User login

Screening Tests for Depression

A Case of Metastatic Chromophobe Renal Cell Carcinoma Masked as Suspected Hepatic Abscesses

Finding new liver lesions on imaging during a febrile illness may indicate hepatic abscesses or malignancy. These can be difficult to diagnose with imaging alone. Differentiating between infectious and neoplastic etiologies may require additional images and/or tissue samples.

Hepatic abscesses are more commonly seen with other abdominal or biliary infections while metastatic disease usually presents in patients with active cancer or on surveillance imaging. While renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common malignant neoplasm of the kidney, chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (chRCC) is a rare subtype that comprises only 5% of RCC cases.1 We present a case of a patient with numerous new liver lesions and fever, initially thought to be hepatic abscesses, who was found to have metastatic chRCC.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 53 year-old male with a history of stage 2 chRCC and right radical nephrectomy 2 years prior presented to the emergency department following 1 week of drenching night sweats, fatigue, and subjective fevers. In addition, the patient reported gradually progressive, dull, right upper-quadrant abdominal pain. He noted no other acute medical complaints at the time of presentation. His history was notable for hyperlipidemia. His only surgery was the nephrectomy 2 years earlier. The patient reported no alcohol, tobacco, or drug use, any recent travel, or pet or animal exposure. On admission, he was afebrile with normal heart rate and was normotensive. His physical examination was remarkable for hepatomegaly with right upper-quadrant abdominal tenderness to palpation with a negative Murphy sign. There were otherwise no abnormal cardiovascular, respiratory, or skin findings.

Laboratory tests during initial evaluation were notable for hemoglobin of 10.0 g/dL, white blood cell count of 16.7×103 μL, alkaline phosphatase of 213 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase of 185 U/L, and alanine aminotransferase of 36 U/L. Screening tests for viral hepatitis A, B, and C were negative. Additional tests for HIV, rapid plasma reagin, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and toxoplasma were negative. Tests for antimitochondrial, antismooth muscle, and serum antinuclear antibodies were negative.

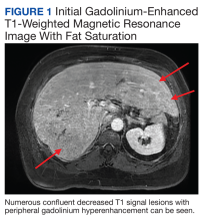

Chest X-ray did not reveal any acute cardiopulmonary process. Computed tomography with contrast of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated numerous hypodensities within the right hepatic lobe. Right upper-quadrant ultrasound demonstrated multiple hyperechoic foci throughout the liver. confluent decreased T1 signal lesions with peripheral gadolinium hyperenhancement were evident on Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with fat saturation demonstrated numerous (Figure 1).

Liver biopsy and tissue cultures demonstrated normal hepatic tissue and no organism growth. Blood cultures demonstrated no growth. The patient was empirically treated with IV ceftriaxone 1 g daily and metronidazole 500 mg every 8 hours for suspected hepatic abscesses after he was admitted to the hospital.

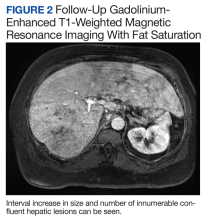

The patient’s symptoms initially improved following antibiotic treatment; however, he reported recurrence of the initial symptoms2 months later at a follow-up appointment with gastroenterology. Liver-associated enzymes also remained elevated despite 4 weeks of antibiotic treatment. Repeat gadolinium-enhanced T1 fat-saturated MRI demonstrated an interval increase in size and number of confluent hepatic lesions throughout the liver (Figure 2).

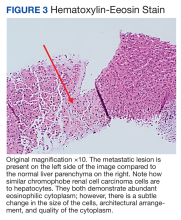

A repeat liver biopsy revealed metastatic chRCC (Figures 3 and 4) that was both morphologically and immunohistochemically similar to the first pathologic diagnosis made following nephrectomy. The first liver biopsy likely did not sample the metastatic lesions that were present but instead sampled the surrounding normal liver. The patient was initiated on lenvatinib and everolimus therapy with oncology, a recommended regimen per the National Comprehensive Cancer Network for patients with nonclear cell RCC.1

DISCUSSION

Chromophobe RCC is a rare form of RCC that has a recurrence-free survival of > 80% when treated in early stages.2 These neoplasms represent only 3000 to 6000 new cases of RCC annually, with an even lower incidence (6% to 7%) resulting in metastatic disease. The liver is the most common site of metastases (39%).2 Previously reported metastatic chRCC hepatic lesions have been incidentally noted on imaging with asymptomatic clinical presentations. In contrast to our patient, most documented cases report metastatic chRCC as a solitary hepatic lesion.3-7

A noteworthy genetic association with ChRCC is the Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, which is an autosomal-dominant genetic disorder that results from germline mutations in the tumor suppressor folliculin gene located on chromosome 17.8 This syndrome is characterized by the development of various benign and malignant tumors, particularly chRCC. Our patient appeared to have a sporadic chRCC with the absence of other tumors and negative family history for malignancies. On his initial staging imaging, in accordance with National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, our patient was identified only as having a 10-cm right renal mass and 1 benign regional lymph node with an otherwise unremarkable computed tomography of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, corresponding to stage 2 cancer.

Common causes of hepatic abscesses, the other potential diagnosis of concern for the patient, were biliary infections, portal vein ascension from abdominal sources, arterial translocation due to bacteremia, and local invasion due to suppuration of adjacent tissue.9 Incidence for hepatic abscesses increases with comorbidities such as diabetes, cirrhosis, malignancy, immunosuppression, and malnutrition.10 Candida is also a common culprit when there are multiple, small abscesses, often in immunocompromised patients.11 Given the high mortality rates associated with hepatic abscesses, prompt treatment is imperative.10,12 Since the clinical signs and symptoms for hepatic abscesses are nonspecific (abdominal pain, fever, and malaise) and liver function tests can vary, the diagnosis primarily relies on imaging or tissue sampling.9

It can be difficult to distinguish abscesses from metastatic lesions based on imaging alone without microbiologic and pathologic confirmation.11,13,14 There are certain radiologic characteristics that have been found to favor abscesses over metastasis, including parenchymal enhancement, arterial rim enhancement, and perilesional hyperemia.15 However, previously described hallmark characteristics of hepatic abscesses, such as the “cluster sign” demonstrating early stages of abscess coalescence, have also been seen in some hepatic metastases.16

CONCLUSIONS

This patient highlights the presentation of a rare case of metastatic chRCC with multiple hepatic lesions. While often differentiated clinically, radiographically, or histologically, malignancy and abscess can be difficult to differentiate in a patient with fevers and leukocytosis with hepatic lesions.17 Early diagnosis of hepatic abscesses and initiation of antibiotic therapy are essential. In cases when it is challenging to characterize the hepatic lesions, repeated tissue sampling and imaging can help direct therapy. Attention should be paid to a previous history of malignancy and should raise suspicion for metastatic disease, particularly with misleading imaging studies and tissue samples.

Acknowledgments

This case was presented as a poster presentation at the Tri-Service American College of Physicians Meeting, September 7-10, 2022, San Antonio, Texas.

1. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Kidney cancer (version 2.2024). Accessed February 5, 2024. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/kidney.pdf

2. Vera-Badillo FE, Conde E, Duran I. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma: a review of an uncommon entity. Int J Urol. 2012;19(10):894-900.doi:10.1111/j.1442-2042.2012.03079.x

3. Lordan JT, Fawcett WJ, Karanjia ND. Solitary liver metastasis of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma 20 years after nephrectomy treated by hepatic resection. Urology. 2008;72(1):230.e5-6. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2007.11.134

4. Talarico F, Buli P, Iusco D, Sangiorgi A, Jovine E. Synchronous nephrectomy and right hepatectomy for metastatic chromophobe renal cell carcinoma: report of a case and review of the literature. Chir Ital. 2007;59(2):257-261.

5. Aslam MI, Spencer L, Garcea G, et al. A case of liver metastasis from an oncocytoma with a focal area of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma: a wolf in sheep’s clothing. Int J Surg Pathol. 2008;17(2):158-162. doi:10.1177/1066896908318741

6. Kyoda Y, Kobayashi K, Takahashi A, et al. Liver metastasis with portal vein tumor thrombosis as a late recurrence of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. Article in Japanese. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2009;55(1):23-25.

7. Talarico F, Capizzi D, Iusco DR. Solitary liver metastasis of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma 17 years after nephrectomy. a case report and review of the literature. Ann Ital Chir. 2013;84(ePub):S2239253X13021816.

8. Garje R, Elhag D, Yasin HA, Acharya L, Vaena D, Dahmoush L. Comprehensive review of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;160:103287. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103287

9. Pearl R, Pancu D, Legome E. Hepatic abscess. J Emerg Med. 2005;28:337-339.doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2004.08.024

10. Huang CJ, Pitt HA, Lipsett PA, et al. Pyogenic hepatic abscess. Changing trends over 42 years. Ann Surg. 1996;223(5):600-607; discussion 607-609.

11. Özgül E. Multiple pyogenic liver abscesses mimicking metastatic disease on computed tomography. Cureus. 2020;12(2):e7050. doi:10.7759/cureus.7050

12. Kuo SH, Lee YT, Li CR, et al. Mortality in Emergency Department Sepsis score as a prognostic indicator in patients with pyogenic liver abscess. Am J Emerg Med. 201331(6):916-921.

