User login

Metastatic BC: Meaningful clinical benefit with trifluridine/tipiracil in phase 2 study

Key clinical point: Trifluridine/tipiracil (FTD/TPI) showed promising anti-tumor activity with a manageable safety profile regardless of prior exposure to fluoropyrimidine therapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: The median durations of progression-free survival were 5.7 months and 9.4 months in patients with and without prior exposure to fluoropyrimidine therapy, respectively. Neutropenia (81.8%), fatigue (29.7%), anorexia (25.7%), and nausea (25.7%) were the most common all-grade treatment-related adverse events.

Study details: Findings are from a phase 2 study including 74 patients with metastatic BC with or without prior exposure to fluoropyrimidine therapy who received FTD/TPI.

Disclosures: This study was funded by a grant from the National Medical Research Council, Singapore. Some authors declared receiving research funding, honoraria, consulting fees, or travel support from or having other ties with various sources.

Source: Lim JSJ et al. Phase II study of trifluridine/tipiracil (FTD/TPI) in metastatic breast cancers with or without prior exposure to fluoropyrimidines. Eur J Cancer. 2023;113311 (Aug 25). doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2023.113311

Key clinical point: Trifluridine/tipiracil (FTD/TPI) showed promising anti-tumor activity with a manageable safety profile regardless of prior exposure to fluoropyrimidine therapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: The median durations of progression-free survival were 5.7 months and 9.4 months in patients with and without prior exposure to fluoropyrimidine therapy, respectively. Neutropenia (81.8%), fatigue (29.7%), anorexia (25.7%), and nausea (25.7%) were the most common all-grade treatment-related adverse events.

Study details: Findings are from a phase 2 study including 74 patients with metastatic BC with or without prior exposure to fluoropyrimidine therapy who received FTD/TPI.

Disclosures: This study was funded by a grant from the National Medical Research Council, Singapore. Some authors declared receiving research funding, honoraria, consulting fees, or travel support from or having other ties with various sources.

Source: Lim JSJ et al. Phase II study of trifluridine/tipiracil (FTD/TPI) in metastatic breast cancers with or without prior exposure to fluoropyrimidines. Eur J Cancer. 2023;113311 (Aug 25). doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2023.113311

Key clinical point: Trifluridine/tipiracil (FTD/TPI) showed promising anti-tumor activity with a manageable safety profile regardless of prior exposure to fluoropyrimidine therapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: The median durations of progression-free survival were 5.7 months and 9.4 months in patients with and without prior exposure to fluoropyrimidine therapy, respectively. Neutropenia (81.8%), fatigue (29.7%), anorexia (25.7%), and nausea (25.7%) were the most common all-grade treatment-related adverse events.

Study details: Findings are from a phase 2 study including 74 patients with metastatic BC with or without prior exposure to fluoropyrimidine therapy who received FTD/TPI.

Disclosures: This study was funded by a grant from the National Medical Research Council, Singapore. Some authors declared receiving research funding, honoraria, consulting fees, or travel support from or having other ties with various sources.

Source: Lim JSJ et al. Phase II study of trifluridine/tipiracil (FTD/TPI) in metastatic breast cancers with or without prior exposure to fluoropyrimidines. Eur J Cancer. 2023;113311 (Aug 25). doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2023.113311

Giredestrant shows promising outcomes in HR+ /HER2− BC in phase 2 study

Key clinical point: Giredestrant demonstrated stronger anti-proliferative activity than anastrozole and was well-tolerated in patients with estrogen receptor-positive (ER+ ), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2−), untreated early breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: At week 2, giredestrant vs anastrozole had a stronger anti-proliferative effect as indicated by greater relative geometric mean reduction of Ki67 scores (−75% vs −67%; P = .043). Neutropenia (26% and 27%, respectively) and decreased neutrophil count (15% and 15%, respectively) were the most common grade 3-4 adverse events observed in the giredestrant + palbociclib and anastrozole + palbociclib treatment arms.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 2 coopERA Breast Cancer trial including 221 postmenopausal patients with clinical T stage (cT)1c to cT4a-c, ER+ /HER2− early BC who were randomly assigned to receive giredestrant or anastrozole in combination with palbociclib.

Disclosures: This study was funded by F Hoffmann-La Roche. Seven authors declared being employees or stockholders of F Hoffmann-La Roche, and the other authors declared ties with various sources.

Source: Hurvitz SA et al on behalf of thecoopERA Breast Cancer study group. Neoadjuvant palbociclib plus either giredestrant or anastrozole in oestrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative, early breast cancer (coopERA Breast Cancer): An open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24(9):1029-1041 (Aug 29). doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00268-1

Key clinical point: Giredestrant demonstrated stronger anti-proliferative activity than anastrozole and was well-tolerated in patients with estrogen receptor-positive (ER+ ), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2−), untreated early breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: At week 2, giredestrant vs anastrozole had a stronger anti-proliferative effect as indicated by greater relative geometric mean reduction of Ki67 scores (−75% vs −67%; P = .043). Neutropenia (26% and 27%, respectively) and decreased neutrophil count (15% and 15%, respectively) were the most common grade 3-4 adverse events observed in the giredestrant + palbociclib and anastrozole + palbociclib treatment arms.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 2 coopERA Breast Cancer trial including 221 postmenopausal patients with clinical T stage (cT)1c to cT4a-c, ER+ /HER2− early BC who were randomly assigned to receive giredestrant or anastrozole in combination with palbociclib.

Disclosures: This study was funded by F Hoffmann-La Roche. Seven authors declared being employees or stockholders of F Hoffmann-La Roche, and the other authors declared ties with various sources.

Source: Hurvitz SA et al on behalf of thecoopERA Breast Cancer study group. Neoadjuvant palbociclib plus either giredestrant or anastrozole in oestrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative, early breast cancer (coopERA Breast Cancer): An open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24(9):1029-1041 (Aug 29). doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00268-1

Key clinical point: Giredestrant demonstrated stronger anti-proliferative activity than anastrozole and was well-tolerated in patients with estrogen receptor-positive (ER+ ), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2−), untreated early breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: At week 2, giredestrant vs anastrozole had a stronger anti-proliferative effect as indicated by greater relative geometric mean reduction of Ki67 scores (−75% vs −67%; P = .043). Neutropenia (26% and 27%, respectively) and decreased neutrophil count (15% and 15%, respectively) were the most common grade 3-4 adverse events observed in the giredestrant + palbociclib and anastrozole + palbociclib treatment arms.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 2 coopERA Breast Cancer trial including 221 postmenopausal patients with clinical T stage (cT)1c to cT4a-c, ER+ /HER2− early BC who were randomly assigned to receive giredestrant or anastrozole in combination with palbociclib.

Disclosures: This study was funded by F Hoffmann-La Roche. Seven authors declared being employees or stockholders of F Hoffmann-La Roche, and the other authors declared ties with various sources.

Source: Hurvitz SA et al on behalf of thecoopERA Breast Cancer study group. Neoadjuvant palbociclib plus either giredestrant or anastrozole in oestrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative, early breast cancer (coopERA Breast Cancer): An open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24(9):1029-1041 (Aug 29). doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00268-1

Luminal A BC patients can skip radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery

Key clinical point: The incidence rate of local recurrence was low even after omitting radiotherapy in women with luminal A breast cancer (BC) age ≥55 years who underwent breast-conserving surgery (BCS) followed by endocrine therapy.

Major finding: At 5 years, the cumulative incidence of local recurrence was low (2.3%; 95% CI 1.2%-4.1%), with 1.9% of patients (90% CI 1.1%-3.2%) reporting contralateral BC recurrences and 2.7% of patients (90% CI 1.6%-4.1%) reporting recurrences of any type.

Study details: This prospective cohort study included 500 women with T1N0 (tumor size < 2 cm and node negative) luminal A BC age ≥ 55 years who had undergone BCS followed by adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Canadian Cancer Society and Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation. Some authors declared serving as consultants or members of data safety and monitoring boards or having ties with various sources.

Source: Whelan TJ et al for the LUMINA Study Investigators. Omitting radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery in luminal A breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(7):612-619 (Aug 17). doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2302344

Key clinical point: The incidence rate of local recurrence was low even after omitting radiotherapy in women with luminal A breast cancer (BC) age ≥55 years who underwent breast-conserving surgery (BCS) followed by endocrine therapy.

Major finding: At 5 years, the cumulative incidence of local recurrence was low (2.3%; 95% CI 1.2%-4.1%), with 1.9% of patients (90% CI 1.1%-3.2%) reporting contralateral BC recurrences and 2.7% of patients (90% CI 1.6%-4.1%) reporting recurrences of any type.

