User login

Benefit-risk profiles of lasmiditan, rimegepant, and ubrogepant for acute treatment of migraine

Key clinical point: Doses of 200 mg lasmiditan and 75 mg rimegepant had the lowest numbers needed to treat (NNT) to achieve immediate and sustained pain freedom, respectively, whereas 25 mg ubrogepant had higher numbers needed to harm (NNH) for nausea and dizziness in acute treatment for migraine.

Major finding: Compared with placebo, 200 mg lasmiditan had the lowest NNT for immediate pain freedom at 2 hours (NNT 7; 95% credible interval [CrI] 5-9) and 75 mg rimegepant had the lowest NNT for sustained pain freedom at 2-24 hours (NNT 7; 95% CrI 5-12); although statistically insignificant, 25 mg ubrogepant had a high NNH for dizziness and nausea.

Study details: Findings are from a fixed-effects Bayesian network meta-analysis of five phase 3 randomized controlled trials including 10,060 patients with migraine who received lasmiditan, rimegepant, ubrogepant, or placebo for acute treatment.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Biohaven Pharmaceuticals. Seven authors declared being employees of and owning stock or stock options in Biohaven or a company funded by Biohaven.

Source: Johnston K et al. Rimegepant, ubrogepant, and lasmiditan in the acute treatment of migraine examining the benefit-risk profile using number needed to treat/harm. Clin J Pain. 2022;38(11):680-685 (Sep 26). Doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000001072

Key clinical point: Doses of 200 mg lasmiditan and 75 mg rimegepant had the lowest numbers needed to treat (NNT) to achieve immediate and sustained pain freedom, respectively, whereas 25 mg ubrogepant had higher numbers needed to harm (NNH) for nausea and dizziness in acute treatment for migraine.

Major finding: Compared with placebo, 200 mg lasmiditan had the lowest NNT for immediate pain freedom at 2 hours (NNT 7; 95% credible interval [CrI] 5-9) and 75 mg rimegepant had the lowest NNT for sustained pain freedom at 2-24 hours (NNT 7; 95% CrI 5-12); although statistically insignificant, 25 mg ubrogepant had a high NNH for dizziness and nausea.

Study details: Findings are from a fixed-effects Bayesian network meta-analysis of five phase 3 randomized controlled trials including 10,060 patients with migraine who received lasmiditan, rimegepant, ubrogepant, or placebo for acute treatment.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Biohaven Pharmaceuticals. Seven authors declared being employees of and owning stock or stock options in Biohaven or a company funded by Biohaven.

Source: Johnston K et al. Rimegepant, ubrogepant, and lasmiditan in the acute treatment of migraine examining the benefit-risk profile using number needed to treat/harm. Clin J Pain. 2022;38(11):680-685 (Sep 26). Doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000001072

Key clinical point: Doses of 200 mg lasmiditan and 75 mg rimegepant had the lowest numbers needed to treat (NNT) to achieve immediate and sustained pain freedom, respectively, whereas 25 mg ubrogepant had higher numbers needed to harm (NNH) for nausea and dizziness in acute treatment for migraine.

Major finding: Compared with placebo, 200 mg lasmiditan had the lowest NNT for immediate pain freedom at 2 hours (NNT 7; 95% credible interval [CrI] 5-9) and 75 mg rimegepant had the lowest NNT for sustained pain freedom at 2-24 hours (NNT 7; 95% CrI 5-12); although statistically insignificant, 25 mg ubrogepant had a high NNH for dizziness and nausea.

Study details: Findings are from a fixed-effects Bayesian network meta-analysis of five phase 3 randomized controlled trials including 10,060 patients with migraine who received lasmiditan, rimegepant, ubrogepant, or placebo for acute treatment.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Biohaven Pharmaceuticals. Seven authors declared being employees of and owning stock or stock options in Biohaven or a company funded by Biohaven.

Source: Johnston K et al. Rimegepant, ubrogepant, and lasmiditan in the acute treatment of migraine examining the benefit-risk profile using number needed to treat/harm. Clin J Pain. 2022;38(11):680-685 (Sep 26). Doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000001072

Overlapping initial symptoms demand careful differential diagnosis of migraine and ischemic stroke

Key clinical point: At the onset of attack, many patients with migraine with aura (MwA) experience stroke-like symptoms, whereas many patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) experience migraine-like symptoms, highlighting the need for additional clinical investigation for careful differential diagnosis.

Major finding: Migraine-like irritative sensations were experienced by 32.1% and 35.2% of patients with stroke who experienced visual disturbances and sensory disturbances, respectively, whereas stroke-like symptoms were reported by 12.0% and 31.4% of patients with MwA who experienced visual disturbances and sensory disturbances, respectively.

Study details: Findings are from a questionnaire-based observational study including 343 patients with MwA and 350 patients with AIS.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Swiss Heart Foundation. Several authors reported receiving research support, grants, personal fees, speaker fees, consulting or advisory support from Swiss Heart Foundation or other sources.

Source: Scutelnic A et al. Migraine aura-like symptoms at onset of stroke and stroke-like symptoms in migraine with aura. Front Neurol. 2022;13:1004058 (Sep 14). Doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.1004058

Key clinical point: At the onset of attack, many patients with migraine with aura (MwA) experience stroke-like symptoms, whereas many patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) experience migraine-like symptoms, highlighting the need for additional clinical investigation for careful differential diagnosis.

Major finding: Migraine-like irritative sensations were experienced by 32.1% and 35.2% of patients with stroke who experienced visual disturbances and sensory disturbances, respectively, whereas stroke-like symptoms were reported by 12.0% and 31.4% of patients with MwA who experienced visual disturbances and sensory disturbances, respectively.

Study details: Findings are from a questionnaire-based observational study including 343 patients with MwA and 350 patients with AIS.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Swiss Heart Foundation. Several authors reported receiving research support, grants, personal fees, speaker fees, consulting or advisory support from Swiss Heart Foundation or other sources.

Source: Scutelnic A et al. Migraine aura-like symptoms at onset of stroke and stroke-like symptoms in migraine with aura. Front Neurol. 2022;13:1004058 (Sep 14). Doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.1004058

Key clinical point: At the onset of attack, many patients with migraine with aura (MwA) experience stroke-like symptoms, whereas many patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) experience migraine-like symptoms, highlighting the need for additional clinical investigation for careful differential diagnosis.

Major finding: Migraine-like irritative sensations were experienced by 32.1% and 35.2% of patients with stroke who experienced visual disturbances and sensory disturbances, respectively, whereas stroke-like symptoms were reported by 12.0% and 31.4% of patients with MwA who experienced visual disturbances and sensory disturbances, respectively.

Study details: Findings are from a questionnaire-based observational study including 343 patients with MwA and 350 patients with AIS.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Swiss Heart Foundation. Several authors reported receiving research support, grants, personal fees, speaker fees, consulting or advisory support from Swiss Heart Foundation or other sources.

Source: Scutelnic A et al. Migraine aura-like symptoms at onset of stroke and stroke-like symptoms in migraine with aura. Front Neurol. 2022;13:1004058 (Sep 14). Doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.1004058

Real-world efficacy of galcanezumab in high frequency episodic and chronic migraine

Key clinical point: Galcanezumab demonstrated persistent efficacy in improving migraine features and disability scores and was well tolerated over 1 year in real-life patients with high frequency episodic migraine (HFEM) or chronic migraine (CM).

Major finding: The monthly migraine days (MMD) significantly reduced in patients with HFEM (from 11.5 ± 3.5 to 5.5 ± 5.5) and CM (from 19.3 ± 5.8 to 7.4 ± 5.9; both P < .00001) over 12 months along with a significant decrease in pain intensity, monthly acute medication intake, Headache Impact Test-6, and Migraine Disability Assessment questionnaire scores (all P < .00001). Overall, 56.5% of patients presented with a response rate of ≥50% reduction in MMD for 9 cumulative months. No serious adverse events were reported.

Study details: Findings are from a prospective ongoing study including 191 patients with HFEM or CM who received galcanezumab and completed the 12 months of observation since galcanezumab initiation.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Campus Bio-Medico University. Several authors reported receiving grants or honoraria from various sources.

Source: Vernieri F et al for the GARLIT Study Group. Maintenance of response and predictive factors of 1-year GalcanezumAb treatment in real-life migraine patients in Italy: The multicenter prospective cohort GARLIT study. Eur J Neurol. 2022 (Sep 13). Doi: 10.1111/ene.15563

Key clinical point: Galcanezumab demonstrated persistent efficacy in improving migraine features and disability scores and was well tolerated over 1 year in real-life patients with high frequency episodic migraine (HFEM) or chronic migraine (CM).

