User login

Prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia: What to look for

Schizophrenia is characterized by psychotic symptoms that typically follow a prodromal period of premonitory signs and symptoms that appear before the manifestation of the full-blown syndrome. Signs and symptoms during the prodromal phase are subsyndromal, which implies a lower degree of intensity, duration, or frequency than observed when the patient meets the full criteria for the syndrome. Early detection of prodromal symptoms can improve prognosis, but these subtle symptoms may go unrecognized.

In schizophrenia, a patient may exhibit prodromal signs and symptoms before the appearance of pathognomonic symptoms, such as delusions, hallucinations, and disorganization. The schizophrenia prodrome can be conceptualized as a period of prepsychotic disturbances depicting an alteration in the individual’s behavior and perception. Prodromal symptoms can last from weeks to years before the psychotic illness clinically manifests.1 The prodromal symptom cluster typically becomes evident during adolescence and young adulthood.2

In the mid-1990s, investigators tried to identify a “putative prodrome” for psychosis. The term “at-risk mental state” (ARMS) for psychosis is based on retrospective reports of prodromal symptoms in first-episode psychosis. Over the next 2 decades, scales such as the Comprehensive Assessment of ARMS (CAARMS)3 and the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndrome4 were designed to enhance the objectivity and diagnostic accuracy of the ARMS. These scales have reasonable interrater reliability.5

Researchers also have attempted to stage the severity of ARMS.6 Key symptom group predictors were studied to determine which individual symptoms or cluster of symptoms are most associated with poor outcomes and progression to psychosis. Raballo et al7 found the severity of the CAARMS disorganization dimension was the strongest predictor of transition to frank psychosis. Other research suggests that approximately one-third of ARMS patients transition to psychosis within 3 years, another one-third have persistent attenuated psychotic symptoms, and the remaining one-third experience symptom remission.8,9

