User login

More New Therapeutics for Psoriasis

New treatments for psoriasis constitute an embarrassment of riches compared to any other area of dermatology. Despite the many advances over the last 25 years, additional topical and systemic treatments have recently become available. Gosh, it’s great!

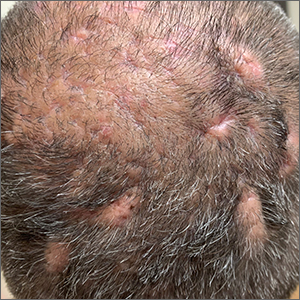

In May 2022, once-daily tapinarof cream 1% was approved for the topical treatment of plaque psoriasis in adults.1 Tapinarof was identified as a metabolite made by bacteria symbiotic to a nematode, allowing the nematode to infect insects.2 Tapinarof’s anti-inflammatory effect extends to mammals. The drug works by activating the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, downregulating proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-17, and normalizing the expression of skin barrier proteins such as filaggrin.2 In two 12-week, phase 3, randomized trials with 510 and 515 patients, respectively, 35% to 40% of tapinarof-treated psoriasis patients were clear or almost clear compared with only 6% of patients in the placebo group. The drug appears safe; common adverse events (AEs) included folliculitis, nasopharyngitis, contact dermatitis, headache, upper respiratory tract infection, and pruritus.3

A second new topical treatment for plaque psoriasis was approved in July 2022—once-daily roflumilast 0.3% cream—for patients 12 years and older.4 Similar to apremilast, roflumilast is a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor that blocks the degradation of cAMP and reduces the downstream production of inflammatory molecules implicated in psoriasis.5 In two 8-week, phase 3 clinical trials (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifiers NCT04211363 and NCT04211389)(N=881), approximately 40% of roflumilast-treated patients were clear or almost clear vs approximately 6% in the placebo group. Topical roflumilast was well-tolerated; the most common AEs included diarrhea, headache, insomnia, nausea, application-site pain, upper respiratory tract infection, and urinary tract infection.6

We have so many patients—and many more people with psoriasis who are not yet patients—with limited psoriasis who would be amenable to topical treatment but who are not responding to current treatments. There is considerable enthusiasm for the new topicals, but it is still questionable how much they will help our patients. The main reason the current topicals fail is poor adherence to the treatment. If we give these new treatments to patients who used existing topicals and failed, thereby inadvertently selecting patients with poor adherence to topicals, it will be surprising if the new treatments live up to expectations. Perhaps tapinarof and roflumilast will revolutionize the management of localized psoriasis; perhaps their impact will be similar to topical crisaborole— exciting in trials and less practical in real life. It may be that apremilast, which is now approved for psoriasis of any severity, will make a bigger difference for patients who can access it for limited psoriasis.

Deucravacitinib is a once-daily oral selective tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor that blocks IL-23 and type I interferon signaling. It was approved for adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in September 2021.7 We know patients want oral treatment; they ask for apremilast even though injections may be much more potent. In a 16-week, phase 3 clinical trial comparing daily deucravacitinib (n=332), apremilast (n=168), and placebo (n=166), rates of clear or almost clear were approximately 55% in the deucravacitinib group, 32% in the apremilast group, and 7% with placebo. The most common AEs included nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, headache, diarrhea, and nausea.8 Although deucravacitinib is much more effective than apremilast, deucravacitinib will require monitoring and may have some risk for viral reactivation of herpes simplex and zoster (and hopefully not much else). Whether physicians view it as a replacement for apremilast, which requires no laboratory monitoring, remains to be seen.

Bimekizumab, a humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody expected to receive US Food and Drug Administration approval in the coming months, inhibits both IL-17A and IL-17F and may become our most effective treatment of psoriasis. Although we are probably not hungering for a more effective psoriasis treatment (given our current embarrassment of riches), bimekizumab’s remarkably high efficacy for psoriatic arthritis may be a quantum leap forward, especially if no new safety signals are identified; bimekizumab treatment is associated with a higher risk of oral candidiasis than other currently available IL-17 antagonists.9 Biosimilars may reduce the cost of psoriasis management to the health system, but it seems unlikely that biosimilars will allow us to help patients who we cannot already help with the existing extensive psoriasis treatment armamentarium.

- Dermavant announces FDA approval for VTAMA® (Tapinarof) cream. International Psoriasis Council. Published May 26, 2022. Accessed January 10, 2023. https://www.psoriasiscouncil.org/treatment/dermavant-vtama/#:~:text=Dermavant%20Sciences%20announced%20that%20VTAMA,and%20Drug%20Administration%20(FDA)

- Bissonnette R, Stein Gold L, Rubenstein DS, et al. Tapinarof in the treatment of psoriasis: a review of the unique mechanism of action of a novel therapeutic aryl hydrocarbon receptor-modulating agent [published online November 3, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1059-1067. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.085

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2103629

- FDA approves Arcutis’ ZORYVE™ (Roflumilast) cream 0.3% for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in individuals age 12 and older. News release. Arcutis Biotherapeutics; July 29, 2022. Accessed January 10, 2023. https://www.arcutis.com/fda-approves-arcutis-zoryve-roflumilast-cream-0-3-for-the-treatment-of-plaque-psoriasis-in-individuals-age-12-and-older/

- Milakovic M, Gooderham MJ. Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibition in psoriasis. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2021;17:11:21-29. doi:10.2147/PTT.S303634

- Zoryve. Package insert. Arcutis Biotherapeutics; 2022.

- Hoy SM. Deucravacitinib: first approval. Drugs. 2022;82:1671-1679. doi:10.1007/s40265-022-01796-y

- Armstrong AW, Gooderham M, Warren RB, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52-week, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:29-39. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.07.002

- Freitas E, Blauvelt A, Torres T. Bimekizumab for the treatment of psoriasis [published online October 8, 2021]. Drugs. 2021;81:1751-1762. doi:10.1007/s40265-021-01612-z

New treatments for psoriasis constitute an embarrassment of riches compared to any other area of dermatology. Despite the many advances over the last 25 years, additional topical and systemic treatments have recently become available. Gosh, it’s great!

In May 2022, once-daily tapinarof cream 1% was approved for the topical treatment of plaque psoriasis in adults.1 Tapinarof was identified as a metabolite made by bacteria symbiotic to a nematode, allowing the nematode to infect insects.2 Tapinarof’s anti-inflammatory effect extends to mammals. The drug works by activating the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, downregulating proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-17, and normalizing the expression of skin barrier proteins such as filaggrin.2 In two 12-week, phase 3, randomized trials with 510 and 515 patients, respectively, 35% to 40% of tapinarof-treated psoriasis patients were clear or almost clear compared with only 6% of patients in the placebo group. The drug appears safe; common adverse events (AEs) included folliculitis, nasopharyngitis, contact dermatitis, headache, upper respiratory tract infection, and pruritus.3

A second new topical treatment for plaque psoriasis was approved in July 2022—once-daily roflumilast 0.3% cream—for patients 12 years and older.4 Similar to apremilast, roflumilast is a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor that blocks the degradation of cAMP and reduces the downstream production of inflammatory molecules implicated in psoriasis.5 In two 8-week, phase 3 clinical trials (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifiers NCT04211363 and NCT04211389)(N=881), approximately 40% of roflumilast-treated patients were clear or almost clear vs approximately 6% in the placebo group. Topical roflumilast was well-tolerated; the most common AEs included diarrhea, headache, insomnia, nausea, application-site pain, upper respiratory tract infection, and urinary tract infection.6

We have so many patients—and many more people with psoriasis who are not yet patients—with limited psoriasis who would be amenable to topical treatment but who are not responding to current treatments. There is considerable enthusiasm for the new topicals, but it is still questionable how much they will help our patients. The main reason the current topicals fail is poor adherence to the treatment. If we give these new treatments to patients who used existing topicals and failed, thereby inadvertently selecting patients with poor adherence to topicals, it will be surprising if the new treatments live up to expectations. Perhaps tapinarof and roflumilast will revolutionize the management of localized psoriasis; perhaps their impact will be similar to topical crisaborole— exciting in trials and less practical in real life. It may be that apremilast, which is now approved for psoriasis of any severity, will make a bigger difference for patients who can access it for limited psoriasis.

Deucravacitinib is a once-daily oral selective tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor that blocks IL-23 and type I interferon signaling. It was approved for adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in September 2021.7 We know patients want oral treatment; they ask for apremilast even though injections may be much more potent. In a 16-week, phase 3 clinical trial comparing daily deucravacitinib (n=332), apremilast (n=168), and placebo (n=166), rates of clear or almost clear were approximately 55% in the deucravacitinib group, 32% in the apremilast group, and 7% with placebo. The most common AEs included nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, headache, diarrhea, and nausea.8 Although deucravacitinib is much more effective than apremilast, deucravacitinib will require monitoring and may have some risk for viral reactivation of herpes simplex and zoster (and hopefully not much else). Whether physicians view it as a replacement for apremilast, which requires no laboratory monitoring, remains to be seen.