13. Lardière-Deguelte S, Ragot E, Amroun K, et al. Hepatic abscess: diagnosis and management. J Visc Surg. 2015;152(4):231-243. doi:10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2015.01.013

14. Halvorsen RA, Korobkin M, Foster WL, Silverman PM, Thompson WM. The variable CT appearance of hepatic abscesses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;142(5):941-946. doi:10.2214/ajr.142.5.941

15. Oh JG, Choi SY, Lee MH, et al. Differentiation of hepatic abscess from metastasis on contrast-enhanced dynamic computed tomography in patients with a history of extrahepatic malignancy: emphasis on dynamic change of arterial rim enhancement. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2019;44(2):529-538.

16. Jeffrey RB Jr, Tolentino CS, Chang FC, Federle MP. CT of small pyogenic hepatic abscesses: the cluster sign. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;151(3):487-489. doi:10.2214/ajr.151.3.487

17. Mavilia MG, Molina M, Wu GY. The evolving nature of hepatic abscess: a review. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2016;4(2):158-168. doi:10.14218/JCTH.2016.00004

Finding new liver lesions on imaging during a febrile illness may indicate hepatic abscesses or malignancy. These can be difficult to diagnose with imaging alone. Differentiating between infectious and neoplastic etiologies may require additional images and/or tissue samples.

Hepatic abscesses are more commonly seen with other abdominal or biliary infections while metastatic disease usually presents in patients with active cancer or on surveillance imaging. While renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common malignant neoplasm of the kidney, chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (chRCC) is a rare subtype that comprises only 5% of RCC cases.1 We present a case of a patient with numerous new liver lesions and fever, initially thought to be hepatic abscesses, who was found to have metastatic chRCC.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 53 year-old male with a history of stage 2 chRCC and right radical nephrectomy 2 years prior presented to the emergency department following 1 week of drenching night sweats, fatigue, and subjective fevers. In addition, the patient reported gradually progressive, dull, right upper-quadrant abdominal pain. He noted no other acute medical complaints at the time of presentation. His history was notable for hyperlipidemia. His only surgery was the nephrectomy 2 years earlier. The patient reported no alcohol, tobacco, or drug use, any recent travel, or pet or animal exposure. On admission, he was afebrile with normal heart rate and was normotensive. His physical examination was remarkable for hepatomegaly with right upper-quadrant abdominal tenderness to palpation with a negative Murphy sign. There were otherwise no abnormal cardiovascular, respiratory, or skin findings.

Laboratory tests during initial evaluation were notable for hemoglobin of 10.0 g/dL, white blood cell count of 16.7×103 μL, alkaline phosphatase of 213 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase of 185 U/L, and alanine aminotransferase of 36 U/L. Screening tests for viral hepatitis A, B, and C were negative. Additional tests for HIV, rapid plasma reagin, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and toxoplasma were negative. Tests for antimitochondrial, antismooth muscle, and serum antinuclear antibodies were negative.

Chest X-ray did not reveal any acute cardiopulmonary process. Computed tomography with contrast of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated numerous hypodensities within the right hepatic lobe. Right upper-quadrant ultrasound demonstrated multiple hyperechoic foci throughout the liver. confluent decreased T1 signal lesions with peripheral gadolinium hyperenhancement were evident on Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with fat saturation demonstrated numerous (Figure 1).

Liver biopsy and tissue cultures demonstrated normal hepatic tissue and no organism growth. Blood cultures demonstrated no growth. The patient was empirically treated with IV ceftriaxone 1 g daily and metronidazole 500 mg every 8 hours for suspected hepatic abscesses after he was admitted to the hospital.

The patient’s symptoms initially improved following antibiotic treatment; however, he reported recurrence of the initial symptoms2 months later at a follow-up appointment with gastroenterology. Liver-associated enzymes also remained elevated despite 4 weeks of antibiotic treatment. Repeat gadolinium-enhanced T1 fat-saturated MRI demonstrated an interval increase in size and number of confluent hepatic lesions throughout the liver (Figure 2).

A repeat liver biopsy revealed metastatic chRCC (Figures 3 and 4) that was both morphologically and immunohistochemically similar to the first pathologic diagnosis made following nephrectomy. The first liver biopsy likely did not sample the metastatic lesions that were present but instead sampled the surrounding normal liver. The patient was initiated on lenvatinib and everolimus therapy with oncology, a recommended regimen per the National Comprehensive Cancer Network for patients with nonclear cell RCC.1

DISCUSSION

Chromophobe RCC is a rare form of RCC that has a recurrence-free survival of > 80% when treated in early stages.2 These neoplasms represent only 3000 to 6000 new cases of RCC annually, with an even lower incidence (6% to 7%) resulting in metastatic disease. The liver is the most common site of metastases (39%).2 Previously reported metastatic chRCC hepatic lesions have been incidentally noted on imaging with asymptomatic clinical presentations. In contrast to our patient, most documented cases report metastatic chRCC as a solitary hepatic lesion.3-7

A noteworthy genetic association with ChRCC is the Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, which is an autosomal-dominant genetic disorder that results from germline mutations in the tumor suppressor folliculin gene located on chromosome 17.8 This syndrome is characterized by the development of various benign and malignant tumors, particularly chRCC. Our patient appeared to have a sporadic chRCC with the absence of other tumors and negative family history for malignancies. On his initial staging imaging, in accordance with National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, our patient was identified only as having a 10-cm right renal mass and 1 benign regional lymph node with an otherwise unremarkable computed tomography of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, corresponding to stage 2 cancer.

Common causes of hepatic abscesses, the other potential diagnosis of concern for the patient, were biliary infections, portal vein ascension from abdominal sources, arterial translocation due to bacteremia, and local invasion due to suppuration of adjacent tissue.9 Incidence for hepatic abscesses increases with comorbidities such as diabetes, cirrhosis, malignancy, immunosuppression, and malnutrition.10 Candida is also a common culprit when there are multiple, small abscesses, often in immunocompromised patients.11 Given the high mortality rates associated with hepatic abscesses, prompt treatment is imperative.10,12 Since the clinical signs and symptoms for hepatic abscesses are nonspecific (abdominal pain, fever, and malaise) and liver function tests can vary, the diagnosis primarily relies on imaging or tissue sampling.9

It can be difficult to distinguish abscesses from metastatic lesions based on imaging alone without microbiologic and pathologic confirmation.11,13,14 There are certain radiologic characteristics that have been found to favor abscesses over metastasis, including parenchymal enhancement, arterial rim enhancement, and perilesional hyperemia.15 However, previously described hallmark characteristics of hepatic abscesses, such as the “cluster sign” demonstrating early stages of abscess coalescence, have also been seen in some hepatic metastases.16

CONCLUSIONS

This patient highlights the presentation of a rare case of metastatic chRCC with multiple hepatic lesions. While often differentiated clinically, radiographically, or histologically, malignancy and abscess can be difficult to differentiate in a patient with fevers and leukocytosis with hepatic lesions.17 Early diagnosis of hepatic abscesses and initiation of antibiotic therapy are essential. In cases when it is challenging to characterize the hepatic lesions, repeated tissue sampling and imaging can help direct therapy. Attention should be paid to a previous history of malignancy and should raise suspicion for metastatic disease, particularly with misleading imaging studies and tissue samples.

Acknowledgments

This case was presented as a poster presentation at the Tri-Service American College of Physicians Meeting, September 7-10, 2022, San Antonio, Texas.

Finding new liver lesions on imaging during a febrile illness may indicate hepatic abscesses or malignancy. These can be difficult to diagnose with imaging alone. Differentiating between infectious and neoplastic etiologies may require additional images and/or tissue samples.

Hepatic abscesses are more commonly seen with other abdominal or biliary infections while metastatic disease usually presents in patients with active cancer or on surveillance imaging. While renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common malignant neoplasm of the kidney, chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (chRCC) is a rare subtype that comprises only 5% of RCC cases.1 We present a case of a patient with numerous new liver lesions and fever, initially thought to be hepatic abscesses, who was found to have metastatic chRCC.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 53 year-old male with a history of stage 2 chRCC and right radical nephrectomy 2 years prior presented to the emergency department following 1 week of drenching night sweats, fatigue, and subjective fevers. In addition, the patient reported gradually progressive, dull, right upper-quadrant abdominal pain. He noted no other acute medical complaints at the time of presentation. His history was notable for hyperlipidemia. His only surgery was the nephrectomy 2 years earlier. The patient reported no alcohol, tobacco, or drug use, any recent travel, or pet or animal exposure. On admission, he was afebrile with normal heart rate and was normotensive. His physical examination was remarkable for hepatomegaly with right upper-quadrant abdominal tenderness to palpation with a negative Murphy sign. There were otherwise no abnormal cardiovascular, respiratory, or skin findings.

Laboratory tests during initial evaluation were notable for hemoglobin of 10.0 g/dL, white blood cell count of 16.7×103 μL, alkaline phosphatase of 213 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase of 185 U/L, and alanine aminotransferase of 36 U/L. Screening tests for viral hepatitis A, B, and C were negative. Additional tests for HIV, rapid plasma reagin, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and toxoplasma were negative. Tests for antimitochondrial, antismooth muscle, and serum antinuclear antibodies were negative.

Chest X-ray did not reveal any acute cardiopulmonary process. Computed tomography with contrast of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated numerous hypodensities within the right hepatic lobe. Right upper-quadrant ultrasound demonstrated multiple hyperechoic foci throughout the liver. confluent decreased T1 signal lesions with peripheral gadolinium hyperenhancement were evident on Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with fat saturation demonstrated numerous (Figure 1).

