User login

Ossification and Migration of a Nodule Following Calcium Hydroxylapatite Injection

To the Editor:

Calcium hydroxylapatite is an injectable filler approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for moderate to severe rhytides of the face and the treatment of facial lipodystrophy in patients with HIV.1 This long-lasting filler generally is well tolerated with minimal side effects; however, there have been reports of nodules or granulomatous formation following injection.2 We present a case of a migrating nodule following injection of a calcium hydroxylapatite filler that appeared ossified on radiographic imaging. We highlight this rarely reported phenomenon to increase awareness of this complication.

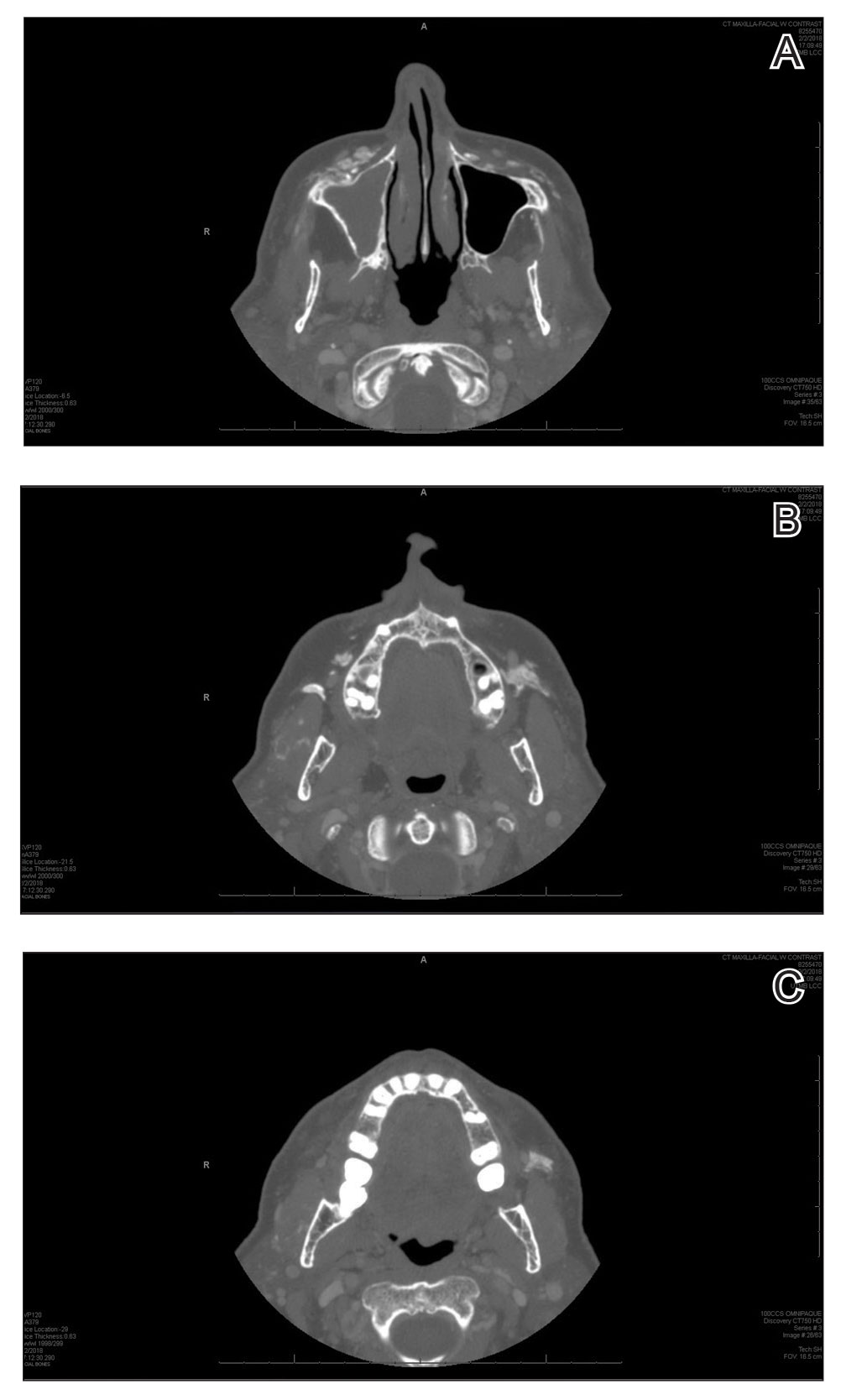

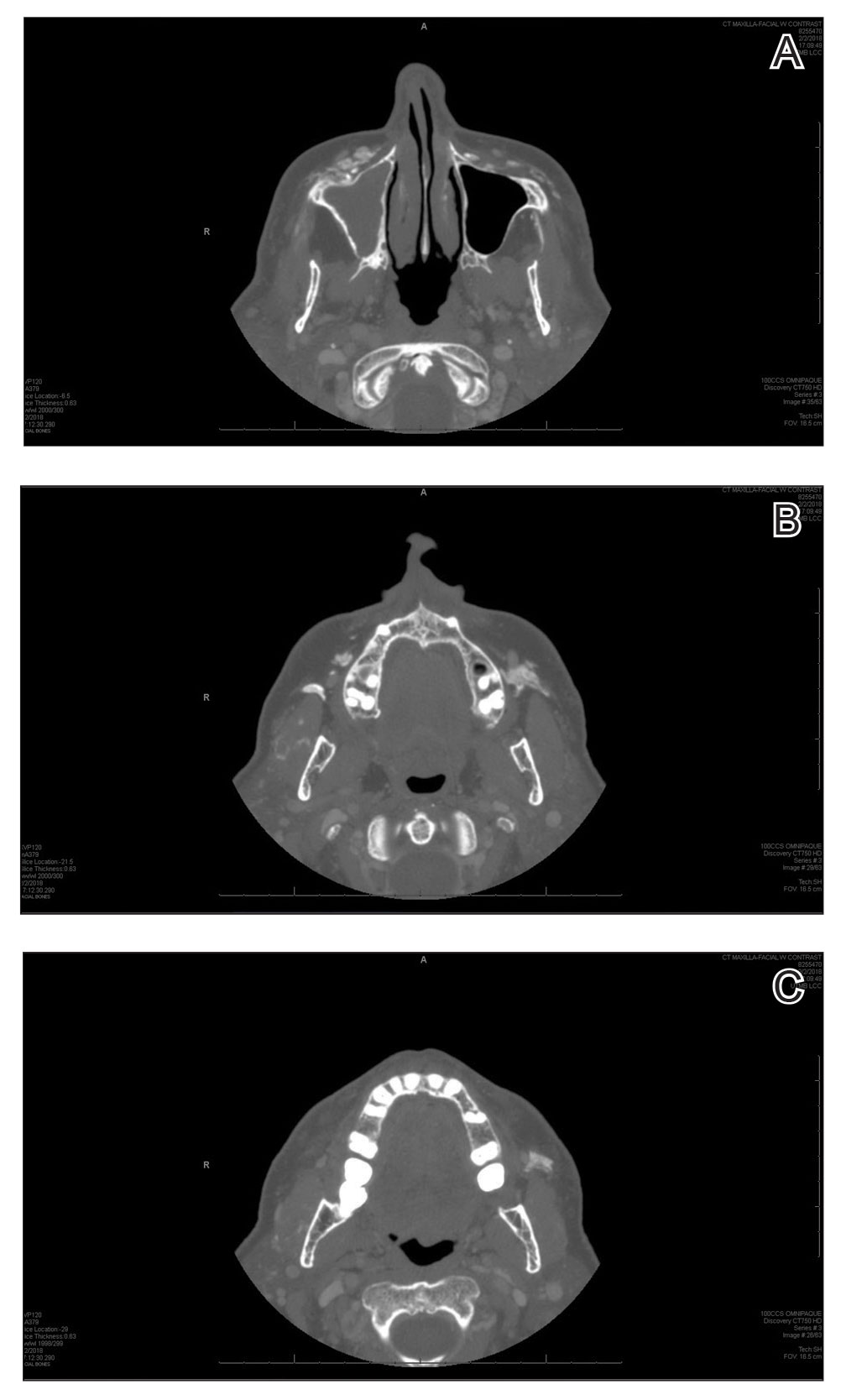

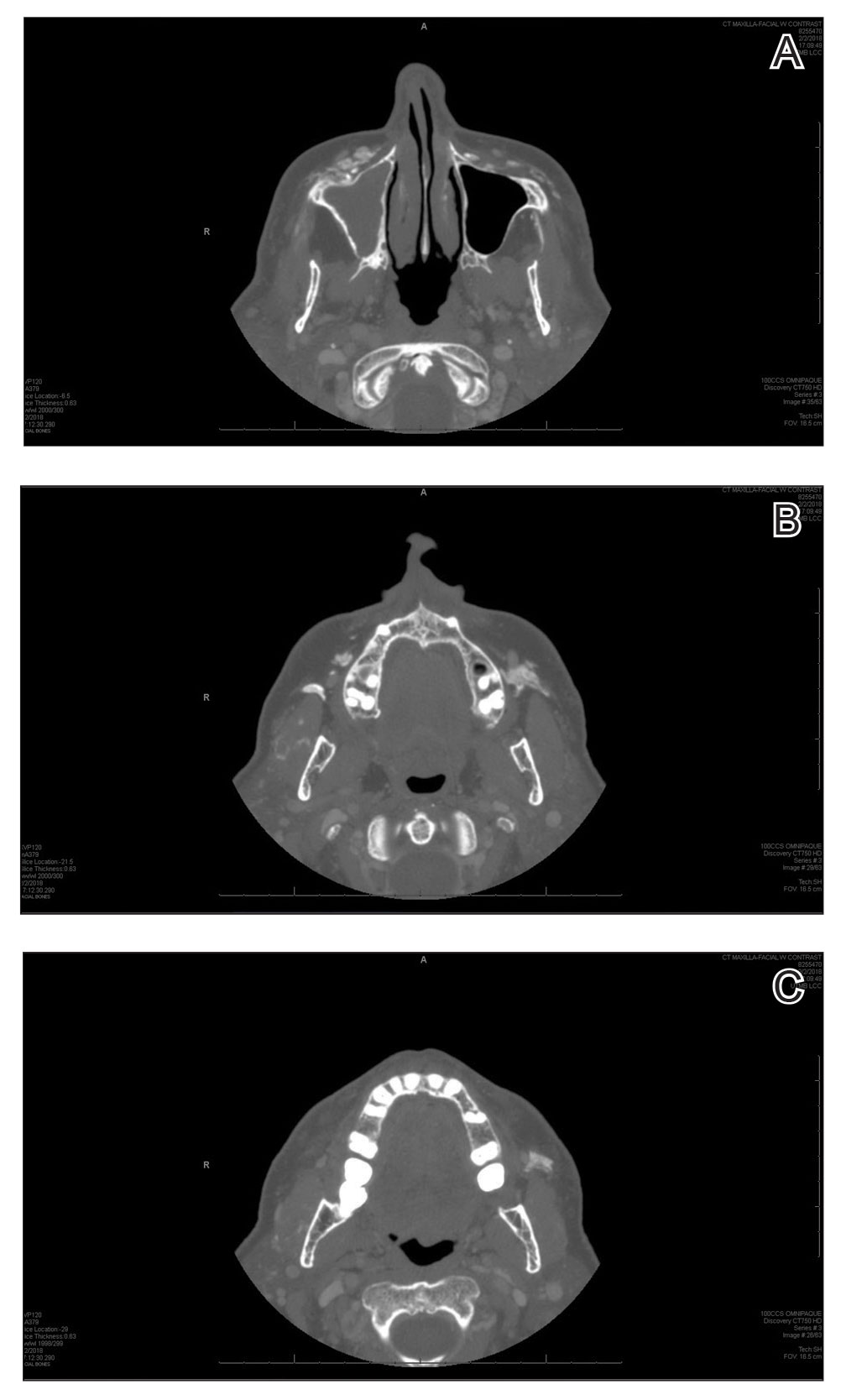

A 72-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a mass on the left cheek. The patient had a history of treatment with facial fillers but no notable medical conditions. She initially received hyaluronic acid injectable gel dermal filler twice—3 years apart—before switching to calcium hydroxylapatite injections twice—4 months apart—from an outside provider. One month after the second treatment, she noticed a mass on the left cheek and promptly returned to the provider who performed the calcium hydroxylapatite injections. The provider, who had originally injected in the infraorbital area, stated it was unlikely that the filler would have migrated to the mid cheek and referred the patient to a general dentist who suspected salivary gland pathology. The patient was referred to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon who suspected the mass was related to the parotid gland. Maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) revealed heterotopic ossification vs myositis ossificans, possibly related to the recent injection. The patient was eventually referred to the Division of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, at the University of Texas Medical Branch (Galveston, Texas) for further evaluation. Physical examination revealed a 2×1-cm firm, mobile, nontender mass in the left cheek in the area of the buccinator muscles. The mass did not express any fluid and was most easily palpable from the oral cavity. Radiography findings showed that the calcium hydroxylapatite filler had migrated to this location and formed a nodule (Figure). Because calcium hydroxylapatite fillers generally last 12 to 18 months, we opted to observe the lesion for spontaneous resolution. Four months later, the patient presented to our clinic for follow-up and the mass had reduced in size and appeared to be spontaneously resolving.

We present a unique case of a migrating nodule that occurred after injection with calcium hydroxylapatite, which led to concern for neoplastic tumor formation. This complication is rare, and it is important for practitioners who inject calcium hydroxylapatite as well as those who these patients may be referred to for evaluation to be aware that migrating nodules can occur. This awareness can help reduce unnecessary referrals, medical procedures, and anxiety.

Calcium hydroxylapatite filler is composed of 30% calcium hydroxylapatite microspheres suspended in a 70% sodium carboxymethylcellulose gel. The water-soluble gel rapidly becomes absorbed upon injection; however, the microspheres form a scaffold for the production of newly synthesized collagen. The filling effect generally lasts 12 to 18 months.1

Calcium hydroxylapatite, similar to most fillers, generally is well tolerated with a low complication rate of 3%.1 Although nodule formation with calcium hydroxylapatite is rare, it is the most common adverse event and encompasses 96% of complications. The remaining 4% of complications include persistent inflammation, swelling, erythema, and technical mistakes leading to overcorrection.1 Migrating nodules are rare; however, Beer3 reported a similar case.

Treatment of calcium hydroxylapatite nodules depends on differentiating a cause based on the time of onset. Early nodules that occur within 1 to 2 weeks of the injection usually represent incorrect positioning of the filler and can be treated by massaging the nodule. Other more invasive techniques involve aspiration or injection of sterile water. Late-onset nodules have shown response to corticosteroid injections. For inflammatory nodules of infectious origin, antibiotics can be useful. Surgical excision of the nodule rarely is required, as most nodules will resolve spontaneously, even without intervention.1,2

Radiologic findings of calcium hydroxylapatite appear as high-attenuation linear streaks or masses on CT (280–700 HU) and as low to intermediate signal intensity on T1- or T2-weighted sequences on magnetic resonance imaging. Oftentimes, calcium hydroxylapatite has a similar radiographic appearance to bone and can persist for 2 years or more on radiographic imaging, longer than they are clinically visible.4 The nodule formation from injection with calcium hydroxylapatite can mimic pathologic conditions such as miliary osteomas, myositis ossificans, heterotrophic/dystrophic calcifications, and foreign bodies on CT. Our patient’s CT findings of high attenuation linear streaks and nodules of similar signal intensity to bone were consistent with those previously described in the radiographic literature.