Bimekizumab, a humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody expected to receive US Food and Drug Administration approval in the coming months, inhibits both IL-17A and IL-17F and may become our most effective treatment of psoriasis. Although we are probably not hungering for a more effective psoriasis treatment (given our current embarrassment of riches), bimekizumab’s remarkably high efficacy for psoriatic arthritis may be a quantum leap forward, especially if no new safety signals are identified; bimekizumab treatment is associated with a higher risk of oral candidiasis than other currently available IL-17 antagonists.9 Biosimilars may reduce the cost of psoriasis management to the health system, but it seems unlikely that biosimilars will allow us to help patients who we cannot already help with the existing extensive psoriasis treatment armamentarium.

New treatments for psoriasis constitute an embarrassment of riches compared to any other area of dermatology. Despite the many advances over the last 25 years, additional topical and systemic treatments have recently become available. Gosh, it’s great!

In May 2022, once-daily tapinarof cream 1% was approved for the topical treatment of plaque psoriasis in adults.1 Tapinarof was identified as a metabolite made by bacteria symbiotic to a nematode, allowing the nematode to infect insects.2 Tapinarof’s anti-inflammatory effect extends to mammals. The drug works by activating the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, downregulating proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-17, and normalizing the expression of skin barrier proteins such as filaggrin.2 In two 12-week, phase 3, randomized trials with 510 and 515 patients, respectively, 35% to 40% of tapinarof-treated psoriasis patients were clear or almost clear compared with only 6% of patients in the placebo group. The drug appears safe; common adverse events (AEs) included folliculitis, nasopharyngitis, contact dermatitis, headache, upper respiratory tract infection, and pruritus.3

A second new topical treatment for plaque psoriasis was approved in July 2022—once-daily roflumilast 0.3% cream—for patients 12 years and older.4 Similar to apremilast, roflumilast is a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor that blocks the degradation of cAMP and reduces the downstream production of inflammatory molecules implicated in psoriasis.5 In two 8-week, phase 3 clinical trials (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifiers NCT04211363 and NCT04211389)(N=881), approximately 40% of roflumilast-treated patients were clear or almost clear vs approximately 6% in the placebo group. Topical roflumilast was well-tolerated; the most common AEs included diarrhea, headache, insomnia, nausea, application-site pain, upper respiratory tract infection, and urinary tract infection.6

We have so many patients—and many more people with psoriasis who are not yet patients—with limited psoriasis who would be amenable to topical treatment but who are not responding to current treatments. There is considerable enthusiasm for the new topicals, but it is still questionable how much they will help our patients. The main reason the current topicals fail is poor adherence to the treatment. If we give these new treatments to patients who used existing topicals and failed, thereby inadvertently selecting patients with poor adherence to topicals, it will be surprising if the new treatments live up to expectations. Perhaps tapinarof and roflumilast will revolutionize the management of localized psoriasis; perhaps their impact will be similar to topical crisaborole— exciting in trials and less practical in real life. It may be that apremilast, which is now approved for psoriasis of any severity, will make a bigger difference for patients who can access it for limited psoriasis.

Deucravacitinib is a once-daily oral selective tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor that blocks IL-23 and type I interferon signaling. It was approved for adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in September 2021.7 We know patients want oral treatment; they ask for apremilast even though injections may be much more potent. In a 16-week, phase 3 clinical trial comparing daily deucravacitinib (n=332), apremilast (n=168), and placebo (n=166), rates of clear or almost clear were approximately 55% in the deucravacitinib group, 32% in the apremilast group, and 7% with placebo. The most common AEs included nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, headache, diarrhea, and nausea.8 Although deucravacitinib is much more effective than apremilast, deucravacitinib will require monitoring and may have some risk for viral reactivation of herpes simplex and zoster (and hopefully not much else). Whether physicians view it as a replacement for apremilast, which requires no laboratory monitoring, remains to be seen.

Bimekizumab, a humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody expected to receive US Food and Drug Administration approval in the coming months, inhibits both IL-17A and IL-17F and may become our most effective treatment of psoriasis. Although we are probably not hungering for a more effective psoriasis treatment (given our current embarrassment of riches), bimekizumab’s remarkably high efficacy for psoriatic arthritis may be a quantum leap forward, especially if no new safety signals are identified; bimekizumab treatment is associated with a higher risk of oral candidiasis than other currently available IL-17 antagonists.9 Biosimilars may reduce the cost of psoriasis management to the health system, but it seems unlikely that biosimilars will allow us to help patients who we cannot already help with the existing extensive psoriasis treatment armamentarium.

- Dermavant announces FDA approval for VTAMA® (Tapinarof) cream. International Psoriasis Council. Published May 26, 2022. Accessed January 10, 2023. https://www.psoriasiscouncil.org/treatment/dermavant-vtama/#:~:text=Dermavant%20Sciences%20announced%20that%20VTAMA,and%20Drug%20Administration%20(FDA)

- Bissonnette R, Stein Gold L, Rubenstein DS, et al. Tapinarof in the treatment of psoriasis: a review of the unique mechanism of action of a novel therapeutic aryl hydrocarbon receptor-modulating agent [published online November 3, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1059-1067. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.085

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2103629

- FDA approves Arcutis’ ZORYVE™ (Roflumilast) cream 0.3% for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in individuals age 12 and older. News release. Arcutis Biotherapeutics; July 29, 2022. Accessed January 10, 2023. https://www.arcutis.com/fda-approves-arcutis-zoryve-roflumilast-cream-0-3-for-the-treatment-of-plaque-psoriasis-in-individuals-age-12-and-older/

- Milakovic M, Gooderham MJ. Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibition in psoriasis. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2021;17:11:21-29. doi:10.2147/PTT.S303634

- Zoryve. Package insert. Arcutis Biotherapeutics; 2022.

- Hoy SM. Deucravacitinib: first approval. Drugs. 2022;82:1671-1679. doi:10.1007/s40265-022-01796-y

- Armstrong AW, Gooderham M, Warren RB, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52-week, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:29-39. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.07.002

- Freitas E, Blauvelt A, Torres T. Bimekizumab for the treatment of psoriasis [published online October 8, 2021]. Drugs. 2021;81:1751-1762. doi:10.1007/s40265-021-01612-z

- Dermavant announces FDA approval for VTAMA® (Tapinarof) cream. International Psoriasis Council. Published May 26, 2022. Accessed January 10, 2023. https://www.psoriasiscouncil.org/treatment/dermavant-vtama/#:~:text=Dermavant%20Sciences%20announced%20that%20VTAMA,and%20Drug%20Administration%20(FDA)

- Bissonnette R, Stein Gold L, Rubenstein DS, et al. Tapinarof in the treatment of psoriasis: a review of the unique mechanism of action of a novel therapeutic aryl hydrocarbon receptor-modulating agent [published online November 3, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1059-1067. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.085

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2103629

- FDA approves Arcutis’ ZORYVE™ (Roflumilast) cream 0.3% for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in individuals age 12 and older. News release. Arcutis Biotherapeutics; July 29, 2022. Accessed January 10, 2023. https://www.arcutis.com/fda-approves-arcutis-zoryve-roflumilast-cream-0-3-for-the-treatment-of-plaque-psoriasis-in-individuals-age-12-and-older/

- Milakovic M, Gooderham MJ. Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibition in psoriasis. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2021;17:11:21-29. doi:10.2147/PTT.S303634

- Zoryve. Package insert. Arcutis Biotherapeutics; 2022.

- Hoy SM. Deucravacitinib: first approval. Drugs. 2022;82:1671-1679. doi:10.1007/s40265-022-01796-y

- Armstrong AW, Gooderham M, Warren RB, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52-week, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:29-39. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.07.002

- Freitas E, Blauvelt A, Torres T. Bimekizumab for the treatment of psoriasis [published online October 8, 2021]. Drugs. 2021;81:1751-1762. doi:10.1007/s40265-021-01612-z

New Treatments for Psoriasis: An Update on a Therapeutic Frontier

The landscape of psoriasis treatments has undergone rapid change within the last decade, and the dizzying speed of drug development has not slowed, with 4 notable entries into the psoriasis treatment armamentarium within the last year: tapinarof, roflumilast, deucravacitinib, and spesolimab. Several others are in late-stage development, and these therapies represent new mechanisms, pathways, and delivery systems that will meaningfully broaden the spectrum of treatment choices for our patients. However, it can be quite difficult to keep track of all of the medication options. This review aims to present the mechanisms and data on both newly available therapeutics for psoriasis and products in the pipeline that may have a major impact on our treatment paradigm for psoriasis in the near future.

Topical Treatments

Tapinarof—Tapinarof is a topical aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)–modulating agent derived from a secondary metabolite produced by a bacterial symbiont of entomopathogenic nematodes.1 Tapinarof binds and activates AhR, inducing a signaling cascade that suppresses the expression of helper T cells TH17 and TH22, upregulates skin barrier protein expression, and reduces epidermal oxidative stress.2 This is a familiar mechanism, as AhR agonism is one of the pathways modulated by coal tar. Tapinarof’s overall effects on immune function, skin barrier integrity, and antioxidant activity show great promise for the treatment of plaque psoriasis.