Study details: This prospective cohort study included 500 women with T1N0 (tumor size < 2 cm and node negative) luminal A BC age ≥ 55 years who had undergone BCS followed by adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Canadian Cancer Society and Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation. Some authors declared serving as consultants or members of data safety and monitoring boards or having ties with various sources.

Source: Whelan TJ et al for the LUMINA Study Investigators. Omitting radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery in luminal A breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(7):612-619 (Aug 17). doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2302344

Key clinical point: The incidence rate of local recurrence was low even after omitting radiotherapy in women with luminal A breast cancer (BC) age ≥55 years who underwent breast-conserving surgery (BCS) followed by endocrine therapy.

Major finding: At 5 years, the cumulative incidence of local recurrence was low (2.3%; 95% CI 1.2%-4.1%), with 1.9% of patients (90% CI 1.1%-3.2%) reporting contralateral BC recurrences and 2.7% of patients (90% CI 1.6%-4.1%) reporting recurrences of any type.

Study details: This prospective cohort study included 500 women with T1N0 (tumor size < 2 cm and node negative) luminal A BC age ≥ 55 years who had undergone BCS followed by adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Canadian Cancer Society and Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation. Some authors declared serving as consultants or members of data safety and monitoring boards or having ties with various sources.

Source: Whelan TJ et al for the LUMINA Study Investigators. Omitting radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery in luminal A breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(7):612-619 (Aug 17). doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2302344

Role of Prophylactic Cranial Irradiation in Small Cell Carcinoma of Urinary Bladder: Case Report and Literature Review

INTRODUCTION

Urinary bladder is an extremely rare site of extrapulmonary small cell cancer (EPSCC). Unlike small cell lung cancer (SCLC), there is no clear guideline for prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) for EPSCC. In this case report and literature review, we discuss small cell cancer of urinary bladder (SCCUB) and the role of PCI in SCCUB.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 74-year-old male presented with gross hematuria and an unremarkable physical examination. CT showed 1.7 cm right anterolateral bladder wall thickening. Cystoscopy revealed a 2-3 cm high-grade bladder lesion. Pathology from transurethral resection of the tumor was consistent with T1N0M0 small cell carcinoma. MRI brain and FDG-PET showed no extravesical disease. Patient received four cycles of neoadjuvant carboplatin/etoposide per his preference as he wanted to protect his hearing due to his profession followed by radical cystoprostatectomy. Post-op pathology showed clear margins. We decided to forego PCI in favor of interval surveillance with MRI and follow- up images remain negative for distant metastases.

DISCUSSION

EPSCC accounts for 2.5-5% of all SCC, very rare in male genitourinary tract. Treatment approach is derived from SCLC, guided by extent of disease and patient’s functional status. Role of PCI in EPSCC has not been clearly described, and even less evidence is available for SCCUB. From a review of eleven studies in PubMed for the role of PCI in SCCUB or EPSCC, we found that SCCUB has lower incidence of brain metastases than SCLC. One study suggested that SCCUB arises from totipotent cells in the submucosa, unlike Kulchitsky cell origin of SCLC. This difference might explain the difference in their metastatic behavior. With this background, PCI is not routinely recommended for limited- stage SCCUB. There might still be a role for PCI in extensive SCCUB with high metastatic burden. More studies are needed to update the guidelines for the role of PCI for these tumors.

CONCLUSIONS

Per this literature review, PCI is not routinely recommended for SCCUB, likely due to different cells of origin compared to SCLC. Future studies should focus on characterizing differences in their metastatic behavior and updating guidelines for PCI for SCCUB.

INTRODUCTION

Urinary bladder is an extremely rare site of extrapulmonary small cell cancer (EPSCC). Unlike small cell lung cancer (SCLC), there is no clear guideline for prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) for EPSCC. In this case report and literature review, we discuss small cell cancer of urinary bladder (SCCUB) and the role of PCI in SCCUB.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 74-year-old male presented with gross hematuria and an unremarkable physical examination. CT showed 1.7 cm right anterolateral bladder wall thickening. Cystoscopy revealed a 2-3 cm high-grade bladder lesion. Pathology from transurethral resection of the tumor was consistent with T1N0M0 small cell carcinoma. MRI brain and FDG-PET showed no extravesical disease. Patient received four cycles of neoadjuvant carboplatin/etoposide per his preference as he wanted to protect his hearing due to his profession followed by radical cystoprostatectomy. Post-op pathology showed clear margins. We decided to forego PCI in favor of interval surveillance with MRI and follow- up images remain negative for distant metastases.

DISCUSSION

EPSCC accounts for 2.5-5% of all SCC, very rare in male genitourinary tract. Treatment approach is derived from SCLC, guided by extent of disease and patient’s functional status. Role of PCI in EPSCC has not been clearly described, and even less evidence is available for SCCUB. From a review of eleven studies in PubMed for the role of PCI in SCCUB or EPSCC, we found that SCCUB has lower incidence of brain metastases than SCLC. One study suggested that SCCUB arises from totipotent cells in the submucosa, unlike Kulchitsky cell origin of SCLC. This difference might explain the difference in their metastatic behavior. With this background, PCI is not routinely recommended for limited- stage SCCUB. There might still be a role for PCI in extensive SCCUB with high metastatic burden. More studies are needed to update the guidelines for the role of PCI for these tumors.

CONCLUSIONS

Per this literature review, PCI is not routinely recommended for SCCUB, likely due to different cells of origin compared to SCLC. Future studies should focus on characterizing differences in their metastatic behavior and updating guidelines for PCI for SCCUB.

INTRODUCTION

Urinary bladder is an extremely rare site of extrapulmonary small cell cancer (EPSCC). Unlike small cell lung cancer (SCLC), there is no clear guideline for prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) for EPSCC. In this case report and literature review, we discuss small cell cancer of urinary bladder (SCCUB) and the role of PCI in SCCUB.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 74-year-old male presented with gross hematuria and an unremarkable physical examination. CT showed 1.7 cm right anterolateral bladder wall thickening. Cystoscopy revealed a 2-3 cm high-grade bladder lesion. Pathology from transurethral resection of the tumor was consistent with T1N0M0 small cell carcinoma. MRI brain and FDG-PET showed no extravesical disease. Patient received four cycles of neoadjuvant carboplatin/etoposide per his preference as he wanted to protect his hearing due to his profession followed by radical cystoprostatectomy. Post-op pathology showed clear margins. We decided to forego PCI in favor of interval surveillance with MRI and follow- up images remain negative for distant metastases.

DISCUSSION

EPSCC accounts for 2.5-5% of all SCC, very rare in male genitourinary tract. Treatment approach is derived from SCLC, guided by extent of disease and patient’s functional status. Role of PCI in EPSCC has not been clearly described, and even less evidence is available for SCCUB. From a review of eleven studies in PubMed for the role of PCI in SCCUB or EPSCC, we found that SCCUB has lower incidence of brain metastases than SCLC. One study suggested that SCCUB arises from totipotent cells in the submucosa, unlike Kulchitsky cell origin of SCLC. This difference might explain the difference in their metastatic behavior. With this background, PCI is not routinely recommended for limited- stage SCCUB. There might still be a role for PCI in extensive SCCUB with high metastatic burden. More studies are needed to update the guidelines for the role of PCI for these tumors.

CONCLUSIONS

Per this literature review, PCI is not routinely recommended for SCCUB, likely due to different cells of origin compared to SCLC. Future studies should focus on characterizing differences in their metastatic behavior and updating guidelines for PCI for SCCUB.

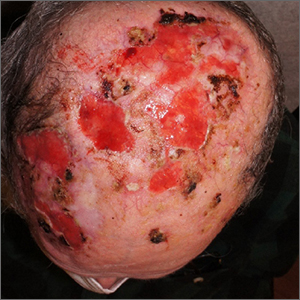

Nonhealing postsurgical scalp ulcers

Two shave biopsies were taken, 1 in the center of a previous SCC site with hyperkeratosis, the other in a site not previously affected by SCC but with the physical features of a pustule. Biopsy results from both sites were consistent with erosive pustular dermatosis, an unusual inflammatory disorder that mimics SCC.

Erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp is an uncommon dermatitis that usually affects older women but may appear in men and women of all ages. It can mimic many other conditions that can affect the scalp, including seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, actinic keratosis, and SCC.

The exact causative mechanism is not understood, and cases may develop spontaneously. Rough papules, pustules, crusts, and ulcers develop and (apart from the pustules) share many features of actinic keratoses, SCCs, and field cancerization. The presence of pustules helps point to the diagnosis.

