User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

Early evidence shows that surgery can alter gut microbiome

SAN DIEGO – Surgery appears to stimulate abrupt changes in both the skin and gut microbiome, which in some patients may increase the risk of surgical site infections and anastomotic leaks. With that knowledge, researchers are exploring the very first steps toward a presurgical microbiome optimization protocol, Heidi Nelson, MD, FACS, said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

It’s very early in the journey, said Dr. Nelson, the Fred C. Andersen Professor of Surgery at Mayo Clinic, Rochester. Minn. And it won’t be a straightforward path: The human microbiome appears to be nearly as individually unique as the human fingerprint, so presurgical protocols might have to be individually tailored to each patient.

Dr. Nelson comoderated a session exploring this topic with John Alverdy, MD, FACS, of the University of Chicago. The panel discussed human and animal studies suggesting that the stress of surgery, when combined with subclinical ischemia and any baseline physiologic stress (chronic illness or radiation, for example) can cause some commensals to begin producing collagenase – a change that endangers even surgically sound anastomoses.

“It’s well known that bacteria can change their function in response to host stress,” said Dr. Shogan, a colorectal surgeon at the University of Chicago. “They recognize these factors and change their entire function. In our work, we found that Enterococcus began to express a tissue-destroying phenotype in response to subclinical ischemia related to surgery.”

The pathogenic flip doesn’t occur unless there are a couple of predisposing factors, he theorized. “There have to be multiple stresses involved. These could include smoking, steroids, obesity, and prior exposure to radiation – all things that we commonly see in our colorectal surgery patients. But when the right situation developed, we can see a proliferation of collagen-destroying bacteria that predispose to leaks.”

The skin microbiome is altered as well, with areas around abdominal incisions beginning to express gut flora, which increase the risk of a surgical site infection, said Andrew Yeh, MD, a general surgery resident at the University of Pittsburgh.

He presented data on 28 colorectal surgery patients, detailing perioperative changes in the chest and abdominal skin microbiome. All of the subjects were adults undergoing colon resection who had not been on any antibiotics at least 1 month before surgery. Skin sampling was performed before and after opening, with additional postoperative skin samples taken daily while the patient was in the hospital recovering. Dr. Yeh had DNA/RNA data on 431 samples taken from this group.

“We saw increases in Staphylococcus and Bacteroides on the skin – normally part of the gut microflora – in relative abundance, while Corynebacterium, a normal constituent of the skin microbiome, had decreased.”

These are all very early observations, though, and the surgical community is nowhere near being able to make any specific presurgical recommendations to optimize the microbiome, or postsurgical recommendations to manage it, said Neil Hyman, MD, FACS, professor of surgery at the University of Chicago.

While it does appear that good bacteria “gone bad” are associated with anastomotic leaks, he agreed that the right constellation of factors has to be in place for this to happen, including “the right bacteria [Enterococcus], the right virulence genes [collagenase], the right activating cures [long operation, blood loss], and the wrong microbiome [altered by smoking, chemotherapy, radiation, or other chronic stressors].”

“I think it’s safe to say that developing collagenase-producing bacteria at an anastomosis site is a bad thing, but the individual genetic makeup of every patient makes any one-size-fits-all protocol approach to treatment really problematic,” Dr. Hyman said.

None of the presenters had any financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

SAN DIEGO – Surgery appears to stimulate abrupt changes in both the skin and gut microbiome, which in some patients may increase the risk of surgical site infections and anastomotic leaks. With that knowledge, researchers are exploring the very first steps toward a presurgical microbiome optimization protocol, Heidi Nelson, MD, FACS, said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

It’s very early in the journey, said Dr. Nelson, the Fred C. Andersen Professor of Surgery at Mayo Clinic, Rochester. Minn. And it won’t be a straightforward path: The human microbiome appears to be nearly as individually unique as the human fingerprint, so presurgical protocols might have to be individually tailored to each patient.

Dr. Nelson comoderated a session exploring this topic with John Alverdy, MD, FACS, of the University of Chicago. The panel discussed human and animal studies suggesting that the stress of surgery, when combined with subclinical ischemia and any baseline physiologic stress (chronic illness or radiation, for example) can cause some commensals to begin producing collagenase – a change that endangers even surgically sound anastomoses.

“It’s well known that bacteria can change their function in response to host stress,” said Dr. Shogan, a colorectal surgeon at the University of Chicago. “They recognize these factors and change their entire function. In our work, we found that Enterococcus began to express a tissue-destroying phenotype in response to subclinical ischemia related to surgery.”

The pathogenic flip doesn’t occur unless there are a couple of predisposing factors, he theorized. “There have to be multiple stresses involved. These could include smoking, steroids, obesity, and prior exposure to radiation – all things that we commonly see in our colorectal surgery patients. But when the right situation developed, we can see a proliferation of collagen-destroying bacteria that predispose to leaks.”

The skin microbiome is altered as well, with areas around abdominal incisions beginning to express gut flora, which increase the risk of a surgical site infection, said Andrew Yeh, MD, a general surgery resident at the University of Pittsburgh.

He presented data on 28 colorectal surgery patients, detailing perioperative changes in the chest and abdominal skin microbiome. All of the subjects were adults undergoing colon resection who had not been on any antibiotics at least 1 month before surgery. Skin sampling was performed before and after opening, with additional postoperative skin samples taken daily while the patient was in the hospital recovering. Dr. Yeh had DNA/RNA data on 431 samples taken from this group.

“We saw increases in Staphylococcus and Bacteroides on the skin – normally part of the gut microflora – in relative abundance, while Corynebacterium, a normal constituent of the skin microbiome, had decreased.”

These are all very early observations, though, and the surgical community is nowhere near being able to make any specific presurgical recommendations to optimize the microbiome, or postsurgical recommendations to manage it, said Neil Hyman, MD, FACS, professor of surgery at the University of Chicago.

While it does appear that good bacteria “gone bad” are associated with anastomotic leaks, he agreed that the right constellation of factors has to be in place for this to happen, including “the right bacteria [Enterococcus], the right virulence genes [collagenase], the right activating cures [long operation, blood loss], and the wrong microbiome [altered by smoking, chemotherapy, radiation, or other chronic stressors].”

“I think it’s safe to say that developing collagenase-producing bacteria at an anastomosis site is a bad thing, but the individual genetic makeup of every patient makes any one-size-fits-all protocol approach to treatment really problematic,” Dr. Hyman said.

None of the presenters had any financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

SAN DIEGO – Surgery appears to stimulate abrupt changes in both the skin and gut microbiome, which in some patients may increase the risk of surgical site infections and anastomotic leaks. With that knowledge, researchers are exploring the very first steps toward a presurgical microbiome optimization protocol, Heidi Nelson, MD, FACS, said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

It’s very early in the journey, said Dr. Nelson, the Fred C. Andersen Professor of Surgery at Mayo Clinic, Rochester. Minn. And it won’t be a straightforward path: The human microbiome appears to be nearly as individually unique as the human fingerprint, so presurgical protocols might have to be individually tailored to each patient.

Dr. Nelson comoderated a session exploring this topic with John Alverdy, MD, FACS, of the University of Chicago. The panel discussed human and animal studies suggesting that the stress of surgery, when combined with subclinical ischemia and any baseline physiologic stress (chronic illness or radiation, for example) can cause some commensals to begin producing collagenase – a change that endangers even surgically sound anastomoses.

“It’s well known that bacteria can change their function in response to host stress,” said Dr. Shogan, a colorectal surgeon at the University of Chicago. “They recognize these factors and change their entire function. In our work, we found that Enterococcus began to express a tissue-destroying phenotype in response to subclinical ischemia related to surgery.”

The pathogenic flip doesn’t occur unless there are a couple of predisposing factors, he theorized. “There have to be multiple stresses involved. These could include smoking, steroids, obesity, and prior exposure to radiation – all things that we commonly see in our colorectal surgery patients. But when the right situation developed, we can see a proliferation of collagen-destroying bacteria that predispose to leaks.”

The skin microbiome is altered as well, with areas around abdominal incisions beginning to express gut flora, which increase the risk of a surgical site infection, said Andrew Yeh, MD, a general surgery resident at the University of Pittsburgh.