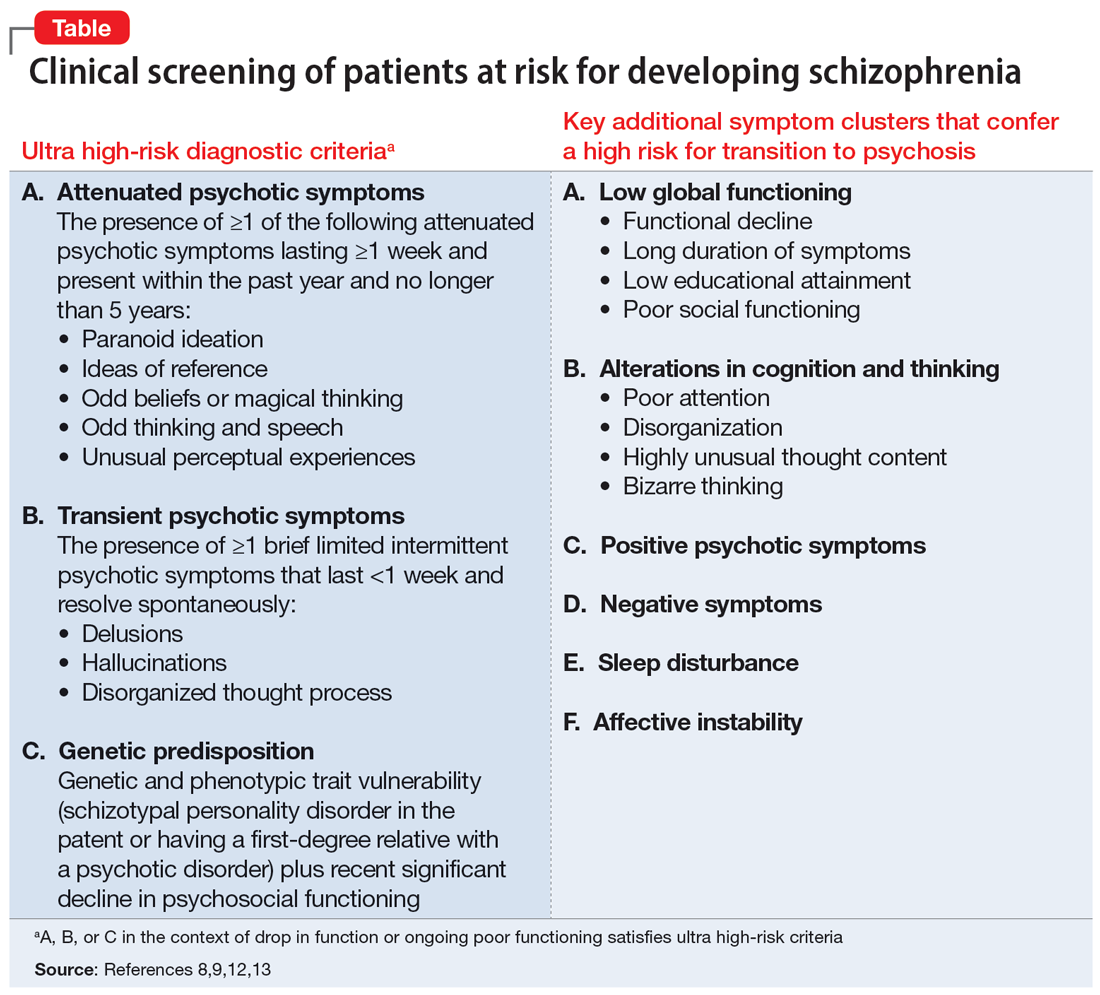

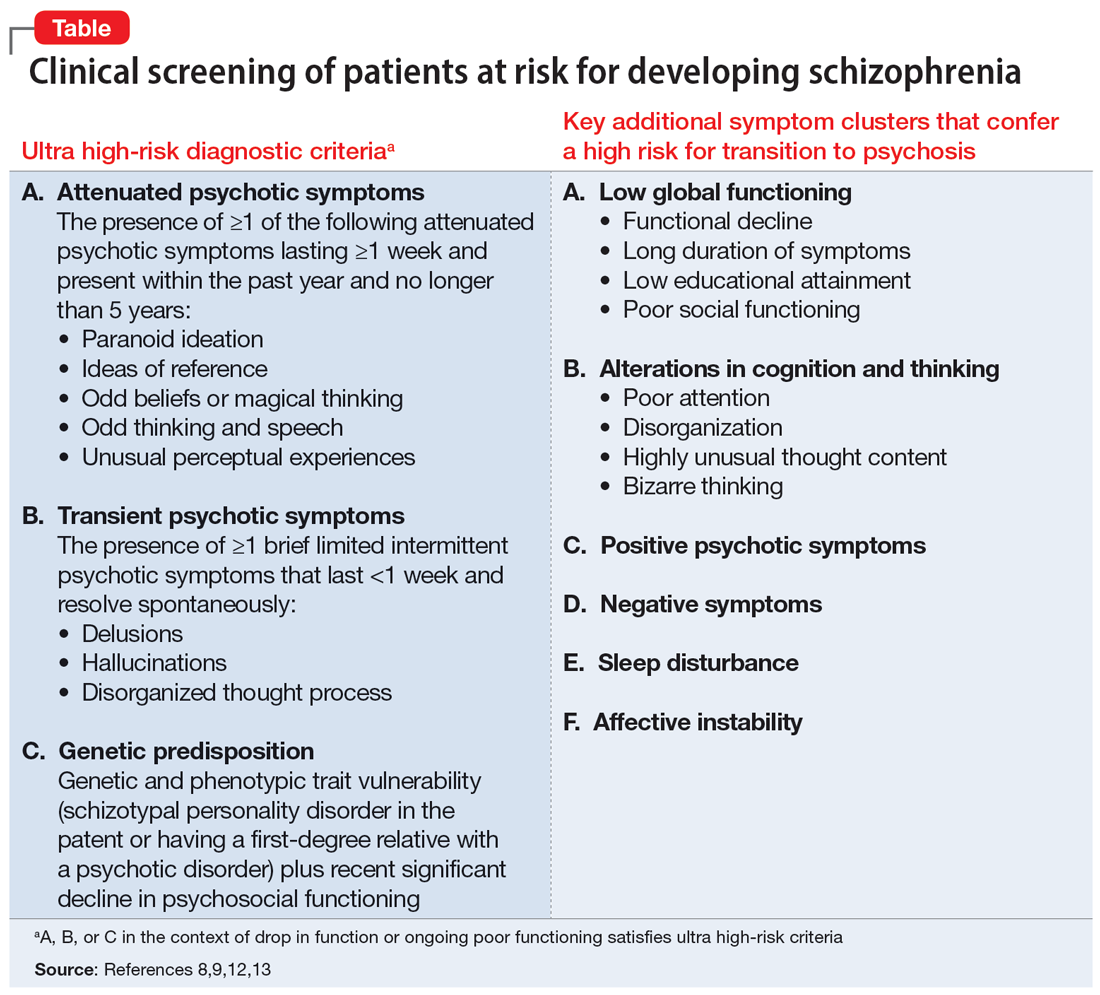

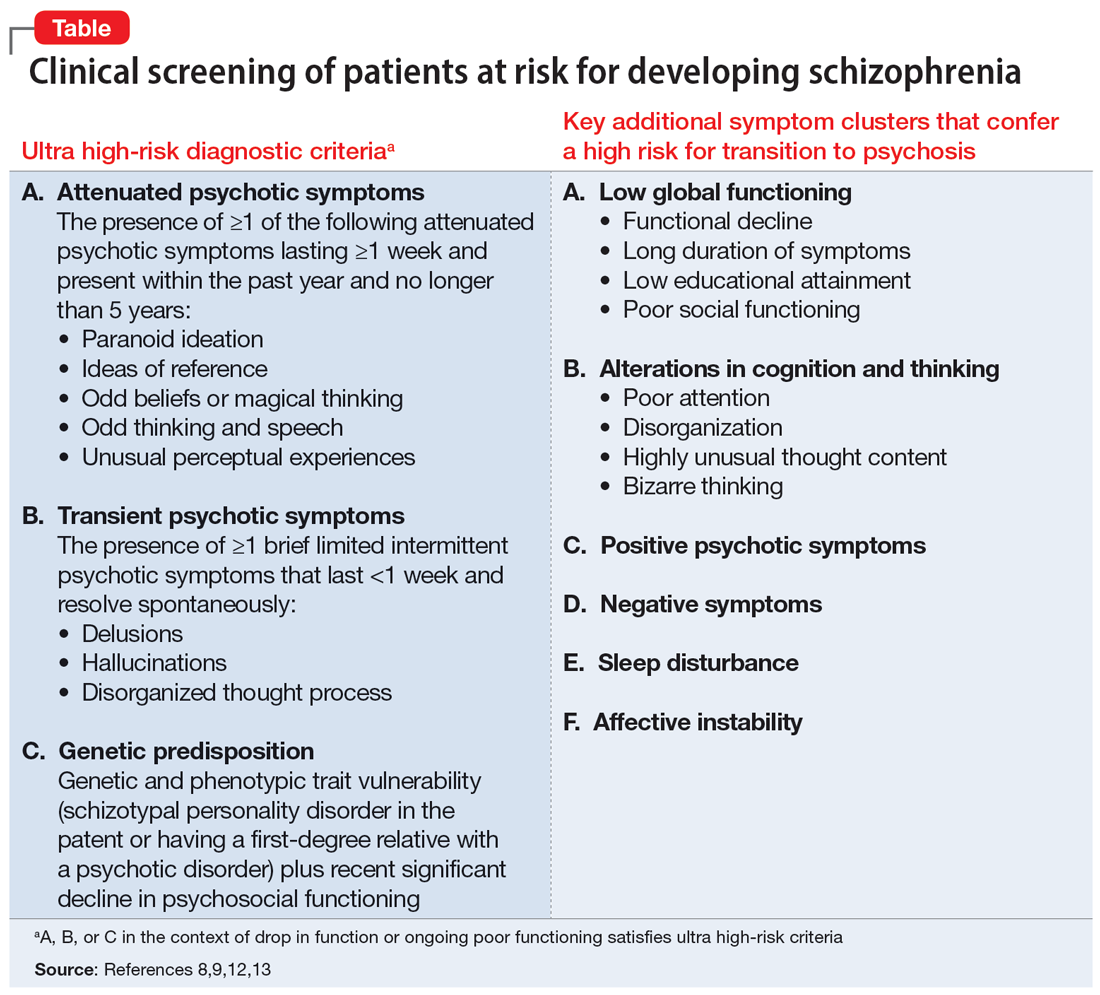

Despite multiple studies and meta-analyses, current scales and clinical predictors continue to be imperfect.8 Efforts to identify specific biological markers and predictors of transition to clinical psychosis have not been successful for ARMS.10,11 The Table8,9,12,13 summarizes diagnostic criteria that have been developed to more clearly identify which ARMS patients face the highest imminent risk for transition to psychosis; these have been referred to as ultra high-risk (UHR) criteria.14 These UHR criteria depict 3 categories of clinical presentation believed to confer risk of transition to psychosis: attenuated psychotic symptoms, transient psychotic symptoms, and genetic predisposition. Subsequent research found that certain additional symptom variables, as well as combinations of specific symptom clusters, conferred increased risk and improved the positive predictive sensitivity to as high as 83%.15 In addition to the UHR criteria, the Table8,9,12,13 also lists these additional variables shown to confer a high positive predictive value (PPV) of transition, alone or in combination with the UHR criterion. Thompson et al16 provide more detailed information on these later variables and their relative PPV.

What about treatment?

While discussion of the optimal treatment options for patients with prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia is beyond the scope of this article, early interventions can focus on preventing the biological, psychological, and social disruption that results from such symptoms. Establishing a therapeutic alliance with the patient while they retain insight and engaging supportive family members is a key starting point. Case management, cognitive-behavioral or supportive therapy, and treatment of comorbid mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders are helpful. There is no clear consensus on the utility of pharmacotherapy in the prodromal stage of psychosis. While scales and structured interviews can guide assessment, clinical judgment is the key driver of the appropriateness of initiating pharmacologic treatment to address symptoms. Because up to two-thirds of patients who satisfy UHR criteria do not go on to develop schizophrenia,16 clinicians should be thoughtful about the risks and benefits of antipsychotics.

1. George M, Maheshwari S, Chandran S, et al. Understanding the schizophrenia prodrome. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59(4):505-509.

2. Yung AR, McGorry PD. The prodromal phase of first-episode psychosis: past and current conceptualizations. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(2):353-370.

3. Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, et al. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39(11-12):964-971.

4. Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, et al. Prodromal assessment with the structured interview for prodromal syndromes and the scale of prodromal symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(4):703-715.

5. Loewy RL, Pearson R, Vinogradov S, et al. Psychosis risk screening with the Prodromal Questionnaire--brief version (PQ-B). Schizophr Res. 2011;129(1):42-46.

6. Nieman DH, McGorry PD. Detection and treatment of at-risk mental state for developing a first psychosis: making up the balance. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(9):825-834.

7. Raballo A, Nelson B, Thompson A, et al. The comprehensive assessment of at-risk mental states: from mapping the onset to mapping the structure. Schizophr Res. 2011;127(1-3):107-114.

8. Fusar-Poli P, Bonoldi I, Yung AR, et al. Predicting psychosis: meta-analysis of transition outcomes in individuals at high clinical risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(3):220-229.

9. Cannon TD. How schizophrenia develops: cognitive and brain mechanisms underlying onset of psychosis. Trends Cogn Sci. 2015;19(12):744-756.

10. Castle DJ. Is it appropriate to treat people at high-risk of psychosis before first onset? - no. Med J Aust. 2012;196(9):557.

11. Wood SJ, Reniers RL, Heinze K. Neuroimaging findings in the at-risk mental state: a review of recent literature. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(1):13-18.

12. Nelson B, Yung AR. Can clinicians predict psychosis in an ultra high risk group? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(7):625-630.

13. Schultze-Lutter F, Michel C, Schmidt SJ, et al. EPA guidance on the early detection of clinical high risk states of psychoses. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(3):405-416.

14. Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, et al. Risk factors for psychosis in an ultra high-risk group: psychopathology and clinical features. Schizophr Res. 2004;67(2-3):131-142.

15. Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Salokangas RK, et al. Prediction of psychosis in adolescents and young adults at high risk: results from the prospective European prediction of psychosis study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):241-251.

16. Thompson A, Marwaha S, Broome MR. At-risk mental state for psychosis: identification and current treatment approaches. BJPsych Advances. 2016;22(3):186-193.

Schizophrenia is characterized by psychotic symptoms that typically follow a prodromal period of premonitory signs and symptoms that appear before the manifestation of the full-blown syndrome. Signs and symptoms during the prodromal phase are subsyndromal, which implies a lower degree of intensity, duration, or frequency than observed when the patient meets the full criteria for the syndrome. Early detection of prodromal symptoms can improve prognosis, but these subtle symptoms may go unrecognized.

In schizophrenia, a patient may exhibit prodromal signs and symptoms before the appearance of pathognomonic symptoms, such as delusions, hallucinations, and disorganization. The schizophrenia prodrome can be conceptualized as a period of prepsychotic disturbances depicting an alteration in the individual’s behavior and perception. Prodromal symptoms can last from weeks to years before the psychotic illness clinically manifests.1 The prodromal symptom cluster typically becomes evident during adolescence and young adulthood.2

In the mid-1990s, investigators tried to identify a “putative prodrome” for psychosis. The term “at-risk mental state” (ARMS) for psychosis is based on retrospective reports of prodromal symptoms in first-episode psychosis. Over the next 2 decades, scales such as the Comprehensive Assessment of ARMS (CAARMS)3 and the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndrome4 were designed to enhance the objectivity and diagnostic accuracy of the ARMS. These scales have reasonable interrater reliability.5

Researchers also have attempted to stage the severity of ARMS.6 Key symptom group predictors were studied to determine which individual symptoms or cluster of symptoms are most associated with poor outcomes and progression to psychosis. Raballo et al7 found the severity of the CAARMS disorganization dimension was the strongest predictor of transition to frank psychosis. Other research suggests that approximately one-third of ARMS patients transition to psychosis within 3 years, another one-third have persistent attenuated psychotic symptoms, and the remaining one-third experience symptom remission.8,9

Despite multiple studies and meta-analyses, current scales and clinical predictors continue to be imperfect.8 Efforts to identify specific biological markers and predictors of transition to clinical psychosis have not been successful for ARMS.10,11 The Table8,9,12,13 summarizes diagnostic criteria that have been developed to more clearly identify which ARMS patients face the highest imminent risk for transition to psychosis; these have been referred to as ultra high-risk (UHR) criteria.14 These UHR criteria depict 3 categories of clinical presentation believed to confer risk of transition to psychosis: attenuated psychotic symptoms, transient psychotic symptoms, and genetic predisposition. Subsequent research found that certain additional symptom variables, as well as combinations of specific symptom clusters, conferred increased risk and improved the positive predictive sensitivity to as high as 83%.15 In addition to the UHR criteria, the Table8,9,12,13 also lists these additional variables shown to confer a high positive predictive value (PPV) of transition, alone or in combination with the UHR criterion. Thompson et al16 provide more detailed information on these later variables and their relative PPV.

