User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

BIMA’s benefits extend to high-risk CABG patients

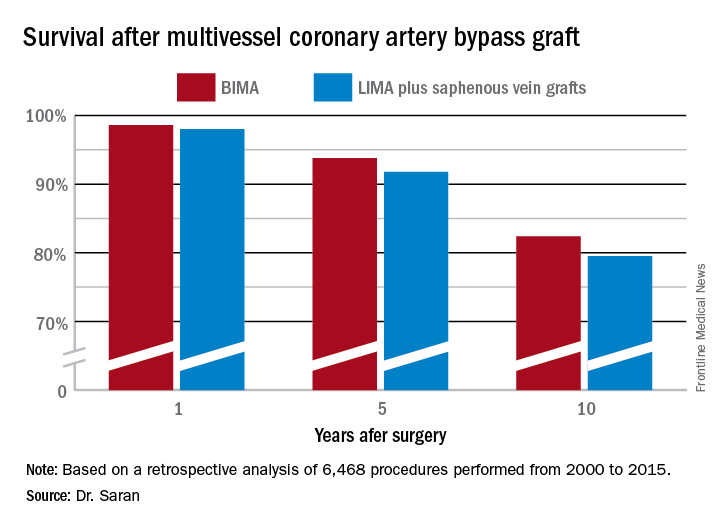

COLORADO SPRINGS – The survival advantage of bilateral internal over left internal mammary artery grafts persists even among multivessel CABG patients perceived to be at high surgical risk, Nishant Saran, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the Western Thoracic Surgical Association.

Many surgeons hesitate to perform bilateral internal mammary artery (BIMA) grafting in high-risk patients on the presumption that BIMA might not benefit them. It’s a concern that appears to be without merit, however, based on a retrospective analysis of the 6,468 multivessel CABG procedures performed at the Mayo Clinic during 2000-2015, said Dr. Saran of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The BIMA patients were as a whole significantly younger, primarily men, and less likely to have diabetes or to be obese than the LIMA patients. Also, LIMA patients were fourfold more likely to have baseline heart failure, twice as likely to have a history of stroke, and had a twofold greater prevalence of chronic lung disease.

“The unmatched comparison shows the clear treatment selection bias we have: BIMA goes to the healthier patients,” Dr. Saran observed.

But is that bias justified? To find out, he and his coinvestigators performed extensive propensity score matching using several dozen baseline variables in order to identify 1,011 closely matched patient pairs. In this propensity score-matched analysis, 5- and 10-year survival rates were significantly better in the BIMA group. The gap between the two survival curves widened after about 7 years and continued to expand steadily through year 10. Incision time averaged 298 minutes in the BIMA group and 254 minutes in the propensity-matched LIMA group.

Discussant Eric J. Lehr, MD, a cardiac surgeon at Swedish Medical Center in Seattle, noted that the impressive survival benefit for BIMA in the retrospective Mayo Clinic study came at what he termed “a modest cost”: a doubled incidence of sternal site infections, from 1.4% in the LIMA group to 3% with BIMA. Importantly, though, there was no significant difference in the more serious deep sternal wound infections.

He agreed with Dr. Saran that BIMA is seriously underutilized, noting that only one cardiothoracic surgery program in the state of Washington uses BIMA more than 10% of the time in multivessel CABG.

Dr. Lehr then posed a provocative question: “Should BIMA grafting be considered a quality metric in coronary revascularization surgery, despite the small increase in sternal site infections, even though sternal wound infections have been declared a ‘never’ event and are tied to reimbursement?”

“I think BIMA should be a gold standard,” Dr. Saran replied. “The first thing that a cardiac surgeon should always think of when a patient is going to have CABG is ‘BIMA first,’ and only then look into reasons for not doing it. But I guess in current real-world practice, things are different.”

Howard K. Song, MD, commented, “I think a study like this doesn’t necessarily show that every surgeon should be using BIMA liberally, it shows that surgeons in your practice who do that have excellent outcomes.”

Dr. Song, professor of surgery and chief of the division of cardiothoracic surgery at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, added that he believes extensive use of BIMA is actually a surrogate marker for a highly skilled subspecialist who would be expected to have very good outcomes as a matter of course.

“That may be one way of looking at it; however, I do think that even very skilled surgeons still have an inherent resistance to doing BIMA,” Dr. Saran responded.

“In the current era, the surgeon is pressured to achieve improved short-term outcomes and improved OR turnover times. An extra half hour for BIMA tends to push the surgeon away,” he added.

Dr. Saran reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

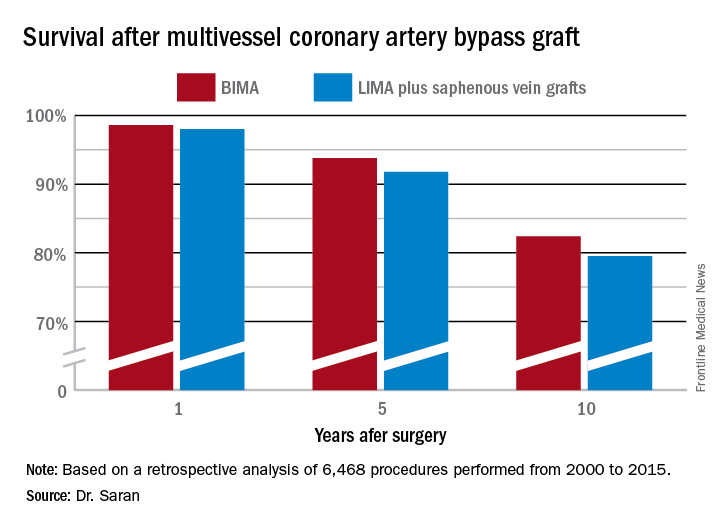

COLORADO SPRINGS – The survival advantage of bilateral internal over left internal mammary artery grafts persists even among multivessel CABG patients perceived to be at high surgical risk, Nishant Saran, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the Western Thoracic Surgical Association.

Many surgeons hesitate to perform bilateral internal mammary artery (BIMA) grafting in high-risk patients on the presumption that BIMA might not benefit them. It’s a concern that appears to be without merit, however, based on a retrospective analysis of the 6,468 multivessel CABG procedures performed at the Mayo Clinic during 2000-2015, said Dr. Saran of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The BIMA patients were as a whole significantly younger, primarily men, and less likely to have diabetes or to be obese than the LIMA patients. Also, LIMA patients were fourfold more likely to have baseline heart failure, twice as likely to have a history of stroke, and had a twofold greater prevalence of chronic lung disease.

“The unmatched comparison shows the clear treatment selection bias we have: BIMA goes to the healthier patients,” Dr. Saran observed.

But is that bias justified? To find out, he and his coinvestigators performed extensive propensity score matching using several dozen baseline variables in order to identify 1,011 closely matched patient pairs. In this propensity score-matched analysis, 5- and 10-year survival rates were significantly better in the BIMA group. The gap between the two survival curves widened after about 7 years and continued to expand steadily through year 10. Incision time averaged 298 minutes in the BIMA group and 254 minutes in the propensity-matched LIMA group.

Discussant Eric J. Lehr, MD, a cardiac surgeon at Swedish Medical Center in Seattle, noted that the impressive survival benefit for BIMA in the retrospective Mayo Clinic study came at what he termed “a modest cost”: a doubled incidence of sternal site infections, from 1.4% in the LIMA group to 3% with BIMA. Importantly, though, there was no significant difference in the more serious deep sternal wound infections.

He agreed with Dr. Saran that BIMA is seriously underutilized, noting that only one cardiothoracic surgery program in the state of Washington uses BIMA more than 10% of the time in multivessel CABG.

Dr. Lehr then posed a provocative question: “Should BIMA grafting be considered a quality metric in coronary revascularization surgery, despite the small increase in sternal site infections, even though sternal wound infections have been declared a ‘never’ event and are tied to reimbursement?”

“I think BIMA should be a gold standard,” Dr. Saran replied. “The first thing that a cardiac surgeon should always think of when a patient is going to have CABG is ‘BIMA first,’ and only then look into reasons for not doing it. But I guess in current real-world practice, things are different.”

