User login

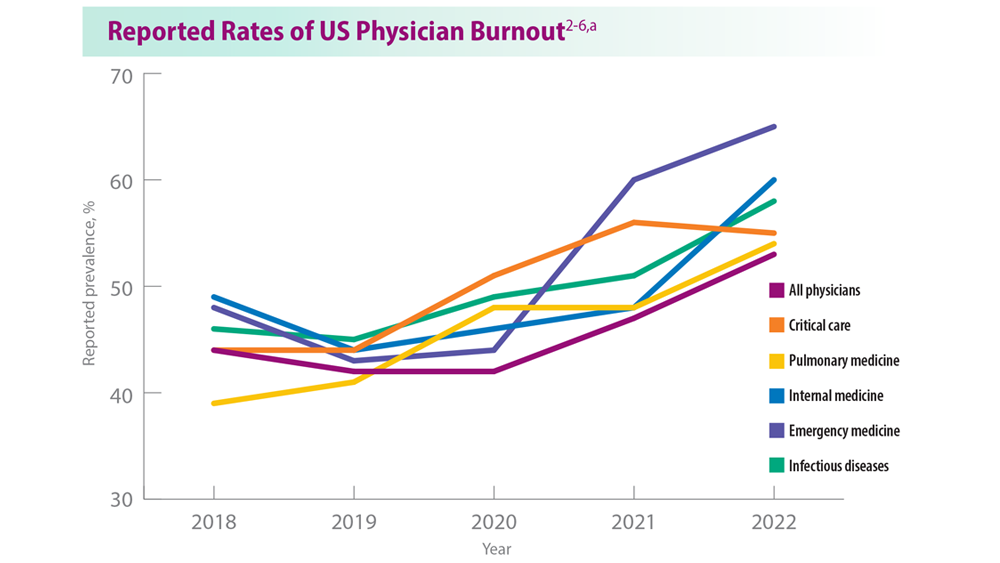

Addressing Physician Burnout in Pulmonology and Critical Care

- Moss M et al. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(7):1414-1421. doi:10.1097/CCM.000000000000188

- Medscape National Physician Burnout, Depression & Suicide Report 2019. Medscape. January 16, 2019. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056#1

- Medscape National Physician Burnout & Suicide Report 2020: The Generational Divide. Medscape. January 15, 2020. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2020-lifestyle-burnout-6012460#1

- ‘Death by 1000 Cuts’: Medscape National Physician Burnout & Suicide Report 2021. Medscape. January 22, 2021. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2021-lifestyle-burnout-6013456#2

- Physician Burnout Report 2022: Stress, Anxiety, and Anger. Medscape. January 21, 2022. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2022-lifestyle-burnout-6014664#1

- ‘I Cry but No One Cares’: Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2023. Medscape. January 27, 2023. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2023-lifestyle-burnout-6016058#1

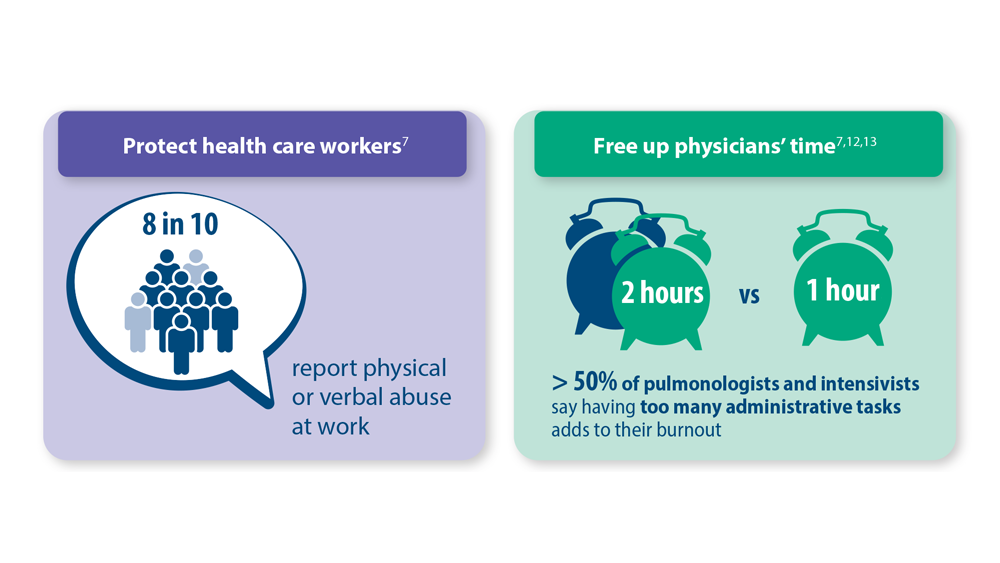

- Murthy VH. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(7):577-579. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2207252

- Vranas KC et al. Chest. 2021;160(5):1714-1728. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.05.041

- Kerlin MP et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2022;19(2):329-331. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202105-567RL

- Dean W et al. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):400-402. PMID: 31571807

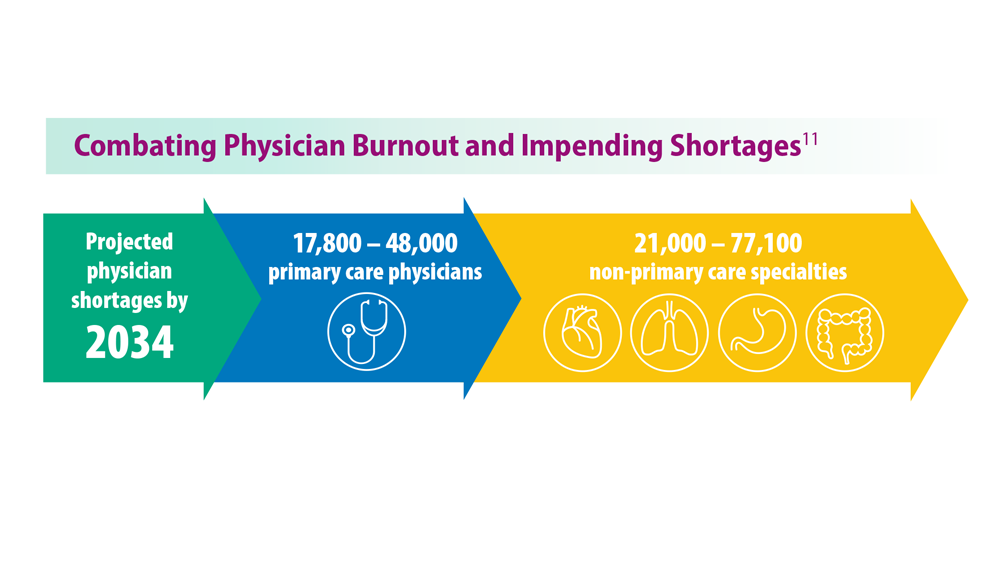

- Association of American Medical Colleges. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2019 to 2034. June 2021. https://www.aamc.org/media/54681/download?attachment

- Medscape Pulmonologist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2023: Contentment Amid Stress. February 24, 2023. Accessed June 28, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2023-lifestyle-pulmonologist-6016092#1

- Medscape Intensivist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2023: Contentment Amid Stress. February 24, 2023. Accessed June 28, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2023-lifestyle-intensivist-6016072#1

- Moss M et al. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(7):1414-1421. doi:10.1097/CCM.000000000000188

- Medscape National Physician Burnout, Depression & Suicide Report 2019. Medscape. January 16, 2019. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056#1

- Medscape National Physician Burnout & Suicide Report 2020: The Generational Divide. Medscape. January 15, 2020. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2020-lifestyle-burnout-6012460#1

- ‘Death by 1000 Cuts’: Medscape National Physician Burnout & Suicide Report 2021. Medscape. January 22, 2021. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2021-lifestyle-burnout-6013456#2

- Physician Burnout Report 2022: Stress, Anxiety, and Anger. Medscape. January 21, 2022. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2022-lifestyle-burnout-6014664#1

- ‘I Cry but No One Cares’: Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2023. Medscape. January 27, 2023. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2023-lifestyle-burnout-6016058#1

- Murthy VH. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(7):577-579. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2207252

- Vranas KC et al. Chest. 2021;160(5):1714-1728. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.05.041

- Kerlin MP et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2022;19(2):329-331. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202105-567RL

- Dean W et al. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):400-402. PMID: 31571807

- Association of American Medical Colleges. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2019 to 2034. June 2021. https://www.aamc.org/media/54681/download?attachment

- Medscape Pulmonologist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2023: Contentment Amid Stress. February 24, 2023. Accessed June 28, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2023-lifestyle-pulmonologist-6016092#1

- Medscape Intensivist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2023: Contentment Amid Stress. February 24, 2023. Accessed June 28, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2023-lifestyle-intensivist-6016072#1

- Moss M et al. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(7):1414-1421. doi:10.1097/CCM.000000000000188

- Medscape National Physician Burnout, Depression & Suicide Report 2019. Medscape. January 16, 2019. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056#1

- Medscape National Physician Burnout & Suicide Report 2020: The Generational Divide. Medscape. January 15, 2020. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2020-lifestyle-burnout-6012460#1

- ‘Death by 1000 Cuts’: Medscape National Physician Burnout & Suicide Report 2021. Medscape. January 22, 2021. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2021-lifestyle-burnout-6013456#2

- Physician Burnout Report 2022: Stress, Anxiety, and Anger. Medscape. January 21, 2022. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2022-lifestyle-burnout-6014664#1

- ‘I Cry but No One Cares’: Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2023. Medscape. January 27, 2023. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2023-lifestyle-burnout-6016058#1

- Murthy VH. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(7):577-579. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2207252

- Vranas KC et al. Chest. 2021;160(5):1714-1728. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.05.041

- Kerlin MP et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2022;19(2):329-331. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202105-567RL

- Dean W et al. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):400-402. PMID: 31571807

- Association of American Medical Colleges. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2019 to 2034. June 2021. https://www.aamc.org/media/54681/download?attachment

- Medscape Pulmonologist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2023: Contentment Amid Stress. February 24, 2023. Accessed June 28, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2023-lifestyle-pulmonologist-6016092#1

- Medscape Intensivist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2023: Contentment Amid Stress. February 24, 2023. Accessed June 28, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2023-lifestyle-intensivist-6016072#1

Enlarging pink patches after traveling

The patient’s multiple pink, subtly annular patches after recent travel to Lyme-endemic areas of the United States demonstrated a classic manifestation of disseminated Lyme disease. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was positive for Borrelia burgdorferi IgM and IgG antibodies, confirming an acute infection.

While not usually necessary, skin biopsy shows a nonspecific perivascular cellular infiltrate that may be comprised of histiocytes, lymphocytes, and plasma cells. Spirochetes are not typically seen, but they may be identified with antibody-labeled or silver stains.

Lyme disease initially manifests as localized disease with erythema migrans, a targetoid lesion on the skin that appears at the site of the tick bite. This initial stage develops within the first few weeks of the bite and may be accompanied by fatigue and a low-grade fever.

If left untreated, the infection may progress to early disseminated disease, which occurs weeks to months after the initial bite. This second stage of Lyme disease manifests with multiple erythema migrans lesions on additional parts of the body, indicating spirochete dissemination through the bloodstream and lymphatic system. Early disseminated disease may also include borrelial lymphocytoma, Lyme neuroborreliosis, and cardiac conduction abnormalities such as AV block.

The third stage of Lyme disease, late Lyme disease, occurs months to years after an initial infection that has gone untreated. The key feature of this stage is arthritis, which tends to affect the knees and may be migratory in nature. Neurological symptoms such as encephalopathy and polyneuropathies may also develop. A minority of patients with late Lyme disease may develop acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, a rash that typically occurs on the dorsal hands and feet as blue-red plaques that turn the affected skin atrophic.1

This patient was treated with a 3-week course of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and was referred to an infectious disease specialist for further work-up of systemic symptoms, given the risk for cardiac pathology in disseminated Lyme disease.

Photo courtesy of Le Wen Chiu, MD. Text courtesy of Le Wen Chiu, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Cardenas-de la Garza JA, De la Cruz-Valadez E, Ocampo-Candiani J, et al. Clinical spectrum of Lyme disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:201-208. doi:10.1007/s10096-018-3417-1

The patient’s multiple pink, subtly annular patches after recent travel to Lyme-endemic areas of the United States demonstrated a classic manifestation of disseminated Lyme disease. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was positive for Borrelia burgdorferi IgM and IgG antibodies, confirming an acute infection.

While not usually necessary, skin biopsy shows a nonspecific perivascular cellular infiltrate that may be comprised of histiocytes, lymphocytes, and plasma cells. Spirochetes are not typically seen, but they may be identified with antibody-labeled or silver stains.

Lyme disease initially manifests as localized disease with erythema migrans, a targetoid lesion on the skin that appears at the site of the tick bite. This initial stage develops within the first few weeks of the bite and may be accompanied by fatigue and a low-grade fever.

If left untreated, the infection may progress to early disseminated disease, which occurs weeks to months after the initial bite. This second stage of Lyme disease manifests with multiple erythema migrans lesions on additional parts of the body, indicating spirochete dissemination through the bloodstream and lymphatic system. Early disseminated disease may also include borrelial lymphocytoma, Lyme neuroborreliosis, and cardiac conduction abnormalities such as AV block.

The third stage of Lyme disease, late Lyme disease, occurs months to years after an initial infection that has gone untreated. The key feature of this stage is arthritis, which tends to affect the knees and may be migratory in nature. Neurological symptoms such as encephalopathy and polyneuropathies may also develop. A minority of patients with late Lyme disease may develop acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, a rash that typically occurs on the dorsal hands and feet as blue-red plaques that turn the affected skin atrophic.1

This patient was treated with a 3-week course of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and was referred to an infectious disease specialist for further work-up of systemic symptoms, given the risk for cardiac pathology in disseminated Lyme disease.

Photo courtesy of Le Wen Chiu, MD. Text courtesy of Le Wen Chiu, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

The patient’s multiple pink, subtly annular patches after recent travel to Lyme-endemic areas of the United States demonstrated a classic manifestation of disseminated Lyme disease. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was positive for Borrelia burgdorferi IgM and IgG antibodies, confirming an acute infection.

While not usually necessary, skin biopsy shows a nonspecific perivascular cellular infiltrate that may be comprised of histiocytes, lymphocytes, and plasma cells. Spirochetes are not typically seen, but they may be identified with antibody-labeled or silver stains.