Liver biopsy and tissue cultures demonstrated normal hepatic tissue and no organism growth. Blood cultures demonstrated no growth. The patient was empirically treated with IV ceftriaxone 1 g daily and metronidazole 500 mg every 8 hours for suspected hepatic abscesses after he was admitted to the hospital.

The patient’s symptoms initially improved following antibiotic treatment; however, he reported recurrence of the initial symptoms2 months later at a follow-up appointment with gastroenterology. Liver-associated enzymes also remained elevated despite 4 weeks of antibiotic treatment. Repeat gadolinium-enhanced T1 fat-saturated MRI demonstrated an interval increase in size and number of confluent hepatic lesions throughout the liver (Figure 2).

A repeat liver biopsy revealed metastatic chRCC (Figures 3 and 4) that was both morphologically and immunohistochemically similar to the first pathologic diagnosis made following nephrectomy. The first liver biopsy likely did not sample the metastatic lesions that were present but instead sampled the surrounding normal liver. The patient was initiated on lenvatinib and everolimus therapy with oncology, a recommended regimen per the National Comprehensive Cancer Network for patients with nonclear cell RCC.1

DISCUSSION

Chromophobe RCC is a rare form of RCC that has a recurrence-free survival of > 80% when treated in early stages.2 These neoplasms represent only 3000 to 6000 new cases of RCC annually, with an even lower incidence (6% to 7%) resulting in metastatic disease. The liver is the most common site of metastases (39%).2 Previously reported metastatic chRCC hepatic lesions have been incidentally noted on imaging with asymptomatic clinical presentations. In contrast to our patient, most documented cases report metastatic chRCC as a solitary hepatic lesion.3-7

A noteworthy genetic association with ChRCC is the Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, which is an autosomal-dominant genetic disorder that results from germline mutations in the tumor suppressor folliculin gene located on chromosome 17.8 This syndrome is characterized by the development of various benign and malignant tumors, particularly chRCC. Our patient appeared to have a sporadic chRCC with the absence of other tumors and negative family history for malignancies. On his initial staging imaging, in accordance with National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, our patient was identified only as having a 10-cm right renal mass and 1 benign regional lymph node with an otherwise unremarkable computed tomography of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, corresponding to stage 2 cancer.

Common causes of hepatic abscesses, the other potential diagnosis of concern for the patient, were biliary infections, portal vein ascension from abdominal sources, arterial translocation due to bacteremia, and local invasion due to suppuration of adjacent tissue.9 Incidence for hepatic abscesses increases with comorbidities such as diabetes, cirrhosis, malignancy, immunosuppression, and malnutrition.10 Candida is also a common culprit when there are multiple, small abscesses, often in immunocompromised patients.11 Given the high mortality rates associated with hepatic abscesses, prompt treatment is imperative.10,12 Since the clinical signs and symptoms for hepatic abscesses are nonspecific (abdominal pain, fever, and malaise) and liver function tests can vary, the diagnosis primarily relies on imaging or tissue sampling.9

It can be difficult to distinguish abscesses from metastatic lesions based on imaging alone without microbiologic and pathologic confirmation.11,13,14 There are certain radiologic characteristics that have been found to favor abscesses over metastasis, including parenchymal enhancement, arterial rim enhancement, and perilesional hyperemia.15 However, previously described hallmark characteristics of hepatic abscesses, such as the “cluster sign” demonstrating early stages of abscess coalescence, have also been seen in some hepatic metastases.16

CONCLUSIONS

This patient highlights the presentation of a rare case of metastatic chRCC with multiple hepatic lesions. While often differentiated clinically, radiographically, or histologically, malignancy and abscess can be difficult to differentiate in a patient with fevers and leukocytosis with hepatic lesions.17 Early diagnosis of hepatic abscesses and initiation of antibiotic therapy are essential. In cases when it is challenging to characterize the hepatic lesions, repeated tissue sampling and imaging can help direct therapy. Attention should be paid to a previous history of malignancy and should raise suspicion for metastatic disease, particularly with misleading imaging studies and tissue samples.

Acknowledgments

This case was presented as a poster presentation at the Tri-Service American College of Physicians Meeting, September 7-10, 2022, San Antonio, Texas.

1. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Kidney cancer (version 2.2024). Accessed February 5, 2024. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/kidney.pdf

2. Vera-Badillo FE, Conde E, Duran I. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma: a review of an uncommon entity. Int J Urol. 2012;19(10):894-900.doi:10.1111/j.1442-2042.2012.03079.x

3. Lordan JT, Fawcett WJ, Karanjia ND. Solitary liver metastasis of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma 20 years after nephrectomy treated by hepatic resection. Urology. 2008;72(1):230.e5-6. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2007.11.134

4. Talarico F, Buli P, Iusco D, Sangiorgi A, Jovine E. Synchronous nephrectomy and right hepatectomy for metastatic chromophobe renal cell carcinoma: report of a case and review of the literature. Chir Ital. 2007;59(2):257-261.

5. Aslam MI, Spencer L, Garcea G, et al. A case of liver metastasis from an oncocytoma with a focal area of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma: a wolf in sheep’s clothing. Int J Surg Pathol. 2008;17(2):158-162. doi:10.1177/1066896908318741

6. Kyoda Y, Kobayashi K, Takahashi A, et al. Liver metastasis with portal vein tumor thrombosis as a late recurrence of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. Article in Japanese. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2009;55(1):23-25.

7. Talarico F, Capizzi D, Iusco DR. Solitary liver metastasis of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma 17 years after nephrectomy. a case report and review of the literature. Ann Ital Chir. 2013;84(ePub):S2239253X13021816.

8. Garje R, Elhag D, Yasin HA, Acharya L, Vaena D, Dahmoush L. Comprehensive review of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;160:103287. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103287

9. Pearl R, Pancu D, Legome E. Hepatic abscess. J Emerg Med. 2005;28:337-339.doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2004.08.024

10. Huang CJ, Pitt HA, Lipsett PA, et al. Pyogenic hepatic abscess. Changing trends over 42 years. Ann Surg. 1996;223(5):600-607; discussion 607-609.

11. Özgül E. Multiple pyogenic liver abscesses mimicking metastatic disease on computed tomography. Cureus. 2020;12(2):e7050. doi:10.7759/cureus.7050

12. Kuo SH, Lee YT, Li CR, et al. Mortality in Emergency Department Sepsis score as a prognostic indicator in patients with pyogenic liver abscess. Am J Emerg Med. 201331(6):916-921.

13. Lardière-Deguelte S, Ragot E, Amroun K, et al. Hepatic abscess: diagnosis and management. J Visc Surg. 2015;152(4):231-243. doi:10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2015.01.013

14. Halvorsen RA, Korobkin M, Foster WL, Silverman PM, Thompson WM. The variable CT appearance of hepatic abscesses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;142(5):941-946. doi:10.2214/ajr.142.5.941

15. Oh JG, Choi SY, Lee MH, et al. Differentiation of hepatic abscess from metastasis on contrast-enhanced dynamic computed tomography in patients with a history of extrahepatic malignancy: emphasis on dynamic change of arterial rim enhancement. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2019;44(2):529-538.

16. Jeffrey RB Jr, Tolentino CS, Chang FC, Federle MP. CT of small pyogenic hepatic abscesses: the cluster sign. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;151(3):487-489. doi:10.2214/ajr.151.3.487

17. Mavilia MG, Molina M, Wu GY. The evolving nature of hepatic abscess: a review. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2016;4(2):158-168. doi:10.14218/JCTH.2016.00004

1. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Kidney cancer (version 2.2024). Accessed February 5, 2024. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/kidney.pdf

2. Vera-Badillo FE, Conde E, Duran I. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma: a review of an uncommon entity. Int J Urol. 2012;19(10):894-900.doi:10.1111/j.1442-2042.2012.03079.x

3. Lordan JT, Fawcett WJ, Karanjia ND. Solitary liver metastasis of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma 20 years after nephrectomy treated by hepatic resection. Urology. 2008;72(1):230.e5-6. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2007.11.134

4. Talarico F, Buli P, Iusco D, Sangiorgi A, Jovine E. Synchronous nephrectomy and right hepatectomy for metastatic chromophobe renal cell carcinoma: report of a case and review of the literature. Chir Ital. 2007;59(2):257-261.

5. Aslam MI, Spencer L, Garcea G, et al. A case of liver metastasis from an oncocytoma with a focal area of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma: a wolf in sheep’s clothing. Int J Surg Pathol. 2008;17(2):158-162. doi:10.1177/1066896908318741

6. Kyoda Y, Kobayashi K, Takahashi A, et al. Liver metastasis with portal vein tumor thrombosis as a late recurrence of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. Article in Japanese. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2009;55(1):23-25.

7. Talarico F, Capizzi D, Iusco DR. Solitary liver metastasis of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma 17 years after nephrectomy. a case report and review of the literature. Ann Ital Chir. 2013;84(ePub):S2239253X13021816.

8. Garje R, Elhag D, Yasin HA, Acharya L, Vaena D, Dahmoush L. Comprehensive review of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;160:103287. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103287

9. Pearl R, Pancu D, Legome E. Hepatic abscess. J Emerg Med. 2005;28:337-339.doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2004.08.024

10. Huang CJ, Pitt HA, Lipsett PA, et al. Pyogenic hepatic abscess. Changing trends over 42 years. Ann Surg. 1996;223(5):600-607; discussion 607-609.