Howard K. Song, MD, commented, “I think a study like this doesn’t necessarily show that every surgeon should be using BIMA liberally, it shows that surgeons in your practice who do that have excellent outcomes.”

Dr. Song, professor of surgery and chief of the division of cardiothoracic surgery at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, added that he believes extensive use of BIMA is actually a surrogate marker for a highly skilled subspecialist who would be expected to have very good outcomes as a matter of course.

“That may be one way of looking at it; however, I do think that even very skilled surgeons still have an inherent resistance to doing BIMA,” Dr. Saran responded.

“In the current era, the surgeon is pressured to achieve improved short-term outcomes and improved OR turnover times. An extra half hour for BIMA tends to push the surgeon away,” he added.

Dr. Saran reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

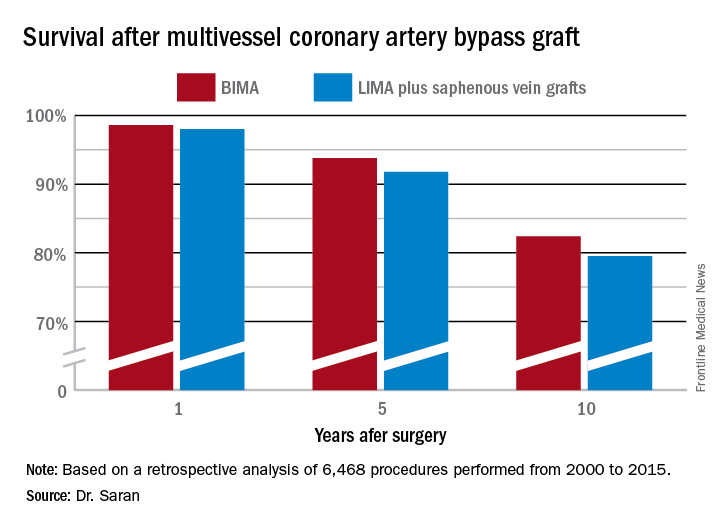

COLORADO SPRINGS – The survival advantage of bilateral internal over left internal mammary artery grafts persists even among multivessel CABG patients perceived to be at high surgical risk, Nishant Saran, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the Western Thoracic Surgical Association.

Many surgeons hesitate to perform bilateral internal mammary artery (BIMA) grafting in high-risk patients on the presumption that BIMA might not benefit them. It’s a concern that appears to be without merit, however, based on a retrospective analysis of the 6,468 multivessel CABG procedures performed at the Mayo Clinic during 2000-2015, said Dr. Saran of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The BIMA patients were as a whole significantly younger, primarily men, and less likely to have diabetes or to be obese than the LIMA patients. Also, LIMA patients were fourfold more likely to have baseline heart failure, twice as likely to have a history of stroke, and had a twofold greater prevalence of chronic lung disease.

“The unmatched comparison shows the clear treatment selection bias we have: BIMA goes to the healthier patients,” Dr. Saran observed.

But is that bias justified? To find out, he and his coinvestigators performed extensive propensity score matching using several dozen baseline variables in order to identify 1,011 closely matched patient pairs. In this propensity score-matched analysis, 5- and 10-year survival rates were significantly better in the BIMA group. The gap between the two survival curves widened after about 7 years and continued to expand steadily through year 10. Incision time averaged 298 minutes in the BIMA group and 254 minutes in the propensity-matched LIMA group.

Discussant Eric J. Lehr, MD, a cardiac surgeon at Swedish Medical Center in Seattle, noted that the impressive survival benefit for BIMA in the retrospective Mayo Clinic study came at what he termed “a modest cost”: a doubled incidence of sternal site infections, from 1.4% in the LIMA group to 3% with BIMA. Importantly, though, there was no significant difference in the more serious deep sternal wound infections.

He agreed with Dr. Saran that BIMA is seriously underutilized, noting that only one cardiothoracic surgery program in the state of Washington uses BIMA more than 10% of the time in multivessel CABG.

Dr. Lehr then posed a provocative question: “Should BIMA grafting be considered a quality metric in coronary revascularization surgery, despite the small increase in sternal site infections, even though sternal wound infections have been declared a ‘never’ event and are tied to reimbursement?”

“I think BIMA should be a gold standard,” Dr. Saran replied. “The first thing that a cardiac surgeon should always think of when a patient is going to have CABG is ‘BIMA first,’ and only then look into reasons for not doing it. But I guess in current real-world practice, things are different.”

Howard K. Song, MD, commented, “I think a study like this doesn’t necessarily show that every surgeon should be using BIMA liberally, it shows that surgeons in your practice who do that have excellent outcomes.”

Dr. Song, professor of surgery and chief of the division of cardiothoracic surgery at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, added that he believes extensive use of BIMA is actually a surrogate marker for a highly skilled subspecialist who would be expected to have very good outcomes as a matter of course.

“That may be one way of looking at it; however, I do think that even very skilled surgeons still have an inherent resistance to doing BIMA,” Dr. Saran responded.

“In the current era, the surgeon is pressured to achieve improved short-term outcomes and improved OR turnover times. An extra half hour for BIMA tends to push the surgeon away,” he added.

Dr. Saran reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AT THE WTSA ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Ten-year survival following multivessel CABG using bilateral internal mammary artery grafting was 82.4%, significantly better than the 79.5% rate with left internal mammary artery grafting plus saphenous vein grafts.

Data source: This retrospective observational single-center included 6,468 patients who underwent multivessel CABG during 2000-2015.

Disclosures: Dr. Saran reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Regional differences in surgical outcomes could unfairly skew bundled payments

Risk-adjusted adverse outcomes for elective colorectal surgery vary significantly across regions in the United States, and, therefore, regionally based Medicare payments could disadvantage some hospitals.

The findings, presented at the annual Central Surgical Association meeting, suggest that alternative payment models (APMs) should consider regional benchmarks as a variable when evaluating quality and pricing of episodes of care to level the playing field among hospitals, the study authors said.

All hospitals with a minimum of 20 evaluable colorectal resection cases from the master data set regardless of coding quality were identified for comparative outcomes. For hospital analysis, the total number of patients with one or more adverse outcomes (AOs) was tabulated. The total predicted AOs were then set equal to the number of observed events for each hospital by multiplication of the hospital-specific predicted value by the ratio of observed-to-predicted events for the entire final hospital population of patients.

Hospitals were then sorted by the nine Census Bureau regions: region 1 (New England), region 2 (Middle Atlantic), region 3 (South Atlantic), region 4 (East South Central), region 5 (West South Central), region 6 (East North Central), region 7 (West North Central), region 8 (Mountain), and region 9 (Pacific).

Within each region, total patients, total observed AOs, and total predicted AOs were derived from the prediction models. Region-specific standard deviations (SDs) were computed and overall region z scores and risk-adjusted AO rates were calculated for comparison.

A total of 1,497 hospitals had 86,624 patients for the comparative analysis of hospitals with 20 or more qualifying cases. Hospitals averaged 57.9 cases with a median of 43 for the study period. Among the AOs, there were 947 IpD (1.1%), 7,268 prLOS (8.4%), 762 PD90 (0.9%), and 14,552 RA90 (16.8%) patients. An additional 1,130 patients died during or following readmission within the 90-day postdischarge period for total postoperative deaths including inpatient and 90 days following discharge of 2,839 (3.3%). Total patients with one or more AOs were 21,064 (24.3%).

Among the hospitals, 49 (3.3%) had z scores of –2.0 or less. These best-performing hospitals had a median z score of –2.24 and a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 10.8%. A total of 159 hospitals (10.6%) had z scores that were greater than –2.0 but less than or equal to –1.0. These hospitals had a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 15.1%. There were 66 hospitals (4.4%) with z scores greater than +2.0. These suboptimal-performing hospitals had a z score of +2.39 and a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 38.8%. A total of 209 hospitals (14.0%) had z scores greater than or equal to +1.0 but less than +2.0. They had a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 32.5%.

Findings showed a nearly 5-SD difference between the Pacific region and the New England region. In addition, the results showed a 2.5% absolute risk–adjusted adverse outcome rate difference between the top- and the lowest-performing regions.

What findings could mean for bundled payments

The findings raise concerns about a lopsided playing field for hospitals when it comes to bundled payments, according to the study authors.