Lyme disease initially manifests as localized disease with erythema migrans, a targetoid lesion on the skin that appears at the site of the tick bite. This initial stage develops within the first few weeks of the bite and may be accompanied by fatigue and a low-grade fever.

If left untreated, the infection may progress to early disseminated disease, which occurs weeks to months after the initial bite. This second stage of Lyme disease manifests with multiple erythema migrans lesions on additional parts of the body, indicating spirochete dissemination through the bloodstream and lymphatic system. Early disseminated disease may also include borrelial lymphocytoma, Lyme neuroborreliosis, and cardiac conduction abnormalities such as AV block.

The third stage of Lyme disease, late Lyme disease, occurs months to years after an initial infection that has gone untreated. The key feature of this stage is arthritis, which tends to affect the knees and may be migratory in nature. Neurological symptoms such as encephalopathy and polyneuropathies may also develop. A minority of patients with late Lyme disease may develop acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, a rash that typically occurs on the dorsal hands and feet as blue-red plaques that turn the affected skin atrophic.1

This patient was treated with a 3-week course of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and was referred to an infectious disease specialist for further work-up of systemic symptoms, given the risk for cardiac pathology in disseminated Lyme disease.

Photo courtesy of Le Wen Chiu, MD. Text courtesy of Le Wen Chiu, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Cardenas-de la Garza JA, De la Cruz-Valadez E, Ocampo-Candiani J, et al. Clinical spectrum of Lyme disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:201-208. doi:10.1007/s10096-018-3417-1

1. Cardenas-de la Garza JA, De la Cruz-Valadez E, Ocampo-Candiani J, et al. Clinical spectrum of Lyme disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:201-208. doi:10.1007/s10096-018-3417-1

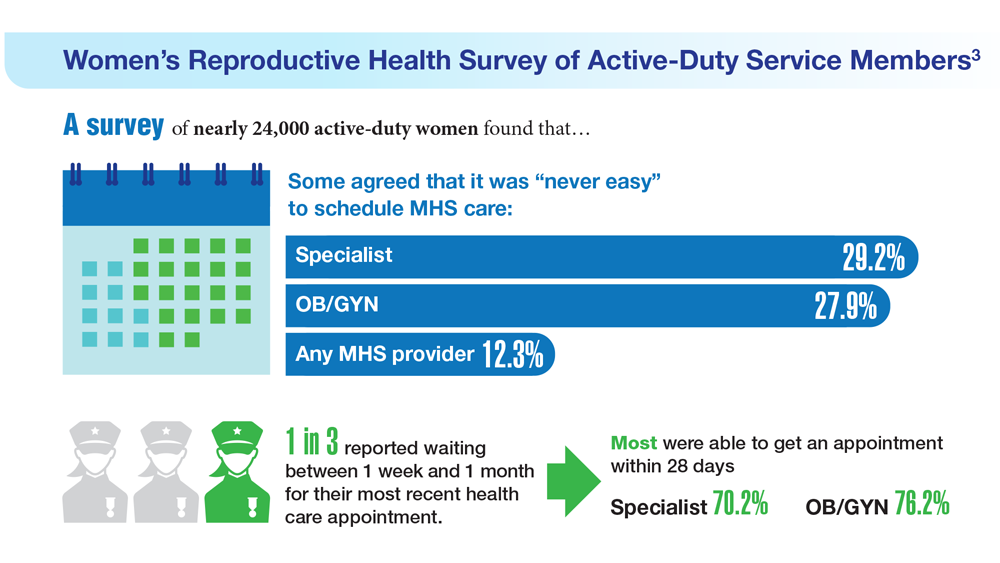

Data Trends 2023: Access to Women's Health Care

- US Department of Veteran Affairs. Facts and statistics: women veterans in focus. Updated January 31, 2023. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/materials-and-resources/facts-and-statistics.asp

- US Department of Defense. Department of Defense Releases Annual Demographics Report — Upward Trend in Number of Women Serving Continues. Published December 14, 2022. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3246268/department-of-defense-releases-annual-demographics-report-upwardtrend-in-numbe/

- Meadows SO, Collins RL, Schuler MS, Beckman RL, Cefalu M. The Women’s Reproductive Health Survey (WRHS) of active-duty service members. RAND Corporation. Published 2022. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA1000/RRA1031-1/RAND_RRA1031-1.pdf

- US Department of Veteran Affairs. Facts and statistics: women veterans in focus. Updated January 31, 2023. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/materials-and-resources/facts-and-statistics.asp

- US Department of Defense. Department of Defense Releases Annual Demographics Report — Upward Trend in Number of Women Serving Continues. Published December 14, 2022. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3246268/department-of-defense-releases-annual-demographics-report-upwardtrend-in-numbe/

- Meadows SO, Collins RL, Schuler MS, Beckman RL, Cefalu M. The Women’s Reproductive Health Survey (WRHS) of active-duty service members. RAND Corporation. Published 2022. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA1000/RRA1031-1/RAND_RRA1031-1.pdf

- US Department of Veteran Affairs. Facts and statistics: women veterans in focus. Updated January 31, 2023. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/materials-and-resources/facts-and-statistics.asp

- US Department of Defense. Department of Defense Releases Annual Demographics Report — Upward Trend in Number of Women Serving Continues. Published December 14, 2022. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3246268/department-of-defense-releases-annual-demographics-report-upwardtrend-in-numbe/

- Meadows SO, Collins RL, Schuler MS, Beckman RL, Cefalu M. The Women’s Reproductive Health Survey (WRHS) of active-duty service members. RAND Corporation. Published 2022. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA1000/RRA1031-1/RAND_RRA1031-1.pdf

Data Trends 2023: Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Morse JL et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2023;159:224-229. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.01.039

- van Vollenhoven RF. BMC Med. 2009;7:12. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-7-12

- US Department of Veteran Affairs, National Center for Veteran Analysis and Statistics. Profile of veterans: 2017. Published March 2019. Accessed April 27, 2023. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Profile_of_Veterans_2017.pdf

- Johnson TM et al. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2022 Nov 4. doi:10.1002/acr.25053

- Ebel AV et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(3):392-400. doi:10.1002/art.41559

- Sokolove J et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55(11):1969-1977. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kew285

- Alpizar-Rodriguez D et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58(3):432-440. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/key311

- Chancay MG et al. Womens Midlife Health. 2019;5:3. doi:10.1186/s40695-019-0047-4

- Bongartz T et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(6):1583-1591. doi:10.1002/art.27405

- Kelly CA et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53(9):1676-1682. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keu165

- Koduri G et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49(8):1483-1489. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keq035

- Olson AL et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(3):372-378. doi:10.1164/rccm.201004-0622OC

- Mikuls TR et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50(1):101-109. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keq232

- England BR et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68(1):36-45. doi:10.1002/acr.22642

- Morse JL et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2023;159:224-229. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.01.039

- van Vollenhoven RF. BMC Med. 2009;7:12. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-7-12

- US Department of Veteran Affairs, National Center for Veteran Analysis and Statistics. Profile of veterans: 2017. Published March 2019. Accessed April 27, 2023. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Profile_of_Veterans_2017.pdf

- Johnson TM et al. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2022 Nov 4. doi:10.1002/acr.25053

- Ebel AV et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(3):392-400. doi:10.1002/art.41559

- Sokolove J et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55(11):1969-1977. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kew285

- Alpizar-Rodriguez D et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58(3):432-440. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/key311

- Chancay MG et al. Womens Midlife Health. 2019;5:3. doi:10.1186/s40695-019-0047-4

- Bongartz T et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(6):1583-1591. doi:10.1002/art.27405

- Kelly CA et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53(9):1676-1682. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keu165

- Koduri G et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49(8):1483-1489. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keq035

- Olson AL et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(3):372-378. doi:10.1164/rccm.201004-0622OC

- Mikuls TR et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50(1):101-109. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keq232

- England BR et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68(1):36-45. doi:10.1002/acr.22642

- Morse JL et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2023;159:224-229. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.01.039

- van Vollenhoven RF. BMC Med. 2009;7:12. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-7-12

- US Department of Veteran Affairs, National Center for Veteran Analysis and Statistics. Profile of veterans: 2017. Published March 2019. Accessed April 27, 2023. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Profile_of_Veterans_2017.pdf

- Johnson TM et al. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2022 Nov 4. doi:10.1002/acr.25053

- Ebel AV et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(3):392-400. doi:10.1002/art.41559

- Sokolove J et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55(11):1969-1977. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kew285

- Alpizar-Rodriguez D et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58(3):432-440. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/key311

- Chancay MG et al. Womens Midlife Health. 2019;5:3. doi:10.1186/s40695-019-0047-4

- Bongartz T et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(6):1583-1591. doi:10.1002/art.27405

- Kelly CA et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53(9):1676-1682. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keu165

- Koduri G et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49(8):1483-1489. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keq035

- Olson AL et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(3):372-378. doi:10.1164/rccm.201004-0622OC

- Mikuls TR et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50(1):101-109. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keq232

- England BR et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68(1):36-45. doi:10.1002/acr.22642