What about treatment?

While discussion of the optimal treatment options for patients with prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia is beyond the scope of this article, early interventions can focus on preventing the biological, psychological, and social disruption that results from such symptoms. Establishing a therapeutic alliance with the patient while they retain insight and engaging supportive family members is a key starting point. Case management, cognitive-behavioral or supportive therapy, and treatment of comorbid mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders are helpful. There is no clear consensus on the utility of pharmacotherapy in the prodromal stage of psychosis. While scales and structured interviews can guide assessment, clinical judgment is the key driver of the appropriateness of initiating pharmacologic treatment to address symptoms. Because up to two-thirds of patients who satisfy UHR criteria do not go on to develop schizophrenia,16 clinicians should be thoughtful about the risks and benefits of antipsychotics.

Schizophrenia is characterized by psychotic symptoms that typically follow a prodromal period of premonitory signs and symptoms that appear before the manifestation of the full-blown syndrome. Signs and symptoms during the prodromal phase are subsyndromal, which implies a lower degree of intensity, duration, or frequency than observed when the patient meets the full criteria for the syndrome. Early detection of prodromal symptoms can improve prognosis, but these subtle symptoms may go unrecognized.

In schizophrenia, a patient may exhibit prodromal signs and symptoms before the appearance of pathognomonic symptoms, such as delusions, hallucinations, and disorganization. The schizophrenia prodrome can be conceptualized as a period of prepsychotic disturbances depicting an alteration in the individual’s behavior and perception. Prodromal symptoms can last from weeks to years before the psychotic illness clinically manifests.1 The prodromal symptom cluster typically becomes evident during adolescence and young adulthood.2

In the mid-1990s, investigators tried to identify a “putative prodrome” for psychosis. The term “at-risk mental state” (ARMS) for psychosis is based on retrospective reports of prodromal symptoms in first-episode psychosis. Over the next 2 decades, scales such as the Comprehensive Assessment of ARMS (CAARMS)3 and the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndrome4 were designed to enhance the objectivity and diagnostic accuracy of the ARMS. These scales have reasonable interrater reliability.5

Researchers also have attempted to stage the severity of ARMS.6 Key symptom group predictors were studied to determine which individual symptoms or cluster of symptoms are most associated with poor outcomes and progression to psychosis. Raballo et al7 found the severity of the CAARMS disorganization dimension was the strongest predictor of transition to frank psychosis. Other research suggests that approximately one-third of ARMS patients transition to psychosis within 3 years, another one-third have persistent attenuated psychotic symptoms, and the remaining one-third experience symptom remission.8,9

Despite multiple studies and meta-analyses, current scales and clinical predictors continue to be imperfect.8 Efforts to identify specific biological markers and predictors of transition to clinical psychosis have not been successful for ARMS.10,11 The Table8,9,12,13 summarizes diagnostic criteria that have been developed to more clearly identify which ARMS patients face the highest imminent risk for transition to psychosis; these have been referred to as ultra high-risk (UHR) criteria.14 These UHR criteria depict 3 categories of clinical presentation believed to confer risk of transition to psychosis: attenuated psychotic symptoms, transient psychotic symptoms, and genetic predisposition. Subsequent research found that certain additional symptom variables, as well as combinations of specific symptom clusters, conferred increased risk and improved the positive predictive sensitivity to as high as 83%.15 In addition to the UHR criteria, the Table8,9,12,13 also lists these additional variables shown to confer a high positive predictive value (PPV) of transition, alone or in combination with the UHR criterion. Thompson et al16 provide more detailed information on these later variables and their relative PPV.

What about treatment?

While discussion of the optimal treatment options for patients with prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia is beyond the scope of this article, early interventions can focus on preventing the biological, psychological, and social disruption that results from such symptoms. Establishing a therapeutic alliance with the patient while they retain insight and engaging supportive family members is a key starting point. Case management, cognitive-behavioral or supportive therapy, and treatment of comorbid mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders are helpful. There is no clear consensus on the utility of pharmacotherapy in the prodromal stage of psychosis. While scales and structured interviews can guide assessment, clinical judgment is the key driver of the appropriateness of initiating pharmacologic treatment to address symptoms. Because up to two-thirds of patients who satisfy UHR criteria do not go on to develop schizophrenia,16 clinicians should be thoughtful about the risks and benefits of antipsychotics.

1. George M, Maheshwari S, Chandran S, et al. Understanding the schizophrenia prodrome. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59(4):505-509.

2. Yung AR, McGorry PD. The prodromal phase of first-episode psychosis: past and current conceptualizations. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(2):353-370.

3. Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, et al. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39(11-12):964-971.

4. Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, et al. Prodromal assessment with the structured interview for prodromal syndromes and the scale of prodromal symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(4):703-715.

5. Loewy RL, Pearson R, Vinogradov S, et al. Psychosis risk screening with the Prodromal Questionnaire--brief version (PQ-B). Schizophr Res. 2011;129(1):42-46.

6. Nieman DH, McGorry PD. Detection and treatment of at-risk mental state for developing a first psychosis: making up the balance. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(9):825-834.

7. Raballo A, Nelson B, Thompson A, et al. The comprehensive assessment of at-risk mental states: from mapping the onset to mapping the structure. Schizophr Res. 2011;127(1-3):107-114.

8. Fusar-Poli P, Bonoldi I, Yung AR, et al. Predicting psychosis: meta-analysis of transition outcomes in individuals at high clinical risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(3):220-229.

9. Cannon TD. How schizophrenia develops: cognitive and brain mechanisms underlying onset of psychosis. Trends Cogn Sci. 2015;19(12):744-756.

10. Castle DJ. Is it appropriate to treat people at high-risk of psychosis before first onset? - no. Med J Aust. 2012;196(9):557.

11. Wood SJ, Reniers RL, Heinze K. Neuroimaging findings in the at-risk mental state: a review of recent literature. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(1):13-18.

12. Nelson B, Yung AR. Can clinicians predict psychosis in an ultra high risk group? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(7):625-630.

13. Schultze-Lutter F, Michel C, Schmidt SJ, et al. EPA guidance on the early detection of clinical high risk states of psychoses. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(3):405-416.

14. Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, et al. Risk factors for psychosis in an ultra high-risk group: psychopathology and clinical features. Schizophr Res. 2004;67(2-3):131-142.

15. Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Salokangas RK, et al. Prediction of psychosis in adolescents and young adults at high risk: results from the prospective European prediction of psychosis study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):241-251.

16. Thompson A, Marwaha S, Broome MR. At-risk mental state for psychosis: identification and current treatment approaches. BJPsych Advances. 2016;22(3):186-193.

1. George M, Maheshwari S, Chandran S, et al. Understanding the schizophrenia prodrome. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59(4):505-509.

2. Yung AR, McGorry PD. The prodromal phase of first-episode psychosis: past and current conceptualizations. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(2):353-370.

3. Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, et al. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39(11-12):964-971.

4. Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, et al. Prodromal assessment with the structured interview for prodromal syndromes and the scale of prodromal symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(4):703-715.

5. Loewy RL, Pearson R, Vinogradov S, et al. Psychosis risk screening with the Prodromal Questionnaire--brief version (PQ-B). Schizophr Res. 2011;129(1):42-46.

6. Nieman DH, McGorry PD. Detection and treatment of at-risk mental state for developing a first psychosis: making up the balance. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(9):825-834.

7. Raballo A, Nelson B, Thompson A, et al. The comprehensive assessment of at-risk mental states: from mapping the onset to mapping the structure. Schizophr Res. 2011;127(1-3):107-114.

8. Fusar-Poli P, Bonoldi I, Yung AR, et al. Predicting psychosis: meta-analysis of transition outcomes in individuals at high clinical risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(3):220-229.

9. Cannon TD. How schizophrenia develops: cognitive and brain mechanisms underlying onset of psychosis. Trends Cogn Sci. 2015;19(12):744-756.

10. Castle DJ. Is it appropriate to treat people at high-risk of psychosis before first onset? - no. Med J Aust. 2012;196(9):557.

11. Wood SJ, Reniers RL, Heinze K. Neuroimaging findings in the at-risk mental state: a review of recent literature. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(1):13-18.

12. Nelson B, Yung AR. Can clinicians predict psychosis in an ultra high risk group? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(7):625-630.

13. Schultze-Lutter F, Michel C, Schmidt SJ, et al. EPA guidance on the early detection of clinical high risk states of psychoses. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(3):405-416.

14. Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, et al. Risk factors for psychosis in an ultra high-risk group: psychopathology and clinical features. Schizophr Res. 2004;67(2-3):131-142.

15. Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Salokangas RK, et al. Prediction of psychosis in adolescents and young adults at high risk: results from the prospective European prediction of psychosis study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):241-251.

16. Thompson A, Marwaha S, Broome MR. At-risk mental state for psychosis: identification and current treatment approaches. BJPsych Advances. 2016;22(3):186-193.

Generic stimulant shortage update: From bad to worse

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

I (MZP) just completed my first semester of medical school. An important lesson imparted in my coursework so far has been to remain a staunch advocate for patients. Yet compared to the rigors of medical school, over the past year it has been far more difficult to help patients locate generic Adderall. Physicians were already overburdened with administrative responsibilities stretching into burnout territory well before the shortage, and now this! Unlike paper prescriptions of old, which patients could take to any pharmacy, e-prescribing apps require selection of a specific pharmacy, and controlled substances such as stimulants require 2-factor authentication. But if the designated pharmacy does not have the medication in stock, the entire process must be repeated with an alternative pharmacy, long after the visit has concluded.

To add insult to injury, the generic stimulant shortage has grown even worse. As of February 2023, generic Adderall remained hard to find and generic Concerta was also in short supply. How did this happen? In 1985, Bulow et al¹ coined the game theory concept of “strategic substitutes,” where (for example) as beef becomes less readily accessible, consumers may switch to eating chicken as their protein. Unable to locate generic Adderall, many patients have turned to generic Concerta as a substitute psychostimulant to continue management of their attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

In addition to the increase in demand, compounding the shortage is that one of the manufacturers of generic Concerta has discontinued production.² Branded methylphenidates and amphetamines, which are much more expensive than their generic counterparts, have remained in ample supply, but many insurers require trials of generics before considering coverage for more expensive brands.

Our approach to this situation

Each morning we call our local and chain pharmacies to take a census of their supply of generic stimulants. Some pharmacies refuse to release this information. Despite these census reports, we have found cases where patients have been turned away from pharmacies when they are not “regular customers,” while patients whom the pharmacies know retain access as “members.” Hence, a patient is unlikely to obtain these medications if their regular pharmacy is out of stock.

We want to share a workaround that has been effective. After unsuccessfully searching for generic stimulants at the patient’s regular pharmacy, I (RLP) write “dispense as written” for the closest branded version and file a prior authorization with the patient’s insurance company, noting “patient unable to trial any generic amphetamines or methylphenidates due to current nationwide shortage.” Even with the most difficult insurers, the response has been “a temporary 3-month authorization has been granted,” which is at least a small victory for our desperate patients and busy prescribers who are both struggling to negotiate a fragmented health care system.

1. Bulow JI, Geanakoplos JD, Klemperer PD. Multimarket oligopoly: strategic substitutes and complements. Journal of Political Economy. 1985;93(3):488-511. https://doi.org/10.1086/261312

2. US Food & Drug Administration. FDA Drug Shortages. Accessed January 7, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/drugshortages/dsp_ActiveIngredientDetails.cfm?AI=Methylphenidate+Hydrochloride+Extended+Release+Tablets&st=d

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

I (MZP) just completed my first semester of medical school. An important lesson imparted in my coursework so far has been to remain a staunch advocate for patients. Yet compared to the rigors of medical school, over the past year it has been far more difficult to help patients locate generic Adderall. Physicians were already overburdened with administrative responsibilities stretching into burnout territory well before the shortage, and now this! Unlike paper prescriptions of old, which patients could take to any pharmacy, e-prescribing apps require selection of a specific pharmacy, and controlled substances such as stimulants require 2-factor authentication. But if the designated pharmacy does not have the medication in stock, the entire process must be repeated with an alternative pharmacy, long after the visit has concluded.

To add insult to injury, the generic stimulant shortage has grown even worse. As of February 2023, generic Adderall remained hard to find and generic Concerta was also in short supply. How did this happen? In 1985, Bulow et al¹ coined the game theory concept of “strategic substitutes,” where (for example) as beef becomes less readily accessible, consumers may switch to eating chicken as their protein. Unable to locate generic Adderall, many patients have turned to generic Concerta as a substitute psychostimulant to continue management of their attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

In addition to the increase in demand, compounding the shortage is that one of the manufacturers of generic Concerta has discontinued production.² Branded methylphenidates and amphetamines, which are much more expensive than their generic counterparts, have remained in ample supply, but many insurers require trials of generics before considering coverage for more expensive brands.

Our approach to this situation

Each morning we call our local and chain pharmacies to take a census of their supply of generic stimulants. Some pharmacies refuse to release this information. Despite these census reports, we have found cases where patients have been turned away from pharmacies when they are not “regular customers,” while patients whom the pharmacies know retain access as “members.” Hence, a patient is unlikely to obtain these medications if their regular pharmacy is out of stock.

We want to share a workaround that has been effective. After unsuccessfully searching for generic stimulants at the patient’s regular pharmacy, I (RLP) write “dispense as written” for the closest branded version and file a prior authorization with the patient’s insurance company, noting “patient unable to trial any generic amphetamines or methylphenidates due to current nationwide shortage.” Even with the most difficult insurers, the response has been “a temporary 3-month authorization has been granted,” which is at least a small victory for our desperate patients and busy prescribers who are both struggling to negotiate a fragmented health care system.

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

I (MZP) just completed my first semester of medical school. An important lesson imparted in my coursework so far has been to remain a staunch advocate for patients. Yet compared to the rigors of medical school, over the past year it has been far more difficult to help patients locate generic Adderall. Physicians were already overburdened with administrative responsibilities stretching into burnout territory well before the shortage, and now this! Unlike paper prescriptions of old, which patients could take to any pharmacy, e-prescribing apps require selection of a specific pharmacy, and controlled substances such as stimulants require 2-factor authentication. But if the designated pharmacy does not have the medication in stock, the entire process must be repeated with an alternative pharmacy, long after the visit has concluded.

To add insult to injury, the generic stimulant shortage has grown even worse. As of February 2023, generic Adderall remained hard to find and generic Concerta was also in short supply. How did this happen? In 1985, Bulow et al¹ coined the game theory concept of “strategic substitutes,” where (for example) as beef becomes less readily accessible, consumers may switch to eating chicken as their protein. Unable to locate generic Adderall, many patients have turned to generic Concerta as a substitute psychostimulant to continue management of their attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

In addition to the increase in demand, compounding the shortage is that one of the manufacturers of generic Concerta has discontinued production.² Branded methylphenidates and amphetamines, which are much more expensive than their generic counterparts, have remained in ample supply, but many insurers require trials of generics before considering coverage for more expensive brands.

Our approach to this situation

Each morning we call our local and chain pharmacies to take a census of their supply of generic stimulants. Some pharmacies refuse to release this information. Despite these census reports, we have found cases where patients have been turned away from pharmacies when they are not “regular customers,” while patients whom the pharmacies know retain access as “members.” Hence, a patient is unlikely to obtain these medications if their regular pharmacy is out of stock.

We want to share a workaround that has been effective. After unsuccessfully searching for generic stimulants at the patient’s regular pharmacy, I (RLP) write “dispense as written” for the closest branded version and file a prior authorization with the patient’s insurance company, noting “patient unable to trial any generic amphetamines or methylphenidates due to current nationwide shortage.” Even with the most difficult insurers, the response has been “a temporary 3-month authorization has been granted,” which is at least a small victory for our desperate patients and busy prescribers who are both struggling to negotiate a fragmented health care system.

1. Bulow JI, Geanakoplos JD, Klemperer PD. Multimarket oligopoly: strategic substitutes and complements. Journal of Political Economy. 1985;93(3):488-511. https://doi.org/10.1086/261312

2. US Food & Drug Administration. FDA Drug Shortages. Accessed January 7, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/drugshortages/dsp_ActiveIngredientDetails.cfm?AI=Methylphenidate+Hydrochloride+Extended+Release+Tablets&st=d

1. Bulow JI, Geanakoplos JD, Klemperer PD. Multimarket oligopoly: strategic substitutes and complements. Journal of Political Economy. 1985;93(3):488-511. https://doi.org/10.1086/261312

2. US Food & Drug Administration. FDA Drug Shortages. Accessed January 7, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/drugshortages/dsp_ActiveIngredientDetails.cfm?AI=Methylphenidate+Hydrochloride+Extended+Release+Tablets&st=d

The Evolving Role for Transplantation in Mantle Cell Lymphoma

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) has served as a paradigm of progress among the non-Hodgkin lymphomas over the past 30 years. It was originally defined within the Kiel classification as centrocytic lymphoma, then renamed MCL once the characteristic translocation and resulting cyclin D1 overexpression were identified. These diagnostic markers allowed for the characterization of MCL subtypes as well as the initiation of MCL-focused clinical trials which, in turn, led to regulatory approval of more effective regimens, new therapeutic agents, and an improvement in overall survival (OS) from around 3 years to more than 10 years for many patients.

Despite this progress, virtually all patients relapse, and a cure remains elusive for most. In younger (< 65 to 70 years), medically-fit patients who are transplant-eligible and have symptomatic MCL, a standard of care has been induction chemoimmunotherapy containing high-dose cytarabine followed by ASCT consolidation. For example, a clinical trial of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) alternating with R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, cisplatin; 3 cycles each) showed a significant benefit over R-CHOP x 6 cycles; at a median follow-up of 10.6 years, the time-to-treatment failure was 8.4 v 3.9 years. In another trial, all patients received induction R-DHAP (with cisplatin or an alternative platinum agent) x 4 cycles followed by ASCT. Those patients randomized to post-ASCT maintenance rituximab for 3 years had significantly improved, 4-year progression-free survival (PFS) as compared with observation only (83% vs 64%, p < 0.001); maintenance also significantly improved OS.