11. Özgül E. Multiple pyogenic liver abscesses mimicking metastatic disease on computed tomography. Cureus. 2020;12(2):e7050. doi:10.7759/cureus.7050

12. Kuo SH, Lee YT, Li CR, et al. Mortality in Emergency Department Sepsis score as a prognostic indicator in patients with pyogenic liver abscess. Am J Emerg Med. 201331(6):916-921.

13. Lardière-Deguelte S, Ragot E, Amroun K, et al. Hepatic abscess: diagnosis and management. J Visc Surg. 2015;152(4):231-243. doi:10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2015.01.013

14. Halvorsen RA, Korobkin M, Foster WL, Silverman PM, Thompson WM. The variable CT appearance of hepatic abscesses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;142(5):941-946. doi:10.2214/ajr.142.5.941

15. Oh JG, Choi SY, Lee MH, et al. Differentiation of hepatic abscess from metastasis on contrast-enhanced dynamic computed tomography in patients with a history of extrahepatic malignancy: emphasis on dynamic change of arterial rim enhancement. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2019;44(2):529-538.

16. Jeffrey RB Jr, Tolentino CS, Chang FC, Federle MP. CT of small pyogenic hepatic abscesses: the cluster sign. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;151(3):487-489. doi:10.2214/ajr.151.3.487

17. Mavilia MG, Molina M, Wu GY. The evolving nature of hepatic abscess: a review. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2016;4(2):158-168. doi:10.14218/JCTH.2016.00004

Myasthenia Gravis: 5 Things to Know

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a rare autoimmune neurologic disorder that occurs when the transmission between nerves and muscles is disrupted. It is caused by autoantibodies against acetylcholine receptors (AChRs), which results in muscle weakness that is often fatigable and affects various muscles in the body, including those that move the eyes, eyelids, and limbs. Ocular MG affects only the muscles that move the eyes and eyelids, whereas generalized MG (gMG) affects muscles throughout the body. When MG occurs with a thymoma, it is called thymoma-associated MG and is considered a paraneoplastic disease. In severe cases of MG, patients can experience a myasthenic crisis (MC), during which respiratory muscles weaken and necessitate mechanical ventilation. Diagnosis of MG is based on clinical examination, and laboratory tests are used to confirm the diagnosis. Treatment options include cholinesterase enzyme inhibitors and immunosuppressive agents, which aim to either reduce symptoms or cause nonspecific immunosuppression, respectively, but do not target the pathogenetic autoantibodies that characterize the disease.

1. The most common age at onset of gMG is the second and third decades in women and the seventh and eighth decades in men.

MG has an annual incidence of approximately four to 30 new cases per million population. Prevalence rates range from 150 to 200 cases per million population, and they have steadily increased over the past 50 years. This increase in prevalence is probably the result of better disease recognition, aging of the population, and an increased life span in patients.

MG can occur at any age; however, onset is more common in females in the second and third decades and is more common in males in the seventh to eighth decades. Before age 40 years, the female-to-male ratio is 3:1, and after age 50 years, the female-to-male ratio is 3:2.

2. gMG commonly weakens muscles responsible for eye movement, facial expressions, and functions such as chewing, swallowing, and speaking.

gMG typically manifests as muscle weakness that worsens with repeated use. Patients often report that their function is best in the morning, with more pronounced weakness at the end of the day. Permanent muscle damage is rare, however, and maximal muscle strength is often good.

Extraocular muscles are more commonly affected, as twitch fibers in these muscles develop tension faster, have a higher frequency of synaptic firing than limb muscles, and have fewer AChRs, making them more susceptible to fatigue. Patients present asymmetrically; intermittent drooping of the upper eyelid (ptosis) and double vision (diplopia) are the most common symptoms.

Muscles innervated by the cranial nerves (bulbar muscles) are involved in 60% of patients with gMG and can lead to fatigable chewing, reduced facial expression, speech difficulties (dysarthria), and weakness of swallowing (dysphagia). Up to 15% of patients initially present with bulbar muscle involvement, including dysarthria and painless dysphagia.

3. Emotional stress can trigger an MC.

MC is a complication of MG characterized by worsening muscle weakness that results in respiratory failure and necessitates mechanical ventilation.

MC is often the result of respiratory muscle weakness but can also be due to bulbar weakness with upper airway collapse. MC can occur in 15%-20% of patients within the first 2-3 years of the disease; however, it can also be the first presentation of MG in 18%-28% of cases.

MC can be triggered by multiple causes, including emotional or physical stress. The most common precipitant is infection; other precipitants include surgery, pregnancy, perimenstrual state, certain medications, tapering of immune-modulating medications, exposure to temperature extremes, pain, and sleep deprivation. Approximately one third to one half of patients with MC may have no obvious cause.

4. High levels of anti-AChR antibodies strongly indicate MG, but normal levels do not rule it out.

All patients with a clinical history suggestive of MG should be tested for antibodies for confirmation. Most patients have anti-AChR antibodies (~85%), and those without have anti–muscle-specific kinase (MuSK antibodies) (6%) and anti–lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4 (LRP4) antibodies (2%).

The sensitivity of anti-AChR antibodies varies depending on whether the antibody is binding, modulating, or blocking the AChR. Binding antibody is the most common, and when combined with blocking antibodies, has a high sensitivity (99.6%) and is typically tested first. Higher AChR antibody titers are more specific for the diagnosis of MG than are low titers, but they do not correlate with disease severity.

For patients who do not have anti-AChR antibodies but do have clinical features of MG, anti-MuSK antibodies and anti-LRP4 antibodies are measured to increase diagnostic sensitivity. For symptomatic patients who do not have any autoantibodies (seronegative), electrodiagnostic testing that shows evidence of impaired signal transmission at the neuromuscular junction is used to confirm the diagnosis of MG.

5. Studies suggest that over 75% of seropositive MG patients show distinct thymus abnormalities.

More than 75% of patients with AChR antibody–positive MG have abnormalities in their thymus, and up to 40% of patients with a thymoma have MG. Among those with thymic pathology, thymic hyperplasia is the most common type (85%), but other thymic tumors (mainly thymoma) can be present in up to 15% of cases. Thymomas are typically noninvasive and cortical, but in some rare cases, invasive thymic carcinoma can occur.

Given this overlap in presentation, it is recommended that patients with seronegative and seropositive MG undergo chest CT or MRI for evaluation of their anterior mediastinal anatomy and to detect the presence of a thymoma. For patients with MG and a thymoma, as well as selected (nonthymomatous) patients with seropositive or seronegative MG, therapeutic thymectomy is recommended.

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a rare autoimmune neurologic disorder that occurs when the transmission between nerves and muscles is disrupted. It is caused by autoantibodies against acetylcholine receptors (AChRs), which results in muscle weakness that is often fatigable and affects various muscles in the body, including those that move the eyes, eyelids, and limbs. Ocular MG affects only the muscles that move the eyes and eyelids, whereas generalized MG (gMG) affects muscles throughout the body. When MG occurs with a thymoma, it is called thymoma-associated MG and is considered a paraneoplastic disease. In severe cases of MG, patients can experience a myasthenic crisis (MC), during which respiratory muscles weaken and necessitate mechanical ventilation. Diagnosis of MG is based on clinical examination, and laboratory tests are used to confirm the diagnosis. Treatment options include cholinesterase enzyme inhibitors and immunosuppressive agents, which aim to either reduce symptoms or cause nonspecific immunosuppression, respectively, but do not target the pathogenetic autoantibodies that characterize the disease.

1. The most common age at onset of gMG is the second and third decades in women and the seventh and eighth decades in men.

MG has an annual incidence of approximately four to 30 new cases per million population. Prevalence rates range from 150 to 200 cases per million population, and they have steadily increased over the past 50 years. This increase in prevalence is probably the result of better disease recognition, aging of the population, and an increased life span in patients.

MG can occur at any age; however, onset is more common in females in the second and third decades and is more common in males in the seventh to eighth decades. Before age 40 years, the female-to-male ratio is 3:1, and after age 50 years, the female-to-male ratio is 3:2.

2. gMG commonly weakens muscles responsible for eye movement, facial expressions, and functions such as chewing, swallowing, and speaking.

gMG typically manifests as muscle weakness that worsens with repeated use. Patients often report that their function is best in the morning, with more pronounced weakness at the end of the day. Permanent muscle damage is rare, however, and maximal muscle strength is often good.

Extraocular muscles are more commonly affected, as twitch fibers in these muscles develop tension faster, have a higher frequency of synaptic firing than limb muscles, and have fewer AChRs, making them more susceptible to fatigue. Patients present asymmetrically; intermittent drooping of the upper eyelid (ptosis) and double vision (diplopia) are the most common symptoms.

Muscles innervated by the cranial nerves (bulbar muscles) are involved in 60% of patients with gMG and can lead to fatigable chewing, reduced facial expression, speech difficulties (dysarthria), and weakness of swallowing (dysphagia). Up to 15% of patients initially present with bulbar muscle involvement, including dysarthria and painless dysphagia.

3. Emotional stress can trigger an MC.

MC is a complication of MG characterized by worsening muscle weakness that results in respiratory failure and necessitates mechanical ventilation.

MC is often the result of respiratory muscle weakness but can also be due to bulbar weakness with upper airway collapse. MC can occur in 15%-20% of patients within the first 2-3 years of the disease; however, it can also be the first presentation of MG in 18%-28% of cases.