“What that means is if you have more readmissions and more complications and your historical profile is being used to pay for care going forward, regions of the country with poorer outcomes would get higher prices than those areas with better outcomes,” Dr. Fry, executive vice president, clinical outcomes management, MPA Healthcare Solutions, Chicago, said in an interview.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has used performance of the Census Bureau region as a major factor in defining target price at the beginning of the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement bundled payment program. Regional performance will become the exclusive basis for the target price as the program matures into successive years, the study authors noted. A colorectal surgery bundle has not yet been proposed by Medicare, but because it’s a common operation with relatively high adverse outcomes rates, it is expected to be included in a future bundled payment strategy, according to the investigators.

Dr. Fry and his coauthors concluded that hospitals and surgeons may find meeting the target price of a bundled payment to improve margins or avoid losses more difficult for any inpatient operation if they are in a best-performing region.

A 2.5% adverse outcome rate difference between regions may not seem like much, but the variance could mean a wide disparity in payments, Dr. Fry said.

“We have done previous research with colon operations and identified that a readmission after an elective colon operation costs about an additional $30,000,” he said. “If cases being done in poorer-performing areas of the country have two or three more readmissions per 100 patients, then it means those areas are going to be paid on average $1,000 more per case than would be the circumstance for those areas where outcomes are better.”

By these parameters, the CMS would basically be rewarding care that is suboptimal in the regions with high adverse outcome rates, he said.

“APMs are going to evolve in health care,” Dr. Fry said. “I feel that regional and local outcomes, as illustrated in this article, are different, and that a national standard for expected outcomes needs to be the benchmark. The national benchmark becomes a method to stimulate hospitals and surgeons to know what the results of their care really are and how they compare nationally.”

Perspectives on the study

However, it remains unclear whether adjustment for quality measures should be based on regions, and, if so, how those regions should be broken down, said Dr. Whitcomb, who is cofounder and past president of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Another question is whether adjustments should take into consideration the characteristics of hospitals, he said, for example, the general demographics of patients who visit academic medical centers, compared with the demographics of community hospitals. Dr. Whitcomb also noted that programs such as the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program has faced criticism for not factoring in the disproportionately high share of low socioeconomic status patients at some hospitals.

“The paper raises the important issue of comparing apples to apples when quality measures are used to determine payment under alternative payment models,” Dr. Whitcomb said in an interview. “But a number of questions remain about how risk should be adjusted and how benchmarking should occur between hospitals.”

“The overall average adverse outcome in the study was 24.3%, but 16.8% of that 24% is due to readmissions,” he said in an interview. “Length of stay and readmissions are correlated – people who tend to have long lengths of stay tend to be readmitted. If you add those two rates together in the study, almost all of the outcome rate is the length of stay and readmissions. You could argue [that] mortality [should] be more heavily weighted than length of stay and readmissions.”

In regard to adjusting risk by region, there is good research that utilization of procedures varies dramatically by region and that some of this variation may have more to do with overutilization of procedures, Dr. Pitt added.

“I would think that risk adjusting for type of operation, diagnosis, and socioeconomic status –across the country – would be more appropriate than risk adjusting by region where there may be major differences in patient selection and indication for operation,” he said.

For example, there is currently an international debate about the management of diverticulitis, including whether and when to operate as well as what procedure(s) to perform.

“It may be in one region, there’s a very low threshold to operate, whereas in another region, there’s a high threshold to operate,” he said. “And the operations that are done may be very different in one region than another.”

Dr. Fry and his colleagues are planning future research in this area, and he said he hopes their studies will impact how the CMS rolls out its bundled payment programs in the future.

“What we’re trying to stimulate is for payment models to be nationally indexed and not regionally indexed,” he said. “CMS is doing that now with [Medicare Severity–Diagnosis Related Groups]. They are paying a price for a total joint replacement, a price for a colon resection, a price for a heart operation – and they do make adjustments based on the local wage and price index, but the core payment is linked to a national payment model, and that’s what we would like to see happen with the bundled payment initiative.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Risk-adjusted adverse outcomes for elective colorectal surgery vary significantly across regions in the United States, and, therefore, regionally based Medicare payments could disadvantage some hospitals.

The findings, presented at the annual Central Surgical Association meeting, suggest that alternative payment models (APMs) should consider regional benchmarks as a variable when evaluating quality and pricing of episodes of care to level the playing field among hospitals, the study authors said.

All hospitals with a minimum of 20 evaluable colorectal resection cases from the master data set regardless of coding quality were identified for comparative outcomes. For hospital analysis, the total number of patients with one or more adverse outcomes (AOs) was tabulated. The total predicted AOs were then set equal to the number of observed events for each hospital by multiplication of the hospital-specific predicted value by the ratio of observed-to-predicted events for the entire final hospital population of patients.

Hospitals were then sorted by the nine Census Bureau regions: region 1 (New England), region 2 (Middle Atlantic), region 3 (South Atlantic), region 4 (East South Central), region 5 (West South Central), region 6 (East North Central), region 7 (West North Central), region 8 (Mountain), and region 9 (Pacific).

Within each region, total patients, total observed AOs, and total predicted AOs were derived from the prediction models. Region-specific standard deviations (SDs) were computed and overall region z scores and risk-adjusted AO rates were calculated for comparison.

A total of 1,497 hospitals had 86,624 patients for the comparative analysis of hospitals with 20 or more qualifying cases. Hospitals averaged 57.9 cases with a median of 43 for the study period. Among the AOs, there were 947 IpD (1.1%), 7,268 prLOS (8.4%), 762 PD90 (0.9%), and 14,552 RA90 (16.8%) patients. An additional 1,130 patients died during or following readmission within the 90-day postdischarge period for total postoperative deaths including inpatient and 90 days following discharge of 2,839 (3.3%). Total patients with one or more AOs were 21,064 (24.3%).

Among the hospitals, 49 (3.3%) had z scores of –2.0 or less. These best-performing hospitals had a median z score of –2.24 and a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 10.8%. A total of 159 hospitals (10.6%) had z scores that were greater than –2.0 but less than or equal to –1.0. These hospitals had a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 15.1%. There were 66 hospitals (4.4%) with z scores greater than +2.0. These suboptimal-performing hospitals had a z score of +2.39 and a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 38.8%. A total of 209 hospitals (14.0%) had z scores greater than or equal to +1.0 but less than +2.0. They had a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 32.5%.

Findings showed a nearly 5-SD difference between the Pacific region and the New England region. In addition, the results showed a 2.5% absolute risk–adjusted adverse outcome rate difference between the top- and the lowest-performing regions.

What findings could mean for bundled payments

The findings raise concerns about a lopsided playing field for hospitals when it comes to bundled payments, according to the study authors.

“What that means is if you have more readmissions and more complications and your historical profile is being used to pay for care going forward, regions of the country with poorer outcomes would get higher prices than those areas with better outcomes,” Dr. Fry, executive vice president, clinical outcomes management, MPA Healthcare Solutions, Chicago, said in an interview.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has used performance of the Census Bureau region as a major factor in defining target price at the beginning of the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement bundled payment program. Regional performance will become the exclusive basis for the target price as the program matures into successive years, the study authors noted. A colorectal surgery bundle has not yet been proposed by Medicare, but because it’s a common operation with relatively high adverse outcomes rates, it is expected to be included in a future bundled payment strategy, according to the investigators.

Dr. Fry and his coauthors concluded that hospitals and surgeons may find meeting the target price of a bundled payment to improve margins or avoid losses more difficult for any inpatient operation if they are in a best-performing region.

A 2.5% adverse outcome rate difference between regions may not seem like much, but the variance could mean a wide disparity in payments, Dr. Fry said.

“We have done previous research with colon operations and identified that a readmission after an elective colon operation costs about an additional $30,000,” he said. “If cases being done in poorer-performing areas of the country have two or three more readmissions per 100 patients, then it means those areas are going to be paid on average $1,000 more per case than would be the circumstance for those areas where outcomes are better.”

By these parameters, the CMS would basically be rewarding care that is suboptimal in the regions with high adverse outcome rates, he said.