Calcium hydroxylapatite fillers have a good safety profile, but it is important to recognize that nodule formation is a common adverse event and that migration of nodules can occur. Practitioners should recognize this possibility in patients presenting with new masses after filler injection before advocating for potentially invasive and costly procedures and diagnostic modalities.

- Kadouch JA. Calcium hydroxylapatite: a review on safety and complications. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:152-161.

- Moulinets I, Arnaud E, Bui P, et al. Foreign body reaction to Radiesse: 2 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:e37-40.

- Beer KR. Radiesse nodule of the lips from a distant injection site: report of a case and consideration of etiology and management. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:846-847.

- Ginat DT, Schatz CJ. Imaging features of midface injectable fillers and associated complications. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:1488-1495.

To the Editor:

Calcium hydroxylapatite is an injectable filler approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for moderate to severe rhytides of the face and the treatment of facial lipodystrophy in patients with HIV.1 This long-lasting filler generally is well tolerated with minimal side effects; however, there have been reports of nodules or granulomatous formation following injection.2 We present a case of a migrating nodule following injection of a calcium hydroxylapatite filler that appeared ossified on radiographic imaging. We highlight this rarely reported phenomenon to increase awareness of this complication.

A 72-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a mass on the left cheek. The patient had a history of treatment with facial fillers but no notable medical conditions. She initially received hyaluronic acid injectable gel dermal filler twice—3 years apart—before switching to calcium hydroxylapatite injections twice—4 months apart—from an outside provider. One month after the second treatment, she noticed a mass on the left cheek and promptly returned to the provider who performed the calcium hydroxylapatite injections. The provider, who had originally injected in the infraorbital area, stated it was unlikely that the filler would have migrated to the mid cheek and referred the patient to a general dentist who suspected salivary gland pathology. The patient was referred to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon who suspected the mass was related to the parotid gland. Maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) revealed heterotopic ossification vs myositis ossificans, possibly related to the recent injection. The patient was eventually referred to the Division of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, at the University of Texas Medical Branch (Galveston, Texas) for further evaluation. Physical examination revealed a 2×1-cm firm, mobile, nontender mass in the left cheek in the area of the buccinator muscles. The mass did not express any fluid and was most easily palpable from the oral cavity. Radiography findings showed that the calcium hydroxylapatite filler had migrated to this location and formed a nodule (Figure). Because calcium hydroxylapatite fillers generally last 12 to 18 months, we opted to observe the lesion for spontaneous resolution. Four months later, the patient presented to our clinic for follow-up and the mass had reduced in size and appeared to be spontaneously resolving.

We present a unique case of a migrating nodule that occurred after injection with calcium hydroxylapatite, which led to concern for neoplastic tumor formation. This complication is rare, and it is important for practitioners who inject calcium hydroxylapatite as well as those who these patients may be referred to for evaluation to be aware that migrating nodules can occur. This awareness can help reduce unnecessary referrals, medical procedures, and anxiety.

Calcium hydroxylapatite filler is composed of 30% calcium hydroxylapatite microspheres suspended in a 70% sodium carboxymethylcellulose gel. The water-soluble gel rapidly becomes absorbed upon injection; however, the microspheres form a scaffold for the production of newly synthesized collagen. The filling effect generally lasts 12 to 18 months.1

Calcium hydroxylapatite, similar to most fillers, generally is well tolerated with a low complication rate of 3%.1 Although nodule formation with calcium hydroxylapatite is rare, it is the most common adverse event and encompasses 96% of complications. The remaining 4% of complications include persistent inflammation, swelling, erythema, and technical mistakes leading to overcorrection.1 Migrating nodules are rare; however, Beer3 reported a similar case.