Triggers include previous surgery or physical trauma, burns, skin or hair grafts, and treatment of actinic keratoses with imiquimod, 5-fluourouracil, or photodynamic therapy. Some autoimmune diseases (including Hashimoto thyroiditis, autoimmune hepatitis, and rheumatoid arthritis) have been linked to disease occurrence and severity.1

Treatment includes potent or super-potent topical steroids such as clobetasol 0.05% ointment. Topical tacrolimus 0.1% ointment and calcipotriene 0.005% cream have been reported as steroid alternatives. Paradoxically, photodynamic therapy, while associated with triggering disease, has also been used therapeutically. Systemic immunomodulators such as cyclosporine 3 mg/kg/d or prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/d may be needed in severe cases. Antibiotics including topical dapsone 5% gel, systemic dapsone from 50 mg bid to tid, and doxycycline have been helpful due, in part, to their immunomodulatory effects.1,2

This patient was told to apply topical triamcinolone 0.1% ointment around and over ulcers and pustules and to take doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. The patient cleared well after 6 weeks. He continued to apply topical triamcinolone every few days as maintenance therapy.

He had some mild recurrence after discontinuing all topical and oral therapy, so he currently is being maintained on topical clobetasol 0.05% ointment every other day. He comes in for follow-up appointments every 3 months to monitor for control of the erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp and for skin cancer surveillance.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME

1. Karanfilian KM, Wassef C. Erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp: causes and treatments. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60:25-32. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14955

2. Sasaki R, Asano Y, Fujimura T. A pediatric case of corticosteroid-resistant erosive pustular dermatosis of scalp-like alopecia treated successfully with oral indomethacin, doxycycline, and topical tacrolimus. J Dermatol. 2022;49: e299-e300. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16425

Two shave biopsies were taken, 1 in the center of a previous SCC site with hyperkeratosis, the other in a site not previously affected by SCC but with the physical features of a pustule. Biopsy results from both sites were consistent with erosive pustular dermatosis, an unusual inflammatory disorder that mimics SCC.

Erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp is an uncommon dermatitis that usually affects older women but may appear in men and women of all ages. It can mimic many other conditions that can affect the scalp, including seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, actinic keratosis, and SCC.

The exact causative mechanism is not understood, and cases may develop spontaneously. Rough papules, pustules, crusts, and ulcers develop and (apart from the pustules) share many features of actinic keratoses, SCCs, and field cancerization. The presence of pustules helps point to the diagnosis.

Triggers include previous surgery or physical trauma, burns, skin or hair grafts, and treatment of actinic keratoses with imiquimod, 5-fluourouracil, or photodynamic therapy. Some autoimmune diseases (including Hashimoto thyroiditis, autoimmune hepatitis, and rheumatoid arthritis) have been linked to disease occurrence and severity.1

Treatment includes potent or super-potent topical steroids such as clobetasol 0.05% ointment. Topical tacrolimus 0.1% ointment and calcipotriene 0.005% cream have been reported as steroid alternatives. Paradoxically, photodynamic therapy, while associated with triggering disease, has also been used therapeutically. Systemic immunomodulators such as cyclosporine 3 mg/kg/d or prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/d may be needed in severe cases. Antibiotics including topical dapsone 5% gel, systemic dapsone from 50 mg bid to tid, and doxycycline have been helpful due, in part, to their immunomodulatory effects.1,2

This patient was told to apply topical triamcinolone 0.1% ointment around and over ulcers and pustules and to take doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. The patient cleared well after 6 weeks. He continued to apply topical triamcinolone every few days as maintenance therapy.

He had some mild recurrence after discontinuing all topical and oral therapy, so he currently is being maintained on topical clobetasol 0.05% ointment every other day. He comes in for follow-up appointments every 3 months to monitor for control of the erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp and for skin cancer surveillance.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME

Two shave biopsies were taken, 1 in the center of a previous SCC site with hyperkeratosis, the other in a site not previously affected by SCC but with the physical features of a pustule. Biopsy results from both sites were consistent with erosive pustular dermatosis, an unusual inflammatory disorder that mimics SCC.

Erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp is an uncommon dermatitis that usually affects older women but may appear in men and women of all ages. It can mimic many other conditions that can affect the scalp, including seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, actinic keratosis, and SCC.

The exact causative mechanism is not understood, and cases may develop spontaneously. Rough papules, pustules, crusts, and ulcers develop and (apart from the pustules) share many features of actinic keratoses, SCCs, and field cancerization. The presence of pustules helps point to the diagnosis.

Triggers include previous surgery or physical trauma, burns, skin or hair grafts, and treatment of actinic keratoses with imiquimod, 5-fluourouracil, or photodynamic therapy. Some autoimmune diseases (including Hashimoto thyroiditis, autoimmune hepatitis, and rheumatoid arthritis) have been linked to disease occurrence and severity.1

Treatment includes potent or super-potent topical steroids such as clobetasol 0.05% ointment. Topical tacrolimus 0.1% ointment and calcipotriene 0.005% cream have been reported as steroid alternatives. Paradoxically, photodynamic therapy, while associated with triggering disease, has also been used therapeutically. Systemic immunomodulators such as cyclosporine 3 mg/kg/d or prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/d may be needed in severe cases. Antibiotics including topical dapsone 5% gel, systemic dapsone from 50 mg bid to tid, and doxycycline have been helpful due, in part, to their immunomodulatory effects.1,2

This patient was told to apply topical triamcinolone 0.1% ointment around and over ulcers and pustules and to take doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. The patient cleared well after 6 weeks. He continued to apply topical triamcinolone every few days as maintenance therapy.

He had some mild recurrence after discontinuing all topical and oral therapy, so he currently is being maintained on topical clobetasol 0.05% ointment every other day. He comes in for follow-up appointments every 3 months to monitor for control of the erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp and for skin cancer surveillance.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME

1. Karanfilian KM, Wassef C. Erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp: causes and treatments. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60:25-32. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14955

2. Sasaki R, Asano Y, Fujimura T. A pediatric case of corticosteroid-resistant erosive pustular dermatosis of scalp-like alopecia treated successfully with oral indomethacin, doxycycline, and topical tacrolimus. J Dermatol. 2022;49: e299-e300. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16425

1. Karanfilian KM, Wassef C. Erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp: causes and treatments. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60:25-32. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14955

2. Sasaki R, Asano Y, Fujimura T. A pediatric case of corticosteroid-resistant erosive pustular dermatosis of scalp-like alopecia treated successfully with oral indomethacin, doxycycline, and topical tacrolimus. J Dermatol. 2022;49: e299-e300. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16425

Olfactory Hallucinations Following COVID-19 Vaccination

The rapid development of multiple vaccines for COVID-19 significantly contributed to reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19 infection.1 The vaccination campaign against COVID-19 started in December 2020 within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system with the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 mRNA vaccines followed by the Johnson & Johnson (J&J) vaccine in March 2021.2,3

Because of the importance of maintaining a safe vaccination campaign, surveillance reports documenting cases of malignant or benign adverse effects (AEs) are fundamental to generate awareness and accurate knowledge on these newly developed vaccines. Here we report the case of a veteran who developed olfactory hallucinations following the administration of the J&J COVID-19 vaccine.

Case Presentation

A 39-year-old veteran with a history of tension-type headaches presented to the neurology clinic with concern of a burning smell sensation in the absence of an identifiable source. He first noticed this symptom approximately 3 weeks after he received the J&J COVID-19 vaccine about 4 months prior. At the symptom’s first occurrence, he underwent a nasal swab antigen COVID-19 test, which was negative. Initially, symptoms would occur daily lasting about 1 hour. Thereafter, they started to decrease in duration, frequency, and intensity, and about 11 months postvaccination, milder episodes were occurring 1 to 2 times weekly. These episodes lasted nearly 2 years (21 months postvaccination). They happened randomly during the day and were not associated with any other symptoms. Specifically, there were no headaches, loss of consciousness, abnormal movements, nausea, vomiting, photophobia or phonophobia, or alteration of consciousness, such as confusion or drowsiness during or after the events. Additionally, there were no clear triggers the veteran could identify. The veteran did not sustain any head injuries or exposure to toxic odors before the onset of symptoms.

At the time of his presentation to the clinic, both his general and neurological examinations were unremarkable.