MC can be triggered by multiple causes, including emotional or physical stress. The most common precipitant is infection; other precipitants include surgery, pregnancy, perimenstrual state, certain medications, tapering of immune-modulating medications, exposure to temperature extremes, pain, and sleep deprivation. Approximately one third to one half of patients with MC may have no obvious cause.

4. High levels of anti-AChR antibodies strongly indicate MG, but normal levels do not rule it out.

All patients with a clinical history suggestive of MG should be tested for antibodies for confirmation. Most patients have anti-AChR antibodies (~85%), and those without have anti–muscle-specific kinase (MuSK antibodies) (6%) and anti–lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4 (LRP4) antibodies (2%).

The sensitivity of anti-AChR antibodies varies depending on whether the antibody is binding, modulating, or blocking the AChR. Binding antibody is the most common, and when combined with blocking antibodies, has a high sensitivity (99.6%) and is typically tested first. Higher AChR antibody titers are more specific for the diagnosis of MG than are low titers, but they do not correlate with disease severity.

For patients who do not have anti-AChR antibodies but do have clinical features of MG, anti-MuSK antibodies and anti-LRP4 antibodies are measured to increase diagnostic sensitivity. For symptomatic patients who do not have any autoantibodies (seronegative), electrodiagnostic testing that shows evidence of impaired signal transmission at the neuromuscular junction is used to confirm the diagnosis of MG.

5. Studies suggest that over 75% of seropositive MG patients show distinct thymus abnormalities.

More than 75% of patients with AChR antibody–positive MG have abnormalities in their thymus, and up to 40% of patients with a thymoma have MG. Among those with thymic pathology, thymic hyperplasia is the most common type (85%), but other thymic tumors (mainly thymoma) can be present in up to 15% of cases. Thymomas are typically noninvasive and cortical, but in some rare cases, invasive thymic carcinoma can occur.

Given this overlap in presentation, it is recommended that patients with seronegative and seropositive MG undergo chest CT or MRI for evaluation of their anterior mediastinal anatomy and to detect the presence of a thymoma. For patients with MG and a thymoma, as well as selected (nonthymomatous) patients with seropositive or seronegative MG, therapeutic thymectomy is recommended.

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a rare autoimmune neurologic disorder that occurs when the transmission between nerves and muscles is disrupted. It is caused by autoantibodies against acetylcholine receptors (AChRs), which results in muscle weakness that is often fatigable and affects various muscles in the body, including those that move the eyes, eyelids, and limbs. Ocular MG affects only the muscles that move the eyes and eyelids, whereas generalized MG (gMG) affects muscles throughout the body. When MG occurs with a thymoma, it is called thymoma-associated MG and is considered a paraneoplastic disease. In severe cases of MG, patients can experience a myasthenic crisis (MC), during which respiratory muscles weaken and necessitate mechanical ventilation. Diagnosis of MG is based on clinical examination, and laboratory tests are used to confirm the diagnosis. Treatment options include cholinesterase enzyme inhibitors and immunosuppressive agents, which aim to either reduce symptoms or cause nonspecific immunosuppression, respectively, but do not target the pathogenetic autoantibodies that characterize the disease.

1. The most common age at onset of gMG is the second and third decades in women and the seventh and eighth decades in men.

MG has an annual incidence of approximately four to 30 new cases per million population. Prevalence rates range from 150 to 200 cases per million population, and they have steadily increased over the past 50 years. This increase in prevalence is probably the result of better disease recognition, aging of the population, and an increased life span in patients.

MG can occur at any age; however, onset is more common in females in the second and third decades and is more common in males in the seventh to eighth decades. Before age 40 years, the female-to-male ratio is 3:1, and after age 50 years, the female-to-male ratio is 3:2.

2. gMG commonly weakens muscles responsible for eye movement, facial expressions, and functions such as chewing, swallowing, and speaking.

gMG typically manifests as muscle weakness that worsens with repeated use. Patients often report that their function is best in the morning, with more pronounced weakness at the end of the day. Permanent muscle damage is rare, however, and maximal muscle strength is often good.

Extraocular muscles are more commonly affected, as twitch fibers in these muscles develop tension faster, have a higher frequency of synaptic firing than limb muscles, and have fewer AChRs, making them more susceptible to fatigue. Patients present asymmetrically; intermittent drooping of the upper eyelid (ptosis) and double vision (diplopia) are the most common symptoms.

Muscles innervated by the cranial nerves (bulbar muscles) are involved in 60% of patients with gMG and can lead to fatigable chewing, reduced facial expression, speech difficulties (dysarthria), and weakness of swallowing (dysphagia). Up to 15% of patients initially present with bulbar muscle involvement, including dysarthria and painless dysphagia.

3. Emotional stress can trigger an MC.

MC is a complication of MG characterized by worsening muscle weakness that results in respiratory failure and necessitates mechanical ventilation.

MC is often the result of respiratory muscle weakness but can also be due to bulbar weakness with upper airway collapse. MC can occur in 15%-20% of patients within the first 2-3 years of the disease; however, it can also be the first presentation of MG in 18%-28% of cases.

MC can be triggered by multiple causes, including emotional or physical stress. The most common precipitant is infection; other precipitants include surgery, pregnancy, perimenstrual state, certain medications, tapering of immune-modulating medications, exposure to temperature extremes, pain, and sleep deprivation. Approximately one third to one half of patients with MC may have no obvious cause.

4. High levels of anti-AChR antibodies strongly indicate MG, but normal levels do not rule it out.

All patients with a clinical history suggestive of MG should be tested for antibodies for confirmation. Most patients have anti-AChR antibodies (~85%), and those without have anti–muscle-specific kinase (MuSK antibodies) (6%) and anti–lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4 (LRP4) antibodies (2%).

The sensitivity of anti-AChR antibodies varies depending on whether the antibody is binding, modulating, or blocking the AChR. Binding antibody is the most common, and when combined with blocking antibodies, has a high sensitivity (99.6%) and is typically tested first. Higher AChR antibody titers are more specific for the diagnosis of MG than are low titers, but they do not correlate with disease severity.

For patients who do not have anti-AChR antibodies but do have clinical features of MG, anti-MuSK antibodies and anti-LRP4 antibodies are measured to increase diagnostic sensitivity. For symptomatic patients who do not have any autoantibodies (seronegative), electrodiagnostic testing that shows evidence of impaired signal transmission at the neuromuscular junction is used to confirm the diagnosis of MG.

5. Studies suggest that over 75% of seropositive MG patients show distinct thymus abnormalities.

More than 75% of patients with AChR antibody–positive MG have abnormalities in their thymus, and up to 40% of patients with a thymoma have MG. Among those with thymic pathology, thymic hyperplasia is the most common type (85%), but other thymic tumors (mainly thymoma) can be present in up to 15% of cases. Thymomas are typically noninvasive and cortical, but in some rare cases, invasive thymic carcinoma can occur.

Given this overlap in presentation, it is recommended that patients with seronegative and seropositive MG undergo chest CT or MRI for evaluation of their anterior mediastinal anatomy and to detect the presence of a thymoma. For patients with MG and a thymoma, as well as selected (nonthymomatous) patients with seropositive or seronegative MG, therapeutic thymectomy is recommended.

Nurturing health equity in smoking cessation care

Thoracic Oncology And Chest Procedures Network

Lung Cancer Section

Lung cancer stands as the leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally, with its prevalence casting a long and challenging shadow. The most important risk factor for lung cancer is tobacco use, a relationship strongly substantiated by data. The impact of smoking cessation to reduce lung cancer incidence is underscored by the US Preventive Services Task Force, which mandates that smoking cessation services be an integral component of lung cancer screening programs.

However, beneath the surface of this overarching concern lies a web of factors contributing to racial and ethnic disparities in smoking cessation. Cultural intricacies play a pivotal role in shaping these disparities. Despite higher instances of light or intermediate smoking, racially ethnic minority groups in the general population often face greater challenges in achieving smoking cessation, as highlighted by Bacio, et al. Adding another layer to this complex scenario is the profound impact of sustained smoking during cancer treatment. Research suggests that for individuals diagnosed with lung cancer, smoking cessation can markedly boost treatment efficacy, reduce the risk of secondary tumors, and even double the chances of survival.1

A study by Harris, et al. delving into the preferences of current smokers within a lung cancer screening setting uncovered noteworthy insights.2 White participants exhibited a fourfold greater likelihood of favoring a digital format for receiving smoking cessation information, while their Black counterparts expressed a preference for face-to-face support, phone assistance, or printed materials.

Moreover, a meta-analysis conducted by Jabari, et al. sheds light on the efficacy of culturally targeted smoking interventions.3 This comprehensive review describes a dual-level approach to tailoring smoking cessation health interventions: surface and deep. Surface adaptations encompass elements like language and imagery, which aim to enhance the acceptability of interventions within specific communities. Simultaneously, deep-tailored elements identify culturally significant factors that can fundamentally influence the behavior of the target population. The findings of this meta-analysis reveal that the integration of culturally tailored components into standard interventions significantly enhances their efficacy in facilitating smoking cessation.

In conclusion, sustained smoking cessation is a crucial element in combating the global burden of lung cancer. Recognizing the importance of individualized approaches in health care, it is imperative to tailor smoking cessation communications and interventions to diverse cultural influences and socioeconomic factors. Culturally tailored smoking cessation programs that account for nuances specific to each community have the potential to significantly enhance their effectiveness. This necessitates a shift towards individualized smoking cessation care, with a targeted focus on increasing cessation rates among racial and ethnic minority groups. In doing so, we take a step closer to a more equitable landscape in the battle against lung cancer.