Treatment of calcium hydroxylapatite nodules depends on differentiating a cause based on the time of onset. Early nodules that occur within 1 to 2 weeks of the injection usually represent incorrect positioning of the filler and can be treated by massaging the nodule. Other more invasive techniques involve aspiration or injection of sterile water. Late-onset nodules have shown response to corticosteroid injections. For inflammatory nodules of infectious origin, antibiotics can be useful. Surgical excision of the nodule rarely is required, as most nodules will resolve spontaneously, even without intervention.1,2

Radiologic findings of calcium hydroxylapatite appear as high-attenuation linear streaks or masses on CT (280–700 HU) and as low to intermediate signal intensity on T1- or T2-weighted sequences on magnetic resonance imaging. Oftentimes, calcium hydroxylapatite has a similar radiographic appearance to bone and can persist for 2 years or more on radiographic imaging, longer than they are clinically visible.4 The nodule formation from injection with calcium hydroxylapatite can mimic pathologic conditions such as miliary osteomas, myositis ossificans, heterotrophic/dystrophic calcifications, and foreign bodies on CT. Our patient’s CT findings of high attenuation linear streaks and nodules of similar signal intensity to bone were consistent with those previously described in the radiographic literature.

Calcium hydroxylapatite fillers have a good safety profile, but it is important to recognize that nodule formation is a common adverse event and that migration of nodules can occur. Practitioners should recognize this possibility in patients presenting with new masses after filler injection before advocating for potentially invasive and costly procedures and diagnostic modalities.

To the Editor:

Calcium hydroxylapatite is an injectable filler approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for moderate to severe rhytides of the face and the treatment of facial lipodystrophy in patients with HIV.1 This long-lasting filler generally is well tolerated with minimal side effects; however, there have been reports of nodules or granulomatous formation following injection.2 We present a case of a migrating nodule following injection of a calcium hydroxylapatite filler that appeared ossified on radiographic imaging. We highlight this rarely reported phenomenon to increase awareness of this complication.

A 72-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a mass on the left cheek. The patient had a history of treatment with facial fillers but no notable medical conditions. She initially received hyaluronic acid injectable gel dermal filler twice—3 years apart—before switching to calcium hydroxylapatite injections twice—4 months apart—from an outside provider. One month after the second treatment, she noticed a mass on the left cheek and promptly returned to the provider who performed the calcium hydroxylapatite injections. The provider, who had originally injected in the infraorbital area, stated it was unlikely that the filler would have migrated to the mid cheek and referred the patient to a general dentist who suspected salivary gland pathology. The patient was referred to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon who suspected the mass was related to the parotid gland. Maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) revealed heterotopic ossification vs myositis ossificans, possibly related to the recent injection. The patient was eventually referred to the Division of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, at the University of Texas Medical Branch (Galveston, Texas) for further evaluation. Physical examination revealed a 2×1-cm firm, mobile, nontender mass in the left cheek in the area of the buccinator muscles. The mass did not express any fluid and was most easily palpable from the oral cavity. Radiography findings showed that the calcium hydroxylapatite filler had migrated to this location and formed a nodule (Figure). Because calcium hydroxylapatite fillers generally last 12 to 18 months, we opted to observe the lesion for spontaneous resolution. Four months later, the patient presented to our clinic for follow-up and the mass had reduced in size and appeared to be spontaneously resolving.

We present a unique case of a migrating nodule that occurred after injection with calcium hydroxylapatite, which led to concern for neoplastic tumor formation. This complication is rare, and it is important for practitioners who inject calcium hydroxylapatite as well as those who these patients may be referred to for evaluation to be aware that migrating nodules can occur. This awareness can help reduce unnecessary referrals, medical procedures, and anxiety.

Calcium hydroxylapatite filler is composed of 30% calcium hydroxylapatite microspheres suspended in a 70% sodium carboxymethylcellulose gel. The water-soluble gel rapidly becomes absorbed upon injection; however, the microspheres form a scaffold for the production of newly synthesized collagen. The filling effect generally lasts 12 to 18 months.1

Calcium hydroxylapatite, similar to most fillers, generally is well tolerated with a low complication rate of 3%.1 Although nodule formation with calcium hydroxylapatite is rare, it is the most common adverse event and encompasses 96% of complications. The remaining 4% of complications include persistent inflammation, swelling, erythema, and technical mistakes leading to overcorrection.1 Migrating nodules are rare; however, Beer3 reported a similar case.

Treatment of calcium hydroxylapatite nodules depends on differentiating a cause based on the time of onset. Early nodules that occur within 1 to 2 weeks of the injection usually represent incorrect positioning of the filler and can be treated by massaging the nodule. Other more invasive techniques involve aspiration or injection of sterile water. Late-onset nodules have shown response to corticosteroid injections. For inflammatory nodules of infectious origin, antibiotics can be useful. Surgical excision of the nodule rarely is required, as most nodules will resolve spontaneously, even without intervention.1,2

Radiologic findings of calcium hydroxylapatite appear as high-attenuation linear streaks or masses on CT (280–700 HU) and as low to intermediate signal intensity on T1- or T2-weighted sequences on magnetic resonance imaging. Oftentimes, calcium hydroxylapatite has a similar radiographic appearance to bone and can persist for 2 years or more on radiographic imaging, longer than they are clinically visible.4 The nodule formation from injection with calcium hydroxylapatite can mimic pathologic conditions such as miliary osteomas, myositis ossificans, heterotrophic/dystrophic calcifications, and foreign bodies on CT. Our patient’s CT findings of high attenuation linear streaks and nodules of similar signal intensity to bone were consistent with those previously described in the radiographic literature.

Calcium hydroxylapatite fillers have a good safety profile, but it is important to recognize that nodule formation is a common adverse event and that migration of nodules can occur. Practitioners should recognize this possibility in patients presenting with new masses after filler injection before advocating for potentially invasive and costly procedures and diagnostic modalities.

- Kadouch JA. Calcium hydroxylapatite: a review on safety and complications. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:152-161.

- Moulinets I, Arnaud E, Bui P, et al. Foreign body reaction to Radiesse: 2 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:e37-40.

- Beer KR. Radiesse nodule of the lips from a distant injection site: report of a case and consideration of etiology and management. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:846-847.

- Ginat DT, Schatz CJ. Imaging features of midface injectable fillers and associated complications. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:1488-1495.

- Kadouch JA. Calcium hydroxylapatite: a review on safety and complications. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:152-161.

- Moulinets I, Arnaud E, Bui P, et al. Foreign body reaction to Radiesse: 2 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:e37-40.

- Beer KR. Radiesse nodule of the lips from a distant injection site: report of a case and consideration of etiology and management. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:846-847.

- Ginat DT, Schatz CJ. Imaging features of midface injectable fillers and associated complications. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:1488-1495.

Practice Points

- Calcium hydroxylapatite filler can migrate and form nodules in distant locations from the original injection site.

- Practitioners of calcium hydroxylapatite fillers should be aware of the potential for nodule migration to avoid costly, time-consuming, and invasive referrals and procedures.

Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Program in a VA Emergency Department

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a public health crisis significantly affecting veterans. A substantial increase in veterans diagnosed with OUD has occurred, nearly tripling from 25,031 in 2003 to 69,142 in 2017

For patients with active OUD, medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) reduce the risk of overdose and all-cause mortality.3 In 2009, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Department of Defense (DoD) published clinical practice guidelines for substance use disorders that strongly recommended MOUD with either buprenorphine or methadone as a first-line treatment. In 2015 updated guidelines encouraged buprenorphine initiation in primary care settings.4,5 This was followed by an academic detailing campaign designed to encourage VA clinicians to initiate MOUD.1 Despite this institutional support, MOUD remains underutilized within the VA, with widely variable rates of prescribing among VA sites.1

Efforts to further expand MOUD cultivated interest in administering buprenorphine in VA emergency departments (EDs). Patients with OUD often use the ED for same-day care, providing opportunities to initiate buprenorphine in the ED 24 hours, 7 days per week. This has been especially true during the COVID-19 pandemic during which reliable access to usual recovery services has been disrupted and EDs have served as a safety net.6

Buprenorphine’s safety profile and prolonged effect duration make it superior to other MOUD options for ED administration. As a partial opioid agonist, buprenorphine is unlikely to cause significant sedation or respiratory depression compared with full agonists like methadone. This is known as the ceiling effect. Additionally, at higher doses, buprenorphine’s effects can last for about 3 days, potentially obviating the need for repeat dosing. D’Onofrio and colleagues seminal 2015 paper conceptually proved the feasibility and value of initiating buprenorphine in the ED; patients who received ED initiation therapy were more likely to be engaged in addiction treatment 30 days after their visit and have reduced rates of illicit opioid drug use.7 Such ED harm-reduction strategies are increasingly recognized as essential, given that 1 in 20 patients treated for a nonfatal opioid overdose in an ED will die within 1 year of their visit, many within 2 days.8 Finally, a significant barrier faced by physicians wanting to administer or prescribe buprenorphine for patients with OUD has been the special licensing required by the Drug Enforcement Administration Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000, also known as an X-waiver. A notable exception to this X-waiver requirement is the 72-hour rule, which allows nonwaivered practitioners to administer (but not prescribe for home use) buprenorphine to a patient to relieve acute withdrawal symptoms for up to 72 hours while arranging for specialist referral.Under the 72-hour rule, ED clinicians have a unique opportunity to treat patients experiencing acute withdrawal symptoms and bridge them to specialty care, without the burden of an X-waiver requirement.

The VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS), therefore, developed and implemented a program to administer buprenorphine in the ED to bridge patients with OUD to an appointment with substance use disorder (SUD) services. We describe our development, implementation and evaluation of this program protocol as a model for other VA EDs. This project was determined to be quality improvement (nonresearch) by the VAGLAHS Institutional Review Board.

ED MOUD Program

We engaged in a 2-month (January-March 2019) preimplementation process during which we (1) obtained stakeholder buy-in; (2) developed a protocol and supporting resources and tools; (3) worked with stakeholders to enact local organizational policy and process modifications; and (4) educated practitioners.

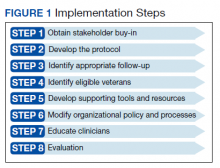

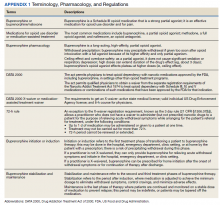

Appendix 1 provides an overview of MOUD terminology, pharmacology, and regulations. We developed an 8-step program implementation plan for the ED MOUD program (Figure 1).

Obtaining Stakeholder Buy-in

Two ED physician champions (MC, JH) organized all activities. Champions obtained stakeholder buy-in from clinical and administrative leaders as well as from frontline personnel in OUD specialty care, ED, and pharmacy services. ED social workers and clerks who schedule post-ED appointments also were engaged. These stakeholders emphasized the importance of fitting the developed protocol into the existing ED workflows as well as minimizing additional resources required to initiate and maintain the program.

We ascertained that in fiscal year 2018, VAGLAHS had 156 ED visits with International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes related to OUD for 108 unique patients. Based on these data and in consultation with OUD specialty care, we determined that the potential number of referrals to the SUD clinic would be manageable with existing resources. Additionally, there was consensus that most opioid withdrawal patients could be treated in the urgent care portion of our ED since these patients generally do not require special monitoring. This consideration was important for obtaining ED stakeholder buy-in and for planning protocol logistics.

Developing the Protocol

We customized resources created by CalBridge Behavioral Health Navigator Program (CA Bridge), formerly called ED Bridge, a program of the Public Health Institute in Oakland, California, funded through California Department of Health Care Services. CA Bridge offers technical assistance and support for hospitals as well as guidance and tools for establishing processes for EDs providing buprenorphine prescriptions for the management of acute opioid withdrawal and serving as a bridge to follow-up care in SUD clinics.9 We also reviewed protocols described by D’Onofrio and colleagues. With iterative input from stakeholders, we created a protocol concretely delineating each process and corresponding responsible party with the overall aim of removing potential barriers to MOUD initiation and follow-up (Appendix 2).

Identifying Appropriate Follow-up

To operationalize protocol implementation, we built on VA’s Emergency Department Rapid Access Clinic (ED-RAC) process, a mechanism for scheduling appointments for post-ED specialty follow-up care. This process facilitated veterans’ access to urgent specialty care follow-up after ED visits by scheduling appointments prior to ED discharge.10 For the ED MOUD program, we adapted the ED-RAC process to schedule appointments in SUD clinic prior to ED discharge. These appointments allowed patients to be seen by an SUD clinician within 72 hours of ED discharge. This step was critical to working within the 72-hour rule without relying on X-waiver licensing of ED clinicians. Alternatively, as was previous practice, per patient preference, patients were also referred to non-VA residential rehabilitation services if the facility had capacity and patients met criteria for admission.

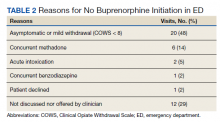

Identification of Eligible Veterans

Target patients were those primarily presenting with a request for treatment of opioid dependence or withdrawal. Patients were not actively screened for OUD. Clinicians diagnosed and assessed for OUD as per their usual practice. Patients with OUD who presented to the ED for other reasons were assessed, at clinician discretion, for their interest in receiving MOUD. If patients presented in moderate-to-severe withdrawal (eg, Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale [COWS] ≥ 8), buprenorphine was initiated in the ED. These patients were subsequently referred to either the local SUD clinic or to a residential treatment center. Patients presenting with a COWS score < 8 were referred to the outpatient SUD clinic or residential treatment centers without initiating buprenorphine from the ED. The SUD clinic or residential treatment centers could offer buprenorphine or other MOUD options. From the ED, prescribing buprenorphine for patients to self-initiate at home was not available as this required an X-waivered prescriber, which were limited during the program time frame.

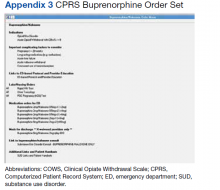

Support Tools and Resources

To facilitate ED clinicians using the protocol, we worked with a programmer experienced with the Computerized Patient Record System, the VA electronic health record (EHR), to create electronic order menu sets that directed clinicians to the protocol and educational materials (Appendix 3). These menus are readily accessible and embedded into the ED clinician workflow. The menus highlight key elements of the protocol, including indications for initiation, contraindications, recommended dosing with quick orders, and how to obtain follow-up for the patient. Links also are provided to the protocol and patient discharge handouts, including the CA Bridge website.

Organizational Policy and Processes

Before implementing the developed protocol, we worked with stakeholders to modify organizational policies and processes. Our pharmacy agreed to stock buprenorphine in the ED to make it readily available. EHR restrictions that historically prohibited ordering buprenorphine for ED administration by nonwaivered clinicians were modified. Additionally, our chief of staff, pharmacy, and credentialing department agreed that physicians did not need to apply for additional delineated privileges.

Clinician Education

The final preparation step was educating clinicians and other protocol users. The VAGLAHS SUD chief presented a lecture and answered questions about MOUD to core ED faculty about the rising prevalence of OUD and use of buprenorphine as a recommended treatment.

Evaluation

To assess adherence to the developed protocol, we conducted a retrospective health record review of all ED visits March 1 to October 25, 2019, in which the patient had OUD and may have qualified for MOUD. To do this, we identified (1) ED visits with an OUD ICD-10 code as a primary or secondary diagnoses; (2) ED referrals to outpatient SUD treatment; and/or (3) ED visits in which buprenorphine was given or prescribed. We included the latter 2 criteria as application of ICD-10 codes for OUD care was inconsistent. Visits were excluded if patients did not have OUD, had OUD in remission, were already maintained on a stable MOUD regimen and no longer using illicit drugs or craving additional opioids, or were presenting solely for a refill or administration of a missed dose. Patients who relapsed were categorized as unstable. Visits were excluded if the patient was admitted to the hospital or left against medical advice. Patients on MOUD who had relapsed or requested a change in MOUD treatment were included. For all included visits, 2 ED physicians (MC, JH) reviewed the ED clinician and nursing notes, pharmacy and referral records, diagnostic codes, and veteran demographics.

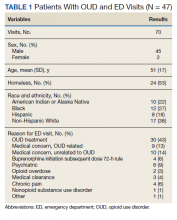

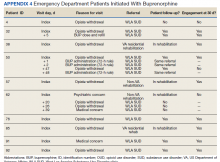

In the evaluation, there were 130 visits with 92 unique veterans meeting inclusion criteria. The final sample included 70 visits with 47 unique veterans (Table 1). Of note, 24 (53%) patients self-identified as homeless or were engaged with VA housing services. Twelve veterans had multiple ED visits (7 patients with 2 visits; 5 patients with ≥ 3 visits). In 30 (43%) visits the veteran’s primary reason for seeking ED care was to obtain treatment for opioid withdrawal or receive MOUD. Type of opiate used was specified in 58% of visits; of these, 69% indicated heroin use and 17% prescription medications. Buprenorphine was initiated in the ED in 18 (26%) visits for 10 veterans. Appendix 4 outlines the clinical course and follow-up after these visits. Some veterans returned to the ED for buprenorphine redosing per the 72-hour rule. SUD clinic appointments were provided in 11 visits, and direct transfer to an inpatient rehabilitation center was arranged in 4 visits. In 42 (60%) visits, across 32 unique veterans, buprenorphine was not given in the ED, but patients were referred for SUD treat

A majority of veterans who received buprenorphine and a referral for an SUD appointment went to their initial SUD follow-up appointment and had ongoing engagement in addiction care 30 days after their index ED visit. Among veterans who did not receive buprenorphine but were referred for SUD treatment, about half went to their SUD appointments and about 1 in 5 had ongoing engagement in addiction care at 30 days after the index ED visit. Of note, 2 patients who received referrals died within 1 year of their index ED visit. The cause of death for one patient was an overdose; the other was unspecified.

DISCUSSION

We developed the ED MOUD program as a bridge to SUD specialty care. Our 8 implementation steps can serve as a model for implementing programs at other VA EDs. We demonstrated feasibility, high follow-up rates, and high retention in treatment.

Patients who received ED buprenorphine initiation were more likely to follow up and had higher rates of ongoing engagement at 30 days than did those who received only a clinic referral. In a similar Canadian study, buprenorphine was initiated in the ED, and patients followed up as a walk-in for addiction services; however, only 54% of patients presented to this initial follow-up.11 Our higher initial follow-up rate may be due to our ability to directly schedule clinic appointments. Our 70% 30-day follow-up rate is comparable, but slightly lower than the 2015 D’Onofrio and colleagues study in which 78% of patients remained engaged at 30 days.7 A possible reason is that in the D’Onofrio and colleagues study, all study physicians obtained X-waiver training and were able to prescribe buprenorphine after ED initiation or for self-initiation at home. X-waiver training was not required of our clinicians, and none of our patients were offered a prescription for self-initiation.