Major finding: The monthly migraine days (MMD) significantly reduced in patients with HFEM (from 11.5 ± 3.5 to 5.5 ± 5.5) and CM (from 19.3 ± 5.8 to 7.4 ± 5.9; both P < .00001) over 12 months along with a significant decrease in pain intensity, monthly acute medication intake, Headache Impact Test-6, and Migraine Disability Assessment questionnaire scores (all P < .00001). Overall, 56.5% of patients presented with a response rate of ≥50% reduction in MMD for 9 cumulative months. No serious adverse events were reported.

Study details: Findings are from a prospective ongoing study including 191 patients with HFEM or CM who received galcanezumab and completed the 12 months of observation since galcanezumab initiation.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Campus Bio-Medico University. Several authors reported receiving grants or honoraria from various sources.

Source: Vernieri F et al for the GARLIT Study Group. Maintenance of response and predictive factors of 1-year GalcanezumAb treatment in real-life migraine patients in Italy: The multicenter prospective cohort GARLIT study. Eur J Neurol. 2022 (Sep 13). Doi: 10.1111/ene.15563

Key clinical point: Galcanezumab demonstrated persistent efficacy in improving migraine features and disability scores and was well tolerated over 1 year in real-life patients with high frequency episodic migraine (HFEM) or chronic migraine (CM).

Major finding: The monthly migraine days (MMD) significantly reduced in patients with HFEM (from 11.5 ± 3.5 to 5.5 ± 5.5) and CM (from 19.3 ± 5.8 to 7.4 ± 5.9; both P < .00001) over 12 months along with a significant decrease in pain intensity, monthly acute medication intake, Headache Impact Test-6, and Migraine Disability Assessment questionnaire scores (all P < .00001). Overall, 56.5% of patients presented with a response rate of ≥50% reduction in MMD for 9 cumulative months. No serious adverse events were reported.

Study details: Findings are from a prospective ongoing study including 191 patients with HFEM or CM who received galcanezumab and completed the 12 months of observation since galcanezumab initiation.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Campus Bio-Medico University. Several authors reported receiving grants or honoraria from various sources.

Source: Vernieri F et al for the GARLIT Study Group. Maintenance of response and predictive factors of 1-year GalcanezumAb treatment in real-life migraine patients in Italy: The multicenter prospective cohort GARLIT study. Eur J Neurol. 2022 (Sep 13). Doi: 10.1111/ene.15563

Meta-analysis corroborates evidence on efficacy of onabotulinumtoxinA for chronic migraine

Key clinical point: Meta-analysis on 10 years of real-world data confirmed the efficacy of onabotulinumtoxinA as a preventive treatment for chronic migraine.

Major finding: At week 24, onabotulinumtoxinA reduced the number of headache days per month (mean change from baseline [MCFB] −10.64; 95% CI −12.31 to −8.97), with a ≥50% reduction in migraine days response rate of 46.57% (95% CI 29.50%-63.65%) and improvements in total Headache Impact Test-6 score (MCFB −11.70; 95% CI −13.86 to −9.54) and Migraine-Specific Quality of Life v2.1 score (MCFB 23.60; 95% CI 21.56-25.64). The improvements were maintained till 52 weeks.

Study details: Findings are from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 44 studies including patients with chronic migraine who received onabotulinumtoxinA.

Disclosures: This study was supported by AbbVie. M Lanteri-Minet reported receiving personal fees and grants from various sources. Four authors declared being employees of AbbVie or working for a consultancy company commissioned by AbbVie or holding stock options in GSK and AbbVie.

Source: Lanteri-Minet M et al. Effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA (BOTOX®) for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine: A meta-analysis on 10 years of real-world data. Cephalalgia. 2022 (Sep 8). Doi: 10.1177/03331024221123058

Key clinical point: Meta-analysis on 10 years of real-world data confirmed the efficacy of onabotulinumtoxinA as a preventive treatment for chronic migraine.

Major finding: At week 24, onabotulinumtoxinA reduced the number of headache days per month (mean change from baseline [MCFB] −10.64; 95% CI −12.31 to −8.97), with a ≥50% reduction in migraine days response rate of 46.57% (95% CI 29.50%-63.65%) and improvements in total Headache Impact Test-6 score (MCFB −11.70; 95% CI −13.86 to −9.54) and Migraine-Specific Quality of Life v2.1 score (MCFB 23.60; 95% CI 21.56-25.64). The improvements were maintained till 52 weeks.

Study details: Findings are from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 44 studies including patients with chronic migraine who received onabotulinumtoxinA.

Disclosures: This study was supported by AbbVie. M Lanteri-Minet reported receiving personal fees and grants from various sources. Four authors declared being employees of AbbVie or working for a consultancy company commissioned by AbbVie or holding stock options in GSK and AbbVie.

Source: Lanteri-Minet M et al. Effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA (BOTOX®) for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine: A meta-analysis on 10 years of real-world data. Cephalalgia. 2022 (Sep 8). Doi: 10.1177/03331024221123058

Key clinical point: Meta-analysis on 10 years of real-world data confirmed the efficacy of onabotulinumtoxinA as a preventive treatment for chronic migraine.

Major finding: At week 24, onabotulinumtoxinA reduced the number of headache days per month (mean change from baseline [MCFB] −10.64; 95% CI −12.31 to −8.97), with a ≥50% reduction in migraine days response rate of 46.57% (95% CI 29.50%-63.65%) and improvements in total Headache Impact Test-6 score (MCFB −11.70; 95% CI −13.86 to −9.54) and Migraine-Specific Quality of Life v2.1 score (MCFB 23.60; 95% CI 21.56-25.64). The improvements were maintained till 52 weeks.

Study details: Findings are from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 44 studies including patients with chronic migraine who received onabotulinumtoxinA.

Disclosures: This study was supported by AbbVie. M Lanteri-Minet reported receiving personal fees and grants from various sources. Four authors declared being employees of AbbVie or working for a consultancy company commissioned by AbbVie or holding stock options in GSK and AbbVie.

Source: Lanteri-Minet M et al. Effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA (BOTOX®) for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine: A meta-analysis on 10 years of real-world data. Cephalalgia. 2022 (Sep 8). Doi: 10.1177/03331024221123058

Anti-CGRP receptor mAb increase blood pressure in patients with migraine

Key clinical point: Patients with migraine treated with anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (anti-CGRP) receptor monoclonal antibodies (mAb), erenumab and fremanezumab, reported an increase in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, with most having blood pressure within normal limits but some requiring antihypertensive treatment.

Major finding: At 3 months, patients treated with erenumab or fremanezumab reported a significant increase in systolic (change from baseline [Δ] 5.0 mm Hg; P < .001) and diastolic (Δ 3.3 mm Hg; P < .001) blood pressure, with sustained effects over 1 year of follow-up (P < .001). Antihypertensive treatment was required by 3.7% of patients treated with erenumab.

Study details: This prospective follow-up study included 196 patients with migraine who previously failed ≥4 migraine preventive treatments and received erenumab or fremanezumab and 109 patients with migraine who did not use any migraine prophylactic medication.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any targeted funding. AM van den Brink and GM Terwindt reported receiving independent, consultancy, or industry support from various sources.

Source: de Vries Lentsch S et al. Blood pressure in migraine patients treated with monoclonal anti-CGRP (receptor) antibodies: A prospective follow-up study. Neurology. 2022 (Oct 4). Doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000201008

Key clinical point: Patients with migraine treated with anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (anti-CGRP) receptor monoclonal antibodies (mAb), erenumab and fremanezumab, reported an increase in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, with most having blood pressure within normal limits but some requiring antihypertensive treatment.

Major finding: At 3 months, patients treated with erenumab or fremanezumab reported a significant increase in systolic (change from baseline [Δ] 5.0 mm Hg; P < .001) and diastolic (Δ 3.3 mm Hg; P < .001) blood pressure, with sustained effects over 1 year of follow-up (P < .001). Antihypertensive treatment was required by 3.7% of patients treated with erenumab.

Study details: This prospective follow-up study included 196 patients with migraine who previously failed ≥4 migraine preventive treatments and received erenumab or fremanezumab and 109 patients with migraine who did not use any migraine prophylactic medication.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any targeted funding. AM van den Brink and GM Terwindt reported receiving independent, consultancy, or industry support from various sources.

Source: de Vries Lentsch S et al. Blood pressure in migraine patients treated with monoclonal anti-CGRP (receptor) antibodies: A prospective follow-up study. Neurology. 2022 (Oct 4). Doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000201008

Key clinical point: Patients with migraine treated with anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (anti-CGRP) receptor monoclonal antibodies (mAb), erenumab and fremanezumab, reported an increase in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, with most having blood pressure within normal limits but some requiring antihypertensive treatment.