He presented data on 28 colorectal surgery patients, detailing perioperative changes in the chest and abdominal skin microbiome. All of the subjects were adults undergoing colon resection who had not been on any antibiotics at least 1 month before surgery. Skin sampling was performed before and after opening, with additional postoperative skin samples taken daily while the patient was in the hospital recovering. Dr. Yeh had DNA/RNA data on 431 samples taken from this group.

“We saw increases in Staphylococcus and Bacteroides on the skin – normally part of the gut microflora – in relative abundance, while Corynebacterium, a normal constituent of the skin microbiome, had decreased.”

These are all very early observations, though, and the surgical community is nowhere near being able to make any specific presurgical recommendations to optimize the microbiome, or postsurgical recommendations to manage it, said Neil Hyman, MD, FACS, professor of surgery at the University of Chicago.

While it does appear that good bacteria “gone bad” are associated with anastomotic leaks, he agreed that the right constellation of factors has to be in place for this to happen, including “the right bacteria [Enterococcus], the right virulence genes [collagenase], the right activating cures [long operation, blood loss], and the wrong microbiome [altered by smoking, chemotherapy, radiation, or other chronic stressors].”

“I think it’s safe to say that developing collagenase-producing bacteria at an anastomosis site is a bad thing, but the individual genetic makeup of every patient makes any one-size-fits-all protocol approach to treatment really problematic,” Dr. Hyman said.

None of the presenters had any financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

VIDEO: Rapid influenza test obviates empiric antivirals

TORONTO – A test that only requires a maximum 2-hour wait for results was highly accurate at detecting influenza and respiratory syncytial virus infection in lung transplant patients, according to research presented at the CHEST annual meeting on Oct. 30.

This rapid and highly accurate test for detecting three common respiratory viruses has dramatically cut the need for empiric treatments and the risk for causing nosocomial infections in lung transplant patients who develop severe upper respiratory infections, Macé M. Schuurmans, MD, noted during the presentation.

This study involved 100 consecutive lung transplant patients who presented at Zurich University Hospital with signs of severe upper respiratory infection. The researchers ran the rapid and standard diagnostic tests for each patient and found that, relative to the standard test, the rapid test had positive and negative predictive values of 95%.

The number of empiric treatments with oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and ribavirin to treat a suspected influenza or respiratory syncytial virus infection (RSV) has “strongly diminished” by about two-thirds, noted Dr. Schuurmans, who is a pulmonologist at the hospital.

Until the rapid test became available, Dr. Shuurmans and his associates used a standard polymerase chain reaction test that takes 36-48 hours to yield a result. Using this test made treating patients empirically with oseltamivir and oral antibiotics for a couple of days a necessity, he said in a video interview. The older test also required isolating patients to avoid the potential spread of influenza or RSV in the hospital.

The rapid test, which became available for U.S. use in early 2017, covers influenza A and B and RSV in a single test with a single mouth-swab specimen.

“We now routinely use the rapid test and don’t prescribe empiric antivirals or antibiotics as often,” Dr. Schuurmans said. “There is much less drug cost and fewer potential adverse effects from empiric treatment.” Specimens still also undergo conventional testing, however, because that can identify eight additional viruses that the rapid test doesn’t cover.

Dr. Schuurmans acknowledged that further study needs to assess the cost-benefit of the rapid test to confirm that its added expense is offset by reduced expenses for empiric treatment and hospital isolation.

He had no disclosures. The study received no commercial support.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

TORONTO – A test that only requires a maximum 2-hour wait for results was highly accurate at detecting influenza and respiratory syncytial virus infection in lung transplant patients, according to research presented at the CHEST annual meeting on Oct. 30.

This rapid and highly accurate test for detecting three common respiratory viruses has dramatically cut the need for empiric treatments and the risk for causing nosocomial infections in lung transplant patients who develop severe upper respiratory infections, Macé M. Schuurmans, MD, noted during the presentation.

This study involved 100 consecutive lung transplant patients who presented at Zurich University Hospital with signs of severe upper respiratory infection. The researchers ran the rapid and standard diagnostic tests for each patient and found that, relative to the standard test, the rapid test had positive and negative predictive values of 95%.

The number of empiric treatments with oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and ribavirin to treat a suspected influenza or respiratory syncytial virus infection (RSV) has “strongly diminished” by about two-thirds, noted Dr. Schuurmans, who is a pulmonologist at the hospital.

Until the rapid test became available, Dr. Shuurmans and his associates used a standard polymerase chain reaction test that takes 36-48 hours to yield a result. Using this test made treating patients empirically with oseltamivir and oral antibiotics for a couple of days a necessity, he said in a video interview. The older test also required isolating patients to avoid the potential spread of influenza or RSV in the hospital.

The rapid test, which became available for U.S. use in early 2017, covers influenza A and B and RSV in a single test with a single mouth-swab specimen.

“We now routinely use the rapid test and don’t prescribe empiric antivirals or antibiotics as often,” Dr. Schuurmans said. “There is much less drug cost and fewer potential adverse effects from empiric treatment.” Specimens still also undergo conventional testing, however, because that can identify eight additional viruses that the rapid test doesn’t cover.

Dr. Schuurmans acknowledged that further study needs to assess the cost-benefit of the rapid test to confirm that its added expense is offset by reduced expenses for empiric treatment and hospital isolation.

He had no disclosures. The study received no commercial support.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

TORONTO – A test that only requires a maximum 2-hour wait for results was highly accurate at detecting influenza and respiratory syncytial virus infection in lung transplant patients, according to research presented at the CHEST annual meeting on Oct. 30.

This rapid and highly accurate test for detecting three common respiratory viruses has dramatically cut the need for empiric treatments and the risk for causing nosocomial infections in lung transplant patients who develop severe upper respiratory infections, Macé M. Schuurmans, MD, noted during the presentation.

This study involved 100 consecutive lung transplant patients who presented at Zurich University Hospital with signs of severe upper respiratory infection. The researchers ran the rapid and standard diagnostic tests for each patient and found that, relative to the standard test, the rapid test had positive and negative predictive values of 95%.

The number of empiric treatments with oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and ribavirin to treat a suspected influenza or respiratory syncytial virus infection (RSV) has “strongly diminished” by about two-thirds, noted Dr. Schuurmans, who is a pulmonologist at the hospital.

Until the rapid test became available, Dr. Shuurmans and his associates used a standard polymerase chain reaction test that takes 36-48 hours to yield a result. Using this test made treating patients empirically with oseltamivir and oral antibiotics for a couple of days a necessity, he said in a video interview. The older test also required isolating patients to avoid the potential spread of influenza or RSV in the hospital.

The rapid test, which became available for U.S. use in early 2017, covers influenza A and B and RSV in a single test with a single mouth-swab specimen.

“We now routinely use the rapid test and don’t prescribe empiric antivirals or antibiotics as often,” Dr. Schuurmans said. “There is much less drug cost and fewer potential adverse effects from empiric treatment.” Specimens still also undergo conventional testing, however, because that can identify eight additional viruses that the rapid test doesn’t cover.

Dr. Schuurmans acknowledged that further study needs to assess the cost-benefit of the rapid test to confirm that its added expense is offset by reduced expenses for empiric treatment and hospital isolation.

He had no disclosures. The study received no commercial support.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT CHEST 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The rapid test had positive and negative predictive values of 95%.

Data source: A single-center observational study of 100 consecutive lung transplant recipients who presented with severe, acute respiratory infection.

Disclosures: Dr. Schuurmans had no disclosures. The study received no commercial support.