“APMs are going to evolve in health care,” Dr. Fry said. “I feel that regional and local outcomes, as illustrated in this article, are different, and that a national standard for expected outcomes needs to be the benchmark. The national benchmark becomes a method to stimulate hospitals and surgeons to know what the results of their care really are and how they compare nationally.”

Perspectives on the study

However, it remains unclear whether adjustment for quality measures should be based on regions, and, if so, how those regions should be broken down, said Dr. Whitcomb, who is cofounder and past president of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Another question is whether adjustments should take into consideration the characteristics of hospitals, he said, for example, the general demographics of patients who visit academic medical centers, compared with the demographics of community hospitals. Dr. Whitcomb also noted that programs such as the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program has faced criticism for not factoring in the disproportionately high share of low socioeconomic status patients at some hospitals.

“The paper raises the important issue of comparing apples to apples when quality measures are used to determine payment under alternative payment models,” Dr. Whitcomb said in an interview. “But a number of questions remain about how risk should be adjusted and how benchmarking should occur between hospitals.”

“The overall average adverse outcome in the study was 24.3%, but 16.8% of that 24% is due to readmissions,” he said in an interview. “Length of stay and readmissions are correlated – people who tend to have long lengths of stay tend to be readmitted. If you add those two rates together in the study, almost all of the outcome rate is the length of stay and readmissions. You could argue [that] mortality [should] be more heavily weighted than length of stay and readmissions.”

In regard to adjusting risk by region, there is good research that utilization of procedures varies dramatically by region and that some of this variation may have more to do with overutilization of procedures, Dr. Pitt added.

“I would think that risk adjusting for type of operation, diagnosis, and socioeconomic status –across the country – would be more appropriate than risk adjusting by region where there may be major differences in patient selection and indication for operation,” he said.

For example, there is currently an international debate about the management of diverticulitis, including whether and when to operate as well as what procedure(s) to perform.

“It may be in one region, there’s a very low threshold to operate, whereas in another region, there’s a high threshold to operate,” he said. “And the operations that are done may be very different in one region than another.”

Dr. Fry and his colleagues are planning future research in this area, and he said he hopes their studies will impact how the CMS rolls out its bundled payment programs in the future.

“What we’re trying to stimulate is for payment models to be nationally indexed and not regionally indexed,” he said. “CMS is doing that now with [Medicare Severity–Diagnosis Related Groups]. They are paying a price for a total joint replacement, a price for a colon resection, a price for a heart operation – and they do make adjustments based on the local wage and price index, but the core payment is linked to a national payment model, and that’s what we would like to see happen with the bundled payment initiative.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Risk-adjusted adverse outcomes for elective colorectal surgery vary significantly across regions in the United States, and, therefore, regionally based Medicare payments could disadvantage some hospitals.

The findings, presented at the annual Central Surgical Association meeting, suggest that alternative payment models (APMs) should consider regional benchmarks as a variable when evaluating quality and pricing of episodes of care to level the playing field among hospitals, the study authors said.

All hospitals with a minimum of 20 evaluable colorectal resection cases from the master data set regardless of coding quality were identified for comparative outcomes. For hospital analysis, the total number of patients with one or more adverse outcomes (AOs) was tabulated. The total predicted AOs were then set equal to the number of observed events for each hospital by multiplication of the hospital-specific predicted value by the ratio of observed-to-predicted events for the entire final hospital population of patients.

Hospitals were then sorted by the nine Census Bureau regions: region 1 (New England), region 2 (Middle Atlantic), region 3 (South Atlantic), region 4 (East South Central), region 5 (West South Central), region 6 (East North Central), region 7 (West North Central), region 8 (Mountain), and region 9 (Pacific).

Within each region, total patients, total observed AOs, and total predicted AOs were derived from the prediction models. Region-specific standard deviations (SDs) were computed and overall region z scores and risk-adjusted AO rates were calculated for comparison.

A total of 1,497 hospitals had 86,624 patients for the comparative analysis of hospitals with 20 or more qualifying cases. Hospitals averaged 57.9 cases with a median of 43 for the study period. Among the AOs, there were 947 IpD (1.1%), 7,268 prLOS (8.4%), 762 PD90 (0.9%), and 14,552 RA90 (16.8%) patients. An additional 1,130 patients died during or following readmission within the 90-day postdischarge period for total postoperative deaths including inpatient and 90 days following discharge of 2,839 (3.3%). Total patients with one or more AOs were 21,064 (24.3%).

Among the hospitals, 49 (3.3%) had z scores of –2.0 or less. These best-performing hospitals had a median z score of –2.24 and a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 10.8%. A total of 159 hospitals (10.6%) had z scores that were greater than –2.0 but less than or equal to –1.0. These hospitals had a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 15.1%. There were 66 hospitals (4.4%) with z scores greater than +2.0. These suboptimal-performing hospitals had a z score of +2.39 and a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 38.8%. A total of 209 hospitals (14.0%) had z scores greater than or equal to +1.0 but less than +2.0. They had a median risk-adjusted AO rate of 32.5%.

Findings showed a nearly 5-SD difference between the Pacific region and the New England region. In addition, the results showed a 2.5% absolute risk–adjusted adverse outcome rate difference between the top- and the lowest-performing regions.

What findings could mean for bundled payments

The findings raise concerns about a lopsided playing field for hospitals when it comes to bundled payments, according to the study authors.

“What that means is if you have more readmissions and more complications and your historical profile is being used to pay for care going forward, regions of the country with poorer outcomes would get higher prices than those areas with better outcomes,” Dr. Fry, executive vice president, clinical outcomes management, MPA Healthcare Solutions, Chicago, said in an interview.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has used performance of the Census Bureau region as a major factor in defining target price at the beginning of the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement bundled payment program. Regional performance will become the exclusive basis for the target price as the program matures into successive years, the study authors noted. A colorectal surgery bundle has not yet been proposed by Medicare, but because it’s a common operation with relatively high adverse outcomes rates, it is expected to be included in a future bundled payment strategy, according to the investigators.

Dr. Fry and his coauthors concluded that hospitals and surgeons may find meeting the target price of a bundled payment to improve margins or avoid losses more difficult for any inpatient operation if they are in a best-performing region.

A 2.5% adverse outcome rate difference between regions may not seem like much, but the variance could mean a wide disparity in payments, Dr. Fry said.

“We have done previous research with colon operations and identified that a readmission after an elective colon operation costs about an additional $30,000,” he said. “If cases being done in poorer-performing areas of the country have two or three more readmissions per 100 patients, then it means those areas are going to be paid on average $1,000 more per case than would be the circumstance for those areas where outcomes are better.”

By these parameters, the CMS would basically be rewarding care that is suboptimal in the regions with high adverse outcome rates, he said.

“APMs are going to evolve in health care,” Dr. Fry said. “I feel that regional and local outcomes, as illustrated in this article, are different, and that a national standard for expected outcomes needs to be the benchmark. The national benchmark becomes a method to stimulate hospitals and surgeons to know what the results of their care really are and how they compare nationally.”

Perspectives on the study

However, it remains unclear whether adjustment for quality measures should be based on regions, and, if so, how those regions should be broken down, said Dr. Whitcomb, who is cofounder and past president of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Another question is whether adjustments should take into consideration the characteristics of hospitals, he said, for example, the general demographics of patients who visit academic medical centers, compared with the demographics of community hospitals. Dr. Whitcomb also noted that programs such as the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program has faced criticism for not factoring in the disproportionately high share of low socioeconomic status patients at some hospitals.

“The paper raises the important issue of comparing apples to apples when quality measures are used to determine payment under alternative payment models,” Dr. Whitcomb said in an interview. “But a number of questions remain about how risk should be adjusted and how benchmarking should occur between hospitals.”

“The overall average adverse outcome in the study was 24.3%, but 16.8% of that 24% is due to readmissions,” he said in an interview. “Length of stay and readmissions are correlated – people who tend to have long lengths of stay tend to be readmitted. If you add those two rates together in the study, almost all of the outcome rate is the length of stay and readmissions. You could argue [that] mortality [should] be more heavily weighted than length of stay and readmissions.”

In regard to adjusting risk by region, there is good research that utilization of procedures varies dramatically by region and that some of this variation may have more to do with overutilization of procedures, Dr. Pitt added.