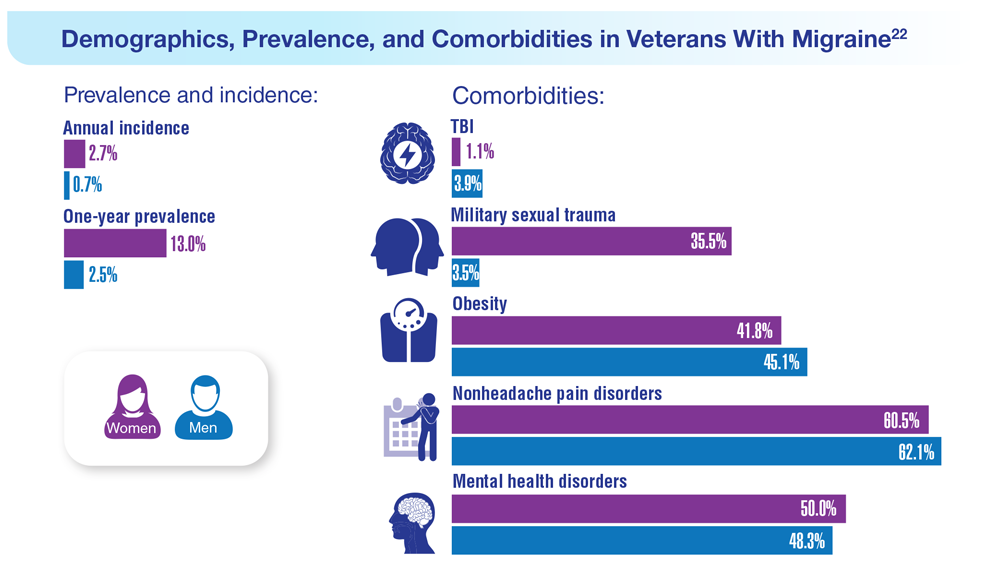

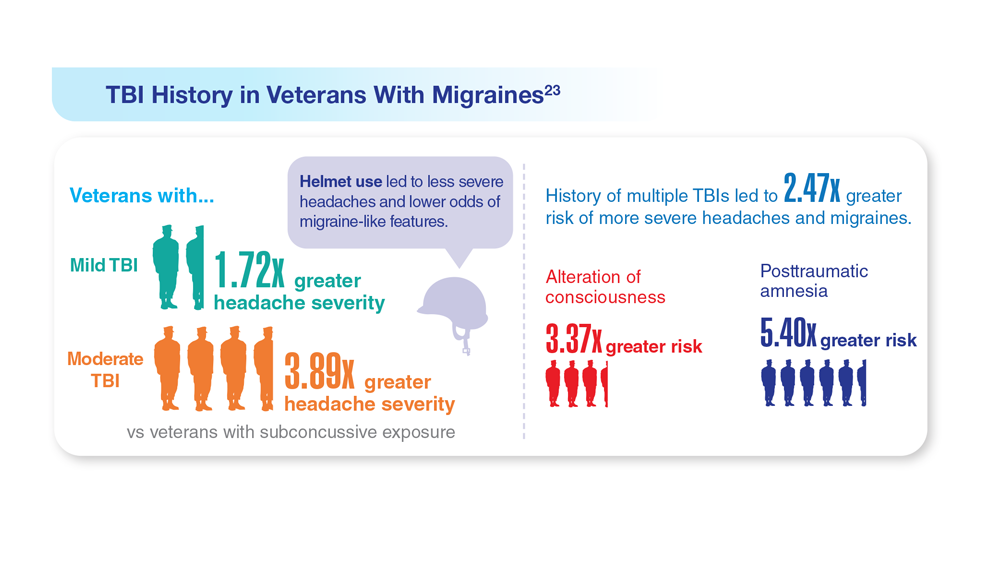

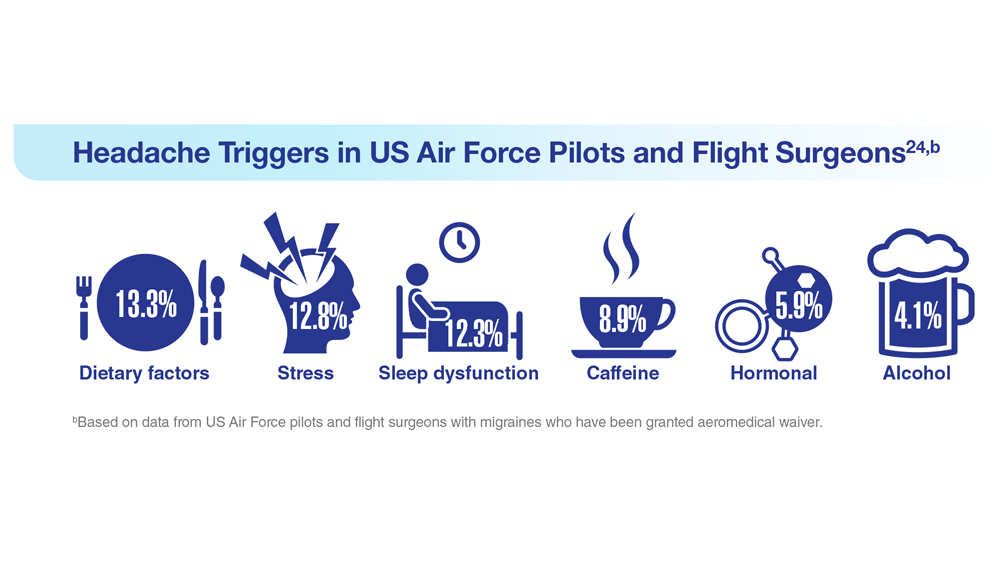

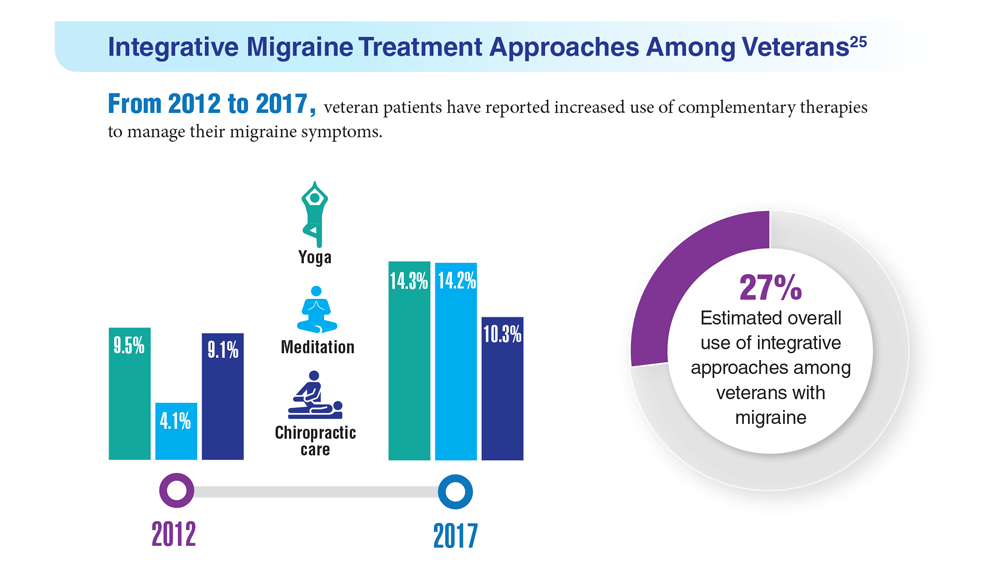

Data Trends 2023: Migraine and Headache

22. Seng EK et al. Neurology. 2022;99(18):e1979-e1992. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000200888

23. Coffman C et al. Neurology. 2022;99(2):e187-e198. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000200518

24. Hesselbrock RR et al. Aerosp Med Hum Perform. 2022;93(1):26-31. doi:10.3357/amhp.5980.2022

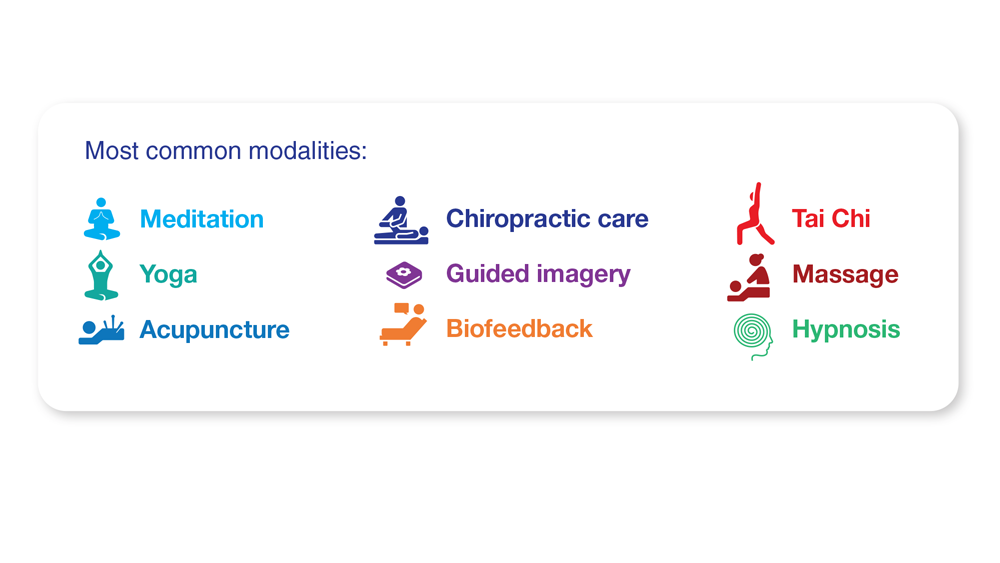

25. Kuruvilla DE et al. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2022;22(1):22. doi:10.1186/s12906-022-03511-6

22. Seng EK et al. Neurology. 2022;99(18):e1979-e1992. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000200888

23. Coffman C et al. Neurology. 2022;99(2):e187-e198. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000200518

24. Hesselbrock RR et al. Aerosp Med Hum Perform. 2022;93(1):26-31. doi:10.3357/amhp.5980.2022

25. Kuruvilla DE et al. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2022;22(1):22. doi:10.1186/s12906-022-03511-6

22. Seng EK et al. Neurology. 2022;99(18):e1979-e1992. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000200888

23. Coffman C et al. Neurology. 2022;99(2):e187-e198. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000200518

24. Hesselbrock RR et al. Aerosp Med Hum Perform. 2022;93(1):26-31. doi:10.3357/amhp.5980.2022

25. Kuruvilla DE et al. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2022;22(1):22. doi:10.1186/s12906-022-03511-6

Data Trends 2023: Parkinson’s Disease

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development.

Parkinson’s disease. Updated October 28, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2023.

https://www.research.va.gov/topics/parkinsons.cfm

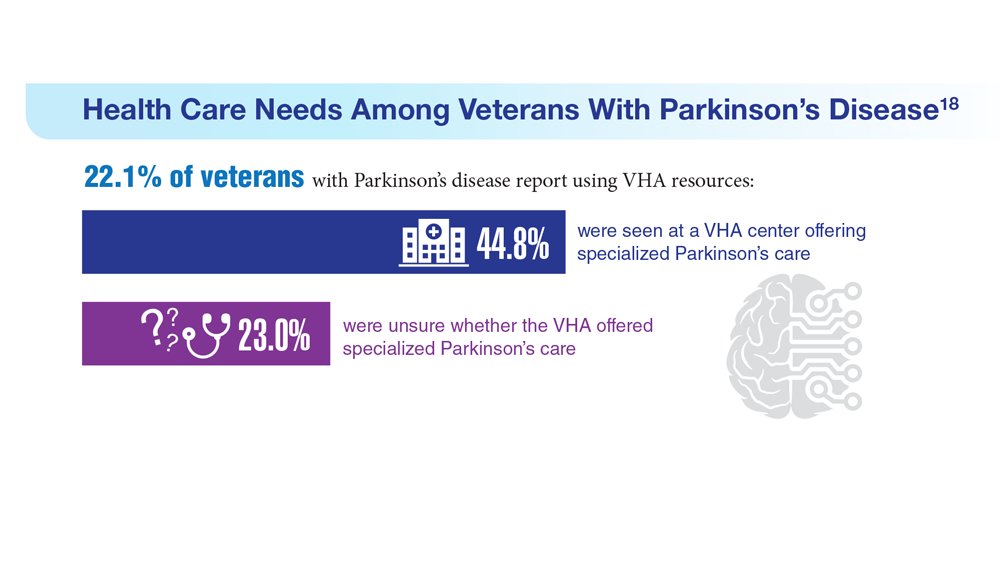

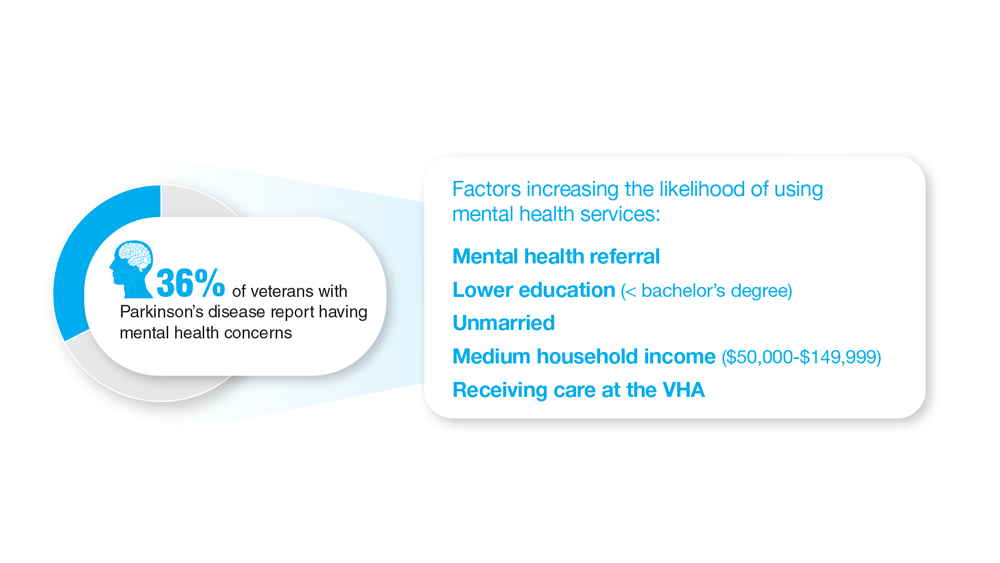

18. Feeney M et al. Front Neurol. 2022;13:924999. doi:10.3389/fneur.2022.924999

19. Heronemus M et al. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2022;105:58-61. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2022.11.003

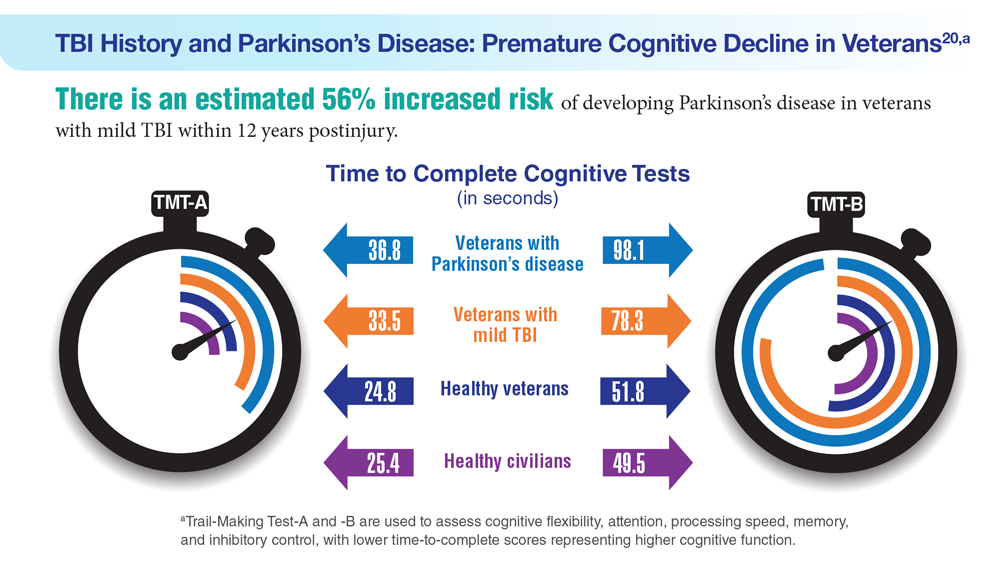

20. Nejtek VA et al. PLoS One. 2021;16(11):e0258851. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0258851

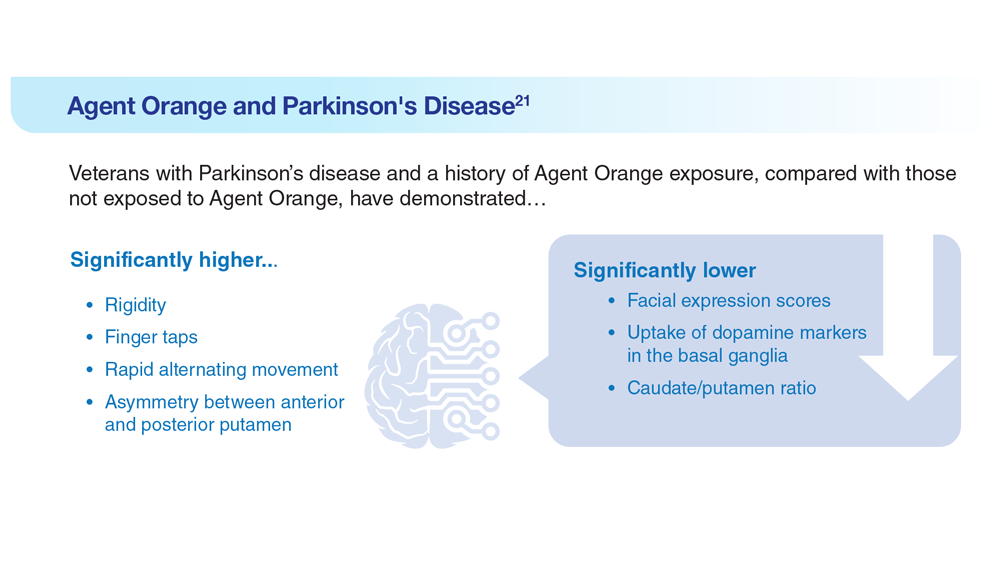

21. Yang Y et al. Dement Neurocogn Disord. 2016;15(3):75-81. doi:10.12779/dnd.2016.15.3.75

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development.

