User login

Brain Cancer: Epidemiology, TBI, and New Treatments

Brain Cancer: Epidemiology, TBI, and New Treatments

Click to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

- Bihn JR, Cioffi G, Waite KA, et al. Brain tumors in United States military veterans.

Neuro Oncol. 2024;26(2):387-396. doi:10.1093/neuonc/noad182 - Stewart IJ, Howard JT, Poltavsky E, et al. Traumatic Brain Injury and Subsequent

Risk of Brain Cancer in US Veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars. JAMA Netw

Open. 2024;7(2):e2354588. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.54588 - DoD/USU Brain Tissue Repository. December 15, 2023. Accessed December 11,

2024. https://researchbraininjury.org/ - Munch TN, Gørtz S, Wohlfahrt J, Melbye M. The long-term risk of malignant

astrocytic tumors after structural brain injury--a nationwide cohort study. Neuro

Oncol. 2015;17(5):718-724. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nou312 - Strowd RE, Dunbar EM, Gan HK, et al. Practical guidance for telemedicine use in

neuro-oncology. Neurooncol Pract. 2022;9(2):91-104. doi:10.1093/nop/npac002 - Parikh DA, Rodgers TD, Passero VA, et al. Teleoncology in the Veterans Health

Administration: Models of Care and the Veteran Experience. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ

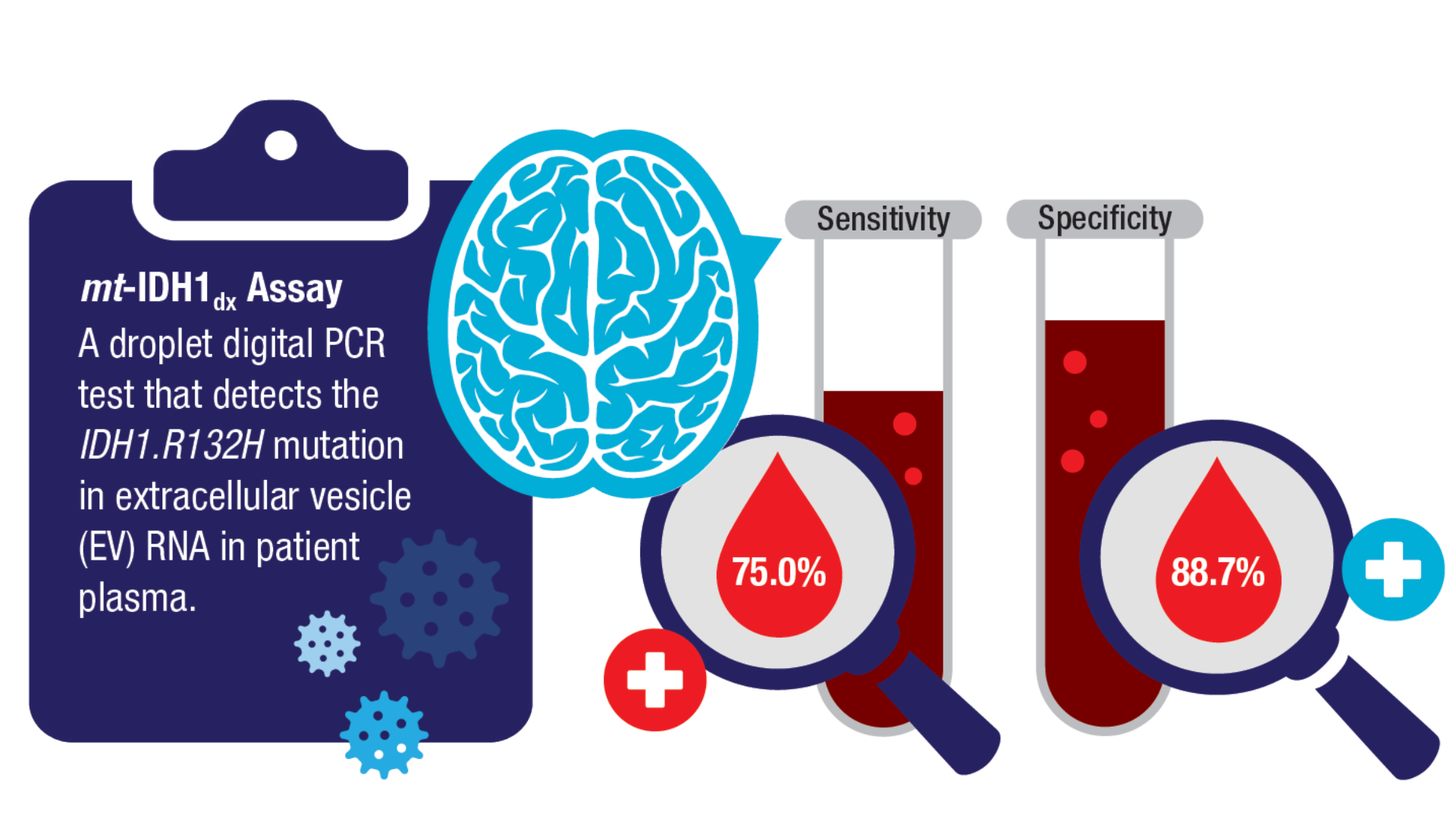

Book. 2024;44(e100042. doi:10.1200/EDBK_100042 - Batool SM, Escobedo AK, Hsia T, et al. Clinical utility of a blood based assay for

the detection of IDH1.R132H-mutant gliomas. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):7074.

doi:10.1038/s41467-024-51332-7 - Mellinghoff IK, van den Bent MJ, Blumenthal DT, et al; INDIGO Trial Investigators.

Vorasidenib in IDH1- or IDH2-Mutant Low-Grade Glioma. N Engl J Med.

2023;389(7):589-601. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2304194 - FDA. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves vorasidenib for Grade 2

astrocytoma or oligodendroglioma with a susceptible IDH1 or IDH2 mutation.

Accessed December 11, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resourcesinformation-

approved-drugs/fda-approves-vorasidenib-grade-2-astrocytoma-oroligodendroglioma-

susceptible-idh1-or-idh2-mutation - NIH. National Cancer Institute. Tovorafenib Approved for Some Children with Low-

Grade Glioma. Accessed December 11, 2024. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/

cancer-currents-blog/2024/pediatric-low-grade-glioma-tovorafenib-braf - The Veteran Population. Accessed December 11, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/

docs/surveysandstudies/vetpop.pdf - Miller AM, Szalontay L, Bouvier N, et al. Next-generation sequencing of

cerebrospinal fluid for clinical molecular diagnostics in pediatric, adolescent

and young adult brain tumor patients. Neuro Oncol. 2022;24(10):1763-1772.

doi:10.1093/neuonc/noac035

Click to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

Click to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

- Bihn JR, Cioffi G, Waite KA, et al. Brain tumors in United States military veterans.

Neuro Oncol. 2024;26(2):387-396. doi:10.1093/neuonc/noad182 - Stewart IJ, Howard JT, Poltavsky E, et al. Traumatic Brain Injury and Subsequent

Risk of Brain Cancer in US Veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars. JAMA Netw

Open. 2024;7(2):e2354588. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.54588 - DoD/USU Brain Tissue Repository. December 15, 2023. Accessed December 11,

2024. https://researchbraininjury.org/ - Munch TN, Gørtz S, Wohlfahrt J, Melbye M. The long-term risk of malignant

astrocytic tumors after structural brain injury--a nationwide cohort study. Neuro

Oncol. 2015;17(5):718-724. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nou312 - Strowd RE, Dunbar EM, Gan HK, et al. Practical guidance for telemedicine use in

neuro-oncology. Neurooncol Pract. 2022;9(2):91-104. doi:10.1093/nop/npac002 - Parikh DA, Rodgers TD, Passero VA, et al. Teleoncology in the Veterans Health

Administration: Models of Care and the Veteran Experience. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ

Book. 2024;44(e100042. doi:10.1200/EDBK_100042 - Batool SM, Escobedo AK, Hsia T, et al. Clinical utility of a blood based assay for

the detection of IDH1.R132H-mutant gliomas. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):7074.

doi:10.1038/s41467-024-51332-7 - Mellinghoff IK, van den Bent MJ, Blumenthal DT, et al; INDIGO Trial Investigators.

Vorasidenib in IDH1- or IDH2-Mutant Low-Grade Glioma. N Engl J Med.

2023;389(7):589-601. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2304194 - FDA. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves vorasidenib for Grade 2

astrocytoma or oligodendroglioma with a susceptible IDH1 or IDH2 mutation.

Accessed December 11, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resourcesinformation-

approved-drugs/fda-approves-vorasidenib-grade-2-astrocytoma-oroligodendroglioma-

susceptible-idh1-or-idh2-mutation - NIH. National Cancer Institute. Tovorafenib Approved for Some Children with Low-

Grade Glioma. Accessed December 11, 2024. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/

cancer-currents-blog/2024/pediatric-low-grade-glioma-tovorafenib-braf - The Veteran Population. Accessed December 11, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/

docs/surveysandstudies/vetpop.pdf - Miller AM, Szalontay L, Bouvier N, et al. Next-generation sequencing of

cerebrospinal fluid for clinical molecular diagnostics in pediatric, adolescent

and young adult brain tumor patients. Neuro Oncol. 2022;24(10):1763-1772.

doi:10.1093/neuonc/noac035

- Bihn JR, Cioffi G, Waite KA, et al. Brain tumors in United States military veterans.

Neuro Oncol. 2024;26(2):387-396. doi:10.1093/neuonc/noad182 - Stewart IJ, Howard JT, Poltavsky E, et al. Traumatic Brain Injury and Subsequent

Risk of Brain Cancer in US Veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars. JAMA Netw

Open. 2024;7(2):e2354588. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.54588 - DoD/USU Brain Tissue Repository. December 15, 2023. Accessed December 11,

2024. https://researchbraininjury.org/ - Munch TN, Gørtz S, Wohlfahrt J, Melbye M. The long-term risk of malignant

astrocytic tumors after structural brain injury--a nationwide cohort study. Neuro

Oncol. 2015;17(5):718-724. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nou312 - Strowd RE, Dunbar EM, Gan HK, et al. Practical guidance for telemedicine use in

neuro-oncology. Neurooncol Pract. 2022;9(2):91-104. doi:10.1093/nop/npac002 - Parikh DA, Rodgers TD, Passero VA, et al. Teleoncology in the Veterans Health

Administration: Models of Care and the Veteran Experience. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ

Book. 2024;44(e100042. doi:10.1200/EDBK_100042 - Batool SM, Escobedo AK, Hsia T, et al. Clinical utility of a blood based assay for

the detection of IDH1.R132H-mutant gliomas. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):7074.

doi:10.1038/s41467-024-51332-7 - Mellinghoff IK, van den Bent MJ, Blumenthal DT, et al; INDIGO Trial Investigators.

Vorasidenib in IDH1- or IDH2-Mutant Low-Grade Glioma. N Engl J Med.

2023;389(7):589-601. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2304194 - FDA. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves vorasidenib for Grade 2

astrocytoma or oligodendroglioma with a susceptible IDH1 or IDH2 mutation.

Accessed December 11, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resourcesinformation-

approved-drugs/fda-approves-vorasidenib-grade-2-astrocytoma-oroligodendroglioma-

susceptible-idh1-or-idh2-mutation - NIH. National Cancer Institute. Tovorafenib Approved for Some Children with Low-

Grade Glioma. Accessed December 11, 2024. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/

cancer-currents-blog/2024/pediatric-low-grade-glioma-tovorafenib-braf - The Veteran Population. Accessed December 11, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/

docs/surveysandstudies/vetpop.pdf - Miller AM, Szalontay L, Bouvier N, et al. Next-generation sequencing of

cerebrospinal fluid for clinical molecular diagnostics in pediatric, adolescent

and young adult brain tumor patients. Neuro Oncol. 2022;24(10):1763-1772.