Our program demonstrates that it is feasible to develop a protocol without X-waiver licensing. This program provides a supportive framework for the use of MOUD and allows nonspecialists to gain experience and confidence in using buprenorphine. Any clinician could administer buprenorphine in the ED, and patients could be bridged at later ED visits until follow-up with a specialist. Of note, only a small percentage of the total visits for buprenorphine initiation required multiple daily visits for buprenorphine. Appointments with the specialist were assured to fall within a 72-hour window.

Our program has some limitations. First, the number of patients who were candidates for our ED MOUD program was small. In our 7-month review, only 47 patients were identified as potential candidates for MOUD treatment across 70 visits, and only 10 were initiated in the ED. Second, all patients were not actively screened for OUD. There was potential for missing eligible veterans as inclusion criteria relied on clinicians both recognizing OUD and manually entering a correct diagnostic code. We attempted to mitigate this by also reviewing all ED referrals to the SUD clinic and all patients who received buprenorphine in the ED. In addition, we do not have data on preimplementation rates of follow-up for comparison.

Future Directions

More than half of our patients did not receive ED buprenorphine initiation because they were not in moderate or severe withdrawal (COWS ≥ 8) similar to 57% of patients cited in the D’Onofrio and colleagues study.7 Teaching veterans how to start buprenorphine at home could greatly expand enrollment. However, this requires a prescription from an X-waiver licensed clinician. In 2021, the US Department of Health and Human Services removed the 8-hour training requirement for obtaining an X-waiver.12 However, clinicians are still required to apply for licensing. Eliminating the X-waiver requirement, as proposed by D’Onofrio and colleagues in a 2021 editorial, would have allowed all clinicians to offer home initiation.13

Previous studies suggest that despite the ability to provide a prescription, clinicians may be reluctant to offer home initiation.14–17 In a national VA 2019 survey, many emergency medicine physicians believe that SUD care is not in their scope of practice, as Dieujuste and colleagues described in Federal Practitioner.14 Although it is likely some attitudes have changed with the increased visibility of ED MOUD programs, there is still much work to be done to change perceptions.

Another area for improvement is screening for OUD in the ED to better reveal MOUD candidates. Missed opportunities (neither referral nor treatment offered) occurred in 21% of our visits. D’Onofrio and colleagues identified 66% of patients by screening all ED patients.7 Although universal screening for SUD in routine health care settings has been recommended, 2021 VA guidelines state that there is insufficient evidence to recommend universal screening.18-20 There are also limited data on the best screening tool for OUD in the ED.21 Further research on how to effectively and efficiently identify OUD patients in the ED is needed.

Conclusions

With minimal resource allocation, we started the program to offer MOUD with buprenorphine for patients with OUD at a VA ED and provided addiction treatment follow-up. This program, the first of its kind within VA, can be modeled and expanded to other VA facilities. Given increasing numbers of fatal opioid overdose, and significant adverse impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the OUD crisis, developing local and national strategies to treat OUD is essential. Future steps include improved screening and expanding capacity to offer home initiation by increasing the number of X-waiver ED clinicians.6

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Jeffrey Balsam, PharmD, BCPS, Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Clinical Applications Coordinator for his contributions in creating a Computerized Patient Record System opioid use disorder screening tool. Thank you to Gracielle Tan, MD, Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Health Science Specialist for her administrative assistance in manuscript preparation.

1. Wyse JJ, Gordon AJ, Dobscha SK, et al. Medications for opioid use disorder in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system: historical perspective, lessons learned, and next steps. Subst Abuse. 2018;39(2):139-144. doi:10.1080/08897077.2018.1452327

2. Bohnert ASB, Ilgen MA, Galea S, McCarthy JF, Blow FC. Accidental poisoning mortality among patients in the Department of Veterans Affairs health system. Med Care. 2011;49(4):393-396. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e318202aa27

3. Ma J, Bao Y-P, Wang R-J, et al. Effects of medication-assisted treatment on mortality among opioids users: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(12):1968-1983. doi:10.1038/s41380-018-0094-5

4. The Management of Substance Use Disorders Work Group. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Substance Use Disorders. Version 2.0. US Department of Veterans Affairs; 2009.

5. The Management of Substance Use Disorders Work Group. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Substance Use Disorders. Version 3.0. US Department of Veterans Affairs. 2015. Accessed July 1, 2022. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/sud/VADoDSUDCPGRevised22216.pdf

6. Hulsey J, Mellis A, Kelly B. COVID-19 pandemic impact on patients, families and individuals in recovery from substance use disorder. Accessed July 7, 2021. https://www.addictionpolicy.org/covid19-report

7. D’Onofrio G, O’Connor PG, Pantalon MV, et al. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opiod dependence. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1636-1644. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.3474

8. Weiner SG, Baker O, Bernson D, Schuur JD. One-year mortality of patients after emergency department treatment for non-fatal opioid overdose. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;75(1):13-17. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.04.020

9. CA Bridge. Updated 2021. Accessed July 1, 2022. https://cabridge.org

10. Penney L, Miake-Lye I, Lewis D, et al. Proceedings from the 11th annual conference on the science of dissemination and implementation: S72 spreading VA’s emergency department-rapid access clinics (ED-RAC) intervention: key factors for success. Implementation Sci. 2019;14(suppl 1). doi:10.1186/s13012-019-0878-2

11. Hu T, Snider-Alder M, Nijmeh L, Pyle A. Buprenorphine/naloxone induction in a Canadian emergency department with rapid access to community-based addictions providers. CJEM. 2019;21(4):492-498. doi:10.1017/cem.2019.24

12. US Department of Health and Human Services. Practice Guidelines for the Administration of Buprenorphine for Treating Opioid Use Disorder. Federal Register. Accessed July 1, 2022. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/04/28/2021-08961/practice-guidelines-for-the-administration-of-buprenorphine-for-treating-opioid-use-disorder

13. D’Onofrio G, Melnick ER, Hawk KF. Improve access to care for opioid use disorder: a call to eliminate the x-waiver requirement now. Ann Emerg Med. 2021;78(2):220-222. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2021.03.023

14. Dieujuste N, Johnson-Koenke R, Celedon M, et al. Provider perceptions of opioid safety measures in VHA emergency department and urgent care centers. Fed Pract. 2021;38(9):412-419. doi:10.12788/fp.0179

15. Hawk KF, D’Onofrio G, Chawarski MC, et al. Barriers and faciliatators to clinician readiness to provide emergency department-initiated buprenorphine. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e204561. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.4561

16. Lowenstein M, Kilaru A, Perrone J, et al. Barriers and facilitators for emergency department initiation of buprenorphine: a physician survey. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(9):1787-1790. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2019.02.025

17. Srivastava A, Kahan M, Leece P, McAndrew A. Buprenorphine unobserved “home” induction: a survey of Ontario’s addiction physicians. Addic Sci Clin Pract. 2019;14(1):18. doi:10.1186/s13722-019-0146-4

18. The Management of Substance Use Disorders Work Group. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Substance Use Disorders. Version 4.0. US Department of Veterans Affairs. 2021. Accessed July 1, 2022. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/sud/VADoDSUDCPG.pdf

19. Patnode CD, Perdue LA, Rushkin M, et al. Screening for unhealthy drug use updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2020;323(22):2310-2338. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.21381

20. Coles S, Vosooney A. Evidence lacking to support universal unhealthy drug use screening. Am Fam Physician. 2021;103(2):72-73.

21. Sahota PK, Sharstry S, Mukamel DB, et al. Screening emergency department patients for opioid drug use: a qualitative systematic review. Addict Behav. 2018;85:139-146. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.05.022

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a public health crisis significantly affecting veterans. A substantial increase in veterans diagnosed with OUD has occurred, nearly tripling from 25,031 in 2003 to 69,142 in 2017

For patients with active OUD, medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) reduce the risk of overdose and all-cause mortality.3 In 2009, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Department of Defense (DoD) published clinical practice guidelines for substance use disorders that strongly recommended MOUD with either buprenorphine or methadone as a first-line treatment. In 2015 updated guidelines encouraged buprenorphine initiation in primary care settings.4,5 This was followed by an academic detailing campaign designed to encourage VA clinicians to initiate MOUD.1 Despite this institutional support, MOUD remains underutilized within the VA, with widely variable rates of prescribing among VA sites.1

Efforts to further expand MOUD cultivated interest in administering buprenorphine in VA emergency departments (EDs). Patients with OUD often use the ED for same-day care, providing opportunities to initiate buprenorphine in the ED 24 hours, 7 days per week. This has been especially true during the COVID-19 pandemic during which reliable access to usual recovery services has been disrupted and EDs have served as a safety net.6

Buprenorphine’s safety profile and prolonged effect duration make it superior to other MOUD options for ED administration. As a partial opioid agonist, buprenorphine is unlikely to cause significant sedation or respiratory depression compared with full agonists like methadone. This is known as the ceiling effect. Additionally, at higher doses, buprenorphine’s effects can last for about 3 days, potentially obviating the need for repeat dosing. D’Onofrio and colleagues seminal 2015 paper conceptually proved the feasibility and value of initiating buprenorphine in the ED; patients who received ED initiation therapy were more likely to be engaged in addiction treatment 30 days after their visit and have reduced rates of illicit opioid drug use.7 Such ED harm-reduction strategies are increasingly recognized as essential, given that 1 in 20 patients treated for a nonfatal opioid overdose in an ED will die within 1 year of their visit, many within 2 days.8 Finally, a significant barrier faced by physicians wanting to administer or prescribe buprenorphine for patients with OUD has been the special licensing required by the Drug Enforcement Administration Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000, also known as an X-waiver. A notable exception to this X-waiver requirement is the 72-hour rule, which allows nonwaivered practitioners to administer (but not prescribe for home use) buprenorphine to a patient to relieve acute withdrawal symptoms for up to 72 hours while arranging for specialist referral.Under the 72-hour rule, ED clinicians have a unique opportunity to treat patients experiencing acute withdrawal symptoms and bridge them to specialty care, without the burden of an X-waiver requirement.

The VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS), therefore, developed and implemented a program to administer buprenorphine in the ED to bridge patients with OUD to an appointment with substance use disorder (SUD) services. We describe our development, implementation and evaluation of this program protocol as a model for other VA EDs. This project was determined to be quality improvement (nonresearch) by the VAGLAHS Institutional Review Board.

ED MOUD Program

We engaged in a 2-month (January-March 2019) preimplementation process during which we (1) obtained stakeholder buy-in; (2) developed a protocol and supporting resources and tools; (3) worked with stakeholders to enact local organizational policy and process modifications; and (4) educated practitioners.

Appendix 1 provides an overview of MOUD terminology, pharmacology, and regulations. We developed an 8-step program implementation plan for the ED MOUD program (Figure 1).

Obtaining Stakeholder Buy-in

Two ED physician champions (MC, JH) organized all activities. Champions obtained stakeholder buy-in from clinical and administrative leaders as well as from frontline personnel in OUD specialty care, ED, and pharmacy services. ED social workers and clerks who schedule post-ED appointments also were engaged. These stakeholders emphasized the importance of fitting the developed protocol into the existing ED workflows as well as minimizing additional resources required to initiate and maintain the program.

We ascertained that in fiscal year 2018, VAGLAHS had 156 ED visits with International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes related to OUD for 108 unique patients. Based on these data and in consultation with OUD specialty care, we determined that the potential number of referrals to the SUD clinic would be manageable with existing resources. Additionally, there was consensus that most opioid withdrawal patients could be treated in the urgent care portion of our ED since these patients generally do not require special monitoring. This consideration was important for obtaining ED stakeholder buy-in and for planning protocol logistics.

Developing the Protocol

We customized resources created by CalBridge Behavioral Health Navigator Program (CA Bridge), formerly called ED Bridge, a program of the Public Health Institute in Oakland, California, funded through California Department of Health Care Services. CA Bridge offers technical assistance and support for hospitals as well as guidance and tools for establishing processes for EDs providing buprenorphine prescriptions for the management of acute opioid withdrawal and serving as a bridge to follow-up care in SUD clinics.9 We also reviewed protocols described by D’Onofrio and colleagues. With iterative input from stakeholders, we created a protocol concretely delineating each process and corresponding responsible party with the overall aim of removing potential barriers to MOUD initiation and follow-up (Appendix 2).

Identifying Appropriate Follow-up

To operationalize protocol implementation, we built on VA’s Emergency Department Rapid Access Clinic (ED-RAC) process, a mechanism for scheduling appointments for post-ED specialty follow-up care. This process facilitated veterans’ access to urgent specialty care follow-up after ED visits by scheduling appointments prior to ED discharge.10 For the ED MOUD program, we adapted the ED-RAC process to schedule appointments in SUD clinic prior to ED discharge. These appointments allowed patients to be seen by an SUD clinician within 72 hours of ED discharge. This step was critical to working within the 72-hour rule without relying on X-waiver licensing of ED clinicians. Alternatively, as was previous practice, per patient preference, patients were also referred to non-VA residential rehabilitation services if the facility had capacity and patients met criteria for admission.

Identification of Eligible Veterans

Target patients were those primarily presenting with a request for treatment of opioid dependence or withdrawal. Patients were not actively screened for OUD. Clinicians diagnosed and assessed for OUD as per their usual practice. Patients with OUD who presented to the ED for other reasons were assessed, at clinician discretion, for their interest in receiving MOUD. If patients presented in moderate-to-severe withdrawal (eg, Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale [COWS] ≥ 8), buprenorphine was initiated in the ED. These patients were subsequently referred to either the local SUD clinic or to a residential treatment center. Patients presenting with a COWS score < 8 were referred to the outpatient SUD clinic or residential treatment centers without initiating buprenorphine from the ED. The SUD clinic or residential treatment centers could offer buprenorphine or other MOUD options. From the ED, prescribing buprenorphine for patients to self-initiate at home was not available as this required an X-waivered prescriber, which were limited during the program time frame.

Support Tools and Resources

To facilitate ED clinicians using the protocol, we worked with a programmer experienced with the Computerized Patient Record System, the VA electronic health record (EHR), to create electronic order menu sets that directed clinicians to the protocol and educational materials (Appendix 3). These menus are readily accessible and embedded into the ED clinician workflow. The menus highlight key elements of the protocol, including indications for initiation, contraindications, recommended dosing with quick orders, and how to obtain follow-up for the patient. Links also are provided to the protocol and patient discharge handouts, including the CA Bridge website.

Organizational Policy and Processes

Before implementing the developed protocol, we worked with stakeholders to modify organizational policies and processes. Our pharmacy agreed to stock buprenorphine in the ED to make it readily available. EHR restrictions that historically prohibited ordering buprenorphine for ED administration by nonwaivered clinicians were modified. Additionally, our chief of staff, pharmacy, and credentialing department agreed that physicians did not need to apply for additional delineated privileges.

Clinician Education

The final preparation step was educating clinicians and other protocol users. The VAGLAHS SUD chief presented a lecture and answered questions about MOUD to core ED faculty about the rising prevalence of OUD and use of buprenorphine as a recommended treatment.

Evaluation

To assess adherence to the developed protocol, we conducted a retrospective health record review of all ED visits March 1 to October 25, 2019, in which the patient had OUD and may have qualified for MOUD. To do this, we identified (1) ED visits with an OUD ICD-10 code as a primary or secondary diagnoses; (2) ED referrals to outpatient SUD treatment; and/or (3) ED visits in which buprenorphine was given or prescribed. We included the latter 2 criteria as application of ICD-10 codes for OUD care was inconsistent. Visits were excluded if patients did not have OUD, had OUD in remission, were already maintained on a stable MOUD regimen and no longer using illicit drugs or craving additional opioids, or were presenting solely for a refill or administration of a missed dose. Patients who relapsed were categorized as unstable. Visits were excluded if the patient was admitted to the hospital or left against medical advice. Patients on MOUD who had relapsed or requested a change in MOUD treatment were included. For all included visits, 2 ED physicians (MC, JH) reviewed the ED clinician and nursing notes, pharmacy and referral records, diagnostic codes, and veteran demographics.

In the evaluation, there were 130 visits with 92 unique veterans meeting inclusion criteria. The final sample included 70 visits with 47 unique veterans (Table 1). Of note, 24 (53%) patients self-identified as homeless or were engaged with VA housing services. Twelve veterans had multiple ED visits (7 patients with 2 visits; 5 patients with ≥ 3 visits). In 30 (43%) visits the veteran’s primary reason for seeking ED care was to obtain treatment for opioid withdrawal or receive MOUD. Type of opiate used was specified in 58% of visits; of these, 69% indicated heroin use and 17% prescription medications. Buprenorphine was initiated in the ED in 18 (26%) visits for 10 veterans. Appendix 4 outlines the clinical course and follow-up after these visits. Some veterans returned to the ED for buprenorphine redosing per the 72-hour rule. SUD clinic appointments were provided in 11 visits, and direct transfer to an inpatient rehabilitation center was arranged in 4 visits. In 42 (60%) visits, across 32 unique veterans, buprenorphine was not given in the ED, but patients were referred for SUD treat

A majority of veterans who received buprenorphine and a referral for an SUD appointment went to their initial SUD follow-up appointment and had ongoing engagement in addiction care 30 days after their index ED visit. Among veterans who did not receive buprenorphine but were referred for SUD treatment, about half went to their SUD appointments and about 1 in 5 had ongoing engagement in addiction care at 30 days after the index ED visit. Of note, 2 patients who received referrals died within 1 year of their index ED visit. The cause of death for one patient was an overdose; the other was unspecified.

DISCUSSION

We developed the ED MOUD program as a bridge to SUD specialty care. Our 8 implementation steps can serve as a model for implementing programs at other VA EDs. We demonstrated feasibility, high follow-up rates, and high retention in treatment.

Patients who received ED buprenorphine initiation were more likely to follow up and had higher rates of ongoing engagement at 30 days than did those who received only a clinic referral. In a similar Canadian study, buprenorphine was initiated in the ED, and patients followed up as a walk-in for addiction services; however, only 54% of patients presented to this initial follow-up.11 Our higher initial follow-up rate may be due to our ability to directly schedule clinic appointments. Our 70% 30-day follow-up rate is comparable, but slightly lower than the 2015 D’Onofrio and colleagues study in which 78% of patients remained engaged at 30 days.7 A possible reason is that in the D’Onofrio and colleagues study, all study physicians obtained X-waiver training and were able to prescribe buprenorphine after ED initiation or for self-initiation at home. X-waiver training was not required of our clinicians, and none of our patients were offered a prescription for self-initiation.

Our program demonstrates that it is feasible to develop a protocol without X-waiver licensing. This program provides a supportive framework for the use of MOUD and allows nonspecialists to gain experience and confidence in using buprenorphine. Any clinician could administer buprenorphine in the ED, and patients could be bridged at later ED visits until follow-up with a specialist. Of note, only a small percentage of the total visits for buprenorphine initiation required multiple daily visits for buprenorphine. Appointments with the specialist were assured to fall within a 72-hour window.