Major finding: At 3 months, patients treated with erenumab or fremanezumab reported a significant increase in systolic (change from baseline [Δ] 5.0 mm Hg; P < .001) and diastolic (Δ 3.3 mm Hg; P < .001) blood pressure, with sustained effects over 1 year of follow-up (P < .001). Antihypertensive treatment was required by 3.7% of patients treated with erenumab.

Study details: This prospective follow-up study included 196 patients with migraine who previously failed ≥4 migraine preventive treatments and received erenumab or fremanezumab and 109 patients with migraine who did not use any migraine prophylactic medication.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any targeted funding. AM van den Brink and GM Terwindt reported receiving independent, consultancy, or industry support from various sources.

Source: de Vries Lentsch S et al. Blood pressure in migraine patients treated with monoclonal anti-CGRP (receptor) antibodies: A prospective follow-up study. Neurology. 2022 (Oct 4). Doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000201008

Complaints of foot pain

This patient's physical findings are consistent with a diagnosis of claw toe, which can be caused by diabetes-related peripheral neuropathy.

According to the International Diabetes Federation, diabetes currently affects approximately 537 million adults worldwide. The number of individuals living with diabetes is expected to exceed 640 million by 2030 and 780 million by 2045. In the United States, more than 37 million people are living with diabetes.

Foot complications related to diabetes represent a significant economic and social burden and can profoundly affect a patient's quality of life and medical outcomes. Common diabetes-related foot complications include foot deformity and peripheral neuropathy, both of which increase the risk for ulceration and amputation. The most common deformity is at the metatarsophalangeal joint (MTPJ). As many as 85% of patients with a history of ulcers and amputation have an MTPJ deformity such as claw toe or hammertoe.

Although they are often grouped together, claw toe and hammertoe have distinct features. Extended MTPJ, flexed proximal interphalangeal joint (PIPJ), and flexed distal interphalangeal joint (DIPJ) are characteristic of claw toe. While hammertoe also has extended MTPJ and flexed PIPJ, the DIPJ is extended rather than flexed. In both cases, the area of high pressure at risk for skin breakdown and ulceration is at the metatarsal head as a result of MTPJ hyperextension deformity.

Prompt detection and care of diabetes-related foot complications can minimize progression and negative consequences on patients' health and quality of life. According to the American Diabetes Association, all patients with diabetes should undergo a comprehensive foot evaluation at least annually to identify risk factors for ulceration and amputation, which include foot deformities, poor glycemic control, peripheral neuropathy, cigarette smoking, preulcerative callus or corn, peripheral artery disease, chronic kidney disease, visual impairment, and a history of ulceration or amputation. When patients present with a history of ulceration or amputation, a foot inspection should be conducted at each visit.

A comprehensive foot evaluation should include inspection of the skin, evaluation of any foot deformities, a neurologic assessment (10-g monofilament testing with at least one other assessment: pinprick, temperature, vibration), and a vascular assessment, including pulses in the legs and feet.

Patients should be educated on risk factors and appropriate management of foot-related complications, including the importance of effective glycemic control and daily monitoring of feet. Treatment may be medical, surgical, or both, as indicated by the individual patient's presentation. Conservative treatment approaches include footwear that is extra wide or deep, avoiding high-heeled and narrow-toed shoes, use of a metatarsal bar or pad, cushioning sleeves or stocking caps with silicon linings, and a longitudinal pad beneath the toes.

Complete recommendations on achieving glycemic control in T2D can be found in the 2022 American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care. Guidelines on foot care are also available.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's physical findings are consistent with a diagnosis of claw toe, which can be caused by diabetes-related peripheral neuropathy.

According to the International Diabetes Federation, diabetes currently affects approximately 537 million adults worldwide. The number of individuals living with diabetes is expected to exceed 640 million by 2030 and 780 million by 2045. In the United States, more than 37 million people are living with diabetes.

Foot complications related to diabetes represent a significant economic and social burden and can profoundly affect a patient's quality of life and medical outcomes. Common diabetes-related foot complications include foot deformity and peripheral neuropathy, both of which increase the risk for ulceration and amputation. The most common deformity is at the metatarsophalangeal joint (MTPJ). As many as 85% of patients with a history of ulcers and amputation have an MTPJ deformity such as claw toe or hammertoe.

Although they are often grouped together, claw toe and hammertoe have distinct features. Extended MTPJ, flexed proximal interphalangeal joint (PIPJ), and flexed distal interphalangeal joint (DIPJ) are characteristic of claw toe. While hammertoe also has extended MTPJ and flexed PIPJ, the DIPJ is extended rather than flexed. In both cases, the area of high pressure at risk for skin breakdown and ulceration is at the metatarsal head as a result of MTPJ hyperextension deformity.

Prompt detection and care of diabetes-related foot complications can minimize progression and negative consequences on patients' health and quality of life. According to the American Diabetes Association, all patients with diabetes should undergo a comprehensive foot evaluation at least annually to identify risk factors for ulceration and amputation, which include foot deformities, poor glycemic control, peripheral neuropathy, cigarette smoking, preulcerative callus or corn, peripheral artery disease, chronic kidney disease, visual impairment, and a history of ulceration or amputation. When patients present with a history of ulceration or amputation, a foot inspection should be conducted at each visit.

A comprehensive foot evaluation should include inspection of the skin, evaluation of any foot deformities, a neurologic assessment (10-g monofilament testing with at least one other assessment: pinprick, temperature, vibration), and a vascular assessment, including pulses in the legs and feet.

Patients should be educated on risk factors and appropriate management of foot-related complications, including the importance of effective glycemic control and daily monitoring of feet. Treatment may be medical, surgical, or both, as indicated by the individual patient's presentation. Conservative treatment approaches include footwear that is extra wide or deep, avoiding high-heeled and narrow-toed shoes, use of a metatarsal bar or pad, cushioning sleeves or stocking caps with silicon linings, and a longitudinal pad beneath the toes.

Complete recommendations on achieving glycemic control in T2D can be found in the 2022 American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care. Guidelines on foot care are also available.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's physical findings are consistent with a diagnosis of claw toe, which can be caused by diabetes-related peripheral neuropathy.

According to the International Diabetes Federation, diabetes currently affects approximately 537 million adults worldwide. The number of individuals living with diabetes is expected to exceed 640 million by 2030 and 780 million by 2045. In the United States, more than 37 million people are living with diabetes.

Foot complications related to diabetes represent a significant economic and social burden and can profoundly affect a patient's quality of life and medical outcomes. Common diabetes-related foot complications include foot deformity and peripheral neuropathy, both of which increase the risk for ulceration and amputation. The most common deformity is at the metatarsophalangeal joint (MTPJ). As many as 85% of patients with a history of ulcers and amputation have an MTPJ deformity such as claw toe or hammertoe.

Although they are often grouped together, claw toe and hammertoe have distinct features. Extended MTPJ, flexed proximal interphalangeal joint (PIPJ), and flexed distal interphalangeal joint (DIPJ) are characteristic of claw toe. While hammertoe also has extended MTPJ and flexed PIPJ, the DIPJ is extended rather than flexed. In both cases, the area of high pressure at risk for skin breakdown and ulceration is at the metatarsal head as a result of MTPJ hyperextension deformity.

Prompt detection and care of diabetes-related foot complications can minimize progression and negative consequences on patients' health and quality of life. According to the American Diabetes Association, all patients with diabetes should undergo a comprehensive foot evaluation at least annually to identify risk factors for ulceration and amputation, which include foot deformities, poor glycemic control, peripheral neuropathy, cigarette smoking, preulcerative callus or corn, peripheral artery disease, chronic kidney disease, visual impairment, and a history of ulceration or amputation. When patients present with a history of ulceration or amputation, a foot inspection should be conducted at each visit.

A comprehensive foot evaluation should include inspection of the skin, evaluation of any foot deformities, a neurologic assessment (10-g monofilament testing with at least one other assessment: pinprick, temperature, vibration), and a vascular assessment, including pulses in the legs and feet.

Patients should be educated on risk factors and appropriate management of foot-related complications, including the importance of effective glycemic control and daily monitoring of feet. Treatment may be medical, surgical, or both, as indicated by the individual patient's presentation. Conservative treatment approaches include footwear that is extra wide or deep, avoiding high-heeled and narrow-toed shoes, use of a metatarsal bar or pad, cushioning sleeves or stocking caps with silicon linings, and a longitudinal pad beneath the toes.