Although ASCT consolidation followed by maintenance became widely adopted on the basis of these and other clinical trials, important questions remain:

First, MCL is biologically and clinically quite heterogeneous. Several prognostic tools such as the MCL International Prognostic Index (MIPI) scoring system and biomarkers are available to define lower- versus higher-risk subtypes, but none is routinely used for treatment planning. About 15% of MCL patients present with a highly-aggressive blastoid or pleomorphic variant that usually carries a TP53 mutation or deletion. Given the short survival and limited benefit from dose-intensive chemotherapy and ASCT in TP53-mutated MCL, should transplant be avoided in these patients?

Second, if deep remission is achieved following front-line therapy, defined as positron emission tomography (PET) negative and measurable residual disease (MRD) negative, will high-dose chemotherapy and ASCT provide additional benefits or only toxicity? This question is being addressed by the ongoing ECOG 4151 study, a risk-adapted trial in which post-induction MRD-negative patients are randomized to standard ASCT consolidation plus maintenance rituximab vs maintenance only.

Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKi) are now among the most used agents for relapsed MCL. Recent clinical trials testing the integration of a BTKi into first- or second-line therapy have shown increased response rates and variable clinical outcomes and toxicities for the combinations, depending upon the chemotherapy- and non-chemotherapy backbones utilized, as well as the BTKi. Combinations with the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax plus chemotherapy or BTKi are also showing promise.

The activity of BTKi in MCL led the European MCL Network (EMCL) to design the 3-arm TRIANGLE study to analyze the potential of ibrutinib to improve outcomes when given in conjunction with standard ASCT consolidation, and the ability to replace the need for ASCT. The TRIANGLE results were presented by Dr. Martin Dreyling in the Plenary Session at the December 2022 American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting. Transplant-eligible MCL patients < 65 years of age were randomized to the EMCL’s established front-line therapy of alternating R-CHOP/R-DHAP plus ASCT; the same regimen plus oral ibrutinib given with the R-CHOP induction cycles and then post-ASCT ibrutinib maintenance therapy for 2 years (Arm A+I); or the A+I regimen minus ASCT (Arm I). Maintenance rituximab was allowed in each arm, on the basis of the treating centers’ institutional guidelines. Overall, 54%-58% of patients in each study arm received rituximab maintenance, with no differential benefit in efficacy noted for those so treated.

The results showed that 94%-98% of patients responded by the end of induction (defined as R-chemo and ASCT), with complete remissions in 36%-45% (from computerized tomography imaging, not PET scan). With a median follow-up of 31 months, failure-free survival (FFS; the primary study endpoint) was significantly improved for A+I vs A (3 year FFS of 88% vs 72%, respectively; p = 0.0008). In a subgroup analysis, FFS was notably improved for A+I in patients with high-level TP53 overexpression by immunohistochemistry. Toxicity did not differ during the induction and ASCT periods among the 3 arms regarding cytopenia, gastrointestinal disorders, and infections. However, neutropenia and infections were increased in the ibrutinib-containing arms during maintenance therapy—especially for Arm A+I.

The authors concluded that ASCT plus ibrutinib (Arm A+I) is superior to ASCT only (Arm A), and that Arm A is not superior to ibrutinib without ASCT (Arm I). No decision can yet be made regarding A+I versus I for which FFS to date remains very similar; however, the authors favor ibrutinib without ASCT due to lower toxicity. OS is trending to favor the ibrutinib arms, but longer follow-up will be needed to fully assess.

Should ASCT consolidation now be replaced by ibrutinib-containing induction R-CHOP/R-DHAP and maintenance ibrutinib, with or without maintenance rituximab? A definitive answer will require the fully-published TRIANGLE results, as well as ongoing analysis with longer follow-up. However, it seems very likely that ASCT indeed will be replaced by the new approach. TP53-mutated MCL should be treated with ibrutinib plus R-CHOP/R-DHAP and ibrutinib maintenance as validated in this trial.

Many centers have begun using a second-generation BTKi, acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib, rather than ibrutinib due to equivalent response rates with more favorable side effect profiles and fewer treatment discontinuations. Caution is warranted regarding simply adding a BTKi to one’s favored MCL induction regimen and foregoing ASCT—pending additional studies and the safety of such alternative approaches.

These are indeed exciting times of therapeutic progress, as they have been improving outcomes and providing longer survival outcomes for MCL patients. Targeted agents facilitate this shift to less intensive and chemotherapy-free regimens that provide enhanced response and mitigate short- and longer-term toxicities. More results will be forthcoming for MRD as a treatment endpoint, guiding maintenance therapy, and for risk-adapted treatment of newly-diagnosed and relapsing patients (based upon MCL subtype and biomarker profiles). Enrolling patients into clinical trials is strongly encouraged as the best mechanism to help answer emerging questions in the field and open the pathway to continued progress.

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) has served as a paradigm of progress among the non-Hodgkin lymphomas over the past 30 years. It was originally defined within the Kiel classification as centrocytic lymphoma, then renamed MCL once the characteristic translocation and resulting cyclin D1 overexpression were identified. These diagnostic markers allowed for the characterization of MCL subtypes as well as the initiation of MCL-focused clinical trials which, in turn, led to regulatory approval of more effective regimens, new therapeutic agents, and an improvement in overall survival (OS) from around 3 years to more than 10 years for many patients.

Despite this progress, virtually all patients relapse, and a cure remains elusive for most. In younger (< 65 to 70 years), medically-fit patients who are transplant-eligible and have symptomatic MCL, a standard of care has been induction chemoimmunotherapy containing high-dose cytarabine followed by ASCT consolidation. For example, a clinical trial of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) alternating with R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, cisplatin; 3 cycles each) showed a significant benefit over R-CHOP x 6 cycles; at a median follow-up of 10.6 years, the time-to-treatment failure was 8.4 v 3.9 years. In another trial, all patients received induction R-DHAP (with cisplatin or an alternative platinum agent) x 4 cycles followed by ASCT. Those patients randomized to post-ASCT maintenance rituximab for 3 years had significantly improved, 4-year progression-free survival (PFS) as compared with observation only (83% vs 64%, p < 0.001); maintenance also significantly improved OS.

Although ASCT consolidation followed by maintenance became widely adopted on the basis of these and other clinical trials, important questions remain:

First, MCL is biologically and clinically quite heterogeneous. Several prognostic tools such as the MCL International Prognostic Index (MIPI) scoring system and biomarkers are available to define lower- versus higher-risk subtypes, but none is routinely used for treatment planning. About 15% of MCL patients present with a highly-aggressive blastoid or pleomorphic variant that usually carries a TP53 mutation or deletion. Given the short survival and limited benefit from dose-intensive chemotherapy and ASCT in TP53-mutated MCL, should transplant be avoided in these patients?

Second, if deep remission is achieved following front-line therapy, defined as positron emission tomography (PET) negative and measurable residual disease (MRD) negative, will high-dose chemotherapy and ASCT provide additional benefits or only toxicity? This question is being addressed by the ongoing ECOG 4151 study, a risk-adapted trial in which post-induction MRD-negative patients are randomized to standard ASCT consolidation plus maintenance rituximab vs maintenance only.

Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKi) are now among the most used agents for relapsed MCL. Recent clinical trials testing the integration of a BTKi into first- or second-line therapy have shown increased response rates and variable clinical outcomes and toxicities for the combinations, depending upon the chemotherapy- and non-chemotherapy backbones utilized, as well as the BTKi. Combinations with the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax plus chemotherapy or BTKi are also showing promise.

The activity of BTKi in MCL led the European MCL Network (EMCL) to design the 3-arm TRIANGLE study to analyze the potential of ibrutinib to improve outcomes when given in conjunction with standard ASCT consolidation, and the ability to replace the need for ASCT. The TRIANGLE results were presented by Dr. Martin Dreyling in the Plenary Session at the December 2022 American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting. Transplant-eligible MCL patients < 65 years of age were randomized to the EMCL’s established front-line therapy of alternating R-CHOP/R-DHAP plus ASCT; the same regimen plus oral ibrutinib given with the R-CHOP induction cycles and then post-ASCT ibrutinib maintenance therapy for 2 years (Arm A+I); or the A+I regimen minus ASCT (Arm I). Maintenance rituximab was allowed in each arm, on the basis of the treating centers’ institutional guidelines. Overall, 54%-58% of patients in each study arm received rituximab maintenance, with no differential benefit in efficacy noted for those so treated.

The results showed that 94%-98% of patients responded by the end of induction (defined as R-chemo and ASCT), with complete remissions in 36%-45% (from computerized tomography imaging, not PET scan). With a median follow-up of 31 months, failure-free survival (FFS; the primary study endpoint) was significantly improved for A+I vs A (3 year FFS of 88% vs 72%, respectively; p = 0.0008). In a subgroup analysis, FFS was notably improved for A+I in patients with high-level TP53 overexpression by immunohistochemistry. Toxicity did not differ during the induction and ASCT periods among the 3 arms regarding cytopenia, gastrointestinal disorders, and infections. However, neutropenia and infections were increased in the ibrutinib-containing arms during maintenance therapy—especially for Arm A+I.