Our program has some limitations. First, the number of patients who were candidates for our ED MOUD program was small. In our 7-month review, only 47 patients were identified as potential candidates for MOUD treatment across 70 visits, and only 10 were initiated in the ED. Second, all patients were not actively screened for OUD. There was potential for missing eligible veterans as inclusion criteria relied on clinicians both recognizing OUD and manually entering a correct diagnostic code. We attempted to mitigate this by also reviewing all ED referrals to the SUD clinic and all patients who received buprenorphine in the ED. In addition, we do not have data on preimplementation rates of follow-up for comparison.

Future Directions

More than half of our patients did not receive ED buprenorphine initiation because they were not in moderate or severe withdrawal (COWS ≥ 8) similar to 57% of patients cited in the D’Onofrio and colleagues study.7 Teaching veterans how to start buprenorphine at home could greatly expand enrollment. However, this requires a prescription from an X-waiver licensed clinician. In 2021, the US Department of Health and Human Services removed the 8-hour training requirement for obtaining an X-waiver.12 However, clinicians are still required to apply for licensing. Eliminating the X-waiver requirement, as proposed by D’Onofrio and colleagues in a 2021 editorial, would have allowed all clinicians to offer home initiation.13

Previous studies suggest that despite the ability to provide a prescription, clinicians may be reluctant to offer home initiation.14–17 In a national VA 2019 survey, many emergency medicine physicians believe that SUD care is not in their scope of practice, as Dieujuste and colleagues described in Federal Practitioner.14 Although it is likely some attitudes have changed with the increased visibility of ED MOUD programs, there is still much work to be done to change perceptions.

Another area for improvement is screening for OUD in the ED to better reveal MOUD candidates. Missed opportunities (neither referral nor treatment offered) occurred in 21% of our visits. D’Onofrio and colleagues identified 66% of patients by screening all ED patients.7 Although universal screening for SUD in routine health care settings has been recommended, 2021 VA guidelines state that there is insufficient evidence to recommend universal screening.18-20 There are also limited data on the best screening tool for OUD in the ED.21 Further research on how to effectively and efficiently identify OUD patients in the ED is needed.

Conclusions

With minimal resource allocation, we started the program to offer MOUD with buprenorphine for patients with OUD at a VA ED and provided addiction treatment follow-up. This program, the first of its kind within VA, can be modeled and expanded to other VA facilities. Given increasing numbers of fatal opioid overdose, and significant adverse impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the OUD crisis, developing local and national strategies to treat OUD is essential. Future steps include improved screening and expanding capacity to offer home initiation by increasing the number of X-waiver ED clinicians.6

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Jeffrey Balsam, PharmD, BCPS, Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Clinical Applications Coordinator for his contributions in creating a Computerized Patient Record System opioid use disorder screening tool. Thank you to Gracielle Tan, MD, Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Health Science Specialist for her administrative assistance in manuscript preparation.

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a public health crisis significantly affecting veterans. A substantial increase in veterans diagnosed with OUD has occurred, nearly tripling from 25,031 in 2003 to 69,142 in 2017

For patients with active OUD, medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) reduce the risk of overdose and all-cause mortality.3 In 2009, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Department of Defense (DoD) published clinical practice guidelines for substance use disorders that strongly recommended MOUD with either buprenorphine or methadone as a first-line treatment. In 2015 updated guidelines encouraged buprenorphine initiation in primary care settings.4,5 This was followed by an academic detailing campaign designed to encourage VA clinicians to initiate MOUD.1 Despite this institutional support, MOUD remains underutilized within the VA, with widely variable rates of prescribing among VA sites.1

Efforts to further expand MOUD cultivated interest in administering buprenorphine in VA emergency departments (EDs). Patients with OUD often use the ED for same-day care, providing opportunities to initiate buprenorphine in the ED 24 hours, 7 days per week. This has been especially true during the COVID-19 pandemic during which reliable access to usual recovery services has been disrupted and EDs have served as a safety net.6

Buprenorphine’s safety profile and prolonged effect duration make it superior to other MOUD options for ED administration. As a partial opioid agonist, buprenorphine is unlikely to cause significant sedation or respiratory depression compared with full agonists like methadone. This is known as the ceiling effect. Additionally, at higher doses, buprenorphine’s effects can last for about 3 days, potentially obviating the need for repeat dosing. D’Onofrio and colleagues seminal 2015 paper conceptually proved the feasibility and value of initiating buprenorphine in the ED; patients who received ED initiation therapy were more likely to be engaged in addiction treatment 30 days after their visit and have reduced rates of illicit opioid drug use.7 Such ED harm-reduction strategies are increasingly recognized as essential, given that 1 in 20 patients treated for a nonfatal opioid overdose in an ED will die within 1 year of their visit, many within 2 days.8 Finally, a significant barrier faced by physicians wanting to administer or prescribe buprenorphine for patients with OUD has been the special licensing required by the Drug Enforcement Administration Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000, also known as an X-waiver. A notable exception to this X-waiver requirement is the 72-hour rule, which allows nonwaivered practitioners to administer (but not prescribe for home use) buprenorphine to a patient to relieve acute withdrawal symptoms for up to 72 hours while arranging for specialist referral.Under the 72-hour rule, ED clinicians have a unique opportunity to treat patients experiencing acute withdrawal symptoms and bridge them to specialty care, without the burden of an X-waiver requirement.

The VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS), therefore, developed and implemented a program to administer buprenorphine in the ED to bridge patients with OUD to an appointment with substance use disorder (SUD) services. We describe our development, implementation and evaluation of this program protocol as a model for other VA EDs. This project was determined to be quality improvement (nonresearch) by the VAGLAHS Institutional Review Board.

ED MOUD Program

We engaged in a 2-month (January-March 2019) preimplementation process during which we (1) obtained stakeholder buy-in; (2) developed a protocol and supporting resources and tools; (3) worked with stakeholders to enact local organizational policy and process modifications; and (4) educated practitioners.

Appendix 1 provides an overview of MOUD terminology, pharmacology, and regulations. We developed an 8-step program implementation plan for the ED MOUD program (Figure 1).

Obtaining Stakeholder Buy-in

Two ED physician champions (MC, JH) organized all activities. Champions obtained stakeholder buy-in from clinical and administrative leaders as well as from frontline personnel in OUD specialty care, ED, and pharmacy services. ED social workers and clerks who schedule post-ED appointments also were engaged. These stakeholders emphasized the importance of fitting the developed protocol into the existing ED workflows as well as minimizing additional resources required to initiate and maintain the program.

We ascertained that in fiscal year 2018, VAGLAHS had 156 ED visits with International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes related to OUD for 108 unique patients. Based on these data and in consultation with OUD specialty care, we determined that the potential number of referrals to the SUD clinic would be manageable with existing resources. Additionally, there was consensus that most opioid withdrawal patients could be treated in the urgent care portion of our ED since these patients generally do not require special monitoring. This consideration was important for obtaining ED stakeholder buy-in and for planning protocol logistics.

Developing the Protocol

We customized resources created by CalBridge Behavioral Health Navigator Program (CA Bridge), formerly called ED Bridge, a program of the Public Health Institute in Oakland, California, funded through California Department of Health Care Services. CA Bridge offers technical assistance and support for hospitals as well as guidance and tools for establishing processes for EDs providing buprenorphine prescriptions for the management of acute opioid withdrawal and serving as a bridge to follow-up care in SUD clinics.9 We also reviewed protocols described by D’Onofrio and colleagues. With iterative input from stakeholders, we created a protocol concretely delineating each process and corresponding responsible party with the overall aim of removing potential barriers to MOUD initiation and follow-up (Appendix 2).

Identifying Appropriate Follow-up

To operationalize protocol implementation, we built on VA’s Emergency Department Rapid Access Clinic (ED-RAC) process, a mechanism for scheduling appointments for post-ED specialty follow-up care. This process facilitated veterans’ access to urgent specialty care follow-up after ED visits by scheduling appointments prior to ED discharge.10 For the ED MOUD program, we adapted the ED-RAC process to schedule appointments in SUD clinic prior to ED discharge. These appointments allowed patients to be seen by an SUD clinician within 72 hours of ED discharge. This step was critical to working within the 72-hour rule without relying on X-waiver licensing of ED clinicians. Alternatively, as was previous practice, per patient preference, patients were also referred to non-VA residential rehabilitation services if the facility had capacity and patients met criteria for admission.

Identification of Eligible Veterans

Target patients were those primarily presenting with a request for treatment of opioid dependence or withdrawal. Patients were not actively screened for OUD. Clinicians diagnosed and assessed for OUD as per their usual practice. Patients with OUD who presented to the ED for other reasons were assessed, at clinician discretion, for their interest in receiving MOUD. If patients presented in moderate-to-severe withdrawal (eg, Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale [COWS] ≥ 8), buprenorphine was initiated in the ED. These patients were subsequently referred to either the local SUD clinic or to a residential treatment center. Patients presenting with a COWS score < 8 were referred to the outpatient SUD clinic or residential treatment centers without initiating buprenorphine from the ED. The SUD clinic or residential treatment centers could offer buprenorphine or other MOUD options. From the ED, prescribing buprenorphine for patients to self-initiate at home was not available as this required an X-waivered prescriber, which were limited during the program time frame.