Complete recommendations on achieving glycemic control in T2D can be found in the 2022 American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care. Guidelines on foot care are also available.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 59-year-old woman newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and hypercholesterolemia presents with complaints of foot pain, particularly while wearing shoes. Physical examination reveals an extended metatarsophalangeal joint, a flexed proximal interphalangeal joint, and flexed distal interphalangeal joint. Her toenails are discolored with a yellowish hue, and callus formation is noted over the metatarsal area. The patient reports pain at the tip of the toe from pressure against the point of the distal phalanx. She states that she has not experienced any numbness, tingling, or muscle weakness. Before her recent diabetes diagnosis, the patient had not been receiving regular medical care. The patient's current medications include metformin 500 mg/d, empagliflozin 10 mg/d, and rosuvastatin 10 mg/d.

Severe abdominal pain and vomiting

On the basis of the patient’s family history, personal history, and presentation, the likely diagnosis is Crohn disease. Although the disease may be diagnosed at any age, onset shows a bimodal distribution, with the first, more predominant wave occurring in adolescence and early adulthood. Peak global onset is between the ages of 15 and 30. Compared with adult-onset disease, pediatric Crohn disease is associated with a more serious disease course. Patients of Ashkenazi Jewish descent are at higher risk of developing this autoimmune disease than any other ethnic group.

Colonoscopy is the first-line approach for diagnosing and monitoring inflammatory bowel disease. Typical findings in patients with Crohn disease include histologic changes, such as focal crypt irregularity, transmural lymphoid aggregates, fissures and fistulas, and perianal disorders. In the differential diagnosis, ulcerative colitis (UC) must be carefully ruled out. UC involves only the large bowel, rarely causes fistulas, and is frequently seen with bleeding. Crohn disease is characteristically noncontiguous, with linear ulcerations of a cobblestone appearance. In addition, noncaseating granulomas are specific for Crohn disease. Micronutrient and vitamin levels are usually low, as seen in the present case. During workup, fecal calprotectin can help differentiate inflammatory bowel disease from irritable bowel syndrome.

The patient in this case may be a candidate for 5-aminosalicylic acid, together with a nutritional plan, used in mild or moderate cases of pediatric Crohn disease. Clinical improvement plus a decrease of fecal calprotectin would be an indication of positive treatment response. Being newly diagnosed, if the patient does not achieve remission after the induction period, he may be at risk for a more complicated disease course. Treatment for Crohn disease in the pediatric setting, as in the adult setting, should be implemented through a step-up approach. Other treatment options for pediatric disease include antibiotics; immunomodulators; and, in moderate-to severe cases, corticosteroids and biologics.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient’s family history, personal history, and presentation, the likely diagnosis is Crohn disease. Although the disease may be diagnosed at any age, onset shows a bimodal distribution, with the first, more predominant wave occurring in adolescence and early adulthood. Peak global onset is between the ages of 15 and 30. Compared with adult-onset disease, pediatric Crohn disease is associated with a more serious disease course. Patients of Ashkenazi Jewish descent are at higher risk of developing this autoimmune disease than any other ethnic group.

Colonoscopy is the first-line approach for diagnosing and monitoring inflammatory bowel disease. Typical findings in patients with Crohn disease include histologic changes, such as focal crypt irregularity, transmural lymphoid aggregates, fissures and fistulas, and perianal disorders. In the differential diagnosis, ulcerative colitis (UC) must be carefully ruled out. UC involves only the large bowel, rarely causes fistulas, and is frequently seen with bleeding. Crohn disease is characteristically noncontiguous, with linear ulcerations of a cobblestone appearance. In addition, noncaseating granulomas are specific for Crohn disease. Micronutrient and vitamin levels are usually low, as seen in the present case. During workup, fecal calprotectin can help differentiate inflammatory bowel disease from irritable bowel syndrome.

The patient in this case may be a candidate for 5-aminosalicylic acid, together with a nutritional plan, used in mild or moderate cases of pediatric Crohn disease. Clinical improvement plus a decrease of fecal calprotectin would be an indication of positive treatment response. Being newly diagnosed, if the patient does not achieve remission after the induction period, he may be at risk for a more complicated disease course. Treatment for Crohn disease in the pediatric setting, as in the adult setting, should be implemented through a step-up approach. Other treatment options for pediatric disease include antibiotics; immunomodulators; and, in moderate-to severe cases, corticosteroids and biologics.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient’s family history, personal history, and presentation, the likely diagnosis is Crohn disease. Although the disease may be diagnosed at any age, onset shows a bimodal distribution, with the first, more predominant wave occurring in adolescence and early adulthood. Peak global onset is between the ages of 15 and 30. Compared with adult-onset disease, pediatric Crohn disease is associated with a more serious disease course. Patients of Ashkenazi Jewish descent are at higher risk of developing this autoimmune disease than any other ethnic group.

Colonoscopy is the first-line approach for diagnosing and monitoring inflammatory bowel disease. Typical findings in patients with Crohn disease include histologic changes, such as focal crypt irregularity, transmural lymphoid aggregates, fissures and fistulas, and perianal disorders. In the differential diagnosis, ulcerative colitis (UC) must be carefully ruled out. UC involves only the large bowel, rarely causes fistulas, and is frequently seen with bleeding. Crohn disease is characteristically noncontiguous, with linear ulcerations of a cobblestone appearance. In addition, noncaseating granulomas are specific for Crohn disease. Micronutrient and vitamin levels are usually low, as seen in the present case. During workup, fecal calprotectin can help differentiate inflammatory bowel disease from irritable bowel syndrome.

The patient in this case may be a candidate for 5-aminosalicylic acid, together with a nutritional plan, used in mild or moderate cases of pediatric Crohn disease. Clinical improvement plus a decrease of fecal calprotectin would be an indication of positive treatment response. Being newly diagnosed, if the patient does not achieve remission after the induction period, he may be at risk for a more complicated disease course. Treatment for Crohn disease in the pediatric setting, as in the adult setting, should be implemented through a step-up approach. Other treatment options for pediatric disease include antibiotics; immunomodulators; and, in moderate-to severe cases, corticosteroids and biologics.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 12-year-old boy presents to an urgent care center with severe abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. His height is 5 ft 3 in and weight is 99 lb (BMI 18.7). The patient has a history of chronic diarrhea and reports intermittent abdominal pain that began about 6 months ago. During this time, he has lost about 12 lb, as many foods exacerbate his symptoms, though his mother notes that even plain foods can bother his stomach. Further questioning reveals that his father has moderate Crohn disease (age of onset, 29 years), his sister has celiac disease, and the patient is of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. His body temperature is 100.2 °F. Vitamin B12, serum iron, total iron binding capacity, calcium, and magnesium are low. Stool cultures are negative. Ileocolonoscopy shows small aphthous erosions in the large intestine and in the terminal ileum.

Severe pulsing headache

On the basis of the patient's presentation and described history, the likely diagnosis is migraine. By adolescence, migraine is much more common among female patients and can be connected to the menstrual cycle. The early symptoms before onset of head pain reported by this patient characterize the prodromal phase, which can occur 1-2 days before the headache, followed by the aura phase. Approximately one third of patients with migraine experience episodes with aura, like the visual disturbance described in this case.

Migraine can be diagnosed on a clinical basis, but certain neurologic symptoms with headache should be considered red flags and prompt further workup (ie, stiff neck or fever, or history of head injury or major trauma). Spontaneous internal carotid artery dissection, for example, should be investigated in the differential of younger patients who have severe headache before onset of neurologic symptoms. Patients who present with migraine are very frequently misdiagnosed as having sinus headaches or sinusitis. Relevant clinical findings of acute sinusitis are sinus tenderness or pressure; pain over the cheek which radiates to the frontal region or teeth; redness of nose, cheeks, or eyelids; pain to the vertex, temple, or occiput; postnasal discharge; a blocked nose; coughing or pharyngeal irritation; facial pain; and hyposmia. Tension-type headaches usually are associated with mild or moderate bilateral pain, causing a steady ache as opposed to the throbbing of migraines. Basilar migraine, common among female patients, is marked by vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

The American Headache Society defines migraine by the occurrence of at least five episodes. These attacks must last 4-72 hours and have at least two of these four characteristics: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe pain intensity, and aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity. During these episodes, the patient must experience either photophobia and phonophobia or nausea and/or vomiting. If these signs and symptoms cannot be explained by another diagnosis, the patient is very likely presenting with migraine.

Identifying an effective treatment for migraines is often associated with a trial-and-error period, with an average 4-year gap between diagnosis and initiation of preventive medications. Because the patient's migraines do not seem to respond to non-steroidal anti inflammatory drugs, she may be a candidate for other treatments of mild-to-moderate migraines: nonopioid analgesics, acetaminophen, or caffeinated analgesic combinations. If attacks are moderate or severe, or even mild to moderate but do not respond well to therapy, migraine-specific agents are recommended: triptans, dihydroergotamine (DHE), small-molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists (gepants), and selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonists (ditans).