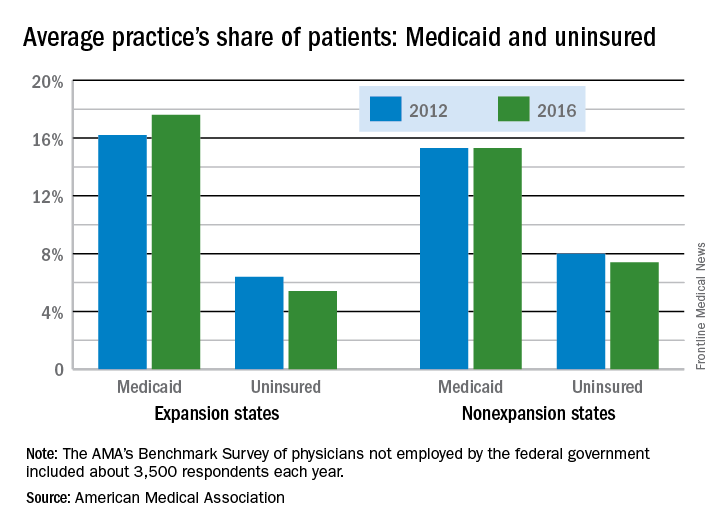

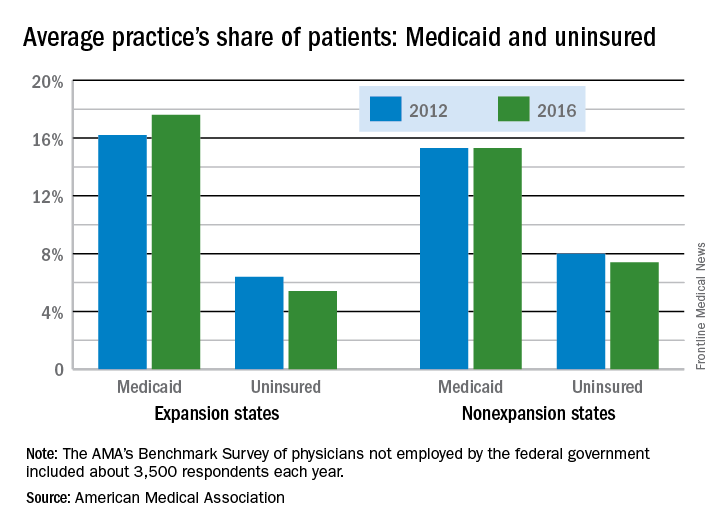

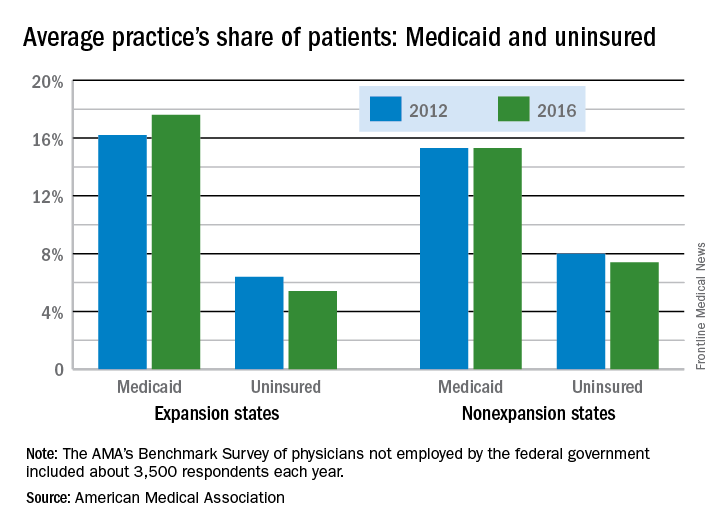

AMA: Patient mix has become less uninsured since 2012

Uninsured patients made up a smaller share of the average physician’s practice in 2016 than in 2012, according to a survey by the American Medical Association.

For the average practice in 2016, 6.1% of patients were uninsured, compared with 6.9% in 2012. That significant drop of 0.8 percentage points was accompanied by significant increases in the number of patients covered by Medicaid and by private insurance, the AMA said in a report released Oct. 30.

“The overall picture from new physician-reported data is of more patients covered and fewer uninsured, but the findings also indicate that the improvement along those lines was concentrated in states that expanded their Medicaid programs under the ACA,” said David O. Barbe, MD, AMA president.

In the 31 states and the District of Columbia that expanded Medicaid, the average patient share dropped from 6.4% uninsured in 2012 to 5.4% in 2016, which was significant. In the states that did not expand Medicaid, the average share of uninsured patients went from 8.0% to 7.4% over that period, a drop that did not reach significance, the AMA said.

The changes involving Medicaid itself were of somewhat greater magnitude, in both directions: nonexpansion states saw a smaller increase and expansion states had a larger increase. In nonexpansion states the average share of a practice’s patients covered by Medicaid basically held steady at 15.3% (there was actually a very slight increase, but the AMA reported the figures for both 2012 and 2016 as 15.3%). In expansion states, the average Medicaid share went from 16.2% to 17.6% – a statistically significant increase of 1.4 percentage points, the AMA analysis shows.

The AMA report covers data from its 2012 and 2016 Benchmark Surveys, which each year involved approximately 3,500 physicians in patient care who were not employed by the federal government.

Uninsured patients made up a smaller share of the average physician’s practice in 2016 than in 2012, according to a survey by the American Medical Association.

For the average practice in 2016, 6.1% of patients were uninsured, compared with 6.9% in 2012. That significant drop of 0.8 percentage points was accompanied by significant increases in the number of patients covered by Medicaid and by private insurance, the AMA said in a report released Oct. 30.

“The overall picture from new physician-reported data is of more patients covered and fewer uninsured, but the findings also indicate that the improvement along those lines was concentrated in states that expanded their Medicaid programs under the ACA,” said David O. Barbe, MD, AMA president.

In the 31 states and the District of Columbia that expanded Medicaid, the average patient share dropped from 6.4% uninsured in 2012 to 5.4% in 2016, which was significant. In the states that did not expand Medicaid, the average share of uninsured patients went from 8.0% to 7.4% over that period, a drop that did not reach significance, the AMA said.

The changes involving Medicaid itself were of somewhat greater magnitude, in both directions: nonexpansion states saw a smaller increase and expansion states had a larger increase. In nonexpansion states the average share of a practice’s patients covered by Medicaid basically held steady at 15.3% (there was actually a very slight increase, but the AMA reported the figures for both 2012 and 2016 as 15.3%). In expansion states, the average Medicaid share went from 16.2% to 17.6% – a statistically significant increase of 1.4 percentage points, the AMA analysis shows.

The AMA report covers data from its 2012 and 2016 Benchmark Surveys, which each year involved approximately 3,500 physicians in patient care who were not employed by the federal government.

Uninsured patients made up a smaller share of the average physician’s practice in 2016 than in 2012, according to a survey by the American Medical Association.

For the average practice in 2016, 6.1% of patients were uninsured, compared with 6.9% in 2012. That significant drop of 0.8 percentage points was accompanied by significant increases in the number of patients covered by Medicaid and by private insurance, the AMA said in a report released Oct. 30.

“The overall picture from new physician-reported data is of more patients covered and fewer uninsured, but the findings also indicate that the improvement along those lines was concentrated in states that expanded their Medicaid programs under the ACA,” said David O. Barbe, MD, AMA president.

In the 31 states and the District of Columbia that expanded Medicaid, the average patient share dropped from 6.4% uninsured in 2012 to 5.4% in 2016, which was significant. In the states that did not expand Medicaid, the average share of uninsured patients went from 8.0% to 7.4% over that period, a drop that did not reach significance, the AMA said.

The changes involving Medicaid itself were of somewhat greater magnitude, in both directions: nonexpansion states saw a smaller increase and expansion states had a larger increase. In nonexpansion states the average share of a practice’s patients covered by Medicaid basically held steady at 15.3% (there was actually a very slight increase, but the AMA reported the figures for both 2012 and 2016 as 15.3%). In expansion states, the average Medicaid share went from 16.2% to 17.6% – a statistically significant increase of 1.4 percentage points, the AMA analysis shows.

The AMA report covers data from its 2012 and 2016 Benchmark Surveys, which each year involved approximately 3,500 physicians in patient care who were not employed by the federal government.

Cold stored platelets control bleeding after complex cardiac surgery

SAN DIEGO – Cold stored leukoreduced apheresis platelets in platelet additive solution were effective for controlling bleeding in a small study of patients undergoing complex cardiothoracic surgery, according to findings presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Blood Banks.