doi:10.1093/neuonc/noac035

Brain Cancer: Epidemiology, TBI, and New Treatments

Brain Cancer: Epidemiology, TBI, and New Treatments

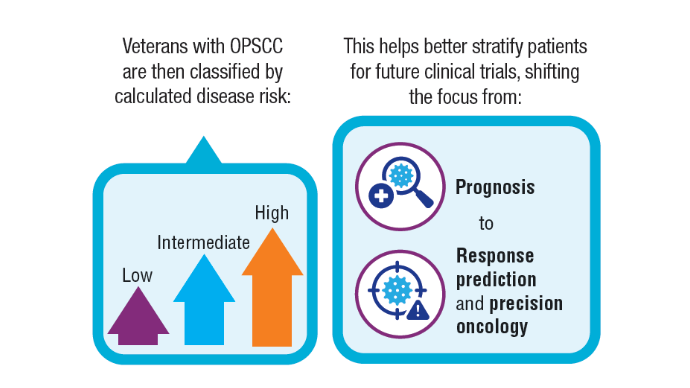

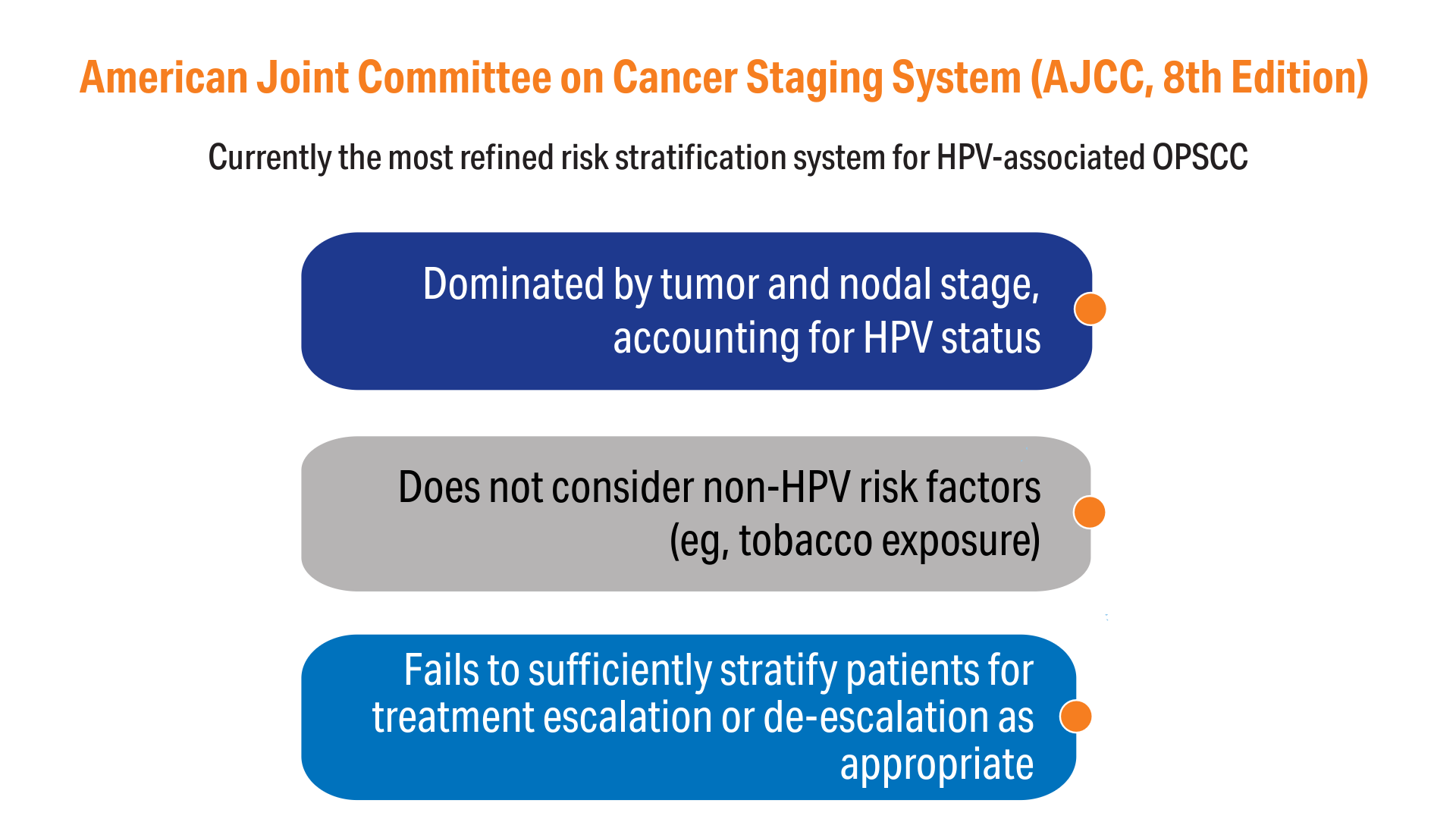

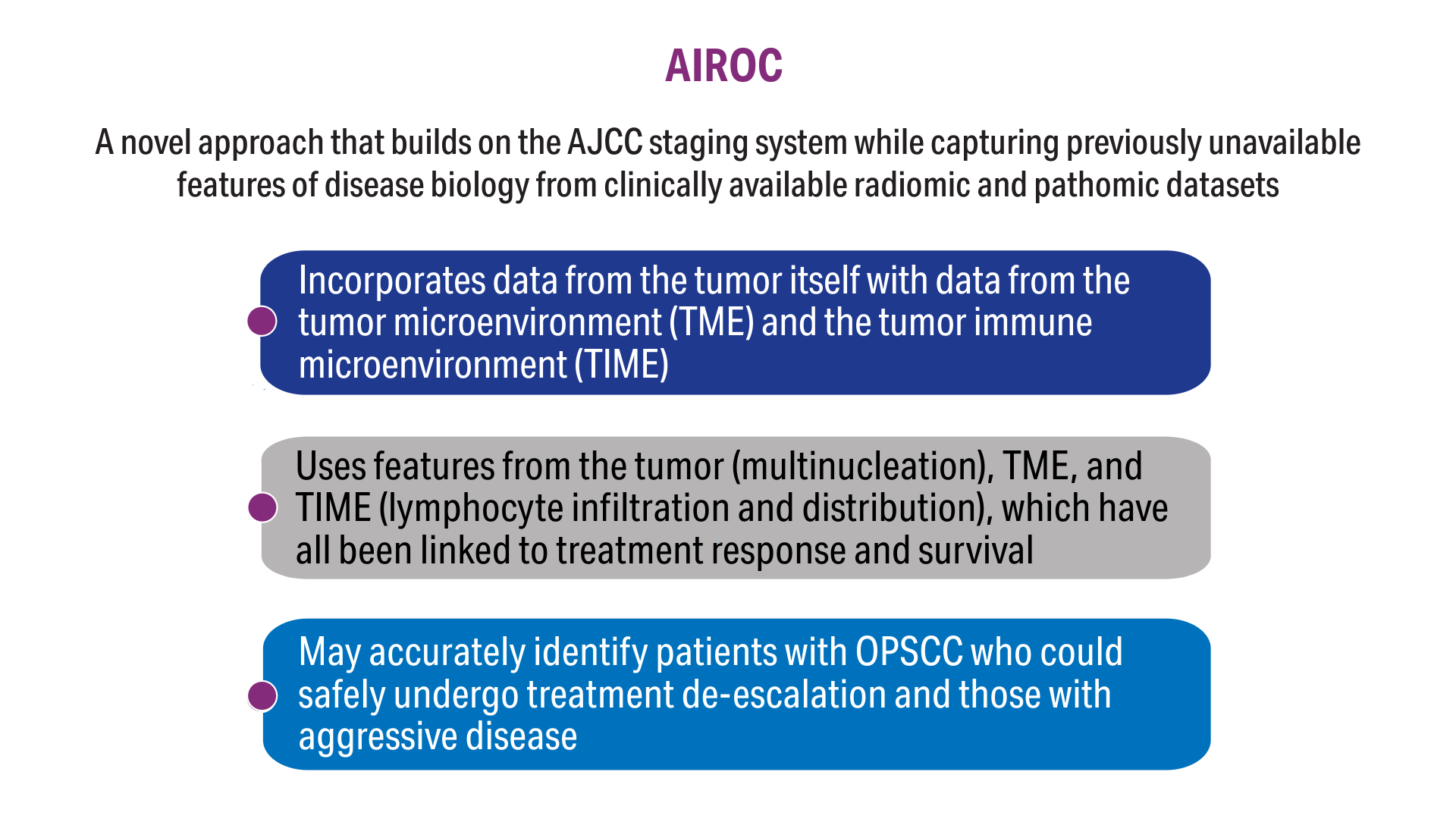

AI-Based Risk Stratification for Oropharyngeal Carcinomas: AIROC

AI-Based Risk Stratification for Oropharyngeal Carcinomas: AIROC

Click here to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

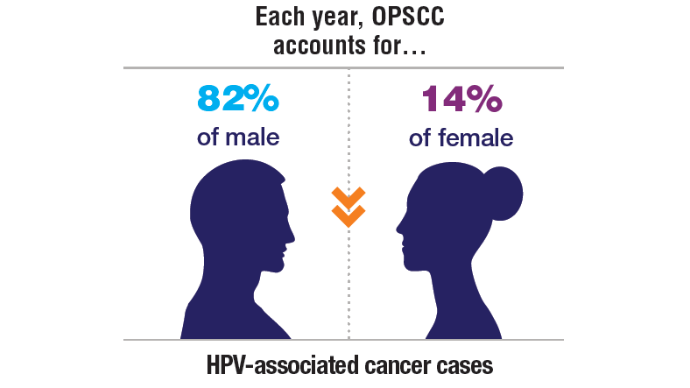

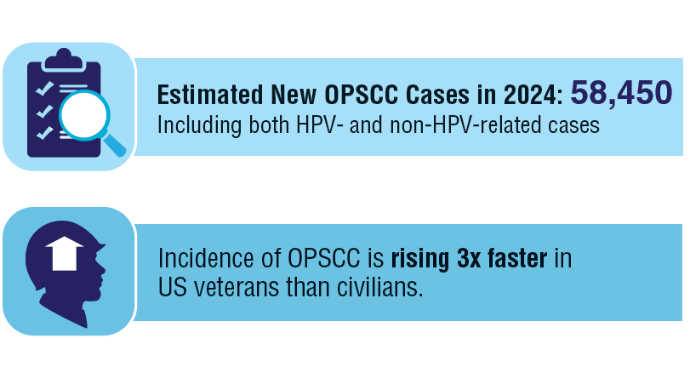

1. Zevallos JP, Kramer JR, Sandulache VC, et al. National trends in oropharyngeal cancer incidence and survival within the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Head Neck. 2021;43(1):108-115. doi:10.1002/hed.26465

2. Fakhry C, Blackford AL, Neuner G, et al. Association of oral human papillomavirus DNA persistence with cancer progression after primary treatment for oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(7):985-992. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0439

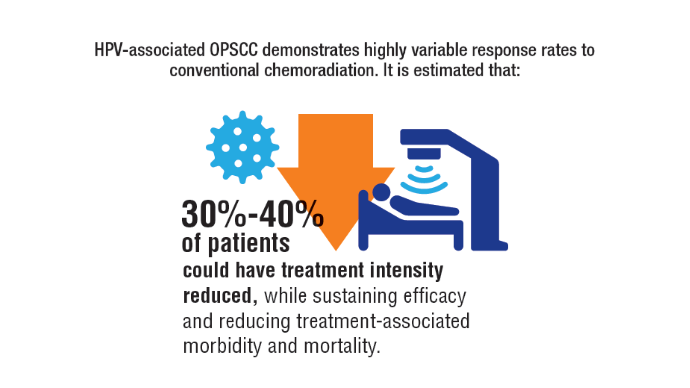

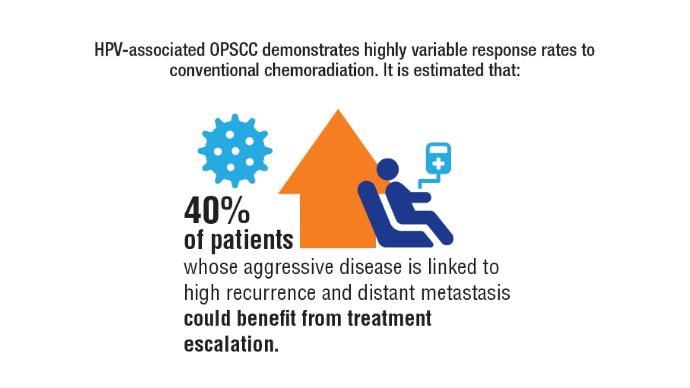

3. Fakhry C, Zhang Q, Gillison ML, et al. Validation of NRG oncology/RTOG-0129 risk groups for HPV-positive and HPV-negative oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer: implications for risk-based therapeutic intensity trials. Cancer. 2019;125(12):2027-2038. doi:10.1002/cncr.32025

4. O'Sullivan B, Huang SH, Su J, et al. Development and validation of a staging system for HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer by the International Collaboration on Oropharyngeal cancer Network for Staging (ICON-S): a multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(4):440-451. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00560-4

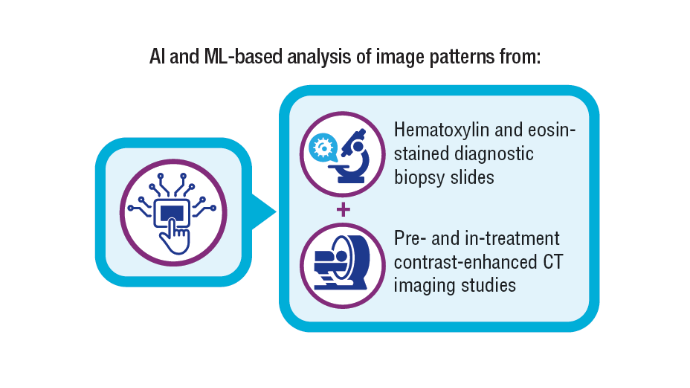

5. Koyuncu CF, Lu C, Bera K, et al. Computerized tumor multinucleation index (MuNI) is prognostic in p16+ oropharyngeal carcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2021;131(8):e145488. doi:10.1172/JCI145488

6. Lu C, Lewis JS Jr, Dupont WD, Plummer WD Jr, Janowczyk A, Madabhushi A. An oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma quantitative histomorphometric-based image classifier of nuclear morphology can risk stratify patients for disease-specific survival. Mod Pathol. 2017;30(12):1655-1665. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2017.98

7. Corredor G, Toro P, Koyuncu C, et al. An imaging biomarker of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes to risk-stratify patients with HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114(4):609-617. doi:10.1093/jnci/djab215

8. Cancer stat facts: oral cavity and pharynx cancer. National Cancer Institute, SEER Program. Accessed November 5, 2024. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/oralcav.html

9. Cancers associated with human papillomavirus. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 18, 2024. Accessed November 5, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/united-states-cancer-statistics/publications/hpv-associated-cancers.html

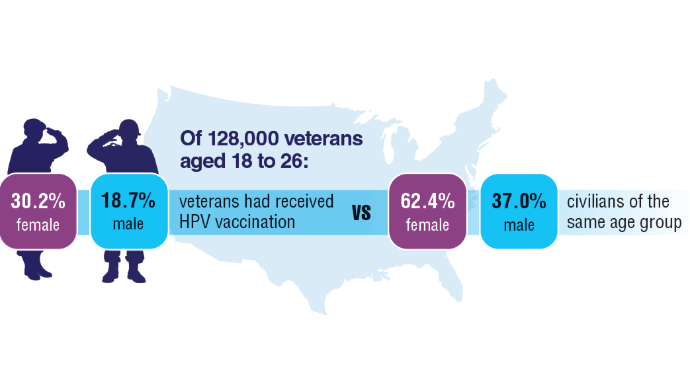

10. Chidambaram S, Chang SH, Sandulache VC, Mazul AL, Zevallos JP. Human papillomavirus vaccination prevalence and disproportionate cancer burden among US veterans. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(5):712-714. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.7944

11. Corredor G, Wang X, Zhou Y, et al. Spatial architecture and arrangement of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for predicting likelihood of recurrence in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(5):1526-1534. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2013

12. Alilou M, Orooji M, Beig N, et al. Quantitative vessel tortuosity: a potential CT imaging biomarker for distinguishing lung granulomas from adenocarcinomas. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):15290. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-33473-0

13. Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC, Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR, Winchester DP. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more "personalized" approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):93-99. doi:10.3322/caac.21388

Click here to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

Click here to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

1. Zevallos JP, Kramer JR, Sandulache VC, et al. National trends in oropharyngeal cancer incidence and survival within the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Head Neck. 2021;43(1):108-115. doi:10.1002/hed.26465

2. Fakhry C, Blackford AL, Neuner G, et al. Association of oral human papillomavirus DNA persistence with cancer progression after primary treatment for oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(7):985-992. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0439

3. Fakhry C, Zhang Q, Gillison ML, et al. Validation of NRG oncology/RTOG-0129 risk groups for HPV-positive and HPV-negative oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer: implications for risk-based therapeutic intensity trials. Cancer. 2019;125(12):2027-2038. doi:10.1002/cncr.32025

4. O'Sullivan B, Huang SH, Su J, et al. Development and validation of a staging system for HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer by the International Collaboration on Oropharyngeal cancer Network for Staging (ICON-S): a multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(4):440-451. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00560-4

5. Koyuncu CF, Lu C, Bera K, et al. Computerized tumor multinucleation index (MuNI) is prognostic in p16+ oropharyngeal carcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2021;131(8):e145488. doi:10.1172/JCI145488

6. Lu C, Lewis JS Jr, Dupont WD, Plummer WD Jr, Janowczyk A, Madabhushi A. An oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma quantitative histomorphometric-based image classifier of nuclear morphology can risk stratify patients for disease-specific survival. Mod Pathol. 2017;30(12):1655-1665. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2017.98

7. Corredor G, Toro P, Koyuncu C, et al. An imaging biomarker of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes to risk-stratify patients with HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114(4):609-617. doi:10.1093/jnci/djab215

8. Cancer stat facts: oral cavity and pharynx cancer. National Cancer Institute, SEER Program. Accessed November 5, 2024. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/oralcav.html

9. Cancers associated with human papillomavirus. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 18, 2024. Accessed November 5, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/united-states-cancer-statistics/publications/hpv-associated-cancers.html

10. Chidambaram S, Chang SH, Sandulache VC, Mazul AL, Zevallos JP. Human papillomavirus vaccination prevalence and disproportionate cancer burden among US veterans. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(5):712-714. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.7944

11. Corredor G, Wang X, Zhou Y, et al. Spatial architecture and arrangement of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for predicting likelihood of recurrence in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(5):1526-1534. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2013

12. Alilou M, Orooji M, Beig N, et al. Quantitative vessel tortuosity: a potential CT imaging biomarker for distinguishing lung granulomas from adenocarcinomas. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):15290. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-33473-0

13. Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC, Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR, Winchester DP. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more "personalized" approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):93-99. doi:10.3322/caac.21388

1. Zevallos JP, Kramer JR, Sandulache VC, et al. National trends in oropharyngeal cancer incidence and survival within the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Head Neck. 2021;43(1):108-115. doi:10.1002/hed.26465

2. Fakhry C, Blackford AL, Neuner G, et al. Association of oral human papillomavirus DNA persistence with cancer progression after primary treatment for oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(7):985-992. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0439

3. Fakhry C, Zhang Q, Gillison ML, et al. Validation of NRG oncology/RTOG-0129 risk groups for HPV-positive and HPV-negative oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer: implications for risk-based therapeutic intensity trials. Cancer. 2019;125(12):2027-2038. doi:10.1002/cncr.32025

4. O'Sullivan B, Huang SH, Su J, et al. Development and validation of a staging system for HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer by the International Collaboration on Oropharyngeal cancer Network for Staging (ICON-S): a multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(4):440-451. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00560-4

5. Koyuncu CF, Lu C, Bera K, et al. Computerized tumor multinucleation index (MuNI) is prognostic in p16+ oropharyngeal carcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2021;131(8):e145488. doi:10.1172/JCI145488