References

1. Dresler et al. Lung Cancer. 2003.

2. J Cancer Educ. 2018;33[5].

3. Addiction. 2023.

Thoracic Oncology And Chest Procedures Network

Lung Cancer Section

Lung cancer stands as the leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally, with its prevalence casting a long and challenging shadow. The most important risk factor for lung cancer is tobacco use, a relationship strongly substantiated by data. The impact of smoking cessation to reduce lung cancer incidence is underscored by the US Preventive Services Task Force, which mandates that smoking cessation services be an integral component of lung cancer screening programs.

However, beneath the surface of this overarching concern lies a web of factors contributing to racial and ethnic disparities in smoking cessation. Cultural intricacies play a pivotal role in shaping these disparities. Despite higher instances of light or intermediate smoking, racially ethnic minority groups in the general population often face greater challenges in achieving smoking cessation, as highlighted by Bacio, et al. Adding another layer to this complex scenario is the profound impact of sustained smoking during cancer treatment. Research suggests that for individuals diagnosed with lung cancer, smoking cessation can markedly boost treatment efficacy, reduce the risk of secondary tumors, and even double the chances of survival.1

A study by Harris, et al. delving into the preferences of current smokers within a lung cancer screening setting uncovered noteworthy insights.2 White participants exhibited a fourfold greater likelihood of favoring a digital format for receiving smoking cessation information, while their Black counterparts expressed a preference for face-to-face support, phone assistance, or printed materials.

Moreover, a meta-analysis conducted by Jabari, et al. sheds light on the efficacy of culturally targeted smoking interventions.3 This comprehensive review describes a dual-level approach to tailoring smoking cessation health interventions: surface and deep. Surface adaptations encompass elements like language and imagery, which aim to enhance the acceptability of interventions within specific communities. Simultaneously, deep-tailored elements identify culturally significant factors that can fundamentally influence the behavior of the target population. The findings of this meta-analysis reveal that the integration of culturally tailored components into standard interventions significantly enhances their efficacy in facilitating smoking cessation.

In conclusion, sustained smoking cessation is a crucial element in combating the global burden of lung cancer. Recognizing the importance of individualized approaches in health care, it is imperative to tailor smoking cessation communications and interventions to diverse cultural influences and socioeconomic factors. Culturally tailored smoking cessation programs that account for nuances specific to each community have the potential to significantly enhance their effectiveness. This necessitates a shift towards individualized smoking cessation care, with a targeted focus on increasing cessation rates among racial and ethnic minority groups. In doing so, we take a step closer to a more equitable landscape in the battle against lung cancer.

References

1. Dresler et al. Lung Cancer. 2003.

2. J Cancer Educ. 2018;33[5].

3. Addiction. 2023.

Thoracic Oncology And Chest Procedures Network

Lung Cancer Section

Lung cancer stands as the leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally, with its prevalence casting a long and challenging shadow. The most important risk factor for lung cancer is tobacco use, a relationship strongly substantiated by data. The impact of smoking cessation to reduce lung cancer incidence is underscored by the US Preventive Services Task Force, which mandates that smoking cessation services be an integral component of lung cancer screening programs.

However, beneath the surface of this overarching concern lies a web of factors contributing to racial and ethnic disparities in smoking cessation. Cultural intricacies play a pivotal role in shaping these disparities. Despite higher instances of light or intermediate smoking, racially ethnic minority groups in the general population often face greater challenges in achieving smoking cessation, as highlighted by Bacio, et al. Adding another layer to this complex scenario is the profound impact of sustained smoking during cancer treatment. Research suggests that for individuals diagnosed with lung cancer, smoking cessation can markedly boost treatment efficacy, reduce the risk of secondary tumors, and even double the chances of survival.1

A study by Harris, et al. delving into the preferences of current smokers within a lung cancer screening setting uncovered noteworthy insights.2 White participants exhibited a fourfold greater likelihood of favoring a digital format for receiving smoking cessation information, while their Black counterparts expressed a preference for face-to-face support, phone assistance, or printed materials.

Moreover, a meta-analysis conducted by Jabari, et al. sheds light on the efficacy of culturally targeted smoking interventions.3 This comprehensive review describes a dual-level approach to tailoring smoking cessation health interventions: surface and deep. Surface adaptations encompass elements like language and imagery, which aim to enhance the acceptability of interventions within specific communities. Simultaneously, deep-tailored elements identify culturally significant factors that can fundamentally influence the behavior of the target population. The findings of this meta-analysis reveal that the integration of culturally tailored components into standard interventions significantly enhances their efficacy in facilitating smoking cessation.

In conclusion, sustained smoking cessation is a crucial element in combating the global burden of lung cancer. Recognizing the importance of individualized approaches in health care, it is imperative to tailor smoking cessation communications and interventions to diverse cultural influences and socioeconomic factors. Culturally tailored smoking cessation programs that account for nuances specific to each community have the potential to significantly enhance their effectiveness. This necessitates a shift towards individualized smoking cessation care, with a targeted focus on increasing cessation rates among racial and ethnic minority groups. In doing so, we take a step closer to a more equitable landscape in the battle against lung cancer.

References

1. Dresler et al. Lung Cancer. 2003.

2. J Cancer Educ. 2018;33[5].

3. Addiction. 2023.

The not-so-silent night: Challenges in improving sleep in inpatients with Dr. Vineet Arora

Sleep Medicine Network

Nonrespiratory Sleep Section

Q: Are there interventions that can be readily implemented to improve sleep quality for hospitalized patients?

Dr. Arora: A patient’s first night in the hospital is probably not the night to liberalize sleep; you’re still figuring out whether they’re stable. But by the second or third day, you should be questioning—do you need vitals at night? Do you need a 4 AM blood draw?

We did an intervention called SIESTA that included both staff education about batching care and system-wide, electronic health record-based interventions to remind clinicians that as patients get better, you can deintensify their care. And we’re currently doing a randomized controlled trial of educating and empowering patients to ask their teams to help them get better sleep.

Q: Does hospital sleep deprivation affect patients after discharge?

Dr. Arora: Absolutely. “Posthospital syndrome” is the idea that 30 days after discharge, you’re vulnerable to getting readmitted – not because of the disease you came in with, but something else. And people who report sleep complaints in the hospital are more likely to be readmitted.

When people are acutely sleep deprived, their blood pressure is higher. Their blood sugar is higher. Their cytokine response and immune function are blunted. And our work shows that sleep deficits from the hospital continue even when you go home. Fatigue becomes a very real issue. And when you’re super fatigued, are you going to want to do your physical therapy? Will you be able to take care of yourself? Will you be able to learn and understand your discharge instructions?

We have such a huge gap to improve sleep. It’s of interest to people, but they are struggling with how to do it. And that’s where I think empowering frontline clinicians to take the lead is a great project for people to take on.

Vineet Arora, MD, MAPP, is the Dean for Medical Education at the University of Chicago and an academic hospitalist who specializes in the quality, safety, and experience of care delivered to hospitalized adults.

Sleep Medicine Network

Nonrespiratory Sleep Section

Q: Are there interventions that can be readily implemented to improve sleep quality for hospitalized patients?

Dr. Arora: A patient’s first night in the hospital is probably not the night to liberalize sleep; you’re still figuring out whether they’re stable. But by the second or third day, you should be questioning—do you need vitals at night? Do you need a 4 AM blood draw?

We did an intervention called SIESTA that included both staff education about batching care and system-wide, electronic health record-based interventions to remind clinicians that as patients get better, you can deintensify their care. And we’re currently doing a randomized controlled trial of educating and empowering patients to ask their teams to help them get better sleep.

Q: Does hospital sleep deprivation affect patients after discharge?

Dr. Arora: Absolutely. “Posthospital syndrome” is the idea that 30 days after discharge, you’re vulnerable to getting readmitted – not because of the disease you came in with, but something else. And people who report sleep complaints in the hospital are more likely to be readmitted.

When people are acutely sleep deprived, their blood pressure is higher. Their blood sugar is higher. Their cytokine response and immune function are blunted. And our work shows that sleep deficits from the hospital continue even when you go home. Fatigue becomes a very real issue. And when you’re super fatigued, are you going to want to do your physical therapy? Will you be able to take care of yourself? Will you be able to learn and understand your discharge instructions?

We have such a huge gap to improve sleep. It’s of interest to people, but they are struggling with how to do it. And that’s where I think empowering frontline clinicians to take the lead is a great project for people to take on.

Vineet Arora, MD, MAPP, is the Dean for Medical Education at the University of Chicago and an academic hospitalist who specializes in the quality, safety, and experience of care delivered to hospitalized adults.

Sleep Medicine Network

Nonrespiratory Sleep Section

Q: Are there interventions that can be readily implemented to improve sleep quality for hospitalized patients?

Dr. Arora: A patient’s first night in the hospital is probably not the night to liberalize sleep; you’re still figuring out whether they’re stable. But by the second or third day, you should be questioning—do you need vitals at night? Do you need a 4 AM blood draw?

We did an intervention called SIESTA that included both staff education about batching care and system-wide, electronic health record-based interventions to remind clinicians that as patients get better, you can deintensify their care. And we’re currently doing a randomized controlled trial of educating and empowering patients to ask their teams to help them get better sleep.

Q: Does hospital sleep deprivation affect patients after discharge?