“I would think that risk adjusting for type of operation, diagnosis, and socioeconomic status –across the country – would be more appropriate than risk adjusting by region where there may be major differences in patient selection and indication for operation,” he said.

For example, there is currently an international debate about the management of diverticulitis, including whether and when to operate as well as what procedure(s) to perform.

“It may be in one region, there’s a very low threshold to operate, whereas in another region, there’s a high threshold to operate,” he said. “And the operations that are done may be very different in one region than another.”

Dr. Fry and his colleagues are planning future research in this area, and he said he hopes their studies will impact how the CMS rolls out its bundled payment programs in the future.

“What we’re trying to stimulate is for payment models to be nationally indexed and not regionally indexed,” he said. “CMS is doing that now with [Medicare Severity–Diagnosis Related Groups]. They are paying a price for a total joint replacement, a price for a colon resection, a price for a heart operation – and they do make adjustments based on the local wage and price index, but the core payment is linked to a national payment model, and that’s what we would like to see happen with the bundled payment initiative.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Ten-year outcomes support skipping axillary lymph node dissection with positive sentinel nodes

A follow-up to a study showing the noninferiority of sentinel lymph node dissection to axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer in overall and disease-free survival at a median of 6.3 years found similar noninferiority in overall survival at 10 years.

Axillary lymph node dissection has a risk of complications including lymphedema, numbness, axillary web syndrome, and decreased upper-extremity range of motion. The American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0011 trial sought to determine if the procedure could be avoided without inferior survival outcomes.

Criticism of the study focused on the potential for later recurrence, particularly in patients with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer. All enrolled patients had one or two sentinel nodes with metastases. At randomization, 436 received sentinel lymph node dissection alone, and 420 received the additional axillary lymph node dissection. The patients were assessed every 6 months for the first 3 years, then annually.

After a median of 9.3 years, 110 of the patients had died of any cause – 51 in the sentinel lymph node dissection group and 59 in the axillary lymph node dissection group – a 10-year overall survival rate of 86.3% and 83.6%, respectively. This met the study’s primary endpoint of showing noninferior overall survival without the riskier procedure. In the study’s secondary endpoint, disease-free survival, there was not a significant difference either (80.2% vs. 78.2%).

“Axillary dissections are associated with considerable morbidity, and the results of this trial demonstrated that this morbidity can be avoided without decreasing cancer control. … These findings do not support routine use of axillary lymph node dissection in this patient population based on 10-year outcomes,” wrote Armando E. Guiliano, MD, of Cedars-Sinai Medical, Los Angeles and his coauthors (JAMA. 2017;318[10]:918-26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11470).

A follow-up to a study showing the noninferiority of sentinel lymph node dissection to axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer in overall and disease-free survival at a median of 6.3 years found similar noninferiority in overall survival at 10 years.

Axillary lymph node dissection has a risk of complications including lymphedema, numbness, axillary web syndrome, and decreased upper-extremity range of motion. The American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0011 trial sought to determine if the procedure could be avoided without inferior survival outcomes.

Criticism of the study focused on the potential for later recurrence, particularly in patients with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer. All enrolled patients had one or two sentinel nodes with metastases. At randomization, 436 received sentinel lymph node dissection alone, and 420 received the additional axillary lymph node dissection. The patients were assessed every 6 months for the first 3 years, then annually.

After a median of 9.3 years, 110 of the patients had died of any cause – 51 in the sentinel lymph node dissection group and 59 in the axillary lymph node dissection group – a 10-year overall survival rate of 86.3% and 83.6%, respectively. This met the study’s primary endpoint of showing noninferior overall survival without the riskier procedure. In the study’s secondary endpoint, disease-free survival, there was not a significant difference either (80.2% vs. 78.2%).

“Axillary dissections are associated with considerable morbidity, and the results of this trial demonstrated that this morbidity can be avoided without decreasing cancer control. … These findings do not support routine use of axillary lymph node dissection in this patient population based on 10-year outcomes,” wrote Armando E. Guiliano, MD, of Cedars-Sinai Medical, Los Angeles and his coauthors (JAMA. 2017;318[10]:918-26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11470).

A follow-up to a study showing the noninferiority of sentinel lymph node dissection to axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer in overall and disease-free survival at a median of 6.3 years found similar noninferiority in overall survival at 10 years.

Axillary lymph node dissection has a risk of complications including lymphedema, numbness, axillary web syndrome, and decreased upper-extremity range of motion. The American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0011 trial sought to determine if the procedure could be avoided without inferior survival outcomes.

Criticism of the study focused on the potential for later recurrence, particularly in patients with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer. All enrolled patients had one or two sentinel nodes with metastases. At randomization, 436 received sentinel lymph node dissection alone, and 420 received the additional axillary lymph node dissection. The patients were assessed every 6 months for the first 3 years, then annually.

After a median of 9.3 years, 110 of the patients had died of any cause – 51 in the sentinel lymph node dissection group and 59 in the axillary lymph node dissection group – a 10-year overall survival rate of 86.3% and 83.6%, respectively. This met the study’s primary endpoint of showing noninferior overall survival without the riskier procedure. In the study’s secondary endpoint, disease-free survival, there was not a significant difference either (80.2% vs. 78.2%).

“Axillary dissections are associated with considerable morbidity, and the results of this trial demonstrated that this morbidity can be avoided without decreasing cancer control. … These findings do not support routine use of axillary lymph node dissection in this patient population based on 10-year outcomes,” wrote Armando E. Guiliano, MD, of Cedars-Sinai Medical, Los Angeles and his coauthors (JAMA. 2017;318[10]:918-26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11470).

FROM JAMA

Study findings support uncapping MELD score

Uncapping the current Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score may provide a better path toward making sure that patients most in need of a liver transplant get one, results from a large, long-term analysis showed.

Established in 2002, the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scoring system “was arbitrarily capped at 40 based on the presumption that transplanting patients with MELD greater than 40 would be futile,” researchers led by Mitra K. Nadim, MD, reported in the September 2017 issue of the Journal of Hepatology (67[3]:517-25. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.04.022). “As a result, patients with MELD greater than 40 receive the same priority as patients with MELD of 40, differentiated only by their time on the wait list.”

The mean age of patients was 53 years, and most were white men. The researchers reported that 3.3% of wait-listed patients had a MELD score of 40 or greater at registration, while 7.3% had MELD scores increase to 40 or greater after wait-list registration. In all, 30,369 patients (40.6%) underwent liver transplantation during the study period. Of these, 2,615 (8.6%) had a MELD score of 40 or greater at the time of their procedure. Compared with patients who had a MELD score of 40, those who had a MELD score of greater than 40 had an increased risk of death within 30 days, and the risk increased with rising scores. Specifically, the hazard ratio was 1.4 for those with a MELD score of 40-44, an HR of 2.6 for those with a MELD score of 45-49, and an HR of 5.0 for those with a MELD score of 50 or greater. There were no survival differences between the two groups at 1 and 3 years, but there was a survival benefit associated with liver transplantation as the MELD score increased above 40, the investigators reported.

“The arbitrary capping of the MELD at 40 has resulted in an unforeseen lack of objectivity for patients with MELD [score of greater than] 40 who are unjustifiably disadvantaged in a system designed to prioritize patients most in need,” they concluded. “Uncapping the MELD score is another necessary step in the evolution of liver allocation and patient prioritization.” They added that a significant number of patients with a MELD score of 40 or greater “likely suffer from acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF), a recently recognized syndrome characterized by acute liver decompensation, other organ system failures, and high short-term mortality in patients with end-stage liver disease. A capped MELD score fails to capture acute liver decompensation adequately, and data suggest that a model incorporating sudden increases in MELD predicts wait-list mortality better.”

Dr. Nadim and her associates acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design “and that factors relating to a patient’s suitability for transplantation or to a center’s decision to accept or reject a liver allograft, both of which affect graft and patient survival, were not accounted for in the analysis. Despite these limitations, the study results have important implications for improving the current liver allocation policy.”

The study was supported in part by the Health Resources and Services Administration. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

PRIMARY SOURCE: J Hepatol. 2017;67[3]:517-25. doi: 1016/j.jhep.2017.04.022

Uncapping the current Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score may provide a better path toward making sure that patients most in need of a liver transplant get one, results from a large, long-term analysis showed.