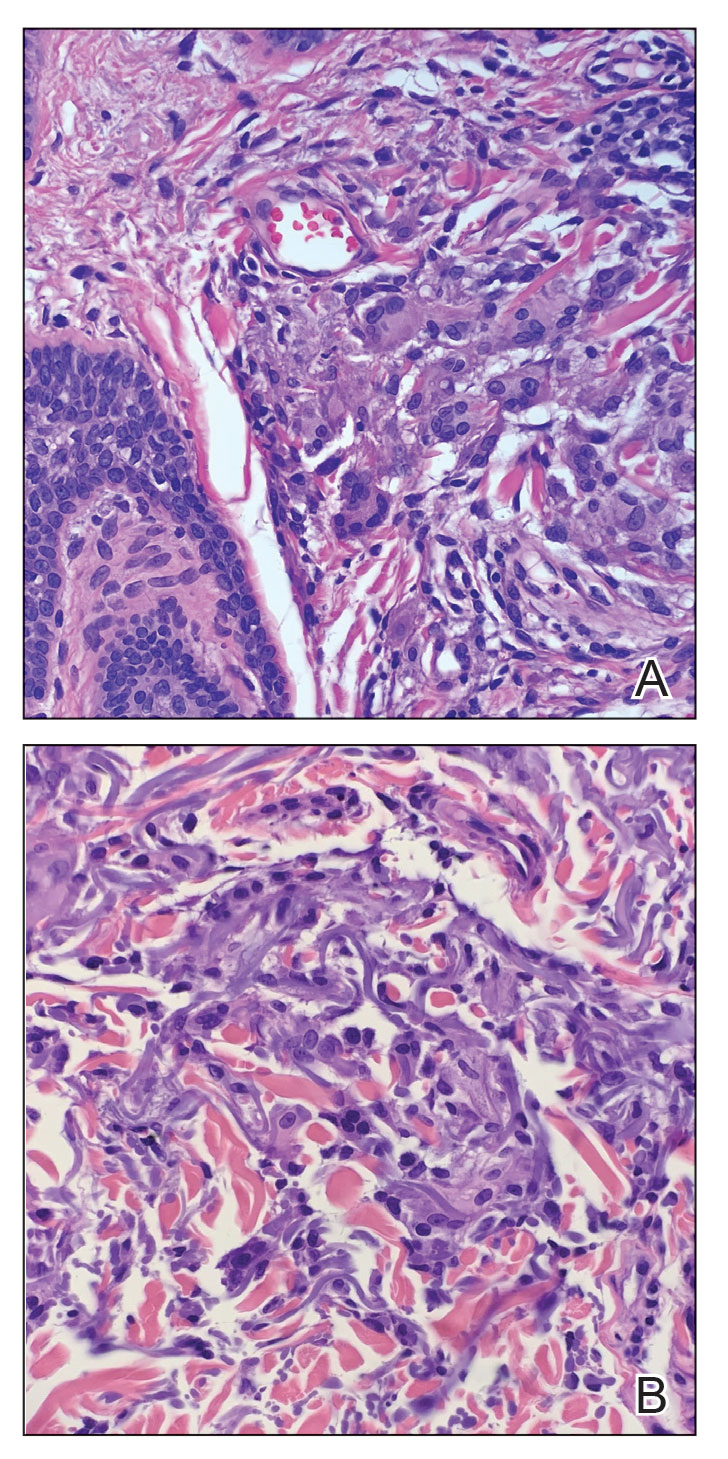

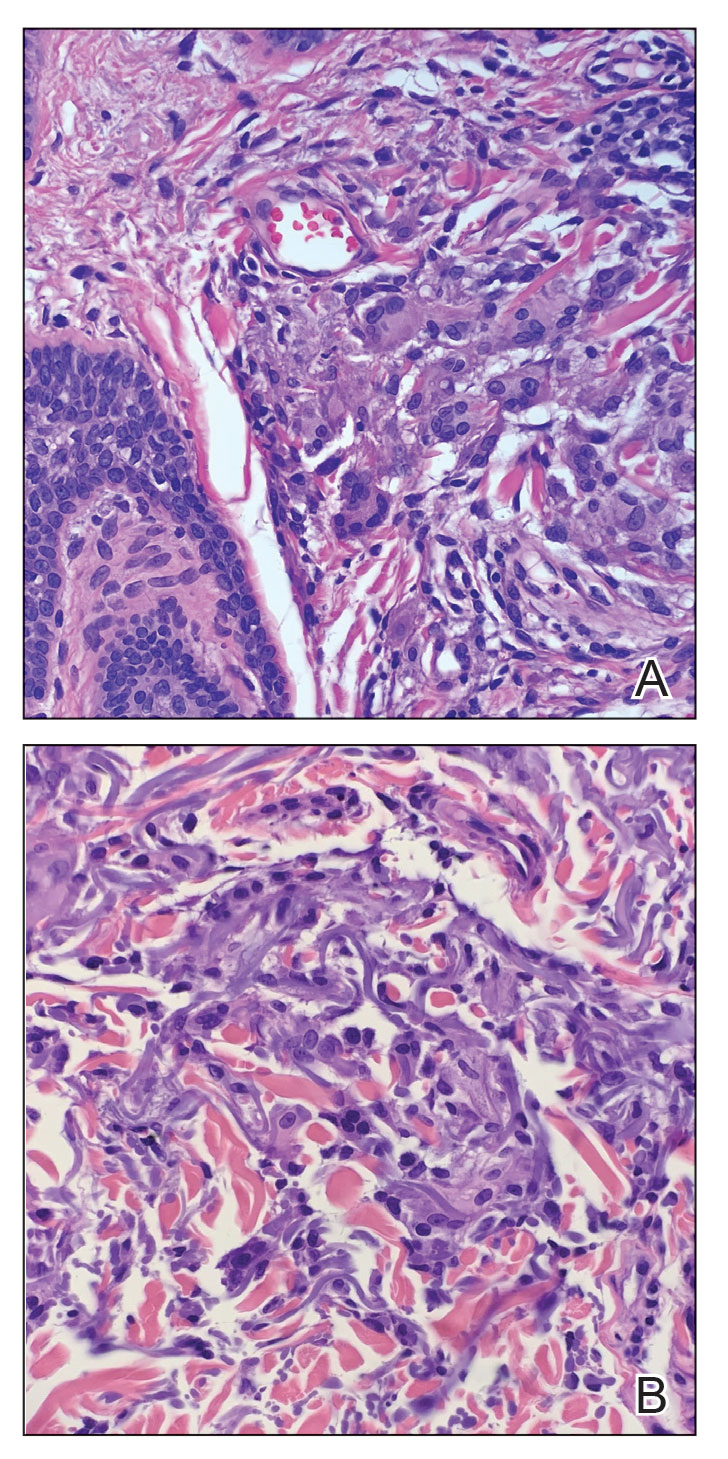

Two phase 3 trials (N=1025) evaluated the efficacy and safety of once-daily tapinarof cream 1% for plaque psoriasis.3 A physician global assessment (PGA) score of 0/1 occurred in 35.4% to 40.2% of patients in the tapinarof group and in 6.0% of patients in the vehicle group. At week 12, 36.1% to 47.6% of patients treated with daily applications of tapinarof cream achieved a 75% reduction in their baseline psoriasis area and severity index (PASI 75) score compared with 6.9% to 10.2% in the vehicle group.3 In a long-term extension study, a substantial remittive effect of at least 4 months off tapinarof therapy was observed in patients who achieved complete clearance (PGA=0).4 Use of tapinarof cream was associated with folliculitis in up to 23.5% of patients.3,4

Roflumilast—

Topical roflumilast is a selective, highly potent PDE-4 inhibitor with greater affinity for PDE-4 compared to crisaborole and apremilast.8 Two phase 3 trials (N=881) evaluated the efficacy and safety profile of roflumilast cream for plaque psoriasis, with a particular interest in its use for intertriginous areas.9 At week 8, 37.5% to 42.4% of roflumilast-treated patients achieved investigator global assessment (IGA) success compared with 6.1% to 6.9% of vehicle-treated patients. Intertriginous IGA success was observed in 68.1% to 71.2% of patients treated with roflumilast cream compared with 13.8% to 18.5% of vehicle-treated patients. At 8-week follow-up, 39.0% to 41.6% of roflumilast-treated patients achieved PASI 75 vs 5.3% to 7.6% of patients in the vehicle group. Few stinging, burning, or application-site reactions were reported with roflumilast, along with rare instances of gastrointestinal AEs (<4%).9

Oral Therapy

Deucravacitinib—Tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) mediates the intracellular signaling of the TH17 and TH1 inflammatory cytokines IL-12/IL-23 and type I interferons, respectively, the former of which are critical in the development of psoriasis via the Janus kinase (JAK) signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway.10 Deucravacitinib is an oral selective TYK2 allosteric inhibitor that binds to the regulatory domain of the enzyme rather than the active catalytic domain, where other TYK2 and JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 inhibitors bind.11 This unique inhibitory mechanism accounts for the high functional selectivity of deucravacitinib for TYK2 vs the closely related JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 kinases, thus avoiding the pitfall of prior JAK inhibitors that were associated with major AEs, including an increased risk for serious infections, malignancies, and thrombosis.12 The selective suppression of the inflammatory TYK2 pathway has the potential to shift future therapeutic targets to a narrower range of receptors that may contribute to favorable benefit-risk profiles.