The authors concluded that ASCT plus ibrutinib (Arm A+I) is superior to ASCT only (Arm A), and that Arm A is not superior to ibrutinib without ASCT (Arm I). No decision can yet be made regarding A+I versus I for which FFS to date remains very similar; however, the authors favor ibrutinib without ASCT due to lower toxicity. OS is trending to favor the ibrutinib arms, but longer follow-up will be needed to fully assess.

Should ASCT consolidation now be replaced by ibrutinib-containing induction R-CHOP/R-DHAP and maintenance ibrutinib, with or without maintenance rituximab? A definitive answer will require the fully-published TRIANGLE results, as well as ongoing analysis with longer follow-up. However, it seems very likely that ASCT indeed will be replaced by the new approach. TP53-mutated MCL should be treated with ibrutinib plus R-CHOP/R-DHAP and ibrutinib maintenance as validated in this trial.

Many centers have begun using a second-generation BTKi, acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib, rather than ibrutinib due to equivalent response rates with more favorable side effect profiles and fewer treatment discontinuations. Caution is warranted regarding simply adding a BTKi to one’s favored MCL induction regimen and foregoing ASCT—pending additional studies and the safety of such alternative approaches.

These are indeed exciting times of therapeutic progress, as they have been improving outcomes and providing longer survival outcomes for MCL patients. Targeted agents facilitate this shift to less intensive and chemotherapy-free regimens that provide enhanced response and mitigate short- and longer-term toxicities. More results will be forthcoming for MRD as a treatment endpoint, guiding maintenance therapy, and for risk-adapted treatment of newly-diagnosed and relapsing patients (based upon MCL subtype and biomarker profiles). Enrolling patients into clinical trials is strongly encouraged as the best mechanism to help answer emerging questions in the field and open the pathway to continued progress.

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) has served as a paradigm of progress among the non-Hodgkin lymphomas over the past 30 years. It was originally defined within the Kiel classification as centrocytic lymphoma, then renamed MCL once the characteristic translocation and resulting cyclin D1 overexpression were identified. These diagnostic markers allowed for the characterization of MCL subtypes as well as the initiation of MCL-focused clinical trials which, in turn, led to regulatory approval of more effective regimens, new therapeutic agents, and an improvement in overall survival (OS) from around 3 years to more than 10 years for many patients.

Despite this progress, virtually all patients relapse, and a cure remains elusive for most. In younger (< 65 to 70 years), medically-fit patients who are transplant-eligible and have symptomatic MCL, a standard of care has been induction chemoimmunotherapy containing high-dose cytarabine followed by ASCT consolidation. For example, a clinical trial of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) alternating with R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, cisplatin; 3 cycles each) showed a significant benefit over R-CHOP x 6 cycles; at a median follow-up of 10.6 years, the time-to-treatment failure was 8.4 v 3.9 years. In another trial, all patients received induction R-DHAP (with cisplatin or an alternative platinum agent) x 4 cycles followed by ASCT. Those patients randomized to post-ASCT maintenance rituximab for 3 years had significantly improved, 4-year progression-free survival (PFS) as compared with observation only (83% vs 64%, p < 0.001); maintenance also significantly improved OS.

Although ASCT consolidation followed by maintenance became widely adopted on the basis of these and other clinical trials, important questions remain:

First, MCL is biologically and clinically quite heterogeneous. Several prognostic tools such as the MCL International Prognostic Index (MIPI) scoring system and biomarkers are available to define lower- versus higher-risk subtypes, but none is routinely used for treatment planning. About 15% of MCL patients present with a highly-aggressive blastoid or pleomorphic variant that usually carries a TP53 mutation or deletion. Given the short survival and limited benefit from dose-intensive chemotherapy and ASCT in TP53-mutated MCL, should transplant be avoided in these patients?

Second, if deep remission is achieved following front-line therapy, defined as positron emission tomography (PET) negative and measurable residual disease (MRD) negative, will high-dose chemotherapy and ASCT provide additional benefits or only toxicity? This question is being addressed by the ongoing ECOG 4151 study, a risk-adapted trial in which post-induction MRD-negative patients are randomized to standard ASCT consolidation plus maintenance rituximab vs maintenance only.

Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKi) are now among the most used agents for relapsed MCL. Recent clinical trials testing the integration of a BTKi into first- or second-line therapy have shown increased response rates and variable clinical outcomes and toxicities for the combinations, depending upon the chemotherapy- and non-chemotherapy backbones utilized, as well as the BTKi. Combinations with the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax plus chemotherapy or BTKi are also showing promise.

The activity of BTKi in MCL led the European MCL Network (EMCL) to design the 3-arm TRIANGLE study to analyze the potential of ibrutinib to improve outcomes when given in conjunction with standard ASCT consolidation, and the ability to replace the need for ASCT. The TRIANGLE results were presented by Dr. Martin Dreyling in the Plenary Session at the December 2022 American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting. Transplant-eligible MCL patients < 65 years of age were randomized to the EMCL’s established front-line therapy of alternating R-CHOP/R-DHAP plus ASCT; the same regimen plus oral ibrutinib given with the R-CHOP induction cycles and then post-ASCT ibrutinib maintenance therapy for 2 years (Arm A+I); or the A+I regimen minus ASCT (Arm I). Maintenance rituximab was allowed in each arm, on the basis of the treating centers’ institutional guidelines. Overall, 54%-58% of patients in each study arm received rituximab maintenance, with no differential benefit in efficacy noted for those so treated.

The results showed that 94%-98% of patients responded by the end of induction (defined as R-chemo and ASCT), with complete remissions in 36%-45% (from computerized tomography imaging, not PET scan). With a median follow-up of 31 months, failure-free survival (FFS; the primary study endpoint) was significantly improved for A+I vs A (3 year FFS of 88% vs 72%, respectively; p = 0.0008). In a subgroup analysis, FFS was notably improved for A+I in patients with high-level TP53 overexpression by immunohistochemistry. Toxicity did not differ during the induction and ASCT periods among the 3 arms regarding cytopenia, gastrointestinal disorders, and infections. However, neutropenia and infections were increased in the ibrutinib-containing arms during maintenance therapy—especially for Arm A+I.

The authors concluded that ASCT plus ibrutinib (Arm A+I) is superior to ASCT only (Arm A), and that Arm A is not superior to ibrutinib without ASCT (Arm I). No decision can yet be made regarding A+I versus I for which FFS to date remains very similar; however, the authors favor ibrutinib without ASCT due to lower toxicity. OS is trending to favor the ibrutinib arms, but longer follow-up will be needed to fully assess.

Should ASCT consolidation now be replaced by ibrutinib-containing induction R-CHOP/R-DHAP and maintenance ibrutinib, with or without maintenance rituximab? A definitive answer will require the fully-published TRIANGLE results, as well as ongoing analysis with longer follow-up. However, it seems very likely that ASCT indeed will be replaced by the new approach. TP53-mutated MCL should be treated with ibrutinib plus R-CHOP/R-DHAP and ibrutinib maintenance as validated in this trial.

Many centers have begun using a second-generation BTKi, acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib, rather than ibrutinib due to equivalent response rates with more favorable side effect profiles and fewer treatment discontinuations. Caution is warranted regarding simply adding a BTKi to one’s favored MCL induction regimen and foregoing ASCT—pending additional studies and the safety of such alternative approaches.

These are indeed exciting times of therapeutic progress, as they have been improving outcomes and providing longer survival outcomes for MCL patients. Targeted agents facilitate this shift to less intensive and chemotherapy-free regimens that provide enhanced response and mitigate short- and longer-term toxicities. More results will be forthcoming for MRD as a treatment endpoint, guiding maintenance therapy, and for risk-adapted treatment of newly-diagnosed and relapsing patients (based upon MCL subtype and biomarker profiles). Enrolling patients into clinical trials is strongly encouraged as the best mechanism to help answer emerging questions in the field and open the pathway to continued progress.

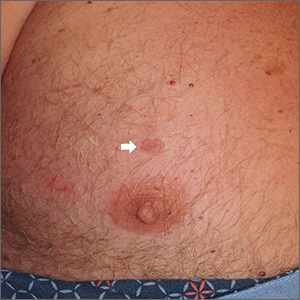

Treatment of Axial Psoriatic Arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a heterogenous inflammatory disease that may involve several different domains, including peripheral joints, entheses, nails, axial skeleton, and skin. A recent increased awareness of PsA has accompanied a large increase in available therapeutic options. In addition to traditional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), new biologics and targeted small molecules have now been shown to be effective in PsA. These agents include those targeting pathways involving tumor necrosis factor (TNF), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), interleukins (IL) 12, 17, 23, janus kinase (JAK), and phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4). These agents have demonstrated efficacy in outcome measures developed for peripheral arthritis, such as the American College of Rheumatology 20 (ACR20) response. However, an ongoing question is whether these agents are equally effective in axial disease. Based on our experience and the existing literature, we believe that some of these agents, including PDE4 and IL-23 inhibitors, are not effective for axial disease.