Dr. Arora: Absolutely. “Posthospital syndrome” is the idea that 30 days after discharge, you’re vulnerable to getting readmitted – not because of the disease you came in with, but something else. And people who report sleep complaints in the hospital are more likely to be readmitted.

When people are acutely sleep deprived, their blood pressure is higher. Their blood sugar is higher. Their cytokine response and immune function are blunted. And our work shows that sleep deficits from the hospital continue even when you go home. Fatigue becomes a very real issue. And when you’re super fatigued, are you going to want to do your physical therapy? Will you be able to take care of yourself? Will you be able to learn and understand your discharge instructions?

We have such a huge gap to improve sleep. It’s of interest to people, but they are struggling with how to do it. And that’s where I think empowering frontline clinicians to take the lead is a great project for people to take on.

Vineet Arora, MD, MAPP, is the Dean for Medical Education at the University of Chicago and an academic hospitalist who specializes in the quality, safety, and experience of care delivered to hospitalized adults.

Compassionate extubation and beyond: Is there a need for more guidance in managing end-of-life in the intensive care unit?

Critical Care Network

Palliative and End-of-Life Care Section

For providers caring for critically ill patients, navigating death and dying in the intensive care unit (ICU) with proficiency and empathy is essential. Approximately 20% of deaths in the United States occur during or shortly after a stay in the ICU and approximately 40% of ICU deaths involve withdrawal of artificial life support (WOALS) or compassionate extubation.

This is a complex process that may involve advanced communication with family, expertise in mechanical ventilation, vasopressors, dialysis, and complex symptom management. Importantly, surrogate medical decision-making for a critically ill patient can be a challenging experience associated with anxiety and depression. How the team approaches WOALS can make a difference to both patients and decision-makers. Unfortunately, there is striking variation in practice and lack of guidance in navigating issues that arise at end-of-life in the ICU. One study of 2,814 hospitals in the US with ICU beds found that 52% had intensivists while 48% did not.2 This highlights the importance of developing resources focusing on end-of-life care in the ICU setting regardless of the providers’ educational training.

Important elements could include the role for protocol-based WOALS, use of oxygen, selection and dosing strategy of comfort-focused medications, establishing expectations, and addressing uncertainties. This would be meaningful in providing effective, ethical end-of-life care based on evidence-based strategies. While death may be unavoidable, a thoughtful approach can allow providers to bring dignity to the dying process and lessen the burden of an already difficult experience for patients and families alike.

References

1. Curtis JR, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186[7]:587-592.

2. Halpern NA, et al. Crit Care Med. 2019;47[4]:517-525.

Critical Care Network

Palliative and End-of-Life Care Section

For providers caring for critically ill patients, navigating death and dying in the intensive care unit (ICU) with proficiency and empathy is essential. Approximately 20% of deaths in the United States occur during or shortly after a stay in the ICU and approximately 40% of ICU deaths involve withdrawal of artificial life support (WOALS) or compassionate extubation.

This is a complex process that may involve advanced communication with family, expertise in mechanical ventilation, vasopressors, dialysis, and complex symptom management. Importantly, surrogate medical decision-making for a critically ill patient can be a challenging experience associated with anxiety and depression. How the team approaches WOALS can make a difference to both patients and decision-makers. Unfortunately, there is striking variation in practice and lack of guidance in navigating issues that arise at end-of-life in the ICU. One study of 2,814 hospitals in the US with ICU beds found that 52% had intensivists while 48% did not.2 This highlights the importance of developing resources focusing on end-of-life care in the ICU setting regardless of the providers’ educational training.

Important elements could include the role for protocol-based WOALS, use of oxygen, selection and dosing strategy of comfort-focused medications, establishing expectations, and addressing uncertainties. This would be meaningful in providing effective, ethical end-of-life care based on evidence-based strategies. While death may be unavoidable, a thoughtful approach can allow providers to bring dignity to the dying process and lessen the burden of an already difficult experience for patients and families alike.

References

1. Curtis JR, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186[7]:587-592.

2. Halpern NA, et al. Crit Care Med. 2019;47[4]:517-525.

Critical Care Network

Palliative and End-of-Life Care Section

For providers caring for critically ill patients, navigating death and dying in the intensive care unit (ICU) with proficiency and empathy is essential. Approximately 20% of deaths in the United States occur during or shortly after a stay in the ICU and approximately 40% of ICU deaths involve withdrawal of artificial life support (WOALS) or compassionate extubation.

This is a complex process that may involve advanced communication with family, expertise in mechanical ventilation, vasopressors, dialysis, and complex symptom management. Importantly, surrogate medical decision-making for a critically ill patient can be a challenging experience associated with anxiety and depression. How the team approaches WOALS can make a difference to both patients and decision-makers. Unfortunately, there is striking variation in practice and lack of guidance in navigating issues that arise at end-of-life in the ICU. One study of 2,814 hospitals in the US with ICU beds found that 52% had intensivists while 48% did not.2 This highlights the importance of developing resources focusing on end-of-life care in the ICU setting regardless of the providers’ educational training.

Important elements could include the role for protocol-based WOALS, use of oxygen, selection and dosing strategy of comfort-focused medications, establishing expectations, and addressing uncertainties. This would be meaningful in providing effective, ethical end-of-life care based on evidence-based strategies. While death may be unavoidable, a thoughtful approach can allow providers to bring dignity to the dying process and lessen the burden of an already difficult experience for patients and families alike.

References

1. Curtis JR, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186[7]:587-592.

2. Halpern NA, et al. Crit Care Med. 2019;47[4]:517-525.

What’s Eating You? Carpet Beetles (Dermestidae)

Carpet beetle larvae of the family Dermestidae have been documented to cause both acute and delayed hypersensitivity reactions in susceptible individuals. These larvae have specialized horizontal rows of spear-shaped hairs called hastisetae, which detach easily into the surrounding environment and are small enough to travel by air. Exposure to hastisetae has been tied to adverse effects ranging from dermatitis to rhinoconjunctivitis and acute asthma, with treatment being mostly empiric and symptom based. Due to the pervasiveness of carpet beetles in homes, improved awareness of dermestid-induced manifestations is valuable for clinicians.

Beetles in the Dermestidae family do not bite humans but have been reported to cause skin reactions in addition to other symptoms typical of an allergic reaction. Skin contact with larval hairs (hastisetae) of these insects—known as carpet, larder, or hide beetles — may cause urticarial or edematous papules that are mistaken for papular urticaria or arthropod bites. 1 There are approximately 500 to 700 species of carpet beetles worldwide. Carpet beetles are a clinically underrecognized cause of allergic contact dermatitis given their frequent presence in homes across the world. 2 Carpet beetle larvae feed on shed skin, feathers, hair, wool, book bindings, felt, leather, wood, silk, and sometimes grains and thus can be found nearly anywhere. Most symptom-inducing exposures to Dermestidae beetles occur occupationally, such as in museum curators working hands-on with collection materials and workers handling infested materials such as wool. 3,4 In-home Dermestidae exposure may lead to symptoms, especially if regularly worn clothing and bedding materials are infested. The broad palate of dermestid members has resulted in substantial contamination of stored materials such as flour and fabric in addition to the destruction of museum collections. 5-7

