.9 fL [reference range, 79.3–98.6 fL), both near the patient’s baseline values prior to vaccination.

Documented cutaneous manifestations of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection have included perniolike lesions (known as COVID toes) and vesicular, urticarial, petechial, livedoid, or retiform purpura eruptions. Less frequently, nail findings in patients infected with COVID-19 have been reported, including Beau lines,2 onychomadesis,3 transverse leukonychia,3,7 and the red half‐moon nail sign.3,5 Single or multiple nails may be affected. Although the pathogenesis of nail manifestations related to COVID-19 remains unclear, complement-mediated microvascular injury and thrombosis as well as the procoagulant state, which have been associated with COVID-19, may offer possible explanations.5,6 The presence of microvascular abnormalities was observed in a nail fold video capillaroscopy study of the nails of 82 patients with COVID-19, revealing pericapillary edema, capillary ectasia, sludge flow, meandering capillaries and microvascular derangement, and low capillary density.8

Our patient exhibited transverse leukonychia of the fingernails, which is thought to result from abnormal keratinization of the nail plate due to systemic disorders that induce a temporary dysfunction of nail growth.9 Fernandez-Nieto et al7 reported transverse leukonychia in a patient with COVID-19 that was hypothesized to be due to a transitory nail matrix injury.

Beau lines and onychomadesis, which represent nail matrix arrest, commonly are seen with systemic drug treatments such as chemotherapy and in infectious diseases that precipitate systemic illness, such as hand, foot, and mouth disease. Although histologic examination was not performed in our patient due to cosmetic concerns, we believe that inflammation induced by the vaccine response also can trigger nail abnormalities such as transverse leukonychia and Beau lines. Both SARS-CoV-2 infections and the COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccines can induce systemic inflammation largely due a TH1-dominant response, and they also can trigger other inflammatory conditions. Reports of lichen planus and psoriasis triggered by vaccination—the hepatitis B vaccine,10 influenza vaccine,11 and even COVID-19 vaccines1,12—have been reported. Beau lines have been observed to spontaneously resolve in a self-limiting manner in asymptomatic patients with COVID-19.

Interestingly, our patient only showed 2 nails with Beau lines. We hypothesize that the immune response triggered by vaccination was more subdued than that caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Additionally, our patient was already being treated with immunosuppressants, which may have been associated with a reduced immune response despite being withheld right before vaccination. One may debate whether the nail abnormalities observed in our patient constituted an isolated finding from COVID-19 vaccination or were caused by reactivation of rheumatoid arthritis. We favor the former, as the rheumatoid arthritis remained stable before and after COVID-19 vaccination. Laboratory evaluations and physical examination revealed no evidence of flares, and our patient was otherwise healthy. Although the splinter hemorrhages also improved, it is difficult to comment as to whether they were caused by the vaccine or had existed prior to vaccination. However, we believe the melanonychia observed in the nails was unrelated to the vaccine and was likely a chronic manifestation due to long-term hydroxychloroquine and/or methotrexate use.

Given accelerated global vaccination efforts to control the COVID-19 pandemic, more cases of adverse nail manifestations associated with COVID-19 vaccines are expected. Dermatologists should be aware of and use the reported nail findings to educate patients and reassure them that ungual abnormalities are potential adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccines, but they should not discourage vaccination because they usually are temporary and self-resolving.

To the Editor:

Nail abnormalities associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection that have been reported in the medical literature include nail psoriasis,1 Beau lines,2 onychomadesis,3 heterogeneous red-white discoloration of the nail bed,4 transverse orange nail lesions,3 and the red half‐moon nail sign.3,5 It has been hypothesized that these nail findings may be an indication of microvascular injury to the distal subungual arcade of the digit or may be indicative of a procoagulant state.5,6 Currently, there is limited knowledge of the effect of COVID-19 vaccines on nail changes. We report a patient who presented with transverse leukonychia (Mees lines) and Beau lines shortly after each dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccine was administered (with a total of 2 doses administered on presentation).

A 64-year-old woman with a history of rheumatoid arthritis presented with peeling of the fingernails and proximal white discoloration of several fingernails of 2 months’ duration. The patient first noticed whitening of the nails 3 weeks after she recevied the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. Five days after receiving the second, she presented to the dermatology clinic and exhibited transverse leukonychia in most fingernails (Figure 1).

Six weeks following the second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, the patient returned to the dermatology clinic with Beau lines on the second and third fingernails on the right hand (Figure 2A). Subtle erythema of the proximal nail folds and distal fingers was observed in both hands. The patient also exhibited mild onychorrhexis of the left thumbnail and mottled red-brown discoloration of the third finger on the left hand (Figure 2B). Splinter hemorrhages and melanonychia of several fingernails also were observed. Our patient denied any known history of infection with SARS-CoV-2, which was confirmed by a negative COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction test result. She also denied fevers, chills, nausea, and vomiting, she and reported feeling generally well in the context of these postvaccination nail changes.

She reported no trauma or worsening of rheumatoid arthritis before or after COVID-19 vaccination. She was seronegative for rheumatoid arthritis and was being treated with hydroxychloroquine for the last year and methotrexate for the last 2 years. After each dose of the vaccine, methotrexate was withheld for 1 week and then resumed.

Subsequent follow-up examinations revealed the migration and resolution of transverse leukonychia and Beau lines. There also was interval improvement of the splinter hemorrhages. At 17 weeks following the second vaccine dose, all transverse leukonychia and Beau lines had resolved (Figure 3). The patient’s melanonychia remained unchanged.

Laboratory evaluations drawn 1 month following the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, including comprehensive metabolic panel; erythrocyte sedimentation rate; C-reactive protein; and vitamin B12, ferritin, and iron levels were within reference range. The complete blood cell count only showed a mildly decreased white blood cell count (3.55×103/µL [reference range, 4.16–9.95×103/µL]) and mildly elevated mean corpuscular volume (101.9 fL [reference range, 79.3–98.6 fL), both near the patient’s baseline values prior to vaccination.

Documented cutaneous manifestations of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection have included perniolike lesions (known as COVID toes) and vesicular, urticarial, petechial, livedoid, or retiform purpura eruptions. Less frequently, nail findings in patients infected with COVID-19 have been reported, including Beau lines,2 onychomadesis,3 transverse leukonychia,3,7 and the red half‐moon nail sign.3,5 Single or multiple nails may be affected. Although the pathogenesis of nail manifestations related to COVID-19 remains unclear, complement-mediated microvascular injury and thrombosis as well as the procoagulant state, which have been associated with COVID-19, may offer possible explanations.5,6 The presence of microvascular abnormalities was observed in a nail fold video capillaroscopy study of the nails of 82 patients with COVID-19, revealing pericapillary edema, capillary ectasia, sludge flow, meandering capillaries and microvascular derangement, and low capillary density.8

Our patient exhibited transverse leukonychia of the fingernails, which is thought to result from abnormal keratinization of the nail plate due to systemic disorders that induce a temporary dysfunction of nail growth.9 Fernandez-Nieto et al7 reported transverse leukonychia in a patient with COVID-19 that was hypothesized to be due to a transitory nail matrix injury.