Support Tools and Resources

To facilitate ED clinicians using the protocol, we worked with a programmer experienced with the Computerized Patient Record System, the VA electronic health record (EHR), to create electronic order menu sets that directed clinicians to the protocol and educational materials (Appendix 3). These menus are readily accessible and embedded into the ED clinician workflow. The menus highlight key elements of the protocol, including indications for initiation, contraindications, recommended dosing with quick orders, and how to obtain follow-up for the patient. Links also are provided to the protocol and patient discharge handouts, including the CA Bridge website.

Organizational Policy and Processes

Before implementing the developed protocol, we worked with stakeholders to modify organizational policies and processes. Our pharmacy agreed to stock buprenorphine in the ED to make it readily available. EHR restrictions that historically prohibited ordering buprenorphine for ED administration by nonwaivered clinicians were modified. Additionally, our chief of staff, pharmacy, and credentialing department agreed that physicians did not need to apply for additional delineated privileges.

Clinician Education

The final preparation step was educating clinicians and other protocol users. The VAGLAHS SUD chief presented a lecture and answered questions about MOUD to core ED faculty about the rising prevalence of OUD and use of buprenorphine as a recommended treatment.

Evaluation

To assess adherence to the developed protocol, we conducted a retrospective health record review of all ED visits March 1 to October 25, 2019, in which the patient had OUD and may have qualified for MOUD. To do this, we identified (1) ED visits with an OUD ICD-10 code as a primary or secondary diagnoses; (2) ED referrals to outpatient SUD treatment; and/or (3) ED visits in which buprenorphine was given or prescribed. We included the latter 2 criteria as application of ICD-10 codes for OUD care was inconsistent. Visits were excluded if patients did not have OUD, had OUD in remission, were already maintained on a stable MOUD regimen and no longer using illicit drugs or craving additional opioids, or were presenting solely for a refill or administration of a missed dose. Patients who relapsed were categorized as unstable. Visits were excluded if the patient was admitted to the hospital or left against medical advice. Patients on MOUD who had relapsed or requested a change in MOUD treatment were included. For all included visits, 2 ED physicians (MC, JH) reviewed the ED clinician and nursing notes, pharmacy and referral records, diagnostic codes, and veteran demographics.

In the evaluation, there were 130 visits with 92 unique veterans meeting inclusion criteria. The final sample included 70 visits with 47 unique veterans (Table 1). Of note, 24 (53%) patients self-identified as homeless or were engaged with VA housing services. Twelve veterans had multiple ED visits (7 patients with 2 visits; 5 patients with ≥ 3 visits). In 30 (43%) visits the veteran’s primary reason for seeking ED care was to obtain treatment for opioid withdrawal or receive MOUD. Type of opiate used was specified in 58% of visits; of these, 69% indicated heroin use and 17% prescription medications. Buprenorphine was initiated in the ED in 18 (26%) visits for 10 veterans. Appendix 4 outlines the clinical course and follow-up after these visits. Some veterans returned to the ED for buprenorphine redosing per the 72-hour rule. SUD clinic appointments were provided in 11 visits, and direct transfer to an inpatient rehabilitation center was arranged in 4 visits. In 42 (60%) visits, across 32 unique veterans, buprenorphine was not given in the ED, but patients were referred for SUD treat

A majority of veterans who received buprenorphine and a referral for an SUD appointment went to their initial SUD follow-up appointment and had ongoing engagement in addiction care 30 days after their index ED visit. Among veterans who did not receive buprenorphine but were referred for SUD treatment, about half went to their SUD appointments and about 1 in 5 had ongoing engagement in addiction care at 30 days after the index ED visit. Of note, 2 patients who received referrals died within 1 year of their index ED visit. The cause of death for one patient was an overdose; the other was unspecified.

DISCUSSION

We developed the ED MOUD program as a bridge to SUD specialty care. Our 8 implementation steps can serve as a model for implementing programs at other VA EDs. We demonstrated feasibility, high follow-up rates, and high retention in treatment.

Patients who received ED buprenorphine initiation were more likely to follow up and had higher rates of ongoing engagement at 30 days than did those who received only a clinic referral. In a similar Canadian study, buprenorphine was initiated in the ED, and patients followed up as a walk-in for addiction services; however, only 54% of patients presented to this initial follow-up.11 Our higher initial follow-up rate may be due to our ability to directly schedule clinic appointments. Our 70% 30-day follow-up rate is comparable, but slightly lower than the 2015 D’Onofrio and colleagues study in which 78% of patients remained engaged at 30 days.7 A possible reason is that in the D’Onofrio and colleagues study, all study physicians obtained X-waiver training and were able to prescribe buprenorphine after ED initiation or for self-initiation at home. X-waiver training was not required of our clinicians, and none of our patients were offered a prescription for self-initiation.

Our program demonstrates that it is feasible to develop a protocol without X-waiver licensing. This program provides a supportive framework for the use of MOUD and allows nonspecialists to gain experience and confidence in using buprenorphine. Any clinician could administer buprenorphine in the ED, and patients could be bridged at later ED visits until follow-up with a specialist. Of note, only a small percentage of the total visits for buprenorphine initiation required multiple daily visits for buprenorphine. Appointments with the specialist were assured to fall within a 72-hour window.

Our program has some limitations. First, the number of patients who were candidates for our ED MOUD program was small. In our 7-month review, only 47 patients were identified as potential candidates for MOUD treatment across 70 visits, and only 10 were initiated in the ED. Second, all patients were not actively screened for OUD. There was potential for missing eligible veterans as inclusion criteria relied on clinicians both recognizing OUD and manually entering a correct diagnostic code. We attempted to mitigate this by also reviewing all ED referrals to the SUD clinic and all patients who received buprenorphine in the ED. In addition, we do not have data on preimplementation rates of follow-up for comparison.

Future Directions

More than half of our patients did not receive ED buprenorphine initiation because they were not in moderate or severe withdrawal (COWS ≥ 8) similar to 57% of patients cited in the D’Onofrio and colleagues study.7 Teaching veterans how to start buprenorphine at home could greatly expand enrollment. However, this requires a prescription from an X-waiver licensed clinician. In 2021, the US Department of Health and Human Services removed the 8-hour training requirement for obtaining an X-waiver.12 However, clinicians are still required to apply for licensing. Eliminating the X-waiver requirement, as proposed by D’Onofrio and colleagues in a 2021 editorial, would have allowed all clinicians to offer home initiation.13

Previous studies suggest that despite the ability to provide a prescription, clinicians may be reluctant to offer home initiation.14–17 In a national VA 2019 survey, many emergency medicine physicians believe that SUD care is not in their scope of practice, as Dieujuste and colleagues described in Federal Practitioner.14 Although it is likely some attitudes have changed with the increased visibility of ED MOUD programs, there is still much work to be done to change perceptions.

Another area for improvement is screening for OUD in the ED to better reveal MOUD candidates. Missed opportunities (neither referral nor treatment offered) occurred in 21% of our visits. D’Onofrio and colleagues identified 66% of patients by screening all ED patients.7 Although universal screening for SUD in routine health care settings has been recommended, 2021 VA guidelines state that there is insufficient evidence to recommend universal screening.18-20 There are also limited data on the best screening tool for OUD in the ED.21 Further research on how to effectively and efficiently identify OUD patients in the ED is needed.

Conclusions

With minimal resource allocation, we started the program to offer MOUD with buprenorphine for patients with OUD at a VA ED and provided addiction treatment follow-up. This program, the first of its kind within VA, can be modeled and expanded to other VA facilities. Given increasing numbers of fatal opioid overdose, and significant adverse impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the OUD crisis, developing local and national strategies to treat OUD is essential. Future steps include improved screening and expanding capacity to offer home initiation by increasing the number of X-waiver ED clinicians.6

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Jeffrey Balsam, PharmD, BCPS, Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Clinical Applications Coordinator for his contributions in creating a Computerized Patient Record System opioid use disorder screening tool. Thank you to Gracielle Tan, MD, Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Health Science Specialist for her administrative assistance in manuscript preparation.

1. Wyse JJ, Gordon AJ, Dobscha SK, et al. Medications for opioid use disorder in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system: historical perspective, lessons learned, and next steps. Subst Abuse. 2018;39(2):139-144. doi:10.1080/08897077.2018.1452327

2. Bohnert ASB, Ilgen MA, Galea S, McCarthy JF, Blow FC. Accidental poisoning mortality among patients in the Department of Veterans Affairs health system. Med Care. 2011;49(4):393-396. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e318202aa27

3. Ma J, Bao Y-P, Wang R-J, et al. Effects of medication-assisted treatment on mortality among opioids users: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(12):1968-1983. doi:10.1038/s41380-018-0094-5

4. The Management of Substance Use Disorders Work Group. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Substance Use Disorders. Version 2.0. US Department of Veterans Affairs; 2009.

5. The Management of Substance Use Disorders Work Group. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Substance Use Disorders. Version 3.0. US Department of Veterans Affairs. 2015. Accessed July 1, 2022. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/sud/VADoDSUDCPGRevised22216.pdf

6. Hulsey J, Mellis A, Kelly B. COVID-19 pandemic impact on patients, families and individuals in recovery from substance use disorder. Accessed July 7, 2021. https://www.addictionpolicy.org/covid19-report

7. D’Onofrio G, O’Connor PG, Pantalon MV, et al. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opiod dependence. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1636-1644. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.3474

8. Weiner SG, Baker O, Bernson D, Schuur JD. One-year mortality of patients after emergency department treatment for non-fatal opioid overdose. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;75(1):13-17. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.04.020

9. CA Bridge. Updated 2021. Accessed July 1, 2022. https://cabridge.org