Moll and Wright’s original description of PsA estimated that 5% of patients with PsA had axial disease1; however, they were describing patients in whom axial arthritis was the predominant, or the only, manifestation. There are many patients for whom axial symptoms are just one of several domains of disease activity. With this in mind, and depending on the cohort studied, the estimated overall prevalence of axial disease ranges from 7% to 32% in patients with PsA.2 This is in contrast to peripheral arthritis, a domain that occurs in most patients with PsA and is the most common manifestation of PsA.2 We believe there are differences in axial and peripheral response among some of the drugs used to treat PsA; therefore it is critical to consider both the presence and magnitude of axial involvement.

An absence of axial PsA–specific clinical trials complicates navigating this treatment domain. Most considerations regarding treatment options for axial disease in PsA are extrapolated from ankylosing spondylitis (AS) trials and experience, as is the case for the TNF and JAK inhibitors. To our knowledge, only one high-quality randomized trial, MAXIMISE, looked specifically at the treatment of axial PsA, in this case with the IL-17 inhibitor secukinumab.3 This trial demonstrated efficacy of secukinumab in reducing symptoms and acute phase reactants in patients with PsA who were categorized as having active axial disease using the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI). Other than conclusions drawn from AS trials and from this single axial PsA randomized controlled trial, data on the treatment of axial PsA are drawn entirely from observational and post-hoc analyses. As there are no consensus criteria for axial PsA, the cohorts included in these data may vary. This heterogeneity showcases the diversity in patients with PsA with axial disease but complicates the generalizability of the findings to individual patients.

Another challenge in understanding axial response to medication is the lack of specific, validated outcome measures for axial PsA. The BASDAI and, more recently, the Assessment in Ankylosing Spondylitis (ASAS) and the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS), all developed specifically for AS, are often used to measure treatment response. The BASDAI incorporates patient-reported symptoms which include fatigue, peripheral joint pain/swelling, tenderness, and morning stiffness not specifically localized to the back. The ASDAS also includes a C-reactive protein measurement.

When used to assess response in PsA, however, these patient-reported outcomes may not be precise enough to separate the impact of axial disease or symptoms from that of peripheral disease. Only question 2 on the BASDAI specifically addresses axial complaints: “How would you describe the overall level of AS-related pain you have had in your neck, back, or hips?” Even this question is vulnerable to confounding from noninflammatory causes of back pain. Although these issues exist with patient-reported outcomes, objective spinal mobility measures used in evaluation of AS, including the modified Schober test, lumbar side flexion, and cervical rotation, have been demonstrated also to perform well in axial PsA.4

This was corroborated in the INSPIRE study, which showed adequate interobserver reliability in primary AS that was equally reproducible in axial PsA, with most measures, including occiput to wall, modified Schober test, cervical rotation, lateral bending, and hip mobility, performing in a “good to excellent” manner.5 Therefore, the inclusion of these objective measures in future therapeutic studies may enhance the external validation of available data.

The Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) has established therapeutic guidelines for psoriatic disease based on currently available literature and data. Similar to previous iterations of guidelines, GRAPPA continues to recommend agents with TNF inhibition or IL-17 inhibition for patients with PsA with axial disease who have failed conservative therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), physical therapy, and/or glucocorticoid injections. Newly recommended in the latest iteration of the GRAPPA guidelines, based on the efficacy of these agents in AS, is the use of JAK inhibitors for axial PsA.6

Although TNF, IL-17, and JAK targeted therapies have demonstrated more likely benefit, albeit subject to the trial limitations previously discussed, the question remains whether agents targeting PDE4 and IL-23 are an effective option for axial PsA. Studies of both PDE4 and IL-23 inhibitors in AS have not demonstrated adequate benefit, which, importantly, contrasts with the previously mentioned and recommended therapies. Additionally, there are no primary randomized control trials that have directly evaluated the efficacy of IL-23 therapy in axial PsA.

Existing data about potential benefit come from post-hoc analyses of the PSUMMIT 1 and 2 trials7-10 with ustekinumab (which inhibits IL-12 and IL-23) and the DISCOVER trials11-13 with guselkumab (a pure IL-23 inhibitor). However, these analyses relied on a physician-reported diagnosis of axial disease and not on prespecified entry criteria. This lack of uniform diagnostic criteria may introduce bias into the interpretation of the results and limit external validation. All patients in these trials had a significant burden of peripheral arthritis; therefore it is hard to know whether, even in patients with physician-reported axial disease, improvement in general outcome measures were due to true amelioration of axial disease or were confounded by improvement in peripheral and skin domains. The analysis of these trials did look specifically at patient answers to BASDAI question 2 regarding level of neck, back, or hip pain. However, it remains difficult to be certain that the results are truly a reflection of axial symptoms and are not driven by patient-perceived improvement in other disease domains and an overall positive trajectory in well-being.

In our years of practice, when we turned to biologic agents, the IL-23 inhibitors and the IL-12/23 inhibitor have not been as effective in patients with PsA who have axial-predominant symptoms. The lack of efficacy of these agents in AS, in contrast to their benefit in psoriatic skin and peripheral joint disease, raises questions about the pathophysiologic role of IL-23 in axial disease, which is yet to be fully understood. For patients with a significant burden of axial pain, in concordance with the consensus from GRAPPA,6 our strategy is to start with TNF, IL-17, or JAK targeted therapies, with the choice based on patient-specific factors, including patient comorbidities, patient administration preference, and insurance coverage. We do believe it is reasonable to try IL-23–targeted therapies in patients who have mild axial symptoms when their predominant symptoms are in other domains, such as the peripheral joints or skin. In our opinion, more convincing data supporting IL-23 inhibition are required to move this into the forefront of axial-predominant PsA therapy. Clearly the investigation of axial disease in PsA lags behind that of peripheral and skin domains. Specific classification criteria for axial PsA, as are being currently developed by GRAPPA, should facilitate more focused therapeutic trials that can better inform optimal treatment of patients with this subset of disease.

- Moll JM, Wright V. Psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1973;3(1):55-78. doi:10.1016/0049-0172(73)90035-8

- Ogdie A, Weiss P. The epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41(4):545-568. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2015.07.001

- Baraliakos X, Gossec L, Pournara E, et al. Secukinumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis and axial manifestations: results from the double-blind, randomised, phase 3 MAXIMISE trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(5):582-590. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218808

- Fernández-Sueiro JL, Willisch A, Pértega-Díaz S, et al. Evaluation of ankylosing spondylitis spinal mobility measurements in the assessment of spinal involvement in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(3):386-392. doi:10.1002/art.24280

- Gladman DD, Inman RD, Cook RJ, et al. International spondyloarthritis interobserver reliability exercise—the INSPIRE study: I. Assessment of spinal measures. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(8):1733-1739.

- Coates LC, Corp N, van der Windt DA, O’Sullivan D, Soriano ER, Kavanaugh A. GRAPPA treatment recommendations: 2021 update. J Rheumatol. 2022;49(6 suppl 1):52-54. doi:10.3899/jrheum.211331

- McInnes IB, Kavanaugh A, Gottlieb AB, et al; PSUMMIT 1 Study Group. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 1 year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled PSUMMIT 1 trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9894):780-789. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60594-2

- Ritchlin C, Rahman P, Kavanaugh A, et al; PSUMMIT 2 Study Group. Efficacy and safety of the anti-IL-12/23 p40 monoclonal antibody, ustekinumab, in patients with active psoriatic arthritis despite conventional non-biological and biological anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy: 6-month and 1-year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised PSUMMIT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(6):990-999. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204655

- Kavanaugh A, Puig L, Gottlieb AB, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in psoriatic arthritis patients with peripheral arthritis and physician-reported spondylitis: post-hoc analyses from two phase III, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies (PSUMMIT-1/PSUMMIT-2). Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(11):1984-1988. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-209068

- McInnes IB, Chakravarty SD, Apaolaza I, et al. Efficacy of ustekinumab in biologic-naïve patients with psoriatic arthritis by prior treatment exposure and disease duration: data from PSUMMIT 1 and PSUMMIT 2. RMD Open. 2019;5(2):e000990. doi:10.1136/rmdopen-2019-000990

- Deodhar A, Helliwell PS, Boehncke WH, et al; DISCOVER-1 Study Group. Guselkumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis who were biologic-naive or had previously received TNFα inhibitor treatment (DISCOVER-1): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10230):1115-1125. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30265-8

- Mease PJ, Rahman P, Gottlieb AB, et al; DISCOVER-2 Study Group. Guselkumab in biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis (DISCOVER-2): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10230):1126-1136. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30263-4

- Mease PJ, Helliwell PS, Gladman DD, et al. Efficacy of guselkumab on axial involvement in patients with active psoriatic arthritis and sacroiliitis: a post-hoc analysis of the phase 3 discover-1 and discover-2 studies. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021;3(10). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00105-3

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a heterogenous inflammatory disease that may involve several different domains, including peripheral joints, entheses, nails, axial skeleton, and skin. A recent increased awareness of PsA has accompanied a large increase in available therapeutic options. In addition to traditional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), new biologics and targeted small molecules have now been shown to be effective in PsA. These agents include those targeting pathways involving tumor necrosis factor (TNF), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), interleukins (IL) 12, 17, 23, janus kinase (JAK), and phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4). These agents have demonstrated efficacy in outcome measures developed for peripheral arthritis, such as the American College of Rheumatology 20 (ACR20) response. However, an ongoing question is whether these agents are equally effective in axial disease. Based on our experience and the existing literature, we believe that some of these agents, including PDE4 and IL-23 inhibitors, are not effective for axial disease.