Parkinson’s disease. Updated October 28, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2023.

https://www.research.va.gov/topics/parkinsons.cfm

18. Feeney M et al. Front Neurol. 2022;13:924999. doi:10.3389/fneur.2022.924999

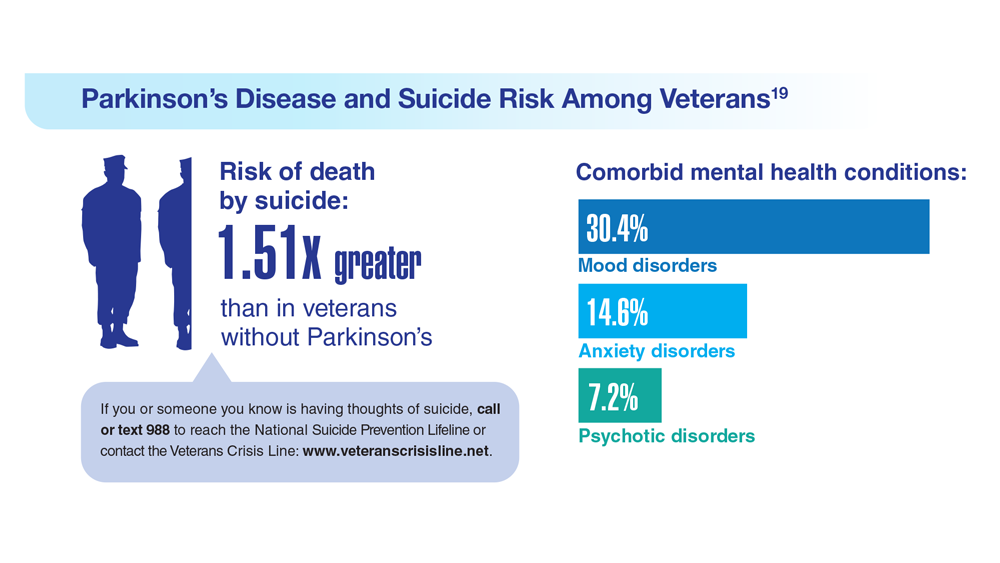

19. Heronemus M et al. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2022;105:58-61. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2022.11.003

20. Nejtek VA et al. PLoS One. 2021;16(11):e0258851. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0258851

21. Yang Y et al. Dement Neurocogn Disord. 2016;15(3):75-81. doi:10.12779/dnd.2016.15.3.75

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development.

Parkinson’s disease. Updated October 28, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2023.

https://www.research.va.gov/topics/parkinsons.cfm

18. Feeney M et al. Front Neurol. 2022;13:924999. doi:10.3389/fneur.2022.924999

19. Heronemus M et al. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2022;105:58-61. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2022.11.003

20. Nejtek VA et al. PLoS One. 2021;16(11):e0258851. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0258851

21. Yang Y et al. Dement Neurocogn Disord. 2016;15(3):75-81. doi:10.12779/dnd.2016.15.3.75

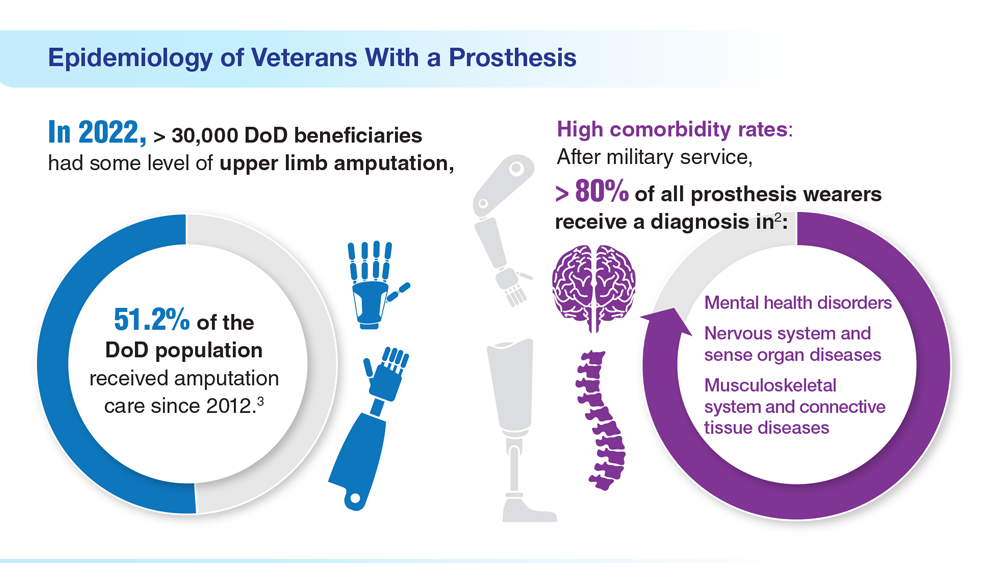

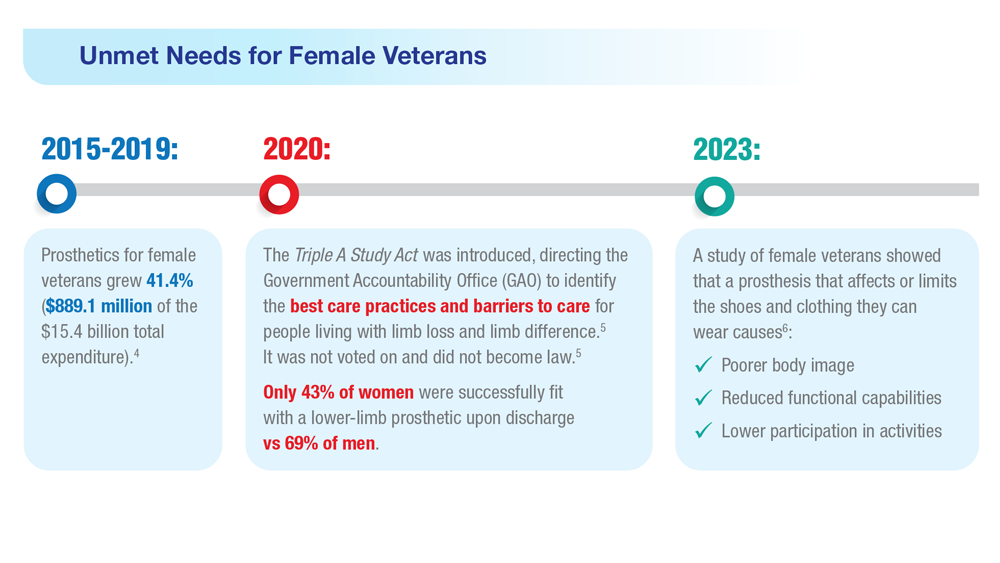

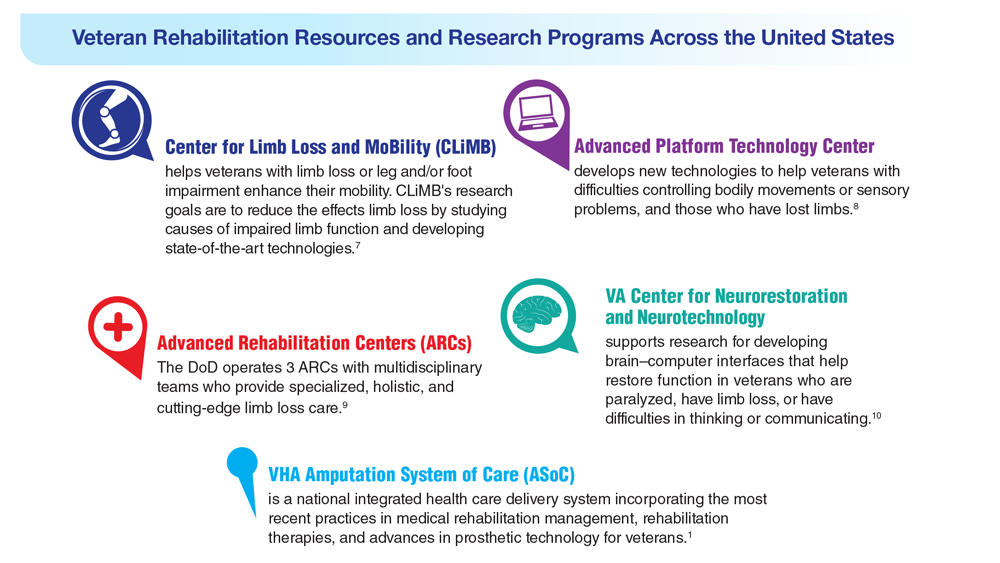

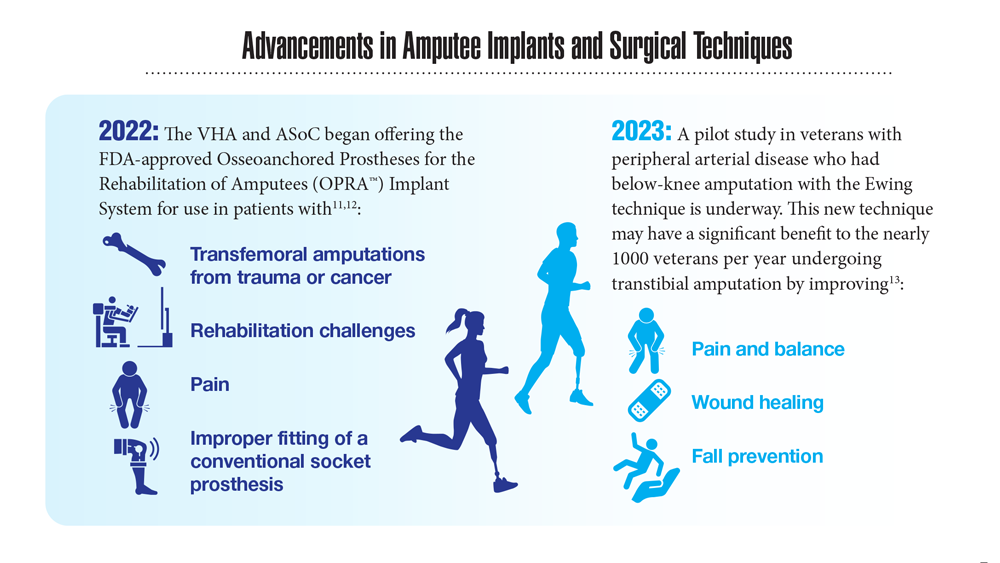

Data Trends 2023: Limb Loss and Prostheses

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Amputation system of care [fact sheet]. Published December 2022. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.prosthetics.va.gov/factsheet/ASoC-FactSheet.pdf

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of the Inspector General. Veteran Affairs Inspector General healthcare inspection: prosthetic limb care in VA facilities. Published March 8, 2012. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-11-02138-116.pdf

- Department of Veterans Affairs; Department of Defense. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Upper Limb Amputation Rehabilitation. Patient Summary. Published March 2022. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Rehab/ULA/VADoDULACPG_PatientSummary_Final_508.pdf

- US Government Accountability Office, Report to Congressional Committees. Veterans Health Care: Agency efforts to provide and study prosthetics for small but growing female veteran population. Published November 2020. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-60.pdf

- 117th Congress. Access to Assistive Technology and Devices for Americans Study Act or the Triple A Study Act (H.R.2461). April 13, 2021. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/housebill/2461

- Russell Esposito E, et al. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2023 Jan 2023. Online ahead of print. doi:10.1097/PXR.0000000000000192

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Center for Limb Loss and MoBility. Updated January 27, 2022. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.amputation.research.va.gov/

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Advanced Platform Technology Center. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.aptcenter.research.va.gov

- Sanchez-Bustamante C. Limb loss: DHA's three advanced rehab centers provide holistic care. Medicine and the Military. Published May 3, 2022. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://health.mil/News/Articles/2022/05/04/Limb-Loss-DHAs-Three-Advanced-Rehab-Centers-Provide-Holistic-Care

- Center for Neurorestoration and Neurotechnology. VA Providence Healthcare System. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://centerforneuro.org

- Webster JB. OPRA™ patient information sheet. US Department of Veteran Affairs, Rehabilitation and Prosthetic Services. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.rehab.va.gov/PROSTHETICS/asoc/resources/OPRA-PatientInformation.pdf

- Hoyt BW, et al. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2020;17(1):17-25. doi:10.1080/17434440.2020.1704623

- Ewing amputation in veterans with PAD undergoing BKA. ClinicalTrials.gov. Updated October 31, 2022. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05437562

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Amputation system of care [fact sheet]. Published December 2022. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.prosthetics.va.gov/factsheet/ASoC-FactSheet.pdf

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of the Inspector General. Veteran Affairs Inspector General healthcare inspection: prosthetic limb care in VA facilities. Published March 8, 2012. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-11-02138-116.pdf

- Department of Veterans Affairs; Department of Defense. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Upper Limb Amputation Rehabilitation. Patient Summary. Published March 2022. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Rehab/ULA/VADoDULACPG_PatientSummary_Final_508.pdf

- US Government Accountability Office, Report to Congressional Committees. Veterans Health Care: Agency efforts to provide and study prosthetics for small but growing female veteran population. Published November 2020. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-60.pdf

- 117th Congress. Access to Assistive Technology and Devices for Americans Study Act or the Triple A Study Act (H.R.2461). April 13, 2021. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/housebill/2461

- Russell Esposito E, et al. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2023 Jan 2023. Online ahead of print. doi:10.1097/PXR.0000000000000192

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Center for Limb Loss and MoBility. Updated January 27, 2022. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.amputation.research.va.gov/

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Advanced Platform Technology Center. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.aptcenter.research.va.gov

- Sanchez-Bustamante C. Limb loss: DHA's three advanced rehab centers provide holistic care. Medicine and the Military. Published May 3, 2022. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://health.mil/News/Articles/2022/05/04/Limb-Loss-DHAs-Three-Advanced-Rehab-Centers-Provide-Holistic-Care

- Center for Neurorestoration and Neurotechnology. VA Providence Healthcare System. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://centerforneuro.org

- Webster JB. OPRA™ patient information sheet. US Department of Veteran Affairs, Rehabilitation and Prosthetic Services. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.rehab.va.gov/PROSTHETICS/asoc/resources/OPRA-PatientInformation.pdf

- Hoyt BW, et al. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2020;17(1):17-25. doi:10.1080/17434440.2020.1704623

- Ewing amputation in veterans with PAD undergoing BKA. ClinicalTrials.gov. Updated October 31, 2022. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05437562

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Amputation system of care [fact sheet]. Published December 2022. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.prosthetics.va.gov/factsheet/ASoC-FactSheet.pdf

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of the Inspector General. Veteran Affairs Inspector General healthcare inspection: prosthetic limb care in VA facilities. Published March 8, 2012. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-11-02138-116.pdf

- Department of Veterans Affairs; Department of Defense. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Upper Limb Amputation Rehabilitation. Patient Summary. Published March 2022. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Rehab/ULA/VADoDULACPG_PatientSummary_Final_508.pdf

- US Government Accountability Office, Report to Congressional Committees. Veterans Health Care: Agency efforts to provide and study prosthetics for small but growing female veteran population. Published November 2020. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-60.pdf

- 117th Congress. Access to Assistive Technology and Devices for Americans Study Act or the Triple A Study Act (H.R.2461). April 13, 2021. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/housebill/2461

- Russell Esposito E, et al. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2023 Jan 2023. Online ahead of print. doi:10.1097/PXR.0000000000000192