Discussion

It has been previously observed that infection with COVID-19 can lead to the loss of taste and smell, but only less commonly olfactory hallucination.4 The pathophysiology of olfactory hallucinations following COVID-19 infection is unknown, but several mechanisms have been proposed. These include obstruction of the olfactory cleft; infection of the sustentacular supporting cells, which express angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE‐2); injury to olfactory sensory cells via neuropilin‐1 receptors (NRP1); and injury to the olfactory bulb.5

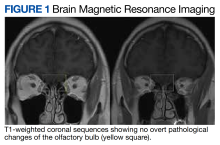

The case we present represents the only report of phantosmia following a J&J COVID-19 vaccination. Phantosmia, featured by a burning or smoke odor, has been reported prior in a case of a 57-year-old woman following the administration of the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine.6 Similar to our case, symptoms were not associated with a concurrent COVID-19 infection ruled out via a COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction test. For the Pfizer-BioNTech phantosmia case, a 3 Tesla (T) brain MRI showed left greater than right olfactory bulb and tract gadolinium enhancement on T1-weighted postcontrast images. On axial T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images, hyperintensity along the left olfactory bulb and bilateral olfactory tracts was noted and interpreted as edema. On sagittal thin sections of T2-weighted images, the olfactory nerve filia were thickened and clumped.6 On the contrary, in the case we present, a brain MRI obtained with a 1.5 T magnet showed no abnormalities. It is possible that a high-resolution scan targeting the olfactory bulb could have disclosed pathological changes. At the time when the veteran presented to the neurology clinic, symptoms were already improving, and repeat MRI was deferred as it would not have changed the clinical management.

Konstantinidis and colleagues reported hyposmia in 2 patients following Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccination.5 Both patients, 42- and 39-year-old women, experienced hyposmia following their second dose of the vaccine with symptom onset 3 and 5 days after vaccination, respectively. The first patient reported improvement of symptoms after 1 week, while the second patient participated in olfactory training and experienced only partial recovery after 1 month. Multiple studies have reported cranial nerve involvement secondary to other COVID-19 vaccines, including olfactory dysfunction, optic neuritis, acute abducens nerve palsy, Bell palsy, tinnitus, and cochleopathy.7

There are no previous reports of phantosmia following the J&J COVID-19 vaccine. In our case, reported symptoms were mild, although they persisted for nearly 2 years following vaccination.

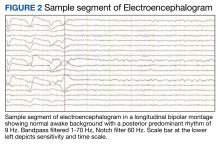

In the evaluation of this veteran, although the timing between symptom onset and vaccination was indicative of a possible link between the 2, other etiologies of phantosmia were ruled out. Isolated olfactory hallucination is most associated with temporal lobe epilepsy, which is the most common form of epilepsy to present in adulthood. However, given the absence of other symptoms suggestive of epilepsy and the duration of the episodes (approximately 1 hour), the clinical suspicion was low. This was reinforced by the EEG that showed no abnormalities in the temporal region. Notwithstanding these considerations, one must keep in mind that no episodes of phantosmia occurred during the EEG recording, the correlates of which are the gold standard to rule out a diagnosis of epilepsy.

A normal brain MRI argued against possible structural abnormalities leading to these symptoms. Thus, the origin of these symptoms remains unknown.

Conclusions

The emergency approval and use of vaccines against COVID-19 was a major victory for public health in 2021. However, given the rapid rollout of these vaccines, the medical community is responsible for reporting adverse effects as they are observed. The authors believe that the clinical events featuring the J&J COVID-19 vaccine in this veteran should not discourage the use of the COVID-19 vaccine. However, sharing the clinical outcome of this veteran is relevant to inform the community regarding this rare and benign possible adverse effect of the J&J COVID-19 vaccine.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Tennessee Valley Veteran Healthcare System (Nashville). The authors thank Dr. Martin Gallagher (Tennessee Valley Veteran Healthcare System) for providing clinical expertise with electroencephalogram interpretation.

1. Xu S, Huang R, Sy LS, et al. COVID-19 vaccination and non-COVID-19 mortality risk - seven integrated health care organizations, United States, December 14, 2020-July 31, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(43):1520-1524. Published 2021 Oct 29. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7043e2

2. Der-Martirosian C, Steers WN, Northcraft H, Chu K, Dobalian A. Vaccinating veterans for COVID-19 at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Am J Prev Med. 2022;62(6):e317-e324. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2021.12.016

3. Bagnato F, Wallin M. COVID-19 vaccine in veterans with multiple sclerosis: protect the vulnerable. Fed Pract. 2021;38(suppl 1):S28-S32. doi:10.12788/fp.0113

4. Işlek A, Balcı MK. Phantosmia with COVID-19 related olfactory dysfunction: report of nine cases. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;74(suppl 2):2891-2893. doi:10.1007/s12070-021-02505-z

5. Konstantinidis I, Tsakiropoulou E, Hähner A, de With K, Poulas K, Hummel T. Olfactory dysfunction after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2021;11(9):1399-1401. doi:10.1002/alr.22809

6. Keir G, Maria NI, Kirsch CFE. Unique imaging findings of neurologic phantosmia following Pfizer-BioNtech COVID-19 vaccination: a case report. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2021;30(3):133-137. doi:10.1097/RMR.0000000000000287

7. Garg RK, Paliwal VK. Spectrum of neurological complications following COVID-19 vaccination. Neurol Sci. 2022;43(1):3-40. doi:10.1007/s10072-021-05662-9

The rapid development of multiple vaccines for COVID-19 significantly contributed to reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19 infection.1 The vaccination campaign against COVID-19 started in December 2020 within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system with the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 mRNA vaccines followed by the Johnson & Johnson (J&J) vaccine in March 2021.2,3

Because of the importance of maintaining a safe vaccination campaign, surveillance reports documenting cases of malignant or benign adverse effects (AEs) are fundamental to generate awareness and accurate knowledge on these newly developed vaccines. Here we report the case of a veteran who developed olfactory hallucinations following the administration of the J&J COVID-19 vaccine.

Case Presentation

A 39-year-old veteran with a history of tension-type headaches presented to the neurology clinic with concern of a burning smell sensation in the absence of an identifiable source. He first noticed this symptom approximately 3 weeks after he received the J&J COVID-19 vaccine about 4 months prior. At the symptom’s first occurrence, he underwent a nasal swab antigen COVID-19 test, which was negative. Initially, symptoms would occur daily lasting about 1 hour. Thereafter, they started to decrease in duration, frequency, and intensity, and about 11 months postvaccination, milder episodes were occurring 1 to 2 times weekly. These episodes lasted nearly 2 years (21 months postvaccination). They happened randomly during the day and were not associated with any other symptoms. Specifically, there were no headaches, loss of consciousness, abnormal movements, nausea, vomiting, photophobia or phonophobia, or alteration of consciousness, such as confusion or drowsiness during or after the events. Additionally, there were no clear triggers the veteran could identify. The veteran did not sustain any head injuries or exposure to toxic odors before the onset of symptoms.

At the time of his presentation to the clinic, both his general and neurological examinations were unremarkable.

Discussion

It has been previously observed that infection with COVID-19 can lead to the loss of taste and smell, but only less commonly olfactory hallucination.4 The pathophysiology of olfactory hallucinations following COVID-19 infection is unknown, but several mechanisms have been proposed. These include obstruction of the olfactory cleft; infection of the sustentacular supporting cells, which express angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE‐2); injury to olfactory sensory cells via neuropilin‐1 receptors (NRP1); and injury to the olfactory bulb.5

The case we present represents the only report of phantosmia following a J&J COVID-19 vaccination. Phantosmia, featured by a burning or smoke odor, has been reported prior in a case of a 57-year-old woman following the administration of the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine.6 Similar to our case, symptoms were not associated with a concurrent COVID-19 infection ruled out via a COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction test. For the Pfizer-BioNTech phantosmia case, a 3 Tesla (T) brain MRI showed left greater than right olfactory bulb and tract gadolinium enhancement on T1-weighted postcontrast images. On axial T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images, hyperintensity along the left olfactory bulb and bilateral olfactory tracts was noted and interpreted as edema. On sagittal thin sections of T2-weighted images, the olfactory nerve filia were thickened and clumped.6 On the contrary, in the case we present, a brain MRI obtained with a 1.5 T magnet showed no abnormalities. It is possible that a high-resolution scan targeting the olfactory bulb could have disclosed pathological changes. At the time when the veteran presented to the neurology clinic, symptoms were already improving, and repeat MRI was deferred as it would not have changed the clinical management.

Konstantinidis and colleagues reported hyposmia in 2 patients following Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccination.5 Both patients, 42- and 39-year-old women, experienced hyposmia following their second dose of the vaccine with symptom onset 3 and 5 days after vaccination, respectively. The first patient reported improvement of symptoms after 1 week, while the second patient participated in olfactory training and experienced only partial recovery after 1 month. Multiple studies have reported cranial nerve involvement secondary to other COVID-19 vaccines, including olfactory dysfunction, optic neuritis, acute abducens nerve palsy, Bell palsy, tinnitus, and cochleopathy.7

There are no previous reports of phantosmia following the J&J COVID-19 vaccine. In our case, reported symptoms were mild, although they persisted for nearly 2 years following vaccination.