Moll and Wright’s original description of PsA estimated that 5% of patients with PsA had axial disease1; however, they were describing patients in whom axial arthritis was the predominant, or the only, manifestation. There are many patients for whom axial symptoms are just one of several domains of disease activity. With this in mind, and depending on the cohort studied, the estimated overall prevalence of axial disease ranges from 7% to 32% in patients with PsA.2 This is in contrast to peripheral arthritis, a domain that occurs in most patients with PsA and is the most common manifestation of PsA.2 We believe there are differences in axial and peripheral response among some of the drugs used to treat PsA; therefore it is critical to consider both the presence and magnitude of axial involvement.

An absence of axial PsA–specific clinical trials complicates navigating this treatment domain. Most considerations regarding treatment options for axial disease in PsA are extrapolated from ankylosing spondylitis (AS) trials and experience, as is the case for the TNF and JAK inhibitors. To our knowledge, only one high-quality randomized trial, MAXIMISE, looked specifically at the treatment of axial PsA, in this case with the IL-17 inhibitor secukinumab.3 This trial demonstrated efficacy of secukinumab in reducing symptoms and acute phase reactants in patients with PsA who were categorized as having active axial disease using the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI). Other than conclusions drawn from AS trials and from this single axial PsA randomized controlled trial, data on the treatment of axial PsA are drawn entirely from observational and post-hoc analyses. As there are no consensus criteria for axial PsA, the cohorts included in these data may vary. This heterogeneity showcases the diversity in patients with PsA with axial disease but complicates the generalizability of the findings to individual patients.

Another challenge in understanding axial response to medication is the lack of specific, validated outcome measures for axial PsA. The BASDAI and, more recently, the Assessment in Ankylosing Spondylitis (ASAS) and the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS), all developed specifically for AS, are often used to measure treatment response. The BASDAI incorporates patient-reported symptoms which include fatigue, peripheral joint pain/swelling, tenderness, and morning stiffness not specifically localized to the back. The ASDAS also includes a C-reactive protein measurement.

When used to assess response in PsA, however, these patient-reported outcomes may not be precise enough to separate the impact of axial disease or symptoms from that of peripheral disease. Only question 2 on the BASDAI specifically addresses axial complaints: “How would you describe the overall level of AS-related pain you have had in your neck, back, or hips?” Even this question is vulnerable to confounding from noninflammatory causes of back pain. Although these issues exist with patient-reported outcomes, objective spinal mobility measures used in evaluation of AS, including the modified Schober test, lumbar side flexion, and cervical rotation, have been demonstrated also to perform well in axial PsA.4

This was corroborated in the INSPIRE study, which showed adequate interobserver reliability in primary AS that was equally reproducible in axial PsA, with most measures, including occiput to wall, modified Schober test, cervical rotation, lateral bending, and hip mobility, performing in a “good to excellent” manner.5 Therefore, the inclusion of these objective measures in future therapeutic studies may enhance the external validation of available data.

The Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) has established therapeutic guidelines for psoriatic disease based on currently available literature and data. Similar to previous iterations of guidelines, GRAPPA continues to recommend agents with TNF inhibition or IL-17 inhibition for patients with PsA with axial disease who have failed conservative therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), physical therapy, and/or glucocorticoid injections. Newly recommended in the latest iteration of the GRAPPA guidelines, based on the efficacy of these agents in AS, is the use of JAK inhibitors for axial PsA.6

Although TNF, IL-17, and JAK targeted therapies have demonstrated more likely benefit, albeit subject to the trial limitations previously discussed, the question remains whether agents targeting PDE4 and IL-23 are an effective option for axial PsA. Studies of both PDE4 and IL-23 inhibitors in AS have not demonstrated adequate benefit, which, importantly, contrasts with the previously mentioned and recommended therapies. Additionally, there are no primary randomized control trials that have directly evaluated the efficacy of IL-23 therapy in axial PsA.

Existing data about potential benefit come from post-hoc analyses of the PSUMMIT 1 and 2 trials7-10 with ustekinumab (which inhibits IL-12 and IL-23) and the DISCOVER trials11-13 with guselkumab (a pure IL-23 inhibitor). However, these analyses relied on a physician-reported diagnosis of axial disease and not on prespecified entry criteria. This lack of uniform diagnostic criteria may introduce bias into the interpretation of the results and limit external validation. All patients in these trials had a significant burden of peripheral arthritis; therefore it is hard to know whether, even in patients with physician-reported axial disease, improvement in general outcome measures were due to true amelioration of axial disease or were confounded by improvement in peripheral and skin domains. The analysis of these trials did look specifically at patient answers to BASDAI question 2 regarding level of neck, back, or hip pain. However, it remains difficult to be certain that the results are truly a reflection of axial symptoms and are not driven by patient-perceived improvement in other disease domains and an overall positive trajectory in well-being.

In our years of practice, when we turned to biologic agents, the IL-23 inhibitors and the IL-12/23 inhibitor have not been as effective in patients with PsA who have axial-predominant symptoms. The lack of efficacy of these agents in AS, in contrast to their benefit in psoriatic skin and peripheral joint disease, raises questions about the pathophysiologic role of IL-23 in axial disease, which is yet to be fully understood. For patients with a significant burden of axial pain, in concordance with the consensus from GRAPPA,6 our strategy is to start with TNF, IL-17, or JAK targeted therapies, with the choice based on patient-specific factors, including patient comorbidities, patient administration preference, and insurance coverage. We do believe it is reasonable to try IL-23–targeted therapies in patients who have mild axial symptoms when their predominant symptoms are in other domains, such as the peripheral joints or skin. In our opinion, more convincing data supporting IL-23 inhibition are required to move this into the forefront of axial-predominant PsA therapy. Clearly the investigation of axial disease in PsA lags behind that of peripheral and skin domains. Specific classification criteria for axial PsA, as are being currently developed by GRAPPA, should facilitate more focused therapeutic trials that can better inform optimal treatment of patients with this subset of disease.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a heterogenous inflammatory disease that may involve several different domains, including peripheral joints, entheses, nails, axial skeleton, and skin. A recent increased awareness of PsA has accompanied a large increase in available therapeutic options. In addition to traditional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), new biologics and targeted small molecules have now been shown to be effective in PsA. These agents include those targeting pathways involving tumor necrosis factor (TNF), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), interleukins (IL) 12, 17, 23, janus kinase (JAK), and phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4). These agents have demonstrated efficacy in outcome measures developed for peripheral arthritis, such as the American College of Rheumatology 20 (ACR20) response. However, an ongoing question is whether these agents are equally effective in axial disease. Based on our experience and the existing literature, we believe that some of these agents, including PDE4 and IL-23 inhibitors, are not effective for axial disease.

Moll and Wright’s original description of PsA estimated that 5% of patients with PsA had axial disease1; however, they were describing patients in whom axial arthritis was the predominant, or the only, manifestation. There are many patients for whom axial symptoms are just one of several domains of disease activity. With this in mind, and depending on the cohort studied, the estimated overall prevalence of axial disease ranges from 7% to 32% in patients with PsA.2 This is in contrast to peripheral arthritis, a domain that occurs in most patients with PsA and is the most common manifestation of PsA.2 We believe there are differences in axial and peripheral response among some of the drugs used to treat PsA; therefore it is critical to consider both the presence and magnitude of axial involvement.

An absence of axial PsA–specific clinical trials complicates navigating this treatment domain. Most considerations regarding treatment options for axial disease in PsA are extrapolated from ankylosing spondylitis (AS) trials and experience, as is the case for the TNF and JAK inhibitors. To our knowledge, only one high-quality randomized trial, MAXIMISE, looked specifically at the treatment of axial PsA, in this case with the IL-17 inhibitor secukinumab.3 This trial demonstrated efficacy of secukinumab in reducing symptoms and acute phase reactants in patients with PsA who were categorized as having active axial disease using the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI). Other than conclusions drawn from AS trials and from this single axial PsA randomized controlled trial, data on the treatment of axial PsA are drawn entirely from observational and post-hoc analyses. As there are no consensus criteria for axial PsA, the cohorts included in these data may vary. This heterogeneity showcases the diversity in patients with PsA with axial disease but complicates the generalizability of the findings to individual patients.

Another challenge in understanding axial response to medication is the lack of specific, validated outcome measures for axial PsA. The BASDAI and, more recently, the Assessment in Ankylosing Spondylitis (ASAS) and the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS), all developed specifically for AS, are often used to measure treatment response. The BASDAI incorporates patient-reported symptoms which include fatigue, peripheral joint pain/swelling, tenderness, and morning stiffness not specifically localized to the back. The ASDAS also includes a C-reactive protein measurement.

When used to assess response in PsA, however, these patient-reported outcomes may not be precise enough to separate the impact of axial disease or symptoms from that of peripheral disease. Only question 2 on the BASDAI specifically addresses axial complaints: “How would you describe the overall level of AS-related pain you have had in your neck, back, or hips?” Even this question is vulnerable to confounding from noninflammatory causes of back pain. Although these issues exist with patient-reported outcomes, objective spinal mobility measures used in evaluation of AS, including the modified Schober test, lumbar side flexion, and cervical rotation, have been demonstrated also to perform well in axial PsA.4