The volume of postoperative bleeding was significantly lower among patients who received cold stored platelets compared with those who received standard room temperature storage platelets. Thromboembolic events did not differ between the two groups, nor did measures of coagulation at varying time points. Platelet counts and blood usage were also similar in the two groups. The study was small, however, and further studies are needed to confirm the findings.

“These patients are undergoing major surgery and are at high risk in every aspect,” said Torunn Oveland Apelseth, MD, PhD, of the Laboratory of Clinical Biochemistry, Haukeland (Norway) University Hospital. “They are at high risk for bleeding, at high risk for thromboembolic events and high blood usage, and there is a need for optimized blood components.”

There has been debate over the use of cold stored platelets, she noted. While storage at 4° C shortens platelet circulation time, some research shows that cold stored platelets have better hemostatic function.

In this study, one patient cohort was transfused with leukoreduced apheresis platelets stored at 4° C in platelet additive solution for up to 7 days under constant agitation, while the other group received platelets stored at standard room temperature. The study endpoints were comparisons between the two groups of postoperative bleeding, total blood usage, and laboratory measures of coagulation and blood cell counts within the first postoperative day. Thromboembolic events in the 28 days after surgery were also evaluated.

The study evaluated 17 patients who received cold stored platelets and 22 who received room temperature storage platelets. Patient demographics for the two groups were similar – as were their international normalized ratios, activated partial thromboplastin times, and fibrinogen levels – before surgery, immediately after heparin reversal, and the morning following the procedure.

Platelet counts and hemoglobin levels also did not significantly differ between groups.

As measured by chest drain output after chest closure, patients who received cold stored platelets had a significantly lower median amount of bleeding in the postoperative period compared with patients given room temperature storage platelets: 576 mL vs. 838 mL. Average chest drain output after chest closure was 594 mL in those who did not receive any transfusions.

Thromboembolic events occurred in 3 patients (18%) who received cold stored platelets and 7 (31%) of those given room temperature storage platelets. The difference was not statistically significant. In addition, blood usage – platelets, red blood cells, and solvent/detergent-treated pooled plasma – was similar for the two cohorts.

“There were also no differences in the number of thromboembolic episodes or length of stay in ICU,” said Dr. Apelseth, who recommended larger studies to explore the use of use of cold stored platelet transfusion in the critical care setting.

SAN DIEGO – Cold stored leukoreduced apheresis platelets in platelet additive solution were effective for controlling bleeding in a small study of patients undergoing complex cardiothoracic surgery, according to findings presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Blood Banks.

The volume of postoperative bleeding was significantly lower among patients who received cold stored platelets compared with those who received standard room temperature storage platelets. Thromboembolic events did not differ between the two groups, nor did measures of coagulation at varying time points. Platelet counts and blood usage were also similar in the two groups. The study was small, however, and further studies are needed to confirm the findings.

“These patients are undergoing major surgery and are at high risk in every aspect,” said Torunn Oveland Apelseth, MD, PhD, of the Laboratory of Clinical Biochemistry, Haukeland (Norway) University Hospital. “They are at high risk for bleeding, at high risk for thromboembolic events and high blood usage, and there is a need for optimized blood components.”

There has been debate over the use of cold stored platelets, she noted. While storage at 4° C shortens platelet circulation time, some research shows that cold stored platelets have better hemostatic function.

In this study, one patient cohort was transfused with leukoreduced apheresis platelets stored at 4° C in platelet additive solution for up to 7 days under constant agitation, while the other group received platelets stored at standard room temperature. The study endpoints were comparisons between the two groups of postoperative bleeding, total blood usage, and laboratory measures of coagulation and blood cell counts within the first postoperative day. Thromboembolic events in the 28 days after surgery were also evaluated.

The study evaluated 17 patients who received cold stored platelets and 22 who received room temperature storage platelets. Patient demographics for the two groups were similar – as were their international normalized ratios, activated partial thromboplastin times, and fibrinogen levels – before surgery, immediately after heparin reversal, and the morning following the procedure.

Platelet counts and hemoglobin levels also did not significantly differ between groups.

As measured by chest drain output after chest closure, patients who received cold stored platelets had a significantly lower median amount of bleeding in the postoperative period compared with patients given room temperature storage platelets: 576 mL vs. 838 mL. Average chest drain output after chest closure was 594 mL in those who did not receive any transfusions.

Thromboembolic events occurred in 3 patients (18%) who received cold stored platelets and 7 (31%) of those given room temperature storage platelets. The difference was not statistically significant. In addition, blood usage – platelets, red blood cells, and solvent/detergent-treated pooled plasma – was similar for the two cohorts.

“There were also no differences in the number of thromboembolic episodes or length of stay in ICU,” said Dr. Apelseth, who recommended larger studies to explore the use of use of cold stored platelet transfusion in the critical care setting.

SAN DIEGO – Cold stored leukoreduced apheresis platelets in platelet additive solution were effective for controlling bleeding in a small study of patients undergoing complex cardiothoracic surgery, according to findings presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Blood Banks.

The volume of postoperative bleeding was significantly lower among patients who received cold stored platelets compared with those who received standard room temperature storage platelets. Thromboembolic events did not differ between the two groups, nor did measures of coagulation at varying time points. Platelet counts and blood usage were also similar in the two groups. The study was small, however, and further studies are needed to confirm the findings.

“These patients are undergoing major surgery and are at high risk in every aspect,” said Torunn Oveland Apelseth, MD, PhD, of the Laboratory of Clinical Biochemistry, Haukeland (Norway) University Hospital. “They are at high risk for bleeding, at high risk for thromboembolic events and high blood usage, and there is a need for optimized blood components.”

There has been debate over the use of cold stored platelets, she noted. While storage at 4° C shortens platelet circulation time, some research shows that cold stored platelets have better hemostatic function.

In this study, one patient cohort was transfused with leukoreduced apheresis platelets stored at 4° C in platelet additive solution for up to 7 days under constant agitation, while the other group received platelets stored at standard room temperature. The study endpoints were comparisons between the two groups of postoperative bleeding, total blood usage, and laboratory measures of coagulation and blood cell counts within the first postoperative day. Thromboembolic events in the 28 days after surgery were also evaluated.

The study evaluated 17 patients who received cold stored platelets and 22 who received room temperature storage platelets. Patient demographics for the two groups were similar – as were their international normalized ratios, activated partial thromboplastin times, and fibrinogen levels – before surgery, immediately after heparin reversal, and the morning following the procedure.

Platelet counts and hemoglobin levels also did not significantly differ between groups.

As measured by chest drain output after chest closure, patients who received cold stored platelets had a significantly lower median amount of bleeding in the postoperative period compared with patients given room temperature storage platelets: 576 mL vs. 838 mL. Average chest drain output after chest closure was 594 mL in those who did not receive any transfusions.

Thromboembolic events occurred in 3 patients (18%) who received cold stored platelets and 7 (31%) of those given room temperature storage platelets. The difference was not statistically significant. In addition, blood usage – platelets, red blood cells, and solvent/detergent-treated pooled plasma – was similar for the two cohorts.

“There were also no differences in the number of thromboembolic episodes or length of stay in ICU,” said Dr. Apelseth, who recommended larger studies to explore the use of use of cold stored platelet transfusion in the critical care setting.

AT AABB17

Key clinical point: Cold stored leukoreduced apheresis platelets in platelet additive solution are effective for treating bleeding in patients undergoing complex cardiothoracic surgery.

Major finding: Patients who underwent procedures requiring cardiopulmonary bypass circulation had a significantly lower median amount of bleeding in the postoperative period with cold stored platelets compared with standard room temperature platelets: 576 mL vs. 838 mL.

Data source: Randomized two-arm pilot trial of cardiothoracic surgery patients.

Disclosures: The authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

Location matters when it comes to thyroidectomy rates

Thyroidectomy rates differ widely across the United States, according to a cross-sectional analysis of Medicare beneficiaries, but researchers aren’t sure what’s driving the variation.

There was a 6.2-fold difference in thyroidectomy rates across U.S. hospital referral regions in 2014, ranging from 22 to 139 per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries. The national average was 60 procedures per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries, David O. Francis, MD, of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and his coauthors, reported (JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017 Oct 12. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2017.1746).

The researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis of 15,888 Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older who underwent a thyroidectomy in 2014. Of the thyroidectomies performed, 7,056 were partial and 8,382 were total thyroidectomies. They compared the frequency of partial and total thyroidectomies to total prostatectomy rates (high variation) and hospitalizations for hip fractures (low variation).

The stark variation in thyroidectomy outpaced those in hip fracture hospitalization (2.2-fold variation) and radical prostatectomy (5.6-fold variation) across U.S. hospital referral regions.

Higher rates of thyroidectomy were seen in Southern, Central, and certain urban regions of the United States.

But the variation in rates did not correlate with health care availability, socioeconomic status, or the availability of surgeons. This suggests that variation is caused by something other than disease burden. The researchers speculated that the “variability in thyroid surgery rates in areas with similar access to surgical services largely relates to local beliefs and practice patterns.”

The researchers also noted that the findings, which are based on Medicare data, may not be generalizable to young patients who account for more than half of all thyroidectomies performed in the United States.

The study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice, with salary support from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Thyroidectomy rates differ widely across the United States, according to a cross-sectional analysis of Medicare beneficiaries, but researchers aren’t sure what’s driving the variation.

There was a 6.2-fold difference in thyroidectomy rates across U.S. hospital referral regions in 2014, ranging from 22 to 139 per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries. The national average was 60 procedures per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries, David O. Francis, MD, of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and his coauthors, reported (JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017 Oct 12. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2017.1746).

The researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis of 15,888 Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older who underwent a thyroidectomy in 2014. Of the thyroidectomies performed, 7,056 were partial and 8,382 were total thyroidectomies. They compared the frequency of partial and total thyroidectomies to total prostatectomy rates (high variation) and hospitalizations for hip fractures (low variation).

The stark variation in thyroidectomy outpaced those in hip fracture hospitalization (2.2-fold variation) and radical prostatectomy (5.6-fold variation) across U.S. hospital referral regions.

Higher rates of thyroidectomy were seen in Southern, Central, and certain urban regions of the United States.

But the variation in rates did not correlate with health care availability, socioeconomic status, or the availability of surgeons. This suggests that variation is caused by something other than disease burden. The researchers speculated that the “variability in thyroid surgery rates in areas with similar access to surgical services largely relates to local beliefs and practice patterns.”

The researchers also noted that the findings, which are based on Medicare data, may not be generalizable to young patients who account for more than half of all thyroidectomies performed in the United States.

The study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice, with salary support from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Thyroidectomy rates differ widely across the United States, according to a cross-sectional analysis of Medicare beneficiaries, but researchers aren’t sure what’s driving the variation.

There was a 6.2-fold difference in thyroidectomy rates across U.S. hospital referral regions in 2014, ranging from 22 to 139 per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries. The national average was 60 procedures per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries, David O. Francis, MD, of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and his coauthors, reported (JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017 Oct 12. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2017.1746).

The researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis of 15,888 Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older who underwent a thyroidectomy in 2014. Of the thyroidectomies performed, 7,056 were partial and 8,382 were total thyroidectomies. They compared the frequency of partial and total thyroidectomies to total prostatectomy rates (high variation) and hospitalizations for hip fractures (low variation).

The stark variation in thyroidectomy outpaced those in hip fracture hospitalization (2.2-fold variation) and radical prostatectomy (5.6-fold variation) across U.S. hospital referral regions.

Higher rates of thyroidectomy were seen in Southern, Central, and certain urban regions of the United States.

But the variation in rates did not correlate with health care availability, socioeconomic status, or the availability of surgeons. This suggests that variation is caused by something other than disease burden. The researchers speculated that the “variability in thyroid surgery rates in areas with similar access to surgical services largely relates to local beliefs and practice patterns.”

The researchers also noted that the findings, which are based on Medicare data, may not be generalizable to young patients who account for more than half of all thyroidectomies performed in the United States.

The study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice, with salary support from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA OTOLARYNGOLOGY–HEAD & NECK SURGERY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Thyroidectomy rates vary 6.2-fold across U.S. hospital referral regions.

Data source: A cross-sectional analysis of Medicare data for 15,888 patients in 2014.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice, with salary support from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Junior surgical trainees hew closer to surgery risk calculators than do faculty members

SAN DIEGO – Researchers say that they’ve developed an easy and inexpensive way to instantly track divergences in thinking by faculty and students as they ponder cases presented in Mortality and Morbidity (M&M) conferences. They’ve already produced an intriguing early finding: Interns and junior residents hew more closely than do their elders to estimates provided by a surgical risk calculator.

The research has the potential to shed light on problems in the much-maligned M&M, says study leader Ira Leeds, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. He presented the study findings at the annual Clinical Congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“This project demonstrates that educational technologies can reveal important gaps in surgical education,” said Dr. Leeds, who made comments during his presentation and in an interview.

At issue: The M&M conference, a mainstay of medical education. “This has been defined as the ‘golden hour’ of surgical education,” Dr. Leeds said. “By discussing someone else’s complications, you can learn how to handle your own in the future.”

However, he added, “there’s very little evidence that we’re currently learning from M&M.”

Dr. Leeds and his colleagues are studying the M&M’s role in medical education to see if it can be improved. The new study, a prospective time-series analysis of weekly M&M conferences, aims to understand the potential value of a real-time feedback system. The idea is to develop a way to alert participants to discrepancies in their perceptions about cases.

The researchers turned to a company called Poll Everywhere, whose technology allowed them to collect instant opinions about M&M cases from those in attendance. During 2016-2017, 110 faculty, residents, and interns used Poll Everywhere’s smartphone app to do two things – make guesses about the root causes of adverse events and estimate the risk of complications from surgical procedures over the next 30 days.

“We can see all the results streaming in real time,” said Dr. Leeds, noting that the service cost $600 per year.

The participants, about two-thirds of whom were male, included faculty (35%), fellows and senior residents (28%), and interns and junior residents (37%). They’d been trained an average of 9 years.

The 34 M&M cases represented a mixture of surgical specialties, including oncology, trauma, transplant, and others.

In terms of the root cause analysis, the technology allowed researchers to instantly detect if the guesses of faculty and students were far apart.

The researchers also compared the risk estimates from the participants to those provided by the NSQIP Risk Calculator. They found that the participants tended to boost their estimate of risk, compared with the calculator, by an absolute mean difference of 7.7 percentage points.

“They were overestimating risk by nearly 8 percentage points,” Dr. Leeds said. This isn’t surprising, since other research has revealed a trend toward overestimation of risk by physicians, compared with calculators, he added.

There wasn’t a major difference between the general level of higher estimation of risk among faculty and senior residents (mean of 8.6 and 7.2 percentage points higher than the calculator, respectively). But interns and junior residents estimated risk higher than the calculator by a mean of 4.9 percentage points.

What’s going on? Are the less experienced staff members outperforming their teachers? Another possibility, Dr. Leeds said, is that “the senior surgeons are better picking up on nuances that aren’t being captured by predictive models or the underdeveloped intuition of a junior trainee.”

Rachel Dawn Aufforth, MD, of Johns Hopkins Medicine, who served as discussant for the presentation by Dr. Leeds, said she looks forward to seeing if this technology can improve resident education. She also wondered why estimates via the risk calculator were chosen as a baseline, especially considering that surgeons tend to estimate higher levels of risk.

“One of the things we’ve been trying to do is look at time-series differences,” Dr. Leeds said. “Are they getting better over an academic year? And does that vary by faculty, especially for interns? The calculator isn’t changing or learning on its own.”

In the big picture, the study shows that “collecting real-time risk estimates and root cause assignment is feasible and can be performed as part of routine M&M conferences,” he said.

The study was funded in part by Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institute for Excellence in Education. Dr. Leeds reports no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Researchers say that they’ve developed an easy and inexpensive way to instantly track divergences in thinking by faculty and students as they ponder cases presented in Mortality and Morbidity (M&M) conferences. They’ve already produced an intriguing early finding: Interns and junior residents hew more closely than do their elders to estimates provided by a surgical risk calculator.