In the evaluation of this veteran, although the timing between symptom onset and vaccination was indicative of a possible link between the 2, other etiologies of phantosmia were ruled out. Isolated olfactory hallucination is most associated with temporal lobe epilepsy, which is the most common form of epilepsy to present in adulthood. However, given the absence of other symptoms suggestive of epilepsy and the duration of the episodes (approximately 1 hour), the clinical suspicion was low. This was reinforced by the EEG that showed no abnormalities in the temporal region. Notwithstanding these considerations, one must keep in mind that no episodes of phantosmia occurred during the EEG recording, the correlates of which are the gold standard to rule out a diagnosis of epilepsy.

A normal brain MRI argued against possible structural abnormalities leading to these symptoms. Thus, the origin of these symptoms remains unknown.

Conclusions

The emergency approval and use of vaccines against COVID-19 was a major victory for public health in 2021. However, given the rapid rollout of these vaccines, the medical community is responsible for reporting adverse effects as they are observed. The authors believe that the clinical events featuring the J&J COVID-19 vaccine in this veteran should not discourage the use of the COVID-19 vaccine. However, sharing the clinical outcome of this veteran is relevant to inform the community regarding this rare and benign possible adverse effect of the J&J COVID-19 vaccine.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Tennessee Valley Veteran Healthcare System (Nashville). The authors thank Dr. Martin Gallagher (Tennessee Valley Veteran Healthcare System) for providing clinical expertise with electroencephalogram interpretation.

The rapid development of multiple vaccines for COVID-19 significantly contributed to reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19 infection.1 The vaccination campaign against COVID-19 started in December 2020 within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system with the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 mRNA vaccines followed by the Johnson & Johnson (J&J) vaccine in March 2021.2,3

Because of the importance of maintaining a safe vaccination campaign, surveillance reports documenting cases of malignant or benign adverse effects (AEs) are fundamental to generate awareness and accurate knowledge on these newly developed vaccines. Here we report the case of a veteran who developed olfactory hallucinations following the administration of the J&J COVID-19 vaccine.

Case Presentation

A 39-year-old veteran with a history of tension-type headaches presented to the neurology clinic with concern of a burning smell sensation in the absence of an identifiable source. He first noticed this symptom approximately 3 weeks after he received the J&J COVID-19 vaccine about 4 months prior. At the symptom’s first occurrence, he underwent a nasal swab antigen COVID-19 test, which was negative. Initially, symptoms would occur daily lasting about 1 hour. Thereafter, they started to decrease in duration, frequency, and intensity, and about 11 months postvaccination, milder episodes were occurring 1 to 2 times weekly. These episodes lasted nearly 2 years (21 months postvaccination). They happened randomly during the day and were not associated with any other symptoms. Specifically, there were no headaches, loss of consciousness, abnormal movements, nausea, vomiting, photophobia or phonophobia, or alteration of consciousness, such as confusion or drowsiness during or after the events. Additionally, there were no clear triggers the veteran could identify. The veteran did not sustain any head injuries or exposure to toxic odors before the onset of symptoms.

At the time of his presentation to the clinic, both his general and neurological examinations were unremarkable.

Discussion

It has been previously observed that infection with COVID-19 can lead to the loss of taste and smell, but only less commonly olfactory hallucination.4 The pathophysiology of olfactory hallucinations following COVID-19 infection is unknown, but several mechanisms have been proposed. These include obstruction of the olfactory cleft; infection of the sustentacular supporting cells, which express angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE‐2); injury to olfactory sensory cells via neuropilin‐1 receptors (NRP1); and injury to the olfactory bulb.5

The case we present represents the only report of phantosmia following a J&J COVID-19 vaccination. Phantosmia, featured by a burning or smoke odor, has been reported prior in a case of a 57-year-old woman following the administration of the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine.6 Similar to our case, symptoms were not associated with a concurrent COVID-19 infection ruled out via a COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction test. For the Pfizer-BioNTech phantosmia case, a 3 Tesla (T) brain MRI showed left greater than right olfactory bulb and tract gadolinium enhancement on T1-weighted postcontrast images. On axial T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images, hyperintensity along the left olfactory bulb and bilateral olfactory tracts was noted and interpreted as edema. On sagittal thin sections of T2-weighted images, the olfactory nerve filia were thickened and clumped.6 On the contrary, in the case we present, a brain MRI obtained with a 1.5 T magnet showed no abnormalities. It is possible that a high-resolution scan targeting the olfactory bulb could have disclosed pathological changes. At the time when the veteran presented to the neurology clinic, symptoms were already improving, and repeat MRI was deferred as it would not have changed the clinical management.

Konstantinidis and colleagues reported hyposmia in 2 patients following Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccination.5 Both patients, 42- and 39-year-old women, experienced hyposmia following their second dose of the vaccine with symptom onset 3 and 5 days after vaccination, respectively. The first patient reported improvement of symptoms after 1 week, while the second patient participated in olfactory training and experienced only partial recovery after 1 month. Multiple studies have reported cranial nerve involvement secondary to other COVID-19 vaccines, including olfactory dysfunction, optic neuritis, acute abducens nerve palsy, Bell palsy, tinnitus, and cochleopathy.7

There are no previous reports of phantosmia following the J&J COVID-19 vaccine. In our case, reported symptoms were mild, although they persisted for nearly 2 years following vaccination.

In the evaluation of this veteran, although the timing between symptom onset and vaccination was indicative of a possible link between the 2, other etiologies of phantosmia were ruled out. Isolated olfactory hallucination is most associated with temporal lobe epilepsy, which is the most common form of epilepsy to present in adulthood. However, given the absence of other symptoms suggestive of epilepsy and the duration of the episodes (approximately 1 hour), the clinical suspicion was low. This was reinforced by the EEG that showed no abnormalities in the temporal region. Notwithstanding these considerations, one must keep in mind that no episodes of phantosmia occurred during the EEG recording, the correlates of which are the gold standard to rule out a diagnosis of epilepsy.

A normal brain MRI argued against possible structural abnormalities leading to these symptoms. Thus, the origin of these symptoms remains unknown.

Conclusions

The emergency approval and use of vaccines against COVID-19 was a major victory for public health in 2021. However, given the rapid rollout of these vaccines, the medical community is responsible for reporting adverse effects as they are observed. The authors believe that the clinical events featuring the J&J COVID-19 vaccine in this veteran should not discourage the use of the COVID-19 vaccine. However, sharing the clinical outcome of this veteran is relevant to inform the community regarding this rare and benign possible adverse effect of the J&J COVID-19 vaccine.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Tennessee Valley Veteran Healthcare System (Nashville). The authors thank Dr. Martin Gallagher (Tennessee Valley Veteran Healthcare System) for providing clinical expertise with electroencephalogram interpretation.

1. Xu S, Huang R, Sy LS, et al. COVID-19 vaccination and non-COVID-19 mortality risk - seven integrated health care organizations, United States, December 14, 2020-July 31, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(43):1520-1524. Published 2021 Oct 29. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7043e2

2. Der-Martirosian C, Steers WN, Northcraft H, Chu K, Dobalian A. Vaccinating veterans for COVID-19 at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Am J Prev Med. 2022;62(6):e317-e324. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2021.12.016

3. Bagnato F, Wallin M. COVID-19 vaccine in veterans with multiple sclerosis: protect the vulnerable. Fed Pract. 2021;38(suppl 1):S28-S32. doi:10.12788/fp.0113

4. Işlek A, Balcı MK. Phantosmia with COVID-19 related olfactory dysfunction: report of nine cases. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;74(suppl 2):2891-2893. doi:10.1007/s12070-021-02505-z

5. Konstantinidis I, Tsakiropoulou E, Hähner A, de With K, Poulas K, Hummel T. Olfactory dysfunction after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2021;11(9):1399-1401. doi:10.1002/alr.22809

6. Keir G, Maria NI, Kirsch CFE. Unique imaging findings of neurologic phantosmia following Pfizer-BioNtech COVID-19 vaccination: a case report. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2021;30(3):133-137. doi:10.1097/RMR.0000000000000287

7. Garg RK, Paliwal VK. Spectrum of neurological complications following COVID-19 vaccination. Neurol Sci. 2022;43(1):3-40. doi:10.1007/s10072-021-05662-9