6. Lu C, Lewis JS Jr, Dupont WD, Plummer WD Jr, Janowczyk A, Madabhushi A. An oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma quantitative histomorphometric-based image classifier of nuclear morphology can risk stratify patients for disease-specific survival. Mod Pathol. 2017;30(12):1655-1665. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2017.98

7. Corredor G, Toro P, Koyuncu C, et al. An imaging biomarker of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes to risk-stratify patients with HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114(4):609-617. doi:10.1093/jnci/djab215

8. Cancer stat facts: oral cavity and pharynx cancer. National Cancer Institute, SEER Program. Accessed November 5, 2024. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/oralcav.html

9. Cancers associated with human papillomavirus. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 18, 2024. Accessed November 5, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/united-states-cancer-statistics/publications/hpv-associated-cancers.html

10. Chidambaram S, Chang SH, Sandulache VC, Mazul AL, Zevallos JP. Human papillomavirus vaccination prevalence and disproportionate cancer burden among US veterans. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(5):712-714. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.7944

11. Corredor G, Wang X, Zhou Y, et al. Spatial architecture and arrangement of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for predicting likelihood of recurrence in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(5):1526-1534. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2013

12. Alilou M, Orooji M, Beig N, et al. Quantitative vessel tortuosity: a potential CT imaging biomarker for distinguishing lung granulomas from adenocarcinomas. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):15290. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-33473-0

13. Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC, Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR, Winchester DP. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more "personalized" approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):93-99. doi:10.3322/caac.21388

AI-Based Risk Stratification for Oropharyngeal Carcinomas: AIROC

AI-Based Risk Stratification for Oropharyngeal Carcinomas: AIROC

Rising Kidney Cancer Cases and Emerging Treatments for Veterans

Rising Kidney Cancer Cases and Emerging Treatments for Veterans

Click here to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

1. American Cancer Society website. Key Statistics About Kidney Cancer. Revised May 2024. Accessed December 18, 2024. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/kidney-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

2. American Cancer Society website. Cancer Facts & Figures 2024. 2024—First Year the US Expects More than 2M New Cases of Cancer. Published January 17, 2024. Accessed December 18, 2024. https://www.cancer.org/research/acs-research-news/facts-and-figures-2024.html

3.United States Department of Veterans Affairs factsheet. Pact Act & Gulf War, Post-911 Era Veterans. Published July 2023. Accessed December 18, 2024. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.va.gov/files/2023-08/PACT%20Act%20and%20Gulf%20War%2C%20Post-911%20Veterans%20NEW%20July%202023.pdf

4. Li M, Li L, Zheng J, Li Z, Li S, Wang K, Chen X. Liquid biopsy at the frontier in renal cell carcinoma: recent analysis of techniques and clinical application. Mol Cancer. 2023 Feb 21;22(1):37. doi:10.1186/s12943-023-01745-7

5. Bellman NL. Incidental Finding of Renal Cell Carcinoma: Detected by a Thrombus in the Inferior Vena Cava. Journal of Diagnostic Medical Sonography. 2015;31(2):118-121. doi:10.1177/8756479314546691

6. Brown JT. Adjuvant Therapy for Non-Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma—The Ascent Continues. JAMA Network Open. 2024 Aug 1;7(8):e2425251. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.25251

7. Siva S, Louie AV, Kotecha R, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for primary renal cell carcinoma: a systematic review and practice guideline from the International Society of Stereotactic Radiosurgery (ISRS). Lancet Oncol. 2024 Jan;25(1):e18-e28. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00513-2.

8. Choueiri TK, Tomczak P, Park SH, et al; for the KEYNOTE-564 Investigators. Overall Survival with Adjuvant Pembrolizumab in Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2024 Apr 18;390(15):1359-1371. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2312695

9. Bytnar JA, McGlynn KA, Kern SQ, Shriver CD, Zhu K. Incidence rates of bladder and kidney cancers among US military servicemen: comparison with the rates in the general US population. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2024 Nov 1;33(6):505-511. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000886

Click here to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

Click here to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

1. American Cancer Society website. Key Statistics About Kidney Cancer. Revised May 2024. Accessed December 18, 2024. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/kidney-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

2. American Cancer Society website. Cancer Facts & Figures 2024. 2024—First Year the US Expects More than 2M New Cases of Cancer. Published January 17, 2024. Accessed December 18, 2024. https://www.cancer.org/research/acs-research-news/facts-and-figures-2024.html

3.United States Department of Veterans Affairs factsheet. Pact Act & Gulf War, Post-911 Era Veterans. Published July 2023. Accessed December 18, 2024. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.va.gov/files/2023-08/PACT%20Act%20and%20Gulf%20War%2C%20Post-911%20Veterans%20NEW%20July%202023.pdf

4. Li M, Li L, Zheng J, Li Z, Li S, Wang K, Chen X. Liquid biopsy at the frontier in renal cell carcinoma: recent analysis of techniques and clinical application. Mol Cancer. 2023 Feb 21;22(1):37. doi:10.1186/s12943-023-01745-7

5. Bellman NL. Incidental Finding of Renal Cell Carcinoma: Detected by a Thrombus in the Inferior Vena Cava. Journal of Diagnostic Medical Sonography. 2015;31(2):118-121. doi:10.1177/8756479314546691

6. Brown JT. Adjuvant Therapy for Non-Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma—The Ascent Continues. JAMA Network Open. 2024 Aug 1;7(8):e2425251. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.25251

7. Siva S, Louie AV, Kotecha R, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for primary renal cell carcinoma: a systematic review and practice guideline from the International Society of Stereotactic Radiosurgery (ISRS). Lancet Oncol. 2024 Jan;25(1):e18-e28. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00513-2.

8. Choueiri TK, Tomczak P, Park SH, et al; for the KEYNOTE-564 Investigators. Overall Survival with Adjuvant Pembrolizumab in Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2024 Apr 18;390(15):1359-1371. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2312695

9. Bytnar JA, McGlynn KA, Kern SQ, Shriver CD, Zhu K. Incidence rates of bladder and kidney cancers among US military servicemen: comparison with the rates in the general US population. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2024 Nov 1;33(6):505-511. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000886

1. American Cancer Society website. Key Statistics About Kidney Cancer. Revised May 2024. Accessed December 18, 2024. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/kidney-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

2. American Cancer Society website. Cancer Facts & Figures 2024. 2024—First Year the US Expects More than 2M New Cases of Cancer. Published January 17, 2024. Accessed December 18, 2024. https://www.cancer.org/research/acs-research-news/facts-and-figures-2024.html

3.United States Department of Veterans Affairs factsheet. Pact Act & Gulf War, Post-911 Era Veterans. Published July 2023. Accessed December 18, 2024. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.va.gov/files/2023-08/PACT%20Act%20and%20Gulf%20War%2C%20Post-911%20Veterans%20NEW%20July%202023.pdf

4. Li M, Li L, Zheng J, Li Z, Li S, Wang K, Chen X. Liquid biopsy at the frontier in renal cell carcinoma: recent analysis of techniques and clinical application. Mol Cancer. 2023 Feb 21;22(1):37. doi:10.1186/s12943-023-01745-7

5. Bellman NL. Incidental Finding of Renal Cell Carcinoma: Detected by a Thrombus in the Inferior Vena Cava. Journal of Diagnostic Medical Sonography. 2015;31(2):118-121. doi:10.1177/8756479314546691

6. Brown JT. Adjuvant Therapy for Non-Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma—The Ascent Continues. JAMA Network Open. 2024 Aug 1;7(8):e2425251. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.25251

7. Siva S, Louie AV, Kotecha R, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for primary renal cell carcinoma: a systematic review and practice guideline from the International Society of Stereotactic Radiosurgery (ISRS). Lancet Oncol. 2024 Jan;25(1):e18-e28. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00513-2.

8. Choueiri TK, Tomczak P, Park SH, et al; for the KEYNOTE-564 Investigators. Overall Survival with Adjuvant Pembrolizumab in Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2024 Apr 18;390(15):1359-1371. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2312695

9. Bytnar JA, McGlynn KA, Kern SQ, Shriver CD, Zhu K. Incidence rates of bladder and kidney cancers among US military servicemen: comparison with the rates in the general US population. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2024 Nov 1;33(6):505-511. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000886

Rising Kidney Cancer Cases and Emerging Treatments for Veterans

Rising Kidney Cancer Cases and Emerging Treatments for Veterans

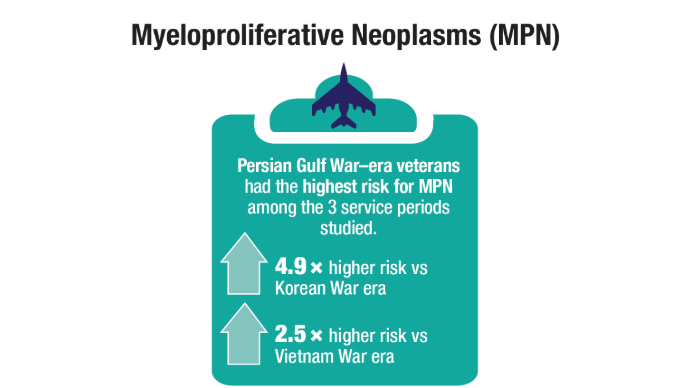

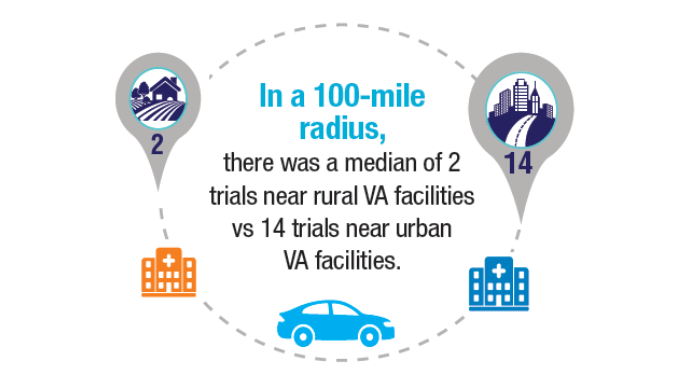

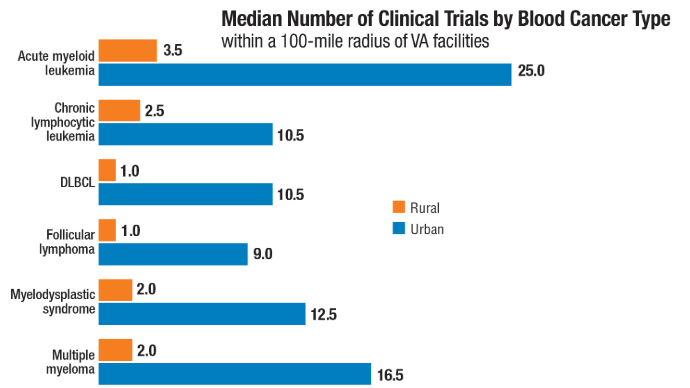

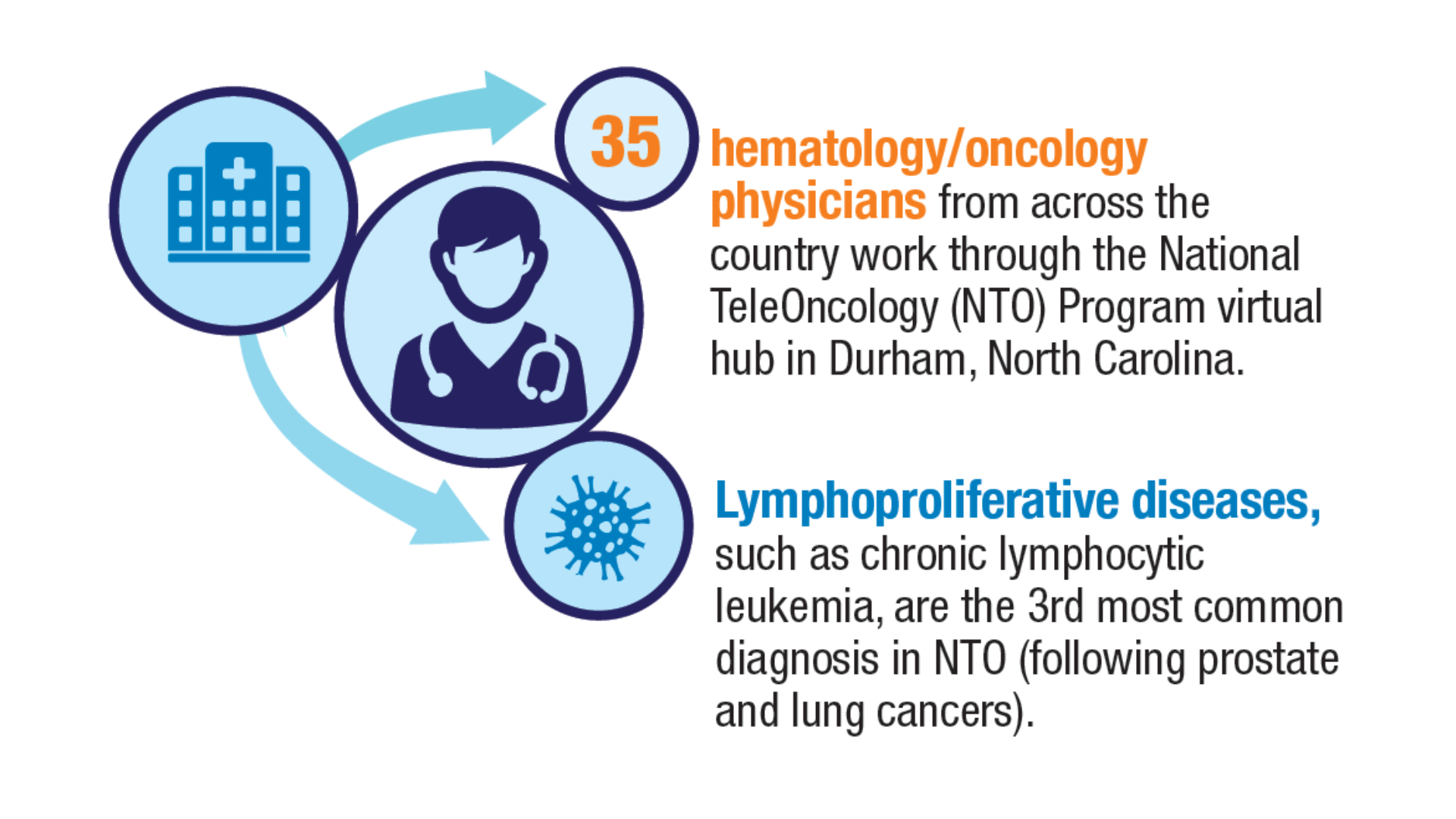

Advances in Blood Cancer Care for Veterans

Advances in Blood Cancer Care for Veterans

Click to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

- Li W, ed. The 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of

Hematolymphoid Tumors. In: Leukemia [Internet]. Brisbane (AU): Exon Publications;

October 16, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK586208/ - Graf SA, Samples LS, Keating TM, Garcia JM. Clinical research in older adults with

hematologic malignancies: Opportunities for alignment in the Veterans Affairs. Semin

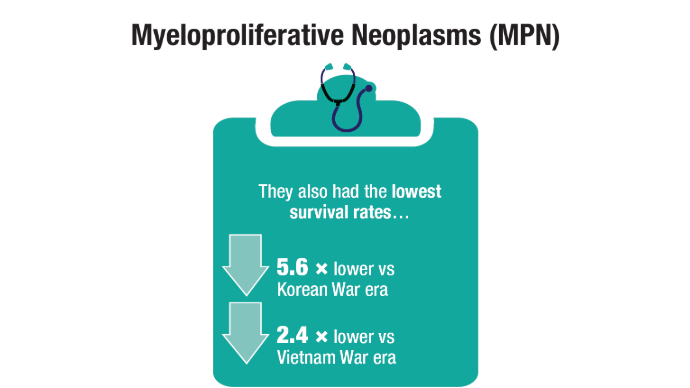

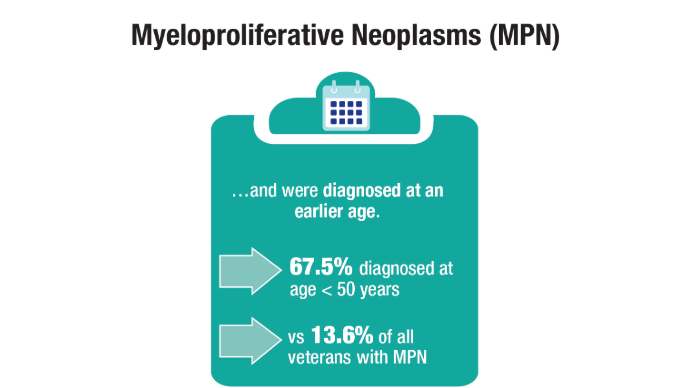

Oncol. 2020;47(1):94-101. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2020.02.010. - Tiu A, McKinnell Z, Liu S, et al. Risk of myeloproliferative neoplasms among

U.S. Veterans from Korean, Vietnam, and Persian Gulf War eras. Am J Hematol.