Two phase 3 trials (N=1686) compared the efficacy and safety of deucravacitinib vs placebo and apremilast in adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.13,14 At week 16, 53.0% to 58.4% of deucravacitinib-treated patients achieved PASI 75 compared with 35.1% to 39.8% of apremilast-treated patients. At 16-week follow-up, static PGA response was observed in 49.5% to 53.6% of patients in the deucravacitinib group and 32.1% to 33.9% of the apremilast group. The most frequent AEs associated with deucravacitinib therapy were nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection, whereas headache, diarrhea, and nausea were more common with apremilast. Treatment with deucravacitinib caused no meaningful changes in laboratory parameters, which are known to change with JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 inhibitors.13,14 A long-term extension study demonstrated that deucravacitinib had persistent efficacy and consistent safety for up to 2 years.15

Other TYK2 Inhibitors in the Pipeline

Novel oral allosteric TYK2 inhibitors—VTX958 and NDI-034858—and the competitive TYK2 inhibitor PF-06826647 are being developed. Theoretically, these new allosteric inhibitors possess unique structural properties to provide greater TYK2 suppression while bypassing JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 pathways that may contribute to improved efficacy and safety profiles compared with other TYK2 inhibitors such as deucravacitinib. The results of a phase 1b trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT04999839) showed a dose-dependent reduction of disease severity associated with NDI-034858 treatment for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, albeit in only 26 patients. At week 4, PASI 50 was achieved in 13%, 57%, and 40% of patients in the 5-, 10-, and 30-mg groups, respectively, compared with 0% in the placebo group.16 In a phase 2 trial of 179 patients, 46.5% and 33.0% of patients treated with 400 and 200 mg of PF-06826647, respectively, achieved PASI 90 at week 16. Conversely, dose-dependent laboratory abnormalities were observed with PF-06826647, including anemia, neutropenia, and increases in creatine phosphokinase.17 At high concentrations, PF-06826647 may disrupt JAK signaling pathways involved in hematopoiesis and renal functions owing to its mode of action as a competitive inhibitor. Overall, these agents are much farther from market, and long-term studies with larger diverse patient cohorts are required to adequately assess the efficacy and safety data of these novel oral TYK2 inhibitors for patients with psoriasis.

EDP1815—EDP1815 is an oral preparation of a single strain of Prevotella histicola being developed for the treatment of inflammatory diseases, including psoriasis. EDP1815 interacts with host intestinal immune cells through the small intestinal axis (SINTAX) to suppress systemic inflammation across the TH1, TH2, and TH17 pathways. Therapy triggers broad immunomodulatory effects without causing systemic absorption, colonic colonization, or modification of the gut microbiome.18 In a phase 2 study (NCT04603027), the primary end point analysis, mean percentage change in PASI between treatment and placebo, demonstrated that at week 16, EDP1815 was superior to placebo with 80% to 90% probability across each cohort. At week 16, 25% to 32% of patients across the 3 cohorts treated with EDP1815 achieved PASI 50 compared with 12% of patients receiving placebo. Gastrointestinal AEs were comparable between treatment and placebo groups. These results suggest that SINTAX-targeted therapies may provide efficacious and safe immunomodulatory effects for patients with mild to moderate psoriasis, who often have limited treatment options. Although improvements may be mild, SINTAX-targeted therapies can be seen as a particularly attractive adjunctive treatment for patients with severe psoriasis taking other medications or as part of a treatment approach for a patient with milder psoriasis.

Biologics

Bimekizumab—Bimekizumab is a monoclonal IgG1 antibody that selectively inhibits IL-17A and IL-17F. Although IL-17A is a more potent cytokine, IL-17F may be more highly expressed in psoriatic lesional skin and independently contribute to the activation of proinflammatory signaling pathways implicated in the pathophysiology of psoriasis.19 Evidence suggests that dual inhibition of IL-17A and IL-17F may provide more complete suppression of inflammation and improved clinical responses than IL-17A inhibition alone.20

Prior bimekizumab phase 3 clinical studies have shown both rapid and durable clinical improvements in skin clearance compared with placebo.21 Three phase 3 trials—BE VIVID (N=567),22 BE SURE (N=478),23 and BE RADIANT (N=743)24—assessed the efficacy and safety of bimekizumab vs the IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor ustekinumab, the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab, and the selective IL-17A inhibitor secukinumab, respectively. At week 4, significantly more patients treated with bimekizumab (71%–77%) achieved PASI 75 than patients treated with ustekinumab (15%; P<.0001), adalimumab (31.4%; P<.001), or secukinumab (47.3%; P<.001).22-24 After 16 weeks of treatment, PASI 90 was achieved by 85% to 86.2%, 50%, and 47.2% of patients treated with bimekizumab, ustekinumab, and adalimumab, respectively.22,23 At week 16, PASI 100 was observed in 59% to 61.7%, 21%, 23.9%, and 48.9% of patients treated with bimekizumab, ustekinumab, adalimumab, and secukinumab, respectively. An IGA response (score of 0/1) at week 16 was achieved by 84% to 85.5%, 53%, 57.2%, and 78.6% of patients receiving bimekizumab, ustekinumab, adalimumab, and secukinumab, respectively.22-24

The most common AEs in bimekizumab-treated patients were nasopharyngitis, oral candidiasis, and upper respiratory tract infection.22-24 The dual inhibition of IL-17A and IL-17F suppresses host defenses against Candida at the oral mucosa, increasing the incidence of bimekizumab-associated oral candidiasis.25 Despite the increased risk of Candida infections, these data suggest that inhibition of both IL-17A and IL-17F with bimekizumab may provide faster and greater clinical benefit for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis than inhibition of IL-17A alone and other biologic therapies, as the PASI 100 clearance rates across the multiple comparator trials and the placebo-controlled pivotal trial are consistently the highest among any biologic for the treatment of psoriasis.

Spesolimab—The IL-36 pathway and IL-36 receptor genes have been linked to the pathogenesis of generalized pustular psoriasis.26 In a phase 2 trial, 19 of 35 patients (54%) receiving an intravenous dose of spesolimab, an IL-36 receptor inhibitor, had a generalized pustular psoriasis PGA pustulation subscore of 0 (no visible pustules) at the end of week 1 vs 6% of patients in the placebo group.27 A generalized pustular psoriasis PGA total score of 0 or 1 was observed in 43% (15/35) of spesolimab-treated patients compared with 11% (2/18) of patients in the placebo group. The most common AEs in patients treated with spesolimab were minor infections.27 Two open-label phase 3 trials—NCT05200247 and NCT05239039—are underway to determine the long-term efficacy and safety of spesolimab in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis.

Conclusion

Although we have seen a renaissance in psoriasis therapies with the advent of biologics in the last 20 years, recent evidence shows that more innovation is underway. Just in the last year, 2 new mechanisms for treating psoriasis topically without steroids have come to fruition, and there have not been truly novel mechanisms for treating psoriasis topically since approvals for tazarotene and calcipotriene in the 1990s. An entirely new class—TYK2 inhibitors—was developed and landed in psoriasis first, greatly improving the efficacy measures attained with oral medications in general. Finally, an orphan diagnosis got its due with an ambitiously designed study looking at a previously unheard-of 1-week end point, but it comes for one of the few true dermatologic emergencies we encounter, generalized pustular psoriasis. We are fortunate to have so many meaningful new treatments available to us, and it is invigorating to see that even more efficacious biologics and treatments are coming, along with novel concepts such as a treatment affecting the microbiome. Now, we just need to make sure that our patients have the access they deserve to the wide array of available treatments.

- Bissonnette R, Stein Gold L, Rubenstein DS, et al. Tapinarof in the treatment of psoriasis: a review of the unique mechanism of action of a novel therapeutic aryl hydrocarbon receptor-modulating agent. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1059-1067.

- Smith SH, Jayawickreme C, Rickard DJ, et al. Tapinarof is a natural AhR agonist that resolves skin inflammation in mice and humans. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:2110-2119.

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229.

- Strober B, Stein Gold L, Bissonnette R, et al. One-year safety and efficacy of tapinarof cream for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: results from the PSOARING 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:800-806.

- Card GL, England BP, Suzuki Y, et al. Structural basis for the activity of drugs that inhibit phosphodiesterases. Structure. 2004;12:2233-2247.

- Milakovic M, Gooderham MJ. Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibition in psoriasis. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2021;11:21-29.

- Papp K, Reich K, Leonardi CL, et al. Apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results of a phase III, randomized, controlled trial (Efficacy and Safety Trial Evaluating the Effects of Apremilast in Psoriasis [ESTEEM] 1). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:37-49.

- Dong C, Virtucio C, Zemska O, et al. Treatment of skin inflammation with benzoxaborole phosphodiesterase inhibitors: selectivity, cellular activity, and effect on cytokines associated with skin inflammation and skin architecture changes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;358:413-422.

- Lebwohl MG, Kircik LH, Moore AY, et al. Effect of roflumilast cream vs vehicle cream on chronic plaque psoriasis: the DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2022;328:1073-1084.

- Nogueira M, Puig L, Torres T. JAK inhibitors for treatment of psoriasis: focus on selective tyk2 inhibitors. Drugs. 2020;80:341-352.

- Wrobleski ST, Moslin R, Lin S, et al. Highly selective inhibition of tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) for the treatment of autoimmune diseases: discovery of the allosteric inhibitor BMS-986165. J Med Chem. 2019;62:8973-8995.

- Chimalakonda A, Burke J, Cheng L, et al. Selectivity profile of the tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor deucravacitinib compared with janus kinase 1/2/3 inhibitors. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1763-1776.