The research has the potential to shed light on problems in the much-maligned M&M, says study leader Ira Leeds, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. He presented the study findings at the annual Clinical Congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“This project demonstrates that educational technologies can reveal important gaps in surgical education,” said Dr. Leeds, who made comments during his presentation and in an interview.

At issue: The M&M conference, a mainstay of medical education. “This has been defined as the ‘golden hour’ of surgical education,” Dr. Leeds said. “By discussing someone else’s complications, you can learn how to handle your own in the future.”

However, he added, “there’s very little evidence that we’re currently learning from M&M.”

Dr. Leeds and his colleagues are studying the M&M’s role in medical education to see if it can be improved. The new study, a prospective time-series analysis of weekly M&M conferences, aims to understand the potential value of a real-time feedback system. The idea is to develop a way to alert participants to discrepancies in their perceptions about cases.

The researchers turned to a company called Poll Everywhere, whose technology allowed them to collect instant opinions about M&M cases from those in attendance. During 2016-2017, 110 faculty, residents, and interns used Poll Everywhere’s smartphone app to do two things – make guesses about the root causes of adverse events and estimate the risk of complications from surgical procedures over the next 30 days.

“We can see all the results streaming in real time,” said Dr. Leeds, noting that the service cost $600 per year.

The participants, about two-thirds of whom were male, included faculty (35%), fellows and senior residents (28%), and interns and junior residents (37%). They’d been trained an average of 9 years.

The 34 M&M cases represented a mixture of surgical specialties, including oncology, trauma, transplant, and others.

In terms of the root cause analysis, the technology allowed researchers to instantly detect if the guesses of faculty and students were far apart.

The researchers also compared the risk estimates from the participants to those provided by the NSQIP Risk Calculator. They found that the participants tended to boost their estimate of risk, compared with the calculator, by an absolute mean difference of 7.7 percentage points.

“They were overestimating risk by nearly 8 percentage points,” Dr. Leeds said. This isn’t surprising, since other research has revealed a trend toward overestimation of risk by physicians, compared with calculators, he added.

There wasn’t a major difference between the general level of higher estimation of risk among faculty and senior residents (mean of 8.6 and 7.2 percentage points higher than the calculator, respectively). But interns and junior residents estimated risk higher than the calculator by a mean of 4.9 percentage points.

What’s going on? Are the less experienced staff members outperforming their teachers? Another possibility, Dr. Leeds said, is that “the senior surgeons are better picking up on nuances that aren’t being captured by predictive models or the underdeveloped intuition of a junior trainee.”

Rachel Dawn Aufforth, MD, of Johns Hopkins Medicine, who served as discussant for the presentation by Dr. Leeds, said she looks forward to seeing if this technology can improve resident education. She also wondered why estimates via the risk calculator were chosen as a baseline, especially considering that surgeons tend to estimate higher levels of risk.

“One of the things we’ve been trying to do is look at time-series differences,” Dr. Leeds said. “Are they getting better over an academic year? And does that vary by faculty, especially for interns? The calculator isn’t changing or learning on its own.”

In the big picture, the study shows that “collecting real-time risk estimates and root cause assignment is feasible and can be performed as part of routine M&M conferences,” he said.

The study was funded in part by Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institute for Excellence in Education. Dr. Leeds reports no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Researchers say that they’ve developed an easy and inexpensive way to instantly track divergences in thinking by faculty and students as they ponder cases presented in Mortality and Morbidity (M&M) conferences. They’ve already produced an intriguing early finding: Interns and junior residents hew more closely than do their elders to estimates provided by a surgical risk calculator.

The research has the potential to shed light on problems in the much-maligned M&M, says study leader Ira Leeds, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. He presented the study findings at the annual Clinical Congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“This project demonstrates that educational technologies can reveal important gaps in surgical education,” said Dr. Leeds, who made comments during his presentation and in an interview.

At issue: The M&M conference, a mainstay of medical education. “This has been defined as the ‘golden hour’ of surgical education,” Dr. Leeds said. “By discussing someone else’s complications, you can learn how to handle your own in the future.”

However, he added, “there’s very little evidence that we’re currently learning from M&M.”

Dr. Leeds and his colleagues are studying the M&M’s role in medical education to see if it can be improved. The new study, a prospective time-series analysis of weekly M&M conferences, aims to understand the potential value of a real-time feedback system. The idea is to develop a way to alert participants to discrepancies in their perceptions about cases.

The researchers turned to a company called Poll Everywhere, whose technology allowed them to collect instant opinions about M&M cases from those in attendance. During 2016-2017, 110 faculty, residents, and interns used Poll Everywhere’s smartphone app to do two things – make guesses about the root causes of adverse events and estimate the risk of complications from surgical procedures over the next 30 days.

“We can see all the results streaming in real time,” said Dr. Leeds, noting that the service cost $600 per year.

The participants, about two-thirds of whom were male, included faculty (35%), fellows and senior residents (28%), and interns and junior residents (37%). They’d been trained an average of 9 years.

The 34 M&M cases represented a mixture of surgical specialties, including oncology, trauma, transplant, and others.

In terms of the root cause analysis, the technology allowed researchers to instantly detect if the guesses of faculty and students were far apart.

The researchers also compared the risk estimates from the participants to those provided by the NSQIP Risk Calculator. They found that the participants tended to boost their estimate of risk, compared with the calculator, by an absolute mean difference of 7.7 percentage points.

“They were overestimating risk by nearly 8 percentage points,” Dr. Leeds said. This isn’t surprising, since other research has revealed a trend toward overestimation of risk by physicians, compared with calculators, he added.

There wasn’t a major difference between the general level of higher estimation of risk among faculty and senior residents (mean of 8.6 and 7.2 percentage points higher than the calculator, respectively). But interns and junior residents estimated risk higher than the calculator by a mean of 4.9 percentage points.

What’s going on? Are the less experienced staff members outperforming their teachers? Another possibility, Dr. Leeds said, is that “the senior surgeons are better picking up on nuances that aren’t being captured by predictive models or the underdeveloped intuition of a junior trainee.”

Rachel Dawn Aufforth, MD, of Johns Hopkins Medicine, who served as discussant for the presentation by Dr. Leeds, said she looks forward to seeing if this technology can improve resident education. She also wondered why estimates via the risk calculator were chosen as a baseline, especially considering that surgeons tend to estimate higher levels of risk.

“One of the things we’ve been trying to do is look at time-series differences,” Dr. Leeds said. “Are they getting better over an academic year? And does that vary by faculty, especially for interns? The calculator isn’t changing or learning on its own.”

In the big picture, the study shows that “collecting real-time risk estimates and root cause assignment is feasible and can be performed as part of routine M&M conferences,” he said.

The study was funded in part by Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institute for Excellence in Education. Dr. Leeds reports no relevant disclosures.

AT THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

DiaRem score predicts remission of type 2 diabetes after sleeve gastrectomy

SAN DIEGO – The DiaRem score was effective in predicting remission of type 2 diabetes following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, results from a single-center study showed.

Developed by clinicians at Geisinger Clinic, the DiaRem is a simple score that helps predict remission of type 2 diabetes in severely obese subjects with metabolic syndrome who undergo Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2[1]:38-45). The DiaRem score spans from 0 to 22 and is divided into five groups corresponding to five probability ranges for type 2 diabetes remission: 0-2 (88%-99%), 3-7 (64%-88%), 8-12 (23%-49%), 13-17 (11%-33%), 18-22 (2%-16%). In an effort to assess the feasibility of using the DiaRem score to predict remission of type 2 diabetes after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, Raul J. Rosenthal, MD, FACS, and his associates conducted a 4-year retrospective review of 162 patients at the Cleveland Clinic Florida, Weston. “This is the first report that uses the DiaRem score for similar subjects that underwent sleeve gastrectomy instead,” Dr. Rosenthal said in an interview in advance of the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

The mean age of the 162 patients was 55 years, 61% were women, 74% were non-Hispanic, their mean body mass index was 43.2 kg/m2, 33% had a preoperative hemoglobin A1c level between 7% and 8.9%, and 22% had an HbA1c of 9%. All had a minimum follow-up of 1 year after their laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and 67% had follow-up of 3 years or more, said Dr. Rosenthal, professor and chairman of the department of general surgery at Cleveland Clinic Florida.