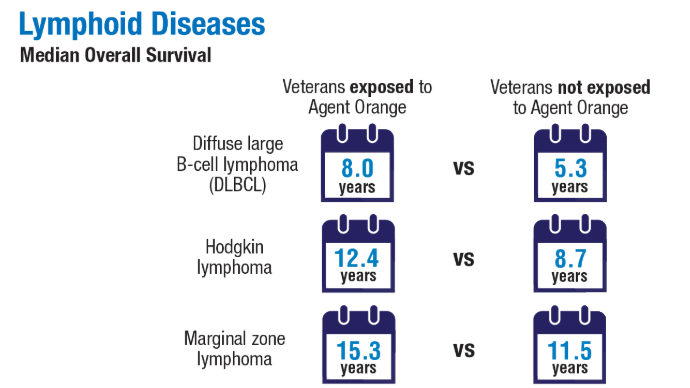

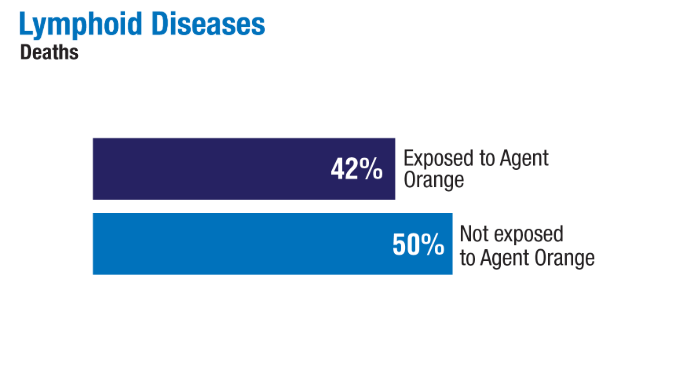

2024;99(10):1969-1978. doi:10.1002/ajh.27438 - Ma H, Wan JY, Cortessis VK, Gupta P, Cozen W. Survival in Agent Orange

exposed and unexposed Vietnam-era veterans who were diagnosed with

lymphoid malignancies. Blood Adv. 2024;8(4):1037-1041. doi:10.1182/

bloodadvances.2023011999 - Friedman DR, Rodgers TD, Kovalick C, Yellapragada S, Szumita L, Weiss ES. Veterans

with blood cancers: Clinical trial navigation and the challenge of rurality. J Rural

Health. 2024;40(1):114-120. doi:10.1111/jrh.12773 - Parikh DA, Rodgers TD, Passero VA, et al. Teleoncology in the Veterans Health

Administration: Models of Care and the Veteran Experience. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ

Book. 2024;44(3):e100042. doi:10.1200/EDBK_100042 - Pulumati A, Pulumati A, Dwarakanath BS, Verma A, Papineni RVL. Technological

advancements in cancer diagnostics: Improvements and limitations. Cancer Rep

(Hoboken). 2023;6(2):e1764. doi:10.1002/cnr2.1764

Click to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

Click to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

- Li W, ed. The 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of

Hematolymphoid Tumors. In: Leukemia [Internet]. Brisbane (AU): Exon Publications;

October 16, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK586208/ - Graf SA, Samples LS, Keating TM, Garcia JM. Clinical research in older adults with

hematologic malignancies: Opportunities for alignment in the Veterans Affairs. Semin

Oncol. 2020;47(1):94-101. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2020.02.010. - Tiu A, McKinnell Z, Liu S, et al. Risk of myeloproliferative neoplasms among

U.S. Veterans from Korean, Vietnam, and Persian Gulf War eras. Am J Hematol.

2024;99(10):1969-1978. doi:10.1002/ajh.27438 - Ma H, Wan JY, Cortessis VK, Gupta P, Cozen W. Survival in Agent Orange

exposed and unexposed Vietnam-era veterans who were diagnosed with

lymphoid malignancies. Blood Adv. 2024;8(4):1037-1041. doi:10.1182/

bloodadvances.2023011999 - Friedman DR, Rodgers TD, Kovalick C, Yellapragada S, Szumita L, Weiss ES. Veterans

with blood cancers: Clinical trial navigation and the challenge of rurality. J Rural

Health. 2024;40(1):114-120. doi:10.1111/jrh.12773 - Parikh DA, Rodgers TD, Passero VA, et al. Teleoncology in the Veterans Health

Administration: Models of Care and the Veteran Experience. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ

Book. 2024;44(3):e100042. doi:10.1200/EDBK_100042 - Pulumati A, Pulumati A, Dwarakanath BS, Verma A, Papineni RVL. Technological

advancements in cancer diagnostics: Improvements and limitations. Cancer Rep

(Hoboken). 2023;6(2):e1764. doi:10.1002/cnr2.1764

- Li W, ed. The 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of

Hematolymphoid Tumors. In: Leukemia [Internet]. Brisbane (AU): Exon Publications;

October 16, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK586208/ - Graf SA, Samples LS, Keating TM, Garcia JM. Clinical research in older adults with

hematologic malignancies: Opportunities for alignment in the Veterans Affairs. Semin

Oncol. 2020;47(1):94-101. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2020.02.010. - Tiu A, McKinnell Z, Liu S, et al. Risk of myeloproliferative neoplasms among

U.S. Veterans from Korean, Vietnam, and Persian Gulf War eras. Am J Hematol.

2024;99(10):1969-1978. doi:10.1002/ajh.27438 - Ma H, Wan JY, Cortessis VK, Gupta P, Cozen W. Survival in Agent Orange

exposed and unexposed Vietnam-era veterans who were diagnosed with

lymphoid malignancies. Blood Adv. 2024;8(4):1037-1041. doi:10.1182/

bloodadvances.2023011999 - Friedman DR, Rodgers TD, Kovalick C, Yellapragada S, Szumita L, Weiss ES. Veterans

with blood cancers: Clinical trial navigation and the challenge of rurality. J Rural

Health. 2024;40(1):114-120. doi:10.1111/jrh.12773 - Parikh DA, Rodgers TD, Passero VA, et al. Teleoncology in the Veterans Health

Administration: Models of Care and the Veteran Experience. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ

Book. 2024;44(3):e100042. doi:10.1200/EDBK_100042 - Pulumati A, Pulumati A, Dwarakanath BS, Verma A, Papineni RVL. Technological

advancements in cancer diagnostics: Improvements and limitations. Cancer Rep

(Hoboken). 2023;6(2):e1764. doi:10.1002/cnr2.1764

Advances in Blood Cancer Care for Veterans

Advances in Blood Cancer Care for Veterans

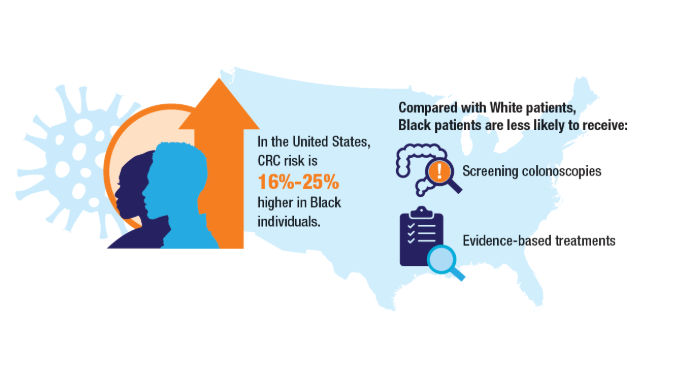

Access, Race, and "Colon Age": Improving CRC Screening

1. Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:12-49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21820.

2. Riviere P, Morgan KM, Deshler LN, et al. Racial disparities in colorectal cancer outcomes and access to care: a multi-cohort analysis. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1414361. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2024.1414361

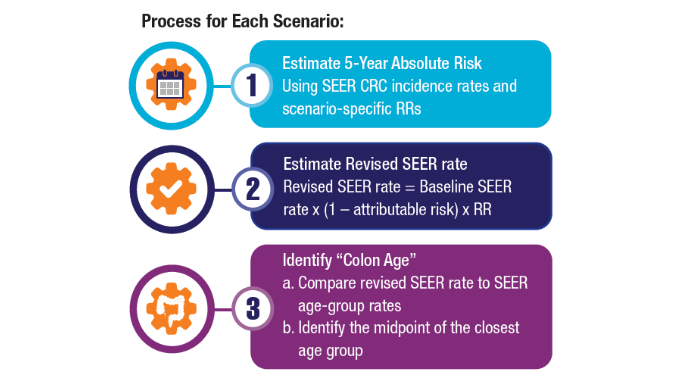

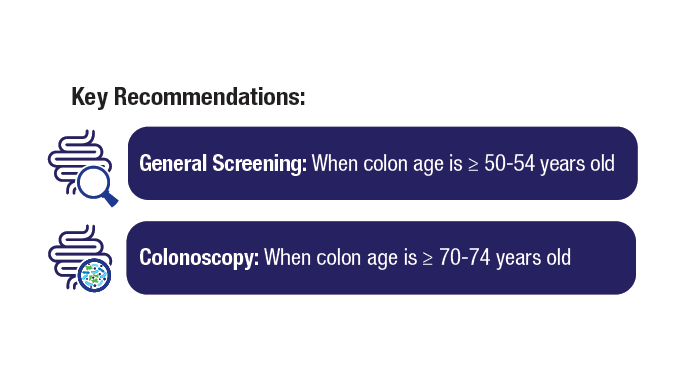

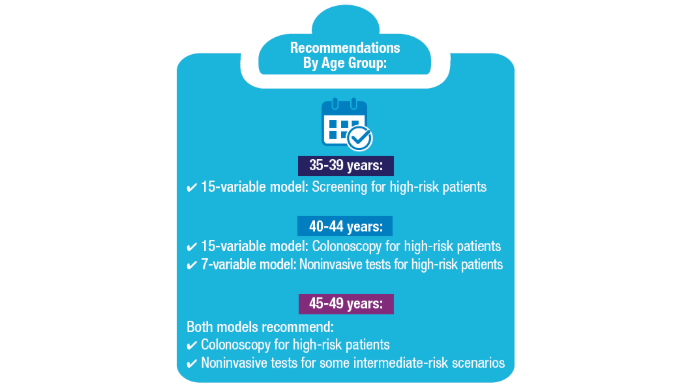

3. Imperiale TF, Myers LJ, Barker BC, Stump TE, Daggy JK. Colon Age: A metric for whether and how to screen male veterans for early-onset colorectal cancer. Cancer Prev Res. 2024:17:377-384. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-23-0544

1. Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:12-49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21820.

2. Riviere P, Morgan KM, Deshler LN, et al. Racial disparities in colorectal cancer outcomes and access to care: a multi-cohort analysis. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1414361. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2024.1414361

3. Imperiale TF, Myers LJ, Barker BC, Stump TE, Daggy JK. Colon Age: A metric for whether and how to screen male veterans for early-onset colorectal cancer. Cancer Prev Res. 2024:17:377-384. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-23-0544

1. Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:12-49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21820.

2. Riviere P, Morgan KM, Deshler LN, et al. Racial disparities in colorectal cancer outcomes and access to care: a multi-cohort analysis. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1414361. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2024.1414361

3. Imperiale TF, Myers LJ, Barker BC, Stump TE, Daggy JK. Colon Age: A metric for whether and how to screen male veterans for early-onset colorectal cancer. Cancer Prev Res. 2024:17:377-384. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-23-0544

HCC Updates: Quality Care Framework and Risk Stratification Data

HCC Updates: Quality Care Framework and Risk Stratification Data

Click here to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

1. Rogal SS, Taddei TH, Monto A, et al. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Diagnosis and Management in 2021: A National Veterans Affairs Quality Improvement Project. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Feb;22(2):324-338. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2023.07.002

2. John BV, Dang Y, Kaplan DE, et al. Liver Stiffness Measurement and Risk Prediction of Hepatocellular Carcinoma After HCV Eradication in Veterans With Cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Apr;22(4):778-788.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2023.11.020

Click here to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

Click here to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

1. Rogal SS, Taddei TH, Monto A, et al. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Diagnosis and Management in 2021: A National Veterans Affairs Quality Improvement Project. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Feb;22(2):324-338. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2023.07.002

2. John BV, Dang Y, Kaplan DE, et al. Liver Stiffness Measurement and Risk Prediction of Hepatocellular Carcinoma After HCV Eradication in Veterans With Cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Apr;22(4):778-788.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2023.11.020

1. Rogal SS, Taddei TH, Monto A, et al. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Diagnosis and Management in 2021: A National Veterans Affairs Quality Improvement Project. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Feb;22(2):324-338. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2023.07.002

2. John BV, Dang Y, Kaplan DE, et al. Liver Stiffness Measurement and Risk Prediction of Hepatocellular Carcinoma After HCV Eradication in Veterans With Cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Apr;22(4):778-788.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2023.11.020

HCC Updates: Quality Care Framework and Risk Stratification Data

HCC Updates: Quality Care Framework and Risk Stratification Data

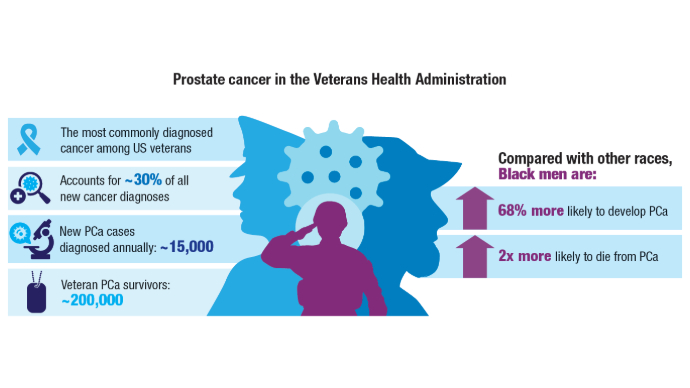

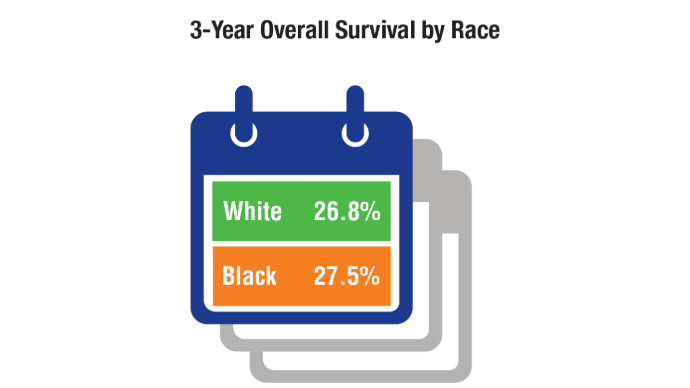

Racial Disparities, Germline Testing, and Improved Overall Survival in Prostate Cancer

Racial Disparities, Germline Testing, and Improved Overall Survival in Prostate Cancer

Click here to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

References

Lillard JW Jr, Moses KA, Mahal BA, George DJ. Racial disparities in Black men with prostate cancer: A literature review. Cancer. 2022 Nov 1;128(21):3787-3795. doi:10.1002/cncr.34433