- Strober B, Thaçi D, Sofen H, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52-week, randomized, double-blinded, phase 3 Program for Evaluation of TYK2 inhibitor psoriasis second trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:40-51.

- Armstrong AW, Gooderham M, Warren RB, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52-week, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:29-39.

- Warren RB, Sofen H, Imafuku S, et al. POS1046 deucravacitinib long-term efficacy and safety in plaque psoriasis: 2-year results from the phase 3 POETYK PSO program [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(suppl 1):841.

- McElwee JJ, Garcet S, Li X, et al. Analysis of histologic, molecular and clinical improvement in moderate-to-severe psoriasis: results from a Phase 1b trial of the novel allosteric TYK2 inhibitor NDI-034858. Poster presented at: American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting; March 25, 2022; Boston, MA.

- Tehlirian C, Singh RSP, Pradhan V, et al. Oral tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor PF-06826647 demonstrates efficacy and an acceptable safety profile in participants with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in a phase 2b, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:333-342.

- Hilliard-Barth K, Cormack T, Ramani K, et al. Immune mechanisms of the systemic effects of EDP1815: an orally delivered, gut-restricted microbial drug candidate for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Poster presented at: Society for Mucosal Immunology Virtual Congress; July 20-22, 2021, Cambridge, MA.

- Glatt S, Baeten D, Baker T, et al. Dual IL-17A and IL-17F neutralisation by bimekizumab in psoriatic arthritis: evidence from preclinical experiments and a randomised placebo-controlled clinical trial that IL-17F contributes to human chronic tissue inflammation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:523-532.

- Adams R, Maroof A, Baker T, et al. Bimekizumab, a novel humanized IgG1 antibody that neutralizes both IL-17A and IL-17F. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1894.

- Gordon KB, Foley P, Krueger JG, et al. Bimekizumab efficacy and safety in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (BE READY): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised withdrawal phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397:475-486.

- Reich K, Papp KA, Blauvelt A, et al. Bimekizumab versus ustekinumab for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (BE VIVID): efficacy and safety from a 52-week, multicentre, double-blind, active comparator and placebo controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397:487-498.

- Warren RB, Blauvelt A, Bagel J, et al. Bimekizumab versus adalimumab in plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:130-141.

- Reich K, Warren RB, Lebwohl M, et al. Bimekizumab versus secukinumab in plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:142-152.

- Blauvelt A, Lebwohl MG, Bissonnette R. IL-23/IL-17A dysfunction phenotypes inform possible clinical effects from anti-IL-17A therapies. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:1946-1953.

- Marrakchi S, Guigue P, Renshaw BR, et al. Interleukin-36-receptor antagonist deficiency and generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:620-628.

- Bachelez H, Choon SE, Marrakchi S, et al. Trial of spesolimab for generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2431-2440.

The landscape of psoriasis treatments has undergone rapid change within the last decade, and the dizzying speed of drug development has not slowed, with 4 notable entries into the psoriasis treatment armamentarium within the last year: tapinarof, roflumilast, deucravacitinib, and spesolimab. Several others are in late-stage development, and these therapies represent new mechanisms, pathways, and delivery systems that will meaningfully broaden the spectrum of treatment choices for our patients. However, it can be quite difficult to keep track of all of the medication options. This review aims to present the mechanisms and data on both newly available therapeutics for psoriasis and products in the pipeline that may have a major impact on our treatment paradigm for psoriasis in the near future.

Topical Treatments

Tapinarof—Tapinarof is a topical aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)–modulating agent derived from a secondary metabolite produced by a bacterial symbiont of entomopathogenic nematodes.1 Tapinarof binds and activates AhR, inducing a signaling cascade that suppresses the expression of helper T cells TH17 and TH22, upregulates skin barrier protein expression, and reduces epidermal oxidative stress.2 This is a familiar mechanism, as AhR agonism is one of the pathways modulated by coal tar. Tapinarof’s overall effects on immune function, skin barrier integrity, and antioxidant activity show great promise for the treatment of plaque psoriasis.

Two phase 3 trials (N=1025) evaluated the efficacy and safety of once-daily tapinarof cream 1% for plaque psoriasis.3 A physician global assessment (PGA) score of 0/1 occurred in 35.4% to 40.2% of patients in the tapinarof group and in 6.0% of patients in the vehicle group. At week 12, 36.1% to 47.6% of patients treated with daily applications of tapinarof cream achieved a 75% reduction in their baseline psoriasis area and severity index (PASI 75) score compared with 6.9% to 10.2% in the vehicle group.3 In a long-term extension study, a substantial remittive effect of at least 4 months off tapinarof therapy was observed in patients who achieved complete clearance (PGA=0).4 Use of tapinarof cream was associated with folliculitis in up to 23.5% of patients.3,4

Roflumilast—

Topical roflumilast is a selective, highly potent PDE-4 inhibitor with greater affinity for PDE-4 compared to crisaborole and apremilast.8 Two phase 3 trials (N=881) evaluated the efficacy and safety profile of roflumilast cream for plaque psoriasis, with a particular interest in its use for intertriginous areas.9 At week 8, 37.5% to 42.4% of roflumilast-treated patients achieved investigator global assessment (IGA) success compared with 6.1% to 6.9% of vehicle-treated patients. Intertriginous IGA success was observed in 68.1% to 71.2% of patients treated with roflumilast cream compared with 13.8% to 18.5% of vehicle-treated patients. At 8-week follow-up, 39.0% to 41.6% of roflumilast-treated patients achieved PASI 75 vs 5.3% to 7.6% of patients in the vehicle group. Few stinging, burning, or application-site reactions were reported with roflumilast, along with rare instances of gastrointestinal AEs (<4%).9

Oral Therapy

Deucravacitinib—Tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) mediates the intracellular signaling of the TH17 and TH1 inflammatory cytokines IL-12/IL-23 and type I interferons, respectively, the former of which are critical in the development of psoriasis via the Janus kinase (JAK) signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway.10 Deucravacitinib is an oral selective TYK2 allosteric inhibitor that binds to the regulatory domain of the enzyme rather than the active catalytic domain, where other TYK2 and JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 inhibitors bind.11 This unique inhibitory mechanism accounts for the high functional selectivity of deucravacitinib for TYK2 vs the closely related JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 kinases, thus avoiding the pitfall of prior JAK inhibitors that were associated with major AEs, including an increased risk for serious infections, malignancies, and thrombosis.12 The selective suppression of the inflammatory TYK2 pathway has the potential to shift future therapeutic targets to a narrower range of receptors that may contribute to favorable benefit-risk profiles.

Two phase 3 trials (N=1686) compared the efficacy and safety of deucravacitinib vs placebo and apremilast in adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.13,14 At week 16, 53.0% to 58.4% of deucravacitinib-treated patients achieved PASI 75 compared with 35.1% to 39.8% of apremilast-treated patients. At 16-week follow-up, static PGA response was observed in 49.5% to 53.6% of patients in the deucravacitinib group and 32.1% to 33.9% of the apremilast group. The most frequent AEs associated with deucravacitinib therapy were nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection, whereas headache, diarrhea, and nausea were more common with apremilast. Treatment with deucravacitinib caused no meaningful changes in laboratory parameters, which are known to change with JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 inhibitors.13,14 A long-term extension study demonstrated that deucravacitinib had persistent efficacy and consistent safety for up to 2 years.15

Other TYK2 Inhibitors in the Pipeline

Novel oral allosteric TYK2 inhibitors—VTX958 and NDI-034858—and the competitive TYK2 inhibitor PF-06826647 are being developed. Theoretically, these new allosteric inhibitors possess unique structural properties to provide greater TYK2 suppression while bypassing JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 pathways that may contribute to improved efficacy and safety profiles compared with other TYK2 inhibitors such as deucravacitinib. The results of a phase 1b trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT04999839) showed a dose-dependent reduction of disease severity associated with NDI-034858 treatment for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, albeit in only 26 patients. At week 4, PASI 50 was achieved in 13%, 57%, and 40% of patients in the 5-, 10-, and 30-mg groups, respectively, compared with 0% in the placebo group.16 In a phase 2 trial of 179 patients, 46.5% and 33.0% of patients treated with 400 and 200 mg of PF-06826647, respectively, achieved PASI 90 at week 16. Conversely, dose-dependent laboratory abnormalities were observed with PF-06826647, including anemia, neutropenia, and increases in creatine phosphokinase.17 At high concentrations, PF-06826647 may disrupt JAK signaling pathways involved in hematopoiesis and renal functions owing to its mode of action as a competitive inhibitor. Overall, these agents are much farther from market, and long-term studies with larger diverse patient cohorts are required to adequately assess the efficacy and safety data of these novel oral TYK2 inhibitors for patients with psoriasis.

EDP1815—EDP1815 is an oral preparation of a single strain of Prevotella histicola being developed for the treatment of inflammatory diseases, including psoriasis. EDP1815 interacts with host intestinal immune cells through the small intestinal axis (SINTAX) to suppress systemic inflammation across the TH1, TH2, and TH17 pathways. Therapy triggers broad immunomodulatory effects without causing systemic absorption, colonic colonization, or modification of the gut microbiome.18 In a phase 2 study (NCT04603027), the primary end point analysis, mean percentage change in PASI between treatment and placebo, demonstrated that at week 16, EDP1815 was superior to placebo with 80% to 90% probability across each cohort. At week 16, 25% to 32% of patients across the 3 cohorts treated with EDP1815 achieved PASI 50 compared with 12% of patients receiving placebo. Gastrointestinal AEs were comparable between treatment and placebo groups. These results suggest that SINTAX-targeted therapies may provide efficacious and safe immunomodulatory effects for patients with mild to moderate psoriasis, who often have limited treatment options. Although improvements may be mild, SINTAX-targeted therapies can be seen as a particularly attractive adjunctive treatment for patients with severe psoriasis taking other medications or as part of a treatment approach for a patient with milder psoriasis.