Established in 2002, the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scoring system “was arbitrarily capped at 40 based on the presumption that transplanting patients with MELD greater than 40 would be futile,” researchers led by Mitra K. Nadim, MD, reported in the September 2017 issue of the Journal of Hepatology (67[3]:517-25. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.04.022). “As a result, patients with MELD greater than 40 receive the same priority as patients with MELD of 40, differentiated only by their time on the wait list.”

The mean age of patients was 53 years, and most were white men. The researchers reported that 3.3% of wait-listed patients had a MELD score of 40 or greater at registration, while 7.3% had MELD scores increase to 40 or greater after wait-list registration. In all, 30,369 patients (40.6%) underwent liver transplantation during the study period. Of these, 2,615 (8.6%) had a MELD score of 40 or greater at the time of their procedure. Compared with patients who had a MELD score of 40, those who had a MELD score of greater than 40 had an increased risk of death within 30 days, and the risk increased with rising scores. Specifically, the hazard ratio was 1.4 for those with a MELD score of 40-44, an HR of 2.6 for those with a MELD score of 45-49, and an HR of 5.0 for those with a MELD score of 50 or greater. There were no survival differences between the two groups at 1 and 3 years, but there was a survival benefit associated with liver transplantation as the MELD score increased above 40, the investigators reported.

“The arbitrary capping of the MELD at 40 has resulted in an unforeseen lack of objectivity for patients with MELD [score of greater than] 40 who are unjustifiably disadvantaged in a system designed to prioritize patients most in need,” they concluded. “Uncapping the MELD score is another necessary step in the evolution of liver allocation and patient prioritization.” They added that a significant number of patients with a MELD score of 40 or greater “likely suffer from acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF), a recently recognized syndrome characterized by acute liver decompensation, other organ system failures, and high short-term mortality in patients with end-stage liver disease. A capped MELD score fails to capture acute liver decompensation adequately, and data suggest that a model incorporating sudden increases in MELD predicts wait-list mortality better.”

Dr. Nadim and her associates acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design “and that factors relating to a patient’s suitability for transplantation or to a center’s decision to accept or reject a liver allograft, both of which affect graft and patient survival, were not accounted for in the analysis. Despite these limitations, the study results have important implications for improving the current liver allocation policy.”

The study was supported in part by the Health Resources and Services Administration. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

PRIMARY SOURCE: J Hepatol. 2017;67[3]:517-25. doi: 1016/j.jhep.2017.04.022

Uncapping the current Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score may provide a better path toward making sure that patients most in need of a liver transplant get one, results from a large, long-term analysis showed.

Established in 2002, the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scoring system “was arbitrarily capped at 40 based on the presumption that transplanting patients with MELD greater than 40 would be futile,” researchers led by Mitra K. Nadim, MD, reported in the September 2017 issue of the Journal of Hepatology (67[3]:517-25. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.04.022). “As a result, patients with MELD greater than 40 receive the same priority as patients with MELD of 40, differentiated only by their time on the wait list.”

The mean age of patients was 53 years, and most were white men. The researchers reported that 3.3% of wait-listed patients had a MELD score of 40 or greater at registration, while 7.3% had MELD scores increase to 40 or greater after wait-list registration. In all, 30,369 patients (40.6%) underwent liver transplantation during the study period. Of these, 2,615 (8.6%) had a MELD score of 40 or greater at the time of their procedure. Compared with patients who had a MELD score of 40, those who had a MELD score of greater than 40 had an increased risk of death within 30 days, and the risk increased with rising scores. Specifically, the hazard ratio was 1.4 for those with a MELD score of 40-44, an HR of 2.6 for those with a MELD score of 45-49, and an HR of 5.0 for those with a MELD score of 50 or greater. There were no survival differences between the two groups at 1 and 3 years, but there was a survival benefit associated with liver transplantation as the MELD score increased above 40, the investigators reported.

“The arbitrary capping of the MELD at 40 has resulted in an unforeseen lack of objectivity for patients with MELD [score of greater than] 40 who are unjustifiably disadvantaged in a system designed to prioritize patients most in need,” they concluded. “Uncapping the MELD score is another necessary step in the evolution of liver allocation and patient prioritization.” They added that a significant number of patients with a MELD score of 40 or greater “likely suffer from acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF), a recently recognized syndrome characterized by acute liver decompensation, other organ system failures, and high short-term mortality in patients with end-stage liver disease. A capped MELD score fails to capture acute liver decompensation adequately, and data suggest that a model incorporating sudden increases in MELD predicts wait-list mortality better.”

Dr. Nadim and her associates acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design “and that factors relating to a patient’s suitability for transplantation or to a center’s decision to accept or reject a liver allograft, both of which affect graft and patient survival, were not accounted for in the analysis. Despite these limitations, the study results have important implications for improving the current liver allocation policy.”

The study was supported in part by the Health Resources and Services Administration. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

PRIMARY SOURCE: J Hepatol. 2017;67[3]:517-25. doi: 1016/j.jhep.2017.04.022

FROM THE JOURNAL OF HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: .

Major finding: Compared with patients who had a MELD score of 40, the increased risk of death within 30 days was 1.4 for those with a MELD score of 40-44.

Study details: A retrospective analysis of 65,776 patients listed for a liver transplant from February 2002 to December 2012.

Disclosures: The study was supported in part by the Health Resources and Services Administration. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Mitra K. Nadim, MD, et al. Inequity in organ allocation for patients awaiting liver transplantation: Rationale for uncapping the model for end-stage liver disease. J Hepatol. 2017;67(3):517-25. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.04.022.

Clinical trial: Complex VHR using biologic or synthetic mesh

The Study Comparing the Efficacy, Safety, and Cost of a Permanent, Synthetic Prosthetic Versus a Biologic Prosthetic in the One-Stage Repair of Ventral Hernias in Clean and Contaminated Wounds is an interventional trial currently recruiting patients with ventral hernias.

The trial will compare results of ventral hernia repair in patients who have received a biologic mesh made from pig skin with those who received a synthetic mesh made in a laboratory. Both study groups will include patients with and without infection near the hernia. Synthetic mesh is hypothesized to have a higher rate of early postoperative infection, while biologic mesh is hypothesized to have a higher rate of recurrence.

Patients will be included in the trial if they have a ventral hernia; are older than 21 years; are not pregnant; and have no allergic, religious, or ethical objections to polypropylene or porcine prosthetics. Reasons for exclusion include severe malnutrition, pre-existing parenchymal liver disease, immunocompromisation, and refractory ascites.

The primary outcome measure is recurrence within 24 months of surgery, and the secondary outcome measure is wound events within 24 months of surgery. Other outcome measures include early postoperative complications within 1 month of surgery and quality of life, pain, activity level, and overall cost with 24 months of surgery.

The study will end in June 2019. About 330 people are expected to be included in the final analysis.

Find more information at the study page on Clinicaltrials.gov.

The Study Comparing the Efficacy, Safety, and Cost of a Permanent, Synthetic Prosthetic Versus a Biologic Prosthetic in the One-Stage Repair of Ventral Hernias in Clean and Contaminated Wounds is an interventional trial currently recruiting patients with ventral hernias.

The trial will compare results of ventral hernia repair in patients who have received a biologic mesh made from pig skin with those who received a synthetic mesh made in a laboratory. Both study groups will include patients with and without infection near the hernia. Synthetic mesh is hypothesized to have a higher rate of early postoperative infection, while biologic mesh is hypothesized to have a higher rate of recurrence.

Patients will be included in the trial if they have a ventral hernia; are older than 21 years; are not pregnant; and have no allergic, religious, or ethical objections to polypropylene or porcine prosthetics. Reasons for exclusion include severe malnutrition, pre-existing parenchymal liver disease, immunocompromisation, and refractory ascites.

The primary outcome measure is recurrence within 24 months of surgery, and the secondary outcome measure is wound events within 24 months of surgery. Other outcome measures include early postoperative complications within 1 month of surgery and quality of life, pain, activity level, and overall cost with 24 months of surgery.

The study will end in June 2019. About 330 people are expected to be included in the final analysis.