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, Headache Fellow, Department of Neurology, Harvard University, John R. Graham Headache Center, Mass General Brigham, Boston, MA

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient's presentation and described history, the likely diagnosis is migraine. By adolescence, migraine is much more common among female patients and can be connected to the menstrual cycle. The early symptoms before onset of head pain reported by this patient characterize the prodromal phase, which can occur 1-2 days before the headache, followed by the aura phase. Approximately one third of patients with migraine experience episodes with aura, like the visual disturbance described in this case.

Migraine can be diagnosed on a clinical basis, but certain neurologic symptoms with headache should be considered red flags and prompt further workup (ie, stiff neck or fever, or history of head injury or major trauma). Spontaneous internal carotid artery dissection, for example, should be investigated in the differential of younger patients who have severe headache before onset of neurologic symptoms. Patients who present with migraine are very frequently misdiagnosed as having sinus headaches or sinusitis. Relevant clinical findings of acute sinusitis are sinus tenderness or pressure; pain over the cheek which radiates to the frontal region or teeth; redness of nose, cheeks, or eyelids; pain to the vertex, temple, or occiput; postnasal discharge; a blocked nose; coughing or pharyngeal irritation; facial pain; and hyposmia. Tension-type headaches usually are associated with mild or moderate bilateral pain, causing a steady ache as opposed to the throbbing of migraines. Basilar migraine, common among female patients, is marked by vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

The American Headache Society defines migraine by the occurrence of at least five episodes. These attacks must last 4-72 hours and have at least two of these four characteristics: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe pain intensity, and aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity. During these episodes, the patient must experience either photophobia and phonophobia or nausea and/or vomiting. If these signs and symptoms cannot be explained by another diagnosis, the patient is very likely presenting with migraine.

Identifying an effective treatment for migraines is often associated with a trial-and-error period, with an average 4-year gap between diagnosis and initiation of preventive medications. Because the patient's migraines do not seem to respond to non-steroidal anti inflammatory drugs, she may be a candidate for other treatments of mild-to-moderate migraines: nonopioid analgesics, acetaminophen, or caffeinated analgesic combinations. If attacks are moderate or severe, or even mild to moderate but do not respond well to therapy, migraine-specific agents are recommended: triptans, dihydroergotamine (DHE), small-molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists (gepants), and selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonists (ditans).

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, Headache Fellow, Department of Neurology, Harvard University, John R. Graham Headache Center, Mass General Brigham, Boston, MA

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient's presentation and described history, the likely diagnosis is migraine. By adolescence, migraine is much more common among female patients and can be connected to the menstrual cycle. The early symptoms before onset of head pain reported by this patient characterize the prodromal phase, which can occur 1-2 days before the headache, followed by the aura phase. Approximately one third of patients with migraine experience episodes with aura, like the visual disturbance described in this case.

Migraine can be diagnosed on a clinical basis, but certain neurologic symptoms with headache should be considered red flags and prompt further workup (ie, stiff neck or fever, or history of head injury or major trauma). Spontaneous internal carotid artery dissection, for example, should be investigated in the differential of younger patients who have severe headache before onset of neurologic symptoms. Patients who present with migraine are very frequently misdiagnosed as having sinus headaches or sinusitis. Relevant clinical findings of acute sinusitis are sinus tenderness or pressure; pain over the cheek which radiates to the frontal region or teeth; redness of nose, cheeks, or eyelids; pain to the vertex, temple, or occiput; postnasal discharge; a blocked nose; coughing or pharyngeal irritation; facial pain; and hyposmia. Tension-type headaches usually are associated with mild or moderate bilateral pain, causing a steady ache as opposed to the throbbing of migraines. Basilar migraine, common among female patients, is marked by vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

The American Headache Society defines migraine by the occurrence of at least five episodes. These attacks must last 4-72 hours and have at least two of these four characteristics: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe pain intensity, and aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity. During these episodes, the patient must experience either photophobia and phonophobia or nausea and/or vomiting. If these signs and symptoms cannot be explained by another diagnosis, the patient is very likely presenting with migraine.

Identifying an effective treatment for migraines is often associated with a trial-and-error period, with an average 4-year gap between diagnosis and initiation of preventive medications. Because the patient's migraines do not seem to respond to non-steroidal anti inflammatory drugs, she may be a candidate for other treatments of mild-to-moderate migraines: nonopioid analgesics, acetaminophen, or caffeinated analgesic combinations. If attacks are moderate or severe, or even mild to moderate but do not respond well to therapy, migraine-specific agents are recommended: triptans, dihydroergotamine (DHE), small-molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists (gepants), and selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonists (ditans).

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, Headache Fellow, Department of Neurology, Harvard University, John R. Graham Headache Center, Mass General Brigham, Boston, MA

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

An 18-year-old female patient presents with severe pulsing headache that began about 6 hours earlier. She describes feeling tired and irritable for the past 2 days and that she has had difficulty concentrating. Earlier in the day, before headache onset, she became extremely fatigued. Describing a "blinding light" in her vision, she is currently highly photophobic. The patient took four ibuprofen 2 hours ago. There is no significant medical history. She is on a regimen of estrogen-progestin and spironolactone for acne. Following advice from her primary care practitioner, she takes magnesium and vitamin B for headache prevention. The patient reports that she does not believe that she has migraines because she has never vomited during an episode. The patient explains that she has always had frequent headaches but that this is the sixth or seventh episode of this type and severity that she has had in the past year. The headaches do not seem to align with her menstrual cycle.

Atypical Localized Scleroderma Development During Nivolumab Therapy for Metastatic Lung Adenocarcinoma

To the Editor:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (anti–PD-1) and anticytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4 therapies are a promising class of cancer therapeutics. However, they are associated with a variety of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including cutaneous toxicity.1 The PD-1/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway is important for the maintenance of immune tolerance, and a blockade has been shown to lead to development of various autoimmune diseases.2 We present the case of a patient who developed new-onset localized scleroderma during treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab.

A 65-year-old woman presented with a rash on the left thigh that was associated with pruritus, pain, and a pulling sensation. She had a history of stage IV lung adenocarcinoma, with a mass in the right upper lobe with metastatic foci to the left femur, right humerus, right hilar, and pretracheal lymph nodes. She received palliative radiation to the left femur and was started on carboplatin and pemetrexed. Metastasis to the liver was noted after completion of 6 cycles of therapy, and the patient’s treatment was changed to nivolumab. After 17 months on nivolumab therapy (2 years after initial diagnosis and 20 months after radiation therapy), she presented to our dermatology clinic with a cutaneous eruption on the buttocks that spread to the left thigh. The rash failed to improve after 1 month of treatment with emollients and triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

At the current presentation, which was 2 months after she initially presented to our clinic, dermatologic examination revealed erythematous and sclerotic plaques on the left lateral thigh (Figure 1A). Betamethasone cream 0.05% was prescribed, and nivolumab was discontinued due to progression of cutaneous symptoms. A punch biopsy from the left thigh demonstrated superficial dermal sclerosis that was suggestive of chronic radiation dermatitis; direct immunofluorescence testing was negative. The patient was started on prednisone 50 mg daily, which resulted in mild improvement in symptoms.