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Center for Limb Loss and MoBility. Updated January 27, 2022. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.amputation.research.va.gov/

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Advanced Platform Technology Center. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.aptcenter.research.va.gov

- Sanchez-Bustamante C. Limb loss: DHA's three advanced rehab centers provide holistic care. Medicine and the Military. Published May 3, 2022. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://health.mil/News/Articles/2022/05/04/Limb-Loss-DHAs-Three-Advanced-Rehab-Centers-Provide-Holistic-Care

- Center for Neurorestoration and Neurotechnology. VA Providence Healthcare System. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://centerforneuro.org

- Webster JB. OPRA™ patient information sheet. US Department of Veteran Affairs, Rehabilitation and Prosthetic Services. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.rehab.va.gov/PROSTHETICS/asoc/resources/OPRA-PatientInformation.pdf

- Hoyt BW, et al. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2020;17(1):17-25. doi:10.1080/17434440.2020.1704623

- Ewing amputation in veterans with PAD undergoing BKA. ClinicalTrials.gov. Updated October 31, 2022. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05437562

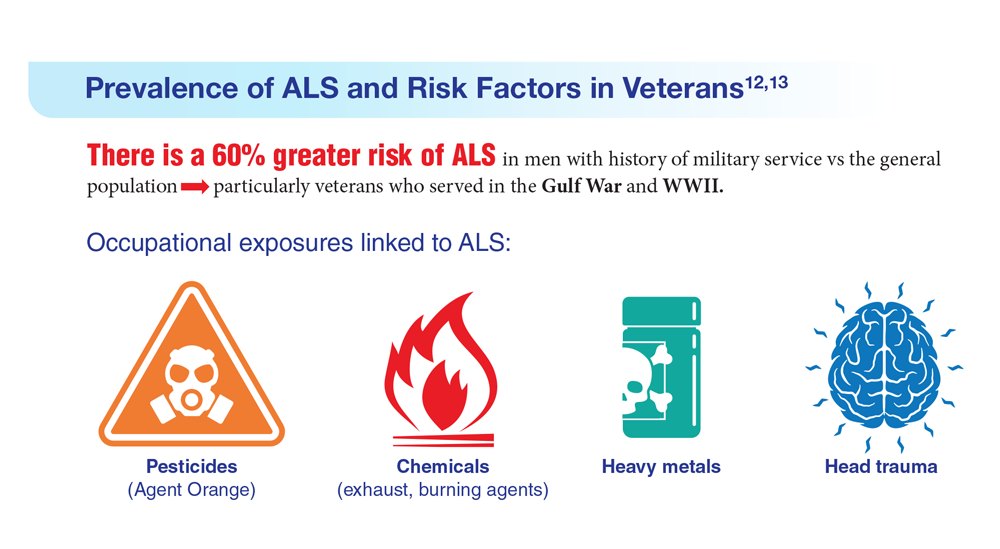

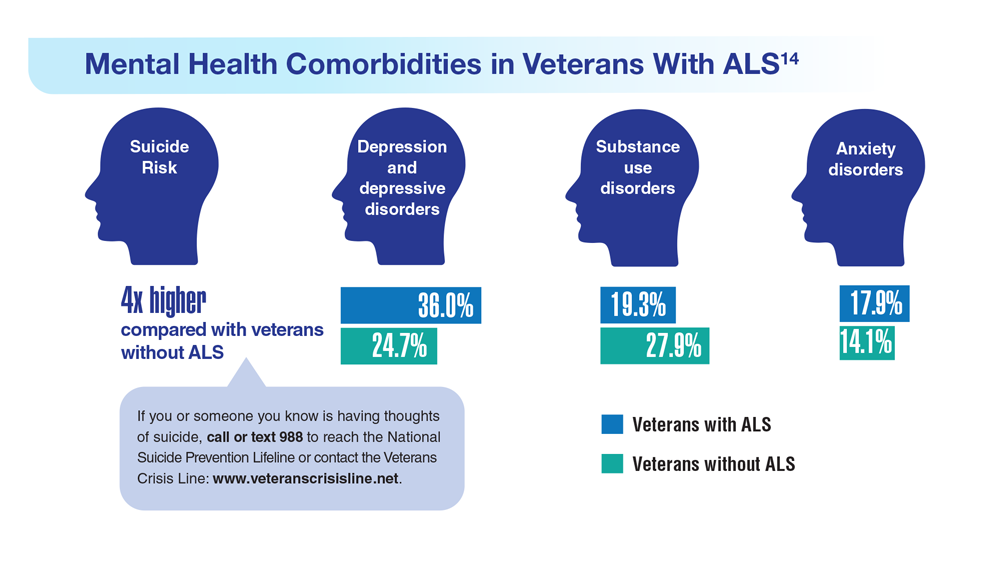

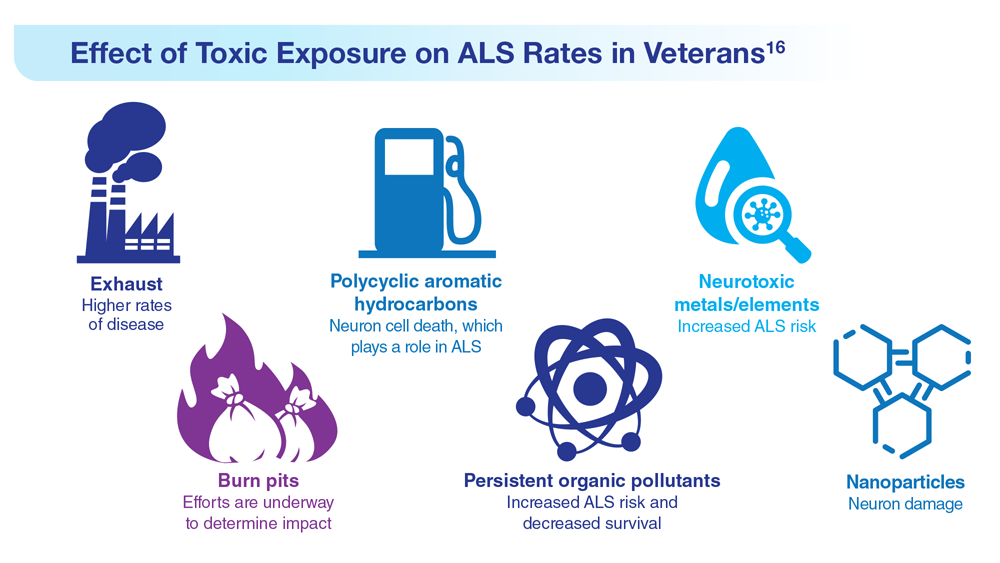

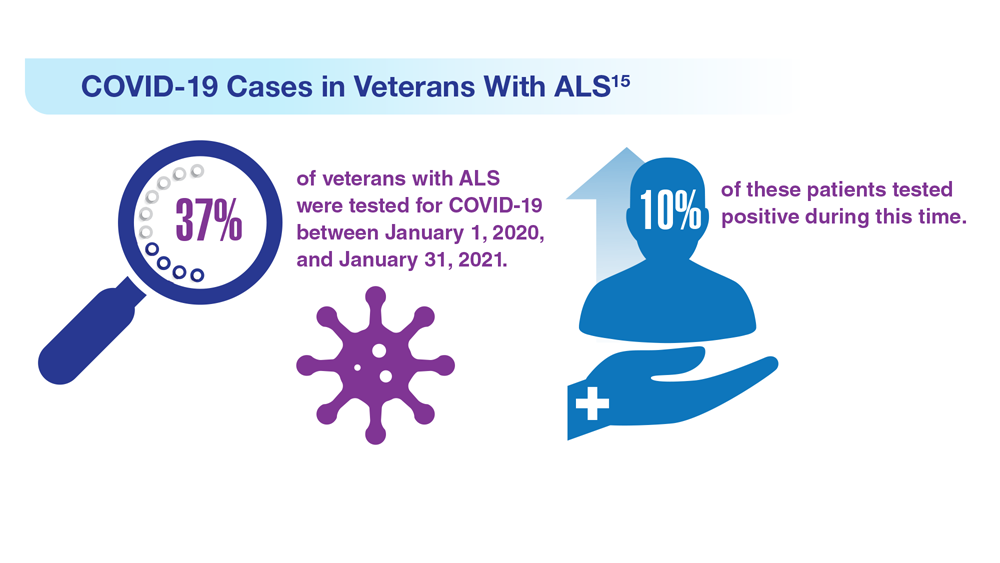

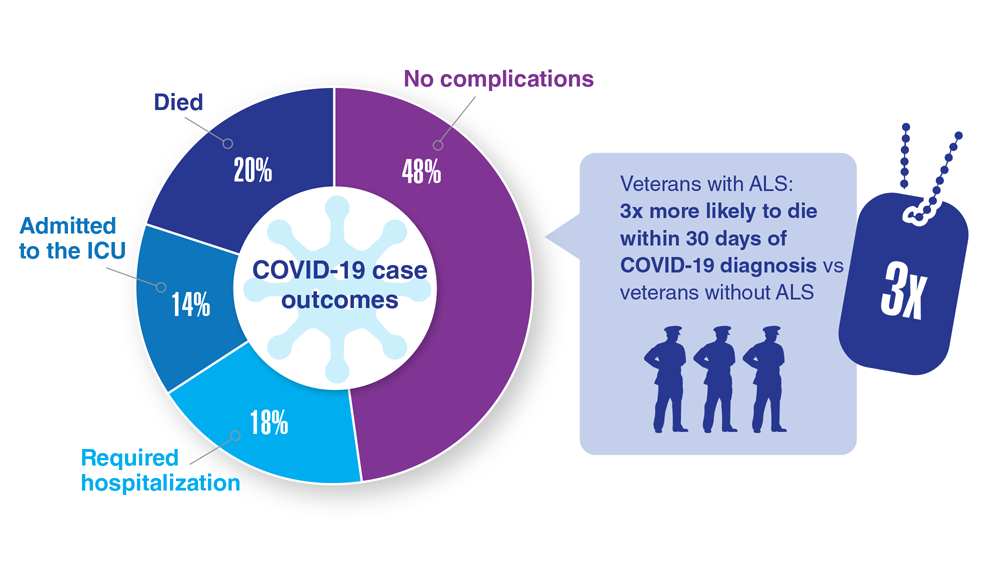

Data Trends 2023: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)