Biologics

Bimekizumab—Bimekizumab is a monoclonal IgG1 antibody that selectively inhibits IL-17A and IL-17F. Although IL-17A is a more potent cytokine, IL-17F may be more highly expressed in psoriatic lesional skin and independently contribute to the activation of proinflammatory signaling pathways implicated in the pathophysiology of psoriasis.19 Evidence suggests that dual inhibition of IL-17A and IL-17F may provide more complete suppression of inflammation and improved clinical responses than IL-17A inhibition alone.20

Prior bimekizumab phase 3 clinical studies have shown both rapid and durable clinical improvements in skin clearance compared with placebo.21 Three phase 3 trials—BE VIVID (N=567),22 BE SURE (N=478),23 and BE RADIANT (N=743)24—assessed the efficacy and safety of bimekizumab vs the IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor ustekinumab, the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab, and the selective IL-17A inhibitor secukinumab, respectively. At week 4, significantly more patients treated with bimekizumab (71%–77%) achieved PASI 75 than patients treated with ustekinumab (15%; P<.0001), adalimumab (31.4%; P<.001), or secukinumab (47.3%; P<.001).22-24 After 16 weeks of treatment, PASI 90 was achieved by 85% to 86.2%, 50%, and 47.2% of patients treated with bimekizumab, ustekinumab, and adalimumab, respectively.22,23 At week 16, PASI 100 was observed in 59% to 61.7%, 21%, 23.9%, and 48.9% of patients treated with bimekizumab, ustekinumab, adalimumab, and secukinumab, respectively. An IGA response (score of 0/1) at week 16 was achieved by 84% to 85.5%, 53%, 57.2%, and 78.6% of patients receiving bimekizumab, ustekinumab, adalimumab, and secukinumab, respectively.22-24

The most common AEs in bimekizumab-treated patients were nasopharyngitis, oral candidiasis, and upper respiratory tract infection.22-24 The dual inhibition of IL-17A and IL-17F suppresses host defenses against Candida at the oral mucosa, increasing the incidence of bimekizumab-associated oral candidiasis.25 Despite the increased risk of Candida infections, these data suggest that inhibition of both IL-17A and IL-17F with bimekizumab may provide faster and greater clinical benefit for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis than inhibition of IL-17A alone and other biologic therapies, as the PASI 100 clearance rates across the multiple comparator trials and the placebo-controlled pivotal trial are consistently the highest among any biologic for the treatment of psoriasis.

Spesolimab—The IL-36 pathway and IL-36 receptor genes have been linked to the pathogenesis of generalized pustular psoriasis.26 In a phase 2 trial, 19 of 35 patients (54%) receiving an intravenous dose of spesolimab, an IL-36 receptor inhibitor, had a generalized pustular psoriasis PGA pustulation subscore of 0 (no visible pustules) at the end of week 1 vs 6% of patients in the placebo group.27 A generalized pustular psoriasis PGA total score of 0 or 1 was observed in 43% (15/35) of spesolimab-treated patients compared with 11% (2/18) of patients in the placebo group. The most common AEs in patients treated with spesolimab were minor infections.27 Two open-label phase 3 trials—NCT05200247 and NCT05239039—are underway to determine the long-term efficacy and safety of spesolimab in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis.

Conclusion

Although we have seen a renaissance in psoriasis therapies with the advent of biologics in the last 20 years, recent evidence shows that more innovation is underway. Just in the last year, 2 new mechanisms for treating psoriasis topically without steroids have come to fruition, and there have not been truly novel mechanisms for treating psoriasis topically since approvals for tazarotene and calcipotriene in the 1990s. An entirely new class—TYK2 inhibitors—was developed and landed in psoriasis first, greatly improving the efficacy measures attained with oral medications in general. Finally, an orphan diagnosis got its due with an ambitiously designed study looking at a previously unheard-of 1-week end point, but it comes for one of the few true dermatologic emergencies we encounter, generalized pustular psoriasis. We are fortunate to have so many meaningful new treatments available to us, and it is invigorating to see that even more efficacious biologics and treatments are coming, along with novel concepts such as a treatment affecting the microbiome. Now, we just need to make sure that our patients have the access they deserve to the wide array of available treatments.

The landscape of psoriasis treatments has undergone rapid change within the last decade, and the dizzying speed of drug development has not slowed, with 4 notable entries into the psoriasis treatment armamentarium within the last year: tapinarof, roflumilast, deucravacitinib, and spesolimab. Several others are in late-stage development, and these therapies represent new mechanisms, pathways, and delivery systems that will meaningfully broaden the spectrum of treatment choices for our patients. However, it can be quite difficult to keep track of all of the medication options. This review aims to present the mechanisms and data on both newly available therapeutics for psoriasis and products in the pipeline that may have a major impact on our treatment paradigm for psoriasis in the near future.

Topical Treatments

Tapinarof—Tapinarof is a topical aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)–modulating agent derived from a secondary metabolite produced by a bacterial symbiont of entomopathogenic nematodes.1 Tapinarof binds and activates AhR, inducing a signaling cascade that suppresses the expression of helper T cells TH17 and TH22, upregulates skin barrier protein expression, and reduces epidermal oxidative stress.2 This is a familiar mechanism, as AhR agonism is one of the pathways modulated by coal tar. Tapinarof’s overall effects on immune function, skin barrier integrity, and antioxidant activity show great promise for the treatment of plaque psoriasis.

Two phase 3 trials (N=1025) evaluated the efficacy and safety of once-daily tapinarof cream 1% for plaque psoriasis.3 A physician global assessment (PGA) score of 0/1 occurred in 35.4% to 40.2% of patients in the tapinarof group and in 6.0% of patients in the vehicle group. At week 12, 36.1% to 47.6% of patients treated with daily applications of tapinarof cream achieved a 75% reduction in their baseline psoriasis area and severity index (PASI 75) score compared with 6.9% to 10.2% in the vehicle group.3 In a long-term extension study, a substantial remittive effect of at least 4 months off tapinarof therapy was observed in patients who achieved complete clearance (PGA=0).4 Use of tapinarof cream was associated with folliculitis in up to 23.5% of patients.3,4

Roflumilast—

Topical roflumilast is a selective, highly potent PDE-4 inhibitor with greater affinity for PDE-4 compared to crisaborole and apremilast.8 Two phase 3 trials (N=881) evaluated the efficacy and safety profile of roflumilast cream for plaque psoriasis, with a particular interest in its use for intertriginous areas.9 At week 8, 37.5% to 42.4% of roflumilast-treated patients achieved investigator global assessment (IGA) success compared with 6.1% to 6.9% of vehicle-treated patients. Intertriginous IGA success was observed in 68.1% to 71.2% of patients treated with roflumilast cream compared with 13.8% to 18.5% of vehicle-treated patients. At 8-week follow-up, 39.0% to 41.6% of roflumilast-treated patients achieved PASI 75 vs 5.3% to 7.6% of patients in the vehicle group. Few stinging, burning, or application-site reactions were reported with roflumilast, along with rare instances of gastrointestinal AEs (<4%).9

Oral Therapy

Deucravacitinib—Tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) mediates the intracellular signaling of the TH17 and TH1 inflammatory cytokines IL-12/IL-23 and type I interferons, respectively, the former of which are critical in the development of psoriasis via the Janus kinase (JAK) signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway.10 Deucravacitinib is an oral selective TYK2 allosteric inhibitor that binds to the regulatory domain of the enzyme rather than the active catalytic domain, where other TYK2 and JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 inhibitors bind.11 This unique inhibitory mechanism accounts for the high functional selectivity of deucravacitinib for TYK2 vs the closely related JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 kinases, thus avoiding the pitfall of prior JAK inhibitors that were associated with major AEs, including an increased risk for serious infections, malignancies, and thrombosis.12 The selective suppression of the inflammatory TYK2 pathway has the potential to shift future therapeutic targets to a narrower range of receptors that may contribute to favorable benefit-risk profiles.