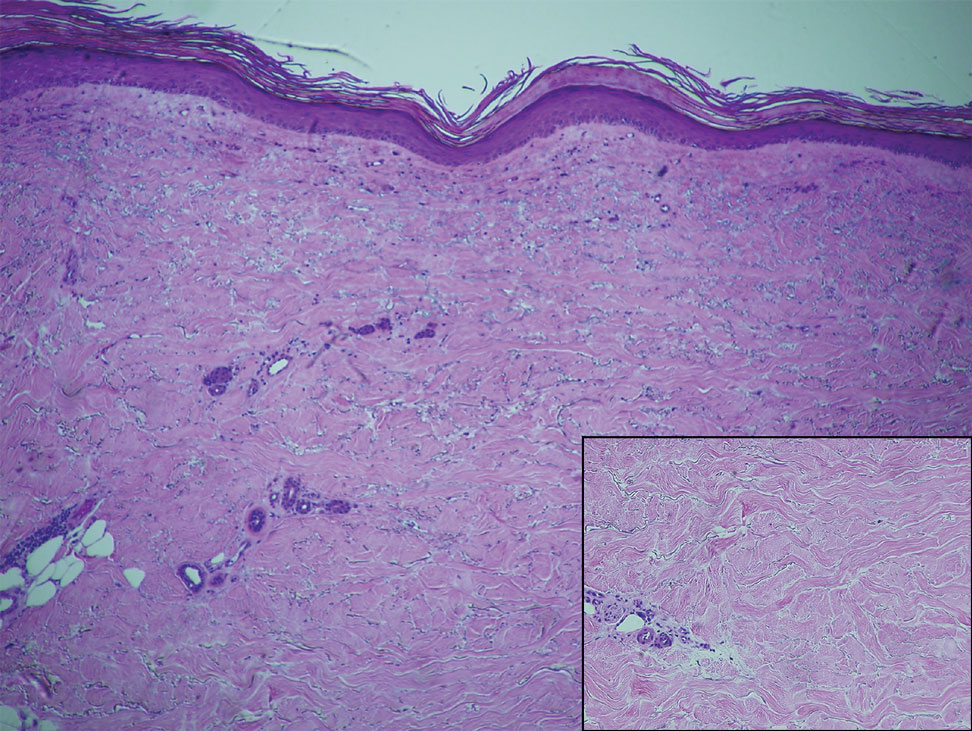

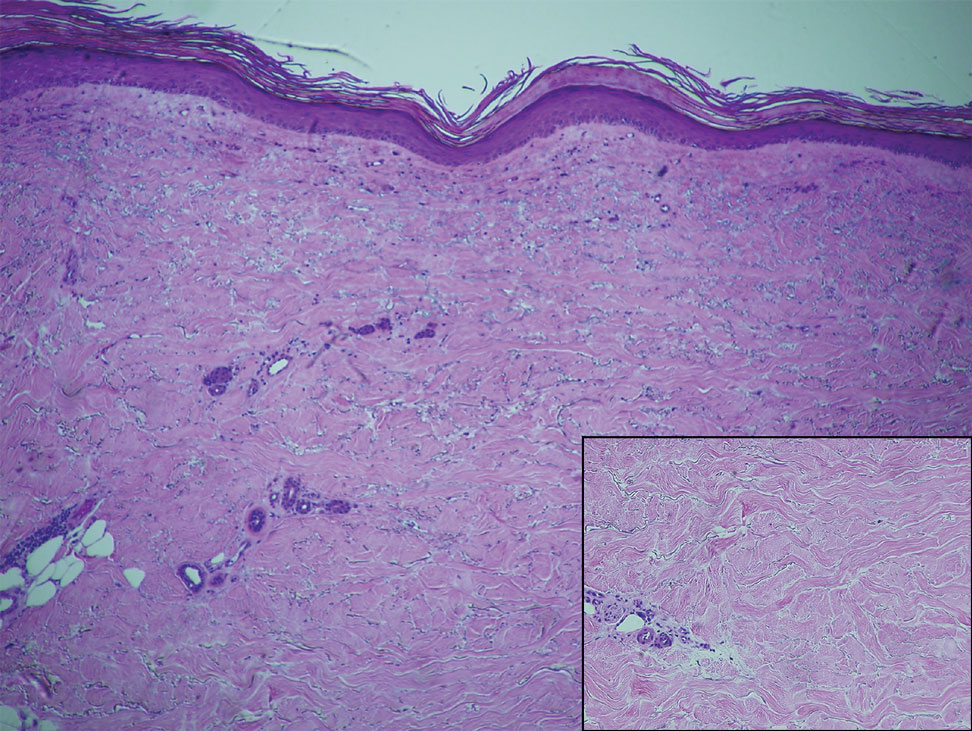

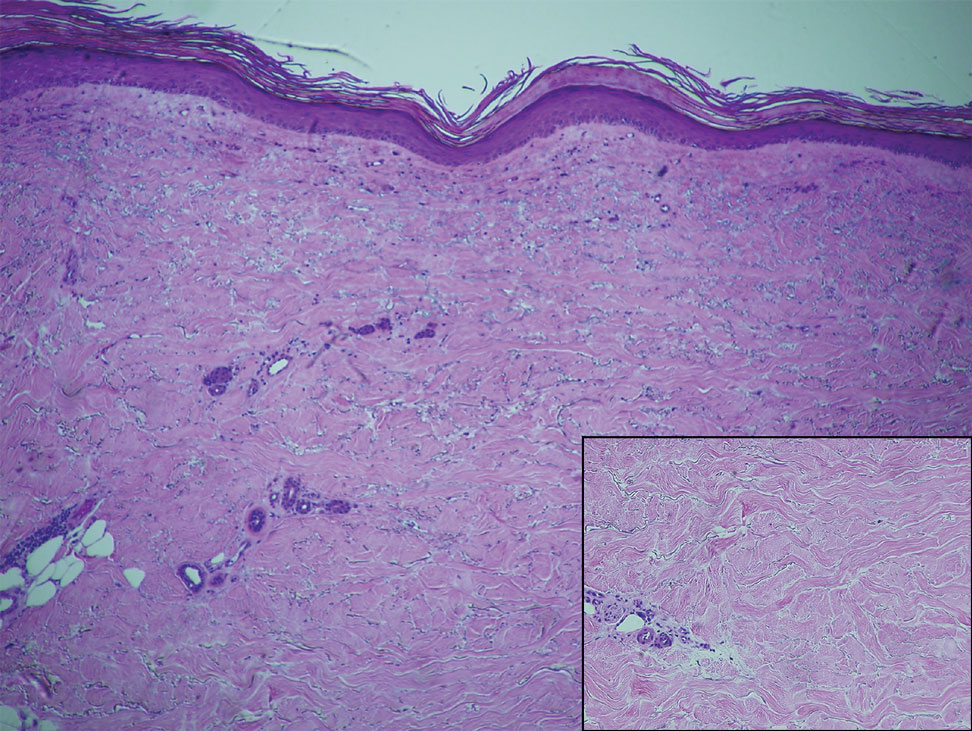

Within 6 months, new sclerotic plaques developed on the patient’s back and right thigh (Figure 1B). Because the lesions were located outside the radiation field of the left femur, a second biopsy was obtained from the right thigh. Histopathology revealed extensive dermal sclerosis and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). An antinuclear antibody test was weakly positive (1:40, nucleolar pattern) with a negative extractable nuclear antigen panel result. Anti–double-stranded DNA, anti–topoisomerase 1, anti-Smith, antiribonucleoprotein, anti–Sjögren syndrome type A, anti–Sjögren syndrome type B, and anticentromere serology test results were negative. The patient denied decreased oral aperture, difficulty swallowing, or Raynaud phenomenon. Due to the atypical clinical presentation in the setting of PD-1 inhibitor therapy, the etiology of the eruption was potentially attributable to nivolumab. She was started on treatment with methotrexate 20 mg weekly and clobetasol cream 0.05% twice daily; she continued taking prednisone 5 mg daily. The cutaneous manifestations on the patient’s back completely resolved, and the legs continued to gradually improve on this regimen. Immunotherapy continued to be held due to skin toxicity.

Localized scleroderma is an autoimmune disorder characterized by inflammation and skin thickening. Overactive fibroblasts produce excess collagen, leading to the clinical symptoms of skin thickening, hardening, and discoloration.3 Lesions frequently develop on the arms, face, or legs and can present as patches or linear bands. Unlike systemic sclerosis, the internal organs typically are uninvolved; however, sclerotic lesions can be disfiguring and cause notable disability if they impede joint movement.

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is a negative regulator of the immune response that inactivates T cells and helps maintain self-tolerance. Modulation of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and overexpression of PD-L1 are seen in various cancers as a mechanism to help malignant cells avoid immune destruction.4 Conversely, inhibition of this pathway can be used to stimulate an antitumor immune response. This checkpoint inhibition strategy has been highly successful for the treatment of various cancers including melanoma and non–small cell lung carcinoma. There are several checkpoint inhibitors approved in the United States that are used for cancer therapy and target the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.4 A downside of checkpoint inhibitor treatment is that uncontrolled T-cell activation can lead to irAEs, including cutaneous eruptions, pruritus, diarrhea, colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies, pneumonitis, and renal insufficiency.5 These toxicities are reversible if treated appropriately but can cause notable morbidity and mortality if left unrecognized. Cutaneous eruption is one of the most common irAEs associated with anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1 therapies and can limit therapeutic efficacy, as the drug may need to be held or discontinued due to the severity of the eruption.6 Mid-potency to high-potency topical corticosteroids and systemic antihistamines are first-line treatments of grades 1 and 2 skin toxicities associated with PD-1 inhibitor therapy. For eruptions classified as grades 3 or 4 or refractory grade 2, discontinuation of the drug and systemic corticosteroids is recommended.7