12. The ALS Association. ALS in the military. https://www.als.org/navigating-als/military-veterans/ALS-in-the-Military

13. McKay KA et al. Acta Neurol Scand. 2021;143(1):39-50. doi:10.1111/ane.13345

14. Lund EM et al. Muscle Nerve. 2021;63(6):807-811. doi:10.1002/mus.27181

15. Galea MD et al. Muscle Nerve. 2021;64(4):E18-E20. doi:10.1002/mus.27373

16. Re DB et al. J Neurol. 2022;269(5):2359-2377. doi:10.1007/s00415-021-10928-5

12. The ALS Association. ALS in the military. https://www.als.org/navigating-als/military-veterans/ALS-in-the-Military

13. McKay KA et al. Acta Neurol Scand. 2021;143(1):39-50. doi:10.1111/ane.13345

14. Lund EM et al. Muscle Nerve. 2021;63(6):807-811. doi:10.1002/mus.27181

15. Galea MD et al. Muscle Nerve. 2021;64(4):E18-E20. doi:10.1002/mus.27373

16. Re DB et al. J Neurol. 2022;269(5):2359-2377. doi:10.1007/s00415-021-10928-5

12. The ALS Association. ALS in the military. https://www.als.org/navigating-als/military-veterans/ALS-in-the-Military

13. McKay KA et al. Acta Neurol Scand. 2021;143(1):39-50. doi:10.1111/ane.13345

14. Lund EM et al. Muscle Nerve. 2021;63(6):807-811. doi:10.1002/mus.27181

15. Galea MD et al. Muscle Nerve. 2021;64(4):E18-E20. doi:10.1002/mus.27373

16. Re DB et al. J Neurol. 2022;269(5):2359-2377. doi:10.1007/s00415-021-10928-5

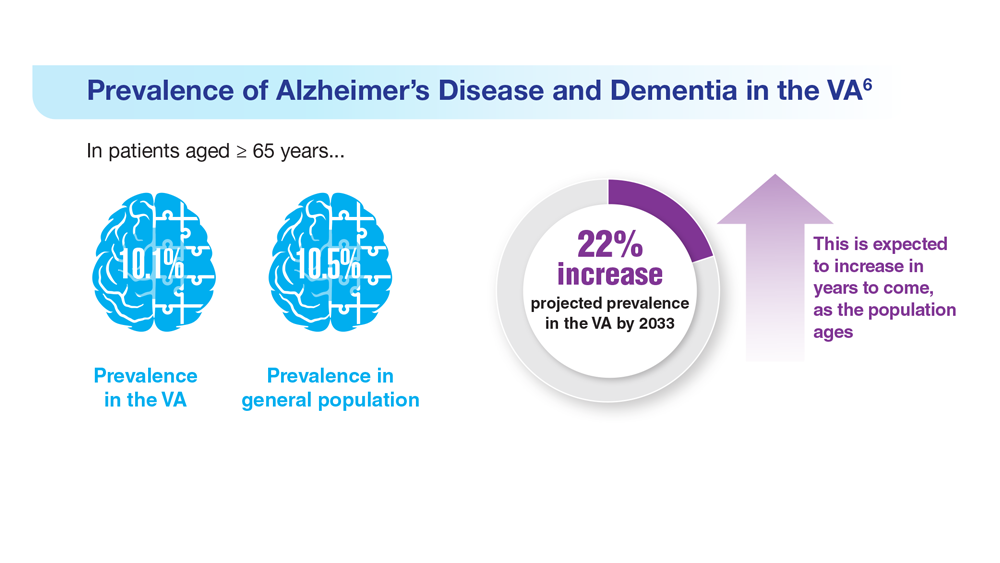

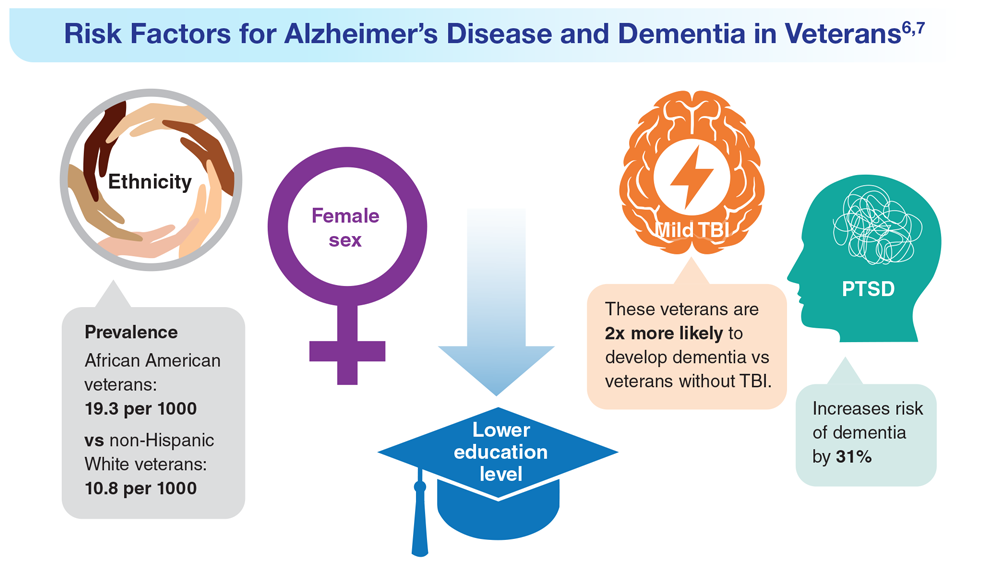

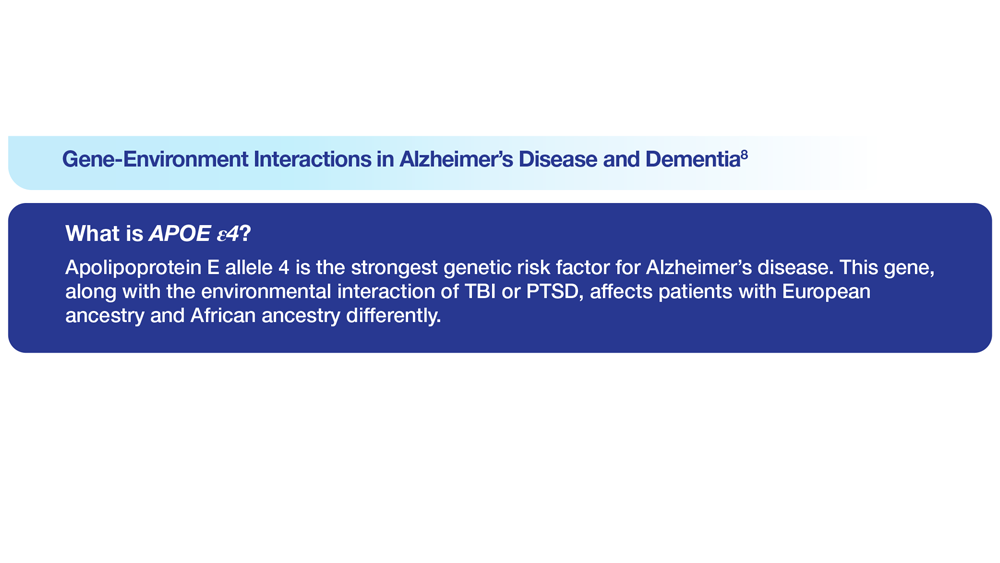

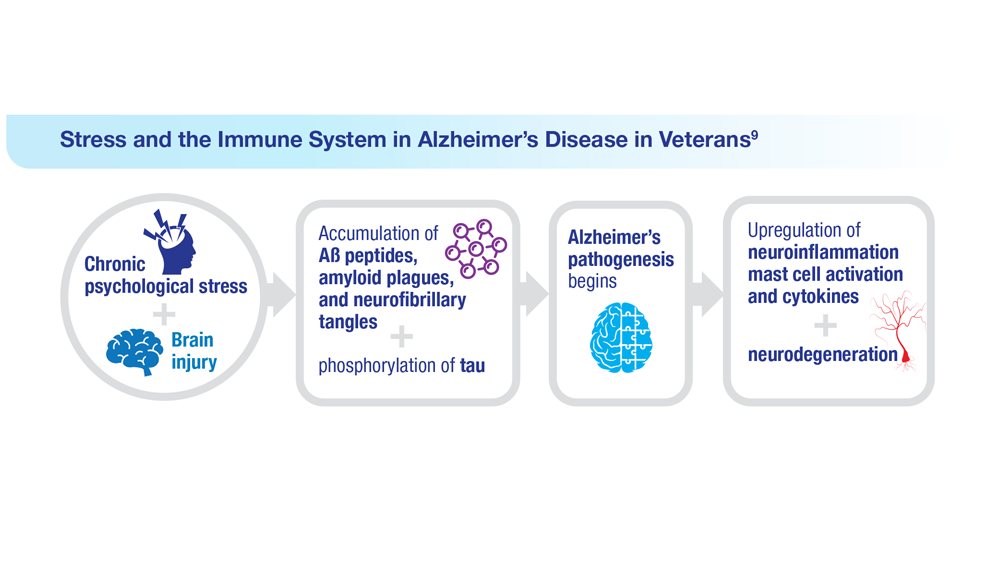

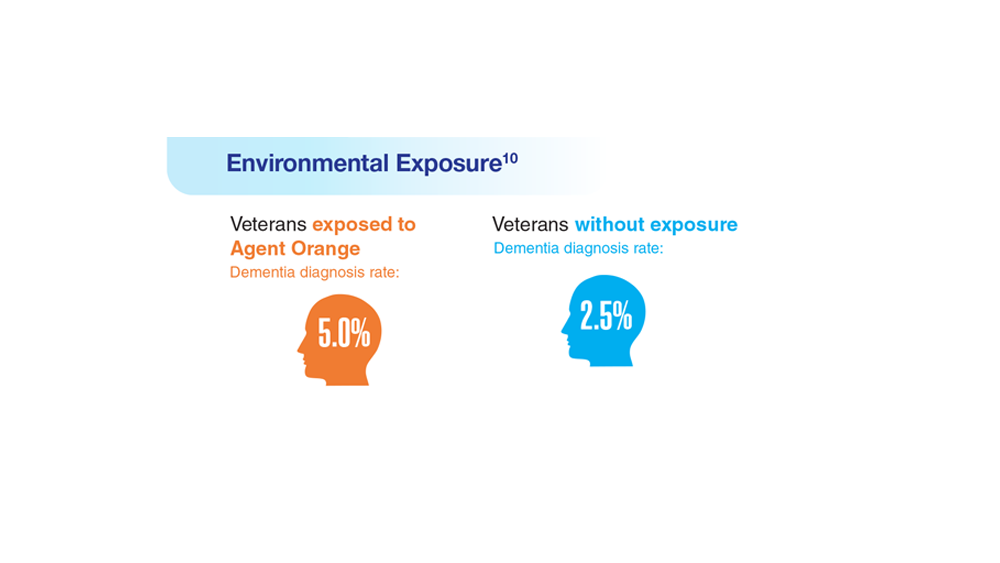

Data Trends 2023: Alzheimer’s and Dementia

6. Zhu CW, Sano M. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:610334. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.610334

7. Nianogo RA et al. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(6):584-591. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.0976

8. Logue MW et al. Alzheimers Dement. 2022 Dec 22. Online ahead of print. doi:10.1002/alz.12870

9. Kempuraj D et al. Clin Ther. 2020;42(6):974-982. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.02.018

10. Martinez S et al. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(4):473-477. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.5011

11. Verger A et al. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2023;50(6):1553-1555. doi:10.1007/s00259-023-06177-5

6. Zhu CW, Sano M. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:610334. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.610334

7. Nianogo RA et al. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(6):584-591. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.0976

8. Logue MW et al. Alzheimers Dement. 2022 Dec 22. Online ahead of print. doi:10.1002/alz.12870

9. Kempuraj D et al. Clin Ther. 2020;42(6):974-982. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.02.018

10. Martinez S et al. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(4):473-477. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.5011

11. Verger A et al. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2023;50(6):1553-1555. doi:10.1007/s00259-023-06177-5

6. Zhu CW, Sano M. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:610334. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.610334

7. Nianogo RA et al. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(6):584-591. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.0976

8. Logue MW et al. Alzheimers Dement. 2022 Dec 22. Online ahead of print. doi:10.1002/alz.12870

9. Kempuraj D et al. Clin Ther. 2020;42(6):974-982. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.02.018

10. Martinez S et al. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(4):473-477. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.5011

11. Verger A et al. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2023;50(6):1553-1555. doi:10.1007/s00259-023-06177-5

Allergic Contact Dermatitis

THE COMPARISON

A An 11-year-old Hispanic boy with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) on the abdomen. The geometric nature of the eruption and proximity to the belt buckle were highly suggestive of ACD to nickel; patch testing was not needed.

B A Black woman with ACD on the neck. A punch biopsy demonstrated spongiotic dermatitis that was typical of ACD. The diagnosis was supported by the patient’s history of dermatitis that developed after new products were applied to the hair. The patient declined patch testing.

C A Hispanic man with ACD on hair-bearing areas on the face where hair dye was used. The patient’s history of dermatitis following the application of hair dye was highly suggestive of ACD; patch testing confirmed the allergen was paraphenylenediamine (PPD).

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is an inflammatory condition of the skin caused by an immunologic response to one or more identifiable allergens. A delayed-type immune response (type IV hypersensitivity reaction) occurs after the skin is reexposed to an offending allergen.1 Severe pruritus is the main symptom of ACD in the early stages, accompanied by erythema, vesicles, and scaling in a distinct pattern corresponding to the allergen’s contact with the skin.2 Delayed widespread dermatitis after exposure to an allergen—a phenomenon known as autoeczematization (id reaction)—also may occur.3

The gold-standard diagnostic tool for ACD is patch testing, in which the patient is re-exposed to the suspected contact allergen(s) and observed for the development of dermatitis.4 However, ACD can be diagnosed with a detailed patient history including occupation, hobbies, personal care practices, and possible triggers with subsequent rashes. Thorough clinical examination of the skin is paramount. Indicators of possible ACD include dermatitis that persists despite use of appropriate treatment, an unexplained flare of previously quiescent dermatitis, and a diagnosis of dermatitis without a clear cause.1

Hairdressers, health care workers, and metal workers are at higher risk for ACD.5 Occupational ACD has notable socioeconomic implications, as it can result in frequent sick days, inability to perform tasks at work, and in some cases job loss.6

Patients with atopic dermatitis have impaired barrier function of the skin, permitting the entrance of allergens and subsequent sensitization.7 Allergic contact dermatitis is a challenge to manage, as complete avoidance of the allergen may not be possible.8

The underrepresentation of patients with skin of color (SOC) in educational materials as well as socioeconomic health disparities may contribute to the lower rates of diagnosis, patch testing, and treatment of ACD in this patient population.

Epidemiology

An ACD prevalence of 15.2% was reported in a study of 793 Danish patients who underwent skin prick and patch testing.9 Alinaghi et al10 conducted a meta-analysis of 20,107 patients across 28 studies who were patch tested to determine the prevalence of ACD in the general population. The researchers concluded that 20.1% (95% CI, 16.8%- 23.7%) of the general population experienced ACD. They analyzed 22 studies to determine the prevalence of ACD based on specific geographic area including 18,709 individuals from Europe with a prevalence of 19.5% (95% CI, 15.8%-23.4%), 1639 individuals from North America with a prevalence of 20.6% (95% CI, 9.2%-35.2%), and 2 studies from China (no other studies from Asia found) with a prevalence of 20.6% (95% CI, 17.4%-23.9%). Researchers did not find data from studies conducted in Africa or South America.10

The current available epidemiologic data on ACD are not representative of SOC populations. DeLeo et al11 looked at patch test reaction patterns in association with race and ethnicity in a large sample size (N=19,457); 17,803 (92.9%) of these patients were White and only 1360 (7.1%) were Black. Large-scale, inclusive studies are needed, which can only be achieved with increased suspicion for ACD and increased access to patch testing.

Allergic contact dermatitis is more common in women, with nickel being the most frequently identified allergen (Figure, A).10 Personal care products often are linked to ACD (Figure, B). An analysis of data from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group revealed that the top 5 personal care product allergens were methylisothiazolinone (a preservative), fragrance mix I, balsam of Peru, quaternium-15 (a preservative), and paraphenylenediamine (PPD)(a common component of hair dye) (Figure, C).12

There is a paucity of epidemiologic data among various ethnic groups; however, a few studies have suggested that there is no difference in the frequency rates of positive patch test results in Black vs White populations.11,13,14 One study of patch test results from 114 Black patients and 877 White patients at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation in Ohio demonstrated a similar allergy frequency of 43.0% and 43.6%, respectively.13 However, there were differences in the types of allergen sensitization. Black patients had higher positive patch test rates for PPD than White patients (10.6% vs 4.5%). Black men had a higher frequency of sensitivity to PPD (21.2% vs 4.2%) and imidazolidinyl urea (a formaldehyde-releasing preservative) (9.1% vs 2.6%) compared to White men.13

Ethnicity and cultural practices influence epidemiologic patterns of ACD. Darker hair dyes used in Black patients14 and deeply pigmented PPD dye found in henna tattoos used in Indian and Black patients15 may lead to increased sensitization to PPD. Allergic contact dermatitis due to formaldehyde is more common in White patients, possibly due to more frequent use of formaldehyde-containing moisturizers, shampoos, and creams.15

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

In patients with SOC, the clinical features of ACD vary, posing a diagnostic challenge. Hyperpigmentation, lichenification, and induration are more likely to be seen than the papules, vesicles, and erythematous dermatitis often described in lighter skin tones or acute ACD. Erythema can be difficult to assess on darker skin and may appear violaceous or very faint pink.16

Worth noting

A high index of suspicion is necessary when interpreting patch tests in patients with SOC, as patch test kits use a reading plate with graduated intensities of erythema, papulation, and vesicular reactions to determine the likelihood of ACD. The potential contact allergens are placed on the skin on day 1 and covered. Then, on day 3 the allergens are removed. The skin is clinically evaluated using visual assessment and skin palpation. The reactions are graded as negative, irritant reaction, equivocal, weak positive, strong positive, or extreme reaction at around days 3 and 5 to capture both early and delayed reactions.17 A patch test may be positive even if obvious signs of erythema are not appreciated as expected.