Wang BR, Chen Y-A, Kao W-H, Lai C-H, Lin H, Hsieh J-T. Developing New Treatment Options for Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer and Recurrent Disease. Biomedicines. 2022 Aug 3;10(8):1872. doi:10.3390/biomedicines10081872

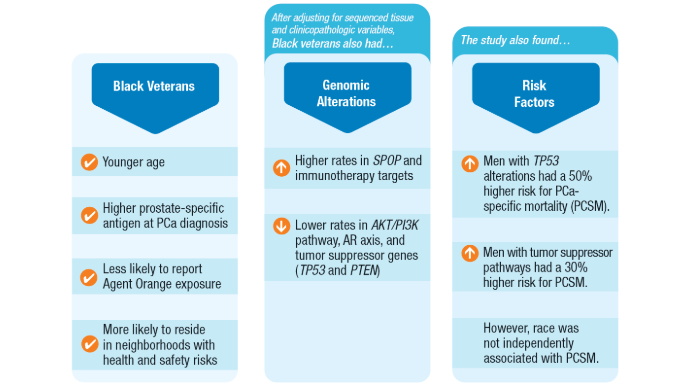

Valle LF, Li J, Desai H, Hausler R, et al. Oncogenic Alterations, Race, and Survival in US Veterans with Metastatic Prostate Cancer Undergoing Somatic Tumor Next Generation Sequencing. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2024 Oct 25:2024.10.24.620071. doi:10.1101/2024.10.24.620071

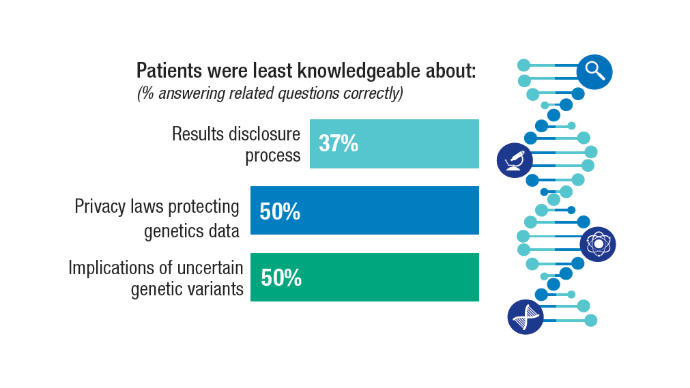

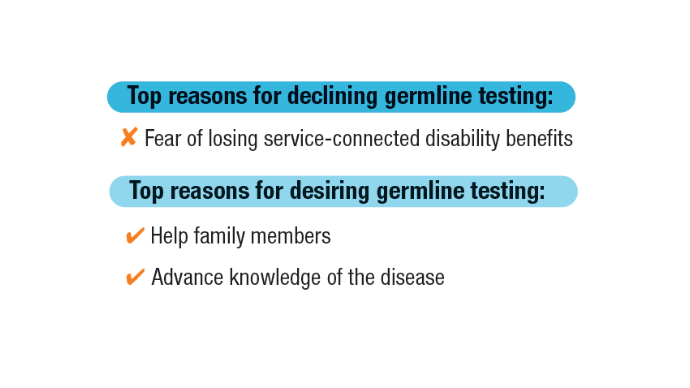

Kwon DH, Scheuner MT, McPhaul M, et al. Germline testing for veterans with advanced prostate cancer: concerns about service-connected benefits. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2024 Sep 2;8(5):pkae079. doi:10.1093/jncics/pkae079

Kwon DH, McPhaul M, Sumra S, et al. Informed decision-making about germline testing among Veterans with advanced prostate cancer (APC): A mixed-methods study. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(16_suppl):5105. doi:10.1200/JCO.2024.42.16_suppl.5105

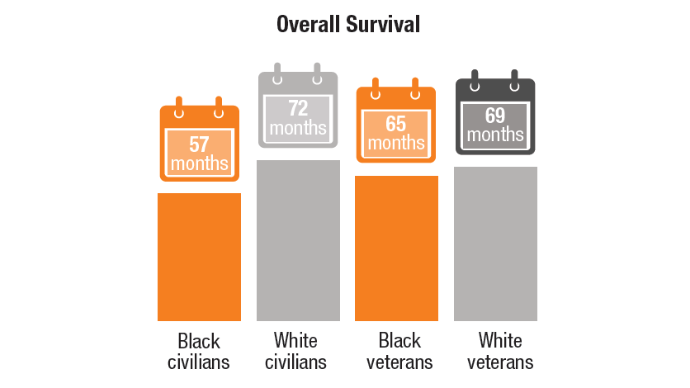

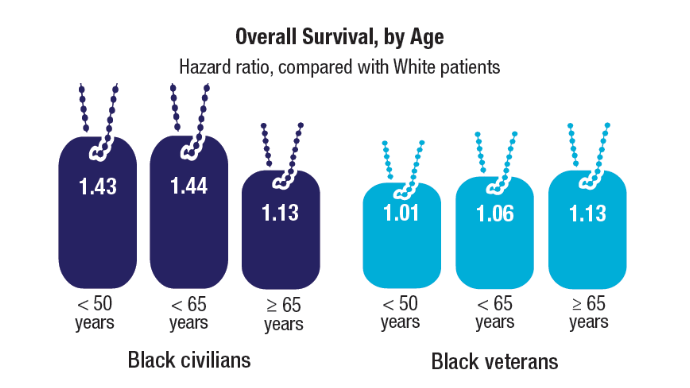

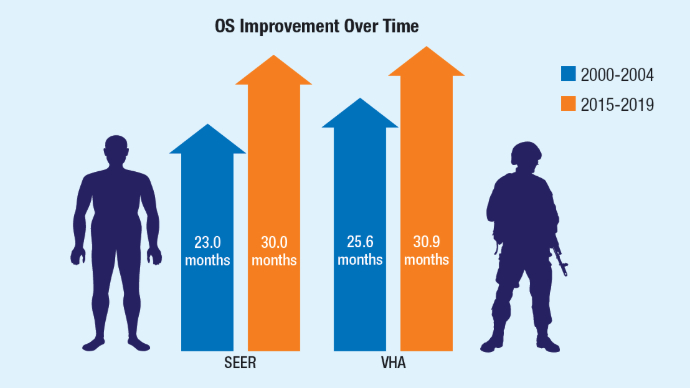

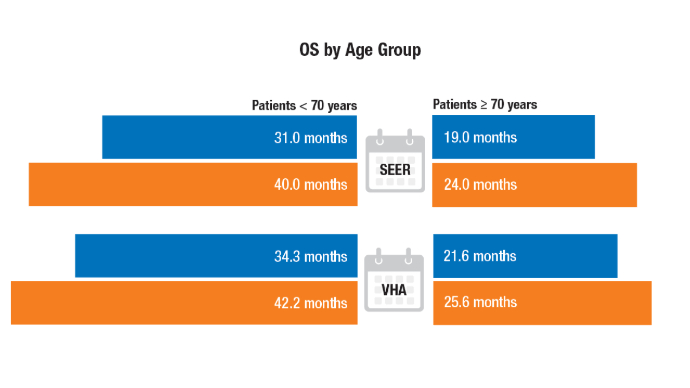

Schoen MW, Montgomery RB, Owens L, Khan S, Sanfilippo KM, Etzioni RB. Survival in Patients With De Novo Metastatic Prostate Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Mar 4;7(3):e241970. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.1970

Schafer EJ, Jemal A, Wiese D, et al. Disparities and Trends in Genitourinary Cancer Incidence and Mortality in the USA. Eur Urol. 2023 Jul;84(1):117-126. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2022.11.023

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Hines VA Hospital & Loyola University Chicago Physician Awarded $8.6M VA Research Grant. November 8, 2021. https://www.va.gov/hines-health-care/news-releases/hines-va-hospital-loyola-university-chicago-physician-awarded-86m-va-research-grant/ Accessed December 31, 2024.

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. National Oncology Program. How VA is Advancing Prostate Cancer Care. https://www.cancer.va.gov/prostate.html Accessed December 31, 2024.

Click here to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

Click here to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

References

Lillard JW Jr, Moses KA, Mahal BA, George DJ. Racial disparities in Black men with prostate cancer: A literature review. Cancer. 2022 Nov 1;128(21):3787-3795. doi:10.1002/cncr.34433

Wang BR, Chen Y-A, Kao W-H, Lai C-H, Lin H, Hsieh J-T. Developing New Treatment Options for Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer and Recurrent Disease. Biomedicines. 2022 Aug 3;10(8):1872. doi:10.3390/biomedicines10081872

Valle LF, Li J, Desai H, Hausler R, et al. Oncogenic Alterations, Race, and Survival in US Veterans with Metastatic Prostate Cancer Undergoing Somatic Tumor Next Generation Sequencing. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2024 Oct 25:2024.10.24.620071. doi:10.1101/2024.10.24.620071

Kwon DH, Scheuner MT, McPhaul M, et al. Germline testing for veterans with advanced prostate cancer: concerns about service-connected benefits. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2024 Sep 2;8(5):pkae079. doi:10.1093/jncics/pkae079

Kwon DH, McPhaul M, Sumra S, et al. Informed decision-making about germline testing among Veterans with advanced prostate cancer (APC): A mixed-methods study. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(16_suppl):5105. doi:10.1200/JCO.2024.42.16_suppl.5105

Schoen MW, Montgomery RB, Owens L, Khan S, Sanfilippo KM, Etzioni RB. Survival in Patients With De Novo Metastatic Prostate Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Mar 4;7(3):e241970. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.1970

Schafer EJ, Jemal A, Wiese D, et al. Disparities and Trends in Genitourinary Cancer Incidence and Mortality in the USA. Eur Urol. 2023 Jul;84(1):117-126. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2022.11.023

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Hines VA Hospital & Loyola University Chicago Physician Awarded $8.6M VA Research Grant. November 8, 2021. https://www.va.gov/hines-health-care/news-releases/hines-va-hospital-loyola-university-chicago-physician-awarded-86m-va-research-grant/ Accessed December 31, 2024.

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. National Oncology Program. How VA is Advancing Prostate Cancer Care. https://www.cancer.va.gov/prostate.html Accessed December 31, 2024.

References

Lillard JW Jr, Moses KA, Mahal BA, George DJ. Racial disparities in Black men with prostate cancer: A literature review. Cancer. 2022 Nov 1;128(21):3787-3795. doi:10.1002/cncr.34433

Wang BR, Chen Y-A, Kao W-H, Lai C-H, Lin H, Hsieh J-T. Developing New Treatment Options for Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer and Recurrent Disease. Biomedicines. 2022 Aug 3;10(8):1872. doi:10.3390/biomedicines10081872

Valle LF, Li J, Desai H, Hausler R, et al. Oncogenic Alterations, Race, and Survival in US Veterans with Metastatic Prostate Cancer Undergoing Somatic Tumor Next Generation Sequencing. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2024 Oct 25:2024.10.24.620071. doi:10.1101/2024.10.24.620071

Kwon DH, Scheuner MT, McPhaul M, et al. Germline testing for veterans with advanced prostate cancer: concerns about service-connected benefits. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2024 Sep 2;8(5):pkae079. doi:10.1093/jncics/pkae079

Kwon DH, McPhaul M, Sumra S, et al. Informed decision-making about germline testing among Veterans with advanced prostate cancer (APC): A mixed-methods study. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(16_suppl):5105. doi:10.1200/JCO.2024.42.16_suppl.5105

Schoen MW, Montgomery RB, Owens L, Khan S, Sanfilippo KM, Etzioni RB. Survival in Patients With De Novo Metastatic Prostate Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Mar 4;7(3):e241970. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.1970

Schafer EJ, Jemal A, Wiese D, et al. Disparities and Trends in Genitourinary Cancer Incidence and Mortality in the USA. Eur Urol. 2023 Jul;84(1):117-126. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2022.11.023

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Hines VA Hospital & Loyola University Chicago Physician Awarded $8.6M VA Research Grant. November 8, 2021. https://www.va.gov/hines-health-care/news-releases/hines-va-hospital-loyola-university-chicago-physician-awarded-86m-va-research-grant/ Accessed December 31, 2024.

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. National Oncology Program. How VA is Advancing Prostate Cancer Care. https://www.cancer.va.gov/prostate.html Accessed December 31, 2024.

Racial Disparities, Germline Testing, and Improved Overall Survival in Prostate Cancer

Racial Disparities, Germline Testing, and Improved Overall Survival in Prostate Cancer

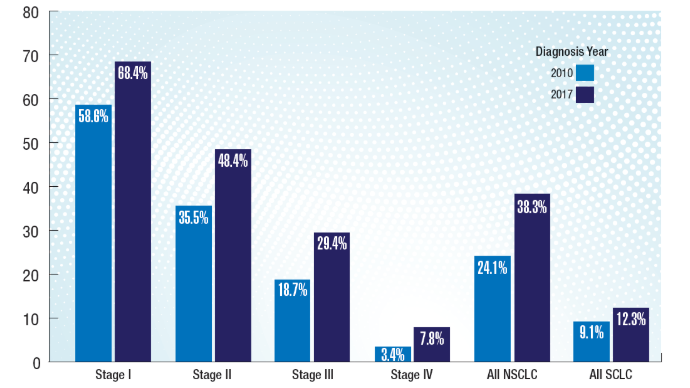

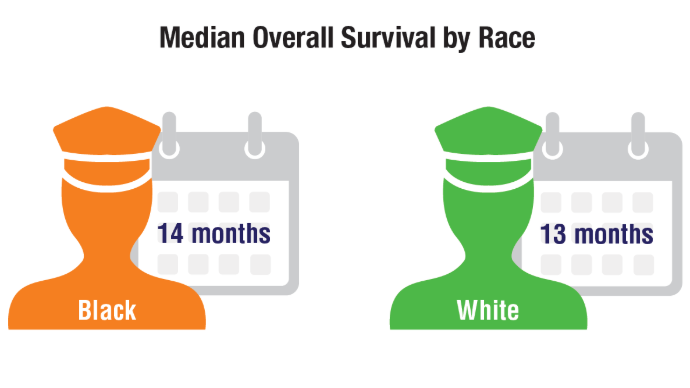

Lung Cancer: Mortality Trends in Veterans and New Treatments

Lung Cancer: Mortality Trends in Veterans and New Treatments

Click to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

- Tehzeeb J, Mahmood F, Gemoets D, Azem A, Mehdi SA. Epidemiology and survival

trends of lung carcinoids in the veteran population. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:e21049.

doi:10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.e21049 - Moghanaki D, Taylor J, Bryant AK, et al. Lung Cancer Survival Trends in the Veterans

Health Administration. Clin Lung Cancer. 2024;25(3):225-232. doi:10.1016/j.

cllc.2024.02.009 - Jalal SI, Guo A, Ahmed S, Kelley MJ. Analysis of actionable genetic alterations in

lung carcinoma from the VA National Precision Oncology Program. Semin Oncol.

2022;49(3-4):265-274. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2022.06.014 - Cascone T, Awad MM, Spicer JD, et al; for the CheckMate 77T Investigators.

Perioperative Nivolumab in Resectable Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med.

2024;390(19):1756-1769. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2311926 - Wakelee H, Liberman M, Kato T, et al; for the KEYNOTE-671 Investigators.

Perioperative Pembrolizumab for Early-Stage Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J

Med. 2023;389(6):491-503. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2302983 - Heymach JV, Harpole D, Mitsudomi T, et al; for the AEGEAN Investigators.

Perioperative Durvalumab for Resectable Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J

Med. 2023;389(18):1672-1684. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2304875 - Duncan FC, Al Nasrallah N, Nephew L, et al. Racial disparities in staging, treatment,

and mortality in non-small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2024;13(1):76-

94. doi:10.21037/tlcr-23-407

Click to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

Click to view more from Cancer Data Trends 2025.

- Tehzeeb J, Mahmood F, Gemoets D, Azem A, Mehdi SA. Epidemiology and survival

trends of lung carcinoids in the veteran population. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:e21049.

doi:10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.e21049 - Moghanaki D, Taylor J, Bryant AK, et al. Lung Cancer Survival Trends in the Veterans

Health Administration. Clin Lung Cancer. 2024;25(3):225-232. doi:10.1016/j.

cllc.2024.02.009 - Jalal SI, Guo A, Ahmed S, Kelley MJ. Analysis of actionable genetic alterations in

lung carcinoma from the VA National Precision Oncology Program. Semin Oncol.