Based on results of the DiaRem scores, 58% of patients achieved complete remission of type 2 diabetes, 6% achieved partial remission, and 36% had no remission. Specifically, 96% had DiaRem scores between 0 and 2; 92% had scores between 3 and 7; 50% had scores between 8 and 12, 20% had scores between 13 and 17, and 24% had scores between 18 and 22. “We were pleased to find out that 58% of patients that underwent sleeve gastrectomy achieved complete remission of type 2 diabetes mellitus,” said Dr. Rosenthal, who also directs the clinic’s bariatric and metabolic institute. “This compares favorably to previous reports in which patients achieved 33% of complete remission after gastric bypass.” The researchers also found that 84% of patients achieved remission in 12 months and the rest in 3 years. They observed medication reduction in 93% of the patients.

“Sleeve gastrectomy is a valid bariatric-metabolic procedure in patients with type 2 diabetes,” Dr. Rosenthal concluded. “The main limitation of this study is that is it a retrospective one, and we do not have a control group of patients that underwent gastric bypass or medical treatment to compare.”

The findings were presented at the meeting by Emanuele Lo Menzo, MD. Dr. Rosenthal disclosed that he is a consultant for Medtronic. Dr. Lo Menzo reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The DiaRem score was effective in predicting remission of type 2 diabetes following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, results from a single-center study showed.

Developed by clinicians at Geisinger Clinic, the DiaRem is a simple score that helps predict remission of type 2 diabetes in severely obese subjects with metabolic syndrome who undergo Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2[1]:38-45). The DiaRem score spans from 0 to 22 and is divided into five groups corresponding to five probability ranges for type 2 diabetes remission: 0-2 (88%-99%), 3-7 (64%-88%), 8-12 (23%-49%), 13-17 (11%-33%), 18-22 (2%-16%). In an effort to assess the feasibility of using the DiaRem score to predict remission of type 2 diabetes after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, Raul J. Rosenthal, MD, FACS, and his associates conducted a 4-year retrospective review of 162 patients at the Cleveland Clinic Florida, Weston. “This is the first report that uses the DiaRem score for similar subjects that underwent sleeve gastrectomy instead,” Dr. Rosenthal said in an interview in advance of the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

The mean age of the 162 patients was 55 years, 61% were women, 74% were non-Hispanic, their mean body mass index was 43.2 kg/m2, 33% had a preoperative hemoglobin A1c level between 7% and 8.9%, and 22% had an HbA1c of 9%. All had a minimum follow-up of 1 year after their laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and 67% had follow-up of 3 years or more, said Dr. Rosenthal, professor and chairman of the department of general surgery at Cleveland Clinic Florida.

Based on results of the DiaRem scores, 58% of patients achieved complete remission of type 2 diabetes, 6% achieved partial remission, and 36% had no remission. Specifically, 96% had DiaRem scores between 0 and 2; 92% had scores between 3 and 7; 50% had scores between 8 and 12, 20% had scores between 13 and 17, and 24% had scores between 18 and 22. “We were pleased to find out that 58% of patients that underwent sleeve gastrectomy achieved complete remission of type 2 diabetes mellitus,” said Dr. Rosenthal, who also directs the clinic’s bariatric and metabolic institute. “This compares favorably to previous reports in which patients achieved 33% of complete remission after gastric bypass.” The researchers also found that 84% of patients achieved remission in 12 months and the rest in 3 years. They observed medication reduction in 93% of the patients.

“Sleeve gastrectomy is a valid bariatric-metabolic procedure in patients with type 2 diabetes,” Dr. Rosenthal concluded. “The main limitation of this study is that is it a retrospective one, and we do not have a control group of patients that underwent gastric bypass or medical treatment to compare.”

The findings were presented at the meeting by Emanuele Lo Menzo, MD. Dr. Rosenthal disclosed that he is a consultant for Medtronic. Dr. Lo Menzo reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The DiaRem score was effective in predicting remission of type 2 diabetes following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, results from a single-center study showed.

Developed by clinicians at Geisinger Clinic, the DiaRem is a simple score that helps predict remission of type 2 diabetes in severely obese subjects with metabolic syndrome who undergo Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2[1]:38-45). The DiaRem score spans from 0 to 22 and is divided into five groups corresponding to five probability ranges for type 2 diabetes remission: 0-2 (88%-99%), 3-7 (64%-88%), 8-12 (23%-49%), 13-17 (11%-33%), 18-22 (2%-16%). In an effort to assess the feasibility of using the DiaRem score to predict remission of type 2 diabetes after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, Raul J. Rosenthal, MD, FACS, and his associates conducted a 4-year retrospective review of 162 patients at the Cleveland Clinic Florida, Weston. “This is the first report that uses the DiaRem score for similar subjects that underwent sleeve gastrectomy instead,” Dr. Rosenthal said in an interview in advance of the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

The mean age of the 162 patients was 55 years, 61% were women, 74% were non-Hispanic, their mean body mass index was 43.2 kg/m2, 33% had a preoperative hemoglobin A1c level between 7% and 8.9%, and 22% had an HbA1c of 9%. All had a minimum follow-up of 1 year after their laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and 67% had follow-up of 3 years or more, said Dr. Rosenthal, professor and chairman of the department of general surgery at Cleveland Clinic Florida.

Based on results of the DiaRem scores, 58% of patients achieved complete remission of type 2 diabetes, 6% achieved partial remission, and 36% had no remission. Specifically, 96% had DiaRem scores between 0 and 2; 92% had scores between 3 and 7; 50% had scores between 8 and 12, 20% had scores between 13 and 17, and 24% had scores between 18 and 22. “We were pleased to find out that 58% of patients that underwent sleeve gastrectomy achieved complete remission of type 2 diabetes mellitus,” said Dr. Rosenthal, who also directs the clinic’s bariatric and metabolic institute. “This compares favorably to previous reports in which patients achieved 33% of complete remission after gastric bypass.” The researchers also found that 84% of patients achieved remission in 12 months and the rest in 3 years. They observed medication reduction in 93% of the patients.

“Sleeve gastrectomy is a valid bariatric-metabolic procedure in patients with type 2 diabetes,” Dr. Rosenthal concluded. “The main limitation of this study is that is it a retrospective one, and we do not have a control group of patients that underwent gastric bypass or medical treatment to compare.”

The findings were presented at the meeting by Emanuele Lo Menzo, MD. Dr. Rosenthal disclosed that he is a consultant for Medtronic. Dr. Lo Menzo reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: The DiaRem score is useful in predicting remission of type 2 diabetes following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy.

Major finding: Results of the DiaRem scores indicated that 58% of patients achieved complete remission of type 2 diabetes.

Study details: A retrospective analysis of 162 patients who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy.

Disclosures: Dr. Rosenthal disclosed that he is a consultant for Medtronic. Dr. Lo Menzo reported having no financial disclosures.

VIDEO: SBO in bariatric patient can mean internal herniation

SAN DIEGO – You get a call from the emergency department at 3 a.m. A 48-year-old woman is presenting with fever, nausea, vomiting, and left upper quadrant pain. And the patient says she had a gastric bypass procedure 3 years ago.

Time to panic? Not necessarily, but things can, and occasionally do, go bad for these patients, even if they have had a long-stable bypass, Jennifer Choi, MD, FACS, said in a video interview at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“We do have to remember that our bariatric surgery patients can develop all of the same kinds of problems that anyone else can,” said Dr. Choi, a general surgeon at Indiana University, Indianapolis. “Appendicitis, diverticulitis, abdominal wall hernias, and other common things do happen.”

In her book, though, a patient with a gastric bypass who presents with a combination of small-bowel obstruction and pain has an internal herniation until proven otherwise.

“The symptoms can be subtle, and they can either have been building for several weeks or have an acute onset,” Dr. Choi said. These can include nausea, dry heaves, bloating, or nonbilious vomiting. Pain is typically located in the left upper quadrant or mid-back, especially if the hernia is located at one of the two most common spots: Petersen’s defect. This is the point where the biliopancreatic loop tends to slip under the alimentary loop and become trapped. Imaging will show a typical swirling of blood vessels around the herniation, accompanied by dilated small bowel at the point of obstruction.