Find more information at the study page on Clinicaltrials.gov.

The Study Comparing the Efficacy, Safety, and Cost of a Permanent, Synthetic Prosthetic Versus a Biologic Prosthetic in the One-Stage Repair of Ventral Hernias in Clean and Contaminated Wounds is an interventional trial currently recruiting patients with ventral hernias.

The trial will compare results of ventral hernia repair in patients who have received a biologic mesh made from pig skin with those who received a synthetic mesh made in a laboratory. Both study groups will include patients with and without infection near the hernia. Synthetic mesh is hypothesized to have a higher rate of early postoperative infection, while biologic mesh is hypothesized to have a higher rate of recurrence.

Patients will be included in the trial if they have a ventral hernia; are older than 21 years; are not pregnant; and have no allergic, religious, or ethical objections to polypropylene or porcine prosthetics. Reasons for exclusion include severe malnutrition, pre-existing parenchymal liver disease, immunocompromisation, and refractory ascites.

The primary outcome measure is recurrence within 24 months of surgery, and the secondary outcome measure is wound events within 24 months of surgery. Other outcome measures include early postoperative complications within 1 month of surgery and quality of life, pain, activity level, and overall cost with 24 months of surgery.

The study will end in June 2019. About 330 people are expected to be included in the final analysis.

Find more information at the study page on Clinicaltrials.gov.

SUMMARY FROM CLINICALTRIALS.GOV

Shinal v. Toms: It’s Now Harder to Get Informed Consent

Question: Which of the following statements regarding Shinal v. Toms, a recent landmark decision on informed consent, is correct?:

A. The case was heard in the Pennsylvania Supreme Court and its decision is binding only in that state.

B. It held that obtaining informed consent is a doctor’s duty that is non-delegable.

C. The decision reversed the lower courts, which had held that the defendant’s qualified assistant could obtain consent.

D. An earlier case heard by the same court had ruled that doctors, not hospitals, owe the legal duty to obtain informed consent.

E. All are correct.

Answer: E.

On Nov. 26, 2007, Megan Shinal and Dr. Steven Toms met for a 20-minute initial consultation to discuss removing a recurrent craniopharyngioma.1 Years earlier, a surgeon had performed a transsphenoidal resection, but was unable to remove all of it. The residual portion of the tumor had increased in size and extended into vital structures of the brain, jeopardizing Mrs. Shinal’s eyesight and her carotid artery, causing headaches, and threatening to impact her pituitary function.

Dr. Toms testified that he reviewed with Mrs. Shinal the alternatives, risks, and benefits of total versus subtotal resection, and shared his opinion that, although a less aggressive approach to removing the tumor was safer in the short term, such an approach would increase the likelihood that the tumor would regrow. Dr. Toms was unable to recall many of the specifics, but he testified that he advised Mrs. Shinal that total surgical resection offered the highest chance for long-term survival. By the end of the visit, Mrs. Shinal had decided to undergo surgery. However, the type of surgery had not yet been determined.

Shortly thereafter, on Dec. 19, 2007, Mrs. Shinal had a telephone conversation with Dr. Toms’ physician assistant. Mrs. Shinal later testified that she asked the physician assistant about scarring that would likely result from surgery, whether radiation would be necessary, and about the date of surgery. The medical record of this telephone call indicated that Dr. Toms’ physician assistant also answered questions about the craniotomy incision. On Jan. 17, 2008, Mrs. Shinal met with the physician assistant at the Geisinger Medical Center’s neurosurgery clinic. The assistant obtained Mrs. Shinal’s medical history, conducted a physical, and provided Mrs. Shinal with information relating to the surgery. Mrs. Shinal signed an informed consent form.

On Jan. 31, 2008, Mrs. Shinal underwent an open craniotomy for a total resection of the pituitary tumor at Geisinger Medical Center. During the operation, Dr. Toms perforated Mrs. Shinal’s carotid artery, which resulted in hemorrhage, stroke, brain injury, and partial blindness.

According to the Shinals’ complaint, Dr. Toms failed to explain the risks of surgery to Mrs. Shinal or to offer her the lower-risk surgical alternative of subtotal resection of the benign tumor, followed by radiation. At trial, Mrs. Shinal was unable to recall being informed of the relative risks of the surgery, other than coma and death. She testified that, had she known the alternative approaches to surgery, i.e., total versus subtotal resection, she would have chosen subtotal resection as the safer, less aggressive alternative.

The trial court instructed the jury with regard to Dr. Toms’ duty to obtain informed consent from Mrs. Shinal as follows: “[I]n considering whether [Dr. Toms] provided consent to [Mrs. Shinal], you may consider any relevant information you find was communicated to [Mrs. Shinal] by any qualified person acting as an assistant to [Dr. Toms].”

On April 21, 2014, the jury returned a verdict in favor of Dr. Toms.

The plaintiffs appealed to the Pennsylvania Superior Court, which affirmed the trial court’s judgment. It rejected the Shinals’ argument that the trial court’s informed consent charge, which permitted the jury to consider information provided by Dr. Toms’ physician assistant to Mrs. Shinal, was erroneous and prejudicial. The Superior Court relied upon two of its prior cases to opine that a qualified professional acting under the attending doctor’s supervision may convey information communicated to a patient for purposes of obtaining informed consent.

The trial court initially instructed the jury that, in assessing whether Dr. Toms obtained Mrs. Shinal’s informed consent, it could consider relevant information communicated by “any qualified person acting as an assistant” to Dr. Toms. The defendant doctor argued that while it is the physician’s duty to obtain the patient’s informed consent, the physician is not required to supply all of the information personally. It is the information conveyed, rather than the person conveying it that determines informed consent. Dr. Toms cited several older Pennsylvania Superior Court cases, which permitted a physician to fulfill through an intermediary the duty to provide sufficient information to obtain a patient’s informed consent.

The plaintiffs then appealed to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, which led to a reversal. In a 4-3 decision, the court disagreed, citing their ruling in the 2002 case of Valles v. Albert Einstein Medical Center,2 where they held that the duty to obtain informed consent could not be imputed to a hospital. In Valles, the court held that the duty to obtain a patient’s informed consent is a nondelegable duty owed by the physician conducting the surgery or treatment, because obtaining informed consent results directly from the duty of disclosure, which lies solely with the physician, and a hospital therefore cannot be liable for a physician’s failure to obtain informed consent.

Reasoning by extension, the court accordingly ruled that a physician may not delegate to others his or her obligation to provide sufficient information in order to obtain a patient’s informed consent. It declared: “Informed consent requires direct communication between physician and patient, and contemplates a back-and-forth, face-to-face exchange, which might include questions that the patient feels the physician must answer personally before the patient feels informed and becomes willing to consent. The duty to obtain the patient’s informed consent belongs solely to the physician.”

The court also held that “a physician cannot rely upon a subordinate to disclose the information required to obtain informed consent. Without direct dialogue and a two-way exchange between the physician and patient, the physician cannot be confident that the patient comprehends the risks, benefits, likelihood of success, and alternatives. ... Informed consent is a product of the physician-patient relationship.

"The patient is in the vulnerable position of entrusting his or her care and well being to the physician based upon the physician’s education, training, and expertise," the court added. "It is incumbent upon the physician to cultivate a relationship with the patient and to familiarize himself or herself with the patient’s understanding and expectations. Were the law to permit physicians to delegate the provision of critical information to staff, it would undermine patient autonomy and bodily integrity by depriving the patient of the opportunity to engage in a dialogue with his or her chosen health care provider. A regime that would countenance delegation of the informed consent process would undermine the primacy of the physician-patient relationship. Only by personally satisfying the duty of disclosure may the physician ensure that consent truly is informed.”