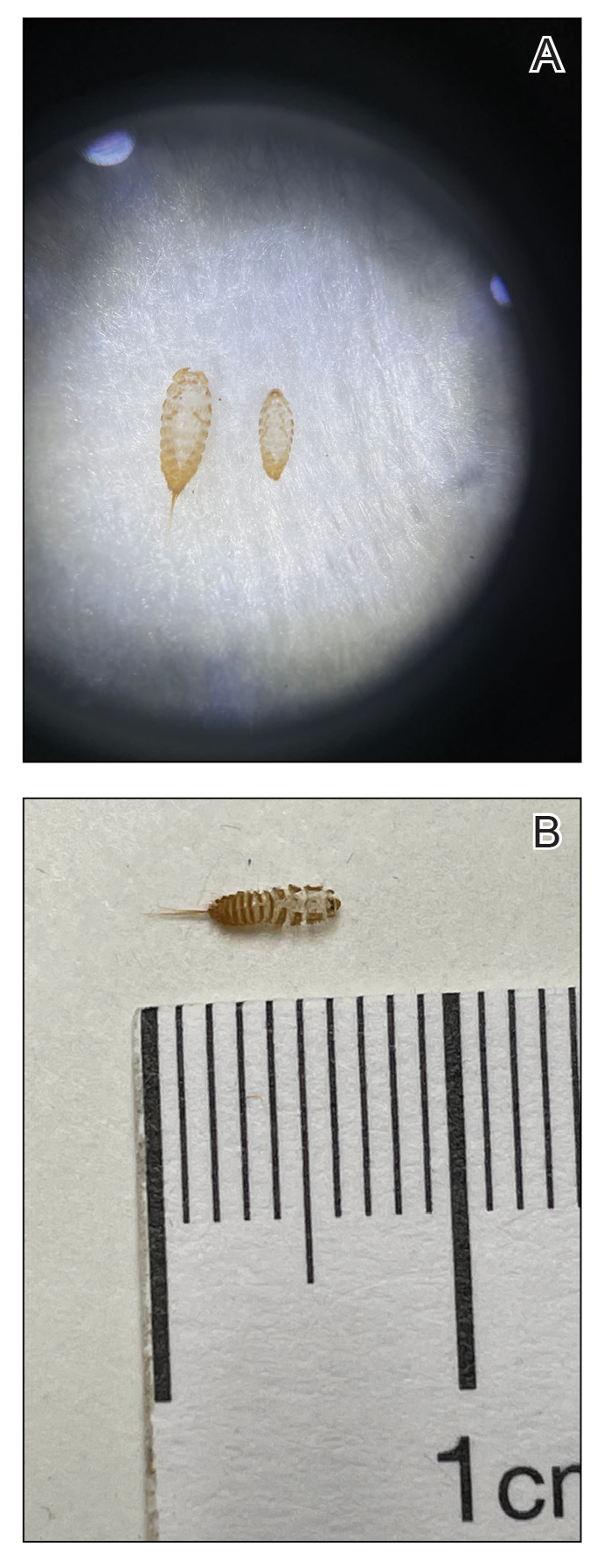

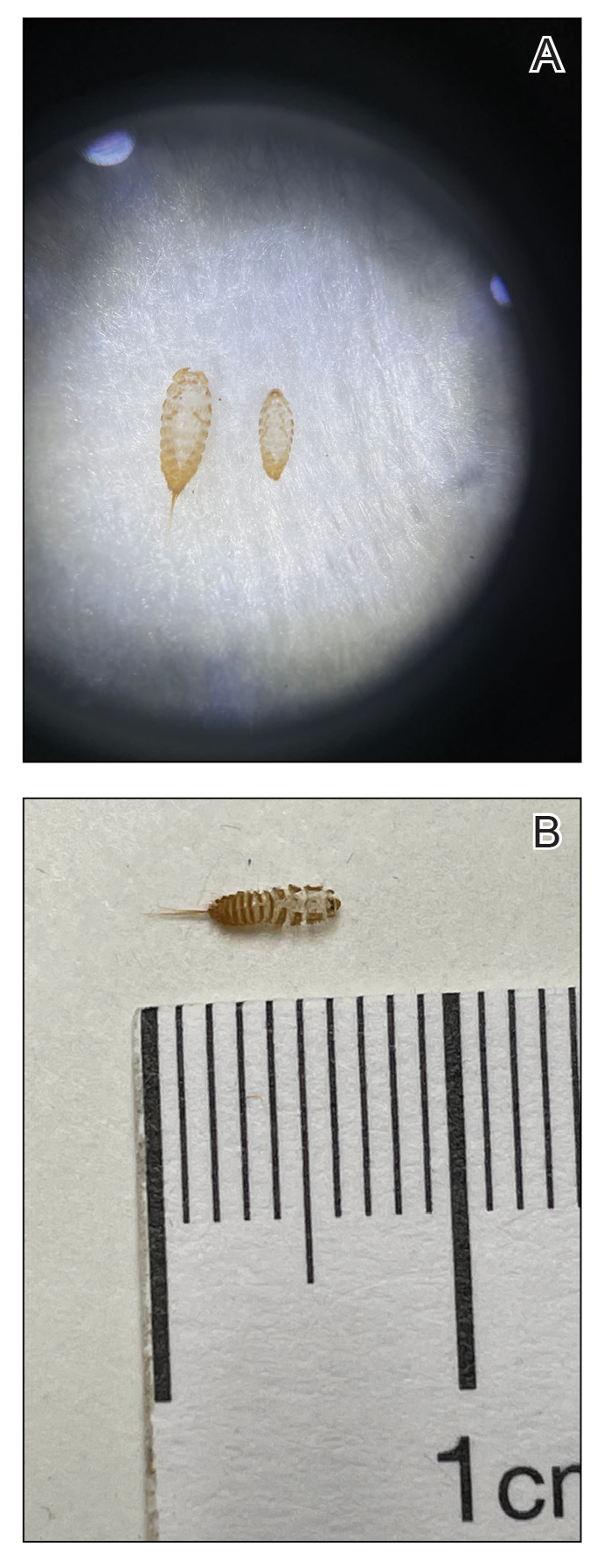

The larvae of some dermestid species, most commonly of the genera Anthrenus and Dermestes, are 2 to 3 mm in length and have detachable hairlike hastisetae that shed into the surrounding environment throughout larval development (Figure 1).8 The hastisetae, located on the thoracic and abdominal segments (tergites), serve as a larval defense mechanism. When prodded, the round, hairy, wormlike larvae tense up and can raise their abdominal tergites while splaying the hastisetae out in a fanlike manner.9 Similar to porcupine quills, the hastisetae easily detach and can entrap the appendages of invertebrate predators. Hastisetae are not known to be sharp enough to puncture human skin, but friction and irritation from skin contact and superficial sticking of the hastisetae into mucous membranes and noncornified epithelium, such as in the bronchial airways, are thought to induce hypersensitivity reactions in susceptible individuals.

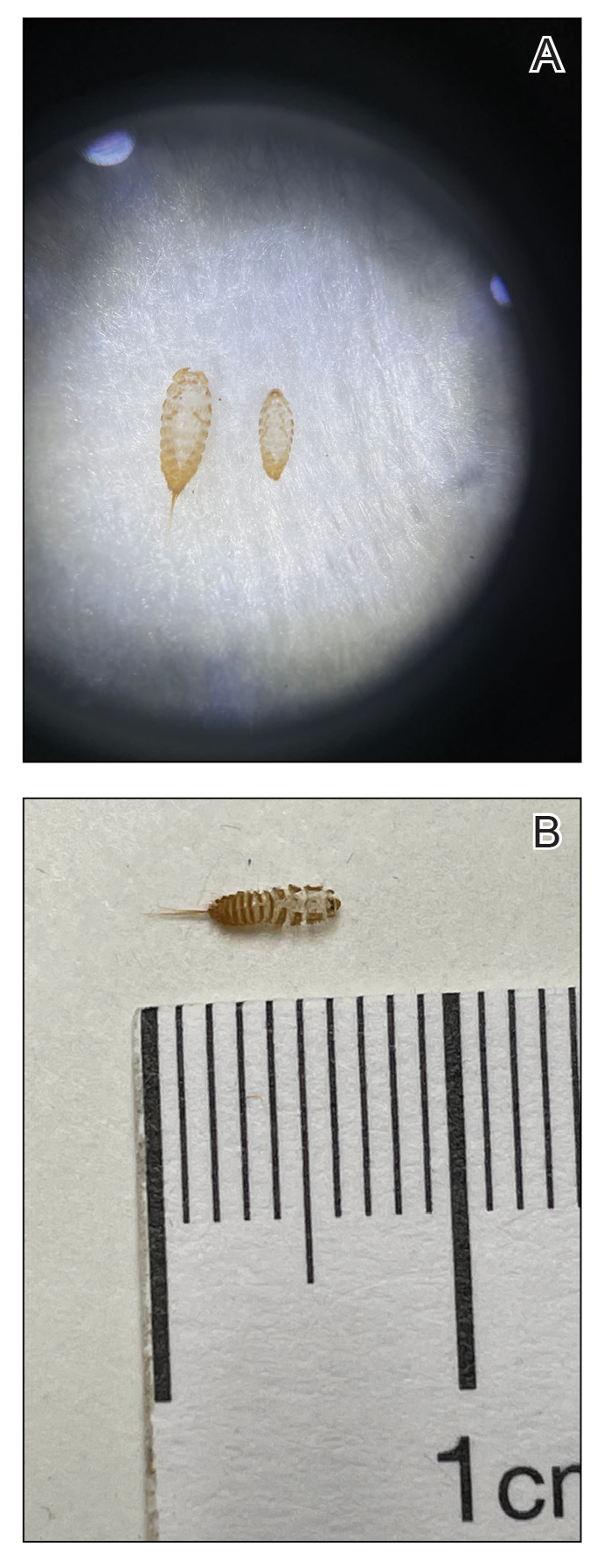

Additionally, hastisetae and the exoskeletons of both adult and larval dermestid beetles are composed mostly of chitin, which is highly allergenic. Chitin has been found to play a proinflammatory role in ocular inflammation, asthma, and bronchial reactivity via T helper cell (TH2)–mediated cellular interactions.10-12 Larvae shed their exoskeletons, including hastisetae, multiple times over the course of their development, which contributes to their potential allergen burden (Figure 2). Reports of positive prick and/or patch testing to larval components indicate some cases of both acute type 1 and delayed type 4 hypersensitivity reactions.4,8,13

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Multiple erythematous urticarial papules, papulopustules, and papulovesicles are the typical manifestations of dermestid dermatitis.3,4,13-16 Figure 3 demonstrates several characteristic edematous papules with background erythema. Unlike the clusters seen with flea and bed bug bites, dermestid-induced lesions typically are single and scattered, with a propensity for exposed limbs and the face. Exposure to hastisetae commonly results in classic allergic symptoms including rhinitis, conjunctivitis, coughing, wheezing, sneezing, and intranasal and periocular pruritus, even in those with no personal history of atopy.17-19 Lymphadenopathy, vasculitis, and allergic alveolitis also have been reported.20 A large infestation in which many individual beetles as well as larvae can be found in 1 or more areas of the inhabited structure has been reported to cause more severe symptoms, including acute eczema, otitis externa, lymphocytic vasculitis, and allergic alveolitis, all of which resolved within 3 months of thorough deinfestation cleaning.21

Skin-prick and/or patch testing is not necessary for this clinical diagnosis of dermestid-induced allergic contact dermatitis. This diagnosis is bolstered by (but does not require a history of) repeated symptom induction upon performing certain activities (eg, handling taxidermy specimens) and/or in certain environments (eg, only at home). Because of individual differences in hypersensitivity to dermestid parts, it is not typical for all members of a household to be affected.