Adjusting the lighting in the examination room, including side lighting, or using a blue background can be helpful in identifying erythema in darker skin tones.15,16,18 Palpation of the skin also is useful, as even slight texture changes and induration are indicators of a possible skin reaction to the test allergen.15

Health disparity highlight

Clinical photographs of ACD and patch test results in patients with SOC are not commonplace in the literature. Positive patch test results in patients with darker skin tones vary from those of patients with lighter skin tones, and if the clinician reading the patch test result is not familiar with the findings in darker skin tones, the diagnosis may be delayed or missed.15

Furthermore, Scott et al15 highlighted that many dermatology residency training programs have a paucity of SOC education in their curriculum. This lack of representation may contribute to the diagnostic challenges encountered by health care providers.

Timely access to health care and education as well as economic stability are essential for the successful management of patients with ACD. Some individuals with SOC have been disproportionately affected by social determinants of health. Rodriguez-Homs et al19 demonstrated that the distance needed to travel to a clinic and the poverty rate of the county the patient lives in play a role in referral to a clinician specializing in contact dermatitis.

A retrospective registry review of 2310 patients undergoing patch testing at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston revealed that 2.5% were Black, 5.5% were Latinx, 8.3% were Asian, and the remaining 83.7% were White.20 Qian et al21 also looked at patch testing patterns among various sociodemographic groups (N=1,107,530) and found that 69% of patients were White and 59% were female. Rates of patch testing among patients who were Black, lesser educated, male, lower income, and younger (children aged 0–12 years) were significantly lower than for other groups when ACD was suspected (P<.0001).21 The lower rates of patch testing in patients with SOC may be due to low suspicion of diagnosis, low referral rates due to limited medical insurance, and financial instability, as well as other socioeconomic factors.20

Tamazian et al16 reviewed pediatric populations at 13 US centers and found that Black children received patch testing less frequently than White and Hispanic children. Another review of pediatric patch testing in patients with SOC found that a less comprehensive panel of allergens was used in this population.22

The key to resolution of ACD is removal of the offending antigen, and if patients are not being tested, then they risk having a prolonged and complicated course of ACD with a poor prognosis. Patients with SOC also experience greater negative psychosocial impact due to ACD disease burden.21,23

The lower rates of patch testing in Black patients cannot solely be attributed to difficulty diagnosing ACD in darker skin tones; it is likely due to the impact of social determinants of health. Alleviating health disparities will improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

- Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient diagnosis and evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74: 1029-1040. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1139

- Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

- Bertoli MJ, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Autoeczematization: a strange id reaction of the skin. Cutis. 2021;108:163-166. doi:10.12788/cutis.0342

- Johansen JD, Bonefeld CM, Schwensen JFB, et al. Novel insights into contact dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149:1162-1171. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2022.02.002

- Karagounis TK, Cohen DE. Occupational hand dermatitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2023;23:201-212. doi:10.1007/s11882-023-01070-5

- Cvetkovski RS, Rothman KJ, Olsen J, et al. Relation between diagnoses on severity, sick leave and loss of job among patients with occupational hand eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:93-98. doi:10.1111/j .1365-2133.2005.06415.x

- Owen JL, Vakharia PP, Silverberg JI. The role and diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:293-302. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0340-7

- Brites GS, Ferreira I, Sebastião AI, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: from pathophysiology to development of new preventive strategies. Pharmacol Res. 2020;162:105282. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105282

- Nielsen NH, Menne T. The relationship between IgE‐mediated and cell‐mediated hypersensitivities in an unselected Danish population: the Glostrup Allergy Study, Denmark. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:669-672. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb06967.x

- Alinaghi F, Bennike NH, Egeberg A, et al. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:77-85. doi:10.1111/cod.13119

- DeLeo VA, Alexis A, Warshaw EM, et al. The association of race/ethnicity and patch test results: North American Contact Dermatitis Group, 1998- 2006. Dermatitis. 2016;27:288-292. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000220

- Warshaw EM, Schlarbaum JP, Silverberg JI, et al. Contact dermatitis to personal care products is increasing (but different!) in males and females: North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 1996-2016. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1446-1455. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.003

- Dickel H, Taylor JS, Evey P, et al. Comparison of patch test results with a standard series among white and black racial groups. Am J Contact Dermatol. 2001;12:77-82. doi:10.1053/ajcd.2001.20110

- DeLeo VA, Taylor SC, Belsito DV, et al. The effect of race and ethnicity on patch test results. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl):S107-S112. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120792

- Scott I, Atwater AR, Reeder M. Update on contact dermatitis and patch testing in patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2021;108:10-12. doi:10.12788/cutis.0292

- Tamazian S, Oboite M, Treat JR. Patch testing in skin of color: a brief report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:952-953. doi:10.1111/pde.14578

- Litchman G, Nair PA, Atwater AR, et al. Contact dermatitis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated February 9, 2023. Accessed September 25, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459230/

- Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, et al. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1722-1729. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.049

- Rodriguez-Homs LG, Liu B, Green CL, et al. Duration of dermatitis before patch test appointment is associated with distance to clinic and county poverty rate. Dermatitis. 2020;31:259-264. doi:10.1097 /DER.0000000000000581

- Foschi CM, Tam I, Schalock PC, et al. Patch testing results in skin of color: a retrospective review from the Massachusetts General Hospital contact dermatitis clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:452-454. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.09.022

- Qian MF, Li S, Honari G, et al. Sociodemographic disparities in patch testing for commercially insured patients with dermatitis: a retrospective analysis of administrative claims data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1411-1413. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.08.041

- Young K, Collis RW, Sheinbein D, et al. Retrospective review of pediatric patch testing results in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:953-954. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.11.031

- Kadyk DL, Hall S, Belsito DV. Quality of life of patients with allergic contact dermatitis: an exploratory analysis by gender, ethnicity, age, and occupation. Dermatitis. 2004;15:117-124.

THE COMPARISON

A An 11-year-old Hispanic boy with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) on the abdomen. The geometric nature of the eruption and proximity to the belt buckle were highly suggestive of ACD to nickel; patch testing was not needed.

B A Black woman with ACD on the neck. A punch biopsy demonstrated spongiotic dermatitis that was typical of ACD. The diagnosis was supported by the patient’s history of dermatitis that developed after new products were applied to the hair. The patient declined patch testing.

C A Hispanic man with ACD on hair-bearing areas on the face where hair dye was used. The patient’s history of dermatitis following the application of hair dye was highly suggestive of ACD; patch testing confirmed the allergen was paraphenylenediamine (PPD).

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is an inflammatory condition of the skin caused by an immunologic response to one or more identifiable allergens. A delayed-type immune response (type IV hypersensitivity reaction) occurs after the skin is reexposed to an offending allergen.1 Severe pruritus is the main symptom of ACD in the early stages, accompanied by erythema, vesicles, and scaling in a distinct pattern corresponding to the allergen’s contact with the skin.2 Delayed widespread dermatitis after exposure to an allergen—a phenomenon known as autoeczematization (id reaction)—also may occur.3

The gold-standard diagnostic tool for ACD is patch testing, in which the patient is re-exposed to the suspected contact allergen(s) and observed for the development of dermatitis.4 However, ACD can be diagnosed with a detailed patient history including occupation, hobbies, personal care practices, and possible triggers with subsequent rashes. Thorough clinical examination of the skin is paramount. Indicators of possible ACD include dermatitis that persists despite use of appropriate treatment, an unexplained flare of previously quiescent dermatitis, and a diagnosis of dermatitis without a clear cause.1

Hairdressers, health care workers, and metal workers are at higher risk for ACD.5 Occupational ACD has notable socioeconomic implications, as it can result in frequent sick days, inability to perform tasks at work, and in some cases job loss.6

Patients with atopic dermatitis have impaired barrier function of the skin, permitting the entrance of allergens and subsequent sensitization.7 Allergic contact dermatitis is a challenge to manage, as complete avoidance of the allergen may not be possible.8

The underrepresentation of patients with skin of color (SOC) in educational materials as well as socioeconomic health disparities may contribute to the lower rates of diagnosis, patch testing, and treatment of ACD in this patient population.

Epidemiology

An ACD prevalence of 15.2% was reported in a study of 793 Danish patients who underwent skin prick and patch testing.9 Alinaghi et al10 conducted a meta-analysis of 20,107 patients across 28 studies who were patch tested to determine the prevalence of ACD in the general population. The researchers concluded that 20.1% (95% CI, 16.8%- 23.7%) of the general population experienced ACD. They analyzed 22 studies to determine the prevalence of ACD based on specific geographic area including 18,709 individuals from Europe with a prevalence of 19.5% (95% CI, 15.8%-23.4%), 1639 individuals from North America with a prevalence of 20.6% (95% CI, 9.2%-35.2%), and 2 studies from China (no other studies from Asia found) with a prevalence of 20.6% (95% CI, 17.4%-23.9%). Researchers did not find data from studies conducted in Africa or South America.10

The current available epidemiologic data on ACD are not representative of SOC populations. DeLeo et al11 looked at patch test reaction patterns in association with race and ethnicity in a large sample size (N=19,457); 17,803 (92.9%) of these patients were White and only 1360 (7.1%) were Black. Large-scale, inclusive studies are needed, which can only be achieved with increased suspicion for ACD and increased access to patch testing.

Allergic contact dermatitis is more common in women, with nickel being the most frequently identified allergen (Figure, A).10 Personal care products often are linked to ACD (Figure, B). An analysis of data from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group revealed that the top 5 personal care product allergens were methylisothiazolinone (a preservative), fragrance mix I, balsam of Peru, quaternium-15 (a preservative), and paraphenylenediamine (PPD)(a common component of hair dye) (Figure, C).12

There is a paucity of epidemiologic data among various ethnic groups; however, a few studies have suggested that there is no difference in the frequency rates of positive patch test results in Black vs White populations.11,13,14 One study of patch test results from 114 Black patients and 877 White patients at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation in Ohio demonstrated a similar allergy frequency of 43.0% and 43.6%, respectively.13 However, there were differences in the types of allergen sensitization. Black patients had higher positive patch test rates for PPD than White patients (10.6% vs 4.5%). Black men had a higher frequency of sensitivity to PPD (21.2% vs 4.2%) and imidazolidinyl urea (a formaldehyde-releasing preservative) (9.1% vs 2.6%) compared to White men.13

Ethnicity and cultural practices influence epidemiologic patterns of ACD. Darker hair dyes used in Black patients14 and deeply pigmented PPD dye found in henna tattoos used in Indian and Black patients15 may lead to increased sensitization to PPD. Allergic contact dermatitis due to formaldehyde is more common in White patients, possibly due to more frequent use of formaldehyde-containing moisturizers, shampoos, and creams.15

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

In patients with SOC, the clinical features of ACD vary, posing a diagnostic challenge. Hyperpigmentation, lichenification, and induration are more likely to be seen than the papules, vesicles, and erythematous dermatitis often described in lighter skin tones or acute ACD. Erythema can be difficult to assess on darker skin and may appear violaceous or very faint pink.16

Worth noting

A high index of suspicion is necessary when interpreting patch tests in patients with SOC, as patch test kits use a reading plate with graduated intensities of erythema, papulation, and vesicular reactions to determine the likelihood of ACD. The potential contact allergens are placed on the skin on day 1 and covered. Then, on day 3 the allergens are removed. The skin is clinically evaluated using visual assessment and skin palpation. The reactions are graded as negative, irritant reaction, equivocal, weak positive, strong positive, or extreme reaction at around days 3 and 5 to capture both early and delayed reactions.17 A patch test may be positive even if obvious signs of erythema are not appreciated as expected.

Adjusting the lighting in the examination room, including side lighting, or using a blue background can be helpful in identifying erythema in darker skin tones.15,16,18 Palpation of the skin also is useful, as even slight texture changes and induration are indicators of a possible skin reaction to the test allergen.15

Health disparity highlight

Clinical photographs of ACD and patch test results in patients with SOC are not commonplace in the literature. Positive patch test results in patients with darker skin tones vary from those of patients with lighter skin tones, and if the clinician reading the patch test result is not familiar with the findings in darker skin tones, the diagnosis may be delayed or missed.15

Furthermore, Scott et al15 highlighted that many dermatology residency training programs have a paucity of SOC education in their curriculum. This lack of representation may contribute to the diagnostic challenges encountered by health care providers.

Timely access to health care and education as well as economic stability are essential for the successful management of patients with ACD. Some individuals with SOC have been disproportionately affected by social determinants of health. Rodriguez-Homs et al19 demonstrated that the distance needed to travel to a clinic and the poverty rate of the county the patient lives in play a role in referral to a clinician specializing in contact dermatitis.

A retrospective registry review of 2310 patients undergoing patch testing at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston revealed that 2.5% were Black, 5.5% were Latinx, 8.3% were Asian, and the remaining 83.7% were White.20 Qian et al21 also looked at patch testing patterns among various sociodemographic groups (N=1,107,530) and found that 69% of patients were White and 59% were female. Rates of patch testing among patients who were Black, lesser educated, male, lower income, and younger (children aged 0–12 years) were significantly lower than for other groups when ACD was suspected (P<.0001).21 The lower rates of patch testing in patients with SOC may be due to low suspicion of diagnosis, low referral rates due to limited medical insurance, and financial instability, as well as other socioeconomic factors.20

Tamazian et al16 reviewed pediatric populations at 13 US centers and found that Black children received patch testing less frequently than White and Hispanic children. Another review of pediatric patch testing in patients with SOC found that a less comprehensive panel of allergens was used in this population.22

The key to resolution of ACD is removal of the offending antigen, and if patients are not being tested, then they risk having a prolonged and complicated course of ACD with a poor prognosis. Patients with SOC also experience greater negative psychosocial impact due to ACD disease burden.21,23

The lower rates of patch testing in Black patients cannot solely be attributed to difficulty diagnosing ACD in darker skin tones; it is likely due to the impact of social determinants of health. Alleviating health disparities will improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

THE COMPARISON

A An 11-year-old Hispanic boy with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) on the abdomen. The geometric nature of the eruption and proximity to the belt buckle were highly suggestive of ACD to nickel; patch testing was not needed.

B A Black woman with ACD on the neck. A punch biopsy demonstrated spongiotic dermatitis that was typical of ACD. The diagnosis was supported by the patient’s history of dermatitis that developed after new products were applied to the hair. The patient declined patch testing.