2022;49(3-4):265-274. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2022.06.014 - Cascone T, Awad MM, Spicer JD, et al; for the CheckMate 77T Investigators.

Perioperative Nivolumab in Resectable Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med.

2024;390(19):1756-1769. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2311926 - Wakelee H, Liberman M, Kato T, et al; for the KEYNOTE-671 Investigators.

Perioperative Pembrolizumab for Early-Stage Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J

Med. 2023;389(6):491-503. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2302983 - Heymach JV, Harpole D, Mitsudomi T, et al; for the AEGEAN Investigators.

Perioperative Durvalumab for Resectable Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J

Med. 2023;389(18):1672-1684. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2304875 - Duncan FC, Al Nasrallah N, Nephew L, et al. Racial disparities in staging, treatment,

and mortality in non-small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2024;13(1):76-

94. doi:10.21037/tlcr-23-407

- Tehzeeb J, Mahmood F, Gemoets D, Azem A, Mehdi SA. Epidemiology and survival

trends of lung carcinoids in the veteran population. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:e21049.

doi:10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.e21049 - Moghanaki D, Taylor J, Bryant AK, et al. Lung Cancer Survival Trends in the Veterans

Health Administration. Clin Lung Cancer. 2024;25(3):225-232. doi:10.1016/j.

cllc.2024.02.009 - Jalal SI, Guo A, Ahmed S, Kelley MJ. Analysis of actionable genetic alterations in

lung carcinoma from the VA National Precision Oncology Program. Semin Oncol.

2022;49(3-4):265-274. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2022.06.014 - Cascone T, Awad MM, Spicer JD, et al; for the CheckMate 77T Investigators.

Perioperative Nivolumab in Resectable Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med.

2024;390(19):1756-1769. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2311926 - Wakelee H, Liberman M, Kato T, et al; for the KEYNOTE-671 Investigators.

Perioperative Pembrolizumab for Early-Stage Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J

Med. 2023;389(6):491-503. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2302983 - Heymach JV, Harpole D, Mitsudomi T, et al; for the AEGEAN Investigators.

Perioperative Durvalumab for Resectable Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J

Med. 2023;389(18):1672-1684. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2304875 - Duncan FC, Al Nasrallah N, Nephew L, et al. Racial disparities in staging, treatment,

and mortality in non-small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2024;13(1):76-

94. doi:10.21037/tlcr-23-407

Lung Cancer: Mortality Trends in Veterans and New Treatments

Lung Cancer: Mortality Trends in Veterans and New Treatments

Beyond the Razor: Managing Pseudofolliculitis Barbae in Skin of Color

Beyond the Razor: Managing Pseudofolliculitis Barbae in Skin of Color

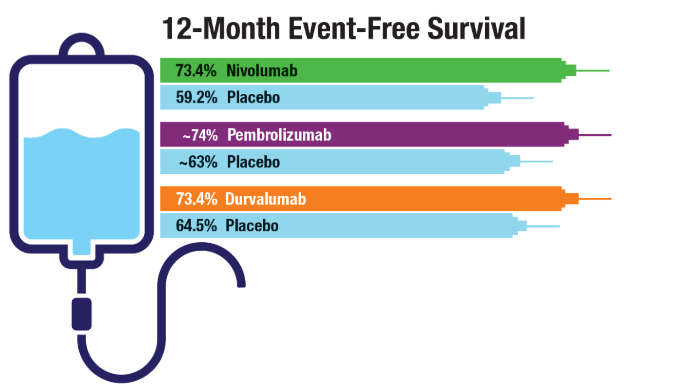

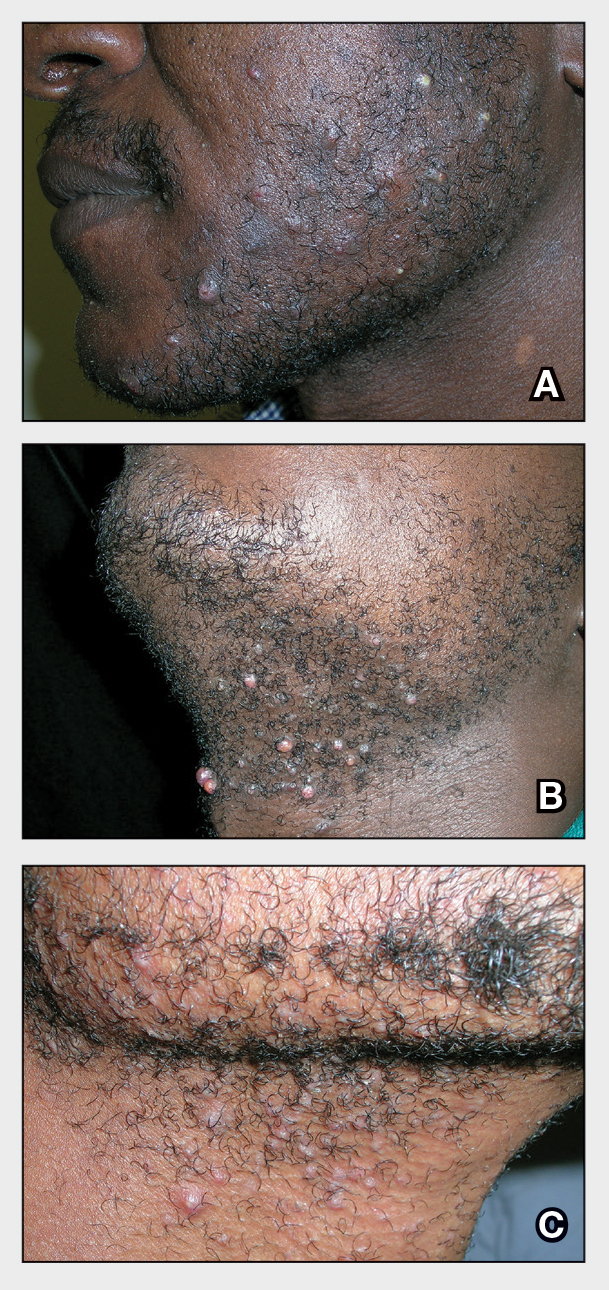

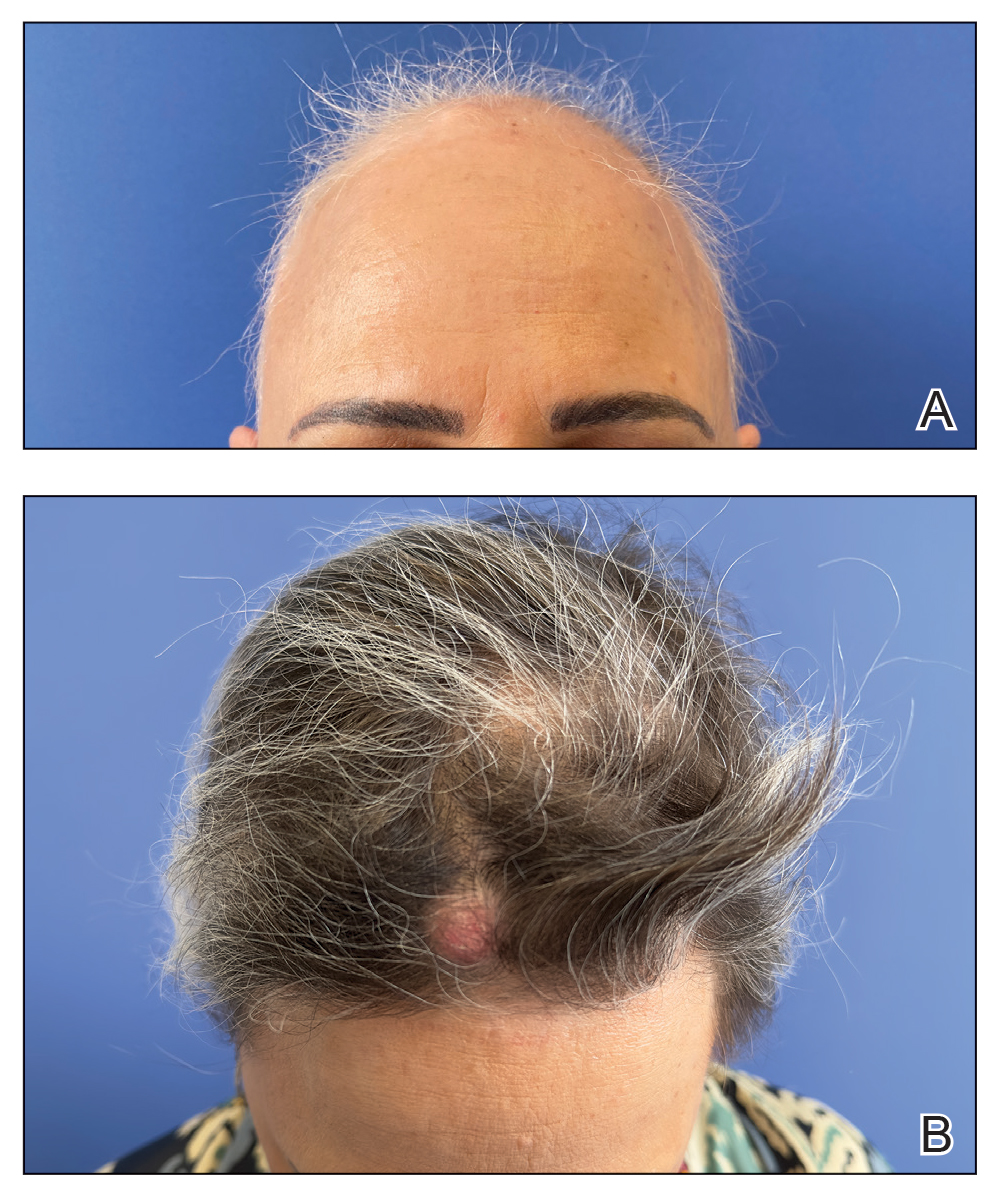

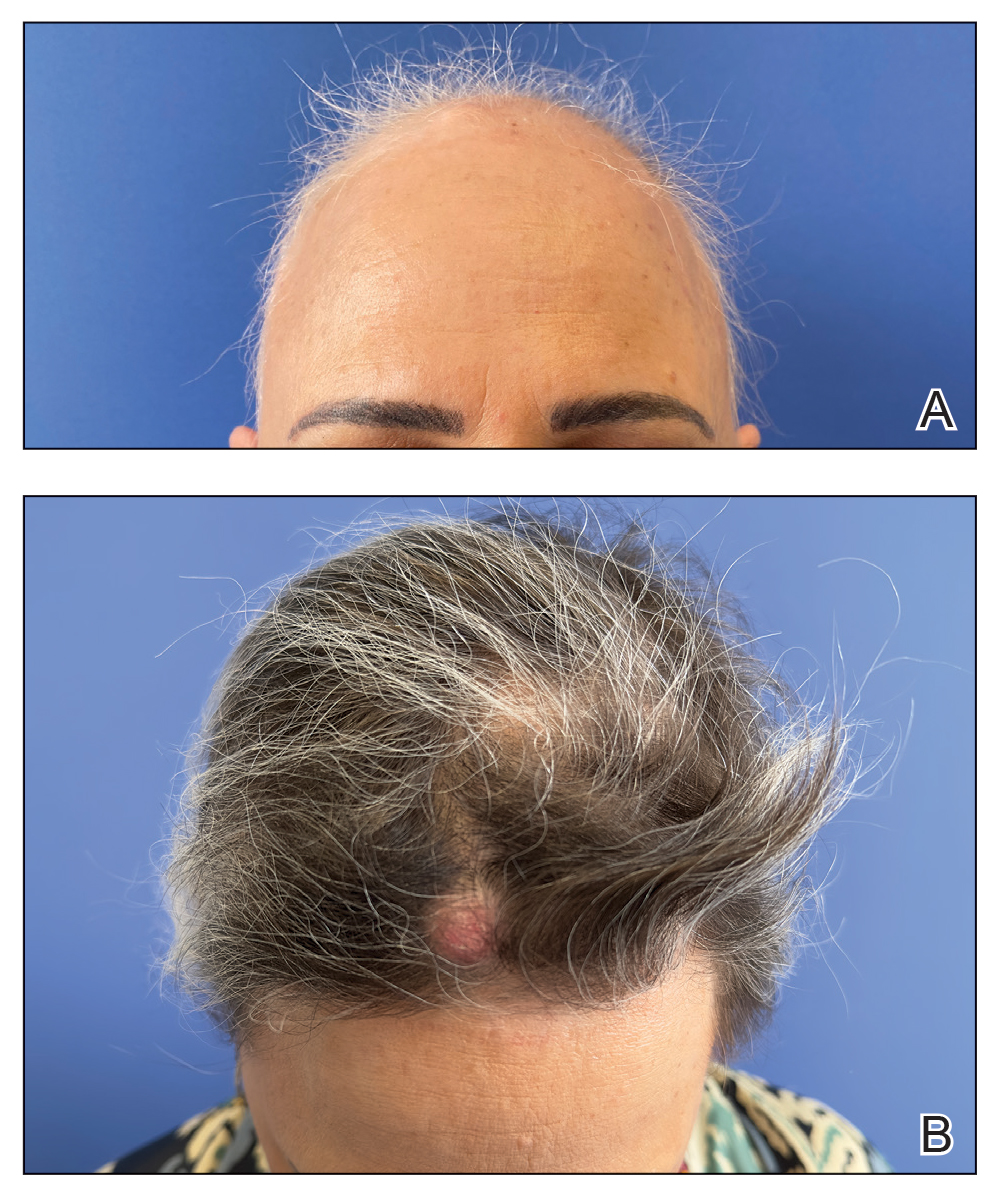

THE COMPARISON

- A. Pustules, erythematous to violaceous nodules, and hyperpigmented patches on the lower cheek and chin.

- B. Brown papules, pink keloidal papules and nodules, pustules, and hyperpigmented papules on the mandibular area and neck.

- C. Coarse hairs, pustules, and pink papules on the mandibular area and neck.

Pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB), also known as razor bumps, is a common inflammatory condition characterized by papules and pustules that typically appear in the beard and cheek regions. It occurs when shaved hair regrows and penetrates the skin, leading to irritation and inflammation. While anyone who shaves can develop PFB, it is more prevalent and severe in individuals with naturally tightly coiled, coarse-textured hair.1,2 Pseudofolliculitis barbae is common in individuals who shave frequently due to personal choice or profession, such as members of the US military3,4 and firefighters, who are required to remain clean shaven for safety (eg, ensuring proper fit of a respirator mask).5 Early diagnosis and treatment of PFB are essential to prevent long-term complications such as scarring or hyperpigmentation, which may be more severe in those with darker skin tones.

Epidemiology

Pseudofolliculitis barbae is most common in Black men, affecting 45% to 83% of men of African ancestry.1,2 This condition also can affect individuals of various ethnicities with coarse or curly hair. The spiral shape of the hair increases the likelihood that it will regrow into the skin after shaving.6 Women with hirsutism who shave also can develop PFB.

Key Clinical Features

The papules and pustules seen in PFB may be flesh colored, erythematous, hyperpigmented, brown, or violaceous. Erythema may be less pronounced in darker vs lighter skin tones. Persistent and severe postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may occur, and hypertrophic or keloidal scars may develop in affected areas. Dermoscopy may reveal extrafollicular hair penetration as well as follicular or perifollicular pustules accompanied by hyperkeratosis.