Two phase 3 trials (N=1686) compared the efficacy and safety of deucravacitinib vs placebo and apremilast in adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.13,14 At week 16, 53.0% to 58.4% of deucravacitinib-treated patients achieved PASI 75 compared with 35.1% to 39.8% of apremilast-treated patients. At 16-week follow-up, static PGA response was observed in 49.5% to 53.6% of patients in the deucravacitinib group and 32.1% to 33.9% of the apremilast group. The most frequent AEs associated with deucravacitinib therapy were nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection, whereas headache, diarrhea, and nausea were more common with apremilast. Treatment with deucravacitinib caused no meaningful changes in laboratory parameters, which are known to change with JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 inhibitors.13,14 A long-term extension study demonstrated that deucravacitinib had persistent efficacy and consistent safety for up to 2 years.15

Other TYK2 Inhibitors in the Pipeline

Novel oral allosteric TYK2 inhibitors—VTX958 and NDI-034858—and the competitive TYK2 inhibitor PF-06826647 are being developed. Theoretically, these new allosteric inhibitors possess unique structural properties to provide greater TYK2 suppression while bypassing JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 pathways that may contribute to improved efficacy and safety profiles compared with other TYK2 inhibitors such as deucravacitinib. The results of a phase 1b trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT04999839) showed a dose-dependent reduction of disease severity associated with NDI-034858 treatment for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, albeit in only 26 patients. At week 4, PASI 50 was achieved in 13%, 57%, and 40% of patients in the 5-, 10-, and 30-mg groups, respectively, compared with 0% in the placebo group.16 In a phase 2 trial of 179 patients, 46.5% and 33.0% of patients treated with 400 and 200 mg of PF-06826647, respectively, achieved PASI 90 at week 16. Conversely, dose-dependent laboratory abnormalities were observed with PF-06826647, including anemia, neutropenia, and increases in creatine phosphokinase.17 At high concentrations, PF-06826647 may disrupt JAK signaling pathways involved in hematopoiesis and renal functions owing to its mode of action as a competitive inhibitor. Overall, these agents are much farther from market, and long-term studies with larger diverse patient cohorts are required to adequately assess the efficacy and safety data of these novel oral TYK2 inhibitors for patients with psoriasis.

EDP1815—EDP1815 is an oral preparation of a single strain of Prevotella histicola being developed for the treatment of inflammatory diseases, including psoriasis. EDP1815 interacts with host intestinal immune cells through the small intestinal axis (SINTAX) to suppress systemic inflammation across the TH1, TH2, and TH17 pathways. Therapy triggers broad immunomodulatory effects without causing systemic absorption, colonic colonization, or modification of the gut microbiome.18 In a phase 2 study (NCT04603027), the primary end point analysis, mean percentage change in PASI between treatment and placebo, demonstrated that at week 16, EDP1815 was superior to placebo with 80% to 90% probability across each cohort. At week 16, 25% to 32% of patients across the 3 cohorts treated with EDP1815 achieved PASI 50 compared with 12% of patients receiving placebo. Gastrointestinal AEs were comparable between treatment and placebo groups. These results suggest that SINTAX-targeted therapies may provide efficacious and safe immunomodulatory effects for patients with mild to moderate psoriasis, who often have limited treatment options. Although improvements may be mild, SINTAX-targeted therapies can be seen as a particularly attractive adjunctive treatment for patients with severe psoriasis taking other medications or as part of a treatment approach for a patient with milder psoriasis.

Biologics

Bimekizumab—Bimekizumab is a monoclonal IgG1 antibody that selectively inhibits IL-17A and IL-17F. Although IL-17A is a more potent cytokine, IL-17F may be more highly expressed in psoriatic lesional skin and independently contribute to the activation of proinflammatory signaling pathways implicated in the pathophysiology of psoriasis.19 Evidence suggests that dual inhibition of IL-17A and IL-17F may provide more complete suppression of inflammation and improved clinical responses than IL-17A inhibition alone.20

Prior bimekizumab phase 3 clinical studies have shown both rapid and durable clinical improvements in skin clearance compared with placebo.21 Three phase 3 trials—BE VIVID (N=567),22 BE SURE (N=478),23 and BE RADIANT (N=743)24—assessed the efficacy and safety of bimekizumab vs the IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor ustekinumab, the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab, and the selective IL-17A inhibitor secukinumab, respectively. At week 4, significantly more patients treated with bimekizumab (71%–77%) achieved PASI 75 than patients treated with ustekinumab (15%; P<.0001), adalimumab (31.4%; P<.001), or secukinumab (47.3%; P<.001).22-24 After 16 weeks of treatment, PASI 90 was achieved by 85% to 86.2%, 50%, and 47.2% of patients treated with bimekizumab, ustekinumab, and adalimumab, respectively.22,23 At week 16, PASI 100 was observed in 59% to 61.7%, 21%, 23.9%, and 48.9% of patients treated with bimekizumab, ustekinumab, adalimumab, and secukinumab, respectively. An IGA response (score of 0/1) at week 16 was achieved by 84% to 85.5%, 53%, 57.2%, and 78.6% of patients receiving bimekizumab, ustekinumab, adalimumab, and secukinumab, respectively.22-24

The most common AEs in bimekizumab-treated patients were nasopharyngitis, oral candidiasis, and upper respiratory tract infection.22-24 The dual inhibition of IL-17A and IL-17F suppresses host defenses against Candida at the oral mucosa, increasing the incidence of bimekizumab-associated oral candidiasis.25 Despite the increased risk of Candida infections, these data suggest that inhibition of both IL-17A and IL-17F with bimekizumab may provide faster and greater clinical benefit for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis than inhibition of IL-17A alone and other biologic therapies, as the PASI 100 clearance rates across the multiple comparator trials and the placebo-controlled pivotal trial are consistently the highest among any biologic for the treatment of psoriasis.

Spesolimab—The IL-36 pathway and IL-36 receptor genes have been linked to the pathogenesis of generalized pustular psoriasis.26 In a phase 2 trial, 19 of 35 patients (54%) receiving an intravenous dose of spesolimab, an IL-36 receptor inhibitor, had a generalized pustular psoriasis PGA pustulation subscore of 0 (no visible pustules) at the end of week 1 vs 6% of patients in the placebo group.27 A generalized pustular psoriasis PGA total score of 0 or 1 was observed in 43% (15/35) of spesolimab-treated patients compared with 11% (2/18) of patients in the placebo group. The most common AEs in patients treated with spesolimab were minor infections.27 Two open-label phase 3 trials—NCT05200247 and NCT05239039—are underway to determine the long-term efficacy and safety of spesolimab in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis.

Conclusion

Although we have seen a renaissance in psoriasis therapies with the advent of biologics in the last 20 years, recent evidence shows that more innovation is underway. Just in the last year, 2 new mechanisms for treating psoriasis topically without steroids have come to fruition, and there have not been truly novel mechanisms for treating psoriasis topically since approvals for tazarotene and calcipotriene in the 1990s. An entirely new class—TYK2 inhibitors—was developed and landed in psoriasis first, greatly improving the efficacy measures attained with oral medications in general. Finally, an orphan diagnosis got its due with an ambitiously designed study looking at a previously unheard-of 1-week end point, but it comes for one of the few true dermatologic emergencies we encounter, generalized pustular psoriasis. We are fortunate to have so many meaningful new treatments available to us, and it is invigorating to see that even more efficacious biologics and treatments are coming, along with novel concepts such as a treatment affecting the microbiome. Now, we just need to make sure that our patients have the access they deserve to the wide array of available treatments.

- Bissonnette R, Stein Gold L, Rubenstein DS, et al. Tapinarof in the treatment of psoriasis: a review of the unique mechanism of action of a novel therapeutic aryl hydrocarbon receptor-modulating agent. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1059-1067.

- Smith SH, Jayawickreme C, Rickard DJ, et al. Tapinarof is a natural AhR agonist that resolves skin inflammation in mice and humans. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:2110-2119.

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229.

- Strober B, Stein Gold L, Bissonnette R, et al. One-year safety and efficacy of tapinarof cream for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: results from the PSOARING 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:800-806.

- Card GL, England BP, Suzuki Y, et al. Structural basis for the activity of drugs that inhibit phosphodiesterases. Structure. 2004;12:2233-2247.

- Milakovic M, Gooderham MJ. Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibition in psoriasis. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2021;11:21-29.

- Papp K, Reich K, Leonardi CL, et al. Apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results of a phase III, randomized, controlled trial (Efficacy and Safety Trial Evaluating the Effects of Apremilast in Psoriasis [ESTEEM] 1). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:37-49.

- Dong C, Virtucio C, Zemska O, et al. Treatment of skin inflammation with benzoxaborole phosphodiesterase inhibitors: selectivity, cellular activity, and effect on cytokines associated with skin inflammation and skin architecture changes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;358:413-422.

- Lebwohl MG, Kircik LH, Moore AY, et al. Effect of roflumilast cream vs vehicle cream on chronic plaque psoriasis: the DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2022;328:1073-1084.

- Nogueira M, Puig L, Torres T. JAK inhibitors for treatment of psoriasis: focus on selective tyk2 inhibitors. Drugs. 2020;80:341-352.

- Wrobleski ST, Moslin R, Lin S, et al. Highly selective inhibition of tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) for the treatment of autoimmune diseases: discovery of the allosteric inhibitor BMS-986165. J Med Chem. 2019;62:8973-8995.

- Chimalakonda A, Burke J, Cheng L, et al. Selectivity profile of the tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor deucravacitinib compared with janus kinase 1/2/3 inhibitors. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1763-1776.

- Strober B, Thaçi D, Sofen H, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52-week, randomized, double-blinded, phase 3 Program for Evaluation of TYK2 inhibitor psoriasis second trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:40-51.

- Armstrong AW, Gooderham M, Warren RB, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52-week, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:29-39.

- Warren RB, Sofen H, Imafuku S, et al. POS1046 deucravacitinib long-term efficacy and safety in plaque psoriasis: 2-year results from the phase 3 POETYK PSO program [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(suppl 1):841.