1. Xu S, Huang R, Sy LS, et al. COVID-19 vaccination and non-COVID-19 mortality risk - seven integrated health care organizations, United States, December 14, 2020-July 31, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(43):1520-1524. Published 2021 Oct 29. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7043e2

2. Der-Martirosian C, Steers WN, Northcraft H, Chu K, Dobalian A. Vaccinating veterans for COVID-19 at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Am J Prev Med. 2022;62(6):e317-e324. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2021.12.016

3. Bagnato F, Wallin M. COVID-19 vaccine in veterans with multiple sclerosis: protect the vulnerable. Fed Pract. 2021;38(suppl 1):S28-S32. doi:10.12788/fp.0113

4. Işlek A, Balcı MK. Phantosmia with COVID-19 related olfactory dysfunction: report of nine cases. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;74(suppl 2):2891-2893. doi:10.1007/s12070-021-02505-z

5. Konstantinidis I, Tsakiropoulou E, Hähner A, de With K, Poulas K, Hummel T. Olfactory dysfunction after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2021;11(9):1399-1401. doi:10.1002/alr.22809

6. Keir G, Maria NI, Kirsch CFE. Unique imaging findings of neurologic phantosmia following Pfizer-BioNtech COVID-19 vaccination: a case report. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2021;30(3):133-137. doi:10.1097/RMR.0000000000000287

7. Garg RK, Paliwal VK. Spectrum of neurological complications following COVID-19 vaccination. Neurol Sci. 2022;43(1):3-40. doi:10.1007/s10072-021-05662-9

Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma Presenting as Mediastinal Lymphadenopathy Without Appreciable Bladder Mass in a Patient With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

INTRODUCTION

Lymphadenopathy in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) is a very common feature. However, sudden increase in lymphadenopathy or other symptoms like weight loss should be evaluated for possible metastatic malignancy. We describe a CLL patient with diffuse mediastinal lymphadenopathy who was diagnosed with metastatic bladder cancer without a primary bladder tumor mass on imaging.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 60-year-old man with a 60 pack-year smoking history, alcoholic cirrhosis, and a 5-year history of stage 1 CLL presented with 3 months of progressive shortness of breath; persistent cough; chills; hemoptysis; and a steady weight loss of 35 lbs. Notably, he had no bladder symptoms. Initial labs showed leukocytosis of 35.8k with a lymphocytic predominance. Screening low-dose chest CT was positive for diffuse mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Subsequent PET/CT revealed numerous hypermetabolic lymph nodes in the neck, mediastinum, left hilum, and right periaortic abdominal region. CT Chest, Abdomen, Pelvis revealed progressive lymphadenopathy as seen in prior imaging, stable pulmonary nodules up to 4 mm in size, and splenomegaly. No distant primary sites, including of the bladder, were identified. Mediastinal lymph node biopsy confirmed metastatic poorly differentiated carcinoma with immunohistochemical staining negative for p40, p63, CK20, TTF-1, Napsin A, CDX2, CA19- 9, Calretinin, and D2-40 and positive for CK7, GATA3, Ber-EP4, and Uroplakin, supporting bladder as primary origin. Urology deferred a cystoscopy given his lack of urinary symptoms and positive biopsy and was started on Carboplatin/Gemcitabine for his metastatic disease. He was ineligible for Cisplatin given his cirrhosis and hearing impairment.

DISCUSSION

In patients with CLL, new onset mediastinal lymphadenopathy is concerning for disease progression and possible transformation to a diffuse b-cell lymphoma. However, this symptom has a broad differential, including primary lung carcinomas, sarcomas, and metastatic disease. While our patient’s PET/CT and pan-CT failed to identify a distant primary site, maintaining a low clinical suspicion for metastatic disease and doing a thorough work-up was paramount. Only through immunohistochemical staining were we able to diagnosis this patient with urothelial carcinoma.

CONCLUSIONS

Biopsy with immunohistochemical staining and maintaining a low suspicion for worsening lymphadenopathy can identify unusually presenting urothelial carcinomas in CLL patients.

INTRODUCTION

Lymphadenopathy in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) is a very common feature. However, sudden increase in lymphadenopathy or other symptoms like weight loss should be evaluated for possible metastatic malignancy. We describe a CLL patient with diffuse mediastinal lymphadenopathy who was diagnosed with metastatic bladder cancer without a primary bladder tumor mass on imaging.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 60-year-old man with a 60 pack-year smoking history, alcoholic cirrhosis, and a 5-year history of stage 1 CLL presented with 3 months of progressive shortness of breath; persistent cough; chills; hemoptysis; and a steady weight loss of 35 lbs. Notably, he had no bladder symptoms. Initial labs showed leukocytosis of 35.8k with a lymphocytic predominance. Screening low-dose chest CT was positive for diffuse mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Subsequent PET/CT revealed numerous hypermetabolic lymph nodes in the neck, mediastinum, left hilum, and right periaortic abdominal region. CT Chest, Abdomen, Pelvis revealed progressive lymphadenopathy as seen in prior imaging, stable pulmonary nodules up to 4 mm in size, and splenomegaly. No distant primary sites, including of the bladder, were identified. Mediastinal lymph node biopsy confirmed metastatic poorly differentiated carcinoma with immunohistochemical staining negative for p40, p63, CK20, TTF-1, Napsin A, CDX2, CA19- 9, Calretinin, and D2-40 and positive for CK7, GATA3, Ber-EP4, and Uroplakin, supporting bladder as primary origin. Urology deferred a cystoscopy given his lack of urinary symptoms and positive biopsy and was started on Carboplatin/Gemcitabine for his metastatic disease. He was ineligible for Cisplatin given his cirrhosis and hearing impairment.

DISCUSSION

In patients with CLL, new onset mediastinal lymphadenopathy is concerning for disease progression and possible transformation to a diffuse b-cell lymphoma. However, this symptom has a broad differential, including primary lung carcinomas, sarcomas, and metastatic disease. While our patient’s PET/CT and pan-CT failed to identify a distant primary site, maintaining a low clinical suspicion for metastatic disease and doing a thorough work-up was paramount. Only through immunohistochemical staining were we able to diagnosis this patient with urothelial carcinoma.

CONCLUSIONS

Biopsy with immunohistochemical staining and maintaining a low suspicion for worsening lymphadenopathy can identify unusually presenting urothelial carcinomas in CLL patients.

INTRODUCTION

Lymphadenopathy in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) is a very common feature. However, sudden increase in lymphadenopathy or other symptoms like weight loss should be evaluated for possible metastatic malignancy. We describe a CLL patient with diffuse mediastinal lymphadenopathy who was diagnosed with metastatic bladder cancer without a primary bladder tumor mass on imaging.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 60-year-old man with a 60 pack-year smoking history, alcoholic cirrhosis, and a 5-year history of stage 1 CLL presented with 3 months of progressive shortness of breath; persistent cough; chills; hemoptysis; and a steady weight loss of 35 lbs. Notably, he had no bladder symptoms. Initial labs showed leukocytosis of 35.8k with a lymphocytic predominance. Screening low-dose chest CT was positive for diffuse mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Subsequent PET/CT revealed numerous hypermetabolic lymph nodes in the neck, mediastinum, left hilum, and right periaortic abdominal region. CT Chest, Abdomen, Pelvis revealed progressive lymphadenopathy as seen in prior imaging, stable pulmonary nodules up to 4 mm in size, and splenomegaly. No distant primary sites, including of the bladder, were identified. Mediastinal lymph node biopsy confirmed metastatic poorly differentiated carcinoma with immunohistochemical staining negative for p40, p63, CK20, TTF-1, Napsin A, CDX2, CA19- 9, Calretinin, and D2-40 and positive for CK7, GATA3, Ber-EP4, and Uroplakin, supporting bladder as primary origin. Urology deferred a cystoscopy given his lack of urinary symptoms and positive biopsy and was started on Carboplatin/Gemcitabine for his metastatic disease. He was ineligible for Cisplatin given his cirrhosis and hearing impairment.

DISCUSSION

In patients with CLL, new onset mediastinal lymphadenopathy is concerning for disease progression and possible transformation to a diffuse b-cell lymphoma. However, this symptom has a broad differential, including primary lung carcinomas, sarcomas, and metastatic disease. While our patient’s PET/CT and pan-CT failed to identify a distant primary site, maintaining a low clinical suspicion for metastatic disease and doing a thorough work-up was paramount. Only through immunohistochemical staining were we able to diagnosis this patient with urothelial carcinoma.

CONCLUSIONS

Biopsy with immunohistochemical staining and maintaining a low suspicion for worsening lymphadenopathy can identify unusually presenting urothelial carcinomas in CLL patients.