The cutaneous eruption in immunotherapy-mediated dermatitis is thought to be largely mediated by activated T cells infiltrating the dermis.8 In localized scleroderma, increased tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IFN-γ–induced protein 10, and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor activity have been shown to correlate with disease activity.9,10 Interestingly, increased tumor necrosis factor α and IFN-γ correlate with better response and increased overall survival in PD-1 inhibition therapy, suggesting a correlation between PD-1 inhibition and T helper activation as noted by the etiology of sclerosis in our patient.11 Additionally, history of radiation was a confounding factor in the diagnosis of our patient, as both sclerodermoid reactions and chronic radiation dermatitis can present with dermal sclerosis. However, the progression of disease outside of the radiation field excluded this etiology. Although new-onset sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, they have been described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions from treatment with pembrolizumab.12,13 One case series reported a case of diffuse sclerodermoid reaction and a limited reaction in response to pembrolizumab treatment, while another case report described a relapse of generalized morphea in response to pembrolizumab treatment.12,13 One case of relapsing morphea in response to nivolumab treatment for stage IV lung adenocarcinoma also has been reported.14

Cutaneous toxicities are one of the most common irAEs associated with checkpoint inhibitors and are seen in more than one-third of treated patients. Most frequently, these irAEs manifest as spongiotic dermatitis on histopathology, but a broad spectrum of cutaneous reactions have been observed.15 Although sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, most are described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions with pembrolizumab and involve relapse of previously diagnosed morphea rather than new-onset disease.12-14

Our case highlights new-onset localized scleroderma in the setting of nivolumab therapy that showed clinical improvement with methotrexate and topical and systemic steroids. This reaction pattern should be considered in all patients who develop cutaneous eruptions when treated with a PD-1 inhibitor. There should be a high index of suspicion for the potential occurrence of irAEs to ensure early recognition and treatment to minimize morbidity and maximize adherence to therapy for the underlying malignancy.

- Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018;360:k793.

- Dai S, Jia R, Zhang X, et al. The PD-1/PD-Ls pathway and autoimmune diseases. Cell Immunol. 2014;290:72-79.

- Badea I, Taylor M, Rosenberg A, et al. Pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches for improved topical treatment in localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:213-221.

- Constantinidou A, Alifieris C, Trafalis DT. Targeting programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and ligand (PD-L1): a new era in cancer active immunotherapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;194:84-106.

- Villadolid J, Asim A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice: update on management of immune-related toxicities. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:560-575.

- Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1362.

- O’Kane GM, Labbé C, Doherty MK, et al. Monitoring and management of immune-related adverse events associated with programmed cell death protein-1 axis inhibitors in lung cancer. Oncologist. 2017;22:70-80.

- Shi VJ, Rodic N, Gettinger S, et al. Clinical and histologic features of lichenoid mucocutaneous eruptions due to anti-programmed celldeath 1 and anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 immunotherapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1128-1136.

- Torok KS, Kurzinski K, Kelsey C, et al. Peripheral blood cytokine and chemokine profiles in juvenile localized scleroderma: T-helper cell-associated cytokine profiles. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;45:284-293.

- Guo X, Higgs BW, Bay-Jensen AC, et al. Suppression of T cell activation and collagen accumulation by an anti-IFNAR1 mAb, anifrolumab, in adult patients with systemic sclerosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2402-2409.

- Boutsikou E, Domvri K, Hardavella G, et al. Tumor necrosis factor, interferon-gamma and interleukins as predictive markers of antiprogrammed cell-death protein-1 treatment in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a pragmatic approach in clinical practice. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1758835918768238.

- Barbosa NS, Wetter DA, Wieland CN, et al. Scleroderma induced by pembrolizumab: a case series. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1158-1163.

- Cheng MW, Hisaw LD, Bernet L. Generalized morphea in the setting of pembrolizumab. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:736-738.

- Alegre-Sánchez A, Fonda-Pascual P, Saceda-Corralo D, et al. Relapse of morphea during nivolumab therapy for lung adenocarcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:69-70.

- Sibaud V. Dermatologic reactions to immune checkpoint inhibitors: skin toxicities and immunotherapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:345-361.

To the Editor:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (anti–PD-1) and anticytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4 therapies are a promising class of cancer therapeutics. However, they are associated with a variety of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including cutaneous toxicity.1 The PD-1/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway is important for the maintenance of immune tolerance, and a blockade has been shown to lead to development of various autoimmune diseases.2 We present the case of a patient who developed new-onset localized scleroderma during treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab.

A 65-year-old woman presented with a rash on the left thigh that was associated with pruritus, pain, and a pulling sensation. She had a history of stage IV lung adenocarcinoma, with a mass in the right upper lobe with metastatic foci to the left femur, right humerus, right hilar, and pretracheal lymph nodes. She received palliative radiation to the left femur and was started on carboplatin and pemetrexed. Metastasis to the liver was noted after completion of 6 cycles of therapy, and the patient’s treatment was changed to nivolumab. After 17 months on nivolumab therapy (2 years after initial diagnosis and 20 months after radiation therapy), she presented to our dermatology clinic with a cutaneous eruption on the buttocks that spread to the left thigh. The rash failed to improve after 1 month of treatment with emollients and triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

At the current presentation, which was 2 months after she initially presented to our clinic, dermatologic examination revealed erythematous and sclerotic plaques on the left lateral thigh (Figure 1A). Betamethasone cream 0.05% was prescribed, and nivolumab was discontinued due to progression of cutaneous symptoms. A punch biopsy from the left thigh demonstrated superficial dermal sclerosis that was suggestive of chronic radiation dermatitis; direct immunofluorescence testing was negative. The patient was started on prednisone 50 mg daily, which resulted in mild improvement in symptoms.

Within 6 months, new sclerotic plaques developed on the patient’s back and right thigh (Figure 1B). Because the lesions were located outside the radiation field of the left femur, a second biopsy was obtained from the right thigh. Histopathology revealed extensive dermal sclerosis and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). An antinuclear antibody test was weakly positive (1:40, nucleolar pattern) with a negative extractable nuclear antigen panel result. Anti–double-stranded DNA, anti–topoisomerase 1, anti-Smith, antiribonucleoprotein, anti–Sjögren syndrome type A, anti–Sjögren syndrome type B, and anticentromere serology test results were negative. The patient denied decreased oral aperture, difficulty swallowing, or Raynaud phenomenon. Due to the atypical clinical presentation in the setting of PD-1 inhibitor therapy, the etiology of the eruption was potentially attributable to nivolumab. She was started on treatment with methotrexate 20 mg weekly and clobetasol cream 0.05% twice daily; she continued taking prednisone 5 mg daily. The cutaneous manifestations on the patient’s back completely resolved, and the legs continued to gradually improve on this regimen. Immunotherapy continued to be held due to skin toxicity.

Localized scleroderma is an autoimmune disorder characterized by inflammation and skin thickening. Overactive fibroblasts produce excess collagen, leading to the clinical symptoms of skin thickening, hardening, and discoloration.3 Lesions frequently develop on the arms, face, or legs and can present as patches or linear bands. Unlike systemic sclerosis, the internal organs typically are uninvolved; however, sclerotic lesions can be disfiguring and cause notable disability if they impede joint movement.

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is a negative regulator of the immune response that inactivates T cells and helps maintain self-tolerance. Modulation of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and overexpression of PD-L1 are seen in various cancers as a mechanism to help malignant cells avoid immune destruction.4 Conversely, inhibition of this pathway can be used to stimulate an antitumor immune response. This checkpoint inhibition strategy has been highly successful for the treatment of various cancers including melanoma and non–small cell lung carcinoma. There are several checkpoint inhibitors approved in the United States that are used for cancer therapy and target the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.4 A downside of checkpoint inhibitor treatment is that uncontrolled T-cell activation can lead to irAEs, including cutaneous eruptions, pruritus, diarrhea, colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies, pneumonitis, and renal insufficiency.5 These toxicities are reversible if treated appropriately but can cause notable morbidity and mortality if left unrecognized. Cutaneous eruption is one of the most common irAEs associated with anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1 therapies and can limit therapeutic efficacy, as the drug may need to be held or discontinued due to the severity of the eruption.6 Mid-potency to high-potency topical corticosteroids and systemic antihistamines are first-line treatments of grades 1 and 2 skin toxicities associated with PD-1 inhibitor therapy. For eruptions classified as grades 3 or 4 or refractory grade 2, discontinuation of the drug and systemic corticosteroids is recommended.7