Worth Noting

The most effective management for PFB is to discontinue shaving.1 If shaving is desired or necessary, it is recommended that patients apply lukewarm water to the affected area followed by a generous amount of shaving foam or gel to create a protective antifriction layer that allows the razor to glide more smoothly over the skin and reduces subsequent irritation.2 Using the right razor technology also may help alleviate symptoms. Research has shown that multiblade razors used in conjunction with preshave hair hydration and postshave moisturization do not worsen PFB.2 A recent study found that multiblade razor technology paired with use of a shave foam or gel actually improved skin appearance in patients with PFB.7

It is important to direct patients to shave in the direction of hair growth; however, this may not be possible for individuals with curly or coarse hair, as the hair may grow in many directions.8,9 Patients also should avoid pulling the skin taut while shaving, as doing so allows the hair to be clipped below the surface, where it can repenetrate the skin and cause further irritation. As an alternative to shaving with a razor, patients can use hair clippers to trim beard hair, which leaves behind stubble and interrupts the cycle of retracted hairs under the skin. Nd:YAG laser therapy has demonstrated efficacy in reduction of PFB papules and pustules.9-12 Greater mean improvement in inflammatory papules and reduction in hair density was noted in participants who received Nd:YAG laser plus eflornithine compared with those who received the laser or eflornithine alone.11 Patients should not pluck or dig into the skin to remove any ingrown hairs. If a tweezer is used, the patient should gently lift the tip of the ingrown hair with the tweezer to dislodge it from the skin and prevent plucking out the hair completely.

To help manage inflammation after shaving, topical treatments such as benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% gel can be used.3,13 A low-potency steroid such as topical hydrocortisone 2.5% applied once or twice daily for up to 2 to 3 days may be helpful.1,14 Adjunctive treatments including keratolytics (eg, topical retinoids, hydroxy acids) reduce perifollicular hyperkeratosis.14,15 Agents containing alpha hydroxy acids (eg, glycolic acid) also can decrease the curvature of the hair itself by reducing the sulfhydryl bonds.6 If secondary bacterial infections occur, oral antibiotics (eg, doxycycline) may be necessary.

Health Disparity Highlight

Individuals with darker skin tones are at higher risk for PFB and associated complications. Limited access to dermatology services may further exacerbate these challenges. Individuals with PFB may not seek medical treatment until the condition becomes severe. Clinicians also may underestimate the severity of PFB—particularly in those with darker skin tones—based on erythema alone because it may be less pronounced in darker vs lighter skin tones.16

While permanent hair reduction with laser therapy is a treatment option for PFB, it may be inaccessible to some patients because it can be expensive and is coded as a cosmetic procedure. Additionally, patients may not have access to specialists who are experienced in performing the procedure in those with darker skin tones.9 Some patients also may not want to permanently reduce the amount of hair that grows in the beard area for personal or religious reasons.17

Pseudofolliculitis barbae also has been linked to professional disparities. One study found that members of the US Air Force who had medical shaving waivers experienced longer times to promotion than those with no waiver.18 Delays in promotion may be linked to perceptions of unprofessionalism, exclusion from high-profile duties, and concerns about career progression. While this delay was similar for individuals of all races, the majority of those in the waiver group were Black/African American. In 2021, 4 Black firefighters with PFB were unsuccessful in their bid to get a medical accommodation regarding a New York City Fire Department policy requiring them to be clean shaven where the oxygen mask seals against the skin.5 More research is needed on mask safety and efficiency relative to the length of facial hair. Accommodations or tailored masks for facial hair conditions also are necessary so individuals with PFB can meet job requirements while managing their condition.

- Alexis A, Heath CR, Halder RM. Folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and pseudofolliculitis barbae: are prevention and effective treatment within reach? em>Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:183-191.

- Gray J, McMichael AJ. Pseudofolliculitis barbae: understanding the condition and the role of facial grooming. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38 (suppl 1):24-27.

- Tshudy MT, Cho S. Pseudofolliculitis barbae in the U.S. military, a review. Mil Med. 2021;186:E52-E57.

- Jung I, Lannan FM, Weiss A, et al. Treatment and current policies on pseudofolliculitis barbae in the US military. Cutis. 2023;112:299-302.

- Jiang YR. Reasonable accommodation and disparate impact: clean shave policy discrimination in today’s workplace. J Law Med Ethics. 2023;51:185-195.

- Taylor SC, Barbosa V, Burgess C, et al. Hair and scalp disorders in adult and pediatric patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2017;100:31-35.

- Moran E, McMichael A, De Souza B, et al. New razor technology improves appearance and quality of life in men with pseudofolliculitis barbae. Cutis. 2022;110:329-334.

- Maurer M, Rietzler M, Burghardt R, et al. The male beard hair and facial skin—challenges for shaving. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38 (suppl 1):3-9.

- Ross EV. How would you treat this patient with lasers & EBDs? casebased panel. Presented at: Skin of Color Update; September 13, 2024; New York, NY.

- Ross EV, Cooke LM, Timko AL, et al. Treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae in skin types IV, V, and VI with a long-pulsed neodymium:yttrium aluminum garnet laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:263-270.

- Shokeir H, Samy N, Taymour M. Pseudofolliculitis barbae treatment: efficacy of topical eflornithine, long-pulsed Nd-YAG laser versus their combination. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3517-3525.

- Amer A, Elsayed A, Gharib K. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of chemical peeling and long-pulse Nd:YAG laser in treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14859.

- Cook-Bolden FE, Barba A, Halder R, et al. Twice-daily applications of benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% gel versus vehicle in the treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae. Cutis. 2004;73(6 suppl):18-24.

- Nussbaum D, Friedman A. Pseudofolliculitis barbae: a review of current treatment options. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:246-250.

- Quarles FN, Brody H, Johnson BA, et al. Pseudofolliculitis barbae. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:133-136.

- McMichael AJ, Frey C. Challenging the tools used to measure cutaneous lupus severity in patients of all skin types. JAMA Dermatol. 2025;161:9-10.

- Okonkwo E, Neal B, Harper HL. Pseudofolliculitis barbae in the military and the need for social awareness. Mil Med. 2021;186:143-144.

- Ritchie S, Park J, Banta J, et al. Shaving waivers in the United States Air Force and their impact on promotions of Black/African-American members. Mil Med. 2023;188:E242-E247.

THE COMPARISON

- A. Pustules, erythematous to violaceous nodules, and hyperpigmented patches on the lower cheek and chin.

- B. Brown papules, pink keloidal papules and nodules, pustules, and hyperpigmented papules on the mandibular area and neck.

- C. Coarse hairs, pustules, and pink papules on the mandibular area and neck.

Pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB), also known as razor bumps, is a common inflammatory condition characterized by papules and pustules that typically appear in the beard and cheek regions. It occurs when shaved hair regrows and penetrates the skin, leading to irritation and inflammation. While anyone who shaves can develop PFB, it is more prevalent and severe in individuals with naturally tightly coiled, coarse-textured hair.1,2 Pseudofolliculitis barbae is common in individuals who shave frequently due to personal choice or profession, such as members of the US military3,4 and firefighters, who are required to remain clean shaven for safety (eg, ensuring proper fit of a respirator mask).5 Early diagnosis and treatment of PFB are essential to prevent long-term complications such as scarring or hyperpigmentation, which may be more severe in those with darker skin tones.

Epidemiology

Pseudofolliculitis barbae is most common in Black men, affecting 45% to 83% of men of African ancestry.1,2 This condition also can affect individuals of various ethnicities with coarse or curly hair. The spiral shape of the hair increases the likelihood that it will regrow into the skin after shaving.6 Women with hirsutism who shave also can develop PFB.

Key Clinical Features

The papules and pustules seen in PFB may be flesh colored, erythematous, hyperpigmented, brown, or violaceous. Erythema may be less pronounced in darker vs lighter skin tones. Persistent and severe postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may occur, and hypertrophic or keloidal scars may develop in affected areas. Dermoscopy may reveal extrafollicular hair penetration as well as follicular or perifollicular pustules accompanied by hyperkeratosis.

Worth Noting

The most effective management for PFB is to discontinue shaving.1 If shaving is desired or necessary, it is recommended that patients apply lukewarm water to the affected area followed by a generous amount of shaving foam or gel to create a protective antifriction layer that allows the razor to glide more smoothly over the skin and reduces subsequent irritation.2 Using the right razor technology also may help alleviate symptoms. Research has shown that multiblade razors used in conjunction with preshave hair hydration and postshave moisturization do not worsen PFB.2 A recent study found that multiblade razor technology paired with use of a shave foam or gel actually improved skin appearance in patients with PFB.7

It is important to direct patients to shave in the direction of hair growth; however, this may not be possible for individuals with curly or coarse hair, as the hair may grow in many directions.8,9 Patients also should avoid pulling the skin taut while shaving, as doing so allows the hair to be clipped below the surface, where it can repenetrate the skin and cause further irritation. As an alternative to shaving with a razor, patients can use hair clippers to trim beard hair, which leaves behind stubble and interrupts the cycle of retracted hairs under the skin. Nd:YAG laser therapy has demonstrated efficacy in reduction of PFB papules and pustules.9-12 Greater mean improvement in inflammatory papules and reduction in hair density was noted in participants who received Nd:YAG laser plus eflornithine compared with those who received the laser or eflornithine alone.11 Patients should not pluck or dig into the skin to remove any ingrown hairs. If a tweezer is used, the patient should gently lift the tip of the ingrown hair with the tweezer to dislodge it from the skin and prevent plucking out the hair completely.

To help manage inflammation after shaving, topical treatments such as benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% gel can be used.3,13 A low-potency steroid such as topical hydrocortisone 2.5% applied once or twice daily for up to 2 to 3 days may be helpful.1,14 Adjunctive treatments including keratolytics (eg, topical retinoids, hydroxy acids) reduce perifollicular hyperkeratosis.14,15 Agents containing alpha hydroxy acids (eg, glycolic acid) also can decrease the curvature of the hair itself by reducing the sulfhydryl bonds.6 If secondary bacterial infections occur, oral antibiotics (eg, doxycycline) may be necessary.

Health Disparity Highlight

Individuals with darker skin tones are at higher risk for PFB and associated complications. Limited access to dermatology services may further exacerbate these challenges. Individuals with PFB may not seek medical treatment until the condition becomes severe. Clinicians also may underestimate the severity of PFB—particularly in those with darker skin tones—based on erythema alone because it may be less pronounced in darker vs lighter skin tones.16

While permanent hair reduction with laser therapy is a treatment option for PFB, it may be inaccessible to some patients because it can be expensive and is coded as a cosmetic procedure. Additionally, patients may not have access to specialists who are experienced in performing the procedure in those with darker skin tones.9 Some patients also may not want to permanently reduce the amount of hair that grows in the beard area for personal or religious reasons.17

Pseudofolliculitis barbae also has been linked to professional disparities. One study found that members of the US Air Force who had medical shaving waivers experienced longer times to promotion than those with no waiver.18 Delays in promotion may be linked to perceptions of unprofessionalism, exclusion from high-profile duties, and concerns about career progression. While this delay was similar for individuals of all races, the majority of those in the waiver group were Black/African American. In 2021, 4 Black firefighters with PFB were unsuccessful in their bid to get a medical accommodation regarding a New York City Fire Department policy requiring them to be clean shaven where the oxygen mask seals against the skin.5 More research is needed on mask safety and efficiency relative to the length of facial hair. Accommodations or tailored masks for facial hair conditions also are necessary so individuals with PFB can meet job requirements while managing their condition.

THE COMPARISON

- A. Pustules, erythematous to violaceous nodules, and hyperpigmented patches on the lower cheek and chin.

- B. Brown papules, pink keloidal papules and nodules, pustules, and hyperpigmented papules on the mandibular area and neck.

- C. Coarse hairs, pustules, and pink papules on the mandibular area and neck.

Pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB), also known as razor bumps, is a common inflammatory condition characterized by papules and pustules that typically appear in the beard and cheek regions. It occurs when shaved hair regrows and penetrates the skin, leading to irritation and inflammation. While anyone who shaves can develop PFB, it is more prevalent and severe in individuals with naturally tightly coiled, coarse-textured hair.1,2 Pseudofolliculitis barbae is common in individuals who shave frequently due to personal choice or profession, such as members of the US military3,4 and firefighters, who are required to remain clean shaven for safety (eg, ensuring proper fit of a respirator mask).5 Early diagnosis and treatment of PFB are essential to prevent long-term complications such as scarring or hyperpigmentation, which may be more severe in those with darker skin tones.

Epidemiology

Pseudofolliculitis barbae is most common in Black men, affecting 45% to 83% of men of African ancestry.1,2 This condition also can affect individuals of various ethnicities with coarse or curly hair. The spiral shape of the hair increases the likelihood that it will regrow into the skin after shaving.6 Women with hirsutism who shave also can develop PFB.

Key Clinical Features

The papules and pustules seen in PFB may be flesh colored, erythematous, hyperpigmented, brown, or violaceous. Erythema may be less pronounced in darker vs lighter skin tones. Persistent and severe postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may occur, and hypertrophic or keloidal scars may develop in affected areas. Dermoscopy may reveal extrafollicular hair penetration as well as follicular or perifollicular pustules accompanied by hyperkeratosis.

Worth Noting

The most effective management for PFB is to discontinue shaving.1 If shaving is desired or necessary, it is recommended that patients apply lukewarm water to the affected area followed by a generous amount of shaving foam or gel to create a protective antifriction layer that allows the razor to glide more smoothly over the skin and reduces subsequent irritation.2 Using the right razor technology also may help alleviate symptoms. Research has shown that multiblade razors used in conjunction with preshave hair hydration and postshave moisturization do not worsen PFB.2 A recent study found that multiblade razor technology paired with use of a shave foam or gel actually improved skin appearance in patients with PFB.7

It is important to direct patients to shave in the direction of hair growth; however, this may not be possible for individuals with curly or coarse hair, as the hair may grow in many directions.8,9 Patients also should avoid pulling the skin taut while shaving, as doing so allows the hair to be clipped below the surface, where it can repenetrate the skin and cause further irritation. As an alternative to shaving with a razor, patients can use hair clippers to trim beard hair, which leaves behind stubble and interrupts the cycle of retracted hairs under the skin. Nd:YAG laser therapy has demonstrated efficacy in reduction of PFB papules and pustules.9-12 Greater mean improvement in inflammatory papules and reduction in hair density was noted in participants who received Nd:YAG laser plus eflornithine compared with those who received the laser or eflornithine alone.11 Patients should not pluck or dig into the skin to remove any ingrown hairs. If a tweezer is used, the patient should gently lift the tip of the ingrown hair with the tweezer to dislodge it from the skin and prevent plucking out the hair completely.

To help manage inflammation after shaving, topical treatments such as benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% gel can be used.3,13 A low-potency steroid such as topical hydrocortisone 2.5% applied once or twice daily for up to 2 to 3 days may be helpful.1,14 Adjunctive treatments including keratolytics (eg, topical retinoids, hydroxy acids) reduce perifollicular hyperkeratosis.14,15 Agents containing alpha hydroxy acids (eg, glycolic acid) also can decrease the curvature of the hair itself by reducing the sulfhydryl bonds.6 If secondary bacterial infections occur, oral antibiotics (eg, doxycycline) may be necessary.

Health Disparity Highlight

Individuals with darker skin tones are at higher risk for PFB and associated complications. Limited access to dermatology services may further exacerbate these challenges. Individuals with PFB may not seek medical treatment until the condition becomes severe. Clinicians also may underestimate the severity of PFB—particularly in those with darker skin tones—based on erythema alone because it may be less pronounced in darker vs lighter skin tones.16

While permanent hair reduction with laser therapy is a treatment option for PFB, it may be inaccessible to some patients because it can be expensive and is coded as a cosmetic procedure. Additionally, patients may not have access to specialists who are experienced in performing the procedure in those with darker skin tones.9 Some patients also may not want to permanently reduce the amount of hair that grows in the beard area for personal or religious reasons.17

Pseudofolliculitis barbae also has been linked to professional disparities. One study found that members of the US Air Force who had medical shaving waivers experienced longer times to promotion than those with no waiver.18 Delays in promotion may be linked to perceptions of unprofessionalism, exclusion from high-profile duties, and concerns about career progression. While this delay was similar for individuals of all races, the majority of those in the waiver group were Black/African American. In 2021, 4 Black firefighters with PFB were unsuccessful in their bid to get a medical accommodation regarding a New York City Fire Department policy requiring them to be clean shaven where the oxygen mask seals against the skin.5 More research is needed on mask safety and efficiency relative to the length of facial hair. Accommodations or tailored masks for facial hair conditions also are necessary so individuals with PFB can meet job requirements while managing their condition.