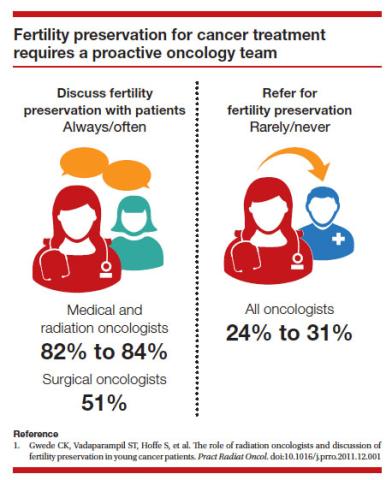

Freezing the biological clock: A 2023 update on preserving fertility

Throughout the 20th century, the management of ectopic pregnancy evolved from preserving the life of the mother to preserving fertility by utilizing the conservative treatment of methotrexate and/or tubal surgery. I make this, seemingly obscure, reference to managing ectopic pregnancy to consider an analogous shift over time in the management of patients with cancer. Over the next decade, the number of people who have lived 5 or more years after their cancer diagnosis is projected to increase approximately 30%, to 16.3 million. Due to the improved survival rates following a cancer diagnosis,1 revolutionary developments have been made in fertility preservation to obviate the impact of gonadotoxic therapy. We have evolved, however, from shielding and transposing ovaries to ovarian tissue cryopreservation,2 with rapid implementation.

While advances in reproductive cryopreservation have allowed for the delay, or even potential “prevention” of infertility, assisted reproductive technology (ART) cannot yet claim a “cure” in ensuring procreation. Nevertheless, fertility preservation is a burgeoning field that has transitioned from an experimental label to a standard of care in 2012, as designated by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM).3 From the original intention of offering oocyte cryopreservation to women at risk of ovarian failure from impending gonadotoxic cancer treatment, fertility preservation has accelerated to include freezing for nonmedical reasons—eg, planned oocyte cryopreservation (POC), or “social” egg freezing, to ovarian tissue cryopreservation to accommodate the expediency needed for the treatment of certain cancer treatments. Additionally, across the United States, the number of donor egg banks, which allow women an easily accessible option, is rivaling enduring sperm banks. Due to the advanced methodology of vitrification and growing demand for the technology due to increasing IVF cycles, cryopreservation has become a specialized area of reproductive medicine, and a target of venture capital and private equity commercialization. This article will review the latest techniques, appropriate counseling, and cost/benefit ratio of fertility preservation, with an emphasis on POC.

CASE 1 Fertility preservation options for patient with breast cancer

A 37-year-old woman with newly diagnosed hormone receptor−positive breast cancer is referred for a fertility preservation consultation prior to initiating treatment. Her oncologist plans chemotherapy, followed by radiation and a minimum of 5 years of tamoxifen therapy.

What is the best consultation approach for this patient?

Consultation involves understanding several factors

The consultation approach to this patient involves ascertaining her medical, social, and family history, along with her reproductive plans.

Medical history. For the medical component, we must focus on her diagnosis, anticipated treatment with timeline, risks of gonadal toxicity with planned treatments, her current medical stability, and prognosis for expected survival.

Social history. Her age, relationship status, and desired family size address her social history.

Family history. Given that her cancer affects the breast, there is the risk of genetic susceptibility and potential for embryo testing for the BRCA gene.

Reproductive plans. These include her and her partner’s, if applicable, number of desired children and their risk factors for infertility.

Regarding the reproductive timeline, the antihormonal therapy that may be required for her treatment may improve overall survival, but it would delay the time to pregnancy. Consequently, the pursuit of fertility preservation prior to cancer treatment is a multidisciplinary approach that can involve medical oncology, radiation oncology, REI, medical genetics, and often, psychology. Fortunately, evidence continues to support fertility preservation, with or without hormonal ovarian stimulation, for patients with breast cancer. Data, with up to 5 years of follow-up, has indicated that it is safe.4

Continue to: Oncofertility...

Oncofertility

To address the need to maximize the reproductive potential of patients with newly diagnosed cancer, the field of oncofertility combines the specialties of oncology and reproductive medicine. The reproductive risk of cancer treatment is gonadotoxicity, with subsequent iatrogenic primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) and infertility. Alkylating agents (including cyclosphosphamide) have the highest risk for amenorrhea, while antimetabolites (including methotrexate, 5–fluorouracil) have the lowest risk.5 Treating bone marrow/stem cell transplantation using high-dose alkylating agents, with or without whole body irradiation, results in ≥80% amenorrhea. The minimum radiation dose to induce ovarian failure decreases with advancing age, from 18.4 Gy at age 10 years to 6 Gy at age 40 years, due to biologically diminishing ovarian reserve and an increase in the radiosensitivity of oocytes.6 An online tool—using varying factors including age, chemotherapy dose, prior treatment, smoking, and baseline diminished ovarian reserve—is available to help predict the chance of ovarian failure following chemotherapy.7

Since 2006, the American Society of Clinical Oncology recommended, as part of the consent prior to therapy, oncologists should address the possibility of infertility with patients “as early in treatment planning as possible” and “...Fertility preservation is an important, if not necessary, consideration when planning cancer treatment in reproductive-age patients.”

Reference

1. Lee SJ, Schover LR, Partridge AH, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on fertility preservation in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2917-2931.

Cryopreservation to the rescue

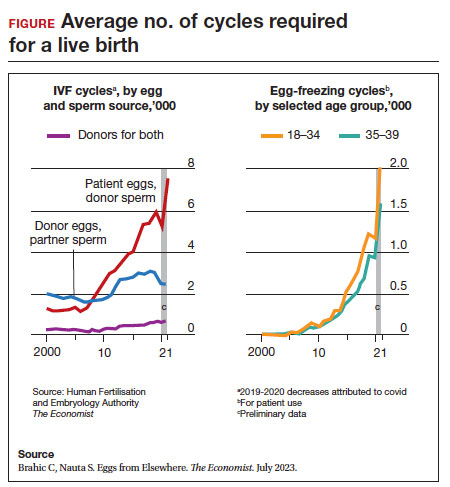

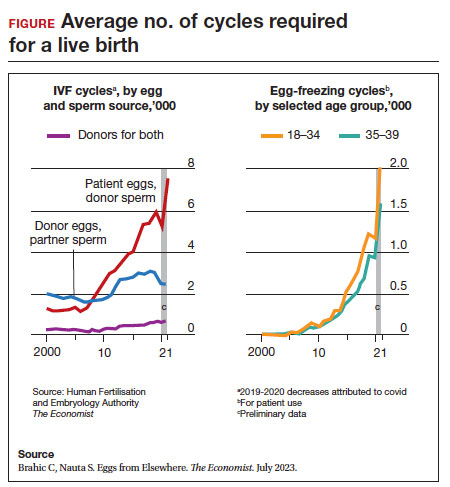

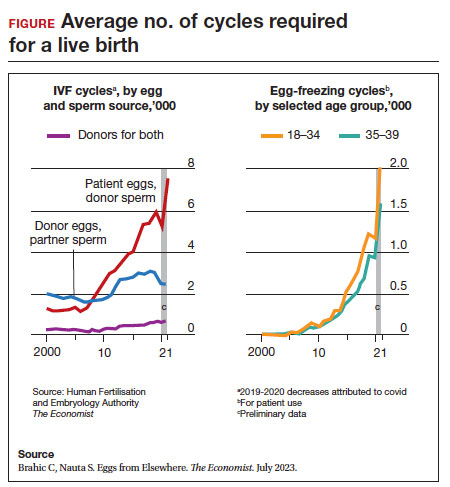

Since 2012, when ASRM removed the experimental designation on oocyte cryopreservation (OC), the number of cycles offered for fertility preservation has increased dramatically (FIGURE),8 initially being used for patients with cancer and now also including women desiring POC.