The cutaneous eruption in immunotherapy-mediated dermatitis is thought to be largely mediated by activated T cells infiltrating the dermis.8 In localized scleroderma, increased tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IFN-γ–induced protein 10, and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor activity have been shown to correlate with disease activity.9,10 Interestingly, increased tumor necrosis factor α and IFN-γ correlate with better response and increased overall survival in PD-1 inhibition therapy, suggesting a correlation between PD-1 inhibition and T helper activation as noted by the etiology of sclerosis in our patient.11 Additionally, history of radiation was a confounding factor in the diagnosis of our patient, as both sclerodermoid reactions and chronic radiation dermatitis can present with dermal sclerosis. However, the progression of disease outside of the radiation field excluded this etiology. Although new-onset sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, they have been described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions from treatment with pembrolizumab.12,13 One case series reported a case of diffuse sclerodermoid reaction and a limited reaction in response to pembrolizumab treatment, while another case report described a relapse of generalized morphea in response to pembrolizumab treatment.12,13 One case of relapsing morphea in response to nivolumab treatment for stage IV lung adenocarcinoma also has been reported.14

Cutaneous toxicities are one of the most common irAEs associated with checkpoint inhibitors and are seen in more than one-third of treated patients. Most frequently, these irAEs manifest as spongiotic dermatitis on histopathology, but a broad spectrum of cutaneous reactions have been observed.15 Although sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, most are described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions with pembrolizumab and involve relapse of previously diagnosed morphea rather than new-onset disease.12-14

Our case highlights new-onset localized scleroderma in the setting of nivolumab therapy that showed clinical improvement with methotrexate and topical and systemic steroids. This reaction pattern should be considered in all patients who develop cutaneous eruptions when treated with a PD-1 inhibitor. There should be a high index of suspicion for the potential occurrence of irAEs to ensure early recognition and treatment to minimize morbidity and maximize adherence to therapy for the underlying malignancy.

To the Editor:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (anti–PD-1) and anticytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4 therapies are a promising class of cancer therapeutics. However, they are associated with a variety of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including cutaneous toxicity.1 The PD-1/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway is important for the maintenance of immune tolerance, and a blockade has been shown to lead to development of various autoimmune diseases.2 We present the case of a patient who developed new-onset localized scleroderma during treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab.

A 65-year-old woman presented with a rash on the left thigh that was associated with pruritus, pain, and a pulling sensation. She had a history of stage IV lung adenocarcinoma, with a mass in the right upper lobe with metastatic foci to the left femur, right humerus, right hilar, and pretracheal lymph nodes. She received palliative radiation to the left femur and was started on carboplatin and pemetrexed. Metastasis to the liver was noted after completion of 6 cycles of therapy, and the patient’s treatment was changed to nivolumab. After 17 months on nivolumab therapy (2 years after initial diagnosis and 20 months after radiation therapy), she presented to our dermatology clinic with a cutaneous eruption on the buttocks that spread to the left thigh. The rash failed to improve after 1 month of treatment with emollients and triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

At the current presentation, which was 2 months after she initially presented to our clinic, dermatologic examination revealed erythematous and sclerotic plaques on the left lateral thigh (Figure 1A). Betamethasone cream 0.05% was prescribed, and nivolumab was discontinued due to progression of cutaneous symptoms. A punch biopsy from the left thigh demonstrated superficial dermal sclerosis that was suggestive of chronic radiation dermatitis; direct immunofluorescence testing was negative. The patient was started on prednisone 50 mg daily, which resulted in mild improvement in symptoms.

Within 6 months, new sclerotic plaques developed on the patient’s back and right thigh (Figure 1B). Because the lesions were located outside the radiation field of the left femur, a second biopsy was obtained from the right thigh. Histopathology revealed extensive dermal sclerosis and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). An antinuclear antibody test was weakly positive (1:40, nucleolar pattern) with a negative extractable nuclear antigen panel result. Anti–double-stranded DNA, anti–topoisomerase 1, anti-Smith, antiribonucleoprotein, anti–Sjögren syndrome type A, anti–Sjögren syndrome type B, and anticentromere serology test results were negative. The patient denied decreased oral aperture, difficulty swallowing, or Raynaud phenomenon. Due to the atypical clinical presentation in the setting of PD-1 inhibitor therapy, the etiology of the eruption was potentially attributable to nivolumab. She was started on treatment with methotrexate 20 mg weekly and clobetasol cream 0.05% twice daily; she continued taking prednisone 5 mg daily. The cutaneous manifestations on the patient’s back completely resolved, and the legs continued to gradually improve on this regimen. Immunotherapy continued to be held due to skin toxicity.

Localized scleroderma is an autoimmune disorder characterized by inflammation and skin thickening. Overactive fibroblasts produce excess collagen, leading to the clinical symptoms of skin thickening, hardening, and discoloration.3 Lesions frequently develop on the arms, face, or legs and can present as patches or linear bands. Unlike systemic sclerosis, the internal organs typically are uninvolved; however, sclerotic lesions can be disfiguring and cause notable disability if they impede joint movement.

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is a negative regulator of the immune response that inactivates T cells and helps maintain self-tolerance. Modulation of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and overexpression of PD-L1 are seen in various cancers as a mechanism to help malignant cells avoid immune destruction.4 Conversely, inhibition of this pathway can be used to stimulate an antitumor immune response. This checkpoint inhibition strategy has been highly successful for the treatment of various cancers including melanoma and non–small cell lung carcinoma. There are several checkpoint inhibitors approved in the United States that are used for cancer therapy and target the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.4 A downside of checkpoint inhibitor treatment is that uncontrolled T-cell activation can lead to irAEs, including cutaneous eruptions, pruritus, diarrhea, colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies, pneumonitis, and renal insufficiency.5 These toxicities are reversible if treated appropriately but can cause notable morbidity and mortality if left unrecognized. Cutaneous eruption is one of the most common irAEs associated with anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1 therapies and can limit therapeutic efficacy, as the drug may need to be held or discontinued due to the severity of the eruption.6 Mid-potency to high-potency topical corticosteroids and systemic antihistamines are first-line treatments of grades 1 and 2 skin toxicities associated with PD-1 inhibitor therapy. For eruptions classified as grades 3 or 4 or refractory grade 2, discontinuation of the drug and systemic corticosteroids is recommended.7

The cutaneous eruption in immunotherapy-mediated dermatitis is thought to be largely mediated by activated T cells infiltrating the dermis.8 In localized scleroderma, increased tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IFN-γ–induced protein 10, and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor activity have been shown to correlate with disease activity.9,10 Interestingly, increased tumor necrosis factor α and IFN-γ correlate with better response and increased overall survival in PD-1 inhibition therapy, suggesting a correlation between PD-1 inhibition and T helper activation as noted by the etiology of sclerosis in our patient.11 Additionally, history of radiation was a confounding factor in the diagnosis of our patient, as both sclerodermoid reactions and chronic radiation dermatitis can present with dermal sclerosis. However, the progression of disease outside of the radiation field excluded this etiology. Although new-onset sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, they have been described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions from treatment with pembrolizumab.12,13 One case series reported a case of diffuse sclerodermoid reaction and a limited reaction in response to pembrolizumab treatment, while another case report described a relapse of generalized morphea in response to pembrolizumab treatment.12,13 One case of relapsing morphea in response to nivolumab treatment for stage IV lung adenocarcinoma also has been reported.14

Cutaneous toxicities are one of the most common irAEs associated with checkpoint inhibitors and are seen in more than one-third of treated patients. Most frequently, these irAEs manifest as spongiotic dermatitis on histopathology, but a broad spectrum of cutaneous reactions have been observed.15 Although sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, most are described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions with pembrolizumab and involve relapse of previously diagnosed morphea rather than new-onset disease.12-14

Our case highlights new-onset localized scleroderma in the setting of nivolumab therapy that showed clinical improvement with methotrexate and topical and systemic steroids. This reaction pattern should be considered in all patients who develop cutaneous eruptions when treated with a PD-1 inhibitor. There should be a high index of suspicion for the potential occurrence of irAEs to ensure early recognition and treatment to minimize morbidity and maximize adherence to therapy for the underlying malignancy.

- Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018;360:k793.

- Dai S, Jia R, Zhang X, et al. The PD-1/PD-Ls pathway and autoimmune diseases. Cell Immunol. 2014;290:72-79.

- Badea I, Taylor M, Rosenberg A, et al. Pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches for improved topical treatment in localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:213-221.

- Constantinidou A, Alifieris C, Trafalis DT. Targeting programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and ligand (PD-L1): a new era in cancer active immunotherapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;194:84-106.

- Villadolid J, Asim A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice: update on management of immune-related toxicities. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:560-575.

- Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1362.

- O’Kane GM, Labbé C, Doherty MK, et al. Monitoring and management of immune-related adverse events associated with programmed cell death protein-1 axis inhibitors in lung cancer. Oncologist. 2017;22:70-80.