C A Hispanic man with ACD on hair-bearing areas on the face where hair dye was used. The patient’s history of dermatitis following the application of hair dye was highly suggestive of ACD; patch testing confirmed the allergen was paraphenylenediamine (PPD).

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is an inflammatory condition of the skin caused by an immunologic response to one or more identifiable allergens. A delayed-type immune response (type IV hypersensitivity reaction) occurs after the skin is reexposed to an offending allergen.1 Severe pruritus is the main symptom of ACD in the early stages, accompanied by erythema, vesicles, and scaling in a distinct pattern corresponding to the allergen’s contact with the skin.2 Delayed widespread dermatitis after exposure to an allergen—a phenomenon known as autoeczematization (id reaction)—also may occur.3

The gold-standard diagnostic tool for ACD is patch testing, in which the patient is re-exposed to the suspected contact allergen(s) and observed for the development of dermatitis.4 However, ACD can be diagnosed with a detailed patient history including occupation, hobbies, personal care practices, and possible triggers with subsequent rashes. Thorough clinical examination of the skin is paramount. Indicators of possible ACD include dermatitis that persists despite use of appropriate treatment, an unexplained flare of previously quiescent dermatitis, and a diagnosis of dermatitis without a clear cause.1

Hairdressers, health care workers, and metal workers are at higher risk for ACD.5 Occupational ACD has notable socioeconomic implications, as it can result in frequent sick days, inability to perform tasks at work, and in some cases job loss.6

Patients with atopic dermatitis have impaired barrier function of the skin, permitting the entrance of allergens and subsequent sensitization.7 Allergic contact dermatitis is a challenge to manage, as complete avoidance of the allergen may not be possible.8

The underrepresentation of patients with skin of color (SOC) in educational materials as well as socioeconomic health disparities may contribute to the lower rates of diagnosis, patch testing, and treatment of ACD in this patient population.

Epidemiology

An ACD prevalence of 15.2% was reported in a study of 793 Danish patients who underwent skin prick and patch testing.9 Alinaghi et al10 conducted a meta-analysis of 20,107 patients across 28 studies who were patch tested to determine the prevalence of ACD in the general population. The researchers concluded that 20.1% (95% CI, 16.8%- 23.7%) of the general population experienced ACD. They analyzed 22 studies to determine the prevalence of ACD based on specific geographic area including 18,709 individuals from Europe with a prevalence of 19.5% (95% CI, 15.8%-23.4%), 1639 individuals from North America with a prevalence of 20.6% (95% CI, 9.2%-35.2%), and 2 studies from China (no other studies from Asia found) with a prevalence of 20.6% (95% CI, 17.4%-23.9%). Researchers did not find data from studies conducted in Africa or South America.10

The current available epidemiologic data on ACD are not representative of SOC populations. DeLeo et al11 looked at patch test reaction patterns in association with race and ethnicity in a large sample size (N=19,457); 17,803 (92.9%) of these patients were White and only 1360 (7.1%) were Black. Large-scale, inclusive studies are needed, which can only be achieved with increased suspicion for ACD and increased access to patch testing.

Allergic contact dermatitis is more common in women, with nickel being the most frequently identified allergen (Figure, A).10 Personal care products often are linked to ACD (Figure, B). An analysis of data from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group revealed that the top 5 personal care product allergens were methylisothiazolinone (a preservative), fragrance mix I, balsam of Peru, quaternium-15 (a preservative), and paraphenylenediamine (PPD)(a common component of hair dye) (Figure, C).12

There is a paucity of epidemiologic data among various ethnic groups; however, a few studies have suggested that there is no difference in the frequency rates of positive patch test results in Black vs White populations.11,13,14 One study of patch test results from 114 Black patients and 877 White patients at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation in Ohio demonstrated a similar allergy frequency of 43.0% and 43.6%, respectively.13 However, there were differences in the types of allergen sensitization. Black patients had higher positive patch test rates for PPD than White patients (10.6% vs 4.5%). Black men had a higher frequency of sensitivity to PPD (21.2% vs 4.2%) and imidazolidinyl urea (a formaldehyde-releasing preservative) (9.1% vs 2.6%) compared to White men.13

Ethnicity and cultural practices influence epidemiologic patterns of ACD. Darker hair dyes used in Black patients14 and deeply pigmented PPD dye found in henna tattoos used in Indian and Black patients15 may lead to increased sensitization to PPD. Allergic contact dermatitis due to formaldehyde is more common in White patients, possibly due to more frequent use of formaldehyde-containing moisturizers, shampoos, and creams.15

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

In patients with SOC, the clinical features of ACD vary, posing a diagnostic challenge. Hyperpigmentation, lichenification, and induration are more likely to be seen than the papules, vesicles, and erythematous dermatitis often described in lighter skin tones or acute ACD. Erythema can be difficult to assess on darker skin and may appear violaceous or very faint pink.16

Worth noting

A high index of suspicion is necessary when interpreting patch tests in patients with SOC, as patch test kits use a reading plate with graduated intensities of erythema, papulation, and vesicular reactions to determine the likelihood of ACD. The potential contact allergens are placed on the skin on day 1 and covered. Then, on day 3 the allergens are removed. The skin is clinically evaluated using visual assessment and skin palpation. The reactions are graded as negative, irritant reaction, equivocal, weak positive, strong positive, or extreme reaction at around days 3 and 5 to capture both early and delayed reactions.17 A patch test may be positive even if obvious signs of erythema are not appreciated as expected.

Adjusting the lighting in the examination room, including side lighting, or using a blue background can be helpful in identifying erythema in darker skin tones.15,16,18 Palpation of the skin also is useful, as even slight texture changes and induration are indicators of a possible skin reaction to the test allergen.15

Health disparity highlight

Clinical photographs of ACD and patch test results in patients with SOC are not commonplace in the literature. Positive patch test results in patients with darker skin tones vary from those of patients with lighter skin tones, and if the clinician reading the patch test result is not familiar with the findings in darker skin tones, the diagnosis may be delayed or missed.15

Furthermore, Scott et al15 highlighted that many dermatology residency training programs have a paucity of SOC education in their curriculum. This lack of representation may contribute to the diagnostic challenges encountered by health care providers.

Timely access to health care and education as well as economic stability are essential for the successful management of patients with ACD. Some individuals with SOC have been disproportionately affected by social determinants of health. Rodriguez-Homs et al19 demonstrated that the distance needed to travel to a clinic and the poverty rate of the county the patient lives in play a role in referral to a clinician specializing in contact dermatitis.

A retrospective registry review of 2310 patients undergoing patch testing at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston revealed that 2.5% were Black, 5.5% were Latinx, 8.3% were Asian, and the remaining 83.7% were White.20 Qian et al21 also looked at patch testing patterns among various sociodemographic groups (N=1,107,530) and found that 69% of patients were White and 59% were female. Rates of patch testing among patients who were Black, lesser educated, male, lower income, and younger (children aged 0–12 years) were significantly lower than for other groups when ACD was suspected (P<.0001).21 The lower rates of patch testing in patients with SOC may be due to low suspicion of diagnosis, low referral rates due to limited medical insurance, and financial instability, as well as other socioeconomic factors.20

Tamazian et al16 reviewed pediatric populations at 13 US centers and found that Black children received patch testing less frequently than White and Hispanic children. Another review of pediatric patch testing in patients with SOC found that a less comprehensive panel of allergens was used in this population.22

The key to resolution of ACD is removal of the offending antigen, and if patients are not being tested, then they risk having a prolonged and complicated course of ACD with a poor prognosis. Patients with SOC also experience greater negative psychosocial impact due to ACD disease burden.21,23

The lower rates of patch testing in Black patients cannot solely be attributed to difficulty diagnosing ACD in darker skin tones; it is likely due to the impact of social determinants of health. Alleviating health disparities will improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

- Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient diagnosis and evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74: 1029-1040. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1139

- Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

- Bertoli MJ, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Autoeczematization: a strange id reaction of the skin. Cutis. 2021;108:163-166. doi:10.12788/cutis.0342

- Johansen JD, Bonefeld CM, Schwensen JFB, et al. Novel insights into contact dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149:1162-1171. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2022.02.002

- Karagounis TK, Cohen DE. Occupational hand dermatitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2023;23:201-212. doi:10.1007/s11882-023-01070-5

- Cvetkovski RS, Rothman KJ, Olsen J, et al. Relation between diagnoses on severity, sick leave and loss of job among patients with occupational hand eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:93-98. doi:10.1111/j .1365-2133.2005.06415.x

- Owen JL, Vakharia PP, Silverberg JI. The role and diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:293-302. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0340-7

- Brites GS, Ferreira I, Sebastião AI, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: from pathophysiology to development of new preventive strategies. Pharmacol Res. 2020;162:105282. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105282

- Nielsen NH, Menne T. The relationship between IgE‐mediated and cell‐mediated hypersensitivities in an unselected Danish population: the Glostrup Allergy Study, Denmark. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:669-672. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb06967.x

- Alinaghi F, Bennike NH, Egeberg A, et al. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:77-85. doi:10.1111/cod.13119

- DeLeo VA, Alexis A, Warshaw EM, et al. The association of race/ethnicity and patch test results: North American Contact Dermatitis Group, 1998- 2006. Dermatitis. 2016;27:288-292. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000220

- Warshaw EM, Schlarbaum JP, Silverberg JI, et al. Contact dermatitis to personal care products is increasing (but different!) in males and females: North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 1996-2016. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1446-1455. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.003

- Dickel H, Taylor JS, Evey P, et al. Comparison of patch test results with a standard series among white and black racial groups. Am J Contact Dermatol. 2001;12:77-82. doi:10.1053/ajcd.2001.20110

- DeLeo VA, Taylor SC, Belsito DV, et al. The effect of race and ethnicity on patch test results. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl):S107-S112. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120792

- Scott I, Atwater AR, Reeder M. Update on contact dermatitis and patch testing in patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2021;108:10-12. doi:10.12788/cutis.0292

- Tamazian S, Oboite M, Treat JR. Patch testing in skin of color: a brief report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:952-953. doi:10.1111/pde.14578

- Litchman G, Nair PA, Atwater AR, et al. Contact dermatitis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated February 9, 2023. Accessed September 25, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459230/

- Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, et al. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1722-1729. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.049

- Rodriguez-Homs LG, Liu B, Green CL, et al. Duration of dermatitis before patch test appointment is associated with distance to clinic and county poverty rate. Dermatitis. 2020;31:259-264. doi:10.1097 /DER.0000000000000581

- Foschi CM, Tam I, Schalock PC, et al. Patch testing results in skin of color: a retrospective review from the Massachusetts General Hospital contact dermatitis clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:452-454. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.09.022

- Qian MF, Li S, Honari G, et al. Sociodemographic disparities in patch testing for commercially insured patients with dermatitis: a retrospective analysis of administrative claims data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1411-1413. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.08.041

- Young K, Collis RW, Sheinbein D, et al. Retrospective review of pediatric patch testing results in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:953-954. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.11.031

- Kadyk DL, Hall S, Belsito DV. Quality of life of patients with allergic contact dermatitis: an exploratory analysis by gender, ethnicity, age, and occupation. Dermatitis. 2004;15:117-124.

- Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient diagnosis and evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74: 1029-1040. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1139

- Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

- Bertoli MJ, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Autoeczematization: a strange id reaction of the skin. Cutis. 2021;108:163-166. doi:10.12788/cutis.0342

- Johansen JD, Bonefeld CM, Schwensen JFB, et al. Novel insights into contact dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149:1162-1171. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2022.02.002

- Karagounis TK, Cohen DE. Occupational hand dermatitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2023;23:201-212. doi:10.1007/s11882-023-01070-5

- Cvetkovski RS, Rothman KJ, Olsen J, et al. Relation between diagnoses on severity, sick leave and loss of job among patients with occupational hand eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:93-98. doi:10.1111/j .1365-2133.2005.06415.x

- Owen JL, Vakharia PP, Silverberg JI. The role and diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:293-302. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0340-7

- Brites GS, Ferreira I, Sebastião AI, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: from pathophysiology to development of new preventive strategies. Pharmacol Res. 2020;162:105282. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105282

- Nielsen NH, Menne T. The relationship between IgE‐mediated and cell‐mediated hypersensitivities in an unselected Danish population: the Glostrup Allergy Study, Denmark. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:669-672. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb06967.x

- Alinaghi F, Bennike NH, Egeberg A, et al. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:77-85. doi:10.1111/cod.13119

- DeLeo VA, Alexis A, Warshaw EM, et al. The association of race/ethnicity and patch test results: North American Contact Dermatitis Group, 1998- 2006. Dermatitis. 2016;27:288-292. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000220

- Warshaw EM, Schlarbaum JP, Silverberg JI, et al. Contact dermatitis to personal care products is increasing (but different!) in males and females: North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 1996-2016. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1446-1455. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.003

- Dickel H, Taylor JS, Evey P, et al. Comparison of patch test results with a standard series among white and black racial groups. Am J Contact Dermatol. 2001;12:77-82. doi:10.1053/ajcd.2001.20110

- DeLeo VA, Taylor SC, Belsito DV, et al. The effect of race and ethnicity on patch test results. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl):S107-S112. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120792

- Scott I, Atwater AR, Reeder M. Update on contact dermatitis and patch testing in patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2021;108:10-12. doi:10.12788/cutis.0292

- Tamazian S, Oboite M, Treat JR. Patch testing in skin of color: a brief report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:952-953. doi:10.1111/pde.14578

- Litchman G, Nair PA, Atwater AR, et al. Contact dermatitis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated February 9, 2023. Accessed September 25, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459230/

- Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, et al. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1722-1729. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.049

- Rodriguez-Homs LG, Liu B, Green CL, et al. Duration of dermatitis before patch test appointment is associated with distance to clinic and county poverty rate. Dermatitis. 2020;31:259-264. doi:10.1097 /DER.0000000000000581

- Foschi CM, Tam I, Schalock PC, et al. Patch testing results in skin of color: a retrospective review from the Massachusetts General Hospital contact dermatitis clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:452-454. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.09.022

- Qian MF, Li S, Honari G, et al. Sociodemographic disparities in patch testing for commercially insured patients with dermatitis: a retrospective analysis of administrative claims data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1411-1413. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.08.041

- Young K, Collis RW, Sheinbein D, et al. Retrospective review of pediatric patch testing results in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:953-954. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.11.031