- Alexis A, Heath CR, Halder RM. Folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and pseudofolliculitis barbae: are prevention and effective treatment within reach? em>Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:183-191.

- Gray J, McMichael AJ. Pseudofolliculitis barbae: understanding the condition and the role of facial grooming. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38 (suppl 1):24-27.

- Tshudy MT, Cho S. Pseudofolliculitis barbae in the U.S. military, a review. Mil Med. 2021;186:E52-E57.

- Jung I, Lannan FM, Weiss A, et al. Treatment and current policies on pseudofolliculitis barbae in the US military. Cutis. 2023;112:299-302.

- Jiang YR. Reasonable accommodation and disparate impact: clean shave policy discrimination in today’s workplace. J Law Med Ethics. 2023;51:185-195.

- Taylor SC, Barbosa V, Burgess C, et al. Hair and scalp disorders in adult and pediatric patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2017;100:31-35.

- Moran E, McMichael A, De Souza B, et al. New razor technology improves appearance and quality of life in men with pseudofolliculitis barbae. Cutis. 2022;110:329-334.

- Maurer M, Rietzler M, Burghardt R, et al. The male beard hair and facial skin—challenges for shaving. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38 (suppl 1):3-9.

- Ross EV. How would you treat this patient with lasers & EBDs? casebased panel. Presented at: Skin of Color Update; September 13, 2024; New York, NY.

- Ross EV, Cooke LM, Timko AL, et al. Treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae in skin types IV, V, and VI with a long-pulsed neodymium:yttrium aluminum garnet laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:263-270.

- Shokeir H, Samy N, Taymour M. Pseudofolliculitis barbae treatment: efficacy of topical eflornithine, long-pulsed Nd-YAG laser versus their combination. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3517-3525.

- Amer A, Elsayed A, Gharib K. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of chemical peeling and long-pulse Nd:YAG laser in treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14859.

- Cook-Bolden FE, Barba A, Halder R, et al. Twice-daily applications of benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% gel versus vehicle in the treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae. Cutis. 2004;73(6 suppl):18-24.

- Nussbaum D, Friedman A. Pseudofolliculitis barbae: a review of current treatment options. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:246-250.

- Quarles FN, Brody H, Johnson BA, et al. Pseudofolliculitis barbae. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:133-136.

- McMichael AJ, Frey C. Challenging the tools used to measure cutaneous lupus severity in patients of all skin types. JAMA Dermatol. 2025;161:9-10.

- Okonkwo E, Neal B, Harper HL. Pseudofolliculitis barbae in the military and the need for social awareness. Mil Med. 2021;186:143-144.

- Ritchie S, Park J, Banta J, et al. Shaving waivers in the United States Air Force and their impact on promotions of Black/African-American members. Mil Med. 2023;188:E242-E247.

- Alexis A, Heath CR, Halder RM. Folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and pseudofolliculitis barbae: are prevention and effective treatment within reach? em>Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:183-191.

- Gray J, McMichael AJ. Pseudofolliculitis barbae: understanding the condition and the role of facial grooming. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38 (suppl 1):24-27.

- Tshudy MT, Cho S. Pseudofolliculitis barbae in the U.S. military, a review. Mil Med. 2021;186:E52-E57.

- Jung I, Lannan FM, Weiss A, et al. Treatment and current policies on pseudofolliculitis barbae in the US military. Cutis. 2023;112:299-302.

- Jiang YR. Reasonable accommodation and disparate impact: clean shave policy discrimination in today’s workplace. J Law Med Ethics. 2023;51:185-195.

- Taylor SC, Barbosa V, Burgess C, et al. Hair and scalp disorders in adult and pediatric patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2017;100:31-35.

- Moran E, McMichael A, De Souza B, et al. New razor technology improves appearance and quality of life in men with pseudofolliculitis barbae. Cutis. 2022;110:329-334.

- Maurer M, Rietzler M, Burghardt R, et al. The male beard hair and facial skin—challenges for shaving. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38 (suppl 1):3-9.

- Ross EV. How would you treat this patient with lasers & EBDs? casebased panel. Presented at: Skin of Color Update; September 13, 2024; New York, NY.

- Ross EV, Cooke LM, Timko AL, et al. Treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae in skin types IV, V, and VI with a long-pulsed neodymium:yttrium aluminum garnet laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:263-270.

- Shokeir H, Samy N, Taymour M. Pseudofolliculitis barbae treatment: efficacy of topical eflornithine, long-pulsed Nd-YAG laser versus their combination. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3517-3525.

- Amer A, Elsayed A, Gharib K. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of chemical peeling and long-pulse Nd:YAG laser in treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14859.

- Cook-Bolden FE, Barba A, Halder R, et al. Twice-daily applications of benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% gel versus vehicle in the treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae. Cutis. 2004;73(6 suppl):18-24.

- Nussbaum D, Friedman A. Pseudofolliculitis barbae: a review of current treatment options. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:246-250.

- Quarles FN, Brody H, Johnson BA, et al. Pseudofolliculitis barbae. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:133-136.

- McMichael AJ, Frey C. Challenging the tools used to measure cutaneous lupus severity in patients of all skin types. JAMA Dermatol. 2025;161:9-10.

- Okonkwo E, Neal B, Harper HL. Pseudofolliculitis barbae in the military and the need for social awareness. Mil Med. 2021;186:143-144.

- Ritchie S, Park J, Banta J, et al. Shaving waivers in the United States Air Force and their impact on promotions of Black/African-American members. Mil Med. 2023;188:E242-E247.

Beyond the Razor: Managing Pseudofolliculitis Barbae in Skin of Color

Beyond the Razor: Managing Pseudofolliculitis Barbae in Skin of Color

Baricitinib-Induced Trichilemmal Cyst Reactivation in a Woman With Alopecia Areata

Baricitinib-Induced Trichilemmal Cyst Reactivation in a Woman With Alopecia Areata

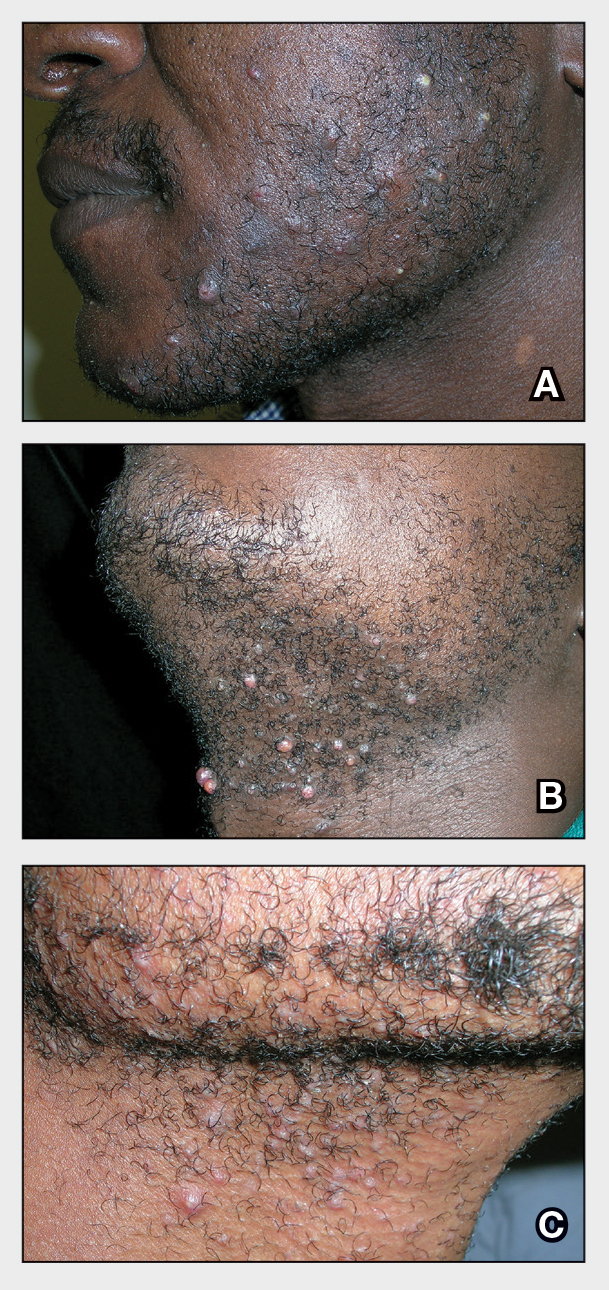

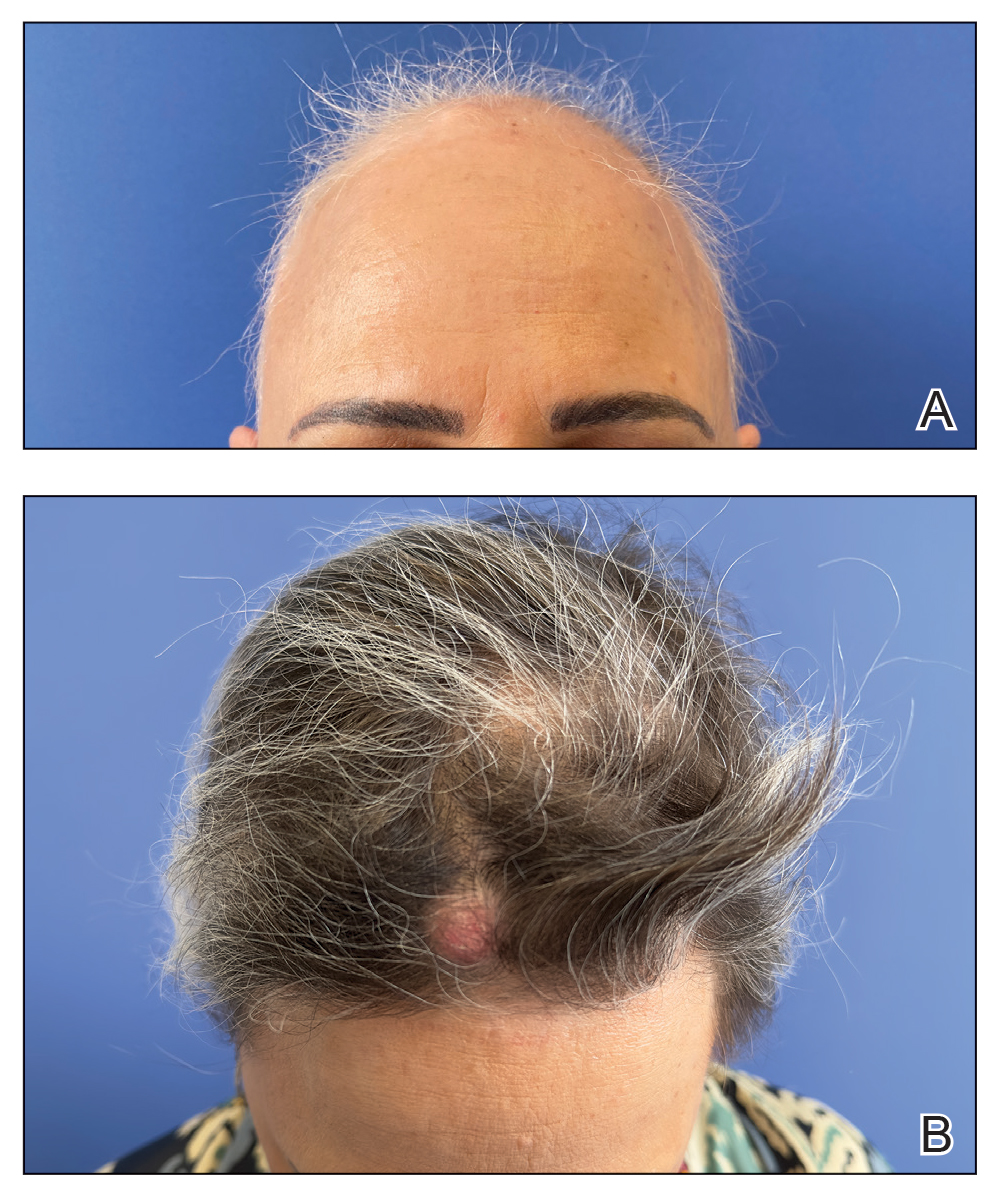

To the Editor:

Alopecia areata (AA), an autoimmune disease characterized by inflammatory and nonscarring hair loss, can have a considerable impact on quality of life.1 Baricitinib is a Janus kinase inhibitor that recently was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of severe AA in adult patients, becoming the only on-label treatment available.2 So far, the most common adverse effects reported in phase 3 trials have been acne, upper respiratory tract infections, headaches, urinary tract infections, and elevated creatine kinase levels.3

At our trichology unit in the dermatology department of a Spanish tertiary-care hospital in Seville, we have successfully used baricitinib to treat 18 patients with severe, therapy-resistant AA. Herein, we present a case of trichilemmal cyst reactivation in one of our patients following successful treatment with baricitinib.

A 53-year-old woman with a history of trichilemmal cysts presented to the dermatology department with total body hair loss of 5 years' duration that was diagnosed as AA universalis (Figure, A). The patient reported that the trichilemmal cysts had shrunk drastically 1 month after complete loss of body hair (Severity of Alopecia Tool [SALT] score, 100)(Figure, B). The largest cyst was surgically removed, and the diagnosis was histologically confirmed by a pathologist. Her mother and sister also had a history of multiple trichilemmal cysts.

The patient previously had failed treatment with oral prednisone 50 mg/d, oral cyclosporine 4 mg/kg/d, oral dexamethasone 4 mg twice weekly, and oral azathioprine 300 mg/wk. Due to the new indication of baricitinib for AA, we opted to start the patient on oral baricitinib 4 mg/d. By week 8 of treatment, she had achieved total hair regrowth (SALT score, 0). This rapid response might indicate a quick-responder phenotype, referring to a subset of patients who exhibit a fast and robust response to treatment (SALT90), generally before week 16, although more evidence is needed.

Notably, we observed the reactivation of 4 trichilemmal cysts on the scalp 6 weeks after starting baricitinib. To our knowledge, this side effect has not previously been reported. We hypothesize that reactivation of the cysts may have been due to the inhibition of the Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway, which reduces the effects of cytokines and leads to reactivation of hair follicles that were inactive because of inflammation.4 As a result, the outer root sheath of the hair follicle can once again be filled with keratin, thereby reactivating the trichilemmal cysts. Based on our experience with this case, it may be relevant to consider personal and family history of trichilemmal cysts before starting treatment with baricitinib for AA and advise the patient about the possibility of this adverse effect.

- Freitas E, Guttman-Yassky E, Torres T. Baricitinib for the treatment of alopecia areata. Drugs. 2023;83:761-770. doi:10.1007 /s40265-023-01873-w

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first systemic treatment for alopecia areata [news release]. July 13, 2022. Accessed March 17, 2025. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/fda-approves-first-systemic-treatment-for-alopecia-areata-301566884.html

- King B, Ohyama M, Kwon O, et al. Two phase 3 trials of baricitinib for alopecia areata. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1687-1699. doi:10.1056 /NEJMoa2110343

- Lensing M, Jabbari A. An overview of JAK/STAT pathways and JAK inhibition in alopecia areata. Front Immunol. 2022;13:955035. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.955035

To the Editor:

Alopecia areata (AA), an autoimmune disease characterized by inflammatory and nonscarring hair loss, can have a considerable impact on quality of life.1 Baricitinib is a Janus kinase inhibitor that recently was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of severe AA in adult patients, becoming the only on-label treatment available.2 So far, the most common adverse effects reported in phase 3 trials have been acne, upper respiratory tract infections, headaches, urinary tract infections, and elevated creatine kinase levels.3

At our trichology unit in the dermatology department of a Spanish tertiary-care hospital in Seville, we have successfully used baricitinib to treat 18 patients with severe, therapy-resistant AA. Herein, we present a case of trichilemmal cyst reactivation in one of our patients following successful treatment with baricitinib.