At the other common herniation point, the site of the jejunojejunostomy, the alimentary loop can slip under the biliopancreatic loop. On imaging, jejunum will be seen in the upper right quadrant.

Both of these can be surgical emergencies, Dr. Choi said. “This needs an operation sooner, rather than later. It needs to be reduced and repaired.”

She typically performs this laparoscopically, but said that some surgeons prefer an open approach, which is a perfectly sound option.

“The key to a successful repair is to start at the ileocecal valve, because it is consistent and fixed, and run the bowel from distal to proximal to reduce the internal hernia. Then close the defect with a permanent suture,” she said.

Chylous ascites is almost always present in these cases because the herniation traumatizes the lymphatic system, Dr. Choi added. “It doesn’t all always have to be removed at the time of surgery, but just be aware that this is definitely something we do see, almost all the time in bariatric patients with these internal hernias.”

Dr. Choi had no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

SAN DIEGO – You get a call from the emergency department at 3 a.m. A 48-year-old woman is presenting with fever, nausea, vomiting, and left upper quadrant pain. And the patient says she had a gastric bypass procedure 3 years ago.

Time to panic? Not necessarily, but things can, and occasionally do, go bad for these patients, even if they have had a long-stable bypass, Jennifer Choi, MD, FACS, said in a video interview at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“We do have to remember that our bariatric surgery patients can develop all of the same kinds of problems that anyone else can,” said Dr. Choi, a general surgeon at Indiana University, Indianapolis. “Appendicitis, diverticulitis, abdominal wall hernias, and other common things do happen.”

In her book, though, a patient with a gastric bypass who presents with a combination of small-bowel obstruction and pain has an internal herniation until proven otherwise.

“The symptoms can be subtle, and they can either have been building for several weeks or have an acute onset,” Dr. Choi said. These can include nausea, dry heaves, bloating, or nonbilious vomiting. Pain is typically located in the left upper quadrant or mid-back, especially if the hernia is located at one of the two most common spots: Petersen’s defect. This is the point where the biliopancreatic loop tends to slip under the alimentary loop and become trapped. Imaging will show a typical swirling of blood vessels around the herniation, accompanied by dilated small bowel at the point of obstruction.

At the other common herniation point, the site of the jejunojejunostomy, the alimentary loop can slip under the biliopancreatic loop. On imaging, jejunum will be seen in the upper right quadrant.

Both of these can be surgical emergencies, Dr. Choi said. “This needs an operation sooner, rather than later. It needs to be reduced and repaired.”

She typically performs this laparoscopically, but said that some surgeons prefer an open approach, which is a perfectly sound option.

“The key to a successful repair is to start at the ileocecal valve, because it is consistent and fixed, and run the bowel from distal to proximal to reduce the internal hernia. Then close the defect with a permanent suture,” she said.

Chylous ascites is almost always present in these cases because the herniation traumatizes the lymphatic system, Dr. Choi added. “It doesn’t all always have to be removed at the time of surgery, but just be aware that this is definitely something we do see, almost all the time in bariatric patients with these internal hernias.”

Dr. Choi had no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

SAN DIEGO – You get a call from the emergency department at 3 a.m. A 48-year-old woman is presenting with fever, nausea, vomiting, and left upper quadrant pain. And the patient says she had a gastric bypass procedure 3 years ago.

Time to panic? Not necessarily, but things can, and occasionally do, go bad for these patients, even if they have had a long-stable bypass, Jennifer Choi, MD, FACS, said in a video interview at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“We do have to remember that our bariatric surgery patients can develop all of the same kinds of problems that anyone else can,” said Dr. Choi, a general surgeon at Indiana University, Indianapolis. “Appendicitis, diverticulitis, abdominal wall hernias, and other common things do happen.”

In her book, though, a patient with a gastric bypass who presents with a combination of small-bowel obstruction and pain has an internal herniation until proven otherwise.

“The symptoms can be subtle, and they can either have been building for several weeks or have an acute onset,” Dr. Choi said. These can include nausea, dry heaves, bloating, or nonbilious vomiting. Pain is typically located in the left upper quadrant or mid-back, especially if the hernia is located at one of the two most common spots: Petersen’s defect. This is the point where the biliopancreatic loop tends to slip under the alimentary loop and become trapped. Imaging will show a typical swirling of blood vessels around the herniation, accompanied by dilated small bowel at the point of obstruction.

At the other common herniation point, the site of the jejunojejunostomy, the alimentary loop can slip under the biliopancreatic loop. On imaging, jejunum will be seen in the upper right quadrant.

Both of these can be surgical emergencies, Dr. Choi said. “This needs an operation sooner, rather than later. It needs to be reduced and repaired.”

She typically performs this laparoscopically, but said that some surgeons prefer an open approach, which is a perfectly sound option.

“The key to a successful repair is to start at the ileocecal valve, because it is consistent and fixed, and run the bowel from distal to proximal to reduce the internal hernia. Then close the defect with a permanent suture,” she said.

Chylous ascites is almost always present in these cases because the herniation traumatizes the lymphatic system, Dr. Choi added. “It doesn’t all always have to be removed at the time of surgery, but just be aware that this is definitely something we do see, almost all the time in bariatric patients with these internal hernias.”

Dr. Choi had no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT THE ACS Clinical Congress

Barbara Lee Bass, MD, FACS, FRCS(Hon), installed as 98th ACS President

Barbara Lee Bass, MD, FACS, FRCS(Hon) the John F. and Carolyn Bookout Distinguished Endowed Chair and chair, department of surgery, Houston Methodist Hospital, TX, was installed as President of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) at the October 22 Convocation Ceremony at Clinical Congress 2017 in San Diego, CA.

Read more about Dr. Bass, Dr. Mabry, and Dr. Pruitt in the November Bulletin at URL TO COME

Barbara Lee Bass, MD, FACS, FRCS(Hon) the John F. and Carolyn Bookout Distinguished Endowed Chair and chair, department of surgery, Houston Methodist Hospital, TX, was installed as President of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) at the October 22 Convocation Ceremony at Clinical Congress 2017 in San Diego, CA.

Read more about Dr. Bass, Dr. Mabry, and Dr. Pruitt in the November Bulletin at URL TO COME

Barbara Lee Bass, MD, FACS, FRCS(Hon) the John F. and Carolyn Bookout Distinguished Endowed Chair and chair, department of surgery, Houston Methodist Hospital, TX, was installed as President of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) at the October 22 Convocation Ceremony at Clinical Congress 2017 in San Diego, CA.

Read more about Dr. Bass, Dr. Mabry, and Dr. Pruitt in the November Bulletin at URL TO COME

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker Award presented to Dr. Kuy

At the Convocation Ceremony at Clinical Congress 2017 in San Diego, CA, the American College of Surgeons (ACS) presented the 2017 Dr. Mary Edwards Walker Inspiring Women in Surgery Award to SreyRam Kuy, MD, MHS, FACS. This award was established by the ACS Women in Surgery Committee (WiSC) and is presented annually at the Clinical Congress in recognition of an individual’s significant contributions to the advancement of women in the field of surgery.

The award is named in honor of Mary Edwards Walker, MD. Dr. Walker volunteered to serve with the Union Army at the outbreak of the American Civil War and was the first female surgeon ever employed by the U.S. Army. Dr. Walker is the only woman to have ever received the Congressional Medal of Honor, the highest U.S. Armed Forces decoration for bravery. Through Dr. Walker’s example of perseverance, excellence, and pioneering behavior, she paved the way for today’s women surgeons.

Dr. Kuy’s career embodies the spirit of this award and demonstrates her personal determination, professional excellence, and commitment to public service.

Inspiration to practice

Dr. Kuy was born in a labor camp in Cambodia in 1978 during the Cambodian genocide known as the Killing Fields. Following the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge, her family fled to a refugee camp in Thailand where Dr. Kuy, her sister, and her mother were severely injured by a grenade. All three lives were saved by surgeons volunteering at the refugee camp. These volunteer surgeons helped inspire Dr. Kuy to pursue a career in medicine.