- McElwee JJ, Garcet S, Li X, et al. Analysis of histologic, molecular and clinical improvement in moderate-to-severe psoriasis: results from a Phase 1b trial of the novel allosteric TYK2 inhibitor NDI-034858. Poster presented at: American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting; March 25, 2022; Boston, MA.

- Tehlirian C, Singh RSP, Pradhan V, et al. Oral tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor PF-06826647 demonstrates efficacy and an acceptable safety profile in participants with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in a phase 2b, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:333-342.

- Hilliard-Barth K, Cormack T, Ramani K, et al. Immune mechanisms of the systemic effects of EDP1815: an orally delivered, gut-restricted microbial drug candidate for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Poster presented at: Society for Mucosal Immunology Virtual Congress; July 20-22, 2021, Cambridge, MA.

- Glatt S, Baeten D, Baker T, et al. Dual IL-17A and IL-17F neutralisation by bimekizumab in psoriatic arthritis: evidence from preclinical experiments and a randomised placebo-controlled clinical trial that IL-17F contributes to human chronic tissue inflammation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:523-532.

- Adams R, Maroof A, Baker T, et al. Bimekizumab, a novel humanized IgG1 antibody that neutralizes both IL-17A and IL-17F. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1894.

- Gordon KB, Foley P, Krueger JG, et al. Bimekizumab efficacy and safety in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (BE READY): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised withdrawal phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397:475-486.

- Reich K, Papp KA, Blauvelt A, et al. Bimekizumab versus ustekinumab for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (BE VIVID): efficacy and safety from a 52-week, multicentre, double-blind, active comparator and placebo controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397:487-498.

- Warren RB, Blauvelt A, Bagel J, et al. Bimekizumab versus adalimumab in plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:130-141.

- Reich K, Warren RB, Lebwohl M, et al. Bimekizumab versus secukinumab in plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:142-152.

- Blauvelt A, Lebwohl MG, Bissonnette R. IL-23/IL-17A dysfunction phenotypes inform possible clinical effects from anti-IL-17A therapies. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:1946-1953.

- Marrakchi S, Guigue P, Renshaw BR, et al. Interleukin-36-receptor antagonist deficiency and generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:620-628.

- Bachelez H, Choon SE, Marrakchi S, et al. Trial of spesolimab for generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2431-2440.

- Bissonnette R, Stein Gold L, Rubenstein DS, et al. Tapinarof in the treatment of psoriasis: a review of the unique mechanism of action of a novel therapeutic aryl hydrocarbon receptor-modulating agent. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1059-1067.

- Smith SH, Jayawickreme C, Rickard DJ, et al. Tapinarof is a natural AhR agonist that resolves skin inflammation in mice and humans. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:2110-2119.

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229.

- Strober B, Stein Gold L, Bissonnette R, et al. One-year safety and efficacy of tapinarof cream for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: results from the PSOARING 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:800-806.

- Card GL, England BP, Suzuki Y, et al. Structural basis for the activity of drugs that inhibit phosphodiesterases. Structure. 2004;12:2233-2247.

- Milakovic M, Gooderham MJ. Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibition in psoriasis. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2021;11:21-29.

- Papp K, Reich K, Leonardi CL, et al. Apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results of a phase III, randomized, controlled trial (Efficacy and Safety Trial Evaluating the Effects of Apremilast in Psoriasis [ESTEEM] 1). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:37-49.

- Dong C, Virtucio C, Zemska O, et al. Treatment of skin inflammation with benzoxaborole phosphodiesterase inhibitors: selectivity, cellular activity, and effect on cytokines associated with skin inflammation and skin architecture changes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;358:413-422.

- Lebwohl MG, Kircik LH, Moore AY, et al. Effect of roflumilast cream vs vehicle cream on chronic plaque psoriasis: the DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2022;328:1073-1084.

- Nogueira M, Puig L, Torres T. JAK inhibitors for treatment of psoriasis: focus on selective tyk2 inhibitors. Drugs. 2020;80:341-352.

- Wrobleski ST, Moslin R, Lin S, et al. Highly selective inhibition of tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) for the treatment of autoimmune diseases: discovery of the allosteric inhibitor BMS-986165. J Med Chem. 2019;62:8973-8995.

- Chimalakonda A, Burke J, Cheng L, et al. Selectivity profile of the tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor deucravacitinib compared with janus kinase 1/2/3 inhibitors. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1763-1776.

- Strober B, Thaçi D, Sofen H, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52-week, randomized, double-blinded, phase 3 Program for Evaluation of TYK2 inhibitor psoriasis second trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:40-51.

- Armstrong AW, Gooderham M, Warren RB, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52-week, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:29-39.

- Warren RB, Sofen H, Imafuku S, et al. POS1046 deucravacitinib long-term efficacy and safety in plaque psoriasis: 2-year results from the phase 3 POETYK PSO program [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(suppl 1):841.

- McElwee JJ, Garcet S, Li X, et al. Analysis of histologic, molecular and clinical improvement in moderate-to-severe psoriasis: results from a Phase 1b trial of the novel allosteric TYK2 inhibitor NDI-034858. Poster presented at: American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting; March 25, 2022; Boston, MA.

- Tehlirian C, Singh RSP, Pradhan V, et al. Oral tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor PF-06826647 demonstrates efficacy and an acceptable safety profile in participants with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in a phase 2b, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:333-342.

- Hilliard-Barth K, Cormack T, Ramani K, et al. Immune mechanisms of the systemic effects of EDP1815: an orally delivered, gut-restricted microbial drug candidate for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Poster presented at: Society for Mucosal Immunology Virtual Congress; July 20-22, 2021, Cambridge, MA.

- Glatt S, Baeten D, Baker T, et al. Dual IL-17A and IL-17F neutralisation by bimekizumab in psoriatic arthritis: evidence from preclinical experiments and a randomised placebo-controlled clinical trial that IL-17F contributes to human chronic tissue inflammation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:523-532.

- Adams R, Maroof A, Baker T, et al. Bimekizumab, a novel humanized IgG1 antibody that neutralizes both IL-17A and IL-17F. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1894.

- Gordon KB, Foley P, Krueger JG, et al. Bimekizumab efficacy and safety in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (BE READY): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised withdrawal phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397:475-486.

- Reich K, Papp KA, Blauvelt A, et al. Bimekizumab versus ustekinumab for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (BE VIVID): efficacy and safety from a 52-week, multicentre, double-blind, active comparator and placebo controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397:487-498.

- Warren RB, Blauvelt A, Bagel J, et al. Bimekizumab versus adalimumab in plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:130-141.

- Reich K, Warren RB, Lebwohl M, et al. Bimekizumab versus secukinumab in plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:142-152.

- Blauvelt A, Lebwohl MG, Bissonnette R. IL-23/IL-17A dysfunction phenotypes inform possible clinical effects from anti-IL-17A therapies. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:1946-1953.

- Marrakchi S, Guigue P, Renshaw BR, et al. Interleukin-36-receptor antagonist deficiency and generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:620-628.

- Bachelez H, Choon SE, Marrakchi S, et al. Trial of spesolimab for generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2431-2440.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Roflumilast, a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, and tapinarof, an aryl hydrocarbon receptor–modulating agent, are 2 novel nonsteroidal topical treatments safe for regular long-term use on all affected areas of the skin in adult patients with plaque psoriasis.

- Deucravacitinib is an oral selective tyrosine kinase 2 allosteric inhibitor that has demonstrated a favorable safety profile and greater levels of efficacy than other available oral medications for plaque psoriasis.

- The dual inhibition of IL-17A and IL-17F with bimekizumab provides faster responses and greater clinical benefits for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis than inhibition of IL-17A alone, achieving higher levels of efficacy than has been reported with any other biologic therapy.

- Spesolimab, an IL-36 receptor inhibitor, is an effective, US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for patients with generalized pustular psoriasis.

CDC updates guidance on opioid prescribing in adults

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently published updated guidelines on prescribing opioids for pain that stress the need for a flexible and individual approach to pain management.1 New recommendations emphasize the use of nonopioid therapies whenever appropriate, support consideration of opioid therapy for patients with acute pain when the benefits are expected to outweigh the risks, and urge clinicians to work with patients receiving opioid therapy to determine whether it should be continued or tapered.

This revision to the agency’s 2016 guidelines is aimed at primary care clinicians who prescribe opioids to adult outpatients for treatment of pain. The recommendations are not meant for patients with sickle-cell disease or cancer-related pain, or those receiving palliative and end-of-life care.

Why an update was needed. In 2021, more than 107,000 Americans died of a drug overdose.2 Although prescription opioids caused only about 16% of these deaths, they account for a population death rate of 4:100,000—which, despite national efforts, has not changed much since 2013.3,4

Following publication of the CDC’s 2016 guidelines on prescribing opioids for chronic pain,5 there was a decline in opioid prescribing but not in related deaths. Furthermore, there appeared to have been some negative effects of reduced prescribing, including untreated and undertreated pain, and rapid tapering or sudden discontinuation of opioids in chronic users, causing withdrawal symptoms and psychological distress in these patients. To address these issues, the CDC published the new guideline in 2022.1

Categories of pain. The guideline panel classified pain into 3 categories: acute pain (duration of < 1 month), subacute pain (duration of 1-3 months), and chronic pain (duration of > 3 months).