The facts of the case appear straightforward, and its legal conclusion clear. Whether one agrees with the court’s decision is, however, another matter. The American Medical Association and the Pennsylvania Medical Society (PAMED) had submitted an amicus brief supporting Dr. Toms’ position, arguing that he had fulfilled his obligations under Pennsylvania’s Medical Care Availability and Reduction of Error Act, as well as common law established in previous Pennsylvania court rulings. The final appellate decision therefore came as a big disappointment. The PAMED website notes that the decision “could have significant ramifications for Pennsylvania physicians” in that they can “seemingly no longer rely on the aid of their qualified staff in the informed consent process.”3

The urgent question now is whether other jurisdictions will adopt this Pennsylvania rule that drastically changes the way doctors obtain informed consent from their patients.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

References

1. Shinal v. Toms, J-106-2016, Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, Decided: June 20, 2017.

2. Valles v. Albert Einstein Medical Center, 805 A.2d (PA, 2002).

3. Informed-consent ruling may have “far-reaching, negative impact.” AMA Wire, Aug 8, 2017.

Question: Which of the following statements regarding Shinal v. Toms, a recent landmark decision on informed consent, is correct?:

A. The case was heard in the Pennsylvania Supreme Court and its decision is binding only in that state.

B. It held that obtaining informed consent is a doctor’s duty that is non-delegable.

C. The decision reversed the lower courts, which had held that the defendant’s qualified assistant could obtain consent.

D. An earlier case heard by the same court had ruled that doctors, not hospitals, owe the legal duty to obtain informed consent.

E. All are correct.

Answer: E.

On Nov. 26, 2007, Megan Shinal and Dr. Steven Toms met for a 20-minute initial consultation to discuss removing a recurrent craniopharyngioma.1 Years earlier, a surgeon had performed a transsphenoidal resection, but was unable to remove all of it. The residual portion of the tumor had increased in size and extended into vital structures of the brain, jeopardizing Mrs. Shinal’s eyesight and her carotid artery, causing headaches, and threatening to impact her pituitary function.

Dr. Toms testified that he reviewed with Mrs. Shinal the alternatives, risks, and benefits of total versus subtotal resection, and shared his opinion that, although a less aggressive approach to removing the tumor was safer in the short term, such an approach would increase the likelihood that the tumor would regrow. Dr. Toms was unable to recall many of the specifics, but he testified that he advised Mrs. Shinal that total surgical resection offered the highest chance for long-term survival. By the end of the visit, Mrs. Shinal had decided to undergo surgery. However, the type of surgery had not yet been determined.

Shortly thereafter, on Dec. 19, 2007, Mrs. Shinal had a telephone conversation with Dr. Toms’ physician assistant. Mrs. Shinal later testified that she asked the physician assistant about scarring that would likely result from surgery, whether radiation would be necessary, and about the date of surgery. The medical record of this telephone call indicated that Dr. Toms’ physician assistant also answered questions about the craniotomy incision. On Jan. 17, 2008, Mrs. Shinal met with the physician assistant at the Geisinger Medical Center’s neurosurgery clinic. The assistant obtained Mrs. Shinal’s medical history, conducted a physical, and provided Mrs. Shinal with information relating to the surgery. Mrs. Shinal signed an informed consent form.

On Jan. 31, 2008, Mrs. Shinal underwent an open craniotomy for a total resection of the pituitary tumor at Geisinger Medical Center. During the operation, Dr. Toms perforated Mrs. Shinal’s carotid artery, which resulted in hemorrhage, stroke, brain injury, and partial blindness.

According to the Shinals’ complaint, Dr. Toms failed to explain the risks of surgery to Mrs. Shinal or to offer her the lower-risk surgical alternative of subtotal resection of the benign tumor, followed by radiation. At trial, Mrs. Shinal was unable to recall being informed of the relative risks of the surgery, other than coma and death. She testified that, had she known the alternative approaches to surgery, i.e., total versus subtotal resection, she would have chosen subtotal resection as the safer, less aggressive alternative.

The trial court instructed the jury with regard to Dr. Toms’ duty to obtain informed consent from Mrs. Shinal as follows: “[I]n considering whether [Dr. Toms] provided consent to [Mrs. Shinal], you may consider any relevant information you find was communicated to [Mrs. Shinal] by any qualified person acting as an assistant to [Dr. Toms].”

On April 21, 2014, the jury returned a verdict in favor of Dr. Toms.

The plaintiffs appealed to the Pennsylvania Superior Court, which affirmed the trial court’s judgment. It rejected the Shinals’ argument that the trial court’s informed consent charge, which permitted the jury to consider information provided by Dr. Toms’ physician assistant to Mrs. Shinal, was erroneous and prejudicial. The Superior Court relied upon two of its prior cases to opine that a qualified professional acting under the attending doctor’s supervision may convey information communicated to a patient for purposes of obtaining informed consent.

The trial court initially instructed the jury that, in assessing whether Dr. Toms obtained Mrs. Shinal’s informed consent, it could consider relevant information communicated by “any qualified person acting as an assistant” to Dr. Toms. The defendant doctor argued that while it is the physician’s duty to obtain the patient’s informed consent, the physician is not required to supply all of the information personally. It is the information conveyed, rather than the person conveying it that determines informed consent. Dr. Toms cited several older Pennsylvania Superior Court cases, which permitted a physician to fulfill through an intermediary the duty to provide sufficient information to obtain a patient’s informed consent.

The plaintiffs then appealed to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, which led to a reversal. In a 4-3 decision, the court disagreed, citing their ruling in the 2002 case of Valles v. Albert Einstein Medical Center,2 where they held that the duty to obtain informed consent could not be imputed to a hospital. In Valles, the court held that the duty to obtain a patient’s informed consent is a nondelegable duty owed by the physician conducting the surgery or treatment, because obtaining informed consent results directly from the duty of disclosure, which lies solely with the physician, and a hospital therefore cannot be liable for a physician’s failure to obtain informed consent.

Reasoning by extension, the court accordingly ruled that a physician may not delegate to others his or her obligation to provide sufficient information in order to obtain a patient’s informed consent. It declared: “Informed consent requires direct communication between physician and patient, and contemplates a back-and-forth, face-to-face exchange, which might include questions that the patient feels the physician must answer personally before the patient feels informed and becomes willing to consent. The duty to obtain the patient’s informed consent belongs solely to the physician.”

The court also held that “a physician cannot rely upon a subordinate to disclose the information required to obtain informed consent. Without direct dialogue and a two-way exchange between the physician and patient, the physician cannot be confident that the patient comprehends the risks, benefits, likelihood of success, and alternatives. ... Informed consent is a product of the physician-patient relationship.

"The patient is in the vulnerable position of entrusting his or her care and well being to the physician based upon the physician’s education, training, and expertise," the court added. "It is incumbent upon the physician to cultivate a relationship with the patient and to familiarize himself or herself with the patient’s understanding and expectations. Were the law to permit physicians to delegate the provision of critical information to staff, it would undermine patient autonomy and bodily integrity by depriving the patient of the opportunity to engage in a dialogue with his or her chosen health care provider. A regime that would countenance delegation of the informed consent process would undermine the primacy of the physician-patient relationship. Only by personally satisfying the duty of disclosure may the physician ensure that consent truly is informed.”

The facts of the case appear straightforward, and its legal conclusion clear. Whether one agrees with the court’s decision is, however, another matter. The American Medical Association and the Pennsylvania Medical Society (PAMED) had submitted an amicus brief supporting Dr. Toms’ position, arguing that he had fulfilled his obligations under Pennsylvania’s Medical Care Availability and Reduction of Error Act, as well as common law established in previous Pennsylvania court rulings. The final appellate decision therefore came as a big disappointment. The PAMED website notes that the decision “could have significant ramifications for Pennsylvania physicians” in that they can “seemingly no longer rely on the aid of their qualified staff in the informed consent process.”3

The urgent question now is whether other jurisdictions will adopt this Pennsylvania rule that drastically changes the way doctors obtain informed consent from their patients.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

References

1. Shinal v. Toms, J-106-2016, Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, Decided: June 20, 2017.

2. Valles v. Albert Einstein Medical Center, 805 A.2d (PA, 2002).

3. Informed-consent ruling may have “far-reaching, negative impact.” AMA Wire, Aug 8, 2017.

Question: Which of the following statements regarding Shinal v. Toms, a recent landmark decision on informed consent, is correct?:

A. The case was heard in the Pennsylvania Supreme Court and its decision is binding only in that state.

B. It held that obtaining informed consent is a doctor’s duty that is non-delegable.

C. The decision reversed the lower courts, which had held that the defendant’s qualified assistant could obtain consent.