Ovarian and embryo cryopreservation. Ovarian stimulation and egg retrieval for OC can now occur within 2 weeks due to a random start protocol whereby women can begin ovarian stimulation any day in their cycle (ie, preovulation or postovulation).9

OC followed by thawing for subsequent fertilization and embryo transfer is employed as a matter of routine when patients with infertility utilize frozen eggs from a donor. While there remains debate over better live birth rates with frozen eggs versus fresh eggs, clinic experience may be a critical factor.10

Ovarian tissue cryopreservation. In addition to the fertility preservation procedures of oocytes and embryo cryopreservation, ovarian tissue cryopreservation became a standard option in 2019 when ASRM removed its experimental designation.11 Given the potential time constraints of urgent cancer treatment, ovarian tissue cryopreservation has the advantage of not requiring ovarian stimulation or sexual maturity and is able to be performed while patients are receiving chemotherapy. If successful, ovarian tissue cryopreservation followed by orthotopic transplantation has the potential to restore natural ovarian function and natural conceptions.12 However, despite first successfully being described in 2004, ovarian tissue cryopreservation, which does require subsequent thawing and tissue transplantation, remains less available to patients due to low usage rates, which have resulted in few clinics having adequate proficiency.13,14

Ovarian tissue cryopreservation involves obtaining ovarian cortical tissue, dissecting the tissue into small fragments, and cryopreserving it using either a slow-cool technique or vitrification. Orthotopic transplantation has been the most successful method for using ovarian tissue in humans. Live birth rates are modest.15 In all cancer survivors, particularly those with leukemia, autologous ovarian tissue transplantation may contain malignant cells that could lead to the reintroduction of cancer as the tissue is removed prior to treatment.16

Pregnancy outcomes using embryos created from ovaries recently exposed to chemotherapy in humans is not known, but animal studies suggest that there may be higher rates of miscarriage and birth defects given the severe DNA damage to oocytes of developing follicles.17 Hence, ovarian stimulation should be initiated and completed before the start of chemotherapy.

Continue to: Planned oocyte cryopreservation...

Planned oocyte cryopreservation

With advances in ART, POC offers patients the opportunity to preserve fertility until desired. However, despite its potential benefits, POC compels the discussion of various considerations in addition to oncofertility, such as ethical concerns and insurance coverage.

CASE 2 Woman plans for elective egg freezing

A 32-year-old single, professional woman is advancing in her career and wishes to delay childbearing. She is concerned about the potential for age-related fertility decline and wants to explore the option of elective egg freezing. Emily has no medical conditions that would impair her fertility, but she wants to ensure that she has the option of having biological children in the future. She is unsure about the potential financial burden of the procedure and whether her employer’s insurance covers such elective procedures.

How do you counsel her about her options?

Medical considerations

Approximately 25% of reproductive-aged women have considered POC.18 An analysis revealed POC was more cost-effective than delaying procreation and undergoing IVF with preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidies at an advanced reproductive age.19

The process of planned oocyte cryopreservation. POC involves ovarian stimulation, usually with parenteral gonadotropins, to produce multiple mature oocytes for same-day cryopreservation following transvaginal retrieval, typically in an office-based surgery center as an outpatient procedure while the patient is under IV sedation. While the procedure has been proven effective, there are inherent risks and limitations. The success rates of subsequent fertility treatments using the cryopreserved eggs are influenced by the woman’s age at the time of freezing, the number of mature oocytes retrieved and vitrified, and the quality of the oocytes following thaw. A recent study reported a 70% live-birth rate in women aged less than 38 years who cryopreserved ≥ 20 mature eggs.20 To increase the number of cryopreserved oocytes, multiple egg retrievals or “batching” may be of benefit for women with diminished ovarian reserve.21

It is important for clinicians to thoroughly assess a patient’s medical history, ovarian reserve (by antral follicle count and levels of anti-müllerian hormone [AMH]), and reproductive goals before recommending proceeding with POC. Of note, AMH is a useful marker for ovarian reserve but has not been shown to predict natural fertility. Its value is in providing a guide to the dosage of ovarian stimulation and an estimation of the number of oocytes to be retrieved. Per ASRM, “Extremely low AMH values should not be used to refuse treatment in IVF.” AMH levels and antral follicle count have only a weak association with such qualitative outcomes as oocyte quality, clinical pregnancy rates, and live birth rates. Complications from egg retrieval, both short and long term, are rare. The inherent risk from POC is the lack of a guaranteed subsequent live birth.22

Ethical and social considerations

POC raises several ethical considerations, including concerns of perpetuating societal pressure on women to defer procreation to prioritize their careers over family planning.23 Despite controversies, POC appears as a chosen strategy against age-related infertility and may allow women to feel that they are more socially, psychologically, and financially stable before pursuing motherhood.24 Open and honest discussions between clinicians and patients are crucial to ensure informed decision making and address these ethical concerns.

Per an ACOG statement from February 2023 (https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/having-a-baby-after-age-35-how-aging-affects-fertility-and-pregnancy) “...egg freezing is recommended mainly for patients having cancer treatment that will affect their future fertility. There is not enough research to recommend routine egg freezing for the sole purpose of delaying childbearing.”

A recent survey of patients who had elected egg freezing at some point included more than 80% who were aged 35 or older, and revealed that 93% of the survey participants had not yet returned to use their frozen oocytes.25 The most common reason cited in the survey for a delay in attempted procreation was lack of a partner. Another reason was undergoing oocyte cryopreservation after an optimal reproductive age, with participants concluding that they felt they had improved their reproductive future after undergoing oocyte cryopreservation and feeling empowered by the process. As part of counseling, women should be informed of the possibility of not utilizing their frozen eggs in the future, whether due to natural conception or other personal reasons.

Continue to: Employer insurance coverage...

Employer insurance coverage

Access to elective egg freezing is largely influenced by insurance coverage. Currently, employer-provided insurance coverage for this procedure varies widely. While some companies offer comprehensive coverage, others provide limited or no coverage at all. The cost of elective egg freezing can range from $10,000 to $15,000, excluding additional expenses such as medications and annual storage fees. The financial burden can create a gap between patients who desire POC and those with an ability to implement the process. The cost can be a significant barrier for many patients considering this option and perpetuates the lack of universal diversity, equity, and inclusion.

CASE 3 Gender dysphoria and fertility preservation

A 22-year-old transgender man is preparing to undergo gender-affirming hormone therapy and surgery. He is concerned about the potential impact of testosterone therapy on his oocytes and wishes to explore options for fertility preservation prior to oophorectomy.26

What are the patient’s options for fertility preservation?

The patient has the fertility preservation options of OC following ovarian stimulation or ovarian tissue cryopreservation at the time of oophorectomy. Preliminary evidence does not demonstrate impairment of ovarian stimulation and oocyte retrieval number with concurrent testosterone exposure. Ethical considerations, in this case, involve respecting the patient’s autonomy, addressing potential conflicts between gender-affirming care and fertility preservation (eg, a risk of dysphoria in transgender patients preserving biological gametes from a prior assigned gender), and ensuring access to fertility preservation services without discrimination. It is essential to provide the patient in this case with comprehensive information regarding the impact of hormone therapy on fertility, the available options, and the potential financial costs involved. Supportive counseling should also be offered to address any psychological or emotional aspects related to fertility preservation for all patients considering this option.

A call for diversity, equity, and inclusion

To improve access to POC, advocating for employer-offered insurance coverage is paramount. Women’s health providers can encourage dialogue between employers, insurers, and policymakers, which can lead to policy changes that prioritize coverage for fertilitypreservation options. This could include mandating coverage for POC as part of comprehensive health care plans or providing tax incentives to employers who offer coverage for these procedures. Furthermore, public awareness campaigns and advocacy efforts can help educate employers about the importance of including fertility preservation coverage in their employee benefits packages.

Conclusion

Just as physicians must recognize their responsibility to patients to distinguish unproven yet promising science from evidence-based and clinically established science, so too must they advise their patients to consider fertility preservation services in a way that is both clinically justified and ethically appropriate. Informed decisions must be made by appropriate counseling of evidence-based medicine to protect the interest of patients. POC provides patients with an opportunity to preserve their fertility and exercise reproductive autonomy. However, access to this procedure is often hindered by limited or nonexistent employer insurance coverage. By recognizing the medical, ethical, and social implications of POC and implementing strategies to improve coverage, collaborative efforts may increase accessibility and defray costs to provide patients with the option of deferring childbearing and preserving their reproductive potential. ●

1. Promptly offer fertility preservation treatment options with sensitivity and clarity.

2. Dedicate ample time and exercise patience during the consultation.

3. Provide education using multiple modalities to help patients assimilate information.

4. Encourage consultation with mental health professionals.

Special considerations for hematologic malignancies:

- Treatment can be associated with significant gonadal toxicity and premature ovarian failure.

- Patients are frequently ill at the time of presentation and ineligible for certain fertility preservation options.

References

1. Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Fertility preservation and reproduction in patients facing gonadotoxic therapies: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2018;110:380-386. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.06.012

2. Kim SS, Klemp J, Fabian C. Breast cancer and fertility preservation. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:15351543. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.01.003

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Treatment & Survivorship Facts & Figures 2022-2024. Atlanta, Georgia: American Cancer Society; 2022.

- Oktay K, Karlikaya G. Ovarian function after autologous transplantation of frozen-banked human ovarian tissue. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1919

- Practice Committees of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. Mature oocyte cryopreservation: a guideline. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:37-43. doi: 10.1016 /j.fertnstert.2012.09.028